User login

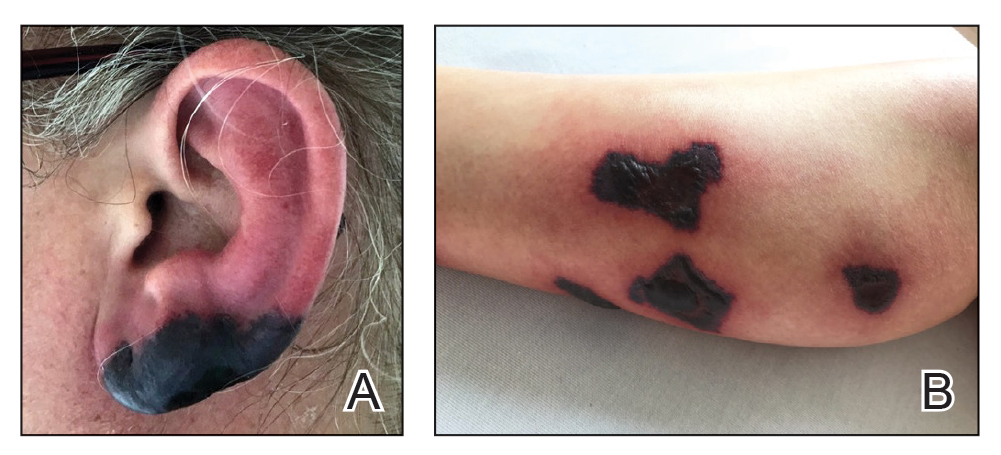

Bullous Retiform Purpura on the Ears and Legs

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Vasculopathy

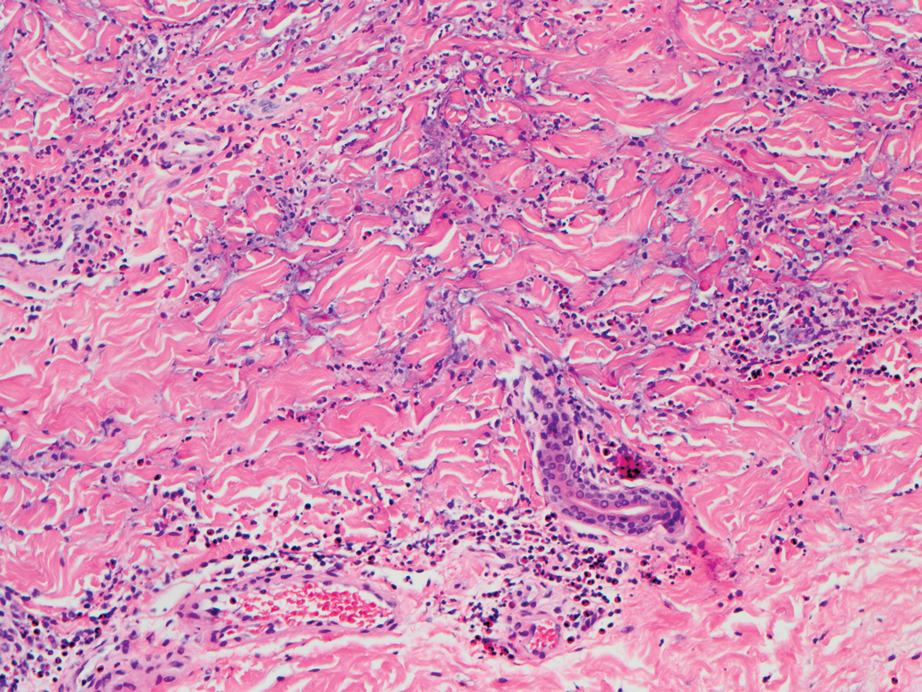

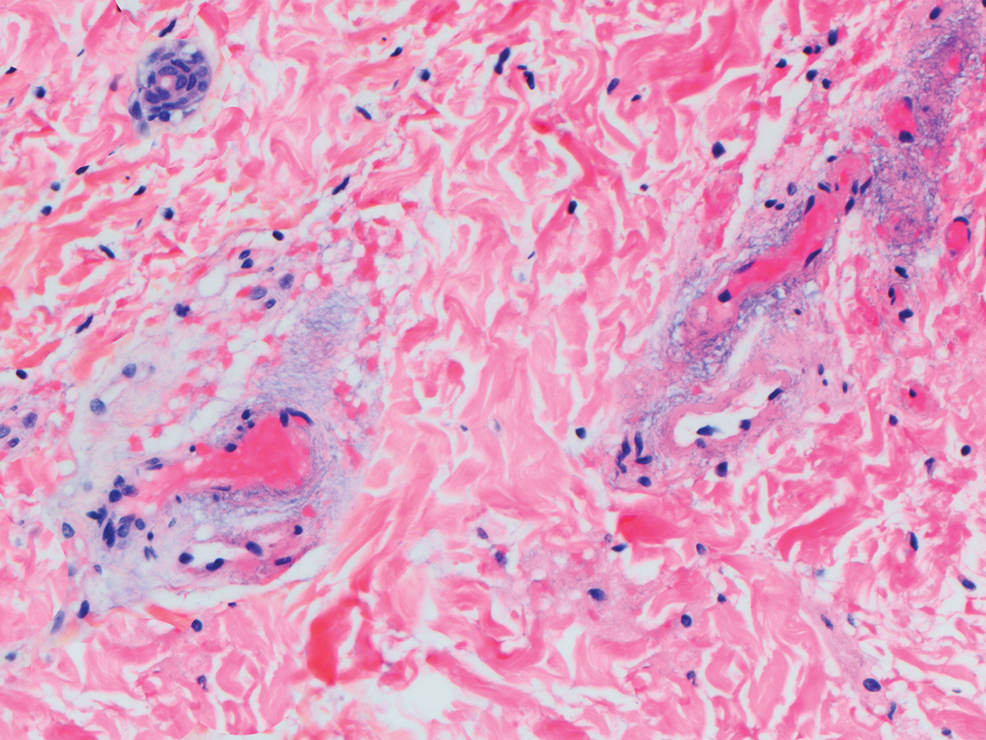

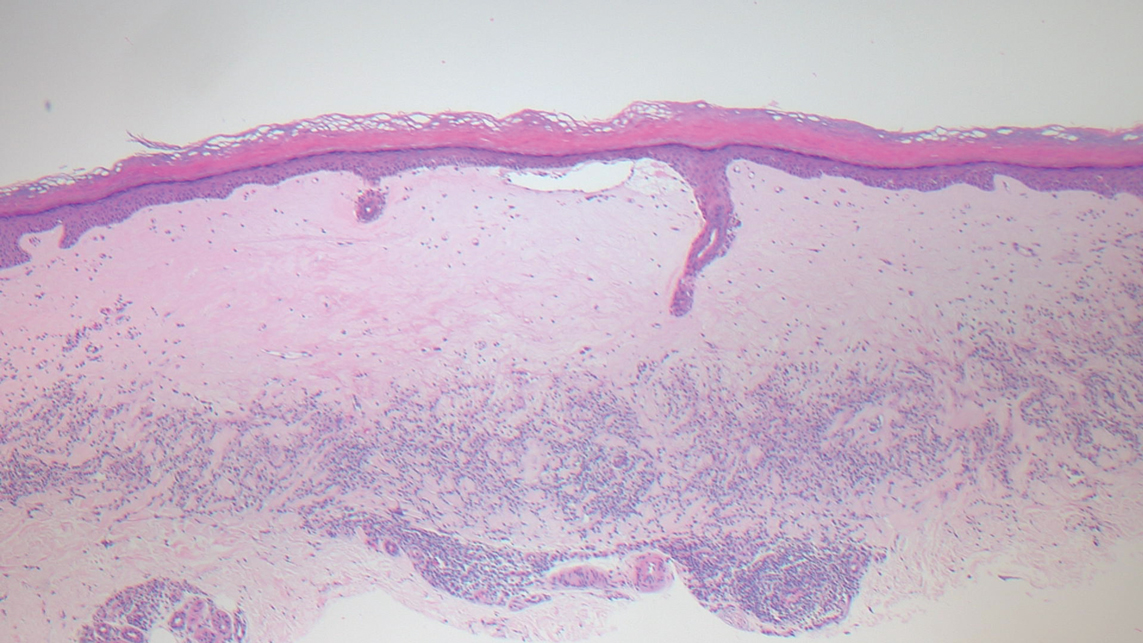

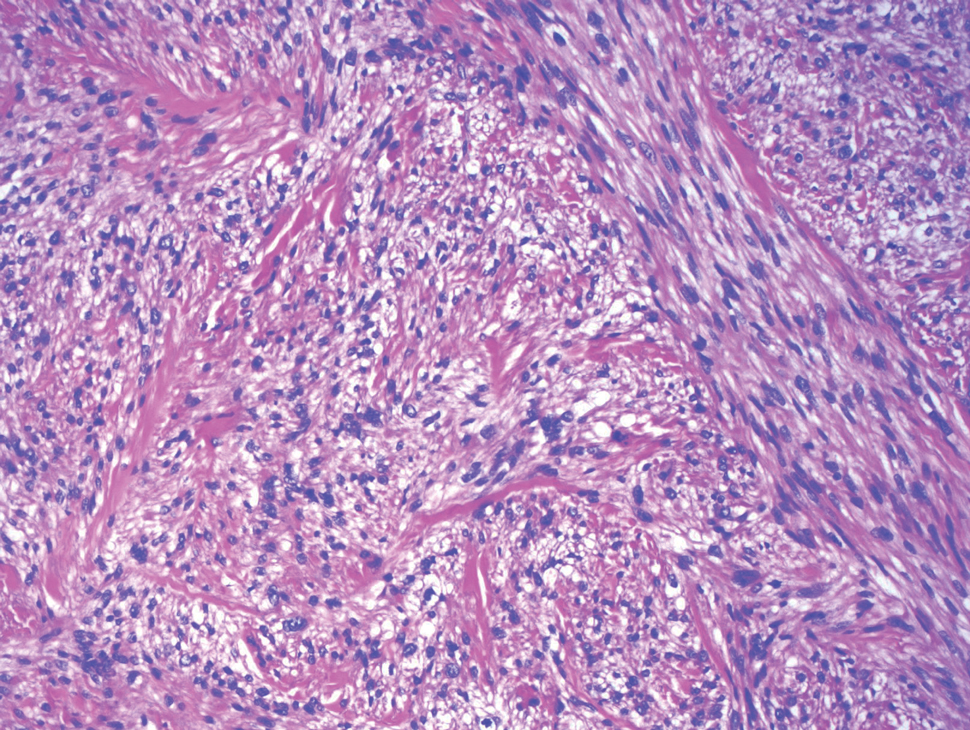

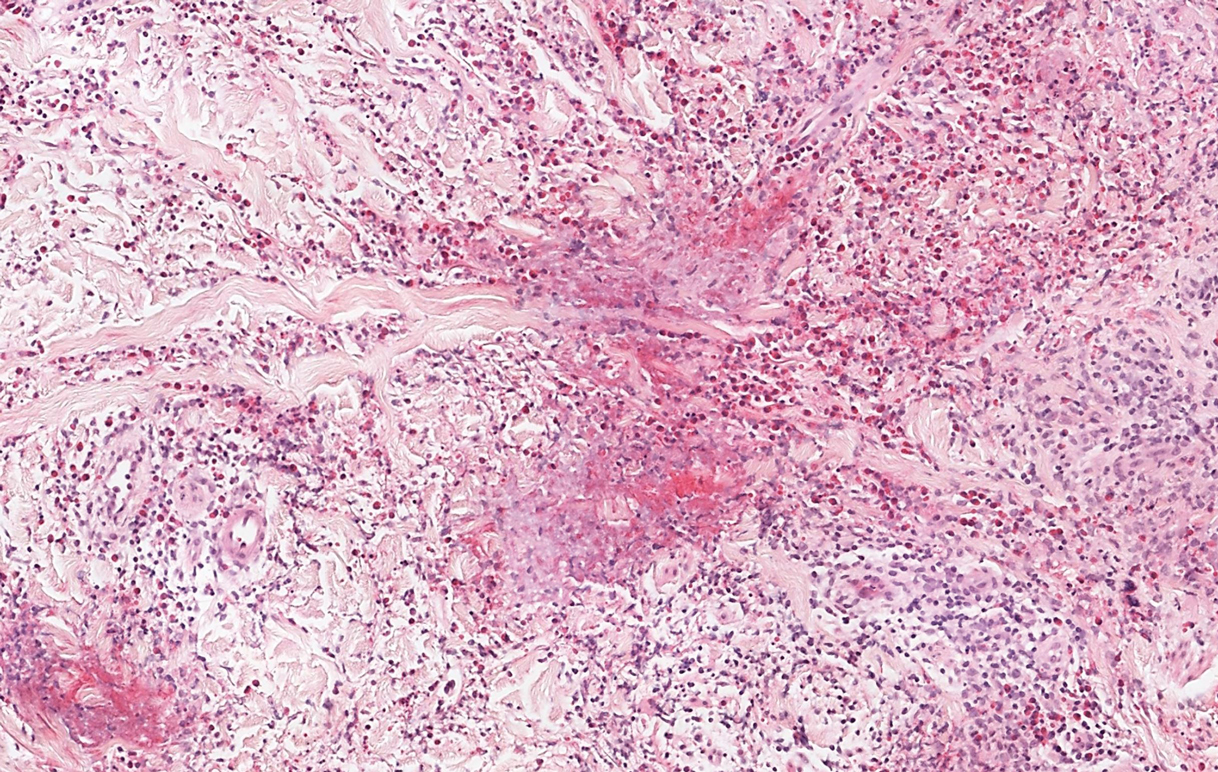

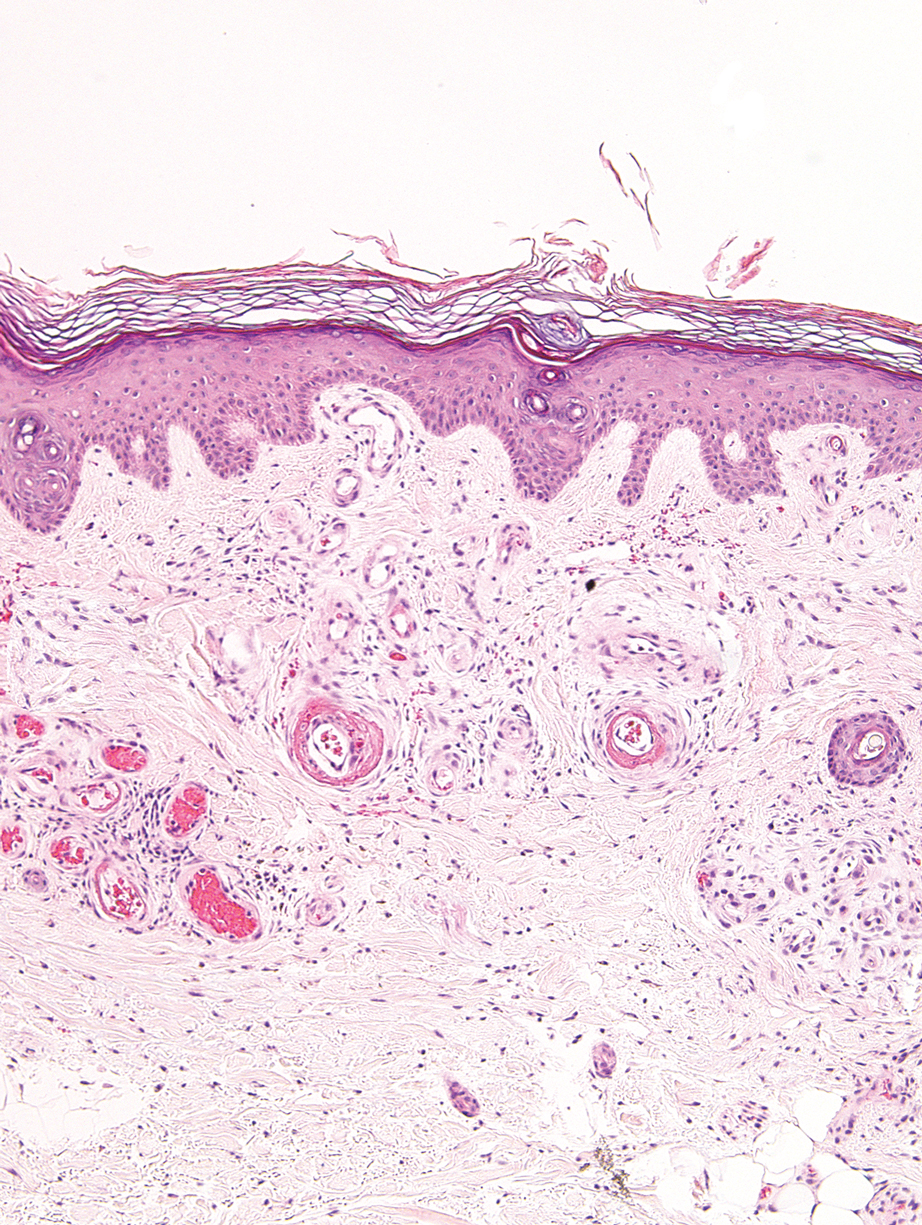

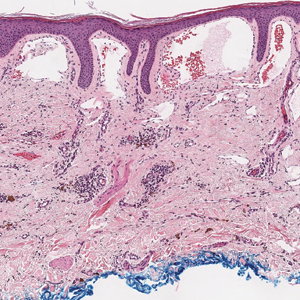

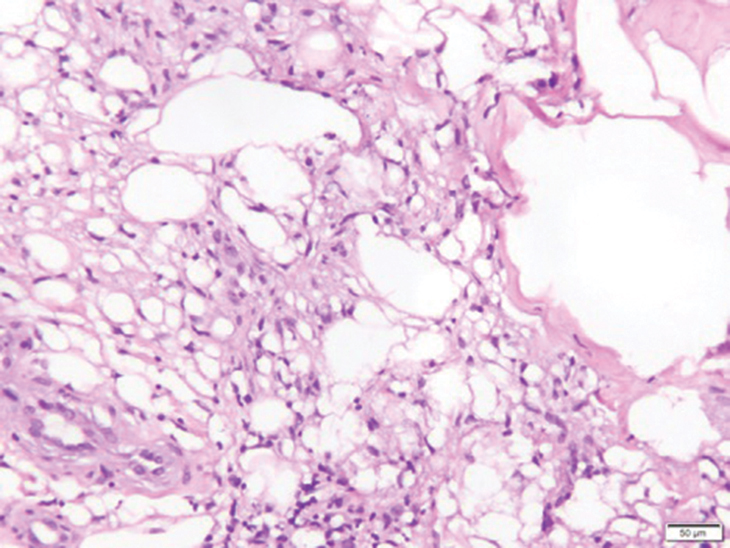

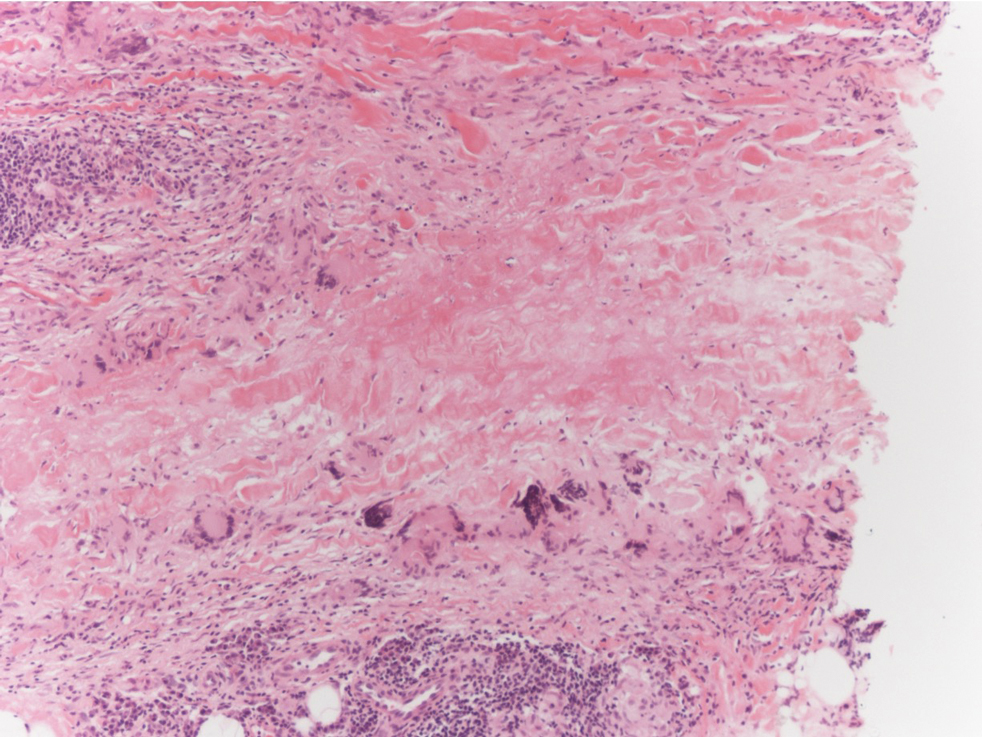

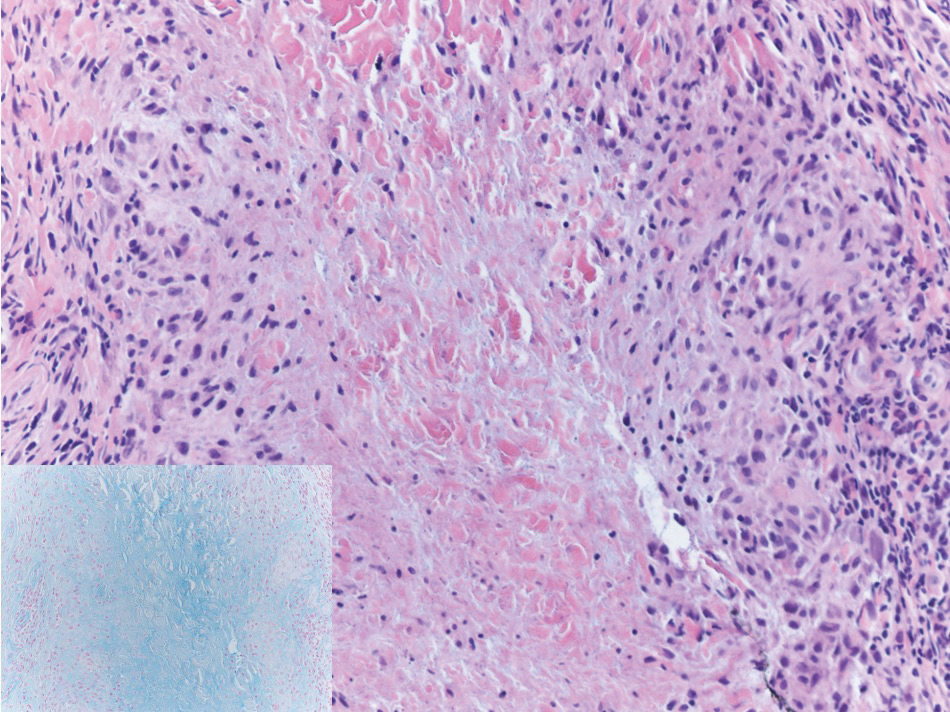

Biopsy of one of the bullous retiform purpura on the leg (Figure 1) revealed a combined leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy (quiz images). Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains, with adequate controls, were negative for pathogenic fungal and bacterial organisms. Although this reaction pattern has an extensive differential, in this clinical setting with associated cocaine-positive urine toxicologic analysis, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), and leukopenia, the histopathologic findings were consistent with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV).1,2 Although not specific, leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy have been reported as the classic histopathologic findings of LIV. In addition, interstitial and perivascular neovascularization have been reported as a potential histopathologic finding associated with this entity but was not seen in our case.3

