User login

Daily Double! Assessing the Effectiveness of Game-Based Learning on the Pharmacy Knowledge of US Coast Guard Health Services Technicians

Daily Double! Assessing the Effectiveness of Game-Based Learning on the Pharmacy Knowledge of US Coast Guard Health Services Technicians

The US Coast Guard (USCG) operates within the US Department of Homeland Security and represents a force of > 50,000 servicemembers.1 The missions of the service include maritime law enforcement (drug interdiction), search and rescue, and defense readiness.2

The USCG operates 42 clinics and numerous smaller sick bays of varying sizes and medical capabilities throughout the country to provide acute and routine medical services. Health services technicians (HSs) are the most common staffing component and provide much of the support services in each USCG health care setting. The HS rating, colloquially referred to as corpsmen, is achieved through a 22-week course known as “A” school that trains servicemembers in outpatient and acute care, including emergency medical technician training.3 There are about 750 USCG HSs.

Within USCG clinics, HSs conduct ambulatory intakes for outpatient appointments, administer immunizations and blood draws, requisition medical equipment and supplies, serve as a pharmacy technician, complete physical examinations, and manage referrals, among other duties. Their familiarity with different aspects of clinic operations and medical practice must be broad. To that end, corpsmen develop and reinforce their medical knowledge through various trainings, including additional courses to specialize in certain medical skills, such as pharmacy technician “C” school or dental assistant “C” school.

The USCG employs < 15 field pharmacists, most of whom serve in an ambulatory care environment.4 Responsibilities of USCG pharmacists include the routine reinforcement of pharmacy knowledge with HSs. For the corpsmen who are not pharmacy technicians or who have not attended pharmacy technician “C” school, the extent of their pharmacy instruction primarily came from the “A” school curriculum, of which only 1 class is specific to pharmacy. Providing routine pharmacy-related training to the HSs further cultivates their pharmacy knowledge and confidence so that they can practice more holistically. These trainings do not need to follow any specific format.

In this study, 3 pharmacists at 3 separate USCG clinics conducted a training inspired by the Jeopardy! game show with the corpsmen at their respective clinics. This study examined the effectiveness of game-based learning on the pharmacy knowledge retention of HSs at 3 USCG clinics. A secondary objective was to evaluate the baseline pharmacy knowledge of corpsmen based on specific corpsmen demographics.

Methods

As part of a USCG quality improvement study in 2024, 28 HSs at the 3 USCG clinics were provided a preintervention assessment, completed game-based educational program (intervention), and then were assessed again following the intervention.

The HSs were presented with a 25-question assessment that included 10 knowledge questions (3 on over-the-counter medications, 2 on use of medications in pregnancy, 2 on precautions and contraindications, 2 on indications, and 1 on immunizations) and 15 brand-generic matching questions. These questions were developed and reviewed by the 3 participating pharmacists to ensure that their scope was commensurate with the overall pharmacy knowledge that could be reasonably expected of corpsmen spanning various points of their HS career.

One to 7 days after the preintervention assessment, the pharmacists hosted the game-based learning modeled after Jeopardy!. The Jeopardy! categories mirrored the assessment knowledge question categories, and brand-generic nomenclature was freely discussed throughout. About 2 weeks later, the same HSs who completed the preintervention assessment and participated in the game were presented with the same assessment.

In addition to capturing the difference in scores between the 2 assessments, additional demographic data were gathered, including service time as an HS and whether they received formalized pharmacy technician training and if so, how long they have served in that capacity. Demographic data were collected to identify potential correlations between demographic characteristics and results.

Results

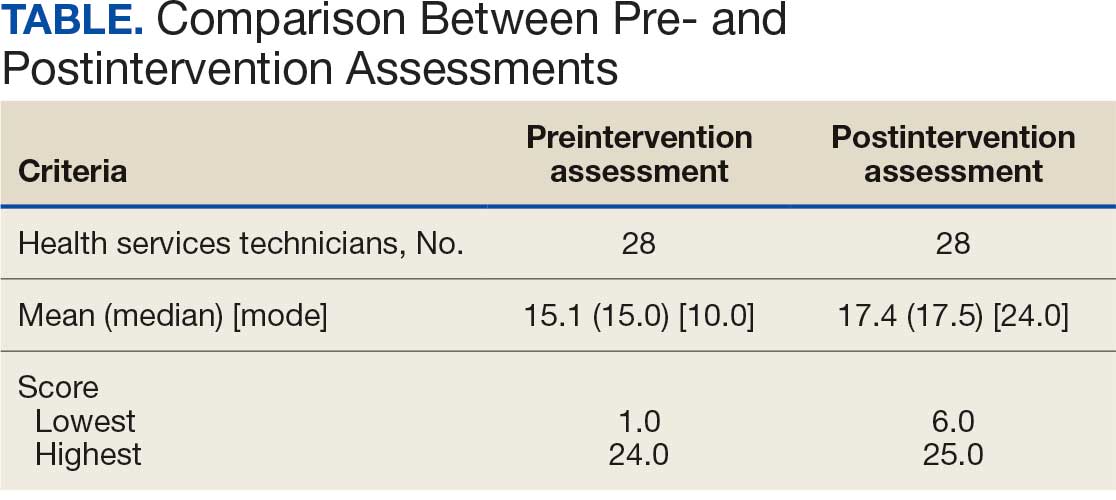

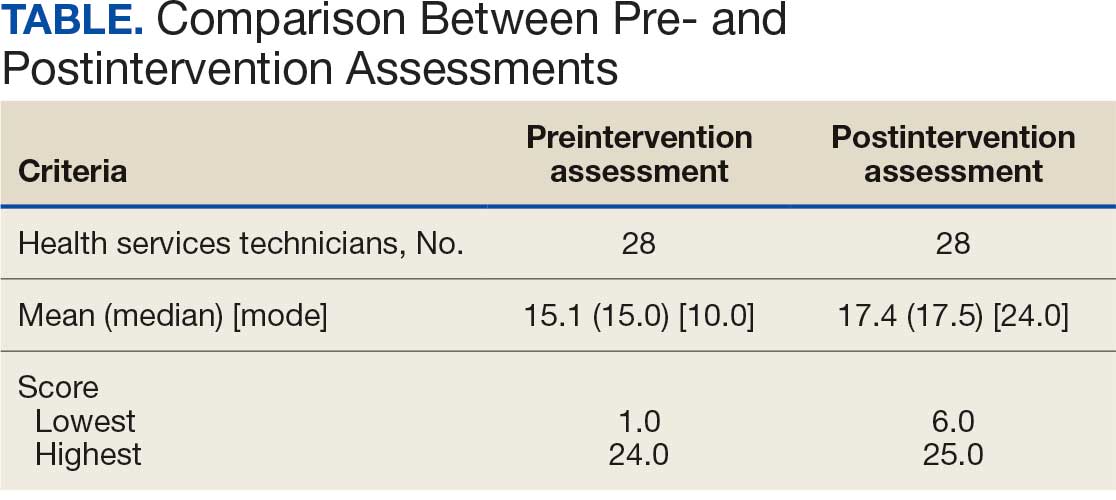

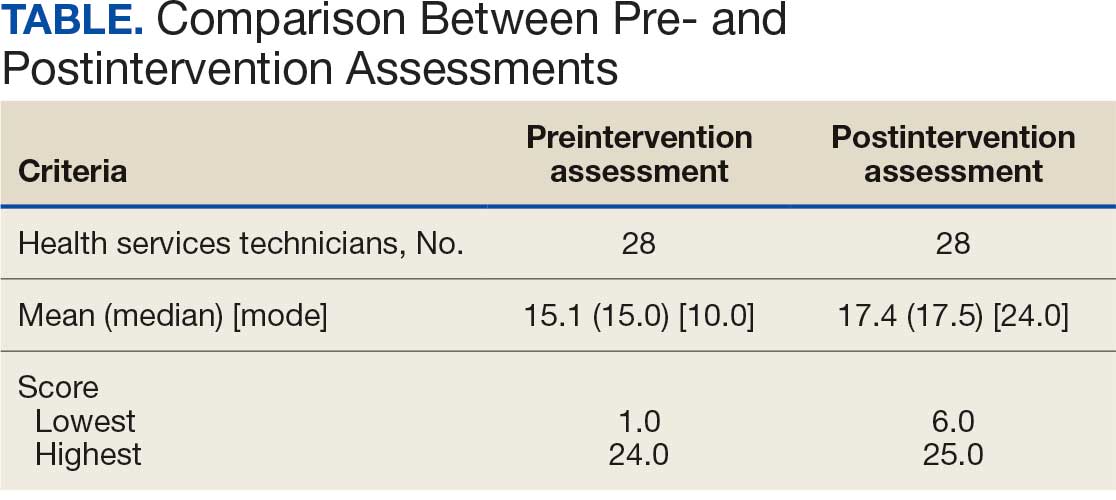

Twenty-eight HSs at the 3 clinics completed the game-based training and both assessments. The mean score increased from 15.1 preintervention to 17.4 postintervention (Table). Preintervention scores ranged from 1 to 24 and postintervention scores ranged from 6 to 25.

There were 19 HSs (68%) whose score increased from preintervention to postintervention and 5 (18%) had decreased scores. The largest score decrease was 4 (from 18 to 14), and the largest score increase was 11 (from 13 to 24). The mean improvement was 3.9 among the 19 HSs with increased scores

Twenty-one HSs reported no formal pharmacy technician training, 3 completed pharmacy technician “C” school, and 4 received informal on-the-job training. The mean score for the “C” school trained HSs was 23.0 preintervention and 23.7 postintervention. The mean score for HSs trained on the job was 16.0 preintervention and 18.5 postintervention. The mean score for HSs with no training was 13.9 preintervention and 16.3 postintervention.

As HSs advance in their careers, they typically assume roles with increasing technical knowledge, responsibility, and oversight, thus aligning with advancement from E-4 (third class petty officer) to E-6 (first class petty officer) and beyond. In this study, there was 1 E-3, 12 E-4s (mean time as an HS, 1.3 years), 8 E-5s (mean time as an HS, 4.8 years), and 7 E-6s (mean time as an HS, 8.6 years). The E-3 had a preintervention score of 1.0 and a postintervention score of 6.0. The E-4s had a mean change in score from pre- to postintervention of 2.4. The E-5s had a mean change in score from pre- to postintervention of 1.6. The E-6s had a mean change in score from pre- to postintervention of 2.3.

Discussion

This study is novel in its examination of the impact of game-based learning on the retention of the pharmacy knowledge of USCG corpsmen. A PubMed literature search of the phrase “((Corpsman) OR (Corpsmen)) AND (Coast Guard)” yields 135 results, though none were relevant to the USCG population described in this study. A PubMed literature search of the phrase “(Jeopardy!) AND (pharmacy)” yields 28 results, only 1 of which discusses using the game-based approach as an instructional tool.5 A PubMed literature search of the phrase “(game) AND (Coast Guard)” yields 55 results, none of which were specifically relevant to game-based learning in the USCG. This study appears to be among the first to discuss results and trends in game-based learning with USCG corpsmen.

The preponderance of literature for game-based learning strategies exists in children; more research in adults is needed.6,7 With studies showing that game-based learning may impact motivation to learn and learning gains, it is unsurprising that there is some research in professional health care education. Games modeled after everything from simulated clinical scenarios to Family Feud and Chutes and Ladders-style games have been compared with traditional learning strategies. However, the results of whether game-based learning strategies improve knowledge, clinical decision-making, and motivation to learn vary, suggesting the need for more research in this field.8

The results of this study suggest that Jeopardy! is likely an effective instructional method for USCG corpsmen on pharmacy topics. While there were some HSs whose postintervention scores decreased, 19 (68%) had increased scores. Because the second assessment was administered about 2 weeks after the game-based learning, the results suggest some level of knowledge retention. Between these results and the informally perceived level of engagement, game-based learning could be a more stimulating alternative training method to a standard slide-based presentation.

Stratifying the data by demographics revealed additional trends, although they should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size. The baseline results strongly illustrate the value of formalized training. It is generally expected that HSs who have completed the “C” school pharmacy technician training program should have more pharmacy knowledge than those with on-the-job or less training. The results indicate that “C” school trained and on-the-job trained HSs scored higher on the preintervention assessment (mean, 23.0 and 16.0, respectively), than those with no such experiences (mean, 13.9). Such results underscore the value of formalized training—whether as a pharmacy technician or in any other “C” school—in enhancing the medical knowledge of HSs that may allow them to hold roles of increased responsibility and medical scope.

In addition to stratification by pharmacy technician training, stratification by years of HS experience (roughly correlated to rank) yields a similar result. It would be expected that as HSs advance in their careers, they gain more exposure to various medical topics, including pharmacy. That is not always the case, however, as it is possible an HS never rotated through a pharmacy technician position or has not been recently exposed to pharmacy knowledge. Nevertheless, the results suggest that increased HS experience was likely associated with an increased baseline pharmacy knowledge, with mean preintervention scores increasing from 11.9 to 18.1 to 19.3 for E-4, E-5, and E-6, respectively.

While there are many explanations for these results, the authors hypothesize that when HSs are E-4s, they might not yet have exposure to all aspects of the clinic and are perhaps not as well-versed in pharmacy practice. An E-5—now a few years into their career—would have completed pharmacy technician “C” school or on-the-job training (if applicable), which could account for the significant jump in pharmacy knowledge scores. An E-6 can still engage in direct patient care activities but take on leadership and supervisory roles within the clinic, perhaps explaining the smaller increase in score.

In terms of increasing responsibility, many USCG corpsmen complete another schooling opportunity—Independent Duty Health Services Technician (IDHS)—so they can serve in independent duty roles, many of which are on USCG cutters. While cutters are deployed, that IDHS could be the sole medical personnel on the cutter and function in a midlevel practitioner extender role. Formalized training in pharmacy—the benefits of which are suggested through these results—or another field of medical practice would strengthen the skillset and confidence of IDHSs.

Though not formally assessed, the 3 pharmacists noted that the game-based learning was met with overwhelmingly positive feedback in terms of excitement, energy, and overall engagement.

Limitations

This cohort of individuals represents a small proportion of the total number of USCG corpsmen, and it is not fully representative of all practice settings. HSs can be assigned to USCG cutters as IDHSs, which would not be captured in this cohort. Even within a single clinic, the knowledge of HSs varies, as not all HS duties consist solely of clinical skills. Additionally, while the overall game framework was consistent among the 3 sites, there may have been unquantifiable differences in overall teaching style by the 3 pharmacists that may have resulted in different levels of content retention. Given the lack of similar studies in this population, this study can best be described as a quantitative descriptor of results rather than a statistical comparison of what instructional method works best.

Conclusions

The USCG greatly benefits from having trained and experienced HSs fulfilling mission support roles in the organization. In addition to traditional slide-based trainings, game-based learning can be considered to create engaging learning environments to support the knowledge retention of pharmacy and other medical topics for USCG corpsmen.

- US Coast Guard. Organizational overview. About the US Coast Guard. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.uscg.mil/About

- US Coast Guard. Missions. About US Coast Guard. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.uscg.mil/About/Missions/

- US Coast Guard. Health services technician. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.gocoastguard.com/careers/enlisted/hs

- Zhou F, Woodward Z. Impact of pharmacist interventions at an outpatient US Coast Guard clinic. Fed Pract. 2023;40(6):174-177. doi:10.12788/fp.0383

- Cusick J. A Jeopardy-style review game using team clickers. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10485. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10485

- Dahalan F, Alias N, Shaharom MSN. Gamification and game based learning for vocational education and training: a systematic literature review. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2023:1-39. doi:10.1007/s10639-022-11548-w

- Wesselink LA. Testing the Effectiveness of Game-Based Learning for Adults by Designing an Educational Game: A Design and Research Study to Investigate the Effectiveness of Educational Games for Adults to Learn Basic Skills of Microsoft Excel. Master’s thesis. University of Twente; 2020. Accessed October 22, 2025. http://essay.utwentw.nl/88229

- Del Cura-González I, Ariza-Cardiel G, Polentinos-Castro E, et al. Effectiveness of a game-based educational strategy e-EDUCAGUIA for implementing antimicrobial clinical practice guidelines in family medicine residents in Spain: a randomized clinical trial by cluster. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:893. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03843-4

The US Coast Guard (USCG) operates within the US Department of Homeland Security and represents a force of > 50,000 servicemembers.1 The missions of the service include maritime law enforcement (drug interdiction), search and rescue, and defense readiness.2

The USCG operates 42 clinics and numerous smaller sick bays of varying sizes and medical capabilities throughout the country to provide acute and routine medical services. Health services technicians (HSs) are the most common staffing component and provide much of the support services in each USCG health care setting. The HS rating, colloquially referred to as corpsmen, is achieved through a 22-week course known as “A” school that trains servicemembers in outpatient and acute care, including emergency medical technician training.3 There are about 750 USCG HSs.

Within USCG clinics, HSs conduct ambulatory intakes for outpatient appointments, administer immunizations and blood draws, requisition medical equipment and supplies, serve as a pharmacy technician, complete physical examinations, and manage referrals, among other duties. Their familiarity with different aspects of clinic operations and medical practice must be broad. To that end, corpsmen develop and reinforce their medical knowledge through various trainings, including additional courses to specialize in certain medical skills, such as pharmacy technician “C” school or dental assistant “C” school.

The USCG employs < 15 field pharmacists, most of whom serve in an ambulatory care environment.4 Responsibilities of USCG pharmacists include the routine reinforcement of pharmacy knowledge with HSs. For the corpsmen who are not pharmacy technicians or who have not attended pharmacy technician “C” school, the extent of their pharmacy instruction primarily came from the “A” school curriculum, of which only 1 class is specific to pharmacy. Providing routine pharmacy-related training to the HSs further cultivates their pharmacy knowledge and confidence so that they can practice more holistically. These trainings do not need to follow any specific format.

In this study, 3 pharmacists at 3 separate USCG clinics conducted a training inspired by the Jeopardy! game show with the corpsmen at their respective clinics. This study examined the effectiveness of game-based learning on the pharmacy knowledge retention of HSs at 3 USCG clinics. A secondary objective was to evaluate the baseline pharmacy knowledge of corpsmen based on specific corpsmen demographics.

Methods

As part of a USCG quality improvement study in 2024, 28 HSs at the 3 USCG clinics were provided a preintervention assessment, completed game-based educational program (intervention), and then were assessed again following the intervention.

The HSs were presented with a 25-question assessment that included 10 knowledge questions (3 on over-the-counter medications, 2 on use of medications in pregnancy, 2 on precautions and contraindications, 2 on indications, and 1 on immunizations) and 15 brand-generic matching questions. These questions were developed and reviewed by the 3 participating pharmacists to ensure that their scope was commensurate with the overall pharmacy knowledge that could be reasonably expected of corpsmen spanning various points of their HS career.

One to 7 days after the preintervention assessment, the pharmacists hosted the game-based learning modeled after Jeopardy!. The Jeopardy! categories mirrored the assessment knowledge question categories, and brand-generic nomenclature was freely discussed throughout. About 2 weeks later, the same HSs who completed the preintervention assessment and participated in the game were presented with the same assessment.

In addition to capturing the difference in scores between the 2 assessments, additional demographic data were gathered, including service time as an HS and whether they received formalized pharmacy technician training and if so, how long they have served in that capacity. Demographic data were collected to identify potential correlations between demographic characteristics and results.

Results

Twenty-eight HSs at the 3 clinics completed the game-based training and both assessments. The mean score increased from 15.1 preintervention to 17.4 postintervention (Table). Preintervention scores ranged from 1 to 24 and postintervention scores ranged from 6 to 25.

There were 19 HSs (68%) whose score increased from preintervention to postintervention and 5 (18%) had decreased scores. The largest score decrease was 4 (from 18 to 14), and the largest score increase was 11 (from 13 to 24). The mean improvement was 3.9 among the 19 HSs with increased scores

Twenty-one HSs reported no formal pharmacy technician training, 3 completed pharmacy technician “C” school, and 4 received informal on-the-job training. The mean score for the “C” school trained HSs was 23.0 preintervention and 23.7 postintervention. The mean score for HSs trained on the job was 16.0 preintervention and 18.5 postintervention. The mean score for HSs with no training was 13.9 preintervention and 16.3 postintervention.

As HSs advance in their careers, they typically assume roles with increasing technical knowledge, responsibility, and oversight, thus aligning with advancement from E-4 (third class petty officer) to E-6 (first class petty officer) and beyond. In this study, there was 1 E-3, 12 E-4s (mean time as an HS, 1.3 years), 8 E-5s (mean time as an HS, 4.8 years), and 7 E-6s (mean time as an HS, 8.6 years). The E-3 had a preintervention score of 1.0 and a postintervention score of 6.0. The E-4s had a mean change in score from pre- to postintervention of 2.4. The E-5s had a mean change in score from pre- to postintervention of 1.6. The E-6s had a mean change in score from pre- to postintervention of 2.3.

Discussion

This study is novel in its examination of the impact of game-based learning on the retention of the pharmacy knowledge of USCG corpsmen. A PubMed literature search of the phrase “((Corpsman) OR (Corpsmen)) AND (Coast Guard)” yields 135 results, though none were relevant to the USCG population described in this study. A PubMed literature search of the phrase “(Jeopardy!) AND (pharmacy)” yields 28 results, only 1 of which discusses using the game-based approach as an instructional tool.5 A PubMed literature search of the phrase “(game) AND (Coast Guard)” yields 55 results, none of which were specifically relevant to game-based learning in the USCG. This study appears to be among the first to discuss results and trends in game-based learning with USCG corpsmen.

The preponderance of literature for game-based learning strategies exists in children; more research in adults is needed.6,7 With studies showing that game-based learning may impact motivation to learn and learning gains, it is unsurprising that there is some research in professional health care education. Games modeled after everything from simulated clinical scenarios to Family Feud and Chutes and Ladders-style games have been compared with traditional learning strategies. However, the results of whether game-based learning strategies improve knowledge, clinical decision-making, and motivation to learn vary, suggesting the need for more research in this field.8

The results of this study suggest that Jeopardy! is likely an effective instructional method for USCG corpsmen on pharmacy topics. While there were some HSs whose postintervention scores decreased, 19 (68%) had increased scores. Because the second assessment was administered about 2 weeks after the game-based learning, the results suggest some level of knowledge retention. Between these results and the informally perceived level of engagement, game-based learning could be a more stimulating alternative training method to a standard slide-based presentation.

Stratifying the data by demographics revealed additional trends, although they should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size. The baseline results strongly illustrate the value of formalized training. It is generally expected that HSs who have completed the “C” school pharmacy technician training program should have more pharmacy knowledge than those with on-the-job or less training. The results indicate that “C” school trained and on-the-job trained HSs scored higher on the preintervention assessment (mean, 23.0 and 16.0, respectively), than those with no such experiences (mean, 13.9). Such results underscore the value of formalized training—whether as a pharmacy technician or in any other “C” school—in enhancing the medical knowledge of HSs that may allow them to hold roles of increased responsibility and medical scope.

In addition to stratification by pharmacy technician training, stratification by years of HS experience (roughly correlated to rank) yields a similar result. It would be expected that as HSs advance in their careers, they gain more exposure to various medical topics, including pharmacy. That is not always the case, however, as it is possible an HS never rotated through a pharmacy technician position or has not been recently exposed to pharmacy knowledge. Nevertheless, the results suggest that increased HS experience was likely associated with an increased baseline pharmacy knowledge, with mean preintervention scores increasing from 11.9 to 18.1 to 19.3 for E-4, E-5, and E-6, respectively.

While there are many explanations for these results, the authors hypothesize that when HSs are E-4s, they might not yet have exposure to all aspects of the clinic and are perhaps not as well-versed in pharmacy practice. An E-5—now a few years into their career—would have completed pharmacy technician “C” school or on-the-job training (if applicable), which could account for the significant jump in pharmacy knowledge scores. An E-6 can still engage in direct patient care activities but take on leadership and supervisory roles within the clinic, perhaps explaining the smaller increase in score.

In terms of increasing responsibility, many USCG corpsmen complete another schooling opportunity—Independent Duty Health Services Technician (IDHS)—so they can serve in independent duty roles, many of which are on USCG cutters. While cutters are deployed, that IDHS could be the sole medical personnel on the cutter and function in a midlevel practitioner extender role. Formalized training in pharmacy—the benefits of which are suggested through these results—or another field of medical practice would strengthen the skillset and confidence of IDHSs.

Though not formally assessed, the 3 pharmacists noted that the game-based learning was met with overwhelmingly positive feedback in terms of excitement, energy, and overall engagement.

Limitations

This cohort of individuals represents a small proportion of the total number of USCG corpsmen, and it is not fully representative of all practice settings. HSs can be assigned to USCG cutters as IDHSs, which would not be captured in this cohort. Even within a single clinic, the knowledge of HSs varies, as not all HS duties consist solely of clinical skills. Additionally, while the overall game framework was consistent among the 3 sites, there may have been unquantifiable differences in overall teaching style by the 3 pharmacists that may have resulted in different levels of content retention. Given the lack of similar studies in this population, this study can best be described as a quantitative descriptor of results rather than a statistical comparison of what instructional method works best.

Conclusions

The USCG greatly benefits from having trained and experienced HSs fulfilling mission support roles in the organization. In addition to traditional slide-based trainings, game-based learning can be considered to create engaging learning environments to support the knowledge retention of pharmacy and other medical topics for USCG corpsmen.

The US Coast Guard (USCG) operates within the US Department of Homeland Security and represents a force of > 50,000 servicemembers.1 The missions of the service include maritime law enforcement (drug interdiction), search and rescue, and defense readiness.2

The USCG operates 42 clinics and numerous smaller sick bays of varying sizes and medical capabilities throughout the country to provide acute and routine medical services. Health services technicians (HSs) are the most common staffing component and provide much of the support services in each USCG health care setting. The HS rating, colloquially referred to as corpsmen, is achieved through a 22-week course known as “A” school that trains servicemembers in outpatient and acute care, including emergency medical technician training.3 There are about 750 USCG HSs.

Within USCG clinics, HSs conduct ambulatory intakes for outpatient appointments, administer immunizations and blood draws, requisition medical equipment and supplies, serve as a pharmacy technician, complete physical examinations, and manage referrals, among other duties. Their familiarity with different aspects of clinic operations and medical practice must be broad. To that end, corpsmen develop and reinforce their medical knowledge through various trainings, including additional courses to specialize in certain medical skills, such as pharmacy technician “C” school or dental assistant “C” school.

The USCG employs < 15 field pharmacists, most of whom serve in an ambulatory care environment.4 Responsibilities of USCG pharmacists include the routine reinforcement of pharmacy knowledge with HSs. For the corpsmen who are not pharmacy technicians or who have not attended pharmacy technician “C” school, the extent of their pharmacy instruction primarily came from the “A” school curriculum, of which only 1 class is specific to pharmacy. Providing routine pharmacy-related training to the HSs further cultivates their pharmacy knowledge and confidence so that they can practice more holistically. These trainings do not need to follow any specific format.

In this study, 3 pharmacists at 3 separate USCG clinics conducted a training inspired by the Jeopardy! game show with the corpsmen at their respective clinics. This study examined the effectiveness of game-based learning on the pharmacy knowledge retention of HSs at 3 USCG clinics. A secondary objective was to evaluate the baseline pharmacy knowledge of corpsmen based on specific corpsmen demographics.

Methods

As part of a USCG quality improvement study in 2024, 28 HSs at the 3 USCG clinics were provided a preintervention assessment, completed game-based educational program (intervention), and then were assessed again following the intervention.

The HSs were presented with a 25-question assessment that included 10 knowledge questions (3 on over-the-counter medications, 2 on use of medications in pregnancy, 2 on precautions and contraindications, 2 on indications, and 1 on immunizations) and 15 brand-generic matching questions. These questions were developed and reviewed by the 3 participating pharmacists to ensure that their scope was commensurate with the overall pharmacy knowledge that could be reasonably expected of corpsmen spanning various points of their HS career.

One to 7 days after the preintervention assessment, the pharmacists hosted the game-based learning modeled after Jeopardy!. The Jeopardy! categories mirrored the assessment knowledge question categories, and brand-generic nomenclature was freely discussed throughout. About 2 weeks later, the same HSs who completed the preintervention assessment and participated in the game were presented with the same assessment.

In addition to capturing the difference in scores between the 2 assessments, additional demographic data were gathered, including service time as an HS and whether they received formalized pharmacy technician training and if so, how long they have served in that capacity. Demographic data were collected to identify potential correlations between demographic characteristics and results.

Results

Twenty-eight HSs at the 3 clinics completed the game-based training and both assessments. The mean score increased from 15.1 preintervention to 17.4 postintervention (Table). Preintervention scores ranged from 1 to 24 and postintervention scores ranged from 6 to 25.

There were 19 HSs (68%) whose score increased from preintervention to postintervention and 5 (18%) had decreased scores. The largest score decrease was 4 (from 18 to 14), and the largest score increase was 11 (from 13 to 24). The mean improvement was 3.9 among the 19 HSs with increased scores

Twenty-one HSs reported no formal pharmacy technician training, 3 completed pharmacy technician “C” school, and 4 received informal on-the-job training. The mean score for the “C” school trained HSs was 23.0 preintervention and 23.7 postintervention. The mean score for HSs trained on the job was 16.0 preintervention and 18.5 postintervention. The mean score for HSs with no training was 13.9 preintervention and 16.3 postintervention.

As HSs advance in their careers, they typically assume roles with increasing technical knowledge, responsibility, and oversight, thus aligning with advancement from E-4 (third class petty officer) to E-6 (first class petty officer) and beyond. In this study, there was 1 E-3, 12 E-4s (mean time as an HS, 1.3 years), 8 E-5s (mean time as an HS, 4.8 years), and 7 E-6s (mean time as an HS, 8.6 years). The E-3 had a preintervention score of 1.0 and a postintervention score of 6.0. The E-4s had a mean change in score from pre- to postintervention of 2.4. The E-5s had a mean change in score from pre- to postintervention of 1.6. The E-6s had a mean change in score from pre- to postintervention of 2.3.

Discussion

This study is novel in its examination of the impact of game-based learning on the retention of the pharmacy knowledge of USCG corpsmen. A PubMed literature search of the phrase “((Corpsman) OR (Corpsmen)) AND (Coast Guard)” yields 135 results, though none were relevant to the USCG population described in this study. A PubMed literature search of the phrase “(Jeopardy!) AND (pharmacy)” yields 28 results, only 1 of which discusses using the game-based approach as an instructional tool.5 A PubMed literature search of the phrase “(game) AND (Coast Guard)” yields 55 results, none of which were specifically relevant to game-based learning in the USCG. This study appears to be among the first to discuss results and trends in game-based learning with USCG corpsmen.

The preponderance of literature for game-based learning strategies exists in children; more research in adults is needed.6,7 With studies showing that game-based learning may impact motivation to learn and learning gains, it is unsurprising that there is some research in professional health care education. Games modeled after everything from simulated clinical scenarios to Family Feud and Chutes and Ladders-style games have been compared with traditional learning strategies. However, the results of whether game-based learning strategies improve knowledge, clinical decision-making, and motivation to learn vary, suggesting the need for more research in this field.8

The results of this study suggest that Jeopardy! is likely an effective instructional method for USCG corpsmen on pharmacy topics. While there were some HSs whose postintervention scores decreased, 19 (68%) had increased scores. Because the second assessment was administered about 2 weeks after the game-based learning, the results suggest some level of knowledge retention. Between these results and the informally perceived level of engagement, game-based learning could be a more stimulating alternative training method to a standard slide-based presentation.

Stratifying the data by demographics revealed additional trends, although they should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size. The baseline results strongly illustrate the value of formalized training. It is generally expected that HSs who have completed the “C” school pharmacy technician training program should have more pharmacy knowledge than those with on-the-job or less training. The results indicate that “C” school trained and on-the-job trained HSs scored higher on the preintervention assessment (mean, 23.0 and 16.0, respectively), than those with no such experiences (mean, 13.9). Such results underscore the value of formalized training—whether as a pharmacy technician or in any other “C” school—in enhancing the medical knowledge of HSs that may allow them to hold roles of increased responsibility and medical scope.

In addition to stratification by pharmacy technician training, stratification by years of HS experience (roughly correlated to rank) yields a similar result. It would be expected that as HSs advance in their careers, they gain more exposure to various medical topics, including pharmacy. That is not always the case, however, as it is possible an HS never rotated through a pharmacy technician position or has not been recently exposed to pharmacy knowledge. Nevertheless, the results suggest that increased HS experience was likely associated with an increased baseline pharmacy knowledge, with mean preintervention scores increasing from 11.9 to 18.1 to 19.3 for E-4, E-5, and E-6, respectively.

While there are many explanations for these results, the authors hypothesize that when HSs are E-4s, they might not yet have exposure to all aspects of the clinic and are perhaps not as well-versed in pharmacy practice. An E-5—now a few years into their career—would have completed pharmacy technician “C” school or on-the-job training (if applicable), which could account for the significant jump in pharmacy knowledge scores. An E-6 can still engage in direct patient care activities but take on leadership and supervisory roles within the clinic, perhaps explaining the smaller increase in score.

In terms of increasing responsibility, many USCG corpsmen complete another schooling opportunity—Independent Duty Health Services Technician (IDHS)—so they can serve in independent duty roles, many of which are on USCG cutters. While cutters are deployed, that IDHS could be the sole medical personnel on the cutter and function in a midlevel practitioner extender role. Formalized training in pharmacy—the benefits of which are suggested through these results—or another field of medical practice would strengthen the skillset and confidence of IDHSs.

Though not formally assessed, the 3 pharmacists noted that the game-based learning was met with overwhelmingly positive feedback in terms of excitement, energy, and overall engagement.

Limitations

This cohort of individuals represents a small proportion of the total number of USCG corpsmen, and it is not fully representative of all practice settings. HSs can be assigned to USCG cutters as IDHSs, which would not be captured in this cohort. Even within a single clinic, the knowledge of HSs varies, as not all HS duties consist solely of clinical skills. Additionally, while the overall game framework was consistent among the 3 sites, there may have been unquantifiable differences in overall teaching style by the 3 pharmacists that may have resulted in different levels of content retention. Given the lack of similar studies in this population, this study can best be described as a quantitative descriptor of results rather than a statistical comparison of what instructional method works best.

Conclusions

The USCG greatly benefits from having trained and experienced HSs fulfilling mission support roles in the organization. In addition to traditional slide-based trainings, game-based learning can be considered to create engaging learning environments to support the knowledge retention of pharmacy and other medical topics for USCG corpsmen.

- US Coast Guard. Organizational overview. About the US Coast Guard. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.uscg.mil/About

- US Coast Guard. Missions. About US Coast Guard. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.uscg.mil/About/Missions/

- US Coast Guard. Health services technician. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.gocoastguard.com/careers/enlisted/hs

- Zhou F, Woodward Z. Impact of pharmacist interventions at an outpatient US Coast Guard clinic. Fed Pract. 2023;40(6):174-177. doi:10.12788/fp.0383

- Cusick J. A Jeopardy-style review game using team clickers. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10485. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10485

- Dahalan F, Alias N, Shaharom MSN. Gamification and game based learning for vocational education and training: a systematic literature review. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2023:1-39. doi:10.1007/s10639-022-11548-w

- Wesselink LA. Testing the Effectiveness of Game-Based Learning for Adults by Designing an Educational Game: A Design and Research Study to Investigate the Effectiveness of Educational Games for Adults to Learn Basic Skills of Microsoft Excel. Master’s thesis. University of Twente; 2020. Accessed October 22, 2025. http://essay.utwentw.nl/88229

- Del Cura-González I, Ariza-Cardiel G, Polentinos-Castro E, et al. Effectiveness of a game-based educational strategy e-EDUCAGUIA for implementing antimicrobial clinical practice guidelines in family medicine residents in Spain: a randomized clinical trial by cluster. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:893. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03843-4

- US Coast Guard. Organizational overview. About the US Coast Guard. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.uscg.mil/About

- US Coast Guard. Missions. About US Coast Guard. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.uscg.mil/About/Missions/

- US Coast Guard. Health services technician. Accessed October 14, 2025. https://www.gocoastguard.com/careers/enlisted/hs

- Zhou F, Woodward Z. Impact of pharmacist interventions at an outpatient US Coast Guard clinic. Fed Pract. 2023;40(6):174-177. doi:10.12788/fp.0383

- Cusick J. A Jeopardy-style review game using team clickers. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10485. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10485

- Dahalan F, Alias N, Shaharom MSN. Gamification and game based learning for vocational education and training: a systematic literature review. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr). 2023:1-39. doi:10.1007/s10639-022-11548-w

- Wesselink LA. Testing the Effectiveness of Game-Based Learning for Adults by Designing an Educational Game: A Design and Research Study to Investigate the Effectiveness of Educational Games for Adults to Learn Basic Skills of Microsoft Excel. Master’s thesis. University of Twente; 2020. Accessed October 22, 2025. http://essay.utwentw.nl/88229

- Del Cura-González I, Ariza-Cardiel G, Polentinos-Castro E, et al. Effectiveness of a game-based educational strategy e-EDUCAGUIA for implementing antimicrobial clinical practice guidelines in family medicine residents in Spain: a randomized clinical trial by cluster. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:893. doi:10.1186/s12909-022-03843-4

Daily Double! Assessing the Effectiveness of Game-Based Learning on the Pharmacy Knowledge of US Coast Guard Health Services Technicians

Daily Double! Assessing the Effectiveness of Game-Based Learning on the Pharmacy Knowledge of US Coast Guard Health Services Technicians