User login

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

Visible light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum and is confined to a range of 400 to 700 nm. Visible light phototherapy can be delivered across various wavelengths within this spectrum, with most research focusing on blue light (BL)(400-500 nm) and red light (RL)(600-700 nm). Blue light commonly is used to treat acne as well as actinic keratosis and other inflammatory disorders,1,2 while RL largely targets signs of skin aging and fibrosis.2,3 Because of its shorter wavelength, the clinically meaningful skin penetration of BL reaches up to1 mm and is confined to the epidermis; in contrast, RL can access the dermal adnexa due to its penetration depth of more than 2 mm.4 Therapeutically, visible light can be utilized alone (eg, photobiomodulation [PBM]) or in combination with a photosensitizing agent (eg, photodynamic therapy [PDT]).5,6

Our laboratory’s prior research has contributed to a greater understanding of the safety profile of visible light at various wavelengths.1,3 Specifically, our work has shown that BL (417 nm [range, 412-422 nm]) and RL (633 nm [range, 627-639 nm]) demonstrated no evidence of DNA damage—via no formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and/or 6-4 photoproducts, the hallmark photolesions caused by UV exposure—in human dermal fibroblasts following visible light exposure at all fluences tested.1,3 This evidence reinforces the safety of visible light at clinically relevant wavelengths, supporting its integration into dermatologic practice. In this editorial, we highlight the key clinical applications of PBM and PDT and outline safety considerations for visible light-based therapies in dermatologic practice.

Photobiomodulation

Photobiomodulation is a noninvasive treatment in which low-level lasers or light-emitting diodes deliver photons from a nonionizing light source to endogenous photoreceptors, primarily cytochrome C oxidase.7-9 On the visible light spectrum, PBM primarily encompasses RL.7-9 Photoactivation leads to production of reactive oxygen species as well as mitochondrial alterations, with resulting modulation of cellular activity.7-9 Upregulation of cellular activity generally occurs at lower fluences (ie, energy delivered per unit area) of light, whereas higher fluences cause downregulation of cellular activity.5

Recent consensus guidelines, established with expert colleagues, define additional key parameters that are crucial to optimizing PBM treatment, including distance from the light source, area of the light beam, wavelength, length of treatment time, and number of treatments.5 Understanding the effects of different parameter combinations is essential for clinicians to select the best treatment regimen for each patient. Our laboratory has conducted National Institutes of Health–funded phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials to determine the safety and efficacy of red-light PBM.10-13 Additionally, we completed several pilot phase 2 clinical studies with commercially available light-emitting diode face masks using PBM technology, which demonstrated a favorable safety profile and high patient satisfaction across multiple self-reported measures.14,15 These findings highlight PBM as a reliable and well-tolerated therapeutic approach that can be administered in clinical settings or by patients at home.

Adverse effects of PBM therapy generally are mild and transient, most commonly manifesting as slight irritation and erythema.5 Overall, PBM is widely regarded as safe with a favorable and nontoxic profile across treatment settings. Growing evidence supports the role of PBM in managing wound healing, acne, alopecia, and skin aging, among other dermatologic concerns.8

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a noninvasive procedure during which a photosensitizer—typically 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or a derivative, methyl aminolevulinate—reacts with a light source and oxygen, resulting in reactive oxygen species.6,16 This reaction ultimately triggers targeted cellular destruction of the intended lesional skin but with negligible effects on adjacent nonlesional tissue.6 The efficacy of PDT is determined by several parameters, including composition and concentration of the photosensitizer, photosensitizer incubation temperature, and incubation time with the photosensitizer. Methyl aminolevulinate is a lipophilic molecule and may promote greater skin penetration and cellular uptake than 5-ALA, which is a hydrophilic molecule.6

Our research further demonstrated that apoptosis increases in a dose- and temperature-dependent manner following 5-ALA exposure, both in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells and in human dermal fibroblasts.17,18 Our mechanistic insights have clinical relevance, as evidenced by an independent pilot study demonstrating that temperature-modulated PDT significantly improved actinic keratosis lesion clearance rates (P<.0001).19 Additionally, we determined that even short periods of incubation with 5-ALA (ie, 15-30 minutes) result in statistically significant increases in apoptosis (P<.05).20 Thus, these findings highlight that the choice of photosensitizing agent and the administration parameters are critical in determining PDT efficacy as well as the need to optimize clinical protocols.

Photodynamic therapy also has demonstrated general clinical and genotoxic safety, with the most common potential adverse events limited to temporary inflammation, erythema, and discomfort.21 A study in murine skin and human keratinocytes revealed that 5-ALA PDT had a photoprotective effect against previous irradiation with UVB (a known inducer of DNA damage) via removal of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers.22 Thus, PDT has been recognized as a safe and effective therapeutic modality with broad applications in dermatology, including treatment of actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers.16

Clinical Safety, Photoprotection, and Precautions

While visible light has shown substantial therapeutic potential in dermatology, there are several safety measures and precautions to be aware of. Visible light constitutes approximately 44% of the solar output; therefore, precautions against both UV and visible light are recommended for the general population.23 Cumulative exposure to visible light has been shown to trigger melanogenesis, resulting in persistent erythema, hyperpigmentation, and uneven skin tones across all Fitzpatrick skin types.24 Individuals with skin of color are more photosensitive to visible light due to increased baseline melanin levels.24 Similarly, patients with pigmentary conditions such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may experience worsening of their dermatologic symptoms due to underlying visible light photosensitivity.25

Patients undergoing PBM or PDT could benefit from visible light protection. The primary form of photoprotection against visible light is tinted sunscreen, which contains iron oxides and titanium dioxide.26 Iron (III) oxide is capable of blocking nearly all visible light damage.26 Use of physical barriers such as wavelength-specific sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats also is important for preventing photodamage from visible light.26

Final Thoughts

Visible light has a role in the treatment of a variety of skin conditions, including actinic keratosis, nonmelanoma skin cancers, acne, wound healing, skin fibrosis, and photodamage. Photobiomodulation and PDT represent 2 noninvasive phototherapeutic options that utilize visible light to enact cellular changes necessary to improve skin health. Integrating visible light phototherapy into standard clinical practice is important for enhancing patient outcomes. Clinicians should remain mindful of the rare pigmentary risks associated with visible light therapy devices. Future research should prioritize optimization of standardized protocols and expansion of clinical indications for visible light phototherapy.

- Kabakova M, Wang J, Stolyar J, et al. Visible blue light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2025;18:E202400510. doi:10.1002/jbio.202400510

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163. doi:10.2147/CCID.S35334

- Wang JY, Austin E, Jagdeo J. Visible red light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2022;15:E202200023. doi:10.1002/jbio.202200023

- Opel DR, Hagstrom E, Pace AK, et al. Light-emitting diodes: a brief review and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-44.

- Maghfour J, Mineroff J, Ozog DM, et al. Evidence-based consensus on the clinical application of photobiomodulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;93:429-443. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.04.031

- Ozog DM, Rkein AM, Fabi SG, et al. Photodynamic therapy: a clinical consensus guide. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:804-827. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000800

- Maghfour J, Ozog DM, Mineroff J, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part I: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:793-802. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.073

- Mineroff J, Maghfour J, Ozog DM, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part II: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:805-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.074

- Mamalis A, Siegel D, Jagdeo J. Visible red light emitting diode photobiomodulation for skin fibrosis: key molecular pathways. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:121-128. doi:10.1007/s13671-016-0141-x

- Kurtti A, Nguyen JK, Weedon J, et al. Light emitting diode-red light for reduction of post-surgical scarring: results from a dose-ranging, split-face, randomized controlled trial. J Biophotonics. 2021;14:E202100073. doi:10.1002/jbio.202100073

- Nguyen JK, Weedon J, Jakus J, et al. A dose-ranging, parallel group, split-face, single-blind phase II study of light emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) for skin scarring prevention: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:432. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3546-6

- Ho D, Kraeva E, Wun T, et al. A single-blind, dose escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) on human skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:385. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1518-7

- Wang EB, Kaur R, Nguyen J, et al. A single-blind, dose-escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light on Caucasian non-Hispanic skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:177. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3278-7

- Wang JY, Kabakova M, Patel P, et al. Outstanding user reported satisfaction for light emitting diodes under-eye rejuvenation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:511. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03254-z

- Mineroff J, Austin E, Feit E, et al. Male facial rejuvenation using a combination 633, 830, and 1072 nm LED face mask. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2605-2611. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02663-w

- Wang JY, Zeitouni N, Austin E, et al. Photodynamic therapy: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.12.050

- Austin E, Koo E, Jagdeo J. Thermal photodynamic therapy increases apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12599. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30908-6

- Mamalis A, Koo E, Sckisel GD, et al. Temperature-dependent impact of thermal aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy on apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in human dermal fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:512-519. doi:10.1111/bjd.14509

- Willey A, Anderson RR, Sakamoto FH. Temperature-modulated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis on the extremities: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1094-1102. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452662.69539.57

- Koo E, Austin E, Mamalis A, et al. Efficacy of ultra short sub-30 minute incubation of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in vitro. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:592-598. doi:10.1002/lsm.22648

