User login

COVID-19 Impact on Veterans Health Administration Nurses: A Retrospective Survey

COVID-19 Impact on Veterans Health Administration Nurses: A Retrospective Survey

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization designated COVID- 19 as a pandemic.1 Pandemics have historically impacted physical and mental health across all populations, but especially health care workers (HCWs).2 Nurses and other HCWs were profoundly impacted by the pandemic.3-8

Throughout the pandemic, nurses continued to provide care while working in short-staffed workplaces, facing increased exposure to COVID-19, and witnessing COVID—19–related morbidity and mortality.9 Many nurses were mandated to cross-train in unfamiliar clinical settings and adjust to new and prolonged shift schedules. Physical and emotional exhaustion associated with managing care for individuals with COVID-19, shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), risk of infection, fear of secondary transmission to family members, feelings of being rejected by others, and social isolation, led to HCWs’ increased vulnerability to psychological impacts of the pandemic.8,10

A meta-analysis of 65 studies with > 79,000 participants found HCWs experienced significant levels of anxiety, depression, stress, insomnia, and other mental health issues, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Female HCWs, nurses, and frontline responders experienced a higher incidence of psychological impact.11 Other meta-analyses revealed that nurses’ compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout levels were significantly impacted with increased levels of burnout among nurses who had a friend or family member diagnosed with COVID- 19 or experienced prolonged threat of exposure to the virus.12,13 A study of 350 nurses found high rates of perceived transgressions by others, and betrayal.8 Nurse leaders and staff nurses had to persevere as moral distress became pervasive among nursing staff, which led to complex and often unsustainable circumstances. 14 The themes identified in the literature about the pandemic’s impact as well as witnessing nurse colleagues’ distress with patient mortality and death of coworkers during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic compelled a group of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) nurses to form a research team to understand the scope of impact and identify possible solutions.

Since published studies on the impact of pandemics on HCWs, including nurses, primarily focused on inpatient settings, the investigators of this study sought to capture the experiences of outpatient and inpatient nurses providing care in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Sierra Pacific Network (Veterans Integrated Service Network [VISN] 21), which has facilities in northern California, Hawaii, and Nevada.15-19 The purpose of this study was to identify the impact of COVID-19 on nurses caring for veterans in both outpatient and inpatient settings at VISN 21 facilities from March 2020 to September 2022, to inform leadership about the extent the virus affected nurses, and identify strategies that address current and future impacts of pandemics.

METHODS

This retrospective descriptive survey adapted the Pandemic Impact Survey by Purcell et al, which included the Moral Injury Events Scale, Primary Care PTSD Screener, the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 for depression, and a modified burnout scale.20-24 The survey of 70 Likert-scale questions was intended to measure nurses’ needs, burnout, moral distress, depression and stress symptoms, work-related factors, and intent to remain working in their current position. A nurse was defined broadly and included those employed as licensed vocational nurses (LVN), licensed practical nurses (LPN), registered nurses (RN), nurses with advanced degrees, advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), and nurses with other certifications or licenses.

The VA Pacific Islands Research and Development Committee reviewed and approved the institutional review board-exempted study. The VISN 21 union was notified; only limited demographic information and broad VA tenure categories were collected to protect privacy. The principal investigator redacted facility identifier data after each facility had participated.

The survey was placed in REDCAP and a confidential link was emailed to all VISN 21 inpatient and outpatient nurses during March 2023. Because a comprehensive VISN 21 list of nurse email addresses was unavailable, the email was distributed by nursing leadership at each facility. Nurses received an email reminder at the 2-week halfway point, prompting them to complete the survey. The email indicated the purpose and voluntary nature of the study and cautioned nurses that they might experience stress while answering survey questions. Stress management resources were provided.

Descriptive statistics were used to report the results. Data were aggregated for analyzing and reporting purposes.

RESULTS

In March 2023, 860 of 5586 nurses (15%) responded to the survey. Respondents included 344 clinical inpatient nurses (40%) and 516 clinical outpatient nurses (60%); 688 (80%) were RNs, 129 (15%) were LPNs/LVNs, and 43 (5%) were APRNs. Of 849 respondents to provide their age, 15 (2%) were < 30 years, 163 (19%) were 30 to 39 years, 232 (27%) were 40 to 49 years, 259 (30%) were 50 to 59 years, and 180 (21%) were ≥ 60 years.

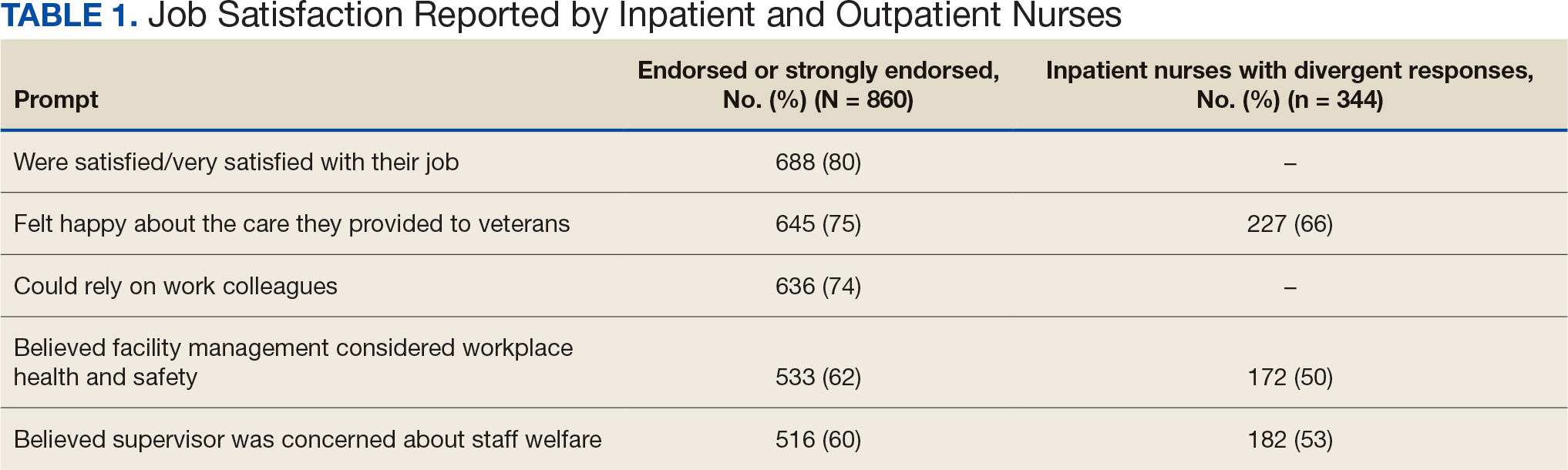

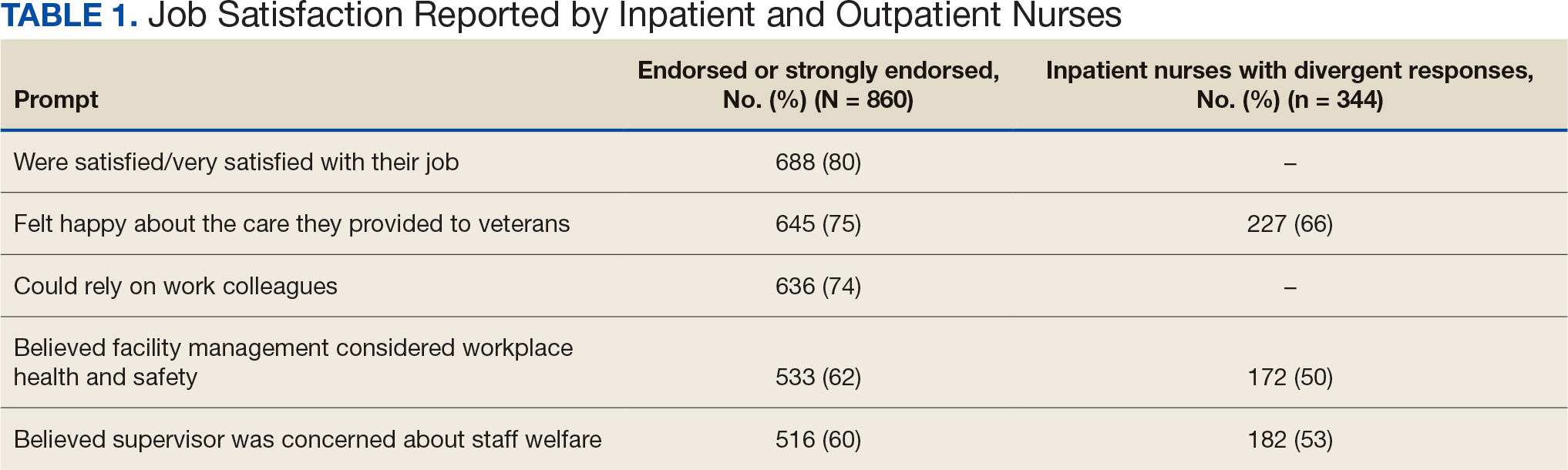

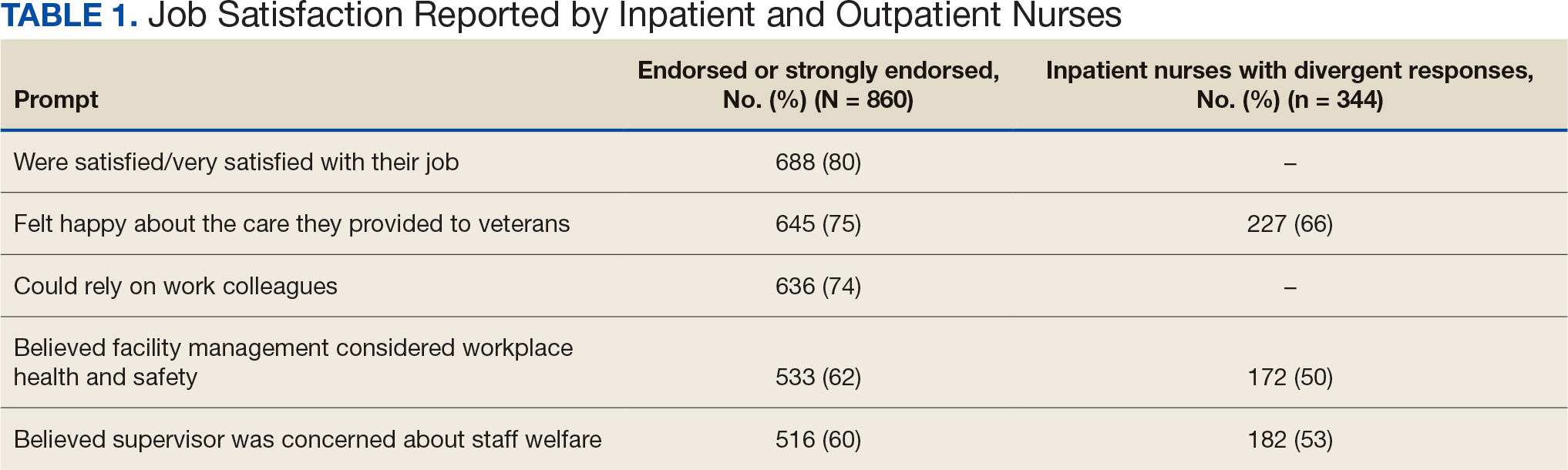

The survey found that 688 nurses reported job satisfaction (80%) and 75% of all respondents (66% among inpatient nurses) reported feeling happy with the care they delivered. Both inpatient and outpatient nurses indicated they could rely on staff. Sixty percent (n = 516) of the nurses indicated that facility management considered workplace health and safety and supervisors showed concern for subordinates, although inpatient nurses reported a lower percentage (Table 1).

