User login

Racemic Epinephrine May Be Better Option for Bronchiolitic Preemies

COVINGTON, KY. – Racemic epinephrine may be more effective in premature than in full-term infants who are hospitalized for bronchiolitis, a chart review suggests.

The positive response rate to inhaled racemic epinephrine was significantly higher at 54.3% among premature infants, compared with 28% among full-term infants (P = .003).

In contrast, there was no significant difference in documented positive response rates to albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin, Volmax, Vospire) among premature and full-term infants (43.4% vs. 38%; P = .18), Dr. Russell J. McCulloh reported in a poster at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

He said that few studies have examined the effectiveness of commonly used bronchiolitis therapies in children with a history of premature birth, even though these children are commonly affected by bronchiolitis and are at higher risk of severe outcomes and prolonged stay.

The chart review included 1,222 infants with and without a history of premature birth who were admitted for bronchiolitis to two academic medical centers. Of these, 229 (19%) were premature.

At baseline, preemies were significantly older than full-term infants (6.6 months vs. 5.4 months) and less likely to have day care exposure (15.3% vs. 24%), but more likely to have a history of wheeze (18% vs. 14%).

Premature patients had a significantly longer mean length of stay of 3.8 days compared with 2.5 days among full-term infants, although this did not differ significantly based on systemic steroid use (31% vs. 27.6%; P = .3), noted Dr. McCulloh of the pediatrics division at Rhode Island Hospital, Providence.

Premature infants were significantly more likely than full-term infants to require an ICU stay (23% vs. 11%), and they trended toward more pneumonia diagnosed (9.3% vs. 6%) and IV hydration (63% vs. 58.4%).

Full-term infants had more fever documented (45% vs. 36%) and urinary tract infections diagnosed (2.4% vs. 0%).

In logistic regression analyses, premature birth was independently associated with improved responsiveness to epinephrine (odds ratio, 1.89), Dr. McCulloh reported at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. McCulloh reported having no conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – Racemic epinephrine may be more effective in premature than in full-term infants who are hospitalized for bronchiolitis, a chart review suggests.

The positive response rate to inhaled racemic epinephrine was significantly higher at 54.3% among premature infants, compared with 28% among full-term infants (P = .003).

In contrast, there was no significant difference in documented positive response rates to albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin, Volmax, Vospire) among premature and full-term infants (43.4% vs. 38%; P = .18), Dr. Russell J. McCulloh reported in a poster at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

He said that few studies have examined the effectiveness of commonly used bronchiolitis therapies in children with a history of premature birth, even though these children are commonly affected by bronchiolitis and are at higher risk of severe outcomes and prolonged stay.

The chart review included 1,222 infants with and without a history of premature birth who were admitted for bronchiolitis to two academic medical centers. Of these, 229 (19%) were premature.

At baseline, preemies were significantly older than full-term infants (6.6 months vs. 5.4 months) and less likely to have day care exposure (15.3% vs. 24%), but more likely to have a history of wheeze (18% vs. 14%).

Premature patients had a significantly longer mean length of stay of 3.8 days compared with 2.5 days among full-term infants, although this did not differ significantly based on systemic steroid use (31% vs. 27.6%; P = .3), noted Dr. McCulloh of the pediatrics division at Rhode Island Hospital, Providence.

Premature infants were significantly more likely than full-term infants to require an ICU stay (23% vs. 11%), and they trended toward more pneumonia diagnosed (9.3% vs. 6%) and IV hydration (63% vs. 58.4%).

Full-term infants had more fever documented (45% vs. 36%) and urinary tract infections diagnosed (2.4% vs. 0%).

In logistic regression analyses, premature birth was independently associated with improved responsiveness to epinephrine (odds ratio, 1.89), Dr. McCulloh reported at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. McCulloh reported having no conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – Racemic epinephrine may be more effective in premature than in full-term infants who are hospitalized for bronchiolitis, a chart review suggests.

The positive response rate to inhaled racemic epinephrine was significantly higher at 54.3% among premature infants, compared with 28% among full-term infants (P = .003).

In contrast, there was no significant difference in documented positive response rates to albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin, Volmax, Vospire) among premature and full-term infants (43.4% vs. 38%; P = .18), Dr. Russell J. McCulloh reported in a poster at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

He said that few studies have examined the effectiveness of commonly used bronchiolitis therapies in children with a history of premature birth, even though these children are commonly affected by bronchiolitis and are at higher risk of severe outcomes and prolonged stay.

The chart review included 1,222 infants with and without a history of premature birth who were admitted for bronchiolitis to two academic medical centers. Of these, 229 (19%) were premature.

At baseline, preemies were significantly older than full-term infants (6.6 months vs. 5.4 months) and less likely to have day care exposure (15.3% vs. 24%), but more likely to have a history of wheeze (18% vs. 14%).

Premature patients had a significantly longer mean length of stay of 3.8 days compared with 2.5 days among full-term infants, although this did not differ significantly based on systemic steroid use (31% vs. 27.6%; P = .3), noted Dr. McCulloh of the pediatrics division at Rhode Island Hospital, Providence.

Premature infants were significantly more likely than full-term infants to require an ICU stay (23% vs. 11%), and they trended toward more pneumonia diagnosed (9.3% vs. 6%) and IV hydration (63% vs. 58.4%).

Full-term infants had more fever documented (45% vs. 36%) and urinary tract infections diagnosed (2.4% vs. 0%).

In logistic regression analyses, premature birth was independently associated with improved responsiveness to epinephrine (odds ratio, 1.89), Dr. McCulloh reported at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. McCulloh reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT THE PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2012 MEETING

Major Finding: The positive response rate to inhaled racemic epinephrine was 54.3% among premature infants and 28% among full-term infants.

Data Source: The data were from a chart review of 1,222 premature and full-term infants who were admitted with bronchiolitis to two children’s hospitals.

Disclosures: Dr. McCulloh reported having no conflicts of interest.

EEG Monitoring at Core of Status Epilepticus

COVINGTON, KY. – Early electroencephalogram monitoring is playing an increasingly critical role in the recognition and management of status epilepticus, the most common neurologic emergency of childhood.

EEG is important for a definitive diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (SE), particularly in children who have been in a convulsive state and in those with encephalopathy of unknown etiology or a seizure history, Dr. Rajit K. Basu of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center said at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

This view is formed in part by a recent study at his institution, in which video EEG monitoring revealed that more than one-third of children admitted for encephalopathy (35%) were in nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Almost all had convulsive seizures prior to presenting (92%) and more than half were being cared for on the floor (Pediatrics 2012;129:e748-55).

Similarly, an earlier study reported that up to 22% of children who had prolonged EEG monitoring after convulsive SE were found to be in nonconvulsive SE (Neurology 2010;74:636-42).

"These are the kids that I think really fall through the cracks for us – the ones that got a bunch of meds in the ER and are admitted to the floor for observation because they’re ‘sleepy’ or need to ‘wake up,’ " Dr. Basu said. "But you don’t know actually that they’ve recovered, and every minute that you let them go – every minute that you don’t know they’re in nonconvulsive status – is a problem."

He acknowledged that not every institution has the capacity for emergency EEG monitoring but said the idea is for clinicians to think about an EEG at 7 or 8 a.m. rather than 2 p.m.

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defined status epilepticus in 1993 as more than 30 minutes of continuous epileptic activity without complete recovery of consciousness, although more recent definitions have shortened the duration to 20, 15, or even 5 minutes of continuous seizure activity.

Essential to the management of SE is an understanding of the inciting disease and that seizures are neurotoxic, said Dr. Basu, lead for the hospital working group on management of refractory SE.

"Seizures are not a benign thing, even if you stop them," he said. "They’re a pre-status state. Your brain is on fire and that fire needs to be put out."

Multiple diagnostic algorithms for SE exist, including one by the ILAE that is expected to be revised soon, but most are center specific or user specific. The common thread, however, is that time matters, both for treatment response and outcomes.

