User login

The Future of Polycythemia Vera

There are several new therapies on the horizon for polycythemia vera. What is the potential impact of these treatments coming to market?

Dr. Richard: There are a number of emerging therapies for polycythemia vera (PV), such as PTG-300, idasanutlin, and givinostat. PTG-300, or rusfertide, is a hepcidin mimetic that works by regulating iron metabolism and potentially controlling erythropoiesis, limiting the need for phlebotomy. Idasanutlin, a selective MDM2 inhibitor, targets p53 activity. Even though this drug is early in its development, everyone who treats patients with cancer has been hoping for a drug that works through p53. If it is effective here, who knows where else it could be effective across various other conditions.

Givinostat is well along the development pathway in advanced trials. This drug shows promise in modulating gene expression and reducing the inflammation and fibrosis associated with PV, potentially improving patient outcomes and quality of life. Everyone is hopeful that givinostat could show some effect on disease control and potentially an effect on the myeloproliferative clone. However, rigorous clinical trials and further research are necessary to validate their efficacy, safety profiles, and long-term impacts on patients with PV.

Now, with the approval of peginterferon, the next step is going to be to see how effective it will be and what the adverse events might be. I think we will be getting more data as it starts to be used more. My prediction is that there will be a slow uptake, largely because many older physicians such as myself remember the significant side effects from interferon in the past. Despite being an FDA-approved treatment, it remains an emerging therapy, particularly in the United States. Its adoption and efficacy will become clearer as time progresses.

Another promising drug early in its development is bomedemstat, which functions through a different mechanism as a deacetylase. While the potential effect of histone deacetylase drugs on patient treatment outcomes remains uncertain this year, there might be significant data—either positive or negative—that accelerate the progress of these drugs in their developmental trajectory.

We know that ruxolitinib can be used effectively for patients once they fail hydroxyurea. And now there has been the development of other JAK2 inhibitors that are approved for myelofibrosis. I am not quite sure how they can be evaluated in PV, since we are talking about relatively small numbers of patients, but they do seem to have some slight differences that may be significant and could be used in this space.

Those are the main therapies that I will have my eye on this year.

What is the potential significance of an accelerated dosing schedule for BESREMi (ropeginterferon-alfa-2b-njft), which is being investigated in the ECLIPSE PV phase 3b clinical trial?

Dr. Richard: The potential significance of an accelerated dosing schedule for BESREMi, as investigated in the ECLIPSE PV phase 3b clinical trial, lies in its capacity to enhance treatment efficacy and outcomes for patients with PV. I am incredibly pleased that it is being done as a trial, partly because a lot of people assume that once a phase 3 study is complete and a drug receives FDA approval, everything is finished and done, and we will move on to the next thing. I really appreciate it when phase 3b or 4 studies are performed, and the data get collected and published.

This study is going to follow a group of patients closely for adverse events and for the JAK2 signal. By administering BESREMi at an accelerated pace, researchers can evaluate its ability to better control hematocrit levels and symptoms associated with PV. In addition, an accelerated dosing schedule could potentially offer patients more efficient symptom management and disease control, leading to improved quality of life and reduced complications associated with PV. I believe that findings from this trial could thus pave the way for optimized treatment strategies and better outcomes for individuals living with PV.

What should future trials focus on to help improve prognosis and survival for patients with PV?

Dr. Richard: We are starting to move increasingly into finding better therapies for patients with PV, and I’ll add in essential thrombocytosis, which are based on informed prognostication. I would love to see studies that just pull out the patients at the highest risk, where the survival is down around 5 years—those are small numbers of patients. To conduct a study like that is exceedingly difficult to do. We are seeing increased consortiums of myeloproliferative neoplasm physicians. Europe has always been particularly good at this. The United States is getting better at it, so it is possible that a trial like that could be pulled together, where centers put in 1 or 2 patients at a time.

Future trials aimed at improving prognosis and survival for PV should prioritize several critical areas. First, there is a need for comprehensive studies to better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying PV pathogenesis, including the JAK2 mutation and its downstream effects. Exploring new therapeutic implications and improve long-term outcomes. Additionally, identifying reliable biomarkers for disease progression and treatment response can facilitate early intervention and personalized treatment approaches. Finally, trials should focus on assessing the impact of treatment on quality of life and addressing the unique needs of patients with PV to optimize overall prognosis and survival.

I have always held hope that the Veterans Administration could serve as a platform for conducting some of these studies, given that we possess the largest healthcare system in the country. Whether we participate in larger studies or conduct our research internally, this is something I have long envisioned.

There are several new therapies on the horizon for polycythemia vera. What is the potential impact of these treatments coming to market?

Dr. Richard: There are a number of emerging therapies for polycythemia vera (PV), such as PTG-300, idasanutlin, and givinostat. PTG-300, or rusfertide, is a hepcidin mimetic that works by regulating iron metabolism and potentially controlling erythropoiesis, limiting the need for phlebotomy. Idasanutlin, a selective MDM2 inhibitor, targets p53 activity. Even though this drug is early in its development, everyone who treats patients with cancer has been hoping for a drug that works through p53. If it is effective here, who knows where else it could be effective across various other conditions.

Givinostat is well along the development pathway in advanced trials. This drug shows promise in modulating gene expression and reducing the inflammation and fibrosis associated with PV, potentially improving patient outcomes and quality of life. Everyone is hopeful that givinostat could show some effect on disease control and potentially an effect on the myeloproliferative clone. However, rigorous clinical trials and further research are necessary to validate their efficacy, safety profiles, and long-term impacts on patients with PV.

Now, with the approval of peginterferon, the next step is going to be to see how effective it will be and what the adverse events might be. I think we will be getting more data as it starts to be used more. My prediction is that there will be a slow uptake, largely because many older physicians such as myself remember the significant side effects from interferon in the past. Despite being an FDA-approved treatment, it remains an emerging therapy, particularly in the United States. Its adoption and efficacy will become clearer as time progresses.

Another promising drug early in its development is bomedemstat, which functions through a different mechanism as a deacetylase. While the potential effect of histone deacetylase drugs on patient treatment outcomes remains uncertain this year, there might be significant data—either positive or negative—that accelerate the progress of these drugs in their developmental trajectory.

We know that ruxolitinib can be used effectively for patients once they fail hydroxyurea. And now there has been the development of other JAK2 inhibitors that are approved for myelofibrosis. I am not quite sure how they can be evaluated in PV, since we are talking about relatively small numbers of patients, but they do seem to have some slight differences that may be significant and could be used in this space.

Those are the main therapies that I will have my eye on this year.

What is the potential significance of an accelerated dosing schedule for BESREMi (ropeginterferon-alfa-2b-njft), which is being investigated in the ECLIPSE PV phase 3b clinical trial?

Dr. Richard: The potential significance of an accelerated dosing schedule for BESREMi, as investigated in the ECLIPSE PV phase 3b clinical trial, lies in its capacity to enhance treatment efficacy and outcomes for patients with PV. I am incredibly pleased that it is being done as a trial, partly because a lot of people assume that once a phase 3 study is complete and a drug receives FDA approval, everything is finished and done, and we will move on to the next thing. I really appreciate it when phase 3b or 4 studies are performed, and the data get collected and published.

This study is going to follow a group of patients closely for adverse events and for the JAK2 signal. By administering BESREMi at an accelerated pace, researchers can evaluate its ability to better control hematocrit levels and symptoms associated with PV. In addition, an accelerated dosing schedule could potentially offer patients more efficient symptom management and disease control, leading to improved quality of life and reduced complications associated with PV. I believe that findings from this trial could thus pave the way for optimized treatment strategies and better outcomes for individuals living with PV.

What should future trials focus on to help improve prognosis and survival for patients with PV?

Dr. Richard: We are starting to move increasingly into finding better therapies for patients with PV, and I’ll add in essential thrombocytosis, which are based on informed prognostication. I would love to see studies that just pull out the patients at the highest risk, where the survival is down around 5 years—those are small numbers of patients. To conduct a study like that is exceedingly difficult to do. We are seeing increased consortiums of myeloproliferative neoplasm physicians. Europe has always been particularly good at this. The United States is getting better at it, so it is possible that a trial like that could be pulled together, where centers put in 1 or 2 patients at a time.

Future trials aimed at improving prognosis and survival for PV should prioritize several critical areas. First, there is a need for comprehensive studies to better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying PV pathogenesis, including the JAK2 mutation and its downstream effects. Exploring new therapeutic implications and improve long-term outcomes. Additionally, identifying reliable biomarkers for disease progression and treatment response can facilitate early intervention and personalized treatment approaches. Finally, trials should focus on assessing the impact of treatment on quality of life and addressing the unique needs of patients with PV to optimize overall prognosis and survival.

I have always held hope that the Veterans Administration could serve as a platform for conducting some of these studies, given that we possess the largest healthcare system in the country. Whether we participate in larger studies or conduct our research internally, this is something I have long envisioned.

There are several new therapies on the horizon for polycythemia vera. What is the potential impact of these treatments coming to market?

Dr. Richard: There are a number of emerging therapies for polycythemia vera (PV), such as PTG-300, idasanutlin, and givinostat. PTG-300, or rusfertide, is a hepcidin mimetic that works by regulating iron metabolism and potentially controlling erythropoiesis, limiting the need for phlebotomy. Idasanutlin, a selective MDM2 inhibitor, targets p53 activity. Even though this drug is early in its development, everyone who treats patients with cancer has been hoping for a drug that works through p53. If it is effective here, who knows where else it could be effective across various other conditions.

Givinostat is well along the development pathway in advanced trials. This drug shows promise in modulating gene expression and reducing the inflammation and fibrosis associated with PV, potentially improving patient outcomes and quality of life. Everyone is hopeful that givinostat could show some effect on disease control and potentially an effect on the myeloproliferative clone. However, rigorous clinical trials and further research are necessary to validate their efficacy, safety profiles, and long-term impacts on patients with PV.

Now, with the approval of peginterferon, the next step is going to be to see how effective it will be and what the adverse events might be. I think we will be getting more data as it starts to be used more. My prediction is that there will be a slow uptake, largely because many older physicians such as myself remember the significant side effects from interferon in the past. Despite being an FDA-approved treatment, it remains an emerging therapy, particularly in the United States. Its adoption and efficacy will become clearer as time progresses.

Another promising drug early in its development is bomedemstat, which functions through a different mechanism as a deacetylase. While the potential effect of histone deacetylase drugs on patient treatment outcomes remains uncertain this year, there might be significant data—either positive or negative—that accelerate the progress of these drugs in their developmental trajectory.

