User login

A Candida Glabrata-Associated Prosthetic Joint Infection: Case Report and Literature Review

A Candida Glabrata-Associated Prosthetic Joint Infection: Case Report and Literature Review

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) occurs in about 1% to 2% of joint replacements. 1 Risk factors include immunosuppression, diabetes, chronic illnesses, and prolonged operative time.2 Bacterial infections constitute most of these infections, while fungal pathogens account for about 1%. Candida (C.) species, predominantly C. albicans, are responsible for most PJIs.1,3 In contrast, C. glabrata is a rare cause of fungal PJI, with only 18 PJI cases currently reported in the literature.4 C. glabrata PJI occurs more frequently among immunosuppressed patients and is associated with a higher treatment failure rate despite antifungal therapy.5 Treatment of fungal PJI is often complicated, involving multiple surgical debridements, prolonged antifungal therapy, and in some cases, prosthesis removal.6 However, given the rarity of C. glabrata as a PJI pathogen, no standardized treatment guidelines exist, leading to potential delays in diagnosis and tailored treatment.7,8

CASE PRESENTATION

A male Vietnam veteran aged 75 years presented to the emergency department in July 2023 with a fluid collection over his left hip surgical incision site. The patient had a complex medical history that included chronic kidney disease, well-controlled type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and osteoarthritis. His history was further complicated by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with hepatocellular carcinoma that was treated with transarterial radioembolization and yttrium-90. The patient had undergone a left total hip arthroplasty in 1996 and subsequent open reduction and internal fixation about 9 months prior to his presentation. The patient reported the fluid had been present for about 6 weeks, while he received outpatient monitoring by the orthopedic surgery service. He sought emergency care after noting a moderate amount of purulent discharge on his clothing originating from his hip. In the week prior to admission, the patient observed progressive erythema, warmth, and tenderness over the incision site. Despite these symptoms, the patient remained ambulatory and able to walk long distances with the use of an assistive device.

