User login

Mitchel is a reporter for MDedge based in the Philadelphia area. He started with the company in 1992, when it was International Medical News Group (IMNG), and has since covered a range of medical specialties. Mitchel trained as a virologist at Roswell Park Memorial Institute in Buffalo, and then worked briefly as a researcher at Boston Children's Hospital before pivoting to journalism as a AAAS Mass Media Fellow in 1980. His first reporting job was with Science Digest magazine, and from the mid-1980s to early-1990s he was a reporter with Medical World News. @mitchelzoler

Quick Statin Use After Stroke Cuts Mortality

LOS ANGELES – Starting or maintaining acute stroke patients on a statin during their initial hospitalization was linked with a dramatic improvement in 1-year survival in a retrospective review of medical records for more than 12,000 U.S. patients.

Based on the finding, Kaiser Permanente of Northern California will issue a revised order set that will recommend to physicians that they start acute stroke patients on 80-mg simvastatin as soon as possible on the first day of their hospitalization, Dr. Alexander C. Flint said at the International Stroke Conference.

"Based on results from the SPARCL [Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels] trial, pretty much everyone in the stroke community believes that patients who have had an ischemic stroke should be treated with high-dose statin to prevent a second stroke (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:549-59). In our study, the question wasn’t whether to treat, but the timing. What our results say is that you should not wait until the patient is discharged or is an outpatient, but that you should start the statin on day 1," Dr. Flint said in an interview.

The data he reported showed that stroke patients who started on a statin during their acute-phase hospitalization had a 15% absolute reduced rate of death during the first year following their stroke, compared with patients who did not start on a statin and did not receive a statin prior to their stroke (Stroke 2011;42:e-42-110). After adjustment for several possible confounding factors, including age; sex; race and ethnicity; year of stroke; and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, stroke patients who started on a statin while hospitalized had a statistically significant (45%) relatively lower risk of death during the subsequent year, compared with patients who did not receive a statin.

The study involved 12,689 patients who received care from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California and had an ischemic stroke during 2000-2007. The total included 3,749 patients who were on steady statin treatment for at least 3 months before their stroke, and 8,940 patients who were not receiving a statin at all before their stroke.* Of the 3,749 patients who were on a statin before their stroke, most (3,280, or 87%) continued to receive a statin during their hospitalization. And among the 8,940 who did not receive regular statin treatment before their stroke, 3,013 (34%) began statin treatment while hospitalized.

Patients who received a statin prior to their stroke but did not continue while hospitalized had a statistically significant 15% relative reduction in their mortality during the following year, compared with patients who never received a statin.

The key element for mortality protection appeared to be treatment while hospitalized. Relative mortality reduction compared with nonstatin users was 41% among patients who were on a statin both before their stroke and while hospitalized, and 45% among those who started on a statin while hospitalized, said Dr. Flint, a neurointensivist and stroke specialist at Kaiser Redwood City (Calif.). Patients who received a statin before their stroke but discontinued the drug once hospitalized had the worst outcomes, with a mortality rate that was 2.5-fold higher than that of patients who never received a statin.

Further analysis highlighted the importance of an early start to statin treatment in hospitalized patients, and also showed a dose-response relationship. Patients who received at least 60 mg of their statin daily either before hospitalization or both before and during hospitalization had a significantly lower mortality rate, compared with patients who took less than 60 mg/day. Dr. Flint noted that about 70% of patients received lovastatin, and about 20% received simvastatin.

Regarding timing, patients who either began on a statin for the first time or restarted their treatment on their first hospitalized day had a significantly lower 1-year mortality, compared with patients who did not start or restart their statin until their third day in hospital.

Dr. Flint also reported an additional analysis that had been run to determine whether patients’ survival prognosis drove their statin treatment instead of their statin treatment’s driving their survival. To do this, he looked at patterns of care at each of the 17 Kaiser Permanente of Northern California hospitals that were involved in the study. This "grouped treatment analysis" showed that although the survival prognosis of patients who were withdrawn from prior statin treatment while hospitalized played some role in the relationship, it was unable to explain all of the survival effect, indicating that statin treatment itself during hospitalization played a significant role in subsequent survival.

The strong impact that early statin treatment during stroke hospitalization has on long-term survival probably depends on the pleiotropic effects of statins. The timing makes it less likely that the effect of statins on lipid levels can explain the observed survival benefits, Dr. Flint said.

Dr. Flint said that he had no disclosures.

* CORRECTION, 3/4/2011: An earlier version of this article stated that some study participants took statins intermittently prior to having a stroke. However, the study included only patients who were taking a statin for at least 3 months prior to the stroke or those not taking a statin at all. This version has been updated.

LOS ANGELES – Starting or maintaining acute stroke patients on a statin during their initial hospitalization was linked with a dramatic improvement in 1-year survival in a retrospective review of medical records for more than 12,000 U.S. patients.

Based on the finding, Kaiser Permanente of Northern California will issue a revised order set that will recommend to physicians that they start acute stroke patients on 80-mg simvastatin as soon as possible on the first day of their hospitalization, Dr. Alexander C. Flint said at the International Stroke Conference.

"Based on results from the SPARCL [Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels] trial, pretty much everyone in the stroke community believes that patients who have had an ischemic stroke should be treated with high-dose statin to prevent a second stroke (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:549-59). In our study, the question wasn’t whether to treat, but the timing. What our results say is that you should not wait until the patient is discharged or is an outpatient, but that you should start the statin on day 1," Dr. Flint said in an interview.

The data he reported showed that stroke patients who started on a statin during their acute-phase hospitalization had a 15% absolute reduced rate of death during the first year following their stroke, compared with patients who did not start on a statin and did not receive a statin prior to their stroke (Stroke 2011;42:e-42-110). After adjustment for several possible confounding factors, including age; sex; race and ethnicity; year of stroke; and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, stroke patients who started on a statin while hospitalized had a statistically significant (45%) relatively lower risk of death during the subsequent year, compared with patients who did not receive a statin.

The study involved 12,689 patients who received care from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California and had an ischemic stroke during 2000-2007. The total included 3,749 patients who were on steady statin treatment for at least 3 months before their stroke, and 8,940 patients who were not receiving a statin at all before their stroke.* Of the 3,749 patients who were on a statin before their stroke, most (3,280, or 87%) continued to receive a statin during their hospitalization. And among the 8,940 who did not receive regular statin treatment before their stroke, 3,013 (34%) began statin treatment while hospitalized.

Patients who received a statin prior to their stroke but did not continue while hospitalized had a statistically significant 15% relative reduction in their mortality during the following year, compared with patients who never received a statin.

The key element for mortality protection appeared to be treatment while hospitalized. Relative mortality reduction compared with nonstatin users was 41% among patients who were on a statin both before their stroke and while hospitalized, and 45% among those who started on a statin while hospitalized, said Dr. Flint, a neurointensivist and stroke specialist at Kaiser Redwood City (Calif.). Patients who received a statin before their stroke but discontinued the drug once hospitalized had the worst outcomes, with a mortality rate that was 2.5-fold higher than that of patients who never received a statin.

Further analysis highlighted the importance of an early start to statin treatment in hospitalized patients, and also showed a dose-response relationship. Patients who received at least 60 mg of their statin daily either before hospitalization or both before and during hospitalization had a significantly lower mortality rate, compared with patients who took less than 60 mg/day. Dr. Flint noted that about 70% of patients received lovastatin, and about 20% received simvastatin.

