User login

Study reveals approaches to aid, prevent apoptosis

apoptosis in cancer cells

Scientists say they have gained new insight into the role Bax plays in apoptosis.

The Bax protein is known to be a key regulator of apoptosis, mediating the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol via oligomerization in the outer mitochondrial membrane before pore formation.

But the exact mechanism of Bax assembly was previously unclear.

Now, research published in Nature Communications has provided some clarity.

Katia Cosentino, PhD, of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research, examining how the mitochondrial membrane becomes permeable.

The team’s experiments on artificial membrane systems showed that Bax is initially inserted into the membrane as a single molecule.

Once inserted, one Bax molecule will join up with a second Bax molecule to form a stable complex, the Bax dimers. From these dimers, larger complexes are formed.

“Surprisingly, Bax complexes have no standard size, but we observed a mixture of different-sized Bax species, and these species are mostly based on dimer units,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues noted that these Bax complexes form the pores through which cytochrome c exits the mitochondrial membrane.

But the process of pore formation is finely controlled by other proteins. Some (such as cBid) enable the assembly of Bax elements, while others (such as Bcl-xL) induce their dismantling.

“The differing size of the Bax complexes in the pore formation is likely part of the reason why earlier investigations on pore formation conveyed contradictory results,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues believe that, based on these findings, they can make some initial recommendations for medical intervention in the apoptotic process.

They think that, to promote apoptosis, it should be enough to initiate the first step of activating Bax proteins because the subsequent steps of self-organization will then happen automatically.

Conversely, the team’s findings suggest apoptosis can be prevented when drugs force the dismantling of the Bax dimers into their individual elements. ![]()

apoptosis in cancer cells

Scientists say they have gained new insight into the role Bax plays in apoptosis.

The Bax protein is known to be a key regulator of apoptosis, mediating the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol via oligomerization in the outer mitochondrial membrane before pore formation.

But the exact mechanism of Bax assembly was previously unclear.

Now, research published in Nature Communications has provided some clarity.

Katia Cosentino, PhD, of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research, examining how the mitochondrial membrane becomes permeable.

The team’s experiments on artificial membrane systems showed that Bax is initially inserted into the membrane as a single molecule.

Once inserted, one Bax molecule will join up with a second Bax molecule to form a stable complex, the Bax dimers. From these dimers, larger complexes are formed.

“Surprisingly, Bax complexes have no standard size, but we observed a mixture of different-sized Bax species, and these species are mostly based on dimer units,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues noted that these Bax complexes form the pores through which cytochrome c exits the mitochondrial membrane.

But the process of pore formation is finely controlled by other proteins. Some (such as cBid) enable the assembly of Bax elements, while others (such as Bcl-xL) induce their dismantling.

“The differing size of the Bax complexes in the pore formation is likely part of the reason why earlier investigations on pore formation conveyed contradictory results,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues believe that, based on these findings, they can make some initial recommendations for medical intervention in the apoptotic process.

They think that, to promote apoptosis, it should be enough to initiate the first step of activating Bax proteins because the subsequent steps of self-organization will then happen automatically.

Conversely, the team’s findings suggest apoptosis can be prevented when drugs force the dismantling of the Bax dimers into their individual elements. ![]()

apoptosis in cancer cells

Scientists say they have gained new insight into the role Bax plays in apoptosis.

The Bax protein is known to be a key regulator of apoptosis, mediating the release of cytochrome c to the cytosol via oligomerization in the outer mitochondrial membrane before pore formation.

But the exact mechanism of Bax assembly was previously unclear.

Now, research published in Nature Communications has provided some clarity.

Katia Cosentino, PhD, of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, Germany, and her colleagues conducted this research, examining how the mitochondrial membrane becomes permeable.

The team’s experiments on artificial membrane systems showed that Bax is initially inserted into the membrane as a single molecule.

Once inserted, one Bax molecule will join up with a second Bax molecule to form a stable complex, the Bax dimers. From these dimers, larger complexes are formed.

“Surprisingly, Bax complexes have no standard size, but we observed a mixture of different-sized Bax species, and these species are mostly based on dimer units,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues noted that these Bax complexes form the pores through which cytochrome c exits the mitochondrial membrane.

But the process of pore formation is finely controlled by other proteins. Some (such as cBid) enable the assembly of Bax elements, while others (such as Bcl-xL) induce their dismantling.

“The differing size of the Bax complexes in the pore formation is likely part of the reason why earlier investigations on pore formation conveyed contradictory results,” Dr Cosentino said.

She and her colleagues believe that, based on these findings, they can make some initial recommendations for medical intervention in the apoptotic process.

They think that, to promote apoptosis, it should be enough to initiate the first step of activating Bax proteins because the subsequent steps of self-organization will then happen automatically.

Conversely, the team’s findings suggest apoptosis can be prevented when drugs force the dismantling of the Bax dimers into their individual elements. ![]()

New proteasome inhibitor exhibits activity against MM

A novel, cancer-selective proteasome inhibitor has shown early promise for treating multiple myeloma (MM) and breast cancer, according to researchers.

The drug, known as VR23, is a quinoline-sulfonyl hybrid proteasome inhibitor.

In preclinical experiments, VR23 preferentially targeted MM cells and breast cancer cells, demonstrated synergy with bortezomib or paclitaxel, and shrank both MM and breast cancer tumors in mice.

Hoyun Lee, PhD, of the Advanced Medical Research Institute of Canada (AMRIC) in Sudbury, Ontario, and his colleagues described these experiments in Cancer Research.

The team noted that VR23 is structurally distinct from other known proteasome inhibitors, and it “potently inhibits” the activities of trypsin-like proteasomes, chymotrypsin-like proteasomes, and caspase-like proteasomes.

In several experiments, VR23 proved active against breast cancer.

In experiments with MM cell lines, VR23 exhibited activity as a single agent and demonstrated synergy with bortezomib. VR23 proved more effective against bortezomib-resistant cells than bortezomib-naïve cells.

When the researchers introduced treatments to bortezomib-naïve RPMI-8226 cells, they found the cell growth rate was 79.3% with VR23, 12.5% with bortezomib, and 1.6% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant RPMI-8226 cells, the cell growth rate was 47% with VR23, 109.7% with bortezomib, and -8.6% with both drugs.

In KAS6/1 cells, the cell growth rate was 65% with VR23, 92% with bortezomib, and 26.5% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant ANBL6 cells, the cell growth rate was 94% with VR23, 102.9% with bortezomib, and 48.9% with both drugs.

The researchers also tested VR23 in mice engrafted with RPMI-8226 MM cells. At 24 days after treatment, the tumor volume for VR23-treated mice was 19.1% that of placebo-treated mice.

The team noted that VR23 selectively killed cancer cells via apoptosis. Cancer cells exposed to the drug underwent an abnormal centrosome amplification cycle caused by the accumulation of ubiquitinated cyclin E.

Dr Lee and his colleagues are now planning to work with the US National Cancer Institute to test VR23 in additional cancers. The team is hoping to progress to clinical trials with the drug in the next 3 years.

AMRIC has applied for international intellectual property protection for VR23 and licensed commercial rights to Ramsey Lake Pharmaceutical Corporation (www.ramseylakepharma.com), an operation of AMRIC. ![]()

A novel, cancer-selective proteasome inhibitor has shown early promise for treating multiple myeloma (MM) and breast cancer, according to researchers.

The drug, known as VR23, is a quinoline-sulfonyl hybrid proteasome inhibitor.

In preclinical experiments, VR23 preferentially targeted MM cells and breast cancer cells, demonstrated synergy with bortezomib or paclitaxel, and shrank both MM and breast cancer tumors in mice.

Hoyun Lee, PhD, of the Advanced Medical Research Institute of Canada (AMRIC) in Sudbury, Ontario, and his colleagues described these experiments in Cancer Research.

