User login

Retinoids, FAK inhibitors may aid TKIs in treating ALL subtype

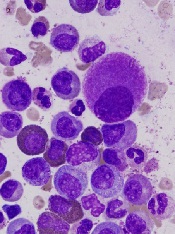

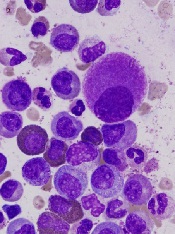

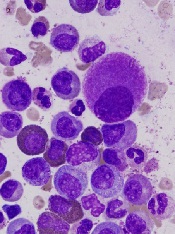

and Charles Mullighan

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

and Peter Barta

Retinoids and FAK inhibitors may override resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in IKZF1-mutated, Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL), according to preclinical research published in Cancer Cell.

Experiments showed that, in Ph+ ALL, IKZF1 mutations prompt changes that reduce responsiveness to TKIs. But combining a TKI with a retinoid or FAK inhibitor can overcome this problem.

“The research shows why, in this era of targeted therapies, Ph+ ALL patients who also have IKZF1 mutations fare so poorly,” said study author Charles Mullighan, MD, MBBS, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. “The insight also led us to a promising new treatment strategy.”

To conduct this research, Dr Mullighan and his colleagues began with mouse models of IKZF1-mutated Ph+ ALL, with and without mutations in the ARF gene. ARF encodes a tumor suppressor protein and is altered in about half of Ph+ ALL cases.

With these models, the researchers showed that the addition of IKZF1 mutations, particularly in combination with ARF mutations, was a central event in driving ALL.

In pre-B cells with BCR-ABL1, IKZF1 mutations induced a stem cell-like phenotype, increased stromal bone marrow adhesion, and reduced responsiveness to the TKI dasatinib.

When the researchers investigated the increased adhesion of mutated cells, they found overexpression of FAK and other molecules implicated in leukemic and stem cell adherence. This led the researchers to speculate that FAK inhibitors might prove useful against IKZF1-mutated Ph+ ALL.

But the team also found, through a screen of 483 compounds, that retinoids can reverse the effects of IKZF1 mutations. The antineoplastic agent bexarotene and 4 nuclear hormone receptor effectors—carbacyclin, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), 9-cis RA, and 13-cis RA—proved particularly effective.

The drugs worked, in part, by inducing expression of wild-type IKZF1. But they also worked in other ways to reverse the stem-cell phenotype, halt cell proliferation, and promote differentiation of altered cells.

The researchers then tested bexarotene and dasatinib, alone and in combination, in mice transplanted with ARF-/- BCR-ABL1 pre-B cells, with or without IK6 expression. Bexarotene alone produced “significant benefit without detectable toxicity.”

Dasatinib alone increased survival, but dasatinib and bexarotene in combination resulted in a greater survival advantage. The combination nearly doubled the survival time of mice with IK6 tumors, when compared to dasatinib alone.

The researchers also established xenografts of Ph+ ALL that recapitulate a range of IKZF1 genotypes. They administered dasatinib plus bexarotene, ATRA, or the FAK inhibitors PF-562271, NVPTAE226, or PF-573228 ex vivo and observed “significant potentiation of cell killing.”

The team is currently investigating how to incorporate retinoids or FAK inhibitors into the existing treatment of IKZF1-mutated Ph+ ALL. ![]()

and Charles Mullighan

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

and Peter Barta

Retinoids and FAK inhibitors may override resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in IKZF1-mutated, Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL), according to preclinical research published in Cancer Cell.

Experiments showed that, in Ph+ ALL, IKZF1 mutations prompt changes that reduce responsiveness to TKIs. But combining a TKI with a retinoid or FAK inhibitor can overcome this problem.

“The research shows why, in this era of targeted therapies, Ph+ ALL patients who also have IKZF1 mutations fare so poorly,” said study author Charles Mullighan, MD, MBBS, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. “The insight also led us to a promising new treatment strategy.”

To conduct this research, Dr Mullighan and his colleagues began with mouse models of IKZF1-mutated Ph+ ALL, with and without mutations in the ARF gene. ARF encodes a tumor suppressor protein and is altered in about half of Ph+ ALL cases.

With these models, the researchers showed that the addition of IKZF1 mutations, particularly in combination with ARF mutations, was a central event in driving ALL.

In pre-B cells with BCR-ABL1, IKZF1 mutations induced a stem cell-like phenotype, increased stromal bone marrow adhesion, and reduced responsiveness to the TKI dasatinib.

When the researchers investigated the increased adhesion of mutated cells, they found overexpression of FAK and other molecules implicated in leukemic and stem cell adherence. This led the researchers to speculate that FAK inhibitors might prove useful against IKZF1-mutated Ph+ ALL.

But the team also found, through a screen of 483 compounds, that retinoids can reverse the effects of IKZF1 mutations. The antineoplastic agent bexarotene and 4 nuclear hormone receptor effectors—carbacyclin, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), 9-cis RA, and 13-cis RA—proved particularly effective.

The drugs worked, in part, by inducing expression of wild-type IKZF1. But they also worked in other ways to reverse the stem-cell phenotype, halt cell proliferation, and promote differentiation of altered cells.

The researchers then tested bexarotene and dasatinib, alone and in combination, in mice transplanted with ARF-/- BCR-ABL1 pre-B cells, with or without IK6 expression. Bexarotene alone produced “significant benefit without detectable toxicity.”

Dasatinib alone increased survival, but dasatinib and bexarotene in combination resulted in a greater survival advantage. The combination nearly doubled the survival time of mice with IK6 tumors, when compared to dasatinib alone.

The researchers also established xenografts of Ph+ ALL that recapitulate a range of IKZF1 genotypes. They administered dasatinib plus bexarotene, ATRA, or the FAK inhibitors PF-562271, NVPTAE226, or PF-573228 ex vivo and observed “significant potentiation of cell killing.”

The team is currently investigating how to incorporate retinoids or FAK inhibitors into the existing treatment of IKZF1-mutated Ph+ ALL. ![]()

and Charles Mullighan

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

and Peter Barta

Retinoids and FAK inhibitors may override resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in IKZF1-mutated, Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL), according to preclinical research published in Cancer Cell.

Experiments showed that, in Ph+ ALL, IKZF1 mutations prompt changes that reduce responsiveness to TKIs. But combining a TKI with a retinoid or FAK inhibitor can overcome this problem.

“The research shows why, in this era of targeted therapies, Ph+ ALL patients who also have IKZF1 mutations fare so poorly,” said study author Charles Mullighan, MD, MBBS, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. “The insight also led us to a promising new treatment strategy.”

To conduct this research, Dr Mullighan and his colleagues began with mouse models of IKZF1-mutated Ph+ ALL, with and without mutations in the ARF gene. ARF encodes a tumor suppressor protein and is altered in about half of Ph+ ALL cases.

With these models, the researchers showed that the addition of IKZF1 mutations, particularly in combination with ARF mutations, was a central event in driving ALL.

In pre-B cells with BCR-ABL1, IKZF1 mutations induced a stem cell-like phenotype, increased stromal bone marrow adhesion, and reduced responsiveness to the TKI dasatinib.

When the researchers investigated the increased adhesion of mutated cells, they found overexpression of FAK and other molecules implicated in leukemic and stem cell adherence. This led the researchers to speculate that FAK inhibitors might prove useful against IKZF1-mutated Ph+ ALL.

But the team also found, through a screen of 483 compounds, that retinoids can reverse the effects of IKZF1 mutations. The antineoplastic agent bexarotene and 4 nuclear hormone receptor effectors—carbacyclin, all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), 9-cis RA, and 13-cis RA—proved particularly effective.

The drugs worked, in part, by inducing expression of wild-type IKZF1. But they also worked in other ways to reverse the stem-cell phenotype, halt cell proliferation, and promote differentiation of altered cells.

The researchers then tested bexarotene and dasatinib, alone and in combination, in mice transplanted with ARF-/- BCR-ABL1 pre-B cells, with or without IK6 expression. Bexarotene alone produced “significant benefit without detectable toxicity.”

Dasatinib alone increased survival, but dasatinib and bexarotene in combination resulted in a greater survival advantage. The combination nearly doubled the survival time of mice with IK6 tumors, when compared to dasatinib alone.