We know that ruxolitinib can be used effectively for patients once they fail hydroxyurea. And now there has been the development of other JAK2 inhibitors that are approved for myelofibrosis. I am not quite sure how they can be evaluated in PV, since we are talking about relatively small numbers of patients, but they do seem to have some slight differences that may be significant and could be used in this space.

Those are the main therapies that I will have my eye on this year.

What is the potential significance of an accelerated dosing schedule for BESREMi (ropeginterferon-alfa-2b-njft), which is being investigated in the ECLIPSE PV phase 3b clinical trial?

Dr. Richard: The potential significance of an accelerated dosing schedule for BESREMi, as investigated in the ECLIPSE PV phase 3b clinical trial, lies in its capacity to enhance treatment efficacy and outcomes for patients with PV. I am incredibly pleased that it is being done as a trial, partly because a lot of people assume that once a phase 3 study is complete and a drug receives FDA approval, everything is finished and done, and we will move on to the next thing. I really appreciate it when phase 3b or 4 studies are performed, and the data get collected and published.

This study is going to follow a group of patients closely for adverse events and for the JAK2 signal. By administering BESREMi at an accelerated pace, researchers can evaluate its ability to better control hematocrit levels and symptoms associated with PV. In addition, an accelerated dosing schedule could potentially offer patients more efficient symptom management and disease control, leading to improved quality of life and reduced complications associated with PV. I believe that findings from this trial could thus pave the way for optimized treatment strategies and better outcomes for individuals living with PV.

What should future trials focus on to help improve prognosis and survival for patients with PV?

Dr. Richard: We are starting to move increasingly into finding better therapies for patients with PV, and I’ll add in essential thrombocytosis, which are based on informed prognostication. I would love to see studies that just pull out the patients at the highest risk, where the survival is down around 5 years—those are small numbers of patients. To conduct a study like that is exceedingly difficult to do. We are seeing increased consortiums of myeloproliferative neoplasm physicians. Europe has always been particularly good at this. The United States is getting better at it, so it is possible that a trial like that could be pulled together, where centers put in 1 or 2 patients at a time.

Future trials aimed at improving prognosis and survival for PV should prioritize several critical areas. First, there is a need for comprehensive studies to better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying PV pathogenesis, including the JAK2 mutation and its downstream effects. Exploring new therapeutic implications and improve long-term outcomes. Additionally, identifying reliable biomarkers for disease progression and treatment response can facilitate early intervention and personalized treatment approaches. Finally, trials should focus on assessing the impact of treatment on quality of life and addressing the unique needs of patients with PV to optimize overall prognosis and survival.

I have always held hope that the Veterans Administration could serve as a platform for conducting some of these studies, given that we possess the largest healthcare system in the country. Whether we participate in larger studies or conduct our research internally, this is something I have long envisioned.

JAK Inhibitors for Vitiligo: Response Continues Over Time

SAN DIEGO — according to presentations at a late-breaking session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD).

In one, the addition of narrow-band ultraviolet-B (NB-UVB) light therapy to ritlecitinib appears more effective than ritlecitinib alone. In the other study, the effectiveness of upadacitinib appears to improve over time.

Based on the ritlecitinib data, “if you have phototherapy in your office, it might be good to couple it with ritlecitinib for vitiligo patients,” said Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, who presented the findings.

However, because of the relatively small numbers in the extension study, Dr. Guttman-Yassky characterized the evidence as preliminary and in need of further investigation.

For vitiligo, the only approved JAK inhibitor is ruxolitinib, 1.5%, in a cream formulation. In June, ritlecitinib (Litfulo) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for alopecia areata. Phototherapy, which has been used for decades in the treatment of vitiligo, has an established efficacy and safety profile as a stand-alone vitiligo treatment. Upadacitinib has numerous indications for inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, and was granted FDA approval for atopic dermatitis in 2022.

NB-UVB Arm Added in Ritlecitinib Extension

The ritlecitinib study population was drawn from patients with non-segmental vitiligo who initially participated in a 24-week dose-ranging period of a phase 2b trial published last year. In that study, 364 patients were randomized to doses of once-daily ritlecitinib ranging from 10 to 50 mg with or without a 4-week loading regimen. Higher doses were generally associated with greater efficacy on the primary endpoint of facial vitiligo area scoring index (F-VASI) but not with a greater risk for adverse events.

In the 24-week extension study, 187 patients received a 4-week loading regimen of 200-mg ritlecitinib daily followed by 50 mg of daily ritlecitinib for the remaining 20 weeks. Another 43 patients were randomized to one of two arms: The same 4-week loading regimen of 200-mg ritlecitinib daily followed by 50 mg of daily ritlecitinib or to 50-mg daily ritlecitinib without a loading dose but combined with NB-UVB delivered twice per week.

Important to interpretation of results, there was an additional twist. Patients in the randomized arm who had < 10% improvement in the total vitiligo area severity index (T-VASI) at week 12 of the extension were discontinued from the study.

The endpoints considered when comparing ritlecitinib with or without NB-UVB at the end of the extension study were F-VASI, T-VASI, patient global impression of change, and adverse events. Responses were assessed on the basis of both observed and last observation carried forward (LOCF).

Of the 43 people, who were randomized in the extension study, nine (21%) had < 10% improvement in T-VASI and were therefore discontinued from the study.

At the end of 24 weeks, both groups had a substantial response to their assigned therapy, but the addition of NB-UVB increased rates of response, although not always at a level of statistical significance, according to Dr. Guttman-Yassky.

For the percent improvement in F-VASI, specifically, the increase did not reach significance on the basis of LOCF (57.9% vs 51.5%; P = .158) but was highly significant on the basis of observed responses (69.6% vs 55.1%; P = .009). For T-VASI, differences for adjunctive NB-UVB over monotherapy did not reach significance for either observed or LOCF responses, but it was significant for observed responses in a patient global impression of change.

Small Numbers Limit Strength of Ritlecitinib, NB-UVB Evidence

However, Dr. Guttman-Yassky said it is important “to pay attention to the sample sizes” when noting the lack of significance.

The combination appeared safe, and there were no side effects associated with the addition of twice-weekly NB-UVB to ritlecitinib.

She acknowledged that the design of this analysis was “complicated” and that the number of randomized patients was small. She suggested the findings support the potential for benefit from the combination of a JAK inhibitor and NB-UVB, both of which have shown efficacy as monotherapy in previous studies. She indicated that a trial of this combination is reasonable while awaiting a more definitive study.

One of the questions that might be posed in a larger study is the timing of NB-UVB, such as whether it is best reserved for those with inadequate early response to a JAK inhibitor or if optimal results are achieved when a JAK inhibitor and NB-UVB are initiated simultaneously.

Upadacitinib Monotherapy Results

One rationale for initiating therapy with the combination of a JAK inhibitor and NB-UVB is the potential for a more rapid response, but extended results from a second phase 2b study with a different oral JAK inhibitor, upadacitinib, suggested responses on JAK inhibitor monotherapy improve steadily over time.

“The overall efficacy continued to improve without reaching a plateau at 1 year,” reported Thierry Passeron, MD, PhD, professor and chair, Department of Dermatology, Université Côte d’Azur, Nice, France. He spoke at the same AAD late-breaking session as Dr. Guttman-Yassky.

The 24-week dose-ranging data from the upadacitinib trial were previously reported at the 2023 annual meeting of the European Association of Dermatology and Venereology. In the placebo-controlled portion, which randomized 185 patients with extensive non-segmental vitiligo to 6 mg, 11 mg, or 22 mg, the two higher doses were significantly more effective than placebo.

In the extension, patients in the placebo group were randomized to 11 mg or 22 mg, while those in the higher dose groups remained on their assigned therapies.

F-VASI Almost Doubled in Extension Trial

From week 24 to week 52, there was nearly a doubling of the percent F-VASI reduction, climbing from 32% to 60.8% in the 11-mg group and from 38.7% to 64.9% in the 22-mg group, Dr. Passeron said. Placebo groups who were switched to active therapy at 24 weeks rapidly approached the rates of F-VASI response of those initiated on upadacitinib.

The percent reductions in T-VASI, although lower, followed the same pattern. For the 11-mg group, the reduction climbed from 16% at 24 weeks to 44.7% at 52 weeks. For the 22-mg group, the reduction climbed from 22.9% to 44.4%. Patients who were switched from placebo to 11 mg or to 22 mg also experienced improvements in T-VASI up to 52 weeks, although the level of improvement was lower than that in patients initially randomized to the higher doses of upadacitinib.

There were “no new safety signals” for upadacitinib, which is FDA-approved for multiple indications, according to Dr. Passeron. He said acne-like lesions were the most bothersome adverse event, and cases of herpes zoster were “rare.”

A version of these data was published in a British Journal of Dermatology supplement just prior to the AAD meeting.

Phase 3 vitiligo trials are planned for both ritlecitinib and upadacitinib.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported financial relationships with approximately 45 pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer, which makes ritlecitinib and provided funding for the study she discussed. Dr. Passeron reported financial relationships with approximately 40 pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, which makes upadacitinib and provided funding for the study he discussed.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — according to presentations at a late-breaking session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD).

In one, the addition of narrow-band ultraviolet-B (NB-UVB) light therapy to ritlecitinib appears more effective than ritlecitinib alone. In the other study, the effectiveness of upadacitinib appears to improve over time.

Based on the ritlecitinib data, “if you have phototherapy in your office, it might be good to couple it with ritlecitinib for vitiligo patients,” said Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, who presented the findings.

However, because of the relatively small numbers in the extension study, Dr. Guttman-Yassky characterized the evidence as preliminary and in need of further investigation.

For vitiligo, the only approved JAK inhibitor is ruxolitinib, 1.5%, in a cream formulation. In June, ritlecitinib (Litfulo) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for alopecia areata. Phototherapy, which has been used for decades in the treatment of vitiligo, has an established efficacy and safety profile as a stand-alone vitiligo treatment. Upadacitinib has numerous indications for inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, and was granted FDA approval for atopic dermatitis in 2022.

NB-UVB Arm Added in Ritlecitinib Extension

The ritlecitinib study population was drawn from patients with non-segmental vitiligo who initially participated in a 24-week dose-ranging period of a phase 2b trial published last year. In that study, 364 patients were randomized to doses of once-daily ritlecitinib ranging from 10 to 50 mg with or without a 4-week loading regimen. Higher doses were generally associated with greater efficacy on the primary endpoint of facial vitiligo area scoring index (F-VASI) but not with a greater risk for adverse events.

