User login

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - February 2018

The patient was diagnosed with pityriasis rosea (PR) on the basis of the clinical findings; a biopsy was not performed. The patient’s pruritus was treated with oral hydroxyzine and topical 1% triamcinolone ointment. She experienced itch relief with these treatments. On follow-up at 3 months, the patient’s lesions had mostly resolved with some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

In some patients, flu-like symptoms precede the onset of skin lesions; this has led to speculation regarding a viral etiology for PR. This prodrome, which is present in as many as half of all cases,can include mild headache, low-grade fever, joint aches, or malaise.2 Pityriasis rosea is thought to occur secondary to a systemic activation of human herpesviruses (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. Three cases of PR have been reported in the setting of H1N1 influenza virus infection.3 In one small study, HHV-8 was detected by polymerase chain reaction in approximately 20% of biopsy samples of lesional skin in patients with PR.4 However, most research on a viral etiology for pityriasis rosea has focused on HHV-6 and to a lesser extent HHV-7. DNA from both viruses has been isolated from PR lesions, but at varying detection rates.5,6 Furthermore, HHV-7 DNA has been isolated in as many as 14% of normal individuals without pityriasis rosea, suggesting that the presence of this virus on the skin is fairly common.7

Pityriasis rosea occurs in males and females of all ethnicities, with a slight female predominance. It is rare in young children and older adults. Most cases occur in adolescents and in adults in their twenties and early thirties. Cases occur most frequently in fall and spring.8

The herald patch of pityriasis rosea is typically solitary, but cases with multiple herald patches have been described. The herald patch can range in size from 1-10 cm and usually contains the best example of trailing scale – scale seen on the inside edge of the annular lesion. The satellite lesions of pityriasis rosea are typically papules or plaques with a collarette of scale. These lesions usually are oriented along the Langer cleavage lines, giving them a “Christmas tree” configuration when they appear on the posterior trunk.

Mimics

The herald patch of pityriasis rosea can resemble tinea corporis, and if there is any doubt as to the diagnosis, potassium hydroxide examination (also known as a KOH test) and/or fungal culture should be done to rule out a fungal etiology. However, certain features of this case, particularly the subsequent development of satellite lesions, are more consistent with pityriasis rosea.

Secondary syphilis should be considered in patients who are sexually active. The lesions of secondary syphilis are not typically pruritic, and involvement of the palms and soles is common (whereas such involvement is rare in pityriasis rosea).

Like pityriasis rosea, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) is characterized by papular lesions that resolve spontaneously; the lesions of PLEVA usually evolve to vesicular, necrotic, and purpuric papules that take longer to resolve than PR lesions. The lesions of PLEVA are more erythematous, pustular, and crusting than the lesions of pityriasis rosea.

Guttate psoriasis, which occurs following streptococcal pharyngitis in over 50% of patients, does not present with a herald lesion or distribution along Langer’s lines.10 If guttate psoriasis is suspected, rapid streptococcal testing of the throat or perianal area may be considered.

Nummular eczema presents as papules that enlarge to form erythematous, lichenified plaques that measure 1-2 cm in diameter. A relatively sudden eruption, such as this patient’s, would be unusual for nummular eczema. Also, nummular eczema typically occurs on xerotic skin, more often on the extremities than the trunk.

Diagnostic tests, treatment

Most patients do not require specific therapy for pityriasis rosea. Patients should be reassured that PR is typically a self-limited disease without long-term sequelae. Pregnant patients who develop pityriasis rosea in the first trimester may be at higher risk for spontaneous abortion,although data on the subject are sorely lacking.11 Oral antihistamines are useful in reducing pruritus associated with PR, and some patients experience relief by applying a low-potency topical corticosteroid.

In more severe cases, or in cases in which the patient is greatly distressed by the lesions, both broadband and narrowband UVB phototherapy effectively improve severity of lesions and reduces symptoms.12 These observations suggest that moderate sun exposure can help to reduce severity of PR lesions and hasten their resolution, but no studies assessing the effect of sun exposure on pityriasis rosea symptoms have been performed.

Furthermore, the possible role of the HHV-6 in PR has led some investigators to explore the utility of acyclovir in managing pityriasis rosea.13 One group recently found that 400 mg of acyclovir three times per day for 7 days decreased the number of lesions and pruritus associated with pityriasis rosea, compared those seen in controls, at 1-month follow-up.13

Timely recognition of the diagnosis, consideration of mimics, and ample reassurance are appropriate when approaching this disease.

Mr. Kusari is with the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and the departments of dermatology and pediatrics, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. They have no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Dermatology. 2015;231(1):9-14.

2. World J Clin Cases. 2017 Jun 16;5(6):203-11.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011 May-Jun;28(3):341-2.

4. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006 Jul;20(6):667-71.

5. Dermatology. 1997;195(4):374-8.

6. J Invest Dermatol. 2005 Jun;124(6):1234-40.

7. Arch Dermatol. 1999 Sep;135(9):1070-2.

8. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982 Jul;7(1):80-9.

9. Iran J Pediatr. 2010 Jun;20(2):237-41.

10. J Pediatr. 1988 Dec;113(6):1037-9.

11. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 May;58(5 Suppl 1):S78-83.

12. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995 Dec;33(6):996-9.

13. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015 May-Jun;6(3):181-4.

The patient was diagnosed with pityriasis rosea (PR) on the basis of the clinical findings; a biopsy was not performed. The patient’s pruritus was treated with oral hydroxyzine and topical 1% triamcinolone ointment. She experienced itch relief with these treatments. On follow-up at 3 months, the patient’s lesions had mostly resolved with some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

In some patients, flu-like symptoms precede the onset of skin lesions; this has led to speculation regarding a viral etiology for PR. This prodrome, which is present in as many as half of all cases,can include mild headache, low-grade fever, joint aches, or malaise.2 Pityriasis rosea is thought to occur secondary to a systemic activation of human herpesviruses (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. Three cases of PR have been reported in the setting of H1N1 influenza virus infection.3 In one small study, HHV-8 was detected by polymerase chain reaction in approximately 20% of biopsy samples of lesional skin in patients with PR.4 However, most research on a viral etiology for pityriasis rosea has focused on HHV-6 and to a lesser extent HHV-7. DNA from both viruses has been isolated from PR lesions, but at varying detection rates.5,6 Furthermore, HHV-7 DNA has been isolated in as many as 14% of normal individuals without pityriasis rosea, suggesting that the presence of this virus on the skin is fairly common.7

Pityriasis rosea occurs in males and females of all ethnicities, with a slight female predominance. It is rare in young children and older adults. Most cases occur in adolescents and in adults in their twenties and early thirties. Cases occur most frequently in fall and spring.8

The herald patch of pityriasis rosea is typically solitary, but cases with multiple herald patches have been described. The herald patch can range in size from 1-10 cm and usually contains the best example of trailing scale – scale seen on the inside edge of the annular lesion. The satellite lesions of pityriasis rosea are typically papules or plaques with a collarette of scale. These lesions usually are oriented along the Langer cleavage lines, giving them a “Christmas tree” configuration when they appear on the posterior trunk.

Mimics

The herald patch of pityriasis rosea can resemble tinea corporis, and if there is any doubt as to the diagnosis, potassium hydroxide examination (also known as a KOH test) and/or fungal culture should be done to rule out a fungal etiology. However, certain features of this case, particularly the subsequent development of satellite lesions, are more consistent with pityriasis rosea.

Secondary syphilis should be considered in patients who are sexually active. The lesions of secondary syphilis are not typically pruritic, and involvement of the palms and soles is common (whereas such involvement is rare in pityriasis rosea).

Like pityriasis rosea, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) is characterized by papular lesions that resolve spontaneously; the lesions of PLEVA usually evolve to vesicular, necrotic, and purpuric papules that take longer to resolve than PR lesions. The lesions of PLEVA are more erythematous, pustular, and crusting than the lesions of pityriasis rosea.

Guttate psoriasis, which occurs following streptococcal pharyngitis in over 50% of patients, does not present with a herald lesion or distribution along Langer’s lines.10 If guttate psoriasis is suspected, rapid streptococcal testing of the throat or perianal area may be considered.

Nummular eczema presents as papules that enlarge to form erythematous, lichenified plaques that measure 1-2 cm in diameter. A relatively sudden eruption, such as this patient’s, would be unusual for nummular eczema. Also, nummular eczema typically occurs on xerotic skin, more often on the extremities than the trunk.

Diagnostic tests, treatment

Most patients do not require specific therapy for pityriasis rosea. Patients should be reassured that PR is typically a self-limited disease without long-term sequelae. Pregnant patients who develop pityriasis rosea in the first trimester may be at higher risk for spontaneous abortion,although data on the subject are sorely lacking.11 Oral antihistamines are useful in reducing pruritus associated with PR, and some patients experience relief by applying a low-potency topical corticosteroid.

In more severe cases, or in cases in which the patient is greatly distressed by the lesions, both broadband and narrowband UVB phototherapy effectively improve severity of lesions and reduces symptoms.12 These observations suggest that moderate sun exposure can help to reduce severity of PR lesions and hasten their resolution, but no studies assessing the effect of sun exposure on pityriasis rosea symptoms have been performed.

Furthermore, the possible role of the HHV-6 in PR has led some investigators to explore the utility of acyclovir in managing pityriasis rosea.13 One group recently found that 400 mg of acyclovir three times per day for 7 days decreased the number of lesions and pruritus associated with pityriasis rosea, compared those seen in controls, at 1-month follow-up.13

Timely recognition of the diagnosis, consideration of mimics, and ample reassurance are appropriate when approaching this disease.

Mr. Kusari is with the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and the departments of dermatology and pediatrics, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. They have no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Dermatology. 2015;231(1):9-14.

2. World J Clin Cases. 2017 Jun 16;5(6):203-11.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011 May-Jun;28(3):341-2.

4. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006 Jul;20(6):667-71.

5. Dermatology. 1997;195(4):374-8.

6. J Invest Dermatol. 2005 Jun;124(6):1234-40.

7. Arch Dermatol. 1999 Sep;135(9):1070-2.

8. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982 Jul;7(1):80-9.

9. Iran J Pediatr. 2010 Jun;20(2):237-41.

10. J Pediatr. 1988 Dec;113(6):1037-9.

11. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 May;58(5 Suppl 1):S78-83.

12. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995 Dec;33(6):996-9.

13. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015 May-Jun;6(3):181-4.

