User login

Pending further study, caution recommended in treating vitiligo patients with lasers, IPL

SAN DIEGO – The .

Those are the preliminary conclusions from a systematic review and survey of experts that Albert Wolkerstorfer, MD, presented during a clinical abstract session at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

According to Dr. Wolkerstorfer, a dermatologist at Amsterdam University Medical Center, clinicians are reluctant to perform laser/intense pulsed light (IPL) treatments in patients with vitiligo because of the absence of clear guidelines, so he and his colleagues set out to investigate the risks of laser/IPL-induced vitiligo in patients with vitiligo and to seek out international consensus on recommendations from experts. “There is hardly any literature about it and certainly no guidelines,” he pointed out.

Dr. Wolkerstorfer and his colleagues designed three consecutive studies: A systematic review of laser/IPL-induced vitiligo; an international survey among 14 vitiligo experts from 10 countries about the occurrence of laser‐induced vitiligo, and a Delphi technique aimed at establishing a broad consensus about recommendations for safe use of lasers in vitiligo patients. At the time of the meeting, the Delphi process was still being carried out, so he did not discuss that study.

For the systematic review, the researchers found 11,073 unique hits on PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL using the terms “vitiligo,” “depigmentation,” “hypopigmentation,” and “leukoderma.” Only six case reports of laser/IPL-induced vitiligo were included in the final analysis. Of these, three had de novo vitiligo and three had vitiligo/halo nevi. These cases included two that occurred following treatment of port wine stains with the 585-nm laser; one that occurred following treatment of dyspigmentation with IPL; one that occurred following treatment of hypertrichosis with the 1,064-nm laser, one that occurred following treatment of hypertrichosis with the 755-nm laser, and one case that occurred following treatment of melasma with the ablative laser.

For the international survey of 14 experts from 10 countries, respondents said they had 10,670 new face-to-face vitiligo consultations in the past year. They reported that 30 of the vitiligo cases (0.3%) were likely caused by laser/IPL. Of these 30 cases, 18 (60%) had de novo vitiligo.

Of these cases, vitiligo occurred most frequently after laser hair reduction (47%), followed by use of the fractional laser (17%), and the ablative laser (13%). The interval between laser/IPL treatment and onset of vitiligo was 0-4 weeks in 27% of cases and 4-12 weeks in 57% of cases. Direct complications such as blistering, crusting, and erosions occurred in 57% of cases.

“Our conclusion is that laser and IPL-induced vitiligo is a rare phenomenon, and it often affects patients without prior vitiligo, which was really a surprise to us,” Dr. Wolkerstorfer said. “Complications seem to increase the risk,” he added.

“Despite the apparently low risk, we recommend caution [in patients with vitiligo], especially with aggressive laser procedures,” he said. “We recommend using conservative settings, not to treat active vitiligo patients ... and to perform test spots prior to treating large areas.” But he characterized this recommendation as “totally preliminary” pending results of the Delphi technique aimed at building consensus about laser/IPL treatments in vitiligo.

In an interview at the meeting, one of the session moderators, Oge Onwudiwe, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Alexandria, Va., said that as clinicians await results of the study’s Delphi consensus, current use of lasers and IPL in patients with vitiligo “is based on your clinical judgment and whether the vitiligo is active or inactive. If the patient has vitiligo and you’re doing laser hair removal in the armpit, they may get active lesions in that area, but they can cover it. So, they may take that as a ‘win’ with the risk. But if it can erupt in other areas, that’s a risk they must be willing to take.”

Dr. Wolkerstorfer disclosed that he has received grant or research funding from Lumenis, Novartis, and Avita Medical. He is an advisory board member for Incyte. Dr. Onwudiwe reported having no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The .

Those are the preliminary conclusions from a systematic review and survey of experts that Albert Wolkerstorfer, MD, presented during a clinical abstract session at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

According to Dr. Wolkerstorfer, a dermatologist at Amsterdam University Medical Center, clinicians are reluctant to perform laser/intense pulsed light (IPL) treatments in patients with vitiligo because of the absence of clear guidelines, so he and his colleagues set out to investigate the risks of laser/IPL-induced vitiligo in patients with vitiligo and to seek out international consensus on recommendations from experts. “There is hardly any literature about it and certainly no guidelines,” he pointed out.

Dr. Wolkerstorfer and his colleagues designed three consecutive studies: A systematic review of laser/IPL-induced vitiligo; an international survey among 14 vitiligo experts from 10 countries about the occurrence of laser‐induced vitiligo, and a Delphi technique aimed at establishing a broad consensus about recommendations for safe use of lasers in vitiligo patients. At the time of the meeting, the Delphi process was still being carried out, so he did not discuss that study.

For the systematic review, the researchers found 11,073 unique hits on PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL using the terms “vitiligo,” “depigmentation,” “hypopigmentation,” and “leukoderma.” Only six case reports of laser/IPL-induced vitiligo were included in the final analysis. Of these, three had de novo vitiligo and three had vitiligo/halo nevi. These cases included two that occurred following treatment of port wine stains with the 585-nm laser; one that occurred following treatment of dyspigmentation with IPL; one that occurred following treatment of hypertrichosis with the 1,064-nm laser, one that occurred following treatment of hypertrichosis with the 755-nm laser, and one case that occurred following treatment of melasma with the ablative laser.

For the international survey of 14 experts from 10 countries, respondents said they had 10,670 new face-to-face vitiligo consultations in the past year. They reported that 30 of the vitiligo cases (0.3%) were likely caused by laser/IPL. Of these 30 cases, 18 (60%) had de novo vitiligo.

Of these cases, vitiligo occurred most frequently after laser hair reduction (47%), followed by use of the fractional laser (17%), and the ablative laser (13%). The interval between laser/IPL treatment and onset of vitiligo was 0-4 weeks in 27% of cases and 4-12 weeks in 57% of cases. Direct complications such as blistering, crusting, and erosions occurred in 57% of cases.

“Our conclusion is that laser and IPL-induced vitiligo is a rare phenomenon, and it often affects patients without prior vitiligo, which was really a surprise to us,” Dr. Wolkerstorfer said. “Complications seem to increase the risk,” he added.

“Despite the apparently low risk, we recommend caution [in patients with vitiligo], especially with aggressive laser procedures,” he said. “We recommend using conservative settings, not to treat active vitiligo patients ... and to perform test spots prior to treating large areas.” But he characterized this recommendation as “totally preliminary” pending results of the Delphi technique aimed at building consensus about laser/IPL treatments in vitiligo.

In an interview at the meeting, one of the session moderators, Oge Onwudiwe, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Alexandria, Va., said that as clinicians await results of the study’s Delphi consensus, current use of lasers and IPL in patients with vitiligo “is based on your clinical judgment and whether the vitiligo is active or inactive. If the patient has vitiligo and you’re doing laser hair removal in the armpit, they may get active lesions in that area, but they can cover it. So, they may take that as a ‘win’ with the risk. But if it can erupt in other areas, that’s a risk they must be willing to take.”

Dr. Wolkerstorfer disclosed that he has received grant or research funding from Lumenis, Novartis, and Avita Medical. He is an advisory board member for Incyte. Dr. Onwudiwe reported having no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – The .

Those are the preliminary conclusions from a systematic review and survey of experts that Albert Wolkerstorfer, MD, presented during a clinical abstract session at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

According to Dr. Wolkerstorfer, a dermatologist at Amsterdam University Medical Center, clinicians are reluctant to perform laser/intense pulsed light (IPL) treatments in patients with vitiligo because of the absence of clear guidelines, so he and his colleagues set out to investigate the risks of laser/IPL-induced vitiligo in patients with vitiligo and to seek out international consensus on recommendations from experts. “There is hardly any literature about it and certainly no guidelines,” he pointed out.

Dr. Wolkerstorfer and his colleagues designed three consecutive studies: A systematic review of laser/IPL-induced vitiligo; an international survey among 14 vitiligo experts from 10 countries about the occurrence of laser‐induced vitiligo, and a Delphi technique aimed at establishing a broad consensus about recommendations for safe use of lasers in vitiligo patients. At the time of the meeting, the Delphi process was still being carried out, so he did not discuss that study.

