User login

Dermatology Immediate Care: A Game Changer for the Health Care System?

Dermatology Immediate Care: A Game Changer for the Health Care System?

Emergency departments (EDs) and immediate care (IC) facilities often do not have prompt dermatologic care available for triage and treatment. Many EDs do not have staff dermatologists on call, instead relying on input from other specialists or quick outpatient dermatology appointments. It can be challenging to obtain a prompt appointment with a board-certified dermatologist, which is preferred for complex cases such as severe drug reactions or infection. In the United States, there are few well-established IC centers equipped to address dermatologic needs. The orthopedic specialty has modeled a concept that has led to the establishment of orthopedic urgent care/IC in many larger institutions,1 and many private practice clinics serve their communities as well. We present a rationale for why a similar IC concept for dermatology would be beneficial, particularly within a large institution or health system.

Dermatology Consultation Changes Disease Management

There is diagnostic and therapeutic utility in dermatology evaluation. In a prospective study of 591 patients who were either hospitalized or evaluated in an ED/urgent care setting, treatment was changed in more than 60% of cases when dermatology consultation was utilized.2 In another prospective review of 691 cases on an inpatient service, dermatology consultation resulted in treatment changes more than 80% of the time.3

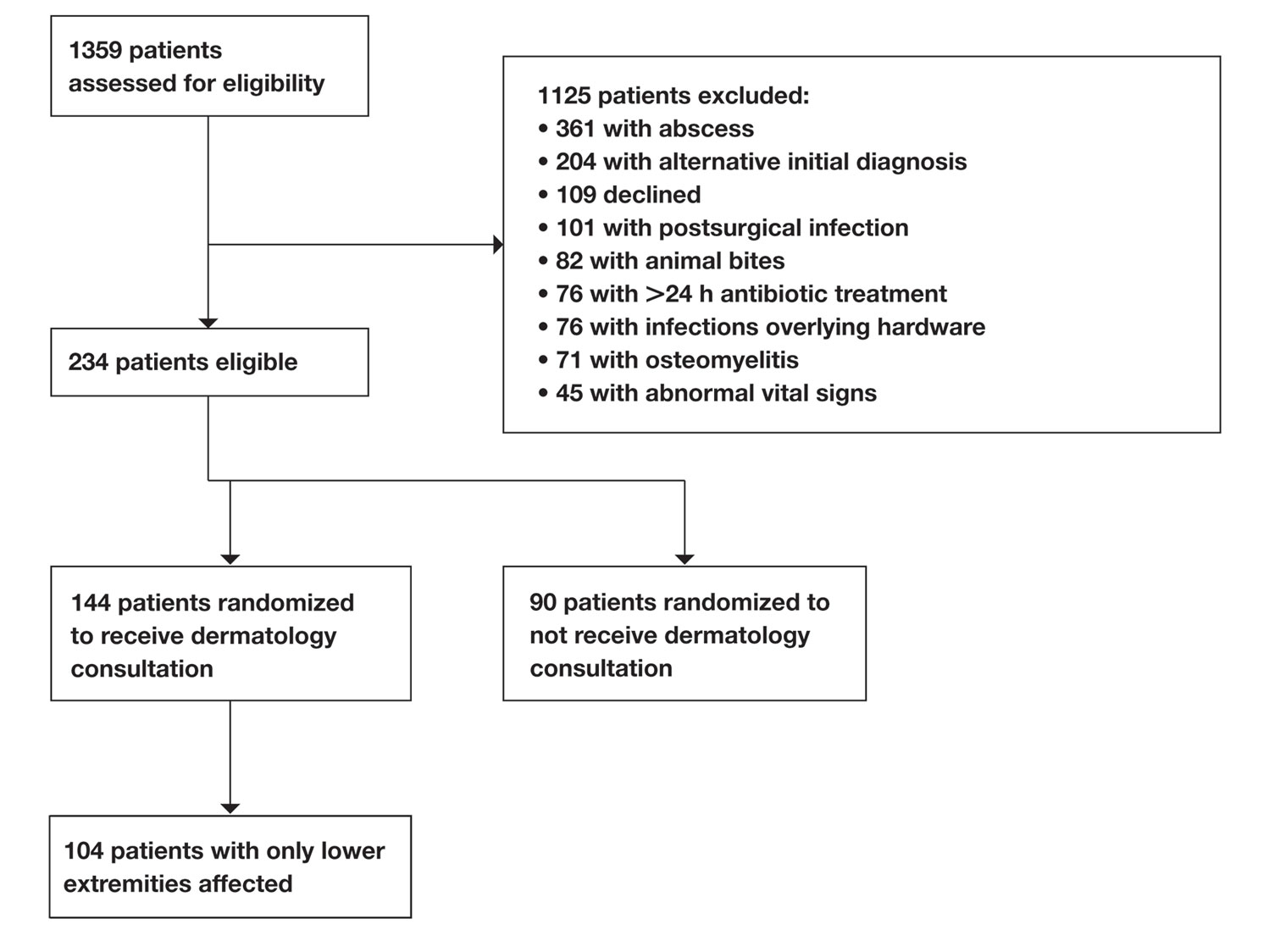

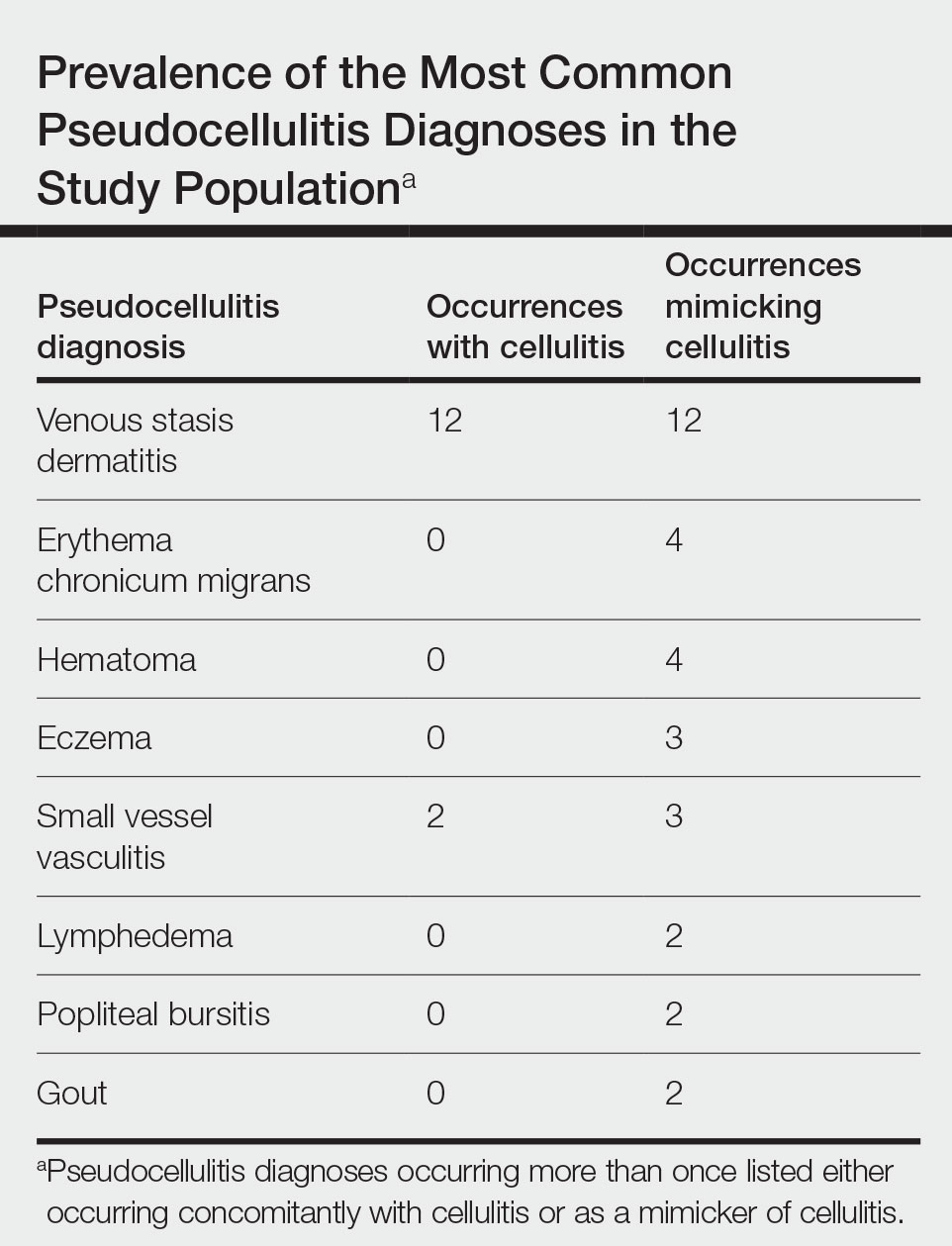

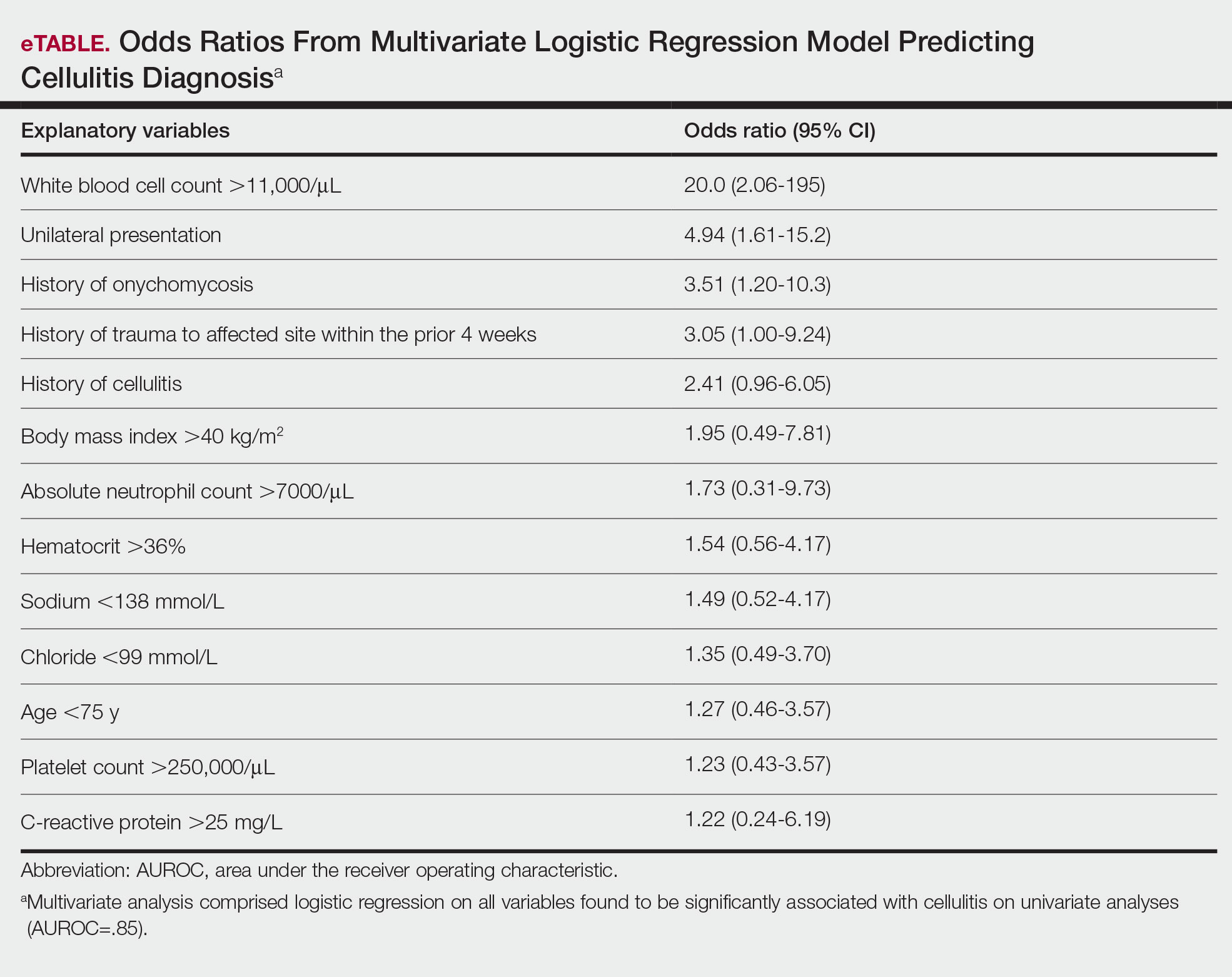

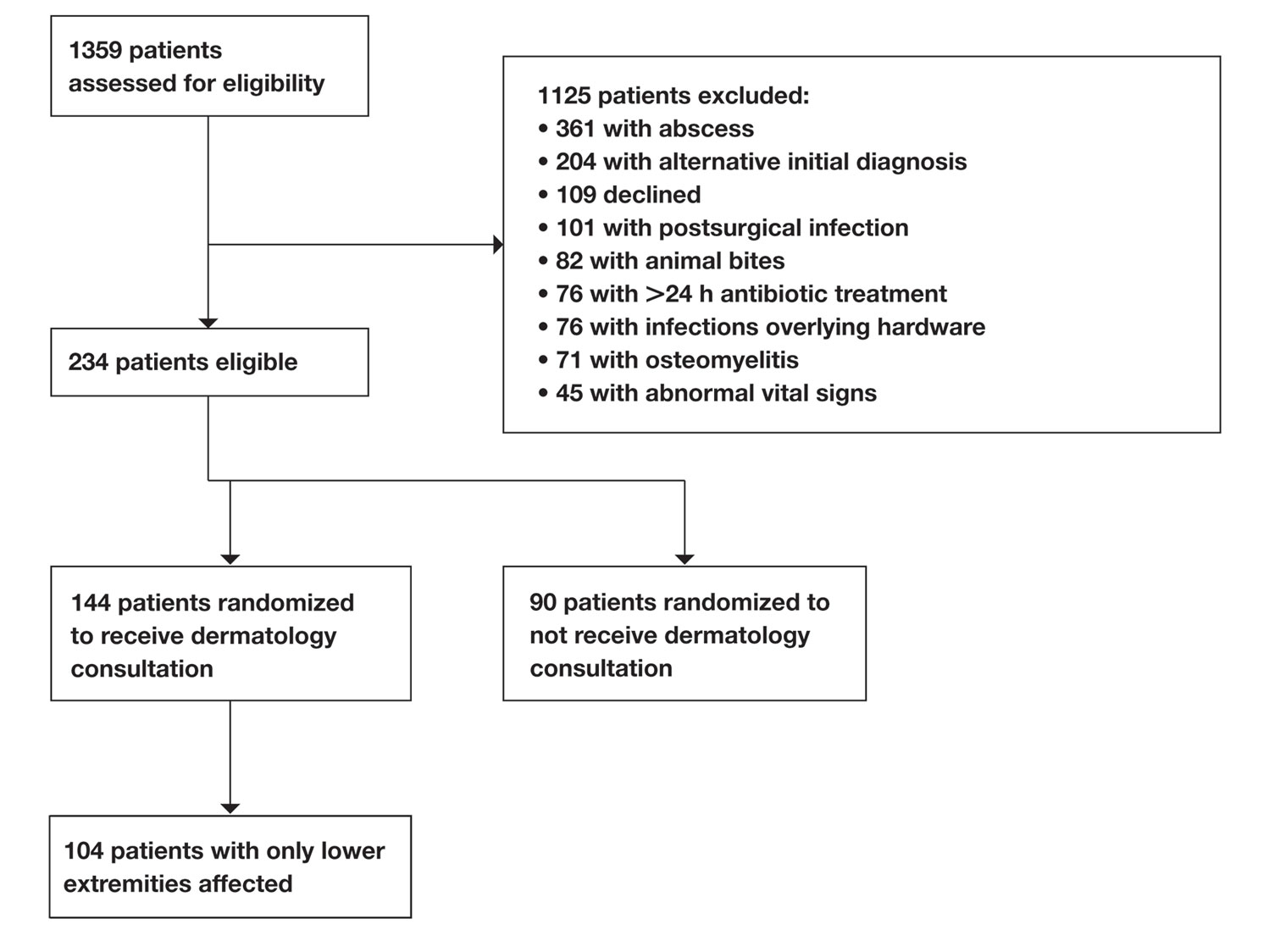

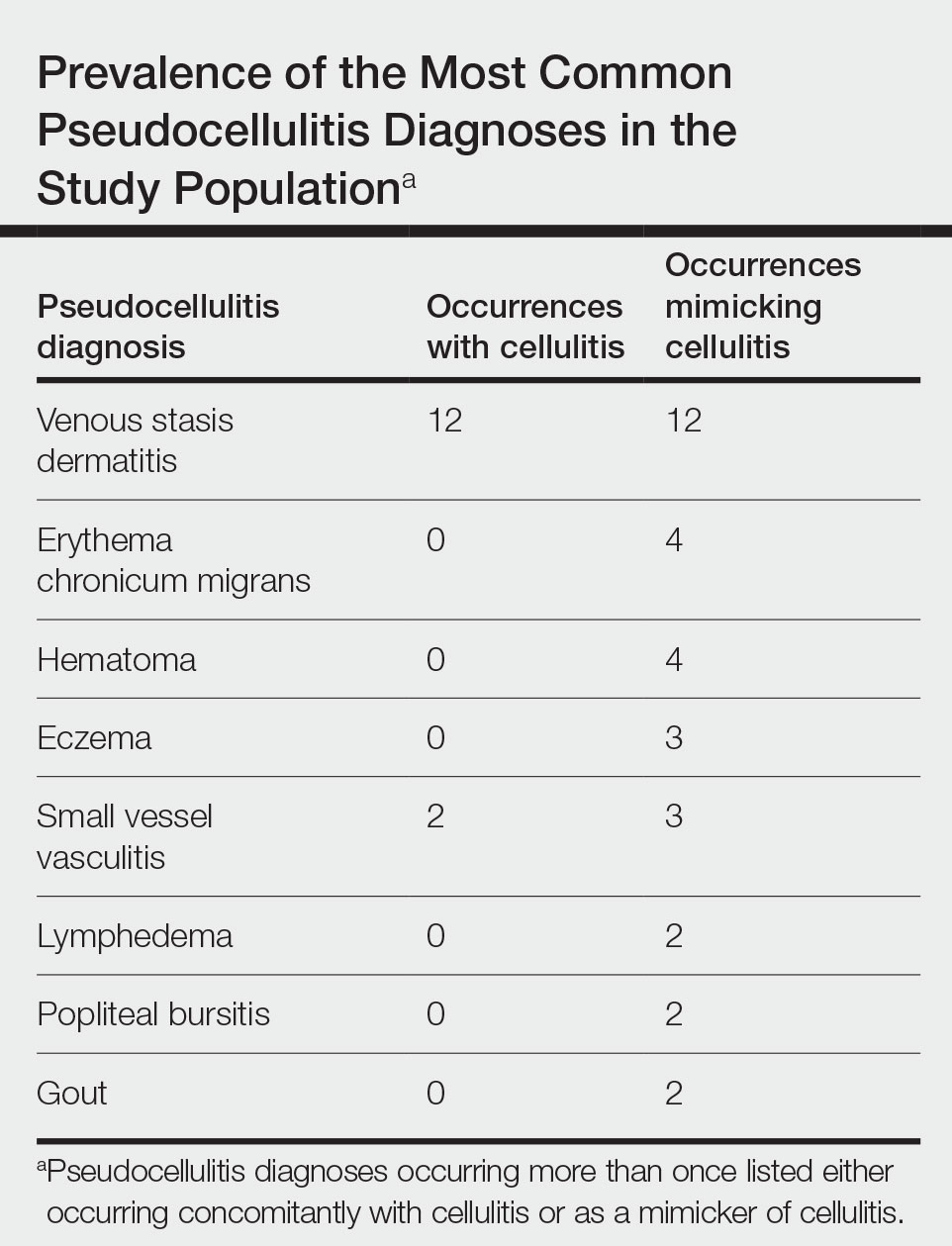

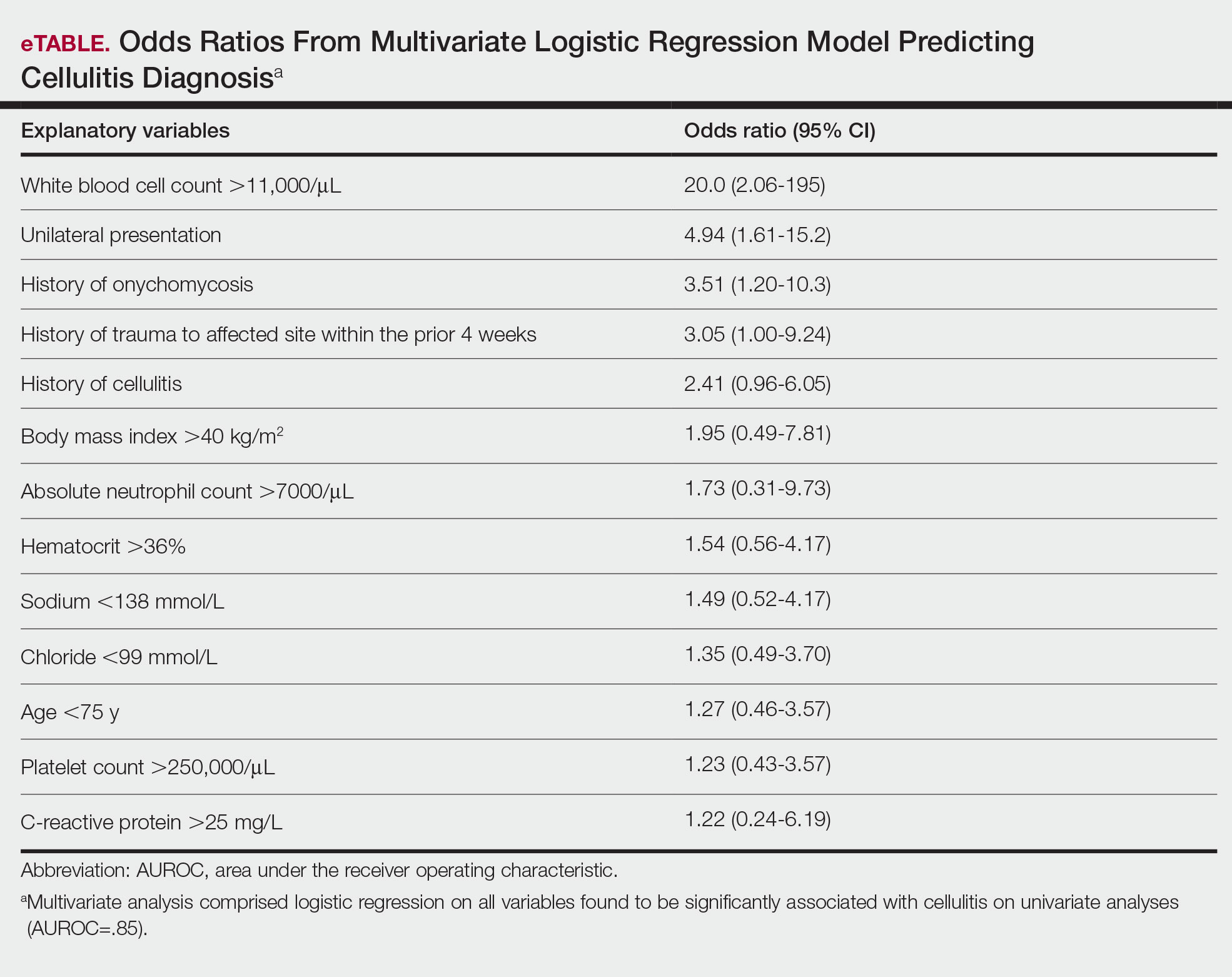

Cellulitis has been a particularly well-studied diagnosis. Dermatologists often change the diagnosis of cellulitis in the hospital setting and reduce antibiotic exposure. In a prospective cohort study of 116 patients, 33.6% had their diagnosis of cellulitis changed to pseudocellulitis following evaluation by the dermatologist; of 34 patients who had started antibiotic therapy, 82.4% were recommended to discontinue the treatment, and all 39 patients with pseudocellulitis had a proven stable clinical course at 1-month follow-up.4 In another trial, 175 patients with presumed cellulitis were given standard management (provided by the medicine inpatient team) either alone or with the addition of dermatology consultation. Duration of antibiotic treatment (including intravenous therapy) was reduced when dermatology was consulted. Two weeks after discharge, patients who had dermatology consultations demonstrated greater clinical improvement.5

Improving ED and IC Access to Dermatology

Emergency department and IC teams across the United States work tirelessly to meet the demands of patients presenting with medically urgent conditions. In a study examining 861 ED cases, dermatology made up only 9.5% of specialist consultations, and in the opinion of the on-call dermatology resident, 51.0% (439/861) of cases warranted ED-level care.6

Data from the 2021 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey showed that the mean wait time to see a physician, nurse, or physician assistant in an ED was 37.5 minutes, but wait times could range from less than 15 minutes to more than 6 hours.7 According to a study of 35,849 ED visits at nonfederal hospitals in the United States, only 47.7% of EDs admitted more than 90% of their patients within 6 hours.8 Moreover, perceived wait times in the ED have been shown to greatly impact patient satisfaction. Two predictors of perceived wait time include appropriate assessment of emergency level and the feeling of being forgotten.9 In a study of 2377 ED visits with primary dermatologic diagnoses, only 5.5% led to admission.10 This suggests many patients