User login

Endocarditis in dental patients rises after guidelines discourage prophylaxis

The number of prescriptions for antibiotic prophylaxis before invasive dental procedures has dropped sharply in England since 2008, while the incidence of infective endocarditis has risen significantly in the same time period, researchers found.

A study led by Dr. Martin Thornhill of the University of Sheffield (England) School of Clinical Dentistry, and published online Nov. 18 in the Lancet (doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62007-9) showed that after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence issued guidelines against antibiotic prophylaxis, even for patients at high risk of endocarditis, prescriptions fell precipitously from a mean 10,900 per month in 2004-2008 in England to a mean 2,236 a month between April 2008 and April 2013, with only 1,235 issued in the last month of the study period. The NICE guidance, which went further than other published recommendations that have aimed to limit, but not eliminate, the use of antibiotic prophylaxis as a form of endocarditis prevention, cited the absence of a robust evidence base supporting its effectiveness, and also the risk of adverse drug reactions.

Dr. Thornhill and his colleagues reviewed both national prescription records and hospital discharge records for patients with a primary diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Prescriptions of antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of infective endocarditis fell significantly after introduction of the NICE guidance.

The incidence of infective endocarditis, in contrast, rose by 0.11 cases per 10 million people per month following the 2008 guidance (95% confidence interval, 0.05-0.16; P < .0001). By March 2013, the researchers found that there were 34.9 more cases per month than would have been expected had the previous trend continued (95% CI, 7.9-61.9). Moreover, the increase was significant for patients determined to be at low or moderate risk as well as for those deemed high risk. The researchers did not find a statistically significant increase in endocarditis-related mortality corresponding to the drop in prescriptions.

Dr. Thornhill and his colleagues cautioned that their results did not establish a causal association between the drop in prescriptions and the rise in cases, and that further investigations were now warranted.

The study was funded by Heart Research UK, Simplyhealth, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Two of its authors were involved in guidelines on infective endocarditis issued by the American Heart Association in 2007. One author helped produce European Society of Cardiology endocarditis guidelines in 2009, and also acted as a consultant to NICE during the drafting of the 2008 guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis in endocarditis.

The number of prescriptions for antibiotic prophylaxis before invasive dental procedures has dropped sharply in England since 2008, while the incidence of infective endocarditis has risen significantly in the same time period, researchers found.

A study led by Dr. Martin Thornhill of the University of Sheffield (England) School of Clinical Dentistry, and published online Nov. 18 in the Lancet (doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62007-9) showed that after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence issued guidelines against antibiotic prophylaxis, even for patients at high risk of endocarditis, prescriptions fell precipitously from a mean 10,900 per month in 2004-2008 in England to a mean 2,236 a month between April 2008 and April 2013, with only 1,235 issued in the last month of the study period. The NICE guidance, which went further than other published recommendations that have aimed to limit, but not eliminate, the use of antibiotic prophylaxis as a form of endocarditis prevention, cited the absence of a robust evidence base supporting its effectiveness, and also the risk of adverse drug reactions.

Dr. Thornhill and his colleagues reviewed both national prescription records and hospital discharge records for patients with a primary diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Prescriptions of antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of infective endocarditis fell significantly after introduction of the NICE guidance.

The incidence of infective endocarditis, in contrast, rose by 0.11 cases per 10 million people per month following the 2008 guidance (95% confidence interval, 0.05-0.16; P < .0001). By March 2013, the researchers found that there were 34.9 more cases per month than would have been expected had the previous trend continued (95% CI, 7.9-61.9). Moreover, the increase was significant for patients determined to be at low or moderate risk as well as for those deemed high risk. The researchers did not find a statistically significant increase in endocarditis-related mortality corresponding to the drop in prescriptions.

Dr. Thornhill and his colleagues cautioned that their results did not establish a causal association between the drop in prescriptions and the rise in cases, and that further investigations were now warranted.

The study was funded by Heart Research UK, Simplyhealth, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Two of its authors were involved in guidelines on infective endocarditis issued by the American Heart Association in 2007. One author helped produce European Society of Cardiology endocarditis guidelines in 2009, and also acted as a consultant to NICE during the drafting of the 2008 guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis in endocarditis.

The number of prescriptions for antibiotic prophylaxis before invasive dental procedures has dropped sharply in England since 2008, while the incidence of infective endocarditis has risen significantly in the same time period, researchers found.

A study led by Dr. Martin Thornhill of the University of Sheffield (England) School of Clinical Dentistry, and published online Nov. 18 in the Lancet (doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62007-9) showed that after the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence issued guidelines against antibiotic prophylaxis, even for patients at high risk of endocarditis, prescriptions fell precipitously from a mean 10,900 per month in 2004-2008 in England to a mean 2,236 a month between April 2008 and April 2013, with only 1,235 issued in the last month of the study period. The NICE guidance, which went further than other published recommendations that have aimed to limit, but not eliminate, the use of antibiotic prophylaxis as a form of endocarditis prevention, cited the absence of a robust evidence base supporting its effectiveness, and also the risk of adverse drug reactions.

Dr. Thornhill and his colleagues reviewed both national prescription records and hospital discharge records for patients with a primary diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Prescriptions of antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of infective endocarditis fell significantly after introduction of the NICE guidance.

The incidence of infective endocarditis, in contrast, rose by 0.11 cases per 10 million people per month following the 2008 guidance (95% confidence interval, 0.05-0.16; P < .0001). By March 2013, the researchers found that there were 34.9 more cases per month than would have been expected had the previous trend continued (95% CI, 7.9-61.9). Moreover, the increase was significant for patients determined to be at low or moderate risk as well as for those deemed high risk. The researchers did not find a statistically significant increase in endocarditis-related mortality corresponding to the drop in prescriptions.

Dr. Thornhill and his colleagues cautioned that their results did not establish a causal association between the drop in prescriptions and the rise in cases, and that further investigations were now warranted.

The study was funded by Heart Research UK, Simplyhealth, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Two of its authors were involved in guidelines on infective endocarditis issued by the American Heart Association in 2007. One author helped produce European Society of Cardiology endocarditis guidelines in 2009, and also acted as a consultant to NICE during the drafting of the 2008 guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis in endocarditis.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Antibiotic prophylaxis before invasive dental procedures dropped sharply while the incidence of infective endocarditis rose significantly.

Major finding: The incidence of infective endocarditis rose by 0.11 cases per 10 million people per month following the 2008 guidance.

Data source: Researchers reviewed both national prescription records and hospital discharge records for patients with a primary diagnosis of infective endocarditis in the United Kingdom.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Heart Research UK, Simplyhealth, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Two of its authors were involved in guidelines on infective endocarditis issued by the American Heart Association in 2007. One author helped produce European Society of Cardiology endocarditis guidelines in 2009, and also acted as a consultant to NICE during the drafting of the 2008 guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis in endocarditis.

Guidelines and RA hot topics at the meeting

Major new clinical guidelines for rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis will be presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology Nov. 15-19, while other sessions will examine aspects of recently published guidelines on polymyalgia rheumatica, gout, and lupus nephritis.

The ACR’s new RA guidelines, which will include recommendations on the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying agents, as well as corticosteroids, will be presented Sunday, Nov. 16. Draft axial spondyloarthritis guidelines, which will also address the management of patients with ankylosing spondylitis, will be discussed the same day.

With the ACR’s gout guidelines, (part 1 and part 2) published in 2012, “some controversial aspects of have emerged,” said Dr. Chester V. Oddis, chair of the meeting’s planning subcommittee. Dr. Oddis highlighted a Monday, Nov. 17, session that will specifically address components of the gout recommendations that have generated concern.

