User login

AMA delegates decry ICD-10, EHRs

CHICAGO – Coding and computers were among key concerns for physician leaders at the American Medical Association’s annual House of Delegates meeting.

Resolutions from several delegations aimed to delay or scuttle the transition to the newest incarnation of the International Classification of Diseases, ICD-10.

Delegates from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) introduced a resolution urging the association to keep up its campaign to stop ICD-10 implementation, specifically via federal legislation.

Without a statement supporting delay, there is a "perception out there that the AMA has essentially caved on the issue of ICD-10," said ACR delegate Dr. Gary Bryant . "Now that’s not my perception, but I believe it’s the perception, to some degree, among American physicians."

The House adopted instead a resolution calling for the AMA to support federal legislation to delay ICD-10 implementation for 2 years. During that time, payers would not be allowed to deny payment based on the specificity of the diagnosis, but they would be required to provide feedback in the case of an incorrect diagnosis. The resolution was brought by the Colorado delegation.

Dr. Reid Blackwelder, president-elect of the American Academy of Family Physicians, spoke in favor of the resolution.

"It’s not likely that we’re moving from ICD-9, we are." Instead, the resolution "allows our members to have a period of time to get used to the sticker shock," he said.

Another issue is that "ICD-10 initially came into use in 1994 and was never designed to be computer-savvy. ICD-11 is due in 2015, and will be designed to be easily coded by computer software," said Dr. Peter Kaufman, the AGA’s delegate to AMA. "If we go to ICD-10 in 2014, or even 2016, when will we be able to go to the newer, more appropriate 11th Revision?"

The AMA has estimated that the cost of implementing ICD-10 could range from $83,290 to more than $2.7 million per practice, depending on practice size.

Delegates cited major problems with electronic health record interoperability, and some also sought to slow the adoption of electronic health records.

Karthik Sarmah medical student alternate delegate in the California delegation, cited interoperability as a major concern.

"The lack of interoperability is the primary driver of why so many people in this room hate their EHR system," he said, adding that interoperability standards exist, but that there are no incentives for venders to create ways to allow physicians to share their patient data with each other.

Dr. Melissa Garretson, a delegate from the American Academy of Pediatrics, agreed.

"I can’t tell you the number of times I have to repeat labs," and CT scans because data can’t be accessed from other physicians, Dr. Garretson said. She called the lack of interoperability an unfunded mandate on physicians because the vendors aren’t making it possible. "If we force them to do this through legislation, it will finally happen."

Kaufman testified \"there are strong interoperability standards already out there. They may only cover limited amounts of data but they work between programs well. The problem is that while they were required when EHRs were certified by CCHIT, with the advent of Meaningful Use, that requirement to use the same specific standard was no longer mandatory.\" Kaufman went on to state that the standards committees were woefully short of practicing physicians, and called for doctors to join the process to the standards could be completed and be workable for clinicians.

Other delegates were skeptical.

"I have been waiting now for about 12 years for this interoperability to occur and I think I’ll either be retired or dead before it finally does," said Dr. Arthur E. Palamara, a vascular surgeon with the Florida delegation.

The House approved a resolution "seeking legislation or regulation to require all EHR vendors to utilize standard and interoperable software technology to enable cost efficient use of electronic health records across all health care delivery systems including institutional and community based settings of care delivery."

On Twitter @aliciaault

CHICAGO – Coding and computers were among key concerns for physician leaders at the American Medical Association’s annual House of Delegates meeting.

Resolutions from several delegations aimed to delay or scuttle the transition to the newest incarnation of the International Classification of Diseases, ICD-10.

Delegates from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) introduced a resolution urging the association to keep up its campaign to stop ICD-10 implementation, specifically via federal legislation.

Without a statement supporting delay, there is a "perception out there that the AMA has essentially caved on the issue of ICD-10," said ACR delegate Dr. Gary Bryant . "Now that’s not my perception, but I believe it’s the perception, to some degree, among American physicians."

The House adopted instead a resolution calling for the AMA to support federal legislation to delay ICD-10 implementation for 2 years. During that time, payers would not be allowed to deny payment based on the specificity of the diagnosis, but they would be required to provide feedback in the case of an incorrect diagnosis. The resolution was brought by the Colorado delegation.

Dr. Reid Blackwelder, president-elect of the American Academy of Family Physicians, spoke in favor of the resolution.

"It’s not likely that we’re moving from ICD-9, we are." Instead, the resolution "allows our members to have a period of time to get used to the sticker shock," he said.

Another issue is that "ICD-10 initially came into use in 1994 and was never designed to be computer-savvy. ICD-11 is due in 2015, and will be designed to be easily coded by computer software," said Dr. Peter Kaufman, the AGA’s delegate to AMA. "If we go to ICD-10 in 2014, or even 2016, when will we be able to go to the newer, more appropriate 11th Revision?"

The AMA has estimated that the cost of implementing ICD-10 could range from $83,290 to more than $2.7 million per practice, depending on practice size.

Delegates cited major problems with electronic health record interoperability, and some also sought to slow the adoption of electronic health records.

Karthik Sarmah medical student alternate delegate in the California delegation, cited interoperability as a major concern.

"The lack of interoperability is the primary driver of why so many people in this room hate their EHR system," he said, adding that interoperability standards exist, but that there are no incentives for venders to create ways to allow physicians to share their patient data with each other.

Dr. Melissa Garretson, a delegate from the American Academy of Pediatrics, agreed.

"I can’t tell you the number of times I have to repeat labs," and CT scans because data can’t be accessed from other physicians, Dr. Garretson said. She called the lack of interoperability an unfunded mandate on physicians because the vendors aren’t making it possible. "If we force them to do this through legislation, it will finally happen."

Kaufman testified \"there are strong interoperability standards already out there. They may only cover limited amounts of data but they work between programs well. The problem is that while they were required when EHRs were certified by CCHIT, with the advent of Meaningful Use, that requirement to use the same specific standard was no longer mandatory.\" Kaufman went on to state that the standards committees were woefully short of practicing physicians, and called for doctors to join the process to the standards could be completed and be workable for clinicians.

Other delegates were skeptical.

"I have been waiting now for about 12 years for this interoperability to occur and I think I’ll either be retired or dead before it finally does," said Dr. Arthur E. Palamara, a vascular surgeon with the Florida delegation.

The House approved a resolution "seeking legislation or regulation to require all EHR vendors to utilize standard and interoperable software technology to enable cost efficient use of electronic health records across all health care delivery systems including institutional and community based settings of care delivery."

On Twitter @aliciaault

CHICAGO – Coding and computers were among key concerns for physician leaders at the American Medical Association’s annual House of Delegates meeting.

Resolutions from several delegations aimed to delay or scuttle the transition to the newest incarnation of the International Classification of Diseases, ICD-10.

Delegates from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) introduced a resolution urging the association to keep up its campaign to stop ICD-10 implementation, specifically via federal legislation.

Without a statement supporting delay, there is a "perception out there that the AMA has essentially caved on the issue of ICD-10," said ACR delegate Dr. Gary Bryant . "Now that’s not my perception, but I believe it’s the perception, to some degree, among American physicians."

The House adopted instead a resolution calling for the AMA to support federal legislation to delay ICD-10 implementation for 2 years. During that time, payers would not be allowed to deny payment based on the specificity of the diagnosis, but they would be required to provide feedback in the case of an incorrect diagnosis. The resolution was brought by the Colorado delegation.

Dr. Reid Blackwelder, president-elect of the American Academy of Family Physicians, spoke in favor of the resolution.