In the 24-week extension study, 187 patients received a 4-week loading regimen of 200-mg ritlecitinib daily followed by 50 mg of daily ritlecitinib for the remaining 20 weeks. Another 43 patients were randomized to one of two arms: The same 4-week loading regimen of 200-mg ritlecitinib daily followed by 50 mg of daily ritlecitinib or to 50-mg daily ritlecitinib without a loading dose but combined with NB-UVB delivered twice per week.

Important to interpretation of results, there was an additional twist. Patients in the randomized arm who had < 10% improvement in the total vitiligo area severity index (T-VASI) at week 12 of the extension were discontinued from the study.

The endpoints considered when comparing ritlecitinib with or without NB-UVB at the end of the extension study were F-VASI, T-VASI, patient global impression of change, and adverse events. Responses were assessed on the basis of both observed and last observation carried forward (LOCF).

Of the 43 people, who were randomized in the extension study, nine (21%) had < 10% improvement in T-VASI and were therefore discontinued from the study.

At the end of 24 weeks, both groups had a substantial response to their assigned therapy, but the addition of NB-UVB increased rates of response, although not always at a level of statistical significance, according to Dr. Guttman-Yassky.

For the percent improvement in F-VASI, specifically, the increase did not reach significance on the basis of LOCF (57.9% vs 51.5%; P = .158) but was highly significant on the basis of observed responses (69.6% vs 55.1%; P = .009). For T-VASI, differences for adjunctive NB-UVB over monotherapy did not reach significance for either observed or LOCF responses, but it was significant for observed responses in a patient global impression of change.

Small Numbers Limit Strength of Ritlecitinib, NB-UVB Evidence

However, Dr. Guttman-Yassky said it is important “to pay attention to the sample sizes” when noting the lack of significance.

The combination appeared safe, and there were no side effects associated with the addition of twice-weekly NB-UVB to ritlecitinib.

She acknowledged that the design of this analysis was “complicated” and that the number of randomized patients was small. She suggested the findings support the potential for benefit from the combination of a JAK inhibitor and NB-UVB, both of which have shown efficacy as monotherapy in previous studies. She indicated that a trial of this combination is reasonable while awaiting a more definitive study.

One of the questions that might be posed in a larger study is the timing of NB-UVB, such as whether it is best reserved for those with inadequate early response to a JAK inhibitor or if optimal results are achieved when a JAK inhibitor and NB-UVB are initiated simultaneously.

Upadacitinib Monotherapy Results

One rationale for initiating therapy with the combination of a JAK inhibitor and NB-UVB is the potential for a more rapid response, but extended results from a second phase 2b study with a different oral JAK inhibitor, upadacitinib, suggested responses on JAK inhibitor monotherapy improve steadily over time.

“The overall efficacy continued to improve without reaching a plateau at 1 year,” reported Thierry Passeron, MD, PhD, professor and chair, Department of Dermatology, Université Côte d’Azur, Nice, France. He spoke at the same AAD late-breaking session as Dr. Guttman-Yassky.

The 24-week dose-ranging data from the upadacitinib trial were previously reported at the 2023 annual meeting of the European Association of Dermatology and Venereology. In the placebo-controlled portion, which randomized 185 patients with extensive non-segmental vitiligo to 6 mg, 11 mg, or 22 mg, the two higher doses were significantly more effective than placebo.

In the extension, patients in the placebo group were randomized to 11 mg or 22 mg, while those in the higher dose groups remained on their assigned therapies.

F-VASI Almost Doubled in Extension Trial

From week 24 to week 52, there was nearly a doubling of the percent F-VASI reduction, climbing from 32% to 60.8% in the 11-mg group and from 38.7% to 64.9% in the 22-mg group, Dr. Passeron said. Placebo groups who were switched to active therapy at 24 weeks rapidly approached the rates of F-VASI response of those initiated on upadacitinib.

The percent reductions in T-VASI, although lower, followed the same pattern. For the 11-mg group, the reduction climbed from 16% at 24 weeks to 44.7% at 52 weeks. For the 22-mg group, the reduction climbed from 22.9% to 44.4%. Patients who were switched from placebo to 11 mg or to 22 mg also experienced improvements in T-VASI up to 52 weeks, although the level of improvement was lower than that in patients initially randomized to the higher doses of upadacitinib.

There were “no new safety signals” for upadacitinib, which is FDA-approved for multiple indications, according to Dr. Passeron. He said acne-like lesions were the most bothersome adverse event, and cases of herpes zoster were “rare.”

A version of these data was published in a British Journal of Dermatology supplement just prior to the AAD meeting.

Phase 3 vitiligo trials are planned for both ritlecitinib and upadacitinib.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported financial relationships with approximately 45 pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer, which makes ritlecitinib and provided funding for the study she discussed. Dr. Passeron reported financial relationships with approximately 40 pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, which makes upadacitinib and provided funding for the study he discussed.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO — according to presentations at a late-breaking session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD).

In one, the addition of narrow-band ultraviolet-B (NB-UVB) light therapy to ritlecitinib appears more effective than ritlecitinib alone. In the other study, the effectiveness of upadacitinib appears to improve over time.

Based on the ritlecitinib data, “if you have phototherapy in your office, it might be good to couple it with ritlecitinib for vitiligo patients,” said Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, who presented the findings.

However, because of the relatively small numbers in the extension study, Dr. Guttman-Yassky characterized the evidence as preliminary and in need of further investigation.

For vitiligo, the only approved JAK inhibitor is ruxolitinib, 1.5%, in a cream formulation. In June, ritlecitinib (Litfulo) was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for alopecia areata. Phototherapy, which has been used for decades in the treatment of vitiligo, has an established efficacy and safety profile as a stand-alone vitiligo treatment. Upadacitinib has numerous indications for inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, and was granted FDA approval for atopic dermatitis in 2022.

NB-UVB Arm Added in Ritlecitinib Extension

The ritlecitinib study population was drawn from patients with non-segmental vitiligo who initially participated in a 24-week dose-ranging period of a phase 2b trial published last year. In that study, 364 patients were randomized to doses of once-daily ritlecitinib ranging from 10 to 50 mg with or without a 4-week loading regimen. Higher doses were generally associated with greater efficacy on the primary endpoint of facial vitiligo area scoring index (F-VASI) but not with a greater risk for adverse events.

In the 24-week extension study, 187 patients received a 4-week loading regimen of 200-mg ritlecitinib daily followed by 50 mg of daily ritlecitinib for the remaining 20 weeks. Another 43 patients were randomized to one of two arms: The same 4-week loading regimen of 200-mg ritlecitinib daily followed by 50 mg of daily ritlecitinib or to 50-mg daily ritlecitinib without a loading dose but combined with NB-UVB delivered twice per week.

Important to interpretation of results, there was an additional twist. Patients in the randomized arm who had < 10% improvement in the total vitiligo area severity index (T-VASI) at week 12 of the extension were discontinued from the study.

The endpoints considered when comparing ritlecitinib with or without NB-UVB at the end of the extension study were F-VASI, T-VASI, patient global impression of change, and adverse events. Responses were assessed on the basis of both observed and last observation carried forward (LOCF).

Of the 43 people, who were randomized in the extension study, nine (21%) had < 10% improvement in T-VASI and were therefore discontinued from the study.

At the end of 24 weeks, both groups had a substantial response to their assigned therapy, but the addition of NB-UVB increased rates of response, although not always at a level of statistical significance, according to Dr. Guttman-Yassky.

For the percent improvement in F-VASI, specifically, the increase did not reach significance on the basis of LOCF (57.9% vs 51.5%; P = .158) but was highly significant on the basis of observed responses (69.6% vs 55.1%; P = .009). For T-VASI, differences for adjunctive NB-UVB over monotherapy did not reach significance for either observed or LOCF responses, but it was significant for observed responses in a patient global impression of change.

Small Numbers Limit Strength of Ritlecitinib, NB-UVB Evidence

However, Dr. Guttman-Yassky said it is important “to pay attention to the sample sizes” when noting the lack of significance.

The combination appeared safe, and there were no side effects associated with the addition of twice-weekly NB-UVB to ritlecitinib.

She acknowledged that the design of this analysis was “complicated” and that the number of randomized patients was small. She suggested the findings support the potential for benefit from the combination of a JAK inhibitor and NB-UVB, both of which have shown efficacy as monotherapy in previous studies. She indicated that a trial of this combination is reasonable while awaiting a more definitive study.

One of the questions that might be posed in a larger study is the timing of NB-UVB, such as whether it is best reserved for those with inadequate early response to a JAK inhibitor or if optimal results are achieved when a JAK inhibitor and NB-UVB are initiated simultaneously.

Upadacitinib Monotherapy Results

One rationale for initiating therapy with the combination of a JAK inhibitor and NB-UVB is the potential for a more rapid response, but extended results from a second phase 2b study with a different oral JAK inhibitor, upadacitinib, suggested responses on JAK inhibitor monotherapy improve steadily over time.

“The overall efficacy continued to improve without reaching a plateau at 1 year,” reported Thierry Passeron, MD, PhD, professor and chair, Department of Dermatology, Université Côte d’Azur, Nice, France. He spoke at the same AAD late-breaking session as Dr. Guttman-Yassky.

The 24-week dose-ranging data from the upadacitinib trial were previously reported at the 2023 annual meeting of the European Association of Dermatology and Venereology. In the placebo-controlled portion, which randomized 185 patients with extensive non-segmental vitiligo to 6 mg, 11 mg, or 22 mg, the two higher doses were significantly more effective than placebo.

In the extension, patients in the placebo group were randomized to 11 mg or 22 mg, while those in the higher dose groups remained on their assigned therapies.

F-VASI Almost Doubled in Extension Trial

From week 24 to week 52, there was nearly a doubling of the percent F-VASI reduction, climbing from 32% to 60.8% in the 11-mg group and from 38.7% to 64.9% in the 22-mg group, Dr. Passeron said. Placebo groups who were switched to active therapy at 24 weeks rapidly approached the rates of F-VASI response of those initiated on upadacitinib.

The percent reductions in T-VASI, although lower, followed the same pattern. For the 11-mg group, the reduction climbed from 16% at 24 weeks to 44.7% at 52 weeks. For the 22-mg group, the reduction climbed from 22.9% to 44.4%. Patients who were switched from placebo to 11 mg or to 22 mg also experienced improvements in T-VASI up to 52 weeks, although the level of improvement was lower than that in patients initially randomized to the higher doses of upadacitinib.

There were “no new safety signals” for upadacitinib, which is FDA-approved for multiple indications, according to Dr. Passeron. He said acne-like lesions were the most bothersome adverse event, and cases of herpes zoster were “rare.”