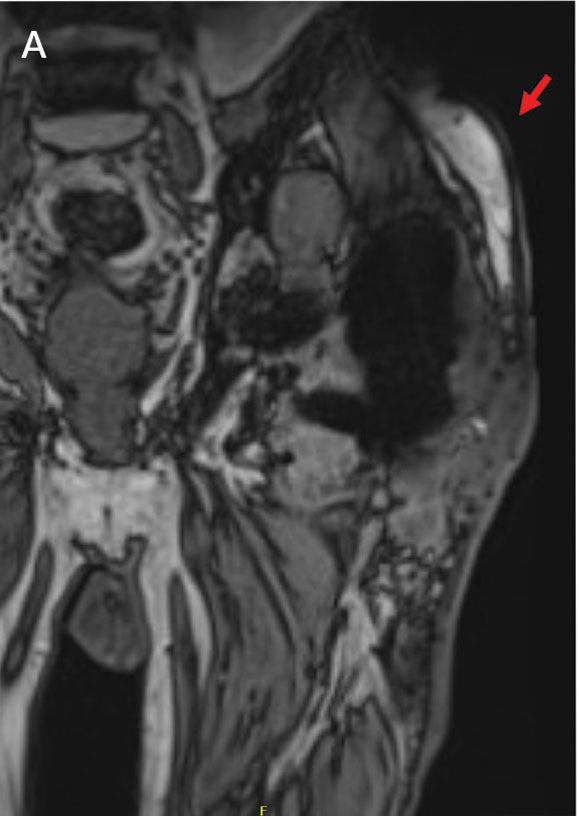

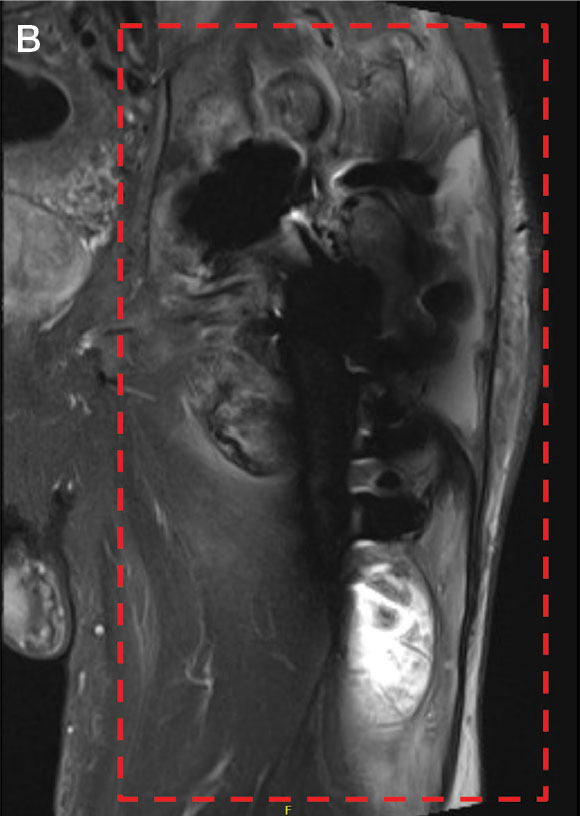

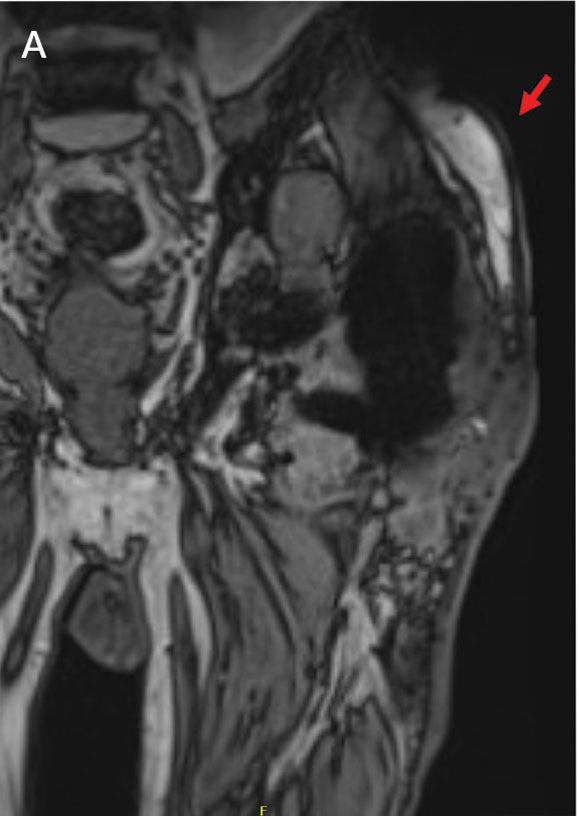

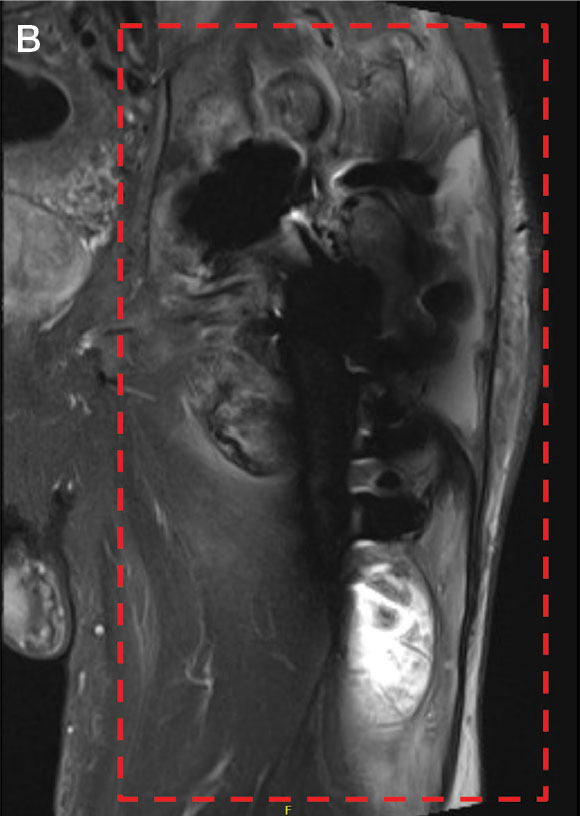

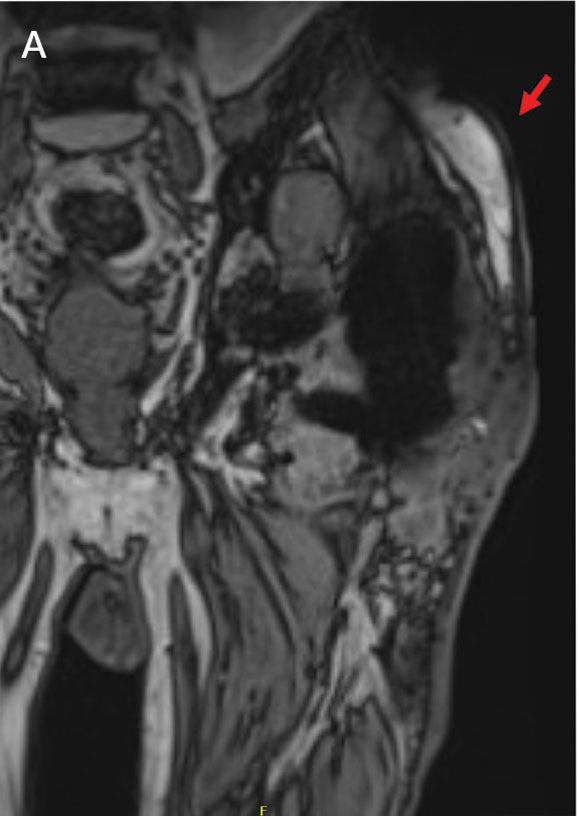

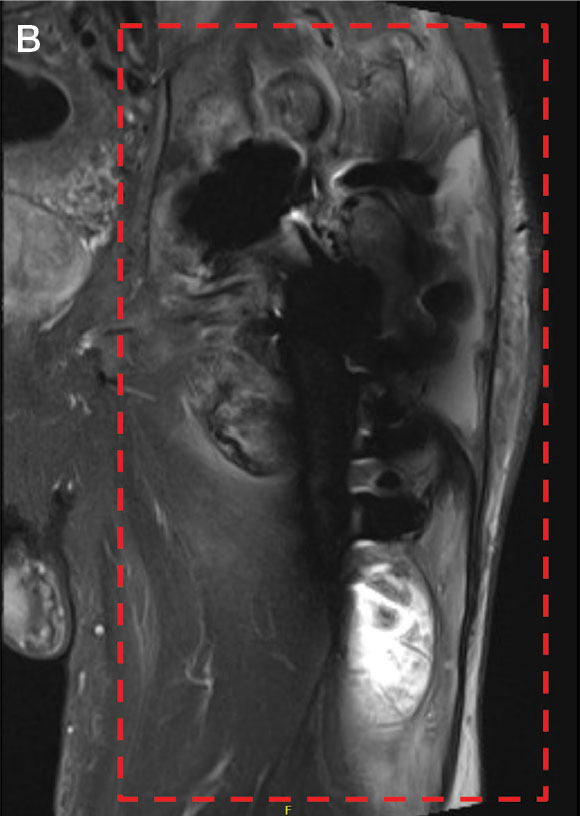

Upon presentation, the patient was afebrile and normotensive. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 77 mm/h (reference range, 0-20 mm/h) and a C-reactive protein of 9.8 mg/L (reference range, 0-2.5 mg/L), suggesting an underlying infectious process. A physical examination revealed a well-healed incision over the left hip with a poorly defined area of fluctuance and evidence of wound dehiscence. The left lower extremity was swollen with 2+ pitting edema, but tenderness was localized to the incision site. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left hip revealed a multiloculated fluid collection abutting the left greater trochanter with extension to the skin surface and inferior extension along the entire length of the surgical fixation hardware (Figure).

Upon admission, orthopedic surgery performed a bedside aspiration of the fluid collection. Samples were sent for analysis, including cell count and bacterial and fungal cultures. Initial blood cultures were sterile. Due to concerns for a bacterial infection, the patient was started on empiric intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone 2 g/day and IV vancomycin 1250 mg/day. Synovial fluid analysis revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 45,000/ìL, but bacterial cultures were negative. Five days after admission, the fungal culture from the left hip wound was notable for presence of C. glabrata, prompting an infectious diseases (ID) consultation. IV micafungin 100 mg/day was initiated as empiric antifungal therapy.

ID and orthopedic surgery teams determined that a combined medical and surgical approach would be best suited for infection control. They proposed 2 main approaches: complete hardware replacement with washout, which carried a higher morbidity risk but a better chance of infection resolution, or partial hardware replacement with washout, which was associated with a lower morbidity risk but a higher risk of infection persistence and recurrence. This decision was particularly challenging for the patient, who prioritized maintaining his functional status, including his ability to continue dancing for pleasure. The patient opted for a more conservative approach, electing to proceed with antifungal therapy and debridement while retaining the prosthetic joint.

After 11 days of hospitalization, the patient was discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter for long-term antifungal infusions of micafungin 150 mg/day at home. Fungal sensitivity test results several days after discharge confirmed susceptibility to micafungin.

About 2 weeks after discharge, the patient underwent debridement and implant retention (DAIR). Wound cultures were positive for C. glabrata, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum. Based on susceptibilities, he completed a 2-month course of IV micafungin 150 mg daily and daptomycin 750 mg daily, followed by an oral suppressive regimen consisting of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, amoxicillin-clavulanate 2 g twice daily, and fluconazole initially 800 mg daily adjusted to 400 mg daily. The patient continued wound management with twice-daily dressing changes.

Nine months after DAIR, the patient remained on suppressive antifungal and antibacterial therapy. He continued to experience serous drainage from the wound, which greatly affected his quality of life. After discussion with his family and the orthopedic surgery team, he agreed to proceed with a 2-staged revision arthroplasty involving prosthetic explant and antibiotic spacer placement. However, the surgery was postponed due to findings of anemia (hemoglobin, 8.9 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 73 x 103/λL). At the time of this report, the patient was being monitored closely with his multidisciplinary care team for the planned orthopedic procedure.

DISCUSSION

PJI is the most common cause of primary hip arthroplasty failure; however, fungal species only make up about 1% of PJIs.3,9-11 Patients are typically immunocompromised, undergoing antineoplastic therapies for malignancy, or have other comorbid conditions such as diabetes.12,13 C. glabrata presents a unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenge as it is not only rare but also notorious for its resistance to common antifungal agents. C. glabrata is known to develop multidrug resistance through the rapid accumulation of genomic mutations.14 Its propensity towards forming protective biofilm also arms it with intrinsic resistance to agents like fluconazole.15 Furthermore, based on a review of the available reports in the literature, C. glabrata PJIs are often insidious and present with symptoms closely mimicking those of bacterial PJIs, as it did in the patient in this case.16

Synovial fluid analysis, fungal cultures, and sensitivity testing are paramount for ensuring proper diagnosis for fungal PJI. The patient in this case was empirically treated with micafungin based on recommendations from the ID team. When the sensitivities results were reviewed, the same antifungal therapy was continued. Echinocandins have a favorable toxicity profile in long-term use, as well as efficacy against biofilm-producing organisms like C. glabrata.17,18

While there are a few cases citing DAIR as a feasible surgical strategy for treating fungal PJI, more recent studies have reported greater success with a 2-staged revision arthroplasty involving some combination of debridement, placement of antibiotic-loaded bone cement spacers, and partial or total exchange of the infected prosthetic joint.4,19-23 In this case, complete hardware replacement would have offered the patient the most favorable outlook for eliminating this fungal infection. However, given the patient’s advanced age, significant underlying comorbidities, and functional status, medical management with antifungal therapy and DAIR was favored.

Based on the discussion from the 6-month follow-up visit, the patient was experiencing progressive and persistent wound drainage and frequent dressing changes, highlighting the limitations of medical management for PJI in the setting of retained prosthesis. If the patient ultimately proceeds with a more invasive surgical intervention, another important consideration will be the likelihood of fungal PJI recurrence. At present, fungal PJI recurrence rates following antifungal and surgical treatment have been reported to range between 0% to 50%, which is too imprecise to be considered clinically useful.22-24

Given the ambiguity surrounding management guidelines and limited treatment options, it is crucial to emphasize the timeline of this patient’s clinical presentation and subsequent course of treatment. Upon presentation to the ED in late July, fungal PJI was considered less likely. Initial blood cultures from presentation were negative, which is common with PJIs. It was not until 5 days later that the left hip wound culture showed moderate growth of C. glabrata. Identifying a PJI is clinically challenging due to the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria. However, timely identification and diagnosis of fungal PJI with appropriate antifungal therapy, in patients with limited curative options due to comorbidities, can significantly improve quality of life and overall outcomes.25 Routine fungal and mycobacterial cultures are not currently recommended in PJI guidelines, but this case illustrates it is imperative in immunocompromised hosts.26

This case and the current paucity of similar cases in the literature stress the importance of clinicians publishing their experience in the management of fungal PJI. We strongly recommend that clinicians approach each suspected PJI with careful consideration of the patient’s unique risk factors, comorbidities, and goals of care, when deciding on a curative vs suppressive approach to therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

This case report highlights the importance of considering fungal pathogens for PJIs, especially in high-risk patients, the value of obtaining fungal cultures, the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach, the role of antifungal susceptibility testing, and consideration for the feasibility of a surgical intervention. It underscores the challenges in diagnosis and treatment of C. glabrata-associated PJI, emphasizing the importance of clinician experience-sharing in developing evidence-based management strategies. As the understanding of fungal PJI evolves, continued research and clinical data collection remain crucial for improving patient outcomes in the management of these complex cases.

- Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. Executive summary: diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(1):1-10. doi:10.1093/cid/cis966

- Eka A, Chen AF. Patient-related medical risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection of the hip and knee. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(16):233. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.09.26

- Darouiche RO, Hamill RJ, Musher DM, Young EJ, Harris RL. Periprosthetic candidal infections following arthroplasty. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(1):89-96. doi:10.1093/clinids/11.1.89

- Koutserimpas C, Zervakis SG, Maraki S, et al. Non-albicans Candida prosthetic joint infections: a systematic review of treatment. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7(12):1430- 1443. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v7.i12.1430

- Fidel PL Jr, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD. Candida glabrata: review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(1):80-96. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.1.80

- Aboltins C, Daffy J, Choong P, Stanley P. Current concepts in the management of prosthetic joint infection. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):834-840. doi:10.1111/imj.12510

- Lee YR, Kim HJ, Lee EJ, Sohn JW, Kim MJ, Yoon YK. Prosthetic joint infections caused by candida species: a systematic review and a case series. Mycopathologia. 2019;184(1):23-33. doi:10.1007/s11046-018-0286-1

- Herndon CL, Rowe TM, Metcalf RW, et al. Treatment outcomes of fungal periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(11):2436-2440.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.05.009

- Delaunay C, Hamadouche M, Girard J, Duhamel A; SoFCOT. What are the causes for failures of primary hip arthroplasties in France? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(12): 3863-3869. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-2935-5

- Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Vail TP, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1): 128-133. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00155

- Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(4):579-586. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.83b4.11223

- Gonzalez MR, Bedi ADS, Karczewski D, Lozano-Calderon SA. Treatment and outcomes of fungal prosthetic joint infections: a systematic review of 225 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(11):2464-2471.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.05.003

- Gonzalez MR, Pretell-Mazzini J, Lozano-Calderon SA. Risk factors and management of prosthetic joint infections in megaprostheses-a review of the literature. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;13(1):25. doi:10.3390/antibiotics13010025

- Biswas C, Chen SC, Halliday C, et al. Identification of genetic markers of resistance to echinocandins, azoles and 5-fluorocytosine in Candida glabrata by next-generation sequencing: a feasibility study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(9):676.e7-676.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.03.014

- Hassan Y, Chew SY, Than LTL. Candida glabrata: pathogenicity and resistance mechanisms for adaptation and survival. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7(8):667. doi:10.3390/jof7080667

- Aboltins C, Daffy J, Choong P, Stanley P. Current concepts in the management of prosthetic joint infection. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):834-840. doi:10.1111/imj.12510

- Pierce CG, Uppuluri P, Tristan AR, et al. A simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(9):1494-1500. doi:10.1038/nport.2008.141

- Koutserimpas C, Samonis G, Velivassakis E, Iliopoulou- Kosmadaki S, Kontakis G, Kofteridis DP. Candida glabrata prosthetic joint infection, successfully treated with anidulafungin: a case report and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2018;61(4):266-269. doi:10.1111/myc.12736

- Brooks DH, Pupparo F. Successful salvage of a primary total knee arthroplasty infected with Candida parapsilosis. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(6):707-712. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(98)80017-x

- Merrer J, Dupont B, Nieszkowska A, De Jonghe B, Outin H. Candida albicans prosthetic arthritis treated with fluconazole alone. J Infect. 2001;42(3):208-209. doi:10.1053/jinf.2001.0819

- Koutserimpas C, Naoum S, Alpantaki K, et al. Fungal prosthetic joint infection in revised knee arthroplasty: an orthopaedic surgeon’s nightmare. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(7):1606. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12071606

- Gao Z, Li X, Du Y, Peng Y, Wu W, Zhou Y. Success rate of fungal peri-prosthetic joint infection treated by 2-stage revision and potential risk factors of treatment failure: a retrospective study. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:5549-5557. doi:10.12659/MSM.909168

- Hwang BH, Yoon JY, Nam CH, et al. Fungal periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(5):656-659. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B5.28125

- Ueng SW, Lee CY, Hu CC, Hsieh PH, Chang Y. What is the success of treatment of hip and knee candidal periprosthetic joint infection? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(9):3002-3009. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3007-6

- Nodzo, Scott R. MD; Bauer, Thomas MD, PhD; Pottinger, et al. Conventional diagnostic challenges in periprosthetic joint infection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23 Suppl:S18-S25. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00385

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Diagnosis and prevention of periprosthetic joint infections. March 11, 2019. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.aaos.org/pjicpg

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) occurs in about 1% to 2% of joint replacements. 1 Risk factors include immunosuppression, diabetes, chronic illnesses, and prolonged operative time.2 Bacterial infections constitute most of these infections, while fungal pathogens account for about 1%. Candida (C.) species, predominantly C. albicans, are responsible for most PJIs.1,3 In contrast, C. glabrata is a rare cause of fungal PJI, with only 18 PJI cases currently reported in the literature.4 C. glabrata PJI occurs more frequently among immunosuppressed patients and is associated with a higher treatment failure rate despite antifungal therapy.5 Treatment of fungal PJI is often complicated, involving multiple surgical debridements, prolonged antifungal therapy, and in some cases, prosthesis removal.6 However, given the rarity of C. glabrata as a PJI pathogen, no standardized treatment guidelines exist, leading to potential delays in diagnosis and tailored treatment.7,8

CASE PRESENTATION

A male Vietnam veteran aged 75 years presented to the emergency department in July 2023 with a fluid collection over his left hip surgical incision site. The patient had a complex medical history that included chronic kidney disease, well-controlled type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and osteoarthritis. His history was further complicated by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with hepatocellular carcinoma that was treated with transarterial radioembolization and yttrium-90. The patient had undergone a left total hip arthroplasty in 1996 and subsequent open reduction and internal fixation about 9 months prior to his presentation. The patient reported the fluid had been present for about 6 weeks, while he received outpatient monitoring by the orthopedic surgery service. He sought emergency care after noting a moderate amount of purulent discharge on his clothing originating from his hip. In the week prior to admission, the patient observed progressive erythema, warmth, and tenderness over the incision site. Despite these symptoms, the patient remained ambulatory and able to walk long distances with the use of an assistive device.

Upon presentation, the patient was afebrile and normotensive. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 77 mm/h (reference range, 0-20 mm/h) and a C-reactive protein of 9.8 mg/L (reference range, 0-2.5 mg/L), suggesting an underlying infectious process. A physical examination revealed a well-healed incision over the left hip with a poorly defined area of fluctuance and evidence of wound dehiscence. The left lower extremity was swollen with 2+ pitting edema, but tenderness was localized to the incision site. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left hip revealed a multiloculated fluid collection abutting the left greater trochanter with extension to the skin surface and inferior extension along the entire length of the surgical fixation hardware (Figure).

Upon admission, orthopedic surgery performed a bedside aspiration of the fluid collection. Samples were sent for analysis, including cell count and bacterial and fungal cultures. Initial blood cultures were sterile. Due to concerns for a bacterial infection, the patient was started on empiric intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone 2 g/day and IV vancomycin 1250 mg/day. Synovial fluid analysis revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 45,000/ìL, but bacterial cultures were negative. Five days after admission, the fungal culture from the left hip wound was notable for presence of C. glabrata, prompting an infectious diseases (ID) consultation. IV micafungin 100 mg/day was initiated as empiric antifungal therapy.

ID and orthopedic surgery teams determined that a combined medical and surgical approach would be best suited for infection control. They proposed 2 main approaches: complete hardware replacement with washout, which carried a higher morbidity risk but a better chance of infection resolution, or partial hardware replacement with washout, which was associated with a lower morbidity risk but a higher risk of infection persistence and recurrence. This decision was particularly challenging for the patient, who prioritized maintaining his functional status, including his ability to continue dancing for pleasure. The patient opted for a more conservative approach, electing to proceed with antifungal therapy and debridement while retaining the prosthetic joint.

After 11 days of hospitalization, the patient was discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter for long-term antifungal infusions of micafungin 150 mg/day at home. Fungal sensitivity test results several days after discharge confirmed susceptibility to micafungin.

About 2 weeks after discharge, the patient underwent debridement and implant retention (DAIR). Wound cultures were positive for C. glabrata, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum. Based on susceptibilities, he completed a 2-month course of IV micafungin 150 mg daily and daptomycin 750 mg daily, followed by an oral suppressive regimen consisting of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, amoxicillin-clavulanate 2 g twice daily, and fluconazole initially 800 mg daily adjusted to 400 mg daily. The patient continued wound management with twice-daily dressing changes.

Nine months after DAIR, the patient remained on suppressive antifungal and antibacterial therapy. He continued to experience serous drainage from the wound, which greatly affected his quality of life. After discussion with his family and the orthopedic surgery team, he agreed to proceed with a 2-staged revision arthroplasty involving prosthetic explant and antibiotic spacer placement. However, the surgery was postponed due to findings of anemia (hemoglobin, 8.9 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 73 x 103/λL). At the time of this report, the patient was being monitored closely with his multidisciplinary care team for the planned orthopedic procedure.

DISCUSSION

PJI is the most common cause of primary hip arthroplasty failure; however, fungal species only make up about 1% of PJIs.3,9-11 Patients are typically immunocompromised, undergoing antineoplastic therapies for malignancy, or have other comorbid conditions such as diabetes.12,13 C. glabrata presents a unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenge as it is not only rare but also notorious for its resistance to common antifungal agents. C. glabrata is known to develop multidrug resistance through the rapid accumulation of genomic mutations.14 Its propensity towards forming protective biofilm also arms it with intrinsic resistance to agents like fluconazole.15 Furthermore, based on a review of the available reports in the literature, C. glabrata PJIs are often insidious and present with symptoms closely mimicking those of bacterial PJIs, as it did in the patient in this case.16

Synovial fluid analysis, fungal cultures, and sensitivity testing are paramount for ensuring proper diagnosis for fungal PJI. The patient in this case was empirically treated with micafungin based on recommendations from the ID team. When the sensitivities results were reviewed, the same antifungal therapy was continued. Echinocandins have a favorable toxicity profile in long-term use, as well as efficacy against biofilm-producing organisms like C. glabrata.17,18

While there are a few cases citing DAIR as a feasible surgical strategy for treating fungal PJI, more recent studies have reported greater success with a 2-staged revision arthroplasty involving some combination of debridement, placement of antibiotic-loaded bone cement spacers, and partial or total exchange of the infected prosthetic joint.4,19-23 In this case, complete hardware replacement would have offered the patient the most favorable outlook for eliminating this fungal infection. However, given the patient’s advanced age, significant underlying comorbidities, and functional status, medical management with antifungal therapy and DAIR was favored.

Based on the discussion from the 6-month follow-up visit, the patient was experiencing progressive and persistent wound drainage and frequent dressing changes, highlighting the limitations of medical management for PJI in the setting of retained prosthesis. If the patient ultimately proceeds with a more invasive surgical intervention, another important consideration will be the likelihood of fungal PJI recurrence. At present, fungal PJI recurrence rates following antifungal and surgical treatment have been reported to range between 0% to 50%, which is too imprecise to be considered clinically useful.22-24

Given the ambiguity surrounding management guidelines and limited treatment options, it is crucial to emphasize the timeline of this patient’s clinical presentation and subsequent course of treatment. Upon presentation to the ED in late July, fungal PJI was considered less likely. Initial blood cultures from presentation were negative, which is common with PJIs. It was not until 5 days later that the left hip wound culture showed moderate growth of C. glabrata. Identifying a PJI is clinically challenging due to the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria. However, timely identification and diagnosis of fungal PJI with appropriate antifungal therapy, in patients with limited curative options due to comorbidities, can significantly improve quality of life and overall outcomes.25 Routine fungal and mycobacterial cultures are not currently recommended in PJI guidelines, but this case illustrates it is imperative in immunocompromised hosts.26

This case and the current paucity of similar cases in the literature stress the importance of clinicians publishing their experience in the management of fungal PJI. We strongly recommend that clinicians approach each suspected PJI with careful consideration of the patient’s unique risk factors, comorbidities, and goals of care, when deciding on a curative vs suppressive approach to therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

This case report highlights the importance of considering fungal pathogens for PJIs, especially in high-risk patients, the value of obtaining fungal cultures, the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach, the role of antifungal susceptibility testing, and consideration for the feasibility of a surgical intervention. It underscores the challenges in diagnosis and treatment of C. glabrata-associated PJI, emphasizing the importance of clinician experience-sharing in developing evidence-based management strategies. As the understanding of fungal PJI evolves, continued research and clinical data collection remain crucial for improving patient outcomes in the management of these complex cases.

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) occurs in about 1% to 2% of joint replacements. 1 Risk factors include immunosuppression, diabetes, chronic illnesses, and prolonged operative time.2 Bacterial infections constitute most of these infections, while fungal pathogens account for about 1%. Candida (C.) species, predominantly C. albicans, are responsible for most PJIs.1,3 In contrast, C. glabrata is a rare cause of fungal PJI, with only 18 PJI cases currently reported in the literature.4 C. glabrata PJI occurs more frequently among immunosuppressed patients and is associated with a higher treatment failure rate despite antifungal therapy.5 Treatment of fungal PJI is often complicated, involving multiple surgical debridements, prolonged antifungal therapy, and in some cases, prosthesis removal.6 However, given the rarity of C. glabrata as a PJI pathogen, no standardized treatment guidelines exist, leading to potential delays in diagnosis and tailored treatment.7,8

CASE PRESENTATION

A male Vietnam veteran aged 75 years presented to the emergency department in July 2023 with a fluid collection over his left hip surgical incision site. The patient had a complex medical history that included chronic kidney disease, well-controlled type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and osteoarthritis. His history was further complicated by nonalcoholic steatohepatitis with hepatocellular carcinoma that was treated with transarterial radioembolization and yttrium-90. The patient had undergone a left total hip arthroplasty in 1996 and subsequent open reduction and internal fixation about 9 months prior to his presentation. The patient reported the fluid had been present for about 6 weeks, while he received outpatient monitoring by the orthopedic surgery service. He sought emergency care after noting a moderate amount of purulent discharge on his clothing originating from his hip. In the week prior to admission, the patient observed progressive erythema, warmth, and tenderness over the incision site. Despite these symptoms, the patient remained ambulatory and able to walk long distances with the use of an assistive device.

Upon presentation, the patient was afebrile and normotensive. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 77 mm/h (reference range, 0-20 mm/h) and a C-reactive protein of 9.8 mg/L (reference range, 0-2.5 mg/L), suggesting an underlying infectious process. A physical examination revealed a well-healed incision over the left hip with a poorly defined area of fluctuance and evidence of wound dehiscence. The left lower extremity was swollen with 2+ pitting edema, but tenderness was localized to the incision site. Magnetic resonance imaging of the left hip revealed a multiloculated fluid collection abutting the left greater trochanter with extension to the skin surface and inferior extension along the entire length of the surgical fixation hardware (Figure).

Upon admission, orthopedic surgery performed a bedside aspiration of the fluid collection. Samples were sent for analysis, including cell count and bacterial and fungal cultures. Initial blood cultures were sterile. Due to concerns for a bacterial infection, the patient was started on empiric intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone 2 g/day and IV vancomycin 1250 mg/day. Synovial fluid analysis revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 45,000/ìL, but bacterial cultures were negative. Five days after admission, the fungal culture from the left hip wound was notable for presence of C. glabrata, prompting an infectious diseases (ID) consultation. IV micafungin 100 mg/day was initiated as empiric antifungal therapy.

ID and orthopedic surgery teams determined that a combined medical and surgical approach would be best suited for infection control. They proposed 2 main approaches: complete hardware replacement with washout, which carried a higher morbidity risk but a better chance of infection resolution, or partial hardware replacement with washout, which was associated with a lower morbidity risk but a higher risk of infection persistence and recurrence. This decision was particularly challenging for the patient, who prioritized maintaining his functional status, including his ability to continue dancing for pleasure. The patient opted for a more conservative approach, electing to proceed with antifungal therapy and debridement while retaining the prosthetic joint.

After 11 days of hospitalization, the patient was discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter for long-term antifungal infusions of micafungin 150 mg/day at home. Fungal sensitivity test results several days after discharge confirmed susceptibility to micafungin.

About 2 weeks after discharge, the patient underwent debridement and implant retention (DAIR). Wound cultures were positive for C. glabrata, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Corynebacterium tuberculostearicum. Based on susceptibilities, he completed a 2-month course of IV micafungin 150 mg daily and daptomycin 750 mg daily, followed by an oral suppressive regimen consisting of doxycycline 100 mg twice daily, amoxicillin-clavulanate 2 g twice daily, and fluconazole initially 800 mg daily adjusted to 400 mg daily. The patient continued wound management with twice-daily dressing changes.

Nine months after DAIR, the patient remained on suppressive antifungal and antibacterial therapy. He continued to experience serous drainage from the wound, which greatly affected his quality of life. After discussion with his family and the orthopedic surgery team, he agreed to proceed with a 2-staged revision arthroplasty involving prosthetic explant and antibiotic spacer placement. However, the surgery was postponed due to findings of anemia (hemoglobin, 8.9 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count, 73 x 103/λL). At the time of this report, the patient was being monitored closely with his multidisciplinary care team for the planned orthopedic procedure.

DISCUSSION

PJI is the most common cause of primary hip arthroplasty failure; however, fungal species only make up about 1% of PJIs.3,9-11 Patients are typically immunocompromised, undergoing antineoplastic therapies for malignancy, or have other comorbid conditions such as diabetes.12,13 C. glabrata presents a unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenge as it is not only rare but also notorious for its resistance to common antifungal agents. C. glabrata is known to develop multidrug resistance through the rapid accumulation of genomic mutations.14 Its propensity towards forming protective biofilm also arms it with intrinsic resistance to agents like fluconazole.15 Furthermore, based on a review of the available reports in the literature, C. glabrata PJIs are often insidious and present with symptoms closely mimicking those of bacterial PJIs, as it did in the patient in this case.16

Synovial fluid analysis, fungal cultures, and sensitivity testing are paramount for ensuring proper diagnosis for fungal PJI. The patient in this case was empirically treated with micafungin based on recommendations from the ID team. When the sensitivities results were reviewed, the same antifungal therapy was continued. Echinocandins have a favorable toxicity profile in long-term use, as well as efficacy against biofilm-producing organisms like C. glabrata.17,18

While there are a few cases citing DAIR as a feasible surgical strategy for treating fungal PJI, more recent studies have reported greater success with a 2-staged revision arthroplasty involving some combination of debridement, placement of antibiotic-loaded bone cement spacers, and partial or total exchange of the infected prosthetic joint.4,19-23 In this case, complete hardware replacement would have offered the patient the most favorable outlook for eliminating this fungal infection. However, given the patient’s advanced age, significant underlying comorbidities, and functional status, medical management with antifungal therapy and DAIR was favored.