"It’s not likely that we’re moving from ICD-9, we are." Instead, the resolution "allows our members to have a period of time to get used to the sticker shock," he said.

Another issue is that "ICD-10 initially came into use in 1994 and was never designed to be computer-savvy. ICD-11 is due in 2015, and will be designed to be easily coded by computer software," said Dr. Peter Kaufman, the AGA’s delegate to AMA. "If we go to ICD-10 in 2014, or even 2016, when will we be able to go to the newer, more appropriate 11th Revision?"

The AMA has estimated that the cost of implementing ICD-10 could range from $83,290 to more than $2.7 million per practice, depending on practice size.

Delegates cited major problems with electronic health record interoperability, and some also sought to slow the adoption of electronic health records.

Karthik Sarmah medical student alternate delegate in the California delegation, cited interoperability as a major concern.

"The lack of interoperability is the primary driver of why so many people in this room hate their EHR system," he said, adding that interoperability standards exist, but that there are no incentives for venders to create ways to allow physicians to share their patient data with each other.

Dr. Melissa Garretson, a delegate from the American Academy of Pediatrics, agreed.

"I can’t tell you the number of times I have to repeat labs," and CT scans because data can’t be accessed from other physicians, Dr. Garretson said. She called the lack of interoperability an unfunded mandate on physicians because the vendors aren’t making it possible. "If we force them to do this through legislation, it will finally happen."

Kaufman testified \"there are strong interoperability standards already out there. They may only cover limited amounts of data but they work between programs well. The problem is that while they were required when EHRs were certified by CCHIT, with the advent of Meaningful Use, that requirement to use the same specific standard was no longer mandatory.\" Kaufman went on to state that the standards committees were woefully short of practicing physicians, and called for doctors to join the process to the standards could be completed and be workable for clinicians.

Other delegates were skeptical.

"I have been waiting now for about 12 years for this interoperability to occur and I think I’ll either be retired or dead before it finally does," said Dr. Arthur E. Palamara, a vascular surgeon with the Florida delegation.

The House approved a resolution "seeking legislation or regulation to require all EHR vendors to utilize standard and interoperable software technology to enable cost efficient use of electronic health records across all health care delivery systems including institutional and community based settings of care delivery."

On Twitter @aliciaault

AT THE AMA HOUSE OF DELEGATES

Kennedy seeks to unite mental health advocates with new foundation

Former congressman Patrick Kennedy has started a new organization that aims to bring mental health advocates together.

Mr. Kennedy, who represented Rhode Island in the House of Representatives from 1995 to 2011, was a coauthor of the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA). The act requires that companies with more that 50 employees provide group health insurance that includes mental health/substance abuse benefits equivalent to medical/surgical benefits at no additional charge. Mr. Kennedy also has spoken at length about his personal struggles with bipolar disorder and addiction.

In debuting the Kennedy Forum – and an inaugural conference in Boston in October – Mr. Kennedy said in a statement, "We need a national conversation on mental health that will allow us to finally remove the stigma surrounding mental illness and to once-and-for-all achieve parity by treating the brain the same way we treat the rest of the body. I look forward to bringing together the brightest minds and boldest voices in the mental health, substance use, and intellectual disability community for this annual event."

Mr. Kennedy also noted that the final rules implementing the 2008 law are due this fall. Interim final rules were released in January 2010 and have been applied to health coverage that began July 1 of that year. A few months later, several behavioral health companies – Magellan Health Services, Beacon Health Strategies, and ValueOptions – filed suit to delay implementation of the final rule, seeking further clarity on how the 2008 law would mesh with the Affordable Care Act.

Last March, the Obama administration gave a little bit more insight into how those laws might interact when it spelled out the ACA’s essential health benefits. The final rule for that aspect of the act emphasized that health insurers must cover mental health and substance abuse services starting in 2014. The essential health benefit rule also broadened the parity requirement for mental health coverage, first established under the MHPAEA.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Former congressman Patrick Kennedy has started a new organization that aims to bring mental health advocates together.

Mr. Kennedy, who represented Rhode Island in the House of Representatives from 1995 to 2011, was a coauthor of the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA). The act requires that companies with more that 50 employees provide group health insurance that includes mental health/substance abuse benefits equivalent to medical/surgical benefits at no additional charge. Mr. Kennedy also has spoken at length about his personal struggles with bipolar disorder and addiction.

In debuting the Kennedy Forum – and an inaugural conference in Boston in October – Mr. Kennedy said in a statement, "We need a national conversation on mental health that will allow us to finally remove the stigma surrounding mental illness and to once-and-for-all achieve parity by treating the brain the same way we treat the rest of the body. I look forward to bringing together the brightest minds and boldest voices in the mental health, substance use, and intellectual disability community for this annual event."

Mr. Kennedy also noted that the final rules implementing the 2008 law are due this fall. Interim final rules were released in January 2010 and have been applied to health coverage that began July 1 of that year. A few months later, several behavioral health companies – Magellan Health Services, Beacon Health Strategies, and ValueOptions – filed suit to delay implementation of the final rule, seeking further clarity on how the 2008 law would mesh with the Affordable Care Act.

Last March, the Obama administration gave a little bit more insight into how those laws might interact when it spelled out the ACA’s essential health benefits. The final rule for that aspect of the act emphasized that health insurers must cover mental health and substance abuse services starting in 2014. The essential health benefit rule also broadened the parity requirement for mental health coverage, first established under the MHPAEA.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Former congressman Patrick Kennedy has started a new organization that aims to bring mental health advocates together.

Mr. Kennedy, who represented Rhode Island in the House of Representatives from 1995 to 2011, was a coauthor of the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA). The act requires that companies with more that 50 employees provide group health insurance that includes mental health/substance abuse benefits equivalent to medical/surgical benefits at no additional charge. Mr. Kennedy also has spoken at length about his personal struggles with bipolar disorder and addiction.

In debuting the Kennedy Forum – and an inaugural conference in Boston in October – Mr. Kennedy said in a statement, "We need a national conversation on mental health that will allow us to finally remove the stigma surrounding mental illness and to once-and-for-all achieve parity by treating the brain the same way we treat the rest of the body. I look forward to bringing together the brightest minds and boldest voices in the mental health, substance use, and intellectual disability community for this annual event."

Mr. Kennedy also noted that the final rules implementing the 2008 law are due this fall. Interim final rules were released in January 2010 and have been applied to health coverage that began July 1 of that year. A few months later, several behavioral health companies – Magellan Health Services, Beacon Health Strategies, and ValueOptions – filed suit to delay implementation of the final rule, seeking further clarity on how the 2008 law would mesh with the Affordable Care Act.

Last March, the Obama administration gave a little bit more insight into how those laws might interact when it spelled out the ACA’s essential health benefits. The final rule for that aspect of the act emphasized that health insurers must cover mental health and substance abuse services starting in 2014. The essential health benefit rule also broadened the parity requirement for mental health coverage, first established under the MHPAEA.

On Twitter @aliciaault

Doctors: Major responsibility for cost control is not ours

When it comes to reducing health costs, physicians believe burden of responsibility lies primarily with plaintiffs attorneys, followed by insurers, hospitals, drug and device makers, patients, and, lastly, themselves.

Those conclusions are based on 2,438 responses from some 3,900 physicians randomly surveyed in 2012. Dr. Jon C. Tilburt of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues reported their findings July 23 in JAMA.

When asked whether individual physicians should have a major responsibility in reducing health costs, 36% of respondents said yes. Sixty percent said that trial lawyers bore the major burden, with health insurers coming in a close second.