Also on Monday, weaknesses of current lupus nephritis recommendations will be hashed out in a session devoted to helping clinicians recognize some of their pitfalls. Key areas of discussion will include the role of rituximab and the problem of steroid use in this difficult-to-treat patient group.

Dr. Oddis, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology and clinical immunology at the University of Pittsburgh, pointed to certain other sessions and presentations on RA during the 5-day meeting as especially compelling.

Morbidity and mortality features in RA will be covered in two presentations at the plenary session on Sunday. Dr. Oddis advised clinicians to “stay tuned” for results from a Dutch study that evaluated treat-to-target approaches in a cohort of more than 500 RA patients. Investigators found survival rates to be comparable with those of the general population after 10 years of treat to target, regardless of medications used. Tight control had more bearing on survival than did any particular course of treatment, with no significant differences seen between the four treatment strategies studied.

Also on Sunday, other key mortality findings will be discussed from a long-term, prospective, cohort study of 121,700 women that found that those diagnosed with RA over 34 years of follow-up (n = 960) had double the risk of death from any cause, compared with women without RA. Respiratory mortality accounted for 16% of deaths among RA patients, suggesting a little-explored cause of death, and women with RA were significantly more likely to die from cardiovascular disease and cancer than were those without RA, the study found.

The comparative effectiveness and harms of biologics are a hot topic in RA, and a Monday session will review findings from registries and direct comparator trials, offering clinicians suggestions on how to best learn from the data.

Dr. Oddis also highlighted a Tuesday session on the epidemiology of cardiovascular risk in RA and clinical CV risk management in patients with RA. The aim, he said, is to demonstrate “how we can best develop a rational approach to assessing this in our practices.”

Major new clinical guidelines for rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis will be presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology Nov. 15-19, while other sessions will examine aspects of recently published guidelines on polymyalgia rheumatica, gout, and lupus nephritis.

The ACR’s new RA guidelines, which will include recommendations on the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying agents, as well as corticosteroids, will be presented Sunday, Nov. 16. Draft axial spondyloarthritis guidelines, which will also address the management of patients with ankylosing spondylitis, will be discussed the same day.

With the ACR’s gout guidelines, (part 1 and part 2) published in 2012, “some controversial aspects of have emerged,” said Dr. Chester V. Oddis, chair of the meeting’s planning subcommittee. Dr. Oddis highlighted a Monday, Nov. 17, session that will specifically address components of the gout recommendations that have generated concern.

Also on Monday, weaknesses of current lupus nephritis recommendations will be hashed out in a session devoted to helping clinicians recognize some of their pitfalls. Key areas of discussion will include the role of rituximab and the problem of steroid use in this difficult-to-treat patient group.

Dr. Oddis, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology and clinical immunology at the University of Pittsburgh, pointed to certain other sessions and presentations on RA during the 5-day meeting as especially compelling.

Morbidity and mortality features in RA will be covered in two presentations at the plenary session on Sunday. Dr. Oddis advised clinicians to “stay tuned” for results from a Dutch study that evaluated treat-to-target approaches in a cohort of more than 500 RA patients. Investigators found survival rates to be comparable with those of the general population after 10 years of treat to target, regardless of medications used. Tight control had more bearing on survival than did any particular course of treatment, with no significant differences seen between the four treatment strategies studied.

Also on Sunday, other key mortality findings will be discussed from a long-term, prospective, cohort study of 121,700 women that found that those diagnosed with RA over 34 years of follow-up (n = 960) had double the risk of death from any cause, compared with women without RA. Respiratory mortality accounted for 16% of deaths among RA patients, suggesting a little-explored cause of death, and women with RA were significantly more likely to die from cardiovascular disease and cancer than were those without RA, the study found.

The comparative effectiveness and harms of biologics are a hot topic in RA, and a Monday session will review findings from registries and direct comparator trials, offering clinicians suggestions on how to best learn from the data.

Dr. Oddis also highlighted a Tuesday session on the epidemiology of cardiovascular risk in RA and clinical CV risk management in patients with RA. The aim, he said, is to demonstrate “how we can best develop a rational approach to assessing this in our practices.”

Major new clinical guidelines for rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthritis will be presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology Nov. 15-19, while other sessions will examine aspects of recently published guidelines on polymyalgia rheumatica, gout, and lupus nephritis.

The ACR’s new RA guidelines, which will include recommendations on the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying agents, as well as corticosteroids, will be presented Sunday, Nov. 16. Draft axial spondyloarthritis guidelines, which will also address the management of patients with ankylosing spondylitis, will be discussed the same day.

With the ACR’s gout guidelines, (part 1 and part 2) published in 2012, “some controversial aspects of have emerged,” said Dr. Chester V. Oddis, chair of the meeting’s planning subcommittee. Dr. Oddis highlighted a Monday, Nov. 17, session that will specifically address components of the gout recommendations that have generated concern.

Also on Monday, weaknesses of current lupus nephritis recommendations will be hashed out in a session devoted to helping clinicians recognize some of their pitfalls. Key areas of discussion will include the role of rituximab and the problem of steroid use in this difficult-to-treat patient group.

Dr. Oddis, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology and clinical immunology at the University of Pittsburgh, pointed to certain other sessions and presentations on RA during the 5-day meeting as especially compelling.

Morbidity and mortality features in RA will be covered in two presentations at the plenary session on Sunday. Dr. Oddis advised clinicians to “stay tuned” for results from a Dutch study that evaluated treat-to-target approaches in a cohort of more than 500 RA patients. Investigators found survival rates to be comparable with those of the general population after 10 years of treat to target, regardless of medications used. Tight control had more bearing on survival than did any particular course of treatment, with no significant differences seen between the four treatment strategies studied.

Also on Sunday, other key mortality findings will be discussed from a long-term, prospective, cohort study of 121,700 women that found that those diagnosed with RA over 34 years of follow-up (n = 960) had double the risk of death from any cause, compared with women without RA. Respiratory mortality accounted for 16% of deaths among RA patients, suggesting a little-explored cause of death, and women with RA were significantly more likely to die from cardiovascular disease and cancer than were those without RA, the study found.

The comparative effectiveness and harms of biologics are a hot topic in RA, and a Monday session will review findings from registries and direct comparator trials, offering clinicians suggestions on how to best learn from the data.

Dr. Oddis also highlighted a Tuesday session on the epidemiology of cardiovascular risk in RA and clinical CV risk management in patients with RA. The aim, he said, is to demonstrate “how we can best develop a rational approach to assessing this in our practices.”

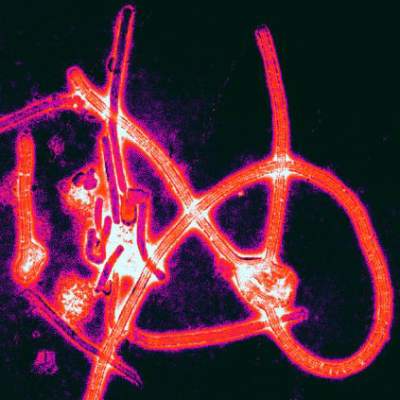

WHO: Ebola vaccines may reach Africa in January

A top scientist with the World Health Organization says that the two leading Ebola vaccine candidates were close to being tested in healthy volunteers, and that if an ideal dosage can be successfully established in the coming weeks, clinical efficacy testing could begin in Africa in January.

Marie-Paule Kieny, Ph.D., WHO’s assistant director-general for health systems and innovation, told reporters at a press conference Oct. 21 that the two experimental live attenuated vaccines, one developed by GlaxoSmithKline and the other by the Canadian government, would be tested in hundreds of healthy volunteers, most of them in Europe, starting in the next 2 weeks. This round of testing involves a range of doses to determine the ideal dose for safety and immunogenicity.

