User login

Combination of energy-based treatments found to improve Becker’s nevi

Denver – out to 40 weeks, results of a small retrospective case series demonstrated.

During an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, presenting author Shelby L. Kubicki, MD, said that NAFR and LHR target the clinically bothersome Becker’s nevi features of hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis via different mechanisms. “NAFR creates microcolumns of thermal injury in the skin, which improves hyperpigmentation,” explained Dr. Kubicki, a 3rd-year dermatology resident at University of Texas Health Sciences Center/University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston.

“LHR targets follicular melanocytes, which are located more deeply in the dermis,” she said. “This improves hypertrichosis and likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting these melanocytes that are not reached by NAFR.”

Dr. Kubicki and her colleagues retrospectively reviewed 12 patients with Becker’s nevus who underwent a mean of 5.3 NAFR treatments at a single dermatology practice at intervals that ranged between 1 and 4 months. The long-pulsed 755-nm alexandrite laser was used for study participants with skin types I-III, while the long-pulsed 1,064-nm Nd: YAG laser was used for those with skin types IV-VI. Ten of the 12 patients underwent concomitant LHR with one of the two devices and three independent physicians used a 5-point visual analog scale (VAS) to rate clinical photographs. All patients completed a strict pre- and postoperative regimen with either 4% hydroquinone or topical 3% tranexamic acid and broad-spectrum sunscreen and postoperative treatment with a midpotency topical corticosteroid for 3 days.

The study is the largest known case series of therapy combining 1,550-nm NAFR and LHR for Becker’s nevus patients with skin types III-VI.

After comparing VAS scores at baseline and follow-up, physicians rated the cosmetic appearance of Becker’s nevus as improving by a range of 51%-75%. Two patients did not undergo LHR: one male patient with Becker’s nevus in his beard region, for whom LHR was undesirable, and a second patient with atrichotic Becker’s nevus. These two patients demonstrated improvements in VAS scores of 26%-50% and 76%-99%, respectively.

No long-term adverse events were observed during follow-up, which ranged from 6 to 40 weeks. “We do want more long-term follow-up,” Dr. Kubicki said, noting that there are more data on some patients to extend the follow-up.

She and her coinvestigators concluded that the results show that treatment with a combination of NAFR and LHR safely addresses both hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis in Becker’s nevi. “In addition, LHR likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting follicular melanocytes,” she said. “In our study, we did have one patient experience recurrence of a Becker’s nevus during follow-up, but [the rest] did not, which we considered a success.”

Vincent Richer, MD, a Vancouver-based medical and cosmetic dermatologist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized Becker’s nevus as a difficult-to-treat condition that is made even more difficult to treat in skin types III-VI.

“Combining laser hair removal using appropriate wavelengths with 1,550-nm nonablative fractional resurfacing yielded good clinical results with few recurrences,” he said in an interview with this news organization. “Though it was a small series, it definitely is an interesting option for practicing dermatologists who encounter patients interested in improving the appearance of a Becker’s nevus.”

The researchers reported having no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Richer disclosed that he performs clinical trials for AbbVie/Allergan, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, and is a member of advisory boards for Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, and Sanofi. He is also a consultant to AbbVie/Allergan, Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, Merz, and Sanofi.

Denver – out to 40 weeks, results of a small retrospective case series demonstrated.

During an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, presenting author Shelby L. Kubicki, MD, said that NAFR and LHR target the clinically bothersome Becker’s nevi features of hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis via different mechanisms. “NAFR creates microcolumns of thermal injury in the skin, which improves hyperpigmentation,” explained Dr. Kubicki, a 3rd-year dermatology resident at University of Texas Health Sciences Center/University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston.

“LHR targets follicular melanocytes, which are located more deeply in the dermis,” she said. “This improves hypertrichosis and likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting these melanocytes that are not reached by NAFR.”

Dr. Kubicki and her colleagues retrospectively reviewed 12 patients with Becker’s nevus who underwent a mean of 5.3 NAFR treatments at a single dermatology practice at intervals that ranged between 1 and 4 months. The long-pulsed 755-nm alexandrite laser was used for study participants with skin types I-III, while the long-pulsed 1,064-nm Nd: YAG laser was used for those with skin types IV-VI. Ten of the 12 patients underwent concomitant LHR with one of the two devices and three independent physicians used a 5-point visual analog scale (VAS) to rate clinical photographs. All patients completed a strict pre- and postoperative regimen with either 4% hydroquinone or topical 3% tranexamic acid and broad-spectrum sunscreen and postoperative treatment with a midpotency topical corticosteroid for 3 days.

The study is the largest known case series of therapy combining 1,550-nm NAFR and LHR for Becker’s nevus patients with skin types III-VI.

After comparing VAS scores at baseline and follow-up, physicians rated the cosmetic appearance of Becker’s nevus as improving by a range of 51%-75%. Two patients did not undergo LHR: one male patient with Becker’s nevus in his beard region, for whom LHR was undesirable, and a second patient with atrichotic Becker’s nevus. These two patients demonstrated improvements in VAS scores of 26%-50% and 76%-99%, respectively.

No long-term adverse events were observed during follow-up, which ranged from 6 to 40 weeks. “We do want more long-term follow-up,” Dr. Kubicki said, noting that there are more data on some patients to extend the follow-up.

She and her coinvestigators concluded that the results show that treatment with a combination of NAFR and LHR safely addresses both hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis in Becker’s nevi. “In addition, LHR likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting follicular melanocytes,” she said. “In our study, we did have one patient experience recurrence of a Becker’s nevus during follow-up, but [the rest] did not, which we considered a success.”

Vincent Richer, MD, a Vancouver-based medical and cosmetic dermatologist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized Becker’s nevus as a difficult-to-treat condition that is made even more difficult to treat in skin types III-VI.

“Combining laser hair removal using appropriate wavelengths with 1,550-nm nonablative fractional resurfacing yielded good clinical results with few recurrences,” he said in an interview with this news organization. “Though it was a small series, it definitely is an interesting option for practicing dermatologists who encounter patients interested in improving the appearance of a Becker’s nevus.”

The researchers reported having no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Richer disclosed that he performs clinical trials for AbbVie/Allergan, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, and is a member of advisory boards for Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, and Sanofi. He is also a consultant to AbbVie/Allergan, Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, Merz, and Sanofi.

Denver – out to 40 weeks, results of a small retrospective case series demonstrated.

During an oral abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, presenting author Shelby L. Kubicki, MD, said that NAFR and LHR target the clinically bothersome Becker’s nevi features of hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis via different mechanisms. “NAFR creates microcolumns of thermal injury in the skin, which improves hyperpigmentation,” explained Dr. Kubicki, a 3rd-year dermatology resident at University of Texas Health Sciences Center/University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston.

“LHR targets follicular melanocytes, which are located more deeply in the dermis,” she said. “This improves hypertrichosis and likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting these melanocytes that are not reached by NAFR.”

Dr. Kubicki and her colleagues retrospectively reviewed 12 patients with Becker’s nevus who underwent a mean of 5.3 NAFR treatments at a single dermatology practice at intervals that ranged between 1 and 4 months. The long-pulsed 755-nm alexandrite laser was used for study participants with skin types I-III, while the long-pulsed 1,064-nm Nd: YAG laser was used for those with skin types IV-VI. Ten of the 12 patients underwent concomitant LHR with one of the two devices and three independent physicians used a 5-point visual analog scale (VAS) to rate clinical photographs. All patients completed a strict pre- and postoperative regimen with either 4% hydroquinone or topical 3% tranexamic acid and broad-spectrum sunscreen and postoperative treatment with a midpotency topical corticosteroid for 3 days.

The study is the largest known case series of therapy combining 1,550-nm NAFR and LHR for Becker’s nevus patients with skin types III-VI.

After comparing VAS scores at baseline and follow-up, physicians rated the cosmetic appearance of Becker’s nevus as improving by a range of 51%-75%. Two patients did not undergo LHR: one male patient with Becker’s nevus in his beard region, for whom LHR was undesirable, and a second patient with atrichotic Becker’s nevus. These two patients demonstrated improvements in VAS scores of 26%-50% and 76%-99%, respectively.

No long-term adverse events were observed during follow-up, which ranged from 6 to 40 weeks. “We do want more long-term follow-up,” Dr. Kubicki said, noting that there are more data on some patients to extend the follow-up.

She and her coinvestigators concluded that the results show that treatment with a combination of NAFR and LHR safely addresses both hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis in Becker’s nevi. “In addition, LHR likely prevents recurrence of hyperpigmentation by targeting follicular melanocytes,” she said. “In our study, we did have one patient experience recurrence of a Becker’s nevus during follow-up, but [the rest] did not, which we considered a success.”

Vincent Richer, MD, a Vancouver-based medical and cosmetic dermatologist who was asked to comment on the study, characterized Becker’s nevus as a difficult-to-treat condition that is made even more difficult to treat in skin types III-VI.

“Combining laser hair removal using appropriate wavelengths with 1,550-nm nonablative fractional resurfacing yielded good clinical results with few recurrences,” he said in an interview with this news organization. “Though it was a small series, it definitely is an interesting option for practicing dermatologists who encounter patients interested in improving the appearance of a Becker’s nevus.”

The researchers reported having no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Richer disclosed that he performs clinical trials for AbbVie/Allergan, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, and is a member of advisory boards for Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, and Sanofi. He is also a consultant to AbbVie/Allergan, Bausch, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal, Merz, and Sanofi.

AT ASDS 2022

Unusual Bilateral Distribution of Neurofibromatosis Type 5 on the Distal Upper Extremities

To the Editor:

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease). Phenotypic manifestations of NF5 include café-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, or both in 1 or more adjacent dermatomes. In contrast to the systemic features of NF1, the dermatomal distribution of NF5 demonstrates mosaicism due to a spontaneous postzygotic mutation in the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. We describe an atypical presentation of NF5 with bilateral features on the upper extremities.

A 74-year-old woman presented with soft pink- to flesh-colored growths on the left dorsal forearm and hand that were observed incidentally during a Mohs procedure for treatment of a basal cell carcinoma on the upper cutaneous lip. The patient reported that the lesions initially appeared on the left dorsal hand at approximately 16 years of age and had since spread proximally up to the mid dorsal forearm over the course of her lifetime. She denied any pain but claimed the affected area could be itchy. The lesions did not interfere with her daily activities, but they negatively impacted her social life due to their cosmetic appearance as well as her fear that they could be contagious. She denied any family history of NF1.

