User login

Comparison of Prescribing Patterns of Intranasal Naloxone in a Veteran Population

Since 1999, annual deaths attributed to opioid overdose in the United States have increased from about 10,000 to about 50,000 in 2019.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic > 74,000 opioid overdose deaths occurred in the US from April 2020 to April 2021.2,3 Opioid-related overdoses now account for about 75% of all drug-related overdose deaths.1 In 2017, the cost of opioid overdose deaths and opioid use disorder (OUD) reached $1.02 trillion in the United States and $26 million in Indiana.4 The total deaths and costs would likely be higher if it were not for naloxone.

Naloxone hydrochloride was first patented in the 1960s and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1971 to treat opioid-related toxicity.1 It is the most frequently prescribed antidote for opioid toxicity due to its activity as a pure υ-opioid receptor competitive antagonist. Naloxone formulations include intramuscular, intravenous, subcutaneous, and intranasal delivery methods.5 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, clinicians should offer naloxone to patients at high risk for opioid-related adverse events. Risk factors include a history of overdose, opioid dosages of ≥ 50 morphine mg equivalents/day, and concurrent use of opioids with benzodiazepines.6

Intranasal naloxone 4 mg has become more accessible following the classification of opioid use as a public health emergency in 2017 and its over-the-counter availability since 2023. Intranasal naloxone 4 mg was approved by the FDA in 2015 for the prevention of opioid overdoses (accidental or intentional), which can be caused by heroin, fentanyl, carfentanil, hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone, and other substances. 7 Fentanyl has most recently been associated with xylazine, a nonopioid tranquilizer linked to increased opioid overdose deaths.8 Recent data suggest that 34% of opioid overdose reversals involved ≥ 2 doses of intranasal naloxone 4 mg, which led to FDA approval of an intranasal naloxone 8 mg spray in April 2021.9-11

Veteran Health Indiana (VHI) has implemented several initiatives to promote naloxone prescribing. Established in 2020, the Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) program sought to prevent opioid-related deaths through education and product distribution. These criteria included an opioid prescription for ≥ 30 days. In 2021, the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) was created to identify patients at high risk of opioid overdose and allowing pharmacists to prescribe naloxone for at-risk patients without restrictions, increasing accessibility.12

Recent cases of fentanyl-related overdoses involving stronger fentanyl analogues highlight the need for higher naloxone dosing to prevent overdose. A pharmacokinetic comparison of intranasal naloxone 8 mg vs 4 mg demonstrated maximum plasma concentrations of 10.3 ng/mL and 5.3 ng/mL, respectively. 13 Patients may be at an increased risk of precipitated opioid withdrawal when using intranasal naloxone 8 mg over 4 mg; however, some patients may benefit from achieving higher serum concentrations and therefore require larger doses of naloxone.

No clinical trials have demonstrated a difference in reversal rates between naloxone doses. No clinical practice guidelines support a specific naloxone formulation, and limited US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)-specific guidance exists. VA Naloxone Rescue: Recommendations for Use states that selection of naloxone 8 mg should be based on shared decision-making between the patient and clinician and based on individual risk factors.12 The purpose of this study is to analyze data to determine if there is a difference in prescribing patterns of intranasal naloxone 4 mg and intranasal naloxone 8 mg.

METHODS

A retrospective chart reviews using the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) analyzed patients prescribed intranasal naloxone 4 mg or intranasal naloxone 8 mg at VHI. A patient list was generated based on active naloxone prescriptions between April 1, 2022, and April 1, 2023. Data were obtained exclusively through CPRS and patients were not contacted. This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Indiana University Health Institutional Review Board and the VHI Research and Development Committee.

Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years and had an active prescription for intranasal naloxone 4 mg or intranasal naloxone 8 mg during the trial period. Patients were excluded if their naloxone prescription was written by a non-VHI clinician, if the dose was not 4 mg or 8 mg, or if the dosage form was other than intranasal spray.

The primary endpoint was the comparison for prescribing patterns for intranasal naloxone 4 mg and intranasal naloxone 8 mg during the study period. Secondary endpoints included total naloxone prescriptions; monthly prescriptions; number of patients with repeated naloxone prescriptions; prescriber type by naloxone dose; clinic type by naloxone dose; and documented indication for naloxone use by dose.

Demographic data collected included baseline age, sex, race, comorbid mental health conditions, and active central nervous system depressant medications on patient profile (ie, opioids, gabapentinoids, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, antipsychotics). Opioid prescriptions that were active or discontinued within the last 3 months were also recorded. Comorbid mental health conditions were collected based on the most recent clinical note before initiating medication.

Prescription-related data included strength of medication prescribed (4 mg, 8 mg, or both), documented use of medication, prescriber name, prescriber discipline, prescription entered by, number of times naloxone was filled or refilled during the study period, indication, clinic location, and clinic name. If > 1 prescription was active during the study period, the number of refills, prescriber name and clinic location of the first prescription in the study period was recorded. Additionally, the indication of OUD was differentiated from substance use disorder (SUD) if the patient was only dependent on opioids, excluding tobacco or alcohol. Patients with SUDs may include opioid dependence in addition to other substance dependence (eg, cannabis, stimulants, gabapentinoids, or benzodiazepines).

Basic descriptive statistics, including mean, ranges, and percentages were used to characterize the study subjects. For nominal data, X2 tests were used. A 2-sided 5% significance level was used for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

