User login

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

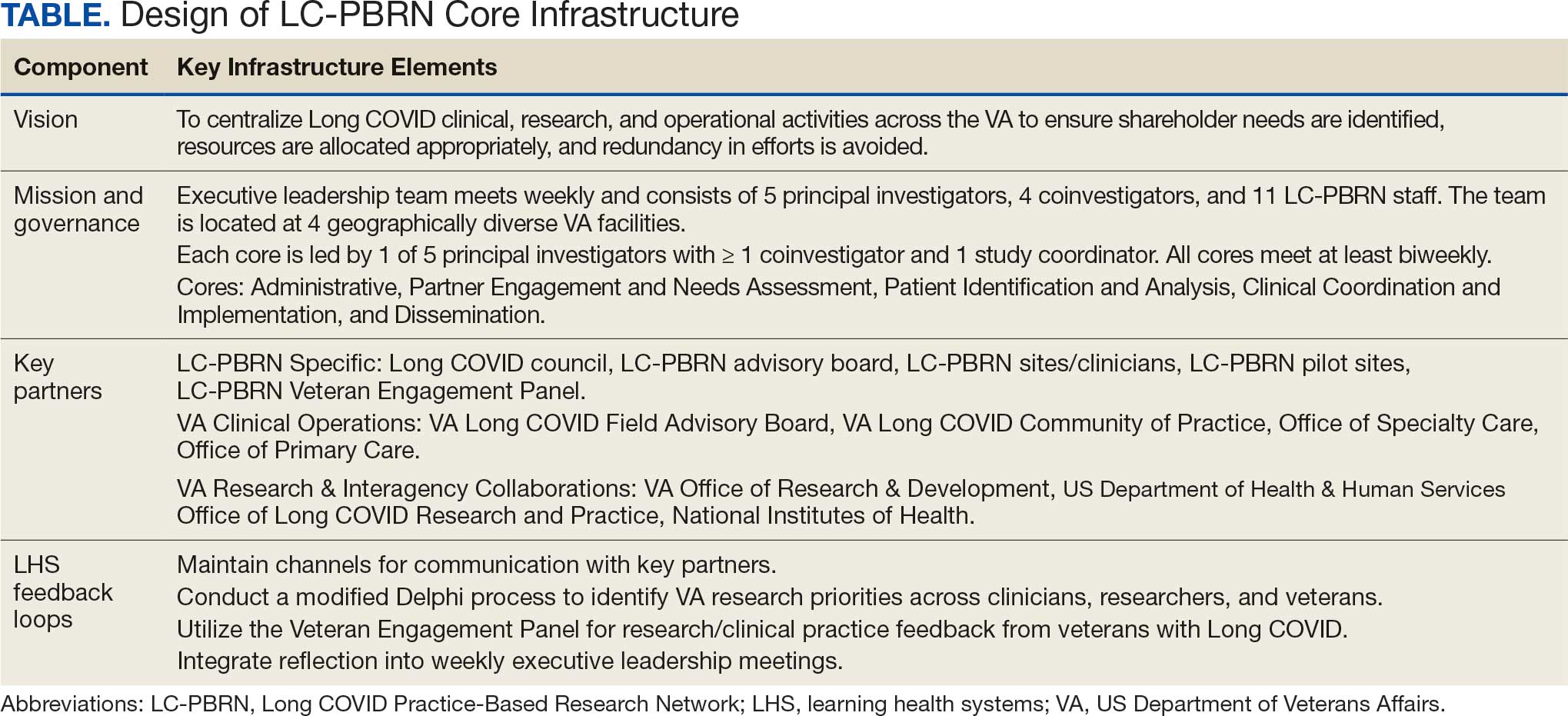

Learning health systems (LHS) promote a continuous process that can assist in making sense of uncertainty when confronting emerging complex conditions such as Long COVID. Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that detrimentally impacts veterans, their families, and the communities in which they live. This complex condition is defined by ongoing, new, or returning symptoms following COVID-19 infection that negatively affect return to meaningful participation in social, recreational, and vocational activities.1,2 The clinical uncertainty surrounding Long COVID is amplified by unclear etiology, prognosis, and expected course of symptoms.3,4 Uncertainty surrounding best clinical practices, processes, and policies for Long COVID care has resulted in practice variation despite the emerging evidence base for Long COVID care.4 Failure to address gaps in clinical evidence and care implementation threatens to perpetuate fragmented and unnecessary care.

The context surrounding Long COVID created an urgency to rapidly address clinically relevant questions and make sense of any uncertainty. Thus, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) funded a Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network (LC-PBRN) to build an infrastructure that supports Long COVID research nationally and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration. The LC-PBRN vision is to centralize Long COVID clinical, research, and operational activities. The research infrastructure of the LC-PBRN is designed with an LHS lens to facilitate feedback loops and integrate knowledge learned while making progress towards this vision.5 This article describes the phases of infrastructure development and network building, as well as associated lessons learned.

Designing the LC-PBRN Infrastructure

Vision

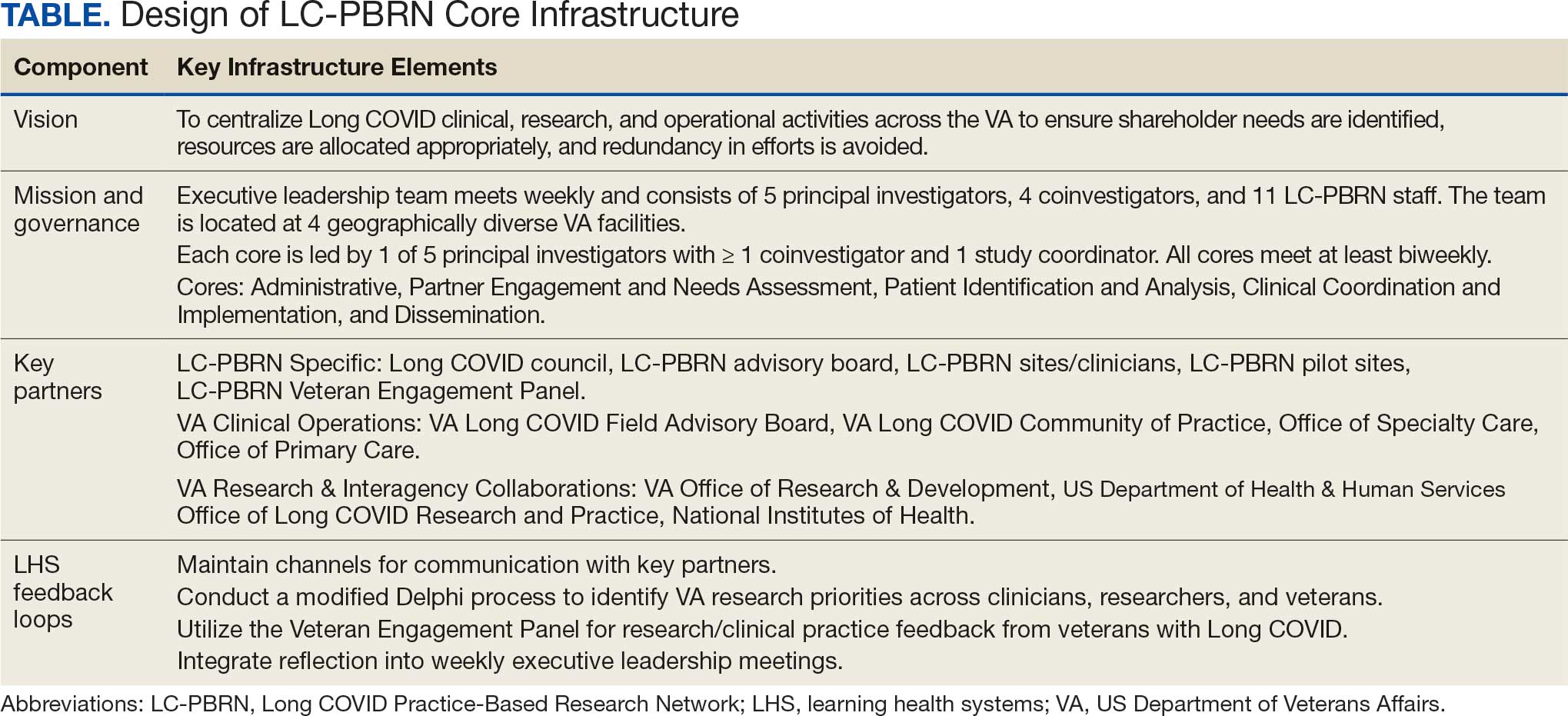

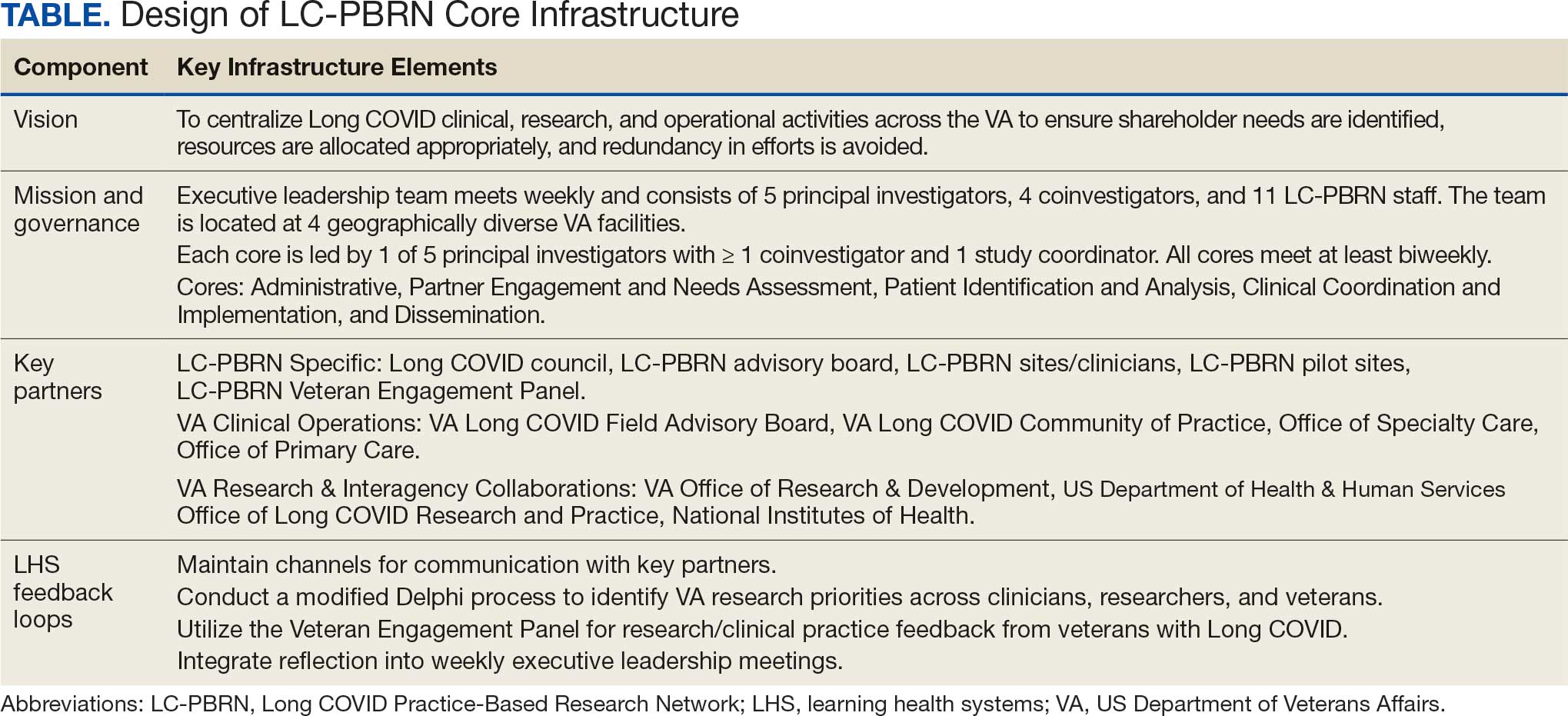

The LC-PBRN’s vision is to create an infrastructure that integrates an LHS framework by unifying the VA research approach to Long COVID to ensure veteran, clinician, operational, and researcher involvement (Figure 1).