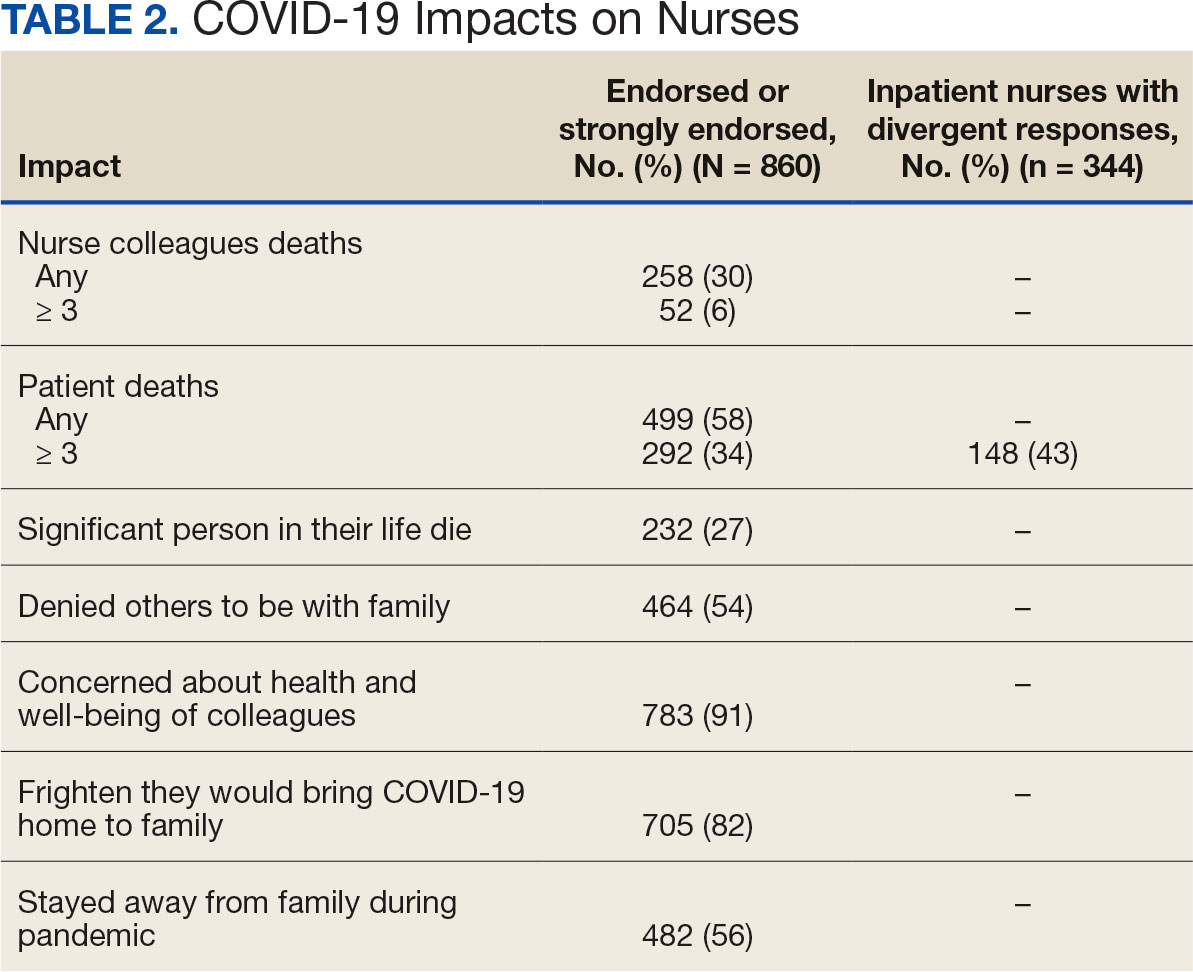

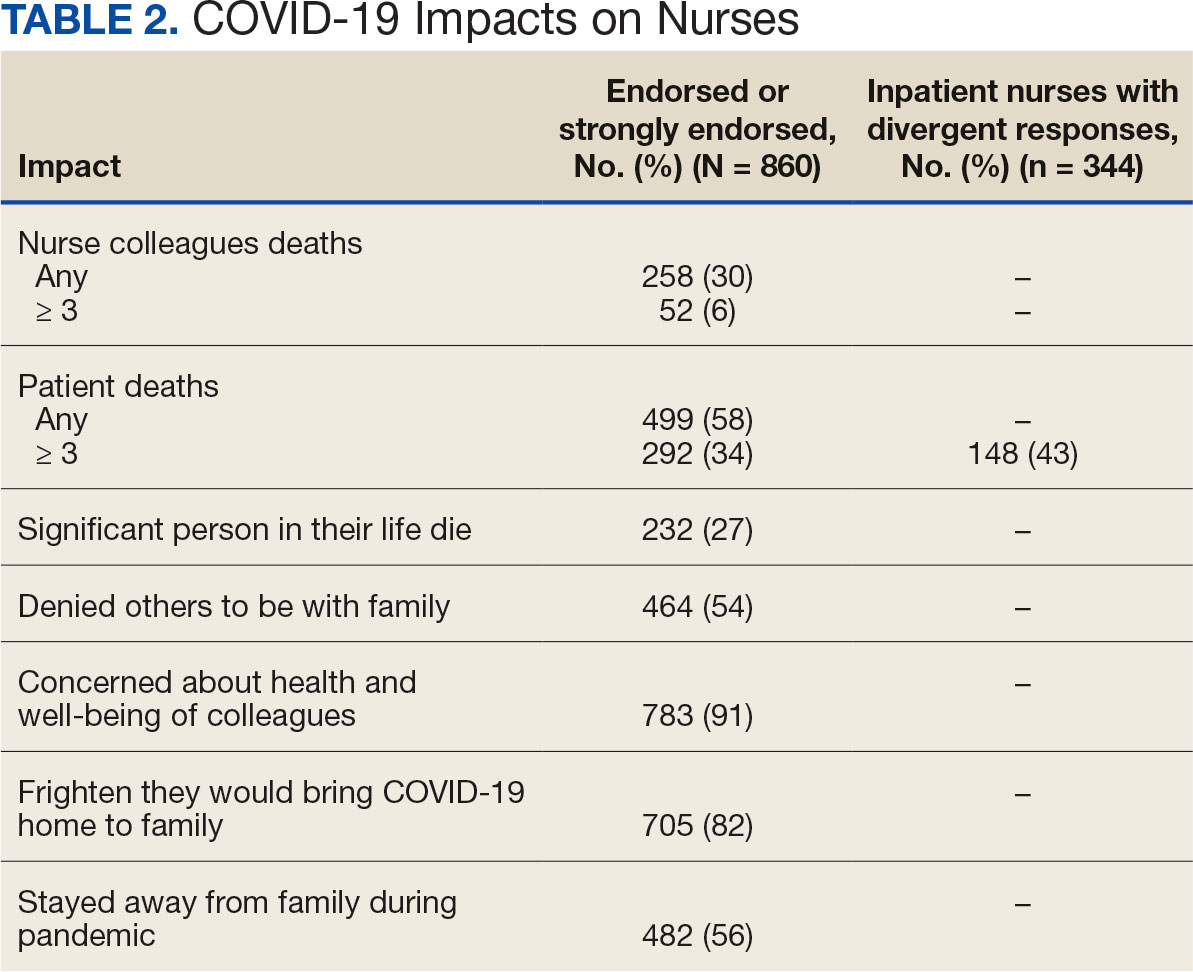

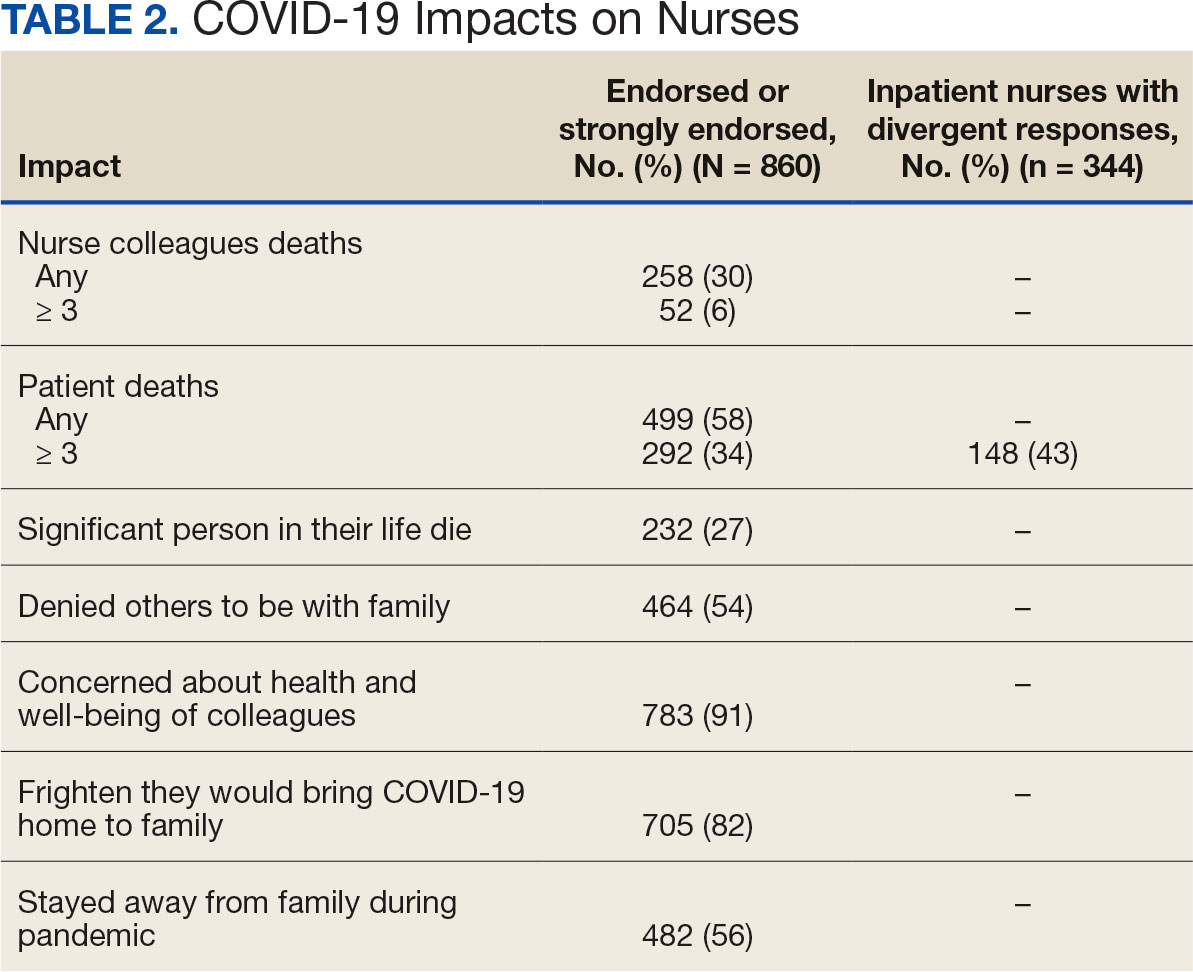

Two hundred fifty-eight nurses (30%) reported having nurse colleagues who died and 52 (6%) had ≥ 3 colleagues who died. Among respondents, 292 had ≥ 3 patients who died after contracting COVID-19 and 232 (27%) had a significant person in their life die. More than one-half (54%; n = 464) of nurses had to limit contact with a family member who had COVID-19. Most nurses reported concerns about their colleagues (91%), were concerned about bringing COVID-19 home (82%), and stayed away from family during the pandemic (56%) (Table 2).

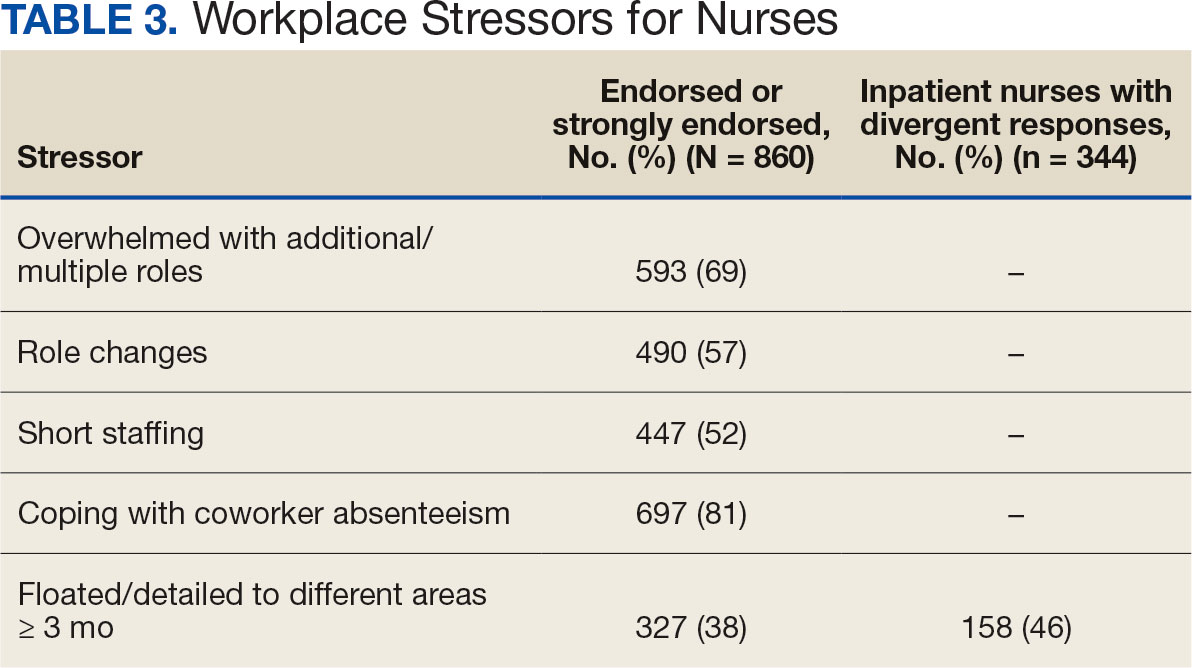

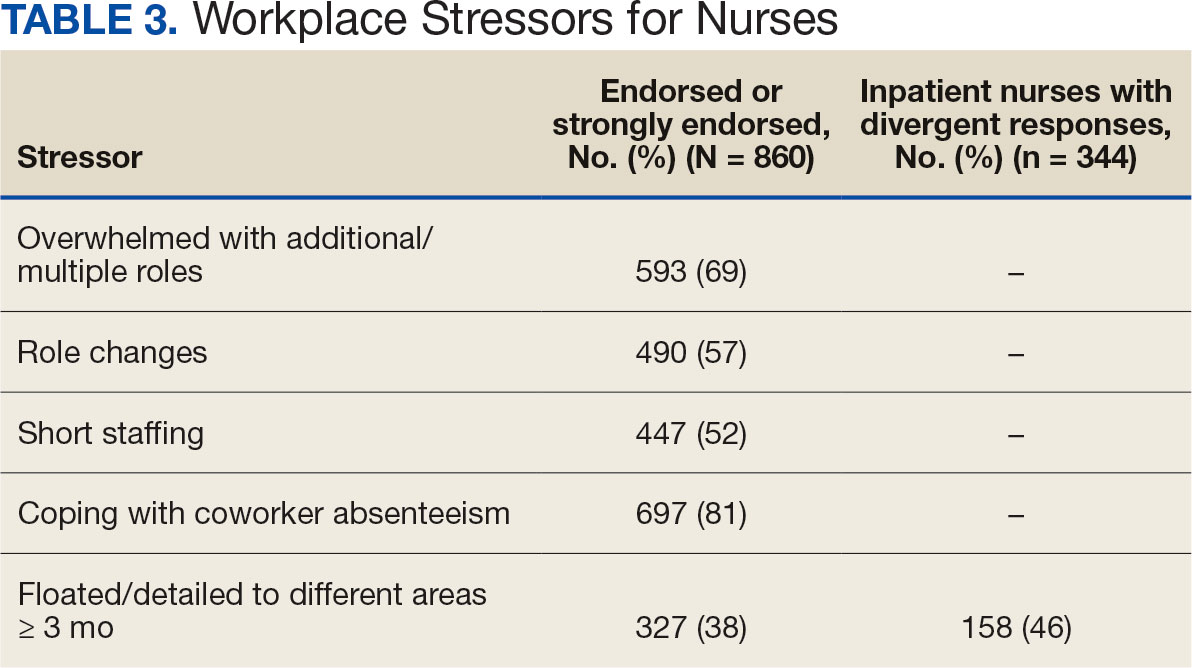

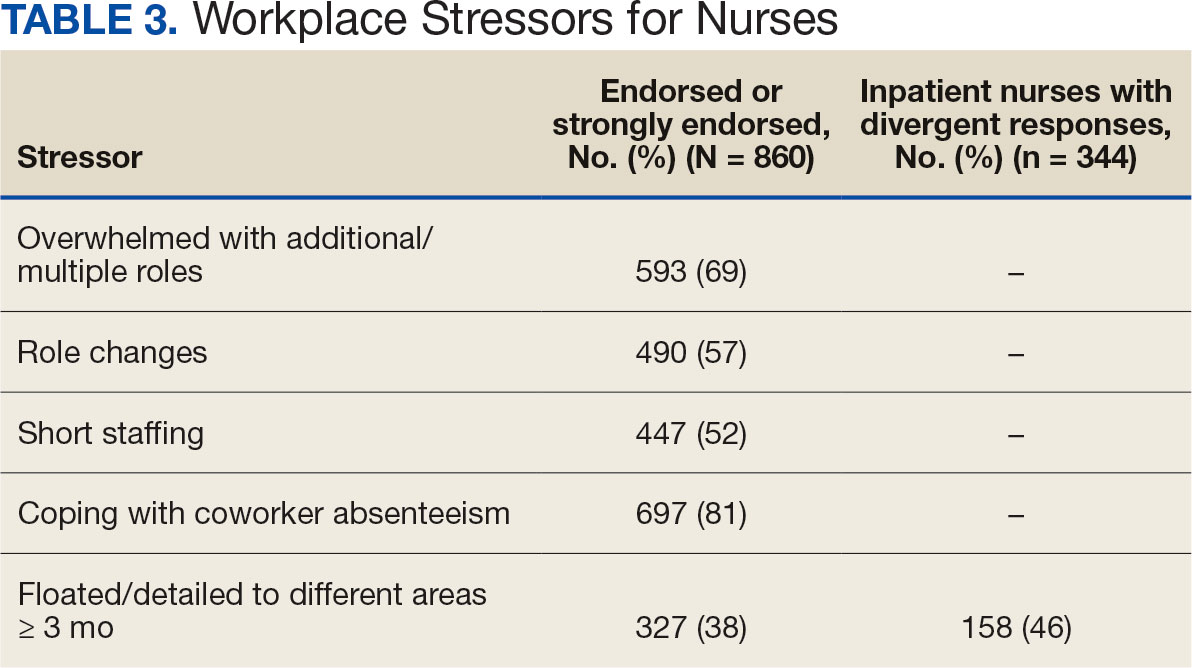

A total of 593 nurses (69%) reported feeling overwhelmed from the workload associated with the pandemic, 490 (57%) felt frustrated with role changes, 447 (52%) were stressed because of short staffing, and 327 (38%) felt stressed because of being assigned or floated to different patient care areas. Among inpatient nurses, 158 (46%) reported stress related to being floated. Coworker absenteeism caused challenges for 697 nurses (81%) (Table 3).