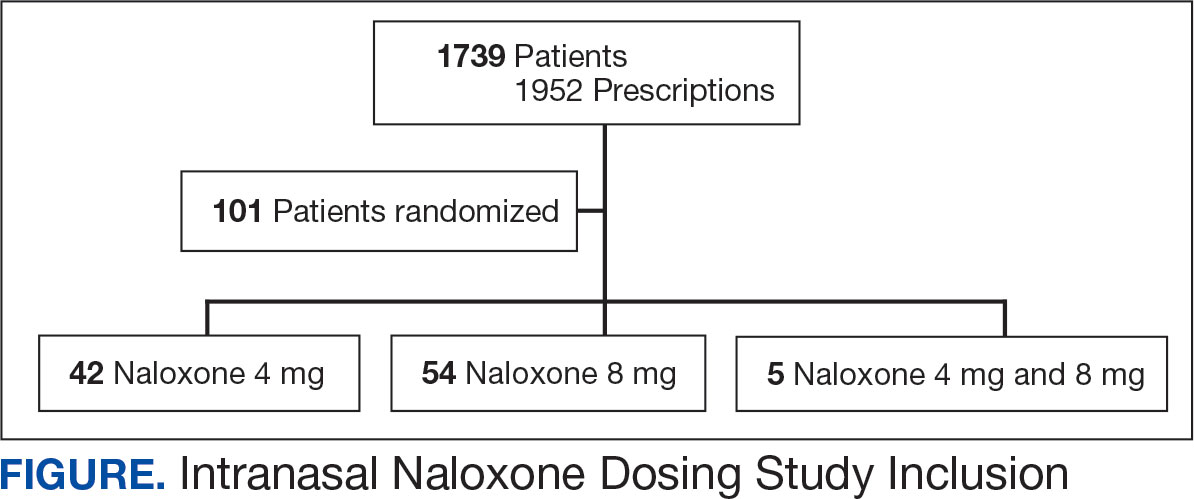

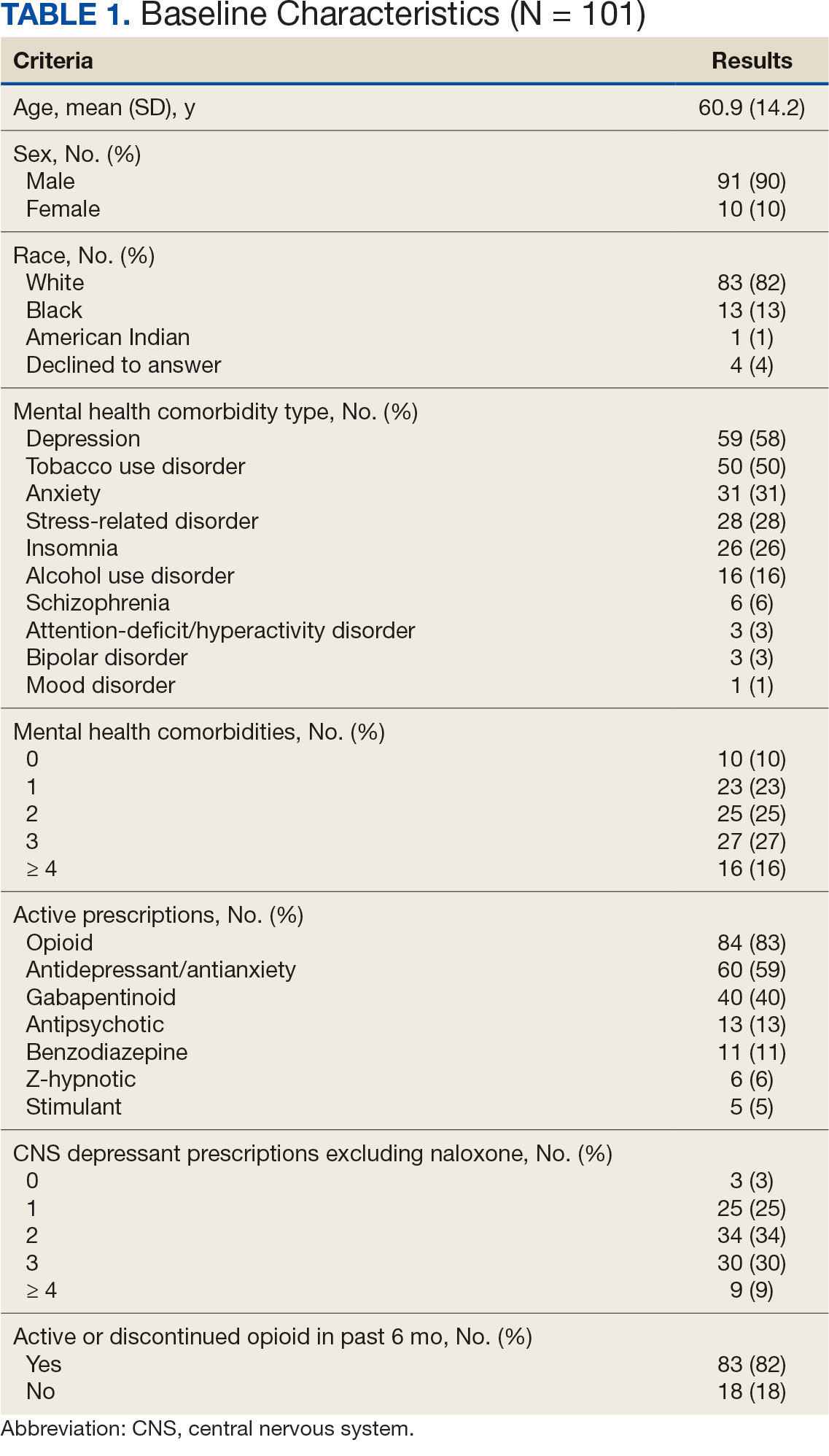

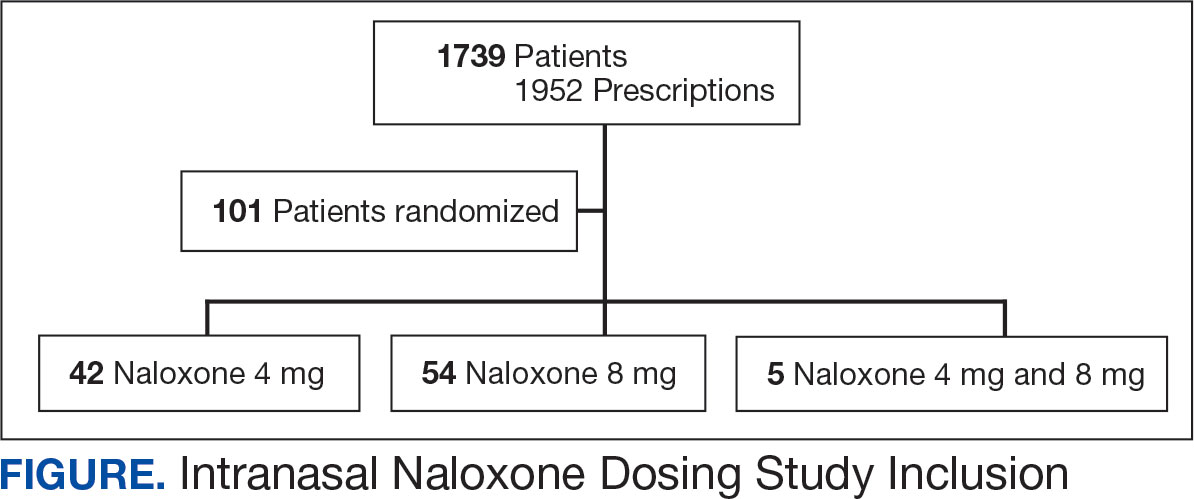

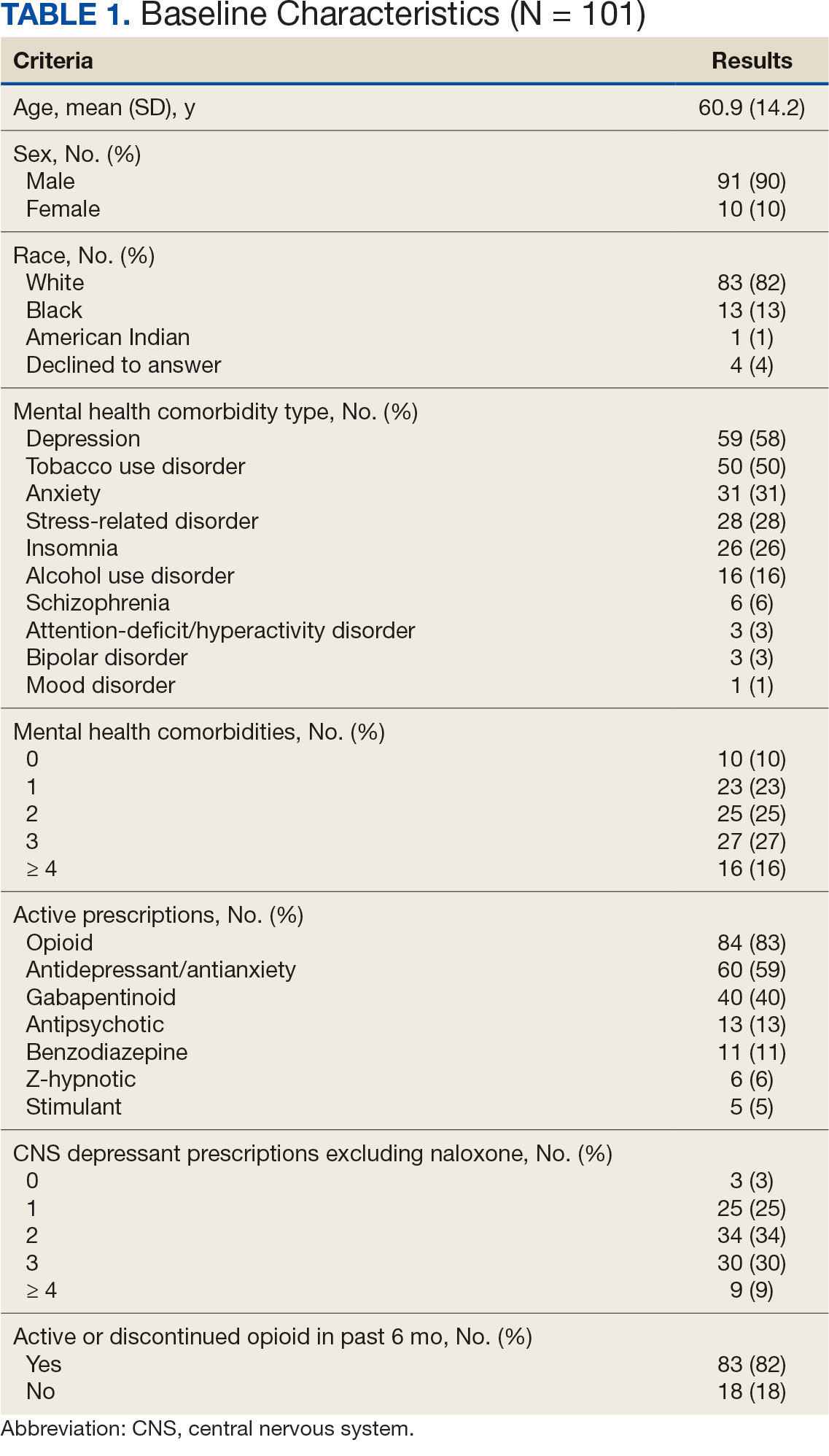

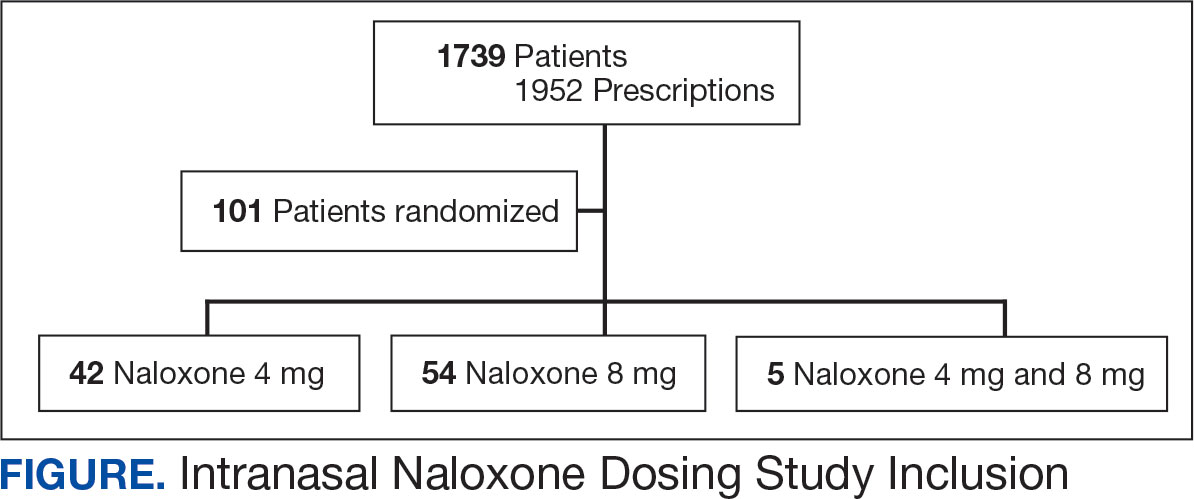

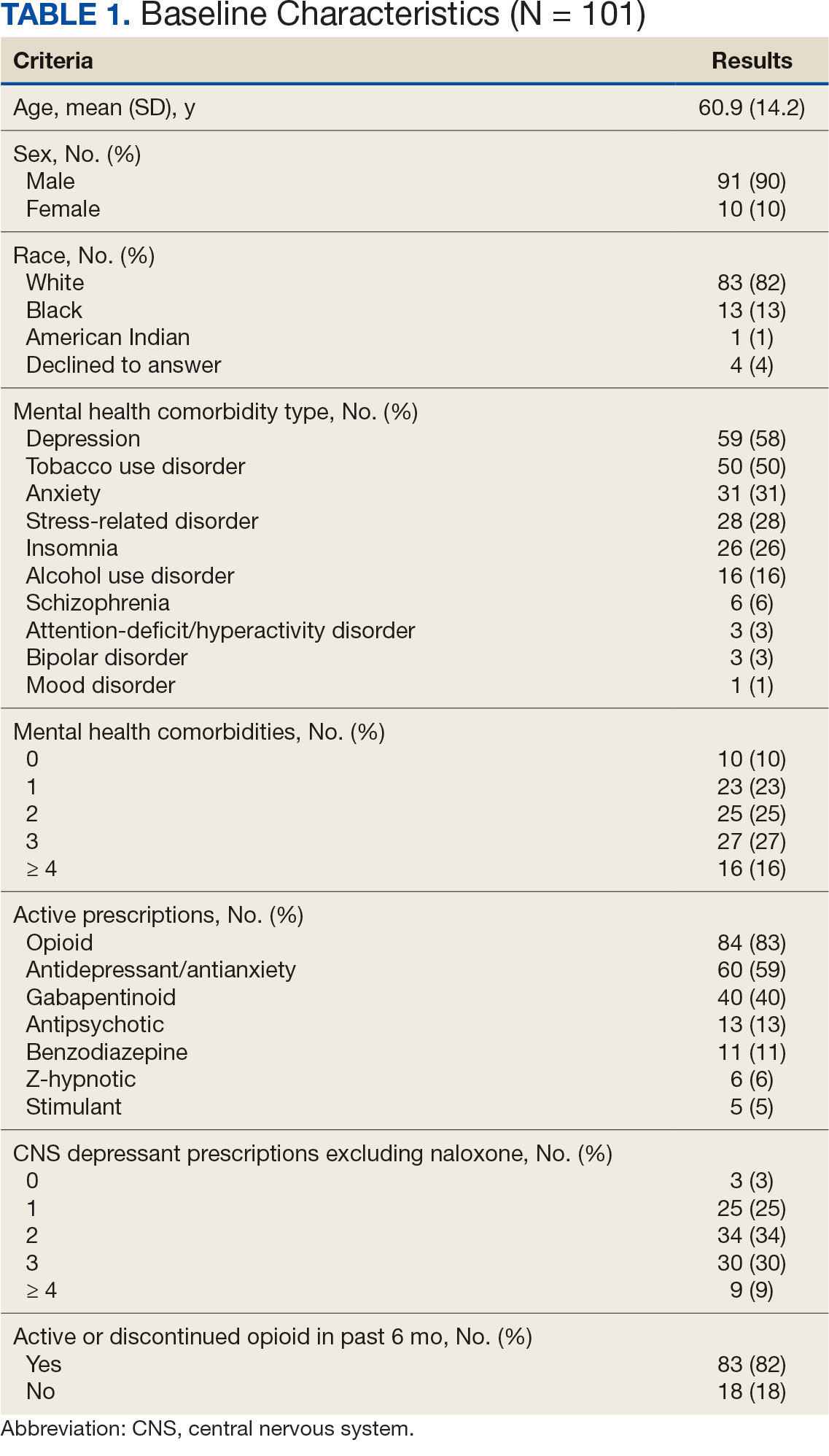

A total of 1952 active naloxone prescriptions from 1739 patients met the inclusion criteria; none were eliminated based on the exclusion criteria and some were included multiple times because data were collected for each active prescription during the study period. One hundred one patients were randomized and included in the final analysis (Figure). Most patients identified as White (81%), male (90%), and had a mean (SD) age of 60.9 (14.2) years. Common mental health comorbidities included 59 patients with depression, 50 with tobacco use disorder, and 31 with anxiety. Eighty-four patients had opioid and 60 had antidepressants/antianxiety, and 40 had gabapentinoids prescriptions. Forty-three patients had ≥ 3 mental health comorbidities. Thirty-four patients had 2 active central nervous system depressant prescriptions, 30 had 3 active prescriptions, and 9 had ≥ 4 active prescriptions. Most patients (n = 83) had an active or recently discontinued opioid prescription (Table 1).

