User login

Optimizing Myelofibrosis Care in the Age of JAK Inhibitors

How do you assess a patient’s prognosis at the time that they are diagnosed with myelofibrosis?

In the clinic, we use several scoring systems that have been developed based on the outcomes of hundreds of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) to try to predict survival from time of diagnosis. Disease features associated with a poor prognosis include anemia, elevated white blood cell count, advanced age, constitutional symptoms, and increased peripheral blasts. Some of these scoring systems also incorporate chromosomal abnormalities as well as gene mutations to further refine prognostication.1

Determining prognosis can be important to creating a treatment plan, particularly to decide if curative allogeneic stem cell transplantation is necessary. However, I always caution patients that these prognostic scoring systems cannot tell the future and that each patient may respond differently to treatment.

How do you monitor for disease progression?

I will discuss with patients how they are feeling in order to determine if there are any new or developing symptoms that could be a sign that their disease is progressing. I will also review their laboratory work looking for changes in blood counts that could be a signal of disease evolution.

For instance, development of anemia or thrombocytopenia may signal worsening bone marrow function or progression to secondary acute leukemia. If there are concerning signs or symptoms, I will then perform a bone marrow biopsy with aspirate that will include assessment of mutations and chromosomal abnormalities to determine if their disease is progressing.

What are the first-line treatment options for a patient newly diagnosed with myelofibrosis, and how do you determine the best course of action?