Regarding timing, patients who either began on a statin for the first time or restarted their treatment on their first hospitalized day had a significantly lower 1-year mortality, compared with patients who did not start or restart their statin until their third day in hospital.

Dr. Flint also reported an additional analysis that had been run to determine whether patients’ survival prognosis drove their statin treatment instead of their statin treatment’s driving their survival. To do this, he looked at patterns of care at each of the 17 Kaiser Permanente of Northern California hospitals that were involved in the study. This "grouped treatment analysis" showed that although the survival prognosis of patients who were withdrawn from prior statin treatment while hospitalized played some role in the relationship, it was unable to explain all of the survival effect, indicating that statin treatment itself during hospitalization played a significant role in subsequent survival.

The strong impact that early statin treatment during stroke hospitalization has on long-term survival probably depends on the pleiotropic effects of statins. The timing makes it less likely that the effect of statins on lipid levels can explain the observed survival benefits, Dr. Flint said.

Dr. Flint said that he had no disclosures.

* CORRECTION, 3/4/2011: An earlier version of this article stated that some study participants took statins intermittently prior to having a stroke. However, the study included only patients who were taking a statin for at least 3 months prior to the stroke or those not taking a statin at all. This version has been updated.

LOS ANGELES – Starting or maintaining acute stroke patients on a statin during their initial hospitalization was linked with a dramatic improvement in 1-year survival in a retrospective review of medical records for more than 12,000 U.S. patients.

Based on the finding, Kaiser Permanente of Northern California will issue a revised order set that will recommend to physicians that they start acute stroke patients on 80-mg simvastatin as soon as possible on the first day of their hospitalization, Dr. Alexander C. Flint said at the International Stroke Conference.

"Based on results from the SPARCL [Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels] trial, pretty much everyone in the stroke community believes that patients who have had an ischemic stroke should be treated with high-dose statin to prevent a second stroke (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:549-59). In our study, the question wasn’t whether to treat, but the timing. What our results say is that you should not wait until the patient is discharged or is an outpatient, but that you should start the statin on day 1," Dr. Flint said in an interview.

The data he reported showed that stroke patients who started on a statin during their acute-phase hospitalization had a 15% absolute reduced rate of death during the first year following their stroke, compared with patients who did not start on a statin and did not receive a statin prior to their stroke (Stroke 2011;42:e-42-110). After adjustment for several possible confounding factors, including age; sex; race and ethnicity; year of stroke; and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, stroke patients who started on a statin while hospitalized had a statistically significant (45%) relatively lower risk of death during the subsequent year, compared with patients who did not receive a statin.

The study involved 12,689 patients who received care from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California and had an ischemic stroke during 2000-2007. The total included 3,749 patients who were on steady statin treatment for at least 3 months before their stroke, and 8,940 patients who were not receiving a statin at all before their stroke.* Of the 3,749 patients who were on a statin before their stroke, most (3,280, or 87%) continued to receive a statin during their hospitalization. And among the 8,940 who did not receive regular statin treatment before their stroke, 3,013 (34%) began statin treatment while hospitalized.

Patients who received a statin prior to their stroke but did not continue while hospitalized had a statistically significant 15% relative reduction in their mortality during the following year, compared with patients who never received a statin.

The key element for mortality protection appeared to be treatment while hospitalized. Relative mortality reduction compared with nonstatin users was 41% among patients who were on a statin both before their stroke and while hospitalized, and 45% among those who started on a statin while hospitalized, said Dr. Flint, a neurointensivist and stroke specialist at Kaiser Redwood City (Calif.). Patients who received a statin before their stroke but discontinued the drug once hospitalized had the worst outcomes, with a mortality rate that was 2.5-fold higher than that of patients who never received a statin.

Further analysis highlighted the importance of an early start to statin treatment in hospitalized patients, and also showed a dose-response relationship. Patients who received at least 60 mg of their statin daily either before hospitalization or both before and during hospitalization had a significantly lower mortality rate, compared with patients who took less than 60 mg/day. Dr. Flint noted that about 70% of patients received lovastatin, and about 20% received simvastatin.

Regarding timing, patients who either began on a statin for the first time or restarted their treatment on their first hospitalized day had a significantly lower 1-year mortality, compared with patients who did not start or restart their statin until their third day in hospital.

Dr. Flint also reported an additional analysis that had been run to determine whether patients’ survival prognosis drove their statin treatment instead of their statin treatment’s driving their survival. To do this, he looked at patterns of care at each of the 17 Kaiser Permanente of Northern California hospitals that were involved in the study. This "grouped treatment analysis" showed that although the survival prognosis of patients who were withdrawn from prior statin treatment while hospitalized played some role in the relationship, it was unable to explain all of the survival effect, indicating that statin treatment itself during hospitalization played a significant role in subsequent survival.

The strong impact that early statin treatment during stroke hospitalization has on long-term survival probably depends on the pleiotropic effects of statins. The timing makes it less likely that the effect of statins on lipid levels can explain the observed survival benefits, Dr. Flint said.

Dr. Flint said that he had no disclosures.

* CORRECTION, 3/4/2011: An earlier version of this article stated that some study participants took statins intermittently prior to having a stroke. However, the study included only patients who were taking a statin for at least 3 months prior to the stroke or those not taking a statin at all. This version has been updated.

Quick Statin Use After Stroke Cuts Mortality

LOS ANGELES – Starting or maintaining acute stroke patients on a statin during their initial hospitalization was linked with a dramatic improvement in 1-year survival in a retrospective review of medical records for more than 12,000 U.S. patients.

Based on the finding, Kaiser Permanente of Northern California will issue a revised order set that will recommend to physicians that they start acute stroke patients on 80-mg simvastatin as soon as possible on the first day of their hospitalization, Dr. Alexander C. Flint said at the International Stroke Conference.

"Based on results from the SPARCL [Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels] trial, pretty much everyone in the stroke community believes that patients who have had an ischemic stroke should be treated with high-dose statin to prevent a second stroke (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:549-59). In our study, the question wasn’t whether to treat, but the timing. What our results say is that you should not wait until the patient is discharged or is an outpatient, but that you should start the statin on day 1," Dr. Flint said in an interview.

The data he reported showed that stroke patients who started on a statin during their acute-phase hospitalization had a 15% absolute reduced rate of death during the first year following their stroke, compared with patients who did not start on a statin and did not receive a statin prior to their stroke (Stroke 2011;42:e-42-110). After adjustment for several possible confounding factors, including age; sex; race and ethnicity; year of stroke; and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, stroke patients who started on a statin while hospitalized had a statistically significant (45%) relatively lower risk of death during the subsequent year, compared with patients who did not receive a statin.

The study involved 12,689 patients who received care from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California and had an ischemic stroke during 2000-2007. The total included 3,749 patients who were on steady statin treatment for at least 3 months before their stroke, and 8,940 patients who were not receiving a statin at all before their stroke.* Of the 3,749 patients who were on a statin before their stroke, most (3,280, or 87%) continued to receive a statin during their hospitalization. And among the 8,940 who did not receive regular statin treatment before their stroke, 3,013 (34%) began statin treatment while hospitalized.

Patients who received a statin prior to their stroke but did not continue while hospitalized had a statistically significant 15% relative reduction in their mortality during the following year, compared with patients who never received a statin.