More than half said that drug and device companies, hospitals and health systems, and patients also should have major responsibility for cost containment. A total of 44% said the government had that responsibility (JAMA 2013;310:380-8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2013.8278]).

Physicians also were asked about their enthusiasm for various cost-control strategies and to examine their own role in cost containment by assessing their knowledge of prices of procedures and tests and their desire to personally curb costs in their practice. The authors asked about and analyzed potential barriers to physicians becoming more cost conscious, as well.

Doctors were very enthusiastic about improving the quality and efficiency of care, primarily through promoting continuity of care and going after fraud and abuse. Expanding access to preventive care was also warmly received. Physicians were also enthusiastic about limiting access to expensive treatments that had shown little benefit, using cost-effectiveness data to choose a therapy, and promoting head-to-head trials of competing therapies.

Just over half of respondents said that cutting pay for the highest-paid specialists should be embraced.

Eliminating fee for service altogether was rejected by 70% of respondents. Ninety percent said that they weren’t enthusiastic about letting the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate cuts take effect. Two-thirds said that bundled pay and penalties for readmissions – both cost-control keystones advanced by the Obama administration – were not attractive.

Not surprisingly, increasing use of electronic health records also got a strong negative response, with 29% saying they were "not enthusiastic."

When it came to their own practice, 76% said they were aware of the costs of treatments or tests they recommended, and 84% said that cost is important whether a patient pays out of pocket or not.

When it comes to individual physicians’ responsibility for reducing health costs, the responses were very mixed.

The survey participants largely agreed that "trying to contain costs is the responsibility of every physician" (85%) and that physicians should take a more prominent role in eliminating unnecessary tests (89%). But by almost the same percentages, physicians also said that they should be devoted to their individual patients, even if a test or therapy was expensive, and that they should not deny services to their patients because someone else might need it more.

"This apparent inconsistency may reflect inherent tensions in professional roles to serve patients individually and society as a whole," Dr. Tilburt and colleagues wrote.

Finally, physicians overwhelmingly said that fear of malpractice had substantially decreased their enjoyment of practicing medicine. The authors rated that fear as a barrier to cost-conscious practice. They also found that 43% of physicians admitted they ordered more tests when they did not know the patient as well. Half said that being more cost conscious was the right thing to do, but large numbers said that it might not make a difference or could make things worse. A total of 40% said it would not limit unreasonable patient demands, and 28% said it could erode patients’ trust.

Dr. Tilburt and his colleagues pointed out that the findings should be viewed with caution in part because it could not fully reflect the opinions of all American physicians. Further, opinions could be in flux, given how much has changed since even a year ago.

They suggested that policy makers move slowly when it comes to changing payment models, and instead target areas where doctors seem to be enthusiastic, including improving quality of care and using comparative effectiveness data.

The study was funded by the Greenwall Foundation and the Mayo Clinic. The authors reported having no financial conflicts.

On Twitter @aliciaault

If there was ever an "all-hands-on-deck" moment in the history of health care, that moment is now. The findings of this study suggest that physician do not yet have the mentality this historical moment demands. Indeed, this survey suggests that in the face of this new and uncertain moment in the reform of the health care system, physicians are lapsing into the well-known, cautious, instinctual approaches humans adopt whenever confronted by uncertainty: Blame others and persevere with "business as usual."

Physicians have moved beyond denying that health care costs are a problem. Yet, they are not quite willing to accept physicians’ primary responsibility and take action. The study findings suggest that physicians are ambivalent; they reject transformative solutions, such as eliminating fee-for-service or bundled payments, which address the seriousness of the cost problem.

This study by Tilburt et al. indicates that the medical profession is not there yet – that many physicians would prefer to sit on the sidelines while other actors in the health care system do the real work of reform.

This could marginalize and demote physicians.

Dr. Ezekiel J. Emanuel is an ethicist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported no related conflicts. These remarks were taken from an editorial accompanying Dr. Tilburt’s study.(JAMA 2013;310:374-5)

If there was ever an "all-hands-on-deck" moment in the history of health care, that moment is now. The findings of this study suggest that physician do not yet have the mentality this historical moment demands. Indeed, this survey suggests that in the face of this new and uncertain moment in the reform of the health care system, physicians are lapsing into the well-known, cautious, instinctual approaches humans adopt whenever confronted by uncertainty: Blame others and persevere with "business as usual."

Physicians have moved beyond denying that health care costs are a problem. Yet, they are not quite willing to accept physicians’ primary responsibility and take action. The study findings suggest that physicians are ambivalent; they reject transformative solutions, such as eliminating fee-for-service or bundled payments, which address the seriousness of the cost problem.

This study by Tilburt et al. indicates that the medical profession is not there yet – that many physicians would prefer to sit on the sidelines while other actors in the health care system do the real work of reform.

This could marginalize and demote physicians.

Dr. Ezekiel J. Emanuel is an ethicist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported no related conflicts. These remarks were taken from an editorial accompanying Dr. Tilburt’s study.(JAMA 2013;310:374-5)

If there was ever an "all-hands-on-deck" moment in the history of health care, that moment is now. The findings of this study suggest that physician do not yet have the mentality this historical moment demands. Indeed, this survey suggests that in the face of this new and uncertain moment in the reform of the health care system, physicians are lapsing into the well-known, cautious, instinctual approaches humans adopt whenever confronted by uncertainty: Blame others and persevere with "business as usual."

Physicians have moved beyond denying that health care costs are a problem. Yet, they are not quite willing to accept physicians’ primary responsibility and take action. The study findings suggest that physicians are ambivalent; they reject transformative solutions, such as eliminating fee-for-service or bundled payments, which address the seriousness of the cost problem.

This study by Tilburt et al. indicates that the medical profession is not there yet – that many physicians would prefer to sit on the sidelines while other actors in the health care system do the real work of reform.

This could marginalize and demote physicians.

Dr. Ezekiel J. Emanuel is an ethicist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He reported no related conflicts. These remarks were taken from an editorial accompanying Dr. Tilburt’s study.(JAMA 2013;310:374-5)

When it comes to reducing health costs, physicians believe burden of responsibility lies primarily with plaintiffs attorneys, followed by insurers, hospitals, drug and device makers, patients, and, lastly, themselves.

Those conclusions are based on 2,438 responses from some 3,900 physicians randomly surveyed in 2012. Dr. Jon C. Tilburt of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues reported their findings July 23 in JAMA.

When asked whether individual physicians should have a major responsibility in reducing health costs, 36% of respondents said yes. Sixty percent said that trial lawyers bore the major burden, with health insurers coming in a close second.

More than half said that drug and device companies, hospitals and health systems, and patients also should have major responsibility for cost containment. A total of 44% said the government had that responsibility (JAMA 2013;310:380-8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2013.8278]).

Physicians also were asked about their enthusiasm for various cost-control strategies and to examine their own role in cost containment by assessing their knowledge of prices of procedures and tests and their desire to personally curb costs in their practice. The authors asked about and analyzed potential barriers to physicians becoming more cost conscious, as well.

Doctors were very enthusiastic about improving the quality and efficiency of care, primarily through promoting continuity of care and going after fraud and abuse. Expanding access to preventive care was also warmly received. Physicians were also enthusiastic about limiting access to expensive treatments that had shown little benefit, using cost-effectiveness data to choose a therapy, and promoting head-to-head trials of competing therapies.

Just over half of respondents said that cutting pay for the highest-paid specialists should be embraced.

