User login

AGA releases clinical practice update for pancreatic necrosis

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis, including 15 recommendations based on a comprehensive literature review and the experiences of leading experts.

Recommendations range from the general, such as the need for a multidisciplinary approach, to the specific, such as the superiority of metal over plastic stents for endoscopic transmural drainage.

The expert review, which was conducted by lead author Todd H. Baron, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and three other colleagues, was vetted by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) and the AGA Governing Board. In addition, the update underwent external peer review prior to publication in Gastroenterology.

In the update, the authors outlined the clinical landscape for pancreatic necrosis, including challenges posed by complex cases and a mortality rate as high as 30%.

“Successful management of these patients requires expert multidisciplinary care by gastroenterologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and specialists in critical care medicine, infectious disease, and nutrition,” the investigators wrote.

They went on to explain how management has evolved over the past 10 years.

“Whereby major surgical intervention and debridement was once the mainstay of therapy for patients with symptomatic necrotic collections, a minimally invasive approach focusing on percutaneous drainage and/or endoscopic drainage or debridement is now favored,” they wrote. They added that debridement is still generally agreed to be the best choice for cases of infected necrosis or patients with sterile necrosis “marked by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and nutritional failure or with associated complications including gastrointestinal luminal obstruction, biliary obstruction, recurrent acute pancreatitis, fistulas, or persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).”

Other elements of care, however, remain debated, the investigators noted, which has led to variations in multiple aspects of care, such as interventional timing, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and nutrition. Within this framework, the present practice update is aimed at offering “concise best practice advice for the optimal management of patients with this highly morbid condition.”

Among these pieces of advice, the authors emphasized that routine prophylactic antibiotics and/or antifungals to prevent infected necrosis are unsupported by multiple clinical trials. When infection is suspected, the update recommends broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, noting that, in most cases, it is unnecessary to perform CT-guided fine-needle aspiration for cultures and gram stain.

Regarding nutrition, the update recommends against “pancreatic rest”; instead, it calls for early oral intake and, if this is not possible, then initiation of total enteral nutrition. Although the authors deemed multiple routes of enteral feeding acceptable, they favored nasogastric or nasoduodenal tubes, when appropriate, because of ease of placement and maintenance. For prolonged total enteral nutrition or patients unable to tolerate nasoenteric feeding, the authors recommended endoscopic feeding tube placement with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube for those who can tolerate gastric feeding or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tube for those who cannot or have a high risk of aspiration.

As described above, the update recommends debridement for cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Ideally, this should be performed at least 4 weeks after onset, and avoided altogether within the first 2 weeks, because of associated risks of morbidity and mortality; instead, during this acute phase, percutaneous drainage may be considered.

For walled-off pancreatic necrosis, the authors recommended transmural drainage via endoscopic therapy because this mitigates risk of pancreatocutaneous fistula. Percutaneous drainage may be considered in addition to, or in absence of, endoscopic drainage, depending on clinical status.

The remainder of the update covers decisions related to stents, other minimally invasive techniques, open operative debridement, and disconnected left pancreatic remnants, along with discussions of key supporting clinical trials.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Olympus, and others.

SOURCE: Baron TH et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

Review the Gastroenterology clinical guidelines collection for AGA Institute statements detailing preferred approaches to specific medical problems or issues based on the most current available data at https://www.gastrojournal.

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis, including 15 recommendations based on a comprehensive literature review and the experiences of leading experts.

Recommendations range from the general, such as the need for a multidisciplinary approach, to the specific, such as the superiority of metal over plastic stents for endoscopic transmural drainage.

The expert review, which was conducted by lead author Todd H. Baron, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and three other colleagues, was vetted by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) and the AGA Governing Board. In addition, the update underwent external peer review prior to publication in Gastroenterology.

In the update, the authors outlined the clinical landscape for pancreatic necrosis, including challenges posed by complex cases and a mortality rate as high as 30%.

“Successful management of these patients requires expert multidisciplinary care by gastroenterologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and specialists in critical care medicine, infectious disease, and nutrition,” the investigators wrote.

They went on to explain how management has evolved over the past 10 years.

“Whereby major surgical intervention and debridement was once the mainstay of therapy for patients with symptomatic necrotic collections, a minimally invasive approach focusing on percutaneous drainage and/or endoscopic drainage or debridement is now favored,” they wrote. They added that debridement is still generally agreed to be the best choice for cases of infected necrosis or patients with sterile necrosis “marked by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and nutritional failure or with associated complications including gastrointestinal luminal obstruction, biliary obstruction, recurrent acute pancreatitis, fistulas, or persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).”

Other elements of care, however, remain debated, the investigators noted, which has led to variations in multiple aspects of care, such as interventional timing, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and nutrition. Within this framework, the present practice update is aimed at offering “concise best practice advice for the optimal management of patients with this highly morbid condition.”

Among these pieces of advice, the authors emphasized that routine prophylactic antibiotics and/or antifungals to prevent infected necrosis are unsupported by multiple clinical trials. When infection is suspected, the update recommends broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, noting that, in most cases, it is unnecessary to perform CT-guided fine-needle aspiration for cultures and gram stain.

Regarding nutrition, the update recommends against “pancreatic rest”; instead, it calls for early oral intake and, if this is not possible, then initiation of total enteral nutrition. Although the authors deemed multiple routes of enteral feeding acceptable, they favored nasogastric or nasoduodenal tubes, when appropriate, because of ease of placement and maintenance. For prolonged total enteral nutrition or patients unable to tolerate nasoenteric feeding, the authors recommended endoscopic feeding tube placement with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube for those who can tolerate gastric feeding or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tube for those who cannot or have a high risk of aspiration.

As described above, the update recommends debridement for cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Ideally, this should be performed at least 4 weeks after onset, and avoided altogether within the first 2 weeks, because of associated risks of morbidity and mortality; instead, during this acute phase, percutaneous drainage may be considered.

For walled-off pancreatic necrosis, the authors recommended transmural drainage via endoscopic therapy because this mitigates risk of pancreatocutaneous fistula. Percutaneous drainage may be considered in addition to, or in absence of, endoscopic drainage, depending on clinical status.

The remainder of the update covers decisions related to stents, other minimally invasive techniques, open operative debridement, and disconnected left pancreatic remnants, along with discussions of key supporting clinical trials.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Olympus, and others.

SOURCE: Baron TH et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

Review the Gastroenterology clinical guidelines collection for AGA Institute statements detailing preferred approaches to specific medical problems or issues based on the most current available data at https://www.gastrojournal.

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis, including 15 recommendations based on a comprehensive literature review and the experiences of leading experts.

Recommendations range from the general, such as the need for a multidisciplinary approach, to the specific, such as the superiority of metal over plastic stents for endoscopic transmural drainage.

The expert review, which was conducted by lead author Todd H. Baron, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and three other colleagues, was vetted by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) and the AGA Governing Board. In addition, the update underwent external peer review prior to publication in Gastroenterology.

In the update, the authors outlined the clinical landscape for pancreatic necrosis, including challenges posed by complex cases and a mortality rate as high as 30%.

“Successful management of these patients requires expert multidisciplinary care by gastroenterologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and specialists in critical care medicine, infectious disease, and nutrition,” the investigators wrote.

They went on to explain how management has evolved over the past 10 years.