The key element for mortality protection appeared to be treatment while hospitalized. Relative mortality reduction compared with nonstatin users was 41% among patients who were on a statin both before their stroke and while hospitalized, and 45% among those who started on a statin while hospitalized, said Dr. Flint, a neurointensivist and stroke specialist at Kaiser Redwood City (Calif.). Patients who received a statin before their stroke but discontinued the drug once hospitalized had the worst outcomes, with a mortality rate that was 2.5-fold higher than that of patients who never received a statin.

Further analysis highlighted the importance of an early start to statin treatment in hospitalized patients, and also showed a dose-response relationship. Patients who received at least 60 mg of their statin daily either before hospitalization or both before and during hospitalization had a significantly lower mortality rate, compared with patients who took less than 60 mg/day. Dr. Flint noted that about 70% of patients received lovastatin, and about 20% received simvastatin.

Regarding timing, patients who either began on a statin for the first time or restarted their treatment on their first hospitalized day had a significantly lower 1-year mortality, compared with patients who did not start or restart their statin until their third day in hospital.

Dr. Flint also reported an additional analysis that had been run to determine whether patients’ survival prognosis drove their statin treatment instead of their statin treatment’s driving their survival. To do this, he looked at patterns of care at each of the 17 Kaiser Permanente of Northern California hospitals that were involved in the study. This "grouped treatment analysis" showed that although the survival prognosis of patients who were withdrawn from prior statin treatment while hospitalized played some role in the relationship, it was unable to explain all of the survival effect, indicating that statin treatment itself during hospitalization played a significant role in subsequent survival.

The strong impact that early statin treatment during stroke hospitalization has on long-term survival probably depends on the pleiotropic effects of statins. The timing makes it less likely that the effect of statins on lipid levels can explain the observed survival benefits, Dr. Flint said.

Dr. Flint said that he had no disclosures.

* CORRECTION, 3/4/2011: An earlier version of this article stated that some study participants took statins intermittently prior to having a stroke. However, the study included only patients who were taking a statin for at least 3 months prior to the stroke or those not taking a statin at all. This version has been updated.

LOS ANGELES – Starting or maintaining acute stroke patients on a statin during their initial hospitalization was linked with a dramatic improvement in 1-year survival in a retrospective review of medical records for more than 12,000 U.S. patients.

Based on the finding, Kaiser Permanente of Northern California will issue a revised order set that will recommend to physicians that they start acute stroke patients on 80-mg simvastatin as soon as possible on the first day of their hospitalization, Dr. Alexander C. Flint said at the International Stroke Conference.

"Based on results from the SPARCL [Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels] trial, pretty much everyone in the stroke community believes that patients who have had an ischemic stroke should be treated with high-dose statin to prevent a second stroke (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:549-59). In our study, the question wasn’t whether to treat, but the timing. What our results say is that you should not wait until the patient is discharged or is an outpatient, but that you should start the statin on day 1," Dr. Flint said in an interview.

The data he reported showed that stroke patients who started on a statin during their acute-phase hospitalization had a 15% absolute reduced rate of death during the first year following their stroke, compared with patients who did not start on a statin and did not receive a statin prior to their stroke (Stroke 2011;42:e-42-110). After adjustment for several possible confounding factors, including age; sex; race and ethnicity; year of stroke; and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, stroke patients who started on a statin while hospitalized had a statistically significant (45%) relatively lower risk of death during the subsequent year, compared with patients who did not receive a statin.

The study involved 12,689 patients who received care from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California and had an ischemic stroke during 2000-2007. The total included 3,749 patients who were on steady statin treatment for at least 3 months before their stroke, and 8,940 patients who were not receiving a statin at all before their stroke.* Of the 3,749 patients who were on a statin before their stroke, most (3,280, or 87%) continued to receive a statin during their hospitalization. And among the 8,940 who did not receive regular statin treatment before their stroke, 3,013 (34%) began statin treatment while hospitalized.

Patients who received a statin prior to their stroke but did not continue while hospitalized had a statistically significant 15% relative reduction in their mortality during the following year, compared with patients who never received a statin.

The key element for mortality protection appeared to be treatment while hospitalized. Relative mortality reduction compared with nonstatin users was 41% among patients who were on a statin both before their stroke and while hospitalized, and 45% among those who started on a statin while hospitalized, said Dr. Flint, a neurointensivist and stroke specialist at Kaiser Redwood City (Calif.). Patients who received a statin before their stroke but discontinued the drug once hospitalized had the worst outcomes, with a mortality rate that was 2.5-fold higher than that of patients who never received a statin.

Further analysis highlighted the importance of an early start to statin treatment in hospitalized patients, and also showed a dose-response relationship. Patients who received at least 60 mg of their statin daily either before hospitalization or both before and during hospitalization had a significantly lower mortality rate, compared with patients who took less than 60 mg/day. Dr. Flint noted that about 70% of patients received lovastatin, and about 20% received simvastatin.

Regarding timing, patients who either began on a statin for the first time or restarted their treatment on their first hospitalized day had a significantly lower 1-year mortality, compared with patients who did not start or restart their statin until their third day in hospital.

Dr. Flint also reported an additional analysis that had been run to determine whether patients’ survival prognosis drove their statin treatment instead of their statin treatment’s driving their survival. To do this, he looked at patterns of care at each of the 17 Kaiser Permanente of Northern California hospitals that were involved in the study. This "grouped treatment analysis" showed that although the survival prognosis of patients who were withdrawn from prior statin treatment while hospitalized played some role in the relationship, it was unable to explain all of the survival effect, indicating that statin treatment itself during hospitalization played a significant role in subsequent survival.

The strong impact that early statin treatment during stroke hospitalization has on long-term survival probably depends on the pleiotropic effects of statins. The timing makes it less likely that the effect of statins on lipid levels can explain the observed survival benefits, Dr. Flint said.

Dr. Flint said that he had no disclosures.

* CORRECTION, 3/4/2011: An earlier version of this article stated that some study participants took statins intermittently prior to having a stroke. However, the study included only patients who were taking a statin for at least 3 months prior to the stroke or those not taking a statin at all. This version has been updated.

LOS ANGELES – Starting or maintaining acute stroke patients on a statin during their initial hospitalization was linked with a dramatic improvement in 1-year survival in a retrospective review of medical records for more than 12,000 U.S. patients.

Based on the finding, Kaiser Permanente of Northern California will issue a revised order set that will recommend to physicians that they start acute stroke patients on 80-mg simvastatin as soon as possible on the first day of their hospitalization, Dr. Alexander C. Flint said at the International Stroke Conference.

"Based on results from the SPARCL [Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels] trial, pretty much everyone in the stroke community believes that patients who have had an ischemic stroke should be treated with high-dose statin to prevent a second stroke (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:549-59). In our study, the question wasn’t whether to treat, but the timing. What our results say is that you should not wait until the patient is discharged or is an outpatient, but that you should start the statin on day 1," Dr. Flint said in an interview.

The data he reported showed that stroke patients who started on a statin during their acute-phase hospitalization had a 15% absolute reduced rate of death during the first year following their stroke, compared with patients who did not start on a statin and did not receive a statin prior to their stroke (Stroke 2011;42:e-42-110). After adjustment for several possible confounding factors, including age; sex; race and ethnicity; year of stroke; and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, stroke patients who started on a statin while hospitalized had a statistically significant (45%) relatively lower risk of death during the subsequent year, compared with patients who did not receive a statin.