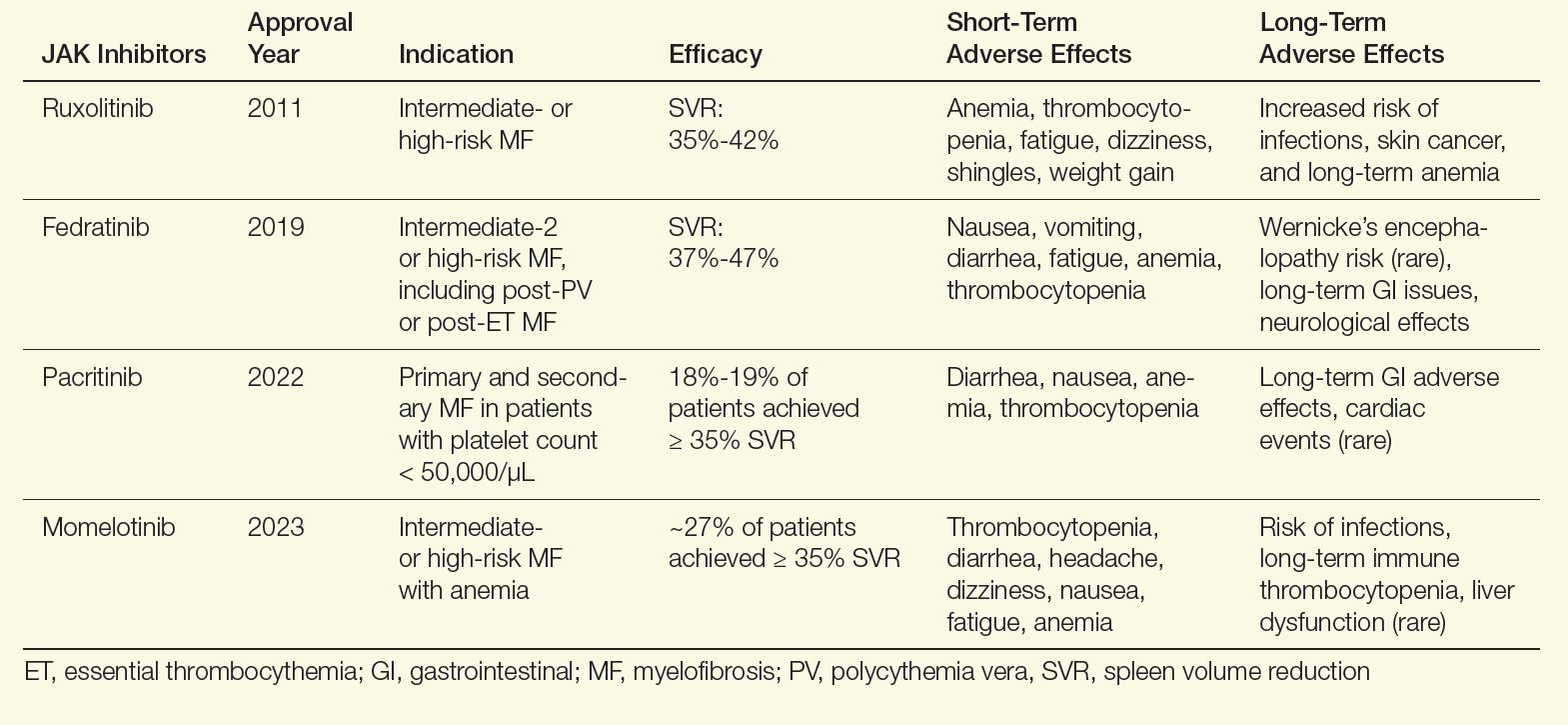

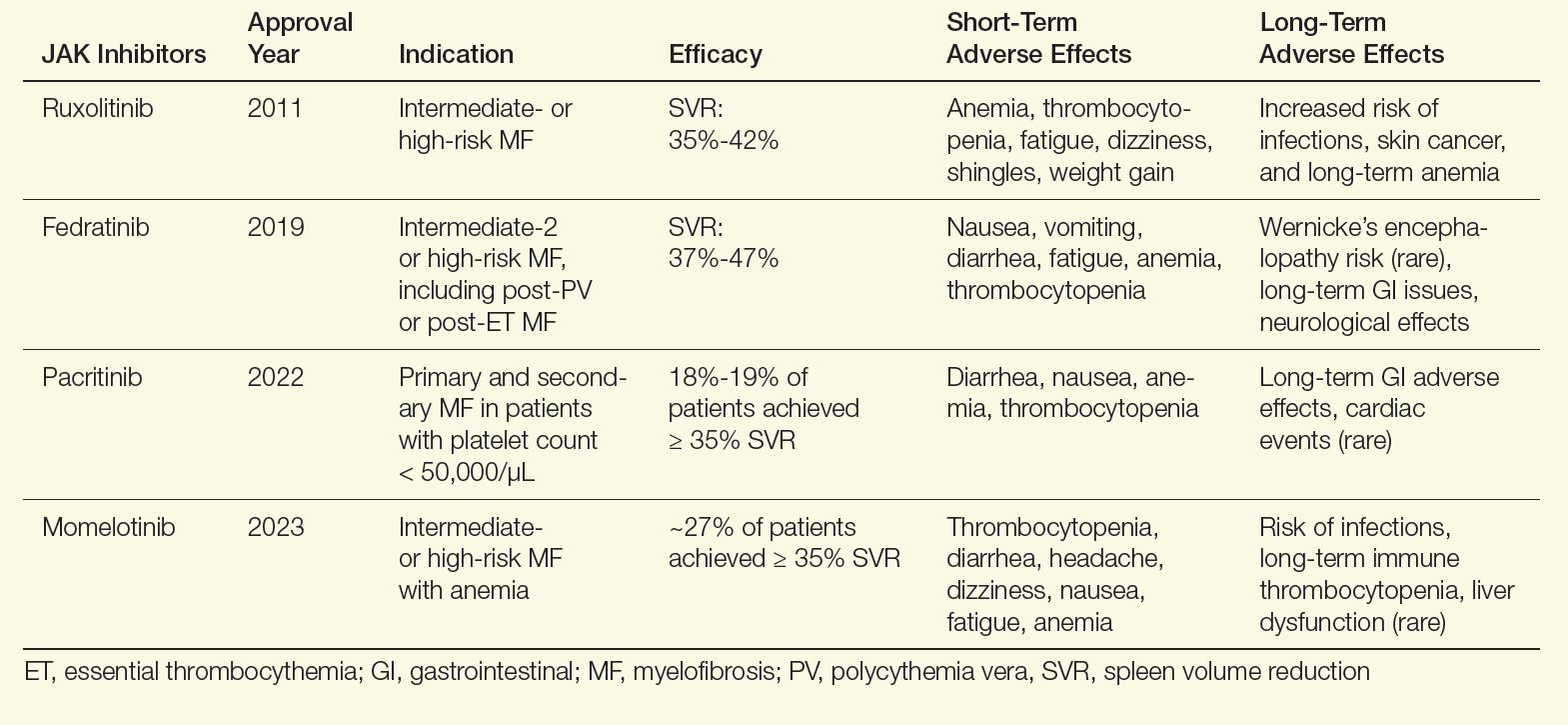

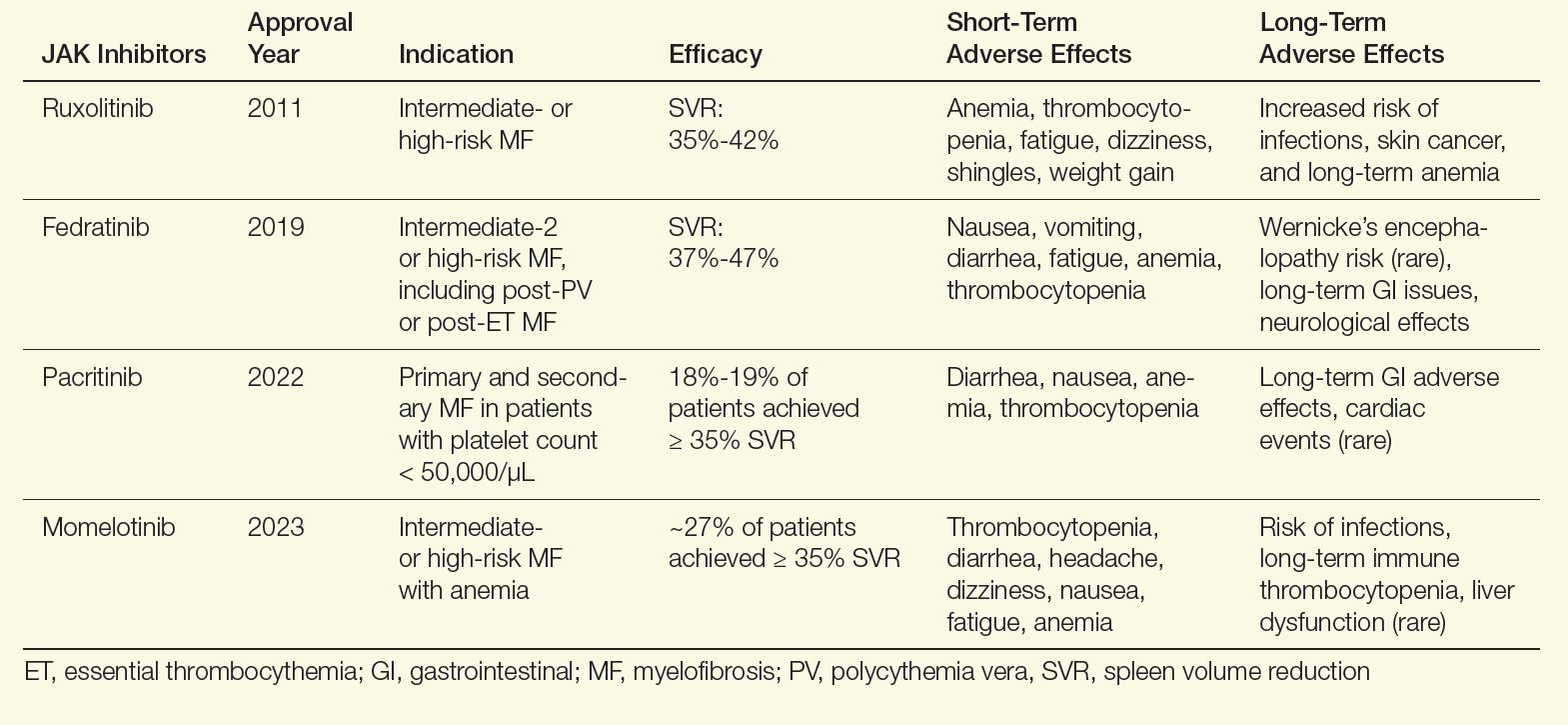

For patients with myelofibrosis, the first-line treatment options include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which are effective at improving spleen size and reducing symptom burden. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 4 JAK inhibitors for the treatment of myelofibrosis: ruxolitinib, fedratinib, pacritinib, and momelotinib (Table).2-13 In general, ruxolitinib is the first-line treatment option unless there is thrombocytopenia, in which case pacritinib is more appropriate. In patients with baseline anemia, momelotinib may be the best choice.

Table. FDA-Approved JAK Inhibitors for Myelofibrosis2-13

Although these agents are effective in reducing spleen size and improving symptoms, they do not affect disease progression. Therefore, I also evaluate all patients for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which is the only curative modality. Appropriate patients are younger than age 75, with a low comorbidity burden and either intermediate-2 or high-risk disease. In addition, patients who do not respond to frontline JAK inhibitors should be considered for this approach. In patients who are transplant candidates, I will concurrently have them evaluated and start the process of finding a donor while initiating a JAK inhibitor.