For the systematic review, the researchers found 11,073 unique hits on PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL using the terms “vitiligo,” “depigmentation,” “hypopigmentation,” and “leukoderma.” Only six case reports of laser/IPL-induced vitiligo were included in the final analysis. Of these, three had de novo vitiligo and three had vitiligo/halo nevi. These cases included two that occurred following treatment of port wine stains with the 585-nm laser; one that occurred following treatment of dyspigmentation with IPL; one that occurred following treatment of hypertrichosis with the 1,064-nm laser, one that occurred following treatment of hypertrichosis with the 755-nm laser, and one case that occurred following treatment of melasma with the ablative laser.

For the international survey of 14 experts from 10 countries, respondents said they had 10,670 new face-to-face vitiligo consultations in the past year. They reported that 30 of the vitiligo cases (0.3%) were likely caused by laser/IPL. Of these 30 cases, 18 (60%) had de novo vitiligo.

Of these cases, vitiligo occurred most frequently after laser hair reduction (47%), followed by use of the fractional laser (17%), and the ablative laser (13%). The interval between laser/IPL treatment and onset of vitiligo was 0-4 weeks in 27% of cases and 4-12 weeks in 57% of cases. Direct complications such as blistering, crusting, and erosions occurred in 57% of cases.

“Our conclusion is that laser and IPL-induced vitiligo is a rare phenomenon, and it often affects patients without prior vitiligo, which was really a surprise to us,” Dr. Wolkerstorfer said. “Complications seem to increase the risk,” he added.

“Despite the apparently low risk, we recommend caution [in patients with vitiligo], especially with aggressive laser procedures,” he said. “We recommend using conservative settings, not to treat active vitiligo patients ... and to perform test spots prior to treating large areas.” But he characterized this recommendation as “totally preliminary” pending results of the Delphi technique aimed at building consensus about laser/IPL treatments in vitiligo.

In an interview at the meeting, one of the session moderators, Oge Onwudiwe, MD, a dermatologist who practices in Alexandria, Va., said that as clinicians await results of the study’s Delphi consensus, current use of lasers and IPL in patients with vitiligo “is based on your clinical judgment and whether the vitiligo is active or inactive. If the patient has vitiligo and you’re doing laser hair removal in the armpit, they may get active lesions in that area, but they can cover it. So, they may take that as a ‘win’ with the risk. But if it can erupt in other areas, that’s a risk they must be willing to take.”

Dr. Wolkerstorfer disclosed that he has received grant or research funding from Lumenis, Novartis, and Avita Medical. He is an advisory board member for Incyte. Dr. Onwudiwe reported having no disclosures.

AT ASLMS 2022

What’s ahead for laser-assisted drug delivery?

SAN DIEGO – Twelve years ago, Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, and colleagues published data from a swine study, which showed for the first time that the ablative fractional laser can be used to boost the uptake of drugs into the skin.

That discovery paved the way for what are now well-established clinical applications of laser-assisted drug delivery for treating actinic keratoses and scars. According to Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, evolving clinical indications for laser-assisted drug delivery include rejuvenation, local anesthesia, melasma, onychomycosis, hyperhidrosis, alopecia, and vitiligo, while emerging indications include treatment of skin cancer with PD-1 inhibitors and combination chemotherapy regimens, and vaccinations.

During a presentation at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, she said that researchers have much to learn about laser-assisted drug delivery, including biodistribution of the drug being delivered. Pointing out that so far, “what we have been dealing with is primarily looking at the skin as a black box,” she asked, “what happens when we drill the holes and drugs are applied on top of the skin and swim through the tiny channels?”

By using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and HPLC mass spectrometry to measure drug concentration in the skin, she and her colleagues have observed enhanced uptake of drugs – 4-fold to 40-fold greater – primarily in ex vivo pig skin. “We do know from ex vivo models that it’s much easier to boost the uptake in the skin” when compared with in vivo human use, where much lower drug concentrations are detected, said Dr. Haedersdal, who, along with Emily Wenande, MD, PhD, and R. Rox Anderson, MD, at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, authored a clinical review, published in 2020, on the basics of laser-assisted drug delivery.

“What we are working on now is visualizing what’s taking place when we apply the holes and the drugs in the skin. This is the key to tailoring laser-assisted uptake to specific dermatologic diseases being treated,” she said. To date, she and her colleagues have examined the interaction with tissue using different devices, including ex vivo confocal microscopy, to view the thermal response to ablative fractional laser and radiofrequency. “We want to take that to the next level and look at the drug biodistribution.”

Efforts are underway to compare the pattern of drug distribution with different modes of delivery, such as comparing ablative fractional laser to intradermal needle injection. “We are also working on pneumatic jet injection, which creates a focal drug distribution,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center. “In the future, we may take advantage of device-tailored biodistribution, depending on which clinical indication we are treating.”

Another important aspect to consider is drug retention in the skin. In a study presented as an abstract at the meeting, led by Dr. Wenande, she, Dr. Haedersdal, and colleagues used a pig model to evaluate the effect of three vasoregulative interventions on ablative fractional laser-assisted 5-fluororacil concentrations in in vivo skin. The three interventions were brimonidine 0.33% solution, epinephrine 10 mcg/mL gel, and a 595-nm pulsed dye laser (PDL) in designated treatment areas.

“What we learned from that was in the short term – 1-4 hours – the ablative fractional laser enhanced the uptake of 5-FU, but it was very transient,” with a twofold increased concentration of 5-FU, Dr. Haedersdal said. Over 48-72 hours, after PDL, there was “sustained enhancement of drug in the skin by three to four times,” she noted.

The synergy of systemic drugs with ablative fractional laser therapy is also being evaluated. In a mouse study led by Dr. Haedersdal’s colleague, senior researcher Uffe H. Olesen, PhD, the treatment of advanced squamous cell carcinoma tumors with a combination of ablative fractional laser and systemic treatment with PD-1 inhibitors resulted in the clearance of more tumors than with either treatment as monotherapy. “What we want to explore is the laser-induced tumor immune response in keratinocyte cancers,” she added.

“When you shine the laser on the skin, there is a robust increase of neutrophilic granulocytes.” Combining this topical immune-boosting response with systemic delivery of PD-1 inhibitors in a mouse model with basal cell carcinoma, she said, “we learned that, when we compare systemic PD-1 inhibitors alone to the laser alone and then with combination therapy, there was an increased tumor clearance of basal cell carcinomas and also enhanced survival of the mice” with the combination, she said. There were also “enhanced neutrophilic counts and both CD4- and CD8-positive cells were increased,” she added.

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received grants or research funding from Lutronic, Venus Concept, Leo Pharma, and Mirai Medical.

SAN DIEGO – Twelve years ago, Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, and colleagues published data from a swine study, which showed for the first time that the ablative fractional laser can be used to boost the uptake of drugs into the skin.

That discovery paved the way for what are now well-established clinical applications of laser-assisted drug delivery for treating actinic keratoses and scars. According to Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, evolving clinical indications for laser-assisted drug delivery include rejuvenation, local anesthesia, melasma, onychomycosis, hyperhidrosis, alopecia, and vitiligo, while emerging indications include treatment of skin cancer with PD-1 inhibitors and combination chemotherapy regimens, and vaccinations.

During a presentation at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, she said that researchers have much to learn about laser-assisted drug delivery, including biodistribution of the drug being delivered. Pointing out that so far, “what we have been dealing with is primarily looking at the skin as a black box,” she asked, “what happens when we drill the holes and drugs are applied on top of the skin and swim through the tiny channels?”

By using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and HPLC mass spectrometry to measure drug concentration in the skin, she and her colleagues have observed enhanced uptake of drugs – 4-fold to 40-fold greater – primarily in ex vivo pig skin. “We do know from ex vivo models that it’s much easier to boost the uptake in the skin” when compared with in vivo human use, where much lower drug concentrations are detected, said Dr. Haedersdal, who, along with Emily Wenande, MD, PhD, and R. Rox Anderson, MD, at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, authored a clinical review, published in 2020, on the basics of laser-assisted drug delivery.

“What we are working on now is visualizing what’s taking place when we apply the holes and the drugs in the skin. This is the key to tailoring laser-assisted uptake to specific dermatologic diseases being treated,” she said. To date, she and her colleagues have examined the interaction with tissue using different devices, including ex vivo confocal microscopy, to view the thermal response to ablative fractional laser and radiofrequency. “We want to take that to the next level and look at the drug biodistribution.”

