User login

Diabetes Drugs Promising for Alcohol Use Disorder

TOPLINE:

Use of the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists semaglutide and liraglutide is linked to a lower risk for alcohol use disorder (AUD)–related hospitalizations, compared with traditional AUD medications, a new study suggested.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a nationwide cohort study from 2006 to 2023 in Sweden that included more than 220,000 individuals with AUD (mean age, 40 years; 64% men).

- Data were obtained from registers of inpatient and specialized outpatient care, sickness absence, and disability pension, with a median follow-up period of 8.8 years.

- The primary exposure measured was the use of individual GLP-1 receptor agonists — commonly used to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity — compared with nonuse.

- The secondary exposure examined was the use of medications indicated for AUD.

- The primary outcome was AUD-related hospitalization; secondary outcomes included hospitalization due to substance use disorder (SUD), somatic hospitalization, and suicide attempts.

TAKEAWAY:

- About 59% of participants experienced AUD-related hospitalization.

- Semaglutide users (n = 4321) had the lowest risk for hospitalization related to AUD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.64; 95% CI, 0.50-0.83) and to any SUD (aHR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.54-0.85).

- Liraglutide users (n = 2509) had the second lowest risk for both AUD-related (aHR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.57-0.92) and SUD-related (aHR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.64-0.97) hospitalizations.

- The use of both semaglutide (aHR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.68-0.90) and liraglutide (aHR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.69-0.91) was linked to a reduced risk for hospitalization because of somatic reasons but was not associated with the risk of suicide attempts.

- Traditional AUD medications showed modest effectiveness with a slightly decreased but nonsignificant risk for AUD-related hospitalization (aHR, 0.98).

IN PRACTICE:

“AUDs and SUDs are undertreated pharmacologically, despite the availability of effective treatments. However, novel treatments are also needed because existing treatments may not be suitable for all patients. Semaglutide and liraglutide may be effective in the treatment of AUD, and clinical trials are urgently needed to confirm these findings,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Markku Lähteenvuo, MD, PhD, University of Eastern Finland, Niuvanniemi Hospital, Kuopio. It was published online on November 13 in JAMA Psychiatry.

LIMITATIONS:

The observational nature of this study limited causal inferences.

DISCLOSURES:

The data used in this study were obtained from the REWHARD consortium, supported by the Swedish Research Council. Four of the six authors reported receiving grants or personal fees from various sources outside the submitted work, which are fully listed in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Use of the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists semaglutide and liraglutide is linked to a lower risk for alcohol use disorder (AUD)–related hospitalizations, compared with traditional AUD medications, a new study suggested.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a nationwide cohort study from 2006 to 2023 in Sweden that included more than 220,000 individuals with AUD (mean age, 40 years; 64% men).

- Data were obtained from registers of inpatient and specialized outpatient care, sickness absence, and disability pension, with a median follow-up period of 8.8 years.

- The primary exposure measured was the use of individual GLP-1 receptor agonists — commonly used to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity — compared with nonuse.

- The secondary exposure examined was the use of medications indicated for AUD.

- The primary outcome was AUD-related hospitalization; secondary outcomes included hospitalization due to substance use disorder (SUD), somatic hospitalization, and suicide attempts.

TAKEAWAY:

- About 59% of participants experienced AUD-related hospitalization.

- Semaglutide users (n = 4321) had the lowest risk for hospitalization related to AUD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.64; 95% CI, 0.50-0.83) and to any SUD (aHR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.54-0.85).

- Liraglutide users (n = 2509) had the second lowest risk for both AUD-related (aHR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.57-0.92) and SUD-related (aHR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.64-0.97) hospitalizations.

- The use of both semaglutide (aHR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.68-0.90) and liraglutide (aHR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.69-0.91) was linked to a reduced risk for hospitalization because of somatic reasons but was not associated with the risk of suicide attempts.

- Traditional AUD medications showed modest effectiveness with a slightly decreased but nonsignificant risk for AUD-related hospitalization (aHR, 0.98).

IN PRACTICE:

“AUDs and SUDs are undertreated pharmacologically, despite the availability of effective treatments. However, novel treatments are also needed because existing treatments may not be suitable for all patients. Semaglutide and liraglutide may be effective in the treatment of AUD, and clinical trials are urgently needed to confirm these findings,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Markku Lähteenvuo, MD, PhD, University of Eastern Finland, Niuvanniemi Hospital, Kuopio. It was published online on November 13 in JAMA Psychiatry.

LIMITATIONS:

The observational nature of this study limited causal inferences.

DISCLOSURES:

The data used in this study were obtained from the REWHARD consortium, supported by the Swedish Research Council. Four of the six authors reported receiving grants or personal fees from various sources outside the submitted work, which are fully listed in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Use of the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists semaglutide and liraglutide is linked to a lower risk for alcohol use disorder (AUD)–related hospitalizations, compared with traditional AUD medications, a new study suggested.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a nationwide cohort study from 2006 to 2023 in Sweden that included more than 220,000 individuals with AUD (mean age, 40 years; 64% men).

- Data were obtained from registers of inpatient and specialized outpatient care, sickness absence, and disability pension, with a median follow-up period of 8.8 years.

- The primary exposure measured was the use of individual GLP-1 receptor agonists — commonly used to treat type 2 diabetes and obesity — compared with nonuse.

- The secondary exposure examined was the use of medications indicated for AUD.

- The primary outcome was AUD-related hospitalization; secondary outcomes included hospitalization due to substance use disorder (SUD), somatic hospitalization, and suicide attempts.

TAKEAWAY:

- About 59% of participants experienced AUD-related hospitalization.

- Semaglutide users (n = 4321) had the lowest risk for hospitalization related to AUD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.64; 95% CI, 0.50-0.83) and to any SUD (aHR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.54-0.85).

- Liraglutide users (n = 2509) had the second lowest risk for both AUD-related (aHR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.57-0.92) and SUD-related (aHR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.64-0.97) hospitalizations.

- The use of both semaglutide (aHR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.68-0.90) and liraglutide (aHR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.69-0.91) was linked to a reduced risk for hospitalization because of somatic reasons but was not associated with the risk of suicide attempts.

- Traditional AUD medications showed modest effectiveness with a slightly decreased but nonsignificant risk for AUD-related hospitalization (aHR, 0.98).

IN PRACTICE:

“AUDs and SUDs are undertreated pharmacologically, despite the availability of effective treatments. However, novel treatments are also needed because existing treatments may not be suitable for all patients. Semaglutide and liraglutide may be effective in the treatment of AUD, and clinical trials are urgently needed to confirm these findings,” the investigators wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Markku Lähteenvuo, MD, PhD, University of Eastern Finland, Niuvanniemi Hospital, Kuopio. It was published online on November 13 in JAMA Psychiatry.

LIMITATIONS:

The observational nature of this study limited causal inferences.

DISCLOSURES:

The data used in this study were obtained from the REWHARD consortium, supported by the Swedish Research Council. Four of the six authors reported receiving grants or personal fees from various sources outside the submitted work, which are fully listed in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hoarding Disorder: A Looming National Crisis?

A report published in July 2024 by the US Senate Special Committee on Aging is calling for a national coordinated response to what the authors claim may be an emerging hoarding disorder (HD) crisis.

While millions of US adults are estimated to have HD, it is the disorder’s prevalence and severity among older adults that sounded the alarm for the Committee Chair Sen. Bob Casey (D-PA).

the report stated. Older adults made up about 16% of the US population in 2019. By 2060, that proportion is projected to soar to 25%.

The country’s aging population alone “could fuel a rise in hoarding in the coming decades,” the report authors noted.

These findings underscore the pressing need for a deeper understanding of HD, particularly as reports of its impact continue to rise. The Senate report also raises critical questions about the nature of HD: What is known about the condition? What evidence-based treatments are currently available, and are there national strategies that will prevent it from becoming a systemic crisis?

Why the Urgency?

An increase in anecdotal reports of HD in his home state prompted Casey, chair of the Senate Committee on Aging, to launch the investigation into the incidence and consequences of HD. Soon after the committee began its work, it became evident that the problem was not unique to communities in Pennsylvania. It was a nationwide issue.

“Communities throughout the United States are already grappling with HD,” the report noted.

HD is characterized by persistent difficulty discarding possessions, regardless of their monetary value. For individuals with HD, such items frequently hold meaningful reminders of past events and provide a sense of security. Difficulties with emotional regulation, executive functioning, and impulse control all contribute to the excessive buildup of clutter. Problems with attention, organization, and problem-solving are also common.

As individuals with HD age, physical limitations or disabilities may hinder their ability to discard clutter. As the accumulation increases, it can pose serious risks not only to their safety but also to public health.

Dozens of statements submitted to the Senate committee by those with HD, clinicians and social workers, first responders, social service organizations, state and federal agencies, and professional societies paint a concerning picture about the impact of hoarding on emergency and community services.

Data from the National Fire Incident Reporting System show the number of hoarding-related residential structural fires increased 26% between 2014 and 2022. Some 5242 residential fires connected to cluttered environments during that time resulted in 1367 fire service injuries, 1119 civilian injuries, and over $396 million in damages.

“For older adults, those consequences include health and safety risks, social isolation, eviction, and homelessness,” the report authors noted. “For communities, those consequences include public health concerns, increased risk of fire, and dangers to emergency responders.”

What Causes HD?

HD was once classified as a symptom of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, with extreme causes meeting the diagnostic criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder. That changed in 2010 when a working group recommended that HD be added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Fifth Edition, as a stand-alone disorder. That recommendation was approved in 2012.

However, a decade later, much about HD’s etiology remains unknown.

Often beginning in early adolescence, HD is a chronic and progressive condition, with genetics and trauma playing a role in its onset and course, Sanjaya Saxena, MD, director of Clinical and Research Affairs at the International OCD Foundation, said in an interview.

