User login

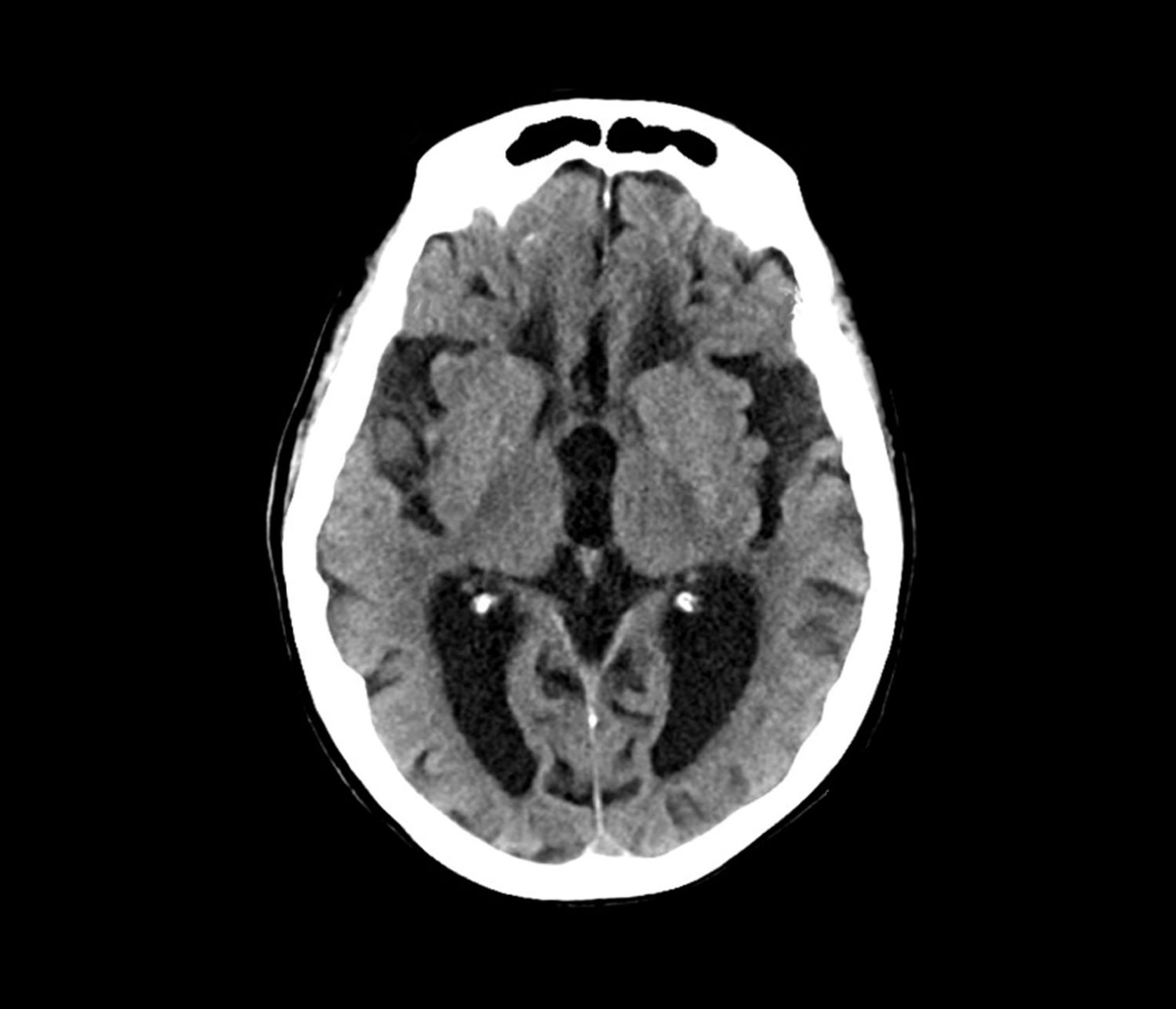

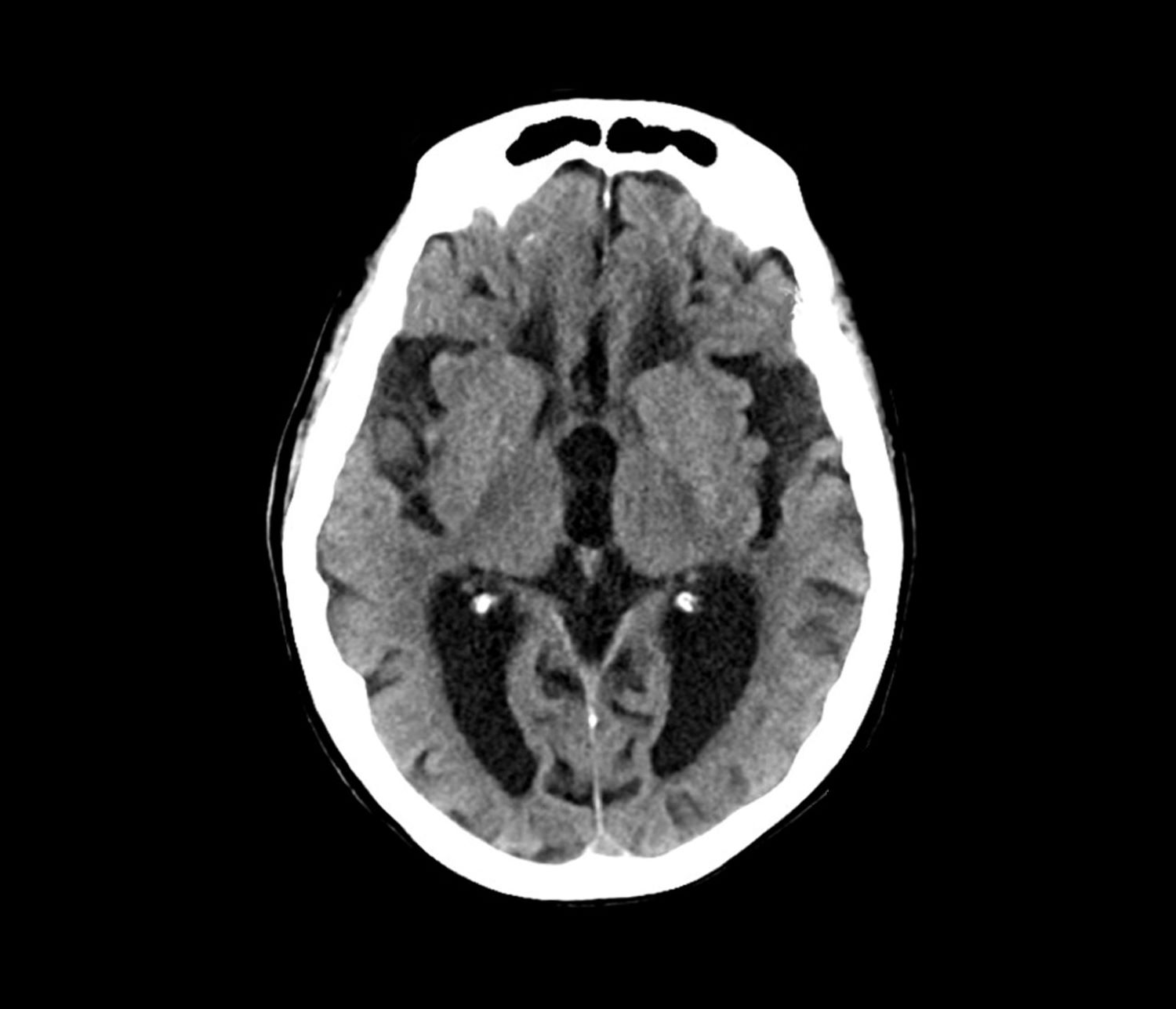

Early-onset AD (EOAD) is the most likely diagnosis for this patient. Her symptoms — cognitive decline, executive function deficits, and visuospatial dysfunction — and brain imaging results are consistent with EOAD. But importantly, her father’s diagnosis of EOAD at age 58 suggests a hereditary component, which greatly increases the genetic risk for this patient. Moreover, neuroimaging shows cortical atrophy in the temporal lobes. A key radiologic feature of AD in this patient is the large increase in the subarachnoid spaces affecting the parietal region.

