User login

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

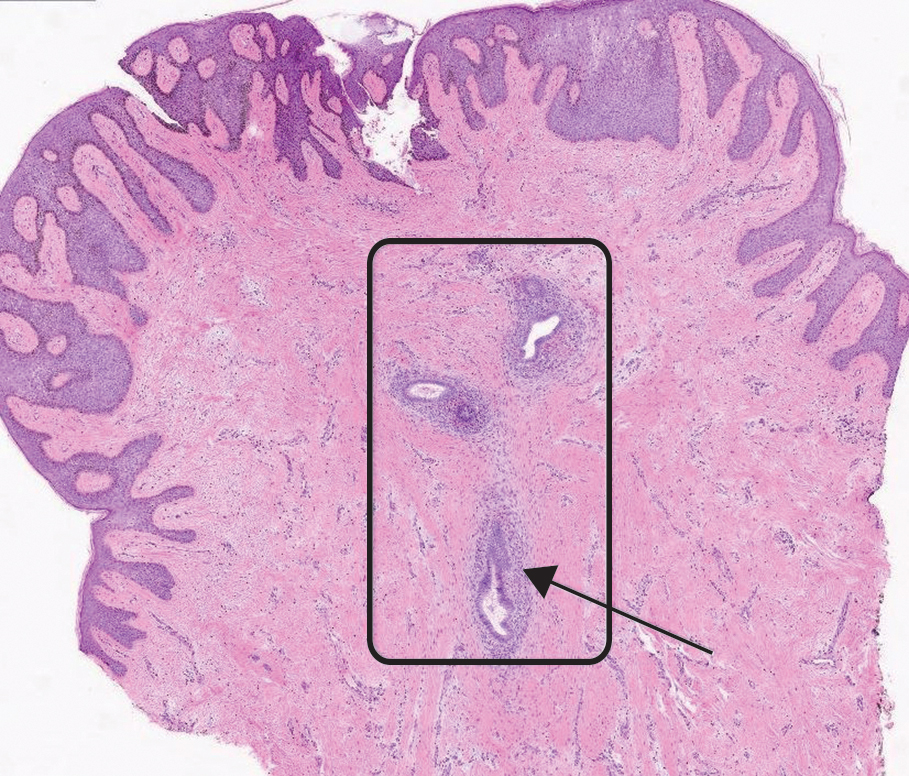

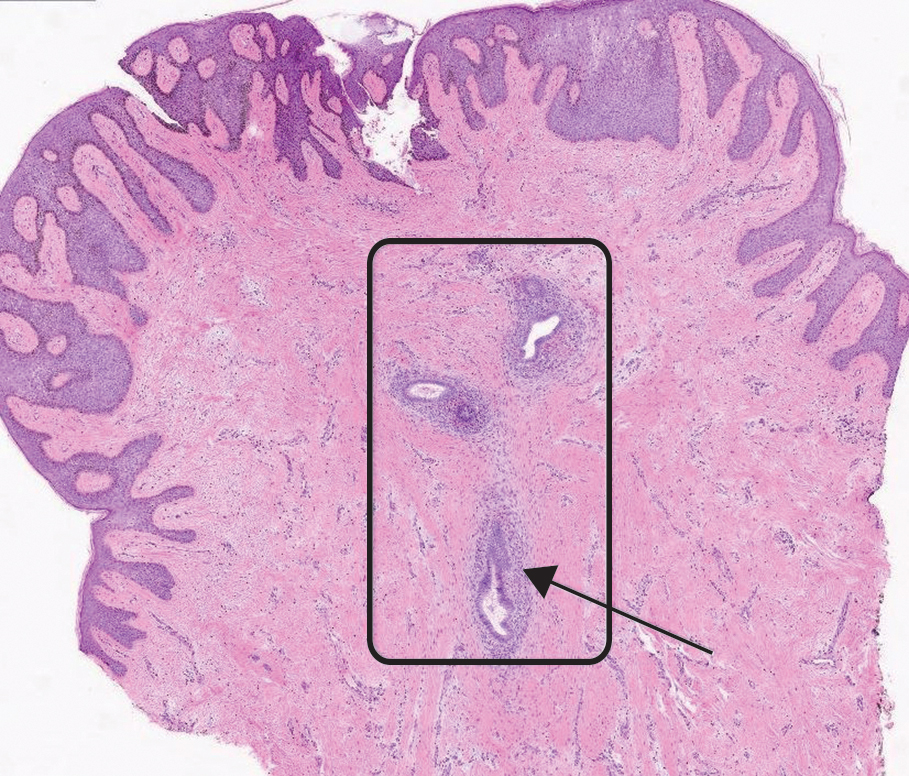

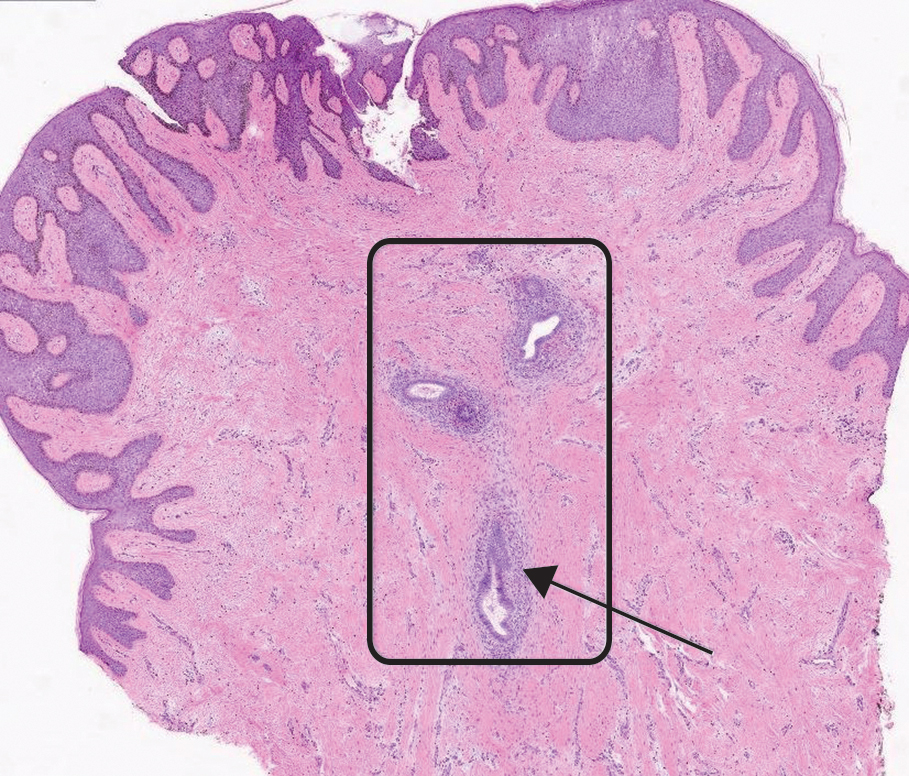

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

A 38-year-old nulligravid female with menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea presented with cyclical umbilical bleeding of 1 year’s duration. Shortly before the onset of symptoms, the patient had discontinued oral contraceptive therapy with the intent to become pregnant. She had an uncomplicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy 10 years prior, but her medical history was otherwise unremarkable. At the current presentation, physical examination revealed multilobular brown papules with serosanguineous crusting in the umbilicus.

Pustular Eruption on the Face

The Diagnosis: Eczema Herpeticum

The patient’s condition with worsening facial edema and notable pain prompted a bedside Tzanck smear using a sample from the base of a deroofed forehead vesicle. In addition, a swab of a deroofed lesion was sent for herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The Tzanck smear demonstrated ballooning multinucleated syncytial giant cells and eosinophilic inclusion bodies (Figure), which are characteristic of certain herpesviruses including herpes simplex virus and VZV. He was started on intravenous acyclovir while PCR results were pending; the PCR test later confirmed positivity for herpes simplex virus type 1. Treatment was transitioned to oral valacyclovir once the lesions started crusting over. Notable healing and epithelialization of the lesions occurred during his hospital stay, and he was discharged home 5 days after starting treatment. He was counseled on autoinoculation, advised that he was considered infectious until all lesions had crusted over, and encouraged to employ frequent handwashing. Complete resolution of eczema herpeticum (EH) was noted at 3-week follow-up.

Eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption) is a potentially life-threatening disseminated cutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in patients with pre-existing skin disease.1 It typically presents as a complication of atopic dermatitis (AD) but also has been identified as a rare complication in other conditions that disrupt the normal skin barrier, including mycosis fungoides, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pityriasis rubra pilaris, contact dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1-4

The pathogenesis of EH is multifactorial. Disruption of the stratum corneum; impaired natural killer cell function; early-onset, untreated, or severe AD; disrupted skin microbiota with skewed colonization by Staphylococcus aureus; immunosuppressive AD therapies such as calcineurin inhibitors; eosinophilia; and helper T cell (TH2) cytokine predominance all have been suggested to play a role in the development of EH.5-8

As seen in our patient, EH presents with a sudden eruption of painful or pruritic, grouped, monomorphic, domeshaped vesicles with background swelling and erythema typically on the head, neck, and trunk. Vesicles then progress to punched-out erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusting that can coalesce to form large denuded areas susceptible to superinfection with bacteria.9 Other accompanying symptoms include high fever, chills, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Associated inflammation, classically described as erythema, may be difficult to discern in patients with darker skin and appears as hyperpigmentation; therefore, identification of clusters of monomorphic vesicles in areas of pre-existing dermatitis is particularly important for clinical diagnosis in people with darker skin types.

Various tests are available to confirm diagnosis in ambiguous cases. Bedside Tzanck smears can be performed rapidly and are considered positive if characteristic multinucleated giant cells are noted; however, they do not differentiate between the various herpesviruses. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of scraped lesions and viral cultures of swabbed vesicular fluid are equally effective in distinguishing between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and VZV; PCR confirms the diagnosis with high specificity and sensitivity.10

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included EH, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, allergic contact dermatitis, and Orthopoxvirus infection. The positive Tzanck smear reduced the likelihood of a nonviral etiology. Additionally, worsening of the rash despite discontinuation of medications and utilization of topical steroids argued against acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and allergic contact dermatitis. The laboratory findings reduced the likelihood of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and PCR findings ultimately ruled out Orthopoxvirus infections. Additional differential diagnoses for EH include dermatitis herpetiformis; primary VZV infection; hand, foot, and mouth disease; disseminated zoster infection; disseminated molluscum contagiosum; and eczema coxsackium.

Complications of EH include scarring; herpetic keratitis due to corneal infection, which if left untreated can progress to blindness; and rarely death due to multiorgan failure or septicemia.11 The traditional smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000) is contraindicated in patients with AD and EH, even when AD is in remission. These patients should avoid contact with recently vaccinated individuals.12 An alternative vaccine—Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic)—is available for these patients and their family members.13 Clinicians should be aware of this guideline, especially given the recent mpox (monkeypox) outbreaks.

Mild cases of EH are more common, may sometimes go unnoticed, and self-resolve in healthy patients. Severe cases may require systemic antiviral therapy. Acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are standard treatments for EH. Alternatively, foscarnet or cidofovir can be used in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant thymidine kinase– deficient herpes simplex virus and other acyclovirresistant cases.14 Any secondary bacterial superinfections, usually due to staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria, should be treated with antibiotics. A thorough ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed for patients with periocular involvement of EH. Empiric treatment should be started immediately, given a relative low toxicity of systemic antiviral therapy and high morbidity and mortality associated with untreated widespread EH.