Some 800 vials of the Canadian vaccine have been sent to WHO’s offices in Geneva for distribution, Dr. Kieny said, and will be forwarded to the testing sites in Germany and Switzerland within days, along with sites in Kenya and Gabon.

With both vaccines, “we should know dose levels by December,” Dr. Kieny said, “and these data will be absolutely crucial to allow decision-making in determining what dose level should go in efficacy testing in Africa allowing for trials of the vaccines in Africa to begin as soon as January.”

Clinical efficacy testing would most likely begin with people at highest risk: health care workers, burial teams, family members, and contacts of known Ebola cases. “These possible targets are being discussed now,” Dr. Kieny said.

Dr. Kieny also noted that there were additional vaccine candidates in advanced stages of development in the United States and Russia.

One Ebola treatment strategy currently being investigated involves transfusions of blood and serum of convalescent patients. In Liberia, progress in collecting and processing blood “is moving quickly,” Dr. Kieny reported. WHO is also in discussions with facilities in Guinea and Sierra Leone, the other two countries where Ebola transmission is intense, to set up blood-processing centers.

On the drug front, Dr. Kieny said that an antiviral agent developed in Japan is about to undergo efficacy testing in Guinea, which would represent the first formal clinical drug trial in this Ebola outbreak, though experimental agents have been used ad-hoc to date.

A top scientist with the World Health Organization says that the two leading Ebola vaccine candidates were close to being tested in healthy volunteers, and that if an ideal dosage can be successfully established in the coming weeks, clinical efficacy testing could begin in Africa in January.

Marie-Paule Kieny, Ph.D., WHO’s assistant director-general for health systems and innovation, told reporters at a press conference Oct. 21 that the two experimental live attenuated vaccines, one developed by GlaxoSmithKline and the other by the Canadian government, would be tested in hundreds of healthy volunteers, most of them in Europe, starting in the next 2 weeks. This round of testing involves a range of doses to determine the ideal dose for safety and immunogenicity.

Some 800 vials of the Canadian vaccine have been sent to WHO’s offices in Geneva for distribution, Dr. Kieny said, and will be forwarded to the testing sites in Germany and Switzerland within days, along with sites in Kenya and Gabon.

With both vaccines, “we should know dose levels by December,” Dr. Kieny said, “and these data will be absolutely crucial to allow decision-making in determining what dose level should go in efficacy testing in Africa allowing for trials of the vaccines in Africa to begin as soon as January.”

Clinical efficacy testing would most likely begin with people at highest risk: health care workers, burial teams, family members, and contacts of known Ebola cases. “These possible targets are being discussed now,” Dr. Kieny said.

Dr. Kieny also noted that there were additional vaccine candidates in advanced stages of development in the United States and Russia.

One Ebola treatment strategy currently being investigated involves transfusions of blood and serum of convalescent patients. In Liberia, progress in collecting and processing blood “is moving quickly,” Dr. Kieny reported. WHO is also in discussions with facilities in Guinea and Sierra Leone, the other two countries where Ebola transmission is intense, to set up blood-processing centers.

On the drug front, Dr. Kieny said that an antiviral agent developed in Japan is about to undergo efficacy testing in Guinea, which would represent the first formal clinical drug trial in this Ebola outbreak, though experimental agents have been used ad-hoc to date.

A top scientist with the World Health Organization says that the two leading Ebola vaccine candidates were close to being tested in healthy volunteers, and that if an ideal dosage can be successfully established in the coming weeks, clinical efficacy testing could begin in Africa in January.

Marie-Paule Kieny, Ph.D., WHO’s assistant director-general for health systems and innovation, told reporters at a press conference Oct. 21 that the two experimental live attenuated vaccines, one developed by GlaxoSmithKline and the other by the Canadian government, would be tested in hundreds of healthy volunteers, most of them in Europe, starting in the next 2 weeks. This round of testing involves a range of doses to determine the ideal dose for safety and immunogenicity.

Some 800 vials of the Canadian vaccine have been sent to WHO’s offices in Geneva for distribution, Dr. Kieny said, and will be forwarded to the testing sites in Germany and Switzerland within days, along with sites in Kenya and Gabon.

With both vaccines, “we should know dose levels by December,” Dr. Kieny said, “and these data will be absolutely crucial to allow decision-making in determining what dose level should go in efficacy testing in Africa allowing for trials of the vaccines in Africa to begin as soon as January.”

Clinical efficacy testing would most likely begin with people at highest risk: health care workers, burial teams, family members, and contacts of known Ebola cases. “These possible targets are being discussed now,” Dr. Kieny said.

Dr. Kieny also noted that there were additional vaccine candidates in advanced stages of development in the United States and Russia.

One Ebola treatment strategy currently being investigated involves transfusions of blood and serum of convalescent patients. In Liberia, progress in collecting and processing blood “is moving quickly,” Dr. Kieny reported. WHO is also in discussions with facilities in Guinea and Sierra Leone, the other two countries where Ebola transmission is intense, to set up blood-processing centers.

On the drug front, Dr. Kieny said that an antiviral agent developed in Japan is about to undergo efficacy testing in Guinea, which would represent the first formal clinical drug trial in this Ebola outbreak, though experimental agents have been used ad-hoc to date.

CDC updates guidance on protecting health care workers from Ebola

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has put forward a revised series of recommendations on the use of personal protective equipment in treating Ebola patients.

The new guidance, issued Oct. 20, closely mirrors the Ebola personal protective equipment (PPE) guidance issued by MSF (Doctors Without Borders).

The CDC’s recommendations update the PPE guidance issued Aug. 1 that is now widely considered inadequate. The new recommendations advise, among other things, that health care workers have no skin exposed, that they be supervised while donning and removing PPE, and that rigorous training and practice accompany any use of PPE in the treatment of patients with Ebola.

Specific equipment recommendations include double gloves, waterproof boot covers to mid-calf or higher, and a disposable fluid-resistant or impermeable gown that extends to at least mid-calf, or a coverall without hood. The agency also recommends the use of respirators (N95 or powered air purifying), disposable single-use full-face shields in lieu of goggles, surgical hoods for complete coverage of the head and neck, and a waterproof apron extending from torso to mid-calf if patients have vomiting or diarrhea.

The guidance specifies that hospitals must have designated areas for putting on and taking off PPE and that trained observers monitor all donning and removal. The guidance also contains instructions for disinfecting PPE prior to its removal.

The agency emphasized that training, not merely having the correct equipment in place, was key to the successful use of PPE. “Focusing only on PPE gives a false sense of security of safe care and worker safety,” the CDC stated. “Training is a critical aspect of ensuring infection control.”

Facilities must make sure all health care providers practice “numerous times” until they understand how to properly and safely use the equipment, the CDC advised.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has put forward a revised series of recommendations on the use of personal protective equipment in treating Ebola patients.

The new guidance, issued Oct. 20, closely mirrors the Ebola personal protective equipment (PPE) guidance issued by MSF (Doctors Without Borders).

The CDC’s recommendations update the PPE guidance issued Aug. 1 that is now widely considered inadequate. The new recommendations advise, among other things, that health care workers have no skin exposed, that they be supervised while donning and removing PPE, and that rigorous training and practice accompany any use of PPE in the treatment of patients with Ebola.

Specific equipment recommendations include double gloves, waterproof boot covers to mid-calf or higher, and a disposable fluid-resistant or impermeable gown that extends to at least mid-calf, or a coverall without hood. The agency also recommends the use of respirators (N95 or powered air purifying), disposable single-use full-face shields in lieu of goggles, surgical hoods for complete coverage of the head and neck, and a waterproof apron extending from torso to mid-calf if patients have vomiting or diarrhea.