Efforts are underway to compare the pattern of drug distribution with different modes of delivery, such as comparing ablative fractional laser to intradermal needle injection. “We are also working on pneumatic jet injection, which creates a focal drug distribution,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center. “In the future, we may take advantage of device-tailored biodistribution, depending on which clinical indication we are treating.”

Another important aspect to consider is drug retention in the skin. In a study presented as an abstract at the meeting, led by Dr. Wenande, she, Dr. Haedersdal, and colleagues used a pig model to evaluate the effect of three vasoregulative interventions on ablative fractional laser-assisted 5-fluororacil concentrations in in vivo skin. The three interventions were brimonidine 0.33% solution, epinephrine 10 mcg/mL gel, and a 595-nm pulsed dye laser (PDL) in designated treatment areas.

“What we learned from that was in the short term – 1-4 hours – the ablative fractional laser enhanced the uptake of 5-FU, but it was very transient,” with a twofold increased concentration of 5-FU, Dr. Haedersdal said. Over 48-72 hours, after PDL, there was “sustained enhancement of drug in the skin by three to four times,” she noted.

The synergy of systemic drugs with ablative fractional laser therapy is also being evaluated. In a mouse study led by Dr. Haedersdal’s colleague, senior researcher Uffe H. Olesen, PhD, the treatment of advanced squamous cell carcinoma tumors with a combination of ablative fractional laser and systemic treatment with PD-1 inhibitors resulted in the clearance of more tumors than with either treatment as monotherapy. “What we want to explore is the laser-induced tumor immune response in keratinocyte cancers,” she added.

“When you shine the laser on the skin, there is a robust increase of neutrophilic granulocytes.” Combining this topical immune-boosting response with systemic delivery of PD-1 inhibitors in a mouse model with basal cell carcinoma, she said, “we learned that, when we compare systemic PD-1 inhibitors alone to the laser alone and then with combination therapy, there was an increased tumor clearance of basal cell carcinomas and also enhanced survival of the mice” with the combination, she said. There were also “enhanced neutrophilic counts and both CD4- and CD8-positive cells were increased,” she added.

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received grants or research funding from Lutronic, Venus Concept, Leo Pharma, and Mirai Medical.

SAN DIEGO – Twelve years ago, Merete Haedersdal, MD, PhD, and colleagues published data from a swine study, which showed for the first time that the ablative fractional laser can be used to boost the uptake of drugs into the skin.

That discovery paved the way for what are now well-established clinical applications of laser-assisted drug delivery for treating actinic keratoses and scars. According to Dr. Haedersdal, professor of dermatology at the University of Copenhagen, evolving clinical indications for laser-assisted drug delivery include rejuvenation, local anesthesia, melasma, onychomycosis, hyperhidrosis, alopecia, and vitiligo, while emerging indications include treatment of skin cancer with PD-1 inhibitors and combination chemotherapy regimens, and vaccinations.

During a presentation at the annual conference of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, she said that researchers have much to learn about laser-assisted drug delivery, including biodistribution of the drug being delivered. Pointing out that so far, “what we have been dealing with is primarily looking at the skin as a black box,” she asked, “what happens when we drill the holes and drugs are applied on top of the skin and swim through the tiny channels?”

By using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and HPLC mass spectrometry to measure drug concentration in the skin, she and her colleagues have observed enhanced uptake of drugs – 4-fold to 40-fold greater – primarily in ex vivo pig skin. “We do know from ex vivo models that it’s much easier to boost the uptake in the skin” when compared with in vivo human use, where much lower drug concentrations are detected, said Dr. Haedersdal, who, along with Emily Wenande, MD, PhD, and R. Rox Anderson, MD, at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, authored a clinical review, published in 2020, on the basics of laser-assisted drug delivery.

“What we are working on now is visualizing what’s taking place when we apply the holes and the drugs in the skin. This is the key to tailoring laser-assisted uptake to specific dermatologic diseases being treated,” she said. To date, she and her colleagues have examined the interaction with tissue using different devices, including ex vivo confocal microscopy, to view the thermal response to ablative fractional laser and radiofrequency. “We want to take that to the next level and look at the drug biodistribution.”

Efforts are underway to compare the pattern of drug distribution with different modes of delivery, such as comparing ablative fractional laser to intradermal needle injection. “We are also working on pneumatic jet injection, which creates a focal drug distribution,” said Dr. Haedersdal, who is a visiting scientist at the Wellman Center. “In the future, we may take advantage of device-tailored biodistribution, depending on which clinical indication we are treating.”

Another important aspect to consider is drug retention in the skin. In a study presented as an abstract at the meeting, led by Dr. Wenande, she, Dr. Haedersdal, and colleagues used a pig model to evaluate the effect of three vasoregulative interventions on ablative fractional laser-assisted 5-fluororacil concentrations in in vivo skin. The three interventions were brimonidine 0.33% solution, epinephrine 10 mcg/mL gel, and a 595-nm pulsed dye laser (PDL) in designated treatment areas.

“What we learned from that was in the short term – 1-4 hours – the ablative fractional laser enhanced the uptake of 5-FU, but it was very transient,” with a twofold increased concentration of 5-FU, Dr. Haedersdal said. Over 48-72 hours, after PDL, there was “sustained enhancement of drug in the skin by three to four times,” she noted.

The synergy of systemic drugs with ablative fractional laser therapy is also being evaluated. In a mouse study led by Dr. Haedersdal’s colleague, senior researcher Uffe H. Olesen, PhD, the treatment of advanced squamous cell carcinoma tumors with a combination of ablative fractional laser and systemic treatment with PD-1 inhibitors resulted in the clearance of more tumors than with either treatment as monotherapy. “What we want to explore is the laser-induced tumor immune response in keratinocyte cancers,” she added.

“When you shine the laser on the skin, there is a robust increase of neutrophilic granulocytes.” Combining this topical immune-boosting response with systemic delivery of PD-1 inhibitors in a mouse model with basal cell carcinoma, she said, “we learned that, when we compare systemic PD-1 inhibitors alone to the laser alone and then with combination therapy, there was an increased tumor clearance of basal cell carcinomas and also enhanced survival of the mice” with the combination, she said. There were also “enhanced neutrophilic counts and both CD4- and CD8-positive cells were increased,” she added.

Dr. Haedersdal disclosed that she has received grants or research funding from Lutronic, Venus Concept, Leo Pharma, and Mirai Medical.

AT ASLMS 2022

Can lasers be used to measure nerve sensitivity in the skin?

SAN DIEGO – In a 2006 report of complications from laser dermatologic surgery, one of the authors, Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD, who had subjected his forearm to treatment with a fractional laser skin resurfacing prototype device, was included as 1 of the 19 featured cases.

Dr. Manstein, of the Cutaneous Biology Research Center in the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, was exposed to three test spots in the evaluation of the effects of different microscopic thermal zone densities for the prototype device, emitting at 1,450 nm and an energy per MTZ of 3 mJ.

Two years later, hypopigmentation persisted at the test site treated with the highest MTZ density, while two other sites treated with the lower MTZ densities did not show any dyspigmentation. But he noticed something else during the experiment: He felt minimal to no pain as each test site was being treated.

“It took 7 minutes without any cooling or anesthesia,” Dr. Manstein recalled at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “It was not completely painless, but each time the laser was applied, sometimes I felt a little prick, sometimes I felt nothing.” Essentially, he added, “we created cell injury with a focused laser beam without anesthesia,” but this could also indicate that if skin is treated with a fractional laser very slowly, anesthesia is not needed. “Current devices are meant to treat very quickly, but if we [treat] slowly, maybe you could remove lesions painlessly without anesthesia.”

The observation from that experiment also led Dr. Manstein and colleagues to wonder: Could a focused laser beam pattern be used to assess cutaneous innervation? If so, they postulated, perhaps it could be used to not only assess nerve sensitivity of candidates for dermatologic surgery, but as a tool to help diagnose small fiber neuropathies such as diabetic neuropathy, and neuropathies in patients with HIV and sarcoidosis.

The current gold standard for making these diagnoses involves a skin biopsy, immunohistochemical analysis, and nerve fiber quantification, which is not widely available. It also requires strict histologic processing and nerve counting rules. Confocal microscopy of nerve fibers in the cornea is another approach, but is very difficult to perform, “so it would be nice if there was a simple way” to determine nerve fiber density in the skin using a focused laser beam, Dr. Manstein said.

