User login

Behavioral Health Trainee Satisfaction at the US Department of Veterans Affairs During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic changed the education and training experiences of health care students and those set to comprise the future workforce. Apart from general training disruptions or delays due to the pandemic, behavioral health trainees such as psychologists and social workers faced limited opportunities to provide in-person services.1-5 Trainees also experienced fewer referrals to mental health services from primary care and more disrupted, no-show, or cancelled appointments.4-6 Behavioral health trainees experienced a limited ability to establish rapport and more difficulty providing effective services because of the limited in-person interaction presented by telehealth.6 The pandemic also resulted in feelings of increased isolation and decreased teamwork.1,7 The virtual or remote setting made it more difficult for trainees to feel as if they were a member of a team or community of behavioral health professionals.1,7

Behavioral health trainees had to adapt to conducting patient visits and educational didactics through virtual platforms.1,3-7 Challenges included access or technological problems with online platforms and a lack of telehealth training use.3,4,6 One study found that while both behavioral health trainees and licensed practitioners reported similar rates of telehealth use for mental health services by early April 2020, trainees had more difficulties implementing telehealth compared with licensed practitioners. This study found that US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) facilities reported higher use of telehealth in February 2020.5

A mission of the VA is to provide education and training to health care professionals through partnerships with affiliated academic institutions. The VA is the largest education and training supplier for health care professions in the US. As many as 50% of psychologists in the US received some training at the VA.8 Additionally, more graduate-level social work students are trained at the VA than at any other organization.9 The VA is a major contributor to not only its own behavioral health workforce, but that of the entire country.

The VA is also the largest employer of psychologists and social workers in the US.10,11 The VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) oversees health care profession education and training at all VA facilities. In 2012, OAA began the Mental Health Education Expansion program to increase training for behavioral health professionals, including psychologists and social workers. 12 The OAA initiative was aligned with VA training and workforce priorities.8,12 To gauge the effectiveness of VA education and training, OAA encourages VA trainees to complete the Trainee Satisfaction Survey (TSS), which measures trainee satisfaction and the likelihood of a trainee to consider the VA for future employment.

Researchers at the Veterans Emergency Management Evaluation Center sought to understand the impact the COVID-19 pandemic had on behavioral health trainees’ experiences by examining TSS data from before and after the onset of the pandemic. This study expands on prior research among physician residents and fellows which found associations between VA training experiences and the COVID- 19 pandemic. The previous study found declines in trainee satisfaction and a decreased likelihood to consider the VA for future employment.13

It is important to understand the effects the pandemic had on the professional development and wellness for both physician and behavioral health professional trainees. Identifying how the pandemic impacted trainee satisfaction may help improve education programs and mitigate the impact of future public health emergencies. This is particularly important due to the shortage of behavioral health professionals in the VA and the US.12,14

METHODS

This study used TSS data collected from August 2018 to July 2021 from 153 VA facilities. A behavioral health trainee was defined as any psychology or social work trainee who completed 1 rotation at a VA facility. Psychiatric trainees were excluded because as physicians their training programs differ markedly from those for psychology and social work. Excluding psychiatry, psychology and social work comprise the 2 largest mental health care training groups.

This study was reviewed and approved as a quality improvement project by the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) Institutional Review Board, which waived informed consent requirements. The OAA granted access to data using a process open to all VA researchers. At the time of data collection, respondents were assured their anonymity; participation was voluntary.

Measures

Any response provided before February 29, 2020, was defined as the prepandemic period. The pandemic period included any response from April 1, 2020, to July 31, 2021. Responses collected in March 2020 were excluded as it would be unclear from the survey whether the training period occurred before or after the onset of the pandemic.

To measure overall trainee satisfaction with the VA training experience, responses were grouped as satisfied (satisfied/ very satisfied) and dissatisfied (dissatisfied/ very dissatisfied). To measure a trainee’s likelihood to consider the VA for future employment as a result of their training experience, responses were grouped as likely (likely/very likely) and unlikely (unlikely/very unlikely).

Other components of satisfaction were also collected including onboarding, clinical faculty/preceptors, clinical learning environment, physical environment, working environment, and respect felt at work. If a respondent chose very dissatisfied or dissatisfied, they were subsequently asked to specify the reason for their dissatisfaction with an open-ended response. Open-ended responses were not permitted if a respondent indicated a satisfied or very satisfied response.

Statistical Analyses

Stata SE 17 was used for statistical analyses. To test the relationship between the pandemic group and the 2 separate outcome variables, logistic regressions were conducted to measure overall satisfaction and likelihood of future VA employment. Margin commands were used to calculate the difference in the probability of reporting satisfied/very satisfied and likely/very likely for the prepandemic and pandemic groups. The association of the COVID-19 group with each outcome variable was expressed as the difference in the percentage of the outcome between the prepandemic and pandemic groups. Preliminary analyses demonstrated similar effects of the pandemic on psychology and social work trainees; therefore, the groups were combined.

Rapid Coding and Thematic Analyses

Qualitative data were based on open-ended responses from behavioral health trainees when they were asked to specify the cause of dissatisfaction in the aforementioned areas of satisfaction. Methods for qualitative data included rapid coding and thematic content analyses.15,16 Additional general information regarding the qualitative data analyses is described elsewhere.13 A keyword search was completed to identify all open-ended responses related to COVID-19 pandemic causes of dissatisfaction. Keywords included: virus, COVID, corona, pandemic, PPE, N95, mask, social distance, and safety. All open-ended responses were reviewed to ensure keywords were appropriately identifying pandemic-related causes of dissatisfaction and did not overlook other references to the pandemic, and to identify initial themes and corresponding definitions based on survey questions. After review, additional keywords were included in the content analyses that were related to providing mental health services using remote or telehealth options. This included the following keywords: remote, video, VVC (VA Video Connect), and tele. The research team completed a review of the initial themes and definitions and created a final coding construct with definitions before completing an independent coding of all identified pandemic-related responses. Frequency counts of each code were provided to identify which pandemic-related causes of dissatisfaction were mentioned most.

RESULTS

A total of 3950 behavioral health trainees responded to the TSS, including 2715 psychology trainees and 1235 social work trainees who indicated they received training at the VA in academic years 2018/2019, 2019/2020, or 2020/2021. The academic year 2018/2019 was considered in an effort to provide a larger sample of prepandemic trainees.