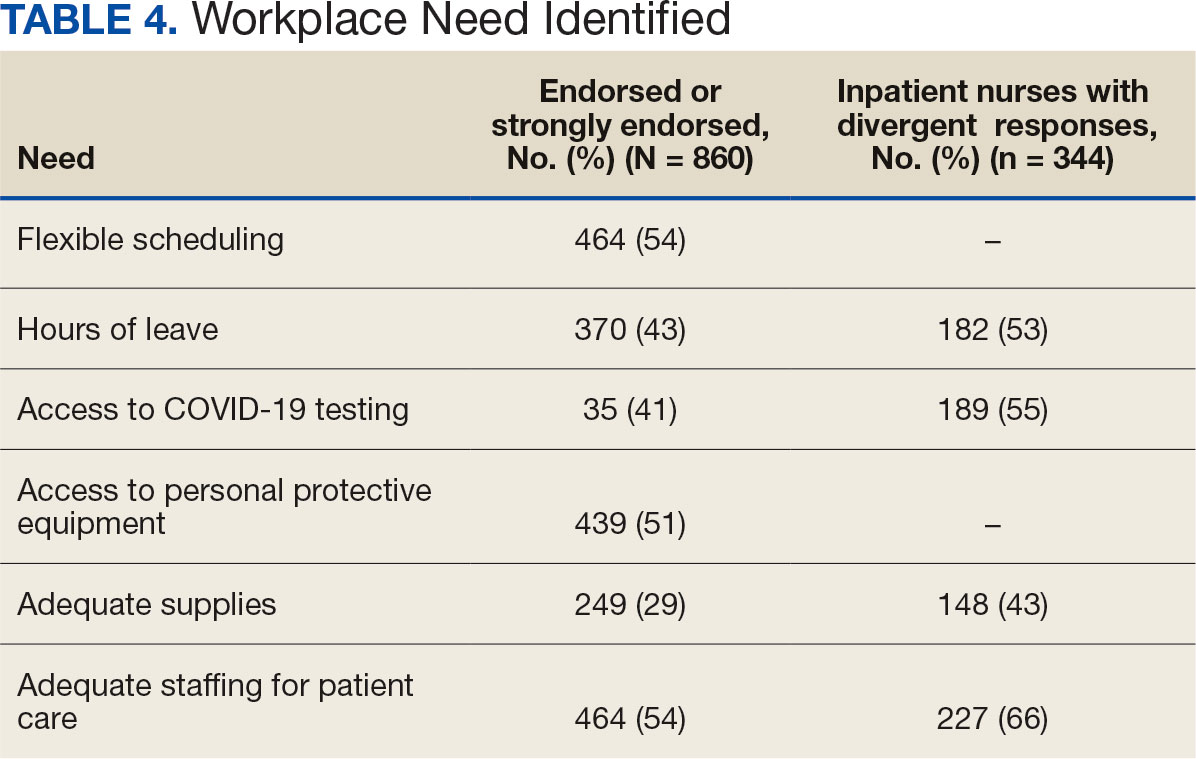

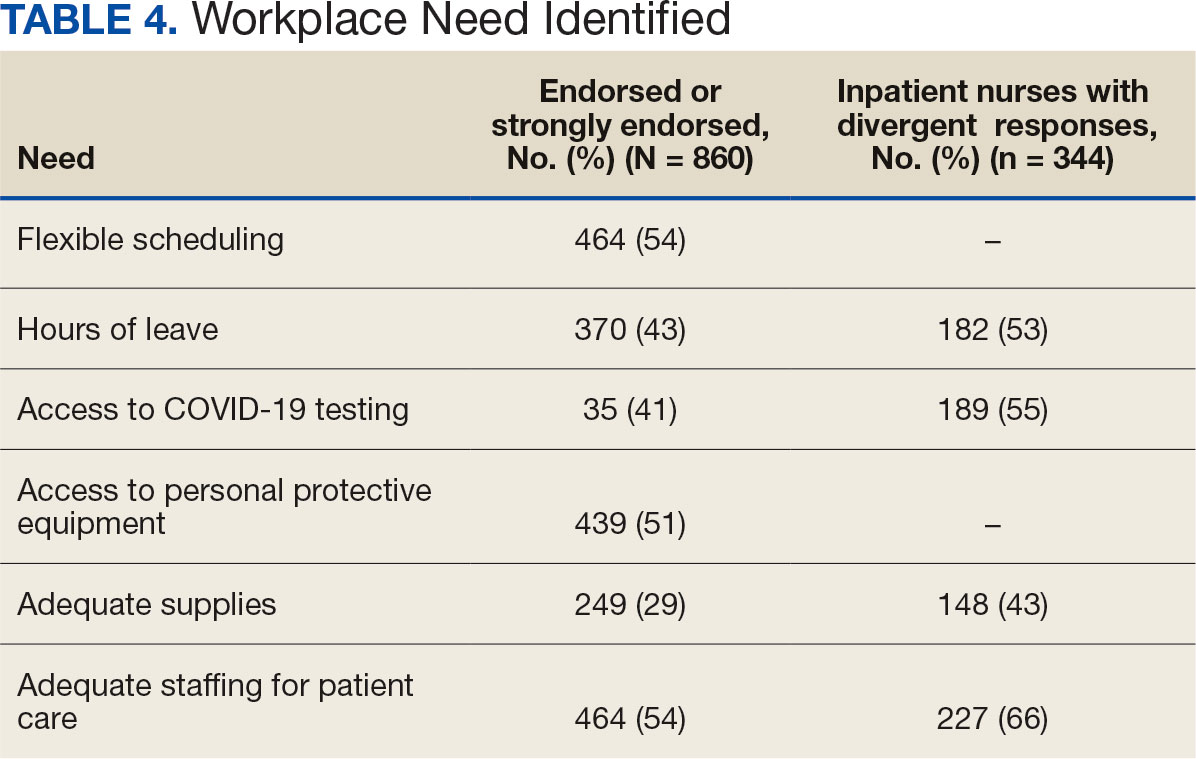

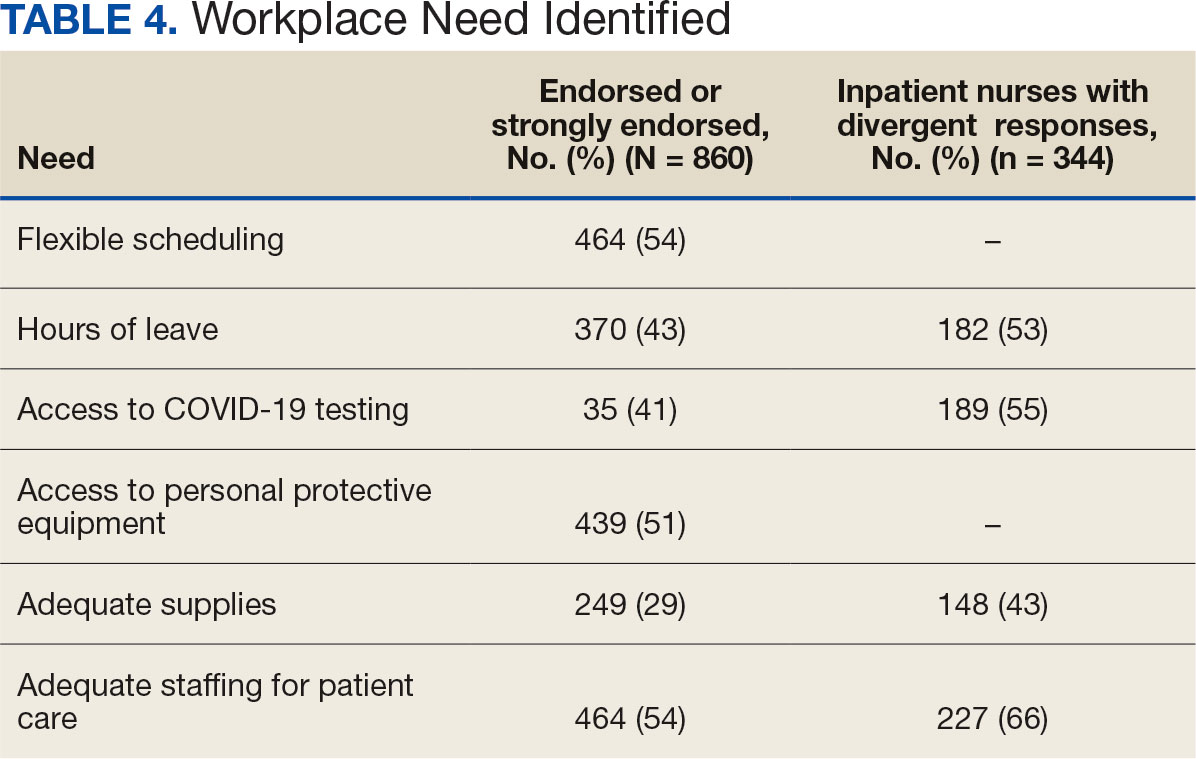

Nurses suggested a number of changes that could improve working conditions, including flexible scheduling (54%) and more hours of leave, which was requested by 43% of outpatient/inpatient nurses and 53% of inpatient alone nurses. Access to COVID-19 testing and PPE was endorsed as a workplace need by 439 nurses; the need for access to PPE was reported by 43% of inpatient-only nurses vs 29% of outpatient/inpatient nurses. The need for adequate staffing was reported by 54% of nurses although the rate was higher among those working inpatient settings (66%) (Table 4).

