User login

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Practice Gap

Tissue processing and complete margin assessment in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) are challenging concepts for residents, yet they are essential components of the dermatology residency curriculum. We propose a hands-on active teaching method using craft foam blocks to help residents master these techniques. Prior educational tools have included instructional videos1 as well as the peanut butter–cup and cantaloupe analogies.2,3 Specifically, our method utilizes inexpensive, readily available supplies that allow for repeated practice in a low-stakes environment without limitation of resources. This method provides an immersive, hands-on experience that allows residents to perform multiple practice excisions and simulate positive peripheral or deep margins, unlike tools that offer only fixed-depth or purely visual representations. Additionally, our learning model uniquely enables residents to flatten the simulated tissue, providing a clearer understanding of how a 3-dimensional specimen is transformed on a slide during histologic preparation. This step is particularly important, as tissue architecture can shift during processing, making it one of the most difficult concepts to grasp without hands-on experience. Having a multitude of teaching methods is crucial to accommodate various learning styles, and active learning has been shown to enhance retention for dermatology residents.4

The Technique

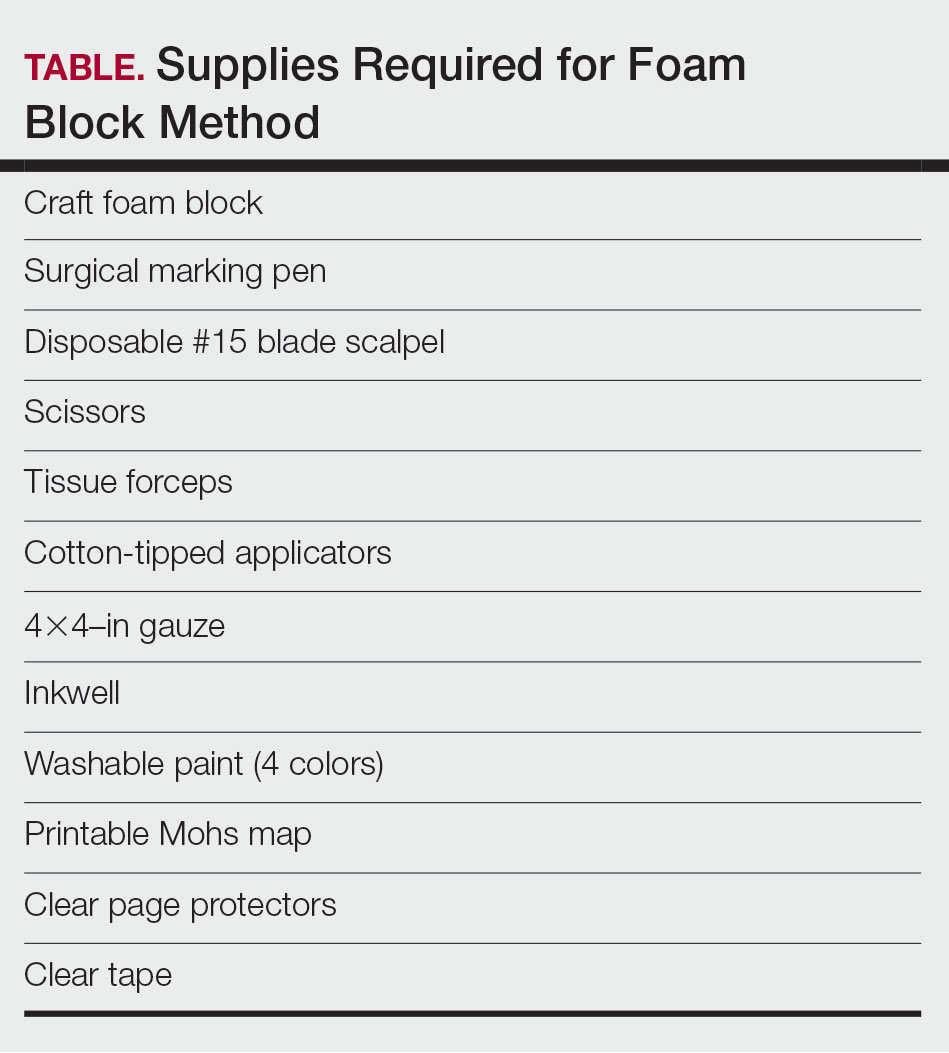

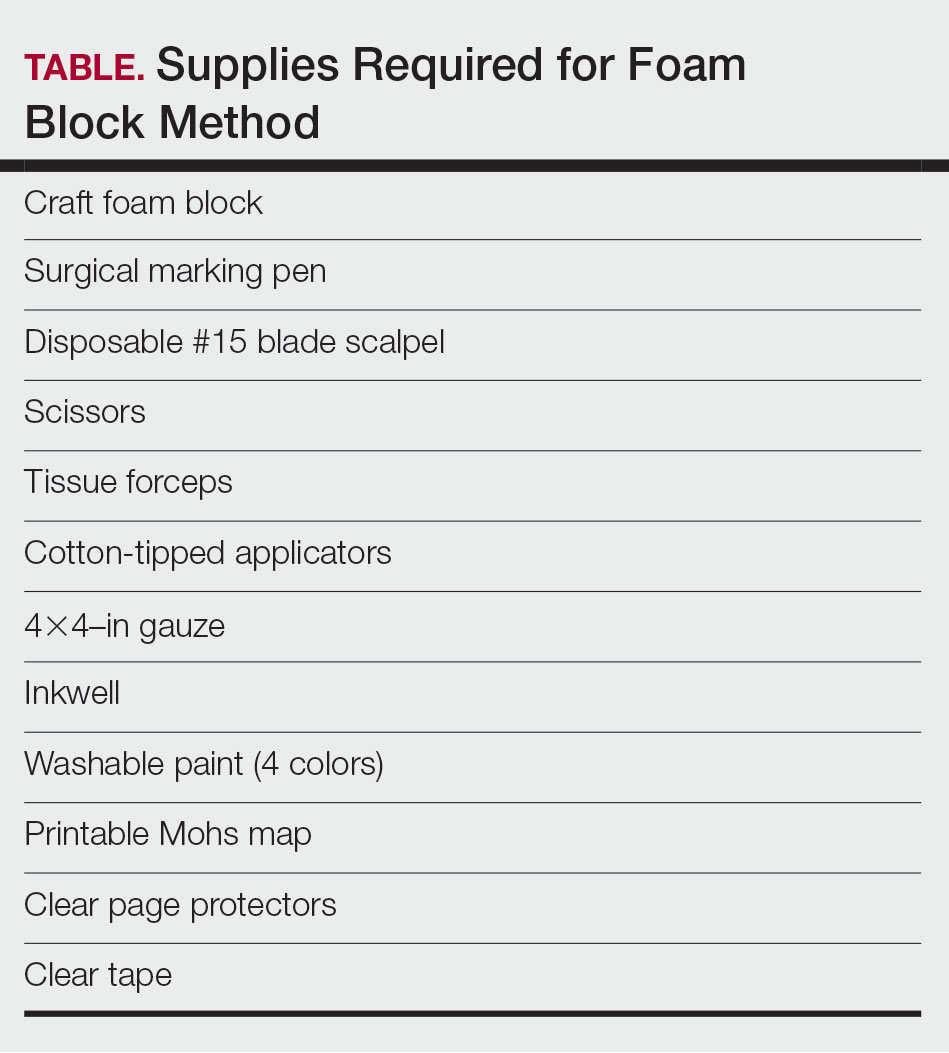

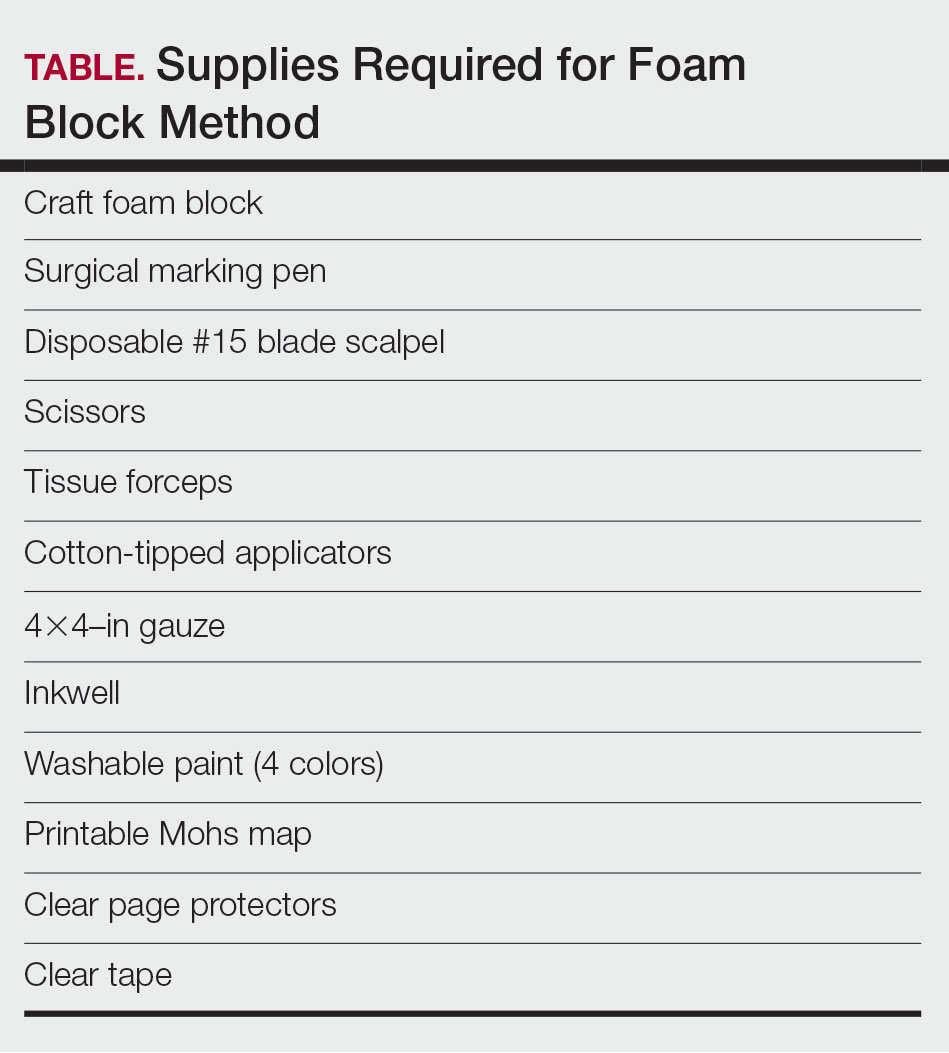

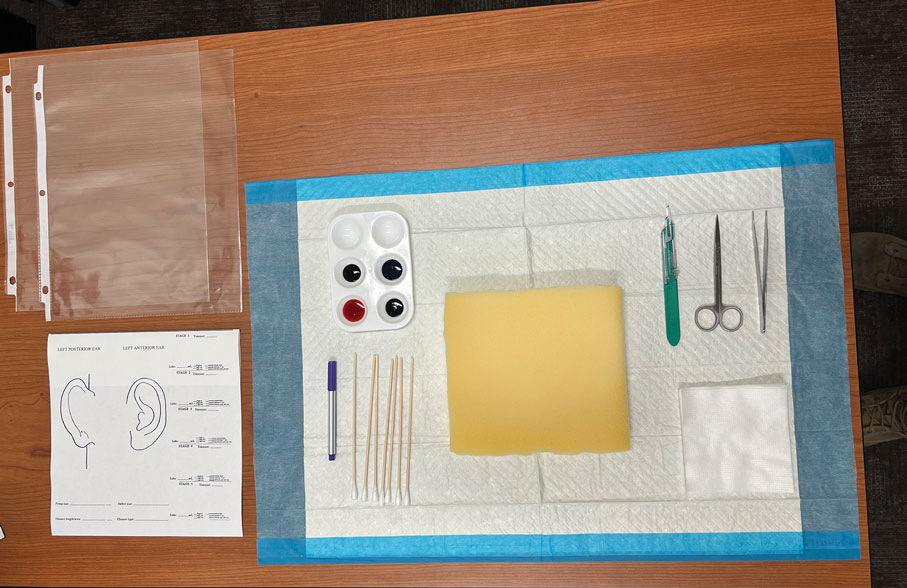

