User login

Mobile Tender Papule on the Scalp

Mobile Tender Papule on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

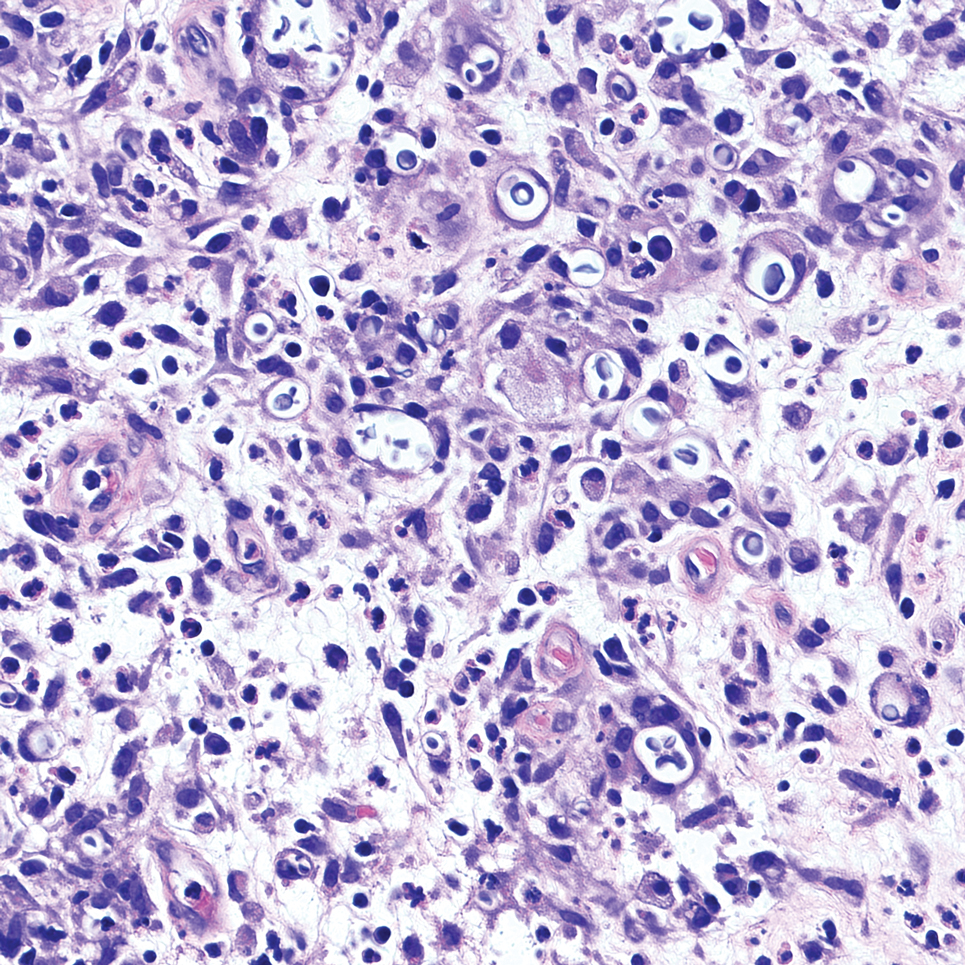

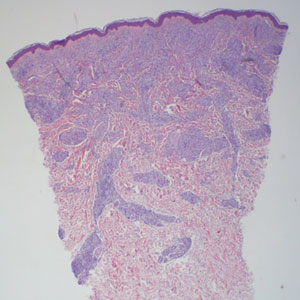

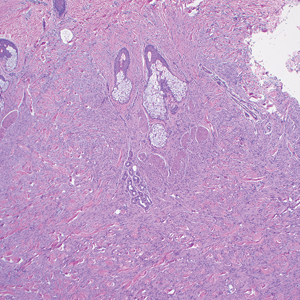

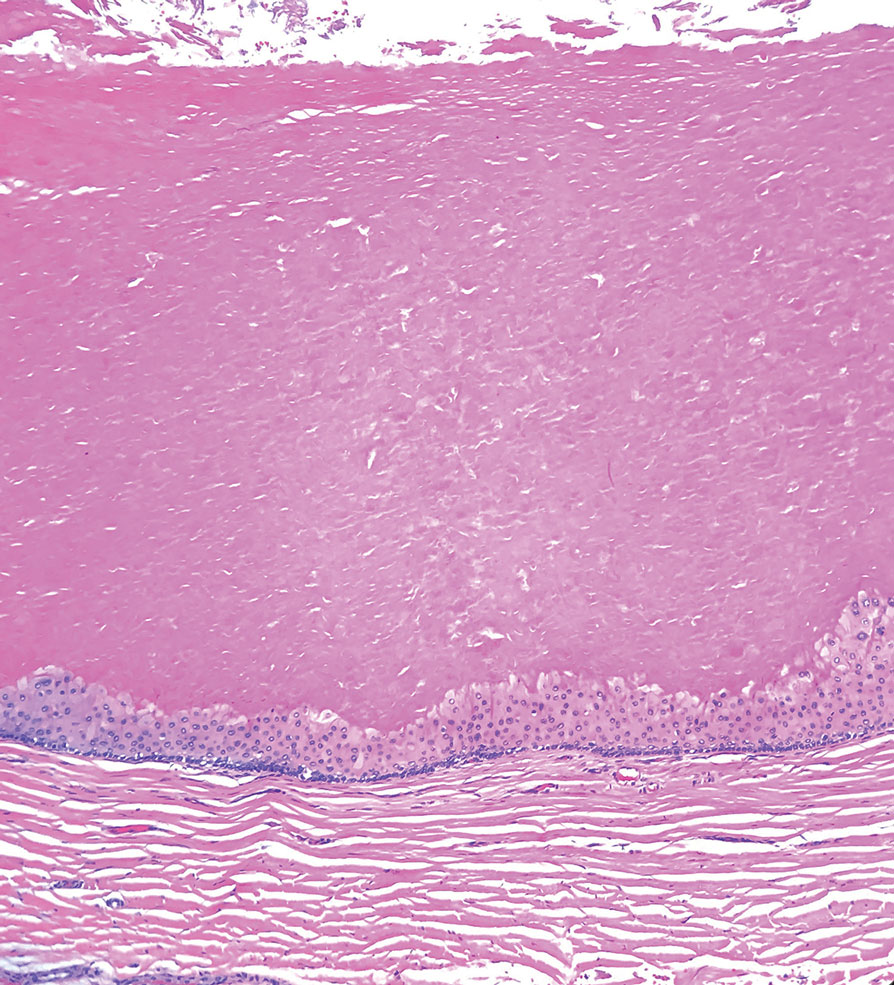

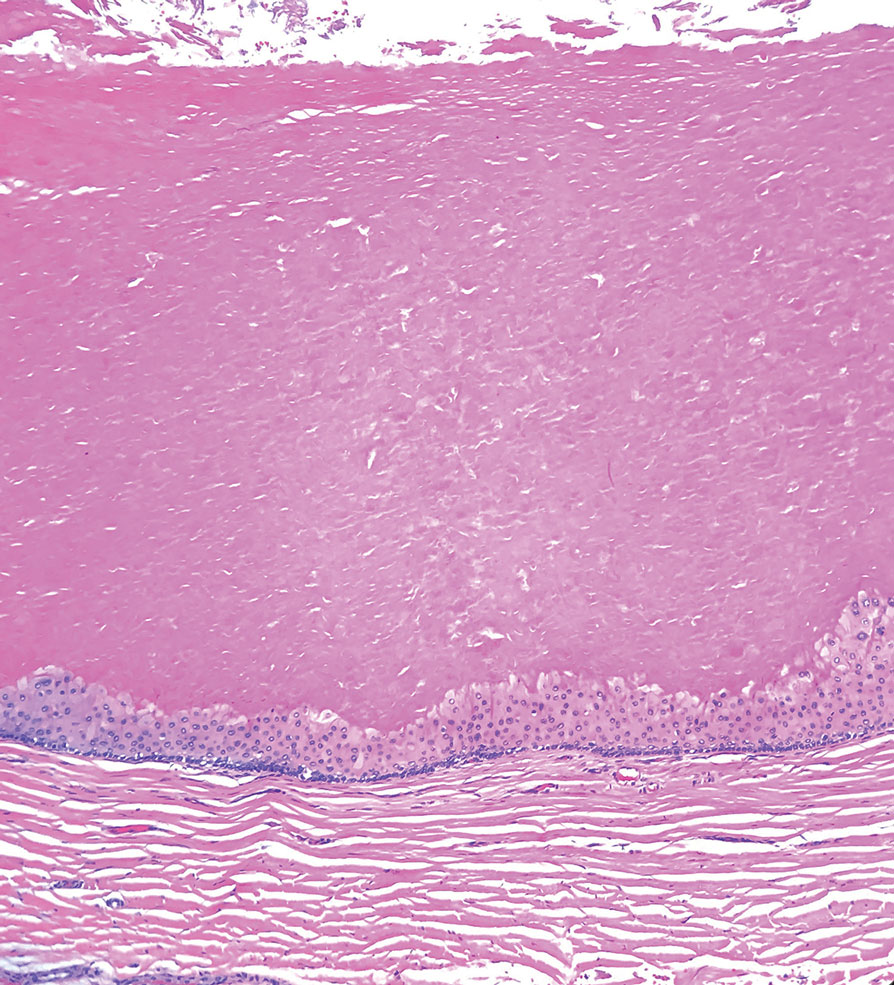

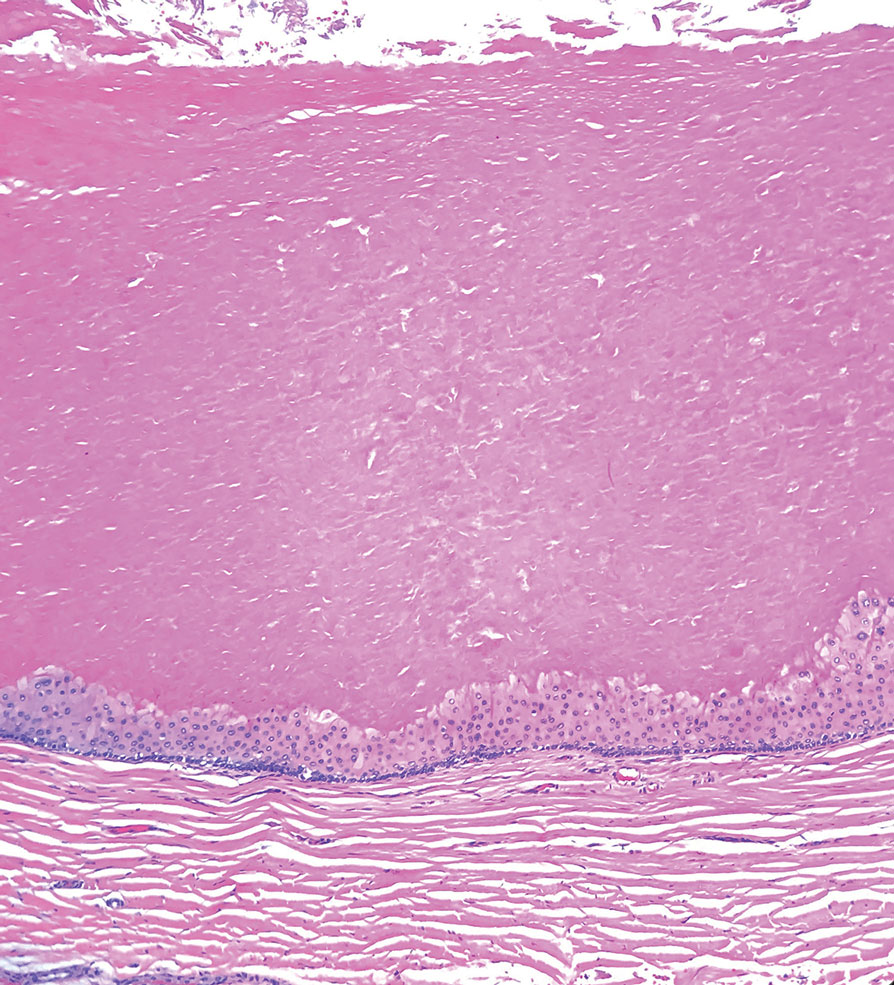

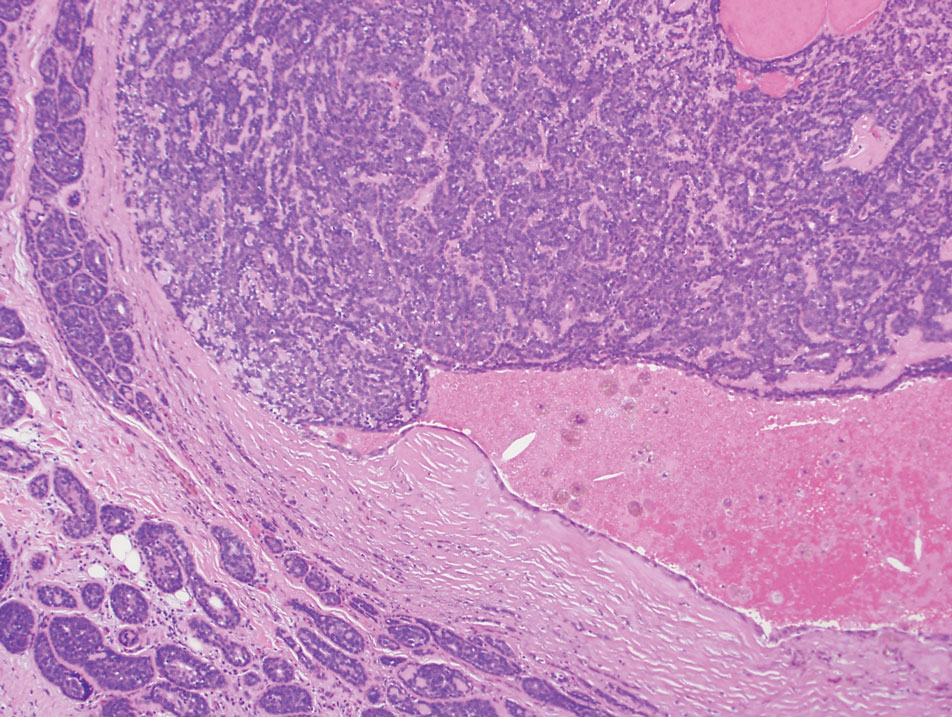

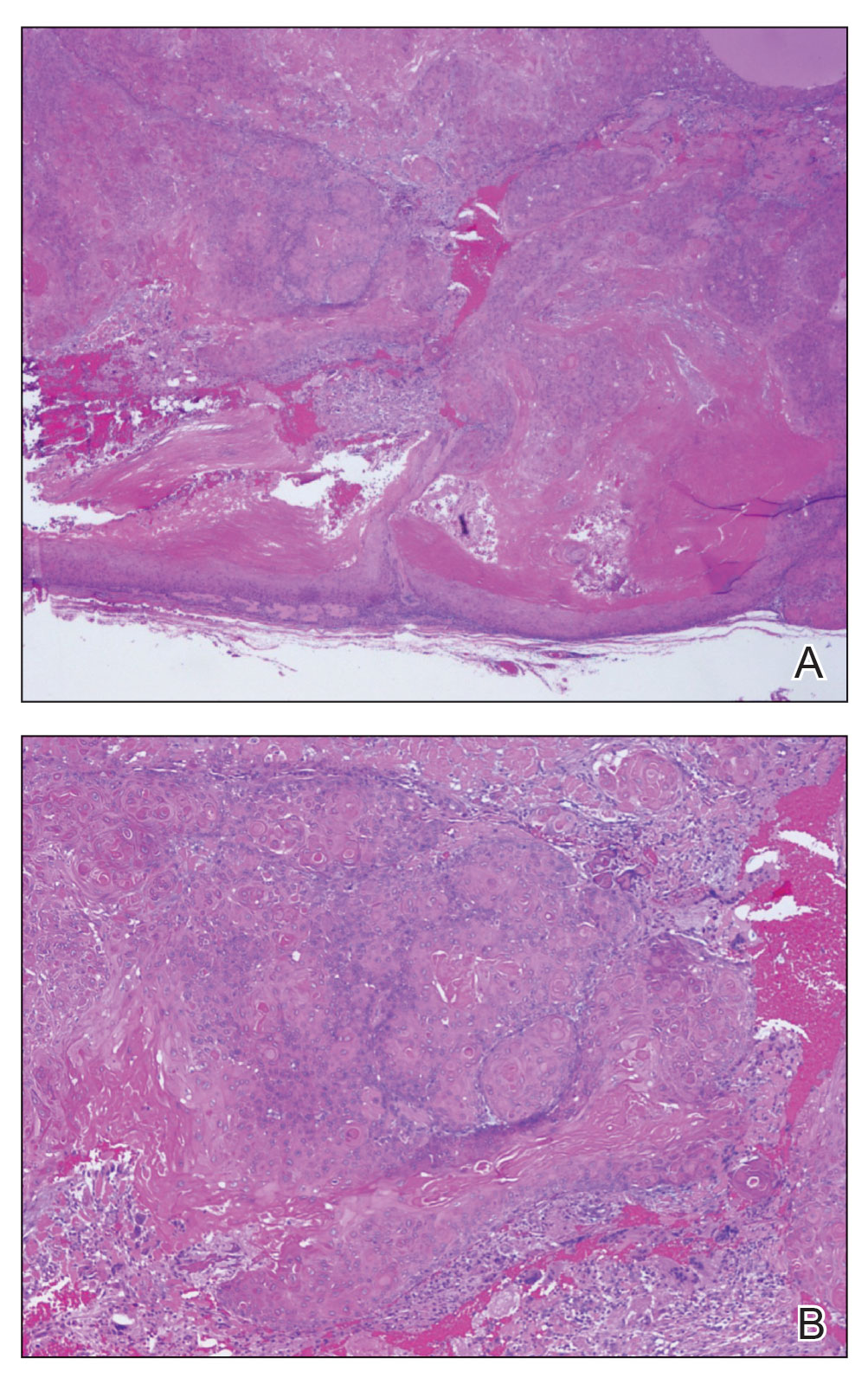

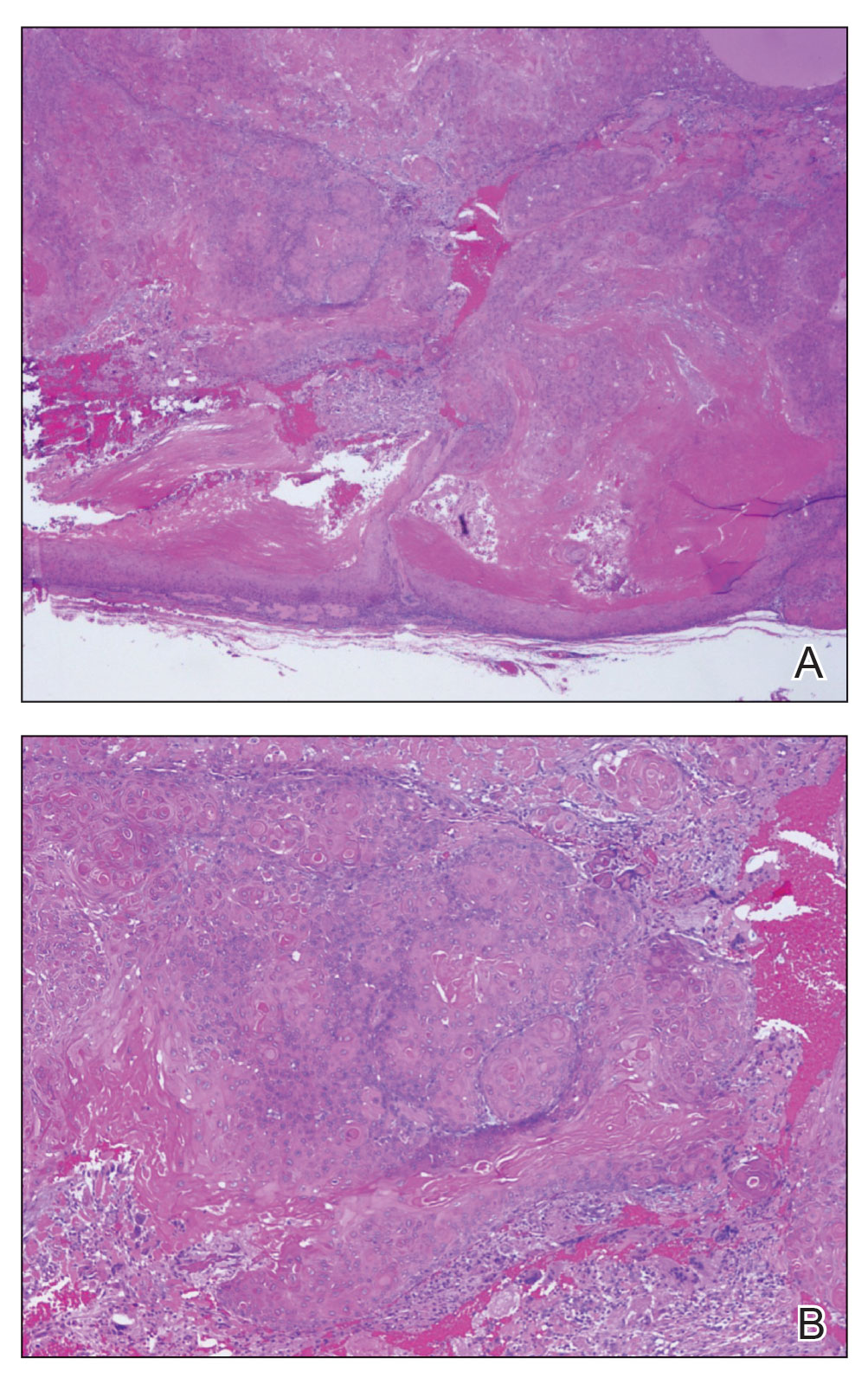

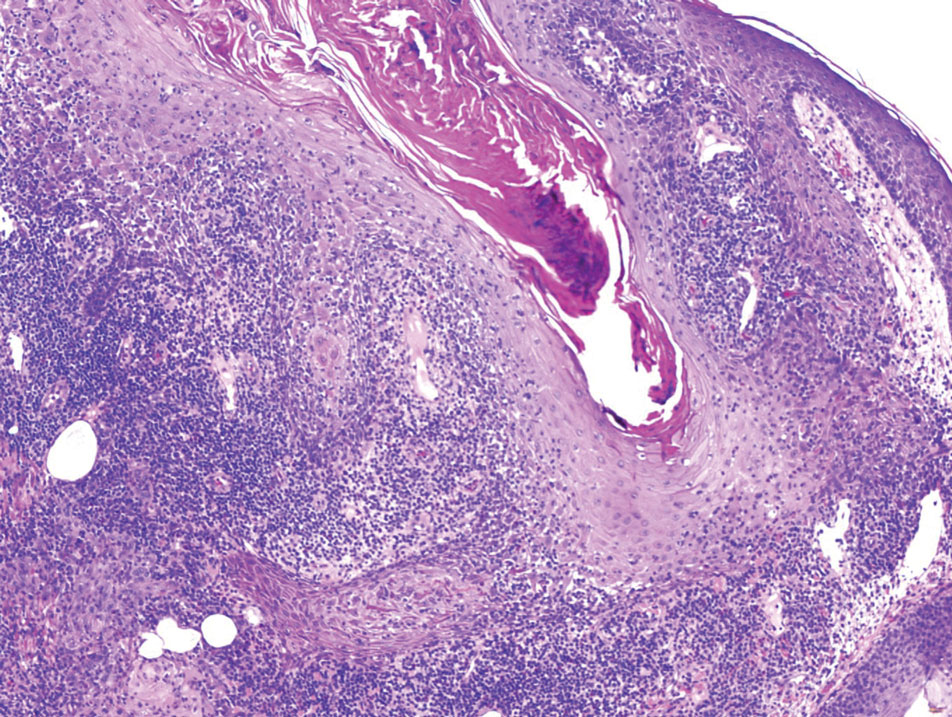

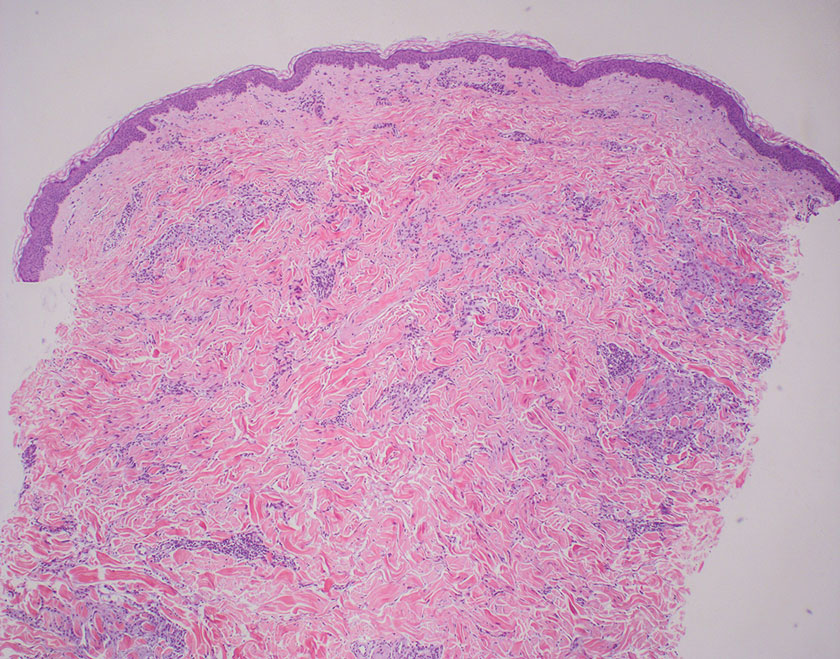

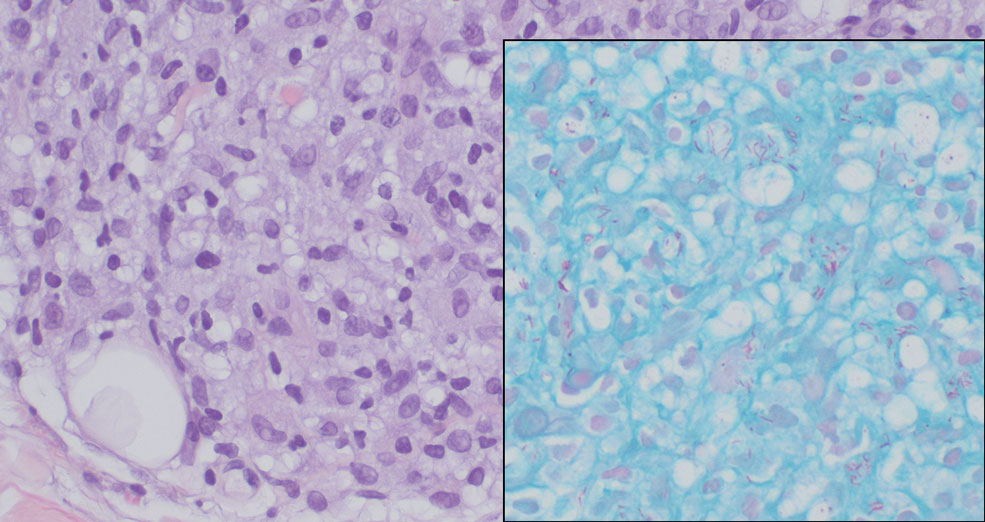

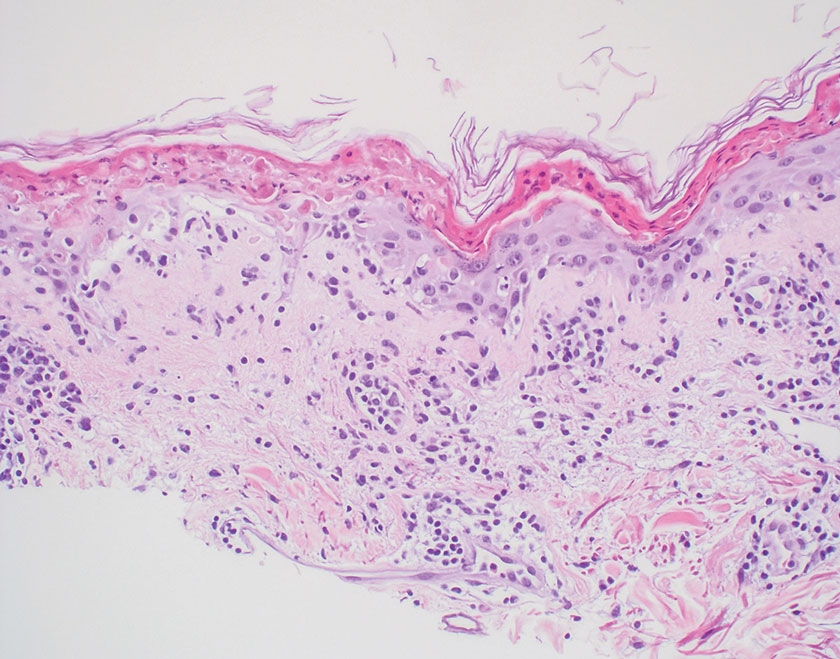

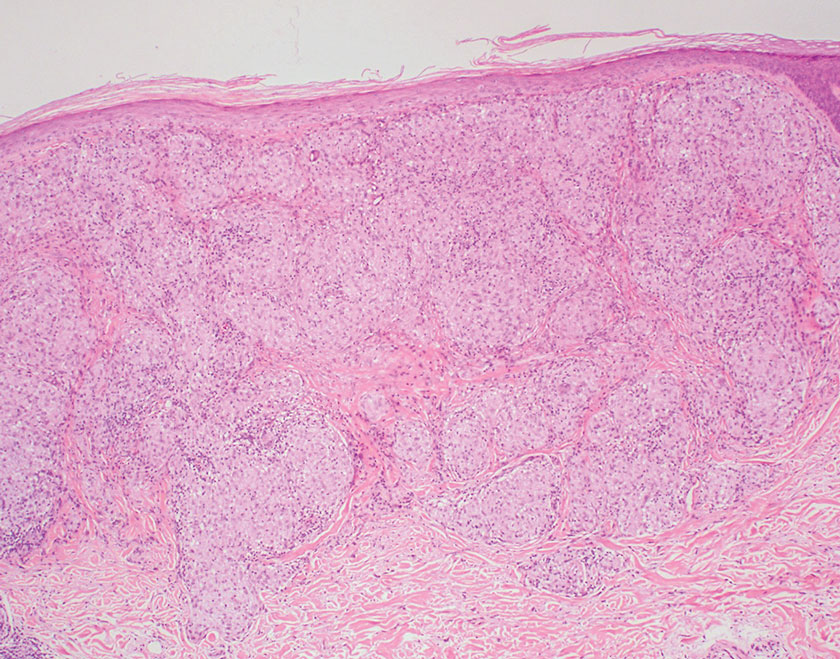

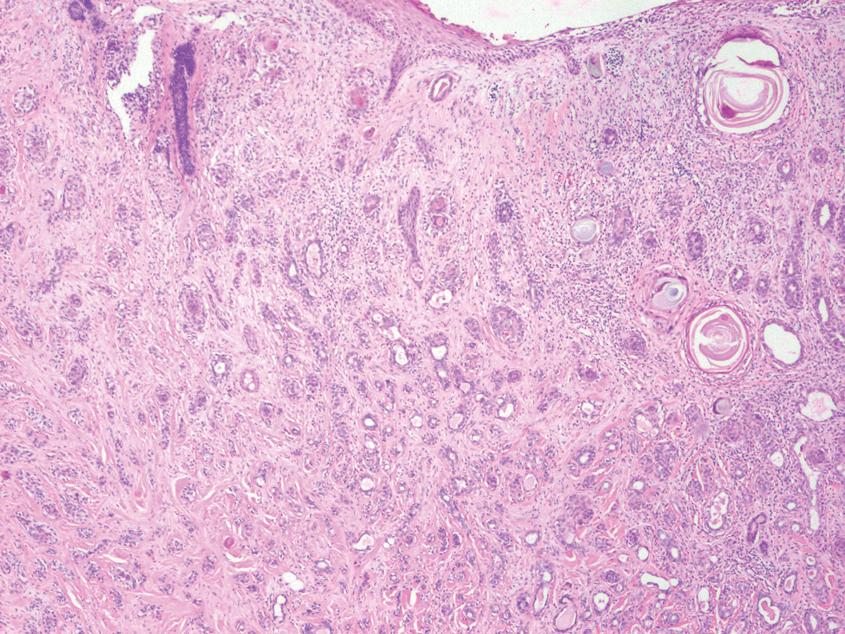

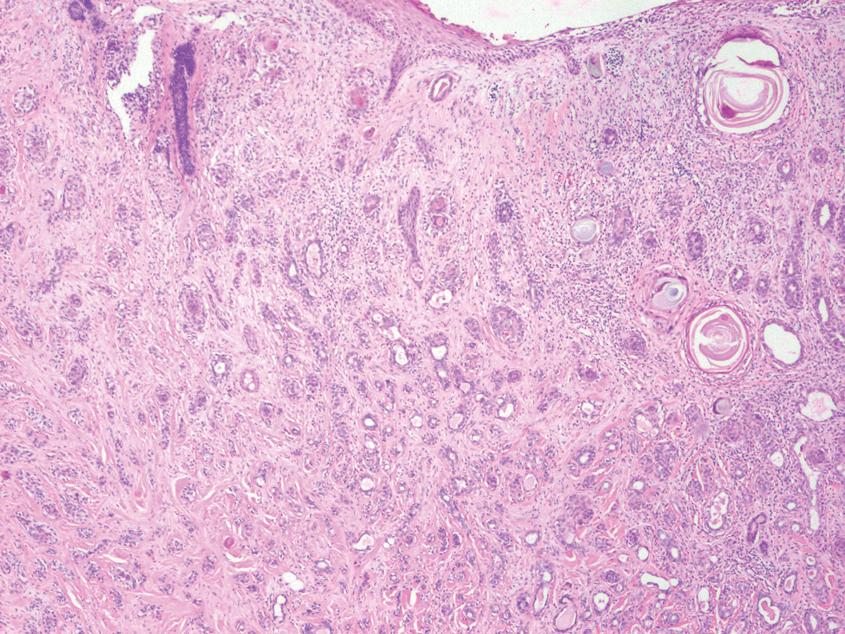

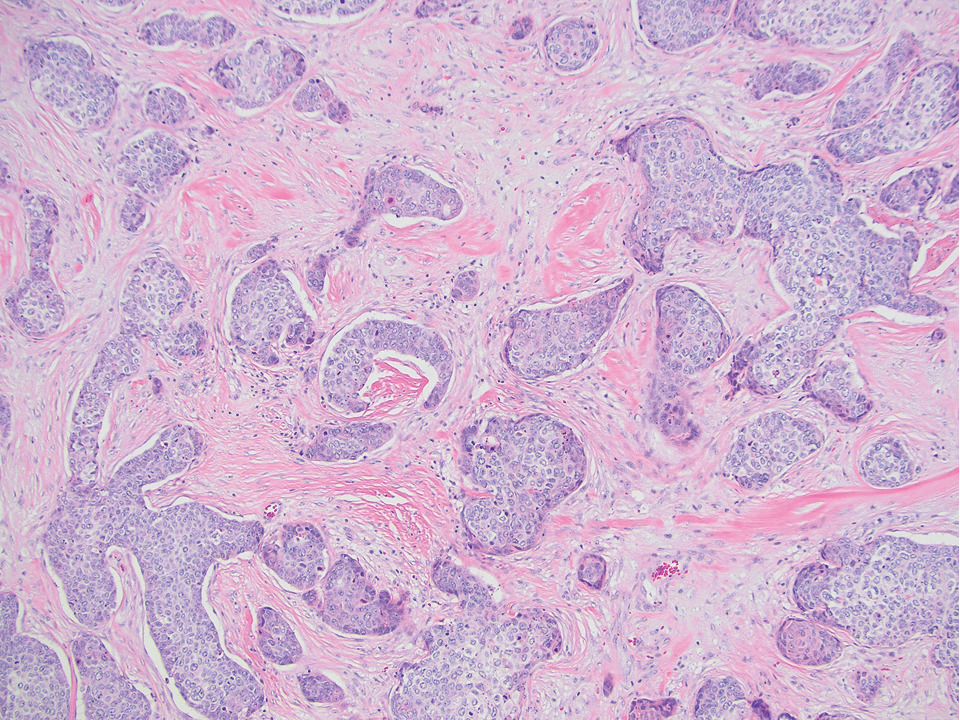

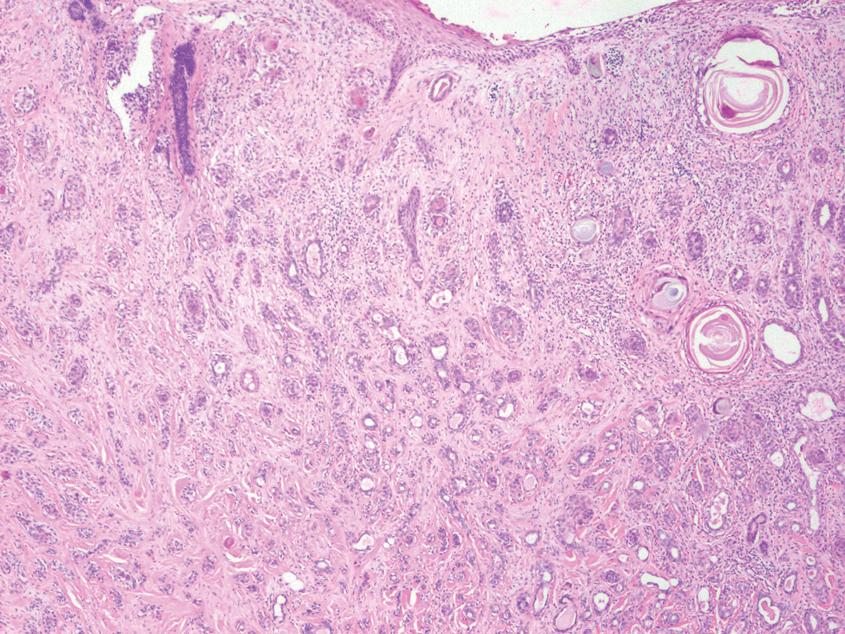

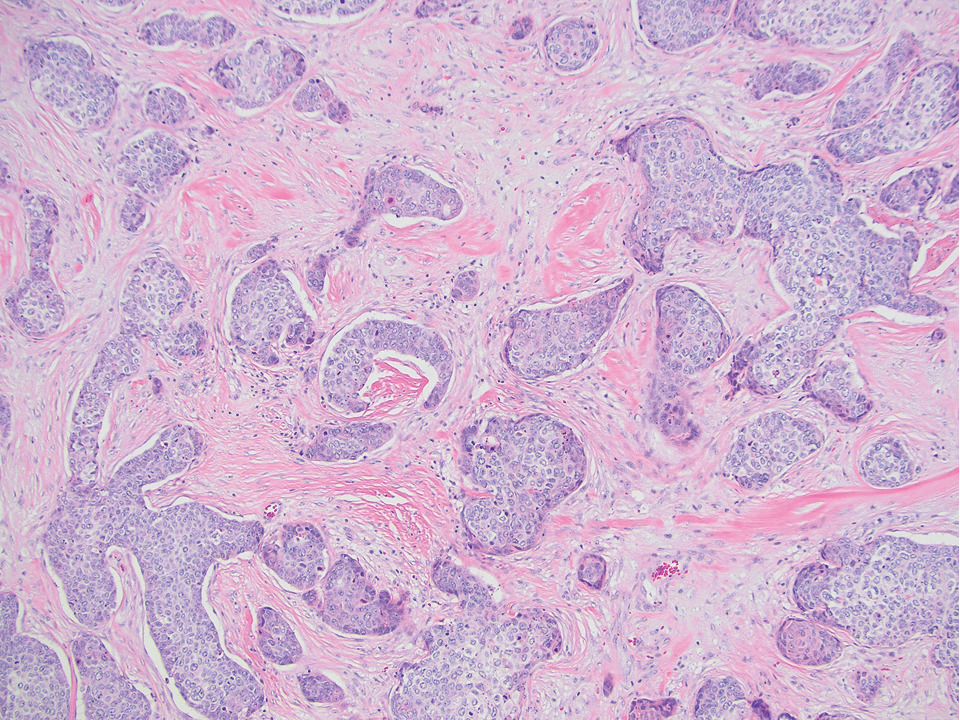

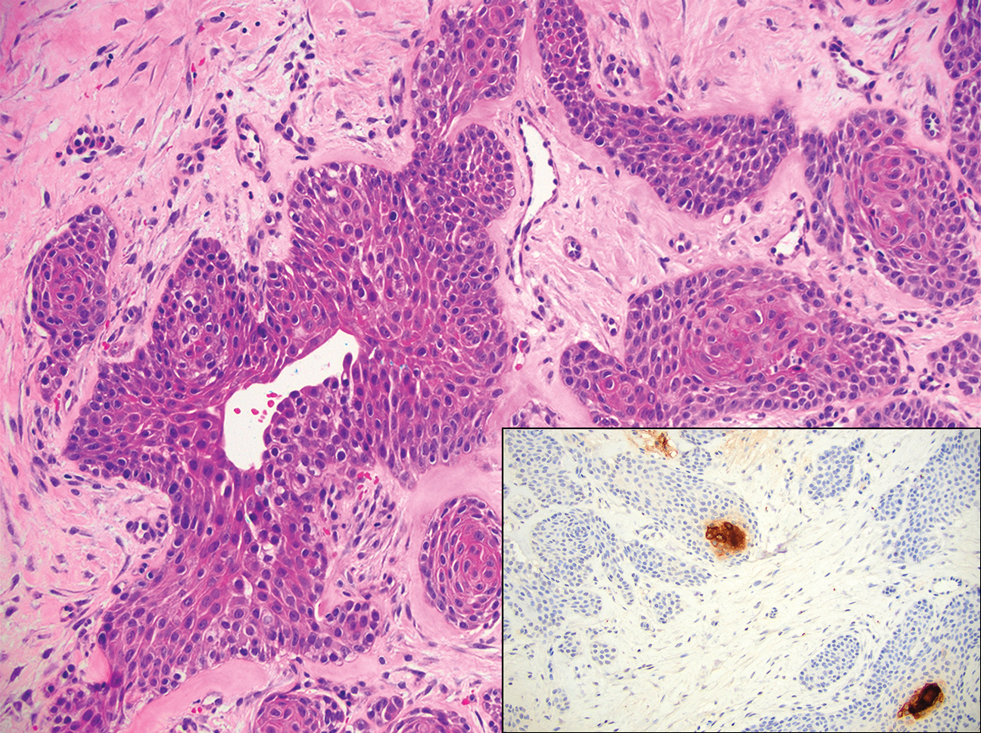

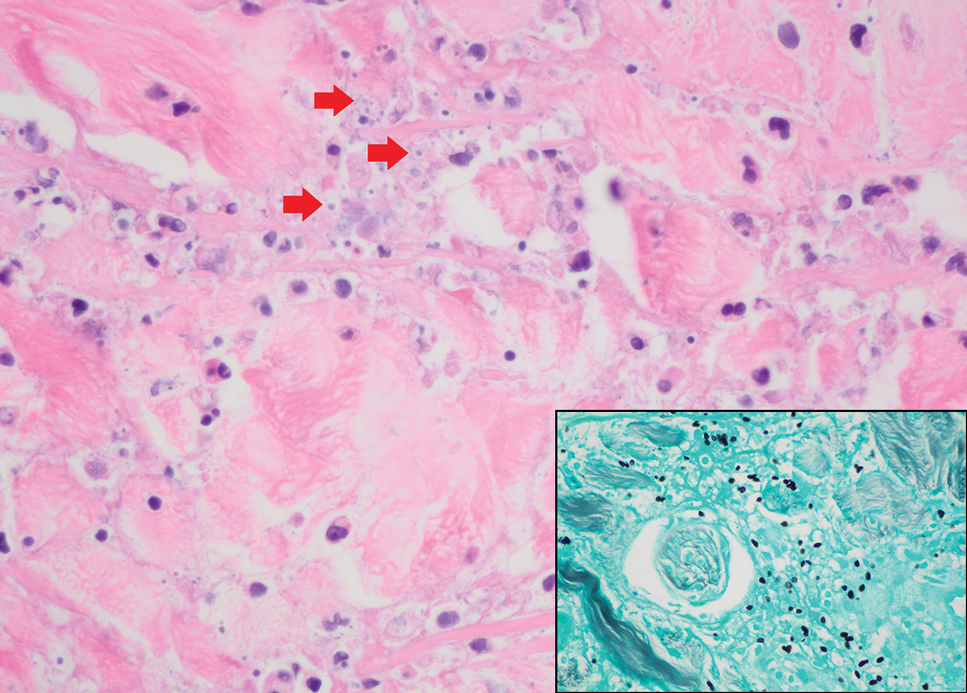

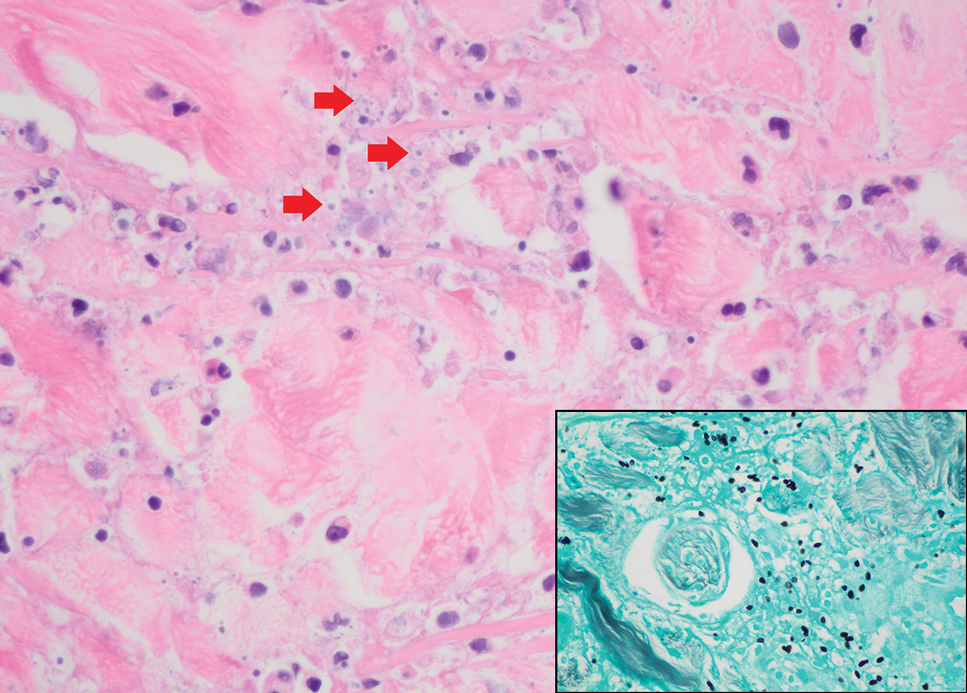

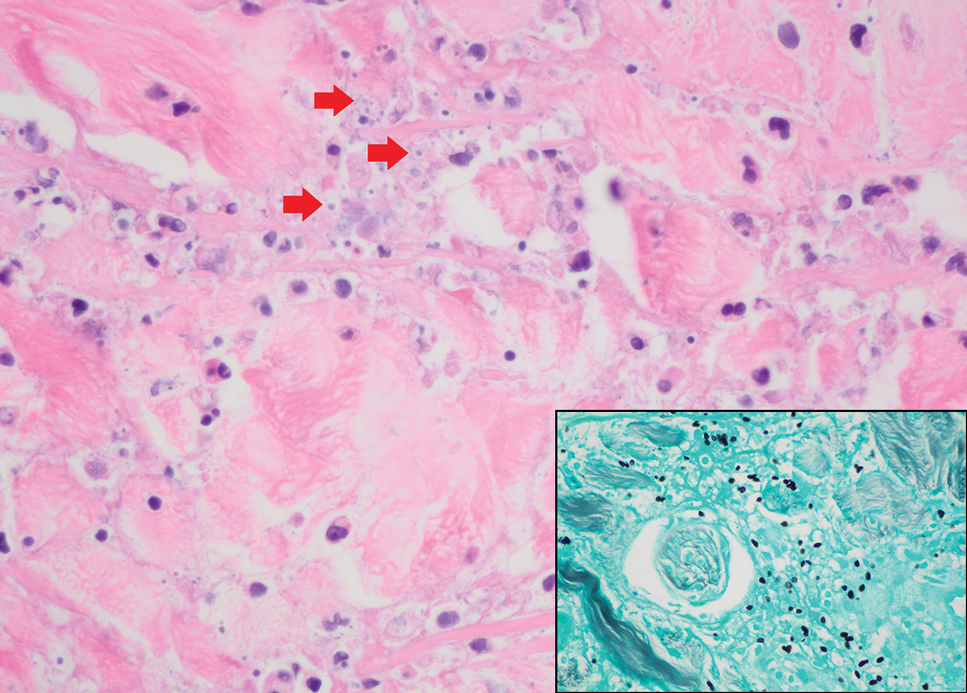

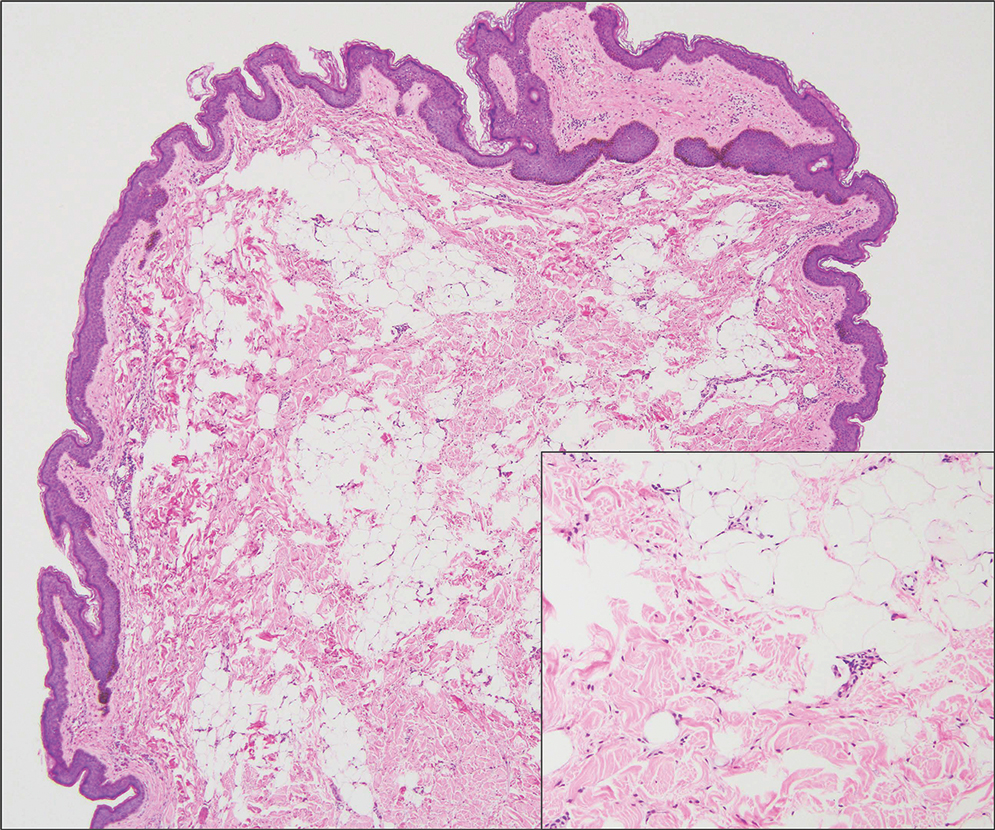

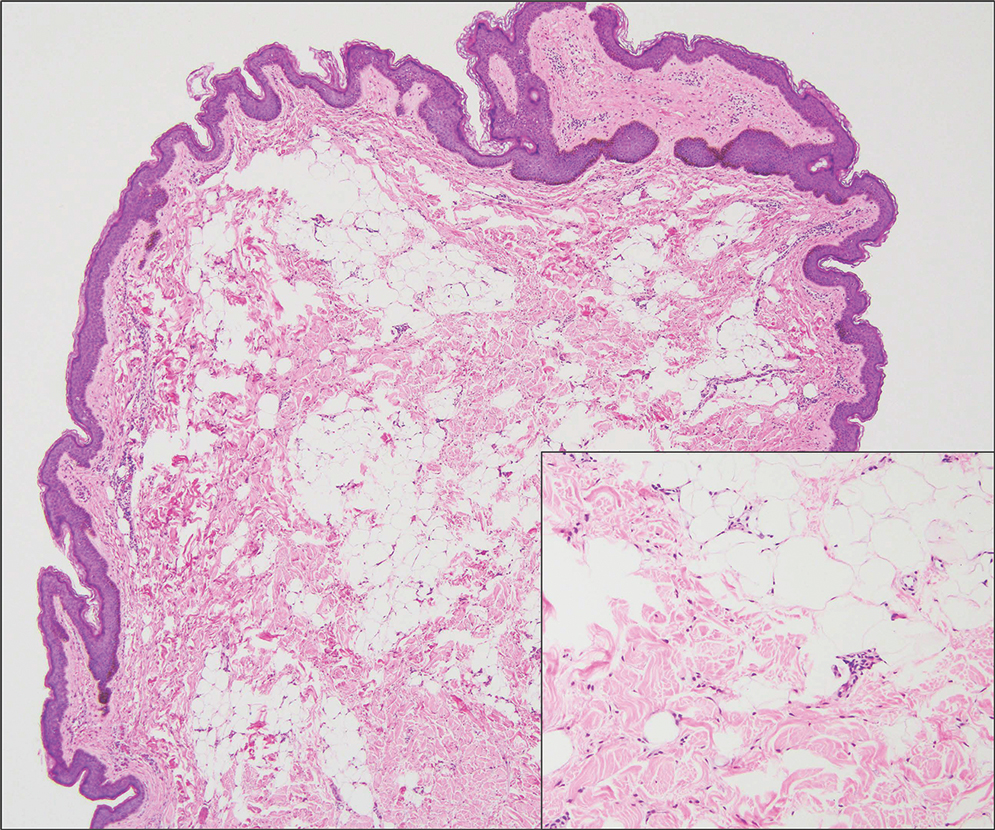

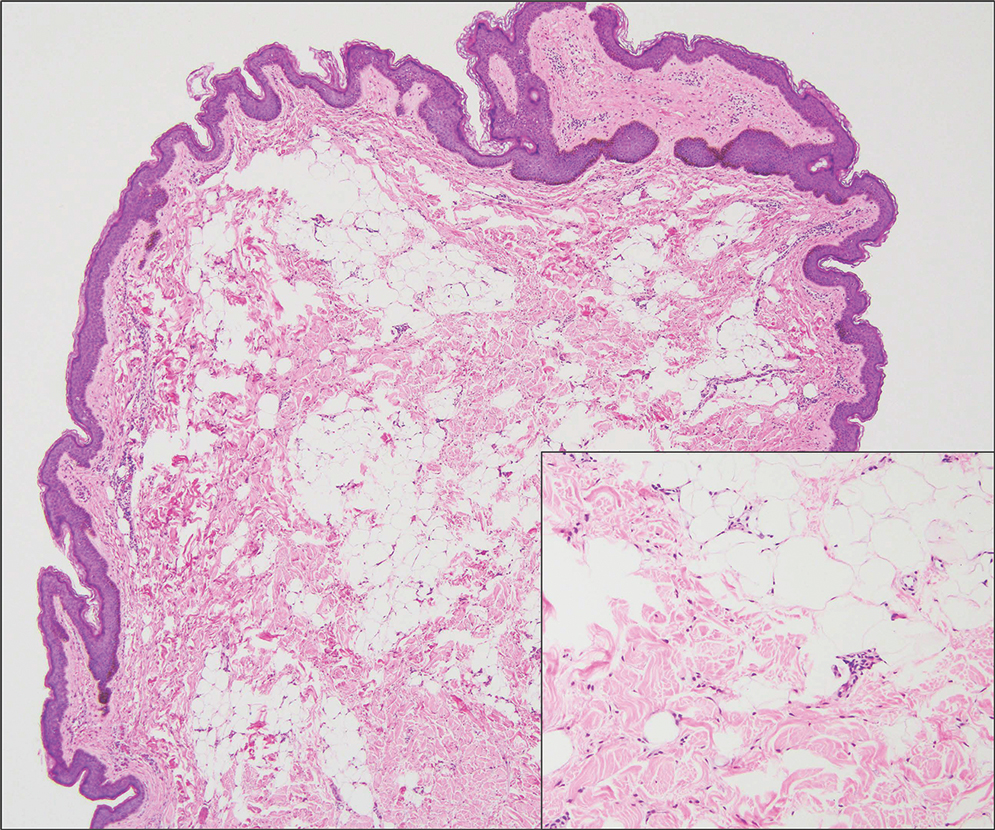

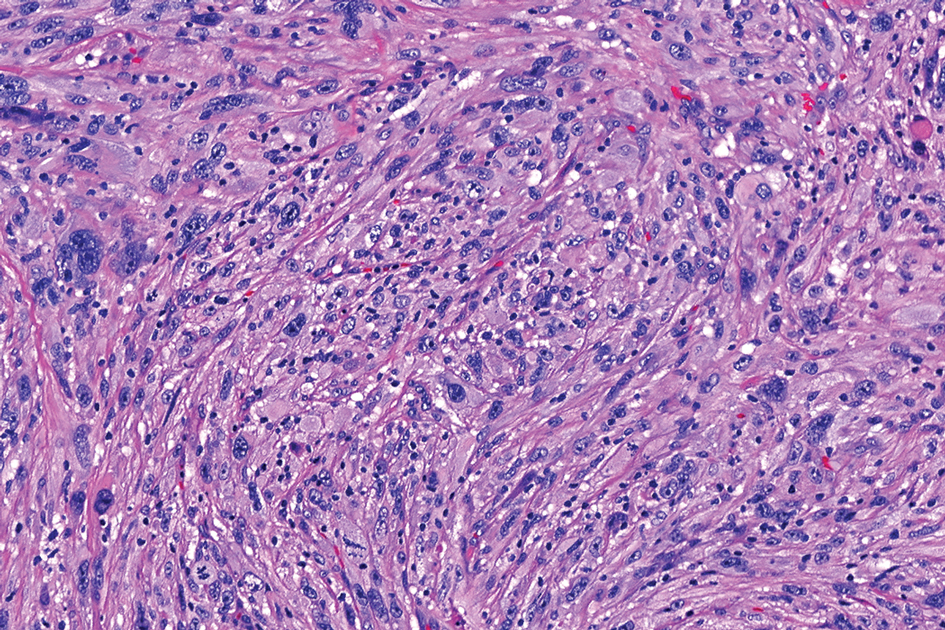

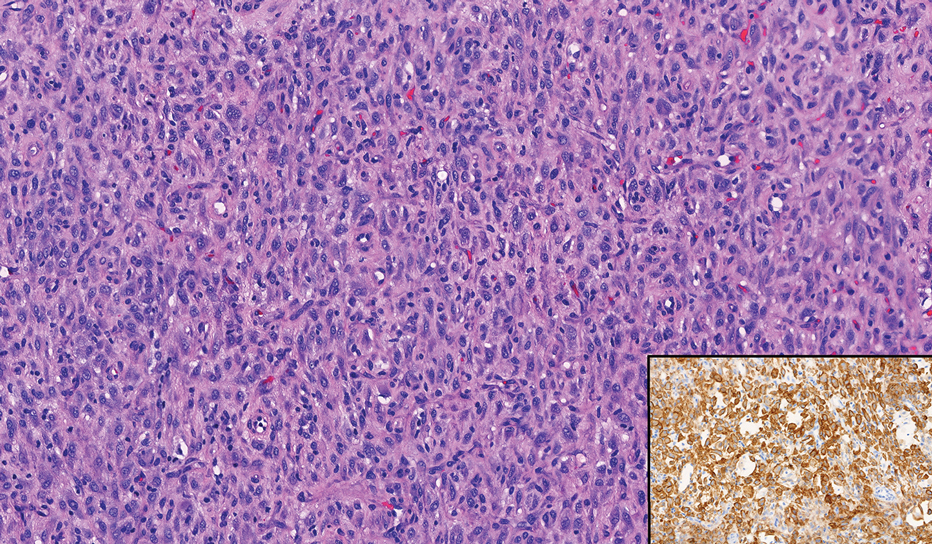

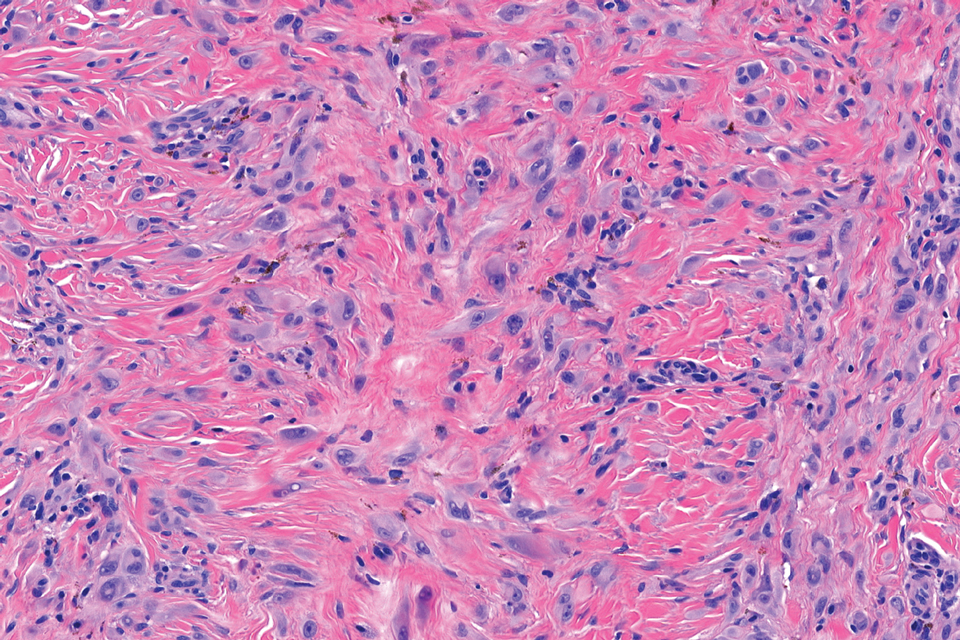

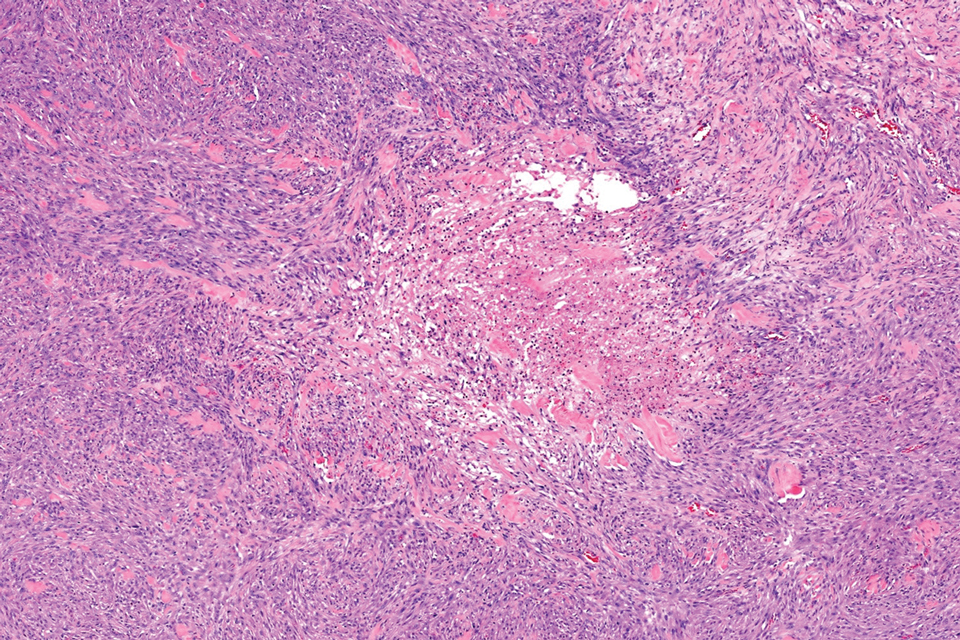

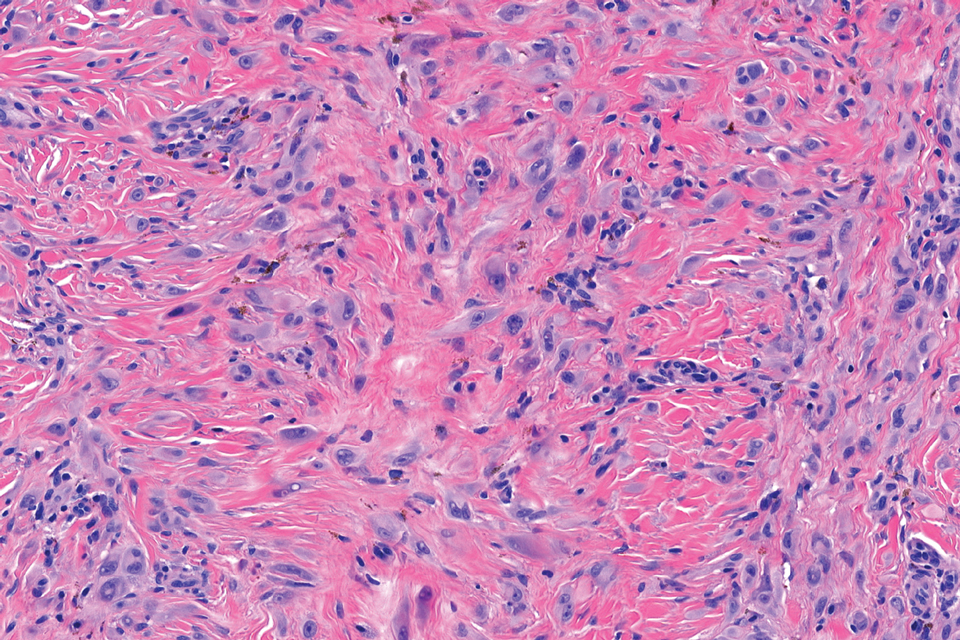

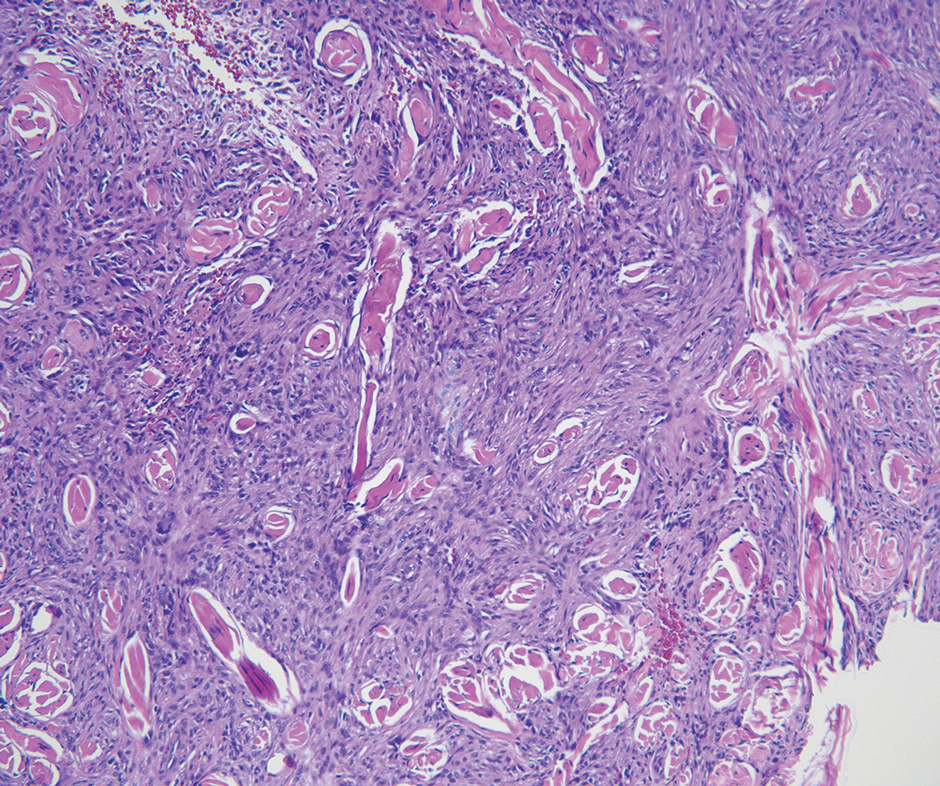

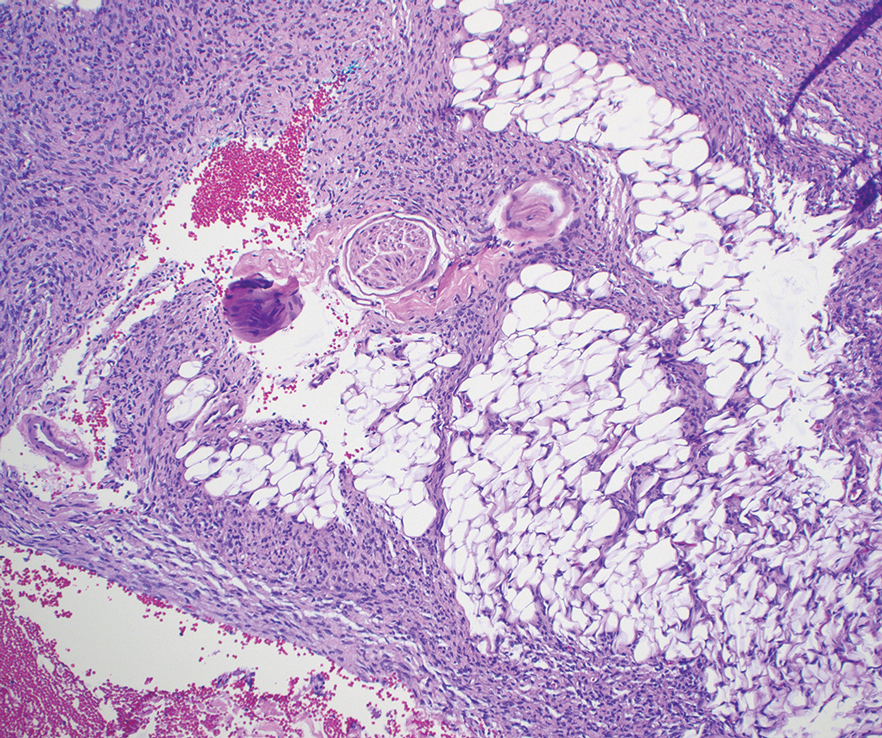

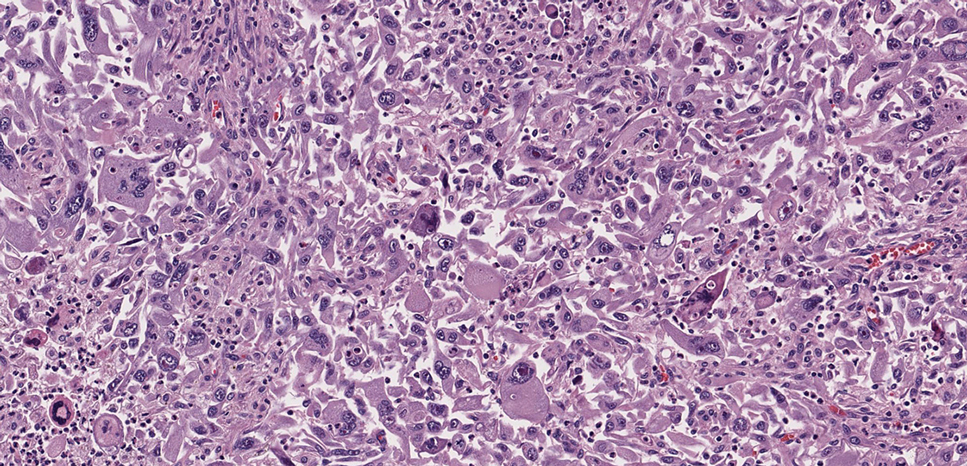

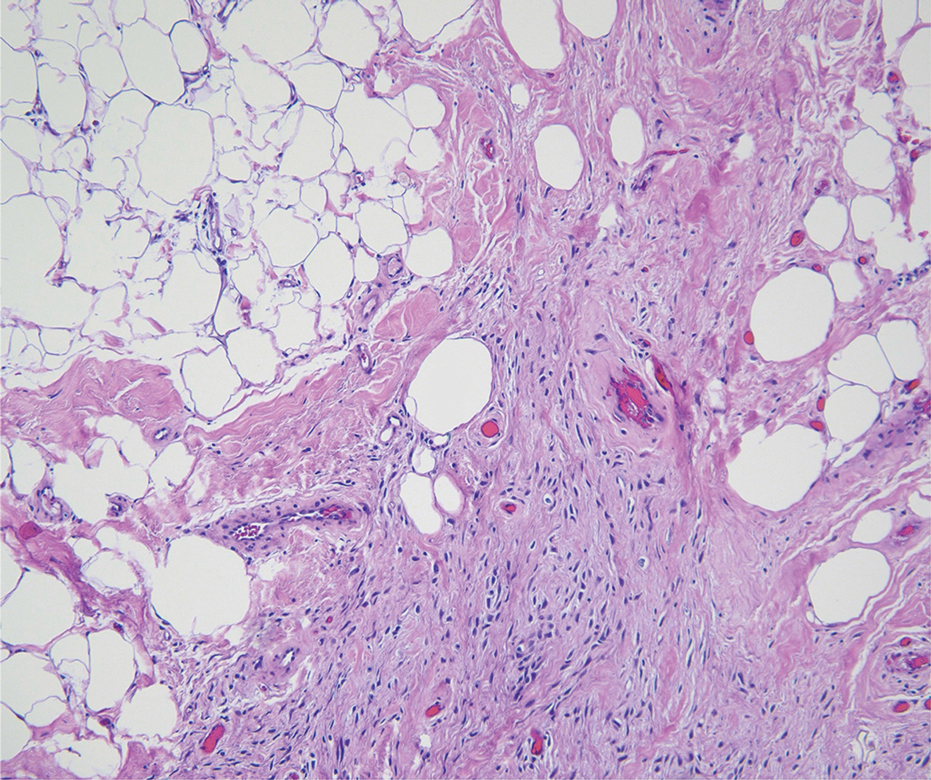

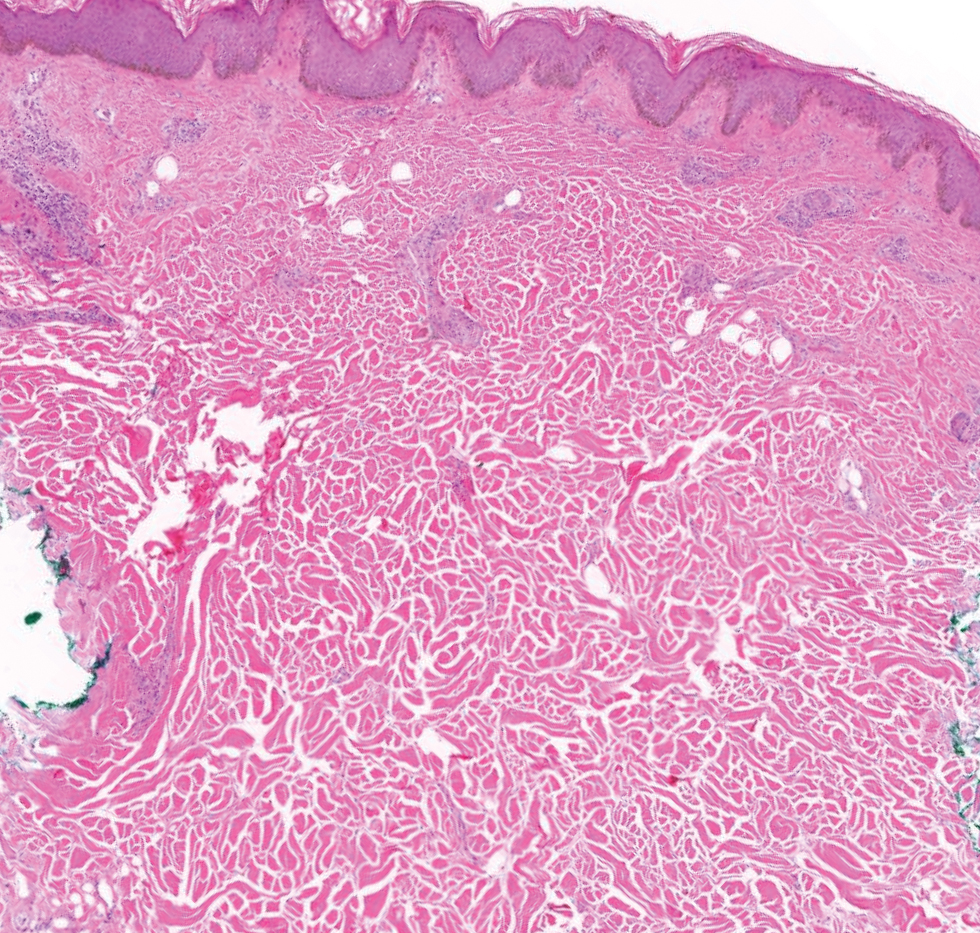

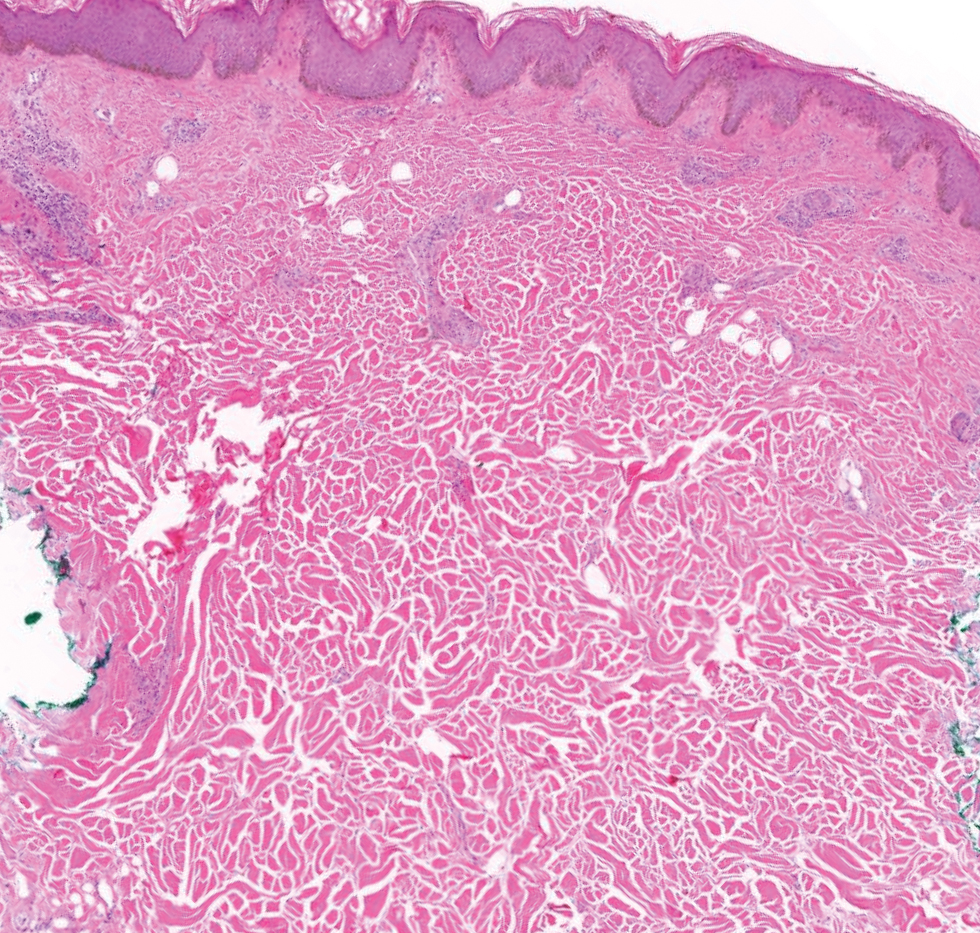

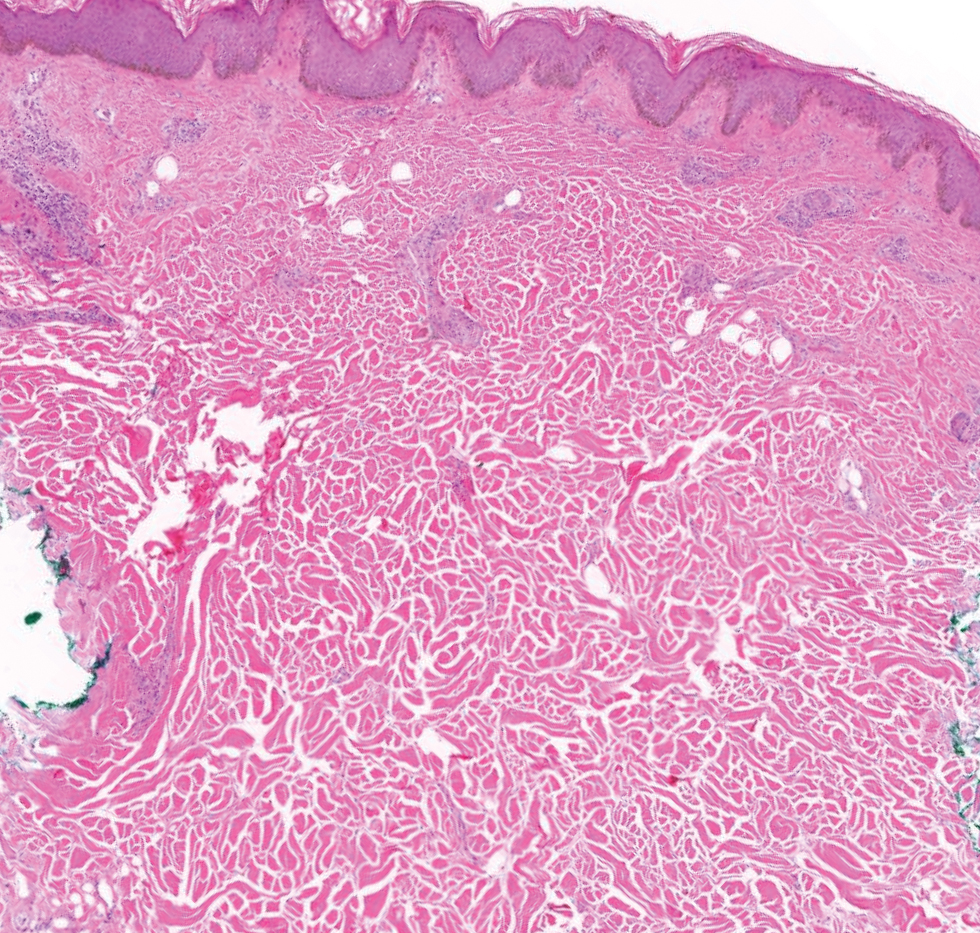

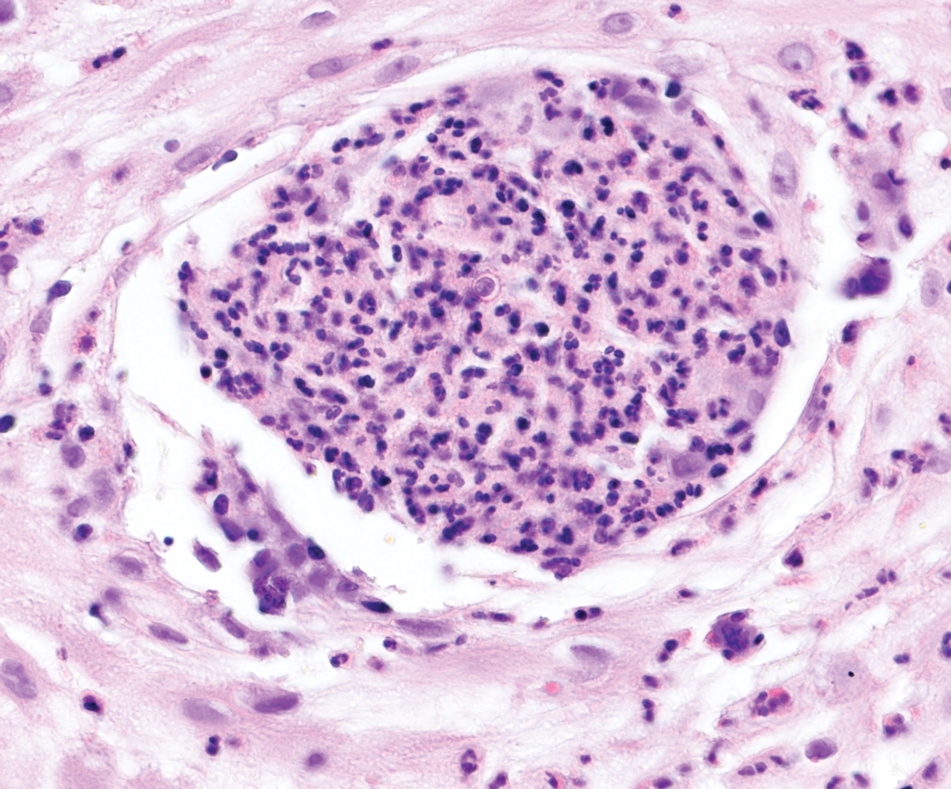

