User login

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

To the Editor:

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of an acquired increase in pigmentation. Belumosudil is an oral selective inhibitor of Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase (ROCK2) that is approved for the treatment of chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD). We describe a patient who developed diffuse skin bronzing 3 weeks after initiation of belumosudil treatment.

A 64-year-old fair-skinned woman presented to the dermatology clinic with bronzing of the skin and dystrophic nails 3 weeks after starting belumosudil for treatment of chronic GVHD. Six months prior to presentation, the patient had received a bone marrow transplant for chronic lymphoid leukemia. She presented to dermatology 6 months after the transplant with a new-onset rash that was suspicious for GVHD. Physical examination revealed pruritic pink papules diffusely scattered on the legs and forearms (Figure 1). The patient declined biopsy at that time and later followed up with oncology. The patient’s oncologist supported a diagnosis of GVHD, and the patient began treatment with belumosudil 200 mg/d which was intended to be taken until treatment failure due to progression of chronic GVHD.

Three weeks after starting belumosudil, the patient developed diffuse bronzing of the skin and brown, evenly colored patches scattered on the trunk, back, and upper and lower extremities on a background of the presumed GVHD rash (Figure 2). The hyperpigmentation was abrupt, starting on the chest and spreading to the abdomen, extremities, and back (Figure 3).

developed on the patient’s chest and back within 3 weeks of initiating treatment with belumosudil.

Again, the patient was offered biopsy for the new-onset pigmentation but declined. During this time, she had no notable sun exposure and primarily stayed indoors despite living in a region with a sunny semi-arid climate. Her medication and supplement list were reviewed and included acalabrutinib, a multivitamin, lutein, biotin, and a fish oil supplement. A compete blood cell count as well as ferritin, transferrin, cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels were unremarkable.

The patient continued to take belumosudil for treatment of GVHD. The hyperpigmentation faded slightly by a 2-month follow-up visit but persisted and was stable. She has not tried other treatments for GVHD to manage the hyperpigmentation.

Conditions known to cause diffuse bronzing of the skin include Addison disease, hemochromatosis, Cushing disease, and medication adverse events. Our patient presented with an absence of systemic symptoms, normal laboratory results, and no clinical indicators suggesting alternate causes. Given that the onset of the hyperpigmentation was 3 weeks after she started a new medication, we hypothesized that the bronzing was an adverse effect of the belumosudil—though this correlation cannot be definitively proven by this case.

The most common offending agents for drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation are nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, amiodarone, cytotoxic drugs, and tetracyclines.1,2 Our patient’s medication list included the cytotoxic agent acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It has been associated with dermatologic findings of ecchymosis, bruising, panniculitis, and cellulitis, but there are no known reports of hyperpigmentation.3 Our patient had been taking acalabrutinib for 6 months when the GVHD rash developed. At the time, she also was taking a multivitamin and lutein, biotin, and fish oil supplements, none of which have been associated with hyperpigmentation.

Polypharmacy adds a layer of difficulty in identifying the inciting cause of pigmentary change. In our case, symptoms began 3 weeks after the initiation of belumosudil. There were no cutaneous reactions observed in the ROCKstar study of belumosudil; the most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, increased liver enzymes, and dyspnea.4,5 Patients on belumosudil have developed aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.6 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acalabrutinib or belumosudil with hyperpigmentation or cutaneous reaction returned no reports of these medications causing hyperpigmentation or cutaneous deposits.

Treatment of drug-induced hyperpigmentation is difficult because discontinuation of the offending agent typically confirms diagnosis, but interruption of treatment is not always possible, as in our patient. The skin changes can fade over time, but effects typically are long lasting.

Dermatologists play a key role in the identification of drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation. After endocrine or metabolic causes of skin hyperpigmentation have been ruled out, a thorough review of the patient’s medication list should be done to assess for a drug-induced cause. Treatment is limited to sun avoidance, as interruption of treatment may not be possible, and lesions typically do fade over time. These chronic skin changes can have a psychosocial effect on patients and regular follow-up is recommended.

- Giménez García RM, Carrasco Molina S. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: review and case series. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:628-638. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180212

- Dereure O. Drug-induced skin pigmentation. epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:253-62. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006

- Sibaud V, Beylot-Barry M, Protin C, et al. Dermatological toxicities of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020; 21:799-812. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00535-x

- Cutler C, Lee SJ, Arai S, et al. Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood. 2021;138:2278-2289. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012021

- Jagasia M, Lazaryan A, Bachier CR, et al. ROCK2 inhibition with belumosudil (KD025) for the treatment of chronic graftversus- host disease. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1888-1898. doi:10.1200 /JCO.20.02754

- Lee GH, Guzman AK, Divito SJ, et al. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma after treatment with ruxolitinib or belumosudil. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:188-190. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2304157

To the Editor:

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of an acquired increase in pigmentation. Belumosudil is an oral selective inhibitor of Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase (ROCK2) that is approved for the treatment of chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD). We describe a patient who developed diffuse skin bronzing 3 weeks after initiation of belumosudil treatment.

A 64-year-old fair-skinned woman presented to the dermatology clinic with bronzing of the skin and dystrophic nails 3 weeks after starting belumosudil for treatment of chronic GVHD. Six months prior to presentation, the patient had received a bone marrow transplant for chronic lymphoid leukemia. She presented to dermatology 6 months after the transplant with a new-onset rash that was suspicious for GVHD. Physical examination revealed pruritic pink papules diffusely scattered on the legs and forearms (Figure 1). The patient declined biopsy at that time and later followed up with oncology. The patient’s oncologist supported a diagnosis of GVHD, and the patient began treatment with belumosudil 200 mg/d which was intended to be taken until treatment failure due to progression of chronic GVHD.

Three weeks after starting belumosudil, the patient developed diffuse bronzing of the skin and brown, evenly colored patches scattered on the trunk, back, and upper and lower extremities on a background of the presumed GVHD rash (Figure 2). The hyperpigmentation was abrupt, starting on the chest and spreading to the abdomen, extremities, and back (Figure 3).

developed on the patient’s chest and back within 3 weeks of initiating treatment with belumosudil.