Residents use simple art supplies (including craft foam blocks and ink) and inexpensive, readily available surgical tools to simulate MMS (Table)(Figure 1). If desired, the resident can follow along with the comprehensive, stepwise textbook description of MMS, outlined by Benedetto et al5 to contextualize this hands-on exercise within a standardized didactic framework.

The foam block, which represents patient tissue, serves as the specimen. The resident begins by freehand drawing a simulated cutaneous tumor directly onto the foam using a surgical marking pen. At this point, the instructor discusses the advantages and limitations of tumor debulking with a sharp blade or curette. Residents then mark appropriate margins (1-3 mm) of normal-appearing “epidermis” on the foam block and add hash marks for orientation. This is another opportunity for the instructor to discuss common methods for marking tissue in vivo and to review situations when larger or smaller margins might be appropriate.

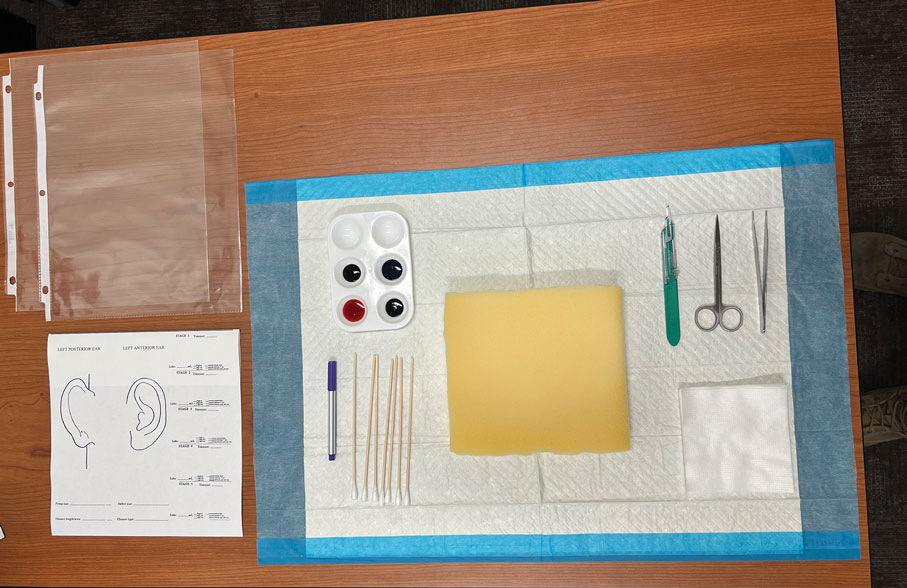

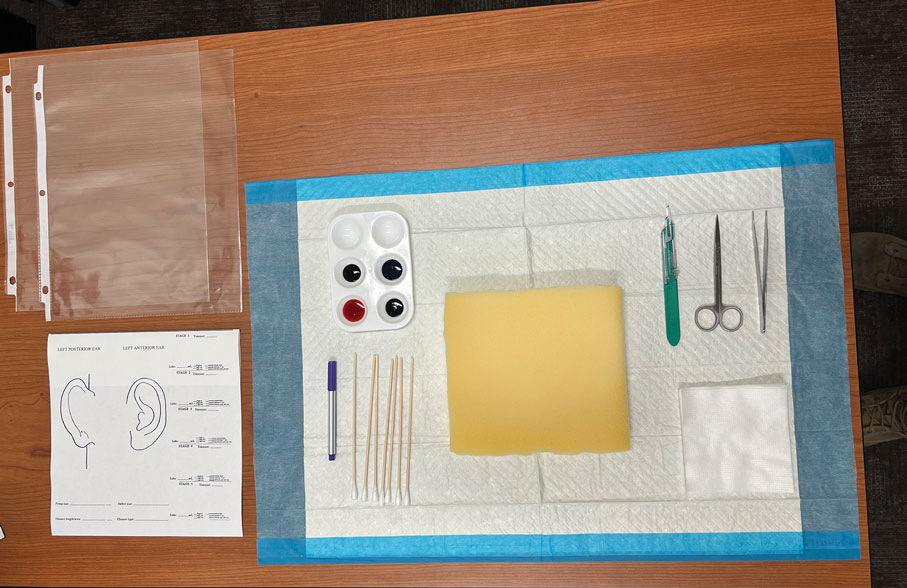

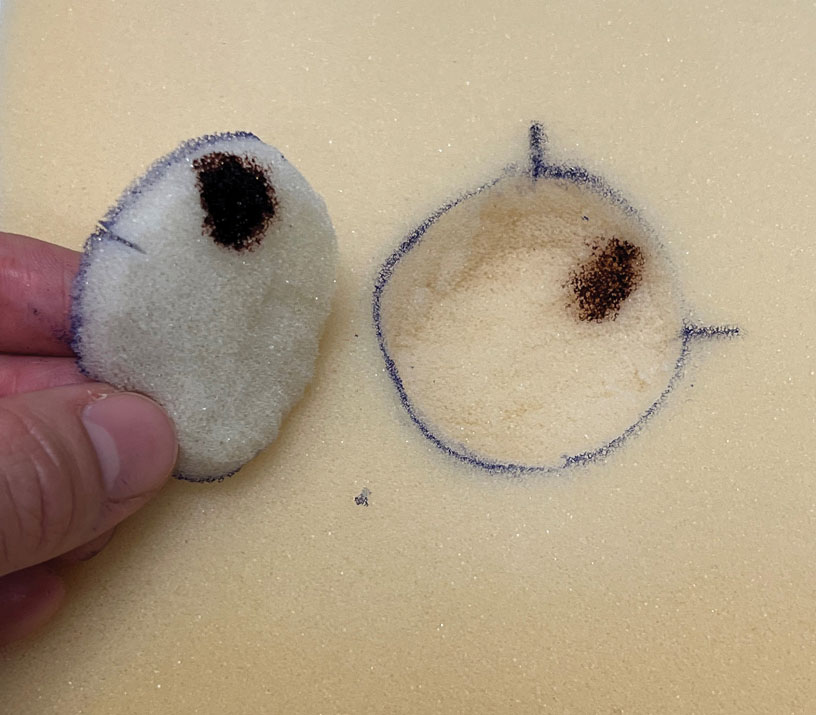

Next, the resident removes the first layer of simulated tissue using a disposable #15 blade scalpel at a 45° angle circumferentially and deep around the representative tumor. The resident also may use scissors and tissue forceps to remove the representative tumor. Next, the excised foam layer (the simulated “specimen”) is transferred to gauze. To demonstrate a positive margin, the resident or instructor marks the deep or peripheral foam block with a surgical marking pen, indicating residual tumor (Figure 2). This allows for multiple sequential layers of foam to be removed, demonstrating successive stages of MMS.