"If you don’t act quickly, the outcome on the backside is severe," Dr. Basu said. "Even if they don’t die, which some kids unfortunately do, there is an increased incidence of epilepsy syndrome and poor neurologic recovery."

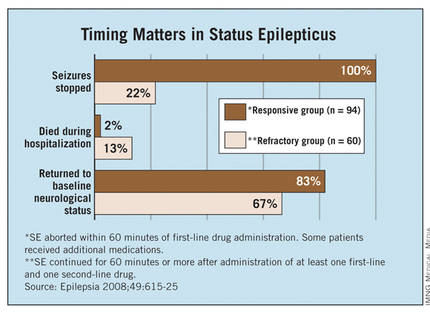

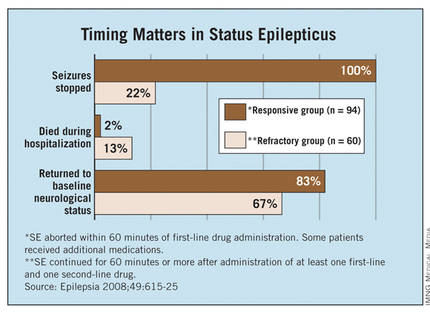

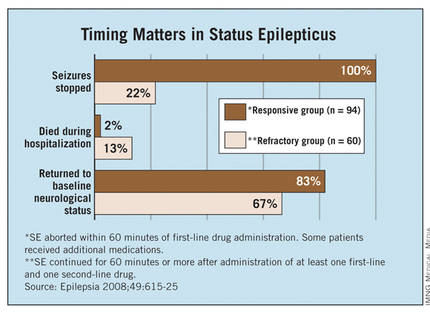

Indeed, the Mayo Clinic reported (Epilepsia 2008;49:615-25) that seizures stopped in 100% of children with SE receiving an additional second-line therapy within less than 60 minutes of the first drug, compared with only 22% of those receiving additional second-line therapy later in the clinical course. (Patients were allowed two second-line therapies before third-line treatment.)

Children in that study’s refractory SE group were significantly less likely than those treated more aggressively to return to baseline neurological status and more likely to die during hospitalization (see graph), and they had a twofold higher risk of developing a new neurological deficit or epilepsy at 4-year follow-up. (Researchers defined the refractory group as "clinical or electrographic seizures lasting longer than 60 minutes despite treatment with at least one first-line AED and one second-line AED.")

"The point is that if you follow some kind of time algorithm and deliver meds early and aggressively, you can get ahead of this and may stop status from developing," Dr. Basu said.

A continuing challenge is predicting which child presenting with SE will progress to refractory SE and likely end up in the ICU on burst suppression. To this end, Cincinnati Children’s recently launched the PARSE (Pediatric Acute Refractory Status Epilepticus) Initiative to derive a predictive model that may actually trigger a change in the "tempo" of SE management, he said.

Until predictive modeling becomes a reality, in-hospital and at-home seizure plans are being created. The London-Innsbruck Colloquium on Acute Seizures and Status Epilepticus has penned several SE protocols, with a recent review (Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011;24:165-70) detailing treatment advances since the first colloquium was held in 2007.

Hospitals are also developing at-home seizure plans that may be tailored to individual at-risk patients, featuring a red, yellow, and green light system similar to that used in at-home asthma action plans. Parents may understand the idea of giving rectal diazepam (Valium, Valrelease) at home, but such remote plans can help address questions such as when a second therapy should be delivered, the correct dosing of benzodiazepines, or when to come to the hospital, Dr. Basu said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. Basu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EEG, nonconvulsive status epilepticus in children, seizures, Dr. Rajit K. Basu, Pediatric Hospital Medicine, convulsive seizures, prolonged EEG monitoring, The International League Against Epilepsy, ILAE,

COVINGTON, KY. – Early electroencephalogram monitoring is playing an increasingly critical role in the recognition and management of status epilepticus, the most common neurologic emergency of childhood.

EEG is important for a definitive diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (SE), particularly in children who have been in a convulsive state and in those with encephalopathy of unknown etiology or a seizure history, Dr. Rajit K. Basu of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center said at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

This view is formed in part by a recent study at his institution, in which video EEG monitoring revealed that more than one-third of children admitted for encephalopathy (35%) were in nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Almost all had convulsive seizures prior to presenting (92%) and more than half were being cared for on the floor (Pediatrics 2012;129:e748-55).

Similarly, an earlier study reported that up to 22% of children who had prolonged EEG monitoring after convulsive SE were found to be in nonconvulsive SE (Neurology 2010;74:636-42).

"These are the kids that I think really fall through the cracks for us – the ones that got a bunch of meds in the ER and are admitted to the floor for observation because they’re ‘sleepy’ or need to ‘wake up,’ " Dr. Basu said. "But you don’t know actually that they’ve recovered, and every minute that you let them go – every minute that you don’t know they’re in nonconvulsive status – is a problem."

He acknowledged that not every institution has the capacity for emergency EEG monitoring but said the idea is for clinicians to think about an EEG at 7 or 8 a.m. rather than 2 p.m.

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defined status epilepticus in 1993 as more than 30 minutes of continuous epileptic activity without complete recovery of consciousness, although more recent definitions have shortened the duration to 20, 15, or even 5 minutes of continuous seizure activity.

Essential to the management of SE is an understanding of the inciting disease and that seizures are neurotoxic, said Dr. Basu, lead for the hospital working group on management of refractory SE.

"Seizures are not a benign thing, even if you stop them," he said. "They’re a pre-status state. Your brain is on fire and that fire needs to be put out."

Multiple diagnostic algorithms for SE exist, including one by the ILAE that is expected to be revised soon, but most are center specific or user specific. The common thread, however, is that time matters, both for treatment response and outcomes.

"If you don’t act quickly, the outcome on the backside is severe," Dr. Basu said. "Even if they don’t die, which some kids unfortunately do, there is an increased incidence of epilepsy syndrome and poor neurologic recovery."

Indeed, the Mayo Clinic reported (Epilepsia 2008;49:615-25) that seizures stopped in 100% of children with SE receiving an additional second-line therapy within less than 60 minutes of the first drug, compared with only 22% of those receiving additional second-line therapy later in the clinical course. (Patients were allowed two second-line therapies before third-line treatment.)

Children in that study’s refractory SE group were significantly less likely than those treated more aggressively to return to baseline neurological status and more likely to die during hospitalization (see graph), and they had a twofold higher risk of developing a new neurological deficit or epilepsy at 4-year follow-up. (Researchers defined the refractory group as "clinical or electrographic seizures lasting longer than 60 minutes despite treatment with at least one first-line AED and one second-line AED.")

"The point is that if you follow some kind of time algorithm and deliver meds early and aggressively, you can get ahead of this and may stop status from developing," Dr. Basu said.

A continuing challenge is predicting which child presenting with SE will progress to refractory SE and likely end up in the ICU on burst suppression. To this end, Cincinnati Children’s recently launched the PARSE (Pediatric Acute Refractory Status Epilepticus) Initiative to derive a predictive model that may actually trigger a change in the "tempo" of SE management, he said.

Until predictive modeling becomes a reality, in-hospital and at-home seizure plans are being created. The London-Innsbruck Colloquium on Acute Seizures and Status Epilepticus has penned several SE protocols, with a recent review (Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011;24:165-70) detailing treatment advances since the first colloquium was held in 2007.

Hospitals are also developing at-home seizure plans that may be tailored to individual at-risk patients, featuring a red, yellow, and green light system similar to that used in at-home asthma action plans. Parents may understand the idea of giving rectal diazepam (Valium, Valrelease) at home, but such remote plans can help address questions such as when a second therapy should be delivered, the correct dosing of benzodiazepines, or when to come to the hospital, Dr. Basu said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. Basu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – Early electroencephalogram monitoring is playing an increasingly critical role in the recognition and management of status epilepticus, the most common neurologic emergency of childhood.

EEG is important for a definitive diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (SE), particularly in children who have been in a convulsive state and in those with encephalopathy of unknown etiology or a seizure history, Dr. Rajit K. Basu of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center said at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

This view is formed in part by a recent study at his institution, in which video EEG monitoring revealed that more than one-third of children admitted for encephalopathy (35%) were in nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Almost all had convulsive seizures prior to presenting (92%) and more than half were being cared for on the floor (Pediatrics 2012;129:e748-55).

Similarly, an earlier study reported that up to 22% of children who had prolonged EEG monitoring after convulsive SE were found to be in nonconvulsive SE (Neurology 2010;74:636-42).

"These are the kids that I think really fall through the cracks for us – the ones that got a bunch of meds in the ER and are admitted to the floor for observation because they’re ‘sleepy’ or need to ‘wake up,’ " Dr. Basu said. "But you don’t know actually that they’ve recovered, and every minute that you let them go – every minute that you don’t know they’re in nonconvulsive status – is a problem."

He acknowledged that not every institution has the capacity for emergency EEG monitoring but said the idea is for clinicians to think about an EEG at 7 or 8 a.m. rather than 2 p.m.

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defined status epilepticus in 1993 as more than 30 minutes of continuous epileptic activity without complete recovery of consciousness, although more recent definitions have shortened the duration to 20, 15, or even 5 minutes of continuous seizure activity.

Essential to the management of SE is an understanding of the inciting disease and that seizures are neurotoxic, said Dr. Basu, lead for the hospital working group on management of refractory SE.

"Seizures are not a benign thing, even if you stop them," he said. "They’re a pre-status state. Your brain is on fire and that fire needs to be put out."

Multiple diagnostic algorithms for SE exist, including one by the ILAE that is expected to be revised soon, but most are center specific or user specific. The common thread, however, is that time matters, both for treatment response and outcomes.

"If you don’t act quickly, the outcome on the backside is severe," Dr. Basu said. "Even if they don’t die, which some kids unfortunately do, there is an increased incidence of epilepsy syndrome and poor neurologic recovery."

Indeed, the Mayo Clinic reported (Epilepsia 2008;49:615-25) that seizures stopped in 100% of children with SE receiving an additional second-line therapy within less than 60 minutes of the first drug, compared with only 22% of those receiving additional second-line therapy later in the clinical course. (Patients were allowed two second-line therapies before third-line treatment.)

Children in that study’s refractory SE group were significantly less likely than those treated more aggressively to return to baseline neurological status and more likely to die during hospitalization (see graph), and they had a twofold higher risk of developing a new neurological deficit or epilepsy at 4-year follow-up. (Researchers defined the refractory group as "clinical or electrographic seizures lasting longer than 60 minutes despite treatment with at least one first-line AED and one second-line AED.")

"The point is that if you follow some kind of time algorithm and deliver meds early and aggressively, you can get ahead of this and may stop status from developing," Dr. Basu said.

A continuing challenge is predicting which child presenting with SE will progress to refractory SE and likely end up in the ICU on burst suppression. To this end, Cincinnati Children’s recently launched the PARSE (Pediatric Acute Refractory Status Epilepticus) Initiative to derive a predictive model that may actually trigger a change in the "tempo" of SE management, he said.

Until predictive modeling becomes a reality, in-hospital and at-home seizure plans are being created. The London-Innsbruck Colloquium on Acute Seizures and Status Epilepticus has penned several SE protocols, with a recent review (Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011;24:165-70) detailing treatment advances since the first colloquium was held in 2007.

Hospitals are also developing at-home seizure plans that may be tailored to individual at-risk patients, featuring a red, yellow, and green light system similar to that used in at-home asthma action plans. Parents may understand the idea of giving rectal diazepam (Valium, Valrelease) at home, but such remote plans can help address questions such as when a second therapy should be delivered, the correct dosing of benzodiazepines, or when to come to the hospital, Dr. Basu said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. Basu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EEG, nonconvulsive status epilepticus in children, seizures, Dr. Rajit K. Basu, Pediatric Hospital Medicine, convulsive seizures, prolonged EEG monitoring, The International League Against Epilepsy, ILAE,

EEG, nonconvulsive status epilepticus in children, seizures, Dr. Rajit K. Basu, Pediatric Hospital Medicine, convulsive seizures, prolonged EEG monitoring, The International League Against Epilepsy, ILAE,

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2012 MEETING

No Easy Answers as Quality Measures for Pediatric Readmissions Loom

COVINGTON, KY. – A healthy 2-year-old is admitted for incision and drainage of a MRSA thigh abscess and is given intravenous clindamycin during a 1-day hospital stay before being discharged home with a prescription for oral clindamycin.

The child refuses to take the clindamycin at home, and is readmitted 3 days later with a new abscess on her arm that requires a 2-day hospital stay.

Was this readmission preventable?

Some attendees at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting thought it was out of the hospital’s hands, while others suggested the hospital was at fault because clindamycin is such an unpalatable medication that an oral dose should have been given at the hospital, along with instructions for how to make it more palatable at home.

The scenario is part of the ongoing Vanderbilt Readmissions Project, which seeks to identify patient and hospitalization characteristics of 15-day readmissions in children, create a 5-point "preventability scale" for early pediatric readmissions that can be applied by multiple reviewers, and institute measures to decrease potentially preventable readmissions.

What the investigators have found so far is that, even after reviewing the same clinical information for 200 pediatric readmissions, a panel of four knowledgeable pediatricians gave exactly the same ratings in 37.5% of cases, Dr. James C. Gay said. There was 94% agreement on planned readmissions (47/50 cases), but only 19% agreement on unplanned readmissions (28/150).

"Further studies are needed to develop concrete rules for assessing preventability that can be applied reproducibly by multiple reviewers in multiple types of readmissions," he said.

The Vanderbilt findings have financial implications for hospitals, as the federal government has already taken to heart the issue of preventable readmissions following the sentinel article reporting that 19.6% of Medicare beneficiaries were readmitted within 30 days at a cost of $17.4 billion in 2004 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1418-28). Many of these readmissions were thought to be avoidable by improvements in care and the discharge planning processes during the initial hospitalization.

The Affordable Care Act has also taken up the issue, and beginning Oct. 1, 2012, prospective payment system (PPS) hospitals will experience decreased Medicare payments for three index admissions – myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia – with "higher than expected" 30-day readmissions, coauthor Dr. Paul Hain explained at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will calculate hospitals’ actual readmissions, excluding planned readmissions and readmissions unrelated to the index admission, and then compare these to hospitals’ expected readmission rates. Hospitals with "higher than expected" rates will be required to pay back the payments they’ve received for readmissions deemed to be excessive.

Beginning in 2015, the CMS may expand the list of conditions to include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and several cardiac and vascular surgical procedures, he said. Similar penalties are likely to befall children’s hospitals, as rules that start in Medicare trickle down to Medicaid in 3-5 years.

Part of the problem is that researchers have yet to identify what can reliably drive down adult or pediatric readmissions or even determine whether the readmission interval should be 3, 7, 15, 60, 90, 365, or 30 days, as the CMS uses.

"We looked at 30 days, and the noise that comes in is incredible," said Dr. Hain, now with Children’s Medical Center, Dallas. Ultimately, the researchers chose 15 days for their analyses because of the intuitively greater relationship to events in the index hospitalization.

Based on 4-year data from Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tenn., the 15-day readmission rate among non-newborns was 9.6% in 2007, 9.6% in 2008, 8.8% in 2009, and 8.9% in 2010; and among newborns, the rates were 2.5%, 3.2%, 2.5%, and 3.0%, respectively.

The first real global study of pediatric readmissions reported that 16.7% of patients between 2 and 18 years old at 38 U.S. children’s hospitals were readmitted within 365 days, and that readmissions were strongly associated with any complex chronic condition, female gender, older age, black race, public insurance coverage, longer length of stay during the initial admission, and number of previous admissions (Pediatrics 2009;123:286-93).

One year later, the same group reported that the likelihood of readmission among children aged 2-18 years actually increased as a states’ health system performance ranking improved (J. Pediatr. 2010;157:98-102.e1), observed Dr. Gay of the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

Similarly vexing results have been observed among adults. The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., recently reported that general medicine patients with a documented follow-up appointment were slightly more likely to have a hospital readmission, make an emergency department visit, or die within 180 days after discharge than those without an appointment (Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170:955-60).

In the Vanderbilt cohort, the final expert consensus was that 40 early readmissions (20%) were more likely preventable (ratings 4 and 5). Nearly half of these were central venous catheter infections or ventriculo-peritoneal shunt malfunctions in children with serious chronic illnesses.

Extrapolating these results, about 1.7% of all hospital admissions would have a significant degree of preventability, Dr. Gay said. In absolute terms, about 250 admissions per year, or less than one admission per day, would be preventable at the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

"With 80% of readmissions planned or likely not preventable, it seems unreasonable to believe that pediatric readmissions are associated with substandard inpatient care, calling into question the validity of an all-cause readmission rate as a quality measure," he said. "If the responsibility for pediatric readmissions is placed on the hospital, then realistic benchmarks should be established."

Dr. Gay said more data is also needed from across the country, with some of that information trickling in from the recent Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. Various investigators reported that there was no relationship between length of stay and pediatric readmissions; 30-day readmission rates were low at 2%-8% in the top 10 APR-DRG (All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups) hospitals; and significant variability exists in readmission rates across hospitals for 10 of the top 30 APR-DRG index admissions.

"This may be where we need to hone our efforts," Dr. Gay said. "If there’s variability, there may be a reason for that variability that we can have an impact on."

Dr. Gay reported funding support for medical consulting for the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions. Dr. Hain reported no conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – A healthy 2-year-old is admitted for incision and drainage of a MRSA thigh abscess and is given intravenous clindamycin during a 1-day hospital stay before being discharged home with a prescription for oral clindamycin.

The child refuses to take the clindamycin at home, and is readmitted 3 days later with a new abscess on her arm that requires a 2-day hospital stay.

Was this readmission preventable?

Some attendees at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting thought it was out of the hospital’s hands, while others suggested the hospital was at fault because clindamycin is such an unpalatable medication that an oral dose should have been given at the hospital, along with instructions for how to make it more palatable at home.

The scenario is part of the ongoing Vanderbilt Readmissions Project, which seeks to identify patient and hospitalization characteristics of 15-day readmissions in children, create a 5-point "preventability scale" for early pediatric readmissions that can be applied by multiple reviewers, and institute measures to decrease potentially preventable readmissions.

What the investigators have found so far is that, even after reviewing the same clinical information for 200 pediatric readmissions, a panel of four knowledgeable pediatricians gave exactly the same ratings in 37.5% of cases, Dr. James C. Gay said. There was 94% agreement on planned readmissions (47/50 cases), but only 19% agreement on unplanned readmissions (28/150).

"Further studies are needed to develop concrete rules for assessing preventability that can be applied reproducibly by multiple reviewers in multiple types of readmissions," he said.

The Vanderbilt findings have financial implications for hospitals, as the federal government has already taken to heart the issue of preventable readmissions following the sentinel article reporting that 19.6% of Medicare beneficiaries were readmitted within 30 days at a cost of $17.4 billion in 2004 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1418-28). Many of these readmissions were thought to be avoidable by improvements in care and the discharge planning processes during the initial hospitalization.

The Affordable Care Act has also taken up the issue, and beginning Oct. 1, 2012, prospective payment system (PPS) hospitals will experience decreased Medicare payments for three index admissions – myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia – with "higher than expected" 30-day readmissions, coauthor Dr. Paul Hain explained at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will calculate hospitals’ actual readmissions, excluding planned readmissions and readmissions unrelated to the index admission, and then compare these to hospitals’ expected readmission rates. Hospitals with "higher than expected" rates will be required to pay back the payments they’ve received for readmissions deemed to be excessive.

Beginning in 2015, the CMS may expand the list of conditions to include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and several cardiac and vascular surgical procedures, he said. Similar penalties are likely to befall children’s hospitals, as rules that start in Medicare trickle down to Medicaid in 3-5 years.

Part of the problem is that researchers have yet to identify what can reliably drive down adult or pediatric readmissions or even determine whether the readmission interval should be 3, 7, 15, 60, 90, 365, or 30 days, as the CMS uses.

"We looked at 30 days, and the noise that comes in is incredible," said Dr. Hain, now with Children’s Medical Center, Dallas. Ultimately, the researchers chose 15 days for their analyses because of the intuitively greater relationship to events in the index hospitalization.

Based on 4-year data from Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tenn., the 15-day readmission rate among non-newborns was 9.6% in 2007, 9.6% in 2008, 8.8% in 2009, and 8.9% in 2010; and among newborns, the rates were 2.5%, 3.2%, 2.5%, and 3.0%, respectively.

The first real global study of pediatric readmissions reported that 16.7% of patients between 2 and 18 years old at 38 U.S. children’s hospitals were readmitted within 365 days, and that readmissions were strongly associated with any complex chronic condition, female gender, older age, black race, public insurance coverage, longer length of stay during the initial admission, and number of previous admissions (Pediatrics 2009;123:286-93).

One year later, the same group reported that the likelihood of readmission among children aged 2-18 years actually increased as a states’ health system performance ranking improved (J. Pediatr. 2010;157:98-102.e1), observed Dr. Gay of the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

Similarly vexing results have been observed among adults. The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., recently reported that general medicine patients with a documented follow-up appointment were slightly more likely to have a hospital readmission, make an emergency department visit, or die within 180 days after discharge than those without an appointment (Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170:955-60).

In the Vanderbilt cohort, the final expert consensus was that 40 early readmissions (20%) were more likely preventable (ratings 4 and 5). Nearly half of these were central venous catheter infections or ventriculo-peritoneal shunt malfunctions in children with serious chronic illnesses.

Extrapolating these results, about 1.7% of all hospital admissions would have a significant degree of preventability, Dr. Gay said. In absolute terms, about 250 admissions per year, or less than one admission per day, would be preventable at the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

"With 80% of readmissions planned or likely not preventable, it seems unreasonable to believe that pediatric readmissions are associated with substandard inpatient care, calling into question the validity of an all-cause readmission rate as a quality measure," he said. "If the responsibility for pediatric readmissions is placed on the hospital, then realistic benchmarks should be established."

Dr. Gay said more data is also needed from across the country, with some of that information trickling in from the recent Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. Various investigators reported that there was no relationship between length of stay and pediatric readmissions; 30-day readmission rates were low at 2%-8% in the top 10 APR-DRG (All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups) hospitals; and significant variability exists in readmission rates across hospitals for 10 of the top 30 APR-DRG index admissions.

"This may be where we need to hone our efforts," Dr. Gay said. "If there’s variability, there may be a reason for that variability that we can have an impact on."

Dr. Gay reported funding support for medical consulting for the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions. Dr. Hain reported no conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – A healthy 2-year-old is admitted for incision and drainage of a MRSA thigh abscess and is given intravenous clindamycin during a 1-day hospital stay before being discharged home with a prescription for oral clindamycin.

The child refuses to take the clindamycin at home, and is readmitted 3 days later with a new abscess on her arm that requires a 2-day hospital stay.

Was this readmission preventable?

Some attendees at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting thought it was out of the hospital’s hands, while others suggested the hospital was at fault because clindamycin is such an unpalatable medication that an oral dose should have been given at the hospital, along with instructions for how to make it more palatable at home.

The scenario is part of the ongoing Vanderbilt Readmissions Project, which seeks to identify patient and hospitalization characteristics of 15-day readmissions in children, create a 5-point "preventability scale" for early pediatric readmissions that can be applied by multiple reviewers, and institute measures to decrease potentially preventable readmissions.