Based on the discussion from the 6-month follow-up visit, the patient was experiencing progressive and persistent wound drainage and frequent dressing changes, highlighting the limitations of medical management for PJI in the setting of retained prosthesis. If the patient ultimately proceeds with a more invasive surgical intervention, another important consideration will be the likelihood of fungal PJI recurrence. At present, fungal PJI recurrence rates following antifungal and surgical treatment have been reported to range between 0% to 50%, which is too imprecise to be considered clinically useful.22-24

Given the ambiguity surrounding management guidelines and limited treatment options, it is crucial to emphasize the timeline of this patient’s clinical presentation and subsequent course of treatment. Upon presentation to the ED in late July, fungal PJI was considered less likely. Initial blood cultures from presentation were negative, which is common with PJIs. It was not until 5 days later that the left hip wound culture showed moderate growth of C. glabrata. Identifying a PJI is clinically challenging due to the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria. However, timely identification and diagnosis of fungal PJI with appropriate antifungal therapy, in patients with limited curative options due to comorbidities, can significantly improve quality of life and overall outcomes.25 Routine fungal and mycobacterial cultures are not currently recommended in PJI guidelines, but this case illustrates it is imperative in immunocompromised hosts.26

This case and the current paucity of similar cases in the literature stress the importance of clinicians publishing their experience in the management of fungal PJI. We strongly recommend that clinicians approach each suspected PJI with careful consideration of the patient’s unique risk factors, comorbidities, and goals of care, when deciding on a curative vs suppressive approach to therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

This case report highlights the importance of considering fungal pathogens for PJIs, especially in high-risk patients, the value of obtaining fungal cultures, the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach, the role of antifungal susceptibility testing, and consideration for the feasibility of a surgical intervention. It underscores the challenges in diagnosis and treatment of C. glabrata-associated PJI, emphasizing the importance of clinician experience-sharing in developing evidence-based management strategies. As the understanding of fungal PJI evolves, continued research and clinical data collection remain crucial for improving patient outcomes in the management of these complex cases.

- Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. Executive summary: diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(1):1-10. doi:10.1093/cid/cis966

- Eka A, Chen AF. Patient-related medical risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection of the hip and knee. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(16):233. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.09.26

- Darouiche RO, Hamill RJ, Musher DM, Young EJ, Harris RL. Periprosthetic candidal infections following arthroplasty. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(1):89-96. doi:10.1093/clinids/11.1.89

- Koutserimpas C, Zervakis SG, Maraki S, et al. Non-albicans Candida prosthetic joint infections: a systematic review of treatment. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7(12):1430- 1443. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v7.i12.1430

- Fidel PL Jr, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD. Candida glabrata: review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(1):80-96. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.1.80

- Aboltins C, Daffy J, Choong P, Stanley P. Current concepts in the management of prosthetic joint infection. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):834-840. doi:10.1111/imj.12510

- Lee YR, Kim HJ, Lee EJ, Sohn JW, Kim MJ, Yoon YK. Prosthetic joint infections caused by candida species: a systematic review and a case series. Mycopathologia. 2019;184(1):23-33. doi:10.1007/s11046-018-0286-1

- Herndon CL, Rowe TM, Metcalf RW, et al. Treatment outcomes of fungal periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(11):2436-2440.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.05.009

- Delaunay C, Hamadouche M, Girard J, Duhamel A; SoFCOT. What are the causes for failures of primary hip arthroplasties in France? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(12): 3863-3869. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-2935-5

- Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Vail TP, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1): 128-133. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00155

- Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(4):579-586. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.83b4.11223

- Gonzalez MR, Bedi ADS, Karczewski D, Lozano-Calderon SA. Treatment and outcomes of fungal prosthetic joint infections: a systematic review of 225 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(11):2464-2471.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.05.003

- Gonzalez MR, Pretell-Mazzini J, Lozano-Calderon SA. Risk factors and management of prosthetic joint infections in megaprostheses-a review of the literature. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;13(1):25. doi:10.3390/antibiotics13010025

- Biswas C, Chen SC, Halliday C, et al. Identification of genetic markers of resistance to echinocandins, azoles and 5-fluorocytosine in Candida glabrata by next-generation sequencing: a feasibility study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(9):676.e7-676.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.03.014

- Hassan Y, Chew SY, Than LTL. Candida glabrata: pathogenicity and resistance mechanisms for adaptation and survival. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7(8):667. doi:10.3390/jof7080667

- Aboltins C, Daffy J, Choong P, Stanley P. Current concepts in the management of prosthetic joint infection. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):834-840. doi:10.1111/imj.12510

- Pierce CG, Uppuluri P, Tristan AR, et al. A simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(9):1494-1500. doi:10.1038/nport.2008.141

- Koutserimpas C, Samonis G, Velivassakis E, Iliopoulou- Kosmadaki S, Kontakis G, Kofteridis DP. Candida glabrata prosthetic joint infection, successfully treated with anidulafungin: a case report and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2018;61(4):266-269. doi:10.1111/myc.12736

- Brooks DH, Pupparo F. Successful salvage of a primary total knee arthroplasty infected with Candida parapsilosis. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(6):707-712. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(98)80017-x

- Merrer J, Dupont B, Nieszkowska A, De Jonghe B, Outin H. Candida albicans prosthetic arthritis treated with fluconazole alone. J Infect. 2001;42(3):208-209. doi:10.1053/jinf.2001.0819

- Koutserimpas C, Naoum S, Alpantaki K, et al. Fungal prosthetic joint infection in revised knee arthroplasty: an orthopaedic surgeon’s nightmare. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(7):1606. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12071606

- Gao Z, Li X, Du Y, Peng Y, Wu W, Zhou Y. Success rate of fungal peri-prosthetic joint infection treated by 2-stage revision and potential risk factors of treatment failure: a retrospective study. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:5549-5557. doi:10.12659/MSM.909168

- Hwang BH, Yoon JY, Nam CH, et al. Fungal periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(5):656-659. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B5.28125

- Ueng SW, Lee CY, Hu CC, Hsieh PH, Chang Y. What is the success of treatment of hip and knee candidal periprosthetic joint infection? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(9):3002-3009. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3007-6

- Nodzo, Scott R. MD; Bauer, Thomas MD, PhD; Pottinger, et al. Conventional diagnostic challenges in periprosthetic joint infection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23 Suppl:S18-S25. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00385

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Diagnosis and prevention of periprosthetic joint infections. March 11, 2019. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.aaos.org/pjicpg

- Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. Executive summary: diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(1):1-10. doi:10.1093/cid/cis966

- Eka A, Chen AF. Patient-related medical risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection of the hip and knee. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3(16):233. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.09.26

- Darouiche RO, Hamill RJ, Musher DM, Young EJ, Harris RL. Periprosthetic candidal infections following arthroplasty. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(1):89-96. doi:10.1093/clinids/11.1.89

- Koutserimpas C, Zervakis SG, Maraki S, et al. Non-albicans Candida prosthetic joint infections: a systematic review of treatment. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7(12):1430- 1443. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v7.i12.1430

- Fidel PL Jr, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD. Candida glabrata: review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, and clinical disease with comparison to C. albicans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(1):80-96. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.1.80

- Aboltins C, Daffy J, Choong P, Stanley P. Current concepts in the management of prosthetic joint infection. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):834-840. doi:10.1111/imj.12510

- Lee YR, Kim HJ, Lee EJ, Sohn JW, Kim MJ, Yoon YK. Prosthetic joint infections caused by candida species: a systematic review and a case series. Mycopathologia. 2019;184(1):23-33. doi:10.1007/s11046-018-0286-1

- Herndon CL, Rowe TM, Metcalf RW, et al. Treatment outcomes of fungal periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(11):2436-2440.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.05.009

- Delaunay C, Hamadouche M, Girard J, Duhamel A; SoFCOT. What are the causes for failures of primary hip arthroplasties in France? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(12): 3863-3869. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-2935-5

- Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Vail TP, Berry DJ. The epidemiology of revision total hip arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1): 128-133. doi:10.2106/JBJS.H.00155

- Furnes O, Lie SA, Espehaug B, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Hip disease and the prognosis of total hip replacements. A review of 53,698 primary total hip replacements reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1987-99. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(4):579-586. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.83b4.11223

- Gonzalez MR, Bedi ADS, Karczewski D, Lozano-Calderon SA. Treatment and outcomes of fungal prosthetic joint infections: a systematic review of 225 cases. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(11):2464-2471.e1. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2023.05.003