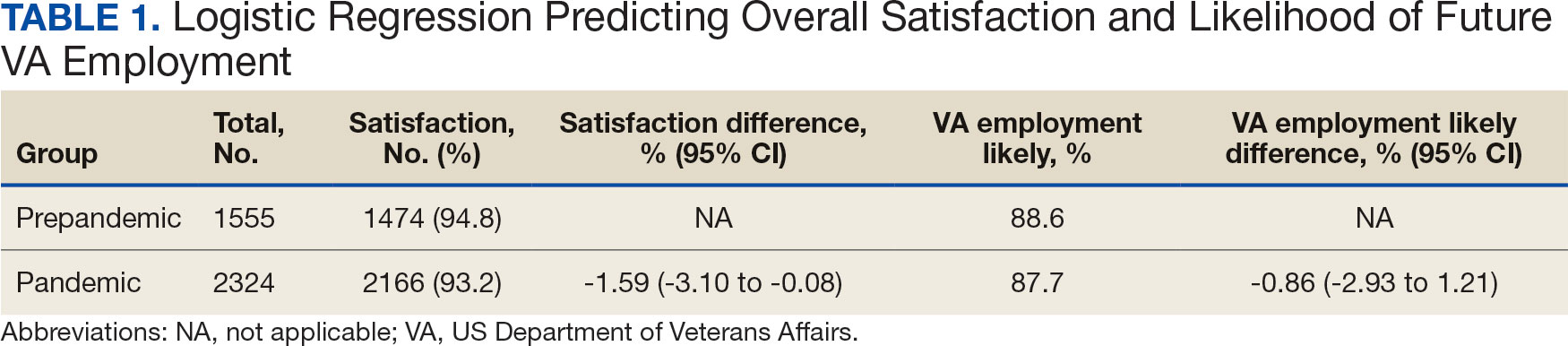

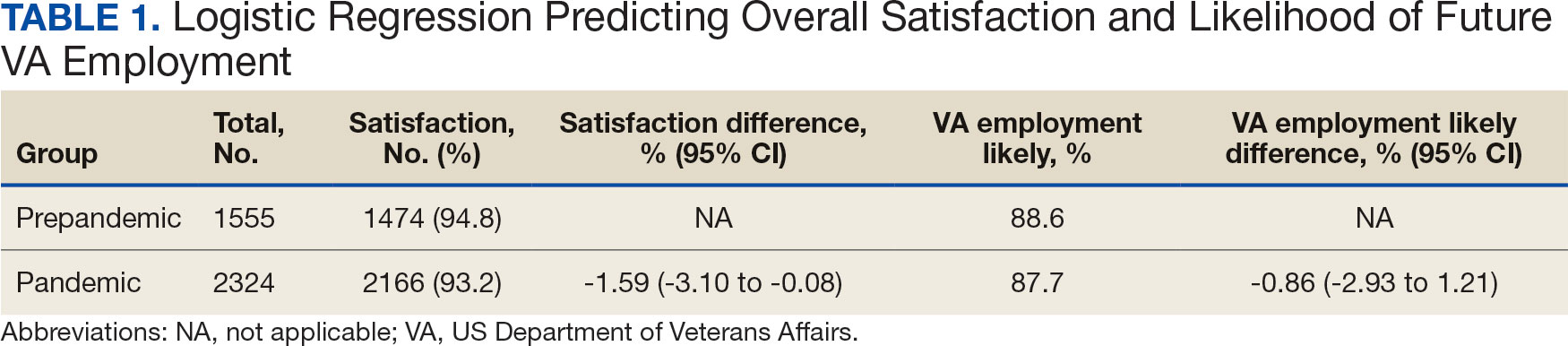

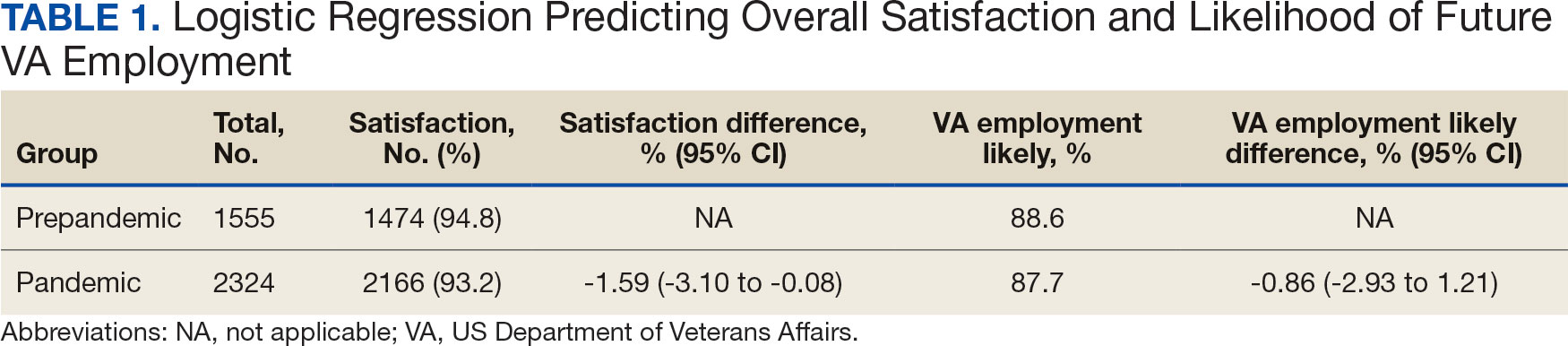

The percentage of trainees reporting satisfaction with their training decreased across prepandemic to pandemic groups. In the pandemic group, 2166 of 2324 respondents (93.2%) reported satisfaction compared to 1474 of 1555 (94.8%) in the prepandemic trainee group (P = .04; 95% CI, -3.10 to -0.08). There was no association between the pandemic group and behavioral health trainees’ reported willingness to consider the VA for future employment (Table 1). Preliminary analyses demonstrated similar effects of the pandemic on psychology and social work trainees, therefore the groups were combined, and overall effects were reported.

