User login

HM16 AUDIO: Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, Chats up His Research on Costs and Complications with PICC Line Usage

RIV winner Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, assistant professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, talks about his research on the costs and complications associated with PICC line use.

RIV winner Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, assistant professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, talks about his research on the costs and complications associated with PICC line use.

RIV winner Vineet Chopra, MD, MSc, assistant professor at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, talks about his research on the costs and complications associated with PICC line use.

Postoperative Clostridium Difficile Infection Associated with Number of Antibiotics, Surgical Procedure Complexity

Clinical question: What are the factors that increase risk of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in postoperative patients?

Background: CDI has become an important infectious etiology for morbidity, lengthy and costly hospital admissions, and mortality. This study focused on the risks for postoperative patients to be infected with C. diff. Awareness of the risk factors for CDI allows for processes to be implemented that can decrease the rate of infection.

Study design: Retrospective, observational study.

Setting: Multiple Veterans Health Administration surgery programs.

Synopsis: The study investigated 468,386 surgical procedures in 134 surgical programs in 12 subspecialties over a four-year period. Overall, the postoperative CDI rate was 0.4% per year. Rates were higher in emergency or complex procedures, older patients, patients with longer preoperative hospital stays, and those who received three or more classes of antibiotics. CDI in postoperative patients was associated with five times higher risk of mortality, a 12 times higher risk of morbidity, and longer hospital stays (17.9 versus 3.6 days) compared with those without CDI. Further studies with a larger population size will confirm the findings of this study.

The study was conducted on middle-aged to elderly male veterans, and it can only be assumed that these results will translate to other populations. Nevertheless, CDI can lead to significant morbidity and mortality, and the study reinforces the importance of infection control and prevention to reduce CDI incidence and disease severity.

Bottom line: Postoperative CDI is significantly associated with the number of postoperative antibiotics, surgical procedure complexity, preoperative length of stay, and patient comorbidities.

Citation: Li X, Wilson M, Nylander W, Smith T, Lynn M, Gunnar W. Analysis of morbidity and mortality outcomes in postoperative Clostridium difficile infection in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Surg. 2015;25:1-9.

Clinical question: What are the factors that increase risk of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in postoperative patients?

Background: CDI has become an important infectious etiology for morbidity, lengthy and costly hospital admissions, and mortality. This study focused on the risks for postoperative patients to be infected with C. diff. Awareness of the risk factors for CDI allows for processes to be implemented that can decrease the rate of infection.

Study design: Retrospective, observational study.

Setting: Multiple Veterans Health Administration surgery programs.

Synopsis: The study investigated 468,386 surgical procedures in 134 surgical programs in 12 subspecialties over a four-year period. Overall, the postoperative CDI rate was 0.4% per year. Rates were higher in emergency or complex procedures, older patients, patients with longer preoperative hospital stays, and those who received three or more classes of antibiotics. CDI in postoperative patients was associated with five times higher risk of mortality, a 12 times higher risk of morbidity, and longer hospital stays (17.9 versus 3.6 days) compared with those without CDI. Further studies with a larger population size will confirm the findings of this study.

The study was conducted on middle-aged to elderly male veterans, and it can only be assumed that these results will translate to other populations. Nevertheless, CDI can lead to significant morbidity and mortality, and the study reinforces the importance of infection control and prevention to reduce CDI incidence and disease severity.

Bottom line: Postoperative CDI is significantly associated with the number of postoperative antibiotics, surgical procedure complexity, preoperative length of stay, and patient comorbidities.

Citation: Li X, Wilson M, Nylander W, Smith T, Lynn M, Gunnar W. Analysis of morbidity and mortality outcomes in postoperative Clostridium difficile infection in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Surg. 2015;25:1-9.

Clinical question: What are the factors that increase risk of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in postoperative patients?

Background: CDI has become an important infectious etiology for morbidity, lengthy and costly hospital admissions, and mortality. This study focused on the risks for postoperative patients to be infected with C. diff. Awareness of the risk factors for CDI allows for processes to be implemented that can decrease the rate of infection.

Study design: Retrospective, observational study.

Setting: Multiple Veterans Health Administration surgery programs.

Synopsis: The study investigated 468,386 surgical procedures in 134 surgical programs in 12 subspecialties over a four-year period. Overall, the postoperative CDI rate was 0.4% per year. Rates were higher in emergency or complex procedures, older patients, patients with longer preoperative hospital stays, and those who received three or more classes of antibiotics. CDI in postoperative patients was associated with five times higher risk of mortality, a 12 times higher risk of morbidity, and longer hospital stays (17.9 versus 3.6 days) compared with those without CDI. Further studies with a larger population size will confirm the findings of this study.

The study was conducted on middle-aged to elderly male veterans, and it can only be assumed that these results will translate to other populations. Nevertheless, CDI can lead to significant morbidity and mortality, and the study reinforces the importance of infection control and prevention to reduce CDI incidence and disease severity.

Bottom line: Postoperative CDI is significantly associated with the number of postoperative antibiotics, surgical procedure complexity, preoperative length of stay, and patient comorbidities.

Citation: Li X, Wilson M, Nylander W, Smith T, Lynn M, Gunnar W. Analysis of morbidity and mortality outcomes in postoperative Clostridium difficile infection in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Surg. 2015;25:1-9.

Most Postoperative Readmissions Due to Patient Factors

Clinical question: What is the etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients?

Background: As the focus of healthcare changes to a quality-focused model, readmissions impact physicians, reimbursements, and patients. Understanding the cause of readmissions becomes essential to preventing them. The etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients has not specifically been studied.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Academic tertiary-care center.

Synopsis: Using administrative claims data, an analysis of 22,559 patients who underwent a major surgical procedure between 2009 and 2013 was performed. A total of 56 surgeons within eight surgical subspecialties were analyzed, showing that variation in 30-day readmissions was largely due to patient-specific factors (82.8%) while only a minority were attributable to surgical subspecialty (14.5%) and individual surgeon levels (2.8%). Factors associated with readmission included race/ethnicity, comorbidities, postoperative complications, and extended length of stay.

Further studies within this area will need to be conducted focusing on one specific subspecialty and one surgeon to exclude confounding factors. Additional meta-analysis can then compare these individual studies. A larger population and multiple care centers will also further validate the findings. Understanding the cause of the readmissions in postoperative patients can prevent further readmissions, improve quality of care, and decrease healthcare costs. If patient factors are identified as a major cause for readmissions in postoperative patients, changes in preoperative management may need to be made.

Bottom line: Postoperative readmissions are more dependent on patient factors than surgeon- or surgical subspecialty-specific factors.

Citation: Gani F, Lucas DJ, Kim Y, Schneider EB, Pawlik TM. Understanding variation in 30-day surgical readmission in the era of accountable care: effect of the patient, surgeon, and surgical subspecialties. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(11):1042-1049.

Clinical question: What is the etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients?

Background: As the focus of healthcare changes to a quality-focused model, readmissions impact physicians, reimbursements, and patients. Understanding the cause of readmissions becomes essential to preventing them. The etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients has not specifically been studied.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Academic tertiary-care center.

