User login

Advancements in the Treatment of Malignant PEComas with mTOR Inhibitors

Advancements in the Treatment of Malignant PEComas with mTOR Inhibitors

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is an attractive therapeutic target for soft tissue sarcomas, as dysregulation of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) can lead to the development of various cancer types. Recently, clinical trial data have demonstrated that mTOR inhibitors can significantly improve long-term outcomes in patients with malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors, or PEComas—a challenging disease to manage in the advanced stage.

Ultrarare Mesenchymal Tumors

PEComas are ultrarare soft tissue tumors that are mesenchymal in origin and are characterized histologically by distinctive epithelioid cells that express smooth muscle and melanocytic markers.1-3 Malignant PEComas affect fewer than 1/1,000,000 people per year,4,5 and have a predominance in women, as they are commonly found in the uterus.4 PEComas include several histological types, such as angiomyolipoma (the most prevalent type), lymphangioleiomyomatosis, clear cell (“sugar”) tumor, and other tumors with similar features.3

Detecting an Ultrarare Malignant PEComa

Most PEComas are diagnosed incidentally via imaging. Patients may also present with symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, and unexplained weight loss.6,7 PEComas in the uterus are often detected through an ultrasound, in which they may have the appearance of fibroids.8 Diagnosis must be confirmed by biopsy, and histological analysis can determine the risk classification based on tumor characteristics.6 Many patients with PEComas harbor loss-of-function mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes, resulting in overactivation of the PIK3/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway9; TP53 mutations and TFE3 rearrangements or fusions have also been identified.6,10

Therapeutic Strategies Are Limited

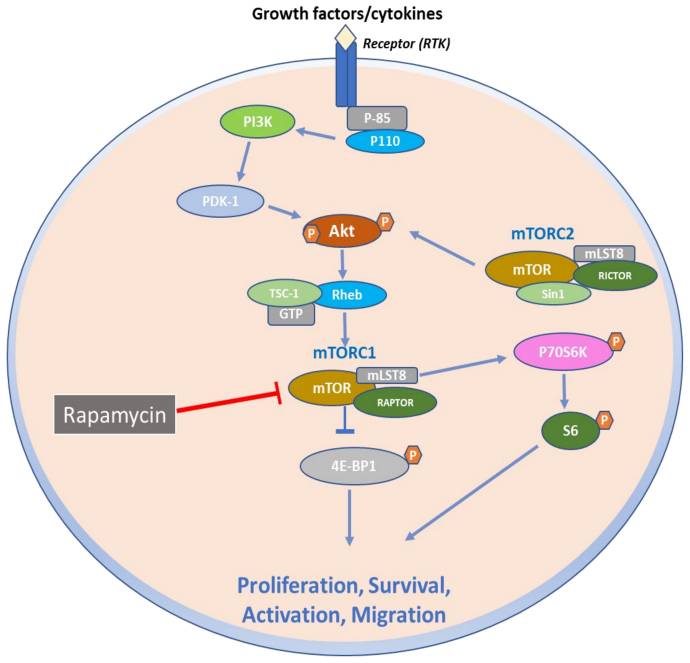

Because PEComas are often resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, resection is considered standard-of-care treatment for localized disease.6 Patients with advanced disease should be considered for systemic therapy. However, there is a substantial unmet need for novel therapies due to the limited efficacy of existing treatment options. Agents that target mTOR have shown important potential in improving long-term outcomes in patients with metastatic PEComas.6 The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is a key signaling system that regulates cell proliferation and survival. TSC1 and TSC2 normally negatively regulate the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1); however, alterations in TSC1 and TSC2 result in increased activity of this pathway, allowing tumors to proliferate (Figure).11,12 Clinical guidelines recommend using mTOR inhibitors for patients with locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic malignant PEComas, and both on and off-label therapies are often used in the clinical setting.13 nab-Sirolimus, a nanoparticle albumin–bound sirolimus, is one such mTOR (previously known as mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitor that binds to and blocks activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1.11,14