The team noted that VR23 is structurally distinct from other known proteasome inhibitors, and it “potently inhibits” the activities of trypsin-like proteasomes, chymotrypsin-like proteasomes, and caspase-like proteasomes.

In several experiments, VR23 proved active against breast cancer.

In experiments with MM cell lines, VR23 exhibited activity as a single agent and demonstrated synergy with bortezomib. VR23 proved more effective against bortezomib-resistant cells than bortezomib-naïve cells.

When the researchers introduced treatments to bortezomib-naïve RPMI-8226 cells, they found the cell growth rate was 79.3% with VR23, 12.5% with bortezomib, and 1.6% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant RPMI-8226 cells, the cell growth rate was 47% with VR23, 109.7% with bortezomib, and -8.6% with both drugs.

In KAS6/1 cells, the cell growth rate was 65% with VR23, 92% with bortezomib, and 26.5% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant ANBL6 cells, the cell growth rate was 94% with VR23, 102.9% with bortezomib, and 48.9% with both drugs.

The researchers also tested VR23 in mice engrafted with RPMI-8226 MM cells. At 24 days after treatment, the tumor volume for VR23-treated mice was 19.1% that of placebo-treated mice.

The team noted that VR23 selectively killed cancer cells via apoptosis. Cancer cells exposed to the drug underwent an abnormal centrosome amplification cycle caused by the accumulation of ubiquitinated cyclin E.

Dr Lee and his colleagues are now planning to work with the US National Cancer Institute to test VR23 in additional cancers. The team is hoping to progress to clinical trials with the drug in the next 3 years.

AMRIC has applied for international intellectual property protection for VR23 and licensed commercial rights to Ramsey Lake Pharmaceutical Corporation (www.ramseylakepharma.com), an operation of AMRIC. ![]()

A novel, cancer-selective proteasome inhibitor has shown early promise for treating multiple myeloma (MM) and breast cancer, according to researchers.

The drug, known as VR23, is a quinoline-sulfonyl hybrid proteasome inhibitor.

In preclinical experiments, VR23 preferentially targeted MM cells and breast cancer cells, demonstrated synergy with bortezomib or paclitaxel, and shrank both MM and breast cancer tumors in mice.

Hoyun Lee, PhD, of the Advanced Medical Research Institute of Canada (AMRIC) in Sudbury, Ontario, and his colleagues described these experiments in Cancer Research.

The team noted that VR23 is structurally distinct from other known proteasome inhibitors, and it “potently inhibits” the activities of trypsin-like proteasomes, chymotrypsin-like proteasomes, and caspase-like proteasomes.

In several experiments, VR23 proved active against breast cancer.

In experiments with MM cell lines, VR23 exhibited activity as a single agent and demonstrated synergy with bortezomib. VR23 proved more effective against bortezomib-resistant cells than bortezomib-naïve cells.

When the researchers introduced treatments to bortezomib-naïve RPMI-8226 cells, they found the cell growth rate was 79.3% with VR23, 12.5% with bortezomib, and 1.6% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant RPMI-8226 cells, the cell growth rate was 47% with VR23, 109.7% with bortezomib, and -8.6% with both drugs.

In KAS6/1 cells, the cell growth rate was 65% with VR23, 92% with bortezomib, and 26.5% with both drugs. In bortezomib-resistant ANBL6 cells, the cell growth rate was 94% with VR23, 102.9% with bortezomib, and 48.9% with both drugs.

The researchers also tested VR23 in mice engrafted with RPMI-8226 MM cells. At 24 days after treatment, the tumor volume for VR23-treated mice was 19.1% that of placebo-treated mice.

The team noted that VR23 selectively killed cancer cells via apoptosis. Cancer cells exposed to the drug underwent an abnormal centrosome amplification cycle caused by the accumulation of ubiquitinated cyclin E.

Dr Lee and his colleagues are now planning to work with the US National Cancer Institute to test VR23 in additional cancers. The team is hoping to progress to clinical trials with the drug in the next 3 years.

AMRIC has applied for international intellectual property protection for VR23 and licensed commercial rights to Ramsey Lake Pharmaceutical Corporation (www.ramseylakepharma.com), an operation of AMRIC. ![]()

FDA expands use of eltrombopag

Photo courtesy of GSK

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an expanded use for eltrombopag (Promacta) to include children 1 year of age and older with chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) who have had an insufficient response to corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, or splenectomy.

The updated label also includes a new oral suspension formulation of eltrombopag designed for younger children who may not be able to swallow tablets.

Eltrombopag was previously approved by the FDA in a tablet formulation in June 2015 for ITP patients ages 6 and older and in 2008 for use in adults with ITP.

The label expansion of eltrombopag was based on data from 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled trials—the phase 2 PETIT trial and the phase 3 PETIT2 trial.

PETIT trials: Efficacy

The PETIT trial included 67 ITP patients stratified by age cohort (12-17 years, 6-11 years, and 1-5 years). They were randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 7 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects achieving platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher at least once between days 8 and 43 of the randomized period of the study.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—62.2%—compared to 31.8% in the placebo arm (P=0.011).

The PETIT2 trial enrolled 92 patients with chronic ITP who were randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 13 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects who achieved platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher for at least 6 out of 8 weeks, between weeks 5 and 12 of the randomized period.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—41.3%—compared to 3.4% of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

PETIT trials: Safety

For both trials, there were 107 eltrombopag-treated patients evaluable for safety.

The most common adverse events that occurred more frequently in the eltrombopag arms than the placebo arms were upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, cough, diarrhea, pyrexia, rhinitis, abdominal pain, oropharyngeal pain, toothache, increased ALT or AST, rash, and rhinorrhea.

Serious adverse events were reported in 8% of patients during the randomized part of both trials, although no serious adverse event occurred in more than 1 patient (1%).

An ALT elevation of at least 3 times the upper limit of normal occurred in 5% of eltrombopag-treated patients. Of those patients, 2% had ALT increases of at least 5 times the upper limit of normal.

There were no deaths or thromboembolic events during either study.

Prescribing information

The recommended dose and schedule of eltrombopag for pediatric patients age 6 and older is 50 mg daily or 25 mg daily of the tablet formulation for patients with East Asian ancestry. The recommended dose for all patients age 1 to 5 years is 25 mg daily of the powder for oral suspension formulation.

Eltrombopag is marketed as Promacta in the US and Revolade in most other countries. For more information on the drug, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Photo courtesy of GSK

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an expanded use for eltrombopag (Promacta) to include children 1 year of age and older with chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) who have had an insufficient response to corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, or splenectomy.

The updated label also includes a new oral suspension formulation of eltrombopag designed for younger children who may not be able to swallow tablets.

Eltrombopag was previously approved by the FDA in a tablet formulation in June 2015 for ITP patients ages 6 and older and in 2008 for use in adults with ITP.

The label expansion of eltrombopag was based on data from 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled trials—the phase 2 PETIT trial and the phase 3 PETIT2 trial.

PETIT trials: Efficacy

The PETIT trial included 67 ITP patients stratified by age cohort (12-17 years, 6-11 years, and 1-5 years). They were randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 7 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects achieving platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher at least once between days 8 and 43 of the randomized period of the study.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—62.2%—compared to 31.8% in the placebo arm (P=0.011).

The PETIT2 trial enrolled 92 patients with chronic ITP who were randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 13 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects who achieved platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher for at least 6 out of 8 weeks, between weeks 5 and 12 of the randomized period.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—41.3%—compared to 3.4% of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

PETIT trials: Safety

For both trials, there were 107 eltrombopag-treated patients evaluable for safety.

The most common adverse events that occurred more frequently in the eltrombopag arms than the placebo arms were upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, cough, diarrhea, pyrexia, rhinitis, abdominal pain, oropharyngeal pain, toothache, increased ALT or AST, rash, and rhinorrhea.