Synopsis: Using administrative claims data, an analysis of 22,559 patients who underwent a major surgical procedure between 2009 and 2013 was performed. A total of 56 surgeons within eight surgical subspecialties were analyzed, showing that variation in 30-day readmissions was largely due to patient-specific factors (82.8%) while only a minority were attributable to surgical subspecialty (14.5%) and individual surgeon levels (2.8%). Factors associated with readmission included race/ethnicity, comorbidities, postoperative complications, and extended length of stay.

Further studies within this area will need to be conducted focusing on one specific subspecialty and one surgeon to exclude confounding factors. Additional meta-analysis can then compare these individual studies. A larger population and multiple care centers will also further validate the findings. Understanding the cause of the readmissions in postoperative patients can prevent further readmissions, improve quality of care, and decrease healthcare costs. If patient factors are identified as a major cause for readmissions in postoperative patients, changes in preoperative management may need to be made.

Bottom line: Postoperative readmissions are more dependent on patient factors than surgeon- or surgical subspecialty-specific factors.

Citation: Gani F, Lucas DJ, Kim Y, Schneider EB, Pawlik TM. Understanding variation in 30-day surgical readmission in the era of accountable care: effect of the patient, surgeon, and surgical subspecialties. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(11):1042-1049.

Clinical question: What is the etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients?

Background: As the focus of healthcare changes to a quality-focused model, readmissions impact physicians, reimbursements, and patients. Understanding the cause of readmissions becomes essential to preventing them. The etiology of 30-day readmissions in postoperative patients has not specifically been studied.

Study design: Retrospective analysis.

Setting: Academic tertiary-care center.

Synopsis: Using administrative claims data, an analysis of 22,559 patients who underwent a major surgical procedure between 2009 and 2013 was performed. A total of 56 surgeons within eight surgical subspecialties were analyzed, showing that variation in 30-day readmissions was largely due to patient-specific factors (82.8%) while only a minority were attributable to surgical subspecialty (14.5%) and individual surgeon levels (2.8%). Factors associated with readmission included race/ethnicity, comorbidities, postoperative complications, and extended length of stay.

Further studies within this area will need to be conducted focusing on one specific subspecialty and one surgeon to exclude confounding factors. Additional meta-analysis can then compare these individual studies. A larger population and multiple care centers will also further validate the findings. Understanding the cause of the readmissions in postoperative patients can prevent further readmissions, improve quality of care, and decrease healthcare costs. If patient factors are identified as a major cause for readmissions in postoperative patients, changes in preoperative management may need to be made.

Bottom line: Postoperative readmissions are more dependent on patient factors than surgeon- or surgical subspecialty-specific factors.

Citation: Gani F, Lucas DJ, Kim Y, Schneider EB, Pawlik TM. Understanding variation in 30-day surgical readmission in the era of accountable care: effect of the patient, surgeon, and surgical subspecialties. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(11):1042-1049.

When Should Harm-Reduction Strategies Be Used for Inpatients with Opioid Misuse?

Case

A 33-year-old male with a history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder is admitted with IV heroin use complicated by injection site cellulitis. He is started on antibiotics with improvement in his cellulitis; however, his hospitalization is complicated by acute opioid withdrawal. Despite his history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder, he has never seen a substance use disorder specialist nor received any education or treatment for his addiction. He reports that he will stop using illicit drugs but declines any further addiction treatment.

What strategies can be employed to reduce his risk of future harm from opioid misuse?

Background

Over the past decade, the U.S. has experienced a rapid increase in the rates of opioid prescriptions and opioid misuse.1 Consequently, the number of ED visits and hospitalizations for opioid-related complications has also increased.2 Many complications result from the practice of injection drug use (IDU), which predisposes individuals to serious blood-borne viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) as well as bacterial infections such as infective endocarditis. In addition, individuals who misuse opioids are at risk of death related to opioid overdose. In 2013, there were more than 24,000 deaths in the U.S. due to opioid overdose (see Figure 1).3

In response to the opioid epidemic, there have been a number of local, state, and federal public health initiatives to monitor and secure the opioid drug supply, improve treatment resources, and promulgate harm-reduction interventions. At a more individual level, hospitalists have an important role to play in combating the opioid epidemic. As frontline providers, hospitalists have access to hospitalized individuals with opioid misuse who may not otherwise be exposed to the healthcare system. Therefore, inpatient hospitalizations serve as a unique and important opportunity to engage individuals in the management of their addiction.

There are a number of interventions that hospitalists and substance use disorder specialists can pursue. Psychiatric evaluation and initiation of medication-assisted treatment often aim to aid patients in abstaining from further opioid misuse. However, many individuals with opioid use disorder are not ready for treatment or experience relapses of opioid misuse despite treatment. Given this, a secondary goal is to reduce any harm that may result from opioid misuse. This is done through the implementation of harm-reduction strategies. These strategies include teaching safe injection practices, facilitating the use of syringe exchange programs, and providing opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution.

Overview of Data

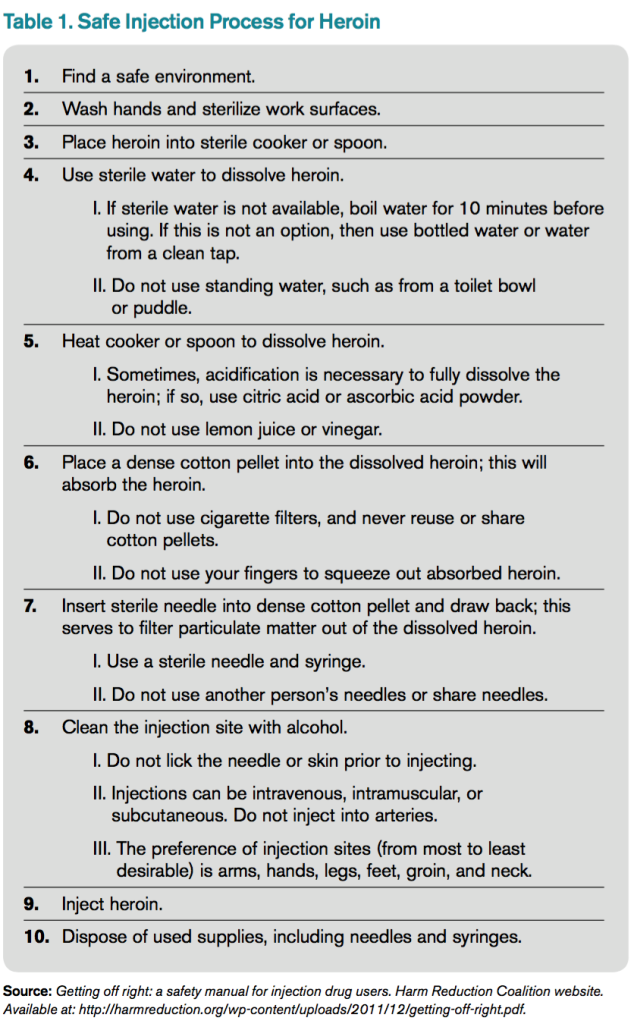

Safe Injection Education. People who inject drugs are at risk for viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. These infections are often the result of nonsterile injection and may be minimized by the utilization of safe injection practices. In order to educate people who inject drugs on safe injection practices, the hospitalist must first understand the process involved in injecting drugs. In Table 1, the process of injecting heroin is outlined (of note, other illicit drugs can be injected, and processes may vary).4

As evidenced by Table 1, the process of sterile injection can be complicated, especially for an individual who may be withdrawing from opioids. Table 1 is also optimistic in that it recommends new and sterile products be used with every injection. If new and sterile equipment is not available, another option is to clean the equipment after every use, which can be done by using bleach and water. This may mitigate the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. However, the risk is still present, so users should not share or use another individual’s equipment even if it has been cleaned. Due to the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections, all hospitalized individuals who inject drugs should receive education on safe injection practices.