Pandemic-Related Dissatisfaction

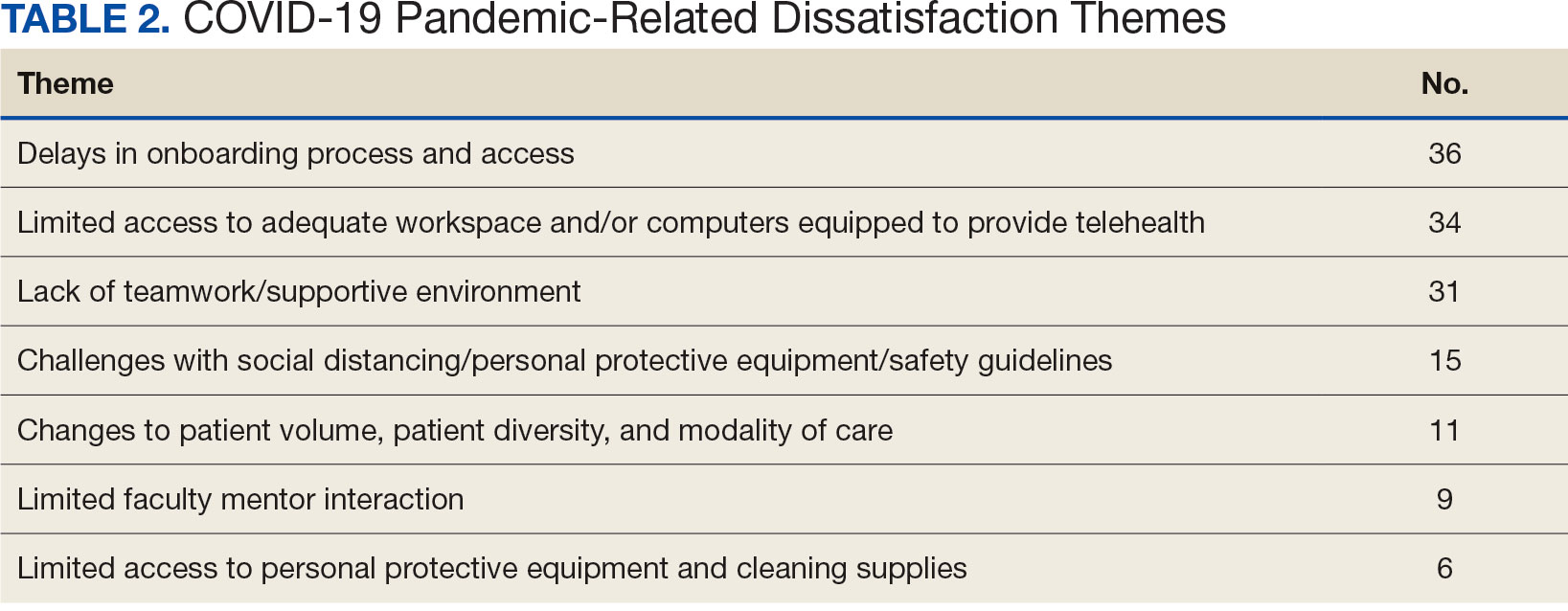

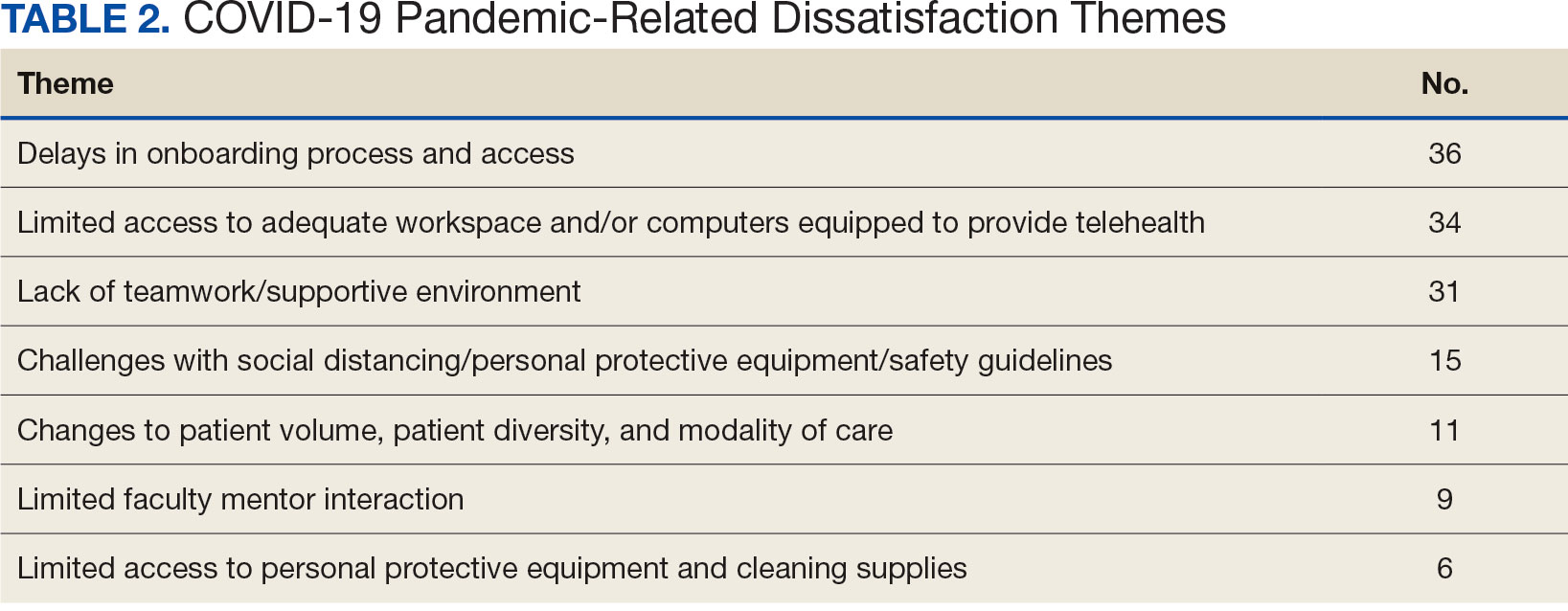

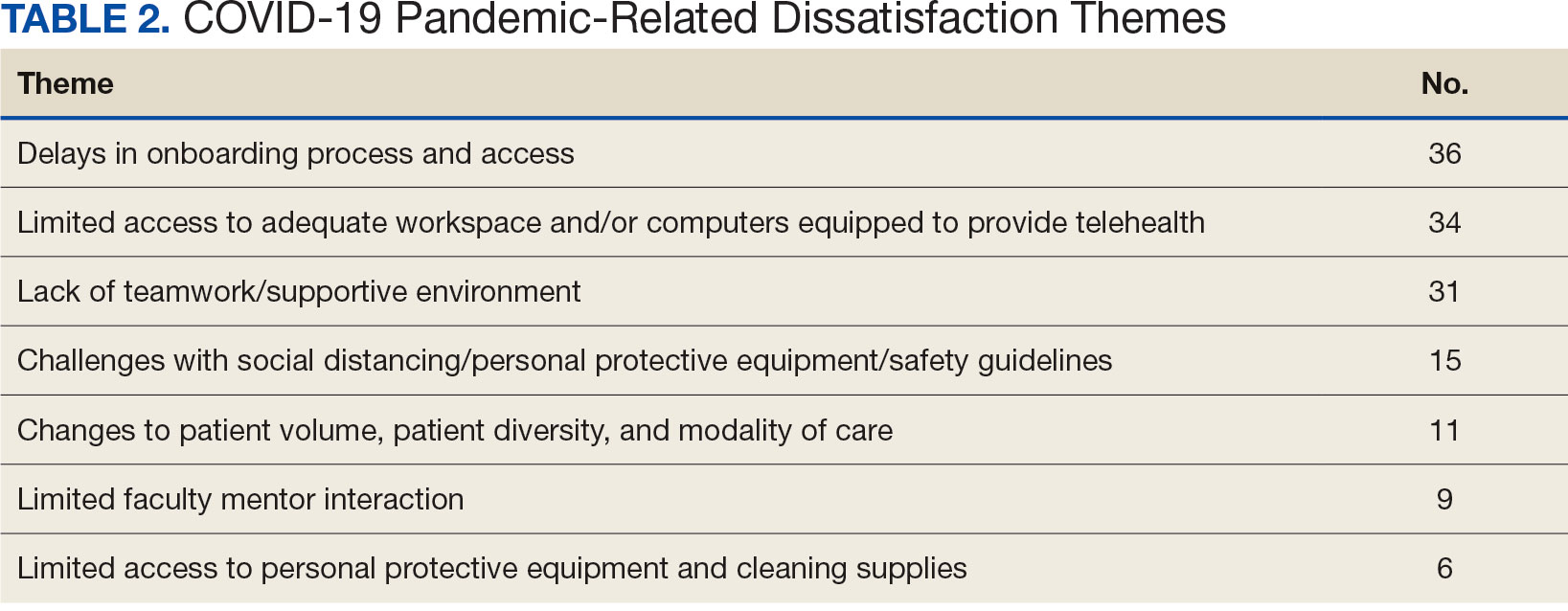

Of the 3950 psychology and social work trainees who responded to the survey, 75 (1.9%) indicated dissatisfaction with their VA training experience using pandemic-related keywords. Open-ended responses were generally short (range, 1-32 words; median, 19 words). Qualitative analyses revealed 7 themes (Table 2).

The most frequently identified theme was challenges with onboarding. One respondent indicated the modified onboarding procedures in place due to the pandemic were difficult to understand and resulted in delays. Another frequently mentioned cause of dissatisfaction was limited work or office space and insufficient computer availability. This was often noted to relate to a lack of private space to conduct telehealth visits or computers that were not equipped to provide telehealth. Several respondents also noted technological issues when attempting to use VVC to provide telehealth.

Another common theme was that the pandemic diminished teamwork, generated feelings of isolation, and created unsupportive environments for trainees. For instance, some trainees indicated that COVID-19 decreased the inclusion of trainees as part of the regular staff groups and accordingly resulted in limited networking opportunities. Other causes of dissatisfaction included the pandemic’s impacts on the learning environment, such as decreases in patient volume, decreased diversity of patient cases, and a limited presence of faculty mentors. Several respondents indicated that the pandemic limited their caseloads and indicated that most patients were seen virtually. Open-ended responses from a few respondents indicated their training environments were noncompliant with social distancing, personal protective equipment requirements, or other safety guidelines.

DISCUSSION

This study illustrates the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the behavioral health trainee experience, which was expressed through decreased satisfaction with their clinical training at the VA. The narrative data indicated that the observed pandemic-related dissatisfaction was linked specifically to onboarding, a lack of safe and private workspaces and computers, as well as a lack of a supportive work environment.

Although the reported decrease in satisfaction was statistically significant, the effect size was not large. Additionally, while satisfaction did decrease, the trainees’ reported likelihood to consider the VA for future employment was not impacted. This may suggest psychologist and social work trainees’ perseverance and dedication to their chosen profession persisted despite the challenges presented by the pandemic. Furthermore, the qualitative data suggest potential ways to mitigate health care profession trainee challenges that can follow a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, although further study is warranted.