Eliminating fee for service altogether was rejected by 70% of respondents. Ninety percent said that they weren’t enthusiastic about letting the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate cuts take effect. Two-thirds said that bundled pay and penalties for readmissions – both cost-control keystones advanced by the Obama administration – were not attractive.

Not surprisingly, increasing use of electronic health records also got a strong negative response, with 29% saying they were "not enthusiastic."

When it came to their own practice, 76% said they were aware of the costs of treatments or tests they recommended, and 84% said that cost is important whether a patient pays out of pocket or not.

When it comes to individual physicians’ responsibility for reducing health costs, the responses were very mixed.

The survey participants largely agreed that "trying to contain costs is the responsibility of every physician" (85%) and that physicians should take a more prominent role in eliminating unnecessary tests (89%). But by almost the same percentages, physicians also said that they should be devoted to their individual patients, even if a test or therapy was expensive, and that they should not deny services to their patients because someone else might need it more.

"This apparent inconsistency may reflect inherent tensions in professional roles to serve patients individually and society as a whole," Dr. Tilburt and colleagues wrote.

Finally, physicians overwhelmingly said that fear of malpractice had substantially decreased their enjoyment of practicing medicine. The authors rated that fear as a barrier to cost-conscious practice. They also found that 43% of physicians admitted they ordered more tests when they did not know the patient as well. Half said that being more cost conscious was the right thing to do, but large numbers said that it might not make a difference or could make things worse. A total of 40% said it would not limit unreasonable patient demands, and 28% said it could erode patients’ trust.

Dr. Tilburt and his colleagues pointed out that the findings should be viewed with caution in part because it could not fully reflect the opinions of all American physicians. Further, opinions could be in flux, given how much has changed since even a year ago.

They suggested that policy makers move slowly when it comes to changing payment models, and instead target areas where doctors seem to be enthusiastic, including improving quality of care and using comparative effectiveness data.

The study was funded by the Greenwall Foundation and the Mayo Clinic. The authors reported having no financial conflicts.

On Twitter @aliciaault

When it comes to reducing health costs, physicians believe burden of responsibility lies primarily with plaintiffs attorneys, followed by insurers, hospitals, drug and device makers, patients, and, lastly, themselves.

Those conclusions are based on 2,438 responses from some 3,900 physicians randomly surveyed in 2012. Dr. Jon C. Tilburt of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues reported their findings July 23 in JAMA.

When asked whether individual physicians should have a major responsibility in reducing health costs, 36% of respondents said yes. Sixty percent said that trial lawyers bore the major burden, with health insurers coming in a close second.

More than half said that drug and device companies, hospitals and health systems, and patients also should have major responsibility for cost containment. A total of 44% said the government had that responsibility (JAMA 2013;310:380-8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2013.8278]).

Physicians also were asked about their enthusiasm for various cost-control strategies and to examine their own role in cost containment by assessing their knowledge of prices of procedures and tests and their desire to personally curb costs in their practice. The authors asked about and analyzed potential barriers to physicians becoming more cost conscious, as well.

Doctors were very enthusiastic about improving the quality and efficiency of care, primarily through promoting continuity of care and going after fraud and abuse. Expanding access to preventive care was also warmly received. Physicians were also enthusiastic about limiting access to expensive treatments that had shown little benefit, using cost-effectiveness data to choose a therapy, and promoting head-to-head trials of competing therapies.

Just over half of respondents said that cutting pay for the highest-paid specialists should be embraced.

Eliminating fee for service altogether was rejected by 70% of respondents. Ninety percent said that they weren’t enthusiastic about letting the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate cuts take effect. Two-thirds said that bundled pay and penalties for readmissions – both cost-control keystones advanced by the Obama administration – were not attractive.

Not surprisingly, increasing use of electronic health records also got a strong negative response, with 29% saying they were "not enthusiastic."

When it came to their own practice, 76% said they were aware of the costs of treatments or tests they recommended, and 84% said that cost is important whether a patient pays out of pocket or not.

When it comes to individual physicians’ responsibility for reducing health costs, the responses were very mixed.

The survey participants largely agreed that "trying to contain costs is the responsibility of every physician" (85%) and that physicians should take a more prominent role in eliminating unnecessary tests (89%). But by almost the same percentages, physicians also said that they should be devoted to their individual patients, even if a test or therapy was expensive, and that they should not deny services to their patients because someone else might need it more.

"This apparent inconsistency may reflect inherent tensions in professional roles to serve patients individually and society as a whole," Dr. Tilburt and colleagues wrote.

Finally, physicians overwhelmingly said that fear of malpractice had substantially decreased their enjoyment of practicing medicine. The authors rated that fear as a barrier to cost-conscious practice. They also found that 43% of physicians admitted they ordered more tests when they did not know the patient as well. Half said that being more cost conscious was the right thing to do, but large numbers said that it might not make a difference or could make things worse. A total of 40% said it would not limit unreasonable patient demands, and 28% said it could erode patients’ trust.

Dr. Tilburt and his colleagues pointed out that the findings should be viewed with caution in part because it could not fully reflect the opinions of all American physicians. Further, opinions could be in flux, given how much has changed since even a year ago.

They suggested that policy makers move slowly when it comes to changing payment models, and instead target areas where doctors seem to be enthusiastic, including improving quality of care and using comparative effectiveness data.

The study was funded by the Greenwall Foundation and the Mayo Clinic. The authors reported having no financial conflicts.

On Twitter @aliciaault

FROM JAMA

Major finding: Sixty percent of responding physicians believe that trial attorneys bear major responsibility for reducing health costs.

Data source: A random survey of 3,900 physicians.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Greenwall Foundation and the Mayo Clinic. The authors reported having no financial conflicts.

Sunshine apps track industry payments

Two new smartphone apps aim to help log drug, device, and diagnostic manufacturer payments to doctors and health care providers, as called for by the Affordable Care Act.

To promote transparency in relationships between providers and industry, the ACA requires that manufacturers track and report payments for consulting, honoraria, and more.

Originally known as the Sunshine Act, the effort is now called the Open Payments Program by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

While physicians are not required to inventory anything of value they receive from manufacturers, CMS and many medical professional societies advise that they do so.

The app for physicians – Open Payments for Physicians – is designed to help doctors keep tabs on all their transactions in real time. Users can manually enter all the information regarding a particular transaction, for example, the receipt of a grant payment or a gift that’s worth more than $10.

The app is free and can be downloaded from the iTunes App Store or from Google Play.

CMS also created an app for industry representatives to use (Open Payments for Industry).

Industry users and physician users can exchange information with their apps. By using a built-in QR (quick response) code reader, the manufacturer can transfer a record of a transaction to the physician for review, according to the agency.

In a blog post, CMS Program Integrity Director Dr. Peter Budetti said the agency’s "foray into mobile technology is about providing user-friendly tools for doctors, manufacturers, and others in the health care industry to use in working with us to implement the law in a smart way."

The idea is that physicians can use the records contained in the app to compare what’s reported by manufacturers to CMS. There is a 45-day lag between when the data are reported to CMS and posted publicly. Physicians have that window to challenge the reports before they are posted on the Open Payments website. Corrections can be made later, but the erroneous data will likely stay public for awhile.

The first year of the program will be a little bit more forgiving. Data collected beginning Aug. 1 won’t be publicly reported until September 2014.