Syringe Exchange Programs. IDU accounts for up to 15% of all new HIV infections and is the primary risk factor for the transmission of HCV.5 These infections occur when people inject using equipment contaminated with blood that contains HIV and/or HCV. Given this, if people who inject drugs could access and consistently use sterile syringes and other injection paraphernalia, the risk of transmitting blood-borne infections would be dramatically reduced. This is the concept behind syringe exchange programs (also known as needle exchange programs), which serve to increase access to sterile syringes while removing contaminated or used syringes from the community.

There is compelling evidence that syringe exchange programs decrease the rate of HIV transmission and likely reduce the rate of HCV transmission as well.6 In addition, syringe exchange programs often provide other beneficial services, such as counseling, testing, and prevention efforts for HIV, HCV, and sexually transmitted infections; distribution of condoms; and referrals to treatment services for substance use disorder.5

Unfortunately, in the U.S., restrictive state laws and lack of funding limit the number of established syringe exchange programs. According to the North American Syringe Exchange Network, there are only 226 programs in 33 states and the District of Columbia. Hospitalists and social workers should be aware of available local resources, including syringe exchange programs, and distribute this information to hospitalized individuals who inject drugs.

Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution. Syringe exchange programs and safe injection education aim to reduce harm by decreasing the transmission of infections; however, they do not address the problem of deaths related to opioid overdose. The primary harm-reduction strategy used to address deaths related to opioid overdose in the U.S is opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND). Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that reverses the respiratory depression and decreased consciousness caused by opioids. The OEND strategy involves educating first responders— including individuals and friends and family of individuals who use opioids—to recognize the signs of an opioid overdose, seek help, provide rescue breathing, administer naloxone, and stay with the individual until emergency medical services arrive.7 This strategy has been observed to decrease rates of death related to opioid overdose.7

Given the evolving opioid epidemic and effectiveness of the OEND strategy, it is not surprising that the number of local opioid overdose prevention programs adopting OEND has risen dramatically. As of 2014, there were 140 organizations, with 644 local sites providing naloxone in 29 states and the District of Columbia. These organizations have distributed 152,000 naloxone kits and have reported more than 26,000 reversals.8 Certainly, OEND has prevented morbidity and mortality in some of these patients.

The adoption of OEND can be performed by individual prescribers as well. Naloxone is U.S. FDA-approved for the treatment of opioid overdose, and thus the liability to prescribers is similar to that of other FDA-approved drugs. However, the distribution of naloxone to third parties, such as friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse, is more complex and regulated by state laws. Many states have created liability protection for naloxone prescription to third parties. Individual state laws and additional information can be found at prescribetoprevent.org.

Hospitalists should provide opioid overdose education to all individuals with opioid misuse and friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse. In addition, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone to individuals with opioid misuse and, in states where the law allows, distribute naloxone to friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse as well.

Controversies. In general, opioid use disorder treatment providers; public health officials; and local, state, and federal government agencies have increasingly embraced harm-reduction strategies. However, some feel that harm-reduction strategies are misguided or even detrimental due to concern that they implicitly condone or enable the use of illicit substances. There have been a number of studies to evaluate the potential unintended consequences of harm-reduction strategies, and overwhelmingly, these have been either neutral or have shown the benefit of harm-reduction interventions. At this point, there is no good evidence to prevent the widespread adoption of harm-reduction strategies for hospitalists.

Back to the Case

The case involves an individual who has already had at least two complications of his IV heroin use, including cellulitis and opioid overdose. Ideally, this individual would be willing to see an addiction specialist and start medication-assisted treatment. Unfortunately, he is unwilling to be further evaluated by a specialist at this time. Regardless, he remains at risk of future complications, and it is the hospitalist’s responsibility to intervene with a goal of reducing future harm that may result from his IV heroin use.

The hospitalist in this case advises the patient to abstain from heroin and IDU, encourages him to seek treatment for his opioid use disorder, and gives him resources for linkage to care if he becomes interested. In addition, the hospitalist educates the patient on safe injection practices and provides a list of local syringe exchange programs to decrease future risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. Furthermore, the hospitalist provides opioid overdose education and distributes naloxone to the patient, along with friends and family of the patient, to reduce the risk of death related to opioid overdose.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists should utilize harm-reduction interventions in individuals hospitalized with opioid misuse. TH

Dr. Theisen-Toupal is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences, both in Washington, D.C.

References

- Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6043a4.htm. Published November 4, 2011.

- Drug abuse warning network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.htm#5. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Hedergaard H, Chen LH, Warner M. Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin: United States, 2000–2013. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db190.htm. Published March 2015.

- Getting off right: a safety manual for injection drug users. Harm Reduction Coalition website. Available at: http://harmreduction.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/getting-off-right.pdf.

- Syringe exchange programs—United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5945a4.htm/Syringe-Exchange-Programs-United-States-2008. Published November 19, 2010.

- Wodak A, Conney A. Effectiveness of sterile needle and syringe programming in reducing HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users. World Health Organization website. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43107/1/9241591641.pdf. Published 2004.

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174.

- Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons—United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6423a2.htm. Published June 19, 2015.

Case

A 33-year-old male with a history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder is admitted with IV heroin use complicated by injection site cellulitis. He is started on antibiotics with improvement in his cellulitis; however, his hospitalization is complicated by acute opioid withdrawal. Despite his history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder, he has never seen a substance use disorder specialist nor received any education or treatment for his addiction. He reports that he will stop using illicit drugs but declines any further addiction treatment.

What strategies can be employed to reduce his risk of future harm from opioid misuse?

Background

Over the past decade, the U.S. has experienced a rapid increase in the rates of opioid prescriptions and opioid misuse.1 Consequently, the number of ED visits and hospitalizations for opioid-related complications has also increased.2 Many complications result from the practice of injection drug use (IDU), which predisposes individuals to serious blood-borne viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) as well as bacterial infections such as infective endocarditis. In addition, individuals who misuse opioids are at risk of death related to opioid overdose. In 2013, there were more than 24,000 deaths in the U.S. due to opioid overdose (see Figure 1).3

In response to the opioid epidemic, there have been a number of local, state, and federal public health initiatives to monitor and secure the opioid drug supply, improve treatment resources, and promulgate harm-reduction interventions. At a more individual level, hospitalists have an important role to play in combating the opioid epidemic. As frontline providers, hospitalists have access to hospitalized individuals with opioid misuse who may not otherwise be exposed to the healthcare system. Therefore, inpatient hospitalizations serve as a unique and important opportunity to engage individuals in the management of their addiction.

There are a number of interventions that hospitalists and substance use disorder specialists can pursue. Psychiatric evaluation and initiation of medication-assisted treatment often aim to aid patients in abstaining from further opioid misuse. However, many individuals with opioid use disorder are not ready for treatment or experience relapses of opioid misuse despite treatment. Given this, a secondary goal is to reduce any harm that may result from opioid misuse. This is done through the implementation of harm-reduction strategies. These strategies include teaching safe injection practices, facilitating the use of syringe exchange programs, and providing opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution.