“Whereby major surgical intervention and debridement was once the mainstay of therapy for patients with symptomatic necrotic collections, a minimally invasive approach focusing on percutaneous drainage and/or endoscopic drainage or debridement is now favored,” they wrote. They added that debridement is still generally agreed to be the best choice for cases of infected necrosis or patients with sterile necrosis “marked by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and nutritional failure or with associated complications including gastrointestinal luminal obstruction, biliary obstruction, recurrent acute pancreatitis, fistulas, or persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).”

Other elements of care, however, remain debated, the investigators noted, which has led to variations in multiple aspects of care, such as interventional timing, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and nutrition. Within this framework, the present practice update is aimed at offering “concise best practice advice for the optimal management of patients with this highly morbid condition.”

Among these pieces of advice, the authors emphasized that routine prophylactic antibiotics and/or antifungals to prevent infected necrosis are unsupported by multiple clinical trials. When infection is suspected, the update recommends broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, noting that, in most cases, it is unnecessary to perform CT-guided fine-needle aspiration for cultures and gram stain.

Regarding nutrition, the update recommends against “pancreatic rest”; instead, it calls for early oral intake and, if this is not possible, then initiation of total enteral nutrition. Although the authors deemed multiple routes of enteral feeding acceptable, they favored nasogastric or nasoduodenal tubes, when appropriate, because of ease of placement and maintenance. For prolonged total enteral nutrition or patients unable to tolerate nasoenteric feeding, the authors recommended endoscopic feeding tube placement with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube for those who can tolerate gastric feeding or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tube for those who cannot or have a high risk of aspiration.

As described above, the update recommends debridement for cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Ideally, this should be performed at least 4 weeks after onset, and avoided altogether within the first 2 weeks, because of associated risks of morbidity and mortality; instead, during this acute phase, percutaneous drainage may be considered.

For walled-off pancreatic necrosis, the authors recommended transmural drainage via endoscopic therapy because this mitigates risk of pancreatocutaneous fistula. Percutaneous drainage may be considered in addition to, or in absence of, endoscopic drainage, depending on clinical status.

The remainder of the update covers decisions related to stents, other minimally invasive techniques, open operative debridement, and disconnected left pancreatic remnants, along with discussions of key supporting clinical trials.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Olympus, and others.

SOURCE: Baron TH et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

Review the Gastroenterology clinical guidelines collection for AGA Institute statements detailing preferred approaches to specific medical problems or issues based on the most current available data at https://www.gastrojournal.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Bile acid diarrhea guideline highlights data shortage

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) recently published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD).

Given a minimal evidence base, 16 out of the 17 guideline recommendations are conditional, according to lead author Daniel C. Sadowski, MD, of Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton, Alta., and colleagues. Considering the shortage of high-quality evidence, the panel called for more randomized clinical trials to address current knowledge gaps.

“BAD is an understudied, often underappreciated condition, and questions remain regarding its diagnosis and treatment,” the panelists wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “There have been guidelines on the management of chronic diarrhea from the American Gastroenterological Association, and the British Society of Gastroenterology, but diagnosis and management of BAD was not assessed extensively in these publications. The British Society of Gastroenterology updated guidelines on the investigation of chronic diarrhea in adults, published after the consensus meeting, addressed some issues related to BAD.”

For the current guideline, using available evidence and clinical experience, expert panelists from Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom aimed to “provide a reasonable and practical approach to care for specialists.” The guideline was further reviewed by the CAG Practice Affairs and Clinical Affairs Committees and the CAG Board of Directors.

The guideline first puts BAD in clinical context, noting a chronic diarrhea prevalence rate of approximately 5%. According to the guideline, approximately 1 out of 4 of these patients with chronic diarrhea may have BAD and prevalence of BAD is likely higher among those with other conditions, such as terminal ileal disease.

While BAD may be relatively common, it isn’t necessarily easy to diagnose, the panelists noted.

“The diagnosis of BAD continues to be a challenge, although this may be improved in the future with the general availability of screening serologic tests and other diagnostic tests,” the panelists wrote. “Although a treatment trial with bile acid sequestrants therapy (BAST) often is used, this approach has not been studied adequately, and likely is imprecise, and may lead to both undertreatment and overtreatment.”

Instead, the panelists recommended testing for BAD with 75-selenium homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) or 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one.

After addressing treatable causes of BAD, the guideline recommends initial therapy with cholestyramine or, if this is poorly tolerated, switching to BAST. However, the panelists advised against BAST for patients with resection or ileal Crohn’s disease, for whom other antidiarrheal agents are more suitable. When appropriate, BAST should be given at the lowest effective dose, with periodic trials of on-demand, intermittent administration, the panelists recommended. When BAST is ineffective, the guideline recommends that clinicians review concurrent medications as a possible cause of BAD or reinvestigate.

Concluding the guideline, the panelists emphasized the need for more high-quality research.

“The group recognized that specific, high-certainty evidence was lacking in many areas and recommended further studies that would improve the data available in future methodologic evaluations,” the panelists wrote.

While improving diagnostic accuracy of BAD should be a major goal of such research, progress is currently limited by an integral shortcoming of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies, the panelists wrote.

“The main challenge in conducting DTA studies for BAD is the lack of a widely accepted or universally agreed-upon reference standard because the condition is defined and classified based on pathophysiologic mechanisms and its response to treatment (BAST),” the panelists wrote. “In addition, the index tests (SeHCAT, C4, FGF19, fecal bile acid assay) provide a continuous measure of metabolic function. Hence, DTA studies are not the most appropriate study design.”

“Therefore, one of the research priorities in BAD is for the scientific and clinical communities to agree on a reference standard that best represents BAD (e.g., response to BAST), with full understanding that the reference standard is and likely will be imperfect.”

The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) recently published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD).

Given a minimal evidence base, 16 out of the 17 guideline recommendations are conditional, according to lead author Daniel C. Sadowski, MD, of Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton, Alta., and colleagues. Considering the shortage of high-quality evidence, the panel called for more randomized clinical trials to address current knowledge gaps.

“BAD is an understudied, often underappreciated condition, and questions remain regarding its diagnosis and treatment,” the panelists wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “There have been guidelines on the management of chronic diarrhea from the American Gastroenterological Association, and the British Society of Gastroenterology, but diagnosis and management of BAD was not assessed extensively in these publications. The British Society of Gastroenterology updated guidelines on the investigation of chronic diarrhea in adults, published after the consensus meeting, addressed some issues related to BAD.”

For the current guideline, using available evidence and clinical experience, expert panelists from Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom aimed to “provide a reasonable and practical approach to care for specialists.” The guideline was further reviewed by the CAG Practice Affairs and Clinical Affairs Committees and the CAG Board of Directors.

The guideline first puts BAD in clinical context, noting a chronic diarrhea prevalence rate of approximately 5%. According to the guideline, approximately 1 out of 4 of these patients with chronic diarrhea may have BAD and prevalence of BAD is likely higher among those with other conditions, such as terminal ileal disease.

While BAD may be relatively common, it isn’t necessarily easy to diagnose, the panelists noted.

“The diagnosis of BAD continues to be a challenge, although this may be improved in the future with the general availability of screening serologic tests and other diagnostic tests,” the panelists wrote. “Although a treatment trial with bile acid sequestrants therapy (BAST) often is used, this approach has not been studied adequately, and likely is imprecise, and may lead to both undertreatment and overtreatment.”

Instead, the panelists recommended testing for BAD with 75-selenium homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) or 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one.

