User login

Study Highlights Some Semaglutide-Associated Skin Effects

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- The Food and Drug Administration’s has not received reports of semaglutide-related safety events, and few studies have characterized skin findings associated with oral or subcutaneous semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist used to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

- In this scoping review, researchers included 22 articles (15 clinical trials, six case reports, and one retrospective cohort study), published through January 2024, of patients receiving either semaglutide or a placebo or comparator, which included reports of semaglutide-associated adverse dermatologic events in 255 participants.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly reported a higher incidence of altered skin sensations, such as dysesthesia (1.8% vs 0%), hyperesthesia (1.2% vs 0%), skin pain (2.4% vs 0%), paresthesia (2.7% vs 0%), and sensitive skin (2.7% vs 0%), than those receiving placebo or comparator.

- Reports of alopecia (6.9% vs 0.3%) were higher in patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly than in those on placebo, but only 0.2% of patients on 2.4 mg of subcutaneous semaglutide reported alopecia vs 0.5% of those on placebo.

- Unspecified dermatologic reactions (4.1% vs 1.5%) were reported in more patients on subcutaneous semaglutide than those on a placebo or comparator. Several case reports described isolated cases of severe skin-related adverse effects, such as bullous pemphigoid, eosinophilic fasciitis, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

- On the contrary, injection site reactions (3.5% vs 6.7%) were less common in patients on subcutaneous semaglutide compared with in those on a placebo or comparator.

IN PRACTICE:

“Variations in dosage and administration routes could influence the types and severity of skin findings, underscoring the need for additional research,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Megan M. Tran, BS, from the Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, led this study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not adjust for confounding factors and could not establish a direct causal association between semaglutide and the adverse reactions reported.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not report any funding sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- The Food and Drug Administration’s has not received reports of semaglutide-related safety events, and few studies have characterized skin findings associated with oral or subcutaneous semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist used to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

- In this scoping review, researchers included 22 articles (15 clinical trials, six case reports, and one retrospective cohort study), published through January 2024, of patients receiving either semaglutide or a placebo or comparator, which included reports of semaglutide-associated adverse dermatologic events in 255 participants.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly reported a higher incidence of altered skin sensations, such as dysesthesia (1.8% vs 0%), hyperesthesia (1.2% vs 0%), skin pain (2.4% vs 0%), paresthesia (2.7% vs 0%), and sensitive skin (2.7% vs 0%), than those receiving placebo or comparator.

- Reports of alopecia (6.9% vs 0.3%) were higher in patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly than in those on placebo, but only 0.2% of patients on 2.4 mg of subcutaneous semaglutide reported alopecia vs 0.5% of those on placebo.

- Unspecified dermatologic reactions (4.1% vs 1.5%) were reported in more patients on subcutaneous semaglutide than those on a placebo or comparator. Several case reports described isolated cases of severe skin-related adverse effects, such as bullous pemphigoid, eosinophilic fasciitis, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

- On the contrary, injection site reactions (3.5% vs 6.7%) were less common in patients on subcutaneous semaglutide compared with in those on a placebo or comparator.

IN PRACTICE:

“Variations in dosage and administration routes could influence the types and severity of skin findings, underscoring the need for additional research,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Megan M. Tran, BS, from the Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, led this study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not adjust for confounding factors and could not establish a direct causal association between semaglutide and the adverse reactions reported.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not report any funding sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

.

METHODOLOGY:

- The Food and Drug Administration’s has not received reports of semaglutide-related safety events, and few studies have characterized skin findings associated with oral or subcutaneous semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist used to treat obesity and type 2 diabetes.

- In this scoping review, researchers included 22 articles (15 clinical trials, six case reports, and one retrospective cohort study), published through January 2024, of patients receiving either semaglutide or a placebo or comparator, which included reports of semaglutide-associated adverse dermatologic events in 255 participants.

TAKEAWAY:

- Patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly reported a higher incidence of altered skin sensations, such as dysesthesia (1.8% vs 0%), hyperesthesia (1.2% vs 0%), skin pain (2.4% vs 0%), paresthesia (2.7% vs 0%), and sensitive skin (2.7% vs 0%), than those receiving placebo or comparator.

- Reports of alopecia (6.9% vs 0.3%) were higher in patients who received 50 mg oral semaglutide weekly than in those on placebo, but only 0.2% of patients on 2.4 mg of subcutaneous semaglutide reported alopecia vs 0.5% of those on placebo.

- Unspecified dermatologic reactions (4.1% vs 1.5%) were reported in more patients on subcutaneous semaglutide than those on a placebo or comparator. Several case reports described isolated cases of severe skin-related adverse effects, such as bullous pemphigoid, eosinophilic fasciitis, and leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

- On the contrary, injection site reactions (3.5% vs 6.7%) were less common in patients on subcutaneous semaglutide compared with in those on a placebo or comparator.

IN PRACTICE:

“Variations in dosage and administration routes could influence the types and severity of skin findings, underscoring the need for additional research,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

Megan M. Tran, BS, from the Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, led this study, which was published online in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

This study could not adjust for confounding factors and could not establish a direct causal association between semaglutide and the adverse reactions reported.

DISCLOSURES:

This study did not report any funding sources. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Genetic Testing of Some Patients With Early-Onset AF Advised

Genetic testing may be considered in patients with early-onset atrial fibrillation (AF), particularly those with a positive family history and lack of conventional clinical risk factors, because specific genetic variants may underlie AF as well as “potentially more sinister cardiac conditions,” a new white paper from the Canadian Cardiovascular Society suggested.

“Given the resources and logistical challenges potentially imposed by genetic testing (that is, the majority of cardiology and arrhythmia clinics are not presently equipped to offer it), we have not recommended routine genetic testing for early-onset AF patients at this time,” lead author Jason D. Roberts, MD, associate professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, told this news organization.

“We do, however, recommend that early-onset AF patients undergo clinical screening for potential coexistence of a ventricular arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy syndrome through careful history, including family history, and physical examination, along with standard clinical testing, including ECG, echocardiogram, and Holter monitoring,” he said.

The white paper was published online in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

Routine Testing Unwarranted

The Canadian Cardiovascular Society reviewed AF research in 2022 and concluded that a guideline update was not yet warranted. One area meriting consideration but lacking sufficient evidence for a formal guideline was the clinical application of AF genetics.

Therefore, the society formed a writing group to assess the evidence linking genetic factors to AF, discuss an approach to using genetic testing for early-onset patients with AF, and consider the potential value of genetic testing in the foreseeable future.

The resulting white paper reviews familial and epidemiologic evidence for a genetic contribution to AF. As an example, the authors pointed to work from the Framingham Heart Study showing a statistically significant risk for AF among first-degree relatives of patients with AF. The overall odds ratio (OR) for AF among first-degree relatives was 1.85. But for first-degree relatives of patients with AF onset at younger than age 75 years, the OR increased to 3.23.

Other evidence included the identification of two rare genetic variants: KCNQ1 in a Chinese family and NPPA in a family with Northern European ancestry. In case-control studies, a single gene, titin (TTN), was linked to an increased burden of loss-of-function variants in patients with AF compared with controls. The variant was associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk for AF.

For example, loss-of-function SCN5A variants are implicated in Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction system disease, whereas gain-of-function variants cause long QT syndrome type 3 and multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contractions. Each of these conditions was associated with an increased prevalence of AF.

Similarly, genes implicated in various other forms of ventricular channelopathies also have been implicated in AF, as have ion channels primarily expressed in the atria and not the ventricles, such as KCNA5 and GJA5.

Nevertheless, in most cases, AF is diagnosed in the context of older age and established cardiovascular risk factors, according to the authors. The contribution of genetic factors in this population is relatively low, highlighting the limited role for genetic testing when AF develops in the presence of multiple conventional clinical risk factors.

Cardiogenetic Expertise Required

“Although significant progress has been made, additional work is needed before [beginning] routine integration of clinical genetic testing for early-onset AF patients,” Dr. Roberts said. The ideal clinical genetic testing panel for AF is still unclear, and the inclusion of genes for which there is no strong evidence of involvement in AF “creates the potential for harm.”

Specifically, “a genetic variant could be incorrectly assigned as the cause of AF, which could create confusion for the patient and family members and lead to inappropriate clinical management,” said Dr. Roberts.

“Beyond cost, routine introduction of genetic testing for AF patients will require allocation of significant resources, given that interpretation of genetic testing results can be nuanced,” he noted. “This nuance is anticipated to be heightened in AF, given that many genetic variants have low-to-intermediate penetrance and can manifest with variable clinical phenotypes.”

“Traditionally, genetic testing has been performed and interpreted, and results communicated, by dedicated cardiogenetic clinics with specialized expertise,” he added. “Existing cardiogenetic clinics, however, are unlikely to be sufficient in number to accommodate the large volume of AF patients that may be eligible for testing.”

Careful Counseling

Jim W. Cheung, MD, chair of the American College of Cardiology Electrophysiology Council, told this news organization that the white paper is consistent with the latest European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement published in 2022.

Overall, the approach suggested for genetic testing “is a sound one, but one that requires implementation by clinicians with access to cardiogenetic expertise,” said Cheung, who was not involved in the study. “Any patient undergoing genetic testing needs to be carefully counseled about the potential uncertainties associated with the actual test results and their implications on clinical management.”

Variants of uncertain significance that are detected with genetic testing “can be a source of stress for clinicians and patients,” he said. “Therefore, patient education prior to and after genetic testing is essential.”

Furthermore, he said, “in many patients with early-onset AF who harbor pathogenic variants, initial imaging studies may not detect any signs of cardiomyopathy. In these patients, regular follow-up to assess for development of cardiomyopathy in the future is necessary.”

The white paper was drafted without outside funding. Dr. Roberts and Dr. Cheung reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Genetic testing may be considered in patients with early-onset atrial fibrillation (AF), particularly those with a positive family history and lack of conventional clinical risk factors, because specific genetic variants may underlie AF as well as “potentially more sinister cardiac conditions,” a new white paper from the Canadian Cardiovascular Society suggested.

“Given the resources and logistical challenges potentially imposed by genetic testing (that is, the majority of cardiology and arrhythmia clinics are not presently equipped to offer it), we have not recommended routine genetic testing for early-onset AF patients at this time,” lead author Jason D. Roberts, MD, associate professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, told this news organization.

“We do, however, recommend that early-onset AF patients undergo clinical screening for potential coexistence of a ventricular arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy syndrome through careful history, including family history, and physical examination, along with standard clinical testing, including ECG, echocardiogram, and Holter monitoring,” he said.

The white paper was published online in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

Routine Testing Unwarranted

The Canadian Cardiovascular Society reviewed AF research in 2022 and concluded that a guideline update was not yet warranted. One area meriting consideration but lacking sufficient evidence for a formal guideline was the clinical application of AF genetics.

Therefore, the society formed a writing group to assess the evidence linking genetic factors to AF, discuss an approach to using genetic testing for early-onset patients with AF, and consider the potential value of genetic testing in the foreseeable future.

The resulting white paper reviews familial and epidemiologic evidence for a genetic contribution to AF. As an example, the authors pointed to work from the Framingham Heart Study showing a statistically significant risk for AF among first-degree relatives of patients with AF. The overall odds ratio (OR) for AF among first-degree relatives was 1.85. But for first-degree relatives of patients with AF onset at younger than age 75 years, the OR increased to 3.23.

Other evidence included the identification of two rare genetic variants: KCNQ1 in a Chinese family and NPPA in a family with Northern European ancestry. In case-control studies, a single gene, titin (TTN), was linked to an increased burden of loss-of-function variants in patients with AF compared with controls. The variant was associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk for AF.

For example, loss-of-function SCN5A variants are implicated in Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction system disease, whereas gain-of-function variants cause long QT syndrome type 3 and multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contractions. Each of these conditions was associated with an increased prevalence of AF.

Similarly, genes implicated in various other forms of ventricular channelopathies also have been implicated in AF, as have ion channels primarily expressed in the atria and not the ventricles, such as KCNA5 and GJA5.

Nevertheless, in most cases, AF is diagnosed in the context of older age and established cardiovascular risk factors, according to the authors. The contribution of genetic factors in this population is relatively low, highlighting the limited role for genetic testing when AF develops in the presence of multiple conventional clinical risk factors.

Cardiogenetic Expertise Required

“Although significant progress has been made, additional work is needed before [beginning] routine integration of clinical genetic testing for early-onset AF patients,” Dr. Roberts said. The ideal clinical genetic testing panel for AF is still unclear, and the inclusion of genes for which there is no strong evidence of involvement in AF “creates the potential for harm.”

Specifically, “a genetic variant could be incorrectly assigned as the cause of AF, which could create confusion for the patient and family members and lead to inappropriate clinical management,” said Dr. Roberts.

“Beyond cost, routine introduction of genetic testing for AF patients will require allocation of significant resources, given that interpretation of genetic testing results can be nuanced,” he noted. “This nuance is anticipated to be heightened in AF, given that many genetic variants have low-to-intermediate penetrance and can manifest with variable clinical phenotypes.”

“Traditionally, genetic testing has been performed and interpreted, and results communicated, by dedicated cardiogenetic clinics with specialized expertise,” he added. “Existing cardiogenetic clinics, however, are unlikely to be sufficient in number to accommodate the large volume of AF patients that may be eligible for testing.”

Careful Counseling

Jim W. Cheung, MD, chair of the American College of Cardiology Electrophysiology Council, told this news organization that the white paper is consistent with the latest European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement published in 2022.

Overall, the approach suggested for genetic testing “is a sound one, but one that requires implementation by clinicians with access to cardiogenetic expertise,” said Cheung, who was not involved in the study. “Any patient undergoing genetic testing needs to be carefully counseled about the potential uncertainties associated with the actual test results and their implications on clinical management.”

Variants of uncertain significance that are detected with genetic testing “can be a source of stress for clinicians and patients,” he said. “Therefore, patient education prior to and after genetic testing is essential.”

Furthermore, he said, “in many patients with early-onset AF who harbor pathogenic variants, initial imaging studies may not detect any signs of cardiomyopathy. In these patients, regular follow-up to assess for development of cardiomyopathy in the future is necessary.”

The white paper was drafted without outside funding. Dr. Roberts and Dr. Cheung reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Genetic testing may be considered in patients with early-onset atrial fibrillation (AF), particularly those with a positive family history and lack of conventional clinical risk factors, because specific genetic variants may underlie AF as well as “potentially more sinister cardiac conditions,” a new white paper from the Canadian Cardiovascular Society suggested.

“Given the resources and logistical challenges potentially imposed by genetic testing (that is, the majority of cardiology and arrhythmia clinics are not presently equipped to offer it), we have not recommended routine genetic testing for early-onset AF patients at this time,” lead author Jason D. Roberts, MD, associate professor of medicine at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, told this news organization.

“We do, however, recommend that early-onset AF patients undergo clinical screening for potential coexistence of a ventricular arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy syndrome through careful history, including family history, and physical examination, along with standard clinical testing, including ECG, echocardiogram, and Holter monitoring,” he said.

The white paper was published online in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology.

Routine Testing Unwarranted

The Canadian Cardiovascular Society reviewed AF research in 2022 and concluded that a guideline update was not yet warranted. One area meriting consideration but lacking sufficient evidence for a formal guideline was the clinical application of AF genetics.

Therefore, the society formed a writing group to assess the evidence linking genetic factors to AF, discuss an approach to using genetic testing for early-onset patients with AF, and consider the potential value of genetic testing in the foreseeable future.

The resulting white paper reviews familial and epidemiologic evidence for a genetic contribution to AF. As an example, the authors pointed to work from the Framingham Heart Study showing a statistically significant risk for AF among first-degree relatives of patients with AF. The overall odds ratio (OR) for AF among first-degree relatives was 1.85. But for first-degree relatives of patients with AF onset at younger than age 75 years, the OR increased to 3.23.

Other evidence included the identification of two rare genetic variants: KCNQ1 in a Chinese family and NPPA in a family with Northern European ancestry. In case-control studies, a single gene, titin (TTN), was linked to an increased burden of loss-of-function variants in patients with AF compared with controls. The variant was associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk for AF.

For example, loss-of-function SCN5A variants are implicated in Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction system disease, whereas gain-of-function variants cause long QT syndrome type 3 and multifocal ectopic Purkinje-related premature contractions. Each of these conditions was associated with an increased prevalence of AF.

Similarly, genes implicated in various other forms of ventricular channelopathies also have been implicated in AF, as have ion channels primarily expressed in the atria and not the ventricles, such as KCNA5 and GJA5.