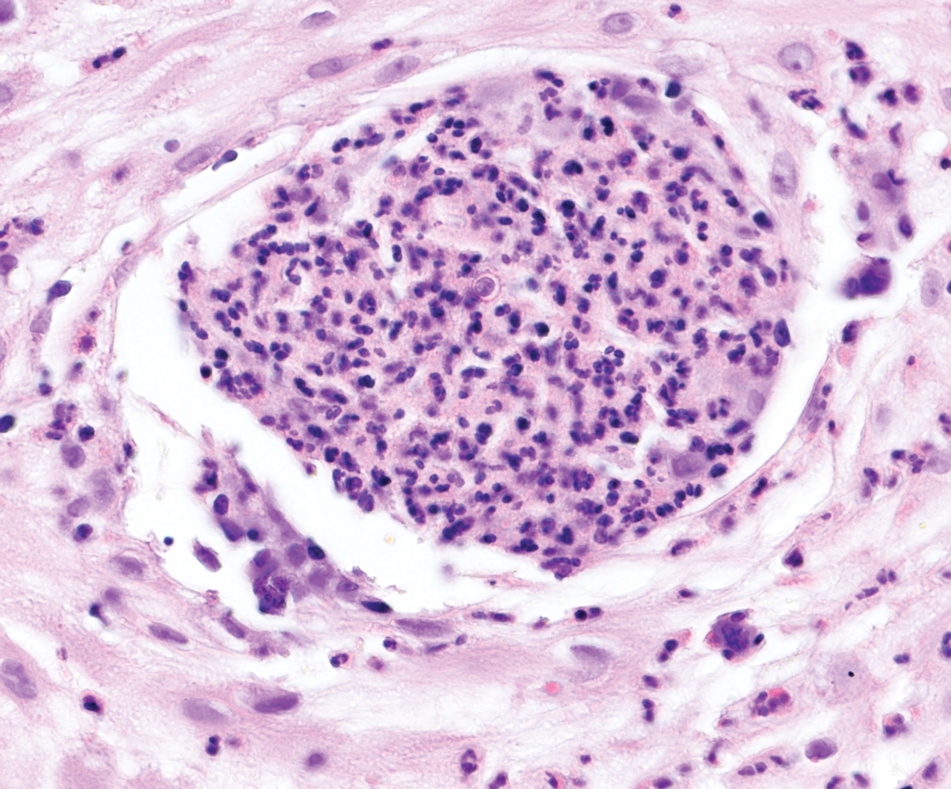

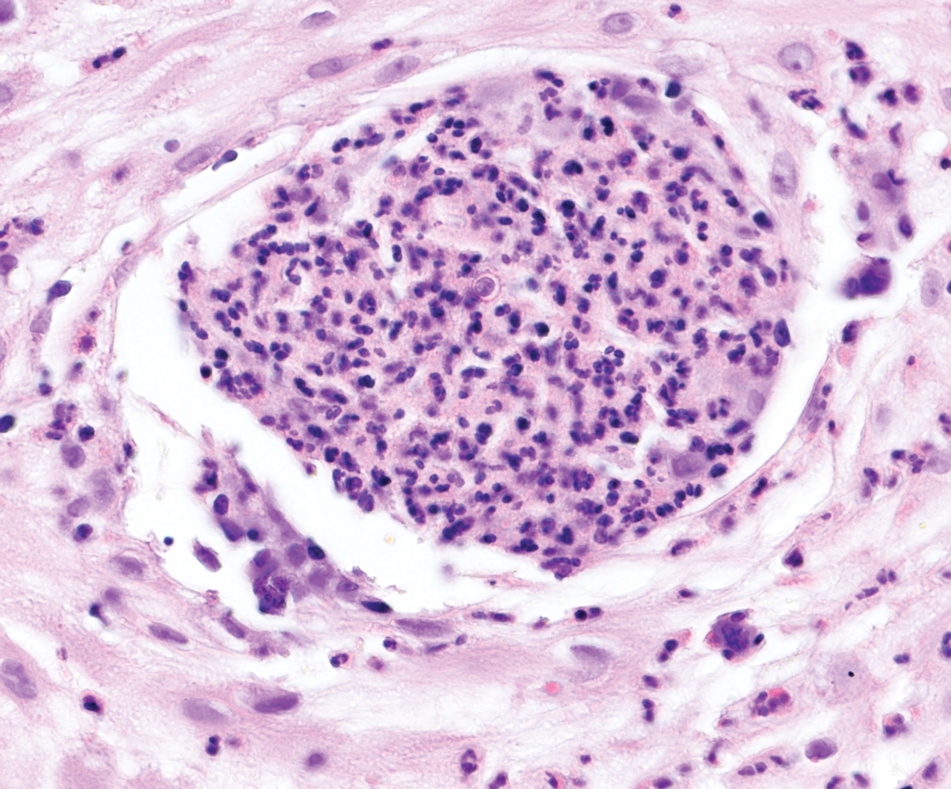

T he biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma with negative margins. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no signs of recurrence. Spiradenocylindroma is a benign hybrid neoplasm consisting of histologically intermixed areas representing the spectrum of morphology between spiradenoma and cylindromas.1,2 Both spiradenoma and cylindroma comprise 2 distinct populations of dark and pale basaloid cells.2,3 The spiradenomatous areas of the spiradenocylindroma are arranged in large, well-circumscribed collections of small, darkly staining cells with interspersed lymphocytes and a thin basement membrane surrounding spiradenocylindroma component.2,3 The spiradenocylindroma regions also may contain tubular structures dilated by hemorrhage.2 In contrast, the cylindromatous regions have a jigsaw-puzzle configuration of polygonal tumor nests containing peripherally palisading dark cells and central pale cells, surrounded by a thick basement membrane (top quiz image).2,3

Clinically, sporadic spiradenocylindromas may resemble other lesions, manifesting as a papule or nodule with coloration ranging from gray-blue to salmon pink along with arborizing telangiectasias.4,5 Although spiradenocylindromas typically are found on the head, neck, and trunk, they also have been reported in the kidney, vulva, anus, and rectum.2,6,7 Not only are spiradenocylindromas clinically indistinct from other adnexal growths, but they also share some features with basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and amelanotic melanomas.8 Features of arborizing telangiectasias on a papule may resemble BCC, requiring histopathology for a definitive diagnosis.

