User login

Apremilast Treatment Outcomes and Adverse Events in Psoriasis Patients With HIV

Apremilast Treatment Outcomes and Adverse Events in Psoriasis Patients With HIV

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that affects 1% to 3% of the global population.1,2 Due to dysregulation of the immune system, patients with HIV who have concurrent moderate to severe psoriasis present a clinical therapeutic challenge for dermatologists. Recent guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology recommended avoiding certain systemic treatments (eg, methotrexate, cyclosporine) in patients who are HIV positive due to their immunosuppressive effects, as well as cautious use of certain biologics in populations with HIV.3 Traditional therapies for managing psoriasis in patients with HIV have included topical agents, antiretroviral therapy (ART), phototherapy, and acitretin; however, phototherapy can be logistically cumbersome for patients, and in the setting of ART, acitretin has the potential to exacerbate hypertriglyceridemia as well as other undesirable adverse effects.3

Apremilast is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that has emerged as a promising alternative in patients with HIV who require treatment for psoriasis. It has demonstrated clinical efficacy in psoriasis and has minimal immunosuppressive risk.4 Despite its potential in this population, reports of apremilast used in patients who are HIV positive are rare, and these patients often are excluded from larges studies. In this study, we reviewed the literature to evaluate outcomes and adverse events in patients with HIV who underwent psoriasis treatment with apremilast.

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE from the inception of the database through January 2023 was conducted using the terms psoriasis, human immunodeficiency virus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, therapy, apremilast, and adverse events. The inclusion criteria were articles that reported patients with HIV and psoriasis undergoing treatment with apremilast with subsequent follow-up to delineate potential outcomes and adverse effects. Non–English language articles were excluded.