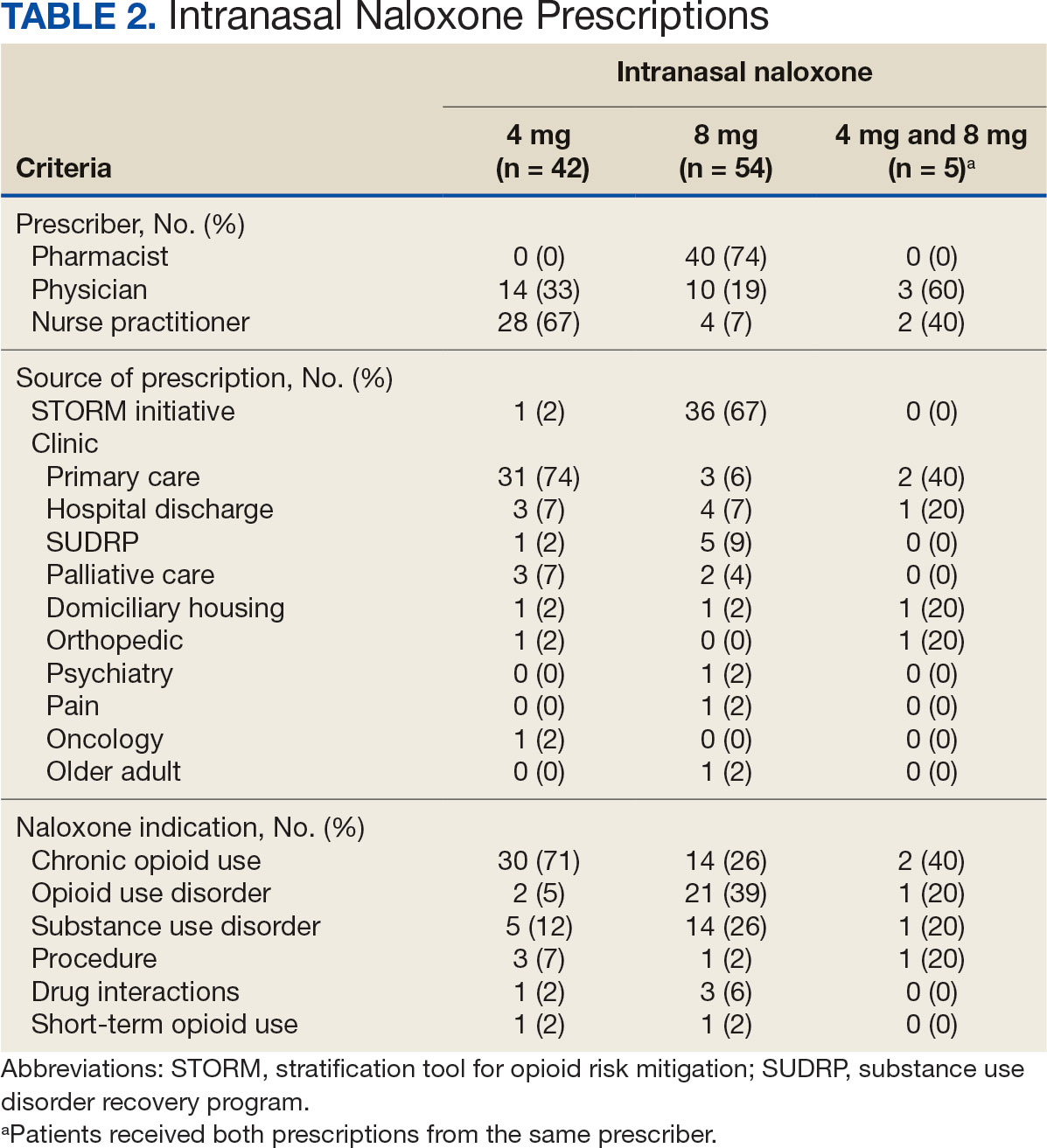

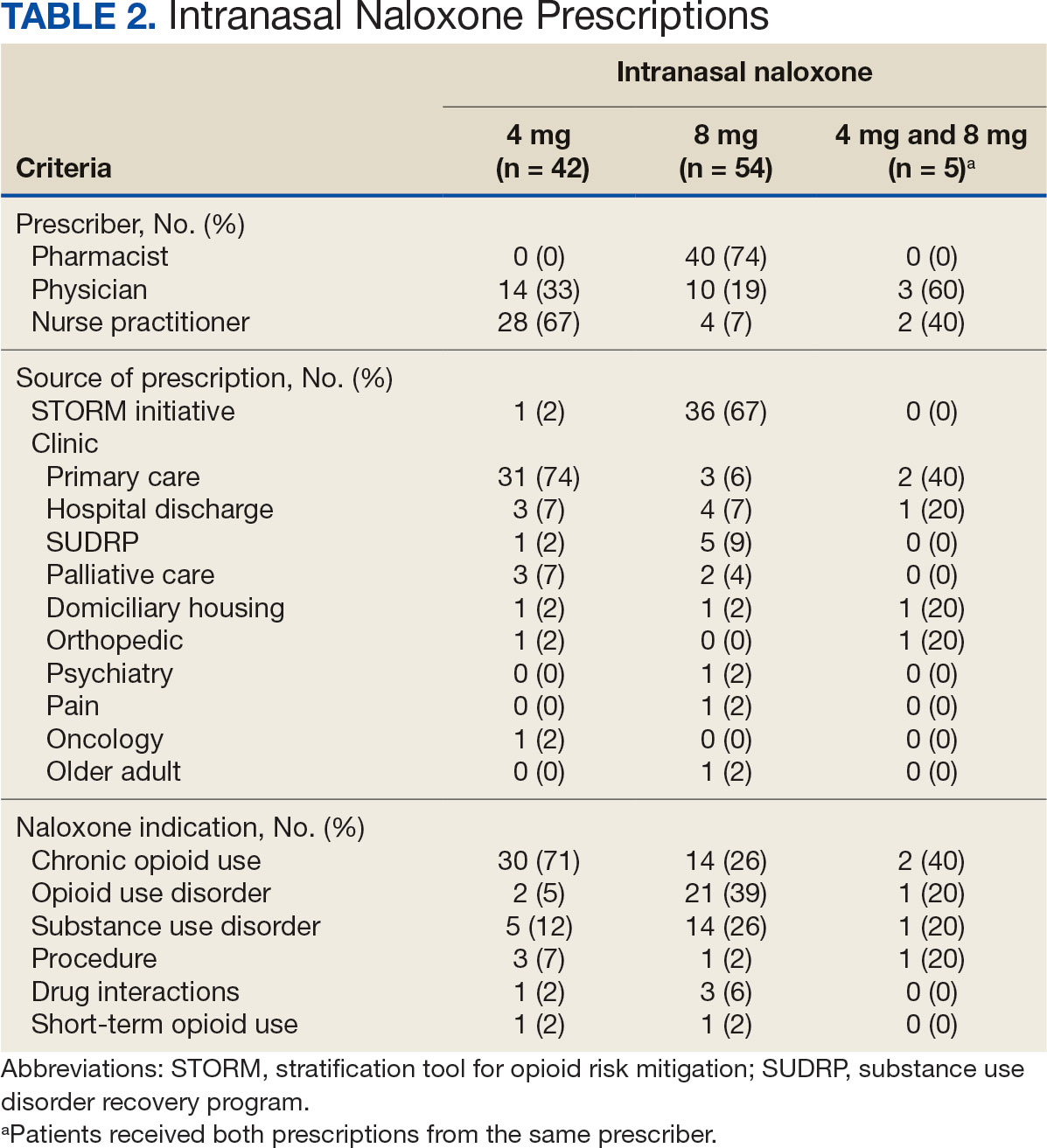

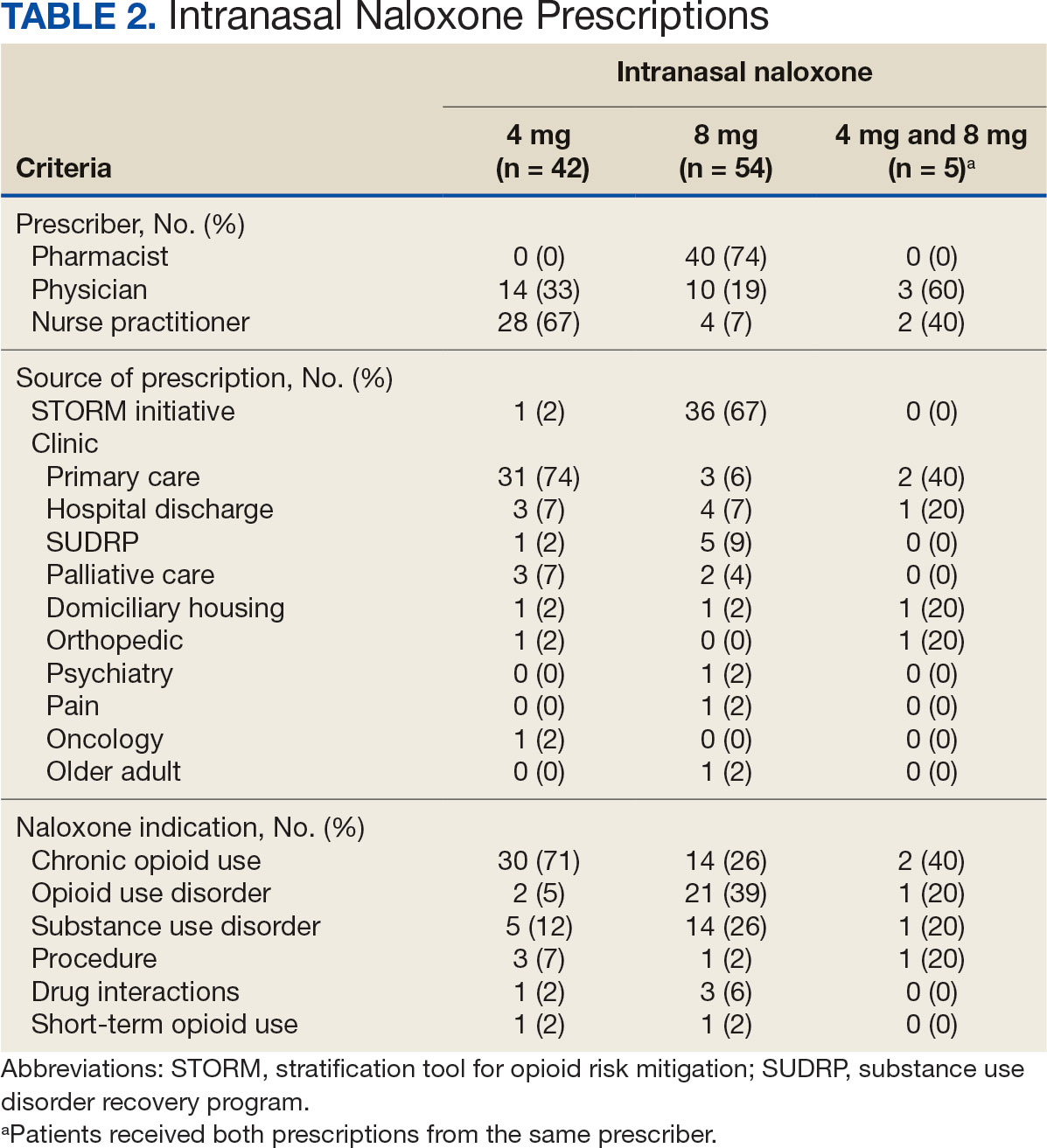

The 101 patients received 54 prescriptions for naloxone 8 mg and 47 for 4 mg (Table 2). Five patients received prescriptions for both the 4 mg and 8 mg intranasal naloxone formulations. Sixty-six patients had naloxone filled once (66%) during the study period. Intranasal naloxone 4 mg was prescribed to 30 patients by nurse practitioners, 17 patients by physicians, and not prescribed by pharmacists. Intranasal naloxone 8 mg was prescribed to 40 patients by pharmacists, 13 patients by physicians, and 6 patients by nurses. Patients who received prescriptions for both intranasal naloxone 4 mg and 8 mg were most routinely ordered by physicians (n = 3; 60%) in primary care (n = 2; 40%) for chronic opioid use (n = 2; 40%).