- Gonzalez MR, Pretell-Mazzini J, Lozano-Calderon SA. Risk factors and management of prosthetic joint infections in megaprostheses-a review of the literature. Antibiotics (Basel). 2023;13(1):25. doi:10.3390/antibiotics13010025

- Biswas C, Chen SC, Halliday C, et al. Identification of genetic markers of resistance to echinocandins, azoles and 5-fluorocytosine in Candida glabrata by next-generation sequencing: a feasibility study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(9):676.e7-676.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.03.014

- Hassan Y, Chew SY, Than LTL. Candida glabrata: pathogenicity and resistance mechanisms for adaptation and survival. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7(8):667. doi:10.3390/jof7080667

- Aboltins C, Daffy J, Choong P, Stanley P. Current concepts in the management of prosthetic joint infection. Intern Med J. 2014;44(9):834-840. doi:10.1111/imj.12510

- Pierce CG, Uppuluri P, Tristan AR, et al. A simple and reproducible 96-well plate-based method for the formation of fungal biofilms and its application to antifungal susceptibility testing. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(9):1494-1500. doi:10.1038/nport.2008.141

- Koutserimpas C, Samonis G, Velivassakis E, Iliopoulou- Kosmadaki S, Kontakis G, Kofteridis DP. Candida glabrata prosthetic joint infection, successfully treated with anidulafungin: a case report and review of the literature. Mycoses. 2018;61(4):266-269. doi:10.1111/myc.12736

- Brooks DH, Pupparo F. Successful salvage of a primary total knee arthroplasty infected with Candida parapsilosis. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13(6):707-712. doi:10.1016/s0883-5403(98)80017-x

- Merrer J, Dupont B, Nieszkowska A, De Jonghe B, Outin H. Candida albicans prosthetic arthritis treated with fluconazole alone. J Infect. 2001;42(3):208-209. doi:10.1053/jinf.2001.0819

- Koutserimpas C, Naoum S, Alpantaki K, et al. Fungal prosthetic joint infection in revised knee arthroplasty: an orthopaedic surgeon’s nightmare. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(7):1606. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12071606

- Gao Z, Li X, Du Y, Peng Y, Wu W, Zhou Y. Success rate of fungal peri-prosthetic joint infection treated by 2-stage revision and potential risk factors of treatment failure: a retrospective study. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:5549-5557. doi:10.12659/MSM.909168

- Hwang BH, Yoon JY, Nam CH, et al. Fungal periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(5):656-659. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.94B5.28125

- Ueng SW, Lee CY, Hu CC, Hsieh PH, Chang Y. What is the success of treatment of hip and knee candidal periprosthetic joint infection? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(9):3002-3009. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3007-6

- Nodzo, Scott R. MD; Bauer, Thomas MD, PhD; Pottinger, et al. Conventional diagnostic challenges in periprosthetic joint infection. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23 Suppl:S18-S25. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00385

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Diagnosis and prevention of periprosthetic joint infections. March 11, 2019. Accessed February 5, 2025. https://www.aaos.org/pjicpg

A Candida Glabrata-Associated Prosthetic Joint Infection: Case Report and Literature Review

A Candida Glabrata-Associated Prosthetic Joint Infection: Case Report and Literature Review

Evaluating the Impact of a Urinalysis to Reflex Culture Process Change in the Emergency Department at a Veterans Affairs Hospital

Automated urine cultures (UCs) following urinalysis (UA) are often used in emergency departments (EDs) to identify urinary tract infections (UTIs). The fast-paced environment of the ED makes this method of proactive collection and facilitation of UC favorable. However, results are often reported as no organism growth or the growth of clinically insignificant organisms, leading to the overdetection and overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB).1-3 An estimated 30 to 60% of patients with ASB receive unwarranted antibiotic treatment, which is associated with an increased risk of developing Clostridioides difficile infection and contributes to the development of antimicrobial resistance.4-10 The costs associated with UC are an important consideration given the use of resources, the time and effort required to collect and process large numbers of negative cultures, and further efforts devoted to the follow-up of ED culture results.

Changes in traditional testing involving testing of both a UA and UC to reflex testing where urine specimens undergo culture only if they meet certain criteria have been described.11-14 This change in traditional testing aims to reduce the number of potentially unnecessary cultures performed without compromising clinical care. Leukocyte quantity in the UA has been shown to be a reliable predictor of true infection.11,15 Fok and colleagues demonstrated that reflex urine testing in ambulatory male urology patients in which cultures were done on only urine specimens with > 5 white blood cells per high-power field (WBC/HPF) would have missed only 7% of positive UCs, while avoiding 69% of cultures.11

At the Edward Hines, Jr Veterans Affairs Hospital (Hines VA), inappropriate UC ordering and treatment for ASB has been identified as an area needing improvement. An evaluation was conducted at the facility to determine the population of inpatient veterans with a positive UC who were appropriately managed. Of the 113 study patients with a positive UC included in this review, 77 (68%) had a diagnosis of ASB, with > 80% of patients with ASB (and no other suspected infections) receiving antimicrobial therapy.8 A subsequent evaluation was conducted at the Hines VA ED to evaluate UTI treatment and follow-up. Of the 173 ED patients included, 23% received antibiotic therapy for an ASB and 60% had a UA and UC collected but did not report symptoms.9 Finally, a review by the Hines VA laboratory showed that in May 2017, of 359 UCs sent from various locations of the hospital, 38% were obtained in the setting of a negative UA.

A multidisciplinary group with representation from primary care, infectious diseases, pharmacy, nursing, laboratory, and informatics was created with a goal to improve the workup and management of UTIs. In addition to periodic education for the clinicians regarding appropriate use and interpretation of UA and UC along with judicious use of antimicrobials especially in the setting of ASB, a UA to reflex culture process change was implemented. This allowed for automatic cancellation of a UC in the setting of a negative UA, which was designed to help facilitate appropriate UC ordering.

Methods

The primary objective of this study was to compare the frequency of inappropriate UC use and inappropriate antibiotic prescribing pre- and postimplementation of this UA to reflex culture process change. An inappropriate UC was defined as a UC ordered despite a negative UA in asymptomatic patients. Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing was defined as treatment of patients with ASB. The secondary objective evaluated postintervention data to assess the frequency of outpatient, ED, and hospital visits for UTI-related symptoms in the group of patients that had a UC cancelled as a result of the new process change (within a 7-day period of the initial UA) to determine whether patients with true infections were missed due to the process change.

Study Design and Setting

This pre-post quality improvement (QI) study analyzed the UC-ordering practices for UTIs sent from the ED at the Hines VA. This VA is a 483-bed tertiary care hospital in Chicago, Illinois, and serves > 57,000 veterans and about 23,000 ED visits annually. This study was approved by the Edward Hines, Jr VA Institutional Review Board as a quality assurance/QI proposal prior to data collection.

Patient Selection

All patients who

When comparing postintervention data with preintervention data for the primary study objective, the same exclusion criteria from the 2015 study were applied to the present study, which excluded ED patients who were admitted for inpatient care, concurrent antibiotic therapy for a non-UTI indication, duplicate cultures, and use of chronic bladder management devices. All patients identified as receiving a UA during the specified postintervention study period were included for evaluation of the secondary study objective.

Interventions

After physician education, an ED process change was implemented on October 3, 2017. This process change involved the creation of new order sets in the EHR that allowed clinicians to order a UA only, a UA with culture that would be cancelled by laboratory personnel if the UA did not result in > 5 WBC/HPF, and a UA with culture designated as do not cancel, where the UC was processed regardless of the UA results. The scenarios in which the latter option was considered appropriate were listed on the ordering screen and included pregnancy, a genitourinary procedure with necessary preoperative culture, and neutropenia.

Measurements

Postimplementation, all UAs were reviewed and grouped as follows: (1) positive UA with subsequent UC; (2) negative UA, culture cancelled; (3) only UA ordered (no culture); or (4) do not cancel UC ordered. Of the UAs that were analyzed, the following data were collected: demographics, comorbidities, concurrent medications for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and/or overactive bladder (OAB), documented allergies/adverse drug reactions to antibiotics, date of ED visit, documented UTI signs/symptoms (defined as frequency, urgency, dysuria, fever, suprapubic pain, or altered mental status in patients unable to verbalize urinary symptoms), UC results and susceptibilities, number of UCs repeated within 7 days after initial UA, requirement of antibiotic for UTI within 7 days of initial UA, antibiotic prescribed, duration of antibiotic therapy, and outpatient visits, ED visits, or need for hospital admission within 7 days of the initial UA for UTI-related symptoms. Other relevant UA and UC data that could not be obtained from the EHR were collected by generating a report using the Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA).

Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS v9.4. Independent t tests and Fisher exact tests were used to describe difference pre- and postintervention. Statistical significance was considered for P < .05. Based on results from the previous study conducted at this facility in addition to a literature review, it was determined that 92 patients in each group (pre- and postintervention) would be necessary to detect a 15% increase in percentage of patients appropriately treated for a UTI.