Between one third to just over one half of patients with EOAD have at least one first-degree relative with the disease. Given the patient’s neuroimaging results and family history of EOAD, she was sent for genetic testing, which revealed mutations in the PSEN1 gene; one the most common genetic causes of EOAD (along with mutations in the APP gene). For those who do have an autosomal dominant familial form of EOAD, clinical presentation is often atypical and includes headaches, myoclonus, seizures, hyperreflexia, and gait abnormalities. This patient did experience headaches but not the other symptoms.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an insult to the brain from an outside mechanical force. It is both non-congenital and non-degenerative but can lead to permanent physical, cognitive, and/or psychosocial functioning. Patients often experience an altered or diminished state of consciousness in the aftermath of such an event. TBI is a diagnostic consideration for this patient, given that she was in a car accident and has experienced unusual cognitive and behavioral symptoms — eg, memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction. However, imaging does not reveal evidence of TBI, with no concussion or cerebral hemorrhage. Thus, TBI is not an accurate diagnosis for this patient.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most common neurologic disorders that is marked by three hallmark features: resting tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia that generally affects people over the age of 60. Even though many patients with PD exhibit some measure of executive function impairment early in the course of the disease, substantial impairment and dementia usually manifest about 8 years after the onset of motor symptoms. Dementia occurs in approximately 20%-40% of patients with PD. Although patients with PD demonstrate executive function deficits, memory loss, and visuospatial dysfunction, they do not experience aphasia. This patient does not have any of the cardinal features of PD, which rules it out as a diagnosis.

Frontotemporal dementia is a progressive dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain, primarily manifesting as language abnormalities, including reduced speech, perseveration, mutism, and echolalia, also known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA). Over time, patients develop other psychiatric symptoms: disinhibition, impulsivity, loss of social awareness, neglect of personal hygiene, mental rigidity, and utilization behavior. Given the patient’s language difficulties, frontotemporal dementia may be an initial diagnostic consideration. However, per the neurologic imaging results, brain abnormalities are located in the temporal regions. Additionally, the patient does not exhibit any of the psychiatric symptoms associated with frontotemporal dementia but does experience short-term memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction, which are not typical of this diagnosis. This patient does not have frontotemporal dementia.

EOAD is characterized by deficits in language, visuospatial skills and executive function. Often, these patients do not exhibit amnestic disorder early in the disease. While their memory recognition and semantic memory is higher than for patients who present with late-onset (normal course) AD, their attention scores are typically lower. As a result of this atypical presentation, patients with EOAD tend to have a longer duration of disease before diagnosis (~1.6 years). They are also likely to have a history of TBI, which is a risk factor for dementia.

In comparison to late-onset AD (LOAD), EOAD has a larger genetic predisposition (92%-100% vs 70%-80%), a more aggressive course, a more frequent delay in initial diagnosis, higher prevalence of TBI, and less memory impairment. However, EOAD has greater decline in other cognitive domains, and because of the young age of onset, greater psychosocial impairment. Overall disease progression in these patients is much faster compared with patients who have LOAD. Neuroimaging in these patients generally features greater hippocampal sparing and posterior neocortical atrophy, with brain changes that affect the frontoparietal networks rather than the classic presentation found in LOAD.

An important aspect of the workup of patients for whom EOAD is a diagnostic consideration is to thoroughly determine their family history and to perform genetic testing along with counseling.

The pharmacological treatment of patients with early-onset AD is identical to patients who have normal course or late-onset AD. Cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) — eg, donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine, with the usual titration schedules — are indicated in these patients. Although these medications target memory, they also provide support to patients with other variants of EOAD — eg, logopenic variant PPA. However, it is imperative that providers monitor these patients carefully, as ChEIs may exacerbate some behaviors.

Management of patients with EOAD varies based on the patient's specific variant. It is vital for clinicians to coordinate patient-centered care individually. For example, patients with logopenic variant PPA should be referred for speech therapy assessment and treatment should focus on improving communication, while patients with posterior cortical atrophy benefit most from interventions for those who experience vision impairments. As this patient’s symptoms revolve primarily around cognition and visuospatial dysfunction, her treatment will focus on interventions to improve coordination, balance, and cognitive function.