Again, the patient was offered biopsy for the new-onset pigmentation but declined. During this time, she had no notable sun exposure and primarily stayed indoors despite living in a region with a sunny semi-arid climate. Her medication and supplement list were reviewed and included acalabrutinib, a multivitamin, lutein, biotin, and a fish oil supplement. A compete blood cell count as well as ferritin, transferrin, cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels were unremarkable.

The patient continued to take belumosudil for treatment of GVHD. The hyperpigmentation faded slightly by a 2-month follow-up visit but persisted and was stable. She has not tried other treatments for GVHD to manage the hyperpigmentation.

Conditions known to cause diffuse bronzing of the skin include Addison disease, hemochromatosis, Cushing disease, and medication adverse events. Our patient presented with an absence of systemic symptoms, normal laboratory results, and no clinical indicators suggesting alternate causes. Given that the onset of the hyperpigmentation was 3 weeks after she started a new medication, we hypothesized that the bronzing was an adverse effect of the belumosudil—though this correlation cannot be definitively proven by this case.

The most common offending agents for drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation are nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, amiodarone, cytotoxic drugs, and tetracyclines.1,2 Our patient’s medication list included the cytotoxic agent acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It has been associated with dermatologic findings of ecchymosis, bruising, panniculitis, and cellulitis, but there are no known reports of hyperpigmentation.3 Our patient had been taking acalabrutinib for 6 months when the GVHD rash developed. At the time, she also was taking a multivitamin and lutein, biotin, and fish oil supplements, none of which have been associated with hyperpigmentation.

Polypharmacy adds a layer of difficulty in identifying the inciting cause of pigmentary change. In our case, symptoms began 3 weeks after the initiation of belumosudil. There were no cutaneous reactions observed in the ROCKstar study of belumosudil; the most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, increased liver enzymes, and dyspnea.4,5 Patients on belumosudil have developed aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.6 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acalabrutinib or belumosudil with hyperpigmentation or cutaneous reaction returned no reports of these medications causing hyperpigmentation or cutaneous deposits.

Treatment of drug-induced hyperpigmentation is difficult because discontinuation of the offending agent typically confirms diagnosis, but interruption of treatment is not always possible, as in our patient. The skin changes can fade over time, but effects typically are long lasting.

Dermatologists play a key role in the identification of drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation. After endocrine or metabolic causes of skin hyperpigmentation have been ruled out, a thorough review of the patient’s medication list should be done to assess for a drug-induced cause. Treatment is limited to sun avoidance, as interruption of treatment may not be possible, and lesions typically do fade over time. These chronic skin changes can have a psychosocial effect on patients and regular follow-up is recommended.

To the Editor:

Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of an acquired increase in pigmentation. Belumosudil is an oral selective inhibitor of Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase (ROCK2) that is approved for the treatment of chronic graft-vs-host disease (GVHD). We describe a patient who developed diffuse skin bronzing 3 weeks after initiation of belumosudil treatment.

A 64-year-old fair-skinned woman presented to the dermatology clinic with bronzing of the skin and dystrophic nails 3 weeks after starting belumosudil for treatment of chronic GVHD. Six months prior to presentation, the patient had received a bone marrow transplant for chronic lymphoid leukemia. She presented to dermatology 6 months after the transplant with a new-onset rash that was suspicious for GVHD. Physical examination revealed pruritic pink papules diffusely scattered on the legs and forearms (Figure 1). The patient declined biopsy at that time and later followed up with oncology. The patient’s oncologist supported a diagnosis of GVHD, and the patient began treatment with belumosudil 200 mg/d which was intended to be taken until treatment failure due to progression of chronic GVHD.

Three weeks after starting belumosudil, the patient developed diffuse bronzing of the skin and brown, evenly colored patches scattered on the trunk, back, and upper and lower extremities on a background of the presumed GVHD rash (Figure 2). The hyperpigmentation was abrupt, starting on the chest and spreading to the abdomen, extremities, and back (Figure 3).

developed on the patient’s chest and back within 3 weeks of initiating treatment with belumosudil.

Again, the patient was offered biopsy for the new-onset pigmentation but declined. During this time, she had no notable sun exposure and primarily stayed indoors despite living in a region with a sunny semi-arid climate. Her medication and supplement list were reviewed and included acalabrutinib, a multivitamin, lutein, biotin, and a fish oil supplement. A compete blood cell count as well as ferritin, transferrin, cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels were unremarkable.

The patient continued to take belumosudil for treatment of GVHD. The hyperpigmentation faded slightly by a 2-month follow-up visit but persisted and was stable. She has not tried other treatments for GVHD to manage the hyperpigmentation.

Conditions known to cause diffuse bronzing of the skin include Addison disease, hemochromatosis, Cushing disease, and medication adverse events. Our patient presented with an absence of systemic symptoms, normal laboratory results, and no clinical indicators suggesting alternate causes. Given that the onset of the hyperpigmentation was 3 weeks after she started a new medication, we hypothesized that the bronzing was an adverse effect of the belumosudil—though this correlation cannot be definitively proven by this case.

The most common offending agents for drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation are nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, amiodarone, cytotoxic drugs, and tetracyclines.1,2 Our patient’s medication list included the cytotoxic agent acalabrutinib, a Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor used for the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It has been associated with dermatologic findings of ecchymosis, bruising, panniculitis, and cellulitis, but there are no known reports of hyperpigmentation.3 Our patient had been taking acalabrutinib for 6 months when the GVHD rash developed. At the time, she also was taking a multivitamin and lutein, biotin, and fish oil supplements, none of which have been associated with hyperpigmentation.