Overview of Data

Safe Injection Education. People who inject drugs are at risk for viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. These infections are often the result of nonsterile injection and may be minimized by the utilization of safe injection practices. In order to educate people who inject drugs on safe injection practices, the hospitalist must first understand the process involved in injecting drugs. In Table 1, the process of injecting heroin is outlined (of note, other illicit drugs can be injected, and processes may vary).4

As evidenced by Table 1, the process of sterile injection can be complicated, especially for an individual who may be withdrawing from opioids. Table 1 is also optimistic in that it recommends new and sterile products be used with every injection. If new and sterile equipment is not available, another option is to clean the equipment after every use, which can be done by using bleach and water. This may mitigate the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. However, the risk is still present, so users should not share or use another individual’s equipment even if it has been cleaned. Due to the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections, all hospitalized individuals who inject drugs should receive education on safe injection practices.

Syringe Exchange Programs. IDU accounts for up to 15% of all new HIV infections and is the primary risk factor for the transmission of HCV.5 These infections occur when people inject using equipment contaminated with blood that contains HIV and/or HCV. Given this, if people who inject drugs could access and consistently use sterile syringes and other injection paraphernalia, the risk of transmitting blood-borne infections would be dramatically reduced. This is the concept behind syringe exchange programs (also known as needle exchange programs), which serve to increase access to sterile syringes while removing contaminated or used syringes from the community.

There is compelling evidence that syringe exchange programs decrease the rate of HIV transmission and likely reduce the rate of HCV transmission as well.6 In addition, syringe exchange programs often provide other beneficial services, such as counseling, testing, and prevention efforts for HIV, HCV, and sexually transmitted infections; distribution of condoms; and referrals to treatment services for substance use disorder.5

Unfortunately, in the U.S., restrictive state laws and lack of funding limit the number of established syringe exchange programs. According to the North American Syringe Exchange Network, there are only 226 programs in 33 states and the District of Columbia. Hospitalists and social workers should be aware of available local resources, including syringe exchange programs, and distribute this information to hospitalized individuals who inject drugs.

Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution. Syringe exchange programs and safe injection education aim to reduce harm by decreasing the transmission of infections; however, they do not address the problem of deaths related to opioid overdose. The primary harm-reduction strategy used to address deaths related to opioid overdose in the U.S is opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND). Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that reverses the respiratory depression and decreased consciousness caused by opioids. The OEND strategy involves educating first responders— including individuals and friends and family of individuals who use opioids—to recognize the signs of an opioid overdose, seek help, provide rescue breathing, administer naloxone, and stay with the individual until emergency medical services arrive.7 This strategy has been observed to decrease rates of death related to opioid overdose.7

Given the evolving opioid epidemic and effectiveness of the OEND strategy, it is not surprising that the number of local opioid overdose prevention programs adopting OEND has risen dramatically. As of 2014, there were 140 organizations, with 644 local sites providing naloxone in 29 states and the District of Columbia. These organizations have distributed 152,000 naloxone kits and have reported more than 26,000 reversals.8 Certainly, OEND has prevented morbidity and mortality in some of these patients.

The adoption of OEND can be performed by individual prescribers as well. Naloxone is U.S. FDA-approved for the treatment of opioid overdose, and thus the liability to prescribers is similar to that of other FDA-approved drugs. However, the distribution of naloxone to third parties, such as friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse, is more complex and regulated by state laws. Many states have created liability protection for naloxone prescription to third parties. Individual state laws and additional information can be found at prescribetoprevent.org.

Hospitalists should provide opioid overdose education to all individuals with opioid misuse and friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse. In addition, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone to individuals with opioid misuse and, in states where the law allows, distribute naloxone to friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse as well.

Controversies. In general, opioid use disorder treatment providers; public health officials; and local, state, and federal government agencies have increasingly embraced harm-reduction strategies. However, some feel that harm-reduction strategies are misguided or even detrimental due to concern that they implicitly condone or enable the use of illicit substances. There have been a number of studies to evaluate the potential unintended consequences of harm-reduction strategies, and overwhelmingly, these have been either neutral or have shown the benefit of harm-reduction interventions. At this point, there is no good evidence to prevent the widespread adoption of harm-reduction strategies for hospitalists.

Back to the Case

The case involves an individual who has already had at least two complications of his IV heroin use, including cellulitis and opioid overdose. Ideally, this individual would be willing to see an addiction specialist and start medication-assisted treatment. Unfortunately, he is unwilling to be further evaluated by a specialist at this time. Regardless, he remains at risk of future complications, and it is the hospitalist’s responsibility to intervene with a goal of reducing future harm that may result from his IV heroin use.

The hospitalist in this case advises the patient to abstain from heroin and IDU, encourages him to seek treatment for his opioid use disorder, and gives him resources for linkage to care if he becomes interested. In addition, the hospitalist educates the patient on safe injection practices and provides a list of local syringe exchange programs to decrease future risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. Furthermore, the hospitalist provides opioid overdose education and distributes naloxone to the patient, along with friends and family of the patient, to reduce the risk of death related to opioid overdose.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists should utilize harm-reduction interventions in individuals hospitalized with opioid misuse. TH

Dr. Theisen-Toupal is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences, both in Washington, D.C.

References

- Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6043a4.htm. Published November 4, 2011.

- Drug abuse warning network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.htm#5. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Hedergaard H, Chen LH, Warner M. Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin: United States, 2000–2013. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db190.htm. Published March 2015.

- Getting off right: a safety manual for injection drug users. Harm Reduction Coalition website. Available at: http://harmreduction.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/getting-off-right.pdf.

- Syringe exchange programs—United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5945a4.htm/Syringe-Exchange-Programs-United-States-2008. Published November 19, 2010.

- Wodak A, Conney A. Effectiveness of sterile needle and syringe programming in reducing HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users. World Health Organization website. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43107/1/9241591641.pdf. Published 2004.

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174.

- Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons—United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6423a2.htm. Published June 19, 2015.

Case

A 33-year-old male with a history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder is admitted with IV heroin use complicated by injection site cellulitis. He is started on antibiotics with improvement in his cellulitis; however, his hospitalization is complicated by acute opioid withdrawal. Despite his history of opioid overdose and opioid use disorder, he has never seen a substance use disorder specialist nor received any education or treatment for his addiction. He reports that he will stop using illicit drugs but declines any further addiction treatment.

What strategies can be employed to reduce his risk of future harm from opioid misuse?

Background

Over the past decade, the U.S. has experienced a rapid increase in the rates of opioid prescriptions and opioid misuse.1 Consequently, the number of ED visits and hospitalizations for opioid-related complications has also increased.2 Many complications result from the practice of injection drug use (IDU), which predisposes individuals to serious blood-borne viral infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) as well as bacterial infections such as infective endocarditis. In addition, individuals who misuse opioids are at risk of death related to opioid overdose. In 2013, there were more than 24,000 deaths in the U.S. due to opioid overdose (see Figure 1).3

In response to the opioid epidemic, there have been a number of local, state, and federal public health initiatives to monitor and secure the opioid drug supply, improve treatment resources, and promulgate harm-reduction interventions. At a more individual level, hospitalists have an important role to play in combating the opioid epidemic. As frontline providers, hospitalists have access to hospitalized individuals with opioid misuse who may not otherwise be exposed to the healthcare system. Therefore, inpatient hospitalizations serve as a unique and important opportunity to engage individuals in the management of their addiction.