The researchers also established xenografts of Ph+ ALL that recapitulate a range of IKZF1 genotypes. They administered dasatinib plus bexarotene, ATRA, or the FAK inhibitors PF-562271, NVPTAE226, or PF-573228 ex vivo and observed “significant potentiation of cell killing.”

The team is currently investigating how to incorporate retinoids or FAK inhibitors into the existing treatment of IKZF1-mutated Ph+ ALL. ![]()

Malaria tests underused despite training

Photo courtesy of USAID

A study conducted in Nigeria has shown that health providers continue to prescribe malaria medicines inappropriately, even after they learn to test for malaria and receive testing kits free of charge.

Health providers were given rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) for malaria and learned to use the tests via 3 different methods.

However, the use of RDTs was “critically low” in all 3 groups, as was the proportion of patients treated appropriately.

“This study confirms that treating malaria based on signs and symptoms alone remains an ingrained behavior that is difficult to change,” said Obinna Onwujekwe, MD, PhD, of the University of Nigeria in Enugu.

Dr Onwujekwe and his colleagues reported these findings in PLOS ONE.

Interventions

Their study included health workers and patients from 40 communities in the Nigerian state of Enugu. Health workers received free RDT kits and were taught to use the tests in 3 different ways.

The first group received comprehensive RDT training, which included instructions on how to use an RDT, guidelines on malaria diagnosis and treatment, information about other causes of fever, and help with communications skills, especially for patients whose test results were negative.

The second group received the same training plus a school-based intervention that involved training 2 teachers per school. The aim was to influence the attitudes of school children and their families as well as the wider community.

And health workers in the third group—the control arm—were invited to a demonstration and practical on how to safely use RDTs and supplied with written instructions on their use.

Results

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who were treated according to guidelines. In other words, they presented with symptoms consistent with malaria, were tested for malaria, and received treatment consistent with the test result.

The researchers assessed the primary outcome in 4946 patients from 40 communities—12 in the control arm and 14 in each intervention arm.

There was no significant difference between the arms with regard to this outcome. The proportion of patients treated according to guidelines was 36% in the comprehensive training arm, 24% in the training-school arm, and 23% in the control arm (P=0.36).

Likewise, the use of testing was low in all arms—34% in the control arm, 48% in the training arm, and 37% in the training-school arm (P=0.47).

The use of testing was lower at private facilities than public ones. Cost may have been a factor here, as public facilities were asked to offer testing free of charge, but private facilities could charge 100 Naira (0.6 USD).

“We have shown that training alone is not enough to realize the full potential of an RDT,” said Virginia Wiseman, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“We must continue to explore alternative ways of encouraging providers to deliver appropriate treatment and avoid the misuse of valuable medicines, especially in the private sector, where we found levels of testing to be lowest.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of USAID

A study conducted in Nigeria has shown that health providers continue to prescribe malaria medicines inappropriately, even after they learn to test for malaria and receive testing kits free of charge.

Health providers were given rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) for malaria and learned to use the tests via 3 different methods.

However, the use of RDTs was “critically low” in all 3 groups, as was the proportion of patients treated appropriately.

“This study confirms that treating malaria based on signs and symptoms alone remains an ingrained behavior that is difficult to change,” said Obinna Onwujekwe, MD, PhD, of the University of Nigeria in Enugu.

Dr Onwujekwe and his colleagues reported these findings in PLOS ONE.

Interventions

Their study included health workers and patients from 40 communities in the Nigerian state of Enugu. Health workers received free RDT kits and were taught to use the tests in 3 different ways.

The first group received comprehensive RDT training, which included instructions on how to use an RDT, guidelines on malaria diagnosis and treatment, information about other causes of fever, and help with communications skills, especially for patients whose test results were negative.

The second group received the same training plus a school-based intervention that involved training 2 teachers per school. The aim was to influence the attitudes of school children and their families as well as the wider community.

And health workers in the third group—the control arm—were invited to a demonstration and practical on how to safely use RDTs and supplied with written instructions on their use.

Results

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who were treated according to guidelines. In other words, they presented with symptoms consistent with malaria, were tested for malaria, and received treatment consistent with the test result.

The researchers assessed the primary outcome in 4946 patients from 40 communities—12 in the control arm and 14 in each intervention arm.

There was no significant difference between the arms with regard to this outcome. The proportion of patients treated according to guidelines was 36% in the comprehensive training arm, 24% in the training-school arm, and 23% in the control arm (P=0.36).

Likewise, the use of testing was low in all arms—34% in the control arm, 48% in the training arm, and 37% in the training-school arm (P=0.47).

The use of testing was lower at private facilities than public ones. Cost may have been a factor here, as public facilities were asked to offer testing free of charge, but private facilities could charge 100 Naira (0.6 USD).

“We have shown that training alone is not enough to realize the full potential of an RDT,” said Virginia Wiseman, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“We must continue to explore alternative ways of encouraging providers to deliver appropriate treatment and avoid the misuse of valuable medicines, especially in the private sector, where we found levels of testing to be lowest.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of USAID

A study conducted in Nigeria has shown that health providers continue to prescribe malaria medicines inappropriately, even after they learn to test for malaria and receive testing kits free of charge.

Health providers were given rapid diagnostic tests (RDT) for malaria and learned to use the tests via 3 different methods.

However, the use of RDTs was “critically low” in all 3 groups, as was the proportion of patients treated appropriately.

“This study confirms that treating malaria based on signs and symptoms alone remains an ingrained behavior that is difficult to change,” said Obinna Onwujekwe, MD, PhD, of the University of Nigeria in Enugu.

Dr Onwujekwe and his colleagues reported these findings in PLOS ONE.

Interventions

Their study included health workers and patients from 40 communities in the Nigerian state of Enugu. Health workers received free RDT kits and were taught to use the tests in 3 different ways.

The first group received comprehensive RDT training, which included instructions on how to use an RDT, guidelines on malaria diagnosis and treatment, information about other causes of fever, and help with communications skills, especially for patients whose test results were negative.

The second group received the same training plus a school-based intervention that involved training 2 teachers per school. The aim was to influence the attitudes of school children and their families as well as the wider community.

And health workers in the third group—the control arm—were invited to a demonstration and practical on how to safely use RDTs and supplied with written instructions on their use.

Results

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who were treated according to guidelines. In other words, they presented with symptoms consistent with malaria, were tested for malaria, and received treatment consistent with the test result.

The researchers assessed the primary outcome in 4946 patients from 40 communities—12 in the control arm and 14 in each intervention arm.

There was no significant difference between the arms with regard to this outcome. The proportion of patients treated according to guidelines was 36% in the comprehensive training arm, 24% in the training-school arm, and 23% in the control arm (P=0.36).

Likewise, the use of testing was low in all arms—34% in the control arm, 48% in the training arm, and 37% in the training-school arm (P=0.47).

The use of testing was lower at private facilities than public ones. Cost may have been a factor here, as public facilities were asked to offer testing free of charge, but private facilities could charge 100 Naira (0.6 USD).

“We have shown that training alone is not enough to realize the full potential of an RDT,” said Virginia Wiseman, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“We must continue to explore alternative ways of encouraging providers to deliver appropriate treatment and avoid the misuse of valuable medicines, especially in the private sector, where we found levels of testing to be lowest.” ![]()

Inhibitors can target CML stem cells

Preclinical research has revealed nutrients that support the activity of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) stem cells and suggests these nutrients may be promising targets for CML therapy.

Investigators discovered that CML stem cells accumulate high levels of certain dipeptide species, and these dipeptides act as nutrients for the cells.

When the team inhibited dipeptide uptake, they observed decreased CML stem cell activity.

Combining agents that inhibit dipeptide uptake with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) proved more effective against CML than TKI treatment alone, both in vitro and in vivo.

Kazuhito Naka, PhD, of Hiroshima University in Japan, and his colleagues conducted this research and disclosed the results in Nature Communications.

The team began by analyzing CML stem cells isolated from a mouse model of the disease. They found that CML stem cells accumulate significantly higher levels of certain dipeptide species—such as Ala-Leu, Asp-Leu, Ser-Tyr, and Thr-Val—than normal hematopoietic stem cells.

Additional investigation revealed that CML stem cells take up dipeptides via the Slc15A2 transporter. And once internalized, the dipeptides act as nutrients and play a role in CML stem cell maintenance.