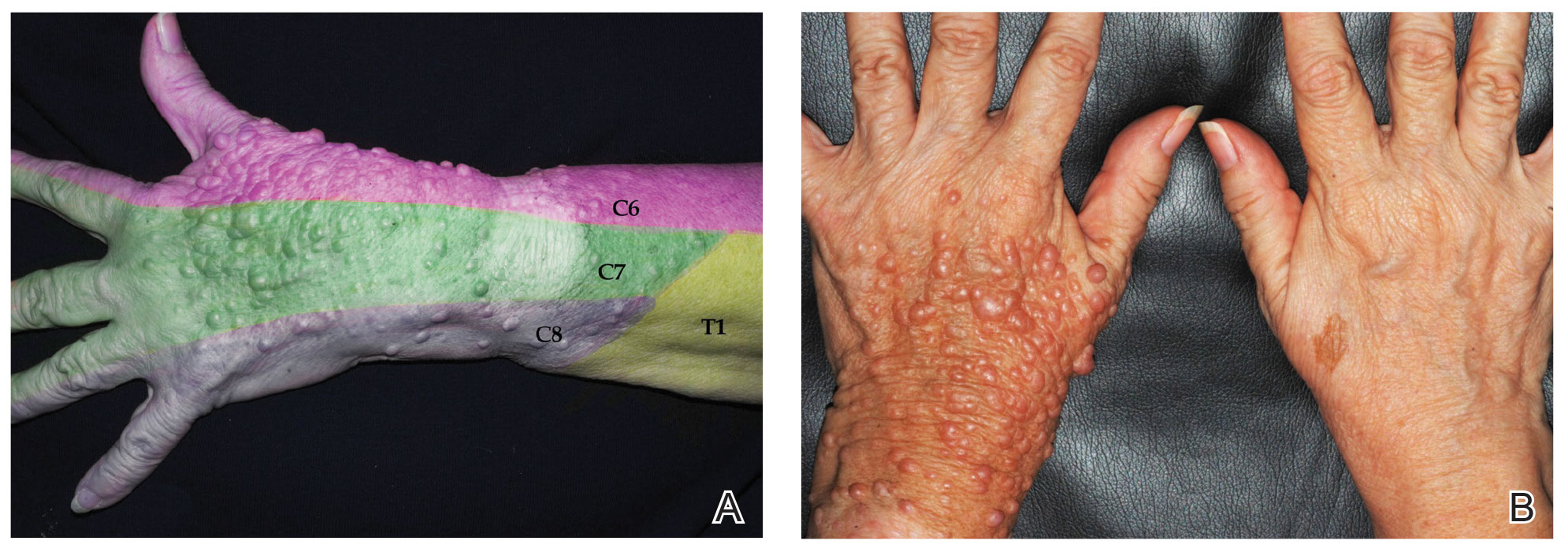

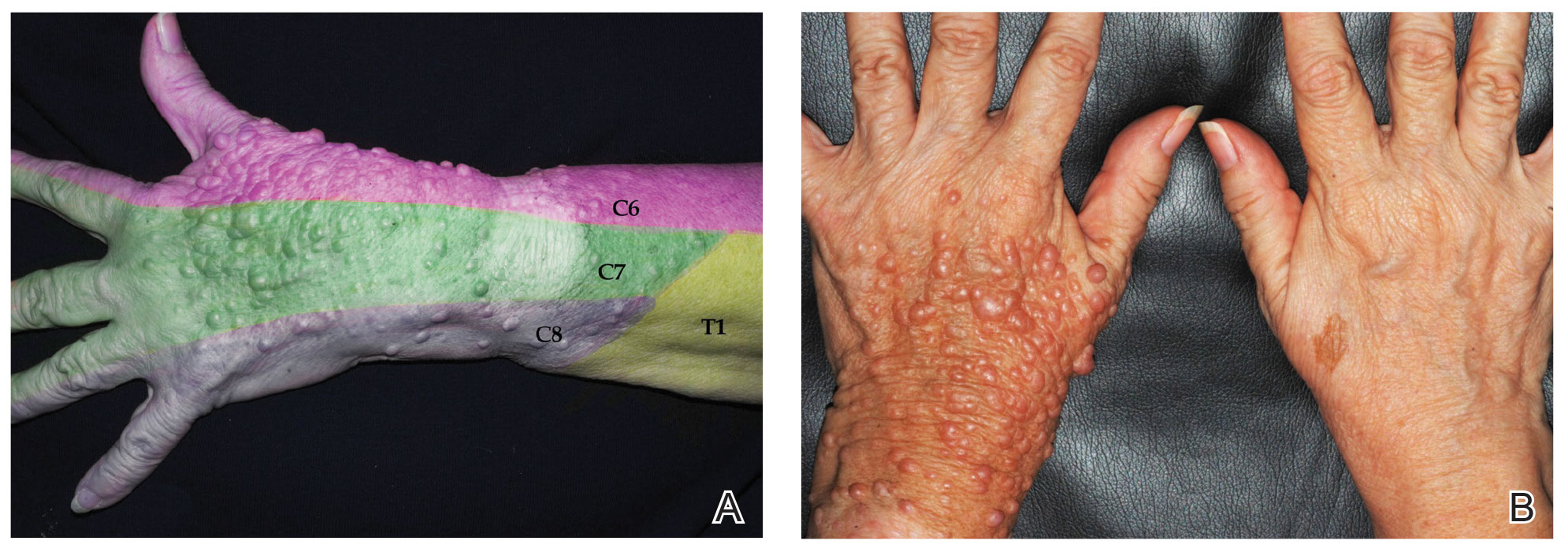

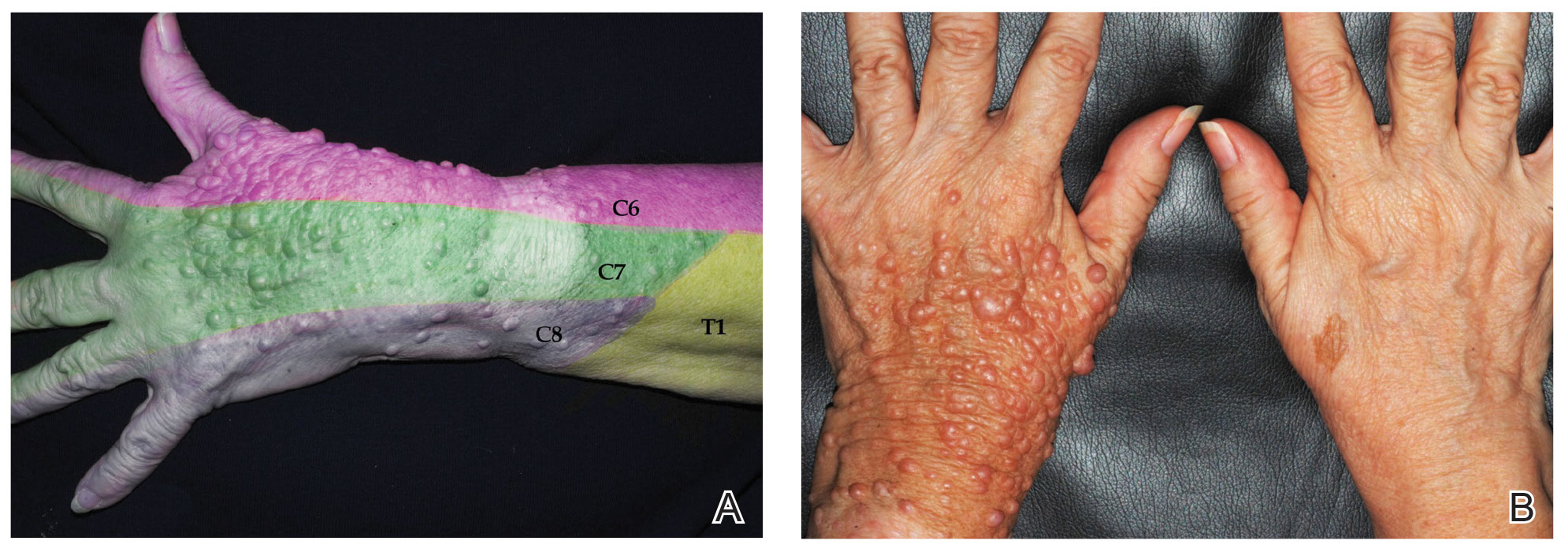

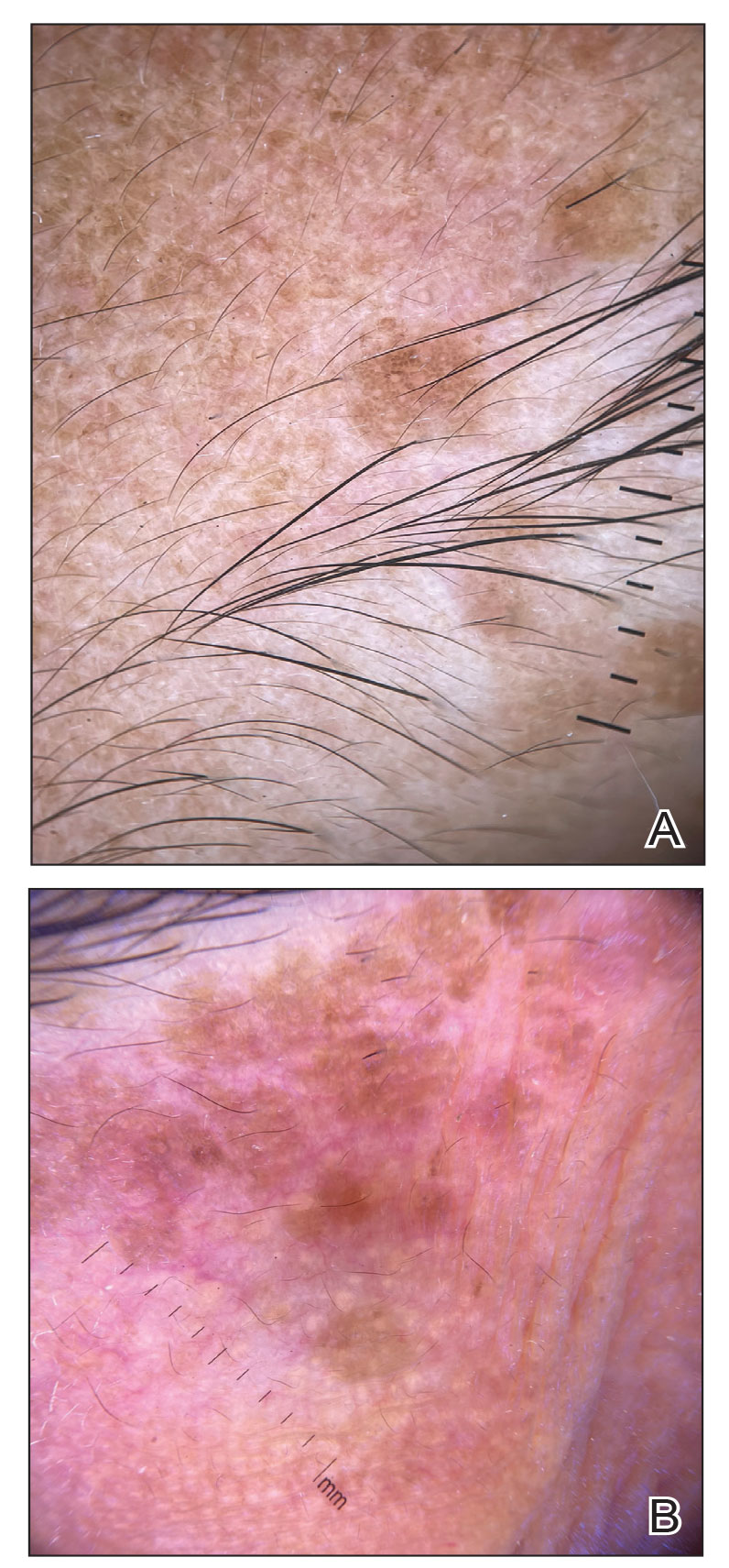

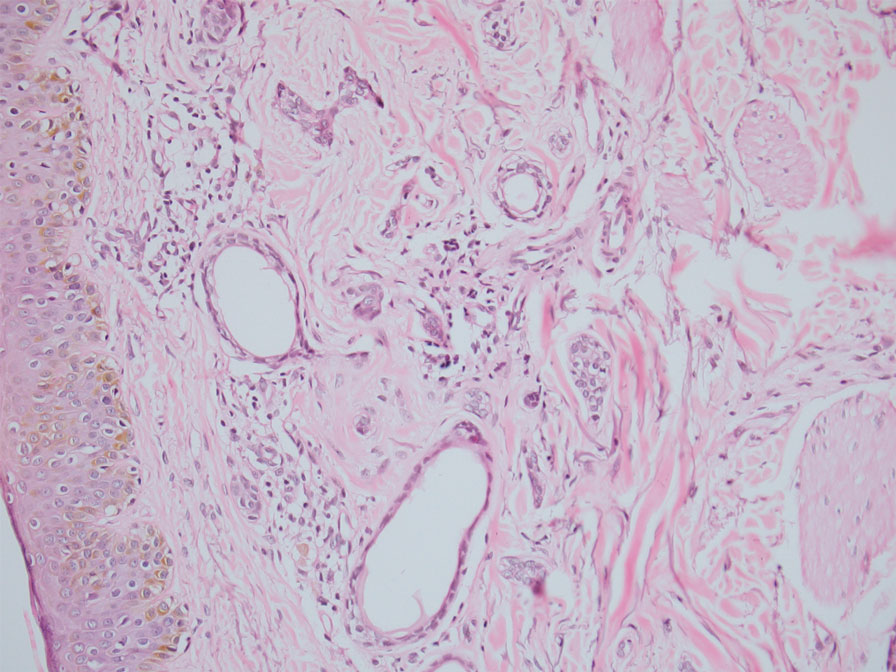

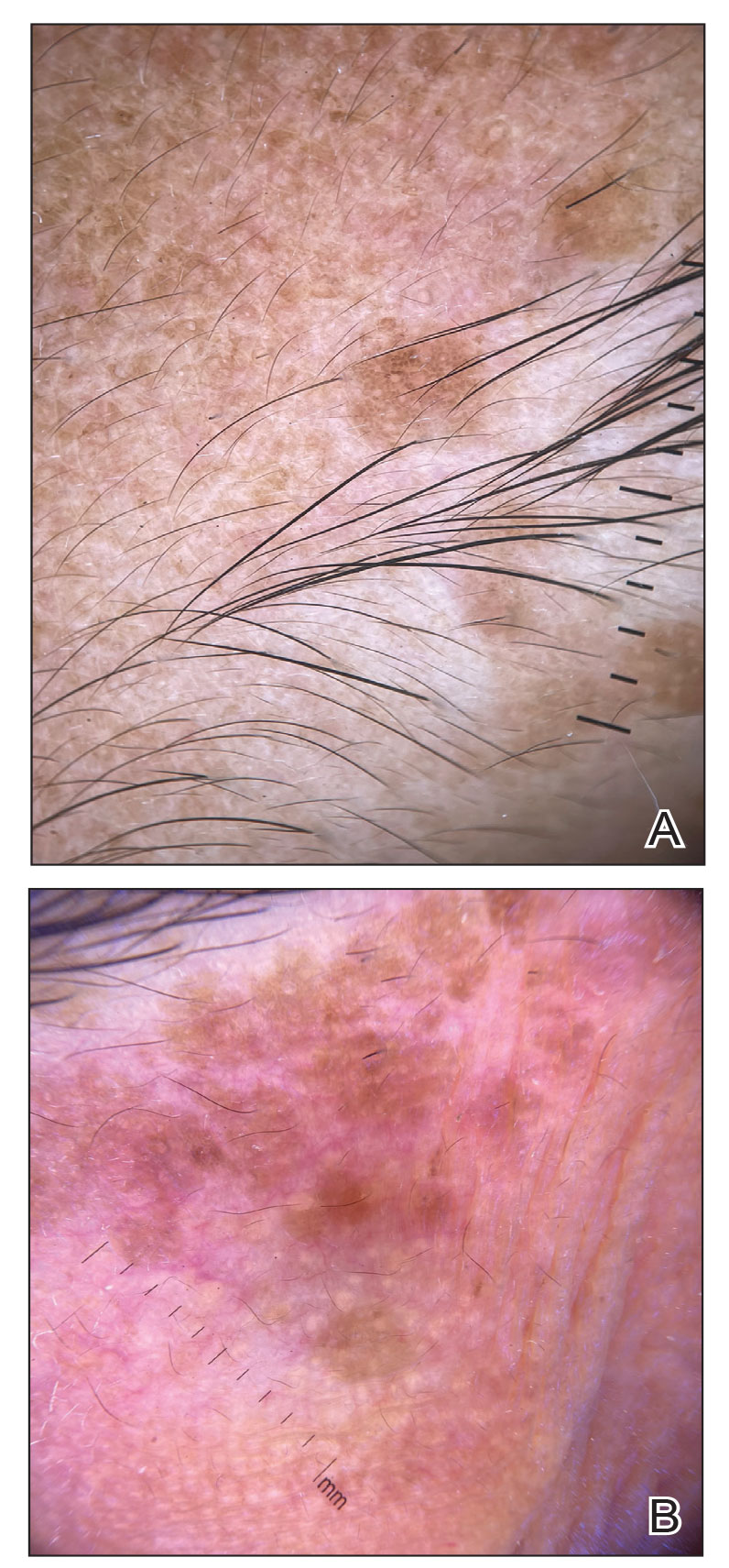

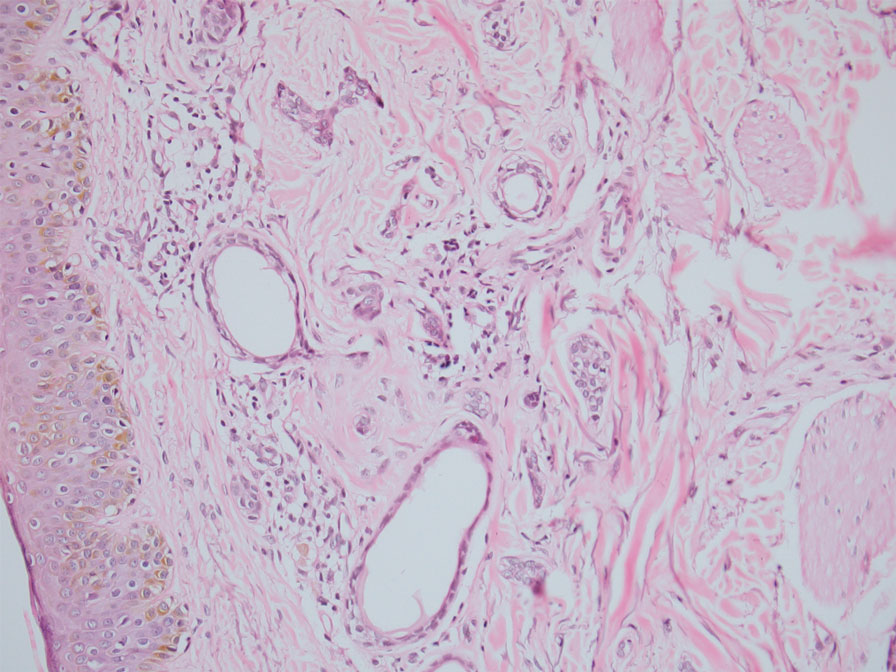

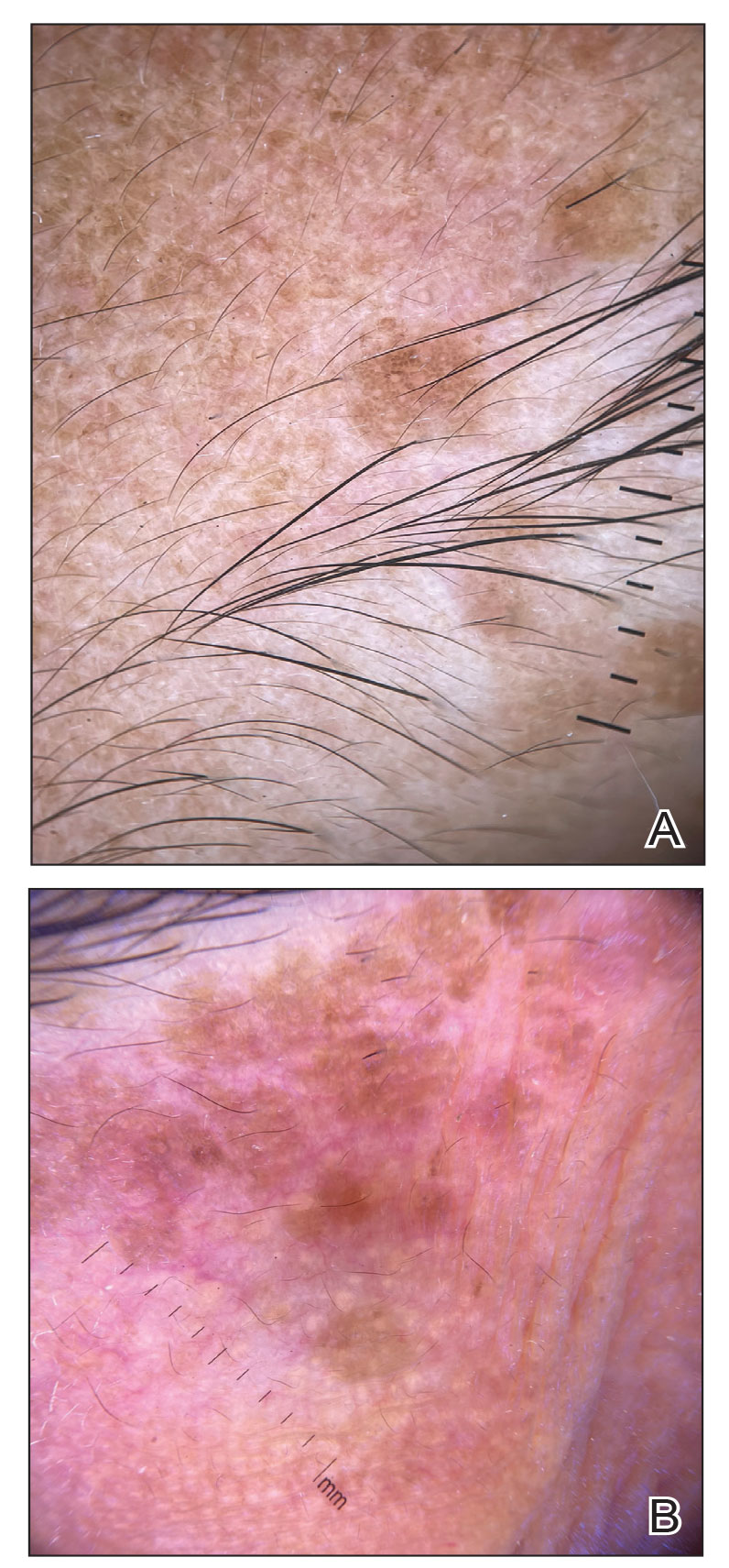

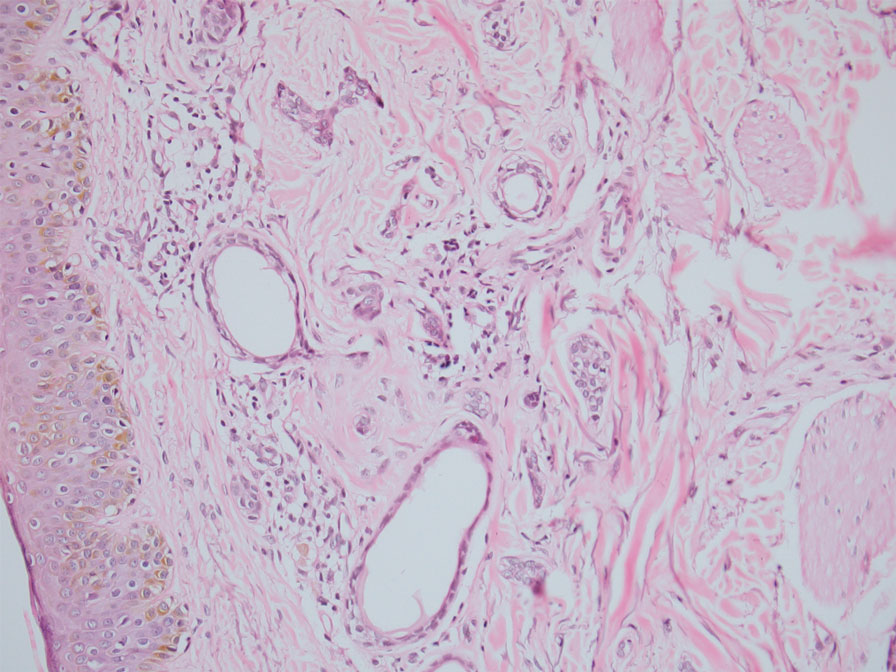

Physical examination revealed innumerable soft, pink- to flesh-colored cutaneous nodules ranging from 3 to 9 mm in diameter clustered uniformly on the left dorsal hand and lower forearm within the C6, C7, and C8 dermatomal regions (Figure, A). A singular brown patch measuring 20 mm in diameter also was observed on the right dorsal hand within the C6 dermatome, which the patient reported had been present since birth (Figure, B). The nodules and pigmented patch were clinically diagnosed as cutaneous neurofibromas on the left arm and a café-au-lait macule on the right arm, each manifesting within the C6 dermatome on separate upper extremities. Lisch nodules, axillary freckling, and acoustic schwannomas were not observed. Because of the dermatomal distribution of the lesions and lack of family history of NF1, a diagnosis of bilateral NF5 was made. The patient stated she had declined treatment of the neurofibromas from her referring general dermatologist due to possible risk for recurrence.

Segmental neurofibromatosis was first described in 1931 by Gammel,1 and in 1982, segmental neurofibromatosis was classified as NF5 by Riccardi.2 After Tinschert et al3 later demonstrated NF5 to be a somatic mutation of NF1,3 Ruggieri and Huson4 proposed the term mosaic neurofibromatosis 1 in 2001.

While the prevalence of NF1 is 1 in 3000 individuals,5 NF5 is rare with an occurrence of 1 in 40,000.6 In NF5, a spontaneous NF1 gene mutation occurs on chromosome 17 in a dividing cell after conception.7 Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the NF1 gene.8 This contrasts with the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells. Patients with NF5 generally are not expected to have affected offspring because the spontaneous mutation usually arises in somatic cells; however, a postzygotic mutation in the gonadal region could potentially affect germline cells, resulting in vertical transmission, with documented cases of offspring with systemic NF1.4 Because of the risk for malignancy with systemic neurofibromatosis, early diagnosis with genetic counseling is imperative in patients with both NF1 and NF5.

Neurofibromatosis type 5 is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of neurofibromas and/or café-au-lait macules in a dermatomal distribution. The clinical presentation depends on when and where the NF1 gene mutation occurs in utero as cells multiply, differentiate, and migrate.8 Earlier mutations result in a broader manifestation of NF5 in comparison to late mutations, which have more localized features. An NF1 gene mutation causes a loss of function of neurofibromin, a tumor suppressor protein, in Schwann cells and fibroblasts.8 This produces neurofibromas and café-au-lait macules, respectively.8

A large literature review on segmental neurofibromatosis by Garcia-Romero et al6 identified 320 individuals who did not meet full inclusion criteria for NF1 between 1977 and 2012. Overall, 76% of cases were unilaterally distributed. The investigators identified 157 individual case reports in which the most to least common presentation was pigmentary changes only, neurofibromas only, mixed pigmentary changes with neurofibromas, and plexiform neurofibromas only; however, many of these cases were children who may have later developed both neurofibromas and pigmentary changes during puberty.6 Additional features of NF5 may include freckling, Lisch nodules, optic gliomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, skeletal abnormalities, precocious puberty, vascular malformations, hypertension, seizures, and/or learning difficulties based on the affected anatomy.

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or NF5, is a rare subtype of NF1. Our case demonstrates an unusual bilateral distribution of NF5 with cutaneous neurofibromas and a café-au-lait macule on the upper extremities. Awareness of variations of neurofibromatosis and their genetic implications is essential in establishing earlier clinical diagnoses in cases with subtle manifestations.