The patient was diagnosed with pityriasis rosea (PR) on the basis of the clinical findings; a biopsy was not performed. The patient’s pruritus was treated with oral hydroxyzine and topical 1% triamcinolone ointment. She experienced itch relief with these treatments. On follow-up at 3 months, the patient’s lesions had mostly resolved with some postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

In some patients, flu-like symptoms precede the onset of skin lesions; this has led to speculation regarding a viral etiology for PR. This prodrome, which is present in as many as half of all cases,can include mild headache, low-grade fever, joint aches, or malaise.2 Pityriasis rosea is thought to occur secondary to a systemic activation of human herpesviruses (HHV) 6 and/or HHV-7. Three cases of PR have been reported in the setting of H1N1 influenza virus infection.3 In one small study, HHV-8 was detected by polymerase chain reaction in approximately 20% of biopsy samples of lesional skin in patients with PR.4 However, most research on a viral etiology for pityriasis rosea has focused on HHV-6 and to a lesser extent HHV-7. DNA from both viruses has been isolated from PR lesions, but at varying detection rates.5,6 Furthermore, HHV-7 DNA has been isolated in as many as 14% of normal individuals without pityriasis rosea, suggesting that the presence of this virus on the skin is fairly common.7

Pityriasis rosea occurs in males and females of all ethnicities, with a slight female predominance. It is rare in young children and older adults. Most cases occur in adolescents and in adults in their twenties and early thirties. Cases occur most frequently in fall and spring.8

The herald patch of pityriasis rosea is typically solitary, but cases with multiple herald patches have been described. The herald patch can range in size from 1-10 cm and usually contains the best example of trailing scale – scale seen on the inside edge of the annular lesion. The satellite lesions of pityriasis rosea are typically papules or plaques with a collarette of scale. These lesions usually are oriented along the Langer cleavage lines, giving them a “Christmas tree” configuration when they appear on the posterior trunk.

Mimics

The herald patch of pityriasis rosea can resemble tinea corporis, and if there is any doubt as to the diagnosis, potassium hydroxide examination (also known as a KOH test) and/or fungal culture should be done to rule out a fungal etiology. However, certain features of this case, particularly the subsequent development of satellite lesions, are more consistent with pityriasis rosea.

Secondary syphilis should be considered in patients who are sexually active. The lesions of secondary syphilis are not typically pruritic, and involvement of the palms and soles is common (whereas such involvement is rare in pityriasis rosea).

Like pityriasis rosea, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) is characterized by papular lesions that resolve spontaneously; the lesions of PLEVA usually evolve to vesicular, necrotic, and purpuric papules that take longer to resolve than PR lesions. The lesions of PLEVA are more erythematous, pustular, and crusting than the lesions of pityriasis rosea.

Guttate psoriasis, which occurs following streptococcal pharyngitis in over 50% of patients, does not present with a herald lesion or distribution along Langer’s lines.10 If guttate psoriasis is suspected, rapid streptococcal testing of the throat or perianal area may be considered.

Nummular eczema presents as papules that enlarge to form erythematous, lichenified plaques that measure 1-2 cm in diameter. A relatively sudden eruption, such as this patient’s, would be unusual for nummular eczema. Also, nummular eczema typically occurs on xerotic skin, more often on the extremities than the trunk.

Diagnostic tests, treatment

Most patients do not require specific therapy for pityriasis rosea. Patients should be reassured that PR is typically a self-limited disease without long-term sequelae. Pregnant patients who develop pityriasis rosea in the first trimester may be at higher risk for spontaneous abortion,although data on the subject are sorely lacking.11 Oral antihistamines are useful in reducing pruritus associated with PR, and some patients experience relief by applying a low-potency topical corticosteroid.

In more severe cases, or in cases in which the patient is greatly distressed by the lesions, both broadband and narrowband UVB phototherapy effectively improve severity of lesions and reduces symptoms.12 These observations suggest that moderate sun exposure can help to reduce severity of PR lesions and hasten their resolution, but no studies assessing the effect of sun exposure on pityriasis rosea symptoms have been performed.

Furthermore, the possible role of the HHV-6 in PR has led some investigators to explore the utility of acyclovir in managing pityriasis rosea.13 One group recently found that 400 mg of acyclovir three times per day for 7 days decreased the number of lesions and pruritus associated with pityriasis rosea, compared those seen in controls, at 1-month follow-up.13

Timely recognition of the diagnosis, consideration of mimics, and ample reassurance are appropriate when approaching this disease.

Mr. Kusari is with the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, and the departments of dermatology and pediatrics, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego. They have no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. Dermatology. 2015;231(1):9-14.

2. World J Clin Cases. 2017 Jun 16;5(6):203-11.

3. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011 May-Jun;28(3):341-2.

4. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006 Jul;20(6):667-71.

5. Dermatology. 1997;195(4):374-8.

6. J Invest Dermatol. 2005 Jun;124(6):1234-40.

7. Arch Dermatol. 1999 Sep;135(9):1070-2.

8. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982 Jul;7(1):80-9.

9. Iran J Pediatr. 2010 Jun;20(2):237-41.

10. J Pediatr. 1988 Dec;113(6):1037-9.

11. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 May;58(5 Suppl 1):S78-83.

12. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995 Dec;33(6):996-9.

13. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015 May-Jun;6(3):181-4.

A 6-year-old female presents to the pediatric dermatology office with a 2-day history of a slightly itchy skin lesion on her back. Her birthday was a week prior, and her mother gave her a new kitten, and since then she has been playing with the kitten daily. She has tried some over-the-counter antifungal cream since the lesion first appeared, but there hasn’t been much improvement. The night prior to presenting to the office, the mother noticed more lesions developing on the child’s torso, and because of this, she became worried.

On physical exam, the patient is well appearing, and vital signs are normal. She has multiple scaly, pink, oval plaques and papules on her torso. There are no oral lesions, and her palms and soles are spared.

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - November 2017

The patient was diagnosed with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) based on clinical presentation of the lesions and associated symptoms of arthralgia and abdominal pain. Urinalysis was obtained and found to be unremarkable, at presentation and follow-up, and treatment with naproxen 5 mg/kg divided into two doses per day was started for pain relief. A prednisone taper starting at 1 mg/kg per day for 3 weeks also was started due to the presence of severe abdominal pain and bullae on exam. The patient was followed with regular urine studies and blood pressure checks for 2 months, and these also were within normal limits.

HSP, also known as anaphylactoid purpura and immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis, is a small vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by the perivascular deposition of IgA1-based immune complexes in the walls of arterioles and postcapillary venules.1 In the vast majority of cases, the condition resolves spontaneously in 4-6 weeks and does not require any specific treatment,2 although NSAIDs and systemic corticosteroids can be used for mild-to-moderate and severe pain, respectively.3

HSP is the most common vasculitis in children, with a peak incidence in boys under the age of 5 years. It occurs worldwide, more commonly among whites and Asians, less commonly among blacks, and recent studies from the Czech Republic,4 Taiwan,5 Spain,6 France,7 South Korea,8 and the United Kingdom9 have shown similar incidence rates of 10-20 per 100,000 children. HSP does occur in adults, but is less common, and is known to carry a worse prognosis – in particular, a higher risk of progression to chronic kidney disease. The disease is more commonly seen in winter months,1 unsurprisingly as upper respiratory tract infections also are more common in these months.10

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis of HSP is the subject of ongoing investigation and continued controversy. Mutations and polymorphisms in mannose-binding lectin, interleukins 1 and 8, vascular endothelial growth factor, and alpha-1-antitrypsin have been associated with HSP.3 Immunoglobulin A (IgA) normally exists in two heavily glycosylated forms – IgA1 and IgA2. Abnormal glycosylation, particularly undergalactosylation, of IgA1, the predominant form of IgA in serum and mucosal secretions, has been linked to HSP.11 HSP has been associated with group A streptococcal infections, Bartonella henselae (cat scratch fever) and numerous drugs,12 although no definitive causal or mechanistic explanation has been identified.

Diagnosis

Two major diagnostic criteria for HSP are widely in use, one developed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 199013 and the other by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) in 2005.14 Both the ACR and EULAR criteria include acute abdominal pain, purpura, and microscopic evidence of vasculitis. Almost all patients with HSP have cutaneous purpura, and many of these patients have palpable purpura, which is pathognomonic of a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, but palpable purpura is not needed for diagnosis. The ACR criteria additionally include age of 20 years or younger, while the EULAR criteria include arthralgias and the presence of hematuria or proteinuria. Ancillary testing usually is not required to make the diagnosis, but when the diagnosis is not clear histopathologic analysis of a skin sample can identify leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Other laboratory studies that may be needed to rule out other conditions, as well as other organ involvement, include a complete blood count, which can be done to rule out thrombocytopenia as a cause of purpura, a metabolic panel, coagulation studies, occult blood test of stool, abdominal imaging, and urinalysis (UA), which can identify proteinuria or hematuria.

Abdominal pain in HSP is believed to be a result of vasculitis of the gastric, mesenteric, and/or colic vasculature. Bleeding from the inflamed vasculature rarely can lead to gross hematochezia, frank melena, or hematemesis. One serious, potential complication of HSP-related mesenteric vasculitis is intussusception, which is otherwise rare in children older than 2 years. Intussusception should be suspected if features of the classic triad of episodic abdominal pain, sausage-shaped abdominal mass, and currant jelly stool are present. Abdominal ultrasound can help to determine whether intussusception is present.

The purpura in HSP presents in waves or crops, and crops last 5-10 days each. Complete resolution takes 4-6 weeks. If biopsy is desired to confirm the diagnosis, it should be done on a lesion less than 24 hours old. This allows for identification of perivascular IgA on histopathology: beyond 24 hours, IgG and IgM also leak out, contributing to a less specific histopathologic picture.

Accurate diagnosis of HSP is important to guide therapy and anticipate potential complications. Wegener’s granulomatosis (A), also known as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, classically involves the upper and lower respiratory tract and the kidneys, leading to a presentation of epistaxis, cough, and hypertension. It occurs more commonly in adults than children. Finkelstein disease (B), also known as acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI), is characterized by the development of petechial, urticarial, or targetoid plaques over 24-48 hours with tender edema and fever in children aged less than 2 years. Unlike HSP, AHEI typically does not involve the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, or joints. Biopsy of skin lesions of AHEI reveals IgA deposition and leukocytoclastic vasculitis, leading some authors to consider it a closely related entity to HSP. Microscopic polyangiitis (D) is an uncommon pauci-immune vasculitis similar to Wegener’s granulomatosis, but lacking granulomas. It presents typically in the 5th decade of life with fever, fatigue, weight loss, and renal involvement. IgA nephropathy (E), also known as synpharyngitic nephritis and Berger disease, is less likely than HSP to cause a rash, joint pain, or abdominal pain. The nomenclature of HSP (whose alternate name is IgA vasculitis) reflects the multi-organ nature of HSP in comparison to IgA nephropathy, which is more likely to be limited to the kidneys.