With help from Payal Patel, MD, a dermatology research fellow at MGH, records each subject’s perception of a stimulus, and maps the areas of stimulus response. Current diameters being studied range from 0.076-1.15 mm and depths less than 0.71 mm. “We can focus the laser beam, preset the beam diameter, and very slowly, in a controlled manner, make a rectangular pattern, and after each time, inquire if the subject felt the pulse or not,” Dr. Manstein explained.

“This laser could become a new method for diagnosing nerve fiber neuropathies. If this works well, I think we can miniaturize the device,” he added.

Dr. Manstein disclosed that he is a consultant for Blossom Innovations, R2 Dermatology, and AVAVA. He is also a member of the advisory board for Blossom Innovations.

SAN DIEGO – In a 2006 report of complications from laser dermatologic surgery, one of the authors, Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD, who had subjected his forearm to treatment with a fractional laser skin resurfacing prototype device, was included as 1 of the 19 featured cases.

Dr. Manstein, of the Cutaneous Biology Research Center in the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, was exposed to three test spots in the evaluation of the effects of different microscopic thermal zone densities for the prototype device, emitting at 1,450 nm and an energy per MTZ of 3 mJ.

Two years later, hypopigmentation persisted at the test site treated with the highest MTZ density, while two other sites treated with the lower MTZ densities did not show any dyspigmentation. But he noticed something else during the experiment: He felt minimal to no pain as each test site was being treated.

“It took 7 minutes without any cooling or anesthesia,” Dr. Manstein recalled at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “It was not completely painless, but each time the laser was applied, sometimes I felt a little prick, sometimes I felt nothing.” Essentially, he added, “we created cell injury with a focused laser beam without anesthesia,” but this could also indicate that if skin is treated with a fractional laser very slowly, anesthesia is not needed. “Current devices are meant to treat very quickly, but if we [treat] slowly, maybe you could remove lesions painlessly without anesthesia.”

The observation from that experiment also led Dr. Manstein and colleagues to wonder: Could a focused laser beam pattern be used to assess cutaneous innervation? If so, they postulated, perhaps it could be used to not only assess nerve sensitivity of candidates for dermatologic surgery, but as a tool to help diagnose small fiber neuropathies such as diabetic neuropathy, and neuropathies in patients with HIV and sarcoidosis.

The current gold standard for making these diagnoses involves a skin biopsy, immunohistochemical analysis, and nerve fiber quantification, which is not widely available. It also requires strict histologic processing and nerve counting rules. Confocal microscopy of nerve fibers in the cornea is another approach, but is very difficult to perform, “so it would be nice if there was a simple way” to determine nerve fiber density in the skin using a focused laser beam, Dr. Manstein said.

With help from Payal Patel, MD, a dermatology research fellow at MGH, records each subject’s perception of a stimulus, and maps the areas of stimulus response. Current diameters being studied range from 0.076-1.15 mm and depths less than 0.71 mm. “We can focus the laser beam, preset the beam diameter, and very slowly, in a controlled manner, make a rectangular pattern, and after each time, inquire if the subject felt the pulse or not,” Dr. Manstein explained.

“This laser could become a new method for diagnosing nerve fiber neuropathies. If this works well, I think we can miniaturize the device,” he added.

Dr. Manstein disclosed that he is a consultant for Blossom Innovations, R2 Dermatology, and AVAVA. He is also a member of the advisory board for Blossom Innovations.

SAN DIEGO – In a 2006 report of complications from laser dermatologic surgery, one of the authors, Dieter Manstein, MD, PhD, who had subjected his forearm to treatment with a fractional laser skin resurfacing prototype device, was included as 1 of the 19 featured cases.

Dr. Manstein, of the Cutaneous Biology Research Center in the department of dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, was exposed to three test spots in the evaluation of the effects of different microscopic thermal zone densities for the prototype device, emitting at 1,450 nm and an energy per MTZ of 3 mJ.

Two years later, hypopigmentation persisted at the test site treated with the highest MTZ density, while two other sites treated with the lower MTZ densities did not show any dyspigmentation. But he noticed something else during the experiment: He felt minimal to no pain as each test site was being treated.

“It took 7 minutes without any cooling or anesthesia,” Dr. Manstein recalled at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “It was not completely painless, but each time the laser was applied, sometimes I felt a little prick, sometimes I felt nothing.” Essentially, he added, “we created cell injury with a focused laser beam without anesthesia,” but this could also indicate that if skin is treated with a fractional laser very slowly, anesthesia is not needed. “Current devices are meant to treat very quickly, but if we [treat] slowly, maybe you could remove lesions painlessly without anesthesia.”

The observation from that experiment also led Dr. Manstein and colleagues to wonder: Could a focused laser beam pattern be used to assess cutaneous innervation? If so, they postulated, perhaps it could be used to not only assess nerve sensitivity of candidates for dermatologic surgery, but as a tool to help diagnose small fiber neuropathies such as diabetic neuropathy, and neuropathies in patients with HIV and sarcoidosis.

The current gold standard for making these diagnoses involves a skin biopsy, immunohistochemical analysis, and nerve fiber quantification, which is not widely available. It also requires strict histologic processing and nerve counting rules. Confocal microscopy of nerve fibers in the cornea is another approach, but is very difficult to perform, “so it would be nice if there was a simple way” to determine nerve fiber density in the skin using a focused laser beam, Dr. Manstein said.

With help from Payal Patel, MD, a dermatology research fellow at MGH, records each subject’s perception of a stimulus, and maps the areas of stimulus response. Current diameters being studied range from 0.076-1.15 mm and depths less than 0.71 mm. “We can focus the laser beam, preset the beam diameter, and very slowly, in a controlled manner, make a rectangular pattern, and after each time, inquire if the subject felt the pulse or not,” Dr. Manstein explained.

“This laser could become a new method for diagnosing nerve fiber neuropathies. If this works well, I think we can miniaturize the device,” he added.

Dr. Manstein disclosed that he is a consultant for Blossom Innovations, R2 Dermatology, and AVAVA. He is also a member of the advisory board for Blossom Innovations.

AT ASLMS 2022

Fractional lasers appear to treat more than a fraction of skin, expert says

SAN DIEGO – Using the according to Molly Wanner, MD, MBA.

As a case in point, Dr. Wanner discussed the results of a trial of 48 people over aged 60 years with actinic damage, who received ablative fractional laser treatment on one arm and no treatment on the other arm, which served as the control. At 24 months, only two nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) developed on the treated arms, compared with 26 on the treated arms.

“What I find interesting is that the treated arm did not develop basal cell carcinoma, only squamous cell carcinoma,” she said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “It appears that this is working through more than just treatment of the AK precursor lesions, for which fractional lasers are cleared for use. It appears to impact both types of NMSCs.”

The ablative fractional laser and other wounding therapies can modulate a response to UV light – a process that naturally diminishes with age, according to Dr. Wanner, a dermatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center in Boston. “This ability to repair DNA is actually modulated by insulin-like growth factor 1,” she said. “IGF-1 is produced by papillary dermal fibroblasts and communicates with keratinocytes. If keratinocytes are exposed to UV light and there is no IGF-1 around, you get a mutated cell, and that keeps spreading, and you could potentially get a skin cancer.”

On the other hand, she continued, if IGF-1 is injected around the keratinocytes, they are able to respond. “Keratinocytes, which are the most superficial layer of the skin, are really active,” noted Dr. Wanner, who is also an assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “They’re dividing and replicating, whereas fibroblasts are more non-proliferative and more long-lived. They stick around for a long time. I think of them as the adults in the room, giving these new keratinocytes direction.”

In a review of wounding therapies for the prevention of photocarcinogenesis, she and her coauthors noted that IGF-1 increases nucleotide excision repair of damaged DNA, promotes checkpoint signaling and suppression of DNA synthesis, favors specialized polymerases that are better able to repair DNA damage, and enhances p53-dependent transcriptional responses to DNA damage.

“Older fibroblasts produce less IGF-1 and lead to a situation where keratinocytes can grow unchecked,” she said. “We can use fractional laser to help with this. Fractional laser increases fibroblast production and decreases senescent fibroblasts.”