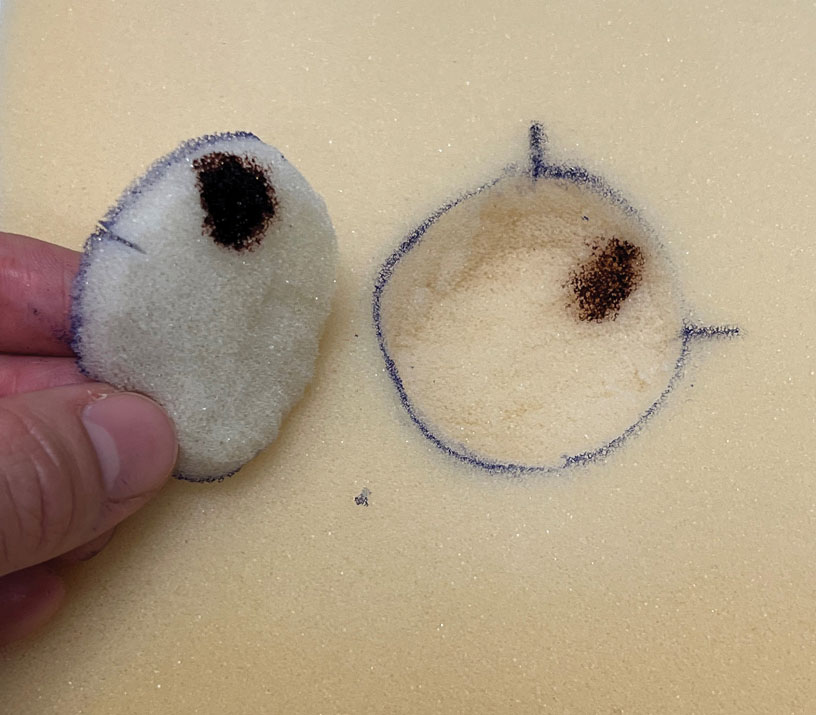

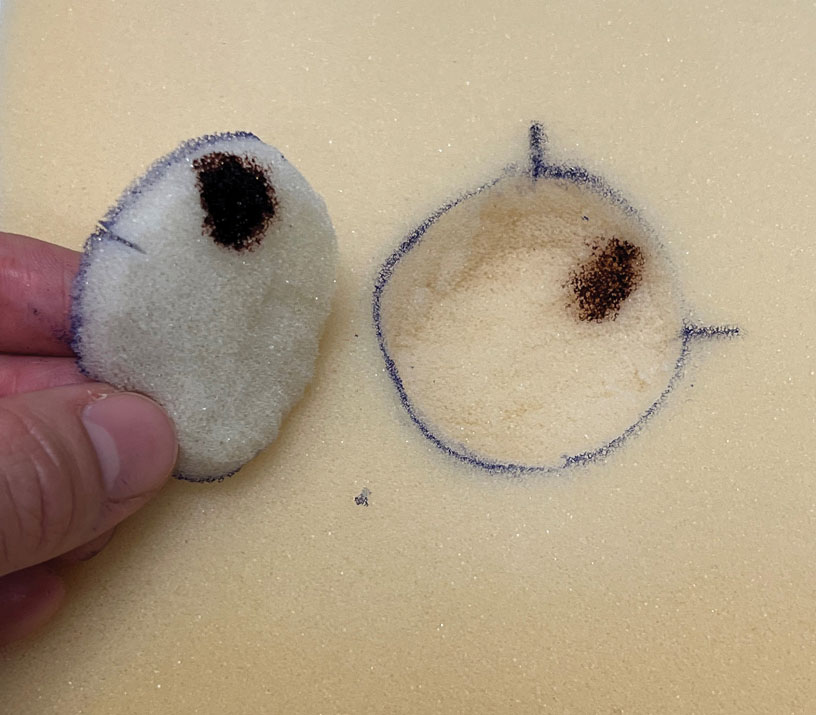

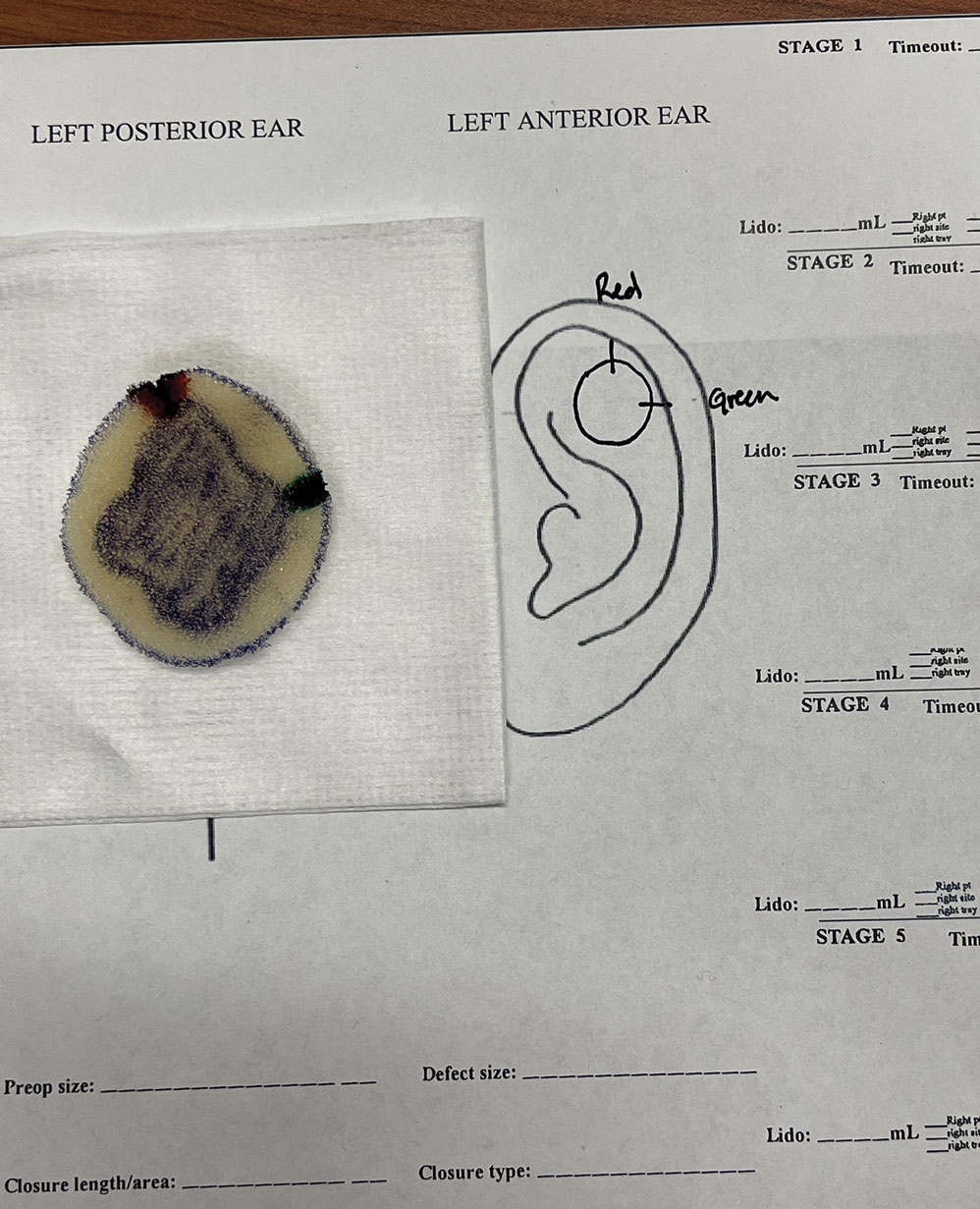

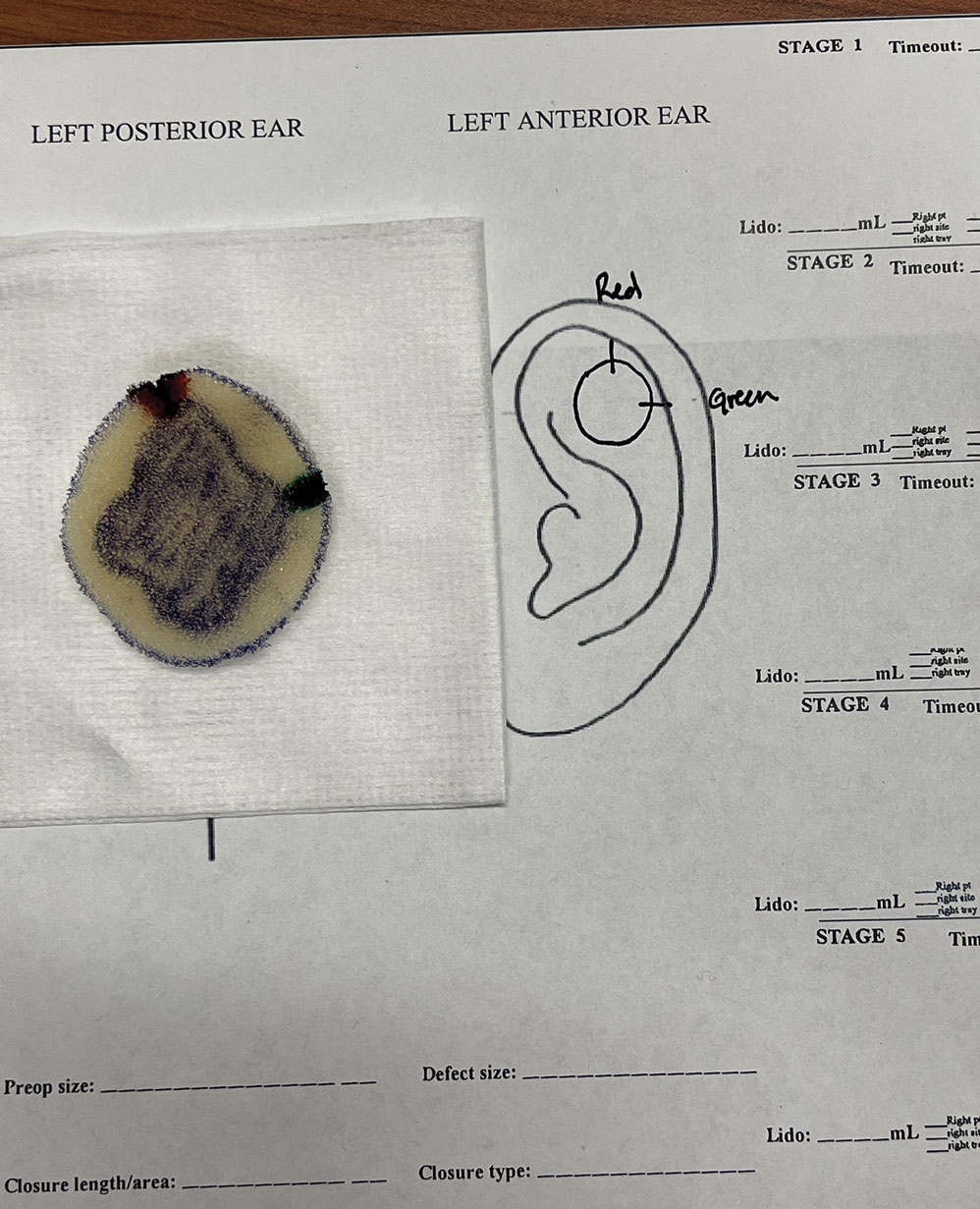

An inkwell holds different colors of washable paint to simulate tissue inking. After excision, the resident uses cotton-tipped applicators to apply different paint colors to the edges of the excised foam specimen at designated orientation points (eg, 3 o'clock and 12 o'clock). The resident then records the location of the excised sample by hand-drawing it on a printable Mohs map, labeling the corresponding paint colors to indicate orientation (Figure 3).

