User login

A New Treatment Target for PTSD?

Adults with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have smaller cerebellums than unaffected adults, suggesting that this part of the brain may be a potential therapeutic target.

According to recent research on more than 4000 adults, cerebellum volume was significantly smaller (by about 2%) in those with PTSD than in trauma-exposed and trauma-naive controls without PTSD.

“The differences were largely within the posterior lobe, where a lot of the more cognitive functions attributed to the cerebellum seem to localize, as well as the vermis, which is linked to a lot of emotional processing functions,” lead author Ashley Huggins, PhD, said in a news release.

“If we know what areas are implicated, then we can start to focus interventions like brain stimulation on the cerebellum and potentially improve treatment outcomes,” said Dr. Huggins, who worked on the study while a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Rajendra A. Morey, MD, at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, and is now at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

While the cerebellum is known for its role in coordinating movement and balance, it also plays a key role in emotions and memory, which are affected by PTSD.

Smaller cerebellar volume has been observed in some adult and pediatric populations with PTSD.

However, those studies have been limited by either small sample sizes, the failure to consider key neuroanatomical subdivisions of the cerebellum, or a focus on certain populations such as veterans of sexual assault victims with PTSD.

To overcome these limitations, the researchers conducted a mega-analysis of total and subregional cerebellar volumes in a large, multicohort dataset from the Enhancing NeuroImaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA)-Psychiatric Genomics Consortium PTSD workgroup that was published online on January 10, 2024, in Molecular Psychiatry.

They employed a novel, standardized ENIGMA cerebellum parcellation protocol to quantify cerebellar lobule volumes using structural MRI data from 1642 adults with PTSD and 2573 healthy controls without PTSD (88% trauma-exposed and 12% trauma-naive).

After adjustment for age, gender, and total intracranial volume, PTSD was associated with significant gray and white matter reductions of the cerebellum.

People with PTSD demonstrated smaller total cerebellum volume as well as reduced volume in subregions primarily within the posterior cerebellum, vermis, and flocculonodular cerebellum than controls.

In general, PTSD severity was more robustly associated with cerebellar volume differences than PTSD diagnosis.

Focusing purely on a “yes-or-no” categorical diagnosis didn’t always provide the clearest picture. “When we looked at PTSD severity, people who had more severe forms of the disorder had an even smaller cerebellar volume,” Dr. Huggins explained in the news release.

Novel Treatment Target

These findings add to “an emerging literature that underscores the relevance of cerebellar structure in the pathophysiology of PTSD,” the researchers noted.

They caution that despite the significant findings suggesting associations between PTSD and smaller cerebellar volumes, effect sizes were small. “As such, it is unlikely that structural cerebellar volumes alone will provide a clinically useful biomarker (eg, for individual-level prediction).”

Nonetheless, the study highlights the cerebellum as a “novel treatment target that may be leveraged to improve treatment outcomes for PTSD,” they wrote.

They noted that prior work has shown that the cerebellum is sensitive to external modulation. For example, noninvasive brain stimulation of the cerebellum has been shown to modulate cognitive, emotional, and social processes commonly disrupted in PTSD.

Commenting on this research, Cyrus A. Raji, MD, PhD, associate professor of radiology and neurology at Washington University in St. Louis, noted that this “large neuroimaging study links PTSD to cerebellar volume loss.”

“However, PTSD and traumatic brain injury frequently co-occur, and PTSD also frequently arises after TBI. Additionally, TBI is strongly linked to cerebellar volume loss,” Dr. Raji pointed out.

“Future studies need to better delineate volume loss from these conditions, especially when they are comorbid, though the expectation is these effects would be additive with TBI being the initial and most severe driving force,” Dr. Raji added.

The research had no commercial funding. Author disclosures are listed with the original article. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution Medicine LLC.

A version of this article appears on Medscape.com.

Adults with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have smaller cerebellums than unaffected adults, suggesting that this part of the brain may be a potential therapeutic target.

According to recent research on more than 4000 adults, cerebellum volume was significantly smaller (by about 2%) in those with PTSD than in trauma-exposed and trauma-naive controls without PTSD.

“The differences were largely within the posterior lobe, where a lot of the more cognitive functions attributed to the cerebellum seem to localize, as well as the vermis, which is linked to a lot of emotional processing functions,” lead author Ashley Huggins, PhD, said in a news release.

“If we know what areas are implicated, then we can start to focus interventions like brain stimulation on the cerebellum and potentially improve treatment outcomes,” said Dr. Huggins, who worked on the study while a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Rajendra A. Morey, MD, at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, and is now at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

While the cerebellum is known for its role in coordinating movement and balance, it also plays a key role in emotions and memory, which are affected by PTSD.

Smaller cerebellar volume has been observed in some adult and pediatric populations with PTSD.

However, those studies have been limited by either small sample sizes, the failure to consider key neuroanatomical subdivisions of the cerebellum, or a focus on certain populations such as veterans of sexual assault victims with PTSD.

To overcome these limitations, the researchers conducted a mega-analysis of total and subregional cerebellar volumes in a large, multicohort dataset from the Enhancing NeuroImaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA)-Psychiatric Genomics Consortium PTSD workgroup that was published online on January 10, 2024, in Molecular Psychiatry.

They employed a novel, standardized ENIGMA cerebellum parcellation protocol to quantify cerebellar lobule volumes using structural MRI data from 1642 adults with PTSD and 2573 healthy controls without PTSD (88% trauma-exposed and 12% trauma-naive).

After adjustment for age, gender, and total intracranial volume, PTSD was associated with significant gray and white matter reductions of the cerebellum.

People with PTSD demonstrated smaller total cerebellum volume as well as reduced volume in subregions primarily within the posterior cerebellum, vermis, and flocculonodular cerebellum than controls.

In general, PTSD severity was more robustly associated with cerebellar volume differences than PTSD diagnosis.

Focusing purely on a “yes-or-no” categorical diagnosis didn’t always provide the clearest picture. “When we looked at PTSD severity, people who had more severe forms of the disorder had an even smaller cerebellar volume,” Dr. Huggins explained in the news release.

Novel Treatment Target

These findings add to “an emerging literature that underscores the relevance of cerebellar structure in the pathophysiology of PTSD,” the researchers noted.

They caution that despite the significant findings suggesting associations between PTSD and smaller cerebellar volumes, effect sizes were small. “As such, it is unlikely that structural cerebellar volumes alone will provide a clinically useful biomarker (eg, for individual-level prediction).”

Nonetheless, the study highlights the cerebellum as a “novel treatment target that may be leveraged to improve treatment outcomes for PTSD,” they wrote.

They noted that prior work has shown that the cerebellum is sensitive to external modulation. For example, noninvasive brain stimulation of the cerebellum has been shown to modulate cognitive, emotional, and social processes commonly disrupted in PTSD.

Commenting on this research, Cyrus A. Raji, MD, PhD, associate professor of radiology and neurology at Washington University in St. Louis, noted that this “large neuroimaging study links PTSD to cerebellar volume loss.”

“However, PTSD and traumatic brain injury frequently co-occur, and PTSD also frequently arises after TBI. Additionally, TBI is strongly linked to cerebellar volume loss,” Dr. Raji pointed out.

“Future studies need to better delineate volume loss from these conditions, especially when they are comorbid, though the expectation is these effects would be additive with TBI being the initial and most severe driving force,” Dr. Raji added.

The research had no commercial funding. Author disclosures are listed with the original article. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution Medicine LLC.

A version of this article appears on Medscape.com.

Adults with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have smaller cerebellums than unaffected adults, suggesting that this part of the brain may be a potential therapeutic target.

According to recent research on more than 4000 adults, cerebellum volume was significantly smaller (by about 2%) in those with PTSD than in trauma-exposed and trauma-naive controls without PTSD.

“The differences were largely within the posterior lobe, where a lot of the more cognitive functions attributed to the cerebellum seem to localize, as well as the vermis, which is linked to a lot of emotional processing functions,” lead author Ashley Huggins, PhD, said in a news release.

“If we know what areas are implicated, then we can start to focus interventions like brain stimulation on the cerebellum and potentially improve treatment outcomes,” said Dr. Huggins, who worked on the study while a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Rajendra A. Morey, MD, at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, and is now at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

While the cerebellum is known for its role in coordinating movement and balance, it also plays a key role in emotions and memory, which are affected by PTSD.

Smaller cerebellar volume has been observed in some adult and pediatric populations with PTSD.

However, those studies have been limited by either small sample sizes, the failure to consider key neuroanatomical subdivisions of the cerebellum, or a focus on certain populations such as veterans of sexual assault victims with PTSD.

To overcome these limitations, the researchers conducted a mega-analysis of total and subregional cerebellar volumes in a large, multicohort dataset from the Enhancing NeuroImaging Genetics through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA)-Psychiatric Genomics Consortium PTSD workgroup that was published online on January 10, 2024, in Molecular Psychiatry.

They employed a novel, standardized ENIGMA cerebellum parcellation protocol to quantify cerebellar lobule volumes using structural MRI data from 1642 adults with PTSD and 2573 healthy controls without PTSD (88% trauma-exposed and 12% trauma-naive).

After adjustment for age, gender, and total intracranial volume, PTSD was associated with significant gray and white matter reductions of the cerebellum.

People with PTSD demonstrated smaller total cerebellum volume as well as reduced volume in subregions primarily within the posterior cerebellum, vermis, and flocculonodular cerebellum than controls.

In general, PTSD severity was more robustly associated with cerebellar volume differences than PTSD diagnosis.

Focusing purely on a “yes-or-no” categorical diagnosis didn’t always provide the clearest picture. “When we looked at PTSD severity, people who had more severe forms of the disorder had an even smaller cerebellar volume,” Dr. Huggins explained in the news release.

Novel Treatment Target

These findings add to “an emerging literature that underscores the relevance of cerebellar structure in the pathophysiology of PTSD,” the researchers noted.

They caution that despite the significant findings suggesting associations between PTSD and smaller cerebellar volumes, effect sizes were small. “As such, it is unlikely that structural cerebellar volumes alone will provide a clinically useful biomarker (eg, for individual-level prediction).”

Nonetheless, the study highlights the cerebellum as a “novel treatment target that may be leveraged to improve treatment outcomes for PTSD,” they wrote.

They noted that prior work has shown that the cerebellum is sensitive to external modulation. For example, noninvasive brain stimulation of the cerebellum has been shown to modulate cognitive, emotional, and social processes commonly disrupted in PTSD.