The dipeptides activate amino-acid signaling via a pathway involving p38MAPK and Smad3, and this promotes CML stem cell maintenance.

To build upon these findings, the investigators assessed the effects of cefadroxil, which inhibits Slc15A2-mediated nutrient signaling, in combination with imatinib as CML treatment.

In murine CML stem cell cultures, the 2 drugs in combination reduced colony formation more effectively than imatinib alone.

In vivo, mice with CML responded to imatinib alone but eventually experienced disease recurrence. And cefadroxil alone promoted disease development. But when cefadroxil was given in combination with imatinib, disease recurrence was significantly lower than in mice that received imatinib alone.

The investigators then showed that cefadroxil decreases the number of CML stem cells in CML-affected mice. And cefadroxil combined with imatinib reduces CML stem cell numbers more effectively than imatinib alone.

In serial transplantation experiments, CML stem cells isolated from cefadroxil-treated mice completely lost their ability to drive BCR-ABL1+ disease in new recipients. These animals survived for more than 90 days, whereas mice that received CML stem cells from vehicle-treated mice developed BCR-ABL1+ disease and died before 80 days.

The investigators also tested cefadroxil in stem cells derived from humans with chronic CML. Cefadroxil suppressed the colony-forming capacity of all 3 samples tested. And combining cefadroxil with imatinib or dasatinib reduced colony formation more effectively than either TKI alone.

Lastly, the team decided to test 3 clinical-grade p38MAPK inhibitors that are already approved for use in the US—Ly2228820 (ralimetinib), VX-702, and BIRB796 (doramapimod). When cultured with CML stem cells, each of these drugs significantly decreased colony formation.

In addition, Ly2228820 combined with dasatinib delayed CML onset in mice and improved their survival when compared with dasatinib alone.

These results suggest p38MAPK inhibitors and cefadroxil may be useful additions to TKI therapy in CML, the investigators said.

“Our proposed approach of using inhibitors to shut down a key nutrient uptake process specific to CML stem cells, in combination with TKI therapy, may thus provide concrete therapeutic benefits to patients with CML,” Dr Naka said. “It will open up a novel avenue for curative CML therapy.” ![]()

Preclinical research has revealed nutrients that support the activity of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) stem cells and suggests these nutrients may be promising targets for CML therapy.

Investigators discovered that CML stem cells accumulate high levels of certain dipeptide species, and these dipeptides act as nutrients for the cells.

When the team inhibited dipeptide uptake, they observed decreased CML stem cell activity.

Combining agents that inhibit dipeptide uptake with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) proved more effective against CML than TKI treatment alone, both in vitro and in vivo.

Kazuhito Naka, PhD, of Hiroshima University in Japan, and his colleagues conducted this research and disclosed the results in Nature Communications.

The team began by analyzing CML stem cells isolated from a mouse model of the disease. They found that CML stem cells accumulate significantly higher levels of certain dipeptide species—such as Ala-Leu, Asp-Leu, Ser-Tyr, and Thr-Val—than normal hematopoietic stem cells.

Additional investigation revealed that CML stem cells take up dipeptides via the Slc15A2 transporter. And once internalized, the dipeptides act as nutrients and play a role in CML stem cell maintenance.

The dipeptides activate amino-acid signaling via a pathway involving p38MAPK and Smad3, and this promotes CML stem cell maintenance.

To build upon these findings, the investigators assessed the effects of cefadroxil, which inhibits Slc15A2-mediated nutrient signaling, in combination with imatinib as CML treatment.

In murine CML stem cell cultures, the 2 drugs in combination reduced colony formation more effectively than imatinib alone.

In vivo, mice with CML responded to imatinib alone but eventually experienced disease recurrence. And cefadroxil alone promoted disease development. But when cefadroxil was given in combination with imatinib, disease recurrence was significantly lower than in mice that received imatinib alone.

The investigators then showed that cefadroxil decreases the number of CML stem cells in CML-affected mice. And cefadroxil combined with imatinib reduces CML stem cell numbers more effectively than imatinib alone.

In serial transplantation experiments, CML stem cells isolated from cefadroxil-treated mice completely lost their ability to drive BCR-ABL1+ disease in new recipients. These animals survived for more than 90 days, whereas mice that received CML stem cells from vehicle-treated mice developed BCR-ABL1+ disease and died before 80 days.

The investigators also tested cefadroxil in stem cells derived from humans with chronic CML. Cefadroxil suppressed the colony-forming capacity of all 3 samples tested. And combining cefadroxil with imatinib or dasatinib reduced colony formation more effectively than either TKI alone.

Lastly, the team decided to test 3 clinical-grade p38MAPK inhibitors that are already approved for use in the US—Ly2228820 (ralimetinib), VX-702, and BIRB796 (doramapimod). When cultured with CML stem cells, each of these drugs significantly decreased colony formation.

In addition, Ly2228820 combined with dasatinib delayed CML onset in mice and improved their survival when compared with dasatinib alone.

These results suggest p38MAPK inhibitors and cefadroxil may be useful additions to TKI therapy in CML, the investigators said.

“Our proposed approach of using inhibitors to shut down a key nutrient uptake process specific to CML stem cells, in combination with TKI therapy, may thus provide concrete therapeutic benefits to patients with CML,” Dr Naka said. “It will open up a novel avenue for curative CML therapy.” ![]()

Preclinical research has revealed nutrients that support the activity of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) stem cells and suggests these nutrients may be promising targets for CML therapy.

Investigators discovered that CML stem cells accumulate high levels of certain dipeptide species, and these dipeptides act as nutrients for the cells.

When the team inhibited dipeptide uptake, they observed decreased CML stem cell activity.

Combining agents that inhibit dipeptide uptake with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) proved more effective against CML than TKI treatment alone, both in vitro and in vivo.

Kazuhito Naka, PhD, of Hiroshima University in Japan, and his colleagues conducted this research and disclosed the results in Nature Communications.

The team began by analyzing CML stem cells isolated from a mouse model of the disease. They found that CML stem cells accumulate significantly higher levels of certain dipeptide species—such as Ala-Leu, Asp-Leu, Ser-Tyr, and Thr-Val—than normal hematopoietic stem cells.

Additional investigation revealed that CML stem cells take up dipeptides via the Slc15A2 transporter. And once internalized, the dipeptides act as nutrients and play a role in CML stem cell maintenance.

The dipeptides activate amino-acid signaling via a pathway involving p38MAPK and Smad3, and this promotes CML stem cell maintenance.

To build upon these findings, the investigators assessed the effects of cefadroxil, which inhibits Slc15A2-mediated nutrient signaling, in combination with imatinib as CML treatment.

In murine CML stem cell cultures, the 2 drugs in combination reduced colony formation more effectively than imatinib alone.

In vivo, mice with CML responded to imatinib alone but eventually experienced disease recurrence. And cefadroxil alone promoted disease development. But when cefadroxil was given in combination with imatinib, disease recurrence was significantly lower than in mice that received imatinib alone.

The investigators then showed that cefadroxil decreases the number of CML stem cells in CML-affected mice. And cefadroxil combined with imatinib reduces CML stem cell numbers more effectively than imatinib alone.

In serial transplantation experiments, CML stem cells isolated from cefadroxil-treated mice completely lost their ability to drive BCR-ABL1+ disease in new recipients. These animals survived for more than 90 days, whereas mice that received CML stem cells from vehicle-treated mice developed BCR-ABL1+ disease and died before 80 days.

The investigators also tested cefadroxil in stem cells derived from humans with chronic CML. Cefadroxil suppressed the colony-forming capacity of all 3 samples tested. And combining cefadroxil with imatinib or dasatinib reduced colony formation more effectively than either TKI alone.

Lastly, the team decided to test 3 clinical-grade p38MAPK inhibitors that are already approved for use in the US—Ly2228820 (ralimetinib), VX-702, and BIRB796 (doramapimod). When cultured with CML stem cells, each of these drugs significantly decreased colony formation.

In addition, Ly2228820 combined with dasatinib delayed CML onset in mice and improved their survival when compared with dasatinib alone.

These results suggest p38MAPK inhibitors and cefadroxil may be useful additions to TKI therapy in CML, the investigators said.

