User login

Ischemia Predicts Poor Functional Outcomes in Diabetic Foot Ulcers

PALM BEACH, Fla. - Neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers can be treated with revascularization, but successful surgery doesn't always translate into good long-term outcomes, a study has shown.

In the review of 917 such ulcers, the 219 revascularized lesions had no better healing or survival outcomes than that of ischemic wounds that were not revascularized, Dr. Spence Taylor said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association. Just 35% of the revascularized ulcers healed completely, and 32% of the patients eventually needed an amputation.

"Assessing this treatment, we must conclude that while revascularization is important to wound healing, favorable functional outcomes can't be assumed," said Dr. Taylor of the Greenville (S.C.) Hospital System. "This suggests that we should realign our financial incentives [away from procedures and] toward foot care and wound prevention, affording a better opportunity of prevention and preservation of functional outcomes."

Dr. Taylor and his colleagues presented a review of 917 limbs with new diabetic foot ulcers that occurred among 706 patients. Most of the patients (87%) had type 2 diabetes, and more than half (52%) were smokers. Other comorbidities included hyperlipidemia (53%), hypertension (90%), and end-stage renal disease (26%).

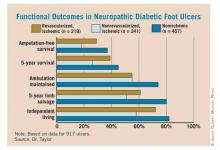

Of the 917 ulcers, 457 were nonischemic and 460 were ischemic. Of the ischemic lesions, 241 were not revascularized and 219 were – 137 by angioplasty and 82 by open surgery. Outcomes measured included primary healing, functional healing (defined as healing to clinical insignificance), limb salvage, amputation-free survival, 5-year survival, and maintenance of ambulation and independent living.

Overall, the data showed primary wound healing in 27%, functional healing in 53%, minor amputations in 28%, and major amputations in 20% of patients. The time to achieve healing was 7-8 months.

For patients with the revascularized ulcers, the 5-year survival rate was 39%, and 5-year limb salvage rate was 61%. The 5-year rate of amputation-free survival was 29%, while 55% of patients maintained ambulation and 72% maintained independent living at 5 years.

When the investigators compared the different groups (nonischemic, revascularized ischemic, and nonrevascularized ischemic), they found no significant differences in the rate of wound healing. But ischemia was a significant predictor of poor functional outcomes, which revascularization did not completely mitigate. "Ischemic patients had twice as many amputations and 50% higher mortality than nonischemic patients, whether they were revascularized or not. It was quite remarkable morbidity," Dr. Taylor said.

The presence of ischemia conferred a 26% increase in the risk of death by 5 years. Also, patients with end-stage renal disease were 2.5 times more likely to die than were those without. However, functional healing was associated with a 42% decreased risk of death.

Those same factors were independent predictors of amputation-free survival. Ischemia conferred a 57% increased risk of losing a limb, while end-stage renal disease doubled that risk. Functional healing, however, decreased the risk of amputation by 58%.

"Patients who were able to heal their wound significantly outperformed those who did not – not only for limb salvage and survival, which is intuitive, but also for amputation-free survival and maintenance of ambulation and independent living status, which is not intuitive," Dr. Taylor said. "The poorest outcomes were in ischemic nonrevascularized patients, whose 5-year mortality was 75% and amputation-free survival only 18% – as bad as any cancer outcomes presented at this meeting."

Conventional wisdom holds that patients who do have revascularization will almost always heal their ulcers. Therefore, Dr. Taylor said, reimbursement has been structured to favor surgical intervention rather than diabetic foot care and prevention.

"Reimbursement is very robust for procedures, while for wound care, it barely covers the cost, implying that revascularization does all the heavy lifting."

His review shows that this is not always the case. "Our functional outcomes were disappointing at best and really reflect an opportunity for improvement. Realigning the financial incentives toward foot wound care and prevention may give us a better opportunity to make these improvements."

Dr. Taylor had no financial disclosures.

PALM BEACH, Fla. - Neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers can be treated with revascularization, but successful surgery doesn't always translate into good long-term outcomes, a study has shown.

In the review of 917 such ulcers, the 219 revascularized lesions had no better healing or survival outcomes than that of ischemic wounds that were not revascularized, Dr. Spence Taylor said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association. Just 35% of the revascularized ulcers healed completely, and 32% of the patients eventually needed an amputation.

"Assessing this treatment, we must conclude that while revascularization is important to wound healing, favorable functional outcomes can't be assumed," said Dr. Taylor of the Greenville (S.C.) Hospital System. "This suggests that we should realign our financial incentives [away from procedures and] toward foot care and wound prevention, affording a better opportunity of prevention and preservation of functional outcomes."

Dr. Taylor and his colleagues presented a review of 917 limbs with new diabetic foot ulcers that occurred among 706 patients. Most of the patients (87%) had type 2 diabetes, and more than half (52%) were smokers. Other comorbidities included hyperlipidemia (53%), hypertension (90%), and end-stage renal disease (26%).

Of the 917 ulcers, 457 were nonischemic and 460 were ischemic. Of the ischemic lesions, 241 were not revascularized and 219 were – 137 by angioplasty and 82 by open surgery. Outcomes measured included primary healing, functional healing (defined as healing to clinical insignificance), limb salvage, amputation-free survival, 5-year survival, and maintenance of ambulation and independent living.

Overall, the data showed primary wound healing in 27%, functional healing in 53%, minor amputations in 28%, and major amputations in 20% of patients. The time to achieve healing was 7-8 months.

For patients with the revascularized ulcers, the 5-year survival rate was 39%, and 5-year limb salvage rate was 61%. The 5-year rate of amputation-free survival was 29%, while 55% of patients maintained ambulation and 72% maintained independent living at 5 years.

When the investigators compared the different groups (nonischemic, revascularized ischemic, and nonrevascularized ischemic), they found no significant differences in the rate of wound healing. But ischemia was a significant predictor of poor functional outcomes, which revascularization did not completely mitigate. "Ischemic patients had twice as many amputations and 50% higher mortality than nonischemic patients, whether they were revascularized or not. It was quite remarkable morbidity," Dr. Taylor said.

The presence of ischemia conferred a 26% increase in the risk of death by 5 years. Also, patients with end-stage renal disease were 2.5 times more likely to die than were those without. However, functional healing was associated with a 42% decreased risk of death.

Those same factors were independent predictors of amputation-free survival. Ischemia conferred a 57% increased risk of losing a limb, while end-stage renal disease doubled that risk. Functional healing, however, decreased the risk of amputation by 58%.

"Patients who were able to heal their wound significantly outperformed those who did not – not only for limb salvage and survival, which is intuitive, but also for amputation-free survival and maintenance of ambulation and independent living status, which is not intuitive," Dr. Taylor said. "The poorest outcomes were in ischemic nonrevascularized patients, whose 5-year mortality was 75% and amputation-free survival only 18% – as bad as any cancer outcomes presented at this meeting."

Conventional wisdom holds that patients who do have revascularization will almost always heal their ulcers. Therefore, Dr. Taylor said, reimbursement has been structured to favor surgical intervention rather than diabetic foot care and prevention.

"Reimbursement is very robust for procedures, while for wound care, it barely covers the cost, implying that revascularization does all the heavy lifting."

His review shows that this is not always the case. "Our functional outcomes were disappointing at best and really reflect an opportunity for improvement. Realigning the financial incentives toward foot wound care and prevention may give us a better opportunity to make these improvements."

Dr. Taylor had no financial disclosures.

PALM BEACH, Fla. - Neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers can be treated with revascularization, but successful surgery doesn't always translate into good long-term outcomes, a study has shown.

In the review of 917 such ulcers, the 219 revascularized lesions had no better healing or survival outcomes than that of ischemic wounds that were not revascularized, Dr. Spence Taylor said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association. Just 35% of the revascularized ulcers healed completely, and 32% of the patients eventually needed an amputation.

"Assessing this treatment, we must conclude that while revascularization is important to wound healing, favorable functional outcomes can't be assumed," said Dr. Taylor of the Greenville (S.C.) Hospital System. "This suggests that we should realign our financial incentives [away from procedures and] toward foot care and wound prevention, affording a better opportunity of prevention and preservation of functional outcomes."

