User login

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas Update: Benefits of a Multidisciplinary Care Approach

Introduction

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) are a heterogenous group of rare extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas that are caused by the accumulation of neoplastic lymphocytes in the skin.1,2 According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, a total of 14,942 CTCL cases were recorded between 2000 and 2018.3 The incidence rate for all CTCLs is 8.55 per million and appears to be rising. The causes of such an increase are multifactorial and may be related to better diagnostic tools and increased physician awareness.

The incidence of CTCLs also increases with age. The median age at diagnosis is mid-50s but the incidence of CTCLs is 4-fold greater in patients aged 70 years and older.2 Furthermore, men and Black individuals have the highest incidence rates for CTCLs.2,3 More than 10 types of CTCLs have been identified based on biology, histopathology, and clinical features. CTCL types can be either indolent or aggressive.1,4 Approximately 75% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas consist of CTCLs, including mycosis fungoides (MF), Sézary syndrome (SS), or CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders (lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma).

The most common CTCL is MF, a clinically heterogeneous, often indolent disease that tends to progress over years or decades.1 This condition classically presents as cutaneous erythematous patches or plaques in sun-protected areas, ie, demonstrating a bathing suit distribution.5 Rarely, MF can present as or progress to more aggressive disease, with infiltrative plaques or tumors. For MF, 5- and 10-year survival ranges from 49% to 100% depending on the stage at diagnosis.1

The most common aggressive CTCL is SS, characterized by erythroderma, intractable pruritis, and the presence of neoplastic clonal T cells (eg, Sézary cells) in the skin, peripheral blood, and/or lymph nodes, with a Sézary cell absolute count of ≥ 1,000 cells/mm3.1,2 SS tends to progress more rapidly than MF and has a worse prognosis, with 5-year survival ranging from 10% to 50%.1,4

Definitive Diagnosis

Diagnosis of CTCL requires the neoplastic T cells be confined to the skin.2 Thus, diagnostic evaluation should involve a comprehensive physical examination, skin biopsy, and staging blood tests including a peripheral blood flow cytometry if indicated. Sometimes, radiologic imaging is needed, and if there are any abnormalities found on staging blood tests or imaging, lymph node and bone marrow biopsy may be necessary.1

MF

MF mimics a wide variety of dermatological diseases, with nearly 50 different clinical entities in the differential, making diagnosis challenging.5 Clinical findings are heterogenous, and symptoms may be attributed to benign diseases, eg, eczema, or psoriasis. Pathological features may be nonspecific and subtle in the early stages of the disease and overlap with reactive processes; therefore, multiple biopsies performed during the disease course may be required to reach a definitive diagnosis. Creating a further challenge is the potential for skin-directed therapies (such as topical steroids) to interfere with pathological assessment at the time of biopsy.2 Thus, obtaining a definitive diagnosis for MF, particularly in the patch or plaque stage, could take a median of 4 years but can take up to 4 decades.2,5

A definitive diagnosis for MF can be made using clinical and histopathological features. Possible ancillary studies (if indicated) include determination of T-cell clonality by polymerase chain reaction or next-generation sequencing methods, and assessment for aberrant loss of T-cell antigen expression by immunohistochemical staining.2

SS

Clinical features of SS may be similar to erythrodermic inflammatory dermatoses, and thus the gold standard for diagnosis is peripheral blood involvement and assessing for clonally related neoplastic T-cell populations.1 Histopathological findings on skin biopsy are often nonspecific.4 The currently proposed International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas criteria for SS integrate clinical, histopathological, immunophenotyping, and molecular studies.2

Benefits of a Multidisciplinary Team Care Approach

Early-stage MF with limited disease can be managed by a dermatologist, but advanced cases often benefit from a multidisciplinary team care model, including hematology-oncology, dermatology, and radiation oncology.5,6 Several different CTCL care models exist that incorporate resource allocation, staffing availability, and institutional practices developed over time. Regardless of whether care is delivered in a specialized CTCL clinic or a community practice setting, a multidisciplinary team care approach is crucial for patients with advanced-stage CTCL. Dermatologists, hematologist-oncologists, and radiation oncologists may see a patient together or separately, depending on clinical context, and collaborate to formulate the assessment, treatment plan, and address the patient’s questions and concerns. In addition, supportive staff including patient assistance coordinators, pharmacists, behavior health specialists, and palliative care specialists may be included to address the patients’ mental health needs as considerable morbidity from pain, itching, and disfigurement occurs with MF and SS—putting patients at a greater risk for social isolation and depression.7

There are several benefits to using a multidisciplinary team care model for managing CTCLs. Different specialties can provide various services and treatment options for patients to consider. Dermatologists perform skin biopsies to monitor disease progression and can administer skin-directed treatments such as phototherapy; radiation oncologists can administer radiation treatment; and oncologists can administer systemic therapies that are outside the scope of dermatology.8 The coordination of specialty visits can improve patient satisfaction.