In a 2017 review on the impact of age and IGF-1 on DNA damage responses in UV-irradiated skin, the authors noted the high levels of IGF-1 in the skin of younger individuals and lower levels in the skin of their older counterparts.

“But once older skin has been treated with either dermabrasion or fractional laser, the levels of IGF-1 are restored to that of a young adult,” Dr. Wanner said. “The restoration of IGF-1 then restores that level of appropriate response to UV light. So, what’s interesting is that fractional lasers treat more than a fraction [of skin]. Fractional lasers were developed to have an easier way to improve wound healing by leaving the skin intact around these columns [of treated skin]. It turns out that treatment of these columns of skin does not just impact the cells in that area. There is a true global effect that’s allowing us to almost normalize skin.”

Dr. Wanner now thinks of fractional lasers as stimulating a laser-cell biology interaction, not just a laser-tissue interaction. “It’s incredible that we can use these photons to not only impact the tissue itself but how the cells actually respond,” she said. “What’s going to be interesting for us in the next few years is to look at how lasers impact our cellular biology. How can we harness it to help our patients?”

She and her colleagues are conducting a trial of different wounding modalities to assess their impact on IGF-1. “Does depth matter? Does density matter? Does the wavelength matter?” she asked. “The bottom line is, it turns out that when the skin looks healthier, it is healthier. Cosmetic treatments can impact medical outcomes.”

Dr. Wanner disclosed that she is a consultant and advisor to Nu Skin. She has also received research funding and equipment from Solta.

SAN DIEGO – Using the according to Molly Wanner, MD, MBA.

As a case in point, Dr. Wanner discussed the results of a trial of 48 people over aged 60 years with actinic damage, who received ablative fractional laser treatment on one arm and no treatment on the other arm, which served as the control. At 24 months, only two nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) developed on the treated arms, compared with 26 on the treated arms.

“What I find interesting is that the treated arm did not develop basal cell carcinoma, only squamous cell carcinoma,” she said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “It appears that this is working through more than just treatment of the AK precursor lesions, for which fractional lasers are cleared for use. It appears to impact both types of NMSCs.”

The ablative fractional laser and other wounding therapies can modulate a response to UV light – a process that naturally diminishes with age, according to Dr. Wanner, a dermatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center in Boston. “This ability to repair DNA is actually modulated by insulin-like growth factor 1,” she said. “IGF-1 is produced by papillary dermal fibroblasts and communicates with keratinocytes. If keratinocytes are exposed to UV light and there is no IGF-1 around, you get a mutated cell, and that keeps spreading, and you could potentially get a skin cancer.”

On the other hand, she continued, if IGF-1 is injected around the keratinocytes, they are able to respond. “Keratinocytes, which are the most superficial layer of the skin, are really active,” noted Dr. Wanner, who is also an assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “They’re dividing and replicating, whereas fibroblasts are more non-proliferative and more long-lived. They stick around for a long time. I think of them as the adults in the room, giving these new keratinocytes direction.”

In a review of wounding therapies for the prevention of photocarcinogenesis, she and her coauthors noted that IGF-1 increases nucleotide excision repair of damaged DNA, promotes checkpoint signaling and suppression of DNA synthesis, favors specialized polymerases that are better able to repair DNA damage, and enhances p53-dependent transcriptional responses to DNA damage.

“Older fibroblasts produce less IGF-1 and lead to a situation where keratinocytes can grow unchecked,” she said. “We can use fractional laser to help with this. Fractional laser increases fibroblast production and decreases senescent fibroblasts.”

In a 2017 review on the impact of age and IGF-1 on DNA damage responses in UV-irradiated skin, the authors noted the high levels of IGF-1 in the skin of younger individuals and lower levels in the skin of their older counterparts.

“But once older skin has been treated with either dermabrasion or fractional laser, the levels of IGF-1 are restored to that of a young adult,” Dr. Wanner said. “The restoration of IGF-1 then restores that level of appropriate response to UV light. So, what’s interesting is that fractional lasers treat more than a fraction [of skin]. Fractional lasers were developed to have an easier way to improve wound healing by leaving the skin intact around these columns [of treated skin]. It turns out that treatment of these columns of skin does not just impact the cells in that area. There is a true global effect that’s allowing us to almost normalize skin.”

Dr. Wanner now thinks of fractional lasers as stimulating a laser-cell biology interaction, not just a laser-tissue interaction. “It’s incredible that we can use these photons to not only impact the tissue itself but how the cells actually respond,” she said. “What’s going to be interesting for us in the next few years is to look at how lasers impact our cellular biology. How can we harness it to help our patients?”

She and her colleagues are conducting a trial of different wounding modalities to assess their impact on IGF-1. “Does depth matter? Does density matter? Does the wavelength matter?” she asked. “The bottom line is, it turns out that when the skin looks healthier, it is healthier. Cosmetic treatments can impact medical outcomes.”

Dr. Wanner disclosed that she is a consultant and advisor to Nu Skin. She has also received research funding and equipment from Solta.

SAN DIEGO – Using the according to Molly Wanner, MD, MBA.

As a case in point, Dr. Wanner discussed the results of a trial of 48 people over aged 60 years with actinic damage, who received ablative fractional laser treatment on one arm and no treatment on the other arm, which served as the control. At 24 months, only two nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) developed on the treated arms, compared with 26 on the treated arms.

“What I find interesting is that the treated arm did not develop basal cell carcinoma, only squamous cell carcinoma,” she said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “It appears that this is working through more than just treatment of the AK precursor lesions, for which fractional lasers are cleared for use. It appears to impact both types of NMSCs.”

The ablative fractional laser and other wounding therapies can modulate a response to UV light – a process that naturally diminishes with age, according to Dr. Wanner, a dermatologist at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Dermatology Laser and Cosmetic Center in Boston. “This ability to repair DNA is actually modulated by insulin-like growth factor 1,” she said. “IGF-1 is produced by papillary dermal fibroblasts and communicates with keratinocytes. If keratinocytes are exposed to UV light and there is no IGF-1 around, you get a mutated cell, and that keeps spreading, and you could potentially get a skin cancer.”

On the other hand, she continued, if IGF-1 is injected around the keratinocytes, they are able to respond. “Keratinocytes, which are the most superficial layer of the skin, are really active,” noted Dr. Wanner, who is also an assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “They’re dividing and replicating, whereas fibroblasts are more non-proliferative and more long-lived. They stick around for a long time. I think of them as the adults in the room, giving these new keratinocytes direction.”

In a review of wounding therapies for the prevention of photocarcinogenesis, she and her coauthors noted that IGF-1 increases nucleotide excision repair of damaged DNA, promotes checkpoint signaling and suppression of DNA synthesis, favors specialized polymerases that are better able to repair DNA damage, and enhances p53-dependent transcriptional responses to DNA damage.

“Older fibroblasts produce less IGF-1 and lead to a situation where keratinocytes can grow unchecked,” she said. “We can use fractional laser to help with this. Fractional laser increases fibroblast production and decreases senescent fibroblasts.”

In a 2017 review on the impact of age and IGF-1 on DNA damage responses in UV-irradiated skin, the authors noted the high levels of IGF-1 in the skin of younger individuals and lower levels in the skin of their older counterparts.

“But once older skin has been treated with either dermabrasion or fractional laser, the levels of IGF-1 are restored to that of a young adult,” Dr. Wanner said. “The restoration of IGF-1 then restores that level of appropriate response to UV light. So, what’s interesting is that fractional lasers treat more than a fraction [of skin]. Fractional lasers were developed to have an easier way to improve wound healing by leaving the skin intact around these columns [of treated skin]. It turns out that treatment of these columns of skin does not just impact the cells in that area. There is a true global effect that’s allowing us to almost normalize skin.”

Dr. Wanner now thinks of fractional lasers as stimulating a laser-cell biology interaction, not just a laser-tissue interaction. “It’s incredible that we can use these photons to not only impact the tissue itself but how the cells actually respond,” she said. “What’s going to be interesting for us in the next few years is to look at how lasers impact our cellular biology. How can we harness it to help our patients?”

She and her colleagues are conducting a trial of different wounding modalities to assess their impact on IGF-1. “Does depth matter? Does density matter? Does the wavelength matter?” she asked. “The bottom line is, it turns out that when the skin looks healthier, it is healthier. Cosmetic treatments can impact medical outcomes.”

Dr. Wanner disclosed that she is a consultant and advisor to Nu Skin. She has also received research funding and equipment from Solta.

AT ASLMS 2022

‘Cool’ way of eradicating fat a promising therapy for many medical conditions

SAN DIEGO – During her third year in the combined Harvard/Massachusetts General Hospital dermatology residency program in 2011, Lilit Garibyan, MD, PhD, attended a lecture presented by R. Rox Anderson, MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at MGH. He described the concept of selective cryolipolysis – the method of removing fat by topical cooling that eventually led to the development of the CoolSculpting device.

“He was saying that this is such a great noninvasive technology for fat removal and that patients love it,” Dr. Garibyan recalled at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “But one of the most common side effects after cryolipolysis that is long-lasting, but completely reversible, is hypoesthesia. I was intrigued by this because even as a dermatology resident, I had seen how pain and itch symptoms are present in many dermatologic diseases, and we don’t have great treatments for them. I thought to myself, not the fat.

Following Dr. Anderson’s lecture, Dr. Garibyan asked him if anyone knew the mechanism of action or if anyone was working to find out. He did not, but Dr. Anderson invited her to join his lab to investigate. “I didn’t have a background in lasers or energy devices, but I thought this was such a great opportunity” and addressed an unmet need, she said at the meeting.

Dr. Garibyan then led a clinical trial to characterize the effect of a single cryolipolysis treatment in 11 healthy people and to quantitatively analyze what sensory functions change with treatment over a period of 56 days. Skin biopsies revealed that cryolipolysis mainly decreased myelinated dermal nerve fiber density, which persisted throughout the study.

“The conclusion was that yes, controlled topical cooling does lead to significant and long-lasting but reversible reduction of sensory function, including pain,” said Dr. Garibyan, who is now an assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Magic Wand Initiative at the Wellman Center.

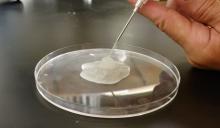

Ice slurry injections

Enter ice slurry, a chilly mix of ice, saline, and glycol that can be directly injected into adipose tissue. In a swine study published online in January 2020, Dr. Garibyan and colleagues at the Wellman Center injected ice slurry into the flanks of swine and followed them for up to 8 weeks, using ultrasound imaging to quantify and show the location of fat loss. The researchers observed about 40%-50% loss of fat in the treated area, compared with a 60% increase of fat in controls. “On histology, this was very selective,” she said. “Only adipose tissue was affected. There was no damage to the underlying muscle or to the dermis or epidermis.”

In 2021, researchers tested the injection of ice slurry in 12 humans for the first time, injected into tissue, and followed them for 12 weeks. As observed by thermal imaging, ultrasound, and tissue histology, they concluded that ice slurry injection was feasible and safe as a way of inducing cryolipolysis, and was well tolerated by patients.

“This can become a promising treatment for a precise, effective, and customizable way of removing unwanted fat for aesthetic application,” Dr. Garibyan said. However, she added, it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration and more studies are needed, “but it’s promising and encouraging to see this move forward in patients.”

Potential nonaesthetic uses

The potential applications of injectable ice slurry extend well beyond cosmetic dermatology, she continued, noting that it is being explored as a treatment for many medical conditions including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). At the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, researchers used MRI to image the tongue fat in a case-control study of 31 obese patients without OSA and 90 obese patients with OSA. They found that patients with OSA had increased deposition of fat at the base of their tongue, which can lead to airway obstruction in this subset of patients with OSA, pointed out Dr. Garibyan, who was not involved with the study. “This also gave us a hint. If we can remove that tongue fat, we could potentially help reduce severity or even cure OSA in this population of patients. This points to tongue fat as a therapeutic target.”

With help from researchers at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., she and her Wellman Center colleagues recently completed a swine study that showed the safety and feasibility of injecting the base of the tongue with ice slurry, targeting adipose tissue. The work has been submitted for publication in a journal, but at the meeting, she said that, 8 weeks after injecting the ice slurry, there were no changes to any tongue tissue other than fat.

“On histology, we only see selective damage to the adipose tissue,” she said. “It is very promising that it’s safe in animal models and we’re hoping to conduct a human trial later this year to test the ability of this injectable ice slurry to remove fat at the base of the tongue with the hope that this will treat OSA.”

Another potential application of this technology is in the cardiology field. Dr. Garibyan is part of a multidisciplinary team at MGH that includes cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, and imaging experts who plan to investigate whether injecting ice slurry into fat around the heart can modify heart disease in humans. “Visceral fat around the heart – pericardial fat and epicardial fat – is involved in cardiovascular disease, arrhythmias, and many other unwanted effects on the heart,” she said. “Imagine if you could inject this around the heart, ablate the fat, and halt cardiovascular disease?”

She led a study that examined the effect of injecting ice slurry into swine with significant amounts of adipose tissue around their hearts, based on baseline CT scans. She and her coinvestigators observed a significant loss of that fat tissue on follow-up CT scans 8 weeks later. “On average, there was about a 30% reduction of this pericardial adipose tissue after a single injection,” and the procedure “was safe and well tolerated by the animals,” she added.

Ice slurry could also play a role in managing pain by targeting peripheral nerves. Peripheral nerves are composed of 75%-80% lipids, such as the myelin sheaths around the nerves, she noted. “That’s lipid-rich tissue. We think that by targeting that we’re able to block pain.”

She led a study that showed that a single injection of ice slurry around the sciatic nerve in rats served as a sustained anesthetic by blocking mechanical pain sensation for up to 56 days. They imaged the peripheral nerves in the rats and showed that the mechanism involved was loss of the lipid-rich myelin tissue around the nerves, which blocks the signaling of the nerve, she said.

Dr. Garibyan disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board for Brixton Biosciences, Vyome Therapeutics, and Aegle Therapeutics. She is also a consultant for Aegle Therapeutics and Blossom Innovations and holds equity in Brixton Biosciences and EyeCool Therapeutics.

SAN DIEGO – During her third year in the combined Harvard/Massachusetts General Hospital dermatology residency program in 2011, Lilit Garibyan, MD, PhD, attended a lecture presented by R. Rox Anderson, MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at MGH. He described the concept of selective cryolipolysis – the method of removing fat by topical cooling that eventually led to the development of the CoolSculpting device.

“He was saying that this is such a great noninvasive technology for fat removal and that patients love it,” Dr. Garibyan recalled at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “But one of the most common side effects after cryolipolysis that is long-lasting, but completely reversible, is hypoesthesia. I was intrigued by this because even as a dermatology resident, I had seen how pain and itch symptoms are present in many dermatologic diseases, and we don’t have great treatments for them. I thought to myself, not the fat.

Following Dr. Anderson’s lecture, Dr. Garibyan asked him if anyone knew the mechanism of action or if anyone was working to find out. He did not, but Dr. Anderson invited her to join his lab to investigate. “I didn’t have a background in lasers or energy devices, but I thought this was such a great opportunity” and addressed an unmet need, she said at the meeting.

Dr. Garibyan then led a clinical trial to characterize the effect of a single cryolipolysis treatment in 11 healthy people and to quantitatively analyze what sensory functions change with treatment over a period of 56 days. Skin biopsies revealed that cryolipolysis mainly decreased myelinated dermal nerve fiber density, which persisted throughout the study.

“The conclusion was that yes, controlled topical cooling does lead to significant and long-lasting but reversible reduction of sensory function, including pain,” said Dr. Garibyan, who is now an assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Magic Wand Initiative at the Wellman Center.

Ice slurry injections

Enter ice slurry, a chilly mix of ice, saline, and glycol that can be directly injected into adipose tissue. In a swine study published online in January 2020, Dr. Garibyan and colleagues at the Wellman Center injected ice slurry into the flanks of swine and followed them for up to 8 weeks, using ultrasound imaging to quantify and show the location of fat loss. The researchers observed about 40%-50% loss of fat in the treated area, compared with a 60% increase of fat in controls. “On histology, this was very selective,” she said. “Only adipose tissue was affected. There was no damage to the underlying muscle or to the dermis or epidermis.”

In 2021, researchers tested the injection of ice slurry in 12 humans for the first time, injected into tissue, and followed them for 12 weeks. As observed by thermal imaging, ultrasound, and tissue histology, they concluded that ice slurry injection was feasible and safe as a way of inducing cryolipolysis, and was well tolerated by patients.

“This can become a promising treatment for a precise, effective, and customizable way of removing unwanted fat for aesthetic application,” Dr. Garibyan said. However, she added, it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration and more studies are needed, “but it’s promising and encouraging to see this move forward in patients.”

Potential nonaesthetic uses

The potential applications of injectable ice slurry extend well beyond cosmetic dermatology, she continued, noting that it is being explored as a treatment for many medical conditions including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). At the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, researchers used MRI to image the tongue fat in a case-control study of 31 obese patients without OSA and 90 obese patients with OSA. They found that patients with OSA had increased deposition of fat at the base of their tongue, which can lead to airway obstruction in this subset of patients with OSA, pointed out Dr. Garibyan, who was not involved with the study. “This also gave us a hint. If we can remove that tongue fat, we could potentially help reduce severity or even cure OSA in this population of patients. This points to tongue fat as a therapeutic target.”

With help from researchers at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., she and her Wellman Center colleagues recently completed a swine study that showed the safety and feasibility of injecting the base of the tongue with ice slurry, targeting adipose tissue. The work has been submitted for publication in a journal, but at the meeting, she said that, 8 weeks after injecting the ice slurry, there were no changes to any tongue tissue other than fat.

“On histology, we only see selective damage to the adipose tissue,” she said. “It is very promising that it’s safe in animal models and we’re hoping to conduct a human trial later this year to test the ability of this injectable ice slurry to remove fat at the base of the tongue with the hope that this will treat OSA.”

Another potential application of this technology is in the cardiology field. Dr. Garibyan is part of a multidisciplinary team at MGH that includes cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, and imaging experts who plan to investigate whether injecting ice slurry into fat around the heart can modify heart disease in humans. “Visceral fat around the heart – pericardial fat and epicardial fat – is involved in cardiovascular disease, arrhythmias, and many other unwanted effects on the heart,” she said. “Imagine if you could inject this around the heart, ablate the fat, and halt cardiovascular disease?”

She led a study that examined the effect of injecting ice slurry into swine with significant amounts of adipose tissue around their hearts, based on baseline CT scans. She and her coinvestigators observed a significant loss of that fat tissue on follow-up CT scans 8 weeks later. “On average, there was about a 30% reduction of this pericardial adipose tissue after a single injection,” and the procedure “was safe and well tolerated by the animals,” she added.

Ice slurry could also play a role in managing pain by targeting peripheral nerves. Peripheral nerves are composed of 75%-80% lipids, such as the myelin sheaths around the nerves, she noted. “That’s lipid-rich tissue. We think that by targeting that we’re able to block pain.”

She led a study that showed that a single injection of ice slurry around the sciatic nerve in rats served as a sustained anesthetic by blocking mechanical pain sensation for up to 56 days. They imaged the peripheral nerves in the rats and showed that the mechanism involved was loss of the lipid-rich myelin tissue around the nerves, which blocks the signaling of the nerve, she said.

Dr. Garibyan disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board for Brixton Biosciences, Vyome Therapeutics, and Aegle Therapeutics. She is also a consultant for Aegle Therapeutics and Blossom Innovations and holds equity in Brixton Biosciences and EyeCool Therapeutics.

SAN DIEGO – During her third year in the combined Harvard/Massachusetts General Hospital dermatology residency program in 2011, Lilit Garibyan, MD, PhD, attended a lecture presented by R. Rox Anderson, MD, director of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at MGH. He described the concept of selective cryolipolysis – the method of removing fat by topical cooling that eventually led to the development of the CoolSculpting device.

“He was saying that this is such a great noninvasive technology for fat removal and that patients love it,” Dr. Garibyan recalled at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery. “But one of the most common side effects after cryolipolysis that is long-lasting, but completely reversible, is hypoesthesia. I was intrigued by this because even as a dermatology resident, I had seen how pain and itch symptoms are present in many dermatologic diseases, and we don’t have great treatments for them. I thought to myself, not the fat.

Following Dr. Anderson’s lecture, Dr. Garibyan asked him if anyone knew the mechanism of action or if anyone was working to find out. He did not, but Dr. Anderson invited her to join his lab to investigate. “I didn’t have a background in lasers or energy devices, but I thought this was such a great opportunity” and addressed an unmet need, she said at the meeting.

Dr. Garibyan then led a clinical trial to characterize the effect of a single cryolipolysis treatment in 11 healthy people and to quantitatively analyze what sensory functions change with treatment over a period of 56 days. Skin biopsies revealed that cryolipolysis mainly decreased myelinated dermal nerve fiber density, which persisted throughout the study.

“The conclusion was that yes, controlled topical cooling does lead to significant and long-lasting but reversible reduction of sensory function, including pain,” said Dr. Garibyan, who is now an assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of the Magic Wand Initiative at the Wellman Center.

Ice slurry injections

Enter ice slurry, a chilly mix of ice, saline, and glycol that can be directly injected into adipose tissue. In a swine study published online in January 2020, Dr. Garibyan and colleagues at the Wellman Center injected ice slurry into the flanks of swine and followed them for up to 8 weeks, using ultrasound imaging to quantify and show the location of fat loss. The researchers observed about 40%-50% loss of fat in the treated area, compared with a 60% increase of fat in controls. “On histology, this was very selective,” she said. “Only adipose tissue was affected. There was no damage to the underlying muscle or to the dermis or epidermis.”

In 2021, researchers tested the injection of ice slurry in 12 humans for the first time, injected into tissue, and followed them for 12 weeks. As observed by thermal imaging, ultrasound, and tissue histology, they concluded that ice slurry injection was feasible and safe as a way of inducing cryolipolysis, and was well tolerated by patients.

“This can become a promising treatment for a precise, effective, and customizable way of removing unwanted fat for aesthetic application,” Dr. Garibyan said. However, she added, it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration and more studies are needed, “but it’s promising and encouraging to see this move forward in patients.”

Potential nonaesthetic uses

The potential applications of injectable ice slurry extend well beyond cosmetic dermatology, she continued, noting that it is being explored as a treatment for many medical conditions including obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). At the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, researchers used MRI to image the tongue fat in a case-control study of 31 obese patients without OSA and 90 obese patients with OSA. They found that patients with OSA had increased deposition of fat at the base of their tongue, which can lead to airway obstruction in this subset of patients with OSA, pointed out Dr. Garibyan, who was not involved with the study. “This also gave us a hint. If we can remove that tongue fat, we could potentially help reduce severity or even cure OSA in this population of patients. This points to tongue fat as a therapeutic target.”

With help from researchers at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md., she and her Wellman Center colleagues recently completed a swine study that showed the safety and feasibility of injecting the base of the tongue with ice slurry, targeting adipose tissue. The work has been submitted for publication in a journal, but at the meeting, she said that, 8 weeks after injecting the ice slurry, there were no changes to any tongue tissue other than fat.

“On histology, we only see selective damage to the adipose tissue,” she said. “It is very promising that it’s safe in animal models and we’re hoping to conduct a human trial later this year to test the ability of this injectable ice slurry to remove fat at the base of the tongue with the hope that this will treat OSA.”

Another potential application of this technology is in the cardiology field. Dr. Garibyan is part of a multidisciplinary team at MGH that includes cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, and imaging experts who plan to investigate whether injecting ice slurry into fat around the heart can modify heart disease in humans. “Visceral fat around the heart – pericardial fat and epicardial fat – is involved in cardiovascular disease, arrhythmias, and many other unwanted effects on the heart,” she said. “Imagine if you could inject this around the heart, ablate the fat, and halt cardiovascular disease?”

She led a study that examined the effect of injecting ice slurry into swine with significant amounts of adipose tissue around their hearts, based on baseline CT scans. She and her coinvestigators observed a significant loss of that fat tissue on follow-up CT scans 8 weeks later. “On average, there was about a 30% reduction of this pericardial adipose tissue after a single injection,” and the procedure “was safe and well tolerated by the animals,” she added.

Ice slurry could also play a role in managing pain by targeting peripheral nerves. Peripheral nerves are composed of 75%-80% lipids, such as the myelin sheaths around the nerves, she noted. “That’s lipid-rich tissue. We think that by targeting that we’re able to block pain.”

She led a study that showed that a single injection of ice slurry around the sciatic nerve in rats served as a sustained anesthetic by blocking mechanical pain sensation for up to 56 days. They imaged the peripheral nerves in the rats and showed that the mechanism involved was loss of the lipid-rich myelin tissue around the nerves, which blocks the signaling of the nerve, she said.

Dr. Garibyan disclosed that she is a member of the advisory board for Brixton Biosciences, Vyome Therapeutics, and Aegle Therapeutics. She is also a consultant for Aegle Therapeutics and Blossom Innovations and holds equity in Brixton Biosciences and EyeCool Therapeutics.

AT ASLMS 2022

Forceps for Milia Extraction

To the Editor:

Several techniques can be used to destroy milia including electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy. Manual extraction of milia uses a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet followed by the application of pressure to the lesion with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Many of these techniques fail to stabilize milia, particularly in sensitive areas such as around the eyes or mouth, which can make extraction challenging, inefficient, and painful for the patient. We report a novel technique that quickly and effectively removes milia with equipment commonly used in the practice of clinical dermatology.

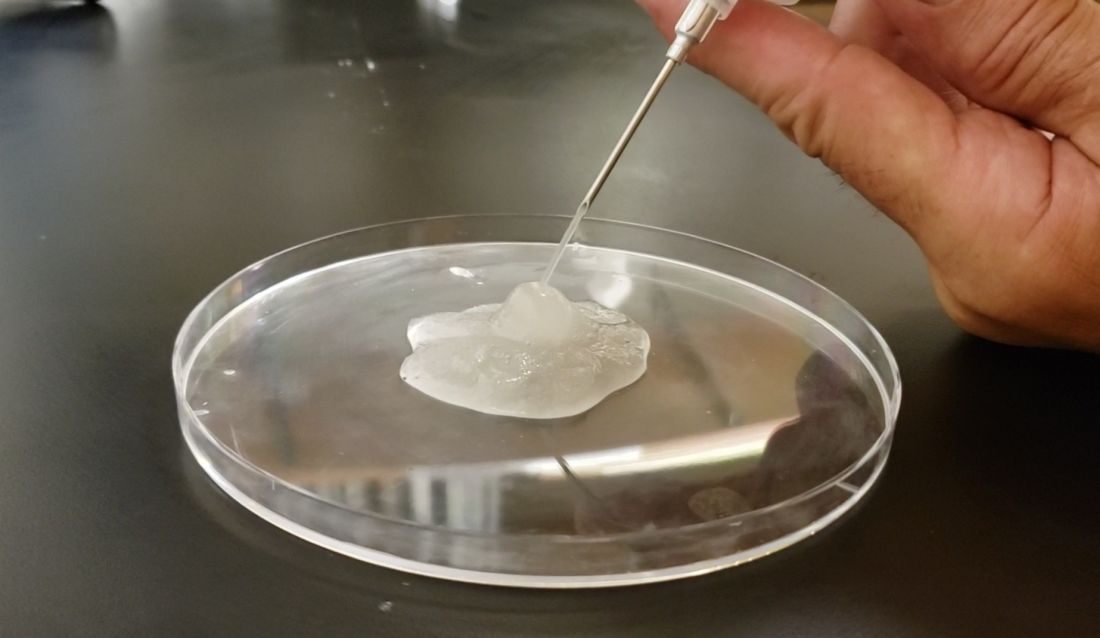

A 74-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic papule on the right lower vermilion border of several years' duration. Physical examination of the lesion revealed a 3-mm, firm, white, dome-shaped papule. Clinical features were most consistent with a benign acquired milium. The patient desired removal for cosmesis. The area was cleaned with an alcohol swab, the surface of the milium was nicked with a No. 11 blade (Figure, A), and then tips of nontoothed Adson forceps were used to gently secure and pinch the base of the papule (Figure, B). The intact cyst was quickly and effortlessly expressed through the epidermal nick. The patient tolerated the procedure well, experiencing minimal pain and bleeding.

Histologically, milia represent infundibular keratin-filled cysts lined with stratified squamous epithelial tissue that contains a granular cell layer. These lesions are classified as primary or secondary; the former represent spontaneous occurrence, and the latter are associated with medications, trauma, or genodermatoses.2 Multiple milia are associated with conditions such as Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome, Rombo syndrome, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, oro-facial-digital syndrome type I, atrichia with papular lesions, pachyonychia congenita type 2, basal cell nevus syndrome, basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome, and hereditary vitamin D–dependent rickets type 2.5-9 The most common subtype seen in clinical practice includes benign primary milia, which tends to favor the cheeks and eyelids.2

Although these lesions are benign, many patients seek extraction for cosmesis. Milia extraction is a common procedure performed in dermatology clinical practice. Proposed extraction techniques using destructive methods include electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy, and manual methods include nicking the surface of the lesion with a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet and then applying tangential pressure with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Topical retinoids have been proposed as treatment of multiple milia.10 Many of these techniques do not use equipment common to clinical practice, or they fail to stabilize milia in sensitive areas, which makes extraction challenging. We describe a case with a new manual technique that successfully extracts milia in an efficient and safe manner.

- Parlette HL III. Management of cutaneous cysts. In: Wheeland RG, ed. Cutaneous Surgery. WB Saunders; 1994:651-652.

- Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. Milia: a review and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:1050-1063.

- George DE, Wasko CA, Hsu S. Surgical pearl: evacuation of milia with a paper clip. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:326.

- Thami GP, Kaur S, Kanwar AJ. Surgical pearl: enucleation of milia with a disposable hypodermic needle. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:602-603.

- Goeteyn M, Geerts ML, Kint A, et al. The Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:337-342.

- Michaëlsson G, Olsson E, Westermark P. The Rombo syndrome: a familial disorder with vermiculate atrophoderma, milia, hypotrichosis, trichoepitheliomas, basal cell carcinomas and peripheral vasodilation with cyanosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1981;61:497-503.

- Gurrieri F, Franco B, Toriello H, et al. Oral-facial-digital syndromes: review and diagnostic guidelines. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143A:3314-3323.

- Zlotogorski A, Panteleyev AA, Aita VM, et al. Clinical and molecular diagnostic criteria of congenital atrichia with papular lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1662-1665.

- Paller AS, Moore JA, Scher R. Pachyonychia congenita tarda. alate-onset form of pachyonychia congenita. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:701-703.

- Connelly T. Eruptive milia and rapid response to topical tretinoin. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:816-817.

To the Editor:

Several techniques can be used to destroy milia including electrocautery, electrodesiccation, and laser therapy. Manual extraction of milia uses a scalpel blade, needle, or stylet followed by the application of pressure to the lesion with a curette, comedone extractor, paper clip, cotton-tipped applicator, tongue blade, or hypodermic needle.1-4 Many of these techniques fail to stabilize milia, particularly in sensitive areas such as around the eyes or mouth, which can make extraction challenging, inefficient, and painful for the patient. We report a novel technique that quickly and effectively removes milia with equipment commonly used in the practice of clinical dermatology.

A 74-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic papule on the right lower vermilion border of several years' duration. Physical examination of the lesion revealed a 3-mm, firm, white, dome-shaped papule. Clinical features were most consistent with a benign acquired milium. The patient desired removal for cosmesis. The area was cleaned with an alcohol swab, the surface of the milium was nicked with a No. 11 blade (Figure, A), and then tips of nontoothed Adson forceps were used to gently secure and pinch the base of the papule (Figure, B). The intact cyst was quickly and effortlessly expressed through the epidermal nick. The patient tolerated the procedure well, experiencing minimal pain and bleeding.

Histologically, milia represent infundibular keratin-filled cysts lined with stratified squamous epithelial tissue that contains a granular cell layer. These lesions are classified as primary or secondary; the former represent spontaneous occurrence, and the latter are associated with medications, trauma, or genodermatoses.2 Multiple milia are associated with conditions such as Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome, Rombo syndrome, Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, oro-facial-digital syndrome type I, atrichia with papular lesions, pachyonychia congenita type 2, basal cell nevus syndrome, basaloid follicular hamartoma syndrome, and hereditary vitamin D–dependent rickets type 2.5-9 The most common subtype seen in clinical practice includes benign primary milia, which tends to favor the cheeks and eyelids.2