Dr. Taylor and his colleagues presented a review of 917 limbs with new diabetic foot ulcers that occurred among 706 patients. Most of the patients (87%) had type 2 diabetes, and more than half (52%) were smokers. Other comorbidities included hyperlipidemia (53%), hypertension (90%), and end-stage renal disease (26%).

Of the 917 ulcers, 457 were nonischemic and 460 were ischemic. Of the ischemic lesions, 241 were not revascularized and 219 were – 137 by angioplasty and 82 by open surgery. Outcomes measured included primary healing, functional healing (defined as healing to clinical insignificance), limb salvage, amputation-free survival, 5-year survival, and maintenance of ambulation and independent living.

Overall, the data showed primary wound healing in 27%, functional healing in 53%, minor amputations in 28%, and major amputations in 20% of patients. The time to achieve healing was 7-8 months.

For patients with the revascularized ulcers, the 5-year survival rate was 39%, and 5-year limb salvage rate was 61%. The 5-year rate of amputation-free survival was 29%, while 55% of patients maintained ambulation and 72% maintained independent living at 5 years.

When the investigators compared the different groups (nonischemic, revascularized ischemic, and nonrevascularized ischemic), they found no significant differences in the rate of wound healing. But ischemia was a significant predictor of poor functional outcomes, which revascularization did not completely mitigate. "Ischemic patients had twice as many amputations and 50% higher mortality than nonischemic patients, whether they were revascularized or not. It was quite remarkable morbidity," Dr. Taylor said.

The presence of ischemia conferred a 26% increase in the risk of death by 5 years. Also, patients with end-stage renal disease were 2.5 times more likely to die than were those without. However, functional healing was associated with a 42% decreased risk of death.

Those same factors were independent predictors of amputation-free survival. Ischemia conferred a 57% increased risk of losing a limb, while end-stage renal disease doubled that risk. Functional healing, however, decreased the risk of amputation by 58%.

"Patients who were able to heal their wound significantly outperformed those who did not – not only for limb salvage and survival, which is intuitive, but also for amputation-free survival and maintenance of ambulation and independent living status, which is not intuitive," Dr. Taylor said. "The poorest outcomes were in ischemic nonrevascularized patients, whose 5-year mortality was 75% and amputation-free survival only 18% – as bad as any cancer outcomes presented at this meeting."

Conventional wisdom holds that patients who do have revascularization will almost always heal their ulcers. Therefore, Dr. Taylor said, reimbursement has been structured to favor surgical intervention rather than diabetic foot care and prevention.

"Reimbursement is very robust for procedures, while for wound care, it barely covers the cost, implying that revascularization does all the heavy lifting."

His review shows that this is not always the case. "Our functional outcomes were disappointing at best and really reflect an opportunity for improvement. Realigning the financial incentives toward foot wound care and prevention may give us a better opportunity to make these improvements."

Dr. Taylor had no financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: Only 35% of revascularized ulcers healed completely, and 32% of the patients eventually needed an amputation because of the ulcer.

Data Source: A review of 917 diabetic foot ulcers in 706 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Spence Taylor had no financial disclosures.

Shave Biopsies Accurately Identify Most Melanomas

PALM BEACH, FLA. - Shave biopsy of possible melanomas usually provides enough diagnostic information to plan a successful surgical treatment, judging by a retrospective study of 600 patients.

The procedure has been controversial, because many surgeons believe it fails to give a full clinical picture of the lesion – especially thickness, said Dr. Stephen Grobmyer of the University of Florida, Gainesville. However, in his review of 600 patients who had shave biopsies at two surgical centers in 2006-2009, just 22% of patients had residual melanoma after the procedure, with tumor upstaging required in 2% and a wider margin excision in 1%.

"We feel the definitive treatment planning for melanoma can be reliably made on results of shave biopsy. We advocate the liberal use of shave biopsy for suspicious cutaneous lesions; this should be emphasized over other techniques of biopsy, as this would advance the early diagnosis of melanoma and improve outcomes," Dr. Grobmyer said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Dermatologists and family physicians can easily perform the shave biopsy, which Dr. Grobmyer said is "easy, quick, cheap, safe, and doesn't require suture closure or postoperative follow-up."

All patients in the study had undergone shave biopsies of lesions less than 2 mm in depth. This was considered the cut-off point because patients with deeper lesions usually go on to have a wide excision and sentinel node biopsy, Dr. Grobmyer said.

The patients' median age was 62 years, and 40% were female. "It's interesting to note that dermatologists performed about 90% of the shave biopsies on patients who were referred, and that on clinical exam, more than two-thirds did not have a diagnosis of melanoma. Most had a diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer or a benign skin lesion."

Based on the results of the shave biopsy, however, 88% of the lesions were confirmed as melanoma. Of these, 11% were invasive, with a median Breslow depth of 0.73 mm. Ulceration was present in 6% of patients, and 37% had a positive deep margin on the shave biopsy.

All who had the shave biopsy went to initial surgical management based on the depth of the shave. "After the sentinel node biopsy, only 3% of patients needed additional surgery," Dr. Grobmyer pointed out.

The researchers especially wanted to analyze the subset of patients who had a diagnosis of melanoma made on clinical observation before the biopsy was done – a total of 179 patients (30%). "On shave, we found that 22% had a positive deep margin, which is statistically significantly less than those patients who did not have a preshave diagnosis of melanoma, suggesting that the shaves were done in a way as to more completely excise the lesion."

Evaluation of these patients after initial surgical management revealed that there were very few instances of tumor upstaging (3%), need for wider excision (3%), or a change in the need for sentinel node biopsy (1%).

Dr. Grobmyer acknowledged that the study's 12-month follow-up period was fairly short. "We saw a 2.3% overall recurrence rate with 1.7% local regional and 0.7% distant recurrences. It’s also important to note that the patients with recurrence had much deeper lesions than those who did not, with an average depth of 1.7 mm."

"It may be time to stop bashing shave biopsies," Dr. Kelly McMasters said during the discussion period. "The conventional dogma among melanoma experts against shave biopsy has been that they're bad because they underestimate true tumor thickness," said Dr. McMasters of the University of Louisville (Ky.) "This suggests that shave biopsies fall below the standard of care, but nearly every melanoma patient I've seen has had a shave biopsy for diagnosis. Are all these physicians practicing below the standard of care? It seems [that] because shave biopsies are what’s being performed most commonly, they are the standard of care."

The most important point of the study, however, is that the easily accessible shave biopsy, in the hands of primary care physicians, can get melanoma patients into surgical treatment faster – and time is life in this case, said Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.

"The only improvement in survival in melanoma has been due to earlier diagnosis, and you don't want to do anything to discourage the dermatologists or the family physicians from doing a biopsy," said Dr. Polk, the Ben A. Reid Sr. Professor of Surgery at the University of Louisville. "The worst thing they can do is say 'come back in 3 months,' or cauterize them. This paper encourages people with lesser surgical skills to get any piece of the lesion, as long as they won't be doing the diagnosis. The shave biopsy is a good thing, and we need to share this and encourage those in dermatology and family medicine to do more of them."

Dr. Grobmyer had no financial conflicts.

PALM BEACH, FLA. - Shave biopsy of possible melanomas usually provides enough diagnostic information to plan a successful surgical treatment, judging by a retrospective study of 600 patients.

The procedure has been controversial, because many surgeons believe it fails to give a full clinical picture of the lesion – especially thickness, said Dr. Stephen Grobmyer of the University of Florida, Gainesville. However, in his review of 600 patients who had shave biopsies at two surgical centers in 2006-2009, just 22% of patients had residual melanoma after the procedure, with tumor upstaging required in 2% and a wider margin excision in 1%.

"We feel the definitive treatment planning for melanoma can be reliably made on results of shave biopsy. We advocate the liberal use of shave biopsy for suspicious cutaneous lesions; this should be emphasized over other techniques of biopsy, as this would advance the early diagnosis of melanoma and improve outcomes," Dr. Grobmyer said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Dermatologists and family physicians can easily perform the shave biopsy, which Dr. Grobmyer said is "easy, quick, cheap, safe, and doesn't require suture closure or postoperative follow-up."