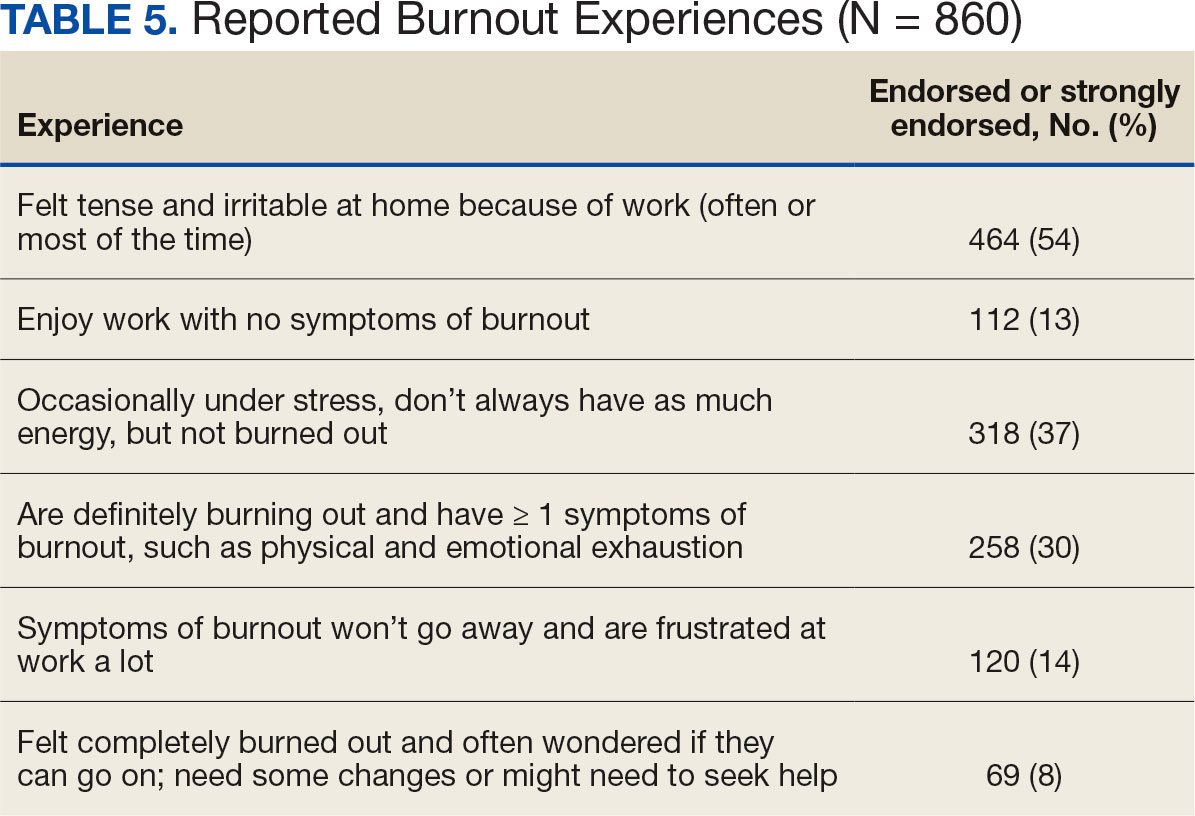

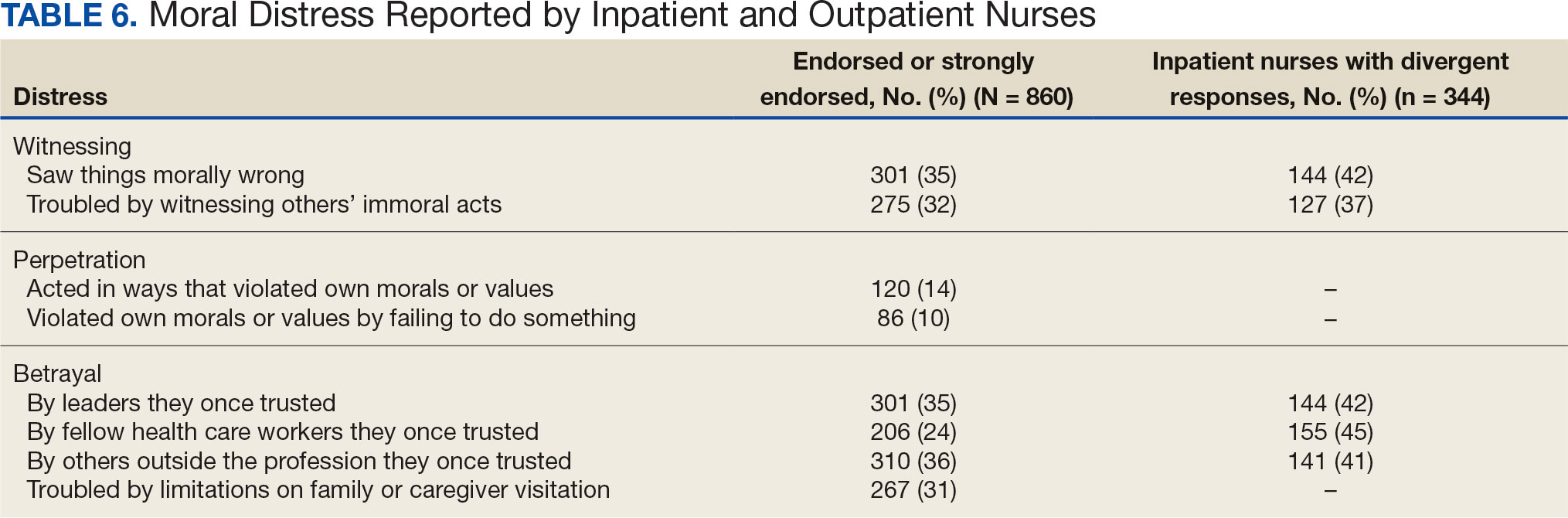

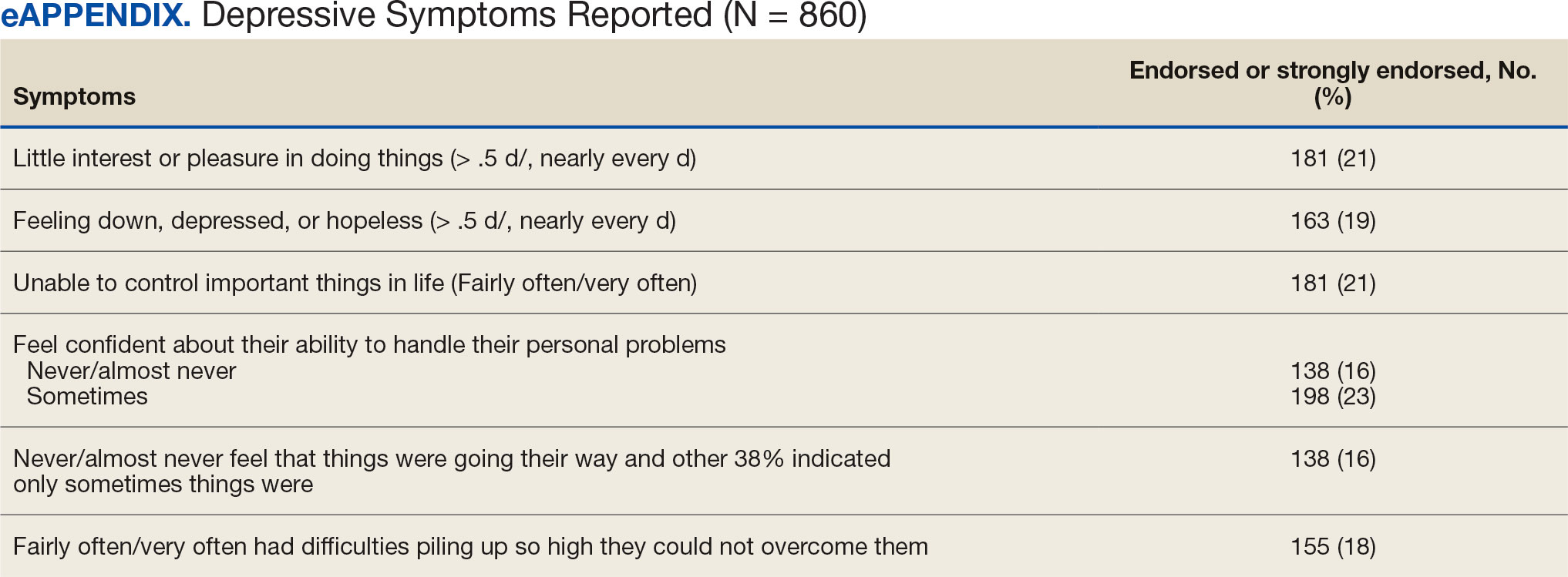

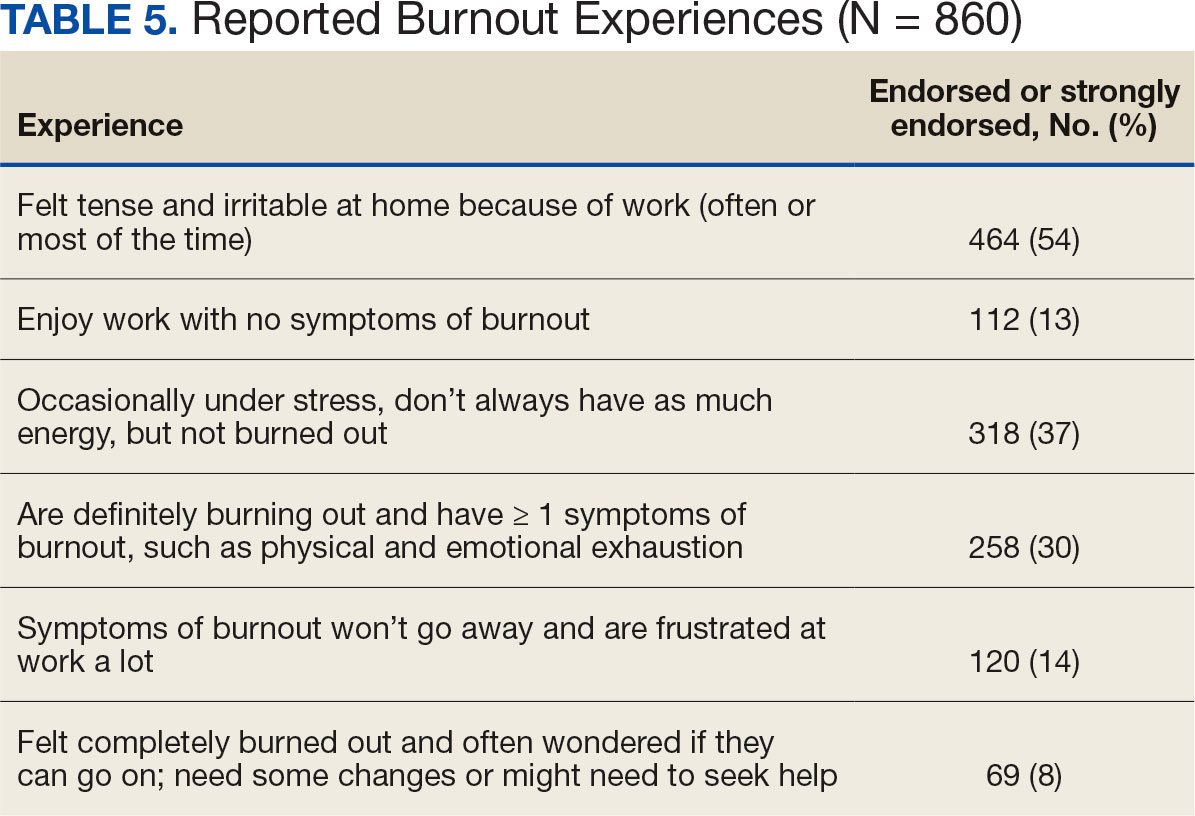

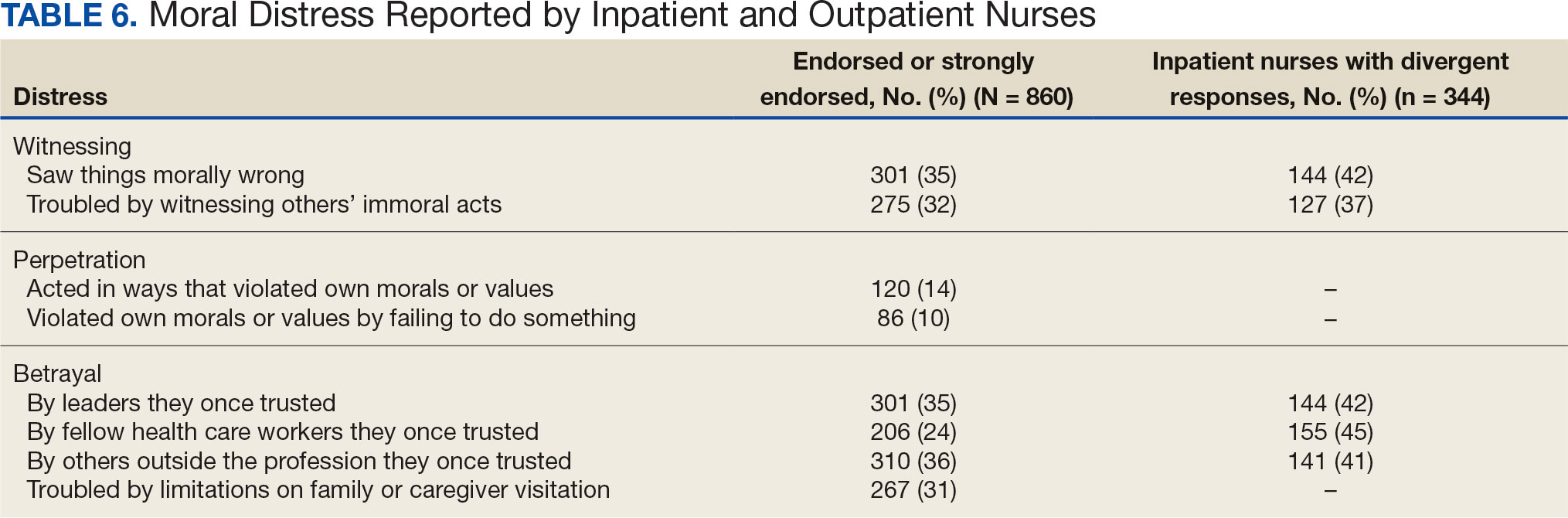

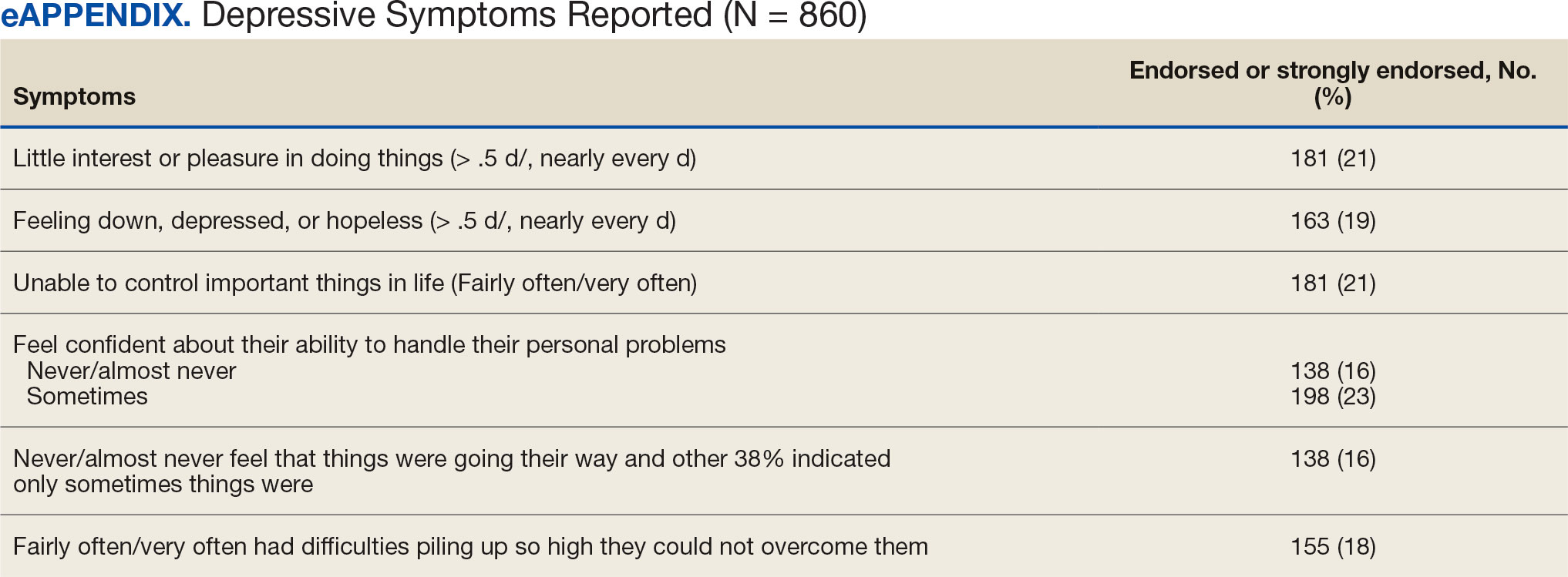

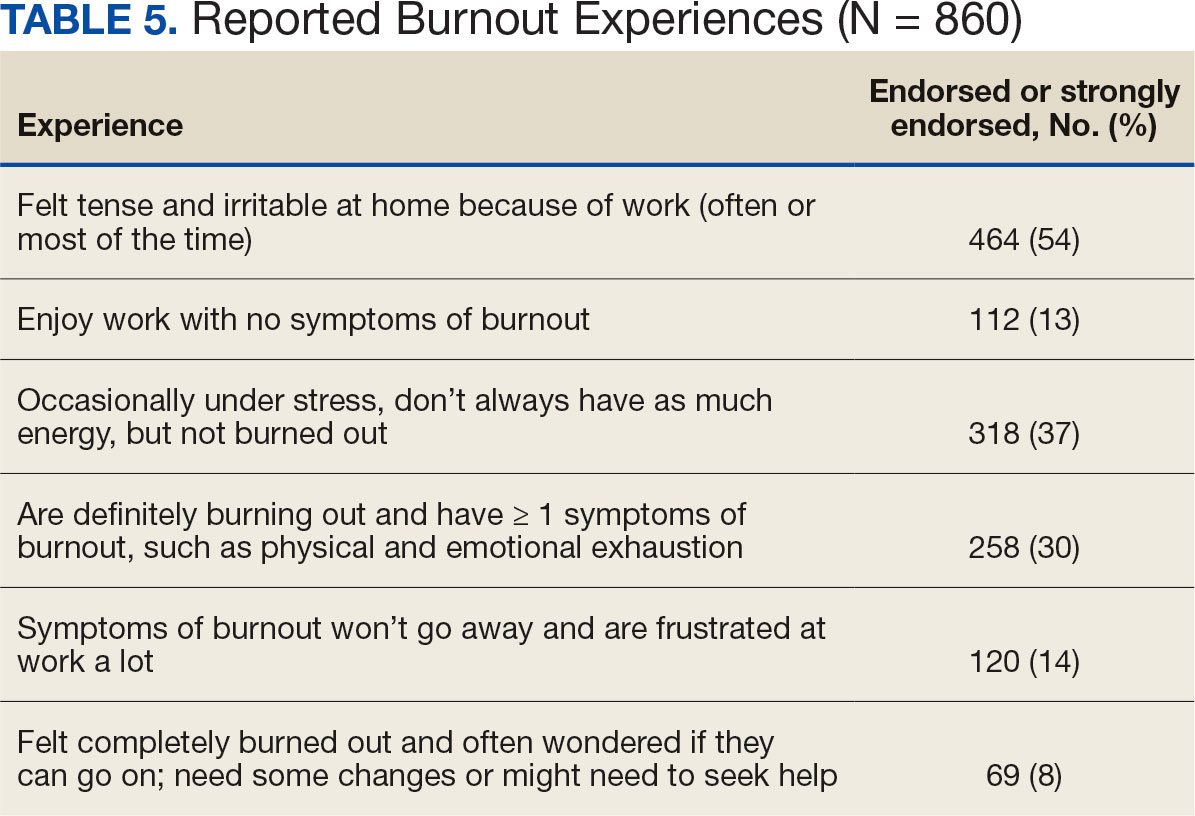

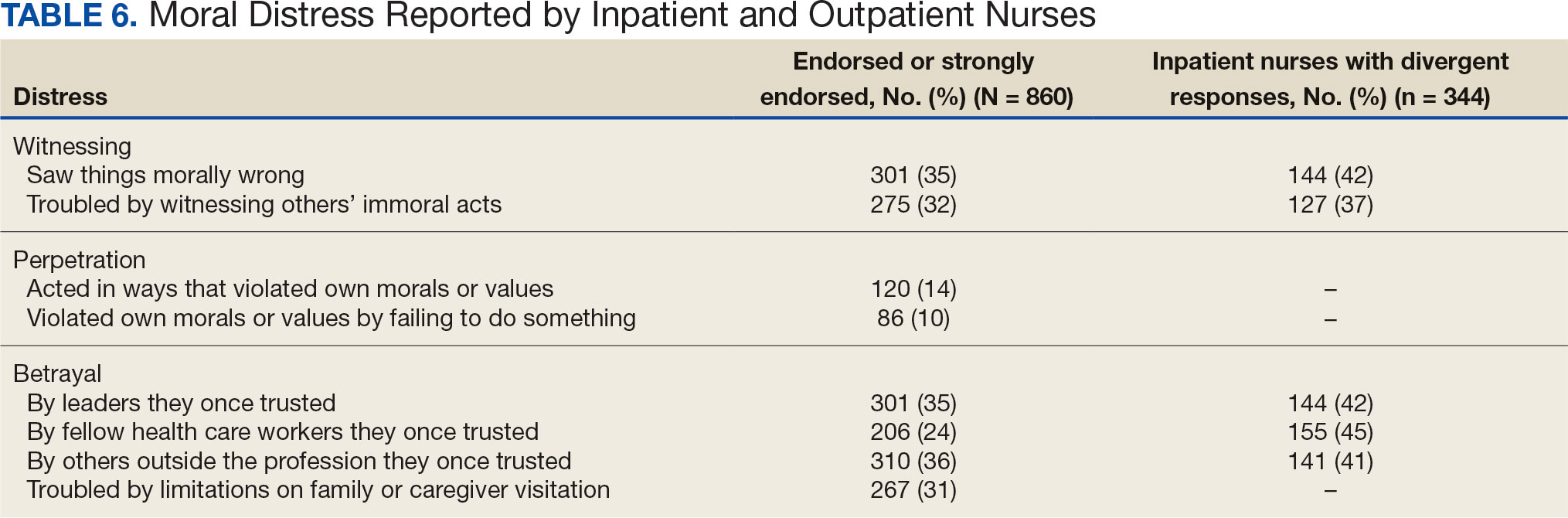

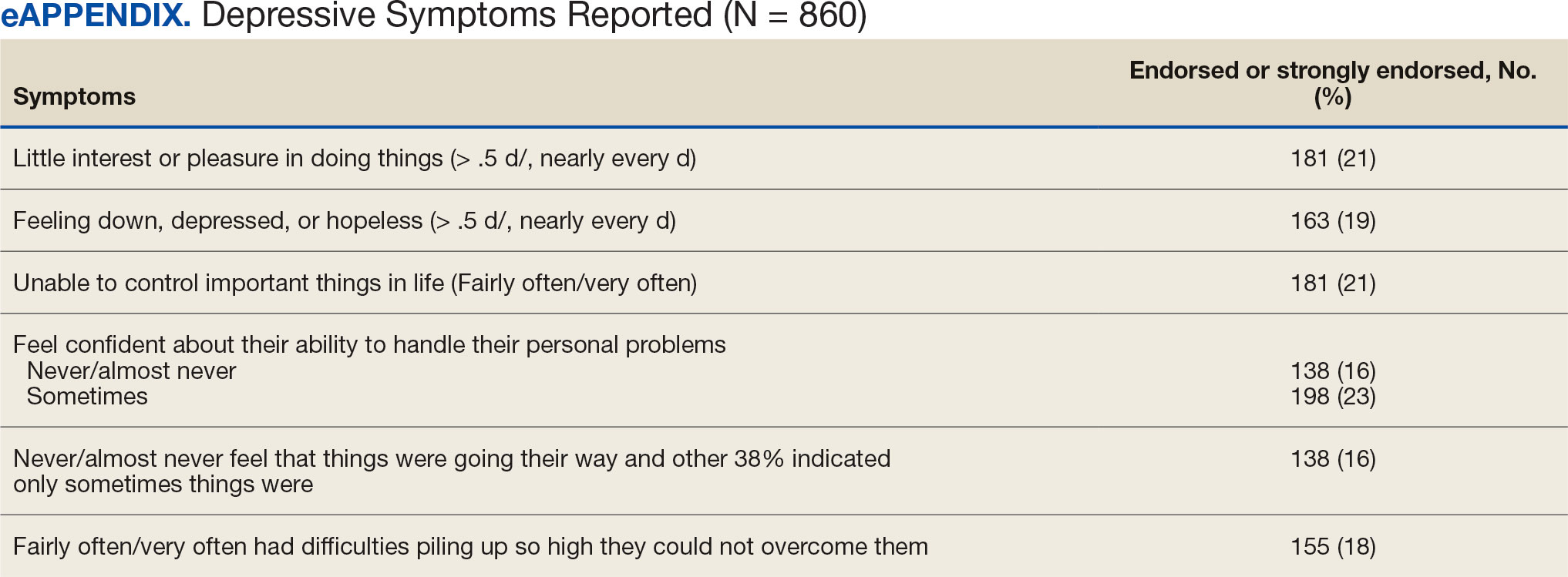

Four hundred sixty-four nurses (54%) felt tense and irritable at home because of work and 447 had ≥ 1 symptoms of burnout (Table 5). In terms of moral distress, > 30% of nurses witnessed morally incongruent situations, 10% felt their own moral code was violated, and > 30% felt betrayed by others (Table 6). Among respondents, 16% to 21% of nurses reported depressive symptoms (eAppendix). About 50% of nurses intended to stay in their current position while 20% indicated an intention to leave for another VA position.

DISCUSSION

This study identified the impact of COVID-19 on nurses who work in VISN 21. The survey included a significant number of nurses who work in outpatient settings, which differed from most other published studies to date.15-19 This study found that inpatient and outpatient nurses were similarly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, although there were differences. A high percentage of nurses reported job satisfaction despite the personal and professional impact of the pandemic.

Caring for veterans can result in a therapeutic relationship with a deep appreciation of veterans’ service and sensitivity to their needs.25 Some nurses reported that they feel it is a privilege to care for veterans.

Most nurses who participated in this study felt they could rely on their colleagues and were concerned about their health and wellbeing. Kissel et al explored protective factors for nurses during the pandemic and found participants often reported that their coworkers were positive safeguards.17 At least 50% of respondents reported that management considered workplace safety and was concerned about their welfare. Previous research has found that a positive working organization that promoted safety and concern for staff were protective factors against stress among HCWs.26 A literature review of 3 coronavirus outbreaks illustrated the support from supervisors and colleagues promoted resiliency and reduced stress disorders.3

Similar to other studies, study respondents experienced profound losses, including the deaths of colleagues, patients, and family. In 2021 Howell reported that HCWs experienced increased stress, fear, anxiety, and other negative emotions following news of colleagues’ deaths from COVID-19.27 Kissel et al reported that nurses frequently described pandemic-related physical and psychological harm and witnessing distress that they had not been previously exposed to.17

Our findings illustrate the tightrope nurses walked while caring for patients and concerns about the health of their colleagues and family. Consistent with our findings, Howell found that HCWs were afraid of contracting the infection at work and then unknowingly giving it to others such as patients, coworkers, and household members. 27 Murat et al reported that some nurses chose to live separately during the pandemic to avoid spreading COVID-19 to relatives.19 Several researchers found that concerns about family and children were prevalent and led to fear, anxiety, and burnout among nurses.18,28,29 Shah et al suggested that nurses experiencing death in the workplace and within their family may have resulted in fear and anxiety about returning to work.29 Garcia and Calvo argued that nurses may have been stigmatized as carriers of COVID-19.16 In addition, the loss of prepandemic workplace rituals may have impacted performance, team connection, and functioning, and led to increased turnover and decreased attachment to the organization.30

This study described the significant workplace issues nurses endured during the pandemic, including being overwhelmed with additional and/or multiple roles and frustrated and stressed with role changes and short staffing. Nurses endorsed workplace challenges in the context of coworker absenteeism and reassignments to different areas, such as intensive care units (ICUs).17 Researchers also reported that displaced team members experienced loneliness and isolation when they were removed from their usual place of work and experienced distress caring for patients beyond their perceived competency or comfort.17,31 Nurses also experienced rapid organizational changes, resource scarcity, high patient-to-nurse ratios, inconsistent or limited communications, and the absence of protocols for prolonged mass casualty events.17 These challenges, such as significant uncertainty and rapidly changing working conditions, were shared experiences suggested to be similar to “tumbling into chaos,” and likened to the overwhelming situations faced during patient surges to a medical “war zone.”17

Study respondents indicated that nurses wanted better access to critical supplies, PPE, and COVID-19 testing; more flexible scheduling; longer leave times; and staffing that was appropriate to the patient volumes. These findings aligned with previous research. Howell found that HCWs, especially nurses, worried about childcare because of school closures and increased work hours.27 Nurses felt that hospital support was inaccessible or inadequate and worried about access to essential resources.17-19,27 Studies also found excessive workloads, and many nurses needed mental or financial assistance from the hospital in addition to more rest and less work.18,28 An editorial highlighted the potential adverse effects that a lack of PPE could have on staff ’s mental health because of perceptions of institutional betrayal, which occurs when trusted and powerful organizations seemingly act in ways that can harm those dependent on them for safety and well-being.32