- Austin E, Wang JY, Ozog DM, et al. Photodynamic therapy: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.02.037

- Hua H, Cheng JW, Bu WB, et al. 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy inhibits ultraviolet B-induced skin photodamage. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2100-2109. doi:10.7150/ijbs.31583

- Liebel F, Kaur S, Ruvolo E, et al. Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1901-1907. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.476

- Austin E, Geisler AN, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part I: properties and cutaneous effects of visible light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1219-1231. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.048

- Fatima S, Braunberger T, Mohammad TF, et al. The role of sunscreen in melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:5-10. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_295_18

- Geisler AN, Austin E, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part II: photoprotection against visible and ultraviolet light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1233-1244. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.074

Visible light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum and is confined to a range of 400 to 700 nm. Visible light phototherapy can be delivered across various wavelengths within this spectrum, with most research focusing on blue light (BL)(400-500 nm) and red light (RL)(600-700 nm). Blue light commonly is used to treat acne as well as actinic keratosis and other inflammatory disorders,1,2 while RL largely targets signs of skin aging and fibrosis.2,3 Because of its shorter wavelength, the clinically meaningful skin penetration of BL reaches up to1 mm and is confined to the epidermis; in contrast, RL can access the dermal adnexa due to its penetration depth of more than 2 mm.4 Therapeutically, visible light can be utilized alone (eg, photobiomodulation [PBM]) or in combination with a photosensitizing agent (eg, photodynamic therapy [PDT]).5,6

Our laboratory’s prior research has contributed to a greater understanding of the safety profile of visible light at various wavelengths.1,3 Specifically, our work has shown that BL (417 nm [range, 412-422 nm]) and RL (633 nm [range, 627-639 nm]) demonstrated no evidence of DNA damage—via no formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and/or 6-4 photoproducts, the hallmark photolesions caused by UV exposure—in human dermal fibroblasts following visible light exposure at all fluences tested.1,3 This evidence reinforces the safety of visible light at clinically relevant wavelengths, supporting its integration into dermatologic practice. In this editorial, we highlight the key clinical applications of PBM and PDT and outline safety considerations for visible light-based therapies in dermatologic practice.

Photobiomodulation

Photobiomodulation is a noninvasive treatment in which low-level lasers or light-emitting diodes deliver photons from a nonionizing light source to endogenous photoreceptors, primarily cytochrome C oxidase.7-9 On the visible light spectrum, PBM primarily encompasses RL.7-9 Photoactivation leads to production of reactive oxygen species as well as mitochondrial alterations, with resulting modulation of cellular activity.7-9 Upregulation of cellular activity generally occurs at lower fluences (ie, energy delivered per unit area) of light, whereas higher fluences cause downregulation of cellular activity.5

Recent consensus guidelines, established with expert colleagues, define additional key parameters that are crucial to optimizing PBM treatment, including distance from the light source, area of the light beam, wavelength, length of treatment time, and number of treatments.5 Understanding the effects of different parameter combinations is essential for clinicians to select the best treatment regimen for each patient. Our laboratory has conducted National Institutes of Health–funded phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials to determine the safety and efficacy of red-light PBM.10-13 Additionally, we completed several pilot phase 2 clinical studies with commercially available light-emitting diode face masks using PBM technology, which demonstrated a favorable safety profile and high patient satisfaction across multiple self-reported measures.14,15 These findings highlight PBM as a reliable and well-tolerated therapeutic approach that can be administered in clinical settings or by patients at home.

Adverse effects of PBM therapy generally are mild and transient, most commonly manifesting as slight irritation and erythema.5 Overall, PBM is widely regarded as safe with a favorable and nontoxic profile across treatment settings. Growing evidence supports the role of PBM in managing wound healing, acne, alopecia, and skin aging, among other dermatologic concerns.8

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a noninvasive procedure during which a photosensitizer—typically 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or a derivative, methyl aminolevulinate—reacts with a light source and oxygen, resulting in reactive oxygen species.6,16 This reaction ultimately triggers targeted cellular destruction of the intended lesional skin but with negligible effects on adjacent nonlesional tissue.6 The efficacy of PDT is determined by several parameters, including composition and concentration of the photosensitizer, photosensitizer incubation temperature, and incubation time with the photosensitizer. Methyl aminolevulinate is a lipophilic molecule and may promote greater skin penetration and cellular uptake than 5-ALA, which is a hydrophilic molecule.6

Our research further demonstrated that apoptosis increases in a dose- and temperature-dependent manner following 5-ALA exposure, both in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells and in human dermal fibroblasts.17,18 Our mechanistic insights have clinical relevance, as evidenced by an independent pilot study demonstrating that temperature-modulated PDT significantly improved actinic keratosis lesion clearance rates (P<.0001).19 Additionally, we determined that even short periods of incubation with 5-ALA (ie, 15-30 minutes) result in statistically significant increases in apoptosis (P<.05).20 Thus, these findings highlight that the choice of photosensitizing agent and the administration parameters are critical in determining PDT efficacy as well as the need to optimize clinical protocols.

Photodynamic therapy also has demonstrated general clinical and genotoxic safety, with the most common potential adverse events limited to temporary inflammation, erythema, and discomfort.21 A study in murine skin and human keratinocytes revealed that 5-ALA PDT had a photoprotective effect against previous irradiation with UVB (a known inducer of DNA damage) via removal of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers.22 Thus, PDT has been recognized as a safe and effective therapeutic modality with broad applications in dermatology, including treatment of actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers.16

Clinical Safety, Photoprotection, and Precautions

While visible light has shown substantial therapeutic potential in dermatology, there are several safety measures and precautions to be aware of. Visible light constitutes approximately 44% of the solar output; therefore, precautions against both UV and visible light are recommended for the general population.23 Cumulative exposure to visible light has been shown to trigger melanogenesis, resulting in persistent erythema, hyperpigmentation, and uneven skin tones across all Fitzpatrick skin types.24 Individuals with skin of color are more photosensitive to visible light due to increased baseline melanin levels.24 Similarly, patients with pigmentary conditions such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may experience worsening of their dermatologic symptoms due to underlying visible light photosensitivity.25

Patients undergoing PBM or PDT could benefit from visible light protection. The primary form of photoprotection against visible light is tinted sunscreen, which contains iron oxides and titanium dioxide.26 Iron (III) oxide is capable of blocking nearly all visible light damage.26 Use of physical barriers such as wavelength-specific sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats also is important for preventing photodamage from visible light.26

Final Thoughts

Visible light has a role in the treatment of a variety of skin conditions, including actinic keratosis, nonmelanoma skin cancers, acne, wound healing, skin fibrosis, and photodamage. Photobiomodulation and PDT represent 2 noninvasive phototherapeutic options that utilize visible light to enact cellular changes necessary to improve skin health. Integrating visible light phototherapy into standard clinical practice is important for enhancing patient outcomes. Clinicians should remain mindful of the rare pigmentary risks associated with visible light therapy devices. Future research should prioritize optimization of standardized protocols and expansion of clinical indications for visible light phototherapy.

Visible light is part of the electromagnetic spectrum and is confined to a range of 400 to 700 nm. Visible light phototherapy can be delivered across various wavelengths within this spectrum, with most research focusing on blue light (BL)(400-500 nm) and red light (RL)(600-700 nm). Blue light commonly is used to treat acne as well as actinic keratosis and other inflammatory disorders,1,2 while RL largely targets signs of skin aging and fibrosis.2,3 Because of its shorter wavelength, the clinically meaningful skin penetration of BL reaches up to1 mm and is confined to the epidermis; in contrast, RL can access the dermal adnexa due to its penetration depth of more than 2 mm.4 Therapeutically, visible light can be utilized alone (eg, photobiomodulation [PBM]) or in combination with a photosensitizing agent (eg, photodynamic therapy [PDT]).5,6

Our laboratory’s prior research has contributed to a greater understanding of the safety profile of visible light at various wavelengths.1,3 Specifically, our work has shown that BL (417 nm [range, 412-422 nm]) and RL (633 nm [range, 627-639 nm]) demonstrated no evidence of DNA damage—via no formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and/or 6-4 photoproducts, the hallmark photolesions caused by UV exposure—in human dermal fibroblasts following visible light exposure at all fluences tested.1,3 This evidence reinforces the safety of visible light at clinically relevant wavelengths, supporting its integration into dermatologic practice. In this editorial, we highlight the key clinical applications of PBM and PDT and outline safety considerations for visible light-based therapies in dermatologic practice.