Results

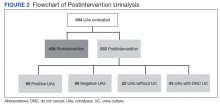

There were 684 UAs evaluated from ED visits, 429 preintervention and 255 postintervention. The 255 patients were evaluated for the secondary objective of the study. Of the 255 patients with UAs identified postintervention, 150 were excluded based on the predefined exclusion criteria, and the remaining 105 were compared with the 173 patients from the preintervention group and were included in the analysis for the primary objective (Figure 1).

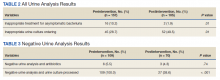

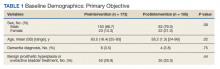

Patients in the postintervention group were younger than those in the preintervention group (P < .02): otherwise the groups were similar (Table 1). Inappropriate antibiotics for ASB decreased from 10.2% preintervention to 1.9% postintervention (odds ratio, 0.17; P = .01) (Table 2). UC processing despite a negative UA significantly decreased from 100% preintervention to 38.6% postintervention (P < .001) (Table 3). In patients with a negative UA, antibiotic prescribing decreased by 25.3% postintervention, but this difference was not statistically significant.

Postintervention, of 255 UAs evaluated, 95 (37.3%) were positive with a processed UC and 95 (37.3%) were negative with UC cancelled, 43 (16.9%) were ordered as DNC, and 22 (8.6%) were ordered without a UC (Figure 2). Twenty-eight of the 95 (29.5%) UAs with processed UCs did not meet the criteria for a positive UA and were not designated as DNC. When the UCs of this subgroup of patients were further analyzed, we found that 2 of the cultures were positive of which 1 patient was symptomatic and required antibiotic therapy.

Of the 95 patients with a negative UA, 69 (72.6%) presented without any UTI-related symptoms. In this group, there were no reports of outpatient visits, ED visits, or hospital admissions within 7 days of initial UA for UTI-related symptoms. None of the UCs ordered as DNC had a supporting reason identified. Nonetheless, the UC results from this patient subgroup also were analyzed further and resulted in 4 patients with negative UA and positive subsequent UC, 1 was symptomatic and required antibiotic therapy.

Discussion

A simple process change at the Hines VA resulted in benefits related to antimicrobial stewardship without conferring adverse outcomes on patient safety. Both UC processing despite a negative UA and inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for ASB were reduced significantly postintervention. This process change was piloted in the ED where UCs are often included as part of the initial diagnostic testing in patients who may not report UTI-related symptoms but for whom a UC is often bundled with other infectious workup, depending on the patient presentation.

Reflex testing of urine specimens has been described in the literature, both in an exploratory nature where impact of a reflex UC cancellation protocol based on certain UA criteria is measured by percent reduction of UCs processed as well as results of such interventions implemented into clinical practice.11-13 A retrospective study performed at the University of North Carolina Medical Center evaluated patients who presented to the ED during a 6-month period and had both an automated UA and UC collected. UC processing was restricted to UA that was positive for nitrites, leukocyte esterase, bacteria, or > 10 WBC/HPF. Use of this reflex culture cancellation protocol could have eliminated 604 of the 1546 (39.1%) cultures processed. However, 11 of the 314 (3.5%) positive cultures could have been missed.13 This same protocol was externally validated at another large academic ED setting, where similar results were found.14

In clinical practice, there is a natural tendency to reflexively prescribe antibiotics based on the results of a positive UC due to the hesitancy in ignoring these results, despite lack of a suspicion for a true infection. Leis and colleagues explored this in a proof-of-concept study evaluating the impact of discontinuing the routine reporting of positive UC results from noncatheterized inpatients and requesting clinicians to call the laboratory for results if a UTI was suspected.16 This intervention resulted in a statistically significant reduction in treatment of ASB in noncatheterized patients from 48 to 12% pre- and postintervention. Clinicians requested culture results only 14% of the time, and there were no adverse outcomes among untreated noncatheterized patients. More recently, a QI study conducted at a large community hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, implemented a 2-step model of care for urine collection.17 UC was collected but only processed by the microbiology laboratory if the ED physicians deemed it necessary after clinical assessment.

After implementation, there was a decrease in the proportion of ED visits associated with processed UC (from 6.0% to 4.7% of visits per week; P < .001), ED visits associated with callbacks for processing UC (1.8% to 1.1% of visits per month; P < .001), and antimicrobial prescriptions for urinary symptoms among hospitalized patients (from 20.6% to 10.9%; P < .001). Equally important, despite the 937 cases in which urine was collected but cultures were not processed, no evidence of untreated UTIs was identified.17

The results from the present study similarly demonstrate minimal concern for potentially undertreating these patients. As seen in the subgroup of patients included in the positive UA group, which did not meet criteria for positive UA per protocol (n = 29), only 2 of the subsequent cultures were positive, of which only 1 patient required antibiotic therapy based on the clinical presentation. In addition, in the group of negative UAs with subsequent cancellation of the UC, there were no found reports of outpatient visits, ED visits, or hospital admissions within 7 days of the initial UA for UTI-related symptoms.

Limitations

This single-center, pre-post QI study was not without limitations. Manual chart reviews were required, and accuracy of information was dependent on clinician documentation and assessment of UTI-related symptoms. The population studied was predominately older males; thus, results may not be applicable to females or young adults. Additionally, recognition of a negative UA and subsequent cancellation of the UC was dependent on laboratory personnel. As noted in the patient group with a positive UA, some of these UAs were negative and may have been overlooked; therefore, subsequent UCs were inappropriately processed. However, this occurred infrequently and confirmed the low probability of true UTI in the setting of a negative UA. Follow-up for UTI-related symptoms may not have been captured if a patient had presented to an outside facility. Last, definitions of a positive UA differed slightly between the pre- and postintervention groups. The preintervention study defined a positive UA as a WBC count > 5 WBC/HPF and positive leukocyte esterase, whereas the present study defined a positive UA with a WBC count > 5. This may have resulted in an overestimation of positive UA in the postintervention group.

Conclusions

Better selective use of UC testing may improve stewardship resources and reduce costs impacting both ED and clinical laboratories. Furthermore, benefits can include a reduction in the use of time and resources required to collect samples for culture, use of test supplies, the time and effort required to process the large number of negative cultures, and resources devoted to the follow-up of these ED culture results. The described UA to reflex culture process change demonstrated a significant reduction in the processing of inappropriate UC and unnecessary antibiotics for ASB. There were no missed UTIs or other adverse patient outcomes noted. This process change has been implemented in all departments at the Hines VA and additional data will be collected to ensure consistent outcomes.

1. Chironda B, Clancy S, Powis JE. Optimizing urine culture collection in the emergency department using frontline ownership interventions. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(7):1038-1039. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu412

2. Nagurney JT, Brown DF, Chang Y, Sane S, Wang AC, Weiner JB. Use of diagnostic testing in the emergency department for patients presenting with non-traumatic abdominal pain. J Emerg Med. 2003;25(4):363-371. doi:10.1016/s0736-4679(03)00237-3

3. Lammers RL, Gibson S, Kovacs D, Sears W, Strachan G. Comparison of test characteristics of urine dipstick and urinalysis at various test cutoff points. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38(5):505-512. doi:10.1067/mem.2001.119427

4. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(10):1611-1615. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy1121

5. Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, et al. Effectiveness of an antimicrobial stewardship approach for urinary catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1120-1127. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1878

6. Hartley S, Valley S, Kuhn L, et al. Overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria: identifying targets for improvement. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(4):470-473. doi:10.1017/ice.2014.73

7. Bader MS, Loeb M, Brooks AA. An update on the management of urinary tract infections in the era of antimicrobial resistance. Postgrad Med. 2017;129(2):242-258. doi:10.1080/00325481.2017.1246055

8. Spivak ES, Burk M, Zhang R, et al. Management of bacteriuria in Veterans Affairs hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(6):910-917. doi:10.1093/cid/cix474

9. Kim EY, Patel U, Patel B, Suda KJ. Evaluation of bacteriuria treatment and follow-up initiated in the emergency department at a Veterans Affairs hospital. J Pharm Technol. 2017;33(5):183-188. doi:10.1177/8755122517718214

10. Brown E, Talbot GH, Axelrod P, Provencher M, Hoegg C. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile toxin-associated diarrhea. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1990;11(6):283-290. doi:10.1086/646173

11. Fok C, Fitzgerald MP, Turk T, Mueller E, Dalaza L, Schreckenberger P. Reflex testing of male urine specimens misses few positive cultures may reduce unnecessary testing of normal specimens. Urology. 2010;75(1):74-76. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2009.08.071

12. Munigala S, Jackups RR Jr, Poirier RF, et al. Impact of order set design on urine culturing practices at an academic medical centre emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(8):587-592. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006899

13. Jones CW, Culbreath KD, Mehrotra A, Gilligan PH. Reflect urine culture cancellation in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(1):71-76. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.08.042

14. Hertz JT, Lescallette RD, Barrett TW, Ward MJ, Self WH. External validation of an ED protocol for reflex urine culture cancelation. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(12):1838-1839. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2015.09.026

15. Stamm WE. Measurement of pyuria and its relation to bacteriuria. Am J Med. 1983;75(1B):53-58. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(83)90073-6

16. Leis JA, Rebick GW, Daneman N, et al. Reducing antimicrobial therapy for asymptomatic bacteriuria among noncatheterized inpatients: a proof-of-concept study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(7):980-983. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu010

17. Stagg A, Lutz H, Kirpalaney S, et al. Impact of two-step urine culture ordering in the emergency department: a time series analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017;27:140-147. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006250

Automated urine cultures (UCs) following urinalysis (UA) are often used in emergency departments (EDs) to identify urinary tract infections (UTIs). The fast-paced environment of the ED makes this method of proactive collection and facilitation of UC favorable. However, results are often reported as no organism growth or the growth of clinically insignificant organisms, leading to the overdetection and overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB).1-3 An estimated 30 to 60% of patients with ASB receive unwarranted antibiotic treatment, which is associated with an increased risk of developing Clostridioides difficile infection and contributes to the development of antimicrobial resistance.4-10 The costs associated with UC are an important consideration given the use of resources, the time and effort required to collect and process large numbers of negative cultures, and further efforts devoted to the follow-up of ED culture results.