What are the most common adverse effects of JAK inhibitors, and how do you help patients manage these issues?

There are short- and long-term effects of JAK inhibitors. Focusing on ruxolitinib, the most frequently used JAK inhibitor, patients can experience bruising, dizziness, and headaches, which generally resolves within a few weeks. Notable longer-term adverse events of ruxolitinib include increased rates of shingles infection, so I encourage my patients to get vaccinated for shingles before initiation.11 Weight gain has also been reported with ruxolitinib, but not with other JAK inhibitors.12,13 The other main adverse effect of ruxolitinib is worsening anemia and thrombocythemia, so I closely monitor blood counts during treatment.

What are some of the key reasons why patients may develop JAK inhibitor resistance or intolerance, and how do you address these problems in clinical practice?

There are a variety of reasons why patients discontinue a JAK inhibitor, but these can be lumped into 2 categories: (1) the medication has not achieved, or is no longer achieving, treatment goals, or (2) adverse effects from the JAK inhibitor require discontinuation. In a large series of patients with myelofibrosis who were treated with ruxolitinib, about 60% of discontinuations were because of JAK inhibitor refractoriness/resistance, and around 40% were from adverse events.14

Resistance can arise from several mechanisms, including activation of alternative pathways and clonal evolution that are ongoing regardless of JAK inhibition. In clinical practice, we are addressing JAK inhibitor resistance through clinical trials of novel therapies, particularly in combination with JAK inhibitors, which can potentially mitigate resistance. New JAK inhibitors are also being developed that may more effectively target the overactive JAK-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway and reduce resistance.

In terms of intolerance, there are many strategies to address nonhematological toxicities, and with the availability of pacritinib and momelotinib, patients in whom thrombocytopenia and anemia develop can be safely and effectively transitioned to an alternative JAK inhibitor if they experience adverse effects with ruxolitinib.

How do you incorporate patient-reported outcomes or quality-of-life measures into treatment planning?

Symptom assessment is a key component of the care for myelofibrosis. There are several well-validated patient-reported symptom assessment forms for myelofibrosis.15 These can be helpful both to quantify the burden of myelofibrosis-related symptoms, as well as to track progress of these symptoms over time. I generally incorporate these assessments into the initial evaluation and several times throughout therapy.

However, many symptoms are not captured on these assessments, and so I spend considerable time speaking to patients about how they are feeling and tracking their symptoms carefully over time. I also find it helpful to assess how a patient feels during treatment using the Patient’s Global Impression of Change (PGIC) questionnaire, which is a 7-point scale reflecting overall improvement compared with baseline.

Can you share any strategies for helping patients navigate the emotional and psychological challenges of living with a chronic disease like myelofibrosis?

In my experience, addressing emotional and psychological stress is one of the greatest challenges in caring for patients with myelofibrosis. Myelofibrosis significantly affects a patient’s quality of life and productivity.16 Some strategies that my patients have found helpful include engaging with the patient community and learning from others who have been living with this disease for years.

Anecdotally, I find that patients who exercise regularly and maintain an active lifestyle benefit psychologically. I have also observed that involving a support system is critical for dealing with the emotional stress of living with a chronic disease. It is particularly helpful if the patient brings a supportive friend or family member to appointments, as they can help the patient process the information discussed.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

- Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, Rotunno G, et al. MIPSS70: Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Score System for transplantation-age patients with primary myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4):310-318. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.76.4886

- Jakafi [package insert]. Incyte Corporation; 2011. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/202192lbl.pdf

- Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799-807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110557

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Inrebic for treatment of patients with myelofibrosis. FDA announcement. August 16, 2019. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approvesfedratinib-myelofibrosis

- Pardanani A, Tefferi A, Masszi T, et al. Updated results of the placebo-controlled, phase III JAKARTA trial of fedratinib in patients with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2021;195(2):244-248. doi:10.1111/bjh.17727

- Vonjo [package insert]. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Vannucchi AM, Mead A, et al. Pacritinib versus best available therapy for the treatment of myelofibrosis irrespective of baseline cytopenias (PERSIST-1): an international, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(5):e225-e236. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30027-3

- Mascarenhas J, Hoffman R, Talpaz M, et al. Pacritinib vs best available therapy, including ruxolitinib, in patients with myelofibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):652-659. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5818

- Ojjaara [package insert]. GSK; 2023. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/216873s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Kiladjian JJ, Catalano JV, et al. SIMPLIFY-1: a phase III randomized trial of momelotinib versus ruxolitinib in Janus kinase inhibitor-naïve patients with myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3844-3850. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4418