It is important to maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for EH, especially in patients with pre-existing conditions such as AD who present with systemic symptoms and facial vesicles, pustules, or erosions to ensure prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Baaniya B, Agrawal S. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:6695342. doi:10.1155/2020/6695342

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Cavalié M, Giacchero D, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in a patient with pityriasis rubra pilaris (pityriasis rubra pilaris herpeticum). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1585-1586. doi:10.1111/JDV.12120

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum— a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1074-1079. doi:10.1111/JDV.16090

- Kawakami Y, Ando T, Lee J-R, et al. Defective natural killer cell activity in a mouse model of eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:997-1006.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.034

- Beck L, Latchney L, Zaccaro D, et al. Biomarkers of disease severity and Th2 polarity are predictors of risk for eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:S37-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.152

- Kim M, Jung M, Hong SP, et al. Topical calcineurin inhibitors compromise stratum corneum integrity, epidermal permeability and antimicrobial barrier function. Exp Dermatol. 2010; 19:501-510. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0625.2009.00941.X

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432/

- Dominguez SR, Pretty K, Hengartner R, et al. Comparison of herpes simplex virus PCR with culture for virus detection in multisource surface swab specimens from neonates [published online September 25, 2018]. J Clin Microbiol. doi:10.1128/JCM.00632-18

- Feye F, De Halleux C, Gillet JB, et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:49-52. doi:10.1097/00063110-200412000-00014

- Casey C, Vellozzi C, Mootrey GT, et al; Vaccinia Case Definition Development Working Group; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices-Armed Forces Epidemiological Board Smallpox Vaccine Safety Working Group. Surveillance guidelines for smallpox vaccine (vaccinia) adverse reactions. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-16.

- Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi:10.15585 /MMWR.MM7122E1

- Piret J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:459. doi:10.1128/AAC.00615-10

The Diagnosis: Eczema Herpeticum

The patient’s condition with worsening facial edema and notable pain prompted a bedside Tzanck smear using a sample from the base of a deroofed forehead vesicle. In addition, a swab of a deroofed lesion was sent for herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The Tzanck smear demonstrated ballooning multinucleated syncytial giant cells and eosinophilic inclusion bodies (Figure), which are characteristic of certain herpesviruses including herpes simplex virus and VZV. He was started on intravenous acyclovir while PCR results were pending; the PCR test later confirmed positivity for herpes simplex virus type 1. Treatment was transitioned to oral valacyclovir once the lesions started crusting over. Notable healing and epithelialization of the lesions occurred during his hospital stay, and he was discharged home 5 days after starting treatment. He was counseled on autoinoculation, advised that he was considered infectious until all lesions had crusted over, and encouraged to employ frequent handwashing. Complete resolution of eczema herpeticum (EH) was noted at 3-week follow-up.

Eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption) is a potentially life-threatening disseminated cutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in patients with pre-existing skin disease.1 It typically presents as a complication of atopic dermatitis (AD) but also has been identified as a rare complication in other conditions that disrupt the normal skin barrier, including mycosis fungoides, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pityriasis rubra pilaris, contact dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1-4

The pathogenesis of EH is multifactorial. Disruption of the stratum corneum; impaired natural killer cell function; early-onset, untreated, or severe AD; disrupted skin microbiota with skewed colonization by Staphylococcus aureus; immunosuppressive AD therapies such as calcineurin inhibitors; eosinophilia; and helper T cell (TH2) cytokine predominance all have been suggested to play a role in the development of EH.5-8

As seen in our patient, EH presents with a sudden eruption of painful or pruritic, grouped, monomorphic, domeshaped vesicles with background swelling and erythema typically on the head, neck, and trunk. Vesicles then progress to punched-out erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusting that can coalesce to form large denuded areas susceptible to superinfection with bacteria.9 Other accompanying symptoms include high fever, chills, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Associated inflammation, classically described as erythema, may be difficult to discern in patients with darker skin and appears as hyperpigmentation; therefore, identification of clusters of monomorphic vesicles in areas of pre-existing dermatitis is particularly important for clinical diagnosis in people with darker skin types.

Various tests are available to confirm diagnosis in ambiguous cases. Bedside Tzanck smears can be performed rapidly and are considered positive if characteristic multinucleated giant cells are noted; however, they do not differentiate between the various herpesviruses. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of scraped lesions and viral cultures of swabbed vesicular fluid are equally effective in distinguishing between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and VZV; PCR confirms the diagnosis with high specificity and sensitivity.10

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included EH, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, allergic contact dermatitis, and Orthopoxvirus infection. The positive Tzanck smear reduced the likelihood of a nonviral etiology. Additionally, worsening of the rash despite discontinuation of medications and utilization of topical steroids argued against acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and allergic contact dermatitis. The laboratory findings reduced the likelihood of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and PCR findings ultimately ruled out Orthopoxvirus infections. Additional differential diagnoses for EH include dermatitis herpetiformis; primary VZV infection; hand, foot, and mouth disease; disseminated zoster infection; disseminated molluscum contagiosum; and eczema coxsackium.