Levamisole is an anthelminthic agent used to adulterate cocaine, a practice first noted in 2003 with increasing incidence.1 Both levamisole and cocaine stimulate the sympathetic nervous system by increasing dopamine in the euphoric areas of the brain.1,3 By combining the 2 substances, preparation costs are reduced and stimulant effects are enhanced. It is estimated that 69% to 80% of cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole.2,4,5 The constellation of findings seen in patients abusing levamisole-contaminated cocaine include agranulocytosis; p-ANCA; and a tender, vasculitic, retiform purpura presentation. The most common sites for the purpura include the cheeks and ears. The purpura can progress to bullous lesions, as seen in our patient, followed by necrosis.4,6 Recurrent use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine is associated with recurrent agranulocytosis and classic skin findings, which is suggestive of a causal relationship.6

Serologic testing for levamisole exposure presents a challenge. The half-life of levamisole is relatively short (estimated at 5.6 hours) and is found in urine samples approximately 3% of the time.1,3,6 The volatile diagnostic characteristics of levamisole make concrete laboratory confirmation difficult. Although a skin biopsy can be helpful to rule out other causes of vasculitislike presentations, it is not specific for LIV. Therefore, clinical suspicion for LIV should remain high in patients who present with the cutaneous findings described as well as agranulocytosis, positive p-ANCA, and a history of cocaine use with a skin biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy.