Polypharmacy adds a layer of difficulty in identifying the inciting cause of pigmentary change. In our case, symptoms began 3 weeks after the initiation of belumosudil. There were no cutaneous reactions observed in the ROCKstar study of belumosudil; the most common adverse events were upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, increased liver enzymes, and dyspnea.4,5 Patients on belumosudil have developed aggressive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.6 However, a search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms acalabrutinib or belumosudil with hyperpigmentation or cutaneous reaction returned no reports of these medications causing hyperpigmentation or cutaneous deposits.

Treatment of drug-induced hyperpigmentation is difficult because discontinuation of the offending agent typically confirms diagnosis, but interruption of treatment is not always possible, as in our patient. The skin changes can fade over time, but effects typically are long lasting.

Dermatologists play a key role in the identification of drug-induced skin hyperpigmentation. After endocrine or metabolic causes of skin hyperpigmentation have been ruled out, a thorough review of the patient’s medication list should be done to assess for a drug-induced cause. Treatment is limited to sun avoidance, as interruption of treatment may not be possible, and lesions typically do fade over time. These chronic skin changes can have a psychosocial effect on patients and regular follow-up is recommended.

- Giménez García RM, Carrasco Molina S. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: review and case series. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:628-638. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180212

- Dereure O. Drug-induced skin pigmentation. epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:253-62. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006

- Sibaud V, Beylot-Barry M, Protin C, et al. Dermatological toxicities of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020; 21:799-812. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00535-x

- Cutler C, Lee SJ, Arai S, et al. Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood. 2021;138:2278-2289. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012021

- Jagasia M, Lazaryan A, Bachier CR, et al. ROCK2 inhibition with belumosudil (KD025) for the treatment of chronic graftversus- host disease. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1888-1898. doi:10.1200 /JCO.20.02754

- Lee GH, Guzman AK, Divito SJ, et al. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma after treatment with ruxolitinib or belumosudil. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:188-190. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2304157

- Giménez García RM, Carrasco Molina S. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation: review and case series. J Am Board Fam Med. 2019;32:628-638. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2019.04.180212

- Dereure O. Drug-induced skin pigmentation. epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:253-62. doi:10.2165/00128071-200102040-00006

- Sibaud V, Beylot-Barry M, Protin C, et al. Dermatological toxicities of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020; 21:799-812. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00535-x

- Cutler C, Lee SJ, Arai S, et al. Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood. 2021;138:2278-2289. doi:10.1182/blood.2021012021

- Jagasia M, Lazaryan A, Bachier CR, et al. ROCK2 inhibition with belumosudil (KD025) for the treatment of chronic graftversus- host disease. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:1888-1898. doi:10.1200 /JCO.20.02754

- Lee GH, Guzman AK, Divito SJ, et al. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma after treatment with ruxolitinib or belumosudil. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:188-190. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2304157

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

Atypical Skin Bronzing in Response to Belumosudil for Graft-vs-Host Disease

PRACTICE POINTS

- Drug-induced hyperpigmentation is a common cause of acquired hyperpigmentation and should be evaluated after metabolic or endocrine causes are ruled out.

- Belumosudil for chronic graft-vs-host disease can induce rapid-onset diffuse bronzing hyperpigmentation, even in the absence of other systemic or laboratory abnormalities.

- Treatment entails discontinuation of the offending agent and limitation of exacerbating factors such as sun exposure.

