User login

Papulonodules on the Ankle in a Patient with Lung Cancer

Papulonodules on the Ankle in a Patient with Lung Cancer

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pembrolizumab-Induced Eruptive Squamous Proliferation

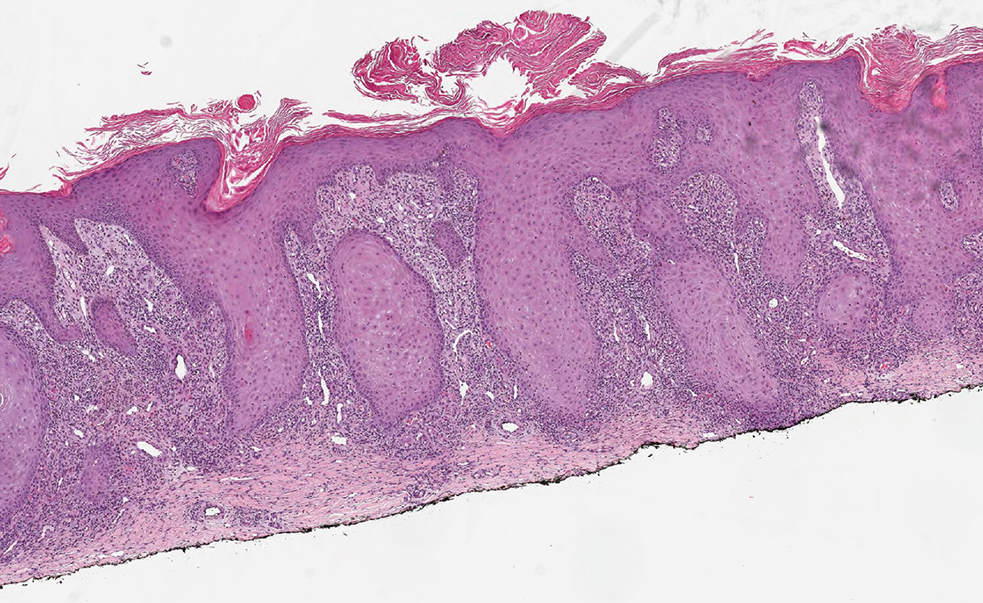

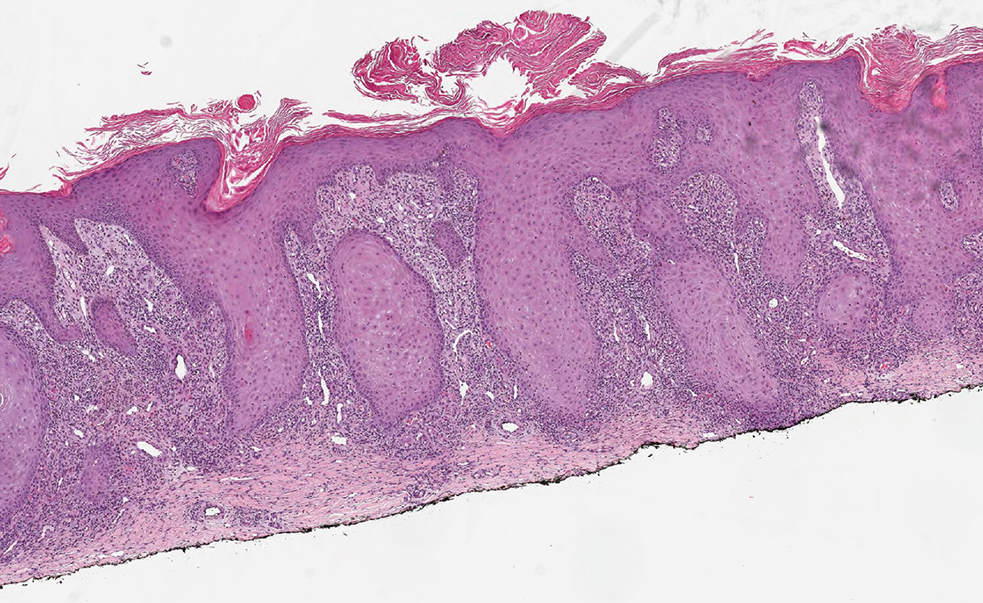

Histopathology showed a broad squamous proliferation with acanthosis of the epidermis. Large glassy keratinocytes were seen with scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure), and a dense lichenoid band of inflammation was present subjacent to the proliferation. Notably, no hypergranulosis, remarkable keratinocyte atypia, or increased mitotic figures were seen. Based on the patient’s medical history and biopsy results, a diagnosis of pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation was made. The diagnosis was supported by a growing body of evidence of this type of reaction in patients taking programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors.1,2 Conservative treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% was initiated with complete resolution of the lesions at the 2-month follow-up appointment. Other common treatments include topical steroids, injected corticosteroids, or cryosurgery to locally control the inflammation and atypical proliferation of cells.3

Pembrolizumab is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody targeting the PD-1 receptor that has been utilized for its antitumor activity against various cancers, including unresectable and metastatic melanoma, head and neck cancers, and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1,4,5 While this drug has extended the lives of many patients with cancer, there are adverse reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors (eg, pembrolizumab, nivolumab). Skin toxicity to PD-1 inhibitors is the one of most common immune-mediated reactions worldwide, occurring in approximately 30% of patients.6,7 Reactions can occur while a patient is taking the inciting drug and can continue up to 2 months after treatment discontinuation.8 Skin reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors vary from lichenoid reactions and vitiligolike patches to psoriasis or eczema flares and are organized into 4 categories: inflammatory, immunobullous, alteration of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes.9 Our patient demonstrated alteration of keratinocytes, which is characterized by overlapping features of hypertrophic lichen planus and early keratoacanthoma.

The differential diagnoses for pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation include squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), psoriasis, hypertrophic lichen planus, and cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus also is a well-documented reaction to use of immune-checkpoint inhibitors.10 Direct immunofluorescence could have helped differentiate hypertrophic lupus erythematosus from an eruptive squamous proliferation in our patient; however, due to her response to treatment, no additional workup was done.

Squamous cell carcinoma, which is the most common type of skin cancer in Black patients in the United States,11 has been shown to manifest after a PD-1 inhibitor is taken.12 Although it typically has a more chronic persistent course, the clinical appearance of SCC can be similar to the findings seen in our patient. Histologically, SCC may demonstrate necrosis, but the atypical proliferations will invade the dermis—a feature not seen in our patient’s histopathology.13

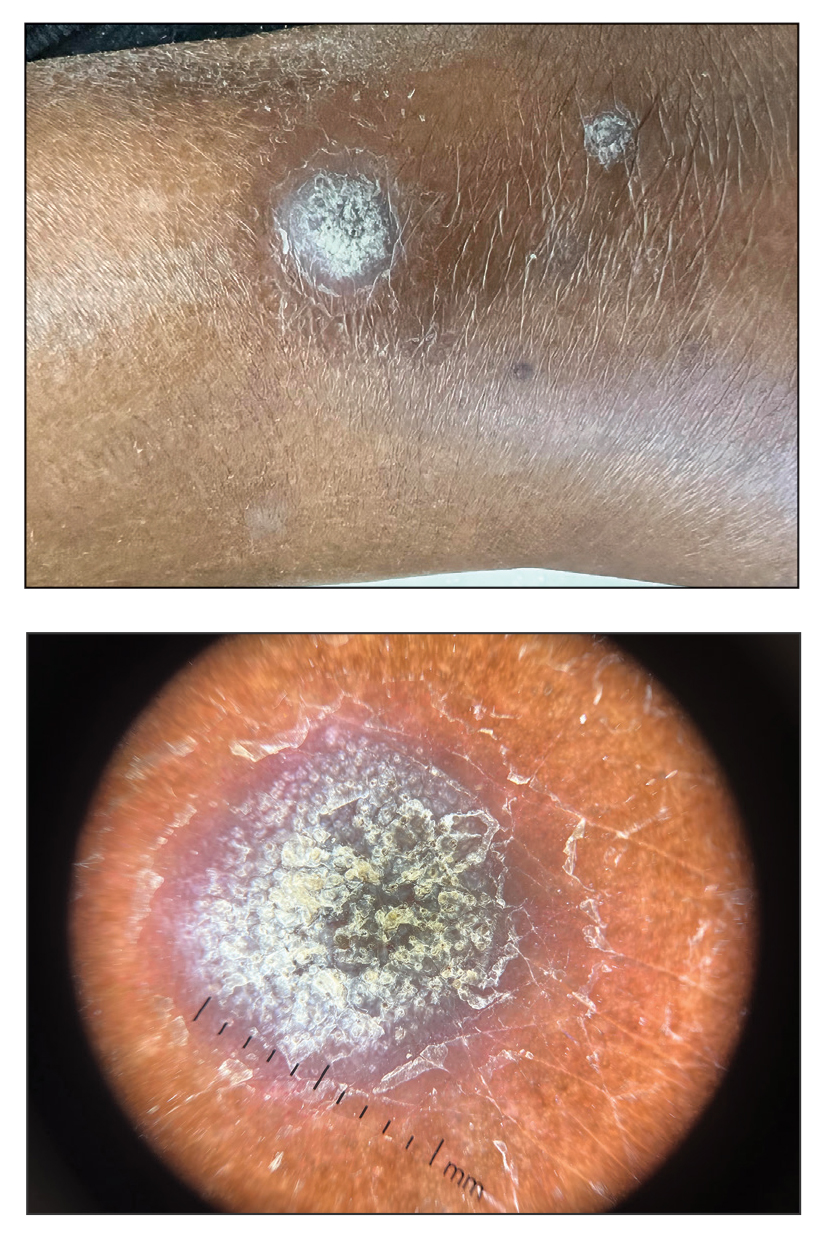

Lichen planus (LP) is an eruptive immune reaction of violaceous polygonal papules and plaques commonly seen on the ankles14 that has been shown to be an adverse effect of pembrolizumab.15 There are several subtypes of LP including hypertrophic versions, which can appear clinically similar to the findings seen in our patient. On dermoscopy, the classic finding of white lines, known as Wickham striae, is seen in all subtypes and can help diagnose this pathologic process. Under the microscope, LP can manifest with hyperkeratosis without parakeratosis, irregular thickening of the stratum granulosum, sawtooth rete ridges, and destruction of the basal layer.14