Consistent with other research, this study found that a majority of nurses experienced significant burnout symptoms. The number of nurses reporting symptoms of burnout increased during the pandemic with ICU nurses reporting the highest levels.17,33 Soto-Rubio et al emphasized that working conditions experienced by nurses, such as interpersonal conflict, lack of trust in administration, workload, and role conflict, contributed to burnout during COVID-19.34 Other studies found that nurses experienced burnout caused by uncertainty, intense work, and extra duties contributed to higher burnout scores.18,19 It is not surprising that researchers have indicated that nurses experiencing burnout might display depressive and stress-related symptoms, insomnia, and concentration and memory problems.19

The results of this study indicate that one-third of participating nurses were experiencing moral distress. Burton et al described COVID-19 as an environment in which nurses witnessed, experienced, and at times had to participate in acts that involved ethical violations in care, institutional betrayal, and traumatic strain.9 Of note, our findings revealed that both inpatient and outpatient nurses experienced moral distress. Interestingly, Mantri et al found that COVID-19 increased moral injury but not burnout among health professionals, which differed from the results of this study.35

The findings of this study indicate that many nurses experienced depressive symptoms. A systematic review found a similar percentage of HCWs experienced depression while caring for patients with COVID- 19, though a Chinese study found a higher percentage.36,37 Previous research also found that the most difficult aspect of the COVID- 19 pandemic for nurses was coping with mental disorders such as depression, and that many experienced difficulty sleeping/ had poor sleep quality, believed a similar disaster would occur in the future, were irritated or angered easily, and experienced emotional exhaustion.15,19 The long-term mental and physical ramifications of caring for individuals with COVID-19 remain unknown. However, previous research suggests a high prevalence of depression, insomnia, anxiety, and distress, which could impair nurses’ professional performance.29

This study reported that a majority of nurses intended to stay in their current position and about 20% intended to leave for another position within the VA. Similar findings conducted early in the pandemic indicated that most participants did not intend to quit nursing.19

This study’s findings suggest the COVID-19 pandemic had an adverse impact on VISN 21 nurses. It is critical to develop, implement, and adopt adequate measures as early as possible to support the health care system, especially nurses.18

Implications

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, discussing burnout and moral anguish was common, primarily in critical care.14 However, these experiences became more widespread throughout nursing settings during the pandemic. Nurse leaders have been identified as responsible for ensuring the environmental safety and personal well-being of their colleagues during and after pandemics.14

Studies of HCW experiences during COVID-19 provide many insights into future preparedness, strategies to best handle another pandemic during its acute stage, and techniques to address issues that might persist. This study and others suggest that comprehensive interventions in preparation for, during, and after a pandemic are needed. We break down strategies into pandemic and postpandemic interventions based on a synthesis of the literature and the research team’s knowledge and expertise.3,14-16,27,29,36,38-44

Pandemic interventions. During a pandemic, it is important that nurses are adequately cared for to ensure they can continue to provide quality care for others. Resources supporting emotional well-being and addressing moral distress offered during a pandemic are essential. Implementing meaningful strategies could enhance nurses’ health and wellbeing. It is essential that leaders provide nurses a safe work environment/experience during a pandemic by instituting meaningful resources. In addition, developing best practices for leadership are critical.

Postpandemic interventions. Personal experiences of depression, burnout, and moral distress have not spontaneously resolved as the pandemic receded. Providing postpandemic interventions to lessen ongoing and lingering depressive, burnout, and moral distress symptoms experienced by frontline workers are critical. These interventions might prevent long-term health issues and the exodus of nurses.

Postpandemic interventions should include the integration of pandemic planning into new or existing educational or training programs for staff. Promotion and support of mental health services by health system leadership for nursing personnel implemented as a usual service will play an important role in preparing for future pandemics. A key role in preparation is developing and maintaining cooperation and ongoing mutual understanding, respect, and communication between leadership and nursing staff.

Future Research

This study’s findings inform VHA leadership and society about how a large group of nurses were impacted by COVID-19 while caring for patients in inpatient and outpatient settings and could provide a basis for extending this research to other groups of nurses or health care personnel. Future research might be helpful in identifying the impact of COVID-19 on nursing leadership. During conversations with nursing leadership, a common theme identified was that nurses did not feel that leadership was fully prepared for the level of emergency the pandemic created both personally and professionally; leadership expressed experiences similar to nurses providing direct care and felt powerless to help their nursing staff. Other areas of research could include identifying underlying factors contributing to burnout and moral distress and describing nurses’ expectations of or needs from leadership to best manage burnout and moral distress.