Photobiomodulation

Photobiomodulation is a noninvasive treatment in which low-level lasers or light-emitting diodes deliver photons from a nonionizing light source to endogenous photoreceptors, primarily cytochrome C oxidase.7-9 On the visible light spectrum, PBM primarily encompasses RL.7-9 Photoactivation leads to production of reactive oxygen species as well as mitochondrial alterations, with resulting modulation of cellular activity.7-9 Upregulation of cellular activity generally occurs at lower fluences (ie, energy delivered per unit area) of light, whereas higher fluences cause downregulation of cellular activity.5

Recent consensus guidelines, established with expert colleagues, define additional key parameters that are crucial to optimizing PBM treatment, including distance from the light source, area of the light beam, wavelength, length of treatment time, and number of treatments.5 Understanding the effects of different parameter combinations is essential for clinicians to select the best treatment regimen for each patient. Our laboratory has conducted National Institutes of Health–funded phase 1 and phase 2 clinical trials to determine the safety and efficacy of red-light PBM.10-13 Additionally, we completed several pilot phase 2 clinical studies with commercially available light-emitting diode face masks using PBM technology, which demonstrated a favorable safety profile and high patient satisfaction across multiple self-reported measures.14,15 These findings highlight PBM as a reliable and well-tolerated therapeutic approach that can be administered in clinical settings or by patients at home.

Adverse effects of PBM therapy generally are mild and transient, most commonly manifesting as slight irritation and erythema.5 Overall, PBM is widely regarded as safe with a favorable and nontoxic profile across treatment settings. Growing evidence supports the role of PBM in managing wound healing, acne, alopecia, and skin aging, among other dermatologic concerns.8

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is a noninvasive procedure during which a photosensitizer—typically 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) or a derivative, methyl aminolevulinate—reacts with a light source and oxygen, resulting in reactive oxygen species.6,16 This reaction ultimately triggers targeted cellular destruction of the intended lesional skin but with negligible effects on adjacent nonlesional tissue.6 The efficacy of PDT is determined by several parameters, including composition and concentration of the photosensitizer, photosensitizer incubation temperature, and incubation time with the photosensitizer. Methyl aminolevulinate is a lipophilic molecule and may promote greater skin penetration and cellular uptake than 5-ALA, which is a hydrophilic molecule.6

Our research further demonstrated that apoptosis increases in a dose- and temperature-dependent manner following 5-ALA exposure, both in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells and in human dermal fibroblasts.17,18 Our mechanistic insights have clinical relevance, as evidenced by an independent pilot study demonstrating that temperature-modulated PDT significantly improved actinic keratosis lesion clearance rates (P<.0001).19 Additionally, we determined that even short periods of incubation with 5-ALA (ie, 15-30 minutes) result in statistically significant increases in apoptosis (P<.05).20 Thus, these findings highlight that the choice of photosensitizing agent and the administration parameters are critical in determining PDT efficacy as well as the need to optimize clinical protocols.

Photodynamic therapy also has demonstrated general clinical and genotoxic safety, with the most common potential adverse events limited to temporary inflammation, erythema, and discomfort.21 A study in murine skin and human keratinocytes revealed that 5-ALA PDT had a photoprotective effect against previous irradiation with UVB (a known inducer of DNA damage) via removal of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers.22 Thus, PDT has been recognized as a safe and effective therapeutic modality with broad applications in dermatology, including treatment of actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers.16

Clinical Safety, Photoprotection, and Precautions

While visible light has shown substantial therapeutic potential in dermatology, there are several safety measures and precautions to be aware of. Visible light constitutes approximately 44% of the solar output; therefore, precautions against both UV and visible light are recommended for the general population.23 Cumulative exposure to visible light has been shown to trigger melanogenesis, resulting in persistent erythema, hyperpigmentation, and uneven skin tones across all Fitzpatrick skin types.24 Individuals with skin of color are more photosensitive to visible light due to increased baseline melanin levels.24 Similarly, patients with pigmentary conditions such as melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation may experience worsening of their dermatologic symptoms due to underlying visible light photosensitivity.25

Patients undergoing PBM or PDT could benefit from visible light protection. The primary form of photoprotection against visible light is tinted sunscreen, which contains iron oxides and titanium dioxide.26 Iron (III) oxide is capable of blocking nearly all visible light damage.26 Use of physical barriers such as wavelength-specific sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats also is important for preventing photodamage from visible light.26

Final Thoughts

Visible light has a role in the treatment of a variety of skin conditions, including actinic keratosis, nonmelanoma skin cancers, acne, wound healing, skin fibrosis, and photodamage. Photobiomodulation and PDT represent 2 noninvasive phototherapeutic options that utilize visible light to enact cellular changes necessary to improve skin health. Integrating visible light phototherapy into standard clinical practice is important for enhancing patient outcomes. Clinicians should remain mindful of the rare pigmentary risks associated with visible light therapy devices. Future research should prioritize optimization of standardized protocols and expansion of clinical indications for visible light phototherapy.

- Kabakova M, Wang J, Stolyar J, et al. Visible blue light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2025;18:E202400510. doi:10.1002/jbio.202400510

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163. doi:10.2147/CCID.S35334

- Wang JY, Austin E, Jagdeo J. Visible red light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2022;15:E202200023. doi:10.1002/jbio.202200023

- Opel DR, Hagstrom E, Pace AK, et al. Light-emitting diodes: a brief review and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-44.

- Maghfour J, Mineroff J, Ozog DM, et al. Evidence-based consensus on the clinical application of photobiomodulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;93:429-443. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.04.031

- Ozog DM, Rkein AM, Fabi SG, et al. Photodynamic therapy: a clinical consensus guide. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:804-827. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000800

- Maghfour J, Ozog DM, Mineroff J, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part I: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:793-802. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.073

- Mineroff J, Maghfour J, Ozog DM, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part II: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:805-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.074

- Mamalis A, Siegel D, Jagdeo J. Visible red light emitting diode photobiomodulation for skin fibrosis: key molecular pathways. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:121-128. doi:10.1007/s13671-016-0141-x

- Kurtti A, Nguyen JK, Weedon J, et al. Light emitting diode-red light for reduction of post-surgical scarring: results from a dose-ranging, split-face, randomized controlled trial. J Biophotonics. 2021;14:E202100073. doi:10.1002/jbio.202100073

- Nguyen JK, Weedon J, Jakus J, et al. A dose-ranging, parallel group, split-face, single-blind phase II study of light emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) for skin scarring prevention: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:432. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3546-6

- Ho D, Kraeva E, Wun T, et al. A single-blind, dose escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) on human skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:385. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1518-7

- Wang EB, Kaur R, Nguyen J, et al. A single-blind, dose-escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light on Caucasian non-Hispanic skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:177. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3278-7

- Wang JY, Kabakova M, Patel P, et al. Outstanding user reported satisfaction for light emitting diodes under-eye rejuvenation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:511. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03254-z

- Mineroff J, Austin E, Feit E, et al. Male facial rejuvenation using a combination 633, 830, and 1072 nm LED face mask. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2605-2611. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02663-w

- Wang JY, Zeitouni N, Austin E, et al. Photodynamic therapy: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.12.050

- Austin E, Koo E, Jagdeo J. Thermal photodynamic therapy increases apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12599. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30908-6

- Mamalis A, Koo E, Sckisel GD, et al. Temperature-dependent impact of thermal aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy on apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in human dermal fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:512-519. doi:10.1111/bjd.14509

- Willey A, Anderson RR, Sakamoto FH. Temperature-modulated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis on the extremities: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1094-1102. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452662.69539.57

- Koo E, Austin E, Mamalis A, et al. Efficacy of ultra short sub-30 minute incubation of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in vitro. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:592-598. doi:10.1002/lsm.22648

- Austin E, Wang JY, Ozog DM, et al. Photodynamic therapy: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.02.037

- Hua H, Cheng JW, Bu WB, et al. 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy inhibits ultraviolet B-induced skin photodamage. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2100-2109. doi:10.7150/ijbs.31583

- Liebel F, Kaur S, Ruvolo E, et al. Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1901-1907. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.476

- Austin E, Geisler AN, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part I: properties and cutaneous effects of visible light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1219-1231. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.048

- Fatima S, Braunberger T, Mohammad TF, et al. The role of sunscreen in melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:5-10. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_295_18

- Geisler AN, Austin E, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part II: photoprotection against visible and ultraviolet light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1233-1244. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.074

- Kabakova M, Wang J, Stolyar J, et al. Visible blue light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2025;18:E202400510. doi:10.1002/jbio.202400510

- Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145-163. doi:10.2147/CCID.S35334

- Wang JY, Austin E, Jagdeo J. Visible red light does not induce DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. J Biophotonics. 2022;15:E202200023. doi:10.1002/jbio.202200023

- Opel DR, Hagstrom E, Pace AK, et al. Light-emitting diodes: a brief review and clinical experience. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:36-44.

