User login

What Dermatology Residents Need to Know About Joining Group Practices

What Dermatology Residents Need to Know About Joining Group Practices

Choosing your first job out of residency can be overwhelming. The things you need to consider go way beyond the job itself: things like geography, work/life balance, and practice focus (eg, skin cancer, cosmetics, medical dermatology, pediatrics) are all relatively independent factors from the specific practice you join. About 1 in 6 dermatologists change practices every year, with even higher rates for new graduates.1

Drawing from my 20 years of experience as a dermatologist (10 in academia and 10 in 3 different private group practice settings—one that was independently owned and 2 with private equity owners, of which I am one), I have seen firsthand what matters and what does not when it comes to joining a group practice, both in my own career and in watching the careers of many young dermatologists. I will do my best to summarize that experience into useful advice.

Important Factors to Consider When Choosing a Practice

As a second- or third-year resident, you likely are excited but nervous about leaping into practice. To approach it with confidence, allow me to outline certain factors that apply to all dermatology practices that you may consider joining as you start your career and beyond.

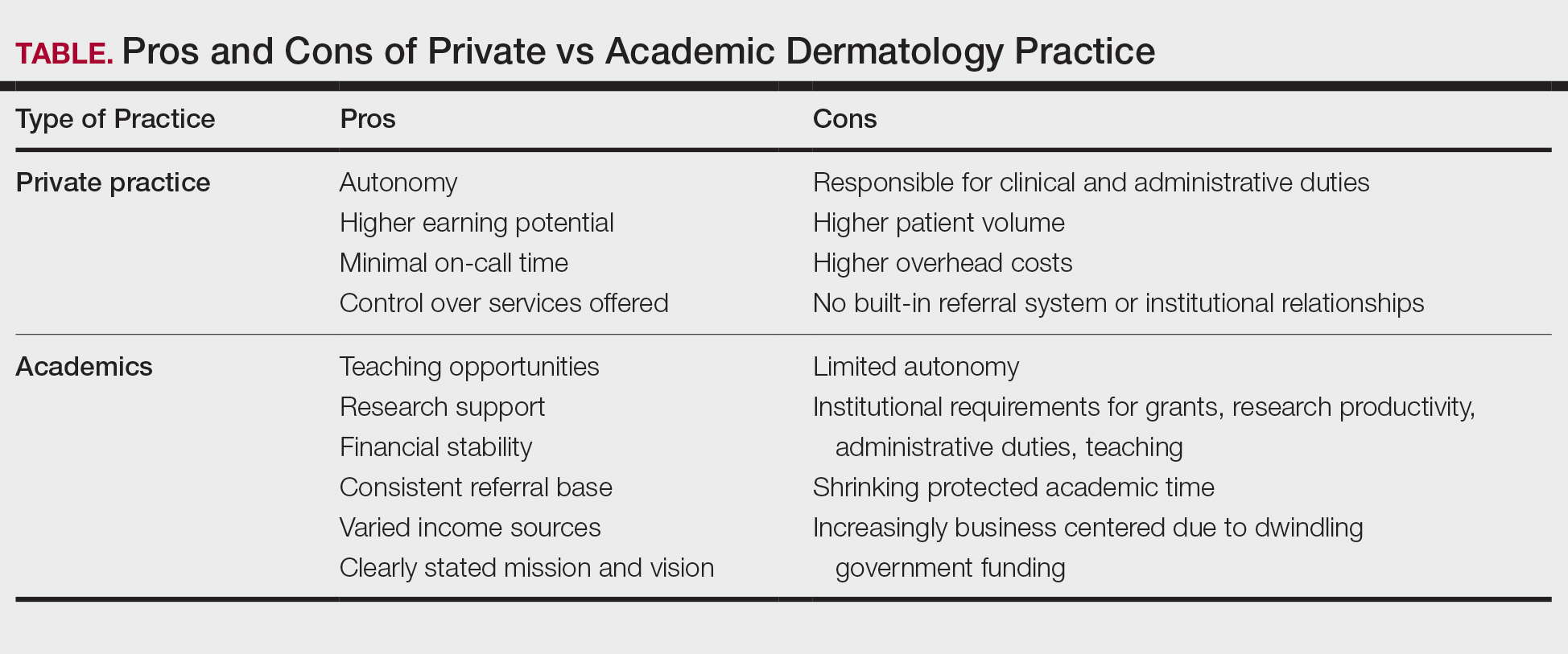

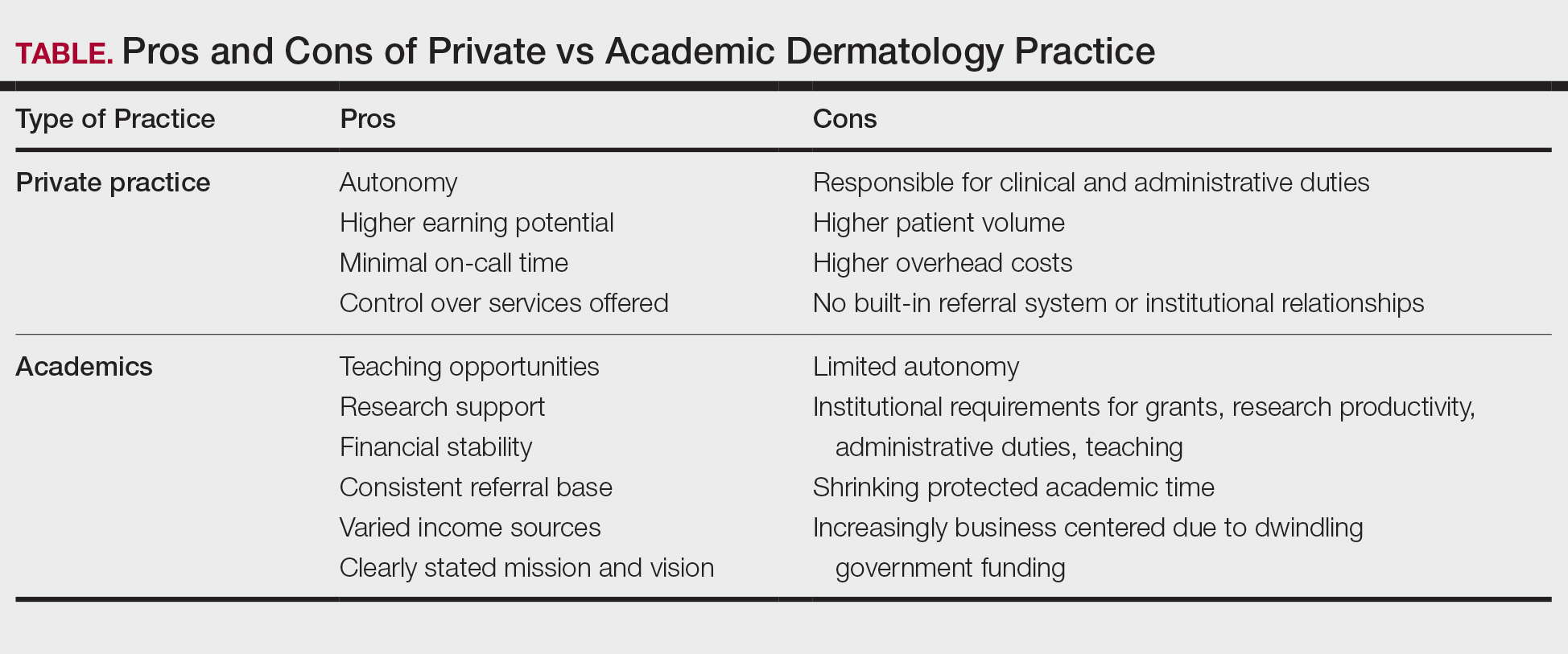

- Every Practice Owner Has to Prioritize Profit. Independent owners need to build the value of their main asset, academics need to fund research and teaching, and private equity owners need to drive returns for their investors. In other words, there are lots of negative situations in academic and independently owned groups, although private equity gets all the bad press.2-5 Nothing inherently makes one type of practice setting better; it depends on the specific organization. Owners do care about other things beyond just profit (eg, providing quality care, performing cutting-edge research), but when the rubber meets the road, if a practice is providing amazing quality care but losing money doing so, in a short time it won’t be providing any care at all.

- There Is No Free Money. Your long-term compensation will 100% be determined by how much revenue you generate minus the overhead. There is no magic fund to boost your pay long term, no matter how badly the practice needs or wants you. Be clear and even blunt: ask how the practice is going to profit from you. Ask how they plan to make back any signing bonus or guaranteed salary. If they are paying you a higher percentage of collections, ask them how they are able to pay more than competitors. If they say it is because they are more efficient with lower overhead, make sure that increased efficiency does not translate into less support.

- Percent of Collections Is Irrelevant. OK, perhaps not completely irrelevant, but it is one of the least important aspects in determining how much you will make or how happy you will be. Percent of collections is the percentage of the money that the practice actually collects that is paid out to you as compensation. For example, if your percentage of collections is 40%, that means that if the practice collects $1,000,000 for the care you deliver, you will be compensated $400,000. Read on to find out why it is not as important as it seems.

- Don’t Get Too Hung Up on the Details of the Contract. I have seen so many young dermatologists spend enormous amounts of time and money on attorneys and negotiating the fine points of the contract, but not a single one has ever said later that because of all that negotiation they were protected or treated well when things got contentious. What it comes down to is that, if the practice wants to treat you well, they will. If they want to treat you badly, no contract on earth can protect you from all the ways they can do so. And if you leave, no matter what the contract says, they can do whatever they want unless you are willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight them in court. So review the contract with an attorney and know what it says, but don’t sweat every period and clause. It isn’t worth it.

- Your Day-to-Day Is Everything. The practice you join may be the best-run practice in the world in every way, except that the office you happen to be going to work in is the one office in the practice that has 2 providers who are jerks and everyone dreads coming to work every morning. There are so many other examples of ways one location can be a disaster even in a great practice—and unfortunately, even great locations can change. The best you can do is to make sure you know where you will be working and with whom. Go and visit the actual office and spend a day shadowing to feel what the vibe is.

What Really Matters

If factors like the percentage of collections you keep are not the big things, what are? The good and bad news is that there isn’t a single answer to this question. Rather, the fundamental question is whether the practice’s plan to maximize profit includes having satisfied, motivated, and engaged long-term providers. Obviously every group practice says this is fundamental to them, but often it isn’t true. Your real job is to find out whether or not it is. The second fundamental question is whether or not the leadership and members of a group practice are competent. It doesn’t matter if they want and intend to do everything right; if the practice is not competent at getting it done, your life practicing dermatology there is not going to be good.

As a dermatologist who has practiced for 20 years in multiple settings, here are some of the questions I would ask when assessing a practice setting I might consider joining. The practice should be able to easily answer all of these questions. If they won’t, can’t, or don’t—or if they answer but don’t give you clear, concrete responses—it is a huge red flag. It could be that they know you won’t like the answers or it could be that they don’t know the answers, but either reason indicates a big problem.