who come to the ED for dermatologic needs do not require inpatient hospital care. In these cases, patients with primary dermatologic concerns may experience longer ED wait times, as higher acuity or emergency cases take precedence. Studies also have shown that more vulnerable populations are utilizing ED visits most for primary dermatologic concerns.10,11 This includes individuals of lower income and/or those with Medicaid/Medicare or those without insurance.11 Predictors of high ED use for dermatologic concerns include prior frequent use of the ED (for nondermatologic concerns) instead of outpatient care, income below the poverty level, and lack of insurance; older individuals (>65 years) also were found to use the ED more frequently for dermatologic concerns when compared to younger individuals.10

Importantly, there is a great need for urgent dermatology consultation for pediatric patients. A single-institution study showed that over a 36-month period, there were 347 pediatric dermatology consultations from the pediatric ED mostly for children aged 0 days to 5 years; nearly half of these consultations required outpatient clinic follow-up.12 However, dermatology outpatient follow-up can be difficult to obtain, especially for vulnerable groups. In a study of 611 dermatology clinics, patients with Medicaid were shown to have longer wait times and less success in obtaining dermatology appointments compared to those with Medicare or private insurance.13 Only about 30% of private dermatology practices accept Medicaid patients, likely pushing these patients toward utilization of emergency services for dermatologic concerns.13,14

There is a clear role for a dermatology IC in our health care system, and the concept already has been identified and trialed in several institutions. At Oregon Health and Science University (Portland, Oregon), a retrospective chart review of patients with diagnoses of Morgellons disease and neurotic excoriations seen in dermatology urgent care between 2018 and 2020 showed an 88% decrease in annual rates of health care visits and a 77% decrease in ED visits after dermatology services were engaged compared to before the opening of the dermatology urgent care.15 Another study showed that uninsured or self-pay patients were more than 14 times more likely to access dermatology urgent care than to schedule a routine clinic appointment, suggesting that there is a barrier to making outpatient dermatologic appointments for uninsured patients. An urgent access model may facilitate the ability of underinsured patients to access care.16

Improving Dermatology Access for Other Specialties

Needs for dermatologic care are encountered in many other specialties. Having direct access to immediate dermatologic treatment is best for patients and may avoid inpatient care and trips to the ED for consultation access. Ideally, a dermatology IC would allow direct care to be provided alongside the oncology outpatient team. New immunologic therapies (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 and programmed cell death protein 1/programmed death-ligand 1 treatments) can cause dermatologic reactions in more than 40% of patients.17 Paraneoplastic syndromes can manifest with cutaneous symptoms, as can acute graft-vs-host-disease.18 In a study at Memorial Sloan Kettering (New York, New York) analyzing 426 same-day outpatient dermatology consultations, 17% of patients experienced interruptions in their cancer therapy, but 83% responded quickly to dermatologic treatment and resumed oncologic therapy—19% of them at a reduced dose.19 This is an important demonstration of prompt dermatologic consultation in an outpatient setting reducing interruptions to anticancer therapy. The heterogeneity of the cutaneous reactions seen from oncologic and immunomodulatory medications is profound, with more than 140 different types of skin-specific reactions.20