While narrative responses with pandemic-related keywords did indicate challenges specific to COVID-19 (ie, limited access to workspaces and/or computers equipped for telehealth), the overall frequency of pandemic-related responses was low. This may indicate these are institutional challenges trainees face independent of the pandemic. These findings warrant longterm attention to the satisfaction of psychology and social worker trainees’ during the pandemic. For example, additional training for the use of telehealth could be provided. One study indicated that < 61% of psychology postdoctoral fellows received telepsychology training during the pandemic, and of those who did receive training, less than half were satisfied with it.3

Similarly, strategies could be developed to ensure a more supportive learning and work environment, and provide additional networking opportunities for trainees, despite social distancing. Education specific to disaster response should be incorporated into behavioral health care professionals’ training, especially because behavioral health care professionals provided major contributions during the pandemic due to reported increases in mental health concerns (eg, anxiety and depression) during the period.7,17,18 As the pandemic progressed, policies and procedures were established or modified to address some of these concerns because they were not necessarily limited to trainees. For example, additional training resources were developed to support the use of various telehealth technologies, virtual resources were used more often for meetings, and supervisors developed more comfort and familiarity with how to manage in a virtual or hybrid environment.

Limitations

Although the TSS data provide a large national sample of behavioral health care trainees, it only includes VA trainees, and therefore may not be completely generalizable across health care. However, because many psychologists and social workers throughout the US train at the VA, and because the VA is the largest employer of practicing psychologists and social workers, understanding the impacts felt at the VA informs institutions nationally.8-11 The TSS has limited demographic data (eg, age, race, ethnicity, and sex), so it is unclear whether the respondent groups before and during the pandemic differed in ways that could relate to outcomes. The data also do not specify exact training dates; however, anecdotal evidence suggests respondents generally complete the survey close to the end of their training.

Additionally, open-ended narrative responses were only asked for replies that indicated dissatisfaction, precluding a more nuanced understanding of potential positive outcomes. Furthermore, the TSS is limited to questions about the trainees’ clinical experiences, but because the pandemic created many stressors, there may have been personal issues that affected their work. It is possible that changes in overall satisfaction may have been rooted in something outside of their clinical experience. Finally, the response rate for the TSS is consistently low both before and during the pandemic and includes a limited number of narrative responses.

CONCLUSIONS

The VA is an important contributor to the education, training, and composition of the behavioral health care workforce. A deeper understanding of the VA trainee experience is important to identify how to improve behavioral health care professional education and training. This is especially true as behavioral health care faces shortages within the VA and nationwide.8,12,19

This study reinforces research that found health care trainees experienced decreased learning opportunities and telehealth-related challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. 13,20 Despite the observed decline in trainee satisfaction, the lack of a corresponding change in likelihood to seek employment with the VA is encouraging for VA efforts to maintain and grow its behavioral health care workforce and for similar efforts outside VA. This resilience may relate to the substantial prepandemic time invested in their professional development. Future studies should examine long term impacts of the pandemic on trainee’s clinical experience and whether the pipeline of behavioral health care workers declines over time as students that are earlier in their career paths instead chose other professions. Future research should also explore ways to improve professional development and wellness of behavioral health care trainees during disasters (eg, telehealth training, additional networking, and social support).

- Muddle S, Rettie H, Harris O, Lawes A, Robinson R. Trainee life under COVID-19: a systemic case report. J Fam Ther. 2022;44(2):239-249. doi:10.1111/1467-6427.12354

- Valenzuela J, Crosby LE, Harrison RR. Commentary: reflections on the COVID-19 pandemic and health disparities in pediatric psychology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2020;45(8):839- 841. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa063

- Frye WS, Feldman M, Katzenstein J, Gardner L. Modified training experiences for psychology interns and fellows during COVID-19: use of telepsychology and telesupervision by child and adolescent training programs. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2022;29(4):840- 848. doi:10.1007/s10880-021-09839-4

- Perrin PB, Rybarczyk BD, Pierce BS, Jones HA, Shaffer C, Islam L. Rapid telepsychology deployment during the COVID-19 pandemic: a special issue commentary and lessons from primary care psychology training. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76(6):1173-1185. doi:10.1002/jclp.22969

- Reilly SE, Zane KL, McCuddy WT, et al. Mental health practitioners’ immediate practical response during the COVID-19 pandemic: observational questionnaire study. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(9):e21237. doi:10.2196/21237

- Sadicario JS, Parlier-Ahmad AB, Brechbiel JK, Islam LZ, Martin CE. Caring for women with substance use disorders through pregnancy and postpartum during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from psychology trainees in an integrated OBGYN/substance use disorder outpatient treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;122:108200. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108200

- Schneider NM, Steinberg DM, Garcia AM, et al. Pediatric consultation-liaison psychology: insights and lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2023;30(1):51-60. doi:10.1007/s10880-022-09887-4

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee to Evaluate the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health. Mental Health Workforce and Facilities Infrastructure. In: Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. National Academies Press (US); 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499512/

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Health Administration. Career as a VA social worker. Updated March 3, 2025. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.socialwork.va.gov/VA_Employment.asp

- United States Senate Committee on Veterans Affairs hearing on “Making the VA the Workplace of Choice for Health Care Providers.” News release. American Psychological Association. April 9, 2008. Accessed April 9, 2025. https:// www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2008/04/testimony

- VA National Professional Social Work Month Planning Committee. The diverse, far-reaching VA social worker profession. March 17, 2023. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://news.va.gov/116804/diverse-far-reaching-social-worker-profession/

- Patel EL, Bates JM, Holguin JK, et al. Program profile: the expansion of associated health training in the VA. Fed Pract. 2021;38(8):374-380. doi:10.12788/fp.0163

- Northcraft H, Bai J, Griffin AR, Hovsepian S, Dobalian A. Association of the COVID-19 pandemic on VA resident and fellow training satisfaction and future VA employment: a mixed methods study. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(5):593- 598. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-22-00168.1

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Health workforce shortage areas. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas

- Gale RC, Wu J, Erhardt T, et al. Comparison of rapid vs in-depth qualitative analytic methods from a process evaluation of academic detailing in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):11. doi:10.1186/s13012-019-0853-y

- Taylor B, Henshall C, Kenyon S, Litchfield I, Greenfield S. Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? A mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e019993. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019993

- Kranke D, Der-Martirosian C, Hovsepian S, et al. Social workers being effective in disaster settings. Soc Work Public Health. 2020;35(8):664-668. doi:10.1080/19371918.20 20.1820928

- Kranke D, Gin JL, Der-Martirosian C, Weiss EL, Dobalian A. VA social work leadership and compassion fatigue during the 2017 hurricane season. Soc Work Ment Health. 2020;18:188-199. doi:10.1080/15332985.2019.1700873

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

- Der-Martirosian C, Wyte-Lake T, Balut M, et al. Implementation of telehealth services at the US Department of Veterans Affairs during the COVID-19 pandemic: mixed methods study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(9):e29429. doi:10.2196/29429

The COVID-19 pandemic changed the education and training experiences of health care students and those set to comprise the future workforce. Apart from general training disruptions or delays due to the pandemic, behavioral health trainees such as psychologists and social workers faced limited opportunities to provide in-person services.1-5 Trainees also experienced fewer referrals to mental health services from primary care and more disrupted, no-show, or cancelled appointments.4-6 Behavioral health trainees experienced a limited ability to establish rapport and more difficulty providing effective services because of the limited in-person interaction presented by telehealth.6 The pandemic also resulted in feelings of increased isolation and decreased teamwork.1,7 The virtual or remote setting made it more difficult for trainees to feel as if they were a member of a team or community of behavioral health professionals.1,7

Behavioral health trainees had to adapt to conducting patient visits and educational didactics through virtual platforms.1,3-7 Challenges included access or technological problems with online platforms and a lack of telehealth training use.3,4,6 One study found that while both behavioral health trainees and licensed practitioners reported similar rates of telehealth use for mental health services by early April 2020, trainees had more difficulties implementing telehealth compared with licensed practitioners. This study found that US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) facilities reported higher use of telehealth in February 2020.5

A mission of the VA is to provide education and training to health care professionals through partnerships with affiliated academic institutions. The VA is the largest education and training supplier for health care professions in the US. As many as 50% of psychologists in the US received some training at the VA.8 Additionally, more graduate-level social work students are trained at the VA than at any other organization.9 The VA is a major contributor to not only its own behavioral health workforce, but that of the entire country.