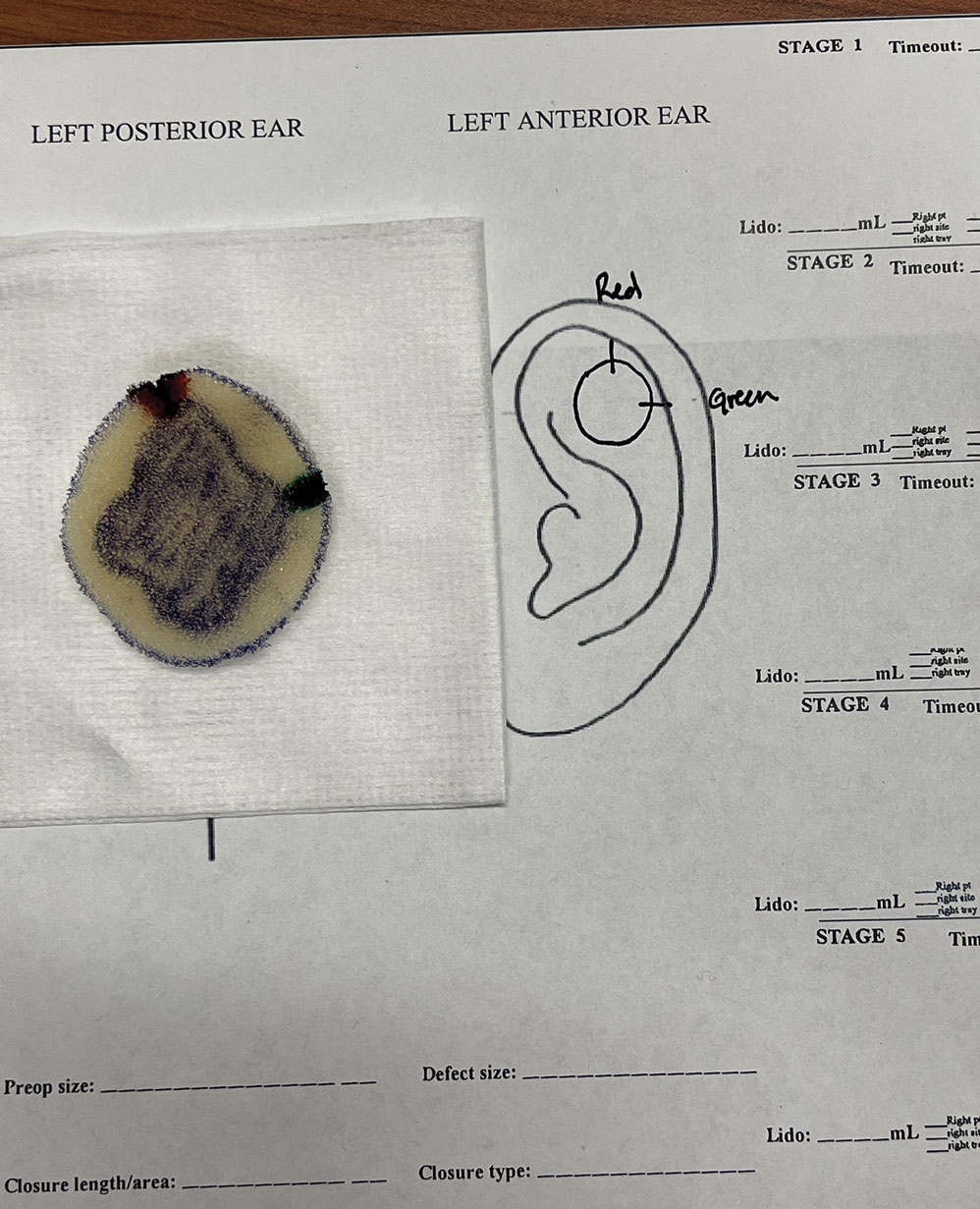

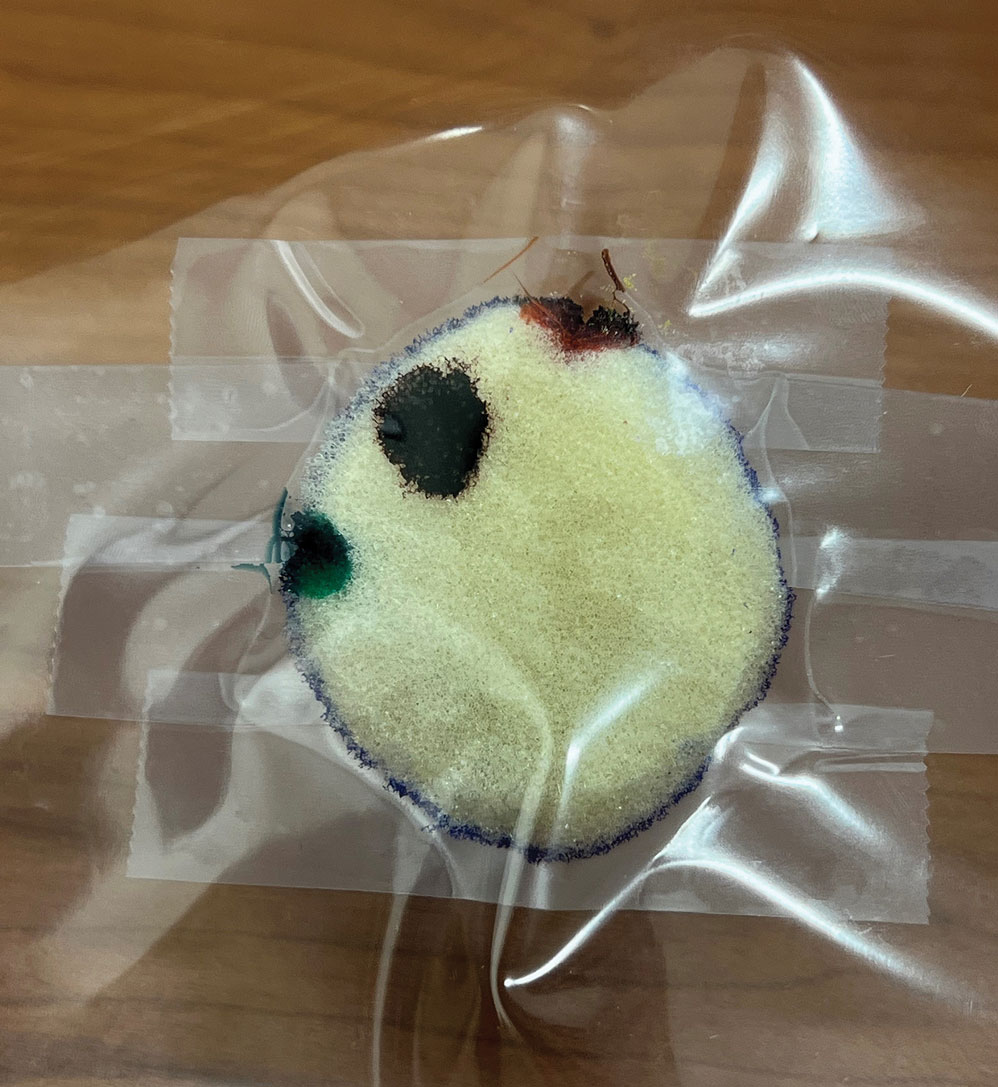

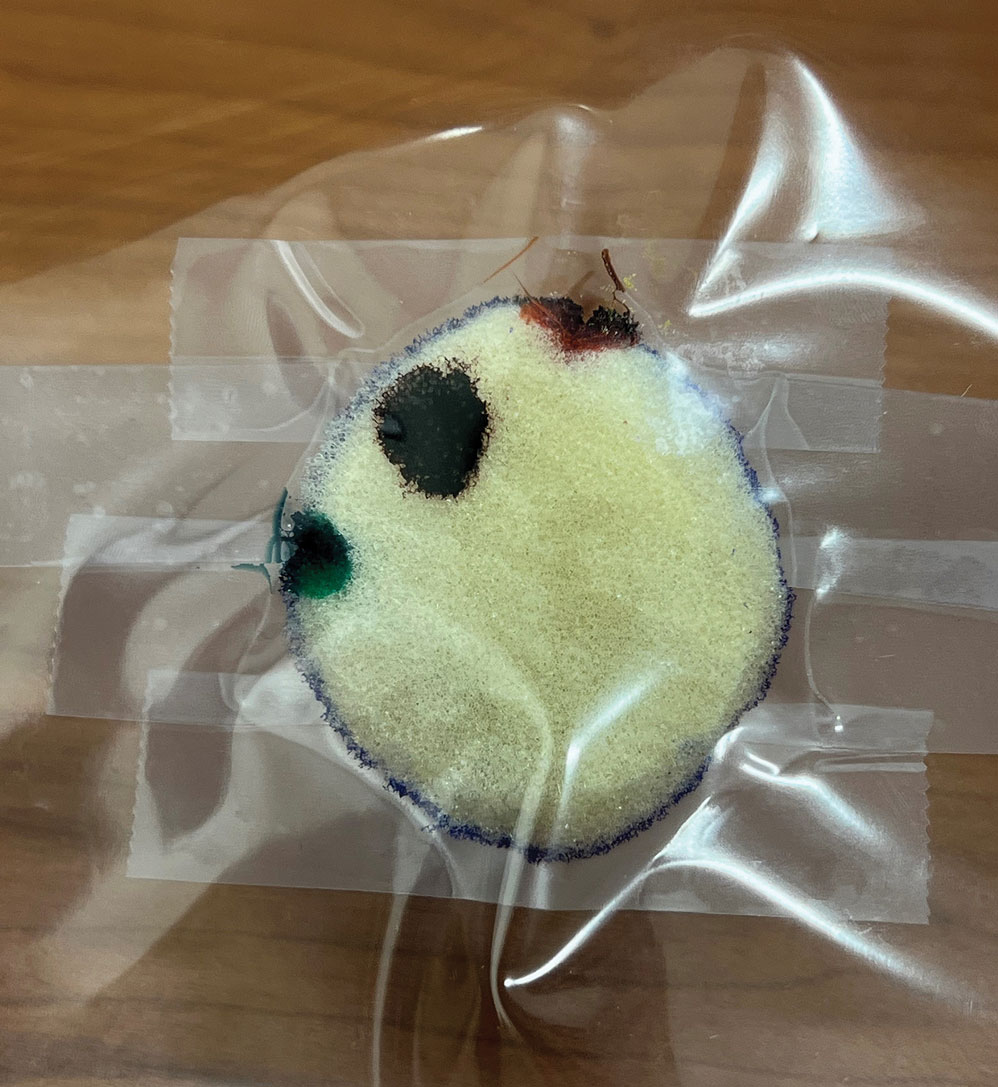

The resident then places the specimen between 2 plastic page protectors mimicking a glass slide and cover slip. Clear tape can be used to help flatten the specimen (Figure 4). The tissue is compressed between the page protector so that the simulated epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat are all in the same plane. At this stage, the instructor may discuss the use of relaxing incisions, especially for deeper tissue specimens or when excision at a 45° bevel is not achieved.5 The view from the underside of the page protector reveals 100% of the specimen’s margin and mimics the first cut off the tissue block. The resident can visualize the complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep margins and can easily identify any positive margins. At this point, the exercise can conclude, or the resident can explore further stages for positive margins, bisected specimens, or other tissue preparation variations.

Practice Implications

By individually designing and removing a representative tumor with margins, creating hash marks, and preparing a tissue specimen for histologic analysis, our interactive teaching method provides dermatology residents with a relatively simple, effective, and active learning experience for MMS outside the surgical setting. Using a piece of craft foam allows the representative tissue to be manipulated and flattened, similar to cutaneous tissue. This method was implemented and refined across 3 separate teaching sessions held by teaching faculty (E.I.P and E.B.W.) at the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium Dermatology Residency Program (San Antonio, Texas). This method has consistently generated strong resident engagement and prompted insightful questions and discussions. Program directors at other residency programs can readily incorporate this method in their surgical curriculum by allocating a brief didactic period to the exercise and facilitating the discussion with a dermatologic surgeon. Its simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness make the foam block model an easily adoptable teaching tool for dermatology residency programs seeking to provide a comprehensive, hands-on understanding of MMS.

- McNeil E, Reich H, Hurliman E. Educational video improves dermatology residents’ understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery: a surveybased matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:926-927. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.013

- Lee E, Wolverton JE, Somani AK. A simple, effective analogy to elucidate the Mohs micrographic surgery procedure—the peanut butter cup. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:743-744. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0614

- Vassantachart JM, Guccione J, Seeburger J. Clinical pearl: Mohs cantaloupe analogy for the dermatology resident. Cutis. 2018; 102:65-66.

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425. doi:10.1080/01421590801946988

- Benedetto PX, Poblete-Lopez C. Mohs micrographic surgery technique. Dermatol Clinics. 2011;29:141-151. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.02.002

Practice Gap

Tissue processing and complete margin assessment in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) are challenging concepts for residents, yet they are essential components of the dermatology residency curriculum. We propose a hands-on active teaching method using craft foam blocks to help residents master these techniques. Prior educational tools have included instructional videos1 as well as the peanut butter–cup and cantaloupe analogies.2,3 Specifically, our method utilizes inexpensive, readily available supplies that allow for repeated practice in a low-stakes environment without limitation