- Gammel JA. Localized neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1931;24:712-713.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis: clinical heterogeneity. Curr Probl Cancer. 1982;7:1-34.

- Tinschert S, Naumann I, Stegmann E, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by somatic mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:455-459.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Crowe FW, Schull WJ, Neel JV. A Clinical, Pathological and Genetic Study of Multiple Neurofibromatosis. Charles C Thomas; 1956.

- García-Romero MT, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. Mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:9-17.

- Ledbetter DH, Rich DC, O’Connell P, et al. Precise localization of NF1 to 17q11.2 by balanced translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:20-24.

- Redlick FP, Shaw JC. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

To the Editor:

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease). Phenotypic manifestations of NF5 include café-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, or both in 1 or more adjacent dermatomes. In contrast to the systemic features of NF1, the dermatomal distribution of NF5 demonstrates mosaicism due to a spontaneous postzygotic mutation in the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. We describe an atypical presentation of NF5 with bilateral features on the upper extremities.

A 74-year-old woman presented with soft pink- to flesh-colored growths on the left dorsal forearm and hand that were observed incidentally during a Mohs procedure for treatment of a basal cell carcinoma on the upper cutaneous lip. The patient reported that the lesions initially appeared on the left dorsal hand at approximately 16 years of age and had since spread proximally up to the mid dorsal forearm over the course of her lifetime. She denied any pain but claimed the affected area could be itchy. The lesions did not interfere with her daily activities, but they negatively impacted her social life due to their cosmetic appearance as well as her fear that they could be contagious. She denied any family history of NF1.

Physical examination revealed innumerable soft, pink- to flesh-colored cutaneous nodules ranging from 3 to 9 mm in diameter clustered uniformly on the left dorsal hand and lower forearm within the C6, C7, and C8 dermatomal regions (Figure, A). A singular brown patch measuring 20 mm in diameter also was observed on the right dorsal hand within the C6 dermatome, which the patient reported had been present since birth (Figure, B). The nodules and pigmented patch were clinically diagnosed as cutaneous neurofibromas on the left arm and a café-au-lait macule on the right arm, each manifesting within the C6 dermatome on separate upper extremities. Lisch nodules, axillary freckling, and acoustic schwannomas were not observed. Because of the dermatomal distribution of the lesions and lack of family history of NF1, a diagnosis of bilateral NF5 was made. The patient stated she had declined treatment of the neurofibromas from her referring general dermatologist due to possible risk for recurrence.

Segmental neurofibromatosis was first described in 1931 by Gammel,1 and in 1982, segmental neurofibromatosis was classified as NF5 by Riccardi.2 After Tinschert et al3 later demonstrated NF5 to be a somatic mutation of NF1,3 Ruggieri and Huson4 proposed the term mosaic neurofibromatosis 1 in 2001.

While the prevalence of NF1 is 1 in 3000 individuals,5 NF5 is rare with an occurrence of 1 in 40,000.6 In NF5, a spontaneous NF1 gene mutation occurs on chromosome 17 in a dividing cell after conception.7 Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the NF1 gene.8 This contrasts with the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells. Patients with NF5 generally are not expected to have affected offspring because the spontaneous mutation usually arises in somatic cells; however, a postzygotic mutation in the gonadal region could potentially affect germline cells, resulting in vertical transmission, with documented cases of offspring with systemic NF1.4 Because of the risk for malignancy with systemic neurofibromatosis, early diagnosis with genetic counseling is imperative in patients with both NF1 and NF5.

