User login

Cutaneous Cold Weather Injuries in the US Military

The US Department of Defense maintains a presence in several cold weather environments such as North Dakota, Alaska, and South Korea. Although much is known about preventing and caring for cold weather injuries, many of these ailments continue to occur. Therefore, it is vital that both military and civilian physicians who care for patients who are exposed to cold weather conditions have a thorough understanding of the prevention, clinical presentation, and treatment of cold weather injuries.

Although the focus of this article is on cutaneous cold weather injuries that occur in military service, these types of injuries are not limited to this population. Civilians who live, work, or seek recreation in cold climates also may experience these injuries. Classically, cold injuries are classified as freezing and nonfreezing injuries. For the purpose of this article, we also consider a third category: dermatologic conditions that flare upon cold exposure. Specifically, we discuss frostbite, cold-weather immersion foot, pernio, Raynaud phenomenon (RP), and cold urticaria. We also present a case of pernio in an active-duty military service member.

Frostbite

For centuries, frostbite has been well documented as a cold weather injury in military history.1 Napoleon’s catastrophic invasion of Russia in 1812 started with 612,000 troops and ended with fewer than 10,000 effective soldiers; while many factors contributed to this attrition, exposure to cold weather and frostbite is thought to have been a major factor. The muddy trench warfare of World War I was no kinder to the poorly equipped soldiers across the European theater. Decades later during World War II, frostbite was a serious source of noncombat injuries, as battles were fought in frigid European winters. From 1942 to 1945, there were 13,196 reported cases of frostbite in the European theater, with most of these injuries occurring in 1945.1

Despite advancements in cold weather clothing and increased knowledge about the causes of and preventative measures for frostbite, cold weather injuries continue to be a relevant topic in today’s military. From 2015 to 2020, there were 1120 reported cases of frostbite in the US military.2 When skin is exposed to cold temperatures, the body peripherally vasoconstricts to reduce core heat loss. This autoregulatory vasoconstriction is part of a normal physiologic response that preserves the core body temperature, often at the expense of the extremities; for instance, the hands and feet are equipped with arteriovenous shunts, known as glomus bodies, which consist of vascular smooth muscle centers that control the flow of blood in response to changing external temperatures.3 This is partially mitigated by cold-induced vasodilation of the digits, also known as the Hunting reaction, which generally occurs 5 to 10 minutes after the start of local cold exposure.4 Additionally, discomfort from cold exposure warrants behavioral modifications such as going indoors, putting on warmer clothing, or building a fire. If an individual is unable to seek shelter in the face of cold exposure, the cold will inevitably cause injury.

Frostbite is caused by both direct and indirect cellular injury. Direct injury results from the crystallization of intracellular and interstitial fluids, cellular dehydration, and electrolyte disturbances. Indirect cellular injury is the result of a progressive microvascular insult and is caused by microvascular thrombosis, endothelial damage, intravascular sludging, inflammatory mediators, free radicals, and reperfusion injury.5

Frostnip is a more superficial injury that does not involve freezing of the skin or underlying tissue and typically does not leave any long-term damage. As severity of injury increases, frostbite is characterized by the depth of injury, presence of tissue loss, and radiotracer uptake on bone scan. There are 2 main classification systems for frostbite: one is based on the severity of the injury outcome, categorized by 4 degrees (1–4), and the other is designed as a predictive model, categorized by 4 grades (1–4).6 The first classification system is similar to the system for the severity of burns and ranges from partial-thickness injury (first degree) to full-thickness skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, tendon, and bone (fourth degree). The latter classification system uses the presence and characteristics of blisters after rewarming on days 0 and 2 and radiotracer uptake on bone scan on day 2. Severity ranges from no blistering, no indicated bone scan, and no long-term sequelae in grade 1 to hemorrhagic blisters overlying the carpal or tarsal bones and absence of radiotracer uptake with predicted extensive amputation, risk for thrombosis or sepsis, and long-term functional sequelae in grade 4.6

Male sex and African descent are associated with increased risk for sustaining frostbite. The ethnic predisposition may be explained by a less robust Hunting reaction in individuals of African descent.4,7 Other risk factors include alcohol use, smoking, homelessness, history of cold-related injury, use of beta-blockers, and working with equipment that uses nitrogen dioxide or CO2.5 Additionally, a history of systemic lupus erythematosus has been reported as a risk factor for frostbite.8

Clinically, frostbite initially may appear pale, blue, or erythematous, and patients may report skin numbness. In severe cases, necrosis can be seen.9 The most commonly affected anatomic locations include the fingers, toes, ears, and nose. Prevention is key for frostbite injuries. Steps to avoid injury include wearing appropriate clothing, minimizing the duration of time the skin is exposed to cold temperatures, avoiding alcohol consumption, and avoiding physical exhaustion in cold weather. These steps can help mitigate the effects of wind chill and low temperatures and decrease the risk of frostbite.10

Management of this condition includes prevention, early diagnosis, prehospital management, hospital management, and long-term sequelae management. Leadership and medical personnel for military units assigned to cold climates should be vigilant in looking for symptoms of frostbite. If any one individual is found to have frostbite or any other cold injury, all other team members should be evaluated.5

After identification of frostbite, seeking shelter and evacuation to a treatment facility are vital next steps. Constrictive clothing or jewelry should be removed. Depending on the situation, rewarming can be attempted in the prehospital setting, but it is imperative to avoid refreezing, as this may further damage the affected tissue due to intracellular ice formation with extensive cell destruction.6 Gentle warming can be attempted by placing the affected extremity in another person’s armpit or groin for up to 10 minutes or by immersing the affected limb in water that is 37° C to 39° C (98.6° F to 102.2° F). Rubbing the affected area and dry heat should be avoided. It should be noted that the decision to thaw in the field introduces the challenge of dealing with the severe pain associated with thawing in a remote or hostile environment. Ibuprofen (400 mg) can be given as an anti-inflammatory and analgesic agent in the prehospital setting.5 Once safely evacuated to the hospital, treatment options expand dramatically, including warming without concern of refreezing, wound care, thrombolytic therapy, and surgical intervention. If local frostbite expertise is not available, there are telemedicine services available.5,6

Frostbite outcomes range from complete recovery to amputation. Previously frostbitten tissue has increased cold sensitivity and is more susceptible to similar injury in the future. Additionally, there can be functional loss, chronic pain, chronic ulceration, and arthritis.5,6 As such, a history of frostbite can be disqualifying for military service and requires a medical waiver.11 If a service member experiences frostbite and does not have any residual effects, they can expect to continue their military service, but if there are sequelae, it may prove to be career limiting.12-14

Immersion Foot

Although frostbite represents a freezing injury, immersion foot (or trench foot) represents a nonfreezing cold injury. It should be noted that in addition to immersion foot associated with cold water exposure, there also are warm-water and tropical variants. For the purpose of this article, we are referring to immersion foot associated with exposure to cold water. Trench foot was described for the first time during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 but came to prominence during World War I, where it is thought to have contributed to the deaths of 75,000 British soldiers. During World War II, there were 25,016 cases of immersion foot reported in the US military.1 More recently, 590 cases of immersion foot were reported in the US military from 2015 to 2020.2

Classically, this condition was seen in individuals whose feet were immersed in cold but not freezing water or mud in trenches or on boats, hence the terms immersion foot and trench foot. The pathogenesis is thought to be related to overhydration of the stratum corneum and repetitive cycles of cold-induced, thermoprotective vasoconstriction, leading to cyclical hypoxic and reperfusion injuries, which eventually damage nerves, muscle, subcutaneous fat, and blood vessels.9,15

A recent case series of 100 military service members in the United Kingdom showed that cold-induced extremity numbness for more than 30 minutes and painful rewarming after cold exposure were highly correlated with the development of immersion foot. Additionally, this case series showed that patients with repeated cycles of cooling and rewarming were more likely to have long-term symptoms.16 As with frostbite, prior cold injury and African descent increases the risk for developing immersion foot, possibly due to a less-pronounced Hunting reaction.4,7

Early reports suggested prehyperemic, hyperemic, and posthyperemic stages. The prehyperemic stage lasts from hours to days and is characterized by cold extremities, discoloration, edema, stocking- or glove-distributed anesthesia, blisters, necrosis, and potential loss of palpable pulses.17 Of note, in Kuht et al’s16 more recent case series, edema was not seen as frequently as in prior reports. The hyperemic stage can last for 6 to 10 weeks and is characterized by vascular disturbances. In addition, the affected extremity typically remains warm and red even when exposed to cold temperatures. Sensory disturbances such as paresthesia and hyperalgesia may be seen, as well as motor disturbances, anhidrosis, blisters, ulcers, and gangrene. The posthyperemic stage can last from months to years and is characterized by cold sensitivity, possible digital blanching, edema, hyperhidrosis, and persistent peripheral neuropathy.16

Prevention is the most important treatment for immersion foot. The first step in preventing this injury is avoiding prolonged cold exposure. When this is not possible due to the demands of training or actual combat conditions, regular hand and foot inspections, frequent sock changes, and regularly rotating out of cold wet conditions can help prevent this injury.15 Vasodilators also have been considered as a possible treatment modality. Iloprost and nicotinyl alcohol tartrate showed some improvement, while aminophylline and papaverine were ineffective.15

As with frostbite, a history of immersion foot may be disqualifying for military service.11 If it occurs during military service and there are no residual effects that limit the service member’s capabilities, they may expect to continue their career; however, if there are residual effects that limit activity or deployment, medical retirement may be indicated.

Pernio

Pernio is another important condition that is related to cold exposure; however, unlike the previous 2 conditions, it is not necessarily caused by cold exposure but rather flares with cold exposure.