Serious adverse events were reported in 8% of patients during the randomized part of both trials, although no serious adverse event occurred in more than 1 patient (1%).

An ALT elevation of at least 3 times the upper limit of normal occurred in 5% of eltrombopag-treated patients. Of those patients, 2% had ALT increases of at least 5 times the upper limit of normal.

There were no deaths or thromboembolic events during either study.

Prescribing information

The recommended dose and schedule of eltrombopag for pediatric patients age 6 and older is 50 mg daily or 25 mg daily of the tablet formulation for patients with East Asian ancestry. The recommended dose for all patients age 1 to 5 years is 25 mg daily of the powder for oral suspension formulation.

Eltrombopag is marketed as Promacta in the US and Revolade in most other countries. For more information on the drug, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

Photo courtesy of GSK

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an expanded use for eltrombopag (Promacta) to include children 1 year of age and older with chronic immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) who have had an insufficient response to corticosteroids, immunoglobulins, or splenectomy.

The updated label also includes a new oral suspension formulation of eltrombopag designed for younger children who may not be able to swallow tablets.

Eltrombopag was previously approved by the FDA in a tablet formulation in June 2015 for ITP patients ages 6 and older and in 2008 for use in adults with ITP.

The label expansion of eltrombopag was based on data from 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled trials—the phase 2 PETIT trial and the phase 3 PETIT2 trial.

PETIT trials: Efficacy

The PETIT trial included 67 ITP patients stratified by age cohort (12-17 years, 6-11 years, and 1-5 years). They were randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 7 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects achieving platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher at least once between days 8 and 43 of the randomized period of the study.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—62.2%—compared to 31.8% in the placebo arm (P=0.011).

The PETIT2 trial enrolled 92 patients with chronic ITP who were randomized (2:1) to receive eltrombopag or placebo for 13 weeks. The eltrombopag dose was titrated to a target platelet count of 50-200 x 109/L.

The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of subjects who achieved platelet counts of 50 x 109/L or higher for at least 6 out of 8 weeks, between weeks 5 and 12 of the randomized period.

Significantly more patients in the eltrombopag arm met this endpoint—41.3%—compared to 3.4% of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

PETIT trials: Safety

For both trials, there were 107 eltrombopag-treated patients evaluable for safety.

The most common adverse events that occurred more frequently in the eltrombopag arms than the placebo arms were upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, cough, diarrhea, pyrexia, rhinitis, abdominal pain, oropharyngeal pain, toothache, increased ALT or AST, rash, and rhinorrhea.

Serious adverse events were reported in 8% of patients during the randomized part of both trials, although no serious adverse event occurred in more than 1 patient (1%).

An ALT elevation of at least 3 times the upper limit of normal occurred in 5% of eltrombopag-treated patients. Of those patients, 2% had ALT increases of at least 5 times the upper limit of normal.

There were no deaths or thromboembolic events during either study.

Prescribing information

The recommended dose and schedule of eltrombopag for pediatric patients age 6 and older is 50 mg daily or 25 mg daily of the tablet formulation for patients with East Asian ancestry. The recommended dose for all patients age 1 to 5 years is 25 mg daily of the powder for oral suspension formulation.

Eltrombopag is marketed as Promacta in the US and Revolade in most other countries. For more information on the drug, see the full prescribing information. ![]()

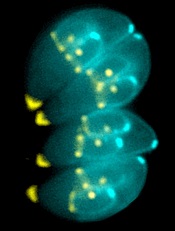

Enzyme may be target for malaria, toxoplasmosis

Image by Ke Hu & John Murray

Researchers say they have determined the structure of an enzyme that is vital to the infectious behavior of the parasites that cause toxoplasmosis and malaria.

And this has revealed a potentially druggable target that could prevent the parasites from entering and exiting host cells.

Sebastian Lourido, PhD, of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues described this work in PNAS.

The researchers noted that the toxoplasmosis-causing parasite Toxoplasma gondii is closely related to the malaria-causing Plasmodium parasites. So research on T gondii can provide insights into Plasmodium’s inner workings.

For this study, Dr Lourido and his colleagues wanted to learn more about calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), enzymes that are needed for T gondii and related parasites to invade and exit host cells, move, and reproduce.

To investigate CDPKs, the team used single-domain antibody fragments derived from alpacas. Unlike humans, whose antibodies have a heavy chain and a light chain, alpacas create heavy-chain-only antibodies, which can be engineered into even smaller antibody fragments known as nanobodies.

Alpaca nanobodies have a unique shape that allows them to reach into a protein’s nooks and crannies, which are inaccessible to conventional antibodies.

The researchers identified a nanobody against the T gondii enzyme CDPK1 that binds the kinase’s regulatory domain and revealed a previously unappreciated feature of its activation.

The nanobody, called 1B7, stabilizes CDPK1 in a conformation that allowed the researchers to determine the kinase’s structure and describe the nanobody’s interaction with the molecule.

With the structure in hand, the team created long-timescale molecular dynamics simulations of the enzyme, to model the events leading to kinase inactivation.

Structural homology between CDPKs and the calmodulin-dependent kinases (CaMKs) found in humans led to earlier assumptions that both types of enzymes are activated in a similar fashion. But this new work shows otherwise.

A CaMK is activated when a wedge holding it in an inactive state is knocked away. In contrast, Dr Lourido likened a CDPK’s active conformation to a broken arm that must be splinted in two places to maintain its integrity.

When the rigid splint is removed, the kinase loses its structural ability to function. By blocking CDPK1’s regulatory domain, the 1B7 nanobody inhibits the kinase by preventing the enzyme’s “splint” from attaching.

“This work reveals something interesting about this class of enzymes,” Dr Lourido said. “It’s the first time a calcium-regulated kinase has been shown to be activated in this manner. The principle that we identify is really important. We’ve found a new vulnerability within an enzyme that we know is extremely important to this class of parasites, including Plasmodium . . . , and is absent from humans.”

Because humans lack similar kinases, drugs that target CDPKs would not affect host cells.

“The location where 1B7 binds to CDPK1 is a new drug target that people had not considered before,” said study author Jessica Ingram, PhD, also of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research.

“We’d like to do some drug screens in the presence of the nanobody to see if we can find small molecules that bind in the same way. We could also look at other nanobodies against other kinases to see if this is applicable to other parasites and systems.” ![]()

Image by Ke Hu & John Murray

Researchers say they have determined the structure of an enzyme that is vital to the infectious behavior of the parasites that cause toxoplasmosis and malaria.

And this has revealed a potentially druggable target that could prevent the parasites from entering and exiting host cells.

Sebastian Lourido, PhD, of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues described this work in PNAS.

The researchers noted that the toxoplasmosis-causing parasite Toxoplasma gondii is closely related to the malaria-causing Plasmodium parasites. So research on T gondii can provide insights into Plasmodium’s inner workings.

For this study, Dr Lourido and his colleagues wanted to learn more about calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), enzymes that are needed for T gondii and related parasites to invade and exit host cells, move, and reproduce.

To investigate CDPKs, the team used single-domain antibody fragments derived from alpacas. Unlike humans, whose antibodies have a heavy chain and a light chain, alpacas create heavy-chain-only antibodies, which can be engineered into even smaller antibody fragments known as nanobodies.

Alpaca nanobodies have a unique shape that allows them to reach into a protein’s nooks and crannies, which are inaccessible to conventional antibodies.

The researchers identified a nanobody against the T gondii enzyme CDPK1 that binds the kinase’s regulatory domain and revealed a previously unappreciated feature of its activation.

The nanobody, called 1B7, stabilizes CDPK1 in a conformation that allowed the researchers to determine the kinase’s structure and describe the nanobody’s interaction with the molecule.

With the structure in hand, the team created long-timescale molecular dynamics simulations of the enzyme, to model the events leading to kinase inactivation.