All patients in the study had undergone shave biopsies of lesions less than 2 mm in depth. This was considered the cut-off point because patients with deeper lesions usually go on to have a wide excision and sentinel node biopsy, Dr. Grobmyer said.

The patients' median age was 62 years, and 40% were female. "It's interesting to note that dermatologists performed about 90% of the shave biopsies on patients who were referred, and that on clinical exam, more than two-thirds did not have a diagnosis of melanoma. Most had a diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer or a benign skin lesion."

Based on the results of the shave biopsy, however, 88% of the lesions were confirmed as melanoma. Of these, 11% were invasive, with a median Breslow depth of 0.73 mm. Ulceration was present in 6% of patients, and 37% had a positive deep margin on the shave biopsy.

All who had the shave biopsy went to initial surgical management based on the depth of the shave. "After the sentinel node biopsy, only 3% of patients needed additional surgery," Dr. Grobmyer pointed out.

The researchers especially wanted to analyze the subset of patients who had a diagnosis of melanoma made on clinical observation before the biopsy was done – a total of 179 patients (30%). "On shave, we found that 22% had a positive deep margin, which is statistically significantly less than those patients who did not have a preshave diagnosis of melanoma, suggesting that the shaves were done in a way as to more completely excise the lesion."

Evaluation of these patients after initial surgical management revealed that there were very few instances of tumor upstaging (3%), need for wider excision (3%), or a change in the need for sentinel node biopsy (1%).

Dr. Grobmyer acknowledged that the study's 12-month follow-up period was fairly short. "We saw a 2.3% overall recurrence rate with 1.7% local regional and 0.7% distant recurrences. It’s also important to note that the patients with recurrence had much deeper lesions than those who did not, with an average depth of 1.7 mm."

"It may be time to stop bashing shave biopsies," Dr. Kelly McMasters said during the discussion period. "The conventional dogma among melanoma experts against shave biopsy has been that they're bad because they underestimate true tumor thickness," said Dr. McMasters of the University of Louisville (Ky.) "This suggests that shave biopsies fall below the standard of care, but nearly every melanoma patient I've seen has had a shave biopsy for diagnosis. Are all these physicians practicing below the standard of care? It seems [that] because shave biopsies are what’s being performed most commonly, they are the standard of care."

The most important point of the study, however, is that the easily accessible shave biopsy, in the hands of primary care physicians, can get melanoma patients into surgical treatment faster – and time is life in this case, said Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.

"The only improvement in survival in melanoma has been due to earlier diagnosis, and you don't want to do anything to discourage the dermatologists or the family physicians from doing a biopsy," said Dr. Polk, the Ben A. Reid Sr. Professor of Surgery at the University of Louisville. "The worst thing they can do is say 'come back in 3 months,' or cauterize them. This paper encourages people with lesser surgical skills to get any piece of the lesion, as long as they won't be doing the diagnosis. The shave biopsy is a good thing, and we need to share this and encourage those in dermatology and family medicine to do more of them."

Dr. Grobmyer had no financial conflicts.

PALM BEACH, FLA. - Shave biopsy of possible melanomas usually provides enough diagnostic information to plan a successful surgical treatment, judging by a retrospective study of 600 patients.

The procedure has been controversial, because many surgeons believe it fails to give a full clinical picture of the lesion – especially thickness, said Dr. Stephen Grobmyer of the University of Florida, Gainesville. However, in his review of 600 patients who had shave biopsies at two surgical centers in 2006-2009, just 22% of patients had residual melanoma after the procedure, with tumor upstaging required in 2% and a wider margin excision in 1%.

"We feel the definitive treatment planning for melanoma can be reliably made on results of shave biopsy. We advocate the liberal use of shave biopsy for suspicious cutaneous lesions; this should be emphasized over other techniques of biopsy, as this would advance the early diagnosis of melanoma and improve outcomes," Dr. Grobmyer said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Dermatologists and family physicians can easily perform the shave biopsy, which Dr. Grobmyer said is "easy, quick, cheap, safe, and doesn't require suture closure or postoperative follow-up."

All patients in the study had undergone shave biopsies of lesions less than 2 mm in depth. This was considered the cut-off point because patients with deeper lesions usually go on to have a wide excision and sentinel node biopsy, Dr. Grobmyer said.

The patients' median age was 62 years, and 40% were female. "It's interesting to note that dermatologists performed about 90% of the shave biopsies on patients who were referred, and that on clinical exam, more than two-thirds did not have a diagnosis of melanoma. Most had a diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer or a benign skin lesion."

Based on the results of the shave biopsy, however, 88% of the lesions were confirmed as melanoma. Of these, 11% were invasive, with a median Breslow depth of 0.73 mm. Ulceration was present in 6% of patients, and 37% had a positive deep margin on the shave biopsy.

All who had the shave biopsy went to initial surgical management based on the depth of the shave. "After the sentinel node biopsy, only 3% of patients needed additional surgery," Dr. Grobmyer pointed out.

The researchers especially wanted to analyze the subset of patients who had a diagnosis of melanoma made on clinical observation before the biopsy was done – a total of 179 patients (30%). "On shave, we found that 22% had a positive deep margin, which is statistically significantly less than those patients who did not have a preshave diagnosis of melanoma, suggesting that the shaves were done in a way as to more completely excise the lesion."

Evaluation of these patients after initial surgical management revealed that there were very few instances of tumor upstaging (3%), need for wider excision (3%), or a change in the need for sentinel node biopsy (1%).

Dr. Grobmyer acknowledged that the study's 12-month follow-up period was fairly short. "We saw a 2.3% overall recurrence rate with 1.7% local regional and 0.7% distant recurrences. It’s also important to note that the patients with recurrence had much deeper lesions than those who did not, with an average depth of 1.7 mm."

"It may be time to stop bashing shave biopsies," Dr. Kelly McMasters said during the discussion period. "The conventional dogma among melanoma experts against shave biopsy has been that they're bad because they underestimate true tumor thickness," said Dr. McMasters of the University of Louisville (Ky.) "This suggests that shave biopsies fall below the standard of care, but nearly every melanoma patient I've seen has had a shave biopsy for diagnosis. Are all these physicians practicing below the standard of care? It seems [that] because shave biopsies are what’s being performed most commonly, they are the standard of care."

The most important point of the study, however, is that the easily accessible shave biopsy, in the hands of primary care physicians, can get melanoma patients into surgical treatment faster – and time is life in this case, said Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.

"The only improvement in survival in melanoma has been due to earlier diagnosis, and you don't want to do anything to discourage the dermatologists or the family physicians from doing a biopsy," said Dr. Polk, the Ben A. Reid Sr. Professor of Surgery at the University of Louisville. "The worst thing they can do is say 'come back in 3 months,' or cauterize them. This paper encourages people with lesser surgical skills to get any piece of the lesion, as long as they won't be doing the diagnosis. The shave biopsy is a good thing, and we need to share this and encourage those in dermatology and family medicine to do more of them."

Dr. Grobmyer had no financial conflicts.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: Eighty-eight percent of shaved biopsy lesions were confirmed as melanoma. Of these, 11% were invasive.

Data Source: A retrospective study of 600 patients with prediagnostic shave biopsies.

Disclosures: Dr.

Grobmyer had no financial conflicts.

Shave Biopsies Accurately Identify Most Melanomas

PALM BEACH, FLA. - Shave biopsy of possible melanomas usually provides enough diagnostic information to plan a successful surgical treatment, judging by a retrospective study of 600 patients.

The procedure has been controversial, because many surgeons believe it fails to give a full clinical picture of the lesion – especially thickness, said Dr. Stephen Grobmyer of the University of Florida, Gainesville. However, in his review of 600 patients who had shave biopsies at two surgical centers in 2006-2009, just 22% of patients had residual melanoma after the procedure, with tumor upstaging required in 2% and a wider margin excision in 1%.