Solid-organ transplant recipients also could benefit from urgent access to dermatology services. These patients are at a much higher risk for skin cancers, and a study showed that those who receive referrals to dermatology are seen sooner after transplantation (5.6 years) than those who self-refer (7.2 years). Importantly, annual skin cancer screenings are recommended to begin 1 year after transplantation.21

Direct access to dermatology care could benefit patients with complicated rheumatologic conditions who present with skin findings; for example, patients with lupus erythematosus or dermatomyositis can have a spectrum of disease ranging from skin-predominant to systemic manifestations. Identification and treatment of such diseases require collaboration between dermatologists and rheumatologists.22 Likewise, a study of a joint rheumatology-dermatology clinic for psoriatic arthritis showed that a multidisciplinary approach to management leads to decreased time for patients to obtain proper rheumatologic and dermatologic examination and a faster time to diagnosis; however, such multidisciplinary clinic models and approaches to care often are found only at large university-based hospitals.23 In a patient population for whom time to diagnosis is crucial to avoid permanent changes such as joint destruction, a dermatology IC could fill this role in community hospitals and clinics. A dermatology IC also can serve patients with specific diagnoses who would benefit from more direct access to care; for example, in 2017 there were 131,430 ED visits for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) in the United States. While HS is not uncommon, it usually is underdiagnosed because it can be challenging to differentiate from an uncomplicated abscess. Emergency department visits often are utilized for first-time presentations as well as flares of HS. In these situations, ED doctors can provide palliative treatment, but prompt referrals to dermatologists should be made for disease management to decrease recurrence.24

Final Thoughts

A huge caveat to the dermatology urgent care system is determining what is deemed “urgent.” We propose starting with a referral-based system only from other physicians (including IC and urgent care) rather than having patients walk in directly. Ideally, as support and staff increases, the availability can increase as well. In our institution, we suggested half-day clinics staffed by varying physicians, with compensation models similar to an ED or IC physician rather than by productivity. Each group considering this kind of addition to patient care will need to assess these points in building an IC for dermatology. The University of Pennsylvania’s (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) system of rapid-access clinics to facilitate access to care for patients requiring urgent appointments may function as a model for future similar clinics.25 Creating a specialized IC/urgent care is not a novel concept. Orthopedic urgent care centers have increased greatly in the past decade, reducing ED burden for musculoskeletal complaints. In a study evaluating the utility of orthopedic urgent care settings, time to see an orthopedic specialist and cost were both greatly reduced with this system.1 The same has been shown in same-day access ophthalmology clinics, which are organized similarly to an urgent care.26

In 2021, there were 107.4 million treat-and-release visits to the ED in the United States for a total cost of $80.3 billion.27 This emphasizes the need to consider care models that not only provide excellent clinical care and treat the most acute diagnoses promptly and accurately but also reduce overall costs. While this may be convoluted for other specialties given the difficulty of having patients self-triage, dermatologic concerns are similar to orthopedic concerns for the patient to decipher the etiology of the concern. As in orthopedics, a dermatology IC could function similarly, increasing access, decreasing ED and IC wait times, saving overall health care spending, and allowing underserved and publicly insured individuals to have improved, prompt care.

- Anderson TJ, Althausen PL. The role of dedicated musculoskeletal urgent care centers in reducing cost and improving access to orthopaedic care. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30:S3-S6.

- Falanga V, Schachner LA, Rae V, et al. Dermatologic consultations in the hospital setting. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1022-1025.

- Galimberti F, Guren L, Fernandez AP, et al. Dermatology consultations significantly contribute quality to care of hospitalized patients: a prospective study of dermatology inpatient consults at a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E547-E551.

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543.

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536.

- Grillo E, Vañó-Galván S, Jiménez-Gómez N, et al. Dermatologic emergencies: descriptive analysis of 861 patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:316-324.

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2021. Accessed September 23, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2021-nhamcs-ed-web-tables-508.pdf

- Horwitz LI, Green J, Bradley EH. US emergency department performance on wait time and length of visit. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:133-141.

- Spechbach H, Rochat J, Gaspoz JM, et al. Patients’ time perception in the waiting room of an ambulatory emergency unit: a cross-sectional study. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19:41.

- Yang JJ, Maloney NJ, Bach DQ, et al. Dermatology in the emergency department: prescriptions, rates of inpatient admission, and predictors of high utilization in the United States from 1996 to 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1480-1483.

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313.

- Moon AT, Castelo-Soccio L, Yan AC. Emergency department utilization of pediatric dermatology (PD) consultations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1173-1177.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188.

- Mazmudar RS, Gupta N, Desai BJ, et al. Dermatologist appointment access and waiting times: a comparative study of insurance types. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1468-1470.

- Johnson J, Cutler B, Latour E, et al. Dermatology urgent care model reduces costs and healthcare utilization for psychodermatology patients-a retrospective chart review. Dermatol Online J. 2022;28:5.

- Wintringham JA, Strock DM, Perkins-Holtsclaw K, et al. Dermatology in the urgent care setting: a retrospective review of patients seen in an urgent access dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:1271-1273.

- Yoo MJ, Long B, Brady WJ, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: an emergency medicine focused review. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;50:335-344.

- Merlo G, Cozzani E, Canale F, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of hematologic malignancies the experience of an Italian dermatology department. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37:285-290.

- Barrios D, Phillips G, Freites-Martinez A, et al. Outpatient dermatology consultations for oncology patients with acute dermatologic adverse events impact anticancer therapy interruption: a retrospective study.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1340-1347.

- Salah S, Kerob D, Pages Laurent C, et al. Evaluation of anticancer therapy-related dermatologic adverse events: insights from Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System dataset. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:863-871. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.07.1456

- Shope C, Andrews L, Girvin A, et al. Referrals to dermatology following solid organ transplant. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1159-1160. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.052

- Werth VP, Askanase AD, Lundberg IE. Importance of collaboration of dermatology and rheumatology to advance the field for lupus and dermatomyositis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:583-587.

- Ziob J, Behning C, Brossart P, et al. Specialized dermatological-rheumatological patient management improves diagnostic outcome and patient journey in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a four-year analysis. BMC Rheumatol. 2021;5:1-8. doi:10.1186/s41927-021-00217-z

- Okun MM, Flamm A, Werley EB, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: diagnosis and management in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2022;63:636-644.

- Jayakumar KL, Samimi SS, Vittorio CC, et al. Expediting patient appointments with dermatology rapid access clinics. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt2zv07510.

- Singman EL, Smith K, Mehta R, et al. Cost and visit duration of same-day access at an academic ophthalmology department vs emergency department. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:729-735. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0864

- Roemer M. Costs of treat-and-release emergency department visits in the United States, 2021. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Published September 2024. Accessed September 16, 2025. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb311-ED-visit-costs-2021.pdf

Emergency departments (EDs) and immediate care (IC) facilities often do not have prompt dermatologic care available for triage and treatment. Many EDs do not have staff dermatologists on call, instead relying on input from other specialists or quick outpatient dermatology appointments. It can be challenging to obtain a prompt appointment with a board-certified dermatologist, which is preferred for complex cases such as severe drug reactions or infection. In the United States, there are few well-established IC centers equipped to address dermatologic needs. The orthopedic specialty has modeled a concept that has led to the establishment of orthopedic urgent care/IC in many larger institutions,1 and many private practice clinics serve their communities as well. We present a rationale for why a similar IC concept for dermatology would be beneficial, particularly within a large institution or health system.

Dermatology Consultation Changes Disease Management

There is diagnostic and therapeutic utility in dermatology evaluation. In a prospective study of 591 patients who were either hospitalized or evaluated in an ED/urgent care setting, treatment was changed in more than 60% of cases when dermatology consultation was utilized.2 In another prospective review of 691 cases on an inpatient service, dermatology consultation resulted in treatment changes more than 80% of the time.3

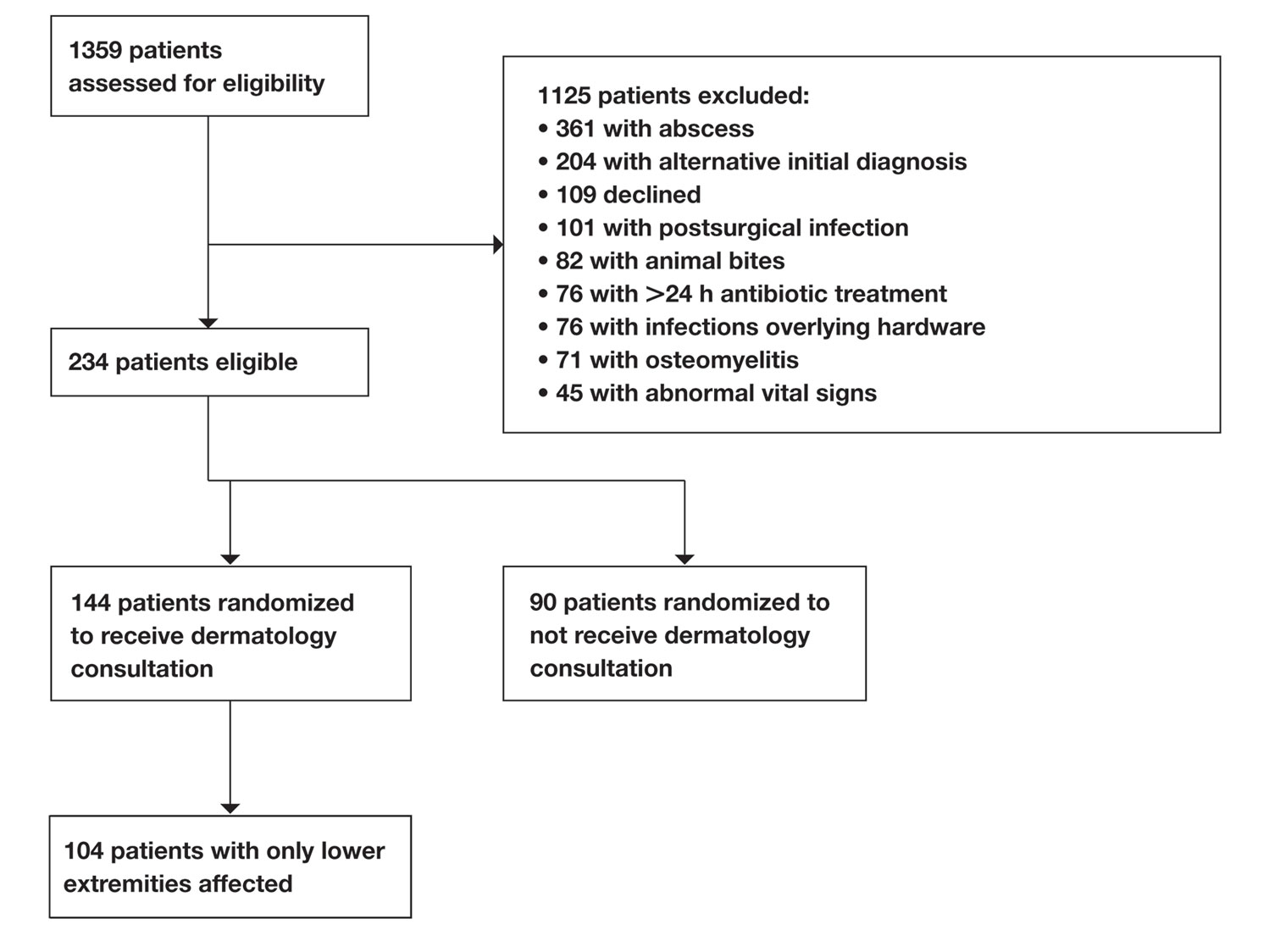

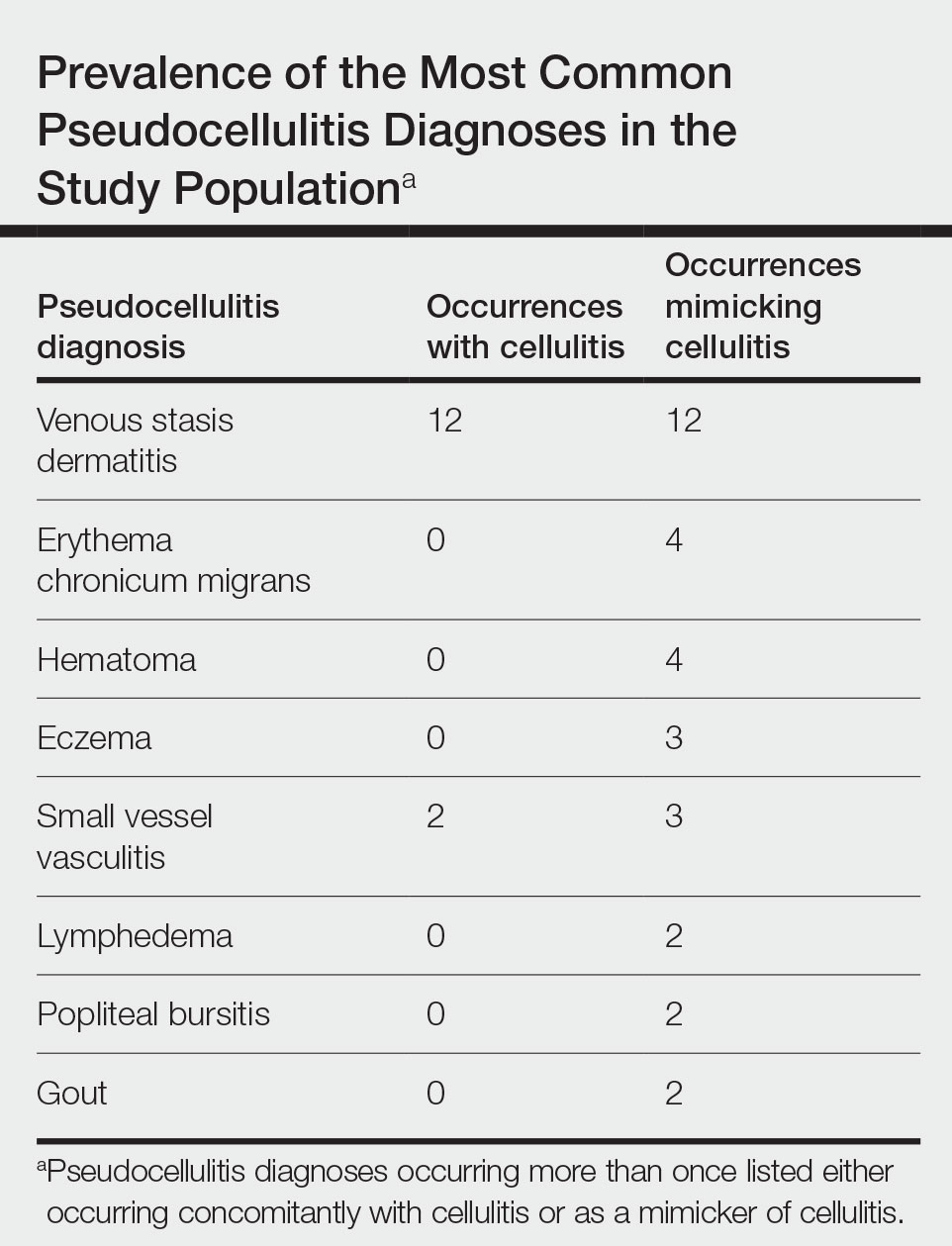

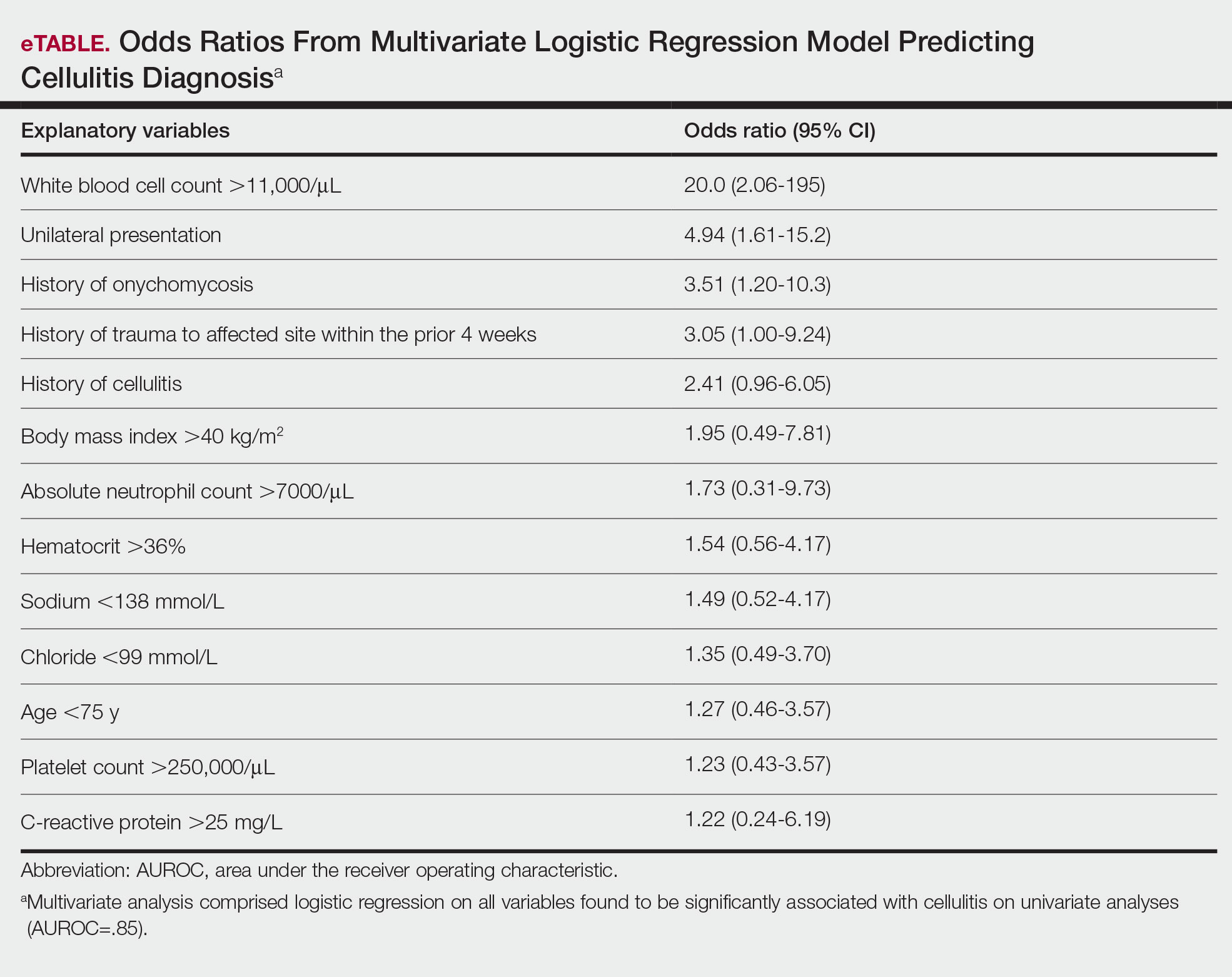

Cellulitis has been a particularly well-studied diagnosis. Dermatologists often change the diagnosis of cellulitis in the hospital setting and reduce antibiotic exposure. In a prospective cohort study of 116 patients, 33.6% had their diagnosis of cellulitis changed to pseudocellulitis following evaluation by the dermatologist; of 34 patients who had started antibiotic therapy, 82.4% were recommended to discontinue the treatment, and all 39 patients with pseudocellulitis had a proven stable clinical course at 1-month follow-up.4 In another trial, 175 patients with presumed cellulitis were given standard management (provided by the medicine inpatient team) either alone or with the addition of dermatology consultation. Duration of antibiotic treatment (including intravenous therapy) was reduced when dermatology was consulted. Two weeks after discharge, patients who had dermatology consultations demonstrated greater clinical improvement.5

Improving ED and IC Access to Dermatology

Emergency department and IC teams across the United States work tirelessly to meet the demands of patients presenting with medically urgent conditions. In a study examining 861 ED cases, dermatology made up only 9.5% of specialist consultations, and in the opinion of the on-call dermatology resident, 51.0% (439/861) of cases warranted ED-level care.6

Data from the 2021 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey showed that the mean wait time to see a physician, nurse, or physician assistant in an ED was 37.5 minutes, but wait times could range from less than 15 minutes to more than 6 hours.7 According to a study of 35,849 ED visits at nonfederal hospitals in the United States, only 47.7% of EDs admitted more than 90% of their patients within 6 hours.8 Moreover, perceived wait times in the ED have been shown to greatly impact patient satisfaction. Two predictors of perceived wait time include appropriate assessment of emergency level and the feeling of being forgotten.9 In a study of 2377 ED visits with primary dermatologic diagnoses, only 5.5% led to admission.10 This suggests many patients who come to the ED for dermatologic needs do not require inpatient hospital care. In these cases, patients with primary dermatologic concerns may experience longer ED wait times, as higher acuity or emergency cases take precedence. Studies also have shown that more vulnerable populations are utilizing ED visits most for primary dermatologic concerns.10,11 This includes individuals of lower income and/or those with Medicaid/Medicare or those without insurance.11 Predictors of high ED use for dermatologic concerns include prior frequent use of the ED (for nondermatologic concerns) instead of outpatient care, income below the poverty level, and lack of insurance; older individuals (>65 years) also were found to use the ED more frequently for dermatologic concerns when compared to younger individuals.10

Importantly, there is a great need for urgent dermatology consultation for pediatric patients. A single-institution study showed that over a 36-month period, there were 347 pediatric dermatology consultations from the pediatric ED mostly for children aged 0 days to 5 years; nearly half of these consultations required outpatient clinic follow-up.12 However, dermatology outpatient follow-up can be difficult to obtain, especially for vulnerable groups. In a study of 611 dermatology clinics, patients with Medicaid were shown to have longer wait times and less success in obtaining dermatology appointments compared to those with Medicare or private insurance.13 Only about 30% of private dermatology practices accept Medicaid patients, likely pushing these patients toward utilization of emergency services for dermatologic concerns.13,14

There is a clear role for a dermatology IC in our health care system, and the concept already has been identified and trialed in several institutions. At Oregon Health and Science University (Portland, Oregon), a retrospective chart review of patients with diagnoses of Morgellons disease and neurotic excoriations seen in dermatology urgent care between 2018 and 2020 showed an 88% decrease in annual rates of health care visits and a 77% decrease in ED visits after dermatology services were engaged compared to before the opening of the dermatology urgent care.15 Another study showed that uninsured or self-pay patients were more than 14 times more likely to access dermatology urgent care than to schedule a routine clinic appointment, suggesting that there is a barrier to making outpatient dermatologic appointments for uninsured patients. An urgent access model may facilitate the ability of underinsured patients to access care.16

Improving Dermatology Access for Other Specialties

Needs for dermatologic care are encountered in many other specialties. Having direct access to immediate dermatologic treatment is best for patients and may avoid inpatient care and trips to the ED for consultation access. Ideally, a dermatology IC would allow direct care to be provided alongside the oncology outpatient team. New immunologic therapies (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 and programmed cell death protein 1/programmed death-ligand 1 treatments) can cause dermatologic reactions in more than 40% of patients.17 Paraneoplastic syndromes can manifest with cutaneous symptoms, as can acute graft-vs-host-disease.18 In a study at Memorial Sloan Kettering (New York, New York) analyzing 426 same-day outpatient dermatology consultations, 17% of patients experienced interruptions in their cancer therapy, but 83% responded quickly to dermatologic treatment and resumed oncologic therapy—19% of them at a reduced dose.19 This is an important demonstration of prompt dermatologic consultation in an outpatient setting reducing interruptions to anticancer therapy. The heterogeneity of the cutaneous reactions seen from oncologic and immunomodulatory medications is profound, with more than 140 different types of skin-specific reactions.20

Solid-organ transplant recipients also could benefit from urgent access to dermatology services. These patients are at a much higher risk for skin cancers, and a study showed that those who receive referrals to dermatology are seen sooner after transplantation (5.6 years) than those who self-refer (7.2 years). Importantly, annual skin cancer screenings are recommended to begin 1 year after transplantation.21

Direct access to dermatology care could benefit patients with complicated rheumatologic conditions who present with skin findings; for example, patients with lupus erythematosus or dermatomyositis can have a spectrum of disease ranging from skin-predominant to systemic manifestations. Identification and treatment of such diseases require collaboration between dermatologists and rheumatologists.22 Likewise, a study of a joint rheumatology-dermatology clinic for psoriatic arthritis showed that a multidisciplinary approach to management leads to decreased time for patients to obtain proper rheumatologic and dermatologic examination and a faster time to diagnosis; however, such multidisciplinary clinic models and approaches to care often are found only at large university-based hospitals.23 In a patient population for whom time to diagnosis is crucial to avoid permanent changes such as joint destruction, a dermatology IC could fill this role in community hospitals and clinics. A dermatology IC also can serve patients with specific diagnoses who would benefit from more direct access to care; for example, in 2017 there were 131,430 ED visits for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) in the United States. While HS is not uncommon, it usually is underdiagnosed because it can be challenging to differentiate from an uncomplicated abscess. Emergency department visits often are utilized for first-time presentations as well as flares of HS. In these situations, ED doctors can provide palliative treatment, but prompt referrals to dermatologists should be made for disease management to decrease recurrence.24

Final Thoughts

A huge caveat to the dermatology urgent care system is determining what is deemed “urgent.” We propose starting with a referral-based system only from other physicians (including IC and urgent care) rather than having patients walk in directly. Ideally, as support and staff increases, the availability can increase as well. In our institution, we suggested half-day clinics staffed by varying physicians, with compensation models similar to an ED or IC physician rather than by productivity. Each group considering this kind of addition to patient care will need to assess these points in building an IC for dermatology. The University of Pennsylvania’s (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) system of rapid-access clinics to facilitate access to care for patients requiring urgent appointments may function as a model for future similar clinics.25 Creating a specialized IC/urgent care is not a novel concept. Orthopedic urgent care centers have increased greatly in the past decade, reducing ED burden for musculoskeletal complaints. In a study evaluating the utility of orthopedic urgent care settings, time to see an orthopedic specialist and cost were both greatly reduced with this system.1 The same has been shown in same-day access ophthalmology clinics, which are organized similarly to an urgent care.26

In 2021, there were 107.4 million treat-and-release visits to the ED in the United States for a total cost of $80.3 billion.27 This emphasizes the need to consider care models that not only provide excellent clinical care and treat the most acute diagnoses promptly and accurately but also reduce overall costs. While this may be convoluted for other specialties given the difficulty of having patients self-triage, dermatologic concerns are similar to orthopedic concerns for the patient to decipher the etiology of the concern. As in orthopedics, a dermatology IC could function similarly, increasing access, decreasing ED and IC wait times, saving overall health care spending, and allowing underserved and publicly insured individuals to have improved, prompt care.

Emergency departments (EDs) and immediate care (IC) facilities often do not have prompt dermatologic care available for triage and treatment. Many EDs do not have staff dermatologists on call, instead relying on input from other specialists or quick outpatient dermatology appointments. It can be challenging to obtain a prompt appointment with a board-certified dermatologist, which is preferred for complex cases such as severe drug reactions or infection. In the United States, there are few well-established IC centers equipped to address dermatologic needs. The orthopedic specialty has modeled a concept that has led to the establishment of orthopedic urgent care/IC in many larger institutions,1 and many private practice clinics serve their communities as well. We present a rationale for why a similar IC concept for dermatology would be beneficial, particularly within a large institution or health system.