Structural homology between CDPKs and the calmodulin-dependent kinases (CaMKs) found in humans led to earlier assumptions that both types of enzymes are activated in a similar fashion. But this new work shows otherwise.

A CaMK is activated when a wedge holding it in an inactive state is knocked away. In contrast, Dr Lourido likened a CDPK’s active conformation to a broken arm that must be splinted in two places to maintain its integrity.

When the rigid splint is removed, the kinase loses its structural ability to function. By blocking CDPK1’s regulatory domain, the 1B7 nanobody inhibits the kinase by preventing the enzyme’s “splint” from attaching.

“This work reveals something interesting about this class of enzymes,” Dr Lourido said. “It’s the first time a calcium-regulated kinase has been shown to be activated in this manner. The principle that we identify is really important. We’ve found a new vulnerability within an enzyme that we know is extremely important to this class of parasites, including Plasmodium . . . , and is absent from humans.”

Because humans lack similar kinases, drugs that target CDPKs would not affect host cells.

“The location where 1B7 binds to CDPK1 is a new drug target that people had not considered before,” said study author Jessica Ingram, PhD, also of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research.

“We’d like to do some drug screens in the presence of the nanobody to see if we can find small molecules that bind in the same way. We could also look at other nanobodies against other kinases to see if this is applicable to other parasites and systems.” ![]()

Image by Ke Hu & John Murray

Researchers say they have determined the structure of an enzyme that is vital to the infectious behavior of the parasites that cause toxoplasmosis and malaria.

And this has revealed a potentially druggable target that could prevent the parasites from entering and exiting host cells.

Sebastian Lourido, PhD, of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues described this work in PNAS.

The researchers noted that the toxoplasmosis-causing parasite Toxoplasma gondii is closely related to the malaria-causing Plasmodium parasites. So research on T gondii can provide insights into Plasmodium’s inner workings.

For this study, Dr Lourido and his colleagues wanted to learn more about calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), enzymes that are needed for T gondii and related parasites to invade and exit host cells, move, and reproduce.

To investigate CDPKs, the team used single-domain antibody fragments derived from alpacas. Unlike humans, whose antibodies have a heavy chain and a light chain, alpacas create heavy-chain-only antibodies, which can be engineered into even smaller antibody fragments known as nanobodies.

Alpaca nanobodies have a unique shape that allows them to reach into a protein’s nooks and crannies, which are inaccessible to conventional antibodies.

The researchers identified a nanobody against the T gondii enzyme CDPK1 that binds the kinase’s regulatory domain and revealed a previously unappreciated feature of its activation.

The nanobody, called 1B7, stabilizes CDPK1 in a conformation that allowed the researchers to determine the kinase’s structure and describe the nanobody’s interaction with the molecule.

With the structure in hand, the team created long-timescale molecular dynamics simulations of the enzyme, to model the events leading to kinase inactivation.

Structural homology between CDPKs and the calmodulin-dependent kinases (CaMKs) found in humans led to earlier assumptions that both types of enzymes are activated in a similar fashion. But this new work shows otherwise.

A CaMK is activated when a wedge holding it in an inactive state is knocked away. In contrast, Dr Lourido likened a CDPK’s active conformation to a broken arm that must be splinted in two places to maintain its integrity.

When the rigid splint is removed, the kinase loses its structural ability to function. By blocking CDPK1’s regulatory domain, the 1B7 nanobody inhibits the kinase by preventing the enzyme’s “splint” from attaching.

“This work reveals something interesting about this class of enzymes,” Dr Lourido said. “It’s the first time a calcium-regulated kinase has been shown to be activated in this manner. The principle that we identify is really important. We’ve found a new vulnerability within an enzyme that we know is extremely important to this class of parasites, including Plasmodium . . . , and is absent from humans.”

Because humans lack similar kinases, drugs that target CDPKs would not affect host cells.

“The location where 1B7 binds to CDPK1 is a new drug target that people had not considered before,” said study author Jessica Ingram, PhD, also of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research.

“We’d like to do some drug screens in the presence of the nanobody to see if we can find small molecules that bind in the same way. We could also look at other nanobodies against other kinases to see if this is applicable to other parasites and systems.” ![]()

Drug gets orphan designation for CDI

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to SER-109 for the prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in adults.

SER-109 is a microbiome therapeutic designed to treat recurrent CDI by correcting dysbiosis of the human microbiome.

In a single dose of 4 capsules, SER-109 re-introduces an ecology of purified bacterial spores that should restore the microbiome to a healthy state, allowing it to carry out key biological functions, including resisting Clostridium difficile.

“SER-109 is intended to re-introduce essential bacteria that restore the body’s natural resistance to CDI by re-establishing the ecology of the colonic microbiome,” explained Roger Pomerantz, MD, of Seres Therapeutics, Inc., the company developing SER-109.

“Because we’re focused on treating the underlying cause of the disease, we believe we have the potential to break the cycle of recurrent CDI and have a significant impact for patients.”

SER-109 is currently being investigated in a phase 2 trial. In addition to orphan designation, SER-109 has breakthrough designation from the FDA.

Trials of SER-109

Researchers reported phase 1/2 results with SER-109 at the 2014 Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The study had 2 cohorts containing 15 patients each. Patients were between 18 and 90 years old, had 3 or more laboratory-confirmed CDI episodes over 1 year, had a life expectancy greater than 3 months, and were able to give informed consent.

Patients in cohort 1 received a mean SER-109 dose of 1.5 x 109 spores, and those in cohort 2 received a mean dose of 1 x 108 spores. SER-109 was deemed effective if patients did not have a CDI recurrence in the 8-week period after they received SER-109.

In cohort 1, 87% of patients (13/15) achieved the efficacy endpoint. Two patients had transient, self-limited diarrhea with a positive C difficile test, but both reached the week 8 endpoint without needing antibiotic therapy for CDI. Thus, in cohort 1, the clinical cure rate was 100%.

In cohort 2, 93% of patients (14/15) reached the 8-week endpoint CDI-free. One patient failed per protocol.

The researchers said there were no drug-related serious adverse events in this trial.

Seres Therapeutics is currently conducting a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study (ECOSPOR) to assess the efficacy and safety of SER-109 in preventing recurrent CDI. The company expects results from this study to be available mid-2016.

About orphan and breakthrough designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

Orphan designation provides the sponsor of a drug with various development incentives, including opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, and 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved.

The FDA’s breakthrough therapy designation is intended to expedite the development and review of a drug candidate intended to treat a serious or life-threatening condition.

The benefits of breakthrough designation include the same benefits as fast track designation—priority review of a new drug application, rolling review, etc.—plus an organizational commitment involving the FDA’s senior managers with more intensive guidance from the FDA. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to SER-109 for the prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in adults.

SER-109 is a microbiome therapeutic designed to treat recurrent CDI by correcting dysbiosis of the human microbiome.

In a single dose of 4 capsules, SER-109 re-introduces an ecology of purified bacterial spores that should restore the microbiome to a healthy state, allowing it to carry out key biological functions, including resisting Clostridium difficile.

“SER-109 is intended to re-introduce essential bacteria that restore the body’s natural resistance to CDI by re-establishing the ecology of the colonic microbiome,” explained Roger Pomerantz, MD, of Seres Therapeutics, Inc., the company developing SER-109.

“Because we’re focused on treating the underlying cause of the disease, we believe we have the potential to break the cycle of recurrent CDI and have a significant impact for patients.”

SER-109 is currently being investigated in a phase 2 trial. In addition to orphan designation, SER-109 has breakthrough designation from the FDA.

Trials of SER-109

Researchers reported phase 1/2 results with SER-109 at the 2014 Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The study had 2 cohorts containing 15 patients each. Patients were between 18 and 90 years old, had 3 or more laboratory-confirmed CDI episodes over 1 year, had a life expectancy greater than 3 months, and were able to give informed consent.