Treatment

Aside from intussusception and renal disease, which may result from HSP, treatment is not typically required for HSP as it resolves spontaneously. Patients with significant arthralgias are likely to benefit from NSAIDs such as naproxen 5-20 mg/kg per day, although NSAIDs should be avoided if there is significant renal dysfunction or GI bleeding. Patients with severe abdominal pain or joint pain may be more likely to benefit from oral corticosteroids, particularly prednisone 1-2 mg/kg per day. A meta-analysis showed that corticosteroids significantly reduce the duration of symptoms if given early in the course of disease.15

The prognosis is usually excellent, except for a very small sample of the population (5%) that can develop end-stage renal disease. It is recommended that all children with HSP continue monitoring blood pressure and UA either weekly or biweekly for the first 2 months and then once a month for 6-12 months.16

First described in 1801 by a British physician, HSP is a common and usually self-limited disease for which our understanding has advanced greatly over the past 2 centuries, yet for which many important questions regarding pathophysiology remain unanswered. No diagnostic tests or treatments are needed for the majority of patients. Providers should include HSP in the differential diagnosis for the child with unexplained abdominal pain, renal dysfunction, or nonthrombocytopenic purpura.

Mr. Kusari is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matiz is a practicing dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group in La Mesa, California. Dr. Matiz and Mr. Kusari said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. “Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence”, 5th ed. (New York: Elsevier, 2016).

2. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):976-8.

3. “Dermatology”, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012).

4. J Rheumatol. 2004 Nov;31(11):2295-9.

5. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005 May;44(5):618-22.

6. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014 Mar;93(2):106-13.

7. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(8):1358-66.

8. J Korean Med Sci. 2014 Feb;29(2):198-203.

9. Lancet. 2002 Oct 19;360(9341):1197-202.

10. Rhinology. 2015 Jun;53(2):99-106.

11. PLoS One. 2016 Nov 21;11(11):e0166700.

12. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002 Jan;21(1):28-31.

13. Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Aug;33(8):1114-21.

14. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Jul;65(7):936-41.

15. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120(5):1079-87.

16. Arch Dis Child. 2010 Nov;95(11):877-82.

The patient was diagnosed with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) based on clinical presentation of the lesions and associated symptoms of arthralgia and abdominal pain. Urinalysis was obtained and found to be unremarkable, at presentation and follow-up, and treatment with naproxen 5 mg/kg divided into two doses per day was started for pain relief. A prednisone taper starting at 1 mg/kg per day for 3 weeks also was started due to the presence of severe abdominal pain and bullae on exam. The patient was followed with regular urine studies and blood pressure checks for 2 months, and these also were within normal limits.

HSP, also known as anaphylactoid purpura and immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis, is a small vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by the perivascular deposition of IgA1-based immune complexes in the walls of arterioles and postcapillary venules.1 In the vast majority of cases, the condition resolves spontaneously in 4-6 weeks and does not require any specific treatment,2 although NSAIDs and systemic corticosteroids can be used for mild-to-moderate and severe pain, respectively.3

HSP is the most common vasculitis in children, with a peak incidence in boys under the age of 5 years. It occurs worldwide, more commonly among whites and Asians, less commonly among blacks, and recent studies from the Czech Republic,4 Taiwan,5 Spain,6 France,7 South Korea,8 and the United Kingdom9 have shown similar incidence rates of 10-20 per 100,000 children. HSP does occur in adults, but is less common, and is known to carry a worse prognosis – in particular, a higher risk of progression to chronic kidney disease. The disease is more commonly seen in winter months,1 unsurprisingly as upper respiratory tract infections also are more common in these months.10

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis of HSP is the subject of ongoing investigation and continued controversy. Mutations and polymorphisms in mannose-binding lectin, interleukins 1 and 8, vascular endothelial growth factor, and alpha-1-antitrypsin have been associated with HSP.3 Immunoglobulin A (IgA) normally exists in two heavily glycosylated forms – IgA1 and IgA2. Abnormal glycosylation, particularly undergalactosylation, of IgA1, the predominant form of IgA in serum and mucosal secretions, has been linked to HSP.11 HSP has been associated with group A streptococcal infections, Bartonella henselae (cat scratch fever) and numerous drugs,12 although no definitive causal or mechanistic explanation has been identified.

Diagnosis

Two major diagnostic criteria for HSP are widely in use, one developed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 199013 and the other by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) in 2005.14 Both the ACR and EULAR criteria include acute abdominal pain, purpura, and microscopic evidence of vasculitis. Almost all patients with HSP have cutaneous purpura, and many of these patients have palpable purpura, which is pathognomonic of a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, but palpable purpura is not needed for diagnosis. The ACR criteria additionally include age of 20 years or younger, while the EULAR criteria include arthralgias and the presence of hematuria or proteinuria. Ancillary testing usually is not required to make the diagnosis, but when the diagnosis is not clear histopathologic analysis of a skin sample can identify leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Other laboratory studies that may be needed to rule out other conditions, as well as other organ involvement, include a complete blood count, which can be done to rule out thrombocytopenia as a cause of purpura, a metabolic panel, coagulation studies, occult blood test of stool, abdominal imaging, and urinalysis (UA), which can identify proteinuria or hematuria.

Abdominal pain in HSP is believed to be a result of vasculitis of the gastric, mesenteric, and/or colic vasculature. Bleeding from the inflamed vasculature rarely can lead to gross hematochezia, frank melena, or hematemesis. One serious, potential complication of HSP-related mesenteric vasculitis is intussusception, which is otherwise rare in children older than 2 years. Intussusception should be suspected if features of the classic triad of episodic abdominal pain, sausage-shaped abdominal mass, and currant jelly stool are present. Abdominal ultrasound can help to determine whether intussusception is present.

The purpura in HSP presents in waves or crops, and crops last 5-10 days each. Complete resolution takes 4-6 weeks. If biopsy is desired to confirm the diagnosis, it should be done on a lesion less than 24 hours old. This allows for identification of perivascular IgA on histopathology: beyond 24 hours, IgG and IgM also leak out, contributing to a less specific histopathologic picture.

Accurate diagnosis of HSP is important to guide therapy and anticipate potential complications. Wegener’s granulomatosis (A), also known as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, classically involves the upper and lower respiratory tract and the kidneys, leading to a presentation of epistaxis, cough, and hypertension. It occurs more commonly in adults than children. Finkelstein disease (B), also known as acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI), is characterized by the development of petechial, urticarial, or targetoid plaques over 24-48 hours with tender edema and fever in children aged less than 2 years. Unlike HSP, AHEI typically does not involve the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, or joints. Biopsy of skin lesions of AHEI reveals IgA deposition and leukocytoclastic vasculitis, leading some authors to consider it a closely related entity to HSP. Microscopic polyangiitis (D) is an uncommon pauci-immune vasculitis similar to Wegener’s granulomatosis, but lacking granulomas. It presents typically in the 5th decade of life with fever, fatigue, weight loss, and renal involvement. IgA nephropathy (E), also known as synpharyngitic nephritis and Berger disease, is less likely than HSP to cause a rash, joint pain, or abdominal pain. The nomenclature of HSP (whose alternate name is IgA vasculitis) reflects the multi-organ nature of HSP in comparison to IgA nephropathy, which is more likely to be limited to the kidneys.

Treatment

Aside from intussusception and renal disease, which may result from HSP, treatment is not typically required for HSP as it resolves spontaneously. Patients with significant arthralgias are likely to benefit from NSAIDs such as naproxen 5-20 mg/kg per day, although NSAIDs should be avoided if there is significant renal dysfunction or GI bleeding. Patients with severe abdominal pain or joint pain may be more likely to benefit from oral corticosteroids, particularly prednisone 1-2 mg/kg per day. A meta-analysis showed that corticosteroids significantly reduce the duration of symptoms if given early in the course of disease.15

The prognosis is usually excellent, except for a very small sample of the population (5%) that can develop end-stage renal disease. It is recommended that all children with HSP continue monitoring blood pressure and UA either weekly or biweekly for the first 2 months and then once a month for 6-12 months.16

First described in 1801 by a British physician, HSP is a common and usually self-limited disease for which our understanding has advanced greatly over the past 2 centuries, yet for which many important questions regarding pathophysiology remain unanswered. No diagnostic tests or treatments are needed for the majority of patients. Providers should include HSP in the differential diagnosis for the child with unexplained abdominal pain, renal dysfunction, or nonthrombocytopenic purpura.

Mr. Kusari is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matiz is a practicing dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group in La Mesa, California. Dr. Matiz and Mr. Kusari said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. “Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence”, 5th ed. (New York: Elsevier, 2016).

2. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):976-8.

3. “Dermatology”, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012).

4. J Rheumatol. 2004 Nov;31(11):2295-9.

5. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005 May;44(5):618-22.

6. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014 Mar;93(2):106-13.

7. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(8):1358-66.

8. J Korean Med Sci. 2014 Feb;29(2):198-203.

9. Lancet. 2002 Oct 19;360(9341):1197-202.

10. Rhinology. 2015 Jun;53(2):99-106.

11. PLoS One. 2016 Nov 21;11(11):e0166700.

12. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002 Jan;21(1):28-31.

13. Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Aug;33(8):1114-21.

14. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Jul;65(7):936-41.

15. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120(5):1079-87.

16. Arch Dis Child. 2010 Nov;95(11):877-82.

The patient was diagnosed with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) based on clinical presentation of the lesions and associated symptoms of arthralgia and abdominal pain. Urinalysis was obtained and found to be unremarkable, at presentation and follow-up, and treatment with naproxen 5 mg/kg divided into two doses per day was started for pain relief. A prednisone taper starting at 1 mg/kg per day for 3 weeks also was started due to the presence of severe abdominal pain and bullae on exam. The patient was followed with regular urine studies and blood pressure checks for 2 months, and these also were within normal limits.