Figure. mTOR Signaling Skin Diseases

The Promise of mTOR Inhibitors for Malignant PEComas

In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved nab-sirolimus to treat patients with locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic malignant PEComas. This approval was based on results from the phase 2 Advanced Malignant Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Tumors (AMPECT) clinical trial (NCT02494570).14,15 AMPECT was a multicenter, open-label, single-arm trial that evaluated nab-sirolimus in 34 patients with metastatic or locally advanced (ineligible for surgery) malignant PEComa and measurable disease who had not been previously treated with an mTOR inhibitor. Most of the patients were women, and the most common site of disease was the uterus.14 Patients received nab-sirolimus (100 mg/m2 intravenously) on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle. The primary outcome of the study was an overall response rate by 6 months, and secondary endpoints included duration of response, progression-free survival (PFS), PFS at 6 months (PFS6), overall survival (OS), and safety; tumor biomarkers were also evaluated as exploratory measures.14 At 6 months, nab-sirolimus demonstrated an overall response rate of 39%, with rapid and durable responses. The median PFS was 10.6 months, with a PFS6 of 70%; median OS was 40.8 months.

Of the 25 patients for whom tumor profiling was performed, 8 of 9 (89%) patients with a TSC2 mutation achieved a response compared with 2 of 16 (13%) without the mutation. The most common adverse events associated with treatment included mucositis, rash, fatigue, and anemia, which are consistent with the medication class.14 Long-term analysis from the AMPECT trial demonstrated a median OS of 53.1 months, with a median duration of response of 39.7 months. Taken together, these results indicate that nab-sirolimus may provide patients with positive long-term clinical benefits with an acceptable safety profile.15 nab-Sirolimus is currently being evaluated in clinical trials in patients harboring TSC1 and TSC2 mutations and is also being investigated as a therapeutic candidate for other cancer types, such as neuroendocrine tumors, endometrial cancer, and ovarian cancer (NCT05997056; NCT05997017; NCT06494150; NCT05103358).

Case Study Spotlight

A 70-year-old woman presented at a local emergency department with several episodes of tingling in her upper and lower extremities. A chest radiograph revealed multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules, and a computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a 21-cm left abdominal mass, innumerable pulmonary nodules, and multiple hepatic lesions. The patient underwent palliative resection of the large left retroperitoneal mass. Pathology revealed malignant PEComa, and a liver biopsy confirmed metastatic disease.

Following referral, the patient was enrolled in the AMPECT clinical trial, during which she received nab-sirolimus treatment. An objective response was confirmed after the initial 6 weeks on therapy and serial imaging revealed continued shrinkage in lung and liver lesions over time; the nab-sirolimus dose was reduced by 25% due to grade 2 pneumonitis after ~18 months of treatment. The patient had a complete response after 4 years on treatment. Unfortunately, the patient died due to complications from an unrelated elective hernia repair. She was 74 at the time of her death, and there was no radiographic evidence of PEComa.

Future Directions

While mTOR inhibitors provide the most favorable outcomes in the advanced disease setting at this time, research is underway to evaluate the utility of additional novel targets to treat malignant PEComa. Anecdotal evidence from case reports indicates that anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be beneficial to patients with malignant PEComa, highlighting the VEGF/VEGF receptor signaling pathway as a potential therapeutic target.16 Some evidence has also suggested that programmed cell death (PD) protein 1/PD ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitors may be effective for patients with metastatic disease with high PD-L1 levels.17 In addition to more treatment options, diagnostic markers could potentially improve prognosis by facilitating earlier detection, a key challenge in managing malignant PEComas, especially for uterine tumors that are often misdiagnosed.18 Future research may also help guide personalized treatment strategies based on tumor genetic composition.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

- Stacchiotti S, Frezza AM, Blay JY, et al. Ultra-rare sarcomas: a consensus paper from the Connective Tissue Oncology Society community of experts on the incidence threshold and the list of entities. Cancer. 2021;127(16):2934-2942. doi:10.1002/cncr.33618

- Bleeker JS, Quevedo JF, Folpe AL. “Malignant” perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm: risk stratification and treatment strategies. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:541626. doi:10.1155/2012/541626

- Thway K, Fisher C. PEComa: morphology and genetics of a complex tumor family. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015;19(5):359-368. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2015.06.003

- Battistella E, Pomba L, Mirabella M, et al. Metastatic adrenal PEComa: case report and short review of the literature. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(1):149. doi:10.3390/medicina59010149

- Meredith L, Chao T, Nevler A, et al. A rare metastatic mesenteric malignant PEComa with TSC2 mutation treated with palliative surgical resection and nab-sirolimus: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2023;18(1):45. doi:10.1186/s13000-023-01323-x