Spiradenocylindromas classically are associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a germline mutation in the cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase tumor-suppressor gene.5 Patients develop adnexal neoplasms of the folliculosebaceous-apocrine unit, including spiradenomas, cylindromas, and trichoepitheliomas.5 Rarely, malignant transformation to spiradenocylindrocarcinoma has been reported.9 Features of malignant transformation include loss of the 2-cell population, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and loss of intratumoral lymphocytes.10

Trichoepitheliomas are benign, firm, flesh-colored papules to nodules that commonly are found on the mid face but may appear on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk.5-11 Trichoepitheliomas are closely related to spiradenomas and cylindromas; the familial form, multiple familial trichoepitheliomas, exists on a spectrum with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.3,11 Multiple familial trichoepithelioma is characterized by multiple trichoepitheliomas without accompanying spiradenomas, cylindromas, or spiradenocylindromas.3 On histopathology, trichoepitheliomas are distinguished by cribriform clusters or nests of basaloid follicular germinative cells with bulbar differentiation, known as papillary mesenchymal bodies, surrounded by an adherent stroma (eFigure 1).3,5,11 In addition to follicular bulbar differentiation, trichoepitheliomas are surrounded by an adherent cellular stroma without the retraction artifact around tumor islands seen in BCC, although artifactual clefts may occur within the stroma.11 In contrast, spiradenocylindromas do not demonstrate keratin cysts or artifactual clefts within the stroma.

Trichilemmal cysts, or pilar cysts, are benign adnexal neoplasms derived from the outer root sheath at the isthmus.12-14 Approximately 90% of pilar cysts are found on the scalp and 2% of trichilemmal cysts may progress to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst, which is locally aggressive and contains an expanding buckled epithelium within the cyst space.12,14 Clinically, trichilemmal cysts are slow-growing, smooth, round, mobile nodules without a central punctum.12,13 On histopathology, the cyst wall contains peripherally palisading basal cells and maturing cells showing no intercellular bridging (eFigure 2). As the cells mature, they swell with pale cytoplasm and abruptly keratinize without a granular layer, a process known as trichilemmal keratinization.12-14 Additionally, cholesterol clefts are common in the keratinous lumen, and about 25% of cysts contain calcifications.13,14 The broadly basophilic spiradenocylindromas sharply contrast the abundant eosinophilic keratin of trichilemmal cysts.

Basal cell carcinoma is a slow-growing, locally destructive neoplasm that develops due to chronic sun exposure; thus, BCCs commonly arise on exposed areas of the face, head, neck, arms, and legs.15 Nodular BCC is the most common subtype and typically manifests as a shiny pearly papule or nodule with a smooth surface, rolled borders, and arborizing telangiectasias.16 On histopathology, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests or nodules of basaloid keratinocytes with peripheral palisading and retraction artifact between the tumor and stroma (eFigure 3).15,16 A lack of retraction artifact, cystic dilation of tubular structures, jigsaw molding of nests, and a distinct 2-cell population distinguish spiradenocylindroma from BCC. Of note, in rare instances BCCs also may display a thick fibrous stroma, similar to the stroma of cylindromas.15

Amelanotic melanoma is a variant of melanoma characterized by little to no pigment. Any of the 4 classic subtypes of melanoma (nodular, superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous) can be amelanotic.17 Clinically, amelanotic melanomas can vary greatly, manifesting as erythematous macules, dermal plaques, or papulonodular lesions, often with scaling.18 On histopathology, findings common to all melanomas include cellular atypia, mitoses, pagetoid spread, and pleomorphism (eFigure 4).18,19 Immunohistochemistry is an important method to distinguish melanoma from other melanocytic proliferations and to aid in the assessment of Breslow depth. Markers include SOX10 (sex-determining region Y-box transcription factor 10), S100, and MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1/melan-A).19,20 Expression of PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) often is positive but is not necessary for diagnosis.21 Histologically, the atypical pleomorphic cells of melanoma are markedly distinct from both spiradenomas and cylindromas.

- Soyer HP, Kerl H, Ott A. Spiradenocylindroma—more than a coincidence? Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:315-317.

- Michal M, Lamovec J, Mukenˇ snabl P, et al. Spiradenocylindromas of the skin: tumors with morphological features of spiradenoma and cylindroma in the same lesion: report of 12 cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:419-425.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bostan E, Boynuyogun E, Gokoz O, et al. Hybrid tumor “spiradenocylindroma” with unusual dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:382-384.

- Pinho AC, Gouveia MJ, Gameiro AR, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome—an underrecognized cause of multiple familial scalp tumors: report of a new germline mutation. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:67-70.

- Ströbel P, Zettl A, Ren Z, et al. Spiradenocylindroma of the kidney: clinical and genetic findings suggesting a role of somatic mutation of the CYLD1 gene in the oncogenesis of an unusual renal neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:119-124.

- Kacerovska D, Szepe P, Vanecek T, et al. Spiradenocylindroma-like basaloid carcinoma of the anus and rectum: case report, including HPV studies and analysis of the CYLD gene mutations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:472-476.

- Silvestri F, Maida P, Venturi F, et al. Scalp spiradenocylindroma: a challenging dermoscopic diagnosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14307.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Saggini A, et al. Metaplastic spiradenocarcinoma: report of two cases with sarcomatous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:384-389.

- Płachta I, Kleibert M, Czarnecka AM, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment options for cutaneous adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5077.

- Johnson H, Robles M, Kamino H, et al. Trichoepithelioma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

- He P, Cui LG, Wang JR, et al. Trichilemmal cyst: clinical and sonographic feature. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:91-96.

- Liu M, Han H, Zheng Y, et al. Pilar cyst on the dorsum of hand: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (United States). 2020;99:E21519.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. In: Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. Vol 141. College of American Pathologists; 2017:1490-1502.

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317.

- Kaizer-Salk KA, Herten RJ, Ragsdale BD, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a unique case study and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2018:bcr2017222751.

- Silva TS, de Araujo LR, Faro GB de A, et al. Nodular amelanotic melanoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:497-498.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321.

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

T he biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma with negative margins. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no signs of recurrence. Spiradenocylindroma is a benign hybrid neoplasm consisting of histologically intermixed areas representing the spectrum of morphology between spiradenoma and cylindromas.1,2 Both spiradenoma and cylindroma comprise 2 distinct populations of dark and pale basaloid cells.2,3 The spiradenomatous areas of the spiradenocylindroma are arranged in large, well-circumscribed collections of small, darkly staining cells with interspersed lymphocytes and a thin basement membrane surrounding spiradenocylindroma component.2,3 The spiradenocylindroma regions also may contain tubular structures dilated by hemorrhage.2 In contrast, the cylindromatous regions have a jigsaw-puzzle configuration of polygonal tumor nests containing peripherally palisading dark cells and central pale cells, surrounded by a thick basement membrane (top quiz image).2,3

Clinically, sporadic spiradenocylindromas may resemble other lesions, manifesting as a papule or nodule with coloration ranging from gray-blue to salmon pink along with arborizing telangiectasias.4,5 Although spiradenocylindromas typically are found on the head, neck, and trunk, they also have been reported in the kidney, vulva, anus, and rectum.2,6,7 Not only are spiradenocylindromas clinically indistinct from other adnexal growths, but they also share some features with basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and amelanotic melanomas.8 Features of arborizing telangiectasias on a papule may resemble BCC, requiring histopathology for a definitive diagnosis.

Spiradenocylindromas classically are associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a germline mutation in the cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase tumor-suppressor gene.5 Patients develop adnexal neoplasms of the folliculosebaceous-apocrine unit, including spiradenomas, cylindromas, and trichoepitheliomas.5 Rarely, malignant transformation to spiradenocylindrocarcinoma has been reported.9 Features of malignant transformation include loss of the 2-cell population, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and loss of intratumoral lymphocytes.10

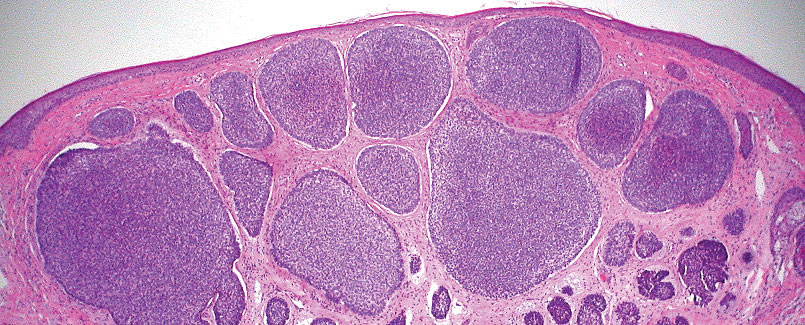

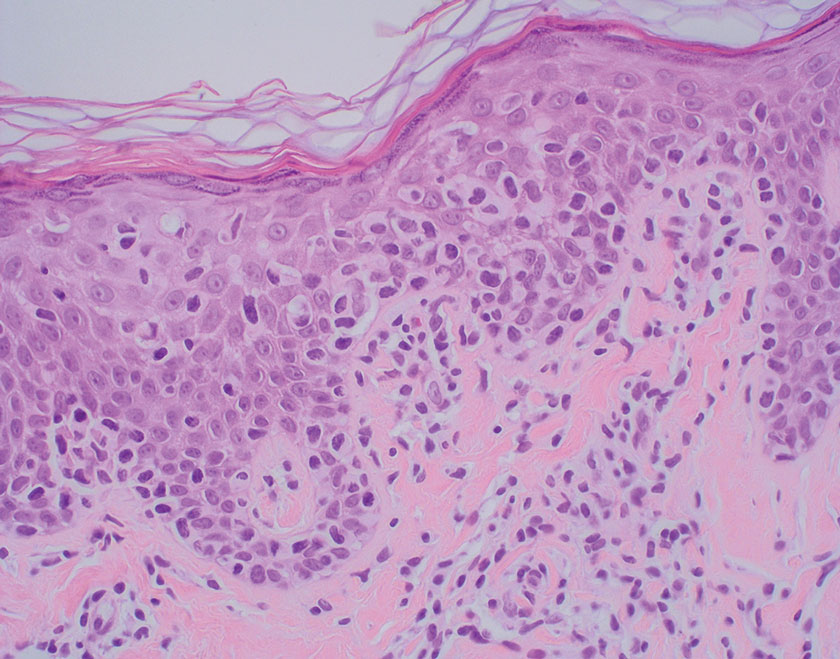

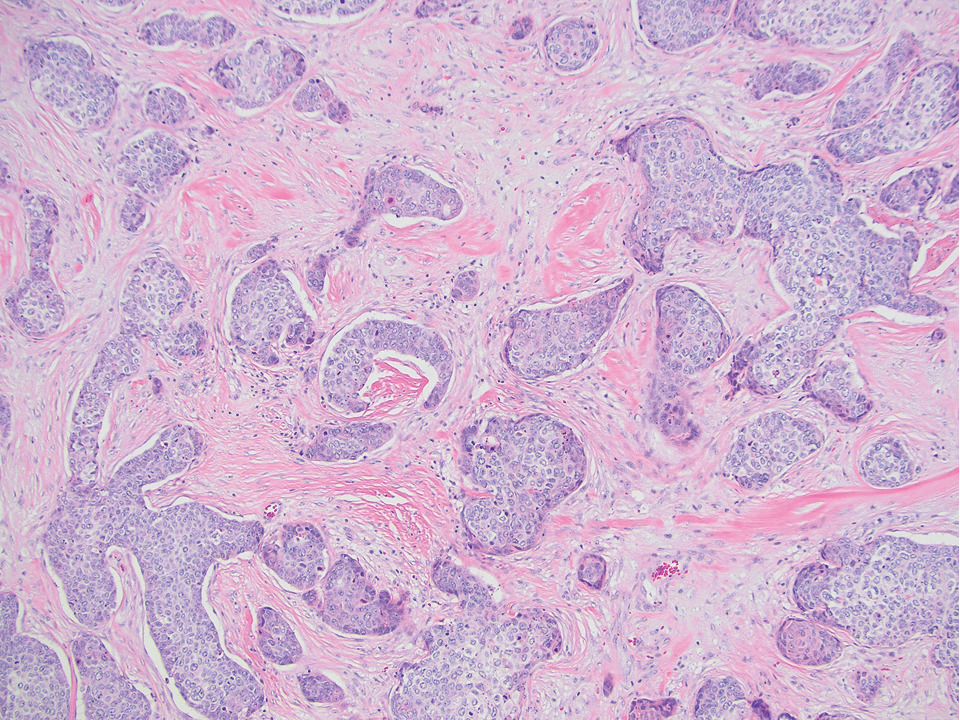

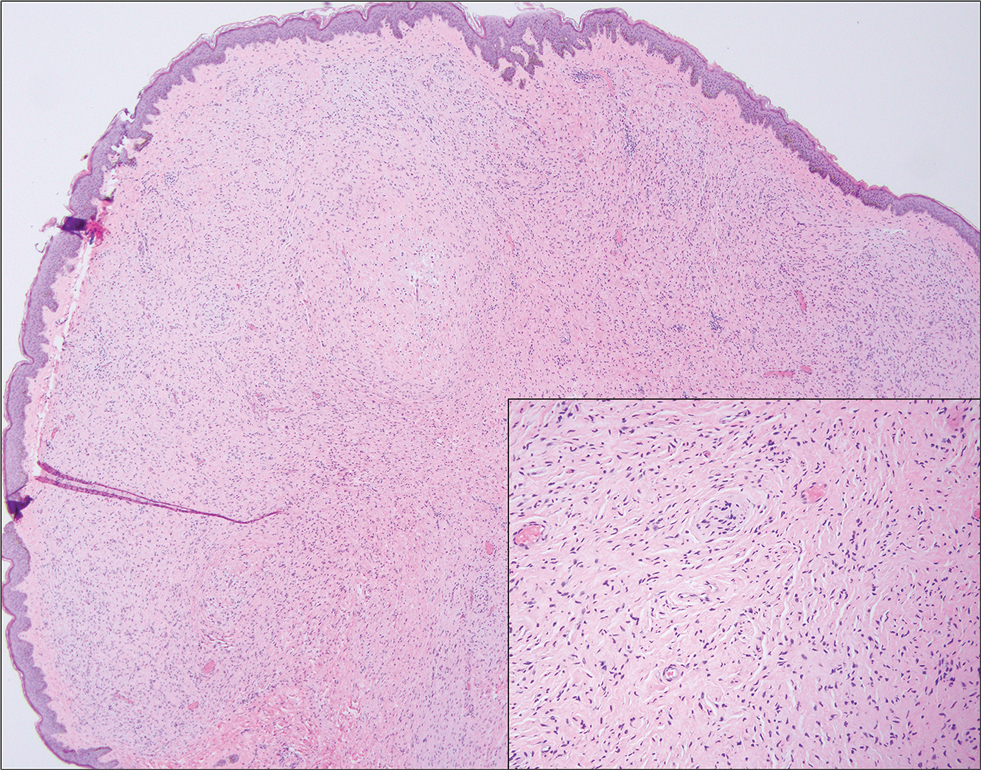

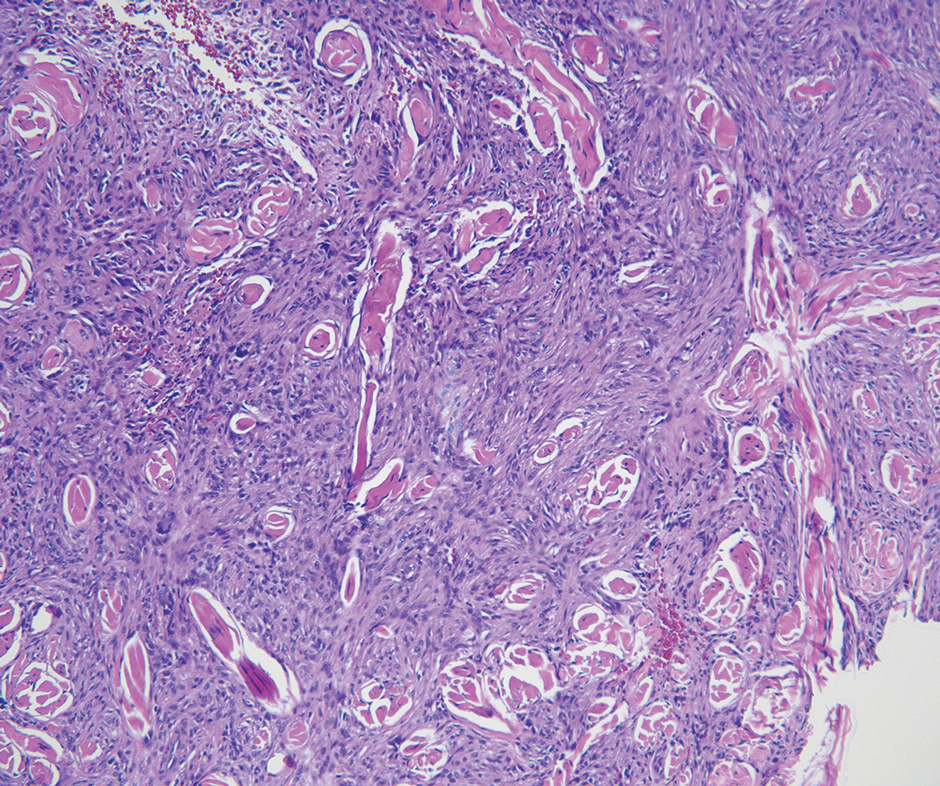

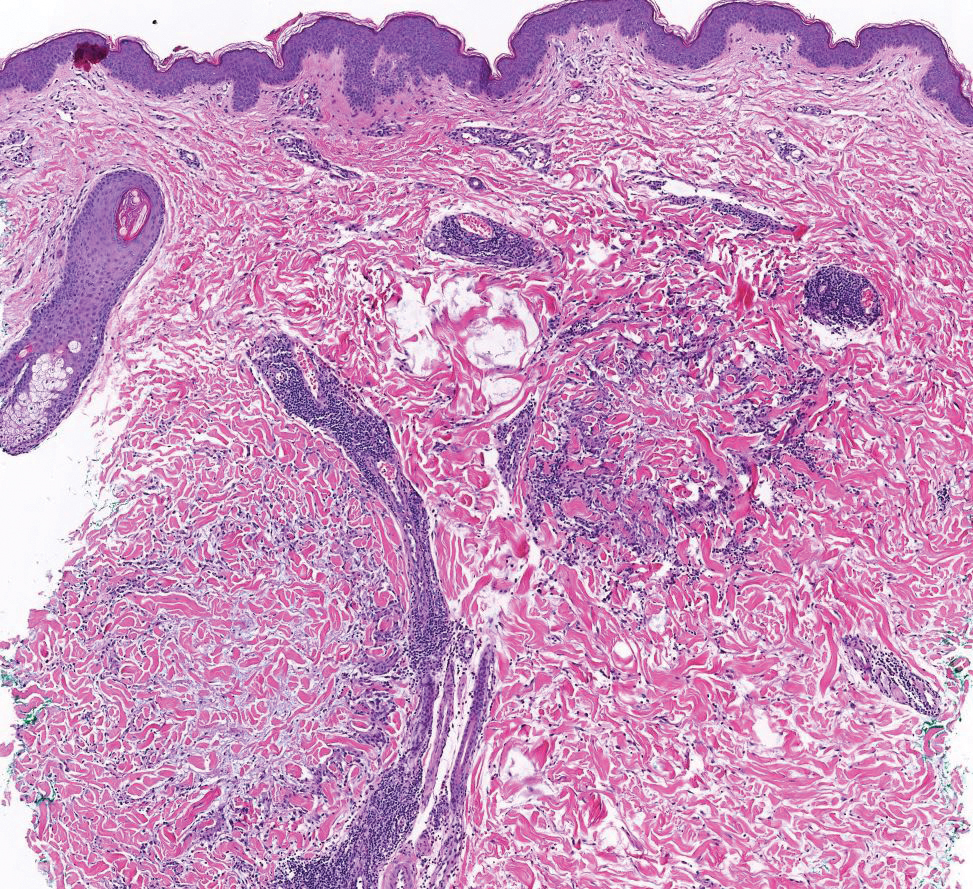

Trichoepitheliomas are benign, firm, flesh-colored papules to nodules that commonly are found on the mid face but may appear on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk.5-11 Trichoepitheliomas are closely related to spiradenomas and cylindromas; the familial form, multiple familial trichoepitheliomas, exists on a spectrum with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.3,11 Multiple familial trichoepithelioma is characterized by multiple trichoepitheliomas without accompanying spiradenomas, cylindromas, or spiradenocylindromas.3 On histopathology, trichoepitheliomas are distinguished by cribriform clusters or nests of basaloid follicular germinative cells with bulbar differentiation, known as papillary mesenchymal bodies, surrounded by an adherent stroma (eFigure 1).3,5,11 In addition to follicular bulbar differentiation, trichoepitheliomas are surrounded by an adherent cellular stroma without the retraction artifact around tumor islands seen in BCC, although artifactual clefts may occur within the stroma.11 In contrast, spiradenocylindromas do not demonstrate keratin cysts or artifactual clefts within the stroma.

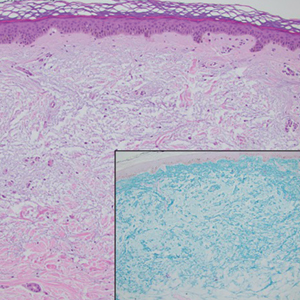

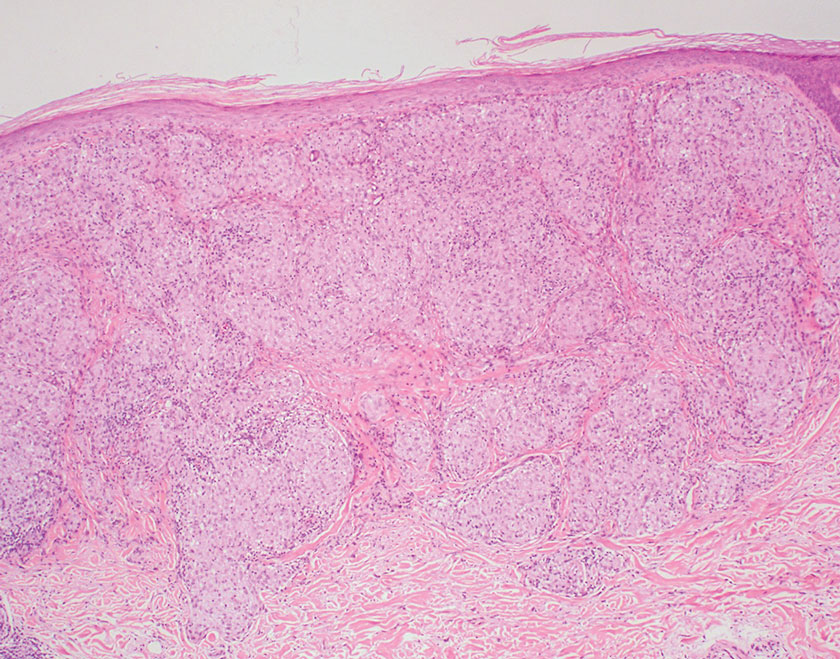

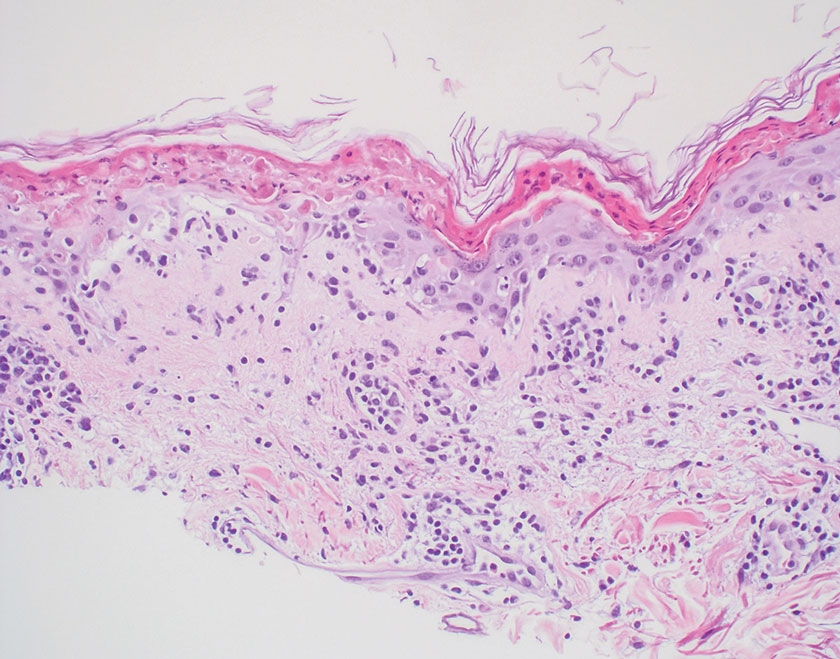

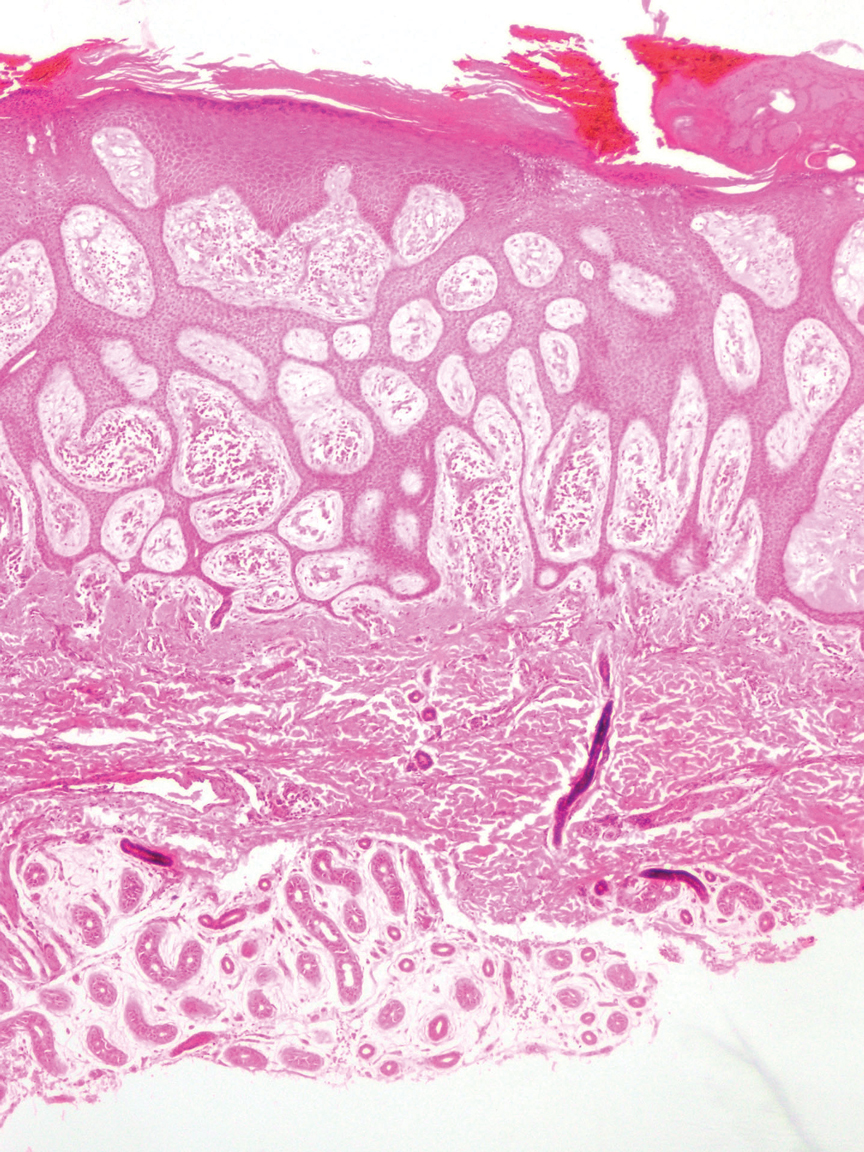

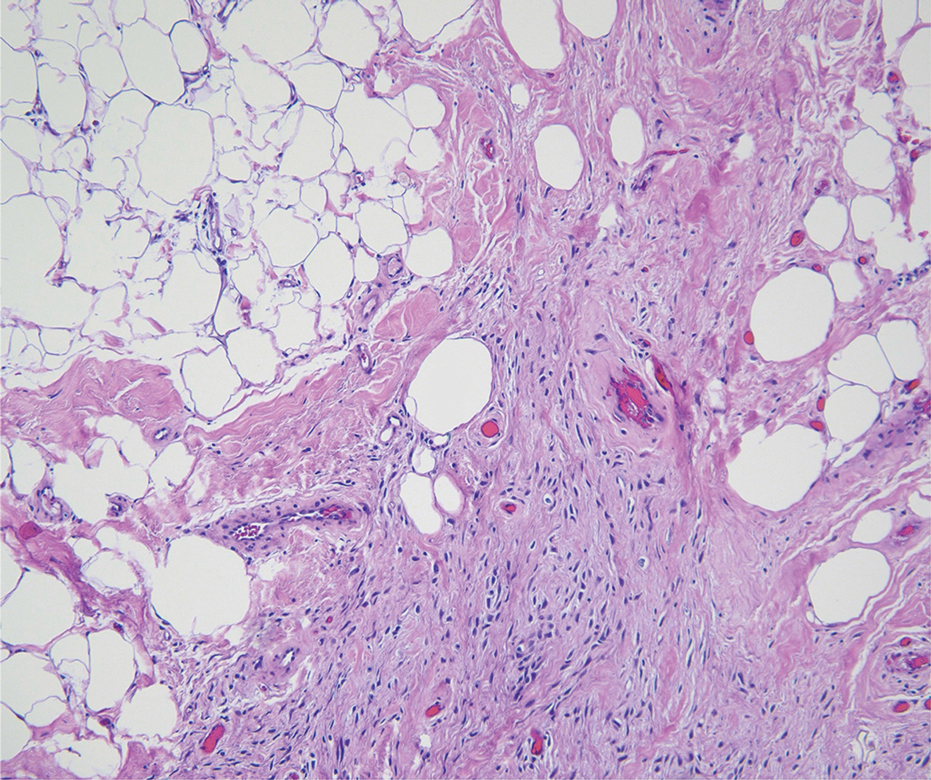

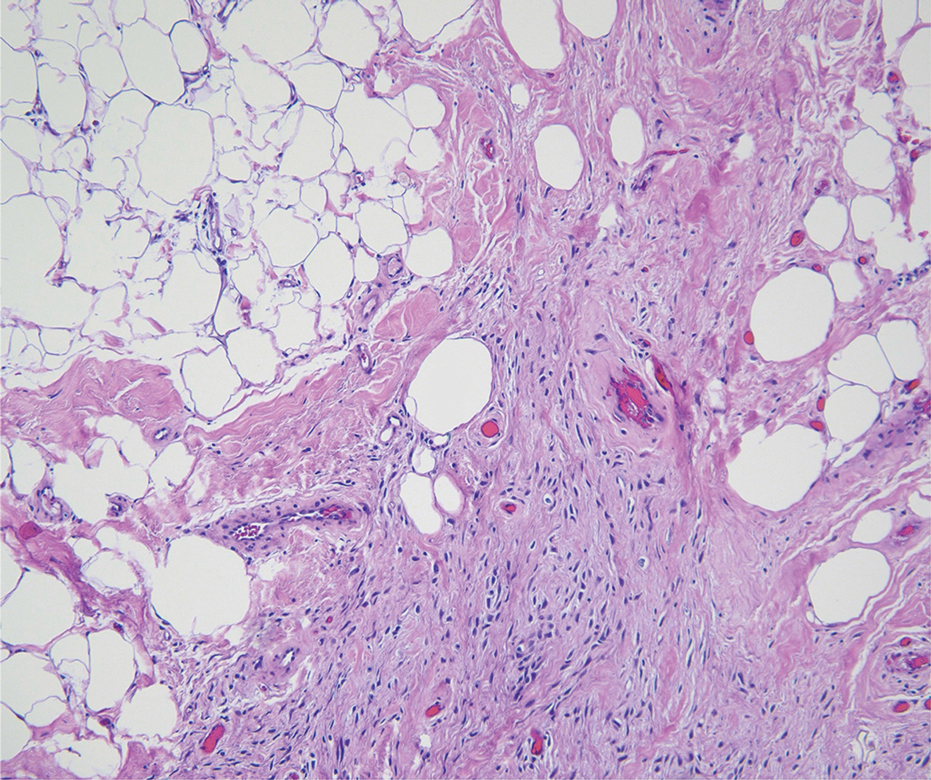

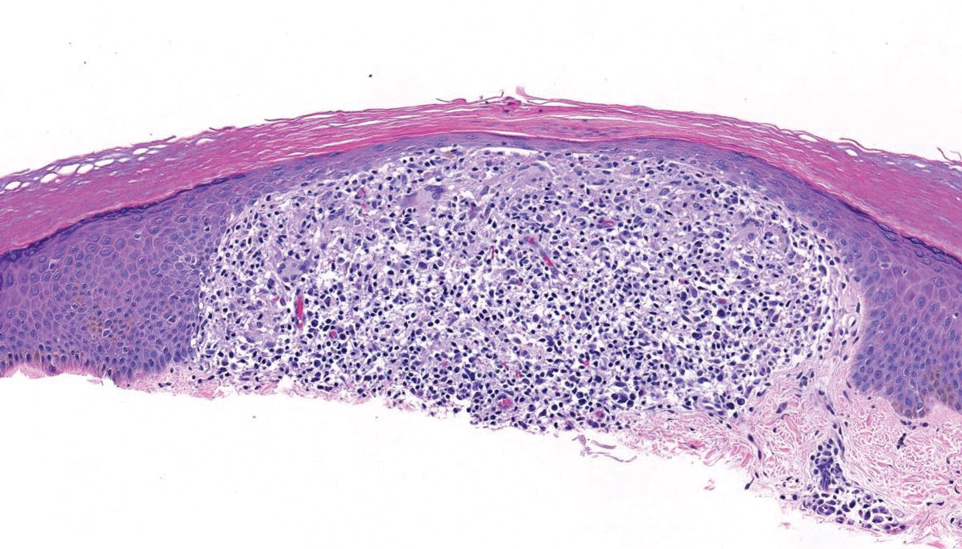

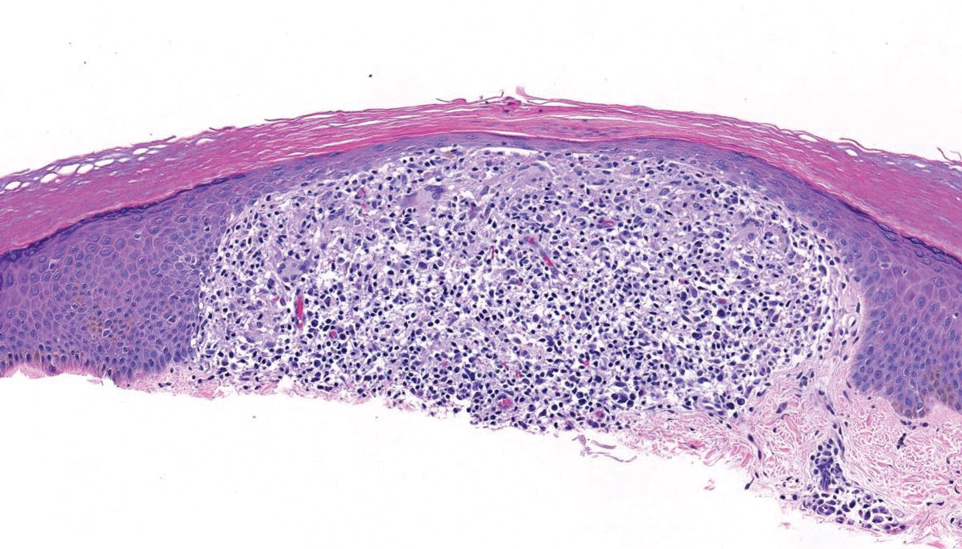

Trichilemmal cysts, or pilar cysts, are benign adnexal neoplasms derived from the outer root sheath at the isthmus.12-14 Approximately 90% of pilar cysts are found on the scalp and 2% of trichilemmal cysts may progress to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst, which is locally aggressive and contains an expanding buckled epithelium within the cyst space.12,14 Clinically, trichilemmal cysts are slow-growing, smooth, round, mobile nodules without a central punctum.12,13 On histopathology, the cyst wall contains peripherally palisading basal cells and maturing cells showing no intercellular bridging (eFigure 2). As the cells mature, they swell with pale cytoplasm and abruptly keratinize without a granular layer, a process known as trichilemmal keratinization.12-14 Additionally, cholesterol clefts are common in the keratinous lumen, and about 25% of cysts contain calcifications.13,14 The broadly basophilic spiradenocylindromas sharply contrast the abundant eosinophilic keratin of trichilemmal cysts.

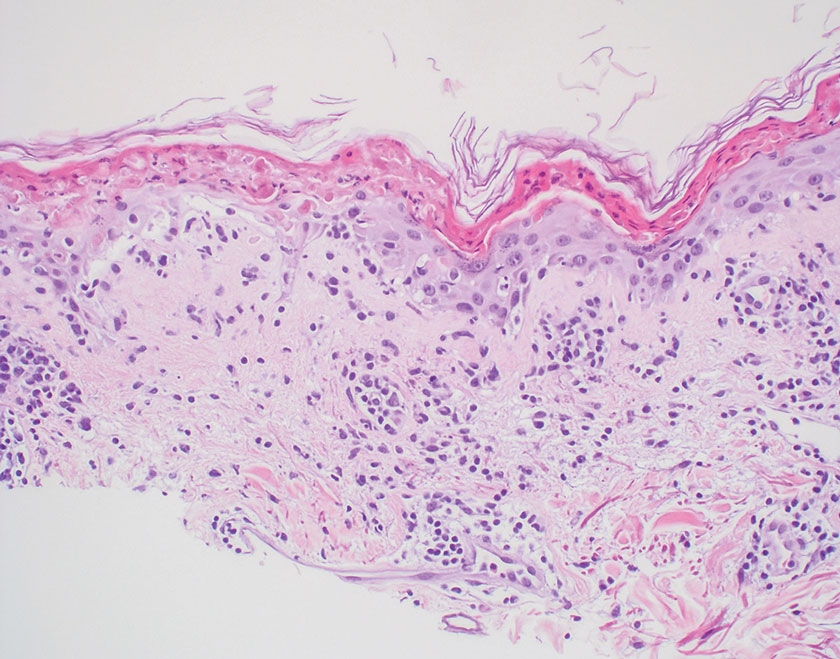

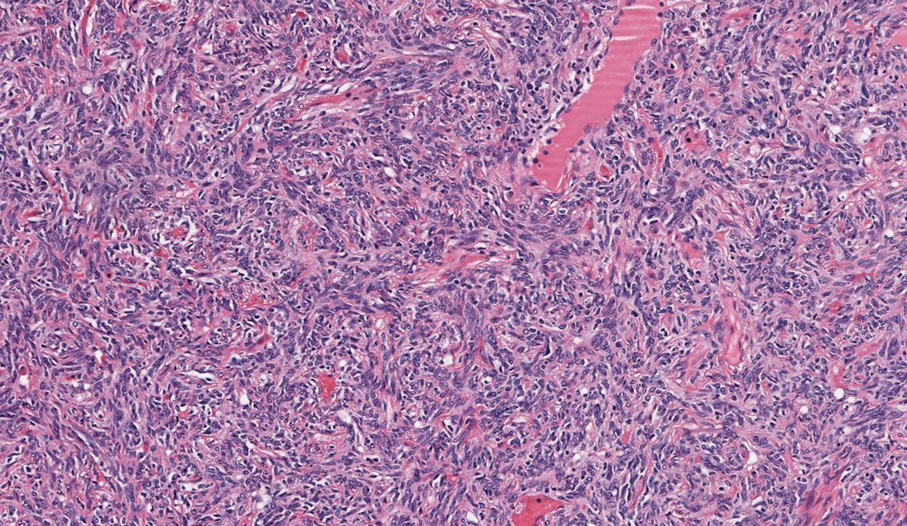

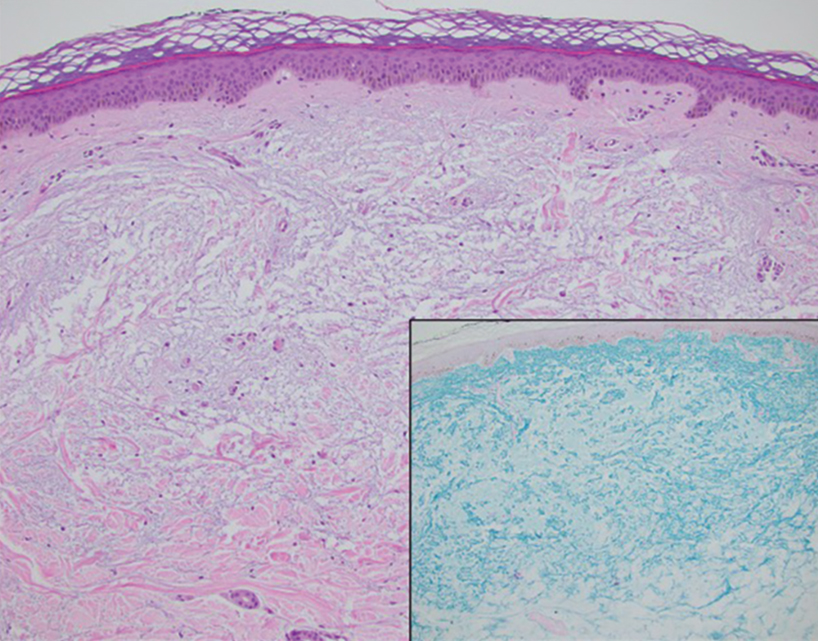

Basal cell carcinoma is a slow-growing, locally destructive neoplasm that develops due to chronic sun exposure; thus, BCCs commonly arise on exposed areas of the face, head, neck, arms, and legs.15 Nodular BCC is the most common subtype and typically manifests as a shiny pearly papule or nodule with a smooth surface, rolled borders, and arborizing telangiectasias.16 On histopathology, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests or nodules of basaloid keratinocytes with peripheral palisading and retraction artifact between the tumor and stroma (eFigure 3).15,16 A lack of retraction artifact, cystic dilation of tubular structures, jigsaw molding of nests, and a distinct 2-cell population distinguish spiradenocylindroma from BCC. Of note, in rare instances BCCs also may display a thick fibrous stroma, similar to the stroma of cylindromas.15

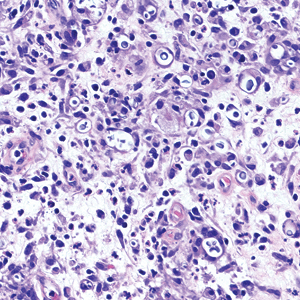

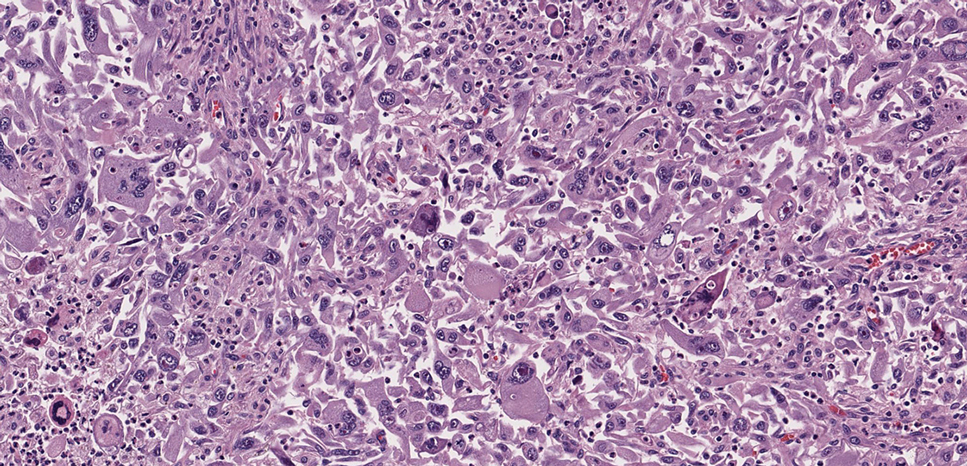

Amelanotic melanoma is a variant of melanoma characterized by little to no pigment. Any of the 4 classic subtypes of melanoma (nodular, superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous) can be amelanotic.17 Clinically, amelanotic melanomas can vary greatly, manifesting as erythematous macules, dermal plaques, or papulonodular lesions, often with scaling.18 On histopathology, findings common to all melanomas include cellular atypia, mitoses, pagetoid spread, and pleomorphism (eFigure 4).18,19 Immunohistochemistry is an important method to distinguish melanoma from other melanocytic proliferations and to aid in the assessment of Breslow depth. Markers include SOX10 (sex-determining region Y-box transcription factor 10), S100, and MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1/melan-A).19,20 Expression of PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) often is positive but is not necessary for diagnosis.21 Histologically, the atypical pleomorphic cells of melanoma are markedly distinct from both spiradenomas and cylindromas.