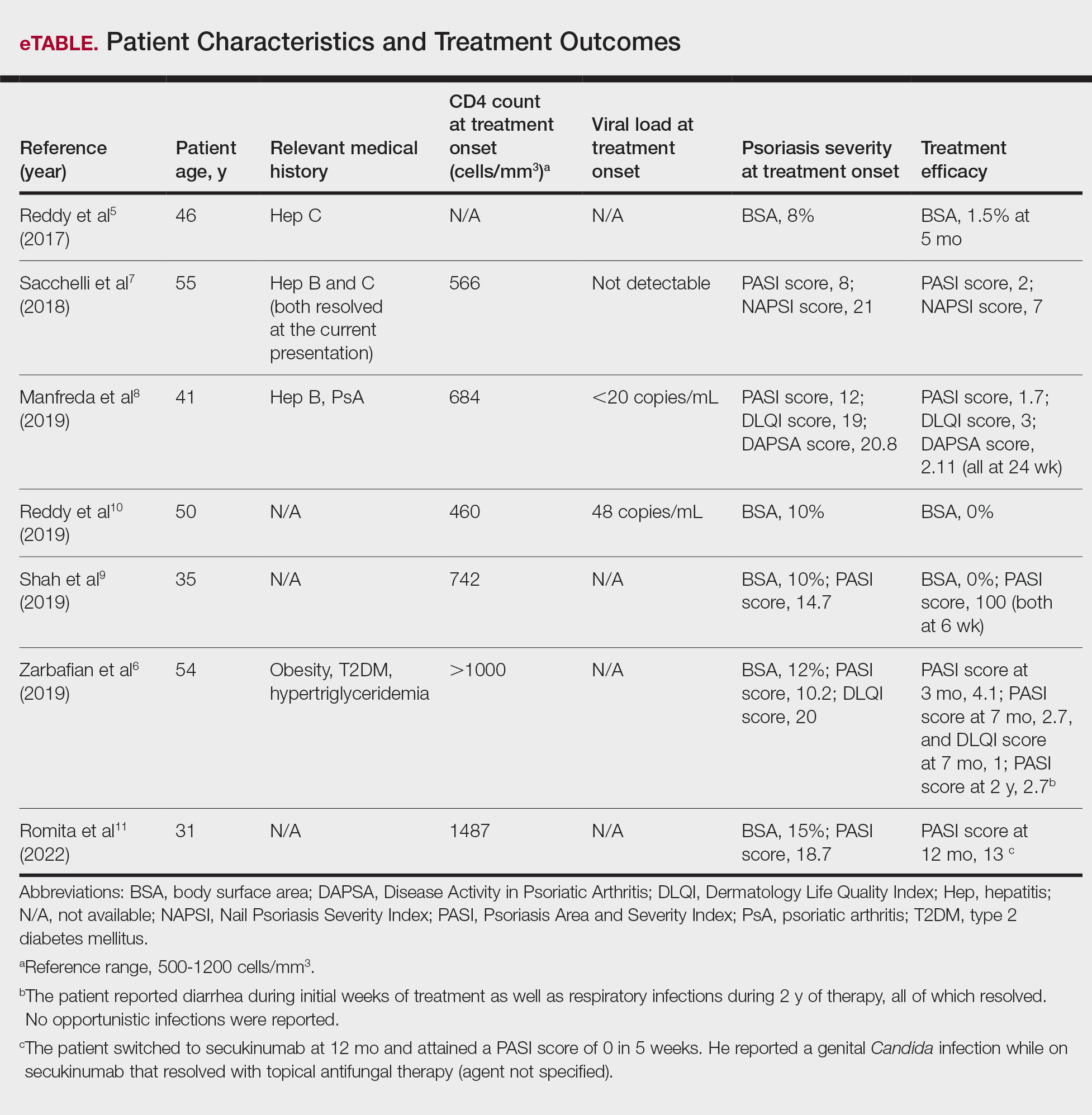

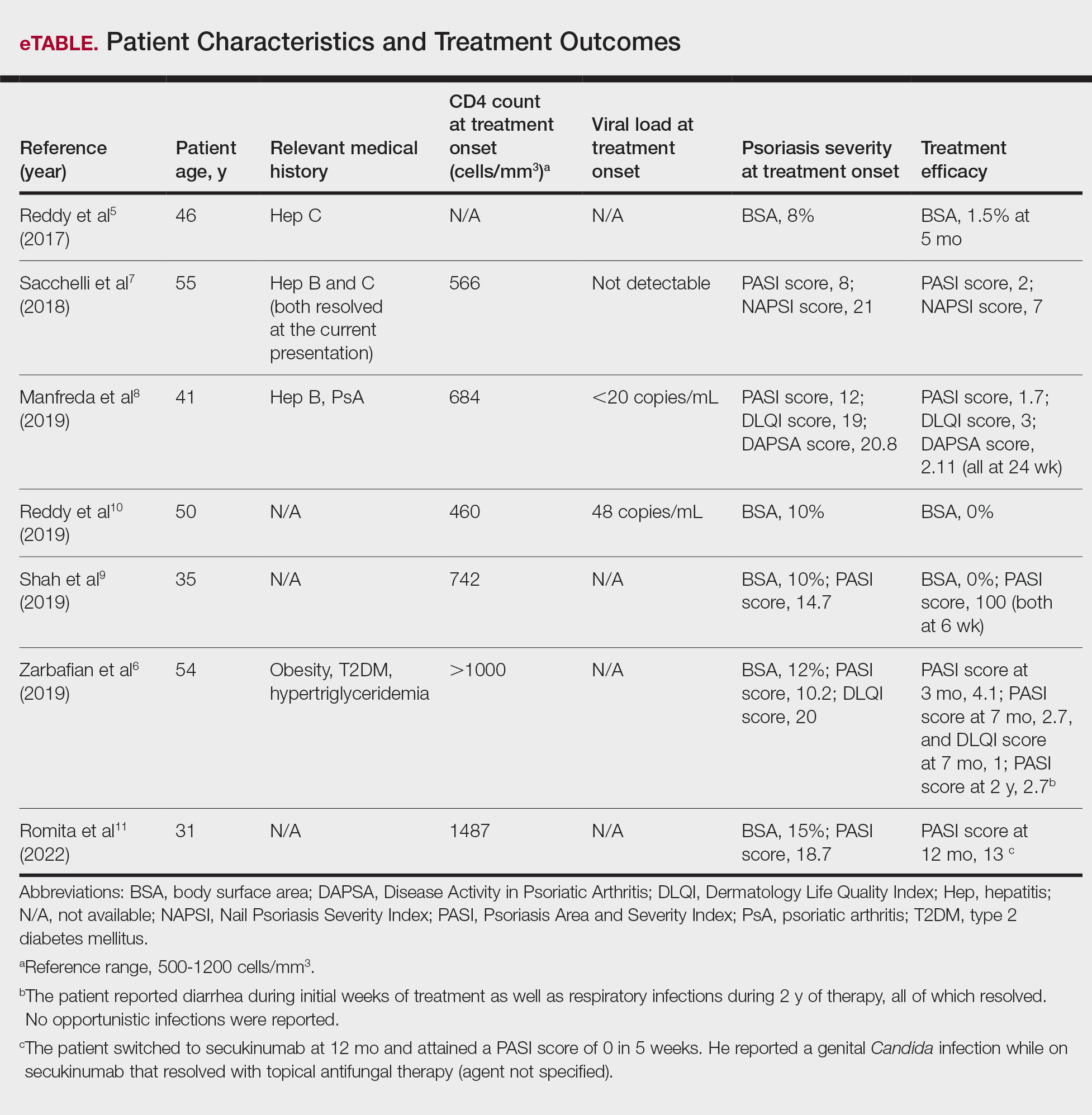

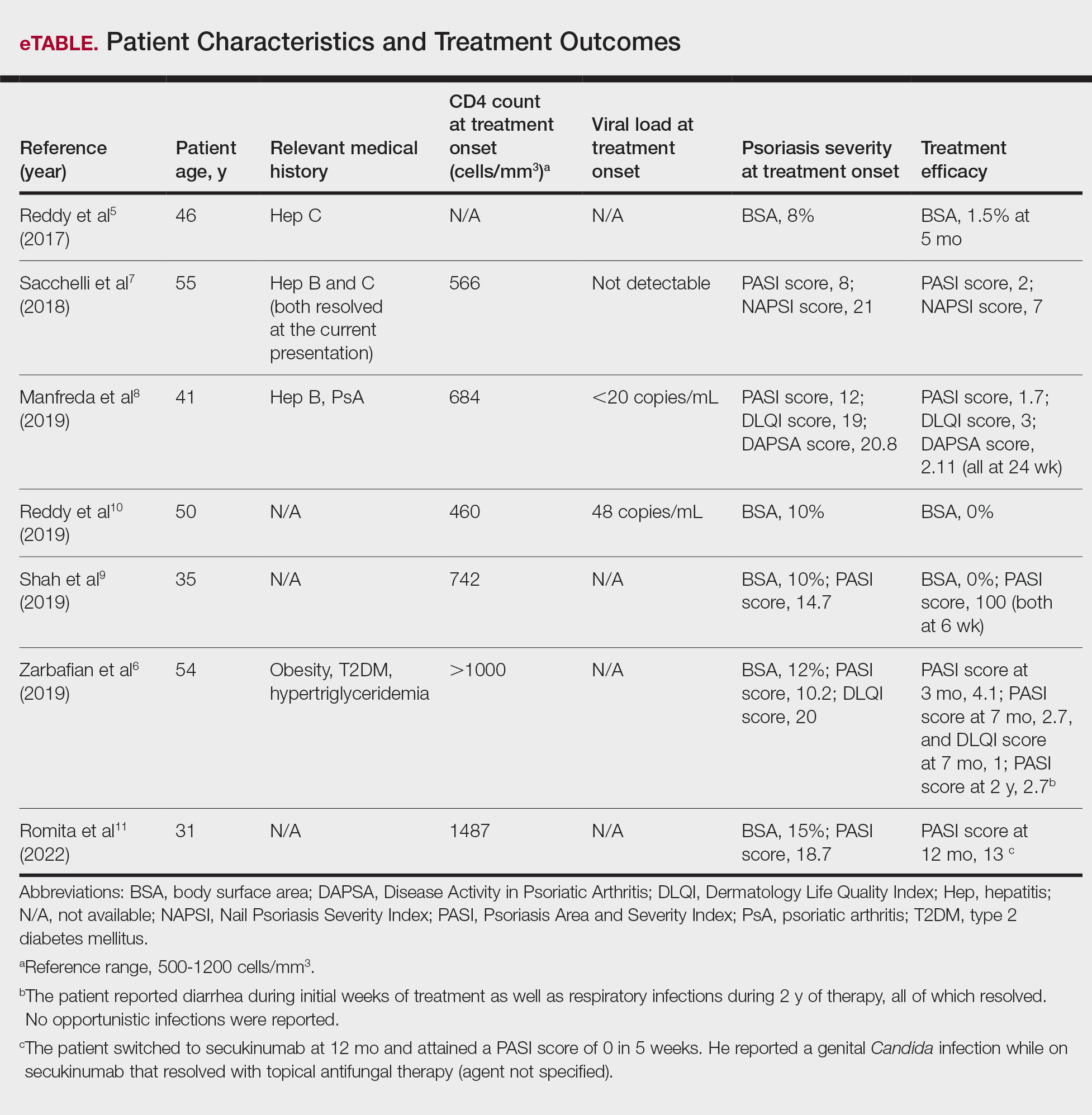

Our search of the literature yielded 7 patients with HIV and psoriasis who were treated with apremilast (eTable).5-11 All of the patients were male and ranged in age from 31 to 55 years, and all had pretreatment CD4 cell counts greater than 450 cells/mm3. All but 1 patient were confirmed to have undergone ART prior to treatment with apremilast, and all were treated using the traditional apremilast titration from 10 mg to 30 mg orally twice daily.

The mean pretreatment Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score in the patients we evaluated was 12.2, with an average reduction in PASI score of 9.3. This equated to achievement of PASI 75 or greater (ie, representing at least a 75% improvement in psoriasis) in 4 (57.1%) patients, with clinical improvement confirmed in all 7 patients (100.0%)(eTable). The average follow-up time was 9.7 months (range, 6 weeks to 24 months). Only 1 (14.3%) patient experienced any adverse effects, which included self-resolving diarrhea and respiratory infections (nonopportunistic) over a follow-up period of 2 years.6 Of note, gastrointestinal upset is common with apremilast and usually improves over time.12

Apremilast represents a safe and effective alternative systemic therapy for patients with HIV and psoriasis.4 As a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, apremilast leads to increased levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which restores an equilibrium between proinflammatory (eg, tumor necrosis factors, interferons, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23) and anti-inflammatory (eg, IL-10) cytokines.13 Unlike most biologics that target and inhibit a specific proinflammatory cytokine, apremilast’s homeostatic mechanism may explain its minimal immunosuppressive adverse effects.

In the majority of patients we evaluated, initiation of apremilast led to documented clinical improvement. It is worth noting that some patients presented with a relevant medical history and/or comorbidities such as hepatitis and metabolic conditions (eg, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia). Despite these comorbidities, initiation of apremilast therapy in these patients led to clinical improvement of psoriasis overall. Notable cases from our study included a 41-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis B and psoriatic arthritis who achieved PASI 90 after 24 weeks of apremilast therapy8; a 46-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis C who went from 8% to 1.5% body surface area affected after 5 months of treatment with apremilast5; and a 54-year-old man with concurrent obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertriglyceridemia who went from a PASI score of 10.2 to 4.1 after 3 months of apremilast treatment and maintained a PASI score of 2.7 at 2 years’ follow up (eTable).6

Limitations of this study included the small sample size and homogeneous demographic consisting only of adult males, which restrict the external validity of the findings. Despite limitations, apremilast was utilized effectively for patients with both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. The observed effectiveness of apremilast in multiple forms of psoriasis provides valuable insights into the drug’s versatility in this patient population.

The use of apremilast for treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV represents an important therapeutic development. Its effectiveness in reducing psoriasis symptoms in these immunocompromised patients makes it a viable alternative to traditional systemic therapies that might be contraindicated in this population. While larger studies would be ideal, the exclusion of patients with HIV from clinical trials presents an obstacle and therefore makes case series and reviews helpful for clinicians in bridging the gap with respect to treatment options for these patients. Apremilast may be a safe and effective medication for patients with HIV and psoriasis who require systemic therapy to treat their skin disease.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

- Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43-53. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.056

- Crowley J, Thaci D, Joly P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of apremilast in patients with psoriasis: pooled safety analysis for >156 weeks from 2 phase 3, randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:310-317.e1.

- Reddy SP, Shah VV, Wu JJ. Apremilast for a psoriasis patient with HIV and hepatitis C. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E481-E482. doi:10.1111/jdv.14301

- Zarbafian M, Cote B, Richer V. Treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with apremilast over 2 years in the context of long-term treated HIV infection: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19845193. doi:10.1177/2050313X19845193 doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.052

- Sacchelli L, Patrizi A, Ferrara F, et al. Apremilast as therapeutic option in a HIV positive patient with severe psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12719. doi:10.1111/dth.12719

- Manfreda V, Esposito M, Campione E, et al. Apremilast efficacy and safety in a psoriatic arthritis patient affected by HIV and HBV virus infections. Postgrad Med. 2019;131:239-240. doi:10.1080/00325481.2019 .1575613

- Shah BJ, Mistry D, Chaudhary N. Apremilast in people living with HIV with psoriasis vulgaris: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:242- 244. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_633_18

- Reddy SP, Lee E, Wu JJ. Apremilast and phototherapy for treatment of psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2019;103:E6-E7.

- Romita P, Foti C, Calianno G, et al. Successful treatment with secukinumab in an HIV-positive psoriatic patient after failure of apremilast. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15610. doi:10.1111/dth.15610

- Zeb L, Mhaskar R, Lewis S, et al. Real-world drug survival and reasons for treatment discontinuation of biologics and apremilast in patients with psoriasis in an academic center. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14826. doi:10.1111/dth.14826

- Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1583-1590. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.001

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that affects 1% to 3% of the global population.1,2 Due to dysregulation of the immune system, patients with HIV who have concurrent moderate to severe psoriasis present a clinical therapeutic challenge for dermatologists. Recent guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology recommended avoiding certain systemic treatments (eg, methotrexate, cyclosporine) in patients who are HIV positive due to their immunosuppressive effects, as well as cautious use of certain biologics in populations with HIV.3 Traditional therapies for managing psoriasis in patients with HIV have included topical agents, antiretroviral therapy (ART), phototherapy, and acitretin; however, phototherapy can be logistically cumbersome for patients, and in the setting of ART, acitretin has the potential to exacerbate hypertriglyceridemia as well as other undesirable adverse effects.3

Apremilast is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that has emerged as a promising alternative in patients with HIV who require treatment for psoriasis. It has demonstrated clinical efficacy in psoriasis and has minimal immunosuppressive risk.4 Despite its potential in this population, reports of apremilast used in patients who are HIV positive are rare, and these patients often are excluded from larges studies. In this study, we reviewed the literature to evaluate outcomes and adverse events in patients with HIV who underwent psoriasis treatment with apremilast.