Patients in cohort 1 received a mean SER-109 dose of 1.5 x 109 spores, and those in cohort 2 received a mean dose of 1 x 108 spores. SER-109 was deemed effective if patients did not have a CDI recurrence in the 8-week period after they received SER-109.

In cohort 1, 87% of patients (13/15) achieved the efficacy endpoint. Two patients had transient, self-limited diarrhea with a positive C difficile test, but both reached the week 8 endpoint without needing antibiotic therapy for CDI. Thus, in cohort 1, the clinical cure rate was 100%.

In cohort 2, 93% of patients (14/15) reached the 8-week endpoint CDI-free. One patient failed per protocol.

The researchers said there were no drug-related serious adverse events in this trial.

Seres Therapeutics is currently conducting a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study (ECOSPOR) to assess the efficacy and safety of SER-109 in preventing recurrent CDI. The company expects results from this study to be available mid-2016.

About orphan and breakthrough designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

Orphan designation provides the sponsor of a drug with various development incentives, including opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, and 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved.

The FDA’s breakthrough therapy designation is intended to expedite the development and review of a drug candidate intended to treat a serious or life-threatening condition.

The benefits of breakthrough designation include the same benefits as fast track designation—priority review of a new drug application, rolling review, etc.—plus an organizational commitment involving the FDA’s senior managers with more intensive guidance from the FDA. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to SER-109 for the prevention of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in adults.

SER-109 is a microbiome therapeutic designed to treat recurrent CDI by correcting dysbiosis of the human microbiome.

In a single dose of 4 capsules, SER-109 re-introduces an ecology of purified bacterial spores that should restore the microbiome to a healthy state, allowing it to carry out key biological functions, including resisting Clostridium difficile.

“SER-109 is intended to re-introduce essential bacteria that restore the body’s natural resistance to CDI by re-establishing the ecology of the colonic microbiome,” explained Roger Pomerantz, MD, of Seres Therapeutics, Inc., the company developing SER-109.

“Because we’re focused on treating the underlying cause of the disease, we believe we have the potential to break the cycle of recurrent CDI and have a significant impact for patients.”

SER-109 is currently being investigated in a phase 2 trial. In addition to orphan designation, SER-109 has breakthrough designation from the FDA.

Trials of SER-109

Researchers reported phase 1/2 results with SER-109 at the 2014 Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The study had 2 cohorts containing 15 patients each. Patients were between 18 and 90 years old, had 3 or more laboratory-confirmed CDI episodes over 1 year, had a life expectancy greater than 3 months, and were able to give informed consent.

Patients in cohort 1 received a mean SER-109 dose of 1.5 x 109 spores, and those in cohort 2 received a mean dose of 1 x 108 spores. SER-109 was deemed effective if patients did not have a CDI recurrence in the 8-week period after they received SER-109.

In cohort 1, 87% of patients (13/15) achieved the efficacy endpoint. Two patients had transient, self-limited diarrhea with a positive C difficile test, but both reached the week 8 endpoint without needing antibiotic therapy for CDI. Thus, in cohort 1, the clinical cure rate was 100%.

In cohort 2, 93% of patients (14/15) reached the 8-week endpoint CDI-free. One patient failed per protocol.

The researchers said there were no drug-related serious adverse events in this trial.

Seres Therapeutics is currently conducting a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study (ECOSPOR) to assess the efficacy and safety of SER-109 in preventing recurrent CDI. The company expects results from this study to be available mid-2016.

About orphan and breakthrough designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs that are intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

Orphan designation provides the sponsor of a drug with various development incentives, including opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, and 7 years of US marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved.

The FDA’s breakthrough therapy designation is intended to expedite the development and review of a drug candidate intended to treat a serious or life-threatening condition.

The benefits of breakthrough designation include the same benefits as fast track designation—priority review of a new drug application, rolling review, etc.—plus an organizational commitment involving the FDA’s senior managers with more intensive guidance from the FDA. ![]()

BET inhibitor appears to cause memory loss in mice

Photo by Aaron Logan

New research suggests the BET inhibitor JQ1 causes molecular changes in mouse neurons and can lead to memory loss in mice.

Investigators believe this discovery, published in Nature Neuroscience, will fuel more research into the neurological effects of BET inhibitors, which are currently under development as potential treatments for a range of hematologic and solid tumor malignancies.

The researchers noted that, although JQ1 has the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, this may not be the case for other BET inhibitors.

Several companies are testing the inhibitors using unique formulations they’ve optimized in proprietary ways—for example, by adding chemical groups to make a compound more targeted or effective—which might make it more difficult for the drug to cross the blood-brain barrier.

Still, the investigators said their findings suggests more research is needed to determine whether other BET inhibitors can enter the brain, since that could potentially cause unwanted side effects.

“We found that if a drug blocks a BET protein throughout the body, and that drug can get into the brain, you could very well produce neurological side effects,” said study author Erica Korb, PhD, of The Rockefeller University in New York, New York.

Experiments with JQ1

To assess the effects of BET inhibitors on the brain, the researchers used a compound that was designed to thwart the activity of a specific BET protein, Brd4. They used the drug JQ1, which they knew could cross the blood-brain barrier.

The investigators added the drug to mouse neurons grown in the lab, then stimulated the cells in a way that mimicked the process of memory formation. Normally, when neurons receive this type of signal, they begin transcribing genes into proteins, resulting in the formation of new memories—a process that is partly regulated by Brd4.

“To turn a recent experience into a long-term memory, you need to have gene transcription in response to these extracellular signals,” Dr Korb said.

Indeed, when the researchers stimulated mouse neurons with signals that mimicked those they would normally receive in the brain, there were “massive changes” in gene transcription. But when the team performed this experiment after adding JQ1, they saw much less activity.

“After administering a Brd4 inhibitor, we no longer saw those changes in transcription after stimuli,” Dr Korb said.

To test how the drug affected the animals’ memories, the investigators placed the mice in a box with two objects they had never seen before, such as pieces of Lego or tiny figurines. Mice typically explore anything unfamiliar, climbing and sniffing around.

After a few minutes, the researchers took the mice out of the box. One day later, the team put the mice back in, this time with one of the objects from the day before and another, unfamiliar one.

Mice that received a placebo were much more interested in the new object, presumably because the one from the day before was familiar. But mice treated with JQ1 were equally interested in both objects, suggesting they didn’t remember the previous day’s experience.

Next, the investigators took their findings a step further. If JQ1 reduces molecular activity in the brain, they wondered if it could help in conditions marked by too much brain activity, such as epilepsy.

Brd4 regulates a receptor protein present at the synapse, a structure where two neurons connect and transmit signals. When the researchers administered the Brd4 inhibitor, they saw decreased levels of that receptor, and neurons fired much less frequently.

Next, the team gave the drug to mice for a week, then added a chemical that induces seizures. Mice that received JQ1 had a much lower rate of seizures than mice given a placebo.

“In the case of the epileptic brain, when there’s too much activity and neurons talking to each other, this drug could be potentially be beneficial,” Dr Korb concluded. ![]()

Photo by Aaron Logan

New research suggests the BET inhibitor JQ1 causes molecular changes in mouse neurons and can lead to memory loss in mice.

Investigators believe this discovery, published in Nature Neuroscience, will fuel more research into the neurological effects of BET inhibitors, which are currently under development as potential treatments for a range of hematologic and solid tumor malignancies.

The researchers noted that, although JQ1 has the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, this may not be the case for other BET inhibitors.

Several companies are testing the inhibitors using unique formulations they’ve optimized in proprietary ways—for example, by adding chemical groups to make a compound more targeted or effective—which might make it more difficult for the drug to cross the blood-brain barrier.

Still, the investigators said their findings suggests more research is needed to determine whether other BET inhibitors can enter the brain, since that could potentially cause unwanted side effects.