Commenting on this research, Cyrus A. Raji, MD, PhD, associate professor of radiology and neurology at Washington University in St. Louis, noted that this “large neuroimaging study links PTSD to cerebellar volume loss.”

“However, PTSD and traumatic brain injury frequently co-occur, and PTSD also frequently arises after TBI. Additionally, TBI is strongly linked to cerebellar volume loss,” Dr. Raji pointed out.

“Future studies need to better delineate volume loss from these conditions, especially when they are comorbid, though the expectation is these effects would be additive with TBI being the initial and most severe driving force,” Dr. Raji added.

The research had no commercial funding. Author disclosures are listed with the original article. Dr. Raji is a consultant for Brainreader, Apollo Health, Pacific Neuroscience Foundation, and Neurevolution Medicine LLC.

A version of this article appears on Medscape.com.

Weight Loss Not Enough to Sustain Type 2 Diabetes Remission

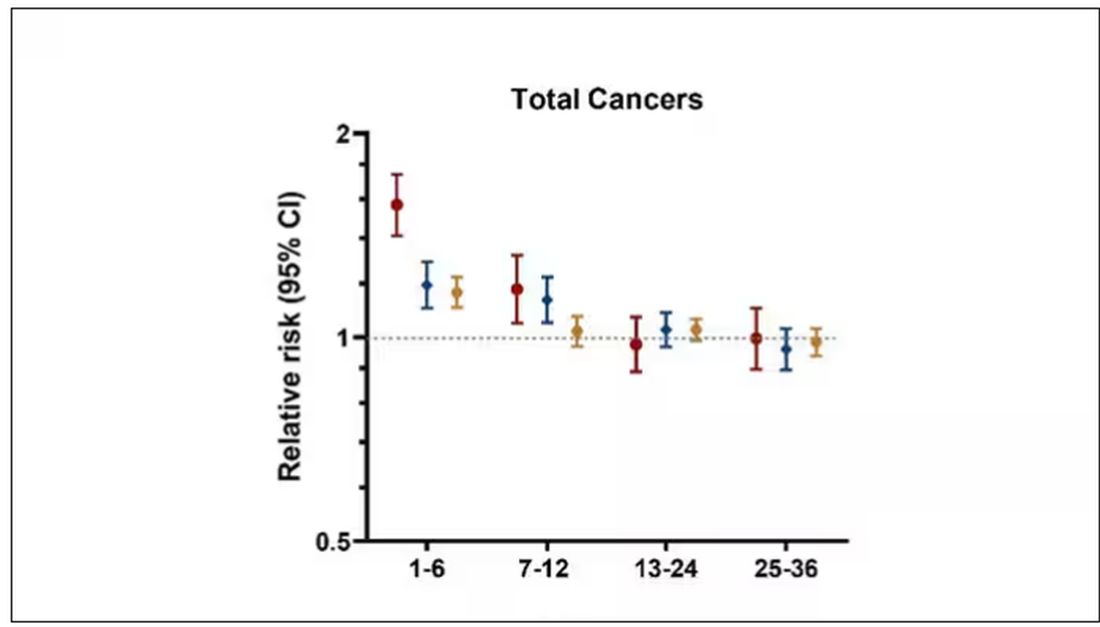

Very few patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) achieve and sustain diabetes remission via weight loss alone, new research suggests.

Among more than 37,000 people with T2D in Hong Kong, only 6% had achieved and sustained diabetes remission solely through weight loss up to 8 years after diagnosis. Among those who initially achieved remission, 67% had hyperglycemia at 3 years.

People who lost the most weight (10% of their body weight or more) in the first year after diagnosis were most likely to have sustained remission.

The study “helped to confirm the low rate of diabetes remission and high rate of returning to hyperglycemia in real-world practice,” Andrea Luk, MD, of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, told this news organization. “Over 80% of diabetes remission occurred within the first 5 years of a diabetes diagnosis. This is in line with our understanding that beta cell function will gradually decline over time, making diabetes remission increasingly difficult even with weight reduction.”

The study was published in PLOS Medicine.