"We feel the definitive treatment planning for melanoma can be reliably made on results of shave biopsy. We advocate the liberal use of shave biopsy for suspicious cutaneous lesions; this should be emphasized over other techniques of biopsy, as this would advance the early diagnosis of melanoma and improve outcomes," Dr. Grobmyer said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Dermatologists and family physicians can easily perform the shave biopsy, which Dr. Grobmyer said is "easy, quick, cheap, safe, and doesn't require suture closure or postoperative follow-up."

All patients in the study had undergone shave biopsies of lesions less than 2 mm in depth. This was considered the cut-off point because patients with deeper lesions usually go on to have a wide excision and sentinel node biopsy, Dr. Grobmyer said.

The patients' median age was 62 years, and 40% were female. "It's interesting to note that dermatologists performed about 90% of the shave biopsies on patients who were referred, and that on clinical exam, more than two-thirds did not have a diagnosis of melanoma. Most had a diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer or a benign skin lesion."

Based on the results of the shave biopsy, however, 88% of the lesions were confirmed as melanoma. Of these, 11% were invasive, with a median Breslow depth of 0.73 mm. Ulceration was present in 6% of patients, and 37% had a positive deep margin on the shave biopsy.

All who had the shave biopsy went to initial surgical management based on the depth of the shave. "After the sentinel node biopsy, only 3% of patients needed additional surgery," Dr. Grobmyer pointed out.

The researchers especially wanted to analyze the subset of patients who had a diagnosis of melanoma made on clinical observation before the biopsy was done – a total of 179 patients (30%). "On shave, we found that 22% had a positive deep margin, which is statistically significantly less than those patients who did not have a preshave diagnosis of melanoma, suggesting that the shaves were done in a way as to more completely excise the lesion."

Evaluation of these patients after initial surgical management revealed that there were very few instances of tumor upstaging (3%), need for wider excision (3%), or a change in the need for sentinel node biopsy (1%).

Dr. Grobmyer acknowledged that the study's 12-month follow-up period was fairly short. "We saw a 2.3% overall recurrence rate with 1.7% local regional and 0.7% distant recurrences. It’s also important to note that the patients with recurrence had much deeper lesions than those who did not, with an average depth of 1.7 mm."

"It may be time to stop bashing shave biopsies," Dr. Kelly McMasters said during the discussion period. "The conventional dogma among melanoma experts against shave biopsy has been that they're bad because they underestimate true tumor thickness," said Dr. McMasters of the University of Louisville (Ky.) "This suggests that shave biopsies fall below the standard of care, but nearly every melanoma patient I've seen has had a shave biopsy for diagnosis. Are all these physicians practicing below the standard of care? It seems [that] because shave biopsies are what’s being performed most commonly, they are the standard of care."

The most important point of the study, however, is that the easily accessible shave biopsy, in the hands of primary care physicians, can get melanoma patients into surgical treatment faster – and time is life in this case, said Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.

"The only improvement in survival in melanoma has been due to earlier diagnosis, and you don't want to do anything to discourage the dermatologists or the family physicians from doing a biopsy," said Dr. Polk, the Ben A. Reid Sr. Professor of Surgery at the University of Louisville. "The worst thing they can do is say 'come back in 3 months,' or cauterize them. This paper encourages people with lesser surgical skills to get any piece of the lesion, as long as they won't be doing the diagnosis. The shave biopsy is a good thing, and we need to share this and encourage those in dermatology and family medicine to do more of them."

Dr. Grobmyer had no financial conflicts.

PALM BEACH, FLA. - Shave biopsy of possible melanomas usually provides enough diagnostic information to plan a successful surgical treatment, judging by a retrospective study of 600 patients.

The procedure has been controversial, because many surgeons believe it fails to give a full clinical picture of the lesion – especially thickness, said Dr. Stephen Grobmyer of the University of Florida, Gainesville. However, in his review of 600 patients who had shave biopsies at two surgical centers in 2006-2009, just 22% of patients had residual melanoma after the procedure, with tumor upstaging required in 2% and a wider margin excision in 1%.

"We feel the definitive treatment planning for melanoma can be reliably made on results of shave biopsy. We advocate the liberal use of shave biopsy for suspicious cutaneous lesions; this should be emphasized over other techniques of biopsy, as this would advance the early diagnosis of melanoma and improve outcomes," Dr. Grobmyer said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Dermatologists and family physicians can easily perform the shave biopsy, which Dr. Grobmyer said is "easy, quick, cheap, safe, and doesn't require suture closure or postoperative follow-up."

All patients in the study had undergone shave biopsies of lesions less than 2 mm in depth. This was considered the cut-off point because patients with deeper lesions usually go on to have a wide excision and sentinel node biopsy, Dr. Grobmyer said.

The patients' median age was 62 years, and 40% were female. "It's interesting to note that dermatologists performed about 90% of the shave biopsies on patients who were referred, and that on clinical exam, more than two-thirds did not have a diagnosis of melanoma. Most had a diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer or a benign skin lesion."

Based on the results of the shave biopsy, however, 88% of the lesions were confirmed as melanoma. Of these, 11% were invasive, with a median Breslow depth of 0.73 mm. Ulceration was present in 6% of patients, and 37% had a positive deep margin on the shave biopsy.

All who had the shave biopsy went to initial surgical management based on the depth of the shave. "After the sentinel node biopsy, only 3% of patients needed additional surgery," Dr. Grobmyer pointed out.

The researchers especially wanted to analyze the subset of patients who had a diagnosis of melanoma made on clinical observation before the biopsy was done – a total of 179 patients (30%). "On shave, we found that 22% had a positive deep margin, which is statistically significantly less than those patients who did not have a preshave diagnosis of melanoma, suggesting that the shaves were done in a way as to more completely excise the lesion."

Evaluation of these patients after initial surgical management revealed that there were very few instances of tumor upstaging (3%), need for wider excision (3%), or a change in the need for sentinel node biopsy (1%).

Dr. Grobmyer acknowledged that the study's 12-month follow-up period was fairly short. "We saw a 2.3% overall recurrence rate with 1.7% local regional and 0.7% distant recurrences. It’s also important to note that the patients with recurrence had much deeper lesions than those who did not, with an average depth of 1.7 mm."

"It may be time to stop bashing shave biopsies," Dr. Kelly McMasters said during the discussion period. "The conventional dogma among melanoma experts against shave biopsy has been that they're bad because they underestimate true tumor thickness," said Dr. McMasters of the University of Louisville (Ky.) "This suggests that shave biopsies fall below the standard of care, but nearly every melanoma patient I've seen has had a shave biopsy for diagnosis. Are all these physicians practicing below the standard of care? It seems [that] because shave biopsies are what’s being performed most commonly, they are the standard of care."

The most important point of the study, however, is that the easily accessible shave biopsy, in the hands of primary care physicians, can get melanoma patients into surgical treatment faster – and time is life in this case, said Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.

"The only improvement in survival in melanoma has been due to earlier diagnosis, and you don't want to do anything to discourage the dermatologists or the family physicians from doing a biopsy," said Dr. Polk, the Ben A. Reid Sr. Professor of Surgery at the University of Louisville. "The worst thing they can do is say 'come back in 3 months,' or cauterize them. This paper encourages people with lesser surgical skills to get any piece of the lesion, as long as they won't be doing the diagnosis. The shave biopsy is a good thing, and we need to share this and encourage those in dermatology and family medicine to do more of them."

Dr. Grobmyer had no financial conflicts.

PALM BEACH, FLA. - Shave biopsy of possible melanomas usually provides enough diagnostic information to plan a successful surgical treatment, judging by a retrospective study of 600 patients.

The procedure has been controversial, because many surgeons believe it fails to give a full clinical picture of the lesion – especially thickness, said Dr. Stephen Grobmyer of the University of Florida, Gainesville. However, in his review of 600 patients who had shave biopsies at two surgical centers in 2006-2009, just 22% of patients had residual melanoma after the procedure, with tumor upstaging required in 2% and a wider margin excision in 1%.