Fluctuant Subcutaneous Nodule in the Axilla of an Adolescent Female

Fluctuant Subcutaneous Nodule in the Axilla of an Adolescent Female

The Diagnosis: Accessory Breast

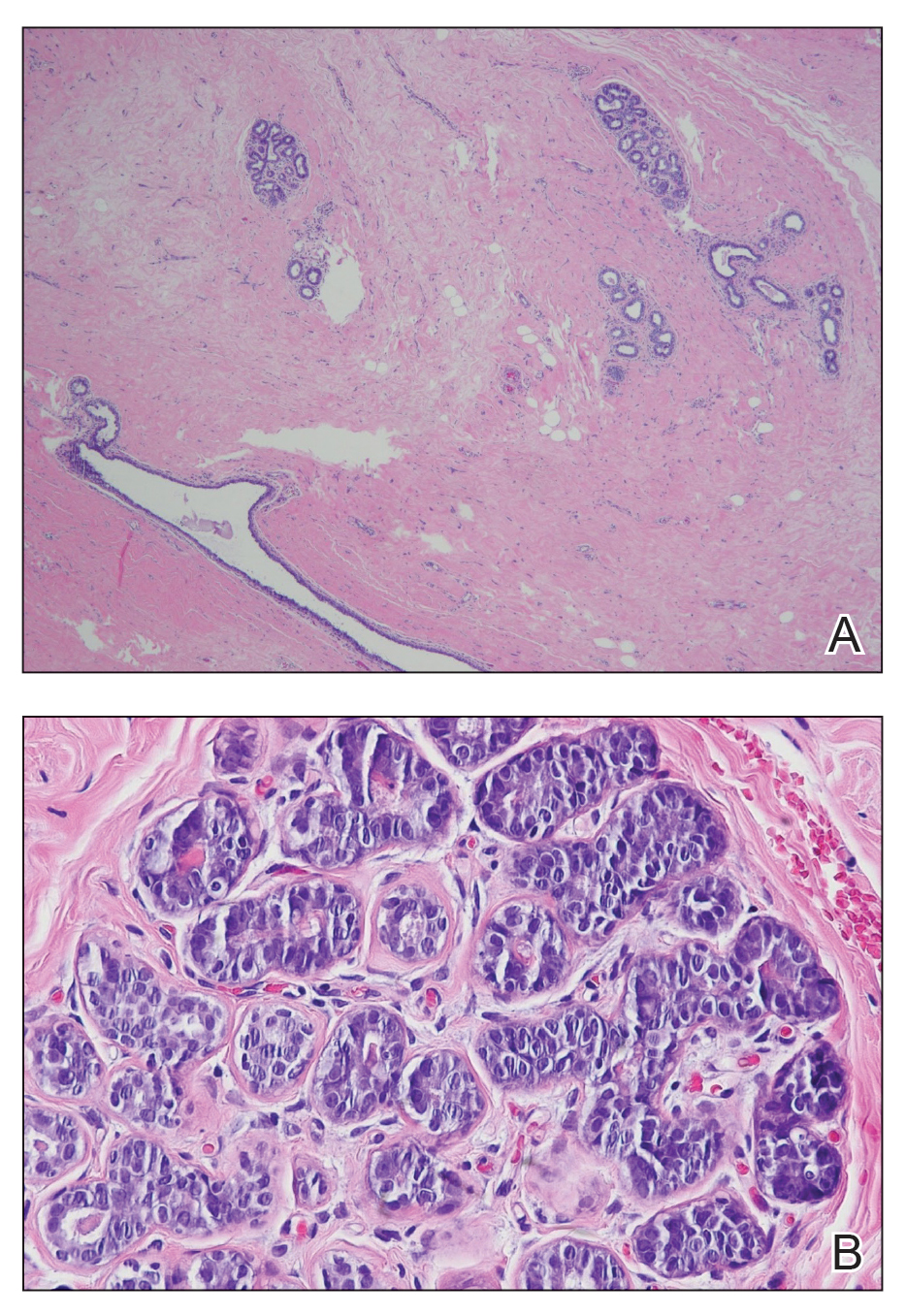

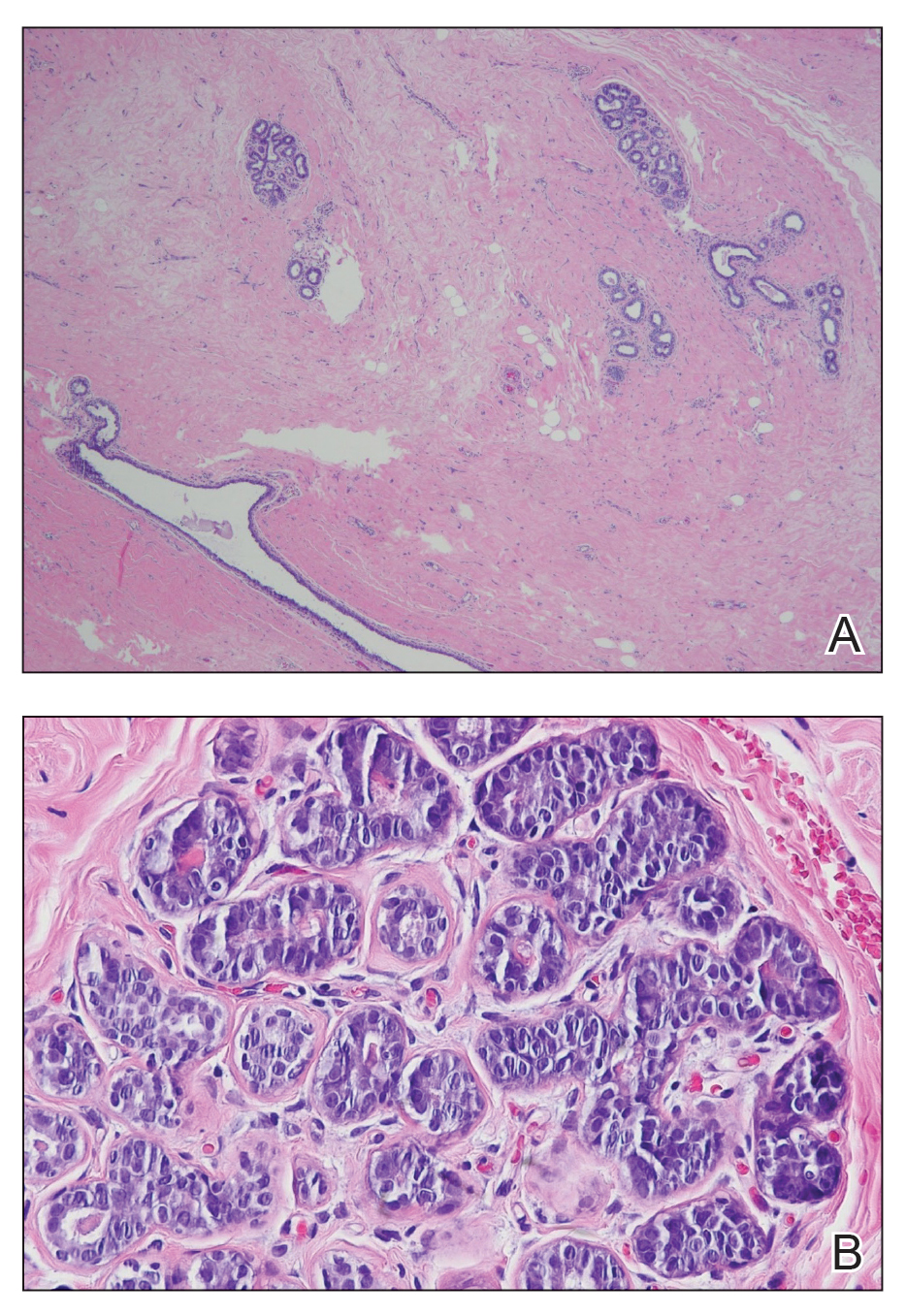

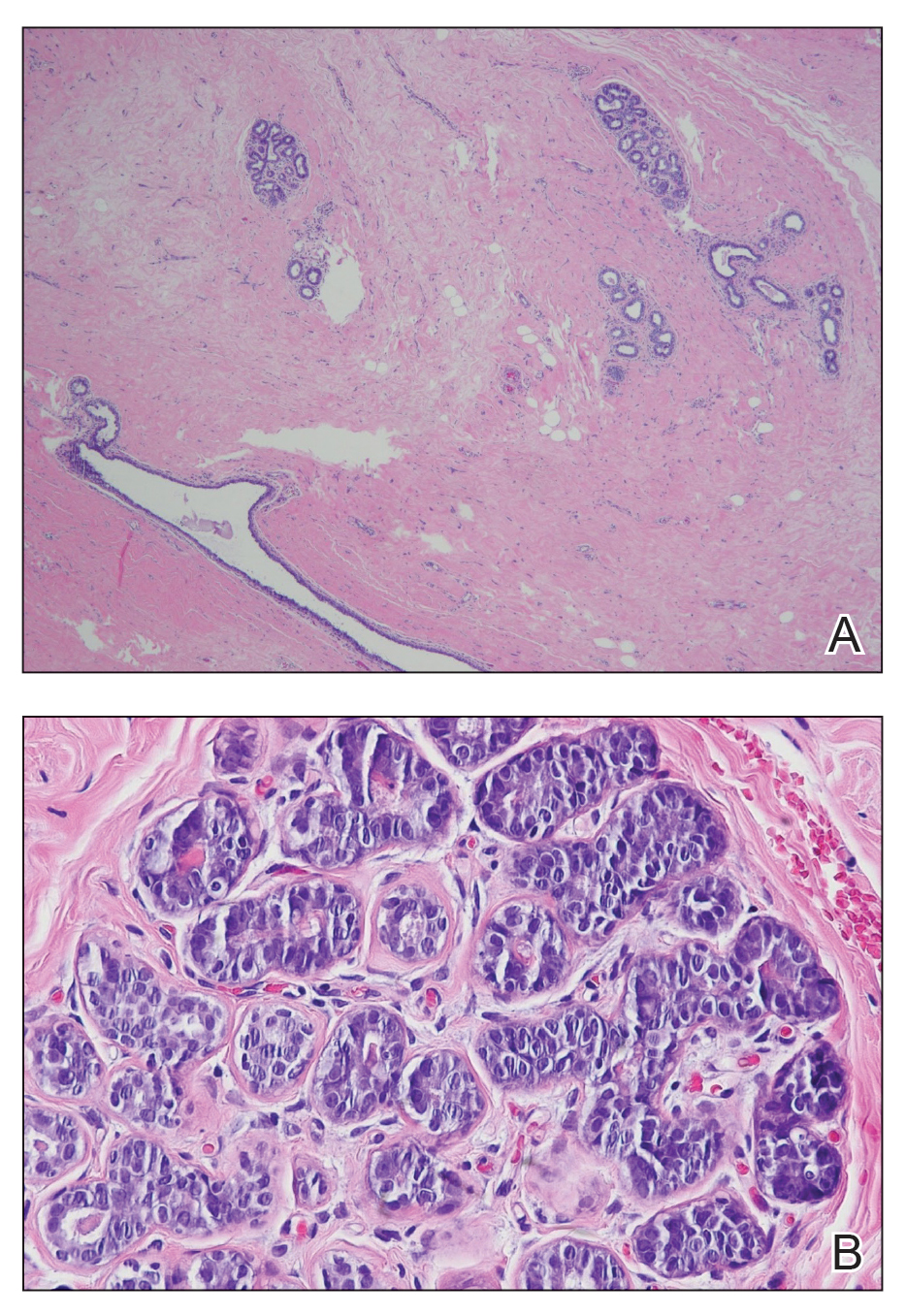

A diagnosis of accessory breast was confirmed on histopathology, which demonstrated a slightly hyperplastic and hyperpigmented epidermis. The dermis contained an increased number of smooth muscle bundles with the presence of apocrine glands and mammary lobules (Figure). Tenderness of the