The study involved 12,689 patients who received care from Kaiser Permanente of Northern California and had an ischemic stroke during 2000-2007. The total included 3,749 patients who were on steady statin treatment for at least 3 months before their stroke, and 8,940 patients who were not receiving a statin at all before their stroke.* Of the 3,749 patients who were on a statin before their stroke, most (3,280, or 87%) continued to receive a statin during their hospitalization. And among the 8,940 who did not receive regular statin treatment before their stroke, 3,013 (34%) began statin treatment while hospitalized.

Patients who received a statin prior to their stroke but did not continue while hospitalized had a statistically significant 15% relative reduction in their mortality during the following year, compared with patients who never received a statin.

The key element for mortality protection appeared to be treatment while hospitalized. Relative mortality reduction compared with nonstatin users was 41% among patients who were on a statin both before their stroke and while hospitalized, and 45% among those who started on a statin while hospitalized, said Dr. Flint, a neurointensivist and stroke specialist at Kaiser Redwood City (Calif.). Patients who received a statin before their stroke but discontinued the drug once hospitalized had the worst outcomes, with a mortality rate that was 2.5-fold higher than that of patients who never received a statin.

Further analysis highlighted the importance of an early start to statin treatment in hospitalized patients, and also showed a dose-response relationship. Patients who received at least 60 mg of their statin daily either before hospitalization or both before and during hospitalization had a significantly lower mortality rate, compared with patients who took less than 60 mg/day. Dr. Flint noted that about 70% of patients received lovastatin, and about 20% received simvastatin.

Regarding timing, patients who either began on a statin for the first time or restarted their treatment on their first hospitalized day had a significantly lower 1-year mortality, compared with patients who did not start or restart their statin until their third day in hospital.

Dr. Flint also reported an additional analysis that had been run to determine whether patients’ survival prognosis drove their statin treatment instead of their statin treatment’s driving their survival. To do this, he looked at patterns of care at each of the 17 Kaiser Permanente of Northern California hospitals that were involved in the study. This "grouped treatment analysis" showed that although the survival prognosis of patients who were withdrawn from prior statin treatment while hospitalized played some role in the relationship, it was unable to explain all of the survival effect, indicating that statin treatment itself during hospitalization played a significant role in subsequent survival.

The strong impact that early statin treatment during stroke hospitalization has on long-term survival probably depends on the pleiotropic effects of statins. The timing makes it less likely that the effect of statins on lipid levels can explain the observed survival benefits, Dr. Flint said.

Dr. Flint said that he had no disclosures.

* CORRECTION, 3/4/2011: An earlier version of this article stated that some study participants took statins intermittently prior to having a stroke. However, the study included only patients who were taking a statin for at least 3 months prior to the stroke or those not taking a statin at all. This version has been updated.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Major Finding: Patients who began statin treatment while hospitalized following an acute ischemic stroke had a 45% reduced relative mortality rate, compared with patients never treated with a statin.

Data Source: Review of 12,689 patients enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California who had an acute ischemic stroke during 2000-2007.

Disclosures: Dr. Flint reported having no relevant disclosures.

Strokes Pose Long-Term Survival Risk in AF Patients

LOS ANGELES – Strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation have long-term consequences.

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who had an ischemic stroke and survived for the first 30 days following the event still had a greater than threefold increased risk of death during the following 5 years, compared with AF patients who had no stroke, in a retrospective study.

"The effects of stroke on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation persist far beyond the initial event," Dr. Margaret Fang said at the International Stroke Conference.

The findings also highlight the importance of using proper anticoagulation regimens in patients with AF, both to prevent strokes and to reduce the severity of the strokes that do occur.

"We talk about preventing in-hospital death and 30-day mortality" with anticoagulation treatment of patients with AF, "but by preventing stroke, we also reduce long-term mortality. And if strokes occur, they are milder, and milder strokes have better long-term mortality outcomes," Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Her study reviewed 13,559 patients with nonvalvular AF (average age, 71 years) who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California. At baseline, about 9% of the patients had a history of a prior stroke. During a median follow-up of 6 years, 1,025 patients had a new-onset ischemic stroke.

About half of the patients were on warfarin at baseline. During follow-up, the incidence of stroke was 1.2% per year among patients on warfarin and 2.0% per year in patients not on warfarin. Warfarin treatment also led to milder strokes: About 46% of the warfarin-treated patients who had a stroke had either no deficit or only minor sequelae from their stroke, compared with 39% in patients not on warfarin. Major or severe deficits or death occurred in 54% of those on warfarin and in 61% of those not receiving anticoagulant treatment. The 30-day mortality rate was 20% in patients on warfarin at the time of their stroke and 28% in those not on warfarin.

The mortality among AF patients who survived longer than 30 days after their stroke was a statistically-significant 3.4-fold higher than in AF patients who did not have a stroke, according to an analysis that controlled for age, sex, prior stroke, and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. At the 5-year follow-up, more than 70% of the AF patients without a stroke remained alive, compared with fewer than 40% of patients who had a stroke during the study period.

Survival beyond 30 days after a stroke also depended on stroke severity. About 60% of patients without disability following their stroke were alive at 5 years. Patients with strokes that produced minor, major, or severe deficits had 5-year survival rates of roughly 50%, 30%, and 10%, respectively.

Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation have long-term consequences.

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who had an ischemic stroke and survived for the first 30 days following the event still had a greater than threefold increased risk of death during the following 5 years, compared with AF patients who had no stroke, in a retrospective study.

"The effects of stroke on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation persist far beyond the initial event," Dr. Margaret Fang said at the International Stroke Conference.

The findings also highlight the importance of using proper anticoagulation regimens in patients with AF, both to prevent strokes and to reduce the severity of the strokes that do occur.

"We talk about preventing in-hospital death and 30-day mortality" with anticoagulation treatment of patients with AF, "but by preventing stroke, we also reduce long-term mortality. And if strokes occur, they are milder, and milder strokes have better long-term mortality outcomes," Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Her study reviewed 13,559 patients with nonvalvular AF (average age, 71 years) who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California. At baseline, about 9% of the patients had a history of a prior stroke. During a median follow-up of 6 years, 1,025 patients had a new-onset ischemic stroke.

About half of the patients were on warfarin at baseline. During follow-up, the incidence of stroke was 1.2% per year among patients on warfarin and 2.0% per year in patients not on warfarin. Warfarin treatment also led to milder strokes: About 46% of the warfarin-treated patients who had a stroke had either no deficit or only minor sequelae from their stroke, compared with 39% in patients not on warfarin. Major or severe deficits or death occurred in 54% of those on warfarin and in 61% of those not receiving anticoagulant treatment. The 30-day mortality rate was 20% in patients on warfarin at the time of their stroke and 28% in those not on warfarin.

The mortality among AF patients who survived longer than 30 days after their stroke was a statistically-significant 3.4-fold higher than in AF patients who did not have a stroke, according to an analysis that controlled for age, sex, prior stroke, and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. At the 5-year follow-up, more than 70% of the AF patients without a stroke remained alive, compared with fewer than 40% of patients who had a stroke during the study period.

Survival beyond 30 days after a stroke also depended on stroke severity. About 60% of patients without disability following their stroke were alive at 5 years. Patients with strokes that produced minor, major, or severe deficits had 5-year survival rates of roughly 50%, 30%, and 10%, respectively.

Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation have long-term consequences.

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who had an ischemic stroke and survived for the first 30 days following the event still had a greater than threefold increased risk of death during the following 5 years, compared with AF patients who had no stroke, in a retrospective study.

"The effects of stroke on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation persist far beyond the initial event," Dr. Margaret Fang said at the International Stroke Conference.

The findings also highlight the importance of using proper anticoagulation regimens in patients with AF, both to prevent strokes and to reduce the severity of the strokes that do occur.

"We talk about preventing in-hospital death and 30-day mortality" with anticoagulation treatment of patients with AF, "but by preventing stroke, we also reduce long-term mortality. And if strokes occur, they are milder, and milder strokes have better long-term mortality outcomes," Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Her study reviewed 13,559 patients with nonvalvular AF (average age, 71 years) who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California. At baseline, about 9% of the patients had a history of a prior stroke. During a median follow-up of 6 years, 1,025 patients had a new-onset ischemic stroke.

About half of the patients were on warfarin at baseline. During follow-up, the incidence of stroke was 1.2% per year among patients on warfarin and 2.0% per year in patients not on warfarin. Warfarin treatment also led to milder strokes: About 46% of the warfarin-treated patients who had a stroke had either no deficit or only minor sequelae from their stroke, compared with 39% in patients not on warfarin. Major or severe deficits or death occurred in 54% of those on warfarin and in 61% of those not receiving anticoagulant treatment. The 30-day mortality rate was 20% in patients on warfarin at the time of their stroke and 28% in those not on warfarin.

The mortality among AF patients who survived longer than 30 days after their stroke was a statistically-significant 3.4-fold higher than in AF patients who did not have a stroke, according to an analysis that controlled for age, sex, prior stroke, and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. At the 5-year follow-up, more than 70% of the AF patients without a stroke remained alive, compared with fewer than 40% of patients who had a stroke during the study period.

Survival beyond 30 days after a stroke also depended on stroke severity. About 60% of patients without disability following their stroke were alive at 5 years. Patients with strokes that produced minor, major, or severe deficits had 5-year survival rates of roughly 50%, 30%, and 10%, respectively.

Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

Major Finding: Patients with AF who had a stroke and survived for at least 30 days had a 3.4-fold increased risk of death at 5 years, compared with AF patients without a stroke.

Data Source: Review of 13,559 patients with AF treated through Kaiser Permanente of Northern California and followed for a median of 6 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

Strokes Pose Long-Term Survival Risk in AF Patients

LOS ANGELES – Strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation have long-term consequences.

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who had an ischemic stroke and survived for the first 30 days following the event still had a greater than threefold increased risk of death during the following 5 years, compared with AF patients who had no stroke, in a retrospective study.

"The effects of stroke on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation persist far beyond the initial event," Dr. Margaret Fang said at the International Stroke Conference.

The findings also highlight the importance of using proper anticoagulation regimens in patients with AF, both to prevent strokes and to reduce the severity of the strokes that do occur.

"We talk about preventing in-hospital death and 30-day mortality" with anticoagulation treatment of patients with AF, "but by preventing stroke, we also reduce long-term mortality. And if strokes occur, they are milder, and milder strokes have better long-term mortality outcomes," Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Her study reviewed 13,559 patients with nonvalvular AF (average age, 71 years) who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California. At baseline, about 9% of the patients had a history of a prior stroke. During a median follow-up of 6 years, 1,025 patients had a new-onset ischemic stroke.

About half of the patients were on warfarin at baseline. During follow-up, the incidence of stroke was 1.2% per year among patients on warfarin and 2.0% per year in patients not on warfarin. Warfarin treatment also led to milder strokes: About 46% of the warfarin-treated patients who had a stroke had either no deficit or only minor sequelae from their stroke, compared with 39% in patients not on warfarin. Major or severe deficits or death occurred in 54% of those on warfarin and in 61% of those not receiving anticoagulant treatment. The 30-day mortality rate was 20% in patients on warfarin at the time of their stroke and 28% in those not on warfarin.

The mortality among AF patients who survived longer than 30 days after their stroke was a statistically-significant 3.4-fold higher than in AF patients who did not have a stroke, according to an analysis that controlled for age, sex, prior stroke, and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. At the 5-year follow-up, more than 70% of the AF patients without a stroke remained alive, compared with fewer than 40% of patients who had a stroke during the study period.

Survival beyond 30 days after a stroke also depended on stroke severity. About 60% of patients without disability following their stroke were alive at 5 years. Patients with strokes that produced minor, major, or severe deficits had 5-year survival rates of roughly 50%, 30%, and 10%, respectively.

Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation have long-term consequences.

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who had an ischemic stroke and survived for the first 30 days following the event still had a greater than threefold increased risk of death during the following 5 years, compared with AF patients who had no stroke, in a retrospective study.

"The effects of stroke on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation persist far beyond the initial event," Dr. Margaret Fang said at the International Stroke Conference.

The findings also highlight the importance of using proper anticoagulation regimens in patients with AF, both to prevent strokes and to reduce the severity of the strokes that do occur.

"We talk about preventing in-hospital death and 30-day mortality" with anticoagulation treatment of patients with AF, "but by preventing stroke, we also reduce long-term mortality. And if strokes occur, they are milder, and milder strokes have better long-term mortality outcomes," Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Her study reviewed 13,559 patients with nonvalvular AF (average age, 71 years) who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California. At baseline, about 9% of the patients had a history of a prior stroke. During a median follow-up of 6 years, 1,025 patients had a new-onset ischemic stroke.

About half of the patients were on warfarin at baseline. During follow-up, the incidence of stroke was 1.2% per year among patients on warfarin and 2.0% per year in patients not on warfarin. Warfarin treatment also led to milder strokes: About 46% of the warfarin-treated patients who had a stroke had either no deficit or only minor sequelae from their stroke, compared with 39% in patients not on warfarin. Major or severe deficits or death occurred in 54% of those on warfarin and in 61% of those not receiving anticoagulant treatment. The 30-day mortality rate was 20% in patients on warfarin at the time of their stroke and 28% in those not on warfarin.

The mortality among AF patients who survived longer than 30 days after their stroke was a statistically-significant 3.4-fold higher than in AF patients who did not have a stroke, according to an analysis that controlled for age, sex, prior stroke, and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. At the 5-year follow-up, more than 70% of the AF patients without a stroke remained alive, compared with fewer than 40% of patients who had a stroke during the study period.

Survival beyond 30 days after a stroke also depended on stroke severity. About 60% of patients without disability following their stroke were alive at 5 years. Patients with strokes that produced minor, major, or severe deficits had 5-year survival rates of roughly 50%, 30%, and 10%, respectively.

Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation have long-term consequences.

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who had an ischemic stroke and survived for the first 30 days following the event still had a greater than threefold increased risk of death during the following 5 years, compared with AF patients who had no stroke, in a retrospective study.

"The effects of stroke on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation persist far beyond the initial event," Dr. Margaret Fang said at the International Stroke Conference.

The findings also highlight the importance of using proper anticoagulation regimens in patients with AF, both to prevent strokes and to reduce the severity of the strokes that do occur.