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE from the inception of the database through January 2023 was conducted using the terms psoriasis, human immunodeficiency virus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, therapy, apremilast, and adverse events. The inclusion criteria were articles that reported patients with HIV and psoriasis undergoing treatment with apremilast with subsequent follow-up to delineate potential outcomes and adverse effects. Non–English language articles were excluded.

Our search of the literature yielded 7 patients with HIV and psoriasis who were treated with apremilast (eTable).5-11 All of the patients were male and ranged in age from 31 to 55 years, and all had pretreatment CD4 cell counts greater than 450 cells/mm3. All but 1 patient were confirmed to have undergone ART prior to treatment with apremilast, and all were treated using the traditional apremilast titration from 10 mg to 30 mg orally twice daily.

The mean pretreatment Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score in the patients we evaluated was 12.2, with an average reduction in PASI score of 9.3. This equated to achievement of PASI 75 or greater (ie, representing at least a 75% improvement in psoriasis) in 4 (57.1%) patients, with clinical improvement confirmed in all 7 patients (100.0%)(eTable). The average follow-up time was 9.7 months (range, 6 weeks to 24 months). Only 1 (14.3%) patient experienced any adverse effects, which included self-resolving diarrhea and respiratory infections (nonopportunistic) over a follow-up period of 2 years.6 Of note, gastrointestinal upset is common with apremilast and usually improves over time.12

Apremilast represents a safe and effective alternative systemic therapy for patients with HIV and psoriasis.4 As a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, apremilast leads to increased levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which restores an equilibrium between proinflammatory (eg, tumor necrosis factors, interferons, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23) and anti-inflammatory (eg, IL-10) cytokines.13 Unlike most biologics that target and inhibit a specific proinflammatory cytokine, apremilast’s homeostatic mechanism may explain its minimal immunosuppressive adverse effects.

In the majority of patients we evaluated, initiation of apremilast led to documented clinical improvement. It is worth noting that some patients presented with a relevant medical history and/or comorbidities such as hepatitis and metabolic conditions (eg, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia). Despite these comorbidities, initiation of apremilast therapy in these patients led to clinical improvement of psoriasis overall. Notable cases from our study included a 41-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis B and psoriatic arthritis who achieved PASI 90 after 24 weeks of apremilast therapy8; a 46-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis C who went from 8% to 1.5% body surface area affected after 5 months of treatment with apremilast5; and a 54-year-old man with concurrent obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertriglyceridemia who went from a PASI score of 10.2 to 4.1 after 3 months of apremilast treatment and maintained a PASI score of 2.7 at 2 years’ follow up (eTable).6

Limitations of this study included the small sample size and homogeneous demographic consisting only of adult males, which restrict the external validity of the findings. Despite limitations, apremilast was utilized effectively for patients with both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. The observed effectiveness of apremilast in multiple forms of psoriasis provides valuable insights into the drug’s versatility in this patient population.

The use of apremilast for treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV represents an important therapeutic development. Its effectiveness in reducing psoriasis symptoms in these immunocompromised patients makes it a viable alternative to traditional systemic therapies that might be contraindicated in this population. While larger studies would be ideal, the exclusion of patients with HIV from clinical trials presents an obstacle and therefore makes case series and reviews helpful for clinicians in bridging the gap with respect to treatment options for these patients. Apremilast may be a safe and effective medication for patients with HIV and psoriasis who require systemic therapy to treat their skin disease.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that affects 1% to 3% of the global population.1,2 Due to dysregulation of the immune system, patients with HIV who have concurrent moderate to severe psoriasis present a clinical therapeutic challenge for dermatologists. Recent guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology recommended avoiding certain systemic treatments (eg, methotrexate, cyclosporine) in patients who are HIV positive due to their immunosuppressive effects, as well as cautious use of certain biologics in populations with HIV.3 Traditional therapies for managing psoriasis in patients with HIV have included topical agents, antiretroviral therapy (ART), phototherapy, and acitretin; however, phototherapy can be logistically cumbersome for patients, and in the setting of ART, acitretin has the potential to exacerbate hypertriglyceridemia as well as other undesirable adverse effects.3

Apremilast is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that has emerged as a promising alternative in patients with HIV who require treatment for psoriasis. It has demonstrated clinical efficacy in psoriasis and has minimal immunosuppressive risk.4 Despite its potential in this population, reports of apremilast used in patients who are HIV positive are rare, and these patients often are excluded from larges studies. In this study, we reviewed the literature to evaluate outcomes and adverse events in patients with HIV who underwent psoriasis treatment with apremilast.

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE from the inception of the database through January 2023 was conducted using the terms psoriasis, human immunodeficiency virus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, therapy, apremilast, and adverse events. The inclusion criteria were articles that reported patients with HIV and psoriasis undergoing treatment with apremilast with subsequent follow-up to delineate potential outcomes and adverse effects. Non–English language articles were excluded.

Our search of the literature yielded 7 patients with HIV and psoriasis who were treated with apremilast (eTable).5-11 All of the patients were male and ranged in age from 31 to 55 years, and all had pretreatment CD4 cell counts greater than 450 cells/mm3. All but 1 patient were confirmed to have undergone ART prior to treatment with apremilast, and all were treated using the traditional apremilast titration from 10 mg to 30 mg orally twice daily.

The mean pretreatment Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score in the patients we evaluated was 12.2, with an average reduction in PASI score of 9.3. This equated to achievement of PASI 75 or greater (ie, representing at least a 75% improvement in psoriasis) in 4 (57.1%) patients, with clinical improvement confirmed in all 7 patients (100.0%)(eTable). The average follow-up time was 9.7 months (range, 6 weeks to 24 months). Only 1 (14.3%) patient experienced any adverse effects, which included self-resolving diarrhea and respiratory infections (nonopportunistic) over a follow-up period of 2 years.6 Of note, gastrointestinal upset is common with apremilast and usually improves over time.12

Apremilast represents a safe and effective alternative systemic therapy for patients with HIV and psoriasis.4 As a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, apremilast leads to increased levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which restores an equilibrium between proinflammatory (eg, tumor necrosis factors, interferons, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23) and anti-inflammatory (eg, IL-10) cytokines.13 Unlike most biologics that target and inhibit a specific proinflammatory cytokine, apremilast’s homeostatic mechanism may explain its minimal immunosuppressive adverse effects.