Neurofibromatosis type 5 is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of neurofibromas and/or café-au-lait macules in a dermatomal distribution. The clinical presentation depends on when and where the NF1 gene mutation occurs in utero as cells multiply, differentiate, and migrate.8 Earlier mutations result in a broader manifestation of NF5 in comparison to late mutations, which have more localized features. An NF1 gene mutation causes a loss of function of neurofibromin, a tumor suppressor protein, in Schwann cells and fibroblasts.8 This produces neurofibromas and café-au-lait macules, respectively.8

A large literature review on segmental neurofibromatosis by Garcia-Romero et al6 identified 320 individuals who did not meet full inclusion criteria for NF1 between 1977 and 2012. Overall, 76% of cases were unilaterally distributed. The investigators identified 157 individual case reports in which the most to least common presentation was pigmentary changes only, neurofibromas only, mixed pigmentary changes with neurofibromas, and plexiform neurofibromas only; however, many of these cases were children who may have later developed both neurofibromas and pigmentary changes during puberty.6 Additional features of NF5 may include freckling, Lisch nodules, optic gliomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, skeletal abnormalities, precocious puberty, vascular malformations, hypertension, seizures, and/or learning difficulties based on the affected anatomy.

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or NF5, is a rare subtype of NF1. Our case demonstrates an unusual bilateral distribution of NF5 with cutaneous neurofibromas and a café-au-lait macule on the upper extremities. Awareness of variations of neurofibromatosis and their genetic implications is essential in establishing earlier clinical diagnoses in cases with subtle manifestations.

To the Editor:

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease). Phenotypic manifestations of NF5 include café-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, or both in 1 or more adjacent dermatomes. In contrast to the systemic features of NF1, the dermatomal distribution of NF5 demonstrates mosaicism due to a spontaneous postzygotic mutation in the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. We describe an atypical presentation of NF5 with bilateral features on the upper extremities.

A 74-year-old woman presented with soft pink- to flesh-colored growths on the left dorsal forearm and hand that were observed incidentally during a Mohs procedure for treatment of a basal cell carcinoma on the upper cutaneous lip. The patient reported that the lesions initially appeared on the left dorsal hand at approximately 16 years of age and had since spread proximally up to the mid dorsal forearm over the course of her lifetime. She denied any pain but claimed the affected area could be itchy. The lesions did not interfere with her daily activities, but they negatively impacted her social life due to their cosmetic appearance as well as her fear that they could be contagious. She denied any family history of NF1.

Physical examination revealed innumerable soft, pink- to flesh-colored cutaneous nodules ranging from 3 to 9 mm in diameter clustered uniformly on the left dorsal hand and lower forearm within the C6, C7, and C8 dermatomal regions (Figure, A). A singular brown patch measuring 20 mm in diameter also was observed on the right dorsal hand within the C6 dermatome, which the patient reported had been present since birth (Figure, B). The nodules and pigmented patch were clinically diagnosed as cutaneous neurofibromas on the left arm and a café-au-lait macule on the right arm, each manifesting within the C6 dermatome on separate upper extremities. Lisch nodules, axillary freckling, and acoustic schwannomas were not observed. Because of the dermatomal distribution of the lesions and lack of family history of NF1, a diagnosis of bilateral NF5 was made. The patient stated she had declined treatment of the neurofibromas from her referring general dermatologist due to possible risk for recurrence.

Segmental neurofibromatosis was first described in 1931 by Gammel,1 and in 1982, segmental neurofibromatosis was classified as NF5 by Riccardi.2 After Tinschert et al3 later demonstrated NF5 to be a somatic mutation of NF1,3 Ruggieri and Huson4 proposed the term mosaic neurofibromatosis 1 in 2001.

While the prevalence of NF1 is 1 in 3000 individuals,5 NF5 is rare with an occurrence of 1 in 40,000.6 In NF5, a spontaneous NF1 gene mutation occurs on chromosome 17 in a dividing cell after conception.7 Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the NF1 gene.8 This contrasts with the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells. Patients with NF5 generally are not expected to have affected offspring because the spontaneous mutation usually arises in somatic cells; however, a postzygotic mutation in the gonadal region could potentially affect germline cells, resulting in vertical transmission, with documented cases of offspring with systemic NF1.4 Because of the risk for malignancy with systemic neurofibromatosis, early diagnosis with genetic counseling is imperative in patients with both NF1 and NF5.

Neurofibromatosis type 5 is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of neurofibromas and/or café-au-lait macules in a dermatomal distribution. The clinical presentation depends on when and where the NF1 gene mutation occurs in utero as cells multiply, differentiate, and migrate.8 Earlier mutations result in a broader manifestation of NF5 in comparison to late mutations, which have more localized features. An NF1 gene mutation causes a loss of function of neurofibromin, a tumor suppressor protein, in Schwann cells and fibroblasts.8 This produces neurofibromas and café-au-lait macules, respectively.8

A large literature review on segmental neurofibromatosis by Garcia-Romero et al6 identified 320 individuals who did not meet full inclusion criteria for NF1 between 1977 and 2012. Overall, 76% of cases were unilaterally distributed. The investigators identified 157 individual case reports in which the most to least common presentation was pigmentary changes only, neurofibromas only, mixed pigmentary changes with neurofibromas, and plexiform neurofibromas only; however, many of these cases were children who may have later developed both neurofibromas and pigmentary changes during puberty.6 Additional features of NF5 may include freckling, Lisch nodules, optic gliomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, skeletal abnormalities, precocious puberty, vascular malformations, hypertension, seizures, and/or learning difficulties based on the affected anatomy.

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or NF5, is a rare subtype of NF1. Our case demonstrates an unusual bilateral distribution of NF5 with cutaneous neurofibromas and a café-au-lait macule on the upper extremities. Awareness of variations of neurofibromatosis and their genetic implications is essential in establishing earlier clinical diagnoses in cases with subtle manifestations.

- Gammel JA. Localized neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1931;24:712-713.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis: clinical heterogeneity. Curr Probl Cancer. 1982;7:1-34.

- Tinschert S, Naumann I, Stegmann E, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by somatic mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:455-459.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Crowe FW, Schull WJ, Neel JV. A Clinical, Pathological and Genetic Study of Multiple Neurofibromatosis. Charles C Thomas; 1956.

- García-Romero MT, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. Mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:9-17.

- Ledbetter DH, Rich DC, O’Connell P, et al. Precise localization of NF1 to 17q11.2 by balanced translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:20-24.

- Redlick FP, Shaw JC. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

- Gammel JA. Localized neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1931;24:712-713.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis: clinical heterogeneity. Curr Probl Cancer. 1982;7:1-34.

- Tinschert S, Naumann I, Stegmann E, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by somatic mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:455-459.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Crowe FW, Schull WJ, Neel JV. A Clinical, Pathological and Genetic Study of Multiple Neurofibromatosis. Charles C Thomas; 1956.

- García-Romero MT, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. Mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:9-17.

- Ledbetter DH, Rich DC, O’Connell P, et al. Precise localization of NF1 to 17q11.2 by balanced translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:20-24.

- Redlick FP, Shaw JC. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

Practice Points

- Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosistype 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease).

- Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. This is in contrast to the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells.

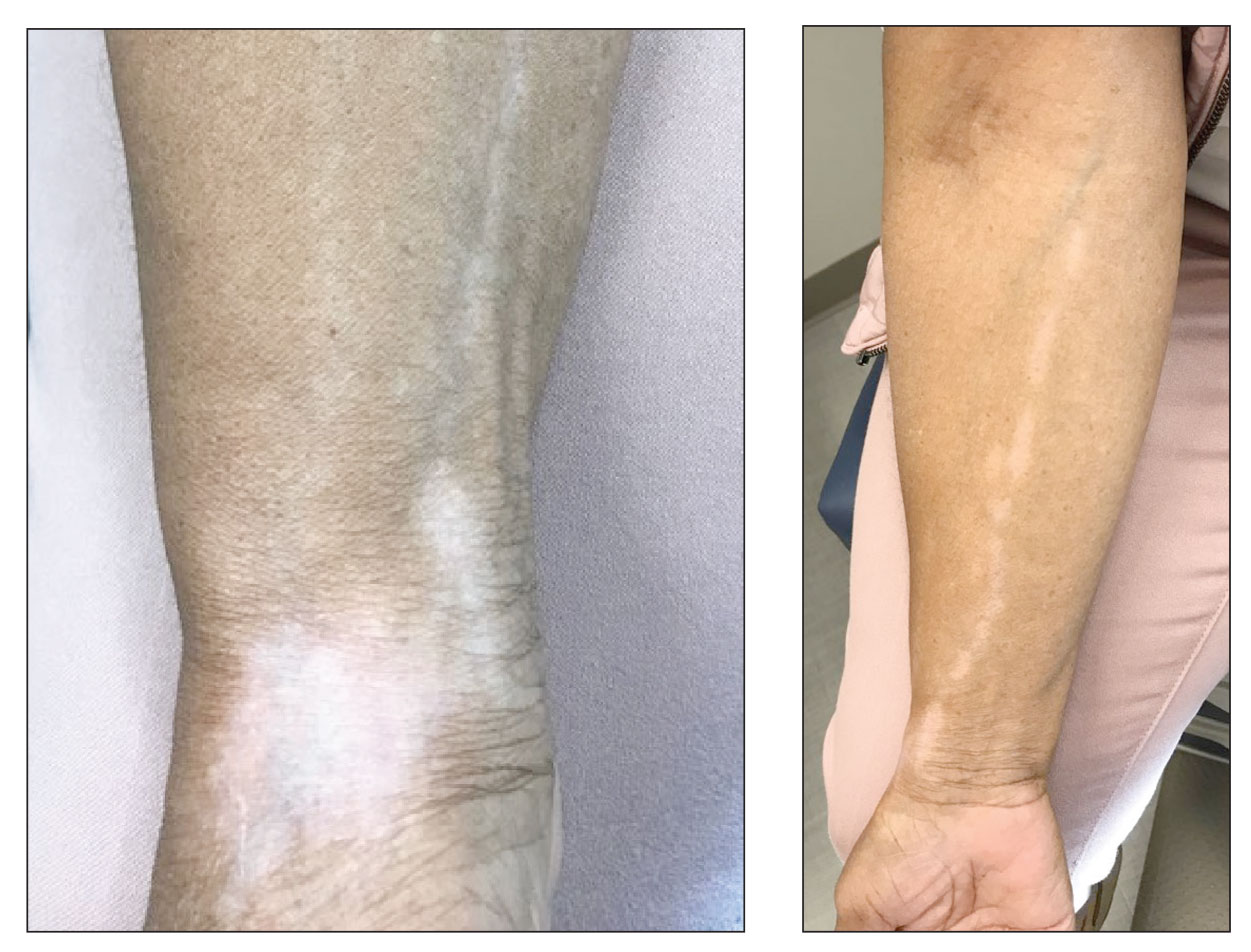

Ruxolitinib repigments many vitiligo-affected body areas

.

Those difficult areas include the hands and feet, said Thierry Passeron, MD, PhD, of Université Côte d’Azur and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nice (France).

Indeed, a 50% or greater improvement in the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI-50) of the hands and feet was achieved with ruxolitinib cream (Opzelura) in around one-third of patients after 52 weeks’ treatment, and more than half of patients showed improvement in the upper and lower extremities.

During one of the late-breaking news sessions, Dr. Passeron presented a pooled analysis of the Topical Ruxolitinib Evaluation in Vitiligo Study 1 (TRuE-V1) and Study 2 (TruE-V2), which assessed VASI-50 data by body regions.

Similarly positive results were seen on the head and neck and the trunk, with VASI-50 being reached in a respective 68% and 48% of patients after a full year of treatment.

“VASI-50 response rates rose steadily through 52 weeks for both the head and trunk,” said Dr. Passeron. He noted that the trials were initially double-blinded for 24 weeks and that there was a further open-label extension phase through week 52.

In the latter phase, all patients were treated with ruxolitinib; those who originally received a vehicle agent as placebo crossed over to the active treatment.

First FDA-approved treatment for adults and adolescents with vitiligo

Ruxolitinib is a Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor that has been available for the treatment for atopic dermatitis for more than a year. It was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of vitiligo in adults and pediatric patients aged 12 years and older.

This approval was based on the positive findings of the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies, which showed that after 24 weeks, 30% of patients treated with ruxolitinib had at least 75% improvement in the facial VASI, compared with 10% of placebo-treated patients.

“These studies demonstrated very nice results, especially on the face, which is the easiest part to repigment in vitiligo,” Dr. Passeron said.

“We know that the location is very important when it comes to repigmentation of vitiligo,” he added. He noted that other body areas, “the extremities, for example, are much more difficult.”

The analysis he presented specifically assessed the effect of ruxolitinib cream on repigmentation in other areas.

Pooled analysis performed

Data from the two TRuE-V trials were pooled. The new analysis included a total of 661 individuals; of those patients, 443 had been treated with topical ruxolitinib, and 218 had received a vehicle cream as a placebo.

For the first 24 weeks, patients received twice-daily 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle cream. This was followed by a 28-week extension phase in which everyone was treated with ruxolitinib cream, after which there was a 30-day final follow-up period.

Dr. Passeron reported data by body region for weeks 12, 24, and 52, which showed an increasing percentage of patients with VASI-50.

“We didn’t look at the face; that we know well, that is a very good result,” he said.

The best results were seen for the head and neck. VASI-50 was reached by 28.3%, 45.3%, and 68.1% of patients treated with ruxolitinib cream at weeks 12, 24, and 52, respectively. Corresponding rates for the placebo-crossover group were 19.8%, 23.8%, and 51%.

Repigmentation rates of the hand, upper extremities, trunk, lower extremities, and feet were about 9%-15% for both ruxolitinib and placebo at 12 weeks, but by 24 weeks, there was a clear increase in repigmentation rates in the ruxolitinib group for all body areas.

The 24-week VASI-50 rates for hand repigmentation were 24.9% for ruxolitinib cream and 14.4% for placebo. Corresponding rates for upper extremity repigmentation were 33.2% and 8.2%; for the trunk, 26.4% and 12.2%; for the lower extremities, 29.5% and 12.2%; and for the feet, 18.5% and 12.5%.

“The results are quite poor at 12 weeks,” Dr. Passeron said. “It’s very important to keep this in mind; it takes time to repigment vitiligo, it takes to 6-24 months. We have to explain to our patients that they will have to wait to see the results.”

Steady improvements, no new safety concerns

Regarding VASI-50 over time, there was a steady increase in total body scores; 47.7% of patients who received ruxolitinib and 23.3% of placebo-treated patients hit this target at 52 weeks.

“And what is also very important to see is that we didn’t reach the plateau,” Dr. Passeron reported.

Similar patterns were seen for all the other body areas. Again there was a suggestion that rates may continue to rise with continued long-term treatment.

“About one-third of the patients reached at least 50% repigmentation after 1 year of treatment in the hands and feet,” Dr. Passeron said. He noted that certain areas, such as the back of the hand or tips of the fingers, may be unresponsive.

“So, we have to also to warn the patient that probably on these areas we have to combine it with other treatment because it remains very, very difficult to treat.”

There were no new safety concerns regarding treatment-emergent adverse events, which were reported in 52% of patients who received ruxolitinib and in 36% of placebo-treated patients.

The most common adverse reactions included COVID-19 (6.1% vs. 3.1%), acne at the application site (5.3% vs. 1.3%), and pruritus at the application site (3.9% vs. 2.7%), although cases were “mild or moderate,” said Dr. Passeron.

An expert’s take-home

“The results of TRuE-V phase 3 studies are encouraging and exciting,” Viktoria Eleftheriadou, MD, MRCP(UK), SCE(Derm), PhD, said in providing an independent comment for this news organization.

“Although ruxolitinib cream is applied on the skin, this novel treatment for vitiligo is not without risks; therefore, careful monitoring of patients who are started on this topical treatment would be prudent,” said Dr. Eleftheriadou, who is a consultant dermatologist for Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust and the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

“I would like to see how many patients achieved VASI-75 or VASI-80 score, which from patients’ perspectives is a more meaningful outcome, as well as how long these results will last for,” she added.

The study was funded by Incyte Corporation. Dr. Passeron has received grants, honoraria, or both from AbbVie, ACM Pharma, Almirall, Amgen, Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Galderma, Genzyme/Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte Corporation, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharmaceuticals, and UCB. Dr. Passeron is the cofounder of YUKIN Therapeutics and has patents on WNT agonists or GSK2b antagonist for repigmentation of vitiligo and on the use of CXCR3B blockers in vitiligo. Dr. Eleftheriadou is an investigator and trial development group member on the HI-Light Vitiligo Trial (specific), a lead investigator on the pilot HI-Light Vitiligo Trial, and a medical advisory panel member of the Vitiligo Society UK. Dr. Eleftheriadou also provides consultancy services to Incyte and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Those difficult areas include the hands and feet, said Thierry Passeron, MD, PhD, of Université Côte d’Azur and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nice (France).

Indeed, a 50% or greater improvement in the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI-50) of the hands and feet was achieved with ruxolitinib cream (Opzelura) in around one-third of patients after 52 weeks’ treatment, and more than half of patients showed improvement in the upper and lower extremities.

During one of the late-breaking news sessions, Dr. Passeron presented a pooled analysis of the Topical Ruxolitinib Evaluation in Vitiligo Study 1 (TRuE-V1) and Study 2 (TruE-V2), which assessed VASI-50 data by body regions.

Similarly positive results were seen on the head and neck and the trunk, with VASI-50 being reached in a respective 68% and 48% of patients after a full year of treatment.

“VASI-50 response rates rose steadily through 52 weeks for both the head and trunk,” said Dr. Passeron. He noted that the trials were initially double-blinded for 24 weeks and that there was a further open-label extension phase through week 52.

In the latter phase, all patients were treated with ruxolitinib; those who originally received a vehicle agent as placebo crossed over to the active treatment.

First FDA-approved treatment for adults and adolescents with vitiligo

Ruxolitinib is a Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor that has been available for the treatment for atopic dermatitis for more than a year. It was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of vitiligo in adults and pediatric patients aged 12 years and older.

This approval was based on the positive findings of the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies, which showed that after 24 weeks, 30% of patients treated with ruxolitinib had at least 75% improvement in the facial VASI, compared with 10% of placebo-treated patients.

“These studies demonstrated very nice results, especially on the face, which is the easiest part to repigment in vitiligo,” Dr. Passeron said.

“We know that the location is very important when it comes to repigmentation of vitiligo,” he added. He noted that other body areas, “the extremities, for example, are much more difficult.”

The analysis he presented specifically assessed the effect of ruxolitinib cream on repigmentation in other areas.

Pooled analysis performed

Data from the two TRuE-V trials were pooled. The new analysis included a total of 661 individuals; of those patients, 443 had been treated with topical ruxolitinib, and 218 had received a vehicle cream as a placebo.

For the first 24 weeks, patients received twice-daily 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle cream. This was followed by a 28-week extension phase in which everyone was treated with ruxolitinib cream, after which there was a 30-day final follow-up period.

Dr. Passeron reported data by body region for weeks 12, 24, and 52, which showed an increasing percentage of patients with VASI-50.

“We didn’t look at the face; that we know well, that is a very good result,” he said.

The best results were seen for the head and neck. VASI-50 was reached by 28.3%, 45.3%, and 68.1% of patients treated with ruxolitinib cream at weeks 12, 24, and 52, respectively. Corresponding rates for the placebo-crossover group were 19.8%, 23.8%, and 51%.

Repigmentation rates of the hand, upper extremities, trunk, lower extremities, and feet were about 9%-15% for both ruxolitinib and placebo at 12 weeks, but by 24 weeks, there was a clear increase in repigmentation rates in the ruxolitinib group for all body areas.

The 24-week VASI-50 rates for hand repigmentation were 24.9% for ruxolitinib cream and 14.4% for placebo. Corresponding rates for upper extremity repigmentation were 33.2% and 8.2%; for the trunk, 26.4% and 12.2%; for the lower extremities, 29.5% and 12.2%; and for the feet, 18.5% and 12.5%.

“The results are quite poor at 12 weeks,” Dr. Passeron said. “It’s very important to keep this in mind; it takes time to repigment vitiligo, it takes to 6-24 months. We have to explain to our patients that they will have to wait to see the results.”

Steady improvements, no new safety concerns

Regarding VASI-50 over time, there was a steady increase in total body scores; 47.7% of patients who received ruxolitinib and 23.3% of placebo-treated patients hit this target at 52 weeks.

“And what is also very important to see is that we didn’t reach the plateau,” Dr. Passeron reported.

Similar patterns were seen for all the other body areas. Again there was a suggestion that rates may continue to rise with continued long-term treatment.

“About one-third of the patients reached at least 50% repigmentation after 1 year of treatment in the hands and feet,” Dr. Passeron said. He noted that certain areas, such as the back of the hand or tips of the fingers, may be unresponsive.

“So, we have to also to warn the patient that probably on these areas we have to combine it with other treatment because it remains very, very difficult to treat.”

There were no new safety concerns regarding treatment-emergent adverse events, which were reported in 52% of patients who received ruxolitinib and in 36% of placebo-treated patients.

The most common adverse reactions included COVID-19 (6.1% vs. 3.1%), acne at the application site (5.3% vs. 1.3%), and pruritus at the application site (3.9% vs. 2.7%), although cases were “mild or moderate,” said Dr. Passeron.

An expert’s take-home

“The results of TRuE-V phase 3 studies are encouraging and exciting,” Viktoria Eleftheriadou, MD, MRCP(UK), SCE(Derm), PhD, said in providing an independent comment for this news organization.

“Although ruxolitinib cream is applied on the skin, this novel treatment for vitiligo is not without risks; therefore, careful monitoring of patients who are started on this topical treatment would be prudent,” said Dr. Eleftheriadou, who is a consultant dermatologist for Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust and the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

“I would like to see how many patients achieved VASI-75 or VASI-80 score, which from patients’ perspectives is a more meaningful outcome, as well as how long these results will last for,” she added.

The study was funded by Incyte Corporation. Dr. Passeron has received grants, honoraria, or both from AbbVie, ACM Pharma, Almirall, Amgen, Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Galderma, Genzyme/Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte Corporation, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharmaceuticals, and UCB. Dr. Passeron is the cofounder of YUKIN Therapeutics and has patents on WNT agonists or GSK2b antagonist for repigmentation of vitiligo and on the use of CXCR3B blockers in vitiligo. Dr. Eleftheriadou is an investigator and trial development group member on the HI-Light Vitiligo Trial (specific), a lead investigator on the pilot HI-Light Vitiligo Trial, and a medical advisory panel member of the Vitiligo Society UK. Dr. Eleftheriadou also provides consultancy services to Incyte and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

Those difficult areas include the hands and feet, said Thierry Passeron, MD, PhD, of Université Côte d’Azur and Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Nice (France).

Indeed, a 50% or greater improvement in the Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (VASI-50) of the hands and feet was achieved with ruxolitinib cream (Opzelura) in around one-third of patients after 52 weeks’ treatment, and more than half of patients showed improvement in the upper and lower extremities.

During one of the late-breaking news sessions, Dr. Passeron presented a pooled analysis of the Topical Ruxolitinib Evaluation in Vitiligo Study 1 (TRuE-V1) and Study 2 (TruE-V2), which assessed VASI-50 data by body regions.

Similarly positive results were seen on the head and neck and the trunk, with VASI-50 being reached in a respective 68% and 48% of patients after a full year of treatment.

“VASI-50 response rates rose steadily through 52 weeks for both the head and trunk,” said Dr. Passeron. He noted that the trials were initially double-blinded for 24 weeks and that there was a further open-label extension phase through week 52.

In the latter phase, all patients were treated with ruxolitinib; those who originally received a vehicle agent as placebo crossed over to the active treatment.

First FDA-approved treatment for adults and adolescents with vitiligo

Ruxolitinib is a Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor that has been available for the treatment for atopic dermatitis for more than a year. It was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of vitiligo in adults and pediatric patients aged 12 years and older.

This approval was based on the positive findings of the TRuE-V1 and TRuE-V2 studies, which showed that after 24 weeks, 30% of patients treated with ruxolitinib had at least 75% improvement in the facial VASI, compared with 10% of placebo-treated patients.

“These studies demonstrated very nice results, especially on the face, which is the easiest part to repigment in vitiligo,” Dr. Passeron said.

“We know that the location is very important when it comes to repigmentation of vitiligo,” he added. He noted that other body areas, “the extremities, for example, are much more difficult.”

The analysis he presented specifically assessed the effect of ruxolitinib cream on repigmentation in other areas.

Pooled analysis performed

Data from the two TRuE-V trials were pooled. The new analysis included a total of 661 individuals; of those patients, 443 had been treated with topical ruxolitinib, and 218 had received a vehicle cream as a placebo.

For the first 24 weeks, patients received twice-daily 1.5% ruxolitinib cream or vehicle cream. This was followed by a 28-week extension phase in which everyone was treated with ruxolitinib cream, after which there was a 30-day final follow-up period.

Dr. Passeron reported data by body region for weeks 12, 24, and 52, which showed an increasing percentage of patients with VASI-50.

“We didn’t look at the face; that we know well, that is a very good result,” he said.

The best results were seen for the head and neck. VASI-50 was reached by 28.3%, 45.3%, and 68.1% of patients treated with ruxolitinib cream at weeks 12, 24, and 52, respectively. Corresponding rates for the placebo-crossover group were 19.8%, 23.8%, and 51%.

Repigmentation rates of the hand, upper extremities, trunk, lower extremities, and feet were about 9%-15% for both ruxolitinib and placebo at 12 weeks, but by 24 weeks, there was a clear increase in repigmentation rates in the ruxolitinib group for all body areas.

The 24-week VASI-50 rates for hand repigmentation were 24.9% for ruxolitinib cream and 14.4% for placebo. Corresponding rates for upper extremity repigmentation were 33.2% and 8.2%; for the trunk, 26.4% and 12.2%; for the lower extremities, 29.5% and 12.2%; and for the feet, 18.5% and 12.5%.

“The results are quite poor at 12 weeks,” Dr. Passeron said. “It’s very important to keep this in mind; it takes time to repigment vitiligo, it takes to 6-24 months. We have to explain to our patients that they will have to wait to see the results.”

Steady improvements, no new safety concerns

Regarding VASI-50 over time, there was a steady increase in total body scores; 47.7% of patients who received ruxolitinib and 23.3% of placebo-treated patients hit this target at 52 weeks.

“And what is also very important to see is that we didn’t reach the plateau,” Dr. Passeron reported.

Similar patterns were seen for all the other body areas. Again there was a suggestion that rates may continue to rise with continued long-term treatment.

“About one-third of the patients reached at least 50% repigmentation after 1 year of treatment in the hands and feet,” Dr. Passeron said. He noted that certain areas, such as the back of the hand or tips of the fingers, may be unresponsive.

“So, we have to also to warn the patient that probably on these areas we have to combine it with other treatment because it remains very, very difficult to treat.”

There were no new safety concerns regarding treatment-emergent adverse events, which were reported in 52% of patients who received ruxolitinib and in 36% of placebo-treated patients.

The most common adverse reactions included COVID-19 (6.1% vs. 3.1%), acne at the application site (5.3% vs. 1.3%), and pruritus at the application site (3.9% vs. 2.7%), although cases were “mild or moderate,” said Dr. Passeron.

An expert’s take-home

“The results of TRuE-V phase 3 studies are encouraging and exciting,” Viktoria Eleftheriadou, MD, MRCP(UK), SCE(Derm), PhD, said in providing an independent comment for this news organization.

“Although ruxolitinib cream is applied on the skin, this novel treatment for vitiligo is not without risks; therefore, careful monitoring of patients who are started on this topical treatment would be prudent,” said Dr. Eleftheriadou, who is a consultant dermatologist for Walsall Healthcare NHS Trust and the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust, Birmingham, United Kingdom.

“I would like to see how many patients achieved VASI-75 or VASI-80 score, which from patients’ perspectives is a more meaningful outcome, as well as how long these results will last for,” she added.

The study was funded by Incyte Corporation. Dr. Passeron has received grants, honoraria, or both from AbbVie, ACM Pharma, Almirall, Amgen, Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Galderma, Genzyme/Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte Corporation, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharmaceuticals, and UCB. Dr. Passeron is the cofounder of YUKIN Therapeutics and has patents on WNT agonists or GSK2b antagonist for repigmentation of vitiligo and on the use of CXCR3B blockers in vitiligo. Dr. Eleftheriadou is an investigator and trial development group member on the HI-Light Vitiligo Trial (specific), a lead investigator on the pilot HI-Light Vitiligo Trial, and a medical advisory panel member of the Vitiligo Society UK. Dr. Eleftheriadou also provides consultancy services to Incyte and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Artemisia capillaris extract

Melasma is a difficult disorder to treat. With the removal of hydroquinone from the cosmetic market and the prevalence of dyschromia, new skin lightening ingredients are being sought and many new discoveries are coming from Asia.

There are more than 500 species of the genus Artemisia (of the Astraceae or Compositae family) dispersed throughout the temperate areas of Asia, Europe, and North America.1 Various parts of the shrub Artemisia capillaris, found abundantly in China, Japan, and Korea, have been used in traditional medicine in Asia for hundreds of years. A. capillaris (Yin-Chen in Chinese) has been deployed in traditional Chinese medicine as a diuretic, to protect the liver, and to treat skin inflammation.2,3 Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antisteatotic, antitumor, and antiviral properties have been associated with this plant,3 and hydrating effects have been recently attributed to it. In Korean medicine, A. capillaris (InJin in Korean) has been used for its hepatoprotective, analgesic, and antipyretic activities.4,5 In this column, the focus will be on recent evidence that suggests possible applications in skin care.

Chemical constituents

In 2008, Kim et al. studied the anticarcinogenic activity of A. capillaris, among other medicinal herbs, using the 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)-induced mouse skin carcinogenesis model. The researchers found that A. capillaris exhibited the most effective anticarcinogenic activity compared to the other herbs tested, with such properties ascribed to its constituent camphor, 1-borneol, coumarin, and achillin. Notably, the chloroform fraction of A. capillaris significantly lowered the number of tumors/mouse and tumor incidence compared with the other tested herbs.6

The wide range of biological functions associated with A. capillaris, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antisteatotic, and antitumor activities have, in various studies, been attributed to the bioactive constituents scoparone, scopoletin, capillarisin, capillin, and chlorogenic acids.3

Tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP-1) and its role in skin pigmentation

Tyrosinase related protein 1 (TYRP-1) is structurally similar to tyrosinase, but its role is still being elucidated. Mutations in TYR-1 results in oculocutaneous albinism. TYRP-1 is involved in eumelanin synthesis, but not in pheomelanin synthesis. Mutations in TYRP-1 affect the quality of melanin synthesized rather than the quantity.4 TYRP-1 is being looked at as a target for treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma.

Effects on melanin synthesis

A. capillaris reduces the expression of TYRP-1, making it attractive for use in skin lightening products. Although there are not a lot of data, this is a developing area of interest and the following will discuss what is known so far.

Kim et al. investigated the antimelanogenic activity of 10 essential oils, including A. capillaris, utilizing the B16F10 cell line model. A. capillaris was among four extracts found to hinder melanogenesis, and the only one that improved cell proliferation, displayed anti-H2O2 activity, and reduced tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-1 expression. The researchers determined that A. capillaris extract suppressed melanin production through the downregulation of the TRP 1 translational level. They concluded that while investigations using in vivo models are necessary to buttress and validate these results, A. capillaris extract appears to be suitable as a natural therapeutic antimelanogenic agent as well as a skin-whitening ingredient in cosmeceutical products.7

Tabassum et al. screened A. capillaris for antipigmentary functions using murine cultured cells (B16-F10 malignant melanocytes). They found that the A. capillaris constituent 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid significantly and dose-dependently diminished melanin production and tyrosinase activity in the melanocytes. The expression of tyrosinase-related protein-1 was also decreased. Further, the researchers observed antipigmentary activity in a zebrafish model, with no toxicity demonstrated by either A. capillaris or its component 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid. They concluded that this compound could be included as an active ingredient in products intended to address pigmentation disorders.8

Anti-inflammatory activity

Inflammation is well known to trigger the production of melanin. This is why anti-inflammatory ingredients are often included in skin lighting products. A. capillaris displays anti-inflammatory activity and has shown some antioxidant activity.

In 2018, Lee et al. confirmed the therapeutic potential of A. capillaris extract to treat psoriasis in HaCaT cells and imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like mouse models. In the murine models, those treated with the ethanol extract of A. capillaris had a significantly lower Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score than that of the mice not given the topical application of the botanical. Epidermal thickness was noted to be significantly lower compared with the mice not treated with A. capillaris.9 Further studies in mice by the same team later that year supported the use of a cream formulation containing A. capillaris that they developed to treat psoriasis, warranting new investigations in human skin.10

Yeo et al. reported, earlier in 2018, on other anti-inflammatory activity of the herb, finding that the aqueous extract from A. capillaris blocked acute gastric mucosal injury by hindering reactive oxygen species and nuclear factor kappa B. They added that A. capillaris maintains oxidant/antioxidant homeostasis and displays potential as a nutraceutical agent for treating gastric ulcers and gastritis.5

In 2011, Kwon et al. studied the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory action of a 70% ethanol extract of aerial parts of A. capillaris. They identified esculetin and quercetin as strong inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase. The botanical agent, and esculetin in particular, robustly suppressed arachidonic acid-induced ear edema in mice as well as delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Further, A. capillaris potently blocked 5-lipoxygenase-catalyzed leukotriene synthesis by ionophore-induced rat basophilic leukemia-1 cells. The researchers concluded that their findings may partially account for the use of A. capillaris as a traditional medical treatment for cutaneous inflammatory conditions.2

Atopic dermatitis and A. capillaris

In 2014, Ha et al. used in vitro and in vivo systems to assess the anti-inflammatory effects of A. capillaris as well as its activity against atopic dermatitis. The in vitro studies revealed that A. capillaris hampered NO and cellular histamine synthesis. In Nc/Nga mice sensitized by Dermatophagoides farinae, dermatitis scores as well as hemorrhage, hypertrophy, and hyperkeratosis of the epidermis in the dorsal skin and ear all declined after the topical application of A. capillaris. Plasma levels of histamine and IgE also significantly decreased after treatment with A. capillaris. The investigators concluded that further study of A. capillaris is warranted as a potential therapeutic option for atopic dermatitis.11

Summary

Many botanical ingredients from Asia are making their way into skin care products in the USA. A. capillaris extract is an example and may have utility in treating hyperpigmentation-associated skin issues such as melasma. Its inhibitory effects on both inflammation and melanin production in addition to possible antioxidant activity make it an interesting compound worthy of more scrutiny.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Bora KS and Sharma A. Pharm Biol. 2011 Jan;49(1):101-9.

2. Kwon OS et al. Arch Pharm Res. 2011 Sep;34(9):1561-9.

3. Hsueh TP et al. Biomedicines. 2021 Oct 8;9(10):1412.

4. Dolinska MB et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jan 3;21(1):331.

5. Yeo D et al. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018 Mar;99:681-7.

6. Kim YS et al. J Food Sci. 2008 Jan;73(1):T16-20.

7. Kim MJ et al. Mol Med Rep. 2022 Apr;25(4):113.

8. Tabassum N et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:7823541.

9. Lee SY et al. Phytother Res. 2018 May;32(5):923-2.

10. Lee SY et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018 Aug 19;2018:3610494.

11. Ha H et al. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014 Mar 14;14:100.

Melasma is a difficult disorder to treat. With the removal of hydroquinone from the cosmetic market and the prevalence of dyschromia, new skin lightening ingredients are being sought and many new discoveries are coming from Asia.

There are more than 500 species of the genus Artemisia (of the Astraceae or Compositae family) dispersed throughout the temperate areas of Asia, Europe, and North America.1 Various parts of the shrub Artemisia capillaris, found abundantly in China, Japan, and Korea, have been used in traditional medicine in Asia for hundreds of years. A. capillaris (Yin-Chen in Chinese) has been deployed in traditional Chinese medicine as a diuretic, to protect the liver, and to treat skin inflammation.2,3 Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antisteatotic, antitumor, and antiviral properties have been associated with this plant,3 and hydrating effects have been recently attributed to it. In Korean medicine, A. capillaris (InJin in Korean) has been used for its hepatoprotective, analgesic, and antipyretic activities.4,5 In this column, the focus will be on recent evidence that suggests possible applications in skin care.

Chemical constituents

In 2008, Kim et al. studied the anticarcinogenic activity of A. capillaris, among other medicinal herbs, using the 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)-induced mouse skin carcinogenesis model. The researchers found that A. capillaris exhibited the most effective anticarcinogenic activity compared to the other herbs tested, with such properties ascribed to its constituent camphor, 1-borneol, coumarin, and achillin. Notably, the chloroform fraction of A. capillaris significantly lowered the number of tumors/mouse and tumor incidence compared with the other tested herbs.6

The wide range of biological functions associated with A. capillaris, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antisteatotic, and antitumor activities have, in various studies, been attributed to the bioactive constituents scoparone, scopoletin, capillarisin, capillin, and chlorogenic acids.3

Tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP-1) and its role in skin pigmentation

Tyrosinase related protein 1 (TYRP-1) is structurally similar to tyrosinase, but its role is still being elucidated. Mutations in TYR-1 results in oculocutaneous albinism. TYRP-1 is involved in eumelanin synthesis, but not in pheomelanin synthesis. Mutations in TYRP-1 affect the quality of melanin synthesized rather than the quantity.4 TYRP-1 is being looked at as a target for treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma.

Effects on melanin synthesis

A. capillaris reduces the expression of TYRP-1, making it attractive for use in skin lightening products. Although there are not a lot of data, this is a developing area of interest and the following will discuss what is known so far.

Kim et al. investigated the antimelanogenic activity of 10 essential oils, including A. capillaris, utilizing the B16F10 cell line model. A. capillaris was among four extracts found to hinder melanogenesis, and the only one that improved cell proliferation, displayed anti-H2O2 activity, and reduced tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-1 expression. The researchers determined that A. capillaris extract suppressed melanin production through the downregulation of the TRP 1 translational level. They concluded that while investigations using in vivo models are necessary to buttress and validate these results, A. capillaris extract appears to be suitable as a natural therapeutic antimelanogenic agent as well as a skin-whitening ingredient in cosmeceutical products.7

Tabassum et al. screened A. capillaris for antipigmentary functions using murine cultured cells (B16-F10 malignant melanocytes). They found that the A. capillaris constituent 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid significantly and dose-dependently diminished melanin production and tyrosinase activity in the melanocytes. The expression of tyrosinase-related protein-1 was also decreased. Further, the researchers observed antipigmentary activity in a zebrafish model, with no toxicity demonstrated by either A. capillaris or its component 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid. They concluded that this compound could be included as an active ingredient in products intended to address pigmentation disorders.8

Anti-inflammatory activity

Inflammation is well known to trigger the production of melanin. This is why anti-inflammatory ingredients are often included in skin lighting products. A. capillaris displays anti-inflammatory activity and has shown some antioxidant activity.

In 2018, Lee et al. confirmed the therapeutic potential of A. capillaris extract to treat psoriasis in HaCaT cells and imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like mouse models. In the murine models, those treated with the ethanol extract of A. capillaris had a significantly lower Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score than that of the mice not given the topical application of the botanical. Epidermal thickness was noted to be significantly lower compared with the mice not treated with A. capillaris.9 Further studies in mice by the same team later that year supported the use of a cream formulation containing A. capillaris that they developed to treat psoriasis, warranting new investigations in human skin.10

Yeo et al. reported, earlier in 2018, on other anti-inflammatory activity of the herb, finding that the aqueous extract from A. capillaris blocked acute gastric mucosal injury by hindering reactive oxygen species and nuclear factor kappa B. They added that A. capillaris maintains oxidant/antioxidant homeostasis and displays potential as a nutraceutical agent for treating gastric ulcers and gastritis.5

In 2011, Kwon et al. studied the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory action of a 70% ethanol extract of aerial parts of A. capillaris. They identified esculetin and quercetin as strong inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase. The botanical agent, and esculetin in particular, robustly suppressed arachidonic acid-induced ear edema in mice as well as delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Further, A. capillaris potently blocked 5-lipoxygenase-catalyzed leukotriene synthesis by ionophore-induced rat basophilic leukemia-1 cells. The researchers concluded that their findings may partially account for the use of A. capillaris as a traditional medical treatment for cutaneous inflammatory conditions.2

Atopic dermatitis and A. capillaris

In 2014, Ha et al. used in vitro and in vivo systems to assess the anti-inflammatory effects of A. capillaris as well as its activity against atopic dermatitis. The in vitro studies revealed that A. capillaris hampered NO and cellular histamine synthesis. In Nc/Nga mice sensitized by Dermatophagoides farinae, dermatitis scores as well as hemorrhage, hypertrophy, and hyperkeratosis of the epidermis in the dorsal skin and ear all declined after the topical application of A. capillaris. Plasma levels of histamine and IgE also significantly decreased after treatment with A. capillaris. The investigators concluded that further study of A. capillaris is warranted as a potential therapeutic option for atopic dermatitis.11

Summary

Many botanical ingredients from Asia are making their way into skin care products in the USA. A. capillaris extract is an example and may have utility in treating hyperpigmentation-associated skin issues such as melasma. Its inhibitory effects on both inflammation and melanin production in addition to possible antioxidant activity make it an interesting compound worthy of more scrutiny.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Bora KS and Sharma A. Pharm Biol. 2011 Jan;49(1):101-9.

2. Kwon OS et al. Arch Pharm Res. 2011 Sep;34(9):1561-9.

3. Hsueh TP et al. Biomedicines. 2021 Oct 8;9(10):1412.

4. Dolinska MB et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jan 3;21(1):331.

5. Yeo D et al. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018 Mar;99:681-7.

6. Kim YS et al. J Food Sci. 2008 Jan;73(1):T16-20.

7. Kim MJ et al. Mol Med Rep. 2022 Apr;25(4):113.

8. Tabassum N et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:7823541.

9. Lee SY et al. Phytother Res. 2018 May;32(5):923-2.

10. Lee SY et al. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2018 Aug 19;2018:3610494.

11. Ha H et al. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014 Mar 14;14:100.

Melasma is a difficult disorder to treat. With the removal of hydroquinone from the cosmetic market and the prevalence of dyschromia, new skin lightening ingredients are being sought and many new discoveries are coming from Asia.

There are more than 500 species of the genus Artemisia (of the Astraceae or Compositae family) dispersed throughout the temperate areas of Asia, Europe, and North America.1 Various parts of the shrub Artemisia capillaris, found abundantly in China, Japan, and Korea, have been used in traditional medicine in Asia for hundreds of years. A. capillaris (Yin-Chen in Chinese) has been deployed in traditional Chinese medicine as a diuretic, to protect the liver, and to treat skin inflammation.2,3 Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antisteatotic, antitumor, and antiviral properties have been associated with this plant,3 and hydrating effects have been recently attributed to it. In Korean medicine, A. capillaris (InJin in Korean) has been used for its hepatoprotective, analgesic, and antipyretic activities.4,5 In this column, the focus will be on recent evidence that suggests possible applications in skin care.

Chemical constituents

In 2008, Kim et al. studied the anticarcinogenic activity of A. capillaris, among other medicinal herbs, using the 7,12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA)-induced mouse skin carcinogenesis model. The researchers found that A. capillaris exhibited the most effective anticarcinogenic activity compared to the other herbs tested, with such properties ascribed to its constituent camphor, 1-borneol, coumarin, and achillin. Notably, the chloroform fraction of A. capillaris significantly lowered the number of tumors/mouse and tumor incidence compared with the other tested herbs.6

The wide range of biological functions associated with A. capillaris, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antisteatotic, and antitumor activities have, in various studies, been attributed to the bioactive constituents scoparone, scopoletin, capillarisin, capillin, and chlorogenic acids.3

Tyrosinase-related protein 1 (TYRP-1) and its role in skin pigmentation

Tyrosinase related protein 1 (TYRP-1) is structurally similar to tyrosinase, but its role is still being elucidated. Mutations in TYR-1 results in oculocutaneous albinism. TYRP-1 is involved in eumelanin synthesis, but not in pheomelanin synthesis. Mutations in TYRP-1 affect the quality of melanin synthesized rather than the quantity.4 TYRP-1 is being looked at as a target for treatment of hyperpigmentation disorders such as melasma.

Effects on melanin synthesis

A. capillaris reduces the expression of TYRP-1, making it attractive for use in skin lightening products. Although there are not a lot of data, this is a developing area of interest and the following will discuss what is known so far.

Kim et al. investigated the antimelanogenic activity of 10 essential oils, including A. capillaris, utilizing the B16F10 cell line model. A. capillaris was among four extracts found to hinder melanogenesis, and the only one that improved cell proliferation, displayed anti-H2O2 activity, and reduced tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-1 expression. The researchers determined that A. capillaris extract suppressed melanin production through the downregulation of the TRP 1 translational level. They concluded that while investigations using in vivo models are necessary to buttress and validate these results, A. capillaris extract appears to be suitable as a natural therapeutic antimelanogenic agent as well as a skin-whitening ingredient in cosmeceutical products.7

Tabassum et al. screened A. capillaris for antipigmentary functions using murine cultured cells (B16-F10 malignant melanocytes). They found that the A. capillaris constituent 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid significantly and dose-dependently diminished melanin production and tyrosinase activity in the melanocytes. The expression of tyrosinase-related protein-1 was also decreased. Further, the researchers observed antipigmentary activity in a zebrafish model, with no toxicity demonstrated by either A. capillaris or its component 4,5-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid. They concluded that this compound could be included as an active ingredient in products intended to address pigmentation disorders.8

Anti-inflammatory activity

Inflammation is well known to trigger the production of melanin. This is why anti-inflammatory ingredients are often included in skin lighting products. A. capillaris displays anti-inflammatory activity and has shown some antioxidant activity.

In 2018, Lee et al. confirmed the therapeutic potential of A. capillaris extract to treat psoriasis in HaCaT cells and imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like mouse models. In the murine models, those treated with the ethanol extract of A. capillaris had a significantly lower Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score than that of the mice not given the topical application of the botanical. Epidermal thickness was noted to be significantly lower compared with the mice not treated with A. capillaris.9 Further studies in mice by the same team later that year supported the use of a cream formulation containing A. capillaris that they developed to treat psoriasis, warranting new investigations in human skin.10

Yeo et al. reported, earlier in 2018, on other anti-inflammatory activity of the herb, finding that the aqueous extract from A. capillaris blocked acute gastric mucosal injury by hindering reactive oxygen species and nuclear factor kappa B. They added that A. capillaris maintains oxidant/antioxidant homeostasis and displays potential as a nutraceutical agent for treating gastric ulcers and gastritis.5

In 2011, Kwon et al. studied the 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory action of a 70% ethanol extract of aerial parts of A. capillaris. They identified esculetin and quercetin as strong inhibitors of 5-lipoxygenase. The botanical agent, and esculetin in particular, robustly suppressed arachidonic acid-induced ear edema in mice as well as delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions. Further, A. capillaris potently blocked 5-lipoxygenase-catalyzed leukotriene synthesis by ionophore-induced rat basophilic leukemia-1 cells. The researchers concluded that their findings may partially account for the use of A. capillaris as a traditional medical treatment for cutaneous inflammatory conditions.2

Atopic dermatitis and A. capillaris

In 2014, Ha et al. used in vitro and in vivo systems to assess the anti-inflammatory effects of A. capillaris as well as its activity against atopic dermatitis. The in vitro studies revealed that A. capillaris hampered NO and cellular histamine synthesis. In Nc/Nga mice sensitized by Dermatophagoides farinae, dermatitis scores as well as hemorrhage, hypertrophy, and hyperkeratosis of the epidermis in the dorsal skin and ear all declined after the topical application of A. capillaris. Plasma levels of histamine and IgE also significantly decreased after treatment with A. capillaris. The investigators concluded that further study of A. capillaris is warranted as a potential therapeutic option for atopic dermatitis.11

Summary