What the investigators have found so far is that, even after reviewing the same clinical information for 200 pediatric readmissions, a panel of four knowledgeable pediatricians gave exactly the same ratings in 37.5% of cases, Dr. James C. Gay said. There was 94% agreement on planned readmissions (47/50 cases), but only 19% agreement on unplanned readmissions (28/150).

"Further studies are needed to develop concrete rules for assessing preventability that can be applied reproducibly by multiple reviewers in multiple types of readmissions," he said.

The Vanderbilt findings have financial implications for hospitals, as the federal government has already taken to heart the issue of preventable readmissions following the sentinel article reporting that 19.6% of Medicare beneficiaries were readmitted within 30 days at a cost of $17.4 billion in 2004 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1418-28). Many of these readmissions were thought to be avoidable by improvements in care and the discharge planning processes during the initial hospitalization.

The Affordable Care Act has also taken up the issue, and beginning Oct. 1, 2012, prospective payment system (PPS) hospitals will experience decreased Medicare payments for three index admissions – myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia – with "higher than expected" 30-day readmissions, coauthor Dr. Paul Hain explained at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will calculate hospitals’ actual readmissions, excluding planned readmissions and readmissions unrelated to the index admission, and then compare these to hospitals’ expected readmission rates. Hospitals with "higher than expected" rates will be required to pay back the payments they’ve received for readmissions deemed to be excessive.

Beginning in 2015, the CMS may expand the list of conditions to include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and several cardiac and vascular surgical procedures, he said. Similar penalties are likely to befall children’s hospitals, as rules that start in Medicare trickle down to Medicaid in 3-5 years.

Part of the problem is that researchers have yet to identify what can reliably drive down adult or pediatric readmissions or even determine whether the readmission interval should be 3, 7, 15, 60, 90, 365, or 30 days, as the CMS uses.

"We looked at 30 days, and the noise that comes in is incredible," said Dr. Hain, now with Children’s Medical Center, Dallas. Ultimately, the researchers chose 15 days for their analyses because of the intuitively greater relationship to events in the index hospitalization.

Based on 4-year data from Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tenn., the 15-day readmission rate among non-newborns was 9.6% in 2007, 9.6% in 2008, 8.8% in 2009, and 8.9% in 2010; and among newborns, the rates were 2.5%, 3.2%, 2.5%, and 3.0%, respectively.

The first real global study of pediatric readmissions reported that 16.7% of patients between 2 and 18 years old at 38 U.S. children’s hospitals were readmitted within 365 days, and that readmissions were strongly associated with any complex chronic condition, female gender, older age, black race, public insurance coverage, longer length of stay during the initial admission, and number of previous admissions (Pediatrics 2009;123:286-93).

One year later, the same group reported that the likelihood of readmission among children aged 2-18 years actually increased as a states’ health system performance ranking improved (J. Pediatr. 2010;157:98-102.e1), observed Dr. Gay of the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

Similarly vexing results have been observed among adults. The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., recently reported that general medicine patients with a documented follow-up appointment were slightly more likely to have a hospital readmission, make an emergency department visit, or die within 180 days after discharge than those without an appointment (Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170:955-60).

In the Vanderbilt cohort, the final expert consensus was that 40 early readmissions (20%) were more likely preventable (ratings 4 and 5). Nearly half of these were central venous catheter infections or ventriculo-peritoneal shunt malfunctions in children with serious chronic illnesses.

Extrapolating these results, about 1.7% of all hospital admissions would have a significant degree of preventability, Dr. Gay said. In absolute terms, about 250 admissions per year, or less than one admission per day, would be preventable at the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

"With 80% of readmissions planned or likely not preventable, it seems unreasonable to believe that pediatric readmissions are associated with substandard inpatient care, calling into question the validity of an all-cause readmission rate as a quality measure," he said. "If the responsibility for pediatric readmissions is placed on the hospital, then realistic benchmarks should be established."

Dr. Gay said more data is also needed from across the country, with some of that information trickling in from the recent Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. Various investigators reported that there was no relationship between length of stay and pediatric readmissions; 30-day readmission rates were low at 2%-8% in the top 10 APR-DRG (All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups) hospitals; and significant variability exists in readmission rates across hospitals for 10 of the top 30 APR-DRG index admissions.

"This may be where we need to hone our efforts," Dr. Gay said. "If there’s variability, there may be a reason for that variability that we can have an impact on."

Dr. Gay reported funding support for medical consulting for the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions. Dr. Hain reported no conflicts of interest.

AT THE PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2012 MEETING

Think Urine When Testing for Concurrent Infection in Pediatric Bronchiolitis

COVINGTON, KY. – Providers continue to rely on blood cultures to detect serious bacterial infections in children with bronchiolitis, even though urinary tract infections are the most common culprit, a chart review shows.

"Even though there is outstanding evidence in the literature that cultures are unnecessary in the vast majority of infants with clinical bronchiolitis, this practice is common, has a cost, and false-positive results can result in prolonged length of stay and exposure to antibiotics that is unnecessary," according to researcher Dr. Brian Alverson.

Dr. Alverson of Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., said the chart review supports other studies that show that the rate of UTI positivity is approximately the same as reported rates of benign transient bacteriuria in infants. Indeed, the incidence of UTI in the analysis was only 2.9% among patients who underwent urine testing, and the rates of meningitis and bacteremia were zero.

The study comprised 652 children, aged 1-24 months, with a discharge diagnosis of bronchiolitis. Of those, 26% had a blood culture obtained and 18.4% had a urinalysis or urine culture. Of patients undergoing blood cultures, 55% also had a urinalysis or urine culture.

"People who are going to look for infections aren’t looking in the right place," the study’s lead author, Dr. Jamie Librizzi, said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012.

The findings are noteworthy since children in the analysis were discharged during 2007-2008 – after the American Academy of Pediatrics bronchiolitis practice guidelines recommending that clinicians should diagnose bronchiolitis and assess disease severity on the basis of history and physical examination.

The 2006 guidelines (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93) state that "the clinical utility of diagnostic testing in infants with suspected bronchiolitis is not well supported by evidence" and that "the occurrence of serious bacterial infections (SBIs) such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), sepsis, and meningitis is very low."

Despite the cohort being drawn from Hasbro Children’s Hospital and University of Missouri Children’s Hospital in Columbia, the misdirected testing could be explained by a knowledge gap and a wide variation in providers including residents, emergency department physicians, and referring community physicians, Dr. Librizzi said.

"Even though we know these guidelines are out there, the practices maybe still haven’t caught up to the evidence," she said. " ... It’s also hard when a kid comes in febrile, not looking great, to sit back and be assured that the numbers are really low for a concurrent infection."

"It’s a good reminder that we still have work to do educating our emergency departments," Dr. Paul Hain, now with Children’s Medical Center, Dallas, commented in a separate interview. "A lot of kids are seen in adult EDs, and folks who are not familiar with children are mostly scared of adult bacteremia and think that blood cultures are what they need, even though bronchiolitis is a special subset."

Children who were evaluated for an SBI received significantly more antibiotics and had significantly longer hospital stays, said Dr. Librizzi, formerly with Hasbro and now a hospitalist fellow at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington.

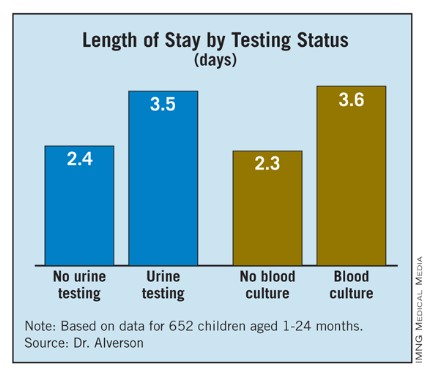

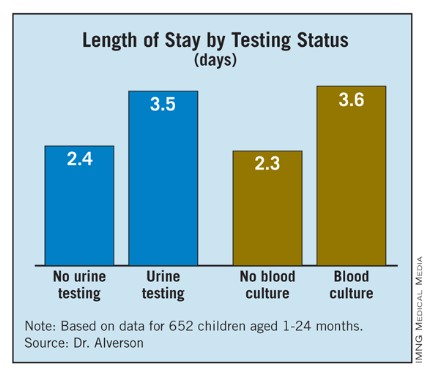

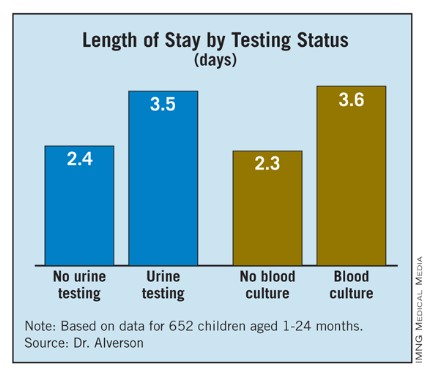

Length of stay (LOS) was 3.6 days for patients with blood cultures and 2.3 days for those without blood cultures, and 3.5 days for patients undergoing urine testing alone vs. 2.4 days for those without urine testing More than half (56.6%) of patients who underwent testing for an SBI received antibiotics, compared with 24% who did not.

Specifically, the percent of children receiving antibiotics was 17.5% among children with no urine testing (48/445); 48.6% for those with urine testing (51/105); 14% for those without blood cultures (58/411); and 51% for those with blood cultures (71/139), Dr. Librizzi said.

LOS for patients without an SBI who were on antibiotics was significantly longer than for patients off antibiotics (3.7 days vs. 2.5 days).

All of the children in the study were deemed to have bronchiolitis based on the note of the ED physician, or the ward’s physician for direct admissions. Their mean age was 5.6 months, 19% were premature infants, and 57% were male.

Patients were considered positive for a UTI if cultures grew more than 10,000 colony-forming U/mL of a single organism, or in the absence of culture results, if urinalysis was positive for leukocyte esterase and/or nitrites with evidence of pyuria (more than five white blood cells/high-power field).

Patients were considered bacteremic if blood cultures were positive for a pathogen not deemed a contaminant in more than one set, the authors reported in a poster at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and Academic Pediatric Association.

The authors and Dr. Hain reported no conflicts of interest. Printing of the poster was funded by a Thrasher Research Fund Early Career Award.

The ABIM Foundation has embarked on a "Choosing Wisely" campaign to identify five tests and procedures in each field of medicine whose necessity should be questioned. Blood cultures and urine testing are key candidates in the field of pediatrics.

|

Researchers Dr. M. Olivia Titus and Dr. Seth W. Wright (Pediatrics 2003;112:282-84) could barely justify urine testing in the febrile 4-week-old with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), much less blood taking cultures. The widespread use of those tests in infants with clinical bronchiolitis who are older that 8 weeks of age, as is well documented in this new study, appears to be wasteful, even harmful.

Dr. Kevin Powell is with the department of pediatrics at St. Louis University and a pediatric hospitalist at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center in St. Louis. He reports having no relevant conflicts of interest.

The ABIM Foundation has embarked on a "Choosing Wisely" campaign to identify five tests and procedures in each field of medicine whose necessity should be questioned. Blood cultures and urine testing are key candidates in the field of pediatrics.

|

Researchers Dr. M. Olivia Titus and Dr. Seth W. Wright (Pediatrics 2003;112:282-84) could barely justify urine testing in the febrile 4-week-old with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), much less blood taking cultures. The widespread use of those tests in infants with clinical bronchiolitis who are older that 8 weeks of age, as is well documented in this new study, appears to be wasteful, even harmful.

Dr. Kevin Powell is with the department of pediatrics at St. Louis University and a pediatric hospitalist at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center in St. Louis. He reports having no relevant conflicts of interest.

The ABIM Foundation has embarked on a "Choosing Wisely" campaign to identify five tests and procedures in each field of medicine whose necessity should be questioned. Blood cultures and urine testing are key candidates in the field of pediatrics.

|

Researchers Dr. M. Olivia Titus and Dr. Seth W. Wright (Pediatrics 2003;112:282-84) could barely justify urine testing in the febrile 4-week-old with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), much less blood taking cultures. The widespread use of those tests in infants with clinical bronchiolitis who are older that 8 weeks of age, as is well documented in this new study, appears to be wasteful, even harmful.

Dr. Kevin Powell is with the department of pediatrics at St. Louis University and a pediatric hospitalist at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center in St. Louis. He reports having no relevant conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – Providers continue to rely on blood cultures to detect serious bacterial infections in children with bronchiolitis, even though urinary tract infections are the most common culprit, a chart review shows.

"Even though there is outstanding evidence in the literature that cultures are unnecessary in the vast majority of infants with clinical bronchiolitis, this practice is common, has a cost, and false-positive results can result in prolonged length of stay and exposure to antibiotics that is unnecessary," according to researcher Dr. Brian Alverson.

Dr. Alverson of Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., said the chart review supports other studies that show that the rate of UTI positivity is approximately the same as reported rates of benign transient bacteriuria in infants. Indeed, the incidence of UTI in the analysis was only 2.9% among patients who underwent urine testing, and the rates of meningitis and bacteremia were zero.

The study comprised 652 children, aged 1-24 months, with a discharge diagnosis of bronchiolitis. Of those, 26% had a blood culture obtained and 18.4% had a urinalysis or urine culture. Of patients undergoing blood cultures, 55% also had a urinalysis or urine culture.

"People who are going to look for infections aren’t looking in the right place," the study’s lead author, Dr. Jamie Librizzi, said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012.

The findings are noteworthy since children in the analysis were discharged during 2007-2008 – after the American Academy of Pediatrics bronchiolitis practice guidelines recommending that clinicians should diagnose bronchiolitis and assess disease severity on the basis of history and physical examination.

The 2006 guidelines (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93) state that "the clinical utility of diagnostic testing in infants with suspected bronchiolitis is not well supported by evidence" and that "the occurrence of serious bacterial infections (SBIs) such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), sepsis, and meningitis is very low."

Despite the cohort being drawn from Hasbro Children’s Hospital and University of Missouri Children’s Hospital in Columbia, the misdirected testing could be explained by a knowledge gap and a wide variation in providers including residents, emergency department physicians, and referring community physicians, Dr. Librizzi said.

"Even though we know these guidelines are out there, the practices maybe still haven’t caught up to the evidence," she said. " ... It’s also hard when a kid comes in febrile, not looking great, to sit back and be assured that the numbers are really low for a concurrent infection."

"It’s a good reminder that we still have work to do educating our emergency departments," Dr. Paul Hain, now with Children’s Medical Center, Dallas, commented in a separate interview. "A lot of kids are seen in adult EDs, and folks who are not familiar with children are mostly scared of adult bacteremia and think that blood cultures are what they need, even though bronchiolitis is a special subset."

Children who were evaluated for an SBI received significantly more antibiotics and had significantly longer hospital stays, said Dr. Librizzi, formerly with Hasbro and now a hospitalist fellow at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington.

Length of stay (LOS) was 3.6 days for patients with blood cultures and 2.3 days for those without blood cultures, and 3.5 days for patients undergoing urine testing alone vs. 2.4 days for those without urine testing More than half (56.6%) of patients who underwent testing for an SBI received antibiotics, compared with 24% who did not.

Specifically, the percent of children receiving antibiotics was 17.5% among children with no urine testing (48/445); 48.6% for those with urine testing (51/105); 14% for those without blood cultures (58/411); and 51% for those with blood cultures (71/139), Dr. Librizzi said.

LOS for patients without an SBI who were on antibiotics was significantly longer than for patients off antibiotics (3.7 days vs. 2.5 days).

All of the children in the study were deemed to have bronchiolitis based on the note of the ED physician, or the ward’s physician for direct admissions. Their mean age was 5.6 months, 19% were premature infants, and 57% were male.

Patients were considered positive for a UTI if cultures grew more than 10,000 colony-forming U/mL of a single organism, or in the absence of culture results, if urinalysis was positive for leukocyte esterase and/or nitrites with evidence of pyuria (more than five white blood cells/high-power field).

Patients were considered bacteremic if blood cultures were positive for a pathogen not deemed a contaminant in more than one set, the authors reported in a poster at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and Academic Pediatric Association.

The authors and Dr. Hain reported no conflicts of interest. Printing of the poster was funded by a Thrasher Research Fund Early Career Award.

COVINGTON, KY. – Providers continue to rely on blood cultures to detect serious bacterial infections in children with bronchiolitis, even though urinary tract infections are the most common culprit, a chart review shows.

"Even though there is outstanding evidence in the literature that cultures are unnecessary in the vast majority of infants with clinical bronchiolitis, this practice is common, has a cost, and false-positive results can result in prolonged length of stay and exposure to antibiotics that is unnecessary," according to researcher Dr. Brian Alverson.

Dr. Alverson of Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., said the chart review supports other studies that show that the rate of UTI positivity is approximately the same as reported rates of benign transient bacteriuria in infants. Indeed, the incidence of UTI in the analysis was only 2.9% among patients who underwent urine testing, and the rates of meningitis and bacteremia were zero.

The study comprised 652 children, aged 1-24 months, with a discharge diagnosis of bronchiolitis. Of those, 26% had a blood culture obtained and 18.4% had a urinalysis or urine culture. Of patients undergoing blood cultures, 55% also had a urinalysis or urine culture.

"People who are going to look for infections aren’t looking in the right place," the study’s lead author, Dr. Jamie Librizzi, said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012.

The findings are noteworthy since children in the analysis were discharged during 2007-2008 – after the American Academy of Pediatrics bronchiolitis practice guidelines recommending that clinicians should diagnose bronchiolitis and assess disease severity on the basis of history and physical examination.

The 2006 guidelines (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93) state that "the clinical utility of diagnostic testing in infants with suspected bronchiolitis is not well supported by evidence" and that "the occurrence of serious bacterial infections (SBIs) such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), sepsis, and meningitis is very low."

Despite the cohort being drawn from Hasbro Children’s Hospital and University of Missouri Children’s Hospital in Columbia, the misdirected testing could be explained by a knowledge gap and a wide variation in providers including residents, emergency department physicians, and referring community physicians, Dr. Librizzi said.

"Even though we know these guidelines are out there, the practices maybe still haven’t caught up to the evidence," she said. " ... It’s also hard when a kid comes in febrile, not looking great, to sit back and be assured that the numbers are really low for a concurrent infection."

"It’s a good reminder that we still have work to do educating our emergency departments," Dr. Paul Hain, now with Children’s Medical Center, Dallas, commented in a separate interview. "A lot of kids are seen in adult EDs, and folks who are not familiar with children are mostly scared of adult bacteremia and think that blood cultures are what they need, even though bronchiolitis is a special subset."

Children who were evaluated for an SBI received significantly more antibiotics and had significantly longer hospital stays, said Dr. Librizzi, formerly with Hasbro and now a hospitalist fellow at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington.

Length of stay (LOS) was 3.6 days for patients with blood cultures and 2.3 days for those without blood cultures, and 3.5 days for patients undergoing urine testing alone vs. 2.4 days for those without urine testing More than half (56.6%) of patients who underwent testing for an SBI received antibiotics, compared with 24% who did not.

Specifically, the percent of children receiving antibiotics was 17.5% among children with no urine testing (48/445); 48.6% for those with urine testing (51/105); 14% for those without blood cultures (58/411); and 51% for those with blood cultures (71/139), Dr. Librizzi said.

LOS for patients without an SBI who were on antibiotics was significantly longer than for patients off antibiotics (3.7 days vs. 2.5 days).

All of the children in the study were deemed to have bronchiolitis based on the note of the ED physician, or the ward’s physician for direct admissions. Their mean age was 5.6 months, 19% were premature infants, and 57% were male.

Patients were considered positive for a UTI if cultures grew more than 10,000 colony-forming U/mL of a single organism, or in the absence of culture results, if urinalysis was positive for leukocyte esterase and/or nitrites with evidence of pyuria (more than five white blood cells/high-power field).

Patients were considered bacteremic if blood cultures were positive for a pathogen not deemed a contaminant in more than one set, the authors reported in a poster at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and Academic Pediatric Association.

The authors and Dr. Hain reported no conflicts of interest. Printing of the poster was funded by a Thrasher Research Fund Early Career Award.

AT THE PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2012 MEETING

Major Finding: Obtaining a blood or urine culture increased the length of stay by more than 1 full day (3.6 days vs. 2.3 days for patients with and without blood cultures, respectively; 3.5 vs. 2.4 days for patients with and without urine testing alone, respectively).

Data Source: Retrospective chart review of 652 hospitalized patients, aged 1-24 months.

Disclosures: The authors and Dr. Hain reported no conflicts of interest. Printing of the poster was funded by a Thrasher Research Fund Early Career Award.

Having Interpreters Down the Hall Improved Discharge Times

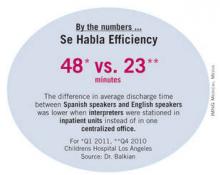

COVINGTON, KY. – Basing an interpreter directly inside inpatient units shaved roughly 30 minutes off a nearly 1-hour delay in discharge times for patients from Spanish-speaking families at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles.

"We have a thousand discharges per month and 60%-70% require a translator, so it made a big difference," Dr. Ara Balkian, chief medical director of inpatient operations and associate chair of inpatient pediatrics, said at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

Prior to the intervention, interpreters were centralized in a single office away from the units and were deployed as requests were submitted. In the fourth quarter of 2010, however, a Spanish-language interpreter was stationed on one of the medical-surgical floors for 4-6 hours per day during peak weekday discharge times to assist with discharge instructions.

Between the third quarters of 2009 and 2010, there was a statistically significant difference of 41 minutes in mean discharge times between English- and Spanish-speaking families, he said. The average time between the discharge order and the patient’s actually being discharged was 2 hours 25 minutes for English-speaking families and 3 hours 6 minutes for Spanish-speaking families.

During the intervention period, the difference decreased to 23 minutes in the fourth quarter of 2010 and to 27 minutes in the first quarter of 2011, and was no longer significant, he said.

As for why times lagged for Spanish-speaking families compared with English speakers, Dr. Balkian said the investigators hypothesize that many discharge components – such as instructions, or the interpretation of pharmacy directions – all require more time to convert to the parent’s or guardian’s primary language. The findings were based on the preferred language of the adults, even if the child spoke perfect English, Dr. Balkian explained.

He said it’s possible that interpreters were spending more time educating Spanish-speaking families, who according to previously published studies may have disparities in health literacy, compared with English speakers. In addition, the use of the unit-based interpreters during discharge and rounds identified more errors in the medication reconciliation and discharge instructions of Spanish-speaking patients. This may have been the result of miscommunication with non–Spanish-speaking providers while the components of the discharge were being prepared.

As fate would have it, funding for the project dried up and the interpreters were pulled off the units in the second quarter of 2011. Once again, the disparity in discharge times between Spanish speakers and English speakers increased significantly, this time to 48 minutes, Dr. Balkian said. The team also required more translators with increased hours on the units to meet the discharge demands in a consistent way.

Based on the results and longer response times resulting from the centralized interpreter office’s move to a location farther away from the inpatient units, funding has been restored and interpreters are again based in the units.

"Anecdotally, the nurses and interpreters do believe the discharge times have improved for Spanish-speaking patients," he said.

The investigators are currently collecting data on discharge times since the second quarter of 2011, and may expand the scope of their research to other non–English-speaking patients.

In a separate study presented at the meeting, interventions to improve awareness of, access to, and accountability for interpreter usage doubled the use of interpreters in a medical unit, compared with the rest of the hospital, to about three interpreter encounters per limited English-proficiency patient-day.

Interventions included staff education, inclusion of language needs in the emergency department admissions request, instructions in how to access face-to-face interpreter services, placement of interpreter phones in all rooms at all time, and providing for documentation of interpreter usage for attending notes.

Increased interpreter usage has been sustained, compared with other inpatient units, although multiple clinical encounters still occur without interpreters, reported Dr. Padmaja Pavuluri, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Balkian and Dr. Pavuluri reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – Basing an interpreter directly inside inpatient units shaved roughly 30 minutes off a nearly 1-hour delay in discharge times for patients from Spanish-speaking families at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles.

"We have a thousand discharges per month and 60%-70% require a translator, so it made a big difference," Dr. Ara Balkian, chief medical director of inpatient operations and associate chair of inpatient pediatrics, said at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

Prior to the intervention, interpreters were centralized in a single office away from the units and were deployed as requests were submitted. In the fourth quarter of 2010, however, a Spanish-language interpreter was stationed on one of the medical-surgical floors for 4-6 hours per day during peak weekday discharge times to assist with discharge instructions.

Between the third quarters of 2009 and 2010, there was a statistically significant difference of 41 minutes in mean discharge times between English- and Spanish-speaking families, he said. The average time between the discharge order and the patient’s actually being discharged was 2 hours 25 minutes for English-speaking families and 3 hours 6 minutes for Spanish-speaking families.

During the intervention period, the difference decreased to 23 minutes in the fourth quarter of 2010 and to 27 minutes in the first quarter of 2011, and was no longer significant, he said.

As for why times lagged for Spanish-speaking families compared with English speakers, Dr. Balkian said the investigators hypothesize that many discharge components – such as instructions, or the interpretation of pharmacy directions – all require more time to convert to the parent’s or guardian’s primary language. The findings were based on the preferred language of the adults, even if the child spoke perfect English, Dr. Balkian explained.

He said it’s possible that interpreters were spending more time educating Spanish-speaking families, who according to previously published studies may have disparities in health literacy, compared with English speakers. In addition, the use of the unit-based interpreters during discharge and rounds identified more errors in the medication reconciliation and discharge instructions of Spanish-speaking patients. This may have been the result of miscommunication with non–Spanish-speaking providers while the components of the discharge were being prepared.

As fate would have it, funding for the project dried up and the interpreters were pulled off the units in the second quarter of 2011. Once again, the disparity in discharge times between Spanish speakers and English speakers increased significantly, this time to 48 minutes, Dr. Balkian said. The team also required more translators with increased hours on the units to meet the discharge demands in a consistent way.

Based on the results and longer response times resulting from the centralized interpreter office’s move to a location farther away from the inpatient units, funding has been restored and interpreters are again based in the units.

"Anecdotally, the nurses and interpreters do believe the discharge times have improved for Spanish-speaking patients," he said.

The investigators are currently collecting data on discharge times since the second quarter of 2011, and may expand the scope of their research to other non–English-speaking patients.

In a separate study presented at the meeting, interventions to improve awareness of, access to, and accountability for interpreter usage doubled the use of interpreters in a medical unit, compared with the rest of the hospital, to about three interpreter encounters per limited English-proficiency patient-day.

Interventions included staff education, inclusion of language needs in the emergency department admissions request, instructions in how to access face-to-face interpreter services, placement of interpreter phones in all rooms at all time, and providing for documentation of interpreter usage for attending notes.

Increased interpreter usage has been sustained, compared with other inpatient units, although multiple clinical encounters still occur without interpreters, reported Dr. Padmaja Pavuluri, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Balkian and Dr. Pavuluri reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – Basing an interpreter directly inside inpatient units shaved roughly 30 minutes off a nearly 1-hour delay in discharge times for patients from Spanish-speaking families at Childrens Hospital Los Angeles.

"We have a thousand discharges per month and 60%-70% require a translator, so it made a big difference," Dr. Ara Balkian, chief medical director of inpatient operations and associate chair of inpatient pediatrics, said at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

Prior to the intervention, interpreters were centralized in a single office away from the units and were deployed as requests were submitted. In the fourth quarter of 2010, however, a Spanish-language interpreter was stationed on one of the medical-surgical floors for 4-6 hours per day during peak weekday discharge times to assist with discharge instructions.

Between the third quarters of 2009 and 2010, there was a statistically significant difference of 41 minutes in mean discharge times between English- and Spanish-speaking families, he said. The average time between the discharge order and the patient’s actually being discharged was 2 hours 25 minutes for English-speaking families and 3 hours 6 minutes for Spanish-speaking families.

During the intervention period, the difference decreased to 23 minutes in the fourth quarter of 2010 and to 27 minutes in the first quarter of 2011, and was no longer significant, he said.

As for why times lagged for Spanish-speaking families compared with English speakers, Dr. Balkian said the investigators hypothesize that many discharge components – such as instructions, or the interpretation of pharmacy directions – all require more time to convert to the parent’s or guardian’s primary language. The findings were based on the preferred language of the adults, even if the child spoke perfect English, Dr. Balkian explained.

He said it’s possible that interpreters were spending more time educating Spanish-speaking families, who according to previously published studies may have disparities in health literacy, compared with English speakers. In addition, the use of the unit-based interpreters during discharge and rounds identified more errors in the medication reconciliation and discharge instructions of Spanish-speaking patients. This may have been the result of miscommunication with non–Spanish-speaking providers while the components of the discharge were being prepared.

As fate would have it, funding for the project dried up and the interpreters were pulled off the units in the second quarter of 2011. Once again, the disparity in discharge times between Spanish speakers and English speakers increased significantly, this time to 48 minutes, Dr. Balkian said. The team also required more translators with increased hours on the units to meet the discharge demands in a consistent way.

Based on the results and longer response times resulting from the centralized interpreter office’s move to a location farther away from the inpatient units, funding has been restored and interpreters are again based in the units.

"Anecdotally, the nurses and interpreters do believe the discharge times have improved for Spanish-speaking patients," he said.

The investigators are currently collecting data on discharge times since the second quarter of 2011, and may expand the scope of their research to other non–English-speaking patients.

In a separate study presented at the meeting, interventions to improve awareness of, access to, and accountability for interpreter usage doubled the use of interpreters in a medical unit, compared with the rest of the hospital, to about three interpreter encounters per limited English-proficiency patient-day.

Interventions included staff education, inclusion of language needs in the emergency department admissions request, instructions in how to access face-to-face interpreter services, placement of interpreter phones in all rooms at all time, and providing for documentation of interpreter usage for attending notes.

Increased interpreter usage has been sustained, compared with other inpatient units, although multiple clinical encounters still occur without interpreters, reported Dr. Padmaja Pavuluri, a pediatric hospitalist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Balkian and Dr. Pavuluri reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT THE PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2012 MEETING

Major Finding: The difference in discharge time delays between patients from Spanish- and English-speaking families decreased from a mean 41 minutes (when interpreters were based in a central office) to 23 minutes in 2010 and to 27 minutes in 2011 (when interpreters were based on the inpatient unit).

Data Source: This was an intervention study of interpreter services for Spanish-speaking families.

Disclosures: Dr. Balkian and Dr. Pavuluri disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Who's Bungling Pediatric Discharge Handoffs?

Someone’s dropping the baton when it comes to pediatric discharge information, but just who that is appears to depend on what part of the relay team you’re on.

A full 85% of hospitalists said they reliably send discharge information and 79% said it contained all elements needed by the primary care physician.

Only 72% of PCPs, however, said they got the information and only 65% felt it was complete.

"Perceptions of PCPs and hospitalists regarding the timeliness and content of discharge communication do differ significantly," Dr. JoAnna Leyenaar said at the recent Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012.

Although the majority of the PCPs surveyed said they receive communication within 2 days of discharge, "the content may be suboptimal," she added.