User login

Solitary Yellow Papule on the Upper Back in an Infant

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

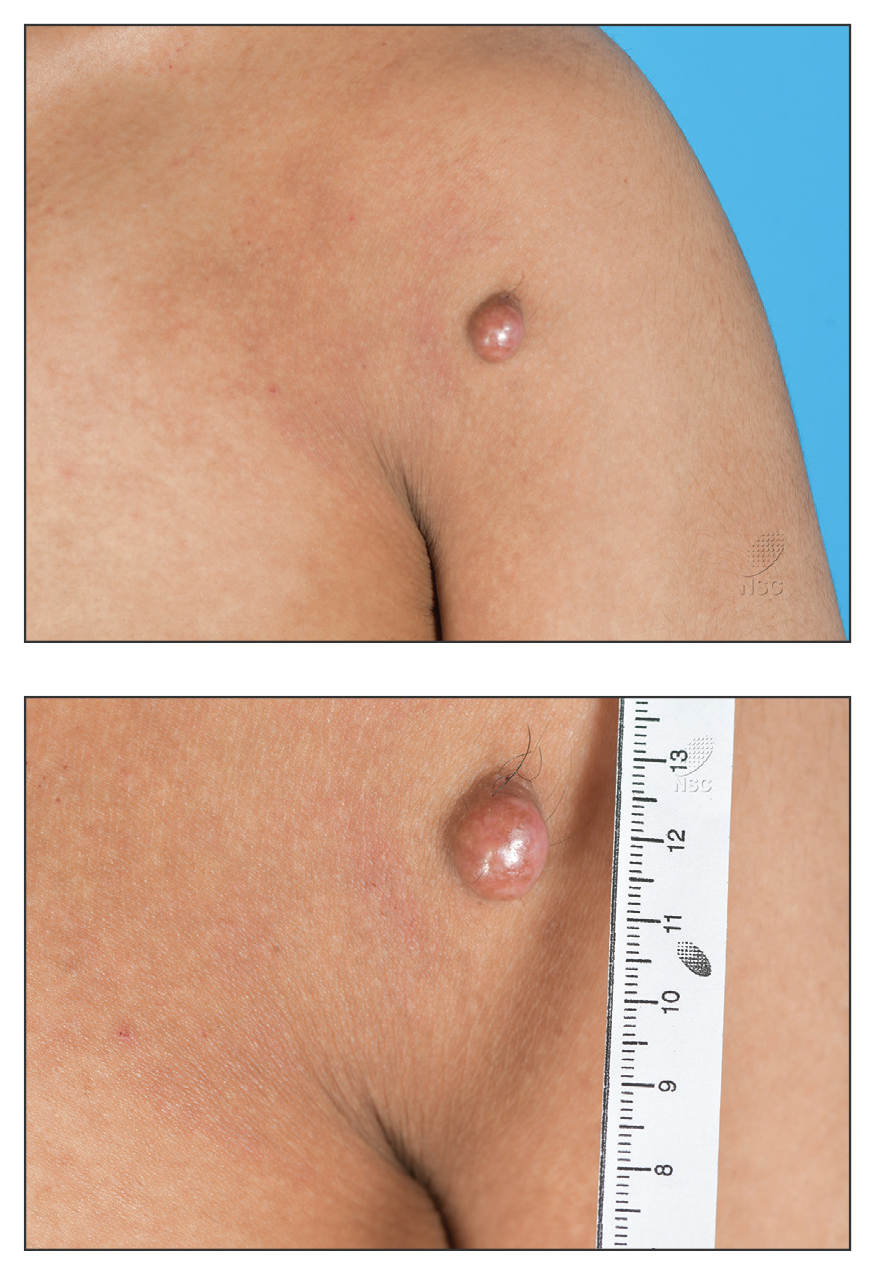

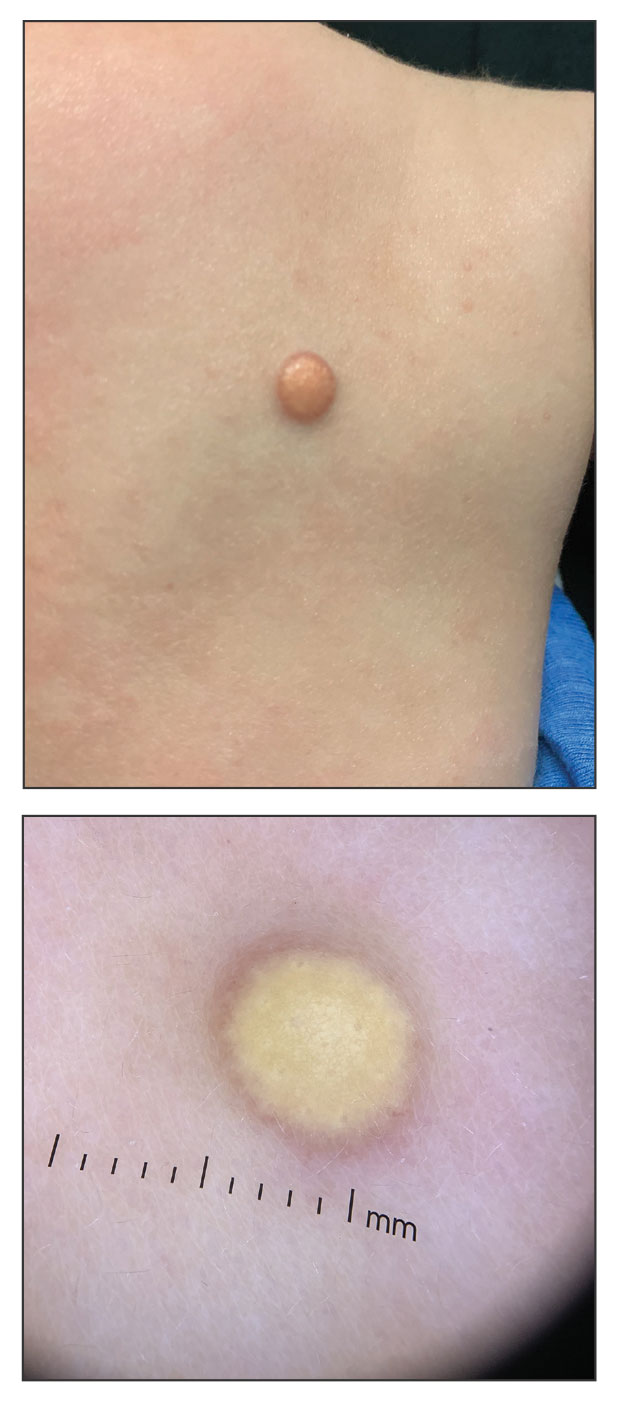

Given the patient’s age, clinical features of the lesion, and characteristic setting-sun pattern on dermoscopy, a diagnosis of juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was made. The patient showed no other signs of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) or systemic disease and was managed conservatively with observation and routine follow-up. Minimal growth of the lesion was noted at 1-year follow-up, and he was meeting all age-appropriate developmental milestones and showed no other symptoms consistent with NF1.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is the most common childhood non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis. While it typically manifests as an isolated condition, JXG also can be associated with NF1 as well as juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.1-3 Neurofibromatosis type 1 is a multisystem disorder with variable clinical manifestations that commonly is associated with skin findings such as café au lait macules, intertriginous freckling, and neurofibromas, in addition to JXG.2,3 Diagnosis of JXG should prompt noninvasive evaluation for further signs and symptoms of NF1, including thorough patient and family history and physical examination to identify other characteristic cutaneous findings, and can include consideration of slit lamp eye examination and radiography for identification of osseous findings.

The pathogenesis of JXG is not fully known, though there is evidence that it may be associated with a mutation in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.1 The majority of cases appear in the first year of life.4 Clinically, JXG can manifest with extracutaneous lesions, including on the eyes and lungs.5-7 Juvenile xanthogranuloma can be noninvasively diagnosed with dermoscopy. As seen in our patient, dermoscopic findings include a red-yellow or yellow-orange background with an erythematous border, typically described as a setting-sun pattern.4,8 Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis; however, given the usually benign course, this often is unnecessary. Most pediatric patients with cutaneous manifestations have a self-limited course with regression over several months to years. Generally, no treatment is required for cutaneous manifestations alone; however, lesions can be removed for aesthetic concerns. For those with systemic involvement, a range of other treatments have been used, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, systemic corticosteroids, and cyclosporine.6,7

The differential diagnosis for JXG includes Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, Fabry disease, solitary cutaneous mastocytoma, and tuberous sclerosis complex. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is an autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the growth of adnexal neoplasms, including trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas. These lesions usually manifest on the face but can include other areas such as the trunk.9 Fabry disease is an X-linked recessive lysosomal storage disorder with cutaneous manifestations such as angiokeratoma corporis diffusum and hypohidrosis. Patients also may present with systemic symptoms including hypertension and renal and cardiovascular disease.10 Mastocytosis encompasses several clinical disorders defined by mast cell hyperplasia and accumulation in various organ systems, and solitary cutaneous mastocytoma is the most common manifestation in children.11,12 Cutaneous mastocytoma can manifest as a single red-brown or yellow papule, usually located on the arms or legs.13 Solitary cutaneous mastocytomas in pediatric patients typically are diagnosed based on clinical appearance and the formation of a wheal upon firm palpation (Darier sign).11-13 Our patient did not demonstrate the Darier sign, and the lesion was asymptomatic. Tuberous sclerosis complex is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder with neurologic and skin findings that occur early in the disease course and include facial angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches, and café-au-lait macules.14

- Durham BH, Lopez Rodrigo E, Picarsic J, et al. Activating mutations in CSF1R and additional receptor tyrosine kinases in histiocytic neoplasms. Nat Med. 2019;25:1839-1842.

- Friedman JM. Neurofibromatosis 1. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1998.

- Miraglia E, Laghi A, Moramarco A, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in neurofibromatosis type 1. Prevalence and possible correlation with lymphoproliferative diseases: experience of a single center and review of the literature. Clin Ther. 2022;173:353-355.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526103/

- Newman B, Hu W, Nigro K, et al. Aggressive histiocytic disorders that can involve the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:302-316.

- Freyer DR, Kennedy R, Bostrom BC, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: forms of systemic disease and their clinical implications. J Pediatr. 1996;129:227-237.

- Murphy JT, Soeken T, Megison S, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: diverse presentations of noncutaneous disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.2014;36:641-645.

- Xu J, Ma L. Dermoscopic patterns in juvenile xanthogranuloma based on the histological classification. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;7:618946.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bokhari SRA, Zulfiqar H, Hariz A. Fabry disease. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Update July 4, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435996/

- Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

- Klaiber N, Kumar S, Irani AM. Mastocytosis in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17:80.

- Sławin´ ska M, Kaszuba A, Lange M, et al. Dermoscopic features of different forms of cutaneous mastocytosis: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4649.

- Teng JM, Cowen EW, Wataya-Kaneda M, et al. Dermatologic and dental aspects of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Statements. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1095-1101.

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Given the patient’s age, clinical features of the lesion, and characteristic setting-sun pattern on dermoscopy, a diagnosis of juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was made. The patient showed no other signs of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) or systemic disease and was managed conservatively with observation and routine follow-up. Minimal growth of the lesion was noted at 1-year follow-up, and he was meeting all age-appropriate developmental milestones and showed no other symptoms consistent with NF1.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is the most common childhood non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis. While it typically manifests as an isolated condition, JXG also can be associated with NF1 as well as juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.1-3 Neurofibromatosis type 1 is a multisystem disorder with variable clinical manifestations that commonly is associated with skin findings such as café au lait macules, intertriginous freckling, and neurofibromas, in addition to JXG.2,3 Diagnosis of JXG should prompt noninvasive evaluation for further signs and symptoms of NF1, including thorough patient and family history and physical examination to identify other characteristic cutaneous findings, and can include consideration of slit lamp eye examination and radiography for identification of osseous findings.

The pathogenesis of JXG is not fully known, though there is evidence that it may be associated with a mutation in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.1 The majority of cases appear in the first year of life.4 Clinically, JXG can manifest with extracutaneous lesions, including on the eyes and lungs.5-7 Juvenile xanthogranuloma can be noninvasively diagnosed with dermoscopy. As seen in our patient, dermoscopic findings include a red-yellow or yellow-orange background with an erythematous border, typically described as a setting-sun pattern.4,8 Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis; however, given the usually benign course, this often is unnecessary. Most pediatric patients with cutaneous manifestations have a self-limited course with regression over several months to years. Generally, no treatment is required for cutaneous manifestations alone; however, lesions can be removed for aesthetic concerns. For those with systemic involvement, a range of other treatments have been used, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, systemic corticosteroids, and cyclosporine.6,7

The differential diagnosis for JXG includes Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, Fabry disease, solitary cutaneous mastocytoma, and tuberous sclerosis complex. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is an autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the growth of adnexal neoplasms, including trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas. These lesions usually manifest on the face but can include other areas such as the trunk.9 Fabry disease is an X-linked recessive lysosomal storage disorder with cutaneous manifestations such as angiokeratoma corporis diffusum and hypohidrosis. Patients also may present with systemic symptoms including hypertension and renal and cardiovascular disease.10 Mastocytosis encompasses several clinical disorders defined by mast cell hyperplasia and accumulation in various organ systems, and solitary cutaneous mastocytoma is the most common manifestation in children.11,12 Cutaneous mastocytoma can manifest as a single red-brown or yellow papule, usually located on the arms or legs.13 Solitary cutaneous mastocytomas in pediatric patients typically are diagnosed based on clinical appearance and the formation of a wheal upon firm palpation (Darier sign).11-13 Our patient did not demonstrate the Darier sign, and the lesion was asymptomatic. Tuberous sclerosis complex is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder with neurologic and skin findings that occur early in the disease course and include facial angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches, and café-au-lait macules.14

The Diagnosis: Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Given the patient’s age, clinical features of the lesion, and characteristic setting-sun pattern on dermoscopy, a diagnosis of juvenile xanthogranuloma (JXG) was made. The patient showed no other signs of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) or systemic disease and was managed conservatively with observation and routine follow-up. Minimal growth of the lesion was noted at 1-year follow-up, and he was meeting all age-appropriate developmental milestones and showed no other symptoms consistent with NF1.

Juvenile xanthogranuloma is the most common childhood non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis. While it typically manifests as an isolated condition, JXG also can be associated with NF1 as well as juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia.1-3 Neurofibromatosis type 1 is a multisystem disorder with variable clinical manifestations that commonly is associated with skin findings such as café au lait macules, intertriginous freckling, and neurofibromas, in addition to JXG.2,3 Diagnosis of JXG should prompt noninvasive evaluation for further signs and symptoms of NF1, including thorough patient and family history and physical examination to identify other characteristic cutaneous findings, and can include consideration of slit lamp eye examination and radiography for identification of osseous findings.