Nevertheless, in most cases, AF is diagnosed in the context of older age and established cardiovascular risk factors, according to the authors. The contribution of genetic factors in this population is relatively low, highlighting the limited role for genetic testing when AF develops in the presence of multiple conventional clinical risk factors.

Cardiogenetic Expertise Required

“Although significant progress has been made, additional work is needed before [beginning] routine integration of clinical genetic testing for early-onset AF patients,” Dr. Roberts said. The ideal clinical genetic testing panel for AF is still unclear, and the inclusion of genes for which there is no strong evidence of involvement in AF “creates the potential for harm.”

Specifically, “a genetic variant could be incorrectly assigned as the cause of AF, which could create confusion for the patient and family members and lead to inappropriate clinical management,” said Dr. Roberts.

“Beyond cost, routine introduction of genetic testing for AF patients will require allocation of significant resources, given that interpretation of genetic testing results can be nuanced,” he noted. “This nuance is anticipated to be heightened in AF, given that many genetic variants have low-to-intermediate penetrance and can manifest with variable clinical phenotypes.”

“Traditionally, genetic testing has been performed and interpreted, and results communicated, by dedicated cardiogenetic clinics with specialized expertise,” he added. “Existing cardiogenetic clinics, however, are unlikely to be sufficient in number to accommodate the large volume of AF patients that may be eligible for testing.”

Careful Counseling

Jim W. Cheung, MD, chair of the American College of Cardiology Electrophysiology Council, told this news organization that the white paper is consistent with the latest European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement published in 2022.

Overall, the approach suggested for genetic testing “is a sound one, but one that requires implementation by clinicians with access to cardiogenetic expertise,” said Cheung, who was not involved in the study. “Any patient undergoing genetic testing needs to be carefully counseled about the potential uncertainties associated with the actual test results and their implications on clinical management.”

Variants of uncertain significance that are detected with genetic testing “can be a source of stress for clinicians and patients,” he said. “Therefore, patient education prior to and after genetic testing is essential.”

Furthermore, he said, “in many patients with early-onset AF who harbor pathogenic variants, initial imaging studies may not detect any signs of cardiomyopathy. In these patients, regular follow-up to assess for development of cardiomyopathy in the future is necessary.”

The white paper was drafted without outside funding. Dr. Roberts and Dr. Cheung reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE CANADIAN JOURNAL OF CARDIOLOGY

Tirzepatide Offers Better Glucose Control, Regardless of Baseline Levels

TOPLINE:

Tirzepatide vs basal insulins led to greater improvements in A1c and postprandial glucose (PPG) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), regardless of different baseline PPG or fasting serum glucose (FSG) levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Tirzepatide led to better glycemic control than insulin degludec and insulin glargine in the SURPASS-3 and SURPASS-4 trials, respectively, but the effect on FSG and PPG levels was not evaluated.

- In this post hoc analysis, the researchers assessed changes in various glycemic parameters in 3314 patients with T2D who were randomly assigned to receive tirzepatide (5, 10, or 15 mg), insulin degludec, or insulin glargine.

- Based on the median baseline glucose values, the patients were stratified into four subgroups: Low FSG/low PPG, low FSG/high PPG, high FSG/low PPG, and high FSG/high PPG.

- The outcomes of interest were changes in FSG, PPG, A1c, and body weight from baseline to week 52.

TAKEAWAY:

- Tirzepatide and basal insulins effectively lowered A1c, PPG levels, and FSG levels at 52 weeks across all patient subgroups (all P < .05).

- All three doses of tirzepatide resulted in greater reductions in both A1c and PPG levels than in basal insulins (all P < .05).

- In the high FSG/high PPG subgroup, a greater reduction in FSG levels was observed with tirzepatide 10- and 15-mg doses vs insulin glargine (both P < .05) and insulin degludec vs tirzepatide 5 mg (P < .001).

- Furthermore, at week 52, tirzepatide led to body weight reduction (P < .05), but insulin treatment led to an increase in body weight (P < .05) in all subgroups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Treatment with tirzepatide was consistently associated with more reduced PPG levels compared with insulin treatment across subgroups, including in participants with lower baseline PPG levels, in turn leading to greater A1c reductions,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Francesco Giorgino, MD, PhD, of the Section of Internal Medicine, Endocrinology, Andrology, and Metabolic Diseases, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy, and was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The limitations include post hoc nature of the study and the short treatment duration. The trials included only patients with diabetes and overweight or obesity, and therefore, the study findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study and the SURPASS trials were funded by Eli Lilly and Company. Four authors declared being employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors declared having several ties with various sources, including Eli Lilly and Company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Tirzepatide vs basal insulins led to greater improvements in A1c and postprandial glucose (PPG) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), regardless of different baseline PPG or fasting serum glucose (FSG) levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Tirzepatide led to better glycemic control than insulin degludec and insulin glargine in the SURPASS-3 and SURPASS-4 trials, respectively, but the effect on FSG and PPG levels was not evaluated.

- In this post hoc analysis, the researchers assessed changes in various glycemic parameters in 3314 patients with T2D who were randomly assigned to receive tirzepatide (5, 10, or 15 mg), insulin degludec, or insulin glargine.

- Based on the median baseline glucose values, the patients were stratified into four subgroups: Low FSG/low PPG, low FSG/high PPG, high FSG/low PPG, and high FSG/high PPG.

- The outcomes of interest were changes in FSG, PPG, A1c, and body weight from baseline to week 52.

TAKEAWAY:

- Tirzepatide and basal insulins effectively lowered A1c, PPG levels, and FSG levels at 52 weeks across all patient subgroups (all P < .05).

- All three doses of tirzepatide resulted in greater reductions in both A1c and PPG levels than in basal insulins (all P < .05).

- In the high FSG/high PPG subgroup, a greater reduction in FSG levels was observed with tirzepatide 10- and 15-mg doses vs insulin glargine (both P < .05) and insulin degludec vs tirzepatide 5 mg (P < .001).

- Furthermore, at week 52, tirzepatide led to body weight reduction (P < .05), but insulin treatment led to an increase in body weight (P < .05) in all subgroups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Treatment with tirzepatide was consistently associated with more reduced PPG levels compared with insulin treatment across subgroups, including in participants with lower baseline PPG levels, in turn leading to greater A1c reductions,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Francesco Giorgino, MD, PhD, of the Section of Internal Medicine, Endocrinology, Andrology, and Metabolic Diseases, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy, and was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The limitations include post hoc nature of the study and the short treatment duration. The trials included only patients with diabetes and overweight or obesity, and therefore, the study findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study and the SURPASS trials were funded by Eli Lilly and Company. Four authors declared being employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors declared having several ties with various sources, including Eli Lilly and Company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Tirzepatide vs basal insulins led to greater improvements in A1c and postprandial glucose (PPG) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D), regardless of different baseline PPG or fasting serum glucose (FSG) levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Tirzepatide led to better glycemic control than insulin degludec and insulin glargine in the SURPASS-3 and SURPASS-4 trials, respectively, but the effect on FSG and PPG levels was not evaluated.

- In this post hoc analysis, the researchers assessed changes in various glycemic parameters in 3314 patients with T2D who were randomly assigned to receive tirzepatide (5, 10, or 15 mg), insulin degludec, or insulin glargine.

- Based on the median baseline glucose values, the patients were stratified into four subgroups: Low FSG/low PPG, low FSG/high PPG, high FSG/low PPG, and high FSG/high PPG.

- The outcomes of interest were changes in FSG, PPG, A1c, and body weight from baseline to week 52.

TAKEAWAY:

- Tirzepatide and basal insulins effectively lowered A1c, PPG levels, and FSG levels at 52 weeks across all patient subgroups (all P < .05).

- All three doses of tirzepatide resulted in greater reductions in both A1c and PPG levels than in basal insulins (all P < .05).

- In the high FSG/high PPG subgroup, a greater reduction in FSG levels was observed with tirzepatide 10- and 15-mg doses vs insulin glargine (both P < .05) and insulin degludec vs tirzepatide 5 mg (P < .001).

- Furthermore, at week 52, tirzepatide led to body weight reduction (P < .05), but insulin treatment led to an increase in body weight (P < .05) in all subgroups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Treatment with tirzepatide was consistently associated with more reduced PPG levels compared with insulin treatment across subgroups, including in participants with lower baseline PPG levels, in turn leading to greater A1c reductions,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Francesco Giorgino, MD, PhD, of the Section of Internal Medicine, Endocrinology, Andrology, and Metabolic Diseases, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy, and was published online in Diabetes Care.

LIMITATIONS:

The limitations include post hoc nature of the study and the short treatment duration. The trials included only patients with diabetes and overweight or obesity, and therefore, the study findings may not be generalizable to other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

This study and the SURPASS trials were funded by Eli Lilly and Company. Four authors declared being employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors declared having several ties with various sources, including Eli Lilly and Company.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Erosive Esophagitis: 5 Things to Know

Erosive esophagitis (EE) is erosion of the esophageal epithelium due to chronic irritation. It can be caused by a number of factors but is primarily a result of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The main symptoms of EE are heartburn and regurgitation; other symptoms can include epigastric pain, odynophagia, dysphagia, nausea, chronic cough, dental erosion, laryngitis, and asthma. , including nonerosive esophagitis and Barrett esophagus (BE). EE occurs in approximately 30% of cases of GERD, and EE may evolve to BE in 1%-13% of cases.

Long-term management of EE focuses on relieving symptoms to allow the esophageal lining to heal, thereby reducing both acute symptoms and the risk for other complications. Management plans may incorporate lifestyle changes, such as dietary modifications and weight loss, alongside pharmacologic therapy. In extreme cases, surgery may be considered to repair a damaged esophagus and/or to prevent ongoing acid reflux. If left untreated, EE may progress, potentially leading to more serious conditions.

Here are five things to know about EE.

1. GERD is the main risk factor for EE, but not the only risk factor.

An estimated 1% of the population has EE. Risk factors other than GERD include:

Radiation therapy toxicity can cause acute or chronic EE. For individuals undergoing radiotherapy, radiation esophagitis is a relatively frequent complication. Acute esophagitis generally occurs in all patients taking radiation doses of 6000 cGy given in fractions of 1000 cGy per week. The risk is lower among patients on longer schedules and lower doses of radiotherapy.

Bacterial, viral, and fungal infections can cause EE. These include herpes, CMV, HIV, Helicobacter pylori, and Candida.

Food allergies, asthma, and eczema are associated with eosinophilic esophagitis, which disproportionately affects young men and has an estimated prevalence of 55 cases per 100,000 population.

Oral medication in pill form causes esophagitis at an estimated rate of 3.9 cases per 100,000 population per year. The mean age at diagnosis is 41.5 years. Oral bisphosphonates such as alendronate are the most common agents, along with antibiotics such as tetracycline, doxycycline, and clindamycin. There have also been reports of pill-induced esophagitis with NSAIDs, aspirin, ferrous sulfate, potassium chloride, and mexiletine.

Excessive vomiting can, in rare cases, cause esophagitis.

Certain autoimmune diseases can manifest as EE.

2. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) remain the preferred treatment for EE.

Several over-the-counter and prescription medications can be used to manage the symptoms of EE. PPIs are the preferred treatment both in the acute setting and for maintenance therapy. PPIs help to alleviate symptoms and promote healing of the esophageal lining by reducing the production of stomach acid. Options include omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, and esomeprazole. Many patients with EE require a dose that exceeds the FDA-approved dose for GERD. For instance, a 40-mg/d dosage of omeprazole is recommended in the latest guidelines, although the FDA-approved dosage is 20 mg/d.

H2-receptor antagonists, including famotidine, cimetidine, and nizatidine, may also be prescribed to reduce stomach acid production and promote healing in patients with EE due to GERD, but these agents are considered less efficacious than PPIs for either acute or maintenance therapy.

The potassium-competitive acid blocker (PCAB) vonoprazan is the latest agent to be indicated for EE and may provide more potent acid suppression for patients. A randomized comparative trial showed noninferiority compared with lansoprazole for healing and maintenance of healing of EE. In another randomized comparative study, the investigational PCAP fexuprazan was shown to be noninferior to the PPI esomeprazole in treating EE.

Mild GERD symptoms can be controlled by traditional antacids taken after each meal and at bedtime or with short-term use of prokinetic agents, which can help reduce acid reflux by improving esophageal and stomach motility and by increasing pressure to the lower esophageal sphincter. Gastric emptying is also accelerated by prokinetic agents. Long-term use is discouraged, as it may cause serious or life-threatening complications.

In patients who do not fully respond to PPI therapy, surgical therapy may be considered. Other candidates for surgery include younger patients, those who have difficulty adhering to treatment, postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, patients with cardiac conduction defects, and those for whom the cost of treatment is prohibitive. Surgery may also be warranted if there are extraesophageal manifestations of GERD, such as enamel erosion; respiratory issues (eg, coughing, wheezing, aspiration); or ear, nose, and throat manifestations (eg, hoarseness, sore throat, otitis media). For those who have progressed to BE, surgical intervention is also indicated.

The types of surgery for patients with EE have evolved to include both transthoracic and transabdominal fundoplication. Usually, a 360° transabdominal fundoplication is performed. General anesthesia is required for laparoscopic fundoplication, in which five small incisions are used to create a new valve at the level of the esophagogastric junction by wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the esophagus.

Laparoscopic insertion of a small band known as the LINX Reflux Management System is FDA approved to augment the lower esophageal sphincter. The system creates a natural barrier to reflux by placing a band consisting of titanium beads with magnetic cores around the esophagus just above the stomach. The magnetic bond is temporarily disrupted by swallowing, allowing food and liquid to pass.

Endoscopic therapies are another treatment option for certain patients who are not considered candidates for surgery or long-term therapy. Among the types of endoscopic procedures are radiofrequency therapy, suturing/plication, and mucosal ablation/resection techniques at the gastroesophageal junction. Full-thickness endoscopic suturing is an area of interest because this technique offers significant durability of the recreated lower esophageal sphincter.

3. PPI therapy for GERD should be stopped before endoscopy is performed to confirm a diagnosis of EE.

A clinical diagnosis of GERD can be made if the presenting symptoms are heartburn and regurgitation, without chest pain or alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding. In this setting, once-daily PPIs are generally prescribed for 8 weeks to see if symptoms resolve. If symptoms have not resolved, a twice-daily PPI regimen may be prescribed. In patients who do not respond to PPIs, or for whom GERD returns after stopping therapy, an upper endoscopy with biopsy is recommended after 2-4 weeks off therapy to rule out other causes. Endoscopy should be the first step in diagnosis for individuals experiencing chest pain without heartburn; those in whom heart disease has been ruled out; individuals experiencing dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding; or those who have multiple risk factors for BE.

4. The most serious complication of EE is BE, which can lead to esophageal cancer.

Several complications can arise from EE. The most serious of these is BE, which can lead to esophageal adenocarcinoma. BE is characterized by the conversion of normal distal squamous esophageal epithelium to columnar epithelium. It has the potential to become malignant if it exhibits intestinal-type metaplasia. In the industrialized world, adenocarcinoma currently represents more than half of all esophageal cancers. The most common symptom of esophageal cancer is dysphagia. Other signs and symptoms include weight loss, hoarseness, chronic or intractable cough, bleeding, epigastric or retrosternal pain, frequent pneumonia, and, if metastatic, bone pain.

5. Lifestyle modifications can help control the symptoms of EE.

Guidelines recommend a number of lifestyle modification strategies to help control the symptoms of EE. Smoking cessation and weight loss are two evidence-based strategies for relieving symptoms of GERD and, ultimately, lowering the risk for esophageal cancer. One large prospective Norwegian cohort study (N = 29,610) found that stopping smoking improved GERD symptoms, but only in those with normal body mass index. In a smaller Japanese study (N = 191) specifically surveying people attempting smoking cessation, individuals who successfully stopped smoking had a 44% improvement in GERD symptoms at 1 year, vs an 18% improvement in those who continued to smoke, with no statistical difference between the success and failure groups based on patient body mass index (P = .60).

Other recommended strategies for nonpharmacologic management of EE symptoms include elevation of the head when lying down in bed and avoidance of lying down after eating, cessation of alcohol consumption, avoidance of food close to bedtime, and avoidance of trigger foods that can incite or worsen symptoms of acid reflux. Such trigger foods vary among individuals, but they often include fatty foods, coffee, chocolate, carbonated beverages, spicy foods, citrus fruits, and tomatoes.