“Our proposed approach of using inhibitors to shut down a key nutrient uptake process specific to CML stem cells, in combination with TKI therapy, may thus provide concrete therapeutic benefits to patients with CML,” Dr Naka said. “It will open up a novel avenue for curative CML therapy.” ![]()

Discovery reveals potential for viral cancer treatment

Image by Eric Smith

Researchers say they have discovered critical details that explain how a cellular response system tells the difference between damage to the body’s own DNA and the foreign DNA of an invading virus.

The team believes this discovery could aid the development of new cancer-selective viral therapies, and it may help explain why aging, cancers, and other diseases

seem to open the door to viral infections.

“Our study reveals fundamental mechanisms that distinguish DNA breaks at cellular and viral genomes to trigger different responses that protect the host,” said Clodagh O’Shea, of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

“The findings may also explain why certain conditions like aging, cancer chemotherapy, and inflammation make us more susceptible to viral infection.”

Dr O’Shea and Govind Shah, PhD, also of the Salk Institute, reported these findings in Cell.

The pair described how a cluster of proteins known as the MRN complex detects DNA breaks and amplifies its response through histones.

MRN starts a domino effect, activating histones on surrounding chromosomes, which summons a cascade of additional proteins and results in a cell-wide, all-hands-on-deck alarm to help mend the DNA.

If the cell can’t fix the DNA break, it will induce apoptosis—a self-destruct mechanism that helps to prevent mutated cells from replicating and therefore prevents tumor growth.

“What’s interesting is that even a single break transmits a global signal through the cell, halting cell division and growth,” Dr O’Shea said. “This response prevents replication so the cell doesn’t pass on a break.”

Drs O’Shea and Shah also found that, when it comes to defending against DNA viruses, the cell’s response system begins the same way—with MRN detecting breaks. But it never progresses to the global alarm signal in the case of the virus.

Typically, a common DNA virus enters the cell’s nucleus and turns on genes to replicate its own DNA. The cell detects the unauthorized replication, and the MRN complex grabs and selectively neutralizes viral DNA without triggering a global response that would arrest or kill the cell.

So the MRN response to the virus stays localized and only selectively prevents viral, but not cellular, replication.

When both threats to the genome are present, MRN will activate the massive response at the DNA break, and no MRN is left to respond to the virus. This means the virus is effectively ignored while the cell responds to the more massive alarm.

“The requirement of MRN for sensing both cellular and viral genome breaks has profound consequences,” Dr O’Shea said.

“When MRN is recruited to cellular DNA breaks, it can no longer sense and respond to incoming viral genomes. Thus, the act of responding to cellular genome breaks inactivates the host’s defenses to viral replication.”

Dr O’Shea said this may explain why people who have high levels of cellular DNA damage—such as cancer patients—are more susceptible to viral infections.

“Having damaged DNA compromises our cells’ ability to fight viral infection, while having healthy DNA boosts our cells’ ability to catch viral DNA,” Dr Shah said. “Our work implies that we may be able to engineer viruses that selectively kill cancer cells.”

The researchers aim to use this new knowledge to create viruses that are destroyed in normal cells but replicate specifically in cancer cells.

Unlike normal cells, cancer cells almost always have very high levels of DNA damage. In cancer cells, MRN is already so preoccupied with responding to DNA breaks that an engineered virus could sneak in undetected.

“Cancer cells, by definition, have high mutation rates and genomic instability even at the very earliest stages,” Dr O’Shea said. “So you could imagine building a virus that could destroy even the earliest lesions and be used as a prophylactic.” ![]()

Image by Eric Smith

Researchers say they have discovered critical details that explain how a cellular response system tells the difference between damage to the body’s own DNA and the foreign DNA of an invading virus.

The team believes this discovery could aid the development of new cancer-selective viral therapies, and it may help explain why aging, cancers, and other diseases

seem to open the door to viral infections.

“Our study reveals fundamental mechanisms that distinguish DNA breaks at cellular and viral genomes to trigger different responses that protect the host,” said Clodagh O’Shea, of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

“The findings may also explain why certain conditions like aging, cancer chemotherapy, and inflammation make us more susceptible to viral infection.”

Dr O’Shea and Govind Shah, PhD, also of the Salk Institute, reported these findings in Cell.

The pair described how a cluster of proteins known as the MRN complex detects DNA breaks and amplifies its response through histones.

MRN starts a domino effect, activating histones on surrounding chromosomes, which summons a cascade of additional proteins and results in a cell-wide, all-hands-on-deck alarm to help mend the DNA.

If the cell can’t fix the DNA break, it will induce apoptosis—a self-destruct mechanism that helps to prevent mutated cells from replicating and therefore prevents tumor growth.

“What’s interesting is that even a single break transmits a global signal through the cell, halting cell division and growth,” Dr O’Shea said. “This response prevents replication so the cell doesn’t pass on a break.”

Drs O’Shea and Shah also found that, when it comes to defending against DNA viruses, the cell’s response system begins the same way—with MRN detecting breaks. But it never progresses to the global alarm signal in the case of the virus.

Typically, a common DNA virus enters the cell’s nucleus and turns on genes to replicate its own DNA. The cell detects the unauthorized replication, and the MRN complex grabs and selectively neutralizes viral DNA without triggering a global response that would arrest or kill the cell.

So the MRN response to the virus stays localized and only selectively prevents viral, but not cellular, replication.

When both threats to the genome are present, MRN will activate the massive response at the DNA break, and no MRN is left to respond to the virus. This means the virus is effectively ignored while the cell responds to the more massive alarm.

“The requirement of MRN for sensing both cellular and viral genome breaks has profound consequences,” Dr O’Shea said.

“When MRN is recruited to cellular DNA breaks, it can no longer sense and respond to incoming viral genomes. Thus, the act of responding to cellular genome breaks inactivates the host’s defenses to viral replication.”

Dr O’Shea said this may explain why people who have high levels of cellular DNA damage—such as cancer patients—are more susceptible to viral infections.

“Having damaged DNA compromises our cells’ ability to fight viral infection, while having healthy DNA boosts our cells’ ability to catch viral DNA,” Dr Shah said. “Our work implies that we may be able to engineer viruses that selectively kill cancer cells.”

The researchers aim to use this new knowledge to create viruses that are destroyed in normal cells but replicate specifically in cancer cells.

Unlike normal cells, cancer cells almost always have very high levels of DNA damage. In cancer cells, MRN is already so preoccupied with responding to DNA breaks that an engineered virus could sneak in undetected.

“Cancer cells, by definition, have high mutation rates and genomic instability even at the very earliest stages,” Dr O’Shea said. “So you could imagine building a virus that could destroy even the earliest lesions and be used as a prophylactic.” ![]()

Image by Eric Smith

Researchers say they have discovered critical details that explain how a cellular response system tells the difference between damage to the body’s own DNA and the foreign DNA of an invading virus.

The team believes this discovery could aid the development of new cancer-selective viral therapies, and it may help explain why aging, cancers, and other diseases

seem to open the door to viral infections.

“Our study reveals fundamental mechanisms that distinguish DNA breaks at cellular and viral genomes to trigger different responses that protect the host,” said Clodagh O’Shea, of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

“The findings may also explain why certain conditions like aging, cancer chemotherapy, and inflammation make us more susceptible to viral infection.”

Dr O’Shea and Govind Shah, PhD, also of the Salk Institute, reported these findings in Cell.

The pair described how a cluster of proteins known as the MRN complex detects DNA breaks and amplifies its response through histones.

MRN starts a domino effect, activating histones on surrounding chromosomes, which summons a cascade of additional proteins and results in a cell-wide, all-hands-on-deck alarm to help mend the DNA.

If the cell can’t fix the DNA break, it will induce apoptosis—a self-destruct mechanism that helps to prevent mutated cells from replicating and therefore prevents tumor growth.

“What’s interesting is that even a single break transmits a global signal through the cell, halting cell division and growth,” Dr O’Shea said. “This response prevents replication so the cell doesn’t pass on a break.”

Drs O’Shea and Shah also found that, when it comes to defending against DNA viruses, the cell’s response system begins the same way—with MRN detecting breaks. But it never progresses to the global alarm signal in the case of the virus.

Typically, a common DNA virus enters the cell’s nucleus and turns on genes to replicate its own DNA. The cell detects the unauthorized replication, and the MRN complex grabs and selectively neutralizes viral DNA without triggering a global response that would arrest or kill the cell.

