User login

Resmetirom Reduces Liver Stiffness in MASH Cirrhosis

PHOENIX — according to the results of a new study.

As well as showing sustained reduction in liver stiffness on vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) after 2 years of treatment with resmetirom, the study suggested that up to 35% of patients could “potentially reverse their cirrhosis,” said lead author Naim Alkhouri, MD, chief medical officer and director of the steatotic liver program at Arizona Liver Health in Phoenix.

Alkhouri presented data on patients with compensated cirrhosis from a 1-year open-label extension of the already-completed MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 study at American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting.

The FDA approved resmetirom (Rezdiffra, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals) in 2024 for MASH and moderate-to-advanced liver fibrosis (consistent with stage F2 and F3 disease), to be used in conjunction with diet and exercise. The agency granted the once-daily, oral thyroid hormone receptor beta-selective agonist breakthrough therapy designation and priority review.

According to the American Liver Foundation, about 5% of adults in the US have MASH — one of the leading causes of liver transplantation in the country. There is currently no FDA-approved therapy for compensated cirrhosis caused by MASH, said Alkhouri. Patients with MASH cirrhosis with clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) experience major adverse liver outcomes.

In an analysis of 122 patients with Child Pugh A MASH cirrhosis who completed both a year in an open-label arm of MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 and a 1-year extension, 113 (93%) completed 2 years of treatment with resmetirom (80 mg). Of the 122 patients, only 114 received MRI proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) testing — 93 (82%) had a baseline of > 5% indicating cirrhosis, while 21 (18%) had an MRI-PDFF of < 5%.

Patients were assessed for baseline portal hypertension (Baveno VII) with FibroScan VCTE and platelet count, which was confirmed using magnetic resonance elastography (MRE). Noninvasive biomarkers and imaging were analyzed at baseline and out to 2 years.

At baseline, 63% of patients were categorized as probable/definitive CSPH (Baveno VII). At 1 year of treatment with resmetirom, 20% of patients who were CSPH positive no longer met the criteria, and at 2 years this number had increased to 28%.

After 2 years of treatment, more than half of the patients had a sustained reduction in liver stiffness of more than 25%, as measured by VCTE; and 35% of patients with confirmed F4 at baseline (liver biopsy F4 and/or platelets < 140/MRE ≥ 5 with VCTE ≥ 15) had a conversion to F3.

Patients taking resmetirom also had significant improvements in MRI-PDFF and MRE at 2 years. Almost a third of those with a baseline MRI-PDFF > 5% improved, while 43% of those with a baseline of < 5% improved.

Although 113 patients had an adverse event — primarily gastrointestinal — the observed events were consistent with previous studies. Twenty-seven patients had a serious adverse event, but none were related to the study drug, said Alkhouri. The researchers reported that only 8% of patients discontinued the medication.

Changing the Treatment Landscape for MASH-Related Cirrhosis

When asked to comment by GI & Hepatology News, Hazem Ayesh, MD, an endocrinologist at Deaconess Health System, Evansville, Indiana, said that “reversal of cirrhosis from F4 to F3 and reduction of portal hypertension are quite surprising, since cirrhosis typically progresses slowly.”

Ayesh said it was notable that the researchers had used imaging to confirm both functional and hemodynamic improvements in liver architecture not just biochemical changes. Given the results, “clinicians may reasonably consider off-label use in selected compensated patients until more outcome data become available,” he said.

A phase 3 study is underway to examine those outcomes, MAESTRO-NASH OUTCOMES, with 845 patients with MASH cirrhosis, and should be completed in 2027.

“Resmetirom could change the treatment landscape for MASH-related cirrhosis,” said Ayesh, adding, “this drug offers a chance to target the disease process itself,” while other therapies focus on preventing complications.

“For patients without access to liver transplant, a therapy that can slow or reverse disease progression could be transformative,” he told GI & Hepatology News.

Alkhouri disclosed that he is a consultant and speaker for Madrigal Pharmaceuticals. Three coauthors are Madrigal employees and own stock options in the company. Two coauthors are Madrigal consultants and advisers. Ayesh reported no conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

PHOENIX — according to the results of a new study.

As well as showing sustained reduction in liver stiffness on vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) after 2 years of treatment with resmetirom, the study suggested that up to 35% of patients could “potentially reverse their cirrhosis,” said lead author Naim Alkhouri, MD, chief medical officer and director of the steatotic liver program at Arizona Liver Health in Phoenix.

Alkhouri presented data on patients with compensated cirrhosis from a 1-year open-label extension of the already-completed MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 study at American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting.

The FDA approved resmetirom (Rezdiffra, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals) in 2024 for MASH and moderate-to-advanced liver fibrosis (consistent with stage F2 and F3 disease), to be used in conjunction with diet and exercise. The agency granted the once-daily, oral thyroid hormone receptor beta-selective agonist breakthrough therapy designation and priority review.

According to the American Liver Foundation, about 5% of adults in the US have MASH — one of the leading causes of liver transplantation in the country. There is currently no FDA-approved therapy for compensated cirrhosis caused by MASH, said Alkhouri. Patients with MASH cirrhosis with clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) experience major adverse liver outcomes.

In an analysis of 122 patients with Child Pugh A MASH cirrhosis who completed both a year in an open-label arm of MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 and a 1-year extension, 113 (93%) completed 2 years of treatment with resmetirom (80 mg). Of the 122 patients, only 114 received MRI proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) testing — 93 (82%) had a baseline of > 5% indicating cirrhosis, while 21 (18%) had an MRI-PDFF of < 5%.

Patients were assessed for baseline portal hypertension (Baveno VII) with FibroScan VCTE and platelet count, which was confirmed using magnetic resonance elastography (MRE). Noninvasive biomarkers and imaging were analyzed at baseline and out to 2 years.

At baseline, 63% of patients were categorized as probable/definitive CSPH (Baveno VII). At 1 year of treatment with resmetirom, 20% of patients who were CSPH positive no longer met the criteria, and at 2 years this number had increased to 28%.

After 2 years of treatment, more than half of the patients had a sustained reduction in liver stiffness of more than 25%, as measured by VCTE; and 35% of patients with confirmed F4 at baseline (liver biopsy F4 and/or platelets < 140/MRE ≥ 5 with VCTE ≥ 15) had a conversion to F3.

Patients taking resmetirom also had significant improvements in MRI-PDFF and MRE at 2 years. Almost a third of those with a baseline MRI-PDFF > 5% improved, while 43% of those with a baseline of < 5% improved.

Although 113 patients had an adverse event — primarily gastrointestinal — the observed events were consistent with previous studies. Twenty-seven patients had a serious adverse event, but none were related to the study drug, said Alkhouri. The researchers reported that only 8% of patients discontinued the medication.

Changing the Treatment Landscape for MASH-Related Cirrhosis

When asked to comment by GI & Hepatology News, Hazem Ayesh, MD, an endocrinologist at Deaconess Health System, Evansville, Indiana, said that “reversal of cirrhosis from F4 to F3 and reduction of portal hypertension are quite surprising, since cirrhosis typically progresses slowly.”

Ayesh said it was notable that the researchers had used imaging to confirm both functional and hemodynamic improvements in liver architecture not just biochemical changes. Given the results, “clinicians may reasonably consider off-label use in selected compensated patients until more outcome data become available,” he said.

A phase 3 study is underway to examine those outcomes, MAESTRO-NASH OUTCOMES, with 845 patients with MASH cirrhosis, and should be completed in 2027.

“Resmetirom could change the treatment landscape for MASH-related cirrhosis,” said Ayesh, adding, “this drug offers a chance to target the disease process itself,” while other therapies focus on preventing complications.

“For patients without access to liver transplant, a therapy that can slow or reverse disease progression could be transformative,” he told GI & Hepatology News.

Alkhouri disclosed that he is a consultant and speaker for Madrigal Pharmaceuticals. Three coauthors are Madrigal employees and own stock options in the company. Two coauthors are Madrigal consultants and advisers. Ayesh reported no conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

PHOENIX — according to the results of a new study.

As well as showing sustained reduction in liver stiffness on vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) after 2 years of treatment with resmetirom, the study suggested that up to 35% of patients could “potentially reverse their cirrhosis,” said lead author Naim Alkhouri, MD, chief medical officer and director of the steatotic liver program at Arizona Liver Health in Phoenix.

Alkhouri presented data on patients with compensated cirrhosis from a 1-year open-label extension of the already-completed MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 study at American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting.

The FDA approved resmetirom (Rezdiffra, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals) in 2024 for MASH and moderate-to-advanced liver fibrosis (consistent with stage F2 and F3 disease), to be used in conjunction with diet and exercise. The agency granted the once-daily, oral thyroid hormone receptor beta-selective agonist breakthrough therapy designation and priority review.

According to the American Liver Foundation, about 5% of adults in the US have MASH — one of the leading causes of liver transplantation in the country. There is currently no FDA-approved therapy for compensated cirrhosis caused by MASH, said Alkhouri. Patients with MASH cirrhosis with clinically significant portal hypertension (CSPH) experience major adverse liver outcomes.

In an analysis of 122 patients with Child Pugh A MASH cirrhosis who completed both a year in an open-label arm of MAESTRO-NAFLD-1 and a 1-year extension, 113 (93%) completed 2 years of treatment with resmetirom (80 mg). Of the 122 patients, only 114 received MRI proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) testing — 93 (82%) had a baseline of > 5% indicating cirrhosis, while 21 (18%) had an MRI-PDFF of < 5%.

Patients were assessed for baseline portal hypertension (Baveno VII) with FibroScan VCTE and platelet count, which was confirmed using magnetic resonance elastography (MRE). Noninvasive biomarkers and imaging were analyzed at baseline and out to 2 years.

At baseline, 63% of patients were categorized as probable/definitive CSPH (Baveno VII). At 1 year of treatment with resmetirom, 20% of patients who were CSPH positive no longer met the criteria, and at 2 years this number had increased to 28%.

After 2 years of treatment, more than half of the patients had a sustained reduction in liver stiffness of more than 25%, as measured by VCTE; and 35% of patients with confirmed F4 at baseline (liver biopsy F4 and/or platelets < 140/MRE ≥ 5 with VCTE ≥ 15) had a conversion to F3.

Patients taking resmetirom also had significant improvements in MRI-PDFF and MRE at 2 years. Almost a third of those with a baseline MRI-PDFF > 5% improved, while 43% of those with a baseline of < 5% improved.

Although 113 patients had an adverse event — primarily gastrointestinal — the observed events were consistent with previous studies. Twenty-seven patients had a serious adverse event, but none were related to the study drug, said Alkhouri. The researchers reported that only 8% of patients discontinued the medication.

Changing the Treatment Landscape for MASH-Related Cirrhosis

When asked to comment by GI & Hepatology News, Hazem Ayesh, MD, an endocrinologist at Deaconess Health System, Evansville, Indiana, said that “reversal of cirrhosis from F4 to F3 and reduction of portal hypertension are quite surprising, since cirrhosis typically progresses slowly.”

Ayesh said it was notable that the researchers had used imaging to confirm both functional and hemodynamic improvements in liver architecture not just biochemical changes. Given the results, “clinicians may reasonably consider off-label use in selected compensated patients until more outcome data become available,” he said.

A phase 3 study is underway to examine those outcomes, MAESTRO-NASH OUTCOMES, with 845 patients with MASH cirrhosis, and should be completed in 2027.

“Resmetirom could change the treatment landscape for MASH-related cirrhosis,” said Ayesh, adding, “this drug offers a chance to target the disease process itself,” while other therapies focus on preventing complications.

“For patients without access to liver transplant, a therapy that can slow or reverse disease progression could be transformative,” he told GI & Hepatology News.

Alkhouri disclosed that he is a consultant and speaker for Madrigal Pharmaceuticals. Three coauthors are Madrigal employees and own stock options in the company. Two coauthors are Madrigal consultants and advisers. Ayesh reported no conflicts.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACG 2025

The Litter Olympics: Addressing Individual Critical Tasks Lists Requirements in a Forward-Deployed Setting

The Litter Olympics: Addressing Individual Critical Tasks Lists Requirements in a Forward-Deployed Setting

Military medical personnel rely on individual critical tasks lists (ICTLs) to maintain proficiency in essential medical skills during deployments. However, sustaining these competencies in a low-casualty operational setting presents unique challenges. Traditional training methods, such as lectures or simulations outside operational contexts, may lack engagement and fail to replicate the stressors of real-world scenarios. Previous research has emphasized the importance of continuous medical readiness training in austere environments, highlighting the need for innovative approaches.1,2

The Litter Olympics was developed as an in-theater training exercise designed to enhance medical readiness, foster interdisciplinary teamwork, and incorporate physical exertion into skill maintenance. By requiring teams to carry a patient litter through multiple “events,” the exercise reinforced teamwork within a medical readiness-focused series inspired by an Olympic decathlon. This article discusses the feasibility, effectiveness, and potential impact of the Litter Olympics as a training tool for maintaining ICTLs in a deployed environment.

Program

The Litter Olympics were implemented at a Role 3 medical facility in Baghdad, Iraq, where teams composed of individuals from military occupational specialties (MOSs) and areas of concentration (AOCs) participated. Role 3 facilities provide specialty surgical and critical care capabilities, enabling a robust medical training environment.3 The event was designed to reflect the interdisciplinary nature of deployed medical teams and incorporated hands-on training stations covering critical medical skills such as traction splinting, spinal precautions, patient movement, hemorrhage control, airway management, and tactical evacuation procedures.