- How do the contracted rates compare to other practices? Pick 5 to 10 Current Procedural Terminology codes you expect to bill the most and ask the practice to tell you the contracted rates for each of those codes with their top 5 payers. Get the same information from all the practices you are considering joining and compare them. The variation between 2 practices in the same market can be as high as 30%. That means that for doing the same work at Practice A you could collect $800,000 and at Practice B in the same market you could collect more than $1,000,000. Getting 45% of your collection from Practice A is a losing proposition compared to getting 40% at Practice B.

- What is the collection rate? If the practice has great contracted rates but terrible revenue cycle management operations, the rates don’t matter. For example, maybe their contracted rate for a given code is $150, compared to another practice whose contracted rate is $125. But if their collection rate is only 60% and the other practice has a collection rate of 80%, they are only getting $90 while the practice with the lower contracted rate is getting $100.

- What billing and coding support does the practice offer? Are you expected to know and keep up with all the procedure codes, modifiers, etc, and use them correctly yourself or do they have professional coders who review every visit? Do they appeal every denied claim? Will you get reports on what charges get denied and why so that you can adjust your practices to avoid further denials?

- How do they train and assign medical assistants (MAs)? The single biggest determinant of your day-to-day productivity and happiness will be your MAs. Having 3 experienced, efficient MAs will allow you to see 50 patients per day with less effort and more fun than seeing 30 patients per day with 2 inexperienced, inefficient MAs. Seeing 50 patients per day at 40% of collections leads to you earning a lot more than seeing 30 per day at 50% of collections. Beyond the basic question of how many MAs you will have, also ask: Will you be expected to train them yourself, or does the practice have a formal training program? Who assesses how well they are performing? Will you have the same MAs every day? When more senior providers have MAs call off sick or leave the practice, will your MAs be pulled to cover their clinics? If that happens, will you be compensated in some way? Get the answers in writing.

- What is the “feel” of the office you will be working in? Ideally you will go and spend a day seeing patients in the office with one of the existing providers to get a sense of whether it’s a place you will be excited to come to every morning. Do you like the other providers? Is there someone who could act as a mentor for you? Does the staff seem happy? Will the physical layout and square footage accommodate the way you imagine practicing? Are the sociodemographics of the patients a fit for what you want?

- Who will be the office manager responsible for your personal practice? Some practices have an on-site manager for every location; others have district or regional managers who are split between multiple practices. Some have both. All can work, but having a competent, supportive office manager with whom you get along with whom and who “gets it” is crucial. You should ask about office manager turnover (high rates are bad, of course) and should ask to meet and interview the office manager who will be the boots on the ground for the practice in your location.

- How much demand for services is there and how are new patients scheduled? If the new hire gets all the hair loss, acne, and eczema cases and the established providers get all the skin cancer/Medicare patients, you are not going to have a balanced patient mix, and you are not going to meet productivity goals because you won’t be doing enough procedures. If there is not enough demand to fill your schedule, what kind of marketing support does the practice offer and what other approaches might they take? If you want to do cosmetics, how are they going to help you grow in that area? Are there other providers who don’t do cosmetics and will refer to you? Is there already someone in the practice who all the referrals go to? Is your percentage of collections based on total collections or on collections after the cost of injectables is deducted?

- What educational support does the practice offer? Do they have an annual meeting for networking and continuing medical education (CME)? If so, will you be expected to use your CME budget to pay to attend? Are there restrictions on what you can use your CME budget for? Is your CME budget considered part of your percentage of collections? Are there experts in the practice you can go to if you have a challenging case or difficult situation?

- Are physician associates and nurse practitioners a big part of the practice? Will you have the opportunity to increase your compensation by supervising them? If so, what is expected of supervising physicians and how are they compensated (flat fee vs percentage of collections vs another model)?

- What does the noncompete say? Obviously the shorter the time period and the smaller the distance, the better. For most practices, a noncompete is nonnegotiable. But there are some nuances to consider: Is the restricted distance from any location that the practice has in the market, or from any location(s) in which you personally have practiced, or from the primary location(s) in which you have practiced? If it is from the primary location(s), get details on how this term is defined: How much do you have to be at a location before it is considered primary? If you stop going to a location, after what period of time is it no longer considered a primary location? Additional questions to ask about noncompetes include: Is there a nonsolicitation clause for employees or patients? Will the practice include a buy-out clause in which you can pay them a set amount to waive the noncompete? Will they make the noncompete time dependent? In other words, if it is a terrible fit and you want to leave in the first year, there is very little justification for them to enforce a noncompete—but unless it is in your contract that they won’t enforce it if you leave before a certain amount of time, they will enforce it.

- Is there a path to having equity in the practice? In academia, this obviously is not a possibility. In independent practices it generally is referred to as an ownership stake or becoming a partner, and in private-equity groups it is literally referred to as “equity,” but they mean essentially the same thing for our purposes. It benefits the practice if you have equity because it gives you a reason to work to help increase the value of the practice. It benefits you to have equity because it means you have more input into decisions that will affect you (and the influence is proportional to how much equity you have) and the equity is an asset that can become very valuable.

The primary advice I have when it comes to being promised an opportunity to become an owner/partner in an independent group is to get the timing and conditions under which you can become an owner in the contract and strongly advocate for a clause that states that if you are not offered the opportunity as defined in the contract that you will be compensated. Also consider what happens if the current owner(s) sell the practice before you become an owner.

In private-equity groups, ask how many of the current providers have equity and ask how the equity is currently divided (what percentage is held by the private equity group, what percentage is held by the CEO and other executives, and what percentage is held by providers). The more equity held by the executive leadership and providers the better, as that means more people are on the same team of trying to increase the value of the practice. Find out how and when you will be able to buy in and try to get this in the contract or at least in writing. Also ask for a guarantee that your equity will not decrease in value. There are instances in which the practice loses value over time due to mismanagement, and the legal structure typically prioritizes the equity of the private-equity owners over the equity of providers. This is called an equity waterfall. Equity that providers were told was worth millions can literally be worth nothing.

One Key Thing You Need to Know

More important than the formal interviews and meetings that will provide you with answers to the questions outlined here, you need to know if you can trust the answers and you need to know the overall culture of the organization. Are they truly pro-provider, and do they believe that engaged and supported providers are the best route to long-term profit maximization? Or do they see providers primarily as replaceable adversaries who need to be placated and managed in order to minimize overhead? The only way to find out is to talk to providers already working there.

If you ask the practice for contact information for providers you can talk to, they likely will put you in touch with those who they know are going to talk about the practice in the best possible light. Be aware that providers may speak positively about a practice for a few different reasons other than that they are actually happy. Maybe the provider has an ownership stake in the practice and will benefit financially if you join. Keep in mind that, if a friend or colleague introduced you to the practice, they are almost certainly getting a substantial referral bonus if you join, so they may not be unbiased; however, if they are an actual friend, the last thing they want is for you to join and be unhappy in the practice because they didn’t tell the truth.

To learn about the experiences of others in your situation who have joined the practice, go to the website and look through the list of providers. Ideally, look for people who are in their first 3 years out of residency who have been there long enough to know the ins and outs but who still are considered newbies and almost certainly don’t have a meaningful ownership stake or strong allegiance to the practice. If it is a geographically widespread practice, focus on people in the region you will be in, but also talk to at least one person from a distant site.

Next, go to the American Academy of Dermatology’s website to find the email addresses for the providers you want to contact in the member directory. Send them an email explaining that you are thinking about joining the practice and that you would like to have an off-the-record phone conversation with them about their experiences. If they decline or don’t respond, it could be a red flag that likely means they don’t think they can speak positively about the practice. If they do agree to speak with you, you can reiterate at that time that the conversation is off the record and that you won’t relay your discussion to anyone at the practice.

Here is a sample email you can use to reach out to providers from a practice you are considering joining:

Subject: Advice on Joining [Practice Name]

Dear Dr. [Name],

I’m a dermatology resident considering joining [Practice Name] and came across your profile. Would you be willing to have a brief (5 to 10 minutes), off-the-record call about your experience? I’d value your perspective and won’t share our conversation with the practice. Thank you!

Best, [Your Name]

Start the conversation with open-ended questions and see where it goes. Some things to ask might be, are you glad you joined the practice? Was there anything that surprised you after you joined? Is there anything you wish you would have asked or known before you joined? I would recommend not asking specifically about their compensation, as it likely will be different from what you are being offered due to variations in location and current market situations.

Final Thoughts

There is no perfect dermatology practice, but the approach outlined here—rooted in first principles and real-world experience—will help you find one that is right for you. Ask tough questions, talk to other providers, and trust your instincts.

- Cwalina TB, Mazmudar RS, Bordeaux JS, et al. Dermatologist workforce mobility: recent trends and characteristics. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:323-325. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5862

- Oscherwitz ME, Godinich BM, Patel RH, et al. Effects of private equity on dermatologic quality of patient care. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:E100-E102. doi:10.1111/jdv.20191

- Walsh S, Seaton E. Private equity in dermatology: a cloud on the horizon of quality care? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:9-10. doi:10.1111/jdv.20272

- Konda S, Patel S, Francis J. Private equity: the bad and the ugly. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:597-610. doi:10.1016/j.det.2023.04.004

- Novice T, Portney D, Eshaq M. Dermatology resident perspectives on practice ownership structures and private equity-backed group practices. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:296-302. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.008

Choosing your first job out of residency can be overwhelming. The things you need to consider go way beyond the job itself: things like geography, work/life balance, and practice focus (eg, skin cancer, cosmetics, medical dermatology, pediatrics) are all relatively independent factors from the specific practice you join. About 1 in 6 dermatologists change practices every year, with even higher rates for new graduates.1

Drawing from my 20 years of experience as a dermatologist (10 in academia and 10 in 3 different private group practice settings—one that was independently owned and 2 with private equity owners, of which I am one), I have seen firsthand what matters and what does not when it comes to joining a group practice, both in my own career and in watching the careers of many young dermatologists. I will do my best to summarize that experience into useful advice.

Important Factors to Consider When Choosing a Practice

As a second- or third-year resident, you likely are excited but nervous about leaping into practice. To approach it with confidence, allow me to outline certain factors that apply to all dermatology practices that you may consider joining as you start your career and beyond.

- Every Practice Owner Has to Prioritize Profit. Independent owners need to build the value of their main asset, academics need to fund research and teaching, and private equity owners need to drive returns for their investors. In other words, there are lots of negative situations in academic and independently owned groups, although private equity gets all the bad press.2-5 Nothing inherently makes one type of practice setting better; it depends on the specific organization. Owners do care about other things beyond just profit (eg, providing quality care, performing cutting-edge research), but when the rubber meets the road, if a practice is providing amazing quality care but losing money doing so, in a short time it won’t be providing any care at all.

- There Is No Free Money. Your long-term compensation will 100% be determined by how much revenue you generate minus the overhead. There is no magic fund to boost your pay long term, no matter how badly the practice needs or wants you. Be clear and even blunt: ask how the practice is going to profit from you. Ask how they plan to make back any signing bonus or guaranteed salary. If they are paying you a higher percentage of collections, ask them how they are able to pay more than competitors. If they say it is because they are more efficient with lower overhead, make sure that increased efficiency does not translate into less support.

- Percent of Collections Is Irrelevant. OK, perhaps not completely irrelevant, but it is one of the least important aspects in determining how much you will make or how happy you will be. Percent of collections is the percentage of the money that the practice actually collects that is paid out to you as compensation. For example, if your percentage of collections is 40%, that means that if the practice collects $1,000,000 for the care you deliver, you will be compensated $400,000. Read on to find out why it is not as important as it seems.

- Don’t Get Too Hung Up on the Details of the Contract. I have seen so many young dermatologists spend enormous amounts of time and money on attorneys and negotiating the fine points of the contract, but not a single one has ever said later that because of all that negotiation they were protected or treated well when things got contentious. What it comes down to is that, if the practice wants to treat you well, they will. If they want to treat you badly, no contract on earth can protect you from all the ways they can do so. And if you leave, no matter what the contract says, they can do whatever they want unless you are willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight them in court. So review the contract with an attorney and know what it says, but don’t sweat every period and clause. It isn’t worth it.

- Your Day-to-Day Is Everything. The practice you join may be the best-run practice in the world in every way, except that the office you happen to be going to work in is the one office in the practice that has 2 providers who are jerks and everyone dreads coming to work every morning. There are so many other examples of ways one location can be a disaster even in a great practice—and unfortunately, even great locations can change. The best you can do is to make sure you know where you will be working and with whom. Go and visit the actual office and spend a day shadowing to feel what the vibe is.

What Really Matters

If factors like the percentage of collections you keep are not the big things, what are? The good and bad news is that there isn’t a single answer to this question. Rather, the fundamental question is whether the practice’s plan to maximize profit includes having satisfied, motivated, and engaged long-term providers. Obviously every group practice says this is fundamental to them, but often it isn’t true. Your real job is to find out whether or not it is. The second fundamental question is whether or not the leadership and members of a group practice are competent. It doesn’t matter if they want and intend to do everything right; if the practice is not competent at getting it done, your life practicing dermatology there is not going to be good.

As a dermatologist who has practiced for 20 years in multiple settings, here are some of the questions I would ask when assessing a practice setting I might consider joining. The practice should be able to easily answer all of these questions. If they won’t, can’t, or don’t—or if they answer but don’t give you clear, concrete responses—it is a huge red flag. It could be that they know you won’t like the answers or it could be that they don’t know the answers, but either reason indicates a big problem.

- How do the contracted rates compare to other practices? Pick 5 to 10 Current Procedural Terminology codes you expect to bill the most and ask the practice to tell you the contracted rates for each of those codes with their top 5 payers. Get the same information from all the practices you are considering joining and compare them. The variation between 2 practices in the same market can be as high as 30%. That means that for doing the same work at Practice A you could collect $800,000 and at Practice B in the same market you could collect more than $1,000,000. Getting 45% of your collection from Practice A is a losing proposition compared to getting 40% at Practice B.

- What is the collection rate? If the practice has great contracted rates but terrible revenue cycle management operations, the rates don’t matter. For example, maybe their contracted rate for a given code is $150, compared to another practice whose contracted rate is $125. But if their collection rate is only 60% and the other practice has a collection rate of 80%, they are only getting $90 while the practice with the lower contracted rate is getting $100.

- What billing and coding support does the practice offer? Are you expected to know and keep up with all the procedure codes, modifiers, etc, and use them correctly yourself or do they have professional coders who review every visit? Do they appeal every denied claim? Will you get reports on what charges get denied and why so that you can adjust your practices to avoid further denials?

- How do they train and assign medical assistants (MAs)? The single biggest determinant of your day-to-day productivity and happiness will be your MAs. Having 3 experienced, efficient MAs will allow you to see 50 patients per day with less effort and more fun than seeing 30 patients per day with 2 inexperienced, inefficient MAs. Seeing 50 patients per day at 40% of collections leads to you earning a lot more than seeing 30 per day at 50% of collections. Beyond the basic question of how many MAs you will have, also ask: Will you be expected to train them yourself, or does the practice have a formal training program? Who assesses how well they are performing? Will you have the same MAs every day? When more senior providers have MAs call off sick or leave the practice, will your MAs be pulled to cover their clinics? If that happens, will you be compensated in some way? Get the answers in writing.

- What is the “feel” of the office you will be working in? Ideally you will go and spend a day seeing patients in the office with one of the existing providers to get a sense of whether it’s a place you will be excited to come to every morning. Do you like the other providers? Is there someone who could act as a mentor for you? Does the staff seem happy? Will the physical layout and square footage accommodate the way you imagine practicing? Are the sociodemographics of the patients a fit for what you want?

- Who will be the office manager responsible for your personal practice? Some practices have an on-site manager for every location; others have district or regional managers who are split between multiple practices. Some have both. All can work, but having a competent, supportive office manager with whom you get along with whom and who “gets it” is crucial. You should ask about office manager turnover (high rates are bad, of course) and should ask to meet and interview the office manager who will be the boots on the ground for the practice in your location.

- How much demand for services is there and how are new patients scheduled? If the new hire gets all the hair loss, acne, and eczema cases and the established providers get all the skin cancer/Medicare patients, you are not going to have a balanced patient mix, and you are not going to meet productivity goals because you won’t be doing enough procedures. If there is not enough demand to fill your schedule, what kind of marketing support does the practice offer and what other approaches might they take? If you want to do cosmetics, how are they going to help you grow in that area? Are there other providers who don’t do cosmetics and will refer to you? Is there already someone in the practice who all the referrals go to? Is your percentage of collections based on total collections or on collections after the cost of injectables is deducted?

- What educational support does the practice offer? Do they have an annual meeting for networking and continuing medical education (CME)? If so, will you be expected to use your CME budget to pay to attend? Are there restrictions on what you can use your CME budget for? Is your CME budget considered part of your percentage of collections? Are there experts in the practice you can go to if you have a challenging case or difficult situation?

- Are physician associates and nurse practitioners a big part of the practice? Will you have the opportunity to increase your compensation by supervising them? If so, what is expected of supervising physicians and how are they compensated (flat fee vs percentage of collections vs another model)?

- What does the noncompete say? Obviously the shorter the time period and the smaller the distance, the better. For most practices, a noncompete is nonnegotiable. But there are some nuances to consider: Is the restricted distance from any location that the practice has in the market, or from any location(s) in which you personally have practiced, or from the primary location(s) in which you have practiced? If it is from the primary location(s), get details on how this term is defined: How much do you have to be at a location before it is considered primary? If you stop going to a location, after what period of time is it no longer considered a primary location? Additional questions to ask about noncompetes include: Is there a nonsolicitation clause for employees or patients? Will the practice include a buy-out clause in which you can pay them a set amount to waive the noncompete? Will they make the noncompete time dependent? In other words, if it is a terrible fit and you want to leave in the first year, there is very little justification for them to enforce a noncompete—but unless it is in your contract that they won’t enforce it if you leave before a certain amount of time, they will enforce it.

- Is there a path to having equity in the practice? In academia, this obviously is not a possibility. In independent practices it generally is referred to as an ownership stake or becoming a partner, and in private-equity groups it is literally referred to as “equity,” but they mean essentially the same thing for our purposes. It benefits the practice if you have equity because it gives you a reason to work to help increase the value of the practice. It benefits you to have equity because it means you have more input into decisions that will affect you (and the influence is proportional to how much equity you have) and the equity is an asset that can become very valuable.

The primary advice I have when it comes to being promised an opportunity to become an owner/partner in an independent group is to get the timing and conditions under which you can become an owner in the contract and strongly advocate for a clause that states that if you are not offered the opportunity as defined in the contract that you will be compensated. Also consider what happens if the current owner(s) sell the practice before you become an owner.

In private-equity groups, ask how many of the current providers have equity and ask how the equity is currently divided (what percentage is held by the private equity group, what percentage is held by the CEO and other executives, and what percentage is held by providers). The more equity held by the executive leadership and providers the better, as that means more people are on the same team of trying to increase the value of the practice. Find out how and when you will be able to buy in and try to get this in the contract or at least in writing. Also ask for a guarantee that your equity will not decrease in value. There are instances in which the practice loses value over time due to mismanagement, and the legal structure typically prioritizes the equity of the private-equity owners over the equity of providers. This is called an equity waterfall. Equity that providers were told was worth millions can literally be worth nothing.

One Key Thing You Need to Know

More important than the formal interviews and meetings that will provide you with answers to the questions outlined here, you need to know if you can trust the answers and you need to know the overall culture of the organization. Are they truly pro-provider, and do they believe that engaged and supported providers are the best route to long-term profit maximization? Or do they see providers primarily as replaceable adversaries who need to be placated and managed in order to minimize overhead? The only way to find out is to talk to providers already working there.

If you ask the practice for contact information for providers you can talk to, they likely will put you in touch with those who they know are going to talk about the practice in the best possible light. Be aware that providers may speak positively about a practice for a few different reasons other than that they are actually happy. Maybe the provider has an ownership stake in the practice and will benefit financially if you join. Keep in mind that, if a friend or colleague introduced you to the practice, they are almost certainly getting a substantial referral bonus if you join, so they may not be unbiased; however, if they are an actual friend, the last thing they want is for you to join and be unhappy in the practice because they didn’t tell the truth.

To learn about the experiences of others in your situation who have joined the practice, go to the website and look through the list of providers. Ideally, look for people who are in their first 3 years out of residency who have been there long enough to know the ins and outs but who still are considered newbies and almost certainly don’t have a meaningful ownership stake or strong allegiance to the practice. If it is a geographically widespread practice, focus on people in the region you will be in, but also talk to at least one person from a distant site.

Next, go to the American Academy of Dermatology’s website to find the email addresses for the providers you want to contact in the member directory. Send them an email explaining that you are thinking about joining the practice and that you would like to have an off-the-record phone conversation with them about their experiences. If they decline or don’t respond, it could be a red flag that likely means they don’t think they can speak positively about the practice. If they do agree to speak with you, you can reiterate at that time that the conversation is off the record and that you won’t relay your discussion to anyone at the practice.

Here is a sample email you can use to reach out to providers from a practice you are considering joining:

Subject: Advice on Joining [Practice Name]

Dear Dr. [Name],

I’m a dermatology resident considering joining [Practice Name] and came across your profile. Would you be willing to have a brief (5 to 10 minutes), off-the-record call about your experience? I’d value your perspective and won’t share our conversation with the practice. Thank you!

Best, [Your Name]

Start the conversation with open-ended questions and see where it goes. Some things to ask might be, are you glad you joined the practice? Was there anything that surprised you after you joined? Is there anything you wish you would have asked or known before you joined? I would recommend not asking specifically about their compensation, as it likely will be different from what you are being offered due to variations in location and current market situations.

Final Thoughts

There is no perfect dermatology practice, but the approach outlined here—rooted in first principles and real-world experience—will help you find one that is right for you. Ask tough questions, talk to other providers, and trust your instincts.

Choosing your first job out of residency can be overwhelming. The things you need to consider go way beyond the job itself: things like geography, work/life balance, and practice focus (eg, skin cancer, cosmetics, medical dermatology, pediatrics) are all relatively independent factors from the specific practice you join. About 1 in 6 dermatologists change practices every year, with even higher rates for new graduates.1

Drawing from my 20 years of experience as a dermatologist (10 in academia and 10 in 3 different private group practice settings—one that was independently owned and 2 with private equity owners, of which I am one), I have seen firsthand what matters and what does not when it comes to joining a group practice, both in my own career and in watching the careers of many young dermatologists. I will do my best to summarize that experience into useful advice.

Important Factors to Consider When Choosing a Practice

As a second- or third-year resident, you likely are excited but nervous about leaping into practice. To approach it with confidence, allow me to outline certain factors that apply to all dermatology practices that you may consider joining as you start your career and beyond.

- Every Practice Owner Has to Prioritize Profit. Independent owners need to build the value of their main asset, academics need to fund research and teaching, and private equity owners need to drive returns for their investors. In other words, there are lots of negative situations in academic and independently owned groups, although private equity gets all the bad press.2-5 Nothing inherently makes one type of practice setting better; it depends on the specific organization. Owners do care about other things beyond just profit (eg, providing quality care, performing cutting-edge research), but when the rubber meets the road, if a practice is providing amazing quality care but losing money doing so, in a short time it won’t be providing any care at all.

- There Is No Free Money. Your long-term compensation will 100% be determined by how much revenue you generate minus the overhead. There is no magic fund to boost your pay long term, no matter how badly the practice needs or wants you. Be clear and even blunt: ask how the practice is going to profit from you. Ask how they plan to make back any signing bonus or guaranteed salary. If they are paying you a higher percentage of collections, ask them how they are able to pay more than competitors. If they say it is because they are more efficient with lower overhead, make sure that increased efficiency does not translate into less support.

- Percent of Collections Is Irrelevant. OK, perhaps not completely irrelevant, but it is one of the least important aspects in determining how much you will make or how happy you will be. Percent of collections is the percentage of the money that the practice actually collects that is paid out to you as compensation. For example, if your percentage of collections is 40%, that means that if the practice collects $1,000,000 for the care you deliver, you will be compensated $400,000. Read on to find out why it is not as important as it seems.

- Don’t Get Too Hung Up on the Details of the Contract. I have seen so many young dermatologists spend enormous amounts of time and money on attorneys and negotiating the fine points of the contract, but not a single one has ever said later that because of all that negotiation they were protected or treated well when things got contentious. What it comes down to is that, if the practice wants to treat you well, they will. If they want to treat you badly, no contract on earth can protect you from all the ways they can do so. And if you leave, no matter what the contract says, they can do whatever they want unless you are willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight them in court. So review the contract with an attorney and know what it says, but don’t sweat every period and clause. It isn’t worth it.

- Your Day-to-Day Is Everything. The practice you join may be the best-run practice in the world in every way, except that the office you happen to be going to work in is the one office in the practice that has 2 providers who are jerks and everyone dreads coming to work every morning. There are so many other examples of ways one location can be a disaster even in a great practice—and unfortunately, even great locations can change. The best you can do is to make sure you know where you will be working and with whom. Go and visit the actual office and spend a day shadowing to feel what the vibe is.

What Really Matters

If factors like the percentage of collections you keep are not the big things, what are? The good and bad news is that there isn’t a single answer to this question. Rather, the fundamental question is whether the practice’s plan to maximize profit includes having satisfied, motivated, and engaged long-term providers. Obviously every group practice says this is fundamental to them, but often it isn’t true. Your real job is to find out whether or not it is. The second fundamental question is whether or not the leadership and members of a group practice are competent. It doesn’t matter if they want and intend to do everything right; if the practice is not competent at getting it done, your life practicing dermatology there is not going to be good.

As a dermatologist who has practiced for 20 years in multiple settings, here are some of the questions I would ask when assessing a practice setting I might consider joining. The practice should be able to easily answer all of these questions. If they won’t, can’t, or don’t—or if they answer but don’t give you clear, concrete responses—it is a huge red flag. It could be that they know you won’t like the answers or it could be that they don’t know the answers, but either reason indicates a big problem.

- How do the contracted rates compare to other practices? Pick 5 to 10 Current Procedural Terminology codes you expect to bill the most and ask the practice to tell you the contracted rates for each of those codes with their top 5 payers. Get the same information from all the practices you are considering joining and compare them. The variation between 2 practices in the same market can be as high as 30%. That means that for doing the same work at Practice A you could collect $800,000 and at Practice B in the same market you could collect more than $1,000,000. Getting 45% of your collection from Practice A is a losing proposition compared to getting 40% at Practice B.

- What is the collection rate? If the practice has great contracted rates but terrible revenue cycle management operations, the rates don’t matter. For example, maybe their contracted rate for a given code is $150, compared to another practice whose contracted rate is $125. But if their collection rate is only 60% and the other practice has a collection rate of 80%, they are only getting $90 while the practice with the lower contracted rate is getting $100.

- What billing and coding support does the practice offer? Are you expected to know and keep up with all the procedure codes, modifiers, etc, and use them correctly yourself or do they have professional coders who review every visit? Do they appeal every denied claim? Will you get reports on what charges get denied and why so that you can adjust your practices to avoid further denials?

- How do they train and assign medical assistants (MAs)? The single biggest determinant of your day-to-day productivity and happiness will be your MAs. Having 3 experienced, efficient MAs will allow you to see 50 patients per day with less effort and more fun than seeing 30 patients per day with 2 inexperienced, inefficient MAs. Seeing 50 patients per day at 40% of collections leads to you earning a lot more than seeing 30 per day at 50% of collections. Beyond the basic question of how many MAs you will have, also ask: Will you be expected to train them yourself, or does the practice have a formal training program? Who assesses how well they are performing? Will you have the same MAs every day? When more senior providers have MAs call off sick or leave the practice, will your MAs be pulled to cover their clinics? If that happens, will you be compensated in some way? Get the answers in writing.

- What is the “feel” of the office you will be working in? Ideally you will go and spend a day seeing patients in the office with one of the existing providers to get a sense of whether it’s a place you will be excited to come to every morning. Do you like the other providers? Is there someone who could act as a mentor for you? Does the staff seem happy? Will the physical layout and square footage accommodate the way you imagine practicing? Are the sociodemographics of the patients a fit for what you want?

- Who will be the office manager responsible for your personal practice? Some practices have an on-site manager for every location; others have district or regional managers who are split between multiple practices. Some have both. All can work, but having a competent, supportive office manager with whom you get along with whom and who “gets it” is crucial. You should ask about office manager turnover (high rates are bad, of course) and should ask to meet and interview the office manager who will be the boots on the ground for the practice in your location.

- How much demand for services is there and how are new patients scheduled? If the new hire gets all the hair loss, acne, and eczema cases and the established providers get all the skin cancer/Medicare patients, you are not going to have a balanced patient mix, and you are not going to meet productivity goals because you won’t be doing enough procedures. If there is not enough demand to fill your schedule, what kind of marketing support does the practice offer and what other approaches might they take? If you want to do cosmetics, how are they going to help you grow in that area? Are there other providers who don’t do cosmetics and will refer to you? Is there already someone in the practice who all the referrals go to? Is your percentage of collections based on total collections or on collections after the cost of injectables is deducted?

- What educational support does the practice offer? Do they have an annual meeting for networking and continuing medical education (CME)? If so, will you be expected to use your CME budget to pay to attend? Are there restrictions on what you can use your CME budget for? Is your CME budget considered part of your percentage of collections? Are there experts in the practice you can go to if you have a challenging case or difficult situation?

- Are physician associates and nurse practitioners a big part of the practice? Will you have the opportunity to increase your compensation by supervising them? If so, what is expected of supervising physicians and how are they compensated (flat fee vs percentage of collections vs another model)?

- What does the noncompete say? Obviously the shorter the time period and the smaller the distance, the better. For most practices, a noncompete is nonnegotiable. But there are some nuances to consider: Is the restricted distance from any location that the practice has in the market, or from any location(s) in which you personally have practiced, or from the primary location(s) in which you have practiced? If it is from the primary location(s), get details on how this term is defined: How much do you have to be at a location before it is considered primary? If you stop going to a location, after what period of time is it no longer considered a primary location? Additional questions to ask about noncompetes include: Is there a nonsolicitation clause for employees or patients? Will the practice include a buy-out clause in which you can pay them a set amount to waive the noncompete? Will they make the noncompete time dependent? In other words, if it is a terrible fit and you want to leave in the first year, there is very little justification for them to enforce a noncompete—but unless it is in your contract that they won’t enforce it if you leave before a certain amount of time, they will enforce it.

- Is there a path to having equity in the practice? In academia, this obviously is not a possibility. In independent practices it generally is referred to as an ownership stake or becoming a partner, and in private-equity groups it is literally referred to as “equity,” but they mean essentially the same thing for our purposes. It benefits the practice if you have equity because it gives you a reason to work to help increase the value of the practice. It benefits you to have equity because it means you have more input into decisions that will affect you (and the influence is proportional to how much equity you have) and the equity is an asset that can become very valuable.

The primary advice I have when it comes to being promised an opportunity to become an owner/partner in an independent group is to get the timing and conditions under which you can become an owner in the contract and strongly advocate for a clause that states that if you are not offered the opportunity as defined in the contract that you will be compensated. Also consider what happens if the current owner(s) sell the practice before you become an owner.

In private-equity groups, ask how many of the current providers have equity and ask how the equity is currently divided (what percentage is held by the private equity group, what percentage is held by the CEO and other executives, and what percentage is held by providers). The more equity held by the executive leadership and providers the better, as that means more people are on the same team of trying to increase the value of the practice. Find out how and when you will be able to buy in and try to get this in the contract or at least in writing. Also ask for a guarantee that your equity will not decrease in value. There are instances in which the practice loses value over time due to mismanagement, and the legal structure typically prioritizes the equity of the private-equity owners over the equity of providers. This is called an equity waterfall. Equity that providers were told was worth millions can literally be worth nothing.

One Key Thing You Need to Know

More important than the formal interviews and meetings that will provide you with answers to the questions outlined here, you need to know if you can trust the answers and you need to know the overall culture of the organization. Are they truly pro-provider, and do they believe that engaged and supported providers are the best route to long-term profit maximization? Or do they see providers primarily as replaceable adversaries who need to be placated and managed in order to minimize overhead? The only way to find out is to talk to providers already working there.

If you ask the practice for contact information for providers you can talk to, they likely will put you in touch with those who they know are going to talk about the practice in the best possible light. Be aware that providers may speak positively about a practice for a few different reasons other than that they are actually happy. Maybe the provider has an ownership stake in the practice and will benefit financially if you join. Keep in mind that, if a friend or colleague introduced you to the practice, they are almost certainly getting a substantial referral bonus if you join, so they may not be unbiased; however, if they are an actual friend, the last thing they want is for you to join and be unhappy in the practice because they didn’t tell the truth.

To learn about the experiences of others in your situation who have joined the practice, go to the website and look through the list of providers. Ideally, look for people who are in their first 3 years out of residency who have been there long enough to know the ins and outs but who still are considered newbies and almost certainly don’t have a meaningful ownership stake or strong allegiance to the practice. If it is a geographically widespread practice, focus on people in the region you will be in, but also talk to at least one person from a distant site.

Next, go to the American Academy of Dermatology’s website to find the email addresses for the providers you want to contact in the member directory. Send them an email explaining that you are thinking about joining the practice and that you would like to have an off-the-record phone conversation with them about their experiences. If they decline or don’t respond, it could be a red flag that likely means they don’t think they can speak positively about the practice. If they do agree to speak with you, you can reiterate at that time that the conversation is off the record and that you won’t relay your discussion to anyone at the practice.

Here is a sample email you can use to reach out to providers from a practice you are considering joining:

Subject: Advice on Joining [Practice Name]

Dear Dr. [Name],

I’m a dermatology resident considering joining [Practice Name] and came across your profile. Would you be willing to have a brief (5 to 10 minutes), off-the-record call about your experience? I’d value your perspective and won’t share our conversation with the practice. Thank you!

Best, [Your Name]

Start the conversation with open-ended questions and see where it goes. Some things to ask might be, are you glad you joined the practice? Was there anything that surprised you after you joined? Is there anything you wish you would have asked or known before you joined? I would recommend not asking specifically about their compensation, as it likely will be different from what you are being offered due to variations in location and current market situations.

Final Thoughts

There is no perfect dermatology practice, but the approach outlined here—rooted in first principles and real-world experience—will help you find one that is right for you. Ask tough questions, talk to other providers, and trust your instincts.

- Cwalina TB, Mazmudar RS, Bordeaux JS, et al. Dermatologist workforce mobility: recent trends and characteristics. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:323-325. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5862

- Oscherwitz ME, Godinich BM, Patel RH, et al. Effects of private equity on dermatologic quality of patient care. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:E100-E102. doi:10.1111/jdv.20191

- Walsh S, Seaton E. Private equity in dermatology: a cloud on the horizon of quality care? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:9-10. doi:10.1111/jdv.20272

- Konda S, Patel S, Francis J. Private equity: the bad and the ugly. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:597-610. doi:10.1016/j.det.2023.04.004

- Novice T, Portney D, Eshaq M. Dermatology resident perspectives on practice ownership structures and private equity-backed group practices. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:296-302. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.008

- Cwalina TB, Mazmudar RS, Bordeaux JS, et al. Dermatologist workforce mobility: recent trends and characteristics. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:323-325. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5862

- Oscherwitz ME, Godinich BM, Patel RH, et al. Effects of private equity on dermatologic quality of patient care. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:E100-E102. doi:10.1111/jdv.20191

- Walsh S, Seaton E. Private equity in dermatology: a cloud on the horizon of quality care? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2025;39:9-10. doi:10.1111/jdv.20272

- Konda S, Patel S, Francis J. Private equity: the bad and the ugly. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:597-610. doi:10.1016/j.det.2023.04.004

- Novice T, Portney D, Eshaq M. Dermatology resident perspectives on practice ownership structures and private equity-backed group practices. Clin Dermatol. 2020;38:296-302. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.008

What Dermatology Residents Need to Know About Joining Group Practices

What Dermatology Residents Need to Know About Joining Group Practices

PRACTICE POINTS

- Finding the right fit in the first position out of dermatology residency can be difficult and feel overwhelming.

- Leaving one practice and joining another is especially common in the first 10 years after residency.

- Asking the right questions can increase the probability of finding the right practice for you and receiving fair compensation.

Dermatology Boards Demystified: Conquer the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams

Dermatology Boards Demystified: Conquer the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams

Dermatology trainees are no strangers to standardized examinations that assess basic science and medical knowledge, from the Medical College Admission Test and the National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examinations to the United States Medical Licensing Examination series (I know, cue the collective flashbacks!). As a dermatology resident, you will complete a series of 6 examinations culminating with the final APPLIED Exam, which assesses a trainee's ability to apply therapeutic knowledge and clinical reasoning in scenarios relevant to the practice of general dermatology.1 This article features high-yield tips and study resources alongside test-day strategies to help you perform at your best.

The Path to Board Certification for Dermatology Trainees

After years of dedicated study in medical school, navigating the demanding match process, and completing your intern year, you have finally made it to dermatology! With the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 3 out of the way, you are now officially able to trade in electrocardiograms for Kodachromes and dermoscopy. As a dermatology trainee, you will complete the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) Certification Pathway—a staged evaluation beginning with a BASIC Exam for first-year residents, which covers dermatology fundamentals and is proctored at your home institution.1 This exam is solely for informational purposes, and ultimately no minimum score is required for certification purposes. Subsequently, second- and third-year residents sit for 4 CORE Exam modules assessing advanced knowledge of the major clinical areas of the specialty: medical dermatology, surgical dermatology, pediatric dermatology, and dermatopathology. These exams consist of 75 to 100 multiple-choice questions per each 2-hour module and are administered either online in a private setting, via a secure online proctoring system, or at an approved testing center. The APPLIED Exam is the final component of the pathway and prioritizes clinical acumen and judgement. This 8-hour, 200-question exam is offered exclusively in person at approved testing centers to residents who have passed all 4 compulsory CORE modules and completed residency training. There is a 20-minute break between sections 1 and 2, a 60-minute break between sections 2 and 3, and a 20-minute break between sections 3 and 4.1 Following successful completion of the ABD Certification Pathway, dermatologists maintain board certification through quarterly CertLink questions, which you must complete at least 3 quarters of each year, and regular completion of focused practice improvement modules every 5 years. Additionally, one must maintain a full and unrestricted medical license in the United States or Canada and pay an annual fee of $150.

High-Yield Study Resources and Exam Preparation Strategies

Growing up, I was taught that proper preparation prevents poor performance. This principle holds particularly true when approaching the ABD Certification Pathway. Before diving into high-yield study resources and comprehensive exam preparation strategies, here are some big-picture essentials you need to know:

- Your residency program covers the fee for the BASIC Exam, but the CORE and APPLIED Exams are out-of-pocket expenses. As of 2026, you should plan to budget $2450 ($200 for 4 CORE module attempts and $2250 for the APPLIED Exam) for all 5 exams.2

- Testing center space is limited for each test date. While the ABD offers CORE Exams 3 times annually in 2-week windows (Winter [February], Summer [July], and Fall [October/November]), the APPLIED Exam is only given once per year. For the best chance of getting your preferred date, be sure to register as early as possible (especially if you live and train in a city with limited testing sites).

- After you have successfully passed your first CORE Exam module, you may take up to 3 in one sitting. When taking multiple modules consecutively on the same day, a 15-minute break is configured between each module.

Study Resources

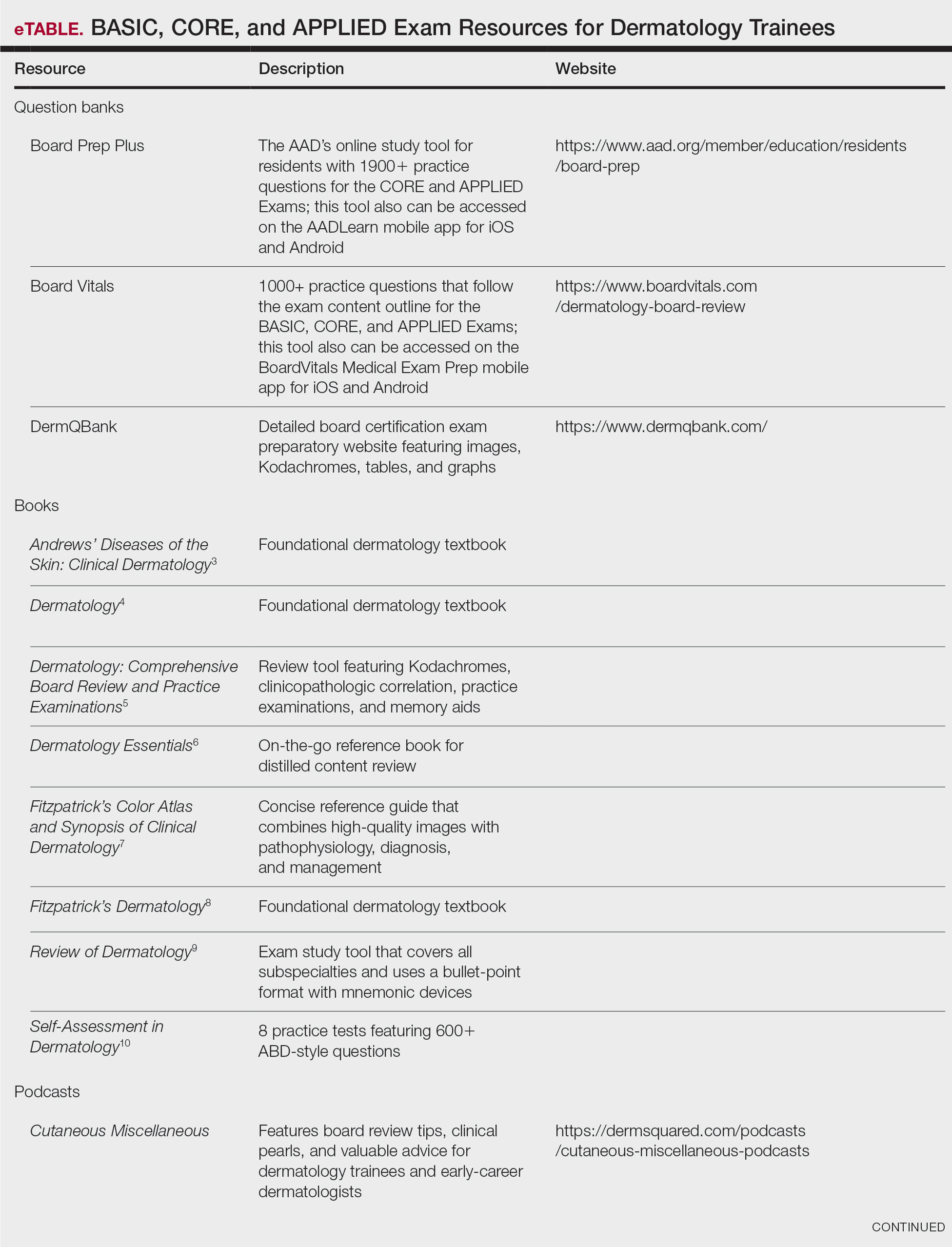

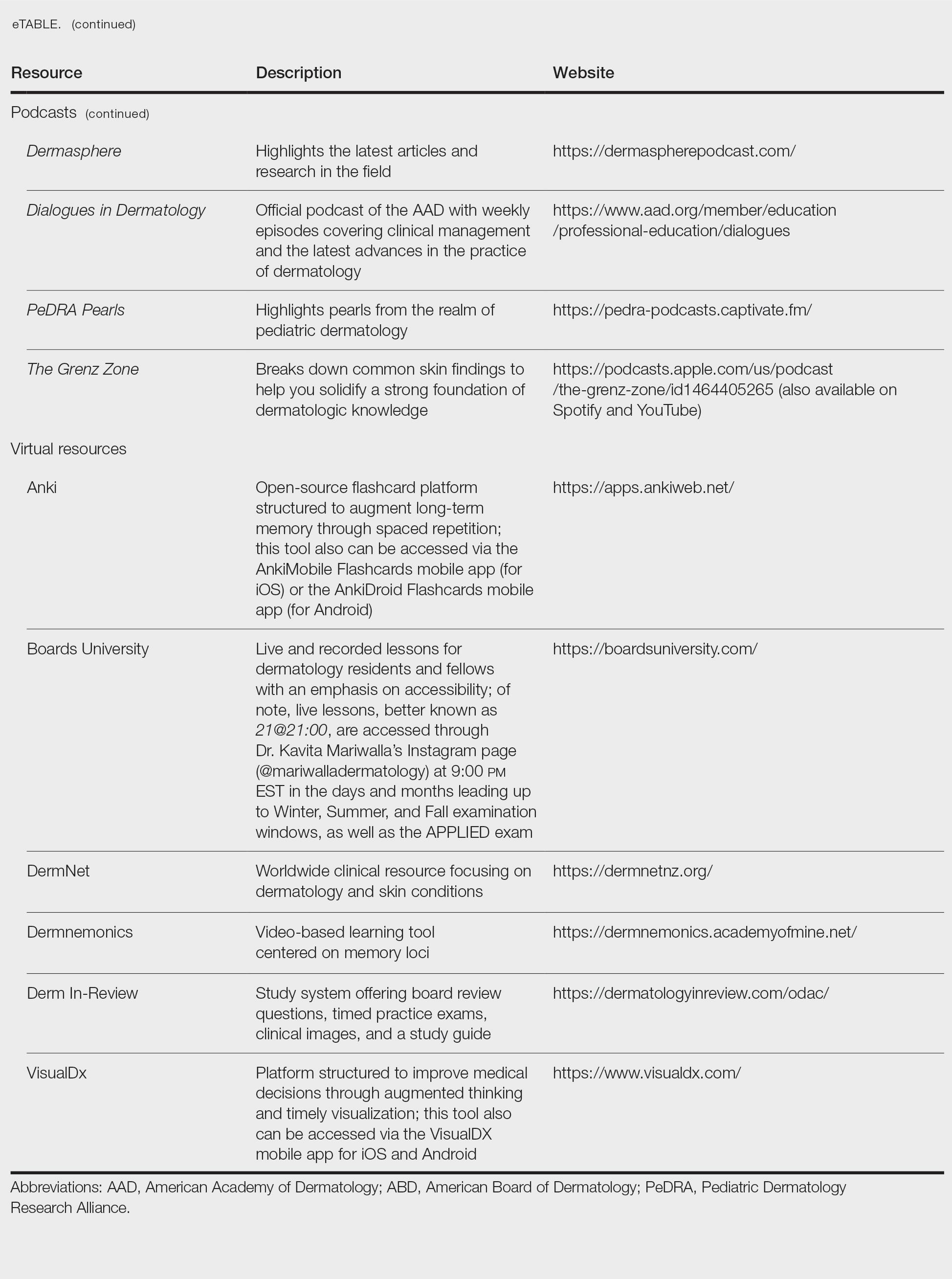

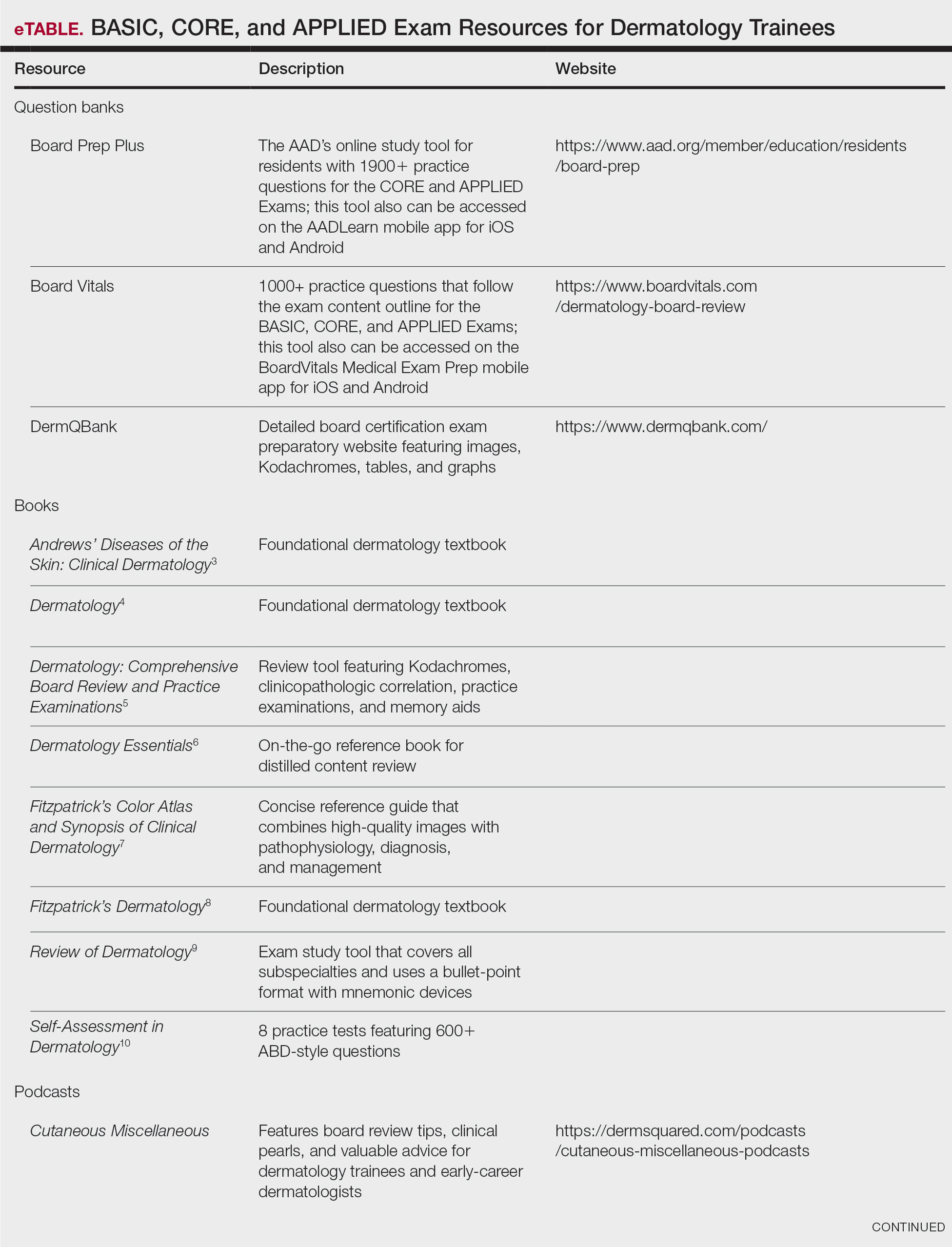

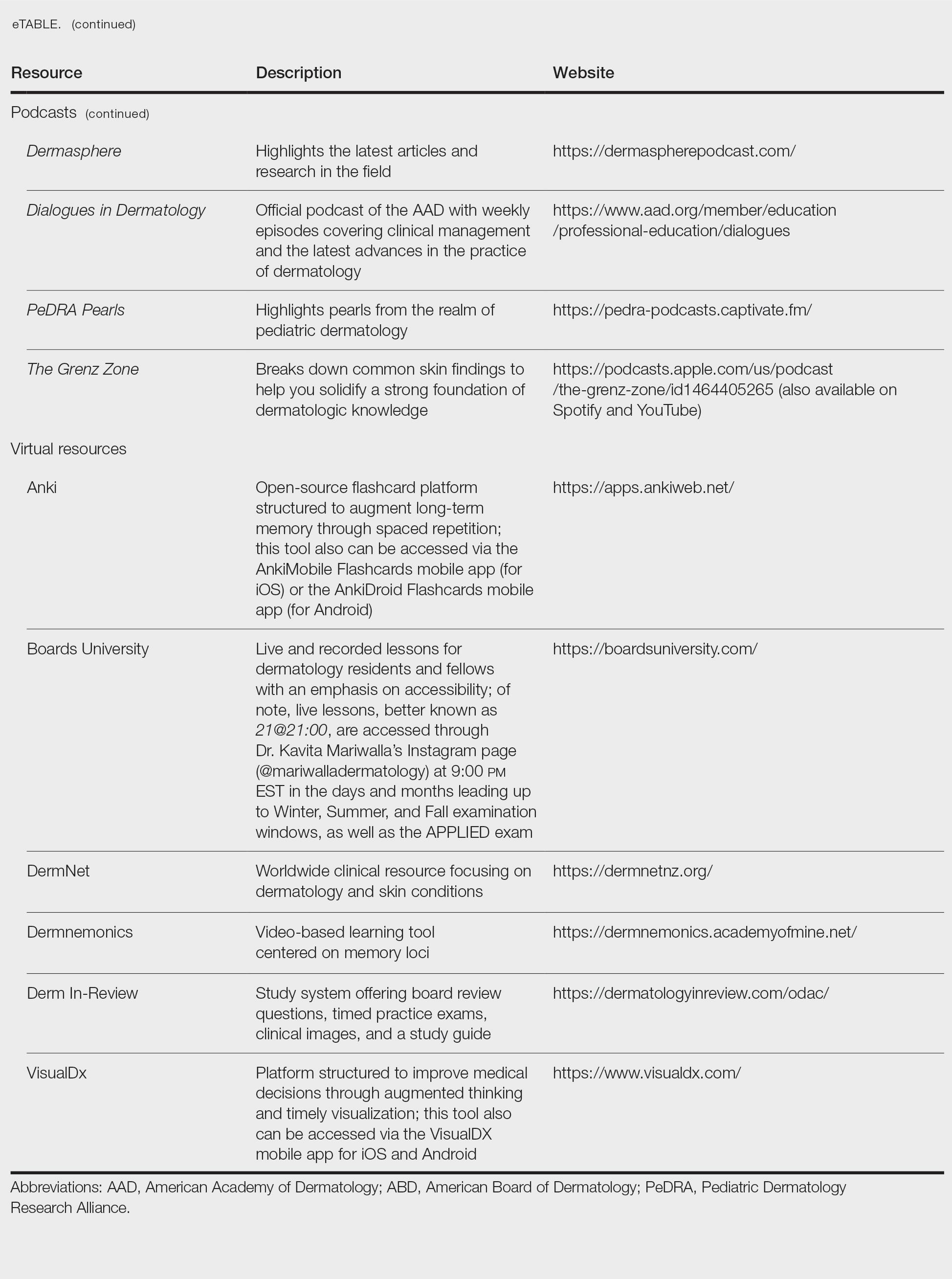

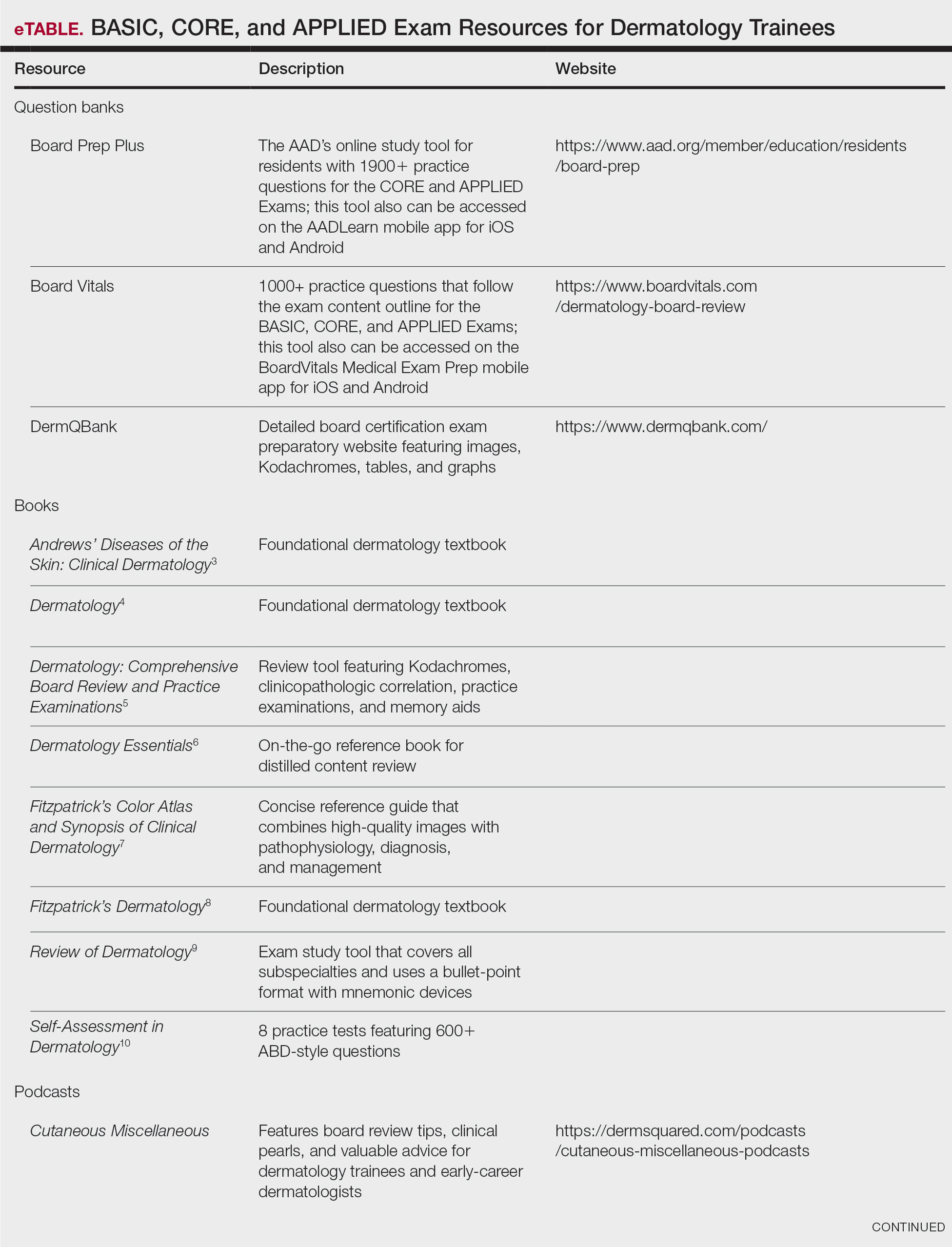

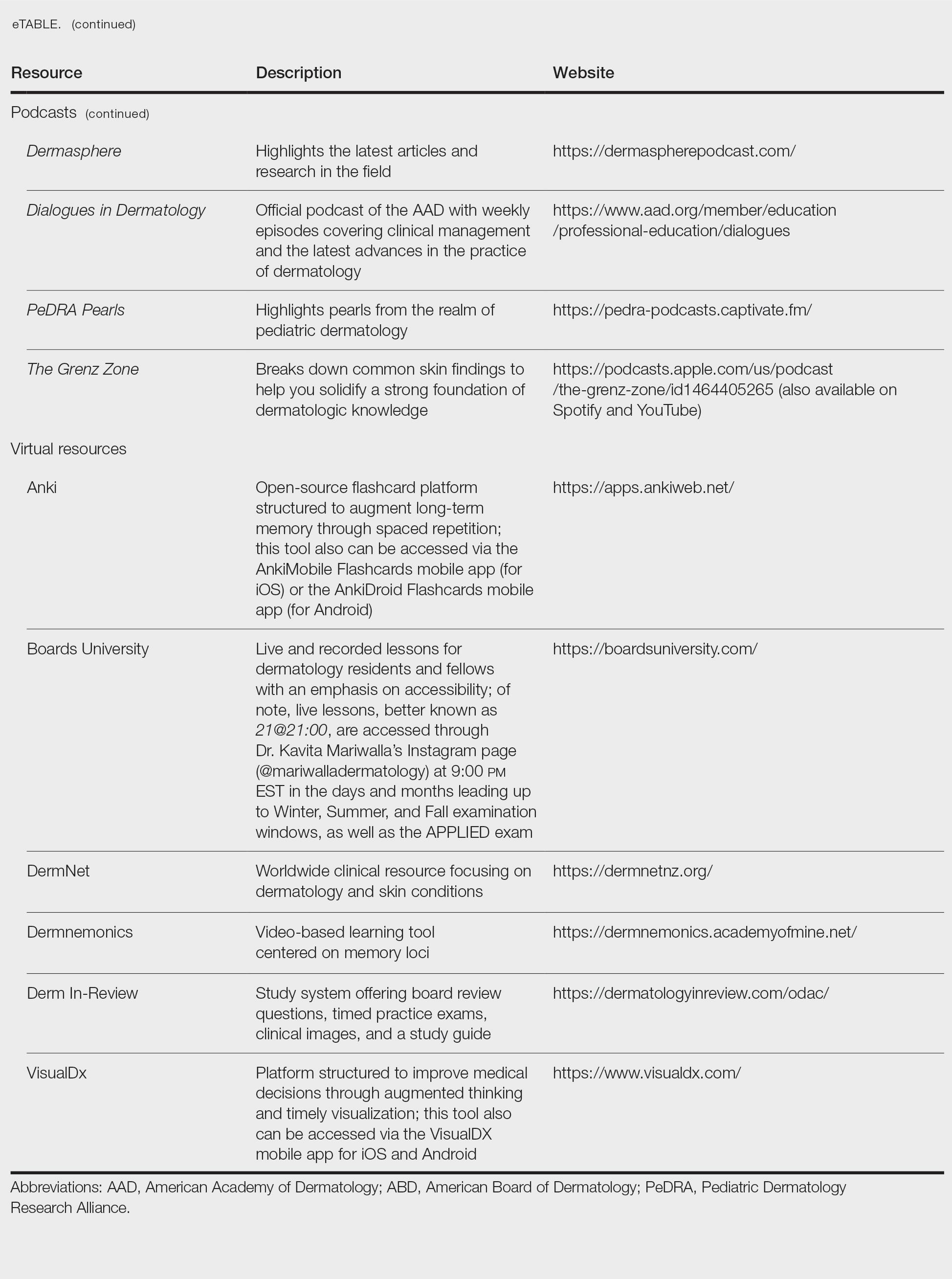

When it comes to studying, there are more resources available than you will have time to explore; therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the ones that best match your learning style. Whether you retain information through visuals, audio, reading comprehension, practice questions, or spaced repetition, there are complimentary and paid high-yield tools designed to support how you learn and make the most of your valuable time outside clinical responsibilities (eTable). Furthermore, there are numerous discipline-specific textbooks and resources encompassing dermatopathology, dermoscopy, trichology, pediatric dermatology, surgical dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, and skin of color.11-13 As a trainee, you also have access to the American Academy of Dermatology’s Learning Center (https://learning.aad.org/Catalogue/AAD-Learning-Center) featuring the Question of the Week series, Board Prep Plus question bank, Dialogues in Dermatology podcast, and continuing medical education articles. Additionally, board review sessions occur at many local, regional, and national dermatology conferences annually.

Exam Preparation Strategy

A comprehensive preparation strategy should begin during your first year of residency and appropriately intensify in the months leading up to the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams. Ultimately, active learning is ongoing, and your daily clinical work combined with program-sanctioned didactics, journal reading, and conference attendance comprise your framework. I often found it helpful to spend 30 to 60 minutes after clinic each evening reviewing high-yield or interesting cases from the day, as our patients are our greatest teachers. To reinforce key concepts, I used a combination of premade Anki decks14 and custom flashcards for topics that required rote memorization and spaced repetition. Podcasts such as Cutaneous Miscellaneous, The Grenz Zone, and Dermasphere became valuable learning tools that I incorporated into my commutes and long runs. I also enjoyed listening to the Derm In-Review audio study guide.19 Early in residency, I also created a digital notebook on OneNote (https://onenote.cloud.microsoft/en-us/)—organized by postgraduate year and subject—to consolidate notes and procedural pearls. As a fellow, I still use this note-taking system to organize notes from laser and energy-based device trainings and catalogue high-yield conference takeaways. Finally, task management applications can further help you achieve your study goals by organizing assignments, setting deadlines, and breaking larger objectives into manageable steps, making it easier to stay focused and on track.

Test-Day Strategies

After sitting for many standardized examinations on the journey to dermatology residency, I am certain that you have cultivated your own reliable test-day rituals and strategies; however, if you are looking for others to add to your toolbox, here are a few that helped me stay calm, focused, and in the zone throughout my time in residency.

The Day Before the Test

- Secure your test-day snacks and preferred form of hydration. I am a fan of cheese sticks for protein and fruit for vitamins and antioxidants. Additionally, I always bring something salty and something sweet (usually chocolate or sour gummy snacks) just in case I happen to get a specific craving on test day.

- Make sure you have valid forms of identification in accordance with the test center policy.16

- Confirm your exam location and time. Testing center details can be found on the Pearson Vue portal,16 which is easily accessed via the “ABD Tools” tab on the official ABD website (https://www.abderm.org/). Additionally, the exam location, time, and directions to the test center are located in your Pearson Vue confirmation email.

- Trust that you are prepared. Try your best to avoid last-minute cramming and prioritize a good night’s sleep.

The Day of the Test

- Center yourself before the exam. I prefer to start my morning with a run to clear my mind; however, you also can consider other mindfulness exercises such as deep breathing or positive grounding affirmations.

- Arrive early and dress in layers. You never know if the testing location will run warm or cold.

- Pace yourself, trust your gut instincts, and do not be afraid to mark and move on if you get stuck on a particular question. Ultimately, make sure you answer every question, as you will not have points deducted for guessing.

- Make sure to plan something you are excited about for after the exam! That may mean celebrating with co-residents, spending time with loved ones, or just relaxing on the couch and finally catching up on that show you have been meaning to watch for weeks but have not had time for because you have been focused on studying (yes, we all have that one show).

Final Thoughts

While this article is not comprehensive of all ABD Certification Pathway preparation materials and resources, I hope that you will find it helpful along your residency journey. Starting dermatology residency can feel like drinking from a firehose: there is an overwhelming volume of new information, unfamiliar terminology, and a demanding workflow that varies considerably from that of intern year.17 As a resident, it is vital to prioritize your mental health and well-being, as the journey is a marathon rather than a sprint.18

Never forget that you have already come this far; trust in your journey and remember what is meant for you will not miss you. Juggling 6 exams during residency alongside clinical and personal responsibilities is no small feat. With a strong study plan and smart test-day strategies, I have no doubt you will become a board-certified dermatologist!

- ABD certification pathway info center. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/abd-certification-pathway/abd-certification-pathway-info-center

- American Board of Dermatology. General exam information. Accessed January 13, 2026. https://www.abderm.org/exams/general-exam-information

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR, et al, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Nelson KC, Cerroni L, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology: Comprehensive Board Review and Practice Examinations. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2023.

- Saavedra AP, Kang S, Amagai M, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023.

- Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Alikhan A, Hocker TL, eds. Review of Dermatology. Elsevier; 2017.

- Leventhal JS, Levy LL. Self-Assessment in Dermatology: Questions and Answers. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2024.

- Association of Academic Cosmetic Dermatology. Resources for dermatology residents. Accessed October 15, 2025. https://theaacd.org/resident-resources/

- Mukosera GT, Ibraheim MK, Lee MP, et al. From scope to screen: a collection of online dermatopathology resources for residents and fellows. JAAD Int. 2023;12:12-14. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2022.12.007

- Shabeeb N. Dermatology resident education for skin of color. Cutis. 2020;106:E18-E20. doi:10.12788/cutis.0099

- Azhar AF. Review of 3 comprehensive Anki flash card decks for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2023;112:E10-E12. doi:10.12788/cutis.0813

- ODAC Dermatology. Derm In-Review. Accessed October 22, 2025. https://dermatologyinreview.com/odac/

- American Board of Dermatology (ABD) certification testing with Pearson VUE. Accessed October 19, 2025. https://www.pearsonvue.com/us/en/abd.html

- Lim YH. Transitioning from an intern to a dermatology resident. Cutis. 2022;110:E14-E16. doi:10.12788/cutis.0638

- Lim YH. Prioritizing mental health in residency. Cutis. 2022;109:E36-E38. doi:10.12788/cutis.0551

Dermatology trainees are no strangers to standardized examinations that assess basic science and medical knowledge, from the Medical College Admission Test and the National Board of Medical Examiners Subject Examinations to the United States Medical Licensing Examination series (I know, cue the collective flashbacks!). As a dermatology resident, you will complete a series of 6 examinations culminating with the final APPLIED Exam, which assesses a trainee's ability to apply therapeutic knowledge and clinical reasoning in scenarios relevant to the practice of general dermatology.1 This article features high-yield tips and study resources alongside test-day strategies to help you perform at your best.

The Path to Board Certification for Dermatology Trainees

After years of dedicated study in medical school, navigating the demanding match process, and completing your intern year, you have finally made it to dermatology! With the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 3 out of the way, you are now officially able to trade in electrocardiograms for Kodachromes and dermoscopy. As a dermatology trainee, you will complete the American Board of Dermatology (ABD) Certification Pathway—a staged evaluation beginning with a BASIC Exam for first-year residents, which covers dermatology fundamentals and is proctored at your home institution.1 This exam is solely for informational purposes, and ultimately no minimum score is required for certification purposes. Subsequently, second- and third-year residents sit for 4 CORE Exam modules assessing advanced knowledge of the major clinical areas of the specialty: medical dermatology, surgical dermatology, pediatric dermatology, and dermatopathology. These exams consist of 75 to 100 multiple-choice questions per each 2-hour module and are administered either online in a private setting, via a secure online proctoring system, or at an approved testing center. The APPLIED Exam is the final component of the pathway and prioritizes clinical acumen and judgement. This 8-hour, 200-question exam is offered exclusively in person at approved testing centers to residents who have passed all 4 compulsory CORE modules and completed residency training. There is a 20-minute break between sections 1 and 2, a 60-minute break between sections 2 and 3, and a 20-minute break between sections 3 and 4.1 Following successful completion of the ABD Certification Pathway, dermatologists maintain board certification through quarterly CertLink questions, which you must complete at least 3 quarters of each year, and regular completion of focused practice improvement modules every 5 years. Additionally, one must maintain a full and unrestricted medical license in the United States or Canada and pay an annual fee of $150.

High-Yield Study Resources and Exam Preparation Strategies

Growing up, I was taught that proper preparation prevents poor performance. This principle holds particularly true when approaching the ABD Certification Pathway. Before diving into high-yield study resources and comprehensive exam preparation strategies, here are some big-picture essentials you need to know:

- Your residency program covers the fee for the BASIC Exam, but the CORE and APPLIED Exams are out-of-pocket expenses. As of 2026, you should plan to budget $2450 ($200 for 4 CORE module attempts and $2250 for the APPLIED Exam) for all 5 exams.2

- Testing center space is limited for each test date. While the ABD offers CORE Exams 3 times annually in 2-week windows (Winter [February], Summer [July], and Fall [October/November]), the APPLIED Exam is only given once per year. For the best chance of getting your preferred date, be sure to register as early as possible (especially if you live and train in a city with limited testing sites).

- After you have successfully passed your first CORE Exam module, you may take up to 3 in one sitting. When taking multiple modules consecutively on the same day, a 15-minute break is configured between each module.

Study Resources

When it comes to studying, there are more resources available than you will have time to explore; therefore, it is crucial to prioritize the ones that best match your learning style. Whether you retain information through visuals, audio, reading comprehension, practice questions, or spaced repetition, there are complimentary and paid high-yield tools designed to support how you learn and make the most of your valuable time outside clinical responsibilities (eTable). Furthermore, there are numerous discipline-specific textbooks and resources encompassing dermatopathology, dermoscopy, trichology, pediatric dermatology, surgical dermatology, cosmetic dermatology, and skin of color.11-13 As a trainee, you also have access to the American Academy of Dermatology’s Learning Center (https://learning.aad.org/Catalogue/AAD-Learning-Center) featuring the Question of the Week series, Board Prep Plus question bank, Dialogues in Dermatology podcast, and continuing medical education articles. Additionally, board review sessions occur at many local, regional, and national dermatology conferences annually.

Exam Preparation Strategy

A comprehensive preparation strategy should begin during your first year of residency and appropriately intensify in the months leading up to the BASIC, CORE, and APPLIED Exams. Ultimately, active learning is ongoing, and your daily clinical work combined with program-sanctioned didactics, journal reading, and conference attendance comprise your framework. I often found it helpful to spend 30 to 60 minutes after clinic each evening reviewing high-yield or interesting cases from the day, as our patients are our greatest teachers. To reinforce key concepts, I used a combination of premade Anki decks14 and custom flashcards for topics that required rote memorization and spaced repetition. Podcasts such as Cutaneous Miscellaneous, The Grenz Zone, and Dermasphere became valuable learning tools that I incorporated into my commutes and long runs. I also enjoyed listening to the Derm In-Review audio study guide.19 Early in residency, I also created a digital notebook on OneNote (https://onenote.cloud.microsoft/en-us/)—organized by postgraduate year and subject—to consolidate notes and procedural pearls. As a fellow, I still use this note-taking system to organize notes from laser and energy-based device trainings and catalogue high-yield conference takeaways. Finally, task management applications can further help you achieve your study goals by organizing assignments, setting deadlines, and breaking larger objectives into manageable steps, making it easier to stay focused and on track.

Test-Day Strategies

After sitting for many standardized examinations on the journey to dermatology residency, I am certain that you have cultivated your own reliable test-day rituals and strategies; however, if you are looking for others to add to your toolbox, here are a few that helped me stay calm, focused, and in the zone throughout my time in residency.

The Day Before the Test

- Secure your test-day snacks and preferred form of hydration. I am a fan of cheese sticks for protein and fruit for vitamins and antioxidants. Additionally, I always bring something salty and something sweet (usually chocolate or sour gummy snacks) just in case I happen to get a specific craving on test day.

- Make sure you have valid forms of identification in accordance with the test center policy.16

- Confirm your exam location and time. Testing center details can be found on the Pearson Vue portal,16 which is easily accessed via the “ABD Tools” tab on the official ABD website (https://www.abderm.org/). Additionally, the exam location, time, and directions to the test center are located in your Pearson Vue confirmation email.

- Trust that you are prepared. Try your best to avoid last-minute cramming and prioritize a good night’s sleep.

The Day of the Test

- Center yourself before the exam. I prefer to start my morning with a run to clear my mind; however, you also can consider other mindfulness exercises such as deep breathing or positive grounding affirmations.

- Arrive early and dress in layers. You never know if the testing location will run warm or cold.

- Pace yourself, trust your gut instincts, and do not be afraid to mark and move on if you get stuck on a particular question. Ultimately, make sure you answer every question, as you will not have points deducted for guessing.

- Make sure to plan something you are excited about for after the exam! That may mean celebrating with co-residents, spending time with loved ones, or just relaxing on the couch and finally catching up on that show you have been meaning to watch for weeks but have not had time for because you have been focused on studying (yes, we all have that one show).

Final Thoughts

While this article is not comprehensive of all ABD Certification Pathway preparation materials and resources, I hope that you will find it helpful along your residency journey. Starting dermatology residency can feel like drinking from a firehose: there is an overwhelming volume of new information, unfamiliar terminology, and a demanding workflow that varies considerably from that of intern year.17 As a resident, it is vital to prioritize your mental health and well-being, as the journey is a marathon rather than a sprint.18