The VA is also the largest employer of psychologists and social workers in the US.10,11 The VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) oversees health care profession education and training at all VA facilities. In 2012, OAA began the Mental Health Education Expansion program to increase training for behavioral health professionals, including psychologists and social workers. 12 The OAA initiative was aligned with VA training and workforce priorities.8,12 To gauge the effectiveness of VA education and training, OAA encourages VA trainees to complete the Trainee Satisfaction Survey (TSS), which measures trainee satisfaction and the likelihood of a trainee to consider the VA for future employment.

Researchers at the Veterans Emergency Management Evaluation Center sought to understand the impact the COVID-19 pandemic had on behavioral health trainees’ experiences by examining TSS data from before and after the onset of the pandemic. This study expands on prior research among physician residents and fellows which found associations between VA training experiences and the COVID- 19 pandemic. The previous study found declines in trainee satisfaction and a decreased likelihood to consider the VA for future employment.13

It is important to understand the effects the pandemic had on the professional development and wellness for both physician and behavioral health professional trainees. Identifying how the pandemic impacted trainee satisfaction may help improve education programs and mitigate the impact of future public health emergencies. This is particularly important due to the shortage of behavioral health professionals in the VA and the US.12,14

METHODS

This study used TSS data collected from August 2018 to July 2021 from 153 VA facilities. A behavioral health trainee was defined as any psychology or social work trainee who completed 1 rotation at a VA facility. Psychiatric trainees were excluded because as physicians their training programs differ markedly from those for psychology and social work. Excluding psychiatry, psychology and social work comprise the 2 largest mental health care training groups.

This study was reviewed and approved as a quality improvement project by the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) Institutional Review Board, which waived informed consent requirements. The OAA granted access to data using a process open to all VA researchers. At the time of data collection, respondents were assured their anonymity; participation was voluntary.

Measures

Any response provided before February 29, 2020, was defined as the prepandemic period. The pandemic period included any response from April 1, 2020, to July 31, 2021. Responses collected in March 2020 were excluded as it would be unclear from the survey whether the training period occurred before or after the onset of the pandemic.

To measure overall trainee satisfaction with the VA training experience, responses were grouped as satisfied (satisfied/ very satisfied) and dissatisfied (dissatisfied/ very dissatisfied). To measure a trainee’s likelihood to consider the VA for future employment as a result of their training experience, responses were grouped as likely (likely/very likely) and unlikely (unlikely/very unlikely).

Other components of satisfaction were also collected including onboarding, clinical faculty/preceptors, clinical learning environment, physical environment, working environment, and respect felt at work. If a respondent chose very dissatisfied or dissatisfied, they were subsequently asked to specify the reason for their dissatisfaction with an open-ended response. Open-ended responses were not permitted if a respondent indicated a satisfied or very satisfied response.

Statistical Analyses

Stata SE 17 was used for statistical analyses. To test the relationship between the pandemic group and the 2 separate outcome variables, logistic regressions were conducted to measure overall satisfaction and likelihood of future VA employment. Margin commands were used to calculate the difference in the probability of reporting satisfied/very satisfied and likely/very likely for the prepandemic and pandemic groups. The association of the COVID-19 group with each outcome variable was expressed as the difference in the percentage of the outcome between the prepandemic and pandemic groups. Preliminary analyses demonstrated similar effects of the pandemic on psychology and social work trainees; therefore, the groups were combined.

Rapid Coding and Thematic Analyses

Qualitative data were based on open-ended responses from behavioral health trainees when they were asked to specify the cause of dissatisfaction in the aforementioned areas of satisfaction. Methods for qualitative data included rapid coding and thematic content analyses.15,16 Additional general information regarding the qualitative data analyses is described elsewhere.13 A keyword search was completed to identify all open-ended responses related to COVID-19 pandemic causes of dissatisfaction. Keywords included: virus, COVID, corona, pandemic, PPE, N95, mask, social distance, and safety. All open-ended responses were reviewed to ensure keywords were appropriately identifying pandemic-related causes of dissatisfaction and did not overlook other references to the pandemic, and to identify initial themes and corresponding definitions based on survey questions. After review, additional keywords were included in the content analyses that were related to providing mental health services using remote or telehealth options. This included the following keywords: remote, video, VVC (VA Video Connect), and tele. The research team completed a review of the initial themes and definitions and created a final coding construct with definitions before completing an independent coding of all identified pandemic-related responses. Frequency counts of each code were provided to identify which pandemic-related causes of dissatisfaction were mentioned most.

RESULTS

A total of 3950 behavioral health trainees responded to the TSS, including 2715 psychology trainees and 1235 social work trainees who indicated they received training at the VA in academic years 2018/2019, 2019/2020, or 2020/2021. The academic year 2018/2019 was considered in an effort to provide a larger sample of prepandemic trainees.

The percentage of trainees reporting satisfaction with their training decreased across prepandemic to pandemic groups. In the pandemic group, 2166 of 2324 respondents (93.2%) reported satisfaction compared to 1474 of 1555 (94.8%) in the prepandemic trainee group (P = .04; 95% CI, -3.10 to -0.08). There was no association between the pandemic group and behavioral health trainees’ reported willingness to consider the VA for future employment (Table 1). Preliminary analyses demonstrated similar effects of the pandemic on psychology and social work trainees, therefore the groups were combined, and overall effects were reported.

Pandemic-Related Dissatisfaction

Of the 3950 psychology and social work trainees who responded to the survey, 75 (1.9%) indicated dissatisfaction with their VA training experience using pandemic-related keywords. Open-ended responses were generally short (range, 1-32 words; median, 19 words). Qualitative analyses revealed 7 themes (Table 2).

The most frequently identified theme was challenges with onboarding. One respondent indicated the modified onboarding procedures in place due to the pandemic were difficult to understand and resulted in delays. Another frequently mentioned cause of dissatisfaction was limited work or office space and insufficient computer availability. This was often noted to relate to a lack of private space to conduct telehealth visits or computers that were not equipped to provide telehealth. Several respondents also noted technological issues when attempting to use VVC to provide telehealth.

Another common theme was that the pandemic diminished teamwork, generated feelings of isolation, and created unsupportive environments for trainees. For instance, some trainees indicated that COVID-19 decreased the inclusion of trainees as part of the regular staff groups and accordingly resulted in limited networking opportunities. Other causes of dissatisfaction included the pandemic’s impacts on the learning environment, such as decreases in patient volume, decreased diversity of patient cases, and a limited presence of faculty mentors. Several respondents indicated that the pandemic limited their caseloads and indicated that most patients were seen virtually. Open-ended responses from a few respondents indicated their training environments were noncompliant with social distancing, personal protective equipment requirements, or other safety guidelines.

DISCUSSION

This study illustrates the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the behavioral health trainee experience, which was expressed through decreased satisfaction with their clinical training at the VA. The narrative data indicated that the observed pandemic-related dissatisfaction was linked specifically to onboarding, a lack of safe and private workspaces and computers, as well as a lack of a supportive work environment.