The apps can’t be used to directly transfer data to CMS, said the agency, which added that although it developed the apps, it will not "validate the accuracy of data stored in the apps, nor will it be responsible for protecting data stored in the apps."

aault@frontlinemedcom.com On Twitter @aliciaault

Two new smartphone apps aim to help log drug, device, and diagnostic manufacturer payments to doctors and health care providers, as called for by the Affordable Care Act.

To promote transparency in relationships between providers and industry, the ACA requires that manufacturers track and report payments for consulting, honoraria, and more.

Originally known as the Sunshine Act, the effort is now called the Open Payments Program by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

While physicians are not required to inventory anything of value they receive from manufacturers, CMS and many medical professional societies advise that they do so.

The app for physicians – Open Payments for Physicians – is designed to help doctors keep tabs on all their transactions in real time. Users can manually enter all the information regarding a particular transaction, for example, the receipt of a grant payment or a gift that’s worth more than $10.

The app is free and can be downloaded from the iTunes App Store or from Google Play.

CMS also created an app for industry representatives to use (Open Payments for Industry).

Industry users and physician users can exchange information with their apps. By using a built-in QR (quick response) code reader, the manufacturer can transfer a record of a transaction to the physician for review, according to the agency.

In a blog post, CMS Program Integrity Director Dr. Peter Budetti said the agency’s "foray into mobile technology is about providing user-friendly tools for doctors, manufacturers, and others in the health care industry to use in working with us to implement the law in a smart way."

The idea is that physicians can use the records contained in the app to compare what’s reported by manufacturers to CMS. There is a 45-day lag between when the data are reported to CMS and posted publicly. Physicians have that window to challenge the reports before they are posted on the Open Payments website. Corrections can be made later, but the erroneous data will likely stay public for awhile.

The first year of the program will be a little bit more forgiving. Data collected beginning Aug. 1 won’t be publicly reported until September 2014.

The apps can’t be used to directly transfer data to CMS, said the agency, which added that although it developed the apps, it will not "validate the accuracy of data stored in the apps, nor will it be responsible for protecting data stored in the apps."

aault@frontlinemedcom.com On Twitter @aliciaault

Two new smartphone apps aim to help log drug, device, and diagnostic manufacturer payments to doctors and health care providers, as called for by the Affordable Care Act.

To promote transparency in relationships between providers and industry, the ACA requires that manufacturers track and report payments for consulting, honoraria, and more.

Originally known as the Sunshine Act, the effort is now called the Open Payments Program by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

While physicians are not required to inventory anything of value they receive from manufacturers, CMS and many medical professional societies advise that they do so.

The app for physicians – Open Payments for Physicians – is designed to help doctors keep tabs on all their transactions in real time. Users can manually enter all the information regarding a particular transaction, for example, the receipt of a grant payment or a gift that’s worth more than $10.

The app is free and can be downloaded from the iTunes App Store or from Google Play.

CMS also created an app for industry representatives to use (Open Payments for Industry).

Industry users and physician users can exchange information with their apps. By using a built-in QR (quick response) code reader, the manufacturer can transfer a record of a transaction to the physician for review, according to the agency.

In a blog post, CMS Program Integrity Director Dr. Peter Budetti said the agency’s "foray into mobile technology is about providing user-friendly tools for doctors, manufacturers, and others in the health care industry to use in working with us to implement the law in a smart way."

The idea is that physicians can use the records contained in the app to compare what’s reported by manufacturers to CMS. There is a 45-day lag between when the data are reported to CMS and posted publicly. Physicians have that window to challenge the reports before they are posted on the Open Payments website. Corrections can be made later, but the erroneous data will likely stay public for awhile.

The first year of the program will be a little bit more forgiving. Data collected beginning Aug. 1 won’t be publicly reported until September 2014.

The apps can’t be used to directly transfer data to CMS, said the agency, which added that although it developed the apps, it will not "validate the accuracy of data stored in the apps, nor will it be responsible for protecting data stored in the apps."

aault@frontlinemedcom.com On Twitter @aliciaault

GAO: In-house pathology is a conflict

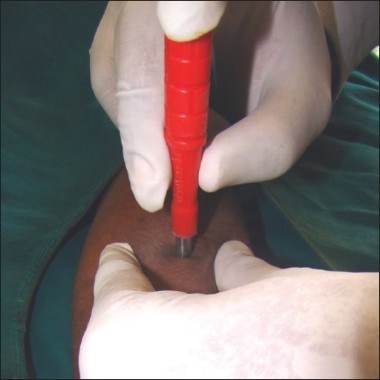

Physicians may be profiting by referring pathology services on biopsies to in-house labs or to pathology labs where they have an ownership stake, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office released July 16.

The agency found that three specialties – dermatology, gastroenterology, and urology – accounted for 90% of the self-referrals in 2010. Dermatologists alone accounted for half of those self-referrals.

The practice is costing Medicare millions and resulting in excess treatments, according to the report. The agency estimated that overall in 2010, self-referring providers likely referred 918,000 more pathology services than did physicians referring to labs in which they did not have a stake. The extra tests cost Medicare about $69 million out of a total $1.28 billion tab paid to physicians, pathologists, and labs in that year.

Overall, from 2004 to 2010, "the number of self-referred anatomic pathology services more than doubled, growing from 1.06 million services to about 2.26 million services, while non–self-referred services grew about 38%, from about 5.64 million services to about 7.77 million services," according to the report.

Self-referring providers include those who have an ownership stake in a clinical lab, but more commonly, those who prepare and/or evaluate specimens in their practices.

Referrals were highest for physicians in the year after they began to self-refer, suggesting that referrals were driven by financial incentives, not by any change in clinical practice or by any demographic change, according to the GAO.

Calling these physicians "switchers," the GAO found a 24% increase in referrals for pathology services among dermatologists who self-referred in 2010, compared to only a 0.3% increase for those who sent biopsy specimens elsewhere.

The GAO conducted its investigation at the request of Rep. Henry A. Waxman (D-Calif.), Rep. Sander Levin (D-Mich.), Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.), and Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa).

"The analysis suggests that financial incentives for self-referring providers is likely a major factor driving the increase in referrals for these services," Rep. Waxman said in a joint statement from the legislators.

"As Congress looks to rein in unnecessary spending, my colleagues and I should explore this area in greater depth," he said.

Sen. Grassley added, "Federal policy should drive doctors to make decisions based on quality of care, not financial relationships. The taxpayers shouldn’t have to pay for services that aren’t medically necessary."

The GAO suggested that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services should require providers to state on claims whether a service was self-referred, and that the agency should limit payment so that physicians aren’t rewarded for higher numbers of specimens per biopsy.

In comments to the GAO on the report, the American Academy of Dermatology Association said that it agreed that the CMS should develop a way to ensure the appropriateness of biopsy procedures. But the AADA expressed concern about limitations on financial incentives, saying that dermatologists should be encouraged to perform biopsies. The AADA also said that dermatologists should be allowed to prepare and review their own specimens "because they receive considerable training as part of their education."

On Twitter @aliciaault

Physicians may be profiting by referring pathology services on biopsies to in-house labs or to pathology labs where they have an ownership stake, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office released July 16.

The agency found that three specialties – dermatology, gastroenterology, and urology – accounted for 90% of the self-referrals in 2010. Dermatologists alone accounted for half of those self-referrals.

The practice is costing Medicare millions and resulting in excess treatments, according to the report. The agency estimated that overall in 2010, self-referring providers likely referred 918,000 more pathology services than did physicians referring to labs in which they did not have a stake. The extra tests cost Medicare about $69 million out of a total $1.28 billion tab paid to physicians, pathologists, and labs in that year.