- Czarnecka AM, Skoczylas J, Bartnik E, Switaj T, Rutkowski P. Management strategies for adults with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): challenges and solutions. Cancer Manag Res. 2023;15:615-623. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S351284

- Kvietkauskas M, Samuolyte A, Rackauskas R, et al. Primary liver perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): case report and literature review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60(3):409. doi:10.3390/medicina60030409

- Giannella L, Delli Carpini G, Montik N, et al. Ultrasound features of a uterine perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): case report and literature review. Diagnostic (Basel). 2020;10(8):553. doi:10.3390/diagnostics10080553

- Liu L, Dehner C, Grandhi N, et al. The impact of TSC-1 and -2 mutations on response to therapy in malignant PEComa: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Genes (Basel). 2022;13(11):1932. doi:10.3390/genes13111932

- Schoolmeester JK, Dao LN, Sukov WR, et al. TFE3 translocation-associated perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) of the gynecologic tract: morphology, immunophenotype, differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(3):394-404.doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000349

- Ali ES, Mitra K, Akter S, et al. Recent advances and limitations of mTOR inhibitors in the treatment of cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22(1):284. doi:10.1186/s12935-022-02706-8

- Sanfilippo R, Jones RL, Blay JY, et al. Role of chemotherapy, VEGFR inhibitors, and mTOR inhibitors in advanced perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas). Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(17):5295-5300. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0288

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: soft tissue sarcoma. Version 2.2024. July 31, 2024. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/sarcoma.pdf

- Wagner AJ, Ravi V, Riedel RF, et al. nab-Sirolimus for patients with malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(33):3660-3670. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.01728

- Wagner AJ, Ravi V, Riedel RF, et al. Phase II trial of nab-sirolimus in patients with advanced malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (AMPECT): long-term efficacy and safety update. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(13):1472-1476. doi:10.1200/JCO.23.02266

- Xu J, Gong XL, Wu H, Zhao L. Case report: gastrointestinal PEComa with TFE3 rearrangement treated with anti-VEGFR TKI apatinib. Front Oncol. 2020;10:582087. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.582087

- McBride A, Garcia AJ, Sanders LJ, et al. Sustained response to pembrolizumab in recurrent perivascular epithelioid cell tumor with elevated expression of programmed death ligand: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15(1):400. doi:10.1186/s13256-021-02997-x

- Levin G, Capella MP, Meyer R, Brezinov Y, Gotlieb WH. Gynecologic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas): a review of recent evidence. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309(6):2381-2386. doi:10.1007/s00404-024-07510-5

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is an attractive therapeutic target for soft tissue sarcomas, as dysregulation of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) can lead to the development of various cancer types. Recently, clinical trial data have demonstrated that mTOR inhibitors can significantly improve long-term outcomes in patients with malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors, or PEComas—a challenging disease to manage in the advanced stage.

Ultrarare Mesenchymal Tumors

PEComas are ultrarare soft tissue tumors that are mesenchymal in origin and are characterized histologically by distinctive epithelioid cells that express smooth muscle and melanocytic markers.1-3 Malignant PEComas affect fewer than 1/1,000,000 people per year,4,5 and have a predominance in women, as they are commonly found in the uterus.4 PEComas include several histological types, such as angiomyolipoma (the most prevalent type), lymphangioleiomyomatosis, clear cell (“sugar”) tumor, and other tumors with similar features.3

Detecting an Ultrarare Malignant PEComa

Most PEComas are diagnosed incidentally via imaging. Patients may also present with symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, and unexplained weight loss.6,7 PEComas in the uterus are often detected through an ultrasound, in which they may have the appearance of fibroids.8 Diagnosis must be confirmed by biopsy, and histological analysis can determine the risk classification based on tumor characteristics.6 Many patients with PEComas harbor loss-of-function mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes, resulting in overactivation of the PIK3/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway9; TP53 mutations and TFE3 rearrangements or fusions have also been identified.6,10

Therapeutic Strategies Are Limited

Because PEComas are often resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, resection is considered standard-of-care treatment for localized disease.6 Patients with advanced disease should be considered for systemic therapy. However, there is a substantial unmet need for novel therapies due to the limited efficacy of existing treatment options. Agents that target mTOR have shown important potential in improving long-term outcomes in patients with metastatic PEComas.6 The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is a key signaling system that regulates cell proliferation and survival. TSC1 and TSC2 normally negatively regulate the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1); however, alterations in TSC1 and TSC2 result in increased activity of this pathway, allowing tumors to proliferate (Figure).11,12 Clinical guidelines recommend using mTOR inhibitors for patients with locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic malignant PEComas, and both on and off-label therapies are often used in the clinical setting.13 nab-Sirolimus, a nanoparticle albumin–bound sirolimus, is one such mTOR (previously known as mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitor that binds to and blocks activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1.11,14