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

T he biopsy results confirmed the diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma with negative margins. At 6-week follow-up, the patient had no signs of recurrence. Spiradenocylindroma is a benign hybrid neoplasm consisting of histologically intermixed areas representing the spectrum of morphology between spiradenoma and cylindromas.1,2 Both spiradenoma and cylindroma comprise 2 distinct populations of dark and pale basaloid cells.2,3 The spiradenomatous areas of the spiradenocylindroma are arranged in large, well-circumscribed collections of small, darkly staining cells with interspersed lymphocytes and a thin basement membrane surrounding spiradenocylindroma component.2,3 The spiradenocylindroma regions also may contain tubular structures dilated by hemorrhage.2 In contrast, the cylindromatous regions have a jigsaw-puzzle configuration of polygonal tumor nests containing peripherally palisading dark cells and central pale cells, surrounded by a thick basement membrane (top quiz image).2,3

Clinically, sporadic spiradenocylindromas may resemble other lesions, manifesting as a papule or nodule with coloration ranging from gray-blue to salmon pink along with arborizing telangiectasias.4,5 Although spiradenocylindromas typically are found on the head, neck, and trunk, they also have been reported in the kidney, vulva, anus, and rectum.2,6,7 Not only are spiradenocylindromas clinically indistinct from other adnexal growths, but they also share some features with basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and amelanotic melanomas.8 Features of arborizing telangiectasias on a papule may resemble BCC, requiring histopathology for a definitive diagnosis.

Spiradenocylindromas classically are associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome, a rare, autosomal-dominant genodermatosis caused by a germline mutation in the cylindromatosis lysine 63 deubiquitinase tumor-suppressor gene.5 Patients develop adnexal neoplasms of the folliculosebaceous-apocrine unit, including spiradenomas, cylindromas, and trichoepitheliomas.5 Rarely, malignant transformation to spiradenocylindrocarcinoma has been reported.9 Features of malignant transformation include loss of the 2-cell population, cytologic atypia, increased mitotic activity, and loss of intratumoral lymphocytes.10

Trichoepitheliomas are benign, firm, flesh-colored papules to nodules that commonly are found on the mid face but may appear on the scalp, neck, and upper trunk.5-11 Trichoepitheliomas are closely related to spiradenomas and cylindromas; the familial form, multiple familial trichoepitheliomas, exists on a spectrum with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.3,11 Multiple familial trichoepithelioma is characterized by multiple trichoepitheliomas without accompanying spiradenomas, cylindromas, or spiradenocylindromas.3 On histopathology, trichoepitheliomas are distinguished by cribriform clusters or nests of basaloid follicular germinative cells with bulbar differentiation, known as papillary mesenchymal bodies, surrounded by an adherent stroma (eFigure 1).3,5,11 In addition to follicular bulbar differentiation, trichoepitheliomas are surrounded by an adherent cellular stroma without the retraction artifact around tumor islands seen in BCC, although artifactual clefts may occur within the stroma.11 In contrast, spiradenocylindromas do not demonstrate keratin cysts or artifactual clefts within the stroma.

Trichilemmal cysts, or pilar cysts, are benign adnexal neoplasms derived from the outer root sheath at the isthmus.12-14 Approximately 90% of pilar cysts are found on the scalp and 2% of trichilemmal cysts may progress to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst, which is locally aggressive and contains an expanding buckled epithelium within the cyst space.12,14 Clinically, trichilemmal cysts are slow-growing, smooth, round, mobile nodules without a central punctum.12,13 On histopathology, the cyst wall contains peripherally palisading basal cells and maturing cells showing no intercellular bridging (eFigure 2). As the cells mature, they swell with pale cytoplasm and abruptly keratinize without a granular layer, a process known as trichilemmal keratinization.12-14 Additionally, cholesterol clefts are common in the keratinous lumen, and about 25% of cysts contain calcifications.13,14 The broadly basophilic spiradenocylindromas sharply contrast the abundant eosinophilic keratin of trichilemmal cysts.

Basal cell carcinoma is a slow-growing, locally destructive neoplasm that develops due to chronic sun exposure; thus, BCCs commonly arise on exposed areas of the face, head, neck, arms, and legs.15 Nodular BCC is the most common subtype and typically manifests as a shiny pearly papule or nodule with a smooth surface, rolled borders, and arborizing telangiectasias.16 On histopathology, nodular BCCs demonstrate nests or nodules of basaloid keratinocytes with peripheral palisading and retraction artifact between the tumor and stroma (eFigure 3).15,16 A lack of retraction artifact, cystic dilation of tubular structures, jigsaw molding of nests, and a distinct 2-cell population distinguish spiradenocylindroma from BCC. Of note, in rare instances BCCs also may display a thick fibrous stroma, similar to the stroma of cylindromas.15

Amelanotic melanoma is a variant of melanoma characterized by little to no pigment. Any of the 4 classic subtypes of melanoma (nodular, superficial spreading, lentigo maligna, acral lentiginous) can be amelanotic.17 Clinically, amelanotic melanomas can vary greatly, manifesting as erythematous macules, dermal plaques, or papulonodular lesions, often with scaling.18 On histopathology, findings common to all melanomas include cellular atypia, mitoses, pagetoid spread, and pleomorphism (eFigure 4).18,19 Immunohistochemistry is an important method to distinguish melanoma from other melanocytic proliferations and to aid in the assessment of Breslow depth. Markers include SOX10 (sex-determining region Y-box transcription factor 10), S100, and MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1/melan-A).19,20 Expression of PRAME (preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma) often is positive but is not necessary for diagnosis.21 Histologically, the atypical pleomorphic cells of melanoma are markedly distinct from both spiradenomas and cylindromas.

- Soyer HP, Kerl H, Ott A. Spiradenocylindroma—more than a coincidence? Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:315-317.

- Michal M, Lamovec J, Mukenˇ snabl P, et al. Spiradenocylindromas of the skin: tumors with morphological features of spiradenoma and cylindroma in the same lesion: report of 12 cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:419-425.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bostan E, Boynuyogun E, Gokoz O, et al. Hybrid tumor “spiradenocylindroma” with unusual dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:382-384.

- Pinho AC, Gouveia MJ, Gameiro AR, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome—an underrecognized cause of multiple familial scalp tumors: report of a new germline mutation. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:67-70.

- Ströbel P, Zettl A, Ren Z, et al. Spiradenocylindroma of the kidney: clinical and genetic findings suggesting a role of somatic mutation of the CYLD1 gene in the oncogenesis of an unusual renal neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:119-124.

- Kacerovska D, Szepe P, Vanecek T, et al. Spiradenocylindroma-like basaloid carcinoma of the anus and rectum: case report, including HPV studies and analysis of the CYLD gene mutations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:472-476.

- Silvestri F, Maida P, Venturi F, et al. Scalp spiradenocylindroma: a challenging dermoscopic diagnosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14307.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Saggini A, et al. Metaplastic spiradenocarcinoma: report of two cases with sarcomatous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:384-389.

- Płachta I, Kleibert M, Czarnecka AM, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment options for cutaneous adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5077.

- Johnson H, Robles M, Kamino H, et al. Trichoepithelioma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

- He P, Cui LG, Wang JR, et al. Trichilemmal cyst: clinical and sonographic feature. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:91-96.

- Liu M, Han H, Zheng Y, et al. Pilar cyst on the dorsum of hand: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (United States). 2020;99:E21519.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. In: Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. Vol 141. College of American Pathologists; 2017:1490-1502.

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317.

- Kaizer-Salk KA, Herten RJ, Ragsdale BD, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a unique case study and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2018:bcr2017222751.

- Silva TS, de Araujo LR, Faro GB de A, et al. Nodular amelanotic melanoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:497-498.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321.

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

- Soyer HP, Kerl H, Ott A. Spiradenocylindroma—more than a coincidence? Am J Dermatopathol. 1998;20:315-317.

- Michal M, Lamovec J, Mukenˇ snabl P, et al. Spiradenocylindromas of the skin: tumors with morphological features of spiradenoma and cylindroma in the same lesion: report of 12 cases. Pathol Int. 1999;49:419-425.

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-130.

- Bostan E, Boynuyogun E, Gokoz O, et al. Hybrid tumor “spiradenocylindroma” with unusual dermoscopic features. An Bras Dermatol. 2023;98:382-384.

- Pinho AC, Gouveia MJ, Gameiro AR, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome—an underrecognized cause of multiple familial scalp tumors: report of a new germline mutation. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2015;9:67-70.

- Ströbel P, Zettl A, Ren Z, et al. Spiradenocylindroma of the kidney: clinical and genetic findings suggesting a role of somatic mutation of the CYLD1 gene in the oncogenesis of an unusual renal neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:119-124.

- Kacerovska D, Szepe P, Vanecek T, et al. Spiradenocylindroma-like basaloid carcinoma of the anus and rectum: case report, including HPV studies and analysis of the CYLD gene mutations. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:472-476.

- Silvestri F, Maida P, Venturi F, et al. Scalp spiradenocylindroma: a challenging dermoscopic diagnosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E14307.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Saggini A, et al. Metaplastic spiradenocarcinoma: report of two cases with sarcomatous differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:384-389.

- Płachta I, Kleibert M, Czarnecka AM, et al. Current diagnosis and treatment options for cutaneous adnexal neoplasms with apocrine and eccrine differentiation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:5077.

- Johnson H, Robles M, Kamino H, et al. Trichoepithelioma. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

- He P, Cui LG, Wang JR, et al. Trichilemmal cyst: clinical and sonographic feature. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:91-96.

- Liu M, Han H, Zheng Y, et al. Pilar cyst on the dorsum of hand: a case report and review of literature. Medicine (United States). 2020;99:E21519.

- Ramaswamy AS, Manjunatha HK, Sunilkumar B, et al. Morphological spectrum of pilar cysts. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:124-128.

- Stanoszek LM, Wang GY, Harms PW. Histologic mimics of basal cell carcinoma. In: Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. Vol 141. College of American Pathologists; 2017:1490-1502.

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317.

- Kaizer-Salk KA, Herten RJ, Ragsdale BD, et al. Amelanotic melanoma: a unique case study and review of the literature. BMJ Case Rep. 2018:bcr2017222751.

- Silva TS, de Araujo LR, Faro GB de A, et al. Nodular amelanotic melanoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:497-498.

- Bobos M. Histopathologic classification and prognostic factors of melanoma: a 2021 update. Ital J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;156:300-321.

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444.

- Lezcano C, Jungbluth AA, Nehal KS, et al. PRAME expression in melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:1456-1465.

Mobile Tender Papule on the Scalp

Mobile Tender Papule on the Scalp

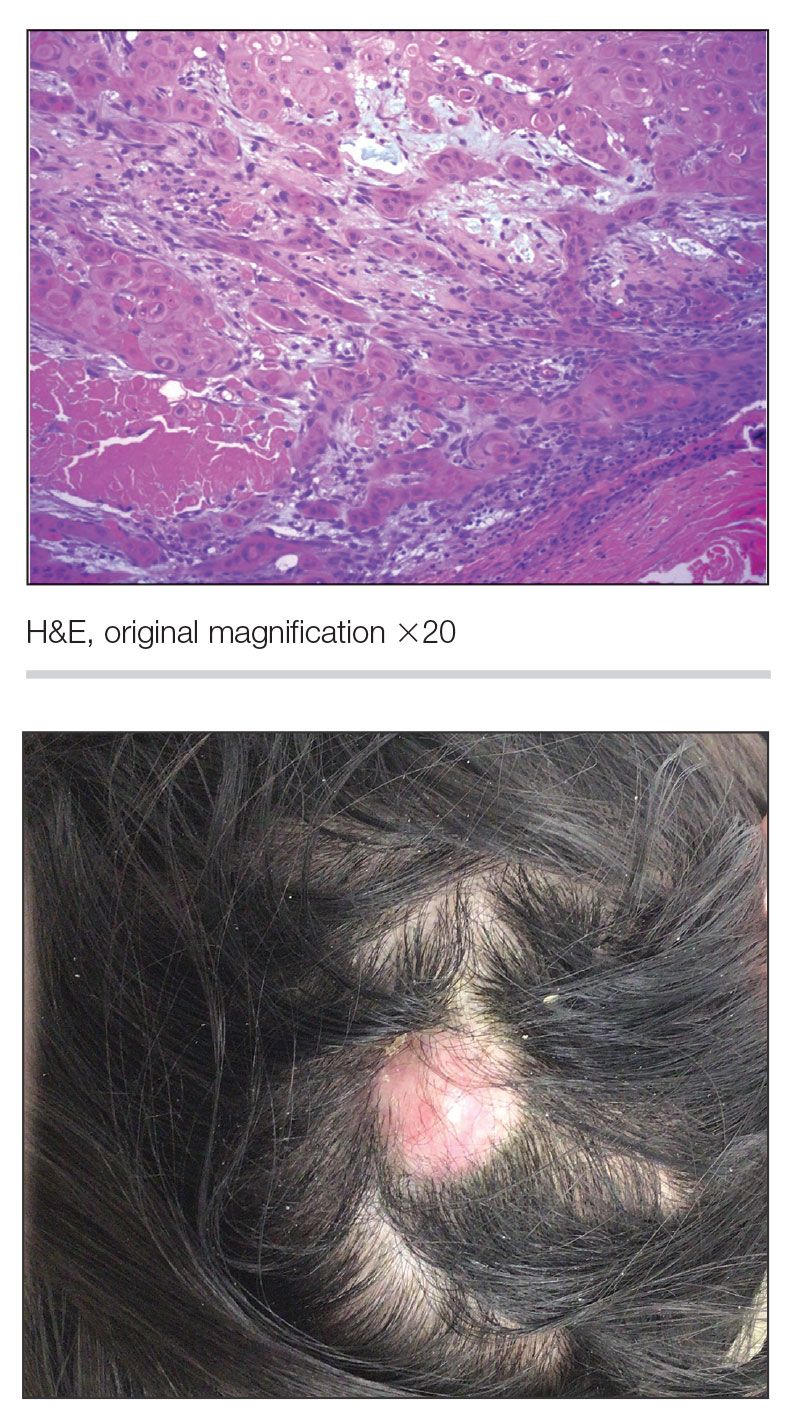

A 73-year-old man presented to the plastic surgery department with a single, progressively enlarging nodule on the scalp of 1 year’s duration. Dermatologic examination revealed a 0.8-cm, soft, mobile, gray-blue, dome-shaped papule on the left postauricular scalp that was tender to palpation. There was no central punctum, and the patient denied any history of drainage or odor. He had no personal or family history of similar lesions. An excisional biopsy of the papule was performed.