- Maghfour J, Mineroff J, Ozog DM, et al. Evidence-based consensus on the clinical application of photobiomodulation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2025;93:429-443. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.04.031

- Ozog DM, Rkein AM, Fabi SG, et al. Photodynamic therapy: a clinical consensus guide. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:804-827. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000800

- Maghfour J, Ozog DM, Mineroff J, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part I: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:793-802. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.073

- Mineroff J, Maghfour J, Ozog DM, et al. Photobiomodulation CME part II: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:805-815. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.10.074

- Mamalis A, Siegel D, Jagdeo J. Visible red light emitting diode photobiomodulation for skin fibrosis: key molecular pathways. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2016;5:121-128. doi:10.1007/s13671-016-0141-x

- Kurtti A, Nguyen JK, Weedon J, et al. Light emitting diode-red light for reduction of post-surgical scarring: results from a dose-ranging, split-face, randomized controlled trial. J Biophotonics. 2021;14:E202100073. doi:10.1002/jbio.202100073

- Nguyen JK, Weedon J, Jakus J, et al. A dose-ranging, parallel group, split-face, single-blind phase II study of light emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) for skin scarring prevention: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:432. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3546-6

- Ho D, Kraeva E, Wun T, et al. A single-blind, dose escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light (LED-RL) on human skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:385. doi:10.1186/s13063-016-1518-7

- Wang EB, Kaur R, Nguyen J, et al. A single-blind, dose-escalation, phase I study of high-fluence light-emitting diode-red light on Caucasian non-Hispanic skin: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:177. doi:10.1186/s13063-019-3278-7

- Wang JY, Kabakova M, Patel P, et al. Outstanding user reported satisfaction for light emitting diodes under-eye rejuvenation. Arch Dermatol Res. 2024;316:511. doi:10.1007/s00403-024-03254-z

- Mineroff J, Austin E, Feit E, et al. Male facial rejuvenation using a combination 633, 830, and 1072 nm LED face mask. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2605-2611. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02663-w

- Wang JY, Zeitouni N, Austin E, et al. Photodynamic therapy: clinical applications in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.12.050

- Austin E, Koo E, Jagdeo J. Thermal photodynamic therapy increases apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in cutaneous and mucosal squamous cell carcinoma cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12599. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-30908-6

- Mamalis A, Koo E, Sckisel GD, et al. Temperature-dependent impact of thermal aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy on apoptosis and reactive oxygen species generation in human dermal fibroblasts. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:512-519. doi:10.1111/bjd.14509

- Willey A, Anderson RR, Sakamoto FH. Temperature-modulated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of actinic keratosis on the extremities: a pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:1094-1102. doi:10.1097/01.DSS.0000452662.69539.57

- Koo E, Austin E, Mamalis A, et al. Efficacy of ultra short sub-30 minute incubation of 5-aminolevulinic acid photodynamic therapy in vitro. Lasers Surg Med. 2017;49:592-598. doi:10.1002/lsm.22648

- Austin E, Wang JY, Ozog DM, et al. Photodynamic therapy: overview and mechanism of action. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online February 20, 2025. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2025.02.037

- Hua H, Cheng JW, Bu WB, et al. 5-aminolaevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy inhibits ultraviolet B-induced skin photodamage. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2100-2109. doi:10.7150/ijbs.31583

- Liebel F, Kaur S, Ruvolo E, et al. Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1901-1907. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.476

- Austin E, Geisler AN, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part I: properties and cutaneous effects of visible light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1219-1231. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.048

- Fatima S, Braunberger T, Mohammad TF, et al. The role of sunscreen in melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2020;65:5-10. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_295_18

- Geisler AN, Austin E, Nguyen J, et al. Visible light. part II: photoprotection against visible and ultraviolet light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1233-1244. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.074

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

Illuminating the Role of Visible Light in Dermatology

Successful Treatment of Severe Dystrophic Nail Psoriasis With Deucravacitinib

Successful Treatment of Severe Dystrophic Nail Psoriasis With Deucravacitinib

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that commonly affects the nail matrix and/or nail bed.1 Nail involvement is present in up to 50% of patients with cutaneous psoriasis and 80% of patients with psoriatic arthritis.1 Approximately 5% to 10% of patients with psoriasis demonstrate isolated nail involvement with no skin or joint manifestations.1 Nail psoriasis can cause severe pain and psychological distress, and extreme cases may cause considerable morbidity and functional impairment.2,3 Treatment often requires a long duration and may not result in complete recovery due to the slow rate of nail growth. Patients can progress to permanent nail loss if not treated properly, making early recognition and treatment crucial.1,2 Despite the availability of various treatment options, many cases remain refractory to standard interventions, which underscores the need for novel therapeutic approaches. Herein, we present a severe case of refractory isolated nail psoriasis that was successfully treated with deucravacitinib, an oral tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor.

A 59-year-old woman presented with a progressive, yellow, hyperkeratotic lesion on the left thumbnail of 2 years’ duration. The patient noted initial discoloration and peeling at the distal end of the nail. Over time, the discoloration progressed to encompass the entire nail. Previous treatments performed by outside physicians including topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and 2 surgeries to remove the nail plate and nail bed all were unsuccessful. The patient also reported severe left thumbnail pain and pruritus that considerably impaired her ability to work. The rest of the nails were unaffected, and she had no personal or family history of psoriasis. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and osteomyelitis of the right thumb without nail involvement. Drug allergies included penicillin G benzathine, sulfonamides, amoxicillin, and ciprofloxacin.

Physical examination of the left thumbnail revealed severe yellow, hyperkeratotic, dystrophic changes with a large, yellow, crumbling hyperkeratotic plaque that extended from approximately 1 cm beyond the nail plate to the proximal end of the distal interphalangeal joint, to and along the lateral nail folds, with extensive distal onycholysis. The proximal and lateral nail folds demonstrated erythema as well as maceration that was extremely tender to minimal palpation (Figure 1). No cutaneous lesions were noted elsewhere on the body. The patient had no tenderness, swelling, or stiffness in any of the joints. The differential diagnosis at the time included squamous cell carcinoma of the nail bed and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau.

Radiography of the left thumb revealed irregular swelling and nonspecific soft tissue enlargement at the tip of the digit. A nail clipping from the left thumbnail and 3-mm punch biopsies of the lateral and proximal nail folds as well as the horn of the proximal nail fold (Figure 2) were negative for fungus and confirmed psoriasiform dermatitis of the nail.

The patient was started on vinegar soaks (1:1 ratio of vinegar to water) every other day as well as urea cream 10%, ammonium lactate 15%, and petrolatum twice daily for 2 months without considerable improvement. Due to lack of improvement during this 2-month period, the patient subsequently was started on oral deucravacitinib 6 mg/d along with continued use of petrolatum twice daily and vinegar soaks every other day. We selected a trial of deucravacitinib for our patient because of its convenient daily oral dosing and promising clinical evidence.4,5 After 2 months of treatment with deucravacitinib, the patient reported substantial improvement and satisfaction with the treatment results. Physical examination of the left thumbnail after 2 months of deucravacitinib treatment revealed mildly hyperkeratotic, yellow, dystrophic changes of the nail with notable improvement of the yellow hyperkeratotic plaque on the distal thumbnail. Normal-appearing nail growth was noted at the proximal nail fold, demonstrating considerable improvement from the initial presentation (Figure 3). However, the patient had developed multiple oral ulcers, generalized pruritus, and an annular urticarial plaque on the left arm. As such, deucravacitinib was discontinued after 2 months of treatment. These symptoms resolved within a week of discontinuing deucravacitinib.

While the etiology of nail psoriasis remains unclear, it is believed to be due to a combination of immunologic, genetic, and environmental factors.3 Classical clinical features include nail pitting, leukonychia, onycholysis, nail bed hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhages.1,3 Our patient exhibited a severe form of nail psoriasis, encompassing the entire nail matrix and bed and extending to the distal interphalangeal joint and lateral nail folds. Previous surgical interventions may have triggered the Koebner phenomenon—which commonly is associated with psoriasis—and resulted in new skin lesions as a secondary response to the surgical trauma.6 The severity of the condition profoundly impacted her quality of life and considerably hindered her ability to work.

Treatment for nail psoriasis includes topical or systemic therapies such as corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, tacrolimus, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 Topical treatment is challenging because it is difficult to deliver medication effectively to the nail bed and nail matrix, and patient adherence may be poor.2 Although it has been shown to be effective, intralesional triamcinolone can be associated with pain as the most common adverse effect.7 Systemic medications such as oral methotrexate also may be effective but are contraindicated in pregnant patients and are associated with potential adverse events (AEs), including hepatotoxicity and acute kidney injury.8 The use of biologics may be challenging due to potential AEs and patient reluctance toward injection-based treatments.9

Deucravacitinib is a TYK2 inhibitor approved for treatment of plaque psoriasis.10 Tyrosine kinase 2 is an intracellular kinase that mediates the signaling of IL-23 and other cytokines involved in psoriasis pathogenesis.10 Deucravacitinib selectively binds to the regulatory domain of TYK2, leading to targeted allosteric inhibition of TYK2-mediated IL-23 and type I interferon signaling.4,5,10 Compared with biologics, deucravacitinib is advantageous because it can be administered as a daily oral pill, encouraging high patient compliance.

In the POETYK PSO-1 and PSO-2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials, 20.9% (n=332) and 20.3% (n=510) of deucravacitinib-treated patients with moderate to severe nail involvement achieved a Physician’s Global Assessment of Fingernail score of 0/1 compared with 8.8% (n=165) and 7.9% (n=254) of patients in the placebo group, respectively. All patients in these trials had a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis with at least 10% body surface area involvement; none of the patients had isolated nail psoriasis.4,5

The phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 and PSO-2 trials demonstrated deucravacitinib to be safe and well tolerated with minimal AEs.4,5 However, the development of AEs in our patient, including oral ulcers and generalized pruritus, underscores the need for close monitoring and consideration of potential risks of treatment. Common AEs associated with deucravacitinib include upper respiratory infections (19.2% [n=840]), increased blood creatine phosphokinase levels (2.7% [n=840]), herpes simplex virus (2.0% [n=840]), and mouth ulcers (1.9% [n=840]).11

Patient education also is a crucial component in the treatment of nail psoriasis. Physicians should emphasize the slow growth of nails and need for prolonged treatment. Clear communication and realistic expectations are essential for ensuring patient adherence to treatment.