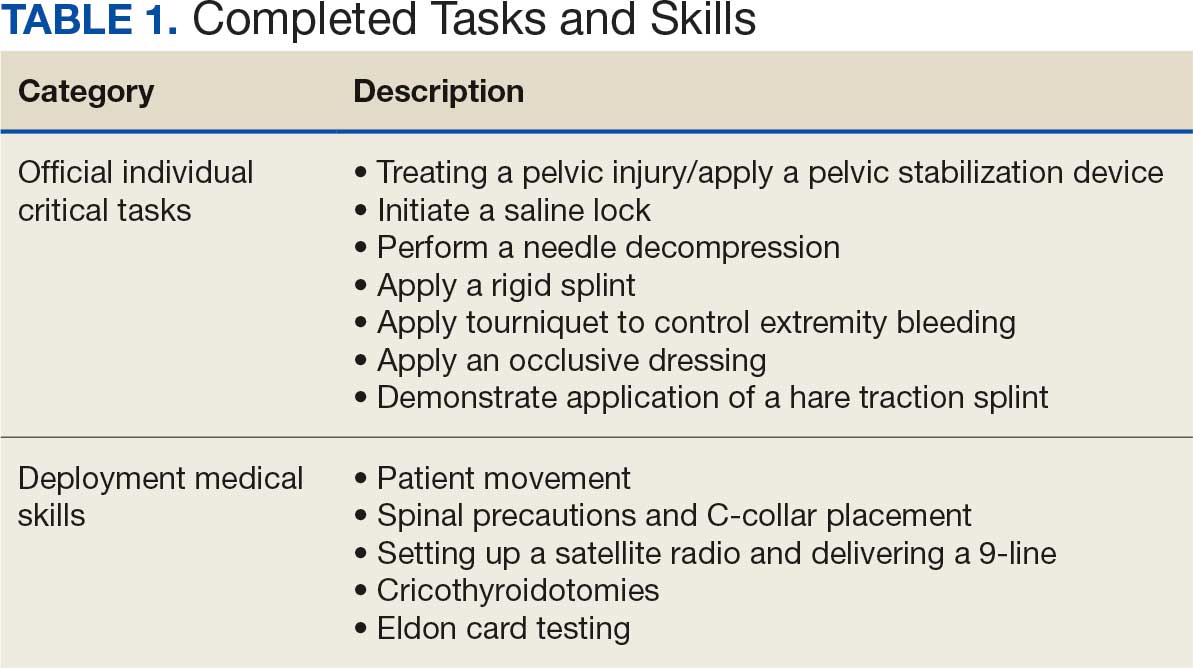

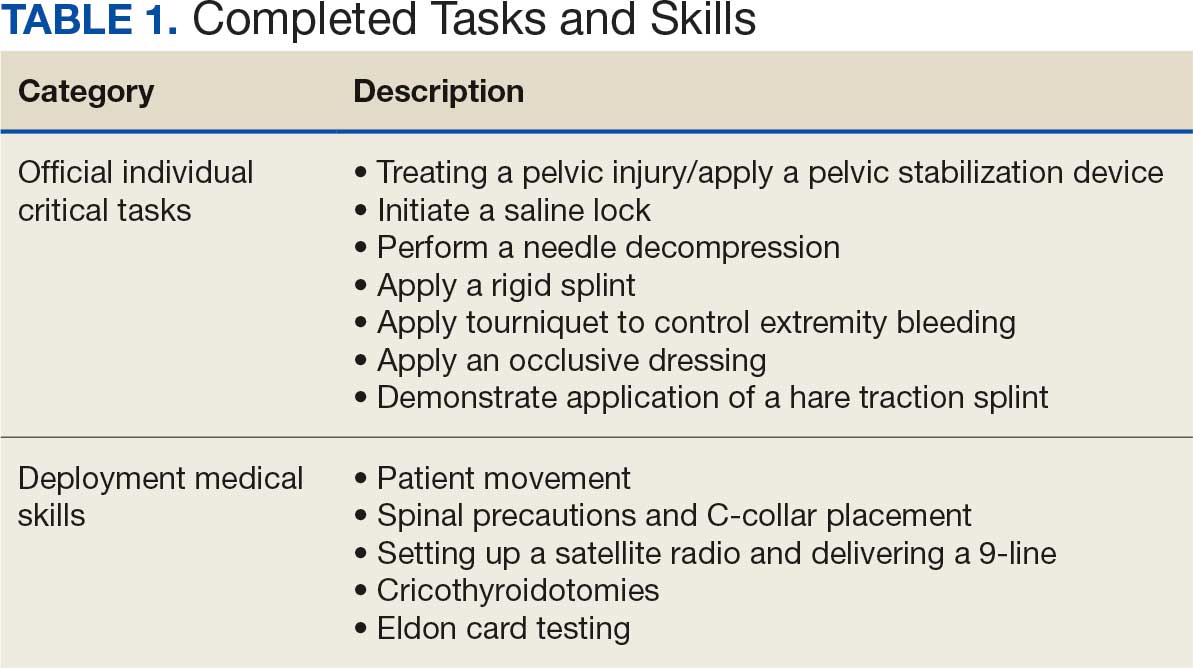

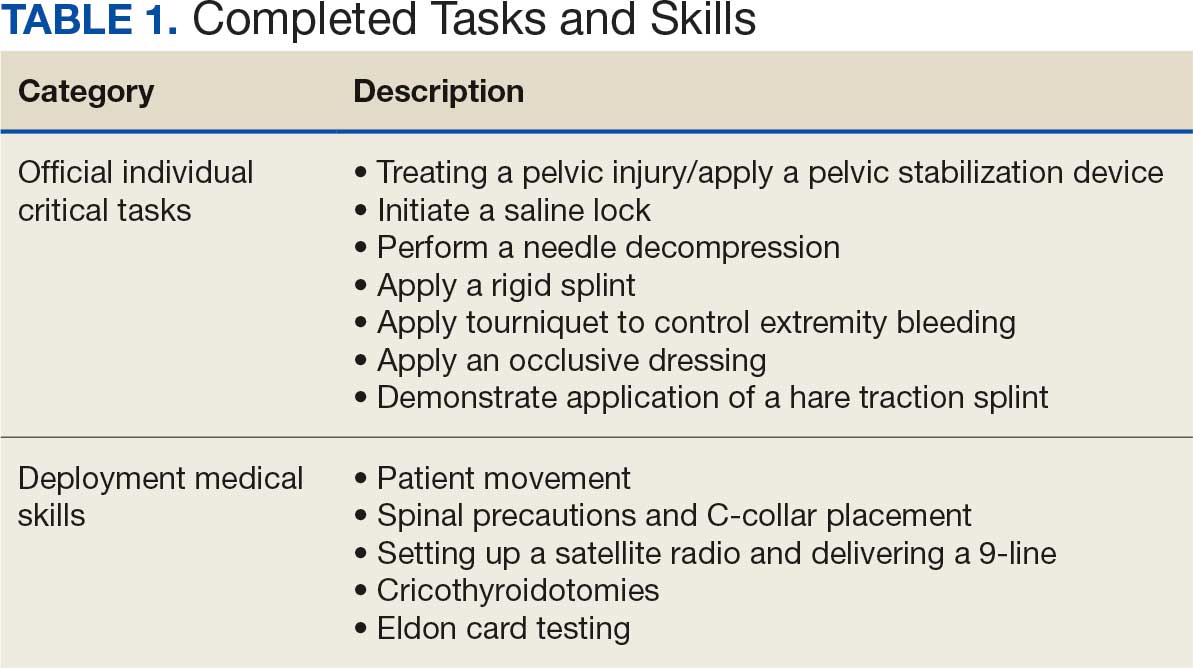

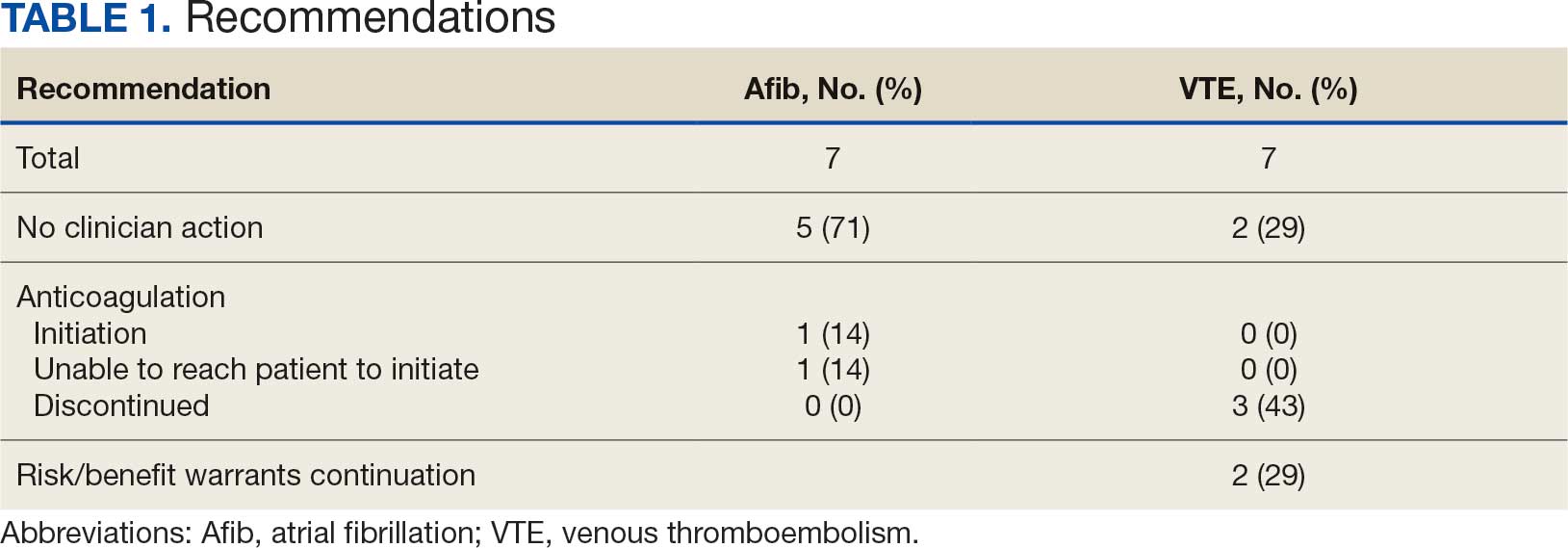

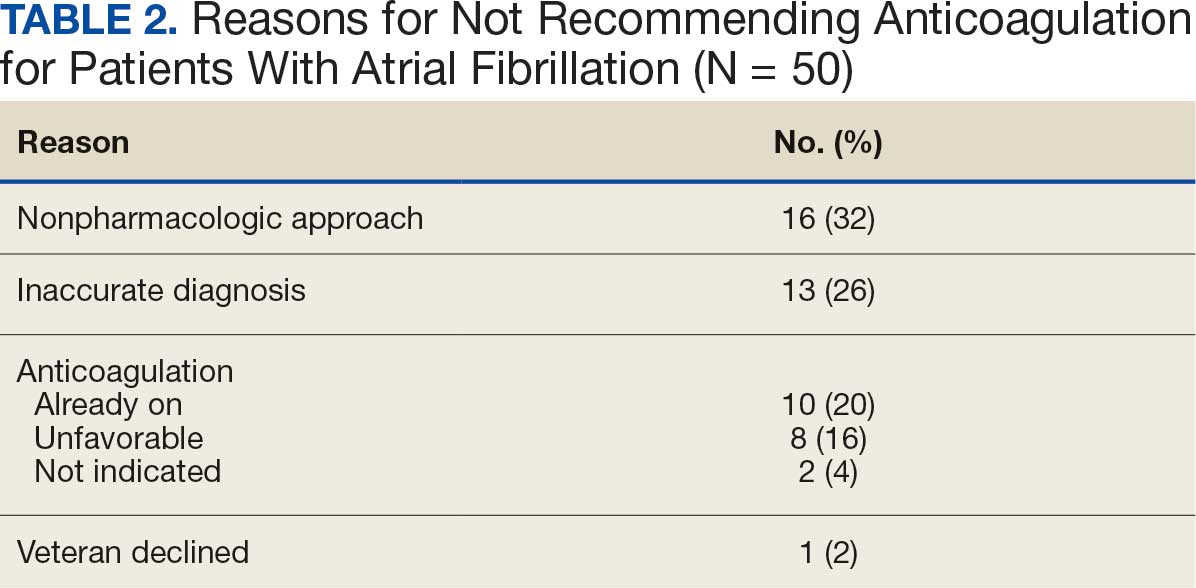

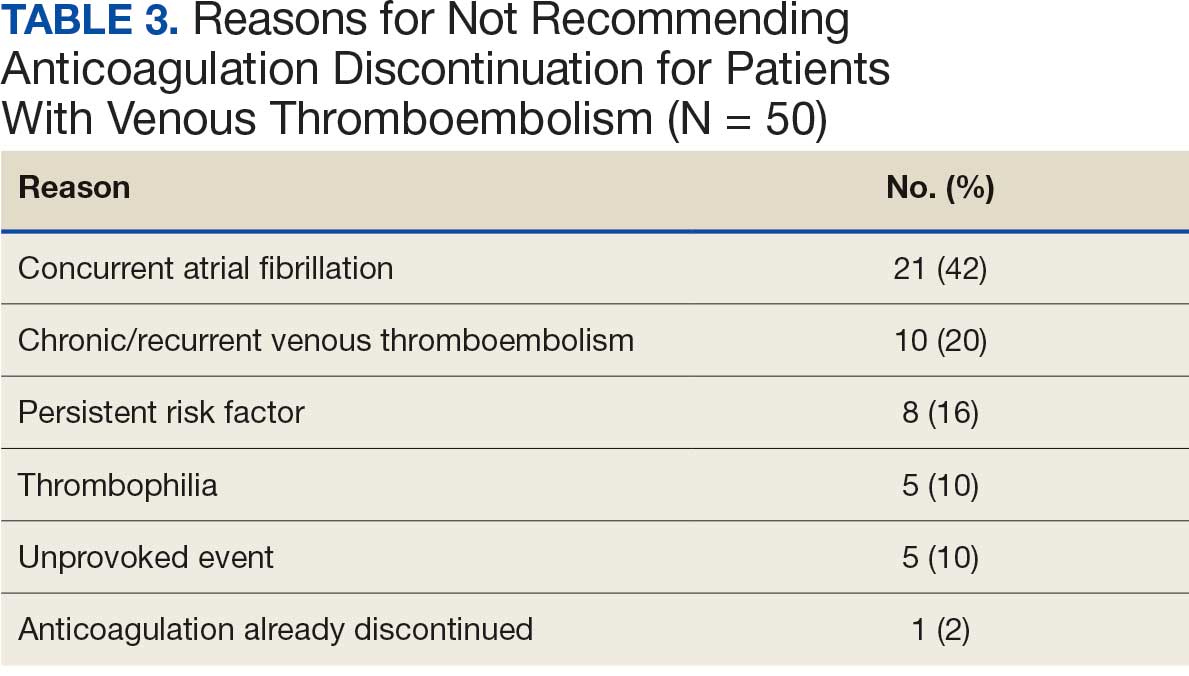

Tasks were selected based on their relevance to deployed medical care and their inclusion in ICTLs, ensuring alignment with mission-essential skills. Participants were evaluated on task completion, efficiency, and teamwork by experienced medical personnel. Postexercise surveys assessed skill improvement, confidence levels, and areas for refinement. Future studies should incorporate structured performance metrics, such as pre- and postevent evaluations, to quantify proficiency gains (Table 1).