The guidance specifies that hospitals must have designated areas for putting on and taking off PPE and that trained observers monitor all donning and removal. The guidance also contains instructions for disinfecting PPE prior to its removal.

The agency emphasized that training, not merely having the correct equipment in place, was key to the successful use of PPE. “Focusing only on PPE gives a false sense of security of safe care and worker safety,” the CDC stated. “Training is a critical aspect of ensuring infection control.”

Facilities must make sure all health care providers practice “numerous times” until they understand how to properly and safely use the equipment, the CDC advised.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has put forward a revised series of recommendations on the use of personal protective equipment in treating Ebola patients.

The new guidance, issued Oct. 20, closely mirrors the Ebola personal protective equipment (PPE) guidance issued by MSF (Doctors Without Borders).

The CDC’s recommendations update the PPE guidance issued Aug. 1 that is now widely considered inadequate. The new recommendations advise, among other things, that health care workers have no skin exposed, that they be supervised while donning and removing PPE, and that rigorous training and practice accompany any use of PPE in the treatment of patients with Ebola.

Specific equipment recommendations include double gloves, waterproof boot covers to mid-calf or higher, and a disposable fluid-resistant or impermeable gown that extends to at least mid-calf, or a coverall without hood. The agency also recommends the use of respirators (N95 or powered air purifying), disposable single-use full-face shields in lieu of goggles, surgical hoods for complete coverage of the head and neck, and a waterproof apron extending from torso to mid-calf if patients have vomiting or diarrhea.

The guidance specifies that hospitals must have designated areas for putting on and taking off PPE and that trained observers monitor all donning and removal. The guidance also contains instructions for disinfecting PPE prior to its removal.

The agency emphasized that training, not merely having the correct equipment in place, was key to the successful use of PPE. “Focusing only on PPE gives a false sense of security of safe care and worker safety,” the CDC stated. “Training is a critical aspect of ensuring infection control.”

Facilities must make sure all health care providers practice “numerous times” until they understand how to properly and safely use the equipment, the CDC advised.

Ebola: Departure screening is better containment policy

Screening of air travelers departing from three West African cities offers a cheaper and simpler way to check the international spread of Ebola virus, compared with screening at points of entry, which would carry many added costs with few added benefits, according to new research.

Without effective exit screening in place, 2.8 infected travelers a month would leave the three countries – Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea – where intense transmission of Ebola is currently occurring, predicted Dr. Isaac I. Bogoch of the University of Toronto and his colleagues, who published their findings Oct. 20 in the Lancet (2014 Oct. 20 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61828-6]).

The investigators used air travel records and viral surveillance data from the World Health Organization to calculate the number of infected travelers likely to board a flight from those countries every month if no exit screening were in place. All three countries currently do conduct screening; however, international support is needed to ensure that it continues, Dr. Bogoch said.

While exit screening will not catch latent cases of Ebola prior to the onset of fever, entry screening likely will not be more effective at doing so, the researchers found, as travel records show that a majority of air travel from the affected countries consists of shorter flights lasting an average of 2.7 hours.

Adding entrance screening would vastly expand the number of people needing to be screened and the number of airports in which screening would occur, from 3 (Conakry, Guinea; Monrovia, Liberia; and Freetown, Sierra Leone) to more than 1,238, if accounting for passengers arriving on indirect flights, according to the study.

Ghana and Senegal were the top two destinations of air travelers from the affected countries, accounting for 17.5% and 14.4% of travel. The United Kingdom received 8.7% and France, 7.1%. The United States received 2% of the volume of travelers from these countries.

Of concern, some 64% of travelers from the affected countries were en route to other low- and middle-income countries, Dr. Bogoch and his colleagues found, meaning the larger share of importation risk fell on “inadequately resourced medical and public health systems [that] might be unable to detect and adequately manage an imported case of Ebola virus disease.”

Outbreaks following imported cases have been stopped in Nigeria and Senegal. The World Health organization declared the Nigeria outbreak over on Oct. 20 and the Senegal outbreak over on Oct. 17.

In an editorial comment accompanying the study, Benjamin Cowling, Ph.D., of the University of Hong Kong, and Dr. Hongjie Yu of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, agreed that international support was “essential” for stringent exit screening, yet noted that no specific funding had been announced to support it (Lancet 2014 Oct. 20 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61895-X]).

Regardless, Dr. Cowling and Dr. Yu argued, screening “might not have a substantial effect on export rates, because of the long incubation period of the disease (average 8-10 days; range 2-21 days), combined with rapid disease progression after onset, meaning that most exportations would be incubating infections missed at border screening points … In addition to any entry or exit screening, vigilance within countries is essential for early detection of imported cases.”

Dr. Bogoch’s study was funded by the Canadian Research Institutes of Health. Dr. Bogoch and two of his coauthors, Dr. Maria Creatore and Dr. Kamran Khan, reported ties to Bio.Diaspora, a company that models global infectious disease threats. Dr. Cowling disclosed financial relationships with MedImmune, Sanofi Pasteur, and Crucell.

Screening of air travelers departing from three West African cities offers a cheaper and simpler way to check the international spread of Ebola virus, compared with screening at points of entry, which would carry many added costs with few added benefits, according to new research.

Without effective exit screening in place, 2.8 infected travelers a month would leave the three countries – Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea – where intense transmission of Ebola is currently occurring, predicted Dr. Isaac I. Bogoch of the University of Toronto and his colleagues, who published their findings Oct. 20 in the Lancet (2014 Oct. 20 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61828-6]).

The investigators used air travel records and viral surveillance data from the World Health Organization to calculate the number of infected travelers likely to board a flight from those countries every month if no exit screening were in place. All three countries currently do conduct screening; however, international support is needed to ensure that it continues, Dr. Bogoch said.

While exit screening will not catch latent cases of Ebola prior to the onset of fever, entry screening likely will not be more effective at doing so, the researchers found, as travel records show that a majority of air travel from the affected countries consists of shorter flights lasting an average of 2.7 hours.

Adding entrance screening would vastly expand the number of people needing to be screened and the number of airports in which screening would occur, from 3 (Conakry, Guinea; Monrovia, Liberia; and Freetown, Sierra Leone) to more than 1,238, if accounting for passengers arriving on indirect flights, according to the study.

Ghana and Senegal were the top two destinations of air travelers from the affected countries, accounting for 17.5% and 14.4% of travel. The United Kingdom received 8.7% and France, 7.1%. The United States received 2% of the volume of travelers from these countries.

Of concern, some 64% of travelers from the affected countries were en route to other low- and middle-income countries, Dr. Bogoch and his colleagues found, meaning the larger share of importation risk fell on “inadequately resourced medical and public health systems [that] might be unable to detect and adequately manage an imported case of Ebola virus disease.”

Outbreaks following imported cases have been stopped in Nigeria and Senegal. The World Health organization declared the Nigeria outbreak over on Oct. 20 and the Senegal outbreak over on Oct. 17.

In an editorial comment accompanying the study, Benjamin Cowling, Ph.D., of the University of Hong Kong, and Dr. Hongjie Yu of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, agreed that international support was “essential” for stringent exit screening, yet noted that no specific funding had been announced to support it (Lancet 2014 Oct. 20 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61895-X]).

Regardless, Dr. Cowling and Dr. Yu argued, screening “might not have a substantial effect on export rates, because of the long incubation period of the disease (average 8-10 days; range 2-21 days), combined with rapid disease progression after onset, meaning that most exportations would be incubating infections missed at border screening points … In addition to any entry or exit screening, vigilance within countries is essential for early detection of imported cases.”

Dr. Bogoch’s study was funded by the Canadian Research Institutes of Health. Dr. Bogoch and two of his coauthors, Dr. Maria Creatore and Dr. Kamran Khan, reported ties to Bio.Diaspora, a company that models global infectious disease threats. Dr. Cowling disclosed financial relationships with MedImmune, Sanofi Pasteur, and Crucell.

Screening of air travelers departing from three West African cities offers a cheaper and simpler way to check the international spread of Ebola virus, compared with screening at points of entry, which would carry many added costs with few added benefits, according to new research.

Without effective exit screening in place, 2.8 infected travelers a month would leave the three countries – Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea – where intense transmission of Ebola is currently occurring, predicted Dr. Isaac I. Bogoch of the University of Toronto and his colleagues, who published their findings Oct. 20 in the Lancet (2014 Oct. 20 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61828-6]).

The investigators used air travel records and viral surveillance data from the World Health Organization to calculate the number of infected travelers likely to board a flight from those countries every month if no exit screening were in place. All three countries currently do conduct screening; however, international support is needed to ensure that it continues, Dr. Bogoch said.

While exit screening will not catch latent cases of Ebola prior to the onset of fever, entry screening likely will not be more effective at doing so, the researchers found, as travel records show that a majority of air travel from the affected countries consists of shorter flights lasting an average of 2.7 hours.

Adding entrance screening would vastly expand the number of people needing to be screened and the number of airports in which screening would occur, from 3 (Conakry, Guinea; Monrovia, Liberia; and Freetown, Sierra Leone) to more than 1,238, if accounting for passengers arriving on indirect flights, according to the study.

Ghana and Senegal were the top two destinations of air travelers from the affected countries, accounting for 17.5% and 14.4% of travel. The United Kingdom received 8.7% and France, 7.1%. The United States received 2% of the volume of travelers from these countries.

Of concern, some 64% of travelers from the affected countries were en route to other low- and middle-income countries, Dr. Bogoch and his colleagues found, meaning the larger share of importation risk fell on “inadequately resourced medical and public health systems [that] might be unable to detect and adequately manage an imported case of Ebola virus disease.”

Outbreaks following imported cases have been stopped in Nigeria and Senegal. The World Health organization declared the Nigeria outbreak over on Oct. 20 and the Senegal outbreak over on Oct. 17.

In an editorial comment accompanying the study, Benjamin Cowling, Ph.D., of the University of Hong Kong, and Dr. Hongjie Yu of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, agreed that international support was “essential” for stringent exit screening, yet noted that no specific funding had been announced to support it (Lancet 2014 Oct. 20 [doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61895-X]).

Regardless, Dr. Cowling and Dr. Yu argued, screening “might not have a substantial effect on export rates, because of the long incubation period of the disease (average 8-10 days; range 2-21 days), combined with rapid disease progression after onset, meaning that most exportations would be incubating infections missed at border screening points … In addition to any entry or exit screening, vigilance within countries is essential for early detection of imported cases.”

Dr. Bogoch’s study was funded by the Canadian Research Institutes of Health. Dr. Bogoch and two of his coauthors, Dr. Maria Creatore and Dr. Kamran Khan, reported ties to Bio.Diaspora, a company that models global infectious disease threats. Dr. Cowling disclosed financial relationships with MedImmune, Sanofi Pasteur, and Crucell.

Key clinical point: Three cases of Ebola virus infection would be exported per month by air travel in the absence of exit airport screening

Major finding: Ghana, Senegal, France, and the United Kingdom were top destinations of travelers from outbreak countries, with higher total importation risk borne by lower-income countries.

Data source: International Air Transport Association records for flights since Sept 1, 2014, and itinerary data from 2013, along with Ebola virus surveillance data from the World Health Organization.

Disclosures: Lead author and coauthors report ties to a for-profit infectious disease modeling firm.

Ebola in the office: What to do?

While plentiful guidance has been published on how hospitals should diagnose, isolate, transfer, and treat patients with Ebola virus infection or suspected infection, little information is available for the office-based physician.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that it is developing on a broader set of guidelines that will include primary care physicians and other clinicians working in outpatient practices. But these guidelines have yet to be published, and physicians at both standalone and hospital-affiliated practices are grappling with tough questions regarding isolation, transport to hospitals, and even whom to call first.

In the event of a patient presenting in an office with a travel history and symptoms suggestive of Ebola, "you would certainly do as much contact isolation as you can," said Dr. Kevin Powell, a pediatrician in St. Louis. "Most offices are prepared to do some, and it would reduce the risk markedly."

At that point, "I think the presumption of most doctors was, you call the CDC and say you need help," Dr. Powell added.

"Then we found out that the CDC isn't prepared to give that answer back."

Because an office-based physician will not be able to diagnose Ebola, regardless, Dr. Powell added, there should be “a strong emphasis toward saying that a person who thinks they have Ebola should stay away from an outpatient office and go to a hospital emergency room.”

Health officials in Ohio have advised primary care physicians to consult with any patient with suspected Ebola symptoms by phone, taking information about travel and also about potential exposures within the United States.

Dr. Jack T. Swanson, described a similar approach at the McFarland Clinic in Ames, Iowa. “If a patient calls for a sick appointment, our triage phone nurse will ask if they have been in western Africa or have had any contact with someone with Ebola in the past 21 days. If the answer is yes, they are to go to our emergency room rather than come to our office,” said Dr. Swanson, a pediatrician in private practice.

Some patients with suspected Ebola may arrive at outpatient clinics anyway. One way to establish a front-line response is to have nonclinical registration desk staff ask the first screening question, regarding travel history, Dr. Amy Gottlieb, said in an interview. At her hospital-linked outpatient practice, “If we [identified] someone with travel exposure, we could isolate them in a room and bring in someone who can do the clinical assessment in a private, controlled setting,” said Dr. Gottlieb of the departments of medicine and ob.gyn. at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

Dr. George DeVito, a pediatrician* in Concord, N.H., treats a large number of resettled and refugee families from all around the world. His outpatient practice has been working closely with infectious disease and infection control specialists at their local hospital to craft a clear and careful strategy, he said, that includes screening for any child presenting with fever.

“As we enter flu season, we’re going to be seeing lots and lots more kids with fever, and many of our refugees don’t speak English, so we’re talking through a translator. Many people here may be very fearful of expressing that someone in their family may have had Ebola-like symptoms or a travel history. There are huge issues for us here,” said Dr. DeVito. Nonetheless, as a hospital-affiliated practice, “at least we know who to call. In an isolated private practice, it would be a different story.”

Should a patient present to a clinic, Dr. Carolyn Lopez, president of the Chicago Board of Health said, “the travel history should be obtained and appropriate precautions implemented. The local and/or state health department should be contacted. They in turn should have a plan in place as to which hospital will be involved and how to transport the patient there. Bottom line is that everyone should have a plan, everyone should know their role in the plan and practice the plan so that if and when it is needed, people can implement the plan.”

Some physicians acknowledge that they currently do not have a strategy in place.

“I will be awaiting the recommendations from the CDC,” said Dr. Karalyn Kinsella, a pediatrician in private practice in Cheshire, Conn. “My questions would be how do we transport patients to the hospital? Will the ambulance companies be prepared?”

Dr. William E. Golden, professor of medicine and public health at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, said that diagnosis and triage might be the easiest task in an office setting. It’s what to do next that’s the hard part. “Offices need guidance on the aftermath,” Dr. Golden said. “Current policy is erratic at best. On the one hand, we are told that asymptomatic patients are not contagious, but now health workers in Dallas are told to stay away from public places for 3 weeks after contact with an Ebola patient. We need consistent clinical leadership, stat.”

*An earlier version of this story misidentified Dr. DeVito's medical specialty.