Dermatology Consultation Changes Disease Management

There is diagnostic and therapeutic utility in dermatology evaluation. In a prospective study of 591 patients who were either hospitalized or evaluated in an ED/urgent care setting, treatment was changed in more than 60% of cases when dermatology consultation was utilized.2 In another prospective review of 691 cases on an inpatient service, dermatology consultation resulted in treatment changes more than 80% of the time.3

Cellulitis has been a particularly well-studied diagnosis. Dermatologists often change the diagnosis of cellulitis in the hospital setting and reduce antibiotic exposure. In a prospective cohort study of 116 patients, 33.6% had their diagnosis of cellulitis changed to pseudocellulitis following evaluation by the dermatologist; of 34 patients who had started antibiotic therapy, 82.4% were recommended to discontinue the treatment, and all 39 patients with pseudocellulitis had a proven stable clinical course at 1-month follow-up.4 In another trial, 175 patients with presumed cellulitis were given standard management (provided by the medicine inpatient team) either alone or with the addition of dermatology consultation. Duration of antibiotic treatment (including intravenous therapy) was reduced when dermatology was consulted. Two weeks after discharge, patients who had dermatology consultations demonstrated greater clinical improvement.5

Improving ED and IC Access to Dermatology

Emergency department and IC teams across the United States work tirelessly to meet the demands of patients presenting with medically urgent conditions. In a study examining 861 ED cases, dermatology made up only 9.5% of specialist consultations, and in the opinion of the on-call dermatology resident, 51.0% (439/861) of cases warranted ED-level care.6

Data from the 2021 National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey showed that the mean wait time to see a physician, nurse, or physician assistant in an ED was 37.5 minutes, but wait times could range from less than 15 minutes to more than 6 hours.7 According to a study of 35,849 ED visits at nonfederal hospitals in the United States, only 47.7% of EDs admitted more than 90% of their patients within 6 hours.8 Moreover, perceived wait times in the ED have been shown to greatly impact patient satisfaction. Two predictors of perceived wait time include appropriate assessment of emergency level and the feeling of being forgotten.9 In a study of 2377 ED visits with primary dermatologic diagnoses, only 5.5% led to admission.10 This suggests many patients who come to the ED for dermatologic needs do not require inpatient hospital care. In these cases, patients with primary dermatologic concerns may experience longer ED wait times, as higher acuity or emergency cases take precedence. Studies also have shown that more vulnerable populations are utilizing ED visits most for primary dermatologic concerns.10,11 This includes individuals of lower income and/or those with Medicaid/Medicare or those without insurance.11 Predictors of high ED use for dermatologic concerns include prior frequent use of the ED (for nondermatologic concerns) instead of outpatient care, income below the poverty level, and lack of insurance; older individuals (>65 years) also were found to use the ED more frequently for dermatologic concerns when compared to younger individuals.10

Importantly, there is a great need for urgent dermatology consultation for pediatric patients. A single-institution study showed that over a 36-month period, there were 347 pediatric dermatology consultations from the pediatric ED mostly for children aged 0 days to 5 years; nearly half of these consultations required outpatient clinic follow-up.12 However, dermatology outpatient follow-up can be difficult to obtain, especially for vulnerable groups. In a study of 611 dermatology clinics, patients with Medicaid were shown to have longer wait times and less success in obtaining dermatology appointments compared to those with Medicare or private insurance.13 Only about 30% of private dermatology practices accept Medicaid patients, likely pushing these patients toward utilization of emergency services for dermatologic concerns.13,14

There is a clear role for a dermatology IC in our health care system, and the concept already has been identified and trialed in several institutions. At Oregon Health and Science University (Portland, Oregon), a retrospective chart review of patients with diagnoses of Morgellons disease and neurotic excoriations seen in dermatology urgent care between 2018 and 2020 showed an 88% decrease in annual rates of health care visits and a 77% decrease in ED visits after dermatology services were engaged compared to before the opening of the dermatology urgent care.15 Another study showed that uninsured or self-pay patients were more than 14 times more likely to access dermatology urgent care than to schedule a routine clinic appointment, suggesting that there is a barrier to making outpatient dermatologic appointments for uninsured patients. An urgent access model may facilitate the ability of underinsured patients to access care.16

Improving Dermatology Access for Other Specialties

Needs for dermatologic care are encountered in many other specialties. Having direct access to immediate dermatologic treatment is best for patients and may avoid inpatient care and trips to the ED for consultation access. Ideally, a dermatology IC would allow direct care to be provided alongside the oncology outpatient team. New immunologic therapies (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 and programmed cell death protein 1/programmed death-ligand 1 treatments) can cause dermatologic reactions in more than 40% of patients.17 Paraneoplastic syndromes can manifest with cutaneous symptoms, as can acute graft-vs-host-disease.18 In a study at Memorial Sloan Kettering (New York, New York) analyzing 426 same-day outpatient dermatology consultations, 17% of patients experienced interruptions in their cancer therapy, but 83% responded quickly to dermatologic treatment and resumed oncologic therapy—19% of them at a reduced dose.19 This is an important demonstration of prompt dermatologic consultation in an outpatient setting reducing interruptions to anticancer therapy. The heterogeneity of the cutaneous reactions seen from oncologic and immunomodulatory medications is profound, with more than 140 different types of skin-specific reactions.20

Solid-organ transplant recipients also could benefit from urgent access to dermatology services. These patients are at a much higher risk for skin cancers, and a study showed that those who receive referrals to dermatology are seen sooner after transplantation (5.6 years) than those who self-refer (7.2 years). Importantly, annual skin cancer screenings are recommended to begin 1 year after transplantation.21

Direct access to dermatology care could benefit patients with complicated rheumatologic conditions who present with skin findings; for example, patients with lupus erythematosus or dermatomyositis can have a spectrum of disease ranging from skin-predominant to systemic manifestations. Identification and treatment of such diseases require collaboration between dermatologists and rheumatologists.22 Likewise, a study of a joint rheumatology-dermatology clinic for psoriatic arthritis showed that a multidisciplinary approach to management leads to decreased time for patients to obtain proper rheumatologic and dermatologic examination and a faster time to diagnosis; however, such multidisciplinary clinic models and approaches to care often are found only at large university-based hospitals.23 In a patient population for whom time to diagnosis is crucial to avoid permanent changes such as joint destruction, a dermatology IC could fill this role in community hospitals and clinics. A dermatology IC also can serve patients with specific diagnoses who would benefit from more direct access to care; for example, in 2017 there were 131,430 ED visits for hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) in the United States. While HS is not uncommon, it usually is underdiagnosed because it can be challenging to differentiate from an uncomplicated abscess. Emergency department visits often are utilized for first-time presentations as well as flares of HS. In these situations, ED doctors can provide palliative treatment, but prompt referrals to dermatologists should be made for disease management to decrease recurrence.24

Final Thoughts

A huge caveat to the dermatology urgent care system is determining what is deemed “urgent.” We propose starting with a referral-based system only from other physicians (including IC and urgent care) rather than having patients walk in directly. Ideally, as support and staff increases, the availability can increase as well. In our institution, we suggested half-day clinics staffed by varying physicians, with compensation models similar to an ED or IC physician rather than by productivity. Each group considering this kind of addition to patient care will need to assess these points in building an IC for dermatology. The University of Pennsylvania’s (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) system of rapid-access clinics to facilitate access to care for patients requiring urgent appointments may function as a model for future similar clinics.25 Creating a specialized IC/urgent care is not a novel concept. Orthopedic urgent care centers have increased greatly in the past decade, reducing ED burden for musculoskeletal complaints. In a study evaluating the utility of orthopedic urgent care settings, time to see an orthopedic specialist and cost were both greatly reduced with this system.1 The same has been shown in same-day access ophthalmology clinics, which are organized similarly to an urgent care.26

In 2021, there were 107.4 million treat-and-release visits to the ED in the United States for a total cost of $80.3 billion.27 This emphasizes the need to consider care models that not only provide excellent clinical care and treat the most acute diagnoses promptly and accurately but also reduce overall costs. While this may be convoluted for other specialties given the difficulty of having patients self-triage, dermatologic concerns are similar to orthopedic concerns for the patient to decipher the etiology of the concern. As in orthopedics, a dermatology IC could function similarly, increasing access, decreasing ED and IC wait times, saving overall health care spending, and allowing underserved and publicly insured individuals to have improved, prompt care.

- Anderson TJ, Althausen PL. The role of dedicated musculoskeletal urgent care centers in reducing cost and improving access to orthopaedic care. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30:S3-S6.

- Falanga V, Schachner LA, Rae V, et al. Dermatologic consultations in the hospital setting. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1022-1025.

- Galimberti F, Guren L, Fernandez AP, et al. Dermatology consultations significantly contribute quality to care of hospitalized patients: a prospective study of dermatology inpatient consults at a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E547-E551.

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543.

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536.

- Grillo E, Vañó-Galván S, Jiménez-Gómez N, et al. Dermatologic emergencies: descriptive analysis of 861 patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:316-324.

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2021. Accessed September 23, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2021-nhamcs-ed-web-tables-508.pdf

- Horwitz LI, Green J, Bradley EH. US emergency department performance on wait time and length of visit. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:133-141.

- Spechbach H, Rochat J, Gaspoz JM, et al. Patients’ time perception in the waiting room of an ambulatory emergency unit: a cross-sectional study. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19:41.

- Yang JJ, Maloney NJ, Bach DQ, et al. Dermatology in the emergency department: prescriptions, rates of inpatient admission, and predictors of high utilization in the United States from 1996 to 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1480-1483.

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313.

- Moon AT, Castelo-Soccio L, Yan AC. Emergency department utilization of pediatric dermatology (PD) consultations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1173-1177.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188.

- Mazmudar RS, Gupta N, Desai BJ, et al. Dermatologist appointment access and waiting times: a comparative study of insurance types. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1468-1470.

- Johnson J, Cutler B, Latour E, et al. Dermatology urgent care model reduces costs and healthcare utilization for psychodermatology patients-a retrospective chart review. Dermatol Online J. 2022;28:5.

- Wintringham JA, Strock DM, Perkins-Holtsclaw K, et al. Dermatology in the urgent care setting: a retrospective review of patients seen in an urgent access dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:1271-1273.

- Yoo MJ, Long B, Brady WJ, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: an emergency medicine focused review. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;50:335-344.

- Merlo G, Cozzani E, Canale F, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of hematologic malignancies the experience of an Italian dermatology department. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37:285-290.

- Barrios D, Phillips G, Freites-Martinez A, et al. Outpatient dermatology consultations for oncology patients with acute dermatologic adverse events impact anticancer therapy interruption: a retrospective study.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1340-1347.

- Salah S, Kerob D, Pages Laurent C, et al. Evaluation of anticancer therapy-related dermatologic adverse events: insights from Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System dataset. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:863-871. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.07.1456

- Shope C, Andrews L, Girvin A, et al. Referrals to dermatology following solid organ transplant. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1159-1160. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.052

- Werth VP, Askanase AD, Lundberg IE. Importance of collaboration of dermatology and rheumatology to advance the field for lupus and dermatomyositis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:583-587.

- Ziob J, Behning C, Brossart P, et al. Specialized dermatological-rheumatological patient management improves diagnostic outcome and patient journey in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a four-year analysis. BMC Rheumatol. 2021;5:1-8. doi:10.1186/s41927-021-00217-z

- Okun MM, Flamm A, Werley EB, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: diagnosis and management in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2022;63:636-644.

- Jayakumar KL, Samimi SS, Vittorio CC, et al. Expediting patient appointments with dermatology rapid access clinics. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt2zv07510.

- Singman EL, Smith K, Mehta R, et al. Cost and visit duration of same-day access at an academic ophthalmology department vs emergency department. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:729-735. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0864

- Roemer M. Costs of treat-and-release emergency department visits in the United States, 2021. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Published September 2024. Accessed September 16, 2025. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb311-ED-visit-costs-2021.pdf

- Anderson TJ, Althausen PL. The role of dedicated musculoskeletal urgent care centers in reducing cost and improving access to orthopaedic care. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30:S3-S6.

- Falanga V, Schachner LA, Rae V, et al. Dermatologic consultations in the hospital setting. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1022-1025.

- Galimberti F, Guren L, Fernandez AP, et al. Dermatology consultations significantly contribute quality to care of hospitalized patients: a prospective study of dermatology inpatient consults at a tertiary care center. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E547-E551.

- Li DG, Xia FD, Khosravi H, et al. Outcomes of early dermatology consultation for inpatients diagnosed with cellulitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:537-543.

- Ko LN, Garza-Mayers AC, St John J, et al. Effect of dermatology consultation on outcomes for patients with presumed cellulitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:529-536.

- Grillo E, Vañó-Galván S, Jiménez-Gómez N, et al. Dermatologic emergencies: descriptive analysis of 861 patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:316-324.

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, 2021. Accessed September 23, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhamcs/web_tables/2021-nhamcs-ed-web-tables-508.pdf

- Horwitz LI, Green J, Bradley EH. US emergency department performance on wait time and length of visit. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:133-141.

- Spechbach H, Rochat J, Gaspoz JM, et al. Patients’ time perception in the waiting room of an ambulatory emergency unit: a cross-sectional study. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19:41.

- Yang JJ, Maloney NJ, Bach DQ, et al. Dermatology in the emergency department: prescriptions, rates of inpatient admission, and predictors of high utilization in the United States from 1996 to 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1480-1483.

- Chen CL, Fitzpatrick L, Kamel H. Who uses the emergency department for dermatologic care? a statewide analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:308-313.

- Moon AT, Castelo-Soccio L, Yan AC. Emergency department utilization of pediatric dermatology (PD) consultations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1173-1177.

- Creadore A, Desai S, Li SJ, et al. Insurance acceptance, appointment wait time, and dermatologist access across practice types in the US. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:181-188.

- Mazmudar RS, Gupta N, Desai BJ, et al. Dermatologist appointment access and waiting times: a comparative study of insurance types. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1468-1470.

- Johnson J, Cutler B, Latour E, et al. Dermatology urgent care model reduces costs and healthcare utilization for psychodermatology patients-a retrospective chart review. Dermatol Online J. 2022;28:5.

- Wintringham JA, Strock DM, Perkins-Holtsclaw K, et al. Dermatology in the urgent care setting: a retrospective review of patients seen in an urgent access dermatology clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:1271-1273.

- Yoo MJ, Long B, Brady WJ, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: an emergency medicine focused review. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;50:335-344.

- Merlo G, Cozzani E, Canale F, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of hematologic malignancies the experience of an Italian dermatology department. Hematol Oncol. 2019;37:285-290.

- Barrios D, Phillips G, Freites-Martinez A, et al. Outpatient dermatology consultations for oncology patients with acute dermatologic adverse events impact anticancer therapy interruption: a retrospective study.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1340-1347.

- Salah S, Kerob D, Pages Laurent C, et al. Evaluation of anticancer therapy-related dermatologic adverse events: insights from Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System dataset. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:863-871. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.07.1456

- Shope C, Andrews L, Girvin A, et al. Referrals to dermatology following solid organ transplant. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1159-1160. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.11.052

- Werth VP, Askanase AD, Lundberg IE. Importance of collaboration of dermatology and rheumatology to advance the field for lupus and dermatomyositis. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:583-587.

- Ziob J, Behning C, Brossart P, et al. Specialized dermatological-rheumatological patient management improves diagnostic outcome and patient journey in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a four-year analysis. BMC Rheumatol. 2021;5:1-8. doi:10.1186/s41927-021-00217-z

- Okun MM, Flamm A, Werley EB, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: diagnosis and management in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2022;63:636-644.

- Jayakumar KL, Samimi SS, Vittorio CC, et al. Expediting patient appointments with dermatology rapid access clinics. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24:13030/qt2zv07510.

- Singman EL, Smith K, Mehta R, et al. Cost and visit duration of same-day access at an academic ophthalmology department vs emergency department. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137:729-735. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0864

- Roemer M. Costs of treat-and-release emergency department visits in the United States, 2021. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Published September 2024. Accessed September 16, 2025. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb311-ED-visit-costs-2021.pdf

Dermatology Immediate Care: A Game Changer for the Health Care System?

Dermatology Immediate Care: A Game Changer for the Health Care System?

Practice Points

- Emergency departments and most immediate care (IC) centers often lack prompt access to board-certified dermatologists.

- A dermatology urgent care/IC model may shorten wait times, improve access for vulnerable patients and pediatric populations, and reduce unnecessary hospital admissions and costs.

- Increased access to dermatology benefits other specialties by enabling multidisciplinary care leading to faster diagnosis and treatment.

- A staged referral-first dermatology IC pilot with defined staffing and triage rules is a practical path to demonstrate value and scale the service.

Scurvy in Hospitalized Patients

Scurvy in Hospitalized Patients

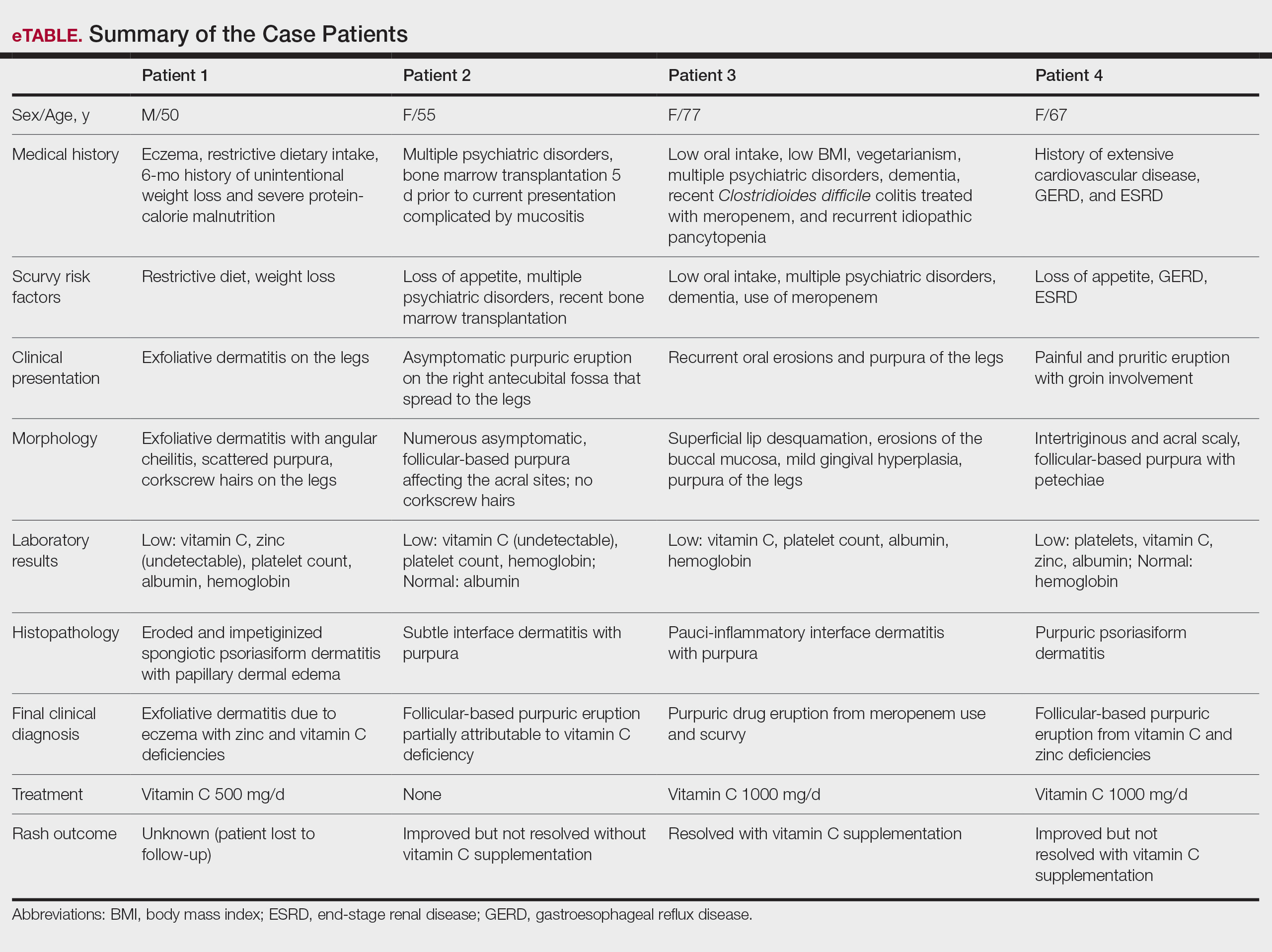

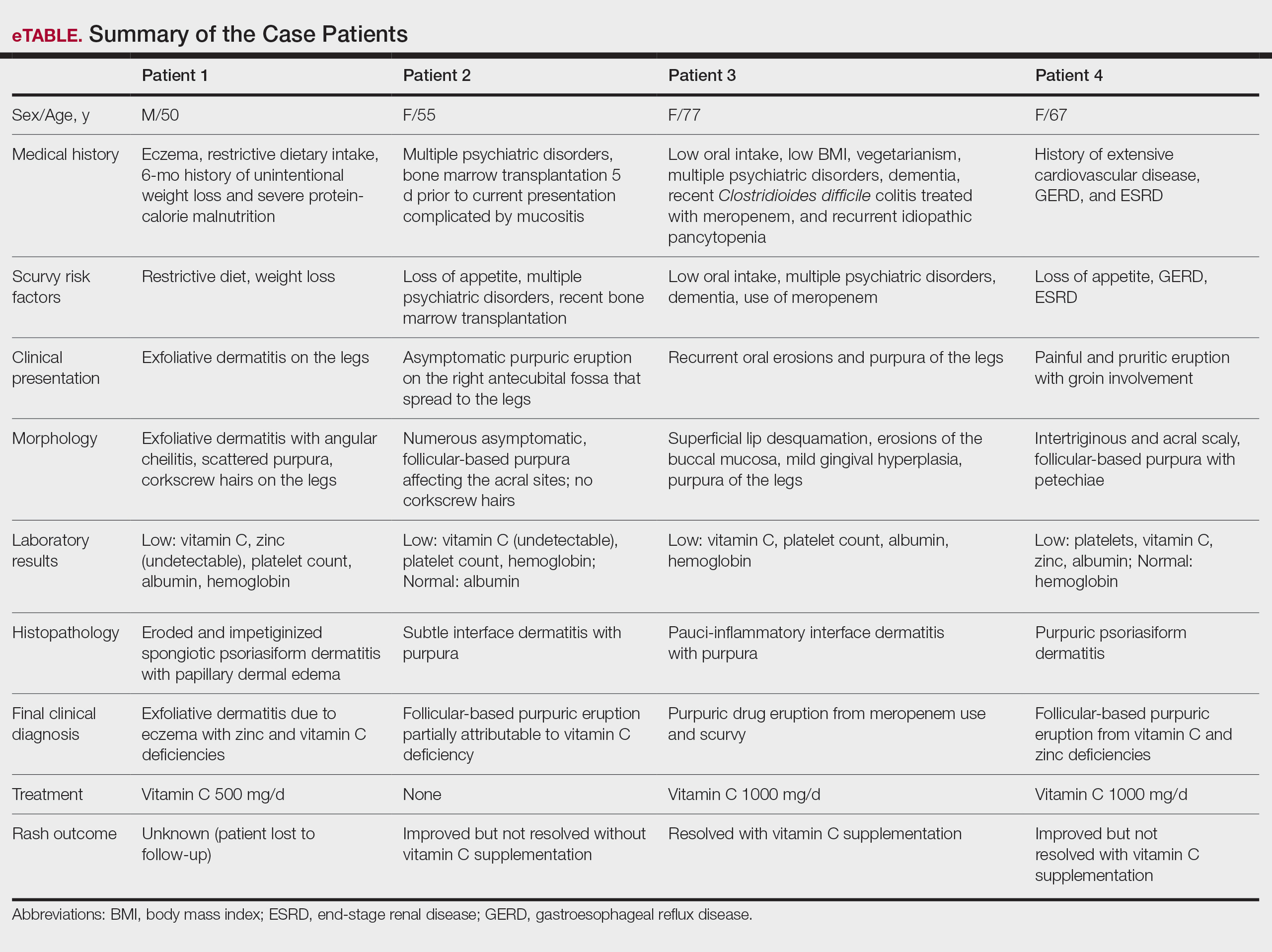

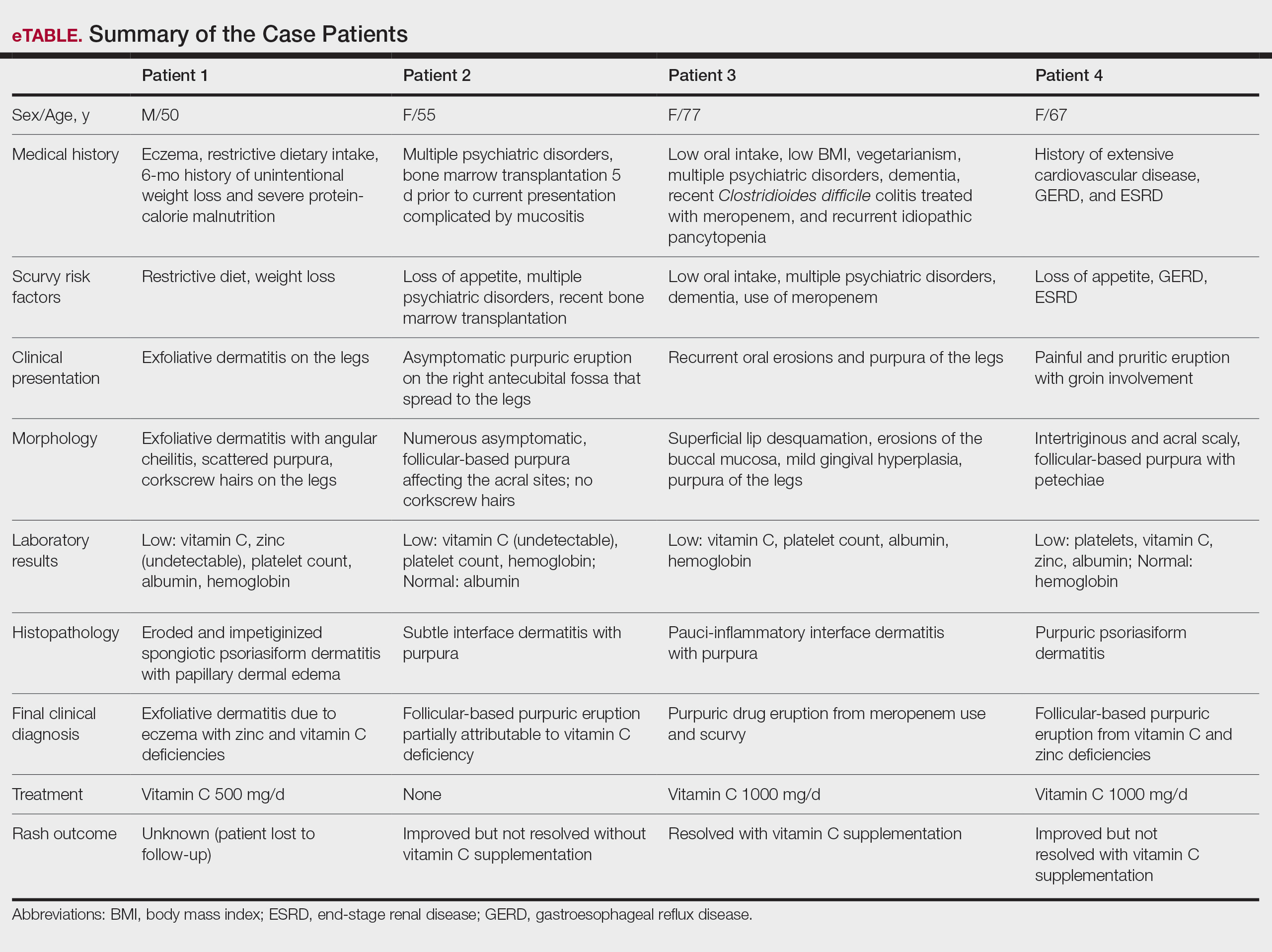

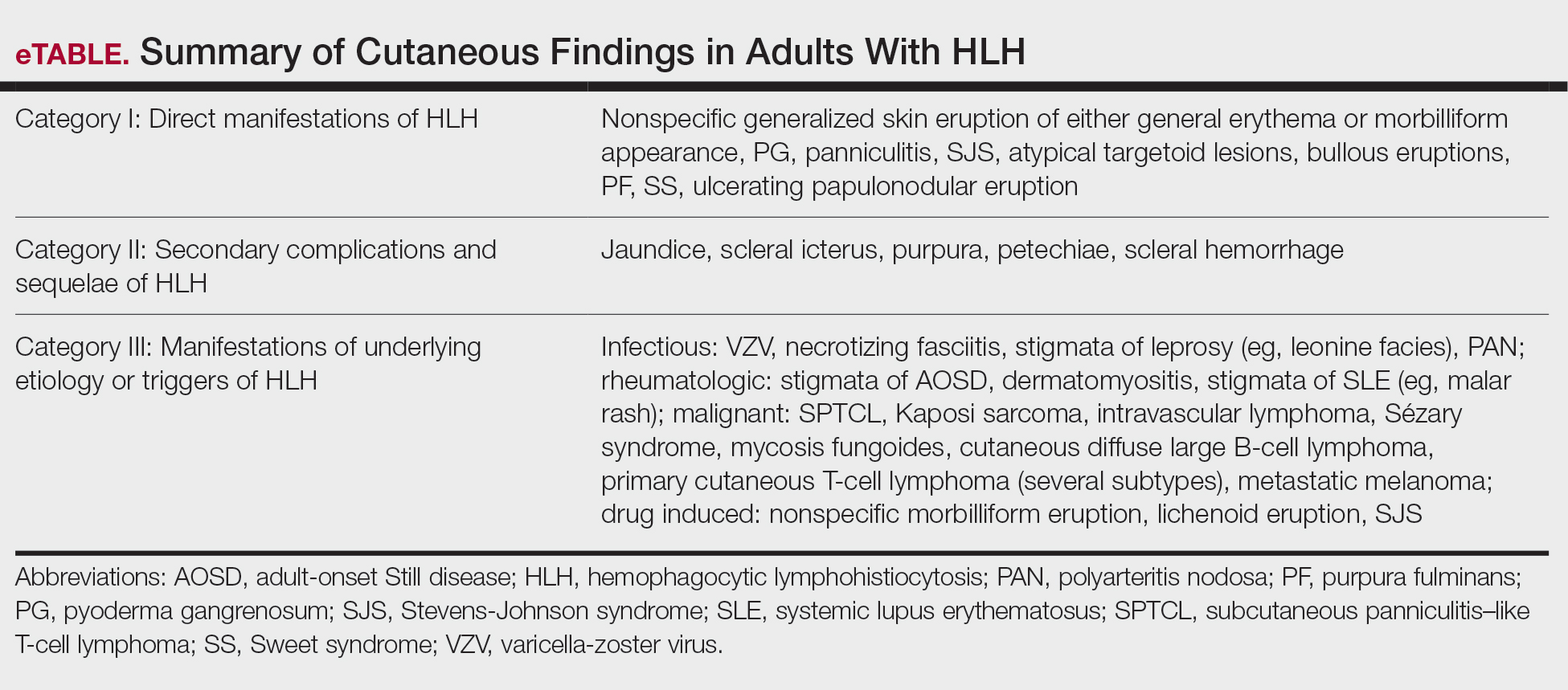

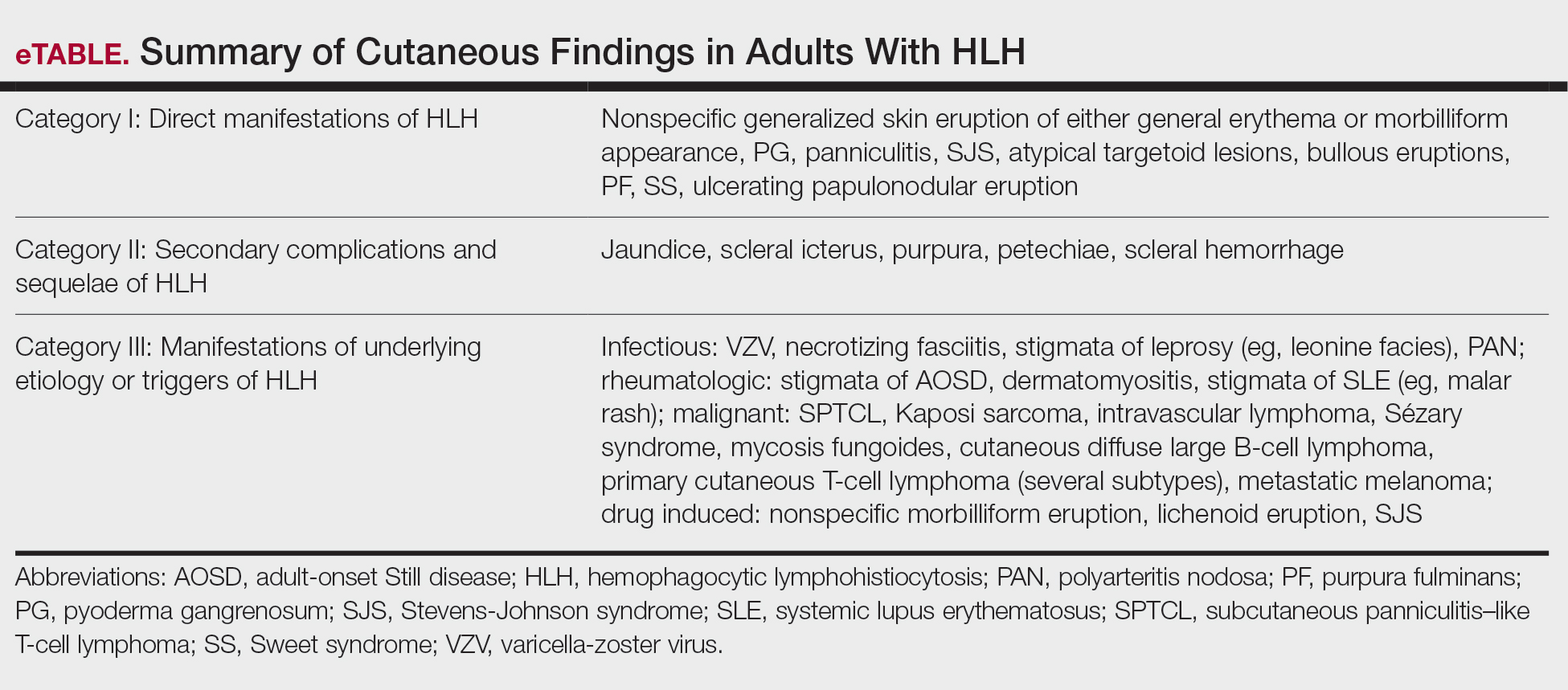

Scurvy, caused by vitamin C or ascorbic acid deficiency, historically has been associated primarily with developing nations and famine; however, specific populations in industrialized nations remain at an increased risk, particularly individuals with a history of smoking, alcohol use, restrictive diet, poor oral intake, psychiatric disorders, dementia, bone marrow transplantation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, end-stage renal disease, and hospitalization.1 Micronutrient deficiency– associated dermatoses have been linked to poor clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients.2 In this case series, we report 4 hospitalized patients with scurvy, each presenting with unique comorbidities and risk factors for vitamin C deficiency (eTable).

Case Reports

Patient 1—A 50-year-old man with a 6-month history of eczema and restrictive dietary intake was admitted to the hospital for septic shock attributed to a left foot infection of 5-days’ duration. The patient had experienced unintentional weight loss with severe protein-calorie malnutrition. His dietary history was notable for selective eating behaviors, intermittent meal skipping, and vegetarianism. Mucocutaneous examination by the dermatology consult team showed exfoliative dermatitis with angular cheilitis, corkscrew hairs on the legs (eFigure 1), and scattered purpura throughout the body. The differential diagnosis included eczema exacerbation, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma/Sézary syndrome, and malnutrition-related dermatosis. Punch biopsies of the left medial knee and right lateral arm revealed impetiginized, spongiotic, psoriasiform dermatitis with papillary dermal edema. The histologic changes were consistent with malnutrition-related dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.2-2.1 mg/dL]), undetectable zinc levels (<10 μg/dL [reference range ,60-130 μg/dL]), a low platelet count (21 kμ/L [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]),low albumin levels (0.9 mg/dL (13.0 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). The final diagnosis was exfoliative dermatitis due to eczema and multiple nutrient deficiencies (vitamin C and zinc). The patient was treated with vitamin C 500 mg/d and was started on mirtazapine to improve his appetite. Following a 3-month hospitalization, the patient was lost to follow-up after discharge.

Patient 2—A 55-year-old woman with a history of multiple psychiatric disorders presented to the dermatology consult service with an asymptomatic purpuric eruption on the right antecubital fossa of 2 days’ duration that spread to the proximal thighs. Five days prior to presentation, she had received an allogeneic bone marrow transplant complicated by mucositis. She also reported a 4-month history of decreased appetite. At the current presentation, numerous acral, follicular based, purpuric macules and papules without associated corkscrew hairs were observed (eFigure 2). The differential diagnosis included a purpuric drug reaction, viral exanthem, acute graft-vs-host disease, neutrophilic dermatoses, and vitamin C deficiency–related dermatosis. Laboratory results revealed undetectable vitamin C levels (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (8 k/μL [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]), normal albumin levels (3.7 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (7.8 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). Based on the histopathologic finding of subtle interface dermatitis with purpura from a punch biopsy of the right forearm, the eruption was attributed to scurvy. Although dermatology recommended supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d, the decision was deferred by the primary team and the purpura improved without it—suggesting the purpura was only partly attributable to low vitamin C.

Patient 3—A 77-year-old woman with a history of low oral intake, a low body mass index (18.15 kg/m2 [reference range, 18.5-24.9]), vegetarianism, multiple psychiatric disorders, dementia, recent Clostridioides difficile colitis treated with meropenem, and recurrent idiopathic pancytopenia presented to the hospital with recurrent oral erosions and purpura of the legs for an unknown period. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team revealed superficial lip desquamation; erosions of the buccal mucosa with no involvement of the inner lip or gingiva; mild gingival hyperplasia (eFigure 3); and scaly, purpuric, follicular macules and papules on the legs. The arms and legs were devoid of hair. Laboratory results were notable for low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (28 k/μL [reference range, 150-500 k/μL]), low albumin levels (2.9 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (8.8 g/dL [reference range, 12.0-16.0 g/ dL]). A punch biopsy from the left thigh revealed pauci-inflammatory interface dermatitis with purpura. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a final diagnosis of purpuric drug eruption (from the meropenem) and scurvy was made. Nutritional support included supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d. The patient’s oral erosions and purpura gradually resolved with treatment throughout her 1.5-month hospitalization.

Patient 4—A 67-year-old woman with a history of extensive cardiovascular disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease without esophagitis, end-stage renal disease not requiring hemodialysis, and loss of appetite presented with a painful pruritic eruption on the legs with groin involvement of 2 months’ duration. The patient was admitted to the hospital for worsening mental status and weakness accompanied by dark stools, hematuria, and a productive cough with red-tinged sputum. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team showed a scaly, follicular, purpuric eruption affecting the acral and intertriginous sites (eFigure 4). The patient had sparse leg hair, making it difficult to assess for hair tortuosity. A punch biopsy of the left posterior knee revealed purpuric psoriasiform dermatitis, which was consistent with nutritional deficiency– associated dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), zinc, (58 μg/dL [reference range, 60-130 μg/dL]), and albumin levels (3.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]) and a low platelet count (67 k/μL [reference range, 150- 500 k/μL]). The patient was started on supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d with improvement of the purpura.

Comment

Micronutrient deficiencies may be common in hospitalized patients due to an increased prevalence of predisposing risk factors including infection, malnutrition, malabsorptive conditions, psychiatric diseases, and chronic illnesses.3 Acute-phase response in hospitalized patients also has been strongly associated with decreased plasma vitamin C levels.4 This phenomenon is postulated to be due to the increase in ascorbic acid uptake by circulating granulocytes in acute disease5; however because low vitamin C levels during the acute-phase response may not always accurately reflect total body stores, other clinical features should be assessed. Previously reported social history risk factors include smoking, alcohol consumption, marijuana use, restrictive diets, vegetarianism, and living alone.6,7

The unifying clinical clues for scurvy in our 4 patients were a history of poor oral intake and purpura. While purpura is nonspecific and can appear after traumatic injury to the skin in elderly patients with photodamage and coagulation disorders, it also is associated with vitamin C deficiency, even with a normal platelet count, circulating von Willebrand factor levels, and prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time.8 This is because vitamin C is vital in forming the collagen and extracellular matrix. Specifically, it is a cofactor for lysine and proline hydroxylase enzymes needed for the á-helix crosslinks in collagen, which are essential for its structural integrity.9 Collagen is a structural protein that maintains the blood vessel walls, skin, and the basement membrane. A deficiency in vitamin C leads to impairment in collagen synthesis, and insufficient collagen results in compromised connective tissue, blood vessels, and hair strength, which may lead to purpura. All of our patients had thrombocytopenia, and similarly, consideration for scurvy in hospitalized patients with risk factors for micronutrient deficiency is a must. Additional findings such as a follicular-based pattern of the purpura, hair tortuosity, restrictive dietary history, histopathology reports consistent with nutritional dermatoses, serum vitamin C levels, and improvement with vitamin C supplementation are more specific for scurvy. All of these factors can assist the clinician in detecting and confirming these micronutrient deficiencies.

Although there are no established therapeutic guidelines for scurvy, the mainstay of treatment is vitamin C repletion, either orally or parenterally. In hospitalized patients, one suggested regimen is 1000 mg of intravenous ascorbic acid daily for 3 days, followed by further supplementation with a dose of 250 to 500 mg twice daily for 1 month as needed after discharge.10 Symptom improvement occurs about 72 hours after vitamin replacement.8 We recommended 500 to 1000 mg of daily vitamin C supplementation for our patients.

Final Thoughts

This case series highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for scurvy in hospitalized patients presenting with purpura, especially in a follicular-based pattern, who have multiple medical comorbidities and risk factors for vitamin C deficiency. The manifestations of scurvy are heterogeneous, necessitating a comprehensive mucocutaneous examination. The diagnosis of scurvy requires correlation of the findings from the patient history, clinical examination, laboratory results, and histopathology.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 41:895-910.

- Marsh RL, Trinidad J, Shearer S, et al. Association between micronutrient deficiency dermatoses and clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1226-1228.

- Hoffman M, Micheletti RG, Shields BE. Nutritional dermatoses in the hospitalized patient. Cutis. 2020;105:296-302, 308, E1-E5.

- Fain O, Pariés J, Jacquart B, et al. Hypovitaminosis C in hospitalized patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2003;14:419-425.

- Moser U, Weber F. Uptake of ascorbic acid by human granulocytes. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1984;54:47-53.

- Swanson AM, Hughey LC. Acute inpatient presentation of scurvy. Cutis. 2010;86:205-207.

- Christopher KL, Menachof KK, Fathi R. Scurvy masquerading as reactive arthritis. Cutis. 2019;103:E21-E23.

- Antonelli M, Burzo ML, Pecorini G, et al. Scurvy as cause of purpura in the XXI century: a review on this “ancient” disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:4355-4358.

- Maxfield L, Daley SF, Crane JS. Vitamin C deficiency. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated November 12, 2023. Accessed September 6, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493187/

- Gandhi M, Elfeky O, Ertugrul H, et al. Scurvy: rediscovering a forgotten disease. Diseases. 2023;11:78.

Scurvy, caused by vitamin C or ascorbic acid deficiency, historically has been associated primarily with developing nations and famine; however, specific populations in industrialized nations remain at an increased risk, particularly individuals with a history of smoking, alcohol use, restrictive diet, poor oral intake, psychiatric disorders, dementia, bone marrow transplantation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, end-stage renal disease, and hospitalization.1 Micronutrient deficiency– associated dermatoses have been linked to poor clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients.2 In this case series, we report 4 hospitalized patients with scurvy, each presenting with unique comorbidities and risk factors for vitamin C deficiency (eTable).

Case Reports

Patient 1—A 50-year-old man with a 6-month history of eczema and restrictive dietary intake was admitted to the hospital for septic shock attributed to a left foot infection of 5-days’ duration. The patient had experienced unintentional weight loss with severe protein-calorie malnutrition. His dietary history was notable for selective eating behaviors, intermittent meal skipping, and vegetarianism. Mucocutaneous examination by the dermatology consult team showed exfoliative dermatitis with angular cheilitis, corkscrew hairs on the legs (eFigure 1), and scattered purpura throughout the body. The differential diagnosis included eczema exacerbation, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma/Sézary syndrome, and malnutrition-related dermatosis. Punch biopsies of the left medial knee and right lateral arm revealed impetiginized, spongiotic, psoriasiform dermatitis with papillary dermal edema. The histologic changes were consistent with malnutrition-related dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.2-2.1 mg/dL]), undetectable zinc levels (<10 μg/dL [reference range ,60-130 μg/dL]), a low platelet count (21 kμ/L [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]),low albumin levels (0.9 mg/dL (13.0 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). The final diagnosis was exfoliative dermatitis due to eczema and multiple nutrient deficiencies (vitamin C and zinc). The patient was treated with vitamin C 500 mg/d and was started on mirtazapine to improve his appetite. Following a 3-month hospitalization, the patient was lost to follow-up after discharge.

Patient 2—A 55-year-old woman with a history of multiple psychiatric disorders presented to the dermatology consult service with an asymptomatic purpuric eruption on the right antecubital fossa of 2 days’ duration that spread to the proximal thighs. Five days prior to presentation, she had received an allogeneic bone marrow transplant complicated by mucositis. She also reported a 4-month history of decreased appetite. At the current presentation, numerous acral, follicular based, purpuric macules and papules without associated corkscrew hairs were observed (eFigure 2). The differential diagnosis included a purpuric drug reaction, viral exanthem, acute graft-vs-host disease, neutrophilic dermatoses, and vitamin C deficiency–related dermatosis. Laboratory results revealed undetectable vitamin C levels (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (8 k/μL [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]), normal albumin levels (3.7 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (7.8 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). Based on the histopathologic finding of subtle interface dermatitis with purpura from a punch biopsy of the right forearm, the eruption was attributed to scurvy. Although dermatology recommended supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d, the decision was deferred by the primary team and the purpura improved without it—suggesting the purpura was only partly attributable to low vitamin C.

Patient 3—A 77-year-old woman with a history of low oral intake, a low body mass index (18.15 kg/m2 [reference range, 18.5-24.9]), vegetarianism, multiple psychiatric disorders, dementia, recent Clostridioides difficile colitis treated with meropenem, and recurrent idiopathic pancytopenia presented to the hospital with recurrent oral erosions and purpura of the legs for an unknown period. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team revealed superficial lip desquamation; erosions of the buccal mucosa with no involvement of the inner lip or gingiva; mild gingival hyperplasia (eFigure 3); and scaly, purpuric, follicular macules and papules on the legs. The arms and legs were devoid of hair. Laboratory results were notable for low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (28 k/μL [reference range, 150-500 k/μL]), low albumin levels (2.9 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (8.8 g/dL [reference range, 12.0-16.0 g/ dL]). A punch biopsy from the left thigh revealed pauci-inflammatory interface dermatitis with purpura. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a final diagnosis of purpuric drug eruption (from the meropenem) and scurvy was made. Nutritional support included supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d. The patient’s oral erosions and purpura gradually resolved with treatment throughout her 1.5-month hospitalization.

Patient 4—A 67-year-old woman with a history of extensive cardiovascular disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease without esophagitis, end-stage renal disease not requiring hemodialysis, and loss of appetite presented with a painful pruritic eruption on the legs with groin involvement of 2 months’ duration. The patient was admitted to the hospital for worsening mental status and weakness accompanied by dark stools, hematuria, and a productive cough with red-tinged sputum. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team showed a scaly, follicular, purpuric eruption affecting the acral and intertriginous sites (eFigure 4). The patient had sparse leg hair, making it difficult to assess for hair tortuosity. A punch biopsy of the left posterior knee revealed purpuric psoriasiform dermatitis, which was consistent with nutritional deficiency– associated dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), zinc, (58 μg/dL [reference range, 60-130 μg/dL]), and albumin levels (3.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]) and a low platelet count (67 k/μL [reference range, 150- 500 k/μL]). The patient was started on supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d with improvement of the purpura.

Comment

Micronutrient deficiencies may be common in hospitalized patients due to an increased prevalence of predisposing risk factors including infection, malnutrition, malabsorptive conditions, psychiatric diseases, and chronic illnesses.3 Acute-phase response in hospitalized patients also has been strongly associated with decreased plasma vitamin C levels.4 This phenomenon is postulated to be due to the increase in ascorbic acid uptake by circulating granulocytes in acute disease5; however because low vitamin C levels during the acute-phase response may not always accurately reflect total body stores, other clinical features should be assessed. Previously reported social history risk factors include smoking, alcohol consumption, marijuana use, restrictive diets, vegetarianism, and living alone.6,7

The unifying clinical clues for scurvy in our 4 patients were a history of poor oral intake and purpura. While purpura is nonspecific and can appear after traumatic injury to the skin in elderly patients with photodamage and coagulation disorders, it also is associated with vitamin C deficiency, even with a normal platelet count, circulating von Willebrand factor levels, and prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time.8 This is because vitamin C is vital in forming the collagen and extracellular matrix. Specifically, it is a cofactor for lysine and proline hydroxylase enzymes needed for the á-helix crosslinks in collagen, which are essential for its structural integrity.9 Collagen is a structural protein that maintains the blood vessel walls, skin, and the basement membrane. A deficiency in vitamin C leads to impairment in collagen synthesis, and insufficient collagen results in compromised connective tissue, blood vessels, and hair strength, which may lead to purpura. All of our patients had thrombocytopenia, and similarly, consideration for scurvy in hospitalized patients with risk factors for micronutrient deficiency is a must. Additional findings such as a follicular-based pattern of the purpura, hair tortuosity, restrictive dietary history, histopathology reports consistent with nutritional dermatoses, serum vitamin C levels, and improvement with vitamin C supplementation are more specific for scurvy. All of these factors can assist the clinician in detecting and confirming these micronutrient deficiencies.

Although there are no established therapeutic guidelines for scurvy, the mainstay of treatment is vitamin C repletion, either orally or parenterally. In hospitalized patients, one suggested regimen is 1000 mg of intravenous ascorbic acid daily for 3 days, followed by further supplementation with a dose of 250 to 500 mg twice daily for 1 month as needed after discharge.10 Symptom improvement occurs about 72 hours after vitamin replacement.8 We recommended 500 to 1000 mg of daily vitamin C supplementation for our patients.

Final Thoughts

This case series highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for scurvy in hospitalized patients presenting with purpura, especially in a follicular-based pattern, who have multiple medical comorbidities and risk factors for vitamin C deficiency. The manifestations of scurvy are heterogeneous, necessitating a comprehensive mucocutaneous examination. The diagnosis of scurvy requires correlation of the findings from the patient history, clinical examination, laboratory results, and histopathology.

Scurvy, caused by vitamin C or ascorbic acid deficiency, historically has been associated primarily with developing nations and famine; however, specific populations in industrialized nations remain at an increased risk, particularly individuals with a history of smoking, alcohol use, restrictive diet, poor oral intake, psychiatric disorders, dementia, bone marrow transplantation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, end-stage renal disease, and hospitalization.1 Micronutrient deficiency– associated dermatoses have been linked to poor clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients.2 In this case series, we report 4 hospitalized patients with scurvy, each presenting with unique comorbidities and risk factors for vitamin C deficiency (eTable).

Case Reports

Patient 1—A 50-year-old man with a 6-month history of eczema and restrictive dietary intake was admitted to the hospital for septic shock attributed to a left foot infection of 5-days’ duration. The patient had experienced unintentional weight loss with severe protein-calorie malnutrition. His dietary history was notable for selective eating behaviors, intermittent meal skipping, and vegetarianism. Mucocutaneous examination by the dermatology consult team showed exfoliative dermatitis with angular cheilitis, corkscrew hairs on the legs (eFigure 1), and scattered purpura throughout the body. The differential diagnosis included eczema exacerbation, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma/Sézary syndrome, and malnutrition-related dermatosis. Punch biopsies of the left medial knee and right lateral arm revealed impetiginized, spongiotic, psoriasiform dermatitis with papillary dermal edema. The histologic changes were consistent with malnutrition-related dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.2-2.1 mg/dL]), undetectable zinc levels (<10 μg/dL [reference range ,60-130 μg/dL]), a low platelet count (21 kμ/L [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]),low albumin levels (0.9 mg/dL (13.0 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). The final diagnosis was exfoliative dermatitis due to eczema and multiple nutrient deficiencies (vitamin C and zinc). The patient was treated with vitamin C 500 mg/d and was started on mirtazapine to improve his appetite. Following a 3-month hospitalization, the patient was lost to follow-up after discharge.

Patient 2—A 55-year-old woman with a history of multiple psychiatric disorders presented to the dermatology consult service with an asymptomatic purpuric eruption on the right antecubital fossa of 2 days’ duration that spread to the proximal thighs. Five days prior to presentation, she had received an allogeneic bone marrow transplant complicated by mucositis. She also reported a 4-month history of decreased appetite. At the current presentation, numerous acral, follicular based, purpuric macules and papules without associated corkscrew hairs were observed (eFigure 2). The differential diagnosis included a purpuric drug reaction, viral exanthem, acute graft-vs-host disease, neutrophilic dermatoses, and vitamin C deficiency–related dermatosis. Laboratory results revealed undetectable vitamin C levels (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (8 k/μL [reference range, 150-400 k/μL]), normal albumin levels (3.7 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (7.8 g/dL [reference range, 14.0-17.4 g/dL]). Based on the histopathologic finding of subtle interface dermatitis with purpura from a punch biopsy of the right forearm, the eruption was attributed to scurvy. Although dermatology recommended supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d, the decision was deferred by the primary team and the purpura improved without it—suggesting the purpura was only partly attributable to low vitamin C.

Patient 3—A 77-year-old woman with a history of low oral intake, a low body mass index (18.15 kg/m2 [reference range, 18.5-24.9]), vegetarianism, multiple psychiatric disorders, dementia, recent Clostridioides difficile colitis treated with meropenem, and recurrent idiopathic pancytopenia presented to the hospital with recurrent oral erosions and purpura of the legs for an unknown period. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team revealed superficial lip desquamation; erosions of the buccal mucosa with no involvement of the inner lip or gingiva; mild gingival hyperplasia (eFigure 3); and scaly, purpuric, follicular macules and papules on the legs. The arms and legs were devoid of hair. Laboratory results were notable for low vitamin C levels (0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), a low platelet count (28 k/μL [reference range, 150-500 k/μL]), low albumin levels (2.9 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]), and low hemoglobin (8.8 g/dL [reference range, 12.0-16.0 g/ dL]). A punch biopsy from the left thigh revealed pauci-inflammatory interface dermatitis with purpura. Based on the clinical and histologic findings, a final diagnosis of purpuric drug eruption (from the meropenem) and scurvy was made. Nutritional support included supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d. The patient’s oral erosions and purpura gradually resolved with treatment throughout her 1.5-month hospitalization.

Patient 4—A 67-year-old woman with a history of extensive cardiovascular disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease without esophagitis, end-stage renal disease not requiring hemodialysis, and loss of appetite presented with a painful pruritic eruption on the legs with groin involvement of 2 months’ duration. The patient was admitted to the hospital for worsening mental status and weakness accompanied by dark stools, hematuria, and a productive cough with red-tinged sputum. Physical examination by the dermatology consult team showed a scaly, follicular, purpuric eruption affecting the acral and intertriginous sites (eFigure 4). The patient had sparse leg hair, making it difficult to assess for hair tortuosity. A punch biopsy of the left posterior knee revealed purpuric psoriasiform dermatitis, which was consistent with nutritional deficiency– associated dermatosis. Laboratory results included low vitamin C (<0.1 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3-2.7 mg/dL]), zinc, (58 μg/dL [reference range, 60-130 μg/dL]), and albumin levels (3.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.5-5.0 g/dL]) and a low platelet count (67 k/μL [reference range, 150- 500 k/μL]). The patient was started on supplementation with vitamin C 1000 mg/d with improvement of the purpura.

Comment