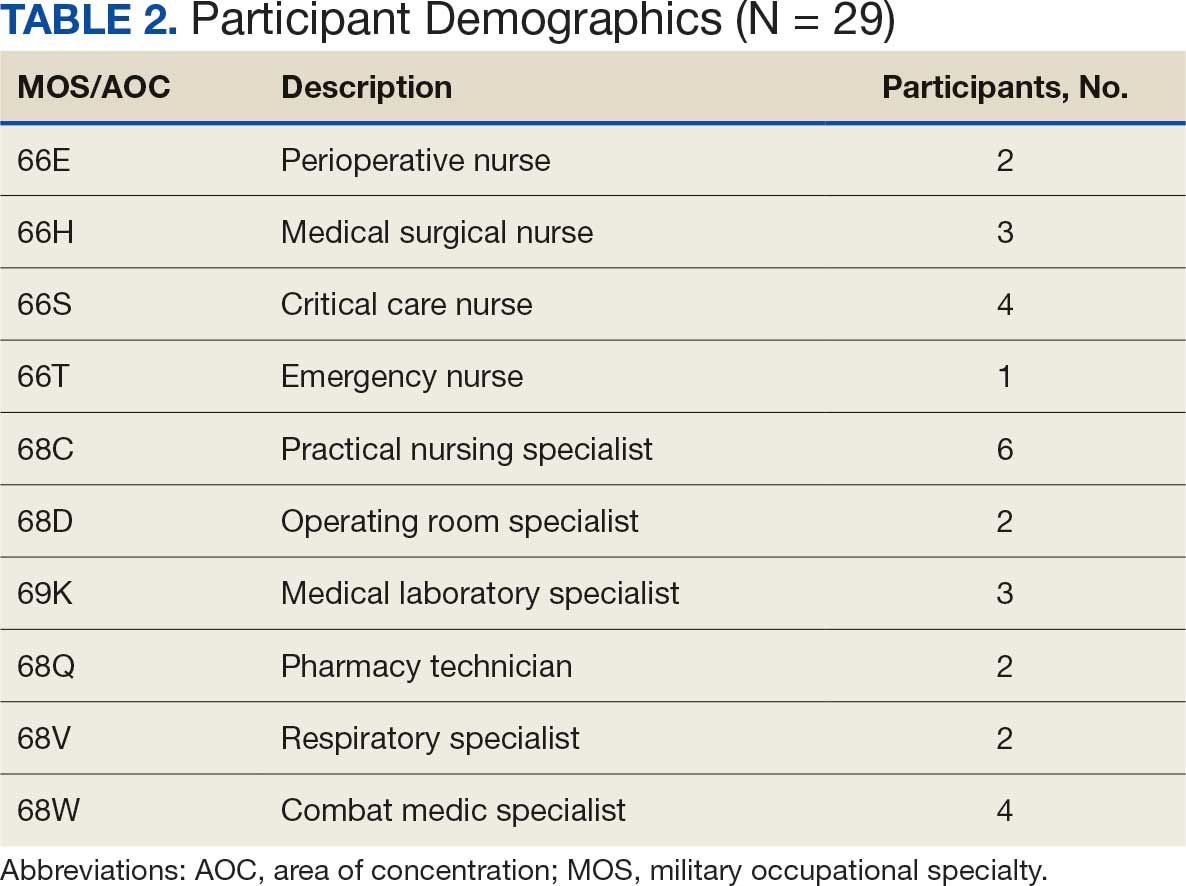

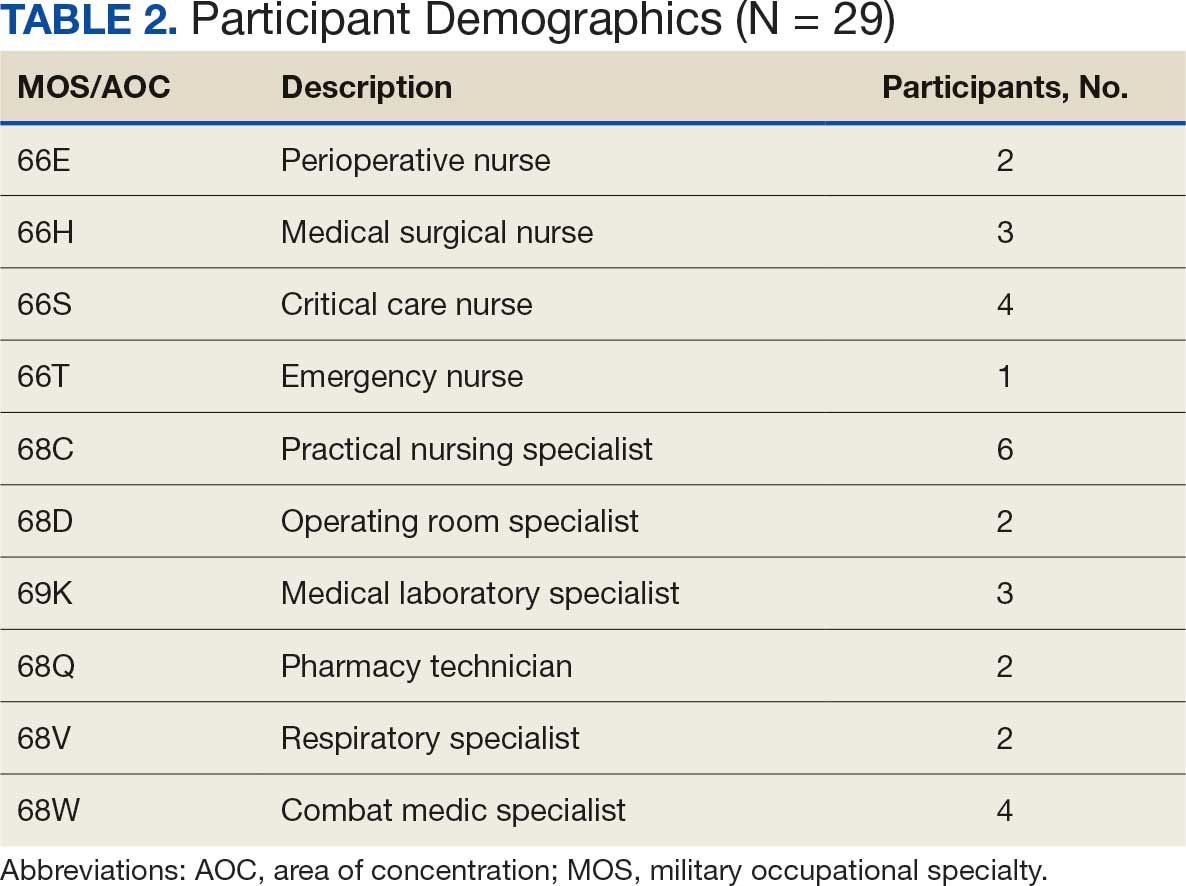

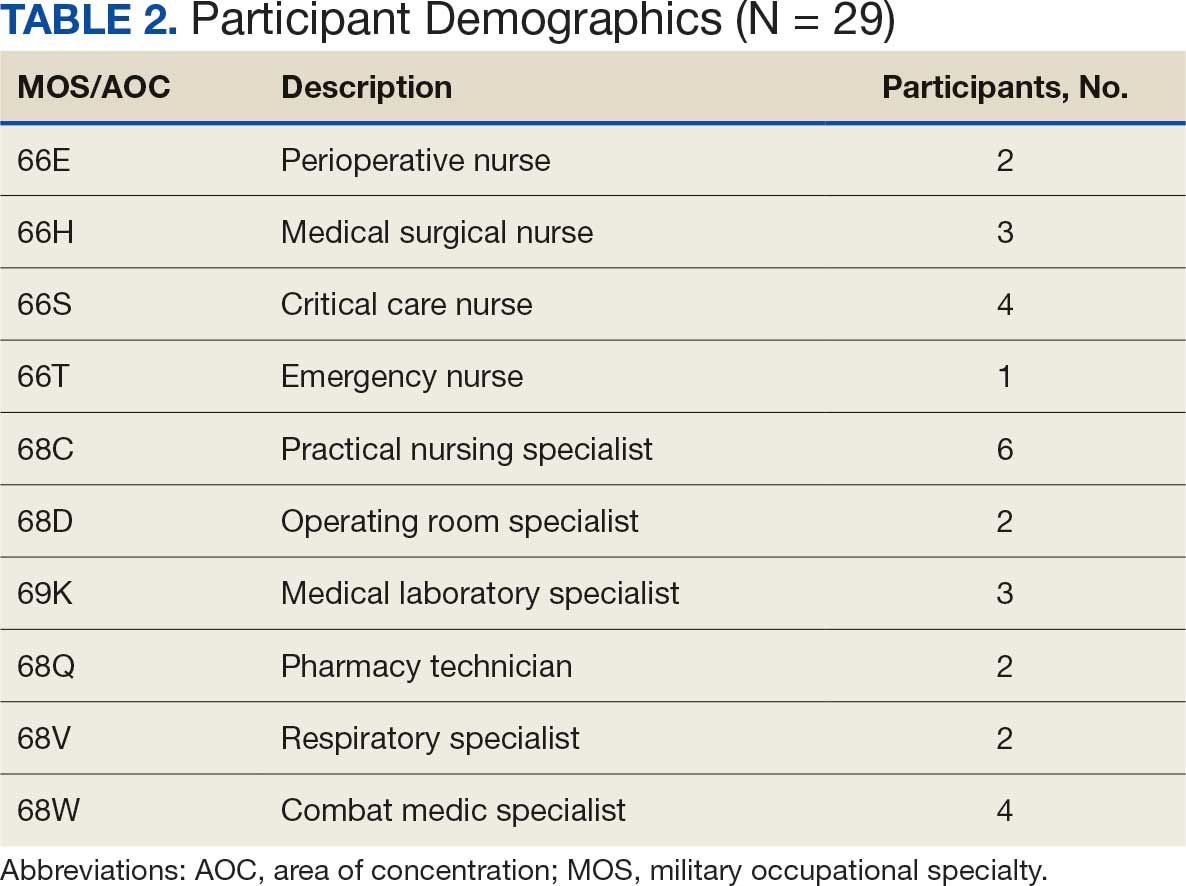

Five mixed MOS/AOC teams participated in the event, completing the exercise in an average time of 50 minutes (Table 2). Participants reported increased confidence in performing ICTs, particularly in patient movement, hemorrhage control, and airway management. The interdisciplinary nature of the teams facilitated peer teaching and cross-training, allowing individuals to better understand each other’s roles and responsibilities. This mirrors findings in previous studies on predeployment training that emphasize the importance of collaborative, hands-on learning.4 The physical aspect of the exercise was well received, as it simulated operational conditions and reinforced endurance in high-stress environments. Some tasks, such as cricothyroidotomy and satellite radio setup, required additional instruction, highlighting areas for improvement in future iterations.

Discussion

The Litter Olympics provide a dynamic alternative to traditional classroom instruction by integrating realistic, scenario-based training. However, several limitations were identified. The most significant was the lack of formalized outcome metrics. While qualitative feedback was overwhelmingly positive, no structured performance assessment tool, such as pre- and postevent skill evaluations, was used. Future studies should incorporate objective measures of competency to strengthen the evidence base for this training model. Additionally, participant feedback suggested that more structured debriefing sessions postexercise would enhance learning retention and provide actionable insights for future program modifications.

Another consideration is the scalability and adaptability of the exercise. While effective in a Role 3 setting, modifications may be required for smaller units or lower levels of care. Future iterations could adapt the format for Role 1 or 2 environments by reducing the number of stations while preserving the core training elements. Furthermore, the event relied on access to specialized personnel and equipment, which may not always be feasible in austere settings. Developing a streamlined version focusing on essential tasks could improve accessibility and sustainability across different operational environments.

Participants expressed a preference for this hands-on, competitive training model over traditional didactic instruction. However, further research should compare skill retention rates between the Litter Olympics and other training modalities to validate effectiveness. While peer teaching was a notable strength of the event, structured mentorship from senior medical personnel could further enhance skill acquisition and reinforce best practices.

Conclusions

The Litter Olympics present a reproducible, engaging, and effective method for sustaining medical readiness in a deployed Role 3 setting. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and incorporating physical and cognitive stressors, it enhances both individual and team preparedness. Future research should develop standardized, measurable outcome assessments, explore application in diverse deployment settings, and optimize scalability for broader military medical training programs. Standardized evaluation tools should be developed to quantify performance improvements, and the training model should be expanded to include lower levels of care and nonmedical personnel. Structured debriefing sessions would also provide valuable insight into lessons learned and potential refinements. By integrating these enhancements, the Litter Olympics can serve as a cornerstone for maintaining operational medical readiness in deployed environments.

- Suresh MR, Valdez-Delgado KK, Staudt AM, et al. An assessment of pre-deployment training for army nurses and medics. Mil Med. 2021;186:203-211. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa291

- Mead KC, Tennent DJ, Stinner DJ. The importance of medical readiness training exercises: maintaining medical readiness in a low-volume combat casualty flow era. Mil Med. 2017;182:e1734-e1737. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-16-00335

- Brisebois R, Hennecke P, Kao R, et al. The Role 3 multinational medical nit at Kandahar airfield 2005–2010. Can J Surg. 2011;54:S124-S129. doi:10.1503/cjs.024811

- Huh J, Brockmeyer JR, Bertsch SR, et al. Conducting pre-deployment training in Honduras: the 240th forward resuscitative surgical team experience. Mil Med. 2021;187:e690-e695. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa545

Military medical personnel rely on individual critical tasks lists (ICTLs) to maintain proficiency in essential medical skills during deployments. However, sustaining these competencies in a low-casualty operational setting presents unique challenges. Traditional training methods, such as lectures or simulations outside operational contexts, may lack engagement and fail to replicate the stressors of real-world scenarios. Previous research has emphasized the importance of continuous medical readiness training in austere environments, highlighting the need for innovative approaches.1,2

The Litter Olympics was developed as an in-theater training exercise designed to enhance medical readiness, foster interdisciplinary teamwork, and incorporate physical exertion into skill maintenance. By requiring teams to carry a patient litter through multiple “events,” the exercise reinforced teamwork within a medical readiness-focused series inspired by an Olympic decathlon. This article discusses the feasibility, effectiveness, and potential impact of the Litter Olympics as a training tool for maintaining ICTLs in a deployed environment.