Growing Nodule on the Parietal Scalp

Growing Nodule on the Parietal Scalp

THE DIAGNOSIS: Malignant Proliferating Trichilemmal Tumor

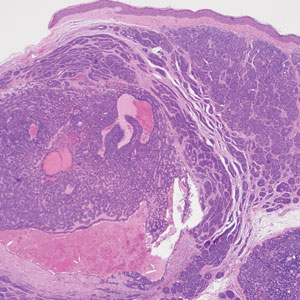

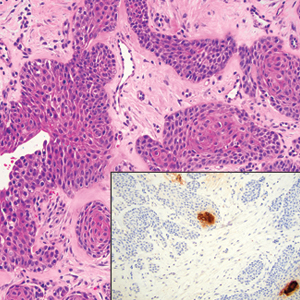

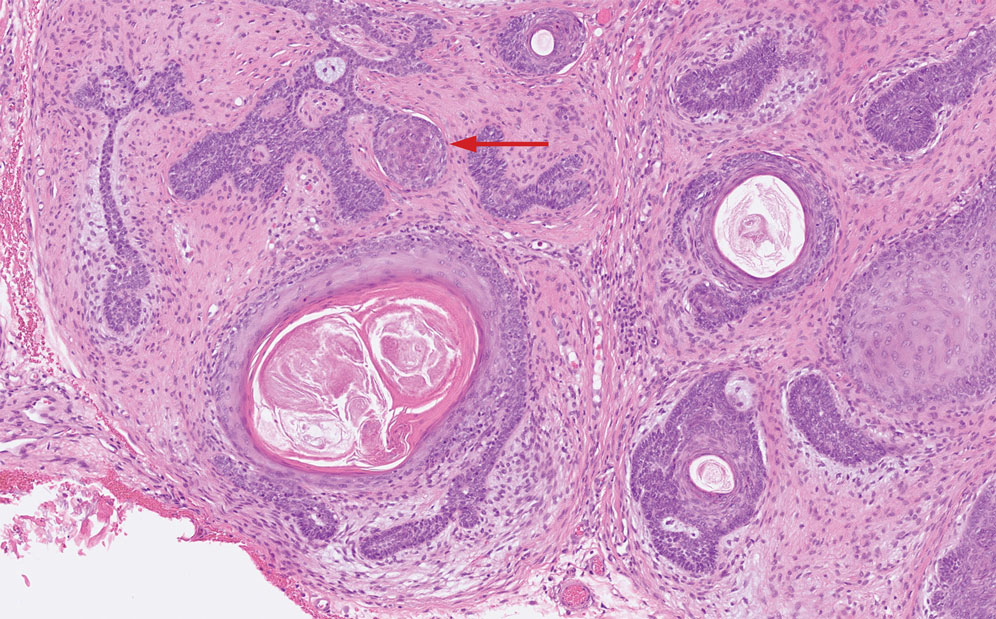

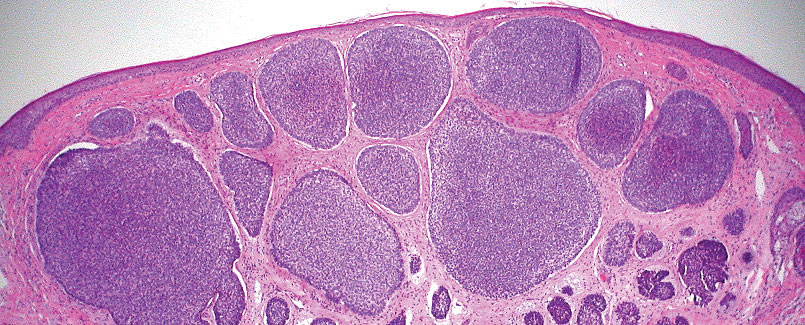

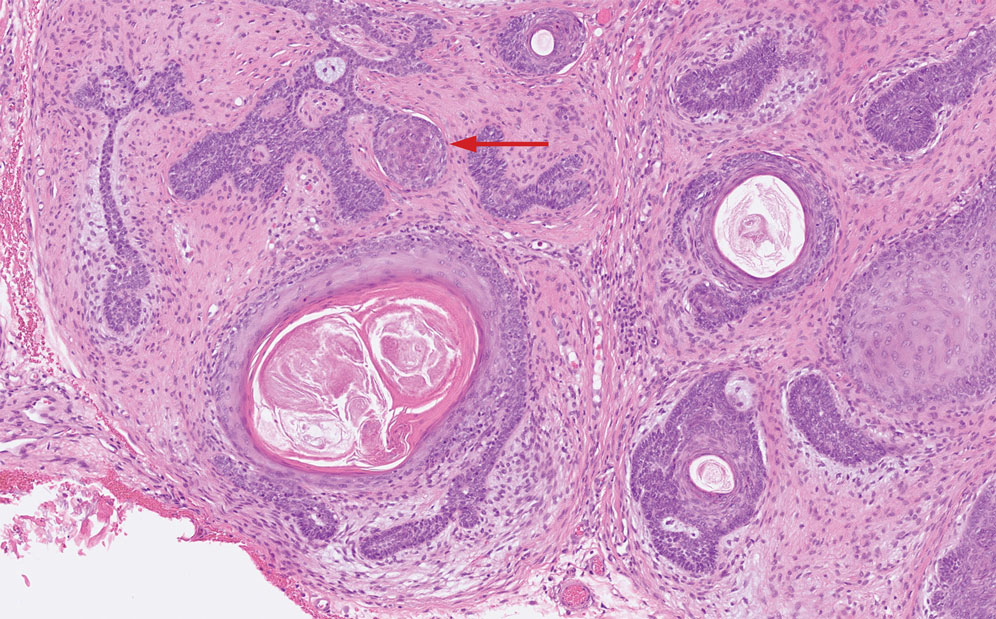

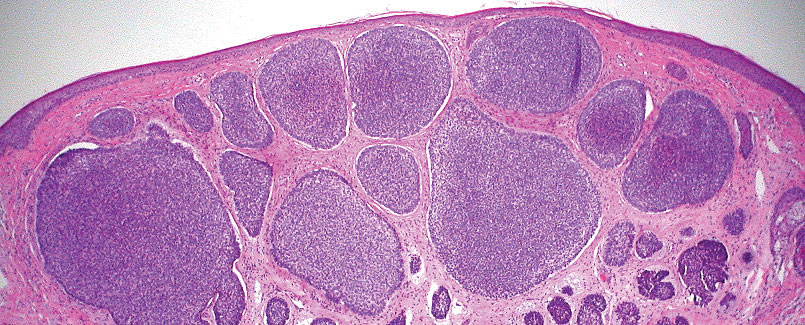

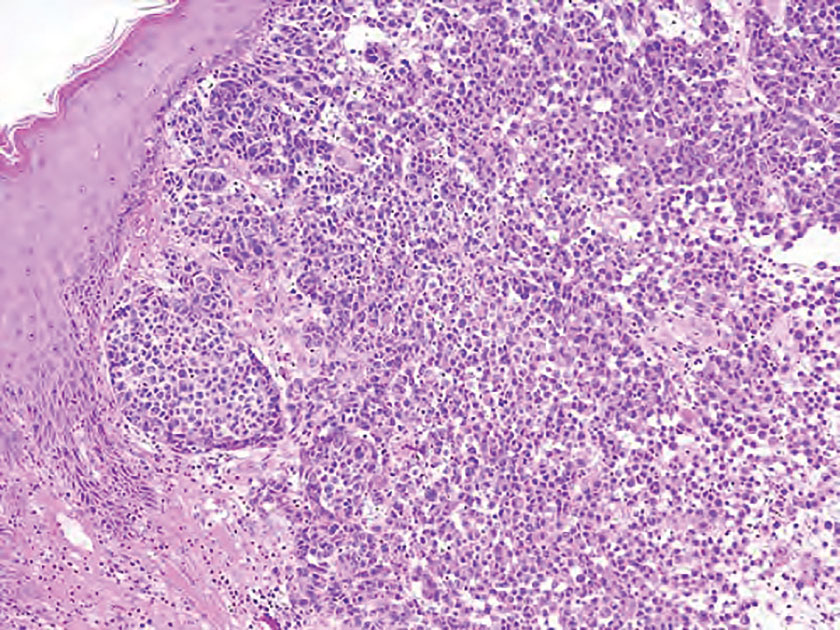

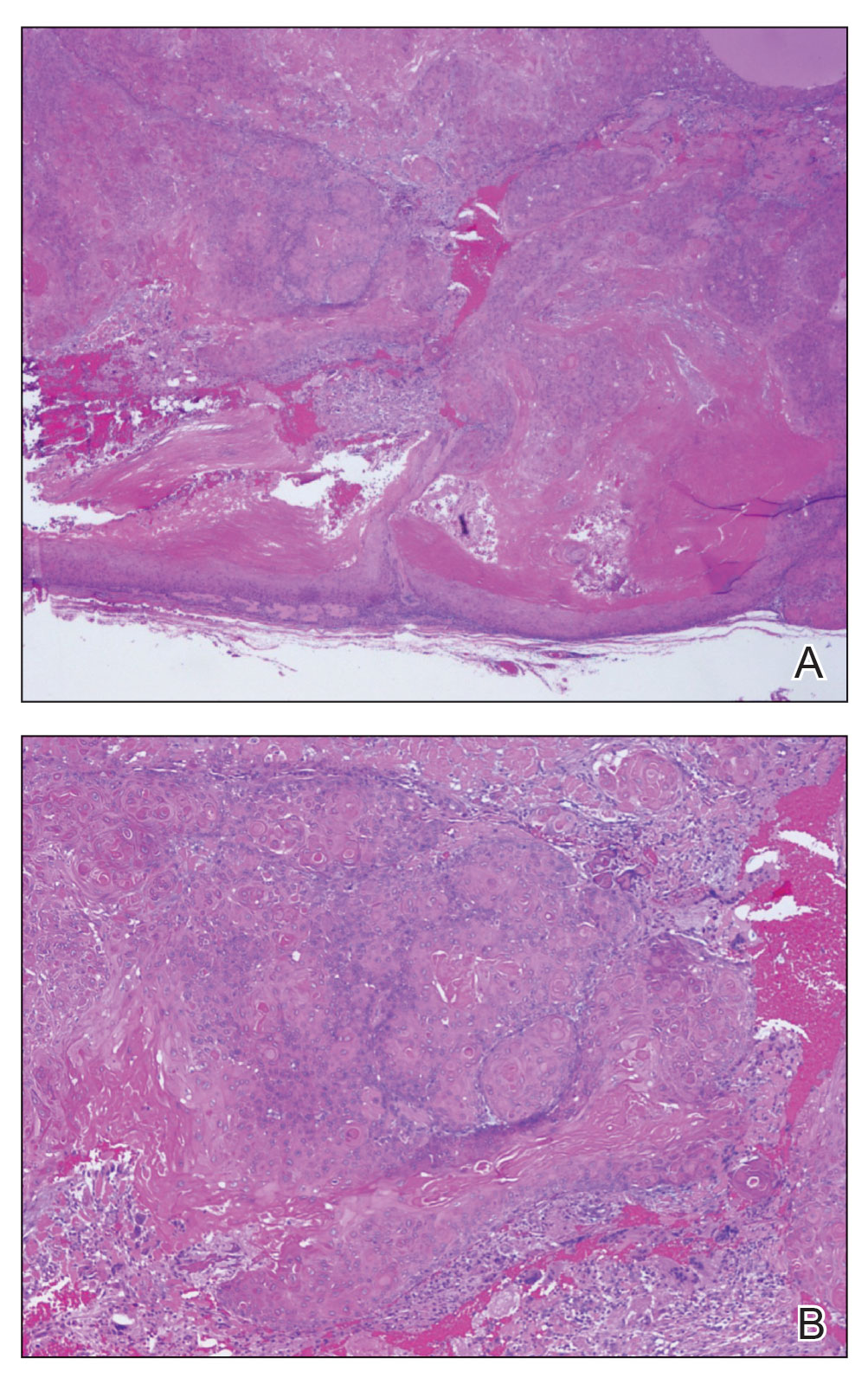

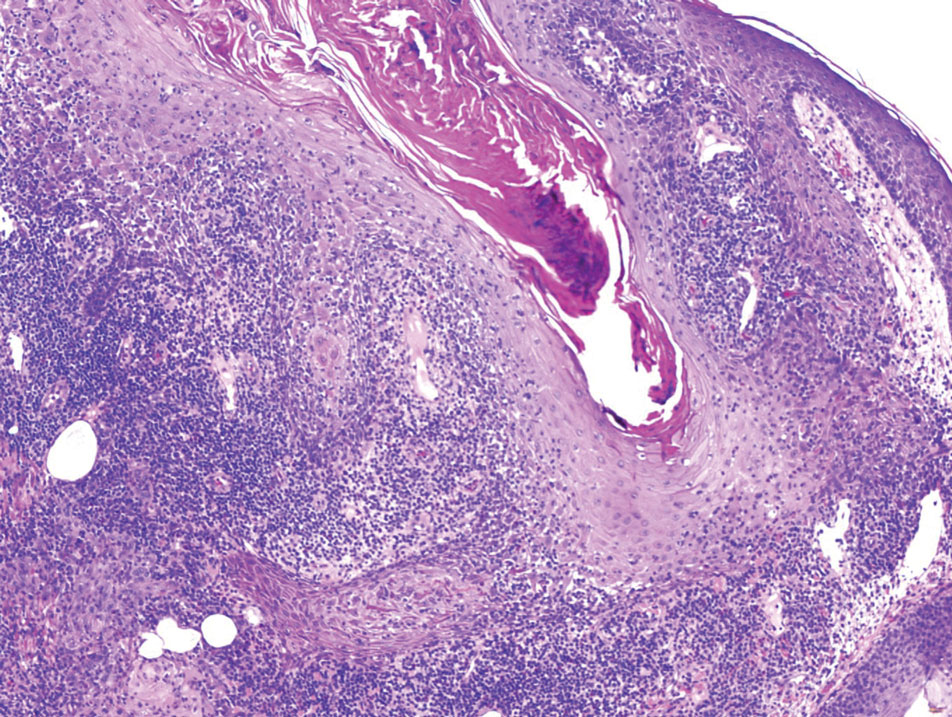

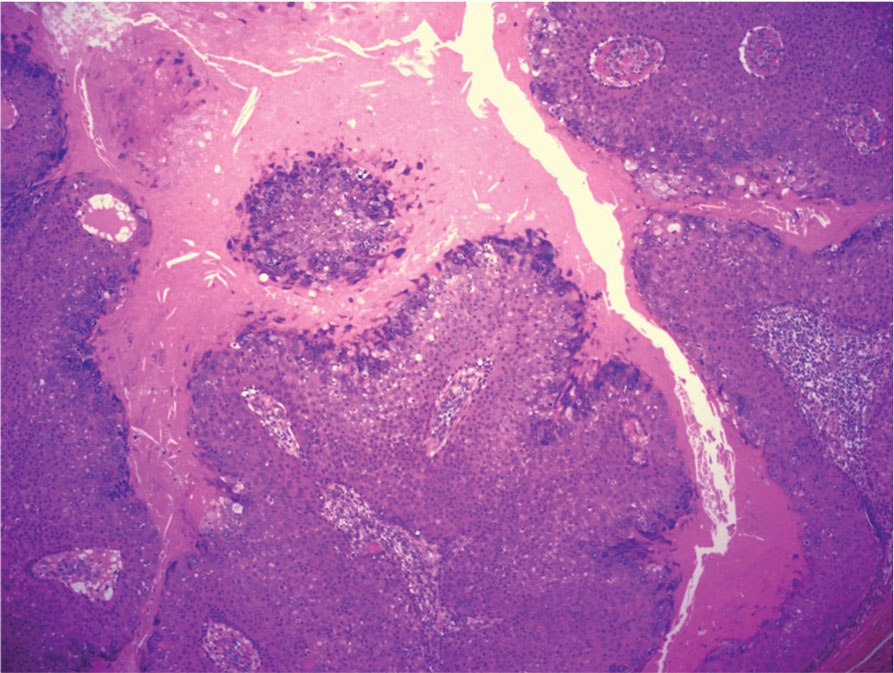

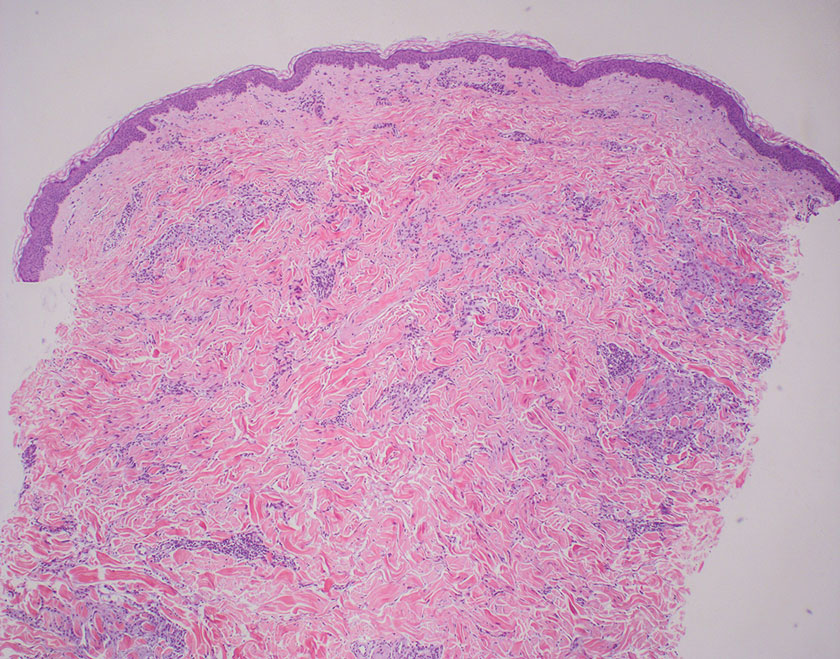

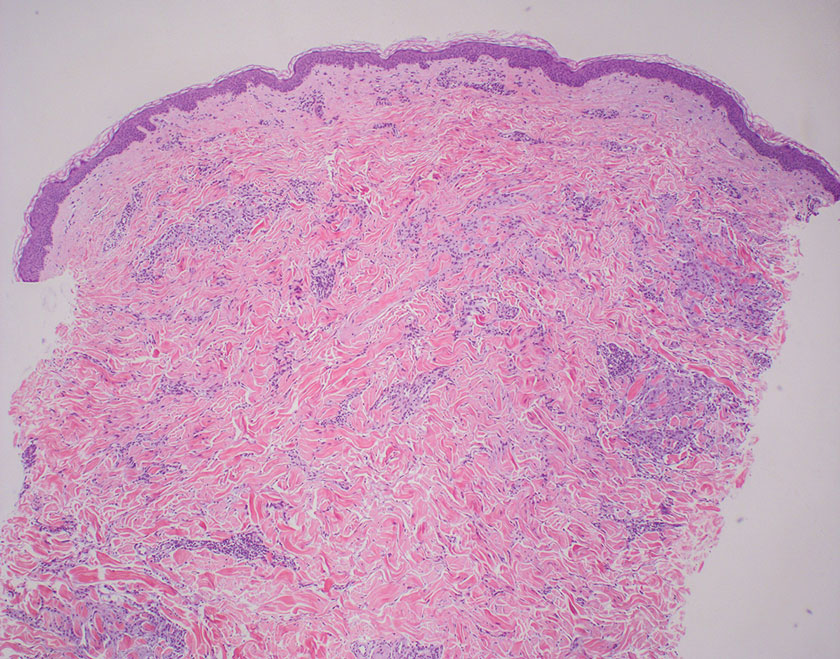

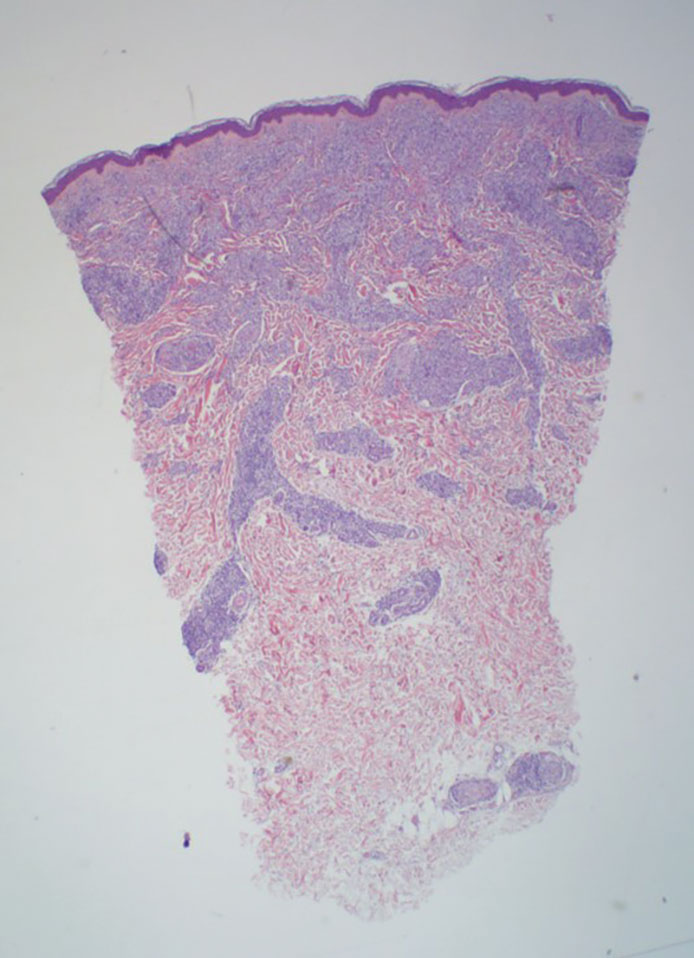

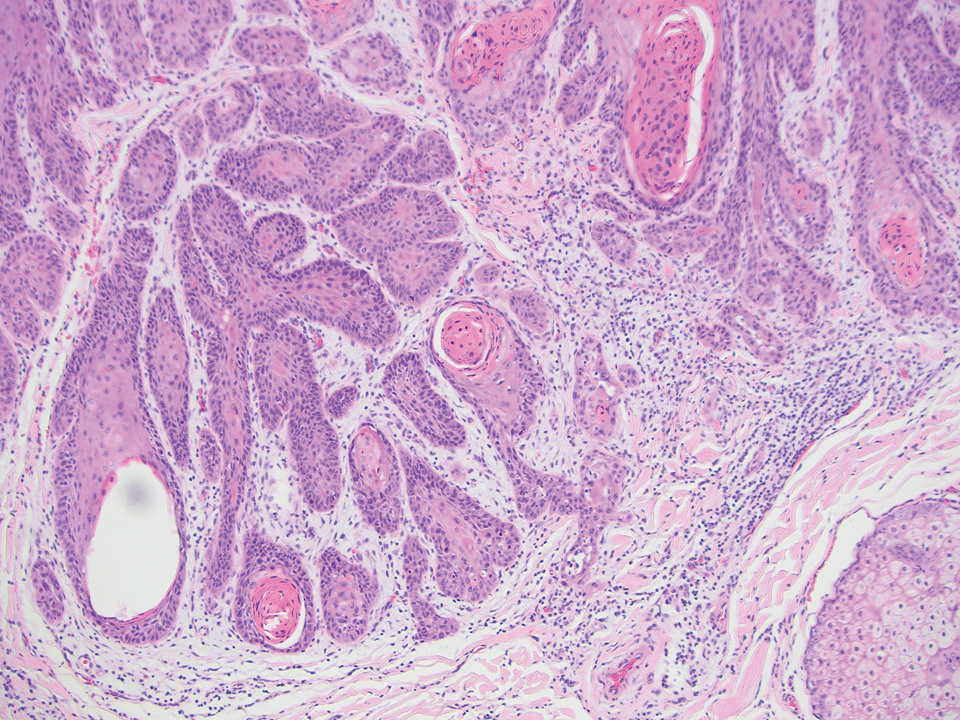

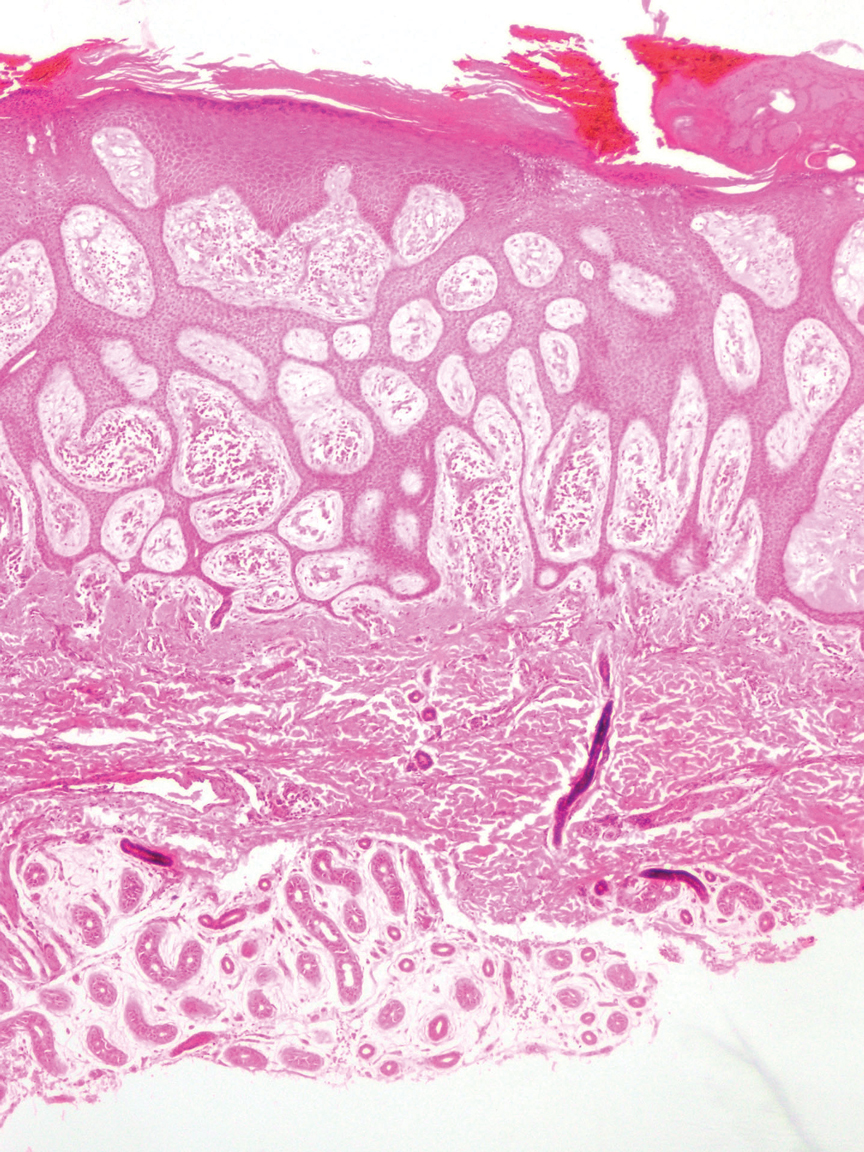

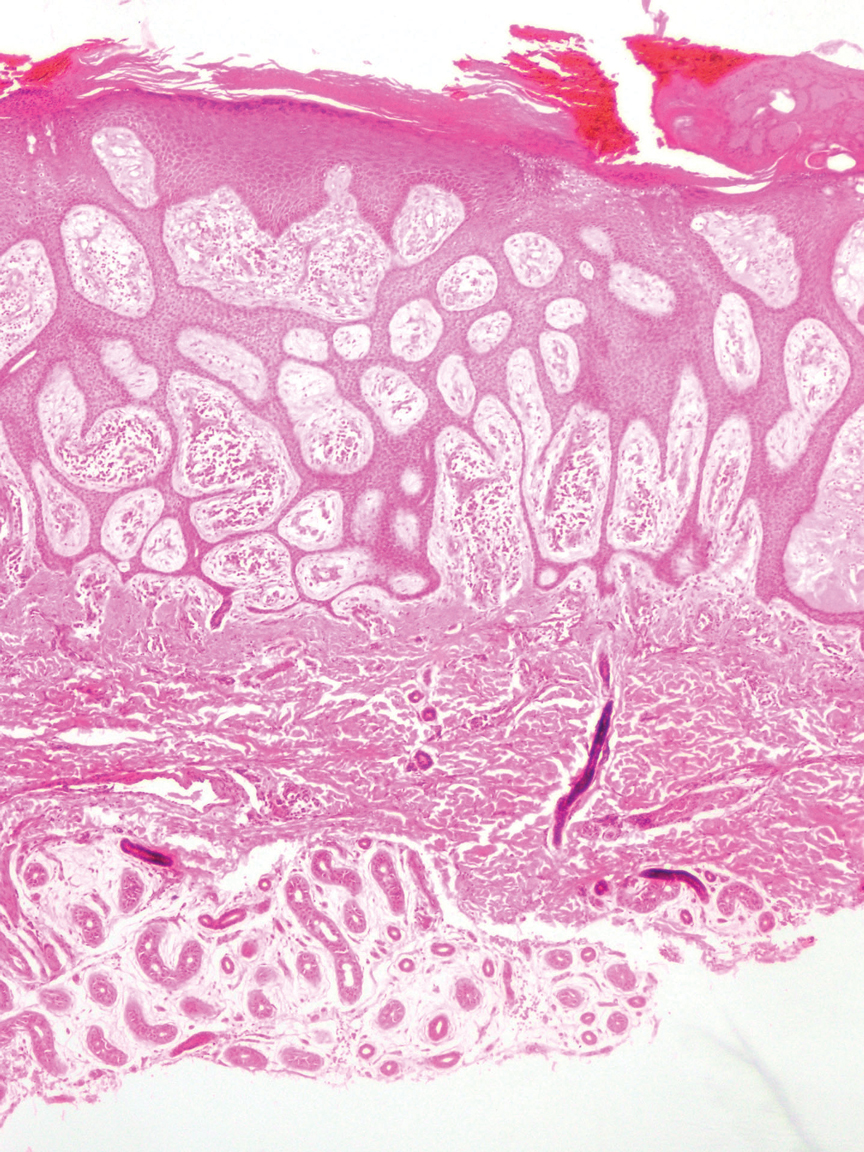

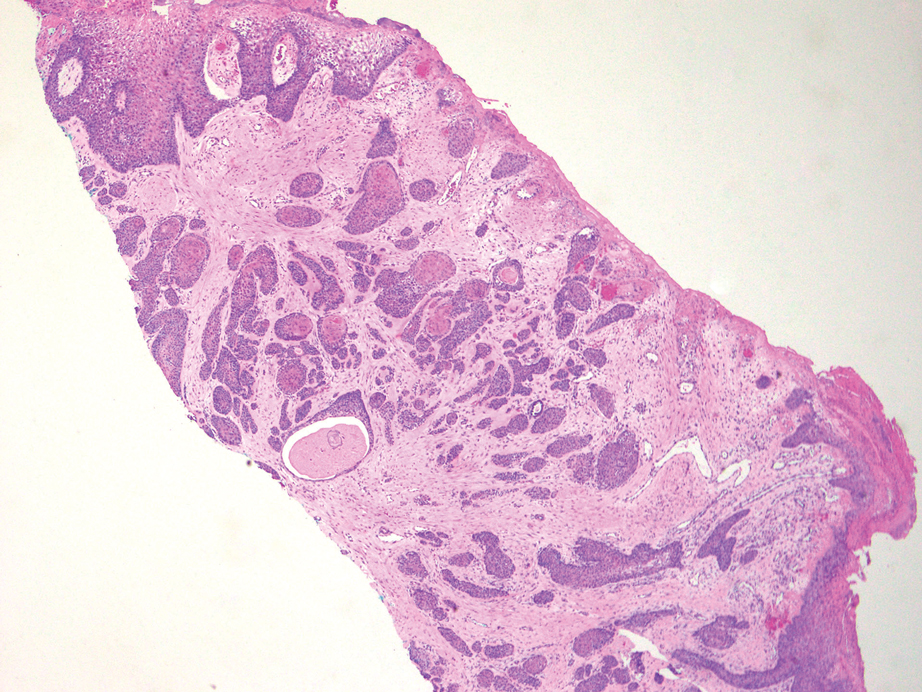

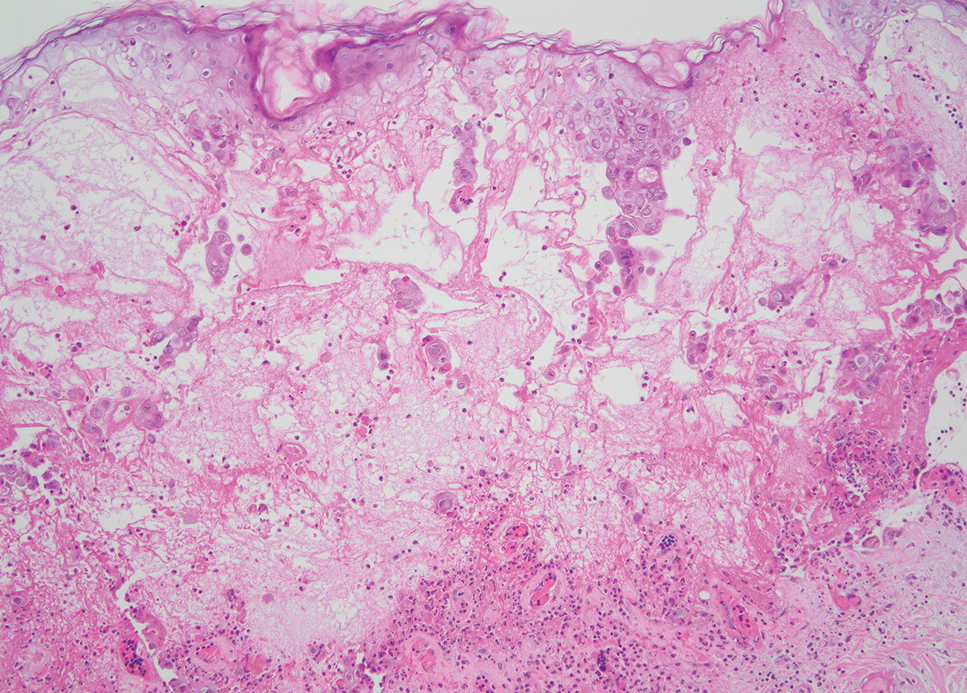

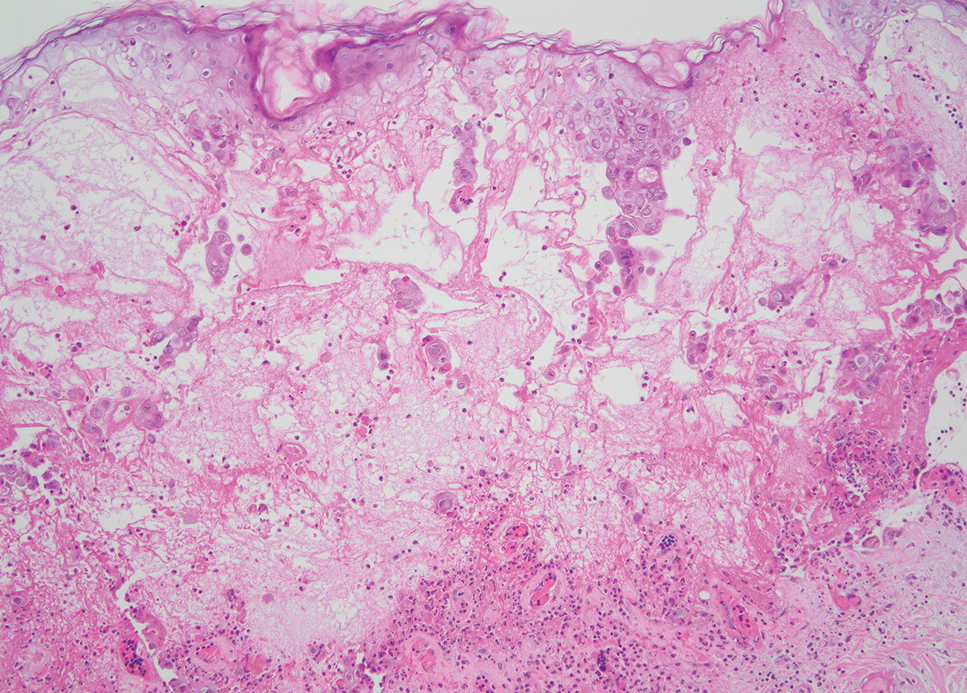

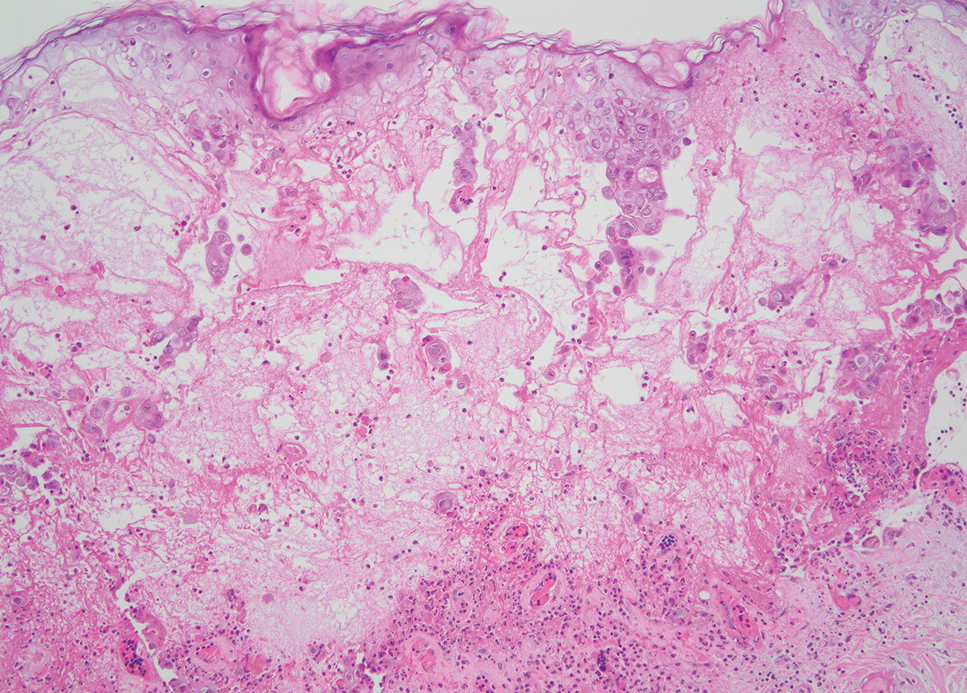

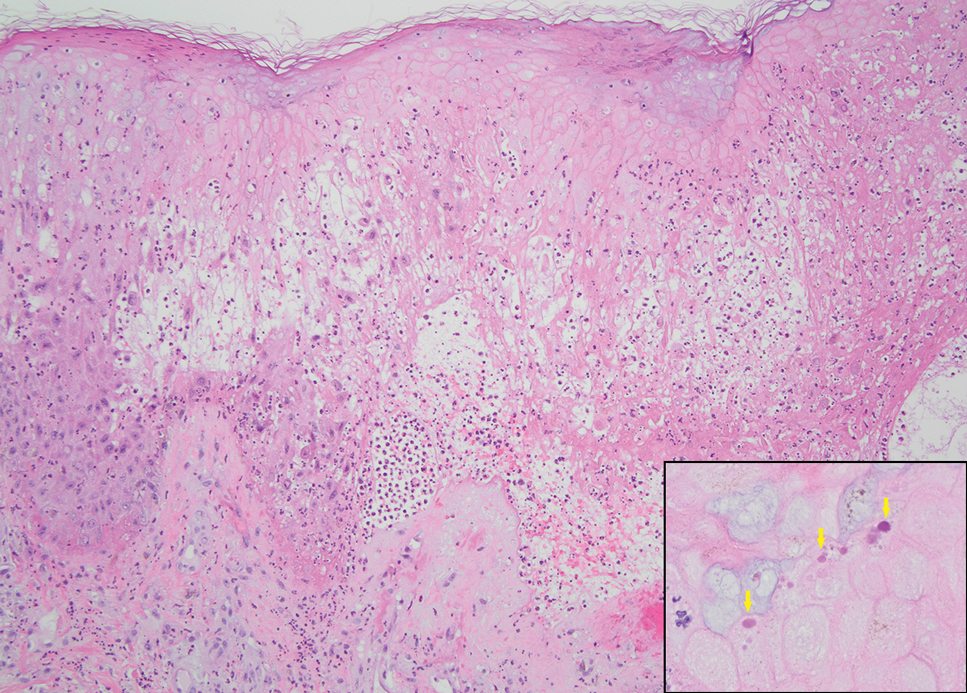

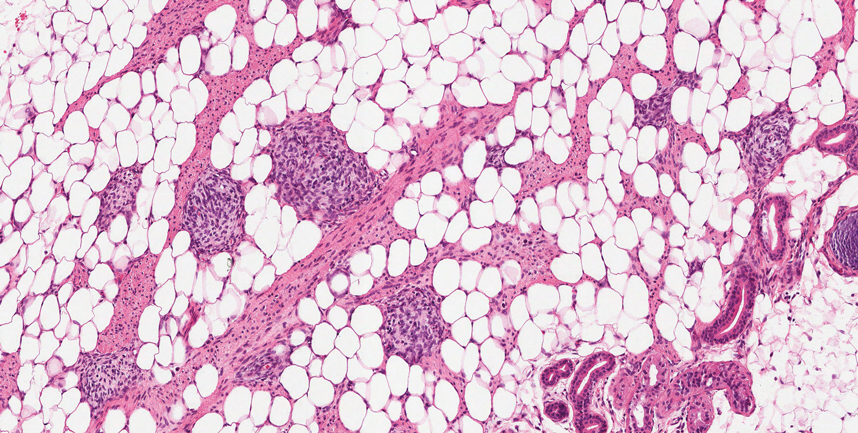

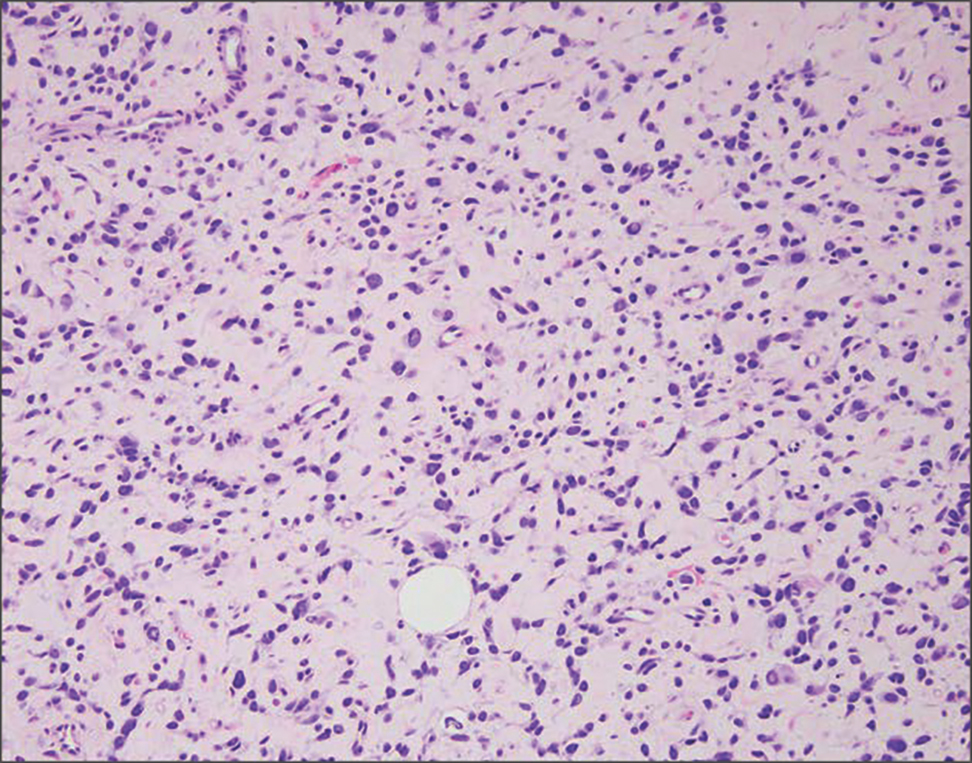

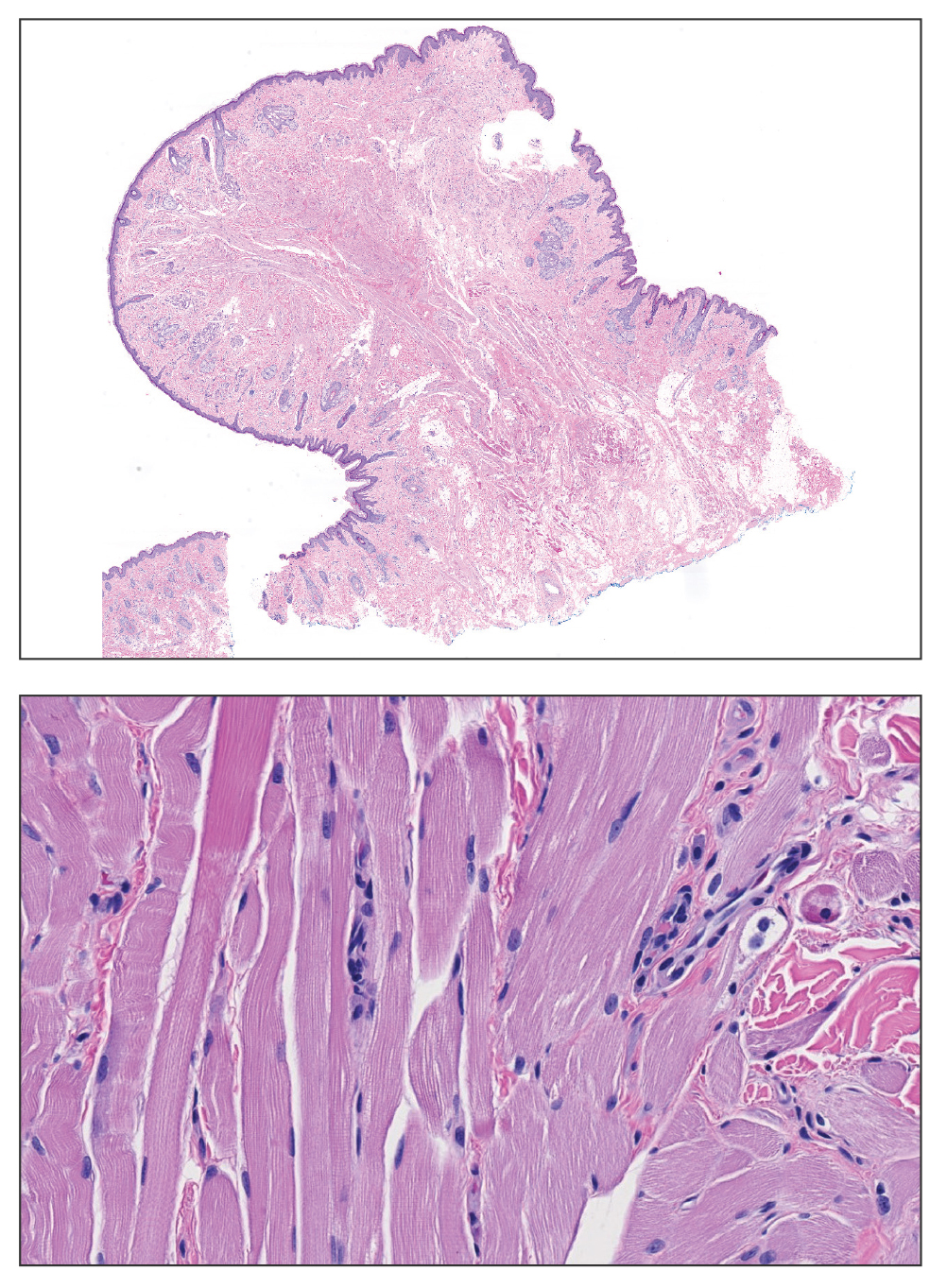

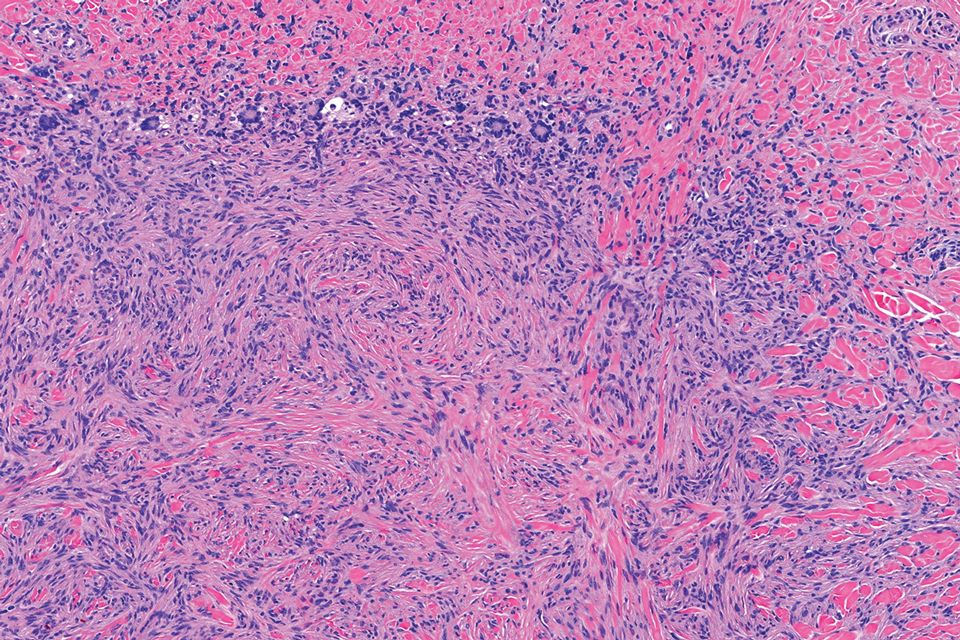

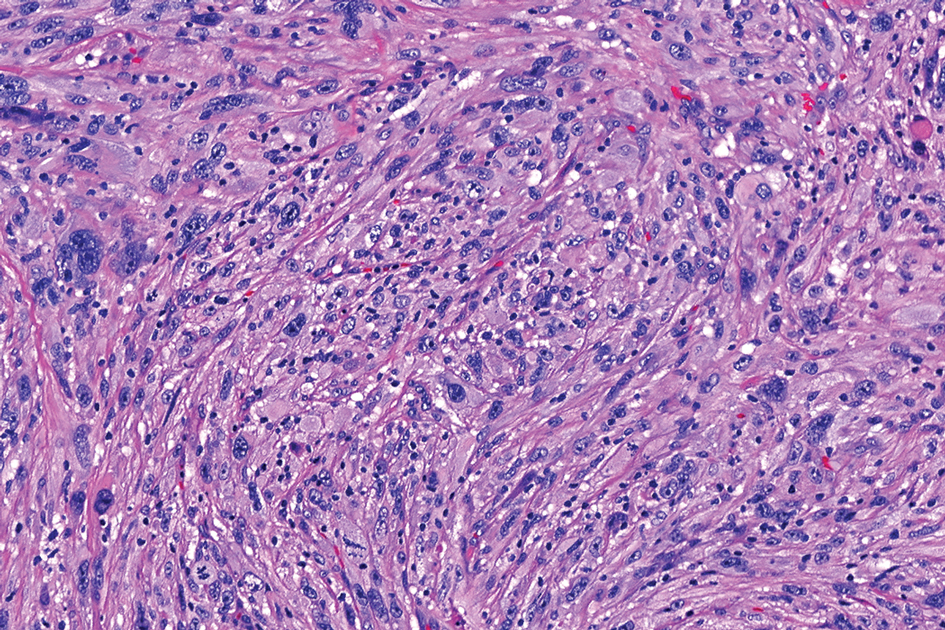

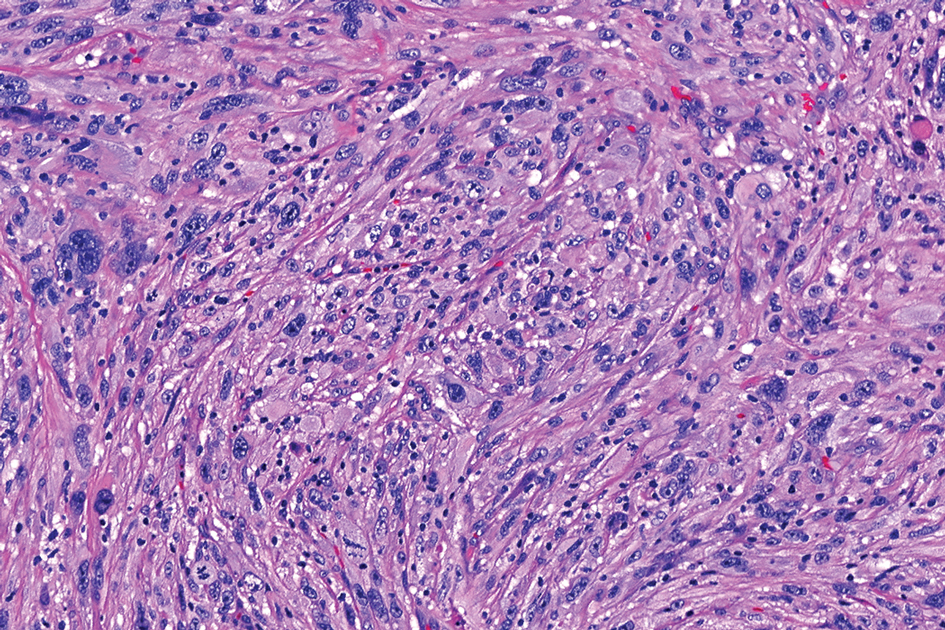

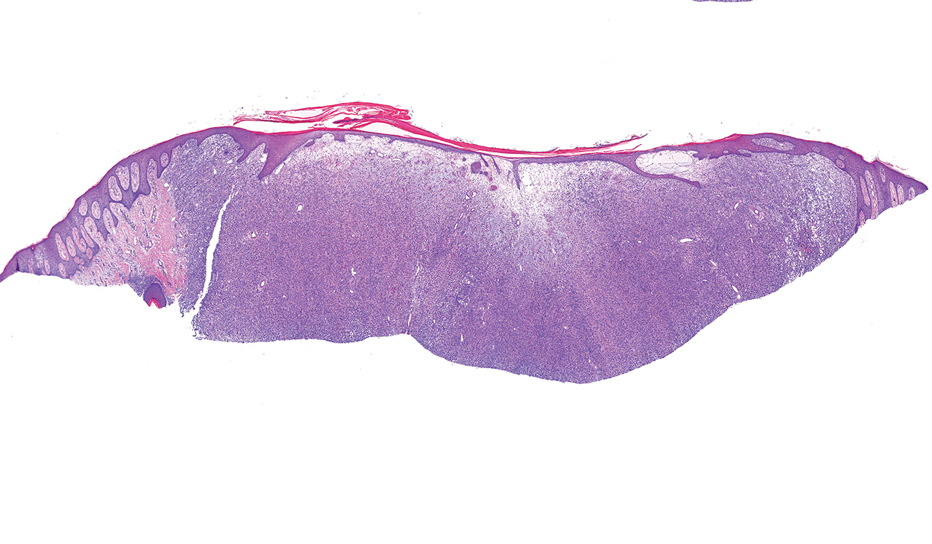

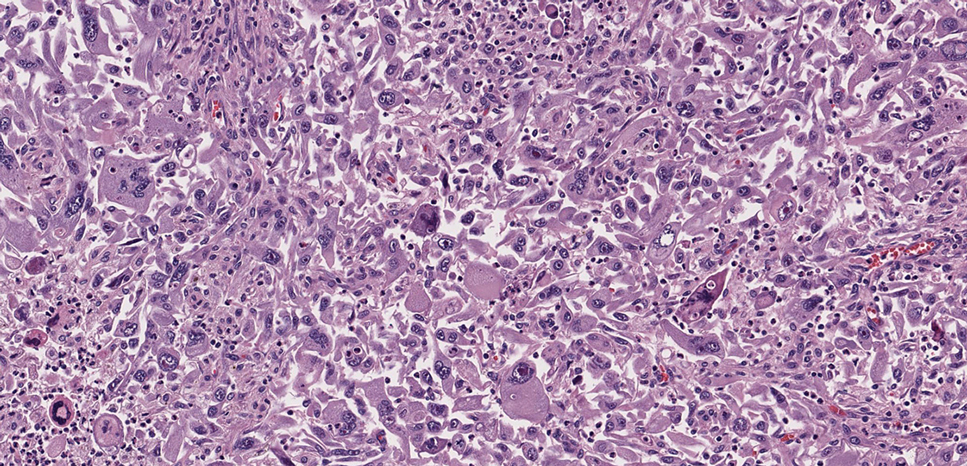

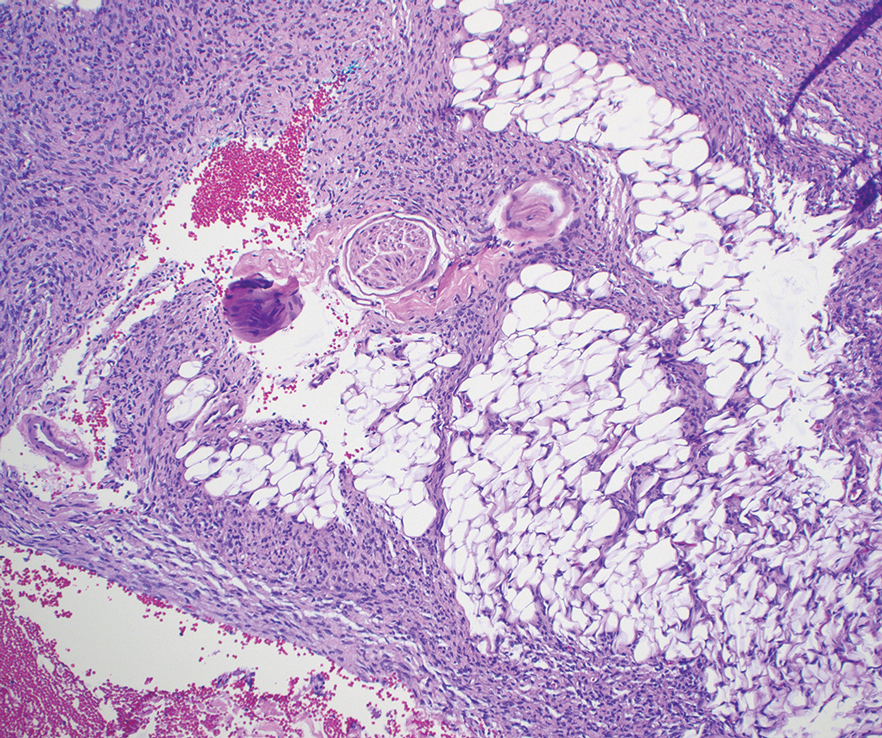

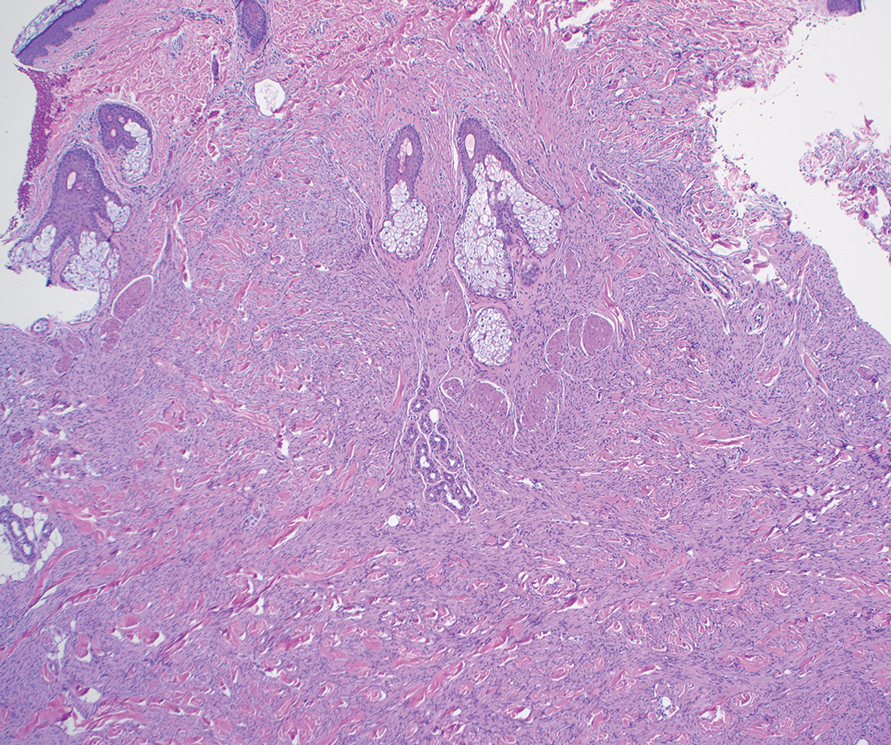

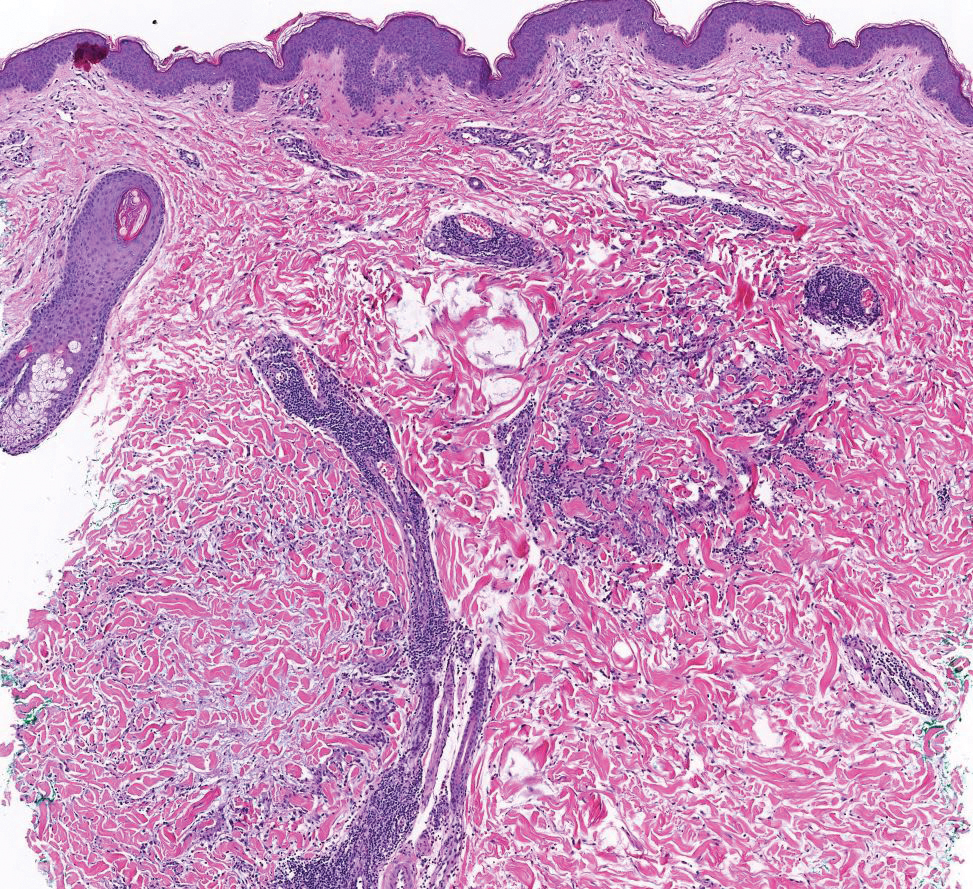

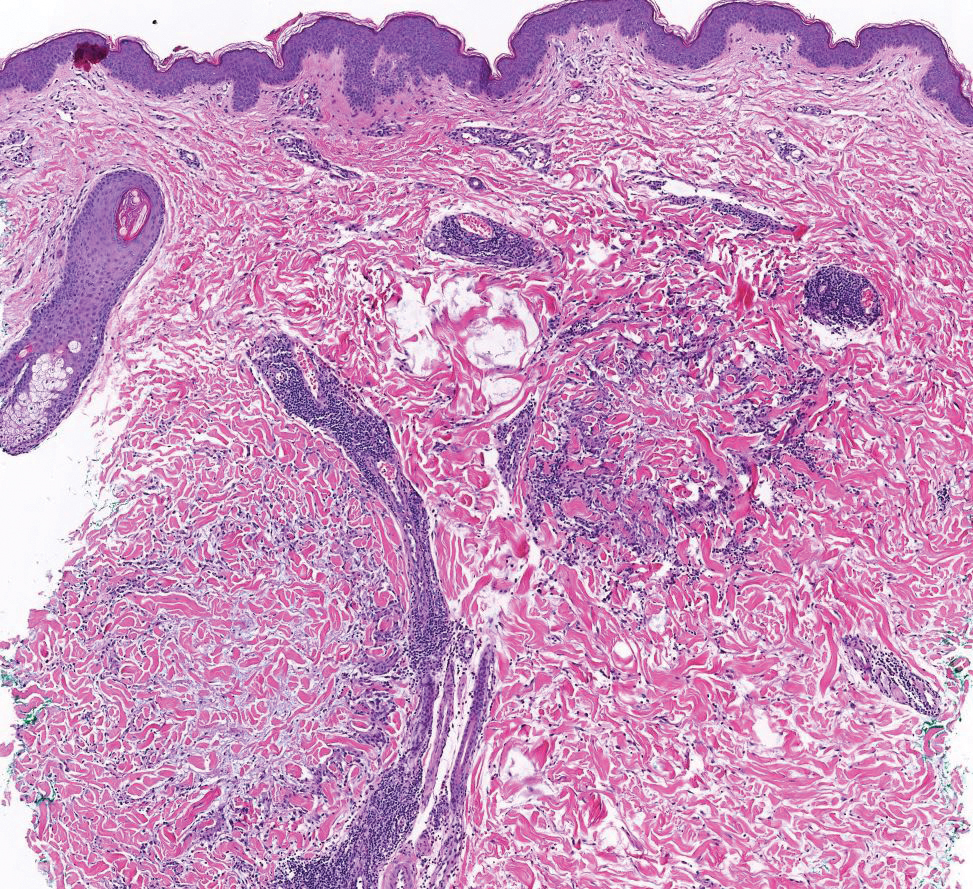

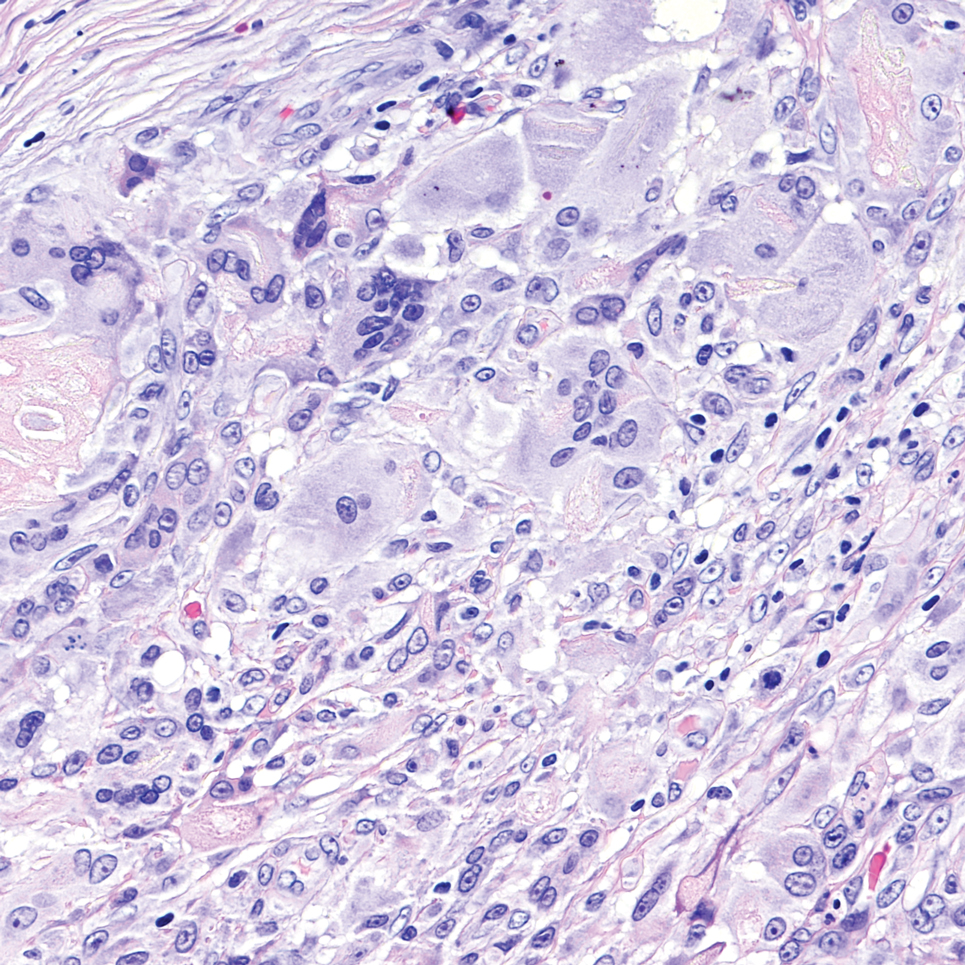

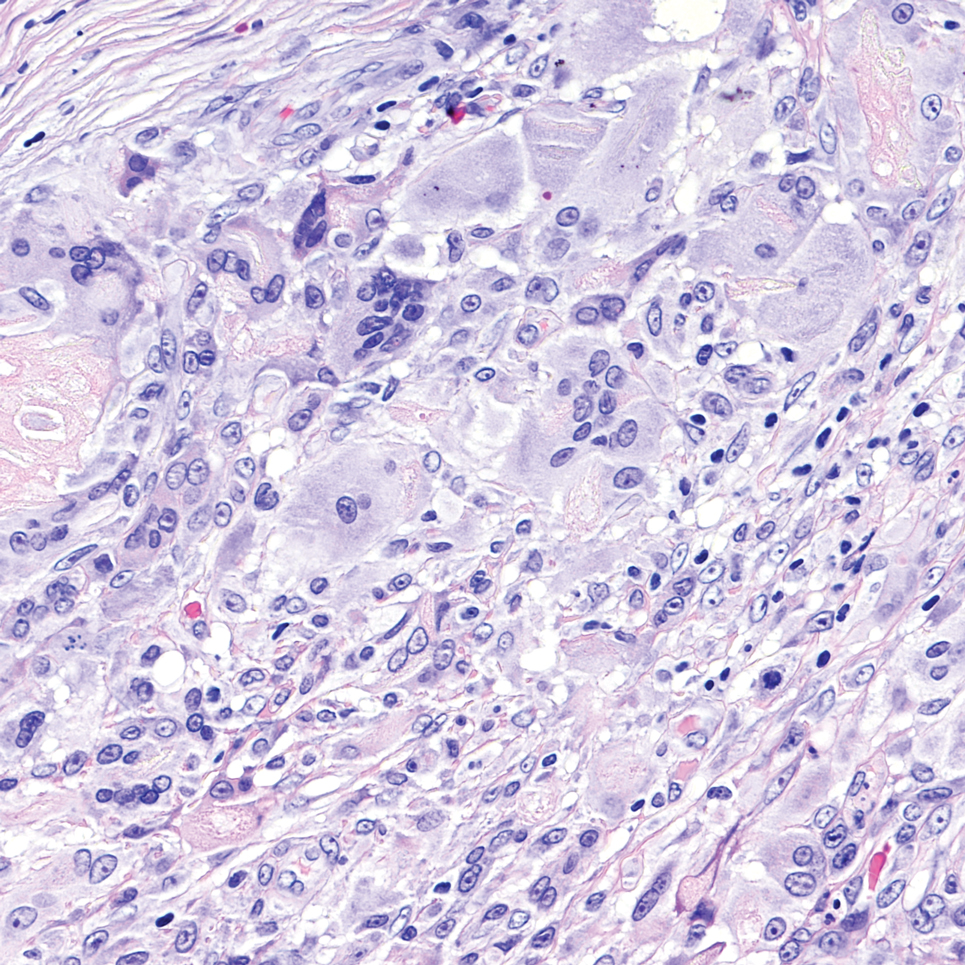

Biopsy revealed a squamous epithelium with cystic changes, trichilemmal differentiation, squamous eddy formation, keratinocyte atypia, focal necrotic changes, and a focus of atypical keratinocytes invading the dermis (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor (MPTT) was made.

Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor is a rare adnexal tumor that develops from the outer root sheath of the hair follicle. It often arises due to malignant transformation of pre-existing trichilemmal cysts, but some cases occur de novo.1 Malignant transformation is thought to start from a trichilemmal cyst in an adenomatous histologic stage, progressing to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst (PTC) in an epitheliomatous phase, ultimately becoming carcinomatous with MPTT.2-4 This transformation has been categorized into 3 morphologic groups to predict tumor behavior, including benign PTCs (curable by excision), low-grade malignant PTCs (minor risk for local recurrence), and high-grade malignant PTCs (risk for regional spread and metastasis with cytologic atypical features and potential for aggressive growth).1

More commonly observed in women in the fourth to eighth decades of life, MPTT may manifest as a fast- growing, painless, solitary nodule or as a progressively enlarging nodule at the site of a previously stable, long-standing lesion. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor manifests frequently on the scalp, face, or neck, but there are reports of MPTT manifesting on the trunk and even as multiple concurrent lesions.1-4 The variability in clinical presentation and the potential to be mistaken for benign conditions makes excisional biopsy essential for diagnosis of MPTT. Histopathology classically demonstrates trichilemmal keratinization, a high mitotic index, and cellular atypia with invasion into the dermis.4 Malignant transformation frequently follows a prior history of trauma to the area or local inflammation.

Given the locally aggressive nature of MPTT, our patient was referred to a Mohs micrographic surgeon. While both wide excision with tumor-free margins and Mohs micrographic surgery are accepted surgical procedures for MPTT, there is no consensus in the literature on a standard treatment recommendation. Following surgery, close monitoring is needed for potential recurrence and metastases intracranially to the dura and muscles,5 as well as to the lungs.6 Further imaging using computed tomography or positron emission tomography can be ordered to rule out metastatic disease.4

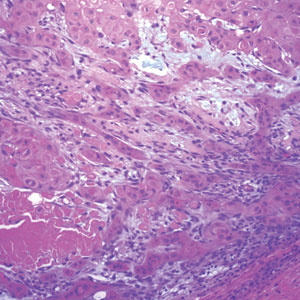

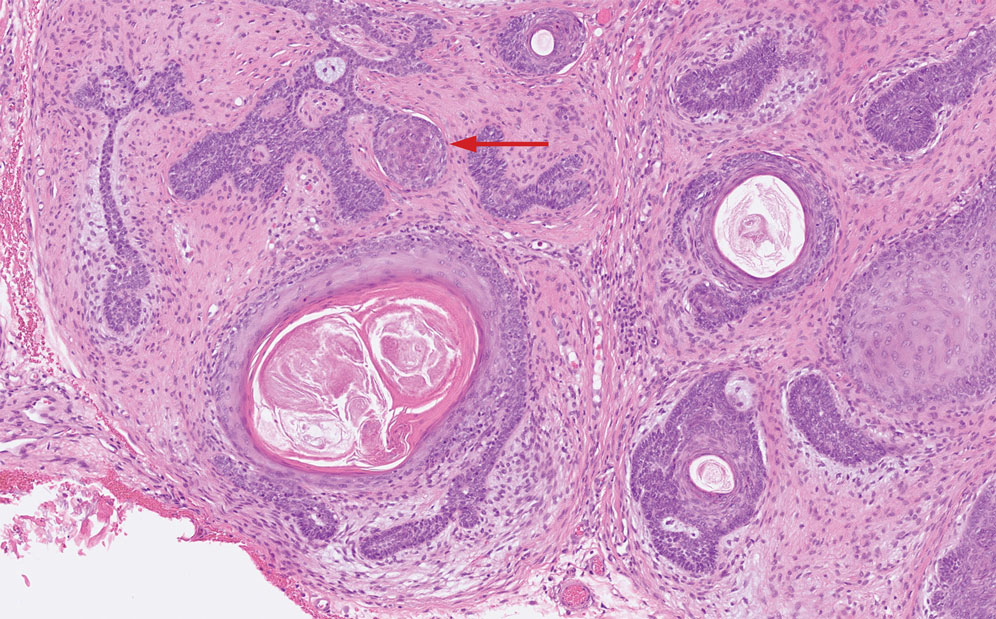

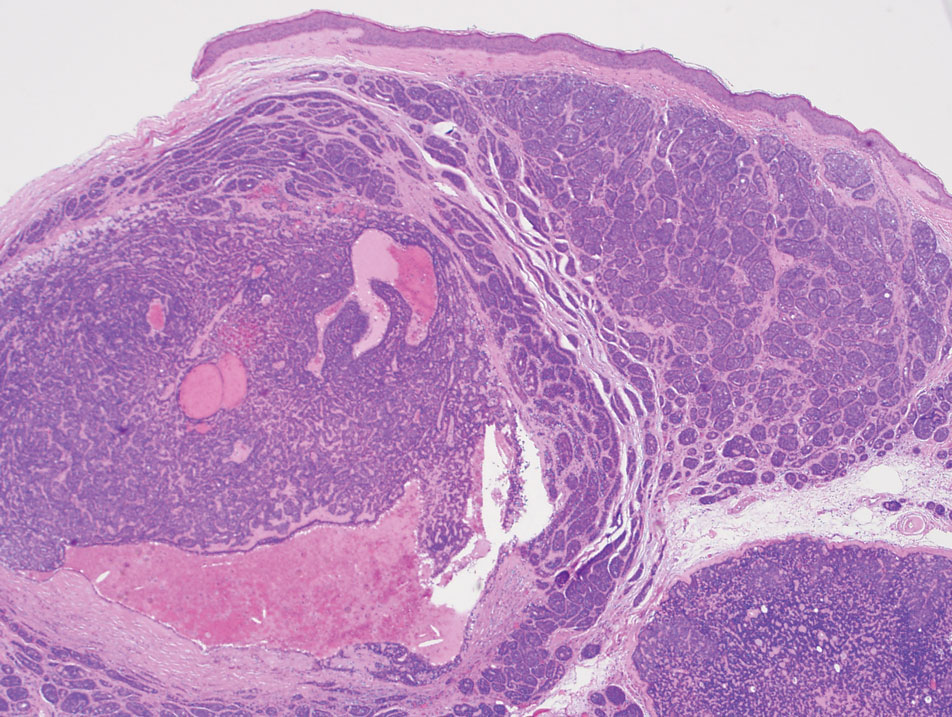

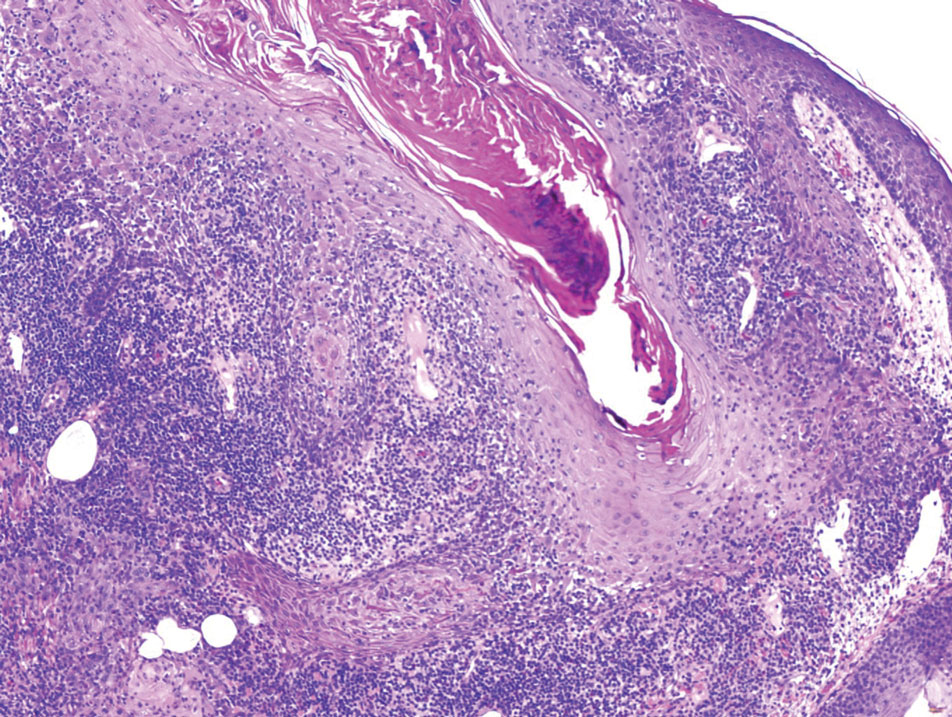

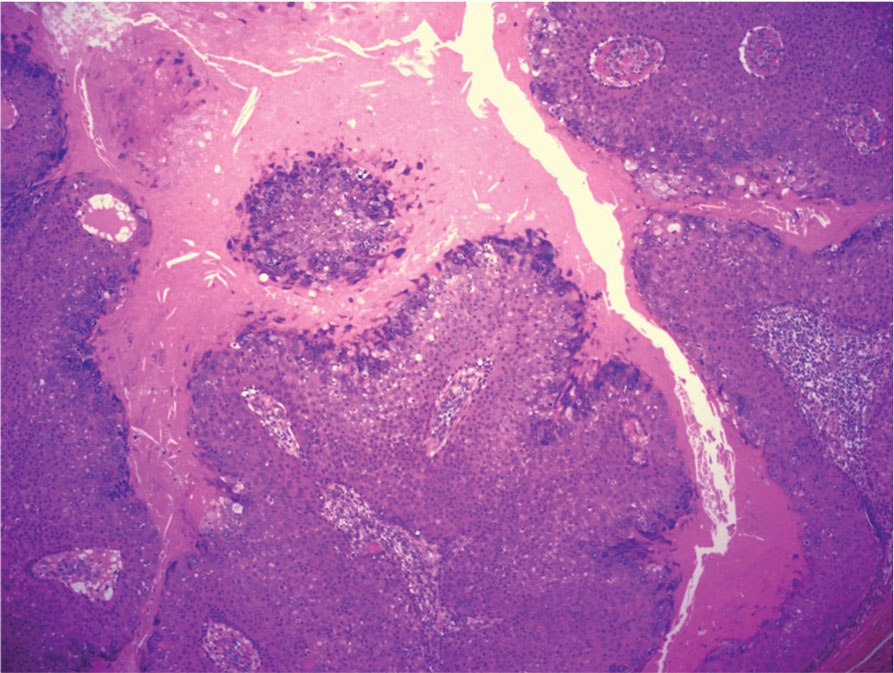

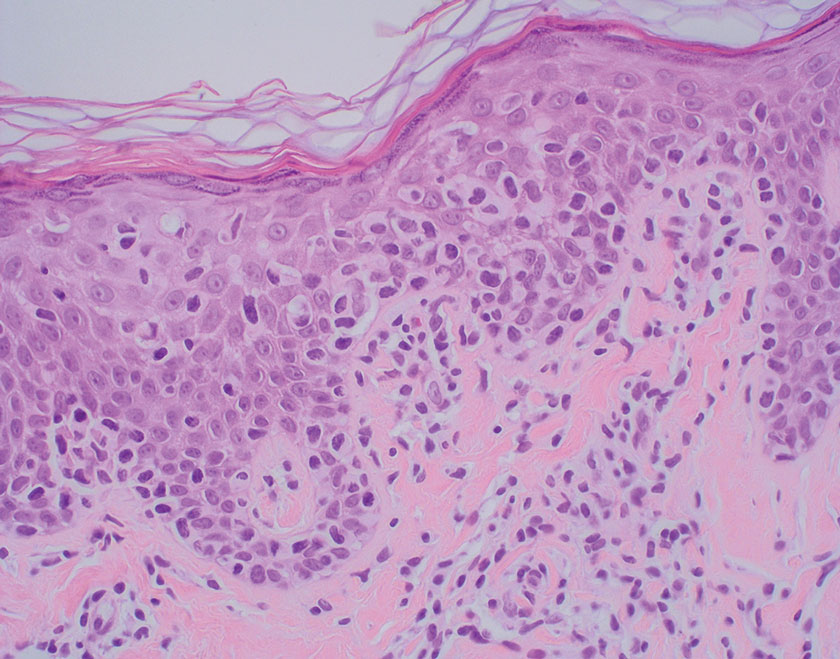

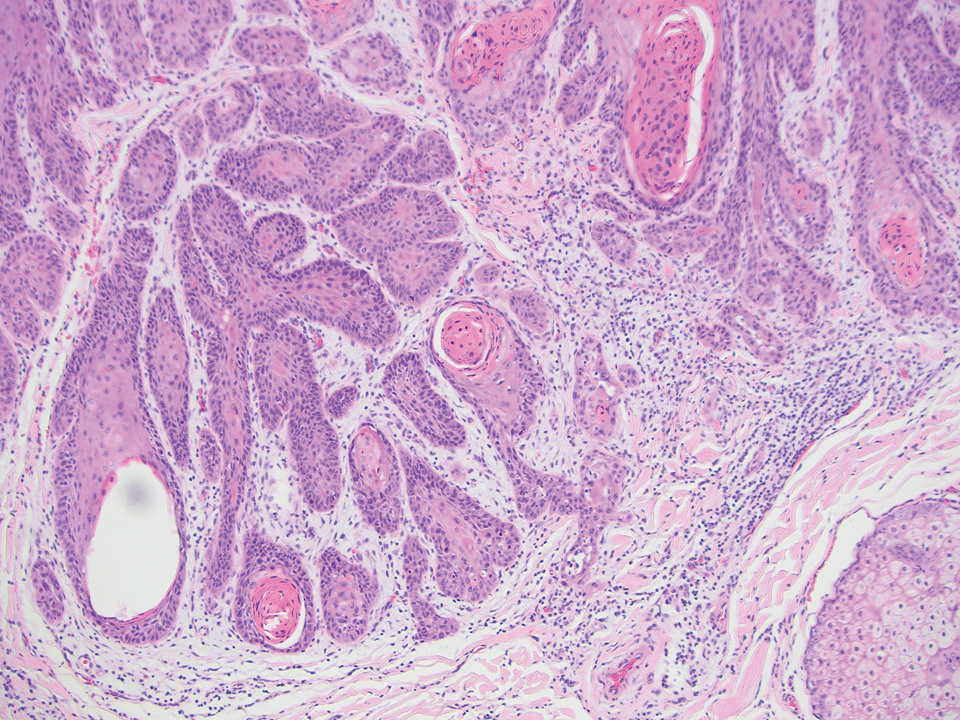

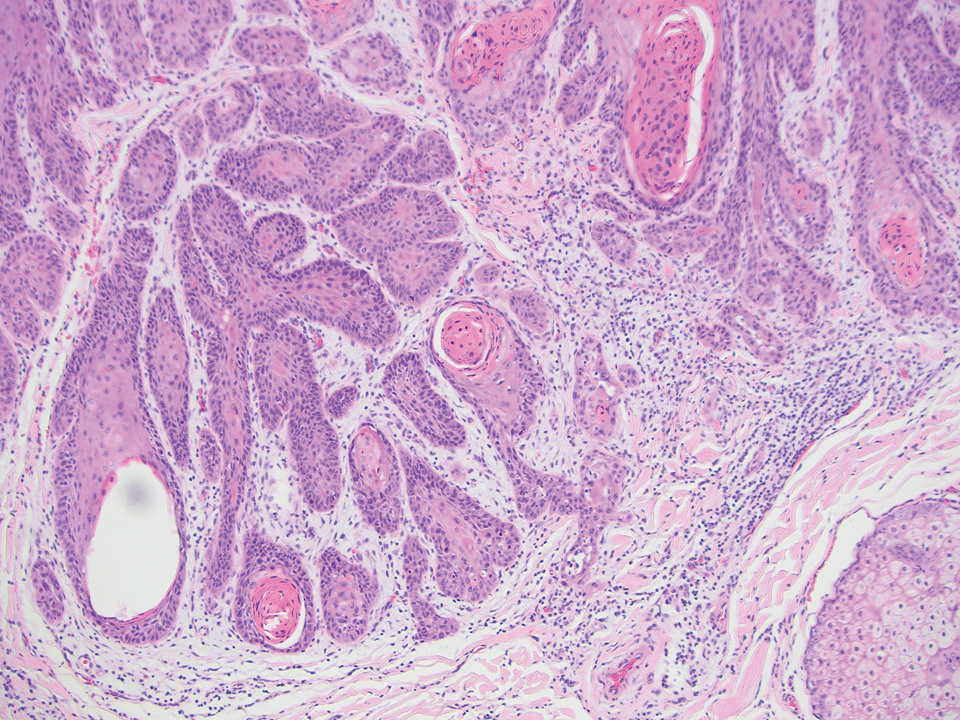

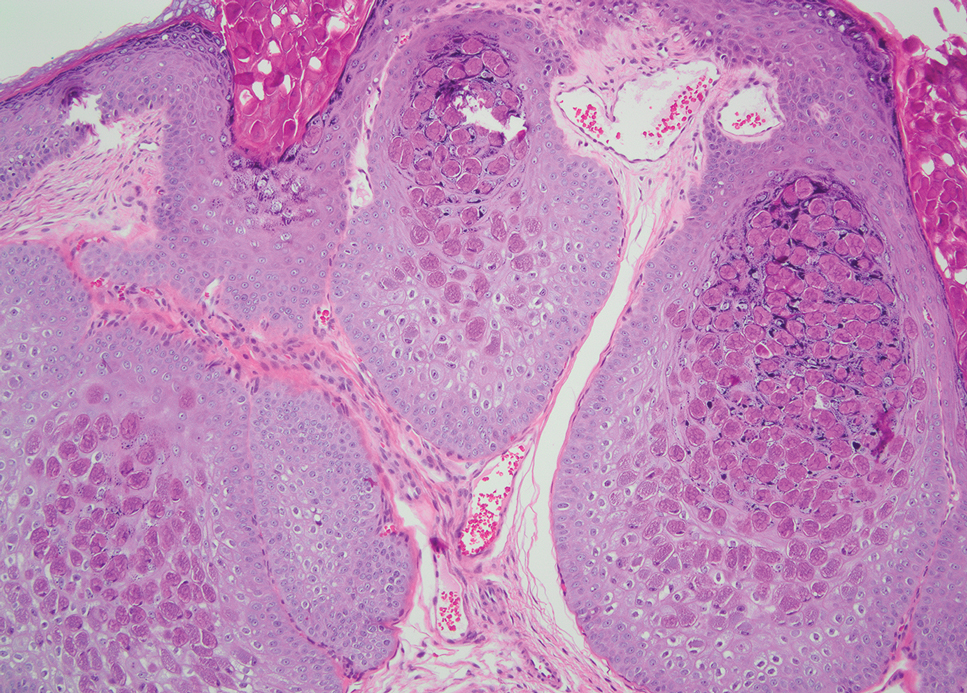

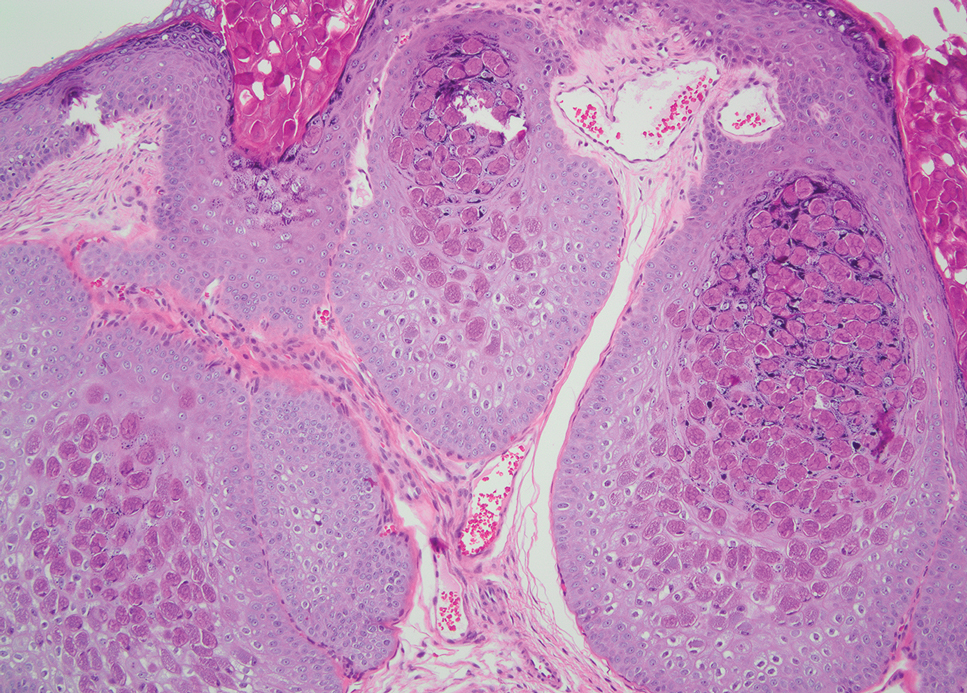

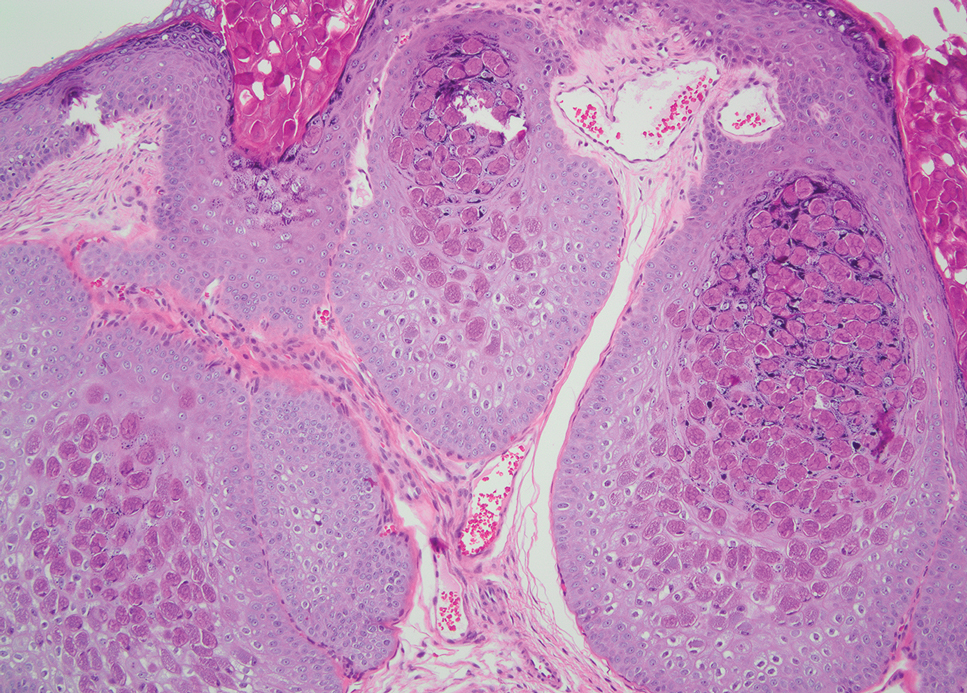

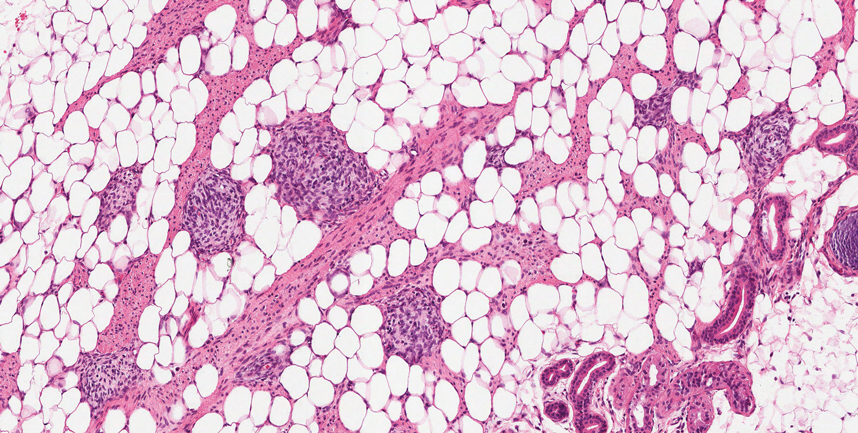

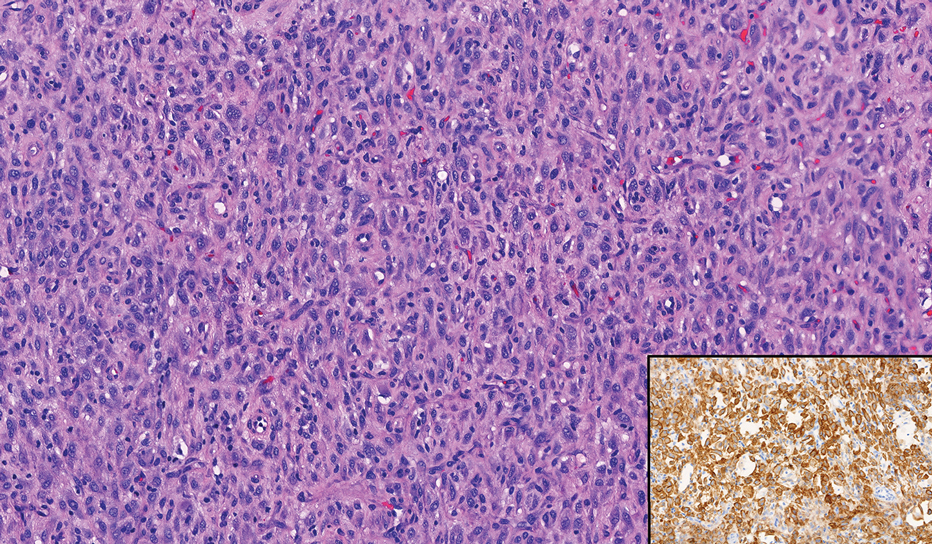

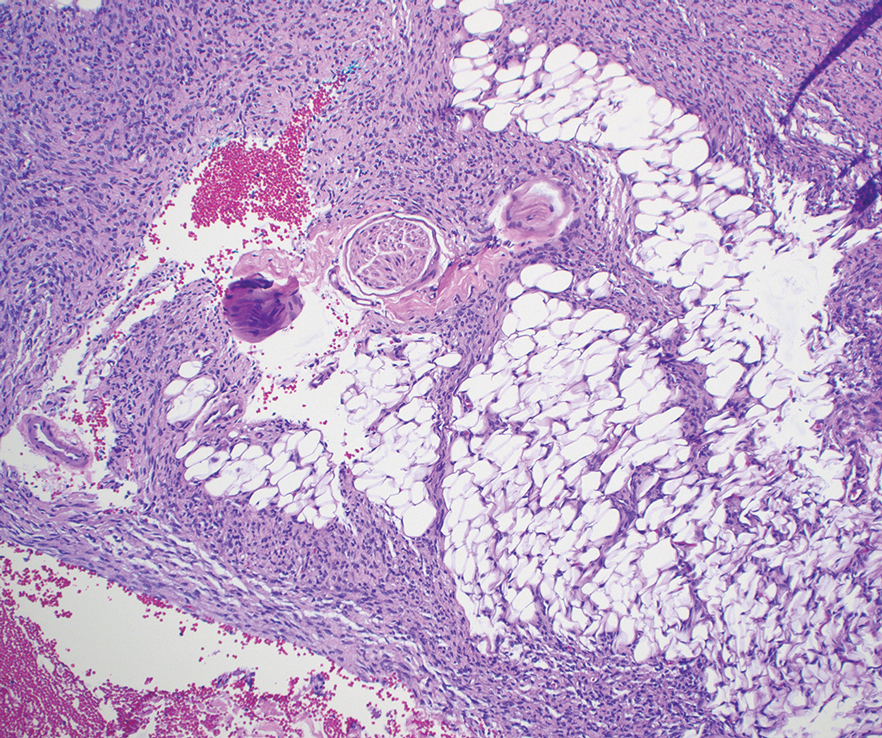

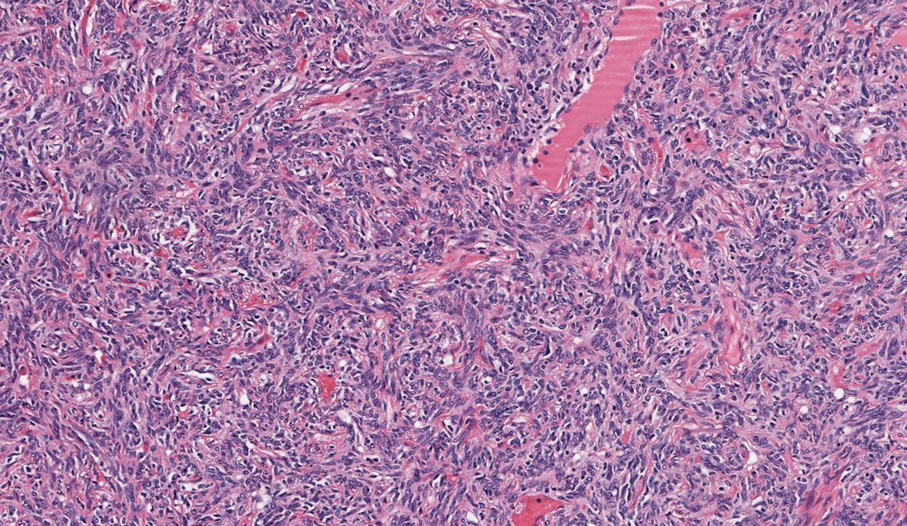

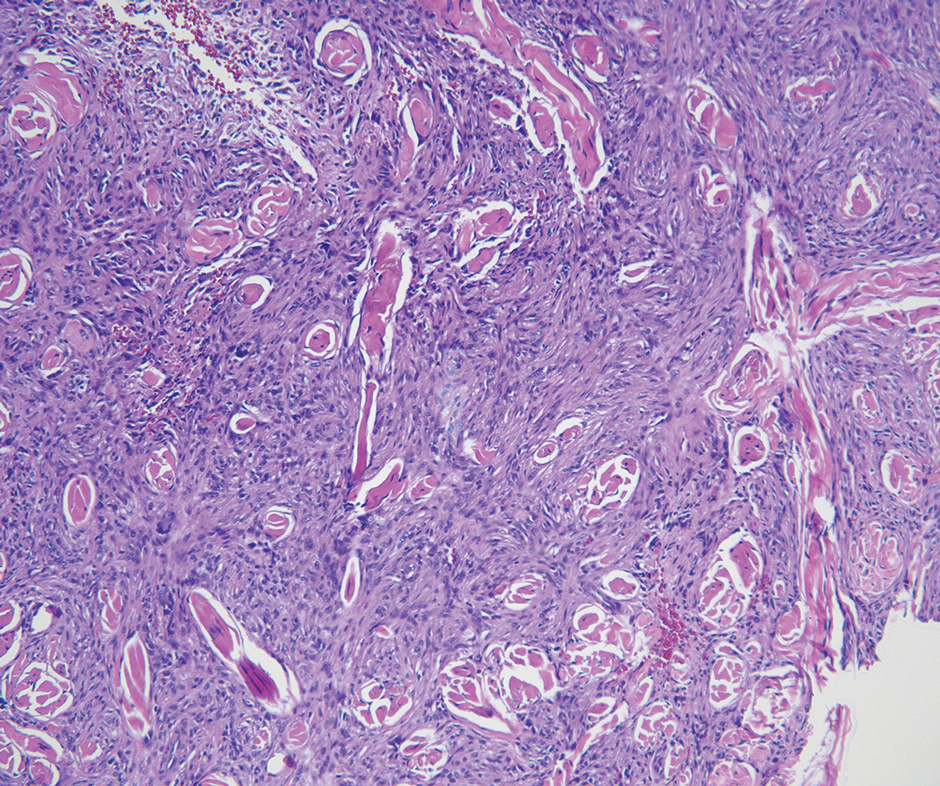

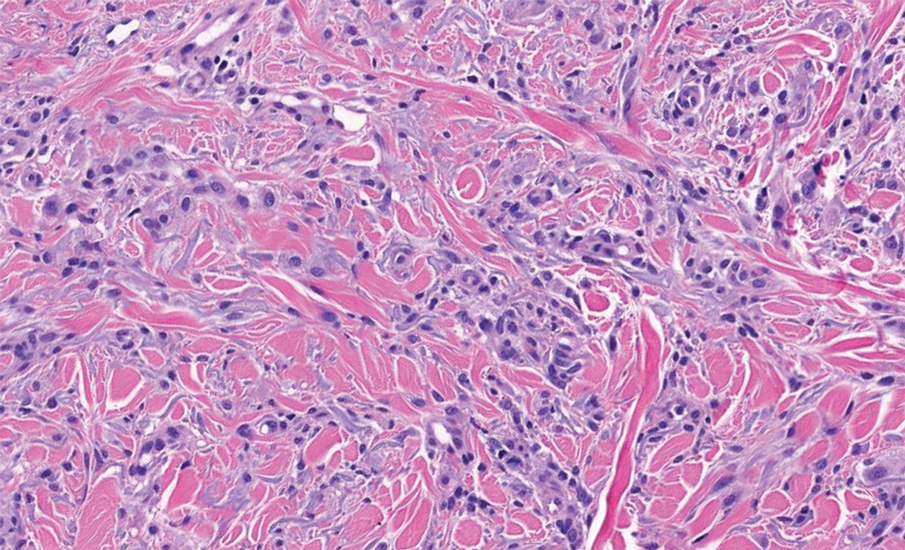

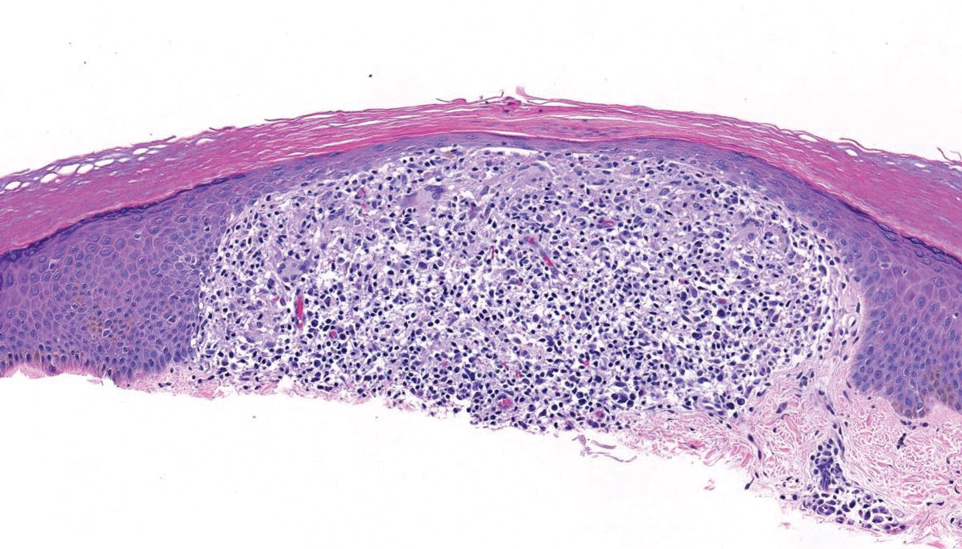

Pilomatrixomas are benign neoplasms that arise from hair matrix cells and have been associated with catenin beta-1 gene mutations, as well as genetic syndromes and trauma.7 Clinically, pilomatrixomas manifest as solitary, firm, painless, slow-growing nodules that commonly are found in the head and neck region. This tumor has a slight predominance in women and occurs frequently in adolescent years. The overlying skin may appear normal or show grey-bluish discoloration.8 Histopathology shows basaloid cells resembling primitive hair matrix cells with an abrupt transition to shadow cells composed of transformed keratinocytes without nuclei and calcification.7-8 This tumor can be differentiated by the presence of basaloid and shadow cells with calcification on histopathology, while MPTT will show atypical, mitotically active squamous cells with trichilemmal keratinization (Figure 2).

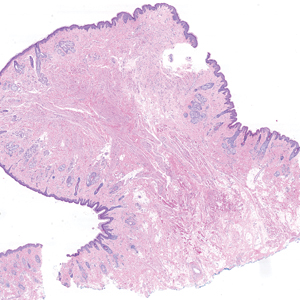

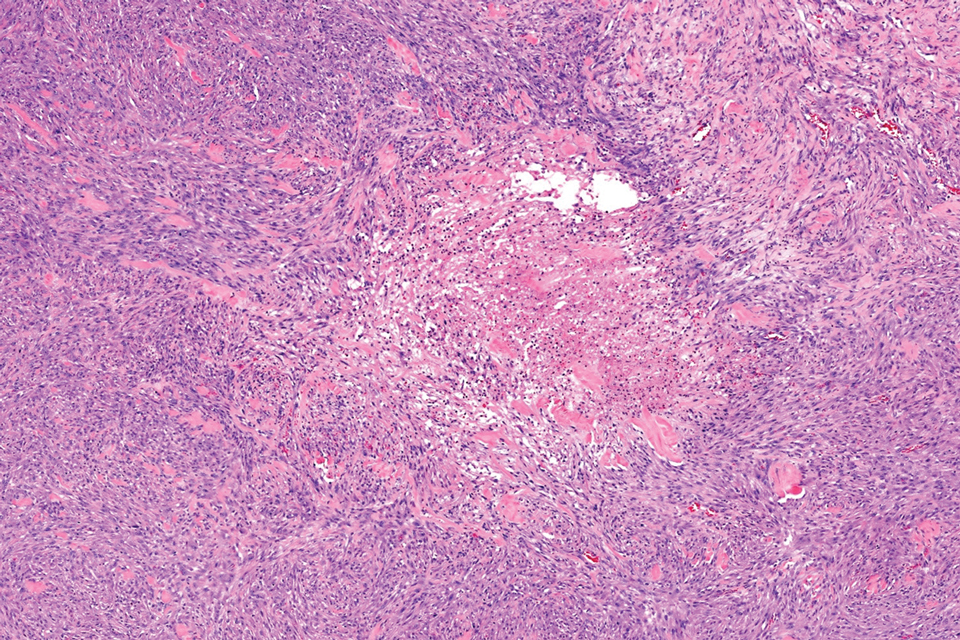

Proliferating trichilemmal cyst is a variant of trichilemmal cyst (TC) arising from the outer root sheath cells of the hair follicle. While TCs usually are slow growing and benign, the proliferating variant can be more aggressive with malignant potential. Patients often present with a solitary, well-circumscribed, rapidly growing nodule on the scalp. The lesion may be painful, and ulceration can occur, exposing the cystic contents. Histopathologically, PTCs resemble TCs with trichilemmal keratinization but also exhibit notable epithelial proliferation within the cystic space.9 While there can be considerable histopathologic overlap between PTC and MPTT—including extensive trichilemmal keratinization, variable atypia, and mitotic activity—PTC typically should not demonstrate invasion into the surrounding soft tissue or the degree of high-grade atypia, brisk mitoses, or necrosis seen in MPTT (eFigure 1).1 Immunohistochemistry may help distinguish PTC from MPTT and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10-11 The pattern of Ki-67 and p53 expression may be helpful with classification of PTC/MPTT into the 3 groups (benign, low-grade malignant, and high-grade malignant) proposed by Ye et al.1 Other investigators have suggested that Ki-67 expression may correlate potential for recurrence and clinical prognosis.12 Expression of CD34 (a marker that supports outer root sheath origin) might favor PTC/MPTT over SCC; however, cases of CD34- negative MPTT have been reported, particularly those with poorly differentiated histopathology.

Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by cystlike spaces containing malignant squamous epithelial cells.13 Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features can manifest as a firm nodule with ulceration similar to MPTT or PTC but also can mimic a benign cyst.14 The diagnosis of invasive SCC with cystic features typically is straightforward and characterized by cords and nests of atypical keratinocytes extending into the dermis with areas of cystic architecture (eFigure 2). While both SCC with cystic features and MPTT may show cystic histopathologic architecture, MPTT typically shows areas of PTC, whereas SCC with cystic features lacks such areas.

Verrucous cysts refer to infundibular cysts or less commonly pilar cysts or hybrid pilar-epidermoid cysts that exhibit superimposed human papillomavirus (HPV) cytopathic changes. Clinically, a verrucous cyst manifests as a single, asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm lesion most commonly manifesting on the face and back. Histopathologically, the cyst wall may show acanthosis, papillomatosis, hypergranulosis with coarse keratohyalin granules, and koilocytic changes (eFigure 3). These histopathologic features are believed to be induced by secondary HPV infection. While HPV-related change, characterized by koilocytic alteration, papillomatosis, and verruciform hyperplasia, more commonly affects epidermal cysts, occasionally trichilemmal (pilar) cysts are involved. In these cases, verrucous cysts should be distinguished from MPTT. Verrucous cysts may contain rare normal mitotic figures, but do not contain atypical mitosis, marked cellular pleomorphism, or an infiltrating pattern similar to MPTT.15

- Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:566-574. doi:10.1309/0XLEGFQ64XYJU4G6

- Saida T, Oohara K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatologica. 1983;166:203-208. doi:10.1159/000249868

- Rao S, Ramakrishnan R, Kamakshi D, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour presenting early in life: an uncommon feature. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:51-55. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.79196

- Kearns-Turcotte S, Thériault M, Blouin MM. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors arising in patients with multiple trichilemmal cysts: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;22:42-46. doi:10.1016

- Karamese M, Akatekin A, Abaci M, et al. Unusual invasion of trichilemmal tumors: two case reports. Modern Plastic Surg. 2012; 2:54-57. doi:10.4236/MPS.2012.23014 /j.jdcr.2022.01.033

- Lobo L, Amonkar AD, Dontamsetty VV. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour of the scalp with intra-cranial extension and lung metastasis-a case report. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:493-495. doi:10.1007/s12262-015-1427-0

- Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-641. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

- Sharma D, Agarwal S, Jain LS, et al. Pilomatrixoma masquerading as metastatic adenocarcinoma. A diagnostic pitfall on cytology. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:FD13-FD14. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/9696.5064

- Valerio E, Parro FHS, Macedo MP, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst with clinical, radiological, macroscopic, and microscopic orrelation. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:452-454. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20198199

- Joshi TP, Marchand S, Tschen J. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor: a subtle presentation in an African American woman and review of immunohistochemical markers for this rare condition. Cureus. 2021;13:E17289. doi:10.7759/cureus.17289

- Gulati HK, Deshmukh SD, Anand M, et al. Low-grade malignant proliferating pilar tumor simulating a squamous-cell carcinoma in an elderly female: a case report and immunohistochemical study. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:98-101. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.90818

- Rangel-Gamboa L, Reyes-Castro M, Dominguez-Cherit J, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: the value of ki67 immunostaining. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:115-117. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.125599

- Asad U, Alkul S, Shimizu I, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma with unusual benign-appearing cystic features on histology. Cureus. 2023;15:E33610. doi:10.7759/cureus.33610

- Alkul S, Nguyen CN, Ramani NS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in an epidermal inclusion cyst. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2022;35:688-690. doi:10.1080/08998280.2022.207760

- Nanes BA, Laknezhad S, Chamseddin B, et al. Verrucous pilar cysts infected with beta human papillomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:381-386. doi:10.1111/cup.13599

THE DIAGNOSIS: Malignant Proliferating Trichilemmal Tumor

Biopsy revealed a squamous epithelium with cystic changes, trichilemmal differentiation, squamous eddy formation, keratinocyte atypia, focal necrotic changes, and a focus of atypical keratinocytes invading the dermis (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor (MPTT) was made.

Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor is a rare adnexal tumor that develops from the outer root sheath of the hair follicle. It often arises due to malignant transformation of pre-existing trichilemmal cysts, but some cases occur de novo.1 Malignant transformation is thought to start from a trichilemmal cyst in an adenomatous histologic stage, progressing to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst (PTC) in an epitheliomatous phase, ultimately becoming carcinomatous with MPTT.2-4 This transformation has been categorized into 3 morphologic groups to predict tumor behavior, including benign PTCs (curable by excision), low-grade malignant PTCs (minor risk for local recurrence), and high-grade malignant PTCs (risk for regional spread and metastasis with cytologic atypical features and potential for aggressive growth).1

More commonly observed in women in the fourth to eighth decades of life, MPTT may manifest as a fast- growing, painless, solitary nodule or as a progressively enlarging nodule at the site of a previously stable, long-standing lesion. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor manifests frequently on the scalp, face, or neck, but there are reports of MPTT manifesting on the trunk and even as multiple concurrent lesions.1-4 The variability in clinical presentation and the potential to be mistaken for benign conditions makes excisional biopsy essential for diagnosis of MPTT. Histopathology classically demonstrates trichilemmal keratinization, a high mitotic index, and cellular atypia with invasion into the dermis.4 Malignant transformation frequently follows a prior history of trauma to the area or local inflammation.