After addressing treatable causes of BAD, the guideline recommends initial therapy with cholestyramine or, if this is poorly tolerated, switching to BAST. However, the panelists advised against BAST for patients with resection or ileal Crohn’s disease, for whom other antidiarrheal agents are more suitable. When appropriate, BAST should be given at the lowest effective dose, with periodic trials of on-demand, intermittent administration, the panelists recommended. When BAST is ineffective, the guideline recommends that clinicians review concurrent medications as a possible cause of BAD or reinvestigate.

Concluding the guideline, the panelists emphasized the need for more high-quality research.

“The group recognized that specific, high-certainty evidence was lacking in many areas and recommended further studies that would improve the data available in future methodologic evaluations,” the panelists wrote.

While improving diagnostic accuracy of BAD should be a major goal of such research, progress is currently limited by an integral shortcoming of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies, the panelists wrote.

“The main challenge in conducting DTA studies for BAD is the lack of a widely accepted or universally agreed-upon reference standard because the condition is defined and classified based on pathophysiologic mechanisms and its response to treatment (BAST),” the panelists wrote. “In addition, the index tests (SeHCAT, C4, FGF19, fecal bile acid assay) provide a continuous measure of metabolic function. Hence, DTA studies are not the most appropriate study design.”

“Therefore, one of the research priorities in BAD is for the scientific and clinical communities to agree on a reference standard that best represents BAD (e.g., response to BAST), with full understanding that the reference standard is and likely will be imperfect.”

The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) recently published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD).

Given a minimal evidence base, 16 out of the 17 guideline recommendations are conditional, according to lead author Daniel C. Sadowski, MD, of Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton, Alta., and colleagues. Considering the shortage of high-quality evidence, the panel called for more randomized clinical trials to address current knowledge gaps.

“BAD is an understudied, often underappreciated condition, and questions remain regarding its diagnosis and treatment,” the panelists wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “There have been guidelines on the management of chronic diarrhea from the American Gastroenterological Association, and the British Society of Gastroenterology, but diagnosis and management of BAD was not assessed extensively in these publications. The British Society of Gastroenterology updated guidelines on the investigation of chronic diarrhea in adults, published after the consensus meeting, addressed some issues related to BAD.”

For the current guideline, using available evidence and clinical experience, expert panelists from Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom aimed to “provide a reasonable and practical approach to care for specialists.” The guideline was further reviewed by the CAG Practice Affairs and Clinical Affairs Committees and the CAG Board of Directors.

The guideline first puts BAD in clinical context, noting a chronic diarrhea prevalence rate of approximately 5%. According to the guideline, approximately 1 out of 4 of these patients with chronic diarrhea may have BAD and prevalence of BAD is likely higher among those with other conditions, such as terminal ileal disease.

While BAD may be relatively common, it isn’t necessarily easy to diagnose, the panelists noted.

“The diagnosis of BAD continues to be a challenge, although this may be improved in the future with the general availability of screening serologic tests and other diagnostic tests,” the panelists wrote. “Although a treatment trial with bile acid sequestrants therapy (BAST) often is used, this approach has not been studied adequately, and likely is imprecise, and may lead to both undertreatment and overtreatment.”

Instead, the panelists recommended testing for BAD with 75-selenium homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) or 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one.

After addressing treatable causes of BAD, the guideline recommends initial therapy with cholestyramine or, if this is poorly tolerated, switching to BAST. However, the panelists advised against BAST for patients with resection or ileal Crohn’s disease, for whom other antidiarrheal agents are more suitable. When appropriate, BAST should be given at the lowest effective dose, with periodic trials of on-demand, intermittent administration, the panelists recommended. When BAST is ineffective, the guideline recommends that clinicians review concurrent medications as a possible cause of BAD or reinvestigate.

Concluding the guideline, the panelists emphasized the need for more high-quality research.

“The group recognized that specific, high-certainty evidence was lacking in many areas and recommended further studies that would improve the data available in future methodologic evaluations,” the panelists wrote.

While improving diagnostic accuracy of BAD should be a major goal of such research, progress is currently limited by an integral shortcoming of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies, the panelists wrote.

“The main challenge in conducting DTA studies for BAD is the lack of a widely accepted or universally agreed-upon reference standard because the condition is defined and classified based on pathophysiologic mechanisms and its response to treatment (BAST),” the panelists wrote. “In addition, the index tests (SeHCAT, C4, FGF19, fecal bile acid assay) provide a continuous measure of metabolic function. Hence, DTA studies are not the most appropriate study design.”

“Therefore, one of the research priorities in BAD is for the scientific and clinical communities to agree on a reference standard that best represents BAD (e.g., response to BAST), with full understanding that the reference standard is and likely will be imperfect.”

The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

SOURCE: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology recently published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD).

Major finding: BAD occurs in up to 35% of patients with chronic diarrhea or diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Study details: A clinical practice guideline for the management of BAD.

Disclosures: The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

Source: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

Bile acid diarrhea guideline highlights data shortage

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) recently co-published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD) in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology.

Given a minimal evidence base, 16 out of the 17 guideline recommendations are conditional, according to lead author Daniel C. Sadowski, MD, of Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton, Alta., and colleagues. Considering the shortage of high-quality evidence, the panel called for more randomized clinical trials to address current knowledge gaps.

“BAD is an understudied, often underappreciated condition, and questions remain regarding its diagnosis and treatment,” the panelists wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “There have been guidelines on the management of chronic diarrhea from the American Gastroenterological Association, and the British Society of Gastroenterology, but diagnosis and management of BAD was not assessed extensively in these publications. The British Society of Gastroenterology updated guidelines on the investigation of chronic diarrhea in adults, published after the consensus meeting, addressed some issues related to BAD.”

For the current guideline, using available evidence and clinical experience, expert panelists from Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom aimed to “provide a reasonable and practical approach to care for specialists.” The guideline was further reviewed by the CAG Practice Affairs and Clinical Affairs Committees and the CAG Board of Directors.

The guideline first puts BAD in clinical context, noting a chronic diarrhea prevalence rate of approximately 5%. According to the guideline, approximately 1 out of 4 of these patients with chronic diarrhea may have BAD and prevalence of BAD is likely higher among those with other conditions, such as terminal ileal disease.

While BAD may be relatively common, it isn’t necessarily easy to diagnose, the panelists noted.

“The diagnosis of BAD continues to be a challenge, although this may be improved in the future with the general availability of screening serologic tests and other diagnostic tests,” the panelists wrote. “Although a treatment trial with bile acid sequestrants therapy (BAST) often is used, this approach has not been studied adequately, and likely is imprecise, and may lead to both undertreatment and overtreatment.”

Instead, the panelists recommended testing for BAD with 75-selenium homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) or 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one.

After addressing treatable causes of BAD, the guideline recommends initial therapy with cholestyramine or, if this is poorly tolerated, switching to BAST. However, the panelists advised against BAST for patients with resection or ileal Crohn’s disease, for whom other antidiarrheal agents are more suitable. When appropriate, BAST should be given at the lowest effective dose, with periodic trials of on-demand, intermittent administration, the panelists recommended. When BAST is ineffective, the guideline recommends that clinicians review concurrent medications as a possible cause of BAD or reinvestigate.

Concluding the guideline, the panelists emphasized the need for more high-quality research.

“The group recognized that specific, high-certainty evidence was lacking in many areas and recommended further studies that would improve the data available in future methodologic evaluations,” the panelists wrote.

While improving diagnostic accuracy of BAD should be a major goal of such research, progress is currently limited by an integral shortcoming of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies, the panelists wrote.