Early Weight Management Works

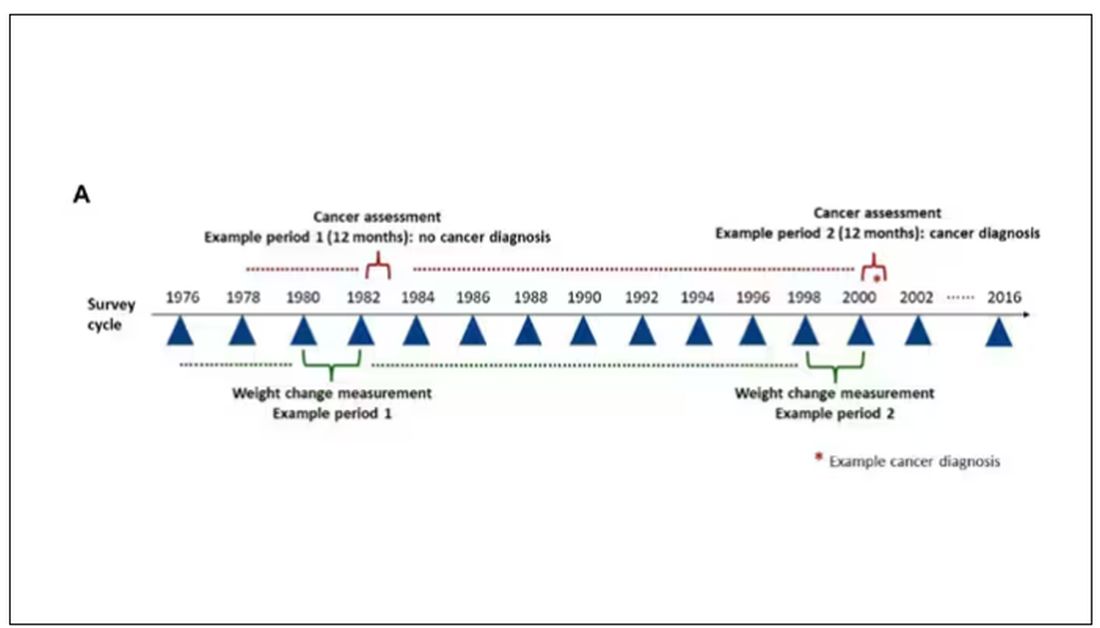

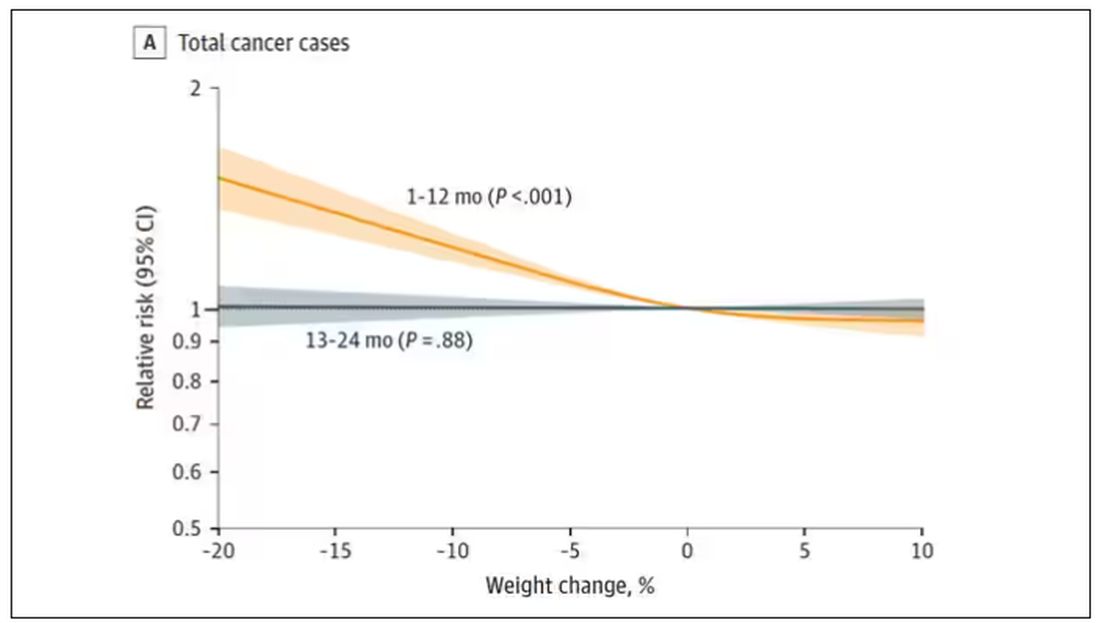

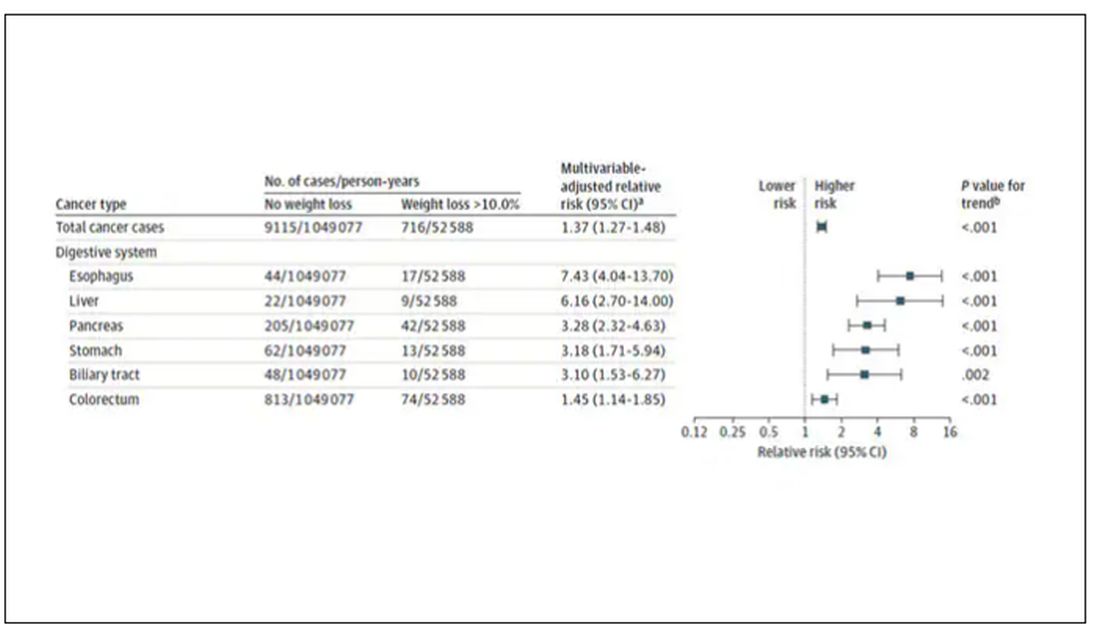

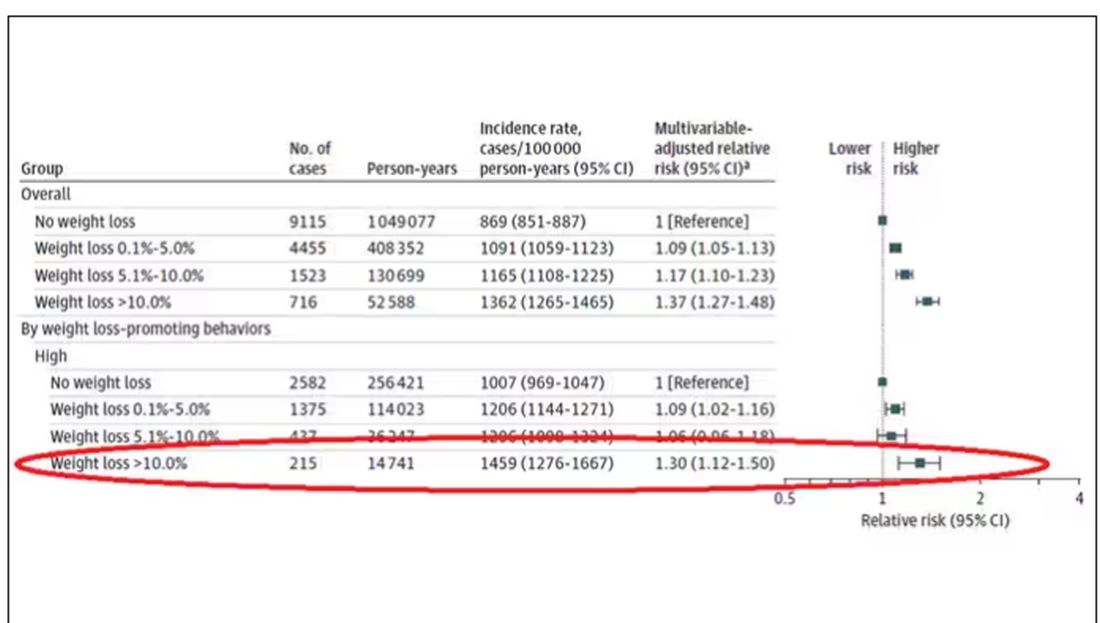

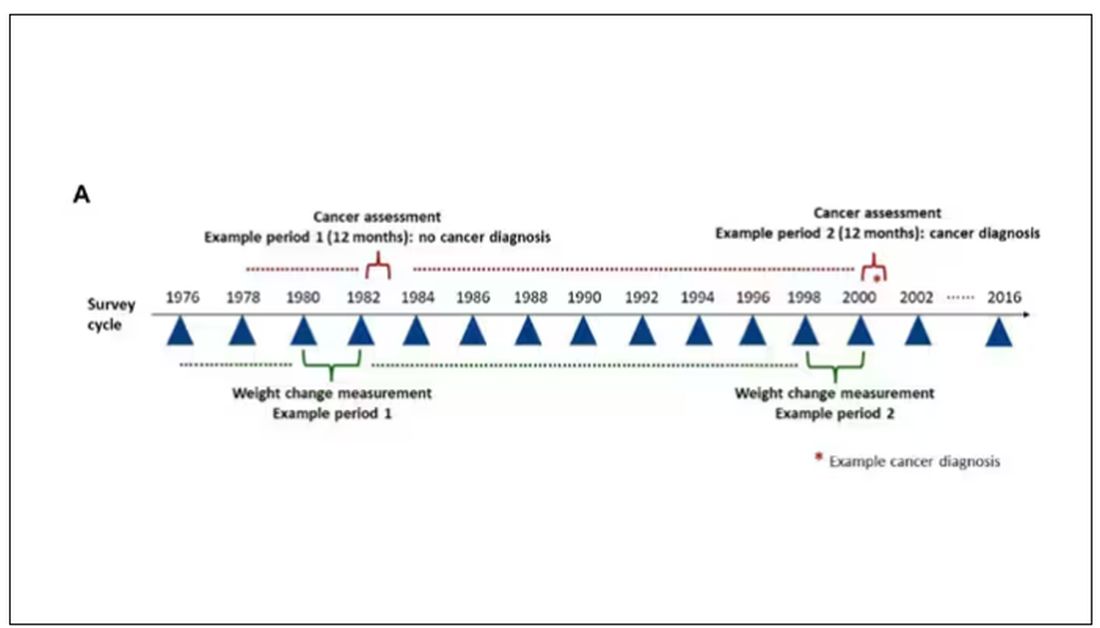

Recent clinical trials have demonstrated that T2D remission can be achieved following sustained weight loss through bariatric surgery or lifestyle interventions, the authors noted. In this study, they investigated the association of weight change at 1 year after a diabetes diagnosis with the long-term incidence and sustainability of T2D remission in real-world settings, using data from the territory-wide Risk Assessment and Management Programme-Diabetes Mellitus (RAMP-DM).

A total of 37,326 people with newly diagnosed T2D who were enrolled in the RAMP-DM between 2000 and 2017 were included and followed until 2019.

At baseline, participants’ mean age was 56.6 years, mean body mass index (BMI) was 26.4 kg/m2, and mean A1c was 7.7%, and 65% were using glucose-lowering drugs (GLDs).

T2D remission was defined as two consecutive A1c < 6.5% measurements at least 6 months apart without GLDs currently or in the previous 3 months.