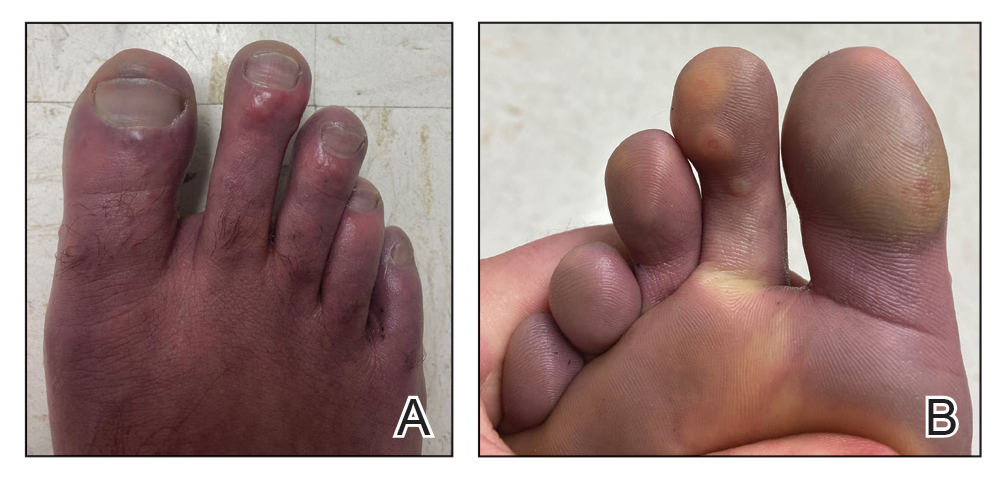

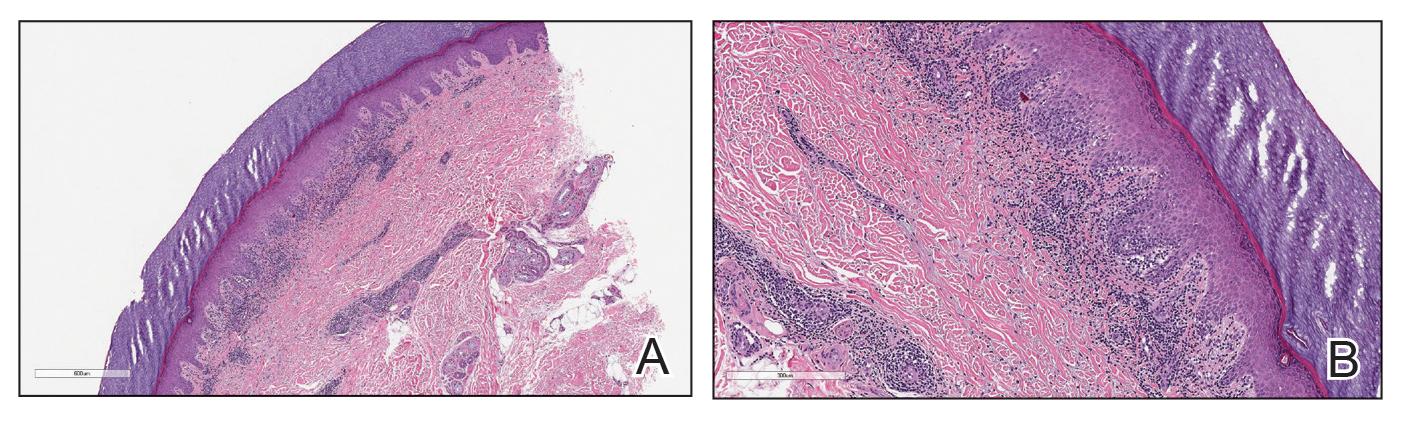

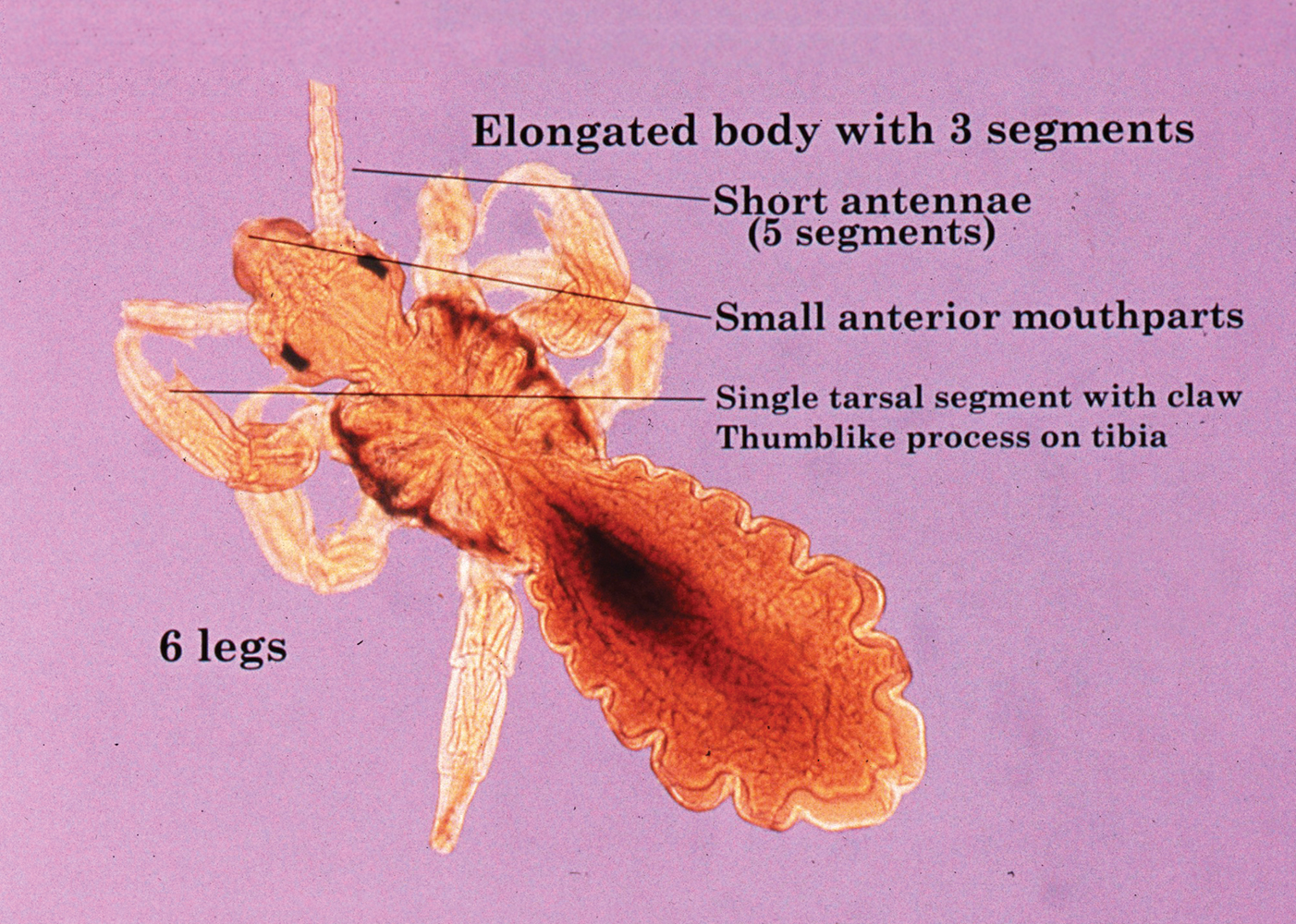

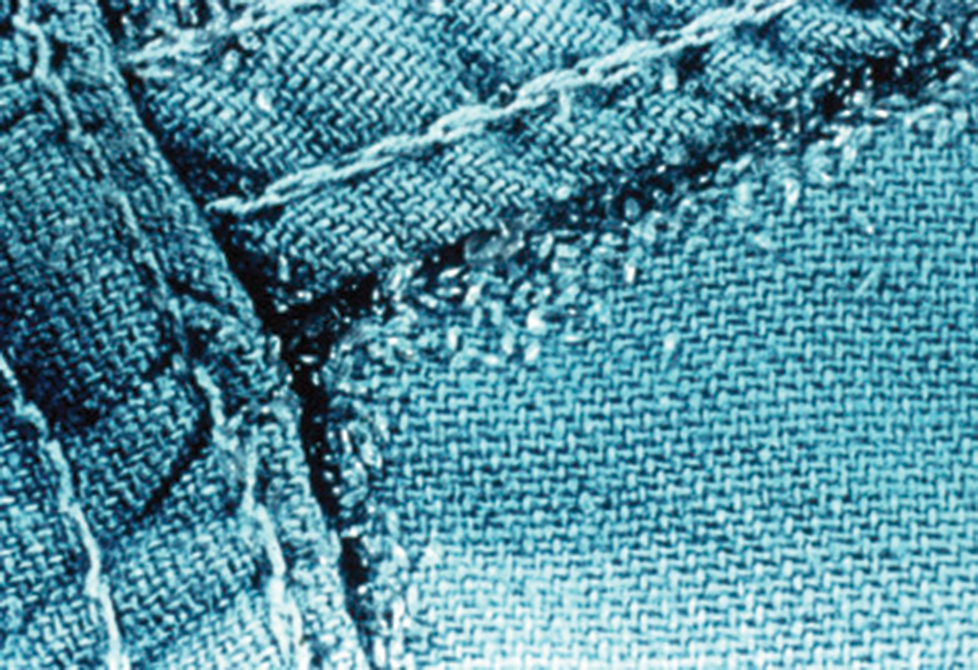

Case Presentation—A 39-year-old active-duty male service member presented to the dermatology clinic for intermittent painful blistering on the toes of both feet lasting approximately 10 to 14 days about 3 to 4 times per year for the last several years. The patient reported that his symptoms started after spending 2 days in the snow with wet nonwinterized boots while stationed in Germany 10 years prior. He reported cold weather as his only associated trigger and denied other associated symptoms. Physical examination revealed mildly cyanotic toes containing scattered bullae, with the dorsal lesions appearing more superficial compared to the deeper plantar bullae (Figure 1). A complete blood cell count, serum protein electrophoresis, and antinuclear and autoimmune antibodies were within reference range. A punch biopsy was obtained from a lesion on the right dorsal great toe. Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lichenoid and vacuolar dermatitis with scattered dyskeratosis and subtle papillary edema (Figure 2). Minimal interstitial mucin was seen on Alcian blue–stained sections. The histologic and clinical findings were most compatible with a diagnosis of chronic pernio. Nifedipine 20 mg once daily was initiated, and he had minimal improvement after a few months of treatment. His condition continued to limit his functionality in cold conditions due to pain. Without improvement of the symptoms, the patient likely will require medical separation from military service, as this condition limits the performance of his duties and his deployability.