Psoriasis also has been shown to be exacerbated by anti–PD-1 therapy, although the majority of patients diagnosed with PD-1–induced psoriasis have a personal or family history of the disease.6 Clinically, psoriasis can have a hyperpigmented or violaceous appearance in patients with skin of color.16 The histopathology of psoriasis typically reveals confluent parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum, regular acanthosis, thinning of the suprapapillary plates, and vessels in the dermal papillae.17

Although cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC may appear clinically similar to the current case, it is one of the rarer organ sites of metastasis for lung cancer.18 In our patient, biopsy quickly ruled out this diagnosis. If it had been a site of metastasis, histopathology would have shown a dermal-based proliferation of dysplastic cells without epidermal connection.19

It is important for dermatologists to recognize eruptive squamous proliferations associated with pembrolizumab, as they often respond to conservative treatment and typically do not require dose reduction or discontinuation of the inciting drug.

- Freshwater T, Kondic A, Ahamadi M, et al. Evaluation of dosing strategy for pembrolizumab for oncology indications. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:43. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0242-5

- Preti BTB, Pencz A, Cowger JJM, et al. Skin deep: a fascinating case report of immunotherapy-triggered, treatment-refractory autoimmune lichen planus and keratoacanthoma. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14: 1189-1193. doi:10.1159/000518313

- Fradet M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Multiple keratoacanthoma-like lesions in a patient treated with pembrolizumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1301-1302. doi:10.2340/00015555-3301

- Flynn JP, Gerriets V. Pembrolizumab. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with Nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Voudouri D, Nikolaou V, Laschos K, et al. Anti-Pd1/Pdl1 induced psoriasis. Curr Probl Cancer. 2017;41:407-412. doi:10.1016 /j.currproblcancer.2017.10.003

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010

- Coscarart A, Martel J, Lee MP, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced pseudoepitheliomatous eruption consistent with hypertrophic lichen planus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:275-279. doi:10.1111/cup.13587

- Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, et al. Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:158-176. doi:10.1111/cup.12858

- Vitzthum von Eckstaedt H, Singh A, Reid P, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and lupus erythematosus. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;2:15;17. doi:10.3390/ph17020252

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Vu M, Chapman S, Lenz B, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma or squamous proliferation associated with nivolumab treatment for metastatic melanoma. Dermatol Online J. 2022;6:28. doi:10.5070/d328357786

- Howell JY, Ramsey ML. Squamous cell skin cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated July 2, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated October 29, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Yamashita A, Akasaka E, Nakano H, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced lichen planus on the scalp of a patient with non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol. 2021;13:487-491. doi:10.1159/000519486

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Murphy M, Kerr P, Grant-Kels JM. The histopathologic spectrum of psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:524-528. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2007.08.005.

- Hidaka T, Ishii Y, Kitamura S. Clinical features of skin metastasis from lung cancer. Intern Med. 1996;35:459-462. doi:10.2169 /internalmedicine.35.459.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613–620. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.5.613

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pembrolizumab-Induced Eruptive Squamous Proliferation

Histopathology showed a broad squamous proliferation with acanthosis of the epidermis. Large glassy keratinocytes were seen with scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure), and a dense lichenoid band of inflammation was present subjacent to the proliferation. Notably, no hypergranulosis, remarkable keratinocyte atypia, or increased mitotic figures were seen. Based on the patient’s medical history and biopsy results, a diagnosis of pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation was made. The diagnosis was supported by a growing body of evidence of this type of reaction in patients taking programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors.1,2 Conservative treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% was initiated with complete resolution of the lesions at the 2-month follow-up appointment. Other common treatments include topical steroids, injected corticosteroids, or cryosurgery to locally control the inflammation and atypical proliferation of cells.3

Pembrolizumab is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody targeting the PD-1 receptor that has been utilized for its antitumor activity against various cancers, including unresectable and metastatic melanoma, head and neck cancers, and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1,4,5 While this drug has extended the lives of many patients with cancer, there are adverse reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors (eg, pembrolizumab, nivolumab). Skin toxicity to PD-1 inhibitors is the one of most common immune-mediated reactions worldwide, occurring in approximately 30% of patients.6,7 Reactions can occur while a patient is taking the inciting drug and can continue up to 2 months after treatment discontinuation.8 Skin reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors vary from lichenoid reactions and vitiligolike patches to psoriasis or eczema flares and are organized into 4 categories: inflammatory, immunobullous, alteration of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes.9 Our patient demonstrated alteration of keratinocytes, which is characterized by overlapping features of hypertrophic lichen planus and early keratoacanthoma.

The differential diagnoses for pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation include squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), psoriasis, hypertrophic lichen planus, and cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus also is a well-documented reaction to use of immune-checkpoint inhibitors.10 Direct immunofluorescence could have helped differentiate hypertrophic lupus erythematosus from an eruptive squamous proliferation in our patient; however, due to her response to treatment, no additional workup was done.

Squamous cell carcinoma, which is the most common type of skin cancer in Black patients in the United States,11 has been shown to manifest after a PD-1 inhibitor is taken.12 Although it typically has a more chronic persistent course, the clinical appearance of SCC can be similar to the findings seen in our patient. Histologically, SCC may demonstrate necrosis, but the atypical proliferations will invade the dermis—a feature not seen in our patient’s histopathology.13

Lichen planus (LP) is an eruptive immune reaction of violaceous polygonal papules and plaques commonly seen on the ankles14 that has been shown to be an adverse effect of pembrolizumab.15 There are several subtypes of LP including hypertrophic versions, which can appear clinically similar to the findings seen in our patient. On dermoscopy, the classic finding of white lines, known as Wickham striae, is seen in all subtypes and can help diagnose this pathologic process. Under the microscope, LP can manifest with hyperkeratosis without parakeratosis, irregular thickening of the stratum granulosum, sawtooth rete ridges, and destruction of the basal layer.14

Psoriasis also has been shown to be exacerbated by anti–PD-1 therapy, although the majority of patients diagnosed with PD-1–induced psoriasis have a personal or family history of the disease.6 Clinically, psoriasis can have a hyperpigmented or violaceous appearance in patients with skin of color.16 The histopathology of psoriasis typically reveals confluent parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum, regular acanthosis, thinning of the suprapapillary plates, and vessels in the dermal papillae.17

Although cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC may appear clinically similar to the current case, it is one of the rarer organ sites of metastasis for lung cancer.18 In our patient, biopsy quickly ruled out this diagnosis. If it had been a site of metastasis, histopathology would have shown a dermal-based proliferation of dysplastic cells without epidermal connection.19

It is important for dermatologists to recognize eruptive squamous proliferations associated with pembrolizumab, as they often respond to conservative treatment and typically do not require dose reduction or discontinuation of the inciting drug.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pembrolizumab-Induced Eruptive Squamous Proliferation

Histopathology showed a broad squamous proliferation with acanthosis of the epidermis. Large glassy keratinocytes were seen with scattered necrotic keratinocytes (Figure), and a dense lichenoid band of inflammation was present subjacent to the proliferation. Notably, no hypergranulosis, remarkable keratinocyte atypia, or increased mitotic figures were seen. Based on the patient’s medical history and biopsy results, a diagnosis of pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation was made. The diagnosis was supported by a growing body of evidence of this type of reaction in patients taking programmed death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors.1,2 Conservative treatment with clobetasol ointment 0.05% was initiated with complete resolution of the lesions at the 2-month follow-up appointment. Other common treatments include topical steroids, injected corticosteroids, or cryosurgery to locally control the inflammation and atypical proliferation of cells.3

Pembrolizumab is a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody targeting the PD-1 receptor that has been utilized for its antitumor activity against various cancers, including unresectable and metastatic melanoma, head and neck cancers, and non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1,4,5 While this drug has extended the lives of many patients with cancer, there are adverse reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors (eg, pembrolizumab, nivolumab). Skin toxicity to PD-1 inhibitors is the one of most common immune-mediated reactions worldwide, occurring in approximately 30% of patients.6,7 Reactions can occur while a patient is taking the inciting drug and can continue up to 2 months after treatment discontinuation.8 Skin reactions associated with PD-1 inhibitors vary from lichenoid reactions and vitiligolike patches to psoriasis or eczema flares and are organized into 4 categories: inflammatory, immunobullous, alteration of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes.9 Our patient demonstrated alteration of keratinocytes, which is characterized by overlapping features of hypertrophic lichen planus and early keratoacanthoma.

The differential diagnoses for pembrolizumab-induced eruptive squamous proliferation include squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), psoriasis, hypertrophic lichen planus, and cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus also is a well-documented reaction to use of immune-checkpoint inhibitors.10 Direct immunofluorescence could have helped differentiate hypertrophic lupus erythematosus from an eruptive squamous proliferation in our patient; however, due to her response to treatment, no additional workup was done.