Mission and Governance

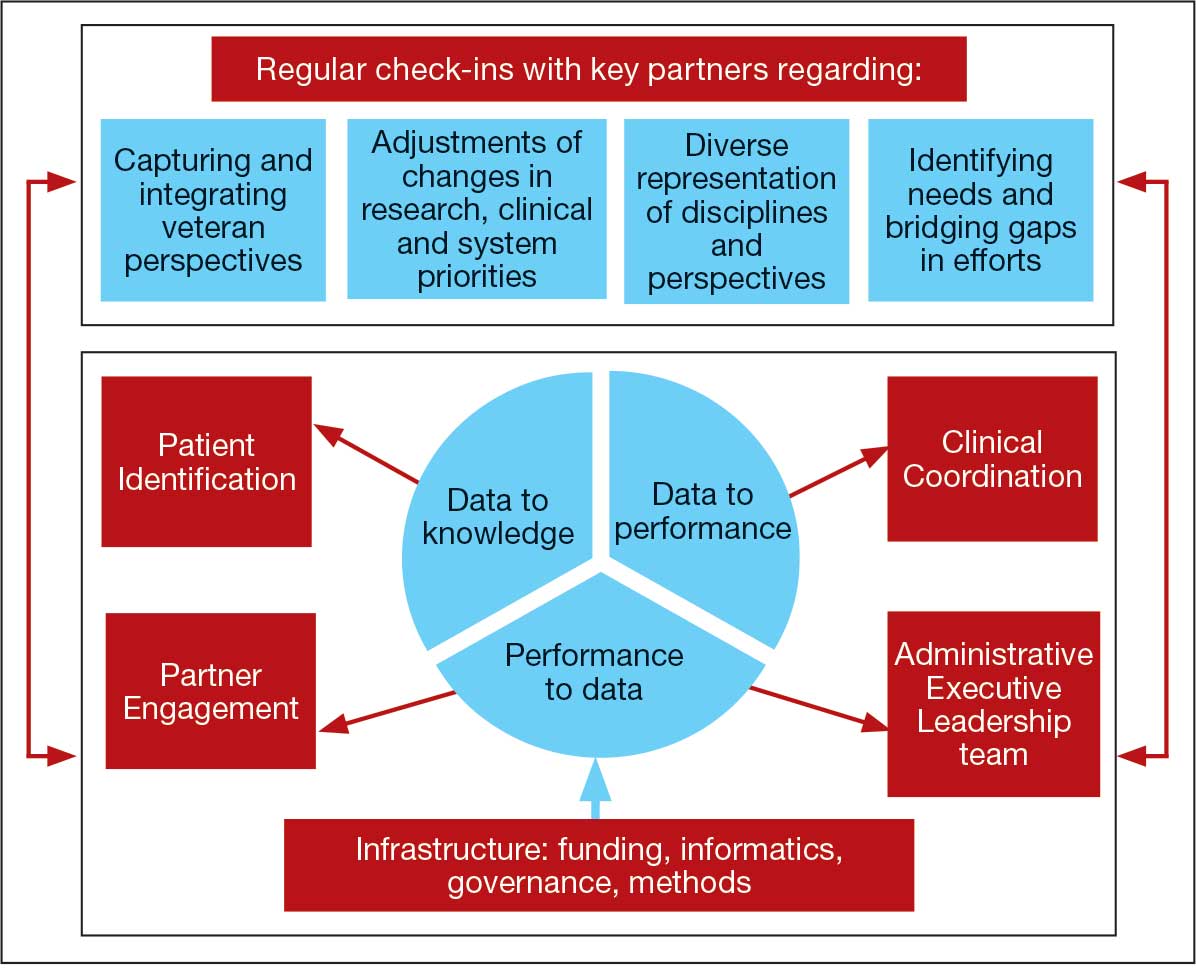

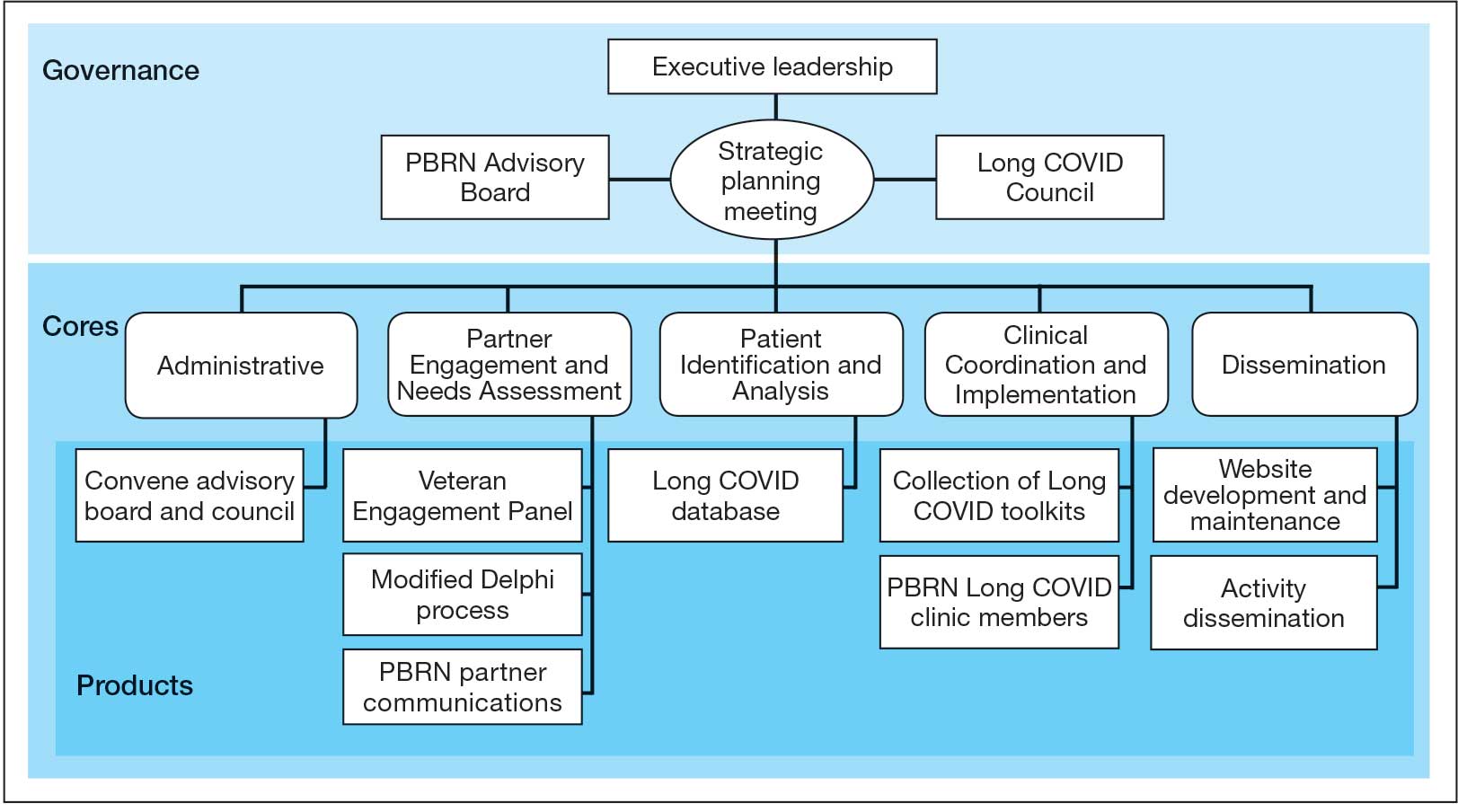

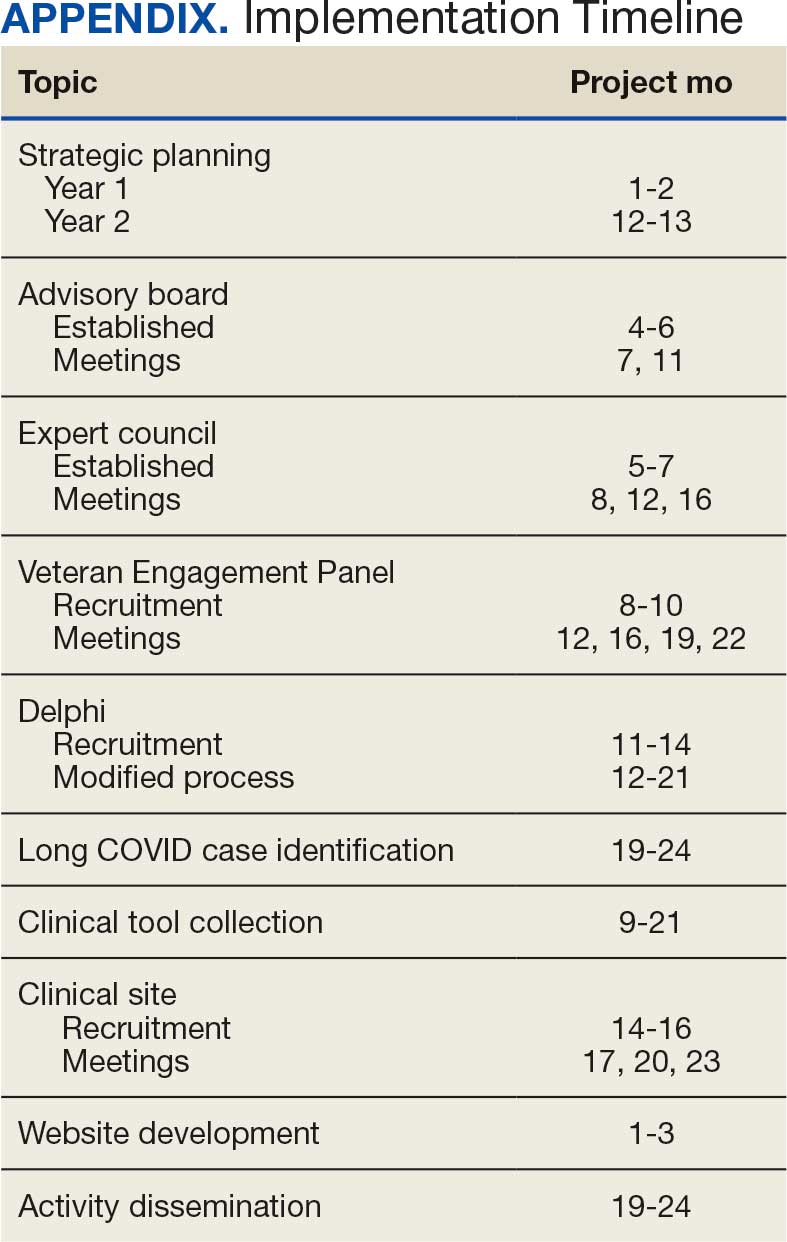

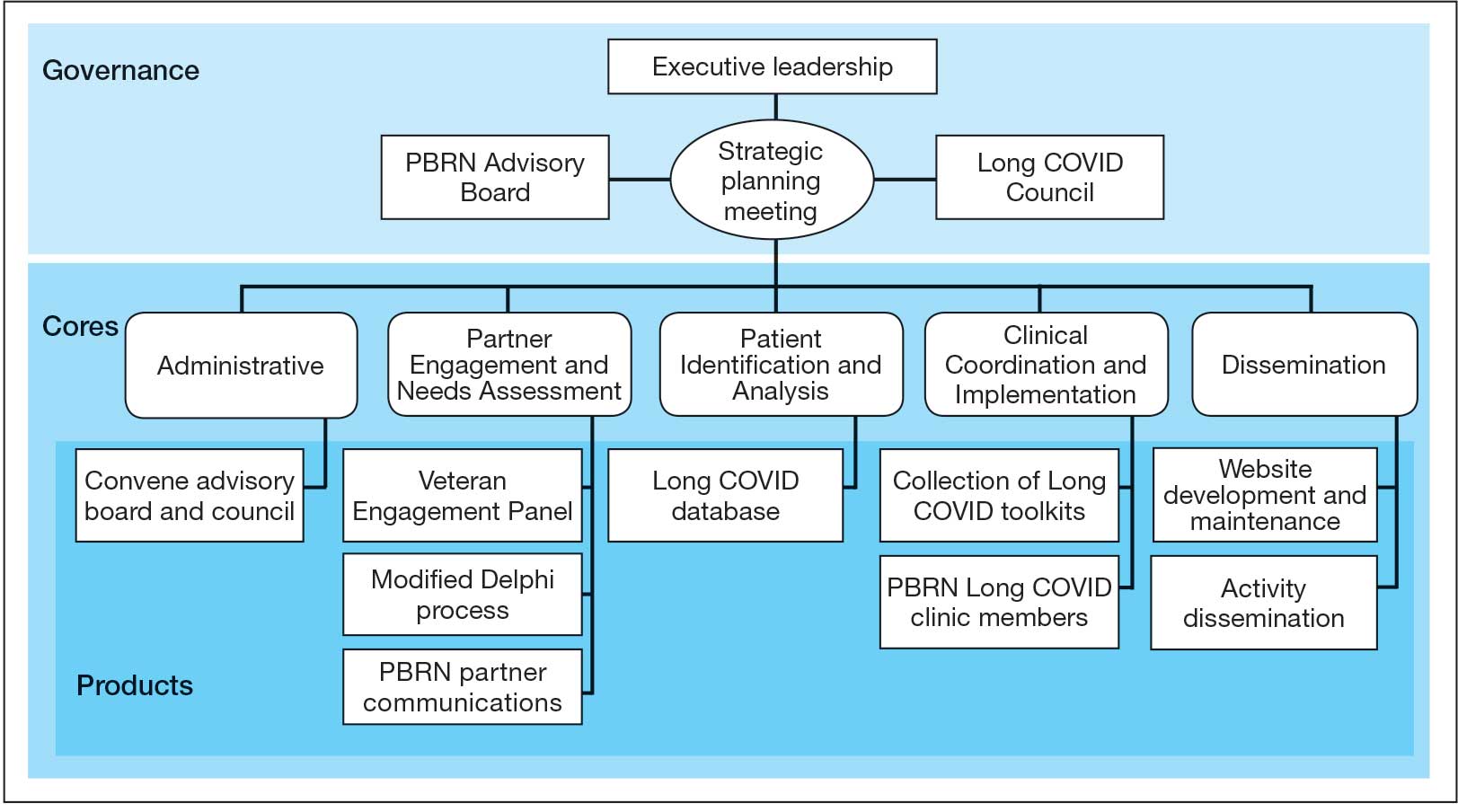

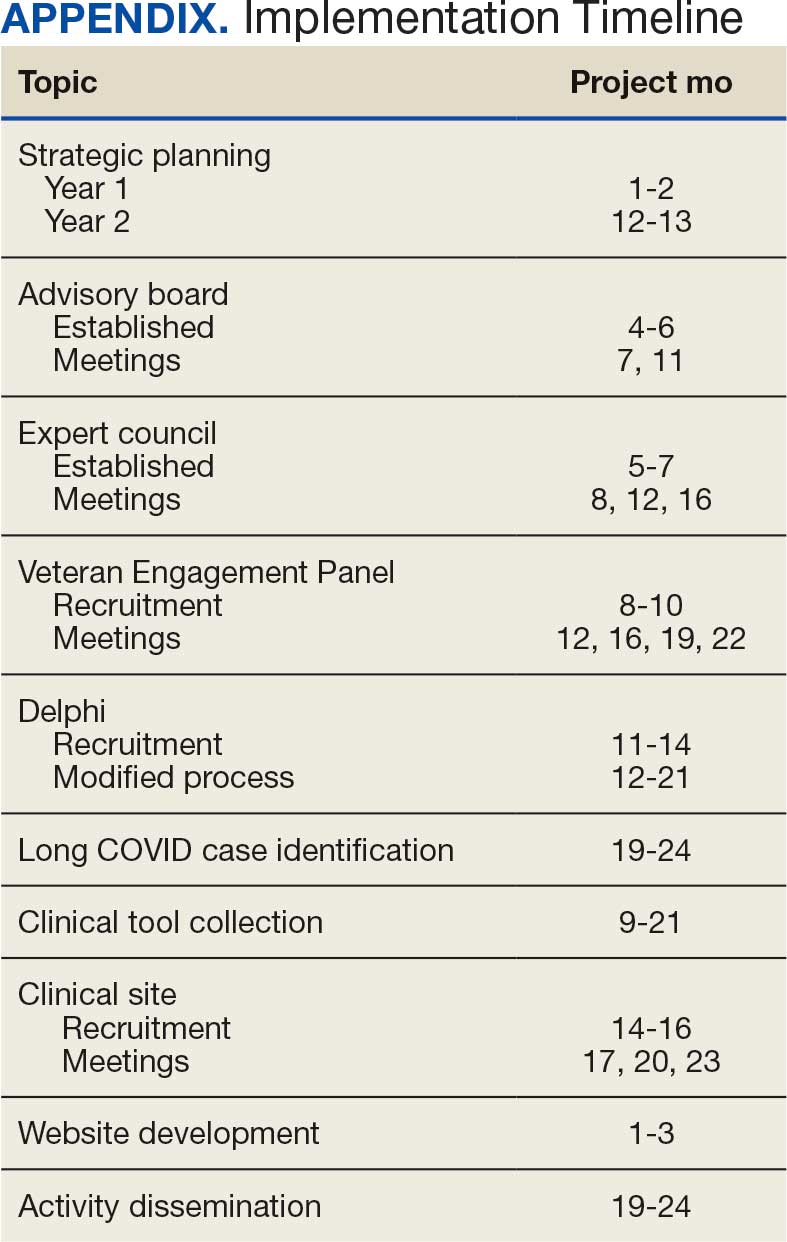

The LC-PBRN operates with an executive leadership team and 5 cores. The executive leadership team is responsible for overall LC-PBRN operations, management, and direction setting of the LC-PBRN. The executive leadership team meets weekly to provide oversight of each core, which specializes in different aspects. The cores include: Administrative, Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment, Patient Identification and Analysis, Clinical Coordination and Implementation, and Dissemination (Figure 2).