Although the reported decrease in satisfaction was statistically significant, the effect size was not large. Additionally, while satisfaction did decrease, the trainees’ reported likelihood to consider the VA for future employment was not impacted. This may suggest psychologist and social work trainees’ perseverance and dedication to their chosen profession persisted despite the challenges presented by the pandemic. Furthermore, the qualitative data suggest potential ways to mitigate health care profession trainee challenges that can follow a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, although further study is warranted.

While narrative responses with pandemic-related keywords did indicate challenges specific to COVID-19 (ie, limited access to workspaces and/or computers equipped for telehealth), the overall frequency of pandemic-related responses was low. This may indicate these are institutional challenges trainees face independent of the pandemic. These findings warrant longterm attention to the satisfaction of psychology and social worker trainees’ during the pandemic. For example, additional training for the use of telehealth could be provided. One study indicated that < 61% of psychology postdoctoral fellows received telepsychology training during the pandemic, and of those who did receive training, less than half were satisfied with it.3

Similarly, strategies could be developed to ensure a more supportive learning and work environment, and provide additional networking opportunities for trainees, despite social distancing. Education specific to disaster response should be incorporated into behavioral health care professionals’ training, especially because behavioral health care professionals provided major contributions during the pandemic due to reported increases in mental health concerns (eg, anxiety and depression) during the period.7,17,18 As the pandemic progressed, policies and procedures were established or modified to address some of these concerns because they were not necessarily limited to trainees. For example, additional training resources were developed to support the use of various telehealth technologies, virtual resources were used more often for meetings, and supervisors developed more comfort and familiarity with how to manage in a virtual or hybrid environment.

Limitations

Although the TSS data provide a large national sample of behavioral health care trainees, it only includes VA trainees, and therefore may not be completely generalizable across health care. However, because many psychologists and social workers throughout the US train at the VA, and because the VA is the largest employer of practicing psychologists and social workers, understanding the impacts felt at the VA informs institutions nationally.8-11 The TSS has limited demographic data (eg, age, race, ethnicity, and sex), so it is unclear whether the respondent groups before and during the pandemic differed in ways that could relate to outcomes. The data also do not specify exact training dates; however, anecdotal evidence suggests respondents generally complete the survey close to the end of their training.

Additionally, open-ended narrative responses were only asked for replies that indicated dissatisfaction, precluding a more nuanced understanding of potential positive outcomes. Furthermore, the TSS is limited to questions about the trainees’ clinical experiences, but because the pandemic created many stressors, there may have been personal issues that affected their work. It is possible that changes in overall satisfaction may have been rooted in something outside of their clinical experience. Finally, the response rate for the TSS is consistently low both before and during the pandemic and includes a limited number of narrative responses.

CONCLUSIONS

The VA is an important contributor to the education, training, and composition of the behavioral health care workforce. A deeper understanding of the VA trainee experience is important to identify how to improve behavioral health care professional education and training. This is especially true as behavioral health care faces shortages within the VA and nationwide.8,12,19

This study reinforces research that found health care trainees experienced decreased learning opportunities and telehealth-related challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. 13,20 Despite the observed decline in trainee satisfaction, the lack of a corresponding change in likelihood to seek employment with the VA is encouraging for VA efforts to maintain and grow its behavioral health care workforce and for similar efforts outside VA. This resilience may relate to the substantial prepandemic time invested in their professional development. Future studies should examine long term impacts of the pandemic on trainee’s clinical experience and whether the pipeline of behavioral health care workers declines over time as students that are earlier in their career paths instead chose other professions. Future research should also explore ways to improve professional development and wellness of behavioral health care trainees during disasters (eg, telehealth training, additional networking, and social support).

The COVID-19 pandemic changed the education and training experiences of health care students and those set to comprise the future workforce. Apart from general training disruptions or delays due to the pandemic, behavioral health trainees such as psychologists and social workers faced limited opportunities to provide in-person services.1-5 Trainees also experienced fewer referrals to mental health services from primary care and more disrupted, no-show, or cancelled appointments.4-6 Behavioral health trainees experienced a limited ability to establish rapport and more difficulty providing effective services because of the limited in-person interaction presented by telehealth.6 The pandemic also resulted in feelings of increased isolation and decreased teamwork.1,7 The virtual or remote setting made it more difficult for trainees to feel as if they were a member of a team or community of behavioral health professionals.1,7

Behavioral health trainees had to adapt to conducting patient visits and educational didactics through virtual platforms.1,3-7 Challenges included access or technological problems with online platforms and a lack of telehealth training use.3,4,6 One study found that while both behavioral health trainees and licensed practitioners reported similar rates of telehealth use for mental health services by early April 2020, trainees had more difficulties implementing telehealth compared with licensed practitioners. This study found that US Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) facilities reported higher use of telehealth in February 2020.5

A mission of the VA is to provide education and training to health care professionals through partnerships with affiliated academic institutions. The VA is the largest education and training supplier for health care professions in the US. As many as 50% of psychologists in the US received some training at the VA.8 Additionally, more graduate-level social work students are trained at the VA than at any other organization.9 The VA is a major contributor to not only its own behavioral health workforce, but that of the entire country.

The VA is also the largest employer of psychologists and social workers in the US.10,11 The VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) oversees health care profession education and training at all VA facilities. In 2012, OAA began the Mental Health Education Expansion program to increase training for behavioral health professionals, including psychologists and social workers. 12 The OAA initiative was aligned with VA training and workforce priorities.8,12 To gauge the effectiveness of VA education and training, OAA encourages VA trainees to complete the Trainee Satisfaction Survey (TSS), which measures trainee satisfaction and the likelihood of a trainee to consider the VA for future employment.

Researchers at the Veterans Emergency Management Evaluation Center sought to understand the impact the COVID-19 pandemic had on behavioral health trainees’ experiences by examining TSS data from before and after the onset of the pandemic. This study expands on prior research among physician residents and fellows which found associations between VA training experiences and the COVID- 19 pandemic. The previous study found declines in trainee satisfaction and a decreased likelihood to consider the VA for future employment.13

It is important to understand the effects the pandemic had on the professional development and wellness for both physician and behavioral health professional trainees. Identifying how the pandemic impacted trainee satisfaction may help improve education programs and mitigate the impact of future public health emergencies. This is particularly important due to the shortage of behavioral health professionals in the VA and the US.12,14

METHODS

This study used TSS data collected from August 2018 to July 2021 from 153 VA facilities. A behavioral health trainee was defined as any psychology or social work trainee who completed 1 rotation at a VA facility. Psychiatric trainees were excluded because as physicians their training programs differ markedly from those for psychology and social work. Excluding psychiatry, psychology and social work comprise the 2 largest mental health care training groups.

This study was reviewed and approved as a quality improvement project by the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS) Institutional Review Board, which waived informed consent requirements. The OAA granted access to data using a process open to all VA researchers. At the time of data collection, respondents were assured their anonymity; participation was voluntary.

Measures

Any response provided before February 29, 2020, was defined as the prepandemic period. The pandemic period included any response from April 1, 2020, to July 31, 2021. Responses collected in March 2020 were excluded as it would be unclear from the survey whether the training period occurred before or after the onset of the pandemic.

To measure overall trainee satisfaction with the VA training experience, responses were grouped as satisfied (satisfied/ very satisfied) and dissatisfied (dissatisfied/ very dissatisfied). To measure a trainee’s likelihood to consider the VA for future employment as a result of their training experience, responses were grouped as likely (likely/very likely) and unlikely (unlikely/very unlikely).

Other components of satisfaction were also collected including onboarding, clinical faculty/preceptors, clinical learning environment, physical environment, working environment, and respect felt at work. If a respondent chose very dissatisfied or dissatisfied, they were subsequently asked to specify the reason for their dissatisfaction with an open-ended response. Open-ended responses were not permitted if a respondent indicated a satisfied or very satisfied response.