Limitations

Experiences of nurses who stopped working were not captured and information about their experiences might have different results. The survey distribution was limited to 2 emails (an initial email and a second at midpoint) sent at the discretion of the nurse executive of each facility. The study timeline was long because of complex regulatory protective processes inherent in the VHA system for researchers to include initial institutional review board review process, union notifications, and each facility’s response to the survey. Although 860 nurses participated, this was 15% of the 5586 VISN 21 nurses at the time of the study. Many clinical inpatient nurses do not have regular access to email, which might have impacted participation rate.

CONCLUSIONS

This study identified the impact COVID-19 had on nurses who worked in a large hospital system. The research team outlined strategies to be employed during and after the pandemic, such as preplanning for future pandemics to provide a framework for a comprehensive pandemic response protocol.

This study adds to generalized knowledge because it captured voices of inpatient and outpatient nurses, the latter had not been previously studied. As nurses and health care organizations move beyond the pandemic with a significant number of nurses continuing to experience effects, there is a need to institute interventions to assist nurses in healing and begin preparations for future pandemics.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

- Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):15-23. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003

- Carmassi C, Foghi C, Dell’Oste V, et al. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: What can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113312. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113312

- De Kock JH, Latham HA, Leslie SJ, et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):104. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-10070-3

- Gualano MR, Sinigaglia T, Lo Moro G, et al. The burden of burnout among healthcare professionals of intensive care units and emergency departments during the covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):8172. doi:10.3390/ijerph18158172

- Sirois FM, Owens J. Factors associated with psychological distress in health-care workers during an infectious disease outbreak: a rapid systematic review of the evidence. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11;589545. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589545

- Talevi D, Socci V, Carai M, et al. Mental health outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Riv Psichiatr. 2020;55(3);137-144. doi:10.1708/3382.33569

- Amsalem D, Lazarov A, Markowitz JC, et al. Psychiatric symptoms and moral injury among US healthcare workers in the COVID-19 era. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):546. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03565-9

- Burton CW, Jenkins DK, Chan G.K, Zellner KL, Zalta AK. A mixed methods study of moral distress among frontline nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2023;16(4):568-575. doi:10.1037/tra0001493

- Stawicki SP, Jeanmonod R, Miller AC, et al. The 2019- 2020 novel coronavirus (Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) Pandemic:a Joint American College of Academic International Medicine-World Academic Council of Emergency Medicine Multidisciplinary COVID-19 Working Group consensus paper. J Glob Infect Dis. 2020;12(2):47- 93. doi:10.4103/jgid.jgid_86_20

- Batra K, Singh TP, Sharma M, Batra R, Schvaneveldt N. Investigating the psychological impact of COVID- 19 among healthcare workers: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):9096. doi:10.3390/ijerph17239096

- Xie W, Chen L, Feng F, et al. The prevalence of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;120:103973. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103973

- Galanis P, Vraka I, Fragkou D, Bilali A, Kaitelidou D. Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(8):3286-3302. doi:10.1111/jan.14839

- Hofmeyer A, Taylor R. Strategies and resources for nurse leaders to use to lead with empathy and prudence so they understand and address sources of anxiety among nurses practicing in the era of COVID-19. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(1- 2):298-305. doi:10.1111/jocn.15520

- Chen R, Sun C, Chen JJ, et al. A large-scale survey on trauma, burnout, and posttraumatic growth among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(1):102-116. doi:10.1111/inm.12796

- García G, Calvo J. The threat of COVID-19 and its influence on nursing staff burnout. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(2):832-844. doi:10.1111/jan.14642

- Kissel KA, Filipek C, Jenkins J. Impact of the COVID- 19 pandemic on nurses working in intensive care units: a scoping review. Crit Care Nurse. 2023;43(2):55-63. doi:10.4037/ccn2023196

- Lin YY, Pan YA, Hsieh YL, et al. COVID-19 pandemic is associated with an adverse impact on burnout and mood disorder in healthcare professionals. Int J Environ Res and Public Health. 2021;18(7):3654. doi:10.3390/ijerph18073654

- Murat M, Köse S, Savas¸er S. Determination of stress, depression and burnout levels of front-line nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(2):533-543. doi:10.1111/inm.12818

- Purcell N, Bertenthal D, Usman H, et al. Moral injury and mental health in healthcare workers are linked to organizational culture and modifiable workplace conditions: results of a national, mixed-methods study conducted at Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers during the COVID- 19 pandemic. PLOS Ment Health. 2024;1(7):e0000085. doi:10.1371/journal.pmen.0000085

- Nash WP, Marino Carper TL, Mills MA, Au T, Goldsmith A, Litz BT. Psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Events Scale. Mil Med. 2013;178(6):646-652. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017

- Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, et al. The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1206-1211. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284-1292. doi:10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

- Rohland BM, Kruse GR, Rohrer JE. Validation of a single- item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress and Health. 2004;20(2):75-79. doi:10.1002/smi.1002

- Carlson J. Baccalaureate nursing faculty competencies and teaching strategies to enhance the care of the veteran population: perspectives of Veteran Affairs Nursing Academy (VANA) faculty. J Prof Nurs. 2016;32(4):314-323. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.01.006

- Denning M, Goh ET, Tan B, et al. Determinants of burnout and other aspects of psychological well-being in healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: a multinational cross-sectional study. PloS One. 2021;16(4):e0238666. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0238666

- Howell BAM. Battling burnout at the frontlines of health care amid COVID-19. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2021;32(2):195- 203. doi:10.4037/aacnacc2021454

- Afshari D, Nourollahi-Darabad M, Chinisaz N. Demographic predictors of resilience among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work. 2021;68(2):297-303. doi:10.3233/WOR-203376

- Shah M, Roggenkamp M, Ferrer L, Burger V, Brassil KJ. Mental health and COVID-19: the psychological implications of a pandemic for nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2021;25(1), 69-75. doi:10.1188/21.CJON.69-75

- Griner T, Souza M, Girard A, Hain P, High H, Williams M. COVID-19’s impact on nurses’ workplace rituals. Nurs Lead. 2021;19(4):425-430. doi:10.1016/j.mnl.2021.06.008

- Koren A, Alam MAU, Koneru S, DeVito A, Abdallah L, Liu B. Nursing perspectives on the impacts of COVID- 19: social media content analysis. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(12):e31358. doi:10.2196/31358

- Gold JA. Covid-19: adverse mental health outcomes for healthcare workers. BMJ. 2020;5:369:m1815. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1815. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1815

- Slusarz R, Cwiekala-Lewis K, Wysokinski M, Filipska- Blejder K, Fidecki W, Biercewicz M. Characteristics of occupational burnout among nurses of various specialties and in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic-review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21):13775. doi:10.3390/ijerph192113775

- Soto-Rubio A, Giménez-Espert MDC, Prado-Gascó V. Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses’ health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7998. doi:10.3390/ijerph17217998

- Mantri S, Song YK, Lawson JM, Berger EJ, Koenig HG. Moral injury and burnout in health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2021;209(10):720-726. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001367

- Salari N, Khazaie H, Hosseinian-Far A, et al. The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-regression. Hum Resour Health 2020;18(1):100. doi:10.1186/s12960-020-00544-1

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

- Chesak SS, Cutshall SM, Bowe CL, Montanari KM, Bhagra A. Stress management interventions for nurses: critical literature review. J Holist Nurs. 2019;37(3):288-295. doi:10.1177/0898010119842693

- Cooper AL, Brown JA, Leslie GD. Nurse resilience for clinical practice: an integrative review. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(6):2623-2640. doi:10.1111/jan.14763

- Melnyk BM, Kelly SA, Stephens J, et al. Interventions to improve mental health, well-being, physical health, and lifestyle behaviors in physicians and nurses: a systematic review. Am J Health Promot. 2020;34(8):929-941. doi:10.1177/0890117120920451

- Cho H, Sagherian K, Steege LM. Hospital staff nurse perceptions of resources and resource needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Outlook. 2023;71(3):101984. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2023.101984

- Bachem R, Tsur N, Levin Y, Abu-Raiya H, Maercker A. Negative affect, fatalism, and perceived institutional betrayal in times of the coronavirus pandemic: a cross-cultural investigation of control beliefs. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:589914. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589914

- Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and addressing sources of anxiety among health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.5893

- Schuster M, Dwyer PA. Post-traumatic stress disorder in nurses: an integrative review. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(15- 16):2769-2787. doi:10.1111/jocn.15288

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization designated COVID- 19 as a pandemic.1 Pandemics have historically impacted physical and mental health across all populations, but especially health care workers (HCWs).2 Nurses and other HCWs were profoundly impacted by the pandemic.3-8

Throughout the pandemic, nurses continued to provide care while working in short-staffed workplaces, facing increased exposure to COVID-19, and witnessing COVID—19–related morbidity and mortality.9 Many nurses were mandated to cross-train in unfamiliar clinical settings and adjust to new and prolonged shift schedules. Physical and emotional exhaustion associated with managing care for individuals with COVID-19, shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), risk of infection, fear of secondary transmission to family members, feelings of being rejected by others, and social isolation, led to HCWs’ increased vulnerability to psychological impacts of the pandemic.8,10

A meta-analysis of 65 studies with > 79,000 participants found HCWs experienced significant levels of anxiety, depression, stress, insomnia, and other mental health issues, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Female HCWs, nurses, and frontline responders experienced a higher incidence of psychological impact.11 Other meta-analyses revealed that nurses’ compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout levels were significantly impacted with increased levels of burnout among nurses who had a friend or family member diagnosed with COVID- 19 or experienced prolonged threat of exposure to the virus.12,13 A study of 350 nurses found high rates of perceived transgressions by others, and betrayal.8 Nurse leaders and staff nurses had to persevere as moral distress became pervasive among nursing staff, which led to complex and often unsustainable circumstances. 14 The themes identified in the literature about the pandemic’s impact as well as witnessing nurse colleagues’ distress with patient mortality and death of coworkers during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic compelled a group of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) nurses to form a research team to understand the scope of impact and identify possible solutions.

Since published studies on the impact of pandemics on HCWs, including nurses, primarily focused on inpatient settings, the investigators of this study sought to capture the experiences of outpatient and inpatient nurses providing care in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Sierra Pacific Network (Veterans Integrated Service Network [VISN] 21), which has facilities in northern California, Hawaii, and Nevada.15-19 The purpose of this study was to identify the impact of COVID-19 on nurses caring for veterans in both outpatient and inpatient settings at VISN 21 facilities from March 2020 to September 2022, to inform leadership about the extent the virus affected nurses, and identify strategies that address current and future impacts of pandemics.

METHODS

This retrospective descriptive survey adapted the Pandemic Impact Survey by Purcell et al, which included the Moral Injury Events Scale, Primary Care PTSD Screener, the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 for depression, and a modified burnout scale.20-24 The survey of 70 Likert-scale questions was intended to measure nurses’ needs, burnout, moral distress, depression and stress symptoms, work-related factors, and intent to remain working in their current position. A nurse was defined broadly and included those employed as licensed vocational nurses (LVN), licensed practical nurses (LPN), registered nurses (RN), nurses with advanced degrees, advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), and nurses with other certifications or licenses.

The VA Pacific Islands Research and Development Committee reviewed and approved the institutional review board-exempted study. The VISN 21 union was notified; only limited demographic information and broad VA tenure categories were collected to protect privacy. The principal investigator redacted facility identifier data after each facility had participated.

The survey was placed in REDCAP and a confidential link was emailed to all VISN 21 inpatient and outpatient nurses during March 2023. Because a comprehensive VISN 21 list of nurse email addresses was unavailable, the email was distributed by nursing leadership at each facility. Nurses received an email reminder at the 2-week halfway point, prompting them to complete the survey. The email indicated the purpose and voluntary nature of the study and cautioned nurses that they might experience stress while answering survey questions. Stress management resources were provided.

Descriptive statistics were used to report the results. Data were aggregated for analyzing and reporting purposes.

RESULTS

In March 2023, 860 of 5586 nurses (15%) responded to the survey. Respondents included 344 clinical inpatient nurses (40%) and 516 clinical outpatient nurses (60%); 688 (80%) were RNs, 129 (15%) were LPNs/LVNs, and 43 (5%) were APRNs. Of 849 respondents to provide their age, 15 (2%) were < 30 years, 163 (19%) were 30 to 39 years, 232 (27%) were 40 to 49 years, 259 (30%) were 50 to 59 years, and 180 (21%) were ≥ 60 years.

The survey found that 688 nurses reported job satisfaction (80%) and 75% of all respondents (66% among inpatient nurses) reported feeling happy with the care they delivered. Both inpatient and outpatient nurses indicated they could rely on staff. Sixty percent (n = 516) of the nurses indicated that facility management considered workplace health and safety and supervisors showed concern for subordinates, although inpatient nurses reported a lower percentage (Table 1).

Two hundred fifty-eight nurses (30%) reported having nurse colleagues who died and 52 (6%) had ≥ 3 colleagues who died. Among respondents, 292 had ≥ 3 patients who died after contracting COVID-19 and 232 (27%) had a significant person in their life die. More than one-half (54%; n = 464) of nurses had to limit contact with a family member who had COVID-19. Most nurses reported concerns about their colleagues (91%), were concerned about bringing COVID-19 home (82%), and stayed away from family during the pandemic (56%) (Table 2).

A total of 593 nurses (69%) reported feeling overwhelmed from the workload associated with the pandemic, 490 (57%) felt frustrated with role changes, 447 (52%) were stressed because of short staffing, and 327 (38%) felt stressed because of being assigned or floated to different patient care areas. Among inpatient nurses, 158 (46%) reported stress related to being floated. Coworker absenteeism caused challenges for 697 nurses (81%) (Table 3).

Nurses suggested a number of changes that could improve working conditions, including flexible scheduling (54%) and more hours of leave, which was requested by 43% of outpatient/inpatient nurses and 53% of inpatient alone nurses. Access to COVID-19 testing and PPE was endorsed as a workplace need by 439 nurses; the need for access to PPE was reported by 43% of inpatient-only nurses vs 29% of outpatient/inpatient nurses. The need for adequate staffing was reported by 54% of nurses although the rate was higher among those working inpatient settings (66%) (Table 4).

Four hundred sixty-four nurses (54%) felt tense and irritable at home because of work and 447 had ≥ 1 symptoms of burnout (Table 5). In terms of moral distress, > 30% of nurses witnessed morally incongruent situations, 10% felt their own moral code was violated, and > 30% felt betrayed by others (Table 6). Among respondents, 16% to 21% of nurses reported depressive symptoms (eAppendix). About 50% of nurses intended to stay in their current position while 20% indicated an intention to leave for another VA position.

DISCUSSION

This study identified the impact of COVID-19 on nurses who work in VISN 21. The survey included a significant number of nurses who work in outpatient settings, which differed from most other published studies to date.15-19 This study found that inpatient and outpatient nurses were similarly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, although there were differences. A high percentage of nurses reported job satisfaction despite the personal and professional impact of the pandemic.

Caring for veterans can result in a therapeutic relationship with a deep appreciation of veterans’ service and sensitivity to their needs.25 Some nurses reported that they feel it is a privilege to care for veterans.