“The main challenge in conducting DTA studies for BAD is the lack of a widely accepted or universally agreed-upon reference standard because the condition is defined and classified based on pathophysiologic mechanisms and its response to treatment (BAST),” the panelists wrote. “In addition, the index tests (SeHCAT, C4, FGF19, fecal bile acid assay) provide a continuous measure of metabolic function. Hence, DTA studies are not the most appropriate study design.”

“Therefore, one of the research priorities in BAD is for the scientific and clinical communities to agree on a reference standard that best represents BAD (e.g., response to BAST), with full understanding that the reference standard is and likely will be imperfect.”

The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

Review the AGA clinical practice guideline on the laboratory evaluation of functional diarrhea and diarrhea-predominan irritable bowel syndrome in adults at https:/www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(19)41083-4/fulltext.

SOURCE: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) recently co-published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD) in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology.

Given a minimal evidence base, 16 out of the 17 guideline recommendations are conditional, according to lead author Daniel C. Sadowski, MD, of Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton, Alta., and colleagues. Considering the shortage of high-quality evidence, the panel called for more randomized clinical trials to address current knowledge gaps.

“BAD is an understudied, often underappreciated condition, and questions remain regarding its diagnosis and treatment,” the panelists wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “There have been guidelines on the management of chronic diarrhea from the American Gastroenterological Association, and the British Society of Gastroenterology, but diagnosis and management of BAD was not assessed extensively in these publications. The British Society of Gastroenterology updated guidelines on the investigation of chronic diarrhea in adults, published after the consensus meeting, addressed some issues related to BAD.”

For the current guideline, using available evidence and clinical experience, expert panelists from Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom aimed to “provide a reasonable and practical approach to care for specialists.” The guideline was further reviewed by the CAG Practice Affairs and Clinical Affairs Committees and the CAG Board of Directors.

The guideline first puts BAD in clinical context, noting a chronic diarrhea prevalence rate of approximately 5%. According to the guideline, approximately 1 out of 4 of these patients with chronic diarrhea may have BAD and prevalence of BAD is likely higher among those with other conditions, such as terminal ileal disease.

While BAD may be relatively common, it isn’t necessarily easy to diagnose, the panelists noted.

“The diagnosis of BAD continues to be a challenge, although this may be improved in the future with the general availability of screening serologic tests and other diagnostic tests,” the panelists wrote. “Although a treatment trial with bile acid sequestrants therapy (BAST) often is used, this approach has not been studied adequately, and likely is imprecise, and may lead to both undertreatment and overtreatment.”

Instead, the panelists recommended testing for BAD with 75-selenium homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) or 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one.

After addressing treatable causes of BAD, the guideline recommends initial therapy with cholestyramine or, if this is poorly tolerated, switching to BAST. However, the panelists advised against BAST for patients with resection or ileal Crohn’s disease, for whom other antidiarrheal agents are more suitable. When appropriate, BAST should be given at the lowest effective dose, with periodic trials of on-demand, intermittent administration, the panelists recommended. When BAST is ineffective, the guideline recommends that clinicians review concurrent medications as a possible cause of BAD or reinvestigate.

Concluding the guideline, the panelists emphasized the need for more high-quality research.

“The group recognized that specific, high-certainty evidence was lacking in many areas and recommended further studies that would improve the data available in future methodologic evaluations,” the panelists wrote.

While improving diagnostic accuracy of BAD should be a major goal of such research, progress is currently limited by an integral shortcoming of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies, the panelists wrote.

“The main challenge in conducting DTA studies for BAD is the lack of a widely accepted or universally agreed-upon reference standard because the condition is defined and classified based on pathophysiologic mechanisms and its response to treatment (BAST),” the panelists wrote. “In addition, the index tests (SeHCAT, C4, FGF19, fecal bile acid assay) provide a continuous measure of metabolic function. Hence, DTA studies are not the most appropriate study design.”

“Therefore, one of the research priorities in BAD is for the scientific and clinical communities to agree on a reference standard that best represents BAD (e.g., response to BAST), with full understanding that the reference standard is and likely will be imperfect.”

The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

Review the AGA clinical practice guideline on the laboratory evaluation of functional diarrhea and diarrhea-predominan irritable bowel syndrome in adults at https:/www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(19)41083-4/fulltext.

SOURCE: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) recently co-published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD) in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology.

Given a minimal evidence base, 16 out of the 17 guideline recommendations are conditional, according to lead author Daniel C. Sadowski, MD, of Royal Alexandra Hospital, Edmonton, Alta., and colleagues. Considering the shortage of high-quality evidence, the panel called for more randomized clinical trials to address current knowledge gaps.

“BAD is an understudied, often underappreciated condition, and questions remain regarding its diagnosis and treatment,” the panelists wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “There have been guidelines on the management of chronic diarrhea from the American Gastroenterological Association, and the British Society of Gastroenterology, but diagnosis and management of BAD was not assessed extensively in these publications. The British Society of Gastroenterology updated guidelines on the investigation of chronic diarrhea in adults, published after the consensus meeting, addressed some issues related to BAD.”

For the current guideline, using available evidence and clinical experience, expert panelists from Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom aimed to “provide a reasonable and practical approach to care for specialists.” The guideline was further reviewed by the CAG Practice Affairs and Clinical Affairs Committees and the CAG Board of Directors.

The guideline first puts BAD in clinical context, noting a chronic diarrhea prevalence rate of approximately 5%. According to the guideline, approximately 1 out of 4 of these patients with chronic diarrhea may have BAD and prevalence of BAD is likely higher among those with other conditions, such as terminal ileal disease.

While BAD may be relatively common, it isn’t necessarily easy to diagnose, the panelists noted.

“The diagnosis of BAD continues to be a challenge, although this may be improved in the future with the general availability of screening serologic tests and other diagnostic tests,” the panelists wrote. “Although a treatment trial with bile acid sequestrants therapy (BAST) often is used, this approach has not been studied adequately, and likely is imprecise, and may lead to both undertreatment and overtreatment.”

Instead, the panelists recommended testing for BAD with 75-selenium homocholic acid taurine (SeHCAT) or 7-alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one.

After addressing treatable causes of BAD, the guideline recommends initial therapy with cholestyramine or, if this is poorly tolerated, switching to BAST. However, the panelists advised against BAST for patients with resection or ileal Crohn’s disease, for whom other antidiarrheal agents are more suitable. When appropriate, BAST should be given at the lowest effective dose, with periodic trials of on-demand, intermittent administration, the panelists recommended. When BAST is ineffective, the guideline recommends that clinicians review concurrent medications as a possible cause of BAD or reinvestigate.

Concluding the guideline, the panelists emphasized the need for more high-quality research.

“The group recognized that specific, high-certainty evidence was lacking in many areas and recommended further studies that would improve the data available in future methodologic evaluations,” the panelists wrote.

While improving diagnostic accuracy of BAD should be a major goal of such research, progress is currently limited by an integral shortcoming of diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) studies, the panelists wrote.

“The main challenge in conducting DTA studies for BAD is the lack of a widely accepted or universally agreed-upon reference standard because the condition is defined and classified based on pathophysiologic mechanisms and its response to treatment (BAST),” the panelists wrote. “In addition, the index tests (SeHCAT, C4, FGF19, fecal bile acid assay) provide a continuous measure of metabolic function. Hence, DTA studies are not the most appropriate study design.”

“Therefore, one of the research priorities in BAD is for the scientific and clinical communities to agree on a reference standard that best represents BAD (e.g., response to BAST), with full understanding that the reference standard is and likely will be imperfect.”