mass fluctuated according to the patient’s menstrual cycle, which supported a diagnosis of accessory breast over lipoma. The patient had no signs of infection or other systemic symptoms that were suggestive of lymphadenopathy. Unlike an epidermoid inclusion cyst, our patient’s mass presented as poorly defined and boggy in texture. Biopsy results were not consistent with malignancy, ruling out soft tissue sarcoma.

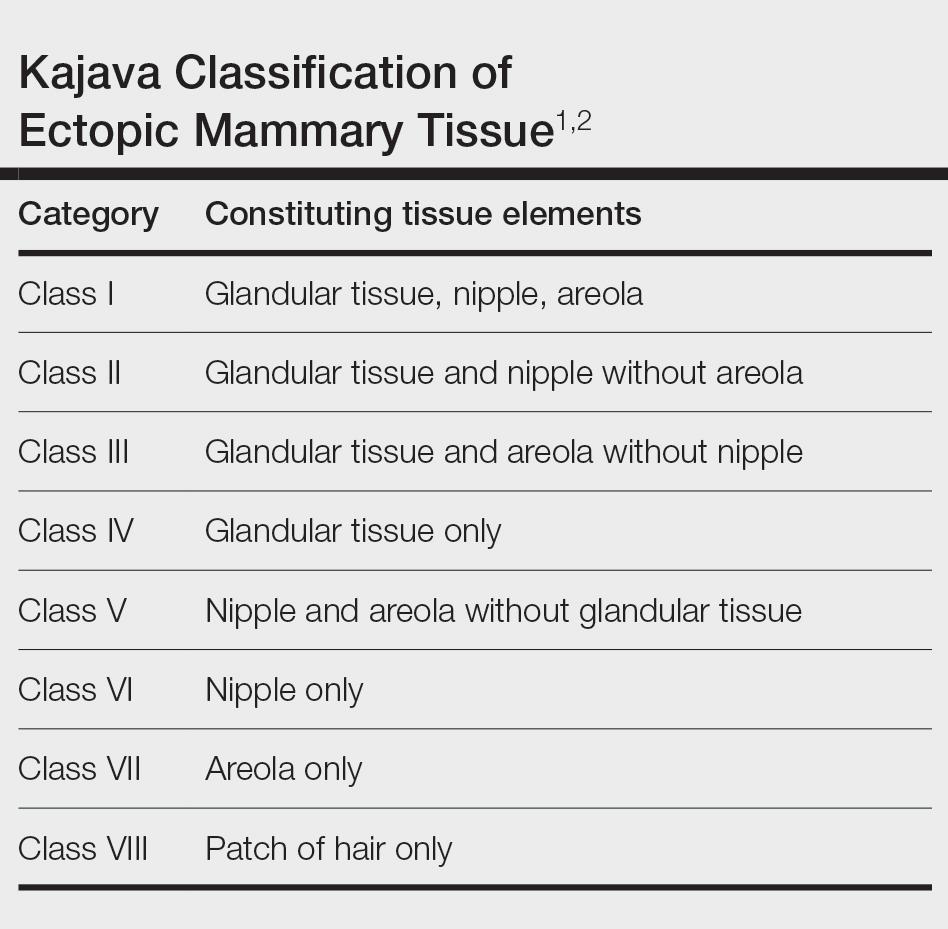

B, Myoepithelial cells lined a stratified columnar epithelium, characteristic of breast tissue (H&E, original magnification x40).