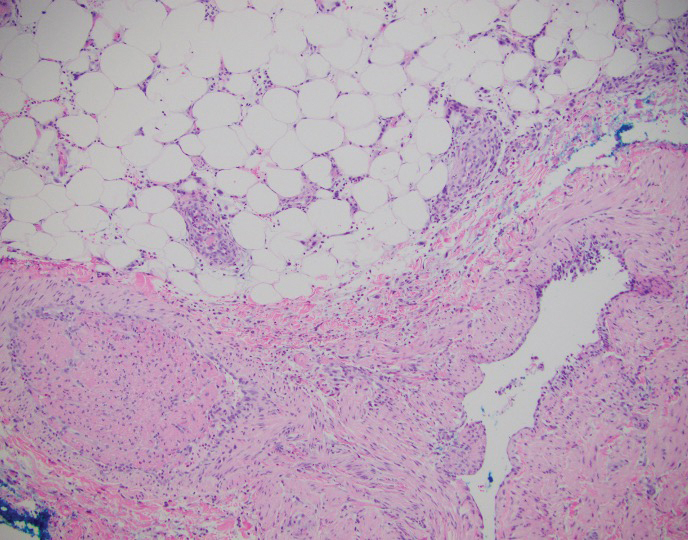

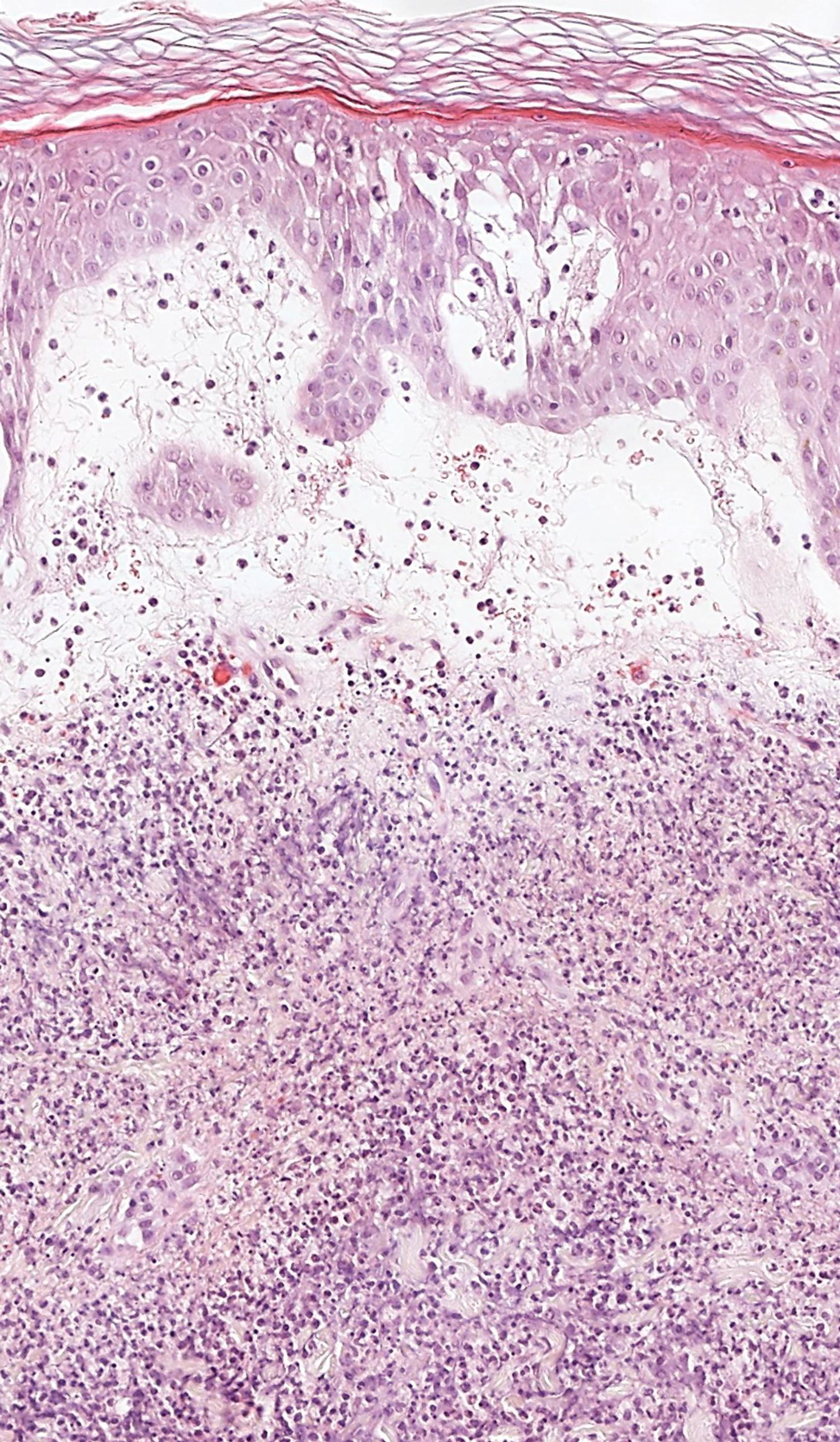

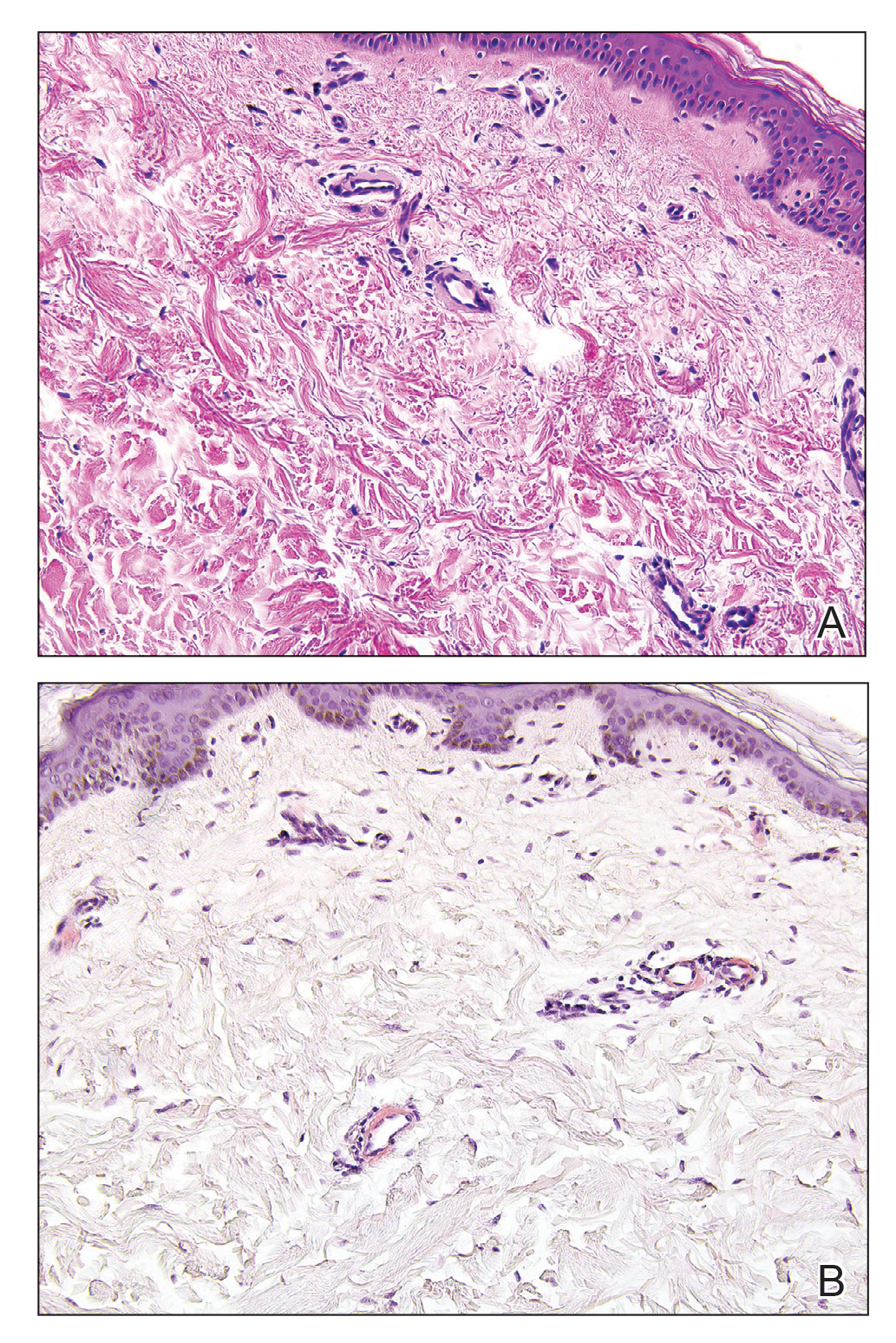

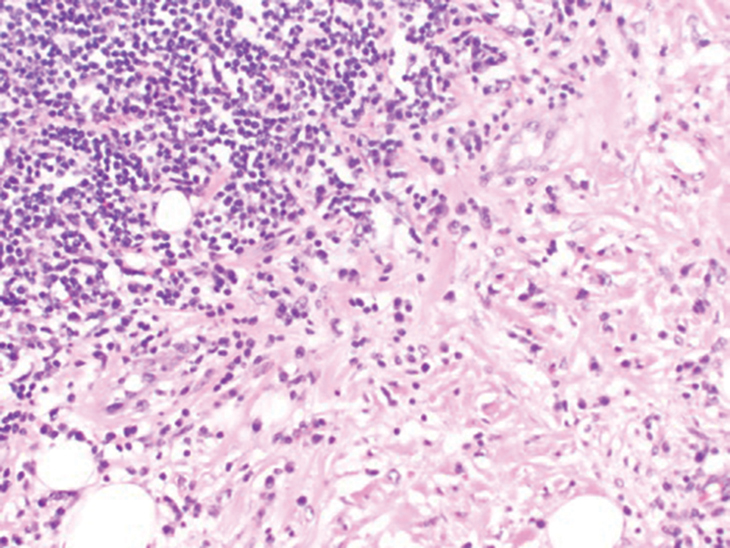

The differential diagnosis for LIV with retiform bullous lesions includes several other vasculitides and vesiculobullous diseases. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a multisystem vasculitis that is characterized by eosinophilia, asthma, and rhinosinusitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis primarily affects small and medium arteries in the skin and respiratory tract and occurs in 3 stages: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic. These stages are characterized by mild asthma or rhinitis, eosinophilia with multiorgan infiltration, and vasculitis with extravascular granulomatosis, respectively. Diagnosis often is clinical based on these findings and laboratory evaluation. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis presents with positive p-ANCA in 40% to 60% of patients.7 The vasculitis stage of EGPA presents with cutaneous findings in 60% of cases, including palpable purpura, infiltrated papules and plaques, urticaria, necrotizing lesions, and rarely vesicles and bullae.8 Classic histopathologic features include leukocytoclastic or eosinophilic vasculitis, an eosinophilic infiltrate, granuloma formation, and eosinophilic granule deposition onto collagen fibrils (otherwise known as flame figures)(Figure 2). Biopsy of these lesions with the aforementioned findings, in constellation with the described systemic signs and symptoms, can aid in diagnosis of EGPA.