Most nurses who participated in this study felt they could rely on their colleagues and were concerned about their health and wellbeing. Kissel et al explored protective factors for nurses during the pandemic and found participants often reported that their coworkers were positive safeguards.17 At least 50% of respondents reported that management considered workplace safety and was concerned about their welfare. Previous research has found that a positive working organization that promoted safety and concern for staff were protective factors against stress among HCWs.26 A literature review of 3 coronavirus outbreaks illustrated the support from supervisors and colleagues promoted resiliency and reduced stress disorders.3

Similar to other studies, study respondents experienced profound losses, including the deaths of colleagues, patients, and family. In 2021 Howell reported that HCWs experienced increased stress, fear, anxiety, and other negative emotions following news of colleagues’ deaths from COVID-19.27 Kissel et al reported that nurses frequently described pandemic-related physical and psychological harm and witnessing distress that they had not been previously exposed to.17

Our findings illustrate the tightrope nurses walked while caring for patients and concerns about the health of their colleagues and family. Consistent with our findings, Howell found that HCWs were afraid of contracting the infection at work and then unknowingly giving it to others such as patients, coworkers, and household members. 27 Murat et al reported that some nurses chose to live separately during the pandemic to avoid spreading COVID-19 to relatives.19 Several researchers found that concerns about family and children were prevalent and led to fear, anxiety, and burnout among nurses.18,28,29 Shah et al suggested that nurses experiencing death in the workplace and within their family may have resulted in fear and anxiety about returning to work.29 Garcia and Calvo argued that nurses may have been stigmatized as carriers of COVID-19.16 In addition, the loss of prepandemic workplace rituals may have impacted performance, team connection, and functioning, and led to increased turnover and decreased attachment to the organization.30

This study described the significant workplace issues nurses endured during the pandemic, including being overwhelmed with additional and/or multiple roles and frustrated and stressed with role changes and short staffing. Nurses endorsed workplace challenges in the context of coworker absenteeism and reassignments to different areas, such as intensive care units (ICUs).17 Researchers also reported that displaced team members experienced loneliness and isolation when they were removed from their usual place of work and experienced distress caring for patients beyond their perceived competency or comfort.17,31 Nurses also experienced rapid organizational changes, resource scarcity, high patient-to-nurse ratios, inconsistent or limited communications, and the absence of protocols for prolonged mass casualty events.17 These challenges, such as significant uncertainty and rapidly changing working conditions, were shared experiences suggested to be similar to “tumbling into chaos,” and likened to the overwhelming situations faced during patient surges to a medical “war zone.”17

Study respondents indicated that nurses wanted better access to critical supplies, PPE, and COVID-19 testing; more flexible scheduling; longer leave times; and staffing that was appropriate to the patient volumes. These findings aligned with previous research. Howell found that HCWs, especially nurses, worried about childcare because of school closures and increased work hours.27 Nurses felt that hospital support was inaccessible or inadequate and worried about access to essential resources.17-19,27 Studies also found excessive workloads, and many nurses needed mental or financial assistance from the hospital in addition to more rest and less work.18,28 An editorial highlighted the potential adverse effects that a lack of PPE could have on staff ’s mental health because of perceptions of institutional betrayal, which occurs when trusted and powerful organizations seemingly act in ways that can harm those dependent on them for safety and well-being.32

Consistent with other research, this study found that a majority of nurses experienced significant burnout symptoms. The number of nurses reporting symptoms of burnout increased during the pandemic with ICU nurses reporting the highest levels.17,33 Soto-Rubio et al emphasized that working conditions experienced by nurses, such as interpersonal conflict, lack of trust in administration, workload, and role conflict, contributed to burnout during COVID-19.34 Other studies found that nurses experienced burnout caused by uncertainty, intense work, and extra duties contributed to higher burnout scores.18,19 It is not surprising that researchers have indicated that nurses experiencing burnout might display depressive and stress-related symptoms, insomnia, and concentration and memory problems.19

The results of this study indicate that one-third of participating nurses were experiencing moral distress. Burton et al described COVID-19 as an environment in which nurses witnessed, experienced, and at times had to participate in acts that involved ethical violations in care, institutional betrayal, and traumatic strain.9 Of note, our findings revealed that both inpatient and outpatient nurses experienced moral distress. Interestingly, Mantri et al found that COVID-19 increased moral injury but not burnout among health professionals, which differed from the results of this study.35

The findings of this study indicate that many nurses experienced depressive symptoms. A systematic review found a similar percentage of HCWs experienced depression while caring for patients with COVID- 19, though a Chinese study found a higher percentage.36,37 Previous research also found that the most difficult aspect of the COVID- 19 pandemic for nurses was coping with mental disorders such as depression, and that many experienced difficulty sleeping/ had poor sleep quality, believed a similar disaster would occur in the future, were irritated or angered easily, and experienced emotional exhaustion.15,19 The long-term mental and physical ramifications of caring for individuals with COVID-19 remain unknown. However, previous research suggests a high prevalence of depression, insomnia, anxiety, and distress, which could impair nurses’ professional performance.29

This study reported that a majority of nurses intended to stay in their current position and about 20% intended to leave for another position within the VA. Similar findings conducted early in the pandemic indicated that most participants did not intend to quit nursing.19

This study’s findings suggest the COVID-19 pandemic had an adverse impact on VISN 21 nurses. It is critical to develop, implement, and adopt adequate measures as early as possible to support the health care system, especially nurses.18

Implications

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, discussing burnout and moral anguish was common, primarily in critical care.14 However, these experiences became more widespread throughout nursing settings during the pandemic. Nurse leaders have been identified as responsible for ensuring the environmental safety and personal well-being of their colleagues during and after pandemics.14

Studies of HCW experiences during COVID-19 provide many insights into future preparedness, strategies to best handle another pandemic during its acute stage, and techniques to address issues that might persist. This study and others suggest that comprehensive interventions in preparation for, during, and after a pandemic are needed. We break down strategies into pandemic and postpandemic interventions based on a synthesis of the literature and the research team’s knowledge and expertise.3,14-16,27,29,36,38-44

Pandemic interventions. During a pandemic, it is important that nurses are adequately cared for to ensure they can continue to provide quality care for others. Resources supporting emotional well-being and addressing moral distress offered during a pandemic are essential. Implementing meaningful strategies could enhance nurses’ health and wellbeing. It is essential that leaders provide nurses a safe work environment/experience during a pandemic by instituting meaningful resources. In addition, developing best practices for leadership are critical.

Postpandemic interventions. Personal experiences of depression, burnout, and moral distress have not spontaneously resolved as the pandemic receded. Providing postpandemic interventions to lessen ongoing and lingering depressive, burnout, and moral distress symptoms experienced by frontline workers are critical. These interventions might prevent long-term health issues and the exodus of nurses.

Postpandemic interventions should include the integration of pandemic planning into new or existing educational or training programs for staff. Promotion and support of mental health services by health system leadership for nursing personnel implemented as a usual service will play an important role in preparing for future pandemics. A key role in preparation is developing and maintaining cooperation and ongoing mutual understanding, respect, and communication between leadership and nursing staff.

Future Research

This study’s findings inform VHA leadership and society about how a large group of nurses were impacted by COVID-19 while caring for patients in inpatient and outpatient settings and could provide a basis for extending this research to other groups of nurses or health care personnel. Future research might be helpful in identifying the impact of COVID-19 on nursing leadership. During conversations with nursing leadership, a common theme identified was that nurses did not feel that leadership was fully prepared for the level of emergency the pandemic created both personally and professionally; leadership expressed experiences similar to nurses providing direct care and felt powerless to help their nursing staff. Other areas of research could include identifying underlying factors contributing to burnout and moral distress and describing nurses’ expectations of or needs from leadership to best manage burnout and moral distress.

Limitations

Experiences of nurses who stopped working were not captured and information about their experiences might have different results. The survey distribution was limited to 2 emails (an initial email and a second at midpoint) sent at the discretion of the nurse executive of each facility. The study timeline was long because of complex regulatory protective processes inherent in the VHA system for researchers to include initial institutional review board review process, union notifications, and each facility’s response to the survey. Although 860 nurses participated, this was 15% of the 5586 VISN 21 nurses at the time of the study. Many clinical inpatient nurses do not have regular access to email, which might have impacted participation rate.

CONCLUSIONS

This study identified the impact COVID-19 had on nurses who worked in a large hospital system. The research team outlined strategies to be employed during and after the pandemic, such as preplanning for future pandemics to provide a framework for a comprehensive pandemic response protocol.

This study adds to generalized knowledge because it captured voices of inpatient and outpatient nurses, the latter had not been previously studied. As nurses and health care organizations move beyond the pandemic with a significant number of nurses continuing to experience effects, there is a need to institute interventions to assist nurses in healing and begin preparations for future pandemics.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization designated COVID- 19 as a pandemic.1 Pandemics have historically impacted physical and mental health across all populations, but especially health care workers (HCWs).2 Nurses and other HCWs were profoundly impacted by the pandemic.3-8

Throughout the pandemic, nurses continued to provide care while working in short-staffed workplaces, facing increased exposure to COVID-19, and witnessing COVID—19–related morbidity and mortality.9 Many nurses were mandated to cross-train in unfamiliar clinical settings and adjust to new and prolonged shift schedules. Physical and emotional exhaustion associated with managing care for individuals with COVID-19, shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), risk of infection, fear of secondary transmission to family members, feelings of being rejected by others, and social isolation, led to HCWs’ increased vulnerability to psychological impacts of the pandemic.8,10

A meta-analysis of 65 studies with > 79,000 participants found HCWs experienced significant levels of anxiety, depression, stress, insomnia, and other mental health issues, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Female HCWs, nurses, and frontline responders experienced a higher incidence of psychological impact.11 Other meta-analyses revealed that nurses’ compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout levels were significantly impacted with increased levels of burnout among nurses who had a friend or family member diagnosed with COVID- 19 or experienced prolonged threat of exposure to the virus.12,13 A study of 350 nurses found high rates of perceived transgressions by others, and betrayal.8 Nurse leaders and staff nurses had to persevere as moral distress became pervasive among nursing staff, which led to complex and often unsustainable circumstances. 14 The themes identified in the literature about the pandemic’s impact as well as witnessing nurse colleagues’ distress with patient mortality and death of coworkers during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic compelled a group of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) nurses to form a research team to understand the scope of impact and identify possible solutions.

Since published studies on the impact of pandemics on HCWs, including nurses, primarily focused on inpatient settings, the investigators of this study sought to capture the experiences of outpatient and inpatient nurses providing care in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Sierra Pacific Network (Veterans Integrated Service Network [VISN] 21), which has facilities in northern California, Hawaii, and Nevada.15-19 The purpose of this study was to identify the impact of COVID-19 on nurses caring for veterans in both outpatient and inpatient settings at VISN 21 facilities from March 2020 to September 2022, to inform leadership about the extent the virus affected nurses, and identify strategies that address current and future impacts of pandemics.

METHODS

This retrospective descriptive survey adapted the Pandemic Impact Survey by Purcell et al, which included the Moral Injury Events Scale, Primary Care PTSD Screener, the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 for depression, and a modified burnout scale.20-24 The survey of 70 Likert-scale questions was intended to measure nurses’ needs, burnout, moral distress, depression and stress symptoms, work-related factors, and intent to remain working in their current position. A nurse was defined broadly and included those employed as licensed vocational nurses (LVN), licensed practical nurses (LPN), registered nurses (RN), nurses with advanced degrees, advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), and nurses with other certifications or licenses.

The VA Pacific Islands Research and Development Committee reviewed and approved the institutional review board-exempted study. The VISN 21 union was notified; only limited demographic information and broad VA tenure categories were collected to protect privacy. The principal investigator redacted facility identifier data after each facility had participated.

The survey was placed in REDCAP and a confidential link was emailed to all VISN 21 inpatient and outpatient nurses during March 2023. Because a comprehensive VISN 21 list of nurse email addresses was unavailable, the email was distributed by nursing leadership at each facility. Nurses received an email reminder at the 2-week halfway point, prompting them to complete the survey. The email indicated the purpose and voluntary nature of the study and cautioned nurses that they might experience stress while answering survey questions. Stress management resources were provided.

Descriptive statistics were used to report the results. Data were aggregated for analyzing and reporting purposes.

RESULTS

In March 2023, 860 of 5586 nurses (15%) responded to the survey. Respondents included 344 clinical inpatient nurses (40%) and 516 clinical outpatient nurses (60%); 688 (80%) were RNs, 129 (15%) were LPNs/LVNs, and 43 (5%) were APRNs. Of 849 respondents to provide their age, 15 (2%) were < 30 years, 163 (19%) were 30 to 39 years, 232 (27%) were 40 to 49 years, 259 (30%) were 50 to 59 years, and 180 (21%) were ≥ 60 years.

The survey found that 688 nurses reported job satisfaction (80%) and 75% of all respondents (66% among inpatient nurses) reported feeling happy with the care they delivered. Both inpatient and outpatient nurses indicated they could rely on staff. Sixty percent (n = 516) of the nurses indicated that facility management considered workplace health and safety and supervisors showed concern for subordinates, although inpatient nurses reported a lower percentage (Table 1).

Two hundred fifty-eight nurses (30%) reported having nurse colleagues who died and 52 (6%) had ≥ 3 colleagues who died. Among respondents, 292 had ≥ 3 patients who died after contracting COVID-19 and 232 (27%) had a significant person in their life die. More than one-half (54%; n = 464) of nurses had to limit contact with a family member who had COVID-19. Most nurses reported concerns about their colleagues (91%), were concerned about bringing COVID-19 home (82%), and stayed away from family during the pandemic (56%) (Table 2).

A total of 593 nurses (69%) reported feeling overwhelmed from the workload associated with the pandemic, 490 (57%) felt frustrated with role changes, 447 (52%) were stressed because of short staffing, and 327 (38%) felt stressed because of being assigned or floated to different patient care areas. Among inpatient nurses, 158 (46%) reported stress related to being floated. Coworker absenteeism caused challenges for 697 nurses (81%) (Table 3).

Nurses suggested a number of changes that could improve working conditions, including flexible scheduling (54%) and more hours of leave, which was requested by 43% of outpatient/inpatient nurses and 53% of inpatient alone nurses. Access to COVID-19 testing and PPE was endorsed as a workplace need by 439 nurses; the need for access to PPE was reported by 43% of inpatient-only nurses vs 29% of outpatient/inpatient nurses. The need for adequate staffing was reported by 54% of nurses although the rate was higher among those working inpatient settings (66%) (Table 4).

Four hundred sixty-four nurses (54%) felt tense and irritable at home because of work and 447 had ≥ 1 symptoms of burnout (Table 5). In terms of moral distress, > 30% of nurses witnessed morally incongruent situations, 10% felt their own moral code was violated, and > 30% felt betrayed by others (Table 6). Among respondents, 16% to 21% of nurses reported depressive symptoms (eAppendix). About 50% of nurses intended to stay in their current position while 20% indicated an intention to leave for another VA position.

DISCUSSION

This study identified the impact of COVID-19 on nurses who work in VISN 21. The survey included a significant number of nurses who work in outpatient settings, which differed from most other published studies to date.15-19 This study found that inpatient and outpatient nurses were similarly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, although there were differences. A high percentage of nurses reported job satisfaction despite the personal and professional impact of the pandemic.