Patients access naloxone from many different VHI clinics. Primary care clinics prescribed the 4 mg formulation to 31 patients, 8 mg to 3 patients, and both to 2 patients. The STORM initiative was used for 37 of 106 prescriptions (35%): 4 mg intranasal naloxone was prescribed to 1 patient, 8 mg to 36 patients, and no patients received both formulations. Chronic opioid use was the most common indication (46%) with 30 patients prescribed intranasal naloxone 4 mg, 14 patients prescribed 8 mg, and 2 patients prescribed both. OUD was the indication for 24% of patients: 2 patients prescribed intranasal naloxone 4 mg, 21 patients prescribed 8 mg, and 1 patient prescribed both.

The 106 intranasal naloxone prescriptions were equally distributed across each month from April 1, 2022, to April 1, 2023. Of the 101 patients, 34 had multiple naloxone prescriptions filled during the study period. Pharmacists wrote 40 of 106 naloxone prescriptions (38%), all for the 8 mg formulation. Nurse practitioners prescribed naloxone 4 mg 30 times and 8 mg 6 times for 36 of 106 prescriptions (34%). Physicians prescribed 30 of 106 prescriptions (28%), including intranasal naloxone 4 mg 17 times and 8 mg 13 times.

Statistics were analyzed using a X2 test; however, it was determined that the expected frequencies made the tests inappropriate. Differences in prescribing patterns between naloxone doses, prescriber disciplines, source of the prescription, or indications were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Many pharmacists possess a scope of practice under state law and/or institution policy to prescribe naloxone. In this study, pharmacists prescribed the most naloxone prescriptions compared to physicians and nurse practitioners. Initiatives such as OEND and STORM have given pharmacists at VHI an avenue to combat the growing opioid epidemic while expanding their scope of practice. A systematic review of 67 studies found that pharmacist-led OEND programs showed a statistically significant increase in naloxone orders. A statistical significance was likely met given the large sample sizes ranging from 10 to 217,000 individuals, whereas this study only assessed a small portion of patients.14 This study contributes to the overwhelming amount of data that highlights pharmacists’ impact on overall naloxone distribution.

The STORM initiative and primary care clinics were responsible for large portions of naloxone prescriptions in this study. STORM was used by pharmacists and contributed to more than half of the higher dose naloxone prescriptions. Following a discussion with members of the pain management team, pharmacists involved in STORM prescribing were revealed to exclusively prescribe intranasal naloxone 8 mg as opposed to 4 mg. At the risk of precipitating withdrawal from higher doses of naloxone, it was agreed that this risk was heavily outweighed by the benefit of successful opioid reversal. In this context, it is expected for this avenue of prescribing to influence naloxone prescribing patterns at VHI.

Prescribing in primary care clinics was shown to be equally as substantial. Primary care-based multidisciplinary transition clinics have been reported to be associated with increased access to OUD treatment.15 Primary care clinics at VHI, or patient aligned care teams (PACT), largely consist of multidisciplinary health care teams. PACT clinicians are heavily involved in transitions of care because one system provides patients with comprehensive acute and chronic care. Continuing to encourage naloxone distribution through primary care and using STORM affords various patient populations access to high-level care.

Notable differences were observed between indications for naloxone use and the corresponding dose. Patients with OUD or SUD were more likely to receive intranasal naloxone 8 mg as opposed to patients receiving intranasal naloxone for chronic opioid use, who were more likely to receive the 4 mg dose. This may be due to a rationale to provide a higher dose of naloxone to combat overdoses in the case of ingesting substances mixed with fentanyl or xylazine.12,13 Without standard of care guidelines, concerns remain for varying outcomes in opioid overdose prevention within vulnerable populations.

Limitations

Chart data were dependent on documentation, which may have omitted pertinent baseline characteristics and risk factors. Additional data collection could have further assessed a patient’s specific risk factors (eg, opioid dose in morphine equivalents) to draw conclusions to the dose of naloxone prescribed. The sample size was small, and the patient population was largely White and male, which minimized the generalizability of the results.

CONCLUSIONS

This study evaluated the differences in intranasal naloxone prescribing patterns within a veteran population at VHI over 12 months. Findings revealed that most prescriptions were written for intranasal naloxone 8 mg, by a pharmacist, in a primary care setting, and for chronic opioid use. The results revealed evidence of differing naloxone prescribing practices, which emphasize the need for clinical guidelines and better defined recommendations in relation to naloxone dosing.

The most evident gap in patient care could be addressed by urging the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management group to update naloxone recommendations for use to include more concrete dosing recommendations. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to re-educate clinicians on naloxone prescribing to increase awareness of different doses and the importance of equipping patients with the correct amount of naloxone in an emergency. Additional research assessing change in prescribing patterns is warranted as the use of higher dose naloxone becomes more routine.

- Britch SC, Walsh SL. Treatment of opioid overdose: current approaches and recent advances. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2022;239(7):2063-2081. doi:10.1007/s00213-022-06125-5

- Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2023. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- O’Donnell J, Tanz LJ, Gladden RM, Davis NL, Bitting J. Trends in and characteristics of drug overdose deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyls — United States, 2019–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1740-1746. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e3

- Luo F, Li M, Florence C. State-level economic costs of opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdose — United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:541-546. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7015a1

- Lexicomp. Lexicomp Online. Accessed April 10, 2025. http://online.lexi.com

- Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC Clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain — United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71(3):1-95. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1

- Narcan (naloxone) FDA approval history. Drugs.com. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.drugs.com/history/narcan.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What you should know about xylazine. May 16, 2024. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/about/what-you-should-know-about-xylazine.html

- Avetian GK, Fiuty P, Mazzella S, Koppa D, Heye V, Hebbar P. Use of naloxone nasal spray 4 mg in the community setting: a survey of use by community organizations. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(4):573-576. doi:10.1080/03007995.2017.1334637

- Kloxxado [package insert]. Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA Inc; 2021.

- FDA approves higher dosage of naloxone nasal spray to treat opioid overdose. News release. FDA. April 30, 2021. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-higher-dosage-naloxone-nasal-spray-treat-opioid-overdose

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefits Management Services and National Formulary Committee in Collaboration with the VA National Harm Reduction Support & Development Workgroup. Naloxone Rescue: Recommendations for Use. June 2014. Updated March 2024. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.va.gov/formularyadvisor/DOC_PDF/CRE_Naloxone_Rescue_Guidance_March_2024.pdf

- Krieter P, Chiang N, Gyaw S, et al. Pharmacokinetic properties and human use characteristics of an FDA-approved intranasal naloxone product for the treatment of opioid overdose. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56(10):1243-1253. doi:10.1002/jcph.759

- Rawal S, Osae SP, Cobran EK, Albert A, Young HN. Pharmacists’ naloxone services beyond community pharmacy settings: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2023;19(2):243-265. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2022.09.002

- Incze MA, Sehgal SL, Hansen A, Garcia L, Stolebarger L. Evaluation of a primary care-based multidisciplinary transition clinic for patients newly initiated on buprenorphine in the emergency department. Subst Abus. 2023;44(3):220-225. doi:10.1177/08897077231188592

Since 1999, annual deaths attributed to opioid overdose in the United States have increased from about 10,000 to about 50,000 in 2019.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic > 74,000 opioid overdose deaths occurred in the US from April 2020 to April 2021.2,3 Opioid-related overdoses now account for about 75% of all drug-related overdose deaths.1 In 2017, the cost of opioid overdose deaths and opioid use disorder (OUD) reached $1.02 trillion in the United States and $26 million in Indiana.4 The total deaths and costs would likely be higher if it were not for naloxone.