HSP, also known as anaphylactoid purpura and immunoglobulin A (IgA) vasculitis, is a small vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by the perivascular deposition of IgA1-based immune complexes in the walls of arterioles and postcapillary venules.1 In the vast majority of cases, the condition resolves spontaneously in 4-6 weeks and does not require any specific treatment,2 although NSAIDs and systemic corticosteroids can be used for mild-to-moderate and severe pain, respectively.3

HSP is the most common vasculitis in children, with a peak incidence in boys under the age of 5 years. It occurs worldwide, more commonly among whites and Asians, less commonly among blacks, and recent studies from the Czech Republic,4 Taiwan,5 Spain,6 France,7 South Korea,8 and the United Kingdom9 have shown similar incidence rates of 10-20 per 100,000 children. HSP does occur in adults, but is less common, and is known to carry a worse prognosis – in particular, a higher risk of progression to chronic kidney disease. The disease is more commonly seen in winter months,1 unsurprisingly as upper respiratory tract infections also are more common in these months.10

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis of HSP is the subject of ongoing investigation and continued controversy. Mutations and polymorphisms in mannose-binding lectin, interleukins 1 and 8, vascular endothelial growth factor, and alpha-1-antitrypsin have been associated with HSP.3 Immunoglobulin A (IgA) normally exists in two heavily glycosylated forms – IgA1 and IgA2. Abnormal glycosylation, particularly undergalactosylation, of IgA1, the predominant form of IgA in serum and mucosal secretions, has been linked to HSP.11 HSP has been associated with group A streptococcal infections, Bartonella henselae (cat scratch fever) and numerous drugs,12 although no definitive causal or mechanistic explanation has been identified.

Diagnosis

Two major diagnostic criteria for HSP are widely in use, one developed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 199013 and the other by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) in 2005.14 Both the ACR and EULAR criteria include acute abdominal pain, purpura, and microscopic evidence of vasculitis. Almost all patients with HSP have cutaneous purpura, and many of these patients have palpable purpura, which is pathognomonic of a leukocytoclastic vasculitis, but palpable purpura is not needed for diagnosis. The ACR criteria additionally include age of 20 years or younger, while the EULAR criteria include arthralgias and the presence of hematuria or proteinuria. Ancillary testing usually is not required to make the diagnosis, but when the diagnosis is not clear histopathologic analysis of a skin sample can identify leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Other laboratory studies that may be needed to rule out other conditions, as well as other organ involvement, include a complete blood count, which can be done to rule out thrombocytopenia as a cause of purpura, a metabolic panel, coagulation studies, occult blood test of stool, abdominal imaging, and urinalysis (UA), which can identify proteinuria or hematuria.

Abdominal pain in HSP is believed to be a result of vasculitis of the gastric, mesenteric, and/or colic vasculature. Bleeding from the inflamed vasculature rarely can lead to gross hematochezia, frank melena, or hematemesis. One serious, potential complication of HSP-related mesenteric vasculitis is intussusception, which is otherwise rare in children older than 2 years. Intussusception should be suspected if features of the classic triad of episodic abdominal pain, sausage-shaped abdominal mass, and currant jelly stool are present. Abdominal ultrasound can help to determine whether intussusception is present.

The purpura in HSP presents in waves or crops, and crops last 5-10 days each. Complete resolution takes 4-6 weeks. If biopsy is desired to confirm the diagnosis, it should be done on a lesion less than 24 hours old. This allows for identification of perivascular IgA on histopathology: beyond 24 hours, IgG and IgM also leak out, contributing to a less specific histopathologic picture.

Accurate diagnosis of HSP is important to guide therapy and anticipate potential complications. Wegener’s granulomatosis (A), also known as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, classically involves the upper and lower respiratory tract and the kidneys, leading to a presentation of epistaxis, cough, and hypertension. It occurs more commonly in adults than children. Finkelstein disease (B), also known as acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI), is characterized by the development of petechial, urticarial, or targetoid plaques over 24-48 hours with tender edema and fever in children aged less than 2 years. Unlike HSP, AHEI typically does not involve the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, or joints. Biopsy of skin lesions of AHEI reveals IgA deposition and leukocytoclastic vasculitis, leading some authors to consider it a closely related entity to HSP. Microscopic polyangiitis (D) is an uncommon pauci-immune vasculitis similar to Wegener’s granulomatosis, but lacking granulomas. It presents typically in the 5th decade of life with fever, fatigue, weight loss, and renal involvement. IgA nephropathy (E), also known as synpharyngitic nephritis and Berger disease, is less likely than HSP to cause a rash, joint pain, or abdominal pain. The nomenclature of HSP (whose alternate name is IgA vasculitis) reflects the multi-organ nature of HSP in comparison to IgA nephropathy, which is more likely to be limited to the kidneys.

Treatment

Aside from intussusception and renal disease, which may result from HSP, treatment is not typically required for HSP as it resolves spontaneously. Patients with significant arthralgias are likely to benefit from NSAIDs such as naproxen 5-20 mg/kg per day, although NSAIDs should be avoided if there is significant renal dysfunction or GI bleeding. Patients with severe abdominal pain or joint pain may be more likely to benefit from oral corticosteroids, particularly prednisone 1-2 mg/kg per day. A meta-analysis showed that corticosteroids significantly reduce the duration of symptoms if given early in the course of disease.15

The prognosis is usually excellent, except for a very small sample of the population (5%) that can develop end-stage renal disease. It is recommended that all children with HSP continue monitoring blood pressure and UA either weekly or biweekly for the first 2 months and then once a month for 6-12 months.16

First described in 1801 by a British physician, HSP is a common and usually self-limited disease for which our understanding has advanced greatly over the past 2 centuries, yet for which many important questions regarding pathophysiology remain unanswered. No diagnostic tests or treatments are needed for the majority of patients. Providers should include HSP in the differential diagnosis for the child with unexplained abdominal pain, renal dysfunction, or nonthrombocytopenic purpura.

Mr. Kusari is a medical student at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matiz is a practicing dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group in La Mesa, California. Dr. Matiz and Mr. Kusari said they had no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

References

1. “Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence”, 5th ed. (New York: Elsevier, 2016).

2. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):976-8.

3. “Dermatology”, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, 2012).

4. J Rheumatol. 2004 Nov;31(11):2295-9.

5. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005 May;44(5):618-22.

6. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014 Mar;93(2):106-13.

7. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(8):1358-66.

8. J Korean Med Sci. 2014 Feb;29(2):198-203.

9. Lancet. 2002 Oct 19;360(9341):1197-202.

10. Rhinology. 2015 Jun;53(2):99-106.

11. PLoS One. 2016 Nov 21;11(11):e0166700.

12. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002 Jan;21(1):28-31.

13. Arthritis Rheum. 1990 Aug;33(8):1114-21.

14. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006 Jul;65(7):936-41.

15. Pediatrics. 2007 Nov;120(5):1079-87.

16. Arch Dis Child. 2010 Nov;95(11):877-82.

Clinical presentation

A healthy 9-year-old boy presents with 1 week history of a rash that began as “bruises” on both ankles that subsequently ascended over a few days to the proximal lower extremities and upper extremities. The rash has been painful and pruritic at times. The patient’s mother reports regular application of hydrocortisone cream for itch and pain relief, and this has been somewhat successful.

The patient has a history of longstanding constipation and abdominal pain, but over the past week has reported abdominal pain that is different and more severe than his usual abdominal pain. This abdominal pain has limited oral intake over the past 2 days. The patient and family also report bilateral pain of the wrists and elbows, which has limited his daily activities. The patient and mother deny fevers, chills, cough, coryza, and any sick contacts.

His vital signs are stable. On physical examination there is mild conjunctival injection, no intraoral lesions, and no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. The abdomen is not distended but it is tender to deep palpation. Bowel sounds are present. On skin examination, there are multiple purpuric annular plaques with central clearing, some with bullae and petechiae, on the bilateral buttocks and legs. There is bilateral pedal edema. On the arms, there are a few polymorphic pink and red annular to targetoid plaques.