A version of these data was published in a British Journal of Dermatology supplement just prior to the AAD meeting.

Phase 3 vitiligo trials are planned for both ritlecitinib and upadacitinib.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported financial relationships with approximately 45 pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer, which makes ritlecitinib and provided funding for the study she discussed. Dr. Passeron reported financial relationships with approximately 40 pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, which makes upadacitinib and provided funding for the study he discussed.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM AAD 2024

Trauma, Racism Linked to Increased Suicide Risk in Black Men

One in three Black men in rural America experienced suicidal or death ideation (SDI) in the past week, new research showed.

A developmental model used in the study showed a direct association between experiences pertaining to threat, deprivation, and racial discrimination during childhood and suicide risk in adulthood, suggesting that a broad range of adverse experiences in early life may affect SDI risk among Black men.

“During the past 20-30 years, young Black men have evinced increasing levels of suicidal behavior and related cognitions,” lead author Steven Kogan, PhD, professor of family and consumer sciences at the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, and colleagues wrote.

“By controlling for depressive symptoms in assessing increases in SDI over time, our study’s design directly informed the extent to which social adversities affect SDI independent of other depressive problems,” they added.

The findings were published online in Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology.

Second Leading Cause of Death

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for Black Americans ages 15-24, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The outlook is worse for Black men, whose death rate from suicide is about four times greater than for Black women.

Previous research suggests Black men are disproportionately exposed to social adversity, including poverty and discrimination, which may increase the risk for SDI. In addition, racial discrimination has been shown to increase the risks for depression, anxiety, and psychological distress among Black youth and adults.

But little research exists to better understand how these negative experiences affect vulnerability to SDI. The new study tested a model linking adversity during childhood and emerging exposure to racial discrimination to increases in suicidal thoughts.

Researchers analyzed data from 504 participants in the African American Men’s Project, which included a series of surveys completed by young men in rural Georgia at three different time points over a period of about 3 years.

Composite scores for childhood threat and deprivation were developed using the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale and Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Everyday discrimination was measured on the Schedule of Racist Events response scale.

To assess their experience with childhood threats, the men in the study, who were about 21 years old on average when they enrolled, were asked if they experienced a series of adverse childhood experiences and deprivation through age 16. Questions explored issues such as directly experiencing physical violence or witnessing abuse in the home and whether the men felt loved and “important or special” as children.

The investigators also asked the men about their experiences of racial discrimination, the quality of their relationships, their belief that aggression is a means of gaining respect, and their cynicism regarding romantic relationships.

Targeted Prevention

Overall, 33.6% of participants reported SDI in the previous week. A history of childhood threats and deprivation was associated with an increased likelihood of SDI (P < .001).

Researchers also found that a history of racial discrimination was significantly associated with the development of negative relational schemas, which are characterized by beliefs that other people are untrustworthy, uncaring, and/or hostile. Negative schemas were in turn associated with an increased risk for suicidal thoughts (P = .03).

“Clinical and preventive interventions for suicidality should target the influence of racism and adverse experiences and the negative relational schemas they induce,” the investigators noted.

“Policy efforts designed to dismantle systemic racism are critically needed. Interventions that address SDI, including programming designed to support Black men through their experiences with racial discrimination and processing of childhood experiences of adversity, may help young Black men resist the psychological impacts of racism, expand their positive support networks, and decrease their risk of SDI,” they added.

The study authors reported no funding sources or relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

One in three Black men in rural America experienced suicidal or death ideation (SDI) in the past week, new research showed.

A developmental model used in the study showed a direct association between experiences pertaining to threat, deprivation, and racial discrimination during childhood and suicide risk in adulthood, suggesting that a broad range of adverse experiences in early life may affect SDI risk among Black men.

“During the past 20-30 years, young Black men have evinced increasing levels of suicidal behavior and related cognitions,” lead author Steven Kogan, PhD, professor of family and consumer sciences at the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, and colleagues wrote.

“By controlling for depressive symptoms in assessing increases in SDI over time, our study’s design directly informed the extent to which social adversities affect SDI independent of other depressive problems,” they added.

The findings were published online in Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology.

Second Leading Cause of Death

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for Black Americans ages 15-24, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The outlook is worse for Black men, whose death rate from suicide is about four times greater than for Black women.

Previous research suggests Black men are disproportionately exposed to social adversity, including poverty and discrimination, which may increase the risk for SDI. In addition, racial discrimination has been shown to increase the risks for depression, anxiety, and psychological distress among Black youth and adults.

But little research exists to better understand how these negative experiences affect vulnerability to SDI. The new study tested a model linking adversity during childhood and emerging exposure to racial discrimination to increases in suicidal thoughts.

Researchers analyzed data from 504 participants in the African American Men’s Project, which included a series of surveys completed by young men in rural Georgia at three different time points over a period of about 3 years.

Composite scores for childhood threat and deprivation were developed using the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale and Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Everyday discrimination was measured on the Schedule of Racist Events response scale.

To assess their experience with childhood threats, the men in the study, who were about 21 years old on average when they enrolled, were asked if they experienced a series of adverse childhood experiences and deprivation through age 16. Questions explored issues such as directly experiencing physical violence or witnessing abuse in the home and whether the men felt loved and “important or special” as children.

The investigators also asked the men about their experiences of racial discrimination, the quality of their relationships, their belief that aggression is a means of gaining respect, and their cynicism regarding romantic relationships.

Targeted Prevention

Overall, 33.6% of participants reported SDI in the previous week. A history of childhood threats and deprivation was associated with an increased likelihood of SDI (P < .001).

Researchers also found that a history of racial discrimination was significantly associated with the development of negative relational schemas, which are characterized by beliefs that other people are untrustworthy, uncaring, and/or hostile. Negative schemas were in turn associated with an increased risk for suicidal thoughts (P = .03).

“Clinical and preventive interventions for suicidality should target the influence of racism and adverse experiences and the negative relational schemas they induce,” the investigators noted.

“Policy efforts designed to dismantle systemic racism are critically needed. Interventions that address SDI, including programming designed to support Black men through their experiences with racial discrimination and processing of childhood experiences of adversity, may help young Black men resist the psychological impacts of racism, expand their positive support networks, and decrease their risk of SDI,” they added.

The study authors reported no funding sources or relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

One in three Black men in rural America experienced suicidal or death ideation (SDI) in the past week, new research showed.

A developmental model used in the study showed a direct association between experiences pertaining to threat, deprivation, and racial discrimination during childhood and suicide risk in adulthood, suggesting that a broad range of adverse experiences in early life may affect SDI risk among Black men.

“During the past 20-30 years, young Black men have evinced increasing levels of suicidal behavior and related cognitions,” lead author Steven Kogan, PhD, professor of family and consumer sciences at the University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia, and colleagues wrote.

“By controlling for depressive symptoms in assessing increases in SDI over time, our study’s design directly informed the extent to which social adversities affect SDI independent of other depressive problems,” they added.

The findings were published online in Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology.

Second Leading Cause of Death

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for Black Americans ages 15-24, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The outlook is worse for Black men, whose death rate from suicide is about four times greater than for Black women.

Previous research suggests Black men are disproportionately exposed to social adversity, including poverty and discrimination, which may increase the risk for SDI. In addition, racial discrimination has been shown to increase the risks for depression, anxiety, and psychological distress among Black youth and adults.

But little research exists to better understand how these negative experiences affect vulnerability to SDI. The new study tested a model linking adversity during childhood and emerging exposure to racial discrimination to increases in suicidal thoughts.

Researchers analyzed data from 504 participants in the African American Men’s Project, which included a series of surveys completed by young men in rural Georgia at three different time points over a period of about 3 years.

Composite scores for childhood threat and deprivation were developed using the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale and Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Everyday discrimination was measured on the Schedule of Racist Events response scale.

To assess their experience with childhood threats, the men in the study, who were about 21 years old on average when they enrolled, were asked if they experienced a series of adverse childhood experiences and deprivation through age 16. Questions explored issues such as directly experiencing physical violence or witnessing abuse in the home and whether the men felt loved and “important or special” as children.

The investigators also asked the men about their experiences of racial discrimination, the quality of their relationships, their belief that aggression is a means of gaining respect, and their cynicism regarding romantic relationships.

Targeted Prevention

Overall, 33.6% of participants reported SDI in the previous week. A history of childhood threats and deprivation was associated with an increased likelihood of SDI (P < .001).

Researchers also found that a history of racial discrimination was significantly associated with the development of negative relational schemas, which are characterized by beliefs that other people are untrustworthy, uncaring, and/or hostile. Negative schemas were in turn associated with an increased risk for suicidal thoughts (P = .03).

“Clinical and preventive interventions for suicidality should target the influence of racism and adverse experiences and the negative relational schemas they induce,” the investigators noted.

“Policy efforts designed to dismantle systemic racism are critically needed. Interventions that address SDI, including programming designed to support Black men through their experiences with racial discrimination and processing of childhood experiences of adversity, may help young Black men resist the psychological impacts of racism, expand their positive support networks, and decrease their risk of SDI,” they added.