Our case highlights the potential efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib for treatment of nail psoriasis, potentially laying the groundwork for future clinical studies. Our patient had a severe case of nail psoriasis that involved the entire nail bed and nail plate, resulting in extreme pain, pruritus, and functional impairment. Her case was unique because involvement was isolated to the nail without any accompanying skin or joint manifestations. She showed a favorable response to deucravacitinib within only 2 months of treatment and exhibited considerable improvement of nail psoriasis, with a reported high level of satisfaction with the treatment. We plan to continue to monitor the patient for long-term results. Future randomized clinical trials with longer follow-up periods are crucial to further establish the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib for treatment of nail psoriasis.

- Hwang JK, Grover C, Iorizzo M, et al. Nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus: updates on diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:585-596. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.11.024

- Ji C, Wang H, Bao C, et al. Challenge of nail psoriasis: an update review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2021;61:377-402. doi:10.1007/s12016-021-08896-9

- Muneer H, Sathe NC, Masood S. Nail psoriasis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Updated March 1, 2024. Accessed October 24, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559260/

- Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:29-39. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.002

- Strober B, Thaçi D, Sofen H, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, phase 3 Program fOr Evaluation of TYK2 inhibitor psoriasis second trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:40-51. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.061

- Sanchez DP, Sonthalia S. Koebner phenomenon. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Updated November 14, 2022. Accessed April 11, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553108/

- Grover C, Kharghoria G, Bansal S. Triamcinolone acetonide injections in nail psoriasis: a pragmatic analysis. Skin Appendage Disord. 2024;10:50-59. doi:10.1159/000534699

- Hanoodi M, Mittal M. Methotrexate. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed April 11, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556114/

- Singh JA, Wells GA, Christensen R, et al. Adverse effects of biologics: a network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011:Cd008794. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008794.pub2

- Thaçi D, Strober B, Gordon KB, et al. Deucravacitinib in moderate to severe psoriasis: clinical and quality-of-life outcomes in a phase 2 trial. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:495-510. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00649-y

- Week 0-16: demonstrated safety profile. Bristol-Myers Squibb. 2024. Accessed October 24, 2024. https://www.sotyktuhcp.com/safety-profile?cid=sem_2465603&gclid=CjwKCAiA9ourBhAVEiwA3L5RFnyYqmxbqkz1_zBNPz3dcyHKCSFf1XQ-7acznV0XbR5DDJHYkZcKJxoCWN0QAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that commonly affects the nail matrix and/or nail bed.1 Nail involvement is present in up to 50% of patients with cutaneous psoriasis and 80% of patients with psoriatic arthritis.1 Approximately 5% to 10% of patients with psoriasis demonstrate isolated nail involvement with no skin or joint manifestations.1 Nail psoriasis can cause severe pain and psychological distress, and extreme cases may cause considerable morbidity and functional impairment.2,3 Treatment often requires a long duration and may not result in complete recovery due to the slow rate of nail growth. Patients can progress to permanent nail loss if not treated properly, making early recognition and treatment crucial.1,2 Despite the availability of various treatment options, many cases remain refractory to standard interventions, which underscores the need for novel therapeutic approaches. Herein, we present a severe case of refractory isolated nail psoriasis that was successfully treated with deucravacitinib, an oral tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor.

A 59-year-old woman presented with a progressive, yellow, hyperkeratotic lesion on the left thumbnail of 2 years’ duration. The patient noted initial discoloration and peeling at the distal end of the nail. Over time, the discoloration progressed to encompass the entire nail. Previous treatments performed by outside physicians including topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and 2 surgeries to remove the nail plate and nail bed all were unsuccessful. The patient also reported severe left thumbnail pain and pruritus that considerably impaired her ability to work. The rest of the nails were unaffected, and she had no personal or family history of psoriasis. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and osteomyelitis of the right thumb without nail involvement. Drug allergies included penicillin G benzathine, sulfonamides, amoxicillin, and ciprofloxacin.

Physical examination of the left thumbnail revealed severe yellow, hyperkeratotic, dystrophic changes with a large, yellow, crumbling hyperkeratotic plaque that extended from approximately 1 cm beyond the nail plate to the proximal end of the distal interphalangeal joint, to and along the lateral nail folds, with extensive distal onycholysis. The proximal and lateral nail folds demonstrated erythema as well as maceration that was extremely tender to minimal palpation (Figure 1). No cutaneous lesions were noted elsewhere on the body. The patient had no tenderness, swelling, or stiffness in any of the joints. The differential diagnosis at the time included squamous cell carcinoma of the nail bed and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau.

Radiography of the left thumb revealed irregular swelling and nonspecific soft tissue enlargement at the tip of the digit. A nail clipping from the left thumbnail and 3-mm punch biopsies of the lateral and proximal nail folds as well as the horn of the proximal nail fold (Figure 2) were negative for fungus and confirmed psoriasiform dermatitis of the nail.

The patient was started on vinegar soaks (1:1 ratio of vinegar to water) every other day as well as urea cream 10%, ammonium lactate 15%, and petrolatum twice daily for 2 months without considerable improvement. Due to lack of improvement during this 2-month period, the patient subsequently was started on oral deucravacitinib 6 mg/d along with continued use of petrolatum twice daily and vinegar soaks every other day. We selected a trial of deucravacitinib for our patient because of its convenient daily oral dosing and promising clinical evidence.4,5 After 2 months of treatment with deucravacitinib, the patient reported substantial improvement and satisfaction with the treatment results. Physical examination of the left thumbnail after 2 months of deucravacitinib treatment revealed mildly hyperkeratotic, yellow, dystrophic changes of the nail with notable improvement of the yellow hyperkeratotic plaque on the distal thumbnail. Normal-appearing nail growth was noted at the proximal nail fold, demonstrating considerable improvement from the initial presentation (Figure 3). However, the patient had developed multiple oral ulcers, generalized pruritus, and an annular urticarial plaque on the left arm. As such, deucravacitinib was discontinued after 2 months of treatment. These symptoms resolved within a week of discontinuing deucravacitinib.

While the etiology of nail psoriasis remains unclear, it is believed to be due to a combination of immunologic, genetic, and environmental factors.3 Classical clinical features include nail pitting, leukonychia, onycholysis, nail bed hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhages.1,3 Our patient exhibited a severe form of nail psoriasis, encompassing the entire nail matrix and bed and extending to the distal interphalangeal joint and lateral nail folds. Previous surgical interventions may have triggered the Koebner phenomenon—which commonly is associated with psoriasis—and resulted in new skin lesions as a secondary response to the surgical trauma.6 The severity of the condition profoundly impacted her quality of life and considerably hindered her ability to work.

Treatment for nail psoriasis includes topical or systemic therapies such as corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, tacrolimus, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 Topical treatment is challenging because it is difficult to deliver medication effectively to the nail bed and nail matrix, and patient adherence may be poor.2 Although it has been shown to be effective, intralesional triamcinolone can be associated with pain as the most common adverse effect.7 Systemic medications such as oral methotrexate also may be effective but are contraindicated in pregnant patients and are associated with potential adverse events (AEs), including hepatotoxicity and acute kidney injury.8 The use of biologics may be challenging due to potential AEs and patient reluctance toward injection-based treatments.9

Deucravacitinib is a TYK2 inhibitor approved for treatment of plaque psoriasis.10 Tyrosine kinase 2 is an intracellular kinase that mediates the signaling of IL-23 and other cytokines involved in psoriasis pathogenesis.10 Deucravacitinib selectively binds to the regulatory domain of TYK2, leading to targeted allosteric inhibition of TYK2-mediated IL-23 and type I interferon signaling.4,5,10 Compared with biologics, deucravacitinib is advantageous because it can be administered as a daily oral pill, encouraging high patient compliance.

In the POETYK PSO-1 and PSO-2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials, 20.9% (n=332) and 20.3% (n=510) of deucravacitinib-treated patients with moderate to severe nail involvement achieved a Physician’s Global Assessment of Fingernail score of 0/1 compared with 8.8% (n=165) and 7.9% (n=254) of patients in the placebo group, respectively. All patients in these trials had a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis with at least 10% body surface area involvement; none of the patients had isolated nail psoriasis.4,5

The phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 and PSO-2 trials demonstrated deucravacitinib to be safe and well tolerated with minimal AEs.4,5 However, the development of AEs in our patient, including oral ulcers and generalized pruritus, underscores the need for close monitoring and consideration of potential risks of treatment. Common AEs associated with deucravacitinib include upper respiratory infections (19.2% [n=840]), increased blood creatine phosphokinase levels (2.7% [n=840]), herpes simplex virus (2.0% [n=840]), and mouth ulcers (1.9% [n=840]).11

Patient education also is a crucial component in the treatment of nail psoriasis. Physicians should emphasize the slow growth of nails and need for prolonged treatment. Clear communication and realistic expectations are essential for ensuring patient adherence to treatment.