"We feel the definitive treatment planning for melanoma can be reliably made on results of shave biopsy. We advocate the liberal use of shave biopsy for suspicious cutaneous lesions; this should be emphasized over other techniques of biopsy, as this would advance the early diagnosis of melanoma and improve outcomes," Dr. Grobmyer said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

Dermatologists and family physicians can easily perform the shave biopsy, which Dr. Grobmyer said is "easy, quick, cheap, safe, and doesn't require suture closure or postoperative follow-up."

All patients in the study had undergone shave biopsies of lesions less than 2 mm in depth. This was considered the cut-off point because patients with deeper lesions usually go on to have a wide excision and sentinel node biopsy, Dr. Grobmyer said.

The patients' median age was 62 years, and 40% were female. "It's interesting to note that dermatologists performed about 90% of the shave biopsies on patients who were referred, and that on clinical exam, more than two-thirds did not have a diagnosis of melanoma. Most had a diagnosis of nonmelanoma skin cancer or a benign skin lesion."

Based on the results of the shave biopsy, however, 88% of the lesions were confirmed as melanoma. Of these, 11% were invasive, with a median Breslow depth of 0.73 mm. Ulceration was present in 6% of patients, and 37% had a positive deep margin on the shave biopsy.

All who had the shave biopsy went to initial surgical management based on the depth of the shave. "After the sentinel node biopsy, only 3% of patients needed additional surgery," Dr. Grobmyer pointed out.

The researchers especially wanted to analyze the subset of patients who had a diagnosis of melanoma made on clinical observation before the biopsy was done – a total of 179 patients (30%). "On shave, we found that 22% had a positive deep margin, which is statistically significantly less than those patients who did not have a preshave diagnosis of melanoma, suggesting that the shaves were done in a way as to more completely excise the lesion."

Evaluation of these patients after initial surgical management revealed that there were very few instances of tumor upstaging (3%), need for wider excision (3%), or a change in the need for sentinel node biopsy (1%).

Dr. Grobmyer acknowledged that the study's 12-month follow-up period was fairly short. "We saw a 2.3% overall recurrence rate with 1.7% local regional and 0.7% distant recurrences. It’s also important to note that the patients with recurrence had much deeper lesions than those who did not, with an average depth of 1.7 mm."

"It may be time to stop bashing shave biopsies," Dr. Kelly McMasters said during the discussion period. "The conventional dogma among melanoma experts against shave biopsy has been that they're bad because they underestimate true tumor thickness," said Dr. McMasters of the University of Louisville (Ky.) "This suggests that shave biopsies fall below the standard of care, but nearly every melanoma patient I've seen has had a shave biopsy for diagnosis. Are all these physicians practicing below the standard of care? It seems [that] because shave biopsies are what’s being performed most commonly, they are the standard of care."

The most important point of the study, however, is that the easily accessible shave biopsy, in the hands of primary care physicians, can get melanoma patients into surgical treatment faster – and time is life in this case, said Dr. Hiram C. Polk Jr.

"The only improvement in survival in melanoma has been due to earlier diagnosis, and you don't want to do anything to discourage the dermatologists or the family physicians from doing a biopsy," said Dr. Polk, the Ben A. Reid Sr. Professor of Surgery at the University of Louisville. "The worst thing they can do is say 'come back in 3 months,' or cauterize them. This paper encourages people with lesser surgical skills to get any piece of the lesion, as long as they won't be doing the diagnosis. The shave biopsy is a good thing, and we need to share this and encourage those in dermatology and family medicine to do more of them."

Dr. Grobmyer had no financial conflicts.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: Eighty-eight percent of shaved biopsy lesions were confirmed as melanoma. Of these, 11% were invasive.

Data Source: A retrospective study of 600 patients with prediagnostic shave biopsies.

Disclosures: Dr.

Grobmyer had no financial conflicts.

Incisional Hernia Repair: Choose Best Technique for Individual Patient

PALM BEACH, Fla. – Mesh type or position during an incisional hernia repair has little impact on the technical difficulty or patient morbidity of any subsequent abdominal operation, a large retrospective study has determined.

Therefore, surgeons performing an initial hernia repair should select what they believe is the optimal method, without undue concern about the potential effects on subsequent operations, Dr. Mary Hawn said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

"Subsequent abdominal operations are common, with nearly 25% of our study population undergoing one over a median 80-month follow-up period," said Dr. Hawn of the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Alabama. Of those subsequent procedures, nearly two-thirds involved treating a recurrent incisional hernia, either as the primary procedure or in combination with another procedure. "We found a limited effect of mesh type and position, so we recommend when doing an incisional hernia repair, don’t limit your technique due to concerns of complications of future operations."

Dr. Hawn and her colleagues presented the results of a large retrospective study, which included 1,444 patients at 16 Veterans Affairs medical centers. All patients underwent an elective incisional hernia repair during 1998-2002. The investigators identified subsequent abdominal operations and associated complications. They also noted intra- and postoperative variables, including the length of the subsequent operation, the need for an enterotomy or unplanned bowel resection, postoperative infections, return to the hospital or operating room, and mortality.

A quarter of the cohort (366) required a subsequent abdominal operation. Most of these (65%) were redo hernia repairs, complications from hernia repair, or another procedure combined with a hernia repair. The remainder were other abdominal procedures – including small bowel, colorectal, biliary, gastric, or duodenal – or esophageal, urologic, or gynecologic procedures.

Most subsequent procedures (77%) were elective. The remainder were emergent repairs, which were significantly more common in patients undergoing a redo hernia repair that had been done with absorbable or biologic mesh.

About one-third of the subsequent procedures (38%) showed extensive or difficult adhesions. The rate of enterotomy or unplanned bowel resection was 10%, as was the necessity of removing the initial repair mesh. The mean operating time was 126 minutes, and the postoperative length of stay averaged 5 days.

Postoperative morbidities included surgical site infections (6%), return to the OR within 30 days (9%), and hospital readmission within 30 days (13%). There were 16 deaths within 30 days of the admission.

The investigators found no significant associations between any characteristics of the initial hernia repair (mesh position or type) when difficult or extensive adhesions were involved. However, the need for mesh removal was significantly associated with both open and laparoscopic placement of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) mesh (24% and 16%, respectively).

The rates of enterotomy or unplanned bowel resection did not differ significantly, regardless of mesh positions or types (ePTFE, polypropylene, or absorbable/biologic meshes). A multivariate analysis found that the most important factors influencing risk for enterotomy or bowel resection were older age (odds ratio 1.04) and previous incisional hernia repair, which was associated with more than a fourfold increased risk of enterotomy or bowel resection. Both associations were statistically significant.

Operative time was used as a surrogate for the difficulty of the operation. "We found that after adjusting for patient variables, those with an underlay or inlay polypropylene or biologic mesh had significantly longer operative times," during the subsequent surgery, Dr. Hawn said.

A multivariate analysis found that the mean operative times were 176 minutes for underlay mesh, 207 minutes for inlay mesh, and 143 minutes for onlay mesh. Absorbable/biologic meshes required a mean operating time of 190 minutes – significantly shorter than the time needed to place polypropylene or ePTFE mesh.

The indication for the subsequent operation also significantly affected operating time. A nonincisional hernia repair (mean 212 minutes) took significantly longer than either a redo of an incisional hernia repair (139 minutes) or a redo hernia repair plus another procedure (159 minutes).

Although Dr. Hawn did not provide specific data, she said that, compared to polypropylene, ePTFE mesh that had been applied in an open repair had a significantly higher explantation rate, a lower operative time, and a similar enterotomy rate. In laparoscopic repair, ePTFE had a lower rate of explantation than did polypropylene, but this finding could have been confounded because of the low number of patients whose index hernia was laparoscopically repaired.

"Also, the patients selected for laparoscopy during that initial operation probably had less of a chance of having had prior surgery, so less of a chance of adhesions," she said.

In discussing the paper, Dr. Todd Heniford of the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C., emphasized the study’s take-home message: "Surgeons should do whatever is needed to perform the best hernia repair they can at the first operation to avoid reoperations and the subsequent risks of morbidity and mortality."

Dr. Hawn had no financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development.