Treatment Goals and Disease Management

Goals for treatment include delaying progression, reducing disease burden, and improving or preserving quality of life.5 Decision-making for treating CTCLs should involve preserving potential active treatments for when they are needed during an extended disease course, and mitigating associated burdens of logistical, financial, and physical toxicity.1

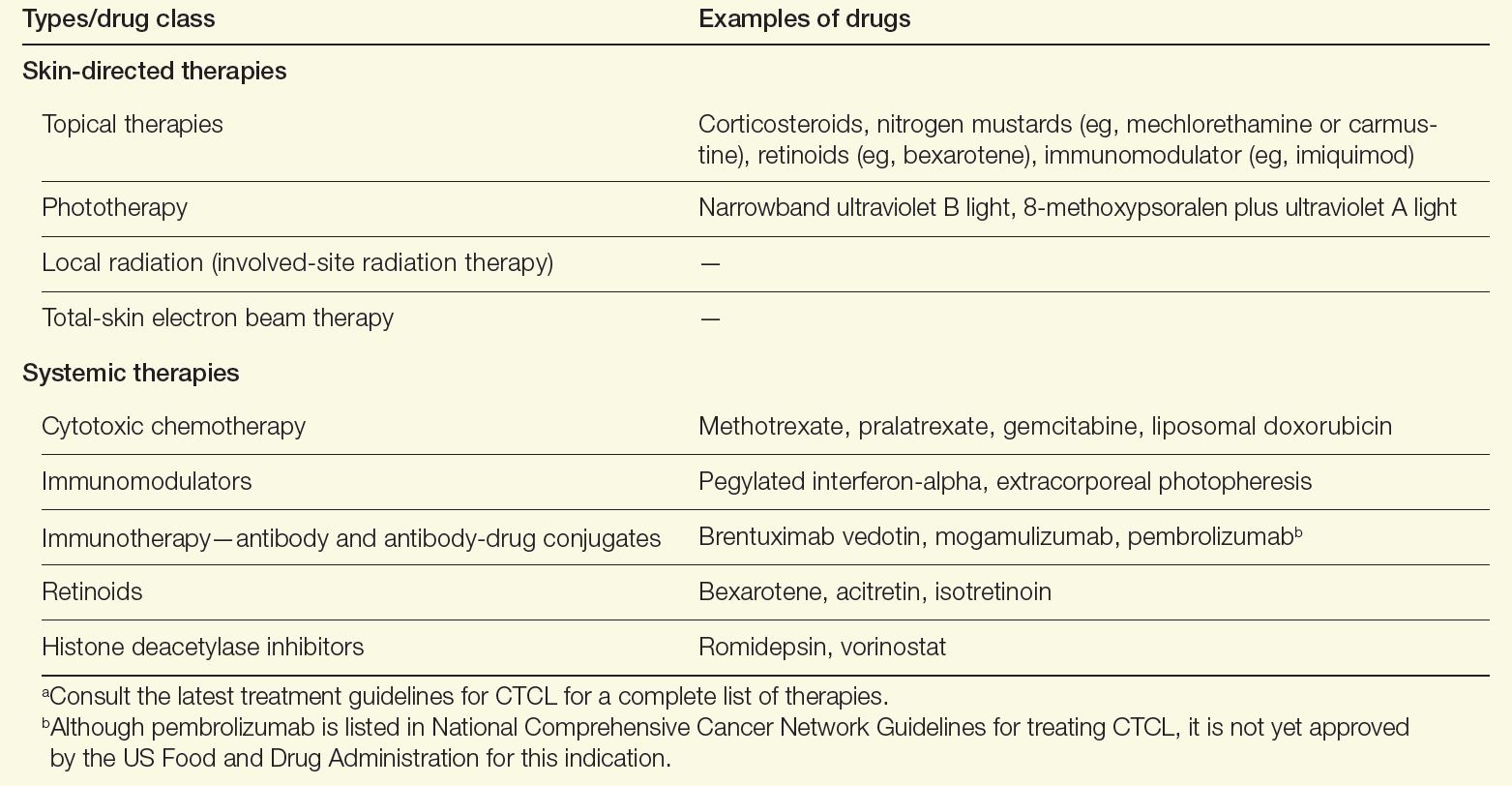

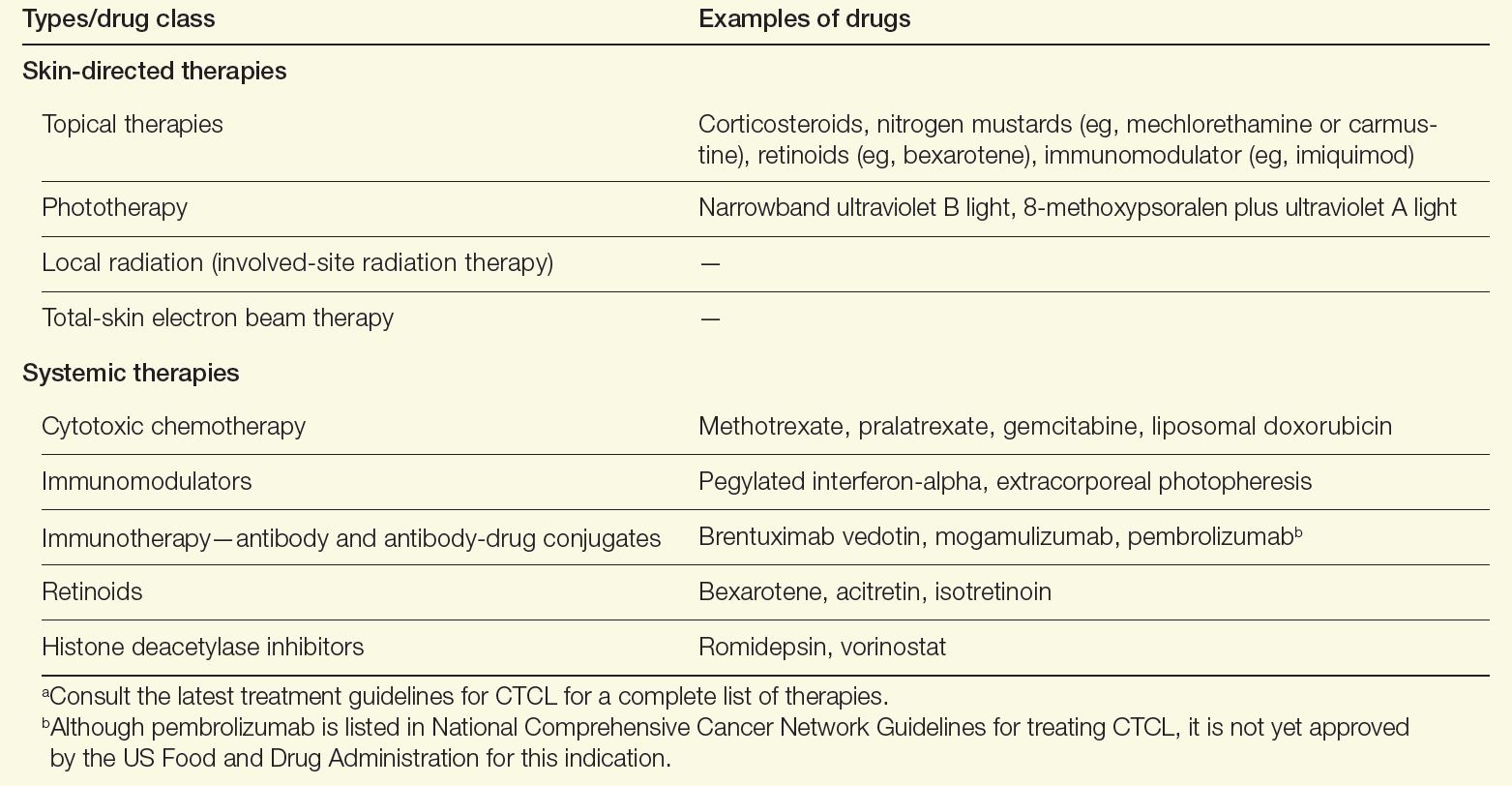

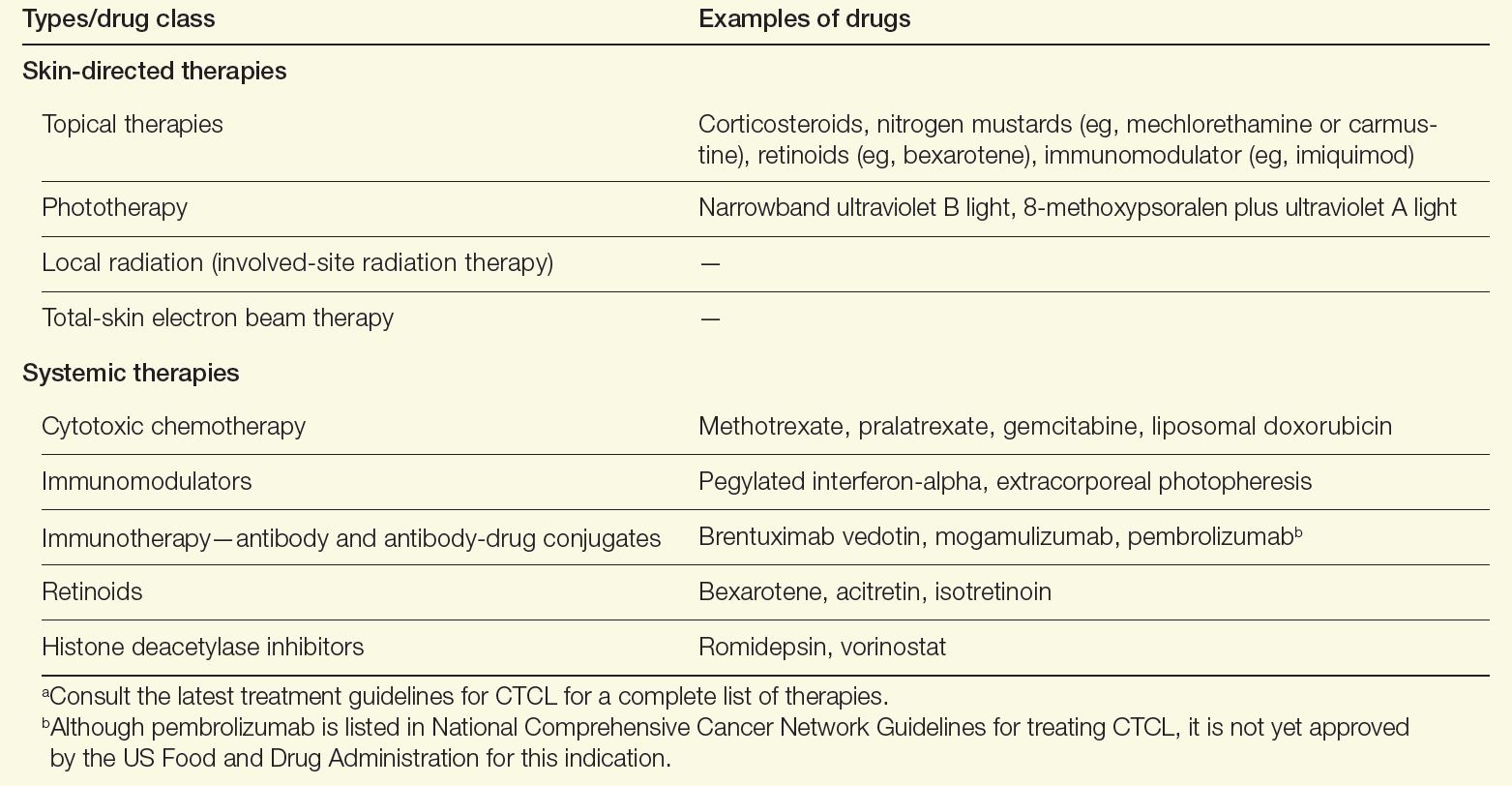

A variety of therapeutic modalities are available for CTCL that target tumor cells and boost antitumor responses, including topical therapies, phototherapy, radiation, chemotherapy, retinoids, and immune-modulating drugs (Table). Because no specific driver mutations have been identified for CTCLs, recent targeted therapy development has focused on various immunomodulators, small molecule inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and antibody-drug conjugates.1 Lastly, for high-risk patients with persistent disease or disease that is refractory to multiple previous therapies, allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as a potential therapy to induce durable remission may be considered, with careful attention paid to the timing of its use as well as disease and patient characteristics.9