Squamous cell carcinoma, which is the most common type of skin cancer in Black patients in the United States,11 has been shown to manifest after a PD-1 inhibitor is taken.12 Although it typically has a more chronic persistent course, the clinical appearance of SCC can be similar to the findings seen in our patient. Histologically, SCC may demonstrate necrosis, but the atypical proliferations will invade the dermis—a feature not seen in our patient’s histopathology.13

Lichen planus (LP) is an eruptive immune reaction of violaceous polygonal papules and plaques commonly seen on the ankles14 that has been shown to be an adverse effect of pembrolizumab.15 There are several subtypes of LP including hypertrophic versions, which can appear clinically similar to the findings seen in our patient. On dermoscopy, the classic finding of white lines, known as Wickham striae, is seen in all subtypes and can help diagnose this pathologic process. Under the microscope, LP can manifest with hyperkeratosis without parakeratosis, irregular thickening of the stratum granulosum, sawtooth rete ridges, and destruction of the basal layer.14

Psoriasis also has been shown to be exacerbated by anti–PD-1 therapy, although the majority of patients diagnosed with PD-1–induced psoriasis have a personal or family history of the disease.6 Clinically, psoriasis can have a hyperpigmented or violaceous appearance in patients with skin of color.16 The histopathology of psoriasis typically reveals confluent parakeratosis, neutrophils in the stratum corneum, regular acanthosis, thinning of the suprapapillary plates, and vessels in the dermal papillae.17

Although cutaneous metastasis of NSCLC may appear clinically similar to the current case, it is one of the rarer organ sites of metastasis for lung cancer.18 In our patient, biopsy quickly ruled out this diagnosis. If it had been a site of metastasis, histopathology would have shown a dermal-based proliferation of dysplastic cells without epidermal connection.19

It is important for dermatologists to recognize eruptive squamous proliferations associated with pembrolizumab, as they often respond to conservative treatment and typically do not require dose reduction or discontinuation of the inciting drug.

- Freshwater T, Kondic A, Ahamadi M, et al. Evaluation of dosing strategy for pembrolizumab for oncology indications. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:43. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0242-5

- Preti BTB, Pencz A, Cowger JJM, et al. Skin deep: a fascinating case report of immunotherapy-triggered, treatment-refractory autoimmune lichen planus and keratoacanthoma. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14: 1189-1193. doi:10.1159/000518313

- Fradet M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Multiple keratoacanthoma-like lesions in a patient treated with pembrolizumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1301-1302. doi:10.2340/00015555-3301

- Flynn JP, Gerriets V. Pembrolizumab. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with Nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Voudouri D, Nikolaou V, Laschos K, et al. Anti-Pd1/Pdl1 induced psoriasis. Curr Probl Cancer. 2017;41:407-412. doi:10.1016 /j.currproblcancer.2017.10.003

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010

- Coscarart A, Martel J, Lee MP, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced pseudoepitheliomatous eruption consistent with hypertrophic lichen planus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:275-279. doi:10.1111/cup.13587

- Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, et al. Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:158-176. doi:10.1111/cup.12858

- Vitzthum von Eckstaedt H, Singh A, Reid P, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and lupus erythematosus. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;2:15;17. doi:10.3390/ph17020252

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Vu M, Chapman S, Lenz B, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma or squamous proliferation associated with nivolumab treatment for metastatic melanoma. Dermatol Online J. 2022;6:28. doi:10.5070/d328357786

- Howell JY, Ramsey ML. Squamous cell skin cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated July 2, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated October 29, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Yamashita A, Akasaka E, Nakano H, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced lichen planus on the scalp of a patient with non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol. 2021;13:487-491. doi:10.1159/000519486

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Murphy M, Kerr P, Grant-Kels JM. The histopathologic spectrum of psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:524-528. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2007.08.005.

- Hidaka T, Ishii Y, Kitamura S. Clinical features of skin metastasis from lung cancer. Intern Med. 1996;35:459-462. doi:10.2169 /internalmedicine.35.459.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613–620. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.5.613

- Freshwater T, Kondic A, Ahamadi M, et al. Evaluation of dosing strategy for pembrolizumab for oncology indications. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:43. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0242-5

- Preti BTB, Pencz A, Cowger JJM, et al. Skin deep: a fascinating case report of immunotherapy-triggered, treatment-refractory autoimmune lichen planus and keratoacanthoma. Case Rep Oncol. 2021;14: 1189-1193. doi:10.1159/000518313

- Fradet M, Sibaud V, Tournier E, et al. Multiple keratoacanthoma-like lesions in a patient treated with pembrolizumab. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1301-1302. doi:10.2340/00015555-3301

- Flynn JP, Gerriets V. Pembrolizumab. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Updated June 26, 2023. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with Nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Voudouri D, Nikolaou V, Laschos K, et al. Anti-Pd1/Pdl1 induced psoriasis. Curr Probl Cancer. 2017;41:407-412. doi:10.1016 /j.currproblcancer.2017.10.003

- Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010

- Coscarart A, Martel J, Lee MP, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced pseudoepitheliomatous eruption consistent with hypertrophic lichen planus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:275-279. doi:10.1111/cup.13587

- Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, et al. Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:158-176. doi:10.1111/cup.12858

- Vitzthum von Eckstaedt H, Singh A, Reid P, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and lupus erythematosus. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;2:15;17. doi:10.3390/ph17020252

- Halder RM, Bridgeman-Shah S. Skin cancer in African Americans. Cancer. 1995;75:667-673.

- Vu M, Chapman S, Lenz B, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma or squamous proliferation associated with nivolumab treatment for metastatic melanoma. Dermatol Online J. 2022;6:28. doi:10.5070/d328357786

- Howell JY, Ramsey ML. Squamous cell skin cancer. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated July 2, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Arnold DL, Krishnamurthy K. Lichen planus. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Updated October 29, 2024. Accessed April 2, 2025.

- Yamashita A, Akasaka E, Nakano H, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced lichen planus on the scalp of a patient with non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Case Rep Dermatol. 2021;13:487-491. doi:10.1159/000519486

- Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Psoriasis in skin of color: epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation, and treatment nuances. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:16-24.

- Murphy M, Kerr P, Grant-Kels JM. The histopathologic spectrum of psoriasis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:524-528. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2007.08.005.

- Hidaka T, Ishii Y, Kitamura S. Clinical features of skin metastasis from lung cancer. Intern Med. 1996;35:459-462. doi:10.2169 /internalmedicine.35.459.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613–620. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.5.613

Papulonodules on the Ankle in a Patient with Lung Cancer

Papulonodules on the Ankle in a Patient with Lung Cancer

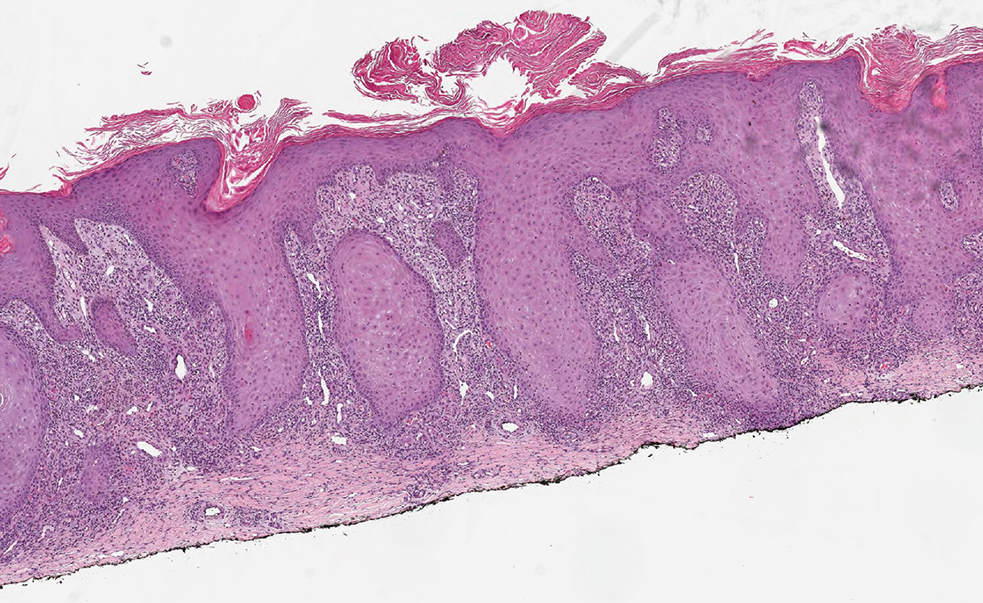

A 75-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with well-circumscribed, round, hyperkeratotic papulonodules on the ankle of 3 months’ duration (top). The papulonodules also were evaluated by dermoscopy, which highlighted in greater detail the hyperkeratosis seen grossly (bottom). The patient had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and metastatic lung cancer and had been taking pembrolizumab for the past 2 years. The lesions initially appeared on the medial right foot and slowly spread proximally. Most of the lesions resolved spontaneously except for 2 on the right ankle. At the current presentation, one lesion was slightly tender to palpation, but both were otherwise asymptomatic. A lesion was biopsied and sent for dermatopathologic evaluation.

Understanding Medical Standards for Entrance Into Military Service and Disqualifying Dermatologic Conditions

Purpose of Medical Standards in the US Military

Young adults in the United States traditionally have viewed military service as a viable career given its stable salary, career training, opportunities for progression, comprehensive health care coverage, tuition assistance, and other benefits; however, not all who desire to serve in the US Military are eligible to join. The Department of Defense (DoD) maintains fitness and health requirements (ie, accession standards), which are codified in DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1,1 that help ensure potential recruits can safely and fully perform their military duties. These accession standards change over time with the evolving understanding of diseases, medical advances, and accrued experience conducting operations in various environments. Accession standards serve to both preserve the health of the applicant and to ensure military mission success.