Dr. Puerta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Erosive esophagitis (EE) is erosion of the esophageal epithelium due to chronic irritation. It can be caused by a number of factors but is primarily a result of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The main symptoms of EE are heartburn and regurgitation; other symptoms can include epigastric pain, odynophagia, dysphagia, nausea, chronic cough, dental erosion, laryngitis, and asthma. , including nonerosive esophagitis and Barrett esophagus (BE). EE occurs in approximately 30% of cases of GERD, and EE may evolve to BE in 1%-13% of cases.

Long-term management of EE focuses on relieving symptoms to allow the esophageal lining to heal, thereby reducing both acute symptoms and the risk for other complications. Management plans may incorporate lifestyle changes, such as dietary modifications and weight loss, alongside pharmacologic therapy. In extreme cases, surgery may be considered to repair a damaged esophagus and/or to prevent ongoing acid reflux. If left untreated, EE may progress, potentially leading to more serious conditions.

Here are five things to know about EE.

1. GERD is the main risk factor for EE, but not the only risk factor.

An estimated 1% of the population has EE. Risk factors other than GERD include:

Radiation therapy toxicity can cause acute or chronic EE. For individuals undergoing radiotherapy, radiation esophagitis is a relatively frequent complication. Acute esophagitis generally occurs in all patients taking radiation doses of 6000 cGy given in fractions of 1000 cGy per week. The risk is lower among patients on longer schedules and lower doses of radiotherapy.

Bacterial, viral, and fungal infections can cause EE. These include herpes, CMV, HIV, Helicobacter pylori, and Candida.

Food allergies, asthma, and eczema are associated with eosinophilic esophagitis, which disproportionately affects young men and has an estimated prevalence of 55 cases per 100,000 population.

Oral medication in pill form causes esophagitis at an estimated rate of 3.9 cases per 100,000 population per year. The mean age at diagnosis is 41.5 years. Oral bisphosphonates such as alendronate are the most common agents, along with antibiotics such as tetracycline, doxycycline, and clindamycin. There have also been reports of pill-induced esophagitis with NSAIDs, aspirin, ferrous sulfate, potassium chloride, and mexiletine.

Excessive vomiting can, in rare cases, cause esophagitis.

Certain autoimmune diseases can manifest as EE.

2. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) remain the preferred treatment for EE.

Several over-the-counter and prescription medications can be used to manage the symptoms of EE. PPIs are the preferred treatment both in the acute setting and for maintenance therapy. PPIs help to alleviate symptoms and promote healing of the esophageal lining by reducing the production of stomach acid. Options include omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, and esomeprazole. Many patients with EE require a dose that exceeds the FDA-approved dose for GERD. For instance, a 40-mg/d dosage of omeprazole is recommended in the latest guidelines, although the FDA-approved dosage is 20 mg/d.

H2-receptor antagonists, including famotidine, cimetidine, and nizatidine, may also be prescribed to reduce stomach acid production and promote healing in patients with EE due to GERD, but these agents are considered less efficacious than PPIs for either acute or maintenance therapy.

The potassium-competitive acid blocker (PCAB) vonoprazan is the latest agent to be indicated for EE and may provide more potent acid suppression for patients. A randomized comparative trial showed noninferiority compared with lansoprazole for healing and maintenance of healing of EE. In another randomized comparative study, the investigational PCAP fexuprazan was shown to be noninferior to the PPI esomeprazole in treating EE.

Mild GERD symptoms can be controlled by traditional antacids taken after each meal and at bedtime or with short-term use of prokinetic agents, which can help reduce acid reflux by improving esophageal and stomach motility and by increasing pressure to the lower esophageal sphincter. Gastric emptying is also accelerated by prokinetic agents. Long-term use is discouraged, as it may cause serious or life-threatening complications.

In patients who do not fully respond to PPI therapy, surgical therapy may be considered. Other candidates for surgery include younger patients, those who have difficulty adhering to treatment, postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, patients with cardiac conduction defects, and those for whom the cost of treatment is prohibitive. Surgery may also be warranted if there are extraesophageal manifestations of GERD, such as enamel erosion; respiratory issues (eg, coughing, wheezing, aspiration); or ear, nose, and throat manifestations (eg, hoarseness, sore throat, otitis media). For those who have progressed to BE, surgical intervention is also indicated.

The types of surgery for patients with EE have evolved to include both transthoracic and transabdominal fundoplication. Usually, a 360° transabdominal fundoplication is performed. General anesthesia is required for laparoscopic fundoplication, in which five small incisions are used to create a new valve at the level of the esophagogastric junction by wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the esophagus.

Laparoscopic insertion of a small band known as the LINX Reflux Management System is FDA approved to augment the lower esophageal sphincter. The system creates a natural barrier to reflux by placing a band consisting of titanium beads with magnetic cores around the esophagus just above the stomach. The magnetic bond is temporarily disrupted by swallowing, allowing food and liquid to pass.

Endoscopic therapies are another treatment option for certain patients who are not considered candidates for surgery or long-term therapy. Among the types of endoscopic procedures are radiofrequency therapy, suturing/plication, and mucosal ablation/resection techniques at the gastroesophageal junction. Full-thickness endoscopic suturing is an area of interest because this technique offers significant durability of the recreated lower esophageal sphincter.

3. PPI therapy for GERD should be stopped before endoscopy is performed to confirm a diagnosis of EE.

A clinical diagnosis of GERD can be made if the presenting symptoms are heartburn and regurgitation, without chest pain or alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding. In this setting, once-daily PPIs are generally prescribed for 8 weeks to see if symptoms resolve. If symptoms have not resolved, a twice-daily PPI regimen may be prescribed. In patients who do not respond to PPIs, or for whom GERD returns after stopping therapy, an upper endoscopy with biopsy is recommended after 2-4 weeks off therapy to rule out other causes. Endoscopy should be the first step in diagnosis for individuals experiencing chest pain without heartburn; those in whom heart disease has been ruled out; individuals experiencing dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding; or those who have multiple risk factors for BE.

4. The most serious complication of EE is BE, which can lead to esophageal cancer.

Several complications can arise from EE. The most serious of these is BE, which can lead to esophageal adenocarcinoma. BE is characterized by the conversion of normal distal squamous esophageal epithelium to columnar epithelium. It has the potential to become malignant if it exhibits intestinal-type metaplasia. In the industrialized world, adenocarcinoma currently represents more than half of all esophageal cancers. The most common symptom of esophageal cancer is dysphagia. Other signs and symptoms include weight loss, hoarseness, chronic or intractable cough, bleeding, epigastric or retrosternal pain, frequent pneumonia, and, if metastatic, bone pain.

5. Lifestyle modifications can help control the symptoms of EE.

Guidelines recommend a number of lifestyle modification strategies to help control the symptoms of EE. Smoking cessation and weight loss are two evidence-based strategies for relieving symptoms of GERD and, ultimately, lowering the risk for esophageal cancer. One large prospective Norwegian cohort study (N = 29,610) found that stopping smoking improved GERD symptoms, but only in those with normal body mass index. In a smaller Japanese study (N = 191) specifically surveying people attempting smoking cessation, individuals who successfully stopped smoking had a 44% improvement in GERD symptoms at 1 year, vs an 18% improvement in those who continued to smoke, with no statistical difference between the success and failure groups based on patient body mass index (P = .60).

Other recommended strategies for nonpharmacologic management of EE symptoms include elevation of the head when lying down in bed and avoidance of lying down after eating, cessation of alcohol consumption, avoidance of food close to bedtime, and avoidance of trigger foods that can incite or worsen symptoms of acid reflux. Such trigger foods vary among individuals, but they often include fatty foods, coffee, chocolate, carbonated beverages, spicy foods, citrus fruits, and tomatoes.

Dr. Puerta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Erosive esophagitis (EE) is erosion of the esophageal epithelium due to chronic irritation. It can be caused by a number of factors but is primarily a result of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The main symptoms of EE are heartburn and regurgitation; other symptoms can include epigastric pain, odynophagia, dysphagia, nausea, chronic cough, dental erosion, laryngitis, and asthma. , including nonerosive esophagitis and Barrett esophagus (BE). EE occurs in approximately 30% of cases of GERD, and EE may evolve to BE in 1%-13% of cases.

Long-term management of EE focuses on relieving symptoms to allow the esophageal lining to heal, thereby reducing both acute symptoms and the risk for other complications. Management plans may incorporate lifestyle changes, such as dietary modifications and weight loss, alongside pharmacologic therapy. In extreme cases, surgery may be considered to repair a damaged esophagus and/or to prevent ongoing acid reflux. If left untreated, EE may progress, potentially leading to more serious conditions.

Here are five things to know about EE.

1. GERD is the main risk factor for EE, but not the only risk factor.

An estimated 1% of the population has EE. Risk factors other than GERD include:

Radiation therapy toxicity can cause acute or chronic EE. For individuals undergoing radiotherapy, radiation esophagitis is a relatively frequent complication. Acute esophagitis generally occurs in all patients taking radiation doses of 6000 cGy given in fractions of 1000 cGy per week. The risk is lower among patients on longer schedules and lower doses of radiotherapy.

Bacterial, viral, and fungal infections can cause EE. These include herpes, CMV, HIV, Helicobacter pylori, and Candida.

Food allergies, asthma, and eczema are associated with eosinophilic esophagitis, which disproportionately affects young men and has an estimated prevalence of 55 cases per 100,000 population.

Oral medication in pill form causes esophagitis at an estimated rate of 3.9 cases per 100,000 population per year. The mean age at diagnosis is 41.5 years. Oral bisphosphonates such as alendronate are the most common agents, along with antibiotics such as tetracycline, doxycycline, and clindamycin. There have also been reports of pill-induced esophagitis with NSAIDs, aspirin, ferrous sulfate, potassium chloride, and mexiletine.

Excessive vomiting can, in rare cases, cause esophagitis.

Certain autoimmune diseases can manifest as EE.

2. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) remain the preferred treatment for EE.

Several over-the-counter and prescription medications can be used to manage the symptoms of EE. PPIs are the preferred treatment both in the acute setting and for maintenance therapy. PPIs help to alleviate symptoms and promote healing of the esophageal lining by reducing the production of stomach acid. Options include omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, and esomeprazole. Many patients with EE require a dose that exceeds the FDA-approved dose for GERD. For instance, a 40-mg/d dosage of omeprazole is recommended in the latest guidelines, although the FDA-approved dosage is 20 mg/d.

H2-receptor antagonists, including famotidine, cimetidine, and nizatidine, may also be prescribed to reduce stomach acid production and promote healing in patients with EE due to GERD, but these agents are considered less efficacious than PPIs for either acute or maintenance therapy.

The potassium-competitive acid blocker (PCAB) vonoprazan is the latest agent to be indicated for EE and may provide more potent acid suppression for patients. A randomized comparative trial showed noninferiority compared with lansoprazole for healing and maintenance of healing of EE. In another randomized comparative study, the investigational PCAP fexuprazan was shown to be noninferior to the PPI esomeprazole in treating EE.

Mild GERD symptoms can be controlled by traditional antacids taken after each meal and at bedtime or with short-term use of prokinetic agents, which can help reduce acid reflux by improving esophageal and stomach motility and by increasing pressure to the lower esophageal sphincter. Gastric emptying is also accelerated by prokinetic agents. Long-term use is discouraged, as it may cause serious or life-threatening complications.

In patients who do not fully respond to PPI therapy, surgical therapy may be considered. Other candidates for surgery include younger patients, those who have difficulty adhering to treatment, postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, patients with cardiac conduction defects, and those for whom the cost of treatment is prohibitive. Surgery may also be warranted if there are extraesophageal manifestations of GERD, such as enamel erosion; respiratory issues (eg, coughing, wheezing, aspiration); or ear, nose, and throat manifestations (eg, hoarseness, sore throat, otitis media). For those who have progressed to BE, surgical intervention is also indicated.

The types of surgery for patients with EE have evolved to include both transthoracic and transabdominal fundoplication. Usually, a 360° transabdominal fundoplication is performed. General anesthesia is required for laparoscopic fundoplication, in which five small incisions are used to create a new valve at the level of the esophagogastric junction by wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the esophagus.

Laparoscopic insertion of a small band known as the LINX Reflux Management System is FDA approved to augment the lower esophageal sphincter. The system creates a natural barrier to reflux by placing a band consisting of titanium beads with magnetic cores around the esophagus just above the stomach. The magnetic bond is temporarily disrupted by swallowing, allowing food and liquid to pass.

Endoscopic therapies are another treatment option for certain patients who are not considered candidates for surgery or long-term therapy. Among the types of endoscopic procedures are radiofrequency therapy, suturing/plication, and mucosal ablation/resection techniques at the gastroesophageal junction. Full-thickness endoscopic suturing is an area of interest because this technique offers significant durability of the recreated lower esophageal sphincter.

3. PPI therapy for GERD should be stopped before endoscopy is performed to confirm a diagnosis of EE.

A clinical diagnosis of GERD can be made if the presenting symptoms are heartburn and regurgitation, without chest pain or alarm symptoms such as dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding. In this setting, once-daily PPIs are generally prescribed for 8 weeks to see if symptoms resolve. If symptoms have not resolved, a twice-daily PPI regimen may be prescribed. In patients who do not respond to PPIs, or for whom GERD returns after stopping therapy, an upper endoscopy with biopsy is recommended after 2-4 weeks off therapy to rule out other causes. Endoscopy should be the first step in diagnosis for individuals experiencing chest pain without heartburn; those in whom heart disease has been ruled out; individuals experiencing dysphagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding; or those who have multiple risk factors for BE.

4. The most serious complication of EE is BE, which can lead to esophageal cancer.

Several complications can arise from EE. The most serious of these is BE, which can lead to esophageal adenocarcinoma. BE is characterized by the conversion of normal distal squamous esophageal epithelium to columnar epithelium. It has the potential to become malignant if it exhibits intestinal-type metaplasia. In the industrialized world, adenocarcinoma currently represents more than half of all esophageal cancers. The most common symptom of esophageal cancer is dysphagia. Other signs and symptoms include weight loss, hoarseness, chronic or intractable cough, bleeding, epigastric or retrosternal pain, frequent pneumonia, and, if metastatic, bone pain.

5. Lifestyle modifications can help control the symptoms of EE.

Guidelines recommend a number of lifestyle modification strategies to help control the symptoms of EE. Smoking cessation and weight loss are two evidence-based strategies for relieving symptoms of GERD and, ultimately, lowering the risk for esophageal cancer. One large prospective Norwegian cohort study (N = 29,610) found that stopping smoking improved GERD symptoms, but only in those with normal body mass index. In a smaller Japanese study (N = 191) specifically surveying people attempting smoking cessation, individuals who successfully stopped smoking had a 44% improvement in GERD symptoms at 1 year, vs an 18% improvement in those who continued to smoke, with no statistical difference between the success and failure groups based on patient body mass index (P = .60).

Other recommended strategies for nonpharmacologic management of EE symptoms include elevation of the head when lying down in bed and avoidance of lying down after eating, cessation of alcohol consumption, avoidance of food close to bedtime, and avoidance of trigger foods that can incite or worsen symptoms of acid reflux. Such trigger foods vary among individuals, but they often include fatty foods, coffee, chocolate, carbonated beverages, spicy foods, citrus fruits, and tomatoes.

Dr. Puerta has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Centrifugally Spreading Lymphocutaneous Sporotrichosis: A Rare Cutaneous Manifestation

To the Editor:

Sporotrichosis refers to a subacute to chronic fungal infection that usually involves the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues and is caused by the introduction of Sporothrix, a dimorphic fungus, through the skin. We present a case of chronic atypical lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.