"We talk about preventing in-hospital death and 30-day mortality" with anticoagulation treatment of patients with AF, "but by preventing stroke, we also reduce long-term mortality. And if strokes occur, they are milder, and milder strokes have better long-term mortality outcomes," Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Her study reviewed 13,559 patients with nonvalvular AF (average age, 71 years) who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California. At baseline, about 9% of the patients had a history of a prior stroke. During a median follow-up of 6 years, 1,025 patients had a new-onset ischemic stroke.

About half of the patients were on warfarin at baseline. During follow-up, the incidence of stroke was 1.2% per year among patients on warfarin and 2.0% per year in patients not on warfarin. Warfarin treatment also led to milder strokes: About 46% of the warfarin-treated patients who had a stroke had either no deficit or only minor sequelae from their stroke, compared with 39% in patients not on warfarin. Major or severe deficits or death occurred in 54% of those on warfarin and in 61% of those not receiving anticoagulant treatment. The 30-day mortality rate was 20% in patients on warfarin at the time of their stroke and 28% in those not on warfarin.

The mortality among AF patients who survived longer than 30 days after their stroke was a statistically-significant 3.4-fold higher than in AF patients who did not have a stroke, according to an analysis that controlled for age, sex, prior stroke, and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. At the 5-year follow-up, more than 70% of the AF patients without a stroke remained alive, compared with fewer than 40% of patients who had a stroke during the study period.

Survival beyond 30 days after a stroke also depended on stroke severity. About 60% of patients without disability following their stroke were alive at 5 years. Patients with strokes that produced minor, major, or severe deficits had 5-year survival rates of roughly 50%, 30%, and 10%, respectively.

Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

Major Finding: Patients with AF who had a stroke and survived for at least 30 days had a 3.4-fold increased risk of death at 5 years, compared with AF patients without a stroke.

Data Source: Review of 13,559 patients with AF treated through Kaiser Permanente of Northern California and followed for a median of 6 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

Strokes Pose Long-Term Survival Risk in AF Patients

LOS ANGELES – Strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation have long-term consequences.

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who had an ischemic stroke and survived for the first 30 days following the event still had a greater than threefold increased risk of death during the following 5 years, compared with AF patients who had no stroke, in a retrospective study.

"The effects of stroke on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation persist far beyond the initial event," Dr. Margaret Fang said at the International Stroke Conference.

The findings also highlight the importance of using proper anticoagulation regimens in patients with AF, both to prevent strokes and to reduce the severity of the strokes that do occur.

"We talk about preventing in-hospital death and 30-day mortality" with anticoagulation treatment of patients with AF, "but by preventing stroke, we also reduce long-term mortality. And if strokes occur, they are milder, and milder strokes have better long-term mortality outcomes," Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Her study reviewed 13,559 patients with nonvalvular AF (average age, 71 years) who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California. At baseline, about 9% of the patients had a history of a prior stroke. During a median follow-up of 6 years, 1,025 patients had a new-onset ischemic stroke.

About half of the patients were on warfarin at baseline. During follow-up, the incidence of stroke was 1.2% per year among patients on warfarin and 2.0% per year in patients not on warfarin. Warfarin treatment also led to milder strokes: About 46% of the warfarin-treated patients who had a stroke had either no deficit or only minor sequelae from their stroke, compared with 39% in patients not on warfarin. Major or severe deficits or death occurred in 54% of those on warfarin and in 61% of those not receiving anticoagulant treatment. The 30-day mortality rate was 20% in patients on warfarin at the time of their stroke and 28% in those not on warfarin.

The mortality among AF patients who survived longer than 30 days after their stroke was a statistically-significant 3.4-fold higher than in AF patients who did not have a stroke, according to an analysis that controlled for age, sex, prior stroke, and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. At the 5-year follow-up, more than 70% of the AF patients without a stroke remained alive, compared with fewer than 40% of patients who had a stroke during the study period.

Survival beyond 30 days after a stroke also depended on stroke severity. About 60% of patients without disability following their stroke were alive at 5 years. Patients with strokes that produced minor, major, or severe deficits had 5-year survival rates of roughly 50%, 30%, and 10%, respectively.

Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation have long-term consequences.

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who had an ischemic stroke and survived for the first 30 days following the event still had a greater than threefold increased risk of death during the following 5 years, compared with AF patients who had no stroke, in a retrospective study.

"The effects of stroke on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation persist far beyond the initial event," Dr. Margaret Fang said at the International Stroke Conference.

The findings also highlight the importance of using proper anticoagulation regimens in patients with AF, both to prevent strokes and to reduce the severity of the strokes that do occur.

"We talk about preventing in-hospital death and 30-day mortality" with anticoagulation treatment of patients with AF, "but by preventing stroke, we also reduce long-term mortality. And if strokes occur, they are milder, and milder strokes have better long-term mortality outcomes," Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Her study reviewed 13,559 patients with nonvalvular AF (average age, 71 years) who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California. At baseline, about 9% of the patients had a history of a prior stroke. During a median follow-up of 6 years, 1,025 patients had a new-onset ischemic stroke.

About half of the patients were on warfarin at baseline. During follow-up, the incidence of stroke was 1.2% per year among patients on warfarin and 2.0% per year in patients not on warfarin. Warfarin treatment also led to milder strokes: About 46% of the warfarin-treated patients who had a stroke had either no deficit or only minor sequelae from their stroke, compared with 39% in patients not on warfarin. Major or severe deficits or death occurred in 54% of those on warfarin and in 61% of those not receiving anticoagulant treatment. The 30-day mortality rate was 20% in patients on warfarin at the time of their stroke and 28% in those not on warfarin.

The mortality among AF patients who survived longer than 30 days after their stroke was a statistically-significant 3.4-fold higher than in AF patients who did not have a stroke, according to an analysis that controlled for age, sex, prior stroke, and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. At the 5-year follow-up, more than 70% of the AF patients without a stroke remained alive, compared with fewer than 40% of patients who had a stroke during the study period.

Survival beyond 30 days after a stroke also depended on stroke severity. About 60% of patients without disability following their stroke were alive at 5 years. Patients with strokes that produced minor, major, or severe deficits had 5-year survival rates of roughly 50%, 30%, and 10%, respectively.

Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – Strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation have long-term consequences.

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who had an ischemic stroke and survived for the first 30 days following the event still had a greater than threefold increased risk of death during the following 5 years, compared with AF patients who had no stroke, in a retrospective study.

"The effects of stroke on mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation persist far beyond the initial event," Dr. Margaret Fang said at the International Stroke Conference.

The findings also highlight the importance of using proper anticoagulation regimens in patients with AF, both to prevent strokes and to reduce the severity of the strokes that do occur.

"We talk about preventing in-hospital death and 30-day mortality" with anticoagulation treatment of patients with AF, "but by preventing stroke, we also reduce long-term mortality. And if strokes occur, they are milder, and milder strokes have better long-term mortality outcomes," Dr. Fang, a hospitalist and director of the anticoagulation clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview.

Her study reviewed 13,559 patients with nonvalvular AF (average age, 71 years) who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California. At baseline, about 9% of the patients had a history of a prior stroke. During a median follow-up of 6 years, 1,025 patients had a new-onset ischemic stroke.

About half of the patients were on warfarin at baseline. During follow-up, the incidence of stroke was 1.2% per year among patients on warfarin and 2.0% per year in patients not on warfarin. Warfarin treatment also led to milder strokes: About 46% of the warfarin-treated patients who had a stroke had either no deficit or only minor sequelae from their stroke, compared with 39% in patients not on warfarin. Major or severe deficits or death occurred in 54% of those on warfarin and in 61% of those not receiving anticoagulant treatment. The 30-day mortality rate was 20% in patients on warfarin at the time of their stroke and 28% in those not on warfarin.