Program

The Litter Olympics were implemented at a Role 3 medical facility in Baghdad, Iraq, where teams composed of individuals from military occupational specialties (MOSs) and areas of concentration (AOCs) participated. Role 3 facilities provide specialty surgical and critical care capabilities, enabling a robust medical training environment.3 The event was designed to reflect the interdisciplinary nature of deployed medical teams and incorporated hands-on training stations covering critical medical skills such as traction splinting, spinal precautions, patient movement, hemorrhage control, airway management, and tactical evacuation procedures.

Tasks were selected based on their relevance to deployed medical care and their inclusion in ICTLs, ensuring alignment with mission-essential skills. Participants were evaluated on task completion, efficiency, and teamwork by experienced medical personnel. Postexercise surveys assessed skill improvement, confidence levels, and areas for refinement. Future studies should incorporate structured performance metrics, such as pre- and postevent evaluations, to quantify proficiency gains (Table 1).

Five mixed MOS/AOC teams participated in the event, completing the exercise in an average time of 50 minutes (Table 2). Participants reported increased confidence in performing ICTs, particularly in patient movement, hemorrhage control, and airway management. The interdisciplinary nature of the teams facilitated peer teaching and cross-training, allowing individuals to better understand each other’s roles and responsibilities. This mirrors findings in previous studies on predeployment training that emphasize the importance of collaborative, hands-on learning.4 The physical aspect of the exercise was well received, as it simulated operational conditions and reinforced endurance in high-stress environments. Some tasks, such as cricothyroidotomy and satellite radio setup, required additional instruction, highlighting areas for improvement in future iterations.

Discussion

The Litter Olympics provide a dynamic alternative to traditional classroom instruction by integrating realistic, scenario-based training. However, several limitations were identified. The most significant was the lack of formalized outcome metrics. While qualitative feedback was overwhelmingly positive, no structured performance assessment tool, such as pre- and postevent skill evaluations, was used. Future studies should incorporate objective measures of competency to strengthen the evidence base for this training model. Additionally, participant feedback suggested that more structured debriefing sessions postexercise would enhance learning retention and provide actionable insights for future program modifications.

Another consideration is the scalability and adaptability of the exercise. While effective in a Role 3 setting, modifications may be required for smaller units or lower levels of care. Future iterations could adapt the format for Role 1 or 2 environments by reducing the number of stations while preserving the core training elements. Furthermore, the event relied on access to specialized personnel and equipment, which may not always be feasible in austere settings. Developing a streamlined version focusing on essential tasks could improve accessibility and sustainability across different operational environments.

Participants expressed a preference for this hands-on, competitive training model over traditional didactic instruction. However, further research should compare skill retention rates between the Litter Olympics and other training modalities to validate effectiveness. While peer teaching was a notable strength of the event, structured mentorship from senior medical personnel could further enhance skill acquisition and reinforce best practices.

Conclusions

The Litter Olympics present a reproducible, engaging, and effective method for sustaining medical readiness in a deployed Role 3 setting. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and incorporating physical and cognitive stressors, it enhances both individual and team preparedness. Future research should develop standardized, measurable outcome assessments, explore application in diverse deployment settings, and optimize scalability for broader military medical training programs. Standardized evaluation tools should be developed to quantify performance improvements, and the training model should be expanded to include lower levels of care and nonmedical personnel. Structured debriefing sessions would also provide valuable insight into lessons learned and potential refinements. By integrating these enhancements, the Litter Olympics can serve as a cornerstone for maintaining operational medical readiness in deployed environments.

Military medical personnel rely on individual critical tasks lists (ICTLs) to maintain proficiency in essential medical skills during deployments. However, sustaining these competencies in a low-casualty operational setting presents unique challenges. Traditional training methods, such as lectures or simulations outside operational contexts, may lack engagement and fail to replicate the stressors of real-world scenarios. Previous research has emphasized the importance of continuous medical readiness training in austere environments, highlighting the need for innovative approaches.1,2

The Litter Olympics was developed as an in-theater training exercise designed to enhance medical readiness, foster interdisciplinary teamwork, and incorporate physical exertion into skill maintenance. By requiring teams to carry a patient litter through multiple “events,” the exercise reinforced teamwork within a medical readiness-focused series inspired by an Olympic decathlon. This article discusses the feasibility, effectiveness, and potential impact of the Litter Olympics as a training tool for maintaining ICTLs in a deployed environment.

Program

The Litter Olympics were implemented at a Role 3 medical facility in Baghdad, Iraq, where teams composed of individuals from military occupational specialties (MOSs) and areas of concentration (AOCs) participated. Role 3 facilities provide specialty surgical and critical care capabilities, enabling a robust medical training environment.3 The event was designed to reflect the interdisciplinary nature of deployed medical teams and incorporated hands-on training stations covering critical medical skills such as traction splinting, spinal precautions, patient movement, hemorrhage control, airway management, and tactical evacuation procedures.

Tasks were selected based on their relevance to deployed medical care and their inclusion in ICTLs, ensuring alignment with mission-essential skills. Participants were evaluated on task completion, efficiency, and teamwork by experienced medical personnel. Postexercise surveys assessed skill improvement, confidence levels, and areas for refinement. Future studies should incorporate structured performance metrics, such as pre- and postevent evaluations, to quantify proficiency gains (Table 1).

Five mixed MOS/AOC teams participated in the event, completing the exercise in an average time of 50 minutes (Table 2). Participants reported increased confidence in performing ICTs, particularly in patient movement, hemorrhage control, and airway management. The interdisciplinary nature of the teams facilitated peer teaching and cross-training, allowing individuals to better understand each other’s roles and responsibilities. This mirrors findings in previous studies on predeployment training that emphasize the importance of collaborative, hands-on learning.4 The physical aspect of the exercise was well received, as it simulated operational conditions and reinforced endurance in high-stress environments. Some tasks, such as cricothyroidotomy and satellite radio setup, required additional instruction, highlighting areas for improvement in future iterations.

Discussion

The Litter Olympics provide a dynamic alternative to traditional classroom instruction by integrating realistic, scenario-based training. However, several limitations were identified. The most significant was the lack of formalized outcome metrics. While qualitative feedback was overwhelmingly positive, no structured performance assessment tool, such as pre- and postevent skill evaluations, was used. Future studies should incorporate objective measures of competency to strengthen the evidence base for this training model. Additionally, participant feedback suggested that more structured debriefing sessions postexercise would enhance learning retention and provide actionable insights for future program modifications.

Another consideration is the scalability and adaptability of the exercise. While effective in a Role 3 setting, modifications may be required for smaller units or lower levels of care. Future iterations could adapt the format for Role 1 or 2 environments by reducing the number of stations while preserving the core training elements. Furthermore, the event relied on access to specialized personnel and equipment, which may not always be feasible in austere settings. Developing a streamlined version focusing on essential tasks could improve accessibility and sustainability across different operational environments.

Participants expressed a preference for this hands-on, competitive training model over traditional didactic instruction. However, further research should compare skill retention rates between the Litter Olympics and other training modalities to validate effectiveness. While peer teaching was a notable strength of the event, structured mentorship from senior medical personnel could further enhance skill acquisition and reinforce best practices.

Conclusions

The Litter Olympics present a reproducible, engaging, and effective method for sustaining medical readiness in a deployed Role 3 setting. By fostering interdisciplinary collaboration and incorporating physical and cognitive stressors, it enhances both individual and team preparedness. Future research should develop standardized, measurable outcome assessments, explore application in diverse deployment settings, and optimize scalability for broader military medical training programs. Standardized evaluation tools should be developed to quantify performance improvements, and the training model should be expanded to include lower levels of care and nonmedical personnel. Structured debriefing sessions would also provide valuable insight into lessons learned and potential refinements. By integrating these enhancements, the Litter Olympics can serve as a cornerstone for maintaining operational medical readiness in deployed environments.

- Suresh MR, Valdez-Delgado KK, Staudt AM, et al. An assessment of pre-deployment training for army nurses and medics. Mil Med. 2021;186:203-211. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa291

- Mead KC, Tennent DJ, Stinner DJ. The importance of medical readiness training exercises: maintaining medical readiness in a low-volume combat casualty flow era. Mil Med. 2017;182:e1734-e1737. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-16-00335

- Brisebois R, Hennecke P, Kao R, et al. The Role 3 multinational medical nit at Kandahar airfield 2005–2010. Can J Surg. 2011;54:S124-S129. doi:10.1503/cjs.024811

- Huh J, Brockmeyer JR, Bertsch SR, et al. Conducting pre-deployment training in Honduras: the 240th forward resuscitative surgical team experience. Mil Med. 2021;187:e690-e695. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa545

- Suresh MR, Valdez-Delgado KK, Staudt AM, et al. An assessment of pre-deployment training for army nurses and medics. Mil Med. 2021;186:203-211. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa291

- Mead KC, Tennent DJ, Stinner DJ. The importance of medical readiness training exercises: maintaining medical readiness in a low-volume combat casualty flow era. Mil Med. 2017;182:e1734-e1737. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-16-00335

- Brisebois R, Hennecke P, Kao R, et al. The Role 3 multinational medical nit at Kandahar airfield 2005–2010. Can J Surg. 2011;54:S124-S129. doi:10.1503/cjs.024811

- Huh J, Brockmeyer JR, Bertsch SR, et al. Conducting pre-deployment training in Honduras: the 240th forward resuscitative surgical team experience. Mil Med. 2021;187:e690-e695. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa545

The Litter Olympics: Addressing Individual Critical Tasks Lists Requirements in a Forward-Deployed Setting

The Litter Olympics: Addressing Individual Critical Tasks Lists Requirements in a Forward-Deployed Setting

Patients With a Positive FIT Fail to Get Follow-Up Colonoscopies

PHOENIX — Patients with or without polyp removal in an index colonoscopy commonly receive follow-up surveillance with a fecal immunochemical test (FIT), yet many of these patients do not receive a recommended colonoscopy after a positive FIT.

“In this large US study, we found interval FITs are frequently performed in patients with and without prior polypectomy,” said first author Natalie J. Wilson, MD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, while presenting the findings at the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting.

“ and colorectal cancer, regardless of polypectomy history,” Wilson said.

Guideline recommendations stress the need for follow-up surveillance with a colonoscopy, particularly in patients who have had a prior polypectomy, because of the higher risk.

Reasons patients may instead turn to FIT may include cost or other factors, she said.

To determine just how often that happens, how having a previous polypectomy affects FIT results, and how adherent patients are to follow up if a FIT result is positive, Wilson and her colleagues evaluated data from nearly 4.8 million individuals in the Veterans Health Administration Corporate Data Warehouse who underwent colonoscopy between 2000 and 2024.

Of the patients, 10.9% were found to have subsequently received interval FIT within 10 years of the index colonoscopy, and of those patients, nearly half (49.9%) had received a polypectomy at the index colonoscopy.

The average time from the colonoscopy/polypectomy to the interval FIT was 5.9 years (5.6 years in the polypectomy group vs 6.2 years in the non-polypectomy group).

Among the FIT screenings, results were positive in 17.2% of post-polypectomy patients and 14.1% of patients with no prior polypectomy, indicating a history of polypectomy to be predictive of a positive interval FIT (odds ratio [OR], 1.12; P < .0001).

Notably, while a follow-up colonoscopy is considered essential following a positive FIT result — and having a previous polypectomy should add further urgency to the matter — the study showed only 50.4% of those who had an earlier polypectomy went on to receive the recommended follow-up colonoscopy after a positive follow-up FIT, and the rate was 49.3% among those who had not received a polypectomy (P = .001).

For those who did receive a follow-up colonoscopy after a positive FIT, the duration of time to receiving the colonoscopy was longer among those who had a prior polypectomy, at 2.9 months compared with 2.5 months in the non-polypectomy group (P < .001).

Colonoscopy results following a positive FIT showed higher rates of detections among patients who had prior polypectomies than among those with no prior polypectomy, including tubular adenomas (54.7% vs 45.8%), tubulovillous adenomas (5.6% vs 4.7%), adenomas with high-grade dysplasia (0.8% vs 0.7%), sessile serrated lesions (3.52% vs 2.4%), advanced colorectal neoplasia (9.2% vs 7.9%), and colorectal cancer (3.3% vs 3.0%).

However, a prior polypectomy was not independently predictive of colorectal cancer (OR, 0.96; P = .65) or advanced colorectal neoplasia (OR, 0.97; P = .57) in the post-colonoscopy interval FIT.

The findings underscore that “positive results carried a high risk of advanced neoplasia or cancer, irrespective of prior polypectomy history,” Wilson said.

Clinicians Must ‘Do a Better Job’

Commenting on the study, William D. Chey, MD, AGAF, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, noted that the study “addresses one of the biggest challenges we face as a profession, which is making sure that patients who have a positive stool test get a colonoscopy.”

He noted that the low rate of just 50% of recipients of positive FITs going on to receive a colonoscopy is consistent with what is observed in other trials.

“Other data suggests that the rate might even be significantly higher — at 70%-80%, depending upon the population and the test,” Chey told Medscape Medical News.

Reasons for the failure to receive the follow-up testing range from income restrictions (due to the high cost of a colonoscopy, especially if not covered by insurance), education, speaking a foreign language, and other factors, he said.

The relatively high rates of colon cancers detected by FIT in the study, in those with and without a prior polypectomy, along with findings from other studies “should raise questions about whether there might be a role for FIT testing in addition to colonoscopy.” However, much stronger evidence would be needed, Chey noted.

In the meantime, a key issue is “how do we do a better job of making sure that individuals who have a positive FIT test get a colonoscopy,” he said.

“I think a lot of this is going to come down to how it’s done at the primary care level.”

Chey added that in that, and any other setting, “the main message that needs to get out to people who are undergoing stool-based screening is that the stool test is only the first part of the screening process, and if it’s positive, a follow-up colonoscopy must be performed.”

“Otherwise, the stool-based test is of no value.”