Overall, from 2004 to 2010, "the number of self-referred anatomic pathology services more than doubled, growing from 1.06 million services to about 2.26 million services, while non–self-referred services grew about 38%, from about 5.64 million services to about 7.77 million services," according to the report.

Self-referring providers include those who have an ownership stake in a clinical lab, but more commonly, those who prepare and/or evaluate specimens in their practices.

Referrals were highest for physicians in the year after they began to self-refer, suggesting that referrals were driven by financial incentives, not by any change in clinical practice or by any demographic change, according to the GAO.

Calling these physicians "switchers," the GAO found a 24% increase in referrals for pathology services among dermatologists who self-referred in 2010, compared to only a 0.3% increase for those who sent biopsy specimens elsewhere.

The GAO conducted its investigation at the request of Rep. Henry A. Waxman (D-Calif.), Rep. Sander Levin (D-Mich.), Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.), and Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa).

"The analysis suggests that financial incentives for self-referring providers is likely a major factor driving the increase in referrals for these services," Rep. Waxman said in a joint statement from the legislators.

"As Congress looks to rein in unnecessary spending, my colleagues and I should explore this area in greater depth," he said.

Sen. Grassley added, "Federal policy should drive doctors to make decisions based on quality of care, not financial relationships. The taxpayers shouldn’t have to pay for services that aren’t medically necessary."

The GAO suggested that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services should require providers to state on claims whether a service was self-referred, and that the agency should limit payment so that physicians aren’t rewarded for higher numbers of specimens per biopsy.

In comments to the GAO on the report, the American Academy of Dermatology Association said that it agreed that the CMS should develop a way to ensure the appropriateness of biopsy procedures. But the AADA expressed concern about limitations on financial incentives, saying that dermatologists should be encouraged to perform biopsies. The AADA also said that dermatologists should be allowed to prepare and review their own specimens "because they receive considerable training as part of their education."

On Twitter @aliciaault

Physicians may be profiting by referring pathology services on biopsies to in-house labs or to pathology labs where they have an ownership stake, according to a report from the Government Accountability Office released July 16.

The agency found that three specialties – dermatology, gastroenterology, and urology – accounted for 90% of the self-referrals in 2010. Dermatologists alone accounted for half of those self-referrals.

The practice is costing Medicare millions and resulting in excess treatments, according to the report. The agency estimated that overall in 2010, self-referring providers likely referred 918,000 more pathology services than did physicians referring to labs in which they did not have a stake. The extra tests cost Medicare about $69 million out of a total $1.28 billion tab paid to physicians, pathologists, and labs in that year.

Overall, from 2004 to 2010, "the number of self-referred anatomic pathology services more than doubled, growing from 1.06 million services to about 2.26 million services, while non–self-referred services grew about 38%, from about 5.64 million services to about 7.77 million services," according to the report.

Self-referring providers include those who have an ownership stake in a clinical lab, but more commonly, those who prepare and/or evaluate specimens in their practices.

Referrals were highest for physicians in the year after they began to self-refer, suggesting that referrals were driven by financial incentives, not by any change in clinical practice or by any demographic change, according to the GAO.

Calling these physicians "switchers," the GAO found a 24% increase in referrals for pathology services among dermatologists who self-referred in 2010, compared to only a 0.3% increase for those who sent biopsy specimens elsewhere.

The GAO conducted its investigation at the request of Rep. Henry A. Waxman (D-Calif.), Rep. Sander Levin (D-Mich.), Sen. Max Baucus (D-Mont.), and Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa).

"The analysis suggests that financial incentives for self-referring providers is likely a major factor driving the increase in referrals for these services," Rep. Waxman said in a joint statement from the legislators.

"As Congress looks to rein in unnecessary spending, my colleagues and I should explore this area in greater depth," he said.

Sen. Grassley added, "Federal policy should drive doctors to make decisions based on quality of care, not financial relationships. The taxpayers shouldn’t have to pay for services that aren’t medically necessary."

The GAO suggested that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services should require providers to state on claims whether a service was self-referred, and that the agency should limit payment so that physicians aren’t rewarded for higher numbers of specimens per biopsy.

In comments to the GAO on the report, the American Academy of Dermatology Association said that it agreed that the CMS should develop a way to ensure the appropriateness of biopsy procedures. But the AADA expressed concern about limitations on financial incentives, saying that dermatologists should be encouraged to perform biopsies. The AADA also said that dermatologists should be allowed to prepare and review their own specimens "because they receive considerable training as part of their education."

On Twitter @aliciaault

Disability, not death, colors Americans' health

WASHINGTON – Americans are increasingly living with disabling conditions rather than dying from fatal diseases, while their nation lags behind its economic peers in addressing risk factors that contribute to poor health and premature death.

That’s according to several studies highlighted at the briefing.

"We’ve identified substantial areas where the U.S. can make progress and hopefully narrow the gap between what we’ve observed in the U.S. and the [peer] countries," Dr. Christopher Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle, and the lead author of the studies, said at an Institute of Medicine briefing July 10. "There’s also a role, we believe, for enhanced primary care – management of blood pressure, cholesterol, and encouragement of physical activity of patients."

The main study, published on July 10 in JAMA, is "an extraordinary publication," said Dr. Howard Bauchner, the journal’s editor in chief. "This is the first comprehensive box score of American health that’s ever been published."

The JAMA study, along with two companions, adds to the growing body of evidence that diet and physical activity – as well as smoking – are among the most important determinants of health, outside of socioeconomic factors.

Both Dr. Murray and Dr. Bauchner said that it was critical for physicians to discuss these lifestyle issues with patients, but also to monitor risk factors like hypertension, cholesterol, and blood sugar, especially in women, who are, in some areas of the country, facing rising death rates from heart disease in particular.

The United States has succeeded in reducing deaths from ischemic heart disease, HIV/AIDS, sudden infant death syndrome, and certain cancers, according to researchers from the U.S. Burden of Disease Collaborators, a group of academic, private, and government researchers from around the world.

But chronic disability from lung cancer, musculoskeletal pain, neurologic conditions, diabetes, and mental health/substance-use disorders – in particular, opioid abuse – is growing rapidly (JAMA 2013 July 10 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805]).

Substance abuse is not only disabling, but also contributes to premature death, the investigators found. More years of life lost were lost due to drug use disorders in 2010 than from prostate cancer and ovarian cancer combined, rising 448% between 1990 and 2010. Drug use went from 44th on the list of leading causes of years of life lost to 15th.

Alzheimer’s disease, liver cancer, Parkinson’s disease, and kidney cancer are also gaining among the causes of premature death.

"The United States spends more than the rest of the world on health care and leads the world in the quality and quantity of its health research, but that doesn’t add up to better health outcomes," Dr. Murray said in a statement. "The country has done a good job of preventing premature deaths from stroke, but when it comes to lung cancer, preterm birth complications, and a range of other causes, the country isn’t keeping pace with high-income countries in Europe, Asia, and elsewhere."

The study looked at death and disability from 291 diseases, conditions, and injuries, and also examined 67 risk factors for death and disability. The authors used the same methodology as that employed in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 (Lancet 2012:380;2055-2058).

In the U.S. study, the top 10 causes of years of life lost in 2010 were ischemic heart disease (16%), lung cancer (7%), stroke (4%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (4%), road injury (4%), self-harm (3%), diabetes (3%), cirrhosis (3%), Alzheimer’s disease (3%), and colorectal cancer (2%).