In the majority of patients we evaluated, initiation of apremilast led to documented clinical improvement. It is worth noting that some patients presented with a relevant medical history and/or comorbidities such as hepatitis and metabolic conditions (eg, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia). Despite these comorbidities, initiation of apremilast therapy in these patients led to clinical improvement of psoriasis overall. Notable cases from our study included a 41-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis B and psoriatic arthritis who achieved PASI 90 after 24 weeks of apremilast therapy8; a 46-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis C who went from 8% to 1.5% body surface area affected after 5 months of treatment with apremilast5; and a 54-year-old man with concurrent obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertriglyceridemia who went from a PASI score of 10.2 to 4.1 after 3 months of apremilast treatment and maintained a PASI score of 2.7 at 2 years’ follow up (eTable).6

Limitations of this study included the small sample size and homogeneous demographic consisting only of adult males, which restrict the external validity of the findings. Despite limitations, apremilast was utilized effectively for patients with both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. The observed effectiveness of apremilast in multiple forms of psoriasis provides valuable insights into the drug’s versatility in this patient population.

The use of apremilast for treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV represents an important therapeutic development. Its effectiveness in reducing psoriasis symptoms in these immunocompromised patients makes it a viable alternative to traditional systemic therapies that might be contraindicated in this population. While larger studies would be ideal, the exclusion of patients with HIV from clinical trials presents an obstacle and therefore makes case series and reviews helpful for clinicians in bridging the gap with respect to treatment options for these patients. Apremilast may be a safe and effective medication for patients with HIV and psoriasis who require systemic therapy to treat their skin disease.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

- Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43-53. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.056

- Crowley J, Thaci D, Joly P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of apremilast in patients with psoriasis: pooled safety analysis for >156 weeks from 2 phase 3, randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:310-317.e1.

- Reddy SP, Shah VV, Wu JJ. Apremilast for a psoriasis patient with HIV and hepatitis C. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E481-E482. doi:10.1111/jdv.14301

- Zarbafian M, Cote B, Richer V. Treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with apremilast over 2 years in the context of long-term treated HIV infection: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19845193. doi:10.1177/2050313X19845193 doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.052

- Sacchelli L, Patrizi A, Ferrara F, et al. Apremilast as therapeutic option in a HIV positive patient with severe psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12719. doi:10.1111/dth.12719

- Manfreda V, Esposito M, Campione E, et al. Apremilast efficacy and safety in a psoriatic arthritis patient affected by HIV and HBV virus infections. Postgrad Med. 2019;131:239-240. doi:10.1080/00325481.2019 .1575613

- Shah BJ, Mistry D, Chaudhary N. Apremilast in people living with HIV with psoriasis vulgaris: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:242- 244. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_633_18

- Reddy SP, Lee E, Wu JJ. Apremilast and phototherapy for treatment of psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2019;103:E6-E7.

- Romita P, Foti C, Calianno G, et al. Successful treatment with secukinumab in an HIV-positive psoriatic patient after failure of apremilast. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15610. doi:10.1111/dth.15610

- Zeb L, Mhaskar R, Lewis S, et al. Real-world drug survival and reasons for treatment discontinuation of biologics and apremilast in patients with psoriasis in an academic center. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14826. doi:10.1111/dth.14826

- Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1583-1590. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.001

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

- Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43-53. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.056

- Crowley J, Thaci D, Joly P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of apremilast in patients with psoriasis: pooled safety analysis for >156 weeks from 2 phase 3, randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:310-317.e1.

- Reddy SP, Shah VV, Wu JJ. Apremilast for a psoriasis patient with HIV and hepatitis C. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E481-E482. doi:10.1111/jdv.14301

- Zarbafian M, Cote B, Richer V. Treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with apremilast over 2 years in the context of long-term treated HIV infection: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19845193. doi:10.1177/2050313X19845193 doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.052

- Sacchelli L, Patrizi A, Ferrara F, et al. Apremilast as therapeutic option in a HIV positive patient with severe psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12719. doi:10.1111/dth.12719

- Manfreda V, Esposito M, Campione E, et al. Apremilast efficacy and safety in a psoriatic arthritis patient affected by HIV and HBV virus infections. Postgrad Med. 2019;131:239-240. doi:10.1080/00325481.2019 .1575613

- Shah BJ, Mistry D, Chaudhary N. Apremilast in people living with HIV with psoriasis vulgaris: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:242- 244. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_633_18

- Reddy SP, Lee E, Wu JJ. Apremilast and phototherapy for treatment of psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2019;103:E6-E7.

- Romita P, Foti C, Calianno G, et al. Successful treatment with secukinumab in an HIV-positive psoriatic patient after failure of apremilast. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15610. doi:10.1111/dth.15610

- Zeb L, Mhaskar R, Lewis S, et al. Real-world drug survival and reasons for treatment discontinuation of biologics and apremilast in patients with psoriasis in an academic center. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14826. doi:10.1111/dth.14826

- Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1583-1590. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.001

Apremilast Treatment Outcomes and Adverse Events in Psoriasis Patients With HIV

Apremilast Treatment Outcomes and Adverse Events in Psoriasis Patients With HIV

PRACTICE POINT

- For patients with HIV who require systemic therapy for psoriasis, apremilast may provide an effective and safe therapeutic option, with minimal immunosuppressive adverse effects.