of resources. This method provides an immersive, hands-on experience that allows residents to perform multiple practice excisions and simulate positive peripheral or deep margins, unlike tools that offer only fixed-depth or purely visual representations. Additionally, our learning model uniquely enables residents to flatten the simulated tissue, providing a clearer understanding of how a 3-dimensional specimen is transformed on a slide during histologic preparation. This step is particularly important, as tissue architecture can shift during processing, making it one of the most difficult concepts to grasp without hands-on experience. Having a multitude of teaching methods is crucial to accommodate various learning styles, and active learning has been shown to enhance retention for dermatology residents.4

The Technique

Residents use simple art supplies (including craft foam blocks and ink) and inexpensive, readily available surgical tools to simulate MMS (Table)(Figure 1). If desired, the resident can follow along with the comprehensive, stepwise textbook description of MMS, outlined by Benedetto et al5 to contextualize this hands-on exercise within a standardized didactic framework.

The foam block, which represents patient tissue, serves as the specimen. The resident begins by freehand drawing a simulated cutaneous tumor directly onto the foam using a surgical marking pen. At this point, the instructor discusses the advantages and limitations of tumor debulking with a sharp blade or curette. Residents then mark appropriate margins (1-3 mm) of normal-appearing “epidermis” on the foam block and add hash marks for orientation. This is another opportunity for the instructor to discuss common methods for marking tissue in vivo and to review situations when larger or smaller margins might be appropriate.

Next, the resident removes the first layer of simulated tissue using a disposable #15 blade scalpel at a 45° angle circumferentially and deep around the representative tumor. The resident also may use scissors and tissue forceps to remove the representative tumor. Next, the excised foam layer (the simulated “specimen”) is transferred to gauze. To demonstrate a positive margin, the resident or instructor marks the deep or peripheral foam block with a surgical marking pen, indicating residual tumor (Figure 2). This allows for multiple sequential layers of foam to be removed, demonstrating successive stages of MMS.

An inkwell holds different colors of washable paint to simulate tissue inking. After excision, the resident uses cotton-tipped applicators to apply different paint colors to the edges of the excised foam specimen at designated orientation points (eg, 3 o'clock and 12 o'clock). The resident then records the location of the excised sample by hand-drawing it on a printable Mohs map, labeling the corresponding paint colors to indicate orientation (Figure 3).

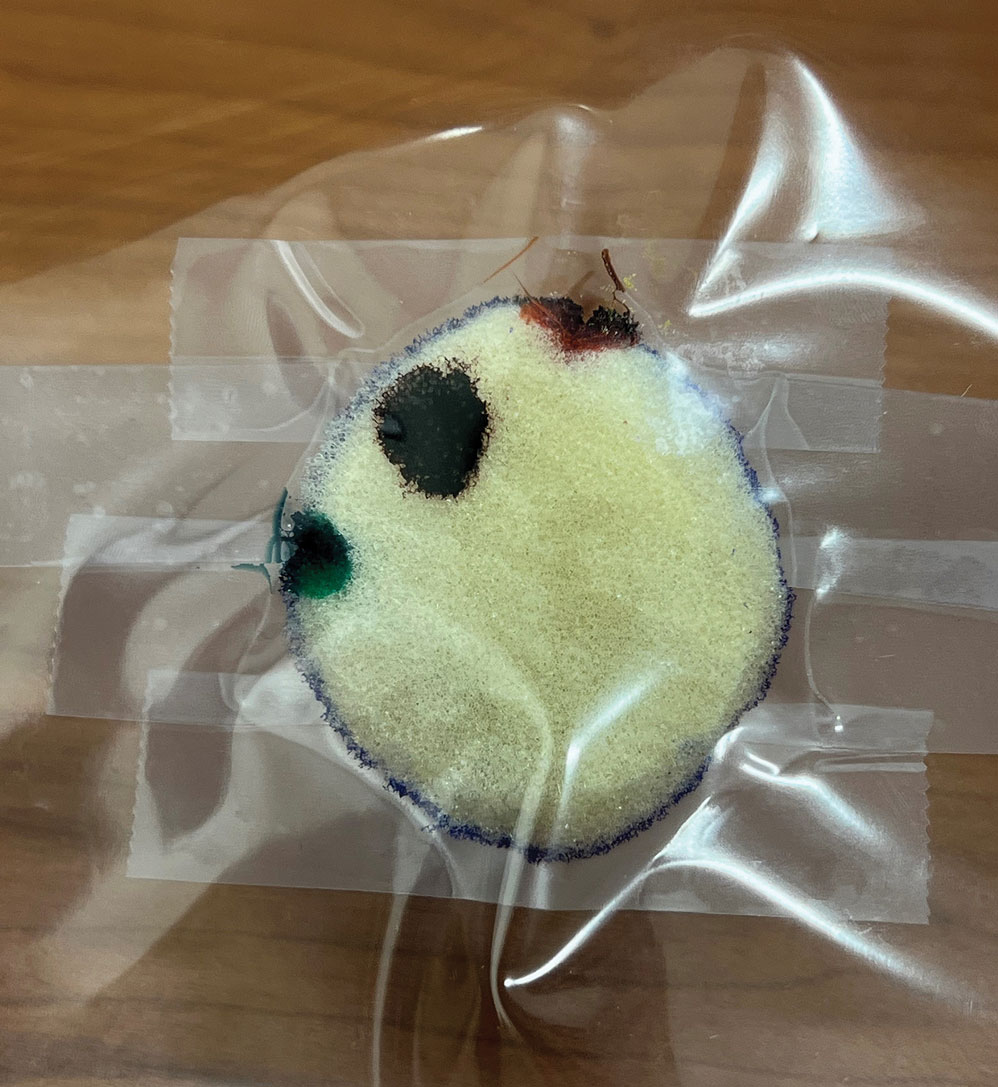

The resident then places the specimen between 2 plastic page protectors mimicking a glass slide and cover slip. Clear tape can be used to help flatten the specimen (Figure 4). The tissue is compressed between the page protector so that the simulated epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat are all in the same plane. At this stage, the instructor may discuss the use of relaxing incisions, especially for deeper tissue specimens or when excision at a 45° bevel is not achieved.5 The view from the underside of the page protector reveals 100% of the specimen’s margin and mimics the first cut off the tissue block. The resident can visualize the complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep margins and can easily identify any positive margins. At this point, the exercise can conclude, or the resident can explore further stages for positive margins, bisected specimens, or other tissue preparation variations.

