User login

Feedback is the purposeful practice of offering constructive, goal-directed input rooted in the power of observation and behavioral assessment. Healthcare inherently fosters a broad range of interactions among people with unique insights, and feedback can naturally emerge from this milieu. In medical training, feedback is an indispensable element that personalizes the learning process and drives the professional development of physicians through all career stages.

If delivered effectively, feedback can strengthen the relationship between the evaluator and recipient, promote self-reflection, and enhance motivation. As such, it has the potential to impact us and those we serve for a lifetime. Feedback has been invaluable to our growth as clinicians and has been embedded into our roles as educators. However, Here, we provide some “tried and true” practical tips on delivering feedback to trainees and co-workers and on navigating potential barriers based on lessons learned.

Barriers to Effective Feedback

- Time: Feedback is predicated on observation over time and consideration of repetitive processes rather than isolated events. Perhaps the most challenging factor faced by both parties is that of time constraints, leading to limited ability to engage and build rapport.

- Fear: Hesitancy by evaluators to provide feedback in fear of negative impacts on the recipient’s morale or rapport can lead them to shy away from personalized corrective feedback strategies and choose to rely on written evaluations or generic advice.

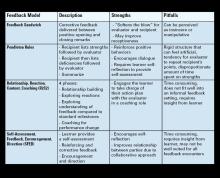

- Varying approaches: Feedback strategies have evolved from unidirectional, critique-based, hierarchical practices that emphasize the evaluator’s skills to models that prioritize the recipient’s goals and participation (see Table 1). Traditionally employed feedback models such as the “Feedback Sandwich” or the “Pendleton Rules” are criticized because of a lack of proven benefit on performance, recipient goal prioritization, and open communication.1,2 Studies showing incongruent perceptions of feedback adequacy between trainees and faculty further support the need for recipient-focused strategies.3 Recognition of the foundational role of the reciprocal learner-teacher alliance in feedback integration inspired newer feedback models, such as the “R2C2” and the “Self-Assessment, Feedback, Encouragement, Direction.”4,5

But which way is best? With increasing abundance and complexity of feedback frameworks, selecting an approach can feel overwhelming and impractical. A generic “one-size-fits-all” strategy or avoidance of feedback altogether can be detrimental. Structured feedback models can also lead to rigid, inauthentic interactions. Below, we suggest a more practical approach through our tips that unifies the common themes of various feedback models and embeds them into daily practice habits while leaving room for personalization.

Our Practical Feedback Tips

Tip 1: Set the scene: Create a positive feedback culture

Proactively creating a culture in which feedback is embedded and encouraged is perhaps the most important step. Priming both parties for feedback clarifies intent, increases receptiveness, and paves the way for growth and open communication. It also prevents the misinterpretation of unexpected feedback as an expression of disapproval. To do this, start by regularly stating your intentions at the start of every experience. Explicitly expressing your vision for mutual learning, bidirectional feedback, and growth in your respective roles attaches a positive intention to feedback. Providing a reminder that we are all works in progress and acknowledging this on a regular basis sets the stage for structured growth opportunities.

Scheduling future feedback encounters from the start maintains accountability and prevents feedback from being perceived as the consequence of a particular behavior. The number and timing of feedback sessions can be customized to the duration of the working relationship, generally allowing enough time for a second interaction (at the end of each week, halfway point, etc.).

Tip 2: Build rapport

Increasing clinical workloads and pressure to teach in time-constrained settings often results in insufficient time to engage in conversation and trust building. However, a foundational relationship is an essential precursor to meaningful feedback. Ramani et al. state that “relationships, not recipes, are more likely to promote feedback that has an impact on learner performance and ultimately patient care.”6 Building this rapport can begin by dedicating a few minutes (before/during rounds, between cases) to exchange information about career interests, hobbies, favorite restaurants, etc. This “small talk” is the beginning of a two-way exchange that ultimately develops into more meaningful exchanges.

In our experience, this simple step is impactful and fulfilling to both parties. This is also a good time for shared vulnerability by talking about what you are currently working on or have worked on at their stage to affirm that feedback is a continuous part of professional development and not a reflection of how far they are from competence at a given point in time.