So the MRN response to the virus stays localized and only selectively prevents viral, but not cellular, replication.

When both threats to the genome are present, MRN will activate the massive response at the DNA break, and no MRN is left to respond to the virus. This means the virus is effectively ignored while the cell responds to the more massive alarm.

“The requirement of MRN for sensing both cellular and viral genome breaks has profound consequences,” Dr O’Shea said.

“When MRN is recruited to cellular DNA breaks, it can no longer sense and respond to incoming viral genomes. Thus, the act of responding to cellular genome breaks inactivates the host’s defenses to viral replication.”

Dr O’Shea said this may explain why people who have high levels of cellular DNA damage—such as cancer patients—are more susceptible to viral infections.

“Having damaged DNA compromises our cells’ ability to fight viral infection, while having healthy DNA boosts our cells’ ability to catch viral DNA,” Dr Shah said. “Our work implies that we may be able to engineer viruses that selectively kill cancer cells.”

The researchers aim to use this new knowledge to create viruses that are destroyed in normal cells but replicate specifically in cancer cells.

Unlike normal cells, cancer cells almost always have very high levels of DNA damage. In cancer cells, MRN is already so preoccupied with responding to DNA breaks that an engineered virus could sneak in undetected.

“Cancer cells, by definition, have high mutation rates and genomic instability even at the very earliest stages,” Dr O’Shea said. “So you could imagine building a virus that could destroy even the earliest lesions and be used as a prophylactic.” ![]()

Drugs don’t play well together in MF

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Simultaneous administration of lenalidomide and ruxolitinib is not feasible in patients with myelofibrosis (MF), according to research published in haematologica.

Investigators said administering the drugs together proved difficult. Most patients had to stop taking lenalidomide at some point, and many did not restart the drug.

In addition, the study did not meet the predetermined efficacy criteria and was therefore terminated early.

Still, the investigators noted that 17 of 31 patients did respond to treatment, and 10 patients were still taking both drugs at the time of analysis.

The team therefore believes a sequential rather than concomitant treatment approach might work with this combination or for other agents to be combined with ruxolitinib.

Srdan Verstovsek, MD, PhD, of the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, and his colleagues conducted this research. It was supported by Incyte Corporation (the company developing ruxolitinib) and MD Anderson.

The investigators initiated this study to determine if lenalidomide and ruxolitinib in combination would target distinct clinical and pathological manifestations of MF and prevent treatment-related decreases in blood counts.

They studied the combination in 31 patients with primary MF (n=15), post-polycythemia vera MF (n=12), or post-essential thrombocythemia MF (n=4). The patients’ median age was 66 (range, 37-82), and 21 had received prior treatments (range, 1-3).

The patients received ruxolitinib at 15 mg twice daily in continuous, 28-day cycles, plus 5 mg of lenalidomide once daily on days 1-21. The median follow-up was 28 months (range, 12-35+).

Dosing troubles

In all, 23 patients required dose interruptions of lenalidomide, with or without a dose decrease due to toxicity. Twenty of these interruptions occurred within the first 3 months of therapy, and 14 of the patients never restarted treatment with lenalidomide.

The reasons for dose interruption (or, ultimately, discontinuation) were low platelet count (n=8), low absolute neutrophil count (n=3), anemia (n=3), diarrhea (n=3), financial constraints (n=2), deep vein thrombosis (n=1), skin rash (n=1), transaminitis (n=1), and arthralgia/fever (n=1).

Conversely, 6 patients required an increased dose of ruxolitinib, 3 within the first 3 months. Doses were increased due to leukocytosis (n=2), suboptimal response (n=2), thrombocytosis (n=1), and progressive splenomegaly (n=1).

Discontinuation and early termination

At a median follow-up of 28 months, 25 patients (81%) were still alive, and 16 remained on study. Ten of these patients were taking both drugs, and 6 were taking ruxolitinib only.

For the 15 patients who came off the study, their reasons included concurrent disease (n=3), disease progression (n=2), myelosuppression (n=2), refractory disease (n=3), toxicities (n=2), persistent and severe lower-extremity cellulitis (n=1), non-compliance (n=1), and financial reasons (n=1).

The investigators noted that only 7 patients met the predetermined definition of efficacy—a response to combination treatment within 6 months of initiation without discontinuing either drug.

For the study to continue after the interim analysis, more than 10 patients would have to fulfill those criteria. As they did not, the study was terminated early.

Response

Seventeen patients (55%) achieved an IWG-MRT-defined response of clinical improvement in palpable spleen size. Seven patients had a 100% spleen reduction, and 10 had reduction of 50% or greater.

The median time to clinical improvement in spleen size was 1.8 months (range, 0.4-31), and the median duration of this response was 19 months (range, 3-32+). At last follow-up, 2 patients had lost their response.

One of the 17 spleen responders also achieved an IWG-MRT-defined clinical improvement in hemoglobin (increase of 2 g/dL or greater that was maintained for more than 8 weeks). The time to this response was 28 months, and the response lasted 6 months.

There were differences in response rate, response duration, time to response, and overall survival between patients who required dose interruptions and those who did not. However, none of these differences were statistically significant.

Toxicity

Grade 3/4 myelosuppression occurred in 16 patients, and there was 1 case of lower-extremity thrombosis. The most common non-hematologic adverse events (AEs) were diarrhea (n=8), nausea and vomiting (n=3), abdominal pain (n=3), and constipation (n=3).

Five patients had grade 3/4 non-hematologic AEs—diarrhea, edema, transaminitis, bilirubinemia, and acute kidney injury. Two patients discontinued treatment due to drug-related AEs—grade 2 persistent nausea and grade 3 diarrhea.

Three of the 6 deaths were documented (including 2 that occurred on-study). They were attributed to pneumonia, kidney failure, and possible stroke. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Simultaneous administration of lenalidomide and ruxolitinib is not feasible in patients with myelofibrosis (MF), according to research published in haematologica.

Investigators said administering the drugs together proved difficult. Most patients had to stop taking lenalidomide at some point, and many did not restart the drug.

In addition, the study did not meet the predetermined efficacy criteria and was therefore terminated early.

Still, the investigators noted that 17 of 31 patients did respond to treatment, and 10 patients were still taking both drugs at the time of analysis.

The team therefore believes a sequential rather than concomitant treatment approach might work with this combination or for other agents to be combined with ruxolitinib.

Srdan Verstovsek, MD, PhD, of the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, and his colleagues conducted this research. It was supported by Incyte Corporation (the company developing ruxolitinib) and MD Anderson.

The investigators initiated this study to determine if lenalidomide and ruxolitinib in combination would target distinct clinical and pathological manifestations of MF and prevent treatment-related decreases in blood counts.

They studied the combination in 31 patients with primary MF (n=15), post-polycythemia vera MF (n=12), or post-essential thrombocythemia MF (n=4). The patients’ median age was 66 (range, 37-82), and 21 had received prior treatments (range, 1-3).

The patients received ruxolitinib at 15 mg twice daily in continuous, 28-day cycles, plus 5 mg of lenalidomide once daily on days 1-21. The median follow-up was 28 months (range, 12-35+).

Dosing troubles

In all, 23 patients required dose interruptions of lenalidomide, with or without a dose decrease due to toxicity. Twenty of these interruptions occurred within the first 3 months of therapy, and 14 of the patients never restarted treatment with lenalidomide.

The reasons for dose interruption (or, ultimately, discontinuation) were low platelet count (n=8), low absolute neutrophil count (n=3), anemia (n=3), diarrhea (n=3), financial constraints (n=2), deep vein thrombosis (n=1), skin rash (n=1), transaminitis (n=1), and arthralgia/fever (n=1).

Conversely, 6 patients required an increased dose of ruxolitinib, 3 within the first 3 months. Doses were increased due to leukocytosis (n=2), suboptimal response (n=2), thrombocytosis (n=1), and progressive splenomegaly (n=1).

Discontinuation and early termination

At a median follow-up of 28 months, 25 patients (81%) were still alive, and 16 remained on study. Ten of these patients were taking both drugs, and 6 were taking ruxolitinib only.

For the 15 patients who came off the study, their reasons included concurrent disease (n=3), disease progression (n=2), myelosuppression (n=2), refractory disease (n=3), toxicities (n=2), persistent and severe lower-extremity cellulitis (n=1), non-compliance (n=1), and financial reasons (n=1).