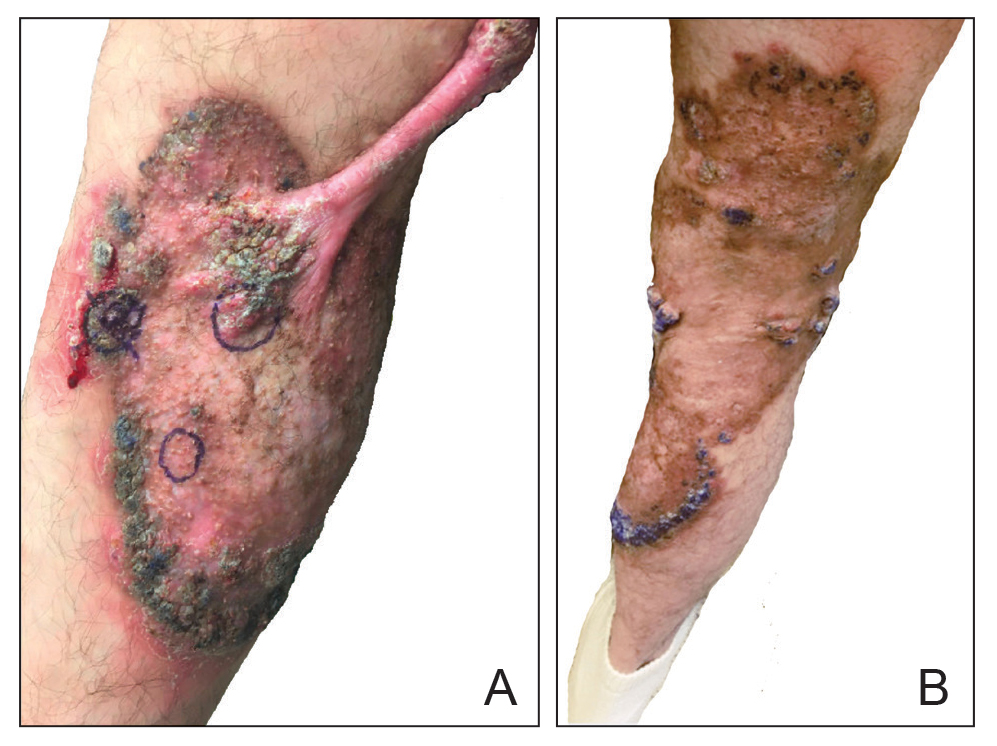

A 46-year-old man presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic for follow-up for a rash on the right leg that spread to the thigh and became painful and pruritic. It initially developed 8 years prior to the current presentation after he sustained trauma to the leg from an electroshock weapon. One year prior to the current presentation, he had presented to the emergency department and was prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days as well as bacitracin ointment. He also was instructed to follow up with dermatology, but a lack of health insurance and other socioeconomic barriers prevented him from seeking dermatologic care. Nine months later, he again presented to the emergency department due to a motor vehicle accident. Computed tomography (CT) of the right leg revealed exophytic dermal masses, inflammatory stranding of the subcutaneous tissue, and right inguinal lymph nodes measuring up to 1.4 cm; there was no osteoarticular involvement. At that time, the patient was applying gentian violet to the skin lesions and taking hydroxyzine 50 mg 3 times daily as needed for pruritus with minimal relief. Financial support was provided for follow-up with dermatology, which occurred almost 5 months later.

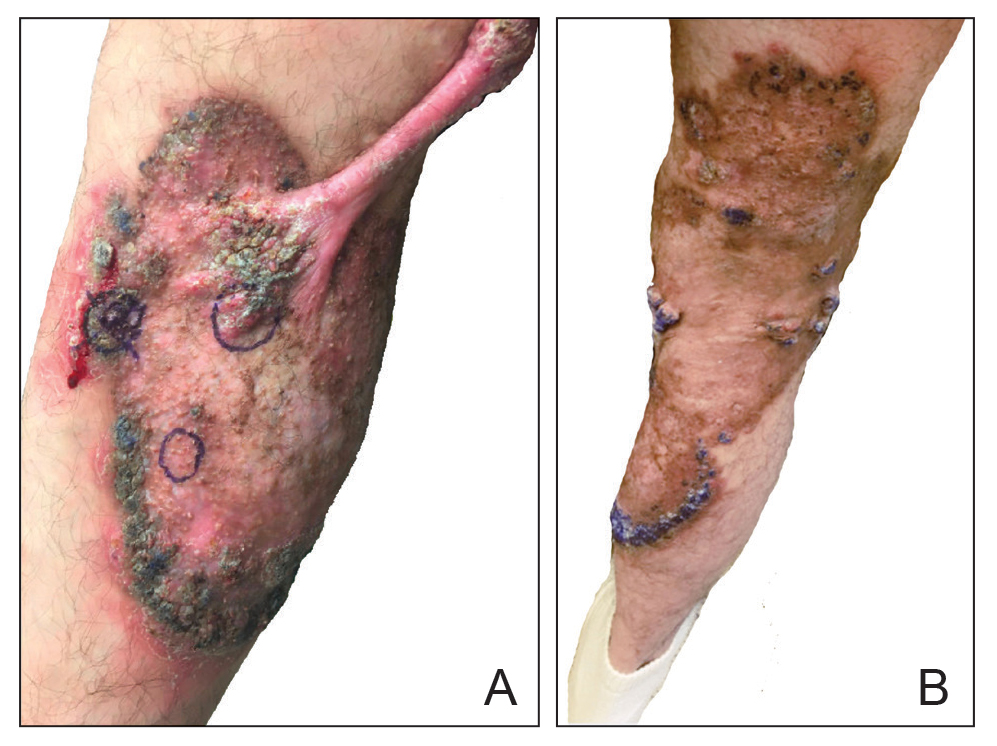

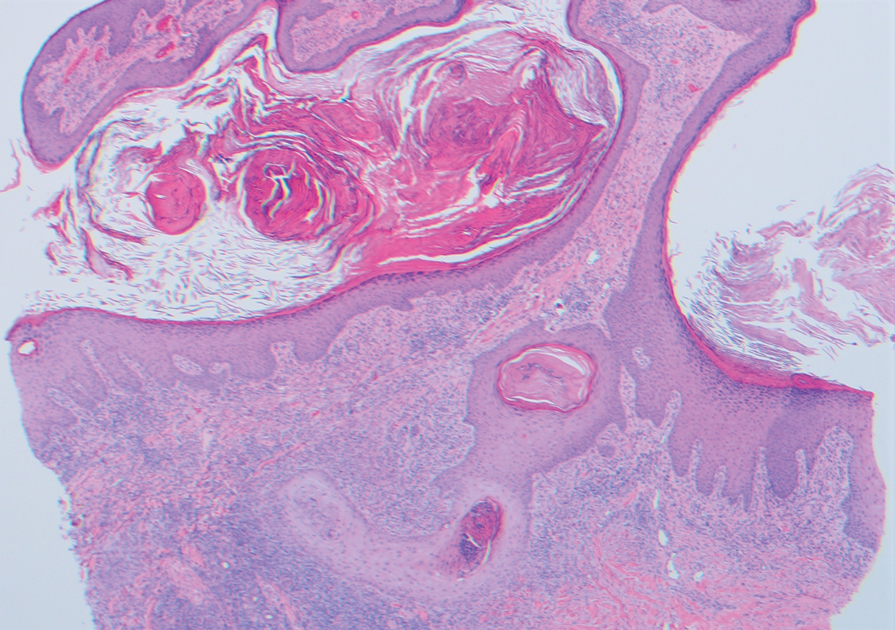

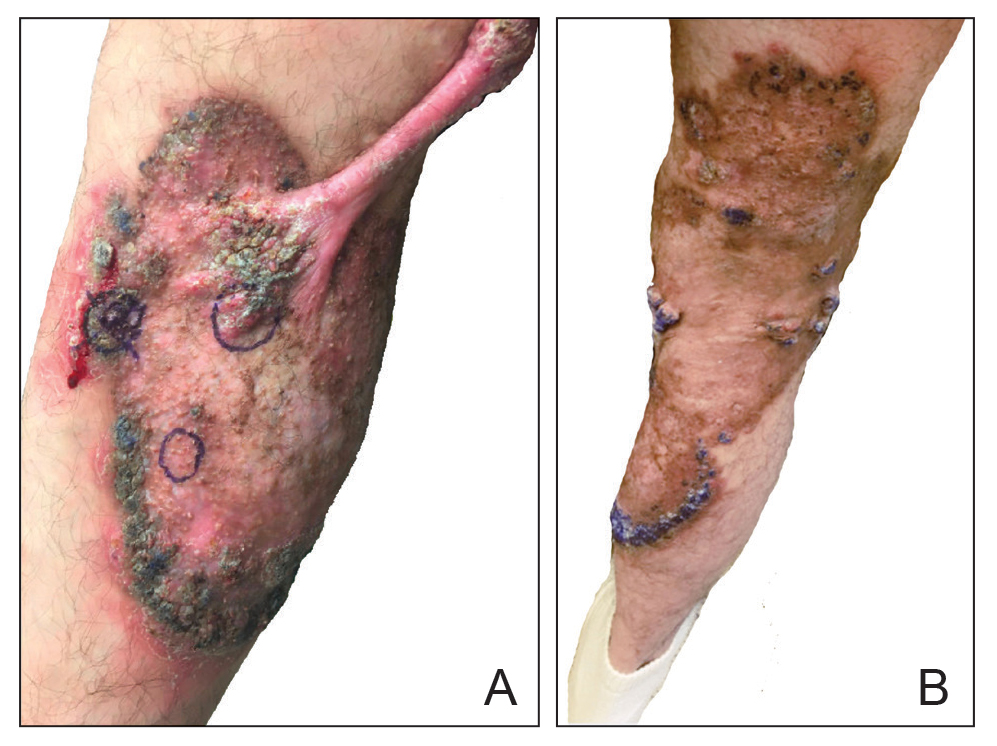

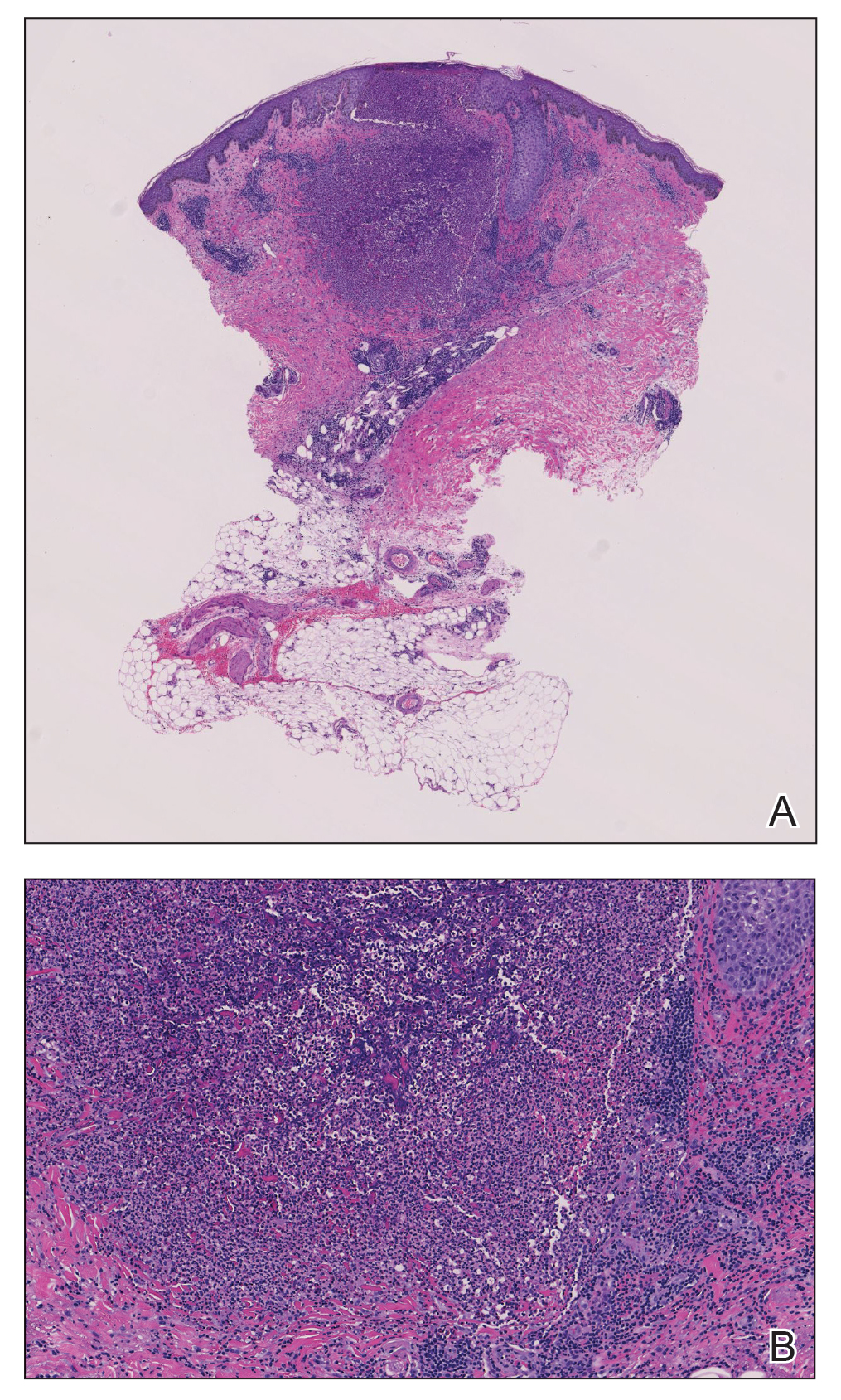

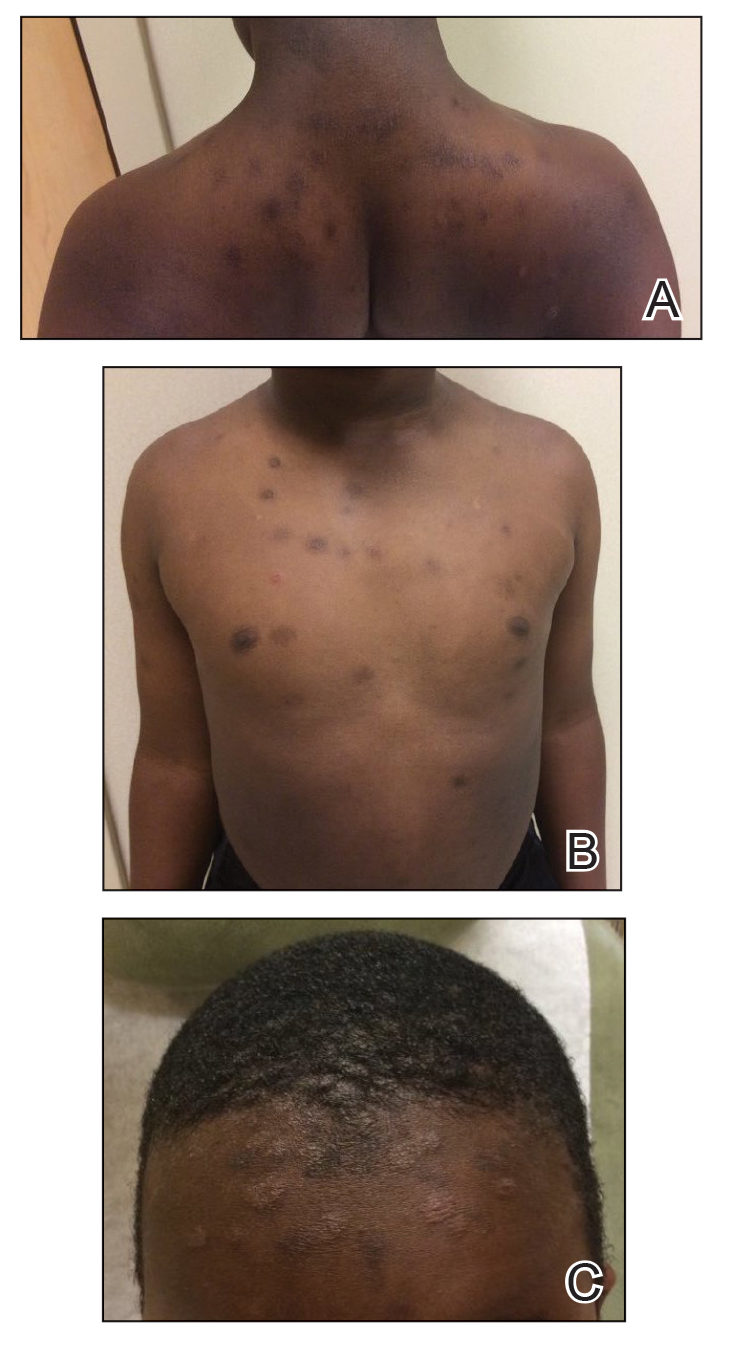

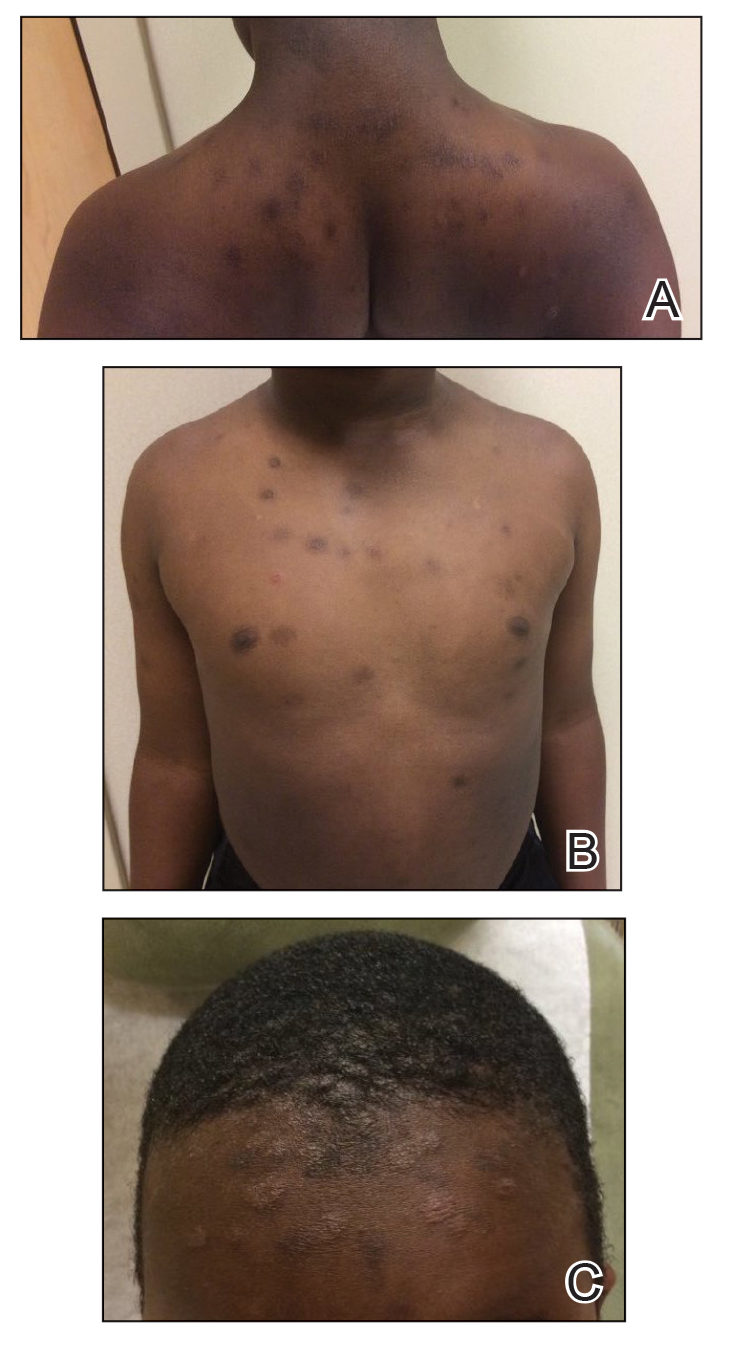

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed a large annular plaque with verrucous, scaly, erythematous borders and a hypopigmented atrophic center extending from the medial aspect of the right leg to the posterior thigh. Numerous pink, scaly, crusted nodules were scattered primarily along the periphery, with some evidence of draining sinus tracts. In addition, a fibrotic pink linear plaque extended from the medial right leg to the popliteal fossa, consistent with a keloid. Violet staining along the periphery of the lesion also was appreciated secondary to the application of topical gentian violet (Figure 1).

Based on the chronic history and morphology, a diagnosis of a chronic fungal or atypical mycobacterial infection was favored. In particular, chromoblastomycosis, cutaneous tuberculosis (eg, scrofuloderma, lupus vulgaris, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis), and atypical mycobacterial infection were highest on the differential, as these conditions often exhibit annular, nodular, verrucous, and/or atrophic lesions. The nodularity, crusting, and draining sinus tracts also raised the possibility of mycetoma. Given the extension of the lesion from the lower to upper leg, a sporotrichoid infection also was considered but was thought to be less likely based on the annular configuration.