Given the locally aggressive nature of MPTT, our patient was referred to a Mohs micrographic surgeon. While both wide excision with tumor-free margins and Mohs micrographic surgery are accepted surgical procedures for MPTT, there is no consensus in the literature on a standard treatment recommendation. Following surgery, close monitoring is needed for potential recurrence and metastases intracranially to the dura and muscles,5 as well as to the lungs.6 Further imaging using computed tomography or positron emission tomography can be ordered to rule out metastatic disease.4

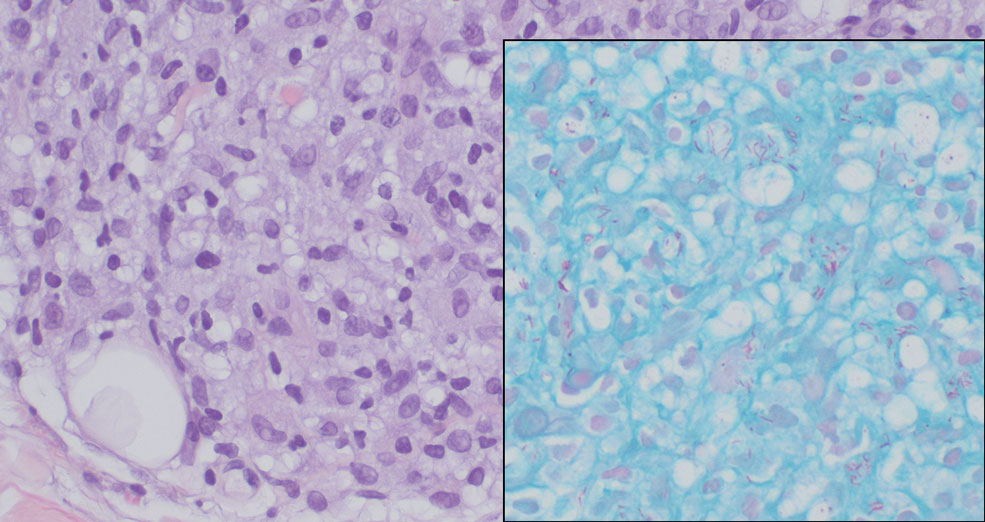

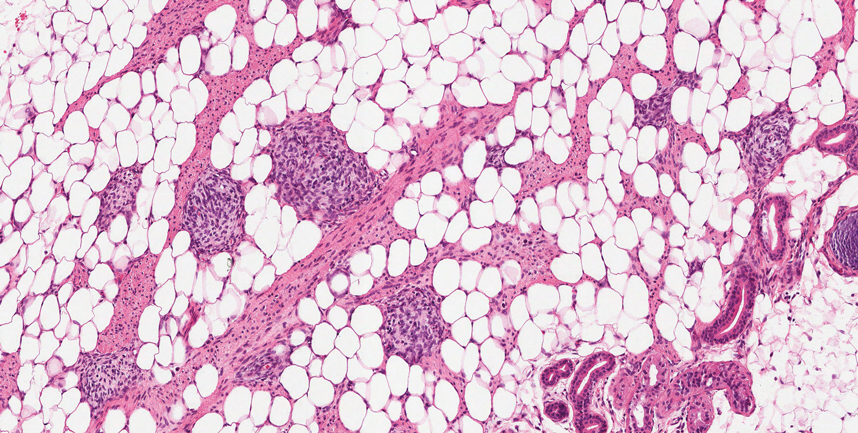

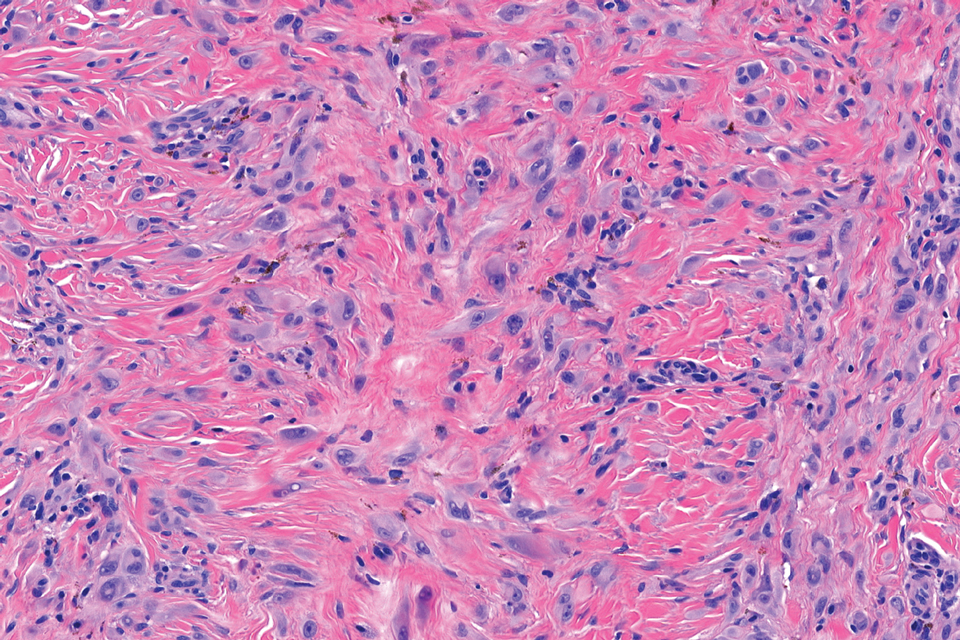

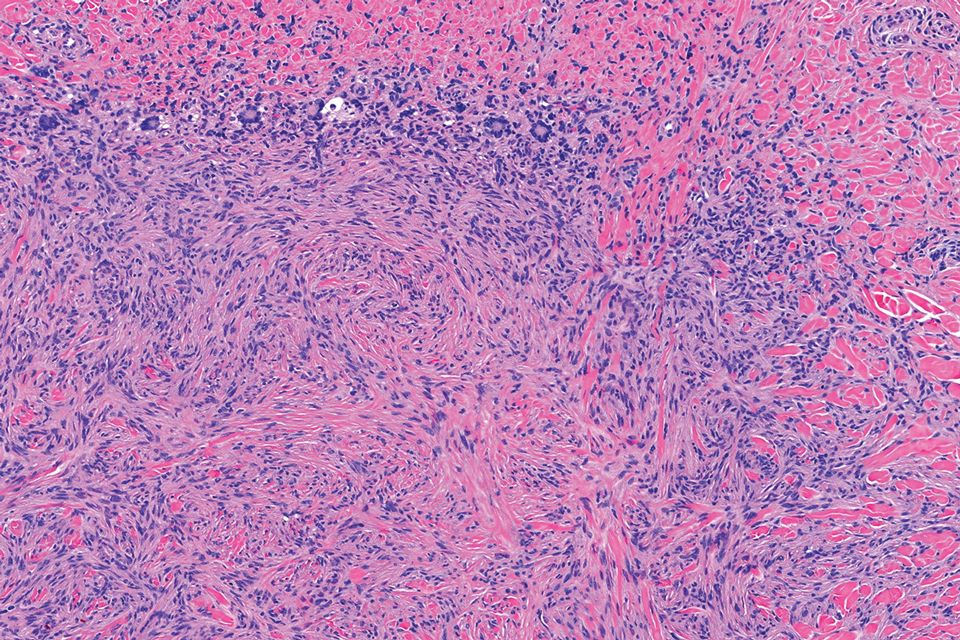

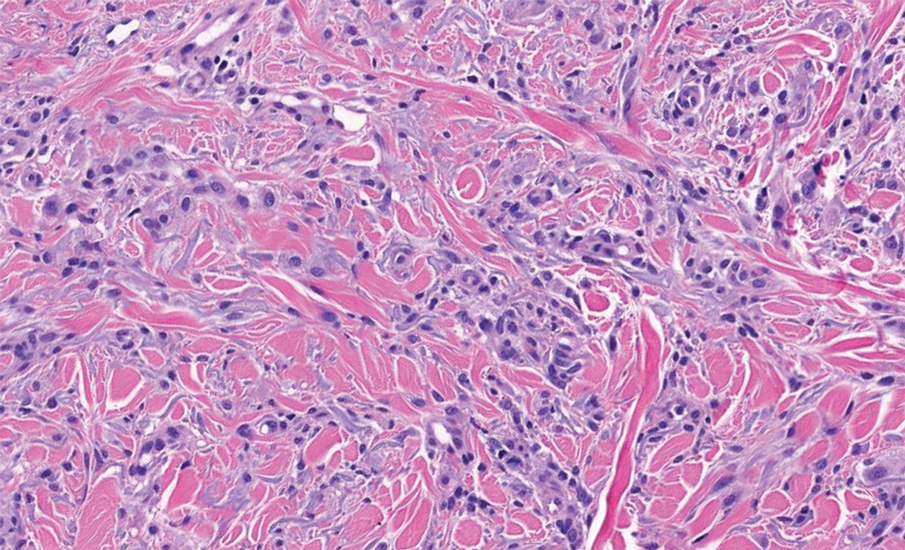

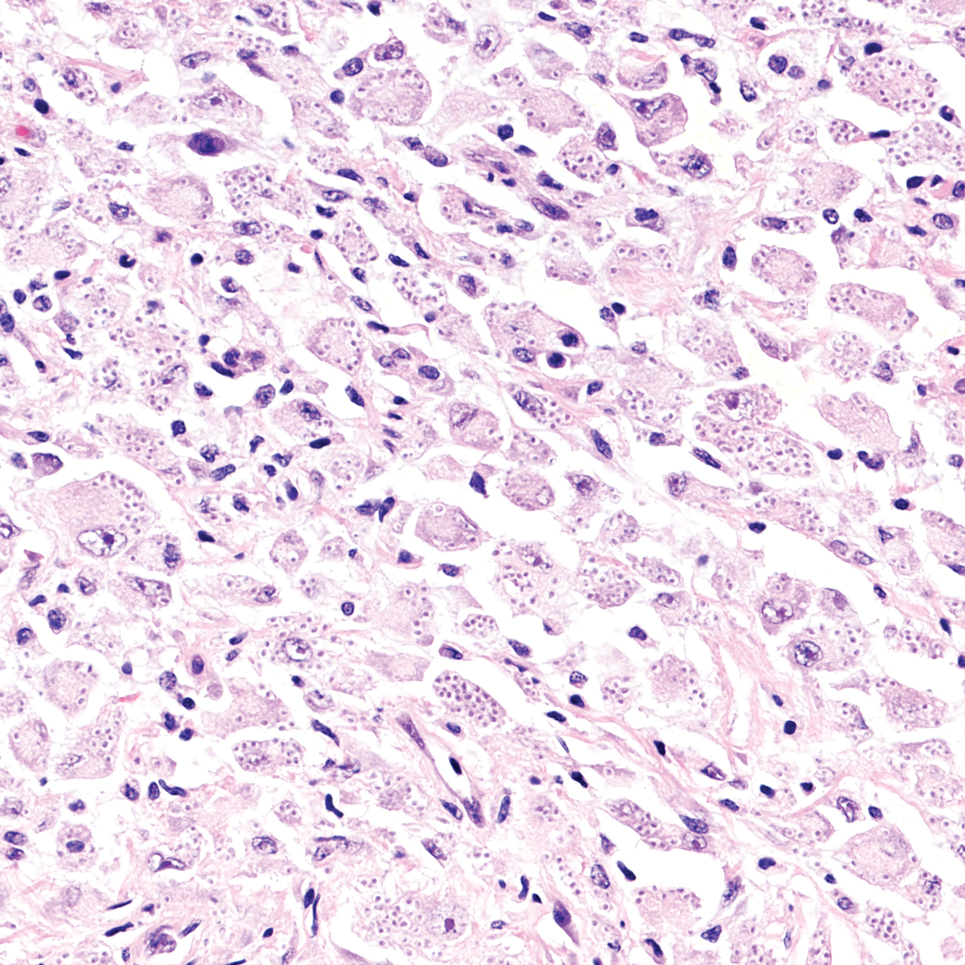

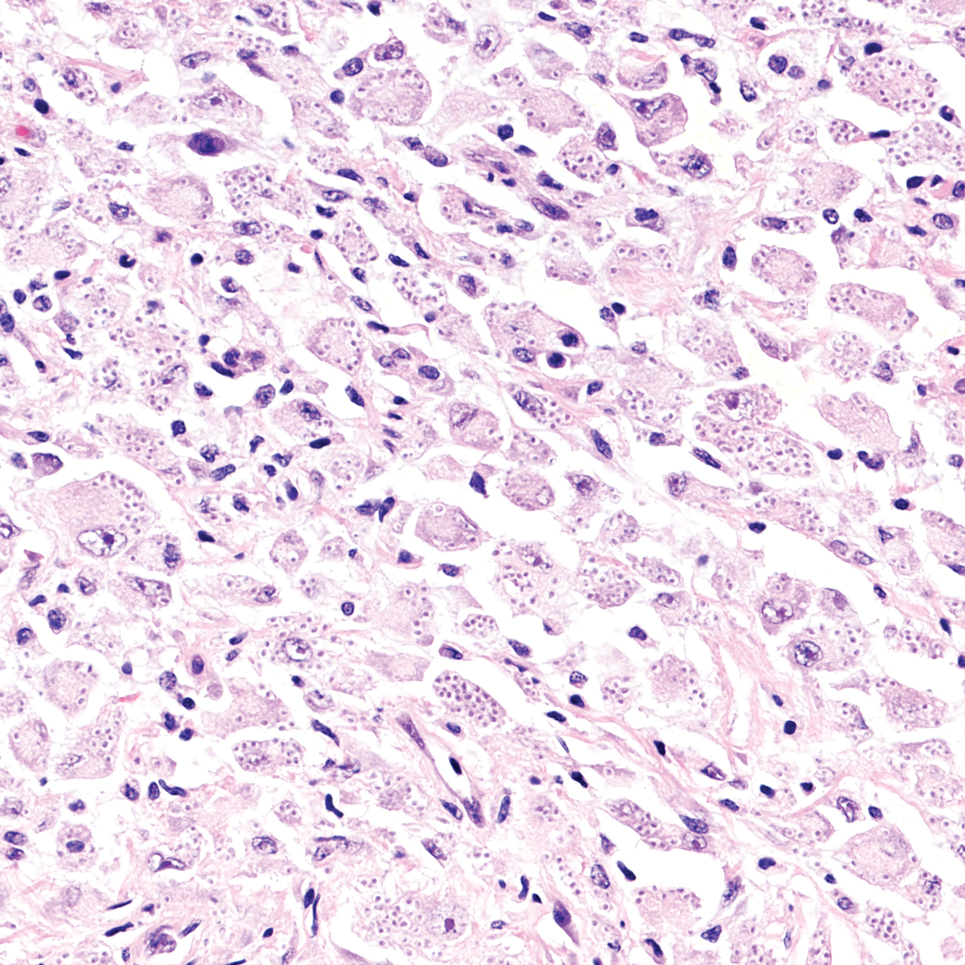

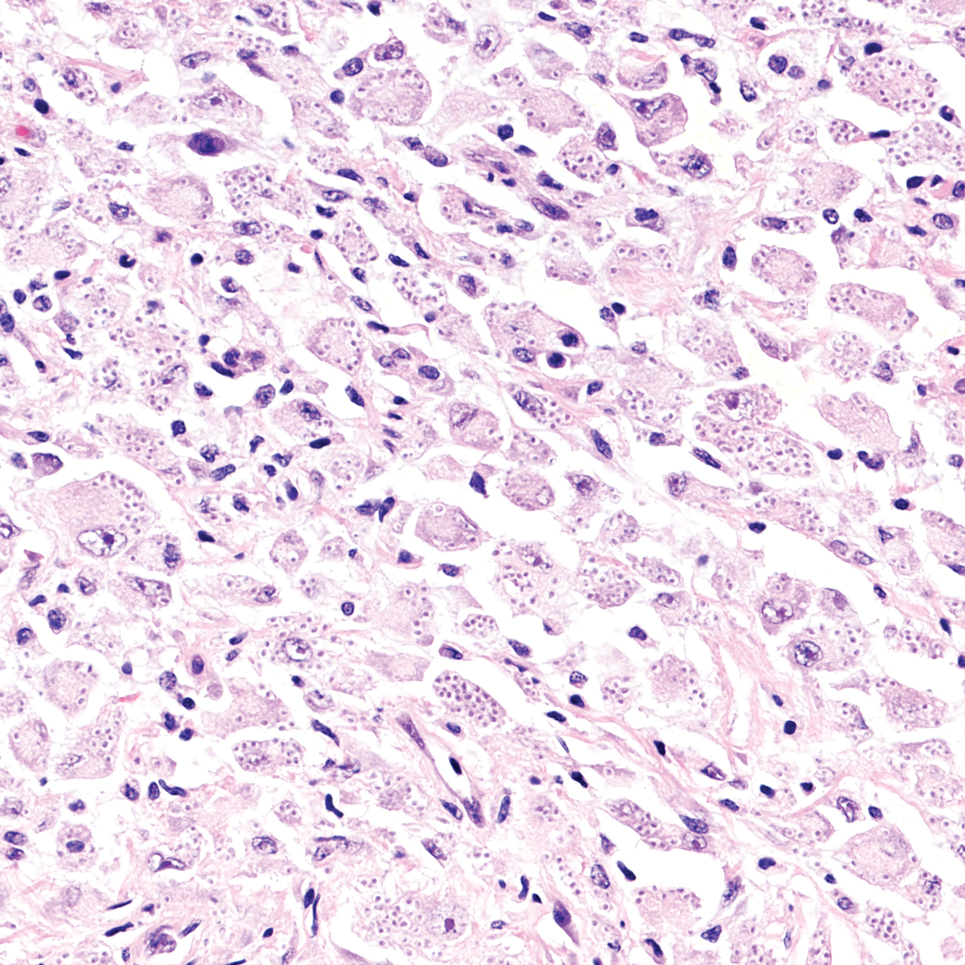

Pilomatrixomas are benign neoplasms that arise from hair matrix cells and have been associated with catenin beta-1 gene mutations, as well as genetic syndromes and trauma.7 Clinically, pilomatrixomas manifest as solitary, firm, painless, slow-growing nodules that commonly are found in the head and neck region. This tumor has a slight predominance in women and occurs frequently in adolescent years. The overlying skin may appear normal or show grey-bluish discoloration.8 Histopathology shows basaloid cells resembling primitive hair matrix cells with an abrupt transition to shadow cells composed of transformed keratinocytes without nuclei and calcification.7-8 This tumor can be differentiated by the presence of basaloid and shadow cells with calcification on histopathology, while MPTT will show atypical, mitotically active squamous cells with trichilemmal keratinization (Figure 2).

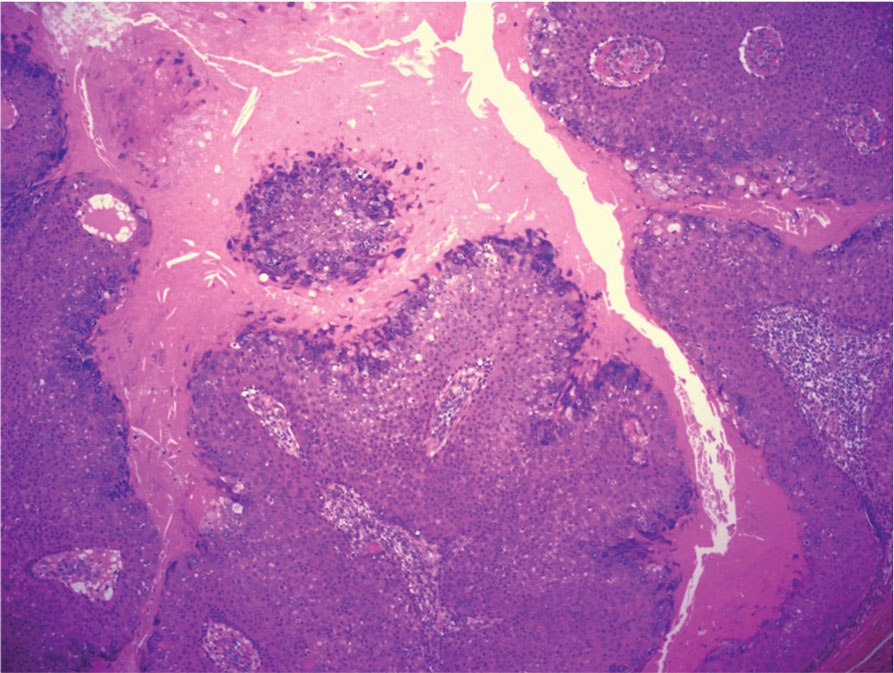

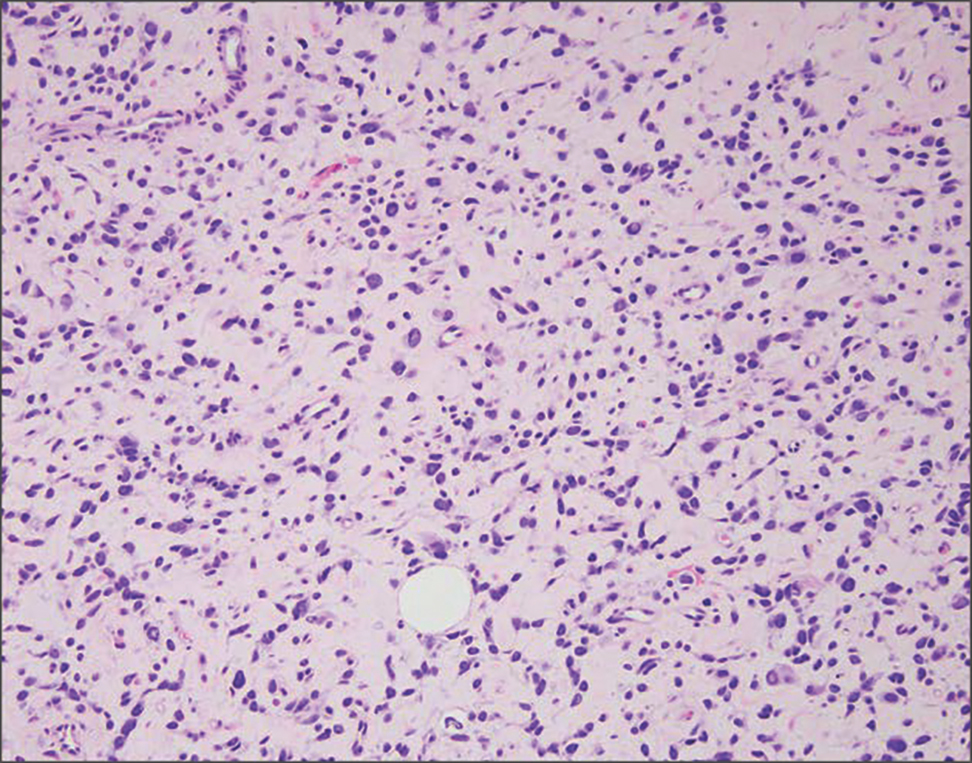

Proliferating trichilemmal cyst is a variant of trichilemmal cyst (TC) arising from the outer root sheath cells of the hair follicle. While TCs usually are slow growing and benign, the proliferating variant can be more aggressive with malignant potential. Patients often present with a solitary, well-circumscribed, rapidly growing nodule on the scalp. The lesion may be painful, and ulceration can occur, exposing the cystic contents. Histopathologically, PTCs resemble TCs with trichilemmal keratinization but also exhibit notable epithelial proliferation within the cystic space.9 While there can be considerable histopathologic overlap between PTC and MPTT—including extensive trichilemmal keratinization, variable atypia, and mitotic activity—PTC typically should not demonstrate invasion into the surrounding soft tissue or the degree of high-grade atypia, brisk mitoses, or necrosis seen in MPTT (eFigure 1).1 Immunohistochemistry may help distinguish PTC from MPTT and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10-11 The pattern of Ki-67 and p53 expression may be helpful with classification of PTC/MPTT into the 3 groups (benign, low-grade malignant, and high-grade malignant) proposed by Ye et al.1 Other investigators have suggested that Ki-67 expression may correlate potential for recurrence and clinical prognosis.12 Expression of CD34 (a marker that supports outer root sheath origin) might favor PTC/MPTT over SCC; however, cases of CD34- negative MPTT have been reported, particularly those with poorly differentiated histopathology.

Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by cystlike spaces containing malignant squamous epithelial cells.13 Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features can manifest as a firm nodule with ulceration similar to MPTT or PTC but also can mimic a benign cyst.14 The diagnosis of invasive SCC with cystic features typically is straightforward and characterized by cords and nests of atypical keratinocytes extending into the dermis with areas of cystic architecture (eFigure 2). While both SCC with cystic features and MPTT may show cystic histopathologic architecture, MPTT typically shows areas of PTC, whereas SCC with cystic features lacks such areas.

Verrucous cysts refer to infundibular cysts or less commonly pilar cysts or hybrid pilar-epidermoid cysts that exhibit superimposed human papillomavirus (HPV) cytopathic changes. Clinically, a verrucous cyst manifests as a single, asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm lesion most commonly manifesting on the face and back. Histopathologically, the cyst wall may show acanthosis, papillomatosis, hypergranulosis with coarse keratohyalin granules, and koilocytic changes (eFigure 3). These histopathologic features are believed to be induced by secondary HPV infection. While HPV-related change, characterized by koilocytic alteration, papillomatosis, and verruciform hyperplasia, more commonly affects epidermal cysts, occasionally trichilemmal (pilar) cysts are involved. In these cases, verrucous cysts should be distinguished from MPTT. Verrucous cysts may contain rare normal mitotic figures, but do not contain atypical mitosis, marked cellular pleomorphism, or an infiltrating pattern similar to MPTT.15

THE DIAGNOSIS: Malignant Proliferating Trichilemmal Tumor

Biopsy revealed a squamous epithelium with cystic changes, trichilemmal differentiation, squamous eddy formation, keratinocyte atypia, focal necrotic changes, and a focus of atypical keratinocytes invading the dermis (Figure 1). Based on these findings, a diagnosis of malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor (MPTT) was made.

Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor is a rare adnexal tumor that develops from the outer root sheath of the hair follicle. It often arises due to malignant transformation of pre-existing trichilemmal cysts, but some cases occur de novo.1 Malignant transformation is thought to start from a trichilemmal cyst in an adenomatous histologic stage, progressing to a proliferating trichilemmal cyst (PTC) in an epitheliomatous phase, ultimately becoming carcinomatous with MPTT.2-4 This transformation has been categorized into 3 morphologic groups to predict tumor behavior, including benign PTCs (curable by excision), low-grade malignant PTCs (minor risk for local recurrence), and high-grade malignant PTCs (risk for regional spread and metastasis with cytologic atypical features and potential for aggressive growth).1

More commonly observed in women in the fourth to eighth decades of life, MPTT may manifest as a fast- growing, painless, solitary nodule or as a progressively enlarging nodule at the site of a previously stable, long-standing lesion. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor manifests frequently on the scalp, face, or neck, but there are reports of MPTT manifesting on the trunk and even as multiple concurrent lesions.1-4 The variability in clinical presentation and the potential to be mistaken for benign conditions makes excisional biopsy essential for diagnosis of MPTT. Histopathology classically demonstrates trichilemmal keratinization, a high mitotic index, and cellular atypia with invasion into the dermis.4 Malignant transformation frequently follows a prior history of trauma to the area or local inflammation.

Given the locally aggressive nature of MPTT, our patient was referred to a Mohs micrographic surgeon. While both wide excision with tumor-free margins and Mohs micrographic surgery are accepted surgical procedures for MPTT, there is no consensus in the literature on a standard treatment recommendation. Following surgery, close monitoring is needed for potential recurrence and metastases intracranially to the dura and muscles,5 as well as to the lungs.6 Further imaging using computed tomography or positron emission tomography can be ordered to rule out metastatic disease.4

Pilomatrixomas are benign neoplasms that arise from hair matrix cells and have been associated with catenin beta-1 gene mutations, as well as genetic syndromes and trauma.7 Clinically, pilomatrixomas manifest as solitary, firm, painless, slow-growing nodules that commonly are found in the head and neck region. This tumor has a slight predominance in women and occurs frequently in adolescent years. The overlying skin may appear normal or show grey-bluish discoloration.8 Histopathology shows basaloid cells resembling primitive hair matrix cells with an abrupt transition to shadow cells composed of transformed keratinocytes without nuclei and calcification.7-8 This tumor can be differentiated by the presence of basaloid and shadow cells with calcification on histopathology, while MPTT will show atypical, mitotically active squamous cells with trichilemmal keratinization (Figure 2).

Proliferating trichilemmal cyst is a variant of trichilemmal cyst (TC) arising from the outer root sheath cells of the hair follicle. While TCs usually are slow growing and benign, the proliferating variant can be more aggressive with malignant potential. Patients often present with a solitary, well-circumscribed, rapidly growing nodule on the scalp. The lesion may be painful, and ulceration can occur, exposing the cystic contents. Histopathologically, PTCs resemble TCs with trichilemmal keratinization but also exhibit notable epithelial proliferation within the cystic space.9 While there can be considerable histopathologic overlap between PTC and MPTT—including extensive trichilemmal keratinization, variable atypia, and mitotic activity—PTC typically should not demonstrate invasion into the surrounding soft tissue or the degree of high-grade atypia, brisk mitoses, or necrosis seen in MPTT (eFigure 1).1 Immunohistochemistry may help distinguish PTC from MPTT and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).10-11 The pattern of Ki-67 and p53 expression may be helpful with classification of PTC/MPTT into the 3 groups (benign, low-grade malignant, and high-grade malignant) proposed by Ye et al.1 Other investigators have suggested that Ki-67 expression may correlate potential for recurrence and clinical prognosis.12 Expression of CD34 (a marker that supports outer root sheath origin) might favor PTC/MPTT over SCC; however, cases of CD34- negative MPTT have been reported, particularly those with poorly differentiated histopathology.

Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by cystlike spaces containing malignant squamous epithelial cells.13 Squamous cell carcinoma with cystic features can manifest as a firm nodule with ulceration similar to MPTT or PTC but also can mimic a benign cyst.14 The diagnosis of invasive SCC with cystic features typically is straightforward and characterized by cords and nests of atypical keratinocytes extending into the dermis with areas of cystic architecture (eFigure 2). While both SCC with cystic features and MPTT may show cystic histopathologic architecture, MPTT typically shows areas of PTC, whereas SCC with cystic features lacks such areas.

Verrucous cysts refer to infundibular cysts or less commonly pilar cysts or hybrid pilar-epidermoid cysts that exhibit superimposed human papillomavirus (HPV) cytopathic changes. Clinically, a verrucous cyst manifests as a single, asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm lesion most commonly manifesting on the face and back. Histopathologically, the cyst wall may show acanthosis, papillomatosis, hypergranulosis with coarse keratohyalin granules, and koilocytic changes (eFigure 3). These histopathologic features are believed to be induced by secondary HPV infection. While HPV-related change, characterized by koilocytic alteration, papillomatosis, and verruciform hyperplasia, more commonly affects epidermal cysts, occasionally trichilemmal (pilar) cysts are involved. In these cases, verrucous cysts should be distinguished from MPTT. Verrucous cysts may contain rare normal mitotic figures, but do not contain atypical mitosis, marked cellular pleomorphism, or an infiltrating pattern similar to MPTT.15

- Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:566-574. doi:10.1309/0XLEGFQ64XYJU4G6

- Saida T, Oohara K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatologica. 1983;166:203-208. doi:10.1159/000249868

- Rao S, Ramakrishnan R, Kamakshi D, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour presenting early in life: an uncommon feature. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:51-55. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.79196

- Kearns-Turcotte S, Thériault M, Blouin MM. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors arising in patients with multiple trichilemmal cysts: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;22:42-46. doi:10.1016

- Karamese M, Akatekin A, Abaci M, et al. Unusual invasion of trichilemmal tumors: two case reports. Modern Plastic Surg. 2012; 2:54-57. doi:10.4236/MPS.2012.23014 /j.jdcr.2022.01.033

- Lobo L, Amonkar AD, Dontamsetty VV. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour of the scalp with intra-cranial extension and lung metastasis-a case report. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:493-495. doi:10.1007/s12262-015-1427-0

- Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-641. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

- Sharma D, Agarwal S, Jain LS, et al. Pilomatrixoma masquerading as metastatic adenocarcinoma. A diagnostic pitfall on cytology. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:FD13-FD14. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/9696.5064

- Valerio E, Parro FHS, Macedo MP, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst with clinical, radiological, macroscopic, and microscopic orrelation. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:452-454. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20198199

- Joshi TP, Marchand S, Tschen J. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor: a subtle presentation in an African American woman and review of immunohistochemical markers for this rare condition. Cureus. 2021;13:E17289. doi:10.7759/cureus.17289

- Gulati HK, Deshmukh SD, Anand M, et al. Low-grade malignant proliferating pilar tumor simulating a squamous-cell carcinoma in an elderly female: a case report and immunohistochemical study. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:98-101. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.90818

- Rangel-Gamboa L, Reyes-Castro M, Dominguez-Cherit J, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: the value of ki67 immunostaining. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:115-117. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.125599

- Asad U, Alkul S, Shimizu I, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma with unusual benign-appearing cystic features on histology. Cureus. 2023;15:E33610. doi:10.7759/cureus.33610

- Alkul S, Nguyen CN, Ramani NS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in an epidermal inclusion cyst. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2022;35:688-690. doi:10.1080/08998280.2022.207760

- Nanes BA, Laknezhad S, Chamseddin B, et al. Verrucous pilar cysts infected with beta human papillomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:381-386. doi:10.1111/cup.13599

- Ye J, Nappi O, Swanson PE, et al. Proliferating pilar tumors: a clinicopathologic study of 76 cases with a proposal for definition of benign and malignant variants. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:566-574. doi:10.1309/0XLEGFQ64XYJU4G6

- Saida T, Oohara K, Hori Y, et al. Development of a malignant proliferating trichilemmal cyst in a patient with multiple trichilemmal cysts. Dermatologica. 1983;166:203-208. doi:10.1159/000249868

- Rao S, Ramakrishnan R, Kamakshi D, et al. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour presenting early in life: an uncommon feature. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2011;4:51-55. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.79196

- Kearns-Turcotte S, Thériault M, Blouin MM. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumors arising in patients with multiple trichilemmal cysts: a case series. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;22:42-46. doi:10.1016

- Karamese M, Akatekin A, Abaci M, et al. Unusual invasion of trichilemmal tumors: two case reports. Modern Plastic Surg. 2012; 2:54-57. doi:10.4236/MPS.2012.23014 /j.jdcr.2022.01.033

- Lobo L, Amonkar AD, Dontamsetty VV. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumour of the scalp with intra-cranial extension and lung metastasis-a case report. Indian J Surg. 2016;78:493-495. doi:10.1007/s12262-015-1427-0

- Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, et al. Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:631-641. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001118

- Sharma D, Agarwal S, Jain LS, et al. Pilomatrixoma masquerading as metastatic adenocarcinoma. A diagnostic pitfall on cytology. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:FD13-FD14. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2014/9696.5064

- Valerio E, Parro FHS, Macedo MP, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst with clinical, radiological, macroscopic, and microscopic orrelation. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:452-454. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20198199

- Joshi TP, Marchand S, Tschen J. Malignant proliferating trichilemmal tumor: a subtle presentation in an African American woman and review of immunohistochemical markers for this rare condition. Cureus. 2021;13:E17289. doi:10.7759/cureus.17289

- Gulati HK, Deshmukh SD, Anand M, et al. Low-grade malignant proliferating pilar tumor simulating a squamous-cell carcinoma in an elderly female: a case report and immunohistochemical study. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:98-101. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.90818

- Rangel-Gamboa L, Reyes-Castro M, Dominguez-Cherit J, et al. Proliferating trichilemmal cyst: the value of ki67 immunostaining. Int J Trichology. 2013;5:115-117. doi:10.4103/0974-7753.125599

- Asad U, Alkul S, Shimizu I, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma with unusual benign-appearing cystic features on histology. Cureus. 2023;15:E33610. doi:10.7759/cureus.33610

- Alkul S, Nguyen CN, Ramani NS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in an epidermal inclusion cyst. Baylor Univ Med Cent Proc. 2022;35:688-690. doi:10.1080/08998280.2022.207760

- Nanes BA, Laknezhad S, Chamseddin B, et al. Verrucous pilar cysts infected with beta human papillomavirus. J Cutan Pathol. 2020;47:381-386. doi:10.1111/cup.13599

Growing Nodule on the Parietal Scalp

Growing Nodule on the Parietal Scalp

A 38-year-old woman with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology department with a firm enlarging nodule on the scalp of many years’ duration. The patient noted there was no drainage or bleeding. Physical examination revealed a mobile, 2.5-cm, subcutaneous nodule on the right parietal medial scalp. An excisional biopsy was performed.