Statistical Analyses

Stata SE 17 was used for statistical analyses. To test the relationship between the pandemic group and the 2 separate outcome variables, logistic regressions were conducted to measure overall satisfaction and likelihood of future VA employment. Margin commands were used to calculate the difference in the probability of reporting satisfied/very satisfied and likely/very likely for the prepandemic and pandemic groups. The association of the COVID-19 group with each outcome variable was expressed as the difference in the percentage of the outcome between the prepandemic and pandemic groups. Preliminary analyses demonstrated similar effects of the pandemic on psychology and social work trainees; therefore, the groups were combined.

Rapid Coding and Thematic Analyses

Qualitative data were based on open-ended responses from behavioral health trainees when they were asked to specify the cause of dissatisfaction in the aforementioned areas of satisfaction. Methods for qualitative data included rapid coding and thematic content analyses.15,16 Additional general information regarding the qualitative data analyses is described elsewhere.13 A keyword search was completed to identify all open-ended responses related to COVID-19 pandemic causes of dissatisfaction. Keywords included: virus, COVID, corona, pandemic, PPE, N95, mask, social distance, and safety. All open-ended responses were reviewed to ensure keywords were appropriately identifying pandemic-related causes of dissatisfaction and did not overlook other references to the pandemic, and to identify initial themes and corresponding definitions based on survey questions. After review, additional keywords were included in the content analyses that were related to providing mental health services using remote or telehealth options. This included the following keywords: remote, video, VVC (VA Video Connect), and tele. The research team completed a review of the initial themes and definitions and created a final coding construct with definitions before completing an independent coding of all identified pandemic-related responses. Frequency counts of each code were provided to identify which pandemic-related causes of dissatisfaction were mentioned most.

RESULTS

A total of 3950 behavioral health trainees responded to the TSS, including 2715 psychology trainees and 1235 social work trainees who indicated they received training at the VA in academic years 2018/2019, 2019/2020, or 2020/2021. The academic year 2018/2019 was considered in an effort to provide a larger sample of prepandemic trainees.

The percentage of trainees reporting satisfaction with their training decreased across prepandemic to pandemic groups. In the pandemic group, 2166 of 2324 respondents (93.2%) reported satisfaction compared to 1474 of 1555 (94.8%) in the prepandemic trainee group (P = .04; 95% CI, -3.10 to -0.08). There was no association between the pandemic group and behavioral health trainees’ reported willingness to consider the VA for future employment (Table 1). Preliminary analyses demonstrated similar effects of the pandemic on psychology and social work trainees, therefore the groups were combined, and overall effects were reported.

Pandemic-Related Dissatisfaction

Of the 3950 psychology and social work trainees who responded to the survey, 75 (1.9%) indicated dissatisfaction with their VA training experience using pandemic-related keywords. Open-ended responses were generally short (range, 1-32 words; median, 19 words). Qualitative analyses revealed 7 themes (Table 2).

The most frequently identified theme was challenges with onboarding. One respondent indicated the modified onboarding procedures in place due to the pandemic were difficult to understand and resulted in delays. Another frequently mentioned cause of dissatisfaction was limited work or office space and insufficient computer availability. This was often noted to relate to a lack of private space to conduct telehealth visits or computers that were not equipped to provide telehealth. Several respondents also noted technological issues when attempting to use VVC to provide telehealth.

Another common theme was that the pandemic diminished teamwork, generated feelings of isolation, and created unsupportive environments for trainees. For instance, some trainees indicated that COVID-19 decreased the inclusion of trainees as part of the regular staff groups and accordingly resulted in limited networking opportunities. Other causes of dissatisfaction included the pandemic’s impacts on the learning environment, such as decreases in patient volume, decreased diversity of patient cases, and a limited presence of faculty mentors. Several respondents indicated that the pandemic limited their caseloads and indicated that most patients were seen virtually. Open-ended responses from a few respondents indicated their training environments were noncompliant with social distancing, personal protective equipment requirements, or other safety guidelines.

DISCUSSION

This study illustrates the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the behavioral health trainee experience, which was expressed through decreased satisfaction with their clinical training at the VA. The narrative data indicated that the observed pandemic-related dissatisfaction was linked specifically to onboarding, a lack of safe and private workspaces and computers, as well as a lack of a supportive work environment.

Although the reported decrease in satisfaction was statistically significant, the effect size was not large. Additionally, while satisfaction did decrease, the trainees’ reported likelihood to consider the VA for future employment was not impacted. This may suggest psychologist and social work trainees’ perseverance and dedication to their chosen profession persisted despite the challenges presented by the pandemic. Furthermore, the qualitative data suggest potential ways to mitigate health care profession trainee challenges that can follow a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, although further study is warranted.

While narrative responses with pandemic-related keywords did indicate challenges specific to COVID-19 (ie, limited access to workspaces and/or computers equipped for telehealth), the overall frequency of pandemic-related responses was low. This may indicate these are institutional challenges trainees face independent of the pandemic. These findings warrant longterm attention to the satisfaction of psychology and social worker trainees’ during the pandemic. For example, additional training for the use of telehealth could be provided. One study indicated that < 61% of psychology postdoctoral fellows received telepsychology training during the pandemic, and of those who did receive training, less than half were satisfied with it.3

Similarly, strategies could be developed to ensure a more supportive learning and work environment, and provide additional networking opportunities for trainees, despite social distancing. Education specific to disaster response should be incorporated into behavioral health care professionals’ training, especially because behavioral health care professionals provided major contributions during the pandemic due to reported increases in mental health concerns (eg, anxiety and depression) during the period.7,17,18 As the pandemic progressed, policies and procedures were established or modified to address some of these concerns because they were not necessarily limited to trainees. For example, additional training resources were developed to support the use of various telehealth technologies, virtual resources were used more often for meetings, and supervisors developed more comfort and familiarity with how to manage in a virtual or hybrid environment.

Limitations

Although the TSS data provide a large national sample of behavioral health care trainees, it only includes VA trainees, and therefore may not be completely generalizable across health care. However, because many psychologists and social workers throughout the US train at the VA, and because the VA is the largest employer of practicing psychologists and social workers, understanding the impacts felt at the VA informs institutions nationally.8-11 The TSS has limited demographic data (eg, age, race, ethnicity, and sex), so it is unclear whether the respondent groups before and during the pandemic differed in ways that could relate to outcomes. The data also do not specify exact training dates; however, anecdotal evidence suggests respondents generally complete the survey close to the end of their training.

Additionally, open-ended narrative responses were only asked for replies that indicated dissatisfaction, precluding a more nuanced understanding of potential positive outcomes. Furthermore, the TSS is limited to questions about the trainees’ clinical experiences, but because the pandemic created many stressors, there may have been personal issues that affected their work. It is possible that changes in overall satisfaction may have been rooted in something outside of their clinical experience. Finally, the response rate for the TSS is consistently low both before and during the pandemic and includes a limited number of narrative responses.

CONCLUSIONS

The VA is an important contributor to the education, training, and composition of the behavioral health care workforce. A deeper understanding of the VA trainee experience is important to identify how to improve behavioral health care professional education and training. This is especially true as behavioral health care faces shortages within the VA and nationwide.8,12,19

This study reinforces research that found health care trainees experienced decreased learning opportunities and telehealth-related challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. 13,20 Despite the observed decline in trainee satisfaction, the lack of a corresponding change in likelihood to seek employment with the VA is encouraging for VA efforts to maintain and grow its behavioral health care workforce and for similar efforts outside VA. This resilience may relate to the substantial prepandemic time invested in their professional development. Future studies should examine long term impacts of the pandemic on trainee’s clinical experience and whether the pipeline of behavioral health care workers declines over time as students that are earlier in their career paths instead chose other professions. Future research should also explore ways to improve professional development and wellness of behavioral health care trainees during disasters (eg, telehealth training, additional networking, and social support).