Practice Implications

By individually designing and removing a representative tumor with margins, creating hash marks, and preparing a tissue specimen for histologic analysis, our interactive teaching method provides dermatology residents with a relatively simple, effective, and active learning experience for MMS outside the surgical setting. Using a piece of craft foam allows the representative tissue to be manipulated and flattened, similar to cutaneous tissue. This method was implemented and refined across 3 separate teaching sessions held by teaching faculty (E.I.P and E.B.W.) at the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium Dermatology Residency Program (San Antonio, Texas). This method has consistently generated strong resident engagement and prompted insightful questions and discussions. Program directors at other residency programs can readily incorporate this method in their surgical curriculum by allocating a brief didactic period to the exercise and facilitating the discussion with a dermatologic surgeon. Its simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness make the foam block model an easily adoptable teaching tool for dermatology residency programs seeking to provide a comprehensive, hands-on understanding of MMS.

Practice Gap

Tissue processing and complete margin assessment in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) are challenging concepts for residents, yet they are essential components of the dermatology residency curriculum. We propose a hands-on active teaching method using craft foam blocks to help residents master these techniques. Prior educational tools have included instructional videos1 as well as the peanut butter–cup and cantaloupe analogies.2,3 Specifically, our method utilizes inexpensive, readily available supplies that allow for repeated practice in a low-stakes environment without limitation of resources. This method provides an immersive, hands-on experience that allows residents to perform multiple practice excisions and simulate positive peripheral or deep margins, unlike tools that offer only fixed-depth or purely visual representations. Additionally, our learning model uniquely enables residents to flatten the simulated tissue, providing a clearer understanding of how a 3-dimensional specimen is transformed on a slide during histologic preparation. This step is particularly important, as tissue architecture can shift during processing, making it one of the most difficult concepts to grasp without hands-on experience. Having a multitude of teaching methods is crucial to accommodate various learning styles, and active learning has been shown to enhance retention for dermatology residents.4

The Technique

Residents use simple art supplies (including craft foam blocks and ink) and inexpensive, readily available surgical tools to simulate MMS (Table)(Figure 1). If desired, the resident can follow along with the comprehensive, stepwise textbook description of MMS, outlined by Benedetto et al5 to contextualize this hands-on exercise within a standardized didactic framework.

The foam block, which represents patient tissue, serves as the specimen. The resident begins by freehand drawing a simulated cutaneous tumor directly onto the foam using a surgical marking pen. At this point, the instructor discusses the advantages and limitations of tumor debulking with a sharp blade or curette. Residents then mark appropriate margins (1-3 mm) of normal-appearing “epidermis” on the foam block and add hash marks for orientation. This is another opportunity for the instructor to discuss common methods for marking tissue in vivo and to review situations when larger or smaller margins might be appropriate.

Next, the resident removes the first layer of simulated tissue using a disposable #15 blade scalpel at a 45° angle circumferentially and deep around the representative tumor. The resident also may use scissors and tissue forceps to remove the representative tumor. Next, the excised foam layer (the simulated “specimen”) is transferred to gauze. To demonstrate a positive margin, the resident or instructor marks the deep or peripheral foam block with a surgical marking pen, indicating residual tumor (Figure 2). This allows for multiple sequential layers of foam to be removed, demonstrating successive stages of MMS.

An inkwell holds different colors of washable paint to simulate tissue inking. After excision, the resident uses cotton-tipped applicators to apply different paint colors to the edges of the excised foam specimen at designated orientation points (eg, 3 o'clock and 12 o'clock). The resident then records the location of the excised sample by hand-drawing it on a printable Mohs map, labeling the corresponding paint colors to indicate orientation (Figure 3).

The resident then places the specimen between 2 plastic page protectors mimicking a glass slide and cover slip. Clear tape can be used to help flatten the specimen (Figure 4). The tissue is compressed between the page protector so that the simulated epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat are all in the same plane. At this stage, the instructor may discuss the use of relaxing incisions, especially for deeper tissue specimens or when excision at a 45° bevel is not achieved.5 The view from the underside of the page protector reveals 100% of the specimen’s margin and mimics the first cut off the tissue block. The resident can visualize the complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep margins and can easily identify any positive margins. At this point, the exercise can conclude, or the resident can explore further stages for positive margins, bisected specimens, or other tissue preparation variations.

Practice Implications

By individually designing and removing a representative tumor with margins, creating hash marks, and preparing a tissue specimen for histologic analysis, our interactive teaching method provides dermatology residents with a relatively simple, effective, and active learning experience for MMS outside the surgical setting. Using a piece of craft foam allows the representative tissue to be manipulated and flattened, similar to cutaneous tissue. This method was implemented and refined across 3 separate teaching sessions held by teaching faculty (E.I.P and E.B.W.) at the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium Dermatology Residency Program (San Antonio, Texas). This method has consistently generated strong resident engagement and prompted insightful questions and discussions. Program directors at other residency programs can readily incorporate this method in their surgical curriculum by allocating a brief didactic period to the exercise and facilitating the discussion with a dermatologic surgeon. Its simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness make the foam block model an easily adoptable teaching tool for dermatology residency programs seeking to provide a comprehensive, hands-on understanding of MMS.

- McNeil E, Reich H, Hurliman E. Educational video improves dermatology residents’ understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery: a surveybased matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:926-927. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.013

- Lee E, Wolverton JE, Somani AK. A simple, effective analogy to elucidate the Mohs micrographic surgery procedure—the peanut butter cup. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:743-744. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0614

- Vassantachart JM, Guccione J, Seeburger J. Clinical pearl: Mohs cantaloupe analogy for the dermatology resident. Cutis. 2018; 102:65-66.

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425. doi:10.1080/01421590801946988

- Benedetto PX, Poblete-Lopez C. Mohs micrographic surgery technique. Dermatol Clinics. 2011;29:141-151. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.02.002

- McNeil E, Reich H, Hurliman E. Educational video improves dermatology residents’ understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery: a surveybased matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:926-927. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.013

- Lee E, Wolverton JE, Somani AK. A simple, effective analogy to elucidate the Mohs micrographic surgery procedure—the peanut butter cup. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:743-744. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0614

- Vassantachart JM, Guccione J, Seeburger J. Clinical pearl: Mohs cantaloupe analogy for the dermatology resident. Cutis. 2018; 102:65-66.

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425. doi:10.1080/01421590801946988

- Benedetto PX, Poblete-Lopez C. Mohs micrographic surgery technique. Dermatol Clinics. 2011;29:141-151. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.02.002

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir

Practice Gap

Brown macules on the feet can pose diagnostic challenges, often raising suspicion of acral melanoma. Talon noir, which is benign and self-resolving, is characterized by dark patches on the skin of the feet due to hemorrhage within the stratum corneum and commonly is observed in athletes who sustain repetitive foot trauma. In one study, nearly 50% (9/20) of talon noir cases initially were misdiagnosed as acral melanoma or melanocytic nevi.1 Accurate identification of talon noir is essential to prevent unnecessary interventions or delayed treatment of malignant lesions. Here, we describe a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique for talon noir using a disposable curette to potentially avoid more invasive procedures.