Wilson had no disclosures to report. Chey’s disclosures included consulting and/or other relationships with Ardelyx, Atmo, Biomerica, Commonwealth Diagnostics International, Corprata, Dieta, Evinature, Food Marble, Gemelli, Kiwi BioScience, Modify Health, Nestlé, Phathom, Redhill, Salix/Valeant, Takeda, and Vibrant.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

PHOENIX — Patients with or without polyp removal in an index colonoscopy commonly receive follow-up surveillance with a fecal immunochemical test (FIT), yet many of these patients do not receive a recommended colonoscopy after a positive FIT.

“In this large US study, we found interval FITs are frequently performed in patients with and without prior polypectomy,” said first author Natalie J. Wilson, MD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, while presenting the findings at the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting.

“ and colorectal cancer, regardless of polypectomy history,” Wilson said.

Guideline recommendations stress the need for follow-up surveillance with a colonoscopy, particularly in patients who have had a prior polypectomy, because of the higher risk.

Reasons patients may instead turn to FIT may include cost or other factors, she said.

To determine just how often that happens, how having a previous polypectomy affects FIT results, and how adherent patients are to follow up if a FIT result is positive, Wilson and her colleagues evaluated data from nearly 4.8 million individuals in the Veterans Health Administration Corporate Data Warehouse who underwent colonoscopy between 2000 and 2024.

Of the patients, 10.9% were found to have subsequently received interval FIT within 10 years of the index colonoscopy, and of those patients, nearly half (49.9%) had received a polypectomy at the index colonoscopy.

The average time from the colonoscopy/polypectomy to the interval FIT was 5.9 years (5.6 years in the polypectomy group vs 6.2 years in the non-polypectomy group).

Among the FIT screenings, results were positive in 17.2% of post-polypectomy patients and 14.1% of patients with no prior polypectomy, indicating a history of polypectomy to be predictive of a positive interval FIT (odds ratio [OR], 1.12; P < .0001).

Notably, while a follow-up colonoscopy is considered essential following a positive FIT result — and having a previous polypectomy should add further urgency to the matter — the study showed only 50.4% of those who had an earlier polypectomy went on to receive the recommended follow-up colonoscopy after a positive follow-up FIT, and the rate was 49.3% among those who had not received a polypectomy (P = .001).

For those who did receive a follow-up colonoscopy after a positive FIT, the duration of time to receiving the colonoscopy was longer among those who had a prior polypectomy, at 2.9 months compared with 2.5 months in the non-polypectomy group (P < .001).

Colonoscopy results following a positive FIT showed higher rates of detections among patients who had prior polypectomies than among those with no prior polypectomy, including tubular adenomas (54.7% vs 45.8%), tubulovillous adenomas (5.6% vs 4.7%), adenomas with high-grade dysplasia (0.8% vs 0.7%), sessile serrated lesions (3.52% vs 2.4%), advanced colorectal neoplasia (9.2% vs 7.9%), and colorectal cancer (3.3% vs 3.0%).

However, a prior polypectomy was not independently predictive of colorectal cancer (OR, 0.96; P = .65) or advanced colorectal neoplasia (OR, 0.97; P = .57) in the post-colonoscopy interval FIT.

The findings underscore that “positive results carried a high risk of advanced neoplasia or cancer, irrespective of prior polypectomy history,” Wilson said.

Clinicians Must ‘Do a Better Job’

Commenting on the study, William D. Chey, MD, AGAF, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, noted that the study “addresses one of the biggest challenges we face as a profession, which is making sure that patients who have a positive stool test get a colonoscopy.”

He noted that the low rate of just 50% of recipients of positive FITs going on to receive a colonoscopy is consistent with what is observed in other trials.

“Other data suggests that the rate might even be significantly higher — at 70%-80%, depending upon the population and the test,” Chey told Medscape Medical News.

Reasons for the failure to receive the follow-up testing range from income restrictions (due to the high cost of a colonoscopy, especially if not covered by insurance), education, speaking a foreign language, and other factors, he said.

The relatively high rates of colon cancers detected by FIT in the study, in those with and without a prior polypectomy, along with findings from other studies “should raise questions about whether there might be a role for FIT testing in addition to colonoscopy.” However, much stronger evidence would be needed, Chey noted.

In the meantime, a key issue is “how do we do a better job of making sure that individuals who have a positive FIT test get a colonoscopy,” he said.

“I think a lot of this is going to come down to how it’s done at the primary care level.”

Chey added that in that, and any other setting, “the main message that needs to get out to people who are undergoing stool-based screening is that the stool test is only the first part of the screening process, and if it’s positive, a follow-up colonoscopy must be performed.”

“Otherwise, the stool-based test is of no value.”

Wilson had no disclosures to report. Chey’s disclosures included consulting and/or other relationships with Ardelyx, Atmo, Biomerica, Commonwealth Diagnostics International, Corprata, Dieta, Evinature, Food Marble, Gemelli, Kiwi BioScience, Modify Health, Nestlé, Phathom, Redhill, Salix/Valeant, Takeda, and Vibrant.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

PHOENIX — Patients with or without polyp removal in an index colonoscopy commonly receive follow-up surveillance with a fecal immunochemical test (FIT), yet many of these patients do not receive a recommended colonoscopy after a positive FIT.

“In this large US study, we found interval FITs are frequently performed in patients with and without prior polypectomy,” said first author Natalie J. Wilson, MD, of the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, while presenting the findings at the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2025 Annual Scientific Meeting.

“ and colorectal cancer, regardless of polypectomy history,” Wilson said.

Guideline recommendations stress the need for follow-up surveillance with a colonoscopy, particularly in patients who have had a prior polypectomy, because of the higher risk.

Reasons patients may instead turn to FIT may include cost or other factors, she said.

To determine just how often that happens, how having a previous polypectomy affects FIT results, and how adherent patients are to follow up if a FIT result is positive, Wilson and her colleagues evaluated data from nearly 4.8 million individuals in the Veterans Health Administration Corporate Data Warehouse who underwent colonoscopy between 2000 and 2024.

Of the patients, 10.9% were found to have subsequently received interval FIT within 10 years of the index colonoscopy, and of those patients, nearly half (49.9%) had received a polypectomy at the index colonoscopy.

The average time from the colonoscopy/polypectomy to the interval FIT was 5.9 years (5.6 years in the polypectomy group vs 6.2 years in the non-polypectomy group).

Among the FIT screenings, results were positive in 17.2% of post-polypectomy patients and 14.1% of patients with no prior polypectomy, indicating a history of polypectomy to be predictive of a positive interval FIT (odds ratio [OR], 1.12; P < .0001).

Notably, while a follow-up colonoscopy is considered essential following a positive FIT result — and having a previous polypectomy should add further urgency to the matter — the study showed only 50.4% of those who had an earlier polypectomy went on to receive the recommended follow-up colonoscopy after a positive follow-up FIT, and the rate was 49.3% among those who had not received a polypectomy (P = .001).

For those who did receive a follow-up colonoscopy after a positive FIT, the duration of time to receiving the colonoscopy was longer among those who had a prior polypectomy, at 2.9 months compared with 2.5 months in the non-polypectomy group (P < .001).

Colonoscopy results following a positive FIT showed higher rates of detections among patients who had prior polypectomies than among those with no prior polypectomy, including tubular adenomas (54.7% vs 45.8%), tubulovillous adenomas (5.6% vs 4.7%), adenomas with high-grade dysplasia (0.8% vs 0.7%), sessile serrated lesions (3.52% vs 2.4%), advanced colorectal neoplasia (9.2% vs 7.9%), and colorectal cancer (3.3% vs 3.0%).

However, a prior polypectomy was not independently predictive of colorectal cancer (OR, 0.96; P = .65) or advanced colorectal neoplasia (OR, 0.97; P = .57) in the post-colonoscopy interval FIT.

The findings underscore that “positive results carried a high risk of advanced neoplasia or cancer, irrespective of prior polypectomy history,” Wilson said.

Clinicians Must ‘Do a Better Job’

Commenting on the study, William D. Chey, MD, AGAF, chief of the Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, noted that the study “addresses one of the biggest challenges we face as a profession, which is making sure that patients who have a positive stool test get a colonoscopy.”

He noted that the low rate of just 50% of recipients of positive FITs going on to receive a colonoscopy is consistent with what is observed in other trials.

“Other data suggests that the rate might even be significantly higher — at 70%-80%, depending upon the population and the test,” Chey told Medscape Medical News.

Reasons for the failure to receive the follow-up testing range from income restrictions (due to the high cost of a colonoscopy, especially if not covered by insurance), education, speaking a foreign language, and other factors, he said.

The relatively high rates of colon cancers detected by FIT in the study, in those with and without a prior polypectomy, along with findings from other studies “should raise questions about whether there might be a role for FIT testing in addition to colonoscopy.” However, much stronger evidence would be needed, Chey noted.

In the meantime, a key issue is “how do we do a better job of making sure that individuals who have a positive FIT test get a colonoscopy,” he said.

“I think a lot of this is going to come down to how it’s done at the primary care level.”

Chey added that in that, and any other setting, “the main message that needs to get out to people who are undergoing stool-based screening is that the stool test is only the first part of the screening process, and if it’s positive, a follow-up colonoscopy must be performed.”

“Otherwise, the stool-based test is of no value.”

Wilson had no disclosures to report. Chey’s disclosures included consulting and/or other relationships with Ardelyx, Atmo, Biomerica, Commonwealth Diagnostics International, Corprata, Dieta, Evinature, Food Marble, Gemelli, Kiwi BioScience, Modify Health, Nestlé, Phathom, Redhill, Salix/Valeant, Takeda, and Vibrant.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

FROM ACG 2025

A True Community: The Vet-to-Vet Program for Chronic Pain

A True Community: The Vet-to-Vet Program for Chronic Pain

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has continued to advance its understanding and treatment of chronic pain. The VHA National Pain Management Strategy emphasizes the significance of the social context of pain while underscoring the importance of self-management.1 This established strategy ensures that all veterans have access to the appropriate pain care in the proper setting.2 VHA has instituted a stepped care model of pain management, delineating the domains of primary care, secondary consultative services, and tertiary care.3 This directive emphasized a biopsychosocial approach to pain management to prioritize the relationship between biological, psychological, and social factors that influence how veterans experience pain and should commensurately influence how it is managed.

The VHA Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation implemented the Whole Health System of Care as part of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which included a VHA directive to expand pain management.4,5 Reorientation within this system shifts from defining veterans as passive care recipients to viewing them as active partners in their own care and health. This partnership places additional emphasis on peer-led explorations of mission, aspiration, and purpose.6

Peer-led groups, also known as mutual aid, mutual support, and mutual help groups, have historically been successful for patients undergoing treatment for substance use disorders (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous).7 Mutual help groups have 3 defining characteristics. First, they are run by participants, not professionals, though the latter may have been integral in the founding of the groups. Second, participants share a similar problem (eg, disease state, experience, disposition). Finally, there is a reciprocal exchange of information and psychological support among participants.8,9 Mutual help groups that address chronic pain are rare but becoming more common.10-12 Emerging evidence suggests a positive relationship between peer support and improved well-being, self-efficacy, pain management, and pain self-management skills (eg, activity pacing).13-15

Storytelling as a tool for healing has a long history in indigenous and Western medical traditions.16-19 This includes the treatment of chronic disease, including pain.20,21 The use of storytelling in health care overlaps with the role it plays within many mutual help groups focused on chronic disease treatment.22 Storytelling allows an individual to share their experience with a disease, and take a more active role in their health, and facilitate stronger bonds with others.22 In effect, storytelling is not only important to group cohesion—it also plays a role in an individual’s healing.

Vet-to-Vet

The VHA Office of Rural Health funds Vet-to-Vet, a peer-to-peer program to address limited access to care for rural veterans with chronic pain. Similar to the VHA National Pain Management Strategy, Vet-to-Vet is grounded in the significance of the social context of pain and underscores the importance of self-management.1 The program combines pain care, mutual help, and storytelling to support veterans living with chronic pain. While the primary focus of Vet-to-Vet is rural veterans, the program serves any veteran experiencing chronic pain who is isolated from services, including home-bound urban veterans.