Perhaps the most important part of managing a patient with EOAD is providing adequate and appropriate psychosocial support. These patients are most often in their most productive time of life, balancing careers and families. EOAD can bring about feelings of loss of independence, anticipatory grief, and anxiety about the future and the increased difficulty in managing the tasks of daily life. It is vital that these patients — and their families — receive adequate education and psychiatric support via therapists, support groups, and community resources that are age appropriate.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Early-onset AD (EOAD) is the most likely diagnosis for this patient. Her symptoms — cognitive decline, executive function deficits, and visuospatial dysfunction — and brain imaging results are consistent with EOAD. But importantly, her father’s diagnosis of EOAD at age 58 suggests a hereditary component, which greatly increases the genetic risk for this patient. Moreover, neuroimaging shows cortical atrophy in the temporal lobes. A key radiologic feature of AD in this patient is the large increase in the subarachnoid spaces affecting the parietal region.

Between one third to just over one half of patients with EOAD have at least one first-degree relative with the disease. Given the patient’s neuroimaging results and family history of EOAD, she was sent for genetic testing, which revealed mutations in the PSEN1 gene; one the most common genetic causes of EOAD (along with mutations in the APP gene). For those who do have an autosomal dominant familial form of EOAD, clinical presentation is often atypical and includes headaches, myoclonus, seizures, hyperreflexia, and gait abnormalities. This patient did experience headaches but not the other symptoms.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an insult to the brain from an outside mechanical force. It is both non-congenital and non-degenerative but can lead to permanent physical, cognitive, and/or psychosocial functioning. Patients often experience an altered or diminished state of consciousness in the aftermath of such an event. TBI is a diagnostic consideration for this patient, given that she was in a car accident and has experienced unusual cognitive and behavioral symptoms — eg, memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction. However, imaging does not reveal evidence of TBI, with no concussion or cerebral hemorrhage. Thus, TBI is not an accurate diagnosis for this patient.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most common neurologic disorders that is marked by three hallmark features: resting tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia that generally affects people over the age of 60. Even though many patients with PD exhibit some measure of executive function impairment early in the course of the disease, substantial impairment and dementia usually manifest about 8 years after the onset of motor symptoms. Dementia occurs in approximately 20%-40% of patients with PD. Although patients with PD demonstrate executive function deficits, memory loss, and visuospatial dysfunction, they do not experience aphasia. This patient does not have any of the cardinal features of PD, which rules it out as a diagnosis.

Frontotemporal dementia is a progressive dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain, primarily manifesting as language abnormalities, including reduced speech, perseveration, mutism, and echolalia, also known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA). Over time, patients develop other psychiatric symptoms: disinhibition, impulsivity, loss of social awareness, neglect of personal hygiene, mental rigidity, and utilization behavior. Given the patient’s language difficulties, frontotemporal dementia may be an initial diagnostic consideration. However, per the neurologic imaging results, brain abnormalities are located in the temporal regions. Additionally, the patient does not exhibit any of the psychiatric symptoms associated with frontotemporal dementia but does experience short-term memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction, which are not typical of this diagnosis. This patient does not have frontotemporal dementia.

EOAD is characterized by deficits in language, visuospatial skills and executive function. Often, these patients do not exhibit amnestic disorder early in the disease. While their memory recognition and semantic memory is higher than for patients who present with late-onset (normal course) AD, their attention scores are typically lower. As a result of this atypical presentation, patients with EOAD tend to have a longer duration of disease before diagnosis (~1.6 years). They are also likely to have a history of TBI, which is a risk factor for dementia.

In comparison to late-onset AD (LOAD), EOAD has a larger genetic predisposition (92%-100% vs 70%-80%), a more aggressive course, a more frequent delay in initial diagnosis, higher prevalence of TBI, and less memory impairment. However, EOAD has greater decline in other cognitive domains, and because of the young age of onset, greater psychosocial impairment. Overall disease progression in these patients is much faster compared with patients who have LOAD. Neuroimaging in these patients generally features greater hippocampal sparing and posterior neocortical atrophy, with brain changes that affect the frontoparietal networks rather than the classic presentation found in LOAD.

An important aspect of the workup of patients for whom EOAD is a diagnostic consideration is to thoroughly determine their family history and to perform genetic testing along with counseling.

The pharmacological treatment of patients with early-onset AD is identical to patients who have normal course or late-onset AD. Cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) — eg, donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine, with the usual titration schedules — are indicated in these patients. Although these medications target memory, they also provide support to patients with other variants of EOAD — eg, logopenic variant PPA. However, it is imperative that providers monitor these patients carefully, as ChEIs may exacerbate some behaviors.

Management of patients with EOAD varies based on the patient's specific variant. It is vital for clinicians to coordinate patient-centered care individually. For example, patients with logopenic variant PPA should be referred for speech therapy assessment and treatment should focus on improving communication, while patients with posterior cortical atrophy benefit most from interventions for those who experience vision impairments. As this patient’s symptoms revolve primarily around cognition and visuospatial dysfunction, her treatment will focus on interventions to improve coordination, balance, and cognitive function.

Perhaps the most important part of managing a patient with EOAD is providing adequate and appropriate psychosocial support. These patients are most often in their most productive time of life, balancing careers and families. EOAD can bring about feelings of loss of independence, anticipatory grief, and anxiety about the future and the increased difficulty in managing the tasks of daily life. It is vital that these patients — and their families — receive adequate education and psychiatric support via therapists, support groups, and community resources that are age appropriate.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Early-onset AD (EOAD) is the most likely diagnosis for this patient. Her symptoms — cognitive decline, executive function deficits, and visuospatial dysfunction — and brain imaging results are consistent with EOAD. But importantly, her father’s diagnosis of EOAD at age 58 suggests a hereditary component, which greatly increases the genetic risk for this patient. Moreover, neuroimaging shows cortical atrophy in the temporal lobes. A key radiologic feature of AD in this patient is the large increase in the subarachnoid spaces affecting the parietal region.

Between one third to just over one half of patients with EOAD have at least one first-degree relative with the disease. Given the patient’s neuroimaging results and family history of EOAD, she was sent for genetic testing, which revealed mutations in the PSEN1 gene; one the most common genetic causes of EOAD (along with mutations in the APP gene). For those who do have an autosomal dominant familial form of EOAD, clinical presentation is often atypical and includes headaches, myoclonus, seizures, hyperreflexia, and gait abnormalities. This patient did experience headaches but not the other symptoms.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an insult to the brain from an outside mechanical force. It is both non-congenital and non-degenerative but can lead to permanent physical, cognitive, and/or psychosocial functioning. Patients often experience an altered or diminished state of consciousness in the aftermath of such an event. TBI is a diagnostic consideration for this patient, given that she was in a car accident and has experienced unusual cognitive and behavioral symptoms — eg, memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction. However, imaging does not reveal evidence of TBI, with no concussion or cerebral hemorrhage. Thus, TBI is not an accurate diagnosis for this patient.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is one of the most common neurologic disorders that is marked by three hallmark features: resting tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia that generally affects people over the age of 60. Even though many patients with PD exhibit some measure of executive function impairment early in the course of the disease, substantial impairment and dementia usually manifest about 8 years after the onset of motor symptoms. Dementia occurs in approximately 20%-40% of patients with PD. Although patients with PD demonstrate executive function deficits, memory loss, and visuospatial dysfunction, they do not experience aphasia. This patient does not have any of the cardinal features of PD, which rules it out as a diagnosis.

Frontotemporal dementia is a progressive dysfunction of the frontal lobes of the brain, primarily manifesting as language abnormalities, including reduced speech, perseveration, mutism, and echolalia, also known as primary progressive aphasia (PPA). Over time, patients develop other psychiatric symptoms: disinhibition, impulsivity, loss of social awareness, neglect of personal hygiene, mental rigidity, and utilization behavior. Given the patient’s language difficulties, frontotemporal dementia may be an initial diagnostic consideration. However, per the neurologic imaging results, brain abnormalities are located in the temporal regions. Additionally, the patient does not exhibit any of the psychiatric symptoms associated with frontotemporal dementia but does experience short-term memory loss and visuospatial dysfunction, which are not typical of this diagnosis. This patient does not have frontotemporal dementia.

EOAD is characterized by deficits in language, visuospatial skills and executive function. Often, these patients do not exhibit amnestic disorder early in the disease. While their memory recognition and semantic memory is higher than for patients who present with late-onset (normal course) AD, their attention scores are typically lower. As a result of this atypical presentation, patients with EOAD tend to have a longer duration of disease before diagnosis (~1.6 years). They are also likely to have a history of TBI, which is a risk factor for dementia.

In comparison to late-onset AD (LOAD), EOAD has a larger genetic predisposition (92%-100% vs 70%-80%), a more aggressive course, a more frequent delay in initial diagnosis, higher prevalence of TBI, and less memory impairment. However, EOAD has greater decline in other cognitive domains, and because of the young age of onset, greater psychosocial impairment. Overall disease progression in these patients is much faster compared with patients who have LOAD. Neuroimaging in these patients generally features greater hippocampal sparing and posterior neocortical atrophy, with brain changes that affect the frontoparietal networks rather than the classic presentation found in LOAD.

An important aspect of the workup of patients for whom EOAD is a diagnostic consideration is to thoroughly determine their family history and to perform genetic testing along with counseling.

The pharmacological treatment of patients with early-onset AD is identical to patients who have normal course or late-onset AD. Cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) — eg, donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine, with the usual titration schedules — are indicated in these patients. Although these medications target memory, they also provide support to patients with other variants of EOAD — eg, logopenic variant PPA. However, it is imperative that providers monitor these patients carefully, as ChEIs may exacerbate some behaviors.

Management of patients with EOAD varies based on the patient's specific variant. It is vital for clinicians to coordinate patient-centered care individually. For example, patients with logopenic variant PPA should be referred for speech therapy assessment and treatment should focus on improving communication, while patients with posterior cortical atrophy benefit most from interventions for those who experience vision impairments. As this patient’s symptoms revolve primarily around cognition and visuospatial dysfunction, her treatment will focus on interventions to improve coordination, balance, and cognitive function.

Perhaps the most important part of managing a patient with EOAD is providing adequate and appropriate psychosocial support. These patients are most often in their most productive time of life, balancing careers and families. EOAD can bring about feelings of loss of independence, anticipatory grief, and anxiety about the future and the increased difficulty in managing the tasks of daily life. It is vital that these patients — and their families — receive adequate education and psychiatric support via therapists, support groups, and community resources that are age appropriate.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 52-year-old female presents complaining of fatigue, brain fog, and headaches. She reports that, over the last year, she feels increasingly more irritable, anxious, overwhelmed, and sometimes disoriented. When prompted, she admits to having trouble keeping track of things — dates, important deadlines, objects like her keys, and things she uses each day. She needs multiple reminder events or tasks and must write everything down. She also reports that she often loses her train of thought and sometimes struggles to find words. She works in a medical office, is married, and has two children in college. She helps with caring for her in-laws on the weekend by doing their bills and grocery shopping. She admits to being moody and does not want to socialize, which she attributes to fatigue and having a busy life. She also complains of muscle stiffness and general clumsiness. Eight months ago, the patient was in an automobile accident in which her car was totaled, but she did not sustain serious injury and opted not to seek medical evaluation.

Physical exam reveals slight visuospatial dysfunction, with issues with both coordination and balance. The patient appears fatigued and has some trouble maintaining her attention during the conversation. Further questioning reveals mild anomic aphasia and some lapses in recent memory. Her reflexes are otherwise normal, as are heart, lung, and breath sounds. All systemic lymph nodes are normal as are liver and spleen on palpation. The patient recently discovered that her estranged father had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) at 58 years of age and passed away 5 years later.

Laboratory testing is performed and reveals nothing remarkable. Considering the car accident and new cognitive/behavioral changes experienced by the patient, a CT of the brain is ordered. Results are negative for concussion and cerebral hemorrhage but show cortical atrophy of the temporal territories and a large increase in the size of the subarachnoid spaces predominantly affecting the parietal region.