From 1990 to 2010, the average life expectancy for Americans increased from 75.2 to 78.2 years. But the "healthy life expectancy" – the number of years someone can expect to live in good health – went from 65.8 years to 68.1 years during the same period. The gap between average life expectancy and healthy life expectancy rose from 9.4 years in 1990 to 10.1 years in 2010.

When compared with 34 nations in Europe, Asia, and North America, the United States fell in rankings on almost every health measure from 1990 to 2010. For life expectancy at birth, the U.S. dropped from 20th to 27th.

Poor diet and not enough physical activity, along with smoking and uncontrolled blood pressure and cholesterol, were behind the drops, according to the investigators. The United States ranked 27th in disease burden risk from dietary factors and was also ranked 27th for body mass index. For healthy blood sugar, the United States was ranked 29th.

The United States is near the bottom when it comes to death rates. America ranks 27th among the 34 comparator countries. Only the Czech Republic, Poland, Estonia, Mexico, Turkey, Slovakia, and Hungary had higher death rates.

Meanwhile, two other studies examined life expectancy and physical activity on a county-by-county basis in America. Both were conducted by researchers at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, and both were published online in the open-access, peer-reviewed journal Population Health Metrics, which is edited by Dr. Murray.

In the first study, "Prevalence of Physical Activity and Obesity in US Counties, 2001-2011: A Road Map for Action," physical activity did not increase overall in the United States during the study period (2001-2009), but the percentage of the population considered obese did. The authors found that just because an area had higher physical activity levels did not mean that there would be a corresponding drop in obesity. They wrote that from 2001 to 2009, "for every 1 percentage point increase in physical activity, obesity prevalence was 0.11 percentage points lower" (Popul. Health Metr. 2013;11:7 [doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-11-7]).

Some counties – in Florida, Georgia, and Kentucky – saw large gains in physical activity. Among women, for instance, the largest increase in sufficient physical activity (defined as 150 minutes of moderate activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity weekly) was seen in Morgan County, Ky., where the rate rose from 26% to 44% during 2001-2009.

Generally, physical activity was worse for men and women who lived along the Texas-Mexico border, the Mississippi Valley, parts of the Deep South, and West Virginia, according to the study.

Douglas County, Colo., had the highest rate of activity in the United States (90%) for men in 2011, while Marin County, Calif., had highest rate for women (90%). Wolfe County, Ky., had the lowest rate for men (55%), and McDowell County, W.Va., had the lowest rate for women (51%).

Obesity rates tended to track with activity rates, with higher rates in the South and lower rates in urban areas like San Francisco, New York, and Washington, D.C.

The authors also published a county-by-county analysis of life expectancy, "Left Behind: Widening Disparities for Males and Females in US County Life Expectancy, 1985-2010." They reported that among the top-achieving counties, female life expectancy in 2010 was 85 years (or about 5 years more than the national average) and male life expectancy was 81.7 years (also about 5 years greater than the national average). But, they said, in many counties there has been no increase, or in some cases, declines in life expectancy, especially for women. There was a dramatic increase in inequality in life expectancy at birth among U.S. counties between 1985 and 2010, they concluded (Popul. Health Metr. 2013;11:8 [doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-11-8]).

Dr. Murray’s work is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health and in part by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

aault@frontlinemedcom.com On Twitter @aliciaault

Despite a level of health expenditures that would have seemed unthinkable a generation ago, the health of the U.S. population has improved only gradually and has fallen behind the pace of progress in many other wealthy nations.

The authors’ determination to generate consistent data across a range of national settings and to focus on specific diseases as causes of death is a source of strength and of limitations to the study. The strength is the capacity to compare in a consistent way. The limitation is reliance on data types that are universally available and on analyses that relate to specific disease conditions rather than to overall mortality. The most glaring omission in the assessment of risk factors, as the authors acknowledge, is the role of social factors such as income and inequality as a risk of premature death and disability. This omission should not be allowed to mislead policy makers, because differences in socioeconomic status and other social circumstances are strongly related to differences in mortality, as has been emphasized in a recent, comprehensive assessment by the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine on U.S. health in comparison with other countries.

Setting the United States on a healthier course will surely require leadership at all levels of government and across the public and private sectors and actively engaging the health professions and the public. Analyses such as the U.S. Burden of Disease can help identify priorities for research and action and monitor the state of progress over time.

Dr. Harvey V. Fineberg is the president of the Institute of Medicine in Washington, D.C. These remarks were taken from his editorial accompanying the JAMA study. He reported no conflicts of interest.

Despite a level of health expenditures that would have seemed unthinkable a generation ago, the health of the U.S. population has improved only gradually and has fallen behind the pace of progress in many other wealthy nations.

The authors’ determination to generate consistent data across a range of national settings and to focus on specific diseases as causes of death is a source of strength and of limitations to the study. The strength is the capacity to compare in a consistent way. The limitation is reliance on data types that are universally available and on analyses that relate to specific disease conditions rather than to overall mortality. The most glaring omission in the assessment of risk factors, as the authors acknowledge, is the role of social factors such as income and inequality as a risk of premature death and disability. This omission should not be allowed to mislead policy makers, because differences in socioeconomic status and other social circumstances are strongly related to differences in mortality, as has been emphasized in a recent, comprehensive assessment by the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine on U.S. health in comparison with other countries.

Setting the United States on a healthier course will surely require leadership at all levels of government and across the public and private sectors and actively engaging the health professions and the public. Analyses such as the U.S. Burden of Disease can help identify priorities for research and action and monitor the state of progress over time.

Dr. Harvey V. Fineberg is the president of the Institute of Medicine in Washington, D.C. These remarks were taken from his editorial accompanying the JAMA study. He reported no conflicts of interest.

Despite a level of health expenditures that would have seemed unthinkable a generation ago, the health of the U.S. population has improved only gradually and has fallen behind the pace of progress in many other wealthy nations.

The authors’ determination to generate consistent data across a range of national settings and to focus on specific diseases as causes of death is a source of strength and of limitations to the study. The strength is the capacity to compare in a consistent way. The limitation is reliance on data types that are universally available and on analyses that relate to specific disease conditions rather than to overall mortality. The most glaring omission in the assessment of risk factors, as the authors acknowledge, is the role of social factors such as income and inequality as a risk of premature death and disability. This omission should not be allowed to mislead policy makers, because differences in socioeconomic status and other social circumstances are strongly related to differences in mortality, as has been emphasized in a recent, comprehensive assessment by the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine on U.S. health in comparison with other countries.

Setting the United States on a healthier course will surely require leadership at all levels of government and across the public and private sectors and actively engaging the health professions and the public. Analyses such as the U.S. Burden of Disease can help identify priorities for research and action and monitor the state of progress over time.

Dr. Harvey V. Fineberg is the president of the Institute of Medicine in Washington, D.C. These remarks were taken from his editorial accompanying the JAMA study. He reported no conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – Americans are increasingly living with disabling conditions rather than dying from fatal diseases, while their nation lags behind its economic peers in addressing risk factors that contribute to poor health and premature death.

That’s according to several studies highlighted at the briefing.

"We’ve identified substantial areas where the U.S. can make progress and hopefully narrow the gap between what we’ve observed in the U.S. and the [peer] countries," Dr. Christopher Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle, and the lead author of the studies, said at an Institute of Medicine briefing July 10. "There’s also a role, we believe, for enhanced primary care – management of blood pressure, cholesterol, and encouragement of physical activity of patients."

The main study, published on July 10 in JAMA, is "an extraordinary publication," said Dr. Howard Bauchner, the journal’s editor in chief. "This is the first comprehensive box score of American health that’s ever been published."