The Technique

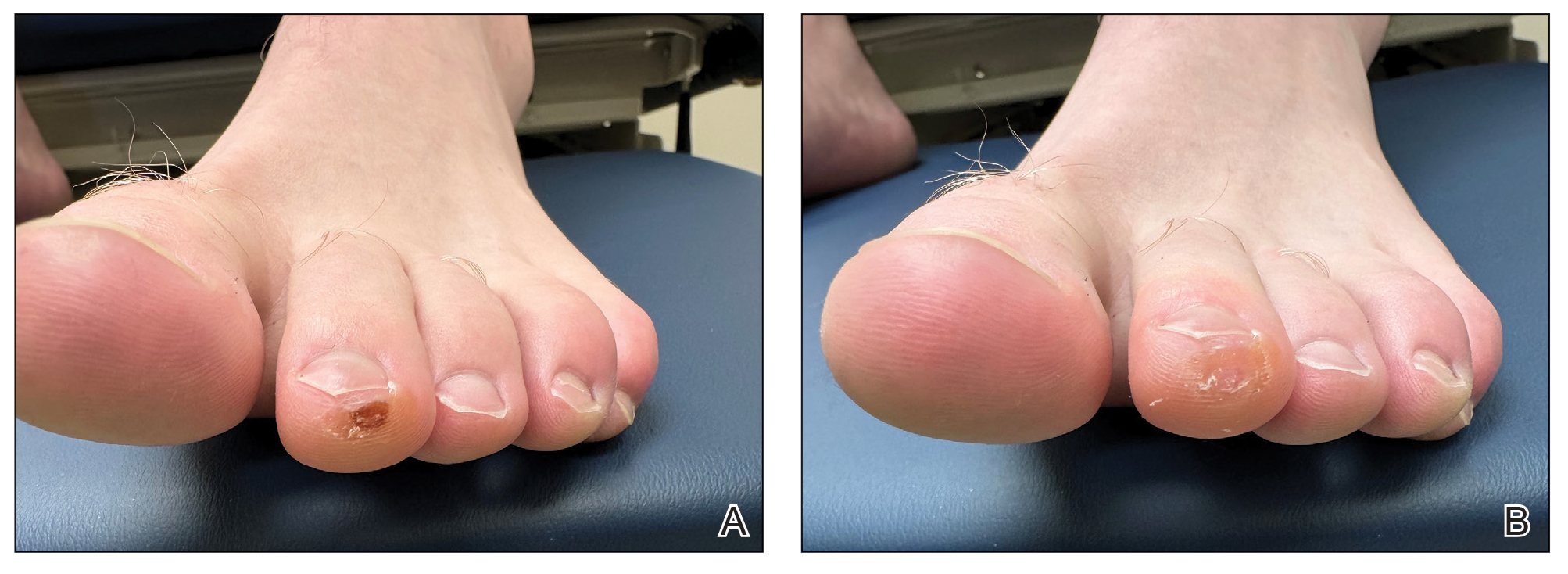

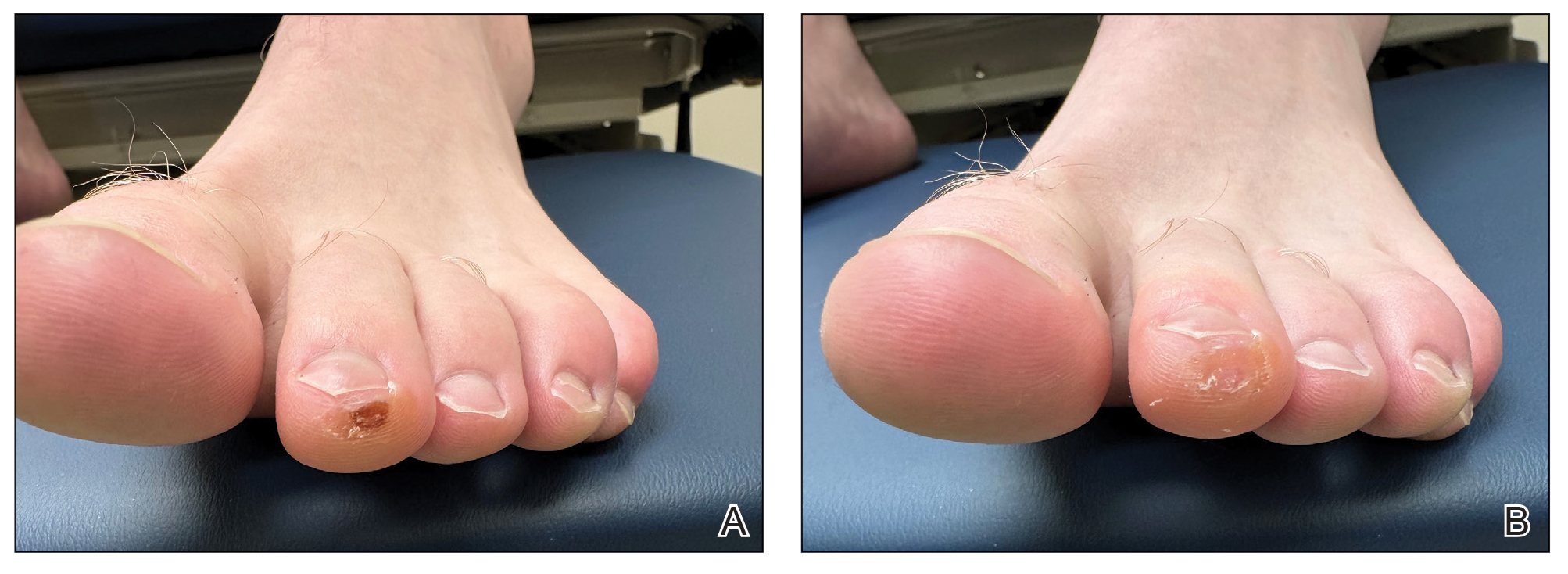

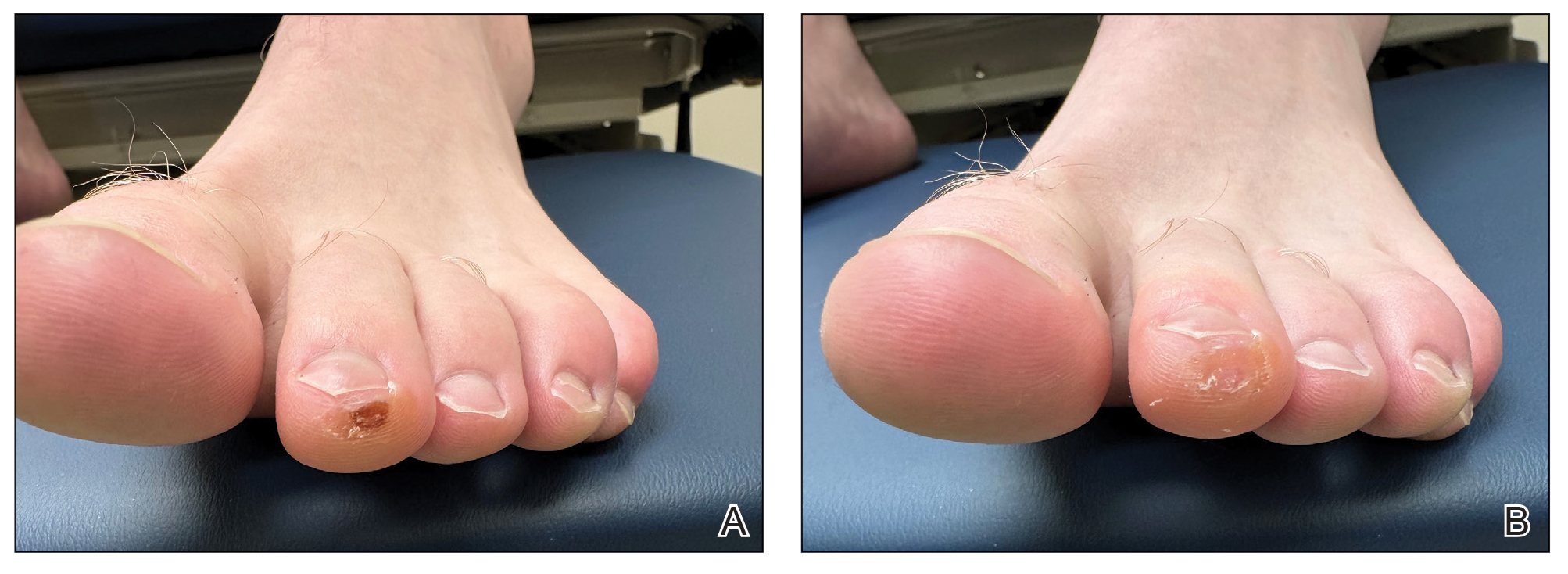

A 34-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a new brown macule on the second toe. The lesion had been present and stable for more than 4 months, showing no changes in shape or color. The patient reported that he was a frequent runner but did not recall any trauma to the toe, and he denied any associated pain, pruritus, or bleeding. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm dark-brown macule on the hyponychium of the left second toe, with numerous petechiae noted on dermoscopic examination. The findings were consistent with talon noir.

Given the clinical suspicion of talon noir, we used a 5-mm disposable curette to gently pare the superficial epidermis. The superficial curettage effectively removed the lesion, leaving behind a healthy epidermis with no pinpoint bleeding, which confirmed the diagnosis of talon noir (Figure). Pathologic changes from acral melanoma reside deeper than talon noir and consequently cannot be effectively removed by superficial curettage alone. Curettage acts as a curative technique for talon noir, but also as a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique to rule out insidious diagnoses, including acral melanoma.2 A follow-up examination performed several weeks later showed no pigmentation or recurrence of the lesion in our patient, further supporting the diagnosis of talon noir.

Practice Implications

Talon noir refers to localized accumulation of blood within the epidermis due to repetitive trauma, pressure, and shearing forces on the skin that results in pigmented macules.3-5 Repetitive trauma damages the microvasculature in areas of the skin with minimal subcutaneous adipose tissue.6 Talon noir also is known as subcorneal hematoma, intracorneal hematoma, black heel, hyperkeratosis hemorrhagica, and basketball heel.1,3 First described by Crissey and Peachey3 in 1961 as calcaneal petechiae, the condition was identified in basketball players with well-circumscribed, deep-red lesions on the posterior lateral heels, located between the Achilles tendon insertion and calcaneal fat pad.3 Subsequent reports have documented talon noir in athletes from a range of sports such as tennis and football, whose activities involve rapid directional changes and shearing forces on the feet.6 Similar lesions, termed tache noir, have been observed on the hands of athletes including gymnasts, weightlifters, golfers, and climbers due to repetitive hand trauma.6 Gross examination reveals blood collecting in the thickened stratum corneum.5

The cutaneous manifestations of talon noir can mimic acral melanoma, highlighting the need for dermatologists to understand its clinical, dermoscopic, and microscopic features. Poor patient recall can complicate diagnosis; for instance, in one study only 20% (4/20) of patients remembered the inciting trauma that caused the subcorneal hematomas.1 Balancing vigilance for melanoma with recognition of more benign conditions such as talon noir—particularly in younger active populations—is essential to minimize patient anxiety and avoid invasive procedures.

Further investigation is warranted in lesions that persist without obvious cause or in those that demonstrate concerning features such as extensive growth. One case of talon noir in a patient with diabetes required an excisional biopsy due to its atypical progression over 1 year with considerable hyperpigmentation and friability.7 Additional investigation such as dermoscopy may be required with paring of the skin to establish a diagnosis.1 Using a curette to pare the thickened stratum corneum, which has no nerve endings, does not require anesthetics.8 In talon noir, paring completely removes the lesion, leaving behind unaffected skin, while melanomas would retain their pigmentation due to melanin in the basal layer.2

Talon noir is a benign condition frequently misdiagnosed due to its resemblance to more serious pathologies such as melanoma. Awareness of its clinical and dermoscopic features can promote cost-effective care while reducing unnecessary procedures. Diagnostic paring of the skin with a curette offers a simple and reliable means of distinguishing talon noir from acral melanoma and other potential conditions.

- Elmas OF, Akdeniz N. Subcorneal hematoma as an imitator of acral melanoma: dermoscopic diagnosis. North Clin Istanb. 2019;7:56-59. doi:10.14744/nci.2019.65481

- Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for a biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

- Crissey JT, Peachey JC. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:501. doi:10.1001/archderm.1961.01580090151017

- Martin SB, Lucas JK, Posa M, et al. Talon noir in a young baseball player: a case report. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35:235-238. doi:10.1016 /j.pedhc.2020.10.009

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

- Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory conditions, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015; 8:31-43.