Dermatologic diseases have been prevalent in conflicts throughout US military history, representing a considerable source of morbidity to service members, inability of service members to remain on active duty, and costly use of resources. Hospitalizations of US Army soldiers for skin conditions led to the loss of more than 2 million days of service in World War I.2 In World War II, skin diseases made up 25% and 75% of all temperate and tropical climate visits, respectively. Cutaneous diseases were the most frequently addressed category for US service members in Vietnam, representing more than 1.5 million visits and nearly 10% of disease-related evacuations.2 Skin disease remains vital in 21st-century conflict. At a military hospital in Afghanistan, a review of 2421 outpatient medical records from June through July 2007 identified that dermatologic conditions resulted in 20% of military patient evaluations, 7% of nontraumatic hospital admissions, and 2% of total patient evacuations, at an estimated cost of $80,000 per evacuee.3 Between 2003 and 2006, 918 service members were evacuated for dermatologic reasons from combat zones in Afghanistan and Iraq.4

Unpredictable military environments may result in flares of a previously controlled condition, new skin diseases, or infection with endemic diseases. Mild cases of common conditions such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis can present an unacceptable risk for severe flare in the setting of deployed military operations.5 Personnel may face extremes in temperature and humidity and work long hours under stress with limited or nonexistent opportunities for hygiene or self-care. Shared equipment and close living quarters permit the spread of infectious diseases and complicate the treatment of infestations. Military equipment and supplies such as gas masks and insect repellents can contain compounds that act as irritants or sensitizing agents, leading to contact dermatitis or urticaria. When dermatologic conditions develop or flare, further challenges are associated with evaluation and management. Health care resources vary considerably by location, with potential limitations in the availability of medications; supplies; refrigeration capabilities; and laboratory, microbiology, and histology services. Furthermore, dermatology referrals and services typically are not feasible in most deployed settings,3 though teledermatology has been available in the armed forces since 2002.

Deployed environments compound the consequences of dermatologic conditions and can impact the military mission. Military units deploy with the number of personnel needed to complete a mission and cannot replace members who become ill or injured or are medically evacuated. Something seemingly trivial, such as poor sleep due to pruritic dermatitis, may impair daytime alertness with potentially grave consequences in critical tasks such as guard or flying duties. The evacuation of a service member can compromise those left behind, and losing a service member with a unique required skill set may jeopardize a unit’s chance of success. Additionally, the impact of an evacuation itself extends beyond its direct cost and effects on the service member’s unit. The military does not maintain dedicated medical evacuation aircraft, instead repurposing aircraft in the deployed setting as needed.6 Evacuations can delay flights initially scheduled to move troops, ammunition, food, or other supplies and equipment elsewhere.