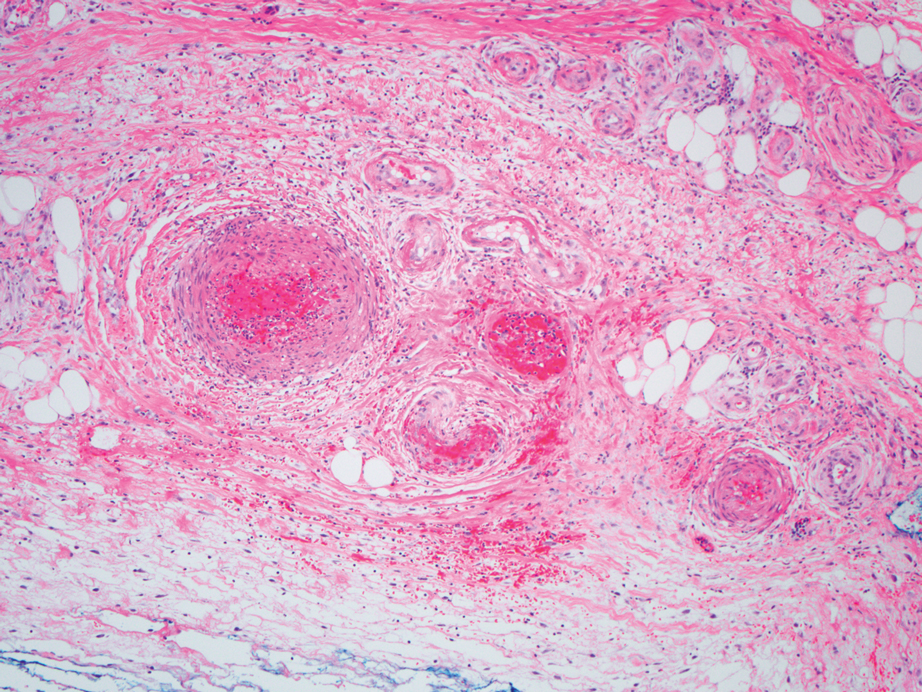

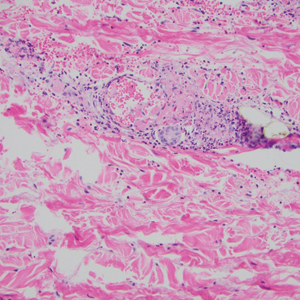

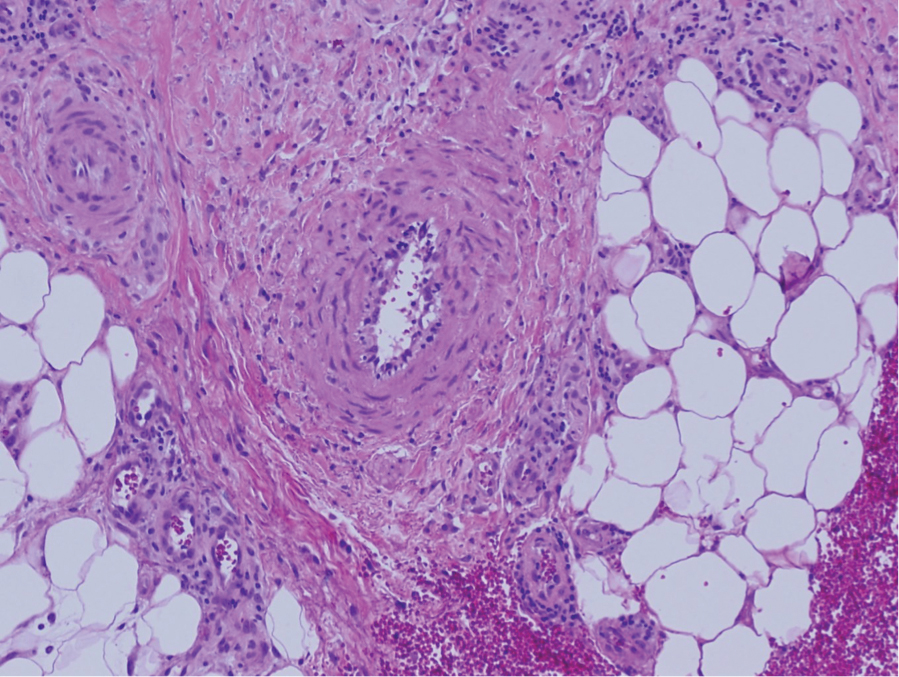

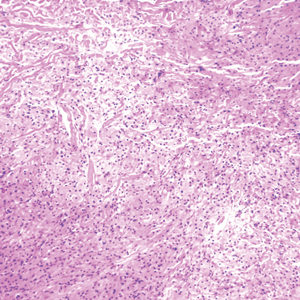

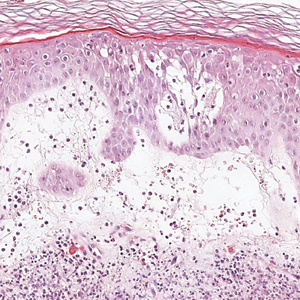

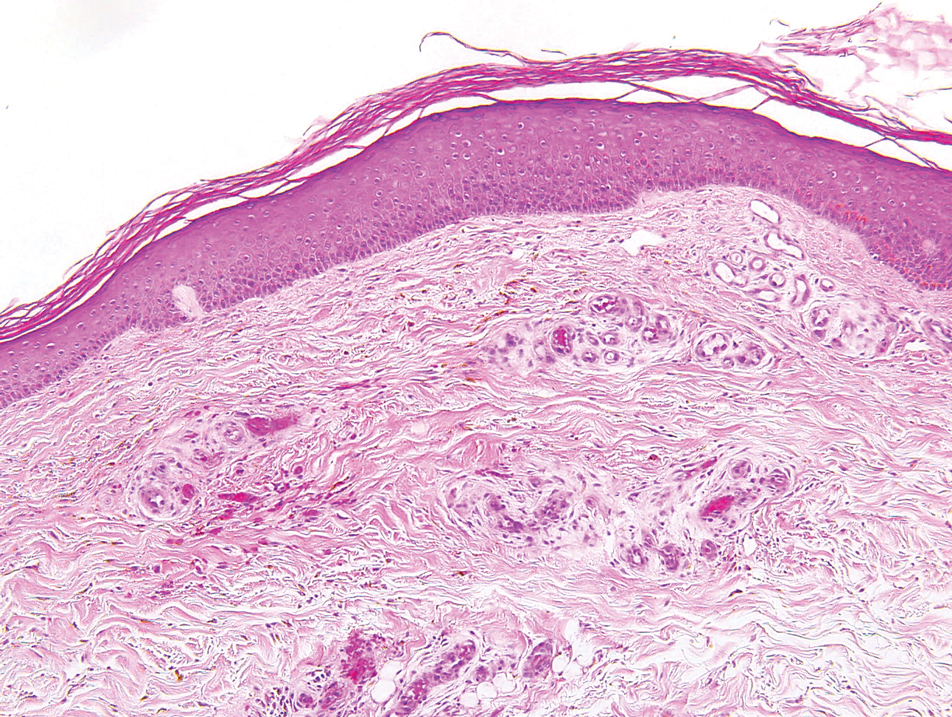

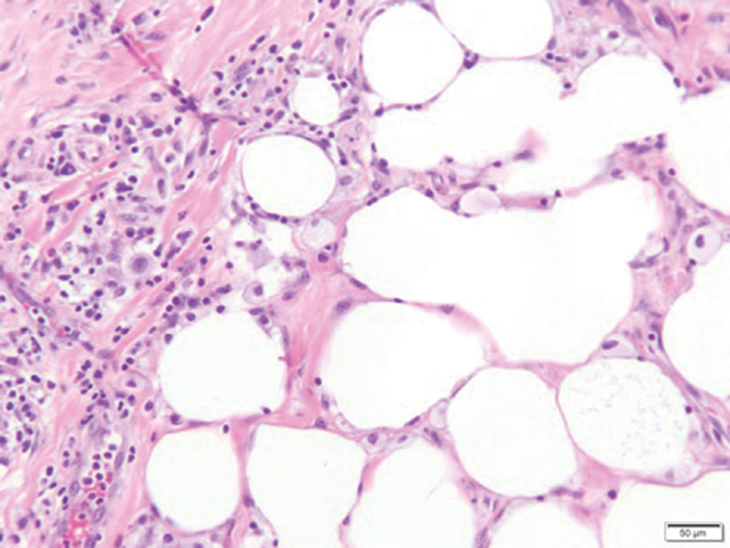

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a vasculitis that can be either multisystem or limited to one organ. Classic PAN affects the small- to medium-sized vessels. When there is multisystem involvement, it most often affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. It presents with subcutaneous or dermal nodules, necrotic lesions, livedo reticularis, hypertension, abdominal pain, and an acute abdomen.9 When PAN is in its limited form, it most commonly occurs in the skin. The cutaneous manifestations of skin-limited PAN are identical to classic PAN, most commonly occurring on the legs and arms and less often on the trunk, head, and neck.10 To aid in diagnosis, biopsies of cutaneous lesions are beneficial. Dermatopathologic examination of PAN reveals fibrinoid necrosis of small and medium vessels with a perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Cutaneous PAN rarely progresses to multisystem classic PAN and carries a more favorable prognosis.

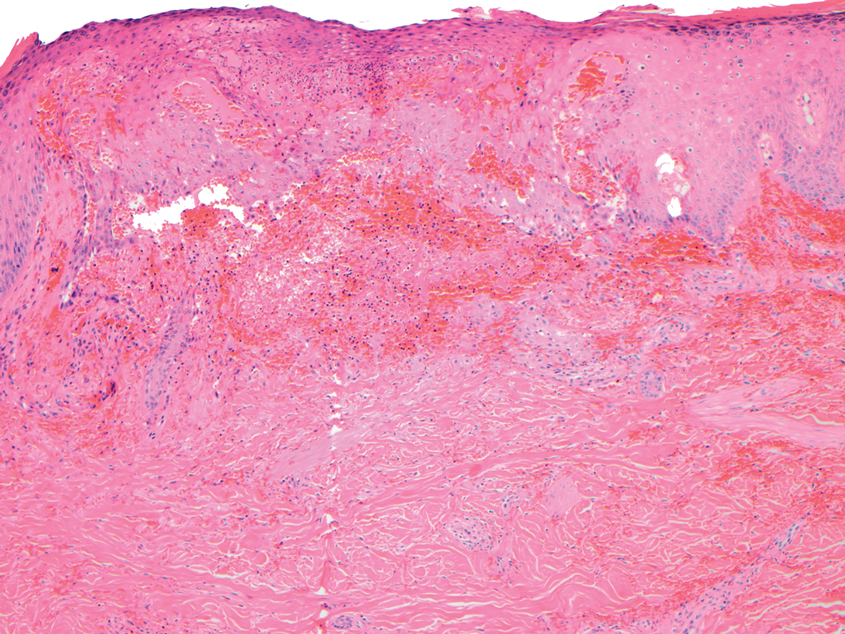

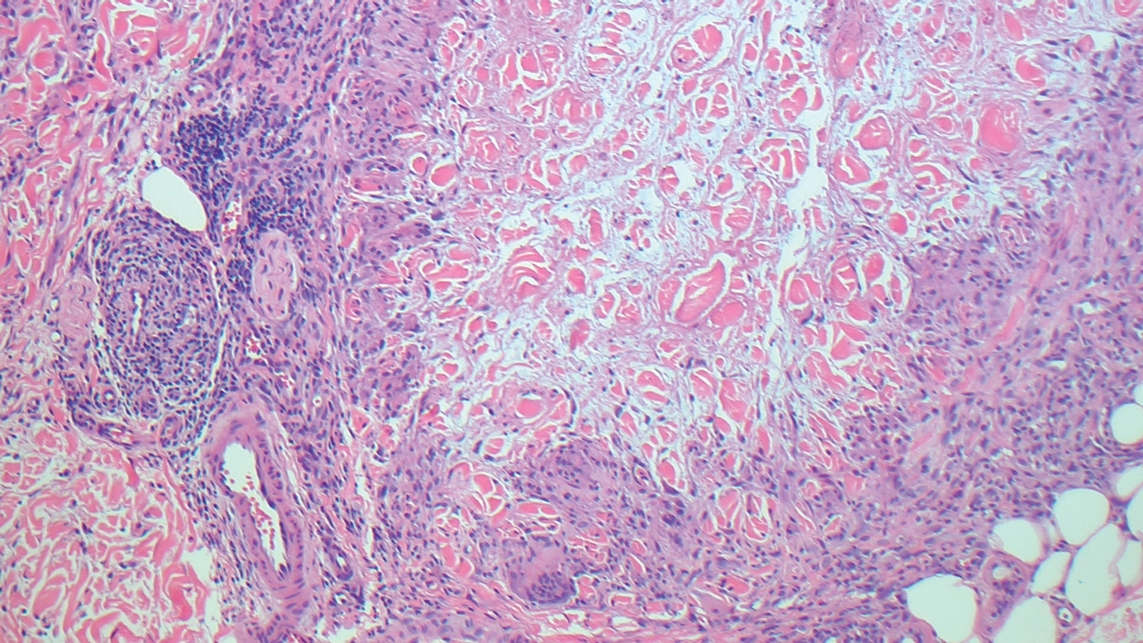

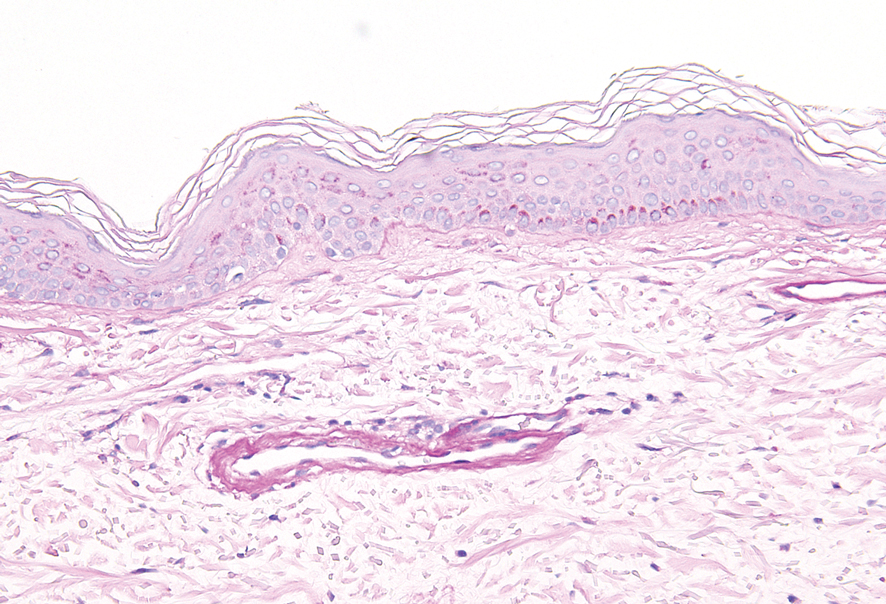

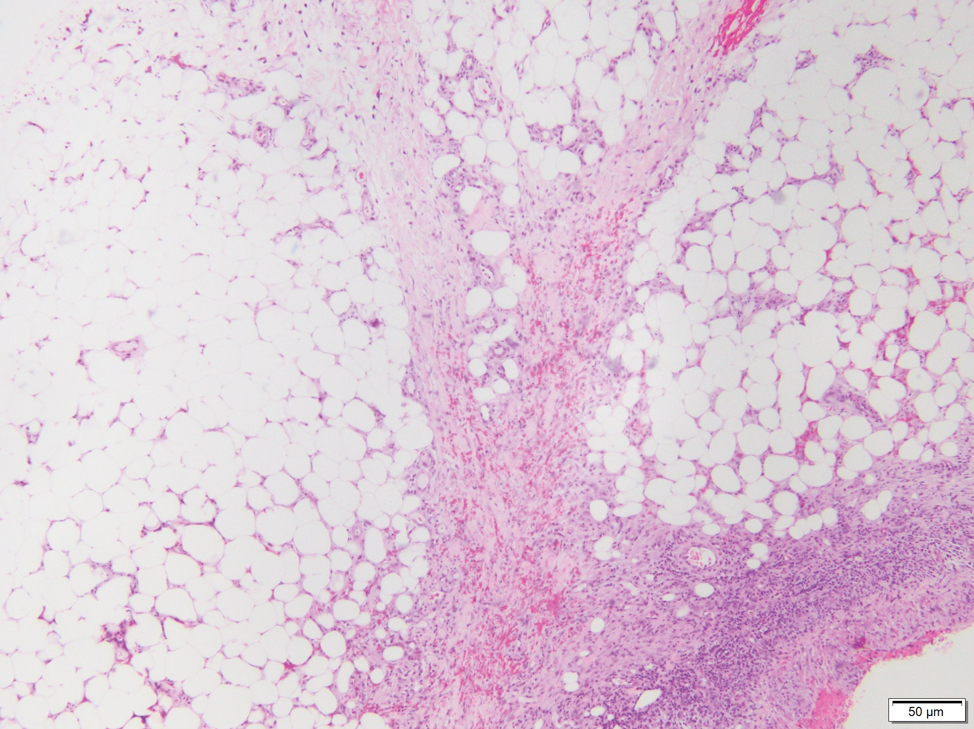

Microvascular occlusion syndromes can result in clinical presentations that resemble LIV. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is a hematologic autoimmune condition resulting in destruction of platelets and subsequent thrombocytopenia. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura can be either primary or secondary to infections, drugs, malignancy, or other autoimmune conditions. Clinically, it presents as mucosal or cutaneous bleeding, epistaxis, hematochezia, or hematuria and can result in substantial hemorrhage. On the skin, it can appear as petechiae and ecchymoses in dependent areas and rarely hemorrhagic bullae of the skin and mucous membranes in cases of severe thrombocytopenia.11,12 Biopsies of these lesions will show notable extravasation of red blood cells with incipient hemorrhagic bullae formation (Figure 4). Recognition of hemorrhagic bullae as a presentation of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is critical to identifying severe underlying disease.

Beyond other vasculitides and microvascular occlusion syndromes, vessel-invasive microorganisms can result in similar histopathologic and clinical presentations to LIV. Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a septic vasculitis, often caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, usually affecting immunocompromised patients. Ecthyma gangrenosum presents with vesiculobullous lesions with erythematous violaceous borders that develop into hemorrhagic bullae with necrotic centers.13 Biopsy of EG will show vascular occlusion and basophilic granular material within or around vessels, suggestive of bacterial sepsis (Figure 5). The detection of an infectious agent on histopathology allows one to easily distinguish between EG and LIV.