“We found that if a drug blocks a BET protein throughout the body, and that drug can get into the brain, you could very well produce neurological side effects,” said study author Erica Korb, PhD, of The Rockefeller University in New York, New York.

Experiments with JQ1

To assess the effects of BET inhibitors on the brain, the researchers used a compound that was designed to thwart the activity of a specific BET protein, Brd4. They used the drug JQ1, which they knew could cross the blood-brain barrier.

The investigators added the drug to mouse neurons grown in the lab, then stimulated the cells in a way that mimicked the process of memory formation. Normally, when neurons receive this type of signal, they begin transcribing genes into proteins, resulting in the formation of new memories—a process that is partly regulated by Brd4.

“To turn a recent experience into a long-term memory, you need to have gene transcription in response to these extracellular signals,” Dr Korb said.

Indeed, when the researchers stimulated mouse neurons with signals that mimicked those they would normally receive in the brain, there were “massive changes” in gene transcription. But when the team performed this experiment after adding JQ1, they saw much less activity.

“After administering a Brd4 inhibitor, we no longer saw those changes in transcription after stimuli,” Dr Korb said.

To test how the drug affected the animals’ memories, the investigators placed the mice in a box with two objects they had never seen before, such as pieces of Lego or tiny figurines. Mice typically explore anything unfamiliar, climbing and sniffing around.

After a few minutes, the researchers took the mice out of the box. One day later, the team put the mice back in, this time with one of the objects from the day before and another, unfamiliar one.

Mice that received a placebo were much more interested in the new object, presumably because the one from the day before was familiar. But mice treated with JQ1 were equally interested in both objects, suggesting they didn’t remember the previous day’s experience.

Next, the investigators took their findings a step further. If JQ1 reduces molecular activity in the brain, they wondered if it could help in conditions marked by too much brain activity, such as epilepsy.

Brd4 regulates a receptor protein present at the synapse, a structure where two neurons connect and transmit signals. When the researchers administered the Brd4 inhibitor, they saw decreased levels of that receptor, and neurons fired much less frequently.

Next, the team gave the drug to mice for a week, then added a chemical that induces seizures. Mice that received JQ1 had a much lower rate of seizures than mice given a placebo.

“In the case of the epileptic brain, when there’s too much activity and neurons talking to each other, this drug could be potentially be beneficial,” Dr Korb concluded. ![]()

Photo by Aaron Logan

New research suggests the BET inhibitor JQ1 causes molecular changes in mouse neurons and can lead to memory loss in mice.

Investigators believe this discovery, published in Nature Neuroscience, will fuel more research into the neurological effects of BET inhibitors, which are currently under development as potential treatments for a range of hematologic and solid tumor malignancies.

The researchers noted that, although JQ1 has the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, this may not be the case for other BET inhibitors.

Several companies are testing the inhibitors using unique formulations they’ve optimized in proprietary ways—for example, by adding chemical groups to make a compound more targeted or effective—which might make it more difficult for the drug to cross the blood-brain barrier.

Still, the investigators said their findings suggests more research is needed to determine whether other BET inhibitors can enter the brain, since that could potentially cause unwanted side effects.

“We found that if a drug blocks a BET protein throughout the body, and that drug can get into the brain, you could very well produce neurological side effects,” said study author Erica Korb, PhD, of The Rockefeller University in New York, New York.

Experiments with JQ1

To assess the effects of BET inhibitors on the brain, the researchers used a compound that was designed to thwart the activity of a specific BET protein, Brd4. They used the drug JQ1, which they knew could cross the blood-brain barrier.

The investigators added the drug to mouse neurons grown in the lab, then stimulated the cells in a way that mimicked the process of memory formation. Normally, when neurons receive this type of signal, they begin transcribing genes into proteins, resulting in the formation of new memories—a process that is partly regulated by Brd4.

“To turn a recent experience into a long-term memory, you need to have gene transcription in response to these extracellular signals,” Dr Korb said.

Indeed, when the researchers stimulated mouse neurons with signals that mimicked those they would normally receive in the brain, there were “massive changes” in gene transcription. But when the team performed this experiment after adding JQ1, they saw much less activity.

“After administering a Brd4 inhibitor, we no longer saw those changes in transcription after stimuli,” Dr Korb said.

To test how the drug affected the animals’ memories, the investigators placed the mice in a box with two objects they had never seen before, such as pieces of Lego or tiny figurines. Mice typically explore anything unfamiliar, climbing and sniffing around.

After a few minutes, the researchers took the mice out of the box. One day later, the team put the mice back in, this time with one of the objects from the day before and another, unfamiliar one.

Mice that received a placebo were much more interested in the new object, presumably because the one from the day before was familiar. But mice treated with JQ1 were equally interested in both objects, suggesting they didn’t remember the previous day’s experience.

Next, the investigators took their findings a step further. If JQ1 reduces molecular activity in the brain, they wondered if it could help in conditions marked by too much brain activity, such as epilepsy.

Brd4 regulates a receptor protein present at the synapse, a structure where two neurons connect and transmit signals. When the researchers administered the Brd4 inhibitor, they saw decreased levels of that receptor, and neurons fired much less frequently.

Next, the team gave the drug to mice for a week, then added a chemical that induces seizures. Mice that received JQ1 had a much lower rate of seizures than mice given a placebo.

“In the case of the epileptic brain, when there’s too much activity and neurons talking to each other, this drug could be potentially be beneficial,” Dr Korb concluded. ![]()

‘Emergency backup system’ replenishes platelets

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

Preclinical research appears to explain how the body can quickly replenish platelets that are lost during infection.

Investigators discovered an “emergency backup system” in mice that bypasses the known pathway of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) differentiation so that platelet numbers can be restored rapidly.

Marieke Essers, PhD, of The German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum) in Heidelberg, Germany, and her colleagues described this phenomenon in Cell Stem Cell.

The team discovered a small cell population within the HSC compartment that induces differentiation in megakaryocytes.

These quiescent stem cells—dubbed stem-like megakaryocyte-committed progenitors (SL-MkPs)—do not provide the normal supply of platelets but serve as a backup in case of emergency.

When quiescent, SL-MkPs express few proteins. In the event of an acute infection, SL-MkPs are aroused from their quiescent state by interferon α, express the typical megakaryocyte proteins, and are rapidly differentiated into advanced precursor cells.

This quickly replaces the platelets that were lost as a result of the infection.

This emergency backup system bypasses the lengthy process of normal HSC differentiation, thereby ensuring that any life-threatening loss of platelets is compensated for quickly.

However, the investigators found that repeat infections can result in the reservoir of SL-MkPs being depleted. ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

Preclinical research appears to explain how the body can quickly replenish platelets that are lost during infection.

Investigators discovered an “emergency backup system” in mice that bypasses the known pathway of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) differentiation so that platelet numbers can be restored rapidly.

Marieke Essers, PhD, of The German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum) in Heidelberg, Germany, and her colleagues described this phenomenon in Cell Stem Cell.

The team discovered a small cell population within the HSC compartment that induces differentiation in megakaryocytes.

These quiescent stem cells—dubbed stem-like megakaryocyte-committed progenitors (SL-MkPs)—do not provide the normal supply of platelets but serve as a backup in case of emergency.

When quiescent, SL-MkPs express few proteins. In the event of an acute infection, SL-MkPs are aroused from their quiescent state by interferon α, express the typical megakaryocyte proteins, and are rapidly differentiated into advanced precursor cells.

This quickly replaces the platelets that were lost as a result of the infection.

This emergency backup system bypasses the lengthy process of normal HSC differentiation, thereby ensuring that any life-threatening loss of platelets is compensated for quickly.

However, the investigators found that repeat infections can result in the reservoir of SL-MkPs being depleted. ![]()

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

Preclinical research appears to explain how the body can quickly replenish platelets that are lost during infection.