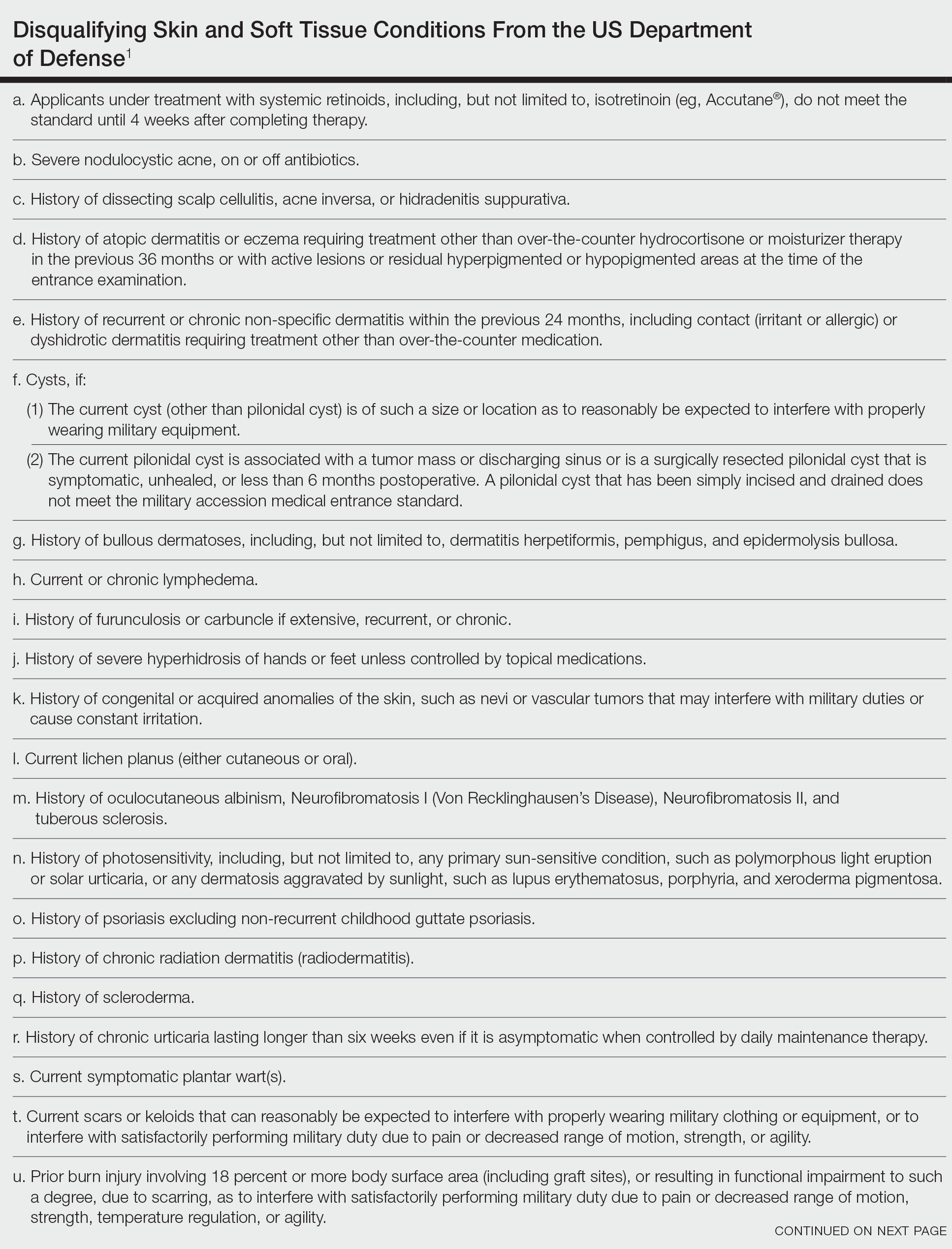

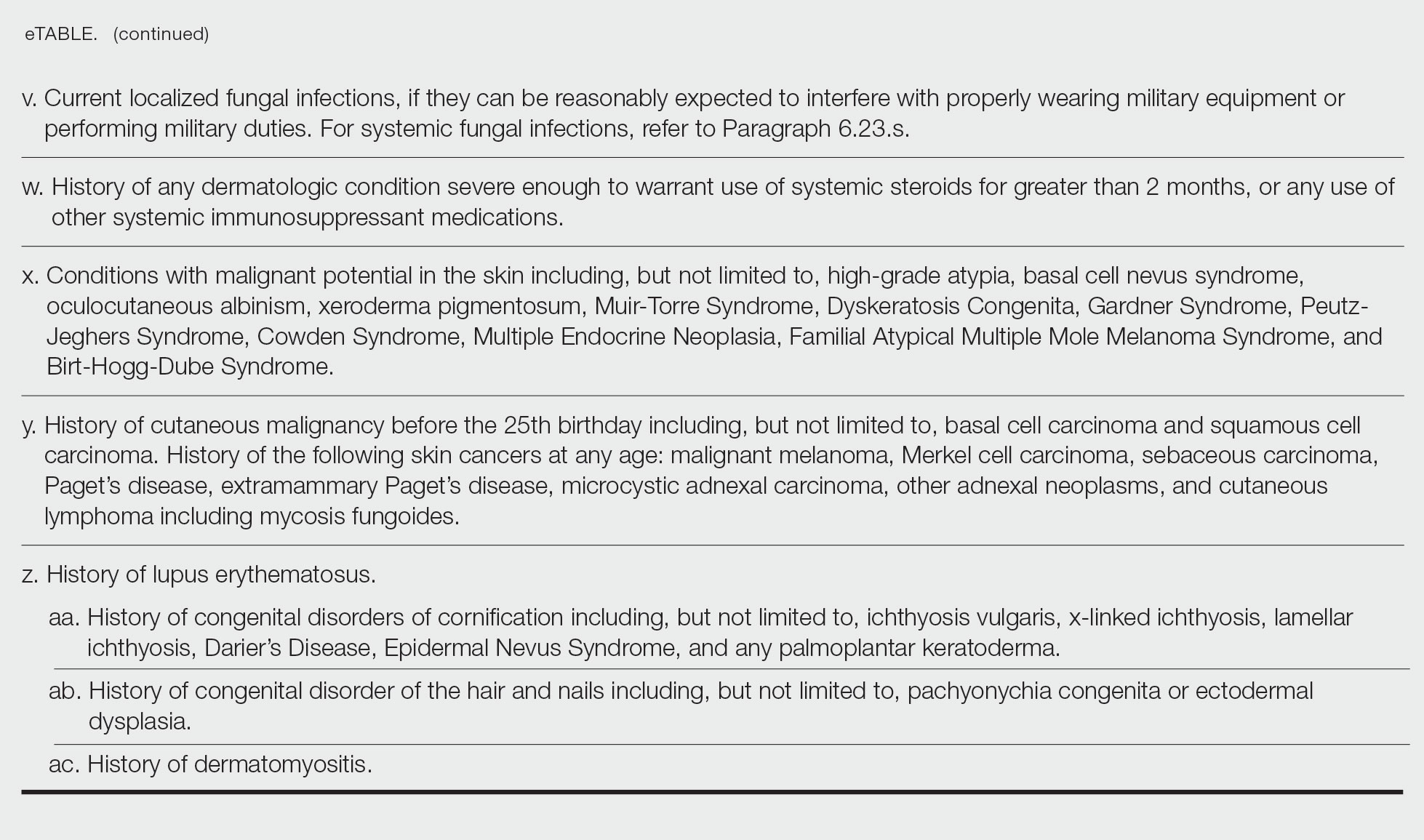

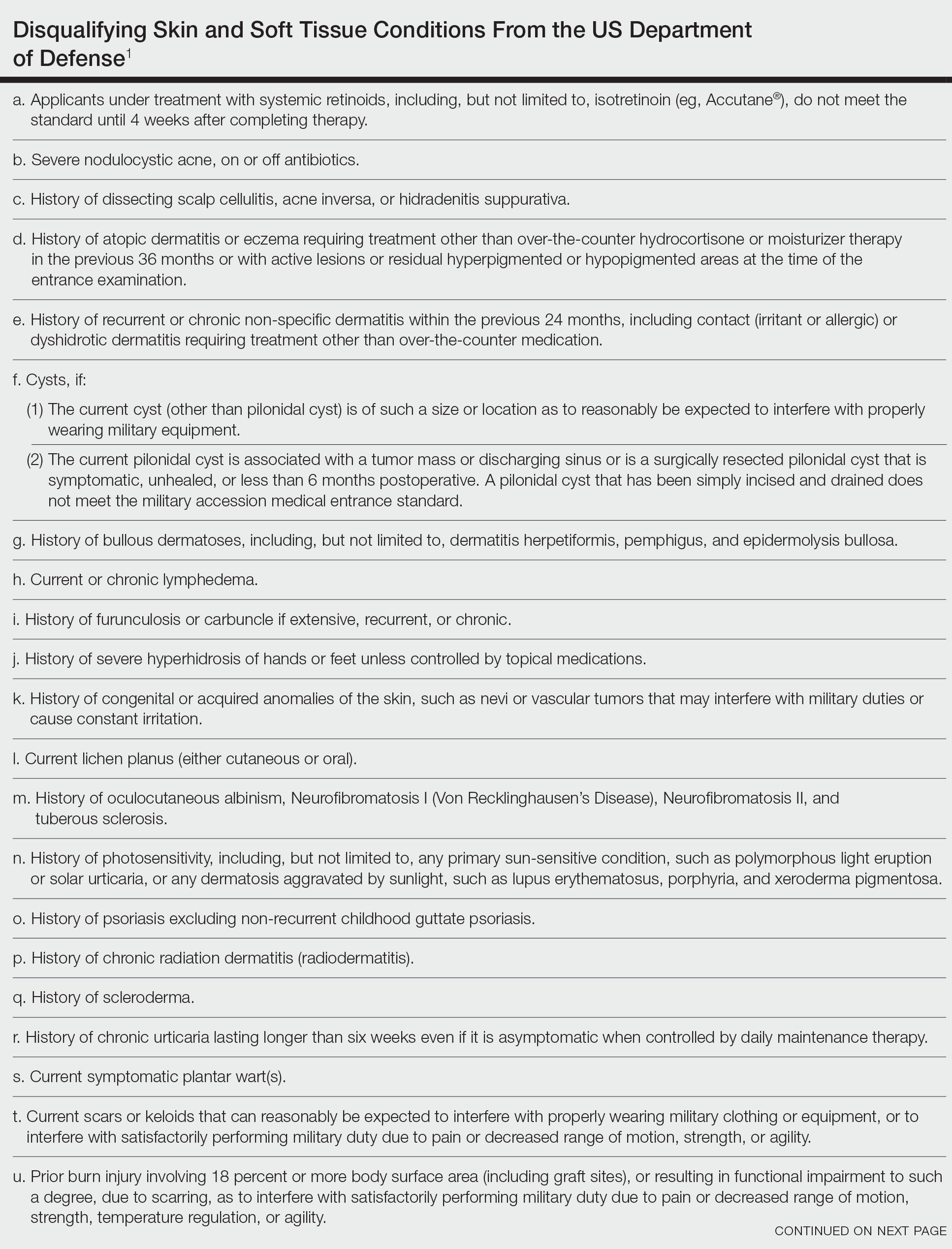

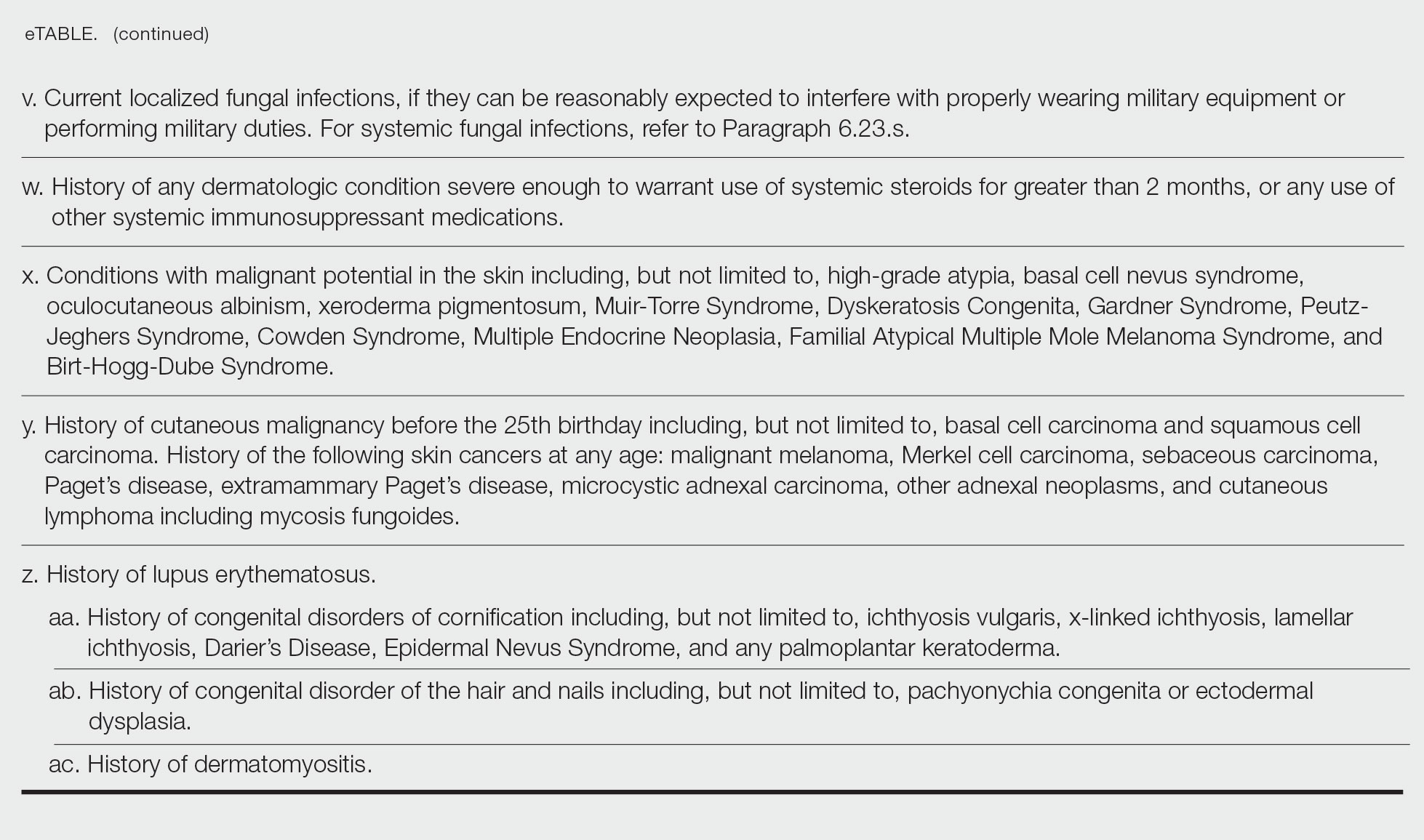

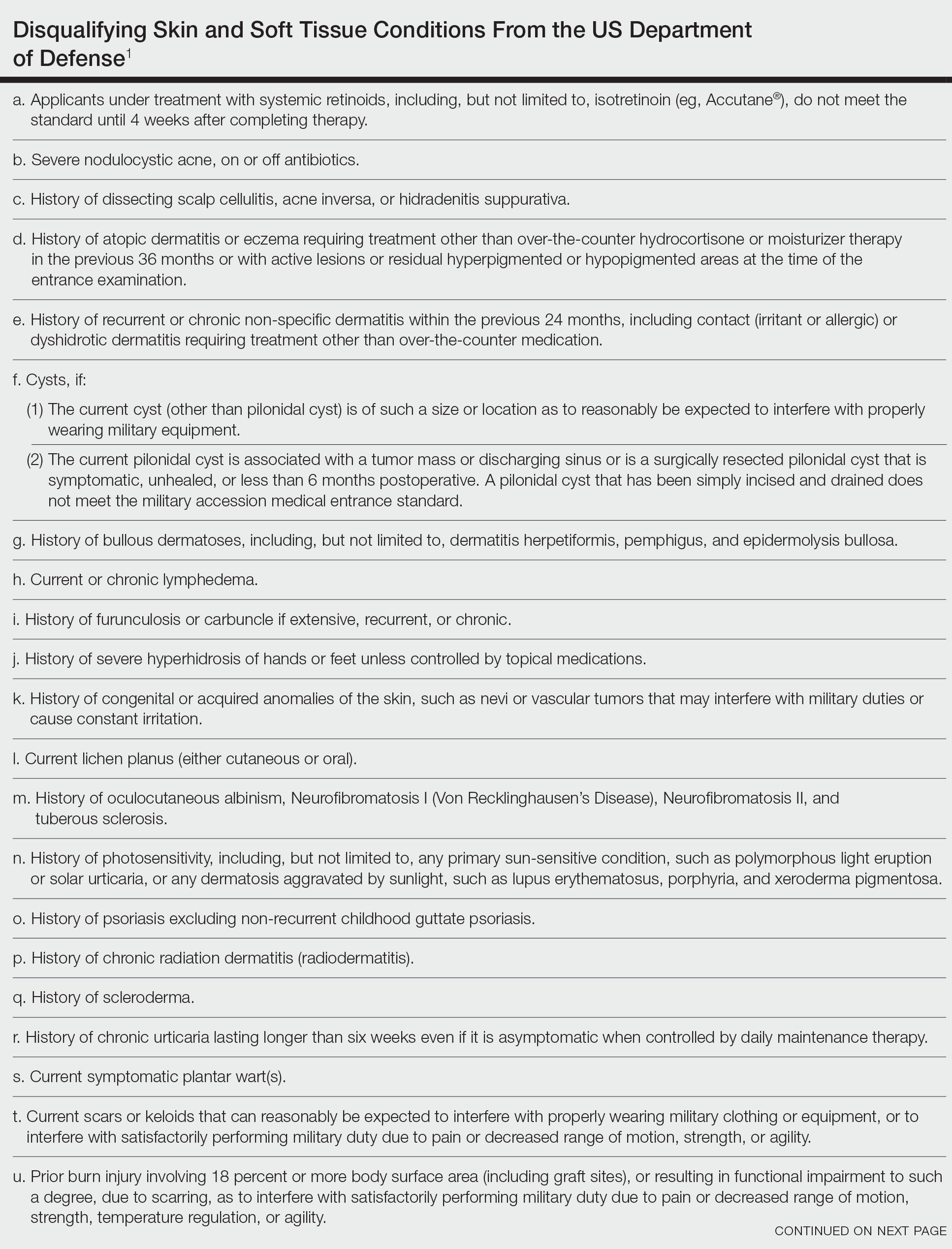

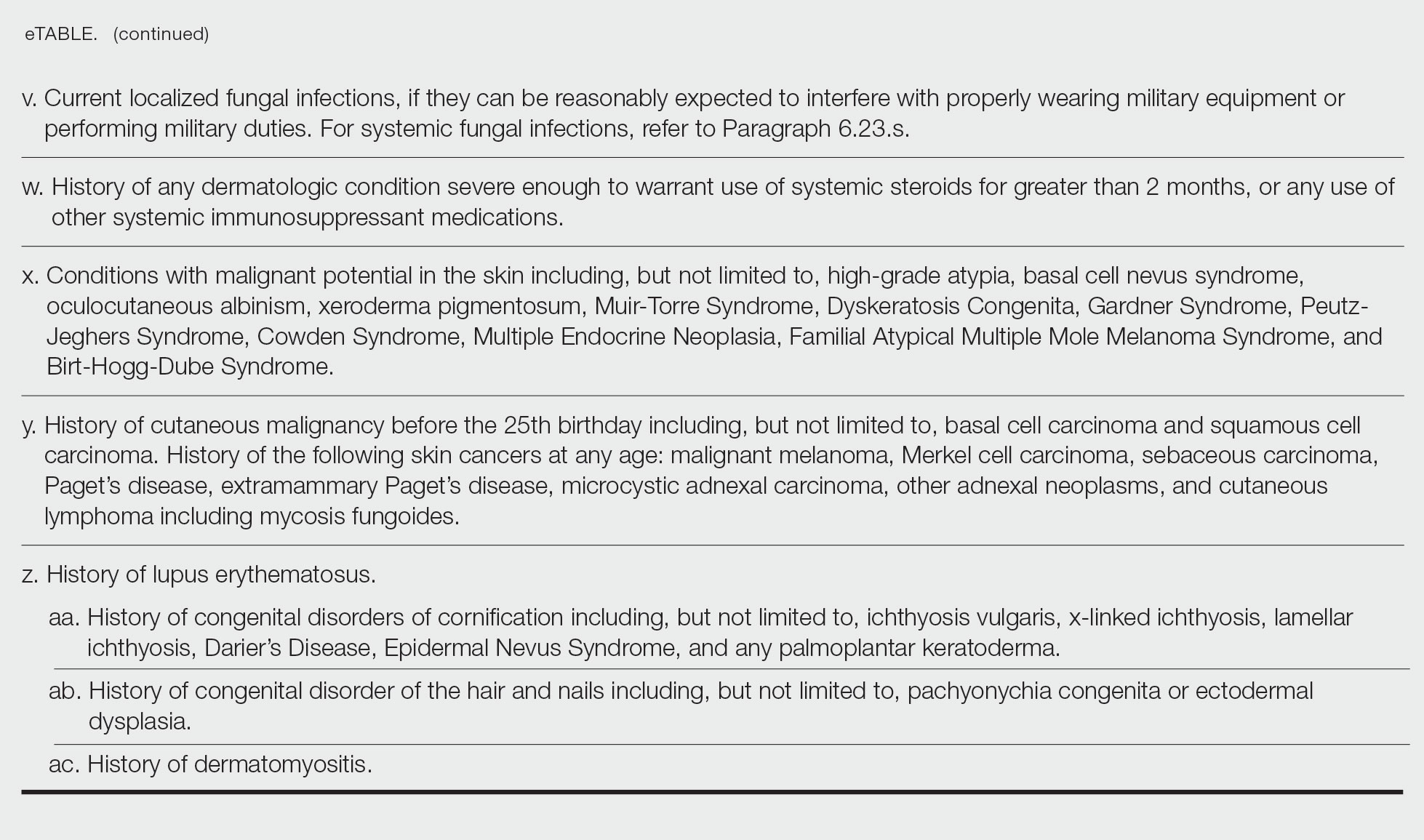

Disqualifying Skin and Soft Tissue Conditions

Current accession standards, which are listed in a publicly released document (DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1), are updated based on medical, societal, and technical advances.1 These standards differ from retention standards, which apply to members actively serving in the military. Although the DoD creates a minimum standard for the entire military, the US Army, Navy, and Air Force adopt these standards and adjust as required for each branch’s needs. An updated copy can be found on the DoD Directives Division website (https://www.esd.whs.mil/dd/) or Med Standards, a third-party mobile application (app) available as a free download for Apple iOS and Android devices (https://www.doc-apps.com/). The app also includes each military branch’s interpretation of the requirements.

The accession standards outline medical conditions that, if present or verified in an applicant’s medical history, preclude joining the military (eTable). These standards are organized into general systems, with a section dedicated to dermatologic (skin and soft tissue) conditions.1 When a candidate has a potentially disqualifying medical condition identified by a screening questionnaire, medical record review, or military entrance physical examination, a referral for a determination of fitness for duty may be required. Medical accession standards are not solely driven by the diagnosis but also by the extent, nature, and timing of medical management. Procedures or prescriptions requiring frequent clinical monitoring, special handling, or severe dietary restrictions may deem the applicant’s condition potentially unsuitable. The need for immunosuppressive, anticoagulant, or refrigerated medications can impact a patient’s eligibility due to future deployment requirements and suitability for prolonged service, especially if treated for any substantial length of time. Chronic dermatologic conditions that are unresponsive to treatment, are susceptible to exacerbation despite treatment, require regular follow-up care, or interfere with the wear of military gear may be inconsistent with future deployment standards. Although the dermatologist should primarily focus on the skin and soft tissue conditions section of the accession standards, some dermatologic conditions can overlap with other medical systems and be located in a different section; for example, the section on lower extremity conditions includes a disqualifying condition of “[c]urrent ingrown toenails, if infected or symptomatic.”1

Waiver Process

Medical conditions listed in the accession standards are deemed ineligible for military service; however, applicants can apply for a waiver.1 The goal is for service members to be well controlled without treatment or with treatment widely available at military clinics and hospitals. Waivers ensure that service members are “[m]edically capable of performing duties without aggravating physical defects or medical conditions,” are “[m]edically adaptable to the military environment without geographical area limitations,” and are “free of medical conditions or physical defects that may reasonably be expected to require excessive time lost from duty for necessary treatment or hospitalization, or may result in separation from the Military Service for unfitness.”1 The waiver process requires an evaluation from specialists with verification and documentation but does not guarantee approval. Although each military branch follows the same guidelines for disqualifying medical conditions, the evaluation and waiver process varies.

Considerations for Civilian Dermatologists

For several reasons, accurate and detailed medical documentation is essential for patients who pursue military service. Applicants must complete detailed health questionnaires and may need to provide copies of health records. The military electronic health record connects to large civilian health information exchanges and pulls primary documentation from records at many hospitals and clinics. Although applicants may request supportive clarification from their dermatologists, the military relies on primary medical documentation throughout the recruitment process. Accurate diagnostic codes reduce ambiguity, as accession standards are organized by diagnosis; for example, an unspecified history of psoriasis disqualifies applicants unless documentation supports nonrecurrent childhood guttate psoriasis.1 Clear documentation of symptom severity, response to treatment, or resolution of a condition may elucidate suitability for service when matching a potentially disqualifying condition to a standard is not straightforward. Correct documentation will ensure that potential service members achieve a waiver when it is appropriate. If they are found to be unfit, it may save a patient from a bad outcome or a military unit from mission failure.

Dermatologists in the United States can reference current military medical accession standards to guide patients when needed. For example, a prospective recruit may be hesitant to start isotretinoin for severe nodulocystic acne, concerned that this medication may preclude them from joining the military. The current standards state that “[a]pplicants under treatment with systemic retinoids . . . do not meet the standard until 4 weeks after completing therapy,” while active severe nodulocystic acne is a disqualifying condition.1 Therefore, the patient could proceed with isotretinoin therapy and, pending clinical response, meet accession standards as soon as 4 weeks after treatment. A clear understanding of the purpose of these standards, including protecting the applicant’s health and maximizing the chance of combat mission accomplishment, helps to reinforce responsibilities when caring for patients who wish to serve.

- US Department of Defense. DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1. Medical Standards for Military Service: Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction. Updated November 16, 2022. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003_vol1.PDF?ver=7fhqacc0jGX_R9_1iexudA%3D%3D

- Becker LE, James WD. Historical overview and principles of diagnosis. In: Becker LE, James WD. Military Dermatology. Office of the Surgeon General, US Department of the Army; 1994: 1-20.

- Arnold JG, Michener MD. Evaluation of dermatologic conditions by primary care providers in deployed military settings. Mil Med. 2008;173:882-888. doi:10.7205/MILMED.173.9.882

- McGraw TA, Norton SA. Military aeromedical evacuations from central and southwest Asia for ill-defined dermatologic diseases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:165-170.

- Gelman AB, Norton SA, Valdes-Rodriguez R, et al. A review of skin conditions in modern warfare and peacekeeping operations. Mil Med. 2015;180:32-37.

- Fang R, Dorlac GR, Allan PF, et al. Intercontinental aeromedical evacuation of patients with traumatic brain injuries during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E11.

Purpose of Medical Standards in the US Military

Young adults in the United States traditionally have viewed military service as a viable career given its stable salary, career training, opportunities for progression, comprehensive health care coverage, tuition assistance, and other benefits; however, not all who desire to serve in the US Military are eligible to join. The Department of Defense (DoD) maintains fitness and health requirements (ie, accession standards), which are codified in DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1,1 that help ensure potential recruits can safely and fully perform their military duties. These accession standards change over time with the evolving understanding of diseases, medical advances, and accrued experience conducting operations in various environments. Accession standards serve to both preserve the health of the applicant and to ensure military mission success.

Dermatologic diseases have been prevalent in conflicts throughout US military history, representing a considerable source of morbidity to service members, inability of service members to remain on active duty, and costly use of resources. Hospitalizations of US Army soldiers for skin conditions led to the loss of more than 2 million days of service in World War I.2 In World War II, skin diseases made up 25% and 75% of all temperate and tropical climate visits, respectively. Cutaneous diseases were the most frequently addressed category for US service members in Vietnam, representing more than 1.5 million visits and nearly 10% of disease-related evacuations.2 Skin disease remains vital in 21st-century conflict. At a military hospital in Afghanistan, a review of 2421 outpatient medical records from June through July 2007 identified that dermatologic conditions resulted in 20% of military patient evaluations, 7% of nontraumatic hospital admissions, and 2% of total patient evacuations, at an estimated cost of $80,000 per evacuee.3 Between 2003 and 2006, 918 service members were evacuated for dermatologic reasons from combat zones in Afghanistan and Iraq.4

Unpredictable military environments may result in flares of a previously controlled condition, new skin diseases, or infection with endemic diseases. Mild cases of common conditions such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis can present an unacceptable risk for severe flare in the setting of deployed military operations.5 Personnel may face extremes in temperature and humidity and work long hours under stress with limited or nonexistent opportunities for hygiene or self-care. Shared equipment and close living quarters permit the spread of infectious diseases and complicate the treatment of infestations. Military equipment and supplies such as gas masks and insect repellents can contain compounds that act as irritants or sensitizing agents, leading to contact dermatitis or urticaria. When dermatologic conditions develop or flare, further challenges are associated with evaluation and management. Health care resources vary considerably by location, with potential limitations in the availability of medications; supplies; refrigeration capabilities; and laboratory, microbiology, and histology services. Furthermore, dermatology referrals and services typically are not feasible in most deployed settings,3 though teledermatology has been available in the armed forces since 2002.

Deployed environments compound the consequences of dermatologic conditions and can impact the military mission. Military units deploy with the number of personnel needed to complete a mission and cannot replace members who become ill or injured or are medically evacuated. Something seemingly trivial, such as poor sleep due to pruritic dermatitis, may impair daytime alertness with potentially grave consequences in critical tasks such as guard or flying duties. The evacuation of a service member can compromise those left behind, and losing a service member with a unique required skill set may jeopardize a unit’s chance of success. Additionally, the impact of an evacuation itself extends beyond its direct cost and effects on the service member’s unit. The military does not maintain dedicated medical evacuation aircraft, instead repurposing aircraft in the deployed setting as needed.6 Evacuations can delay flights initially scheduled to move troops, ammunition, food, or other supplies and equipment elsewhere.

Disqualifying Skin and Soft Tissue Conditions

Current accession standards, which are listed in a publicly released document (DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1), are updated based on medical, societal, and technical advances.1 These standards differ from retention standards, which apply to members actively serving in the military. Although the DoD creates a minimum standard for the entire military, the US Army, Navy, and Air Force adopt these standards and adjust as required for each branch’s needs. An updated copy can be found on the DoD Directives Division website (https://www.esd.whs.mil/dd/) or Med Standards, a third-party mobile application (app) available as a free download for Apple iOS and Android devices (https://www.doc-apps.com/). The app also includes each military branch’s interpretation of the requirements.

The accession standards outline medical conditions that, if present or verified in an applicant’s medical history, preclude joining the military (eTable). These standards are organized into general systems, with a section dedicated to dermatologic (skin and soft tissue) conditions.1 When a candidate has a potentially disqualifying medical condition identified by a screening questionnaire, medical record review, or military entrance physical examination, a referral for a determination of fitness for duty may be required. Medical accession standards are not solely driven by the diagnosis but also by the extent, nature, and timing of medical management. Procedures or prescriptions requiring frequent clinical monitoring, special handling, or severe dietary restrictions may deem the applicant’s condition potentially unsuitable. The need for immunosuppressive, anticoagulant, or refrigerated medications can impact a patient’s eligibility due to future deployment requirements and suitability for prolonged service, especially if treated for any substantial length of time. Chronic dermatologic conditions that are unresponsive to treatment, are susceptible to exacerbation despite treatment, require regular follow-up care, or interfere with the wear of military gear may be inconsistent with future deployment standards. Although the dermatologist should primarily focus on the skin and soft tissue conditions section of the accession standards, some dermatologic conditions can overlap with other medical systems and be located in a different section; for example, the section on lower extremity conditions includes a disqualifying condition of “[c]urrent ingrown toenails, if infected or symptomatic.”1

Waiver Process

Medical conditions listed in the accession standards are deemed ineligible for military service; however, applicants can apply for a waiver.1 The goal is for service members to be well controlled without treatment or with treatment widely available at military clinics and hospitals. Waivers ensure that service members are “[m]edically capable of performing duties without aggravating physical defects or medical conditions,” are “[m]edically adaptable to the military environment without geographical area limitations,” and are “free of medical conditions or physical defects that may reasonably be expected to require excessive time lost from duty for necessary treatment or hospitalization, or may result in separation from the Military Service for unfitness.”1 The waiver process requires an evaluation from specialists with verification and documentation but does not guarantee approval. Although each military branch follows the same guidelines for disqualifying medical conditions, the evaluation and waiver process varies.

Considerations for Civilian Dermatologists

For several reasons, accurate and detailed medical documentation is essential for patients who pursue military service. Applicants must complete detailed health questionnaires and may need to provide copies of health records. The military electronic health record connects to large civilian health information exchanges and pulls primary documentation from records at many hospitals and clinics. Although applicants may request supportive clarification from their dermatologists, the military relies on primary medical documentation throughout the recruitment process. Accurate diagnostic codes reduce ambiguity, as accession standards are organized by diagnosis; for example, an unspecified history of psoriasis disqualifies applicants unless documentation supports nonrecurrent childhood guttate psoriasis.1 Clear documentation of symptom severity, response to treatment, or resolution of a condition may elucidate suitability for service when matching a potentially disqualifying condition to a standard is not straightforward. Correct documentation will ensure that potential service members achieve a waiver when it is appropriate. If they are found to be unfit, it may save a patient from a bad outcome or a military unit from mission failure.

Dermatologists in the United States can reference current military medical accession standards to guide patients when needed. For example, a prospective recruit may be hesitant to start isotretinoin for severe nodulocystic acne, concerned that this medication may preclude them from joining the military. The current standards state that “[a]pplicants under treatment with systemic retinoids . . . do not meet the standard until 4 weeks after completing therapy,” while active severe nodulocystic acne is a disqualifying condition.1 Therefore, the patient could proceed with isotretinoin therapy and, pending clinical response, meet accession standards as soon as 4 weeks after treatment. A clear understanding of the purpose of these standards, including protecting the applicant’s health and maximizing the chance of combat mission accomplishment, helps to reinforce responsibilities when caring for patients who wish to serve.

Purpose of Medical Standards in the US Military

Young adults in the United States traditionally have viewed military service as a viable career given its stable salary, career training, opportunities for progression, comprehensive health care coverage, tuition assistance, and other benefits; however, not all who desire to serve in the US Military are eligible to join. The Department of Defense (DoD) maintains fitness and health requirements (ie, accession standards), which are codified in DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1,1 that help ensure potential recruits can safely and fully perform their military duties. These accession standards change over time with the evolving understanding of diseases, medical advances, and accrued experience conducting operations in various environments. Accession standards serve to both preserve the health of the applicant and to ensure military mission success.

Dermatologic diseases have been prevalent in conflicts throughout US military history, representing a considerable source of morbidity to service members, inability of service members to remain on active duty, and costly use of resources. Hospitalizations of US Army soldiers for skin conditions led to the loss of more than 2 million days of service in World War I.2 In World War II, skin diseases made up 25% and 75% of all temperate and tropical climate visits, respectively. Cutaneous diseases were the most frequently addressed category for US service members in Vietnam, representing more than 1.5 million visits and nearly 10% of disease-related evacuations.2 Skin disease remains vital in 21st-century conflict. At a military hospital in Afghanistan, a review of 2421 outpatient medical records from June through July 2007 identified that dermatologic conditions resulted in 20% of military patient evaluations, 7% of nontraumatic hospital admissions, and 2% of total patient evacuations, at an estimated cost of $80,000 per evacuee.3 Between 2003 and 2006, 918 service members were evacuated for dermatologic reasons from combat zones in Afghanistan and Iraq.4

Unpredictable military environments may result in flares of a previously controlled condition, new skin diseases, or infection with endemic diseases. Mild cases of common conditions such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis can present an unacceptable risk for severe flare in the setting of deployed military operations.5 Personnel may face extremes in temperature and humidity and work long hours under stress with limited or nonexistent opportunities for hygiene or self-care. Shared equipment and close living quarters permit the spread of infectious diseases and complicate the treatment of infestations. Military equipment and supplies such as gas masks and insect repellents can contain compounds that act as irritants or sensitizing agents, leading to contact dermatitis or urticaria. When dermatologic conditions develop or flare, further challenges are associated with evaluation and management. Health care resources vary considerably by location, with potential limitations in the availability of medications; supplies; refrigeration capabilities; and laboratory, microbiology, and histology services. Furthermore, dermatology referrals and services typically are not feasible in most deployed settings,3 though teledermatology has been available in the armed forces since 2002.

Deployed environments compound the consequences of dermatologic conditions and can impact the military mission. Military units deploy with the number of personnel needed to complete a mission and cannot replace members who become ill or injured or are medically evacuated. Something seemingly trivial, such as poor sleep due to pruritic dermatitis, may impair daytime alertness with potentially grave consequences in critical tasks such as guard or flying duties. The evacuation of a service member can compromise those left behind, and losing a service member with a unique required skill set may jeopardize a unit’s chance of success. Additionally, the impact of an evacuation itself extends beyond its direct cost and effects on the service member’s unit. The military does not maintain dedicated medical evacuation aircraft, instead repurposing aircraft in the deployed setting as needed.6 Evacuations can delay flights initially scheduled to move troops, ammunition, food, or other supplies and equipment elsewhere.

Disqualifying Skin and Soft Tissue Conditions

Current accession standards, which are listed in a publicly released document (DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1), are updated based on medical, societal, and technical advances.1 These standards differ from retention standards, which apply to members actively serving in the military. Although the DoD creates a minimum standard for the entire military, the US Army, Navy, and Air Force adopt these standards and adjust as required for each branch’s needs. An updated copy can be found on the DoD Directives Division website (https://www.esd.whs.mil/dd/) or Med Standards, a third-party mobile application (app) available as a free download for Apple iOS and Android devices (https://www.doc-apps.com/). The app also includes each military branch’s interpretation of the requirements.

The accession standards outline medical conditions that, if present or verified in an applicant’s medical history, preclude joining the military (eTable). These standards are organized into general systems, with a section dedicated to dermatologic (skin and soft tissue) conditions.1 When a candidate has a potentially disqualifying medical condition identified by a screening questionnaire, medical record review, or military entrance physical examination, a referral for a determination of fitness for duty may be required. Medical accession standards are not solely driven by the diagnosis but also by the extent, nature, and timing of medical management. Procedures or prescriptions requiring frequent clinical monitoring, special handling, or severe dietary restrictions may deem the applicant’s condition potentially unsuitable. The need for immunosuppressive, anticoagulant, or refrigerated medications can impact a patient’s eligibility due to future deployment requirements and suitability for prolonged service, especially if treated for any substantial length of time. Chronic dermatologic conditions that are unresponsive to treatment, are susceptible to exacerbation despite treatment, require regular follow-up care, or interfere with the wear of military gear may be inconsistent with future deployment standards. Although the dermatologist should primarily focus on the skin and soft tissue conditions section of the accession standards, some dermatologic conditions can overlap with other medical systems and be located in a different section; for example, the section on lower extremity conditions includes a disqualifying condition of “[c]urrent ingrown toenails, if infected or symptomatic.”1

Waiver Process

Medical conditions listed in the accession standards are deemed ineligible for military service; however, applicants can apply for a waiver.1 The goal is for service members to be well controlled without treatment or with treatment widely available at military clinics and hospitals. Waivers ensure that service members are “[m]edically capable of performing duties without aggravating physical defects or medical conditions,” are “[m]edically adaptable to the military environment without geographical area limitations,” and are “free of medical conditions or physical defects that may reasonably be expected to require excessive time lost from duty for necessary treatment or hospitalization, or may result in separation from the Military Service for unfitness.”1 The waiver process requires an evaluation from specialists with verification and documentation but does not guarantee approval. Although each military branch follows the same guidelines for disqualifying medical conditions, the evaluation and waiver process varies.

Considerations for Civilian Dermatologists

For several reasons, accurate and detailed medical documentation is essential for patients who pursue military service. Applicants must complete detailed health questionnaires and may need to provide copies of health records. The military electronic health record connects to large civilian health information exchanges and pulls primary documentation from records at many hospitals and clinics. Although applicants may request supportive clarification from their dermatologists, the military relies on primary medical documentation throughout the recruitment process. Accurate diagnostic codes reduce ambiguity, as accession standards are organized by diagnosis; for example, an unspecified history of psoriasis disqualifies applicants unless documentation supports nonrecurrent childhood guttate psoriasis.1 Clear documentation of symptom severity, response to treatment, or resolution of a condition may elucidate suitability for service when matching a potentially disqualifying condition to a standard is not straightforward. Correct documentation will ensure that potential service members achieve a waiver when it is appropriate. If they are found to be unfit, it may save a patient from a bad outcome or a military unit from mission failure.

Dermatologists in the United States can reference current military medical accession standards to guide patients when needed. For example, a prospective recruit may be hesitant to start isotretinoin for severe nodulocystic acne, concerned that this medication may preclude them from joining the military. The current standards state that “[a]pplicants under treatment with systemic retinoids . . . do not meet the standard until 4 weeks after completing therapy,” while active severe nodulocystic acne is a disqualifying condition.1 Therefore, the patient could proceed with isotretinoin therapy and, pending clinical response, meet accession standards as soon as 4 weeks after treatment. A clear understanding of the purpose of these standards, including protecting the applicant’s health and maximizing the chance of combat mission accomplishment, helps to reinforce responsibilities when caring for patients who wish to serve.

- US Department of Defense. DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1. Medical Standards for Military Service: Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction. Updated November 16, 2022. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003_vol1.PDF?ver=7fhqacc0jGX_R9_1iexudA%3D%3D

- Becker LE, James WD. Historical overview and principles of diagnosis. In: Becker LE, James WD. Military Dermatology. Office of the Surgeon General, US Department of the Army; 1994: 1-20.

- Arnold JG, Michener MD. Evaluation of dermatologic conditions by primary care providers in deployed military settings. Mil Med. 2008;173:882-888. doi:10.7205/MILMED.173.9.882

- McGraw TA, Norton SA. Military aeromedical evacuations from central and southwest Asia for ill-defined dermatologic diseases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:165-170.

- Gelman AB, Norton SA, Valdes-Rodriguez R, et al. A review of skin conditions in modern warfare and peacekeeping operations. Mil Med. 2015;180:32-37.

- Fang R, Dorlac GR, Allan PF, et al. Intercontinental aeromedical evacuation of patients with traumatic brain injuries during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E11.

- US Department of Defense. DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1. Medical Standards for Military Service: Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction. Updated November 16, 2022. Accessed May 22, 2023. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/613003_vol1.PDF?ver=7fhqacc0jGX_R9_1iexudA%3D%3D

- Becker LE, James WD. Historical overview and principles of diagnosis. In: Becker LE, James WD. Military Dermatology. Office of the Surgeon General, US Department of the Army; 1994: 1-20.

- Arnold JG, Michener MD. Evaluation of dermatologic conditions by primary care providers in deployed military settings. Mil Med. 2008;173:882-888. doi:10.7205/MILMED.173.9.882

- McGraw TA, Norton SA. Military aeromedical evacuations from central and southwest Asia for ill-defined dermatologic diseases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:165-170.

- Gelman AB, Norton SA, Valdes-Rodriguez R, et al. A review of skin conditions in modern warfare and peacekeeping operations. Mil Med. 2015;180:32-37.

- Fang R, Dorlac GR, Allan PF, et al. Intercontinental aeromedical evacuation of patients with traumatic brain injuries during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28:E11.

Practice Points

- Dermatologic diseases have played a substantial role in conflicts throughout US military history, representing a considerable source of morbidity to service members, loss of active-duty service members trained with necessary skills, and costly use of resources.

- The strict standards are designed to protect the health of the individual and maximize mission success.

- The Department of Defense has a publicly available document (DoD Instruction 6130.03, Volume 1) that details conditions that are disqualifying for entrance into the military. Dermatologists can reference this to provide guidance to adolescents and young adults interested in joining the military.