- Lussana F, Cattaneo M, Rambaldi A, Squizzato A. Ruxolitinib-associated infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(3):339-347. doi:10.1002/ajh.24976

- Sapre M, Tremblay D, Wilck E, et al. Metabolic effects of JAK1/2 inhibition in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16609. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53056-x

- Tremblay D, Cavalli L, Sy O, Rose S, Mascarenhas J. The effect of fedratinib, a selective inhibitor of Janus kinase 2, on weight and metabolic parameters in patients with intermediate- or high-risk myelofibrosis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022;22(7):e463-e466. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2022.01.003

- Palandri F, Breccia M, Bonifacio M, et al. Life after ruxolitinib: reasons for discontinuation, impact of disease phase, and outcomes in 218 patients with myelofibrosis. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1243-1252. doi:10.1002/cncr.32664

- Tremblay D, Mesa R. Addressing symptom burden in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2022;35(2):101372. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2022.101372

- Harrison CN, Koschmieder S, Foltz L, et al. The impact of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) on patient quality of life and productivity: results from the international MPN Landmark survey. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(10):1653-1665. doi:10.1007/s00277-017-3082-y

How do you assess a patient’s prognosis at the time that they are diagnosed with myelofibrosis?

In the clinic, we use several scoring systems that have been developed based on the outcomes of hundreds of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) to try to predict survival from time of diagnosis. Disease features associated with a poor prognosis include anemia, elevated white blood cell count, advanced age, constitutional symptoms, and increased peripheral blasts. Some of these scoring systems also incorporate chromosomal abnormalities as well as gene mutations to further refine prognostication.1

Determining prognosis can be important to creating a treatment plan, particularly to decide if curative allogeneic stem cell transplantation is necessary. However, I always caution patients that these prognostic scoring systems cannot tell the future and that each patient may respond differently to treatment.

How do you monitor for disease progression?

I will discuss with patients how they are feeling in order to determine if there are any new or developing symptoms that could be a sign that their disease is progressing. I will also review their laboratory work looking for changes in blood counts that could be a signal of disease evolution.

For instance, development of anemia or thrombocytopenia may signal worsening bone marrow function or progression to secondary acute leukemia. If there are concerning signs or symptoms, I will then perform a bone marrow biopsy with aspirate that will include assessment of mutations and chromosomal abnormalities to determine if their disease is progressing.

What are the first-line treatment options for a patient newly diagnosed with myelofibrosis, and how do you determine the best course of action?

For patients with myelofibrosis, the first-line treatment options include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which are effective at improving spleen size and reducing symptom burden. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 4 JAK inhibitors for the treatment of myelofibrosis: ruxolitinib, fedratinib, pacritinib, and momelotinib (Table).2-13 In general, ruxolitinib is the first-line treatment option unless there is thrombocytopenia, in which case pacritinib is more appropriate. In patients with baseline anemia, momelotinib may be the best choice.

Table. FDA-Approved JAK Inhibitors for Myelofibrosis2-13

Although these agents are effective in reducing spleen size and improving symptoms, they do not affect disease progression. Therefore, I also evaluate all patients for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which is the only curative modality. Appropriate patients are younger than age 75, with a low comorbidity burden and either intermediate-2 or high-risk disease. In addition, patients who do not respond to frontline JAK inhibitors should be considered for this approach. In patients who are transplant candidates, I will concurrently have them evaluated and start the process of finding a donor while initiating a JAK inhibitor.

What are the most common adverse effects of JAK inhibitors, and how do you help patients manage these issues?

There are short- and long-term effects of JAK inhibitors. Focusing on ruxolitinib, the most frequently used JAK inhibitor, patients can experience bruising, dizziness, and headaches, which generally resolves within a few weeks. Notable longer-term adverse events of ruxolitinib include increased rates of shingles infection, so I encourage my patients to get vaccinated for shingles before initiation.11 Weight gain has also been reported with ruxolitinib, but not with other JAK inhibitors.12,13 The other main adverse effect of ruxolitinib is worsening anemia and thrombocythemia, so I closely monitor blood counts during treatment.

What are some of the key reasons why patients may develop JAK inhibitor resistance or intolerance, and how do you address these problems in clinical practice?