- Choudhury S, Mandal A. Talon noir: a case report and literature review. Cureus. 2023;15:E35905. doi:10.7759/cureus.35905

- Oberdorfer KL, Farshchian M, Moossavi M. Paring of skin for superficially lodged foreign body removal. Cureus. 2023;15:E42396. doi:10.7759/cureus.42396

Practice Gap

Brown macules on the feet can pose diagnostic challenges, often raising suspicion of acral melanoma. Talon noir, which is benign and self-resolving, is characterized by dark patches on the skin of the feet due to hemorrhage within the stratum corneum and commonly is observed in athletes who sustain repetitive foot trauma. In one study, nearly 50% (9/20) of talon noir cases initially were misdiagnosed as acral melanoma or melanocytic nevi.1 Accurate identification of talon noir is essential to prevent unnecessary interventions or delayed treatment of malignant lesions. Here, we describe a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique for talon noir using a disposable curette to potentially avoid more invasive procedures.

The Technique

A 34-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a new brown macule on the second toe. The lesion had been present and stable for more than 4 months, showing no changes in shape or color. The patient reported that he was a frequent runner but did not recall any trauma to the toe, and he denied any associated pain, pruritus, or bleeding. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm dark-brown macule on the hyponychium of the left second toe, with numerous petechiae noted on dermoscopic examination. The findings were consistent with talon noir.

Given the clinical suspicion of talon noir, we used a 5-mm disposable curette to gently pare the superficial epidermis. The superficial curettage effectively removed the lesion, leaving behind a healthy epidermis with no pinpoint bleeding, which confirmed the diagnosis of talon noir (Figure). Pathologic changes from acral melanoma reside deeper than talon noir and consequently cannot be effectively removed by superficial curettage alone. Curettage acts as a curative technique for talon noir, but also as a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique to rule out insidious diagnoses, including acral melanoma.2 A follow-up examination performed several weeks later showed no pigmentation or recurrence of the lesion in our patient, further supporting the diagnosis of talon noir.

Practice Implications

Talon noir refers to localized accumulation of blood within the epidermis due to repetitive trauma, pressure, and shearing forces on the skin that results in pigmented macules.3-5 Repetitive trauma damages the microvasculature in areas of the skin with minimal subcutaneous adipose tissue.6 Talon noir also is known as subcorneal hematoma, intracorneal hematoma, black heel, hyperkeratosis hemorrhagica, and basketball heel.1,3 First described by Crissey and Peachey3 in 1961 as calcaneal petechiae, the condition was identified in basketball players with well-circumscribed, deep-red lesions on the posterior lateral heels, located between the Achilles tendon insertion and calcaneal fat pad.3 Subsequent reports have documented talon noir in athletes from a range of sports such as tennis and football, whose activities involve rapid directional changes and shearing forces on the feet.6 Similar lesions, termed tache noir, have been observed on the hands of athletes including gymnasts, weightlifters, golfers, and climbers due to repetitive hand trauma.6 Gross examination reveals blood collecting in the thickened stratum corneum.5

The cutaneous manifestations of talon noir can mimic acral melanoma, highlighting the need for dermatologists to understand its clinical, dermoscopic, and microscopic features. Poor patient recall can complicate diagnosis; for instance, in one study only 20% (4/20) of patients remembered the inciting trauma that caused the subcorneal hematomas.1 Balancing vigilance for melanoma with recognition of more benign conditions such as talon noir—particularly in younger active populations—is essential to minimize patient anxiety and avoid invasive procedures.

Further investigation is warranted in lesions that persist without obvious cause or in those that demonstrate concerning features such as extensive growth. One case of talon noir in a patient with diabetes required an excisional biopsy due to its atypical progression over 1 year with considerable hyperpigmentation and friability.7 Additional investigation such as dermoscopy may be required with paring of the skin to establish a diagnosis.1 Using a curette to pare the thickened stratum corneum, which has no nerve endings, does not require anesthetics.8 In talon noir, paring completely removes the lesion, leaving behind unaffected skin, while melanomas would retain their pigmentation due to melanin in the basal layer.2

Talon noir is a benign condition frequently misdiagnosed due to its resemblance to more serious pathologies such as melanoma. Awareness of its clinical and dermoscopic features can promote cost-effective care while reducing unnecessary procedures. Diagnostic paring of the skin with a curette offers a simple and reliable means of distinguishing talon noir from acral melanoma and other potential conditions.

Practice Gap

Brown macules on the feet can pose diagnostic challenges, often raising suspicion of acral melanoma. Talon noir, which is benign and self-resolving, is characterized by dark patches on the skin of the feet due to hemorrhage within the stratum corneum and commonly is observed in athletes who sustain repetitive foot trauma. In one study, nearly 50% (9/20) of talon noir cases initially were misdiagnosed as acral melanoma or melanocytic nevi.1 Accurate identification of talon noir is essential to prevent unnecessary interventions or delayed treatment of malignant lesions. Here, we describe a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique for talon noir using a disposable curette to potentially avoid more invasive procedures.

The Technique

A 34-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a new brown macule on the second toe. The lesion had been present and stable for more than 4 months, showing no changes in shape or color. The patient reported that he was a frequent runner but did not recall any trauma to the toe, and he denied any associated pain, pruritus, or bleeding. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm dark-brown macule on the hyponychium of the left second toe, with numerous petechiae noted on dermoscopic examination. The findings were consistent with talon noir.

Given the clinical suspicion of talon noir, we used a 5-mm disposable curette to gently pare the superficial epidermis. The superficial curettage effectively removed the lesion, leaving behind a healthy epidermis with no pinpoint bleeding, which confirmed the diagnosis of talon noir (Figure). Pathologic changes from acral melanoma reside deeper than talon noir and consequently cannot be effectively removed by superficial curettage alone. Curettage acts as a curative technique for talon noir, but also as a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique to rule out insidious diagnoses, including acral melanoma.2 A follow-up examination performed several weeks later showed no pigmentation or recurrence of the lesion in our patient, further supporting the diagnosis of talon noir.

Practice Implications

Talon noir refers to localized accumulation of blood within the epidermis due to repetitive trauma, pressure, and shearing forces on the skin that results in pigmented macules.3-5 Repetitive trauma damages the microvasculature in areas of the skin with minimal subcutaneous adipose tissue.6 Talon noir also is known as subcorneal hematoma, intracorneal hematoma, black heel, hyperkeratosis hemorrhagica, and basketball heel.1,3 First described by Crissey and Peachey3 in 1961 as calcaneal petechiae, the condition was identified in basketball players with well-circumscribed, deep-red lesions on the posterior lateral heels, located between the Achilles tendon insertion and calcaneal fat pad.3 Subsequent reports have documented talon noir in athletes from a range of sports such as tennis and football, whose activities involve rapid directional changes and shearing forces on the feet.6 Similar lesions, termed tache noir, have been observed on the hands of athletes including gymnasts, weightlifters, golfers, and climbers due to repetitive hand trauma.6 Gross examination reveals blood collecting in the thickened stratum corneum.5

The cutaneous manifestations of talon noir can mimic acral melanoma, highlighting the need for dermatologists to understand its clinical, dermoscopic, and microscopic features. Poor patient recall can complicate diagnosis; for instance, in one study only 20% (4/20) of patients remembered the inciting trauma that caused the subcorneal hematomas.1 Balancing vigilance for melanoma with recognition of more benign conditions such as talon noir—particularly in younger active populations—is essential to minimize patient anxiety and avoid invasive procedures.

Further investigation is warranted in lesions that persist without obvious cause or in those that demonstrate concerning features such as extensive growth. One case of talon noir in a patient with diabetes required an excisional biopsy due to its atypical progression over 1 year with considerable hyperpigmentation and friability.7 Additional investigation such as dermoscopy may be required with paring of the skin to establish a diagnosis.1 Using a curette to pare the thickened stratum corneum, which has no nerve endings, does not require anesthetics.8 In talon noir, paring completely removes the lesion, leaving behind unaffected skin, while melanomas would retain their pigmentation due to melanin in the basal layer.2

Talon noir is a benign condition frequently misdiagnosed due to its resemblance to more serious pathologies such as melanoma. Awareness of its clinical and dermoscopic features can promote cost-effective care while reducing unnecessary procedures. Diagnostic paring of the skin with a curette offers a simple and reliable means of distinguishing talon noir from acral melanoma and other potential conditions.

- Elmas OF, Akdeniz N. Subcorneal hematoma as an imitator of acral melanoma: dermoscopic diagnosis. North Clin Istanb. 2019;7:56-59. doi:10.14744/nci.2019.65481

- Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for a biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

- Crissey JT, Peachey JC. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:501. doi:10.1001/archderm.1961.01580090151017

- Martin SB, Lucas JK, Posa M, et al. Talon noir in a young baseball player: a case report. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35:235-238. doi:10.1016 /j.pedhc.2020.10.009

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

- Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory conditions, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015; 8:31-43.

- Choudhury S, Mandal A. Talon noir: a case report and literature review. Cureus. 2023;15:E35905. doi:10.7759/cureus.35905

- Oberdorfer KL, Farshchian M, Moossavi M. Paring of skin for superficially lodged foreign body removal. Cureus. 2023;15:E42396. doi:10.7759/cureus.42396

- Elmas OF, Akdeniz N. Subcorneal hematoma as an imitator of acral melanoma: dermoscopic diagnosis. North Clin Istanb. 2019;7:56-59. doi:10.14744/nci.2019.65481

- Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for a biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

- Crissey JT, Peachey JC. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:501. doi:10.1001/archderm.1961.01580090151017

- Martin SB, Lucas JK, Posa M, et al. Talon noir in a young baseball player: a case report. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35:235-238. doi:10.1016 /j.pedhc.2020.10.009

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

- Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory conditions, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015; 8:31-43.

- Choudhury S, Mandal A. Talon noir: a case report and literature review. Cureus. 2023;15:E35905. doi:10.7759/cureus.35905

- Oberdorfer KL, Farshchian M, Moossavi M. Paring of skin for superficially lodged foreign body removal. Cureus. 2023;15:E42396. doi:10.7759/cureus.42396

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir