User login

Racial disparities in maternal morbidity persist even with equal access to care

An analysis of data from the U.S. military suggests that the maternal morbidity disparities between Black and White women cannot be attributed solely to differences in access to care and socioeconomics.

Even in the U.S. military health care system, where all service members have universal access to the same facilities and providers, researchers found substantial racial disparities in cesarean deliveries, maternal ICU admission, and overall severe maternal morbidity and mortality between Black patients and White patients, according to findings from a new study presented Jan. 28, 2021, at a meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“This was surprising given some of the driving theories behind maternal race disparities encountered in this country, such as access to care and socioeconomic status, are controlled for in this health care system,” Capt. Jameaka Hamilton, MD, who presented the research, said in an interview. “Our findings indicate that there are likely additional factors at play which impact the obstetrical outcomes of women based upon their race, including systems-based barriers to accessing the military health care system which contribute to health care disparities, or in systemic or implicit biases which occur within our health care delivery.”

Plenty of recent research has documented the rise in maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States and the considerable racial disparities within those statistics. Black women are twice as likely to suffer morbidity and three to four times more likely to die in childbirth, compared with White women, Dr. Hamilton, an ob.gyn. from the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium at Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, reminded attendees. So far, much of this disparity has been attributed to social determinants of health.

Military retirees, active-duty personnel, and dependents, however, have equal access to federal health insurance and care at military health care facilities, or at covered civilian facilities where needed. Hence the researchers’ hypothesis that the military medical system would not show the same disparities by race that are seen in civilian populations.

The researchers analyzed maternal morbidity data from the Neonatal Perinatal Information Center from April 2018 to March 2019. The retrospective study included data from 13 military treatment facilities that had more than 1,000 deliveries per year. In addition to statistics on cesarean delivery and adult ICU admission, the researchers compared numbers on overall severe maternal morbidity based on the indicators defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 15,305 deliveries included 23% Black patients and 77% White patients from the Air Force, Army, and Navy branches.

The cesarean delivery rate ranged from 19.4% to 35.5%. ICU admissions totaled 38 women, 190 women had postpartum hemorrhage, and 282 women experienced severe maternal morbidity. All three measures revealed racial disparities:

- Overall severe maternal morbidity occurred in 2.66% of Black women and 1.66% of White women (P =.0001).

- ICU admission occurred in 0.49% of Black women and 0.18% of White women (P =.0026).

- 31.68% of Black women had a cesarean delivery, compared with 23.58% of White women (P <.0001).

After excluding cases with blood transfusions, Black women were twice as likely to have severe maternal morbidity (0.64% vs. 0.32%). There were no significant differences in postpartum hemorrhage rates between Black and White women, but this analysis was limited by the small overall numbers of postpartum hemorrhage.

Among the study’s limitations were the inability to stratify patients by retiree, active duty, or dependent status, and the lack of data on preeclampsia rates, maternal age, obesity, or other preexisting conditions. In addition, the initial dataset included 61% of patients who reported their race as “other” than Black or White, limiting the number of patients whose data could be analyzed. Since low-volume hospitals were excluded, the outcomes could be skewed if lower-volume facilities are more likely to care for more complex cases, Dr. Hamilton added.

Allison Bryant Mantha, MD, MPH, vice chair for quality, equity, and safety in the ob.gyn. department at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, praised Dr. Hamilton’s work for revealing that differential access – though still problematic – cannot fully explain inequities between Black women and other women.

“The findings are not shocking given that what underlies some of these inequities – namely structural and institutional racism, and differential treatment within the system – are not exclusive to civilian health care settings,” Dr. Bryant Mantha, who moderated the session, said in an interview. “That said, doing the work to demonstrate this is extremely valuable.”

Although the causes of these disparities are systemic, Dr. Hamilton said individual providers can play a role in addressing them.

“There can certainly be more done to address this dangerous trend at the provider, hospital/institution, and national level,” she said. I think we as providers should continue to self-reflect and address our own biases. Hospitals and institutions should continue to develop policies that draw attention health care disparities.”

Completely removing these inequalities, however, will require confronting the racism embedded in U.S. health care at all levels, Dr. Bryant Mantha suggested.

“Ultimately, moving to an antiracist health care system – and criminal justice system, educational system, political system, etc. – and dismantling the existing structural racism in policies and practices will be needed to drive this change,” Dr. Bryant Mantha said. “Individual clinicians can use their voices to advocate for these changes in their health systems, communities, and states. Awareness of these inequities is critical, as is a sense of collective efficacy that we can, indeed, change the status quo.”

Dr. Hamilton and Dr. Bryant Mantha reported no disclosures.

An analysis of data from the U.S. military suggests that the maternal morbidity disparities between Black and White women cannot be attributed solely to differences in access to care and socioeconomics.

Even in the U.S. military health care system, where all service members have universal access to the same facilities and providers, researchers found substantial racial disparities in cesarean deliveries, maternal ICU admission, and overall severe maternal morbidity and mortality between Black patients and White patients, according to findings from a new study presented Jan. 28, 2021, at a meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“This was surprising given some of the driving theories behind maternal race disparities encountered in this country, such as access to care and socioeconomic status, are controlled for in this health care system,” Capt. Jameaka Hamilton, MD, who presented the research, said in an interview. “Our findings indicate that there are likely additional factors at play which impact the obstetrical outcomes of women based upon their race, including systems-based barriers to accessing the military health care system which contribute to health care disparities, or in systemic or implicit biases which occur within our health care delivery.”

Plenty of recent research has documented the rise in maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States and the considerable racial disparities within those statistics. Black women are twice as likely to suffer morbidity and three to four times more likely to die in childbirth, compared with White women, Dr. Hamilton, an ob.gyn. from the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium at Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, reminded attendees. So far, much of this disparity has been attributed to social determinants of health.

Military retirees, active-duty personnel, and dependents, however, have equal access to federal health insurance and care at military health care facilities, or at covered civilian facilities where needed. Hence the researchers’ hypothesis that the military medical system would not show the same disparities by race that are seen in civilian populations.

The researchers analyzed maternal morbidity data from the Neonatal Perinatal Information Center from April 2018 to March 2019. The retrospective study included data from 13 military treatment facilities that had more than 1,000 deliveries per year. In addition to statistics on cesarean delivery and adult ICU admission, the researchers compared numbers on overall severe maternal morbidity based on the indicators defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 15,305 deliveries included 23% Black patients and 77% White patients from the Air Force, Army, and Navy branches.

The cesarean delivery rate ranged from 19.4% to 35.5%. ICU admissions totaled 38 women, 190 women had postpartum hemorrhage, and 282 women experienced severe maternal morbidity. All three measures revealed racial disparities:

- Overall severe maternal morbidity occurred in 2.66% of Black women and 1.66% of White women (P =.0001).

- ICU admission occurred in 0.49% of Black women and 0.18% of White women (P =.0026).

- 31.68% of Black women had a cesarean delivery, compared with 23.58% of White women (P <.0001).

After excluding cases with blood transfusions, Black women were twice as likely to have severe maternal morbidity (0.64% vs. 0.32%). There were no significant differences in postpartum hemorrhage rates between Black and White women, but this analysis was limited by the small overall numbers of postpartum hemorrhage.

Among the study’s limitations were the inability to stratify patients by retiree, active duty, or dependent status, and the lack of data on preeclampsia rates, maternal age, obesity, or other preexisting conditions. In addition, the initial dataset included 61% of patients who reported their race as “other” than Black or White, limiting the number of patients whose data could be analyzed. Since low-volume hospitals were excluded, the outcomes could be skewed if lower-volume facilities are more likely to care for more complex cases, Dr. Hamilton added.

Allison Bryant Mantha, MD, MPH, vice chair for quality, equity, and safety in the ob.gyn. department at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, praised Dr. Hamilton’s work for revealing that differential access – though still problematic – cannot fully explain inequities between Black women and other women.

“The findings are not shocking given that what underlies some of these inequities – namely structural and institutional racism, and differential treatment within the system – are not exclusive to civilian health care settings,” Dr. Bryant Mantha, who moderated the session, said in an interview. “That said, doing the work to demonstrate this is extremely valuable.”

Although the causes of these disparities are systemic, Dr. Hamilton said individual providers can play a role in addressing them.

“There can certainly be more done to address this dangerous trend at the provider, hospital/institution, and national level,” she said. I think we as providers should continue to self-reflect and address our own biases. Hospitals and institutions should continue to develop policies that draw attention health care disparities.”

Completely removing these inequalities, however, will require confronting the racism embedded in U.S. health care at all levels, Dr. Bryant Mantha suggested.

“Ultimately, moving to an antiracist health care system – and criminal justice system, educational system, political system, etc. – and dismantling the existing structural racism in policies and practices will be needed to drive this change,” Dr. Bryant Mantha said. “Individual clinicians can use their voices to advocate for these changes in their health systems, communities, and states. Awareness of these inequities is critical, as is a sense of collective efficacy that we can, indeed, change the status quo.”

Dr. Hamilton and Dr. Bryant Mantha reported no disclosures.

An analysis of data from the U.S. military suggests that the maternal morbidity disparities between Black and White women cannot be attributed solely to differences in access to care and socioeconomics.

Even in the U.S. military health care system, where all service members have universal access to the same facilities and providers, researchers found substantial racial disparities in cesarean deliveries, maternal ICU admission, and overall severe maternal morbidity and mortality between Black patients and White patients, according to findings from a new study presented Jan. 28, 2021, at a meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“This was surprising given some of the driving theories behind maternal race disparities encountered in this country, such as access to care and socioeconomic status, are controlled for in this health care system,” Capt. Jameaka Hamilton, MD, who presented the research, said in an interview. “Our findings indicate that there are likely additional factors at play which impact the obstetrical outcomes of women based upon their race, including systems-based barriers to accessing the military health care system which contribute to health care disparities, or in systemic or implicit biases which occur within our health care delivery.”

Plenty of recent research has documented the rise in maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States and the considerable racial disparities within those statistics. Black women are twice as likely to suffer morbidity and three to four times more likely to die in childbirth, compared with White women, Dr. Hamilton, an ob.gyn. from the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium at Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, reminded attendees. So far, much of this disparity has been attributed to social determinants of health.

Military retirees, active-duty personnel, and dependents, however, have equal access to federal health insurance and care at military health care facilities, or at covered civilian facilities where needed. Hence the researchers’ hypothesis that the military medical system would not show the same disparities by race that are seen in civilian populations.

The researchers analyzed maternal morbidity data from the Neonatal Perinatal Information Center from April 2018 to March 2019. The retrospective study included data from 13 military treatment facilities that had more than 1,000 deliveries per year. In addition to statistics on cesarean delivery and adult ICU admission, the researchers compared numbers on overall severe maternal morbidity based on the indicators defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The 15,305 deliveries included 23% Black patients and 77% White patients from the Air Force, Army, and Navy branches.

The cesarean delivery rate ranged from 19.4% to 35.5%. ICU admissions totaled 38 women, 190 women had postpartum hemorrhage, and 282 women experienced severe maternal morbidity. All three measures revealed racial disparities:

- Overall severe maternal morbidity occurred in 2.66% of Black women and 1.66% of White women (P =.0001).

- ICU admission occurred in 0.49% of Black women and 0.18% of White women (P =.0026).

- 31.68% of Black women had a cesarean delivery, compared with 23.58% of White women (P <.0001).

After excluding cases with blood transfusions, Black women were twice as likely to have severe maternal morbidity (0.64% vs. 0.32%). There were no significant differences in postpartum hemorrhage rates between Black and White women, but this analysis was limited by the small overall numbers of postpartum hemorrhage.

Among the study’s limitations were the inability to stratify patients by retiree, active duty, or dependent status, and the lack of data on preeclampsia rates, maternal age, obesity, or other preexisting conditions. In addition, the initial dataset included 61% of patients who reported their race as “other” than Black or White, limiting the number of patients whose data could be analyzed. Since low-volume hospitals were excluded, the outcomes could be skewed if lower-volume facilities are more likely to care for more complex cases, Dr. Hamilton added.

Allison Bryant Mantha, MD, MPH, vice chair for quality, equity, and safety in the ob.gyn. department at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, praised Dr. Hamilton’s work for revealing that differential access – though still problematic – cannot fully explain inequities between Black women and other women.

“The findings are not shocking given that what underlies some of these inequities – namely structural and institutional racism, and differential treatment within the system – are not exclusive to civilian health care settings,” Dr. Bryant Mantha, who moderated the session, said in an interview. “That said, doing the work to demonstrate this is extremely valuable.”

Although the causes of these disparities are systemic, Dr. Hamilton said individual providers can play a role in addressing them.

“There can certainly be more done to address this dangerous trend at the provider, hospital/institution, and national level,” she said. I think we as providers should continue to self-reflect and address our own biases. Hospitals and institutions should continue to develop policies that draw attention health care disparities.”

Completely removing these inequalities, however, will require confronting the racism embedded in U.S. health care at all levels, Dr. Bryant Mantha suggested.

“Ultimately, moving to an antiracist health care system – and criminal justice system, educational system, political system, etc. – and dismantling the existing structural racism in policies and practices will be needed to drive this change,” Dr. Bryant Mantha said. “Individual clinicians can use their voices to advocate for these changes in their health systems, communities, and states. Awareness of these inequities is critical, as is a sense of collective efficacy that we can, indeed, change the status quo.”

Dr. Hamilton and Dr. Bryant Mantha reported no disclosures.

FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Low-dose aspirin did not reduce preterm birth rates but don’t rule it out yet

Women at risk of preterm birth who took daily low-dose aspirin did not have significantly lower rates of preterm birth than those who did not take aspirin, according to preliminary findings from a small randomized controlled trial. There was a trend toward lower rates, especially among those with the highest compliance, but the study was underpowered to detect a difference with statistical significance, said Anadeijda Landman, MD, of the Amsterdam University Medical Center. Dr. Landman presented the findings Jan. 28 at a meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Preterm birth accounts for a third of all neonatal mortality, she told attendees. Among 15 million preterm births worldwide each year, 65% are spontaneous, indicating the need for effective preventive interventions. Dr. Landman reviewed several mechanisms by which aspirin may help reduce preterm birth via different pathways.

The researchers’ multicenter, placebo-controlled trial involved 8 tertiary care and 26 secondary care hospitals in the Netherlands between May 2016 and June 2019. Starting between 8 and 15 weeks’ gestation, women took either 80 mg of aspirin or a placebo daily until 36 weeks’ gestation or delivery. Women also received progesterone, cerclage, or pessary as indicated according to local protocols.

The study enrolled 406 women with singleton pregnancy and a history of preterm birth delivered between 22 and 37 weeks’ gestation. The final analysis, after exclusions for pregnancy termination, congenital anomalies, multiples pregnancy, or similar reasons, included 193 women in the intervention group and 194 in the placebo group. The women had similar baseline characteristics across both groups except a higher number of past mid-trimester fetal deaths in the aspirin group.

“It’s important to realize these women had multiple preterm births, as one of our inclusion criteria was previous spontaneous preterm birth later than 22 weeks’ gestation, so this particular group is very high risk for cervical insufficiency as a probable cause,” Dr. Landman told attendees.

Among women in the aspirin group, 21.2% delivered before 37 weeks, compared with 25.4% in the placebo group (P = .323). The rate of spontaneous birth was 20.1% in the aspirin group and 23.8% in the placebo group (P = .376). Though still not statistically significant, the difference between the groups was larger when the researchers limited their analysis to the 245 women with at least 80% compliance: 18.5% of women in the aspirin group had a preterm birth, compared with 24.8% of women in the placebo group (P = .238).

There were no significant differences between the groups in composite poor neonatal outcomes or in a range of prespecified newborn complications. The aspirin group did have two stillbirths, two mid-trimester fetal losses, and two extremely preterm newborns (at 24+2 weeks and 25+2 weeks). The placebo group had two mid-trimester fetal losses.

“These deaths are inherent to the study population, and it seems unlikely they are related to the use of aspirin,” Dr. Landman said. “Moreover other aspirin studies have not found an increased perinatal mortality rate, and some large studies indicated the neonatal mortality rate is even reduced.”

Although preterm birth only trended lower in the aspirin group, Dr. Landman said the researchers believe they cannot rule out an effect from aspirin.

“It’s also important to note that our study was underpowered as the recurrence risk of preterm birth in our study was lower than expected, so it’s possible a small treatment effect of aspirin could not be demonstrated in our study,” she said. “And, despite the proper randomization procedure, many more women in the aspirin group had a previous mid-trimester fetal loss. This indicates that the aspirin group might be more at risk for preterm birth than the placebo group, and this imbalance could also have diminished a small protective effect of aspirin.”

In response to an audience question, Dr. Landman acknowledged that more recent studies on aspirin have used 100- to 150-mg dosages, but that evidence was not as clear when their study began in 2015. She added that her research team does not advise changing clinical care currently and believes it is too soon to recommend aspirin to this population.

Tracy Manuck, MD, MS, an associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, agreed that it is premature to begin prescribing aspirin for preterm birth prevention, but she noted that most of the patients she cares for clinically already meet criteria for aspirin based on their risk factors for preeclampsia.

“Additional research is needed in the form of a well-designed and large [randomized, controlled trial],” Dr Manuck, who moderated the session, said in an interview. “However, such a trial is becoming increasingly difficult to conduct because so many pregnant women qualify to receive aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia due to their weight, medical comorbidities, or prior pregnancy history.”

She said she anticipates seeing patient-level data meta-analyses in the coming months as more data on aspirin for preterm birth prevention are published.

“Given that these data are supportive of the overall trends seen in prior publications, I do think that low-dose aspirin will eventually bear out as a helpful preventative measure to prevent recurrent preterm birth. Aspirin is low risk, readily available, and is inexpensive,” Dr. Manuck said. “I hope that meta-analysis data will provide additional information regarding the benefit of low-dose aspirin for prematurity prevention.”

The research was funded by the Dutch Organization for Health Care Research and the Dutch Consortium for Research in Women’s Health. Dr. Landman and Dr. Manuck had no disclosures.

Women at risk of preterm birth who took daily low-dose aspirin did not have significantly lower rates of preterm birth than those who did not take aspirin, according to preliminary findings from a small randomized controlled trial. There was a trend toward lower rates, especially among those with the highest compliance, but the study was underpowered to detect a difference with statistical significance, said Anadeijda Landman, MD, of the Amsterdam University Medical Center. Dr. Landman presented the findings Jan. 28 at a meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Preterm birth accounts for a third of all neonatal mortality, she told attendees. Among 15 million preterm births worldwide each year, 65% are spontaneous, indicating the need for effective preventive interventions. Dr. Landman reviewed several mechanisms by which aspirin may help reduce preterm birth via different pathways.

The researchers’ multicenter, placebo-controlled trial involved 8 tertiary care and 26 secondary care hospitals in the Netherlands between May 2016 and June 2019. Starting between 8 and 15 weeks’ gestation, women took either 80 mg of aspirin or a placebo daily until 36 weeks’ gestation or delivery. Women also received progesterone, cerclage, or pessary as indicated according to local protocols.

The study enrolled 406 women with singleton pregnancy and a history of preterm birth delivered between 22 and 37 weeks’ gestation. The final analysis, after exclusions for pregnancy termination, congenital anomalies, multiples pregnancy, or similar reasons, included 193 women in the intervention group and 194 in the placebo group. The women had similar baseline characteristics across both groups except a higher number of past mid-trimester fetal deaths in the aspirin group.

“It’s important to realize these women had multiple preterm births, as one of our inclusion criteria was previous spontaneous preterm birth later than 22 weeks’ gestation, so this particular group is very high risk for cervical insufficiency as a probable cause,” Dr. Landman told attendees.

Among women in the aspirin group, 21.2% delivered before 37 weeks, compared with 25.4% in the placebo group (P = .323). The rate of spontaneous birth was 20.1% in the aspirin group and 23.8% in the placebo group (P = .376). Though still not statistically significant, the difference between the groups was larger when the researchers limited their analysis to the 245 women with at least 80% compliance: 18.5% of women in the aspirin group had a preterm birth, compared with 24.8% of women in the placebo group (P = .238).

There were no significant differences between the groups in composite poor neonatal outcomes or in a range of prespecified newborn complications. The aspirin group did have two stillbirths, two mid-trimester fetal losses, and two extremely preterm newborns (at 24+2 weeks and 25+2 weeks). The placebo group had two mid-trimester fetal losses.

“These deaths are inherent to the study population, and it seems unlikely they are related to the use of aspirin,” Dr. Landman said. “Moreover other aspirin studies have not found an increased perinatal mortality rate, and some large studies indicated the neonatal mortality rate is even reduced.”

Although preterm birth only trended lower in the aspirin group, Dr. Landman said the researchers believe they cannot rule out an effect from aspirin.

“It’s also important to note that our study was underpowered as the recurrence risk of preterm birth in our study was lower than expected, so it’s possible a small treatment effect of aspirin could not be demonstrated in our study,” she said. “And, despite the proper randomization procedure, many more women in the aspirin group had a previous mid-trimester fetal loss. This indicates that the aspirin group might be more at risk for preterm birth than the placebo group, and this imbalance could also have diminished a small protective effect of aspirin.”

In response to an audience question, Dr. Landman acknowledged that more recent studies on aspirin have used 100- to 150-mg dosages, but that evidence was not as clear when their study began in 2015. She added that her research team does not advise changing clinical care currently and believes it is too soon to recommend aspirin to this population.

Tracy Manuck, MD, MS, an associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, agreed that it is premature to begin prescribing aspirin for preterm birth prevention, but she noted that most of the patients she cares for clinically already meet criteria for aspirin based on their risk factors for preeclampsia.

“Additional research is needed in the form of a well-designed and large [randomized, controlled trial],” Dr Manuck, who moderated the session, said in an interview. “However, such a trial is becoming increasingly difficult to conduct because so many pregnant women qualify to receive aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia due to their weight, medical comorbidities, or prior pregnancy history.”

She said she anticipates seeing patient-level data meta-analyses in the coming months as more data on aspirin for preterm birth prevention are published.

“Given that these data are supportive of the overall trends seen in prior publications, I do think that low-dose aspirin will eventually bear out as a helpful preventative measure to prevent recurrent preterm birth. Aspirin is low risk, readily available, and is inexpensive,” Dr. Manuck said. “I hope that meta-analysis data will provide additional information regarding the benefit of low-dose aspirin for prematurity prevention.”

The research was funded by the Dutch Organization for Health Care Research and the Dutch Consortium for Research in Women’s Health. Dr. Landman and Dr. Manuck had no disclosures.

Women at risk of preterm birth who took daily low-dose aspirin did not have significantly lower rates of preterm birth than those who did not take aspirin, according to preliminary findings from a small randomized controlled trial. There was a trend toward lower rates, especially among those with the highest compliance, but the study was underpowered to detect a difference with statistical significance, said Anadeijda Landman, MD, of the Amsterdam University Medical Center. Dr. Landman presented the findings Jan. 28 at a meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Preterm birth accounts for a third of all neonatal mortality, she told attendees. Among 15 million preterm births worldwide each year, 65% are spontaneous, indicating the need for effective preventive interventions. Dr. Landman reviewed several mechanisms by which aspirin may help reduce preterm birth via different pathways.

The researchers’ multicenter, placebo-controlled trial involved 8 tertiary care and 26 secondary care hospitals in the Netherlands between May 2016 and June 2019. Starting between 8 and 15 weeks’ gestation, women took either 80 mg of aspirin or a placebo daily until 36 weeks’ gestation or delivery. Women also received progesterone, cerclage, or pessary as indicated according to local protocols.

The study enrolled 406 women with singleton pregnancy and a history of preterm birth delivered between 22 and 37 weeks’ gestation. The final analysis, after exclusions for pregnancy termination, congenital anomalies, multiples pregnancy, or similar reasons, included 193 women in the intervention group and 194 in the placebo group. The women had similar baseline characteristics across both groups except a higher number of past mid-trimester fetal deaths in the aspirin group.

“It’s important to realize these women had multiple preterm births, as one of our inclusion criteria was previous spontaneous preterm birth later than 22 weeks’ gestation, so this particular group is very high risk for cervical insufficiency as a probable cause,” Dr. Landman told attendees.

Among women in the aspirin group, 21.2% delivered before 37 weeks, compared with 25.4% in the placebo group (P = .323). The rate of spontaneous birth was 20.1% in the aspirin group and 23.8% in the placebo group (P = .376). Though still not statistically significant, the difference between the groups was larger when the researchers limited their analysis to the 245 women with at least 80% compliance: 18.5% of women in the aspirin group had a preterm birth, compared with 24.8% of women in the placebo group (P = .238).

There were no significant differences between the groups in composite poor neonatal outcomes or in a range of prespecified newborn complications. The aspirin group did have two stillbirths, two mid-trimester fetal losses, and two extremely preterm newborns (at 24+2 weeks and 25+2 weeks). The placebo group had two mid-trimester fetal losses.

“These deaths are inherent to the study population, and it seems unlikely they are related to the use of aspirin,” Dr. Landman said. “Moreover other aspirin studies have not found an increased perinatal mortality rate, and some large studies indicated the neonatal mortality rate is even reduced.”

Although preterm birth only trended lower in the aspirin group, Dr. Landman said the researchers believe they cannot rule out an effect from aspirin.

“It’s also important to note that our study was underpowered as the recurrence risk of preterm birth in our study was lower than expected, so it’s possible a small treatment effect of aspirin could not be demonstrated in our study,” she said. “And, despite the proper randomization procedure, many more women in the aspirin group had a previous mid-trimester fetal loss. This indicates that the aspirin group might be more at risk for preterm birth than the placebo group, and this imbalance could also have diminished a small protective effect of aspirin.”

In response to an audience question, Dr. Landman acknowledged that more recent studies on aspirin have used 100- to 150-mg dosages, but that evidence was not as clear when their study began in 2015. She added that her research team does not advise changing clinical care currently and believes it is too soon to recommend aspirin to this population.

Tracy Manuck, MD, MS, an associate professor of ob.gyn. at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, agreed that it is premature to begin prescribing aspirin for preterm birth prevention, but she noted that most of the patients she cares for clinically already meet criteria for aspirin based on their risk factors for preeclampsia.

“Additional research is needed in the form of a well-designed and large [randomized, controlled trial],” Dr Manuck, who moderated the session, said in an interview. “However, such a trial is becoming increasingly difficult to conduct because so many pregnant women qualify to receive aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia due to their weight, medical comorbidities, or prior pregnancy history.”

She said she anticipates seeing patient-level data meta-analyses in the coming months as more data on aspirin for preterm birth prevention are published.

“Given that these data are supportive of the overall trends seen in prior publications, I do think that low-dose aspirin will eventually bear out as a helpful preventative measure to prevent recurrent preterm birth. Aspirin is low risk, readily available, and is inexpensive,” Dr. Manuck said. “I hope that meta-analysis data will provide additional information regarding the benefit of low-dose aspirin for prematurity prevention.”

The research was funded by the Dutch Organization for Health Care Research and the Dutch Consortium for Research in Women’s Health. Dr. Landman and Dr. Manuck had no disclosures.

FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

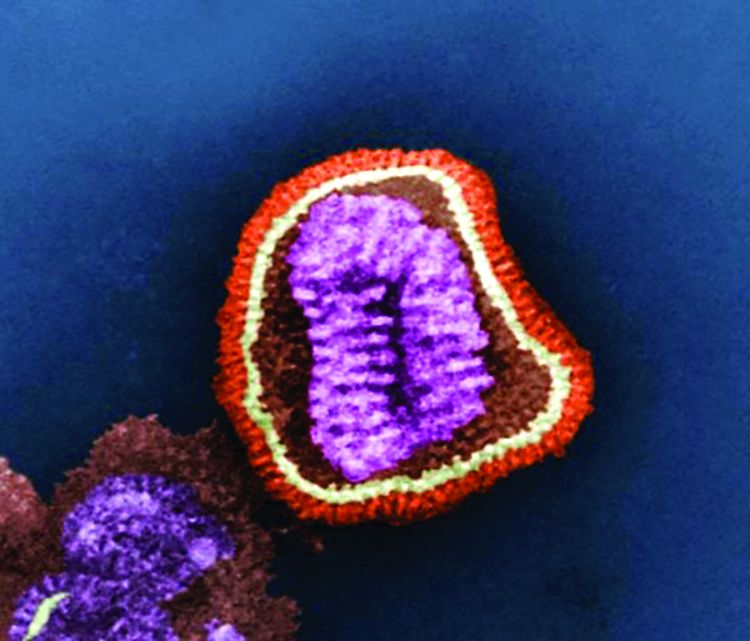

COVID-19 in pregnancy tied to hypertension, preeclampsia

Having COVID-19 during pregnancy is linked to a significantly increased risk for gestational hypertension and preeclampsia compared with not having COVID-19 while pregnant, according to findings from a retrospective study presented Jan. 28 at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine 2021 Annual Pregnancy Meeting.

“This was not entirely surprising given that inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of both hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and COVID-19 infection and thus may serve to exacerbate each other,” Nigel Madden, MD, a resident physician in the ob.gyn. department at Columbia University, New York. , told this news organization after she presented the results.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy occur in 10%-15% of all pregnancies and are the leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide, Dr. Madden told attendees of the meeting. Although it’s not clear what causes hypertensive diseases in pregnancy generally, “it is possible that the acute inflammatory state of the COVID infection may incite or exacerbate hypertensive disease of pregnancy,” Dr. Madden said.

The researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of 1,715 patients who had a singleton pregnancy and who underwent routine nasal polymerase chain reaction testing at admission to one institution’s labor and delivery department between March and June 2020. The researchers excluded patients who had a history of chronic hypertension.

Overall, 10% of the patients tested positive for COVID-19 (n = 167), and 90% tested negative (n = 1,548). There were several differences at baseline between the groups. Those who tested positive tended to be younger, with an average age of 28, compared with an average age of 31 years for the group that tested negative. The group that tested negative also had a higher proportion of mothers aged 35 and older (P < .01). There were also significant differences in the racial makeup of the groups. Half of those in the COVID-positive group reported “other” for their race. The biggest baseline disparity between the groups was with regard to insurance type: 73% of those who tested positive for COVID-19 used Medicaid; only 36% of patients in the COVID-negative group used Medicaid. Those with private insurance were more likely to test negative (43%) than positive (25%) (P < .01).

The researchers defined gestational hypertension as having a systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg on two occasions at least 4 hours apart. A preeclampsia diagnosis required elevated blood pressure (using the same definition as for hypertension) as well as proteinuria, characterized by a protein/creatine ratio greater than or equal to 0.3 mg/dL or greater than or equal to 300 mg of protein on a 24-hour urine collection. Preeclampsia with severe features required prespecified laboratory abnormalities, pulmonary edema, or symptoms of headache, vision changes, chest pain, shortness of breath, or right upper quadrant pain.

More than twice as many patients with COVID had a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (18%) as those who tested negative (8%). The patients who were COVID positive were significantly more likely than those who tested negative to have gestational hypertension and preeclampsia without severe features. Rates of preeclampsia with severe features were not significantly different between the groups.

The severity of hypertensive disease did not differ between the groups. Limitations of the study included its retrospective design, the small number of COVID-positive patients, and the fact that it was conducted at a single institution in New York. However, the study population was diverse, and it was conducted during the height of infections at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This was a study of great clinical significance,” said Kim Boggess, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, while moderating the session. “I would argue that you guys in New York are the best poised to answer some of the questions that need to be answered as it relates to the effect of coronavirus infection in pregnancy.”

Dr. Boggess asked whether the study examined associations related to the severity of COVID-19. Only 10 of the patients were symptomatic, Dr. Madden said, and only one of those patients developed preeclampsia with severe features.

Michelle Y. Owens, MD, professor and chief of maternal fetal medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, who also moderated the session, said in an interview that the findings call for physicians to remain vigilant about evaluating patients who test positive for COVID-19 for hypertensive disease and disorders.

“Additionally, these women should be educated about hypertensive disorders and the common symptoms to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment when indicated,” Dr. Owens said. “I believe this is of particular interest in those women who are not severely affected by COVID, as these changes may occur while they are undergoing quarantine or being monitored remotely. This amplifies the need for remote assessment or home monitoring of maternal blood pressures.”

Dr. Madden, Dr. Boggess, and Dr. Owens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Having COVID-19 during pregnancy is linked to a significantly increased risk for gestational hypertension and preeclampsia compared with not having COVID-19 while pregnant, according to findings from a retrospective study presented Jan. 28 at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine 2021 Annual Pregnancy Meeting.

“This was not entirely surprising given that inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of both hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and COVID-19 infection and thus may serve to exacerbate each other,” Nigel Madden, MD, a resident physician in the ob.gyn. department at Columbia University, New York. , told this news organization after she presented the results.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy occur in 10%-15% of all pregnancies and are the leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide, Dr. Madden told attendees of the meeting. Although it’s not clear what causes hypertensive diseases in pregnancy generally, “it is possible that the acute inflammatory state of the COVID infection may incite or exacerbate hypertensive disease of pregnancy,” Dr. Madden said.

The researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of 1,715 patients who had a singleton pregnancy and who underwent routine nasal polymerase chain reaction testing at admission to one institution’s labor and delivery department between March and June 2020. The researchers excluded patients who had a history of chronic hypertension.

Overall, 10% of the patients tested positive for COVID-19 (n = 167), and 90% tested negative (n = 1,548). There were several differences at baseline between the groups. Those who tested positive tended to be younger, with an average age of 28, compared with an average age of 31 years for the group that tested negative. The group that tested negative also had a higher proportion of mothers aged 35 and older (P < .01). There were also significant differences in the racial makeup of the groups. Half of those in the COVID-positive group reported “other” for their race. The biggest baseline disparity between the groups was with regard to insurance type: 73% of those who tested positive for COVID-19 used Medicaid; only 36% of patients in the COVID-negative group used Medicaid. Those with private insurance were more likely to test negative (43%) than positive (25%) (P < .01).

The researchers defined gestational hypertension as having a systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg on two occasions at least 4 hours apart. A preeclampsia diagnosis required elevated blood pressure (using the same definition as for hypertension) as well as proteinuria, characterized by a protein/creatine ratio greater than or equal to 0.3 mg/dL or greater than or equal to 300 mg of protein on a 24-hour urine collection. Preeclampsia with severe features required prespecified laboratory abnormalities, pulmonary edema, or symptoms of headache, vision changes, chest pain, shortness of breath, or right upper quadrant pain.

More than twice as many patients with COVID had a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (18%) as those who tested negative (8%). The patients who were COVID positive were significantly more likely than those who tested negative to have gestational hypertension and preeclampsia without severe features. Rates of preeclampsia with severe features were not significantly different between the groups.

The severity of hypertensive disease did not differ between the groups. Limitations of the study included its retrospective design, the small number of COVID-positive patients, and the fact that it was conducted at a single institution in New York. However, the study population was diverse, and it was conducted during the height of infections at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This was a study of great clinical significance,” said Kim Boggess, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, while moderating the session. “I would argue that you guys in New York are the best poised to answer some of the questions that need to be answered as it relates to the effect of coronavirus infection in pregnancy.”

Dr. Boggess asked whether the study examined associations related to the severity of COVID-19. Only 10 of the patients were symptomatic, Dr. Madden said, and only one of those patients developed preeclampsia with severe features.

Michelle Y. Owens, MD, professor and chief of maternal fetal medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, who also moderated the session, said in an interview that the findings call for physicians to remain vigilant about evaluating patients who test positive for COVID-19 for hypertensive disease and disorders.

“Additionally, these women should be educated about hypertensive disorders and the common symptoms to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment when indicated,” Dr. Owens said. “I believe this is of particular interest in those women who are not severely affected by COVID, as these changes may occur while they are undergoing quarantine or being monitored remotely. This amplifies the need for remote assessment or home monitoring of maternal blood pressures.”

Dr. Madden, Dr. Boggess, and Dr. Owens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Having COVID-19 during pregnancy is linked to a significantly increased risk for gestational hypertension and preeclampsia compared with not having COVID-19 while pregnant, according to findings from a retrospective study presented Jan. 28 at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine 2021 Annual Pregnancy Meeting.

“This was not entirely surprising given that inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of both hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and COVID-19 infection and thus may serve to exacerbate each other,” Nigel Madden, MD, a resident physician in the ob.gyn. department at Columbia University, New York. , told this news organization after she presented the results.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy occur in 10%-15% of all pregnancies and are the leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality worldwide, Dr. Madden told attendees of the meeting. Although it’s not clear what causes hypertensive diseases in pregnancy generally, “it is possible that the acute inflammatory state of the COVID infection may incite or exacerbate hypertensive disease of pregnancy,” Dr. Madden said.

The researchers conducted a retrospective chart review of 1,715 patients who had a singleton pregnancy and who underwent routine nasal polymerase chain reaction testing at admission to one institution’s labor and delivery department between March and June 2020. The researchers excluded patients who had a history of chronic hypertension.

Overall, 10% of the patients tested positive for COVID-19 (n = 167), and 90% tested negative (n = 1,548). There were several differences at baseline between the groups. Those who tested positive tended to be younger, with an average age of 28, compared with an average age of 31 years for the group that tested negative. The group that tested negative also had a higher proportion of mothers aged 35 and older (P < .01). There were also significant differences in the racial makeup of the groups. Half of those in the COVID-positive group reported “other” for their race. The biggest baseline disparity between the groups was with regard to insurance type: 73% of those who tested positive for COVID-19 used Medicaid; only 36% of patients in the COVID-negative group used Medicaid. Those with private insurance were more likely to test negative (43%) than positive (25%) (P < .01).

The researchers defined gestational hypertension as having a systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 140 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 mm Hg on two occasions at least 4 hours apart. A preeclampsia diagnosis required elevated blood pressure (using the same definition as for hypertension) as well as proteinuria, characterized by a protein/creatine ratio greater than or equal to 0.3 mg/dL or greater than or equal to 300 mg of protein on a 24-hour urine collection. Preeclampsia with severe features required prespecified laboratory abnormalities, pulmonary edema, or symptoms of headache, vision changes, chest pain, shortness of breath, or right upper quadrant pain.

More than twice as many patients with COVID had a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (18%) as those who tested negative (8%). The patients who were COVID positive were significantly more likely than those who tested negative to have gestational hypertension and preeclampsia without severe features. Rates of preeclampsia with severe features were not significantly different between the groups.

The severity of hypertensive disease did not differ between the groups. Limitations of the study included its retrospective design, the small number of COVID-positive patients, and the fact that it was conducted at a single institution in New York. However, the study population was diverse, and it was conducted during the height of infections at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This was a study of great clinical significance,” said Kim Boggess, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, while moderating the session. “I would argue that you guys in New York are the best poised to answer some of the questions that need to be answered as it relates to the effect of coronavirus infection in pregnancy.”

Dr. Boggess asked whether the study examined associations related to the severity of COVID-19. Only 10 of the patients were symptomatic, Dr. Madden said, and only one of those patients developed preeclampsia with severe features.

Michelle Y. Owens, MD, professor and chief of maternal fetal medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, who also moderated the session, said in an interview that the findings call for physicians to remain vigilant about evaluating patients who test positive for COVID-19 for hypertensive disease and disorders.

“Additionally, these women should be educated about hypertensive disorders and the common symptoms to facilitate early diagnosis and treatment when indicated,” Dr. Owens said. “I believe this is of particular interest in those women who are not severely affected by COVID, as these changes may occur while they are undergoing quarantine or being monitored remotely. This amplifies the need for remote assessment or home monitoring of maternal blood pressures.”

Dr. Madden, Dr. Boggess, and Dr. Owens have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Maternal COVID antibodies cross placenta, detected in newborns

Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 cross the placenta during pregnancy and are detectable in most newborns born to mothers who had COVID-19 during pregnancy, according to findings from a study presented Jan. 28 at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“I think the most striking finding is that we noticed a high degree of neutralizing response to natural infection even among asymptomatic infection, but of course a higher degree was seen in those with symptomatic infection,” Naima Joseph, MD, MPH, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“Our data demonstrate maternal capacity to mount an appropriate and robust immune response,” and maternal protective immunity lasted at least 28 days after infection, Dr. Joseph said. “Also, we noted higher neonatal cord blood titers in moms with higher titers, which suggests a relationship, but we need to better understand how transplacental transfer occurs as well as establish neonatal correlates of protection in order to see if and how maternal immunity may also benefit neonates.”

The researchers analyzed the amount of IgG and IgM antibodies in maternal and cord blood samples prospectively collected at delivery from women who tested positive for COVID-19 at any time while pregnant. They used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to assess for antibodies for the receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

The 32 pairs of mothers and infants in the study were predominantly non-Hispanic Black (72%) and Hispanic (25%), and 84% used Medicaid as their payer. Most of the mothers (72%) had at least one comorbidity, most commonly obesity, hypertension, and asthma or pulmonary disease. Just over half the women (53%) were symptomatic while they were infected, and 88% were ill with COVID-19 during the third trimester. The average time from infection to delivery was 28 days.

All the mothers had IgG antibodies, 94% had IgM antibodies, and 94% had neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Among the cord blood samples, 91% had IgG antibodies, 9% had IgM antibodies, and 25% had neutralizing antibodies.

“It’s reassuring that, so far, the physiological response is exactly what we expected it to be,” Judette Louis, MD, MPH, an associate professor of ob.gyn. and the ob.gyn. department chair at the University of South Florida, Tampa, said in an interview. “It’s what we would expect, but it’s always helpful to have more data to support that. Otherwise, you’re extrapolating from what you know from other conditions,” said Dr. Louis, who moderated the oral abstracts session.

Symptomatic infection was associated with significantly higher IgG titers than asymptomatic infection (P = .03), but no correlation was seen for IgM or neutralizing antibodies. In addition, although mothers who delivered more than 28 days after their infection had higher IgG titers (P = .05), no differences existed in IgM or neutralizing response.

Infants’ cord blood titers were significantly lower than their corresponding maternal samples, independently of symptoms or latency from infection to delivery (P < .001), Dr. Joseph reported.

“Transplacental efficiency in other pathogens has been shown to be correlated with neonatal immunity when the ratio of cord to maternal blood is greater than 1,” Dr. Joseph said in her presentation. Their data showed “suboptimal efficiency” at a ratio of 0.81.

The study’s small sample size and lack of a control group were weaknesses, but a major strength was having a population at disproportionately higher risk for infection and severe morbidity than the general population.

Implications for maternal COVID-19 vaccination

Although the data are not yet available, Dr. Joseph said they have expanded their protocol to include vaccinated pregnant women.

“The key to developing an effective vaccine [for pregnant people] is in really characterizing adaptive immunity in pregnancy,” Dr. Joseph told SMFM attendees. “I think that these findings inform further vaccine development in demonstrating that maternal immunity is robust.”

The World Health Organization recently recommended withholding COVID-19 vaccines from pregnant people, but the SMFM and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists subsequently issued a joint statement reaffirming that the COVID-19 vaccines authorized by the FDA “should not be withheld from pregnant individuals who choose to receive the vaccine.”

“One of the questions people ask is whether in pregnancy you’re going to mount a good response to the vaccine the way you would outside of pregnancy,” Dr. Louis said. “If we can demonstrate that you do, that may provide the information that some mothers need to make their decisions.” Data such as those from Dr. Joseph’s study can also inform recommendations on timing of maternal vaccination.

“For instance, Dr. Joseph demonstrated that, 28 days out from the infection, you had more antibodies, so there may be a scenario where we say this vaccine may be more beneficial in the middle of the pregnancy for the purpose of forming those antibodies,” Dr. Louis said.

Consensus emerging from maternal antibodies data

The findings from Dr. Joseph’s study mirror those reported in a study published online Jan. 29 in JAMA Pediatrics. That study, led by Dustin D. Flannery, DO, MSCE, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, also examined maternal and neonatal levels of IgG and IgM antibodies against the receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. They also found a positive correlation between cord blood and maternal IgG concentrations (P < .001), but notably, the ratio of cord to maternal blood titers was greater than 1, unlike in Dr. Joseph’s study.

For their study, Dr. Flannery and colleagues obtained maternal and cord blood sera at the time of delivery from 1471 pairs of mothers and infants, independently of COVID status during pregnancy. The average maternal age was 32 years, and just over a quarter of the population (26%) were Black, non-Hispanic women. About half (51%) were White, 12% were Hispanic, and 7% were Asian.

About 6% of the women had either IgG or IgM antibodies at delivery, and 87% of infants born to those mothers had measurable IgG in their cord blood. No infants had IgM antibodies. As with the study presented at SMFM, the mothers’ infections included asymptomatic, mild, moderate, and severe cases, and the degree of severity of cases had no apparent effect on infant antibody concentrations. Most of the women who tested positive for COVID-19 (60%) were asymptomatic.

Among the 11 mothers who had antibodies but whose infants’ cord blood did not, 5 had only IgM antibodies, and 6 had significantly lower IgG concentrations than those seen in the other mothers.

In a commentary about the JAMA Pediatrics study, Flor Munoz, MD, of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, suggested that the findings are grounds for optimism about a maternal vaccination strategy to protect infants from COVID-19.

“However, the timing of maternal vaccination to protect the infant, as opposed to the mother alone, would necessitate an adequate interval from vaccination to delivery (of at least 4 weeks), while vaccination early in gestation and even late in the third trimester could still be protective for the mother,” Dr. Munoz wrote.

Given the interval between two-dose vaccination regimens and the fact that transplacental transfer begins at about the 17th week of gestation, “maternal vaccination starting in the early second trimester of gestation might be optimal to achieve the highest levels of antibodies in the newborn,” Dr. Munoz wrote. But questions remain, such as how effective the neonatal antibodies would be in protecting against COVID-19 and how long they last after birth.

No external funding was used in Dr. Joseph’s study. Dr. Joseph and Dr. Louis have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The JAMA Pediatrics study was funded by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. One coauthor received consultancy fees from Sanofi Pasteur, Lumen, Novavax, and Merck unrelated to the study. Dr. Munoz served on the data and safety monitoring boards of Moderna, Pfizer, Virometix, and Meissa Vaccines and has received grants from Novavax Research and Gilead Research.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 cross the placenta during pregnancy and are detectable in most newborns born to mothers who had COVID-19 during pregnancy, according to findings from a study presented Jan. 28 at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“I think the most striking finding is that we noticed a high degree of neutralizing response to natural infection even among asymptomatic infection, but of course a higher degree was seen in those with symptomatic infection,” Naima Joseph, MD, MPH, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“Our data demonstrate maternal capacity to mount an appropriate and robust immune response,” and maternal protective immunity lasted at least 28 days after infection, Dr. Joseph said. “Also, we noted higher neonatal cord blood titers in moms with higher titers, which suggests a relationship, but we need to better understand how transplacental transfer occurs as well as establish neonatal correlates of protection in order to see if and how maternal immunity may also benefit neonates.”

The researchers analyzed the amount of IgG and IgM antibodies in maternal and cord blood samples prospectively collected at delivery from women who tested positive for COVID-19 at any time while pregnant. They used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to assess for antibodies for the receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

The 32 pairs of mothers and infants in the study were predominantly non-Hispanic Black (72%) and Hispanic (25%), and 84% used Medicaid as their payer. Most of the mothers (72%) had at least one comorbidity, most commonly obesity, hypertension, and asthma or pulmonary disease. Just over half the women (53%) were symptomatic while they were infected, and 88% were ill with COVID-19 during the third trimester. The average time from infection to delivery was 28 days.

All the mothers had IgG antibodies, 94% had IgM antibodies, and 94% had neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Among the cord blood samples, 91% had IgG antibodies, 9% had IgM antibodies, and 25% had neutralizing antibodies.

“It’s reassuring that, so far, the physiological response is exactly what we expected it to be,” Judette Louis, MD, MPH, an associate professor of ob.gyn. and the ob.gyn. department chair at the University of South Florida, Tampa, said in an interview. “It’s what we would expect, but it’s always helpful to have more data to support that. Otherwise, you’re extrapolating from what you know from other conditions,” said Dr. Louis, who moderated the oral abstracts session.

Symptomatic infection was associated with significantly higher IgG titers than asymptomatic infection (P = .03), but no correlation was seen for IgM or neutralizing antibodies. In addition, although mothers who delivered more than 28 days after their infection had higher IgG titers (P = .05), no differences existed in IgM or neutralizing response.

Infants’ cord blood titers were significantly lower than their corresponding maternal samples, independently of symptoms or latency from infection to delivery (P < .001), Dr. Joseph reported.

“Transplacental efficiency in other pathogens has been shown to be correlated with neonatal immunity when the ratio of cord to maternal blood is greater than 1,” Dr. Joseph said in her presentation. Their data showed “suboptimal efficiency” at a ratio of 0.81.

The study’s small sample size and lack of a control group were weaknesses, but a major strength was having a population at disproportionately higher risk for infection and severe morbidity than the general population.

Implications for maternal COVID-19 vaccination

Although the data are not yet available, Dr. Joseph said they have expanded their protocol to include vaccinated pregnant women.

“The key to developing an effective vaccine [for pregnant people] is in really characterizing adaptive immunity in pregnancy,” Dr. Joseph told SMFM attendees. “I think that these findings inform further vaccine development in demonstrating that maternal immunity is robust.”

The World Health Organization recently recommended withholding COVID-19 vaccines from pregnant people, but the SMFM and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists subsequently issued a joint statement reaffirming that the COVID-19 vaccines authorized by the FDA “should not be withheld from pregnant individuals who choose to receive the vaccine.”

“One of the questions people ask is whether in pregnancy you’re going to mount a good response to the vaccine the way you would outside of pregnancy,” Dr. Louis said. “If we can demonstrate that you do, that may provide the information that some mothers need to make their decisions.” Data such as those from Dr. Joseph’s study can also inform recommendations on timing of maternal vaccination.

“For instance, Dr. Joseph demonstrated that, 28 days out from the infection, you had more antibodies, so there may be a scenario where we say this vaccine may be more beneficial in the middle of the pregnancy for the purpose of forming those antibodies,” Dr. Louis said.

Consensus emerging from maternal antibodies data

The findings from Dr. Joseph’s study mirror those reported in a study published online Jan. 29 in JAMA Pediatrics. That study, led by Dustin D. Flannery, DO, MSCE, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, also examined maternal and neonatal levels of IgG and IgM antibodies against the receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. They also found a positive correlation between cord blood and maternal IgG concentrations (P < .001), but notably, the ratio of cord to maternal blood titers was greater than 1, unlike in Dr. Joseph’s study.

For their study, Dr. Flannery and colleagues obtained maternal and cord blood sera at the time of delivery from 1471 pairs of mothers and infants, independently of COVID status during pregnancy. The average maternal age was 32 years, and just over a quarter of the population (26%) were Black, non-Hispanic women. About half (51%) were White, 12% were Hispanic, and 7% were Asian.

About 6% of the women had either IgG or IgM antibodies at delivery, and 87% of infants born to those mothers had measurable IgG in their cord blood. No infants had IgM antibodies. As with the study presented at SMFM, the mothers’ infections included asymptomatic, mild, moderate, and severe cases, and the degree of severity of cases had no apparent effect on infant antibody concentrations. Most of the women who tested positive for COVID-19 (60%) were asymptomatic.

Among the 11 mothers who had antibodies but whose infants’ cord blood did not, 5 had only IgM antibodies, and 6 had significantly lower IgG concentrations than those seen in the other mothers.

In a commentary about the JAMA Pediatrics study, Flor Munoz, MD, of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, suggested that the findings are grounds for optimism about a maternal vaccination strategy to protect infants from COVID-19.

“However, the timing of maternal vaccination to protect the infant, as opposed to the mother alone, would necessitate an adequate interval from vaccination to delivery (of at least 4 weeks), while vaccination early in gestation and even late in the third trimester could still be protective for the mother,” Dr. Munoz wrote.

Given the interval between two-dose vaccination regimens and the fact that transplacental transfer begins at about the 17th week of gestation, “maternal vaccination starting in the early second trimester of gestation might be optimal to achieve the highest levels of antibodies in the newborn,” Dr. Munoz wrote. But questions remain, such as how effective the neonatal antibodies would be in protecting against COVID-19 and how long they last after birth.

No external funding was used in Dr. Joseph’s study. Dr. Joseph and Dr. Louis have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The JAMA Pediatrics study was funded by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. One coauthor received consultancy fees from Sanofi Pasteur, Lumen, Novavax, and Merck unrelated to the study. Dr. Munoz served on the data and safety monitoring boards of Moderna, Pfizer, Virometix, and Meissa Vaccines and has received grants from Novavax Research and Gilead Research.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 cross the placenta during pregnancy and are detectable in most newborns born to mothers who had COVID-19 during pregnancy, according to findings from a study presented Jan. 28 at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“I think the most striking finding is that we noticed a high degree of neutralizing response to natural infection even among asymptomatic infection, but of course a higher degree was seen in those with symptomatic infection,” Naima Joseph, MD, MPH, of Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“Our data demonstrate maternal capacity to mount an appropriate and robust immune response,” and maternal protective immunity lasted at least 28 days after infection, Dr. Joseph said. “Also, we noted higher neonatal cord blood titers in moms with higher titers, which suggests a relationship, but we need to better understand how transplacental transfer occurs as well as establish neonatal correlates of protection in order to see if and how maternal immunity may also benefit neonates.”

The researchers analyzed the amount of IgG and IgM antibodies in maternal and cord blood samples prospectively collected at delivery from women who tested positive for COVID-19 at any time while pregnant. They used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to assess for antibodies for the receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

The 32 pairs of mothers and infants in the study were predominantly non-Hispanic Black (72%) and Hispanic (25%), and 84% used Medicaid as their payer. Most of the mothers (72%) had at least one comorbidity, most commonly obesity, hypertension, and asthma or pulmonary disease. Just over half the women (53%) were symptomatic while they were infected, and 88% were ill with COVID-19 during the third trimester. The average time from infection to delivery was 28 days.

All the mothers had IgG antibodies, 94% had IgM antibodies, and 94% had neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Among the cord blood samples, 91% had IgG antibodies, 9% had IgM antibodies, and 25% had neutralizing antibodies.

“It’s reassuring that, so far, the physiological response is exactly what we expected it to be,” Judette Louis, MD, MPH, an associate professor of ob.gyn. and the ob.gyn. department chair at the University of South Florida, Tampa, said in an interview. “It’s what we would expect, but it’s always helpful to have more data to support that. Otherwise, you’re extrapolating from what you know from other conditions,” said Dr. Louis, who moderated the oral abstracts session.

Symptomatic infection was associated with significantly higher IgG titers than asymptomatic infection (P = .03), but no correlation was seen for IgM or neutralizing antibodies. In addition, although mothers who delivered more than 28 days after their infection had higher IgG titers (P = .05), no differences existed in IgM or neutralizing response.

Infants’ cord blood titers were significantly lower than their corresponding maternal samples, independently of symptoms or latency from infection to delivery (P < .001), Dr. Joseph reported.

“Transplacental efficiency in other pathogens has been shown to be correlated with neonatal immunity when the ratio of cord to maternal blood is greater than 1,” Dr. Joseph said in her presentation. Their data showed “suboptimal efficiency” at a ratio of 0.81.

The study’s small sample size and lack of a control group were weaknesses, but a major strength was having a population at disproportionately higher risk for infection and severe morbidity than the general population.

Implications for maternal COVID-19 vaccination

Although the data are not yet available, Dr. Joseph said they have expanded their protocol to include vaccinated pregnant women.

“The key to developing an effective vaccine [for pregnant people] is in really characterizing adaptive immunity in pregnancy,” Dr. Joseph told SMFM attendees. “I think that these findings inform further vaccine development in demonstrating that maternal immunity is robust.”

The World Health Organization recently recommended withholding COVID-19 vaccines from pregnant people, but the SMFM and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists subsequently issued a joint statement reaffirming that the COVID-19 vaccines authorized by the FDA “should not be withheld from pregnant individuals who choose to receive the vaccine.”

“One of the questions people ask is whether in pregnancy you’re going to mount a good response to the vaccine the way you would outside of pregnancy,” Dr. Louis said. “If we can demonstrate that you do, that may provide the information that some mothers need to make their decisions.” Data such as those from Dr. Joseph’s study can also inform recommendations on timing of maternal vaccination.

“For instance, Dr. Joseph demonstrated that, 28 days out from the infection, you had more antibodies, so there may be a scenario where we say this vaccine may be more beneficial in the middle of the pregnancy for the purpose of forming those antibodies,” Dr. Louis said.

Consensus emerging from maternal antibodies data

The findings from Dr. Joseph’s study mirror those reported in a study published online Jan. 29 in JAMA Pediatrics. That study, led by Dustin D. Flannery, DO, MSCE, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, also examined maternal and neonatal levels of IgG and IgM antibodies against the receptor binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. They also found a positive correlation between cord blood and maternal IgG concentrations (P < .001), but notably, the ratio of cord to maternal blood titers was greater than 1, unlike in Dr. Joseph’s study.

For their study, Dr. Flannery and colleagues obtained maternal and cord blood sera at the time of delivery from 1471 pairs of mothers and infants, independently of COVID status during pregnancy. The average maternal age was 32 years, and just over a quarter of the population (26%) were Black, non-Hispanic women. About half (51%) were White, 12% were Hispanic, and 7% were Asian.

About 6% of the women had either IgG or IgM antibodies at delivery, and 87% of infants born to those mothers had measurable IgG in their cord blood. No infants had IgM antibodies. As with the study presented at SMFM, the mothers’ infections included asymptomatic, mild, moderate, and severe cases, and the degree of severity of cases had no apparent effect on infant antibody concentrations. Most of the women who tested positive for COVID-19 (60%) were asymptomatic.

Among the 11 mothers who had antibodies but whose infants’ cord blood did not, 5 had only IgM antibodies, and 6 had significantly lower IgG concentrations than those seen in the other mothers.

In a commentary about the JAMA Pediatrics study, Flor Munoz, MD, of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, suggested that the findings are grounds for optimism about a maternal vaccination strategy to protect infants from COVID-19.

“However, the timing of maternal vaccination to protect the infant, as opposed to the mother alone, would necessitate an adequate interval from vaccination to delivery (of at least 4 weeks), while vaccination early in gestation and even late in the third trimester could still be protective for the mother,” Dr. Munoz wrote.

Given the interval between two-dose vaccination regimens and the fact that transplacental transfer begins at about the 17th week of gestation, “maternal vaccination starting in the early second trimester of gestation might be optimal to achieve the highest levels of antibodies in the newborn,” Dr. Munoz wrote. But questions remain, such as how effective the neonatal antibodies would be in protecting against COVID-19 and how long they last after birth.

No external funding was used in Dr. Joseph’s study. Dr. Joseph and Dr. Louis have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The JAMA Pediatrics study was funded by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. One coauthor received consultancy fees from Sanofi Pasteur, Lumen, Novavax, and Merck unrelated to the study. Dr. Munoz served on the data and safety monitoring boards of Moderna, Pfizer, Virometix, and Meissa Vaccines and has received grants from Novavax Research and Gilead Research.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Disparities in child abuse evaluation arise from implicit bias

according to research discussed by Tiffani J. Johnson, MD, an assistant professor of emergency medicine at the University of California, Davis.

“These disparities in child abuse evaluation and reporting are bidirectional,” she said. “We also recognize that abuse is more likely to be unrecognized in White children.”

Dr. Johnson presented data on the health disparities in child abuse reporting in a session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics, held virtually this year. Health care disparities, as defined by the National Academy of Sciences, refers to differences in the quality of care between minority and nonminority populations that are not caused by clinical appropriateness, access, need, or patient preference, she explained. Instead, they result from discrimination, bias, stereotyping, and uncertainty.

Disparities lead to harm in all children

For example, a 2018 systematic review found that Black and other non-White children were significantly more likely than White children to be evaluated with a skeletal survey. In one of the studies included, at a large urban academic center, Black and Latinx children with accidental fractures were 8.75 times more likely to undergo a skeletal survey than White children and 4.3 times more likely to be reported to child protective services.

“And let me emphasize that these are children who were ultimately found to have accidental fractures,” Dr. Johnson said.

Meanwhile, in an analysis of known cases of head trauma, researchers found that abuse was missed in 37% of White children, compared with 19% of non-White children.