Changes in traditional testing involving testing of both a UA and UC to reflex testing where urine specimens undergo culture only if they meet certain criteria have been described.11-14 This change in traditional testing aims to reduce the number of potentially unnecessary cultures performed without compromising clinical care. Leukocyte quantity in the UA has been shown to be a reliable predictor of true infection.11,15 Fok and colleagues demonstrated that reflex urine testing in ambulatory male urology patients in which cultures were done on only urine specimens with > 5 white blood cells per high-power field (WBC/HPF) would have missed only 7% of positive UCs, while avoiding 69% of cultures.11

At the Edward Hines, Jr Veterans Affairs Hospital (Hines VA), inappropriate UC ordering and treatment for ASB has been identified as an area needing improvement. An evaluation was conducted at the facility to determine the population of inpatient veterans with a positive UC who were appropriately managed. Of the 113 study patients with a positive UC included in this review, 77 (68%) had a diagnosis of ASB, with > 80% of patients with ASB (and no other suspected infections) receiving antimicrobial therapy.8 A subsequent evaluation was conducted at the Hines VA ED to evaluate UTI treatment and follow-up. Of the 173 ED patients included, 23% received antibiotic therapy for an ASB and 60% had a UA and UC collected but did not report symptoms.9 Finally, a review by the Hines VA laboratory showed that in May 2017, of 359 UCs sent from various locations of the hospital, 38% were obtained in the setting of a negative UA.

A multidisciplinary group with representation from primary care, infectious diseases, pharmacy, nursing, laboratory, and informatics was created with a goal to improve the workup and management of UTIs. In addition to periodic education for the clinicians regarding appropriate use and interpretation of UA and UC along with judicious use of antimicrobials especially in the setting of ASB, a UA to reflex culture process change was implemented. This allowed for automatic cancellation of a UC in the setting of a negative UA, which was designed to help facilitate appropriate UC ordering.

Methods

The primary objective of this study was to compare the frequency of inappropriate UC use and inappropriate antibiotic prescribing pre- and postimplementation of this UA to reflex culture process change. An inappropriate UC was defined as a UC ordered despite a negative UA in asymptomatic patients. Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing was defined as treatment of patients with ASB. The secondary objective evaluated postintervention data to assess the frequency of outpatient, ED, and hospital visits for UTI-related symptoms in the group of patients that had a UC cancelled as a result of the new process change (within a 7-day period of the initial UA) to determine whether patients with true infections were missed due to the process change.

Study Design and Setting

This pre-post quality improvement (QI) study analyzed the UC-ordering practices for UTIs sent from the ED at the Hines VA. This VA is a 483-bed tertiary care hospital in Chicago, Illinois, and serves > 57,000 veterans and about 23,000 ED visits annually. This study was approved by the Edward Hines, Jr VA Institutional Review Board as a quality assurance/QI proposal prior to data collection.

Patient Selection

All patients who

When comparing postintervention data with preintervention data for the primary study objective, the same exclusion criteria from the 2015 study were applied to the present study, which excluded ED patients who were admitted for inpatient care, concurrent antibiotic therapy for a non-UTI indication, duplicate cultures, and use of chronic bladder management devices. All patients identified as receiving a UA during the specified postintervention study period were included for evaluation of the secondary study objective.

Interventions

After physician education, an ED process change was implemented on October 3, 2017. This process change involved the creation of new order sets in the EHR that allowed clinicians to order a UA only, a UA with culture that would be cancelled by laboratory personnel if the UA did not result in > 5 WBC/HPF, and a UA with culture designated as do not cancel, where the UC was processed regardless of the UA results. The scenarios in which the latter option was considered appropriate were listed on the ordering screen and included pregnancy, a genitourinary procedure with necessary preoperative culture, and neutropenia.

Measurements

Postimplementation, all UAs were reviewed and grouped as follows: (1) positive UA with subsequent UC; (2) negative UA, culture cancelled; (3) only UA ordered (no culture); or (4) do not cancel UC ordered. Of the UAs that were analyzed, the following data were collected: demographics, comorbidities, concurrent medications for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and/or overactive bladder (OAB), documented allergies/adverse drug reactions to antibiotics, date of ED visit, documented UTI signs/symptoms (defined as frequency, urgency, dysuria, fever, suprapubic pain, or altered mental status in patients unable to verbalize urinary symptoms), UC results and susceptibilities, number of UCs repeated within 7 days after initial UA, requirement of antibiotic for UTI within 7 days of initial UA, antibiotic prescribed, duration of antibiotic therapy, and outpatient visits, ED visits, or need for hospital admission within 7 days of the initial UA for UTI-related symptoms. Other relevant UA and UC data that could not be obtained from the EHR were collected by generating a report using the Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VistA).

Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS v9.4. Independent t tests and Fisher exact tests were used to describe difference pre- and postintervention. Statistical significance was considered for P < .05. Based on results from the previous study conducted at this facility in addition to a literature review, it was determined that 92 patients in each group (pre- and postintervention) would be necessary to detect a 15% increase in percentage of patients appropriately treated for a UTI.

Results

There were 684 UAs evaluated from ED visits, 429 preintervention and 255 postintervention. The 255 patients were evaluated for the secondary objective of the study. Of the 255 patients with UAs identified postintervention, 150 were excluded based on the predefined exclusion criteria, and the remaining 105 were compared with the 173 patients from the preintervention group and were included in the analysis for the primary objective (Figure 1).

Patients in the postintervention group were younger than those in the preintervention group (P < .02): otherwise the groups were similar (Table 1). Inappropriate antibiotics for ASB decreased from 10.2% preintervention to 1.9% postintervention (odds ratio, 0.17; P = .01) (Table 2). UC processing despite a negative UA significantly decreased from 100% preintervention to 38.6% postintervention (P < .001) (Table 3). In patients with a negative UA, antibiotic prescribing decreased by 25.3% postintervention, but this difference was not statistically significant.

Postintervention, of 255 UAs evaluated, 95 (37.3%) were positive with a processed UC and 95 (37.3%) were negative with UC cancelled, 43 (16.9%) were ordered as DNC, and 22 (8.6%) were ordered without a UC (Figure 2). Twenty-eight of the 95 (29.5%) UAs with processed UCs did not meet the criteria for a positive UA and were not designated as DNC. When the UCs of this subgroup of patients were further analyzed, we found that 2 of the cultures were positive of which 1 patient was symptomatic and required antibiotic therapy.

Of the 95 patients with a negative UA, 69 (72.6%) presented without any UTI-related symptoms. In this group, there were no reports of outpatient visits, ED visits, or hospital admissions within 7 days of initial UA for UTI-related symptoms. None of the UCs ordered as DNC had a supporting reason identified. Nonetheless, the UC results from this patient subgroup also were analyzed further and resulted in 4 patients with negative UA and positive subsequent UC, 1 was symptomatic and required antibiotic therapy.

Discussion

A simple process change at the Hines VA resulted in benefits related to antimicrobial stewardship without conferring adverse outcomes on patient safety. Both UC processing despite a negative UA and inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for ASB were reduced significantly postintervention. This process change was piloted in the ED where UCs are often included as part of the initial diagnostic testing in patients who may not report UTI-related symptoms but for whom a UC is often bundled with other infectious workup, depending on the patient presentation.

Reflex testing of urine specimens has been described in the literature, both in an exploratory nature where impact of a reflex UC cancellation protocol based on certain UA criteria is measured by percent reduction of UCs processed as well as results of such interventions implemented into clinical practice.11-13 A retrospective study performed at the University of North Carolina Medical Center evaluated patients who presented to the ED during a 6-month period and had both an automated UA and UC collected. UC processing was restricted to UA that was positive for nitrites, leukocyte esterase, bacteria, or > 10 WBC/HPF. Use of this reflex culture cancellation protocol could have eliminated 604 of the 1546 (39.1%) cultures processed. However, 11 of the 314 (3.5%) positive cultures could have been missed.13 This same protocol was externally validated at another large academic ED setting, where similar results were found.14