The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

Review the AGA clinical practice guideline on the laboratory evaluation of functional diarrhea and diarrhea-predominan irritable bowel syndrome in adults at https:/www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(19)41083-4/fulltext.

SOURCE: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology recently published a clinical practice guideline for the management of bile acid diarrhea (BAD).

Major finding: BAD occurs in up to 35% of patients with chronic diarrhea or diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Study details: A clinical practice guideline for the management of BAD.

Disclosures: The guideline was funded by unrestricted grants from Pendopharm and GE Healthcare Canada. The panelists disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, Merck, Pfizer, and others.

Source: Sadowski DC et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 14. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.062.

AGA releases clinical practice update for pancreatic necrosis

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis, including 15 recommendations based on a comprehensive literature review and the experiences of leading experts.

Recommendations range from the general, such as the need for a multidisciplinary approach, to the specific, such as the superiority of metal over plastic stents for endoscopic transmural drainage.

The expert review, which was conducted by lead author Todd H. Baron, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and three other colleagues, was vetted by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) and the AGA Governing Board. In addition, the update underwent external peer review prior to publication in Gastroenterology.

In the update, the authors outlined the clinical landscape for pancreatic necrosis, including challenges posed by complex cases and a mortality rate as high as 30%.

“Successful management of these patients requires expert multidisciplinary care by gastroenterologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and specialists in critical care medicine, infectious disease, and nutrition,” the investigators wrote.

They went on to explain how management has evolved over the past 10 years.

“Whereby major surgical intervention and debridement was once the mainstay of therapy for patients with symptomatic necrotic collections, a minimally invasive approach focusing on percutaneous drainage and/or endoscopic drainage or debridement is now favored,” they wrote. They added that debridement is still generally agreed to be the best choice for cases of infected necrosis or patients with sterile necrosis “marked by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and nutritional failure or with associated complications including gastrointestinal luminal obstruction, biliary obstruction, recurrent acute pancreatitis, fistulas, or persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).”

Other elements of care, however, remain debated, the investigators noted, which has led to variations in multiple aspects of care, such as interventional timing, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and nutrition. Within this framework, the present practice update is aimed at offering “concise best practice advice for the optimal management of patients with this highly morbid condition.”

Among these pieces of advice, the authors emphasized that routine prophylactic antibiotics and/or antifungals to prevent infected necrosis are unsupported by multiple clinical trials. When infection is suspected, the update recommends broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, noting that, in most cases, it is unnecessary to perform CT-guided fine-needle aspiration for cultures and gram stain.

Regarding nutrition, the update recommends against “pancreatic rest”; instead, it calls for early oral intake and, if this is not possible, then initiation of total enteral nutrition. Although the authors deemed multiple routes of enteral feeding acceptable, they favored nasogastric or nasoduodenal tubes, when appropriate, because of ease of placement and maintenance. For prolonged total enteral nutrition or patients unable to tolerate nasoenteric feeding, the authors recommended endoscopic feeding tube placement with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube for those who can tolerate gastric feeding or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tube for those who cannot or have a high risk of aspiration.

As described above, the update recommends debridement for cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Ideally, this should be performed at least 4 weeks after onset, and avoided altogether within the first 2 weeks, because of associated risks of morbidity and mortality; instead, during this acute phase, percutaneous drainage may be considered.

For walled-off pancreatic necrosis, the authors recommended transmural drainage via endoscopic therapy because this mitigates risk of pancreatocutaneous fistula. Percutaneous drainage may be considered in addition to, or in absence of, endoscopic drainage, depending on clinical status.

The remainder of the update covers decisions related to stents, other minimally invasive techniques, open operative debridement, and disconnected left pancreatic remnants, along with discussions of key supporting clinical trials.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Olympus, and others.

SOURCE: Baron TH et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis, including 15 recommendations based on a comprehensive literature review and the experiences of leading experts.

Recommendations range from the general, such as the need for a multidisciplinary approach, to the specific, such as the superiority of metal over plastic stents for endoscopic transmural drainage.

The expert review, which was conducted by lead author Todd H. Baron, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and three other colleagues, was vetted by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) and the AGA Governing Board. In addition, the update underwent external peer review prior to publication in Gastroenterology.

In the update, the authors outlined the clinical landscape for pancreatic necrosis, including challenges posed by complex cases and a mortality rate as high as 30%.

“Successful management of these patients requires expert multidisciplinary care by gastroenterologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and specialists in critical care medicine, infectious disease, and nutrition,” the investigators wrote.

They went on to explain how management has evolved over the past 10 years.

“Whereby major surgical intervention and debridement was once the mainstay of therapy for patients with symptomatic necrotic collections, a minimally invasive approach focusing on percutaneous drainage and/or endoscopic drainage or debridement is now favored,” they wrote. They added that debridement is still generally agreed to be the best choice for cases of infected necrosis or patients with sterile necrosis “marked by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and nutritional failure or with associated complications including gastrointestinal luminal obstruction, biliary obstruction, recurrent acute pancreatitis, fistulas, or persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).”

Other elements of care, however, remain debated, the investigators noted, which has led to variations in multiple aspects of care, such as interventional timing, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and nutrition. Within this framework, the present practice update is aimed at offering “concise best practice advice for the optimal management of patients with this highly morbid condition.”

Among these pieces of advice, the authors emphasized that routine prophylactic antibiotics and/or antifungals to prevent infected necrosis are unsupported by multiple clinical trials. When infection is suspected, the update recommends broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, noting that, in most cases, it is unnecessary to perform CT-guided fine-needle aspiration for cultures and gram stain.

Regarding nutrition, the update recommends against “pancreatic rest”; instead, it calls for early oral intake and, if this is not possible, then initiation of total enteral nutrition. Although the authors deemed multiple routes of enteral feeding acceptable, they favored nasogastric or nasoduodenal tubes, when appropriate, because of ease of placement and maintenance. For prolonged total enteral nutrition or patients unable to tolerate nasoenteric feeding, the authors recommended endoscopic feeding tube placement with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube for those who can tolerate gastric feeding or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tube for those who cannot or have a high risk of aspiration.

As described above, the update recommends debridement for cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Ideally, this should be performed at least 4 weeks after onset, and avoided altogether within the first 2 weeks, because of associated risks of morbidity and mortality; instead, during this acute phase, percutaneous drainage may be considered.

For walled-off pancreatic necrosis, the authors recommended transmural drainage via endoscopic therapy because this mitigates risk of pancreatocutaneous fistula. Percutaneous drainage may be considered in addition to, or in absence of, endoscopic drainage, depending on clinical status.

The remainder of the update covers decisions related to stents, other minimally invasive techniques, open operative debridement, and disconnected left pancreatic remnants, along with discussions of key supporting clinical trials.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Olympus, and others.

SOURCE: Baron TH et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

The American Gastroenterological Association recently issued a clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis, including 15 recommendations based on a comprehensive literature review and the experiences of leading experts.

Recommendations range from the general, such as the need for a multidisciplinary approach, to the specific, such as the superiority of metal over plastic stents for endoscopic transmural drainage.

The expert review, which was conducted by lead author Todd H. Baron, MD, of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and three other colleagues, was vetted by the AGA Institute Clinical Practice Updates Committee (CPUC) and the AGA Governing Board. In addition, the update underwent external peer review prior to publication in Gastroenterology.

In the update, the authors outlined the clinical landscape for pancreatic necrosis, including challenges posed by complex cases and a mortality rate as high as 30%.