Our case highlights the potential efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib for treatment of nail psoriasis, potentially laying the groundwork for future clinical studies. Our patient had a severe case of nail psoriasis that involved the entire nail bed and nail plate, resulting in extreme pain, pruritus, and functional impairment. Her case was unique because involvement was isolated to the nail without any accompanying skin or joint manifestations. She showed a favorable response to deucravacitinib within only 2 months of treatment and exhibited considerable improvement of nail psoriasis, with a reported high level of satisfaction with the treatment. We plan to continue to monitor the patient for long-term results. Future randomized clinical trials with longer follow-up periods are crucial to further establish the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib for treatment of nail psoriasis.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin condition that commonly affects the nail matrix and/or nail bed.1 Nail involvement is present in up to 50% of patients with cutaneous psoriasis and 80% of patients with psoriatic arthritis.1 Approximately 5% to 10% of patients with psoriasis demonstrate isolated nail involvement with no skin or joint manifestations.1 Nail psoriasis can cause severe pain and psychological distress, and extreme cases may cause considerable morbidity and functional impairment.2,3 Treatment often requires a long duration and may not result in complete recovery due to the slow rate of nail growth. Patients can progress to permanent nail loss if not treated properly, making early recognition and treatment crucial.1,2 Despite the availability of various treatment options, many cases remain refractory to standard interventions, which underscores the need for novel therapeutic approaches. Herein, we present a severe case of refractory isolated nail psoriasis that was successfully treated with deucravacitinib, an oral tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) inhibitor.

A 59-year-old woman presented with a progressive, yellow, hyperkeratotic lesion on the left thumbnail of 2 years’ duration. The patient noted initial discoloration and peeling at the distal end of the nail. Over time, the discoloration progressed to encompass the entire nail. Previous treatments performed by outside physicians including topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and 2 surgeries to remove the nail plate and nail bed all were unsuccessful. The patient also reported severe left thumbnail pain and pruritus that considerably impaired her ability to work. The rest of the nails were unaffected, and she had no personal or family history of psoriasis. Her medical history was notable for hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and osteomyelitis of the right thumb without nail involvement. Drug allergies included penicillin G benzathine, sulfonamides, amoxicillin, and ciprofloxacin.

Physical examination of the left thumbnail revealed severe yellow, hyperkeratotic, dystrophic changes with a large, yellow, crumbling hyperkeratotic plaque that extended from approximately 1 cm beyond the nail plate to the proximal end of the distal interphalangeal joint, to and along the lateral nail folds, with extensive distal onycholysis. The proximal and lateral nail folds demonstrated erythema as well as maceration that was extremely tender to minimal palpation (Figure 1). No cutaneous lesions were noted elsewhere on the body. The patient had no tenderness, swelling, or stiffness in any of the joints. The differential diagnosis at the time included squamous cell carcinoma of the nail bed and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau.

Radiography of the left thumb revealed irregular swelling and nonspecific soft tissue enlargement at the tip of the digit. A nail clipping from the left thumbnail and 3-mm punch biopsies of the lateral and proximal nail folds as well as the horn of the proximal nail fold (Figure 2) were negative for fungus and confirmed psoriasiform dermatitis of the nail.

The patient was started on vinegar soaks (1:1 ratio of vinegar to water) every other day as well as urea cream 10%, ammonium lactate 15%, and petrolatum twice daily for 2 months without considerable improvement. Due to lack of improvement during this 2-month period, the patient subsequently was started on oral deucravacitinib 6 mg/d along with continued use of petrolatum twice daily and vinegar soaks every other day. We selected a trial of deucravacitinib for our patient because of its convenient daily oral dosing and promising clinical evidence.4,5 After 2 months of treatment with deucravacitinib, the patient reported substantial improvement and satisfaction with the treatment results. Physical examination of the left thumbnail after 2 months of deucravacitinib treatment revealed mildly hyperkeratotic, yellow, dystrophic changes of the nail with notable improvement of the yellow hyperkeratotic plaque on the distal thumbnail. Normal-appearing nail growth was noted at the proximal nail fold, demonstrating considerable improvement from the initial presentation (Figure 3). However, the patient had developed multiple oral ulcers, generalized pruritus, and an annular urticarial plaque on the left arm. As such, deucravacitinib was discontinued after 2 months of treatment. These symptoms resolved within a week of discontinuing deucravacitinib.

While the etiology of nail psoriasis remains unclear, it is believed to be due to a combination of immunologic, genetic, and environmental factors.3 Classical clinical features include nail pitting, leukonychia, onycholysis, nail bed hyperkeratosis, and splinter hemorrhages.1,3 Our patient exhibited a severe form of nail psoriasis, encompassing the entire nail matrix and bed and extending to the distal interphalangeal joint and lateral nail folds. Previous surgical interventions may have triggered the Koebner phenomenon—which commonly is associated with psoriasis—and resulted in new skin lesions as a secondary response to the surgical trauma.6 The severity of the condition profoundly impacted her quality of life and considerably hindered her ability to work.

Treatment for nail psoriasis includes topical or systemic therapies such as corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, tacrolimus, and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors.1,3 Topical treatment is challenging because it is difficult to deliver medication effectively to the nail bed and nail matrix, and patient adherence may be poor.2 Although it has been shown to be effective, intralesional triamcinolone can be associated with pain as the most common adverse effect.7 Systemic medications such as oral methotrexate also may be effective but are contraindicated in pregnant patients and are associated with potential adverse events (AEs), including hepatotoxicity and acute kidney injury.8 The use of biologics may be challenging due to potential AEs and patient reluctance toward injection-based treatments.9

Deucravacitinib is a TYK2 inhibitor approved for treatment of plaque psoriasis.10 Tyrosine kinase 2 is an intracellular kinase that mediates the signaling of IL-23 and other cytokines involved in psoriasis pathogenesis.10 Deucravacitinib selectively binds to the regulatory domain of TYK2, leading to targeted allosteric inhibition of TYK2-mediated IL-23 and type I interferon signaling.4,5,10 Compared with biologics, deucravacitinib is advantageous because it can be administered as a daily oral pill, encouraging high patient compliance.

In the POETYK PSO-1 and PSO-2 phase 3 randomized controlled trials, 20.9% (n=332) and 20.3% (n=510) of deucravacitinib-treated patients with moderate to severe nail involvement achieved a Physician’s Global Assessment of Fingernail score of 0/1 compared with 8.8% (n=165) and 7.9% (n=254) of patients in the placebo group, respectively. All patients in these trials had a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis with at least 10% body surface area involvement; none of the patients had isolated nail psoriasis.4,5

The phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 and PSO-2 trials demonstrated deucravacitinib to be safe and well tolerated with minimal AEs.4,5 However, the development of AEs in our patient, including oral ulcers and generalized pruritus, underscores the need for close monitoring and consideration of potential risks of treatment. Common AEs associated with deucravacitinib include upper respiratory infections (19.2% [n=840]), increased blood creatine phosphokinase levels (2.7% [n=840]), herpes simplex virus (2.0% [n=840]), and mouth ulcers (1.9% [n=840]).11

Patient education also is a crucial component in the treatment of nail psoriasis. Physicians should emphasize the slow growth of nails and need for prolonged treatment. Clear communication and realistic expectations are essential for ensuring patient adherence to treatment.

Our case highlights the potential efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib for treatment of nail psoriasis, potentially laying the groundwork for future clinical studies. Our patient had a severe case of nail psoriasis that involved the entire nail bed and nail plate, resulting in extreme pain, pruritus, and functional impairment. Her case was unique because involvement was isolated to the nail without any accompanying skin or joint manifestations. She showed a favorable response to deucravacitinib within only 2 months of treatment and exhibited considerable improvement of nail psoriasis, with a reported high level of satisfaction with the treatment. We plan to continue to monitor the patient for long-term results. Future randomized clinical trials with longer follow-up periods are crucial to further establish the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib for treatment of nail psoriasis.