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

Smooth Symmetric Plaques on the Face, Trunk, and Extremities

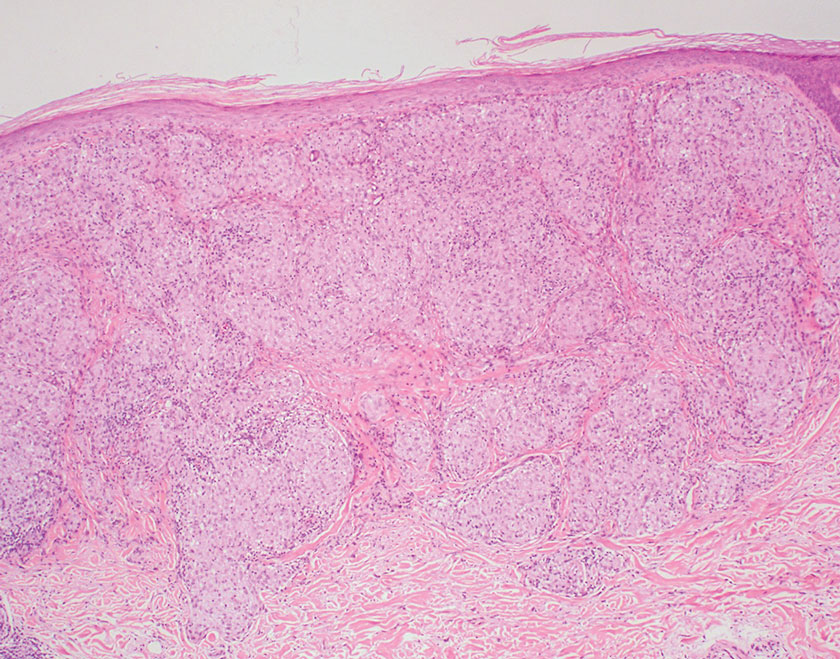

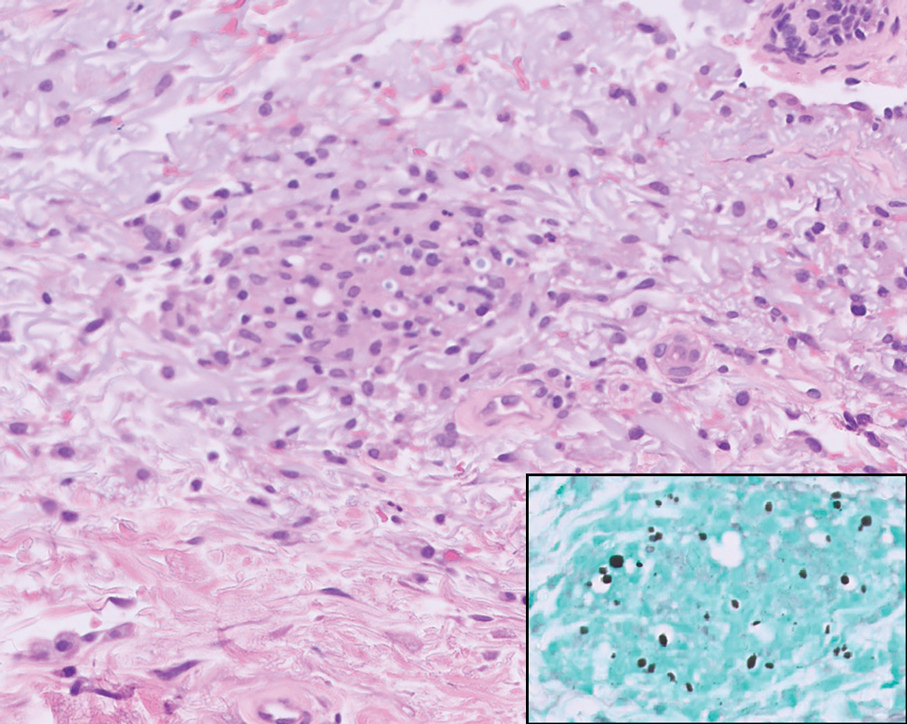

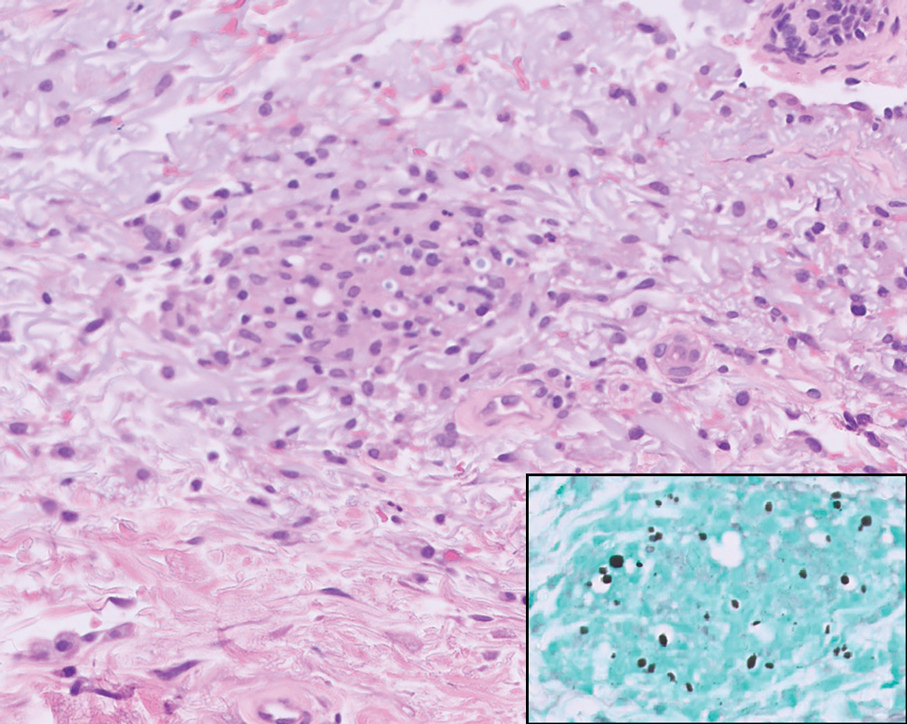

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

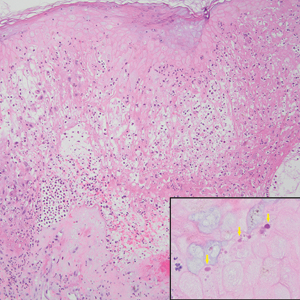

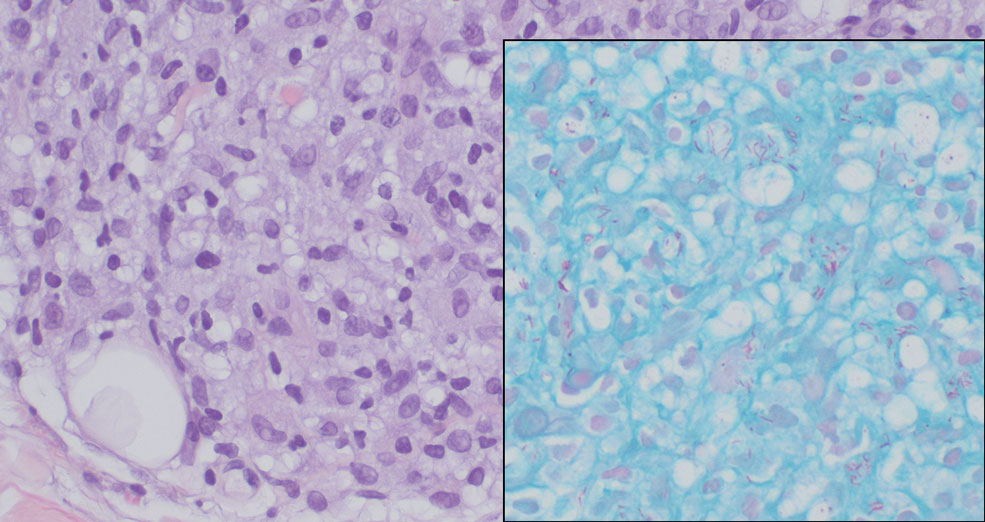

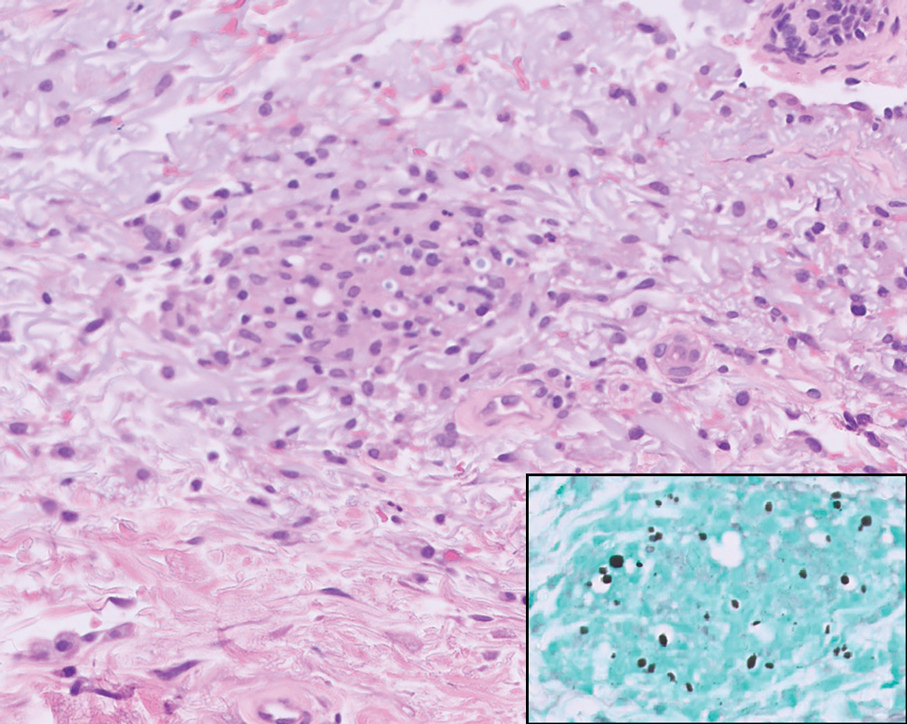

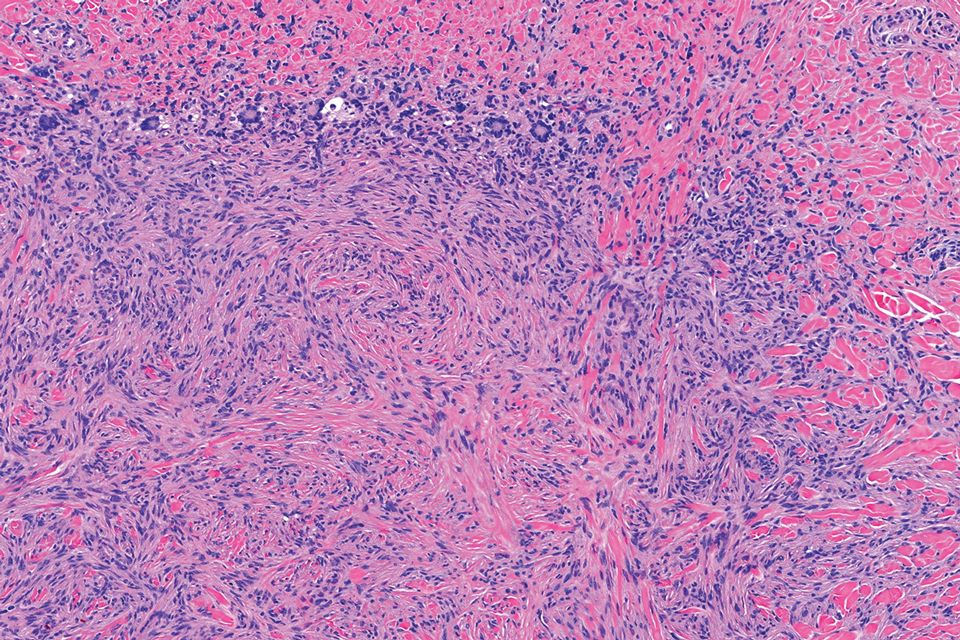

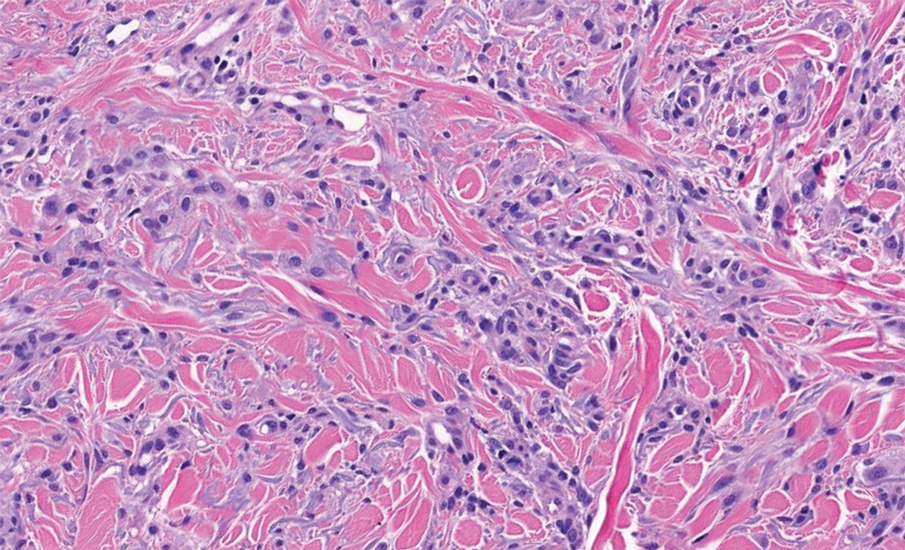

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

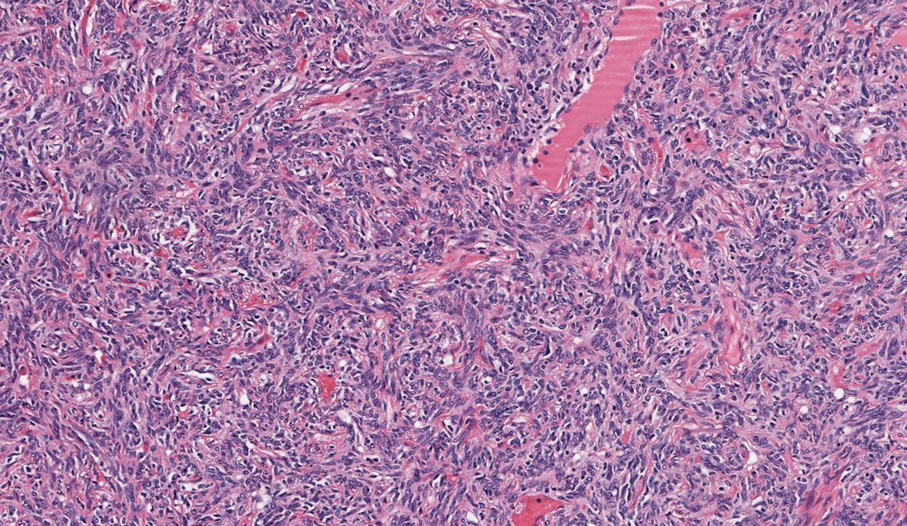

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

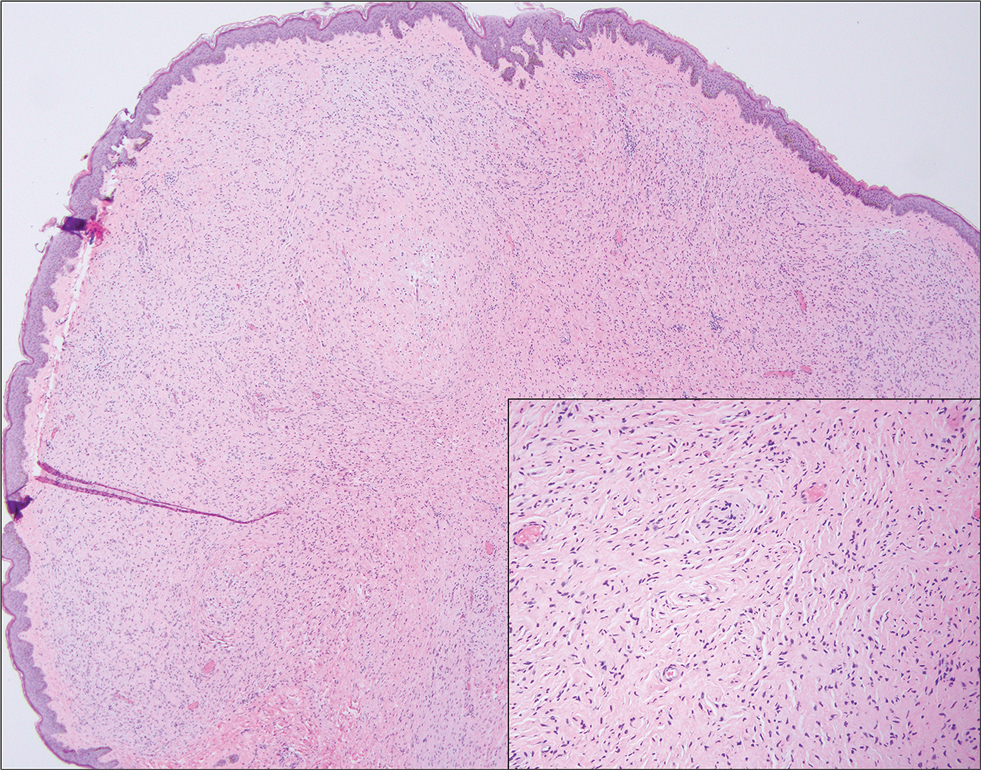

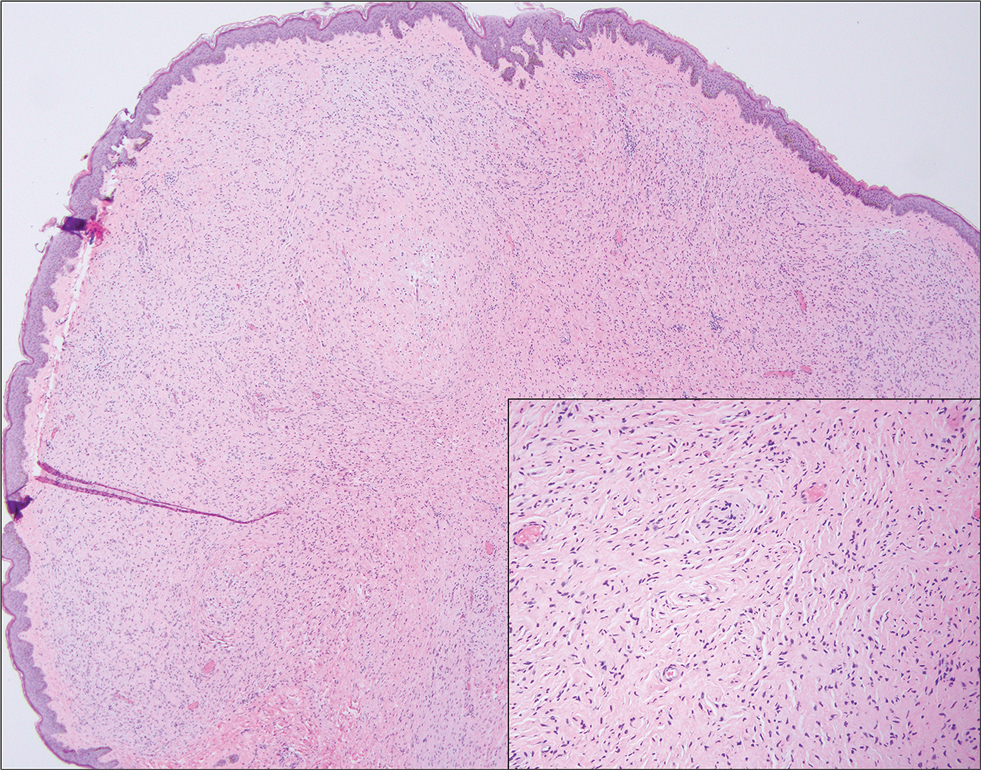

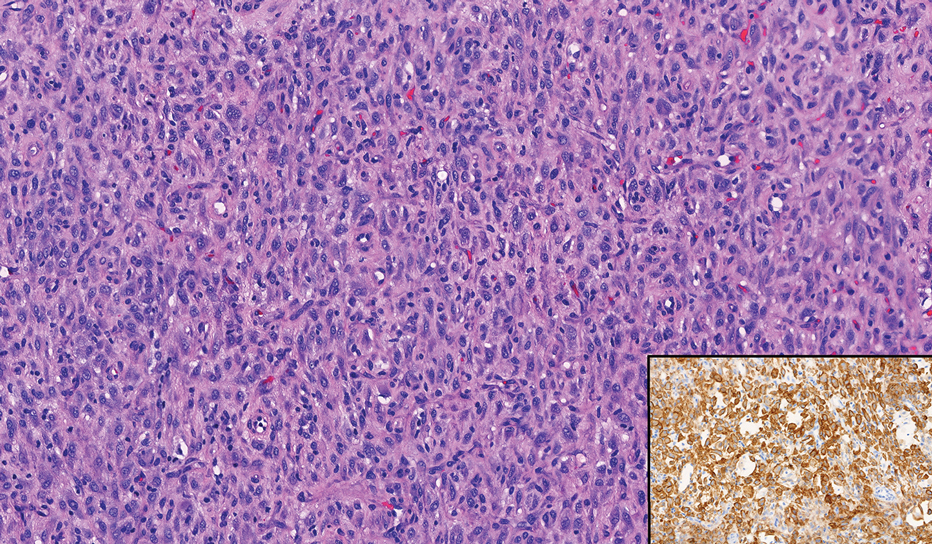

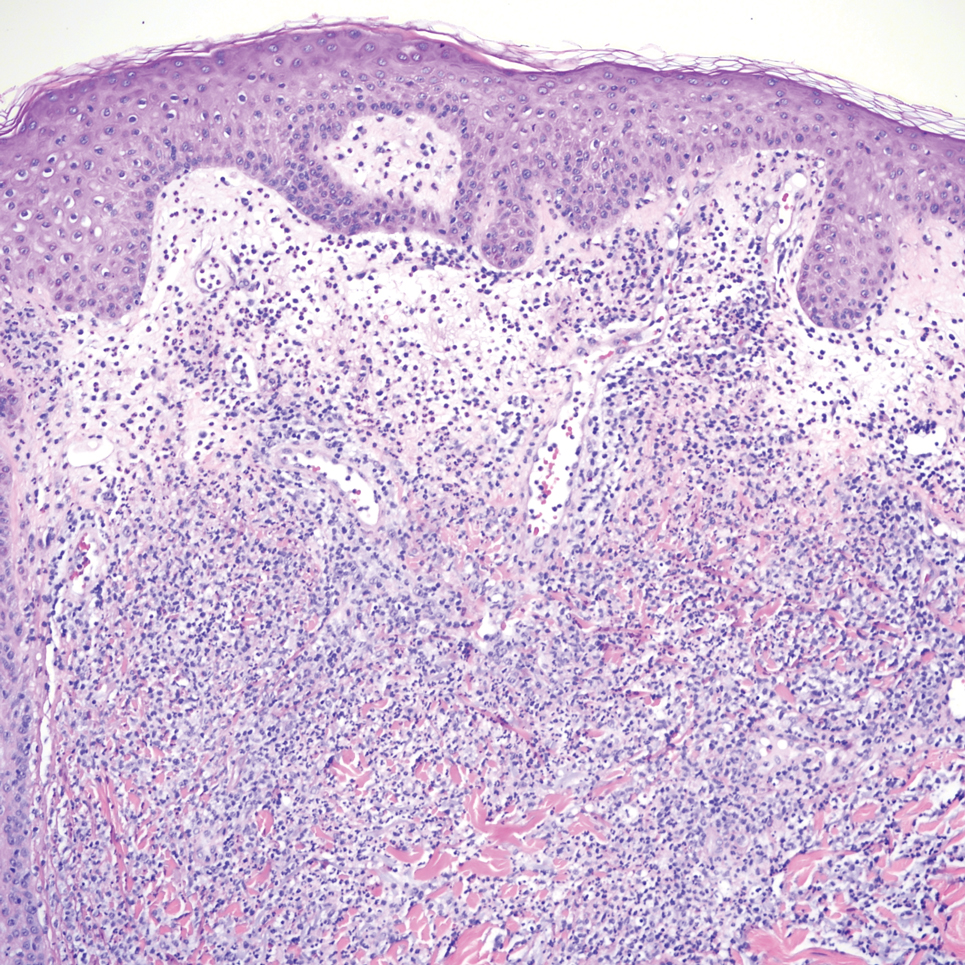

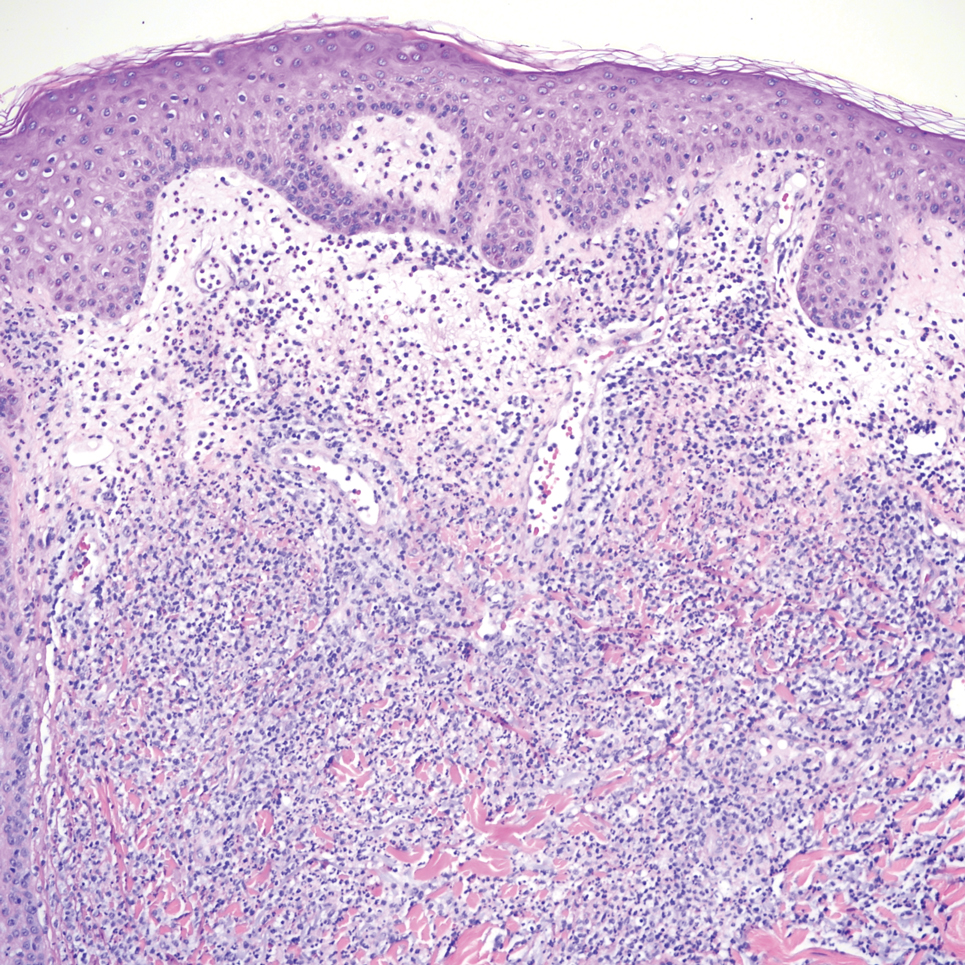

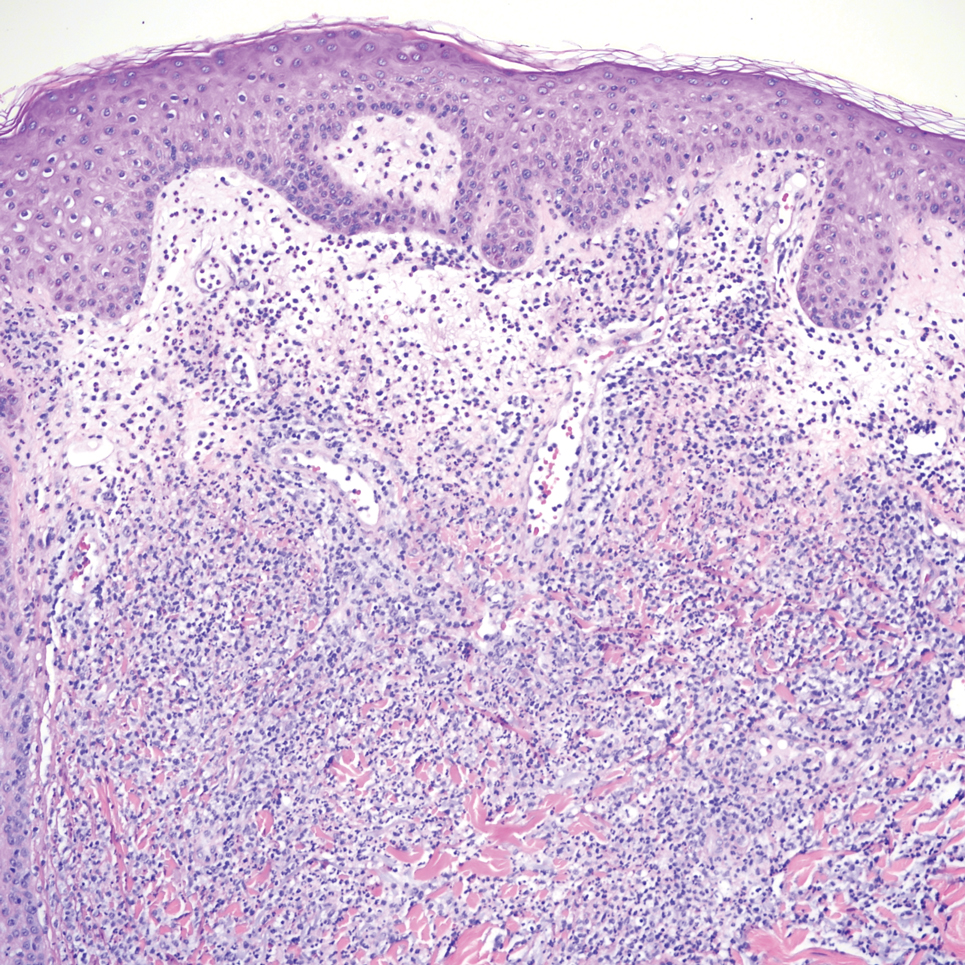

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

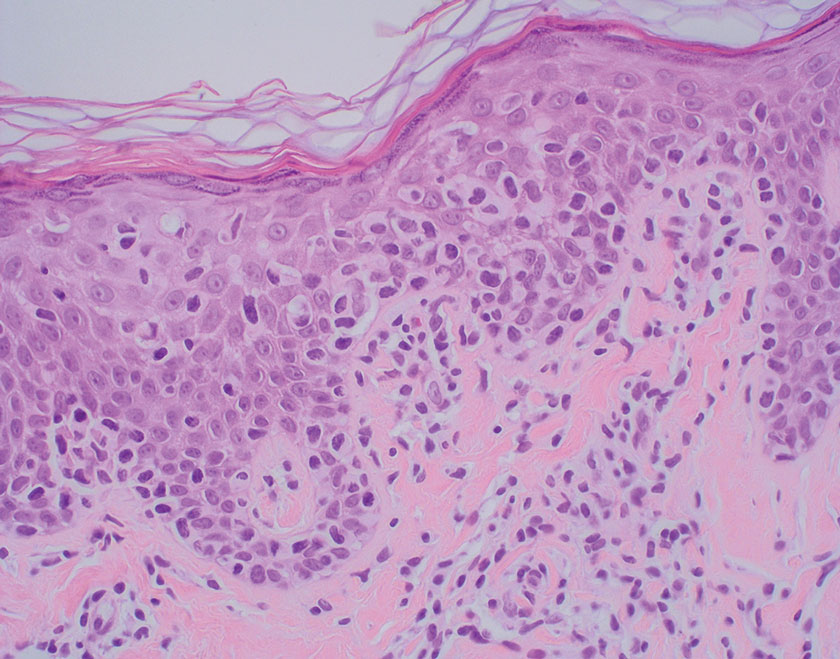

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

- Bobosha K, Wilson L, van Meijgaarden KE, et al. T-cell regulation in lepromatous leprosy. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:E2773. doi:10.1371 /journal.pntd.0002773

- Fischer M. Leprosy–an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:801-827. doi:10.1111/ddg.13301

- Jolly M, Pickard SA, Mikolaitis RA, et al. Lupus QoL-US benchmarks for US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1828-1833. doi:10.3899/jrheum.091443

- Chan MMF, Smoller BR. Overview of the histopathology and other laboratory investigations in leprosy. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2016;3:131-137. doi:10.1007/s40475-016-0086-y

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016; 75:457-465. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.054

- Lukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of generalized granuloma annulare–a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1467-1480. doi:10.1111/jdv.12976

- Zinzani PL, Ferreri AJM, Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:172-182. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.08.004

- Ahn CS, ALSayyah A, Sangüeza OP. Mycosis fungoides: an updated review of clinicopathologic variants. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:933- 951. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000207

- Gutte R, Kharkar V, Mahajan S, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides with hypohidrosis mimicking lepromatous leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:686. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.72470

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the cutaneous lymphoma histopathology task force group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001 /archdermatol.2008.46

- Miyashiro D, Cardona C, Valente N, et al. Ulcers in leprosy patients, an unrecognized clinical manifestation: a report of 8 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:1013. doi:10.1186/s12879-019-4639-2

- Cerroni L. Mycosis fungoides-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37:2-10. doi:10.12788/j.sder.2018.002

- Jain R, Yadav D, Puranik N, et al. Sarcoidosis: causes, diagnosis, clinical features, and treatments. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1081. doi:10.3390 /jcm9041081

- Zÿ ychowska M, Reich A. Dermoscopic features of acute, subacute, chronic and intermittent subtypes of cutaneous lupus erythematosus in Caucasians. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4088. doi:10.3390/jcm11144088

- Lazar AL. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a facultative paraneoplastic dermatosis. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:728-742. doi:10.1016 /j.clindermatol.2022.07.007

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

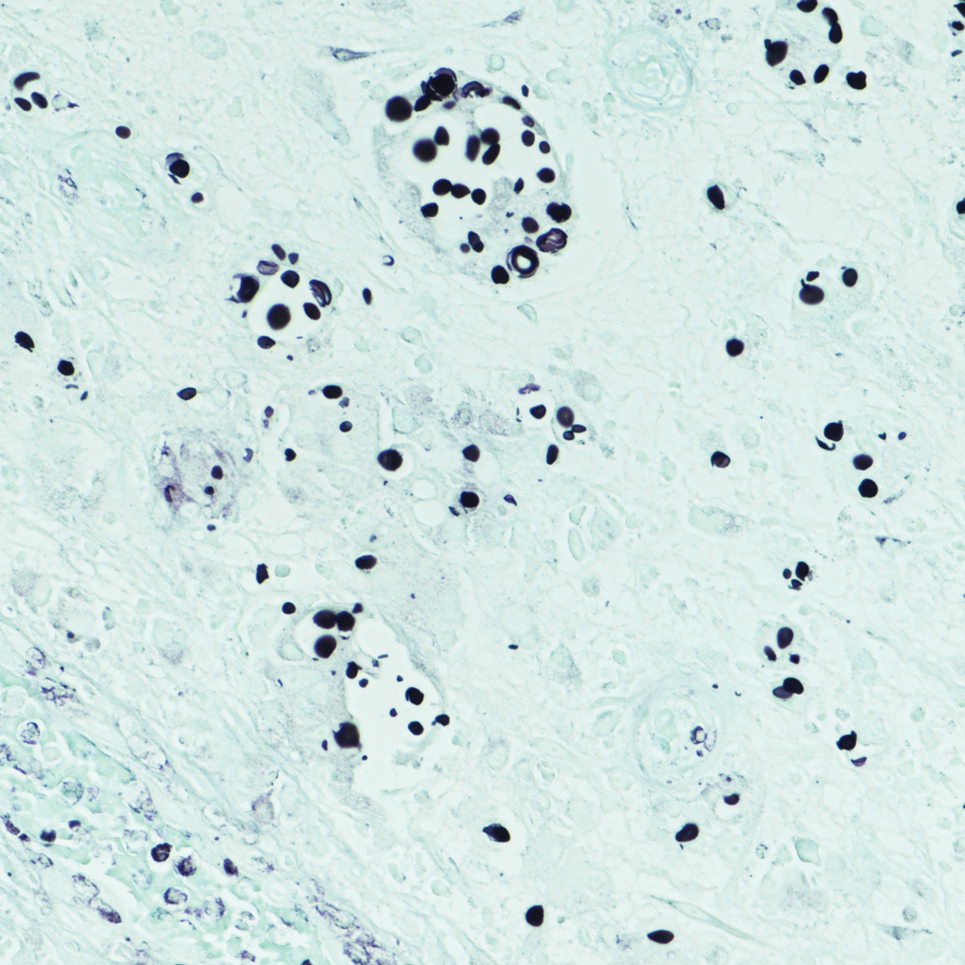

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.

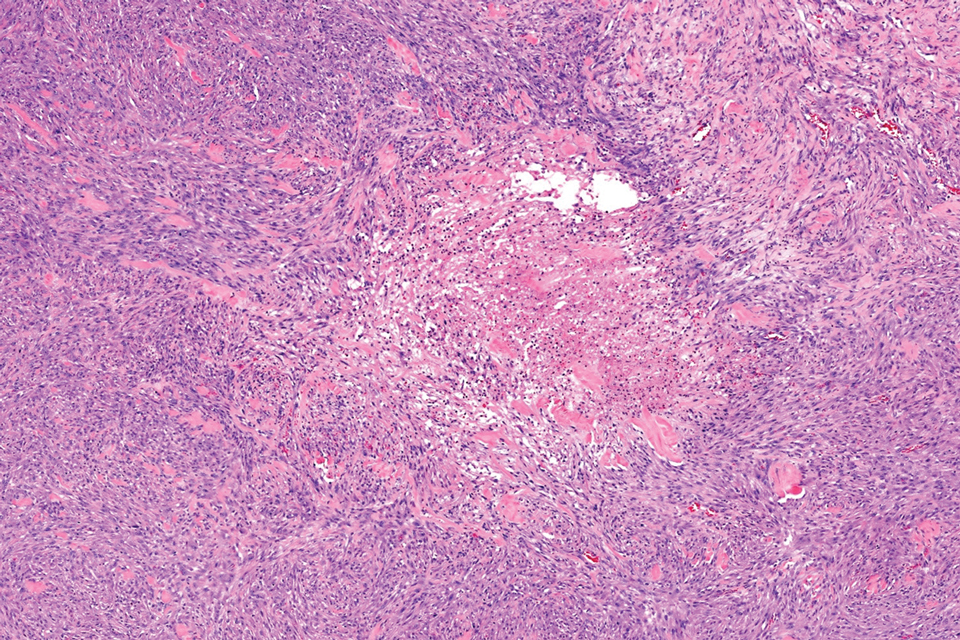

The differential diagnosis for LL includes granuloma annulare (GA), mycosis fungoides (MF), sarcoidosis, and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE). Granuloma annulare is a noninfectious inflammatory granulomatous skin disease that manifests in a localized, generalized, or subcutaneous pattern. Localized GA is the most common form and manifests as self-resolving, flesh-colored or erythematous papules or plaques limited to the extremities.5,6 Generalized GA is defined by more than 10 widespread annular plaques involving the trunk and extremities and can persist for decades.6 This form can be associated with hyperlipidemia, diabetes, autoimmune disease and immunodeficiency (eg, HIV), and rarely with lymphoma or solid tumors. On histology, GA shows necrobiosis surrounded by palisading histiocytes and mucin (palisading GA) or patchy interstitial histiocytes and lymphocytes (interstitial GA)(Figure 2).6 This palisading pattern differs from the histiocytes in LL, which contain numerous acid-fast bacilli and bacterial clumps. Topical and intralesional corticosteroids are first-line therapies for GA.

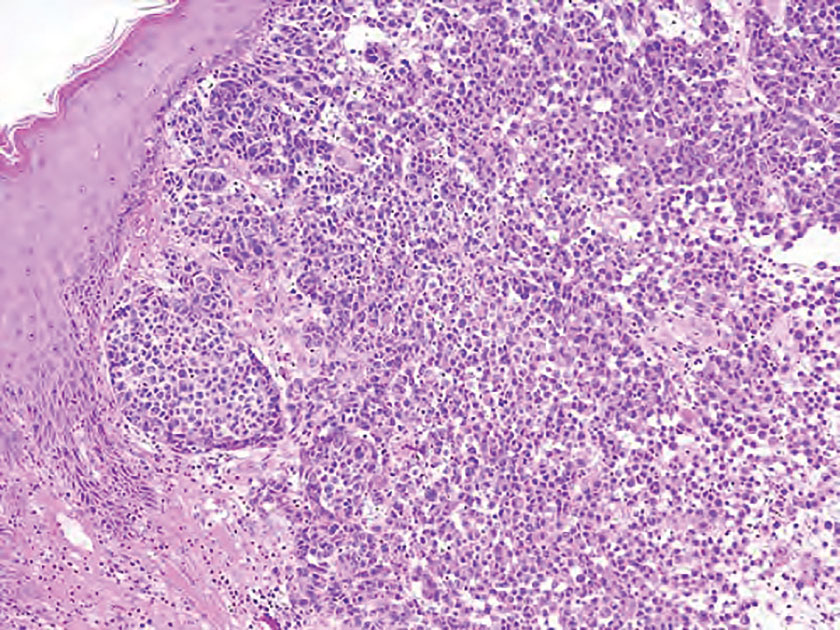

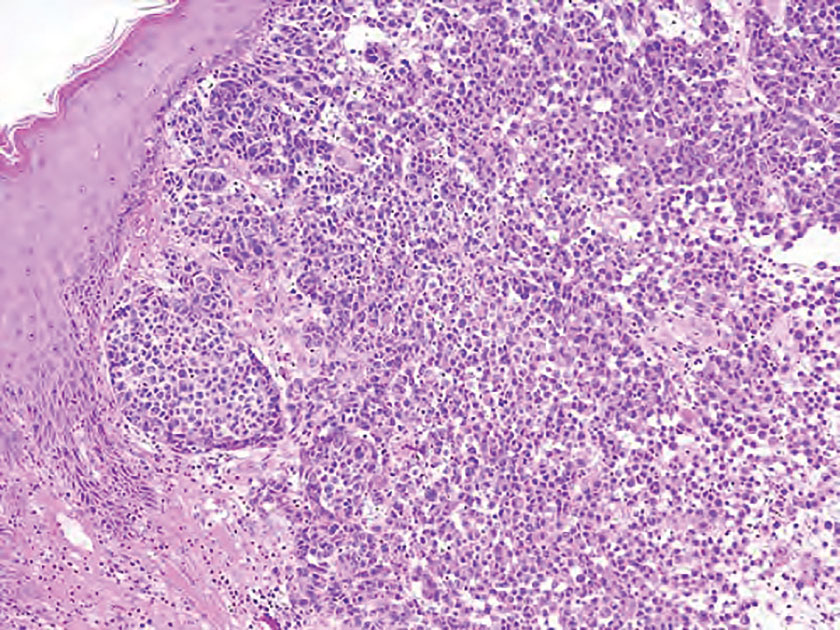

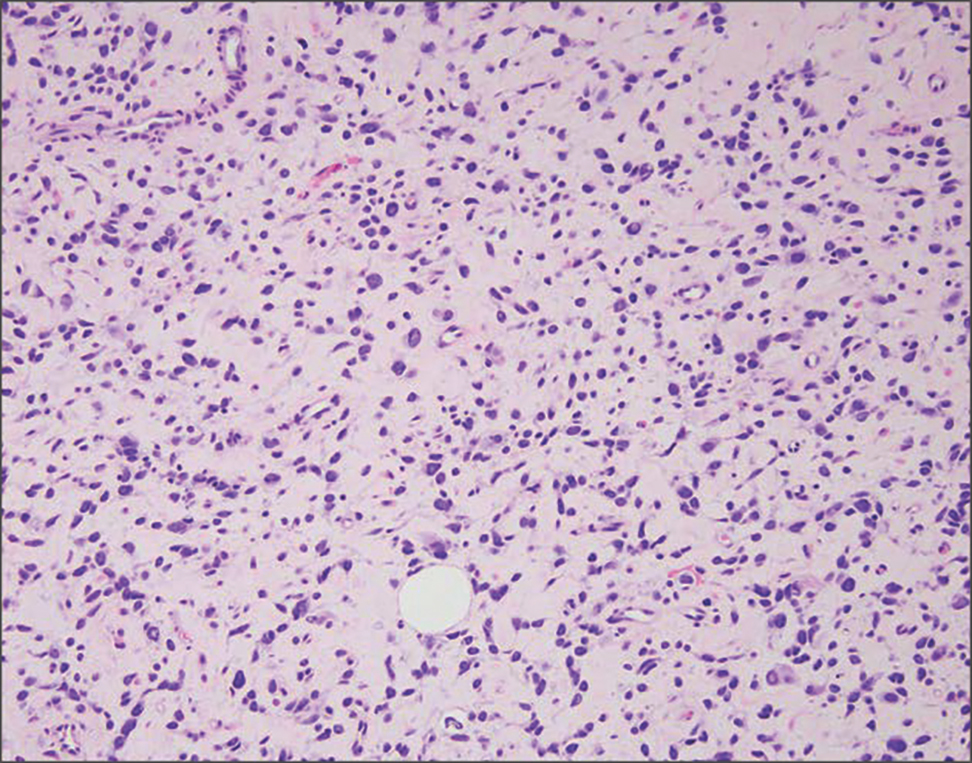

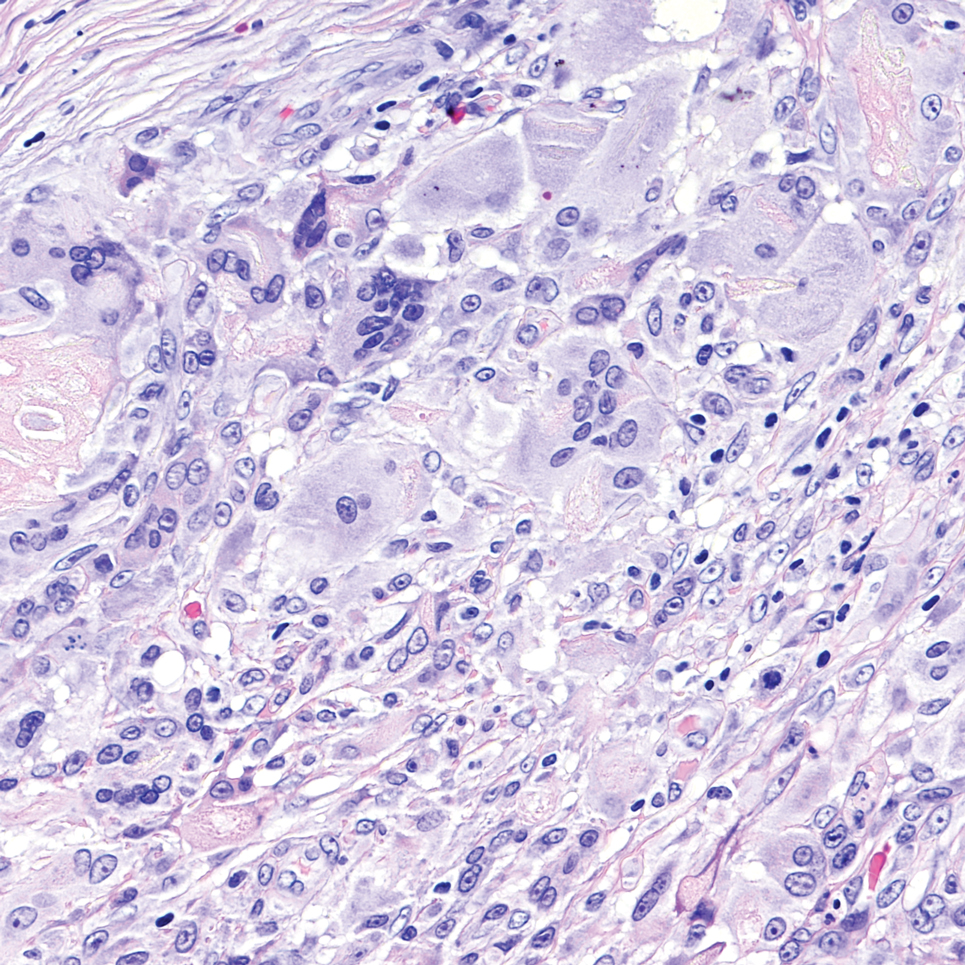

Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma characterized by proliferation of CD4+ T cells.7 In the early stages of MF, patients may present with multiple erythematous and scaly patches, plaques, or nodules that most commonly develop on unexposed areas of the skin, but specific variants frequently may cause lesions on the face or scalp.8 Tumors may be solitary, localized, or generalized and may be observed alongside patches and plaques or in the absence of cutaneous lesions.7 The pathologic features of MF include fibrosis of the papillary dermis, individual haloed atypical lymphocytes in the epidermis, and atypical lymphoid cells with cerebriform nuclei (Figure 3).9 Granulomatous MF is characterized by diffuse nodular and perivascular infiltrates of histiocytes with small lymphocytes without atypia, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Small lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and larger lymphocytes with hyperconvoluted nuclei also may be seen, in addition to multinucleated histiocytic giant cells. Although MF commonly manifests with epidermotropism, it typically is absent in granulomatous MF (GMF).10 Granulomatous MF may manifest similarly to LL. Noduloulcerative lesions and infiltration of atypical lymphocytes into the epidermis (epidermotropism) are much more common in GMF than in LL; however, although ulcerative nodules are not a common feature in patients with leprosy (except during reactional states [ie, Lucio phenomenon]) or secondary to neuropathies, they also can occur in LL.11 In GMF, the infiltrate does not follow a specific pattern, whereas LL infiltrates tend to follow a nerve distribution. Treatment for MF is determined by disease severity.12 First-line therapy includes local corticosteroids and phototherapy with UVB irradiation.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease that demonstrates nonspecific clinical manifestations affecting the lungs, eyes, liver, and skin.13 Environmental exposures to silica and inorganic matter have been linked to an increased risk for sarcoidosis, with patients presenting with fatigue, fever, and arthralgia.13 Skin manifestations include subcutaneous nodules, polymorphous plaques, and erythema nodosum—nodosum—the most common cutaneous presentation of sarcoidosis. Erythema nodosum manifests as symmetrically distributed, nonulcerative, painful red nodules on the skin, especially the lower legs. The histopathology of sarcoidosis shows noncaseating granulomas with activated T-lymphocytes, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4). Although granulomas occur in both LL and sarcoidosis, those in sarcoidosis typically consist of epithelioid cells surrounded by a rim of lymphocytes, whereas LL granulomas contain foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Treatment of sarcoidosis depends on disease progression and generally involves oral corticosteroids, followed by corticosteroid-sparing regimens.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease that predominantly affects younger women. Common findings in SCLE include red scaly plaques and ring-shaped lesions on sun-exposed areas of the skin.14 Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus primarily is characterized by a photosensitive rash, often with arthralgia, myalgia, and/or oral ulcers; less commonly, a small percentage of patients can experience central nervous system involvement, vasculitis, or nephritis. The histologic findings of SCLE include hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and periadnexal infiltrates (Figure 5). The incidence of SCLE often is associated with anti-Ro (SSA) and anti-La (SSB) antibodies.15 Treatment of SCLE focuses on managing skin symptoms with corticosteroids, antimalarials, and sun protection.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Lepromatous Leprosy

Histopathology showed collections of epithelioid to sarcoidal granulomas throughout the dermis and clustered around nerve bundles with a grenz zone at the dermoepidermal junction. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacteria, which were confirmed to be Mycobacterium leprae by by the National Hansen’s Disease program. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (LL) was made. The patient was treated by the infectious disease department with multidrug therapy that included monthly rifampin, moxifloxacin, and minocycline; weekly methotrexate with daily folic acid; and an extended prednisone taper with prophylactic cholecalciferol.

Lepromatous leprosy is characterized by high antibody titers to the acid-fast, gram-positive bacillus Mycobacterium leprae as well as a high bacillary load.1 Patients typically present with muscle weakness, anesthetic skin patches, and claw hands. Patients also may present with foot drop, ulcerations of the hands and feet, autonomic dysfunction with anhidrosis or impaired sweating, and localized alopecia.2 Over months to years, LL may progress to extensive sensory loss and indurated lesions that infiltrate the skin and cause thickening, especially on the face (known as leonine facies). Furthermore, LL is characterized by extensive bilaterally symmetric cutaneous lesions with poorly defined borders and raised indurated centers.3

Lepromatous leprosy transmission is not fully understood but is thought to occur via airborne droplets from coughing/sneezing and nasal secretions.2 Histopathology generally shows a dense and diffuse granulomatous infiltrate that involves the dermis but is separated from the epidermis by a zone of collagen (grenz zone).3 Histology is characterized by the presence of lymphocytes and numerous foamy macrophages (lepra or Virchow cells) containing M leprae organisms. In persistent lesions, the high density of uncleared bacilli forms spherical cytoplasmic clumps known as globi within enlarged foamy histiocytes (Figure 1).4 The macrophages form granulomatous lesions in the skin and around nerve bundles, resulting in tissue damage and decreased sensation. The current standard of care for LL is a multidrug combination of dapsone, rifampin, and clofazimine. Early diagnosis and complete treatment of LL is crucial, as this approach typically leads to complete cure of the disease.