The mortality among AF patients who survived longer than 30 days after their stroke was a statistically-significant 3.4-fold higher than in AF patients who did not have a stroke, according to an analysis that controlled for age, sex, prior stroke, and comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes. At the 5-year follow-up, more than 70% of the AF patients without a stroke remained alive, compared with fewer than 40% of patients who had a stroke during the study period.

Survival beyond 30 days after a stroke also depended on stroke severity. About 60% of patients without disability following their stroke were alive at 5 years. Patients with strokes that produced minor, major, or severe deficits had 5-year survival rates of roughly 50%, 30%, and 10%, respectively.

Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

Major Finding: Patients with AF who had a stroke and survived for at least 30 days had a 3.4-fold increased risk of death at 5 years, compared with AF patients without a stroke.

Data Source: Review of 13,559 patients with AF treated through Kaiser Permanente of Northern California and followed for a median of 6 years.

Disclosures: Dr. Fang said that she had no disclosures.

Carotid Stents Caused Excess Strokes in Older Patients and Women

LOS ANGELES – Women, as well as all patients aged 65 years or older who have substantial carotid artery stenosis that needs revascularization, may prefer endarterectomy, and would want to steer clear of carotid stenting, according to new data from CREST, the largest randomized trial to compare these two carotid interventions.

All patients aged 65 or older who were randomized to treatment by carotid artery stenting had a statistically significant excess of strokes, compared with similar subgroups who were treated with endarterectomy during the periprocedural period and 4-year follow-up, George Howard, Dr.P.H., said at the International Stroke Conference. "Patient age should be an important factor in selecting the treatment option for carotid stenosis," said Dr. Howard, professor and chairman of biostatistics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Analysis of the patients enrolled in CREST (Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs. Stenting Trial) by sex showed that the treatment of carotid stenosis by stenting led to an excess rate of periprocedural strokes among women, but not in men, Virginia J. Howard, Ph.D., said in a separate talk at the conference. Women who underwent an endarterectomy also had no excess risk for myocardial infarctions, compared with women who received a carotid stent, unlike men who had a significantly increased rate of MIs following open surgery, compared with those who got stented, said Dr. Howard, an epidemiologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The primary results from CREST, first reported last year, showed that all patients who were enrolled in the study had similar rates of stroke, MI, or death regardless of whether they underwent carotid endarterectomy or stenting (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:11-23). But these new details, which show an excess rate of periprocedural strokes in women undergoing stenting as well as the excess of all strokes in patients aged 65 or older undergoing stenting, may tip the balance away from stenting in these patient subgroups.

Another CREST analysis that was also reported at the conference showed that patients who had a stroke had significant decrements in several measures of their health status at 1 year following their intervention, whereas patients who had an MI generally had a much more average health status profile after 1 year.

Going into CREST, which began in 2000, "we thought the results would be the opposite. [At that time,] we preferred to take older patients to stenting," commented Dr. Thomas G. Brott, lead investigator for CREST and a professor of neurology and director or research at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida. "Our interventionalists believe that age is a surrogate marker for patients with calcified and tortuous vessels that might not be suitable for stenting." Regarding the sex-related finding, the implications "depend on how a woman would value [the risk of having] a stroke or a MI. If the woman is more concerned about a periprocedural stroke, then the results suggest there could be a preference for endarterectomy," Dr. Brott said in an interview.

In the sex-based analysis, the rate of periprocedural stroke was 5.5% in stented women and 2.2% in those who underwent endarterectomy, a statistically significant 2.6-fold increased rate with stenting, Dr. Virginia Howard reported. During the entire follow-up, which added the rate of ipsilateral strokes during 4 years following the intervention, stroke rates were 7.8% in stented women and 5.0% in those who had endarterectomy, a nonsignificant difference. The two treatment options produced no difference in stroke rates in men, either periprocedurally or after 4 years. MI rates were similar in women following either intervention, both periprocedurally and after 4 years. The periprocedural and 4-year MI rates in men were significantly higher with endarterectomy.

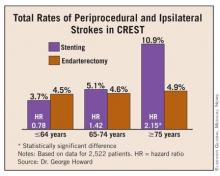

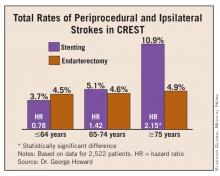

In the age-based analyses, a calculation that used age as a continuous variable showed that the number of strokes occurring with either endarterectomy or stenting was similar for patients aged 64 years. For those aged 65 or older, fewer strokes occurred with endarterectomy, a relationship that grew stronger with increasing age. For patients aged 63 or younger, stenting produced fewer strokes, and the relationship grew stronger with decreasing age.

The age analysis also examined the data by dividing patients into three prespecified age group: younger than 65, 65-74 years, and 75 and older. (See box.) The most striking age effect occurred in patients aged 75 or older: In this subgroup, treatment with stenting more than doubled the total stroke risk, both periprocedural and long-term strokes, compared with patients who were treated with endarterectomy.

The incidence of MI showed a much weaker age effect, and patients who underwent stenting had a reduced rate of MI at all ages, compared with those who had endarterectomy. In addition, in the endarterectomy arm, age had no significant effect on the MI rate. Among patients treated with endarterectomy, the incidence of MI was 1.6% in patients younger than 65 years and 3.2% in those aged 75 or older, differences that were not statistically significant, Dr. George Howard said.

Dr. Christopher J. Moran said that a physician who wants to prevent strokes in patients with carotid artery disease would have to "think long and hard before treating a woman with carotid stenting." In some cases, endarterectomy may not be an option: The woman may be a poor operative candidate, or may not be a good candidate for anesthesia. "But if a woman is a good operative candidate, she should be treated with endarterectomy," he said.

Conventional angiography or CT angiography lets an operator assess the size of a woman’s arteries, explained Dr. Moran, a professor of radiology and neurological surgery at Washington University, St. Louis, who performs carotid artery stenting but did not participate in CREST. The smallest self-expanding stents available for treating carotid disease are 5 mm in diameter, and because these are ideally oversized to the artery, the smallest diameter carotid that should be stented is 4 mm, he said. "Many women have carotids that are smaller than 4 mm, and in those cases you should definitely think twice about stenting."

The same considerations apply to patients who are 70-80 years old, Dr. Moran added. "If they are good operative candidates, they should undergo endarterectomy." The assessment of calcification and tortuosity in patients – factors that may be causing the worse outcomes in elderly patients who are treated with carotid stenting – might not be easy preoperatively. CT angiography may be able to identify these features. MR angiography will reveal tortuosity but not calcification. "The best assessment is by conventional angiography, although this is done much less frequently today than in the past. It is critical to initially assess a patient’s anatomy to determine whether he or she is a good candidate for stenting before starting the procedure," he concluded.

CREST received its primary funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, but received supplemental funding from Abbott Vascular Solutions, the company that markets the carotid stents and embolic protection devices used in the study. Dr. Virginia J. Howard said that she had no disclosures. Dr. George Howard said that he has been a consultant to Abbott. Dr. Brott had no disclosures. Dr. Moran said that he has been a speaker and a proctor for, and a consultant to, Codman and EV3 Inc.