There are a number of interventions that hospitalists and substance use disorder specialists can pursue. Psychiatric evaluation and initiation of medication-assisted treatment often aim to aid patients in abstaining from further opioid misuse. However, many individuals with opioid use disorder are not ready for treatment or experience relapses of opioid misuse despite treatment. Given this, a secondary goal is to reduce any harm that may result from opioid misuse. This is done through the implementation of harm-reduction strategies. These strategies include teaching safe injection practices, facilitating the use of syringe exchange programs, and providing opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution.

Overview of Data

Safe Injection Education. People who inject drugs are at risk for viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. These infections are often the result of nonsterile injection and may be minimized by the utilization of safe injection practices. In order to educate people who inject drugs on safe injection practices, the hospitalist must first understand the process involved in injecting drugs. In Table 1, the process of injecting heroin is outlined (of note, other illicit drugs can be injected, and processes may vary).4

As evidenced by Table 1, the process of sterile injection can be complicated, especially for an individual who may be withdrawing from opioids. Table 1 is also optimistic in that it recommends new and sterile products be used with every injection. If new and sterile equipment is not available, another option is to clean the equipment after every use, which can be done by using bleach and water. This may mitigate the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. However, the risk is still present, so users should not share or use another individual’s equipment even if it has been cleaned. Due to the risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections, all hospitalized individuals who inject drugs should receive education on safe injection practices.

Syringe Exchange Programs. IDU accounts for up to 15% of all new HIV infections and is the primary risk factor for the transmission of HCV.5 These infections occur when people inject using equipment contaminated with blood that contains HIV and/or HCV. Given this, if people who inject drugs could access and consistently use sterile syringes and other injection paraphernalia, the risk of transmitting blood-borne infections would be dramatically reduced. This is the concept behind syringe exchange programs (also known as needle exchange programs), which serve to increase access to sterile syringes while removing contaminated or used syringes from the community.

There is compelling evidence that syringe exchange programs decrease the rate of HIV transmission and likely reduce the rate of HCV transmission as well.6 In addition, syringe exchange programs often provide other beneficial services, such as counseling, testing, and prevention efforts for HIV, HCV, and sexually transmitted infections; distribution of condoms; and referrals to treatment services for substance use disorder.5

Unfortunately, in the U.S., restrictive state laws and lack of funding limit the number of established syringe exchange programs. According to the North American Syringe Exchange Network, there are only 226 programs in 33 states and the District of Columbia. Hospitalists and social workers should be aware of available local resources, including syringe exchange programs, and distribute this information to hospitalized individuals who inject drugs.

Opioid Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution. Syringe exchange programs and safe injection education aim to reduce harm by decreasing the transmission of infections; however, they do not address the problem of deaths related to opioid overdose. The primary harm-reduction strategy used to address deaths related to opioid overdose in the U.S is opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND). Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that reverses the respiratory depression and decreased consciousness caused by opioids. The OEND strategy involves educating first responders— including individuals and friends and family of individuals who use opioids—to recognize the signs of an opioid overdose, seek help, provide rescue breathing, administer naloxone, and stay with the individual until emergency medical services arrive.7 This strategy has been observed to decrease rates of death related to opioid overdose.7

Given the evolving opioid epidemic and effectiveness of the OEND strategy, it is not surprising that the number of local opioid overdose prevention programs adopting OEND has risen dramatically. As of 2014, there were 140 organizations, with 644 local sites providing naloxone in 29 states and the District of Columbia. These organizations have distributed 152,000 naloxone kits and have reported more than 26,000 reversals.8 Certainly, OEND has prevented morbidity and mortality in some of these patients.

The adoption of OEND can be performed by individual prescribers as well. Naloxone is U.S. FDA-approved for the treatment of opioid overdose, and thus the liability to prescribers is similar to that of other FDA-approved drugs. However, the distribution of naloxone to third parties, such as friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse, is more complex and regulated by state laws. Many states have created liability protection for naloxone prescription to third parties. Individual state laws and additional information can be found at prescribetoprevent.org.

Hospitalists should provide opioid overdose education to all individuals with opioid misuse and friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse. In addition, hospitalists should prescribe naloxone to individuals with opioid misuse and, in states where the law allows, distribute naloxone to friends and family of individuals with opioid misuse as well.

Controversies. In general, opioid use disorder treatment providers; public health officials; and local, state, and federal government agencies have increasingly embraced harm-reduction strategies. However, some feel that harm-reduction strategies are misguided or even detrimental due to concern that they implicitly condone or enable the use of illicit substances. There have been a number of studies to evaluate the potential unintended consequences of harm-reduction strategies, and overwhelmingly, these have been either neutral or have shown the benefit of harm-reduction interventions. At this point, there is no good evidence to prevent the widespread adoption of harm-reduction strategies for hospitalists.

Back to the Case

The case involves an individual who has already had at least two complications of his IV heroin use, including cellulitis and opioid overdose. Ideally, this individual would be willing to see an addiction specialist and start medication-assisted treatment. Unfortunately, he is unwilling to be further evaluated by a specialist at this time. Regardless, he remains at risk of future complications, and it is the hospitalist’s responsibility to intervene with a goal of reducing future harm that may result from his IV heroin use.

The hospitalist in this case advises the patient to abstain from heroin and IDU, encourages him to seek treatment for his opioid use disorder, and gives him resources for linkage to care if he becomes interested. In addition, the hospitalist educates the patient on safe injection practices and provides a list of local syringe exchange programs to decrease future risk of viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. Furthermore, the hospitalist provides opioid overdose education and distributes naloxone to the patient, along with friends and family of the patient, to reduce the risk of death related to opioid overdose.

Bottom Line

Hospitalists should utilize harm-reduction interventions in individuals hospitalized with opioid misuse. TH

Dr. Theisen-Toupal is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and assistant professor of medicine at the George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences, both in Washington, D.C.

References

- Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers—United States, 1999–2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6043a4.htm. Published November 4, 2011.

- Drug abuse warning network, 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.htm#5. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Hedergaard H, Chen LH, Warner M. Drug-poisoning deaths involving heroin: United States, 2000–2013. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db190.htm. Published March 2015.

- Getting off right: a safety manual for injection drug users. Harm Reduction Coalition website. Available at: http://harmreduction.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/getting-off-right.pdf.

- Syringe exchange programs—United States, 2008. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5945a4.htm/Syringe-Exchange-Programs-United-States-2008. Published November 19, 2010.

- Wodak A, Conney A. Effectiveness of sterile needle and syringe programming in reducing HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users. World Health Organization website. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43107/1/9241591641.pdf. Published 2004.

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174.

- Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons—United States, 2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6423a2.htm. Published June 19, 2015.

QUIZ: Which Strategy Should Hospitalists Employ to Reduce the Risk of Opioid Misuse?