Figure. mTOR Signaling Skin Diseases

The Promise of mTOR Inhibitors for Malignant PEComas

In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved nab-sirolimus to treat patients with locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic malignant PEComas. This approval was based on results from the phase 2 Advanced Malignant Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Tumors (AMPECT) clinical trial (NCT02494570).14,15 AMPECT was a multicenter, open-label, single-arm trial that evaluated nab-sirolimus in 34 patients with metastatic or locally advanced (ineligible for surgery) malignant PEComa and measurable disease who had not been previously treated with an mTOR inhibitor. Most of the patients were women, and the most common site of disease was the uterus.14 Patients received nab-sirolimus (100 mg/m2 intravenously) on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle. The primary outcome of the study was an overall response rate by 6 months, and secondary endpoints included duration of response, progression-free survival (PFS), PFS at 6 months (PFS6), overall survival (OS), and safety; tumor biomarkers were also evaluated as exploratory measures.14 At 6 months, nab-sirolimus demonstrated an overall response rate of 39%, with rapid and durable responses. The median PFS was 10.6 months, with a PFS6 of 70%; median OS was 40.8 months.

Of the 25 patients for whom tumor profiling was performed, 8 of 9 (89%) patients with a TSC2 mutation achieved a response compared with 2 of 16 (13%) without the mutation. The most common adverse events associated with treatment included mucositis, rash, fatigue, and anemia, which are consistent with the medication class.14 Long-term analysis from the AMPECT trial demonstrated a median OS of 53.1 months, with a median duration of response of 39.7 months. Taken together, these results indicate that nab-sirolimus may provide patients with positive long-term clinical benefits with an acceptable safety profile.15 nab-Sirolimus is currently being evaluated in clinical trials in patients harboring TSC1 and TSC2 mutations and is also being investigated as a therapeutic candidate for other cancer types, such as neuroendocrine tumors, endometrial cancer, and ovarian cancer (NCT05997056; NCT05997017; NCT06494150; NCT05103358).

Case Study Spotlight

A 70-year-old woman presented at a local emergency department with several episodes of tingling in her upper and lower extremities. A chest radiograph revealed multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules, and a computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a 21-cm left abdominal mass, innumerable pulmonary nodules, and multiple hepatic lesions. The patient underwent palliative resection of the large left retroperitoneal mass. Pathology revealed malignant PEComa, and a liver biopsy confirmed metastatic disease.

Following referral, the patient was enrolled in the AMPECT clinical trial, during which she received nab-sirolimus treatment. An objective response was confirmed after the initial 6 weeks on therapy and serial imaging revealed continued shrinkage in lung and liver lesions over time; the nab-sirolimus dose was reduced by 25% due to grade 2 pneumonitis after ~18 months of treatment. The patient had a complete response after 4 years on treatment. Unfortunately, the patient died due to complications from an unrelated elective hernia repair. She was 74 at the time of her death, and there was no radiographic evidence of PEComa.

Future Directions

While mTOR inhibitors provide the most favorable outcomes in the advanced disease setting at this time, research is underway to evaluate the utility of additional novel targets to treat malignant PEComa. Anecdotal evidence from case reports indicates that anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be beneficial to patients with malignant PEComa, highlighting the VEGF/VEGF receptor signaling pathway as a potential therapeutic target.16 Some evidence has also suggested that programmed cell death (PD) protein 1/PD ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitors may be effective for patients with metastatic disease with high PD-L1 levels.17 In addition to more treatment options, diagnostic markers could potentially improve prognosis by facilitating earlier detection, a key challenge in managing malignant PEComas, especially for uterine tumors that are often misdiagnosed.18 Future research may also help guide personalized treatment strategies based on tumor genetic composition.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is an attractive therapeutic target for soft tissue sarcomas, as dysregulation of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) can lead to the development of various cancer types. Recently, clinical trial data have demonstrated that mTOR inhibitors can significantly improve long-term outcomes in patients with malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors, or PEComas—a challenging disease to manage in the advanced stage.