The pathogenesis of JXG is not fully known, though there is evidence that it may be associated with a mutation in the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway.1 The majority of cases appear in the first year of life.4 Clinically, JXG can manifest with extracutaneous lesions, including on the eyes and lungs.5-7 Juvenile xanthogranuloma can be noninvasively diagnosed with dermoscopy. As seen in our patient, dermoscopic findings include a red-yellow or yellow-orange background with an erythematous border, typically described as a setting-sun pattern.4,8 Biopsy can confirm the diagnosis; however, given the usually benign course, this often is unnecessary. Most pediatric patients with cutaneous manifestations have a self-limited course with regression over several months to years. Generally, no treatment is required for cutaneous manifestations alone; however, lesions can be removed for aesthetic concerns. For those with systemic involvement, a range of other treatments have been used, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, systemic corticosteroids, and cyclosporine.6,7

The differential diagnosis for JXG includes Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, Fabry disease, solitary cutaneous mastocytoma, and tuberous sclerosis complex. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome is an autosomal-dominant condition characterized by the growth of adnexal neoplasms, including trichoepitheliomas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas. These lesions usually manifest on the face but can include other areas such as the trunk.9 Fabry disease is an X-linked recessive lysosomal storage disorder with cutaneous manifestations such as angiokeratoma corporis diffusum and hypohidrosis. Patients also may present with systemic symptoms including hypertension and renal and cardiovascular disease.10 Mastocytosis encompasses several clinical disorders defined by mast cell hyperplasia and accumulation in various organ systems, and solitary cutaneous mastocytoma is the most common manifestation in children.11,12 Cutaneous mastocytoma can manifest as a single red-brown or yellow papule, usually located on the arms or legs.13 Solitary cutaneous mastocytomas in pediatric patients typically are diagnosed based on clinical appearance and the formation of a wheal upon firm palpation (Darier sign).11-13 Our patient did not demonstrate the Darier sign, and the lesion was asymptomatic. Tuberous sclerosis complex is an autosomal-dominant neurocutaneous disorder with neurologic and skin findings that occur early in the disease course and include facial angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches, and café-au-lait macules.14

- Durham BH, Lopez Rodrigo E, Picarsic J, et al. Activating mutations in CSF1R and additional receptor tyrosine kinases in histiocytic neoplasms. Nat Med. 2019;25:1839-1842.

- Friedman JM. Neurofibromatosis 1. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1998.

- Miraglia E, Laghi A, Moramarco A, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in neurofibromatosis type 1. Prevalence and possible correlation with lymphoproliferative diseases: experience of a single center and review of the literature. Clin Ther. 2022;173:353-355.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526103/

- Newman B, Hu W, Nigro K, et al. Aggressive histiocytic disorders that can involve the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:302-316.

- Freyer DR, Kennedy R, Bostrom BC, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: forms of systemic disease and their clinical implications. J Pediatr. 1996;129:227-237.

- Murphy JT, Soeken T, Megison S, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: diverse presentations of noncutaneous disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.2014;36:641-645.

- Xu J, Ma L. Dermoscopic patterns in juvenile xanthogranuloma based on the histological classification. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;7:618946.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bokhari SRA, Zulfiqar H, Hariz A. Fabry disease. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Update July 4, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435996/

- Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

- Klaiber N, Kumar S, Irani AM. Mastocytosis in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17:80.

- Sławin´ ska M, Kaszuba A, Lange M, et al. Dermoscopic features of different forms of cutaneous mastocytosis: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4649.

- Teng JM, Cowen EW, Wataya-Kaneda M, et al. Dermatologic and dental aspects of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Statements. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1095-1101.

- Durham BH, Lopez Rodrigo E, Picarsic J, et al. Activating mutations in CSF1R and additional receptor tyrosine kinases in histiocytic neoplasms. Nat Med. 2019;25:1839-1842.

- Friedman JM. Neurofibromatosis 1. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al, eds. GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle; 1998.

- Miraglia E, Laghi A, Moramarco A, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in neurofibromatosis type 1. Prevalence and possible correlation with lymphoproliferative diseases: experience of a single center and review of the literature. Clin Ther. 2022;173:353-355.

- Collie JS, Harper CD, Fillman EP. Juvenile xanthogranuloma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Updated August 8, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526103/

- Newman B, Hu W, Nigro K, et al. Aggressive histiocytic disorders that can involve the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:302-316.

- Freyer DR, Kennedy R, Bostrom BC, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: forms of systemic disease and their clinical implications. J Pediatr. 1996;129:227-237.

- Murphy JT, Soeken T, Megison S, et al. Juvenile xanthogranuloma: diverse presentations of noncutaneous disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol.2014;36:641-645.

- Xu J, Ma L. Dermoscopic patterns in juvenile xanthogranuloma based on the histological classification. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;7:618946.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bokhari SRA, Zulfiqar H, Hariz A. Fabry disease. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Update July 4, 2023. Accessed November 4, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435996/

- Hartmann K, Escribano L, Grattan C, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with mastocytosis: consensus report of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis; the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:35-45.

- Klaiber N, Kumar S, Irani AM. Mastocytosis in children. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2017;17:80.

- Sławin´ ska M, Kaszuba A, Lange M, et al. Dermoscopic features of different forms of cutaneous mastocytosis: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4649.

- Teng JM, Cowen EW, Wataya-Kaneda M, et al. Dermatologic and dental aspects of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Statements. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:1095-1101.

A 6-month-old male infant with a history of cradle cap and an infantile hemangioma on the left shoulder presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a slow-growing yellow papule on the upper back of 3 months’ duration. The lesion initially was noted 2 months prior to the current presentation by the patient’s pediatrician, who recommended follow-up with dermatology after an unsuccessful attempt at incision and drainage. Physical examination revealed a 7-mm, yellow, dome-shaped papule with a red collarette on the right upper back. No axillary freckling, ocular findings, or other skin findings were found. The patient was born at term with no complications, and his mother reported that he was otherwise healthy. There were no developmental concerns or known allergies, and his family history was negative for any similar lesions. Dermoscopic examination of the lesion revealed a well-circumscribed, circular, yellow-orange papule with an erythematous border and setting-sun appearance.

Reticulated Hyperpigmentation on the Knee and Thigh

Reticulated Hyperpigmentation on the Knee and Thigh

The patient was diagnosed with erythema ab igne based on characteristic skin findings on physical examination along with a convincing history of chronic localized heat exposure. Erythema ab igne manifests as a persistent reticulated, erythematous, or hyperpigmented rash at sites of chronic heat exposure.1 Commonplace items that emit heat such as electric heaters, car heaters, heating pads, hot water bottles, and, in our case, laptops also emit infrared radiation, which can lead to changes in the skin with long-term exposure.2 Because exposure to these sources often is limited to one area of the body, erythema ab igne usually manifests locally, as exemplified in this case. Chronic heat exposure and infrared radiation from these sources are thought to induce hyperthermia below the threshold for a thermal burn, and the cutaneous findings correspond with the dermal venous plexus.3

Diagnosis of erythema ab igne primarily is made clinically based on characteristic skin findings and exposure history. Relevant history may include occupations with prolonged heat exposure, such as baking, silversmithing, or foundry work. Heat exposure also may result from cultural practices such as cupping with moxibustion.4 Additionally, repeated use of heating pads or hot water bottles for pain relief by patients diagnosed with chronic pain or an underlying illness may contribute to development of erythema ab igne.1,4

Biopsy was not needed for diagnosis of this patient, but if the presentation is equivocal and history of potential exposures is unclear, a biopsy may be taken. A hematoxylin and eosin stain would reveal dilation of small vascular channels in the superficial dermis, contributing to the classic reticulated appearance. Biopsy findings also would reveal either an interface dermatitis or pigment incontinence containing melanin-laden macrophages correlating to either the erythema or hyperpigmentation, respectively.4

The prognosis for erythema ab igne is excellent, especially if diagnosed early. Treatment involves removal of the inciting heat source.1 The discoloration may resolve within a few months to years or may persist. If the hyperpigmentation is persistent, patients may consider laser treatments or lightening agents such as topical hydroquinone or topical tretinoin.4 However, if undiagnosed, patients may be at risk for development of a cutaneous malignancy, such as squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, or cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.2,4 Malignant transformation has been reported to occur decades after the initial skin eruption, although the risk is rare5; however, due to this risk, patients with erythema ab igne should be followed regularly and screened for new lesions in the affected areas.

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162:77-78.

- Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

- Kesty K, Feldman SR. Erythema ab igne: evolving technology, evolving presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030.

- Harview CL, Krenitsky A. Erythema ab igne: a clinical review. Cutis. 2023;111:E33-E38. doi:10.12788/cutis.0771

- Wipf AJ, Brown MR. Malignant transformation of erythema ab igne. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:85-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.018

The patient was diagnosed with erythema ab igne based on characteristic skin findings on physical examination along with a convincing history of chronic localized heat exposure. Erythema ab igne manifests as a persistent reticulated, erythematous, or hyperpigmented rash at sites of chronic heat exposure.1 Commonplace items that emit heat such as electric heaters, car heaters, heating pads, hot water bottles, and, in our case, laptops also emit infrared radiation, which can lead to changes in the skin with long-term exposure.2 Because exposure to these sources often is limited to one area of the body, erythema ab igne usually manifests locally, as exemplified in this case. Chronic heat exposure and infrared radiation from these sources are thought to induce hyperthermia below the threshold for a thermal burn, and the cutaneous findings correspond with the dermal venous plexus.3

Diagnosis of erythema ab igne primarily is made clinically based on characteristic skin findings and exposure history. Relevant history may include occupations with prolonged heat exposure, such as baking, silversmithing, or foundry work. Heat exposure also may result from cultural practices such as cupping with moxibustion.4 Additionally, repeated use of heating pads or hot water bottles for pain relief by patients diagnosed with chronic pain or an underlying illness may contribute to development of erythema ab igne.1,4

Biopsy was not needed for diagnosis of this patient, but if the presentation is equivocal and history of potential exposures is unclear, a biopsy may be taken. A hematoxylin and eosin stain would reveal dilation of small vascular channels in the superficial dermis, contributing to the classic reticulated appearance. Biopsy findings also would reveal either an interface dermatitis or pigment incontinence containing melanin-laden macrophages correlating to either the erythema or hyperpigmentation, respectively.4

The prognosis for erythema ab igne is excellent, especially if diagnosed early. Treatment involves removal of the inciting heat source.1 The discoloration may resolve within a few months to years or may persist. If the hyperpigmentation is persistent, patients may consider laser treatments or lightening agents such as topical hydroquinone or topical tretinoin.4 However, if undiagnosed, patients may be at risk for development of a cutaneous malignancy, such as squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, or cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.2,4 Malignant transformation has been reported to occur decades after the initial skin eruption, although the risk is rare5; however, due to this risk, patients with erythema ab igne should be followed regularly and screened for new lesions in the affected areas.

The patient was diagnosed with erythema ab igne based on characteristic skin findings on physical examination along with a convincing history of chronic localized heat exposure. Erythema ab igne manifests as a persistent reticulated, erythematous, or hyperpigmented rash at sites of chronic heat exposure.1 Commonplace items that emit heat such as electric heaters, car heaters, heating pads, hot water bottles, and, in our case, laptops also emit infrared radiation, which can lead to changes in the skin with long-term exposure.2 Because exposure to these sources often is limited to one area of the body, erythema ab igne usually manifests locally, as exemplified in this case. Chronic heat exposure and infrared radiation from these sources are thought to induce hyperthermia below the threshold for a thermal burn, and the cutaneous findings correspond with the dermal venous plexus.3

Diagnosis of erythema ab igne primarily is made clinically based on characteristic skin findings and exposure history. Relevant history may include occupations with prolonged heat exposure, such as baking, silversmithing, or foundry work. Heat exposure also may result from cultural practices such as cupping with moxibustion.4 Additionally, repeated use of heating pads or hot water bottles for pain relief by patients diagnosed with chronic pain or an underlying illness may contribute to development of erythema ab igne.1,4

Biopsy was not needed for diagnosis of this patient, but if the presentation is equivocal and history of potential exposures is unclear, a biopsy may be taken. A hematoxylin and eosin stain would reveal dilation of small vascular channels in the superficial dermis, contributing to the classic reticulated appearance. Biopsy findings also would reveal either an interface dermatitis or pigment incontinence containing melanin-laden macrophages correlating to either the erythema or hyperpigmentation, respectively.4

The prognosis for erythema ab igne is excellent, especially if diagnosed early. Treatment involves removal of the inciting heat source.1 The discoloration may resolve within a few months to years or may persist. If the hyperpigmentation is persistent, patients may consider laser treatments or lightening agents such as topical hydroquinone or topical tretinoin.4 However, if undiagnosed, patients may be at risk for development of a cutaneous malignancy, such as squamous cell carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, or cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma.2,4 Malignant transformation has been reported to occur decades after the initial skin eruption, although the risk is rare5; however, due to this risk, patients with erythema ab igne should be followed regularly and screened for new lesions in the affected areas.

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162:77-78.

- Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

- Kesty K, Feldman SR. Erythema ab igne: evolving technology, evolving presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030.

- Harview CL, Krenitsky A. Erythema ab igne: a clinical review. Cutis. 2023;111:E33-E38. doi:10.12788/cutis.0771

- Wipf AJ, Brown MR. Malignant transformation of erythema ab igne. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:85-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.018

- Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162:77-78.

- Miller K, Hunt R, Chu J, et al. Erythema ab igne. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:28.

- Kesty K, Feldman SR. Erythema ab igne: evolving technology, evolving presentation. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030.

- Harview CL, Krenitsky A. Erythema ab igne: a clinical review. Cutis. 2023;111:E33-E38. doi:10.12788/cutis.0771

- Wipf AJ, Brown MR. Malignant transformation of erythema ab igne. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;26:85-87. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.06.018

Reticulated Hyperpigmentation on the Knee and Thigh

Reticulated Hyperpigmentation on the Knee and Thigh

A 25-year-old woman with an unremarkable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a persistent rash on the right knee and distal thigh of several months’ duration. The patient noted that the rash had been asymptomatic, and she denied any history of trauma to the area. She reported that she worked as a teacher and had repeatedly stayed up late using her laptop for months. Rather than use a desk, she often would work sitting with her laptop in her lap.