Table. Therapies for CTCL Care9,10,a

Alternatively for early-stage MF, a “watch-and-wait” approach depending on the site of lesions and disease evolution may be an option, as this approach is not associated with a worsening of the disease course or survival.1 Furthermore, aggressive treatments during early stages have not been found to modify the disease course or survival, emphasizing the need for tailoring treatments based on the extent of involvement of the skin and extracutaneous sites.1,10 New strategies in development to treat CTCL include immune-checkpoint inhibitors and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies. Both strategies focus on engaging the immune system to better combat lymphoma.11,12

Outlook for Patients With CTCL

Using a multidisciplinary care approach is the optimal way to deliver the complex care required for CTCL.5 Such an approach can reduce the time to a definitive diagnosis and accurately stage and risk-stratify the disease. A stage-based treatment approach using sequential therapies in an escalated fashion can help reserve active treatments for advanced disease management and maintain quality of life for patients with CTCL.1,2

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

- Dummer R, Vermeer MH, Scarisbrick JJ, et al. Cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):61. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00296-9

- Hristov AC, Tejasvi T, Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2023;98(1):193-209. doi:10.1002/ajh.26760

- Cai ZR, Chen ML, Weinstock MA, Kim YH, Novoa RA, Linos E. Incidence trends of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the US from 2000 to 2018: a SEER population data analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(11):1690-1692. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.3236

- Saleh JS, Subtil A, Hristov AC. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a review of the most common entities with focus on recent updates. Hum Pathol. 2023;140:75-100. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2023.09.009

- Vitiello P, Sagnelli C, Ronchi A, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and therapy of mycosis fungoides. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(4):614. doi:10.3390/healthcare11040614