The investigators noted that only 7 patients met the predetermined definition of efficacy—a response to combination treatment within 6 months of initiation without discontinuing either drug.

For the study to continue after the interim analysis, more than 10 patients would have to fulfill those criteria. As they did not, the study was terminated early.

Response

Seventeen patients (55%) achieved an IWG-MRT-defined response of clinical improvement in palpable spleen size. Seven patients had a 100% spleen reduction, and 10 had reduction of 50% or greater.

The median time to clinical improvement in spleen size was 1.8 months (range, 0.4-31), and the median duration of this response was 19 months (range, 3-32+). At last follow-up, 2 patients had lost their response.

One of the 17 spleen responders also achieved an IWG-MRT-defined clinical improvement in hemoglobin (increase of 2 g/dL or greater that was maintained for more than 8 weeks). The time to this response was 28 months, and the response lasted 6 months.

There were differences in response rate, response duration, time to response, and overall survival between patients who required dose interruptions and those who did not. However, none of these differences were statistically significant.

Toxicity

Grade 3/4 myelosuppression occurred in 16 patients, and there was 1 case of lower-extremity thrombosis. The most common non-hematologic adverse events (AEs) were diarrhea (n=8), nausea and vomiting (n=3), abdominal pain (n=3), and constipation (n=3).

Five patients had grade 3/4 non-hematologic AEs—diarrhea, edema, transaminitis, bilirubinemia, and acute kidney injury. Two patients discontinued treatment due to drug-related AEs—grade 2 persistent nausea and grade 3 diarrhea.

Three of the 6 deaths were documented (including 2 that occurred on-study). They were attributed to pneumonia, kidney failure, and possible stroke. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Simultaneous administration of lenalidomide and ruxolitinib is not feasible in patients with myelofibrosis (MF), according to research published in haematologica.

Investigators said administering the drugs together proved difficult. Most patients had to stop taking lenalidomide at some point, and many did not restart the drug.

In addition, the study did not meet the predetermined efficacy criteria and was therefore terminated early.

Still, the investigators noted that 17 of 31 patients did respond to treatment, and 10 patients were still taking both drugs at the time of analysis.

The team therefore believes a sequential rather than concomitant treatment approach might work with this combination or for other agents to be combined with ruxolitinib.

Srdan Verstovsek, MD, PhD, of the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, and his colleagues conducted this research. It was supported by Incyte Corporation (the company developing ruxolitinib) and MD Anderson.

The investigators initiated this study to determine if lenalidomide and ruxolitinib in combination would target distinct clinical and pathological manifestations of MF and prevent treatment-related decreases in blood counts.

They studied the combination in 31 patients with primary MF (n=15), post-polycythemia vera MF (n=12), or post-essential thrombocythemia MF (n=4). The patients’ median age was 66 (range, 37-82), and 21 had received prior treatments (range, 1-3).

The patients received ruxolitinib at 15 mg twice daily in continuous, 28-day cycles, plus 5 mg of lenalidomide once daily on days 1-21. The median follow-up was 28 months (range, 12-35+).

Dosing troubles

In all, 23 patients required dose interruptions of lenalidomide, with or without a dose decrease due to toxicity. Twenty of these interruptions occurred within the first 3 months of therapy, and 14 of the patients never restarted treatment with lenalidomide.

The reasons for dose interruption (or, ultimately, discontinuation) were low platelet count (n=8), low absolute neutrophil count (n=3), anemia (n=3), diarrhea (n=3), financial constraints (n=2), deep vein thrombosis (n=1), skin rash (n=1), transaminitis (n=1), and arthralgia/fever (n=1).

Conversely, 6 patients required an increased dose of ruxolitinib, 3 within the first 3 months. Doses were increased due to leukocytosis (n=2), suboptimal response (n=2), thrombocytosis (n=1), and progressive splenomegaly (n=1).

Discontinuation and early termination

At a median follow-up of 28 months, 25 patients (81%) were still alive, and 16 remained on study. Ten of these patients were taking both drugs, and 6 were taking ruxolitinib only.

For the 15 patients who came off the study, their reasons included concurrent disease (n=3), disease progression (n=2), myelosuppression (n=2), refractory disease (n=3), toxicities (n=2), persistent and severe lower-extremity cellulitis (n=1), non-compliance (n=1), and financial reasons (n=1).

The investigators noted that only 7 patients met the predetermined definition of efficacy—a response to combination treatment within 6 months of initiation without discontinuing either drug.

For the study to continue after the interim analysis, more than 10 patients would have to fulfill those criteria. As they did not, the study was terminated early.

Response

Seventeen patients (55%) achieved an IWG-MRT-defined response of clinical improvement in palpable spleen size. Seven patients had a 100% spleen reduction, and 10 had reduction of 50% or greater.

The median time to clinical improvement in spleen size was 1.8 months (range, 0.4-31), and the median duration of this response was 19 months (range, 3-32+). At last follow-up, 2 patients had lost their response.

One of the 17 spleen responders also achieved an IWG-MRT-defined clinical improvement in hemoglobin (increase of 2 g/dL or greater that was maintained for more than 8 weeks). The time to this response was 28 months, and the response lasted 6 months.

There were differences in response rate, response duration, time to response, and overall survival between patients who required dose interruptions and those who did not. However, none of these differences were statistically significant.

Toxicity

Grade 3/4 myelosuppression occurred in 16 patients, and there was 1 case of lower-extremity thrombosis. The most common non-hematologic adverse events (AEs) were diarrhea (n=8), nausea and vomiting (n=3), abdominal pain (n=3), and constipation (n=3).

Five patients had grade 3/4 non-hematologic AEs—diarrhea, edema, transaminitis, bilirubinemia, and acute kidney injury. Two patients discontinued treatment due to drug-related AEs—grade 2 persistent nausea and grade 3 diarrhea.

Three of the 6 deaths were documented (including 2 that occurred on-study). They were attributed to pneumonia, kidney failure, and possible stroke. ![]()

Database details driver mutations

Photo by Darren Baker

Scientists have created an online database of mutations that have been shown to drive cancers in preclinical or clinical research.

The database, called the Cancer Driver Log (CanDL), currently includes mutations in 62 genes, with hundreds of distinct variants across multiple cancers.

Sameek Roychowdhury, MD, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus, and his colleauges described CanDL in the Journal of Molecular Diagnostics.

“CanDL is a database of gene mutations that have been functionally characterized or have been targeted clinically or preclinically with approved or investigational agents,” Dr Roychowdhury explained.

“Currently, pathology laboratories that sequence tumor tissue must manually research the scientific literature for individual mutations to determine whether they are considered a driver or a passenger to facilitate clinical interpretation.”

“CanDL expedites this time-consuming process by placing key information about known and possible driver mutations that might be effective targets for drug development at their fingertips.”

CanDL entries can be searched by gene or amino acid variants, and they can be downloaded for custom analyses.

The database also includes a mechanism for users to contribute novel driver mutations in open collaboration with the Roychowdhury lab. The team plans to update the database quarterly. ![]()

Photo by Darren Baker

Scientists have created an online database of mutations that have been shown to drive cancers in preclinical or clinical research.

The database, called the Cancer Driver Log (CanDL), currently includes mutations in 62 genes, with hundreds of distinct variants across multiple cancers.

Sameek Roychowdhury, MD, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus, and his colleauges described CanDL in the Journal of Molecular Diagnostics.

“CanDL is a database of gene mutations that have been functionally characterized or have been targeted clinically or preclinically with approved or investigational agents,” Dr Roychowdhury explained.

“Currently, pathology laboratories that sequence tumor tissue must manually research the scientific literature for individual mutations to determine whether they are considered a driver or a passenger to facilitate clinical interpretation.”

“CanDL expedites this time-consuming process by placing key information about known and possible driver mutations that might be effective targets for drug development at their fingertips.”

CanDL entries can be searched by gene or amino acid variants, and they can be downloaded for custom analyses.

The database also includes a mechanism for users to contribute novel driver mutations in open collaboration with the Roychowdhury lab. The team plans to update the database quarterly. ![]()

Photo by Darren Baker

Scientists have created an online database of mutations that have been shown to drive cancers in preclinical or clinical research.

The database, called the Cancer Driver Log (CanDL), currently includes mutations in 62 genes, with hundreds of distinct variants across multiple cancers.

Sameek Roychowdhury, MD, PhD, of The Ohio State University in Columbus, and his colleauges described CanDL in the Journal of Molecular Diagnostics.

“CanDL is a database of gene mutations that have been functionally characterized or have been targeted clinically or preclinically with approved or investigational agents,” Dr Roychowdhury explained.

“Currently, pathology laboratories that sequence tumor tissue must manually research the scientific literature for individual mutations to determine whether they are considered a driver or a passenger to facilitate clinical interpretation.”

“CanDL expedites this time-consuming process by placing key information about known and possible driver mutations that might be effective targets for drug development at their fingertips.”

CanDL entries can be searched by gene or amino acid variants, and they can be downloaded for custom analyses.

The database also includes a mechanism for users to contribute novel driver mutations in open collaboration with the Roychowdhury lab. The team plans to update the database quarterly. ![]()

mAb produces ‘encouraging’ results in rel/ref MM

The anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab has demonstrated a “favorable safety profile” and “encouraging efficacy” in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to researchers.

Results of a phase 1/2 study suggested the drug was most effective at a dose of 16 mg/kg. At this dose, the overall response rate was 36%.

Most adverse events (AEs) were grade 1 or 2, although serious AEs did occur.

“As a single-agent therapy, daratumumab showed significant promise against difficult-to-treat disease in our patients with advanced myeloma who have few other therapeutic options,” said Paul G. Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Because it targets a key receptor and works through different mechanisms than other available agents, it clearly has merited comprehensive testing in larger clinical trials. Preliminary results from these studies have been very encouraging.”

Dr Richardson and his colleagues reported results of the phase 1/2 study in NEJM. The research was previously presented at the 18th Congress of the EHA in 2013. It was sponsored by Janssen Research and Development and Genmab.

Another phase 2 study of single-agent daratumumab in MM was recently presented at the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting.

Patients and treatment

The current study enrolled patients with relapsed MM or relapsed MM that was refractory to 2 or more prior lines of therapy. The study consisted of 2 parts.

In part 1 (n=30), researchers administered daratumumab in 10 different dosing cohorts at doses ranging from 0.005 to 24 mg/kg of body weight.

In part 2 (n=72), patients received 2 different doses of daratumumab on varying schedules. In schedules A (n=16), B (n=8), and C (n=6), patients received daratumumab at 8 mg/kg in 8 once-weekly infusions and then in twice-monthly infusions for 16 weeks.

In schedules D (n=20) and E (n=22), patients received daratumumab at 16 mg/kg, and, after the first infusion, they had a 3-week washout period to allow for the collection of pharmacokinetic data. They then received weekly treatment for 7 weeks, followed by twice-monthly treatment for 14 weeks.

Safety

There was no maximum tolerated dose identified in part 1 of the study. Infusion-related AEs occurred in 20 patients (63%), serious AEs occurred in 12 patients (37%), and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 5 patients (16%).

In part 2, 71% of patients had infusion-related AEs. The most common AEs among patients in both dosing cohorts (8 mg/kg and 16 mg/kg) were fatigue (42%), allergic rhinitis (31%), pyrexia (28%), diarrhea (21%), upper respiratory tract infection (21%), and dyspnea (19%). The most frequent hematologic AE was neutropenia (12%).

Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 53% of patients in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 26% in the 16 mg/kg cohort. Grade 3/4 AEs that were reported in 2 or more patients included pneumonia (n=5), thrombocytopenia (n=4), neutropenia (n=2), leukopenia (n=2), anemia (n=2), and hyperglycemia (n=2).

Serious AEs occurred in 40% of patients in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 33% in the 16 mg/kg cohort. The most frequent serious AEs were infection-related events.

Efficacy

In part 1, there were no responses among patients who received daratumumab at 2 mg/kg or less (n=18), but responses did occur in patients treated at doses of 4 mg/kg or higher (n=12).

There were 4 partial responses—1 in the 4 mg/kg group, 1 in the 16 mg/kg group, and 2 in the 24 mg/kg group. And there were 3 minimal responses—2 in the 4 mg/kg group and 1 in the 8 mg/kg group.

Three patients had stable disease—1 each in the 8 mg/kg, 16 mg/kg, and 24 mg/kg groups. One patient progressed (16 mg/kg), and 1 was not evaluable (8 mg/kg).

In part 2, the overall response rate was 10% in the 8 mg/kg cohort (3/30) and 36% (15/42) in the 16 mg/kg cohort.

There were 2 complete responses (16 mg/kg), 2 very good partial responses (16 mg/kg), 14 partial responses (3 in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 11 in the 16 mg/kg), and 10 minimal responses (6 in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 4 in the 16 mg/kg cohort).

Thirty-six patients had stable disease (14 in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 22 in the 16 mg/kg cohort). Six patients progressed (all in the 8 mg/kg cohort), and 2 patients were not evaluable (1 in each cohort).

The estimated median progression-free survival was 2.4 months in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 5.6 months in the 16 mg/kg cohort. The overall survival rate at 12 months was 77% in both cohorts. ![]()

The anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab has demonstrated a “favorable safety profile” and “encouraging efficacy” in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to researchers.

Results of a phase 1/2 study suggested the drug was most effective at a dose of 16 mg/kg. At this dose, the overall response rate was 36%.

Most adverse events (AEs) were grade 1 or 2, although serious AEs did occur.

“As a single-agent therapy, daratumumab showed significant promise against difficult-to-treat disease in our patients with advanced myeloma who have few other therapeutic options,” said Paul G. Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Because it targets a key receptor and works through different mechanisms than other available agents, it clearly has merited comprehensive testing in larger clinical trials. Preliminary results from these studies have been very encouraging.”

Dr Richardson and his colleagues reported results of the phase 1/2 study in NEJM. The research was previously presented at the 18th Congress of the EHA in 2013. It was sponsored by Janssen Research and Development and Genmab.

Another phase 2 study of single-agent daratumumab in MM was recently presented at the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting.

Patients and treatment

The current study enrolled patients with relapsed MM or relapsed MM that was refractory to 2 or more prior lines of therapy. The study consisted of 2 parts.

In part 1 (n=30), researchers administered daratumumab in 10 different dosing cohorts at doses ranging from 0.005 to 24 mg/kg of body weight.

In part 2 (n=72), patients received 2 different doses of daratumumab on varying schedules. In schedules A (n=16), B (n=8), and C (n=6), patients received daratumumab at 8 mg/kg in 8 once-weekly infusions and then in twice-monthly infusions for 16 weeks.

In schedules D (n=20) and E (n=22), patients received daratumumab at 16 mg/kg, and, after the first infusion, they had a 3-week washout period to allow for the collection of pharmacokinetic data. They then received weekly treatment for 7 weeks, followed by twice-monthly treatment for 14 weeks.

Safety

There was no maximum tolerated dose identified in part 1 of the study. Infusion-related AEs occurred in 20 patients (63%), serious AEs occurred in 12 patients (37%), and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 5 patients (16%).

In part 2, 71% of patients had infusion-related AEs. The most common AEs among patients in both dosing cohorts (8 mg/kg and 16 mg/kg) were fatigue (42%), allergic rhinitis (31%), pyrexia (28%), diarrhea (21%), upper respiratory tract infection (21%), and dyspnea (19%). The most frequent hematologic AE was neutropenia (12%).

Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 53% of patients in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 26% in the 16 mg/kg cohort. Grade 3/4 AEs that were reported in 2 or more patients included pneumonia (n=5), thrombocytopenia (n=4), neutropenia (n=2), leukopenia (n=2), anemia (n=2), and hyperglycemia (n=2).

Serious AEs occurred in 40% of patients in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 33% in the 16 mg/kg cohort. The most frequent serious AEs were infection-related events.

Efficacy

In part 1, there were no responses among patients who received daratumumab at 2 mg/kg or less (n=18), but responses did occur in patients treated at doses of 4 mg/kg or higher (n=12).

There were 4 partial responses—1 in the 4 mg/kg group, 1 in the 16 mg/kg group, and 2 in the 24 mg/kg group. And there were 3 minimal responses—2 in the 4 mg/kg group and 1 in the 8 mg/kg group.