Accessory breasts are characterized by the presence of breast tissue outside the breast and can be found anywhere along the milk line from the axillae to the vulva.1 The prevalence of accessory breasts is 2% to 6% of women, with an average age of presentation for treatment of 42 years.2 Ninety percent of accessory breasts are found in the thorax, 5% are found in the abdomen, and 5% are found in the axillae.3 Incidence is uncommon in adolescents; however, in addition to our patient, there are several cases in the literature of adolescents with accessory breasts in the axillae.4,5

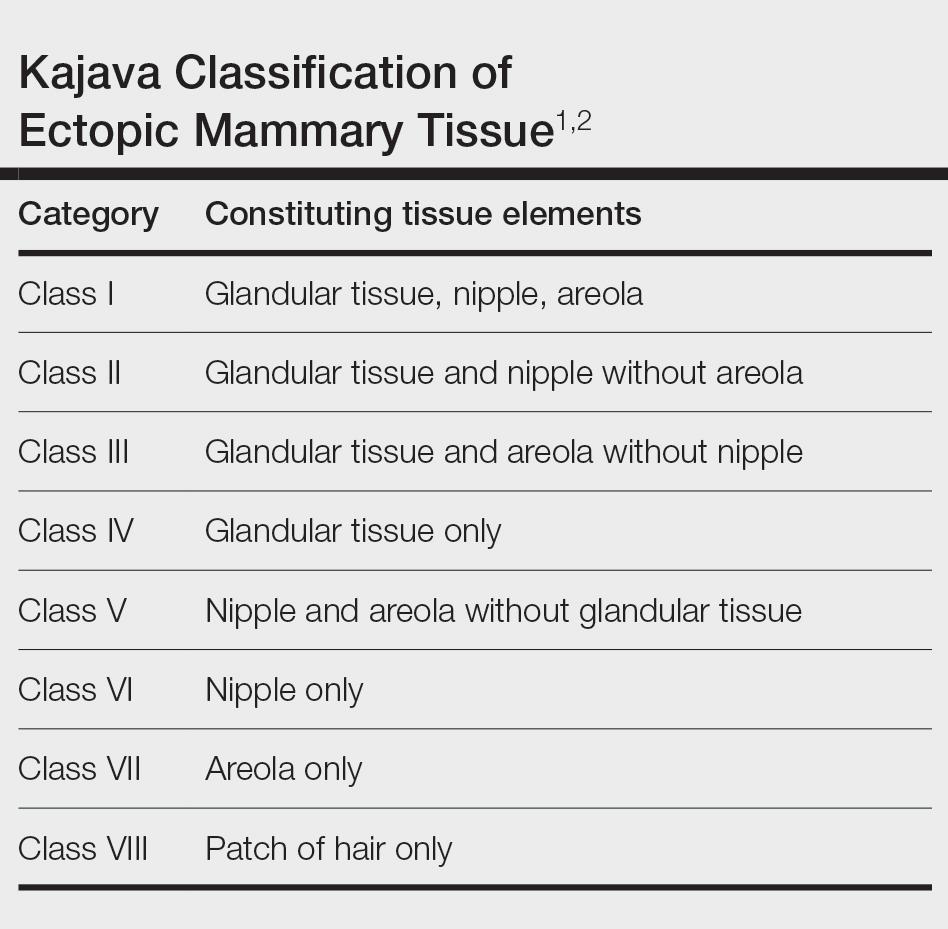

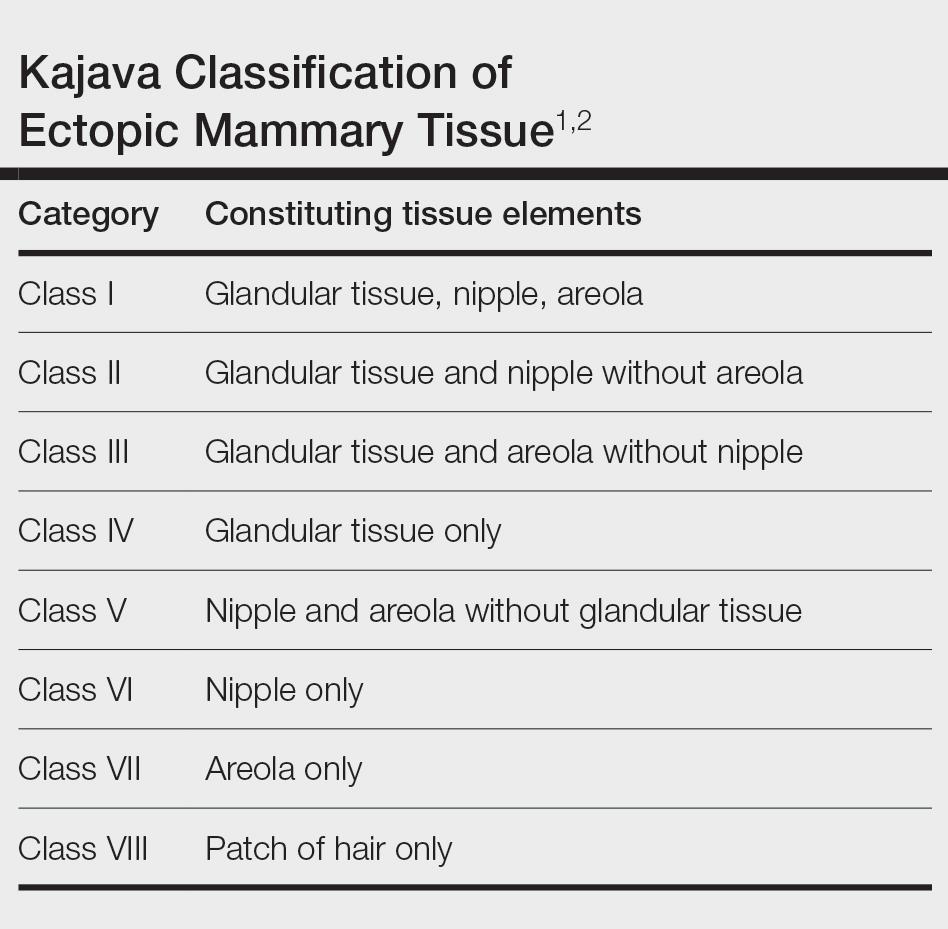

Ectopic mammary tissue is divided into 8 classes based on the Kajava classification system (Table). In a retrospective study of adolescent females with accessory breasts, 91% (10/11) of patients were classified as class IV, and 1 was class II.6 Similarly, our patient was classified as class IV since her accessory breast was composed entirely of glandular tissue and did not include an areola and nipple.

Supernumerary breast structures such as areolas and nipples typically are diagnosed at birth, whereas supernumerary breast tissue is not diagnosed until after hormonal stimulation typically seen during puberty, pregnancy, or breastfeeding. Common symptoms include cyclic pain with menstruation, fluctuation in the size of the mass, and tenderness of the ectopic tissue. There also can be restricted range of motion and increased irritation from clothing. Ultrasonography generally shows a hypoechoic septate indicative of mammary tissue.6 Diagnosis is confirmed by histopathologic studies that show mammary lobules in the dermis with smooth muscle, mammary ducts connected to the nipple, and connective stroma.6

If bothersome, ectopic breast tissue can be surgically removed, either by direct excision or suction lipectomy depending on the size of the mass.2 Postoperative complications are low but can include seroma, bleeding, infection, remnant tissue, or undesired cosmetic results. As with normal breast tissue, ectopic breast tissue can manifest with benign and malignant pathologies.

In conclusion, accessory breast is a benign condition that can cause cyclical pain with menstruation, restricted range of motion, discomfort, anxiety, and cosmetic problems. It is important to keep this diagnosis on the differential when evaluating a soft tissue mass that appears in the axillary region.

- Loukas M, Clarke P, Tubbs RS. Accessory breasts: a historical and current perspective. Am Surg. 2007;73:525-528.

- Bartsich SA, Ofodile FA. Accessory breast tissue in the axilla: classification and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:35E-36E. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182173f95

- Mazine K, Bouassria A, Elbouhaddouti H. Bilateral supernumerary axillary breasts: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:282. doi:10.11604 /pamj.2020.36.282.20445

- Patel RV, Govani D, Patel R, et al. Adolescent right axillary accessory breast with galactorrhoea. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014204215. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204215