Painful Necrotic Ulcer on the Vulva

The Diagnosis: Mucormycosis

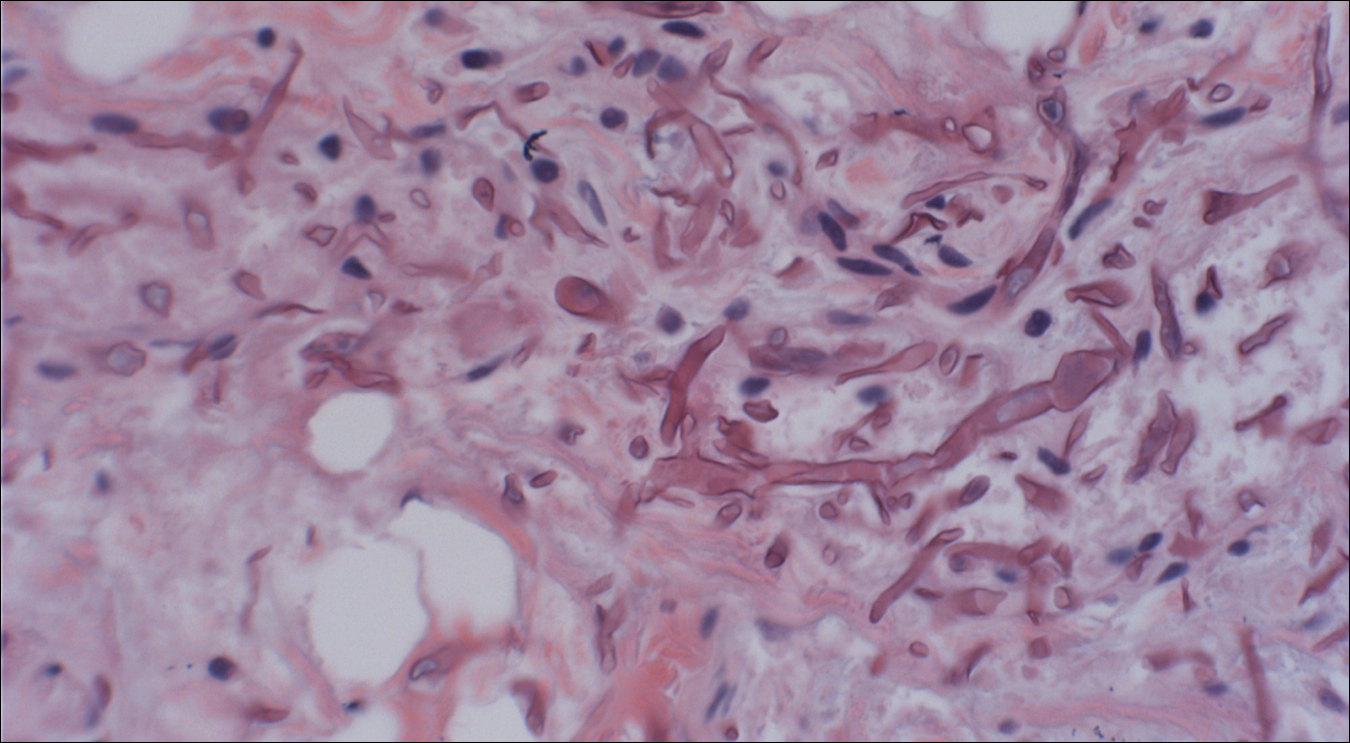

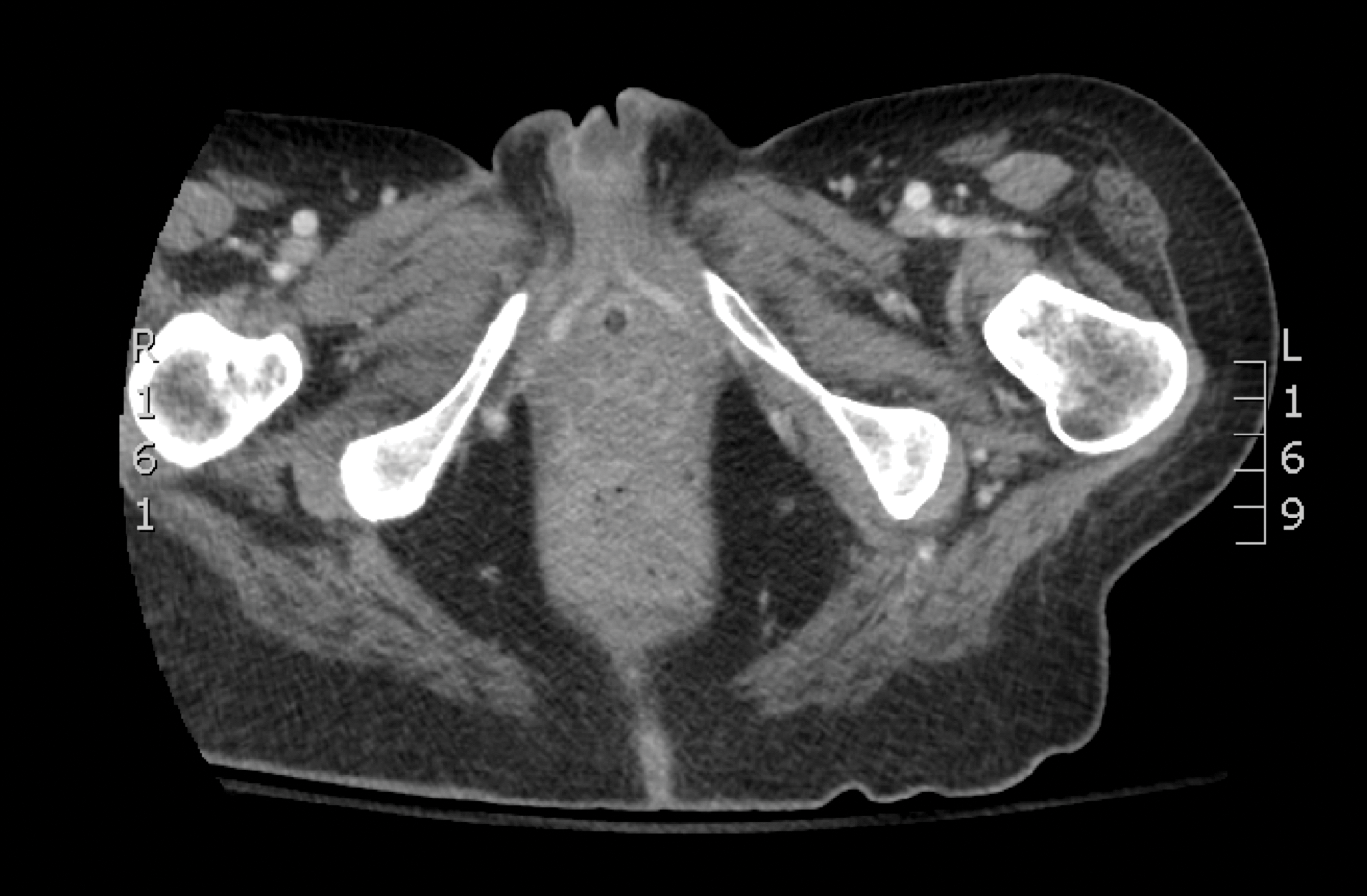

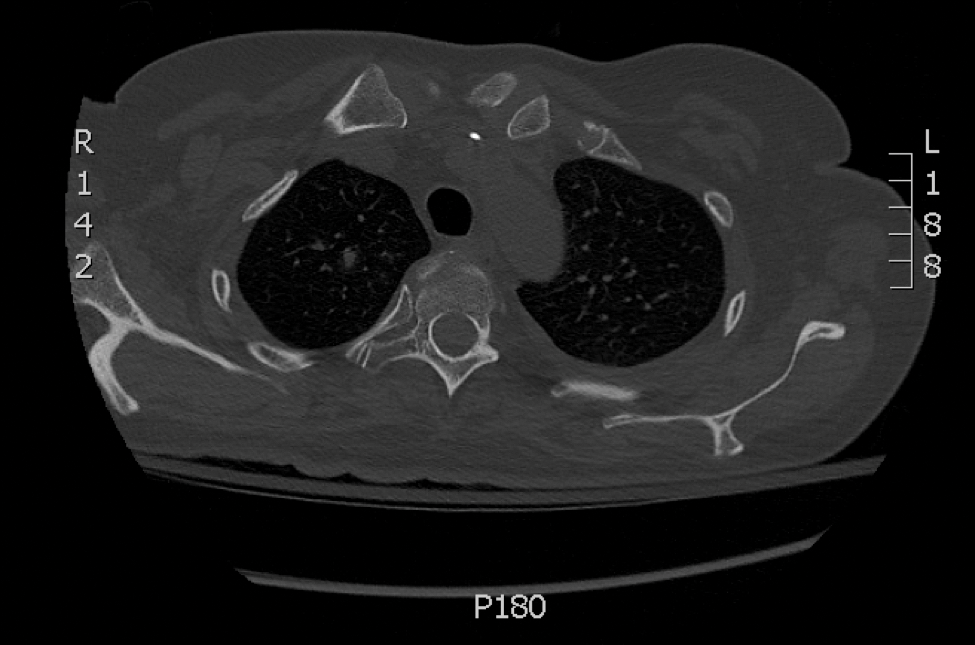

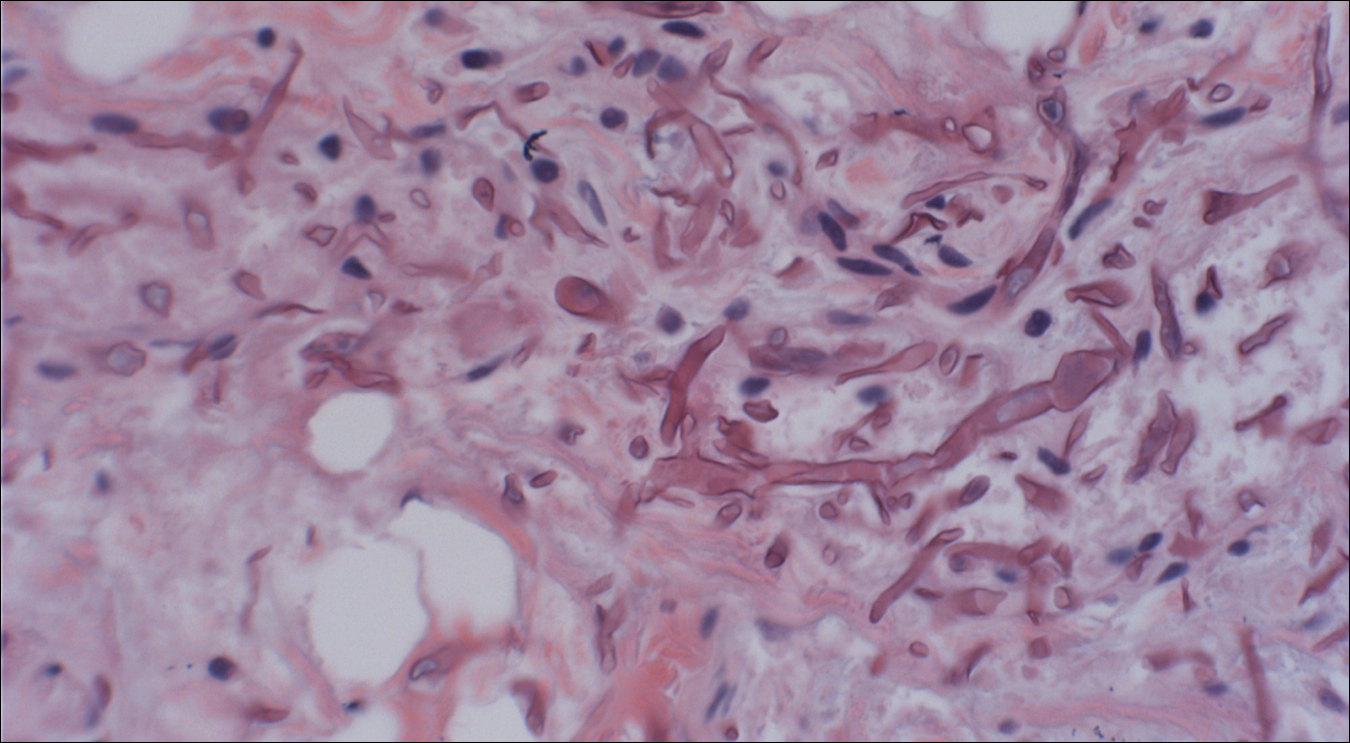

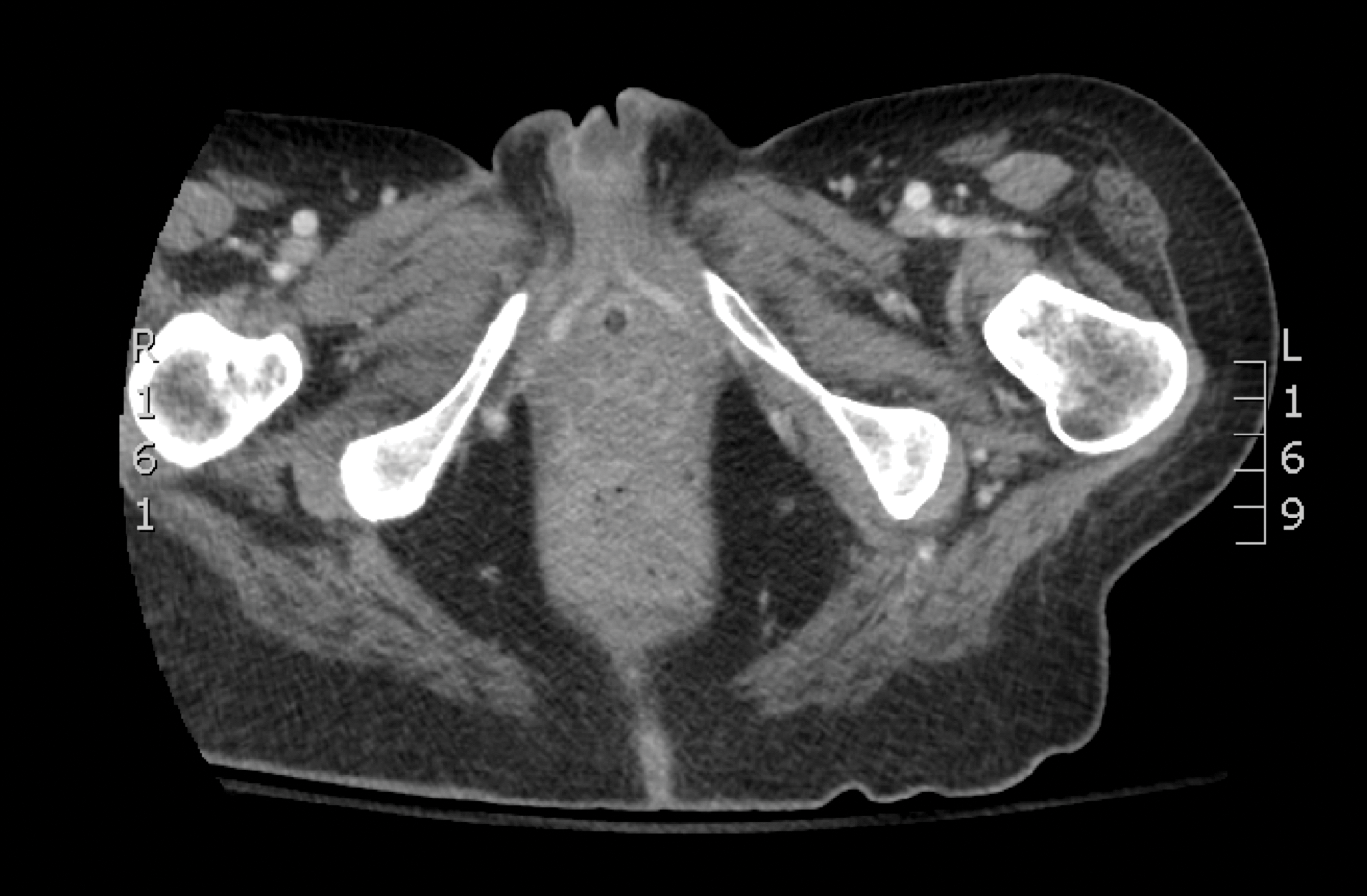

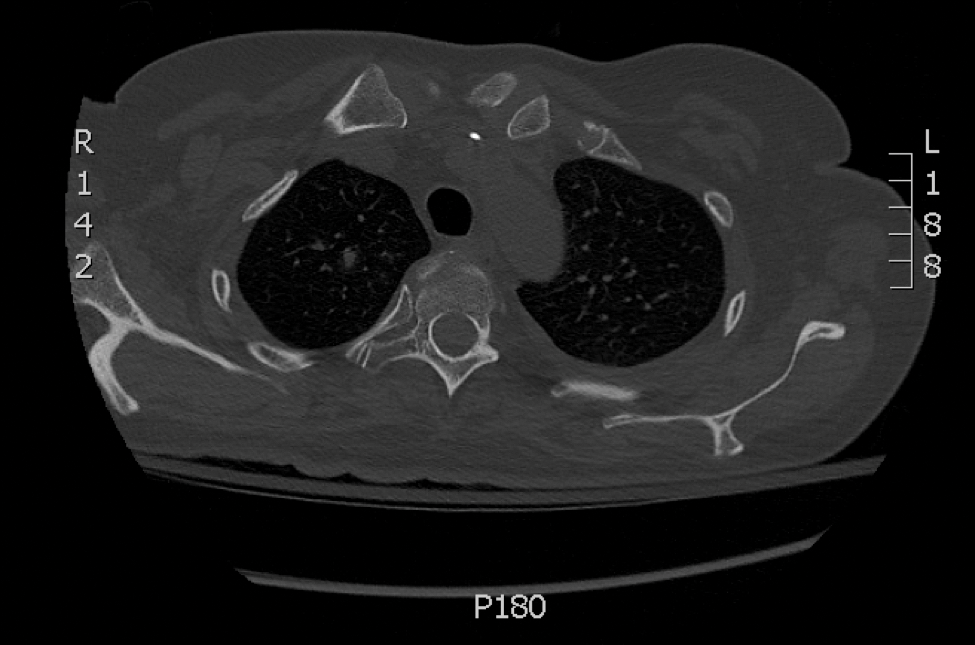

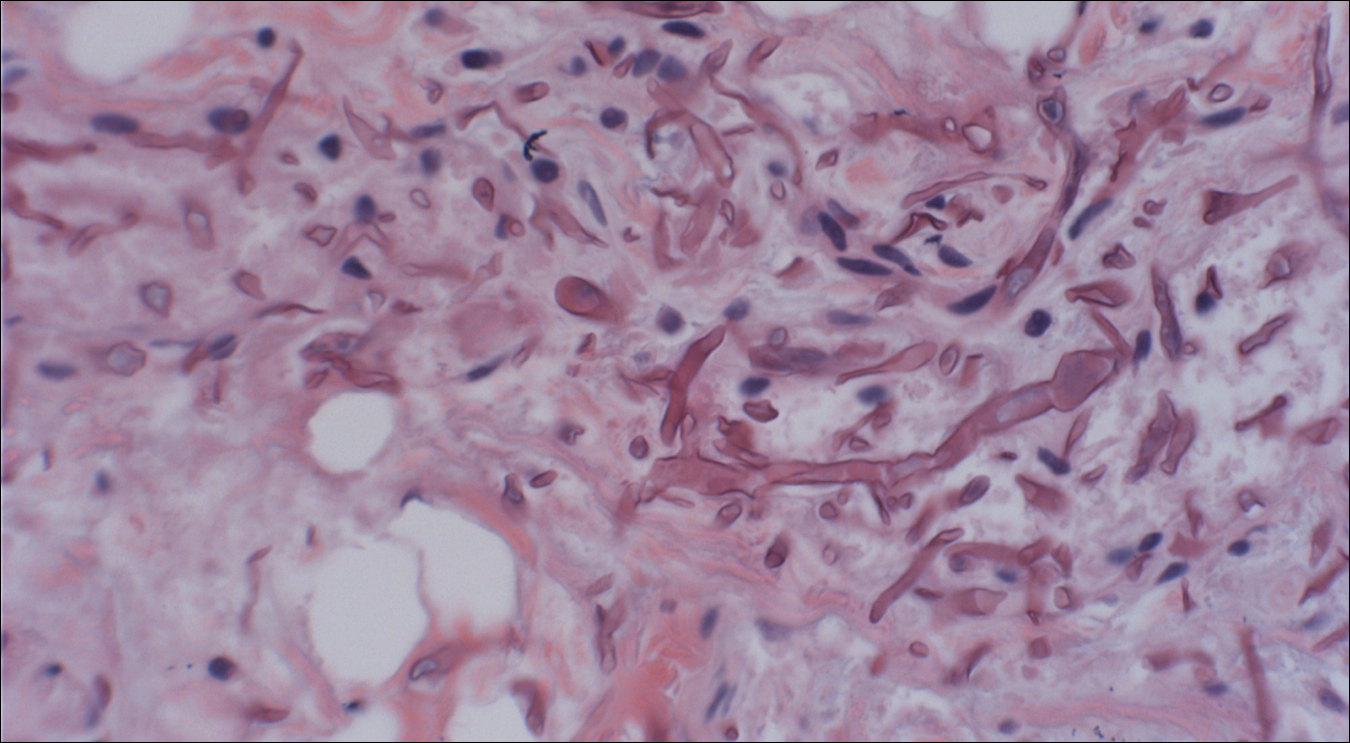

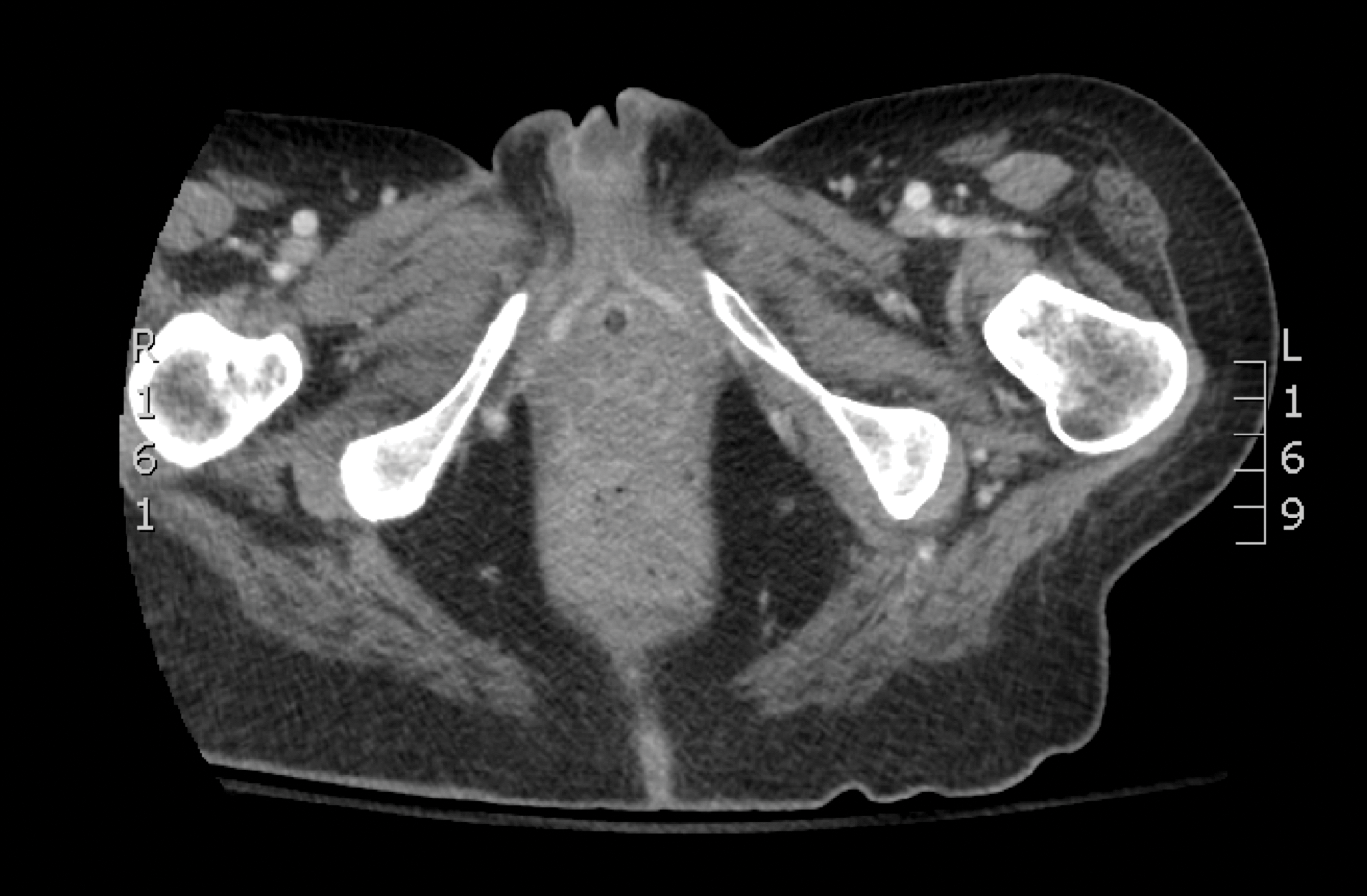

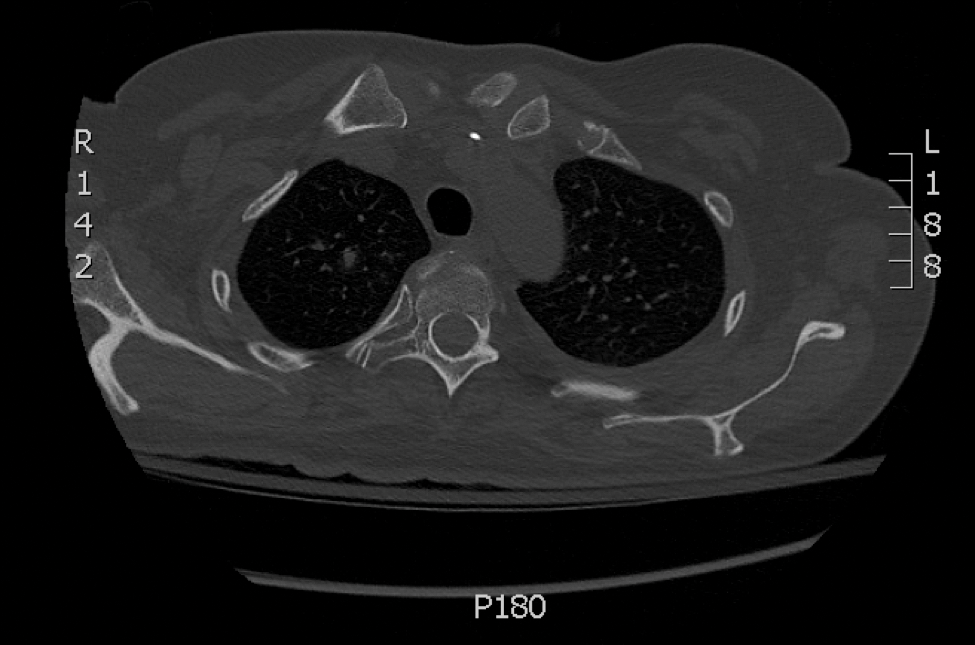

Skin biopsy and histology revealed broad, wide-angle, branched, nonseptate hyphae suggestive of mucormycosis infection (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed marked stranding in the vulvar region and urothelial thickening and enhancement suggestive of infection (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the chest demonstrated multiple irregular nodules in the bilateral upper lobes consistent with disseminated mucormycosis (Figure 3). The patient was started on intravenous amphotericin B and posaconazole. Surgery was not pursued given the poor prognosis of her refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia, pancytopenia, and disseminated fungal infection. The patient was discharged home with hospice care.

Mucormycosis is an infection caused by fungi that belong to the order Mucorales. The most common genera responsible for human disease are Rhizopus, Mucor, and Rhizomucor, which are organisms ubiquitous in nature and found in soil.1 Mucorales hyphae are widely branched and primarily nonseptate, which distinguishes them from hyphae of ascomycetous molds such as Aspergillus, which are narrowly branched and septate.

Mucormycosis primarily affects immunocompromised individuals. The overall incidence of mucormycosis is difficult to estimate, and the risk for infection varies based on the patient population. For example, the incidence of mucormycosis in hematologic malignancy ranges from 1% to 8% and from 0.4% to 16.0% in solid organ transplant recipients.2 One large series of 929 cases noted that the most common risk factors were associated with impaired immune function including diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis (36% of cases), hematologic malignancy (17%), and solid organ (7%) or bone marrow transplantation (5%). Other risk factors include neutropenia, steroid therapy, and other immunocompromising conditions.3 Healthy individuals have a strong natural immunity to mucormycosis and rarely are affected by the disease.2

The host response to Mucorales is primarily driven by phagocyte-mediated killing via oxidative metabolites and cationic peptides called defensins.1 Thus, severely neutropenic patients are at high risk for developing mucormycosis.1 In contrast, it appears as though AIDS patients are not at increased risk for mucormycosis, supporting the theory that T lymphocytes are not involved in the host response.1 The conditions of diabetic ketoacidosis leave patients susceptible to mucormycosis for several reasons. First, hyperglycemia and low pH induce phagocyte dysfunction and thus inhibit the host response to Mucorales.4 Second, these organisms have an active ketone reductase system that may allow them to grow more readily in high glucose, acidic conditions.1 Third, diabetic ketoacidosis conditions increase serum free iron, and Mucorales utilizes host iron for cell growth and development.1 Individuals such as hemodialysis patients receiving the iron chelator deferoxamine also are at risk for mucormycosis, as Rhizopus can bind to this molecule and transport the bound iron intracellularly for growth utilization.1

Mucormycosis infection is characterized by infarction and rapid necrosis of host tissues resulting from vascular infiltration by fungal hyphae. The most common site of infection is rhino-orbital-cerebral (39%), followed by lungs (24%) and skin (19%).3 Dissemination occurs in 23% of cases.3 Inoculation most commonly occurs via inhalation of airborne fungal spores by an immunocompromised host with resultant fungal proliferation in the paranasal sinuses, bronchioles, or alveoli. Gastrointestinal tract infection is presumed to occur via ingestion of spores.5

Cutaneous infection, as in our patient, occurs via the inoculation of spores into the dermis through breaks in the skin such as from intravenous lines, urinary catheters, injection sites, surgical sites, and traumatic wounds. Cutaneous infections typically present as a single erythematous, painful, indurated papule that rapidly progresses to a necrotic ulcer with overlying black eschar. In some cases, the progression may be more indolent over the course of several weeks.2 There are few reported cases of primary vulvar mucormycosis, as in our patient.6,7 The previously reported cases involved severely immunocompromised patients who developed large necrotic lesions over the vulva that demonstrated widely branching, nonseptate hyphae on histologic examination. Each patient required extensive surgical debridement with systemic antifungal treatment.6,7

A timely diagnosis of mucormycosis often hinges on a high index of suspicion on behalf of the clinician. A fungal etiology always should be considered for an infection in an immunocompromised patient. Furthermore, nonresponse to antibiotic treatment should be an important diagnostic clue that the infection could be fungal in origin. The definitive diagnosis of mucormycosis is confirmed by tissue biopsy and the presence of broad, widely branching, nonseptate hyphae seen on histopathologic examination.

Treatment involves aggressive surgical debridement of all necrotic tissues and elimination of predisposing factors for infection such as hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, deferoxamine administration, and immunosuppressive medications. Early initiation of antifungal therapy with the lipid formulation of amphotericin B is recommended. Oral posaconazole or isavuconazole typically are used as step-down therapy after a favorable clinical response with initial amphotericin B treatment. Deferasirox, in contrast to deferoxamine, is an iron chelator that may reduce the pathogenicity of Mucorales and may help as an adjunctive therapy.8 In addition, hyperbaric oxygen therapy may have limited benefit in some cases.9 In spite of these treatments, the overall mortality of mucormycosis is 50% or higher and approaches nearly 100% in cases of disseminated disease, such as in our patient.1,3

- Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, et al. Pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S16-S22.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S23-S34.

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634-653.

- Chinn RY, Diamond RD. Generation of chemotactic factors by Rhizopus oryzae in the presence and absence of serum: relationship to hyphal damage mediated by human neutrophils and effects of hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis. Infect Immun. 1982;38:1123-1129.

- Cheng VC, Chan JF, Ngan AH, et al. Outbreak of intestinal infection due to Rhizopus microsporus [published online July 29, 2009]. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2834-2843.

- Colon M, Romaguera J, Mendez K, et al. Mucormycosis of the vulva in an immunocompromised pediatric patient. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2013;105:65-67.

- Nomura J, Ruskin J, Sahebi F, et al. Mucormycosis of the vulva following bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:859-860.

- Spellberg B, Andes D, Perez M, et al. Safety and outcomes of open-label deferasirox iron chelation therapy for mucormycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3122-3125.

- Ferguson BJ, Mitchell TG, Moon R, et al. Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen for treatment of rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:551-559.

The Diagnosis: Mucormycosis

Skin biopsy and histology revealed broad, wide-angle, branched, nonseptate hyphae suggestive of mucormycosis infection (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed marked stranding in the vulvar region and urothelial thickening and enhancement suggestive of infection (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the chest demonstrated multiple irregular nodules in the bilateral upper lobes consistent with disseminated mucormycosis (Figure 3). The patient was started on intravenous amphotericin B and posaconazole. Surgery was not pursued given the poor prognosis of her refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia, pancytopenia, and disseminated fungal infection. The patient was discharged home with hospice care.

Mucormycosis is an infection caused by fungi that belong to the order Mucorales. The most common genera responsible for human disease are Rhizopus, Mucor, and Rhizomucor, which are organisms ubiquitous in nature and found in soil.1 Mucorales hyphae are widely branched and primarily nonseptate, which distinguishes them from hyphae of ascomycetous molds such as Aspergillus, which are narrowly branched and septate.

