User login

Large Subcutaneous Masses

The Diagnosis: Madelung Disease (Benign Symmetric Lipomatosis)

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs (Figures 1 and 2) that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. In addition, he was beginning to develop symptoms of neuropathy of the bilateral hands. The patient had a long-standing history of alcohol abuse. Biopsies performed by the patient’s primary care physician revealed benign adipose tissue. He was referred to the dermatology clinic and subsequently diagnosed with Madelung disease.

|

|

Madelung disease, also known as benign symmetric lipomatosis and Launois-Bensaude syndrome, is characterized by multiple large masses of nonencapsulated adipose tissue. These masses are symmetric and most prominent on the head, neck, trunk, and proximal extremities. Classically, a pseudoathletic appearance is described. Madelung disease most frequently affects men aged 30 to 60 years. In more than 90% of cases, it is associated with alcoholism.

In general, the masses of adipose tissue are asymptomatic. However, airway compression and dysphagia requiring surgical intervention has been reported in the otolaryngology literature.1 In addition, neuropathy develops in 84% of cases.2 Nerve biopsies from patients with Madelung disease have revealed a pattern of axonopathy that is distinct from alcohol-induced neuropathy.3 This neuropathy can involve sensory and motor nerves, with the most prominent findings being muscle weakness, tendon areflexia, interosseous muscle atrophy, vibratory sensation loss, and hypoesthesia. Furthermore, dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system can lead to segmental hyperhidrosis, gustatory sweating, and abnormal autonomic cardiovascular reflexes.2 Many patients who develop neuropathy will eventually become incapacitated.

The etiology of Madelung disease is not fully understood. There are several theories on the pathogenesis of this disease, most describing metabolic disturbances induced by alcohol. Specifically, studies have revealed chronic alcohol use causes numerous deletions in mitochondrial DNA.4,5 The mitochondrial DNA damage may explain both the resistance of the lipomatous masses to lipolysis and the nerve-related changes. Comparisons between human immunodeficiency virus/highly active antiretroviral therapy–associated lipodystrophy and Madelung disease lend credence to the metabolic disturbance theory and may help clarify the specific mechanisms involved.6

There have been no cases of spontaneous resolution, even in patients who stop consuming alcohol. For this reason, most patients are referred to a surgeon. Many surgeons prefer open excision for debulking large lipomatous masses, but this technique typically requires general anesthesia. For those in whom this treatment is not an appropriate option, liposuction can be considered with tumescent anesthesia.7 A combination of these surgical modalities also is an option.

Madelung disease is a distinctive disorder typically affecting chronic alcoholics. Recognition of this clinical entity is important, as severe neuropathy and airway compromise may ensue. Although surgical excision is an attractive option for cosmesis and airway compromise, the associated neuropathy can be extremely difficult to treat and can be quite debilitating.

1. Palacios E, Neitzschman HR, Nguyen J. Madelung disease: multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:94-96.

2. Enzi G, Angelini C, Negrin P, et al. Sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy in patients with multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:388-393.

3. Pollock M, Nicholson GI, Nukada H, et al. Neuropathy in multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Madelung’s disease. Brain. 1988;111:1157-1171.

4. Klopstock T, Naumann M, Schalke B, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: abnormalities in complex IV and multiple deletions in mitochondrial DNA. Neurology. 1994;44:862-866.

5. Mansouri A, Fromenty B, Berson A, et al. Multiple hepatic mitochondrial DNA deletions suggest premature oxidative aging in alcoholic patients. J Hepatol. 1997;27:96-102.

6. Urso R, Gentile M. Are ‘buffalo hump’ syndrome, Madelung's disease and multiple symmetrical lipomatosis variants of the same dysmetabolism? AIDS. 2001;15:290-291.

7. Grassegger A, Häussler R, Schmalzl F. Tumescent liposuction in a patient with Launois-Bensaude syndrome and severe hepatopathy. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:982-985.

The Diagnosis: Madelung Disease (Benign Symmetric Lipomatosis)

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs (Figures 1 and 2) that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. In addition, he was beginning to develop symptoms of neuropathy of the bilateral hands. The patient had a long-standing history of alcohol abuse. Biopsies performed by the patient’s primary care physician revealed benign adipose tissue. He was referred to the dermatology clinic and subsequently diagnosed with Madelung disease.

|

|

Madelung disease, also known as benign symmetric lipomatosis and Launois-Bensaude syndrome, is characterized by multiple large masses of nonencapsulated adipose tissue. These masses are symmetric and most prominent on the head, neck, trunk, and proximal extremities. Classically, a pseudoathletic appearance is described. Madelung disease most frequently affects men aged 30 to 60 years. In more than 90% of cases, it is associated with alcoholism.

In general, the masses of adipose tissue are asymptomatic. However, airway compression and dysphagia requiring surgical intervention has been reported in the otolaryngology literature.1 In addition, neuropathy develops in 84% of cases.2 Nerve biopsies from patients with Madelung disease have revealed a pattern of axonopathy that is distinct from alcohol-induced neuropathy.3 This neuropathy can involve sensory and motor nerves, with the most prominent findings being muscle weakness, tendon areflexia, interosseous muscle atrophy, vibratory sensation loss, and hypoesthesia. Furthermore, dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system can lead to segmental hyperhidrosis, gustatory sweating, and abnormal autonomic cardiovascular reflexes.2 Many patients who develop neuropathy will eventually become incapacitated.

The etiology of Madelung disease is not fully understood. There are several theories on the pathogenesis of this disease, most describing metabolic disturbances induced by alcohol. Specifically, studies have revealed chronic alcohol use causes numerous deletions in mitochondrial DNA.4,5 The mitochondrial DNA damage may explain both the resistance of the lipomatous masses to lipolysis and the nerve-related changes. Comparisons between human immunodeficiency virus/highly active antiretroviral therapy–associated lipodystrophy and Madelung disease lend credence to the metabolic disturbance theory and may help clarify the specific mechanisms involved.6

There have been no cases of spontaneous resolution, even in patients who stop consuming alcohol. For this reason, most patients are referred to a surgeon. Many surgeons prefer open excision for debulking large lipomatous masses, but this technique typically requires general anesthesia. For those in whom this treatment is not an appropriate option, liposuction can be considered with tumescent anesthesia.7 A combination of these surgical modalities also is an option.

Madelung disease is a distinctive disorder typically affecting chronic alcoholics. Recognition of this clinical entity is important, as severe neuropathy and airway compromise may ensue. Although surgical excision is an attractive option for cosmesis and airway compromise, the associated neuropathy can be extremely difficult to treat and can be quite debilitating.

The Diagnosis: Madelung Disease (Benign Symmetric Lipomatosis)

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs (Figures 1 and 2) that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. In addition, he was beginning to develop symptoms of neuropathy of the bilateral hands. The patient had a long-standing history of alcohol abuse. Biopsies performed by the patient’s primary care physician revealed benign adipose tissue. He was referred to the dermatology clinic and subsequently diagnosed with Madelung disease.

|

|

Madelung disease, also known as benign symmetric lipomatosis and Launois-Bensaude syndrome, is characterized by multiple large masses of nonencapsulated adipose tissue. These masses are symmetric and most prominent on the head, neck, trunk, and proximal extremities. Classically, a pseudoathletic appearance is described. Madelung disease most frequently affects men aged 30 to 60 years. In more than 90% of cases, it is associated with alcoholism.

In general, the masses of adipose tissue are asymptomatic. However, airway compression and dysphagia requiring surgical intervention has been reported in the otolaryngology literature.1 In addition, neuropathy develops in 84% of cases.2 Nerve biopsies from patients with Madelung disease have revealed a pattern of axonopathy that is distinct from alcohol-induced neuropathy.3 This neuropathy can involve sensory and motor nerves, with the most prominent findings being muscle weakness, tendon areflexia, interosseous muscle atrophy, vibratory sensation loss, and hypoesthesia. Furthermore, dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system can lead to segmental hyperhidrosis, gustatory sweating, and abnormal autonomic cardiovascular reflexes.2 Many patients who develop neuropathy will eventually become incapacitated.