LOS ANGELES – Women, as well as all patients aged 65 years or older who have substantial carotid artery stenosis that needs revascularization, may prefer endarterectomy, and would want to steer clear of carotid stenting, according to new data from CREST, the largest randomized trial to compare these two carotid interventions.

All patients aged 65 or older who were randomized to treatment by carotid artery stenting had a statistically significant excess of strokes, compared with similar subgroups who were treated with endarterectomy during the periprocedural period and 4-year follow-up, George Howard, Dr.P.H., said at the International Stroke Conference. "Patient age should be an important factor in selecting the treatment option for carotid stenosis," said Dr. Howard, professor and chairman of biostatistics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Analysis of the patients enrolled in CREST (Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs. Stenting Trial) by sex showed that the treatment of carotid stenosis by stenting led to an excess rate of periprocedural strokes among women, but not in men, Virginia J. Howard, Ph.D., said in a separate talk at the conference. Women who underwent an endarterectomy also had no excess risk for myocardial infarctions, compared with women who received a carotid stent, unlike men who had a significantly increased rate of MIs following open surgery, compared with those who got stented, said Dr. Howard, an epidemiologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The primary results from CREST, first reported last year, showed that all patients who were enrolled in the study had similar rates of stroke, MI, or death regardless of whether they underwent carotid endarterectomy or stenting (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:11-23). But these new details, which show an excess rate of periprocedural strokes in women undergoing stenting as well as the excess of all strokes in patients aged 65 or older undergoing stenting, may tip the balance away from stenting in these patient subgroups.

Another CREST analysis that was also reported at the conference showed that patients who had a stroke had significant decrements in several measures of their health status at 1 year following their intervention, whereas patients who had an MI generally had a much more average health status profile after 1 year.

Going into CREST, which began in 2000, "we thought the results would be the opposite. [At that time,] we preferred to take older patients to stenting," commented Dr. Thomas G. Brott, lead investigator for CREST and a professor of neurology and director or research at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida. "Our interventionalists believe that age is a surrogate marker for patients with calcified and tortuous vessels that might not be suitable for stenting." Regarding the sex-related finding, the implications "depend on how a woman would value [the risk of having] a stroke or a MI. If the woman is more concerned about a periprocedural stroke, then the results suggest there could be a preference for endarterectomy," Dr. Brott said in an interview.

In the sex-based analysis, the rate of periprocedural stroke was 5.5% in stented women and 2.2% in those who underwent endarterectomy, a statistically significant 2.6-fold increased rate with stenting, Dr. Virginia Howard reported. During the entire follow-up, which added the rate of ipsilateral strokes during 4 years following the intervention, stroke rates were 7.8% in stented women and 5.0% in those who had endarterectomy, a nonsignificant difference. The two treatment options produced no difference in stroke rates in men, either periprocedurally or after 4 years. MI rates were similar in women following either intervention, both periprocedurally and after 4 years. The periprocedural and 4-year MI rates in men were significantly higher with endarterectomy.

In the age-based analyses, a calculation that used age as a continuous variable showed that the number of strokes occurring with either endarterectomy or stenting was similar for patients aged 64 years. For those aged 65 or older, fewer strokes occurred with endarterectomy, a relationship that grew stronger with increasing age. For patients aged 63 or younger, stenting produced fewer strokes, and the relationship grew stronger with decreasing age.

The age analysis also examined the data by dividing patients into three prespecified age group: younger than 65, 65-74 years, and 75 and older. (See box.) The most striking age effect occurred in patients aged 75 or older: In this subgroup, treatment with stenting more than doubled the total stroke risk, both periprocedural and long-term strokes, compared with patients who were treated with endarterectomy.

The incidence of MI showed a much weaker age effect, and patients who underwent stenting had a reduced rate of MI at all ages, compared with those who had endarterectomy. In addition, in the endarterectomy arm, age had no significant effect on the MI rate. Among patients treated with endarterectomy, the incidence of MI was 1.6% in patients younger than 65 years and 3.2% in those aged 75 or older, differences that were not statistically significant, Dr. George Howard said.

Dr. Christopher J. Moran said that a physician who wants to prevent strokes in patients with carotid artery disease would have to "think long and hard before treating a woman with carotid stenting." In some cases, endarterectomy may not be an option: The woman may be a poor operative candidate, or may not be a good candidate for anesthesia. "But if a woman is a good operative candidate, she should be treated with endarterectomy," he said.

Conventional angiography or CT angiography lets an operator assess the size of a woman’s arteries, explained Dr. Moran, a professor of radiology and neurological surgery at Washington University, St. Louis, who performs carotid artery stenting but did not participate in CREST. The smallest self-expanding stents available for treating carotid disease are 5 mm in diameter, and because these are ideally oversized to the artery, the smallest diameter carotid that should be stented is 4 mm, he said. "Many women have carotids that are smaller than 4 mm, and in those cases you should definitely think twice about stenting."

The same considerations apply to patients who are 70-80 years old, Dr. Moran added. "If they are good operative candidates, they should undergo endarterectomy." The assessment of calcification and tortuosity in patients – factors that may be causing the worse outcomes in elderly patients who are treated with carotid stenting – might not be easy preoperatively. CT angiography may be able to identify these features. MR angiography will reveal tortuosity but not calcification. "The best assessment is by conventional angiography, although this is done much less frequently today than in the past. It is critical to initially assess a patient’s anatomy to determine whether he or she is a good candidate for stenting before starting the procedure," he concluded.

CREST received its primary funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, but received supplemental funding from Abbott Vascular Solutions, the company that markets the carotid stents and embolic protection devices used in the study. Dr. Virginia J. Howard said that she had no disclosures. Dr. George Howard said that he has been a consultant to Abbott. Dr. Brott had no disclosures. Dr. Moran said that he has been a speaker and a proctor for, and a consultant to, Codman and EV3 Inc.

LOS ANGELES – Women, as well as all patients aged 65 years or older who have substantial carotid artery stenosis that needs revascularization, may prefer endarterectomy, and would want to steer clear of carotid stenting, according to new data from CREST, the largest randomized trial to compare these two carotid interventions.

All patients aged 65 or older who were randomized to treatment by carotid artery stenting had a statistically significant excess of strokes, compared with similar subgroups who were treated with endarterectomy during the periprocedural period and 4-year follow-up, George Howard, Dr.P.H., said at the International Stroke Conference. "Patient age should be an important factor in selecting the treatment option for carotid stenosis," said Dr. Howard, professor and chairman of biostatistics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Analysis of the patients enrolled in CREST (Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs. Stenting Trial) by sex showed that the treatment of carotid stenosis by stenting led to an excess rate of periprocedural strokes among women, but not in men, Virginia J. Howard, Ph.D., said in a separate talk at the conference. Women who underwent an endarterectomy also had no excess risk for myocardial infarctions, compared with women who received a carotid stent, unlike men who had a significantly increased rate of MIs following open surgery, compared with those who got stented, said Dr. Howard, an epidemiologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The primary results from CREST, first reported last year, showed that all patients who were enrolled in the study had similar rates of stroke, MI, or death regardless of whether they underwent carotid endarterectomy or stenting (N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:11-23). But these new details, which show an excess rate of periprocedural strokes in women undergoing stenting as well as the excess of all strokes in patients aged 65 or older undergoing stenting, may tip the balance away from stenting in these patient subgroups.