The study authors reported no funding sources or relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CULTURAL DIVERSITY AND ETHNIC MINORITY PSYCHOLOGY

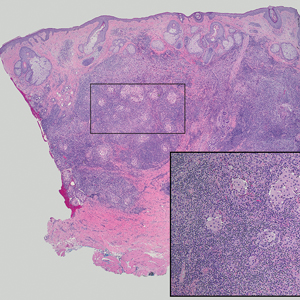

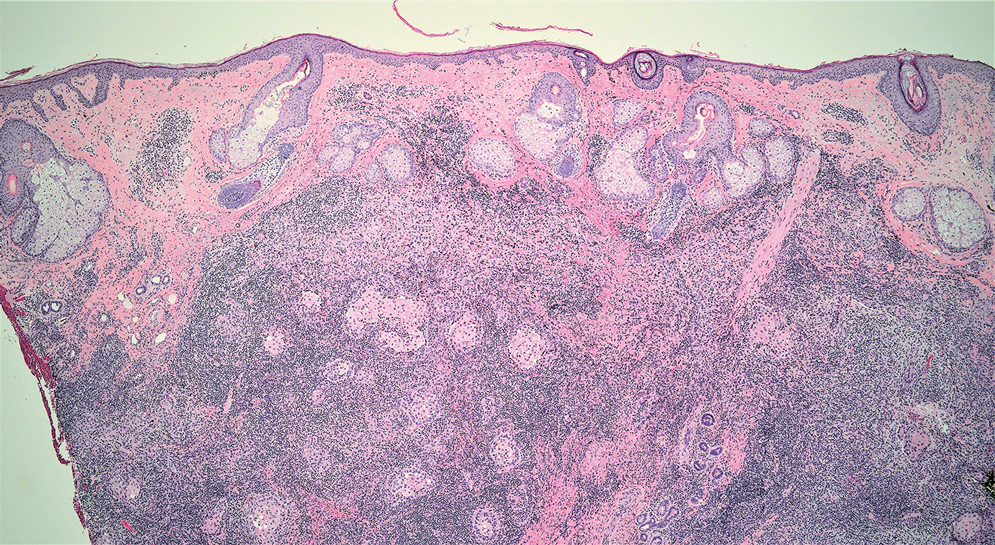

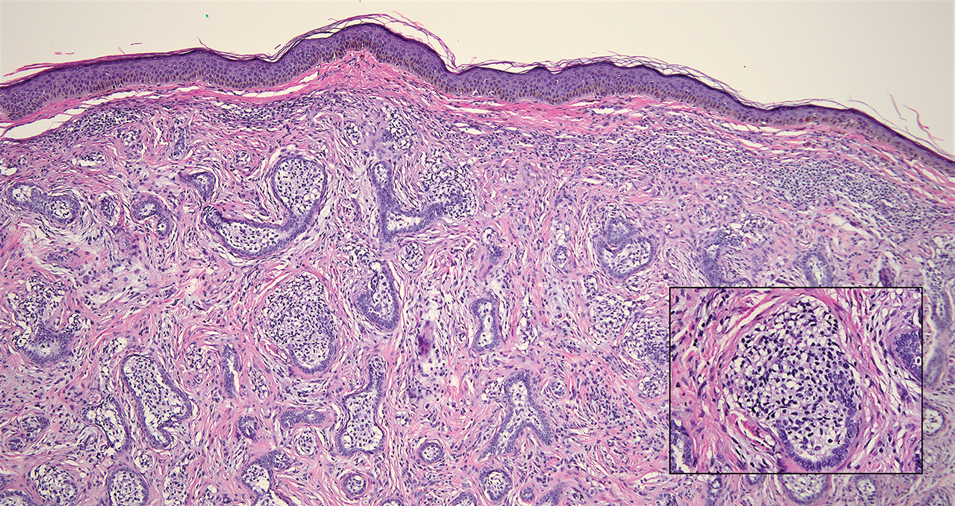

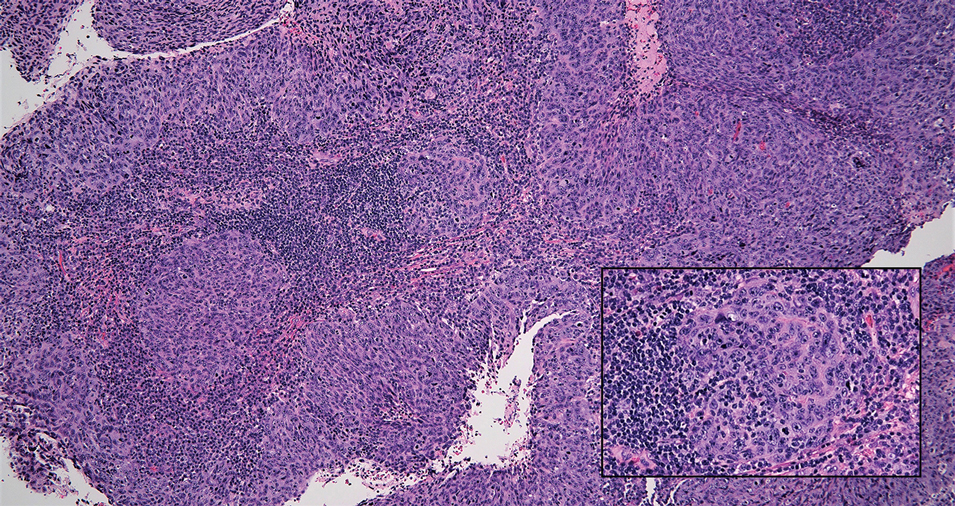

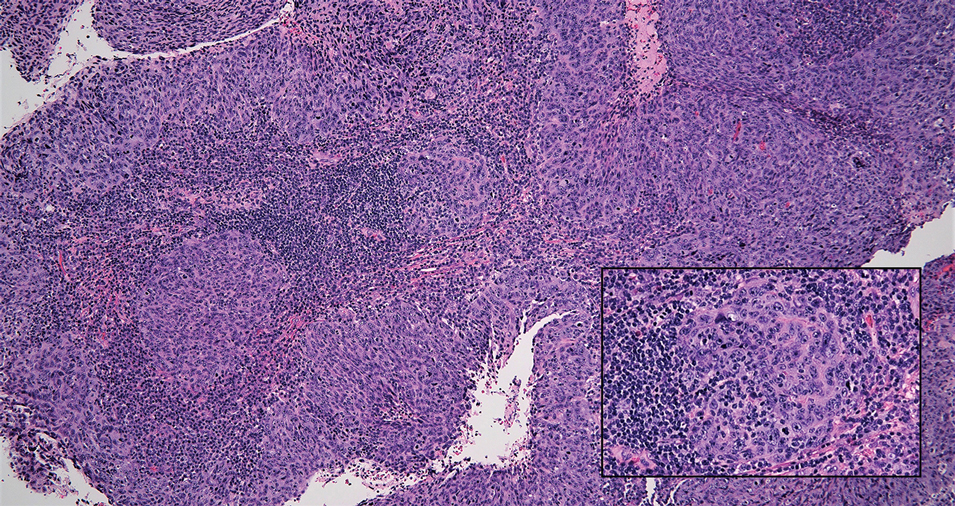

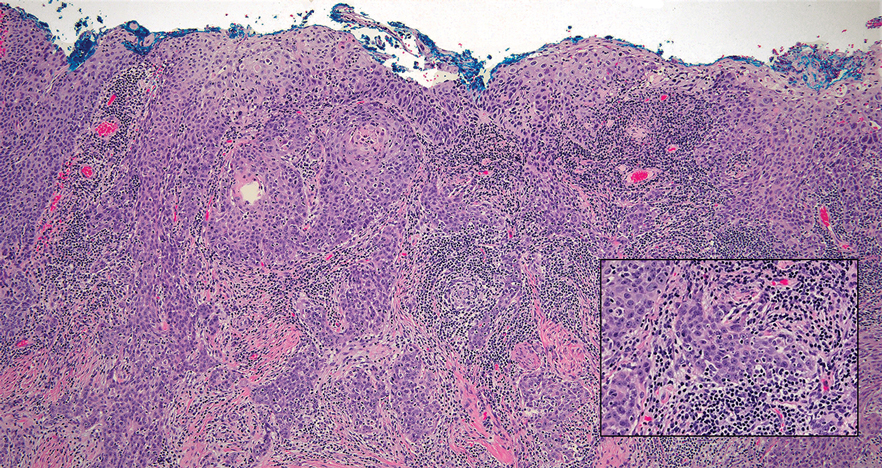

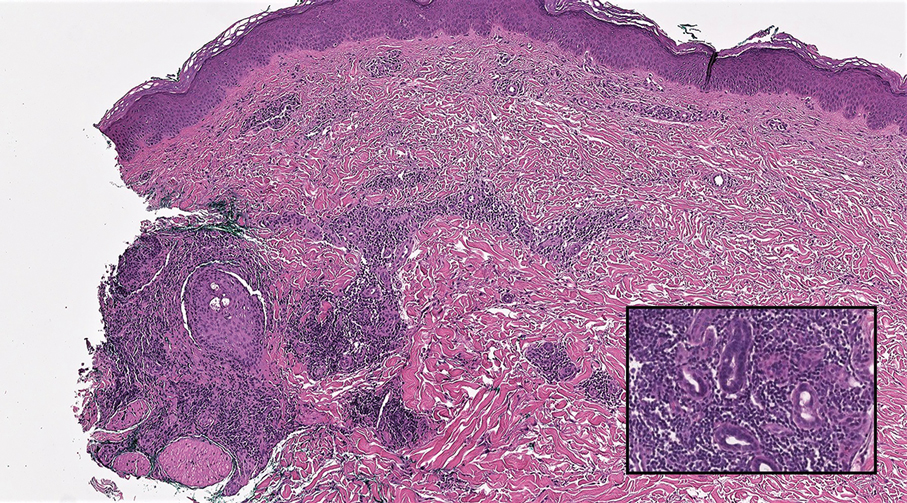

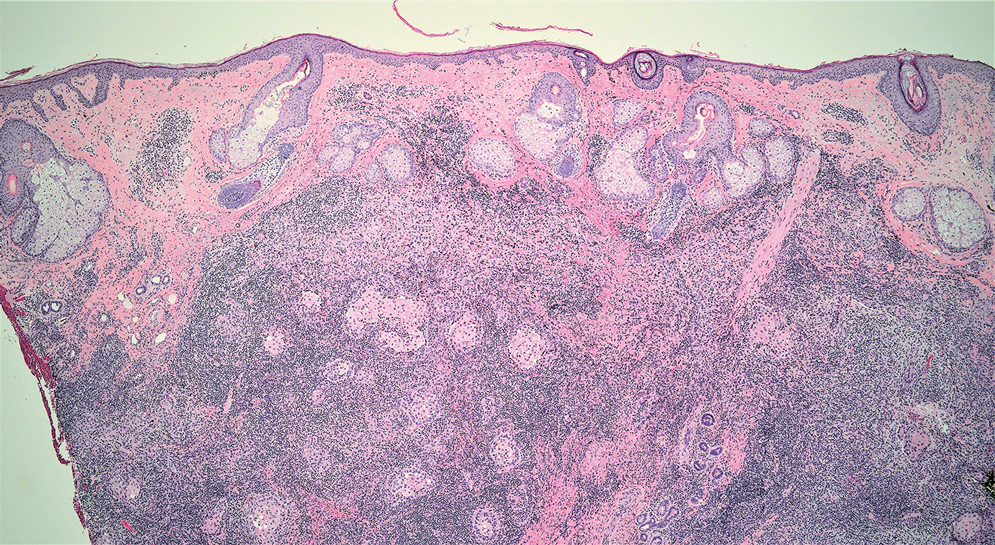

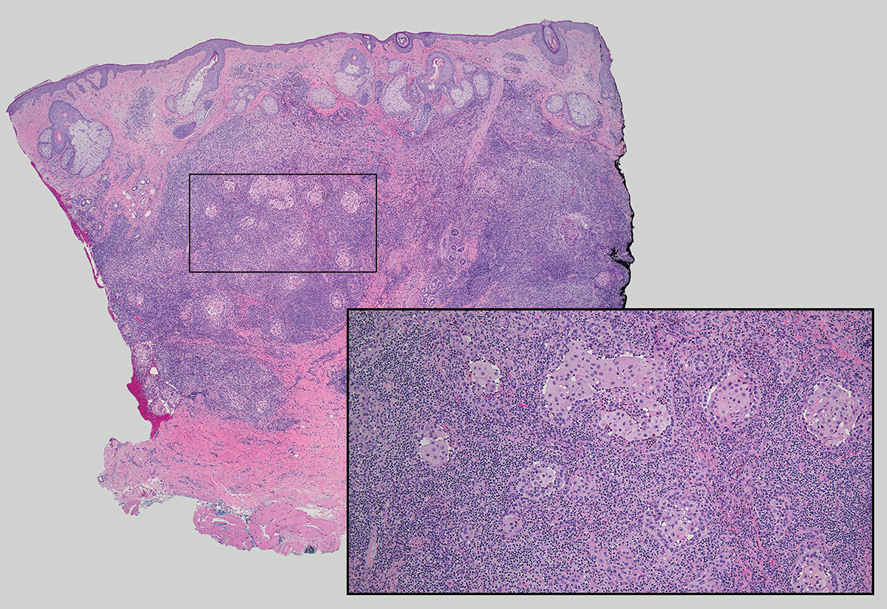

Do Tumor-infiltrating Lymphocytes Predict Better Breast Cancer Outcomes?