The etiology of Madelung disease is not fully understood. There are several theories on the pathogenesis of this disease, most describing metabolic disturbances induced by alcohol. Specifically, studies have revealed chronic alcohol use causes numerous deletions in mitochondrial DNA.4,5 The mitochondrial DNA damage may explain both the resistance of the lipomatous masses to lipolysis and the nerve-related changes. Comparisons between human immunodeficiency virus/highly active antiretroviral therapy–associated lipodystrophy and Madelung disease lend credence to the metabolic disturbance theory and may help clarify the specific mechanisms involved.6

There have been no cases of spontaneous resolution, even in patients who stop consuming alcohol. For this reason, most patients are referred to a surgeon. Many surgeons prefer open excision for debulking large lipomatous masses, but this technique typically requires general anesthesia. For those in whom this treatment is not an appropriate option, liposuction can be considered with tumescent anesthesia.7 A combination of these surgical modalities also is an option.

Madelung disease is a distinctive disorder typically affecting chronic alcoholics. Recognition of this clinical entity is important, as severe neuropathy and airway compromise may ensue. Although surgical excision is an attractive option for cosmesis and airway compromise, the associated neuropathy can be extremely difficult to treat and can be quite debilitating.

1. Palacios E, Neitzschman HR, Nguyen J. Madelung disease: multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:94-96.

2. Enzi G, Angelini C, Negrin P, et al. Sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy in patients with multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:388-393.

3. Pollock M, Nicholson GI, Nukada H, et al. Neuropathy in multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Madelung’s disease. Brain. 1988;111:1157-1171.

4. Klopstock T, Naumann M, Schalke B, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: abnormalities in complex IV and multiple deletions in mitochondrial DNA. Neurology. 1994;44:862-866.

5. Mansouri A, Fromenty B, Berson A, et al. Multiple hepatic mitochondrial DNA deletions suggest premature oxidative aging in alcoholic patients. J Hepatol. 1997;27:96-102.

6. Urso R, Gentile M. Are ‘buffalo hump’ syndrome, Madelung's disease and multiple symmetrical lipomatosis variants of the same dysmetabolism? AIDS. 2001;15:290-291.

7. Grassegger A, Häussler R, Schmalzl F. Tumescent liposuction in a patient with Launois-Bensaude syndrome and severe hepatopathy. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:982-985.

1. Palacios E, Neitzschman HR, Nguyen J. Madelung disease: multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:94-96.

2. Enzi G, Angelini C, Negrin P, et al. Sensory, motor, and autonomic neuropathy in patients with multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1985;64:388-393.

3. Pollock M, Nicholson GI, Nukada H, et al. Neuropathy in multiple symmetric lipomatosis. Madelung’s disease. Brain. 1988;111:1157-1171.

4. Klopstock T, Naumann M, Schalke B, et al. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis: abnormalities in complex IV and multiple deletions in mitochondrial DNA. Neurology. 1994;44:862-866.

5. Mansouri A, Fromenty B, Berson A, et al. Multiple hepatic mitochondrial DNA deletions suggest premature oxidative aging in alcoholic patients. J Hepatol. 1997;27:96-102.

6. Urso R, Gentile M. Are ‘buffalo hump’ syndrome, Madelung's disease and multiple symmetrical lipomatosis variants of the same dysmetabolism? AIDS. 2001;15:290-291.

7. Grassegger A, Häussler R, Schmalzl F. Tumescent liposuction in a patient with Launois-Bensaude syndrome and severe hepatopathy. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:982-985.

A 56-year-old man presented for evaluation of massive subcutaneous nodules on the bilateral upper arms, shoulders, chest, abdomen, and lateral aspect of the proximal thighs that developed over the last 12 to 18 months and continued to enlarge. His medical history was remarkable for alcoholism, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension.

Cutaneous Manifestations of Cocaine Use

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Cutaneous Vasculopathy

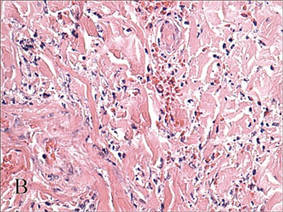

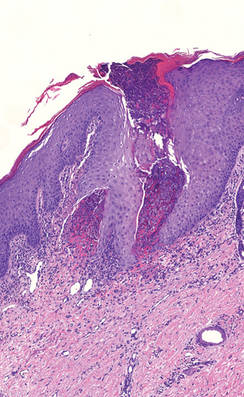

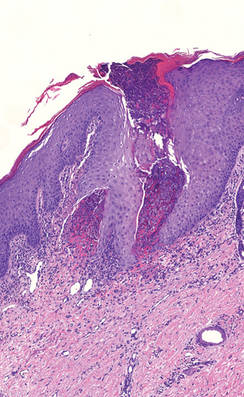

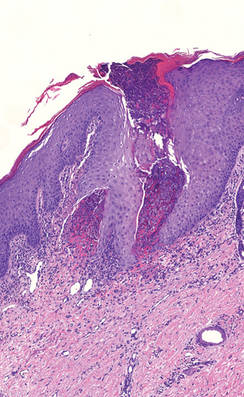

In our patient, tender stellate purpura and occasional bullae were present on the ears, arms and legs, groin, and buttocks (Figure 1). Histopathologic examination revealed subepidermal detachment, perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, and red blood cell extravasation, consistent with early leukocyctoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2).

|

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy is a condition related primarily to cocaine use. Levamisole is an immunomodulatory agent, historically used as a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug for rheumatoid arthritis and as adjuvant chemotherapy for various types of cancer. However, levamisole for human use was banned from US and Canadian markets in 1999 and 2003, respectively, due to increased risk for agranulocytosis, retiform purpura, and epilepsy.1 Currently, veterinarians use levamisole as an anthelminthic agent to deworm house and farm animals. In Europe, pediatric nephrologists use it as a steroid-sparing agent in children with steroid-dependent nephritic syndrome.

Over the last decade, levamisole has increasingly been used as a cocaine adulterant or bulking agent. This contaminant closely resembles cocaine physically and is theorized to prolong or attenuate cocaine’s “high.” Approximately 69% of cocaine sampled by the US Drug Enforcement Administration is adulterated with levamisole.2 Similarly, levamisole-contaminated cocaine also has been found in Europe, Australia, and other parts of the world. Potential complications include vasculitis, thromboembolism, neutropenia, and agranulocytosis.3

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy appears to affect cocaine users of all ages, ethnicities, and genders. Cocaine can be smoked, snorted, or injected. In nearly all reported cases, patients characteristically present with hemorrhagic bullae of the bilateral ear helix, cheeks, or nasal tip. Any body site can be affected with retiform purpura or necrotic bullae. Along with skin lesions, arthralgia is commonly reported, as are constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, night sweats, weight loss, malaise)4; oral mucosal involvement also has been reported.5 Laboratory investigation can reveal neutropenia, positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) in the perinuclear or cytoplasmic pattern, positive proteinase 3, and negative or mildly elevated antimyeloperoxidase.3-5 Acute renal injury and pulmonary hemorrhage are other potentially serious copmlications.4 Antihuman neutrophil elastase antibody testing can help distinguish levamisole-induced vasculopathy from other forms of immune-mediated vasculitis and will be negative in immune-mediated vasculitides such as Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis), Wegener granulomatosis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis), and polyarteritis nodosa.6 On histology, microvascular thrombosis or leukocytoclastic vasculitis can both, or individually, be seen. Epidermal necrosis, dermal hemorrhage, and endothelial hyperplasia have all been noted in skin biopsied from necrotic bullae.

|

Levamisole’s short half-life (approximately 5–6 hours) makes it difficult to detect on routine blood draws. An astute physician suspecting this diagnosis on initial presentation can ask for levamisole detection on urine toxicology screening.7 Urine samples also can be sent for testing with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, though this test may only be available at major research centers.8

Differential diagnosis of levamisole toxicity includes different types of vasculitides such as cryoglobulinemia (positive serum IgM and IgG cryoglobulins; possible hepatitis C infection), Wegener granulomatosis (cytoplasmic ANCA positive; associated with upper and lower respiratory tract inflammation, glomerulonephritis), Churg-Strauss syndrome (perinuclear ANCA positive; associated with asthma and eosinophilia), and polyarteritis nodosa (medium vessel involvement only; associated with livedo reticularis, subcutaneous nodules, ulcers).9 Necrotic lesions also may raise the possibility of warfarin necrosis, heparin necrosis, or cholesterol emboli. Cholesterol embolism most frequently presents with small vessel vasculitis and necrosis of distal extremities such as the toes. With large areas of skin involvement and bullae, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis also should be considered.9

Definitive treatment of this condition requires complete and immediate cessation of cocaine use. Levamisole also has been found as a contaminant in heroin.1 Thus, it may be prudent to recommend heroin avoidance to the patient to prevent recurrences. Management of acute levamisole-induced vasculopathy is primarily symptomatic. Some patients with severe neutropenia at risk for infection have been treated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, while others have only required pain control, usually with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.10 Oral prednisone and colchicine also have been used with reported success.5

Given the increasing incidence of levamisole toxicity and public health implications, clinicians should be aware of this association and the classic clinical and laboratory findings.

1. Aberastury MN, Silva WH, Vaccarezza MM, et al. Epilepsia partialis continua associated with levamisole. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;44:385-388.

2. Nationwide public health alert issued concerning life-threatening risk posed by cocaine laced with veterinary anti-parasite drug [press release]. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; September 21, 2009. http://beta.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/200909211245. Accessed October 9, 2014.

3. Lee KC, Culpepper K, Kessler M. Levamisole-induced thrombosis: literature review and pertinent laboratory findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e128-e129.

4. McGrath MM, Isakova T, Rennke HG, et al. Contaminated cocaine and antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2799-2805.

5. Poon SH, Baliog CR Jr, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leucopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

6. Walsh NM, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

7. Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

8. Trehy ML, Brown DJ, Woodruff JT, et al. Determination of levamisole in urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol. 2001;35:545-550.

9. Lee KC, Ladizinski B, Federman DG. Complications associated with use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine: an emerging public health challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:581-586.

10. Zhu NY, Legatt DF, Turner AR. Agranulocytosis after consumption of cocaine adulterated with levamisole. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:287-289.

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Cutaneous Vasculopathy

In our patient, tender stellate purpura and occasional bullae were present on the ears, arms and legs, groin, and buttocks (Figure 1). Histopathologic examination revealed subepidermal detachment, perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, and red blood cell extravasation, consistent with early leukocyctoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2).

|

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy is a condition related primarily to cocaine use. Levamisole is an immunomodulatory agent, historically used as a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug for rheumatoid arthritis and as adjuvant chemotherapy for various types of cancer. However, levamisole for human use was banned from US and Canadian markets in 1999 and 2003, respectively, due to increased risk for agranulocytosis, retiform purpura, and epilepsy.1 Currently, veterinarians use levamisole as an anthelminthic agent to deworm house and farm animals. In Europe, pediatric nephrologists use it as a steroid-sparing agent in children with steroid-dependent nephritic syndrome.

Over the last decade, levamisole has increasingly been used as a cocaine adulterant or bulking agent. This contaminant closely resembles cocaine physically and is theorized to prolong or attenuate cocaine’s “high.” Approximately 69% of cocaine sampled by the US Drug Enforcement Administration is adulterated with levamisole.2 Similarly, levamisole-contaminated cocaine also has been found in Europe, Australia, and other parts of the world. Potential complications include vasculitis, thromboembolism, neutropenia, and agranulocytosis.3

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy appears to affect cocaine users of all ages, ethnicities, and genders. Cocaine can be smoked, snorted, or injected. In nearly all reported cases, patients characteristically present with hemorrhagic bullae of the bilateral ear helix, cheeks, or nasal tip. Any body site can be affected with retiform purpura or necrotic bullae. Along with skin lesions, arthralgia is commonly reported, as are constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, night sweats, weight loss, malaise)4; oral mucosal involvement also has been reported.5 Laboratory investigation can reveal neutropenia, positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) in the perinuclear or cytoplasmic pattern, positive proteinase 3, and negative or mildly elevated antimyeloperoxidase.3-5 Acute renal injury and pulmonary hemorrhage are other potentially serious copmlications.4 Antihuman neutrophil elastase antibody testing can help distinguish levamisole-induced vasculopathy from other forms of immune-mediated vasculitis and will be negative in immune-mediated vasculitides such as Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis), Wegener granulomatosis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis), and polyarteritis nodosa.6 On histology, microvascular thrombosis or leukocytoclastic vasculitis can both, or individually, be seen. Epidermal necrosis, dermal hemorrhage, and endothelial hyperplasia have all been noted in skin biopsied from necrotic bullae.

|

Levamisole’s short half-life (approximately 5–6 hours) makes it difficult to detect on routine blood draws. An astute physician suspecting this diagnosis on initial presentation can ask for levamisole detection on urine toxicology screening.7 Urine samples also can be sent for testing with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, though this test may only be available at major research centers.8

Differential diagnosis of levamisole toxicity includes different types of vasculitides such as cryoglobulinemia (positive serum IgM and IgG cryoglobulins; possible hepatitis C infection), Wegener granulomatosis (cytoplasmic ANCA positive; associated with upper and lower respiratory tract inflammation, glomerulonephritis), Churg-Strauss syndrome (perinuclear ANCA positive; associated with asthma and eosinophilia), and polyarteritis nodosa (medium vessel involvement only; associated with livedo reticularis, subcutaneous nodules, ulcers).9 Necrotic lesions also may raise the possibility of warfarin necrosis, heparin necrosis, or cholesterol emboli. Cholesterol embolism most frequently presents with small vessel vasculitis and necrosis of distal extremities such as the toes. With large areas of skin involvement and bullae, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis also should be considered.9

Definitive treatment of this condition requires complete and immediate cessation of cocaine use. Levamisole also has been found as a contaminant in heroin.1 Thus, it may be prudent to recommend heroin avoidance to the patient to prevent recurrences. Management of acute levamisole-induced vasculopathy is primarily symptomatic. Some patients with severe neutropenia at risk for infection have been treated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, while others have only required pain control, usually with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.10 Oral prednisone and colchicine also have been used with reported success.5

Given the increasing incidence of levamisole toxicity and public health implications, clinicians should be aware of this association and the classic clinical and laboratory findings.

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Cutaneous Vasculopathy

In our patient, tender stellate purpura and occasional bullae were present on the ears, arms and legs, groin, and buttocks (Figure 1). Histopathologic examination revealed subepidermal detachment, perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, and red blood cell extravasation, consistent with early leukocyctoclastic vasculitis (Figure 2).

|

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy is a condition related primarily to cocaine use. Levamisole is an immunomodulatory agent, historically used as a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug for rheumatoid arthritis and as adjuvant chemotherapy for various types of cancer. However, levamisole for human use was banned from US and Canadian markets in 1999 and 2003, respectively, due to increased risk for agranulocytosis, retiform purpura, and epilepsy.1 Currently, veterinarians use levamisole as an anthelminthic agent to deworm house and farm animals. In Europe, pediatric nephrologists use it as a steroid-sparing agent in children with steroid-dependent nephritic syndrome.

Over the last decade, levamisole has increasingly been used as a cocaine adulterant or bulking agent. This contaminant closely resembles cocaine physically and is theorized to prolong or attenuate cocaine’s “high.” Approximately 69% of cocaine sampled by the US Drug Enforcement Administration is adulterated with levamisole.2 Similarly, levamisole-contaminated cocaine also has been found in Europe, Australia, and other parts of the world. Potential complications include vasculitis, thromboembolism, neutropenia, and agranulocytosis.3

Levamisole-induced vasculopathy appears to affect cocaine users of all ages, ethnicities, and genders. Cocaine can be smoked, snorted, or injected. In nearly all reported cases, patients characteristically present with hemorrhagic bullae of the bilateral ear helix, cheeks, or nasal tip. Any body site can be affected with retiform purpura or necrotic bullae. Along with skin lesions, arthralgia is commonly reported, as are constitutional symptoms (eg, fever, night sweats, weight loss, malaise)4; oral mucosal involvement also has been reported.5 Laboratory investigation can reveal neutropenia, positive antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) in the perinuclear or cytoplasmic pattern, positive proteinase 3, and negative or mildly elevated antimyeloperoxidase.3-5 Acute renal injury and pulmonary hemorrhage are other potentially serious copmlications.4 Antihuman neutrophil elastase antibody testing can help distinguish levamisole-induced vasculopathy from other forms of immune-mediated vasculitis and will be negative in immune-mediated vasculitides such as Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis), Wegener granulomatosis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis), and polyarteritis nodosa.6 On histology, microvascular thrombosis or leukocytoclastic vasculitis can both, or individually, be seen. Epidermal necrosis, dermal hemorrhage, and endothelial hyperplasia have all been noted in skin biopsied from necrotic bullae.

|

Levamisole’s short half-life (approximately 5–6 hours) makes it difficult to detect on routine blood draws. An astute physician suspecting this diagnosis on initial presentation can ask for levamisole detection on urine toxicology screening.7 Urine samples also can be sent for testing with gas chromatography–mass spectrometry, though this test may only be available at major research centers.8

Differential diagnosis of levamisole toxicity includes different types of vasculitides such as cryoglobulinemia (positive serum IgM and IgG cryoglobulins; possible hepatitis C infection), Wegener granulomatosis (cytoplasmic ANCA positive; associated with upper and lower respiratory tract inflammation, glomerulonephritis), Churg-Strauss syndrome (perinuclear ANCA positive; associated with asthma and eosinophilia), and polyarteritis nodosa (medium vessel involvement only; associated with livedo reticularis, subcutaneous nodules, ulcers).9 Necrotic lesions also may raise the possibility of warfarin necrosis, heparin necrosis, or cholesterol emboli. Cholesterol embolism most frequently presents with small vessel vasculitis and necrosis of distal extremities such as the toes. With large areas of skin involvement and bullae, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis also should be considered.9

Definitive treatment of this condition requires complete and immediate cessation of cocaine use. Levamisole also has been found as a contaminant in heroin.1 Thus, it may be prudent to recommend heroin avoidance to the patient to prevent recurrences. Management of acute levamisole-induced vasculopathy is primarily symptomatic. Some patients with severe neutropenia at risk for infection have been treated with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, while others have only required pain control, usually with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.10 Oral prednisone and colchicine also have been used with reported success.5

Given the increasing incidence of levamisole toxicity and public health implications, clinicians should be aware of this association and the classic clinical and laboratory findings.

1. Aberastury MN, Silva WH, Vaccarezza MM, et al. Epilepsia partialis continua associated with levamisole. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;44:385-388.

2. Nationwide public health alert issued concerning life-threatening risk posed by cocaine laced with veterinary anti-parasite drug [press release]. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; September 21, 2009. http://beta.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/200909211245. Accessed October 9, 2014.

3. Lee KC, Culpepper K, Kessler M. Levamisole-induced thrombosis: literature review and pertinent laboratory findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e128-e129.

4. McGrath MM, Isakova T, Rennke HG, et al. Contaminated cocaine and antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2799-2805.

5. Poon SH, Baliog CR Jr, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leucopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

6. Walsh NM, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

7. Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

8. Trehy ML, Brown DJ, Woodruff JT, et al. Determination of levamisole in urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol. 2001;35:545-550.

9. Lee KC, Ladizinski B, Federman DG. Complications associated with use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine: an emerging public health challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:581-586.

10. Zhu NY, Legatt DF, Turner AR. Agranulocytosis after consumption of cocaine adulterated with levamisole. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:287-289.

1. Aberastury MN, Silva WH, Vaccarezza MM, et al. Epilepsia partialis continua associated with levamisole. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;44:385-388.

2. Nationwide public health alert issued concerning life-threatening risk posed by cocaine laced with veterinary anti-parasite drug [press release]. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; September 21, 2009. http://beta.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/200909211245. Accessed October 9, 2014.

3. Lee KC, Culpepper K, Kessler M. Levamisole-induced thrombosis: literature review and pertinent laboratory findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e128-e129.

4. McGrath MM, Isakova T, Rennke HG, et al. Contaminated cocaine and antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2799-2805.

5. Poon SH, Baliog CR Jr, Sams RN, et al. Syndrome of cocaine-levamisole-induced cutaneous vasculitis and immune-mediated leucopenia. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:434-444.

6. Walsh NM, Green PJ, Burlingame RW, et al. Cocaine-related retiform purpura: evidence to incriminate the adulterant, levamisole. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1212-1219.

7. Buchanan JA, Heard K, Burbach C, et al. Prevalence of levamisole in urine toxicology screens positive for cocaine in an inner-city hospital. JAMA. 2011;305:1657-1658.

8. Trehy ML, Brown DJ, Woodruff JT, et al. Determination of levamisole in urine by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Anal Toxicol. 2001;35:545-550.

9. Lee KC, Ladizinski B, Federman DG. Complications associated with use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine: an emerging public health challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:581-586.

10. Zhu NY, Legatt DF, Turner AR. Agranulocytosis after consumption of cocaine adulterated with levamisole. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:287-289.

A 43-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with painful skin lesions of 1 day’s duration. Physical examination revealed tender stellate purpura and occasional bullae on the ears, arms and legs, groin, and buttocks. Laboratory results revealed neutropenia and positive lupus anticoagulant; antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, antinuclear antibody, and double-stranded DNA antibodies were all negative. Urine toxicology was positive for cocaine and opioids. An incisional biopsy of the left arm was performed.

Hairs With an Irregular Shape

The Diagnosis: Circle Hairs

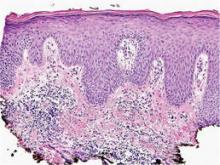

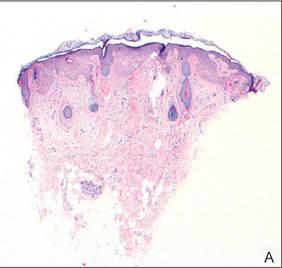

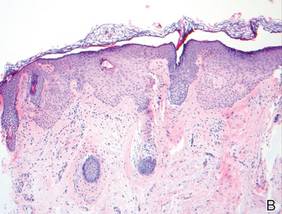

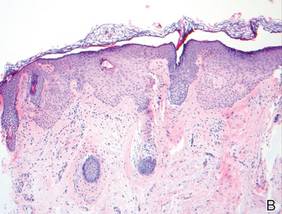

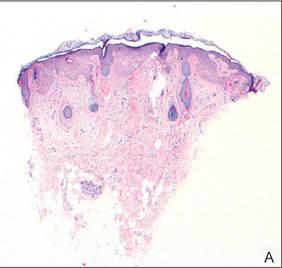

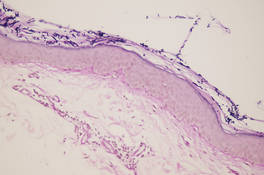

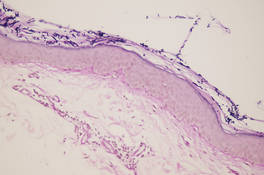

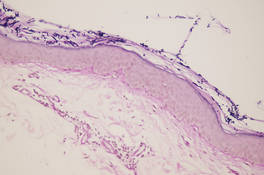

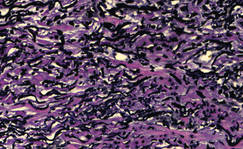

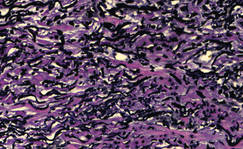

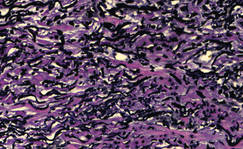

The patient’s hairs were visualized under dermoscopy (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with circle hairs.

Circle hairs were first described in 1963.1 These peculiar hairs grow in a circular horizontal distribution beneath the stratum corneum and are considered benign incidental findings. Their exact cause is unknown. If taken out and unrolled, their length and diameter tends to be smaller than surrounding hairs. It has been hypothesized that they are the result of hairs that lack the size necessary to perforate the stratum corneum.2 Others propose that they are vestigial remains that once had a part in preserving body heat.3 Circle hairs tend to grow in elderly, hairy, and obese males, predominantly on the torso and thighs.2,4

It is important to distinguish between circle hairs and rolled hairs. Rolled hairs may be found on the surface or beneath the stratum corneum and are associated with inflammation and keratinization abnormalities.2 If taken together, these latter findings can help differentiate between the two. The importance stands in recognizing that both circle hairs and rolled hairs are benign; however, rolled hairs can be related to other skin disorders that need additional treatment.

|

|

| Figure 2. A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (A and B)(both Verhoeff-van Gieson, original magnifications ×40). |

1. Adatto R. Poils en spirale (poils enroules). Dermatologica. 1963;127:145-147.

2. Smith JB, Hogan DJ. Circle hairs are not rolled hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:634-635.

3. Contreras-Ruiz J, Duran-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sanchez L, et al. Circle hairs: a clinical curiosity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:495-497.

4. Levit F, Scott MJ Jr. Circle hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:423-425.

The Diagnosis: Circle Hairs

The patient’s hairs were visualized under dermoscopy (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with circle hairs.

Circle hairs were first described in 1963.1 These peculiar hairs grow in a circular horizontal distribution beneath the stratum corneum and are considered benign incidental findings. Their exact cause is unknown. If taken out and unrolled, their length and diameter tends to be smaller than surrounding hairs. It has been hypothesized that they are the result of hairs that lack the size necessary to perforate the stratum corneum.2 Others propose that they are vestigial remains that once had a part in preserving body heat.3 Circle hairs tend to grow in elderly, hairy, and obese males, predominantly on the torso and thighs.2,4

It is important to distinguish between circle hairs and rolled hairs. Rolled hairs may be found on the surface or beneath the stratum corneum and are associated with inflammation and keratinization abnormalities.2 If taken together, these latter findings can help differentiate between the two. The importance stands in recognizing that both circle hairs and rolled hairs are benign; however, rolled hairs can be related to other skin disorders that need additional treatment.

|

|

| Figure 2. A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (A and B)(both Verhoeff-van Gieson, original magnifications ×40). |

The Diagnosis: Circle Hairs

The patient’s hairs were visualized under dermoscopy (Figure 1). A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with circle hairs.

Circle hairs were first described in 1963.1 These peculiar hairs grow in a circular horizontal distribution beneath the stratum corneum and are considered benign incidental findings. Their exact cause is unknown. If taken out and unrolled, their length and diameter tends to be smaller than surrounding hairs. It has been hypothesized that they are the result of hairs that lack the size necessary to perforate the stratum corneum.2 Others propose that they are vestigial remains that once had a part in preserving body heat.3 Circle hairs tend to grow in elderly, hairy, and obese males, predominantly on the torso and thighs.2,4

It is important to distinguish between circle hairs and rolled hairs. Rolled hairs may be found on the surface or beneath the stratum corneum and are associated with inflammation and keratinization abnormalities.2 If taken together, these latter findings can help differentiate between the two. The importance stands in recognizing that both circle hairs and rolled hairs are benign; however, rolled hairs can be related to other skin disorders that need additional treatment.

|

|

| Figure 2. A skin biopsy showed a terminal hair in a horizontal distribution that was located beneath the stratum corneum (A and B)(both Verhoeff-van Gieson, original magnifications ×40). |

1. Adatto R. Poils en spirale (poils enroules). Dermatologica. 1963;127:145-147.

2. Smith JB, Hogan DJ. Circle hairs are not rolled hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:634-635.

3. Contreras-Ruiz J, Duran-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sanchez L, et al. Circle hairs: a clinical curiosity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:495-497.

4. Levit F, Scott MJ Jr. Circle hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:423-425.

1. Adatto R. Poils en spirale (poils enroules). Dermatologica. 1963;127:145-147.

2. Smith JB, Hogan DJ. Circle hairs are not rolled hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:634-635.

3. Contreras-Ruiz J, Duran-McKinster C, Tamayo-Sanchez L, et al. Circle hairs: a clinical curiosity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:495-497.

4. Levit F, Scott MJ Jr. Circle hairs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:423-425.

A 74-year-old man was evaluated for numerous peculiar hairs on the back that had been present for several years. He reported no other dermatologic concerns. The patient was obese and led a sedentary lifestyle, spending most of the day sitting or lying down. Physical examination revealed a hairy back with many irregularly shaped hairs.

Hypopigmented Facial Papules on the Cheeks

The Diagnosis: Tumor of the Follicular Infundibulum

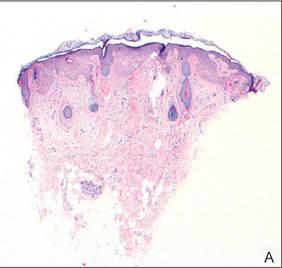

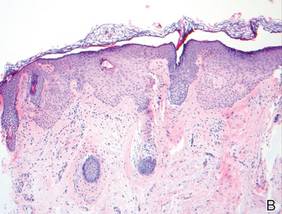

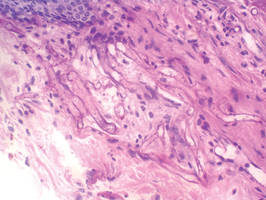

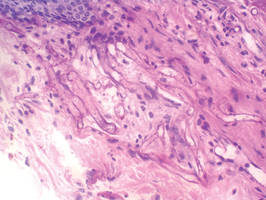

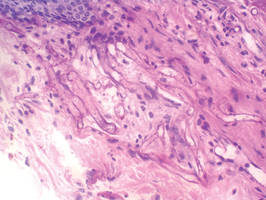

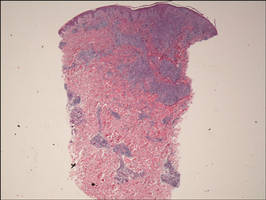

Histopathologic findings from a facial papule in our patient revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There was no atypia. Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains for fungi were negative. The combined clinical presentation and histopathologic findings supported the diagnosis of multiple tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI).

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum was diagnosed based on a biopsy from the right cheek that revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×100). |

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is an uncommon benign neoplasm that was first described in 1961 by Mehregan and Butler.1 The reported frequency is 10 per 100,000 biopsies.2 The majority of cases have been reported as solitary lesions, and multiple TFI are rare.3 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum affects middle-aged and elderly individuals with a female predominance.4 Multiple lesions generally range in number from 10 to 20, but there are few reports of more than 100 lesions.2,3,5,6 The solitary tumors often are initially misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) or seborrheic keratosis. Multiple TFI have been described variably as hypopigmented, flesh-colored and pink, flat and slightly depressed macules and thin papules. Sites of predilection include the scalp, face, neck, and upper trunk.2,3,5

There is no histopathologic difference between solitary and multiple TFI. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum displays a characteristic pale platelike proliferation of keratinocytes within the upper dermis attached to the overlying epidermis. The proliferating cells stain positive with periodic acid–Schiff, diastase-digestible glycogen is present in the cells at the base of the tumor, and a thickened network or brushlike pattern of elastic fibers surrounds the periphery of the tumor.1 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is occasionally discovered incidentally on biopsy and has been observed in the margin of wide excisions of a variety of neoplasms including BCC.7 Based on the close association of TFI and BCC in the same specimens, Weyers et al7 concluded that TFI may be a nonaggressive type of BCC. Cribier and Grosshans2 reported 2 cases of TFI overlying a nevus sebaceous and a fibroma.

Treatment of TFI includes topical keratolytics, topical retinoic acid,5 imiquimod,8 topical steroids, and oral etretinate,6 all of which result in minimal improvement or incomplete resolution. Destructive treatments include cryotherapy, curettage, electrosurgery, laser ablation, and surgical excision, but all may lead to an unacceptable cosmetic result.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:78-81.

2. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

3. Kolenik SA 3rd, Bolognia JL, Castiglione FM Jr, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:282-284.

4. Ackerman AB, Reddy VB, Soyer HP. Neoplasms With Follicular Differentiation. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2001.

5. Kossard S, Finley AG, Poyzer K, et al. Eruptive infundibulomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:361-366.

6. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

7. Weyers W, Horster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

8. Martin JE, Hsu M, Wang LC. An unusual clinical presentation of multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:885-886.

The Diagnosis: Tumor of the Follicular Infundibulum

Histopathologic findings from a facial papule in our patient revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There was no atypia. Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains for fungi were negative. The combined clinical presentation and histopathologic findings supported the diagnosis of multiple tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI).

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum was diagnosed based on a biopsy from the right cheek that revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×100). |

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is an uncommon benign neoplasm that was first described in 1961 by Mehregan and Butler.1 The reported frequency is 10 per 100,000 biopsies.2 The majority of cases have been reported as solitary lesions, and multiple TFI are rare.3 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum affects middle-aged and elderly individuals with a female predominance.4 Multiple lesions generally range in number from 10 to 20, but there are few reports of more than 100 lesions.2,3,5,6 The solitary tumors often are initially misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) or seborrheic keratosis. Multiple TFI have been described variably as hypopigmented, flesh-colored and pink, flat and slightly depressed macules and thin papules. Sites of predilection include the scalp, face, neck, and upper trunk.2,3,5

There is no histopathologic difference between solitary and multiple TFI. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum displays a characteristic pale platelike proliferation of keratinocytes within the upper dermis attached to the overlying epidermis. The proliferating cells stain positive with periodic acid–Schiff, diastase-digestible glycogen is present in the cells at the base of the tumor, and a thickened network or brushlike pattern of elastic fibers surrounds the periphery of the tumor.1 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is occasionally discovered incidentally on biopsy and has been observed in the margin of wide excisions of a variety of neoplasms including BCC.7 Based on the close association of TFI and BCC in the same specimens, Weyers et al7 concluded that TFI may be a nonaggressive type of BCC. Cribier and Grosshans2 reported 2 cases of TFI overlying a nevus sebaceous and a fibroma.

Treatment of TFI includes topical keratolytics, topical retinoic acid,5 imiquimod,8 topical steroids, and oral etretinate,6 all of which result in minimal improvement or incomplete resolution. Destructive treatments include cryotherapy, curettage, electrosurgery, laser ablation, and surgical excision, but all may lead to an unacceptable cosmetic result.

The Diagnosis: Tumor of the Follicular Infundibulum

Histopathologic findings from a facial papule in our patient revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (Figure). There was no atypia. Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid–Schiff stains for fungi were negative. The combined clinical presentation and histopathologic findings supported the diagnosis of multiple tumor of the follicular infundibulum (TFI).

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum was diagnosed based on a biopsy from the right cheek that revealed multifocal hyperplasia of anastomosing follicular infundibular cells with multiple connections to the overlying epidermis (A and B)(H&E, original magnifications ×40 and ×100). |

Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is an uncommon benign neoplasm that was first described in 1961 by Mehregan and Butler.1 The reported frequency is 10 per 100,000 biopsies.2 The majority of cases have been reported as solitary lesions, and multiple TFI are rare.3 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum affects middle-aged and elderly individuals with a female predominance.4 Multiple lesions generally range in number from 10 to 20, but there are few reports of more than 100 lesions.2,3,5,6 The solitary tumors often are initially misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) or seborrheic keratosis. Multiple TFI have been described variably as hypopigmented, flesh-colored and pink, flat and slightly depressed macules and thin papules. Sites of predilection include the scalp, face, neck, and upper trunk.2,3,5

There is no histopathologic difference between solitary and multiple TFI. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum displays a characteristic pale platelike proliferation of keratinocytes within the upper dermis attached to the overlying epidermis. The proliferating cells stain positive with periodic acid–Schiff, diastase-digestible glycogen is present in the cells at the base of the tumor, and a thickened network or brushlike pattern of elastic fibers surrounds the periphery of the tumor.1 Tumor of the follicular infundibulum is occasionally discovered incidentally on biopsy and has been observed in the margin of wide excisions of a variety of neoplasms including BCC.7 Based on the close association of TFI and BCC in the same specimens, Weyers et al7 concluded that TFI may be a nonaggressive type of BCC. Cribier and Grosshans2 reported 2 cases of TFI overlying a nevus sebaceous and a fibroma.

Treatment of TFI includes topical keratolytics, topical retinoic acid,5 imiquimod,8 topical steroids, and oral etretinate,6 all of which result in minimal improvement or incomplete resolution. Destructive treatments include cryotherapy, curettage, electrosurgery, laser ablation, and surgical excision, but all may lead to an unacceptable cosmetic result.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:78-81.

2. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

3. Kolenik SA 3rd, Bolognia JL, Castiglione FM Jr, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:282-284.

4. Ackerman AB, Reddy VB, Soyer HP. Neoplasms With Follicular Differentiation. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2001.

5. Kossard S, Finley AG, Poyzer K, et al. Eruptive infundibulomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:361-366.

6. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

7. Weyers W, Horster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

8. Martin JE, Hsu M, Wang LC. An unusual clinical presentation of multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:885-886.

1. Mehregan AH, Butler JD. A tumor of follicular infundibulum. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:78-81.

2. Cribier B, Grosshans E. Tumor of the follicular infundibulum: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:979-984.

3. Kolenik SA 3rd, Bolognia JL, Castiglione FM Jr, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:282-284.

4. Ackerman AB, Reddy VB, Soyer HP. Neoplasms With Follicular Differentiation. New York, NY: Ardor Scribendi; 2001.

5. Kossard S, Finley AG, Poyzer K, et al. Eruptive infundibulomas. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:361-366.

6. Schnitzler L, Civatte J, Robin F, et al. Multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum with basocellular degeneration. apropos of a case [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1987;114:551-556.

7. Weyers W, Horster S, Diaz-Cascajo C. Tumor of follicular infundibulum is basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:634-641.

8. Martin JE, Hsu M, Wang LC. An unusual clinical presentation of multiple tumors of the follicular infundibulum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:885-886.

A 73-year-old woman presented with multiple mildly pruritic, hypopigmented, thin papules involving both cheeks of 5 months’ duration. The patient had no improvement with ketoconazole cream 2% and hydrocortisone cream 1% used daily for 1 month for presumed tinea versicolor. Physical examination revealed 10 ill-defined, 2- to 5-mm, round and oval, smooth hypopigmented, slightly raised papules located on the lower aspect of both cheeks.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

A 59-year-old white man presented with 2 large erythematous lesions on the right side of the chest wall that had gradually progressed over the last 1.5 years. The patient denied any fever, night sweats, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or loss of appetite. Physical examination revealed 2 large, well-circumscribed, nearly contiguous, firm, erythematous tumors. One tumor measured 7.5×4.5 cm and the other measured 4×3.5 cm.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

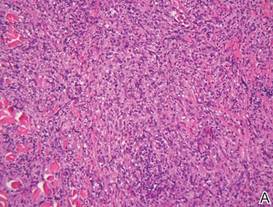

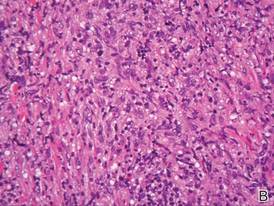

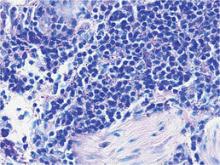

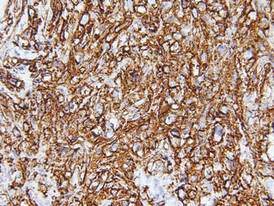

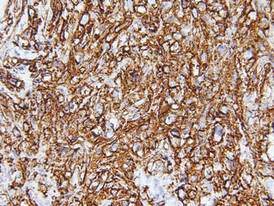

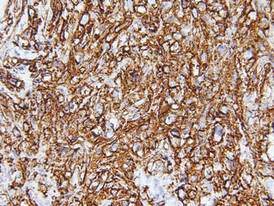

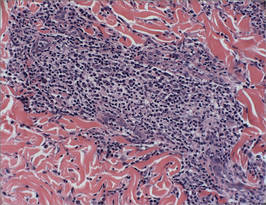

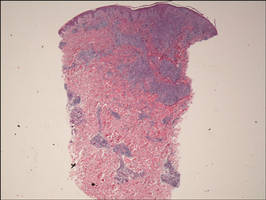

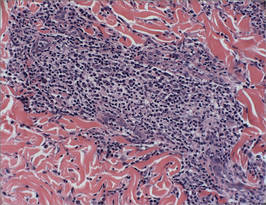

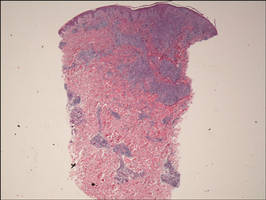

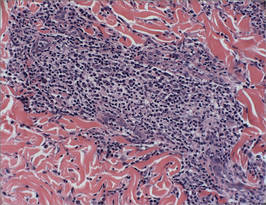

Biopsies from the right side of the chest wall (Figure 1) revealed an atypical dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis. There was extensive crush artifact throughout the specimen. However, the findings were consistent with cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), and the diffuse large B-cell type was favored (Figure 2). Atypical lymphocytes stained positively for antibodies against CD20 (Figure 3), CD79a, and BCL-6, and stained negatively for antibodies against MUM-1 and BCL-2. Although flow cytometry revealed no definitive immunophenotypic lymphoma population, polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed a monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable. A preliminary diagnosis of primary CBCL (PCBCL) was formulated. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicle center lymphoma subtypes were each considered, which triggered further workup to rule out systemic involvement.

|

|

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy from the posterior iliac crest revealed normocellular bone marrow with normal trilineage hematopoiesis. However, whole-body staging with positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scanning revealed osseous disease in the left proximal humerus (Figure 4) as well as a slightly hypermetabolic right axillary lymph node. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no evidence of intracranial disease. Because of the apparent systemic involvement, stage IV non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL) became the new suspected diagnosis. The patient was started on the first of 6 cycles of chemotherapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), and the skin lesions quickly dissipated and flattened. A faint pink discoloration remained over a slightly indented area. A repeat PET-CT scan following 4 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy also confirmed a complete response to therapy.

In general, CBCL tends to affect adults and presents as relatively firm and plum-colored papules, nodules, tumors, or plaques, which can be either fast or slow growing. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma may be primary or secondary to systemic involvement. Primary CBCL refers to a group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that initially present in the skin with no evidence of extracutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis.1,2 Secondary CBCL (SCBCL) refers to cutaneous disease that occurs secondary to systemic B-cell lymphoma. Detecting systemic involvement and distinguishing between PCBCL and SCBCL is valuable in determining prognosis and therapeutic options, as subtypes of PCBCL often have an improved prognosis and may be treated with local irradiation.

The initial staging techniques that are preferred for cutaneous lymphomas have been debated.3-5 For cutaneous lymphomas, except mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer recommends obtaining a complete blood cell count with differential; complete metabolic studies including lactate dehydrogenase; and imaging studies of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Bone marrow biopsies and imaging studies of the neck or whole-body PET-CT scanning also may be useful depending on the clinical scenario.3 Although a more limited workup may be sufficient for PCBCLs such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,5 a bone marrow biopsy is recommended for cases of primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).3 Senff et al5 supported the use of a bone marrow biopsy in the evaluation of follicle center lymphomas first presenting in the skin, though this method is controversial. In our patient, the laboratory results; bone marrow biopsy; and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis failed to suggest extracutaneous disease, while the PET-CT scan revealed systemic involvement.

The differential diagnosis of CBCL includes cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma), which may be the result of insults such as arthropod bites, stings, vaccinations, or trauma. The clinical presentation, histology, and results of molecular studies and immunohistochemistry are essential in differentiating benign versus malignant processes.6 Lymphomas are expected to be larger and more persistent than benign processes, demonstrating an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate and monoclonality; immunohistochemistry will aid in the distinction between B-cell and T-cell processes and can delineate the type of B-cell lymphoma. Histology for CBCL typically reveals an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate showing a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype. Staining for antibodies against BCL-2, BCL-6, CD10, and MUM-1 also plays an important role in the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma and determining where the lesion(s) falls within the classification schemes. For example, to differentiate between primary cutaneous lymphoma subtypes, BCL-2 negativity and BCL-6 positivity in the context of a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype supports a follicle center lymphoma or a DLBCL (non–leg type). By contrast, CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and MUM-1 positivity would favor a DLBCL (leg type).7

The natural history and therapeutic options differ greatly between subtypes of CBCL. For example, the prognosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is generally favorable with a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of roughly 95%, and radiation therapy is recommended as a first-line therapy for localized disease.2,8 Conversely, primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type) frequently spreads to extracutaneous sites8 and carries a much lower estimated 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 55%.2 Chemotherapy with R-CHOP is typically included in initial therapy for primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).8 The prognosis of systemic B-cell lymphomas also is highly variable and may depend on the type of B-cell lymphoma, the stage of disease at diagnosis, histologic and immunologic characteristics, and the therapy received. Wright et al9 reported that patients with systemic germinal center B cell–like DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 62%, whereas patients with activated B cell–like variants of DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 26%. Expression of CD40 may be a favorable prognostic factor following treatment with systemic chemotherapy in patients with DLBCL,10 whereas FOXP1 protein overexpression is correlated with poor disease-specific survival in certain DLBCL phenotypes.11

Although it is uncertain whether the cutaneous lesions preceded systemic disease in our patient, the cutaneous lesions could be arbitrarily classified as secondary because extracutaneous disease was discovered within 6 months of the initial diagnosis.1 However, classifying the CBCL as primary or secondary did not alter the course of treatment in our patient, as the presumed systemic disease necessitated treatment with systemic chemotherapy; both PCBCLs that develop systemic involvement and SCBCLs (primary extracutaneous disease) usually are treated with systemic chemotherapy. Our case highlights the importance of whole-body staging, as PET-CT scanning changed the course of care by detecting osseous involvement, necessitating systemic therapy as opposed to local radiation therapy alone. A multidisciplinary team with a focus on the diagnosis and management of cutaneous lymphomas helped streamline our patient’s laboratory testing and imaging studies, diagnostic and therapeutic decision making, and treatment implementation. Open channels and frequent opportunities for communication among dermatologists, dermatopathologists, medical oncologists, hematopathologists, radiologists, and radiation oncologists are needed to optimize and coordinate care for patients with cutaneous lymphoma who require transdisciplinary care.

Acknowledgement—The authors would like to thank Henry Koon, MD (hematology/oncology), for his input and expertise.

1. Willemze R, Kerl H, Sterry W, et al. EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas: a proposal from the cutaneous lymphoma study group of the European organization for research and treatment of cancer. Blood. 1997;90:354-371.

2. Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768-3785.

3. Kim YH, Willemze R, Pimpinelli N, et al. TNM classification system for primary cutaneous lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Blood. 2007;110:479-484.

4. Quereux G, Frot AS, Brocard A, et al. Routine bone marrow biopsy in the initial evaluation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma does not appear justified. Eur J Dermatol. 2009;19:216-220.

5. Senff NJ, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Willemze R. Results of bone marrow examination in 275 patients with histological features that suggest an indolent type of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:52-56.

6. Gilliam AC, Wood GS. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasias. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2000;19:133-141.

7. Burg G, Kempf W, Cozzio A, et al. WHO/EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas 2005: histological and molecular aspects. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:647-674.

8. Senff NJ, Noordijk EM, Kim YH, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and International Society for Cutaneous Lymphoma consensus recommendations for the management of cutaneous B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2008;112:1600-1609.

9. Wright G, Tan B, Rosenwald A, et al. A gene expression-based method to diagnose clinically distinct subgroups of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9991-9996.

10. Rydström K, Linderoth J, Nyman H, et al. CD40 is a potential marker of favorable prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:1643-1648.

11. Hoeller S, Schneider A, Haralambieva E, et al. FOXP1 protein overexpression is associated with inferior outcome in nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphomas with non-gerzminal centre phenotype, independent of gains and structural aberrations at 3p14.1. Histopathology. 2010;57:73-80.

A 59-year-old white man presented with 2 large erythematous lesions on the right side of the chest wall that had gradually progressed over the last 1.5 years. The patient denied any fever, night sweats, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or loss of appetite. Physical examination revealed 2 large, well-circumscribed, nearly contiguous, firm, erythematous tumors. One tumor measured 7.5×4.5 cm and the other measured 4×3.5 cm.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Biopsies from the right side of the chest wall (Figure 1) revealed an atypical dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis. There was extensive crush artifact throughout the specimen. However, the findings were consistent with cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), and the diffuse large B-cell type was favored (Figure 2). Atypical lymphocytes stained positively for antibodies against CD20 (Figure 3), CD79a, and BCL-6, and stained negatively for antibodies against MUM-1 and BCL-2. Although flow cytometry revealed no definitive immunophenotypic lymphoma population, polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed a monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable. A preliminary diagnosis of primary CBCL (PCBCL) was formulated. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicle center lymphoma subtypes were each considered, which triggered further workup to rule out systemic involvement.

|

|

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy from the posterior iliac crest revealed normocellular bone marrow with normal trilineage hematopoiesis. However, whole-body staging with positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scanning revealed osseous disease in the left proximal humerus (Figure 4) as well as a slightly hypermetabolic right axillary lymph node. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no evidence of intracranial disease. Because of the apparent systemic involvement, stage IV non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL) became the new suspected diagnosis. The patient was started on the first of 6 cycles of chemotherapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), and the skin lesions quickly dissipated and flattened. A faint pink discoloration remained over a slightly indented area. A repeat PET-CT scan following 4 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy also confirmed a complete response to therapy.

In general, CBCL tends to affect adults and presents as relatively firm and plum-colored papules, nodules, tumors, or plaques, which can be either fast or slow growing. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma may be primary or secondary to systemic involvement. Primary CBCL refers to a group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that initially present in the skin with no evidence of extracutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis.1,2 Secondary CBCL (SCBCL) refers to cutaneous disease that occurs secondary to systemic B-cell lymphoma. Detecting systemic involvement and distinguishing between PCBCL and SCBCL is valuable in determining prognosis and therapeutic options, as subtypes of PCBCL often have an improved prognosis and may be treated with local irradiation.

The initial staging techniques that are preferred for cutaneous lymphomas have been debated.3-5 For cutaneous lymphomas, except mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer recommends obtaining a complete blood cell count with differential; complete metabolic studies including lactate dehydrogenase; and imaging studies of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Bone marrow biopsies and imaging studies of the neck or whole-body PET-CT scanning also may be useful depending on the clinical scenario.3 Although a more limited workup may be sufficient for PCBCLs such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,5 a bone marrow biopsy is recommended for cases of primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).3 Senff et al5 supported the use of a bone marrow biopsy in the evaluation of follicle center lymphomas first presenting in the skin, though this method is controversial. In our patient, the laboratory results; bone marrow biopsy; and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis failed to suggest extracutaneous disease, while the PET-CT scan revealed systemic involvement.

The differential diagnosis of CBCL includes cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma), which may be the result of insults such as arthropod bites, stings, vaccinations, or trauma. The clinical presentation, histology, and results of molecular studies and immunohistochemistry are essential in differentiating benign versus malignant processes.6 Lymphomas are expected to be larger and more persistent than benign processes, demonstrating an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate and monoclonality; immunohistochemistry will aid in the distinction between B-cell and T-cell processes and can delineate the type of B-cell lymphoma. Histology for CBCL typically reveals an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate showing a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype. Staining for antibodies against BCL-2, BCL-6, CD10, and MUM-1 also plays an important role in the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma and determining where the lesion(s) falls within the classification schemes. For example, to differentiate between primary cutaneous lymphoma subtypes, BCL-2 negativity and BCL-6 positivity in the context of a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype supports a follicle center lymphoma or a DLBCL (non–leg type). By contrast, CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and MUM-1 positivity would favor a DLBCL (leg type).7

The natural history and therapeutic options differ greatly between subtypes of CBCL. For example, the prognosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is generally favorable with a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of roughly 95%, and radiation therapy is recommended as a first-line therapy for localized disease.2,8 Conversely, primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type) frequently spreads to extracutaneous sites8 and carries a much lower estimated 5-year disease-specific survival rate of 55%.2 Chemotherapy with R-CHOP is typically included in initial therapy for primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).8 The prognosis of systemic B-cell lymphomas also is highly variable and may depend on the type of B-cell lymphoma, the stage of disease at diagnosis, histologic and immunologic characteristics, and the therapy received. Wright et al9 reported that patients with systemic germinal center B cell–like DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 62%, whereas patients with activated B cell–like variants of DLBCL had a 5-year survival rate of 26%. Expression of CD40 may be a favorable prognostic factor following treatment with systemic chemotherapy in patients with DLBCL,10 whereas FOXP1 protein overexpression is correlated with poor disease-specific survival in certain DLBCL phenotypes.11

Although it is uncertain whether the cutaneous lesions preceded systemic disease in our patient, the cutaneous lesions could be arbitrarily classified as secondary because extracutaneous disease was discovered within 6 months of the initial diagnosis.1 However, classifying the CBCL as primary or secondary did not alter the course of treatment in our patient, as the presumed systemic disease necessitated treatment with systemic chemotherapy; both PCBCLs that develop systemic involvement and SCBCLs (primary extracutaneous disease) usually are treated with systemic chemotherapy. Our case highlights the importance of whole-body staging, as PET-CT scanning changed the course of care by detecting osseous involvement, necessitating systemic therapy as opposed to local radiation therapy alone. A multidisciplinary team with a focus on the diagnosis and management of cutaneous lymphomas helped streamline our patient’s laboratory testing and imaging studies, diagnostic and therapeutic decision making, and treatment implementation. Open channels and frequent opportunities for communication among dermatologists, dermatopathologists, medical oncologists, hematopathologists, radiologists, and radiation oncologists are needed to optimize and coordinate care for patients with cutaneous lymphoma who require transdisciplinary care.

Acknowledgement—The authors would like to thank Henry Koon, MD (hematology/oncology), for his input and expertise.

A 59-year-old white man presented with 2 large erythematous lesions on the right side of the chest wall that had gradually progressed over the last 1.5 years. The patient denied any fever, night sweats, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, or loss of appetite. Physical examination revealed 2 large, well-circumscribed, nearly contiguous, firm, erythematous tumors. One tumor measured 7.5×4.5 cm and the other measured 4×3.5 cm.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Biopsies from the right side of the chest wall (Figure 1) revealed an atypical dense and diffuse lymphocytic infiltrate throughout the dermis. There was extensive crush artifact throughout the specimen. However, the findings were consistent with cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL), and the diffuse large B-cell type was favored (Figure 2). Atypical lymphocytes stained positively for antibodies against CD20 (Figure 3), CD79a, and BCL-6, and stained negatively for antibodies against MUM-1 and BCL-2. Although flow cytometry revealed no definitive immunophenotypic lymphoma population, polymerase chain reaction analysis revealed a monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable. A preliminary diagnosis of primary CBCL (PCBCL) was formulated. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicle center lymphoma subtypes were each considered, which triggered further workup to rule out systemic involvement.

|

|

|

|

A bone marrow biopsy from the posterior iliac crest revealed normocellular bone marrow with normal trilineage hematopoiesis. However, whole-body staging with positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scanning revealed osseous disease in the left proximal humerus (Figure 4) as well as a slightly hypermetabolic right axillary lymph node. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed no evidence of intracranial disease. Because of the apparent systemic involvement, stage IV non-Hodgkin lymphoma (DLBCL) became the new suspected diagnosis. The patient was started on the first of 6 cycles of chemotherapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), and the skin lesions quickly dissipated and flattened. A faint pink discoloration remained over a slightly indented area. A repeat PET-CT scan following 4 cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy also confirmed a complete response to therapy.

In general, CBCL tends to affect adults and presents as relatively firm and plum-colored papules, nodules, tumors, or plaques, which can be either fast or slow growing. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma may be primary or secondary to systemic involvement. Primary CBCL refers to a group of non-Hodgkin lymphomas that initially present in the skin with no evidence of extracutaneous involvement at the time of diagnosis.1,2 Secondary CBCL (SCBCL) refers to cutaneous disease that occurs secondary to systemic B-cell lymphoma. Detecting systemic involvement and distinguishing between PCBCL and SCBCL is valuable in determining prognosis and therapeutic options, as subtypes of PCBCL often have an improved prognosis and may be treated with local irradiation.

The initial staging techniques that are preferred for cutaneous lymphomas have been debated.3-5 For cutaneous lymphomas, except mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer recommends obtaining a complete blood cell count with differential; complete metabolic studies including lactate dehydrogenase; and imaging studies of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Bone marrow biopsies and imaging studies of the neck or whole-body PET-CT scanning also may be useful depending on the clinical scenario.3 Although a more limited workup may be sufficient for PCBCLs such as primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma,5 a bone marrow biopsy is recommended for cases of primary cutaneous DLBCL (leg type).3 Senff et al5 supported the use of a bone marrow biopsy in the evaluation of follicle center lymphomas first presenting in the skin, though this method is controversial. In our patient, the laboratory results; bone marrow biopsy; and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis failed to suggest extracutaneous disease, while the PET-CT scan revealed systemic involvement.

The differential diagnosis of CBCL includes cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma), which may be the result of insults such as arthropod bites, stings, vaccinations, or trauma. The clinical presentation, histology, and results of molecular studies and immunohistochemistry are essential in differentiating benign versus malignant processes.6 Lymphomas are expected to be larger and more persistent than benign processes, demonstrating an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate and monoclonality; immunohistochemistry will aid in the distinction between B-cell and T-cell processes and can delineate the type of B-cell lymphoma. Histology for CBCL typically reveals an atypical lymphocytic infiltrate showing a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype. Staining for antibodies against BCL-2, BCL-6, CD10, and MUM-1 also plays an important role in the diagnosis of cutaneous lymphoma and determining where the lesion(s) falls within the classification schemes. For example, to differentiate between primary cutaneous lymphoma subtypes, BCL-2 negativity and BCL-6 positivity in the context of a CD20+ and CD79a+ immunophenotype supports a follicle center lymphoma or a DLBCL (non–leg type). By contrast, CD20, CD79a, BCL-2, and MUM-1 positivity would favor a DLBCL (leg type).7