- Morgenroth S, Roggo A, Pawlik L, Dummer R, Ramelyte E. What is new in cutaneous T cell lymphoma? Curr Oncol Rep. 2023;25(11):1397-1408. doi:10.1007/s11912-023-01464-8

- Molloy K, Jonak C, Woei-A-Jin FJSH, et al. Characteristics associated with significantly worse quality of life in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome from the Prospective Cutaneous Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (PROCLIPI) study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(3):770-779. doi:10.1111/bjd.18089

- Tyler KH, Haverkos BM, Hastings J, et al. The role of an integrated multidisciplinary clinic in the management of patients with cutaneous lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2015;5:136. doi:10.3389/fonc.2015.00136

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: primary cutaneous lymphomas. Version 3.2024. August 22, 2024. Accessed October 6, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/primary_cutaneous.pdf

- Goel RR, Rook AH. Immunobiology and treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2024;20(8):985-996. doi:10.1080/1744666X.2024.2326035

- Iyer SP, Sica RA, Ho PJ, et al. S262: The COBALT-LYM study of CTX130: a phase 1 dose escalation study of CD70-targeted allogeneic CRISPR-Cas9–engineered CAR T cells in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) T-cell malignancies. HemaSphere. 2022;6(S3):163-164. doi:10.1097/01.HS9.0000843940.96598.e2

- Khodadoust MS, Rook AH, Porcu P, et al. Pembrolizumab in relapsed and refractory mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(1):20-28. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.01056

Introduction

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) are a heterogenous group of rare extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas that are caused by the accumulation of neoplastic lymphocytes in the skin.1,2 According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, a total of 14,942 CTCL cases were recorded between 2000 and 2018.3 The incidence rate for all CTCLs is 8.55 per million and appears to be rising. The causes of such an increase are multifactorial and may be related to better diagnostic tools and increased physician awareness.

The incidence of CTCLs also increases with age. The median age at diagnosis is mid-50s but the incidence of CTCLs is 4-fold greater in patients aged 70 years and older.2 Furthermore, men and Black individuals have the highest incidence rates for CTCLs.2,3 More than 10 types of CTCLs have been identified based on biology, histopathology, and clinical features. CTCL types can be either indolent or aggressive.1,4 Approximately 75% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas consist of CTCLs, including mycosis fungoides (MF), Sézary syndrome (SS), or CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders (lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma).

The most common CTCL is MF, a clinically heterogeneous, often indolent disease that tends to progress over years or decades.1 This condition classically presents as cutaneous erythematous patches or plaques in sun-protected areas, ie, demonstrating a bathing suit distribution.5 Rarely, MF can present as or progress to more aggressive disease, with infiltrative plaques or tumors. For MF, 5- and 10-year survival ranges from 49% to 100% depending on the stage at diagnosis.1

The most common aggressive CTCL is SS, characterized by erythroderma, intractable pruritis, and the presence of neoplastic clonal T cells (eg, Sézary cells) in the skin, peripheral blood, and/or lymph nodes, with a Sézary cell absolute count of ≥ 1,000 cells/mm3.1,2 SS tends to progress more rapidly than MF and has a worse prognosis, with 5-year survival ranging from 10% to 50%.1,4

Definitive Diagnosis

Diagnosis of CTCL requires the neoplastic T cells be confined to the skin.2 Thus, diagnostic evaluation should involve a comprehensive physical examination, skin biopsy, and staging blood tests including a peripheral blood flow cytometry if indicated. Sometimes, radiologic imaging is needed, and if there are any abnormalities found on staging blood tests or imaging, lymph node and bone marrow biopsy may be necessary.1

MF

MF mimics a wide variety of dermatological diseases, with nearly 50 different clinical entities in the differential, making diagnosis challenging.5 Clinical findings are heterogenous, and symptoms may be attributed to benign diseases, eg, eczema, or psoriasis. Pathological features may be nonspecific and subtle in the early stages of the disease and overlap with reactive processes; therefore, multiple biopsies performed during the disease course may be required to reach a definitive diagnosis. Creating a further challenge is the potential for skin-directed therapies (such as topical steroids) to interfere with pathological assessment at the time of biopsy.2 Thus, obtaining a definitive diagnosis for MF, particularly in the patch or plaque stage, could take a median of 4 years but can take up to 4 decades.2,5

A definitive diagnosis for MF can be made using clinical and histopathological features. Possible ancillary studies (if indicated) include determination of T-cell clonality by polymerase chain reaction or next-generation sequencing methods, and assessment for aberrant loss of T-cell antigen expression by immunohistochemical staining.2

SS

Clinical features of SS may be similar to erythrodermic inflammatory dermatoses, and thus the gold standard for diagnosis is peripheral blood involvement and assessing for clonally related neoplastic T-cell populations.1 Histopathological findings on skin biopsy are often nonspecific.4 The currently proposed International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas criteria for SS integrate clinical, histopathological, immunophenotyping, and molecular studies.2