Ergonomics in Dermatologic Procedures: Mobility Exercises to Incorporate In and Out of the Office

Ergonomics in Dermatologic Procedures: Mobility Exercises to Incorporate In and Out of the Office

Practice Gap

Dermatology encompasses a wide range of procedures performed in both clinical and surgical settings. One comprehensive review of ergonomics in dermatologic surgery found a high prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries (MSIs).1 A survey conducted in 2010 revealed that 90% of dermatologic surgeons experienced MSIs, which commonly resulted in neck, shoulder, and/or back pain.2

Prolonged abnormal static postures and repetitive motions, which are common in dermatologic practice, can lead to muscle imbalances and focal muscular ischemia, increasing physicians’ susceptibility to MSIs. When muscle fibers experience enough repeated focal ischemia, they may enter a constant state of contraction leading to myofascial pain syndrome (MPS); these painful areas are known as trigger points and often are refractory to traditional stretching.3

Musculoskeletal injuries can potentially impact dermatologists’ career longevity and satisfaction. To date, the literature on techniques and exercises that may prevent or alleviate MSIs is limited.1,4 We collaborated with a colleague in physical therapy (R.P.) to present stretching, mobility, and strengthening techniques and exercises dermatologists can perform both in and outside the procedure room to potentially reduce pain and prevent future MSIs.

The Techniques

Stretching and Mobility Exercises—When dermatologists adopt abnormal static postures, they are at risk for muscular imbalances caused by repetitive flexion and/or rotation in one direction. Over time, these repetitive movements can result in loss of flexibility in the direction opposite to that in which they are consistently positioned.3 Regular stretching offers physiologic benefits such as maintaining joint range of motion, increasing blood flow to muscles, and increasing synovial fluid production—all of which contribute to reduced risk for MSIs.3 Multiple studies and a systematic review have found that regular stretching throughout the day serves as an effective method for preventing and mitigating MSI pain in health care providers.1,3-5

Considering the directional manner of MSIs induced by prolonged static positions, the most benefit will be derived from stretches or extension in the opposite direction of that in which the practitioner usually works. For most dermatologic surgeons, stretches should target the trapezius muscles, shoulders, and cervical musculature. Techniques such as the neck and shoulder combination stretch, the upper trapezius stretch, and the downward shoulder blade squeeze stretch can be performed regularly throughout the day.3,4 To perform the neck and shoulder combination stretch, place the arm in flexion to shoulder height and bend the elbow at a 90° angle. Gently pull the arm across the front of the body, point the head gazing in the direction of the shoulder being stretched, and hold for 10 to 20 seconds. Repeat with the other side (eFigure 1).

Some surgeons may experience pain that is refractory to stretching, potentially indicating the presence of MPS.3 Managing MPS via stretching alone may be a challenge. Physical therapists utilize various techniques to manually massage the tissue, but self-myofascial release—which involves the use of a tool such as a dense foam roller or massage ball, both of which can easily be purchased—may be convenient and effective for busy providers. To perform this technique, the operator lies with their back on a dense foam roller positioned perpendicular to the body and uses their legs to undulate or roll back and forth in a smooth motion (Figure 1). This may help to alleviate myofascial pain in the spinal intrinsic muscles, which often are prone to injury due to posture; it also warms the fascia and breaks up adhesions. Self-myofascial release may have similar acute analgesic effects to classic stretching while also helping to alleviate MPS.

Strengthening Exercises—Musculoskeletal injuries often begin with fatigue in postural stabilizing muscles of the trunk and shoulders, leading the dermatologist to assume a slouched posture. Dermatologists should perform strengthening exercises targeting the trunk and shoulder girdle, which help to promote good working posture while optimizing the function of the arms and hands. Ideally, dermatologists should incorporate strengthening exercises 3 to 4 times per week in combination with daily stretching.

The 4-point kneeling alternate arm and leg extensions technique targets many muscle groups that commonly are affected in dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons. While on all fours, the operator positions the hands under the shoulders and the knees under the hips. The neck remains in line with the back with the eyes facing the floor. The abdominal muscles are then pulled up and in while simultaneously extending the left arm and right leg until both are parallel to the floor. This position should be held for 5 seconds and then repeated with the opposite contralateral extremities (Figure 2). Exercises specific to each muscle group also can be performed, such as planks to enhance truncal stability or scapular wall clocks to strengthen the shoulder girdle (eFigure 2). To perform scapular wall clocks, wrap a single resistance band around both wrists. Next, press the hands and elbows gently into a wall pointing superiorly and imagine there is a clock on the wall with 12 o’clock at the top and 6 o’clock at the bottom. Press the wrists outward on the band, keep the elbows straight, and reach out with the right hand while keeping the left hand stable. Move the right hand to the 1-, 3-, and 5-o’clock positions. Repeat with the left hand while holding the right hand stable. Move the left hand to the 11-, 9-, 7-, and 6-o’clock positions. Repeat these steps for 3 to 5 sets.

It is important to note that a decreased flow of oxygen and nutrients to muscles contributes to MSIs. Aerobic exercises increase blood flow and improve the ability of the muscles to utilize oxygen. Engaging in an enjoyable aerobic activity (eg, walking, running, swimming, cycling) 3 to 4 times per week can help prevent MSIs; however, as with any new exercise regimen (including the strengthening techniques described here), it is important to consult your primary care physician before getting started.

Practice Implications

As dermatologists progress in their careers, implementation of these techniques can mitigate MSIs and their sequelae. The long-term benefits of stretching, mobility, and strengthening exercises are dependent on having ergonomically suitable environmental factors. In addition to their own mechanics and posture, dermatologists must consider all elements that may affect the ergonomics of their daily practice, including operating room layout, instrumentation and workflow, and patient positioning. Through a consistent approach to prevention using the techniques described here, dermatologists can minimize the risk for MSIs and foster sustainability in their careers.

- Chan J, Kim DJ, Kassira-Carley S, et al. Ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: lessons learned across related specialties and opportunities for improvement. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:763-772. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000002295

- Liang CA, Levine VJ, Dusza SW, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: a survey of Mohs surgeons in 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:240-248. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02237.x

- Valachi B, Valachi K. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry: strategies to address the mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1604-1612. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0106

- Carley SK, Strauss JD, Vidal NY. Ergonomic solutions for dermatologists. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(5 part B):863-866. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.08.006

- da Costa BR, Vieira ER. Stretching to reduce work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:321-328. doi:10.2340/16501977-0204

Practice Gap

Dermatology encompasses a wide range of procedures performed in both clinical and surgical settings. One comprehensive review of ergonomics in dermatologic surgery found a high prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries (MSIs).1 A survey conducted in 2010 revealed that 90% of dermatologic surgeons experienced MSIs, which commonly resulted in neck, shoulder, and/or back pain.2

Prolonged abnormal static postures and repetitive motions, which are common in dermatologic practice, can lead to muscle imbalances and focal muscular ischemia, increasing physicians’ susceptibility to MSIs. When muscle fibers experience enough repeated focal ischemia, they may enter a constant state of contraction leading to myofascial pain syndrome (MPS); these painful areas are known as trigger points and often are refractory to traditional stretching.3

Musculoskeletal injuries can potentially impact dermatologists’ career longevity and satisfaction. To date, the literature on techniques and exercises that may prevent or alleviate MSIs is limited.1,4 We collaborated with a colleague in physical therapy (R.P.) to present stretching, mobility, and strengthening techniques and exercises dermatologists can perform both in and outside the procedure room to potentially reduce pain and prevent future MSIs.