There are a variety of reasons why patients discontinue a JAK inhibitor, but these can be lumped into 2 categories: (1) the medication has not achieved, or is no longer achieving, treatment goals, or (2) adverse effects from the JAK inhibitor require discontinuation. In a large series of patients with myelofibrosis who were treated with ruxolitinib, about 60% of discontinuations were because of JAK inhibitor refractoriness/resistance, and around 40% were from adverse events.14

Resistance can arise from several mechanisms, including activation of alternative pathways and clonal evolution that are ongoing regardless of JAK inhibition. In clinical practice, we are addressing JAK inhibitor resistance through clinical trials of novel therapies, particularly in combination with JAK inhibitors, which can potentially mitigate resistance. New JAK inhibitors are also being developed that may more effectively target the overactive JAK-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway and reduce resistance.

In terms of intolerance, there are many strategies to address nonhematological toxicities, and with the availability of pacritinib and momelotinib, patients in whom thrombocytopenia and anemia develop can be safely and effectively transitioned to an alternative JAK inhibitor if they experience adverse effects with ruxolitinib.

How do you incorporate patient-reported outcomes or quality-of-life measures into treatment planning?

Symptom assessment is a key component of the care for myelofibrosis. There are several well-validated patient-reported symptom assessment forms for myelofibrosis.15 These can be helpful both to quantify the burden of myelofibrosis-related symptoms, as well as to track progress of these symptoms over time. I generally incorporate these assessments into the initial evaluation and several times throughout therapy.

However, many symptoms are not captured on these assessments, and so I spend considerable time speaking to patients about how they are feeling and tracking their symptoms carefully over time. I also find it helpful to assess how a patient feels during treatment using the Patient’s Global Impression of Change (PGIC) questionnaire, which is a 7-point scale reflecting overall improvement compared with baseline.

Can you share any strategies for helping patients navigate the emotional and psychological challenges of living with a chronic disease like myelofibrosis?

In my experience, addressing emotional and psychological stress is one of the greatest challenges in caring for patients with myelofibrosis. Myelofibrosis significantly affects a patient’s quality of life and productivity.16 Some strategies that my patients have found helpful include engaging with the patient community and learning from others who have been living with this disease for years.

Anecdotally, I find that patients who exercise regularly and maintain an active lifestyle benefit psychologically. I have also observed that involving a support system is critical for dealing with the emotional stress of living with a chronic disease. It is particularly helpful if the patient brings a supportive friend or family member to appointments, as they can help the patient process the information discussed.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

How do you assess a patient’s prognosis at the time that they are diagnosed with myelofibrosis?

In the clinic, we use several scoring systems that have been developed based on the outcomes of hundreds of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) to try to predict survival from time of diagnosis. Disease features associated with a poor prognosis include anemia, elevated white blood cell count, advanced age, constitutional symptoms, and increased peripheral blasts. Some of these scoring systems also incorporate chromosomal abnormalities as well as gene mutations to further refine prognostication.1

Determining prognosis can be important to creating a treatment plan, particularly to decide if curative allogeneic stem cell transplantation is necessary. However, I always caution patients that these prognostic scoring systems cannot tell the future and that each patient may respond differently to treatment.

How do you monitor for disease progression?

I will discuss with patients how they are feeling in order to determine if there are any new or developing symptoms that could be a sign that their disease is progressing. I will also review their laboratory work looking for changes in blood counts that could be a signal of disease evolution.

For instance, development of anemia or thrombocytopenia may signal worsening bone marrow function or progression to secondary acute leukemia. If there are concerning signs or symptoms, I will then perform a bone marrow biopsy with aspirate that will include assessment of mutations and chromosomal abnormalities to determine if their disease is progressing.

What are the first-line treatment options for a patient newly diagnosed with myelofibrosis, and how do you determine the best course of action?

For patients with myelofibrosis, the first-line treatment options include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which are effective at improving spleen size and reducing symptom burden. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 4 JAK inhibitors for the treatment of myelofibrosis: ruxolitinib, fedratinib, pacritinib, and momelotinib (Table).2-13 In general, ruxolitinib is the first-line treatment option unless there is thrombocytopenia, in which case pacritinib is more appropriate. In patients with baseline anemia, momelotinib may be the best choice.

Table. FDA-Approved JAK Inhibitors for Myelofibrosis2-13

Although these agents are effective in reducing spleen size and improving symptoms, they do not affect disease progression. Therefore, I also evaluate all patients for allogeneic stem cell transplantation, which is the only curative modality. Appropriate patients are younger than age 75, with a low comorbidity burden and either intermediate-2 or high-risk disease. In addition, patients who do not respond to frontline JAK inhibitors should be considered for this approach. In patients who are transplant candidates, I will concurrently have them evaluated and start the process of finding a donor while initiating a JAK inhibitor.

What are the most common adverse effects of JAK inhibitors, and how do you help patients manage these issues?

There are short- and long-term effects of JAK inhibitors. Focusing on ruxolitinib, the most frequently used JAK inhibitor, patients can experience bruising, dizziness, and headaches, which generally resolves within a few weeks. Notable longer-term adverse events of ruxolitinib include increased rates of shingles infection, so I encourage my patients to get vaccinated for shingles before initiation.11 Weight gain has also been reported with ruxolitinib, but not with other JAK inhibitors.12,13 The other main adverse effect of ruxolitinib is worsening anemia and thrombocythemia, so I closely monitor blood counts during treatment.

What are some of the key reasons why patients may develop JAK inhibitor resistance or intolerance, and how do you address these problems in clinical practice?

There are a variety of reasons why patients discontinue a JAK inhibitor, but these can be lumped into 2 categories: (1) the medication has not achieved, or is no longer achieving, treatment goals, or (2) adverse effects from the JAK inhibitor require discontinuation. In a large series of patients with myelofibrosis who were treated with ruxolitinib, about 60% of discontinuations were because of JAK inhibitor refractoriness/resistance, and around 40% were from adverse events.14

Resistance can arise from several mechanisms, including activation of alternative pathways and clonal evolution that are ongoing regardless of JAK inhibition. In clinical practice, we are addressing JAK inhibitor resistance through clinical trials of novel therapies, particularly in combination with JAK inhibitors, which can potentially mitigate resistance. New JAK inhibitors are also being developed that may more effectively target the overactive JAK-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway and reduce resistance.

In terms of intolerance, there are many strategies to address nonhematological toxicities, and with the availability of pacritinib and momelotinib, patients in whom thrombocytopenia and anemia develop can be safely and effectively transitioned to an alternative JAK inhibitor if they experience adverse effects with ruxolitinib.

How do you incorporate patient-reported outcomes or quality-of-life measures into treatment planning?

Symptom assessment is a key component of the care for myelofibrosis. There are several well-validated patient-reported symptom assessment forms for myelofibrosis.15 These can be helpful both to quantify the burden of myelofibrosis-related symptoms, as well as to track progress of these symptoms over time. I generally incorporate these assessments into the initial evaluation and several times throughout therapy.

However, many symptoms are not captured on these assessments, and so I spend considerable time speaking to patients about how they are feeling and tracking their symptoms carefully over time. I also find it helpful to assess how a patient feels during treatment using the Patient’s Global Impression of Change (PGIC) questionnaire, which is a 7-point scale reflecting overall improvement compared with baseline.

Can you share any strategies for helping patients navigate the emotional and psychological challenges of living with a chronic disease like myelofibrosis?

In my experience, addressing emotional and psychological stress is one of the greatest challenges in caring for patients with myelofibrosis. Myelofibrosis significantly affects a patient’s quality of life and productivity.16 Some strategies that my patients have found helpful include engaging with the patient community and learning from others who have been living with this disease for years.

Anecdotally, I find that patients who exercise regularly and maintain an active lifestyle benefit psychologically. I have also observed that involving a support system is critical for dealing with the emotional stress of living with a chronic disease. It is particularly helpful if the patient brings a supportive friend or family member to appointments, as they can help the patient process the information discussed.

Read more from the 2024 Rare Diseases Report: Hematology and Oncology.

- Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, Rotunno G, et al. MIPSS70: Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Score System for transplantation-age patients with primary myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4):310-318. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.76.4886

- Jakafi [package insert]. Incyte Corporation; 2011. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/202192lbl.pdf

- Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799-807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110557

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Inrebic for treatment of patients with myelofibrosis. FDA announcement. August 16, 2019. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approvesfedratinib-myelofibrosis

- Pardanani A, Tefferi A, Masszi T, et al. Updated results of the placebo-controlled, phase III JAKARTA trial of fedratinib in patients with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2021;195(2):244-248. doi:10.1111/bjh.17727

- Vonjo [package insert]. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Vannucchi AM, Mead A, et al. Pacritinib versus best available therapy for the treatment of myelofibrosis irrespective of baseline cytopenias (PERSIST-1): an international, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(5):e225-e236. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30027-3

- Mascarenhas J, Hoffman R, Talpaz M, et al. Pacritinib vs best available therapy, including ruxolitinib, in patients with myelofibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):652-659. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5818

- Ojjaara [package insert]. GSK; 2023. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/216873s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Kiladjian JJ, Catalano JV, et al. SIMPLIFY-1: a phase III randomized trial of momelotinib versus ruxolitinib in Janus kinase inhibitor-naïve patients with myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3844-3850. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4418

- Lussana F, Cattaneo M, Rambaldi A, Squizzato A. Ruxolitinib-associated infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(3):339-347. doi:10.1002/ajh.24976

- Sapre M, Tremblay D, Wilck E, et al. Metabolic effects of JAK1/2 inhibition in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16609. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53056-x

- Tremblay D, Cavalli L, Sy O, Rose S, Mascarenhas J. The effect of fedratinib, a selective inhibitor of Janus kinase 2, on weight and metabolic parameters in patients with intermediate- or high-risk myelofibrosis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022;22(7):e463-e466. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2022.01.003

- Palandri F, Breccia M, Bonifacio M, et al. Life after ruxolitinib: reasons for discontinuation, impact of disease phase, and outcomes in 218 patients with myelofibrosis. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1243-1252. doi:10.1002/cncr.32664

- Tremblay D, Mesa R. Addressing symptom burden in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2022;35(2):101372. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2022.101372

- Harrison CN, Koschmieder S, Foltz L, et al. The impact of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) on patient quality of life and productivity: results from the international MPN Landmark survey. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(10):1653-1665. doi:10.1007/s00277-017-3082-y

- Guglielmelli P, Lasho TL, Rotunno G, et al. MIPSS70: Mutation-Enhanced International Prognostic Score System for transplantation-age patients with primary myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4):310-318. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.76.4886

- Jakafi [package insert]. Incyte Corporation; 2011. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/202192lbl.pdf

- Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):799-807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1110557

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Inrebic for treatment of patients with myelofibrosis. FDA announcement. August 16, 2019. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approvesfedratinib-myelofibrosis

- Pardanani A, Tefferi A, Masszi T, et al. Updated results of the placebo-controlled, phase III JAKARTA trial of fedratinib in patients with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelofibrosis. Br J Haematol. 2021;195(2):244-248. doi:10.1111/bjh.17727

- Vonjo [package insert]. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Vannucchi AM, Mead A, et al. Pacritinib versus best available therapy for the treatment of myelofibrosis irrespective of baseline cytopenias (PERSIST-1): an international, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(5):e225-e236. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30027-3

- Mascarenhas J, Hoffman R, Talpaz M, et al. Pacritinib vs best available therapy, including ruxolitinib, in patients with myelofibrosis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):652-659. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5818

- Ojjaara [package insert]. GSK; 2023. Accessed October 10, 2024. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/216873s000lbl.pdf

- Mesa RA, Kiladjian JJ, Catalano JV, et al. SIMPLIFY-1: a phase III randomized trial of momelotinib versus ruxolitinib in Janus kinase inhibitor-naïve patients with myelofibrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3844-3850. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.73.4418

- Lussana F, Cattaneo M, Rambaldi A, Squizzato A. Ruxolitinib-associated infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(3):339-347. doi:10.1002/ajh.24976

- Sapre M, Tremblay D, Wilck E, et al. Metabolic effects of JAK1/2 inhibition in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):16609. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53056-x

- Tremblay D, Cavalli L, Sy O, Rose S, Mascarenhas J. The effect of fedratinib, a selective inhibitor of Janus kinase 2, on weight and metabolic parameters in patients with intermediate- or high-risk myelofibrosis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022;22(7):e463-e466. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2022.01.003

- Palandri F, Breccia M, Bonifacio M, et al. Life after ruxolitinib: reasons for discontinuation, impact of disease phase, and outcomes in 218 patients with myelofibrosis. Cancer. 2020;126(6):1243-1252. doi:10.1002/cncr.32664

- Tremblay D, Mesa R. Addressing symptom burden in myeloproliferative neoplasms. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2022;35(2):101372. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2022.101372

- Harrison CN, Koschmieder S, Foltz L, et al. The impact of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) on patient quality of life and productivity: results from the international MPN Landmark survey. Ann Hematol. 2017;96(10):1653-1665. doi:10.1007/s00277-017-3082-y

Optimizing Myelofibrosis Care in the Age of JAK Inhibitors

Optimizing Myelofibrosis Care in the Age of JAK Inhibitors