Naloxone hydrochloride was first patented in the 1960s and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1971 to treat opioid-related toxicity.1 It is the most frequently prescribed antidote for opioid toxicity due to its activity as a pure υ-opioid receptor competitive antagonist. Naloxone formulations include intramuscular, intravenous, subcutaneous, and intranasal delivery methods.5 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, clinicians should offer naloxone to patients at high risk for opioid-related adverse events. Risk factors include a history of overdose, opioid dosages of ≥ 50 morphine mg equivalents/day, and concurrent use of opioids with benzodiazepines.6

Intranasal naloxone 4 mg has become more accessible following the classification of opioid use as a public health emergency in 2017 and its over-the-counter availability since 2023. Intranasal naloxone 4 mg was approved by the FDA in 2015 for the prevention of opioid overdoses (accidental or intentional), which can be caused by heroin, fentanyl, carfentanil, hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone, and other substances. 7 Fentanyl has most recently been associated with xylazine, a nonopioid tranquilizer linked to increased opioid overdose deaths.8 Recent data suggest that 34% of opioid overdose reversals involved ≥ 2 doses of intranasal naloxone 4 mg, which led to FDA approval of an intranasal naloxone 8 mg spray in April 2021.9-11

Veteran Health Indiana (VHI) has implemented several initiatives to promote naloxone prescribing. Established in 2020, the Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) program sought to prevent opioid-related deaths through education and product distribution. These criteria included an opioid prescription for ≥ 30 days. In 2021, the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) was created to identify patients at high risk of opioid overdose and allowing pharmacists to prescribe naloxone for at-risk patients without restrictions, increasing accessibility.12

Recent cases of fentanyl-related overdoses involving stronger fentanyl analogues highlight the need for higher naloxone dosing to prevent overdose. A pharmacokinetic comparison of intranasal naloxone 8 mg vs 4 mg demonstrated maximum plasma concentrations of 10.3 ng/mL and 5.3 ng/mL, respectively. 13 Patients may be at an increased risk of precipitated opioid withdrawal when using intranasal naloxone 8 mg over 4 mg; however, some patients may benefit from achieving higher serum concentrations and therefore require larger doses of naloxone.

No clinical trials have demonstrated a difference in reversal rates between naloxone doses. No clinical practice guidelines support a specific naloxone formulation, and limited US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)-specific guidance exists. VA Naloxone Rescue: Recommendations for Use states that selection of naloxone 8 mg should be based on shared decision-making between the patient and clinician and based on individual risk factors.12 The purpose of this study is to analyze data to determine if there is a difference in prescribing patterns of intranasal naloxone 4 mg and intranasal naloxone 8 mg.

METHODS

A retrospective chart reviews using the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) analyzed patients prescribed intranasal naloxone 4 mg or intranasal naloxone 8 mg at VHI. A patient list was generated based on active naloxone prescriptions between April 1, 2022, and April 1, 2023. Data were obtained exclusively through CPRS and patients were not contacted. This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Indiana University Health Institutional Review Board and the VHI Research and Development Committee.

Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years and had an active prescription for intranasal naloxone 4 mg or intranasal naloxone 8 mg during the trial period. Patients were excluded if their naloxone prescription was written by a non-VHI clinician, if the dose was not 4 mg or 8 mg, or if the dosage form was other than intranasal spray.

The primary endpoint was the comparison for prescribing patterns for intranasal naloxone 4 mg and intranasal naloxone 8 mg during the study period. Secondary endpoints included total naloxone prescriptions; monthly prescriptions; number of patients with repeated naloxone prescriptions; prescriber type by naloxone dose; clinic type by naloxone dose; and documented indication for naloxone use by dose.

Demographic data collected included baseline age, sex, race, comorbid mental health conditions, and active central nervous system depressant medications on patient profile (ie, opioids, gabapentinoids, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, antipsychotics). Opioid prescriptions that were active or discontinued within the last 3 months were also recorded. Comorbid mental health conditions were collected based on the most recent clinical note before initiating medication.

Prescription-related data included strength of medication prescribed (4 mg, 8 mg, or both), documented use of medication, prescriber name, prescriber discipline, prescription entered by, number of times naloxone was filled or refilled during the study period, indication, clinic location, and clinic name. If > 1 prescription was active during the study period, the number of refills, prescriber name and clinic location of the first prescription in the study period was recorded. Additionally, the indication of OUD was differentiated from substance use disorder (SUD) if the patient was only dependent on opioids, excluding tobacco or alcohol. Patients with SUDs may include opioid dependence in addition to other substance dependence (eg, cannabis, stimulants, gabapentinoids, or benzodiazepines).

Basic descriptive statistics, including mean, ranges, and percentages were used to characterize the study subjects. For nominal data, X2 tests were used. A 2-sided 5% significance level was used for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

A total of 1952 active naloxone prescriptions from 1739 patients met the inclusion criteria; none were eliminated based on the exclusion criteria and some were included multiple times because data were collected for each active prescription during the study period. One hundred one patients were randomized and included in the final analysis (Figure). Most patients identified as White (81%), male (90%), and had a mean (SD) age of 60.9 (14.2) years. Common mental health comorbidities included 59 patients with depression, 50 with tobacco use disorder, and 31 with anxiety. Eighty-four patients had opioid and 60 had antidepressants/antianxiety, and 40 had gabapentinoids prescriptions. Forty-three patients had ≥ 3 mental health comorbidities. Thirty-four patients had 2 active central nervous system depressant prescriptions, 30 had 3 active prescriptions, and 9 had ≥ 4 active prescriptions. Most patients (n = 83) had an active or recently discontinued opioid prescription (Table 1).

The 101 patients received 54 prescriptions for naloxone 8 mg and 47 for 4 mg (Table 2). Five patients received prescriptions for both the 4 mg and 8 mg intranasal naloxone formulations. Sixty-six patients had naloxone filled once (66%) during the study period. Intranasal naloxone 4 mg was prescribed to 30 patients by nurse practitioners, 17 patients by physicians, and not prescribed by pharmacists. Intranasal naloxone 8 mg was prescribed to 40 patients by pharmacists, 13 patients by physicians, and 6 patients by nurses. Patients who received prescriptions for both intranasal naloxone 4 mg and 8 mg were most routinely ordered by physicians (n = 3; 60%) in primary care (n = 2; 40%) for chronic opioid use (n = 2; 40%).

Patients access naloxone from many different VHI clinics. Primary care clinics prescribed the 4 mg formulation to 31 patients, 8 mg to 3 patients, and both to 2 patients. The STORM initiative was used for 37 of 106 prescriptions (35%): 4 mg intranasal naloxone was prescribed to 1 patient, 8 mg to 36 patients, and no patients received both formulations. Chronic opioid use was the most common indication (46%) with 30 patients prescribed intranasal naloxone 4 mg, 14 patients prescribed 8 mg, and 2 patients prescribed both. OUD was the indication for 24% of patients: 2 patients prescribed intranasal naloxone 4 mg, 21 patients prescribed 8 mg, and 1 patient prescribed both.

The 106 intranasal naloxone prescriptions were equally distributed across each month from April 1, 2022, to April 1, 2023. Of the 101 patients, 34 had multiple naloxone prescriptions filled during the study period. Pharmacists wrote 40 of 106 naloxone prescriptions (38%), all for the 8 mg formulation. Nurse practitioners prescribed naloxone 4 mg 30 times and 8 mg 6 times for 36 of 106 prescriptions (34%). Physicians prescribed 30 of 106 prescriptions (28%), including intranasal naloxone 4 mg 17 times and 8 mg 13 times.

Statistics were analyzed using a X2 test; however, it was determined that the expected frequencies made the tests inappropriate. Differences in prescribing patterns between naloxone doses, prescriber disciplines, source of the prescription, or indications were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Many pharmacists possess a scope of practice under state law and/or institution policy to prescribe naloxone. In this study, pharmacists prescribed the most naloxone prescriptions compared to physicians and nurse practitioners. Initiatives such as OEND and STORM have given pharmacists at VHI an avenue to combat the growing opioid epidemic while expanding their scope of practice. A systematic review of 67 studies found that pharmacist-led OEND programs showed a statistically significant increase in naloxone orders. A statistical significance was likely met given the large sample sizes ranging from 10 to 217,000 individuals, whereas this study only assessed a small portion of patients.14 This study contributes to the overwhelming amount of data that highlights pharmacists’ impact on overall naloxone distribution.

The STORM initiative and primary care clinics were responsible for large portions of naloxone prescriptions in this study. STORM was used by pharmacists and contributed to more than half of the higher dose naloxone prescriptions. Following a discussion with members of the pain management team, pharmacists involved in STORM prescribing were revealed to exclusively prescribe intranasal naloxone 8 mg as opposed to 4 mg. At the risk of precipitating withdrawal from higher doses of naloxone, it was agreed that this risk was heavily outweighed by the benefit of successful opioid reversal. In this context, it is expected for this avenue of prescribing to influence naloxone prescribing patterns at VHI.

Prescribing in primary care clinics was shown to be equally as substantial. Primary care-based multidisciplinary transition clinics have been reported to be associated with increased access to OUD treatment.15 Primary care clinics at VHI, or patient aligned care teams (PACT), largely consist of multidisciplinary health care teams. PACT clinicians are heavily involved in transitions of care because one system provides patients with comprehensive acute and chronic care. Continuing to encourage naloxone distribution through primary care and using STORM affords various patient populations access to high-level care.

Notable differences were observed between indications for naloxone use and the corresponding dose. Patients with OUD or SUD were more likely to receive intranasal naloxone 8 mg as opposed to patients receiving intranasal naloxone for chronic opioid use, who were more likely to receive the 4 mg dose. This may be due to a rationale to provide a higher dose of naloxone to combat overdoses in the case of ingesting substances mixed with fentanyl or xylazine.12,13 Without standard of care guidelines, concerns remain for varying outcomes in opioid overdose prevention within vulnerable populations.