Ultrarare Mesenchymal Tumors

PEComas are ultrarare soft tissue tumors that are mesenchymal in origin and are characterized histologically by distinctive epithelioid cells that express smooth muscle and melanocytic markers.1-3 Malignant PEComas affect fewer than 1/1,000,000 people per year,4,5 and have a predominance in women, as they are commonly found in the uterus.4 PEComas include several histological types, such as angiomyolipoma (the most prevalent type), lymphangioleiomyomatosis, clear cell (“sugar”) tumor, and other tumors with similar features.3

Detecting an Ultrarare Malignant PEComa

Most PEComas are diagnosed incidentally via imaging. Patients may also present with symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, and unexplained weight loss.6,7 PEComas in the uterus are often detected through an ultrasound, in which they may have the appearance of fibroids.8 Diagnosis must be confirmed by biopsy, and histological analysis can determine the risk classification based on tumor characteristics.6 Many patients with PEComas harbor loss-of-function mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes, resulting in overactivation of the PIK3/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway9; TP53 mutations and TFE3 rearrangements or fusions have also been identified.6,10

Therapeutic Strategies Are Limited

Because PEComas are often resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, resection is considered standard-of-care treatment for localized disease.6 Patients with advanced disease should be considered for systemic therapy. However, there is a substantial unmet need for novel therapies due to the limited efficacy of existing treatment options. Agents that target mTOR have shown important potential in improving long-term outcomes in patients with metastatic PEComas.6 The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is a key signaling system that regulates cell proliferation and survival. TSC1 and TSC2 normally negatively regulate the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1); however, alterations in TSC1 and TSC2 result in increased activity of this pathway, allowing tumors to proliferate (Figure).11,12 Clinical guidelines recommend using mTOR inhibitors for patients with locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic malignant PEComas, and both on and off-label therapies are often used in the clinical setting.13 nab-Sirolimus, a nanoparticle albumin–bound sirolimus, is one such mTOR (previously known as mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitor that binds to and blocks activation of the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1.11,14

Figure. mTOR Signaling Skin Diseases

The Promise of mTOR Inhibitors for Malignant PEComas

In 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved nab-sirolimus to treat patients with locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic malignant PEComas. This approval was based on results from the phase 2 Advanced Malignant Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Tumors (AMPECT) clinical trial (NCT02494570).14,15 AMPECT was a multicenter, open-label, single-arm trial that evaluated nab-sirolimus in 34 patients with metastatic or locally advanced (ineligible for surgery) malignant PEComa and measurable disease who had not been previously treated with an mTOR inhibitor. Most of the patients were women, and the most common site of disease was the uterus.14 Patients received nab-sirolimus (100 mg/m2 intravenously) on days 1 and 8 of a 21-day cycle. The primary outcome of the study was an overall response rate by 6 months, and secondary endpoints included duration of response, progression-free survival (PFS), PFS at 6 months (PFS6), overall survival (OS), and safety; tumor biomarkers were also evaluated as exploratory measures.14 At 6 months, nab-sirolimus demonstrated an overall response rate of 39%, with rapid and durable responses. The median PFS was 10.6 months, with a PFS6 of 70%; median OS was 40.8 months.

Of the 25 patients for whom tumor profiling was performed, 8 of 9 (89%) patients with a TSC2 mutation achieved a response compared with 2 of 16 (13%) without the mutation. The most common adverse events associated with treatment included mucositis, rash, fatigue, and anemia, which are consistent with the medication class.14 Long-term analysis from the AMPECT trial demonstrated a median OS of 53.1 months, with a median duration of response of 39.7 months. Taken together, these results indicate that nab-sirolimus may provide patients with positive long-term clinical benefits with an acceptable safety profile.15 nab-Sirolimus is currently being evaluated in clinical trials in patients harboring TSC1 and TSC2 mutations and is also being investigated as a therapeutic candidate for other cancer types, such as neuroendocrine tumors, endometrial cancer, and ovarian cancer (NCT05997056; NCT05997017; NCT06494150; NCT05103358).

Case Study Spotlight

A 70-year-old woman presented at a local emergency department with several episodes of tingling in her upper and lower extremities. A chest radiograph revealed multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules, and a computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a 21-cm left abdominal mass, innumerable pulmonary nodules, and multiple hepatic lesions. The patient underwent palliative resection of the large left retroperitoneal mass. Pathology revealed malignant PEComa, and a liver biopsy confirmed metastatic disease.

Following referral, the patient was enrolled in the AMPECT clinical trial, during which she received nab-sirolimus treatment. An objective response was confirmed after the initial 6 weeks on therapy and serial imaging revealed continued shrinkage in lung and liver lesions over time; the nab-sirolimus dose was reduced by 25% due to grade 2 pneumonitis after ~18 months of treatment. The patient had a complete response after 4 years on treatment. Unfortunately, the patient died due to complications from an unrelated elective hernia repair. She was 74 at the time of her death, and there was no radiographic evidence of PEComa.

Future Directions

While mTOR inhibitors provide the most favorable outcomes in the advanced disease setting at this time, research is underway to evaluate the utility of additional novel targets to treat malignant PEComa. Anecdotal evidence from case reports indicates that anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be beneficial to patients with malignant PEComa, highlighting the VEGF/VEGF receptor signaling pathway as a potential therapeutic target.16 Some evidence has also suggested that programmed cell death (PD) protein 1/PD ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitors may be effective for patients with metastatic disease with high PD-L1 levels.17 In addition to more treatment options, diagnostic markers could potentially improve prognosis by facilitating earlier detection, a key challenge in managing malignant PEComas, especially for uterine tumors that are often misdiagnosed.18 Future research may also help guide personalized treatment strategies based on tumor genetic composition.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

- Stacchiotti S, Frezza AM, Blay JY, et al. Ultra-rare sarcomas: a consensus paper from the Connective Tissue Oncology Society community of experts on the incidence threshold and the list of entities. Cancer. 2021;127(16):2934-2942. doi:10.1002/cncr.33618

- Bleeker JS, Quevedo JF, Folpe AL. “Malignant” perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm: risk stratification and treatment strategies. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:541626. doi:10.1155/2012/541626

- Thway K, Fisher C. PEComa: morphology and genetics of a complex tumor family. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015;19(5):359-368. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2015.06.003

- Battistella E, Pomba L, Mirabella M, et al. Metastatic adrenal PEComa: case report and short review of the literature. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(1):149. doi:10.3390/medicina59010149

- Meredith L, Chao T, Nevler A, et al. A rare metastatic mesenteric malignant PEComa with TSC2 mutation treated with palliative surgical resection and nab-sirolimus: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2023;18(1):45. doi:10.1186/s13000-023-01323-x

- Czarnecka AM, Skoczylas J, Bartnik E, Switaj T, Rutkowski P. Management strategies for adults with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): challenges and solutions. Cancer Manag Res. 2023;15:615-623. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S351284

- Kvietkauskas M, Samuolyte A, Rackauskas R, et al. Primary liver perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): case report and literature review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60(3):409. doi:10.3390/medicina60030409

- Giannella L, Delli Carpini G, Montik N, et al. Ultrasound features of a uterine perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): case report and literature review. Diagnostic (Basel). 2020;10(8):553. doi:10.3390/diagnostics10080553

- Liu L, Dehner C, Grandhi N, et al. The impact of TSC-1 and -2 mutations on response to therapy in malignant PEComa: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Genes (Basel). 2022;13(11):1932. doi:10.3390/genes13111932

- Schoolmeester JK, Dao LN, Sukov WR, et al. TFE3 translocation-associated perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) of the gynecologic tract: morphology, immunophenotype, differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(3):394-404.doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000349

- Ali ES, Mitra K, Akter S, et al. Recent advances and limitations of mTOR inhibitors in the treatment of cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22(1):284. doi:10.1186/s12935-022-02706-8

- Sanfilippo R, Jones RL, Blay JY, et al. Role of chemotherapy, VEGFR inhibitors, and mTOR inhibitors in advanced perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas). Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(17):5295-5300. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0288

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: soft tissue sarcoma. Version 2.2024. July 31, 2024. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/sarcoma.pdf

- Wagner AJ, Ravi V, Riedel RF, et al. nab-Sirolimus for patients with malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(33):3660-3670. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.01728

- Wagner AJ, Ravi V, Riedel RF, et al. Phase II trial of nab-sirolimus in patients with advanced malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (AMPECT): long-term efficacy and safety update. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(13):1472-1476. doi:10.1200/JCO.23.02266

- Xu J, Gong XL, Wu H, Zhao L. Case report: gastrointestinal PEComa with TFE3 rearrangement treated with anti-VEGFR TKI apatinib. Front Oncol. 2020;10:582087. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.582087

- McBride A, Garcia AJ, Sanders LJ, et al. Sustained response to pembrolizumab in recurrent perivascular epithelioid cell tumor with elevated expression of programmed death ligand: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15(1):400. doi:10.1186/s13256-021-02997-x

- Levin G, Capella MP, Meyer R, Brezinov Y, Gotlieb WH. Gynecologic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas): a review of recent evidence. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309(6):2381-2386. doi:10.1007/s00404-024-07510-5

- Stacchiotti S, Frezza AM, Blay JY, et al. Ultra-rare sarcomas: a consensus paper from the Connective Tissue Oncology Society community of experts on the incidence threshold and the list of entities. Cancer. 2021;127(16):2934-2942. doi:10.1002/cncr.33618

- Bleeker JS, Quevedo JF, Folpe AL. “Malignant” perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm: risk stratification and treatment strategies. Sarcoma. 2012;2012:541626. doi:10.1155/2012/541626

- Thway K, Fisher C. PEComa: morphology and genetics of a complex tumor family. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2015;19(5):359-368. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2015.06.003

- Battistella E, Pomba L, Mirabella M, et al. Metastatic adrenal PEComa: case report and short review of the literature. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59(1):149. doi:10.3390/medicina59010149

- Meredith L, Chao T, Nevler A, et al. A rare metastatic mesenteric malignant PEComa with TSC2 mutation treated with palliative surgical resection and nab-sirolimus: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2023;18(1):45. doi:10.1186/s13000-023-01323-x

- Czarnecka AM, Skoczylas J, Bartnik E, Switaj T, Rutkowski P. Management strategies for adults with locally advanced, unresectable or metastatic malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): challenges and solutions. Cancer Manag Res. 2023;15:615-623. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S351284

- Kvietkauskas M, Samuolyte A, Rackauskas R, et al. Primary liver perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): case report and literature review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60(3):409. doi:10.3390/medicina60030409

- Giannella L, Delli Carpini G, Montik N, et al. Ultrasound features of a uterine perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa): case report and literature review. Diagnostic (Basel). 2020;10(8):553. doi:10.3390/diagnostics10080553

- Liu L, Dehner C, Grandhi N, et al. The impact of TSC-1 and -2 mutations on response to therapy in malignant PEComa: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Genes (Basel). 2022;13(11):1932. doi:10.3390/genes13111932

- Schoolmeester JK, Dao LN, Sukov WR, et al. TFE3 translocation-associated perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) of the gynecologic tract: morphology, immunophenotype, differential diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(3):394-404.doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000349

- Ali ES, Mitra K, Akter S, et al. Recent advances and limitations of mTOR inhibitors in the treatment of cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22(1):284. doi:10.1186/s12935-022-02706-8

- Sanfilippo R, Jones RL, Blay JY, et al. Role of chemotherapy, VEGFR inhibitors, and mTOR inhibitors in advanced perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas). Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(17):5295-5300. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0288

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: soft tissue sarcoma. Version 2.2024. July 31, 2024. Accessed September 10, 2024. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/sarcoma.pdf

- Wagner AJ, Ravi V, Riedel RF, et al. nab-Sirolimus for patients with malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(33):3660-3670. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.01728

- Wagner AJ, Ravi V, Riedel RF, et al. Phase II trial of nab-sirolimus in patients with advanced malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (AMPECT): long-term efficacy and safety update. J Clin Oncol. 2024;42(13):1472-1476. doi:10.1200/JCO.23.02266

- Xu J, Gong XL, Wu H, Zhao L. Case report: gastrointestinal PEComa with TFE3 rearrangement treated with anti-VEGFR TKI apatinib. Front Oncol. 2020;10:582087. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.582087

- McBride A, Garcia AJ, Sanders LJ, et al. Sustained response to pembrolizumab in recurrent perivascular epithelioid cell tumor with elevated expression of programmed death ligand: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15(1):400. doi:10.1186/s13256-021-02997-x

- Levin G, Capella MP, Meyer R, Brezinov Y, Gotlieb WH. Gynecologic perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas): a review of recent evidence. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309(6):2381-2386. doi:10.1007/s00404-024-07510-5

Advancements in the Treatment of Malignant PEComas with mTOR Inhibitors

Advancements in the Treatment of Malignant PEComas with mTOR Inhibitors