User login

Weakness on one side of the body

FHM is a rare phenotype of migraine with aura with a characteristic presentation of motor aura. Motor aura presents as unilateral muscle weakness that tends to be felt first in the hands or arm and may spread to the face. To date, three distinct types have been identified by mutations in one of three genes. Type 1 is the most common and is associated with mutations in the gene CACNA1A. Mutations in ATP1A2 underlie type 2 FHM, and mutations in SCN1A underlie type 3 FHM.

FHM is distinguished from other hemiplegic migraine by family history of one or more affected first- or second-degree relatives. Genetic studies have shown FHM to have autosomal dominant inheritance. From half to three quarters of patients with FHM will have one of the more than 30 identified mutations on CACNA1A that diagnose type 1 FHM. These mutations affect transmission of glutamate in the neurons and neuronal reactions, increasing the susceptibility to cortical spreading depression associated with migraine. Mutations in ATP1A2 are found in about 20% of patients with FHM (type 2). More than 80 individual mutations have been identified, which alter sodium-potassium metabolism in neurons. About 5% of patients have type 3 FHM, associated with mutations in SCN1A that create gain of function or loss of function in neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels. Studies of other possible genes and mutations in relation to FHM, including PRRT2, are ongoing, but to date the associations are not clearly established.

Patients with FHM may also report sensory symptoms, visual disturbances, or aphasia. FHM generally affects people in their teens and twenties (women more than men) and has an estimated prevalence of 0.003% of the population. On average, patients report having two to three attacks per year, and some patients go for extended periods without a recurrent attack. Motor aura may occur on the same or opposite side of the body as headache and may alternate affected sides with each attack. Differential diagnoses that should be ruled out include transient ischemic attacks, infections (eg, meningitis, encephalitis), tumors, seizures, other inherited disorders, and metabolic issues.

Like other forms of migraine with aura, FHM is treated with abortive and/or preventive medications. Given the rarity of FHM, there are few studies specifically in families with this phenotype. Patients should be counseled on trigger avoidance to limit exposure. Acute treatment includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and other nonopioid pain relievers. The class of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonists (rimegepant, ubrogepant, zavegepant) may be considered. However, with FHM, medications associated with ischemia must be avoided. As such, triptans and ergotamines are generally contraindicated, as are beta-blockers. Patients with FHM and more frequent or severe attacks may be considered for preventive treatment to improve function and quality of life and avoid reliance on acute therapies. Options include CGRP monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), administered subcutaneously or by intravenous infusion, and onabotulinumtoxinA injection. Current CGRP mAbs include eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab. Combined CGRP mAb therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA may be an effective alternative for patients with resistant FHM.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

FHM is a rare phenotype of migraine with aura with a characteristic presentation of motor aura. Motor aura presents as unilateral muscle weakness that tends to be felt first in the hands or arm and may spread to the face. To date, three distinct types have been identified by mutations in one of three genes. Type 1 is the most common and is associated with mutations in the gene CACNA1A. Mutations in ATP1A2 underlie type 2 FHM, and mutations in SCN1A underlie type 3 FHM.

FHM is distinguished from other hemiplegic migraine by family history of one or more affected first- or second-degree relatives. Genetic studies have shown FHM to have autosomal dominant inheritance. From half to three quarters of patients with FHM will have one of the more than 30 identified mutations on CACNA1A that diagnose type 1 FHM. These mutations affect transmission of glutamate in the neurons and neuronal reactions, increasing the susceptibility to cortical spreading depression associated with migraine. Mutations in ATP1A2 are found in about 20% of patients with FHM (type 2). More than 80 individual mutations have been identified, which alter sodium-potassium metabolism in neurons. About 5% of patients have type 3 FHM, associated with mutations in SCN1A that create gain of function or loss of function in neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels. Studies of other possible genes and mutations in relation to FHM, including PRRT2, are ongoing, but to date the associations are not clearly established.

Patients with FHM may also report sensory symptoms, visual disturbances, or aphasia. FHM generally affects people in their teens and twenties (women more than men) and has an estimated prevalence of 0.003% of the population. On average, patients report having two to three attacks per year, and some patients go for extended periods without a recurrent attack. Motor aura may occur on the same or opposite side of the body as headache and may alternate affected sides with each attack. Differential diagnoses that should be ruled out include transient ischemic attacks, infections (eg, meningitis, encephalitis), tumors, seizures, other inherited disorders, and metabolic issues.

Like other forms of migraine with aura, FHM is treated with abortive and/or preventive medications. Given the rarity of FHM, there are few studies specifically in families with this phenotype. Patients should be counseled on trigger avoidance to limit exposure. Acute treatment includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and other nonopioid pain relievers. The class of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonists (rimegepant, ubrogepant, zavegepant) may be considered. However, with FHM, medications associated with ischemia must be avoided. As such, triptans and ergotamines are generally contraindicated, as are beta-blockers. Patients with FHM and more frequent or severe attacks may be considered for preventive treatment to improve function and quality of life and avoid reliance on acute therapies. Options include CGRP monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), administered subcutaneously or by intravenous infusion, and onabotulinumtoxinA injection. Current CGRP mAbs include eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab. Combined CGRP mAb therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA may be an effective alternative for patients with resistant FHM.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

FHM is a rare phenotype of migraine with aura with a characteristic presentation of motor aura. Motor aura presents as unilateral muscle weakness that tends to be felt first in the hands or arm and may spread to the face. To date, three distinct types have been identified by mutations in one of three genes. Type 1 is the most common and is associated with mutations in the gene CACNA1A. Mutations in ATP1A2 underlie type 2 FHM, and mutations in SCN1A underlie type 3 FHM.

FHM is distinguished from other hemiplegic migraine by family history of one or more affected first- or second-degree relatives. Genetic studies have shown FHM to have autosomal dominant inheritance. From half to three quarters of patients with FHM will have one of the more than 30 identified mutations on CACNA1A that diagnose type 1 FHM. These mutations affect transmission of glutamate in the neurons and neuronal reactions, increasing the susceptibility to cortical spreading depression associated with migraine. Mutations in ATP1A2 are found in about 20% of patients with FHM (type 2). More than 80 individual mutations have been identified, which alter sodium-potassium metabolism in neurons. About 5% of patients have type 3 FHM, associated with mutations in SCN1A that create gain of function or loss of function in neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels. Studies of other possible genes and mutations in relation to FHM, including PRRT2, are ongoing, but to date the associations are not clearly established.

Patients with FHM may also report sensory symptoms, visual disturbances, or aphasia. FHM generally affects people in their teens and twenties (women more than men) and has an estimated prevalence of 0.003% of the population. On average, patients report having two to three attacks per year, and some patients go for extended periods without a recurrent attack. Motor aura may occur on the same or opposite side of the body as headache and may alternate affected sides with each attack. Differential diagnoses that should be ruled out include transient ischemic attacks, infections (eg, meningitis, encephalitis), tumors, seizures, other inherited disorders, and metabolic issues.