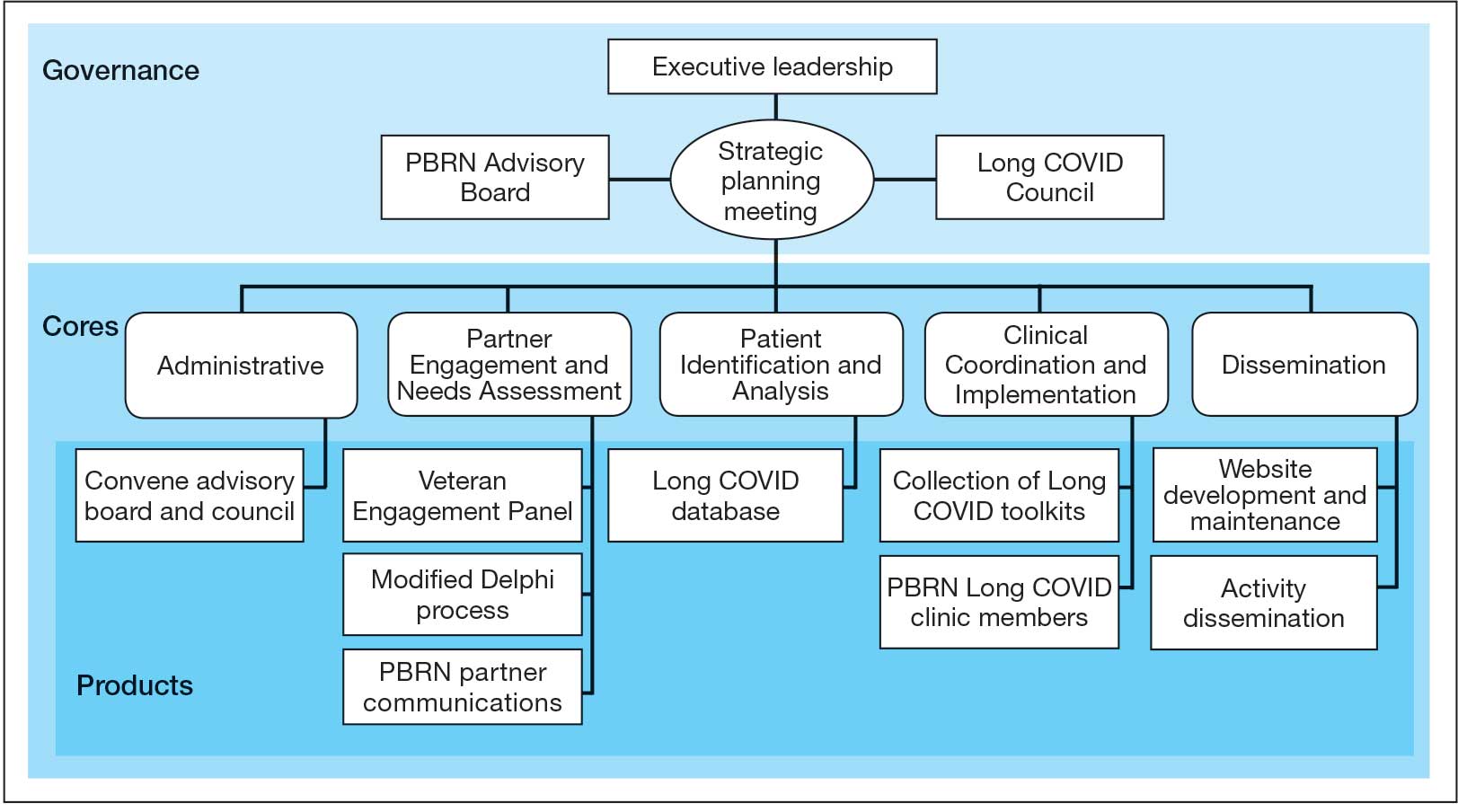

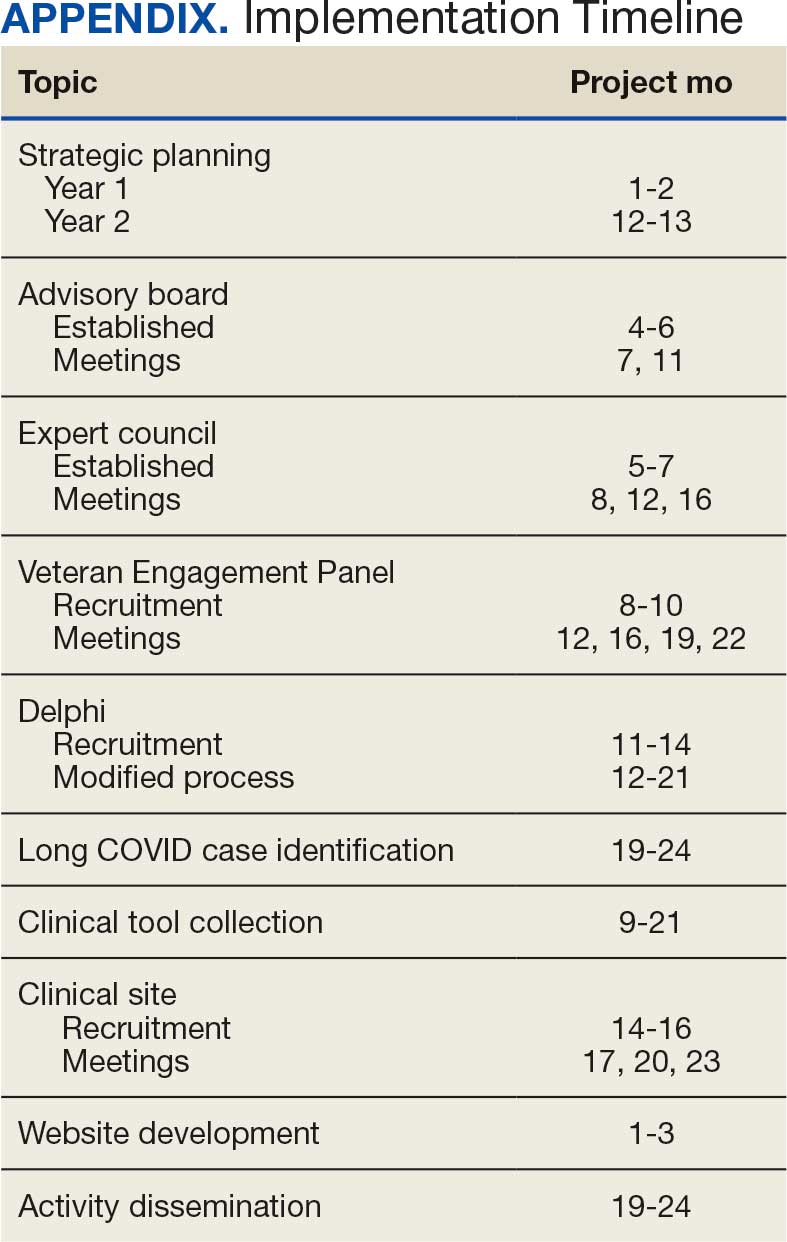

The Administrative core focuses on interagency collaboration to identify and network with key operational and agency leaders to allow for ongoing exploration of funding strategies for Long COVID research. The Administrative core manages 3 teams: an advisory board, Long COVID council, and the strategic planning team. The advisory board meets biannually to oversee achievement of LC-PBRN goals, deliverables, and tactics for meeting these goals. The advisory board includes the LC-PBRN executive leadership team and 13 interagency members from various shareholders (eg, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and specialty departments within the VA).