- Bajaj S, Hibler B, Rossi A. Painful violaceous purpura on a 44-year-old woman. Am J Med. 2016;129:E5-E7.

- Munoz-Vahos CH, Herrera-Uribe S, Arbelaez-Cortes A, et al. Clinical profile of levamisole-adulterated cocaine-induced vasculitis/vasculopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:E16-E26.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Gillis JA, Green P, Williams J. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: staging and management. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:E29-E31.

- Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chafins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1320-1321.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia-a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;65:722-725.

- Negbenebor NA, Khalifian S, Foreman RK, et al. A 92-year-old male with eosinophilic asthma presenting with recurrent palpable purpuric plaques. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:44-48.

- Sherman S, Gal N, Didkovsky E, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) relapsing as bullous eruption. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:406-407.

- Braungart S, Campbell A, Besarovic S. Atypical Henoch-Schonlein purpura? consider polyarteritis nodosa! BMJ Case Rep. 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201764

- Alquorain NAA, Aljabr ASH, Alghamdi NJ. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with pentoxifylline and clobetasol propionate: a case report. Saudi J Med Sci. 2018;6:104-107.

- Helms AE, Schaffer RI. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with black oral mucosal lesions. Cutis. 2007;79:456-458.

- Lountzis N, Maroon M, Tyler W. Mucocutaneous hemorrhagic bullae in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:AB124.

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegeria V, Santos-Briz A, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662.

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Vasculopathy

Biopsy of one of the bullous retiform purpura on the leg (Figure 1) revealed a combined leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy (quiz images). Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains, with adequate controls, were negative for pathogenic fungal and bacterial organisms. Although this reaction pattern has an extensive differential, in this clinical setting with associated cocaine-positive urine toxicologic analysis, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), and leukopenia, the histopathologic findings were consistent with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV).1,2 Although not specific, leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy have been reported as the classic histopathologic findings of LIV. In addition, interstitial and perivascular neovascularization have been reported as a potential histopathologic finding associated with this entity but was not seen in our case.3

Levamisole is an anthelminthic agent used to adulterate cocaine, a practice first noted in 2003 with increasing incidence.1 Both levamisole and cocaine stimulate the sympathetic nervous system by increasing dopamine in the euphoric areas of the brain.1,3 By combining the 2 substances, preparation costs are reduced and stimulant effects are enhanced. It is estimated that 69% to 80% of cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole.2,4,5 The constellation of findings seen in patients abusing levamisole-contaminated cocaine include agranulocytosis; p-ANCA; and a tender, vasculitic, retiform purpura presentation. The most common sites for the purpura include the cheeks and ears. The purpura can progress to bullous lesions, as seen in our patient, followed by necrosis.4,6 Recurrent use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine is associated with recurrent agranulocytosis and classic skin findings, which is suggestive of a causal relationship.6

Serologic testing for levamisole exposure presents a challenge. The half-life of levamisole is relatively short (estimated at 5.6 hours) and is found in urine samples approximately 3% of the time.1,3,6 The volatile diagnostic characteristics of levamisole make concrete laboratory confirmation difficult. Although a skin biopsy can be helpful to rule out other causes of vasculitislike presentations, it is not specific for LIV. Therefore, clinical suspicion for LIV should remain high in patients who present with the cutaneous findings described as well as agranulocytosis, positive p-ANCA, and a history of cocaine use with a skin biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy.

The differential diagnosis for LIV with retiform bullous lesions includes several other vasculitides and vesiculobullous diseases. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a multisystem vasculitis that is characterized by eosinophilia, asthma, and rhinosinusitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis primarily affects small and medium arteries in the skin and respiratory tract and occurs in 3 stages: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic. These stages are characterized by mild asthma or rhinitis, eosinophilia with multiorgan infiltration, and vasculitis with extravascular granulomatosis, respectively. Diagnosis often is clinical based on these findings and laboratory evaluation. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis presents with positive p-ANCA in 40% to 60% of patients.7 The vasculitis stage of EGPA presents with cutaneous findings in 60% of cases, including palpable purpura, infiltrated papules and plaques, urticaria, necrotizing lesions, and rarely vesicles and bullae.8 Classic histopathologic features include leukocytoclastic or eosinophilic vasculitis, an eosinophilic infiltrate, granuloma formation, and eosinophilic granule deposition onto collagen fibrils (otherwise known as flame figures)(Figure 2). Biopsy of these lesions with the aforementioned findings, in constellation with the described systemic signs and symptoms, can aid in diagnosis of EGPA.

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a vasculitis that can be either multisystem or limited to one organ. Classic PAN affects the small- to medium-sized vessels. When there is multisystem involvement, it most often affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. It presents with subcutaneous or dermal nodules, necrotic lesions, livedo reticularis, hypertension, abdominal pain, and an acute abdomen.9 When PAN is in its limited form, it most commonly occurs in the skin. The cutaneous manifestations of skin-limited PAN are identical to classic PAN, most commonly occurring on the legs and arms and less often on the trunk, head, and neck.10 To aid in diagnosis, biopsies of cutaneous lesions are beneficial. Dermatopathologic examination of PAN reveals fibrinoid necrosis of small and medium vessels with a perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Cutaneous PAN rarely progresses to multisystem classic PAN and carries a more favorable prognosis.

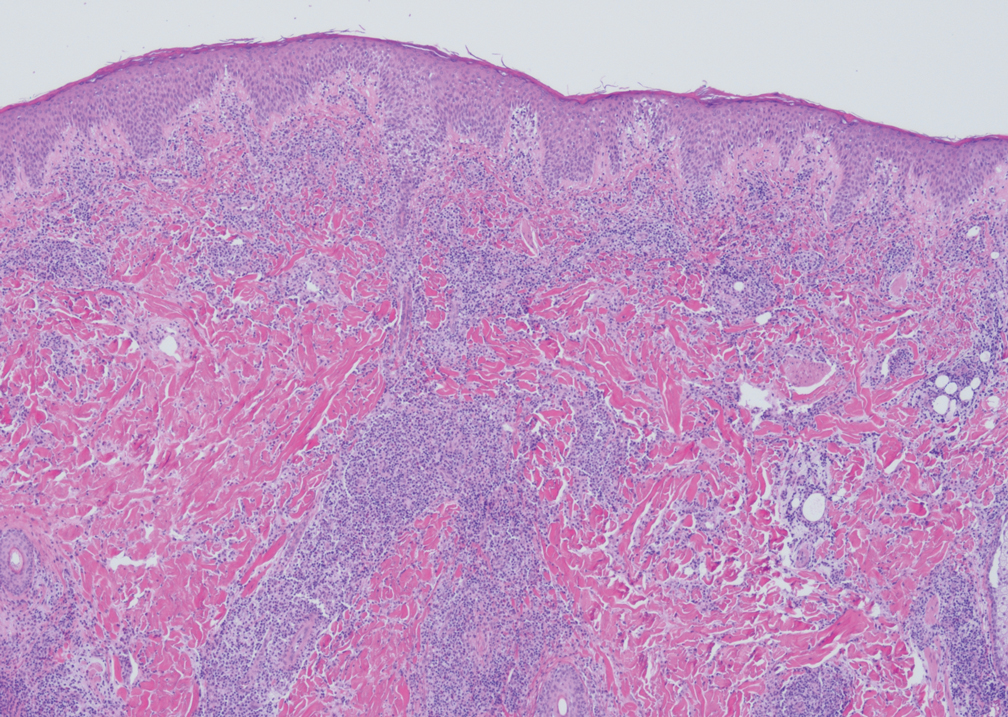

Microvascular occlusion syndromes can result in clinical presentations that resemble LIV. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is a hematologic autoimmune condition resulting in destruction of platelets and subsequent thrombocytopenia. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura can be either primary or secondary to infections, drugs, malignancy, or other autoimmune conditions. Clinically, it presents as mucosal or cutaneous bleeding, epistaxis, hematochezia, or hematuria and can result in substantial hemorrhage. On the skin, it can appear as petechiae and ecchymoses in dependent areas and rarely hemorrhagic bullae of the skin and mucous membranes in cases of severe thrombocytopenia.11,12 Biopsies of these lesions will show notable extravasation of red blood cells with incipient hemorrhagic bullae formation (Figure 4). Recognition of hemorrhagic bullae as a presentation of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is critical to identifying severe underlying disease.

Beyond other vasculitides and microvascular occlusion syndromes, vessel-invasive microorganisms can result in similar histopathologic and clinical presentations to LIV. Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a septic vasculitis, often caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, usually affecting immunocompromised patients. Ecthyma gangrenosum presents with vesiculobullous lesions with erythematous violaceous borders that develop into hemorrhagic bullae with necrotic centers.13 Biopsy of EG will show vascular occlusion and basophilic granular material within or around vessels, suggestive of bacterial sepsis (Figure 5). The detection of an infectious agent on histopathology allows one to easily distinguish between EG and LIV.

The Diagnosis: Levamisole-Induced Vasculopathy

Biopsy of one of the bullous retiform purpura on the leg (Figure 1) revealed a combined leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy (quiz images). Periodic acid-Schiff and Gram stains, with adequate controls, were negative for pathogenic fungal and bacterial organisms. Although this reaction pattern has an extensive differential, in this clinical setting with associated cocaine-positive urine toxicologic analysis, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA), and leukopenia, the histopathologic findings were consistent with levamisole-induced vasculopathy (LIV).1,2 Although not specific, leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy have been reported as the classic histopathologic findings of LIV. In addition, interstitial and perivascular neovascularization have been reported as a potential histopathologic finding associated with this entity but was not seen in our case.3

Levamisole is an anthelminthic agent used to adulterate cocaine, a practice first noted in 2003 with increasing incidence.1 Both levamisole and cocaine stimulate the sympathetic nervous system by increasing dopamine in the euphoric areas of the brain.1,3 By combining the 2 substances, preparation costs are reduced and stimulant effects are enhanced. It is estimated that 69% to 80% of cocaine in the United States is contaminated with levamisole.2,4,5 The constellation of findings seen in patients abusing levamisole-contaminated cocaine include agranulocytosis; p-ANCA; and a tender, vasculitic, retiform purpura presentation. The most common sites for the purpura include the cheeks and ears. The purpura can progress to bullous lesions, as seen in our patient, followed by necrosis.4,6 Recurrent use of levamisole-contaminated cocaine is associated with recurrent agranulocytosis and classic skin findings, which is suggestive of a causal relationship.6

Serologic testing for levamisole exposure presents a challenge. The half-life of levamisole is relatively short (estimated at 5.6 hours) and is found in urine samples approximately 3% of the time.1,3,6 The volatile diagnostic characteristics of levamisole make concrete laboratory confirmation difficult. Although a skin biopsy can be helpful to rule out other causes of vasculitislike presentations, it is not specific for LIV. Therefore, clinical suspicion for LIV should remain high in patients who present with the cutaneous findings described as well as agranulocytosis, positive p-ANCA, and a history of cocaine use with a skin biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic vasculopathy.

The differential diagnosis for LIV with retiform bullous lesions includes several other vasculitides and vesiculobullous diseases. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a multisystem vasculitis that is characterized by eosinophilia, asthma, and rhinosinusitis. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis primarily affects small and medium arteries in the skin and respiratory tract and occurs in 3 stages: prodromal, eosinophilic, and vasculitic. These stages are characterized by mild asthma or rhinitis, eosinophilia with multiorgan infiltration, and vasculitis with extravascular granulomatosis, respectively. Diagnosis often is clinical based on these findings and laboratory evaluation. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis presents with positive p-ANCA in 40% to 60% of patients.7 The vasculitis stage of EGPA presents with cutaneous findings in 60% of cases, including palpable purpura, infiltrated papules and plaques, urticaria, necrotizing lesions, and rarely vesicles and bullae.8 Classic histopathologic features include leukocytoclastic or eosinophilic vasculitis, an eosinophilic infiltrate, granuloma formation, and eosinophilic granule deposition onto collagen fibrils (otherwise known as flame figures)(Figure 2). Biopsy of these lesions with the aforementioned findings, in constellation with the described systemic signs and symptoms, can aid in diagnosis of EGPA.

Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a vasculitis that can be either multisystem or limited to one organ. Classic PAN affects the small- to medium-sized vessels. When there is multisystem involvement, it most often affects the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and kidneys. It presents with subcutaneous or dermal nodules, necrotic lesions, livedo reticularis, hypertension, abdominal pain, and an acute abdomen.9 When PAN is in its limited form, it most commonly occurs in the skin. The cutaneous manifestations of skin-limited PAN are identical to classic PAN, most commonly occurring on the legs and arms and less often on the trunk, head, and neck.10 To aid in diagnosis, biopsies of cutaneous lesions are beneficial. Dermatopathologic examination of PAN reveals fibrinoid necrosis of small and medium vessels with a perivascular mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 3). Cutaneous PAN rarely progresses to multisystem classic PAN and carries a more favorable prognosis.

Microvascular occlusion syndromes can result in clinical presentations that resemble LIV. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is a hematologic autoimmune condition resulting in destruction of platelets and subsequent thrombocytopenia. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura can be either primary or secondary to infections, drugs, malignancy, or other autoimmune conditions. Clinically, it presents as mucosal or cutaneous bleeding, epistaxis, hematochezia, or hematuria and can result in substantial hemorrhage. On the skin, it can appear as petechiae and ecchymoses in dependent areas and rarely hemorrhagic bullae of the skin and mucous membranes in cases of severe thrombocytopenia.11,12 Biopsies of these lesions will show notable extravasation of red blood cells with incipient hemorrhagic bullae formation (Figure 4). Recognition of hemorrhagic bullae as a presentation of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is critical to identifying severe underlying disease.

Beyond other vasculitides and microvascular occlusion syndromes, vessel-invasive microorganisms can result in similar histopathologic and clinical presentations to LIV. Ecthyma gangrenosum (EG) is a septic vasculitis, often caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, usually affecting immunocompromised patients. Ecthyma gangrenosum presents with vesiculobullous lesions with erythematous violaceous borders that develop into hemorrhagic bullae with necrotic centers.13 Biopsy of EG will show vascular occlusion and basophilic granular material within or around vessels, suggestive of bacterial sepsis (Figure 5). The detection of an infectious agent on histopathology allows one to easily distinguish between EG and LIV.

- Bajaj S, Hibler B, Rossi A. Painful violaceous purpura on a 44-year-old woman. Am J Med. 2016;129:E5-E7.

- Munoz-Vahos CH, Herrera-Uribe S, Arbelaez-Cortes A, et al. Clinical profile of levamisole-adulterated cocaine-induced vasculitis/vasculopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:E16-E26.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Gillis JA, Green P, Williams J. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: staging and management. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:E29-E31.

- Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chafins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1320-1321.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia-a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;65:722-725.

- Negbenebor NA, Khalifian S, Foreman RK, et al. A 92-year-old male with eosinophilic asthma presenting with recurrent palpable purpuric plaques. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:44-48.

- Sherman S, Gal N, Didkovsky E, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) relapsing as bullous eruption. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:406-407.

- Braungart S, Campbell A, Besarovic S. Atypical Henoch-Schonlein purpura? consider polyarteritis nodosa! BMJ Case Rep. 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201764

- Alquorain NAA, Aljabr ASH, Alghamdi NJ. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with pentoxifylline and clobetasol propionate: a case report. Saudi J Med Sci. 2018;6:104-107.

- Helms AE, Schaffer RI. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with black oral mucosal lesions. Cutis. 2007;79:456-458.

- Lountzis N, Maroon M, Tyler W. Mucocutaneous hemorrhagic bullae in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:AB124.

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegeria V, Santos-Briz A, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662.

- Bajaj S, Hibler B, Rossi A. Painful violaceous purpura on a 44-year-old woman. Am J Med. 2016;129:E5-E7.

- Munoz-Vahos CH, Herrera-Uribe S, Arbelaez-Cortes A, et al. Clinical profile of levamisole-adulterated cocaine-induced vasculitis/vasculopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:E16-E26.

- Jacob RS, Silva CY, Powers JG, et al. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: a report of 2 cases and a novel histopathologic finding. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:208-213.

- Gillis JA, Green P, Williams J. Levamisole-induced vasculopathy: staging and management. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67:E29-E31.

- Farhat EK, Muirhead TT, Chafins ML, et al. Levamisole-induced cutaneous necrosis mimicking coagulopathy. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1320-1321.

- Chung C, Tumeh PC, Birnbaum R, et al. Characteristic purpura of the ears, vasculitis, and neutropenia-a potential public health epidemic associated with levamisole-adulterated cocaine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;65:722-725.

- Negbenebor NA, Khalifian S, Foreman RK, et al. A 92-year-old male with eosinophilic asthma presenting with recurrent palpable purpuric plaques. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2018;5:44-48.

- Sherman S, Gal N, Didkovsky E, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) relapsing as bullous eruption. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:406-407.

- Braungart S, Campbell A, Besarovic S. Atypical Henoch-Schonlein purpura? consider polyarteritis nodosa! BMJ Case Rep. 2014. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-201764

- Alquorain NAA, Aljabr ASH, Alghamdi NJ. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa treated with pentoxifylline and clobetasol propionate: a case report. Saudi J Med Sci. 2018;6:104-107.

- Helms AE, Schaffer RI. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with black oral mucosal lesions. Cutis. 2007;79:456-458.

- Lountzis N, Maroon M, Tyler W. Mucocutaneous hemorrhagic bullae in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:AB124.

- Llamas-Velasco M, Alegeria V, Santos-Briz A, et al. Occlusive nonvasculitic vasculopathy. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:637-662.

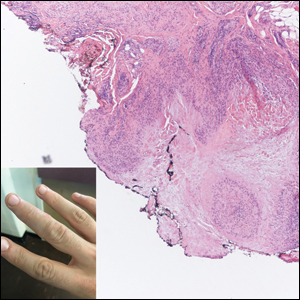

A 40-year-old woman presented with a progressive painful rash on the ears and legs of 2 weeks’ duration. She described the rash as initially red and nonpainful; it started on the right leg and progressed to the left leg, eventually involving the earlobes 4 days prior to presentation. Physical examination revealed edematous purpura of the earlobes and bullous retiform purpura on the lower extremities. Laboratory studies revealed leukopenia (3.6×103 /cm2 [reference range, 4.0–10.5×103 /cm2 ]) and elevated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (1:320 titer [reference range, <1:40]) in a perinuclear pattern (perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies). Urine toxicology screening was positive for cocaine and opiates. A punch biopsy of a bullous retiform purpura on the right thigh was obtained for standard hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Subcutaneous Nodule on the Chest

The Diagnosis: Cystic Panfolliculoma

Panfolliculoma is a rare tumor of follicular origin.1 Clinical examination can reveal a papule, nodule, or tumor that typically is mistaken for an epidermal inclusion cyst, trichoepithelioma, or basal cell carcinoma (BCC).2 As with other benign follicular neoplasms, it often exhibits a protracted growth pattern.3,4 Most cases reported in the literature have been shown to occur in the head or neck region. One hypothesis is that separation into the various components of the hair follicle occurs at a higher frequency in areas with a higher hair density such as the face and scalp.4 The lesion typically presents in patients aged 20 to 70 years, as in our patient, with cases equally distributed among males and females.4,5 Neill et al1 reported a rare case of cystic panfolliculoma occurring on the right forearm of a 64-year-old woman.

As its name suggests, panfolliculoma is exceptional in that it displays features of all segments of the hair follicle, including the infundibulum, isthmus, stem, and bulb.6 Although not necessary for diagnosis, immunohistochemical staining can be utilized to identify each hair follicle component on histopathologic examination. Panfolliculoma stains positive for 34βE12 and cytokeratin 5/6, highlighting infundibular and isthmus keratinocytes and the outer root sheath, respectively. Additionally, Ber-EP4 labels germinative cells, while CD34 highlights contiguous fibrotic stroma and trichilemmal areas.3,4

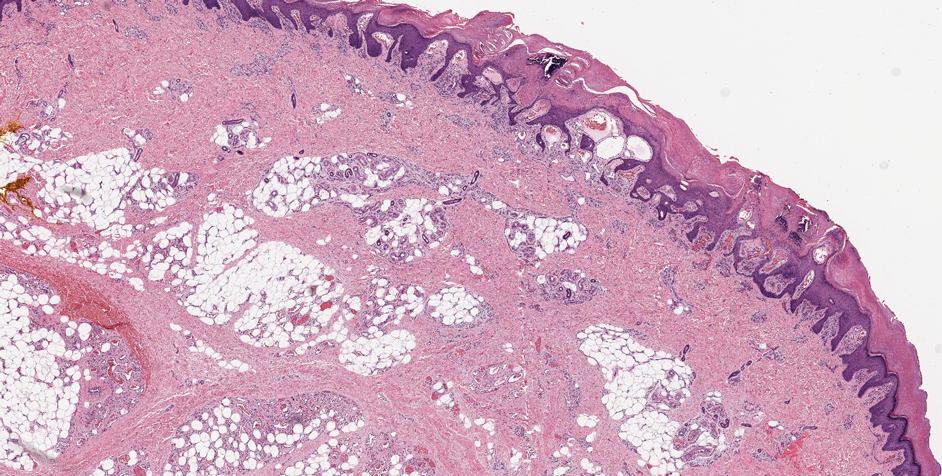

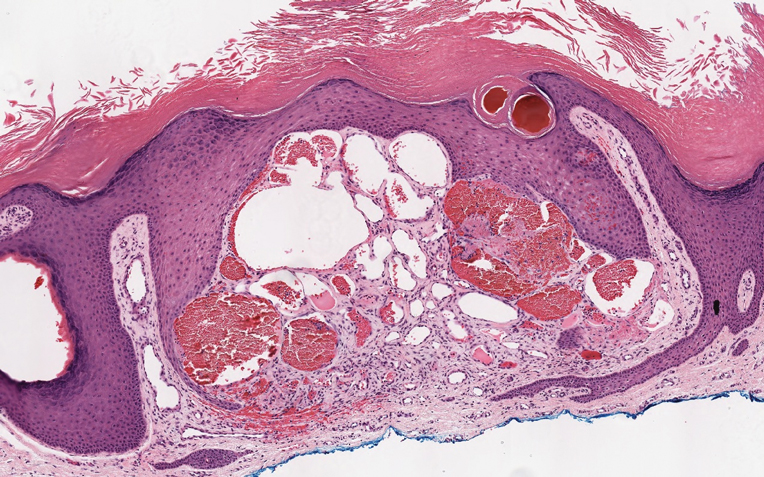

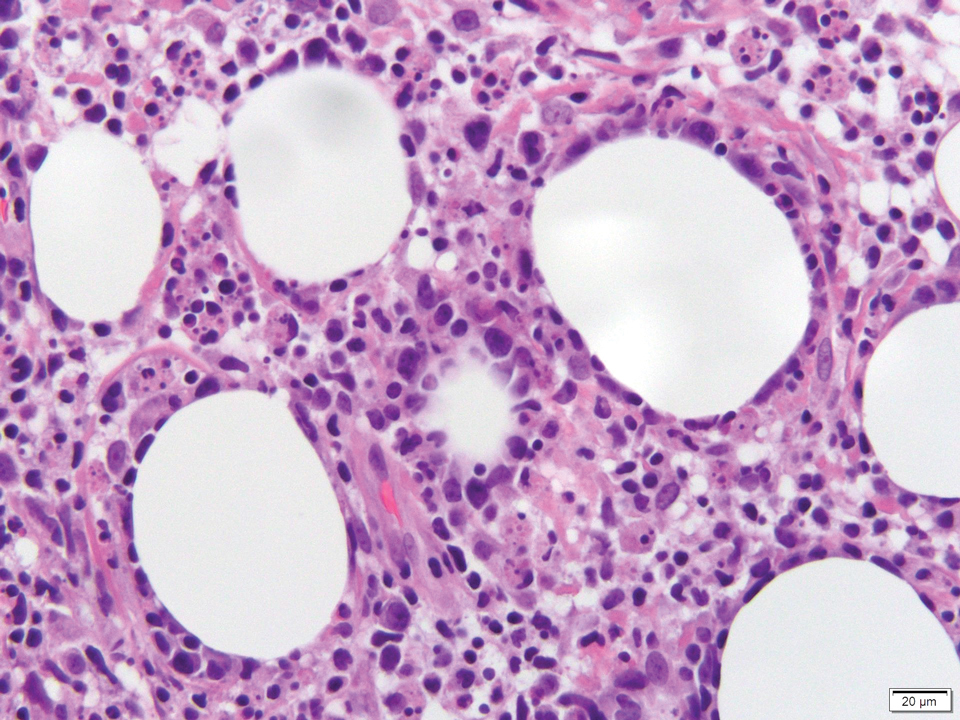

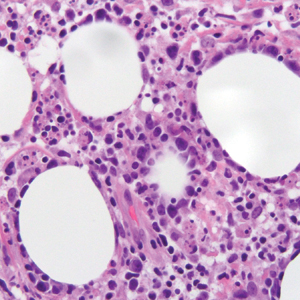

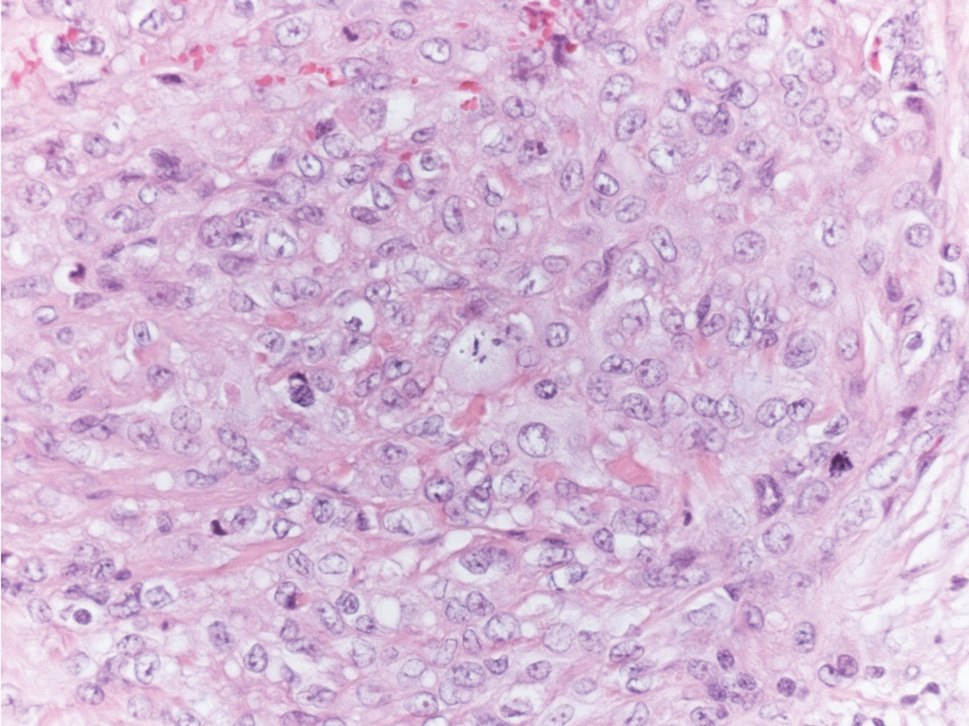

In our patient, histopathology revealed a cystic structure that was lined by an infundibular epithelium with a prominent granular layer. Solid collections of basaloid germinative cells that demonstrated peripheral palisading were observed (quiz image [top]). Cells with trichohyalin granules, indicative of inner root sheath differentiation, were encased by matrical cells (quiz image [bottom]).

Historically, panfolliculomas characteristically have been known to reside in the dermis, with only focal connection to the epidermis, if at all present. Nevertheless, Harris et al7 detailed 2 cases that displayed predominant epidermal involvement, defined by the term epidermal panfolliculoma. In a study performed by Shan and Guo,2 an additional 9 cases (19 panfolliculomas) were found to have similar findings, for which the term superficial panfolliculoma was suggested. In cases that display a primary epidermal component, common mimickers include tumor of the follicular infundibulum and the reactive process of follicular induction.7

Cystic panfolliculoma is a rare subtype further characterized as a lesion with distinctive features of a panfolliculoma that arises from a cyst wall composed of the follicular infundibulum.2,6 The origin of cystic panfolliculoma has not been fully elucidated. It has been hypothesized that the formation of such lesions may arise due to epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. One explanation is that basal cells with stem cell capability may progress into hair follicle structures after communication with underlying dermal cells during invagination of the epidermis, while the epithelial cells not in close proximity to dermal cells maintain stem cell capability.8

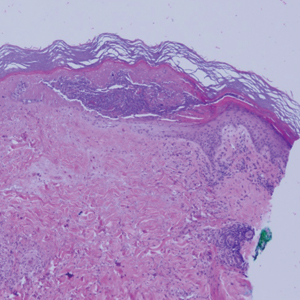

The histologic differential diagnosis of cystic panfolliculoma includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermal inclusion cyst, pilar cyst, trichofolliculoma, folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma, cystic trichoblastoma, and BCC.5 Panfolliculoma can mimic both trichoblastoma and trichoepithelioma on a low-power field; however, the latter follicular tumors lack differentiation to the infundibulum, isthmus, outer root sheath, or hair shaft, as in a panfolliculoma.4 Trichoblastoma is composed of germinative hair follicle cells, with differentiation limited to the hair germ and papilla (Figure 1).9 Panfolliculoma additionally differs from trichoblastoma by having a more prevalent epithelial factor compared to a more pronounced stromal factor in trichoblastoma.1 The cystic subtype of trichoblastoma differs from cystic panfolliculoma in that the cyst wall develops from the infundibulum only and has germinative cells protruding outwards from the cyst wall.

Although BCCs may arise in cystic structures, panfolliculomas can be discerned from this entity by their sharp demarcation, lack of peritumoral clefting, and presence of cytokeratin 20-positive Merkel cells.5 Unlike panfolliculoma, the tumor islands in BCC commonly display peripheral palisading of nuclei with a surrounding fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 2). Additionally, BCCs can exhibit crowding of nuclei, atypia, and mitoses.6

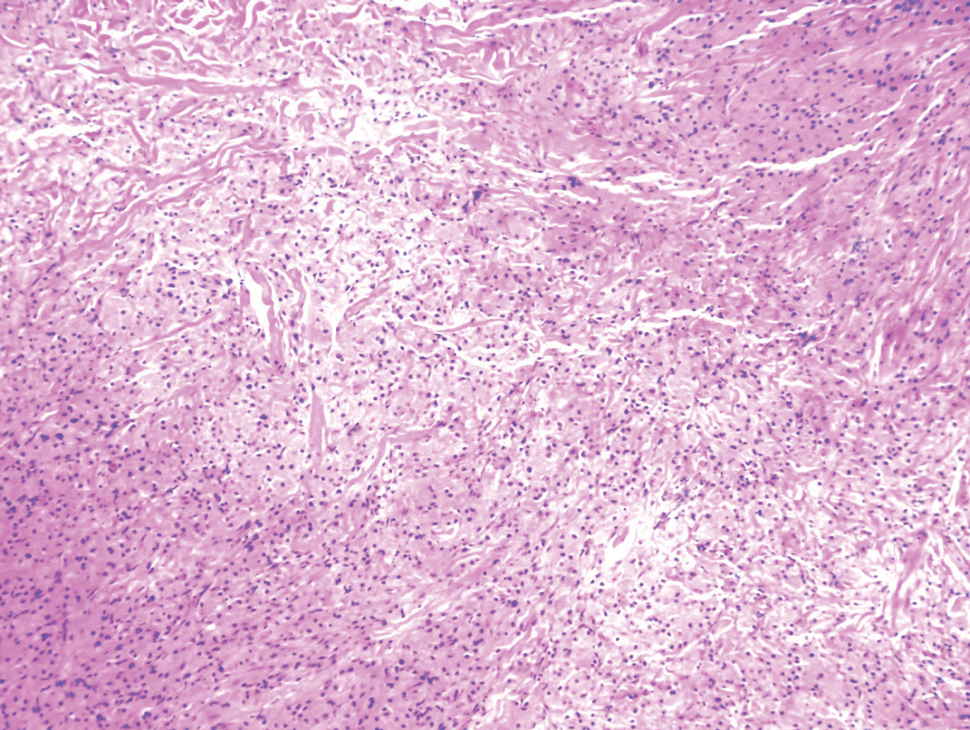

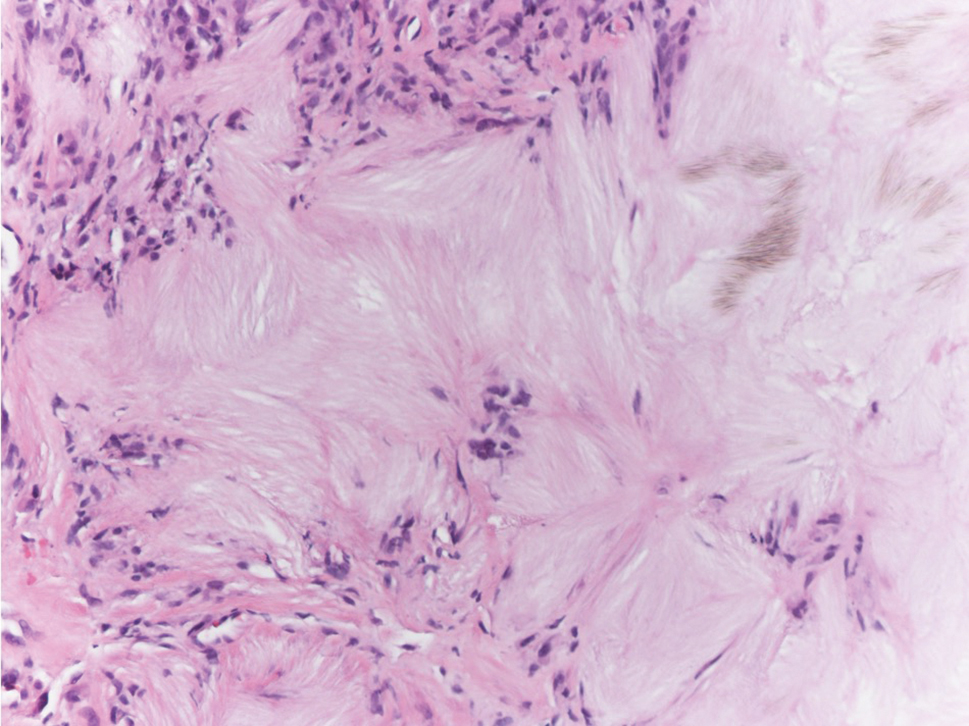

Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas and cystic panfolliculomas both contain a cystic structure with differentiation of the cyst wall to the hair follicle. However, folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas are dilated infundibulocystic configurations that contain sebaceous glands emanating from the cyst wall (Figure 3). Kimura et al10 described defining features of the mesenchymal component of this follicular tumor, including an increase in fibroplasia, vascularity, and adipose tissue. In addition, the epithelial aspect exhibits clefting among the stroma and uninvolved dermis.6

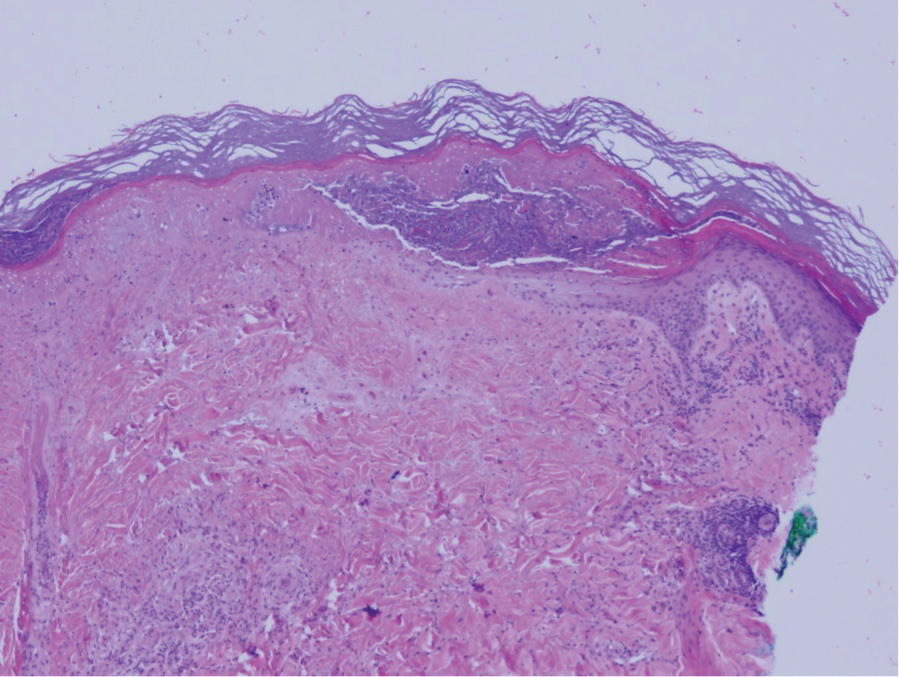

Dilated pore of Winer consists of a cystic opening with connection to the epidermis. The cyst wall resembles the follicular infundibulum, and the cavity is filled with lamellar orthokeratosis (Figure 4).5,11 Epidermal inclusion cysts also contain a cyst wall that resembles the infundibular epithelium, without differentiation to all segments of the hair follicle. They are lined by a stratified squamous epithelium, retain a granular layer, and contain lamellar keratin within the cyst cavity.5,12

In summary, panfolliculoma is a rare benign neoplasm that demonstrates differentiation to each component of the hair follicle structure. Our case demonstrates a unique subtype showcasing cystic changes that infrequently has been described in the literature.

- Neill B, Bingham C, Braudis K, et al. A rare cutaneous adnexal neoplasm: cystic panfolliculoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1183-1185.

- Shan SJ, Guo Y. Panfolliculoma and histopathologic variants: a study of 19 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:965-971.

- Hoang MP, Levenson BM. Cystic panfolliculoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:389-392.

- Huang CY, Wu YH. Panfolliculoma: report of two cases. Dermatol Sínica. 2010;28:73-76.

- Alkhalidi HM, Alhumaidy AA. Cystic panfolliculoma of the scalp: report of a very rare case and brief review. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2013;56:437-439.

- López-Takegami JC, Wolter M, Löser C, et al. Classification of cysts with follicular germinative differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:191-199.

- Harris A, Faulkner-Jones B, Zimarowski MJ. Epidermal panfolliculoma: a report of 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:E7-E10.

- Fukuyama M, Sato Y, Yamazaki Y, et al. Immunohistochemical dissection of cystic panfolliculoma focusing on the expression of multiple hair follicle lineage markers with an insight into the pathogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:861-866.

- Tellechea O, Cardoso JC, Reis JP, et al. Benign follicular tumors. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:780-796; quiz 797-788.

- Kimura T, Miyazawa H, Aoyagi T, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma. a distinctive malformation of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:213-220.

- Misago N, Inoue T, Narisawa Y. Cystic trichoblastoma: a report of two cases with an immunohistochemical study. J Dermatol. 2015;42:305-310.

- Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal inclusion cyst. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

The Diagnosis: Cystic Panfolliculoma

Panfolliculoma is a rare tumor of follicular origin.1 Clinical examination can reveal a papule, nodule, or tumor that typically is mistaken for an epidermal inclusion cyst, trichoepithelioma, or basal cell carcinoma (BCC).2 As with other benign follicular neoplasms, it often exhibits a protracted growth pattern.3,4 Most cases reported in the literature have been shown to occur in the head or neck region. One hypothesis is that separation into the various components of the hair follicle occurs at a higher frequency in areas with a higher hair density such as the face and scalp.4 The lesion typically presents in patients aged 20 to 70 years, as in our patient, with cases equally distributed among males and females.4,5 Neill et al1 reported a rare case of cystic panfolliculoma occurring on the right forearm of a 64-year-old woman.

As its name suggests, panfolliculoma is exceptional in that it displays features of all segments of the hair follicle, including the infundibulum, isthmus, stem, and bulb.6 Although not necessary for diagnosis, immunohistochemical staining can be utilized to identify each hair follicle component on histopathologic examination. Panfolliculoma stains positive for 34βE12 and cytokeratin 5/6, highlighting infundibular and isthmus keratinocytes and the outer root sheath, respectively. Additionally, Ber-EP4 labels germinative cells, while CD34 highlights contiguous fibrotic stroma and trichilemmal areas.3,4

In our patient, histopathology revealed a cystic structure that was lined by an infundibular epithelium with a prominent granular layer. Solid collections of basaloid germinative cells that demonstrated peripheral palisading were observed (quiz image [top]). Cells with trichohyalin granules, indicative of inner root sheath differentiation, were encased by matrical cells (quiz image [bottom]).