Complications of EH include scarring; herpetic keratitis due to corneal infection, which if left untreated can progress to blindness; and rarely death due to multiorgan failure or septicemia.11 The traditional smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000) is contraindicated in patients with AD and EH, even when AD is in remission. These patients should avoid contact with recently vaccinated individuals.12 An alternative vaccine—Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic)—is available for these patients and their family members.13 Clinicians should be aware of this guideline, especially given the recent mpox (monkeypox) outbreaks.

Mild cases of EH are more common, may sometimes go unnoticed, and self-resolve in healthy patients. Severe cases may require systemic antiviral therapy. Acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are standard treatments for EH. Alternatively, foscarnet or cidofovir can be used in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant thymidine kinase– deficient herpes simplex virus and other acyclovirresistant cases.14 Any secondary bacterial superinfections, usually due to staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria, should be treated with antibiotics. A thorough ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed for patients with periocular involvement of EH. Empiric treatment should be started immediately, given a relative low toxicity of systemic antiviral therapy and high morbidity and mortality associated with untreated widespread EH.

It is important to maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for EH, especially in patients with pre-existing conditions such as AD who present with systemic symptoms and facial vesicles, pustules, or erosions to ensure prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Eczema Herpeticum

The patient’s condition with worsening facial edema and notable pain prompted a bedside Tzanck smear using a sample from the base of a deroofed forehead vesicle. In addition, a swab of a deroofed lesion was sent for herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. The Tzanck smear demonstrated ballooning multinucleated syncytial giant cells and eosinophilic inclusion bodies (Figure), which are characteristic of certain herpesviruses including herpes simplex virus and VZV. He was started on intravenous acyclovir while PCR results were pending; the PCR test later confirmed positivity for herpes simplex virus type 1. Treatment was transitioned to oral valacyclovir once the lesions started crusting over. Notable healing and epithelialization of the lesions occurred during his hospital stay, and he was discharged home 5 days after starting treatment. He was counseled on autoinoculation, advised that he was considered infectious until all lesions had crusted over, and encouraged to employ frequent handwashing. Complete resolution of eczema herpeticum (EH) was noted at 3-week follow-up.

Eczema herpeticum (also known as Kaposi varicelliform eruption) is a potentially life-threatening disseminated cutaneous infection caused by herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in patients with pre-existing skin disease.1 It typically presents as a complication of atopic dermatitis (AD) but also has been identified as a rare complication in other conditions that disrupt the normal skin barrier, including mycosis fungoides, pemphigus foliaceus, pemphigus vulgaris, Darier disease, pityriasis rubra pilaris, contact dermatitis, and seborrheic dermatitis.1-4

The pathogenesis of EH is multifactorial. Disruption of the stratum corneum; impaired natural killer cell function; early-onset, untreated, or severe AD; disrupted skin microbiota with skewed colonization by Staphylococcus aureus; immunosuppressive AD therapies such as calcineurin inhibitors; eosinophilia; and helper T cell (TH2) cytokine predominance all have been suggested to play a role in the development of EH.5-8

As seen in our patient, EH presents with a sudden eruption of painful or pruritic, grouped, monomorphic, domeshaped vesicles with background swelling and erythema typically on the head, neck, and trunk. Vesicles then progress to punched-out erosions with overlying hemorrhagic crusting that can coalesce to form large denuded areas susceptible to superinfection with bacteria.9 Other accompanying symptoms include high fever, chills, malaise, and lymphadenopathy. Associated inflammation, classically described as erythema, may be difficult to discern in patients with darker skin and appears as hyperpigmentation; therefore, identification of clusters of monomorphic vesicles in areas of pre-existing dermatitis is particularly important for clinical diagnosis in people with darker skin types.