Between 50% and 85% of people with HD symptoms have family members with similar behavior. HD is often comorbid with other psychiatric and medical disorders, which can complicate treatment.

Results of a 2022 study showed that, compared with healthy control individuals, people with HD had widespread abnormalities in the prefrontal white matter tract which connects cortical regions involved in executive functioning, including working memory, attention, reward processing, and decision-making.

Some research also suggests that dysregulation of serotonin transmission may contribute to compulsive behaviors and the difficulty in letting go of possessions.

“We do know that there are factors that contribute to worsening of hoarding symptoms, but that’s not the same thing as what really causes it. So unfortunately, it’s still very understudied, and we don’t have great knowledge of what causes it,” Saxena said.

What Treatments Are Available?

There are currently no Food and Drug Administration–approved medications to treat HD, although some research has shown antidepressants paroxetine and venlafaxine may have some benefit. Methylphenidate and atomoxetine are also under study for HD.

Nonpharmacological therapies have shown more promising results. Among the first was a specialized cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) program developed by Randy Frost, PhD, professor emeritus of psychology at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, and Gail Steketee, PhD, dean emerita and professor emerita of social work at Boston University in Massachusetts.

First published in 2007 and the subject of many clinical trials and studies since, the 26-session program has served as a model for psychosocial treatments for HD. The evidence-based therapy addresses various symptoms, including impulse control. One module encourages participants to develop a set of questions to consider before acquiring new items, gradually helping them build resistance to the urge to accumulate more possessions, said Frost, whose early work on HD was cited by those who supported adding the condition to the DSM in 2012.

“There are several features that I think are important including exercises in resisting acquiring and processing information when making decisions about discarding,” Frost said in an interview.

A number of studies have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT for HD, including a 2015 meta-analysis coauthored by Frost. The research showed symptom severity decreased significantly following CBT, with the largest gains in difficulty discarding and moderate improvements in clutter and acquiring.

Responses were better among women and younger patients, and although symptoms improved, posttreatment scores remained closer to the clinical range, researchers noted. It’s possible that more intervention beyond what is usually included in clinical trials — such as more sessions or adding home decluttering visits — could improve treatment response, they added.

A workshop based on the specialized CBT program has expanded the reach of the treatment. The group therapy project, Buried in Treasures (BiT), was developed by Frost, Steketee, and David Tolin, PhD, founder and director of the Anxiety Disorders Center at the Institute of Living, Hartford, and an adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut. The workshop is designed as a facilitated treatment that can be delivered by clinicians or trained nonclinician facilitators.

A study published in May found that more than half the participants with HD responded to the treatment, and of those, 39% reported significant reductions in HD symptoms. BiT sessions were led by trained facilitators, and the study included in-home decluttering sessions, also led by trained volunteers. Researchers said adding the home intervention could increase engagement with the group therapy.

Another study of a modified version of BiT found a 32% decrease in HD symptoms after 15 weeks of treatment delivered via video teleconference.

“The BiT workshop has been expanding around the world and has the advantage of being relatively inexpensive,” Frost said. Another advantage is that it can be run by nonclinicians, which expands treatment options in areas where mental health professionals trained to treat HD are in short supply.

However, the workshop “is not perfect, and clients usually still have symptoms at the end of the workshop,” Frost noted.

“The point is that the BiT workshop is the first step in changing a lifestyle related to possessions,” he continued. “We do certainly need to train more people in how to treat hoarding, and we need to facilitate research to make our treatments more effective.”

What’s New in the Field?

One novel program currently under study combines CBT with a cognitive rehabilitation protocol. Called Cognitive Rehabilitation and Exposure/Sorting Therapy (CREST), the program has been shown to help older adults with HD who don’t respond to traditional CBT for HD.

The program, led by Catherine Ayers, PhD, professor of clinical psychiatry at University of California, San Diego, involves memory training and problem-solving combined with exposure therapy to help participants learn how to tolerate distress associated with discarding their possessions.

Early findings pointed to symptom improvement in older adults following 24 sessions with CREST. The program fared better than geriatric case management in a 2018 study — the first randomized controlled trial of a treatment for HD in older adults — and offered additional benefits compared with exposure therapy in a study published in February 2024.

Virtual reality is also helping people with HD. A program developed at Stanford University in California, allows people with HD to work with a therapist as they practice decluttering in a three-dimensional virtual environment created using photographs and videos of actual hoarded objects and cluttered rooms in patients’ homes.

In a small pilot study, nine people older than 55 years with HD attended 16 weeks of online facilitated therapy where they learned to better understand their attachment to those items. They practiced decluttering by selecting virtual items for recycling, donation, or trash. A virtual garbage truck even hauled away the items they had placed in the trash.

Participants were then asked to discard the actual items at home. Most participants reported a decrease in hoarding symptoms, which was confirmed following a home assessment by a clinician.

“When you pick up an object from a loved one, it still maybe has the scent of the loved one. It has these tactile cues, colors. But in the virtual world, you can take a little bit of a step back,” lead researchers Carolyn Rodriguez, MD, PhD, director of Stanford’s Hoarding Disorders Research Program, said in an interview.

“It’s a little ramp to help people practice these skills. And then what we find is that it actually translated really well. They were able to go home and actually do the real uncluttering,” Rodriguez added.

What Else Can Be Done?

While researchers like Rodriguez continue studies of new and existing treatments, the Senate report draws attention to other responses that could aid people with HD. Because of its significant impact on emergency responders, adult protective services, aging services, and housing providers, the report recommends a nationwide response to older adults with HD.

Currently, federal agencies in charge of mental and community health are not doing enough to address HD, the report’s authors noted.

The report demonstrates “the scope and severity of these challenges and offers a path forward for how we can help people, communities, and local governments contend with this condition,” Casey said.

Specifically, the document cites a lack of HD services and tracking by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Administration for Community Living, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The committee recommended these agencies collaborate to improve HD data collection, which will be critical to managing a potential spike in cases as the population ages. The committee also suggested awareness and training campaigns to better educate clinicians, social service providers, court officials, and first responders about HD.

Further, the report’s authors called for the Department of Housing and Urban Development to provide guidance and technical assistance on HD for landlords and housing assistance programs and urged Congress to collaborate with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to expand coverage for hoarding treatments.

Finally, the committee encouraged policymakers to engage directly with individuals affected by HD and their families to better understand the impact of the disorder and inform policy development.

“I think the Senate report focuses on education, not just for therapists, but other stakeholders too,” Frost said. “There are lots of other professionals who have a stake in this process, housing specialists, elder service folks, health and human services. Awareness of this problem is something that’s important for them as well.”

Rodriguez characterized the report’s recommendations as “potentially lifesaving” for individuals with HD. She added that it represents the first step in an ongoing effort to address an impending public health crisis related to HD in older adults and its broader impact on communities.

A spokesperson with Casey’s office said it’s unclear whether any federal agencies have acted on the report recommendations since it was released in June. It’s also unknown whether the Senate Committee on Aging will pursue any additional work on HD when new committee leaders are appointed in 2025.

“Although some federal agencies have taken steps to address HD, those steps are frequently limited. Other relevant agencies have not addressed HD at all in recent years,” report authors wrote. “The federal government can, and should, do more to bolster the response to HD.”

Frost agreed.

“I think federal agencies can have a positive effect by promoting, supporting, and tracking local efforts in dealing with this problem,” he said.

With reporting from Eve Bender.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A report published in July 2024 by the US Senate Special Committee on Aging is calling for a national coordinated response to what the authors claim may be an emerging hoarding disorder (HD) crisis.

While millions of US adults are estimated to have HD, it is the disorder’s prevalence and severity among older adults that sounded the alarm for the Committee Chair Sen. Bob Casey (D-PA).

the report stated. Older adults made up about 16% of the US population in 2019. By 2060, that proportion is projected to soar to 25%.

The country’s aging population alone “could fuel a rise in hoarding in the coming decades,” the report authors noted.

These findings underscore the pressing need for a deeper understanding of HD, particularly as reports of its impact continue to rise. The Senate report also raises critical questions about the nature of HD: What is known about the condition? What evidence-based treatments are currently available, and are there national strategies that will prevent it from becoming a systemic crisis?

Why the Urgency?

An increase in anecdotal reports of HD in his home state prompted Casey, chair of the Senate Committee on Aging, to launch the investigation into the incidence and consequences of HD. Soon after the committee began its work, it became evident that the problem was not unique to communities in Pennsylvania. It was a nationwide issue.

“Communities throughout the United States are already grappling with HD,” the report noted.

HD is characterized by persistent difficulty discarding possessions, regardless of their monetary value. For individuals with HD, such items frequently hold meaningful reminders of past events and provide a sense of security. Difficulties with emotional regulation, executive functioning, and impulse control all contribute to the excessive buildup of clutter. Problems with attention, organization, and problem-solving are also common.

As individuals with HD age, physical limitations or disabilities may hinder their ability to discard clutter. As the accumulation increases, it can pose serious risks not only to their safety but also to public health.

Dozens of statements submitted to the Senate committee by those with HD, clinicians and social workers, first responders, social service organizations, state and federal agencies, and professional societies paint a concerning picture about the impact of hoarding on emergency and community services.

Data from the National Fire Incident Reporting System show the number of hoarding-related residential structural fires increased 26% between 2014 and 2022. Some 5242 residential fires connected to cluttered environments during that time resulted in 1367 fire service injuries, 1119 civilian injuries, and over $396 million in damages.

“For older adults, those consequences include health and safety risks, social isolation, eviction, and homelessness,” the report authors noted. “For communities, those consequences include public health concerns, increased risk of fire, and dangers to emergency responders.”

What Causes HD?

HD was once classified as a symptom of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, with extreme causes meeting the diagnostic criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder. That changed in 2010 when a working group recommended that HD be added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Fifth Edition, as a stand-alone disorder. That recommendation was approved in 2012.

However, a decade later, much about HD’s etiology remains unknown.