- Surd A, Mironescu A, Gocan H. Fibroadenoma in axillary supernumerary breast in a 17-year-old girl: case report. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:E79-E81. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2016.04.008

- De la Torre M, Lorca-García C, de Tomás E, et al. Axillary ectopic breast tissue in the adolescent. Pediatr Surg Int. 2022;38:1445-1451. doi:10.1007/s00383-022-05184-1

The Diagnosis: Accessory Breast

A diagnosis of accessory breast was confirmed on histopathology, which demonstrated a slightly hyperplastic and hyperpigmented epidermis. The dermis contained an increased number of smooth muscle bundles with the presence of apocrine glands and mammary lobules (Figure). Tenderness of the mass fluctuated according to the patient’s menstrual cycle, which supported a diagnosis of accessory breast over lipoma. The patient had no signs of infection or other systemic symptoms that were suggestive of lymphadenopathy. Unlike an epidermoid inclusion cyst, our patient’s mass presented as poorly defined and boggy in texture. Biopsy results were not consistent with malignancy, ruling out soft tissue sarcoma.

B, Myoepithelial cells lined a stratified columnar epithelium, characteristic of breast tissue (H&E, original magnification x40).

Accessory breasts are characterized by the presence of breast tissue outside the breast and can be found anywhere along the milk line from the axillae to the vulva.1 The prevalence of accessory breasts is 2% to 6% of women, with an average age of presentation for treatment of 42 years.2 Ninety percent of accessory breasts are found in the thorax, 5% are found in the abdomen, and 5% are found in the axillae.3 Incidence is uncommon in adolescents; however, in addition to our patient, there are several cases in the literature of adolescents with accessory breasts in the axillae.4,5

Ectopic mammary tissue is divided into 8 classes based on the Kajava classification system (Table). In a retrospective study of adolescent females with accessory breasts, 91% (10/11) of patients were classified as class IV, and 1 was class II.6 Similarly, our patient was classified as class IV since her accessory breast was composed entirely of glandular tissue and did not include an areola and nipple.

Supernumerary breast structures such as areolas and nipples typically are diagnosed at birth, whereas supernumerary breast tissue is not diagnosed until after hormonal stimulation typically seen during puberty, pregnancy, or breastfeeding. Common symptoms include cyclic pain with menstruation, fluctuation in the size of the mass, and tenderness of the ectopic tissue. There also can be restricted range of motion and increased irritation from clothing. Ultrasonography generally shows a hypoechoic septate indicative of mammary tissue.6 Diagnosis is confirmed by histopathologic studies that show mammary lobules in the dermis with smooth muscle, mammary ducts connected to the nipple, and connective stroma.6

If bothersome, ectopic breast tissue can be surgically removed, either by direct excision or suction lipectomy depending on the size of the mass.2 Postoperative complications are low but can include seroma, bleeding, infection, remnant tissue, or undesired cosmetic results. As with normal breast tissue, ectopic breast tissue can manifest with benign and malignant pathologies.