PALM BEACH, Fla. – Mesh type or position during an incisional hernia repair has little impact on the technical difficulty or patient morbidity of any subsequent abdominal operation, a large retrospective study has determined.

Therefore, surgeons performing an initial hernia repair should select what they believe is the optimal method, without undue concern about the potential effects on subsequent operations, Dr. Mary Hawn said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

"Subsequent abdominal operations are common, with nearly 25% of our study population undergoing one over a median 80-month follow-up period," said Dr. Hawn of the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Alabama. Of those subsequent procedures, nearly two-thirds involved treating a recurrent incisional hernia, either as the primary procedure or in combination with another procedure. "We found a limited effect of mesh type and position, so we recommend when doing an incisional hernia repair, don’t limit your technique due to concerns of complications of future operations."

Dr. Hawn and her colleagues presented the results of a large retrospective study, which included 1,444 patients at 16 Veterans Affairs medical centers. All patients underwent an elective incisional hernia repair during 1998-2002. The investigators identified subsequent abdominal operations and associated complications. They also noted intra- and postoperative variables, including the length of the subsequent operation, the need for an enterotomy or unplanned bowel resection, postoperative infections, return to the hospital or operating room, and mortality.

A quarter of the cohort (366) required a subsequent abdominal operation. Most of these (65%) were redo hernia repairs, complications from hernia repair, or another procedure combined with a hernia repair. The remainder were other abdominal procedures – including small bowel, colorectal, biliary, gastric, or duodenal – or esophageal, urologic, or gynecologic procedures.

Most subsequent procedures (77%) were elective. The remainder were emergent repairs, which were significantly more common in patients undergoing a redo hernia repair that had been done with absorbable or biologic mesh.

About one-third of the subsequent procedures (38%) showed extensive or difficult adhesions. The rate of enterotomy or unplanned bowel resection was 10%, as was the necessity of removing the initial repair mesh. The mean operating time was 126 minutes, and the postoperative length of stay averaged 5 days.

Postoperative morbidities included surgical site infections (6%), return to the OR within 30 days (9%), and hospital readmission within 30 days (13%). There were 16 deaths within 30 days of the admission.

The investigators found no significant associations between any characteristics of the initial hernia repair (mesh position or type) when difficult or extensive adhesions were involved. However, the need for mesh removal was significantly associated with both open and laparoscopic placement of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) mesh (24% and 16%, respectively).

The rates of enterotomy or unplanned bowel resection did not differ significantly, regardless of mesh positions or types (ePTFE, polypropylene, or absorbable/biologic meshes). A multivariate analysis found that the most important factors influencing risk for enterotomy or bowel resection were older age (odds ratio 1.04) and previous incisional hernia repair, which was associated with more than a fourfold increased risk of enterotomy or bowel resection. Both associations were statistically significant.

Operative time was used as a surrogate for the difficulty of the operation. "We found that after adjusting for patient variables, those with an underlay or inlay polypropylene or biologic mesh had significantly longer operative times," during the subsequent surgery, Dr. Hawn said.

A multivariate analysis found that the mean operative times were 176 minutes for underlay mesh, 207 minutes for inlay mesh, and 143 minutes for onlay mesh. Absorbable/biologic meshes required a mean operating time of 190 minutes – significantly shorter than the time needed to place polypropylene or ePTFE mesh.

The indication for the subsequent operation also significantly affected operating time. A nonincisional hernia repair (mean 212 minutes) took significantly longer than either a redo of an incisional hernia repair (139 minutes) or a redo hernia repair plus another procedure (159 minutes).

Although Dr. Hawn did not provide specific data, she said that, compared to polypropylene, ePTFE mesh that had been applied in an open repair had a significantly higher explantation rate, a lower operative time, and a similar enterotomy rate. In laparoscopic repair, ePTFE had a lower rate of explantation than did polypropylene, but this finding could have been confounded because of the low number of patients whose index hernia was laparoscopically repaired.

"Also, the patients selected for laparoscopy during that initial operation probably had less of a chance of having had prior surgery, so less of a chance of adhesions," she said.

In discussing the paper, Dr. Todd Heniford of the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C., emphasized the study’s take-home message: "Surgeons should do whatever is needed to perform the best hernia repair they can at the first operation to avoid reoperations and the subsequent risks of morbidity and mortality."

Dr. Hawn had no financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development.

PALM BEACH, Fla. – Mesh type or position during an incisional hernia repair has little impact on the technical difficulty or patient morbidity of any subsequent abdominal operation, a large retrospective study has determined.

Therefore, surgeons performing an initial hernia repair should select what they believe is the optimal method, without undue concern about the potential effects on subsequent operations, Dr. Mary Hawn said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

"Subsequent abdominal operations are common, with nearly 25% of our study population undergoing one over a median 80-month follow-up period," said Dr. Hawn of the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Alabama. Of those subsequent procedures, nearly two-thirds involved treating a recurrent incisional hernia, either as the primary procedure or in combination with another procedure. "We found a limited effect of mesh type and position, so we recommend when doing an incisional hernia repair, don’t limit your technique due to concerns of complications of future operations."

Dr. Hawn and her colleagues presented the results of a large retrospective study, which included 1,444 patients at 16 Veterans Affairs medical centers. All patients underwent an elective incisional hernia repair during 1998-2002. The investigators identified subsequent abdominal operations and associated complications. They also noted intra- and postoperative variables, including the length of the subsequent operation, the need for an enterotomy or unplanned bowel resection, postoperative infections, return to the hospital or operating room, and mortality.

A quarter of the cohort (366) required a subsequent abdominal operation. Most of these (65%) were redo hernia repairs, complications from hernia repair, or another procedure combined with a hernia repair. The remainder were other abdominal procedures – including small bowel, colorectal, biliary, gastric, or duodenal – or esophageal, urologic, or gynecologic procedures.

Most subsequent procedures (77%) were elective. The remainder were emergent repairs, which were significantly more common in patients undergoing a redo hernia repair that had been done with absorbable or biologic mesh.

About one-third of the subsequent procedures (38%) showed extensive or difficult adhesions. The rate of enterotomy or unplanned bowel resection was 10%, as was the necessity of removing the initial repair mesh. The mean operating time was 126 minutes, and the postoperative length of stay averaged 5 days.

Postoperative morbidities included surgical site infections (6%), return to the OR within 30 days (9%), and hospital readmission within 30 days (13%). There were 16 deaths within 30 days of the admission.

The investigators found no significant associations between any characteristics of the initial hernia repair (mesh position or type) when difficult or extensive adhesions were involved. However, the need for mesh removal was significantly associated with both open and laparoscopic placement of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) mesh (24% and 16%, respectively).

The rates of enterotomy or unplanned bowel resection did not differ significantly, regardless of mesh positions or types (ePTFE, polypropylene, or absorbable/biologic meshes). A multivariate analysis found that the most important factors influencing risk for enterotomy or bowel resection were older age (odds ratio 1.04) and previous incisional hernia repair, which was associated with more than a fourfold increased risk of enterotomy or bowel resection. Both associations were statistically significant.

Operative time was used as a surrogate for the difficulty of the operation. "We found that after adjusting for patient variables, those with an underlay or inlay polypropylene or biologic mesh had significantly longer operative times," during the subsequent surgery, Dr. Hawn said.

A multivariate analysis found that the mean operative times were 176 minutes for underlay mesh, 207 minutes for inlay mesh, and 143 minutes for onlay mesh. Absorbable/biologic meshes required a mean operating time of 190 minutes – significantly shorter than the time needed to place polypropylene or ePTFE mesh.

The indication for the subsequent operation also significantly affected operating time. A nonincisional hernia repair (mean 212 minutes) took significantly longer than either a redo of an incisional hernia repair (139 minutes) or a redo hernia repair plus another procedure (159 minutes).

Although Dr. Hawn did not provide specific data, she said that, compared to polypropylene, ePTFE mesh that had been applied in an open repair had a significantly higher explantation rate, a lower operative time, and a similar enterotomy rate. In laparoscopic repair, ePTFE had a lower rate of explantation than did polypropylene, but this finding could have been confounded because of the low number of patients whose index hernia was laparoscopically repaired.