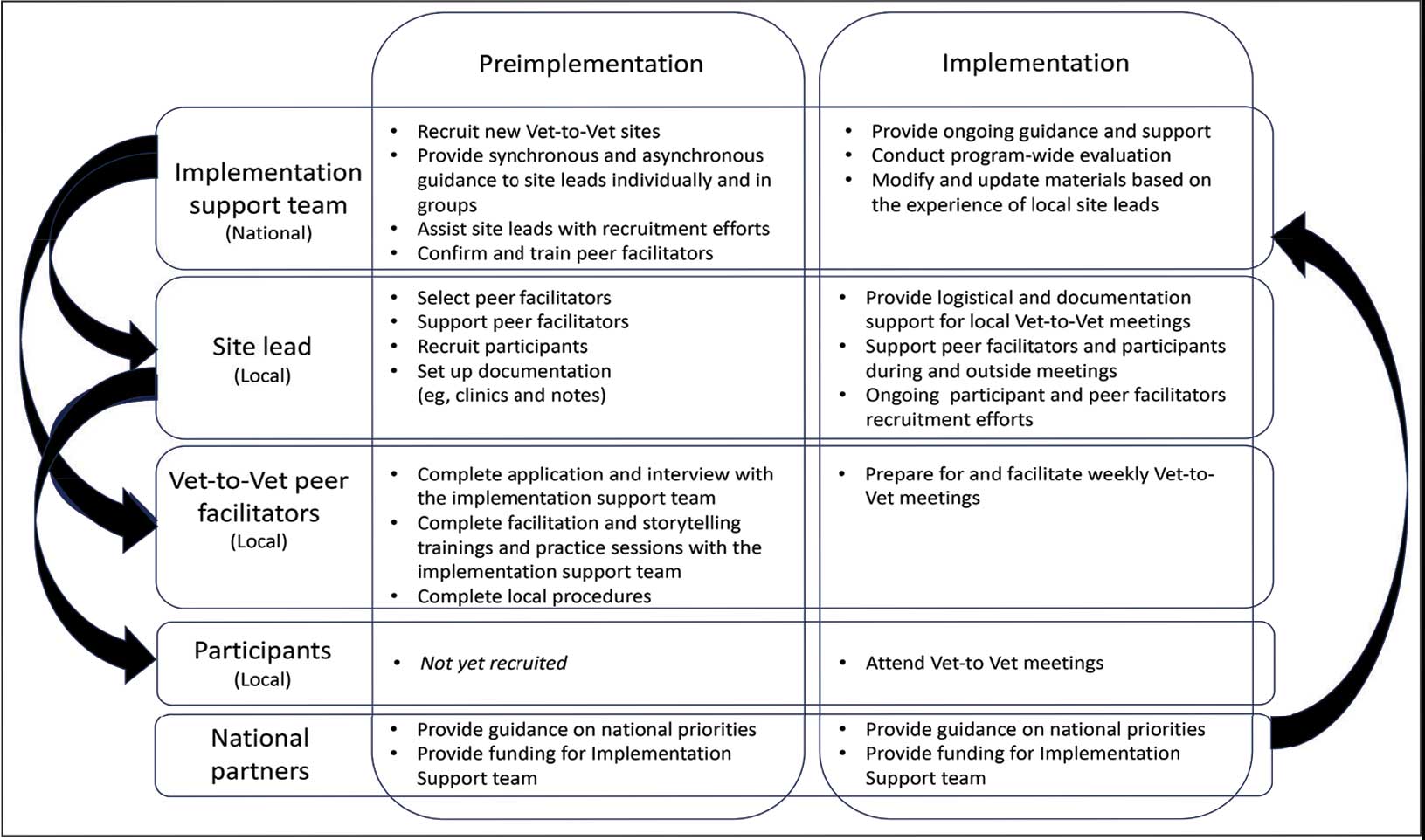

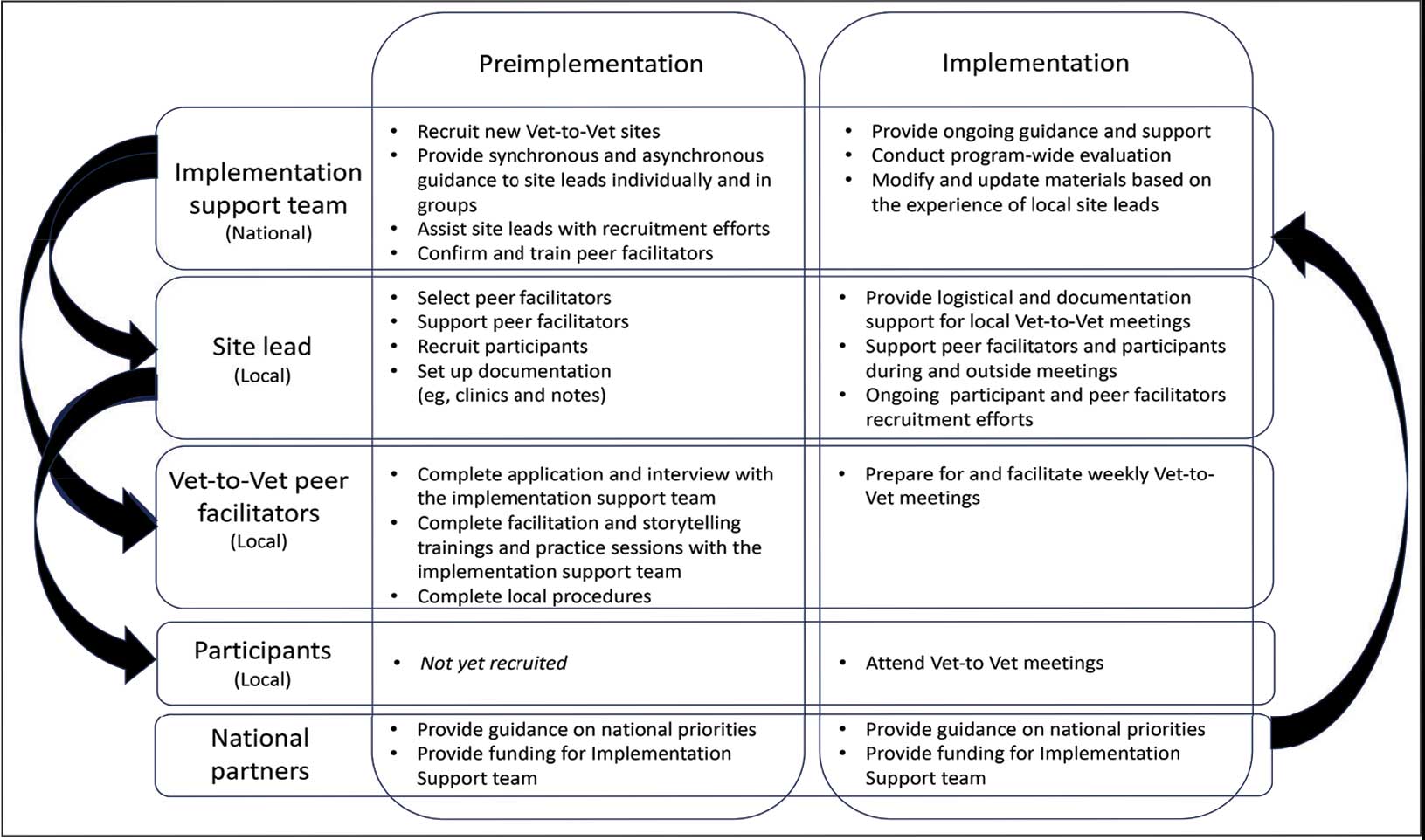

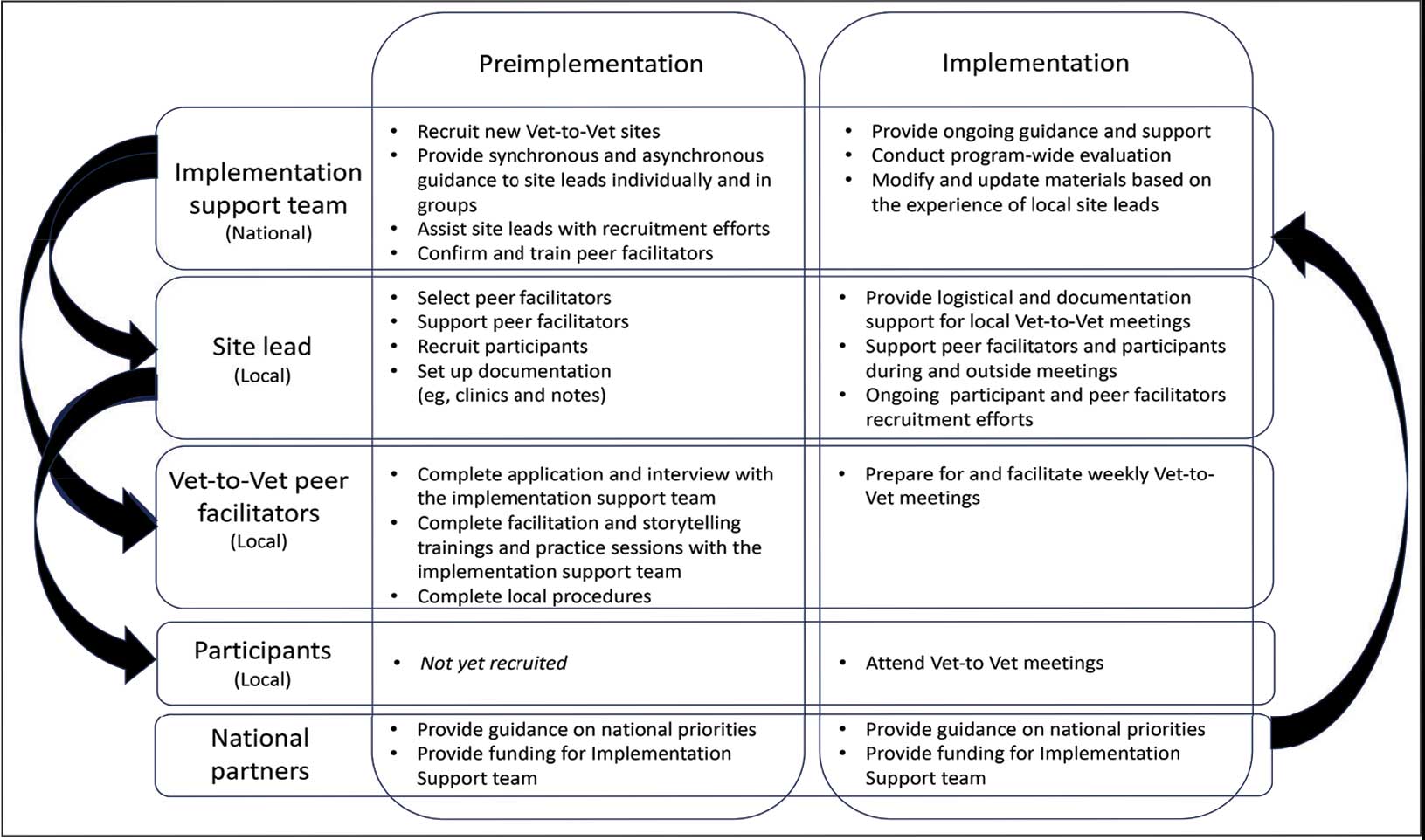

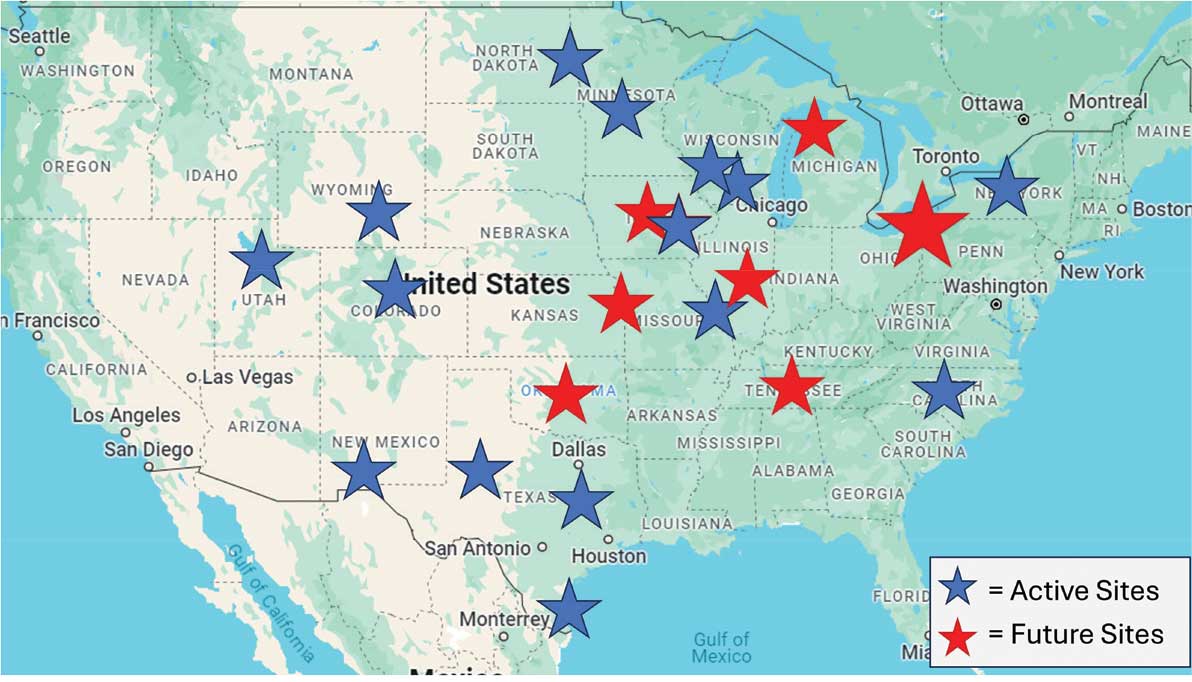

Following mutual help principles, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators lead weekly online drop-in meetings. Meetings follow the general structure of reiterating group ground rules and sharing an individual pain story, followed by open discussions centered on well-being, chronic pain management, or any topic the group wishes to discuss. Meetings typically end with a mindfulness exercise. The organizational structure that supports Vet-to-Vet includes the implementation support team, site leads, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators, and national partners (Figure 1).

Implementation Support Team

The implementation support team consists of a principal investigator, coinvestigator, program manager, and program support specialist. The team provides facilitator training, monthly community practice sessions for Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and site leads, and weekly office hours for site leads. The implementation support team also recruits new Vet-to-Vet sites; potential new locations ideally have an existing whole health program, leadership support, committed site and cosite leads, and ≥ 3 peer facilitator volunteers.

Site Leads

Most site and cosite leads are based in whole health or pain management teams and are whole health coaches or peer support specialists. The site lead is responsible for standing up the program and documenting encounters, recruiting and supporting peer facilitators and participants, and overseeing the meeting. During meetings, site leads generally leave their cameras off and only speak when called into the group; the peer facilitators lead the meetings. The implementation support team recommends that site leads dedicate ≥ 4 hours per week to Vet-to-Vet; 2 hours for weekly group meetings and 2 hours for documentation (ie, entering notes into the participants’ electronic health records) and supporting peer facilitators and participants. Cosite lead responsibilities vary by location, with some sites having 2 leads that equally share duties and others having a primary lead and a colead available if the site lead is unable to attend a meeting.

Vet-to-Vet Peer Facilitators

Peer facilitators are the core of the program. They lead meetings from start to finish. Like participants, they also experience chronic pain and are volunteers. The implementation support team encourages sites to establish volunteer peer facilitators, rather than assigning peer support specialists to facilitate meetings. Veterans are eager to connect and give back to their communities, and the Vet-to-Vet peer facilitator role is an opportunity for those unable to work to connect with peers and add meaning to their lives. Even if a VHA employee is a veteran who has chronic pain, they are not eligible to serve as this could create a service provider/service recipient dynamic that is not in the spirit of mutual help.

Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators attend a virtual 3-day training held by the implementation support team prior to starting. These training sessions are available on a quarterly basis and facilitated by the Vet-to-Vet program manager and 2 current peer facilitators. Training content includes established whole health facilitator training materials and program-specific storytelling training materials. Once trained, peer facilitators attend storytelling practice sessions and collaborate with their site leads during weekly meetings.

Participants

Vet-to-Vet participants find the program through direct outreach from site leads, word of mouth, and referrals. The only criteria to join are that the individual is a veteran who experiences chronic pain and is enrolled in the VHA (site leads can assist with enrollment if needed). Participants are not required to have a diagnosis or engage in any other health care. There is no commitment and no end date. Some participants only come once; others have attended for > 3 years. This approach is intended to embrace the idea that the need for support ebbs and flows.

