User login

Reducing or Discontinuing Insulin or Sulfonylurea When Initiating a Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Agonist

Hypoglycemia and weight gain are well-known adverse effects that can result from insulin and sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1,2 Insulin and sulfonylurea medications can cause additional weight gain in patients who are overweight or obese, which can increase the burden of diabetes therapy with added medications, raise the risk of hypoglycemia complications, and raise atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors.3 Although increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option health care practitioners or pharmacists have, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in older adults, such as the veteran population, which could lead to complications, such as falls.2

Previous studies focusing on hypoglycemic events in patients with T2DM showed that glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist monotherapy has a low incidence of a hypoglycemic events. However, when a GLP-1 agonist is combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, patients have an increased chance of a hypoglycemic event.3-8 According to the prescribing information for semaglutide, 1.6% to 3.8% of patients on a GLP-1 agonist monotherapy reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event (blood glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL), based on semaglutide dosing. 9 Patients on combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist and basal insulin and a GLP-1 agonist and a sulfonylurea reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event ranging from 16.7% to 29.8% and 17.3% to 24.4%, respectively.9 The incidences of hypoglycemia thus dramatically increase with combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist plus insulin or a sulfonylurea.

When adding a GLP-1 agonist to insulin or a sulfonylurea, clinicians must be mindful of the increased risk of hypoglycemia. Per the warnings and precautions in the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists, concomitant use with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia, and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 According to the American College of Cardiology guidelines, when starting a GLP-1 agonist, the insulin dose should be decreased by about 20% in patients with a well-controlled hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).12

This study aimed to determine the percentage of patients who required dose reductions or discontinuations of insulin and sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist. Understanding necessary dose reductions or discontinuations of these concomitant diabetes agents can assist pharmacists in preventing hypoglycemia and minimizing weight gain.

Methods

This clinical review was a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed a GLP-1 agonist while on insulin or a sulfonylurea between January 1, 2019, and September 30, 2022, at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WBVAMC) in Pennsylvania and managed in a pharmacist-led patient aligned care team (PACT) clinic. It was determined by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development that an institutional review board or other review committee approval was not needed for this nonresearch Veterans Health Administration quality assurance and improvement project. Patients aged ≥ 18 years were included in this study. Patients were excluded if they were not on insulin or a sulfonylurea when starting a GLP-1 agonist, started a GLP-1 agonist outside of the retrospective chart review dates, or were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by anyone other than a pharmacist in their PACT clinic. This included if a GLP-1 agonist was prescribed by a primary care physician, endocrinologist, or someone outside the VA system.

The primary study outcomes were to determine the percentage of patients with a dose reduction of insulin or sulfonylurea and discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea at intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes included changes in HbA1c and body weight measured at the same intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months.

Data were collected using the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and stored in a locked spreadsheet. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. Patient data included the number of patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea when initiating a GLP-1 agonist, the percentage of patients started on a certain GLP-1 agonist (dulaglutide, liraglutide, exenatide, and semaglutide), and the percentage of patients with a baseline HbA1c of < 8%, 8% to 10%, and > 10%. The GLP-1 agonist formulary was adjusted during the time of this retrospective chart review. Patients who were not on semaglutide were switched over if they were on another GLP-1 agonist as semaglutide became the preferred GLP-1 agonist.

Patients were considered to have a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea if the dose or medication they were on decreased or was discontinued permanently within 12 months of starting a GLP-1 agonist. For example, if a patient who was administering 10 units of insulin daily was decreased to 8 but later increased back to 10, this was not counted as a dose reduction. If a patient discontinued insulin or a sulfonylurea and then restarted it within 12 months of initiating a GLP-1 agonist, this was not counted as a discontinuation.

Results

This retrospective review included 136 patients; 96 patients taking insulin and 54 taking a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist. Fourteen patients were on both. Criteria for use, which are clinical criteria to determine if a patient is eligible for the use of a given medication, are used within the VA. The inclusion criteria for a patient initiating a GLP-1 agonist is that the patient must have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease with the patient receiving metformin (unless unable to use metformin) and empagliflozin (unless unable to use empagliflozin).

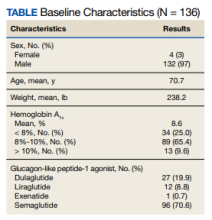

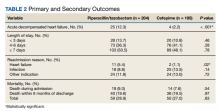

The baseline mean age and weight for the patient population in this retrospective chart review was 70.7 years and 238.2 lb, respectively. Ninety-six patients (70.6%) were started on semaglutide, 27 (19.9%) on dulaglutide, 12 (8.8%) on liraglutide, and 1 (0.7%) on exenatide. The mean HbA1c when patients initiated a GLP-1 agonist was 8.6%. When starting a GLP-1 agonist, 34 patients (25.0%) had an HbA1c < 8%, 89 (65.4%) had an HbA1c between 8% to 10%, and 13 (9.6%) had an HbA1c > 10% (Table).

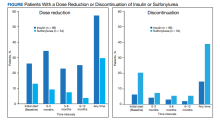

For the primary results, 25 patients (26.0%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 55 patients (57.3%) had at least 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Seven patients (13.0%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 16 patients (29.6%) had at least 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Six patients (6.3%) discontinued insulin use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 14 patients (14.6%) discontinued insulin use within the year follow-up. Eleven patients (20.4%) discontinued sulfonylurea use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 21 patients (38.9%) discontinued sulfonylurea use within the year follow-up (Figure).

Fourteen patients were on both insulin and a sulfonylurea. Two patients (14.3%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 5 (35.7%) had ≥ 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Three patients (21.4%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 6 (42.9%) had ≥ 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Seven patients (50.0%) discontinued sulfonylurea and 3 (21.4%) discontinued insulin at any time throughout the year. The majority of the discontinuations were at the initial start of GLP-1 agonist therapy.

The mean HbA1c for patients on GLP-1 agonist was 8.6% at baseline, 8.0% at 0 to 3 months, 7.6% at 3 to 6 months, and 7.5% at 12 months. Patients experienced a mean HbA1c reduction of 1.1%. The mean weight when a GLP-1 agonist was started was 238.2 lb, 236.0 lb at 0 to 3 months, 223.8 lb at 3 to 6 months, and 224.3 lb after 12 months. Study participants lost a mean weight of 13.9 lb while on a GLP-1 agonist.

Discussion

While this study did not examine why there were dose reductions or discontinuations, we can hypothesize that insulin or sulfonylureas were reduced or discontinued due to a myriad of reasons, such as prophylactic dosing per guidelines, patients having a hypoglycemic event, or pharmacists anticipating potential low blood glucose trends. Also, there could have been numerous reasons GLP-1 agonists were started in patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea, such as HbA1c not being within goal range, cardiovascular benefits (reduce risk of stroke, heart attack, and death), weight loss, and renal protection, such as preventing albuminuria.13,14

This retrospective chart review found a large proportion of patients had a dose reduction of insulin (57.3%) or sulfonylurea (29.6%). The percentage of patients with a dose reduction was potentially underestimated as patients were not counted if they discontinued insulin or sulfonylurea. Concomitant use of GLP-1 agonists with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 The dose reductions in this study show that pharmacists within pharmacy-led PACT clinics monitor for or attempt to prevent hypoglycemia, which aligns with the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists. While increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option for patients, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in an older population, like this one with a mean age > 70 years. The large proportions of patients with dose reductions or insulin and sulfonylurea discontinuations suggest that pharmacists may need to take a more cautious approach when initiating a GLP-1 agonist to prevent adverse health outcomes related to low blood sugar for older adults, such as falls and fractures.

Insulin was discontinued in 20.4% of patients and sulfonylurea was discontinued in 38.9% of patients within 12 months after starting a GLP-1 agonist. When a patient was on both insulin and a sulfonylurea, the percentage of patients who discontinued insulin (21.4%) or a sulfonylurea (50.0%) was higher compared with patients just on insulin (14.6%) or a sulfonylurea (38.9%) alone. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to a higher incidence of discontinuations when these diabetes agents are administered in combination.

Within 12 months of patients receiving a GLP-1 agonist, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.1%, which is comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. For semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.4% and 1.6%, respectively.9 For dulaglutide 0.75 mg and 1.5 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 0.7% to 1.6% and 0.8% to 1.6%, respectively.10 For liraglutide 1.8 mg dosage, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 1.0% to 1.5%.11 The mean weight loss in this study was 13.9 lb. Along with HbA1c, weight loss in this review was comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. Patients administering semaglutide lost up to 14 lb, patients taking dulaglutide lost up to 10.1 lb, and patients on liraglutide lost on average 6.2 lb.9-11 Even with medications such as insulin and sulfonylurea that have the side effects of hypoglycemia and weight gain, adding a GLP-1 agonist showed a reduction in HbA1c and weight loss relatively similar to previous clinical trials.

A study on the effects of adding semaglutide to insulin regimens in March 2023 by Meyer and colleagues displayed similar results to this retrospective chart review. That study concluded that there was blood glucose improvement (HbA1c reduction of 1.3%) in patients after 6 months despite a decrease in the insulin dose. Also, patients lost a mean weight of 11 lb during the 6-month trial.3 This retrospective chart review at the WBVAMC adds to the body of research that supports potential reductions or discontinuations of insulin and/or sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered when evaluating the results. This review was comprised of a mostly older, male population, which results in a low generalizability to organizations other than VA medical centers. In addition, this study only evaluated patients on a GLP-1 agonist followed in a pharmacist-led PACT clinic. This study excluded patients who were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by an endocrinologist or a pharmacist at one of the community-based outpatient clinics affiliated with WBVAMC, or a pharmacist or clinician outside the VA. The sole focus of this study was patients in a pharmacist-led VAMC clinic. Not all patient data may have been included in the study. If a patient did not have an appointment at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months or did not obtain laboratory tests, HbA1c and weights were not recorded. Data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and in-person appointments were potentially switched to phone or video appointments. There were many instances during this chart review where a weight was not recorded at each time interval. Also, this study did not consider any other diabetes medications the patient was taking. There were many instances where the patient was taking metformin and/or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. These medications along with diet could have affected the weight results as metformin is weight neutral and SGLT-2 inhibitors promote weight loss.15 Lastly, this study did not evaluate the amount of insulin reduced, only if there was a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin and/or a sulfonylurea.

Conclusions

Dose reductions and a discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist may be needed. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to the higher incidences of discontinuations compared with patients on just 1 of these agents. Dose reductions or discontinuations of these diabetic agents can promote positive patient outcomes, such as preventing hypoglycemia, minimizing weight gain, increasing weight loss, and reducing HbA1c levels.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Pennsylvania.

1. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S128-S139. doi:10.2337/dc23-S008

2. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VE, et al. Older adults: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S216-S229. doi:10.2337/dc23-S013

3. Meyer J, Dreischmeier E, Lehmann M, Phelan J. The effects of adding semaglutide to high daily dose insulin regimens in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother. 2023;57(3):241-250. doi:10.1177/10600280221107381

4. Rodbard HW, Lingvay I, Reed J, et al. Semaglutide added to basal insulin in type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 5): a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(6):2291-2301. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00070

5. Anderson SL, Trujillo JM. Basal insulin use with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Spectr. 2016;29(3):152-160. doi:10.2337/diaspect.29.3.152

6. Castek SL, Healey LC, Kania DS, Vernon VP, Dawson AJ. Assessment of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in veterans taking basal/bolus insulin regimens. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 5):S18-S23. doi:10.12788/fp.0317

7. Chen M, Vider E, Plakogiannis R. Insulin dosage adjustments after initiation of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Pharm Pract. 2022;35(4):511-517. doi:10.1177/0897190021993625

8. Seino Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, Takami A; EFC10887 GETGOAL-L Asia Study Investigators. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal-L-Asia). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(10):910-917. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01618.x.

9. Ozempic (semaglutide) injection. Package insert. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. https://www.ozempic.com/prescribing-information.html

10. Trulicity (dulaglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://pi.lilly.com/us/trulicity-uspi.pdf

11. Victoza (liraglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.novo-pi.com/victoza.pdf

12. Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KK, et al. 2020 expert consensus decision pathway on novel therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(9):1117-1145. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.037

13. Granata A, Maccarrone R, Anzaldi M, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and renal outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 and diabetic kidney disease: state of the art. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(9):1657-1665. Published 2022 Mar 12. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfac069

14. Marx N, Husain M, Lehrke M, Verma S, Sattar N. GLP-1 receptor agonists for the reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation. 2022;146(24):1882-1894. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059595

15. Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2022;65(12):1925-1966. doi:10.1007/s00125-022-05787-2

Hypoglycemia and weight gain are well-known adverse effects that can result from insulin and sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1,2 Insulin and sulfonylurea medications can cause additional weight gain in patients who are overweight or obese, which can increase the burden of diabetes therapy with added medications, raise the risk of hypoglycemia complications, and raise atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors.3 Although increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option health care practitioners or pharmacists have, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in older adults, such as the veteran population, which could lead to complications, such as falls.2

Previous studies focusing on hypoglycemic events in patients with T2DM showed that glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist monotherapy has a low incidence of a hypoglycemic events. However, when a GLP-1 agonist is combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, patients have an increased chance of a hypoglycemic event.3-8 According to the prescribing information for semaglutide, 1.6% to 3.8% of patients on a GLP-1 agonist monotherapy reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event (blood glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL), based on semaglutide dosing. 9 Patients on combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist and basal insulin and a GLP-1 agonist and a sulfonylurea reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event ranging from 16.7% to 29.8% and 17.3% to 24.4%, respectively.9 The incidences of hypoglycemia thus dramatically increase with combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist plus insulin or a sulfonylurea.

When adding a GLP-1 agonist to insulin or a sulfonylurea, clinicians must be mindful of the increased risk of hypoglycemia. Per the warnings and precautions in the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists, concomitant use with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia, and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 According to the American College of Cardiology guidelines, when starting a GLP-1 agonist, the insulin dose should be decreased by about 20% in patients with a well-controlled hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).12

This study aimed to determine the percentage of patients who required dose reductions or discontinuations of insulin and sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist. Understanding necessary dose reductions or discontinuations of these concomitant diabetes agents can assist pharmacists in preventing hypoglycemia and minimizing weight gain.

Methods

This clinical review was a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed a GLP-1 agonist while on insulin or a sulfonylurea between January 1, 2019, and September 30, 2022, at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WBVAMC) in Pennsylvania and managed in a pharmacist-led patient aligned care team (PACT) clinic. It was determined by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development that an institutional review board or other review committee approval was not needed for this nonresearch Veterans Health Administration quality assurance and improvement project. Patients aged ≥ 18 years were included in this study. Patients were excluded if they were not on insulin or a sulfonylurea when starting a GLP-1 agonist, started a GLP-1 agonist outside of the retrospective chart review dates, or were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by anyone other than a pharmacist in their PACT clinic. This included if a GLP-1 agonist was prescribed by a primary care physician, endocrinologist, or someone outside the VA system.

The primary study outcomes were to determine the percentage of patients with a dose reduction of insulin or sulfonylurea and discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea at intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes included changes in HbA1c and body weight measured at the same intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months.

Data were collected using the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and stored in a locked spreadsheet. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. Patient data included the number of patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea when initiating a GLP-1 agonist, the percentage of patients started on a certain GLP-1 agonist (dulaglutide, liraglutide, exenatide, and semaglutide), and the percentage of patients with a baseline HbA1c of < 8%, 8% to 10%, and > 10%. The GLP-1 agonist formulary was adjusted during the time of this retrospective chart review. Patients who were not on semaglutide were switched over if they were on another GLP-1 agonist as semaglutide became the preferred GLP-1 agonist.

Patients were considered to have a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea if the dose or medication they were on decreased or was discontinued permanently within 12 months of starting a GLP-1 agonist. For example, if a patient who was administering 10 units of insulin daily was decreased to 8 but later increased back to 10, this was not counted as a dose reduction. If a patient discontinued insulin or a sulfonylurea and then restarted it within 12 months of initiating a GLP-1 agonist, this was not counted as a discontinuation.

Results

This retrospective review included 136 patients; 96 patients taking insulin and 54 taking a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist. Fourteen patients were on both. Criteria for use, which are clinical criteria to determine if a patient is eligible for the use of a given medication, are used within the VA. The inclusion criteria for a patient initiating a GLP-1 agonist is that the patient must have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease with the patient receiving metformin (unless unable to use metformin) and empagliflozin (unless unable to use empagliflozin).

The baseline mean age and weight for the patient population in this retrospective chart review was 70.7 years and 238.2 lb, respectively. Ninety-six patients (70.6%) were started on semaglutide, 27 (19.9%) on dulaglutide, 12 (8.8%) on liraglutide, and 1 (0.7%) on exenatide. The mean HbA1c when patients initiated a GLP-1 agonist was 8.6%. When starting a GLP-1 agonist, 34 patients (25.0%) had an HbA1c < 8%, 89 (65.4%) had an HbA1c between 8% to 10%, and 13 (9.6%) had an HbA1c > 10% (Table).

For the primary results, 25 patients (26.0%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 55 patients (57.3%) had at least 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Seven patients (13.0%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 16 patients (29.6%) had at least 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Six patients (6.3%) discontinued insulin use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 14 patients (14.6%) discontinued insulin use within the year follow-up. Eleven patients (20.4%) discontinued sulfonylurea use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 21 patients (38.9%) discontinued sulfonylurea use within the year follow-up (Figure).

Fourteen patients were on both insulin and a sulfonylurea. Two patients (14.3%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 5 (35.7%) had ≥ 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Three patients (21.4%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 6 (42.9%) had ≥ 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Seven patients (50.0%) discontinued sulfonylurea and 3 (21.4%) discontinued insulin at any time throughout the year. The majority of the discontinuations were at the initial start of GLP-1 agonist therapy.

The mean HbA1c for patients on GLP-1 agonist was 8.6% at baseline, 8.0% at 0 to 3 months, 7.6% at 3 to 6 months, and 7.5% at 12 months. Patients experienced a mean HbA1c reduction of 1.1%. The mean weight when a GLP-1 agonist was started was 238.2 lb, 236.0 lb at 0 to 3 months, 223.8 lb at 3 to 6 months, and 224.3 lb after 12 months. Study participants lost a mean weight of 13.9 lb while on a GLP-1 agonist.

Discussion

While this study did not examine why there were dose reductions or discontinuations, we can hypothesize that insulin or sulfonylureas were reduced or discontinued due to a myriad of reasons, such as prophylactic dosing per guidelines, patients having a hypoglycemic event, or pharmacists anticipating potential low blood glucose trends. Also, there could have been numerous reasons GLP-1 agonists were started in patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea, such as HbA1c not being within goal range, cardiovascular benefits (reduce risk of stroke, heart attack, and death), weight loss, and renal protection, such as preventing albuminuria.13,14

This retrospective chart review found a large proportion of patients had a dose reduction of insulin (57.3%) or sulfonylurea (29.6%). The percentage of patients with a dose reduction was potentially underestimated as patients were not counted if they discontinued insulin or sulfonylurea. Concomitant use of GLP-1 agonists with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 The dose reductions in this study show that pharmacists within pharmacy-led PACT clinics monitor for or attempt to prevent hypoglycemia, which aligns with the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists. While increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option for patients, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in an older population, like this one with a mean age > 70 years. The large proportions of patients with dose reductions or insulin and sulfonylurea discontinuations suggest that pharmacists may need to take a more cautious approach when initiating a GLP-1 agonist to prevent adverse health outcomes related to low blood sugar for older adults, such as falls and fractures.

Insulin was discontinued in 20.4% of patients and sulfonylurea was discontinued in 38.9% of patients within 12 months after starting a GLP-1 agonist. When a patient was on both insulin and a sulfonylurea, the percentage of patients who discontinued insulin (21.4%) or a sulfonylurea (50.0%) was higher compared with patients just on insulin (14.6%) or a sulfonylurea (38.9%) alone. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to a higher incidence of discontinuations when these diabetes agents are administered in combination.

Within 12 months of patients receiving a GLP-1 agonist, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.1%, which is comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. For semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.4% and 1.6%, respectively.9 For dulaglutide 0.75 mg and 1.5 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 0.7% to 1.6% and 0.8% to 1.6%, respectively.10 For liraglutide 1.8 mg dosage, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 1.0% to 1.5%.11 The mean weight loss in this study was 13.9 lb. Along with HbA1c, weight loss in this review was comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. Patients administering semaglutide lost up to 14 lb, patients taking dulaglutide lost up to 10.1 lb, and patients on liraglutide lost on average 6.2 lb.9-11 Even with medications such as insulin and sulfonylurea that have the side effects of hypoglycemia and weight gain, adding a GLP-1 agonist showed a reduction in HbA1c and weight loss relatively similar to previous clinical trials.

A study on the effects of adding semaglutide to insulin regimens in March 2023 by Meyer and colleagues displayed similar results to this retrospective chart review. That study concluded that there was blood glucose improvement (HbA1c reduction of 1.3%) in patients after 6 months despite a decrease in the insulin dose. Also, patients lost a mean weight of 11 lb during the 6-month trial.3 This retrospective chart review at the WBVAMC adds to the body of research that supports potential reductions or discontinuations of insulin and/or sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered when evaluating the results. This review was comprised of a mostly older, male population, which results in a low generalizability to organizations other than VA medical centers. In addition, this study only evaluated patients on a GLP-1 agonist followed in a pharmacist-led PACT clinic. This study excluded patients who were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by an endocrinologist or a pharmacist at one of the community-based outpatient clinics affiliated with WBVAMC, or a pharmacist or clinician outside the VA. The sole focus of this study was patients in a pharmacist-led VAMC clinic. Not all patient data may have been included in the study. If a patient did not have an appointment at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months or did not obtain laboratory tests, HbA1c and weights were not recorded. Data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and in-person appointments were potentially switched to phone or video appointments. There were many instances during this chart review where a weight was not recorded at each time interval. Also, this study did not consider any other diabetes medications the patient was taking. There were many instances where the patient was taking metformin and/or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. These medications along with diet could have affected the weight results as metformin is weight neutral and SGLT-2 inhibitors promote weight loss.15 Lastly, this study did not evaluate the amount of insulin reduced, only if there was a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin and/or a sulfonylurea.

Conclusions

Dose reductions and a discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist may be needed. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to the higher incidences of discontinuations compared with patients on just 1 of these agents. Dose reductions or discontinuations of these diabetic agents can promote positive patient outcomes, such as preventing hypoglycemia, minimizing weight gain, increasing weight loss, and reducing HbA1c levels.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Pennsylvania.

Hypoglycemia and weight gain are well-known adverse effects that can result from insulin and sulfonylureas in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1,2 Insulin and sulfonylurea medications can cause additional weight gain in patients who are overweight or obese, which can increase the burden of diabetes therapy with added medications, raise the risk of hypoglycemia complications, and raise atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors.3 Although increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option health care practitioners or pharmacists have, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in older adults, such as the veteran population, which could lead to complications, such as falls.2

Previous studies focusing on hypoglycemic events in patients with T2DM showed that glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist monotherapy has a low incidence of a hypoglycemic events. However, when a GLP-1 agonist is combined with insulin or sulfonylureas, patients have an increased chance of a hypoglycemic event.3-8 According to the prescribing information for semaglutide, 1.6% to 3.8% of patients on a GLP-1 agonist monotherapy reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event (blood glucose ≤ 70 mg/dL), based on semaglutide dosing. 9 Patients on combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist and basal insulin and a GLP-1 agonist and a sulfonylurea reported a documented symptomatic hypoglycemic event ranging from 16.7% to 29.8% and 17.3% to 24.4%, respectively.9 The incidences of hypoglycemia thus dramatically increase with combination therapy of a GLP-1 agonist plus insulin or a sulfonylurea.

When adding a GLP-1 agonist to insulin or a sulfonylurea, clinicians must be mindful of the increased risk of hypoglycemia. Per the warnings and precautions in the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists, concomitant use with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia, and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 According to the American College of Cardiology guidelines, when starting a GLP-1 agonist, the insulin dose should be decreased by about 20% in patients with a well-controlled hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).12

This study aimed to determine the percentage of patients who required dose reductions or discontinuations of insulin and sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist. Understanding necessary dose reductions or discontinuations of these concomitant diabetes agents can assist pharmacists in preventing hypoglycemia and minimizing weight gain.

Methods

This clinical review was a single-center, retrospective chart review of patients prescribed a GLP-1 agonist while on insulin or a sulfonylurea between January 1, 2019, and September 30, 2022, at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center (WBVAMC) in Pennsylvania and managed in a pharmacist-led patient aligned care team (PACT) clinic. It was determined by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development that an institutional review board or other review committee approval was not needed for this nonresearch Veterans Health Administration quality assurance and improvement project. Patients aged ≥ 18 years were included in this study. Patients were excluded if they were not on insulin or a sulfonylurea when starting a GLP-1 agonist, started a GLP-1 agonist outside of the retrospective chart review dates, or were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by anyone other than a pharmacist in their PACT clinic. This included if a GLP-1 agonist was prescribed by a primary care physician, endocrinologist, or someone outside the VA system.

The primary study outcomes were to determine the percentage of patients with a dose reduction of insulin or sulfonylurea and discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea at intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months. Secondary outcomes included changes in HbA1c and body weight measured at the same intervals of 0 (baseline), 3, 6, and 12 months.

Data were collected using the VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and stored in a locked spreadsheet. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the data. Patient data included the number of patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea when initiating a GLP-1 agonist, the percentage of patients started on a certain GLP-1 agonist (dulaglutide, liraglutide, exenatide, and semaglutide), and the percentage of patients with a baseline HbA1c of < 8%, 8% to 10%, and > 10%. The GLP-1 agonist formulary was adjusted during the time of this retrospective chart review. Patients who were not on semaglutide were switched over if they were on another GLP-1 agonist as semaglutide became the preferred GLP-1 agonist.

Patients were considered to have a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea if the dose or medication they were on decreased or was discontinued permanently within 12 months of starting a GLP-1 agonist. For example, if a patient who was administering 10 units of insulin daily was decreased to 8 but later increased back to 10, this was not counted as a dose reduction. If a patient discontinued insulin or a sulfonylurea and then restarted it within 12 months of initiating a GLP-1 agonist, this was not counted as a discontinuation.

Results

This retrospective review included 136 patients; 96 patients taking insulin and 54 taking a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist. Fourteen patients were on both. Criteria for use, which are clinical criteria to determine if a patient is eligible for the use of a given medication, are used within the VA. The inclusion criteria for a patient initiating a GLP-1 agonist is that the patient must have atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease with the patient receiving metformin (unless unable to use metformin) and empagliflozin (unless unable to use empagliflozin).

The baseline mean age and weight for the patient population in this retrospective chart review was 70.7 years and 238.2 lb, respectively. Ninety-six patients (70.6%) were started on semaglutide, 27 (19.9%) on dulaglutide, 12 (8.8%) on liraglutide, and 1 (0.7%) on exenatide. The mean HbA1c when patients initiated a GLP-1 agonist was 8.6%. When starting a GLP-1 agonist, 34 patients (25.0%) had an HbA1c < 8%, 89 (65.4%) had an HbA1c between 8% to 10%, and 13 (9.6%) had an HbA1c > 10% (Table).

For the primary results, 25 patients (26.0%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 55 patients (57.3%) had at least 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Seven patients (13.0%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 16 patients (29.6%) had at least 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Six patients (6.3%) discontinued insulin use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 14 patients (14.6%) discontinued insulin use within the year follow-up. Eleven patients (20.4%) discontinued sulfonylurea use when they initially started a GLP-1 agonist, and 21 patients (38.9%) discontinued sulfonylurea use within the year follow-up (Figure).

Fourteen patients were on both insulin and a sulfonylurea. Two patients (14.3%) had a dose reduction of insulin when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 5 (35.7%) had ≥ 1 insulin dose reduction within the year follow-up. Three patients (21.4%) had a dose reduction of a sulfonylurea when they started a GLP-1 agonist, and 6 (42.9%) had ≥ 1 dose reduction of a sulfonylurea within the year follow-up. Seven patients (50.0%) discontinued sulfonylurea and 3 (21.4%) discontinued insulin at any time throughout the year. The majority of the discontinuations were at the initial start of GLP-1 agonist therapy.

The mean HbA1c for patients on GLP-1 agonist was 8.6% at baseline, 8.0% at 0 to 3 months, 7.6% at 3 to 6 months, and 7.5% at 12 months. Patients experienced a mean HbA1c reduction of 1.1%. The mean weight when a GLP-1 agonist was started was 238.2 lb, 236.0 lb at 0 to 3 months, 223.8 lb at 3 to 6 months, and 224.3 lb after 12 months. Study participants lost a mean weight of 13.9 lb while on a GLP-1 agonist.

Discussion

While this study did not examine why there were dose reductions or discontinuations, we can hypothesize that insulin or sulfonylureas were reduced or discontinued due to a myriad of reasons, such as prophylactic dosing per guidelines, patients having a hypoglycemic event, or pharmacists anticipating potential low blood glucose trends. Also, there could have been numerous reasons GLP-1 agonists were started in patients on insulin or a sulfonylurea, such as HbA1c not being within goal range, cardiovascular benefits (reduce risk of stroke, heart attack, and death), weight loss, and renal protection, such as preventing albuminuria.13,14

This retrospective chart review found a large proportion of patients had a dose reduction of insulin (57.3%) or sulfonylurea (29.6%). The percentage of patients with a dose reduction was potentially underestimated as patients were not counted if they discontinued insulin or sulfonylurea. Concomitant use of GLP-1 agonists with insulin or a sulfonylurea may increase the risk of hypoglycemia and reducing the dose of insulin or a sulfonylurea may be necessary.9-11 The dose reductions in this study show that pharmacists within pharmacy-led PACT clinics monitor for or attempt to prevent hypoglycemia, which aligns with the prescribing information of GLP-1 agonists. While increasing the insulin or sulfonylurea dose is an option for patients, this approach can increase the risk of hypoglycemia, especially in an older population, like this one with a mean age > 70 years. The large proportions of patients with dose reductions or insulin and sulfonylurea discontinuations suggest that pharmacists may need to take a more cautious approach when initiating a GLP-1 agonist to prevent adverse health outcomes related to low blood sugar for older adults, such as falls and fractures.

Insulin was discontinued in 20.4% of patients and sulfonylurea was discontinued in 38.9% of patients within 12 months after starting a GLP-1 agonist. When a patient was on both insulin and a sulfonylurea, the percentage of patients who discontinued insulin (21.4%) or a sulfonylurea (50.0%) was higher compared with patients just on insulin (14.6%) or a sulfonylurea (38.9%) alone. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to a higher incidence of discontinuations when these diabetes agents are administered in combination.

Within 12 months of patients receiving a GLP-1 agonist, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.1%, which is comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. For semaglutide 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction was 1.4% and 1.6%, respectively.9 For dulaglutide 0.75 mg and 1.5 mg dosages, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 0.7% to 1.6% and 0.8% to 1.6%, respectively.10 For liraglutide 1.8 mg dosage, the mean HbA1c reduction ranged from 1.0% to 1.5%.11 The mean weight loss in this study was 13.9 lb. Along with HbA1c, weight loss in this review was comparable to other GLP-1 agonist clinical trials. Patients administering semaglutide lost up to 14 lb, patients taking dulaglutide lost up to 10.1 lb, and patients on liraglutide lost on average 6.2 lb.9-11 Even with medications such as insulin and sulfonylurea that have the side effects of hypoglycemia and weight gain, adding a GLP-1 agonist showed a reduction in HbA1c and weight loss relatively similar to previous clinical trials.

A study on the effects of adding semaglutide to insulin regimens in March 2023 by Meyer and colleagues displayed similar results to this retrospective chart review. That study concluded that there was blood glucose improvement (HbA1c reduction of 1.3%) in patients after 6 months despite a decrease in the insulin dose. Also, patients lost a mean weight of 11 lb during the 6-month trial.3 This retrospective chart review at the WBVAMC adds to the body of research that supports potential reductions or discontinuations of insulin and/or sulfonylureas with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be considered when evaluating the results. This review was comprised of a mostly older, male population, which results in a low generalizability to organizations other than VA medical centers. In addition, this study only evaluated patients on a GLP-1 agonist followed in a pharmacist-led PACT clinic. This study excluded patients who were prescribed a GLP-1 agonist by an endocrinologist or a pharmacist at one of the community-based outpatient clinics affiliated with WBVAMC, or a pharmacist or clinician outside the VA. The sole focus of this study was patients in a pharmacist-led VAMC clinic. Not all patient data may have been included in the study. If a patient did not have an appointment at baseline, 3, 6, and 12 months or did not obtain laboratory tests, HbA1c and weights were not recorded. Data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and in-person appointments were potentially switched to phone or video appointments. There were many instances during this chart review where a weight was not recorded at each time interval. Also, this study did not consider any other diabetes medications the patient was taking. There were many instances where the patient was taking metformin and/or sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors. These medications along with diet could have affected the weight results as metformin is weight neutral and SGLT-2 inhibitors promote weight loss.15 Lastly, this study did not evaluate the amount of insulin reduced, only if there was a dose reduction or discontinuation of insulin and/or a sulfonylurea.

Conclusions

Dose reductions and a discontinuation of insulin or a sulfonylurea with the addition of a GLP-1 agonist may be needed. Patients on both insulin and a sulfonylurea may need closer monitoring due to the higher incidences of discontinuations compared with patients on just 1 of these agents. Dose reductions or discontinuations of these diabetic agents can promote positive patient outcomes, such as preventing hypoglycemia, minimizing weight gain, increasing weight loss, and reducing HbA1c levels.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Wilkes-Barre Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Pennsylvania.

1. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S128-S139. doi:10.2337/dc23-S008

2. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VE, et al. Older adults: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S216-S229. doi:10.2337/dc23-S013

3. Meyer J, Dreischmeier E, Lehmann M, Phelan J. The effects of adding semaglutide to high daily dose insulin regimens in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother. 2023;57(3):241-250. doi:10.1177/10600280221107381

4. Rodbard HW, Lingvay I, Reed J, et al. Semaglutide added to basal insulin in type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 5): a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(6):2291-2301. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00070

5. Anderson SL, Trujillo JM. Basal insulin use with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Spectr. 2016;29(3):152-160. doi:10.2337/diaspect.29.3.152

6. Castek SL, Healey LC, Kania DS, Vernon VP, Dawson AJ. Assessment of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in veterans taking basal/bolus insulin regimens. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 5):S18-S23. doi:10.12788/fp.0317

7. Chen M, Vider E, Plakogiannis R. Insulin dosage adjustments after initiation of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Pharm Pract. 2022;35(4):511-517. doi:10.1177/0897190021993625

8. Seino Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, Takami A; EFC10887 GETGOAL-L Asia Study Investigators. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal-L-Asia). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(10):910-917. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01618.x.

9. Ozempic (semaglutide) injection. Package insert. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. https://www.ozempic.com/prescribing-information.html

10. Trulicity (dulaglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://pi.lilly.com/us/trulicity-uspi.pdf

11. Victoza (liraglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.novo-pi.com/victoza.pdf

12. Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KK, et al. 2020 expert consensus decision pathway on novel therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(9):1117-1145. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.037

13. Granata A, Maccarrone R, Anzaldi M, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and renal outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 and diabetic kidney disease: state of the art. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(9):1657-1665. Published 2022 Mar 12. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfac069

14. Marx N, Husain M, Lehrke M, Verma S, Sattar N. GLP-1 receptor agonists for the reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation. 2022;146(24):1882-1894. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059595

15. Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2022;65(12):1925-1966. doi:10.1007/s00125-022-05787-2

1. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S128-S139. doi:10.2337/dc23-S008

2. ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VE, et al. Older adults: standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(suppl 1):S216-S229. doi:10.2337/dc23-S013

3. Meyer J, Dreischmeier E, Lehmann M, Phelan J. The effects of adding semaglutide to high daily dose insulin regimens in patients with type 2 diabetes. Ann Pharmacother. 2023;57(3):241-250. doi:10.1177/10600280221107381

4. Rodbard HW, Lingvay I, Reed J, et al. Semaglutide added to basal insulin in type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 5): a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(6):2291-2301. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-00070

5. Anderson SL, Trujillo JM. Basal insulin use with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Diabetes Spectr. 2016;29(3):152-160. doi:10.2337/diaspect.29.3.152

6. Castek SL, Healey LC, Kania DS, Vernon VP, Dawson AJ. Assessment of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in veterans taking basal/bolus insulin regimens. Fed Pract. 2022;39(suppl 5):S18-S23. doi:10.12788/fp.0317

7. Chen M, Vider E, Plakogiannis R. Insulin dosage adjustments after initiation of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Pharm Pract. 2022;35(4):511-517. doi:10.1177/0897190021993625

8. Seino Y, Min KW, Niemoeller E, Takami A; EFC10887 GETGOAL-L Asia Study Investigators. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the once-daily GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on basal insulin with or without a sulfonylurea (GetGoal-L-Asia). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(10):910-917. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01618.x.

9. Ozempic (semaglutide) injection. Package insert. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. https://www.ozempic.com/prescribing-information.html

10. Trulicity (dulaglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://pi.lilly.com/us/trulicity-uspi.pdf

11. Victoza (liraglutide) injection. Prescribing information. Novo Nordisk Inc; 2022. Accessed December 20, 2023. https://www.novo-pi.com/victoza.pdf

12. Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KK, et al. 2020 expert consensus decision pathway on novel therapies for cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with type 2 diabetes: a report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(9):1117-1145. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.037

13. Granata A, Maccarrone R, Anzaldi M, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and renal outcomes in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 and diabetic kidney disease: state of the art. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(9):1657-1665. Published 2022 Mar 12. doi:10.1093/ckj/sfac069

14. Marx N, Husain M, Lehrke M, Verma S, Sattar N. GLP-1 receptor agonists for the reduction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation. 2022;146(24):1882-1894. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059595

15. Davies MJ, Aroda VR, Collins BS, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2022. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetologia. 2022;65(12):1925-1966. doi:10.1007/s00125-022-05787-2

The Impact of a Paracentesis Clinic on Internal Medicine Resident Procedural Competency

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

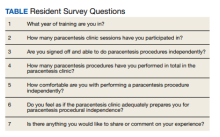

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.

Based on our study, most residents were cleared to independently perform paracentesis procedures across all 3 years, with 79% of residents having completed the required 5 supervised procedures to independently practice. A study assessing unsupervised practice standards showed that paracentesis skill declines as soon as 3 months after training. However, retraining was shown to potentially interrupt this skill decline.5 Studies have shown that procedure-driven electives or services significantly improved paracentesis certification rates and total logged procedures, with minimal funding or scheduling changes required.6 Our clinic showed a significant increase in the number of procedures logged starting with the minimum of 38 procedures in 2015 and ending with 188 procedures logged at the end of 2022.

By allowing residents to routinely return to the paracentesis clinic across all 3 years, residents were more likely to feel comfortable independently performing the procedure, with residents reporting a mean comfort score of 7.9. The spaced repetition and ability to work with the clinic during elective time allows regular opportunities to undergo supervised training in a controlled environment and created scheduled retraining opportunities. Future studies should evaluate residents prior to each paracentesis clinic to ascertain if skill decline is occurring at a slower rate.

The inpatient effect of the clinic is also multifocal. Pham and colleagues showed that integrating paracentesis into timely training can reduce paracentesis delay and delays in care.7 By increasing the volume of procedures each resident performs and creating a sense of confidence amongst residents, the clinic increases the number of residents able and willing to perform inpatient procedures, thus reducing the number of unnecessary consultations and hospital resources. One of the reasons the paracentesis clinic was started was to allow patients to have scheduled times to remove fluid from their abdomen, thus cutting down on emergency department procedures and unnecessary admissions. Additionally, the benefits of early paracentesis procedural performance by residents and internal medicine physicians have been demonstrated in the literature. A study by Gaetano and colleagues noted that patients undergoing early paracentesis had reduced mortality of 5.5% vs 7.5% in those undergoing late paracentesis.8 This study also showed the in-hospital mortality rate was decreased with paracentesis (6.3%) vs without paracentesis (8.9%).8 By offering residents a chance to participate in the clinic, we have shown that regular opportunities to perform paracentesis may increase the number of physicians capable of independently practicing, improve procedural competency, and improve patient access to this procedure.

Limitations

Our study was not free of bias and has potential weaknesses. The survey was sent to all current residents who have participated in the paracentesis clinic, but not every resident filled out the survey (55% of all residents across 3 years completed the survey, 68.7% who had done clinic that year completed the survey). There is a possibility that those not signed off avoided doing the survey, but we are unable to confirm this. The survey also depended on resident recall of the number of paracenteses completed or looking at their procedure log. It is possible that some procedures were not documented, changing the true number. Additionally, rating comfortability with procedures is subjective, which may also create a source of potential weakness. Future projects should include a baseline survey for residents, followed by a repeat survey a year later to show changes from baseline competency.

Conclusions

A dedicated paracentesis clinic with internal medicine resident involvement may increase resident paracentesis procedural independence, the number of procedures available and performed, and procedural comfort level.

1. Aponte EM, O’Rourke MC, Katta S. Paracentesis. StatPearls [internet]. September 5, 2022. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435998

2. Barsuk JH, Feinglass J, Kozmic SE, Hohmann SF, Ganger D, Wayne DB. Specialties performing paracentesis procedures at university hospitals: implications for training and certification. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):162-168. doi:10.1002/jhm.2153

3. Cheng Y-W, Sandrasegaran K, Cheng K, et al. A dedicated paracentesis clinic decreases healthcare utilization for serial paracenteses in decompensated cirrhosis. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;43(8):2190-2197. doi:10.1007/s00261-017-1406-y

4. Wang J, Khan S, Wyer P, et al. The role of ultrasound-guided therapeutic paracentesis in an outpatient transitional care program: A case series. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2018;35(9):1256-1260. doi:10.1177/1049909118755378

5. Sall D, Warm EJ, Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Jandarov R, O’Toole J. See one, do one, forget one: early skill decay after paracentesis training. J Gen Int Med. 2020;36(5):1346-1351. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06242-x

6. Berger M, Divilov V, Paredes H, Kesar V, Sun E. Improving resident paracentesis certification rates by using an innovative resident driven procedure service. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(suppl). doi:10.14309/00000434-201810001-00980

7. Pham C, Xu A, Suaez MG. S1250 a pilot study to improve resident paracentesis training and reduce paracentesis delay in admitted patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S). doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000861640.53682.93

8. Gaetano JN, Micic D, Aronsohn A, et al. The benefit of paracentesis on hospitalized adults with cirrhosis and ascites. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1025-1030. doi:10.1111/jgh.13255

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.

Based on our study, most residents were cleared to independently perform paracentesis procedures across all 3 years, with 79% of residents having completed the required 5 supervised procedures to independently practice. A study assessing unsupervised practice standards showed that paracentesis skill declines as soon as 3 months after training. However, retraining was shown to potentially interrupt this skill decline.5 Studies have shown that procedure-driven electives or services significantly improved paracentesis certification rates and total logged procedures, with minimal funding or scheduling changes required.6 Our clinic showed a significant increase in the number of procedures logged starting with the minimum of 38 procedures in 2015 and ending with 188 procedures logged at the end of 2022.

By allowing residents to routinely return to the paracentesis clinic across all 3 years, residents were more likely to feel comfortable independently performing the procedure, with residents reporting a mean comfort score of 7.9. The spaced repetition and ability to work with the clinic during elective time allows regular opportunities to undergo supervised training in a controlled environment and created scheduled retraining opportunities. Future studies should evaluate residents prior to each paracentesis clinic to ascertain if skill decline is occurring at a slower rate.

The inpatient effect of the clinic is also multifocal. Pham and colleagues showed that integrating paracentesis into timely training can reduce paracentesis delay and delays in care.7 By increasing the volume of procedures each resident performs and creating a sense of confidence amongst residents, the clinic increases the number of residents able and willing to perform inpatient procedures, thus reducing the number of unnecessary consultations and hospital resources. One of the reasons the paracentesis clinic was started was to allow patients to have scheduled times to remove fluid from their abdomen, thus cutting down on emergency department procedures and unnecessary admissions. Additionally, the benefits of early paracentesis procedural performance by residents and internal medicine physicians have been demonstrated in the literature. A study by Gaetano and colleagues noted that patients undergoing early paracentesis had reduced mortality of 5.5% vs 7.5% in those undergoing late paracentesis.8 This study also showed the in-hospital mortality rate was decreased with paracentesis (6.3%) vs without paracentesis (8.9%).8 By offering residents a chance to participate in the clinic, we have shown that regular opportunities to perform paracentesis may increase the number of physicians capable of independently practicing, improve procedural competency, and improve patient access to this procedure.

Limitations

Our study was not free of bias and has potential weaknesses. The survey was sent to all current residents who have participated in the paracentesis clinic, but not every resident filled out the survey (55% of all residents across 3 years completed the survey, 68.7% who had done clinic that year completed the survey). There is a possibility that those not signed off avoided doing the survey, but we are unable to confirm this. The survey also depended on resident recall of the number of paracenteses completed or looking at their procedure log. It is possible that some procedures were not documented, changing the true number. Additionally, rating comfortability with procedures is subjective, which may also create a source of potential weakness. Future projects should include a baseline survey for residents, followed by a repeat survey a year later to show changes from baseline competency.

Conclusions

A dedicated paracentesis clinic with internal medicine resident involvement may increase resident paracentesis procedural independence, the number of procedures available and performed, and procedural comfort level.

Competency in paracentesis is an important procedural skill for medical practitioners caring for patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Paracentesis is performed to drain ascitic fluid for both diagnosis and/or therapeutic purposes.1 While this procedure can be performed without the use of ultrasound, it is preferable to use ultrasound to identify an area of fluid that is away from dangerous anatomy including bowel loops, the liver, and spleen. After prepping the area, lidocaine is administered locally. A catheter is then inserted until fluid begins flowing freely. The catheter is connected to a suction canister or collection kit, and the patient is monitored until the flow ceases. Samples can be sent for analysis to determine the etiology of ascites, identify concerns for infection, and more.

Paracentesis is a very common procedure. Barsuk and colleagues noted that between 2010 and 2012, 97,577 procedures were performed across 120 academic medical centers and 290 affiliated hospitals.2 Patients undergo paracentesis in a variety of settings including the emergency department, inpatient hospitalizations, and clinics. Some patients may require only 1 paracentesis procedure while others may require it regularly.

Due to the rising need for paracentesis in the Central Texas Veterans Affairs Hospital (CTVAH) in Temple, a paracentesis clinic was started in February 2018. The goal of the paracentesis clinic was multifocal—to reduce hospital admissions, improve access to regularly scheduled procedures, decrease wait times, and increase patient satisfaction.3 Through the CTVAH affiliation with the Texas A&M internal medicine residency program, the paracentesis clinic started involving and training residents on this procedure. Up to 3 residents are on weekly rotation and can perform up to 6 paracentesis procedures in a week. The purpose of this article was to evaluate resident competency in paracentesis after completion of the paracentesis clinic.

Methods

The paracentesis clinic schedules up to 3 patients on Tuesdays and Thursdays between 8

A survey was sent via email to all categorical internal medicine residents across all 3 program years at the time of data collection. Competency for paracentesis sign-off was defined as completing and logging 5 procedures supervised by a competent physician who confirmed that all portions of the procedure were performed correctly. Residents were also asked to answer questions on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 representing no confidence and 10 representing strong confidence to practice independently (Table).

We also evaluated the number of procedures performed by internal medicine residents 3 years before the clinic was started in 2015 up to the completion of 2022. The numbers were obtained by examining procedural log data for each year for all internal medicine residents.

Results

Thirty-three residents completed the survey: 10 first-year internal medicine residents (PGY1), 12 second-year residents (PGY2), and 11 third-year residents (PGY3). The mean participation was 4.8 paracentesis sessions per person for the duration of the study. The range of paracentesis procedures performed varied based on PGY year: PGY1s performed 1 to > 10 procedures, PGY2s performed 2 to > 10 procedures, and PGY3s performed 5 to > 10 procedures. Thirty-six percent of residents completed > 10 procedures in the paracentesis clinic; 82% of PGY3s had completed > 10 procedures by December of their third year. Twenty-six residents (79%) were credentialed to perform paracentesis procedures independently after performing > 5 procedures, and 7 residents were not yet cleared for procedural independence.

In the survey, residents rated their comfort with performing paracentesis procedures independently at a mean of 7.9. The mean comfort reported by PGY1s was 7.2, PGY2s was 7.3, and PGY3s was 9.3. Residents also rated their opinion on whether or not the paracentesis clinic adequately prepared them for paracentesis procedural independence; the mean was 8.9 across all residents.

The total number of procedures performed by residents at CTVAH also increased. Starting in 2015, 3 years before the clinic was started, 38 procedures were performed by internal medicine residents, followed by 72 procedures in 2016; 76 in 2017; 58 in 2018; 94 in 2019; 88 in 2020; 136 in 2021; and 188 in 2022.

Discussion

Paracentesis is a simple but invasive procedure to relieve ascites, often relieving patients’ symptoms, preventing hospital admission, and increasing patient satisfaction.4 The CTVAH does not have the capacity to perform outpatient paracentesis effectively in its emergency or radiology departments. Furthermore, the use of the emergency or radiology departments for routine paracentesis may not be feasible due to the acuity of care being provided, as these procedures can be time consuming and can draw away critical resources and time from patients that need emergent care. The paracentesis clinic was then formed to provide veterans access to the procedural care they need, while also preparing residents to ably and confidently perform the procedure independently.