- Muddle S, Rettie H, Harris O, Lawes A, Robinson R. Trainee life under COVID-19: a systemic case report. J Fam Ther. 2022;44(2):239-249. doi:10.1111/1467-6427.12354

- Valenzuela J, Crosby LE, Harrison RR. Commentary: reflections on the COVID-19 pandemic and health disparities in pediatric psychology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2020;45(8):839- 841. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa063

- Frye WS, Feldman M, Katzenstein J, Gardner L. Modified training experiences for psychology interns and fellows during COVID-19: use of telepsychology and telesupervision by child and adolescent training programs. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2022;29(4):840- 848. doi:10.1007/s10880-021-09839-4

- Perrin PB, Rybarczyk BD, Pierce BS, Jones HA, Shaffer C, Islam L. Rapid telepsychology deployment during the COVID-19 pandemic: a special issue commentary and lessons from primary care psychology training. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76(6):1173-1185. doi:10.1002/jclp.22969

- Reilly SE, Zane KL, McCuddy WT, et al. Mental health practitioners’ immediate practical response during the COVID-19 pandemic: observational questionnaire study. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(9):e21237. doi:10.2196/21237

- Sadicario JS, Parlier-Ahmad AB, Brechbiel JK, Islam LZ, Martin CE. Caring for women with substance use disorders through pregnancy and postpartum during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from psychology trainees in an integrated OBGYN/substance use disorder outpatient treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;122:108200. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108200

- Schneider NM, Steinberg DM, Garcia AM, et al. Pediatric consultation-liaison psychology: insights and lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2023;30(1):51-60. doi:10.1007/s10880-022-09887-4

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee to Evaluate the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health. Mental Health Workforce and Facilities Infrastructure. In: Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. National Academies Press (US); 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499512/

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Health Administration. Career as a VA social worker. Updated March 3, 2025. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.socialwork.va.gov/VA_Employment.asp

- United States Senate Committee on Veterans Affairs hearing on “Making the VA the Workplace of Choice for Health Care Providers.” News release. American Psychological Association. April 9, 2008. Accessed April 9, 2025. https:// www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2008/04/testimony

- VA National Professional Social Work Month Planning Committee. The diverse, far-reaching VA social worker profession. March 17, 2023. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://news.va.gov/116804/diverse-far-reaching-social-worker-profession/

- Patel EL, Bates JM, Holguin JK, et al. Program profile: the expansion of associated health training in the VA. Fed Pract. 2021;38(8):374-380. doi:10.12788/fp.0163

- Northcraft H, Bai J, Griffin AR, Hovsepian S, Dobalian A. Association of the COVID-19 pandemic on VA resident and fellow training satisfaction and future VA employment: a mixed methods study. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(5):593- 598. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-22-00168.1

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Health workforce shortage areas. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas

- Gale RC, Wu J, Erhardt T, et al. Comparison of rapid vs in-depth qualitative analytic methods from a process evaluation of academic detailing in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):11. doi:10.1186/s13012-019-0853-y

- Taylor B, Henshall C, Kenyon S, Litchfield I, Greenfield S. Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? A mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e019993. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019993

- Kranke D, Der-Martirosian C, Hovsepian S, et al. Social workers being effective in disaster settings. Soc Work Public Health. 2020;35(8):664-668. doi:10.1080/19371918.20 20.1820928

- Kranke D, Gin JL, Der-Martirosian C, Weiss EL, Dobalian A. VA social work leadership and compassion fatigue during the 2017 hurricane season. Soc Work Ment Health. 2020;18:188-199. doi:10.1080/15332985.2019.1700873

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

- Der-Martirosian C, Wyte-Lake T, Balut M, et al. Implementation of telehealth services at the US Department of Veterans Affairs during the COVID-19 pandemic: mixed methods study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(9):e29429. doi:10.2196/29429

- Muddle S, Rettie H, Harris O, Lawes A, Robinson R. Trainee life under COVID-19: a systemic case report. J Fam Ther. 2022;44(2):239-249. doi:10.1111/1467-6427.12354

- Valenzuela J, Crosby LE, Harrison RR. Commentary: reflections on the COVID-19 pandemic and health disparities in pediatric psychology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2020;45(8):839- 841. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa063

- Frye WS, Feldman M, Katzenstein J, Gardner L. Modified training experiences for psychology interns and fellows during COVID-19: use of telepsychology and telesupervision by child and adolescent training programs. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2022;29(4):840- 848. doi:10.1007/s10880-021-09839-4

- Perrin PB, Rybarczyk BD, Pierce BS, Jones HA, Shaffer C, Islam L. Rapid telepsychology deployment during the COVID-19 pandemic: a special issue commentary and lessons from primary care psychology training. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76(6):1173-1185. doi:10.1002/jclp.22969

- Reilly SE, Zane KL, McCuddy WT, et al. Mental health practitioners’ immediate practical response during the COVID-19 pandemic: observational questionnaire study. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(9):e21237. doi:10.2196/21237

- Sadicario JS, Parlier-Ahmad AB, Brechbiel JK, Islam LZ, Martin CE. Caring for women with substance use disorders through pregnancy and postpartum during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from psychology trainees in an integrated OBGYN/substance use disorder outpatient treatment program. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;122:108200. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108200

- Schneider NM, Steinberg DM, Garcia AM, et al. Pediatric consultation-liaison psychology: insights and lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2023;30(1):51-60. doi:10.1007/s10880-022-09887-4

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee to Evaluate the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health. Mental Health Workforce and Facilities Infrastructure. In: Evaluation of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Services. National Academies Press (US); 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499512/

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Health Administration. Career as a VA social worker. Updated March 3, 2025. Accessed May 6, 2025. https://www.socialwork.va.gov/VA_Employment.asp

- United States Senate Committee on Veterans Affairs hearing on “Making the VA the Workplace of Choice for Health Care Providers.” News release. American Psychological Association. April 9, 2008. Accessed April 9, 2025. https:// www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2008/04/testimony

- VA National Professional Social Work Month Planning Committee. The diverse, far-reaching VA social worker profession. March 17, 2023. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://news.va.gov/116804/diverse-far-reaching-social-worker-profession/

- Patel EL, Bates JM, Holguin JK, et al. Program profile: the expansion of associated health training in the VA. Fed Pract. 2021;38(8):374-380. doi:10.12788/fp.0163

- Northcraft H, Bai J, Griffin AR, Hovsepian S, Dobalian A. Association of the COVID-19 pandemic on VA resident and fellow training satisfaction and future VA employment: a mixed methods study. J Grad Med Educ. 2022;14(5):593- 598. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-22-00168.1

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Health workforce shortage areas. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas

- Gale RC, Wu J, Erhardt T, et al. Comparison of rapid vs in-depth qualitative analytic methods from a process evaluation of academic detailing in the Veterans Health Administration. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):11. doi:10.1186/s13012-019-0853-y

- Taylor B, Henshall C, Kenyon S, Litchfield I, Greenfield S. Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? A mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8(10):e019993. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019993

- Kranke D, Der-Martirosian C, Hovsepian S, et al. Social workers being effective in disaster settings. Soc Work Public Health. 2020;35(8):664-668. doi:10.1080/19371918.20 20.1820928

- Kranke D, Gin JL, Der-Martirosian C, Weiss EL, Dobalian A. VA social work leadership and compassion fatigue during the 2017 hurricane season. Soc Work Ment Health. 2020;18:188-199. doi:10.1080/15332985.2019.1700873

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Workforce projections. Accessed April 9, 2025. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

- Der-Martirosian C, Wyte-Lake T, Balut M, et al. Implementation of telehealth services at the US Department of Veterans Affairs during the COVID-19 pandemic: mixed methods study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(9):e29429. doi:10.2196/29429

Behavioral Health Trainee Satisfaction at the US Department of Veterans Affairs During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Behavioral Health Trainee Satisfaction at the US Department of Veterans Affairs During the COVID-19 Pandemic