The association of abundant tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer tissue with outcomes in patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who do not receive chemotherapy has not been well studied, wrote Roberto A. Leon-Ferre, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, and colleagues, in JAMA.

Biomarkers to guide systemic treatment and avoid overtreatment are lacking, and such markers could help identify patients who could achieve increased survival with less intensive therapy, continued the authors of the new study of nearly 2000 individuals.

“TNBC is the most aggressive subtype of breast cancer, and for this reason, current treatment guidelines recommend chemotherapy using multiple drugs either before or after surgery,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said in an interview. “We have learned over the last several years that TNBC is not a single disease, but that there are several subtypes of TNBC that have different risks and different vulnerabilities, and treating all patients similarly may not be optimal.”

What is Known About Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Cancer?

Previous studies have shown improved survival in patients with early-stage TNBC and high levels of TILs who were treated with adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, compared with those with lower TILs. In a pooled analysis of 2148 patients from nine studies published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2019, a higher percentage of TILs in the stroma surrounding a tumor was significantly associated with improved survival in TNBC patients after adjuvant chemotherapy.

Another study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2022 showed that elevated TILs were significant predictors of overall survival, but the study included fewer than 500 patients.

The potential mechanisms that drive the association between elevated TILs and improved survival include the ability of TILs to attack cancer cells, Dr. Leon-Ferre said in an interview.

The goal of this study was to evaluate whether TILs could identify a subset of patients with TNBC who had a very low risk of cancer recurrence even if chemotherapy was not given.

“Indeed, we found that patients with stage I TNBC and high TILs had a very low risk of recurrence even when chemotherapy was not administered. These findings will pave the way for future studies aiming to reduce the need for multiple chemotherapy drugs in patients with stage I TNBC and decrease the side effects that patients face,” he said.

What Does the New Study Add?

The current study included 1966 individuals from 13 sites in North America, Europe, and Asia who were diagnosed with TNBC between 1979 and 2017 and were treated with surgery, with or without radiotherapy but with no adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The researchers examined the abundance of TILs in the breast tissue of resected primary tumors; the primary outcome was invasive disease-free survival (iDFS), with recurrence-free survival, distant recurrence-free survival, and overall survival as secondary outcomes.

The median age of the patients was 56 years, 55% had stage I TNBC, and the median TIL level was 15%.

A total of 417 patients had a TIL level of 50% or more, and the 5-year iDFS for these patients was 94%, compared with 78% for those with a TIL level less than 30%. Similarly, 5-year overall survival was 95% in patients with a TIL level of 50% or more, compared with 82% for patients with TIL levels of less than 30%.

Additionally, each 10% increase in TILs was independently associated not only with improved iDFS (hazard ratio[HR], 0.92), but also improved recurrence-free survival (HR, 0.90), distant recurrence-free survival (HR, 0.87), and overall survival (HR, 0.88) over a median follow-up of 18 years.

The current study shows that cancer stage based on tumor size and the number of lymph nodes should not be the only considerations for making treatment decisions and predicting outcomes, Dr. Leon-Ferre said in an interview.

“In fact, our study shows that for tumors of the same stage (particularly for stage I), the risk of recurrence is different depending on the number of TILs seen in the breast cancer tissue. When chemo is not given, those with high TILs have lower risk of recurrence, whereas those with low TILs have a higher risk of recurrence,” he said.

What are the Limitations of This Research?

The current study findings are limited by the retrospective design and use of observational data, so the researchers could not make conclusions about causality. Other limitations included lack of data on germline mutations and race or ethnicity, and the potential irrelevance of data from patients treated as long as 45 years ago.

“Because most patients with TNBC receive chemotherapy in the modern times, we needed to work with 13 hospitals around the world to find data on patients with TNBC who never received chemotherapy for various reasons,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said.

To address these limitations, Dr. Leone-Ferre and his colleagues are planning prospective studies where TILs will be used to make treatment decisions.

“Many of the patients in our cohort were treated many years ago, when chemotherapy was not routinely given. Advances in cancer detection, surgical and radiation techniques may lead to different results in patients treated today,” he added.

What Do Oncologists Need to Know?

The current study findings may provide additional information on prognosis that is important to share with patients for decision-making on the risks versus benefits of chemotherapy, Dr. Leon-Ferre said.

“Like any test, TILs should not be used in isolation to make decisions, but should be integrated with other factors including the cancer stage, the overall patient health, patient preferences, and concerns about treatment complications,” he emphasized. “The results of this study allow oncologists to offer a more refined calculation of recurrence risk if patients opt to not receive chemotherapy.”

In the current study, although younger age was associated with higher TIL levels, a finding consistent with previous studies, increased TIL, remained significantly associated with improved survival after adjusting for age, tumor size, nodal status, and histological grade.

Overall, “the findings suggest that for patients with stage I TNBC and TILs greater than 50%, chemotherapy may not be as necessary as it was previously thought,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said.

What Additional Research is Needed?

Prospective studies are needed to validate the findings, including studies in diverse populations, and additional studies may investigate whether early TBNC patients with high TIL levels could achieve high cure rates with less intensive and less toxic chemotherapy regiments than those currently recommended, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“There are many additional research questions that we need to answer, and look forward to working on,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said, in an interview. These topics include whether TILs can be used to decide on the number of chemotherapy drugs a patient really needs and whether artificial intelligence can be used to evaluate TILs more quickly and effectively than the human eye, he said. Other research topics include identifying which particular type of TILs attack cancer cells most effectively and whether TILs could be increased in patients with low levels in order to improve their prognosis, he added.

The study was supported by the National Research Agency and General Secretariat for Investment, Clinical and Translational Science Awards, the Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer SPORE grant, the Cancer Research Society of Canada, institutional grants from the Dutch Cancer Society, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research, and several foundations. Dr. Leon-Ferre disclosed consulting honoraria to his institution for research activities from AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences, and Lyell Immunopharma, with no personal fees outside the submitted work.

The association of abundant tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer tissue with outcomes in patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who do not receive chemotherapy has not been well studied, wrote Roberto A. Leon-Ferre, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, and colleagues, in JAMA.

Biomarkers to guide systemic treatment and avoid overtreatment are lacking, and such markers could help identify patients who could achieve increased survival with less intensive therapy, continued the authors of the new study of nearly 2000 individuals.

“TNBC is the most aggressive subtype of breast cancer, and for this reason, current treatment guidelines recommend chemotherapy using multiple drugs either before or after surgery,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said in an interview. “We have learned over the last several years that TNBC is not a single disease, but that there are several subtypes of TNBC that have different risks and different vulnerabilities, and treating all patients similarly may not be optimal.”

What is Known About Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Cancer?

Previous studies have shown improved survival in patients with early-stage TNBC and high levels of TILs who were treated with adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, compared with those with lower TILs. In a pooled analysis of 2148 patients from nine studies published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2019, a higher percentage of TILs in the stroma surrounding a tumor was significantly associated with improved survival in TNBC patients after adjuvant chemotherapy.

Another study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2022 showed that elevated TILs were significant predictors of overall survival, but the study included fewer than 500 patients.

The potential mechanisms that drive the association between elevated TILs and improved survival include the ability of TILs to attack cancer cells, Dr. Leon-Ferre said in an interview.

The goal of this study was to evaluate whether TILs could identify a subset of patients with TNBC who had a very low risk of cancer recurrence even if chemotherapy was not given.

“Indeed, we found that patients with stage I TNBC and high TILs had a very low risk of recurrence even when chemotherapy was not administered. These findings will pave the way for future studies aiming to reduce the need for multiple chemotherapy drugs in patients with stage I TNBC and decrease the side effects that patients face,” he said.

What Does the New Study Add?

The current study included 1966 individuals from 13 sites in North America, Europe, and Asia who were diagnosed with TNBC between 1979 and 2017 and were treated with surgery, with or without radiotherapy but with no adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The researchers examined the abundance of TILs in the breast tissue of resected primary tumors; the primary outcome was invasive disease-free survival (iDFS), with recurrence-free survival, distant recurrence-free survival, and overall survival as secondary outcomes.

The median age of the patients was 56 years, 55% had stage I TNBC, and the median TIL level was 15%.

A total of 417 patients had a TIL level of 50% or more, and the 5-year iDFS for these patients was 94%, compared with 78% for those with a TIL level less than 30%. Similarly, 5-year overall survival was 95% in patients with a TIL level of 50% or more, compared with 82% for patients with TIL levels of less than 30%.

Additionally, each 10% increase in TILs was independently associated not only with improved iDFS (hazard ratio[HR], 0.92), but also improved recurrence-free survival (HR, 0.90), distant recurrence-free survival (HR, 0.87), and overall survival (HR, 0.88) over a median follow-up of 18 years.

The current study shows that cancer stage based on tumor size and the number of lymph nodes should not be the only considerations for making treatment decisions and predicting outcomes, Dr. Leon-Ferre said in an interview.

“In fact, our study shows that for tumors of the same stage (particularly for stage I), the risk of recurrence is different depending on the number of TILs seen in the breast cancer tissue. When chemo is not given, those with high TILs have lower risk of recurrence, whereas those with low TILs have a higher risk of recurrence,” he said.