Clinical Discussion—Pernio, also known as chilblains, is characterized by cold-induced erythematous patches and plaques, pain, and pruritus on the affected skin.18 Bullae and ulceration can be seen in more severe and chronic cases.19 Pernio most commonly is seen in young women but also can be seen in children, men, and older adults. It usually occurs on the tips of toes but also may affect the fingers, nose, and ears. It typically is observed in cold and damp conditions and is thought to be caused by an inflammatory response to vasospasms in the setting of nonfreezing cold. Acute pernio typically resolves after a few weeks; however, it also can persist in a chronic form after repeated cold exposure.18

Predisposing factors include excessive cold exposure, connective tissue disease, hematologic malignancy, antiphospholipid antibodies in adults, and anorexia nervosa in children.18,20,21 More recently, perniolike lesions have been associated with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.22 Histologically, pernio is characterized by a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and dermal edema.23 Cold avoidance, warming, drying, and smoking cessation are primary treatments, while vasodilating medications such as nifedipine have been used with success in more resistant cases.20,24

Although the prognosis generally is excellent, this condition also can be career limiting for military service members. If it resolves with no residual effects, patients can expect to continue their service; however, if it persists and limits their activity or ability to deploy, a medical retirement may be indicated.11-14

Raynaud Phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon (also known as Raynaud’s) is characterized by cold-induced extremity triphasic color changes—initial blanching and pallor that transitions to cyanosis and finally erythema with associated pain during the recovery stage. The fingers are the most commonly involved appendages and can have a symmetric distribution, but RP also has been observed on the feet, lips, nose, and ears. In severe cases, it can cause ulceration.25 The prevalence of RP may be as high as 5% in the general population.26 It more commonly is primary or idiopathic with no underlying cause or secondary with an associated underlying systemic disease.

Cold-induced vasoconstriction is a normal physiologic response, but in RP, the response becomes a vasospasm and is pathological. Autoimmune and connective tissue diseases often are associated with secondary RP. Other risk factors include female sex, smoking, family history in a first-degree relative, and certain medications.25 A study in northern Sweden also identified a history of frostbite as a risk factor for the development of RP.27 This condition can notably restrict mobility and deployability of affected service members as well as the types of manual tasks that they may be required to perform. As such, this condition can be disqualifying for military service.11

Many patients improve with conservative treatment consisting of cold avoidance, smoking cessation, and avoidance of medications that worsen the vasospasm; however, some patients develop pain and chronic disease, which can become so severe and ischemic that digital loss is threatened.25 When needed, calcium channel blockers commonly are used for treatment and can be used prophylactically to reduce flare rates and severity of disease. If this class of medications is ineffective or is not tolerated, there are other medications and treatments to consider, which are beyond the scope of this article.25

Cold Urticaria

Cold urticaria is a subset of physical urticaria in which symptoms occur in response to a cutaneous cold stimulus. It can be primary or secondary, with potential underlying causes including cryoglobulinemia, infections, and some medications. Systemic involvement is possible with extensive cold contact and can include severe anaphylaxis. This condition is diagnosed using a cold stimulation test. Cold exposure avoidance and second-generation antihistamines are considered first-line treatment. Because anaphylaxis is possible, patients should be given an epinephrine pen and should be instructed to avoid swimming in cold water.28 Cold urticaria is disqualifying for military service.11

A 2013 case report described a 29-year-old woman on active duty in the US Air Force whose presenting symptoms included urticaria on the exposed skin on the arms when doing physical training in the rain.29 In this case, secondary causes were eliminated, and she was diagnosed with primary acquired cold urticaria. This patient was eventually medically discharged from the air force because management with antihistamines failed, and her symptoms limited her ability to function in even mildly cold environments.29

Final Thoughts

An understanding of cold weather injuries and other dermatologic conditions that may be flared by cold exposure is important for a medically ready military force, as there are implications for accession, training, and combat operations. Although the focus of this article has been on the military, these conditions also are seen in civilian medicine in patient populations routinely exposed to cold weather. This becomes especially pertinent in high-risk patients such as extreme athletes, homeless individuals, or those who have other predisposing characteristics such as chronic alcohol use. Appropriate cold weather gear, training, and deliberate mission or activity planning are important interventions in preventing cutaneous cold weather injuries within the military.

- Patton BC. Cold, casualties, and conquests: the effects of cold on warfare. In: Pandolf KB, Burr RE, eds. Medical Aspects of HarshEnvironments. Office of the Surgeon General, United States Army; 2001:313-349.

- Update: cold weather injuries, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, July 2015–June 2020. Military Health System website. Published November 1, 2020. Accessed September 15, 2021. https://www.health.mil/News/Articles/2020/11/01/Update-Cold-Weather-Injuries-MSMR-2020

- Lee W, Kwon SB, Cho SH, et al. Glomus tumor of the hand. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42:295-301.

- Daanen HA. Finger cold-induced vasodilation: a review. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;89:411-426.

- Handford C, Thomas O, Imray CHE. Frostbite. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:281-299.

- Grieve AW, Davis P, Dhillon S, et al. A clinical review of the management of frostbite. J R Army Med Corps. 2011;157:73-78.

- Maley MJ, Eglin CM, House JR, et al. The effect of ethnicity on the vascular responses to cold exposure of the extremities. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114:2369-2379.

- Wong NWK, NG Vt-Y, Ibrahim S, et al. Lupus—the cold, hard facts. Lupus. 2014;23:837-839.

- Smith ML. Environmental and sports related skin diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, et al, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1574-1579.

- Rintamäki H. Predisposing factors and prevention of frostbite. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2000;59:114-121.

- Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction into the Military Services (DOD Instructions 6130.03). Washington, DC: US Department of Defense; 2018. Updated April 30, 2021. Accessed September 15, 2021. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003v1p.pdf?ver=aNVBgIeuKy0Gbrm-foyDSA%3D%3D

- Medical Examinations. In: Manual of the Medical Department (MANMED), NAVMED P-117. US Navy; 2019:15-40–15-46. Updated October 20, 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.med.navy.mil/Portals/62/Documents/BUMED/Directives/MANMED/Chapter%2015%20Medical%20Examinations%20(incorporates%20Changes%20126_135-138_140_145_150-152_154-156_160_164-167).pdf?ver=Rj7AoH54dNAX5uS3F1JUfw%3d%3d

- United States Air Force. Medical standards directory. Approved May 13, 2020. Accessed September 16, 2021. https://afspecialwarfare.com/files/MSD%20May%202020%20FINAL%2013%20MAY%202020.pdf

- Department of the Army. Standards of medical fitness. AR 40-501. Revised June 27, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2021. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/ARN8673_AR40_501_FINAL_WEB.pdf

- Mistry K, Ondhia C, Levell NJ. A review of trench foot: a disease of the past in the present. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:10-14.

- Kuht JA, Woods D, Hollis S. Case series of non-freezing cold injury: epidemiology and risk factors. J R Army Med Corps. 2019;165:400-404.

- Ungley CC, Blackwood W. Peripheral vasoneuropathy after chilling. Lancet. 1942;2:447-451.

- Simon TD, Soap JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2005;116:E472-E475.

- Spittel Jr JA, Spittell PC. Chronic pernio: another cause of blue toes. Int Angiol. 1992;11:46-50.

- Cappel JA, Wetter DA. Clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, laboratory findings, treatment, and proposal of diagnostic criteria of pernio (chilblains) in a series of 104 patients at Mayo Clinic, 2000 to 2011. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:207-215.

- White KP, Rothe MJ, Milanese A, et al. Perniosis in association with anorexia nervosa. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:1-5.

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:486-492.

- Cribier B, Djeridi N, Peltre B, et al. A histologic and immunohistochemical study of chilblains. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:924-929.

- Rustin MH, Newton JA, Smith NP, et al. The treatment of chilblains with nifedipine: the results of a pilot study, a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized study and a long-term open trial. Br J Dermatol.1989;120:267-275.

- Pope JE. The diagnosis and treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a practical approach. Drugs. 2007;67:517-525.

- Garner R, Kumari R, Lanyon P, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and associations of primary Raynaud’s phenomenon: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2015;5:E006389.

- Stjerbrant A, Pettersson H, Liljelind I, et al. Raynaud’s phenomenon in Northern Sweden: a population-based nested case-control study. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39:265-275.

- Singleton R, Halverstam CP. Diagnosis and management of cold urticaria. Cutis. 2016;97:59-62.

- Barnes M, Linthicum C, Hardin C. Cold, red, itching, and miserable. Mil Med. 2013;178:E1043-E1044.

The US Department of Defense maintains a presence in several cold weather environments such as North Dakota, Alaska, and South Korea. Although much is known about preventing and caring for cold weather injuries, many of these ailments continue to occur. Therefore, it is vital that both military and civilian physicians who care for patients who are exposed to cold weather conditions have a thorough understanding of the prevention, clinical presentation, and treatment of cold weather injuries.

Although the focus of this article is on cutaneous cold weather injuries that occur in military service, these types of injuries are not limited to this population. Civilians who live, work, or seek recreation in cold climates also may experience these injuries. Classically, cold injuries are classified as freezing and nonfreezing injuries. For the purpose of this article, we also consider a third category: dermatologic conditions that flare upon cold exposure. Specifically, we discuss frostbite, cold-weather immersion foot, pernio, Raynaud phenomenon (RP), and cold urticaria. We also present a case of pernio in an active-duty military service member.

Frostbite

For centuries, frostbite has been well documented as a cold weather injury in military history.1 Napoleon’s catastrophic invasion of Russia in 1812 started with 612,000 troops and ended with fewer than 10,000 effective soldiers; while many factors contributed to this attrition, exposure to cold weather and frostbite is thought to have been a major factor. The muddy trench warfare of World War I was no kinder to the poorly equipped soldiers across the European theater. Decades later during World War II, frostbite was a serious source of noncombat injuries, as battles were fought in frigid European winters. From 1942 to 1945, there were 13,196 reported cases of frostbite in the European theater, with most of these injuries occurring in 1945.1

Despite advancements in cold weather clothing and increased knowledge about the causes of and preventative measures for frostbite, cold weather injuries continue to be a relevant topic in today’s military. From 2015 to 2020, there were 1120 reported cases of frostbite in the US military.2 When skin is exposed to cold temperatures, the body peripherally vasoconstricts to reduce core heat loss. This autoregulatory vasoconstriction is part of a normal physiologic response that preserves the core body temperature, often at the expense of the extremities; for instance, the hands and feet are equipped with arteriovenous shunts, known as glomus bodies, which consist of vascular smooth muscle centers that control the flow of blood in response to changing external temperatures.3 This is partially mitigated by cold-induced vasodilation of the digits, also known as the Hunting reaction, which generally occurs 5 to 10 minutes after the start of local cold exposure.4 Additionally, discomfort from cold exposure warrants behavioral modifications such as going indoors, putting on warmer clothing, or building a fire. If an individual is unable to seek shelter in the face of cold exposure, the cold will inevitably cause injury.

Frostbite is caused by both direct and indirect cellular injury. Direct injury results from the crystallization of intracellular and interstitial fluids, cellular dehydration, and electrolyte disturbances. Indirect cellular injury is the result of a progressive microvascular insult and is caused by microvascular thrombosis, endothelial damage, intravascular sludging, inflammatory mediators, free radicals, and reperfusion injury.5

Frostnip is a more superficial injury that does not involve freezing of the skin or underlying tissue and typically does not leave any long-term damage. As severity of injury increases, frostbite is characterized by the depth of injury, presence of tissue loss, and radiotracer uptake on bone scan. There are 2 main classification systems for frostbite: one is based on the severity of the injury outcome, categorized by 4 degrees (1–4), and the other is designed as a predictive model, categorized by 4 grades (1–4).6 The first classification system is similar to the system for the severity of burns and ranges from partial-thickness injury (first degree) to full-thickness skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, tendon, and bone (fourth degree). The latter classification system uses the presence and characteristics of blisters after rewarming on days 0 and 2 and radiotracer uptake on bone scan on day 2. Severity ranges from no blistering, no indicated bone scan, and no long-term sequelae in grade 1 to hemorrhagic blisters overlying the carpal or tarsal bones and absence of radiotracer uptake with predicted extensive amputation, risk for thrombosis or sepsis, and long-term functional sequelae in grade 4.6

Male sex and African descent are associated with increased risk for sustaining frostbite. The ethnic predisposition may be explained by a less robust Hunting reaction in individuals of African descent.4,7 Other risk factors include alcohol use, smoking, homelessness, history of cold-related injury, use of beta-blockers, and working with equipment that uses nitrogen dioxide or CO2.5 Additionally, a history of systemic lupus erythematosus has been reported as a risk factor for frostbite.8

Clinically, frostbite initially may appear pale, blue, or erythematous, and patients may report skin numbness. In severe cases, necrosis can be seen.9 The most commonly affected anatomic locations include the fingers, toes, ears, and nose. Prevention is key for frostbite injuries. Steps to avoid injury include wearing appropriate clothing, minimizing the duration of time the skin is exposed to cold temperatures, avoiding alcohol consumption, and avoiding physical exhaustion in cold weather. These steps can help mitigate the effects of wind chill and low temperatures and decrease the risk of frostbite.10

Management of this condition includes prevention, early diagnosis, prehospital management, hospital management, and long-term sequelae management. Leadership and medical personnel for military units assigned to cold climates should be vigilant in looking for symptoms of frostbite. If any one individual is found to have frostbite or any other cold injury, all other team members should be evaluated.5

After identification of frostbite, seeking shelter and evacuation to a treatment facility are vital next steps. Constrictive clothing or jewelry should be removed. Depending on the situation, rewarming can be attempted in the prehospital setting, but it is imperative to avoid refreezing, as this may further damage the affected tissue due to intracellular ice formation with extensive cell destruction.6 Gentle warming can be attempted by placing the affected extremity in another person’s armpit or groin for up to 10 minutes or by immersing the affected limb in water that is 37° C to 39° C (98.6° F to 102.2° F). Rubbing the affected area and dry heat should be avoided. It should be noted that the decision to thaw in the field introduces the challenge of dealing with the severe pain associated with thawing in a remote or hostile environment. Ibuprofen (400 mg) can be given as an anti-inflammatory and analgesic agent in the prehospital setting.5 Once safely evacuated to the hospital, treatment options expand dramatically, including warming without concern of refreezing, wound care, thrombolytic therapy, and surgical intervention. If local frostbite expertise is not available, there are telemedicine services available.5,6

Frostbite outcomes range from complete recovery to amputation. Previously frostbitten tissue has increased cold sensitivity and is more susceptible to similar injury in the future. Additionally, there can be functional loss, chronic pain, chronic ulceration, and arthritis.5,6 As such, a history of frostbite can be disqualifying for military service and requires a medical waiver.11 If a service member experiences frostbite and does not have any residual effects, they can expect to continue their military service, but if there are sequelae, it may prove to be career limiting.12-14

Immersion Foot

Although frostbite represents a freezing injury, immersion foot (or trench foot) represents a nonfreezing cold injury. It should be noted that in addition to immersion foot associated with cold water exposure, there also are warm-water and tropical variants. For the purpose of this article, we are referring to immersion foot associated with exposure to cold water. Trench foot was described for the first time during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 but came to prominence during World War I, where it is thought to have contributed to the deaths of 75,000 British soldiers. During World War II, there were 25,016 cases of immersion foot reported in the US military.1 More recently, 590 cases of immersion foot were reported in the US military from 2015 to 2020.2

Classically, this condition was seen in individuals whose feet were immersed in cold but not freezing water or mud in trenches or on boats, hence the terms immersion foot and trench foot. The pathogenesis is thought to be related to overhydration of the stratum corneum and repetitive cycles of cold-induced, thermoprotective vasoconstriction, leading to cyclical hypoxic and reperfusion injuries, which eventually damage nerves, muscle, subcutaneous fat, and blood vessels.9,15

A recent case series of 100 military service members in the United Kingdom showed that cold-induced extremity numbness for more than 30 minutes and painful rewarming after cold exposure were highly correlated with the development of immersion foot. Additionally, this case series showed that patients with repeated cycles of cooling and rewarming were more likely to have long-term symptoms.16 As with frostbite, prior cold injury and African descent increases the risk for developing immersion foot, possibly due to a less-pronounced Hunting reaction.4,7

Early reports suggested prehyperemic, hyperemic, and posthyperemic stages. The prehyperemic stage lasts from hours to days and is characterized by cold extremities, discoloration, edema, stocking- or glove-distributed anesthesia, blisters, necrosis, and potential loss of palpable pulses.17 Of note, in Kuht et al’s16 more recent case series, edema was not seen as frequently as in prior reports. The hyperemic stage can last for 6 to 10 weeks and is characterized by vascular disturbances. In addition, the affected extremity typically remains warm and red even when exposed to cold temperatures. Sensory disturbances such as paresthesia and hyperalgesia may be seen, as well as motor disturbances, anhidrosis, blisters, ulcers, and gangrene. The posthyperemic stage can last from months to years and is characterized by cold sensitivity, possible digital blanching, edema, hyperhidrosis, and persistent peripheral neuropathy.16

Prevention is the most important treatment for immersion foot. The first step in preventing this injury is avoiding prolonged cold exposure. When this is not possible due to the demands of training or actual combat conditions, regular hand and foot inspections, frequent sock changes, and regularly rotating out of cold wet conditions can help prevent this injury.15 Vasodilators also have been considered as a possible treatment modality. Iloprost and nicotinyl alcohol tartrate showed some improvement, while aminophylline and papaverine were ineffective.15

As with frostbite, a history of immersion foot may be disqualifying for military service.11 If it occurs during military service and there are no residual effects that limit the service member’s capabilities, they may expect to continue their career; however, if there are residual effects that limit activity or deployment, medical retirement may be indicated.

Pernio

Pernio is another important condition that is related to cold exposure; however, unlike the previous 2 conditions, it is not necessarily caused by cold exposure but rather flares with cold exposure.

Case Presentation—A 39-year-old active-duty male service member presented to the dermatology clinic for intermittent painful blistering on the toes of both feet lasting approximately 10 to 14 days about 3 to 4 times per year for the last several years. The patient reported that his symptoms started after spending 2 days in the snow with wet nonwinterized boots while stationed in Germany 10 years prior. He reported cold weather as his only associated trigger and denied other associated symptoms. Physical examination revealed mildly cyanotic toes containing scattered bullae, with the dorsal lesions appearing more superficial compared to the deeper plantar bullae (Figure 1). A complete blood cell count, serum protein electrophoresis, and antinuclear and autoimmune antibodies were within reference range. A punch biopsy was obtained from a lesion on the right dorsal great toe. Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lichenoid and vacuolar dermatitis with scattered dyskeratosis and subtle papillary edema (Figure 2). Minimal interstitial mucin was seen on Alcian blue–stained sections. The histologic and clinical findings were most compatible with a diagnosis of chronic pernio. Nifedipine 20 mg once daily was initiated, and he had minimal improvement after a few months of treatment. His condition continued to limit his functionality in cold conditions due to pain. Without improvement of the symptoms, the patient likely will require medical separation from military service, as this condition limits the performance of his duties and his deployability.

Clinical Discussion—Pernio, also known as chilblains, is characterized by cold-induced erythematous patches and plaques, pain, and pruritus on the affected skin.18 Bullae and ulceration can be seen in more severe and chronic cases.19 Pernio most commonly is seen in young women but also can be seen in children, men, and older adults. It usually occurs on the tips of toes but also may affect the fingers, nose, and ears. It typically is observed in cold and damp conditions and is thought to be caused by an inflammatory response to vasospasms in the setting of nonfreezing cold. Acute pernio typically resolves after a few weeks; however, it also can persist in a chronic form after repeated cold exposure.18

Predisposing factors include excessive cold exposure, connective tissue disease, hematologic malignancy, antiphospholipid antibodies in adults, and anorexia nervosa in children.18,20,21 More recently, perniolike lesions have been associated with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.22 Histologically, pernio is characterized by a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and dermal edema.23 Cold avoidance, warming, drying, and smoking cessation are primary treatments, while vasodilating medications such as nifedipine have been used with success in more resistant cases.20,24

Although the prognosis generally is excellent, this condition also can be career limiting for military service members. If it resolves with no residual effects, patients can expect to continue their service; however, if it persists and limits their activity or ability to deploy, a medical retirement may be indicated.11-14

Raynaud Phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon (also known as Raynaud’s) is characterized by cold-induced extremity triphasic color changes—initial blanching and pallor that transitions to cyanosis and finally erythema with associated pain during the recovery stage. The fingers are the most commonly involved appendages and can have a symmetric distribution, but RP also has been observed on the feet, lips, nose, and ears. In severe cases, it can cause ulceration.25 The prevalence of RP may be as high as 5% in the general population.26 It more commonly is primary or idiopathic with no underlying cause or secondary with an associated underlying systemic disease.

Cold-induced vasoconstriction is a normal physiologic response, but in RP, the response becomes a vasospasm and is pathological. Autoimmune and connective tissue diseases often are associated with secondary RP. Other risk factors include female sex, smoking, family history in a first-degree relative, and certain medications.25 A study in northern Sweden also identified a history of frostbite as a risk factor for the development of RP.27 This condition can notably restrict mobility and deployability of affected service members as well as the types of manual tasks that they may be required to perform. As such, this condition can be disqualifying for military service.11

Many patients improve with conservative treatment consisting of cold avoidance, smoking cessation, and avoidance of medications that worsen the vasospasm; however, some patients develop pain and chronic disease, which can become so severe and ischemic that digital loss is threatened.25 When needed, calcium channel blockers commonly are used for treatment and can be used prophylactically to reduce flare rates and severity of disease. If this class of medications is ineffective or is not tolerated, there are other medications and treatments to consider, which are beyond the scope of this article.25

Cold Urticaria

Cold urticaria is a subset of physical urticaria in which symptoms occur in response to a cutaneous cold stimulus. It can be primary or secondary, with potential underlying causes including cryoglobulinemia, infections, and some medications. Systemic involvement is possible with extensive cold contact and can include severe anaphylaxis. This condition is diagnosed using a cold stimulation test. Cold exposure avoidance and second-generation antihistamines are considered first-line treatment. Because anaphylaxis is possible, patients should be given an epinephrine pen and should be instructed to avoid swimming in cold water.28 Cold urticaria is disqualifying for military service.11

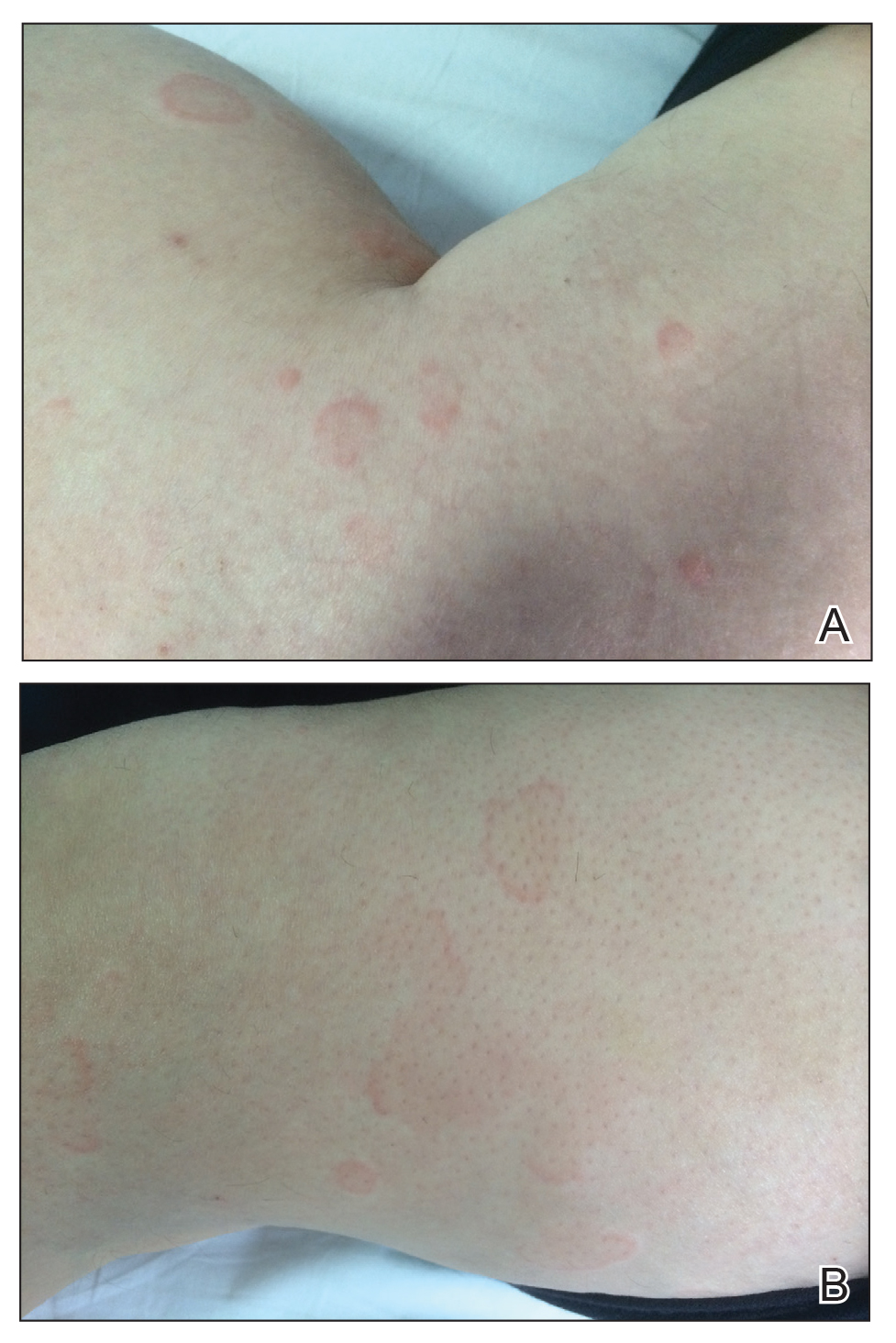

A 2013 case report described a 29-year-old woman on active duty in the US Air Force whose presenting symptoms included urticaria on the exposed skin on the arms when doing physical training in the rain.29 In this case, secondary causes were eliminated, and she was diagnosed with primary acquired cold urticaria. This patient was eventually medically discharged from the air force because management with antihistamines failed, and her symptoms limited her ability to function in even mildly cold environments.29

Final Thoughts

An understanding of cold weather injuries and other dermatologic conditions that may be flared by cold exposure is important for a medically ready military force, as there are implications for accession, training, and combat operations. Although the focus of this article has been on the military, these conditions also are seen in civilian medicine in patient populations routinely exposed to cold weather. This becomes especially pertinent in high-risk patients such as extreme athletes, homeless individuals, or those who have other predisposing characteristics such as chronic alcohol use. Appropriate cold weather gear, training, and deliberate mission or activity planning are important interventions in preventing cutaneous cold weather injuries within the military.

The US Department of Defense maintains a presence in several cold weather environments such as North Dakota, Alaska, and South Korea. Although much is known about preventing and caring for cold weather injuries, many of these ailments continue to occur. Therefore, it is vital that both military and civilian physicians who care for patients who are exposed to cold weather conditions have a thorough understanding of the prevention, clinical presentation, and treatment of cold weather injuries.

Although the focus of this article is on cutaneous cold weather injuries that occur in military service, these types of injuries are not limited to this population. Civilians who live, work, or seek recreation in cold climates also may experience these injuries. Classically, cold injuries are classified as freezing and nonfreezing injuries. For the purpose of this article, we also consider a third category: dermatologic conditions that flare upon cold exposure. Specifically, we discuss frostbite, cold-weather immersion foot, pernio, Raynaud phenomenon (RP), and cold urticaria. We also present a case of pernio in an active-duty military service member.

Frostbite

For centuries, frostbite has been well documented as a cold weather injury in military history.1 Napoleon’s catastrophic invasion of Russia in 1812 started with 612,000 troops and ended with fewer than 10,000 effective soldiers; while many factors contributed to this attrition, exposure to cold weather and frostbite is thought to have been a major factor. The muddy trench warfare of World War I was no kinder to the poorly equipped soldiers across the European theater. Decades later during World War II, frostbite was a serious source of noncombat injuries, as battles were fought in frigid European winters. From 1942 to 1945, there were 13,196 reported cases of frostbite in the European theater, with most of these injuries occurring in 1945.1

Despite advancements in cold weather clothing and increased knowledge about the causes of and preventative measures for frostbite, cold weather injuries continue to be a relevant topic in today’s military. From 2015 to 2020, there were 1120 reported cases of frostbite in the US military.2 When skin is exposed to cold temperatures, the body peripherally vasoconstricts to reduce core heat loss. This autoregulatory vasoconstriction is part of a normal physiologic response that preserves the core body temperature, often at the expense of the extremities; for instance, the hands and feet are equipped with arteriovenous shunts, known as glomus bodies, which consist of vascular smooth muscle centers that control the flow of blood in response to changing external temperatures.3 This is partially mitigated by cold-induced vasodilation of the digits, also known as the Hunting reaction, which generally occurs 5 to 10 minutes after the start of local cold exposure.4 Additionally, discomfort from cold exposure warrants behavioral modifications such as going indoors, putting on warmer clothing, or building a fire. If an individual is unable to seek shelter in the face of cold exposure, the cold will inevitably cause injury.

Frostbite is caused by both direct and indirect cellular injury. Direct injury results from the crystallization of intracellular and interstitial fluids, cellular dehydration, and electrolyte disturbances. Indirect cellular injury is the result of a progressive microvascular insult and is caused by microvascular thrombosis, endothelial damage, intravascular sludging, inflammatory mediators, free radicals, and reperfusion injury.5

Frostnip is a more superficial injury that does not involve freezing of the skin or underlying tissue and typically does not leave any long-term damage. As severity of injury increases, frostbite is characterized by the depth of injury, presence of tissue loss, and radiotracer uptake on bone scan. There are 2 main classification systems for frostbite: one is based on the severity of the injury outcome, categorized by 4 degrees (1–4), and the other is designed as a predictive model, categorized by 4 grades (1–4).6 The first classification system is similar to the system for the severity of burns and ranges from partial-thickness injury (first degree) to full-thickness skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, tendon, and bone (fourth degree). The latter classification system uses the presence and characteristics of blisters after rewarming on days 0 and 2 and radiotracer uptake on bone scan on day 2. Severity ranges from no blistering, no indicated bone scan, and no long-term sequelae in grade 1 to hemorrhagic blisters overlying the carpal or tarsal bones and absence of radiotracer uptake with predicted extensive amputation, risk for thrombosis or sepsis, and long-term functional sequelae in grade 4.6

Male sex and African descent are associated with increased risk for sustaining frostbite. The ethnic predisposition may be explained by a less robust Hunting reaction in individuals of African descent.4,7 Other risk factors include alcohol use, smoking, homelessness, history of cold-related injury, use of beta-blockers, and working with equipment that uses nitrogen dioxide or CO2.5 Additionally, a history of systemic lupus erythematosus has been reported as a risk factor for frostbite.8

Clinically, frostbite initially may appear pale, blue, or erythematous, and patients may report skin numbness. In severe cases, necrosis can be seen.9 The most commonly affected anatomic locations include the fingers, toes, ears, and nose. Prevention is key for frostbite injuries. Steps to avoid injury include wearing appropriate clothing, minimizing the duration of time the skin is exposed to cold temperatures, avoiding alcohol consumption, and avoiding physical exhaustion in cold weather. These steps can help mitigate the effects of wind chill and low temperatures and decrease the risk of frostbite.10

Management of this condition includes prevention, early diagnosis, prehospital management, hospital management, and long-term sequelae management. Leadership and medical personnel for military units assigned to cold climates should be vigilant in looking for symptoms of frostbite. If any one individual is found to have frostbite or any other cold injury, all other team members should be evaluated.5

After identification of frostbite, seeking shelter and evacuation to a treatment facility are vital next steps. Constrictive clothing or jewelry should be removed. Depending on the situation, rewarming can be attempted in the prehospital setting, but it is imperative to avoid refreezing, as this may further damage the affected tissue due to intracellular ice formation with extensive cell destruction.6 Gentle warming can be attempted by placing the affected extremity in another person’s armpit or groin for up to 10 minutes or by immersing the affected limb in water that is 37° C to 39° C (98.6° F to 102.2° F). Rubbing the affected area and dry heat should be avoided. It should be noted that the decision to thaw in the field introduces the challenge of dealing with the severe pain associated with thawing in a remote or hostile environment. Ibuprofen (400 mg) can be given as an anti-inflammatory and analgesic agent in the prehospital setting.5 Once safely evacuated to the hospital, treatment options expand dramatically, including warming without concern of refreezing, wound care, thrombolytic therapy, and surgical intervention. If local frostbite expertise is not available, there are telemedicine services available.5,6

Frostbite outcomes range from complete recovery to amputation. Previously frostbitten tissue has increased cold sensitivity and is more susceptible to similar injury in the future. Additionally, there can be functional loss, chronic pain, chronic ulceration, and arthritis.5,6 As such, a history of frostbite can be disqualifying for military service and requires a medical waiver.11 If a service member experiences frostbite and does not have any residual effects, they can expect to continue their military service, but if there are sequelae, it may prove to be career limiting.12-14

Immersion Foot

Although frostbite represents a freezing injury, immersion foot (or trench foot) represents a nonfreezing cold injury. It should be noted that in addition to immersion foot associated with cold water exposure, there also are warm-water and tropical variants. For the purpose of this article, we are referring to immersion foot associated with exposure to cold water. Trench foot was described for the first time during Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 but came to prominence during World War I, where it is thought to have contributed to the deaths of 75,000 British soldiers. During World War II, there were 25,016 cases of immersion foot reported in the US military.1 More recently, 590 cases of immersion foot were reported in the US military from 2015 to 2020.2

Classically, this condition was seen in individuals whose feet were immersed in cold but not freezing water or mud in trenches or on boats, hence the terms immersion foot and trench foot. The pathogenesis is thought to be related to overhydration of the stratum corneum and repetitive cycles of cold-induced, thermoprotective vasoconstriction, leading to cyclical hypoxic and reperfusion injuries, which eventually damage nerves, muscle, subcutaneous fat, and blood vessels.9,15

A recent case series of 100 military service members in the United Kingdom showed that cold-induced extremity numbness for more than 30 minutes and painful rewarming after cold exposure were highly correlated with the development of immersion foot. Additionally, this case series showed that patients with repeated cycles of cooling and rewarming were more likely to have long-term symptoms.16 As with frostbite, prior cold injury and African descent increases the risk for developing immersion foot, possibly due to a less-pronounced Hunting reaction.4,7

Early reports suggested prehyperemic, hyperemic, and posthyperemic stages. The prehyperemic stage lasts from hours to days and is characterized by cold extremities, discoloration, edema, stocking- or glove-distributed anesthesia, blisters, necrosis, and potential loss of palpable pulses.17 Of note, in Kuht et al’s16 more recent case series, edema was not seen as frequently as in prior reports. The hyperemic stage can last for 6 to 10 weeks and is characterized by vascular disturbances. In addition, the affected extremity typically remains warm and red even when exposed to cold temperatures. Sensory disturbances such as paresthesia and hyperalgesia may be seen, as well as motor disturbances, anhidrosis, blisters, ulcers, and gangrene. The posthyperemic stage can last from months to years and is characterized by cold sensitivity, possible digital blanching, edema, hyperhidrosis, and persistent peripheral neuropathy.16

Prevention is the most important treatment for immersion foot. The first step in preventing this injury is avoiding prolonged cold exposure. When this is not possible due to the demands of training or actual combat conditions, regular hand and foot inspections, frequent sock changes, and regularly rotating out of cold wet conditions can help prevent this injury.15 Vasodilators also have been considered as a possible treatment modality. Iloprost and nicotinyl alcohol tartrate showed some improvement, while aminophylline and papaverine were ineffective.15

As with frostbite, a history of immersion foot may be disqualifying for military service.11 If it occurs during military service and there are no residual effects that limit the service member’s capabilities, they may expect to continue their career; however, if there are residual effects that limit activity or deployment, medical retirement may be indicated.

Pernio

Pernio is another important condition that is related to cold exposure; however, unlike the previous 2 conditions, it is not necessarily caused by cold exposure but rather flares with cold exposure.

Case Presentation—A 39-year-old active-duty male service member presented to the dermatology clinic for intermittent painful blistering on the toes of both feet lasting approximately 10 to 14 days about 3 to 4 times per year for the last several years. The patient reported that his symptoms started after spending 2 days in the snow with wet nonwinterized boots while stationed in Germany 10 years prior. He reported cold weather as his only associated trigger and denied other associated symptoms. Physical examination revealed mildly cyanotic toes containing scattered bullae, with the dorsal lesions appearing more superficial compared to the deeper plantar bullae (Figure 1). A complete blood cell count, serum protein electrophoresis, and antinuclear and autoimmune antibodies were within reference range. A punch biopsy was obtained from a lesion on the right dorsal great toe. Hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections revealed lichenoid and vacuolar dermatitis with scattered dyskeratosis and subtle papillary edema (Figure 2). Minimal interstitial mucin was seen on Alcian blue–stained sections. The histologic and clinical findings were most compatible with a diagnosis of chronic pernio. Nifedipine 20 mg once daily was initiated, and he had minimal improvement after a few months of treatment. His condition continued to limit his functionality in cold conditions due to pain. Without improvement of the symptoms, the patient likely will require medical separation from military service, as this condition limits the performance of his duties and his deployability.

Clinical Discussion—Pernio, also known as chilblains, is characterized by cold-induced erythematous patches and plaques, pain, and pruritus on the affected skin.18 Bullae and ulceration can be seen in more severe and chronic cases.19 Pernio most commonly is seen in young women but also can be seen in children, men, and older adults. It usually occurs on the tips of toes but also may affect the fingers, nose, and ears. It typically is observed in cold and damp conditions and is thought to be caused by an inflammatory response to vasospasms in the setting of nonfreezing cold. Acute pernio typically resolves after a few weeks; however, it also can persist in a chronic form after repeated cold exposure.18

Predisposing factors include excessive cold exposure, connective tissue disease, hematologic malignancy, antiphospholipid antibodies in adults, and anorexia nervosa in children.18,20,21 More recently, perniolike lesions have been associated with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.22 Histologically, pernio is characterized by a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and dermal edema.23 Cold avoidance, warming, drying, and smoking cessation are primary treatments, while vasodilating medications such as nifedipine have been used with success in more resistant cases.20,24

Although the prognosis generally is excellent, this condition also can be career limiting for military service members. If it resolves with no residual effects, patients can expect to continue their service; however, if it persists and limits their activity or ability to deploy, a medical retirement may be indicated.11-14

Raynaud Phenomenon

Raynaud phenomenon (also known as Raynaud’s) is characterized by cold-induced extremity triphasic color changes—initial blanching and pallor that transitions to cyanosis and finally erythema with associated pain during the recovery stage. The fingers are the most commonly involved appendages and can have a symmetric distribution, but RP also has been observed on the feet, lips, nose, and ears. In severe cases, it can cause ulceration.25 The prevalence of RP may be as high as 5% in the general population.26 It more commonly is primary or idiopathic with no underlying cause or secondary with an associated underlying systemic disease.

Cold-induced vasoconstriction is a normal physiologic response, but in RP, the response becomes a vasospasm and is pathological. Autoimmune and connective tissue diseases often are associated with secondary RP. Other risk factors include female sex, smoking, family history in a first-degree relative, and certain medications.25 A study in northern Sweden also identified a history of frostbite as a risk factor for the development of RP.27 This condition can notably restrict mobility and deployability of affected service members as well as the types of manual tasks that they may be required to perform. As such, this condition can be disqualifying for military service.11

Many patients improve with conservative treatment consisting of cold avoidance, smoking cessation, and avoidance of medications that worsen the vasospasm; however, some patients develop pain and chronic disease, which can become so severe and ischemic that digital loss is threatened.25 When needed, calcium channel blockers commonly are used for treatment and can be used prophylactically to reduce flare rates and severity of disease. If this class of medications is ineffective or is not tolerated, there are other medications and treatments to consider, which are beyond the scope of this article.25

Cold Urticaria

Cold urticaria is a subset of physical urticaria in which symptoms occur in response to a cutaneous cold stimulus. It can be primary or secondary, with potential underlying causes including cryoglobulinemia, infections, and some medications. Systemic involvement is possible with extensive cold contact and can include severe anaphylaxis. This condition is diagnosed using a cold stimulation test. Cold exposure avoidance and second-generation antihistamines are considered first-line treatment. Because anaphylaxis is possible, patients should be given an epinephrine pen and should be instructed to avoid swimming in cold water.28 Cold urticaria is disqualifying for military service.11

A 2013 case report described a 29-year-old woman on active duty in the US Air Force whose presenting symptoms included urticaria on the exposed skin on the arms when doing physical training in the rain.29 In this case, secondary causes were eliminated, and she was diagnosed with primary acquired cold urticaria. This patient was eventually medically discharged from the air force because management with antihistamines failed, and her symptoms limited her ability to function in even mildly cold environments.29

Final Thoughts

An understanding of cold weather injuries and other dermatologic conditions that may be flared by cold exposure is important for a medically ready military force, as there are implications for accession, training, and combat operations. Although the focus of this article has been on the military, these conditions also are seen in civilian medicine in patient populations routinely exposed to cold weather. This becomes especially pertinent in high-risk patients such as extreme athletes, homeless individuals, or those who have other predisposing characteristics such as chronic alcohol use. Appropriate cold weather gear, training, and deliberate mission or activity planning are important interventions in preventing cutaneous cold weather injuries within the military.

- Patton BC. Cold, casualties, and conquests: the effects of cold on warfare. In: Pandolf KB, Burr RE, eds. Medical Aspects of HarshEnvironments. Office of the Surgeon General, United States Army; 2001:313-349.

- Update: cold weather injuries, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, July 2015–June 2020. Military Health System website. Published November 1, 2020. Accessed September 15, 2021. https://www.health.mil/News/Articles/2020/11/01/Update-Cold-Weather-Injuries-MSMR-2020

- Lee W, Kwon SB, Cho SH, et al. Glomus tumor of the hand. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42:295-301.

- Daanen HA. Finger cold-induced vasodilation: a review. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;89:411-426.

- Handford C, Thomas O, Imray CHE. Frostbite. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:281-299.

- Grieve AW, Davis P, Dhillon S, et al. A clinical review of the management of frostbite. J R Army Med Corps. 2011;157:73-78.

- Maley MJ, Eglin CM, House JR, et al. The effect of ethnicity on the vascular responses to cold exposure of the extremities. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114:2369-2379.

- Wong NWK, NG Vt-Y, Ibrahim S, et al. Lupus—the cold, hard facts. Lupus. 2014;23:837-839.

- Smith ML. Environmental and sports related skin diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, et al, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1574-1579.

- Rintamäki H. Predisposing factors and prevention of frostbite. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2000;59:114-121.

- Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction into the Military Services (DOD Instructions 6130.03). Washington, DC: US Department of Defense; 2018. Updated April 30, 2021. Accessed September 15, 2021. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003v1p.pdf?ver=aNVBgIeuKy0Gbrm-foyDSA%3D%3D

- Medical Examinations. In: Manual of the Medical Department (MANMED), NAVMED P-117. US Navy; 2019:15-40–15-46. Updated October 20, 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.med.navy.mil/Portals/62/Documents/BUMED/Directives/MANMED/Chapter%2015%20Medical%20Examinations%20(incorporates%20Changes%20126_135-138_140_145_150-152_154-156_160_164-167).pdf?ver=Rj7AoH54dNAX5uS3F1JUfw%3d%3d

- United States Air Force. Medical standards directory. Approved May 13, 2020. Accessed September 16, 2021. https://afspecialwarfare.com/files/MSD%20May%202020%20FINAL%2013%20MAY%202020.pdf

- Department of the Army. Standards of medical fitness. AR 40-501. Revised June 27, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2021. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/ARN8673_AR40_501_FINAL_WEB.pdf

- Mistry K, Ondhia C, Levell NJ. A review of trench foot: a disease of the past in the present. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:10-14.

- Kuht JA, Woods D, Hollis S. Case series of non-freezing cold injury: epidemiology and risk factors. J R Army Med Corps. 2019;165:400-404.

- Ungley CC, Blackwood W. Peripheral vasoneuropathy after chilling. Lancet. 1942;2:447-451.

- Simon TD, Soap JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2005;116:E472-E475.

- Spittel Jr JA, Spittell PC. Chronic pernio: another cause of blue toes. Int Angiol. 1992;11:46-50.

- Cappel JA, Wetter DA. Clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, laboratory findings, treatment, and proposal of diagnostic criteria of pernio (chilblains) in a series of 104 patients at Mayo Clinic, 2000 to 2011. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:207-215.

- White KP, Rothe MJ, Milanese A, et al. Perniosis in association with anorexia nervosa. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:1-5.

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:486-492.

- Cribier B, Djeridi N, Peltre B, et al. A histologic and immunohistochemical study of chilblains. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:924-929.

- Rustin MH, Newton JA, Smith NP, et al. The treatment of chilblains with nifedipine: the results of a pilot study, a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized study and a long-term open trial. Br J Dermatol.1989;120:267-275.

- Pope JE. The diagnosis and treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a practical approach. Drugs. 2007;67:517-525.

- Garner R, Kumari R, Lanyon P, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and associations of primary Raynaud’s phenomenon: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2015;5:E006389.

- Stjerbrant A, Pettersson H, Liljelind I, et al. Raynaud’s phenomenon in Northern Sweden: a population-based nested case-control study. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39:265-275.

- Singleton R, Halverstam CP. Diagnosis and management of cold urticaria. Cutis. 2016;97:59-62.

- Barnes M, Linthicum C, Hardin C. Cold, red, itching, and miserable. Mil Med. 2013;178:E1043-E1044.

- Patton BC. Cold, casualties, and conquests: the effects of cold on warfare. In: Pandolf KB, Burr RE, eds. Medical Aspects of HarshEnvironments. Office of the Surgeon General, United States Army; 2001:313-349.

- Update: cold weather injuries, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, July 2015–June 2020. Military Health System website. Published November 1, 2020. Accessed September 15, 2021. https://www.health.mil/News/Articles/2020/11/01/Update-Cold-Weather-Injuries-MSMR-2020

- Lee W, Kwon SB, Cho SH, et al. Glomus tumor of the hand. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42:295-301.

- Daanen HA. Finger cold-induced vasodilation: a review. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;89:411-426.

- Handford C, Thomas O, Imray CHE. Frostbite. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:281-299.

- Grieve AW, Davis P, Dhillon S, et al. A clinical review of the management of frostbite. J R Army Med Corps. 2011;157:73-78.

- Maley MJ, Eglin CM, House JR, et al. The effect of ethnicity on the vascular responses to cold exposure of the extremities. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114:2369-2379.

- Wong NWK, NG Vt-Y, Ibrahim S, et al. Lupus—the cold, hard facts. Lupus. 2014;23:837-839.

- Smith ML. Environmental and sports related skin diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, et al, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1574-1579.

- Rintamäki H. Predisposing factors and prevention of frostbite. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2000;59:114-121.

- Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction into the Military Services (DOD Instructions 6130.03). Washington, DC: US Department of Defense; 2018. Updated April 30, 2021. Accessed September 15, 2021. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003v1p.pdf?ver=aNVBgIeuKy0Gbrm-foyDSA%3D%3D

- Medical Examinations. In: Manual of the Medical Department (MANMED), NAVMED P-117. US Navy; 2019:15-40–15-46. Updated October 20, 2020. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.med.navy.mil/Portals/62/Documents/BUMED/Directives/MANMED/Chapter%2015%20Medical%20Examinations%20(incorporates%20Changes%20126_135-138_140_145_150-152_154-156_160_164-167).pdf?ver=Rj7AoH54dNAX5uS3F1JUfw%3d%3d

- United States Air Force. Medical standards directory. Approved May 13, 2020. Accessed September 16, 2021. https://afspecialwarfare.com/files/MSD%20May%202020%20FINAL%2013%20MAY%202020.pdf

- Department of the Army. Standards of medical fitness. AR 40-501. Revised June 27, 2019. Accessed September 16, 2021. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/pdf/web/ARN8673_AR40_501_FINAL_WEB.pdf

- Mistry K, Ondhia C, Levell NJ. A review of trench foot: a disease of the past in the present. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45:10-14.

- Kuht JA, Woods D, Hollis S. Case series of non-freezing cold injury: epidemiology and risk factors. J R Army Med Corps. 2019;165:400-404.

- Ungley CC, Blackwood W. Peripheral vasoneuropathy after chilling. Lancet. 1942;2:447-451.

- Simon TD, Soap JB, Hollister JR. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2005;116:E472-E475.

- Spittel Jr JA, Spittell PC. Chronic pernio: another cause of blue toes. Int Angiol. 1992;11:46-50.

- Cappel JA, Wetter DA. Clinical characteristics, etiologic associations, laboratory findings, treatment, and proposal of diagnostic criteria of pernio (chilblains) in a series of 104 patients at Mayo Clinic, 2000 to 2011. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:207-215.

- White KP, Rothe MJ, Milanese A, et al. Perniosis in association with anorexia nervosa. Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;11:1-5.

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:486-492.

- Cribier B, Djeridi N, Peltre B, et al. A histologic and immunohistochemical study of chilblains. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:924-929.

- Rustin MH, Newton JA, Smith NP, et al. The treatment of chilblains with nifedipine: the results of a pilot study, a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized study and a long-term open trial. Br J Dermatol.1989;120:267-275.

- Pope JE. The diagnosis and treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a practical approach. Drugs. 2007;67:517-525.

- Garner R, Kumari R, Lanyon P, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and associations of primary Raynaud’s phenomenon: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2015;5:E006389.

- Stjerbrant A, Pettersson H, Liljelind I, et al. Raynaud’s phenomenon in Northern Sweden: a population-based nested case-control study. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39:265-275.

- Singleton R, Halverstam CP. Diagnosis and management of cold urticaria. Cutis. 2016;97:59-62.

- Barnes M, Linthicum C, Hardin C. Cold, red, itching, and miserable. Mil Med. 2013;178:E1043-E1044.

Practice Points

- Military service members are at an increased risk for cutaneous cold weather injuries in certain circumstances due to the demands of military training and combat operations.

- Cold weather may cause injury by directly damaging tissues, leading to neurovascular disruption, and by exacerbating existing medical conditions.

Rashes in Pregnancy

Rashes that develop during pregnancy often result in considerable anxiety or concern for patients and their families. Recognizing these pregnancy-specific dermatoses is important in identifying fetal risks as well as providing appropriate management and expert guidance for patients regarding future pregnancies. Managing cutaneous manifestations of pregnancy-related disorders is challenging and requires knowledge of potential side effects of therapy for both the mother and fetus. It also is important to appreciate the physiologic cutaneous changes of pregnancy along with their clinical significance and management.

In 2006, Ambrose-Rudolph et al1 proposed reclassification of pregnancy-specific dermatoses, which has since been widely accepted by the academic dermatology community. The 4 most prominent disorders include intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP); pemphigoid gestationis (PG); polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), also known as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy; and atopic eruption of pregnancy.2 It is important to recognize these pregnancy-specific disorders and to understand their clinical significance. The morphology of the eruption as well as the location and timing of the onset of the rash are important clues in making an accurate diagnosis.3

Clinical Presentation

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy presents with severe generalized pruritus, usually with involvement of the palms and soles, in the late second or third trimester. Pemphigoid gestationis presents with urticarial papules and/or bullae, often in the second or third trimester or postpartum. An important diagnostic clue for PG is involvement near the umbilicus. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy presents with urticarial papules and plaques; onset occurs in the third trimester or postpartum and initially involves the striae while sparing the umbilicus, unlike in PG. Atopic eruption of pregnancy has an earlier onset than the other pregnancy-specific dermatoses, often in the first or second trimester, and presents with widespread eczematous lesions.3

Diagnosis

The pregnancy dermatoses with the greatest potential for fetal risks are ICP and PG; therefore, it is critical for health care providers to diagnose these dermatoses in a timely manner and initiate appropriate management. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is confirmed by elevated serum bile acids (ie, >10 µmol/L), often during the third trimester. The risk of fetal morbidity is high in ICP with increased bile acids crossing the placenta causing placental anoxia and impaired cardiomyocyte function.4 Fetal risks, including preterm delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and stillbirth, correlate with the level of bile acids in the serum.5 Maternal prognosis is favorable, but there is an increased association with hepatitis C and hepatobiliary disease.6

Diagnosis of PG is confirmed by classic biopsy results and direct immunofluorescence revealing C3 with or without IgG in a linear band along the basement membrane zone. Additionally, complement indirect immunofluorescence reveals circulating IgG anti–basement membrane zone antibodies. Pemphigoid gestationis is associated with increased fetal risks of preterm labor and intrauterine growth retardation.7 Clinical findings of PG may present in the fetus upon delivery due to transmission of autoantibodies across the placenta. The symptoms usually are mild.8 An increased risk of Graves disease has been reported in mothers with PG.

In most cases, diagnosis of PEP is based on history and morphology, but if the presentation is not classic, skin biopsy must be used to differentiate it from PG as well as more common dermatologic conditions such as contact dermatitis, drug and viral eruptions, and urticaria.

Atopic eruption of pregnancy manifests as widespread eczematous excoriated papules and plaques. Lesions of prurigo nodularis are common.

Comorbidities

It is important to be aware of specific clinical associations related to pregnancy-specific dermatoses. Pemphigoid gestationis has been associated with gestational trophoblastic tumors including hydatiform mole and choriocarcinoma.4 An increased risk for Graves disease has been reported in patients with PG.9 Patients who develop ICP have a higher incidence of hepatitis C, postpartum cholecystitis, gallstones, and nonalcoholic cirrhosis.8 Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy is associated with a notably higher incidence in multiple gestation pregnancies.2

Treatment and Management

Management of ICP requires an accurate and timely diagnosis, and advanced neonatal-obstetric management is critical.3 Ursodeoxycholic acid is the treatment of choice and reduces pruritus, prolongs pregnancy, and reduces fetal risk.4 Most stillbirths cluster at the 38th week of pregnancy, and patients with ICP and highly elevated serum bile acids (>40 µmol/L) should be considered for delivery at 37 weeks or earlier.5

Management of the other cutaneous disorders of pregnancy can be challenging for health care providers based on safety concerns for the fetus. Although it is important to minimize risks to the fetus, it also is important to adequately treat the mother’s cutaneous disease, which requires a solid knowledge of drug safety during pregnancy. The former US Food and Drug Administration classification system using A, B, C, D, and X pregnancy categories was replaced by the Pregnancy Lactation Label Final Rule, which provides counseling on medication safety during pregnancy.10 In 2014, Murase et al11 published a review of dermatologic medication safety during pregnancy, which serves as an excellent guide.

Before instituting treatment, the therapeutic plan should be discussed with the physician managing the patient’s pregnancy. In general, topical steroids are considered safe during pregnancy, and low-potency to moderate-potency topical steroids are preferred. If possible, use of topical steroids should be limited to less than 300 g for the duration of the pregnancy. Fluticasone propionate should be avoided during pregnancy because it is not metabolized by the placenta. When systemic steroids are considered appropriate for management during pregnancy, nonhalogenated corticosteroids such as prednisone and prednisolone are preferred because they are enzymatically inactivated by the placenta, which results in a favorable maternal-fetal gradient.12 There has been concern expressed in the medical literature that systemic steroids during the first trimester may increase the risk of cleft lip and cleft palate.3,12 When managing pregnancy dermatoses, consideration should be given to keep prednisone exposure below 20 mg/d, and try to limit prolonged use to 7.5 mg/d. However, this may not be possible in PG.3 Vitamin D and calcium supplementation may be appropriate when patients are on prolonged systemic steroids to control disease.