Flesh-Colored Lesion on the Ear

Flesh-Colored Lesion on the Ear

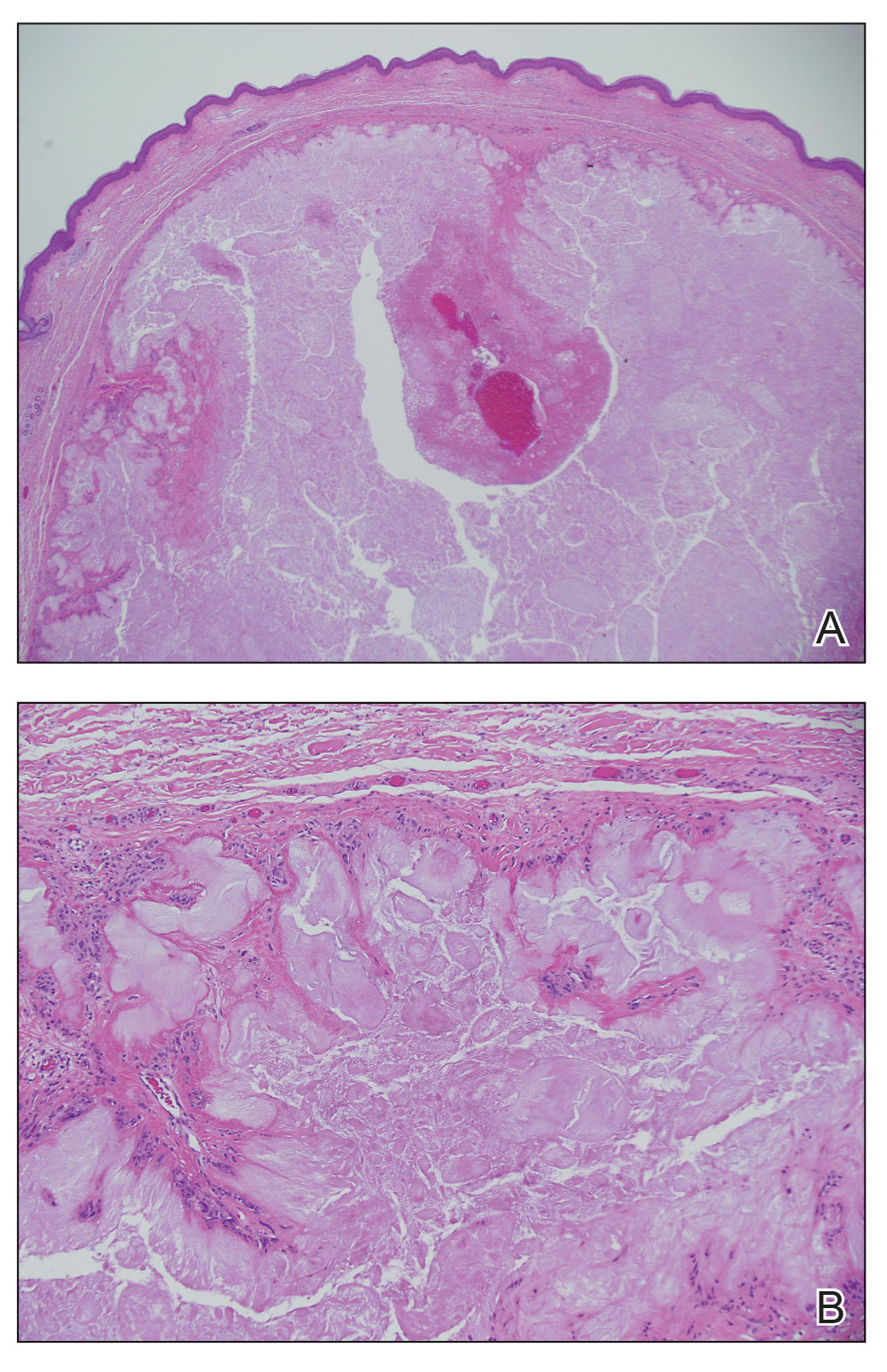

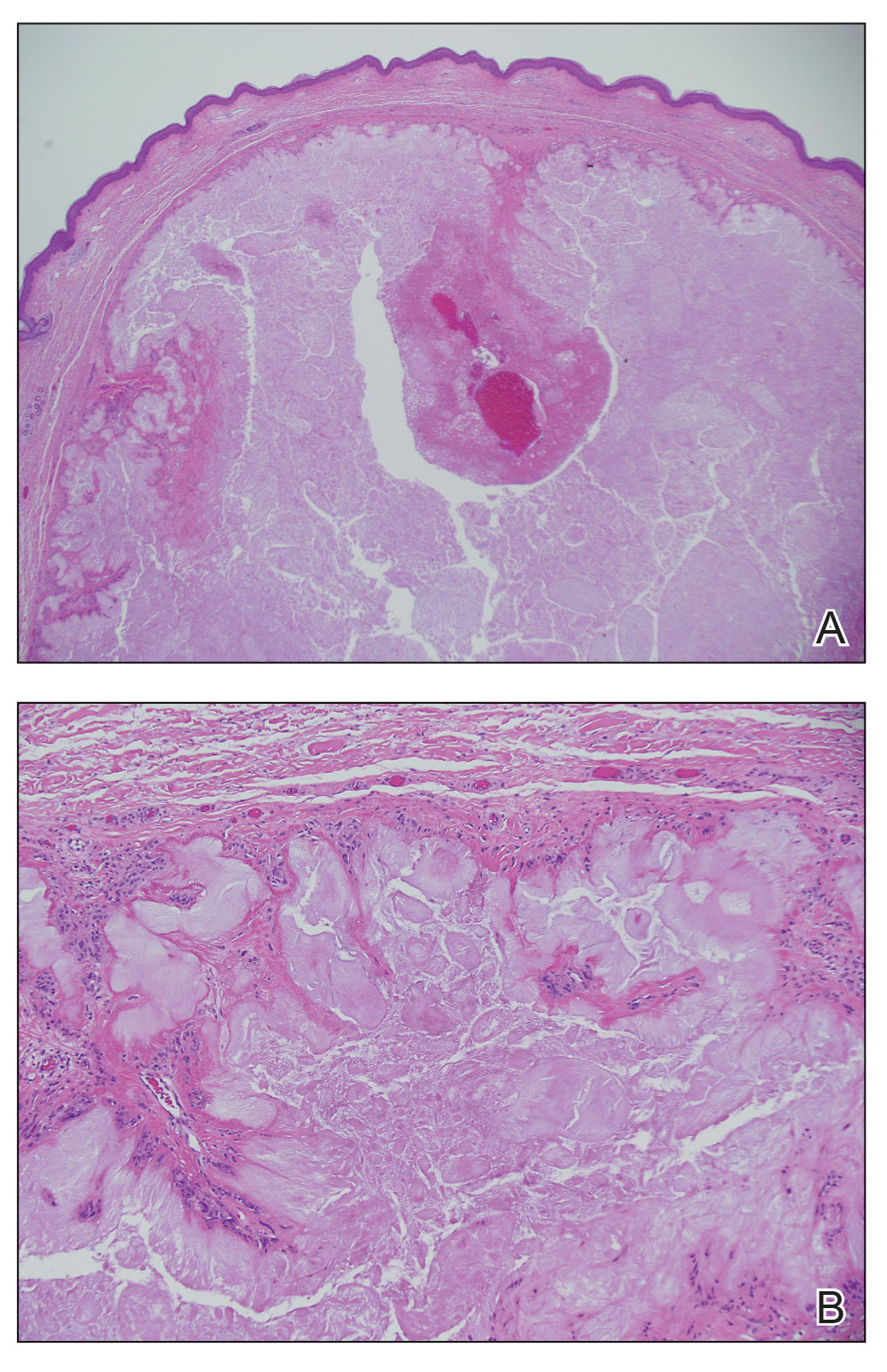

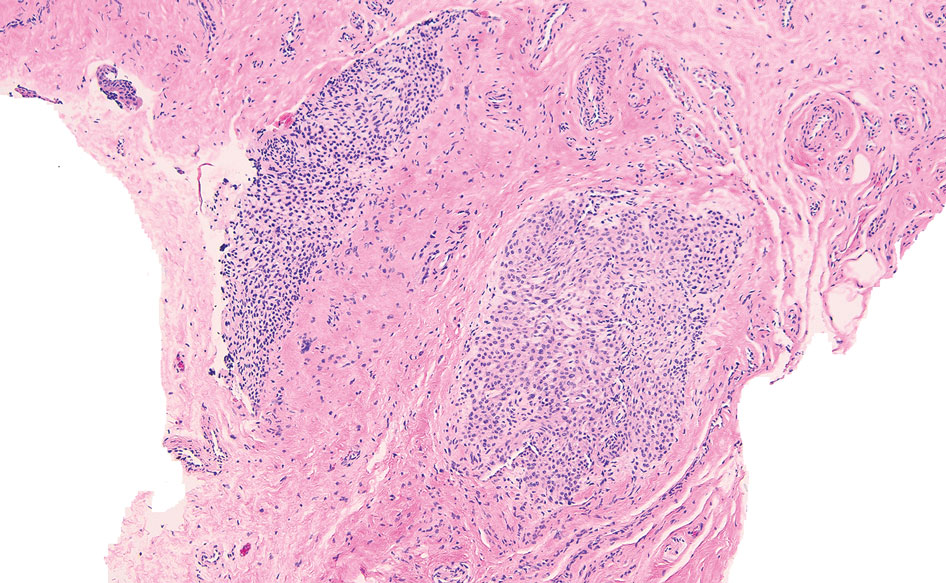

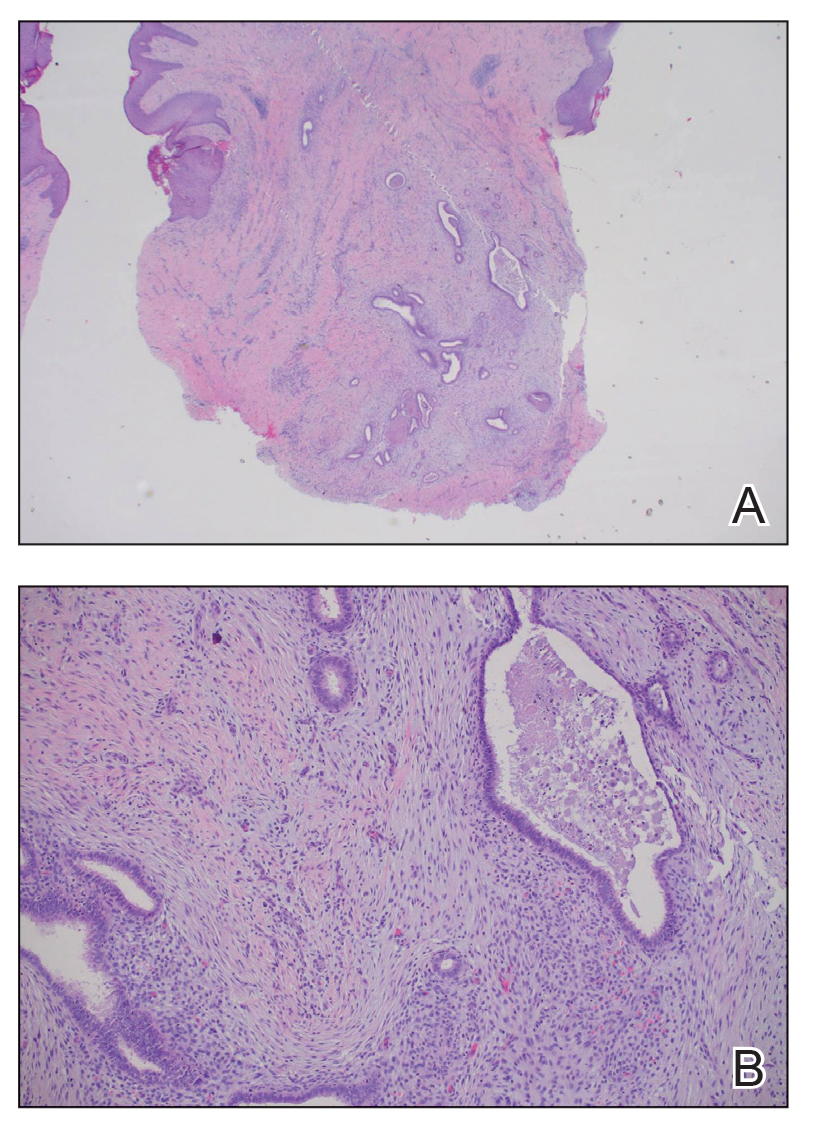

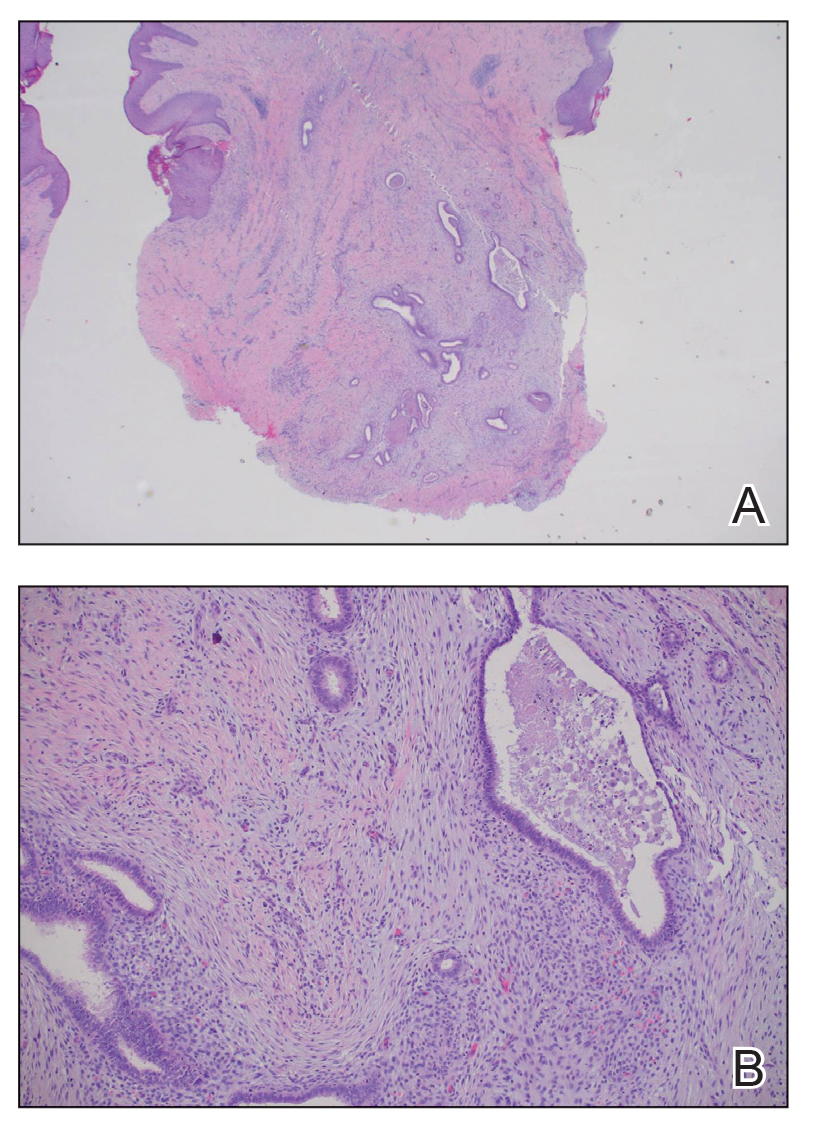

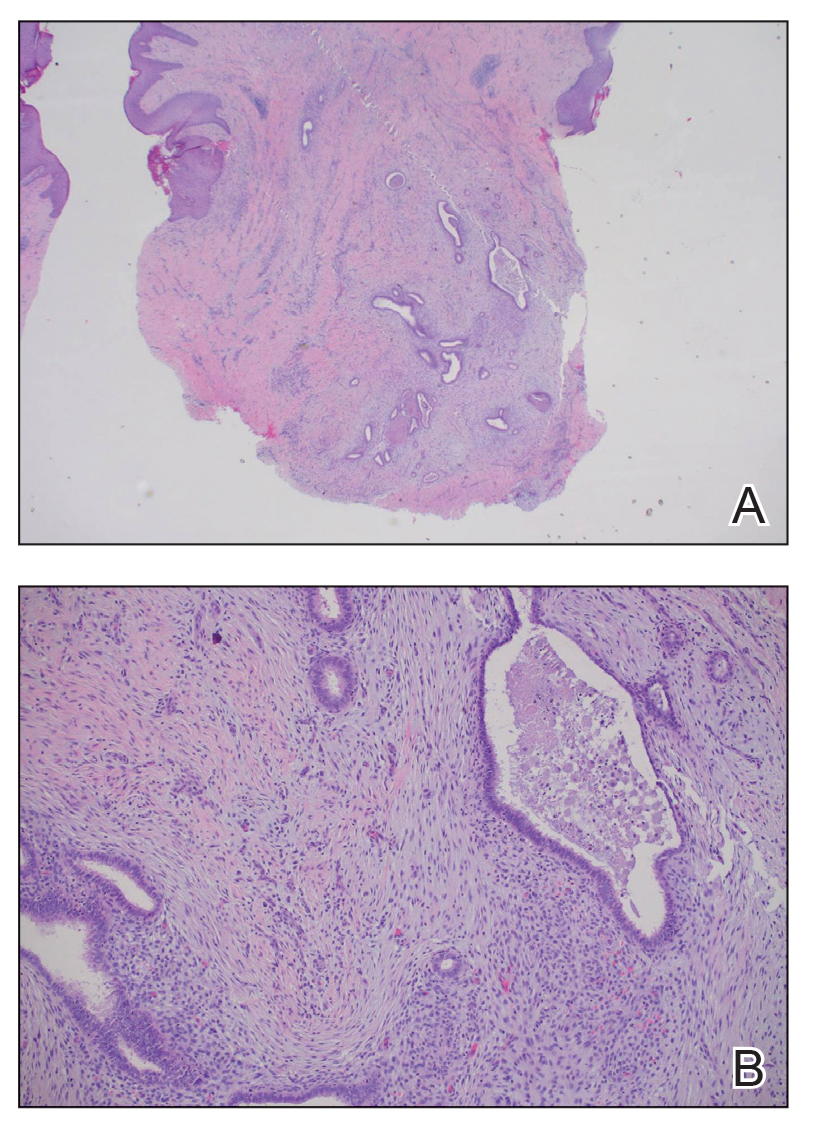

THE DIAGNOSIS: Gouty Tophus

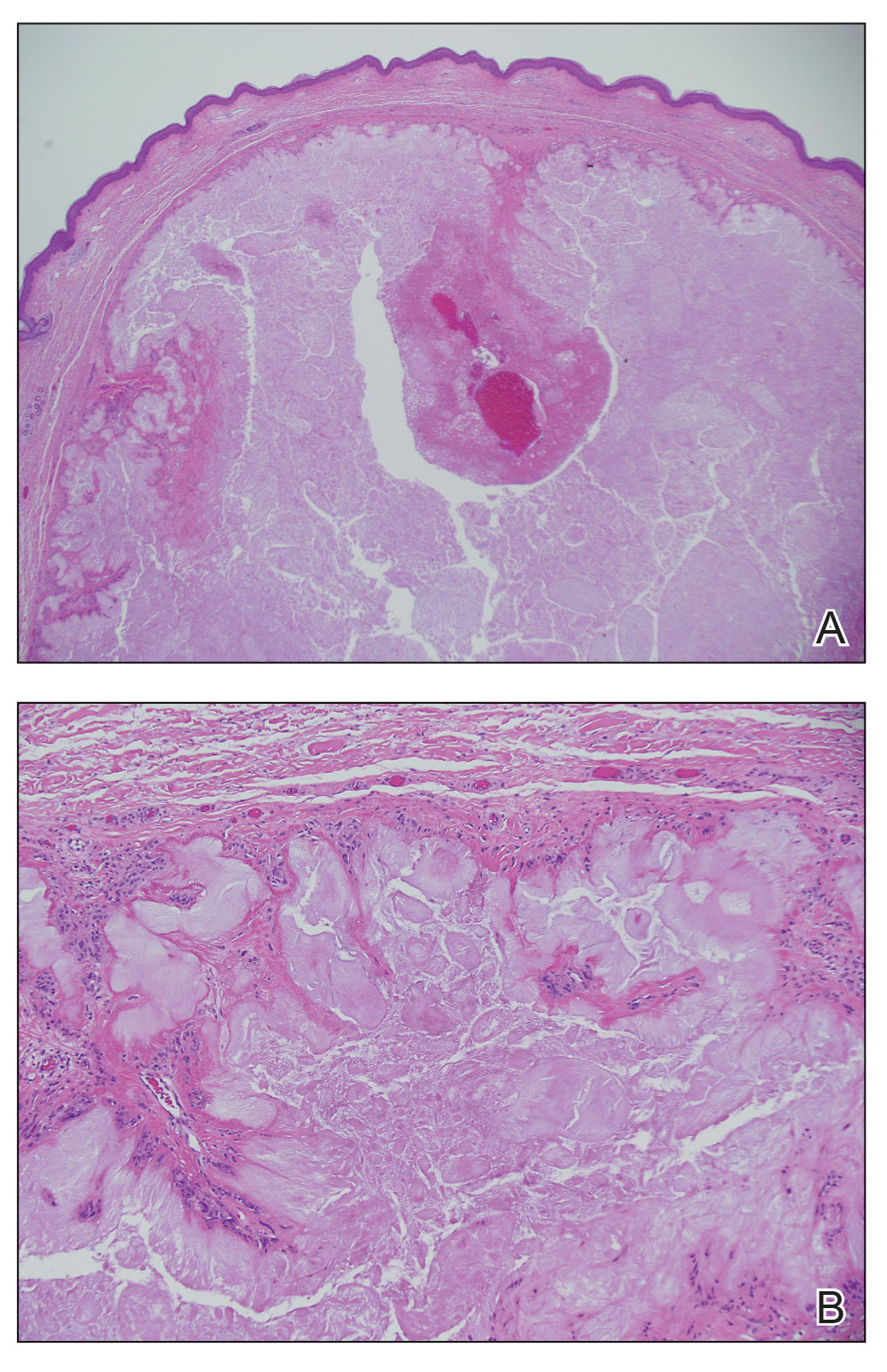

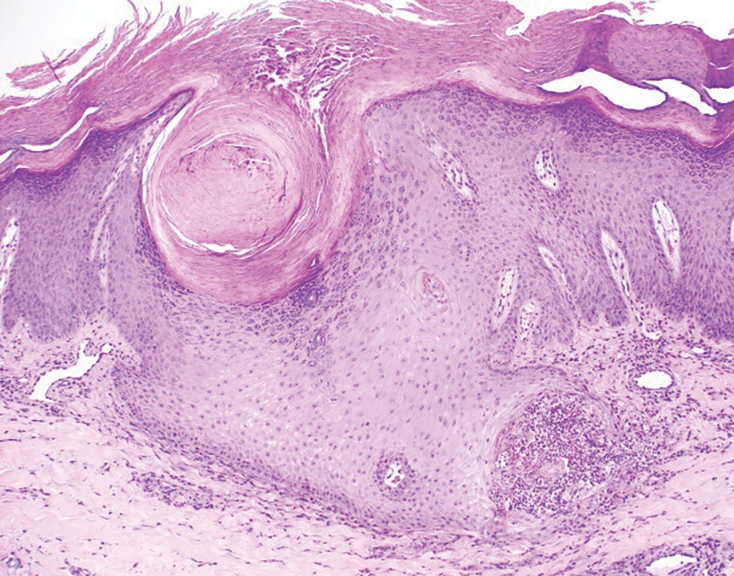

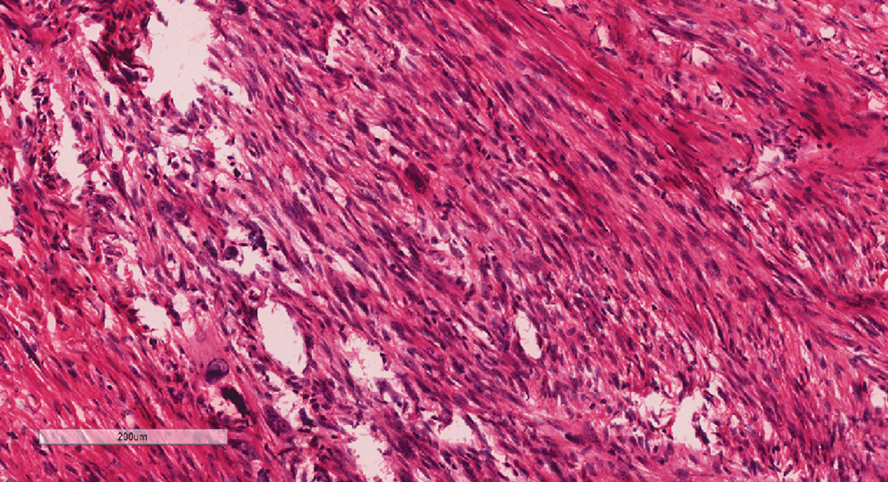

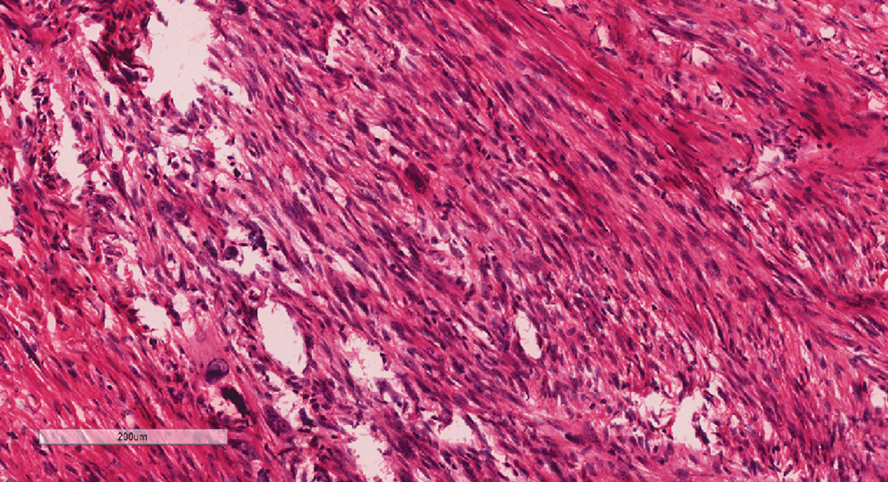

The lesion was excised and sent for histopathologic examination (eFigures 1 and 2), revealing aggregates of feathery, amorphous, pale-pink material, which confirmed the diagnosis of gouty tophus. The surgical site was left to heal by secondary intention. Upon further evaluation, the patient reported recurrent monoarticular joint pain in the ankles and feet, and laboratory workup revealed elevated serum uric acid. He was advised to follow up with his primary care physician to discuss systemic treatment options for gout.

Gout is an inflammatory arthritis characterized by the deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals in the joints, soft tissue, and bone due to elevated serum uric acid. Uric acid is the final product of purine metabolism, and serum levels may be elevated due to excess production or underexcretion. Multiple genetic, environmental, and metabolic factors influence these processes.1 Collections of monosodium urate crystals may develop intra- or extra-articularly, the latter of which are known as gouty tophi. These nodules have a classic chalklike consistency and typically are seen in patients with untreated gout starting approximately 10 years after the first flare. The most common locations for subcutaneous gouty tophi are acral sites (eg, fingertips, ears) as well as the wrists, knees, and elbows (olecranon bursae). Rarely, gouty panniculitis also may develop.2

Histopathology of gouty tophi reveals nodular aggregates of acellular, amorphous, pale-pink material surrounded by palisading histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. The presence of needlelike monosodium urate crystals, which display negative birefringence, is diagnostic. Unfortunately, these crystals are destroyed in routine formalin processing.3

There are limited data regarding treatment of gouty tophi. Urate-lowering systemic medications such as pegloticase may be beneficial, but more data are needed.4 We pursued surgical excision in our case for definitive diagnosis; however, it is not a common treatment for gouty tophi. Typically, urate-lowering therapy is utilized to resolve or shrink lesions over time.5

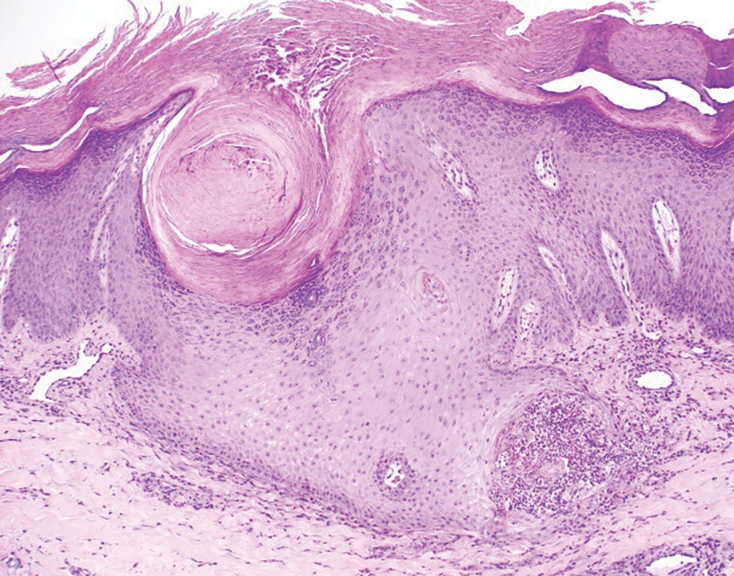

The differential diagnosis for gouty tophi includes epidermal inclusion cyst (EIC), the most common type of cutaneous cyst. Though EICs can manifest anywhere on the body, they are not as common on the ears as gouty tophi. Epidermal inclusion cysts clinically manifest as soft subcutaneous nodules, and a central punctum often is noted. These lesions are derived from the follicular infundibulum and histologically are characterized by a cystic cavity lined by a stratified squamous epithelium with a granular layer. The cavity contains loose laminated keratin material.6

Pseudocyst of the auricle is a benign cystic swelling of the pinna that can develop spontaneously but most often manifests following trauma to the area, which is believed to separate the tissue planes in the cartilage, allowing fluid to accumulate. This lesion typically is asymptomatic, though some patients report mild tenderness.7 Histology shows a cystic structure within the cartilage without an epithelial lining, and a perivascular inflammatory response often is observed.8

Pilomatricoma, also known as pilomatrixoma, is a benign tumor derived from the hair follicle matrix that manifests as a firm, slow-growing, painless subcutaneous nodule. It most often is found on the head and neck, commonly in the periauricular area.9 Though rare, it has been found on the auricle and external auditory canal.10 Histologically, pilomatricomas are well-defined tumors containing internal trabeculae. They contain populations of basaloid and ghost cells and often calcify, sometimes with resultant bone formation.9

Dermoid cysts are benign tumors that develop along lines of embryonic closure and often are diagnosed at birth or in early childhood. They most commonly manifest on the head and neck, typically in the supraorbital area. Rarely, they have been reported on the ear.6 Dermoid cysts may resemble EICs clinically and histopathologically, except that the cyst wall contains mature adnexal structures such as hair follicles and sebaceous glands.

- Dalbeth N, Merriman TR, Stamp LK. Gout. Lancet. 2016;388:2039-2052. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00346-9

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000000420

- Towiwat P, Chhana A, Dalbeth N. The anatomical pathology of gout: a systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:140. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2519-y

- Sriranganathan MK, Vinik O, Pardo Pardo J, et al. Interventions for tophi in gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;8:CD010069. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010069.pub3

- Evidence review for surgical excision of tophi. Gout: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). June 2022. Accessed October 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK583526/

- Cho Y, Lee DH. Clinical characteristics of idiopathic epidermoid and dermoid cysts of the ear. J Audiol Otol. 2017;21:77-80. doi:10.7874 /jao.2017.21.2.77

- Ballan A, Zogheib S, Hanna C, et al. Auricular pseudocysts: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:109-117. doi:10.1111/ijd.15816

- Lim CM, Goh YH, Chao SS, et al. Pseudocyst of the auricle: a histologic perspective. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1281-1284. doi:10.1097/00005537-200407000-00026

- Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018; 40:631-641. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

- McInerney NJ, Nae A, Brennan S, et al. Pilomatricoma of the external auditory canal. Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. 2023. doi:10.1016/j.xocr.2023.10053

THE DIAGNOSIS: Gouty Tophus

The lesion was excised and sent for histopathologic examination (eFigures 1 and 2), revealing aggregates of feathery, amorphous, pale-pink material, which confirmed the diagnosis of gouty tophus. The surgical site was left to heal by secondary intention. Upon further evaluation, the patient reported recurrent monoarticular joint pain in the ankles and feet, and laboratory workup revealed elevated serum uric acid. He was advised to follow up with his primary care physician to discuss systemic treatment options for gout.

Gout is an inflammatory arthritis characterized by the deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals in the joints, soft tissue, and bone due to elevated serum uric acid. Uric acid is the final product of purine metabolism, and serum levels may be elevated due to excess production or underexcretion. Multiple genetic, environmental, and metabolic factors influence these processes.1 Collections of monosodium urate crystals may develop intra- or extra-articularly, the latter of which are known as gouty tophi. These nodules have a classic chalklike consistency and typically are seen in patients with untreated gout starting approximately 10 years after the first flare. The most common locations for subcutaneous gouty tophi are acral sites (eg, fingertips, ears) as well as the wrists, knees, and elbows (olecranon bursae). Rarely, gouty panniculitis also may develop.2

Histopathology of gouty tophi reveals nodular aggregates of acellular, amorphous, pale-pink material surrounded by palisading histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. The presence of needlelike monosodium urate crystals, which display negative birefringence, is diagnostic. Unfortunately, these crystals are destroyed in routine formalin processing.3

There are limited data regarding treatment of gouty tophi. Urate-lowering systemic medications such as pegloticase may be beneficial, but more data are needed.4 We pursued surgical excision in our case for definitive diagnosis; however, it is not a common treatment for gouty tophi. Typically, urate-lowering therapy is utilized to resolve or shrink lesions over time.5

The differential diagnosis for gouty tophi includes epidermal inclusion cyst (EIC), the most common type of cutaneous cyst. Though EICs can manifest anywhere on the body, they are not as common on the ears as gouty tophi. Epidermal inclusion cysts clinically manifest as soft subcutaneous nodules, and a central punctum often is noted. These lesions are derived from the follicular infundibulum and histologically are characterized by a cystic cavity lined by a stratified squamous epithelium with a granular layer. The cavity contains loose laminated keratin material.6

Pseudocyst of the auricle is a benign cystic swelling of the pinna that can develop spontaneously but most often manifests following trauma to the area, which is believed to separate the tissue planes in the cartilage, allowing fluid to accumulate. This lesion typically is asymptomatic, though some patients report mild tenderness.7 Histology shows a cystic structure within the cartilage without an epithelial lining, and a perivascular inflammatory response often is observed.8

Pilomatricoma, also known as pilomatrixoma, is a benign tumor derived from the hair follicle matrix that manifests as a firm, slow-growing, painless subcutaneous nodule. It most often is found on the head and neck, commonly in the periauricular area.9 Though rare, it has been found on the auricle and external auditory canal.10 Histologically, pilomatricomas are well-defined tumors containing internal trabeculae. They contain populations of basaloid and ghost cells and often calcify, sometimes with resultant bone formation.9

Dermoid cysts are benign tumors that develop along lines of embryonic closure and often are diagnosed at birth or in early childhood. They most commonly manifest on the head and neck, typically in the supraorbital area. Rarely, they have been reported on the ear.6 Dermoid cysts may resemble EICs clinically and histopathologically, except that the cyst wall contains mature adnexal structures such as hair follicles and sebaceous glands.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Gouty Tophus

The lesion was excised and sent for histopathologic examination (eFigures 1 and 2), revealing aggregates of feathery, amorphous, pale-pink material, which confirmed the diagnosis of gouty tophus. The surgical site was left to heal by secondary intention. Upon further evaluation, the patient reported recurrent monoarticular joint pain in the ankles and feet, and laboratory workup revealed elevated serum uric acid. He was advised to follow up with his primary care physician to discuss systemic treatment options for gout.

Gout is an inflammatory arthritis characterized by the deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals in the joints, soft tissue, and bone due to elevated serum uric acid. Uric acid is the final product of purine metabolism, and serum levels may be elevated due to excess production or underexcretion. Multiple genetic, environmental, and metabolic factors influence these processes.1 Collections of monosodium urate crystals may develop intra- or extra-articularly, the latter of which are known as gouty tophi. These nodules have a classic chalklike consistency and typically are seen in patients with untreated gout starting approximately 10 years after the first flare. The most common locations for subcutaneous gouty tophi are acral sites (eg, fingertips, ears) as well as the wrists, knees, and elbows (olecranon bursae). Rarely, gouty panniculitis also may develop.2

Histopathology of gouty tophi reveals nodular aggregates of acellular, amorphous, pale-pink material surrounded by palisading histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. The presence of needlelike monosodium urate crystals, which display negative birefringence, is diagnostic. Unfortunately, these crystals are destroyed in routine formalin processing.3

There are limited data regarding treatment of gouty tophi. Urate-lowering systemic medications such as pegloticase may be beneficial, but more data are needed.4 We pursued surgical excision in our case for definitive diagnosis; however, it is not a common treatment for gouty tophi. Typically, urate-lowering therapy is utilized to resolve or shrink lesions over time.5

The differential diagnosis for gouty tophi includes epidermal inclusion cyst (EIC), the most common type of cutaneous cyst. Though EICs can manifest anywhere on the body, they are not as common on the ears as gouty tophi. Epidermal inclusion cysts clinically manifest as soft subcutaneous nodules, and a central punctum often is noted. These lesions are derived from the follicular infundibulum and histologically are characterized by a cystic cavity lined by a stratified squamous epithelium with a granular layer. The cavity contains loose laminated keratin material.6

Pseudocyst of the auricle is a benign cystic swelling of the pinna that can develop spontaneously but most often manifests following trauma to the area, which is believed to separate the tissue planes in the cartilage, allowing fluid to accumulate. This lesion typically is asymptomatic, though some patients report mild tenderness.7 Histology shows a cystic structure within the cartilage without an epithelial lining, and a perivascular inflammatory response often is observed.8

Pilomatricoma, also known as pilomatrixoma, is a benign tumor derived from the hair follicle matrix that manifests as a firm, slow-growing, painless subcutaneous nodule. It most often is found on the head and neck, commonly in the periauricular area.9 Though rare, it has been found on the auricle and external auditory canal.10 Histologically, pilomatricomas are well-defined tumors containing internal trabeculae. They contain populations of basaloid and ghost cells and often calcify, sometimes with resultant bone formation.9

Dermoid cysts are benign tumors that develop along lines of embryonic closure and often are diagnosed at birth or in early childhood. They most commonly manifest on the head and neck, typically in the supraorbital area. Rarely, they have been reported on the ear.6 Dermoid cysts may resemble EICs clinically and histopathologically, except that the cyst wall contains mature adnexal structures such as hair follicles and sebaceous glands.

- Dalbeth N, Merriman TR, Stamp LK. Gout. Lancet. 2016;388:2039-2052. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00346-9

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000000420

- Towiwat P, Chhana A, Dalbeth N. The anatomical pathology of gout: a systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:140. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2519-y

- Sriranganathan MK, Vinik O, Pardo Pardo J, et al. Interventions for tophi in gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;8:CD010069. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010069.pub3

- Evidence review for surgical excision of tophi. Gout: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). June 2022. Accessed October 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK583526/

- Cho Y, Lee DH. Clinical characteristics of idiopathic epidermoid and dermoid cysts of the ear. J Audiol Otol. 2017;21:77-80. doi:10.7874 /jao.2017.21.2.77

- Ballan A, Zogheib S, Hanna C, et al. Auricular pseudocysts: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:109-117. doi:10.1111/ijd.15816

- Lim CM, Goh YH, Chao SS, et al. Pseudocyst of the auricle: a histologic perspective. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1281-1284. doi:10.1097/00005537-200407000-00026

- Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018; 40:631-641. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

- McInerney NJ, Nae A, Brennan S, et al. Pilomatricoma of the external auditory canal. Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. 2023. doi:10.1016/j.xocr.2023.10053

- Dalbeth N, Merriman TR, Stamp LK. Gout. Lancet. 2016;388:2039-2052. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00346-9

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000000420

- Towiwat P, Chhana A, Dalbeth N. The anatomical pathology of gout: a systematic literature review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:140. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2519-y

- Sriranganathan MK, Vinik O, Pardo Pardo J, et al. Interventions for tophi in gout. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;8:CD010069. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010069.pub3

- Evidence review for surgical excision of tophi. Gout: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). June 2022. Accessed October 8, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK583526/

- Cho Y, Lee DH. Clinical characteristics of idiopathic epidermoid and dermoid cysts of the ear. J Audiol Otol. 2017;21:77-80. doi:10.7874 /jao.2017.21.2.77

- Ballan A, Zogheib S, Hanna C, et al. Auricular pseudocysts: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:109-117. doi:10.1111/ijd.15816

- Lim CM, Goh YH, Chao SS, et al. Pseudocyst of the auricle: a histologic perspective. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1281-1284. doi:10.1097/00005537-200407000-00026

- Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018; 40:631-641. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

- McInerney NJ, Nae A, Brennan S, et al. Pilomatricoma of the external auditory canal. Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. 2023. doi:10.1016/j.xocr.2023.10053

Flesh-Colored Lesion on the Ear

Flesh-Colored Lesion on the Ear

A 46-year-old man with a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes presented to the dermatology clinic with a painless nodule on the left ear of 2 years’ duration. The patient denied any bleeding, drainage, or prior trauma to the area. He noted that the lesion had grown slowly over time. Physical examination revealed a 1.5×1.5-cm, flesh-colored, subcutaneous nodule with overlying telangiectasias on the left antihelix.

Longitudinal Erythronychia Manifesting With Pain and Cold Sensitivity

The Diagnosis: Glomangiomyoma

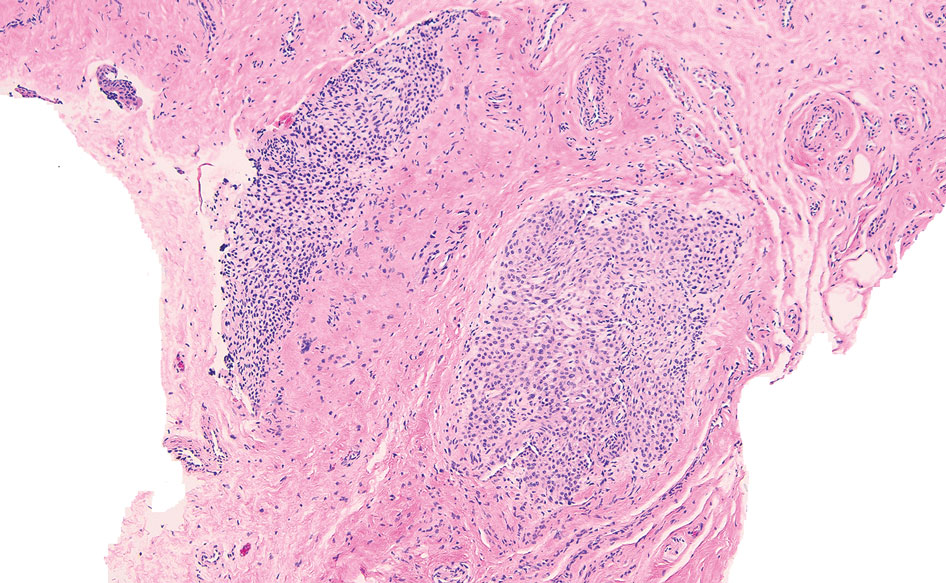

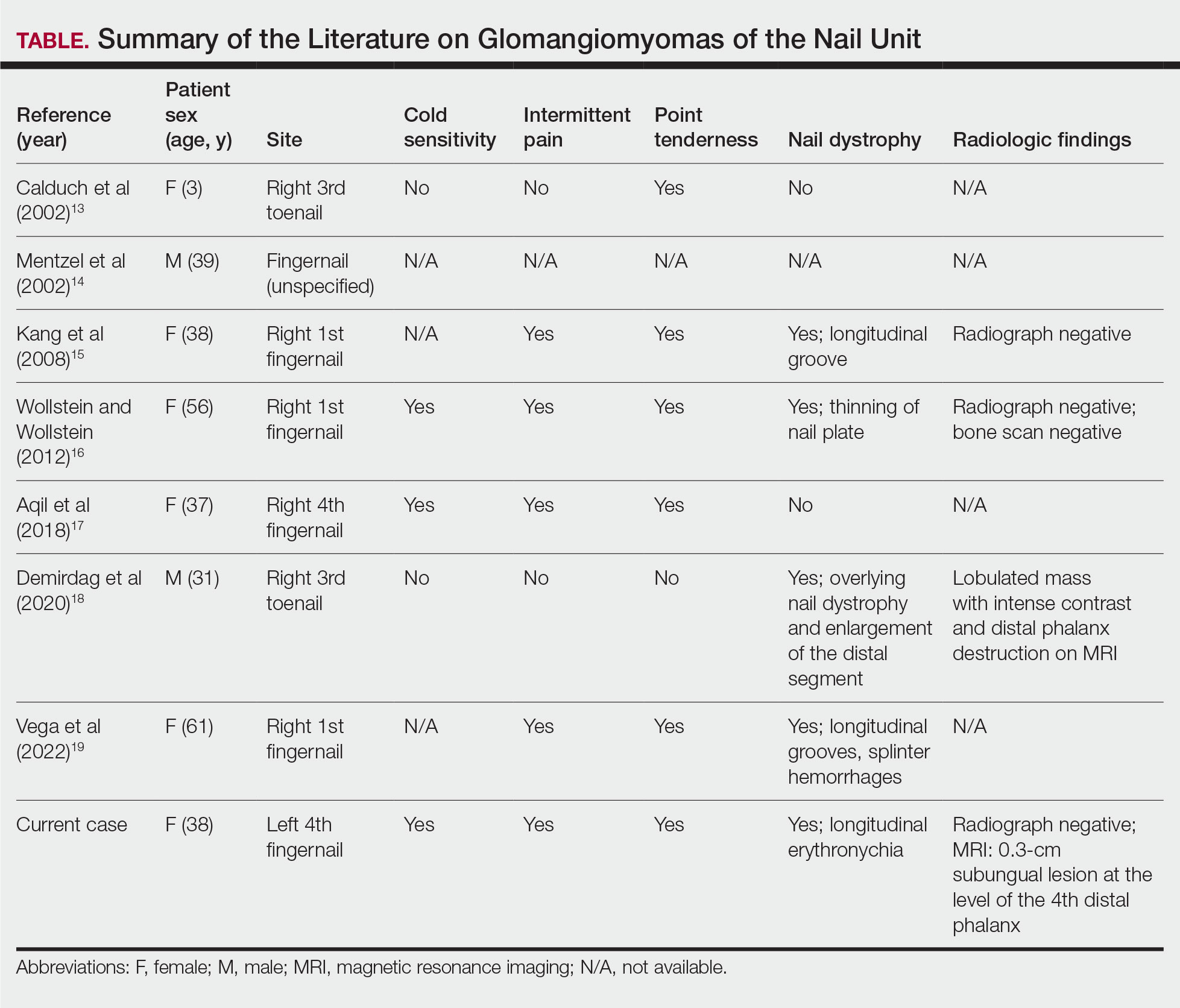

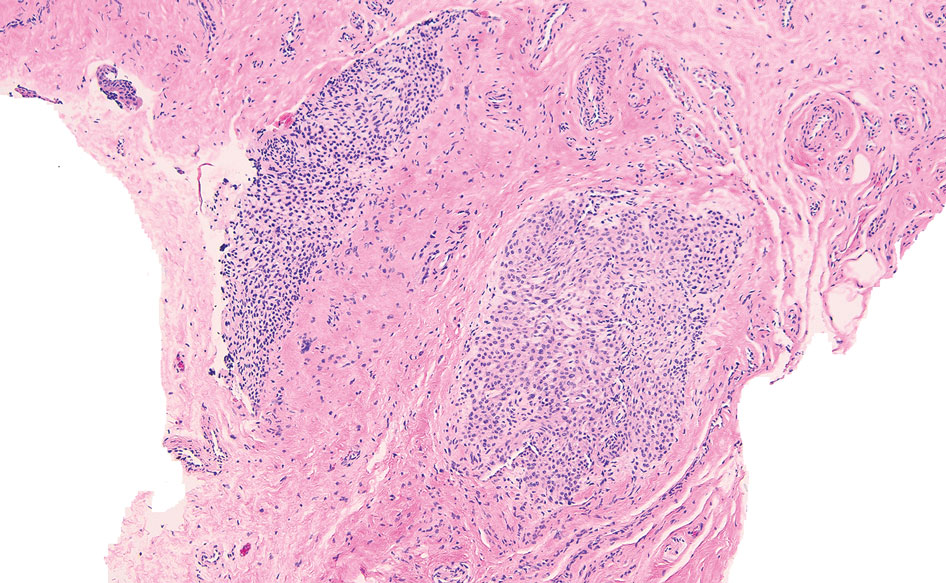

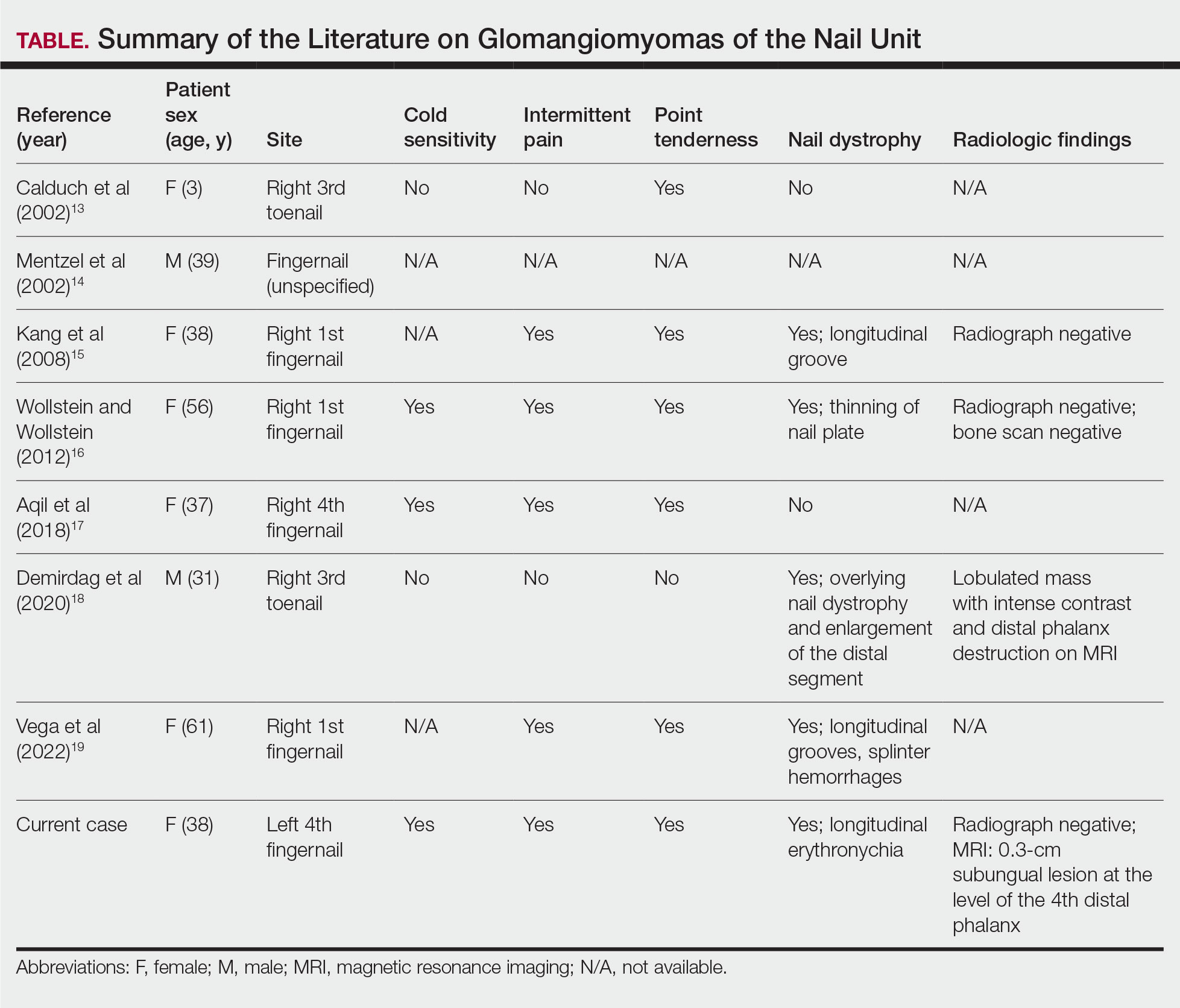

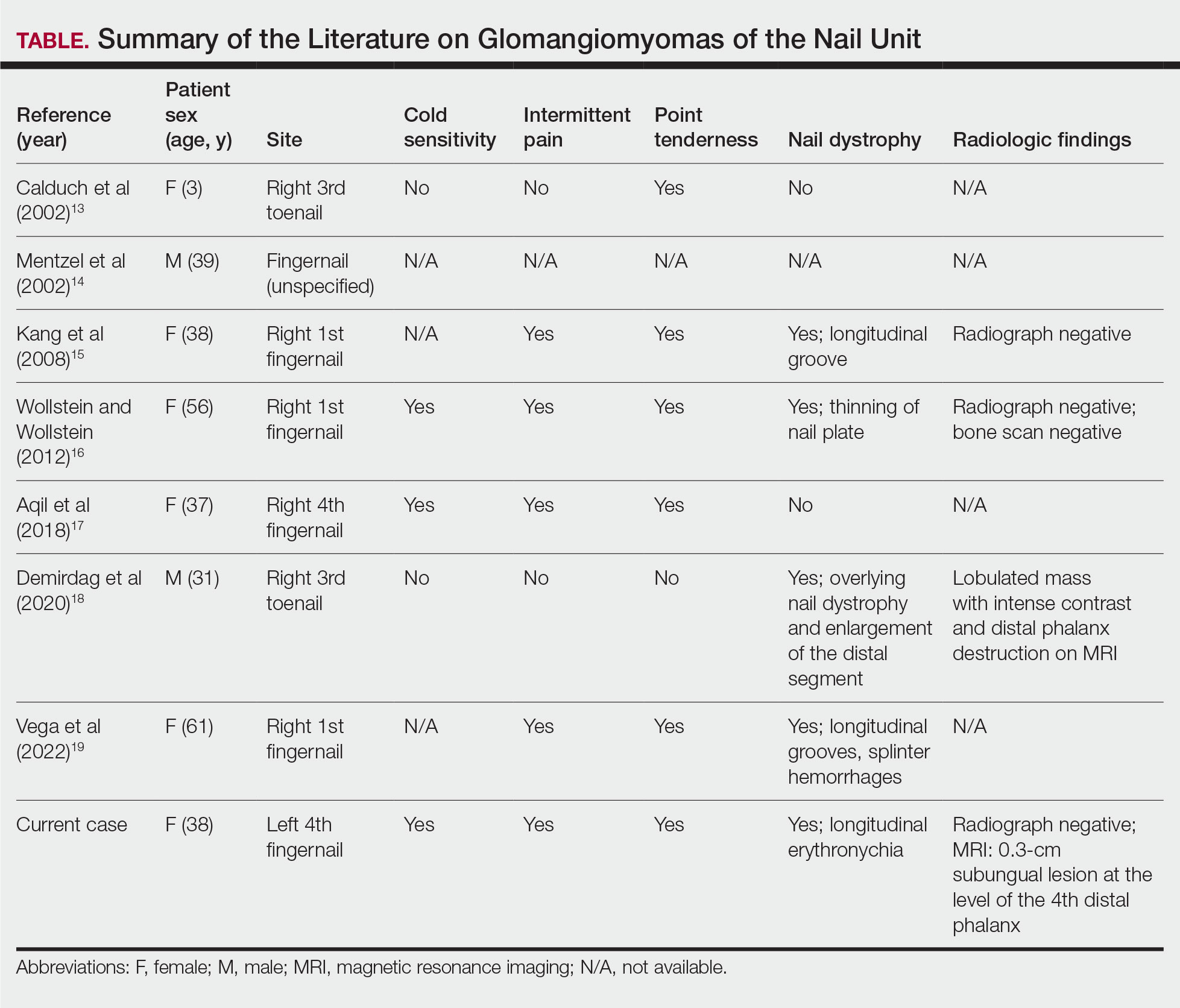

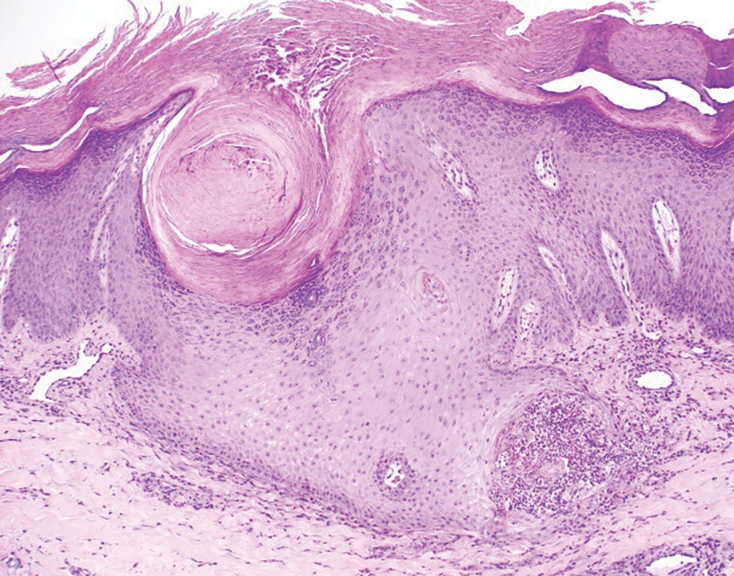

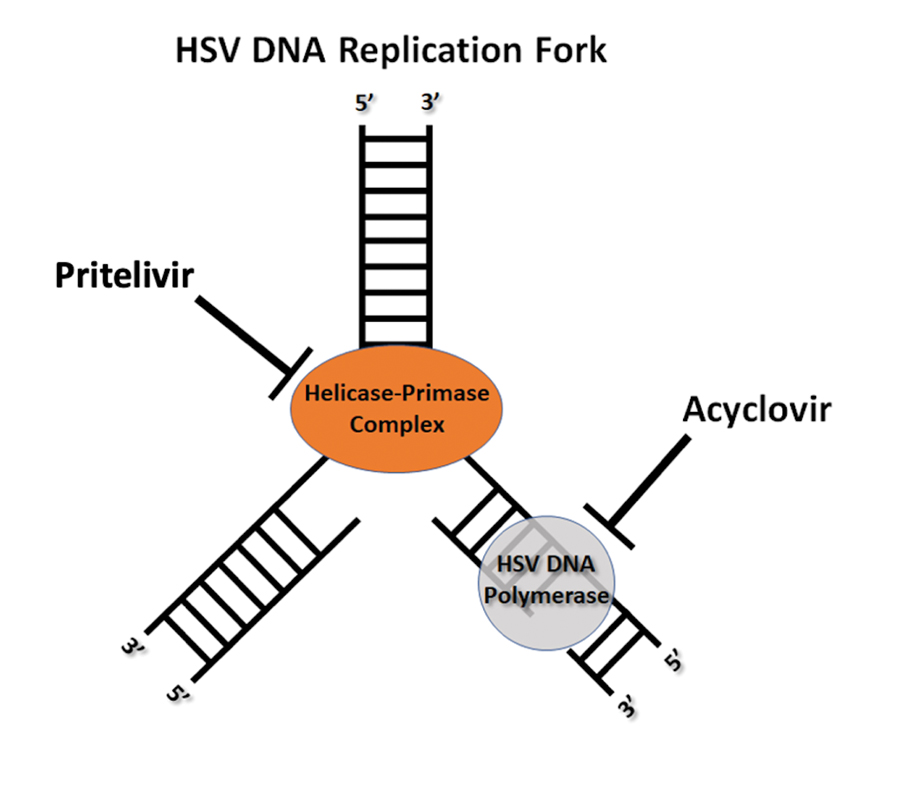

The nail unit excision specimen showed collections of cuboidal cells and spindled cells within the corium that were consistent with a diagnosis of a glomangiomyoma, a rare glomus tumor variant (Figure). Glomus tumors are benign neoplasms comprising glomus bodies, which are arteriovenous anastomoses involved in thermoregulation.1 They develop in areas densely populated by glomus bodies, including the fingers, toes, and subungual areas. Glomus tumors most commonly develop in middle-aged women.2 Clinically, they manifest with a characteristic triad of intense pain, point tenderness, and cold sensitivity and may appear as reddish-pink or blue macules under the nail plate and/or longitudinal erythronychia.2-6 The presence of multiple glomus tumors is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.7

Advanced imaging including ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help confirm the diagnosis but may not be cost effective, as excision with histopathology is needed to relieve symptoms and render a definitive diagnosis. Radiography is highly insensitive in identifying bone erosions associated with glomus tumors.8 With ultrasonography, glomus tumors appear hypoechoic; with Doppler ultrasonography, they appear hypervascular. With MRI, glomus tumors appear as well-defined nodular lesions with hypointense signal intensity on T1-weighted sequence and hyperintense signal intensity on T2-weighted sequence, with strong enhancement using gadolinium-based contrast.9,10 On histopathology, a glomus tumor appears as a nodular tumor with sheets of oval-nucleated cells arranged in multicellular layers surrounding blood vessels and are immunoreactive for α-smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and type IV collagen.11,12

There are several glomus tumor variants. The most common is a solid glomus tumor, which predominantly is composed of glomus cells, followed by glomangioma, which mainly is composed of blood vessels. Glomangiomyoma, which mostly is composed of smooth muscle cells, is the rarest variant.13

While glomus tumors are common in the subungual areas, it is an uncommon location for glomangiomyomas, which have been reported in the nail unit in only 7 prior case reports identified through searches of PubMed and Google Scholar using the terms glomangiomyoma, glomangiomyoma nail, and subungual glomangiomyoma (Table).13-19 Glomangiomyomas more commonly are described in solid organs, including the stomach, kidney, pancreas, and bladder.16 The mean age of patients with subungual glomangiomyomas, including our patient, was 40.4 years (range, 3-61 years), with the majority being female (75.0% [6/8]). Most patients presented with fingernail involvement (75.0% [6/8]), nail dystrophy (eg, nail plate thinning, longitudinal grooves, splinter hemorrhages, longitudinal erythronychia)(62.5% [5/8]), and intermittent pain and/or point tenderness in the affected nail (75.0% [6/8]).13-19 Notably, only our patient had longitudinal erythronychia as a clinical feature, and only one other case described MRI findings, which included a lobulated mass with intense contrast and distal phalanx destruction.18 One patient was a 3-year-old girl with a family history of generalized multiple glomangiomyomas. Although subungual glomangiomyoma was not confirmed on histopathology, the diagnosis in this patient was presumed based on her family history.13 On histopathology, glomangiomyomas are composed of oval-nucleated cells surrounding blood vessels. These oval-nucleated cells then gradually transition to smooth muscle cells.20

A myxoid cyst is composed of a pseudocyst, which lacks a cyst lining, and is a result of synovial fluid from the distal interphalangeal joint entering the pseudocyst space.2 It typically manifests with a longitudinal groove in the nail plate. A flesh-colored nodule may be appreciated between the cuticle and the distal interphalangeal joint.2 The depth of the longitudinal groove may vary depending on the volume of synovial fluid within the myxoid cyst.21 In a series of 35 cases of subungual myxoid cysts, none manifested with longitudinal erythronychia. Due to their composition, myxoid cysts can be distinguished easily from solid tumors of the nail unit via transillumination.22 Pain is a much less common with myxoid cysts vs glomus tumors, as the filling of the pseudocyst space with synovial fluid typically is gradual, allowing the surrounding tissue to accommodate and adapt over time.21 In equivocal cases, MRI or high-resolution ultrasonography may be used to distinguish myxoid cysts and glomus tumors.8 Histopathology shows accumulation of mucin in the dermis with surrounding fibrous stroma.23

Subungual neuromas are painful benign tumors that develop due to disorganized neural proliferation following disruption to peripheral nerves secondary to trauma or surgery. In 3 case reports, subungual neuromas manifested as painful subungual nodules, with proximal nail plate ridging, or onycholysis.24-26 Since neuromas have only rarely been described in the subungual region, reports of MRI and ultrasonography findings are unknown. Histopathology is needed to distinguish neuromas from glomus tumors. Histopathology shows an acapsular structure consisting of disorganized spindle-cell proliferation and nerve fibers arranged in a tangle of fascicles within fibrotic tissue.25 On immunochemistry, spindle cells typically are positive for cellular antigen protein S100.26

Leiomyomas are benign neoplasms derived from smooth muscle, typically localized to the uterus or gastrointestinal tract, and have been described rarely in the nail unit.27,28 It is hypothesized that subungual leiomyomas originate from the vascular smooth muscle in the subcutaneous layer of the nail unit.28 Like glomus tumors, leiomyomas of the subungual region often manifest with pain and longitudinal erythronychia.27-30 Subungual leiomyomas may be distinguished from glomus tumors via advanced imaging techniques, including ultrasonography and MRI. Cutaneous leiomyomas have been described with mild to moderate internal low flow vascularity on Doppler ultrasonography, while glomus tumors typically reveal high internal vascularity.28 Biopsy with histopathology is needed for definitive diagnosis. On histopathology, leiomyomas demonstrate bland-appearing spindle-shaped cells with elongated nuclei arranged in fascicles.27 They typically are positive for α-smooth muscle actin and caldesmon on immunostaining.

Eccrine spiradenomas are benign adnexal tumors likely of apocrine origin with limited case reports in the literature.31,32 Clinically, eccrine spiradenomas involving the nail unit may manifest with longitudinal nail splitting of the nail or as a papule on the proximal nail fold, with associated tenderness.31,32 In a report of a 50-year-old woman with a histopathologically confirmed eccrine spiradenoma manifesting with longitudinal splitting of the nail and pain in the proximal nail fold, the mass appeared hypoechoic on ultrasonography with increased intramass vascularity on Doppler, while MRI showed an intensely enhancing lesion.31 These imaging features, combined with a classically manifesting feature of pain, make eccrine spiradenomas difficult to distinguish from glomus tumors; therefore, histopathologic examination can provide a definitive diagnosis, and surgical excision is used for treatment.31 On histopathology, these tumors are well circumscribed and composed of both small dark basaloid cells with peripheral compact nuclei and larger cells with central pale nuclei, which may be arranged in tubules.31,32

- Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132: 1448-1452. doi:10.5858/2008-132-1448-gt

- Hare AQ, Rich P. Nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:281-292. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.007

- Hazani R, Houle JM, Kasdan ML, et al. Glomus tumors of the hand. Eplasty. 2008;8:E48.

- Hwang JK, Lipner SR. Blue nail discoloration: literature review and diagnostic algorithms. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:419-441. doi:10.1007/s40257-023-00768-6

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Longitudinal erythronychia of the fingernail. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1271-1272. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.2747

- Jellinek NJ, Lipner SR. Longitudinal erythronychia: retrospective single-center study evaluating differential diagnosis and the likelihood of malignancy. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:310-319. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000000594

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Subungual glomus tumors: underrecognized clinical findings in neurofibromatosis 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E269. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.129

- Dhami A, Vale SM, Richardson ML, et al. Comparing ultrasound with magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of subungual glomus tumors and subungual myxoid cysts. Skin Appendage Disord. 2023;9:262-267. doi:10.1159/000530397

- Baek HJ, Lee SJ, Cho KH, et al. Subungual tumors: clinicopathologic correlation with US and MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2010;30:1621-1636. doi:10.1148/rg.306105514

- Patel T, Meena V, Meena P. Hand and foot glomus tumors: significance of MRI diagnosis followed by histopathological assessment. Cureus. 2022;14:E30038. doi:10.7759/cureus.30038

- Mravic M, LaChaud G, Nguyen A, et al. Clinical and histopathological diagnosis of glomus tumor: an institutional experience of 138 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2015;23:181-188. doi:10.1177/1066896914567330

- Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, et al. Atypical and malignant glomus tumors: analysis of 52 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of glomus tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1-12. doi:10.1097/00000478-200101000-00001

- Calduch L, Monteagudo C, Martínez-Ruiz E, et al. Familial generalized multiple glomangiomyoma: report of a new family, with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:402-408. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00114.x

- Mentzel T, Hügel H, Kutzner H. CD34-positive glomus tumor: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of six cases with myxoid stromal changes. J Cutan Pathol. 2002;29:421-425. doi:10.1034 /j.1600-0560.2002.290706.x

- Kang TW, Lee KH, Park CJ. A case of subungual glomangiomyoma with myxoid stromal change. Korean J Dermatol. 2008;46:550-553.

- Wollstein A, Wollstein R. Subungual glomangiomyoma—a case report. Hand Surg. 2012;17:271-273. doi:10.1142/S021881041272032X

- Aqil N, Gallouj S, Moustaide K, et al. Painful tumors in a patient with neurofibromatosis type 1: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:319. doi:10.1186/s13256-018-1847-0

- Demirdag HG, Akay BN, Kirmizi A, et al. Subungual glomangiomyoma. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2020;110:Article_13. doi:10.7547/19-051

- Vega SML, Ruiz SJA, Ramírez CS, et al. Subungual glomangiomyoma: a case report. Dermatol Cosmet Med Quir. 2022;20:258-262.

- Chalise S, Jha A, Neupane PR. Glomangiomyoma of uncertain malignant potential in the urinary bladder: a case report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2021;59:719-722. doi:10.31729/jnma.5388

- de Berker D, Goettman S, Baran R. Subungual myxoid cysts: clinical manifestations and response to therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:394-398. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.119652

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Transillumination for improved diagnosis of digital myxoid cysts. Cutis. 2020;105:82.

- Fernandez-Flores A, Saeb-Lima M. Mucin as a diagnostic clue in dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1005-1016. doi:10.1111/cup.12782

- Choi R, Kim SR, Glusac EJ, et al. Subungual neuroma masquerading as green nail syndrome. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;20:17-19. doi:10.1016 /j.jdcr.2021.11.025

- Rashid RM, Rashid RM, Thomas V. Subungal traumatic neuroma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:E7-E8. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.028

- Whitehouse HJ, Urwin R, Stables G. Traumatic subungual neuroma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:65-66. doi:10.1111/ced.13247

- Lipner SR, Ko D, Husain S. Subungual leiyomyoma presenting as erythronychia: case report and review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:465-467.