Benefits of a Multidisciplinary Team Care Approach

Early-stage MF with limited disease can be managed by a dermatologist, but advanced cases often benefit from a multidisciplinary team care model, including hematology-oncology, dermatology, and radiation oncology.5,6 Several different CTCL care models exist that incorporate resource allocation, staffing availability, and institutional practices developed over time. Regardless of whether care is delivered in a specialized CTCL clinic or a community practice setting, a multidisciplinary team care approach is crucial for patients with advanced-stage CTCL. Dermatologists, hematologist-oncologists, and radiation oncologists may see a patient together or separately, depending on clinical context, and collaborate to formulate the assessment, treatment plan, and address the patient’s questions and concerns. In addition, supportive staff including patient assistance coordinators, pharmacists, behavior health specialists, and palliative care specialists may be included to address the patients’ mental health needs as considerable morbidity from pain, itching, and disfigurement occurs with MF and SS—putting patients at a greater risk for social isolation and depression.7

There are several benefits to using a multidisciplinary team care model for managing CTCLs. Different specialties can provide various services and treatment options for patients to consider. Dermatologists perform skin biopsies to monitor disease progression and can administer skin-directed treatments such as phototherapy; radiation oncologists can administer radiation treatment; and oncologists can administer systemic therapies that are outside the scope of dermatology.8 The coordination of specialty visits can improve patient satisfaction.

Treatment Goals and Disease Management

Goals for treatment include delaying progression, reducing disease burden, and improving or preserving quality of life.5 Decision-making for treating CTCLs should involve preserving potential active treatments for when they are needed during an extended disease course, and mitigating associated burdens of logistical, financial, and physical toxicity.1

A variety of therapeutic modalities are available for CTCL that target tumor cells and boost antitumor responses, including topical therapies, phototherapy, radiation, chemotherapy, retinoids, and immune-modulating drugs (Table). Because no specific driver mutations have been identified for CTCLs, recent targeted therapy development has focused on various immunomodulators, small molecule inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and antibody-drug conjugates.1 Lastly, for high-risk patients with persistent disease or disease that is refractory to multiple previous therapies, allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as a potential therapy to induce durable remission may be considered, with careful attention paid to the timing of its use as well as disease and patient characteristics.9

Table. Therapies for CTCL Care9,10,a

Alternatively for early-stage MF, a “watch-and-wait” approach depending on the site of lesions and disease evolution may be an option, as this approach is not associated with a worsening of the disease course or survival.1 Furthermore, aggressive treatments during early stages have not been found to modify the disease course or survival, emphasizing the need for tailoring treatments based on the extent of involvement of the skin and extracutaneous sites.1,10 New strategies in development to treat CTCL include immune-checkpoint inhibitors and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies. Both strategies focus on engaging the immune system to better combat lymphoma.11,12

Outlook for Patients With CTCL

Using a multidisciplinary care approach is the optimal way to deliver the complex care required for CTCL.5 Such an approach can reduce the time to a definitive diagnosis and accurately stage and risk-stratify the disease. A stage-based treatment approach using sequential therapies in an escalated fashion can help reserve active treatments for advanced disease management and maintain quality of life for patients with CTCL.1,2

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

Introduction

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) are a heterogenous group of rare extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas that are caused by the accumulation of neoplastic lymphocytes in the skin.1,2 According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, a total of 14,942 CTCL cases were recorded between 2000 and 2018.3 The incidence rate for all CTCLs is 8.55 per million and appears to be rising. The causes of such an increase are multifactorial and may be related to better diagnostic tools and increased physician awareness.

The incidence of CTCLs also increases with age. The median age at diagnosis is mid-50s but the incidence of CTCLs is 4-fold greater in patients aged 70 years and older.2 Furthermore, men and Black individuals have the highest incidence rates for CTCLs.2,3 More than 10 types of CTCLs have been identified based on biology, histopathology, and clinical features. CTCL types can be either indolent or aggressive.1,4 Approximately 75% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas consist of CTCLs, including mycosis fungoides (MF), Sézary syndrome (SS), or CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders (lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma).