The Long COVID council convenes quarterly to provide scientific input on important overarching issues in Long COVID research, practice, and policy. The council consists of 22 scientific representatives in VA and non-VA contexts, university affiliates, and veteran representatives. The strategic planning team convenes annually to identify how the LC-PBRN and its partners can meet the needs of the broader Long COVID ecosystem and conduct a strengths, opportunities, weaknesses, and threats analysis to identify strategic objectives and expected outcomes. The strategic planning team includes the executive leadership team and key Long COVID shareholders within VHA and affiliated partners. The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core aims to solicit feedback from veterans, clinicians, researchers, and operational leadership. Input is gathered through a Veteran Engagement Panel and a modified Delphi consensus process. The panel was formed using a Community Engagement Studio model to engage veterans as consultants on research.7 Currently, 10 members represent a range of ages, genders, racial and ethnic backgrounds, and military experience. All veterans have a history of Long COVID and are paid as consultants. Video conference panel meetings occur quarterly for 1 to 2 hours; the meeting length is shorter than typical engagement studios to accommodate for fatigue-related symptoms that may limit attention and ability to participate in longer meetings. Before each panel, the Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core helps identify key questions and creates a structured agenda. Each panel begins with a presentation of a research study followed by a group discussion led by a trained facilitator. The modified Delphi consensus process focuses on identifying research priority areas for Long COVID within the VA. Veterans living with Long COVID, as well as clinicians and researchers who work closely with patients who have Long COVID, complete a series of progressive surveys to provide input on research priorities.

The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core also actively provides outreach to important partners in research, clinical care, and operational leadership to facilitate introductory meetings to (1) ask partners to describe their 5 largest pain points, (2) find pain points within the scope of LC-PBRN resources, and (3) discuss the strengths and capacity of the PBRN. During introductory meetings, communications preferences and a cadence for subsequent meetings are established. Subsequent engagement meetings aim to provide updates and codevelop solutions to emerging issues. This core maintains a living document to track engagement efforts, points of contact for identified and emerging partners, and ensure all communication is timely.

The Patient Identification and Analysis core develops a database of veterans with confirmed or suspected Long COVID. The goal is for researchers to use the database to identify potential participants for clinical trials and monitor clinical care outcomes. When possible, this core works with existing VA data to facilitate research that aligns with the LC-PBRN mission. The core can also use natural language processing and machine learning to work with researchers conducting clinical trials to help identify patients who may meet eligibility criteria.

The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core gathers information on the best practices for identifying and recruiting veterans for Long COVID research as well as compiles strategies for standardized clinical assessments that can both facilitate ongoing research and the successful implementation of evidence-based care. The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core provides support to pilot and multisite trials in 3 ways. First, it develops toolkits such as best practice strategies for recruiting participants for research, template examples of recruitment materials, and a library of patient-reported outcome measures, standardized clinical note titles and templates in use for Long COVID in the national electronic health record. Second, it partners with the Patient Identification and Analysis core to facilitate access to and use of algorithms that identify Long COVID cases based on electronic health records for recruitment. Finally, it compiles a detailed list of potential collaborating sites. The steps to facilitate patient identification and recruitment inform feasibility assessments and improve efficiency of launching pilot studies and multisite trials. The library of outcome measures, standardized clinical notes, and templates can aid and expedite data collection.

The Dissemination core focuses on developing a website, creating a dissemination plan, and actively disseminating products of the LC-PBRN and its partners. This core’s foundational framework is based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Quick-Start Guide to Dissemination for PBRNs.8,9 The core built an internal- and external-facing website to connect users with LC-PBRN products, potential outreach contacts, and promote timely updates on LC-PBRN activities. A manual of operating procedures will be drafted to include the development of training for practitioners involved in research projects to learn the processes involved in presenting clinical results for education and training initiatives, presentations, and manuscript preparation. A toolkit will also be developed to support dissemination activities designed to reach a variety of end-users, such as education materials, policy briefings, educational briefs, newsletters, and presentations at local, regional, and national levels.

Key Partners

Key partners exist specific to the LC-PBRN and within the broader VA ecosystem, including VA clinical operations, VA research, and intra-agency collaborations.

LC-PBRN Specific. In addition to the LC-PBRN council, advisory board, and Veteran Engagement Panel discussed earlier,

VA Clinical Operations. To support clinical operations, a Long COVID Field Advisory Board was formed through the VA Office of Specialty Care as an operational effort to develop clinical best practice. The LC-PBRN consults with this group on veteran engagement strategies for input on clinical guides and dissemination of practice guide materials. The LC-PBRN also partners with an existing Long COVID Community of Practice and the Office of Primary Care. The Community of Practice provides a learning space for VA staff interested in advancing Long COVID care and assists with disseminating LC-PBRN to the broader Long COVID clinical community. A member of the Office of Primary Care sits on the PBRN advisory board to provide input on engaging primary care practitioners and ensure their unique needs are considered in LC-PBRN initiatives.

VA Research & Interagency Collaborations. The LC-PBRN engages monthly with an interagency workgroup led by the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. These engagements support identification of research gaps that the VA may help address, monitor emerging funding opportunities, and foster collaborations. LC-PBRN representatives also meet with staff at the National Institutes of Health Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery initiative to identify pathways for veteran recruitment.

LHS Feedback Loops

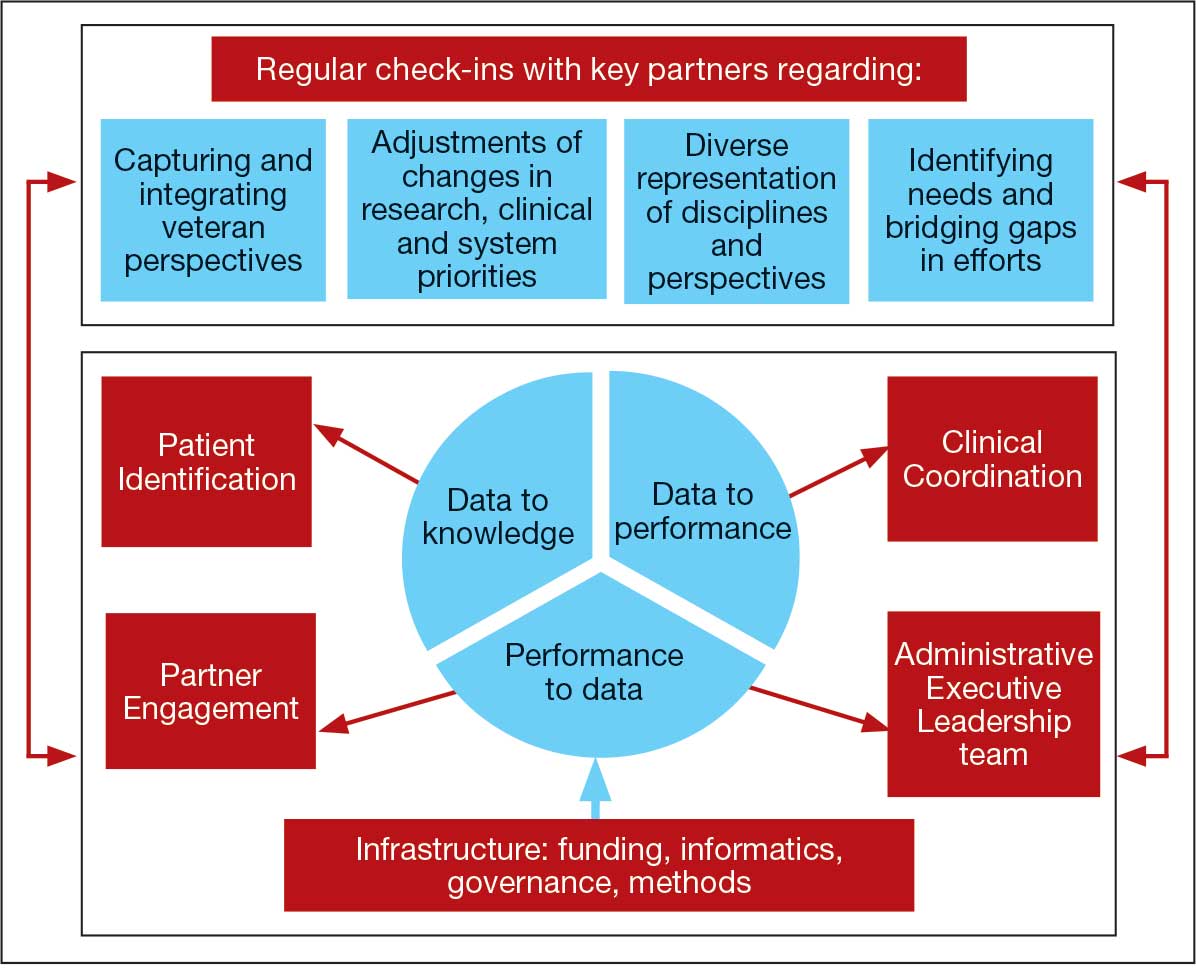

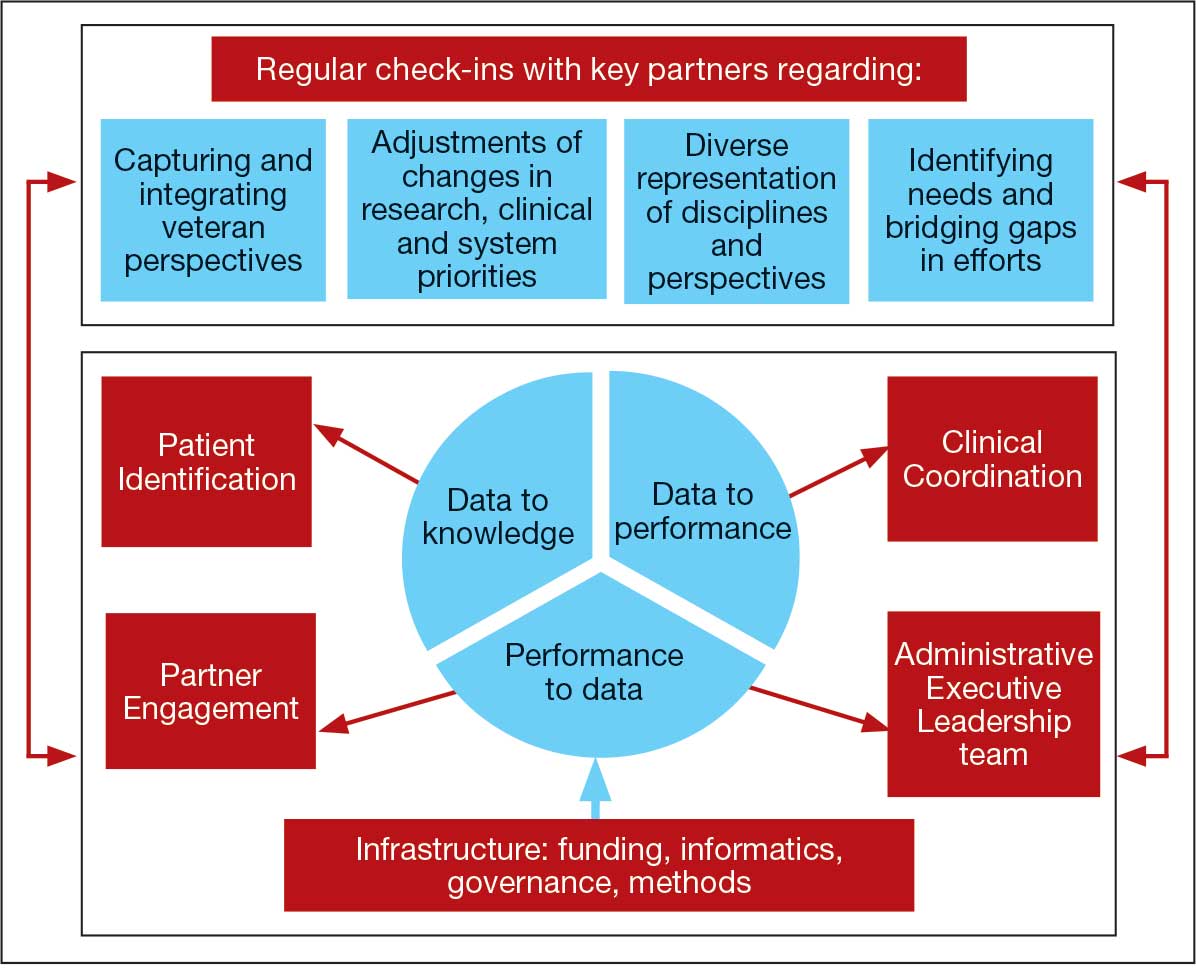

The LC-PBRN was designed with an LHS approach in mind.10 Throughout development of the LC-PBRN, consideration was given to (1) capture data on new efforts within the Long COVID ecosystem (performance to data), (2) examine performance gaps and identify approaches for best practice (data to knowledge), and (3) implement best practices, develop toolkits, disseminate findings, and measure impacts (knowledge to performance). With this approach, the LC-PBRN is constantly evolving based on new information coming from the internal and external Long COVID ecosystem. Each element was deliberatively considered in relation to how data can be transformed into knowledge, knowledge into performance, and performance into data.