The Techniques

Stretching and Mobility Exercises—When dermatologists adopt abnormal static postures, they are at risk for muscular imbalances caused by repetitive flexion and/or rotation in one direction. Over time, these repetitive movements can result in loss of flexibility in the direction opposite to that in which they are consistently positioned.3 Regular stretching offers physiologic benefits such as maintaining joint range of motion, increasing blood flow to muscles, and increasing synovial fluid production—all of which contribute to reduced risk for MSIs.3 Multiple studies and a systematic review have found that regular stretching throughout the day serves as an effective method for preventing and mitigating MSI pain in health care providers.1,3-5

Considering the directional manner of MSIs induced by prolonged static positions, the most benefit will be derived from stretches or extension in the opposite direction of that in which the practitioner usually works. For most dermatologic surgeons, stretches should target the trapezius muscles, shoulders, and cervical musculature. Techniques such as the neck and shoulder combination stretch, the upper trapezius stretch, and the downward shoulder blade squeeze stretch can be performed regularly throughout the day.3,4 To perform the neck and shoulder combination stretch, place the arm in flexion to shoulder height and bend the elbow at a 90° angle. Gently pull the arm across the front of the body, point the head gazing in the direction of the shoulder being stretched, and hold for 10 to 20 seconds. Repeat with the other side (eFigure 1).

Some surgeons may experience pain that is refractory to stretching, potentially indicating the presence of MPS.3 Managing MPS via stretching alone may be a challenge. Physical therapists utilize various techniques to manually massage the tissue, but self-myofascial release—which involves the use of a tool such as a dense foam roller or massage ball, both of which can easily be purchased—may be convenient and effective for busy providers. To perform this technique, the operator lies with their back on a dense foam roller positioned perpendicular to the body and uses their legs to undulate or roll back and forth in a smooth motion (Figure 1). This may help to alleviate myofascial pain in the spinal intrinsic muscles, which often are prone to injury due to posture; it also warms the fascia and breaks up adhesions. Self-myofascial release may have similar acute analgesic effects to classic stretching while also helping to alleviate MPS.

Strengthening Exercises—Musculoskeletal injuries often begin with fatigue in postural stabilizing muscles of the trunk and shoulders, leading the dermatologist to assume a slouched posture. Dermatologists should perform strengthening exercises targeting the trunk and shoulder girdle, which help to promote good working posture while optimizing the function of the arms and hands. Ideally, dermatologists should incorporate strengthening exercises 3 to 4 times per week in combination with daily stretching.

The 4-point kneeling alternate arm and leg extensions technique targets many muscle groups that commonly are affected in dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons. While on all fours, the operator positions the hands under the shoulders and the knees under the hips. The neck remains in line with the back with the eyes facing the floor. The abdominal muscles are then pulled up and in while simultaneously extending the left arm and right leg until both are parallel to the floor. This position should be held for 5 seconds and then repeated with the opposite contralateral extremities (Figure 2). Exercises specific to each muscle group also can be performed, such as planks to enhance truncal stability or scapular wall clocks to strengthen the shoulder girdle (eFigure 2). To perform scapular wall clocks, wrap a single resistance band around both wrists. Next, press the hands and elbows gently into a wall pointing superiorly and imagine there is a clock on the wall with 12 o’clock at the top and 6 o’clock at the bottom. Press the wrists outward on the band, keep the elbows straight, and reach out with the right hand while keeping the left hand stable. Move the right hand to the 1-, 3-, and 5-o’clock positions. Repeat with the left hand while holding the right hand stable. Move the left hand to the 11-, 9-, 7-, and 6-o’clock positions. Repeat these steps for 3 to 5 sets.

It is important to note that a decreased flow of oxygen and nutrients to muscles contributes to MSIs. Aerobic exercises increase blood flow and improve the ability of the muscles to utilize oxygen. Engaging in an enjoyable aerobic activity (eg, walking, running, swimming, cycling) 3 to 4 times per week can help prevent MSIs; however, as with any new exercise regimen (including the strengthening techniques described here), it is important to consult your primary care physician before getting started.

Practice Implications

As dermatologists progress in their careers, implementation of these techniques can mitigate MSIs and their sequelae. The long-term benefits of stretching, mobility, and strengthening exercises are dependent on having ergonomically suitable environmental factors. In addition to their own mechanics and posture, dermatologists must consider all elements that may affect the ergonomics of their daily practice, including operating room layout, instrumentation and workflow, and patient positioning. Through a consistent approach to prevention using the techniques described here, dermatologists can minimize the risk for MSIs and foster sustainability in their careers.

Practice Gap

Dermatology encompasses a wide range of procedures performed in both clinical and surgical settings. One comprehensive review of ergonomics in dermatologic surgery found a high prevalence of musculoskeletal injuries (MSIs).1 A survey conducted in 2010 revealed that 90% of dermatologic surgeons experienced MSIs, which commonly resulted in neck, shoulder, and/or back pain.2

Prolonged abnormal static postures and repetitive motions, which are common in dermatologic practice, can lead to muscle imbalances and focal muscular ischemia, increasing physicians’ susceptibility to MSIs. When muscle fibers experience enough repeated focal ischemia, they may enter a constant state of contraction leading to myofascial pain syndrome (MPS); these painful areas are known as trigger points and often are refractory to traditional stretching.3

Musculoskeletal injuries can potentially impact dermatologists’ career longevity and satisfaction. To date, the literature on techniques and exercises that may prevent or alleviate MSIs is limited.1,4 We collaborated with a colleague in physical therapy (R.P.) to present stretching, mobility, and strengthening techniques and exercises dermatologists can perform both in and outside the procedure room to potentially reduce pain and prevent future MSIs.