“Successful management of these patients requires expert multidisciplinary care by gastroenterologists, surgeons, interventional radiologists, and specialists in critical care medicine, infectious disease, and nutrition,” the investigators wrote.

They went on to explain how management has evolved over the past 10 years.

“Whereby major surgical intervention and debridement was once the mainstay of therapy for patients with symptomatic necrotic collections, a minimally invasive approach focusing on percutaneous drainage and/or endoscopic drainage or debridement is now favored,” they wrote. They added that debridement is still generally agreed to be the best choice for cases of infected necrosis or patients with sterile necrosis “marked by abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and nutritional failure or with associated complications including gastrointestinal luminal obstruction, biliary obstruction, recurrent acute pancreatitis, fistulas, or persistent systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).”

Other elements of care, however, remain debated, the investigators noted, which has led to variations in multiple aspects of care, such as interventional timing, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and nutrition. Within this framework, the present practice update is aimed at offering “concise best practice advice for the optimal management of patients with this highly morbid condition.”

Among these pieces of advice, the authors emphasized that routine prophylactic antibiotics and/or antifungals to prevent infected necrosis are unsupported by multiple clinical trials. When infection is suspected, the update recommends broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, noting that, in most cases, it is unnecessary to perform CT-guided fine-needle aspiration for cultures and gram stain.

Regarding nutrition, the update recommends against “pancreatic rest”; instead, it calls for early oral intake and, if this is not possible, then initiation of total enteral nutrition. Although the authors deemed multiple routes of enteral feeding acceptable, they favored nasogastric or nasoduodenal tubes, when appropriate, because of ease of placement and maintenance. For prolonged total enteral nutrition or patients unable to tolerate nasoenteric feeding, the authors recommended endoscopic feeding tube placement with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube for those who can tolerate gastric feeding or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy tube for those who cannot or have a high risk of aspiration.

As described above, the update recommends debridement for cases of infected pancreatic necrosis. Ideally, this should be performed at least 4 weeks after onset, and avoided altogether within the first 2 weeks, because of associated risks of morbidity and mortality; instead, during this acute phase, percutaneous drainage may be considered.

For walled-off pancreatic necrosis, the authors recommended transmural drainage via endoscopic therapy because this mitigates risk of pancreatocutaneous fistula. Percutaneous drainage may be considered in addition to, or in absence of, endoscopic drainage, depending on clinical status.

The remainder of the update covers decisions related to stents, other minimally invasive techniques, open operative debridement, and disconnected left pancreatic remnants, along with discussions of key supporting clinical trials.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Olympus, and others.

SOURCE: Baron TH et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: The American Gastroenterological Association has issued a clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis.

Major finding: N/A

Study details: A clinical practice update for the management of pancreatic necrosis.

Disclosures: The investigators disclosed relationships with Cook Endoscopy, Boston Scientific, Olympus, and others.

Source: Baron TH et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Aug 31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064.

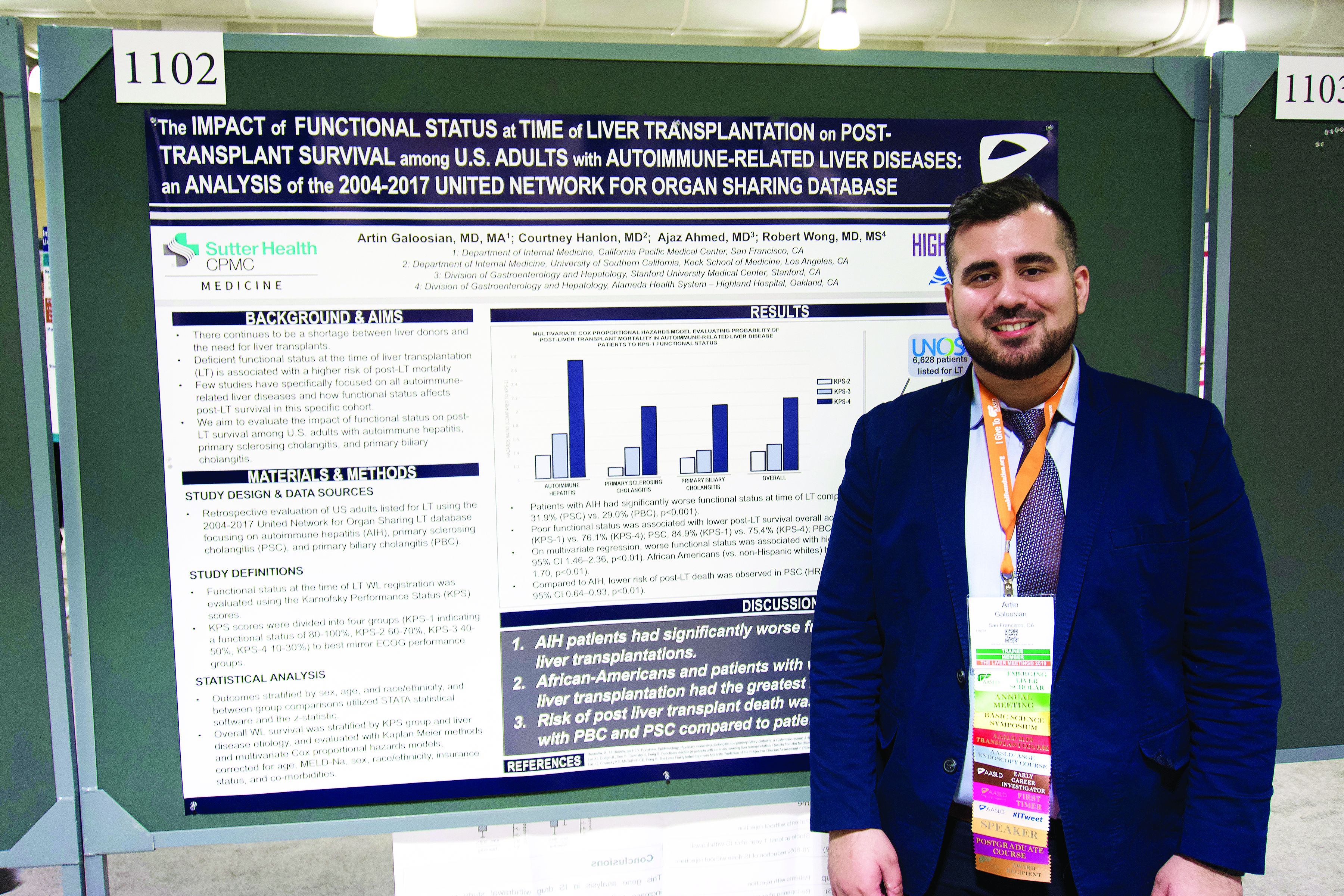

Autoimmune liver disease: Karnofsky score predicts transplant survival

BOSTON – The Karnofsky Performance Status is predictive of 5-year survival among patients with autoimmune-related liver disease who undergo a transplant, based on a retrospective look at more than 6,500 patients.

The analysis also showed that African American patients had a 33% higher mortality risk than non-Hispanic white patients, reported lead author Artin Galoosian, MD, of California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco, who presented findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

According to Dr. Galoosian, previous research has shown that Karnofsky scores are a quick and reliable means of predicting survival with liver transplant, but minimal research has evaluated this clinical tool specifically for patients with autoimmune-related liver diseases, which prompted the present study.