[WpProQuiz 6]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 6]

[WpProQuiz 6]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 6]

[WpProQuiz 6]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 6]

Ischemic Hepatitis Associated with High Inpatient Mortality

Clinical question: What is the incidence and outcome of patients with ischemic hepatitis?

Background: Ischemic hepatitis, or shock liver, is often diagnosed in patients with massive increase in aminotransferase levels most often exceeding 1000 IU/L in the setting of hepatic hypoperfusion. The data on overall incidence and mortality of these patients are limited.

Study Design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Variable.

Synopsis: Using a combination of PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science, the study included 24 papers on incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis published between 1965 and 2015 with a combined total of 1,782 cases. The incidence of ischemic hepatitis varied based on patient location with incidence of 2/1000 in all inpatient admissions and 2.5/100 in ICU admissions. The majority of patients suffered from cardiac comorbidities and decompensation during their admission. Inpatient mortality with ischemic hepatitis was 49%.

Interestingly, only 52.9% of patients had an episode of documented hypotension.

Hospitalists taking care of patients with massive rise in aminotransferases should consider ischemic hepatitis higher in their differential, even in the absence of documented hypotension.

There was significant variability in study design, sample size, and inclusion criteria among the studies, which reduces generalizability of this systematic review.

Bottom line: Ischemic hepatitis is associated with very high mortality and should be suspected in patients with high levels of alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase even in the absence of documented hypotension.

Citation: Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321.

Short Take

Music Can Help Ease Pain and Anxiety after Surgery

A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that music reduces pain and anxiety and decreases the need for pain medication in postoperative patients regardless of type of music or at what interval of the operative period the music was initiated.

Citation: Hole J, Hirsch M, Ball E, Meads C. Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1659-1671

Clinical question: What is the incidence and outcome of patients with ischemic hepatitis?

Background: Ischemic hepatitis, or shock liver, is often diagnosed in patients with massive increase in aminotransferase levels most often exceeding 1000 IU/L in the setting of hepatic hypoperfusion. The data on overall incidence and mortality of these patients are limited.

Study Design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Variable.

Synopsis: Using a combination of PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science, the study included 24 papers on incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis published between 1965 and 2015 with a combined total of 1,782 cases. The incidence of ischemic hepatitis varied based on patient location with incidence of 2/1000 in all inpatient admissions and 2.5/100 in ICU admissions. The majority of patients suffered from cardiac comorbidities and decompensation during their admission. Inpatient mortality with ischemic hepatitis was 49%.

Interestingly, only 52.9% of patients had an episode of documented hypotension.

Hospitalists taking care of patients with massive rise in aminotransferases should consider ischemic hepatitis higher in their differential, even in the absence of documented hypotension.

There was significant variability in study design, sample size, and inclusion criteria among the studies, which reduces generalizability of this systematic review.

Bottom line: Ischemic hepatitis is associated with very high mortality and should be suspected in patients with high levels of alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase even in the absence of documented hypotension.

Citation: Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321.

Short Take

Music Can Help Ease Pain and Anxiety after Surgery

A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that music reduces pain and anxiety and decreases the need for pain medication in postoperative patients regardless of type of music or at what interval of the operative period the music was initiated.

Citation: Hole J, Hirsch M, Ball E, Meads C. Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1659-1671

Clinical question: What is the incidence and outcome of patients with ischemic hepatitis?

Background: Ischemic hepatitis, or shock liver, is often diagnosed in patients with massive increase in aminotransferase levels most often exceeding 1000 IU/L in the setting of hepatic hypoperfusion. The data on overall incidence and mortality of these patients are limited.

Study Design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Variable.

Synopsis: Using a combination of PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science, the study included 24 papers on incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis published between 1965 and 2015 with a combined total of 1,782 cases. The incidence of ischemic hepatitis varied based on patient location with incidence of 2/1000 in all inpatient admissions and 2.5/100 in ICU admissions. The majority of patients suffered from cardiac comorbidities and decompensation during their admission. Inpatient mortality with ischemic hepatitis was 49%.

Interestingly, only 52.9% of patients had an episode of documented hypotension.

Hospitalists taking care of patients with massive rise in aminotransferases should consider ischemic hepatitis higher in their differential, even in the absence of documented hypotension.

There was significant variability in study design, sample size, and inclusion criteria among the studies, which reduces generalizability of this systematic review.

Bottom line: Ischemic hepatitis is associated with very high mortality and should be suspected in patients with high levels of alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase even in the absence of documented hypotension.

Citation: Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1314-1321.

Short Take

Music Can Help Ease Pain and Anxiety after Surgery

A systematic review and meta-analysis showed that music reduces pain and anxiety and decreases the need for pain medication in postoperative patients regardless of type of music or at what interval of the operative period the music was initiated.

Citation: Hole J, Hirsch M, Ball E, Meads C. Music as an aid for postoperative recovery in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;386(10004):1659-1671

AIMS65 Score Helps Predict Inpatient Mortality in Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleed

Clinical question: Does AIMS65 risk stratification score predict inpatient mortality in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleed (UGIB)?

Background: Acute UGIB is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, which makes it crucial to identify high-risk patients early. Several prognostic algorithms such as Glasgow-Blatchford (GBS) and pre-endoscopy (pre-RS) and post-endoscopy (post-RS) Rockall scores are available to triage such patients. The goal of this study was to validate AIMS65 score as a predictor of inpatient mortality in patients with acute UGIB compared to these other prognostic scores.

Study Design: Retrospective, cohort study.

Setting: Tertiary-care center in Australia, January 2010 to June 2013.

Synopsis: Using ICD-10 diagnosis codes, investigators identified 424 patients with UGIB requiring endoscopy. All patients were risk-stratified using AIMS65, GBS, pre-RS, and post-RS. The AIMS65 score was found to be superior in predicting inpatient mortality compared to GBS and pre-RS scores and statistically superior to all other scores in predicting need for ICU admission.

In addition to being a single-center, retrospective study, other limitations include the use of ICD-10 codes to identify patients. Further prospective studies are needed to further validate the AIMS65 in acute UGIB.

Bottom line: AIMS65 is a simple and useful tool in predicting inpatient mortality in patients with acute UGIB. However, its applicability in making clinical decisions remains unclear.

Citation: Robertson M, Majumdar A, Boyapati R, et al. Risk stratification in acute upper GI bleeding: comparison of the AIMS65 score with the Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall scoring systems [published online ahead of print October 16, 2015]. Gastrointest Endosc. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2015.10.021.

Clinical question: Does AIMS65 risk stratification score predict inpatient mortality in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleed (UGIB)?

Background: Acute UGIB is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, which makes it crucial to identify high-risk patients early. Several prognostic algorithms such as Glasgow-Blatchford (GBS) and pre-endoscopy (pre-RS) and post-endoscopy (post-RS) Rockall scores are available to triage such patients. The goal of this study was to validate AIMS65 score as a predictor of inpatient mortality in patients with acute UGIB compared to these other prognostic scores.

Study Design: Retrospective, cohort study.

Setting: Tertiary-care center in Australia, January 2010 to June 2013.

Synopsis: Using ICD-10 diagnosis codes, investigators identified 424 patients with UGIB requiring endoscopy. All patients were risk-stratified using AIMS65, GBS, pre-RS, and post-RS. The AIMS65 score was found to be superior in predicting inpatient mortality compared to GBS and pre-RS scores and statistically superior to all other scores in predicting need for ICU admission.

In addition to being a single-center, retrospective study, other limitations include the use of ICD-10 codes to identify patients. Further prospective studies are needed to further validate the AIMS65 in acute UGIB.

Bottom line: AIMS65 is a simple and useful tool in predicting inpatient mortality in patients with acute UGIB. However, its applicability in making clinical decisions remains unclear.

Citation: Robertson M, Majumdar A, Boyapati R, et al. Risk stratification in acute upper GI bleeding: comparison of the AIMS65 score with the Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall scoring systems [published online ahead of print October 16, 2015]. Gastrointest Endosc. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2015.10.021.

Clinical question: Does AIMS65 risk stratification score predict inpatient mortality in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleed (UGIB)?

Background: Acute UGIB is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, which makes it crucial to identify high-risk patients early. Several prognostic algorithms such as Glasgow-Blatchford (GBS) and pre-endoscopy (pre-RS) and post-endoscopy (post-RS) Rockall scores are available to triage such patients. The goal of this study was to validate AIMS65 score as a predictor of inpatient mortality in patients with acute UGIB compared to these other prognostic scores.

Study Design: Retrospective, cohort study.

Setting: Tertiary-care center in Australia, January 2010 to June 2013.

Synopsis: Using ICD-10 diagnosis codes, investigators identified 424 patients with UGIB requiring endoscopy. All patients were risk-stratified using AIMS65, GBS, pre-RS, and post-RS. The AIMS65 score was found to be superior in predicting inpatient mortality compared to GBS and pre-RS scores and statistically superior to all other scores in predicting need for ICU admission.

In addition to being a single-center, retrospective study, other limitations include the use of ICD-10 codes to identify patients. Further prospective studies are needed to further validate the AIMS65 in acute UGIB.

Bottom line: AIMS65 is a simple and useful tool in predicting inpatient mortality in patients with acute UGIB. However, its applicability in making clinical decisions remains unclear.

Citation: Robertson M, Majumdar A, Boyapati R, et al. Risk stratification in acute upper GI bleeding: comparison of the AIMS65 score with the Glasgow-Blatchford and Rockall scoring systems [published online ahead of print October 16, 2015]. Gastrointest Endosc. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2015.10.021.

No Mortality Benefit to Cardiac Catheterization in Patients with Stable Ischemic Heart Disease

Clinical question: Can cardiac catheterization prolong survival in patients with stable ischemic heart disease?

Background: Previous results from the COURAGE trial found no benefit of percutaneous intervention (PCI) as compared to medical therapy on a composite endpoint of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction or in total mortality at 4.6 years follow-up. The authors now report 15-year follow-up of the same patients.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: The majority of the patients were from Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers, although non-VA hospitals in the U.S. also were included.

Synopsis: Originally, 2,287 patients with stable ischemic heart disease and either an abnormal stress test or evidence of ischemia on ECG, as well at least 70% stenosis on angiography, were randomized to medical therapy or medical therapy plus PCI. Now, investigators have obtained extended follow-up information for 1,211 of the original patients (53%). They concluded that after 15 years of follow-up, there was no survival difference for the patients who initially received PCI in addition to medical management.

One limitation of the study was that it did not reflect important advances in both medical and interventional management of ischemic heart disease that have taken place since the study was conducted, which may affect patient mortality. It is also noteworthy that the investigators were unable to determine how many patients in the medical management group subsequently underwent revascularization after the study concluded and therefore may have crossed over between groups. Nevertheless, for now it appears that the major utility of PCI in stable ischemic heart disease is in symptomatic management.

Bottom Line: After 15 years of follow-up, there was still no mortality benefit to PCI as compared to optimal medical therapy for stable ischemic heart disease.

Citation: Sedlis SP, Hartigan PM, Teo KK, et al. Effect of PCI on long-term survival in patients with stable ischemic heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(20):1937-1946

Short Take

Cauti Infections Are Rarely Clinically Relevant and Associated with Low Complication Rate

A single-center retrospective study in the ICU setting shows that the definition of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) is nonspecific and they’re mostly diagnosed when urine cultures are sent for workup of fever. Most of the time, there are alternative explanations for the fever.

Citation: Tedja R, Wentink J, O’Horo J, Thompson R, Sampathkumar P et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in intensive care unit patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(11):1330-1334.

Clinical question: Can cardiac catheterization prolong survival in patients with stable ischemic heart disease?

Background: Previous results from the COURAGE trial found no benefit of percutaneous intervention (PCI) as compared to medical therapy on a composite endpoint of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction or in total mortality at 4.6 years follow-up. The authors now report 15-year follow-up of the same patients.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: The majority of the patients were from Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers, although non-VA hospitals in the U.S. also were included.

Synopsis: Originally, 2,287 patients with stable ischemic heart disease and either an abnormal stress test or evidence of ischemia on ECG, as well at least 70% stenosis on angiography, were randomized to medical therapy or medical therapy plus PCI. Now, investigators have obtained extended follow-up information for 1,211 of the original patients (53%). They concluded that after 15 years of follow-up, there was no survival difference for the patients who initially received PCI in addition to medical management.

One limitation of the study was that it did not reflect important advances in both medical and interventional management of ischemic heart disease that have taken place since the study was conducted, which may affect patient mortality. It is also noteworthy that the investigators were unable to determine how many patients in the medical management group subsequently underwent revascularization after the study concluded and therefore may have crossed over between groups. Nevertheless, for now it appears that the major utility of PCI in stable ischemic heart disease is in symptomatic management.

Bottom Line: After 15 years of follow-up, there was still no mortality benefit to PCI as compared to optimal medical therapy for stable ischemic heart disease.

Citation: Sedlis SP, Hartigan PM, Teo KK, et al. Effect of PCI on long-term survival in patients with stable ischemic heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(20):1937-1946

Short Take

Cauti Infections Are Rarely Clinically Relevant and Associated with Low Complication Rate

A single-center retrospective study in the ICU setting shows that the definition of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) is nonspecific and they’re mostly diagnosed when urine cultures are sent for workup of fever. Most of the time, there are alternative explanations for the fever.

Citation: Tedja R, Wentink J, O’Horo J, Thompson R, Sampathkumar P et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in intensive care unit patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(11):1330-1334.

Clinical question: Can cardiac catheterization prolong survival in patients with stable ischemic heart disease?

Background: Previous results from the COURAGE trial found no benefit of percutaneous intervention (PCI) as compared to medical therapy on a composite endpoint of death or nonfatal myocardial infarction or in total mortality at 4.6 years follow-up. The authors now report 15-year follow-up of the same patients.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: The majority of the patients were from Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers, although non-VA hospitals in the U.S. also were included.

Synopsis: Originally, 2,287 patients with stable ischemic heart disease and either an abnormal stress test or evidence of ischemia on ECG, as well at least 70% stenosis on angiography, were randomized to medical therapy or medical therapy plus PCI. Now, investigators have obtained extended follow-up information for 1,211 of the original patients (53%). They concluded that after 15 years of follow-up, there was no survival difference for the patients who initially received PCI in addition to medical management.

One limitation of the study was that it did not reflect important advances in both medical and interventional management of ischemic heart disease that have taken place since the study was conducted, which may affect patient mortality. It is also noteworthy that the investigators were unable to determine how many patients in the medical management group subsequently underwent revascularization after the study concluded and therefore may have crossed over between groups. Nevertheless, for now it appears that the major utility of PCI in stable ischemic heart disease is in symptomatic management.

Bottom Line: After 15 years of follow-up, there was still no mortality benefit to PCI as compared to optimal medical therapy for stable ischemic heart disease.

Citation: Sedlis SP, Hartigan PM, Teo KK, et al. Effect of PCI on long-term survival in patients with stable ischemic heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(20):1937-1946

Short Take

Cauti Infections Are Rarely Clinically Relevant and Associated with Low Complication Rate

A single-center retrospective study in the ICU setting shows that the definition of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs) is nonspecific and they’re mostly diagnosed when urine cultures are sent for workup of fever. Most of the time, there are alternative explanations for the fever.

Citation: Tedja R, Wentink J, O’Horo J, Thompson R, Sampathkumar P et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in intensive care unit patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(11):1330-1334.

Increase in Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics Disproportionate to Rate of Resistant Organisms

Clinical question: Have healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP) guidelines improved treatment accuracy?

Background: Guidelines released in 2005 call for the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for patients presenting with pneumonia who have had recent healthcare exposure. However, there is scant evidence to support the risk factors they identify, and the guidelines are likely to increase use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Study design: Observational, retrospective.

Setting: VA medical centers, 2006–2010.

Synopsis: In this study, VA medical center physicians evaluated 95,511 hospitalizations for pneumonia at 128 hospitals between 2006 and 2010, the years following the 2005 guidelines. Annual analyses were performed to assess antibiotics selection as well as evidence of resistant bacteria from blood and respiratory cultures. Researchers found that while the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics increased drastically during the study period (vancomycin from 16% to 31% and piperacillin-tazobactam from 16% to 27%, P<0.001 for both), the incidence of resistant organisms either decreased or remained stable.

Additionally, physicians were no better at matching broad-spectrum antibiotics to patients infected with resistant organisms at the end of the study period than they were at the start. They conclude that more research is urgently needed to identify patients at risk for resistant organisms in order to more appropriately prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics.

This study did not evaluate patients’ clinical outcomes, so it is unclear whether they may have benefitted clinically from the implementation of the guidelines. For now, the optimal approach to empiric therapy for HCAP remains undefined.

Bottom line: Despite a marked increase in the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for HCAP in the years following a change in treatment guidelines, doctors showed no improvement at matching these antibiotics to patients infected with resistant organisms.

Citation: Jones BE, Jones MM, Huttner B, et al. Trends in antibiotic use and nosocomial pathogens in hospitalized veterans with pneumonia at 128 medical centers, 2006-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1403-1410.

Clinical question: Have healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP) guidelines improved treatment accuracy?

Background: Guidelines released in 2005 call for the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for patients presenting with pneumonia who have had recent healthcare exposure. However, there is scant evidence to support the risk factors they identify, and the guidelines are likely to increase use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Study design: Observational, retrospective.

Setting: VA medical centers, 2006–2010.

Synopsis: In this study, VA medical center physicians evaluated 95,511 hospitalizations for pneumonia at 128 hospitals between 2006 and 2010, the years following the 2005 guidelines. Annual analyses were performed to assess antibiotics selection as well as evidence of resistant bacteria from blood and respiratory cultures. Researchers found that while the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics increased drastically during the study period (vancomycin from 16% to 31% and piperacillin-tazobactam from 16% to 27%, P<0.001 for both), the incidence of resistant organisms either decreased or remained stable.

Additionally, physicians were no better at matching broad-spectrum antibiotics to patients infected with resistant organisms at the end of the study period than they were at the start. They conclude that more research is urgently needed to identify patients at risk for resistant organisms in order to more appropriately prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics.

This study did not evaluate patients’ clinical outcomes, so it is unclear whether they may have benefitted clinically from the implementation of the guidelines. For now, the optimal approach to empiric therapy for HCAP remains undefined.

Bottom line: Despite a marked increase in the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for HCAP in the years following a change in treatment guidelines, doctors showed no improvement at matching these antibiotics to patients infected with resistant organisms.

Citation: Jones BE, Jones MM, Huttner B, et al. Trends in antibiotic use and nosocomial pathogens in hospitalized veterans with pneumonia at 128 medical centers, 2006-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1403-1410.

Clinical question: Have healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP) guidelines improved treatment accuracy?

Background: Guidelines released in 2005 call for the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for patients presenting with pneumonia who have had recent healthcare exposure. However, there is scant evidence to support the risk factors they identify, and the guidelines are likely to increase use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Study design: Observational, retrospective.

Setting: VA medical centers, 2006–2010.

Synopsis: In this study, VA medical center physicians evaluated 95,511 hospitalizations for pneumonia at 128 hospitals between 2006 and 2010, the years following the 2005 guidelines. Annual analyses were performed to assess antibiotics selection as well as evidence of resistant bacteria from blood and respiratory cultures. Researchers found that while the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics increased drastically during the study period (vancomycin from 16% to 31% and piperacillin-tazobactam from 16% to 27%, P<0.001 for both), the incidence of resistant organisms either decreased or remained stable.

Additionally, physicians were no better at matching broad-spectrum antibiotics to patients infected with resistant organisms at the end of the study period than they were at the start. They conclude that more research is urgently needed to identify patients at risk for resistant organisms in order to more appropriately prescribe broad-spectrum antibiotics.

This study did not evaluate patients’ clinical outcomes, so it is unclear whether they may have benefitted clinically from the implementation of the guidelines. For now, the optimal approach to empiric therapy for HCAP remains undefined.

Bottom line: Despite a marked increase in the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics for HCAP in the years following a change in treatment guidelines, doctors showed no improvement at matching these antibiotics to patients infected with resistant organisms.

Citation: Jones BE, Jones MM, Huttner B, et al. Trends in antibiotic use and nosocomial pathogens in hospitalized veterans with pneumonia at 128 medical centers, 2006-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(9):1403-1410.

Discontinuing Inhaled Corticosteroids in COPD Reduces Risk of Pneumonia

Clinical question: Is discontinuation of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) in patients with COPD associated with a decreased risk of pneumonia?

Background: ICSs are used in up to 85% of patients treated for COPD but may be associated with adverse systemic side effects including pneumonia. Trials looking at weaning patients off ICSs and replacing with long-acting bronchodilators have found few adverse outcomes; however, the benefits of discontinuation on adverse events, including pneumonia, have been unclear.

Study design: Case-control study.

Setting: Quebec health systems.

Synopsis: Using the Quebec health insurance databases, a study cohort of 103,386 patients with COPD on ICSs was created. Patients were followed for a mean of 4.9 years; 14,020 patients who were hospitalized for pneumonia or died from pneumonia outside the hospital were matched to control subjects. Discontinuation of ICSs was associated with a 37% decrease in serious pneumonia (relative risk [RR] 0.63; 95% CI, 0.60–0.66). The risk reduction occurred as early as one month after discontinuation of ICSs. Risk reduction was greater with fluticasone (RR 0.58; 95% CI, 0.54–0.61) than with budesonide (RR 0.87; 95% CI, 0.7–0.97).