Caring for veterans can result in a therapeutic relationship with a deep appreciation of veterans’ service and sensitivity to their needs.25 Some nurses reported that they feel it is a privilege to care for veterans.

Most nurses who participated in this study felt they could rely on their colleagues and were concerned about their health and wellbeing. Kissel et al explored protective factors for nurses during the pandemic and found participants often reported that their coworkers were positive safeguards.17 At least 50% of respondents reported that management considered workplace safety and was concerned about their welfare. Previous research has found that a positive working organization that promoted safety and concern for staff were protective factors against stress among HCWs.26 A literature review of 3 coronavirus outbreaks illustrated the support from supervisors and colleagues promoted resiliency and reduced stress disorders.3

Similar to other studies, study respondents experienced profound losses, including the deaths of colleagues, patients, and family. In 2021 Howell reported that HCWs experienced increased stress, fear, anxiety, and other negative emotions following news of colleagues’ deaths from COVID-19.27 Kissel et al reported that nurses frequently described pandemic-related physical and psychological harm and witnessing distress that they had not been previously exposed to.17

Our findings illustrate the tightrope nurses walked while caring for patients and concerns about the health of their colleagues and family. Consistent with our findings, Howell found that HCWs were afraid of contracting the infection at work and then unknowingly giving it to others such as patients, coworkers, and household members. 27 Murat et al reported that some nurses chose to live separately during the pandemic to avoid spreading COVID-19 to relatives.19 Several researchers found that concerns about family and children were prevalent and led to fear, anxiety, and burnout among nurses.18,28,29 Shah et al suggested that nurses experiencing death in the workplace and within their family may have resulted in fear and anxiety about returning to work.29 Garcia and Calvo argued that nurses may have been stigmatized as carriers of COVID-19.16 In addition, the loss of prepandemic workplace rituals may have impacted performance, team connection, and functioning, and led to increased turnover and decreased attachment to the organization.30

This study described the significant workplace issues nurses endured during the pandemic, including being overwhelmed with additional and/or multiple roles and frustrated and stressed with role changes and short staffing. Nurses endorsed workplace challenges in the context of coworker absenteeism and reassignments to different areas, such as intensive care units (ICUs).17 Researchers also reported that displaced team members experienced loneliness and isolation when they were removed from their usual place of work and experienced distress caring for patients beyond their perceived competency or comfort.17,31 Nurses also experienced rapid organizational changes, resource scarcity, high patient-to-nurse ratios, inconsistent or limited communications, and the absence of protocols for prolonged mass casualty events.17 These challenges, such as significant uncertainty and rapidly changing working conditions, were shared experiences suggested to be similar to “tumbling into chaos,” and likened to the overwhelming situations faced during patient surges to a medical “war zone.”17

Study respondents indicated that nurses wanted better access to critical supplies, PPE, and COVID-19 testing; more flexible scheduling; longer leave times; and staffing that was appropriate to the patient volumes. These findings aligned with previous research. Howell found that HCWs, especially nurses, worried about childcare because of school closures and increased work hours.27 Nurses felt that hospital support was inaccessible or inadequate and worried about access to essential resources.17-19,27 Studies also found excessive workloads, and many nurses needed mental or financial assistance from the hospital in addition to more rest and less work.18,28 An editorial highlighted the potential adverse effects that a lack of PPE could have on staff ’s mental health because of perceptions of institutional betrayal, which occurs when trusted and powerful organizations seemingly act in ways that can harm those dependent on them for safety and well-being.32

Consistent with other research, this study found that a majority of nurses experienced significant burnout symptoms. The number of nurses reporting symptoms of burnout increased during the pandemic with ICU nurses reporting the highest levels.17,33 Soto-Rubio et al emphasized that working conditions experienced by nurses, such as interpersonal conflict, lack of trust in administration, workload, and role conflict, contributed to burnout during COVID-19.34 Other studies found that nurses experienced burnout caused by uncertainty, intense work, and extra duties contributed to higher burnout scores.18,19 It is not surprising that researchers have indicated that nurses experiencing burnout might display depressive and stress-related symptoms, insomnia, and concentration and memory problems.19

The results of this study indicate that one-third of participating nurses were experiencing moral distress. Burton et al described COVID-19 as an environment in which nurses witnessed, experienced, and at times had to participate in acts that involved ethical violations in care, institutional betrayal, and traumatic strain.9 Of note, our findings revealed that both inpatient and outpatient nurses experienced moral distress. Interestingly, Mantri et al found that COVID-19 increased moral injury but not burnout among health professionals, which differed from the results of this study.35

The findings of this study indicate that many nurses experienced depressive symptoms. A systematic review found a similar percentage of HCWs experienced depression while caring for patients with COVID- 19, though a Chinese study found a higher percentage.36,37 Previous research also found that the most difficult aspect of the COVID- 19 pandemic for nurses was coping with mental disorders such as depression, and that many experienced difficulty sleeping/ had poor sleep quality, believed a similar disaster would occur in the future, were irritated or angered easily, and experienced emotional exhaustion.15,19 The long-term mental and physical ramifications of caring for individuals with COVID-19 remain unknown. However, previous research suggests a high prevalence of depression, insomnia, anxiety, and distress, which could impair nurses’ professional performance.29

This study reported that a majority of nurses intended to stay in their current position and about 20% intended to leave for another position within the VA. Similar findings conducted early in the pandemic indicated that most participants did not intend to quit nursing.19

This study’s findings suggest the COVID-19 pandemic had an adverse impact on VISN 21 nurses. It is critical to develop, implement, and adopt adequate measures as early as possible to support the health care system, especially nurses.18

Implications

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, discussing burnout and moral anguish was common, primarily in critical care.14 However, these experiences became more widespread throughout nursing settings during the pandemic. Nurse leaders have been identified as responsible for ensuring the environmental safety and personal well-being of their colleagues during and after pandemics.14

Studies of HCW experiences during COVID-19 provide many insights into future preparedness, strategies to best handle another pandemic during its acute stage, and techniques to address issues that might persist. This study and others suggest that comprehensive interventions in preparation for, during, and after a pandemic are needed. We break down strategies into pandemic and postpandemic interventions based on a synthesis of the literature and the research team’s knowledge and expertise.3,14-16,27,29,36,38-44

Pandemic interventions. During a pandemic, it is important that nurses are adequately cared for to ensure they can continue to provide quality care for others. Resources supporting emotional well-being and addressing moral distress offered during a pandemic are essential. Implementing meaningful strategies could enhance nurses’ health and wellbeing. It is essential that leaders provide nurses a safe work environment/experience during a pandemic by instituting meaningful resources. In addition, developing best practices for leadership are critical.

Postpandemic interventions. Personal experiences of depression, burnout, and moral distress have not spontaneously resolved as the pandemic receded. Providing postpandemic interventions to lessen ongoing and lingering depressive, burnout, and moral distress symptoms experienced by frontline workers are critical. These interventions might prevent long-term health issues and the exodus of nurses.

Postpandemic interventions should include the integration of pandemic planning into new or existing educational or training programs for staff. Promotion and support of mental health services by health system leadership for nursing personnel implemented as a usual service will play an important role in preparing for future pandemics. A key role in preparation is developing and maintaining cooperation and ongoing mutual understanding, respect, and communication between leadership and nursing staff.

Future Research

This study’s findings inform VHA leadership and society about how a large group of nurses were impacted by COVID-19 while caring for patients in inpatient and outpatient settings and could provide a basis for extending this research to other groups of nurses or health care personnel. Future research might be helpful in identifying the impact of COVID-19 on nursing leadership. During conversations with nursing leadership, a common theme identified was that nurses did not feel that leadership was fully prepared for the level of emergency the pandemic created both personally and professionally; leadership expressed experiences similar to nurses providing direct care and felt powerless to help their nursing staff. Other areas of research could include identifying underlying factors contributing to burnout and moral distress and describing nurses’ expectations of or needs from leadership to best manage burnout and moral distress.

Limitations

Experiences of nurses who stopped working were not captured and information about their experiences might have different results. The survey distribution was limited to 2 emails (an initial email and a second at midpoint) sent at the discretion of the nurse executive of each facility. The study timeline was long because of complex regulatory protective processes inherent in the VHA system for researchers to include initial institutional review board review process, union notifications, and each facility’s response to the survey. Although 860 nurses participated, this was 15% of the 5586 VISN 21 nurses at the time of the study. Many clinical inpatient nurses do not have regular access to email, which might have impacted participation rate.

CONCLUSIONS

This study identified the impact COVID-19 had on nurses who worked in a large hospital system. The research team outlined strategies to be employed during and after the pandemic, such as preplanning for future pandemics to provide a framework for a comprehensive pandemic response protocol.

This study adds to generalized knowledge because it captured voices of inpatient and outpatient nurses, the latter had not been previously studied. As nurses and health care organizations move beyond the pandemic with a significant number of nurses continuing to experience effects, there is a need to institute interventions to assist nurses in healing and begin preparations for future pandemics.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497-506. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

- Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):15-23. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003

- Carmassi C, Foghi C, Dell’Oste V, et al. PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: What can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113312. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113312

- De Kock JH, Latham HA, Leslie SJ, et al. A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: implications for supporting psychological well-being. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):104. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-10070-3

- Gualano MR, Sinigaglia T, Lo Moro G, et al. The burden of burnout among healthcare professionals of intensive care units and emergency departments during the covid-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):8172. doi:10.3390/ijerph18158172

- Sirois FM, Owens J. Factors associated with psychological distress in health-care workers during an infectious disease outbreak: a rapid systematic review of the evidence. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11;589545. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589545

- Talevi D, Socci V, Carai M, et al. Mental health outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Riv Psichiatr. 2020;55(3);137-144. doi:10.1708/3382.33569

- Amsalem D, Lazarov A, Markowitz JC, et al. Psychiatric symptoms and moral injury among US healthcare workers in the COVID-19 era. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):546. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03565-9

- Burton CW, Jenkins DK, Chan G.K, Zellner KL, Zalta AK. A mixed methods study of moral distress among frontline nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2023;16(4):568-575. doi:10.1037/tra0001493

- Stawicki SP, Jeanmonod R, Miller AC, et al. The 2019- 2020 novel coronavirus (Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) Pandemic:a Joint American College of Academic International Medicine-World Academic Council of Emergency Medicine Multidisciplinary COVID-19 Working Group consensus paper. J Glob Infect Dis. 2020;12(2):47- 93. doi:10.4103/jgid.jgid_86_20

- Batra K, Singh TP, Sharma M, Batra R, Schvaneveldt N. Investigating the psychological impact of COVID- 19 among healthcare workers: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):9096. doi:10.3390/ijerph17239096

- Xie W, Chen L, Feng F, et al. The prevalence of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue among nurses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;120:103973. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103973

- Galanis P, Vraka I, Fragkou D, Bilali A, Kaitelidou D. Nurses’ burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(8):3286-3302. doi:10.1111/jan.14839

- Hofmeyer A, Taylor R. Strategies and resources for nurse leaders to use to lead with empathy and prudence so they understand and address sources of anxiety among nurses practicing in the era of COVID-19. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(1- 2):298-305. doi:10.1111/jocn.15520

- Chen R, Sun C, Chen JJ, et al. A large-scale survey on trauma, burnout, and posttraumatic growth among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(1):102-116. doi:10.1111/inm.12796

- García G, Calvo J. The threat of COVID-19 and its influence on nursing staff burnout. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(2):832-844. doi:10.1111/jan.14642

- Kissel KA, Filipek C, Jenkins J. Impact of the COVID- 19 pandemic on nurses working in intensive care units: a scoping review. Crit Care Nurse. 2023;43(2):55-63. doi:10.4037/ccn2023196

- Lin YY, Pan YA, Hsieh YL, et al. COVID-19 pandemic is associated with an adverse impact on burnout and mood disorder in healthcare professionals. Int J Environ Res and Public Health. 2021;18(7):3654. doi:10.3390/ijerph18073654

- Murat M, Köse S, Savas¸er S. Determination of stress, depression and burnout levels of front-line nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(2):533-543. doi:10.1111/inm.12818

- Purcell N, Bertenthal D, Usman H, et al. Moral injury and mental health in healthcare workers are linked to organizational culture and modifiable workplace conditions: results of a national, mixed-methods study conducted at Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers during the COVID- 19 pandemic. PLOS Ment Health. 2024;1(7):e0000085. doi:10.1371/journal.pmen.0000085

- Nash WP, Marino Carper TL, Mills MA, Au T, Goldsmith A, Litz BT. Psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Events Scale. Mil Med. 2013;178(6):646-652. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017

- Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, et al. The Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(10):1206-1211. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3703-5

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284-1292. doi:10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

- Rohland BM, Kruse GR, Rohrer JE. Validation of a single- item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress and Health. 2004;20(2):75-79. doi:10.1002/smi.1002

- Carlson J. Baccalaureate nursing faculty competencies and teaching strategies to enhance the care of the veteran population: perspectives of Veteran Affairs Nursing Academy (VANA) faculty. J Prof Nurs. 2016;32(4):314-323. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.01.006

- Denning M, Goh ET, Tan B, et al. Determinants of burnout and other aspects of psychological well-being in healthcare workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: a multinational cross-sectional study. PloS One. 2021;16(4):e0238666. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0238666

- Howell BAM. Battling burnout at the frontlines of health care amid COVID-19. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2021;32(2):195- 203. doi:10.4037/aacnacc2021454

- Afshari D, Nourollahi-Darabad M, Chinisaz N. Demographic predictors of resilience among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Work. 2021;68(2):297-303. doi:10.3233/WOR-203376

- Shah M, Roggenkamp M, Ferrer L, Burger V, Brassil KJ. Mental health and COVID-19: the psychological implications of a pandemic for nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2021;25(1), 69-75. doi:10.1188/21.CJON.69-75

- Griner T, Souza M, Girard A, Hain P, High H, Williams M. COVID-19’s impact on nurses’ workplace rituals. Nurs Lead. 2021;19(4):425-430. doi:10.1016/j.mnl.2021.06.008

- Koren A, Alam MAU, Koneru S, DeVito A, Abdallah L, Liu B. Nursing perspectives on the impacts of COVID- 19: social media content analysis. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5(12):e31358. doi:10.2196/31358

- Gold JA. Covid-19: adverse mental health outcomes for healthcare workers. BMJ. 2020;5:369:m1815. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1815. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1815

- Slusarz R, Cwiekala-Lewis K, Wysokinski M, Filipska- Blejder K, Fidecki W, Biercewicz M. Characteristics of occupational burnout among nurses of various specialties and in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic-review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21):13775. doi:10.3390/ijerph192113775

- Soto-Rubio A, Giménez-Espert MDC, Prado-Gascó V. Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses’ health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7998. doi:10.3390/ijerph17217998

- Mantri S, Song YK, Lawson JM, Berger EJ, Koenig HG. Moral injury and burnout in health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2021;209(10):720-726. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000001367

- Salari N, Khazaie H, Hosseinian-Far A, et al. The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-regression. Hum Resour Health 2020;18(1):100. doi:10.1186/s12960-020-00544-1