Investigators discovered an “emergency backup system” in mice that bypasses the known pathway of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) differentiation so that platelet numbers can be restored rapidly.

Marieke Essers, PhD, of The German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum) in Heidelberg, Germany, and her colleagues described this phenomenon in Cell Stem Cell.

The team discovered a small cell population within the HSC compartment that induces differentiation in megakaryocytes.

These quiescent stem cells—dubbed stem-like megakaryocyte-committed progenitors (SL-MkPs)—do not provide the normal supply of platelets but serve as a backup in case of emergency.

When quiescent, SL-MkPs express few proteins. In the event of an acute infection, SL-MkPs are aroused from their quiescent state by interferon α, express the typical megakaryocyte proteins, and are rapidly differentiated into advanced precursor cells.

This quickly replaces the platelets that were lost as a result of the infection.

This emergency backup system bypasses the lengthy process of normal HSC differentiation, thereby ensuring that any life-threatening loss of platelets is compensated for quickly.

However, the investigators found that repeat infections can result in the reservoir of SL-MkPs being depleted.

Pathway appears key to fighting adenovirus

Using an animal model they developed, researchers have identified a pathway that inhibits replication of the adenovirus.

The team generated a new strain of Syrian hamster, a model in which human adenovirus replicates and causes illness similar to that observed in humans.

Experiments with this model suggested the Type I interferon pathway plays a key role in inhibiting adenovirus replication.

“[L]ike many other viruses, adenovirus can replicate at will when a patient’s immune system is suppressed,” said William Wold, PhD, of Saint Louis University in Missouri.

“Adenovirus can become very dangerous, such as for a child who is undergoing a bone marrow transplant to treat leukemia.”

Previously, Dr Wold led a research team that identified the Syrian hamster as an appropriate animal model to study adenovirus because species C human adenoviruses replicate in these animals.

For the current study, which was published in PLOS Pathogens, Dr Wold and his colleagues conducted experiments with a new Syrian hamster strain. In these animals, the STAT2 gene was functionally knocked out by site-specific gene targeting.

The researchers found that STAT2-knockout hamsters were extremely sensitive to infection with type 5 human adenovirus (Ad5).

The team infected both STAT2-knockout hamsters and wild-type controls with Ad5. Knockout hamsters had 100 to 1000 times the viral load of controls.

The knockout hamsters also had pathology characteristic of advanced adenovirus infection—yellow, mottled livers and enlarged gall bladders—whereas controls did not.

The adaptive immune response to Ad5 remained intact in the STAT2-knockout hamsters, as surviving animals were able to clear the virus.

However, the Type 1 interferon response was hampered in these animals. Knocking out STAT2 disrupted the Type 1 interferon pathway by interrupting the cascade of cell signaling.

The researchers said their findings suggest the disrupted Type I interferon pathway contributed to the increased Ad5 replication in the STAT2-knockout hamsters.

“Besides providing an insight into adenovirus infection in humans, our results are also interesting from the perspective of the animal model,” Dr Wold said. “The STAT2-knockout Syrian hamster may also be an important animal model for studying other viral infections, including Ebola, hanta, and dengue viruses.”

The model was created by Zhongde Wang, PhD, and his colleagues at Utah State University in Logan, Utah. Dr Wang’s lab is the first to develop gene-targeting technologies in the Syrian hamster.

“The success we achieved in conducting gene-targeting in the Syrian hamster has provided the opportunity to create models for many of the human diseases for which there are either no existent animal models or severe limitations in the available animal models,” Dr Wang said.

Using an animal model they developed, researchers have identified a pathway that inhibits replication of the adenovirus.

The team generated a new strain of Syrian hamster, a model in which human adenovirus replicates and causes illness similar to that observed in humans.

Experiments with this model suggested the Type I interferon pathway plays a key role in inhibiting adenovirus replication.

“[L]ike many other viruses, adenovirus can replicate at will when a patient’s immune system is suppressed,” said William Wold, PhD, of Saint Louis University in Missouri.

“Adenovirus can become very dangerous, such as for a child who is undergoing a bone marrow transplant to treat leukemia.”

Previously, Dr Wold led a research team that identified the Syrian hamster as an appropriate animal model to study adenovirus because species C human adenoviruses replicate in these animals.

For the current study, which was published in PLOS Pathogens, Dr Wold and his colleagues conducted experiments with a new Syrian hamster strain. In these animals, the STAT2 gene was functionally knocked out by site-specific gene targeting.

The researchers found that STAT2-knockout hamsters were extremely sensitive to infection with type 5 human adenovirus (Ad5).

The team infected both STAT2-knockout hamsters and wild-type controls with Ad5. Knockout hamsters had 100 to 1000 times the viral load of controls.

The knockout hamsters also had pathology characteristic of advanced adenovirus infection—yellow, mottled livers and enlarged gall bladders—whereas controls did not.

The adaptive immune response to Ad5 remained intact in the STAT2-knockout hamsters, as surviving animals were able to clear the virus.

However, the Type 1 interferon response was hampered in these animals. Knocking out STAT2 disrupted the Type 1 interferon pathway by interrupting the cascade of cell signaling.

The researchers said their findings suggest the disrupted Type I interferon pathway contributed to the increased Ad5 replication in the STAT2-knockout hamsters.

“Besides providing an insight into adenovirus infection in humans, our results are also interesting from the perspective of the animal model,” Dr Wold said. “The STAT2-knockout Syrian hamster may also be an important animal model for studying other viral infections, including Ebola, hanta, and dengue viruses.”

The model was created by Zhongde Wang, PhD, and his colleagues at Utah State University in Logan, Utah. Dr Wang’s lab is the first to develop gene-targeting technologies in the Syrian hamster.

“The success we achieved in conducting gene-targeting in the Syrian hamster has provided the opportunity to create models for many of the human diseases for which there are either no existent animal models or severe limitations in the available animal models,” Dr Wang said.

Using an animal model they developed, researchers have identified a pathway that inhibits replication of the adenovirus.

The team generated a new strain of Syrian hamster, a model in which human adenovirus replicates and causes illness similar to that observed in humans.

Experiments with this model suggested the Type I interferon pathway plays a key role in inhibiting adenovirus replication.

“[L]ike many other viruses, adenovirus can replicate at will when a patient’s immune system is suppressed,” said William Wold, PhD, of Saint Louis University in Missouri.

“Adenovirus can become very dangerous, such as for a child who is undergoing a bone marrow transplant to treat leukemia.”

Previously, Dr Wold led a research team that identified the Syrian hamster as an appropriate animal model to study adenovirus because species C human adenoviruses replicate in these animals.

For the current study, which was published in PLOS Pathogens, Dr Wold and his colleagues conducted experiments with a new Syrian hamster strain. In these animals, the STAT2 gene was functionally knocked out by site-specific gene targeting.

The researchers found that STAT2-knockout hamsters were extremely sensitive to infection with type 5 human adenovirus (Ad5).

The team infected both STAT2-knockout hamsters and wild-type controls with Ad5. Knockout hamsters had 100 to 1000 times the viral load of controls.

The knockout hamsters also had pathology characteristic of advanced adenovirus infection—yellow, mottled livers and enlarged gall bladders—whereas controls did not.

The adaptive immune response to Ad5 remained intact in the STAT2-knockout hamsters, as surviving animals were able to clear the virus.

However, the Type 1 interferon response was hampered in these animals. Knocking out STAT2 disrupted the Type 1 interferon pathway by interrupting the cascade of cell signaling.

The researchers said their findings suggest the disrupted Type I interferon pathway contributed to the increased Ad5 replication in the STAT2-knockout hamsters.

“Besides providing an insight into adenovirus infection in humans, our results are also interesting from the perspective of the animal model,” Dr Wold said. “The STAT2-knockout Syrian hamster may also be an important animal model for studying other viral infections, including Ebola, hanta, and dengue viruses.”