While plentiful guidance has been published on how hospitals should diagnose, isolate, transfer, and treat patients with Ebola virus infection or suspected infection, little information is available for the office-based physician.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that it is developing on a broader set of guidelines that will include primary care physicians and other clinicians working in outpatient practices. But these guidelines have yet to be published, and physicians at both standalone and hospital-affiliated practices are grappling with tough questions regarding isolation, transport to hospitals, and even whom to call first.

In the event of a patient presenting in an office with a travel history and symptoms suggestive of Ebola, "you would certainly do as much contact isolation as you can," said Dr. Kevin Powell, a pediatrician in St. Louis. "Most offices are prepared to do some, and it would reduce the risk markedly."

At that point, "I think the presumption of most doctors was, you call the CDC and say you need help," Dr. Powell added.

"Then we found out that the CDC isn't prepared to give that answer back."

Because an office-based physician will not be able to diagnose Ebola, regardless, Dr. Powell added, there should be “a strong emphasis toward saying that a person who thinks they have Ebola should stay away from an outpatient office and go to a hospital emergency room.”

Health officials in Ohio have advised primary care physicians to consult with any patient with suspected Ebola symptoms by phone, taking information about travel and also about potential exposures within the United States.

Dr. Jack T. Swanson, described a similar approach at the McFarland Clinic in Ames, Iowa. “If a patient calls for a sick appointment, our triage phone nurse will ask if they have been in western Africa or have had any contact with someone with Ebola in the past 21 days. If the answer is yes, they are to go to our emergency room rather than come to our office,” said Dr. Swanson, a pediatrician in private practice.

Some patients with suspected Ebola may arrive at outpatient clinics anyway. One way to establish a front-line response is to have nonclinical registration desk staff ask the first screening question, regarding travel history, Dr. Amy Gottlieb, said in an interview. At her hospital-linked outpatient practice, “If we [identified] someone with travel exposure, we could isolate them in a room and bring in someone who can do the clinical assessment in a private, controlled setting,” said Dr. Gottlieb of the departments of medicine and ob.gyn. at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

Dr. George DeVito, a pediatrician* in Concord, N.H., treats a large number of resettled and refugee families from all around the world. His outpatient practice has been working closely with infectious disease and infection control specialists at their local hospital to craft a clear and careful strategy, he said, that includes screening for any child presenting with fever.

“As we enter flu season, we’re going to be seeing lots and lots more kids with fever, and many of our refugees don’t speak English, so we’re talking through a translator. Many people here may be very fearful of expressing that someone in their family may have had Ebola-like symptoms or a travel history. There are huge issues for us here,” said Dr. DeVito. Nonetheless, as a hospital-affiliated practice, “at least we know who to call. In an isolated private practice, it would be a different story.”

Should a patient present to a clinic, Dr. Carolyn Lopez, president of the Chicago Board of Health said, “the travel history should be obtained and appropriate precautions implemented. The local and/or state health department should be contacted. They in turn should have a plan in place as to which hospital will be involved and how to transport the patient there. Bottom line is that everyone should have a plan, everyone should know their role in the plan and practice the plan so that if and when it is needed, people can implement the plan.”

Some physicians acknowledge that they currently do not have a strategy in place.

“I will be awaiting the recommendations from the CDC,” said Dr. Karalyn Kinsella, a pediatrician in private practice in Cheshire, Conn. “My questions would be how do we transport patients to the hospital? Will the ambulance companies be prepared?”

Dr. William E. Golden, professor of medicine and public health at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, said that diagnosis and triage might be the easiest task in an office setting. It’s what to do next that’s the hard part. “Offices need guidance on the aftermath,” Dr. Golden said. “Current policy is erratic at best. On the one hand, we are told that asymptomatic patients are not contagious, but now health workers in Dallas are told to stay away from public places for 3 weeks after contact with an Ebola patient. We need consistent clinical leadership, stat.”

*An earlier version of this story misidentified Dr. DeVito's medical specialty.

While plentiful guidance has been published on how hospitals should diagnose, isolate, transfer, and treat patients with Ebola virus infection or suspected infection, little information is available for the office-based physician.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that it is developing on a broader set of guidelines that will include primary care physicians and other clinicians working in outpatient practices. But these guidelines have yet to be published, and physicians at both standalone and hospital-affiliated practices are grappling with tough questions regarding isolation, transport to hospitals, and even whom to call first.

In the event of a patient presenting in an office with a travel history and symptoms suggestive of Ebola, "you would certainly do as much contact isolation as you can," said Dr. Kevin Powell, a pediatrician in St. Louis. "Most offices are prepared to do some, and it would reduce the risk markedly."

At that point, "I think the presumption of most doctors was, you call the CDC and say you need help," Dr. Powell added.

"Then we found out that the CDC isn't prepared to give that answer back."

Because an office-based physician will not be able to diagnose Ebola, regardless, Dr. Powell added, there should be “a strong emphasis toward saying that a person who thinks they have Ebola should stay away from an outpatient office and go to a hospital emergency room.”

Health officials in Ohio have advised primary care physicians to consult with any patient with suspected Ebola symptoms by phone, taking information about travel and also about potential exposures within the United States.

Dr. Jack T. Swanson, described a similar approach at the McFarland Clinic in Ames, Iowa. “If a patient calls for a sick appointment, our triage phone nurse will ask if they have been in western Africa or have had any contact with someone with Ebola in the past 21 days. If the answer is yes, they are to go to our emergency room rather than come to our office,” said Dr. Swanson, a pediatrician in private practice.

Some patients with suspected Ebola may arrive at outpatient clinics anyway. One way to establish a front-line response is to have nonclinical registration desk staff ask the first screening question, regarding travel history, Dr. Amy Gottlieb, said in an interview. At her hospital-linked outpatient practice, “If we [identified] someone with travel exposure, we could isolate them in a room and bring in someone who can do the clinical assessment in a private, controlled setting,” said Dr. Gottlieb of the departments of medicine and ob.gyn. at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

Dr. George DeVito, a pediatrician* in Concord, N.H., treats a large number of resettled and refugee families from all around the world. His outpatient practice has been working closely with infectious disease and infection control specialists at their local hospital to craft a clear and careful strategy, he said, that includes screening for any child presenting with fever.

“As we enter flu season, we’re going to be seeing lots and lots more kids with fever, and many of our refugees don’t speak English, so we’re talking through a translator. Many people here may be very fearful of expressing that someone in their family may have had Ebola-like symptoms or a travel history. There are huge issues for us here,” said Dr. DeVito. Nonetheless, as a hospital-affiliated practice, “at least we know who to call. In an isolated private practice, it would be a different story.”

Should a patient present to a clinic, Dr. Carolyn Lopez, president of the Chicago Board of Health said, “the travel history should be obtained and appropriate precautions implemented. The local and/or state health department should be contacted. They in turn should have a plan in place as to which hospital will be involved and how to transport the patient there. Bottom line is that everyone should have a plan, everyone should know their role in the plan and practice the plan so that if and when it is needed, people can implement the plan.”

Some physicians acknowledge that they currently do not have a strategy in place.

“I will be awaiting the recommendations from the CDC,” said Dr. Karalyn Kinsella, a pediatrician in private practice in Cheshire, Conn. “My questions would be how do we transport patients to the hospital? Will the ambulance companies be prepared?”

Dr. William E. Golden, professor of medicine and public health at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock, said that diagnosis and triage might be the easiest task in an office setting. It’s what to do next that’s the hard part. “Offices need guidance on the aftermath,” Dr. Golden said. “Current policy is erratic at best. On the one hand, we are told that asymptomatic patients are not contagious, but now health workers in Dallas are told to stay away from public places for 3 weeks after contact with an Ebola patient. We need consistent clinical leadership, stat.”

*An earlier version of this story misidentified Dr. DeVito's medical specialty.

President Obama names Ebola czar

President Obama has named attorney Ronald Klain its Ebola czar to oversee the federal goverment’s response to the Ebola crisis.

Mr. Klain, 53, has extensive management experience but no background in medicine. He is a long-time Democratic political operative and chief of staff to two vice presidents, Al Gore and Joe Biden. Mr. Klain left the Obama administration in January 2011 to work at a private law firm.

Mr. Klain’s career has been divided among work in the private sector, politics, and government. In addition to his service as vice-presidential chief of staff, he has played a key role in presidential election campaigns, including Al Gore’s 2000 campaign. He clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Byron R. White, served as chief counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee, and lobbied the federal government on behalf of corporate clients, according to the biography page published by his current firm, Revolution.

“Klain, an attorney, comes to the job with strong management credentials, extensive federal government experience overseeing complex operations, and good working relationships with leading members of Congress, as well as senior Obama administration officials, including the president,” said a senior administration official in a statement emailed to reporters on Friday.

President Obama has named attorney Ronald Klain its Ebola czar to oversee the federal goverment’s response to the Ebola crisis.

Mr. Klain, 53, has extensive management experience but no background in medicine. He is a long-time Democratic political operative and chief of staff to two vice presidents, Al Gore and Joe Biden. Mr. Klain left the Obama administration in January 2011 to work at a private law firm.

Mr. Klain’s career has been divided among work in the private sector, politics, and government. In addition to his service as vice-presidential chief of staff, he has played a key role in presidential election campaigns, including Al Gore’s 2000 campaign. He clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Byron R. White, served as chief counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee, and lobbied the federal government on behalf of corporate clients, according to the biography page published by his current firm, Revolution.

“Klain, an attorney, comes to the job with strong management credentials, extensive federal government experience overseeing complex operations, and good working relationships with leading members of Congress, as well as senior Obama administration officials, including the president,” said a senior administration official in a statement emailed to reporters on Friday.

President Obama has named attorney Ronald Klain its Ebola czar to oversee the federal goverment’s response to the Ebola crisis.

Mr. Klain, 53, has extensive management experience but no background in medicine. He is a long-time Democratic political operative and chief of staff to two vice presidents, Al Gore and Joe Biden. Mr. Klain left the Obama administration in January 2011 to work at a private law firm.

Mr. Klain’s career has been divided among work in the private sector, politics, and government. In addition to his service as vice-presidential chief of staff, he has played a key role in presidential election campaigns, including Al Gore’s 2000 campaign. He clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Byron R. White, served as chief counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee, and lobbied the federal government on behalf of corporate clients, according to the biography page published by his current firm, Revolution.

“Klain, an attorney, comes to the job with strong management credentials, extensive federal government experience overseeing complex operations, and good working relationships with leading members of Congress, as well as senior Obama administration officials, including the president,” said a senior administration official in a statement emailed to reporters on Friday.

CDC: Second nurse diagnosed with Ebola being transferred

A second health care worker infected with Ebola will be transferred to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta for care, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The first health care worker to be infected, nurse Nina Pham, remains at Texas Health Presbyterian in Dallas and is in good condition, top officials from both agencies said in a joint press conference Oct. 15.

The second health care worker, also said to be a nurse, was isolated in the morning of Oct. 14 and was diagnosed in preliminary testing that night. Officials revealed that she had traveled on a commercial airline Oct. 13 from Ohio to Dallas. The CDC said it was working with the airline to notify fellow passengers.

Facing increasing criticism over poor preparedness at Texas Health Presbyterian and concern that only certain U.S. hospitals may be ready to treat Ebola patients safely, CDC director Tom Frieden told reporters that “we’ll assess each day whether this is the right place” for Ms. Pham or whether she would be moved as well.

Both nurses had contact with Thomas Eric Duncan, the first patient in the United States to be diagnosed with Ebola, during times when the patient “had extensive production of body fluids because of vomiting and diarrhea,” Dr. Frieden said. Mr. Duncan died last week at Texas Health Presbyterian.

Dr. Frieden acknowledged the possibility or even likelihood of more Ebola cases “in the coming days” among the 76 health care workers at Texas Health Presbyterian who had been exposed to Mr. Duncan or his blood during his illness.

In the early days of Mr. Duncan’s care, “a variety of forms of [personal protective equipment] were used at the hospital” and that these were used in “several ways,” some of which may have led to infection, he said.

Three people have been identified as having had close contact with newest Ebola case before her isolation Oct. 14.

Dr. Frieden said that the nurse “should not have been allowed to travel by plane” per CDC guidelines, because she was being monitored as part of a group potentially exposed to Ebola and because she already had a temperature of 99.5°, though she was without further symptoms of illness.

Dr. Frieden said that health officials “think there is an extremely low risk” of other passengers on the plane having been exposed to Ebola.

A second health care worker infected with Ebola will be transferred to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta for care, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The first health care worker to be infected, nurse Nina Pham, remains at Texas Health Presbyterian in Dallas and is in good condition, top officials from both agencies said in a joint press conference Oct. 15.

The second health care worker, also said to be a nurse, was isolated in the morning of Oct. 14 and was diagnosed in preliminary testing that night. Officials revealed that she had traveled on a commercial airline Oct. 13 from Ohio to Dallas. The CDC said it was working with the airline to notify fellow passengers.

Facing increasing criticism over poor preparedness at Texas Health Presbyterian and concern that only certain U.S. hospitals may be ready to treat Ebola patients safely, CDC director Tom Frieden told reporters that “we’ll assess each day whether this is the right place” for Ms. Pham or whether she would be moved as well.

Both nurses had contact with Thomas Eric Duncan, the first patient in the United States to be diagnosed with Ebola, during times when the patient “had extensive production of body fluids because of vomiting and diarrhea,” Dr. Frieden said. Mr. Duncan died last week at Texas Health Presbyterian.

Dr. Frieden acknowledged the possibility or even likelihood of more Ebola cases “in the coming days” among the 76 health care workers at Texas Health Presbyterian who had been exposed to Mr. Duncan or his blood during his illness.

In the early days of Mr. Duncan’s care, “a variety of forms of [personal protective equipment] were used at the hospital” and that these were used in “several ways,” some of which may have led to infection, he said.

Three people have been identified as having had close contact with newest Ebola case before her isolation Oct. 14.

Dr. Frieden said that the nurse “should not have been allowed to travel by plane” per CDC guidelines, because she was being monitored as part of a group potentially exposed to Ebola and because she already had a temperature of 99.5°, though she was without further symptoms of illness.

Dr. Frieden said that health officials “think there is an extremely low risk” of other passengers on the plane having been exposed to Ebola.

A second health care worker infected with Ebola will be transferred to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta for care, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The first health care worker to be infected, nurse Nina Pham, remains at Texas Health Presbyterian in Dallas and is in good condition, top officials from both agencies said in a joint press conference Oct. 15.

The second health care worker, also said to be a nurse, was isolated in the morning of Oct. 14 and was diagnosed in preliminary testing that night. Officials revealed that she had traveled on a commercial airline Oct. 13 from Ohio to Dallas. The CDC said it was working with the airline to notify fellow passengers.

Facing increasing criticism over poor preparedness at Texas Health Presbyterian and concern that only certain U.S. hospitals may be ready to treat Ebola patients safely, CDC director Tom Frieden told reporters that “we’ll assess each day whether this is the right place” for Ms. Pham or whether she would be moved as well.

Both nurses had contact with Thomas Eric Duncan, the first patient in the United States to be diagnosed with Ebola, during times when the patient “had extensive production of body fluids because of vomiting and diarrhea,” Dr. Frieden said. Mr. Duncan died last week at Texas Health Presbyterian.

Dr. Frieden acknowledged the possibility or even likelihood of more Ebola cases “in the coming days” among the 76 health care workers at Texas Health Presbyterian who had been exposed to Mr. Duncan or his blood during his illness.

In the early days of Mr. Duncan’s care, “a variety of forms of [personal protective equipment] were used at the hospital” and that these were used in “several ways,” some of which may have led to infection, he said.

Three people have been identified as having had close contact with newest Ebola case before her isolation Oct. 14.

Dr. Frieden said that the nurse “should not have been allowed to travel by plane” per CDC guidelines, because she was being monitored as part of a group potentially exposed to Ebola and because she already had a temperature of 99.5°, though she was without further symptoms of illness.

Dr. Frieden said that health officials “think there is an extremely low risk” of other passengers on the plane having been exposed to Ebola.

FROM A CDC TELEBRIEFING

CDC: 76 HCWs being monitored for Ebola in Dallas

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will now send response teams that include specialized nurse trainers to any hospital with an Ebola diagnosis.

In a press conference on Oct.14, CDC director Thomas Frieden said the response teams would consist of experts in infection control, nursing, laboratory science, management of Ebola units, infectious waste management, and personal protective equipment. Teams would deploy “within hours” of an Ebola diagnosis and assist with transfer of patients if necessary, Dr. Frieden said.

The announcement comes as concerns grow among health care workers that hospitals are neither prepared nor equipped to protect them from Ebola infection.

“We wish we had put a team like this on the ground the minute the [index] patient was diagnosed, but we will going forward,” Dr. Frieden said, referring to Thomas Eric Duncan, the first Ebola patient diagnosed in the United States, who died last week at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. A nurse who treated Mr. Duncan, Nina Pham, became infected with Ebola and is now being treated at the same hospital. She is in stable condition.

Dr. Frieden said that 76 health care workers at Texas Health Presbyterian were now being actively monitored for symptoms of Ebola infection because of possible exposure to Mr. Duncan or his blood. This is in addition to 48 contacts of Mr. Duncan prior to his admission, and one contact of Ms. Pham’s, none of whom have shown evidence of infection.

Dr. Frieden acknowledged that the agency has not ruled out the possibility of transferring any newly diagnosed Ebola patients to one of four U.S. hospitals with special biocontainment units and Ebola expertise, such as Emory University Hospital in Atlanta. Expert nurses from Emory have recently arrived at Texas Health Presbyterian to perform Ebola-specific training.

The breach in infection control that led to Ms. Pham’s infection still has not been identified and may never be, Dr. Frieden said, but he highlighted the use of additional or excessive layers of protective gear and clothing as an area of concern. He also identified the proper use and removal of these as an intense focus of the CDC-led training efforts ongoing at Texas Health Presbyterian.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will now send response teams that include specialized nurse trainers to any hospital with an Ebola diagnosis.

In a press conference on Oct.14, CDC director Thomas Frieden said the response teams would consist of experts in infection control, nursing, laboratory science, management of Ebola units, infectious waste management, and personal protective equipment. Teams would deploy “within hours” of an Ebola diagnosis and assist with transfer of patients if necessary, Dr. Frieden said.

The announcement comes as concerns grow among health care workers that hospitals are neither prepared nor equipped to protect them from Ebola infection.

“We wish we had put a team like this on the ground the minute the [index] patient was diagnosed, but we will going forward,” Dr. Frieden said, referring to Thomas Eric Duncan, the first Ebola patient diagnosed in the United States, who died last week at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. A nurse who treated Mr. Duncan, Nina Pham, became infected with Ebola and is now being treated at the same hospital. She is in stable condition.

Dr. Frieden said that 76 health care workers at Texas Health Presbyterian were now being actively monitored for symptoms of Ebola infection because of possible exposure to Mr. Duncan or his blood. This is in addition to 48 contacts of Mr. Duncan prior to his admission, and one contact of Ms. Pham’s, none of whom have shown evidence of infection.

Dr. Frieden acknowledged that the agency has not ruled out the possibility of transferring any newly diagnosed Ebola patients to one of four U.S. hospitals with special biocontainment units and Ebola expertise, such as Emory University Hospital in Atlanta. Expert nurses from Emory have recently arrived at Texas Health Presbyterian to perform Ebola-specific training.

The breach in infection control that led to Ms. Pham’s infection still has not been identified and may never be, Dr. Frieden said, but he highlighted the use of additional or excessive layers of protective gear and clothing as an area of concern. He also identified the proper use and removal of these as an intense focus of the CDC-led training efforts ongoing at Texas Health Presbyterian.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will now send response teams that include specialized nurse trainers to any hospital with an Ebola diagnosis.

In a press conference on Oct.14, CDC director Thomas Frieden said the response teams would consist of experts in infection control, nursing, laboratory science, management of Ebola units, infectious waste management, and personal protective equipment. Teams would deploy “within hours” of an Ebola diagnosis and assist with transfer of patients if necessary, Dr. Frieden said.

The announcement comes as concerns grow among health care workers that hospitals are neither prepared nor equipped to protect them from Ebola infection.

“We wish we had put a team like this on the ground the minute the [index] patient was diagnosed, but we will going forward,” Dr. Frieden said, referring to Thomas Eric Duncan, the first Ebola patient diagnosed in the United States, who died last week at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. A nurse who treated Mr. Duncan, Nina Pham, became infected with Ebola and is now being treated at the same hospital. She is in stable condition.

Dr. Frieden said that 76 health care workers at Texas Health Presbyterian were now being actively monitored for symptoms of Ebola infection because of possible exposure to Mr. Duncan or his blood. This is in addition to 48 contacts of Mr. Duncan prior to his admission, and one contact of Ms. Pham’s, none of whom have shown evidence of infection.

Dr. Frieden acknowledged that the agency has not ruled out the possibility of transferring any newly diagnosed Ebola patients to one of four U.S. hospitals with special biocontainment units and Ebola expertise, such as Emory University Hospital in Atlanta. Expert nurses from Emory have recently arrived at Texas Health Presbyterian to perform Ebola-specific training.

The breach in infection control that led to Ms. Pham’s infection still has not been identified and may never be, Dr. Frieden said, but he highlighted the use of additional or excessive layers of protective gear and clothing as an area of concern. He also identified the proper use and removal of these as an intense focus of the CDC-led training efforts ongoing at Texas Health Presbyterian.

CDC: Breaches at Liberia hospital likely led to HCW infections

An investigation into a cluster of five health care workers infected with Ebola virus while treating patients at a designated center in Monrovia, Liberia, has revealed no common source or chain of transmission, according to a report published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nonetheless, the investigators, led by the CDC’s Dr. Joseph D. Forrester, found several opportunities for transmission at the hospital and treatment center during an on-site evaluation conducted in late July 2014. All five infections occurred over a 2-week period ending July 29.

Potential means of transmission included exposure to patients with undetected Ebola infection in the emergency department (before they could be transferred to the hospital’s Ebola treatment unit); inadequate or inconsistent use of personal protective equipment, particularly during or after cleaning; and transmission of Ebola virus from one health care worker (HCW) to another, Dr. Forrester and his colleagues report in an early release of the Oct. 14 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR 2014;63).

Two of the five health care workers who became ill died as a result of their infections.

Opportunities for transmission to the HCWs identified by Dr. Forrester and his colleagues included a patient with unrecognized Ebola who died in the emergency department, potentially exposing HCWs there. They also found that HCWs were not being monitored for fever or other symptoms, and that some had cleaned grossly contaminated surfaces without adequate protective equipment.

“None of the information collected suggested a mode of Ebola virus transmission that had not previously been described,” the investigators wrote in their analysis.

They noted as limitations of their study that interviews had not been conducted in a standardized format, and that one of the HCWs had died before investigators could conduct an interview, forcing them to rely on information provided by that individual’s colleagues.