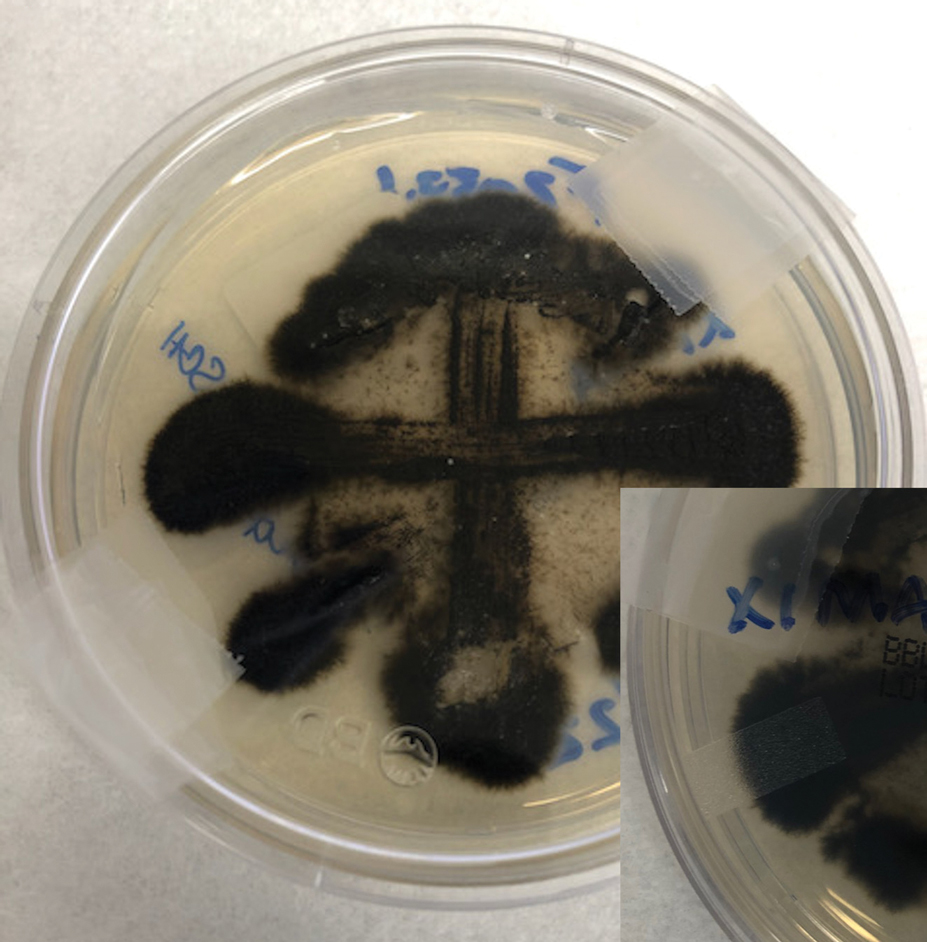

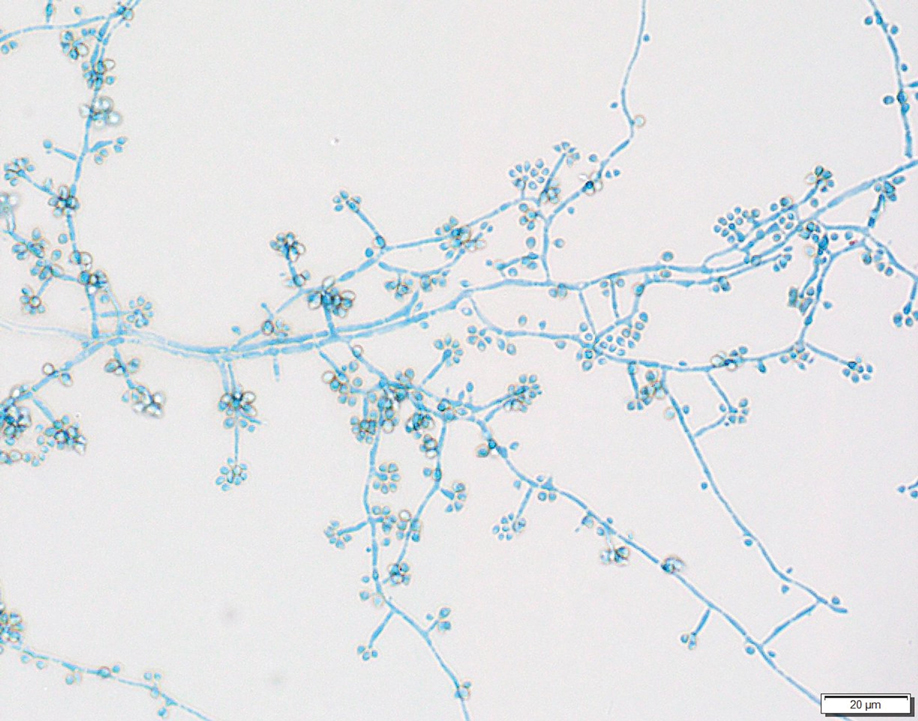

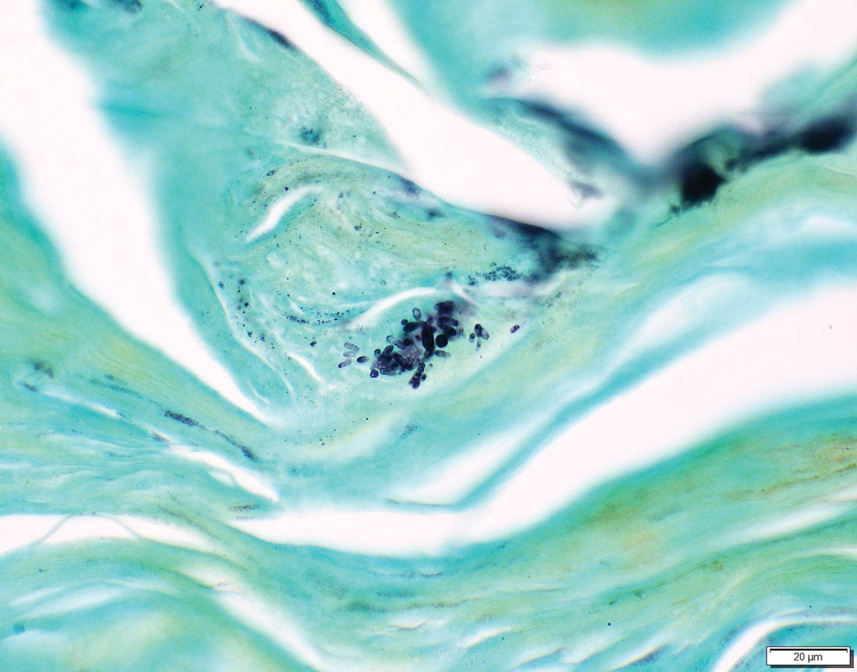

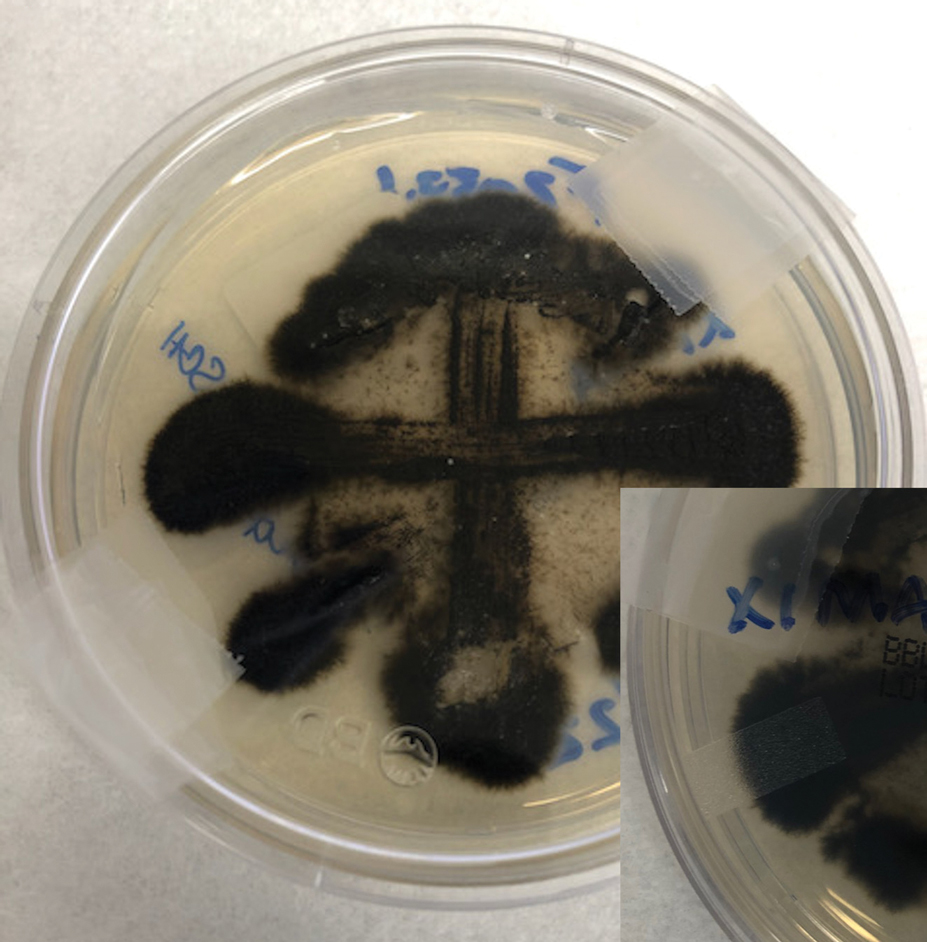

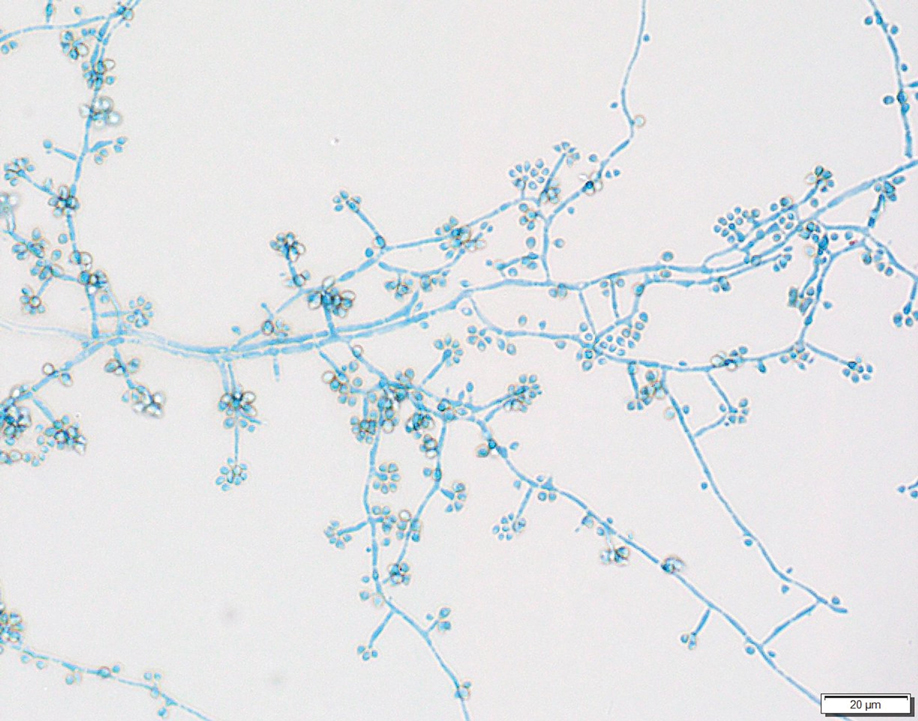

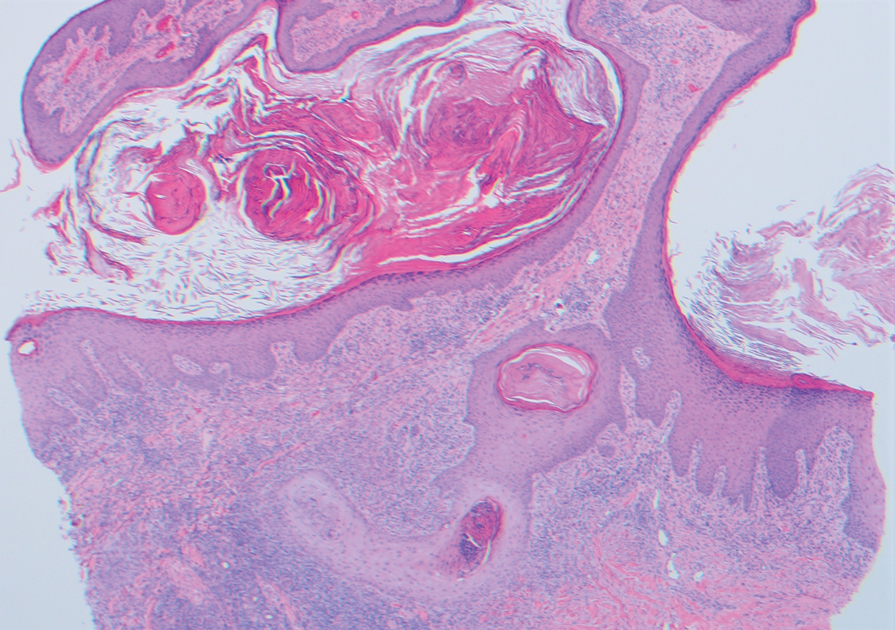

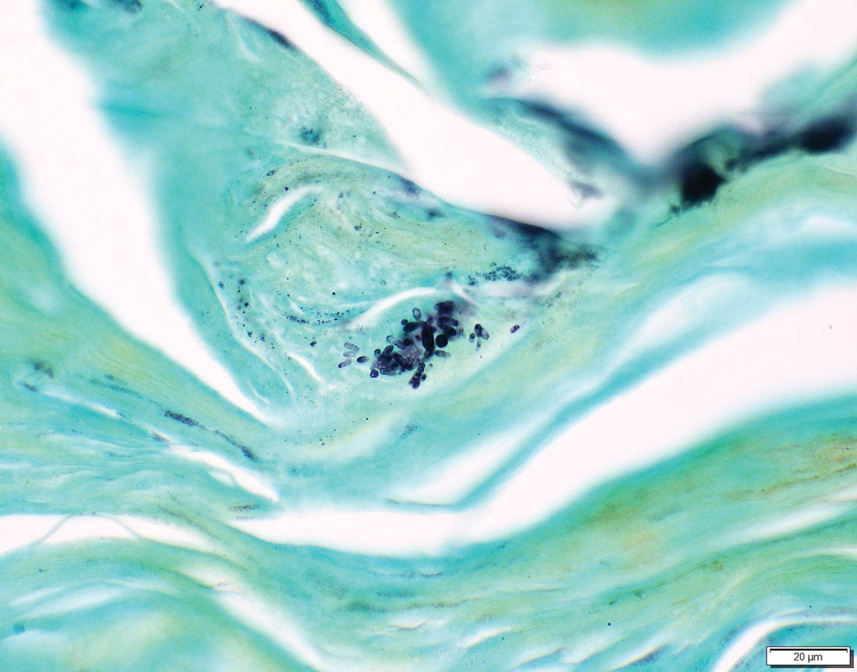

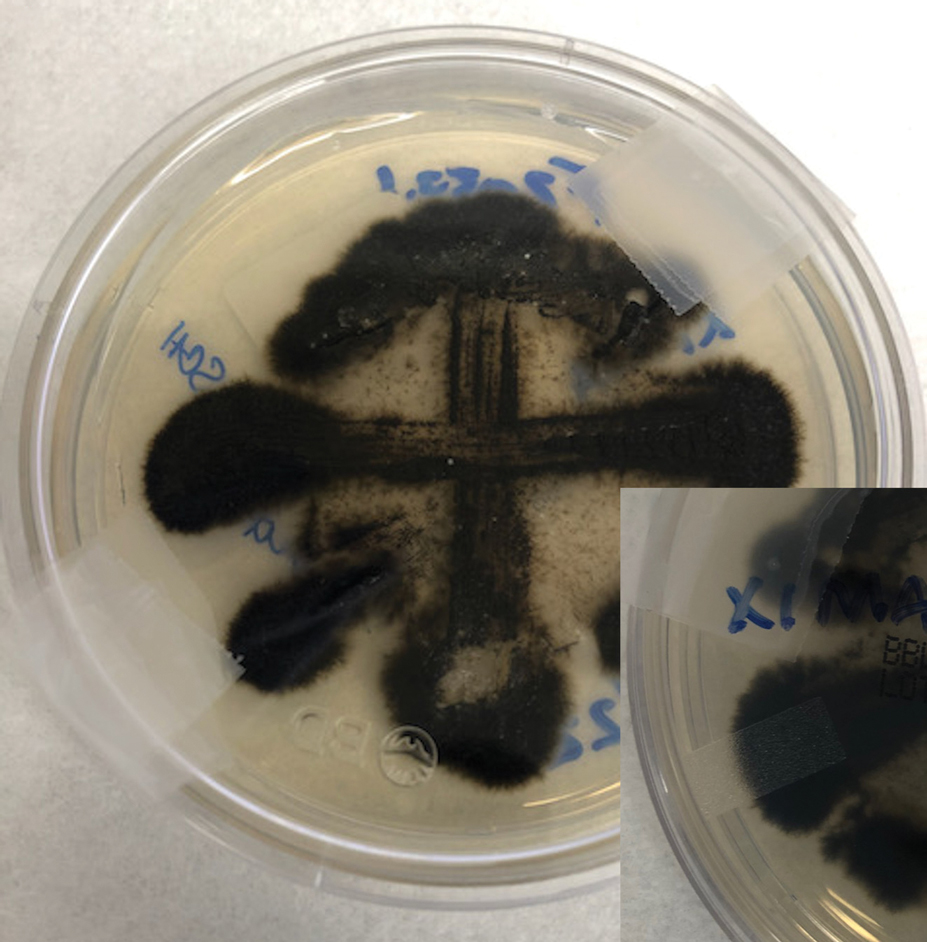

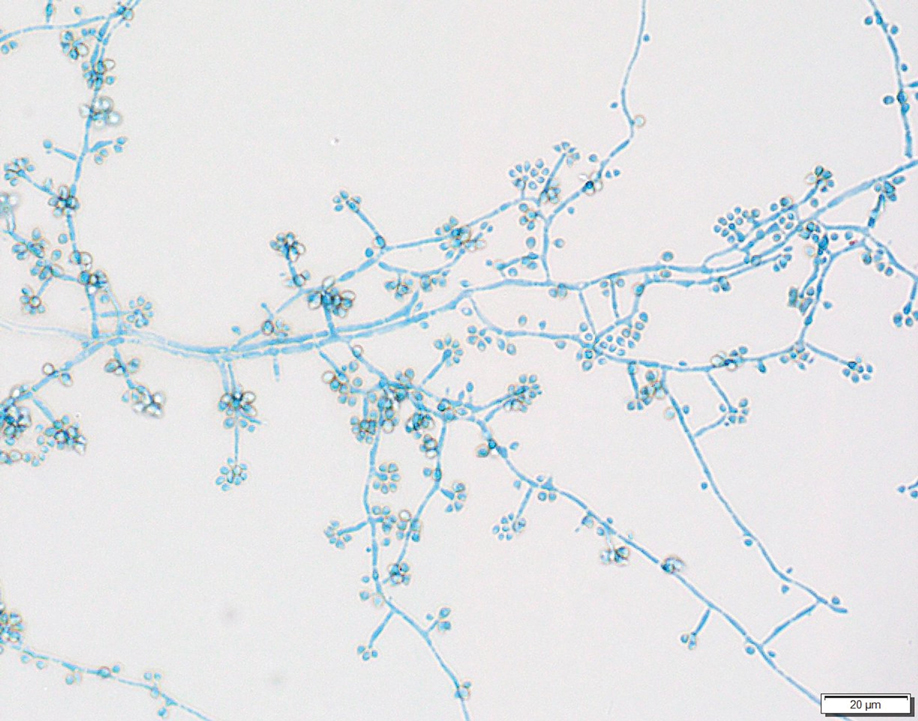

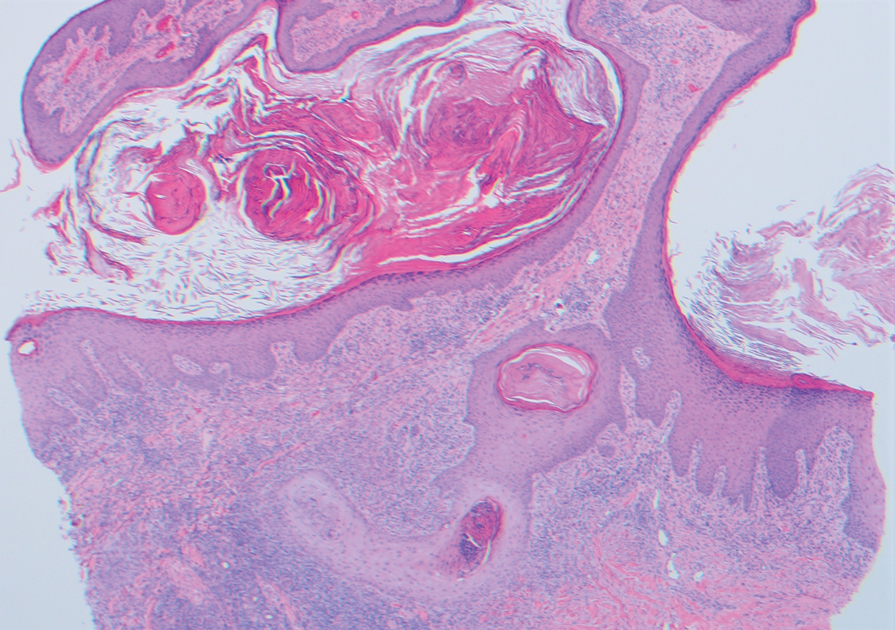

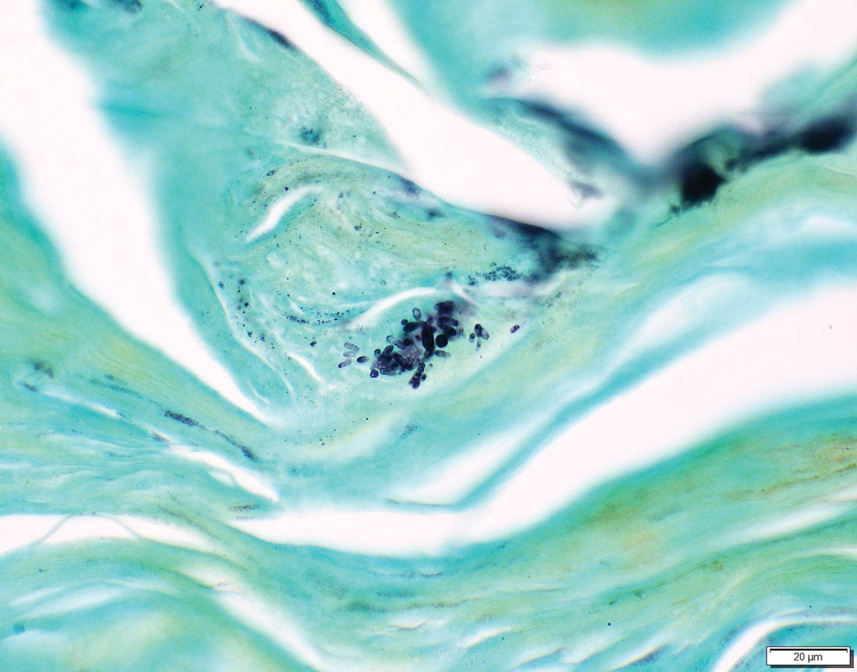

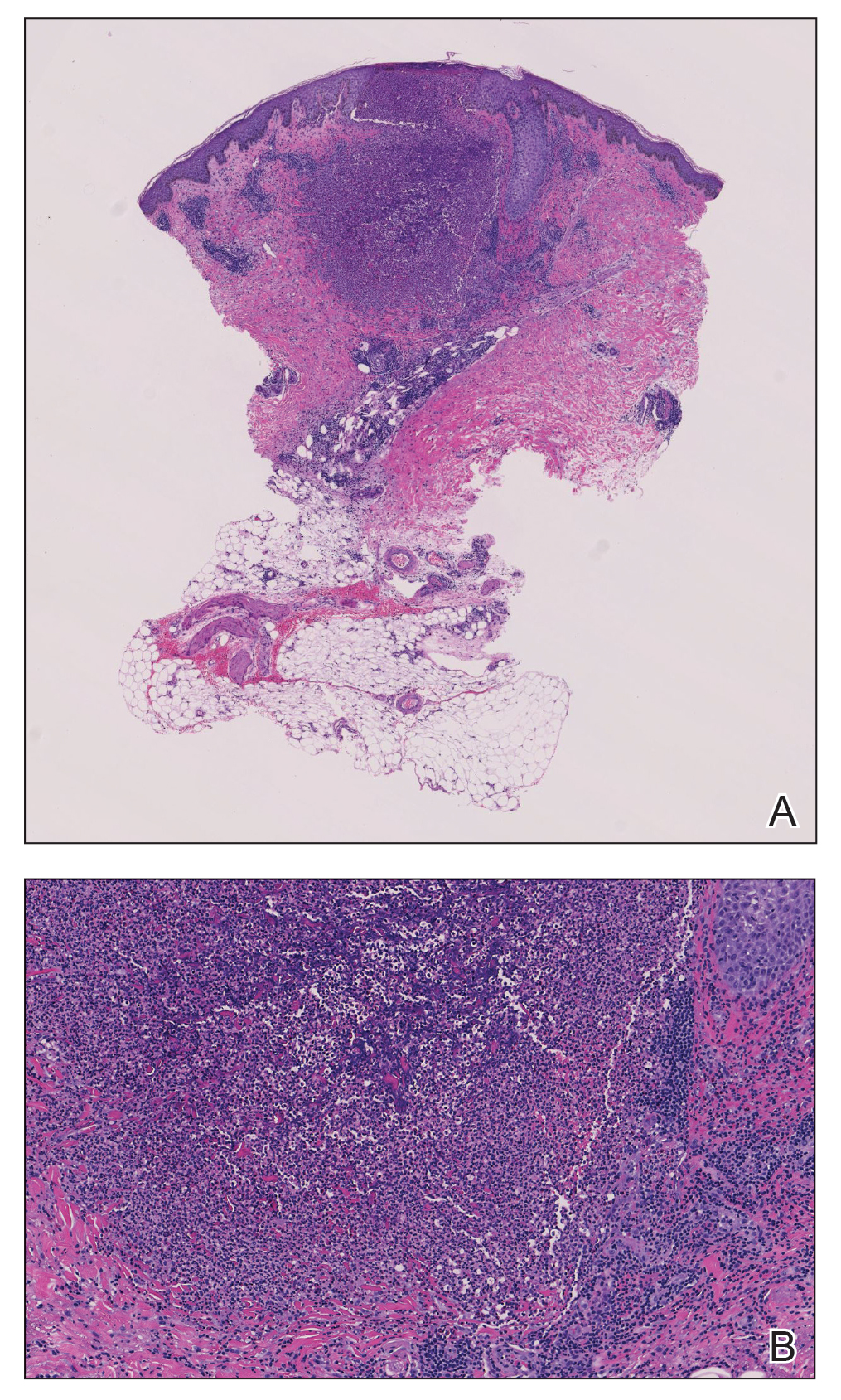

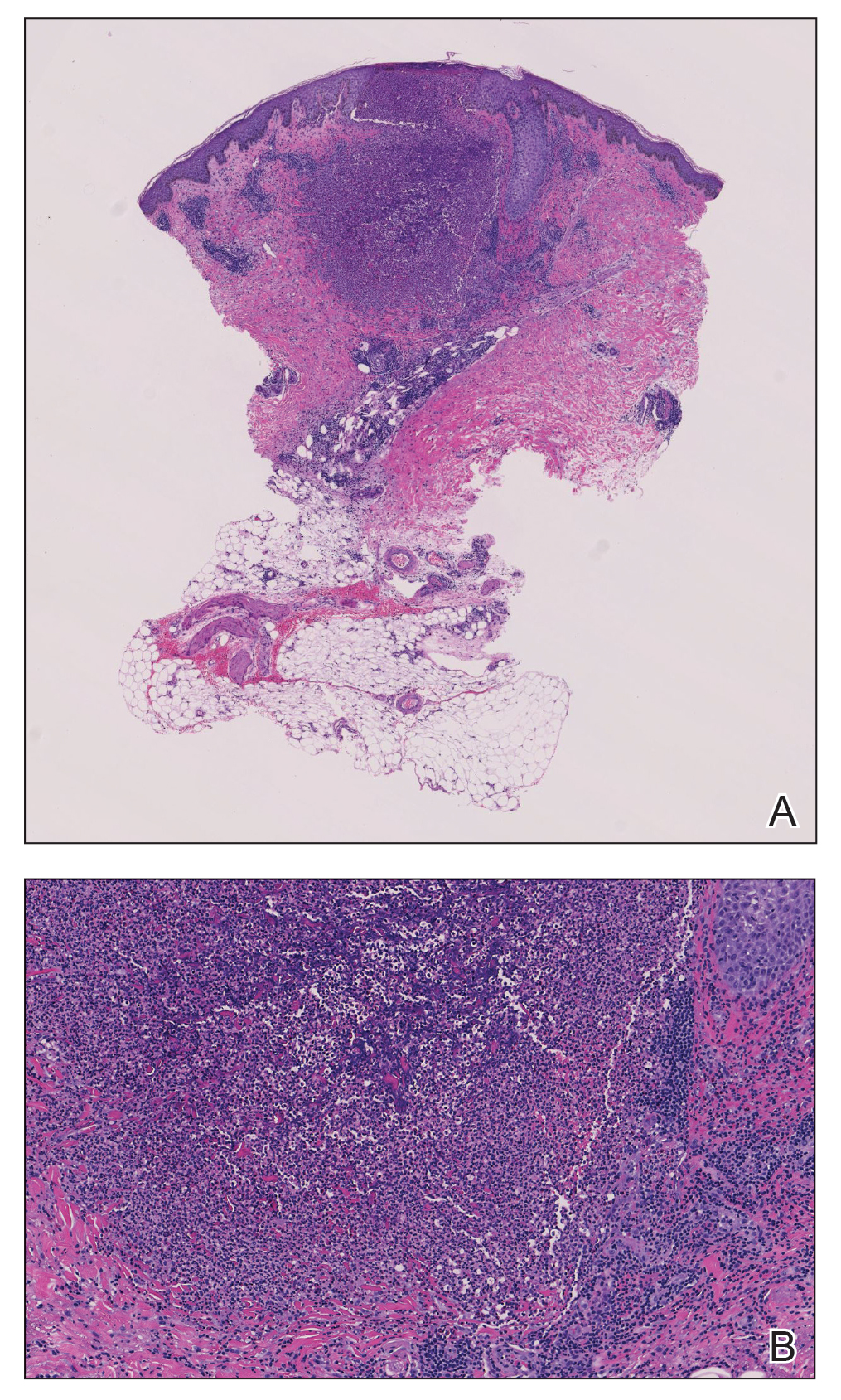

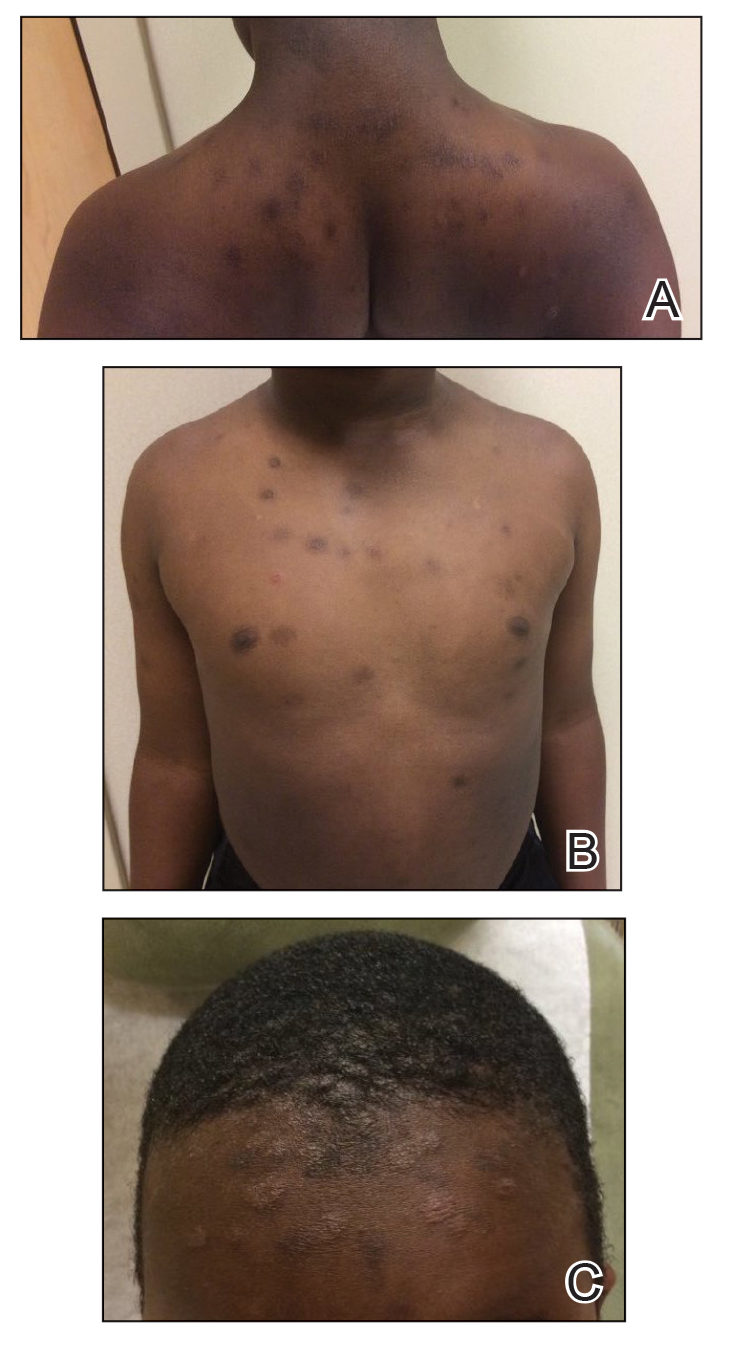

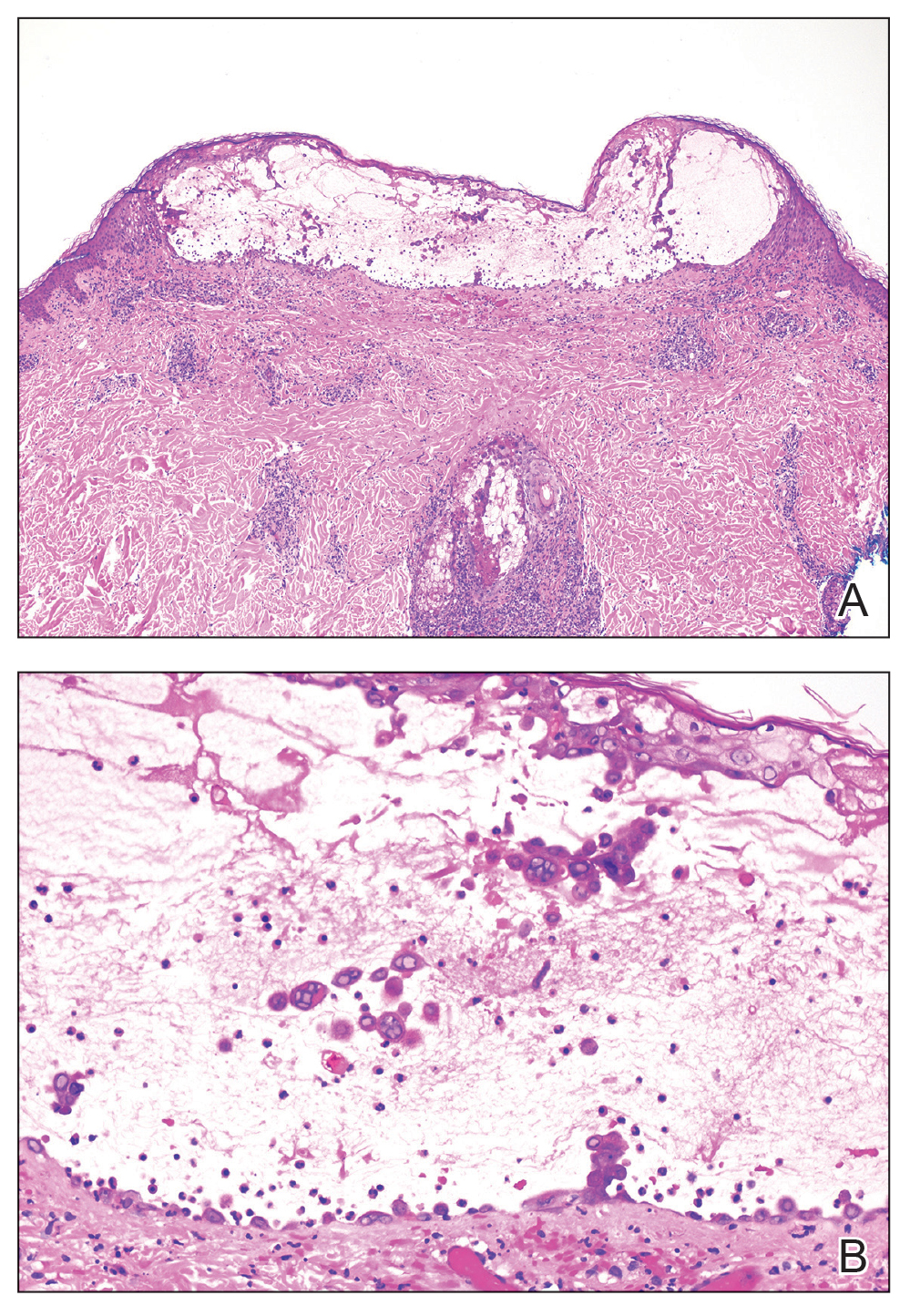

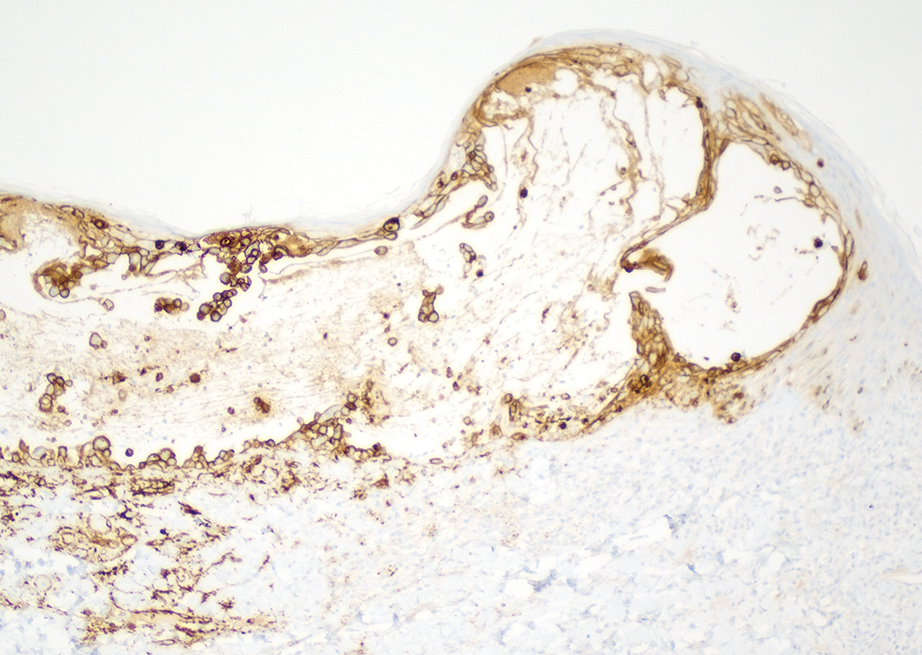

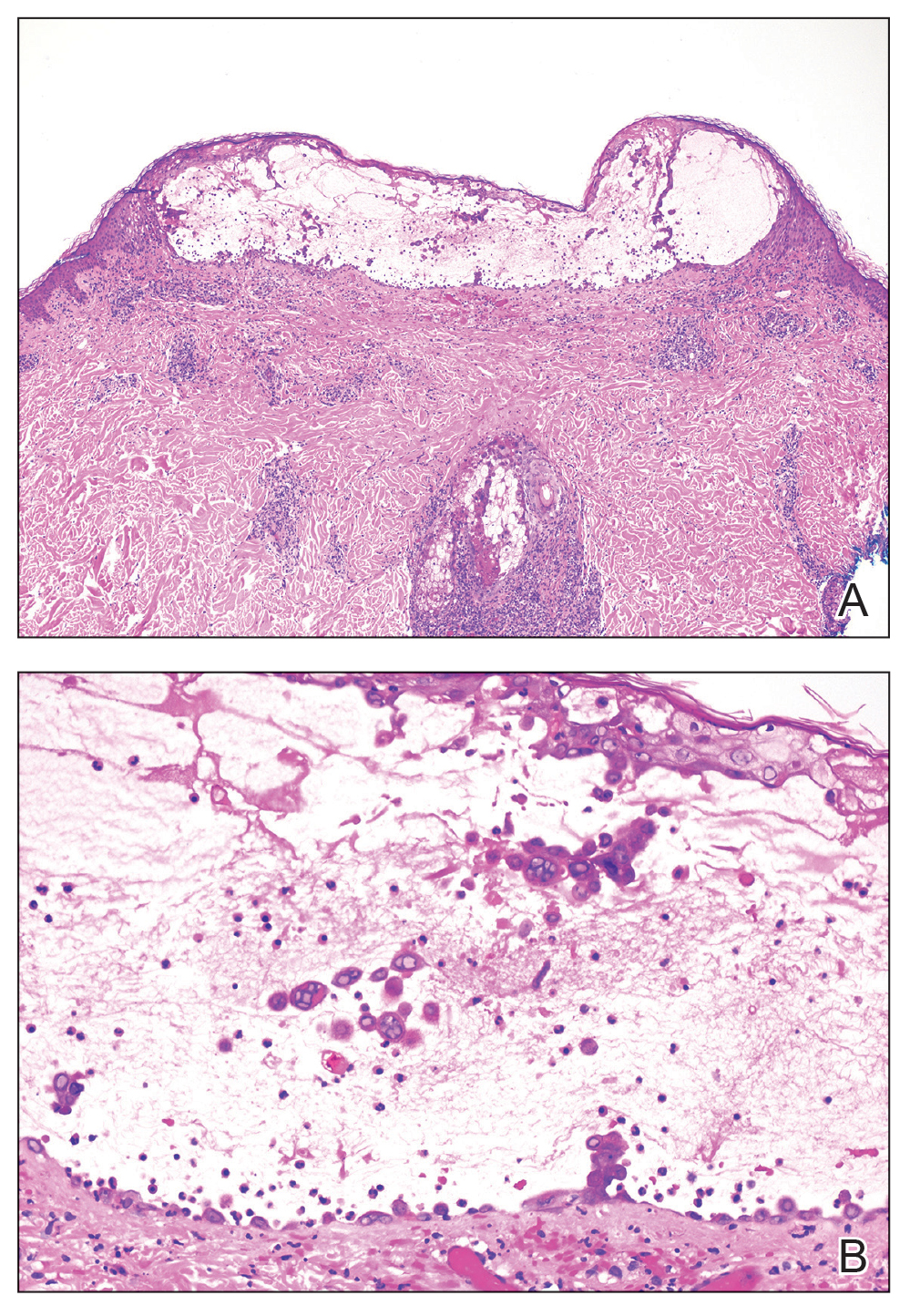

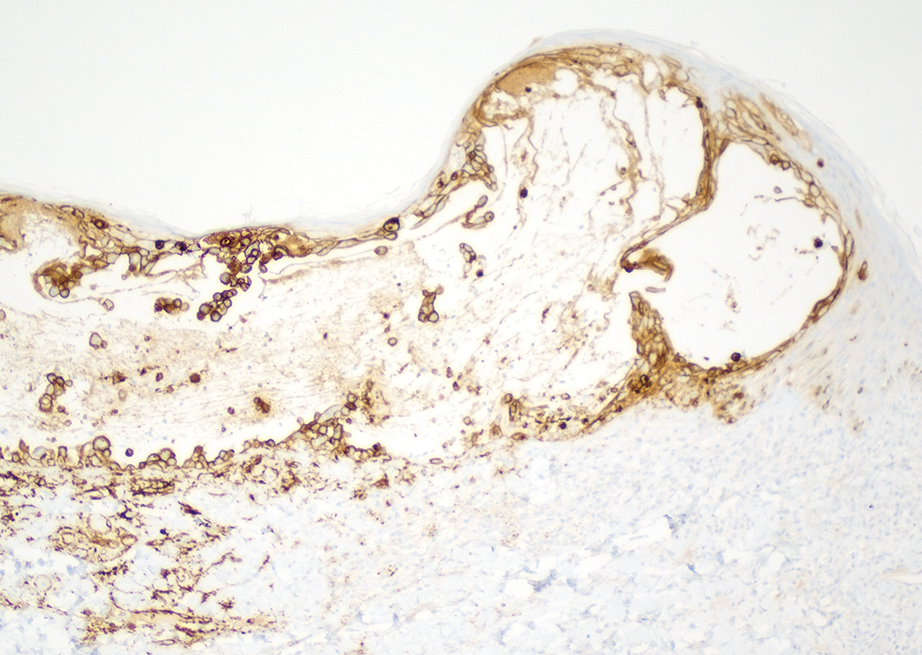

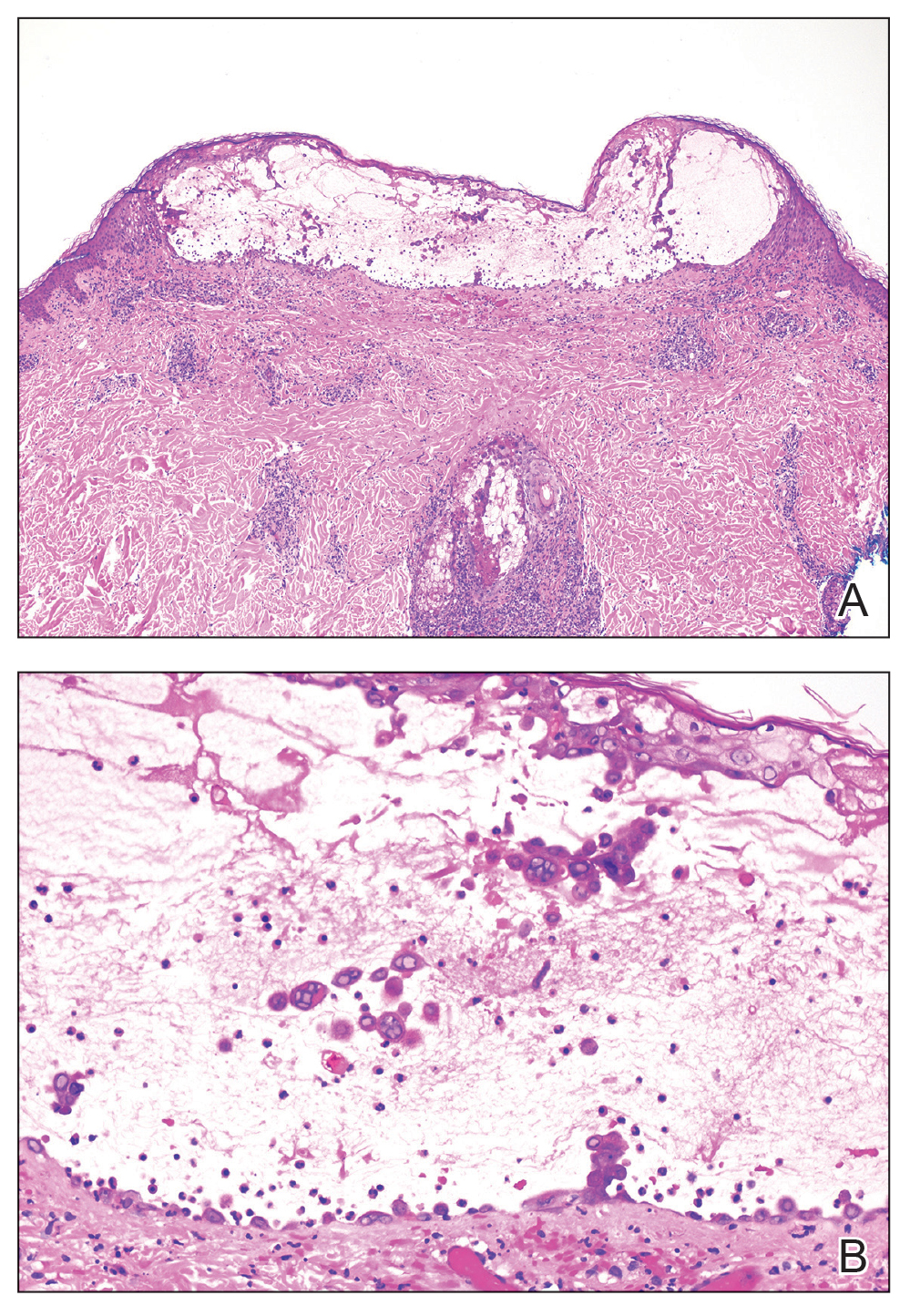

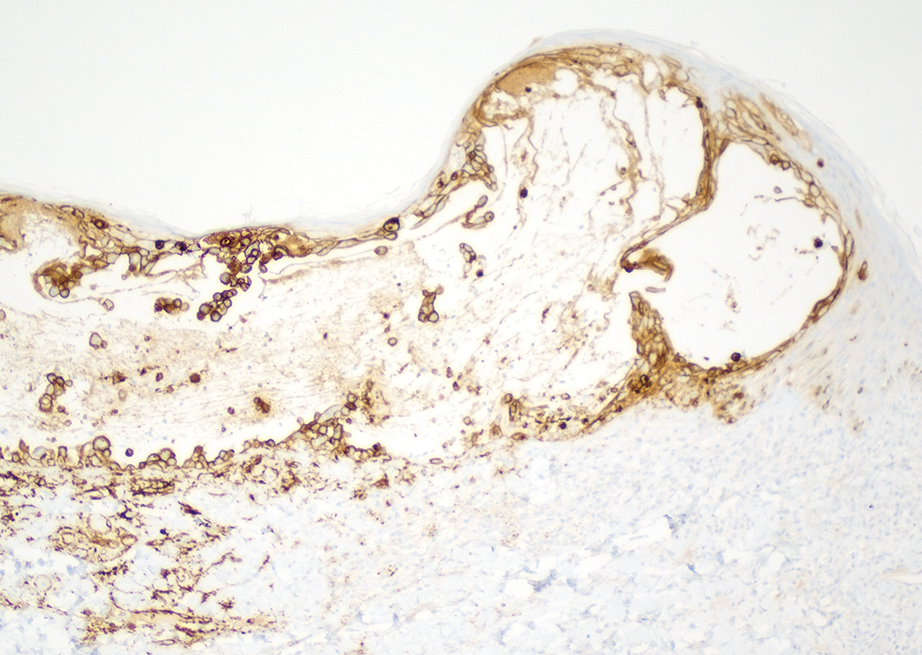

Two 4-mm punch biopsies were taken from a peripheral nodule—one for routine histology and another for bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial cultures. An interferon-gamma release assay also was ordered to evaluate for immune responses indicative of prior Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, but the patient did not obtain this for unknown reasons. Histology demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and necrotizing granulomas, which suggested an infectious etiology, but no organisms were identified on tissue staining and all cultures were negative for growth at 6 weeks. The patient was asked to return at that point, and 4 additional scouting biopsies were performed and sent for routine histology, M tuberculosis nucleic acid amplification testing, and microbiologic cultures (ie, bacterial, mycobacterial, fungal, nocardia, actinomycetes). Within 1 week, a filamentous organism with pigmentation visible on the front and back of a Sabouraud dextrose agar plate was identified on fungal culture (Figure 2). Microscopic evaluation of this mold with lactophenol blue stain revealed thin septate hyphae with conidiophores arising at right angles that bore clusters of microconidia (Figure 3). Sequencing analysis ultimately identified this organism as Sporothrix schenckii. Routine histology demonstrated pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with scattered intraepidermal collections of neutrophils (Figure 4). The dermis showed a dense, superficial, and deep infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells with occasional neutrophils and eosinophils. A Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain revealed a cluster of ovoid yeast forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 5). The patient was referred to infectious disease for follow-up and treatment.

The patient later visited a community clinic providing dermatologic care for patients without insurance. He was started on itraconazole 200 mg daily for a total of 6 months until dermatologic clearance of the cutaneous lesions was observed. He was followed by the clinic with laboratory tests including a liver function test. At follow-up 8 months later, a repeat biopsy was performed to ensure histologic clearance of the sporotrichosis, which revealed a dermal scar and no evidence of residual infection.

Sporothrix schenckii was first isolated in 1898 by Benjamin Schenck, a student at Johns Hopkins Medicine (Baltimore, Maryland), and identified by a mycologist as sporotricha.1 Species within the genus Sporothrix are unique in that the fungi are both dimorphic (growing as a mold at 25 °C but as a yeast at 37 °C) and dematiaceous (dark pigmentation from melanin is visible on inspection of the anterior and reverse sides of culture plates). Infection usually occurs when cutaneous or subcutaneous tissues are exposed to the fungus via microabrasions; activities thought to contribute to exposure include gardening, agricultural work, animal husbandry, and feline scratches.2 Although skin trauma frequently is considered the primary route of infection, patient recall is variable, with one study noting that only 37.7% of patients recalled trauma and another study similarly demonstrating a patient recall rate of 25%.3,4

Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis is the most common presentation of the fungal infection,5 and clinical cases may be classified into 1 of 4 categories: (1) lymphangitic lesions—papules at the site of inoculation with spread along the lymphatic channels; (2) localized (fixed) cutaneous lesions—1 or 2 lesions at the inoculation site; (3) disseminated (multifocal) cutaneous lesions; and (4) extracutaneous lesions.6 Extracutaneous manifestations of this infection most notably have been reported as pulmonary disease through inhalation of conidia or through dissemination in immunocompromised hosts.7 Our patient’s infection was categorized as lymphangitic lesions due to spread from the lower to upper leg, albeit in a highly atypical, annular fashion. A review of systems was otherwise negative, and CT ruled out osteoarticular involvement.

In addition to socioeconomic barriers, several factors contributed to a delayed diagnosis in this patient including the annular presentation with central hypopigmentation and atrophy, negative initial microbiological cultures and lack of visualization of organisms on histopathology, and the consequent need for repeat biopsies. For lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the typical presentation consists of a papule or ulcerated nodule at the site of inoculation with subsequent linear spread along lymphatic channels. This classic sporotrichoid pattern is a key diagnostic clue for identifying sporotrichosis but was absent at the time our patient presented for medical care. Rather, the sporotrichoid spread seemed to have occurred in a centrifugal fashion up the leg. Few case reports have documented an annular presentation of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis,8-13 and one report described central atrophy and hypopigmentation.10 Pain and pruritus, which were present in our patient, rarely are documented.9 Finally, the diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infections may require multiple biopsies due to the variable abundance of viable organisms in tissue specimens as well as the fastidious growth characteristics of these organisms. Furthermore, sensitivity often is low for both fungal and mycobacterial cultures, and cultures may take days to weeks to yield growth.14,15 For these reasons, empiric therapy and repeat biopsies often are pursued if clinical suspicion is high enough.16 Our patient returned for multiple scouting biopsies after the initial tissue culture was negative and was even considered for empiric treatment against Mycobacterium prior to positive fungal cultures.

Another unique aspect of our case was the presence of a keloid. It is difficult to know if this keloid was secondary to the trauma the patient sustained in the inciting incident or formed from the fungal infection. Interestingly, it has been hypothesized that fungal infections may contribute to keloid and hypertrophic scar formation.17 In a case series of 3 patients with either keloids or hypertrophic scars and concomitant tinea infection, there was notable improvement in the appearance of the scars 2 weeks after beginning itraconazole therapy.17 However, it is not yet known if a fungal infection can contribute to the pathogenesis of keloid formation.

As with other aspects of this case, the length of time the patient went without diagnosis and treatment was unusual and may help explain the atypical presentation. Although the incubation period for S schenckii can vary, most reports identify patients as seeking medical attention within 1 year of rash onset.18-20 In our case, the patient was not diagnosed until 8 years after his symptoms began, requiring multiple referrals, multiple health system touchpoints, and an institution-specific financial aid program. As such, this case also highlights the potential need for a multidisciplinary team approach when caring for patients with poor access to health care.

In conclusion, this case illustrates a unique presentation of lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis that may mimic other chronic infections and result in delayed diagnosis. Although lymphangitic sporotrichosis generally is recognized as having a linear distribution, mounting evidence from this report and others suggests an annular presentation also is possible. Pruritus or pain is rare but should not preclude a diagnosis of sporotrichosis if present. For patients with limited access to health care resources, it is especially important to involve multiple members of the health care team, including social workers and specialists, to prevent a protracted and severe course of disease.

- Schenck BR. On refractory subcutaneous abscesses caused by a fungus possibly related to the sporotricha. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. 1898;93:286-290.

- de Lima Barros MB, de Almeida Paes R, Schubach AO. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:633-654. doi:10.1128/CMR.00007-11

- Crevasse L, Ellner PD. An outbreak of sporotrichosis in florida. J Am Med Assoc. 1960;173:29-33. doi:10.1001/jama.1960.03020190031006

- Mayorga R, Cáceres A, Toriello C, et al. An endemic area of sporotrichosis in Guatemala [in French]. Sabouraudia. 1978;16:185-198.

- Morris-Jones R. Sporotrichosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:427-431. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01087.x

- Sampaio SA, Da Lacaz CS. Clinical and statistical studies on sporotrichosis in Sao Paulo (Brazil). Article in German. Hautarzt. 1959;10:490-493.

- Ramos-e-Silva M, Vasconcelos C, Carneiro S, et al. Sporotrichosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:181-187. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2006.05.006

- Williams BA, Jennings TA, Rushing EC, et al. Sporotrichosis on the face of a 7-year-old boy following a bicycle accident. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:E246-E247. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01696.x

- Vaishampayan SS, Borde P. An unusual presentation of sporotrichosis. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:409. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.117350

- Qin J, Zhang J. Sporotrichosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:771. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1809179

- Patel A, Mudenda V, Lakhi S, et al. A 27-year-old severely immunosuppressed female with misleading clinical features of disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2016;2016:1-4. doi:10.1155/2016/9403690

- de Oliveira-Esteves ICMR, Almeida Rosa da Silva G, Eyer-Silva WA, et al. Rapidly progressive disseminated sporotrichosis as the first presentation of HIV infection in a patient with a very low CD4 cell count. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2017;2017:4713140. doi:10.1155/2017/4713140

- Singh S, Bachaspatimayum R, Meetei U, et al. Terbinafine in fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis: a case series. J Clin Diagnostic Res. 2018;12:FR01-FR03. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2018/25315.12223

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280. doi:10.1128/CMR.00053-10

- Peters F, Batinica M, Plum G, et al. Bug or no bug: challenges in diagnosing cutaneous mycobacterial infections. J Ger Soc Dermatol. 2016;14:1227-1236. doi:10.1111/ddg.13001

- Khadka P, Koirala S, Thapaliya J. Cutaneous tuberculosis: clinicopathologic arrays and diagnostic challenges. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:7201973. doi:10.1155/2018/7201973

- Okada E, Maruyama Y. Are keloids and hypertrophic scars caused by fungal infection? . Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:814-815. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000278813.23244.3f

- Pappas PG, Tellez I, Deep AE, et al. Sporotrichosis in Peru: description of an area of hyperendemicity. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:65-70. doi:10.1086/313607

- McGuinness SL, Boyd R, Kidd S, et al. Epidemiological investigation of an outbreak of cutaneous sporotrichosis, Northern Territory, Australia. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:1-7. doi:10.1186/s12879-016-1338-0

- Rojas FD, Fernández MS, Lucchelli JM, et al. Cavitary pulmonary sporotrichosis: case report and literature review. Mycopathologia. 2017;182:1119-1123. doi:10.1007/s11046-017-0197-6

To the Editor:

Sporotrichosis refers to a subacute to chronic fungal infection that usually involves the cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues and is caused by the introduction of Sporothrix, a dimorphic fungus, through the skin. We present a case of chronic atypical lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis.

A 46-year-old man presented to the outpatient dermatology clinic for follow-up for a rash on the right leg that spread to the thigh and became painful and pruritic. It initially developed 8 years prior to the current presentation after he sustained trauma to the leg from an electroshock weapon. One year prior to the current presentation, he had presented to the emergency department and was prescribed doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days as well as bacitracin ointment. He also was instructed to follow up with dermatology, but a lack of health insurance and other socioeconomic barriers prevented him from seeking dermatologic care. Nine months later, he again presented to the emergency department due to a motor vehicle accident. Computed tomography (CT) of the right leg revealed exophytic dermal masses, inflammatory stranding of the subcutaneous tissue, and right inguinal lymph nodes measuring up to 1.4 cm; there was no osteoarticular involvement. At that time, the patient was applying gentian violet to the skin lesions and taking hydroxyzine 50 mg 3 times daily as needed for pruritus with minimal relief. Financial support was provided for follow-up with dermatology, which occurred almost 5 months later.