What are the Limitations of This Research?

The current study findings are limited by the retrospective design and use of observational data, so the researchers could not make conclusions about causality. Other limitations included lack of data on germline mutations and race or ethnicity, and the potential irrelevance of data from patients treated as long as 45 years ago.

“Because most patients with TNBC receive chemotherapy in the modern times, we needed to work with 13 hospitals around the world to find data on patients with TNBC who never received chemotherapy for various reasons,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said.

To address these limitations, Dr. Leone-Ferre and his colleagues are planning prospective studies where TILs will be used to make treatment decisions.

“Many of the patients in our cohort were treated many years ago, when chemotherapy was not routinely given. Advances in cancer detection, surgical and radiation techniques may lead to different results in patients treated today,” he added.

What Do Oncologists Need to Know?

The current study findings may provide additional information on prognosis that is important to share with patients for decision-making on the risks versus benefits of chemotherapy, Dr. Leon-Ferre said.

“Like any test, TILs should not be used in isolation to make decisions, but should be integrated with other factors including the cancer stage, the overall patient health, patient preferences, and concerns about treatment complications,” he emphasized. “The results of this study allow oncologists to offer a more refined calculation of recurrence risk if patients opt to not receive chemotherapy.”

In the current study, although younger age was associated with higher TIL levels, a finding consistent with previous studies, increased TIL, remained significantly associated with improved survival after adjusting for age, tumor size, nodal status, and histological grade.

Overall, “the findings suggest that for patients with stage I TNBC and TILs greater than 50%, chemotherapy may not be as necessary as it was previously thought,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said.

What Additional Research is Needed?

Prospective studies are needed to validate the findings, including studies in diverse populations, and additional studies may investigate whether early TBNC patients with high TIL levels could achieve high cure rates with less intensive and less toxic chemotherapy regiments than those currently recommended, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“There are many additional research questions that we need to answer, and look forward to working on,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said, in an interview. These topics include whether TILs can be used to decide on the number of chemotherapy drugs a patient really needs and whether artificial intelligence can be used to evaluate TILs more quickly and effectively than the human eye, he said. Other research topics include identifying which particular type of TILs attack cancer cells most effectively and whether TILs could be increased in patients with low levels in order to improve their prognosis, he added.

The study was supported by the National Research Agency and General Secretariat for Investment, Clinical and Translational Science Awards, the Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer SPORE grant, the Cancer Research Society of Canada, institutional grants from the Dutch Cancer Society, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research, and several foundations. Dr. Leon-Ferre disclosed consulting honoraria to his institution for research activities from AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences, and Lyell Immunopharma, with no personal fees outside the submitted work.

The association of abundant tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer tissue with outcomes in patients with early-stage triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) who do not receive chemotherapy has not been well studied, wrote Roberto A. Leon-Ferre, MD, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, and colleagues, in JAMA.

Biomarkers to guide systemic treatment and avoid overtreatment are lacking, and such markers could help identify patients who could achieve increased survival with less intensive therapy, continued the authors of the new study of nearly 2000 individuals.

“TNBC is the most aggressive subtype of breast cancer, and for this reason, current treatment guidelines recommend chemotherapy using multiple drugs either before or after surgery,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said in an interview. “We have learned over the last several years that TNBC is not a single disease, but that there are several subtypes of TNBC that have different risks and different vulnerabilities, and treating all patients similarly may not be optimal.”

What is Known About Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Cancer?

Previous studies have shown improved survival in patients with early-stage TNBC and high levels of TILs who were treated with adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, compared with those with lower TILs. In a pooled analysis of 2148 patients from nine studies published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2019, a higher percentage of TILs in the stroma surrounding a tumor was significantly associated with improved survival in TNBC patients after adjuvant chemotherapy.

Another study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2022 showed that elevated TILs were significant predictors of overall survival, but the study included fewer than 500 patients.

The potential mechanisms that drive the association between elevated TILs and improved survival include the ability of TILs to attack cancer cells, Dr. Leon-Ferre said in an interview.

The goal of this study was to evaluate whether TILs could identify a subset of patients with TNBC who had a very low risk of cancer recurrence even if chemotherapy was not given.

“Indeed, we found that patients with stage I TNBC and high TILs had a very low risk of recurrence even when chemotherapy was not administered. These findings will pave the way for future studies aiming to reduce the need for multiple chemotherapy drugs in patients with stage I TNBC and decrease the side effects that patients face,” he said.

What Does the New Study Add?

The current study included 1966 individuals from 13 sites in North America, Europe, and Asia who were diagnosed with TNBC between 1979 and 2017 and were treated with surgery, with or without radiotherapy but with no adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The researchers examined the abundance of TILs in the breast tissue of resected primary tumors; the primary outcome was invasive disease-free survival (iDFS), with recurrence-free survival, distant recurrence-free survival, and overall survival as secondary outcomes.

The median age of the patients was 56 years, 55% had stage I TNBC, and the median TIL level was 15%.

A total of 417 patients had a TIL level of 50% or more, and the 5-year iDFS for these patients was 94%, compared with 78% for those with a TIL level less than 30%. Similarly, 5-year overall survival was 95% in patients with a TIL level of 50% or more, compared with 82% for patients with TIL levels of less than 30%.

Additionally, each 10% increase in TILs was independently associated not only with improved iDFS (hazard ratio[HR], 0.92), but also improved recurrence-free survival (HR, 0.90), distant recurrence-free survival (HR, 0.87), and overall survival (HR, 0.88) over a median follow-up of 18 years.

The current study shows that cancer stage based on tumor size and the number of lymph nodes should not be the only considerations for making treatment decisions and predicting outcomes, Dr. Leon-Ferre said in an interview.

“In fact, our study shows that for tumors of the same stage (particularly for stage I), the risk of recurrence is different depending on the number of TILs seen in the breast cancer tissue. When chemo is not given, those with high TILs have lower risk of recurrence, whereas those with low TILs have a higher risk of recurrence,” he said.

What are the Limitations of This Research?

The current study findings are limited by the retrospective design and use of observational data, so the researchers could not make conclusions about causality. Other limitations included lack of data on germline mutations and race or ethnicity, and the potential irrelevance of data from patients treated as long as 45 years ago.

“Because most patients with TNBC receive chemotherapy in the modern times, we needed to work with 13 hospitals around the world to find data on patients with TNBC who never received chemotherapy for various reasons,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said.

To address these limitations, Dr. Leone-Ferre and his colleagues are planning prospective studies where TILs will be used to make treatment decisions.

“Many of the patients in our cohort were treated many years ago, when chemotherapy was not routinely given. Advances in cancer detection, surgical and radiation techniques may lead to different results in patients treated today,” he added.

What Do Oncologists Need to Know?

The current study findings may provide additional information on prognosis that is important to share with patients for decision-making on the risks versus benefits of chemotherapy, Dr. Leon-Ferre said.

“Like any test, TILs should not be used in isolation to make decisions, but should be integrated with other factors including the cancer stage, the overall patient health, patient preferences, and concerns about treatment complications,” he emphasized. “The results of this study allow oncologists to offer a more refined calculation of recurrence risk if patients opt to not receive chemotherapy.”

In the current study, although younger age was associated with higher TIL levels, a finding consistent with previous studies, increased TIL, remained significantly associated with improved survival after adjusting for age, tumor size, nodal status, and histological grade.

Overall, “the findings suggest that for patients with stage I TNBC and TILs greater than 50%, chemotherapy may not be as necessary as it was previously thought,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said.

What Additional Research is Needed?

Prospective studies are needed to validate the findings, including studies in diverse populations, and additional studies may investigate whether early TBNC patients with high TIL levels could achieve high cure rates with less intensive and less toxic chemotherapy regiments than those currently recommended, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“There are many additional research questions that we need to answer, and look forward to working on,” Dr. Leon-Ferre said, in an interview. These topics include whether TILs can be used to decide on the number of chemotherapy drugs a patient really needs and whether artificial intelligence can be used to evaluate TILs more quickly and effectively than the human eye, he said. Other research topics include identifying which particular type of TILs attack cancer cells most effectively and whether TILs could be increased in patients with low levels in order to improve their prognosis, he added.

The study was supported by the National Research Agency and General Secretariat for Investment, Clinical and Translational Science Awards, the Mayo Clinic Breast Cancer SPORE grant, the Cancer Research Society of Canada, institutional grants from the Dutch Cancer Society, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research, and several foundations. Dr. Leon-Ferre disclosed consulting honoraria to his institution for research activities from AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences, and Lyell Immunopharma, with no personal fees outside the submitted work.