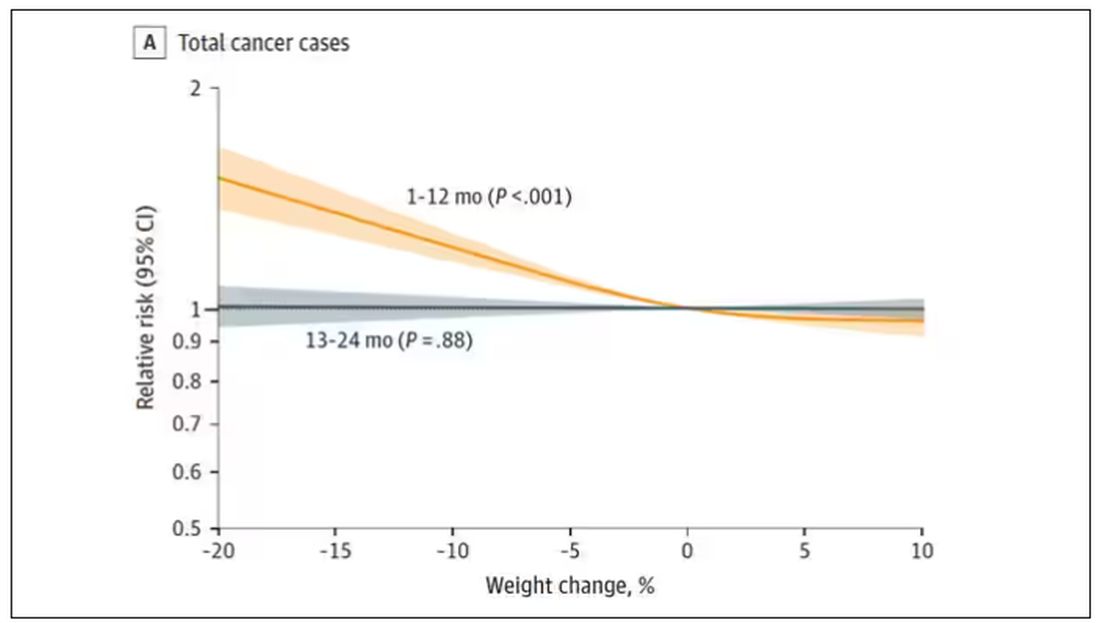

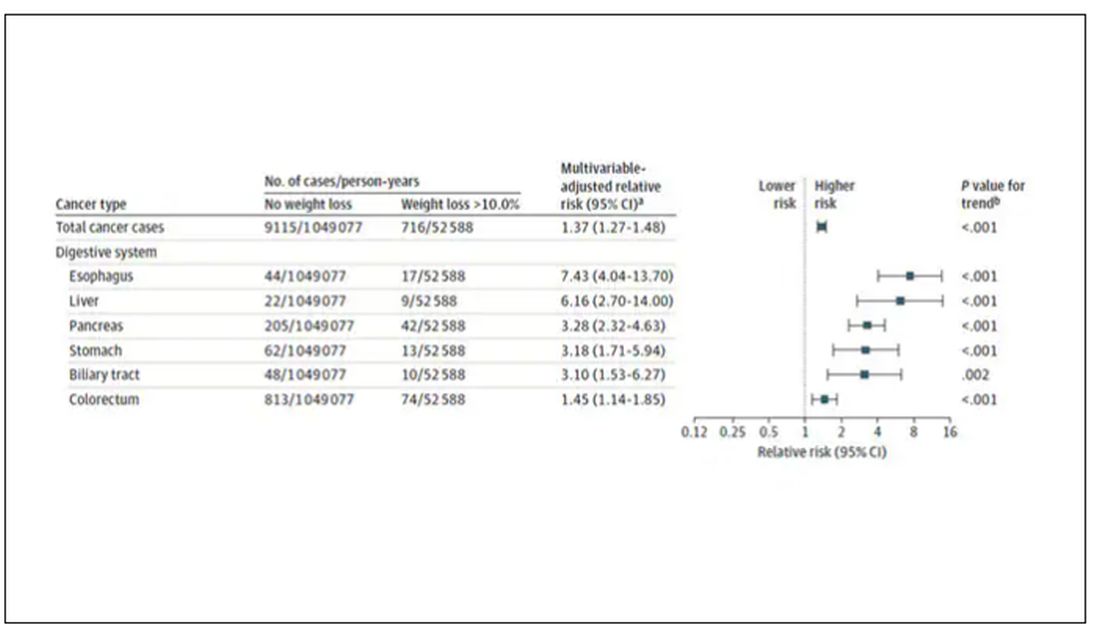

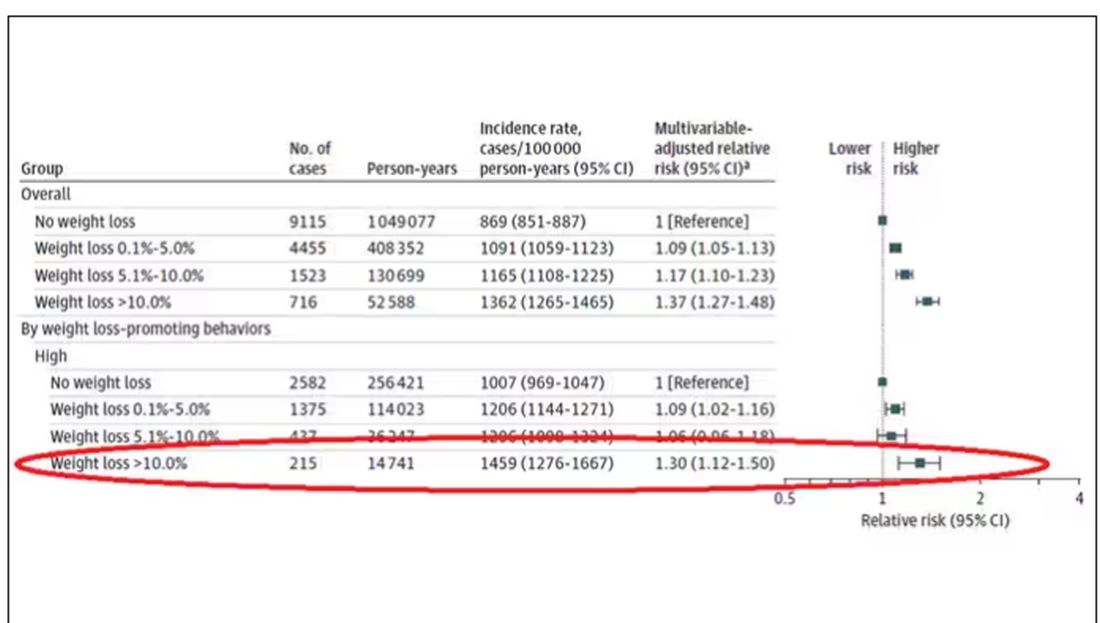

During a median follow-up of 7.9 years, 6.1% of people achieved remission, with an incidence rate of 7.8 per 1000 person-years. The proportion was higher among those with greater weight loss: 14.4% of people who lost 10% of their body weight or more achieved remission compared with 9.9% of those with 5%-9.9% weight loss, 6.5% of those with 0%-4.9% weight loss, and 4.5% of those who gained weight.

After adjustment for age at diagnosis, sex, assessment year, BMI, other metabolic indices, smoking, alcohol drinking, and medication use, the hazard ratio (HR) for diabetes remission was 3.28 for those with 10% or greater weight loss within 1 year of diagnosis, 2.29 for 5%-9.9% weight loss, and 1.34 for 0%-4.9% weight loss compared to weight gain.

The incidence of diabetes remission in the study was significantly lower than that in clinical trials, possibly because trial participants were in structured programs that included intensive lifestyle interventions, regular monitoring and feedback, and reinforcement of a holistic approach to managing diabetes, the authors noted. Real-world settings may or may not include such interventions.

Further analyses showed that within a median follow-up of 3.1 years, 67.2% of people who had achieved diabetes remission returned to hyperglycemia — an incidence rate of 184.8 per 1000 person-years.

The adjusted HR for returning to hyperglycemia was 0.52 for people with 10% or greater weight loss, 0.78 for those with 5%-9.9% weight loss, and 0.90 for those with 0%-4.9% weight loss compared to people with weight gain.

In addition, diabetes remission was associated with a 31% (HR, 0.69) decreased risk for all-cause mortality.

The study “provides evidence for policymakers to design and implement early weight management interventions” for people diagnosed with T2D, the authors concluded.

Clinicians also have a role to play, Dr. Luk said. “At the first encounter with an individual with newly diagnosed T2D, clinicians should emphasize the importance of weight reduction and guide the individual on how this can be achieved through making healthy lifestyle choices. Pharmacotherapy and metabolic surgery for weight management can be considered in appropriate individuals.”

Overall, she added, “clinicians should be informed that the likelihood of achieving and maintaining diabetes remission is low, and patients should be counseled accordingly.”

Similar to US Experience

Mona Mshayekhi, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine in the division of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, commented on the study for this news organization.

“These findings mirror clinical experience in the US very well,” she said. “We know that sustained weight loss without the use of medications or surgery is extremely difficult in the real-world setting due to the hormonal drivers of obesity, in combination with socioeconomic challenges.”

The study was done before newer weight-management strategies such as glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists were widely available, she noted. “This actually strengthens the finding that weight loss without the routine use of medications has a multitude of benefits, including diabetes remission and reduction of all-cause mortality.”

That said, she added, “I suspect that future studies with more modern cohorts will reveal much higher rates of diabetes remission with the use of newer medications.”

“Our ability to help our patients lose meaningful weight has been limited until recently,” she said. “With new tools in our armamentarium, clinicians need to take the lead in helping patients address and treat obesity and fight the stigma that prevents many from even discussing it with their providers.”

The study did not receive funding. Dr. Luk has received research grants or contracts from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Junshi, Lee Pharmaceutical, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi, Shanghai Junshi Biosciences, Sugardown, and Takeda and received travel grants and honoraria for speaking from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and MSD. Dr. Mshayekhi reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Very few patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) achieve and sustain diabetes remission via weight loss alone, new research suggests.

Among more than 37,000 people with T2D in Hong Kong, only 6% had achieved and sustained diabetes remission solely through weight loss up to 8 years after diagnosis. Among those who initially achieved remission, 67% had hyperglycemia at 3 years.

People who lost the most weight (10% of their body weight or more) in the first year after diagnosis were most likely to have sustained remission.

The study “helped to confirm the low rate of diabetes remission and high rate of returning to hyperglycemia in real-world practice,” Andrea Luk, MD, of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, told this news organization. “Over 80% of diabetes remission occurred within the first 5 years of a diabetes diagnosis. This is in line with our understanding that beta cell function will gradually decline over time, making diabetes remission increasingly difficult even with weight reduction.”

The study was published in PLOS Medicine.

Early Weight Management Works

Recent clinical trials have demonstrated that T2D remission can be achieved following sustained weight loss through bariatric surgery or lifestyle interventions, the authors noted. In this study, they investigated the association of weight change at 1 year after a diabetes diagnosis with the long-term incidence and sustainability of T2D remission in real-world settings, using data from the territory-wide Risk Assessment and Management Programme-Diabetes Mellitus (RAMP-DM).

A total of 37,326 people with newly diagnosed T2D who were enrolled in the RAMP-DM between 2000 and 2017 were included and followed until 2019.

At baseline, participants’ mean age was 56.6 years, mean body mass index (BMI) was 26.4 kg/m2, and mean A1c was 7.7%, and 65% were using glucose-lowering drugs (GLDs).

T2D remission was defined as two consecutive A1c < 6.5% measurements at least 6 months apart without GLDs currently or in the previous 3 months.

During a median follow-up of 7.9 years, 6.1% of people achieved remission, with an incidence rate of 7.8 per 1000 person-years. The proportion was higher among those with greater weight loss: 14.4% of people who lost 10% of their body weight or more achieved remission compared with 9.9% of those with 5%-9.9% weight loss, 6.5% of those with 0%-4.9% weight loss, and 4.5% of those who gained weight.

After adjustment for age at diagnosis, sex, assessment year, BMI, other metabolic indices, smoking, alcohol drinking, and medication use, the hazard ratio (HR) for diabetes remission was 3.28 for those with 10% or greater weight loss within 1 year of diagnosis, 2.29 for 5%-9.9% weight loss, and 1.34 for 0%-4.9% weight loss compared to weight gain.

The incidence of diabetes remission in the study was significantly lower than that in clinical trials, possibly because trial participants were in structured programs that included intensive lifestyle interventions, regular monitoring and feedback, and reinforcement of a holistic approach to managing diabetes, the authors noted. Real-world settings may or may not include such interventions.

Further analyses showed that within a median follow-up of 3.1 years, 67.2% of people who had achieved diabetes remission returned to hyperglycemia — an incidence rate of 184.8 per 1000 person-years.

The adjusted HR for returning to hyperglycemia was 0.52 for people with 10% or greater weight loss, 0.78 for those with 5%-9.9% weight loss, and 0.90 for those with 0%-4.9% weight loss compared to people with weight gain.

In addition, diabetes remission was associated with a 31% (HR, 0.69) decreased risk for all-cause mortality.

The study “provides evidence for policymakers to design and implement early weight management interventions” for people diagnosed with T2D, the authors concluded.

Clinicians also have a role to play, Dr. Luk said. “At the first encounter with an individual with newly diagnosed T2D, clinicians should emphasize the importance of weight reduction and guide the individual on how this can be achieved through making healthy lifestyle choices. Pharmacotherapy and metabolic surgery for weight management can be considered in appropriate individuals.”

Overall, she added, “clinicians should be informed that the likelihood of achieving and maintaining diabetes remission is low, and patients should be counseled accordingly.”

Similar to US Experience

Mona Mshayekhi, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine in the division of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, commented on the study for this news organization.

“These findings mirror clinical experience in the US very well,” she said. “We know that sustained weight loss without the use of medications or surgery is extremely difficult in the real-world setting due to the hormonal drivers of obesity, in combination with socioeconomic challenges.”

The study was done before newer weight-management strategies such as glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists were widely available, she noted. “This actually strengthens the finding that weight loss without the routine use of medications has a multitude of benefits, including diabetes remission and reduction of all-cause mortality.”

That said, she added, “I suspect that future studies with more modern cohorts will reveal much higher rates of diabetes remission with the use of newer medications.”

“Our ability to help our patients lose meaningful weight has been limited until recently,” she said. “With new tools in our armamentarium, clinicians need to take the lead in helping patients address and treat obesity and fight the stigma that prevents many from even discussing it with their providers.”

The study did not receive funding. Dr. Luk has received research grants or contracts from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Junshi, Lee Pharmaceutical, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi, Shanghai Junshi Biosciences, Sugardown, and Takeda and received travel grants and honoraria for speaking from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and MSD. Dr. Mshayekhi reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Very few patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) achieve and sustain diabetes remission via weight loss alone, new research suggests.

Among more than 37,000 people with T2D in Hong Kong, only 6% had achieved and sustained diabetes remission solely through weight loss up to 8 years after diagnosis. Among those who initially achieved remission, 67% had hyperglycemia at 3 years.

People who lost the most weight (10% of their body weight or more) in the first year after diagnosis were most likely to have sustained remission.

The study “helped to confirm the low rate of diabetes remission and high rate of returning to hyperglycemia in real-world practice,” Andrea Luk, MD, of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, told this news organization. “Over 80% of diabetes remission occurred within the first 5 years of a diabetes diagnosis. This is in line with our understanding that beta cell function will gradually decline over time, making diabetes remission increasingly difficult even with weight reduction.”

The study was published in PLOS Medicine.

Early Weight Management Works

Recent clinical trials have demonstrated that T2D remission can be achieved following sustained weight loss through bariatric surgery or lifestyle interventions, the authors noted. In this study, they investigated the association of weight change at 1 year after a diabetes diagnosis with the long-term incidence and sustainability of T2D remission in real-world settings, using data from the territory-wide Risk Assessment and Management Programme-Diabetes Mellitus (RAMP-DM).

A total of 37,326 people with newly diagnosed T2D who were enrolled in the RAMP-DM between 2000 and 2017 were included and followed until 2019.

At baseline, participants’ mean age was 56.6 years, mean body mass index (BMI) was 26.4 kg/m2, and mean A1c was 7.7%, and 65% were using glucose-lowering drugs (GLDs).

T2D remission was defined as two consecutive A1c < 6.5% measurements at least 6 months apart without GLDs currently or in the previous 3 months.

During a median follow-up of 7.9 years, 6.1% of people achieved remission, with an incidence rate of 7.8 per 1000 person-years. The proportion was higher among those with greater weight loss: 14.4% of people who lost 10% of their body weight or more achieved remission compared with 9.9% of those with 5%-9.9% weight loss, 6.5% of those with 0%-4.9% weight loss, and 4.5% of those who gained weight.

After adjustment for age at diagnosis, sex, assessment year, BMI, other metabolic indices, smoking, alcohol drinking, and medication use, the hazard ratio (HR) for diabetes remission was 3.28 for those with 10% or greater weight loss within 1 year of diagnosis, 2.29 for 5%-9.9% weight loss, and 1.34 for 0%-4.9% weight loss compared to weight gain.

The incidence of diabetes remission in the study was significantly lower than that in clinical trials, possibly because trial participants were in structured programs that included intensive lifestyle interventions, regular monitoring and feedback, and reinforcement of a holistic approach to managing diabetes, the authors noted. Real-world settings may or may not include such interventions.

Further analyses showed that within a median follow-up of 3.1 years, 67.2% of people who had achieved diabetes remission returned to hyperglycemia — an incidence rate of 184.8 per 1000 person-years.

The adjusted HR for returning to hyperglycemia was 0.52 for people with 10% or greater weight loss, 0.78 for those with 5%-9.9% weight loss, and 0.90 for those with 0%-4.9% weight loss compared to people with weight gain.

In addition, diabetes remission was associated with a 31% (HR, 0.69) decreased risk for all-cause mortality.

The study “provides evidence for policymakers to design and implement early weight management interventions” for people diagnosed with T2D, the authors concluded.

Clinicians also have a role to play, Dr. Luk said. “At the first encounter with an individual with newly diagnosed T2D, clinicians should emphasize the importance of weight reduction and guide the individual on how this can be achieved through making healthy lifestyle choices. Pharmacotherapy and metabolic surgery for weight management can be considered in appropriate individuals.”

Overall, she added, “clinicians should be informed that the likelihood of achieving and maintaining diabetes remission is low, and patients should be counseled accordingly.”

Similar to US Experience

Mona Mshayekhi, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine in the division of Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, commented on the study for this news organization.

“These findings mirror clinical experience in the US very well,” she said. “We know that sustained weight loss without the use of medications or surgery is extremely difficult in the real-world setting due to the hormonal drivers of obesity, in combination with socioeconomic challenges.”

The study was done before newer weight-management strategies such as glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists were widely available, she noted. “This actually strengthens the finding that weight loss without the routine use of medications has a multitude of benefits, including diabetes remission and reduction of all-cause mortality.”

That said, she added, “I suspect that future studies with more modern cohorts will reveal much higher rates of diabetes remission with the use of newer medications.”

“Our ability to help our patients lose meaningful weight has been limited until recently,” she said. “With new tools in our armamentarium, clinicians need to take the lead in helping patients address and treat obesity and fight the stigma that prevents many from even discussing it with their providers.”

The study did not receive funding. Dr. Luk has received research grants or contracts from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Junshi, Lee Pharmaceutical, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Roche, Sanofi, Shanghai Junshi Biosciences, Sugardown, and Takeda and received travel grants and honoraria for speaking from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, and MSD. Dr. Mshayekhi reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Young Myeloma Specialist Forges Ahead, Gives Back

Ahead of the conference held in San Diego in December, Dr. Mohyuddin, a blood cancer specialist with a focus on multiple myeloma and medical education, put out a heartfelt appeal on X (formerly Twitter): “If you’re a trainee and interested in meeting me at #ASH23, please reach out … (especially if [international medical graduate]) I’d love to meet and offer support in whatever capacity I can! I can’t have a research project for each one of you, but happy to help/mentor in any other way possible,” he posted on X back in late November.

An international medical graduate himself, Dr. Mohyuddin recalls how overwhelmed he felt when he first attended an annual ASH conference as a trainee, so he aims to reassure others that they “don’t have to know everything.”

“It’s about networking and broadening horizons,” he said in an interview that took place between ASH sessions, his own research presentations, and meetings with the many trainees who took him up on the offer he made via X. “I’ve spent most of this ASH meeting trainees — it’s the most rewarding thing for me at these meetings.

“Reassurance is a lot of what we do in oncology,” he continued, drawing a connection between his affinity for helping trainees and providing compassionate care to patients. “For an oncologist, the single most important thing is having excellent communication skills and being able to express support and empathy. The ability to connect deeply with your patients during their time of need is profoundly important.

“You can compensate for lack of knowledge, because we have so many other sources of support for knowledge, but you simply cannot compensate for poor communication skills, and your patient suffers as a result,” he said.

Relationship Building

In addition to the guidance he received from mentors, Dr. Mohyuddin noted that it was the chance to build supportive, empathetic relationships that drew him to specialize in blood cancer and, in particular, to caring for patients with multiple myeloma and conducting research focused on improving the patient experience.

Dr. Mohyuddin attended medical school at the Aga Khan University in Pakistan, then completed his internal medicine residency and fellowship at the University of Kansas in Kansas City. As a chief resident there, he focused on novel approaches to education delivery and improving access to research for trainees. As a fellow, he developed clinical and research interests in multiple myeloma, which he describes as an “incredibly rewarding field” marked by “truly spectacular advances over the last two decades.”

“There are some cancers you can cure, which means you don’t get to see patients often, and there are some you can’t cure, where patients die early, and there’s not a lot of time to build a relationship,” he said. “But there are some where patients can do well even though they aren’t currently cured, and you get to form really amazing and meaningful relationships over a long period of time.

“Multiple myeloma occupies that space, and that’s why I’m drawn to it,” Dr. Mohyuddin added, noting that he doesn’t shy away from forging emotional connections with patients. “I recognize that makes me vulnerable, but I think that is essentially what your patients deserve from you — to be invested at an emotional level with them through their suffering.”

Improving value and the patient experience

“One thing, philosophically, that I research is value in multiple myeloma care: identifying areas where we are overtreating patients and where we can do less and get away with it,” he said.

Despite the major advances in multiple myeloma in recent years, which “represent a lot of what is going right with oncology,” this blood cancer still “also represents a lot of what is wrong with oncology,” he noted. As an example, he cited “the approval of low-value drugs, the sequencing of drugs, adding more and more drugs without responsibly addressing quality-of-life questions, and identifying more responsible ways to provide high-value efficacious care without bankrupting the economy.

“So my research and policy work apply to that,” he explained. “What can we do better? What sort of trials should we be doing? What populations do we enroll? Are we asking the right questions or looking at trivialities? Are we serving patients foremost?”

Sometimes, this means comparing multiple myeloma staging systems in a real-world cohort, or assessing whether a widely available, cheap, and safe drug like budesonide can help patients avoid diarrhea during chemotherapy, whether control arms in myeloma randomized trials are fair, whether drugs ever get approved in low- or middle-income countries after their approval in the United States, and whether smoldering myeloma, a multiple myeloma precursor, really requires treatment, as current guidelines suggest, or if patients would do just as well — or perhaps better — with a close surveillance protocol.

“Pharma won’t do those studies and many key opinion leaders feel the question [about whether smoldering myeloma needs to be treated] has already been answered, so we are launching a prospective study that will define the natural history of smoldering myeloma and allow for patients to stay off therapy while undergoing rigorous surveillance with imaging,” he said.

Another study Dr. Mohyuddin hopes to launch soon will look at a “start low, go slow” treatment approach for the frailest patients with newly diagnosed myeloma.

His upbringing in Pakistan, where there are “mind-boggling” differences in health care access, affordability, and outcomes when compared with the United States, provided a foundation for both his “enthusiasm for cost-effective care” and his desire to give back, he said.

Another aspect of life in Pakistan — an across-the-board sense of closeness and solidarity in families and communities that is sometimes lacking in the United States — contributed to his desire to build relationships.

“That is something I dearly miss,” he said. “I am very privileged and so thankful to be here in the US, but that is one thing I do deeply miss.”

Connecting and Making a Difference

Dr. Mohyuddin seeks connection through his relationships with patients, trainees, and his many followers on social media platforms like X, where he frequently shares his thoughts on research quality and findings, heme/onc trends, and treatment-related insight.

“How to treat myeloma after #ASH23,” he posted on X as the conference came to a close. His takeaways: Don’t treat smoldering myeloma, do quadruple therapy for transplant-eligible patients (but no cd38 maintenance therapy afterward), don’t do quads for carfilzomib in newly diagnosed frail or older patients, and don’t do a salvage autologous transplant, no matter how good the first transplant was.

Dr. Mohyuddin also works to make a difference through his research and involvement in helping to launch initiatives like Common Sense Oncology, an ambitious global effort to reform cancer clinical trials and care, and through a current project with colleagues in India and Pakistan to create a consortium for pooling data on hematologic malignancies from South Asian countries. The hope is that such a collaborative effort will lead to good prospective research relevant to the needs of participating countries, he explained.

“Those are things where I want to make a difference. Taking care of patients is number one, but more than research, the number two thing for me is teaching and hopefully inspiring trainees and others to think differently, to look at data differently,” he said, noting that despite the major advances in myeloma, the reality is that “a lot of what we offer in oncology is very marginal.”

The effect sizes of interventions are often very small, and outcomes can still be really bad, he explained, adding that “[i]t really hits you when you see a lot of death and suffering. It’s a huge wake-up call … we have so many advances, but the reality is very, very sobering.

“Critically understanding and interpreting data is something where education really fails us. I’m incredibly passionate about it. I’ve found great resources to help me interpret data better, and I want to make them more accessible and inspire others to understand better,” he said. “We need to know how to defend ourselves from the hype.”

His efforts have not gone unnoticed. Dr. Mohyuddin was the recipient of the 2023 Hematology and Medical Oncology Fellowship Faculty Teaching Award at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, where he is currently a faculty member.

“The recognition means more than any publication or grant award,” he said. “It’s great to know that medical education is appreciated, because so often we are in a rat race of getting more papers and grants out, but teaching and inspiring people is what is really, really important to me.”

Ahead of the conference held in San Diego in December, Dr. Mohyuddin, a blood cancer specialist with a focus on multiple myeloma and medical education, put out a heartfelt appeal on X (formerly Twitter): “If you’re a trainee and interested in meeting me at #ASH23, please reach out … (especially if [international medical graduate]) I’d love to meet and offer support in whatever capacity I can! I can’t have a research project for each one of you, but happy to help/mentor in any other way possible,” he posted on X back in late November.

An international medical graduate himself, Dr. Mohyuddin recalls how overwhelmed he felt when he first attended an annual ASH conference as a trainee, so he aims to reassure others that they “don’t have to know everything.”

“It’s about networking and broadening horizons,” he said in an interview that took place between ASH sessions, his own research presentations, and meetings with the many trainees who took him up on the offer he made via X. “I’ve spent most of this ASH meeting trainees — it’s the most rewarding thing for me at these meetings.

“Reassurance is a lot of what we do in oncology,” he continued, drawing a connection between his affinity for helping trainees and providing compassionate care to patients. “For an oncologist, the single most important thing is having excellent communication skills and being able to express support and empathy. The ability to connect deeply with your patients during their time of need is profoundly important.

“You can compensate for lack of knowledge, because we have so many other sources of support for knowledge, but you simply cannot compensate for poor communication skills, and your patient suffers as a result,” he said.

Relationship Building

In addition to the guidance he received from mentors, Dr. Mohyuddin noted that it was the chance to build supportive, empathetic relationships that drew him to specialize in blood cancer and, in particular, to caring for patients with multiple myeloma and conducting research focused on improving the patient experience.

Dr. Mohyuddin attended medical school at the Aga Khan University in Pakistan, then completed his internal medicine residency and fellowship at the University of Kansas in Kansas City. As a chief resident there, he focused on novel approaches to education delivery and improving access to research for trainees. As a fellow, he developed clinical and research interests in multiple myeloma, which he describes as an “incredibly rewarding field” marked by “truly spectacular advances over the last two decades.”

“There are some cancers you can cure, which means you don’t get to see patients often, and there are some you can’t cure, where patients die early, and there’s not a lot of time to build a relationship,” he said. “But there are some where patients can do well even though they aren’t currently cured, and you get to form really amazing and meaningful relationships over a long period of time.

“Multiple myeloma occupies that space, and that’s why I’m drawn to it,” Dr. Mohyuddin added, noting that he doesn’t shy away from forging emotional connections with patients. “I recognize that makes me vulnerable, but I think that is essentially what your patients deserve from you — to be invested at an emotional level with them through their suffering.”

Improving value and the patient experience

“One thing, philosophically, that I research is value in multiple myeloma care: identifying areas where we are overtreating patients and where we can do less and get away with it,” he said.

Despite the major advances in multiple myeloma in recent years, which “represent a lot of what is going right with oncology,” this blood cancer still “also represents a lot of what is wrong with oncology,” he noted. As an example, he cited “the approval of low-value drugs, the sequencing of drugs, adding more and more drugs without responsibly addressing quality-of-life questions, and identifying more responsible ways to provide high-value efficacious care without bankrupting the economy.

“So my research and policy work apply to that,” he explained. “What can we do better? What sort of trials should we be doing? What populations do we enroll? Are we asking the right questions or looking at trivialities? Are we serving patients foremost?”

Sometimes, this means comparing multiple myeloma staging systems in a real-world cohort, or assessing whether a widely available, cheap, and safe drug like budesonide can help patients avoid diarrhea during chemotherapy, whether control arms in myeloma randomized trials are fair, whether drugs ever get approved in low- or middle-income countries after their approval in the United States, and whether smoldering myeloma, a multiple myeloma precursor, really requires treatment, as current guidelines suggest, or if patients would do just as well — or perhaps better — with a close surveillance protocol.

“Pharma won’t do those studies and many key opinion leaders feel the question [about whether smoldering myeloma needs to be treated] has already been answered, so we are launching a prospective study that will define the natural history of smoldering myeloma and allow for patients to stay off therapy while undergoing rigorous surveillance with imaging,” he said.

Another study Dr. Mohyuddin hopes to launch soon will look at a “start low, go slow” treatment approach for the frailest patients with newly diagnosed myeloma.

His upbringing in Pakistan, where there are “mind-boggling” differences in health care access, affordability, and outcomes when compared with the United States, provided a foundation for both his “enthusiasm for cost-effective care” and his desire to give back, he said.

Another aspect of life in Pakistan — an across-the-board sense of closeness and solidarity in families and communities that is sometimes lacking in the United States — contributed to his desire to build relationships.

“That is something I dearly miss,” he said. “I am very privileged and so thankful to be here in the US, but that is one thing I do deeply miss.”

Connecting and Making a Difference

Dr. Mohyuddin seeks connection through his relationships with patients, trainees, and his many followers on social media platforms like X, where he frequently shares his thoughts on research quality and findings, heme/onc trends, and treatment-related insight.

“How to treat myeloma after #ASH23,” he posted on X as the conference came to a close. His takeaways: Don’t treat smoldering myeloma, do quadruple therapy for transplant-eligible patients (but no cd38 maintenance therapy afterward), don’t do quads for carfilzomib in newly diagnosed frail or older patients, and don’t do a salvage autologous transplant, no matter how good the first transplant was.

Dr. Mohyuddin also works to make a difference through his research and involvement in helping to launch initiatives like Common Sense Oncology, an ambitious global effort to reform cancer clinical trials and care, and through a current project with colleagues in India and Pakistan to create a consortium for pooling data on hematologic malignancies from South Asian countries. The hope is that such a collaborative effort will lead to good prospective research relevant to the needs of participating countries, he explained.

“Those are things where I want to make a difference. Taking care of patients is number one, but more than research, the number two thing for me is teaching and hopefully inspiring trainees and others to think differently, to look at data differently,” he said, noting that despite the major advances in myeloma, the reality is that “a lot of what we offer in oncology is very marginal.”

The effect sizes of interventions are often very small, and outcomes can still be really bad, he explained, adding that “[i]t really hits you when you see a lot of death and suffering. It’s a huge wake-up call … we have so many advances, but the reality is very, very sobering.

“Critically understanding and interpreting data is something where education really fails us. I’m incredibly passionate about it. I’ve found great resources to help me interpret data better, and I want to make them more accessible and inspire others to understand better,” he said. “We need to know how to defend ourselves from the hype.”

His efforts have not gone unnoticed. Dr. Mohyuddin was the recipient of the 2023 Hematology and Medical Oncology Fellowship Faculty Teaching Award at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, where he is currently a faculty member.

“The recognition means more than any publication or grant award,” he said. “It’s great to know that medical education is appreciated, because so often we are in a rat race of getting more papers and grants out, but teaching and inspiring people is what is really, really important to me.”

Ahead of the conference held in San Diego in December, Dr. Mohyuddin, a blood cancer specialist with a focus on multiple myeloma and medical education, put out a heartfelt appeal on X (formerly Twitter): “If you’re a trainee and interested in meeting me at #ASH23, please reach out … (especially if [international medical graduate]) I’d love to meet and offer support in whatever capacity I can! I can’t have a research project for each one of you, but happy to help/mentor in any other way possible,” he posted on X back in late November.

An international medical graduate himself, Dr. Mohyuddin recalls how overwhelmed he felt when he first attended an annual ASH conference as a trainee, so he aims to reassure others that they “don’t have to know everything.”

“It’s about networking and broadening horizons,” he said in an interview that took place between ASH sessions, his own research presentations, and meetings with the many trainees who took him up on the offer he made via X. “I’ve spent most of this ASH meeting trainees — it’s the most rewarding thing for me at these meetings.

“Reassurance is a lot of what we do in oncology,” he continued, drawing a connection between his affinity for helping trainees and providing compassionate care to patients. “For an oncologist, the single most important thing is having excellent communication skills and being able to express support and empathy. The ability to connect deeply with your patients during their time of need is profoundly important.

“You can compensate for lack of knowledge, because we have so many other sources of support for knowledge, but you simply cannot compensate for poor communication skills, and your patient suffers as a result,” he said.

Relationship Building

In addition to the guidance he received from mentors, Dr. Mohyuddin noted that it was the chance to build supportive, empathetic relationships that drew him to specialize in blood cancer and, in particular, to caring for patients with multiple myeloma and conducting research focused on improving the patient experience.

Dr. Mohyuddin attended medical school at the Aga Khan University in Pakistan, then completed his internal medicine residency and fellowship at the University of Kansas in Kansas City. As a chief resident there, he focused on novel approaches to education delivery and improving access to research for trainees. As a fellow, he developed clinical and research interests in multiple myeloma, which he describes as an “incredibly rewarding field” marked by “truly spectacular advances over the last two decades.”

“There are some cancers you can cure, which means you don’t get to see patients often, and there are some you can’t cure, where patients die early, and there’s not a lot of time to build a relationship,” he said. “But there are some where patients can do well even though they aren’t currently cured, and you get to form really amazing and meaningful relationships over a long period of time.

“Multiple myeloma occupies that space, and that’s why I’m drawn to it,” Dr. Mohyuddin added, noting that he doesn’t shy away from forging emotional connections with patients. “I recognize that makes me vulnerable, but I think that is essentially what your patients deserve from you — to be invested at an emotional level with them through their suffering.”

Improving value and the patient experience

“One thing, philosophically, that I research is value in multiple myeloma care: identifying areas where we are overtreating patients and where we can do less and get away with it,” he said.

Despite the major advances in multiple myeloma in recent years, which “represent a lot of what is going right with oncology,” this blood cancer still “also represents a lot of what is wrong with oncology,” he noted. As an example, he cited “the approval of low-value drugs, the sequencing of drugs, adding more and more drugs without responsibly addressing quality-of-life questions, and identifying more responsible ways to provide high-value efficacious care without bankrupting the economy.

“So my research and policy work apply to that,” he explained. “What can we do better? What sort of trials should we be doing? What populations do we enroll? Are we asking the right questions or looking at trivialities? Are we serving patients foremost?”

Sometimes, this means comparing multiple myeloma staging systems in a real-world cohort, or assessing whether a widely available, cheap, and safe drug like budesonide can help patients avoid diarrhea during chemotherapy, whether control arms in myeloma randomized trials are fair, whether drugs ever get approved in low- or middle-income countries after their approval in the United States, and whether smoldering myeloma, a multiple myeloma precursor, really requires treatment, as current guidelines suggest, or if patients would do just as well — or perhaps better — with a close surveillance protocol.

“Pharma won’t do those studies and many key opinion leaders feel the question [about whether smoldering myeloma needs to be treated] has already been answered, so we are launching a prospective study that will define the natural history of smoldering myeloma and allow for patients to stay off therapy while undergoing rigorous surveillance with imaging,” he said.

Another study Dr. Mohyuddin hopes to launch soon will look at a “start low, go slow” treatment approach for the frailest patients with newly diagnosed myeloma.

His upbringing in Pakistan, where there are “mind-boggling” differences in health care access, affordability, and outcomes when compared with the United States, provided a foundation for both his “enthusiasm for cost-effective care” and his desire to give back, he said.

Another aspect of life in Pakistan — an across-the-board sense of closeness and solidarity in families and communities that is sometimes lacking in the United States — contributed to his desire to build relationships.

“That is something I dearly miss,” he said. “I am very privileged and so thankful to be here in the US, but that is one thing I do deeply miss.”

Connecting and Making a Difference

Dr. Mohyuddin seeks connection through his relationships with patients, trainees, and his many followers on social media platforms like X, where he frequently shares his thoughts on research quality and findings, heme/onc trends, and treatment-related insight.

“How to treat myeloma after #ASH23,” he posted on X as the conference came to a close. His takeaways: Don’t treat smoldering myeloma, do quadruple therapy for transplant-eligible patients (but no cd38 maintenance therapy afterward), don’t do quads for carfilzomib in newly diagnosed frail or older patients, and don’t do a salvage autologous transplant, no matter how good the first transplant was.

Dr. Mohyuddin also works to make a difference through his research and involvement in helping to launch initiatives like Common Sense Oncology, an ambitious global effort to reform cancer clinical trials and care, and through a current project with colleagues in India and Pakistan to create a consortium for pooling data on hematologic malignancies from South Asian countries. The hope is that such a collaborative effort will lead to good prospective research relevant to the needs of participating countries, he explained.

“Those are things where I want to make a difference. Taking care of patients is number one, but more than research, the number two thing for me is teaching and hopefully inspiring trainees and others to think differently, to look at data differently,” he said, noting that despite the major advances in myeloma, the reality is that “a lot of what we offer in oncology is very marginal.”

The effect sizes of interventions are often very small, and outcomes can still be really bad, he explained, adding that “[i]t really hits you when you see a lot of death and suffering. It’s a huge wake-up call … we have so many advances, but the reality is very, very sobering.

“Critically understanding and interpreting data is something where education really fails us. I’m incredibly passionate about it. I’ve found great resources to help me interpret data better, and I want to make them more accessible and inspire others to understand better,” he said. “We need to know how to defend ourselves from the hype.”

His efforts have not gone unnoticed. Dr. Mohyuddin was the recipient of the 2023 Hematology and Medical Oncology Fellowship Faculty Teaching Award at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, where he is currently a faculty member.

“The recognition means more than any publication or grant award,” he said. “It’s great to know that medical education is appreciated, because so often we are in a rat race of getting more papers and grants out, but teaching and inspiring people is what is really, really important to me.”

Bladder Cancer: Is Active Surveillance the Way Forward?

PARIS — Should clinicians promote active surveillance for non–muscle-invasive bladder tumors (NMIBT) and establish it as a comprehensive management approach, as with prostate and kidney cancers?

During the 117th congress of the French Association of Urology (AFU), Benjamin Pradère, MD, urologic surgeon at Croix du Sud Clinic in Quint-Fonsegrives, France, advocated for this approach, suggesting that the use of biomarkers could enhance its effectiveness.

However, it requires careful patient selection, proper information, and relevant follow-up,” said Dr. Pradère, who is a member of the AFU Cancer Committee (CCAFU).

Low-Grade Tumors

NMIBTs are precancerous lesions and constitute 70%-80% of diagnosed bladder tumors. The remaining tumors are more severe invasive tumors that infiltrate deep tissues. NMIBTs, however, entail a high risk for recurrence (reaching 80% after endoscopic resection), as well as a high risk for progression.

As a result, the diagnosis of NMIBT involves follow-up that significantly impacts patients’ quality of life due to repeated cystoscopies and endovesical treatments. “Tumors with the most impact are low-grade Ta tumors”, with longer-term monitoring required for these low-risk tumors.

Hematuria is the most frequent clinical sign. NMIBT diagnosis occurs after endoscopic tumor resection via transurethral resection, followed by an anatomopathological analysis to determine cell grade and tumor stage. Treatment depends on the risk of recurrence and progression, as well as the risk of therapeutic failure after the initial resection.

Risk stratification distinguishes the following four levels:

- Low-risk tumors: Low-grade pTa urothelial tumors, unifocal, < 3 cm, no history of bladder tumors. Low risk of recurrence and progression.

- Intermediate-risk tumors: Other low-grade pTa urothelial tumors with no high-risk criteria. Low risk of progression but high risk of recurrence.

- High-risk tumors: Tumors with at least one risk factor: Stage pT1, high grade, presence of carcinoma in situ. High risks of progression and recurrence.

- Very high-risk tumors: Tumors combining all risk factors (pT1 grade with carcinoma in situ). Very high and early risk of progression.

“We know that low-grade NMIBTs have no impact on survival,” said Dr. Pradère. For these tumors, which represent 60% of diagnosed NMIBTs, or approximately 250,000 new cases annually in France, specific survival is > 99%, meaning that most diagnosed patients will not die of bladder cancer.

The recurrence rate for low-grade tumors is 50%, but recurrences are “almost always low-grade and rarely invade the basement membrane,” said Pradère. Implementing active surveillance to limit surgical intervention to more advanced forms seems to be relevant for these tumors.

Cystoscopy Every 3 Months

According to CCAFU recommendations, “active surveillance is a therapeutic alternative that can be proposed for patients with recurrent low-risk NMIBT after the initial diagnosis.” Criteria include low-grade pTa, fewer than five tumors, size ≤ 15 mm, negative urinary cytology, asymptomatic nature, and the patient’s acceptance of closer monitoring.

While active surveillance has become the standard treatment for low-risk prostate cancer, this therapeutic option remains marginal in bladder cancer, as in kidney cancer. The goal is to defer or avoid surgical treatment by closely monitoring the natural progression of the disease.

For NMIBTs, follow-up modalities are not yet specifically recommended because of a lack of data, said Dr. Pradère. According to a consensus, cystoscopy should be repeated every 3 months for a year and then every 6 months. Unlike standard follow-up, it includes cytology “to not miss the transition to high grade.”

CCAFU recommends discontinuing active surveillance if any of the following criteria are present:

- More than 10 lesions

- Size > 30 mm

- Positive cytology

- Symptoms (hematuria, micturition disorders, and recurring infections).

Literature on the benefits of active surveillance in bladder tumors is still limited. Only seven studies are available. Overall, for nearly 600 included patients, tumors progressed in about 12% of cases. Progression to invasive tumors occurred in 0.8% of patients (n = 5).

13 Months’ Surveillance

According to a long-term study (median follow-up of 38 months), patients mostly exit active surveillance in the first year. The median duration of active surveillance is 13 months. Active surveillance is discontinued to surgically treat tumors that turn out to be low-grade Ta tumors in 70% of cases.

The following factors predicting recurrence and progression of tumors have been identified: Multiple tumors, early recurrence (within a year of initial diagnosis), frequent recurrence (more than one recurrence per year), tumors > 3 cm, and failure of previous endovesical treatment.

Recent studies have shown that with at least three of these recurrence and progression factors, the median duration under active surveillance is 15 months compared with 28 months in the absence of such factors. “Considering these factors, it is possible to assess the benefit of active surveillance for the patient,” said Dr. Pradère.

If active surveillance for bladder tumors is still not widely practiced, then the contribution of imaging (MRI and ultrasound) and biomarkers could promote its adoption. “The use of biomarkers should change the game and encourage active surveillance in patients with small polyps,” said Dr. Pradère.

ADXBladder Test Utility

A study highlighted the importance of evaluating minichromosome maintenance protein 5 expression during active surveillance using the ADXBladder ELISA test on a urine sample. This test is usually used in bladder cancer diagnosis.

“This study showed that a negative result in two consecutive tests during active surveillance is associated with an almost zero recurrence risk. After two negative tests, most patients do not exit active surveillance,” said Dr. Pradère. But the positive predictive value of biomarkers remains low for low-grade tumors.

The future of active surveillance in bladder cancer should involve better patient selection that relies on risk factors, enhanced modalities through imaging and biomarkers, and the advent of artificial intelligence to analyze cystoscopy results, concluded Dr. Pradère.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

PARIS — Should clinicians promote active surveillance for non–muscle-invasive bladder tumors (NMIBT) and establish it as a comprehensive management approach, as with prostate and kidney cancers?

During the 117th congress of the French Association of Urology (AFU), Benjamin Pradère, MD, urologic surgeon at Croix du Sud Clinic in Quint-Fonsegrives, France, advocated for this approach, suggesting that the use of biomarkers could enhance its effectiveness.

However, it requires careful patient selection, proper information, and relevant follow-up,” said Dr. Pradère, who is a member of the AFU Cancer Committee (CCAFU).

Low-Grade Tumors

NMIBTs are precancerous lesions and constitute 70%-80% of diagnosed bladder tumors. The remaining tumors are more severe invasive tumors that infiltrate deep tissues. NMIBTs, however, entail a high risk for recurrence (reaching 80% after endoscopic resection), as well as a high risk for progression.

As a result, the diagnosis of NMIBT involves follow-up that significantly impacts patients’ quality of life due to repeated cystoscopies and endovesical treatments. “Tumors with the most impact are low-grade Ta tumors”, with longer-term monitoring required for these low-risk tumors.

Hematuria is the most frequent clinical sign. NMIBT diagnosis occurs after endoscopic tumor resection via transurethral resection, followed by an anatomopathological analysis to determine cell grade and tumor stage. Treatment depends on the risk of recurrence and progression, as well as the risk of therapeutic failure after the initial resection.

Risk stratification distinguishes the following four levels:

- Low-risk tumors: Low-grade pTa urothelial tumors, unifocal, < 3 cm, no history of bladder tumors. Low risk of recurrence and progression.

- Intermediate-risk tumors: Other low-grade pTa urothelial tumors with no high-risk criteria. Low risk of progression but high risk of recurrence.

- High-risk tumors: Tumors with at least one risk factor: Stage pT1, high grade, presence of carcinoma in situ. High risks of progression and recurrence.

- Very high-risk tumors: Tumors combining all risk factors (pT1 grade with carcinoma in situ). Very high and early risk of progression.

“We know that low-grade NMIBTs have no impact on survival,” said Dr. Pradère. For these tumors, which represent 60% of diagnosed NMIBTs, or approximately 250,000 new cases annually in France, specific survival is > 99%, meaning that most diagnosed patients will not die of bladder cancer.

The recurrence rate for low-grade tumors is 50%, but recurrences are “almost always low-grade and rarely invade the basement membrane,” said Pradère. Implementing active surveillance to limit surgical intervention to more advanced forms seems to be relevant for these tumors.

Cystoscopy Every 3 Months

According to CCAFU recommendations, “active surveillance is a therapeutic alternative that can be proposed for patients with recurrent low-risk NMIBT after the initial diagnosis.” Criteria include low-grade pTa, fewer than five tumors, size ≤ 15 mm, negative urinary cytology, asymptomatic nature, and the patient’s acceptance of closer monitoring.

While active surveillance has become the standard treatment for low-risk prostate cancer, this therapeutic option remains marginal in bladder cancer, as in kidney cancer. The goal is to defer or avoid surgical treatment by closely monitoring the natural progression of the disease.

For NMIBTs, follow-up modalities are not yet specifically recommended because of a lack of data, said Dr. Pradère. According to a consensus, cystoscopy should be repeated every 3 months for a year and then every 6 months. Unlike standard follow-up, it includes cytology “to not miss the transition to high grade.”

CCAFU recommends discontinuing active surveillance if any of the following criteria are present:

- More than 10 lesions

- Size > 30 mm

- Positive cytology

- Symptoms (hematuria, micturition disorders, and recurring infections).

Literature on the benefits of active surveillance in bladder tumors is still limited. Only seven studies are available. Overall, for nearly 600 included patients, tumors progressed in about 12% of cases. Progression to invasive tumors occurred in 0.8% of patients (n = 5).

13 Months’ Surveillance

According to a long-term study (median follow-up of 38 months), patients mostly exit active surveillance in the first year. The median duration of active surveillance is 13 months. Active surveillance is discontinued to surgically treat tumors that turn out to be low-grade Ta tumors in 70% of cases.

The following factors predicting recurrence and progression of tumors have been identified: Multiple tumors, early recurrence (within a year of initial diagnosis), frequent recurrence (more than one recurrence per year), tumors > 3 cm, and failure of previous endovesical treatment.

Recent studies have shown that with at least three of these recurrence and progression factors, the median duration under active surveillance is 15 months compared with 28 months in the absence of such factors. “Considering these factors, it is possible to assess the benefit of active surveillance for the patient,” said Dr. Pradère.

If active surveillance for bladder tumors is still not widely practiced, then the contribution of imaging (MRI and ultrasound) and biomarkers could promote its adoption. “The use of biomarkers should change the game and encourage active surveillance in patients with small polyps,” said Dr. Pradère.

ADXBladder Test Utility

A study highlighted the importance of evaluating minichromosome maintenance protein 5 expression during active surveillance using the ADXBladder ELISA test on a urine sample. This test is usually used in bladder cancer diagnosis.

“This study showed that a negative result in two consecutive tests during active surveillance is associated with an almost zero recurrence risk. After two negative tests, most patients do not exit active surveillance,” said Dr. Pradère. But the positive predictive value of biomarkers remains low for low-grade tumors.

The future of active surveillance in bladder cancer should involve better patient selection that relies on risk factors, enhanced modalities through imaging and biomarkers, and the advent of artificial intelligence to analyze cystoscopy results, concluded Dr. Pradère.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

PARIS — Should clinicians promote active surveillance for non–muscle-invasive bladder tumors (NMIBT) and establish it as a comprehensive management approach, as with prostate and kidney cancers?

During the 117th congress of the French Association of Urology (AFU), Benjamin Pradère, MD, urologic surgeon at Croix du Sud Clinic in Quint-Fonsegrives, France, advocated for this approach, suggesting that the use of biomarkers could enhance its effectiveness.

However, it requires careful patient selection, proper information, and relevant follow-up,” said Dr. Pradère, who is a member of the AFU Cancer Committee (CCAFU).

Low-Grade Tumors

NMIBTs are precancerous lesions and constitute 70%-80% of diagnosed bladder tumors. The remaining tumors are more severe invasive tumors that infiltrate deep tissues. NMIBTs, however, entail a high risk for recurrence (reaching 80% after endoscopic resection), as well as a high risk for progression.

As a result, the diagnosis of NMIBT involves follow-up that significantly impacts patients’ quality of life due to repeated cystoscopies and endovesical treatments. “Tumors with the most impact are low-grade Ta tumors”, with longer-term monitoring required for these low-risk tumors.

Hematuria is the most frequent clinical sign. NMIBT diagnosis occurs after endoscopic tumor resection via transurethral resection, followed by an anatomopathological analysis to determine cell grade and tumor stage. Treatment depends on the risk of recurrence and progression, as well as the risk of therapeutic failure after the initial resection.

Risk stratification distinguishes the following four levels:

- Low-risk tumors: Low-grade pTa urothelial tumors, unifocal, < 3 cm, no history of bladder tumors. Low risk of recurrence and progression.

- Intermediate-risk tumors: Other low-grade pTa urothelial tumors with no high-risk criteria. Low risk of progression but high risk of recurrence.

- High-risk tumors: Tumors with at least one risk factor: Stage pT1, high grade, presence of carcinoma in situ. High risks of progression and recurrence.

- Very high-risk tumors: Tumors combining all risk factors (pT1 grade with carcinoma in situ). Very high and early risk of progression.

“We know that low-grade NMIBTs have no impact on survival,” said Dr. Pradère. For these tumors, which represent 60% of diagnosed NMIBTs, or approximately 250,000 new cases annually in France, specific survival is > 99%, meaning that most diagnosed patients will not die of bladder cancer.

The recurrence rate for low-grade tumors is 50%, but recurrences are “almost always low-grade and rarely invade the basement membrane,” said Pradère. Implementing active surveillance to limit surgical intervention to more advanced forms seems to be relevant for these tumors.

Cystoscopy Every 3 Months

According to CCAFU recommendations, “active surveillance is a therapeutic alternative that can be proposed for patients with recurrent low-risk NMIBT after the initial diagnosis.” Criteria include low-grade pTa, fewer than five tumors, size ≤ 15 mm, negative urinary cytology, asymptomatic nature, and the patient’s acceptance of closer monitoring.

While active surveillance has become the standard treatment for low-risk prostate cancer, this therapeutic option remains marginal in bladder cancer, as in kidney cancer. The goal is to defer or avoid surgical treatment by closely monitoring the natural progression of the disease.

For NMIBTs, follow-up modalities are not yet specifically recommended because of a lack of data, said Dr. Pradère. According to a consensus, cystoscopy should be repeated every 3 months for a year and then every 6 months. Unlike standard follow-up, it includes cytology “to not miss the transition to high grade.”

CCAFU recommends discontinuing active surveillance if any of the following criteria are present:

- More than 10 lesions

- Size > 30 mm

- Positive cytology

- Symptoms (hematuria, micturition disorders, and recurring infections).

Literature on the benefits of active surveillance in bladder tumors is still limited. Only seven studies are available. Overall, for nearly 600 included patients, tumors progressed in about 12% of cases. Progression to invasive tumors occurred in 0.8% of patients (n = 5).

13 Months’ Surveillance

According to a long-term study (median follow-up of 38 months), patients mostly exit active surveillance in the first year. The median duration of active surveillance is 13 months. Active surveillance is discontinued to surgically treat tumors that turn out to be low-grade Ta tumors in 70% of cases.

The following factors predicting recurrence and progression of tumors have been identified: Multiple tumors, early recurrence (within a year of initial diagnosis), frequent recurrence (more than one recurrence per year), tumors > 3 cm, and failure of previous endovesical treatment.

Recent studies have shown that with at least three of these recurrence and progression factors, the median duration under active surveillance is 15 months compared with 28 months in the absence of such factors. “Considering these factors, it is possible to assess the benefit of active surveillance for the patient,” said Dr. Pradère.

If active surveillance for bladder tumors is still not widely practiced, then the contribution of imaging (MRI and ultrasound) and biomarkers could promote its adoption. “The use of biomarkers should change the game and encourage active surveillance in patients with small polyps,” said Dr. Pradère.

ADXBladder Test Utility

A study highlighted the importance of evaluating minichromosome maintenance protein 5 expression during active surveillance using the ADXBladder ELISA test on a urine sample. This test is usually used in bladder cancer diagnosis.