Often beginning in early adolescence, HD is a chronic and progressive condition, with genetics and trauma playing a role in its onset and course, Sanjaya Saxena, MD, director of Clinical and Research Affairs at the International OCD Foundation, said in an interview.

Between 50% and 85% of people with HD symptoms have family members with similar behavior. HD is often comorbid with other psychiatric and medical disorders, which can complicate treatment.

Results of a 2022 study showed that, compared with healthy control individuals, people with HD had widespread abnormalities in the prefrontal white matter tract which connects cortical regions involved in executive functioning, including working memory, attention, reward processing, and decision-making.

Some research also suggests that dysregulation of serotonin transmission may contribute to compulsive behaviors and the difficulty in letting go of possessions.

“We do know that there are factors that contribute to worsening of hoarding symptoms, but that’s not the same thing as what really causes it. So unfortunately, it’s still very understudied, and we don’t have great knowledge of what causes it,” Saxena said.

What Treatments Are Available?

There are currently no Food and Drug Administration–approved medications to treat HD, although some research has shown antidepressants paroxetine and venlafaxine may have some benefit. Methylphenidate and atomoxetine are also under study for HD.

Nonpharmacological therapies have shown more promising results. Among the first was a specialized cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) program developed by Randy Frost, PhD, professor emeritus of psychology at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, and Gail Steketee, PhD, dean emerita and professor emerita of social work at Boston University in Massachusetts.

First published in 2007 and the subject of many clinical trials and studies since, the 26-session program has served as a model for psychosocial treatments for HD. The evidence-based therapy addresses various symptoms, including impulse control. One module encourages participants to develop a set of questions to consider before acquiring new items, gradually helping them build resistance to the urge to accumulate more possessions, said Frost, whose early work on HD was cited by those who supported adding the condition to the DSM in 2012.

“There are several features that I think are important including exercises in resisting acquiring and processing information when making decisions about discarding,” Frost said in an interview.

A number of studies have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT for HD, including a 2015 meta-analysis coauthored by Frost. The research showed symptom severity decreased significantly following CBT, with the largest gains in difficulty discarding and moderate improvements in clutter and acquiring.

Responses were better among women and younger patients, and although symptoms improved, posttreatment scores remained closer to the clinical range, researchers noted. It’s possible that more intervention beyond what is usually included in clinical trials — such as more sessions or adding home decluttering visits — could improve treatment response, they added.

A workshop based on the specialized CBT program has expanded the reach of the treatment. The group therapy project, Buried in Treasures (BiT), was developed by Frost, Steketee, and David Tolin, PhD, founder and director of the Anxiety Disorders Center at the Institute of Living, Hartford, and an adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut. The workshop is designed as a facilitated treatment that can be delivered by clinicians or trained nonclinician facilitators.

A study published in May found that more than half the participants with HD responded to the treatment, and of those, 39% reported significant reductions in HD symptoms. BiT sessions were led by trained facilitators, and the study included in-home decluttering sessions, also led by trained volunteers. Researchers said adding the home intervention could increase engagement with the group therapy.

Another study of a modified version of BiT found a 32% decrease in HD symptoms after 15 weeks of treatment delivered via video teleconference.

“The BiT workshop has been expanding around the world and has the advantage of being relatively inexpensive,” Frost said. Another advantage is that it can be run by nonclinicians, which expands treatment options in areas where mental health professionals trained to treat HD are in short supply.

However, the workshop “is not perfect, and clients usually still have symptoms at the end of the workshop,” Frost noted.

“The point is that the BiT workshop is the first step in changing a lifestyle related to possessions,” he continued. “We do certainly need to train more people in how to treat hoarding, and we need to facilitate research to make our treatments more effective.”

What’s New in the Field?

One novel program currently under study combines CBT with a cognitive rehabilitation protocol. Called Cognitive Rehabilitation and Exposure/Sorting Therapy (CREST), the program has been shown to help older adults with HD who don’t respond to traditional CBT for HD.

The program, led by Catherine Ayers, PhD, professor of clinical psychiatry at University of California, San Diego, involves memory training and problem-solving combined with exposure therapy to help participants learn how to tolerate distress associated with discarding their possessions.

Early findings pointed to symptom improvement in older adults following 24 sessions with CREST. The program fared better than geriatric case management in a 2018 study — the first randomized controlled trial of a treatment for HD in older adults — and offered additional benefits compared with exposure therapy in a study published in February 2024.

Virtual reality is also helping people with HD. A program developed at Stanford University in California, allows people with HD to work with a therapist as they practice decluttering in a three-dimensional virtual environment created using photographs and videos of actual hoarded objects and cluttered rooms in patients’ homes.

In a small pilot study, nine people older than 55 years with HD attended 16 weeks of online facilitated therapy where they learned to better understand their attachment to those items. They practiced decluttering by selecting virtual items for recycling, donation, or trash. A virtual garbage truck even hauled away the items they had placed in the trash.

Participants were then asked to discard the actual items at home. Most participants reported a decrease in hoarding symptoms, which was confirmed following a home assessment by a clinician.

“When you pick up an object from a loved one, it still maybe has the scent of the loved one. It has these tactile cues, colors. But in the virtual world, you can take a little bit of a step back,” lead researchers Carolyn Rodriguez, MD, PhD, director of Stanford’s Hoarding Disorders Research Program, said in an interview.

“It’s a little ramp to help people practice these skills. And then what we find is that it actually translated really well. They were able to go home and actually do the real uncluttering,” Rodriguez added.

What Else Can Be Done?

While researchers like Rodriguez continue studies of new and existing treatments, the Senate report draws attention to other responses that could aid people with HD. Because of its significant impact on emergency responders, adult protective services, aging services, and housing providers, the report recommends a nationwide response to older adults with HD.

Currently, federal agencies in charge of mental and community health are not doing enough to address HD, the report’s authors noted.

The report demonstrates “the scope and severity of these challenges and offers a path forward for how we can help people, communities, and local governments contend with this condition,” Casey said.

Specifically, the document cites a lack of HD services and tracking by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Administration for Community Living, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The committee recommended these agencies collaborate to improve HD data collection, which will be critical to managing a potential spike in cases as the population ages. The committee also suggested awareness and training campaigns to better educate clinicians, social service providers, court officials, and first responders about HD.

Further, the report’s authors called for the Department of Housing and Urban Development to provide guidance and technical assistance on HD for landlords and housing assistance programs and urged Congress to collaborate with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to expand coverage for hoarding treatments.

Finally, the committee encouraged policymakers to engage directly with individuals affected by HD and their families to better understand the impact of the disorder and inform policy development.

“I think the Senate report focuses on education, not just for therapists, but other stakeholders too,” Frost said. “There are lots of other professionals who have a stake in this process, housing specialists, elder service folks, health and human services. Awareness of this problem is something that’s important for them as well.”

Rodriguez characterized the report’s recommendations as “potentially lifesaving” for individuals with HD. She added that it represents the first step in an ongoing effort to address an impending public health crisis related to HD in older adults and its broader impact on communities.

A spokesperson with Casey’s office said it’s unclear whether any federal agencies have acted on the report recommendations since it was released in June. It’s also unknown whether the Senate Committee on Aging will pursue any additional work on HD when new committee leaders are appointed in 2025.

“Although some federal agencies have taken steps to address HD, those steps are frequently limited. Other relevant agencies have not addressed HD at all in recent years,” report authors wrote. “The federal government can, and should, do more to bolster the response to HD.”

Frost agreed.

“I think federal agencies can have a positive effect by promoting, supporting, and tracking local efforts in dealing with this problem,” he said.

With reporting from Eve Bender.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A report published in July 2024 by the US Senate Special Committee on Aging is calling for a national coordinated response to what the authors claim may be an emerging hoarding disorder (HD) crisis.

While millions of US adults are estimated to have HD, it is the disorder’s prevalence and severity among older adults that sounded the alarm for the Committee Chair Sen. Bob Casey (D-PA).

the report stated. Older adults made up about 16% of the US population in 2019. By 2060, that proportion is projected to soar to 25%.

The country’s aging population alone “could fuel a rise in hoarding in the coming decades,” the report authors noted.

These findings underscore the pressing need for a deeper understanding of HD, particularly as reports of its impact continue to rise. The Senate report also raises critical questions about the nature of HD: What is known about the condition? What evidence-based treatments are currently available, and are there national strategies that will prevent it from becoming a systemic crisis?

Why the Urgency?

An increase in anecdotal reports of HD in his home state prompted Casey, chair of the Senate Committee on Aging, to launch the investigation into the incidence and consequences of HD. Soon after the committee began its work, it became evident that the problem was not unique to communities in Pennsylvania. It was a nationwide issue.

“Communities throughout the United States are already grappling with HD,” the report noted.

HD is characterized by persistent difficulty discarding possessions, regardless of their monetary value. For individuals with HD, such items frequently hold meaningful reminders of past events and provide a sense of security. Difficulties with emotional regulation, executive functioning, and impulse control all contribute to the excessive buildup of clutter. Problems with attention, organization, and problem-solving are also common.

As individuals with HD age, physical limitations or disabilities may hinder their ability to discard clutter. As the accumulation increases, it can pose serious risks not only to their safety but also to public health.

Dozens of statements submitted to the Senate committee by those with HD, clinicians and social workers, first responders, social service organizations, state and federal agencies, and professional societies paint a concerning picture about the impact of hoarding on emergency and community services.

Data from the National Fire Incident Reporting System show the number of hoarding-related residential structural fires increased 26% between 2014 and 2022. Some 5242 residential fires connected to cluttered environments during that time resulted in 1367 fire service injuries, 1119 civilian injuries, and over $396 million in damages.

“For older adults, those consequences include health and safety risks, social isolation, eviction, and homelessness,” the report authors noted. “For communities, those consequences include public health concerns, increased risk of fire, and dangers to emergency responders.”

What Causes HD?

HD was once classified as a symptom of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, with extreme causes meeting the diagnostic criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder. That changed in 2010 when a working group recommended that HD be added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), Fifth Edition, as a stand-alone disorder. That recommendation was approved in 2012.

However, a decade later, much about HD’s etiology remains unknown.

Often beginning in early adolescence, HD is a chronic and progressive condition, with genetics and trauma playing a role in its onset and course, Sanjaya Saxena, MD, director of Clinical and Research Affairs at the International OCD Foundation, said in an interview.

Between 50% and 85% of people with HD symptoms have family members with similar behavior. HD is often comorbid with other psychiatric and medical disorders, which can complicate treatment.

Results of a 2022 study showed that, compared with healthy control individuals, people with HD had widespread abnormalities in the prefrontal white matter tract which connects cortical regions involved in executive functioning, including working memory, attention, reward processing, and decision-making.

Some research also suggests that dysregulation of serotonin transmission may contribute to compulsive behaviors and the difficulty in letting go of possessions.

“We do know that there are factors that contribute to worsening of hoarding symptoms, but that’s not the same thing as what really causes it. So unfortunately, it’s still very understudied, and we don’t have great knowledge of what causes it,” Saxena said.

What Treatments Are Available?

There are currently no Food and Drug Administration–approved medications to treat HD, although some research has shown antidepressants paroxetine and venlafaxine may have some benefit. Methylphenidate and atomoxetine are also under study for HD.

Nonpharmacological therapies have shown more promising results. Among the first was a specialized cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) program developed by Randy Frost, PhD, professor emeritus of psychology at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, and Gail Steketee, PhD, dean emerita and professor emerita of social work at Boston University in Massachusetts.

First published in 2007 and the subject of many clinical trials and studies since, the 26-session program has served as a model for psychosocial treatments for HD. The evidence-based therapy addresses various symptoms, including impulse control. One module encourages participants to develop a set of questions to consider before acquiring new items, gradually helping them build resistance to the urge to accumulate more possessions, said Frost, whose early work on HD was cited by those who supported adding the condition to the DSM in 2012.

“There are several features that I think are important including exercises in resisting acquiring and processing information when making decisions about discarding,” Frost said in an interview.

A number of studies have demonstrated the efficacy of CBT for HD, including a 2015 meta-analysis coauthored by Frost. The research showed symptom severity decreased significantly following CBT, with the largest gains in difficulty discarding and moderate improvements in clutter and acquiring.

Responses were better among women and younger patients, and although symptoms improved, posttreatment scores remained closer to the clinical range, researchers noted. It’s possible that more intervention beyond what is usually included in clinical trials — such as more sessions or adding home decluttering visits — could improve treatment response, they added.

A workshop based on the specialized CBT program has expanded the reach of the treatment. The group therapy project, Buried in Treasures (BiT), was developed by Frost, Steketee, and David Tolin, PhD, founder and director of the Anxiety Disorders Center at the Institute of Living, Hartford, and an adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut. The workshop is designed as a facilitated treatment that can be delivered by clinicians or trained nonclinician facilitators.

A study published in May found that more than half the participants with HD responded to the treatment, and of those, 39% reported significant reductions in HD symptoms. BiT sessions were led by trained facilitators, and the study included in-home decluttering sessions, also led by trained volunteers. Researchers said adding the home intervention could increase engagement with the group therapy.

Another study of a modified version of BiT found a 32% decrease in HD symptoms after 15 weeks of treatment delivered via video teleconference.

“The BiT workshop has been expanding around the world and has the advantage of being relatively inexpensive,” Frost said. Another advantage is that it can be run by nonclinicians, which expands treatment options in areas where mental health professionals trained to treat HD are in short supply.

However, the workshop “is not perfect, and clients usually still have symptoms at the end of the workshop,” Frost noted.

“The point is that the BiT workshop is the first step in changing a lifestyle related to possessions,” he continued. “We do certainly need to train more people in how to treat hoarding, and we need to facilitate research to make our treatments more effective.”

What’s New in the Field?

One novel program currently under study combines CBT with a cognitive rehabilitation protocol. Called Cognitive Rehabilitation and Exposure/Sorting Therapy (CREST), the program has been shown to help older adults with HD who don’t respond to traditional CBT for HD.

The program, led by Catherine Ayers, PhD, professor of clinical psychiatry at University of California, San Diego, involves memory training and problem-solving combined with exposure therapy to help participants learn how to tolerate distress associated with discarding their possessions.

Early findings pointed to symptom improvement in older adults following 24 sessions with CREST. The program fared better than geriatric case management in a 2018 study — the first randomized controlled trial of a treatment for HD in older adults — and offered additional benefits compared with exposure therapy in a study published in February 2024.

Virtual reality is also helping people with HD. A program developed at Stanford University in California, allows people with HD to work with a therapist as they practice decluttering in a three-dimensional virtual environment created using photographs and videos of actual hoarded objects and cluttered rooms in patients’ homes.

In a small pilot study, nine people older than 55 years with HD attended 16 weeks of online facilitated therapy where they learned to better understand their attachment to those items. They practiced decluttering by selecting virtual items for recycling, donation, or trash. A virtual garbage truck even hauled away the items they had placed in the trash.

Participants were then asked to discard the actual items at home. Most participants reported a decrease in hoarding symptoms, which was confirmed following a home assessment by a clinician.

“When you pick up an object from a loved one, it still maybe has the scent of the loved one. It has these tactile cues, colors. But in the virtual world, you can take a little bit of a step back,” lead researchers Carolyn Rodriguez, MD, PhD, director of Stanford’s Hoarding Disorders Research Program, said in an interview.

“It’s a little ramp to help people practice these skills. And then what we find is that it actually translated really well. They were able to go home and actually do the real uncluttering,” Rodriguez added.

What Else Can Be Done?

While researchers like Rodriguez continue studies of new and existing treatments, the Senate report draws attention to other responses that could aid people with HD. Because of its significant impact on emergency responders, adult protective services, aging services, and housing providers, the report recommends a nationwide response to older adults with HD.

Currently, federal agencies in charge of mental and community health are not doing enough to address HD, the report’s authors noted.

The report demonstrates “the scope and severity of these challenges and offers a path forward for how we can help people, communities, and local governments contend with this condition,” Casey said.

Specifically, the document cites a lack of HD services and tracking by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Administration for Community Living, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The committee recommended these agencies collaborate to improve HD data collection, which will be critical to managing a potential spike in cases as the population ages. The committee also suggested awareness and training campaigns to better educate clinicians, social service providers, court officials, and first responders about HD.

Further, the report’s authors called for the Department of Housing and Urban Development to provide guidance and technical assistance on HD for landlords and housing assistance programs and urged Congress to collaborate with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to expand coverage for hoarding treatments.

Finally, the committee encouraged policymakers to engage directly with individuals affected by HD and their families to better understand the impact of the disorder and inform policy development.

“I think the Senate report focuses on education, not just for therapists, but other stakeholders too,” Frost said. “There are lots of other professionals who have a stake in this process, housing specialists, elder service folks, health and human services. Awareness of this problem is something that’s important for them as well.”

Rodriguez characterized the report’s recommendations as “potentially lifesaving” for individuals with HD. She added that it represents the first step in an ongoing effort to address an impending public health crisis related to HD in older adults and its broader impact on communities.

A spokesperson with Casey’s office said it’s unclear whether any federal agencies have acted on the report recommendations since it was released in June. It’s also unknown whether the Senate Committee on Aging will pursue any additional work on HD when new committee leaders are appointed in 2025.

“Although some federal agencies have taken steps to address HD, those steps are frequently limited. Other relevant agencies have not addressed HD at all in recent years,” report authors wrote. “The federal government can, and should, do more to bolster the response to HD.”

Frost agreed.

“I think federal agencies can have a positive effect by promoting, supporting, and tracking local efforts in dealing with this problem,” he said.

With reporting from Eve Bender.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

US Alcohol-Related Deaths Double Over 2 Decades, With Notable Age and Gender Disparities

TOPLINE:

US alcohol-related mortality rates increased from 10.7 to 21.6 per 100,000 between 1999 and 2020, with the largest rise of 3.8-fold observed in adults aged 25-34 years. Women experienced a 2.5-fold increase, while the Midwest region showed a similar rise in mortality rates.

METHODOLOGY:

- Analysis utilized the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research to examine alcohol-related mortality trends from 1999 to 2020.

- Researchers analyzed data from a total US population of 180,408,769 people aged 25 to 85+ years in 1999 and 226,635,013 people in 2020.

- International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were used to identify deaths with alcohol attribution, including mental and behavioral disorders, alcoholic organ damage, and alcohol-related poisoning.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall mortality rates increased from 10.7 (95% CI, 10.6-10.8) per 100,000 in 1999 to 21.6 (95% CI, 21.4-21.8) per 100,000 in 2020, representing a significant twofold increase.

- Adults aged 55-64 years demonstrated both the steepest increase and highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020.

- American Indian and Alaska Native individuals experienced the steepest increase and highest absolute rates among all racial groups.

- The West region maintained the highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020, despite the Midwest showing the largest increase.

IN PRACTICE:

“Individuals who consume large amounts of alcohol tend to have the highest risks of total mortality as well as deaths from cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular disease deaths are predominantly due to myocardial infarction and stroke. To mitigate these risks, health providers may wish to implement screening for alcohol use in primary care and other healthcare settings. By providing brief interventions and referrals to treatment, healthcare providers would be able to achieve the early identification of individuals at risk of alcohol-related harm and offer them the support and resources they need to reduce their alcohol consumption,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Alexandra Matarazzo, BS, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton. It was published online in The American Journal of Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

According to the authors, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the study to descriptive analysis only, making it suitable for hypothesis generation but not hypothesis testing. While the validity and generalizability within the United States are secure because of the use of complete population data, potential bias and uncontrolled confounding may exist because of different population mixes between the two time points.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest. One coauthor disclosed serving as an independent scientist in an advisory role to investigators and sponsors as Chair of Data Monitoring Committees for Amgen and UBC, to the Food and Drug Administration, and to Up to Date. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

US alcohol-related mortality rates increased from 10.7 to 21.6 per 100,000 between 1999 and 2020, with the largest rise of 3.8-fold observed in adults aged 25-34 years. Women experienced a 2.5-fold increase, while the Midwest region showed a similar rise in mortality rates.