The Techniques

Stretching and Mobility Exercises—When dermatologists adopt abnormal static postures, they are at risk for muscular imbalances caused by repetitive flexion and/or rotation in one direction. Over time, these repetitive movements can result in loss of flexibility in the direction opposite to that in which they are consistently positioned.3 Regular stretching offers physiologic benefits such as maintaining joint range of motion, increasing blood flow to muscles, and increasing synovial fluid production—all of which contribute to reduced risk for MSIs.3 Multiple studies and a systematic review have found that regular stretching throughout the day serves as an effective method for preventing and mitigating MSI pain in health care providers.1,3-5

Considering the directional manner of MSIs induced by prolonged static positions, the most benefit will be derived from stretches or extension in the opposite direction of that in which the practitioner usually works. For most dermatologic surgeons, stretches should target the trapezius muscles, shoulders, and cervical musculature. Techniques such as the neck and shoulder combination stretch, the upper trapezius stretch, and the downward shoulder blade squeeze stretch can be performed regularly throughout the day.3,4 To perform the neck and shoulder combination stretch, place the arm in flexion to shoulder height and bend the elbow at a 90° angle. Gently pull the arm across the front of the body, point the head gazing in the direction of the shoulder being stretched, and hold for 10 to 20 seconds. Repeat with the other side (eFigure 1).

Some surgeons may experience pain that is refractory to stretching, potentially indicating the presence of MPS.3 Managing MPS via stretching alone may be a challenge. Physical therapists utilize various techniques to manually massage the tissue, but self-myofascial release—which involves the use of a tool such as a dense foam roller or massage ball, both of which can easily be purchased—may be convenient and effective for busy providers. To perform this technique, the operator lies with their back on a dense foam roller positioned perpendicular to the body and uses their legs to undulate or roll back and forth in a smooth motion (Figure 1). This may help to alleviate myofascial pain in the spinal intrinsic muscles, which often are prone to injury due to posture; it also warms the fascia and breaks up adhesions. Self-myofascial release may have similar acute analgesic effects to classic stretching while also helping to alleviate MPS.

Strengthening Exercises—Musculoskeletal injuries often begin with fatigue in postural stabilizing muscles of the trunk and shoulders, leading the dermatologist to assume a slouched posture. Dermatologists should perform strengthening exercises targeting the trunk and shoulder girdle, which help to promote good working posture while optimizing the function of the arms and hands. Ideally, dermatologists should incorporate strengthening exercises 3 to 4 times per week in combination with daily stretching.

The 4-point kneeling alternate arm and leg extensions technique targets many muscle groups that commonly are affected in dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons. While on all fours, the operator positions the hands under the shoulders and the knees under the hips. The neck remains in line with the back with the eyes facing the floor. The abdominal muscles are then pulled up and in while simultaneously extending the left arm and right leg until both are parallel to the floor. This position should be held for 5 seconds and then repeated with the opposite contralateral extremities (Figure 2). Exercises specific to each muscle group also can be performed, such as planks to enhance truncal stability or scapular wall clocks to strengthen the shoulder girdle (eFigure 2). To perform scapular wall clocks, wrap a single resistance band around both wrists. Next, press the hands and elbows gently into a wall pointing superiorly and imagine there is a clock on the wall with 12 o’clock at the top and 6 o’clock at the bottom. Press the wrists outward on the band, keep the elbows straight, and reach out with the right hand while keeping the left hand stable. Move the right hand to the 1-, 3-, and 5-o’clock positions. Repeat with the left hand while holding the right hand stable. Move the left hand to the 11-, 9-, 7-, and 6-o’clock positions. Repeat these steps for 3 to 5 sets.

It is important to note that a decreased flow of oxygen and nutrients to muscles contributes to MSIs. Aerobic exercises increase blood flow and improve the ability of the muscles to utilize oxygen. Engaging in an enjoyable aerobic activity (eg, walking, running, swimming, cycling) 3 to 4 times per week can help prevent MSIs; however, as with any new exercise regimen (including the strengthening techniques described here), it is important to consult your primary care physician before getting started.

Practice Implications

As dermatologists progress in their careers, implementation of these techniques can mitigate MSIs and their sequelae. The long-term benefits of stretching, mobility, and strengthening exercises are dependent on having ergonomically suitable environmental factors. In addition to their own mechanics and posture, dermatologists must consider all elements that may affect the ergonomics of their daily practice, including operating room layout, instrumentation and workflow, and patient positioning. Through a consistent approach to prevention using the techniques described here, dermatologists can minimize the risk for MSIs and foster sustainability in their careers.

- Chan J, Kim DJ, Kassira-Carley S, et al. Ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: lessons learned across related specialties and opportunities for improvement. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:763-772. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000002295

- Liang CA, Levine VJ, Dusza SW, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: a survey of Mohs surgeons in 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:240-248. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02237.x

- Valachi B, Valachi K. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry: strategies to address the mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1604-1612. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0106

- Carley SK, Strauss JD, Vidal NY. Ergonomic solutions for dermatologists. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(5 part B):863-866. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.08.006

- da Costa BR, Vieira ER. Stretching to reduce work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:321-328. doi:10.2340/16501977-0204

- Chan J, Kim DJ, Kassira-Carley S, et al. Ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: lessons learned across related specialties and opportunities for improvement. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46:763-772. doi:10.1097 /DSS.0000000000002295

- Liang CA, Levine VJ, Dusza SW, et al. Musculoskeletal disorders and ergonomics in dermatologic surgery: a survey of Mohs surgeons in 2010. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:240-248. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02237.x

- Valachi B, Valachi K. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry: strategies to address the mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1604-1612. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0106

- Carley SK, Strauss JD, Vidal NY. Ergonomic solutions for dermatologists. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(5 part B):863-866. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.08.006

- da Costa BR, Vieira ER. Stretching to reduce work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:321-328. doi:10.2340/16501977-0204

Ergonomics in Dermatologic Procedures: Mobility Exercises to Incorporate In and Out of the Office

Ergonomics in Dermatologic Procedures: Mobility Exercises to Incorporate In and Out of the Office