Tip 3: Consider Timing, assess readiness, and preschedule sessions

Lack of attention to timing can hinder feedback acceptance. We suggest adhering to delivering positive feedback publicly and corrective feedback privately (“Praise in public, perfect in private”). This reinforces positive behaviors, increases motivation, and minimizes demoralization. Prolonged delays between the observed behavior and feedback can decrease its relevance. Conversely, delivering feedback too soon after an emotionally charged experience can be perceived as blame. Pre-designated times for feedback can minimize the guesswork and maintain your accountability for giving feedback without inadvertently linking it to one particular behavior. If the recipient does not appear to be in a state to receive feedback at the predesignated time, you can pivot to a “check-in” session to show support and strengthen rapport.

Tip 4: Customize to the learner and set shared goals

Diversity in backgrounds, perspectives, and personalities can impact how people perceive their own performances and experience feedback. Given the profound impact of sociocultural factors on feedback assimilation, maintaining the recipient and their goals at the core of performance evaluations is key to feedback acceptance.

A. Trainees

We suggest starting by introducing the idea of feedback as a partnership and something you feel privileged to do to help them achieve mutual goals. It helps to ask them to use the first day to get oriented with the experience, general expectations, challenges they expect to encounter, and their feedback goals. Tailoring your feedback to their goals creates a sense of shared purpose which increases motivation. Encouraging them to develop their own strategies allows them to play an active role in their growth. Giving them the opportunity to share their perceived strengths and deficiencies provides you with valuable information regarding their insight and ability to self-evaluate. This can help you predict their readiness for your feedback and to tailor your approach when there is a mismatch.

Examples:

- Medical student: Start with “What do you think you are doing well?” and “What do you think you need to work on?” Build on their response with encouragement and empathy. This helps make them more deliberate with what they work on because being a medical student can be overwhelming and can feel as though they have everything to work on.

- Resident/Fellow: By this point, trainees usually have an increased awareness of their strengths and deficiencies. Your questions can then be more specific, giving them autonomy over their learning, such as “What are some of the things you are working on that you want me to give you feedback on this week?” This makes them more aware, intentional, and receptive to your feedback because it is framed as something that they sought out.

B. Colleagues/Staff

Unlike the training environment in which feedback is built-in, giving feedback to co-workers requires you to establish a feedback-conducive environment and to develop a more in-depth understanding of coworkers’ personalities. Similar strategies can be applied, such as proactively setting the scene for open communication, scheduling check-ins, demonstrating receptiveness to feedback, and investing in trust-building.

Longer working relationships allow for strong foundational connections that make feedback less threatening. Personality assessment testing like Myers-Briggs Type Indicator or DiSC Assessment can aid in tailoring feedback to different individuals.7,8 An analytical thinker may appreciate direct, data-driven feedback. Relationship-oriented individuals might respond better to softer, encouragement-based approaches. Always maintain shared goals at the center of your interactions and consider collaborative opportunities such as quality improvement projects. This can improve your working relationship in a constructive way without casting blame.

Tip 5: Work on delivery: Bidirectional communication and body language

Non-verbal cues can have a profound impact on how your feedback is interpreted and on the recipient’s comfort to engage in conversation. Sitting down, making eye contact, nodding, and avoiding closed-off body posture can project support and feel less judgmental. Creating a safe and non-distracted environment with privacy can make them feel valued. Use motivating, respectful language focused on directly observed behaviors rather than personal attributes or second-hand reports.

Remember that focusing on repetitive patterns is likely more helpful than isolated incidents. Validate their hard work and give them a global idea of where they stand before diving into individual behaviors. Encourage their participation and empower them to suggest changes they plan to implement. Conclude by having them summarize their action plan to give them ownership and to verify that your feedback was interpreted as you intended. Thank them for being a part of the process, as it does take a partnership for feedback to be effective.

Tip 6: Be open to feedback

Demonstrating your willingness to accept and act on feedback reinforces a positive culture where feedback is normalized and valued. After an unintended outcome, initiate a two-way conversation and ask their input on anything they wish you would have done differently. This reaffirms your commitment to maintaining culture that does not revolve around one-sided critiques. Frequently soliciting feedback about your feedback skills can also guide you to adapt your approach and to recognize any ineffective feedback practices.

Tip 7: When things don’t go as planned

Receiving feedback, no matter how thoughtfully it is delivered, can be an emotionally-charged experience ending in hurt feelings. This happens because of misinterpretation of feedback as an indicator of inadequacy, heightened awareness of underlying insecurities, sociocultural or personal circumstances, frustration with oneself, needing additional guidance, or being caught off-guard by the assessment.

The evaluator should always acknowledge the recipient’s feelings, show compassion, and allow time for processing. When they are ready to talk, it is important to help reframe the recipients’ mindsets to recognize that feedback is not personal or defining and is not a “one and done” reflection of whether they have “made it.” Instead, it is a continual process that we benefit from through all career stages. Again, shared vulnerability can help to normalize feedback and maintain open dialogue. Setting an opportunity for a future check-in can reinforce support and lead to a more productive conversation after they have had time to process.

Conclusion

Effective feedback delivery is an invaluable skill that can result in meaningful goal-directed changes while strengthening professional relationships. Given the complexity of feedback interactions and the many factors that influence its acceptance, no single approach is suitable for all recipients and frequent adaptation of the approach is essential.

In our experience, adhering to these general overarching feedback principles (see Figure 1) has allowed us to have more successful interactions with trainees and colleagues.

Dr. Baliss is based in the Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. Dr. Hachem is director of the Division of Gastroenterology and Digestive Health at Intermountain Medical, Sandy, Utah. Both authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Parkes J, et al. Feedback sandwiches affect perceptions but not performance. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2013 Aug. doi:10.1007/s10459-012-9377-9.

2. van de Ridder JMM and Wijnen-Meijer M. Pendleton’s Rules: A Mini Review of a Feedback Method. Am J Biomed Sci & Res. 2023 May. doi: 10.34297/AJBSR.2023.19.002542.

3. Sender Liberman A, et al. Surgery residents and attending surgeons have different perceptions of feedback. Med Teach. 2005 Aug. doi: 10.1080/0142590500129183.

4. Sargeant J, et al. R2C2 in Action: Testing an Evidence-Based Model to Facilitate Feedback and Coaching in Residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2017 Apr. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00398.1.

5. Liakos W, et al. Frameworks for Effective Feedback in Health Professions Education. Acad Med. 2023 May. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004884.

6. Ramani S, et al. Feedback Redefined: Principles and Practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 May. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04874-2.

7. Woods RA and Hill PB. Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. 2022 Sept. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554596/

8. Slowikowski MK. Using the DISC behavioral instrument to guide leadership and communication. AORN J. 2005 Nov. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)60276-7.

Feedback is the purposeful practice of offering constructive, goal-directed input rooted in the power of observation and behavioral assessment. Healthcare inherently fosters a broad range of interactions among people with unique insights, and feedback can naturally emerge from this milieu. In medical training, feedback is an indispensable element that personalizes the learning process and drives the professional development of physicians through all career stages.

If delivered effectively, feedback can strengthen the relationship between the evaluator and recipient, promote self-reflection, and enhance motivation. As such, it has the potential to impact us and those we serve for a lifetime. Feedback has been invaluable to our growth as clinicians and has been embedded into our roles as educators. However, Here, we provide some “tried and true” practical tips on delivering feedback to trainees and co-workers and on navigating potential barriers based on lessons learned.

Barriers to Effective Feedback

- Time: Feedback is predicated on observation over time and consideration of repetitive processes rather than isolated events. Perhaps the most challenging factor faced by both parties is that of time constraints, leading to limited ability to engage and build rapport.

- Fear: Hesitancy by evaluators to provide feedback in fear of negative impacts on the recipient’s morale or rapport can lead them to shy away from personalized corrective feedback strategies and choose to rely on written evaluations or generic advice.

- Varying approaches: Feedback strategies have evolved from unidirectional, critique-based, hierarchical practices that emphasize the evaluator’s skills to models that prioritize the recipient’s goals and participation (see Table 1). Traditionally employed feedback models such as the “Feedback Sandwich” or the “Pendleton Rules” are criticized because of a lack of proven benefit on performance, recipient goal prioritization, and open communication.1,2 Studies showing incongruent perceptions of feedback adequacy between trainees and faculty further support the need for recipient-focused strategies.3 Recognition of the foundational role of the reciprocal learner-teacher alliance in feedback integration inspired newer feedback models, such as the “R2C2” and the “Self-Assessment, Feedback, Encouragement, Direction.”4,5

But which way is best? With increasing abundance and complexity of feedback frameworks, selecting an approach can feel overwhelming and impractical. A generic “one-size-fits-all” strategy or avoidance of feedback altogether can be detrimental. Structured feedback models can also lead to rigid, inauthentic interactions. Below, we suggest a more practical approach through our tips that unifies the common themes of various feedback models and embeds them into daily practice habits while leaving room for personalization.

Our Practical Feedback Tips

Tip 1: Set the scene: Create a positive feedback culture

Proactively creating a culture in which feedback is embedded and encouraged is perhaps the most important step. Priming both parties for feedback clarifies intent, increases receptiveness, and paves the way for growth and open communication. It also prevents the misinterpretation of unexpected feedback as an expression of disapproval. To do this, start by regularly stating your intentions at the start of every experience. Explicitly expressing your vision for mutual learning, bidirectional feedback, and growth in your respective roles attaches a positive intention to feedback. Providing a reminder that we are all works in progress and acknowledging this on a regular basis sets the stage for structured growth opportunities.

Scheduling future feedback encounters from the start maintains accountability and prevents feedback from being perceived as the consequence of a particular behavior. The number and timing of feedback sessions can be customized to the duration of the working relationship, generally allowing enough time for a second interaction (at the end of each week, halfway point, etc.).

Tip 2: Build rapport

Increasing clinical workloads and pressure to teach in time-constrained settings often results in insufficient time to engage in conversation and trust building. However, a foundational relationship is an essential precursor to meaningful feedback. Ramani et al. state that “relationships, not recipes, are more likely to promote feedback that has an impact on learner performance and ultimately patient care.”6 Building this rapport can begin by dedicating a few minutes (before/during rounds, between cases) to exchange information about career interests, hobbies, favorite restaurants, etc. This “small talk” is the beginning of a two-way exchange that ultimately develops into more meaningful exchanges.

In our experience, this simple step is impactful and fulfilling to both parties. This is also a good time for shared vulnerability by talking about what you are currently working on or have worked on at their stage to affirm that feedback is a continuous part of professional development and not a reflection of how far they are from competence at a given point in time.

Tip 3: Consider Timing, assess readiness, and preschedule sessions

Lack of attention to timing can hinder feedback acceptance. We suggest adhering to delivering positive feedback publicly and corrective feedback privately (“Praise in public, perfect in private”). This reinforces positive behaviors, increases motivation, and minimizes demoralization. Prolonged delays between the observed behavior and feedback can decrease its relevance. Conversely, delivering feedback too soon after an emotionally charged experience can be perceived as blame. Pre-designated times for feedback can minimize the guesswork and maintain your accountability for giving feedback without inadvertently linking it to one particular behavior. If the recipient does not appear to be in a state to receive feedback at the predesignated time, you can pivot to a “check-in” session to show support and strengthen rapport.

Tip 4: Customize to the learner and set shared goals

Diversity in backgrounds, perspectives, and personalities can impact how people perceive their own performances and experience feedback. Given the profound impact of sociocultural factors on feedback assimilation, maintaining the recipient and their goals at the core of performance evaluations is key to feedback acceptance.

A. Trainees

We suggest starting by introducing the idea of feedback as a partnership and something you feel privileged to do to help them achieve mutual goals. It helps to ask them to use the first day to get oriented with the experience, general expectations, challenges they expect to encounter, and their feedback goals. Tailoring your feedback to their goals creates a sense of shared purpose which increases motivation. Encouraging them to develop their own strategies allows them to play an active role in their growth. Giving them the opportunity to share their perceived strengths and deficiencies provides you with valuable information regarding their insight and ability to self-evaluate. This can help you predict their readiness for your feedback and to tailor your approach when there is a mismatch.

Examples:

- Medical student: Start with “What do you think you are doing well?” and “What do you think you need to work on?” Build on their response with encouragement and empathy. This helps make them more deliberate with what they work on because being a medical student can be overwhelming and can feel as though they have everything to work on.

- Resident/Fellow: By this point, trainees usually have an increased awareness of their strengths and deficiencies. Your questions can then be more specific, giving them autonomy over their learning, such as “What are some of the things you are working on that you want me to give you feedback on this week?” This makes them more aware, intentional, and receptive to your feedback because it is framed as something that they sought out.

B. Colleagues/Staff

Unlike the training environment in which feedback is built-in, giving feedback to co-workers requires you to establish a feedback-conducive environment and to develop a more in-depth understanding of coworkers’ personalities. Similar strategies can be applied, such as proactively setting the scene for open communication, scheduling check-ins, demonstrating receptiveness to feedback, and investing in trust-building.

Longer working relationships allow for strong foundational connections that make feedback less threatening. Personality assessment testing like Myers-Briggs Type Indicator or DiSC Assessment can aid in tailoring feedback to different individuals.7,8 An analytical thinker may appreciate direct, data-driven feedback. Relationship-oriented individuals might respond better to softer, encouragement-based approaches. Always maintain shared goals at the center of your interactions and consider collaborative opportunities such as quality improvement projects. This can improve your working relationship in a constructive way without casting blame.

Tip 5: Work on delivery: Bidirectional communication and body language

Non-verbal cues can have a profound impact on how your feedback is interpreted and on the recipient’s comfort to engage in conversation. Sitting down, making eye contact, nodding, and avoiding closed-off body posture can project support and feel less judgmental. Creating a safe and non-distracted environment with privacy can make them feel valued. Use motivating, respectful language focused on directly observed behaviors rather than personal attributes or second-hand reports.

Remember that focusing on repetitive patterns is likely more helpful than isolated incidents. Validate their hard work and give them a global idea of where they stand before diving into individual behaviors. Encourage their participation and empower them to suggest changes they plan to implement. Conclude by having them summarize their action plan to give them ownership and to verify that your feedback was interpreted as you intended. Thank them for being a part of the process, as it does take a partnership for feedback to be effective.

Tip 6: Be open to feedback

Demonstrating your willingness to accept and act on feedback reinforces a positive culture where feedback is normalized and valued. After an unintended outcome, initiate a two-way conversation and ask their input on anything they wish you would have done differently. This reaffirms your commitment to maintaining culture that does not revolve around one-sided critiques. Frequently soliciting feedback about your feedback skills can also guide you to adapt your approach and to recognize any ineffective feedback practices.

Tip 7: When things don’t go as planned

Receiving feedback, no matter how thoughtfully it is delivered, can be an emotionally-charged experience ending in hurt feelings. This happens because of misinterpretation of feedback as an indicator of inadequacy, heightened awareness of underlying insecurities, sociocultural or personal circumstances, frustration with oneself, needing additional guidance, or being caught off-guard by the assessment.

The evaluator should always acknowledge the recipient’s feelings, show compassion, and allow time for processing. When they are ready to talk, it is important to help reframe the recipients’ mindsets to recognize that feedback is not personal or defining and is not a “one and done” reflection of whether they have “made it.” Instead, it is a continual process that we benefit from through all career stages. Again, shared vulnerability can help to normalize feedback and maintain open dialogue. Setting an opportunity for a future check-in can reinforce support and lead to a more productive conversation after they have had time to process.

Conclusion

Effective feedback delivery is an invaluable skill that can result in meaningful goal-directed changes while strengthening professional relationships. Given the complexity of feedback interactions and the many factors that influence its acceptance, no single approach is suitable for all recipients and frequent adaptation of the approach is essential.

In our experience, adhering to these general overarching feedback principles (see Figure 1) has allowed us to have more successful interactions with trainees and colleagues.

Dr. Baliss is based in the Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. Dr. Hachem is director of the Division of Gastroenterology and Digestive Health at Intermountain Medical, Sandy, Utah. Both authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Parkes J, et al. Feedback sandwiches affect perceptions but not performance. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2013 Aug. doi:10.1007/s10459-012-9377-9.

2. van de Ridder JMM and Wijnen-Meijer M. Pendleton’s Rules: A Mini Review of a Feedback Method. Am J Biomed Sci & Res. 2023 May. doi: 10.34297/AJBSR.2023.19.002542.

3. Sender Liberman A, et al. Surgery residents and attending surgeons have different perceptions of feedback. Med Teach. 2005 Aug. doi: 10.1080/0142590500129183.

4. Sargeant J, et al. R2C2 in Action: Testing an Evidence-Based Model to Facilitate Feedback and Coaching in Residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2017 Apr. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00398.1.

5. Liakos W, et al. Frameworks for Effective Feedback in Health Professions Education. Acad Med. 2023 May. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004884.

6. Ramani S, et al. Feedback Redefined: Principles and Practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 May. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04874-2.

7. Woods RA and Hill PB. Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. 2022 Sept. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554596/

8. Slowikowski MK. Using the DISC behavioral instrument to guide leadership and communication. AORN J. 2005 Nov. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)60276-7.

Feedback is the purposeful practice of offering constructive, goal-directed input rooted in the power of observation and behavioral assessment. Healthcare inherently fosters a broad range of interactions among people with unique insights, and feedback can naturally emerge from this milieu. In medical training, feedback is an indispensable element that personalizes the learning process and drives the professional development of physicians through all career stages.

If delivered effectively, feedback can strengthen the relationship between the evaluator and recipient, promote self-reflection, and enhance motivation. As such, it has the potential to impact us and those we serve for a lifetime. Feedback has been invaluable to our growth as clinicians and has been embedded into our roles as educators. However, Here, we provide some “tried and true” practical tips on delivering feedback to trainees and co-workers and on navigating potential barriers based on lessons learned.

Barriers to Effective Feedback

- Time: Feedback is predicated on observation over time and consideration of repetitive processes rather than isolated events. Perhaps the most challenging factor faced by both parties is that of time constraints, leading to limited ability to engage and build rapport.

- Fear: Hesitancy by evaluators to provide feedback in fear of negative impacts on the recipient’s morale or rapport can lead them to shy away from personalized corrective feedback strategies and choose to rely on written evaluations or generic advice.

- Varying approaches: Feedback strategies have evolved from unidirectional, critique-based, hierarchical practices that emphasize the evaluator’s skills to models that prioritize the recipient’s goals and participation (see Table 1). Traditionally employed feedback models such as the “Feedback Sandwich” or the “Pendleton Rules” are criticized because of a lack of proven benefit on performance, recipient goal prioritization, and open communication.1,2 Studies showing incongruent perceptions of feedback adequacy between trainees and faculty further support the need for recipient-focused strategies.3 Recognition of the foundational role of the reciprocal learner-teacher alliance in feedback integration inspired newer feedback models, such as the “R2C2” and the “Self-Assessment, Feedback, Encouragement, Direction.”4,5

But which way is best? With increasing abundance and complexity of feedback frameworks, selecting an approach can feel overwhelming and impractical. A generic “one-size-fits-all” strategy or avoidance of feedback altogether can be detrimental. Structured feedback models can also lead to rigid, inauthentic interactions. Below, we suggest a more practical approach through our tips that unifies the common themes of various feedback models and embeds them into daily practice habits while leaving room for personalization.

Our Practical Feedback Tips

Tip 1: Set the scene: Create a positive feedback culture

Proactively creating a culture in which feedback is embedded and encouraged is perhaps the most important step. Priming both parties for feedback clarifies intent, increases receptiveness, and paves the way for growth and open communication. It also prevents the misinterpretation of unexpected feedback as an expression of disapproval. To do this, start by regularly stating your intentions at the start of every experience. Explicitly expressing your vision for mutual learning, bidirectional feedback, and growth in your respective roles attaches a positive intention to feedback. Providing a reminder that we are all works in progress and acknowledging this on a regular basis sets the stage for structured growth opportunities.

Scheduling future feedback encounters from the start maintains accountability and prevents feedback from being perceived as the consequence of a particular behavior. The number and timing of feedback sessions can be customized to the duration of the working relationship, generally allowing enough time for a second interaction (at the end of each week, halfway point, etc.).

Tip 2: Build rapport

Increasing clinical workloads and pressure to teach in time-constrained settings often results in insufficient time to engage in conversation and trust building. However, a foundational relationship is an essential precursor to meaningful feedback. Ramani et al. state that “relationships, not recipes, are more likely to promote feedback that has an impact on learner performance and ultimately patient care.”6 Building this rapport can begin by dedicating a few minutes (before/during rounds, between cases) to exchange information about career interests, hobbies, favorite restaurants, etc. This “small talk” is the beginning of a two-way exchange that ultimately develops into more meaningful exchanges.

In our experience, this simple step is impactful and fulfilling to both parties. This is also a good time for shared vulnerability by talking about what you are currently working on or have worked on at their stage to affirm that feedback is a continuous part of professional development and not a reflection of how far they are from competence at a given point in time.

Tip 3: Consider Timing, assess readiness, and preschedule sessions

Lack of attention to timing can hinder feedback acceptance. We suggest adhering to delivering positive feedback publicly and corrective feedback privately (“Praise in public, perfect in private”). This reinforces positive behaviors, increases motivation, and minimizes demoralization. Prolonged delays between the observed behavior and feedback can decrease its relevance. Conversely, delivering feedback too soon after an emotionally charged experience can be perceived as blame. Pre-designated times for feedback can minimize the guesswork and maintain your accountability for giving feedback without inadvertently linking it to one particular behavior. If the recipient does not appear to be in a state to receive feedback at the predesignated time, you can pivot to a “check-in” session to show support and strengthen rapport.

Tip 4: Customize to the learner and set shared goals

Diversity in backgrounds, perspectives, and personalities can impact how people perceive their own performances and experience feedback. Given the profound impact of sociocultural factors on feedback assimilation, maintaining the recipient and their goals at the core of performance evaluations is key to feedback acceptance.

A. Trainees

We suggest starting by introducing the idea of feedback as a partnership and something you feel privileged to do to help them achieve mutual goals. It helps to ask them to use the first day to get oriented with the experience, general expectations, challenges they expect to encounter, and their feedback goals. Tailoring your feedback to their goals creates a sense of shared purpose which increases motivation. Encouraging them to develop their own strategies allows them to play an active role in their growth. Giving them the opportunity to share their perceived strengths and deficiencies provides you with valuable information regarding their insight and ability to self-evaluate. This can help you predict their readiness for your feedback and to tailor your approach when there is a mismatch.

Examples:

- Medical student: Start with “What do you think you are doing well?” and “What do you think you need to work on?” Build on their response with encouragement and empathy. This helps make them more deliberate with what they work on because being a medical student can be overwhelming and can feel as though they have everything to work on.

- Resident/Fellow: By this point, trainees usually have an increased awareness of their strengths and deficiencies. Your questions can then be more specific, giving them autonomy over their learning, such as “What are some of the things you are working on that you want me to give you feedback on this week?” This makes them more aware, intentional, and receptive to your feedback because it is framed as something that they sought out.

B. Colleagues/Staff

Unlike the training environment in which feedback is built-in, giving feedback to co-workers requires you to establish a feedback-conducive environment and to develop a more in-depth understanding of coworkers’ personalities. Similar strategies can be applied, such as proactively setting the scene for open communication, scheduling check-ins, demonstrating receptiveness to feedback, and investing in trust-building.

Longer working relationships allow for strong foundational connections that make feedback less threatening. Personality assessment testing like Myers-Briggs Type Indicator or DiSC Assessment can aid in tailoring feedback to different individuals.7,8 An analytical thinker may appreciate direct, data-driven feedback. Relationship-oriented individuals might respond better to softer, encouragement-based approaches. Always maintain shared goals at the center of your interactions and consider collaborative opportunities such as quality improvement projects. This can improve your working relationship in a constructive way without casting blame.

Tip 5: Work on delivery: Bidirectional communication and body language

Non-verbal cues can have a profound impact on how your feedback is interpreted and on the recipient’s comfort to engage in conversation. Sitting down, making eye contact, nodding, and avoiding closed-off body posture can project support and feel less judgmental. Creating a safe and non-distracted environment with privacy can make them feel valued. Use motivating, respectful language focused on directly observed behaviors rather than personal attributes or second-hand reports.

Remember that focusing on repetitive patterns is likely more helpful than isolated incidents. Validate their hard work and give them a global idea of where they stand before diving into individual behaviors. Encourage their participation and empower them to suggest changes they plan to implement. Conclude by having them summarize their action plan to give them ownership and to verify that your feedback was interpreted as you intended. Thank them for being a part of the process, as it does take a partnership for feedback to be effective.

Tip 6: Be open to feedback

Demonstrating your willingness to accept and act on feedback reinforces a positive culture where feedback is normalized and valued. After an unintended outcome, initiate a two-way conversation and ask their input on anything they wish you would have done differently. This reaffirms your commitment to maintaining culture that does not revolve around one-sided critiques. Frequently soliciting feedback about your feedback skills can also guide you to adapt your approach and to recognize any ineffective feedback practices.

Tip 7: When things don’t go as planned

Receiving feedback, no matter how thoughtfully it is delivered, can be an emotionally-charged experience ending in hurt feelings. This happens because of misinterpretation of feedback as an indicator of inadequacy, heightened awareness of underlying insecurities, sociocultural or personal circumstances, frustration with oneself, needing additional guidance, or being caught off-guard by the assessment.

The evaluator should always acknowledge the recipient’s feelings, show compassion, and allow time for processing. When they are ready to talk, it is important to help reframe the recipients’ mindsets to recognize that feedback is not personal or defining and is not a “one and done” reflection of whether they have “made it.” Instead, it is a continual process that we benefit from through all career stages. Again, shared vulnerability can help to normalize feedback and maintain open dialogue. Setting an opportunity for a future check-in can reinforce support and lead to a more productive conversation after they have had time to process.

Conclusion

Effective feedback delivery is an invaluable skill that can result in meaningful goal-directed changes while strengthening professional relationships. Given the complexity of feedback interactions and the many factors that influence its acceptance, no single approach is suitable for all recipients and frequent adaptation of the approach is essential.

In our experience, adhering to these general overarching feedback principles (see Figure 1) has allowed us to have more successful interactions with trainees and colleagues.

Dr. Baliss is based in the Division of Gastroenterology, Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. Dr. Hachem is director of the Division of Gastroenterology and Digestive Health at Intermountain Medical, Sandy, Utah. Both authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Parkes J, et al. Feedback sandwiches affect perceptions but not performance. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2013 Aug. doi:10.1007/s10459-012-9377-9.

2. van de Ridder JMM and Wijnen-Meijer M. Pendleton’s Rules: A Mini Review of a Feedback Method. Am J Biomed Sci & Res. 2023 May. doi: 10.34297/AJBSR.2023.19.002542.

3. Sender Liberman A, et al. Surgery residents and attending surgeons have different perceptions of feedback. Med Teach. 2005 Aug. doi: 10.1080/0142590500129183.

4. Sargeant J, et al. R2C2 in Action: Testing an Evidence-Based Model to Facilitate Feedback and Coaching in Residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2017 Apr. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00398.1.

5. Liakos W, et al. Frameworks for Effective Feedback in Health Professions Education. Acad Med. 2023 May. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004884.

6. Ramani S, et al. Feedback Redefined: Principles and Practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2019 May. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04874-2.

7. Woods RA and Hill PB. Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. 2022 Sept. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554596/

8. Slowikowski MK. Using the DISC behavioral instrument to guide leadership and communication. AORN J. 2005 Nov. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)60276-7.