- Hwang JK, Grover C, Iorizzo M, et al. Nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus: updates on diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:585-596. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.11.024

- Ji C, Wang H, Bao C, et al. Challenge of nail psoriasis: an update review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2021;61:377-402. doi:10.1007/s12016-021-08896-9

- Muneer H, Sathe NC, Masood S. Nail psoriasis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Updated March 1, 2024. Accessed October 24, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559260/

- Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:29-39. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.002

- Strober B, Thaçi D, Sofen H, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, phase 3 Program fOr Evaluation of TYK2 inhibitor psoriasis second trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:40-51. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.061

- Sanchez DP, Sonthalia S. Koebner phenomenon. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Updated November 14, 2022. Accessed April 11, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553108/

- Grover C, Kharghoria G, Bansal S. Triamcinolone acetonide injections in nail psoriasis: a pragmatic analysis. Skin Appendage Disord. 2024;10:50-59. doi:10.1159/000534699

- Hanoodi M, Mittal M. Methotrexate. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed April 11, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556114/

- Singh JA, Wells GA, Christensen R, et al. Adverse effects of biologics: a network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011:Cd008794. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008794.pub2

- Thaçi D, Strober B, Gordon KB, et al. Deucravacitinib in moderate to severe psoriasis: clinical and quality-of-life outcomes in a phase 2 trial. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:495-510. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00649-y

- Week 0-16: demonstrated safety profile. Bristol-Myers Squibb. 2024. Accessed October 24, 2024. https://www.sotyktuhcp.com/safety-profile?cid=sem_2465603&gclid=CjwKCAiA9ourBhAVEiwA3L5RFnyYqmxbqkz1_zBNPz3dcyHKCSFf1XQ-7acznV0XbR5DDJHYkZcKJxoCWN0QAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds

- Hwang JK, Grover C, Iorizzo M, et al. Nail psoriasis and nail lichen planus: updates on diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:585-596. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.11.024

- Ji C, Wang H, Bao C, et al. Challenge of nail psoriasis: an update review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2021;61:377-402. doi:10.1007/s12016-021-08896-9

- Muneer H, Sathe NC, Masood S. Nail psoriasis. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Updated March 1, 2024. Accessed October 24, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559260/

- Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:29-39. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.07.002

- Strober B, Thaçi D, Sofen H, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, phase 3 Program fOr Evaluation of TYK2 inhibitor psoriasis second trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:40-51. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.08.061

- Sanchez DP, Sonthalia S. Koebner phenomenon. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Updated November 14, 2022. Accessed April 11, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553108/

- Grover C, Kharghoria G, Bansal S. Triamcinolone acetonide injections in nail psoriasis: a pragmatic analysis. Skin Appendage Disord. 2024;10:50-59. doi:10.1159/000534699

- Hanoodi M, Mittal M. Methotrexate. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed April 11, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556114/

- Singh JA, Wells GA, Christensen R, et al. Adverse effects of biologics: a network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2011:Cd008794. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008794.pub2

- Thaçi D, Strober B, Gordon KB, et al. Deucravacitinib in moderate to severe psoriasis: clinical and quality-of-life outcomes in a phase 2 trial. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:495-510. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00649-y

- Week 0-16: demonstrated safety profile. Bristol-Myers Squibb. 2024. Accessed October 24, 2024. https://www.sotyktuhcp.com/safety-profile?cid=sem_2465603&gclid=CjwKCAiA9ourBhAVEiwA3L5RFnyYqmxbqkz1_zBNPz3dcyHKCSFf1XQ-7acznV0XbR5DDJHYkZcKJxoCWN0QAvD_BwE&gclsrc=aw.ds

Successful Treatment of Severe Dystrophic Nail Psoriasis With Deucravacitinib

Successful Treatment of Severe Dystrophic Nail Psoriasis With Deucravacitinib

PRACTICE POINTS

- Nail psoriasis can masquerade as other dermatologic conditions, including squamous cell carcinoma of the nail bed and acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau.

- Nail psoriasis can progress to permanent nail loss if not treated properly, making early recognition and treatment crucial.

- Deucravacitinib, an oral tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor approved for the treatment of plaque psoriasis, has shown promise as an effective treatment for nail psoriasis in cases that are refractory to standard therapies.

Botulinum Toxin Injection for Treatment of Scleroderma-Related Anterior Neck Sclerosis

To the Editor:

Scleroderma is a chronic autoimmune connective tissue disease that results in excessive collagen deposition in the skin and other organs throughout the body. On its own or in the setting of mixed connective tissue disease, scleroderma can result in systemic or localized symptoms that can limit patients’ functional capabilities, cause pain and discomfort, and reduce self-esteem—all negatively impacting patients’ quality of life.1,2 Neck sclerosis is a common manifestation of scleroderma. There is no curative treatment for scleroderma; thus, therapy is focused on slowing disease progression and improving quality of life. We present a case of neck sclerosis in a 44-year-old woman with scleroderma that was successfully treated with botulinum toxin (BTX) type A injection, resulting in improved skin laxity and appearance with high patient satisfaction. Our case demonstrates the potential positive effects of BTX treatment in patients with features of sclerosis or fibrosis, particularly in the neck region.