National Partners

The VHA Office of Rural Health provides technical support. The Center for Development and Civic Engagement onboards peer facilitators as VHA volunteers. The Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation provides national guidance and site-level collaboration. The VHA Pain Management, Opioid Safety, and Prescription Drug Monitoring Program supports site recruitment. In addition to the VHA partners, 4 veteran evaluation consultants who have experience with chronic pain but do not participate in Vet-to-Vet meetings provide advice on evaluation activities, such as question development and communication strategies.

Evaluation

This evaluation shares preliminary results from a pilot evaluation of the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center (RMRVAMC) Vet-to-Vet group. It is intended for program improvement, was deemed nonresearch by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, and was structured using the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework.23 This evaluation focused on capturing measures related to reach and effectiveness, while a forthcoming evaluation includes elements of adoption, implementation, and maintenance.

In 2022, 16 Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and participants completed surveys and interviews to share their experience. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded in ATLAS.ti. A priori codes were based on interview guide questions and emergent descriptive codes were used to identify specific topics which were categorized into RE-AIM domains, barriers, facilitators, what participants learned, how participants applied what they learned to their lives, and participant reported outcomes. This article contains high-level findings from the evaluation; more detailed results will be included in the ongoing evaluation.

Results

The RMRVAMC Vet-to-Vet group has met weekly since April 2022. Four Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and 12 individuals participated in the pilot Vet-to-Vet group and evaluation. The mean age was 62 years, most were men, and half were married. Most participants lived in rural areas with a mean distance of 125 miles to the nearest VAMC. Many experienced multiple kinds of pain, with a mean 4.5 on a 10-point scale (bothered “a lot”). All participants reported that they experienced pain daily.

Participation in Vet-to-Vet meetings was high; 3 of 4 peer facilitators and 7 of 12 participants completed the first 6 months of the program. In interviews, participants described the positive impact of the program. They emphasized the importance of connecting with other veterans and helping one another, with one noting that opportunities to connect with other veterans “just drops off a lot” (peer facilitator 3) after leaving active duty.

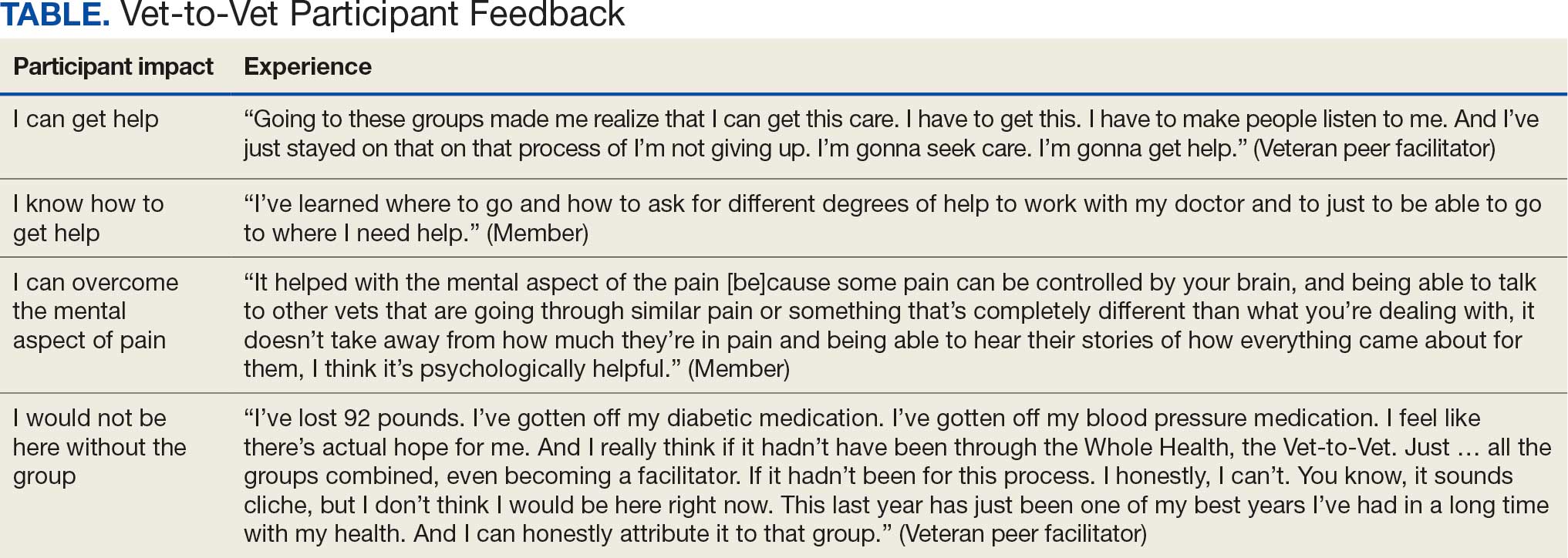

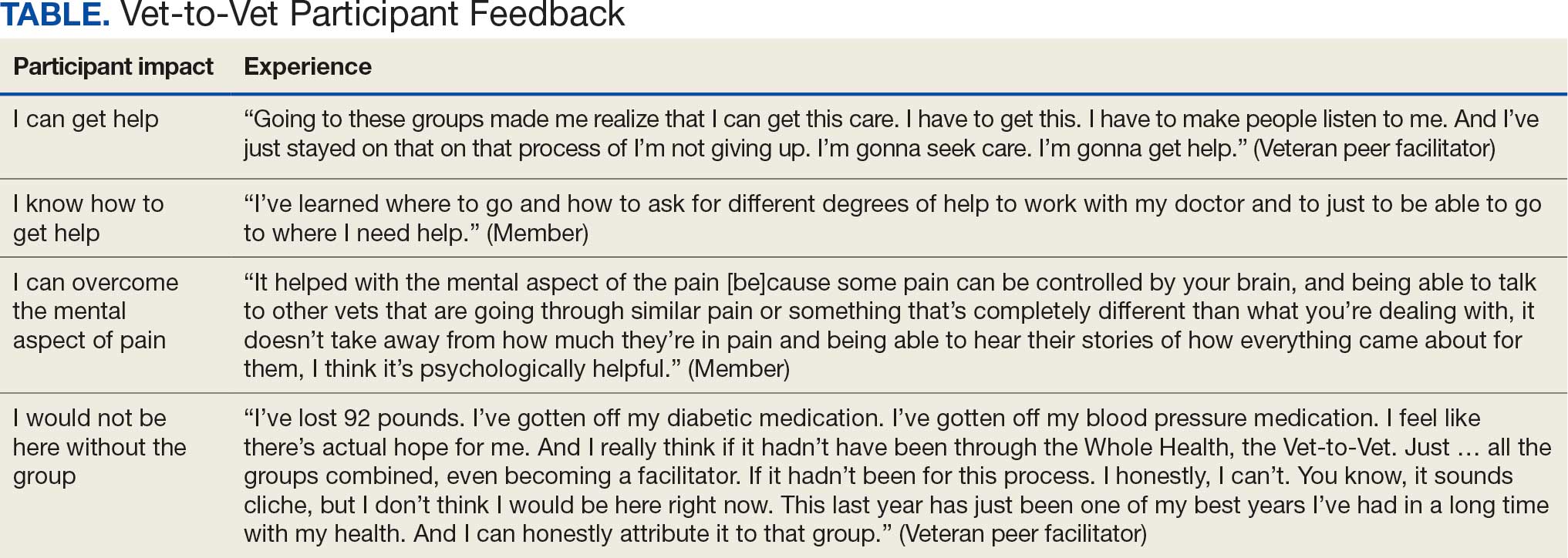

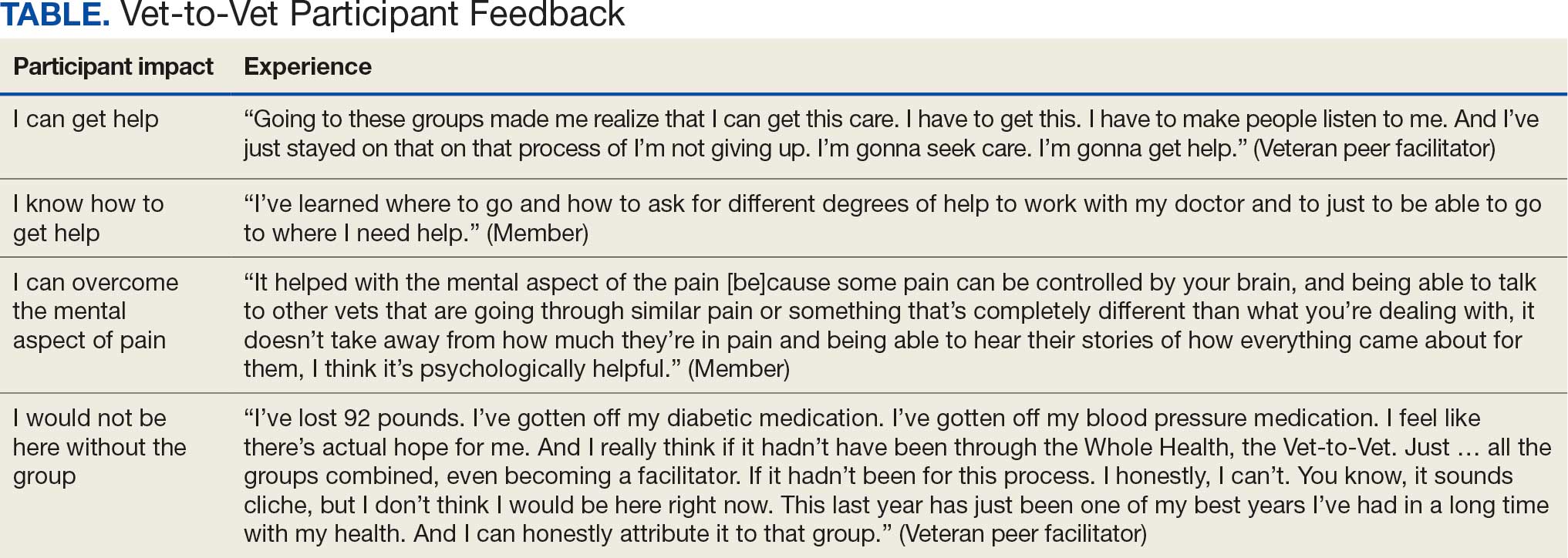

Some participants and Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators outlined the content of the sessions (eg, learning about how pain impacts the body and one’s family relationships) and shared the skills they learned (eg, goal setting, self-advocacy) (Table). Most spoke about learning from one another and the power of sharing stories with one peer facilitator sharing how they felt that witnessing another participant’s story “really shifted how I was thinking about things and how I perceived people” (peer facilitator 1).

Participants reported several ways the program impacted their lives, such as learning that they could get help, how to get help, and how to overcome the mental aspects of chronic pain. One veteran shared profound health impacts and attributed the Vet-to-Vet program to having one of the best years of their life. Even those who did not attend many meetings spoke of it positively and stated that it should continue so others could try (Table).

From January 2022 to September 2025, > 80 veterans attended ≥ 1 meeting at RMRVAMC; 29 attended ≥ 1 meeting in the last quarter. There were > 1400 Vet-to-Vet encounters at RMRVAMC, with a mean (SD) of 14.2 (19.2) and a median of 4.5 encounters per participant. Half of the veterans attend ≥ 5 meetings, and one-third attended ≥ 10 meetings.

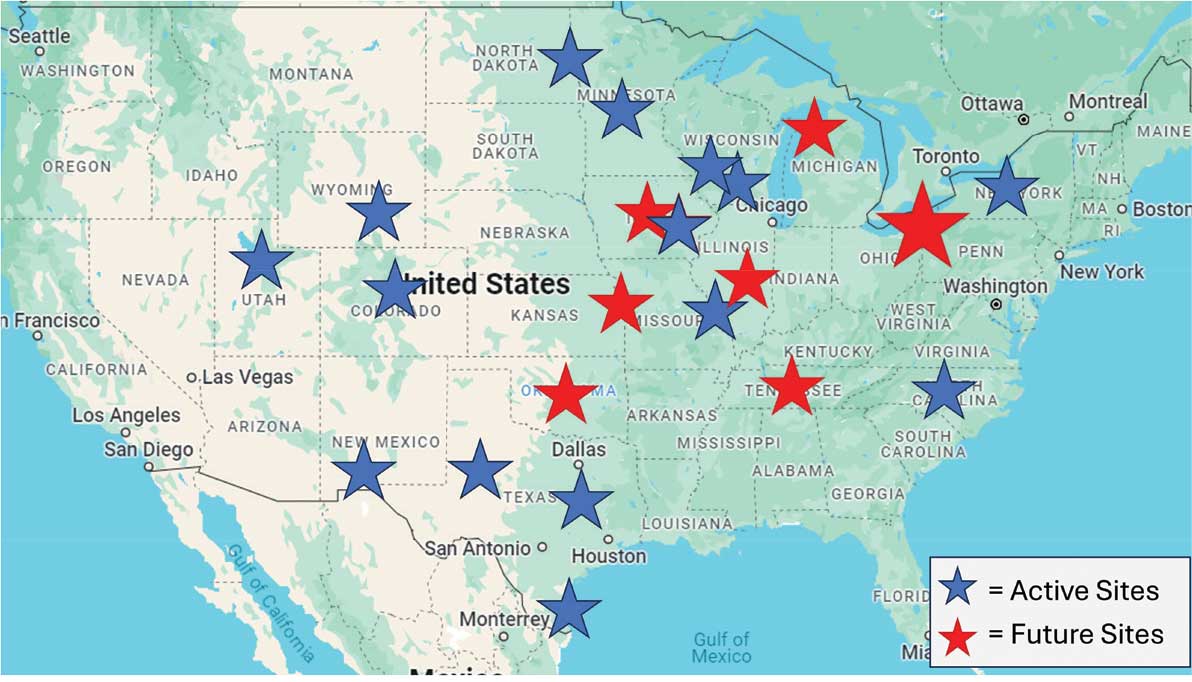

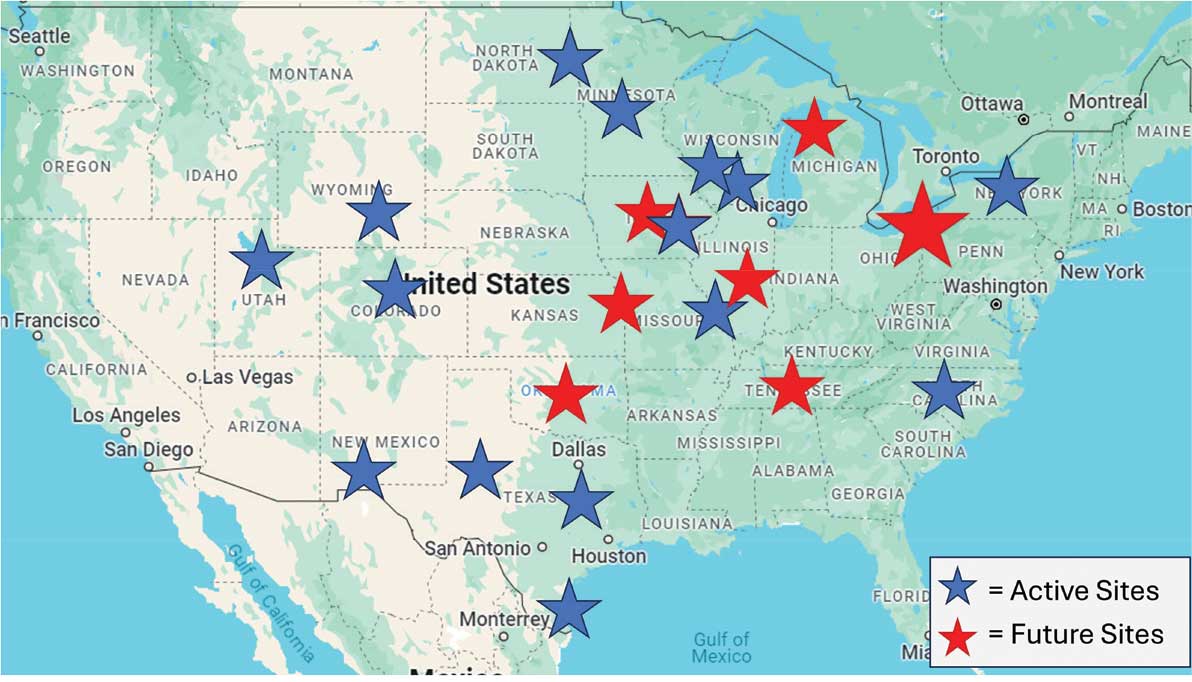

Since June 2023, 15 additional VHA facilities launched Vet-to-Vet programs. As of October 2025, > 350 veterans have participated in ≥ 1 Vet-to-Vet meeting, totaling > 4500 Vet-to-Vet encounters since the program’s inception (Figure 2).

Challenges

The RMRVAMC site and cosite leads are part of the national implementation team and dedicate substantial time to developing the program: 40 and 10 hours per week, respectively. Site leads at new locations do not receive funding for Vet-to-Vet activities and are recommended to dedicate only 4 hours per week to the program. Formally embedding Vet-to-Vet into the site leads’ roles is critical for sustainment.

The Vet-to-Vet model has changed. The initial Vet-to-Vet cohort included the 6-week Taking Charge of My Life and Health curriculum prior to moving to the mutual help format.24 While this curriculum still informs peer facilitator training, it is not used in new groups. It has anecdotally been reported that this change was positive, but the impact of this adaptation is unknown.

This evaluation cohort was small (16 participants) and initial patient reported and administrative outcomes were inconclusive. However, most veterans who stopped participating in Vet-to-Vet spoke fondly of their experiences with the program.

CONCLUSIONS

Vet-to-Vet is a promising new initiative to support self-management and social connection in chronic pain care. The program employs a mutual help approach and storytelling to empower veterans living with chronic pain. The effectiveness of these strategies will be evaluated, which will inform its continued growth. The program's current goals focus on sustainment at existing sites and expansion to new sites to reach more rural veterans across the VA enterprise. While Vet-to-Vet is designed to serve those who experience chronic pain, a partnership with the Office of Whole Health has established goals to begin expanding this model to other chronic conditions in 2026.

- Kerns RD, Philip EJ, Lee AW, Rosenberger PH. Implementation of the Veterans Health Administration national pain management strategy. Transl Behav Med. 2011;1:635-643. doi:10.1007/s13142-011-0094-3

- Pain Management, Opioid Safety, and PDMP (PMOP). US Department of Veterans Affairs. Updated August 21, 2025. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/Providers/IntegratedTeambasedPainCare.asp

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA Directive 2009-053. October 28, 2009. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/docs/VHA09PainDirective.pdf

- Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016, S524, 114th Cong (2015-2016). Pub L No. 114-198. July 22, 2016. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/524

- Bokhour B, Hyde J, Zeliadt, Mohr D. Whole Health System of Care Evaluation. US Department of Veterans Affairs. February 18, 2020. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.va.gov/WHOLEHEALTH/docs/EPCC_WHSevaluation_FinalReport_508.pdf

- Gaudet T, Kligler B. Whole health in the whole system of the veterans administration: how will we know we have reached this future state? J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25:S7-S11. doi:10.1089/acm.2018.29061.gau

- Kelly JF, Yeterian JD. The role of mutual-help groups in extending the framework of treatment. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;33:350-355.

- Humphreys K. Self-help/mutual aid organizations: the view from Mars. Subst Use Misuse. 1997;32:2105-2109. doi:10.3109/10826089709035622

- Chinman M, Kloos B, O’Connell M, Davidson L. Service providers’ views of psychiatric mutual support groups. J Community Psychol. 2002;30:349-366. doi:10.1002/jcop.10010

- Shue SA, McGuire AB, Matthias MS. Facilitators and barriers to implementation of a peer support intervention for patients with chronic pain: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2019;20:1311-1320. doi:10.1093/pm/pny229

- Pester BD, Tankha H, Caño A, et al. Facing pain together: a randomized controlled trial of the effects of Facebook support groups on adults with chronic pain. J Pain. 2022;23:2121-2134. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2022.07.013

- Matthias MS, McGuire AB, Kukla M, Daggy J, Myers LJ, Bair MJ. A brief peer support intervention for veterans with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a pilot study of feasibility and effectiveness. Pain Med. 2015;16:81-87. doi:10.1111/pme.12571

- Finlay KA, Elander J. Reflecting the transition from pain management services to chronic pain support group attendance: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Br J Health Psychol. 2016;21:660-676. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12194

- Finlay KA, Peacock S, Elander J. Developing successful social support: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of mechanisms and processes in a chronic pain support group. Psychol Health. 2018;33:846-871. doi:10.1080/08870446.2017.1421188

- Farr M, Brant H, Patel R, et al. Experiences of patient-led chronic pain peer support groups after pain management programs: a qualitative study. Pain Med. 2021;22:2884-2895. doi:10.1093/pm/pnab189

- Mehl-Madrona L. Narrative Medicine: The Use of History and Story in the Healing Process. Bear & Company; 2007.

- Fioretti C, Mazzocco K, Riva S, Oliveri S, Masiero M, Pravettoni G. Research studies on patients’ illness experience using the Narrative Medicine approach: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011220. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011220

- Hall JM, Powell J. Understanding the person through narrative. Nurs Res Pract. 2011;2011:293837. doi:10.1155/2011/293837

- Ricks L, Kitchens S, Goodrich T, Hancock E. My story: the use of narrative therapy in individual and group counseling. J Creat Ment Health. 2014;9:99-110. doi:10.1080/15401383.2013.870947

- Hydén L-C. Illness and narrative. Sociol Health Illn. 1997;19:48-69. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.1997.tb00015.x

- Georgiadis E, Johnson MI. Incorporating personal narratives in positive psychology interventions to manage chronic pain. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2023;4:1253310. doi:10.3389/fpain.2023.1253310

- Gucciardi E, Jean-Pierre N, Karam G, Sidani S. Designing and delivering facilitated storytelling interventions for chronic disease self-management: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:249. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1474-7

- Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322-1327. doi:10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322

- Abadi M, Richard B, Shamblen S, et al. Achieving whole health: a preliminary study of TCMLH, a group-based program promoting self-care and empowerment among veterans. Health Educ Behav. 2022;49:347-357. doi:10.1177/10901981211011043

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has continued to advance its understanding and treatment of chronic pain. The VHA National Pain Management Strategy emphasizes the significance of the social context of pain while underscoring the importance of self-management.1 This established strategy ensures that all veterans have access to the appropriate pain care in the proper setting.2 VHA has instituted a stepped care model of pain management, delineating the domains of primary care, secondary consultative services, and tertiary care.3 This directive emphasized a biopsychosocial approach to pain management to prioritize the relationship between biological, psychological, and social factors that influence how veterans experience pain and should commensurately influence how it is managed.

The VHA Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation implemented the Whole Health System of Care as part of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which included a VHA directive to expand pain management.4,5 Reorientation within this system shifts from defining veterans as passive care recipients to viewing them as active partners in their own care and health. This partnership places additional emphasis on peer-led explorations of mission, aspiration, and purpose.6

Peer-led groups, also known as mutual aid, mutual support, and mutual help groups, have historically been successful for patients undergoing treatment for substance use disorders (eg, Alcoholics Anonymous).7 Mutual help groups have 3 defining characteristics. First, they are run by participants, not professionals, though the latter may have been integral in the founding of the groups. Second, participants share a similar problem (eg, disease state, experience, disposition). Finally, there is a reciprocal exchange of information and psychological support among participants.8,9 Mutual help groups that address chronic pain are rare but becoming more common.10-12 Emerging evidence suggests a positive relationship between peer support and improved well-being, self-efficacy, pain management, and pain self-management skills (eg, activity pacing).13-15

Storytelling as a tool for healing has a long history in indigenous and Western medical traditions.16-19 This includes the treatment of chronic disease, including pain.20,21 The use of storytelling in health care overlaps with the role it plays within many mutual help groups focused on chronic disease treatment.22 Storytelling allows an individual to share their experience with a disease, and take a more active role in their health, and facilitate stronger bonds with others.22 In effect, storytelling is not only important to group cohesion—it also plays a role in an individual’s healing.

Vet-to-Vet

The VHA Office of Rural Health funds Vet-to-Vet, a peer-to-peer program to address limited access to care for rural veterans with chronic pain. Similar to the VHA National Pain Management Strategy, Vet-to-Vet is grounded in the significance of the social context of pain and underscores the importance of self-management.1 The program combines pain care, mutual help, and storytelling to support veterans living with chronic pain. While the primary focus of Vet-to-Vet is rural veterans, the program serves any veteran experiencing chronic pain who is isolated from services, including home-bound urban veterans.

Following mutual help principles, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators lead weekly online drop-in meetings. Meetings follow the general structure of reiterating group ground rules and sharing an individual pain story, followed by open discussions centered on well-being, chronic pain management, or any topic the group wishes to discuss. Meetings typically end with a mindfulness exercise. The organizational structure that supports Vet-to-Vet includes the implementation support team, site leads, Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators, and national partners (Figure 1).

Implementation Support Team

The implementation support team consists of a principal investigator, coinvestigator, program manager, and program support specialist. The team provides facilitator training, monthly community practice sessions for Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and site leads, and weekly office hours for site leads. The implementation support team also recruits new Vet-to-Vet sites; potential new locations ideally have an existing whole health program, leadership support, committed site and cosite leads, and ≥ 3 peer facilitator volunteers.

Site Leads

Most site and cosite leads are based in whole health or pain management teams and are whole health coaches or peer support specialists. The site lead is responsible for standing up the program and documenting encounters, recruiting and supporting peer facilitators and participants, and overseeing the meeting. During meetings, site leads generally leave their cameras off and only speak when called into the group; the peer facilitators lead the meetings. The implementation support team recommends that site leads dedicate ≥ 4 hours per week to Vet-to-Vet; 2 hours for weekly group meetings and 2 hours for documentation (ie, entering notes into the participants’ electronic health records) and supporting peer facilitators and participants. Cosite lead responsibilities vary by location, with some sites having 2 leads that equally share duties and others having a primary lead and a colead available if the site lead is unable to attend a meeting.

Vet-to-Vet Peer Facilitators

Peer facilitators are the core of the program. They lead meetings from start to finish. Like participants, they also experience chronic pain and are volunteers. The implementation support team encourages sites to establish volunteer peer facilitators, rather than assigning peer support specialists to facilitate meetings. Veterans are eager to connect and give back to their communities, and the Vet-to-Vet peer facilitator role is an opportunity for those unable to work to connect with peers and add meaning to their lives. Even if a VHA employee is a veteran who has chronic pain, they are not eligible to serve as this could create a service provider/service recipient dynamic that is not in the spirit of mutual help.

Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators attend a virtual 3-day training held by the implementation support team prior to starting. These training sessions are available on a quarterly basis and facilitated by the Vet-to-Vet program manager and 2 current peer facilitators. Training content includes established whole health facilitator training materials and program-specific storytelling training materials. Once trained, peer facilitators attend storytelling practice sessions and collaborate with their site leads during weekly meetings.

Participants

Vet-to-Vet participants find the program through direct outreach from site leads, word of mouth, and referrals. The only criteria to join are that the individual is a veteran who experiences chronic pain and is enrolled in the VHA (site leads can assist with enrollment if needed). Participants are not required to have a diagnosis or engage in any other health care. There is no commitment and no end date. Some participants only come once; others have attended for > 3 years. This approach is intended to embrace the idea that the need for support ebbs and flows.

National Partners

The VHA Office of Rural Health provides technical support. The Center for Development and Civic Engagement onboards peer facilitators as VHA volunteers. The Office of Patient-Centered Care and Cultural Transformation provides national guidance and site-level collaboration. The VHA Pain Management, Opioid Safety, and Prescription Drug Monitoring Program supports site recruitment. In addition to the VHA partners, 4 veteran evaluation consultants who have experience with chronic pain but do not participate in Vet-to-Vet meetings provide advice on evaluation activities, such as question development and communication strategies.

Evaluation

This evaluation shares preliminary results from a pilot evaluation of the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center (RMRVAMC) Vet-to-Vet group. It is intended for program improvement, was deemed nonresearch by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, and was structured using the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework.23 This evaluation focused on capturing measures related to reach and effectiveness, while a forthcoming evaluation includes elements of adoption, implementation, and maintenance.

In 2022, 16 Vet-to-Vet peer facilitators and participants completed surveys and interviews to share their experience. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded in ATLAS.ti. A priori codes were based on interview guide questions and emergent descriptive codes were used to identify specific topics which were categorized into RE-AIM domains, barriers, facilitators, what participants learned, how participants applied what they learned to their lives, and participant reported outcomes. This article contains high-level findings from the evaluation; more detailed results will be included in the ongoing evaluation.

Results