METHODOLOGY:

- Analysis utilized the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research to examine alcohol-related mortality trends from 1999 to 2020.

- Researchers analyzed data from a total US population of 180,408,769 people aged 25 to 85+ years in 1999 and 226,635,013 people in 2020.

- International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were used to identify deaths with alcohol attribution, including mental and behavioral disorders, alcoholic organ damage, and alcohol-related poisoning.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall mortality rates increased from 10.7 (95% CI, 10.6-10.8) per 100,000 in 1999 to 21.6 (95% CI, 21.4-21.8) per 100,000 in 2020, representing a significant twofold increase.

- Adults aged 55-64 years demonstrated both the steepest increase and highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020.

- American Indian and Alaska Native individuals experienced the steepest increase and highest absolute rates among all racial groups.

- The West region maintained the highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020, despite the Midwest showing the largest increase.

IN PRACTICE:

“Individuals who consume large amounts of alcohol tend to have the highest risks of total mortality as well as deaths from cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular disease deaths are predominantly due to myocardial infarction and stroke. To mitigate these risks, health providers may wish to implement screening for alcohol use in primary care and other healthcare settings. By providing brief interventions and referrals to treatment, healthcare providers would be able to achieve the early identification of individuals at risk of alcohol-related harm and offer them the support and resources they need to reduce their alcohol consumption,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Alexandra Matarazzo, BS, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton. It was published online in The American Journal of Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

According to the authors, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the study to descriptive analysis only, making it suitable for hypothesis generation but not hypothesis testing. While the validity and generalizability within the United States are secure because of the use of complete population data, potential bias and uncontrolled confounding may exist because of different population mixes between the two time points.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest. One coauthor disclosed serving as an independent scientist in an advisory role to investigators and sponsors as Chair of Data Monitoring Committees for Amgen and UBC, to the Food and Drug Administration, and to Up to Date. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

US alcohol-related mortality rates increased from 10.7 to 21.6 per 100,000 between 1999 and 2020, with the largest rise of 3.8-fold observed in adults aged 25-34 years. Women experienced a 2.5-fold increase, while the Midwest region showed a similar rise in mortality rates.

METHODOLOGY:

- Analysis utilized the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research to examine alcohol-related mortality trends from 1999 to 2020.

- Researchers analyzed data from a total US population of 180,408,769 people aged 25 to 85+ years in 1999 and 226,635,013 people in 2020.

- International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were used to identify deaths with alcohol attribution, including mental and behavioral disorders, alcoholic organ damage, and alcohol-related poisoning.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall mortality rates increased from 10.7 (95% CI, 10.6-10.8) per 100,000 in 1999 to 21.6 (95% CI, 21.4-21.8) per 100,000 in 2020, representing a significant twofold increase.

- Adults aged 55-64 years demonstrated both the steepest increase and highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020.

- American Indian and Alaska Native individuals experienced the steepest increase and highest absolute rates among all racial groups.

- The West region maintained the highest absolute rates in both 1999 and 2020, despite the Midwest showing the largest increase.

IN PRACTICE:

“Individuals who consume large amounts of alcohol tend to have the highest risks of total mortality as well as deaths from cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular disease deaths are predominantly due to myocardial infarction and stroke. To mitigate these risks, health providers may wish to implement screening for alcohol use in primary care and other healthcare settings. By providing brief interventions and referrals to treatment, healthcare providers would be able to achieve the early identification of individuals at risk of alcohol-related harm and offer them the support and resources they need to reduce their alcohol consumption,” wrote the authors of the study.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Alexandra Matarazzo, BS, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton. It was published online in The American Journal of Medicine.

LIMITATIONS:

According to the authors, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the study to descriptive analysis only, making it suitable for hypothesis generation but not hypothesis testing. While the validity and generalizability within the United States are secure because of the use of complete population data, potential bias and uncontrolled confounding may exist because of different population mixes between the two time points.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest. One coauthor disclosed serving as an independent scientist in an advisory role to investigators and sponsors as Chair of Data Monitoring Committees for Amgen and UBC, to the Food and Drug Administration, and to Up to Date. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

We Haven’t Kicked Our Pandemic Drinking Habit

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

You’re stuck in your house. Work is closed or you’re working remotely. Your kids’ school is closed or is offering an hour or two a day of Zoom-based instruction. You have a bit of cabin fever which, you suppose, is better than the actual fever that comes with COVID infections, which are running rampant during the height of the pandemic. But still — it’s stressful. What do you do?

We all coped in our own way. We baked sourdough bread. We built that tree house we’d been meaning to build. We started podcasts. And ... we drank. Quite a bit, actually.

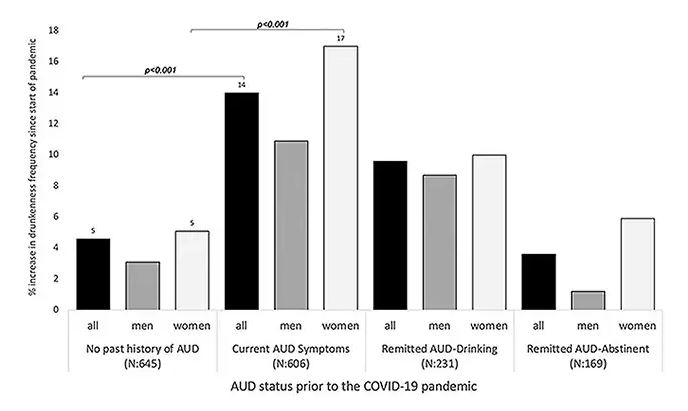

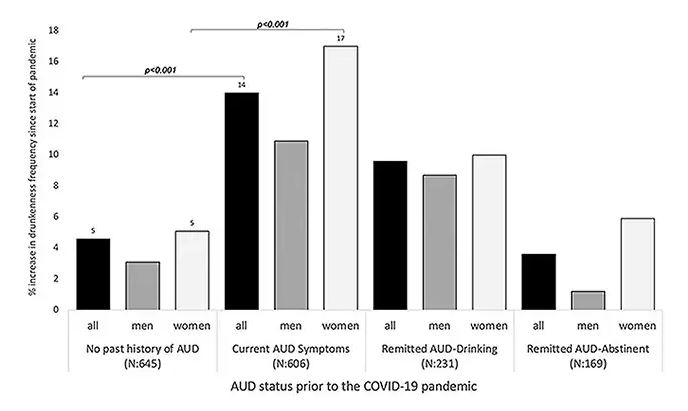

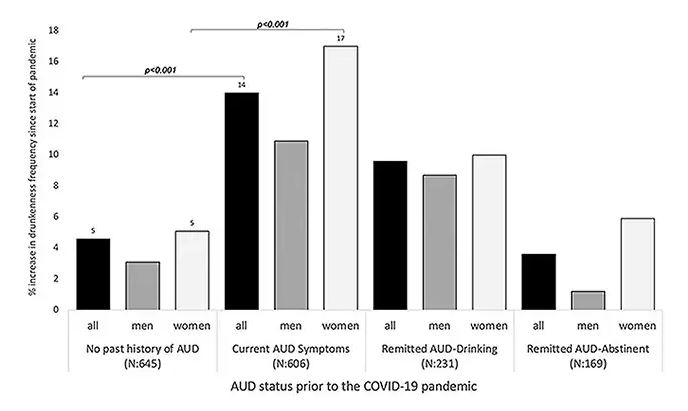

During the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales increased 3%, the largest year-on-year increase in more than 50 years. There was also an increase in drunkenness across the board, though it was most pronounced in those who were already at risk from alcohol use disorder.

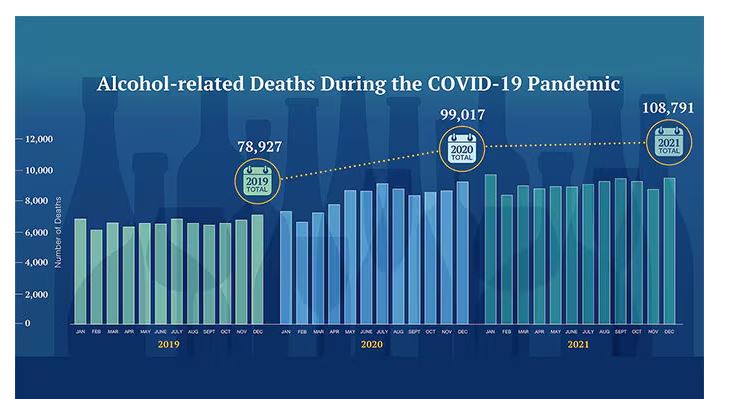

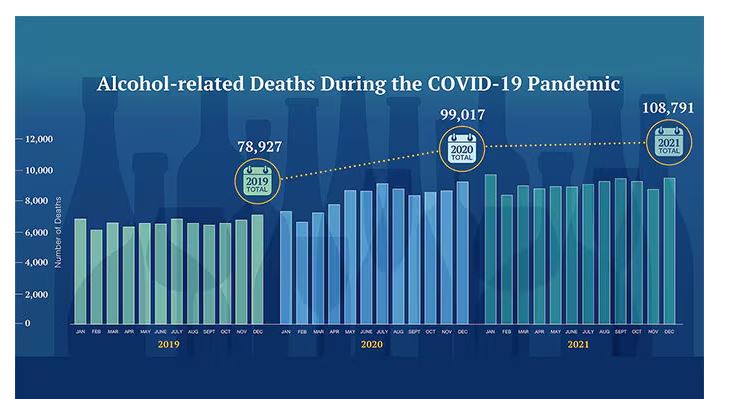

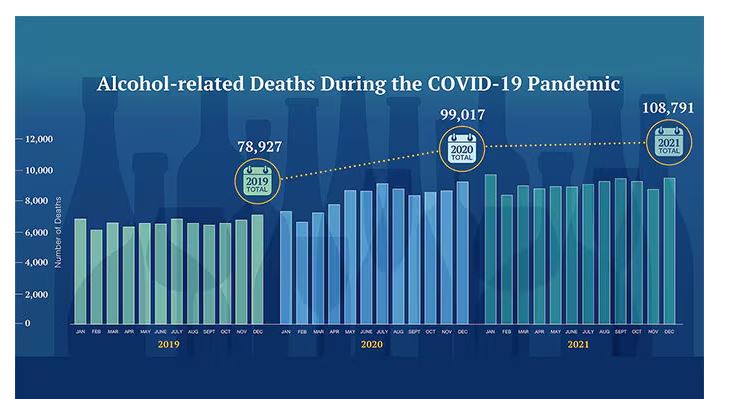

Alcohol-associated deaths increased by around 10% from 2019 to 2020. Obviously, this is a small percentage of COVID-associated deaths, but it is nothing to sneeze at.

But look, we were anxious. And say what you will about alcohol as a risk factor for liver disease, heart disease, and cancer — not to mention traffic accidents — it is an anxiolytic, at least in the short term.

But as the pandemic waned, as society reopened, as we got back to work and reintegrated into our social circles and escaped the confines of our houses and apartments, our drinking habits went back to normal, right?

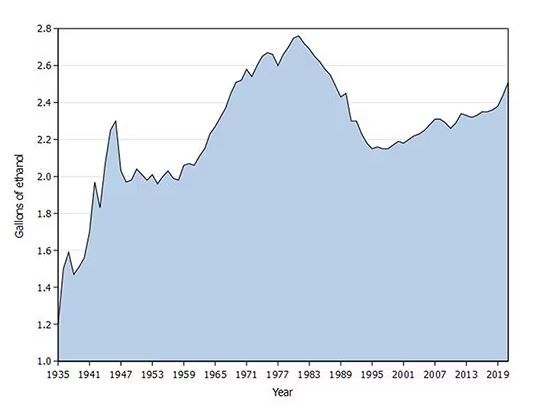

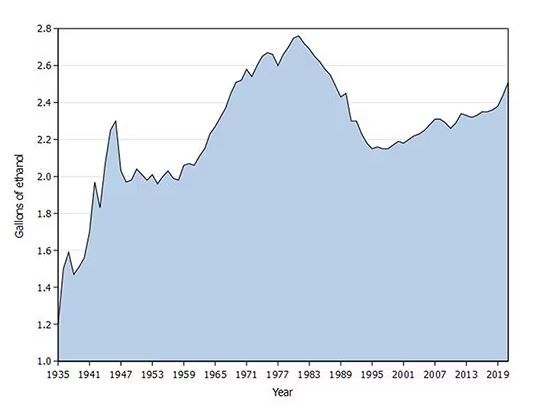

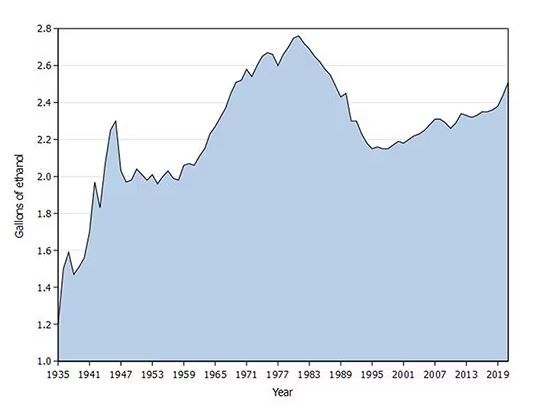

Americans’ love affair with alcohol has been a torrid one, as this graph showing gallons of ethanol consumed per capita over time shows you.

What you see is a steady increase in alcohol consumption from the end of prohibition in 1933 to its peak in the heady days of the early 1980s, followed by a steady decline until the mid-1990s. Since then, there has been another increase with, as you will note, a notable uptick during the early part of the COVID pandemic.

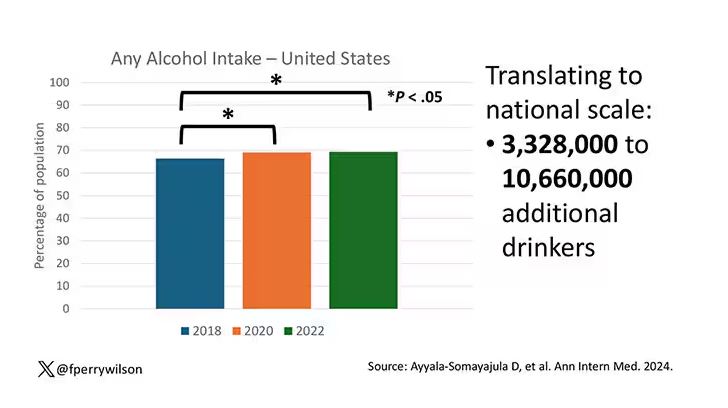

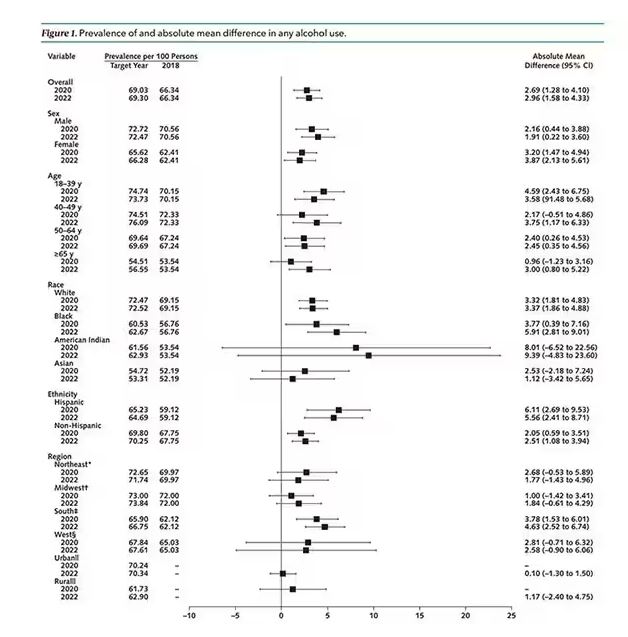

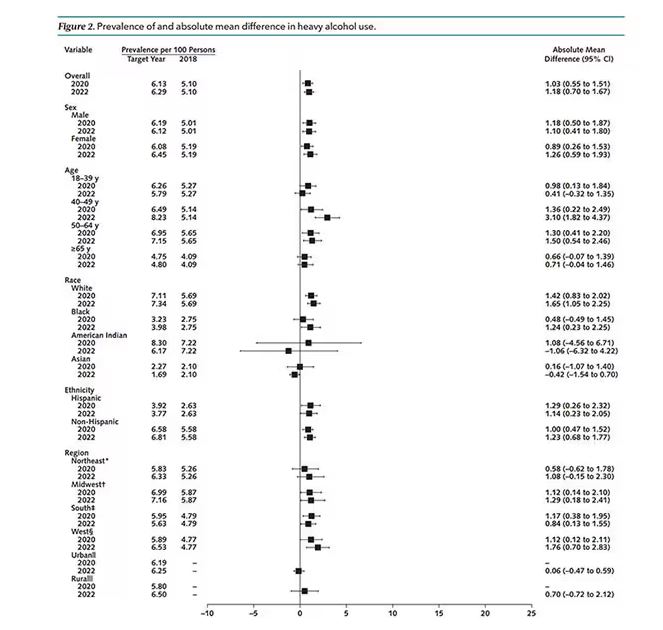

What came across my desk this week was updated data, appearing in a research letter in Annals of Internal Medicine, that compared alcohol consumption in 2020 — the first year of the COVID pandemic — with that in 2022 (the latest available data). And it looks like not much has changed.

This was a population-based survey study leveraging the National Health Interview Survey, including around 80,000 respondents from 2018, 2020, and 2022.

They created two main categories of drinking: drinking any alcohol at all and heavy drinking.

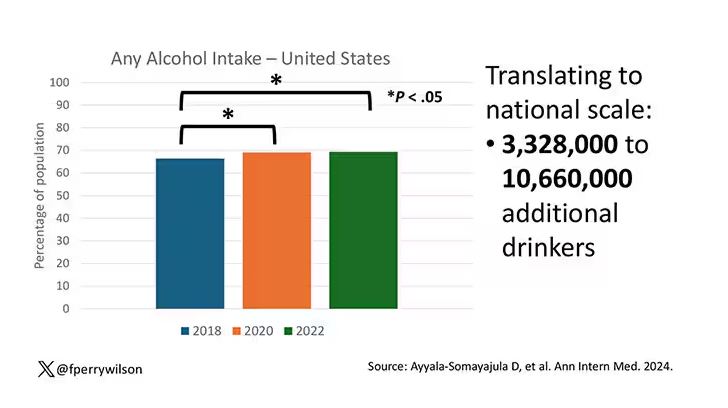

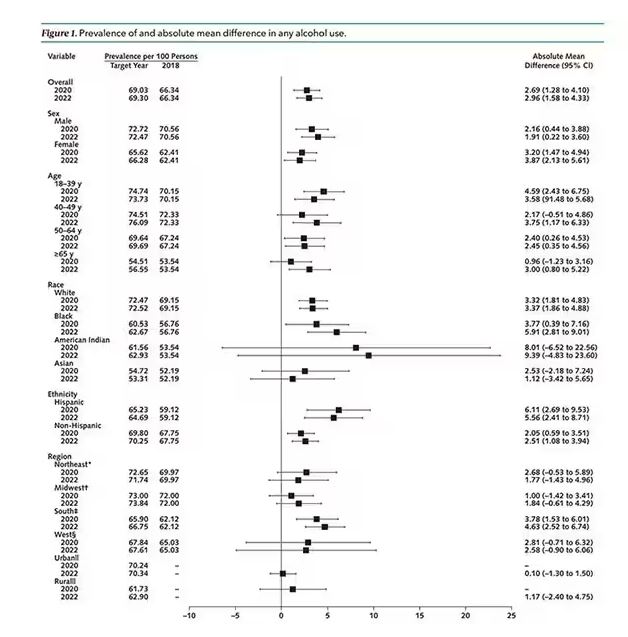

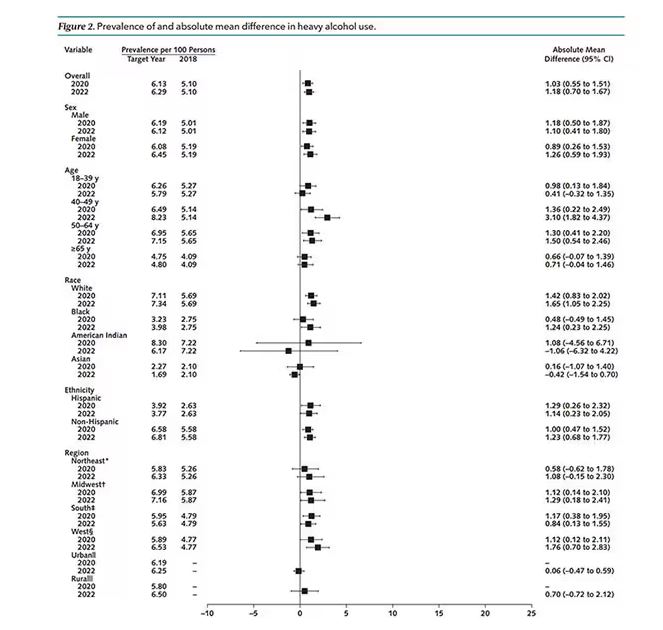

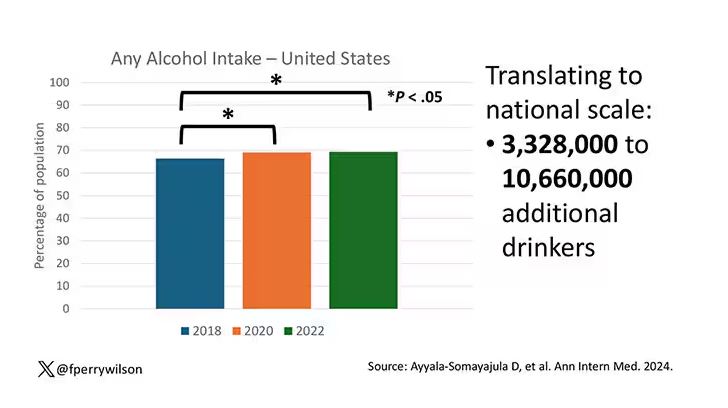

In 2018, 66% of Americans reported drinking any alcohol. That had risen to 69% by 2020, and it stayed at that level even after the lockdown had ended, as you can see here. This may seem like a small increase, but this was a highly significant result. Translating into absolute numbers, it suggests that we have added between 3,328,000 and 10,660,000 net additional drinkers to the population over this time period.

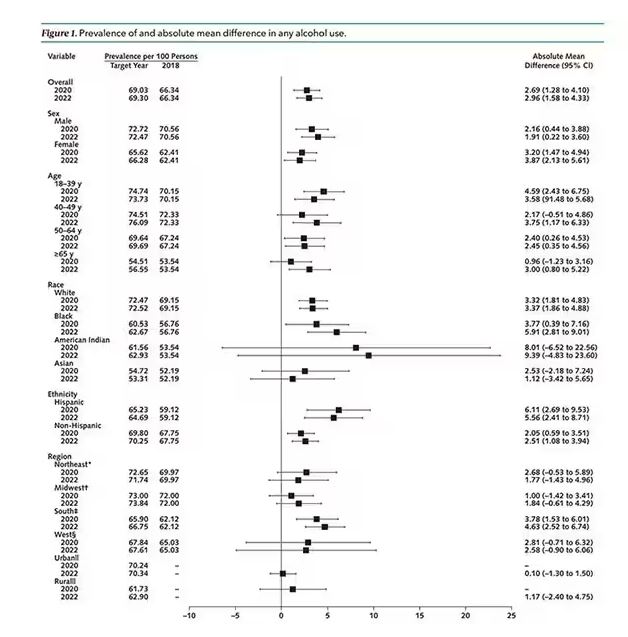

This trend was seen across basically every demographic group, with some notably larger increases among Black and Hispanic individuals, and marginally higher rates among people under age 30.

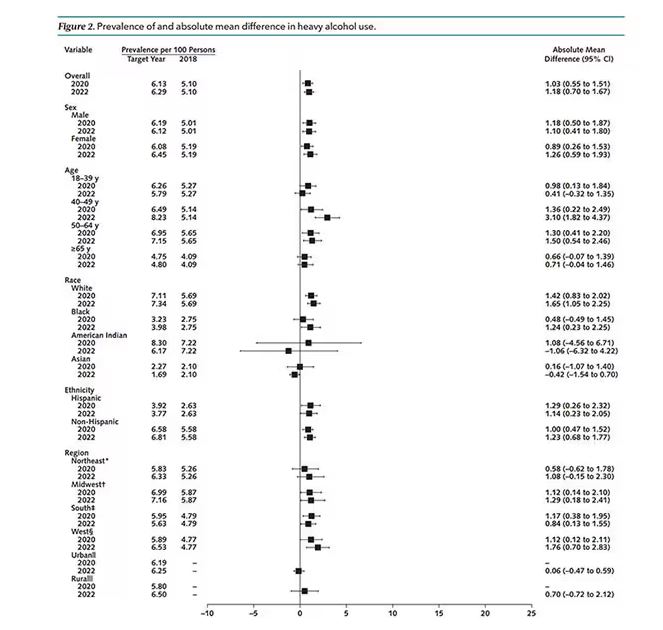

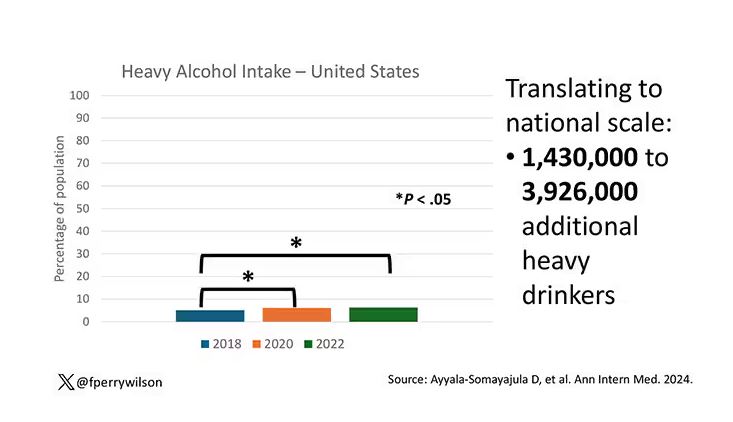

But far be it from me to deny someone a tot of brandy on a cold winter’s night. More interesting is the rate of heavy alcohol use reported in the study. For context, the definitions of heavy alcohol use appear here. For men, it’s any one day with five or more drinks or 15 or more drinks per week. For women it’s four or more drinks on a given day or eight drinks or more per week.

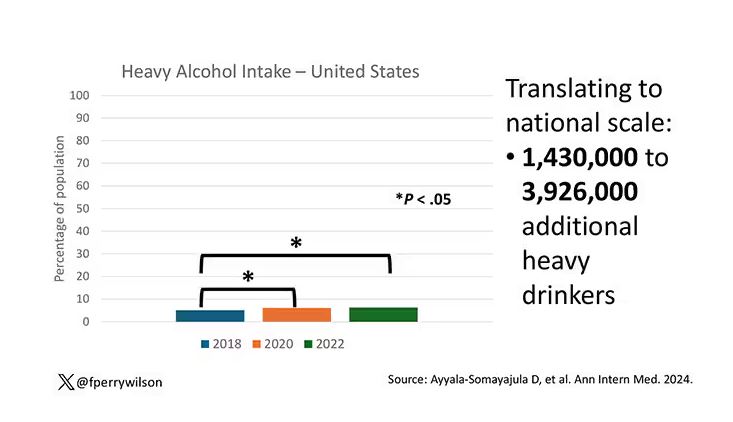

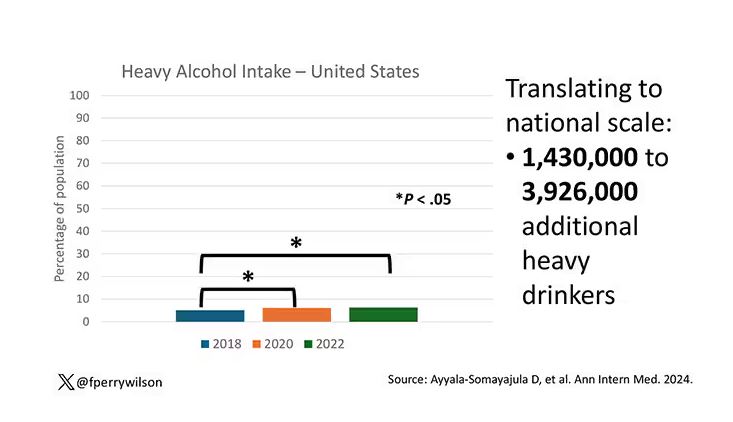

The overall rate of heavy drinking was about 5.1% in 2018 before the start of the pandemic. That rose to more than 6% in 2020 and it rose a bit more into 2022. The net change here, on a population level, is from 1,430,000 to 3,926,000 new heavy drinkers. That’s a number that rises to the level of an actual public health issue.

Again, this trend was fairly broad across demographic groups. Although in this case, the changes were a bit larger among White people and those in the 40- to 49-year age group. This is my cohort, I guess. Cheers.

The information we have from this study is purely descriptive. It tells us that people are drinking more since the pandemic. It doesn’t tell us why, or the impact that this excess drinking will have on subsequent health outcomes, although other studies would suggest that it will contribute to certain chronic conditions, both physical and mental.

Maybe more important is that it reminds us that habits are sticky. Once we become accustomed to something — that glass of wine or two with dinner, and before bed — it has a tendency to stay with us. There’s an upside to that phenomenon as well, of course; it means that we can train good habits too. And those, once they become ingrained, can be just as hard to break. We just need to be mindful of the habits we pick. New Year 2025 is just around the corner. Start brainstorming those resolutions now.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

You’re stuck in your house. Work is closed or you’re working remotely. Your kids’ school is closed or is offering an hour or two a day of Zoom-based instruction. You have a bit of cabin fever which, you suppose, is better than the actual fever that comes with COVID infections, which are running rampant during the height of the pandemic. But still — it’s stressful. What do you do?

We all coped in our own way. We baked sourdough bread. We built that tree house we’d been meaning to build. We started podcasts. And ... we drank. Quite a bit, actually.

During the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales increased 3%, the largest year-on-year increase in more than 50 years. There was also an increase in drunkenness across the board, though it was most pronounced in those who were already at risk from alcohol use disorder.

Alcohol-associated deaths increased by around 10% from 2019 to 2020. Obviously, this is a small percentage of COVID-associated deaths, but it is nothing to sneeze at.

But look, we were anxious. And say what you will about alcohol as a risk factor for liver disease, heart disease, and cancer — not to mention traffic accidents — it is an anxiolytic, at least in the short term.

But as the pandemic waned, as society reopened, as we got back to work and reintegrated into our social circles and escaped the confines of our houses and apartments, our drinking habits went back to normal, right?

Americans’ love affair with alcohol has been a torrid one, as this graph showing gallons of ethanol consumed per capita over time shows you.

What you see is a steady increase in alcohol consumption from the end of prohibition in 1933 to its peak in the heady days of the early 1980s, followed by a steady decline until the mid-1990s. Since then, there has been another increase with, as you will note, a notable uptick during the early part of the COVID pandemic.

What came across my desk this week was updated data, appearing in a research letter in Annals of Internal Medicine, that compared alcohol consumption in 2020 — the first year of the COVID pandemic — with that in 2022 (the latest available data). And it looks like not much has changed.

This was a population-based survey study leveraging the National Health Interview Survey, including around 80,000 respondents from 2018, 2020, and 2022.

They created two main categories of drinking: drinking any alcohol at all and heavy drinking.

In 2018, 66% of Americans reported drinking any alcohol. That had risen to 69% by 2020, and it stayed at that level even after the lockdown had ended, as you can see here. This may seem like a small increase, but this was a highly significant result. Translating into absolute numbers, it suggests that we have added between 3,328,000 and 10,660,000 net additional drinkers to the population over this time period.

This trend was seen across basically every demographic group, with some notably larger increases among Black and Hispanic individuals, and marginally higher rates among people under age 30.

But far be it from me to deny someone a tot of brandy on a cold winter’s night. More interesting is the rate of heavy alcohol use reported in the study. For context, the definitions of heavy alcohol use appear here. For men, it’s any one day with five or more drinks or 15 or more drinks per week. For women it’s four or more drinks on a given day or eight drinks or more per week.

The overall rate of heavy drinking was about 5.1% in 2018 before the start of the pandemic. That rose to more than 6% in 2020 and it rose a bit more into 2022. The net change here, on a population level, is from 1,430,000 to 3,926,000 new heavy drinkers. That’s a number that rises to the level of an actual public health issue.

Again, this trend was fairly broad across demographic groups. Although in this case, the changes were a bit larger among White people and those in the 40- to 49-year age group. This is my cohort, I guess. Cheers.

The information we have from this study is purely descriptive. It tells us that people are drinking more since the pandemic. It doesn’t tell us why, or the impact that this excess drinking will have on subsequent health outcomes, although other studies would suggest that it will contribute to certain chronic conditions, both physical and mental.

Maybe more important is that it reminds us that habits are sticky. Once we become accustomed to something — that glass of wine or two with dinner, and before bed — it has a tendency to stay with us. There’s an upside to that phenomenon as well, of course; it means that we can train good habits too. And those, once they become ingrained, can be just as hard to break. We just need to be mindful of the habits we pick. New Year 2025 is just around the corner. Start brainstorming those resolutions now.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

You’re stuck in your house. Work is closed or you’re working remotely. Your kids’ school is closed or is offering an hour or two a day of Zoom-based instruction. You have a bit of cabin fever which, you suppose, is better than the actual fever that comes with COVID infections, which are running rampant during the height of the pandemic. But still — it’s stressful. What do you do?

We all coped in our own way. We baked sourdough bread. We built that tree house we’d been meaning to build. We started podcasts. And ... we drank. Quite a bit, actually.

During the first year of the pandemic, alcohol sales increased 3%, the largest year-on-year increase in more than 50 years. There was also an increase in drunkenness across the board, though it was most pronounced in those who were already at risk from alcohol use disorder.

Alcohol-associated deaths increased by around 10% from 2019 to 2020. Obviously, this is a small percentage of COVID-associated deaths, but it is nothing to sneeze at.

But look, we were anxious. And say what you will about alcohol as a risk factor for liver disease, heart disease, and cancer — not to mention traffic accidents — it is an anxiolytic, at least in the short term.

But as the pandemic waned, as society reopened, as we got back to work and reintegrated into our social circles and escaped the confines of our houses and apartments, our drinking habits went back to normal, right?

Americans’ love affair with alcohol has been a torrid one, as this graph showing gallons of ethanol consumed per capita over time shows you.

What you see is a steady increase in alcohol consumption from the end of prohibition in 1933 to its peak in the heady days of the early 1980s, followed by a steady decline until the mid-1990s. Since then, there has been another increase with, as you will note, a notable uptick during the early part of the COVID pandemic.

What came across my desk this week was updated data, appearing in a research letter in Annals of Internal Medicine, that compared alcohol consumption in 2020 — the first year of the COVID pandemic — with that in 2022 (the latest available data). And it looks like not much has changed.

This was a population-based survey study leveraging the National Health Interview Survey, including around 80,000 respondents from 2018, 2020, and 2022.

They created two main categories of drinking: drinking any alcohol at all and heavy drinking.

In 2018, 66% of Americans reported drinking any alcohol. That had risen to 69% by 2020, and it stayed at that level even after the lockdown had ended, as you can see here. This may seem like a small increase, but this was a highly significant result. Translating into absolute numbers, it suggests that we have added between 3,328,000 and 10,660,000 net additional drinkers to the population over this time period.

This trend was seen across basically every demographic group, with some notably larger increases among Black and Hispanic individuals, and marginally higher rates among people under age 30.

But far be it from me to deny someone a tot of brandy on a cold winter’s night. More interesting is the rate of heavy alcohol use reported in the study. For context, the definitions of heavy alcohol use appear here. For men, it’s any one day with five or more drinks or 15 or more drinks per week. For women it’s four or more drinks on a given day or eight drinks or more per week.

The overall rate of heavy drinking was about 5.1% in 2018 before the start of the pandemic. That rose to more than 6% in 2020 and it rose a bit more into 2022. The net change here, on a population level, is from 1,430,000 to 3,926,000 new heavy drinkers. That’s a number that rises to the level of an actual public health issue.

Again, this trend was fairly broad across demographic groups. Although in this case, the changes were a bit larger among White people and those in the 40- to 49-year age group. This is my cohort, I guess. Cheers.

The information we have from this study is purely descriptive. It tells us that people are drinking more since the pandemic. It doesn’t tell us why, or the impact that this excess drinking will have on subsequent health outcomes, although other studies would suggest that it will contribute to certain chronic conditions, both physical and mental.

Maybe more important is that it reminds us that habits are sticky. Once we become accustomed to something — that glass of wine or two with dinner, and before bed — it has a tendency to stay with us. There’s an upside to that phenomenon as well, of course; it means that we can train good habits too. And those, once they become ingrained, can be just as hard to break. We just need to be mindful of the habits we pick. New Year 2025 is just around the corner. Start brainstorming those resolutions now.

Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Case Series Highlight Necrotic Wounds Associated with Xylazine-Tainted Fentanyl

TOPLINE:

including 9% that involved exposed deep structures such as bone or tendon.

METHODOLOGY:

- The alpha-2 agonist xylazine, a veterinary sedative, is increasingly detected in fentanyl used illicitly in the United States and may be causing necrotizing wounds in drug users.

- To characterize specific clinical features of xylazine-associated wounds, researchers conducted a case series at three academic medical hospitals in Philadelphia from April 2022 to February 2023.

- They included 29 patients with confirmed xylazine exposure and a chief complaint that was wound-related, seen as inpatients or in the emergency department.

TAKEAWAY:

- The 29 patients (mean age, 39.4 years; 52% men) had a total of 59 wounds, 90% were located on the arms and legs, and 69% were on the posterior upper or anterior lower extremities. Five wounds (9%) involved exposed deep structures such as the bone or tendon.

- Of the 57 wounds with available photographs, 60% had wound beds with predominantly devitalized tissue (eschar or slough), 11% were blisters, 9% had granulation tissue, and 21% had mixed tissue or other types of wound beds. Devitalized tissue was more commonly observed in medium or large wounds (odds ratio [OR], 5.2; P = .02) than in small wounds.