The JAMA study, along with two companions, adds to the growing body of evidence that diet and physical activity – as well as smoking – are among the most important determinants of health, outside of socioeconomic factors.

Both Dr. Murray and Dr. Bauchner said that it was critical for physicians to discuss these lifestyle issues with patients, but also to monitor risk factors like hypertension, cholesterol, and blood sugar, especially in women, who are, in some areas of the country, facing rising death rates from heart disease in particular.

The United States has succeeded in reducing deaths from ischemic heart disease, HIV/AIDS, sudden infant death syndrome, and certain cancers, according to researchers from the U.S. Burden of Disease Collaborators, a group of academic, private, and government researchers from around the world.

But chronic disability from lung cancer, musculoskeletal pain, neurologic conditions, diabetes, and mental health/substance-use disorders – in particular, opioid abuse – is growing rapidly (JAMA 2013 July 10 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805]).

Substance abuse is not only disabling, but also contributes to premature death, the investigators found. More years of life lost were lost due to drug use disorders in 2010 than from prostate cancer and ovarian cancer combined, rising 448% between 1990 and 2010. Drug use went from 44th on the list of leading causes of years of life lost to 15th.

Alzheimer’s disease, liver cancer, Parkinson’s disease, and kidney cancer are also gaining among the causes of premature death.

"The United States spends more than the rest of the world on health care and leads the world in the quality and quantity of its health research, but that doesn’t add up to better health outcomes," Dr. Murray said in a statement. "The country has done a good job of preventing premature deaths from stroke, but when it comes to lung cancer, preterm birth complications, and a range of other causes, the country isn’t keeping pace with high-income countries in Europe, Asia, and elsewhere."

The study looked at death and disability from 291 diseases, conditions, and injuries, and also examined 67 risk factors for death and disability. The authors used the same methodology as that employed in the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 (Lancet 2012:380;2055-2058).

In the U.S. study, the top 10 causes of years of life lost in 2010 were ischemic heart disease (16%), lung cancer (7%), stroke (4%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (4%), road injury (4%), self-harm (3%), diabetes (3%), cirrhosis (3%), Alzheimer’s disease (3%), and colorectal cancer (2%).

From 1990 to 2010, the average life expectancy for Americans increased from 75.2 to 78.2 years. But the "healthy life expectancy" – the number of years someone can expect to live in good health – went from 65.8 years to 68.1 years during the same period. The gap between average life expectancy and healthy life expectancy rose from 9.4 years in 1990 to 10.1 years in 2010.

When compared with 34 nations in Europe, Asia, and North America, the United States fell in rankings on almost every health measure from 1990 to 2010. For life expectancy at birth, the U.S. dropped from 20th to 27th.

Poor diet and not enough physical activity, along with smoking and uncontrolled blood pressure and cholesterol, were behind the drops, according to the investigators. The United States ranked 27th in disease burden risk from dietary factors and was also ranked 27th for body mass index. For healthy blood sugar, the United States was ranked 29th.

The United States is near the bottom when it comes to death rates. America ranks 27th among the 34 comparator countries. Only the Czech Republic, Poland, Estonia, Mexico, Turkey, Slovakia, and Hungary had higher death rates.

Meanwhile, two other studies examined life expectancy and physical activity on a county-by-county basis in America. Both were conducted by researchers at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, and both were published online in the open-access, peer-reviewed journal Population Health Metrics, which is edited by Dr. Murray.

In the first study, "Prevalence of Physical Activity and Obesity in US Counties, 2001-2011: A Road Map for Action," physical activity did not increase overall in the United States during the study period (2001-2009), but the percentage of the population considered obese did. The authors found that just because an area had higher physical activity levels did not mean that there would be a corresponding drop in obesity. They wrote that from 2001 to 2009, "for every 1 percentage point increase in physical activity, obesity prevalence was 0.11 percentage points lower" (Popul. Health Metr. 2013;11:7 [doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-11-7]).

Some counties – in Florida, Georgia, and Kentucky – saw large gains in physical activity. Among women, for instance, the largest increase in sufficient physical activity (defined as 150 minutes of moderate activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity weekly) was seen in Morgan County, Ky., where the rate rose from 26% to 44% during 2001-2009.

Generally, physical activity was worse for men and women who lived along the Texas-Mexico border, the Mississippi Valley, parts of the Deep South, and West Virginia, according to the study.

Douglas County, Colo., had the highest rate of activity in the United States (90%) for men in 2011, while Marin County, Calif., had highest rate for women (90%). Wolfe County, Ky., had the lowest rate for men (55%), and McDowell County, W.Va., had the lowest rate for women (51%).

Obesity rates tended to track with activity rates, with higher rates in the South and lower rates in urban areas like San Francisco, New York, and Washington, D.C.

The authors also published a county-by-county analysis of life expectancy, "Left Behind: Widening Disparities for Males and Females in US County Life Expectancy, 1985-2010." They reported that among the top-achieving counties, female life expectancy in 2010 was 85 years (or about 5 years more than the national average) and male life expectancy was 81.7 years (also about 5 years greater than the national average). But, they said, in many counties there has been no increase, or in some cases, declines in life expectancy, especially for women. There was a dramatic increase in inequality in life expectancy at birth among U.S. counties between 1985 and 2010, they concluded (Popul. Health Metr. 2013;11:8 [doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-11-8]).

Dr. Murray’s work is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health and in part by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

aault@frontlinemedcom.com On Twitter @aliciaault

WASHINGTON – Americans are increasingly living with disabling conditions rather than dying from fatal diseases, while their nation lags behind its economic peers in addressing risk factors that contribute to poor health and premature death.

That’s according to several studies highlighted at the briefing.

"We’ve identified substantial areas where the U.S. can make progress and hopefully narrow the gap between what we’ve observed in the U.S. and the [peer] countries," Dr. Christopher Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle, and the lead author of the studies, said at an Institute of Medicine briefing July 10. "There’s also a role, we believe, for enhanced primary care – management of blood pressure, cholesterol, and encouragement of physical activity of patients."

The main study, published on July 10 in JAMA, is "an extraordinary publication," said Dr. Howard Bauchner, the journal’s editor in chief. "This is the first comprehensive box score of American health that’s ever been published."

The JAMA study, along with two companions, adds to the growing body of evidence that diet and physical activity – as well as smoking – are among the most important determinants of health, outside of socioeconomic factors.

Both Dr. Murray and Dr. Bauchner said that it was critical for physicians to discuss these lifestyle issues with patients, but also to monitor risk factors like hypertension, cholesterol, and blood sugar, especially in women, who are, in some areas of the country, facing rising death rates from heart disease in particular.

The United States has succeeded in reducing deaths from ischemic heart disease, HIV/AIDS, sudden infant death syndrome, and certain cancers, according to researchers from the U.S. Burden of Disease Collaborators, a group of academic, private, and government researchers from around the world.

But chronic disability from lung cancer, musculoskeletal pain, neurologic conditions, diabetes, and mental health/substance-use disorders – in particular, opioid abuse – is growing rapidly (JAMA 2013 July 10 [doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805]).

Substance abuse is not only disabling, but also contributes to premature death, the investigators found. More years of life lost were lost due to drug use disorders in 2010 than from prostate cancer and ovarian cancer combined, rising 448% between 1990 and 2010. Drug use went from 44th on the list of leading causes of years of life lost to 15th.

Alzheimer’s disease, liver cancer, Parkinson’s disease, and kidney cancer are also gaining among the causes of premature death.