FROM JAMA

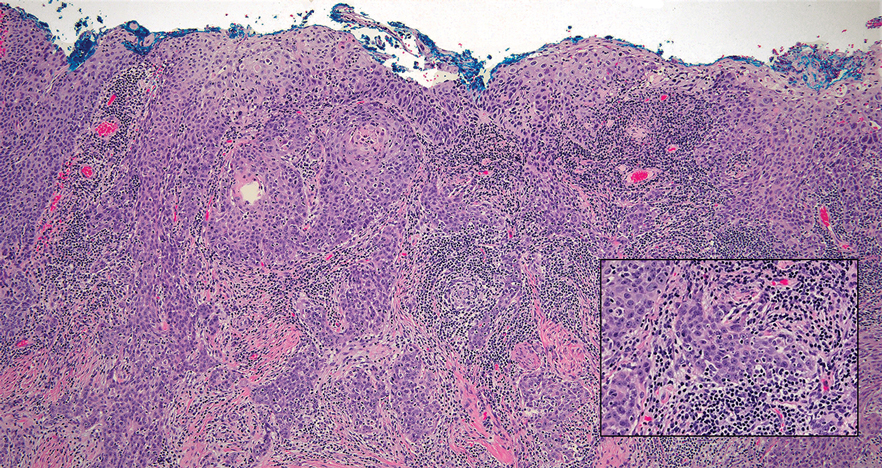

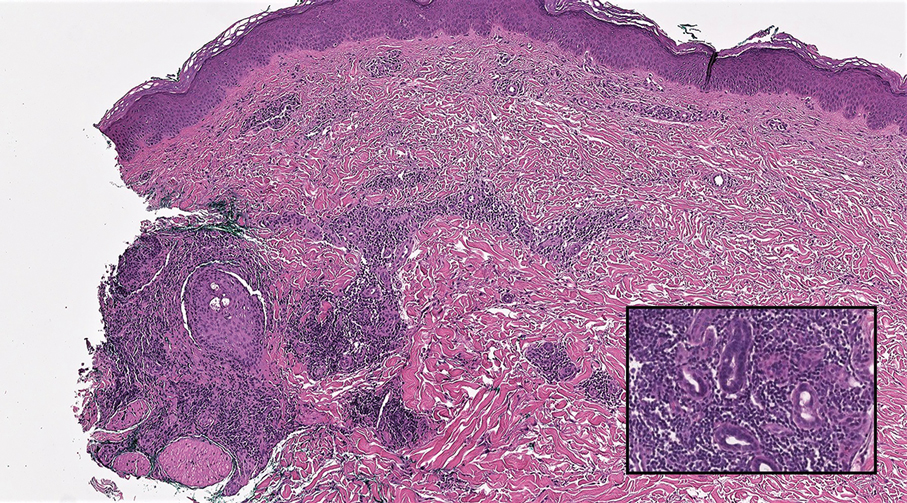

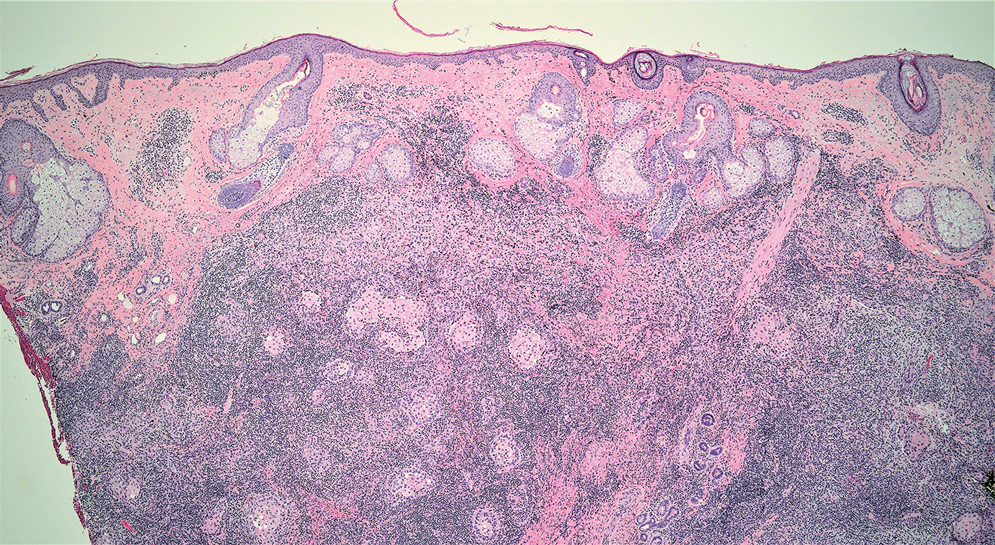

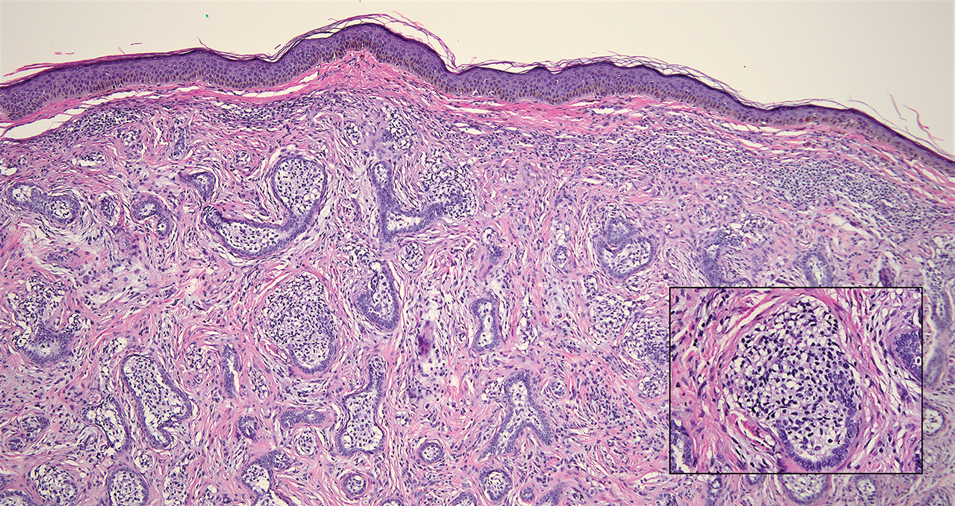

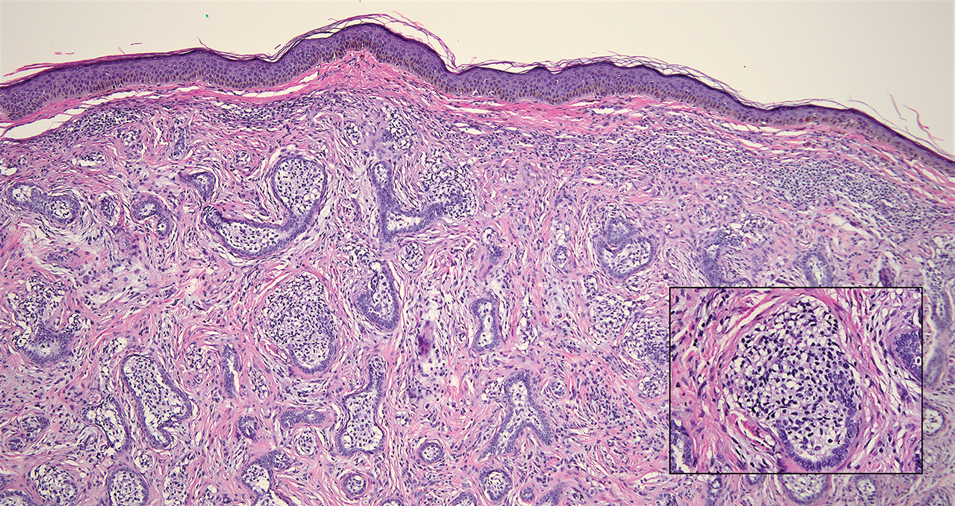

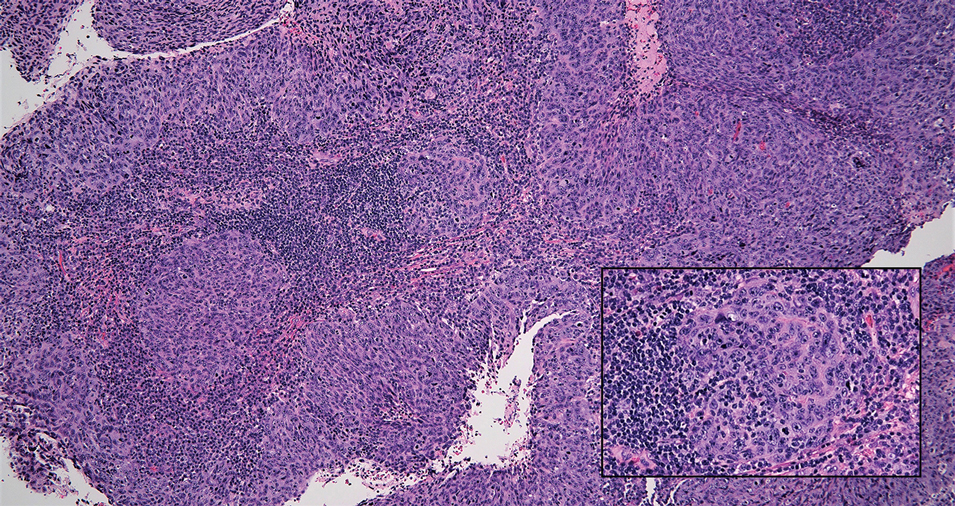

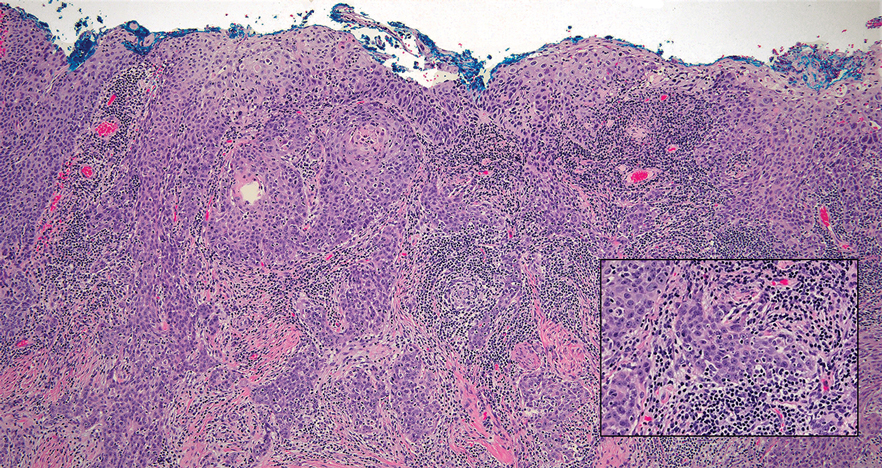

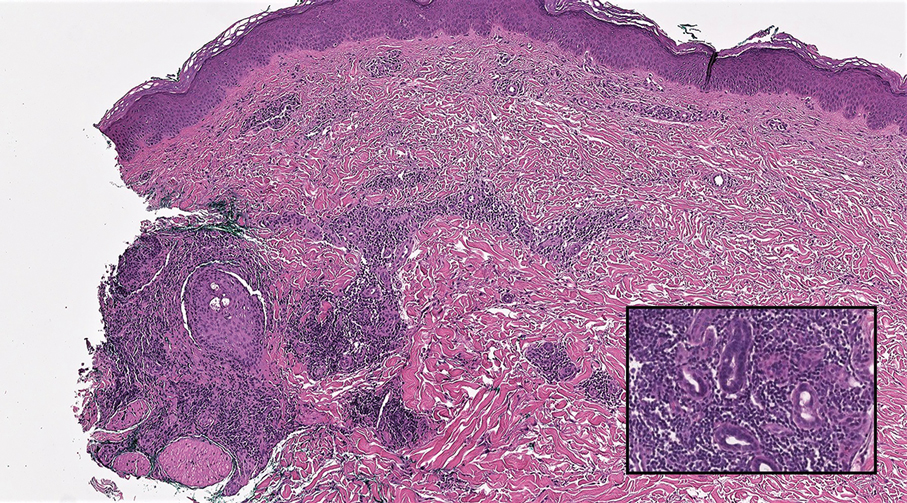

Tender Dermal Nodule on the Temple

The Diagnosis: Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma