User login

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin ... will obtain the clearest view of them. Politics, Book I, Part II by Aristotle

Many seasoned observers of federal practice have signaled that the future of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care is threatened as never before. Political forces and economic interests are siphoning Veterans Health Administration (VHA) capital and human resources into the community with an ineluctable push toward privatization.1

This Veterans Day, the vitality, if not the very viability of veteran health care, is in serious jeopardy, so it seems fitting to review the rationale for having institutions dedicated to the specialized medical treatment of veterans. Aristotle advises us on how to undertake this intellectual exercise in the epigraph. This column will revisit the historical origins of VA medicine to better appreciate the justification of an agency committed to this unique purpose and what may be sacrificed if it is decimated.

The provision of medical care focused on the injuries and illnesses of warriors is as old as war. The ancient Romans had among the first veterans’ hospital, named a valetudinarium. Sick and injured members of the Roman legions received state-of-the-art medical and surgical care from military doctors inside these facilities.2

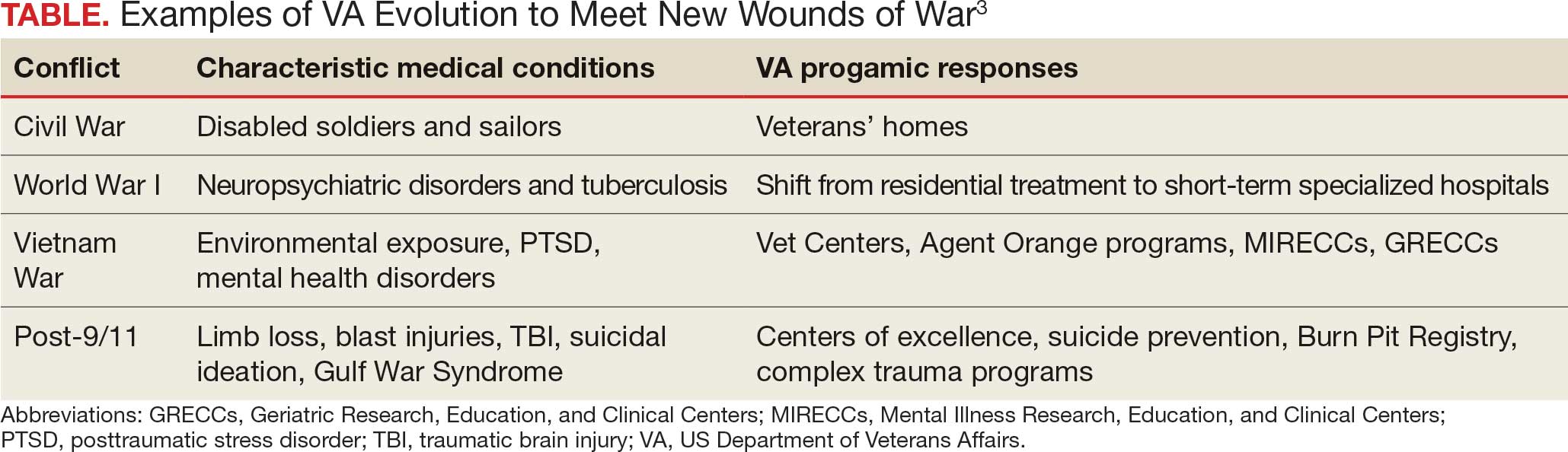

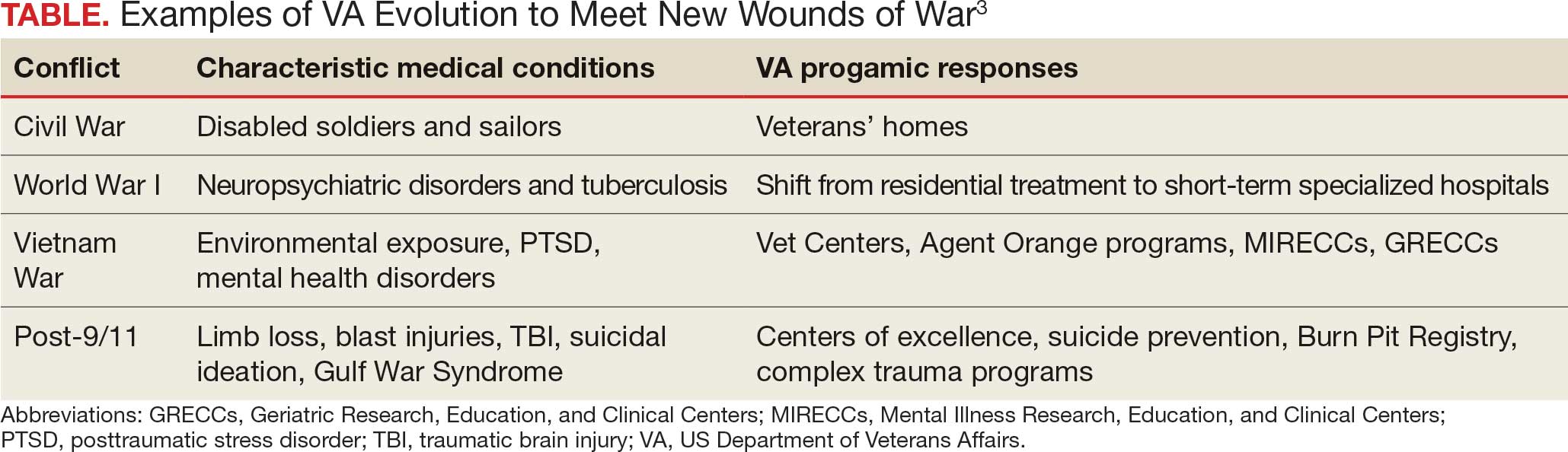

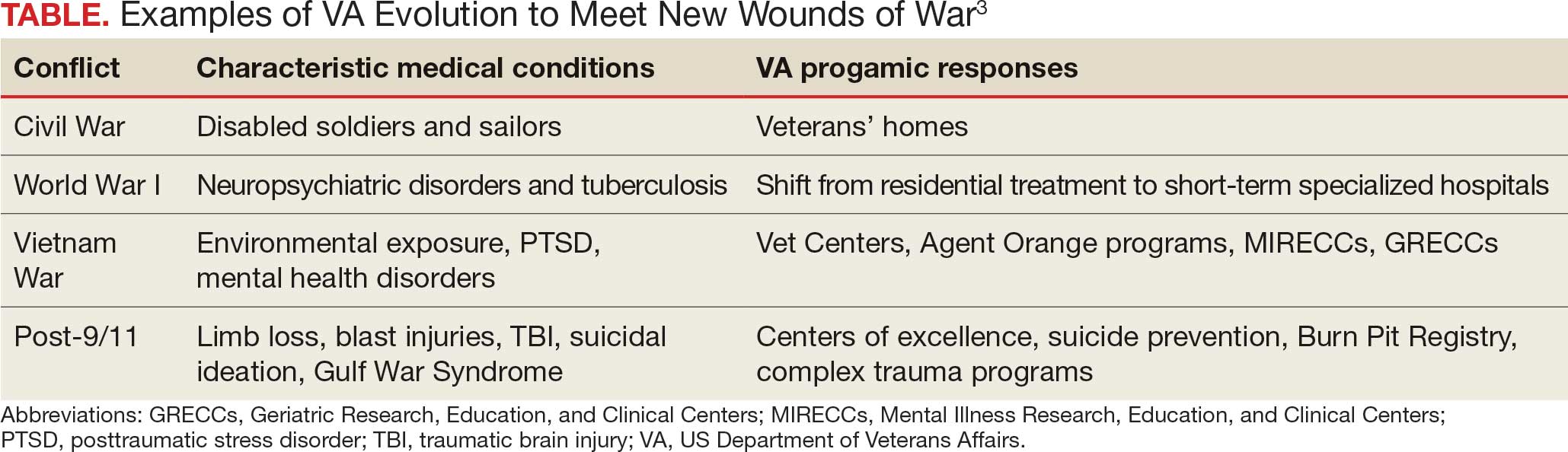

In the United States, federal practice emerged almost simultaneously with the birth of a nation. Wounded troops and families of slain soldiers required rehabilitation and support from the fledgling federal government. This began a pattern of development in which each war generated novel injuries and disorders that required the VA to evolve (Table).3

Many arguments can be marshalled to demonstrate the importance of not just ensuring VA health care survives but also has the resources needed to thrive. I will highlight what I argue are the most important justifications for its existence.

The ethical argument: President Abraham Lincoln and a long line of government officials for more than 2 centuries have called the provision of high-quality health care focused on veterans a sacred trust. Failing to fulfill that promise is a violation of the deepest principles of veracity and fidelity that those who govern owe to the citizens who selflessly sacrificed time, health, and even in some cases life, for the safety and well-being of their country.4

The quality argument: Dozens of studies have found that compared to the community, many areas of veteran medical care are just plain better. Two surveys particularly salient in the aging veteran population illustrate this growing body of positive research. The most recent and largest survey of Medicare patients found that VHA hospitals surpassed community-based hospitals on all 10 metrics.5 A retrospective cohort study of mortality compared veterans transported by ambulance to VHA or community-based hospitals. The researchers found that those taken to VHA facilities had a 30-day all cause adjustment mortality 20 times lower than those taken to civilian hospitals, especially among minoritized populations who generally have higher mortality.6

The cultural argument: Glance at almost any form of communication from veterans or about their health care and you will apprehend common cultural themes. Even when frustrated that the system has not lived up to their expectations, and perhaps because of their sense of belonging, they voice ownership of VHA as their medical home. Surveys of veteran experiences have shown many feel more comfortable receiving care in the company of comrades in arms and from health care professionals with expertise and experience with veterans’ distinctive medical problems and the military values that inform their preferences for care.7

The complexity argument: Anyone who has worked even a short time in a VHA hospital or clinic knows the patients are in general more complicated than similar patients in the community. Multiple medical, geriatric, neuropsychiatric, substance use, and social comorbidities are the expectation, not the exception, as in some civilian systems. Many of the conditions common in the VHA such as traumatic brain injury, service-connected cancers, suicidal ideation, environmental exposures, and posttraumatic stress disorder would be encountered in community health care settings. The differences between VHA and community care led the RAND Corporation to caution that “Community care providers might not be equipped to handle the needs of veterans.”8

Let me bring this 1000-foot view of the crisis facing federal practice down to the literal level of my own home. For many years I have had a wonderful mechanic who has a mobile bike service. I was talking to him as he fixed my trike. I never knew he was a Vietnam era veteran, and he didn’t realize that I was a career VA health care professional at the very VHA hospital where he received care. He spontaneously told me that, “when I first got out, the VA was awful, but now it is wonderful and they are so good to me. I would not go anywhere else.” For the many veterans of that era who would echo his sentiments, we must not allow the VA to lose all it has gained since that painful time

Another philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, wrote that “life must be understood backwards but lived forwards.”9 Our own brief back to the future journey in this editorial has, I hope, shown that VHA medical institutions and health professionals cannot be replaced with or replicated by civilian systems and clinicians. Continued attempts to do so betray the trust and risks the health and well-being of veterans. It also would deprive the country of research, innovation, and education that make unparalleled contributions to public health. Ultimately, these efforts to diminish VHA compromise the solidarity of service members with each other and with their federal practitioners. If this trend to dismantle an organization that originated with the sole purpose of caring for veterans continues, then the public expressions of respect and gratitude will sound shallower and more tentative with each passing Veterans Day.

- Quil L. Hundreds of VA clinicians warn that cuts threaten vet’s health care. National Public Radio. October 1, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/10/01/nx-s1-5554394/hundreds-of-va-clinicians-warn-that-cuts-threaten-vets-health-care

- Nutton V. Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. Routledge; 2012.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History Summary. Updated June 13, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://department.va.gov/history/history-overview/

- Geppert CMA. Learning from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33:6-7.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Nationwide patient survey shows VA hospitals outperform non-VA hospitals. News release. June 14, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/nationwide-patient-survey-shows-va-hospitals-outperform-non-va-hospitals

- Chan DC, Danesh K, Costantini S, Card D, Taylor L, Studdert DM. Mortality among US veterans after emergency visits to Veterans Affairs and other hospitals: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068099. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068099

- Vigilante K, Batten SV, Shang Q, et al. Camaraderie among US veterans and their preferences for health care systems and practitioners. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e255253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.5253

- Rasmussen P, Farmer CM. The promise and challenges of VA community care: veterans’ issues in focus. Rand Health Q. 2023;10:9.

- Kierkegaard S. Journalen JJ:167 (1843) in: Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. Vol 18. Copenhagen; 1997:306.

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin ... will obtain the clearest view of them. Politics, Book I, Part II by Aristotle

Many seasoned observers of federal practice have signaled that the future of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care is threatened as never before. Political forces and economic interests are siphoning Veterans Health Administration (VHA) capital and human resources into the community with an ineluctable push toward privatization.1

This Veterans Day, the vitality, if not the very viability of veteran health care, is in serious jeopardy, so it seems fitting to review the rationale for having institutions dedicated to the specialized medical treatment of veterans. Aristotle advises us on how to undertake this intellectual exercise in the epigraph. This column will revisit the historical origins of VA medicine to better appreciate the justification of an agency committed to this unique purpose and what may be sacrificed if it is decimated.

The provision of medical care focused on the injuries and illnesses of warriors is as old as war. The ancient Romans had among the first veterans’ hospital, named a valetudinarium. Sick and injured members of the Roman legions received state-of-the-art medical and surgical care from military doctors inside these facilities.2

In the United States, federal practice emerged almost simultaneously with the birth of a nation. Wounded troops and families of slain soldiers required rehabilitation and support from the fledgling federal government. This began a pattern of development in which each war generated novel injuries and disorders that required the VA to evolve (Table).3

Many arguments can be marshalled to demonstrate the importance of not just ensuring VA health care survives but also has the resources needed to thrive. I will highlight what I argue are the most important justifications for its existence.

The ethical argument: President Abraham Lincoln and a long line of government officials for more than 2 centuries have called the provision of high-quality health care focused on veterans a sacred trust. Failing to fulfill that promise is a violation of the deepest principles of veracity and fidelity that those who govern owe to the citizens who selflessly sacrificed time, health, and even in some cases life, for the safety and well-being of their country.4

The quality argument: Dozens of studies have found that compared to the community, many areas of veteran medical care are just plain better. Two surveys particularly salient in the aging veteran population illustrate this growing body of positive research. The most recent and largest survey of Medicare patients found that VHA hospitals surpassed community-based hospitals on all 10 metrics.5 A retrospective cohort study of mortality compared veterans transported by ambulance to VHA or community-based hospitals. The researchers found that those taken to VHA facilities had a 30-day all cause adjustment mortality 20 times lower than those taken to civilian hospitals, especially among minoritized populations who generally have higher mortality.6

The cultural argument: Glance at almost any form of communication from veterans or about their health care and you will apprehend common cultural themes. Even when frustrated that the system has not lived up to their expectations, and perhaps because of their sense of belonging, they voice ownership of VHA as their medical home. Surveys of veteran experiences have shown many feel more comfortable receiving care in the company of comrades in arms and from health care professionals with expertise and experience with veterans’ distinctive medical problems and the military values that inform their preferences for care.7

The complexity argument: Anyone who has worked even a short time in a VHA hospital or clinic knows the patients are in general more complicated than similar patients in the community. Multiple medical, geriatric, neuropsychiatric, substance use, and social comorbidities are the expectation, not the exception, as in some civilian systems. Many of the conditions common in the VHA such as traumatic brain injury, service-connected cancers, suicidal ideation, environmental exposures, and posttraumatic stress disorder would be encountered in community health care settings. The differences between VHA and community care led the RAND Corporation to caution that “Community care providers might not be equipped to handle the needs of veterans.”8

Let me bring this 1000-foot view of the crisis facing federal practice down to the literal level of my own home. For many years I have had a wonderful mechanic who has a mobile bike service. I was talking to him as he fixed my trike. I never knew he was a Vietnam era veteran, and he didn’t realize that I was a career VA health care professional at the very VHA hospital where he received care. He spontaneously told me that, “when I first got out, the VA was awful, but now it is wonderful and they are so good to me. I would not go anywhere else.” For the many veterans of that era who would echo his sentiments, we must not allow the VA to lose all it has gained since that painful time

Another philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, wrote that “life must be understood backwards but lived forwards.”9 Our own brief back to the future journey in this editorial has, I hope, shown that VHA medical institutions and health professionals cannot be replaced with or replicated by civilian systems and clinicians. Continued attempts to do so betray the trust and risks the health and well-being of veterans. It also would deprive the country of research, innovation, and education that make unparalleled contributions to public health. Ultimately, these efforts to diminish VHA compromise the solidarity of service members with each other and with their federal practitioners. If this trend to dismantle an organization that originated with the sole purpose of caring for veterans continues, then the public expressions of respect and gratitude will sound shallower and more tentative with each passing Veterans Day.

He who thus considers things in their first growth and origin ... will obtain the clearest view of them. Politics, Book I, Part II by Aristotle

Many seasoned observers of federal practice have signaled that the future of US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care is threatened as never before. Political forces and economic interests are siphoning Veterans Health Administration (VHA) capital and human resources into the community with an ineluctable push toward privatization.1

This Veterans Day, the vitality, if not the very viability of veteran health care, is in serious jeopardy, so it seems fitting to review the rationale for having institutions dedicated to the specialized medical treatment of veterans. Aristotle advises us on how to undertake this intellectual exercise in the epigraph. This column will revisit the historical origins of VA medicine to better appreciate the justification of an agency committed to this unique purpose and what may be sacrificed if it is decimated.

The provision of medical care focused on the injuries and illnesses of warriors is as old as war. The ancient Romans had among the first veterans’ hospital, named a valetudinarium. Sick and injured members of the Roman legions received state-of-the-art medical and surgical care from military doctors inside these facilities.2

In the United States, federal practice emerged almost simultaneously with the birth of a nation. Wounded troops and families of slain soldiers required rehabilitation and support from the fledgling federal government. This began a pattern of development in which each war generated novel injuries and disorders that required the VA to evolve (Table).3

Many arguments can be marshalled to demonstrate the importance of not just ensuring VA health care survives but also has the resources needed to thrive. I will highlight what I argue are the most important justifications for its existence.

The ethical argument: President Abraham Lincoln and a long line of government officials for more than 2 centuries have called the provision of high-quality health care focused on veterans a sacred trust. Failing to fulfill that promise is a violation of the deepest principles of veracity and fidelity that those who govern owe to the citizens who selflessly sacrificed time, health, and even in some cases life, for the safety and well-being of their country.4

The quality argument: Dozens of studies have found that compared to the community, many areas of veteran medical care are just plain better. Two surveys particularly salient in the aging veteran population illustrate this growing body of positive research. The most recent and largest survey of Medicare patients found that VHA hospitals surpassed community-based hospitals on all 10 metrics.5 A retrospective cohort study of mortality compared veterans transported by ambulance to VHA or community-based hospitals. The researchers found that those taken to VHA facilities had a 30-day all cause adjustment mortality 20 times lower than those taken to civilian hospitals, especially among minoritized populations who generally have higher mortality.6

The cultural argument: Glance at almost any form of communication from veterans or about their health care and you will apprehend common cultural themes. Even when frustrated that the system has not lived up to their expectations, and perhaps because of their sense of belonging, they voice ownership of VHA as their medical home. Surveys of veteran experiences have shown many feel more comfortable receiving care in the company of comrades in arms and from health care professionals with expertise and experience with veterans’ distinctive medical problems and the military values that inform their preferences for care.7

The complexity argument: Anyone who has worked even a short time in a VHA hospital or clinic knows the patients are in general more complicated than similar patients in the community. Multiple medical, geriatric, neuropsychiatric, substance use, and social comorbidities are the expectation, not the exception, as in some civilian systems. Many of the conditions common in the VHA such as traumatic brain injury, service-connected cancers, suicidal ideation, environmental exposures, and posttraumatic stress disorder would be encountered in community health care settings. The differences between VHA and community care led the RAND Corporation to caution that “Community care providers might not be equipped to handle the needs of veterans.”8

Let me bring this 1000-foot view of the crisis facing federal practice down to the literal level of my own home. For many years I have had a wonderful mechanic who has a mobile bike service. I was talking to him as he fixed my trike. I never knew he was a Vietnam era veteran, and he didn’t realize that I was a career VA health care professional at the very VHA hospital where he received care. He spontaneously told me that, “when I first got out, the VA was awful, but now it is wonderful and they are so good to me. I would not go anywhere else.” For the many veterans of that era who would echo his sentiments, we must not allow the VA to lose all it has gained since that painful time

Another philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, wrote that “life must be understood backwards but lived forwards.”9 Our own brief back to the future journey in this editorial has, I hope, shown that VHA medical institutions and health professionals cannot be replaced with or replicated by civilian systems and clinicians. Continued attempts to do so betray the trust and risks the health and well-being of veterans. It also would deprive the country of research, innovation, and education that make unparalleled contributions to public health. Ultimately, these efforts to diminish VHA compromise the solidarity of service members with each other and with their federal practitioners. If this trend to dismantle an organization that originated with the sole purpose of caring for veterans continues, then the public expressions of respect and gratitude will sound shallower and more tentative with each passing Veterans Day.

- Quil L. Hundreds of VA clinicians warn that cuts threaten vet’s health care. National Public Radio. October 1, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/10/01/nx-s1-5554394/hundreds-of-va-clinicians-warn-that-cuts-threaten-vets-health-care

- Nutton V. Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. Routledge; 2012.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History Summary. Updated June 13, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://department.va.gov/history/history-overview/

- Geppert CMA. Learning from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33:6-7.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Nationwide patient survey shows VA hospitals outperform non-VA hospitals. News release. June 14, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/nationwide-patient-survey-shows-va-hospitals-outperform-non-va-hospitals

- Chan DC, Danesh K, Costantini S, Card D, Taylor L, Studdert DM. Mortality among US veterans after emergency visits to Veterans Affairs and other hospitals: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068099. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068099

- Vigilante K, Batten SV, Shang Q, et al. Camaraderie among US veterans and their preferences for health care systems and practitioners. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e255253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.5253

- Rasmussen P, Farmer CM. The promise and challenges of VA community care: veterans’ issues in focus. Rand Health Q. 2023;10:9.

- Kierkegaard S. Journalen JJ:167 (1843) in: Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. Vol 18. Copenhagen; 1997:306.

- Quil L. Hundreds of VA clinicians warn that cuts threaten vet’s health care. National Public Radio. October 1, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://www.npr.org/2025/10/01/nx-s1-5554394/hundreds-of-va-clinicians-warn-that-cuts-threaten-vets-health-care

- Nutton V. Ancient Medicine. 2nd ed. Routledge; 2012.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA History Summary. Updated June 13, 2025. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://department.va.gov/history/history-overview/

- Geppert CMA. Learning from history: the ethical foundation of VA health care. Fed Pract. 2016;33:6-7.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. Nationwide patient survey shows VA hospitals outperform non-VA hospitals. News release. June 14, 2023. Accessed October 27, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/nationwide-patient-survey-shows-va-hospitals-outperform-non-va-hospitals

- Chan DC, Danesh K, Costantini S, Card D, Taylor L, Studdert DM. Mortality among US veterans after emergency visits to Veterans Affairs and other hospitals: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2022;376:e068099. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-068099

- Vigilante K, Batten SV, Shang Q, et al. Camaraderie among US veterans and their preferences for health care systems and practitioners. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(4):e255253. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.5253

- Rasmussen P, Farmer CM. The promise and challenges of VA community care: veterans’ issues in focus. Rand Health Q. 2023;10:9.

- Kierkegaard S. Journalen JJ:167 (1843) in: Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter. Vol 18. Copenhagen; 1997:306.

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

The Once and Future Veterans Health Administration

American Hunger Games: Food Insecurity Among the Military and Veterans

American Hunger Games: Food Insecurity Among the Military and Veterans

The requisites of government are that there be sufficiency of food, sufficiency of military equipment, and the confidence of the people in their ruler.

Analects by Confucius1

From ancient festivals to modern holidays, autumn has long been associated with the gathering of the harvest. Friends and families come together around tables laden with delicious food to enjoy the pleasures of peace and plenty. During these celebrations, we must never forget that without the strength of the nation’s military and the service of its veterans, this freedom and abundance would not be possible. Our debt of gratitude to the current and former members of the armed services makes the fact that a substantial minority experiences food insecurity not only a human tragedy, but a travesty of the nation’s promise to support those who wear or have worn the uniform.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 charged the Secretary of Defense to investigate food insecurity among active-duty service members and their dependents.2 The RAND Corporation conducted the assessment and, based on the results of its analysis, made recommendations to reduce hunger among armed forces members and their families.3

The RAND study found that 10% of active-duty military met US Department of Agriculture (USDA) criteria for very low food security; another 15% were classified as having low food security. The USDA defines food insecurity with hunger as “reports of multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.” USDA defines low food security as “reports of reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet. Little or no indication of reduced food intake.”4

As someone who grew up on an Army base with the commissary a short trip from military housing, I was unpleasantly surprised that food insecurity was more common among in-service members living on post. I was even more dismayed to read that a variety of factors constrained 14% of active-duty military experiencing food insecurity to seek public assistance to feed themselves and their families. As with so many health care and social services, (eg, mental health care), those wearing the uniform were concerned that participating in a food assistance program would damage their career or stigmatize them. Others did not seek help, perhaps because they believed they were not eligible, and in many cases were correct: they did not qualify for food banks or food stamps due to receiving other benefits. A variety of factors contribute to periods of food insecurity among military families, including remote or rural bases that lack access to grocery stores or jobs for partners or other family members, and low base military pay.5

Food insecurity is an even more serious concern among veterans who are frequently older and have more comorbidities, often leading to unemployment and homelessness. Feeding America, the nation’s largest organization of community food banks, estimates that 1 in 9 working-age veterans are food insecure.5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) statistics indicate that veterans are 7% more likely to experience food insecurity than other sectors of the population.6 The Veterans Health Administration has recognized that food insecurity is directly related to medical problems already common among veterans, including diabetes, obesity, and depression. Women and minority veterans are the most at risk of food insecurity.7

Recognizing that many veterans are at risk of food insecurity, the US Department of Defense and VA have taken steps to try and reduce hunger among those who serve. In response to the shocking statistic that food insecurity was found in 27% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, the VA and Rockefeller Foundation are partnering on the Food as Medicine initiative to improve veteran nutrition as a means of improving nutrition-related health consequences of food insecurity.8

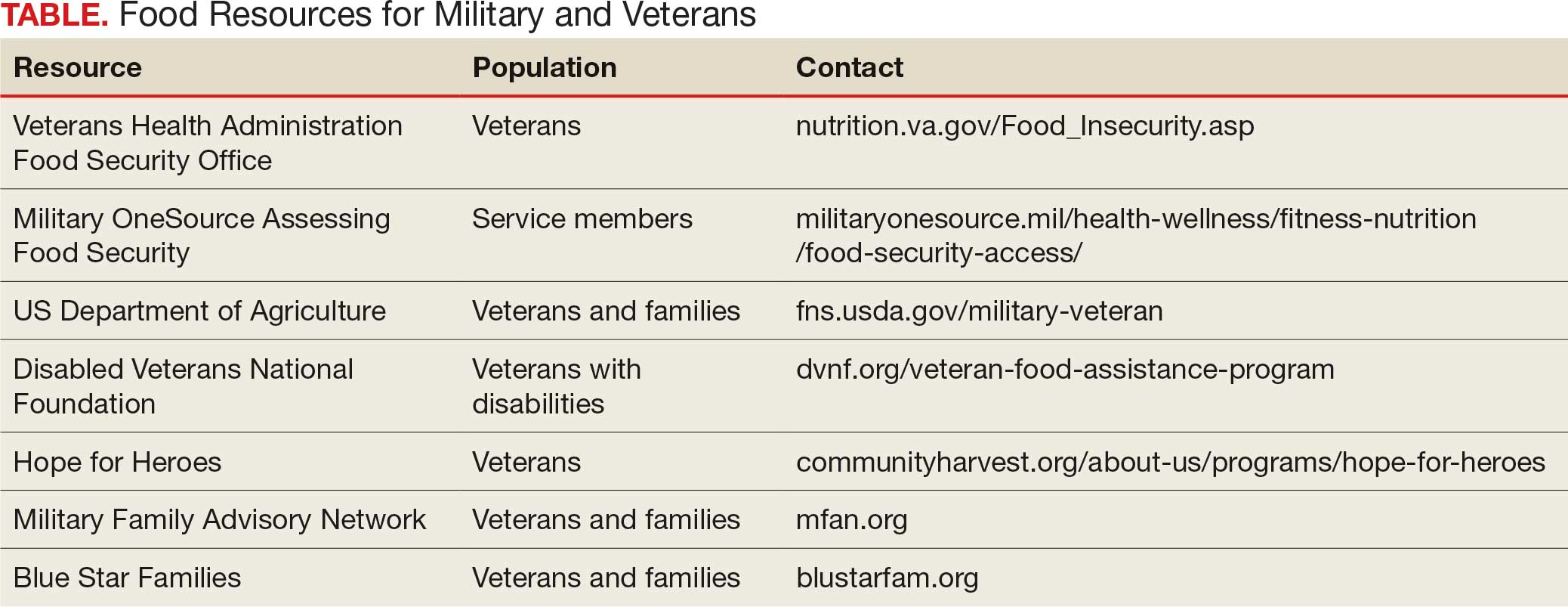

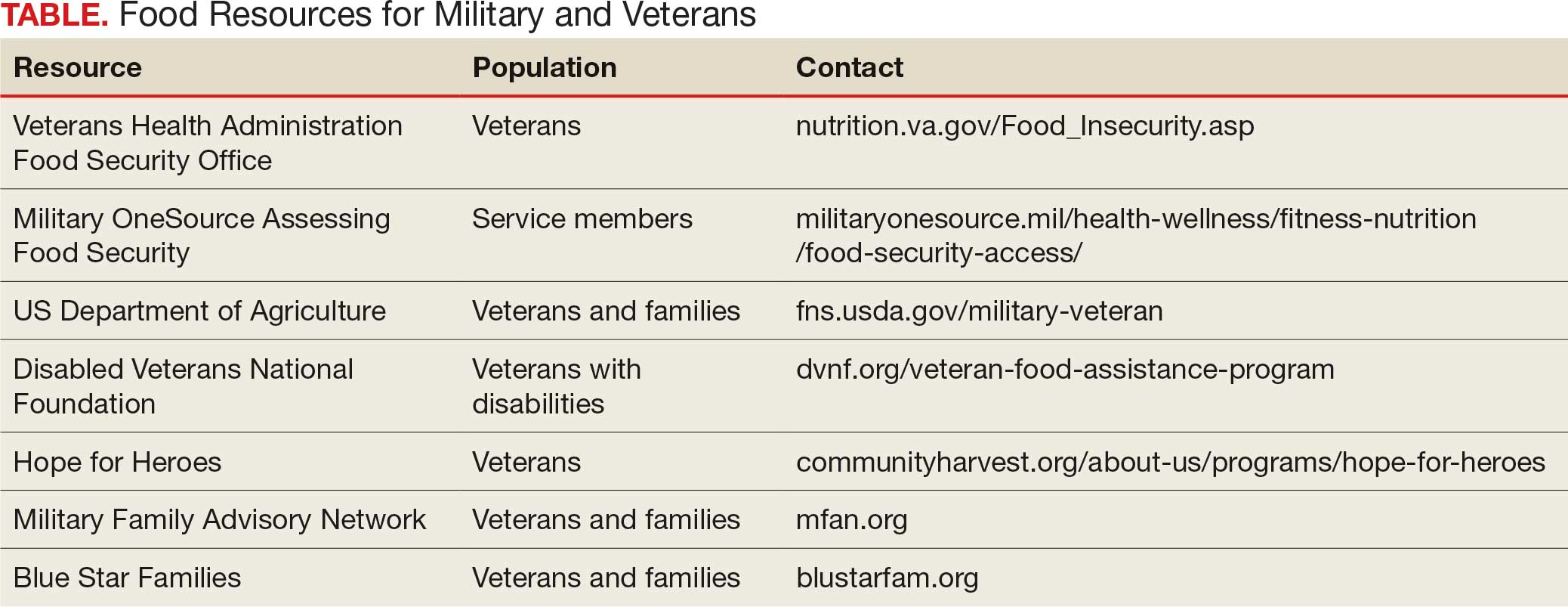

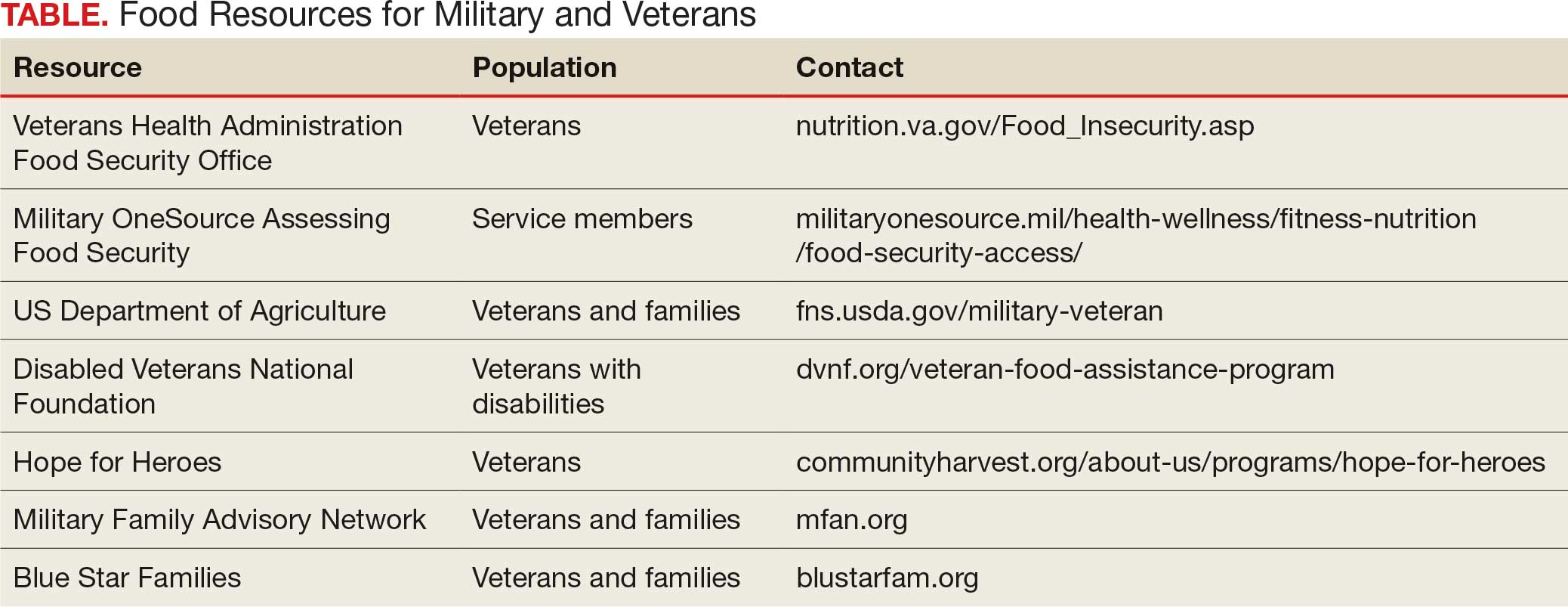

Like many federal practitioners, I was unaware of the food insecurity assistance available to active-duty service members or veterans, or how to help individuals access it. In addition to the resources outlined in the Table, there are many community-based options open to anyone, including veterans and service members.

I have written columns on many difficult issues in my years as the Editor-in-Chief of Federal Practitioner, but personally this is one of the most distressing editorials I have ever published. That individuals dedicated to defending our rights and protecting our safety should be compelled to go hungry or not know if they have enough money at the end of the month to buy food is manifestly unjust. It is challenging when faced with such a large-scale injustice to think we cannot make a difference, but that resignation or abdication only magnifies this inequity. I have a friend who kept giving back even after they retired from federal service: they volunteered at a community garden and brought produce to the local food bank and helped distribute it. That may seem too much for those still working yet almost anyone can pick up a few items on their weekly shopping trip and donate them to a food drive.

As we approach Veterans Day, let’s not just express our gratitude to our military and veterans in words but in deeds like feeding the hungry and urging elected representatives to fulfill their commitment to ensure that service members and veterans and their families do not experience food insecurity. Confucian wisdom written in a very distant time and vastly dissimilar context still rings true: there are direct and critical links between food and trust and between hunger and the military.1

Dawson MM. The Wisdom of Confucius: A Collection of the Ethical Sayings of Confucius and of his disciples. International Pocket Library; 1932.

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020. 116th Cong (2019), Public Law 116-92. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-116publ92/html/PLAW-116publ92.htm

Asch BJ, Rennane S, Trail TE, et al. Food insecurity among members of the armed forces and their dependents. RAND Corporation. January 3, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1230-1.html

US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Food Security in the U.S.—Definitions of Food Security. US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. January 10, 2025. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security

Active military and veteran food insecurity. Feeding America. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/food-insecurity-in-veterans

Pradun S. Find access to stop food insecurity in your community. VA News. September 19, 2025. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/142733/find-access-stop-food-insecurity-your-community/

Cohen AJ, Dosa DM, Rudolph JL, et al. Risk factors for veteran food insecurity: findings from a National US Department of Veterans Affairs Food Insecurity Screener. Public Health Nutr. 2022;25:819-828. doi:10.1017/S1368980021004584

Chen C. VA and Rockefeller Foundation collaborate to access food for Veterans. VA News. September 5, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/123228/va-rockefeller-foundation-expand-access-to-food/

The requisites of government are that there be sufficiency of food, sufficiency of military equipment, and the confidence of the people in their ruler.

Analects by Confucius1

From ancient festivals to modern holidays, autumn has long been associated with the gathering of the harvest. Friends and families come together around tables laden with delicious food to enjoy the pleasures of peace and plenty. During these celebrations, we must never forget that without the strength of the nation’s military and the service of its veterans, this freedom and abundance would not be possible. Our debt of gratitude to the current and former members of the armed services makes the fact that a substantial minority experiences food insecurity not only a human tragedy, but a travesty of the nation’s promise to support those who wear or have worn the uniform.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 charged the Secretary of Defense to investigate food insecurity among active-duty service members and their dependents.2 The RAND Corporation conducted the assessment and, based on the results of its analysis, made recommendations to reduce hunger among armed forces members and their families.3

The RAND study found that 10% of active-duty military met US Department of Agriculture (USDA) criteria for very low food security; another 15% were classified as having low food security. The USDA defines food insecurity with hunger as “reports of multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.” USDA defines low food security as “reports of reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet. Little or no indication of reduced food intake.”4

As someone who grew up on an Army base with the commissary a short trip from military housing, I was unpleasantly surprised that food insecurity was more common among in-service members living on post. I was even more dismayed to read that a variety of factors constrained 14% of active-duty military experiencing food insecurity to seek public assistance to feed themselves and their families. As with so many health care and social services, (eg, mental health care), those wearing the uniform were concerned that participating in a food assistance program would damage their career or stigmatize them. Others did not seek help, perhaps because they believed they were not eligible, and in many cases were correct: they did not qualify for food banks or food stamps due to receiving other benefits. A variety of factors contribute to periods of food insecurity among military families, including remote or rural bases that lack access to grocery stores or jobs for partners or other family members, and low base military pay.5

Food insecurity is an even more serious concern among veterans who are frequently older and have more comorbidities, often leading to unemployment and homelessness. Feeding America, the nation’s largest organization of community food banks, estimates that 1 in 9 working-age veterans are food insecure.5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) statistics indicate that veterans are 7% more likely to experience food insecurity than other sectors of the population.6 The Veterans Health Administration has recognized that food insecurity is directly related to medical problems already common among veterans, including diabetes, obesity, and depression. Women and minority veterans are the most at risk of food insecurity.7

Recognizing that many veterans are at risk of food insecurity, the US Department of Defense and VA have taken steps to try and reduce hunger among those who serve. In response to the shocking statistic that food insecurity was found in 27% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, the VA and Rockefeller Foundation are partnering on the Food as Medicine initiative to improve veteran nutrition as a means of improving nutrition-related health consequences of food insecurity.8

Like many federal practitioners, I was unaware of the food insecurity assistance available to active-duty service members or veterans, or how to help individuals access it. In addition to the resources outlined in the Table, there are many community-based options open to anyone, including veterans and service members.

I have written columns on many difficult issues in my years as the Editor-in-Chief of Federal Practitioner, but personally this is one of the most distressing editorials I have ever published. That individuals dedicated to defending our rights and protecting our safety should be compelled to go hungry or not know if they have enough money at the end of the month to buy food is manifestly unjust. It is challenging when faced with such a large-scale injustice to think we cannot make a difference, but that resignation or abdication only magnifies this inequity. I have a friend who kept giving back even after they retired from federal service: they volunteered at a community garden and brought produce to the local food bank and helped distribute it. That may seem too much for those still working yet almost anyone can pick up a few items on their weekly shopping trip and donate them to a food drive.

As we approach Veterans Day, let’s not just express our gratitude to our military and veterans in words but in deeds like feeding the hungry and urging elected representatives to fulfill their commitment to ensure that service members and veterans and their families do not experience food insecurity. Confucian wisdom written in a very distant time and vastly dissimilar context still rings true: there are direct and critical links between food and trust and between hunger and the military.1

The requisites of government are that there be sufficiency of food, sufficiency of military equipment, and the confidence of the people in their ruler.

Analects by Confucius1

From ancient festivals to modern holidays, autumn has long been associated with the gathering of the harvest. Friends and families come together around tables laden with delicious food to enjoy the pleasures of peace and plenty. During these celebrations, we must never forget that without the strength of the nation’s military and the service of its veterans, this freedom and abundance would not be possible. Our debt of gratitude to the current and former members of the armed services makes the fact that a substantial minority experiences food insecurity not only a human tragedy, but a travesty of the nation’s promise to support those who wear or have worn the uniform.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020 charged the Secretary of Defense to investigate food insecurity among active-duty service members and their dependents.2 The RAND Corporation conducted the assessment and, based on the results of its analysis, made recommendations to reduce hunger among armed forces members and their families.3

The RAND study found that 10% of active-duty military met US Department of Agriculture (USDA) criteria for very low food security; another 15% were classified as having low food security. The USDA defines food insecurity with hunger as “reports of multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake.” USDA defines low food security as “reports of reduced quality, variety, or desirability of diet. Little or no indication of reduced food intake.”4

As someone who grew up on an Army base with the commissary a short trip from military housing, I was unpleasantly surprised that food insecurity was more common among in-service members living on post. I was even more dismayed to read that a variety of factors constrained 14% of active-duty military experiencing food insecurity to seek public assistance to feed themselves and their families. As with so many health care and social services, (eg, mental health care), those wearing the uniform were concerned that participating in a food assistance program would damage their career or stigmatize them. Others did not seek help, perhaps because they believed they were not eligible, and in many cases were correct: they did not qualify for food banks or food stamps due to receiving other benefits. A variety of factors contribute to periods of food insecurity among military families, including remote or rural bases that lack access to grocery stores or jobs for partners or other family members, and low base military pay.5

Food insecurity is an even more serious concern among veterans who are frequently older and have more comorbidities, often leading to unemployment and homelessness. Feeding America, the nation’s largest organization of community food banks, estimates that 1 in 9 working-age veterans are food insecure.5 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) statistics indicate that veterans are 7% more likely to experience food insecurity than other sectors of the population.6 The Veterans Health Administration has recognized that food insecurity is directly related to medical problems already common among veterans, including diabetes, obesity, and depression. Women and minority veterans are the most at risk of food insecurity.7

Recognizing that many veterans are at risk of food insecurity, the US Department of Defense and VA have taken steps to try and reduce hunger among those who serve. In response to the shocking statistic that food insecurity was found in 27% of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, the VA and Rockefeller Foundation are partnering on the Food as Medicine initiative to improve veteran nutrition as a means of improving nutrition-related health consequences of food insecurity.8

Like many federal practitioners, I was unaware of the food insecurity assistance available to active-duty service members or veterans, or how to help individuals access it. In addition to the resources outlined in the Table, there are many community-based options open to anyone, including veterans and service members.

I have written columns on many difficult issues in my years as the Editor-in-Chief of Federal Practitioner, but personally this is one of the most distressing editorials I have ever published. That individuals dedicated to defending our rights and protecting our safety should be compelled to go hungry or not know if they have enough money at the end of the month to buy food is manifestly unjust. It is challenging when faced with such a large-scale injustice to think we cannot make a difference, but that resignation or abdication only magnifies this inequity. I have a friend who kept giving back even after they retired from federal service: they volunteered at a community garden and brought produce to the local food bank and helped distribute it. That may seem too much for those still working yet almost anyone can pick up a few items on their weekly shopping trip and donate them to a food drive.

As we approach Veterans Day, let’s not just express our gratitude to our military and veterans in words but in deeds like feeding the hungry and urging elected representatives to fulfill their commitment to ensure that service members and veterans and their families do not experience food insecurity. Confucian wisdom written in a very distant time and vastly dissimilar context still rings true: there are direct and critical links between food and trust and between hunger and the military.1

Dawson MM. The Wisdom of Confucius: A Collection of the Ethical Sayings of Confucius and of his disciples. International Pocket Library; 1932.

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020. 116th Cong (2019), Public Law 116-92. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-116publ92/html/PLAW-116publ92.htm

Asch BJ, Rennane S, Trail TE, et al. Food insecurity among members of the armed forces and their dependents. RAND Corporation. January 3, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1230-1.html

US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Food Security in the U.S.—Definitions of Food Security. US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. January 10, 2025. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security

Active military and veteran food insecurity. Feeding America. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/food-insecurity-in-veterans

Pradun S. Find access to stop food insecurity in your community. VA News. September 19, 2025. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/142733/find-access-stop-food-insecurity-your-community/

Cohen AJ, Dosa DM, Rudolph JL, et al. Risk factors for veteran food insecurity: findings from a National US Department of Veterans Affairs Food Insecurity Screener. Public Health Nutr. 2022;25:819-828. doi:10.1017/S1368980021004584

Chen C. VA and Rockefeller Foundation collaborate to access food for Veterans. VA News. September 5, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/123228/va-rockefeller-foundation-expand-access-to-food/

Dawson MM. The Wisdom of Confucius: A Collection of the Ethical Sayings of Confucius and of his disciples. International Pocket Library; 1932.

National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020. 116th Cong (2019), Public Law 116-92. U.S. Government Printing Office. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-116publ92/html/PLAW-116publ92.htm

Asch BJ, Rennane S, Trail TE, et al. Food insecurity among members of the armed forces and their dependents. RAND Corporation. January 3, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1230-1.html

US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Food Security in the U.S.—Definitions of Food Security. US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. January 10, 2025. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security

Active military and veteran food insecurity. Feeding America. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/food-insecurity-in-veterans

Pradun S. Find access to stop food insecurity in your community. VA News. September 19, 2025. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/142733/find-access-stop-food-insecurity-your-community/

Cohen AJ, Dosa DM, Rudolph JL, et al. Risk factors for veteran food insecurity: findings from a National US Department of Veterans Affairs Food Insecurity Screener. Public Health Nutr. 2022;25:819-828. doi:10.1017/S1368980021004584

Chen C. VA and Rockefeller Foundation collaborate to access food for Veterans. VA News. September 5, 2023. Accessed September 22, 2025. https://news.va.gov/123228/va-rockefeller-foundation-expand-access-to-food/

American Hunger Games: Food Insecurity Among the Military and Veterans

American Hunger Games: Food Insecurity Among the Military and Veterans

When The Giants and Those Who Stand on Their Shoulders Are Gone: The Loss of VA Institutional Memory

When The Giants and Those Who Stand on Their Shoulders Are Gone: The Loss of VA Institutional Memory

If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) 1

Early in residency, I decided I only wanted to work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). It was a way to follow the example of service that my parents, an Army doctor and nurse, had set. I spent much of my residency, including all of my last year of training, at a VA medical center, hoping a vacancy would open in the psychiatry service. In those days, VA jobs were hard to come by; doctors spent their entire careers in the system, only retiring after decades of commitment to its unique mission. Finally, close to graduation, one of my favorite attending physicians left his post. After mountains of paperwork and running the human resources obstacle course with the usual stumbles, I arrived at my dream job as a VA psychiatrist.

So, it is with immense sadness and even shock that I read a recent ProPublica article reporting that from January to March 2025 almost 40% of the physicians who received employment offers from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) declined the positions.2 Medical media rapidly picked up the story, likely further discouraging potential applicants.3

There have always been health care professionals (HCPs) who had zero interest in working for the VA. Medical students and residents often have a love/hate relationship with the VA, with some trainees not having the patience for the behemoth pace of the bureaucracy or finding the old-style physical environment and more relaxed pace antiquated and inefficient.

The reasons doctors are saying no to VA employment at 4 times the previous rate are different and more disturbing. According to ProPublica, VA officials in Texas reported in a June internal presentation that about 90 people had turned down job offers due to the “uncertainty of reorganization.”2 They reported that low morale was causing existing employees to recommend against working at the VA. My own anecdotal experience is similar: contrary to prior years, few residents, if any, are interested in working at the VA because of concerns about the stability of employment and the direction of its organizational culture.

It is fair to question the objectivity of the ProPublica report. However, the latest VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) analysis of staffing had similar findings. “Despite the ability to make noncompetitive appointments for such occupations, VHA continues to experience severe occupational staffing shortages for these occupations that are fundamental to the delivery of health care.” The 4434 severe occupational shortage figures in fiscal year (FY) 2025 were 50% higher than in FY 2024.4 OIG reported that 57% of facilities noted severe occupational staffing shortages for psychology, making it the most frequently reported clinical shortage.

At this critical juncture, when new health care professional energy is not flowing into the VHA, there is an unprecedented drain of the lifeblood of any system—the departure of the bearers of institutional memory. Early and scheduled retirements, the deferred resignation program, and severance have decimated the ranks of senior HCPs, experienced leaders, and career clinicians. ProPublica noted the loss of 600 doctors and 1900 nurses at the VHA so far in 2025.2 Internal VA data from exit interviews suggest similar motivations. Many cited lack of trust and confidence in senior leaders and job stress/pressure.5

It should be noted the VA has an alternative and plausible explanation for the expected departure of 30,000 employees. They argue that the VHA was overstaffed and the increased workforce decreased the efficiency of service. Voluntary separation from employment, VA contends, has avoided the need for a far more disruptive reduction in force. VA leaders avow that downsizing has not adversely impacted its ability to deliver high-quality health care and benefits and they assert that a reduction in red tape will enable VA to provide easier access to care. VA Secretary Doug Collins has concluded that because of these difficult but necessary changes, “VA is headed in the right direction.”6

What is institutional memory, and why is it important? “The core of institutional memory is collective awareness and understanding of a collective set of facts, concepts, experiences, and know-how,” Bhugra and Ventriglio explain. “These are all held collectively at various levels in any given institution. Thus, collective memory or history can be utilized to build on what has gone before and how we take things forward.”7

The authors of this quote offer a modern twist on what Sir Isaac Newton described in more metaphorical language in the epigraph: to survive, and even more to thrive, an enterprise must have those who have accumulated technical knowledge and professional wisdom as well as those who assume responsibility for appropriating and adding to this storehouse of operational skill, expertise, unique cultural values, and ethical commitments. The VHA is losing its instructors and students of institutional memory which deals a serious blow to the stability and vitality of any learning health system.6 As Bhugra and Ventriglio put it, institutional memory identifies “what has worked in delivering the aims in the past and what has not, thereby ensuring the lessons learnt are remembered and passed on to the next generation.”7

Nearly every week, at all levels of the agency, I have encountered this exodus of builders and bearers of institutional memory. Those who have left did so for many of the same reasons cited by those who declined to come, leaving incalculable gaps at both ends of the career spectrum. Both the old and new are essential for organizational resilience: fresh ideas enable an institution to be agile in responding to challenges, while operational savvy ensures responses are ecologically aligned with the organizational mission.8

The dire shortage of HCPs—especially in mental health and primary care—has opened up unprecedented opportunities.9 Colleagues have noted that with only a little searching they found multiple lucrative positions. Once, HCPs picked the VA because they valued the commitment to public service and being part of a community of education and research more than fame or fortune. Having the best benefits packages in the industry only reinforced its value.

Even so, surpassing a genius such as Sir Isaac Newton, writing to a scientific competitor, Robert Hooke, recognized that progress and discovery in science and medicine are nigh well impossible without the collective achievements housed in institutional memory.1 It was inspiring teachers and attending physicians—Newton’s giants—who attracted the best and brightest in medicine and nursing, other HCPs, and research, to the VA, where they could participate in a transactive organizational learning process from their seniors, and then grow that fund of knowledge to improve patient care, educate their learners, and innovate. What will happen when there are no longer shoulders of giants or anyone to stand on them?

- Chen C. Mapping Scientific Frontiers: The Quest for Knowledge Visualization. Springer; 2013:135.

- Armstrong D, Umansky E, Coleman V. Veterans’ care at risk under Trump as hundreds of doctors and nurses reject working at VA hospitals. ProPublica. August 8, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.propublica.org/article/veterans-affairs-hospital-shortages-trump

- Kuchno K. VA physician job offers rejections up fourfold in 2025: report. Becker’s Hospital Review. August 12, 2025. Accessed August 26, 2025. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/workforce/va-physician-job-offer-rejections-up-fourfold-in-2025-report/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. OIG determination of Veterans Health Administration’s severe occupational staffing shortages fiscal year 2025. August 12, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.vaoig.gov/reports/national-healthcare-review/oig-determination-veterans-health-administrations-severe-1

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA workforce dashboard. July 25, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/EMPLOYEE/docs/workforce/VA-Workforce-Dashboard-Issue-27.pdf

- VA to reduce staff by nearly 30K by end of FY2025. News release. Veterans Affairs News. July 7, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-to-reduce-staff-by-nearly-30k-by-end-of-fy2025/

- Bhugra D, Ventriglio A. Institutions, institutional memory, healthcare and research. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2023;69(8):1843-1844. doi:10.1177/00207640231213905

- Jain A. Is organizational memory a useful capability? An analysis of its effects on productivity, absorptive capacity adaptation. In Argote L, Levine JM. The Oxford Handbook of Group and Organizational Learning. Oxford; 2020.

- Broder J. Ready to pick a specialty? These may have the brightest futures. Medscape. April 21, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/ready-pick-specialty-these-may-have-brightest-futures-2025a10009if

If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) 1

Early in residency, I decided I only wanted to work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). It was a way to follow the example of service that my parents, an Army doctor and nurse, had set. I spent much of my residency, including all of my last year of training, at a VA medical center, hoping a vacancy would open in the psychiatry service. In those days, VA jobs were hard to come by; doctors spent their entire careers in the system, only retiring after decades of commitment to its unique mission. Finally, close to graduation, one of my favorite attending physicians left his post. After mountains of paperwork and running the human resources obstacle course with the usual stumbles, I arrived at my dream job as a VA psychiatrist.

So, it is with immense sadness and even shock that I read a recent ProPublica article reporting that from January to March 2025 almost 40% of the physicians who received employment offers from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) declined the positions.2 Medical media rapidly picked up the story, likely further discouraging potential applicants.3

There have always been health care professionals (HCPs) who had zero interest in working for the VA. Medical students and residents often have a love/hate relationship with the VA, with some trainees not having the patience for the behemoth pace of the bureaucracy or finding the old-style physical environment and more relaxed pace antiquated and inefficient.

The reasons doctors are saying no to VA employment at 4 times the previous rate are different and more disturbing. According to ProPublica, VA officials in Texas reported in a June internal presentation that about 90 people had turned down job offers due to the “uncertainty of reorganization.”2 They reported that low morale was causing existing employees to recommend against working at the VA. My own anecdotal experience is similar: contrary to prior years, few residents, if any, are interested in working at the VA because of concerns about the stability of employment and the direction of its organizational culture.

It is fair to question the objectivity of the ProPublica report. However, the latest VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) analysis of staffing had similar findings. “Despite the ability to make noncompetitive appointments for such occupations, VHA continues to experience severe occupational staffing shortages for these occupations that are fundamental to the delivery of health care.” The 4434 severe occupational shortage figures in fiscal year (FY) 2025 were 50% higher than in FY 2024.4 OIG reported that 57% of facilities noted severe occupational staffing shortages for psychology, making it the most frequently reported clinical shortage.

At this critical juncture, when new health care professional energy is not flowing into the VHA, there is an unprecedented drain of the lifeblood of any system—the departure of the bearers of institutional memory. Early and scheduled retirements, the deferred resignation program, and severance have decimated the ranks of senior HCPs, experienced leaders, and career clinicians. ProPublica noted the loss of 600 doctors and 1900 nurses at the VHA so far in 2025.2 Internal VA data from exit interviews suggest similar motivations. Many cited lack of trust and confidence in senior leaders and job stress/pressure.5

It should be noted the VA has an alternative and plausible explanation for the expected departure of 30,000 employees. They argue that the VHA was overstaffed and the increased workforce decreased the efficiency of service. Voluntary separation from employment, VA contends, has avoided the need for a far more disruptive reduction in force. VA leaders avow that downsizing has not adversely impacted its ability to deliver high-quality health care and benefits and they assert that a reduction in red tape will enable VA to provide easier access to care. VA Secretary Doug Collins has concluded that because of these difficult but necessary changes, “VA is headed in the right direction.”6

What is institutional memory, and why is it important? “The core of institutional memory is collective awareness and understanding of a collective set of facts, concepts, experiences, and know-how,” Bhugra and Ventriglio explain. “These are all held collectively at various levels in any given institution. Thus, collective memory or history can be utilized to build on what has gone before and how we take things forward.”7

The authors of this quote offer a modern twist on what Sir Isaac Newton described in more metaphorical language in the epigraph: to survive, and even more to thrive, an enterprise must have those who have accumulated technical knowledge and professional wisdom as well as those who assume responsibility for appropriating and adding to this storehouse of operational skill, expertise, unique cultural values, and ethical commitments. The VHA is losing its instructors and students of institutional memory which deals a serious blow to the stability and vitality of any learning health system.6 As Bhugra and Ventriglio put it, institutional memory identifies “what has worked in delivering the aims in the past and what has not, thereby ensuring the lessons learnt are remembered and passed on to the next generation.”7

Nearly every week, at all levels of the agency, I have encountered this exodus of builders and bearers of institutional memory. Those who have left did so for many of the same reasons cited by those who declined to come, leaving incalculable gaps at both ends of the career spectrum. Both the old and new are essential for organizational resilience: fresh ideas enable an institution to be agile in responding to challenges, while operational savvy ensures responses are ecologically aligned with the organizational mission.8

The dire shortage of HCPs—especially in mental health and primary care—has opened up unprecedented opportunities.9 Colleagues have noted that with only a little searching they found multiple lucrative positions. Once, HCPs picked the VA because they valued the commitment to public service and being part of a community of education and research more than fame or fortune. Having the best benefits packages in the industry only reinforced its value.

Even so, surpassing a genius such as Sir Isaac Newton, writing to a scientific competitor, Robert Hooke, recognized that progress and discovery in science and medicine are nigh well impossible without the collective achievements housed in institutional memory.1 It was inspiring teachers and attending physicians—Newton’s giants—who attracted the best and brightest in medicine and nursing, other HCPs, and research, to the VA, where they could participate in a transactive organizational learning process from their seniors, and then grow that fund of knowledge to improve patient care, educate their learners, and innovate. What will happen when there are no longer shoulders of giants or anyone to stand on them?

If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) 1

Early in residency, I decided I only wanted to work at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). It was a way to follow the example of service that my parents, an Army doctor and nurse, had set. I spent much of my residency, including all of my last year of training, at a VA medical center, hoping a vacancy would open in the psychiatry service. In those days, VA jobs were hard to come by; doctors spent their entire careers in the system, only retiring after decades of commitment to its unique mission. Finally, close to graduation, one of my favorite attending physicians left his post. After mountains of paperwork and running the human resources obstacle course with the usual stumbles, I arrived at my dream job as a VA psychiatrist.

So, it is with immense sadness and even shock that I read a recent ProPublica article reporting that from January to March 2025 almost 40% of the physicians who received employment offers from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) declined the positions.2 Medical media rapidly picked up the story, likely further discouraging potential applicants.3

There have always been health care professionals (HCPs) who had zero interest in working for the VA. Medical students and residents often have a love/hate relationship with the VA, with some trainees not having the patience for the behemoth pace of the bureaucracy or finding the old-style physical environment and more relaxed pace antiquated and inefficient.

The reasons doctors are saying no to VA employment at 4 times the previous rate are different and more disturbing. According to ProPublica, VA officials in Texas reported in a June internal presentation that about 90 people had turned down job offers due to the “uncertainty of reorganization.”2 They reported that low morale was causing existing employees to recommend against working at the VA. My own anecdotal experience is similar: contrary to prior years, few residents, if any, are interested in working at the VA because of concerns about the stability of employment and the direction of its organizational culture.

It is fair to question the objectivity of the ProPublica report. However, the latest VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) analysis of staffing had similar findings. “Despite the ability to make noncompetitive appointments for such occupations, VHA continues to experience severe occupational staffing shortages for these occupations that are fundamental to the delivery of health care.” The 4434 severe occupational shortage figures in fiscal year (FY) 2025 were 50% higher than in FY 2024.4 OIG reported that 57% of facilities noted severe occupational staffing shortages for psychology, making it the most frequently reported clinical shortage.

At this critical juncture, when new health care professional energy is not flowing into the VHA, there is an unprecedented drain of the lifeblood of any system—the departure of the bearers of institutional memory. Early and scheduled retirements, the deferred resignation program, and severance have decimated the ranks of senior HCPs, experienced leaders, and career clinicians. ProPublica noted the loss of 600 doctors and 1900 nurses at the VHA so far in 2025.2 Internal VA data from exit interviews suggest similar motivations. Many cited lack of trust and confidence in senior leaders and job stress/pressure.5

It should be noted the VA has an alternative and plausible explanation for the expected departure of 30,000 employees. They argue that the VHA was overstaffed and the increased workforce decreased the efficiency of service. Voluntary separation from employment, VA contends, has avoided the need for a far more disruptive reduction in force. VA leaders avow that downsizing has not adversely impacted its ability to deliver high-quality health care and benefits and they assert that a reduction in red tape will enable VA to provide easier access to care. VA Secretary Doug Collins has concluded that because of these difficult but necessary changes, “VA is headed in the right direction.”6

What is institutional memory, and why is it important? “The core of institutional memory is collective awareness and understanding of a collective set of facts, concepts, experiences, and know-how,” Bhugra and Ventriglio explain. “These are all held collectively at various levels in any given institution. Thus, collective memory or history can be utilized to build on what has gone before and how we take things forward.”7

The authors of this quote offer a modern twist on what Sir Isaac Newton described in more metaphorical language in the epigraph: to survive, and even more to thrive, an enterprise must have those who have accumulated technical knowledge and professional wisdom as well as those who assume responsibility for appropriating and adding to this storehouse of operational skill, expertise, unique cultural values, and ethical commitments. The VHA is losing its instructors and students of institutional memory which deals a serious blow to the stability and vitality of any learning health system.6 As Bhugra and Ventriglio put it, institutional memory identifies “what has worked in delivering the aims in the past and what has not, thereby ensuring the lessons learnt are remembered and passed on to the next generation.”7

Nearly every week, at all levels of the agency, I have encountered this exodus of builders and bearers of institutional memory. Those who have left did so for many of the same reasons cited by those who declined to come, leaving incalculable gaps at both ends of the career spectrum. Both the old and new are essential for organizational resilience: fresh ideas enable an institution to be agile in responding to challenges, while operational savvy ensures responses are ecologically aligned with the organizational mission.8

The dire shortage of HCPs—especially in mental health and primary care—has opened up unprecedented opportunities.9 Colleagues have noted that with only a little searching they found multiple lucrative positions. Once, HCPs picked the VA because they valued the commitment to public service and being part of a community of education and research more than fame or fortune. Having the best benefits packages in the industry only reinforced its value.

Even so, surpassing a genius such as Sir Isaac Newton, writing to a scientific competitor, Robert Hooke, recognized that progress and discovery in science and medicine are nigh well impossible without the collective achievements housed in institutional memory.1 It was inspiring teachers and attending physicians—Newton’s giants—who attracted the best and brightest in medicine and nursing, other HCPs, and research, to the VA, where they could participate in a transactive organizational learning process from their seniors, and then grow that fund of knowledge to improve patient care, educate their learners, and innovate. What will happen when there are no longer shoulders of giants or anyone to stand on them?

- Chen C. Mapping Scientific Frontiers: The Quest for Knowledge Visualization. Springer; 2013:135.

- Armstrong D, Umansky E, Coleman V. Veterans’ care at risk under Trump as hundreds of doctors and nurses reject working at VA hospitals. ProPublica. August 8, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.propublica.org/article/veterans-affairs-hospital-shortages-trump

- Kuchno K. VA physician job offers rejections up fourfold in 2025: report. Becker’s Hospital Review. August 12, 2025. Accessed August 26, 2025. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/workforce/va-physician-job-offer-rejections-up-fourfold-in-2025-report/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. OIG determination of Veterans Health Administration’s severe occupational staffing shortages fiscal year 2025. August 12, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.vaoig.gov/reports/national-healthcare-review/oig-determination-veterans-health-administrations-severe-1

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA workforce dashboard. July 25, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/EMPLOYEE/docs/workforce/VA-Workforce-Dashboard-Issue-27.pdf

- VA to reduce staff by nearly 30K by end of FY2025. News release. Veterans Affairs News. July 7, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-to-reduce-staff-by-nearly-30k-by-end-of-fy2025/

- Bhugra D, Ventriglio A. Institutions, institutional memory, healthcare and research. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2023;69(8):1843-1844. doi:10.1177/00207640231213905

- Jain A. Is organizational memory a useful capability? An analysis of its effects on productivity, absorptive capacity adaptation. In Argote L, Levine JM. The Oxford Handbook of Group and Organizational Learning. Oxford; 2020.

- Broder J. Ready to pick a specialty? These may have the brightest futures. Medscape. April 21, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/ready-pick-specialty-these-may-have-brightest-futures-2025a10009if

- Chen C. Mapping Scientific Frontiers: The Quest for Knowledge Visualization. Springer; 2013:135.

- Armstrong D, Umansky E, Coleman V. Veterans’ care at risk under Trump as hundreds of doctors and nurses reject working at VA hospitals. ProPublica. August 8, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.propublica.org/article/veterans-affairs-hospital-shortages-trump

- Kuchno K. VA physician job offers rejections up fourfold in 2025: report. Becker’s Hospital Review. August 12, 2025. Accessed August 26, 2025. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/workforce/va-physician-job-offer-rejections-up-fourfold-in-2025-report/

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. OIG determination of Veterans Health Administration’s severe occupational staffing shortages fiscal year 2025. August 12, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.vaoig.gov/reports/national-healthcare-review/oig-determination-veterans-health-administrations-severe-1

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA workforce dashboard. July 25, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/EMPLOYEE/docs/workforce/VA-Workforce-Dashboard-Issue-27.pdf

- VA to reduce staff by nearly 30K by end of FY2025. News release. Veterans Affairs News. July 7, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://news.va.gov/press-room/va-to-reduce-staff-by-nearly-30k-by-end-of-fy2025/

- Bhugra D, Ventriglio A. Institutions, institutional memory, healthcare and research. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2023;69(8):1843-1844. doi:10.1177/00207640231213905

- Jain A. Is organizational memory a useful capability? An analysis of its effects on productivity, absorptive capacity adaptation. In Argote L, Levine JM. The Oxford Handbook of Group and Organizational Learning. Oxford; 2020.

- Broder J. Ready to pick a specialty? These may have the brightest futures. Medscape. April 21, 2025. Accessed August 25, 2025. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/ready-pick-specialty-these-may-have-brightest-futures-2025a10009if

When The Giants and Those Who Stand on Their Shoulders Are Gone: The Loss of VA Institutional Memory

When The Giants and Those Who Stand on Their Shoulders Are Gone: The Loss of VA Institutional Memory

Military Imposters: What Drives Them and How They Damage Us All

Military Imposters: What Drives Them and How They Damage Us All

The better part of valor is discretion.

Henry IV, Part 1 by William Shakespeare1

This is the second part of an exploration of the phenomenon of stolen valor, where individuals claim military exploits or acts of heroism that are either fabricated or exaggerated, and/or awards and medals they did not earn.2 In June, I focused on the unsettling story of Sarah Cavanaugh, a young US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) social worker who posed as a decorated, heroic, and seriously wounded Marine veteran for years. Cavanaugh’s manipulative masquerade allowed her to receive coveted spots in veteran recovery programs, thousands of dollars in fraudulent donations, the leadership of a local Veterans of Foreign Wars post, and eventually a federal conviction and prison sentence.3 The first column focused on the legal history of stolen valor; this editorial analyzes the clinical import and ethical impact of the behavior of military imposters. Military imposters are the culprits who steal valor.

It would be easy and perhaps reassuring to assume that stolen valor has emerged as another deplorable example of a national culture in which the betrayal of trust in human beings and loss of faith in institutions and aspirations has reached a nadir. Ironically, stolen valor is inextricably linked to the founding of the United States. When General George Washington inaugurated the American military tradition of awarding decorations to honor the bravery and sacrifices of the patriot Army, he anticipated military imposters. He tried to deter stolen valor through the threat of chastisement: “Should any who are not entitled to these honors have the insolence to assume the badges of them, they shall be severely punished,” Washington warned.4

It is plausible to think such despicable conduct occurs only as the ugly side of the beauty of our unparalleled national freedom, but this is a mistake. Cases of stolen valor have been reported in many countries around the world, with some of the most infamous found in the United Kingdom.5

While many brazen military imposters like Cavanaugh never serve, there is a small subset who honorably wore a uniform yet embellish their service record with secret missions and meritorious gallantry that purportedly earned them high rank and even higher awards. A most puzzling and disturbing example of this group is an allegation that surfaced when celebrated Navy SEAL Chris Kyle declared in American Sniper that he had won 3 additional combat awards for combat valor in addition to the Silver Star and 3 Bronze Stars actually listed in his service record.6

The fact that for centuries stolen valor has plagued multiple nations suggests, at least to this psychiatrically trained mind, that something deeper and darker in human nature than profit alone drives military imposters. Philosopher Verna Gehring has distilled these less tangible motivations into the concept of virtue imposters. According to Gehring, military phonies are a notorious exemplar: “The military phony adopts a past not her own, acts of courage she did not perform—she impersonates the heroic character and virtues she does not possess.”7 There could be no more apposite depiction of Cavanaugh, other military imposters, or a legion of other offenders of honor. 8

As with Cavanaugh, financial gain is a byproduct of the machinations of military imposters and is usually secondary to the pursuit of nonmaterial rewards such as power, influence, admiration, emulation, empathy, and charity. Gehring contends, and I agree, that virtue imposters are more pernicious and culpable than the plethora of more prosaic scammers and swindlers who use deceit primarily as a means of economic exploitation: “The virtue impostor by contrast plays on people’s better natures—their generosity, humility, and their need for heroes.”7

Military imposters cause real and lasting harm. Every veteran who exaggerates claims or scams the VA unjustly steals human and monetary resources from other deserving veterans whose integrity would not permit them to break the rules.9 Yet, even more harmful is the potential damage to therapeutic relationships: federal practitioners may become skeptical of a veteran’s history even when there is little to no grounds for suspicion. Veterans, in turn, may experience a breach of trust and betrayal not only from health care professionals and VA leaders but from their brothers and sisters in arms. On an ever-wider scale, every military impostor who is exposed may diminish the respect and honor all veterans have earned.

It is clear, then, why a small group of former service members has adopted the cause of uncovering military imposters and adroitly using the media to identify signs of stolen valor.10 Yet deception mars even these mostly well-intentioned campaigns, as some more zealous stolen valor hunters may make allegations that turn out to be false.11 Nevertheless, 500 years ago and in a very different context Shakespeare was, right on the mark: the better part of valor is discretion in describing one’s achievements, in relying on the veracity of our veteran’s narratives, and when there are sound reasons to do so verifying the truth of what our patients, friends, and even family tell us about their time in the military.1

- Shakespeare W. Introduction in: Henry IV, Part 1. Folger Sharespeare Library. Accessed July 24, 2025. https://www.folger.edu/explore/shakespeares-works/henry-iv-part-1/

- Geppert CM. What about stolen valor actually is illegal? Fed Pract. 2025;42(6):218-219. doi:10.12788/fp.0599