Limitations

Chart data were dependent on documentation, which may have omitted pertinent baseline characteristics and risk factors. Additional data collection could have further assessed a patient’s specific risk factors (eg, opioid dose in morphine equivalents) to draw conclusions to the dose of naloxone prescribed. The sample size was small, and the patient population was largely White and male, which minimized the generalizability of the results.

CONCLUSIONS

This study evaluated the differences in intranasal naloxone prescribing patterns within a veteran population at VHI over 12 months. Findings revealed that most prescriptions were written for intranasal naloxone 8 mg, by a pharmacist, in a primary care setting, and for chronic opioid use. The results revealed evidence of differing naloxone prescribing practices, which emphasize the need for clinical guidelines and better defined recommendations in relation to naloxone dosing.

The most evident gap in patient care could be addressed by urging the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management group to update naloxone recommendations for use to include more concrete dosing recommendations. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to re-educate clinicians on naloxone prescribing to increase awareness of different doses and the importance of equipping patients with the correct amount of naloxone in an emergency. Additional research assessing change in prescribing patterns is warranted as the use of higher dose naloxone becomes more routine.

Since 1999, annual deaths attributed to opioid overdose in the United States have increased from about 10,000 to about 50,000 in 2019.1 During the COVID-19 pandemic > 74,000 opioid overdose deaths occurred in the US from April 2020 to April 2021.2,3 Opioid-related overdoses now account for about 75% of all drug-related overdose deaths.1 In 2017, the cost of opioid overdose deaths and opioid use disorder (OUD) reached $1.02 trillion in the United States and $26 million in Indiana.4 The total deaths and costs would likely be higher if it were not for naloxone.

Naloxone hydrochloride was first patented in the 1960s and approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1971 to treat opioid-related toxicity.1 It is the most frequently prescribed antidote for opioid toxicity due to its activity as a pure υ-opioid receptor competitive antagonist. Naloxone formulations include intramuscular, intravenous, subcutaneous, and intranasal delivery methods.5 According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, clinicians should offer naloxone to patients at high risk for opioid-related adverse events. Risk factors include a history of overdose, opioid dosages of ≥ 50 morphine mg equivalents/day, and concurrent use of opioids with benzodiazepines.6

Intranasal naloxone 4 mg has become more accessible following the classification of opioid use as a public health emergency in 2017 and its over-the-counter availability since 2023. Intranasal naloxone 4 mg was approved by the FDA in 2015 for the prevention of opioid overdoses (accidental or intentional), which can be caused by heroin, fentanyl, carfentanil, hydrocodone, oxycodone, methadone, and other substances. 7 Fentanyl has most recently been associated with xylazine, a nonopioid tranquilizer linked to increased opioid overdose deaths.8 Recent data suggest that 34% of opioid overdose reversals involved ≥ 2 doses of intranasal naloxone 4 mg, which led to FDA approval of an intranasal naloxone 8 mg spray in April 2021.9-11

Veteran Health Indiana (VHI) has implemented several initiatives to promote naloxone prescribing. Established in 2020, the Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) program sought to prevent opioid-related deaths through education and product distribution. These criteria included an opioid prescription for ≥ 30 days. In 2021, the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) was created to identify patients at high risk of opioid overdose and allowing pharmacists to prescribe naloxone for at-risk patients without restrictions, increasing accessibility.12

Recent cases of fentanyl-related overdoses involving stronger fentanyl analogues highlight the need for higher naloxone dosing to prevent overdose. A pharmacokinetic comparison of intranasal naloxone 8 mg vs 4 mg demonstrated maximum plasma concentrations of 10.3 ng/mL and 5.3 ng/mL, respectively. 13 Patients may be at an increased risk of precipitated opioid withdrawal when using intranasal naloxone 8 mg over 4 mg; however, some patients may benefit from achieving higher serum concentrations and therefore require larger doses of naloxone.

No clinical trials have demonstrated a difference in reversal rates between naloxone doses. No clinical practice guidelines support a specific naloxone formulation, and limited US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)-specific guidance exists. VA Naloxone Rescue: Recommendations for Use states that selection of naloxone 8 mg should be based on shared decision-making between the patient and clinician and based on individual risk factors.12 The purpose of this study is to analyze data to determine if there is a difference in prescribing patterns of intranasal naloxone 4 mg and intranasal naloxone 8 mg.

METHODS

A retrospective chart reviews using the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) analyzed patients prescribed intranasal naloxone 4 mg or intranasal naloxone 8 mg at VHI. A patient list was generated based on active naloxone prescriptions between April 1, 2022, and April 1, 2023. Data were obtained exclusively through CPRS and patients were not contacted. This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Indiana University Health Institutional Review Board and the VHI Research and Development Committee.

Patients were included if they were aged ≥ 18 years and had an active prescription for intranasal naloxone 4 mg or intranasal naloxone 8 mg during the trial period. Patients were excluded if their naloxone prescription was written by a non-VHI clinician, if the dose was not 4 mg or 8 mg, or if the dosage form was other than intranasal spray.

The primary endpoint was the comparison for prescribing patterns for intranasal naloxone 4 mg and intranasal naloxone 8 mg during the study period. Secondary endpoints included total naloxone prescriptions; monthly prescriptions; number of patients with repeated naloxone prescriptions; prescriber type by naloxone dose; clinic type by naloxone dose; and documented indication for naloxone use by dose.

Demographic data collected included baseline age, sex, race, comorbid mental health conditions, and active central nervous system depressant medications on patient profile (ie, opioids, gabapentinoids, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, antipsychotics). Opioid prescriptions that were active or discontinued within the last 3 months were also recorded. Comorbid mental health conditions were collected based on the most recent clinical note before initiating medication.

Prescription-related data included strength of medication prescribed (4 mg, 8 mg, or both), documented use of medication, prescriber name, prescriber discipline, prescription entered by, number of times naloxone was filled or refilled during the study period, indication, clinic location, and clinic name. If > 1 prescription was active during the study period, the number of refills, prescriber name and clinic location of the first prescription in the study period was recorded. Additionally, the indication of OUD was differentiated from substance use disorder (SUD) if the patient was only dependent on opioids, excluding tobacco or alcohol. Patients with SUDs may include opioid dependence in addition to other substance dependence (eg, cannabis, stimulants, gabapentinoids, or benzodiazepines).

Basic descriptive statistics, including mean, ranges, and percentages were used to characterize the study subjects. For nominal data, X2 tests were used. A 2-sided 5% significance level was used for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

A total of 1952 active naloxone prescriptions from 1739 patients met the inclusion criteria; none were eliminated based on the exclusion criteria and some were included multiple times because data were collected for each active prescription during the study period. One hundred one patients were randomized and included in the final analysis (Figure). Most patients identified as White (81%), male (90%), and had a mean (SD) age of 60.9 (14.2) years. Common mental health comorbidities included 59 patients with depression, 50 with tobacco use disorder, and 31 with anxiety. Eighty-four patients had opioid and 60 had antidepressants/antianxiety, and 40 had gabapentinoids prescriptions. Forty-three patients had ≥ 3 mental health comorbidities. Thirty-four patients had 2 active central nervous system depressant prescriptions, 30 had 3 active prescriptions, and 9 had ≥ 4 active prescriptions. Most patients (n = 83) had an active or recently discontinued opioid prescription (Table 1).

The 101 patients received 54 prescriptions for naloxone 8 mg and 47 for 4 mg (Table 2). Five patients received prescriptions for both the 4 mg and 8 mg intranasal naloxone formulations. Sixty-six patients had naloxone filled once (66%) during the study period. Intranasal naloxone 4 mg was prescribed to 30 patients by nurse practitioners, 17 patients by physicians, and not prescribed by pharmacists. Intranasal naloxone 8 mg was prescribed to 40 patients by pharmacists, 13 patients by physicians, and 6 patients by nurses. Patients who received prescriptions for both intranasal naloxone 4 mg and 8 mg were most routinely ordered by physicians (n = 3; 60%) in primary care (n = 2; 40%) for chronic opioid use (n = 2; 40%).

Patients access naloxone from many different VHI clinics. Primary care clinics prescribed the 4 mg formulation to 31 patients, 8 mg to 3 patients, and both to 2 patients. The STORM initiative was used for 37 of 106 prescriptions (35%): 4 mg intranasal naloxone was prescribed to 1 patient, 8 mg to 36 patients, and no patients received both formulations. Chronic opioid use was the most common indication (46%) with 30 patients prescribed intranasal naloxone 4 mg, 14 patients prescribed 8 mg, and 2 patients prescribed both. OUD was the indication for 24% of patients: 2 patients prescribed intranasal naloxone 4 mg, 21 patients prescribed 8 mg, and 1 patient prescribed both.

The 106 intranasal naloxone prescriptions were equally distributed across each month from April 1, 2022, to April 1, 2023. Of the 101 patients, 34 had multiple naloxone prescriptions filled during the study period. Pharmacists wrote 40 of 106 naloxone prescriptions (38%), all for the 8 mg formulation. Nurse practitioners prescribed naloxone 4 mg 30 times and 8 mg 6 times for 36 of 106 prescriptions (34%). Physicians prescribed 30 of 106 prescriptions (28%), including intranasal naloxone 4 mg 17 times and 8 mg 13 times.

Statistics were analyzed using a X2 test; however, it was determined that the expected frequencies made the tests inappropriate. Differences in prescribing patterns between naloxone doses, prescriber disciplines, source of the prescription, or indications were not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

Many pharmacists possess a scope of practice under state law and/or institution policy to prescribe naloxone. In this study, pharmacists prescribed the most naloxone prescriptions compared to physicians and nurse practitioners. Initiatives such as OEND and STORM have given pharmacists at VHI an avenue to combat the growing opioid epidemic while expanding their scope of practice. A systematic review of 67 studies found that pharmacist-led OEND programs showed a statistically significant increase in naloxone orders. A statistical significance was likely met given the large sample sizes ranging from 10 to 217,000 individuals, whereas this study only assessed a small portion of patients.14 This study contributes to the overwhelming amount of data that highlights pharmacists’ impact on overall naloxone distribution.

The STORM initiative and primary care clinics were responsible for large portions of naloxone prescriptions in this study. STORM was used by pharmacists and contributed to more than half of the higher dose naloxone prescriptions. Following a discussion with members of the pain management team, pharmacists involved in STORM prescribing were revealed to exclusively prescribe intranasal naloxone 8 mg as opposed to 4 mg. At the risk of precipitating withdrawal from higher doses of naloxone, it was agreed that this risk was heavily outweighed by the benefit of successful opioid reversal. In this context, it is expected for this avenue of prescribing to influence naloxone prescribing patterns at VHI.

Prescribing in primary care clinics was shown to be equally as substantial. Primary care-based multidisciplinary transition clinics have been reported to be associated with increased access to OUD treatment.15 Primary care clinics at VHI, or patient aligned care teams (PACT), largely consist of multidisciplinary health care teams. PACT clinicians are heavily involved in transitions of care because one system provides patients with comprehensive acute and chronic care. Continuing to encourage naloxone distribution through primary care and using STORM affords various patient populations access to high-level care.

Notable differences were observed between indications for naloxone use and the corresponding dose. Patients with OUD or SUD were more likely to receive intranasal naloxone 8 mg as opposed to patients receiving intranasal naloxone for chronic opioid use, who were more likely to receive the 4 mg dose. This may be due to a rationale to provide a higher dose of naloxone to combat overdoses in the case of ingesting substances mixed with fentanyl or xylazine.12,13 Without standard of care guidelines, concerns remain for varying outcomes in opioid overdose prevention within vulnerable populations.

Limitations

Chart data were dependent on documentation, which may have omitted pertinent baseline characteristics and risk factors. Additional data collection could have further assessed a patient’s specific risk factors (eg, opioid dose in morphine equivalents) to draw conclusions to the dose of naloxone prescribed. The sample size was small, and the patient population was largely White and male, which minimized the generalizability of the results.

CONCLUSIONS

This study evaluated the differences in intranasal naloxone prescribing patterns within a veteran population at VHI over 12 months. Findings revealed that most prescriptions were written for intranasal naloxone 8 mg, by a pharmacist, in a primary care setting, and for chronic opioid use. The results revealed evidence of differing naloxone prescribing practices, which emphasize the need for clinical guidelines and better defined recommendations in relation to naloxone dosing.

The most evident gap in patient care could be addressed by urging the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management group to update naloxone recommendations for use to include more concrete dosing recommendations. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to re-educate clinicians on naloxone prescribing to increase awareness of different doses and the importance of equipping patients with the correct amount of naloxone in an emergency. Additional research assessing change in prescribing patterns is warranted as the use of higher dose naloxone becomes more routine.

- Britch SC, Walsh SL. Treatment of opioid overdose: current approaches and recent advances. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2022;239(7):2063-2081. doi:10.1007/s00213-022-06125-5

- Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2023. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- O’Donnell J, Tanz LJ, Gladden RM, Davis NL, Bitting J. Trends in and characteristics of drug overdose deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyls — United States, 2019–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1740-1746. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e3

- Luo F, Li M, Florence C. State-level economic costs of opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdose — United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:541-546. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7015a1

- Lexicomp. Lexicomp Online. Accessed April 10, 2025. http://online.lexi.com

- Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC Clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain — United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71(3):1-95. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1

- Narcan (naloxone) FDA approval history. Drugs.com. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.drugs.com/history/narcan.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What you should know about xylazine. May 16, 2024. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/about/what-you-should-know-about-xylazine.html

- Avetian GK, Fiuty P, Mazzella S, Koppa D, Heye V, Hebbar P. Use of naloxone nasal spray 4 mg in the community setting: a survey of use by community organizations. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(4):573-576. doi:10.1080/03007995.2017.1334637

- Kloxxado [package insert]. Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA Inc; 2021.

- FDA approves higher dosage of naloxone nasal spray to treat opioid overdose. News release. FDA. April 30, 2021. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-higher-dosage-naloxone-nasal-spray-treat-opioid-overdose

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefits Management Services and National Formulary Committee in Collaboration with the VA National Harm Reduction Support & Development Workgroup. Naloxone Rescue: Recommendations for Use. June 2014. Updated March 2024. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.va.gov/formularyadvisor/DOC_PDF/CRE_Naloxone_Rescue_Guidance_March_2024.pdf

- Krieter P, Chiang N, Gyaw S, et al. Pharmacokinetic properties and human use characteristics of an FDA-approved intranasal naloxone product for the treatment of opioid overdose. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56(10):1243-1253. doi:10.1002/jcph.759

- Rawal S, Osae SP, Cobran EK, Albert A, Young HN. Pharmacists’ naloxone services beyond community pharmacy settings: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2023;19(2):243-265. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2022.09.002

- Incze MA, Sehgal SL, Hansen A, Garcia L, Stolebarger L. Evaluation of a primary care-based multidisciplinary transition clinic for patients newly initiated on buprenorphine in the emergency department. Subst Abus. 2023;44(3):220-225. doi:10.1177/08897077231188592

- Britch SC, Walsh SL. Treatment of opioid overdose: current approaches and recent advances. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2022;239(7):2063-2081. doi:10.1007/s00213-022-06125-5

- Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2023. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- O’Donnell J, Tanz LJ, Gladden RM, Davis NL, Bitting J. Trends in and characteristics of drug overdose deaths involving illicitly manufactured fentanyls — United States, 2019–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1740-1746. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e3

- Luo F, Li M, Florence C. State-level economic costs of opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdose — United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:541-546. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7015a1

- Lexicomp. Lexicomp Online. Accessed April 10, 2025. http://online.lexi.com

- Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC Clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain — United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71(3):1-95. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1

- Narcan (naloxone) FDA approval history. Drugs.com. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.drugs.com/history/narcan.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What you should know about xylazine. May 16, 2024. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/about/what-you-should-know-about-xylazine.html

- Avetian GK, Fiuty P, Mazzella S, Koppa D, Heye V, Hebbar P. Use of naloxone nasal spray 4 mg in the community setting: a survey of use by community organizations. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(4):573-576. doi:10.1080/03007995.2017.1334637

- Kloxxado [package insert]. Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA Inc; 2021.

- FDA approves higher dosage of naloxone nasal spray to treat opioid overdose. News release. FDA. April 30, 2021. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-higher-dosage-naloxone-nasal-spray-treat-opioid-overdose

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Pharmacy Benefits Management Services and National Formulary Committee in Collaboration with the VA National Harm Reduction Support & Development Workgroup. Naloxone Rescue: Recommendations for Use. June 2014. Updated March 2024. Accessed April 10, 2025. https://www.va.gov/formularyadvisor/DOC_PDF/CRE_Naloxone_Rescue_Guidance_March_2024.pdf

- Krieter P, Chiang N, Gyaw S, et al. Pharmacokinetic properties and human use characteristics of an FDA-approved intranasal naloxone product for the treatment of opioid overdose. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;56(10):1243-1253. doi:10.1002/jcph.759

- Rawal S, Osae SP, Cobran EK, Albert A, Young HN. Pharmacists’ naloxone services beyond community pharmacy settings: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2023;19(2):243-265. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2022.09.002

- Incze MA, Sehgal SL, Hansen A, Garcia L, Stolebarger L. Evaluation of a primary care-based multidisciplinary transition clinic for patients newly initiated on buprenorphine in the emergency department. Subst Abus. 2023;44(3):220-225. doi:10.1177/08897077231188592

Comparison of Prescribing Patterns of Intranasal Naloxone in a Veteran Population

Comparison of Prescribing Patterns of Intranasal Naloxone in a Veteran Population