First, an important mechanism for feedback involves establishing clear channels of communication. Regular check-ins with key partners occur through virtual meetings to provide updates, assess needs and challenges, and codevelop action plans. For example, during a check-in with the Long COVID Field Advisory Board, members expressed a desire to incorporate veteran feedback into VA clinical practice recommendations. We provided expertise on different engagement modalities (eg, focus groups vs individual interviews), and collaboration occurred to identify key interview questions for veterans. This process resulted in a published clinician-facing Long COVID Nervous System Clinical Guide (available at longcovid@hhs.gov) that integrated critical feedback from veterans related to neurological symptoms.

Second, weekly executive leadership meetings include dedicated time for reflection on partner feedback, the current state of Long COVID, and contextual changes that impact deliverable priorities and timelines. Outcomes from these discussions are communicated with VHA Health Services Research and, when appropriate, to key partners to ensure alignment. For example, the Patient Identification and Analysis core was originally tasked with identifying a definition of Long COVID. However, as the broader community moved away from a singular definition, efforts were redirected toward higher-priority issues within the VA Long COVID ecosystem, including veteran enrollment in clinical trials.

Third, the Veteran Engagement Panel captures feedback from those with lived experience to inform Long COVID research and clinical efforts. The panel meetings are strategically designed to ask veterans living with Long COVID specific questions related to a given research or clinical topic of interest. For example, panel sessions with the Field Advisory Board focused on concerns articulated by veterans related to the mental health and gastroenterological symptoms associated with Long COVID. Insights from these discussions will inform development of Long COVID mental health and gastroenterological clinical care guides, with several PBRN investigators serving as subject matter experts. This collaborative approach ensures that veteran perspectives are represented in developing Long COVID clinical care processes.

Fourth, research priorities identified through the Delphi consensus process will inform development of VA Request for Funding Proposals related to Long COVID. The initial survey was developed in collaboration with veterans, clinicians, and researchers across the Veteran Engagement Panel, the Field Advisory Board, and the National Research Action Plan on Long COVID.11 The process was launched in October 2024 and concluded in June 2025. The team conducted 3 consensus rounds with veterans and VA clinicians and researchers. Top priority areas included the testing assessments for diagnosing Long COVID, studying subtypes of Long COVID and treatments for each, and finding biomarkers for Long COVID. A formal publication of the results and analysis is the focus of a future publication.

Fifth, ongoing engagement with the Field Advisory Board has supported adoption of a preliminary set of clinical outcome measures. If universally adopted, these instruments may contribute to the development of a standardized data collection process and serve as common data elements collected for epidemiologic, health services, or clinical trial research.

Lessons Learned and Practice Implications

Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, several decisions were identified that have impacted infrastructure development and implementation.

Include veterans’ voices to ensure network efforts align with patient needs. Given the novelty of Long COVID, practitioners and researchers are learning as they go. It is important to listen to individuals who live with Long COVID. Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, veteran perspective has proven how vital it is for them to be heard when it comes to their health care. Clinicians similarly highlighted the value of incorporating patient perspectives into the development of tools and treatment strategies. Develop an interdisciplinary leadership team to foster the diverse viewpoints needed to tackle multifaceted problems. It is important to consider as many clinical and research perspectives as possible because Long COVID is a complex condition with symptoms impacting major organ systems.12-15 Therefore, the team spans across a multitude of specialties and locations.

Set clear expectations and goals with partners to uphold timely deliverables and stay within the PBRN’s capacity. When including a multitude of partners, teams should consider each of those partners’ experiences and opinions in decision-making conversations. Expectation setting is important to ensure all partners are on the same page and understand the capacity of the LC-PBRN. This allows the team to focus its efforts, avoid being overwhelmed with requests, and provide quality deliverables.

Build engaging relationships to bridge gaps between internal and external partners. A substantial number of resources focus on building relationships with partners so they can trust the LC-PBRN has their best interests in mind. These relationships are important to ensure the VA avoids duplicate efforts. This includes prioritizing connecting partners who are working on similar efforts to promote collaboration across facilities.

Conclusions

PBRNs provide an important mechanism to use LHS approaches to successfully convene research around complex issues. PBRNs can support integration across the LHS cycle, allowing for multiple feedback loops, and coordinate activities that work to achieve a larger vision. PBRNs offer centralized mechanisms to collaboratively understand and address complex problems, such as Long COVID, where the uncertainty regarding how to treat occurs in tandem with the urgency to treat. The LC-PBRN model described in this article has the potential to transcend Long COVID by building infrastructure necessary to proactively address current or future clinical conditions or populations with a LHS lens. The infrastructure can require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient- and family-centeredness. Future efforts will focus on building out a larger network of VHA sites, facilitating recruitment at site and veteran levels into Long COVID trials through case identification, and systematically support the standardization of clinical data for clinical utility and evaluation of quality and/or outcomes across the VHA.

- Ottiger M, Poppele I, Sperling N, et al. Work ability and return-to-work of patients with post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1811. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19328-6

- Ziauddeen N, Gurdasani D, O’Hara ME, et al. Characteristics and impact of Long Covid: findings from an online survey. PLOS ONE. 2022;17:e0264331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264331

- Graham F. Daily briefing: Answers emerge about long COVID recovery. Nature. Published online June 28, 2023. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02190-8

- Al-Aly Z, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat Med. 2024;30:2148-2164. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

- Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

- Ely EW, Brown LM, Fineberg HV. Long covid defined. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1746-1753.doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2408466

- Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, et al. Community engagement studios: a structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Acad Med. 2015;90:1646-1650. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794

- AHRQ. Quick-start guide to dissemination for practice-based research networks. Revised June 2014. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/ncepcr/resources/dissemination-quick-start-guide.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Morrow CD, Brown RJ, et al. Reimagining how we synthesize information to impact clinical care, policy, and research priorities in real time: examples and lessons learned from COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39:2554-2559. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08855-y

- University of Minnesota. About the Center for Learning Health System Sciences. Updated December 11, 2025. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://med.umn.edu/clhss/about-us

- AHRQ. National Research Action Plan. Published online 2022. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.covid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/National-Research-Action-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Eaton TL, Schapira RM, et al. Approaches to long COVID care: the Veterans Health Administration experience in 2021. BMJ Mil Health. 2024;170:179-180. doi:10.1136/military-2022-002185

- Gustavson AM. A learning health system approach to long COVID care. Fed Pract. 2022;39:7. doi:10.12788/fp.0288

- Palacio A, Bast E, Klimas N, et al. Lessons learned in implementing a multidisciplinary long COVID clinic. Am J Med. 2025;138:843-849.doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.05.020

- Prusinski C, Yan D, Klasova J, et al. Multidisciplinary management strategies for long COVID: a narrative review. Cureus. 2024;16:e59478. doi:10.7759/cureus.59478

Learning health systems (LHS) promote a continuous process that can assist in making sense of uncertainty when confronting emerging complex conditions such as Long COVID. Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that detrimentally impacts veterans, their families, and the communities in which they live. This complex condition is defined by ongoing, new, or returning symptoms following COVID-19 infection that negatively affect return to meaningful participation in social, recreational, and vocational activities.1,2 The clinical uncertainty surrounding Long COVID is amplified by unclear etiology, prognosis, and expected course of symptoms.3,4 Uncertainty surrounding best clinical practices, processes, and policies for Long COVID care has resulted in practice variation despite the emerging evidence base for Long COVID care.4 Failure to address gaps in clinical evidence and care implementation threatens to perpetuate fragmented and unnecessary care.

The context surrounding Long COVID created an urgency to rapidly address clinically relevant questions and make sense of any uncertainty. Thus, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) funded a Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network (LC-PBRN) to build an infrastructure that supports Long COVID research nationally and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration. The LC-PBRN vision is to centralize Long COVID clinical, research, and operational activities. The research infrastructure of the LC-PBRN is designed with an LHS lens to facilitate feedback loops and integrate knowledge learned while making progress towards this vision.5 This article describes the phases of infrastructure development and network building, as well as associated lessons learned.

Designing the LC-PBRN Infrastructure

Vision

The LC-PBRN’s vision is to create an infrastructure that integrates an LHS framework by unifying the VA research approach to Long COVID to ensure veteran, clinician, operational, and researcher involvement (Figure 1).

Mission and Governance

The LC-PBRN operates with an executive leadership team and 5 cores. The executive leadership team is responsible for overall LC-PBRN operations, management, and direction setting of the LC-PBRN. The executive leadership team meets weekly to provide oversight of each core, which specializes in different aspects. The cores include: Administrative, Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment, Patient Identification and Analysis, Clinical Coordination and Implementation, and Dissemination (Figure 2).

The Administrative core focuses on interagency collaboration to identify and network with key operational and agency leaders to allow for ongoing exploration of funding strategies for Long COVID research. The Administrative core manages 3 teams: an advisory board, Long COVID council, and the strategic planning team. The advisory board meets biannually to oversee achievement of LC-PBRN goals, deliverables, and tactics for meeting these goals. The advisory board includes the LC-PBRN executive leadership team and 13 interagency members from various shareholders (eg, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and specialty departments within the VA).

The Long COVID council convenes quarterly to provide scientific input on important overarching issues in Long COVID research, practice, and policy. The council consists of 22 scientific representatives in VA and non-VA contexts, university affiliates, and veteran representatives. The strategic planning team convenes annually to identify how the LC-PBRN and its partners can meet the needs of the broader Long COVID ecosystem and conduct a strengths, opportunities, weaknesses, and threats analysis to identify strategic objectives and expected outcomes. The strategic planning team includes the executive leadership team and key Long COVID shareholders within VHA and affiliated partners. The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core aims to solicit feedback from veterans, clinicians, researchers, and operational leadership. Input is gathered through a Veteran Engagement Panel and a modified Delphi consensus process. The panel was formed using a Community Engagement Studio model to engage veterans as consultants on research.7 Currently, 10 members represent a range of ages, genders, racial and ethnic backgrounds, and military experience. All veterans have a history of Long COVID and are paid as consultants. Video conference panel meetings occur quarterly for 1 to 2 hours; the meeting length is shorter than typical engagement studios to accommodate for fatigue-related symptoms that may limit attention and ability to participate in longer meetings. Before each panel, the Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core helps identify key questions and creates a structured agenda. Each panel begins with a presentation of a research study followed by a group discussion led by a trained facilitator. The modified Delphi consensus process focuses on identifying research priority areas for Long COVID within the VA. Veterans living with Long COVID, as well as clinicians and researchers who work closely with patients who have Long COVID, complete a series of progressive surveys to provide input on research priorities.

The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core also actively provides outreach to important partners in research, clinical care, and operational leadership to facilitate introductory meetings to (1) ask partners to describe their 5 largest pain points, (2) find pain points within the scope of LC-PBRN resources, and (3) discuss the strengths and capacity of the PBRN. During introductory meetings, communications preferences and a cadence for subsequent meetings are established. Subsequent engagement meetings aim to provide updates and codevelop solutions to emerging issues. This core maintains a living document to track engagement efforts, points of contact for identified and emerging partners, and ensure all communication is timely.

The Patient Identification and Analysis core develops a database of veterans with confirmed or suspected Long COVID. The goal is for researchers to use the database to identify potential participants for clinical trials and monitor clinical care outcomes. When possible, this core works with existing VA data to facilitate research that aligns with the LC-PBRN mission. The core can also use natural language processing and machine learning to work with researchers conducting clinical trials to help identify patients who may meet eligibility criteria.

The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core gathers information on the best practices for identifying and recruiting veterans for Long COVID research as well as compiles strategies for standardized clinical assessments that can both facilitate ongoing research and the successful implementation of evidence-based care. The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core provides support to pilot and multisite trials in 3 ways. First, it develops toolkits such as best practice strategies for recruiting participants for research, template examples of recruitment materials, and a library of patient-reported outcome measures, standardized clinical note titles and templates in use for Long COVID in the national electronic health record. Second, it partners with the Patient Identification and Analysis core to facilitate access to and use of algorithms that identify Long COVID cases based on electronic health records for recruitment. Finally, it compiles a detailed list of potential collaborating sites. The steps to facilitate patient identification and recruitment inform feasibility assessments and improve efficiency of launching pilot studies and multisite trials. The library of outcome measures, standardized clinical notes, and templates can aid and expedite data collection.

The Dissemination core focuses on developing a website, creating a dissemination plan, and actively disseminating products of the LC-PBRN and its partners. This core’s foundational framework is based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Quick-Start Guide to Dissemination for PBRNs.8,9 The core built an internal- and external-facing website to connect users with LC-PBRN products, potential outreach contacts, and promote timely updates on LC-PBRN activities. A manual of operating procedures will be drafted to include the development of training for practitioners involved in research projects to learn the processes involved in presenting clinical results for education and training initiatives, presentations, and manuscript preparation. A toolkit will also be developed to support dissemination activities designed to reach a variety of end-users, such as education materials, policy briefings, educational briefs, newsletters, and presentations at local, regional, and national levels.

Key Partners

Key partners exist specific to the LC-PBRN and within the broader VA ecosystem, including VA clinical operations, VA research, and intra-agency collaborations.

LC-PBRN Specific. In addition to the LC-PBRN council, advisory board, and Veteran Engagement Panel discussed earlier,

VA Clinical Operations. To support clinical operations, a Long COVID Field Advisory Board was formed through the VA Office of Specialty Care as an operational effort to develop clinical best practice. The LC-PBRN consults with this group on veteran engagement strategies for input on clinical guides and dissemination of practice guide materials. The LC-PBRN also partners with an existing Long COVID Community of Practice and the Office of Primary Care. The Community of Practice provides a learning space for VA staff interested in advancing Long COVID care and assists with disseminating LC-PBRN to the broader Long COVID clinical community. A member of the Office of Primary Care sits on the PBRN advisory board to provide input on engaging primary care practitioners and ensure their unique needs are considered in LC-PBRN initiatives.

VA Research & Interagency Collaborations. The LC-PBRN engages monthly with an interagency workgroup led by the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. These engagements support identification of research gaps that the VA may help address, monitor emerging funding opportunities, and foster collaborations. LC-PBRN representatives also meet with staff at the National Institutes of Health Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery initiative to identify pathways for veteran recruitment.

LHS Feedback Loops

The LC-PBRN was designed with an LHS approach in mind.10 Throughout development of the LC-PBRN, consideration was given to (1) capture data on new efforts within the Long COVID ecosystem (performance to data), (2) examine performance gaps and identify approaches for best practice (data to knowledge), and (3) implement best practices, develop toolkits, disseminate findings, and measure impacts (knowledge to performance). With this approach, the LC-PBRN is constantly evolving based on new information coming from the internal and external Long COVID ecosystem. Each element was deliberatively considered in relation to how data can be transformed into knowledge, knowledge into performance, and performance into data.

First, an important mechanism for feedback involves establishing clear channels of communication. Regular check-ins with key partners occur through virtual meetings to provide updates, assess needs and challenges, and codevelop action plans. For example, during a check-in with the Long COVID Field Advisory Board, members expressed a desire to incorporate veteran feedback into VA clinical practice recommendations. We provided expertise on different engagement modalities (eg, focus groups vs individual interviews), and collaboration occurred to identify key interview questions for veterans. This process resulted in a published clinician-facing Long COVID Nervous System Clinical Guide (available at longcovid@hhs.gov) that integrated critical feedback from veterans related to neurological symptoms.

Second, weekly executive leadership meetings include dedicated time for reflection on partner feedback, the current state of Long COVID, and contextual changes that impact deliverable priorities and timelines. Outcomes from these discussions are communicated with VHA Health Services Research and, when appropriate, to key partners to ensure alignment. For example, the Patient Identification and Analysis core was originally tasked with identifying a definition of Long COVID. However, as the broader community moved away from a singular definition, efforts were redirected toward higher-priority issues within the VA Long COVID ecosystem, including veteran enrollment in clinical trials.

Third, the Veteran Engagement Panel captures feedback from those with lived experience to inform Long COVID research and clinical efforts. The panel meetings are strategically designed to ask veterans living with Long COVID specific questions related to a given research or clinical topic of interest. For example, panel sessions with the Field Advisory Board focused on concerns articulated by veterans related to the mental health and gastroenterological symptoms associated with Long COVID. Insights from these discussions will inform development of Long COVID mental health and gastroenterological clinical care guides, with several PBRN investigators serving as subject matter experts. This collaborative approach ensures that veteran perspectives are represented in developing Long COVID clinical care processes.

Fourth, research priorities identified through the Delphi consensus process will inform development of VA Request for Funding Proposals related to Long COVID. The initial survey was developed in collaboration with veterans, clinicians, and researchers across the Veteran Engagement Panel, the Field Advisory Board, and the National Research Action Plan on Long COVID.11 The process was launched in October 2024 and concluded in June 2025. The team conducted 3 consensus rounds with veterans and VA clinicians and researchers. Top priority areas included the testing assessments for diagnosing Long COVID, studying subtypes of Long COVID and treatments for each, and finding biomarkers for Long COVID. A formal publication of the results and analysis is the focus of a future publication.

Fifth, ongoing engagement with the Field Advisory Board has supported adoption of a preliminary set of clinical outcome measures. If universally adopted, these instruments may contribute to the development of a standardized data collection process and serve as common data elements collected for epidemiologic, health services, or clinical trial research.

Lessons Learned and Practice Implications

Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, several decisions were identified that have impacted infrastructure development and implementation.

Include veterans’ voices to ensure network efforts align with patient needs. Given the novelty of Long COVID, practitioners and researchers are learning as they go. It is important to listen to individuals who live with Long COVID. Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, veteran perspective has proven how vital it is for them to be heard when it comes to their health care. Clinicians similarly highlighted the value of incorporating patient perspectives into the development of tools and treatment strategies. Develop an interdisciplinary leadership team to foster the diverse viewpoints needed to tackle multifaceted problems. It is important to consider as many clinical and research perspectives as possible because Long COVID is a complex condition with symptoms impacting major organ systems.12-15 Therefore, the team spans across a multitude of specialties and locations.

Set clear expectations and goals with partners to uphold timely deliverables and stay within the PBRN’s capacity. When including a multitude of partners, teams should consider each of those partners’ experiences and opinions in decision-making conversations. Expectation setting is important to ensure all partners are on the same page and understand the capacity of the LC-PBRN. This allows the team to focus its efforts, avoid being overwhelmed with requests, and provide quality deliverables.

Build engaging relationships to bridge gaps between internal and external partners. A substantial number of resources focus on building relationships with partners so they can trust the LC-PBRN has their best interests in mind. These relationships are important to ensure the VA avoids duplicate efforts. This includes prioritizing connecting partners who are working on similar efforts to promote collaboration across facilities.

Conclusions

PBRNs provide an important mechanism to use LHS approaches to successfully convene research around complex issues. PBRNs can support integration across the LHS cycle, allowing for multiple feedback loops, and coordinate activities that work to achieve a larger vision. PBRNs offer centralized mechanisms to collaboratively understand and address complex problems, such as Long COVID, where the uncertainty regarding how to treat occurs in tandem with the urgency to treat. The LC-PBRN model described in this article has the potential to transcend Long COVID by building infrastructure necessary to proactively address current or future clinical conditions or populations with a LHS lens. The infrastructure can require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient- and family-centeredness. Future efforts will focus on building out a larger network of VHA sites, facilitating recruitment at site and veteran levels into Long COVID trials through case identification, and systematically support the standardization of clinical data for clinical utility and evaluation of quality and/or outcomes across the VHA.

Learning health systems (LHS) promote a continuous process that can assist in making sense of uncertainty when confronting emerging complex conditions such as Long COVID. Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that detrimentally impacts veterans, their families, and the communities in which they live. This complex condition is defined by ongoing, new, or returning symptoms following COVID-19 infection that negatively affect return to meaningful participation in social, recreational, and vocational activities.1,2 The clinical uncertainty surrounding Long COVID is amplified by unclear etiology, prognosis, and expected course of symptoms.3,4 Uncertainty surrounding best clinical practices, processes, and policies for Long COVID care has resulted in practice variation despite the emerging evidence base for Long COVID care.4 Failure to address gaps in clinical evidence and care implementation threatens to perpetuate fragmented and unnecessary care.

The context surrounding Long COVID created an urgency to rapidly address clinically relevant questions and make sense of any uncertainty. Thus, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) funded a Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network (LC-PBRN) to build an infrastructure that supports Long COVID research nationally and promotes interdisciplinary collaboration. The LC-PBRN vision is to centralize Long COVID clinical, research, and operational activities. The research infrastructure of the LC-PBRN is designed with an LHS lens to facilitate feedback loops and integrate knowledge learned while making progress towards this vision.5 This article describes the phases of infrastructure development and network building, as well as associated lessons learned.

Designing the LC-PBRN Infrastructure

Vision

The LC-PBRN’s vision is to create an infrastructure that integrates an LHS framework by unifying the VA research approach to Long COVID to ensure veteran, clinician, operational, and researcher involvement (Figure 1).

Mission and Governance

The LC-PBRN operates with an executive leadership team and 5 cores. The executive leadership team is responsible for overall LC-PBRN operations, management, and direction setting of the LC-PBRN. The executive leadership team meets weekly to provide oversight of each core, which specializes in different aspects. The cores include: Administrative, Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment, Patient Identification and Analysis, Clinical Coordination and Implementation, and Dissemination (Figure 2).

The Administrative core focuses on interagency collaboration to identify and network with key operational and agency leaders to allow for ongoing exploration of funding strategies for Long COVID research. The Administrative core manages 3 teams: an advisory board, Long COVID council, and the strategic planning team. The advisory board meets biannually to oversee achievement of LC-PBRN goals, deliverables, and tactics for meeting these goals. The advisory board includes the LC-PBRN executive leadership team and 13 interagency members from various shareholders (eg, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and specialty departments within the VA).

The Long COVID council convenes quarterly to provide scientific input on important overarching issues in Long COVID research, practice, and policy. The council consists of 22 scientific representatives in VA and non-VA contexts, university affiliates, and veteran representatives. The strategic planning team convenes annually to identify how the LC-PBRN and its partners can meet the needs of the broader Long COVID ecosystem and conduct a strengths, opportunities, weaknesses, and threats analysis to identify strategic objectives and expected outcomes. The strategic planning team includes the executive leadership team and key Long COVID shareholders within VHA and affiliated partners. The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core aims to solicit feedback from veterans, clinicians, researchers, and operational leadership. Input is gathered through a Veteran Engagement Panel and a modified Delphi consensus process. The panel was formed using a Community Engagement Studio model to engage veterans as consultants on research.7 Currently, 10 members represent a range of ages, genders, racial and ethnic backgrounds, and military experience. All veterans have a history of Long COVID and are paid as consultants. Video conference panel meetings occur quarterly for 1 to 2 hours; the meeting length is shorter than typical engagement studios to accommodate for fatigue-related symptoms that may limit attention and ability to participate in longer meetings. Before each panel, the Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core helps identify key questions and creates a structured agenda. Each panel begins with a presentation of a research study followed by a group discussion led by a trained facilitator. The modified Delphi consensus process focuses on identifying research priority areas for Long COVID within the VA. Veterans living with Long COVID, as well as clinicians and researchers who work closely with patients who have Long COVID, complete a series of progressive surveys to provide input on research priorities.

The Partner Engagement and Needs Assessment core also actively provides outreach to important partners in research, clinical care, and operational leadership to facilitate introductory meetings to (1) ask partners to describe their 5 largest pain points, (2) find pain points within the scope of LC-PBRN resources, and (3) discuss the strengths and capacity of the PBRN. During introductory meetings, communications preferences and a cadence for subsequent meetings are established. Subsequent engagement meetings aim to provide updates and codevelop solutions to emerging issues. This core maintains a living document to track engagement efforts, points of contact for identified and emerging partners, and ensure all communication is timely.

The Patient Identification and Analysis core develops a database of veterans with confirmed or suspected Long COVID. The goal is for researchers to use the database to identify potential participants for clinical trials and monitor clinical care outcomes. When possible, this core works with existing VA data to facilitate research that aligns with the LC-PBRN mission. The core can also use natural language processing and machine learning to work with researchers conducting clinical trials to help identify patients who may meet eligibility criteria.