- Taleb E, Saldías C, Gonzalez S, et al. Sonographic characteristics of leiomyomatous tumors of skin and nail: a case series. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2022;12:e2022082. doi:10.5826/dpc.1203a82

- Baran R, Requena L, Drapé JL. Subungual angioleiomyoma masquerading as a glomus tumour. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:1239-1241. doi:10.1046/ j.1365-2133.2000.03560.x

- Watabe D, Sakurai E, Mori S, et al. Subungual angioleiomyoma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83:74-75. doi:10.4103/0378-6323 .185045

- Jha AK, Sinha R, Kumar A, et al. Spiradenoma causing longitudinal splitting of the nail. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:754-756. doi:10.1111 /ced.12886

- Leach BC, Graham BS. Papular lesion of the proximal nail fold. eccrine spiradenoma. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1003-1008. doi:10.1001 /archderm.140.8.1003-a

The Diagnosis: Glomangiomyoma

The nail unit excision specimen showed collections of cuboidal cells and spindled cells within the corium that were consistent with a diagnosis of a glomangiomyoma, a rare glomus tumor variant (Figure). Glomus tumors are benign neoplasms comprising glomus bodies, which are arteriovenous anastomoses involved in thermoregulation.1 They develop in areas densely populated by glomus bodies, including the fingers, toes, and subungual areas. Glomus tumors most commonly develop in middle-aged women.2 Clinically, they manifest with a characteristic triad of intense pain, point tenderness, and cold sensitivity and may appear as reddish-pink or blue macules under the nail plate and/or longitudinal erythronychia.2-6 The presence of multiple glomus tumors is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.7

Advanced imaging including ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help confirm the diagnosis but may not be cost effective, as excision with histopathology is needed to relieve symptoms and render a definitive diagnosis. Radiography is highly insensitive in identifying bone erosions associated with glomus tumors.8 With ultrasonography, glomus tumors appear hypoechoic; with Doppler ultrasonography, they appear hypervascular. With MRI, glomus tumors appear as well-defined nodular lesions with hypointense signal intensity on T1-weighted sequence and hyperintense signal intensity on T2-weighted sequence, with strong enhancement using gadolinium-based contrast.9,10 On histopathology, a glomus tumor appears as a nodular tumor with sheets of oval-nucleated cells arranged in multicellular layers surrounding blood vessels and are immunoreactive for α-smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and type IV collagen.11,12

There are several glomus tumor variants. The most common is a solid glomus tumor, which predominantly is composed of glomus cells, followed by glomangioma, which mainly is composed of blood vessels. Glomangiomyoma, which mostly is composed of smooth muscle cells, is the rarest variant.13

While glomus tumors are common in the subungual areas, it is an uncommon location for glomangiomyomas, which have been reported in the nail unit in only 7 prior case reports identified through searches of PubMed and Google Scholar using the terms glomangiomyoma, glomangiomyoma nail, and subungual glomangiomyoma (Table).13-19 Glomangiomyomas more commonly are described in solid organs, including the stomach, kidney, pancreas, and bladder.16 The mean age of patients with subungual glomangiomyomas, including our patient, was 40.4 years (range, 3-61 years), with the majority being female (75.0% [6/8]). Most patients presented with fingernail involvement (75.0% [6/8]), nail dystrophy (eg, nail plate thinning, longitudinal grooves, splinter hemorrhages, longitudinal erythronychia)(62.5% [5/8]), and intermittent pain and/or point tenderness in the affected nail (75.0% [6/8]).13-19 Notably, only our patient had longitudinal erythronychia as a clinical feature, and only one other case described MRI findings, which included a lobulated mass with intense contrast and distal phalanx destruction.18 One patient was a 3-year-old girl with a family history of generalized multiple glomangiomyomas. Although subungual glomangiomyoma was not confirmed on histopathology, the diagnosis in this patient was presumed based on her family history.13 On histopathology, glomangiomyomas are composed of oval-nucleated cells surrounding blood vessels. These oval-nucleated cells then gradually transition to smooth muscle cells.20

A myxoid cyst is composed of a pseudocyst, which lacks a cyst lining, and is a result of synovial fluid from the distal interphalangeal joint entering the pseudocyst space.2 It typically manifests with a longitudinal groove in the nail plate. A flesh-colored nodule may be appreciated between the cuticle and the distal interphalangeal joint.2 The depth of the longitudinal groove may vary depending on the volume of synovial fluid within the myxoid cyst.21 In a series of 35 cases of subungual myxoid cysts, none manifested with longitudinal erythronychia. Due to their composition, myxoid cysts can be distinguished easily from solid tumors of the nail unit via transillumination.22 Pain is a much less common with myxoid cysts vs glomus tumors, as the filling of the pseudocyst space with synovial fluid typically is gradual, allowing the surrounding tissue to accommodate and adapt over time.21 In equivocal cases, MRI or high-resolution ultrasonography may be used to distinguish myxoid cysts and glomus tumors.8 Histopathology shows accumulation of mucin in the dermis with surrounding fibrous stroma.23

Subungual neuromas are painful benign tumors that develop due to disorganized neural proliferation following disruption to peripheral nerves secondary to trauma or surgery. In 3 case reports, subungual neuromas manifested as painful subungual nodules, with proximal nail plate ridging, or onycholysis.24-26 Since neuromas have only rarely been described in the subungual region, reports of MRI and ultrasonography findings are unknown. Histopathology is needed to distinguish neuromas from glomus tumors. Histopathology shows an acapsular structure consisting of disorganized spindle-cell proliferation and nerve fibers arranged in a tangle of fascicles within fibrotic tissue.25 On immunochemistry, spindle cells typically are positive for cellular antigen protein S100.26

Leiomyomas are benign neoplasms derived from smooth muscle, typically localized to the uterus or gastrointestinal tract, and have been described rarely in the nail unit.27,28 It is hypothesized that subungual leiomyomas originate from the vascular smooth muscle in the subcutaneous layer of the nail unit.28 Like glomus tumors, leiomyomas of the subungual region often manifest with pain and longitudinal erythronychia.27-30 Subungual leiomyomas may be distinguished from glomus tumors via advanced imaging techniques, including ultrasonography and MRI. Cutaneous leiomyomas have been described with mild to moderate internal low flow vascularity on Doppler ultrasonography, while glomus tumors typically reveal high internal vascularity.28 Biopsy with histopathology is needed for definitive diagnosis. On histopathology, leiomyomas demonstrate bland-appearing spindle-shaped cells with elongated nuclei arranged in fascicles.27 They typically are positive for α-smooth muscle actin and caldesmon on immunostaining.

Eccrine spiradenomas are benign adnexal tumors likely of apocrine origin with limited case reports in the literature.31,32 Clinically, eccrine spiradenomas involving the nail unit may manifest with longitudinal nail splitting of the nail or as a papule on the proximal nail fold, with associated tenderness.31,32 In a report of a 50-year-old woman with a histopathologically confirmed eccrine spiradenoma manifesting with longitudinal splitting of the nail and pain in the proximal nail fold, the mass appeared hypoechoic on ultrasonography with increased intramass vascularity on Doppler, while MRI showed an intensely enhancing lesion.31 These imaging features, combined with a classically manifesting feature of pain, make eccrine spiradenomas difficult to distinguish from glomus tumors; therefore, histopathologic examination can provide a definitive diagnosis, and surgical excision is used for treatment.31 On histopathology, these tumors are well circumscribed and composed of both small dark basaloid cells with peripheral compact nuclei and larger cells with central pale nuclei, which may be arranged in tubules.31,32

The Diagnosis: Glomangiomyoma

The nail unit excision specimen showed collections of cuboidal cells and spindled cells within the corium that were consistent with a diagnosis of a glomangiomyoma, a rare glomus tumor variant (Figure). Glomus tumors are benign neoplasms comprising glomus bodies, which are arteriovenous anastomoses involved in thermoregulation.1 They develop in areas densely populated by glomus bodies, including the fingers, toes, and subungual areas. Glomus tumors most commonly develop in middle-aged women.2 Clinically, they manifest with a characteristic triad of intense pain, point tenderness, and cold sensitivity and may appear as reddish-pink or blue macules under the nail plate and/or longitudinal erythronychia.2-6 The presence of multiple glomus tumors is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1.7

Advanced imaging including ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help confirm the diagnosis but may not be cost effective, as excision with histopathology is needed to relieve symptoms and render a definitive diagnosis. Radiography is highly insensitive in identifying bone erosions associated with glomus tumors.8 With ultrasonography, glomus tumors appear hypoechoic; with Doppler ultrasonography, they appear hypervascular. With MRI, glomus tumors appear as well-defined nodular lesions with hypointense signal intensity on T1-weighted sequence and hyperintense signal intensity on T2-weighted sequence, with strong enhancement using gadolinium-based contrast.9,10 On histopathology, a glomus tumor appears as a nodular tumor with sheets of oval-nucleated cells arranged in multicellular layers surrounding blood vessels and are immunoreactive for α-smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and type IV collagen.11,12

There are several glomus tumor variants. The most common is a solid glomus tumor, which predominantly is composed of glomus cells, followed by glomangioma, which mainly is composed of blood vessels. Glomangiomyoma, which mostly is composed of smooth muscle cells, is the rarest variant.13

While glomus tumors are common in the subungual areas, it is an uncommon location for glomangiomyomas, which have been reported in the nail unit in only 7 prior case reports identified through searches of PubMed and Google Scholar using the terms glomangiomyoma, glomangiomyoma nail, and subungual glomangiomyoma (Table).13-19 Glomangiomyomas more commonly are described in solid organs, including the stomach, kidney, pancreas, and bladder.16 The mean age of patients with subungual glomangiomyomas, including our patient, was 40.4 years (range, 3-61 years), with the majority being female (75.0% [6/8]). Most patients presented with fingernail involvement (75.0% [6/8]), nail dystrophy (eg, nail plate thinning, longitudinal grooves, splinter hemorrhages, longitudinal erythronychia)(62.5% [5/8]), and intermittent pain and/or point tenderness in the affected nail (75.0% [6/8]).13-19 Notably, only our patient had longitudinal erythronychia as a clinical feature, and only one other case described MRI findings, which included a lobulated mass with intense contrast and distal phalanx destruction.18 One patient was a 3-year-old girl with a family history of generalized multiple glomangiomyomas. Although subungual glomangiomyoma was not confirmed on histopathology, the diagnosis in this patient was presumed based on her family history.13 On histopathology, glomangiomyomas are composed of oval-nucleated cells surrounding blood vessels. These oval-nucleated cells then gradually transition to smooth muscle cells.20

A myxoid cyst is composed of a pseudocyst, which lacks a cyst lining, and is a result of synovial fluid from the distal interphalangeal joint entering the pseudocyst space.2 It typically manifests with a longitudinal groove in the nail plate. A flesh-colored nodule may be appreciated between the cuticle and the distal interphalangeal joint.2 The depth of the longitudinal groove may vary depending on the volume of synovial fluid within the myxoid cyst.21 In a series of 35 cases of subungual myxoid cysts, none manifested with longitudinal erythronychia. Due to their composition, myxoid cysts can be distinguished easily from solid tumors of the nail unit via transillumination.22 Pain is a much less common with myxoid cysts vs glomus tumors, as the filling of the pseudocyst space with synovial fluid typically is gradual, allowing the surrounding tissue to accommodate and adapt over time.21 In equivocal cases, MRI or high-resolution ultrasonography may be used to distinguish myxoid cysts and glomus tumors.8 Histopathology shows accumulation of mucin in the dermis with surrounding fibrous stroma.23

Subungual neuromas are painful benign tumors that develop due to disorganized neural proliferation following disruption to peripheral nerves secondary to trauma or surgery. In 3 case reports, subungual neuromas manifested as painful subungual nodules, with proximal nail plate ridging, or onycholysis.24-26 Since neuromas have only rarely been described in the subungual region, reports of MRI and ultrasonography findings are unknown. Histopathology is needed to distinguish neuromas from glomus tumors. Histopathology shows an acapsular structure consisting of disorganized spindle-cell proliferation and nerve fibers arranged in a tangle of fascicles within fibrotic tissue.25 On immunochemistry, spindle cells typically are positive for cellular antigen protein S100.26

Leiomyomas are benign neoplasms derived from smooth muscle, typically localized to the uterus or gastrointestinal tract, and have been described rarely in the nail unit.27,28 It is hypothesized that subungual leiomyomas originate from the vascular smooth muscle in the subcutaneous layer of the nail unit.28 Like glomus tumors, leiomyomas of the subungual region often manifest with pain and longitudinal erythronychia.27-30 Subungual leiomyomas may be distinguished from glomus tumors via advanced imaging techniques, including ultrasonography and MRI. Cutaneous leiomyomas have been described with mild to moderate internal low flow vascularity on Doppler ultrasonography, while glomus tumors typically reveal high internal vascularity.28 Biopsy with histopathology is needed for definitive diagnosis. On histopathology, leiomyomas demonstrate bland-appearing spindle-shaped cells with elongated nuclei arranged in fascicles.27 They typically are positive for α-smooth muscle actin and caldesmon on immunostaining.

Eccrine spiradenomas are benign adnexal tumors likely of apocrine origin with limited case reports in the literature.31,32 Clinically, eccrine spiradenomas involving the nail unit may manifest with longitudinal nail splitting of the nail or as a papule on the proximal nail fold, with associated tenderness.31,32 In a report of a 50-year-old woman with a histopathologically confirmed eccrine spiradenoma manifesting with longitudinal splitting of the nail and pain in the proximal nail fold, the mass appeared hypoechoic on ultrasonography with increased intramass vascularity on Doppler, while MRI showed an intensely enhancing lesion.31 These imaging features, combined with a classically manifesting feature of pain, make eccrine spiradenomas difficult to distinguish from glomus tumors; therefore, histopathologic examination can provide a definitive diagnosis, and surgical excision is used for treatment.31 On histopathology, these tumors are well circumscribed and composed of both small dark basaloid cells with peripheral compact nuclei and larger cells with central pale nuclei, which may be arranged in tubules.31,32

- Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132: 1448-1452. doi:10.5858/2008-132-1448-gt

- Hare AQ, Rich P. Nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:281-292. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.007

- Hazani R, Houle JM, Kasdan ML, et al. Glomus tumors of the hand. Eplasty. 2008;8:E48.

- Hwang JK, Lipner SR. Blue nail discoloration: literature review and diagnostic algorithms. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:419-441. doi:10.1007/s40257-023-00768-6

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Longitudinal erythronychia of the fingernail. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1271-1272. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.2747

- Jellinek NJ, Lipner SR. Longitudinal erythronychia: retrospective single-center study evaluating differential diagnosis and the likelihood of malignancy. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:310-319. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000000594

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Subungual glomus tumors: underrecognized clinical findings in neurofibromatosis 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:E269. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.129

- Dhami A, Vale SM, Richardson ML, et al. Comparing ultrasound with magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of subungual glomus tumors and subungual myxoid cysts. Skin Appendage Disord. 2023;9:262-267. doi:10.1159/000530397

- Baek HJ, Lee SJ, Cho KH, et al. Subungual tumors: clinicopathologic correlation with US and MR imaging findings. Radiographics. 2010;30:1621-1636. doi:10.1148/rg.306105514

- Patel T, Meena V, Meena P. Hand and foot glomus tumors: significance of MRI diagnosis followed by histopathological assessment. Cureus. 2022;14:E30038. doi:10.7759/cureus.30038

- Mravic M, LaChaud G, Nguyen A, et al. Clinical and histopathological diagnosis of glomus tumor: an institutional experience of 138 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2015;23:181-188. doi:10.1177/1066896914567330