Like other forms of migraine with aura, FHM is treated with abortive and/or preventive medications. Given the rarity of FHM, there are few studies specifically in families with this phenotype. Patients should be counseled on trigger avoidance to limit exposure. Acute treatment includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and other nonopioid pain relievers. The class of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antagonists (rimegepant, ubrogepant, zavegepant) may be considered. However, with FHM, medications associated with ischemia must be avoided. As such, triptans and ergotamines are generally contraindicated, as are beta-blockers. Patients with FHM and more frequent or severe attacks may be considered for preventive treatment to improve function and quality of life and avoid reliance on acute therapies. Options include CGRP monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), administered subcutaneously or by intravenous infusion, and onabotulinumtoxinA injection. Current CGRP mAbs include eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab. Combined CGRP mAb therapy with onabotulinumtoxinA may be an effective alternative for patients with resistant FHM.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

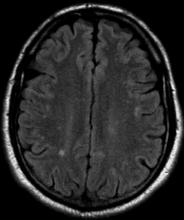

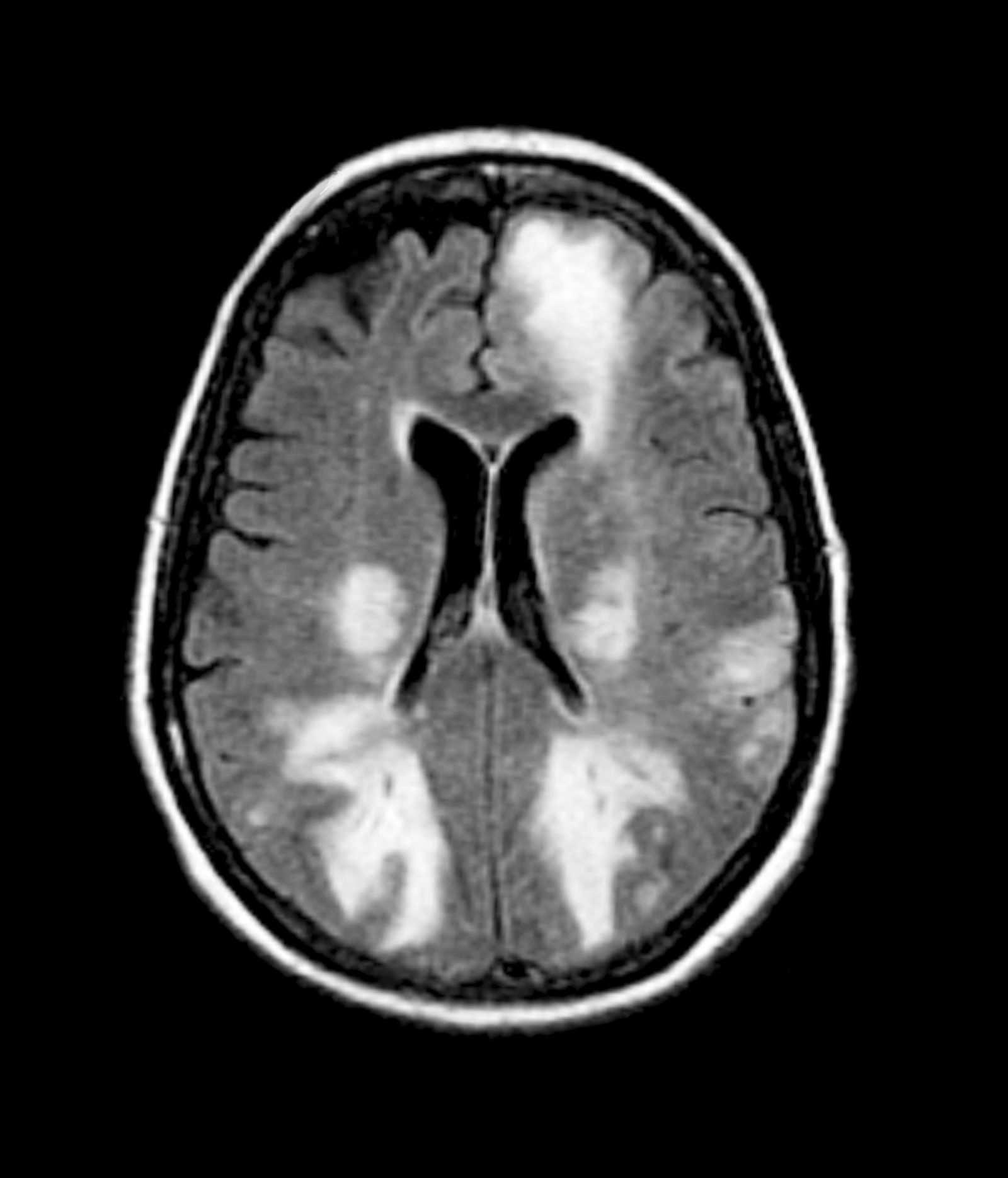

The patient is 35-year-old woman presenting for recurrent, unilateral headaches associated with weakness in the hand, arm, or face on one side of the body. The patient says this weakness sometimes occurs on the right side and other times on the left, often with a tingling sensation in the affected side, and is followed by an intense headache lasting for several hours.

She notes that the headaches started after recovery from a mild case of COVID. Over the past 2 years, five attacks have occurred, all following a similar pattern. With each attack, the motor weakness fully resolved with resolution of the headache. Two of the headaches were preceded by visual disturbances that resolved with headache onset.

Physical exam reveals an apparently healthy woman without fever or respiratory symptoms. Weight, blood pressure, and heart rate are within healthy ranges. All lab work is within normal ranges. Her facial appearance is normal at presentation, but she shows a photo taken during her last attack, in which she shows left side facial paralysis. Family history includes her mother with hemiplegic migraine and father with type 2 diabetes. You suspect familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM) and order genetic testing.

Knee pain on walking

Overall, persons with schizophrenia are more likely than the general population to be overweight and have cardiovascular risk factors before starting treatment with antipsychotics, and such treatment generally worsens these measures. Weight gain and associated morbidity and mortality are common side effects of antipsychotic medications. Olanzapine is associated with significant weight gain of 7% or more, higher than other second-generation antipsychotics. Olanzapine treatment is the major contributor to this patient's additional weight gain over the past 2 years. This added weight has translated to excess wear and tear on her joints, leading to evidence of osteoarthritis. Treatment with olanzapine is also independently associated with detrimental changes in cardiometabolic parameters.

Interventions to prevent or mitigate weight gain with antipsychotics are limited. In general, the American Psychiatric Association does not recommend switching antipsychotics for patients whose schizophrenia is well managed. However, there is increasing evidence that metformin may have a role in mitigating weight gain as well as beneficially modifying cardiometabolic factors in patients with schizophrenia being treated with olanzapine. A systematic review of emerging evidence with metformin in patients with schizophrenia suggests that metformin may also improve some cognitive symptoms of the illness, although further research is needed. The randomized, double-blind MELIA trial of metformin plus lifestyle intervention in antipsychotic-induced weight gain is ongoing. Starting metformin as a preventive measure at the same time as antipsychotic therapy may help to limit excess weight gain.

Research continues on the potential benefit of adding weight loss medications, including glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, to antipsychotics. Daily liraglutide is most widely studied, but a published case series with weekly semaglutide also demonstrated weight loss in this setting. Liraglutide also has shown beneficial cardiometabolic effects in patients using antipsychotic medications. More studies of these drugs and of GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonists are needed to elucidate the optimal use of these therapies for patients with schizophrenia.

There are few other effective ways to mitigate weight gain with olanzapine. Patients should be counseled on nutrition and lifestyle modifications. Evidence supports improvement with structured lifestyle modifications across a range of patients with less severe mental health issues, and structured programs combined with motivational interviewing were associated with reductions in antipsychotic-induced weight gain in patients with severe mental illness. As with any patient with obesity, however, the success of lifestyle modifications is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions.

Nonpharmacologic interventions to address joint pain include heat or cold compresses, physical therapy, and strength and resistance training to improve the strength of muscles supporting the joints. If these measures are ineffective, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including ibuprofen, naproxen, meloxicam, diclofenac, or celecoxib may be used with regular follow-up to assess cardiovascular and gastrointestinal health. Topical NSAIDs also may be useful. For more intractable joint pain, options include injecting a corticosteroid or sodium hyaluronate into the affected joints or joint replacement.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Overall, persons with schizophrenia are more likely than the general population to be overweight and have cardiovascular risk factors before starting treatment with antipsychotics, and such treatment generally worsens these measures. Weight gain and associated morbidity and mortality are common side effects of antipsychotic medications. Olanzapine is associated with significant weight gain of 7% or more, higher than other second-generation antipsychotics. Olanzapine treatment is the major contributor to this patient's additional weight gain over the past 2 years. This added weight has translated to excess wear and tear on her joints, leading to evidence of osteoarthritis. Treatment with olanzapine is also independently associated with detrimental changes in cardiometabolic parameters.

Interventions to prevent or mitigate weight gain with antipsychotics are limited. In general, the American Psychiatric Association does not recommend switching antipsychotics for patients whose schizophrenia is well managed. However, there is increasing evidence that metformin may have a role in mitigating weight gain as well as beneficially modifying cardiometabolic factors in patients with schizophrenia being treated with olanzapine. A systematic review of emerging evidence with metformin in patients with schizophrenia suggests that metformin may also improve some cognitive symptoms of the illness, although further research is needed. The randomized, double-blind MELIA trial of metformin plus lifestyle intervention in antipsychotic-induced weight gain is ongoing. Starting metformin as a preventive measure at the same time as antipsychotic therapy may help to limit excess weight gain.

Research continues on the potential benefit of adding weight loss medications, including glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, to antipsychotics. Daily liraglutide is most widely studied, but a published case series with weekly semaglutide also demonstrated weight loss in this setting. Liraglutide also has shown beneficial cardiometabolic effects in patients using antipsychotic medications. More studies of these drugs and of GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonists are needed to elucidate the optimal use of these therapies for patients with schizophrenia.

There are few other effective ways to mitigate weight gain with olanzapine. Patients should be counseled on nutrition and lifestyle modifications. Evidence supports improvement with structured lifestyle modifications across a range of patients with less severe mental health issues, and structured programs combined with motivational interviewing were associated with reductions in antipsychotic-induced weight gain in patients with severe mental illness. As with any patient with obesity, however, the success of lifestyle modifications is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions.

Nonpharmacologic interventions to address joint pain include heat or cold compresses, physical therapy, and strength and resistance training to improve the strength of muscles supporting the joints. If these measures are ineffective, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including ibuprofen, naproxen, meloxicam, diclofenac, or celecoxib may be used with regular follow-up to assess cardiovascular and gastrointestinal health. Topical NSAIDs also may be useful. For more intractable joint pain, options include injecting a corticosteroid or sodium hyaluronate into the affected joints or joint replacement.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Overall, persons with schizophrenia are more likely than the general population to be overweight and have cardiovascular risk factors before starting treatment with antipsychotics, and such treatment generally worsens these measures. Weight gain and associated morbidity and mortality are common side effects of antipsychotic medications. Olanzapine is associated with significant weight gain of 7% or more, higher than other second-generation antipsychotics. Olanzapine treatment is the major contributor to this patient's additional weight gain over the past 2 years. This added weight has translated to excess wear and tear on her joints, leading to evidence of osteoarthritis. Treatment with olanzapine is also independently associated with detrimental changes in cardiometabolic parameters.

Interventions to prevent or mitigate weight gain with antipsychotics are limited. In general, the American Psychiatric Association does not recommend switching antipsychotics for patients whose schizophrenia is well managed. However, there is increasing evidence that metformin may have a role in mitigating weight gain as well as beneficially modifying cardiometabolic factors in patients with schizophrenia being treated with olanzapine. A systematic review of emerging evidence with metformin in patients with schizophrenia suggests that metformin may also improve some cognitive symptoms of the illness, although further research is needed. The randomized, double-blind MELIA trial of metformin plus lifestyle intervention in antipsychotic-induced weight gain is ongoing. Starting metformin as a preventive measure at the same time as antipsychotic therapy may help to limit excess weight gain.

Research continues on the potential benefit of adding weight loss medications, including glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, to antipsychotics. Daily liraglutide is most widely studied, but a published case series with weekly semaglutide also demonstrated weight loss in this setting. Liraglutide also has shown beneficial cardiometabolic effects in patients using antipsychotic medications. More studies of these drugs and of GLP-1/glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide agonists are needed to elucidate the optimal use of these therapies for patients with schizophrenia.

There are few other effective ways to mitigate weight gain with olanzapine. Patients should be counseled on nutrition and lifestyle modifications. Evidence supports improvement with structured lifestyle modifications across a range of patients with less severe mental health issues, and structured programs combined with motivational interviewing were associated with reductions in antipsychotic-induced weight gain in patients with severe mental illness. As with any patient with obesity, however, the success of lifestyle modifications is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions.

Nonpharmacologic interventions to address joint pain include heat or cold compresses, physical therapy, and strength and resistance training to improve the strength of muscles supporting the joints. If these measures are ineffective, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including ibuprofen, naproxen, meloxicam, diclofenac, or celecoxib may be used with regular follow-up to assess cardiovascular and gastrointestinal health. Topical NSAIDs also may be useful. For more intractable joint pain, options include injecting a corticosteroid or sodium hyaluronate into the affected joints or joint replacement.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 32-year-old woman presents with knee pain on walking and elbow pain. She is 5 ft 6 in tall and weighs 187 lb (BMI 30.2). She was diagnosed with schizophrenia 2 years ago and began treatment with olanzapine at diagnosis; her symptoms currently are controlled, and she has tolerated the medication well.

The patient says that she has been overweight since her teenage years and weighed 170 lb (BMI ~27) at age 30. However, she remained physically active until development of painful joints over the past 18 months. She works remotely full time and lives alone. She describes her long-standing diet as heavy on meat protein and light on vegetables and snacks and says it hasn't changed; she denies binge eating or other disordered eating.

Physical exam reveals tender joints at knees and elbows and central obesity (waist circumference, 42 in). Blood pressure is 135/90 mm Hg. Lab results indicate a fasting glucose level of 115 mg/dL and a triglyceride level of 170 mg/dL. She is negative for rheumatoid factor. Radiography shows premature joint erosion at the knees and elbows.

Throbbing headache and nausea

Migraine is a form of recurrent headache that can present as migraine with aura or migraine without aura, with the latter being the most common form. As in this patient, migraine without aura is a chronic form of headache of moderate to severe intensity that usually lasts for several hours but rarely may persist for up to 3 days. Headache pain is unilateral and often aggravated by triggers such as routine physical activity. The American Headache Society diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura include having symptoms of nausea and/or hypersensitivity to light or sound. This patient also described symptoms typical of the prodromal phase of migraine, which include yawning, temperature control, excessive thirst, and mood swings.

Patients who have migraine with aura also have unilateral headache pain of several hours' duration but experience visual (eg, dots or flashes) or sensory (prickly sensation on skin) symptoms, or may have brief difficulty with speech or motor function. These aura symptoms generally last 5 to 60 minutes before abating.

The worldwide impact of migraine potentially reaches a billion individuals. Its prevalence is second only to tension-type headaches. Migraine occurs in patients of all ages and affects women at a rate two to three times higher than in men. Prevalence appears to peak in the third and fourth decades of life and tends to be lower among older adults. Migraine also has a negative effect on patients' work, school, or social lives, and is associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety in adults. For patients who are prone to migraines, potential triggers include some foods and beverages (including those that contain caffeine and alcohol), menstrual cycles in women, exposure to strobing or bright lights or loud sounds, stressful situations, extra physical activity, and too much or too little sleep.

Migraine is a clinical diagnosis based on number of headaches (five or more episodes) plus two or more of the characteristic signs (unilateral, throbbing pain, pain intensity of ≥ 5 on a 10-point scale, and pain aggravated by routine physical motion, such as climbing stairs or bending over) plus nausea and/or photosensitivity or phonosensitivity. Prodrome symptoms are reported by about 70% of adult patients. Diagnosis rarely requires neuroimaging; however, before prescribing medication, a complete lab and metabolic workup should be done.

Management of migraine without aura includes acute and preventive interventions. Acute interventions cited by the American Headache Society include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen for mild pain, and migraine-specific therapies such as the triptans, ergotamine derivatives, gepants (rimegepant, ubrogepant), and lasmiditan. Because response to any of these therapies will differ among patients with migraine, shared decision-making with patients about benefits and potential side effects is necessary and should include flexibility to change therapy if needed.

Preventive therapy should be offered to patients experiencing six or more migraines a month (regardless of impairment) and those, like this patient, with three or more migraines a month that significantly impair daily activities. Preventive therapy can be considered for those with fewer monthly episodes, depending on the degree of impairment. Oral preventive therapies with established efficacy include candesartan, certain beta-blockers, topiramate, and valproate. Parenteral monoclonal antibodies that inhibit calcitonin gene-related peptide activity (eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab) and onabotulinumtoxinA may be considered if oral therapies provide inadequate prevention.

Tension-type headache is the most common form of primary headache. These headaches are bilateral and characterized by a pressing or dull sensation that is often mild in intensity. They are different from migraine in that they occur infrequently, lack sensory symptoms, and generally are of shorter duration (30 minutes to 24 hours). Fasting-related headache is characterized by diffuse, nonpulsating pain and is relieved with food.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Migraine is a form of recurrent headache that can present as migraine with aura or migraine without aura, with the latter being the most common form. As in this patient, migraine without aura is a chronic form of headache of moderate to severe intensity that usually lasts for several hours but rarely may persist for up to 3 days. Headache pain is unilateral and often aggravated by triggers such as routine physical activity. The American Headache Society diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura include having symptoms of nausea and/or hypersensitivity to light or sound. This patient also described symptoms typical of the prodromal phase of migraine, which include yawning, temperature control, excessive thirst, and mood swings.

Patients who have migraine with aura also have unilateral headache pain of several hours' duration but experience visual (eg, dots or flashes) or sensory (prickly sensation on skin) symptoms, or may have brief difficulty with speech or motor function. These aura symptoms generally last 5 to 60 minutes before abating.

The worldwide impact of migraine potentially reaches a billion individuals. Its prevalence is second only to tension-type headaches. Migraine occurs in patients of all ages and affects women at a rate two to three times higher than in men. Prevalence appears to peak in the third and fourth decades of life and tends to be lower among older adults. Migraine also has a negative effect on patients' work, school, or social lives, and is associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety in adults. For patients who are prone to migraines, potential triggers include some foods and beverages (including those that contain caffeine and alcohol), menstrual cycles in women, exposure to strobing or bright lights or loud sounds, stressful situations, extra physical activity, and too much or too little sleep.

Migraine is a clinical diagnosis based on number of headaches (five or more episodes) plus two or more of the characteristic signs (unilateral, throbbing pain, pain intensity of ≥ 5 on a 10-point scale, and pain aggravated by routine physical motion, such as climbing stairs or bending over) plus nausea and/or photosensitivity or phonosensitivity. Prodrome symptoms are reported by about 70% of adult patients. Diagnosis rarely requires neuroimaging; however, before prescribing medication, a complete lab and metabolic workup should be done.

Management of migraine without aura includes acute and preventive interventions. Acute interventions cited by the American Headache Society include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen for mild pain, and migraine-specific therapies such as the triptans, ergotamine derivatives, gepants (rimegepant, ubrogepant), and lasmiditan. Because response to any of these therapies will differ among patients with migraine, shared decision-making with patients about benefits and potential side effects is necessary and should include flexibility to change therapy if needed.

Preventive therapy should be offered to patients experiencing six or more migraines a month (regardless of impairment) and those, like this patient, with three or more migraines a month that significantly impair daily activities. Preventive therapy can be considered for those with fewer monthly episodes, depending on the degree of impairment. Oral preventive therapies with established efficacy include candesartan, certain beta-blockers, topiramate, and valproate. Parenteral monoclonal antibodies that inhibit calcitonin gene-related peptide activity (eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab) and onabotulinumtoxinA may be considered if oral therapies provide inadequate prevention.

Tension-type headache is the most common form of primary headache. These headaches are bilateral and characterized by a pressing or dull sensation that is often mild in intensity. They are different from migraine in that they occur infrequently, lack sensory symptoms, and generally are of shorter duration (30 minutes to 24 hours). Fasting-related headache is characterized by diffuse, nonpulsating pain and is relieved with food.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Migraine is a form of recurrent headache that can present as migraine with aura or migraine without aura, with the latter being the most common form. As in this patient, migraine without aura is a chronic form of headache of moderate to severe intensity that usually lasts for several hours but rarely may persist for up to 3 days. Headache pain is unilateral and often aggravated by triggers such as routine physical activity. The American Headache Society diagnostic criteria for migraine without aura include having symptoms of nausea and/or hypersensitivity to light or sound. This patient also described symptoms typical of the prodromal phase of migraine, which include yawning, temperature control, excessive thirst, and mood swings.

Patients who have migraine with aura also have unilateral headache pain of several hours' duration but experience visual (eg, dots or flashes) or sensory (prickly sensation on skin) symptoms, or may have brief difficulty with speech or motor function. These aura symptoms generally last 5 to 60 minutes before abating.

The worldwide impact of migraine potentially reaches a billion individuals. Its prevalence is second only to tension-type headaches. Migraine occurs in patients of all ages and affects women at a rate two to three times higher than in men. Prevalence appears to peak in the third and fourth decades of life and tends to be lower among older adults. Migraine also has a negative effect on patients' work, school, or social lives, and is associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety in adults. For patients who are prone to migraines, potential triggers include some foods and beverages (including those that contain caffeine and alcohol), menstrual cycles in women, exposure to strobing or bright lights or loud sounds, stressful situations, extra physical activity, and too much or too little sleep.

Migraine is a clinical diagnosis based on number of headaches (five or more episodes) plus two or more of the characteristic signs (unilateral, throbbing pain, pain intensity of ≥ 5 on a 10-point scale, and pain aggravated by routine physical motion, such as climbing stairs or bending over) plus nausea and/or photosensitivity or phonosensitivity. Prodrome symptoms are reported by about 70% of adult patients. Diagnosis rarely requires neuroimaging; however, before prescribing medication, a complete lab and metabolic workup should be done.

Management of migraine without aura includes acute and preventive interventions. Acute interventions cited by the American Headache Society include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and acetaminophen for mild pain, and migraine-specific therapies such as the triptans, ergotamine derivatives, gepants (rimegepant, ubrogepant), and lasmiditan. Because response to any of these therapies will differ among patients with migraine, shared decision-making with patients about benefits and potential side effects is necessary and should include flexibility to change therapy if needed.

Preventive therapy should be offered to patients experiencing six or more migraines a month (regardless of impairment) and those, like this patient, with three or more migraines a month that significantly impair daily activities. Preventive therapy can be considered for those with fewer monthly episodes, depending on the degree of impairment. Oral preventive therapies with established efficacy include candesartan, certain beta-blockers, topiramate, and valproate. Parenteral monoclonal antibodies that inhibit calcitonin gene-related peptide activity (eptinezumab, erenumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab) and onabotulinumtoxinA may be considered if oral therapies provide inadequate prevention.

Tension-type headache is the most common form of primary headache. These headaches are bilateral and characterized by a pressing or dull sensation that is often mild in intensity. They are different from migraine in that they occur infrequently, lack sensory symptoms, and generally are of shorter duration (30 minutes to 24 hours). Fasting-related headache is characterized by diffuse, nonpulsating pain and is relieved with food.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 30-year-old female patient (140 lb and 5 ft 7 in; BMI 21.9) presents at the emergency department with a throbbing headache that began after dinner and was accompanied by queasy nausea. She reports immediately going to bed and sleeping through the night, but pain and other symptoms were still present in the morning. At this point, headache duration is approaching 15 hours. The patient describes the headache pain as throbbing and intense on the left side of her head.

The patient has a demanding job in advertising and often works very long hours on little sleep; this latest headache developed after working through the night before. When asked, she admits to feeling lethargic, yawning (to the point where coworkers commented), and experiencing intervals of excessive sweating earlier in the day before the headache emerged. The patient attributed these to being tired and hungry because of skipped meals since the previous night's dinner.

She has no history of cardiovascular or other chronic illness, and her blood pressure is within normal range. She describes having had about seven similar headaches of shorter duration, over the past 2 months; in each case, the headache led to a missed workday or having to leave work early and/or cancel social plans.

Dyspnea and mild edema

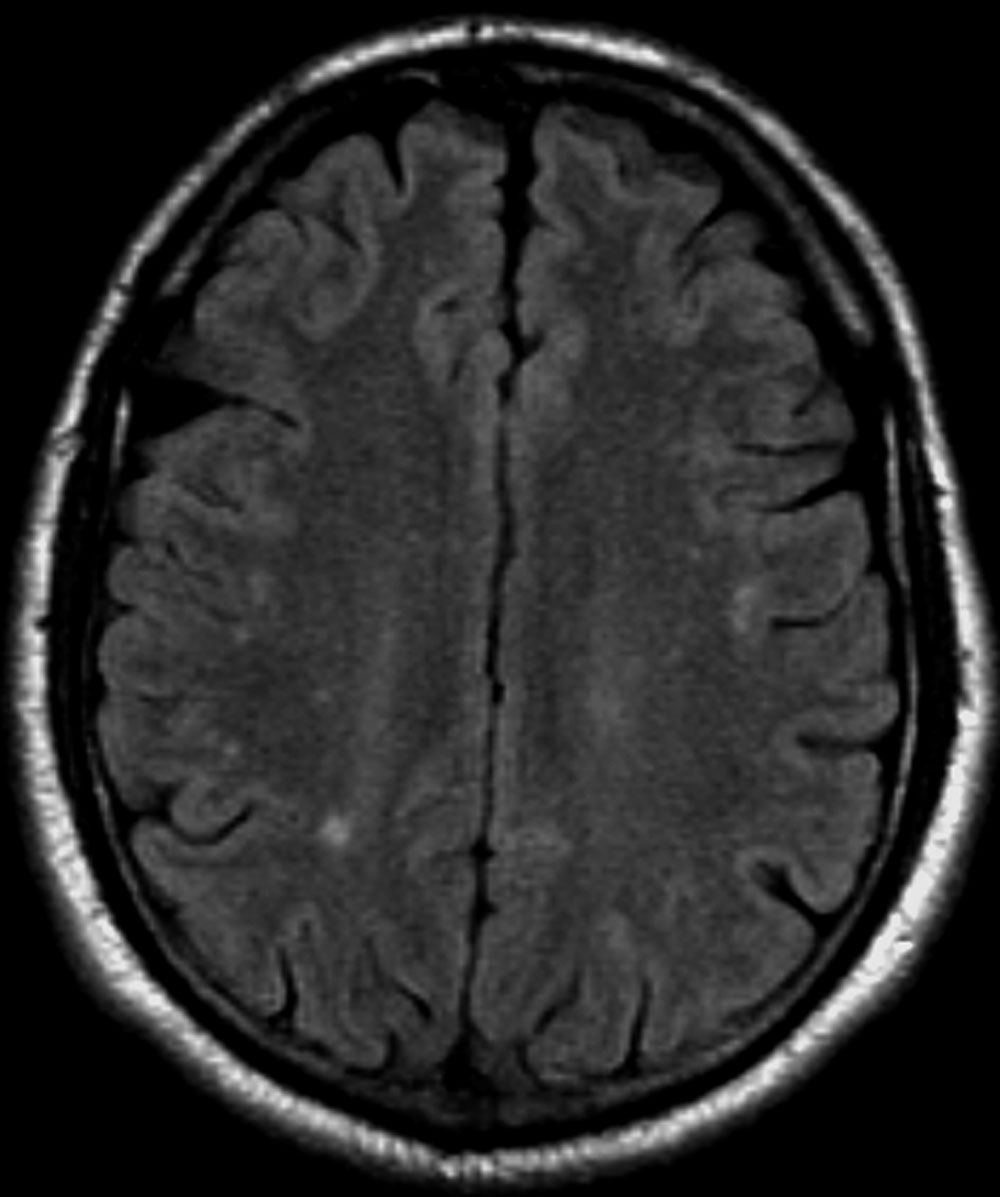

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

As seen in red on the radiogram, the patient's heart is grossly enlarged, indicating cardiomegaly. Cardiomegaly often is first diagnosed on chest imaging, with diagnosis based on a cardiothoracic ratio of < 0.5. It is not a disease but rather a manifestation of an underlying cause. Patients may have few or no cardiomegaly-related symptoms or have symptoms typical of cardiac dysfunction, like this patient's dyspnea and edema. Conditions that impair normal circulation and that are associated with cardiomegaly development include hypertension, obesity, heart valve disorders, thyroid dysfunction, and anemia. In this patient, cardiomegaly probably has been triggered by uncontrolled hypertension and ongoing obesity. This patient's bloodwork also indicates prediabetes and incipient type 2 diabetes (T2D) (the diagnostic criteria for which are A1c ≥ 6.5% and fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL).

As many as 42% of adults in the United States meet criteria for obesity and are at risk for obesity-related conditions, including cardiomegaly. Guidelines for management of patients with obesity have been published by The Obesity Society and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and management of obesity is a necessary part of comprehensive care of patients with T2D as well. For most patients, a BMI ≥ 30 diagnoses obesity; this patient has class 1 obesity, based on a BMI of 30 to 34.9. The patient also has complications of obesity, including stage 2 hypertension and prediabetes. As such, lifestyle management plus medical therapy is the recommended approach to weight loss, with a goal of losing 5% to 10% or more of baseline body weight.

The Obesity Society states that all patients with obesity should be offered effective, evidence-based interventions. Medical management of obesity includes use of pharmacologic interventions with proven benefit in weight loss, such as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs; eg, semaglutide) or dual gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP)/GLP-1 RAs (eg, tirzepatide). Semaglutide and tirzepatide are likely to have cardiovascular benefits for patients with obesity as well. Other medications approved for management of obesity include liraglutide, orlistat, phentermine HCl (with or without topiramate), and naltrexone plus bupropion. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations for management of obesity in patients with T2D give preference to semaglutide 2.4 mg/wk and tirzepatide at weekly doses of 5, 10, or 15 mg, depending on patient factors.

As important for this patient is to get control of hypertension. Studies have shown that lowering blood pressure improves left ventricular hypertrophy, a common source of cardiomegaly. Hypertension guidelines from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association recommend a blood pressure goal < 130/80 mm Hg for most adults, which is consistent with the current recommendation from the ADA. Management of hypertension should first incorporate a low-sodium, healthy diet (such as the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension [DASH] diet), physical activity, and weight loss; however, many patients (especially with stage 2 hypertension) require pharmacologic therapy as well. Single-pill combination therapies of drugs from different classes (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor plus calcium channel blocker) are preferred for patients with stage 2 hypertension to improve efficacy and enhance adherence.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolic Disorders, Eastern Virginia Medical School; EVMS Medical Group, Norfolk, Virginia.

Romesh K. Khardori, MD, PhD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 55-year-old patient with obesity presents with dyspnea and mild edema. The patient is 5 ft 9 in, weighs 210 lb (BMI 31), and received an obesity diagnosis 1 year ago with a weight of 220 lb (BMI 32.5) but notes having lived with a BMI ≥ 30 for at least 5 years. Since being diagnosed with obesity, the patient has participated in regular counseling with a clinical nutrition specialist and exercise therapy, reports satisfaction with these, and is happy to have lost 10 lb. The patient presents today for follow-up physical exam and lab workup, with a complaint of increasing dyspnea that has limited participation in exercise therapy over the past 2 months.

On physical exam, the patient appears pale, with shortness of breath and mild edema in the ankles. The heart rhythm is fluttery and the heart rate is elevated at 90 beats/min. Blood pressure is 150/90 mm Hg. Lab results show A1c 6.6% and fasting glucose of 115 mg/dL. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol is 101 mg/dL. Thyroid and hematologic findings are within normal parameters. The patient is sent for chest radiography, shown above (colorized).

Sudden onset of symptoms

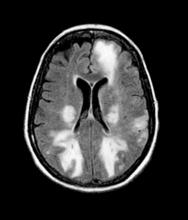

Migraines are episodic or chronic headaches, typically occurring on one side of the head, that have distinct characteristics and definitions from the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD 3). Migraine can occur at any age and is thought to affect about 5% of children before puberty, increases in prevalence after puberty, and reaches about 30% prevalence at age 25-30 years. Patients with migraine with aura have recurrent, fully reversible symptoms that can include diplopia, motor or sensory disturbances, and/or trouble with language that generally precede headache development. In some cases, aura may develop and resolve without headache. Migraine with aura can present at any age from early childhood onward and is present in about 30% of children and adolescents with migraine. In general, migraine with aura is more prevalent in female than in male individuals, especially adolescents.

Migraine with brainstem aura, as is the case here, is a specific subtype of migraine with aura, in which the aura specifically reflects an origin within the brainstem. Brainstem symptoms include diplopia, vertigo, difficulty controlling speech muscles, tinnitus, hearing loss, loss of coordination, and possibly impaired consciousness. For the diagnosis of migraine with brainstem aura, patients must not have motor or retinal symptoms. Aura development often is preceded by premonitory symptoms, such as fatigue, hunger or food cravings, and mood elevations.

Migraine without aura, in contrast, is characterized by recurrent moderate to severe pulsating headache lasting from a few hours to up to 3 days. Migraine without aura often causes nausea and sensitivity to light and/or sound.

Chronic migraine is defined as headache (with or without aura) occurring 15 or more days per month for at least the past 3 months. This patient's history does not fit the definition of chronic migraine.

Tension-type headaches generally are bilateral, with durations ranging from minutes to days. They tend to be mild to moderate in intensity and symptoms are not worsened by physical activity. In addition to their bilateral nature, these headaches differ from migraine in lacking associated visual, cortical, or other symptoms.

Any diagnosis of migraine requires assessment over time, using diagnostic criteria established by the International Headache Society in ICHD 3. It is not necessary to perform neuroimaging studies or CT in patients with migraine symptoms and an otherwise normal neurologic exam.

When a diagnosis of migraine with brainstem aura is established, pediatric or adolescent patients and their families should first be counseled on nonpharmacologic interventions. These interventions, which have demonstrated benefits in reducing headache frequency, include lifestyle modifications, regular sleep and meal schedules, adequate fluid intake, cognitive-behavioral therapy, stress management techniques, massage, and biofeedback techniques. Recommended for acute treatment of migraine are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and triptans. There is limited evidence in pediatric or adolescent patients with use of preventive medications, such as topiramate, amitriptyline, or onabotulinumtoxinA. In clinical trials, patients receiving placebo saw improvements, and active treatments were only marginally, if at all, more effective. Current guidelines recommend a frank discussion with parents about the limitations of preventive therapies before making decisions to use them.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Migraines are episodic or chronic headaches, typically occurring on one side of the head, that have distinct characteristics and definitions from the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD 3). Migraine can occur at any age and is thought to affect about 5% of children before puberty, increases in prevalence after puberty, and reaches about 30% prevalence at age 25-30 years. Patients with migraine with aura have recurrent, fully reversible symptoms that can include diplopia, motor or sensory disturbances, and/or trouble with language that generally precede headache development. In some cases, aura may develop and resolve without headache. Migraine with aura can present at any age from early childhood onward and is present in about 30% of children and adolescents with migraine. In general, migraine with aura is more prevalent in female than in male individuals, especially adolescents.

Migraine with brainstem aura, as is the case here, is a specific subtype of migraine with aura, in which the aura specifically reflects an origin within the brainstem. Brainstem symptoms include diplopia, vertigo, difficulty controlling speech muscles, tinnitus, hearing loss, loss of coordination, and possibly impaired consciousness. For the diagnosis of migraine with brainstem aura, patients must not have motor or retinal symptoms. Aura development often is preceded by premonitory symptoms, such as fatigue, hunger or food cravings, and mood elevations.

Migraine without aura, in contrast, is characterized by recurrent moderate to severe pulsating headache lasting from a few hours to up to 3 days. Migraine without aura often causes nausea and sensitivity to light and/or sound.

Chronic migraine is defined as headache (with or without aura) occurring 15 or more days per month for at least the past 3 months. This patient's history does not fit the definition of chronic migraine.

Tension-type headaches generally are bilateral, with durations ranging from minutes to days. They tend to be mild to moderate in intensity and symptoms are not worsened by physical activity. In addition to their bilateral nature, these headaches differ from migraine in lacking associated visual, cortical, or other symptoms.

Any diagnosis of migraine requires assessment over time, using diagnostic criteria established by the International Headache Society in ICHD 3. It is not necessary to perform neuroimaging studies or CT in patients with migraine symptoms and an otherwise normal neurologic exam.

When a diagnosis of migraine with brainstem aura is established, pediatric or adolescent patients and their families should first be counseled on nonpharmacologic interventions. These interventions, which have demonstrated benefits in reducing headache frequency, include lifestyle modifications, regular sleep and meal schedules, adequate fluid intake, cognitive-behavioral therapy, stress management techniques, massage, and biofeedback techniques. Recommended for acute treatment of migraine are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and triptans. There is limited evidence in pediatric or adolescent patients with use of preventive medications, such as topiramate, amitriptyline, or onabotulinumtoxinA. In clinical trials, patients receiving placebo saw improvements, and active treatments were only marginally, if at all, more effective. Current guidelines recommend a frank discussion with parents about the limitations of preventive therapies before making decisions to use them.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Migraines are episodic or chronic headaches, typically occurring on one side of the head, that have distinct characteristics and definitions from the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD 3). Migraine can occur at any age and is thought to affect about 5% of children before puberty, increases in prevalence after puberty, and reaches about 30% prevalence at age 25-30 years. Patients with migraine with aura have recurrent, fully reversible symptoms that can include diplopia, motor or sensory disturbances, and/or trouble with language that generally precede headache development. In some cases, aura may develop and resolve without headache. Migraine with aura can present at any age from early childhood onward and is present in about 30% of children and adolescents with migraine. In general, migraine with aura is more prevalent in female than in male individuals, especially adolescents.

Migraine with brainstem aura, as is the case here, is a specific subtype of migraine with aura, in which the aura specifically reflects an origin within the brainstem. Brainstem symptoms include diplopia, vertigo, difficulty controlling speech muscles, tinnitus, hearing loss, loss of coordination, and possibly impaired consciousness. For the diagnosis of migraine with brainstem aura, patients must not have motor or retinal symptoms. Aura development often is preceded by premonitory symptoms, such as fatigue, hunger or food cravings, and mood elevations.

Migraine without aura, in contrast, is characterized by recurrent moderate to severe pulsating headache lasting from a few hours to up to 3 days. Migraine without aura often causes nausea and sensitivity to light and/or sound.

Chronic migraine is defined as headache (with or without aura) occurring 15 or more days per month for at least the past 3 months. This patient's history does not fit the definition of chronic migraine.

Tension-type headaches generally are bilateral, with durations ranging from minutes to days. They tend to be mild to moderate in intensity and symptoms are not worsened by physical activity. In addition to their bilateral nature, these headaches differ from migraine in lacking associated visual, cortical, or other symptoms.

Any diagnosis of migraine requires assessment over time, using diagnostic criteria established by the International Headache Society in ICHD 3. It is not necessary to perform neuroimaging studies or CT in patients with migraine symptoms and an otherwise normal neurologic exam.

When a diagnosis of migraine with brainstem aura is established, pediatric or adolescent patients and their families should first be counseled on nonpharmacologic interventions. These interventions, which have demonstrated benefits in reducing headache frequency, include lifestyle modifications, regular sleep and meal schedules, adequate fluid intake, cognitive-behavioral therapy, stress management techniques, massage, and biofeedback techniques. Recommended for acute treatment of migraine are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen, and triptans. There is limited evidence in pediatric or adolescent patients with use of preventive medications, such as topiramate, amitriptyline, or onabotulinumtoxinA. In clinical trials, patients receiving placebo saw improvements, and active treatments were only marginally, if at all, more effective. Current guidelines recommend a frank discussion with parents about the limitations of preventive therapies before making decisions to use them.

Heidi Moawad, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medical Education, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, Ohio.

Heidi Moawad, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 13-year-old girl presents with symptoms of sudden onset of double vision, vertigo, and ataxia that have occurred six or seven times over the past 2 months and usually precede a headache. These symptoms generally last less than 10 minutes. The girl says she has noticed that she often feels a bit manic and has food cravings a few hours before the double vision and other symptoms occur. She is an athlete at school but says during these attacks she avoids even walking around the house because the movement makes her symptoms worse. She has no muscle weakness or changes on her ophthalmologic exam.

No obvious issues on physical exam nor evidence of visual or neurologic deficits are present at the time of the office visit; the patient has 20/20 vision. Relevant medical history includes menarche at age 12 years. The patient is on the track team at school and is physically fit, without previous evidence of balance or other neurologic issues.

Lump in breast

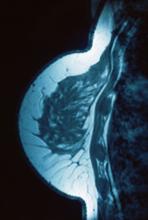

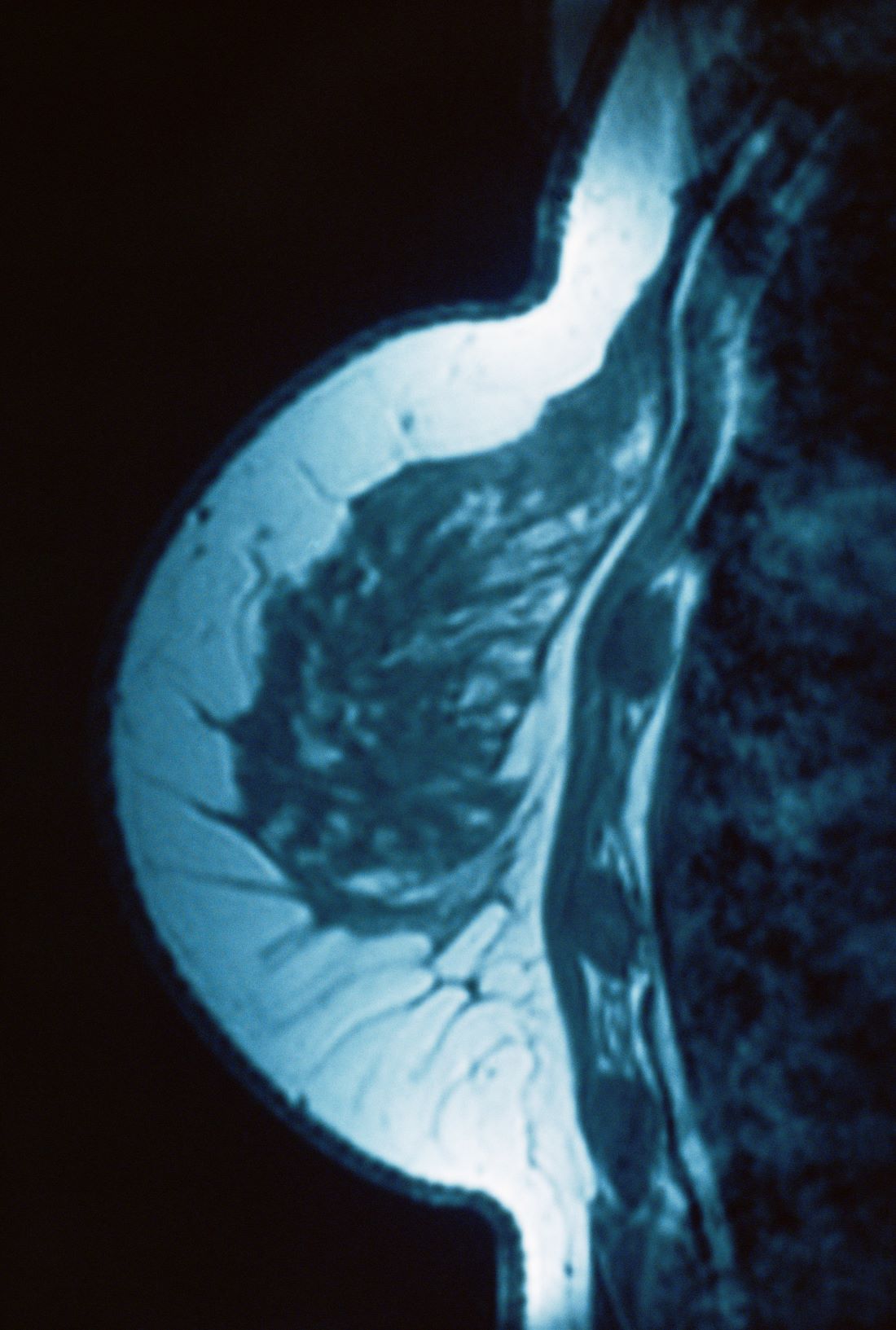

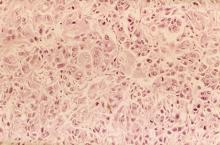

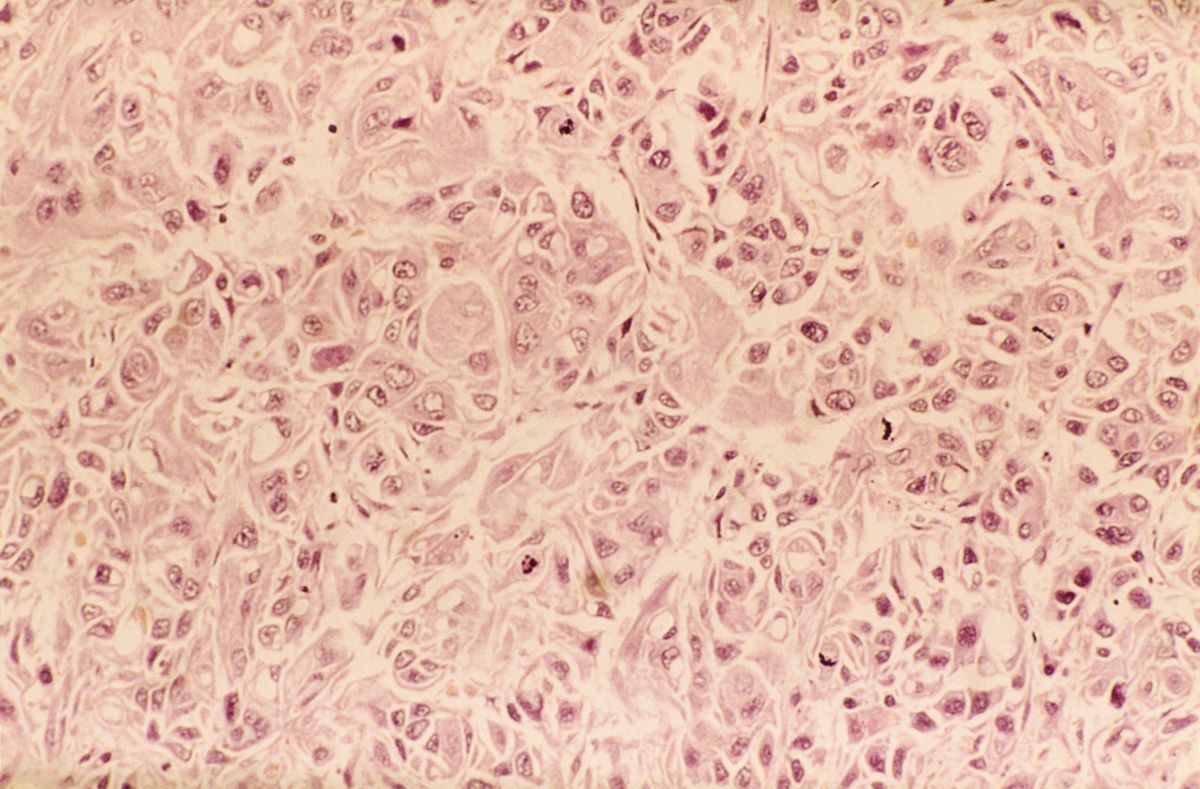

Given clinical and imaging outcomes, as well as results on IHC assay, this patient is diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer and is referred for further consultation with a multidisciplinary care team.

Triple-negative breast cancer accounts for 15% of all female breast cancer cases. The term "triple-negative" refers to the absence of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) targets and the HER2 target for treatment. Otherwise, triple-negative breast cancer is highly heterogeneous and includes multiple molecular subtypes. Typically, triple-negative breast cancer occurs in younger patients, has a higher grade, a greater tumor size, a higher clinical stage at diagnosis, and a poorer prognosis than non–triple-negative breast cancers.

Biopsy samples from patients with a new primary or newly metastatic breast cancer diagnosis should undergo HR testing, both ER and PR, as well as HER2 receptor testing. Results of ER and PR testing are negative if a validated IHC assay shows 0% to < 1% of nuclei stain, according to the latest American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) HR testing guideline. HER2 results are negative if a validated IHC assay shows weak to moderate complete membrane staining in < 10% of tumor cells, according to ASCO/CAP guidelines. If HER2 results of a primary tumor are negative and specific clinical criteria suggest further testing, the oncologist may choose to order another IHC assay or a validated dual probe in situ hybridization (ISH) assay to aid in clinical decision-making.

Pathologic classification of triple-negative breast cancers includes multiple subgroups determined by therapeutic possibilities: low-risk histologic types (salivary gland–like carcinomas, fibromatosis-like carcinoma, low-grade adenosquamous breast carcinoma), immune activation (tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, CD8, programmed death–ligand 1, tumor mutational burden), HER2-low status (IHC score 1+/2+ nonamplified), associated germline BRCA mutations, and other targets (trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2, HER3).

Family history is the most common risk factor for developing breast cancer. If a person's mother or sister had breast cancer, the lifetime risk for that individual is four times greater than that of the general population. Risk for breast cancer grows even more if two or more first-degree relatives are diagnosed, or if one first-degree relative was diagnosed with breast cancer at ≤ 50 years of age. About 25% of triple-negative breast cancer cases have accompanying germline BRCA mutations. A recent study by Ahearn and colleagues found that 85 variants were linked to one or more tumor feature of ER-negative disease, and 32 of those variants were associated with triple-negative disease.

For a breast cancer diagnosis, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends multidisciplinary care as well as the development of a personalized survivorship treatment plan, which includes a customized summary of possible long-term treatment toxicities. In addition, multidisciplinary care coordination encourages close follow-up that helps patients adhere to their medications and stay current with ongoing screening.

Because triple-negative breast cancer lacks HR and HER2 therapeutic targets, it can be difficult to treat. Standard therapy for high-risk triple-negative tumors includes chemotherapy with taxanes (paclitaxel or docetaxel) plus anthracycline-based treatment (cyclophosphamide plus doxorubicin). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for patients with stage 2 and 3 tumors to reduce locoregional surgical extension and to allow for personalized treatment based on pathologic response. In 2018, two poly ADP ribose polymerase inhibitors, olaparib and talazoparib, were approved for use in select patients with triple-negative breast cancer, significantly changing the treatment paradigm for this disease. Other promising treatments have emerged recently in clinical trials for triple-negative disease, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, PI3K/AKT pathway inhibitors, and cytotoxin-conjugated antibodies.

Daniel S. Schwartz, MD, is Medical Director of Thoracic Oncology, St. Catherine of Siena Medical Center, Catholic Health Services, Smithtown, New York.

Dr. Schwartz serve(d) as a member of the following medical societies:

American College of Chest Physicians, American College of Surgeons, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Disclosure: Daniel S. Schwartz, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given clinical and imaging outcomes, as well as results on IHC assay, this patient is diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer and is referred for further consultation with a multidisciplinary care team.

Triple-negative breast cancer accounts for 15% of all female breast cancer cases. The term "triple-negative" refers to the absence of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) targets and the HER2 target for treatment. Otherwise, triple-negative breast cancer is highly heterogeneous and includes multiple molecular subtypes. Typically, triple-negative breast cancer occurs in younger patients, has a higher grade, a greater tumor size, a higher clinical stage at diagnosis, and a poorer prognosis than non–triple-negative breast cancers.

Biopsy samples from patients with a new primary or newly metastatic breast cancer diagnosis should undergo HR testing, both ER and PR, as well as HER2 receptor testing. Results of ER and PR testing are negative if a validated IHC assay shows 0% to < 1% of nuclei stain, according to the latest American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) HR testing guideline. HER2 results are negative if a validated IHC assay shows weak to moderate complete membrane staining in < 10% of tumor cells, according to ASCO/CAP guidelines. If HER2 results of a primary tumor are negative and specific clinical criteria suggest further testing, the oncologist may choose to order another IHC assay or a validated dual probe in situ hybridization (ISH) assay to aid in clinical decision-making.

Pathologic classification of triple-negative breast cancers includes multiple subgroups determined by therapeutic possibilities: low-risk histologic types (salivary gland–like carcinomas, fibromatosis-like carcinoma, low-grade adenosquamous breast carcinoma), immune activation (tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, CD8, programmed death–ligand 1, tumor mutational burden), HER2-low status (IHC score 1+/2+ nonamplified), associated germline BRCA mutations, and other targets (trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2, HER3).

Family history is the most common risk factor for developing breast cancer. If a person's mother or sister had breast cancer, the lifetime risk for that individual is four times greater than that of the general population. Risk for breast cancer grows even more if two or more first-degree relatives are diagnosed, or if one first-degree relative was diagnosed with breast cancer at ≤ 50 years of age. About 25% of triple-negative breast cancer cases have accompanying germline BRCA mutations. A recent study by Ahearn and colleagues found that 85 variants were linked to one or more tumor feature of ER-negative disease, and 32 of those variants were associated with triple-negative disease.

For a breast cancer diagnosis, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends multidisciplinary care as well as the development of a personalized survivorship treatment plan, which includes a customized summary of possible long-term treatment toxicities. In addition, multidisciplinary care coordination encourages close follow-up that helps patients adhere to their medications and stay current with ongoing screening.

Because triple-negative breast cancer lacks HR and HER2 therapeutic targets, it can be difficult to treat. Standard therapy for high-risk triple-negative tumors includes chemotherapy with taxanes (paclitaxel or docetaxel) plus anthracycline-based treatment (cyclophosphamide plus doxorubicin). Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for patients with stage 2 and 3 tumors to reduce locoregional surgical extension and to allow for personalized treatment based on pathologic response. In 2018, two poly ADP ribose polymerase inhibitors, olaparib and talazoparib, were approved for use in select patients with triple-negative breast cancer, significantly changing the treatment paradigm for this disease. Other promising treatments have emerged recently in clinical trials for triple-negative disease, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, PI3K/AKT pathway inhibitors, and cytotoxin-conjugated antibodies.

Daniel S. Schwartz, MD, is Medical Director of Thoracic Oncology, St. Catherine of Siena Medical Center, Catholic Health Services, Smithtown, New York.

Dr. Schwartz serve(d) as a member of the following medical societies:

American College of Chest Physicians, American College of Surgeons, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Disclosure: Daniel S. Schwartz, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given clinical and imaging outcomes, as well as results on IHC assay, this patient is diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer and is referred for further consultation with a multidisciplinary care team.

Triple-negative breast cancer accounts for 15% of all female breast cancer cases. The term "triple-negative" refers to the absence of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) targets and the HER2 target for treatment. Otherwise, triple-negative breast cancer is highly heterogeneous and includes multiple molecular subtypes. Typically, triple-negative breast cancer occurs in younger patients, has a higher grade, a greater tumor size, a higher clinical stage at diagnosis, and a poorer prognosis than non–triple-negative breast cancers.

Biopsy samples from patients with a new primary or newly metastatic breast cancer diagnosis should undergo HR testing, both ER and PR, as well as HER2 receptor testing. Results of ER and PR testing are negative if a validated IHC assay shows 0% to < 1% of nuclei stain, according to the latest American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) HR testing guideline. HER2 results are negative if a validated IHC assay shows weak to moderate complete membrane staining in < 10% of tumor cells, according to ASCO/CAP guidelines. If HER2 results of a primary tumor are negative and specific clinical criteria suggest further testing, the oncologist may choose to order another IHC assay or a validated dual probe in situ hybridization (ISH) assay to aid in clinical decision-making.

Pathologic classification of triple-negative breast cancers includes multiple subgroups determined by therapeutic possibilities: low-risk histologic types (salivary gland–like carcinomas, fibromatosis-like carcinoma, low-grade adenosquamous breast carcinoma), immune activation (tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, CD8, programmed death–ligand 1, tumor mutational burden), HER2-low status (IHC score 1+/2+ nonamplified), associated germline BRCA mutations, and other targets (trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2, HER3).

Family history is the most common risk factor for developing breast cancer. If a person's mother or sister had breast cancer, the lifetime risk for that individual is four times greater than that of the general population. Risk for breast cancer grows even more if two or more first-degree relatives are diagnosed, or if one first-degree relative was diagnosed with breast cancer at ≤ 50 years of age. About 25% of triple-negative breast cancer cases have accompanying germline BRCA mutations. A recent study by Ahearn and colleagues found that 85 variants were linked to one or more tumor feature of ER-negative disease, and 32 of those variants were associated with triple-negative disease.

For a breast cancer diagnosis, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends multidisciplinary care as well as the development of a personalized survivorship treatment plan, which includes a customized summary of possible long-term treatment toxicities. In addition, multidisciplinary care coordination encourages close follow-up that helps patients adhere to their medications and stay current with ongoing screening.