The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core gathers information on the best practices for identifying and recruiting veterans for Long COVID research as well as compiles strategies for standardized clinical assessments that can both facilitate ongoing research and the successful implementation of evidence-based care. The Clinical Coordination and Implementation core provides support to pilot and multisite trials in 3 ways. First, it develops toolkits such as best practice strategies for recruiting participants for research, template examples of recruitment materials, and a library of patient-reported outcome measures, standardized clinical note titles and templates in use for Long COVID in the national electronic health record. Second, it partners with the Patient Identification and Analysis core to facilitate access to and use of algorithms that identify Long COVID cases based on electronic health records for recruitment. Finally, it compiles a detailed list of potential collaborating sites. The steps to facilitate patient identification and recruitment inform feasibility assessments and improve efficiency of launching pilot studies and multisite trials. The library of outcome measures, standardized clinical notes, and templates can aid and expedite data collection.

The Dissemination core focuses on developing a website, creating a dissemination plan, and actively disseminating products of the LC-PBRN and its partners. This core’s foundational framework is based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Quick-Start Guide to Dissemination for PBRNs.8,9 The core built an internal- and external-facing website to connect users with LC-PBRN products, potential outreach contacts, and promote timely updates on LC-PBRN activities. A manual of operating procedures will be drafted to include the development of training for practitioners involved in research projects to learn the processes involved in presenting clinical results for education and training initiatives, presentations, and manuscript preparation. A toolkit will also be developed to support dissemination activities designed to reach a variety of end-users, such as education materials, policy briefings, educational briefs, newsletters, and presentations at local, regional, and national levels.

Key Partners

Key partners exist specific to the LC-PBRN and within the broader VA ecosystem, including VA clinical operations, VA research, and intra-agency collaborations.

LC-PBRN Specific. In addition to the LC-PBRN council, advisory board, and Veteran Engagement Panel discussed earlier,

VA Clinical Operations. To support clinical operations, a Long COVID Field Advisory Board was formed through the VA Office of Specialty Care as an operational effort to develop clinical best practice. The LC-PBRN consults with this group on veteran engagement strategies for input on clinical guides and dissemination of practice guide materials. The LC-PBRN also partners with an existing Long COVID Community of Practice and the Office of Primary Care. The Community of Practice provides a learning space for VA staff interested in advancing Long COVID care and assists with disseminating LC-PBRN to the broader Long COVID clinical community. A member of the Office of Primary Care sits on the PBRN advisory board to provide input on engaging primary care practitioners and ensure their unique needs are considered in LC-PBRN initiatives.

VA Research & Interagency Collaborations. The LC-PBRN engages monthly with an interagency workgroup led by the US Department of Health and Human Services Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. These engagements support identification of research gaps that the VA may help address, monitor emerging funding opportunities, and foster collaborations. LC-PBRN representatives also meet with staff at the National Institutes of Health Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery initiative to identify pathways for veteran recruitment.

LHS Feedback Loops

The LC-PBRN was designed with an LHS approach in mind.10 Throughout development of the LC-PBRN, consideration was given to (1) capture data on new efforts within the Long COVID ecosystem (performance to data), (2) examine performance gaps and identify approaches for best practice (data to knowledge), and (3) implement best practices, develop toolkits, disseminate findings, and measure impacts (knowledge to performance). With this approach, the LC-PBRN is constantly evolving based on new information coming from the internal and external Long COVID ecosystem. Each element was deliberatively considered in relation to how data can be transformed into knowledge, knowledge into performance, and performance into data.

First, an important mechanism for feedback involves establishing clear channels of communication. Regular check-ins with key partners occur through virtual meetings to provide updates, assess needs and challenges, and codevelop action plans. For example, during a check-in with the Long COVID Field Advisory Board, members expressed a desire to incorporate veteran feedback into VA clinical practice recommendations. We provided expertise on different engagement modalities (eg, focus groups vs individual interviews), and collaboration occurred to identify key interview questions for veterans. This process resulted in a published clinician-facing Long COVID Nervous System Clinical Guide (available at longcovid@hhs.gov) that integrated critical feedback from veterans related to neurological symptoms.

Second, weekly executive leadership meetings include dedicated time for reflection on partner feedback, the current state of Long COVID, and contextual changes that impact deliverable priorities and timelines. Outcomes from these discussions are communicated with VHA Health Services Research and, when appropriate, to key partners to ensure alignment. For example, the Patient Identification and Analysis core was originally tasked with identifying a definition of Long COVID. However, as the broader community moved away from a singular definition, efforts were redirected toward higher-priority issues within the VA Long COVID ecosystem, including veteran enrollment in clinical trials.

Third, the Veteran Engagement Panel captures feedback from those with lived experience to inform Long COVID research and clinical efforts. The panel meetings are strategically designed to ask veterans living with Long COVID specific questions related to a given research or clinical topic of interest. For example, panel sessions with the Field Advisory Board focused on concerns articulated by veterans related to the mental health and gastroenterological symptoms associated with Long COVID. Insights from these discussions will inform development of Long COVID mental health and gastroenterological clinical care guides, with several PBRN investigators serving as subject matter experts. This collaborative approach ensures that veteran perspectives are represented in developing Long COVID clinical care processes.

Fourth, research priorities identified through the Delphi consensus process will inform development of VA Request for Funding Proposals related to Long COVID. The initial survey was developed in collaboration with veterans, clinicians, and researchers across the Veteran Engagement Panel, the Field Advisory Board, and the National Research Action Plan on Long COVID.11 The process was launched in October 2024 and concluded in June 2025. The team conducted 3 consensus rounds with veterans and VA clinicians and researchers. Top priority areas included the testing assessments for diagnosing Long COVID, studying subtypes of Long COVID and treatments for each, and finding biomarkers for Long COVID. A formal publication of the results and analysis is the focus of a future publication.

Fifth, ongoing engagement with the Field Advisory Board has supported adoption of a preliminary set of clinical outcome measures. If universally adopted, these instruments may contribute to the development of a standardized data collection process and serve as common data elements collected for epidemiologic, health services, or clinical trial research.

Lessons Learned and Practice Implications

Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, several decisions were identified that have impacted infrastructure development and implementation.

Include veterans’ voices to ensure network efforts align with patient needs. Given the novelty of Long COVID, practitioners and researchers are learning as they go. It is important to listen to individuals who live with Long COVID. Throughout the development of the LC-PBRN, veteran perspective has proven how vital it is for them to be heard when it comes to their health care. Clinicians similarly highlighted the value of incorporating patient perspectives into the development of tools and treatment strategies. Develop an interdisciplinary leadership team to foster the diverse viewpoints needed to tackle multifaceted problems. It is important to consider as many clinical and research perspectives as possible because Long COVID is a complex condition with symptoms impacting major organ systems.12-15 Therefore, the team spans across a multitude of specialties and locations.

Set clear expectations and goals with partners to uphold timely deliverables and stay within the PBRN’s capacity. When including a multitude of partners, teams should consider each of those partners’ experiences and opinions in decision-making conversations. Expectation setting is important to ensure all partners are on the same page and understand the capacity of the LC-PBRN. This allows the team to focus its efforts, avoid being overwhelmed with requests, and provide quality deliverables.

Build engaging relationships to bridge gaps between internal and external partners. A substantial number of resources focus on building relationships with partners so they can trust the LC-PBRN has their best interests in mind. These relationships are important to ensure the VA avoids duplicate efforts. This includes prioritizing connecting partners who are working on similar efforts to promote collaboration across facilities.

Conclusions

PBRNs provide an important mechanism to use LHS approaches to successfully convene research around complex issues. PBRNs can support integration across the LHS cycle, allowing for multiple feedback loops, and coordinate activities that work to achieve a larger vision. PBRNs offer centralized mechanisms to collaboratively understand and address complex problems, such as Long COVID, where the uncertainty regarding how to treat occurs in tandem with the urgency to treat. The LC-PBRN model described in this article has the potential to transcend Long COVID by building infrastructure necessary to proactively address current or future clinical conditions or populations with a LHS lens. The infrastructure can require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient- and family-centeredness. Future efforts will focus on building out a larger network of VHA sites, facilitating recruitment at site and veteran levels into Long COVID trials through case identification, and systematically support the standardization of clinical data for clinical utility and evaluation of quality and/or outcomes across the VHA.

- Ottiger M, Poppele I, Sperling N, et al. Work ability and return-to-work of patients with post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1811. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19328-6

- Ziauddeen N, Gurdasani D, O’Hara ME, et al. Characteristics and impact of Long Covid: findings from an online survey. PLOS ONE. 2022;17:e0264331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264331

- Graham F. Daily briefing: Answers emerge about long COVID recovery. Nature. Published online June 28, 2023. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02190-8

- Al-Aly Z, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat Med. 2024;30:2148-2164. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

- Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

- Ely EW, Brown LM, Fineberg HV. Long covid defined. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1746-1753.doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2408466

- Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, et al. Community engagement studios: a structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Acad Med. 2015;90:1646-1650. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794

- AHRQ. Quick-start guide to dissemination for practice-based research networks. Revised June 2014. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/ncepcr/resources/dissemination-quick-start-guide.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Morrow CD, Brown RJ, et al. Reimagining how we synthesize information to impact clinical care, policy, and research priorities in real time: examples and lessons learned from COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39:2554-2559. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08855-y

- University of Minnesota. About the Center for Learning Health System Sciences. Updated December 11, 2025. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://med.umn.edu/clhss/about-us

- AHRQ. National Research Action Plan. Published online 2022. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.covid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/National-Research-Action-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Eaton TL, Schapira RM, et al. Approaches to long COVID care: the Veterans Health Administration experience in 2021. BMJ Mil Health. 2024;170:179-180. doi:10.1136/military-2022-002185

- Gustavson AM. A learning health system approach to long COVID care. Fed Pract. 2022;39:7. doi:10.12788/fp.0288

- Palacio A, Bast E, Klimas N, et al. Lessons learned in implementing a multidisciplinary long COVID clinic. Am J Med. 2025;138:843-849.doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.05.020

- Prusinski C, Yan D, Klasova J, et al. Multidisciplinary management strategies for long COVID: a narrative review. Cureus. 2024;16:e59478. doi:10.7759/cureus.59478

- Ottiger M, Poppele I, Sperling N, et al. Work ability and return-to-work of patients with post-COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:1811. doi:10.1186/s12889-024-19328-6

- Ziauddeen N, Gurdasani D, O’Hara ME, et al. Characteristics and impact of Long Covid: findings from an online survey. PLOS ONE. 2022;17:e0264331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264331

- Graham F. Daily briefing: Answers emerge about long COVID recovery. Nature. Published online June 28, 2023. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02190-8

- Al-Aly Z, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. Long COVID science, research and policy. Nat Med. 2024;30:2148-2164. doi:10.1038/s41591-024-03173-6

- Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

- Ely EW, Brown LM, Fineberg HV. Long covid defined. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:1746-1753.doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2408466

- Joosten YA, Israel TL, Williams NA, et al. Community engagement studios: a structured approach to obtaining meaningful input from stakeholders to inform research. Acad Med. 2015;90:1646-1650. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000794

- AHRQ. Quick-start guide to dissemination for practice-based research networks. Revised June 2014. Accessed December 2, 2025. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/ncepcr/resources/dissemination-quick-start-guide.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Morrow CD, Brown RJ, et al. Reimagining how we synthesize information to impact clinical care, policy, and research priorities in real time: examples and lessons learned from COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2024;39:2554-2559. doi:10.1007/s11606-024-08855-y

- University of Minnesota. About the Center for Learning Health System Sciences. Updated December 11, 2025. Accessed December 12, 2025. https://med.umn.edu/clhss/about-us

- AHRQ. National Research Action Plan. Published online 2022. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.covid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/National-Research-Action-Plan-on-Long-COVID-08012022.pdf

- Gustavson AM, Eaton TL, Schapira RM, et al. Approaches to long COVID care: the Veterans Health Administration experience in 2021. BMJ Mil Health. 2024;170:179-180. doi:10.1136/military-2022-002185

- Gustavson AM. A learning health system approach to long COVID care. Fed Pract. 2022;39:7. doi:10.12788/fp.0288

- Palacio A, Bast E, Klimas N, et al. Lessons learned in implementing a multidisciplinary long COVID clinic. Am J Med. 2025;138:843-849.doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.05.020

- Prusinski C, Yan D, Klasova J, et al. Multidisciplinary management strategies for long COVID: a narrative review. Cureus. 2024;16:e59478. doi:10.7759/cureus.59478

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

Confronting Uncertainty and Addressing Urgency for Action Through the Establishment of a VA Long COVID Practice-Based Research Network

Behavioral Interventions in Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a chronic demyelinating disease of the central nervous system that affects nearly 1 million people in the US.1 In addition to the accumulation of functional limitations, patients with MS commonly experience mental health and physical symptoms such as depression, anxiety, stress, fatigue, and pain. Day-to-day life with MS requires adaptation to challenges and active maintenance of health and well-being over time. Behavioral intervention and treatment, whether in the form of psychotherapy, health behavior coaching, or the promotion of active self-management, is an integral component of interprofessional care and key aspect of living well with MS.

Behavioral Comorbidities

Depression

Depression is a common concern among individuals with MS. Population-based studies suggest that individuals with MS have a roughly 1 in 4 chance of developing major depressive disorder over their lifetime.2 However, at any given time, between 40% and 60% of individuals with MS report clinically meaningful levels of depressive symptoms.3 Although the relationship between MS disease characteristics and depression is unclear, some evidence suggests that depressive symptoms are more common at certain points in illness, such as early in the disease process as individuals grapple with the onset of new symptoms, late in the disease process as they accumulate greater disability, and during active clinical relapses.3-5

Depression often is comorbid with, and adds to the symptom burden of, other common conditions in MS such as fatigue and cognitive dysfunction.6-8 Thus, it is not surprising that it associated with poorer overall quality of life (QOL).9 Depression also is a risk factor for suicidal ideation and suicide for patients with MS.10,11

Fortunately, several behavioral interventions show promise in treating depression in patients with MS. Both individual and group formats of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a treatment focused on challenging maladaptive patterns of thought and behavior, have been shown to improve depressive symptoms for people with MS.12,13 Several brief and efficient group-based programs grounded in CBT and focused on the development of specific skills, including problem solving, goal setting, relationship management, and managing emotions, have been shown to reduce depressive symptoms.13,14 CBT for depression in MS has been shown to be effective when delivered via telephone.15,16

Anxiety

Anxiety is common among individuals with MS. Existing data suggest more than one-third of individuals with MS will qualify for a diagnosis of anxiety disorder during their lifetime.17 The characteristics of anxiety disorders are broad and heterogenous, including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorders, and health-specific phobias such as needle/injection anxiety. Some estimates suggest a point prevalence of 34% for the presence of clinically meaningful symptoms.18 Similar to depression, anxiety symptoms can be more common during periods of stress, threat, and transition including early in the disease course while adapting to new diagnosis, late in the disease course with increasing disability, and during clinical relapses.19-21

The efficacy of behavioral interventions for anxiety in MS is less well established than it is for depression, but some preliminary evidence suggests that individual CBT may be effective for reducing general symptoms of anxiety as well as health-related anxiety.22,23 Brief, targeted CBT also has been shown to improve injection anxiety, removing a barrier to self-care including the administration of MS disease modifying therapies (DMTs).24

Stress

Stress is commonly conceptualized as a person’s perception that efforts to manage internal and external demands exceed available coping resources.25 Such demands involve both psychological and physiological processes and come in many forms for people with MS and can include daily hassles, major life events, traumatic stress, and perceptions of global nonspecific stress. The relationship between stress and MS remains complex and poorly understood. Nonetheless, individuals with MS frequently report that stress exacerbates their symptoms.26

Some evidence also suggests stress may exacerbate the MS disease process, resulting in more frequent relapses and increased lesion activity visible on MRI.27,28 In addition to mindfulness (described below), stress inoculation training (CBT and relaxation training), and stress-focused group-based self-management have been shown to be beneficial.29,30 In an intriguing and rigorous trial, a 24-week stress management therapy based on CBT was associated with the development of fewer new MS lesions visible on MRI.31

Adaptation to Illness

MS presents challenges that vary between patients and over time. Individuals may confront new physical and cognitive limitations that inhibit the completion of daily tasks, reduce independence, and limit participation in valued and meaningful activities. In addition, the unpredictability of the disease contributes to perceptions of uncertainty and uncontrollability, which in turn result in higher illness impact and poorer psychological outcomes.32 Building cognitive and behavioral skills to address these challenges can promote adaptation to illness and reduce overall distress associated with chronic illness.33 Psychosocial intervention also can address the uncertainty commonly experienced by individuals with MS.34

Self-Management

As with any chronic illness, living well with MS requires ongoing commitment and active engagement with health and personal care over time. The process of building knowledge and skills to manage the day-to-day physical, emotional, and social aspects of living with illness often is referred to as self-management.35 For individuals with MS, this may take the form of participation in programs that address adaptation and psychological distress like those described above, but it also may include improving health behavior (eg, physical activity, DMT adherence, modification of maladaptive habits like smoking or hazardous alcohol use) and symptom management (eg, fatigue, pain). Self-management programs typically include education, the practice of identifying, problem solving, and following through with specific and realistic health and wellness goals, as well as the bolstering of self-efficacy.

Physical Activity

Once discouraged for patients with MS, physical activity is now considered a cornerstone of health and wellness. Physical activity and interventions that target various forms of exercise have been shown to improve strength and endurance, reduce functional decline, enhance QOL, and likely reduce mortality.35-39 A variety of brief behavioral interventions have been shown to improve physical activity in MS. Structured group-based exercise classes focusing on various activities such as aerobic training (eg, cycling) or resistance training (eg, lower extremity strengthening) have demonstrated improvements in various measures of fitness and mood states such as depression and QOL. Brief home-based telephone counseling interventions based in social cognitive theory (eg, goal setting, navigating obstacles) and motivational interviewing strategies (eg, open-ended questions, affirmation, reflective listening, summarizing) also have been shown to be effective not only at increasing physical activity and improving depression and fatigue.40,41

Adherence to Treatment

One primary focus of adherence to treatment is medication management. For individuals with MS, DMTs represent a primary means of reducing disease burden and delaying functional decline. Many DMTs require consistent self-administration over time. Some evidence suggests that poorer adherence is associated with a greater risk of relapse and more rapid disease progression.42,43 Brief telephone counseling, again based on social cognitive theory, and principles of motivational interviewing combined with home telehealth monitoring by a care coordinator has been shown to improve adherence to DMTs.44

Mindfulness

In recent years, mindfulness training has emerged as a popular and common behavioral intervention among individuals with MS. Programs like Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) provide training in meditation techniques designed to promote mindfulness, which is defined as paying attention to present moment experience, including sensations, thoughts, and emotions, without judgment or attachment.45 Cultivating mindfulness helps people with MS cope with and adapt to symptoms and stressors.46 Mindfulness interventions typically are delivered in a group format. For example, MBSR consists of 8 in-person group sessions with daily meditation practice homework. Mindfulness interventions also have been delivered effectively with smartphone apps.47 Mindfulness programs have been shown to improve depression, anxiety, fatigue, stress, and QOL for patients with MS.48-50

Fatigue

More than 90% of individuals with MS report fatigue, and many identify it as their most disabling symptom.51 Often defined as “a subjective lack of physical and/or mental energy that is perceived by the individual or caregiver to interfere with usual and desired activities,” fatigue has been shown to be associated with longer disease duration, greater physical disability, progressive subtype, and depressive symptoms, although the relative and possibly overlapping impact of these issues is only partially understood.52,53 Fatigue is associated with poorer overall mental health and negatively impacts work and social roles.54

Several behavioral interventions have been developed to address fatigue in MS. Using both individual and group based formats and across several modalities (eg, in-person, telephone, online modules, or a combination), behavioral fatigue interventions most commonly combine traditional general CBT skills (eg, addressing maladaptive thoughts and behaviors) with a variety of fatigue-specific skill building exercises that may include fatigue education, energy conservation strategies, improving sleep, enlisting social support, and self-management goal setting strategies.35,55-57

Pain

Chronic pain is common and disabling in people with MS.58,59 Nearly 50% report experiencing moderate to severe chronic pain.59,60 Individuals with MS reporting pain often are older, more disabled (higher Expanded Disability Status Scale score), and have longer disease duration that those who are not experiencing chronic pain.61 Patients report various types of pain in the following order of frequency: dysesthetic pain (18.1%), back pain (16.4%), painful tonic spasms (11.0%), Lhermitte sign (9.0%), visceral pain (2.9%), and trigeminal neuralgia (2.0%).61 Chronic pain has a negative impact on QOL in the areas of sleep, work, maintaining relationships, recreational activities, and overall life enjoyment.59 Additionally, research has shown that greater pain intensity and pain-related interference with activities of daily living are both associated with greater depression severity.62,63

The literature supports the use of behavioral interventions for pain in people with MS.61 Behavioral interventions include in-person exercise interventions (eg, water aerobics, cycling, rowing ergometer, treadmill walking, and resistance training), self-hypnosis, and telephone-based self-management programs based on CBT.35,64,65 As described above, CBT-based self-management programs combine learning CBT skills (eg, modifying maladaptive thoughts) with pain-specific skill building such as pain education, pacing activities, and improving sleep. Of note, MS education including, but not limited to, pain was as effective as a CBT-based self-management program in reducing pain intensity and interference.35 In addition, there is evidence to support acceptance- and mindfulness-based interventions for chronic pain, and online mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for MS related pain is currently being tested in a randomized controlled trial.35,66

Conclusion

People with MS face significant challenges in coping with and adapting to a chronic and unpredictable disease. However, there is considerable evidence that behavioral interventions can improve many of the most common and disabling symptoms in MS including depression, anxiety, stress, fatigue, and pain as well as health behavior and self-care. Research also suggests that improvements in one of these problems (eg, physical inactivity) can influence improvement in other symptoms (eg, depression and fatigue). Unlike other treatment options, behavioral interventions can be delivered in various formats (eg, in-person and electronic health), are time-limited, and cause few (if any) undesirable systemic adverse effects. Behavioral interventions are therefore, an essential part of interprofessional care and rehabilitation for patients with MS.

1. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al; US Multiple Sclerosis Workgroup. The prevalence of MS in the United States: a population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040.

2. Marrie RA, Reingold S, Cohen J, et al. The incidence and prevalence of psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Mult Scler. 2015;21(3):305-317.

3. Chwastiak L, Ehde DM, Gibbons LE, Sullivan M, Bowen JD, Kraft GH. Depressive symptoms and severity of illness in multiple sclerosis: epidemiologic study of a large community sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1862-1868.

4. Williams RM, Turner AP, Hatzakis M Jr, Bowen JD, Rodriquez AA, Haselkorn JK. Prevalence and correlates of depression among veterans with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;64(1):75-80.

5. Moore P, Hirst C, Harding KE, Clarkson H, Pickersgill TP, Robertson NP. Multiple sclerosis relapses and depression. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73(4):272-276.

6. Wood B, van der Mei IA, Ponsonby AL, et al. Prevalence and concurrence of anxiety, depression and fatigue over time in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013;19(2):217-224.

7. Arnett PA, Higginson CI, Voss WD, et al. Depressed mood in multiple sclerosis: relationship to capacity-demanding memory and attentional functioning. Neuropsychology. 1999;13(3):434-446.

8. Diamond BJ, Johnson SK, Kaufman M, Graves L. Relationships between information processing, depression, fatigue and cognition in multiple sclerosis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;23(2):189-199.

9. Benedict RH, Wahlig E, Bakshi R, et al. Predicting quality of life in multiple sclerosis: accounting for physical disability, fatigue, cognition, mood disorder, personality, and behavior change. J Neurol Sci. 2005;231(1-2):29-34.

10. Turner AP, Williams RM, Bowen JD, Kivlahan DR, Haselkorn JK. Suicidal ideation in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87(8):1073-1078.

11. Stenager EN, Koch-Henriksen N, Stenager E. Risk factors for suicide in multiple sclerosis. Psychother Psychosom. 1996;65(2):86-90.

12. Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Goodkin DE, Bostrom A, Epstein L. Comparative outcomes for individual cognitive-behavior therapy, supportive-expressive group psychotherapy, and sertraline for the treatment of depression in multiple sclerosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(6):942-949.

13. Larcombe NA, Wilson PH. An evaluation of cognitive-behaviour therapy for depression in patients with multiple sclerosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;145:366-371.

14. Lincoln NB, Yuill F, Holmes J, et al. Evaluation of an adjustment group for people with multiple sclerosis and low mood: a randomized controlled trial. Mult Scler. 2011;17(10):1250-1257.

15. Mohr DC, Likosky W, Bertagnolli A, et al. Telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(2):356-361.

16. Mohr DC, Hart SL, Julian L, et al. Telephone-administered psychotherapy for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(9):1007-1014.

17. Korostil M, Feinstein A. Anxiety disorders and their clinical correlates in multiple sclerosis patients. Mult Scler. 2007;13(1):67-72.

18. Boeschoten RE, Braamse AMJ, Beekman ATF, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2017;372:331-341.