Drawing data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS; 2004-2017), the investigators evaluated performance status and survival in 6,628 patients who underwent liver transplant for one of three diseases: autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), or primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). Karnofsky scores were divided into quartiles 1 through 4, from best to worst functional status. The investigators used Kaplan-Meier methods and multivariate Cox proportional hazard ratios to determine relationships between disease etiology, Karnofsky score, and survival; in addition, they evaluated the impact of demographic factors on outcomes.

The population was predominantly non-Hispanic white (73.0%) with smaller proportions of African American (13.4%) and Hispanic patients (11.5%). Of the three diseases, PBC was most common (38.2%), followed by PSC (32.1%), then AIH (29.7%).

Across all etiologies, Karnofsky status was significantly associated with survival; a score of 4 came with a 90% increased risk of posttransplant death, compared with a score of 1. Patients with AIH were most likely to have poor pretransplant functional status, as 39.1% of these patients had a Karnofsky score of 4, compared with 31.9% of patients with PSC and 29.0% of patients with PBC. AIH was also associated with a significantly higher risk of posttransplant death; relative risks for PSC and PBC were 20% and 17% lower, respectively.

Five years after surgery, 84.9% of AIH patients with a Karnofsky score of 1 were alive, compared with 76.1% of patients who had a score of 4. A similar association with functional status was found for PSC (84.9% vs. 75.4%), while PBC had a narrower survival margin (88.7% vs. 86.9%).

Analysis also revealed a wide survival gap between patients of different ethnic backgrounds. Compared with white patients, African American patients had a 33% higher risk of dying on the wait list or after transplant.

“[This gap] could reflect a multitude of issues, one being delayed referral to a hepatologist and being listed for transplant much later, so [patients] tend to be more sick,” Dr. Galoosian said.

He also offered some insight into clinical relevance.

“A broader implication of this research could be in the primary care setting,” Dr. Galoosian said. “[Clinicians need to be] aware that someone’s functional status has a broader impact on their health and be aware that ethnic minorities need to be more vigilantly up to date on their health care maintenance and more vigilantly connected to social workers if needed, in terms of getting the resources that they need to help break the [chain] of worse outcomes.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with Gilead, Salix, and AbbVie.

SOURCE: Galoosian A et al. The Liver Meeting 2019. Abstract 1102.

BOSTON – The Karnofsky Performance Status is predictive of 5-year survival among patients with autoimmune-related liver disease who undergo a transplant, based on a retrospective look at more than 6,500 patients.

The analysis also showed that African American patients had a 33% higher mortality risk than non-Hispanic white patients, reported lead author Artin Galoosian, MD, of California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco, who presented findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

According to Dr. Galoosian, previous research has shown that Karnofsky scores are a quick and reliable means of predicting survival with liver transplant, but minimal research has evaluated this clinical tool specifically for patients with autoimmune-related liver diseases, which prompted the present study.

Drawing data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS; 2004-2017), the investigators evaluated performance status and survival in 6,628 patients who underwent liver transplant for one of three diseases: autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), or primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). Karnofsky scores were divided into quartiles 1 through 4, from best to worst functional status. The investigators used Kaplan-Meier methods and multivariate Cox proportional hazard ratios to determine relationships between disease etiology, Karnofsky score, and survival; in addition, they evaluated the impact of demographic factors on outcomes.

The population was predominantly non-Hispanic white (73.0%) with smaller proportions of African American (13.4%) and Hispanic patients (11.5%). Of the three diseases, PBC was most common (38.2%), followed by PSC (32.1%), then AIH (29.7%).

Across all etiologies, Karnofsky status was significantly associated with survival; a score of 4 came with a 90% increased risk of posttransplant death, compared with a score of 1. Patients with AIH were most likely to have poor pretransplant functional status, as 39.1% of these patients had a Karnofsky score of 4, compared with 31.9% of patients with PSC and 29.0% of patients with PBC. AIH was also associated with a significantly higher risk of posttransplant death; relative risks for PSC and PBC were 20% and 17% lower, respectively.

Five years after surgery, 84.9% of AIH patients with a Karnofsky score of 1 were alive, compared with 76.1% of patients who had a score of 4. A similar association with functional status was found for PSC (84.9% vs. 75.4%), while PBC had a narrower survival margin (88.7% vs. 86.9%).

Analysis also revealed a wide survival gap between patients of different ethnic backgrounds. Compared with white patients, African American patients had a 33% higher risk of dying on the wait list or after transplant.

“[This gap] could reflect a multitude of issues, one being delayed referral to a hepatologist and being listed for transplant much later, so [patients] tend to be more sick,” Dr. Galoosian said.

He also offered some insight into clinical relevance.

“A broader implication of this research could be in the primary care setting,” Dr. Galoosian said. “[Clinicians need to be] aware that someone’s functional status has a broader impact on their health and be aware that ethnic minorities need to be more vigilantly up to date on their health care maintenance and more vigilantly connected to social workers if needed, in terms of getting the resources that they need to help break the [chain] of worse outcomes.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with Gilead, Salix, and AbbVie.

SOURCE: Galoosian A et al. The Liver Meeting 2019. Abstract 1102.

BOSTON – The Karnofsky Performance Status is predictive of 5-year survival among patients with autoimmune-related liver disease who undergo a transplant, based on a retrospective look at more than 6,500 patients.

The analysis also showed that African American patients had a 33% higher mortality risk than non-Hispanic white patients, reported lead author Artin Galoosian, MD, of California Pacific Medical Center in San Francisco, who presented findings at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

According to Dr. Galoosian, previous research has shown that Karnofsky scores are a quick and reliable means of predicting survival with liver transplant, but minimal research has evaluated this clinical tool specifically for patients with autoimmune-related liver diseases, which prompted the present study.

Drawing data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS; 2004-2017), the investigators evaluated performance status and survival in 6,628 patients who underwent liver transplant for one of three diseases: autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), or primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). Karnofsky scores were divided into quartiles 1 through 4, from best to worst functional status. The investigators used Kaplan-Meier methods and multivariate Cox proportional hazard ratios to determine relationships between disease etiology, Karnofsky score, and survival; in addition, they evaluated the impact of demographic factors on outcomes.

The population was predominantly non-Hispanic white (73.0%) with smaller proportions of African American (13.4%) and Hispanic patients (11.5%). Of the three diseases, PBC was most common (38.2%), followed by PSC (32.1%), then AIH (29.7%).

Across all etiologies, Karnofsky status was significantly associated with survival; a score of 4 came with a 90% increased risk of posttransplant death, compared with a score of 1. Patients with AIH were most likely to have poor pretransplant functional status, as 39.1% of these patients had a Karnofsky score of 4, compared with 31.9% of patients with PSC and 29.0% of patients with PBC. AIH was also associated with a significantly higher risk of posttransplant death; relative risks for PSC and PBC were 20% and 17% lower, respectively.

Five years after surgery, 84.9% of AIH patients with a Karnofsky score of 1 were alive, compared with 76.1% of patients who had a score of 4. A similar association with functional status was found for PSC (84.9% vs. 75.4%), while PBC had a narrower survival margin (88.7% vs. 86.9%).

Analysis also revealed a wide survival gap between patients of different ethnic backgrounds. Compared with white patients, African American patients had a 33% higher risk of dying on the wait list or after transplant.

“[This gap] could reflect a multitude of issues, one being delayed referral to a hepatologist and being listed for transplant much later, so [patients] tend to be more sick,” Dr. Galoosian said.

He also offered some insight into clinical relevance.

“A broader implication of this research could be in the primary care setting,” Dr. Galoosian said. “[Clinicians need to be] aware that someone’s functional status has a broader impact on their health and be aware that ethnic minorities need to be more vigilantly up to date on their health care maintenance and more vigilantly connected to social workers if needed, in terms of getting the resources that they need to help break the [chain] of worse outcomes.”

The investigators disclosed relationships with Gilead, Salix, and AbbVie.

SOURCE: Galoosian A et al. The Liver Meeting 2019. Abstract 1102.

REPORTING FROM THE LIVER MEETING 2019

ED-based HCV screening found feasible, linkage low

BOSTON – ED-based screening is a feasible method of detecting hepatitis C virus (HCV) in high-risk populations, but linkage to care remains low, according to investigators.

An HCV screening program involving three Seattle hospitals and more than 4,000 patients showed that linkage to care was lowest among patients who were younger, homeless, or used injection drugs, reported lead author Charles S. Landis, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle.

“In the U.S., rates of acute HCV infections are increasing in younger patients and in areas disproportionally affected by the opiate epidemic,” Dr. Landis said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “In order to achieve a goal of elimination, HCV screening, appropriate linkage to care, and treatment will need to be directed toward younger, marginalized, and underserved populations.”

Dr. Landis explained that EDs are suitable for HCV screening because users of emergency services are disproportionately affected by HCV, compared with patients in primary and specialty care settings. Despite this, linkage to care remains historically higher in primary and specialty care settings at approximately 70%, compared with 30% via the ED, Dr. Landis said.

Historically, EDs have been resistant to HCV screening programs, Dr. Landis said, but with the model used in the present study, which relied upon a full-time staff member in each ED who was employed by the infectious disease or hepatology department, no ED resources were needed.

Participants were willing adults who had reliable contact information. Patients were excluded if they were non–English speaking, incarcerated, enrolled or expected to enroll in another clinical study which excludes coenrollment, planned to move out of the region in the next 6 months, admitted to the ED with an acute life-threatening illness, or admitted to the ED for sexual assault. The program had three objectives: Screening, linkage to care, and treatment, all of which were coordinated by the aforementioned case manager.

To date, 4,182 patients have been screened, 936 have been enrolled, 95 have tested positive for HCV RNA, 32 have been linked with care, and 19 have been treated.

“So you can see, a lot of squeeze for a just a little bit of juice here,” Dr. Landis said, referring to the relatively low number of treated patients, compared with how many were screened.

The prevalence of HCV infection based on RNA testing was 2%, though one hospital had a rate of 5%. “This [prevalence] compares to, but is maybe slightly less than, the prevalence seen in others studies based in the emergency department,” Dr. Landis said. “The thought is, not all emergency departments are equal in terms of the patient population that they serve.”

Data analysis showed that the overall linkage to care was 36%. “This is still suboptimal, from my perspective,” Dr. Landis said, “but it does compare with several other ED-based studies.”

A closer look at the data showed that linkage was not uniform across the population. Among patients with homes, linkage to care was 59%, compared with 20% for patients who were homeless (P = .02).

“Ultimately, we need to tailor our approaches for linking homeless patients differently than patients who are not homeless,” Dr. Landis said.

Patients who reported no injection-drug use had a linkage to care of 50%, which was numerically higher than the rate of 20% among users of injection drugs; this difference was not statistically significant, which Dr. Landis attributed to insufficient population size. Similarly, younger patients showed numerical trends toward lower linkage to care.

“Future work will attempt to optimize linkage to care strategies based on patient demographic factors, such as active injection drug use or homelessness,” Dr. Landis said.

During discussion, a conference attendee from the United States expressed skepticism of the program’s merits.

“I may be a glass-half-empty person, but is it worth all this effort?” the attendee asked. “In all honesty, you treated a few dozen [patients] for 180,000 visits [per year]. I’m really not sure it’s worth those efforts, and I’m wondering if those efforts could be placed in different areas, especially for a higher yield.”

“Point well taken,” Dr. Landis said. “I think that was the purpose of the study, to see if the emergency department is a place to screen and link patients to care, and we’re trying to optimize that. Remember, there were 4,000 patients, but for many of those, it took literally a minute to screen them.”

An attendee from Australia offered a slightly more positive take on the findings, followed by a suggestion to improve linkage in marginalized populations.

“I’m not sure I’d be pessimistic,” the attendee said. “I think you ought to be commended for getting that number of people to link, because it is very difficult when we are looking at linking people from a hospital-based setting who actually live in the community and suffer from homelessness and mental health issues and incarceration and a whole range of other things. ... Maybe we need to change our idea of having these centralized silos where people are referred, and go out into the community, much like [tuberculosis] clinics used to do, and track people down.”

The study was funded by Gilead. The investigators disclosed additional relationships with HighTide Therapeutics, Intercept, AbbVie, and others.

SOURCE: Landis CS et al. The Liver Meeting 2019, Abstract 168.

BOSTON – ED-based screening is a feasible method of detecting hepatitis C virus (HCV) in high-risk populations, but linkage to care remains low, according to investigators.

An HCV screening program involving three Seattle hospitals and more than 4,000 patients showed that linkage to care was lowest among patients who were younger, homeless, or used injection drugs, reported lead author Charles S. Landis, MD, PhD, of the University of Washington, Seattle.

“In the U.S., rates of acute HCV infections are increasing in younger patients and in areas disproportionally affected by the opiate epidemic,” Dr. Landis said in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “In order to achieve a goal of elimination, HCV screening, appropriate linkage to care, and treatment will need to be directed toward younger, marginalized, and underserved populations.”

Dr. Landis explained that EDs are suitable for HCV screening because users of emergency services are disproportionately affected by HCV, compared with patients in primary and specialty care settings. Despite this, linkage to care remains historically higher in primary and specialty care settings at approximately 70%, compared with 30% via the ED, Dr. Landis said.

Historically, EDs have been resistant to HCV screening programs, Dr. Landis said, but with the model used in the present study, which relied upon a full-time staff member in each ED who was employed by the infectious disease or hepatology department, no ED resources were needed.

Participants were willing adults who had reliable contact information. Patients were excluded if they were non–English speaking, incarcerated, enrolled or expected to enroll in another clinical study which excludes coenrollment, planned to move out of the region in the next 6 months, admitted to the ED with an acute life-threatening illness, or admitted to the ED for sexual assault. The program had three objectives: Screening, linkage to care, and treatment, all of which were coordinated by the aforementioned case manager.

To date, 4,182 patients have been screened, 936 have been enrolled, 95 have tested positive for HCV RNA, 32 have been linked with care, and 19 have been treated.

“So you can see, a lot of squeeze for a just a little bit of juice here,” Dr. Landis said, referring to the relatively low number of treated patients, compared with how many were screened.

The prevalence of HCV infection based on RNA testing was 2%, though one hospital had a rate of 5%. “This [prevalence] compares to, but is maybe slightly less than, the prevalence seen in others studies based in the emergency department,” Dr. Landis said. “The thought is, not all emergency departments are equal in terms of the patient population that they serve.”

Data analysis showed that the overall linkage to care was 36%. “This is still suboptimal, from my perspective,” Dr. Landis said, “but it does compare with several other ED-based studies.”

A closer look at the data showed that linkage was not uniform across the population. Among patients with homes, linkage to care was 59%, compared with 20% for patients who were homeless (P = .02).

“Ultimately, we need to tailor our approaches for linking homeless patients differently than patients who are not homeless,” Dr. Landis said.