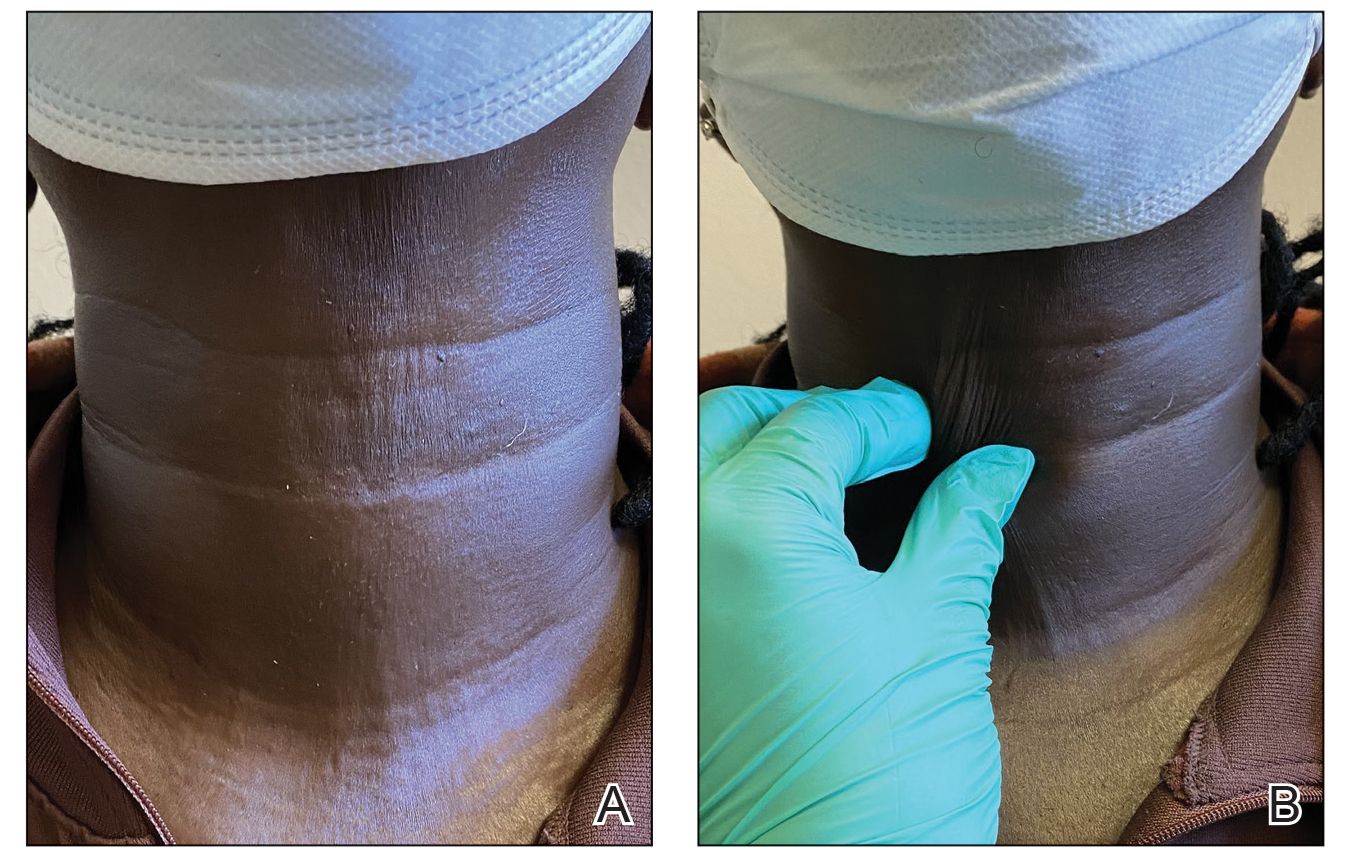

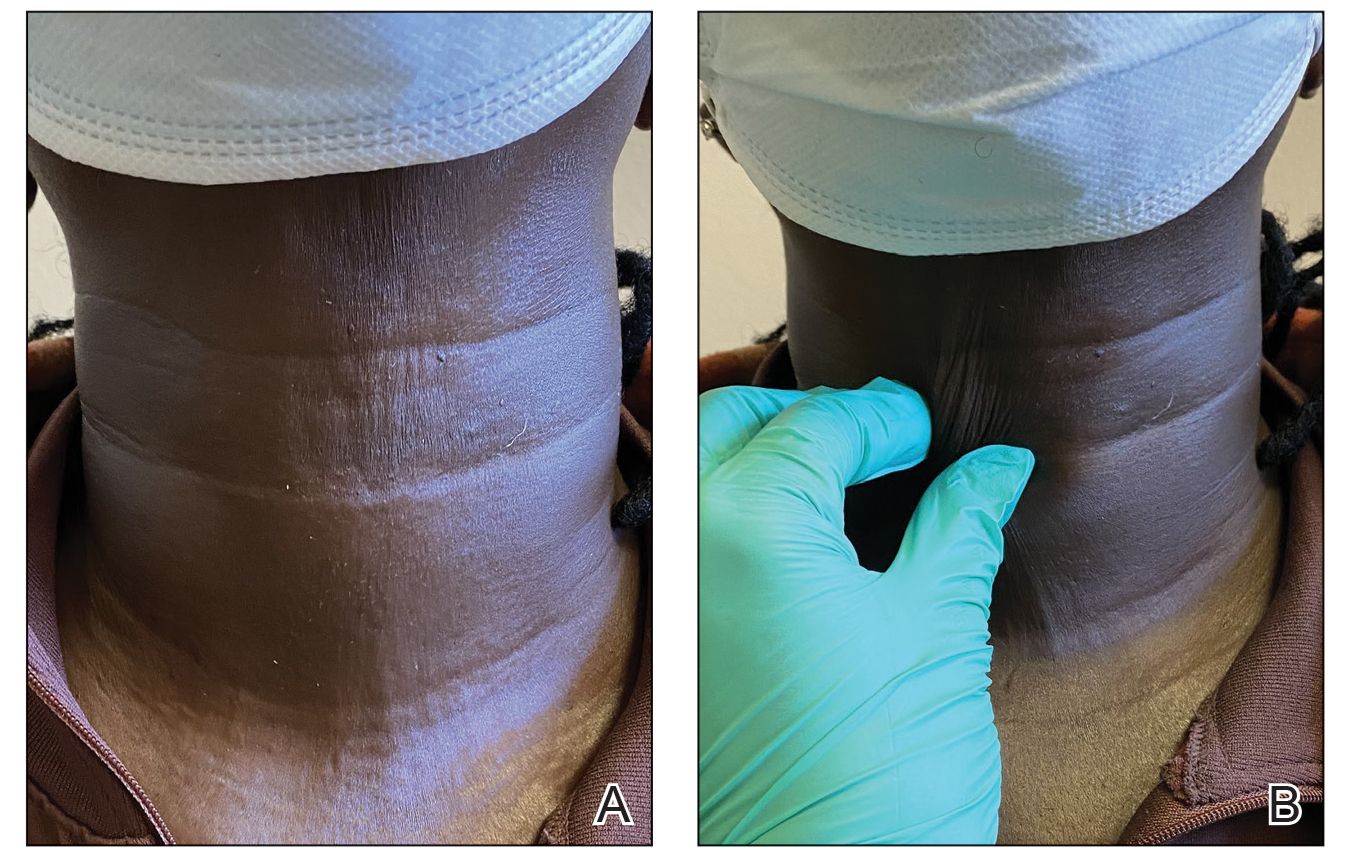

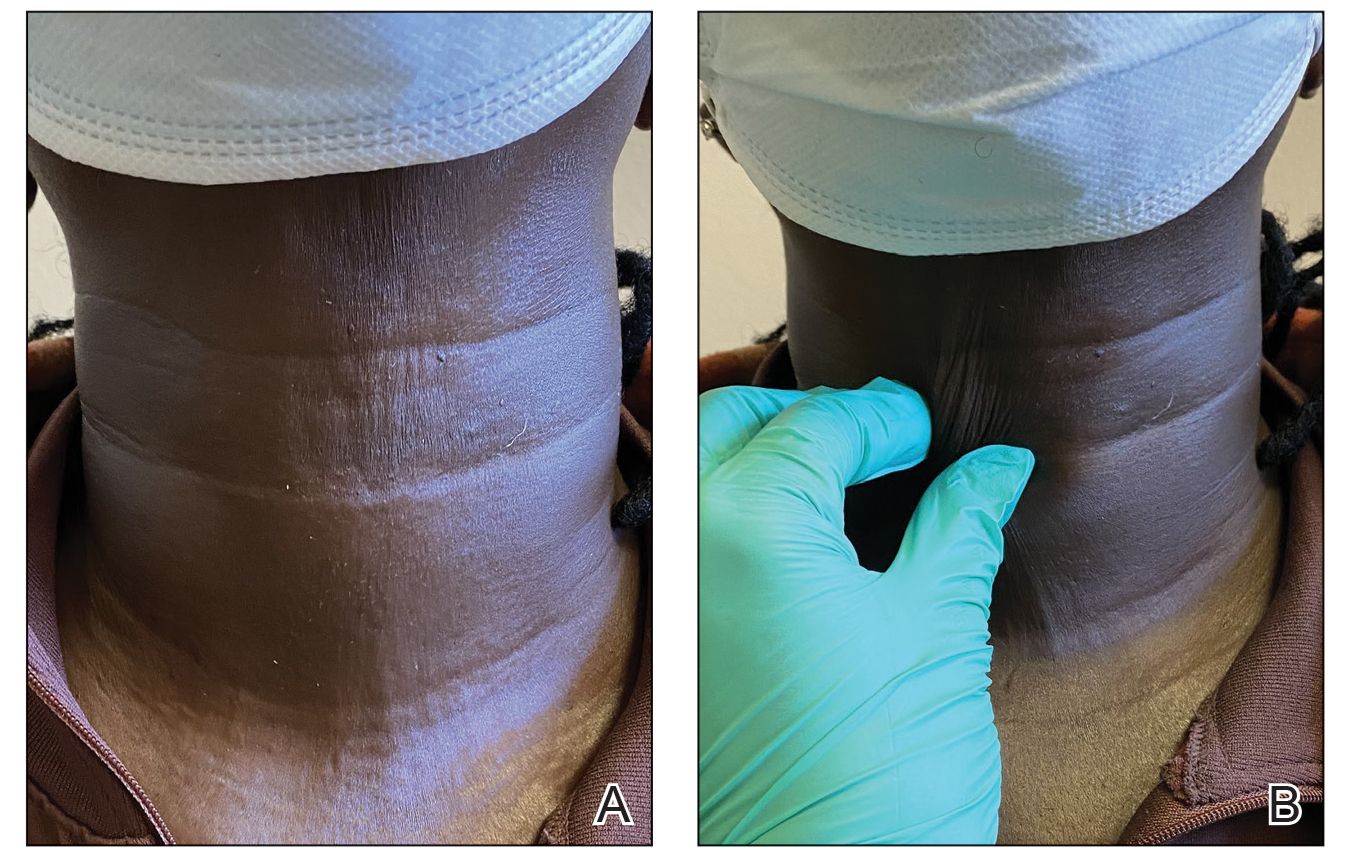

A 44-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic for treatment of thickened neck skin with stiffness and tightness that had been present for months to years. She had a history of mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD)(positive anti-ribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen, and anti-Smith antibodies) with features of scleroderma and polyarthritis. The patient currently was taking sulfasalazine for the polyarthritis; she previously had taken hydroxychloroquine but discontinued treatment due to ineffectiveness. She was not taking any topical or systemic medications for scleroderma. On physical examination, the skin on the anterior neck appeared thickened with shiny patches (Figure 1). Pinching the skin in the affected area demonstrated sclerosis with high tension.

The dermatologist (J.J.) discussed potential treatment options to help relax the tension in the skin of the anterior neck, including BTX injections. After receiving counsel on adverse effects, alternative treatments, and postprocedural care, the patient decided to proceed with the procedure. The anterior neck was cleansed with an alcohol swab and 37 units (range, 25–50 units) of incobotulinumtoxinA (reconstituted using 2.5-mL bacteriostatic normal saline per 100 units) was injected transdermally using a 9-point injection technique, with each injection placed approximately 1 cm apart. The approximate treatment area included the space between the sternocleidomastoid anterior edges and below the hyoid bone up to the cricothyroid membrane (anatomic zone II).

When the patient returned for follow-up 3 weeks later, she reported considerable improvement in the stiffness and appearance of the skin on the anterior neck. On physical examination, the skin of the neck appeared softened, and improved laxity was seen on pinching the skin compared to the initial presentation (Figure 2). The patient expressed satisfaction with the results and denied any adverse events following the procedure.

Mixed connective tissue disease manifests with a combination of features from various disorders—mainly lupus, scleroderma, polymyositis, and rheumatoid arthritis. It is most prevalent in females and often is diagnosed in the third decade of life.3 It is associated with positive antinuclear antibodies and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) II alleles (HLA-DR4, HLA-DR1, and HLA-DR2). Raynaud phenomenon (RP), one of the most common skin manifestations in both scleroderma and MCTD, is present in 75% to 90% of patients with MCTD.3

Scleroderma is a chronic connective tissue disorder that results in excessive collagen deposition in the skin and other organs throughout the body.4 Although the etiology is unknown, scleroderma develops when overactivation of the immune system leads to CD4+ T-lymphocyte infiltration in the skin, along with the release of profibrotic interleukins and growth factors, resulting in fibrosis.4 Subtypes include localized scleroderma (morphea), limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (formerly known as CREST [calcinosis, RP, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia] syndrome), diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis, and systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma.5 Scleroderma is associated with positive antinuclear antibodies and HLA II alleles (HLA-DR2 and HLA-DR5).