Various tests are available to confirm diagnosis in ambiguous cases. Bedside Tzanck smears can be performed rapidly and are considered positive if characteristic multinucleated giant cells are noted; however, they do not differentiate between the various herpesviruses. Direct fluorescent antibody testing of scraped lesions and viral cultures of swabbed vesicular fluid are equally effective in distinguishing between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and VZV; PCR confirms the diagnosis with high specificity and sensitivity.10

In our patient, the initial differential diagnosis included EH, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, allergic contact dermatitis, and Orthopoxvirus infection. The positive Tzanck smear reduced the likelihood of a nonviral etiology. Additionally, worsening of the rash despite discontinuation of medications and utilization of topical steroids argued against acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and allergic contact dermatitis. The laboratory findings reduced the likelihood of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and PCR findings ultimately ruled out Orthopoxvirus infections. Additional differential diagnoses for EH include dermatitis herpetiformis; primary VZV infection; hand, foot, and mouth disease; disseminated zoster infection; disseminated molluscum contagiosum; and eczema coxsackium.

Complications of EH include scarring; herpetic keratitis due to corneal infection, which if left untreated can progress to blindness; and rarely death due to multiorgan failure or septicemia.11 The traditional smallpox vaccine (ACAM2000) is contraindicated in patients with AD and EH, even when AD is in remission. These patients should avoid contact with recently vaccinated individuals.12 An alternative vaccine—Jynneos (Bavarian Nordic)—is available for these patients and their family members.13 Clinicians should be aware of this guideline, especially given the recent mpox (monkeypox) outbreaks.

Mild cases of EH are more common, may sometimes go unnoticed, and self-resolve in healthy patients. Severe cases may require systemic antiviral therapy. Acyclovir and its prodrug valacyclovir are standard treatments for EH. Alternatively, foscarnet or cidofovir can be used in the treatment of acyclovir-resistant thymidine kinase– deficient herpes simplex virus and other acyclovirresistant cases.14 Any secondary bacterial superinfections, usually due to staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria, should be treated with antibiotics. A thorough ophthalmologic evaluation should be performed for patients with periocular involvement of EH. Empiric treatment should be started immediately, given a relative low toxicity of systemic antiviral therapy and high morbidity and mortality associated with untreated widespread EH.

It is important to maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for EH, especially in patients with pre-existing conditions such as AD who present with systemic symptoms and facial vesicles, pustules, or erosions to ensure prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

- Baaniya B, Agrawal S. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:6695342. doi:10.1155/2020/6695342

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Cavalié M, Giacchero D, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in a patient with pityriasis rubra pilaris (pityriasis rubra pilaris herpeticum). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1585-1586. doi:10.1111/JDV.12120

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum— a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1074-1079. doi:10.1111/JDV.16090

- Kawakami Y, Ando T, Lee J-R, et al. Defective natural killer cell activity in a mouse model of eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:997-1006.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.034

- Beck L, Latchney L, Zaccaro D, et al. Biomarkers of disease severity and Th2 polarity are predictors of risk for eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:S37-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.152

- Kim M, Jung M, Hong SP, et al. Topical calcineurin inhibitors compromise stratum corneum integrity, epidermal permeability and antimicrobial barrier function. Exp Dermatol. 2010; 19:501-510. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0625.2009.00941.X

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432/

- Dominguez SR, Pretty K, Hengartner R, et al. Comparison of herpes simplex virus PCR with culture for virus detection in multisource surface swab specimens from neonates [published online September 25, 2018]. J Clin Microbiol. doi:10.1128/JCM.00632-18

- Feye F, De Halleux C, Gillet JB, et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:49-52. doi:10.1097/00063110-200412000-00014

- Casey C, Vellozzi C, Mootrey GT, et al; Vaccinia Case Definition Development Working Group; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices-Armed Forces Epidemiological Board Smallpox Vaccine Safety Working Group. Surveillance guidelines for smallpox vaccine (vaccinia) adverse reactions. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-16.

- Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi:10.15585 /MMWR.MM7122E1

- Piret J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:459. doi:10.1128/AAC.00615-10

- Baaniya B, Agrawal S. Kaposi varicelliform eruption in a patient with pemphigus vulgaris: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2020;2020:6695342. doi:10.1155/2020/6695342

- Tayabali K, Pothiwalla H, Lowitt M. Eczema herpeticum in Darier’s disease: a topical storm. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2019;9:347. doi:10.1080/20009666.2019.1650590

- Cavalié M, Giacchero D, Cardot-Leccia N, et al. Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption in a patient with pityriasis rubra pilaris (pityriasis rubra pilaris herpeticum). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1585-1586. doi:10.1111/JDV.12120

- Lee GH, Kim YM, Lee SY, et al. A case of eczema herpeticum with Hailey-Hailey disease. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:311-314. doi:10.5021/ad.2009.21.3.311

- Seegräber M, Worm M, Werfel T, et al. Recurrent eczema herpeticum— a retrospective European multicenter study evaluating the clinical characteristics of eczema herpeticum cases in atopic dermatitis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1074-1079. doi:10.1111/JDV.16090

- Kawakami Y, Ando T, Lee J-R, et al. Defective natural killer cell activity in a mouse model of eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:997-1006.e10. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.034

- Beck L, Latchney L, Zaccaro D, et al. Biomarkers of disease severity and Th2 polarity are predictors of risk for eczema herpeticum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:S37-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.152

- Kim M, Jung M, Hong SP, et al. Topical calcineurin inhibitors compromise stratum corneum integrity, epidermal permeability and antimicrobial barrier function. Exp Dermatol. 2010; 19:501-510. doi:10.1111/J.1600-0625.2009.00941.X

- Karray M, Kwan E, Souissi A. Kaposi varicelliform eruption. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482432/

- Dominguez SR, Pretty K, Hengartner R, et al. Comparison of herpes simplex virus PCR with culture for virus detection in multisource surface swab specimens from neonates [published online September 25, 2018]. J Clin Microbiol. doi:10.1128/JCM.00632-18

- Feye F, De Halleux C, Gillet JB, et al. Exacerbation of atopic dermatitis in the emergency department. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004;11:49-52. doi:10.1097/00063110-200412000-00014

- Casey C, Vellozzi C, Mootrey GT, et al; Vaccinia Case Definition Development Working Group; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices-Armed Forces Epidemiological Board Smallpox Vaccine Safety Working Group. Surveillance guidelines for smallpox vaccine (vaccinia) adverse reactions. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1-16.

- Rao AK, Petersen BW, Whitehill F, et al. Use of JYNNEOS (Smallpox and Monkeypox Vaccine, Live, Nonreplicating) for preexposure vaccination of persons at risk for occupational exposure to orthopoxviruses: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:734-742. doi:10.15585 /MMWR.MM7122E1

- Piret J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:459. doi:10.1128/AAC.00615-10

A 52-year-old man developed a sudden eruption of small pustules on background erythema and edema covering the forehead, nasal bridge, periorbital region, cheeks, and perioral region on day 3 of hospitalization in the intensive care unit for management of septic shock secondary to a complicated urinary tract infection. He had a medical history of benign prostatic hyperplasia, sarcoidosis, and atopic dermatitis. He initially presented to the emergency department with fever, chills, and dysuria of 2 days’ duration. Because he received ceftriaxone, vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, and tamsulosin while hospitalized for the infection, the primary medical team suspected a drug reaction and empirically started applying hydrocortisone cream 2.5%. The rash continued to spread over the ensuing day, prompting a dermatology consultation to rule out a drug eruption and to help guide further management. The patient was in substantial distress and pain. Physical examination revealed numerous discrete and confluent monomorphic pustules on background erythema with faint collarettes of scale covering most of the face. Substantial periorbital and facial edema forced the eyes closed. There was no mucous membrane involvement. A review of systems was negative for dyspnea and dysphagia, and the rash was not present elsewhere on the body. Ophthalmologic evaluation revealed no ocular involvement or vision changes. Laboratory studies demonstrated neutrophilia (17.27×109 cells/L [reference range, 2.0–6.9×109 cells/L]). The eosinophil count, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine, and liver function tests were within reference range.