In conclusion, accessory breast is a benign condition that can cause cyclical pain with menstruation, restricted range of motion, discomfort, anxiety, and cosmetic problems. It is important to keep this diagnosis on the differential when evaluating a soft tissue mass that appears in the axillary region.

The Diagnosis: Accessory Breast

A diagnosis of accessory breast was confirmed on histopathology, which demonstrated a slightly hyperplastic and hyperpigmented epidermis. The dermis contained an increased number of smooth muscle bundles with the presence of apocrine glands and mammary lobules (Figure). Tenderness of the mass fluctuated according to the patient’s menstrual cycle, which supported a diagnosis of accessory breast over lipoma. The patient had no signs of infection or other systemic symptoms that were suggestive of lymphadenopathy. Unlike an epidermoid inclusion cyst, our patient’s mass presented as poorly defined and boggy in texture. Biopsy results were not consistent with malignancy, ruling out soft tissue sarcoma.

B, Myoepithelial cells lined a stratified columnar epithelium, characteristic of breast tissue (H&E, original magnification x40).

Accessory breasts are characterized by the presence of breast tissue outside the breast and can be found anywhere along the milk line from the axillae to the vulva.1 The prevalence of accessory breasts is 2% to 6% of women, with an average age of presentation for treatment of 42 years.2 Ninety percent of accessory breasts are found in the thorax, 5% are found in the abdomen, and 5% are found in the axillae.3 Incidence is uncommon in adolescents; however, in addition to our patient, there are several cases in the literature of adolescents with accessory breasts in the axillae.4,5

Ectopic mammary tissue is divided into 8 classes based on the Kajava classification system (Table). In a retrospective study of adolescent females with accessory breasts, 91% (10/11) of patients were classified as class IV, and 1 was class II.6 Similarly, our patient was classified as class IV since her accessory breast was composed entirely of glandular tissue and did not include an areola and nipple.

Supernumerary breast structures such as areolas and nipples typically are diagnosed at birth, whereas supernumerary breast tissue is not diagnosed until after hormonal stimulation typically seen during puberty, pregnancy, or breastfeeding. Common symptoms include cyclic pain with menstruation, fluctuation in the size of the mass, and tenderness of the ectopic tissue. There also can be restricted range of motion and increased irritation from clothing. Ultrasonography generally shows a hypoechoic septate indicative of mammary tissue.6 Diagnosis is confirmed by histopathologic studies that show mammary lobules in the dermis with smooth muscle, mammary ducts connected to the nipple, and connective stroma.6

If bothersome, ectopic breast tissue can be surgically removed, either by direct excision or suction lipectomy depending on the size of the mass.2 Postoperative complications are low but can include seroma, bleeding, infection, remnant tissue, or undesired cosmetic results. As with normal breast tissue, ectopic breast tissue can manifest with benign and malignant pathologies.

In conclusion, accessory breast is a benign condition that can cause cyclical pain with menstruation, restricted range of motion, discomfort, anxiety, and cosmetic problems. It is important to keep this diagnosis on the differential when evaluating a soft tissue mass that appears in the axillary region.

- Loukas M, Clarke P, Tubbs RS. Accessory breasts: a historical and current perspective. Am Surg. 2007;73:525-528.

- Bartsich SA, Ofodile FA. Accessory breast tissue in the axilla: classification and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:35E-36E. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182173f95

- Mazine K, Bouassria A, Elbouhaddouti H. Bilateral supernumerary axillary breasts: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:282. doi:10.11604 /pamj.2020.36.282.20445

- Patel RV, Govani D, Patel R, et al. Adolescent right axillary accessory breast with galactorrhoea. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014204215. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204215

- Surd A, Mironescu A, Gocan H. Fibroadenoma in axillary supernumerary breast in a 17-year-old girl: case report. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:E79-E81. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2016.04.008

- De la Torre M, Lorca-García C, de Tomás E, et al. Axillary ectopic breast tissue in the adolescent. Pediatr Surg Int. 2022;38:1445-1451. doi:10.1007/s00383-022-05184-1

- Loukas M, Clarke P, Tubbs RS. Accessory breasts: a historical and current perspective. Am Surg. 2007;73:525-528.

- Bartsich SA, Ofodile FA. Accessory breast tissue in the axilla: classification and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:35E-36E. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182173f95

- Mazine K, Bouassria A, Elbouhaddouti H. Bilateral supernumerary axillary breasts: a case report. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;36:282. doi:10.11604 /pamj.2020.36.282.20445

- Patel RV, Govani D, Patel R, et al. Adolescent right axillary accessory breast with galactorrhoea. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014204215. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204215

- Surd A, Mironescu A, Gocan H. Fibroadenoma in axillary supernumerary breast in a 17-year-old girl: case report. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:E79-E81. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2016.04.008

- De la Torre M, Lorca-García C, de Tomás E, et al. Axillary ectopic breast tissue in the adolescent. Pediatr Surg Int. 2022;38:1445-1451. doi:10.1007/s00383-022-05184-1

Fluctuant Subcutaneous Nodule in the Axilla of an Adolescent Female

Fluctuant Subcutaneous Nodule in the Axilla of an Adolescent Female

A 15-year-old adolescent female with an unremarkable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with a mass in the left axilla of 2 years’ duration. The patient reported that there was no drainage of the lesion nor did she have any other similar lesions. She reported tenderness of the lesion during menstruation that resolved after this phase ended. Dermatologic examination revealed a solitary 4.4-cm, flesh-colored, poorly defined, boggy, fluctuant subcutaneous nodule with no central punctum or surface changes. Ultrasonography of the axilla showed a 6.4-cm hypoechoic heterogenous mass. A biopsy of the lesion was performed.