Three patients had stable disease—1 each in the 8 mg/kg, 16 mg/kg, and 24 mg/kg groups. One patient progressed (16 mg/kg), and 1 was not evaluable (8 mg/kg).

In part 2, the overall response rate was 10% in the 8 mg/kg cohort (3/30) and 36% (15/42) in the 16 mg/kg cohort.

There were 2 complete responses (16 mg/kg), 2 very good partial responses (16 mg/kg), 14 partial responses (3 in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 11 in the 16 mg/kg), and 10 minimal responses (6 in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 4 in the 16 mg/kg cohort).

Thirty-six patients had stable disease (14 in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 22 in the 16 mg/kg cohort). Six patients progressed (all in the 8 mg/kg cohort), and 2 patients were not evaluable (1 in each cohort).

The estimated median progression-free survival was 2.4 months in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 5.6 months in the 16 mg/kg cohort. The overall survival rate at 12 months was 77% in both cohorts. ![]()

The anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab has demonstrated a “favorable safety profile” and “encouraging efficacy” in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to researchers.

Results of a phase 1/2 study suggested the drug was most effective at a dose of 16 mg/kg. At this dose, the overall response rate was 36%.

Most adverse events (AEs) were grade 1 or 2, although serious AEs did occur.

“As a single-agent therapy, daratumumab showed significant promise against difficult-to-treat disease in our patients with advanced myeloma who have few other therapeutic options,” said Paul G. Richardson, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Because it targets a key receptor and works through different mechanisms than other available agents, it clearly has merited comprehensive testing in larger clinical trials. Preliminary results from these studies have been very encouraging.”

Dr Richardson and his colleagues reported results of the phase 1/2 study in NEJM. The research was previously presented at the 18th Congress of the EHA in 2013. It was sponsored by Janssen Research and Development and Genmab.

Another phase 2 study of single-agent daratumumab in MM was recently presented at the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting.

Patients and treatment

The current study enrolled patients with relapsed MM or relapsed MM that was refractory to 2 or more prior lines of therapy. The study consisted of 2 parts.

In part 1 (n=30), researchers administered daratumumab in 10 different dosing cohorts at doses ranging from 0.005 to 24 mg/kg of body weight.

In part 2 (n=72), patients received 2 different doses of daratumumab on varying schedules. In schedules A (n=16), B (n=8), and C (n=6), patients received daratumumab at 8 mg/kg in 8 once-weekly infusions and then in twice-monthly infusions for 16 weeks.

In schedules D (n=20) and E (n=22), patients received daratumumab at 16 mg/kg, and, after the first infusion, they had a 3-week washout period to allow for the collection of pharmacokinetic data. They then received weekly treatment for 7 weeks, followed by twice-monthly treatment for 14 weeks.

Safety

There was no maximum tolerated dose identified in part 1 of the study. Infusion-related AEs occurred in 20 patients (63%), serious AEs occurred in 12 patients (37%), and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 5 patients (16%).

In part 2, 71% of patients had infusion-related AEs. The most common AEs among patients in both dosing cohorts (8 mg/kg and 16 mg/kg) were fatigue (42%), allergic rhinitis (31%), pyrexia (28%), diarrhea (21%), upper respiratory tract infection (21%), and dyspnea (19%). The most frequent hematologic AE was neutropenia (12%).

Grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 53% of patients in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 26% in the 16 mg/kg cohort. Grade 3/4 AEs that were reported in 2 or more patients included pneumonia (n=5), thrombocytopenia (n=4), neutropenia (n=2), leukopenia (n=2), anemia (n=2), and hyperglycemia (n=2).

Serious AEs occurred in 40% of patients in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 33% in the 16 mg/kg cohort. The most frequent serious AEs were infection-related events.

Efficacy

In part 1, there were no responses among patients who received daratumumab at 2 mg/kg or less (n=18), but responses did occur in patients treated at doses of 4 mg/kg or higher (n=12).

There were 4 partial responses—1 in the 4 mg/kg group, 1 in the 16 mg/kg group, and 2 in the 24 mg/kg group. And there were 3 minimal responses—2 in the 4 mg/kg group and 1 in the 8 mg/kg group.

Three patients had stable disease—1 each in the 8 mg/kg, 16 mg/kg, and 24 mg/kg groups. One patient progressed (16 mg/kg), and 1 was not evaluable (8 mg/kg).

In part 2, the overall response rate was 10% in the 8 mg/kg cohort (3/30) and 36% (15/42) in the 16 mg/kg cohort.

There were 2 complete responses (16 mg/kg), 2 very good partial responses (16 mg/kg), 14 partial responses (3 in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 11 in the 16 mg/kg), and 10 minimal responses (6 in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 4 in the 16 mg/kg cohort).

Thirty-six patients had stable disease (14 in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 22 in the 16 mg/kg cohort). Six patients progressed (all in the 8 mg/kg cohort), and 2 patients were not evaluable (1 in each cohort).

The estimated median progression-free survival was 2.4 months in the 8 mg/kg cohort and 5.6 months in the 16 mg/kg cohort. The overall survival rate at 12 months was 77% in both cohorts.

Team quantifies CAM use among seniors with cancer

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study suggests that seniors with cancer may be taking complementary or alternative medicines (CAMs) without their oncologists’ knowledge.

In this single-center study, 27% of senior cancer patients took CAMs at some point during their cancer care.

CAM usage was highest among patients ages 80 to 89, women, Caucasians, and patients with solid tumor malignancies.

Polypharmacy and certain comorbidities were linked to CAM use as well.

Researchers reported these findings in the Journal of Geriatric Oncology.

“Currently, few oncologists are aware of the alternative medicines their patients take,” said study author Ginah Nightingale, PharmD, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“Patients often fail to disclose the CAMs they take because they think they are safe, natural, nontoxic, and not relevant to their cancer care; because they think their doctor will disapprove; or because the doctor doesn’t specifically ask.”

To quantify CAM use in older cancer patients treated at their institution, Dr Nightingale and her colleagues surveyed patients who came to the Senior Adult Oncology Center at Thomas Jefferson University.

In a single visit, patients were seen by a medical oncologist, geriatrician, clinical pharmacist, social worker, and dietician. As part of this assessment, the patients brought in the contents of their medicine cabinets, and the medications they actively used were reviewed and recorded.

A total of 234 patients were included in the final analysis. Their mean age was 79.9 (range, 61–98). Most (87%) had solid tumor malignancies, were Caucasian (74%), and were female (64%).

In all, 26.5% of patients (n=62) had taken at least 1 CAM during their cancer care, with 19.2% taking 1 CAM, 6.4% taking 2, 0.4% taking 3, and 0.4% taking 4 or more CAMs. The highest number of CAMs taken was 10.

CAM usage was highest among patients ages 80 to 89, women, Caucasians, and patients with solid tumor malignancies.

Comorbidities significantly associated with CAM use were vision impairment (P=0.048) and urologic comorbidities (P=0.021). Polypharmacy (concurrent use of 5 or more medications) was significantly associated with CAM use as well (P=0.045).

Some of the commonly used CAMs were mega-dose vitamins or minerals, as well as treatments for macular degeneration, stomach probiotics, and joint health.

The researchers did not examine the potential adverse effects of these medications, but Dr Nightingale said some are known to have a biochemical effect on the body and other drugs.

“It is very important to do a comprehensive screen of all of the medications that older cancer patients take, including CAMs,” she added. “Clear and transparent documentation of CAM use should be recorded in the patient’s medical record. This documentation should indicate that patient-specific communication and/or education was provided so that shared and informed decisions by the patient can be made regarding the continued use of these medications.”

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study suggests that seniors with cancer may be taking complementary or alternative medicines (CAMs) without their oncologists’ knowledge.

In this single-center study, 27% of senior cancer patients took CAMs at some point during their cancer care.

CAM usage was highest among patients ages 80 to 89, women, Caucasians, and patients with solid tumor malignancies.

Polypharmacy and certain comorbidities were linked to CAM use as well.

Researchers reported these findings in the Journal of Geriatric Oncology.

“Currently, few oncologists are aware of the alternative medicines their patients take,” said study author Ginah Nightingale, PharmD, of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

“Patients often fail to disclose the CAMs they take because they think they are safe, natural, nontoxic, and not relevant to their cancer care; because they think their doctor will disapprove; or because the doctor doesn’t specifically ask.”