Mucormycosis primarily affects immunocompromised individuals. The overall incidence of mucormycosis is difficult to estimate, and the risk for infection varies based on the patient population. For example, the incidence of mucormycosis in hematologic malignancy ranges from 1% to 8% and from 0.4% to 16.0% in solid organ transplant recipients.2 One large series of 929 cases noted that the most common risk factors were associated with impaired immune function including diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis (36% of cases), hematologic malignancy (17%), and solid organ (7%) or bone marrow transplantation (5%). Other risk factors include neutropenia, steroid therapy, and other immunocompromising conditions.3 Healthy individuals have a strong natural immunity to mucormycosis and rarely are affected by the disease.2

The host response to Mucorales is primarily driven by phagocyte-mediated killing via oxidative metabolites and cationic peptides called defensins.1 Thus, severely neutropenic patients are at high risk for developing mucormycosis.1 In contrast, it appears as though AIDS patients are not at increased risk for mucormycosis, supporting the theory that T lymphocytes are not involved in the host response.1 The conditions of diabetic ketoacidosis leave patients susceptible to mucormycosis for several reasons. First, hyperglycemia and low pH induce phagocyte dysfunction and thus inhibit the host response to Mucorales.4 Second, these organisms have an active ketone reductase system that may allow them to grow more readily in high glucose, acidic conditions.1 Third, diabetic ketoacidosis conditions increase serum free iron, and Mucorales utilizes host iron for cell growth and development.1 Individuals such as hemodialysis patients receiving the iron chelator deferoxamine also are at risk for mucormycosis, as Rhizopus can bind to this molecule and transport the bound iron intracellularly for growth utilization.1

Mucormycosis infection is characterized by infarction and rapid necrosis of host tissues resulting from vascular infiltration by fungal hyphae. The most common site of infection is rhino-orbital-cerebral (39%), followed by lungs (24%) and skin (19%).3 Dissemination occurs in 23% of cases.3 Inoculation most commonly occurs via inhalation of airborne fungal spores by an immunocompromised host with resultant fungal proliferation in the paranasal sinuses, bronchioles, or alveoli. Gastrointestinal tract infection is presumed to occur via ingestion of spores.5

Cutaneous infection, as in our patient, occurs via the inoculation of spores into the dermis through breaks in the skin such as from intravenous lines, urinary catheters, injection sites, surgical sites, and traumatic wounds. Cutaneous infections typically present as a single erythematous, painful, indurated papule that rapidly progresses to a necrotic ulcer with overlying black eschar. In some cases, the progression may be more indolent over the course of several weeks.2 There are few reported cases of primary vulvar mucormycosis, as in our patient.6,7 The previously reported cases involved severely immunocompromised patients who developed large necrotic lesions over the vulva that demonstrated widely branching, nonseptate hyphae on histologic examination. Each patient required extensive surgical debridement with systemic antifungal treatment.6,7

A timely diagnosis of mucormycosis often hinges on a high index of suspicion on behalf of the clinician. A fungal etiology always should be considered for an infection in an immunocompromised patient. Furthermore, nonresponse to antibiotic treatment should be an important diagnostic clue that the infection could be fungal in origin. The definitive diagnosis of mucormycosis is confirmed by tissue biopsy and the presence of broad, widely branching, nonseptate hyphae seen on histopathologic examination.

Treatment involves aggressive surgical debridement of all necrotic tissues and elimination of predisposing factors for infection such as hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, deferoxamine administration, and immunosuppressive medications. Early initiation of antifungal therapy with the lipid formulation of amphotericin B is recommended. Oral posaconazole or isavuconazole typically are used as step-down therapy after a favorable clinical response with initial amphotericin B treatment. Deferasirox, in contrast to deferoxamine, is an iron chelator that may reduce the pathogenicity of Mucorales and may help as an adjunctive therapy.8 In addition, hyperbaric oxygen therapy may have limited benefit in some cases.9 In spite of these treatments, the overall mortality of mucormycosis is 50% or higher and approaches nearly 100% in cases of disseminated disease, such as in our patient.1,3

The Diagnosis: Mucormycosis

Skin biopsy and histology revealed broad, wide-angle, branched, nonseptate hyphae suggestive of mucormycosis infection (Figure 1). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed marked stranding in the vulvar region and urothelial thickening and enhancement suggestive of infection (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the chest demonstrated multiple irregular nodules in the bilateral upper lobes consistent with disseminated mucormycosis (Figure 3). The patient was started on intravenous amphotericin B and posaconazole. Surgery was not pursued given the poor prognosis of her refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia, pancytopenia, and disseminated fungal infection. The patient was discharged home with hospice care.

Mucormycosis is an infection caused by fungi that belong to the order Mucorales. The most common genera responsible for human disease are Rhizopus, Mucor, and Rhizomucor, which are organisms ubiquitous in nature and found in soil.1 Mucorales hyphae are widely branched and primarily nonseptate, which distinguishes them from hyphae of ascomycetous molds such as Aspergillus, which are narrowly branched and septate.

Mucormycosis primarily affects immunocompromised individuals. The overall incidence of mucormycosis is difficult to estimate, and the risk for infection varies based on the patient population. For example, the incidence of mucormycosis in hematologic malignancy ranges from 1% to 8% and from 0.4% to 16.0% in solid organ transplant recipients.2 One large series of 929 cases noted that the most common risk factors were associated with impaired immune function including diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis (36% of cases), hematologic malignancy (17%), and solid organ (7%) or bone marrow transplantation (5%). Other risk factors include neutropenia, steroid therapy, and other immunocompromising conditions.3 Healthy individuals have a strong natural immunity to mucormycosis and rarely are affected by the disease.2

The host response to Mucorales is primarily driven by phagocyte-mediated killing via oxidative metabolites and cationic peptides called defensins.1 Thus, severely neutropenic patients are at high risk for developing mucormycosis.1 In contrast, it appears as though AIDS patients are not at increased risk for mucormycosis, supporting the theory that T lymphocytes are not involved in the host response.1 The conditions of diabetic ketoacidosis leave patients susceptible to mucormycosis for several reasons. First, hyperglycemia and low pH induce phagocyte dysfunction and thus inhibit the host response to Mucorales.4 Second, these organisms have an active ketone reductase system that may allow them to grow more readily in high glucose, acidic conditions.1 Third, diabetic ketoacidosis conditions increase serum free iron, and Mucorales utilizes host iron for cell growth and development.1 Individuals such as hemodialysis patients receiving the iron chelator deferoxamine also are at risk for mucormycosis, as Rhizopus can bind to this molecule and transport the bound iron intracellularly for growth utilization.1

Mucormycosis infection is characterized by infarction and rapid necrosis of host tissues resulting from vascular infiltration by fungal hyphae. The most common site of infection is rhino-orbital-cerebral (39%), followed by lungs (24%) and skin (19%).3 Dissemination occurs in 23% of cases.3 Inoculation most commonly occurs via inhalation of airborne fungal spores by an immunocompromised host with resultant fungal proliferation in the paranasal sinuses, bronchioles, or alveoli. Gastrointestinal tract infection is presumed to occur via ingestion of spores.5

Cutaneous infection, as in our patient, occurs via the inoculation of spores into the dermis through breaks in the skin such as from intravenous lines, urinary catheters, injection sites, surgical sites, and traumatic wounds. Cutaneous infections typically present as a single erythematous, painful, indurated papule that rapidly progresses to a necrotic ulcer with overlying black eschar. In some cases, the progression may be more indolent over the course of several weeks.2 There are few reported cases of primary vulvar mucormycosis, as in our patient.6,7 The previously reported cases involved severely immunocompromised patients who developed large necrotic lesions over the vulva that demonstrated widely branching, nonseptate hyphae on histologic examination. Each patient required extensive surgical debridement with systemic antifungal treatment.6,7

A timely diagnosis of mucormycosis often hinges on a high index of suspicion on behalf of the clinician. A fungal etiology always should be considered for an infection in an immunocompromised patient. Furthermore, nonresponse to antibiotic treatment should be an important diagnostic clue that the infection could be fungal in origin. The definitive diagnosis of mucormycosis is confirmed by tissue biopsy and the presence of broad, widely branching, nonseptate hyphae seen on histopathologic examination.

Treatment involves aggressive surgical debridement of all necrotic tissues and elimination of predisposing factors for infection such as hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, deferoxamine administration, and immunosuppressive medications. Early initiation of antifungal therapy with the lipid formulation of amphotericin B is recommended. Oral posaconazole or isavuconazole typically are used as step-down therapy after a favorable clinical response with initial amphotericin B treatment. Deferasirox, in contrast to deferoxamine, is an iron chelator that may reduce the pathogenicity of Mucorales and may help as an adjunctive therapy.8 In addition, hyperbaric oxygen therapy may have limited benefit in some cases.9 In spite of these treatments, the overall mortality of mucormycosis is 50% or higher and approaches nearly 100% in cases of disseminated disease, such as in our patient.1,3

- Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, et al. Pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S16-S22.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S23-S34.

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634-653.

- Chinn RY, Diamond RD. Generation of chemotactic factors by Rhizopus oryzae in the presence and absence of serum: relationship to hyphal damage mediated by human neutrophils and effects of hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis. Infect Immun. 1982;38:1123-1129.

- Cheng VC, Chan JF, Ngan AH, et al. Outbreak of intestinal infection due to Rhizopus microsporus [published online July 29, 2009]. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2834-2843.

- Colon M, Romaguera J, Mendez K, et al. Mucormycosis of the vulva in an immunocompromised pediatric patient. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2013;105:65-67.

- Nomura J, Ruskin J, Sahebi F, et al. Mucormycosis of the vulva following bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:859-860.

- Spellberg B, Andes D, Perez M, et al. Safety and outcomes of open-label deferasirox iron chelation therapy for mucormycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3122-3125.

- Ferguson BJ, Mitchell TG, Moon R, et al. Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen for treatment of rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:551-559.

- Ibrahim AS, Spellberg B, Walsh TJ, et al. Pathogenesis of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S16-S22.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(suppl 1):S23-S34.

- Roden MM, Zaoutis TE, Buchanan WL, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of zygomycosis: a review of 929 reported cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:634-653.

- Chinn RY, Diamond RD. Generation of chemotactic factors by Rhizopus oryzae in the presence and absence of serum: relationship to hyphal damage mediated by human neutrophils and effects of hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis. Infect Immun. 1982;38:1123-1129.

- Cheng VC, Chan JF, Ngan AH, et al. Outbreak of intestinal infection due to Rhizopus microsporus [published online July 29, 2009]. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2834-2843.

- Colon M, Romaguera J, Mendez K, et al. Mucormycosis of the vulva in an immunocompromised pediatric patient. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2013;105:65-67.

- Nomura J, Ruskin J, Sahebi F, et al. Mucormycosis of the vulva following bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:859-860.

- Spellberg B, Andes D, Perez M, et al. Safety and outcomes of open-label deferasirox iron chelation therapy for mucormycosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3122-3125.

- Ferguson BJ, Mitchell TG, Moon R, et al. Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen for treatment of rhinocerebral mucormycosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:551-559.

A 48-year-old woman with relapsed T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia was admitted to the oncology service for salvage chemotherapy and allogeneic stem cell transplant. Her admission was complicated by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli sepsis and persistent pancytopenia, which required transfer to the intensive care unit. After 2 weeks and while still in the intensive care unit, she developed a painful necrotic vulvar ulcer over the right labia and clitoris that progressed and formed an overlying black eschar.