The model was created by Zhongde Wang, PhD, and his colleagues at Utah State University in Logan, Utah. Dr Wang’s lab is the first to develop gene-targeting technologies in the Syrian hamster.

“The success we achieved in conducting gene-targeting in the Syrian hamster has provided the opportunity to create models for many of the human diseases for which there are either no existent animal models or severe limitations in the available animal models,” Dr Wang said.

Clotting tests fail to predict internal bleeding

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

A new study indicates that coagulation tests are an unreliable means for measuring the risk of internal bleeding in patients taking the factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban.

For most patients who experienced internal bleeding in this study, results of coagulation tests were normal.

Prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and international normalized ratios (INRs) were elevated in a minority of patients treated with rivaroxaban and none of the patients treated with apixaban.

Henry Spiller, of the Central Ohio Poison Center at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and his colleagues conducted this retrospective study and reported the results in Annals of Emergency Medicine.

The study included data on 223 patients from more than 800 hospitals and 8 regional poison centers covering 9 states. The patients’ mean age was 60, and 56% were female. Nine percent of patients (n=20) were children younger than 12.

Eighty-nine percent of patients had taken rivaroxaban (n=198), and 11% had taken apixaban (n=25). The mean dose of rivaroxaban (reported in 182 patients) was 64.5 mg (range, 15 mg to 1200 mg). And the mean dose of apixaban (reported in 21 patients) was 9.6 mg (range, 2.5 mg to 20 mg).

For rivaroxaban, PT was measured in 49 patients (25%) and elevated in 7. PTT was measured in 49 patients (25%) and elevated in 5. And INR was measured in 61 patients (31%) and elevated in 13.

For apixaban, PT and PTT were both measured in 6 patients (24%) and elevated in none. INR was measured in 5 patients (20%) and elevated in none.

Cases of bleeding

Bleeding was reported in 15 patients (7%)—11 on rivaroxaban and 4 on apixaban. The sites of bleeding were gastrointestinal (n=8), oral (n=2), nose (n=1), bruising (n=1), urine (n=1), and subdural (n=1).

All bleeds occurred in adults who were taking the anticoagulants long-term. Twelve bleeds were considered adverse drug reactions, 2 were therapeutic error, and the reason was unknown in 1 case.

Coagulation test results were normal in most patients with bleeding. PT and PTT were both normal in 5 of 6 patients tested (83%), and INR was normal in 5 of 9 patients tested (55%).

PT and PTT were elevated in 1 of 4 patients treated with rivaroxaban and none of the patients treated with apixaban. The INR was elevated in 5 of 8 patients treated with rivaroxaban and none of the patients treated with apixaban.

The researchers said these results suggest that, without specific clarification of methodology and reagent use, PT, PTT, and INR may not reliably predict the risk of bleeding after rivaroxaban or apixaban ingestion.

“One way to overcome the variation in these tests is to use anti-factor Xa chromogenic assays to measure Xa plasma concentrations,” Spiller said.

“However, these are not widely available, and a potential drawback with measuring anti-factor Xa concentrations and plasma rivaroxaban and apixaban concentrations is that the turnaround time for results may be too long to guide a treatment plan.”

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

A new study indicates that coagulation tests are an unreliable means for measuring the risk of internal bleeding in patients taking the factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban.

For most patients who experienced internal bleeding in this study, results of coagulation tests were normal.

Prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and international normalized ratios (INRs) were elevated in a minority of patients treated with rivaroxaban and none of the patients treated with apixaban.

Henry Spiller, of the Central Ohio Poison Center at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and his colleagues conducted this retrospective study and reported the results in Annals of Emergency Medicine.

The study included data on 223 patients from more than 800 hospitals and 8 regional poison centers covering 9 states. The patients’ mean age was 60, and 56% were female. Nine percent of patients (n=20) were children younger than 12.

Eighty-nine percent of patients had taken rivaroxaban (n=198), and 11% had taken apixaban (n=25). The mean dose of rivaroxaban (reported in 182 patients) was 64.5 mg (range, 15 mg to 1200 mg). And the mean dose of apixaban (reported in 21 patients) was 9.6 mg (range, 2.5 mg to 20 mg).

For rivaroxaban, PT was measured in 49 patients (25%) and elevated in 7. PTT was measured in 49 patients (25%) and elevated in 5. And INR was measured in 61 patients (31%) and elevated in 13.

For apixaban, PT and PTT were both measured in 6 patients (24%) and elevated in none. INR was measured in 5 patients (20%) and elevated in none.

Cases of bleeding

Bleeding was reported in 15 patients (7%)—11 on rivaroxaban and 4 on apixaban. The sites of bleeding were gastrointestinal (n=8), oral (n=2), nose (n=1), bruising (n=1), urine (n=1), and subdural (n=1).

All bleeds occurred in adults who were taking the anticoagulants long-term. Twelve bleeds were considered adverse drug reactions, 2 were therapeutic error, and the reason was unknown in 1 case.

Coagulation test results were normal in most patients with bleeding. PT and PTT were both normal in 5 of 6 patients tested (83%), and INR was normal in 5 of 9 patients tested (55%).

PT and PTT were elevated in 1 of 4 patients treated with rivaroxaban and none of the patients treated with apixaban. The INR was elevated in 5 of 8 patients treated with rivaroxaban and none of the patients treated with apixaban.

The researchers said these results suggest that, without specific clarification of methodology and reagent use, PT, PTT, and INR may not reliably predict the risk of bleeding after rivaroxaban or apixaban ingestion.

“One way to overcome the variation in these tests is to use anti-factor Xa chromogenic assays to measure Xa plasma concentrations,” Spiller said.

“However, these are not widely available, and a potential drawback with measuring anti-factor Xa concentrations and plasma rivaroxaban and apixaban concentrations is that the turnaround time for results may be too long to guide a treatment plan.”

Photo by Juan D. Alfonso

A new study indicates that coagulation tests are an unreliable means for measuring the risk of internal bleeding in patients taking the factor Xa inhibitors rivaroxaban and apixaban.

For most patients who experienced internal bleeding in this study, results of coagulation tests were normal.

Prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and international normalized ratios (INRs) were elevated in a minority of patients treated with rivaroxaban and none of the patients treated with apixaban.

Henry Spiller, of the Central Ohio Poison Center at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, and his colleagues conducted this retrospective study and reported the results in Annals of Emergency Medicine.

The study included data on 223 patients from more than 800 hospitals and 8 regional poison centers covering 9 states. The patients’ mean age was 60, and 56% were female. Nine percent of patients (n=20) were children younger than 12.

Eighty-nine percent of patients had taken rivaroxaban (n=198), and 11% had taken apixaban (n=25). The mean dose of rivaroxaban (reported in 182 patients) was 64.5 mg (range, 15 mg to 1200 mg). And the mean dose of apixaban (reported in 21 patients) was 9.6 mg (range, 2.5 mg to 20 mg).

For rivaroxaban, PT was measured in 49 patients (25%) and elevated in 7. PTT was measured in 49 patients (25%) and elevated in 5. And INR was measured in 61 patients (31%) and elevated in 13.

For apixaban, PT and PTT were both measured in 6 patients (24%) and elevated in none. INR was measured in 5 patients (20%) and elevated in none.

Cases of bleeding

Bleeding was reported in 15 patients (7%)—11 on rivaroxaban and 4 on apixaban. The sites of bleeding were gastrointestinal (n=8), oral (n=2), nose (n=1), bruising (n=1), urine (n=1), and subdural (n=1).

All bleeds occurred in adults who were taking the anticoagulants long-term. Twelve bleeds were considered adverse drug reactions, 2 were therapeutic error, and the reason was unknown in 1 case.

Coagulation test results were normal in most patients with bleeding. PT and PTT were both normal in 5 of 6 patients tested (83%), and INR was normal in 5 of 9 patients tested (55%).