"Also, the patients selected for laparoscopy during that initial operation probably had less of a chance of having had prior surgery, so less of a chance of adhesions," she said.

In discussing the paper, Dr. Todd Heniford of the Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, N.C., emphasized the study’s take-home message: "Surgeons should do whatever is needed to perform the best hernia repair they can at the first operation to avoid reoperations and the subsequent risks of morbidity and mortality."

Dr. Hawn had no financial disclosures. The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Bariatric Surgery Benefits Ethnic Minorities with Diabetes

PALM BEACH, FLA. – Bariatric surgery resulted in complete remission of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes in a group of mostly Hispanic and black patients.

Within 1 year of surgery, 100% of patients with those disorders experienced a normalization of fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C, and they lost a mean of 40 kg, Dr. Alan Livingstone said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association. By the end of the 3-year follow-up period, all patients still had normal levels of blood glucose and insulin.

"Uncontrolled type 2 diabetes is highly prevalent among ethnic minorities," said Dr. Livingstone, the Lucille and DeWitt Daughtry Professor and Chairman at Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami. "Bariatric surgery helps to effectively treat these diverse minority groups and is a safe and effective option for permanent weight loss and chronic disease risk improvement in this population."

He reported on a cohort of 1,603 adult bariatric surgery patients, of whom 66% were Hispanic, 17% were black, and rest were other ethnicities. They were prospectively entered into a research database and then retrospectively studied.

"Minorities are at a particularly high risk for type 2 diabetes and its associated complications," Dr. Livingstone said. "While only 6% of whites have [the disorder], it’s present in 10% of Hispanics and 12% of blacks – a huge burden of disease."

The patients’ mean age was 45 years; most (77%) were female. The mean preoperative weight was 130 kg; the mean body mass index, 47 kg/m2.

Most of the group already had some insulin abnormality; 377 had diagnosed type 2 diabetes, 107 had undiagnosed type 2 (fasting blood glucose of more than 126 mg/dL), and 276 had prediabetes (fasting blood glucose of 100-125 mg/dL). Among those with elevated blood glucose, the mean HbA1c was 8%. The rest of the group had a normal insulin profile.

Most patients underwent gastric banding (90%); the rest had gastric bypass. "The amount of weight loss was profound in the first year, as expected," Dr. Livingstone said. There was no significant difference in weight loss between the diagnostic groups. Body mass index also fell quickly, correlating with weight loss. By the end of the first 6 months, the mean BMI had dropped to 35 kg/ m2, and by the end of the first postoperative year, it was 30 kg/m2. Among the 57% of patients with full 3-year follow-up, there was no significant regain of weight.

Fasting blood glucose and HbA1c also improved rapidly and significantly in all those with preoperatively elevated levels. "It’s important to note how quickly this happened," Dr. Livingstone said. "Within the first year, all of these patients had normal fasting blood glucose and an HbA1c of 6% or below." Again, these values remained steady and in the normal range in the entire 3-year follow-up cohort. "This is a tremendous accomplishment," he said.

However, Dr. Bruce Schirmer of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, cautioned that a 3-year follow-up period may not be long enough to proclaim bariatric surgery as a cure for type 2 diabetes in any population. "In mostly Caucasian populations, if you follow the patients for up to 5 years, you see that 15%-20%, at least, have some weight regain and with it, a return to diabetes. So to make this statement that there is no weight regain and no return to the disorder is a little premature."

Dr. Livingstone had no financial disclosures. Dr. Nestor F. De La Cruz-Munoz Jr., a coauthor and chief of laparoendoscopic and bariatric surgery at the University of Miami, is a consultant and proctor for Ethicon.

PALM BEACH, FLA. – Bariatric surgery resulted in complete remission of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes in a group of mostly Hispanic and black patients.

Within 1 year of surgery, 100% of patients with those disorders experienced a normalization of fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C, and they lost a mean of 40 kg, Dr. Alan Livingstone said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association. By the end of the 3-year follow-up period, all patients still had normal levels of blood glucose and insulin.

"Uncontrolled type 2 diabetes is highly prevalent among ethnic minorities," said Dr. Livingstone, the Lucille and DeWitt Daughtry Professor and Chairman at Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami. "Bariatric surgery helps to effectively treat these diverse minority groups and is a safe and effective option for permanent weight loss and chronic disease risk improvement in this population."

He reported on a cohort of 1,603 adult bariatric surgery patients, of whom 66% were Hispanic, 17% were black, and rest were other ethnicities. They were prospectively entered into a research database and then retrospectively studied.

"Minorities are at a particularly high risk for type 2 diabetes and its associated complications," Dr. Livingstone said. "While only 6% of whites have [the disorder], it’s present in 10% of Hispanics and 12% of blacks – a huge burden of disease."

The patients’ mean age was 45 years; most (77%) were female. The mean preoperative weight was 130 kg; the mean body mass index, 47 kg/m2.

Most of the group already had some insulin abnormality; 377 had diagnosed type 2 diabetes, 107 had undiagnosed type 2 (fasting blood glucose of more than 126 mg/dL), and 276 had prediabetes (fasting blood glucose of 100-125 mg/dL). Among those with elevated blood glucose, the mean HbA1c was 8%. The rest of the group had a normal insulin profile.

Most patients underwent gastric banding (90%); the rest had gastric bypass. "The amount of weight loss was profound in the first year, as expected," Dr. Livingstone said. There was no significant difference in weight loss between the diagnostic groups. Body mass index also fell quickly, correlating with weight loss. By the end of the first 6 months, the mean BMI had dropped to 35 kg/ m2, and by the end of the first postoperative year, it was 30 kg/m2. Among the 57% of patients with full 3-year follow-up, there was no significant regain of weight.

Fasting blood glucose and HbA1c also improved rapidly and significantly in all those with preoperatively elevated levels. "It’s important to note how quickly this happened," Dr. Livingstone said. "Within the first year, all of these patients had normal fasting blood glucose and an HbA1c of 6% or below." Again, these values remained steady and in the normal range in the entire 3-year follow-up cohort. "This is a tremendous accomplishment," he said.

However, Dr. Bruce Schirmer of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, cautioned that a 3-year follow-up period may not be long enough to proclaim bariatric surgery as a cure for type 2 diabetes in any population. "In mostly Caucasian populations, if you follow the patients for up to 5 years, you see that 15%-20%, at least, have some weight regain and with it, a return to diabetes. So to make this statement that there is no weight regain and no return to the disorder is a little premature."

Dr. Livingstone had no financial disclosures. Dr. Nestor F. De La Cruz-Munoz Jr., a coauthor and chief of laparoendoscopic and bariatric surgery at the University of Miami, is a consultant and proctor for Ethicon.

PALM BEACH, FLA. – Bariatric surgery resulted in complete remission of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes in a group of mostly Hispanic and black patients.

Within 1 year of surgery, 100% of patients with those disorders experienced a normalization of fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C, and they lost a mean of 40 kg, Dr. Alan Livingstone said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association. By the end of the 3-year follow-up period, all patients still had normal levels of blood glucose and insulin.

"Uncontrolled type 2 diabetes is highly prevalent among ethnic minorities," said Dr. Livingstone, the Lucille and DeWitt Daughtry Professor and Chairman at Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami. "Bariatric surgery helps to effectively treat these diverse minority groups and is a safe and effective option for permanent weight loss and chronic disease risk improvement in this population."

He reported on a cohort of 1,603 adult bariatric surgery patients, of whom 66% were Hispanic, 17% were black, and rest were other ethnicities. They were prospectively entered into a research database and then retrospectively studied.

"Minorities are at a particularly high risk for type 2 diabetes and its associated complications," Dr. Livingstone said. "While only 6% of whites have [the disorder], it’s present in 10% of Hispanics and 12% of blacks – a huge burden of disease."

The patients’ mean age was 45 years; most (77%) were female. The mean preoperative weight was 130 kg; the mean body mass index, 47 kg/m2.