The most common CTCL is MF, a clinically heterogeneous, often indolent disease that tends to progress over years or decades.1 This condition classically presents as cutaneous erythematous patches or plaques in sun-protected areas, ie, demonstrating a bathing suit distribution.5 Rarely, MF can present as or progress to more aggressive disease, with infiltrative plaques or tumors. For MF, 5- and 10-year survival ranges from 49% to 100% depending on the stage at diagnosis.1

The most common aggressive CTCL is SS, characterized by erythroderma, intractable pruritis, and the presence of neoplastic clonal T cells (eg, Sézary cells) in the skin, peripheral blood, and/or lymph nodes, with a Sézary cell absolute count of ≥ 1,000 cells/mm3.1,2 SS tends to progress more rapidly than MF and has a worse prognosis, with 5-year survival ranging from 10% to 50%.1,4

Definitive Diagnosis

Diagnosis of CTCL requires the neoplastic T cells be confined to the skin.2 Thus, diagnostic evaluation should involve a comprehensive physical examination, skin biopsy, and staging blood tests including a peripheral blood flow cytometry if indicated. Sometimes, radiologic imaging is needed, and if there are any abnormalities found on staging blood tests or imaging, lymph node and bone marrow biopsy may be necessary.1

MF

MF mimics a wide variety of dermatological diseases, with nearly 50 different clinical entities in the differential, making diagnosis challenging.5 Clinical findings are heterogenous, and symptoms may be attributed to benign diseases, eg, eczema, or psoriasis. Pathological features may be nonspecific and subtle in the early stages of the disease and overlap with reactive processes; therefore, multiple biopsies performed during the disease course may be required to reach a definitive diagnosis. Creating a further challenge is the potential for skin-directed therapies (such as topical steroids) to interfere with pathological assessment at the time of biopsy.2 Thus, obtaining a definitive diagnosis for MF, particularly in the patch or plaque stage, could take a median of 4 years but can take up to 4 decades.2,5

A definitive diagnosis for MF can be made using clinical and histopathological features. Possible ancillary studies (if indicated) include determination of T-cell clonality by polymerase chain reaction or next-generation sequencing methods, and assessment for aberrant loss of T-cell antigen expression by immunohistochemical staining.2

SS

Clinical features of SS may be similar to erythrodermic inflammatory dermatoses, and thus the gold standard for diagnosis is peripheral blood involvement and assessing for clonally related neoplastic T-cell populations.1 Histopathological findings on skin biopsy are often nonspecific.4 The currently proposed International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas criteria for SS integrate clinical, histopathological, immunophenotyping, and molecular studies.2

Benefits of a Multidisciplinary Team Care Approach

Early-stage MF with limited disease can be managed by a dermatologist, but advanced cases often benefit from a multidisciplinary team care model, including hematology-oncology, dermatology, and radiation oncology.5,6 Several different CTCL care models exist that incorporate resource allocation, staffing availability, and institutional practices developed over time. Regardless of whether care is delivered in a specialized CTCL clinic or a community practice setting, a multidisciplinary team care approach is crucial for patients with advanced-stage CTCL. Dermatologists, hematologist-oncologists, and radiation oncologists may see a patient together or separately, depending on clinical context, and collaborate to formulate the assessment, treatment plan, and address the patient’s questions and concerns. In addition, supportive staff including patient assistance coordinators, pharmacists, behavior health specialists, and palliative care specialists may be included to address the patients’ mental health needs as considerable morbidity from pain, itching, and disfigurement occurs with MF and SS—putting patients at a greater risk for social isolation and depression.7

There are several benefits to using a multidisciplinary team care model for managing CTCLs. Different specialties can provide various services and treatment options for patients to consider. Dermatologists perform skin biopsies to monitor disease progression and can administer skin-directed treatments such as phototherapy; radiation oncologists can administer radiation treatment; and oncologists can administer systemic therapies that are outside the scope of dermatology.8 The coordination of specialty visits can improve patient satisfaction.

Treatment Goals and Disease Management

Goals for treatment include delaying progression, reducing disease burden, and improving or preserving quality of life.5 Decision-making for treating CTCLs should involve preserving potential active treatments for when they are needed during an extended disease course, and mitigating associated burdens of logistical, financial, and physical toxicity.1

A variety of therapeutic modalities are available for CTCL that target tumor cells and boost antitumor responses, including topical therapies, phototherapy, radiation, chemotherapy, retinoids, and immune-modulating drugs (Table). Because no specific driver mutations have been identified for CTCLs, recent targeted therapy development has focused on various immunomodulators, small molecule inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and antibody-drug conjugates.1 Lastly, for high-risk patients with persistent disease or disease that is refractory to multiple previous therapies, allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation as a potential therapy to induce durable remission may be considered, with careful attention paid to the timing of its use as well as disease and patient characteristics.9

Table. Therapies for CTCL Care9,10,a

Alternatively for early-stage MF, a “watch-and-wait” approach depending on the site of lesions and disease evolution may be an option, as this approach is not associated with a worsening of the disease course or survival.1 Furthermore, aggressive treatments during early stages have not been found to modify the disease course or survival, emphasizing the need for tailoring treatments based on the extent of involvement of the skin and extracutaneous sites.1,10 New strategies in development to treat CTCL include immune-checkpoint inhibitors and chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies. Both strategies focus on engaging the immune system to better combat lymphoma.11,12

Outlook for Patients With CTCL

Using a multidisciplinary care approach is the optimal way to deliver the complex care required for CTCL.5 Such an approach can reduce the time to a definitive diagnosis and accurately stage and risk-stratify the disease. A stage-based treatment approach using sequential therapies in an escalated fashion can help reserve active treatments for advanced disease management and maintain quality of life for patients with CTCL.1,2

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

- Dummer R, Vermeer MH, Scarisbrick JJ, et al. Cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):61. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00296-9

- Hristov AC, Tejasvi T, Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2023;98(1):193-209. doi:10.1002/ajh.26760

- Cai ZR, Chen ML, Weinstock MA, Kim YH, Novoa RA, Linos E. Incidence trends of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the US from 2000 to 2018: a SEER population data analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(11):1690-1692. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.3236

- Saleh JS, Subtil A, Hristov AC. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a review of the most common entities with focus on recent updates. Hum Pathol. 2023;140:75-100. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2023.09.009

- Vitiello P, Sagnelli C, Ronchi A, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and therapy of mycosis fungoides. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(4):614. doi:10.3390/healthcare11040614

- Morgenroth S, Roggo A, Pawlik L, Dummer R, Ramelyte E. What is new in cutaneous T cell lymphoma? Curr Oncol Rep. 2023;25(11):1397-1408. doi:10.1007/s11912-023-01464-8

- Molloy K, Jonak C, Woei-A-Jin FJSH, et al. Characteristics associated with significantly worse quality of life in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome from the Prospective Cutaneous Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (PROCLIPI) study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(3):770-779. doi:10.1111/bjd.18089

- Tyler KH, Haverkos BM, Hastings J, et al. The role of an integrated multidisciplinary clinic in the management of patients with cutaneous lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2015;5:136. doi:10.3389/fonc.2015.00136

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: primary cutaneous lymphomas. Version 3.2024. August 22, 2024. Accessed October 6, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/primary_cutaneous.pdf

- Goel RR, Rook AH. Immunobiology and treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2024;20(8):985-996. doi:10.1080/1744666X.2024.2326035

- Iyer SP, Sica RA, Ho PJ, et al. S262: The COBALT-LYM study of CTX130: a phase 1 dose escalation study of CD70-targeted allogeneic CRISPR-Cas9–engineered CAR T cells in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) T-cell malignancies. HemaSphere. 2022;6(S3):163-164. doi:10.1097/01.HS9.0000843940.96598.e2

- Khodadoust MS, Rook AH, Porcu P, et al. Pembrolizumab in relapsed and refractory mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(1):20-28. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.01056

- Dummer R, Vermeer MH, Scarisbrick JJ, et al. Cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):61. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00296-9

- Hristov AC, Tejasvi T, Wilcox RA. Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2023;98(1):193-209. doi:10.1002/ajh.26760

- Cai ZR, Chen ML, Weinstock MA, Kim YH, Novoa RA, Linos E. Incidence trends of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma in the US from 2000 to 2018: a SEER population data analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(11):1690-1692. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.3236

- Saleh JS, Subtil A, Hristov AC. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a review of the most common entities with focus on recent updates. Hum Pathol. 2023;140:75-100. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2023.09.009

- Vitiello P, Sagnelli C, Ronchi A, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and therapy of mycosis fungoides. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(4):614. doi:10.3390/healthcare11040614

- Morgenroth S, Roggo A, Pawlik L, Dummer R, Ramelyte E. What is new in cutaneous T cell lymphoma? Curr Oncol Rep. 2023;25(11):1397-1408. doi:10.1007/s11912-023-01464-8

- Molloy K, Jonak C, Woei-A-Jin FJSH, et al. Characteristics associated with significantly worse quality of life in mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome from the Prospective Cutaneous Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (PROCLIPI) study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(3):770-779. doi:10.1111/bjd.18089

- Tyler KH, Haverkos BM, Hastings J, et al. The role of an integrated multidisciplinary clinic in the management of patients with cutaneous lymphoma. Front Oncol. 2015;5:136. doi:10.3389/fonc.2015.00136

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: primary cutaneous lymphomas. Version 3.2024. August 22, 2024. Accessed October 6, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/primary_cutaneous.pdf

- Goel RR, Rook AH. Immunobiology and treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2024;20(8):985-996. doi:10.1080/1744666X.2024.2326035

- Iyer SP, Sica RA, Ho PJ, et al. S262: The COBALT-LYM study of CTX130: a phase 1 dose escalation study of CD70-targeted allogeneic CRISPR-Cas9–engineered CAR T cells in patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) T-cell malignancies. HemaSphere. 2022;6(S3):163-164. doi:10.1097/01.HS9.0000843940.96598.e2

- Khodadoust MS, Rook AH, Porcu P, et al. Pembrolizumab in relapsed and refractory mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(1):20-28. doi:10.1200/JCO.19.01056

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas Update: Benefits of a Multidisciplinary Care Approach

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas Update: Benefits of a Multidisciplinary Care Approach