Most of the group already had some insulin abnormality; 377 had diagnosed type 2 diabetes, 107 had undiagnosed type 2 (fasting blood glucose of more than 126 mg/dL), and 276 had prediabetes (fasting blood glucose of 100-125 mg/dL). Among those with elevated blood glucose, the mean HbA1c was 8%. The rest of the group had a normal insulin profile.

Most patients underwent gastric banding (90%); the rest had gastric bypass. "The amount of weight loss was profound in the first year, as expected," Dr. Livingstone said. There was no significant difference in weight loss between the diagnostic groups. Body mass index also fell quickly, correlating with weight loss. By the end of the first 6 months, the mean BMI had dropped to 35 kg/ m2, and by the end of the first postoperative year, it was 30 kg/m2. Among the 57% of patients with full 3-year follow-up, there was no significant regain of weight.

Fasting blood glucose and HbA1c also improved rapidly and significantly in all those with preoperatively elevated levels. "It’s important to note how quickly this happened," Dr. Livingstone said. "Within the first year, all of these patients had normal fasting blood glucose and an HbA1c of 6% or below." Again, these values remained steady and in the normal range in the entire 3-year follow-up cohort. "This is a tremendous accomplishment," he said.

However, Dr. Bruce Schirmer of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, cautioned that a 3-year follow-up period may not be long enough to proclaim bariatric surgery as a cure for type 2 diabetes in any population. "In mostly Caucasian populations, if you follow the patients for up to 5 years, you see that 15%-20%, at least, have some weight regain and with it, a return to diabetes. So to make this statement that there is no weight regain and no return to the disorder is a little premature."

Dr. Livingstone had no financial disclosures. Dr. Nestor F. De La Cruz-Munoz Jr., a coauthor and chief of laparoendoscopic and bariatric surgery at the University of Miami, is a consultant and proctor for Ethicon.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Bariatric Surgery Benefits Ethnic Minorities with Diabetes

PALM BEACH, FLA. – Bariatric surgery resulted in complete remission of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes in a group of mostly Hispanic and black patients.

Within 1 year of surgery, 100% of patients with those disorders experienced a normalization of fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C, and they lost a mean of 40 kg, Dr. Alan Livingstone said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association. By the end of the 3-year follow-up period, all patients still had normal levels of blood glucose and insulin.

[Medication Costs Can Plummet After Bariatric Surgery]

"Uncontrolled type 2 diabetes is highly prevalent among ethnic minorities," said Dr. Livingstone, the Lucille and DeWitt Daughtry Professor and Chairman at Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami. "Bariatric surgery helps to effectively treat these diverse minority groups and is a safe and effective option for permanent weight loss and chronic disease risk improvement in this population."

He reported on a cohort of 1,603 adult bariatric surgery patients, of whom 66% were Hispanic, 17% were black, and rest were other ethnicities. They were prospectively entered into a research database and then retrospectively studied.

"Minorities are at a particularly high risk for type 2 diabetes and its associated complications," Dr. Livingstone said. "While only 6% of whites have [the disorder], it’s present in 10% of Hispanics and 12% of blacks – a huge burden of disease."

The patients’ mean age was 45 years; most (77%) were female. The mean preoperative weight was 130 kg; the mean body mass index, 47 kg/m2.

Most of the group already had some insulin abnormality; 377 had diagnosed type 2 diabetes, 107 had undiagnosed type 2 (fasting blood glucose of more than 126 mg/dL), and 276 had prediabetes (fasting blood glucose of 100-125 mg/dL). Among those with elevated blood glucose, the mean HbA1c was 8%. The rest of the group had a normal insulin profile.

[Mindful Practice: Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents]

Most patients underwent gastric banding (90%); the rest had gastric bypass. "The amount of weight loss was profound in the first year, as expected," Dr. Livingstone said. There was no significant difference in weight loss between the diagnostic groups. Body mass index also fell quickly, correlating with weight loss. By the end of the first 6 months, the mean BMI had dropped to 35 kg/ m2, and by the end of the first postoperative year, it was 30 kg/m2. Among the 57% of patients with full 3-year follow-up, there was no significant regain of weight.

Fasting blood glucose and HbA1c also improved rapidly and significantly in all those with preoperatively elevated levels. "It’s important to note how quickly this happened," Dr. Livingstone said. "Within the first year, all of these patients had normal fasting blood glucose and an HbA1c of 6% or below." Again, these values remained steady and in the normal range in the entire 3-year follow-up cohort. "This is a tremendous accomplishment," he said.

However, Dr. Bruce Schirmer of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, cautioned that a 3-year follow-up period may not be long enough to proclaim bariatric surgery as a cure for type 2 diabetes in any population. "In mostly Caucasian populations, if you follow the patients for up to 5 years, you see that 15%-20%, at least, have some weight regain and with it, a return to diabetes. So to make this statement that there is no weight regain and no return to the disorder is a little premature."

Dr. Livingstone had no financial disclosures. Dr. Nestor F. De La Cruz-Munoz Jr., a coauthor and chief of laparoendoscopic and bariatric surgery at the University of Miami, is a consultant and proctor for Ethicon.

PALM BEACH, FLA. – Bariatric surgery resulted in complete remission of type 2 diabetes and prediabetes in a group of mostly Hispanic and black patients.

Within 1 year of surgery, 100% of patients with those disorders experienced a normalization of fasting blood glucose and hemoglobin A1C, and they lost a mean of 40 kg, Dr. Alan Livingstone said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association. By the end of the 3-year follow-up period, all patients still had normal levels of blood glucose and insulin.

[Medication Costs Can Plummet After Bariatric Surgery]

"Uncontrolled type 2 diabetes is highly prevalent among ethnic minorities," said Dr. Livingstone, the Lucille and DeWitt Daughtry Professor and Chairman at Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami. "Bariatric surgery helps to effectively treat these diverse minority groups and is a safe and effective option for permanent weight loss and chronic disease risk improvement in this population."

He reported on a cohort of 1,603 adult bariatric surgery patients, of whom 66% were Hispanic, 17% were black, and rest were other ethnicities. They were prospectively entered into a research database and then retrospectively studied.

"Minorities are at a particularly high risk for type 2 diabetes and its associated complications," Dr. Livingstone said. "While only 6% of whites have [the disorder], it’s present in 10% of Hispanics and 12% of blacks – a huge burden of disease."

The patients’ mean age was 45 years; most (77%) were female. The mean preoperative weight was 130 kg; the mean body mass index, 47 kg/m2.

Most of the group already had some insulin abnormality; 377 had diagnosed type 2 diabetes, 107 had undiagnosed type 2 (fasting blood glucose of more than 126 mg/dL), and 276 had prediabetes (fasting blood glucose of 100-125 mg/dL). Among those with elevated blood glucose, the mean HbA1c was 8%. The rest of the group had a normal insulin profile.

[Mindful Practice: Bariatric Surgery in Adolescents]

Most patients underwent gastric banding (90%); the rest had gastric bypass. "The amount of weight loss was profound in the first year, as expected," Dr. Livingstone said. There was no significant difference in weight loss between the diagnostic groups. Body mass index also fell quickly, correlating with weight loss. By the end of the first 6 months, the mean BMI had dropped to 35 kg/ m2, and by the end of the first postoperative year, it was 30 kg/m2. Among the 57% of patients with full 3-year follow-up, there was no significant regain of weight.

Fasting blood glucose and HbA1c also improved rapidly and significantly in all those with preoperatively elevated levels. "It’s important to note how quickly this happened," Dr. Livingstone said. "Within the first year, all of these patients had normal fasting blood glucose and an HbA1c of 6% or below." Again, these values remained steady and in the normal range in the entire 3-year follow-up cohort. "This is a tremendous accomplishment," he said.

However, Dr. Bruce Schirmer of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, cautioned that a 3-year follow-up period may not be long enough to proclaim bariatric surgery as a cure for type 2 diabetes in any population. "In mostly Caucasian populations, if you follow the patients for up to 5 years, you see that 15%-20%, at least, have some weight regain and with it, a return to diabetes. So to make this statement that there is no weight regain and no return to the disorder is a little premature."