Historically, panfolliculomas characteristically have been known to reside in the dermis, with only focal connection to the epidermis, if at all present. Nevertheless, Harris et al7 detailed 2 cases that displayed predominant epidermal involvement, defined by the term epidermal panfolliculoma. In a study performed by Shan and Guo,2 an additional 9 cases (19 panfolliculomas) were found to have similar findings, for which the term superficial panfolliculoma was suggested. In cases that display a primary epidermal component, common mimickers include tumor of the follicular infundibulum and the reactive process of follicular induction.7

Cystic panfolliculoma is a rare subtype further characterized as a lesion with distinctive features of a panfolliculoma that arises from a cyst wall composed of the follicular infundibulum.2,6 The origin of cystic panfolliculoma has not been fully elucidated. It has been hypothesized that the formation of such lesions may arise due to epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. One explanation is that basal cells with stem cell capability may progress into hair follicle structures after communication with underlying dermal cells during invagination of the epidermis, while the epithelial cells not in close proximity to dermal cells maintain stem cell capability.8

The histologic differential diagnosis of cystic panfolliculoma includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermal inclusion cyst, pilar cyst, trichofolliculoma, folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma, cystic trichoblastoma, and BCC.5 Panfolliculoma can mimic both trichoblastoma and trichoepithelioma on a low-power field; however, the latter follicular tumors lack differentiation to the infundibulum, isthmus, outer root sheath, or hair shaft, as in a panfolliculoma.4 Trichoblastoma is composed of germinative hair follicle cells, with differentiation limited to the hair germ and papilla (Figure 1).9 Panfolliculoma additionally differs from trichoblastoma by having a more prevalent epithelial factor compared to a more pronounced stromal factor in trichoblastoma.1 The cystic subtype of trichoblastoma differs from cystic panfolliculoma in that the cyst wall develops from the infundibulum only and has germinative cells protruding outwards from the cyst wall.

Although BCCs may arise in cystic structures, panfolliculomas can be discerned from this entity by their sharp demarcation, lack of peritumoral clefting, and presence of cytokeratin 20-positive Merkel cells.5 Unlike panfolliculoma, the tumor islands in BCC commonly display peripheral palisading of nuclei with a surrounding fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 2). Additionally, BCCs can exhibit crowding of nuclei, atypia, and mitoses.6

Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas and cystic panfolliculomas both contain a cystic structure with differentiation of the cyst wall to the hair follicle. However, folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas are dilated infundibulocystic configurations that contain sebaceous glands emanating from the cyst wall (Figure 3). Kimura et al10 described defining features of the mesenchymal component of this follicular tumor, including an increase in fibroplasia, vascularity, and adipose tissue. In addition, the epithelial aspect exhibits clefting among the stroma and uninvolved dermis.6

Dilated pore of Winer consists of a cystic opening with connection to the epidermis. The cyst wall resembles the follicular infundibulum, and the cavity is filled with lamellar orthokeratosis (Figure 4).5,11 Epidermal inclusion cysts also contain a cyst wall that resembles the infundibular epithelium, without differentiation to all segments of the hair follicle. They are lined by a stratified squamous epithelium, retain a granular layer, and contain lamellar keratin within the cyst cavity.5,12

In summary, panfolliculoma is a rare benign neoplasm that demonstrates differentiation to each component of the hair follicle structure. Our case demonstrates a unique subtype showcasing cystic changes that infrequently has been described in the literature.

The Diagnosis: Cystic Panfolliculoma

Panfolliculoma is a rare tumor of follicular origin.1 Clinical examination can reveal a papule, nodule, or tumor that typically is mistaken for an epidermal inclusion cyst, trichoepithelioma, or basal cell carcinoma (BCC).2 As with other benign follicular neoplasms, it often exhibits a protracted growth pattern.3,4 Most cases reported in the literature have been shown to occur in the head or neck region. One hypothesis is that separation into the various components of the hair follicle occurs at a higher frequency in areas with a higher hair density such as the face and scalp.4 The lesion typically presents in patients aged 20 to 70 years, as in our patient, with cases equally distributed among males and females.4,5 Neill et al1 reported a rare case of cystic panfolliculoma occurring on the right forearm of a 64-year-old woman.

As its name suggests, panfolliculoma is exceptional in that it displays features of all segments of the hair follicle, including the infundibulum, isthmus, stem, and bulb.6 Although not necessary for diagnosis, immunohistochemical staining can be utilized to identify each hair follicle component on histopathologic examination. Panfolliculoma stains positive for 34βE12 and cytokeratin 5/6, highlighting infundibular and isthmus keratinocytes and the outer root sheath, respectively. Additionally, Ber-EP4 labels germinative cells, while CD34 highlights contiguous fibrotic stroma and trichilemmal areas.3,4

In our patient, histopathology revealed a cystic structure that was lined by an infundibular epithelium with a prominent granular layer. Solid collections of basaloid germinative cells that demonstrated peripheral palisading were observed (quiz image [top]). Cells with trichohyalin granules, indicative of inner root sheath differentiation, were encased by matrical cells (quiz image [bottom]).

Historically, panfolliculomas characteristically have been known to reside in the dermis, with only focal connection to the epidermis, if at all present. Nevertheless, Harris et al7 detailed 2 cases that displayed predominant epidermal involvement, defined by the term epidermal panfolliculoma. In a study performed by Shan and Guo,2 an additional 9 cases (19 panfolliculomas) were found to have similar findings, for which the term superficial panfolliculoma was suggested. In cases that display a primary epidermal component, common mimickers include tumor of the follicular infundibulum and the reactive process of follicular induction.7

Cystic panfolliculoma is a rare subtype further characterized as a lesion with distinctive features of a panfolliculoma that arises from a cyst wall composed of the follicular infundibulum.2,6 The origin of cystic panfolliculoma has not been fully elucidated. It has been hypothesized that the formation of such lesions may arise due to epithelial-mesenchymal interactions. One explanation is that basal cells with stem cell capability may progress into hair follicle structures after communication with underlying dermal cells during invagination of the epidermis, while the epithelial cells not in close proximity to dermal cells maintain stem cell capability.8

The histologic differential diagnosis of cystic panfolliculoma includes dilated pore of Winer, epidermal inclusion cyst, pilar cyst, trichofolliculoma, folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma, cystic trichoblastoma, and BCC.5 Panfolliculoma can mimic both trichoblastoma and trichoepithelioma on a low-power field; however, the latter follicular tumors lack differentiation to the infundibulum, isthmus, outer root sheath, or hair shaft, as in a panfolliculoma.4 Trichoblastoma is composed of germinative hair follicle cells, with differentiation limited to the hair germ and papilla (Figure 1).9 Panfolliculoma additionally differs from trichoblastoma by having a more prevalent epithelial factor compared to a more pronounced stromal factor in trichoblastoma.1 The cystic subtype of trichoblastoma differs from cystic panfolliculoma in that the cyst wall develops from the infundibulum only and has germinative cells protruding outwards from the cyst wall.

Although BCCs may arise in cystic structures, panfolliculomas can be discerned from this entity by their sharp demarcation, lack of peritumoral clefting, and presence of cytokeratin 20-positive Merkel cells.5 Unlike panfolliculoma, the tumor islands in BCC commonly display peripheral palisading of nuclei with a surrounding fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 2). Additionally, BCCs can exhibit crowding of nuclei, atypia, and mitoses.6

Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas and cystic panfolliculomas both contain a cystic structure with differentiation of the cyst wall to the hair follicle. However, folliculosebaceous cystic hamartomas are dilated infundibulocystic configurations that contain sebaceous glands emanating from the cyst wall (Figure 3). Kimura et al10 described defining features of the mesenchymal component of this follicular tumor, including an increase in fibroplasia, vascularity, and adipose tissue. In addition, the epithelial aspect exhibits clefting among the stroma and uninvolved dermis.6

Dilated pore of Winer consists of a cystic opening with connection to the epidermis. The cyst wall resembles the follicular infundibulum, and the cavity is filled with lamellar orthokeratosis (Figure 4).5,11 Epidermal inclusion cysts also contain a cyst wall that resembles the infundibular epithelium, without differentiation to all segments of the hair follicle. They are lined by a stratified squamous epithelium, retain a granular layer, and contain lamellar keratin within the cyst cavity.5,12

In summary, panfolliculoma is a rare benign neoplasm that demonstrates differentiation to each component of the hair follicle structure. Our case demonstrates a unique subtype showcasing cystic changes that infrequently has been described in the literature.

- Neill B, Bingham C, Braudis K, et al. A rare cutaneous adnexal neoplasm: cystic panfolliculoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1183-1185.

- Shan SJ, Guo Y. Panfolliculoma and histopathologic variants: a study of 19 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:965-971.

- Hoang MP, Levenson BM. Cystic panfolliculoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:389-392.

- Huang CY, Wu YH. Panfolliculoma: report of two cases. Dermatol Sínica. 2010;28:73-76.

- Alkhalidi HM, Alhumaidy AA. Cystic panfolliculoma of the scalp: report of a very rare case and brief review. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2013;56:437-439.

- López-Takegami JC, Wolter M, Löser C, et al. Classification of cysts with follicular germinative differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:191-199.

- Harris A, Faulkner-Jones B, Zimarowski MJ. Epidermal panfolliculoma: a report of 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:E7-E10.

- Fukuyama M, Sato Y, Yamazaki Y, et al. Immunohistochemical dissection of cystic panfolliculoma focusing on the expression of multiple hair follicle lineage markers with an insight into the pathogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:861-866.

- Tellechea O, Cardoso JC, Reis JP, et al. Benign follicular tumors. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:780-796; quiz 797-788.

- Kimura T, Miyazawa H, Aoyagi T, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma. a distinctive malformation of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:213-220.

- Misago N, Inoue T, Narisawa Y. Cystic trichoblastoma: a report of two cases with an immunohistochemical study. J Dermatol. 2015;42:305-310.

- Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal inclusion cyst. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Neill B, Bingham C, Braudis K, et al. A rare cutaneous adnexal neoplasm: cystic panfolliculoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1183-1185.

- Shan SJ, Guo Y. Panfolliculoma and histopathologic variants: a study of 19 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:965-971.

- Hoang MP, Levenson BM. Cystic panfolliculoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:389-392.

- Huang CY, Wu YH. Panfolliculoma: report of two cases. Dermatol Sínica. 2010;28:73-76.

- Alkhalidi HM, Alhumaidy AA. Cystic panfolliculoma of the scalp: report of a very rare case and brief review. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2013;56:437-439.

- López-Takegami JC, Wolter M, Löser C, et al. Classification of cysts with follicular germinative differentiation. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:191-199.

- Harris A, Faulkner-Jones B, Zimarowski MJ. Epidermal panfolliculoma: a report of 2 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:E7-E10.

- Fukuyama M, Sato Y, Yamazaki Y, et al. Immunohistochemical dissection of cystic panfolliculoma focusing on the expression of multiple hair follicle lineage markers with an insight into the pathogenesis. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:861-866.

- Tellechea O, Cardoso JC, Reis JP, et al. Benign follicular tumors. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:780-796; quiz 797-788.

- Kimura T, Miyazawa H, Aoyagi T, et al. Folliculosebaceous cystic hamartoma. a distinctive malformation of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1991;13:213-220.

- Misago N, Inoue T, Narisawa Y. Cystic trichoblastoma: a report of two cases with an immunohistochemical study. J Dermatol. 2015;42:305-310.

- Weir CB, St. Hilaire NJ. Epidermal inclusion cyst. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

A healthy 45-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic with a slow-growing subcutaneous nodule on the left chest that had been present for years.

Atrophic Lesions in a Pregnant Woman

The Diagnosis: Degos Disease

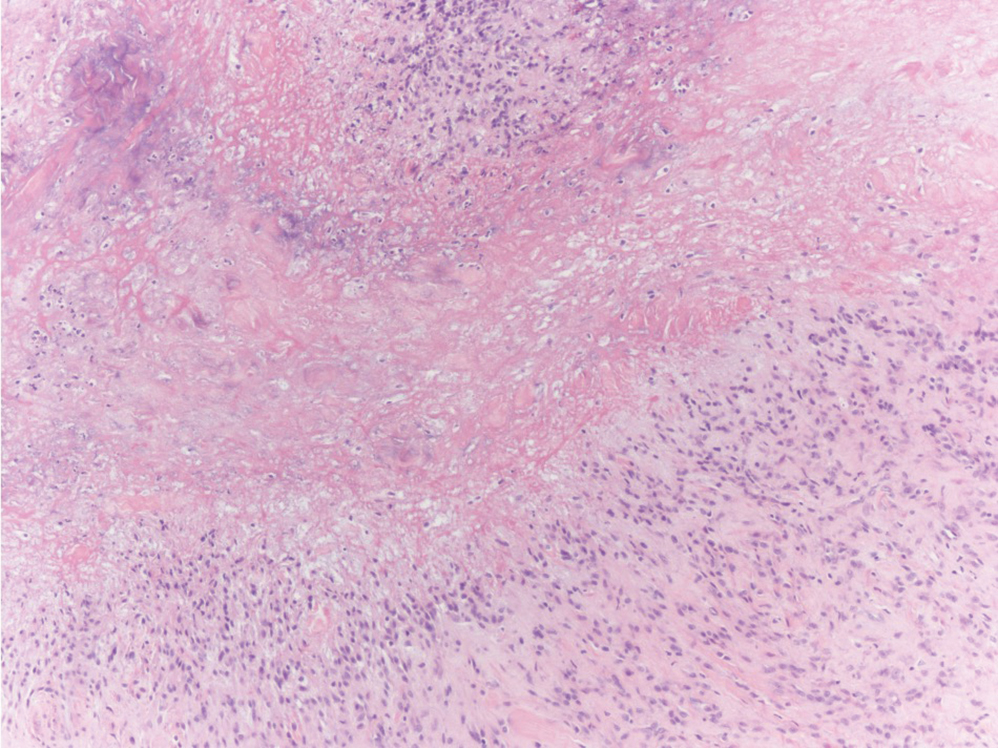

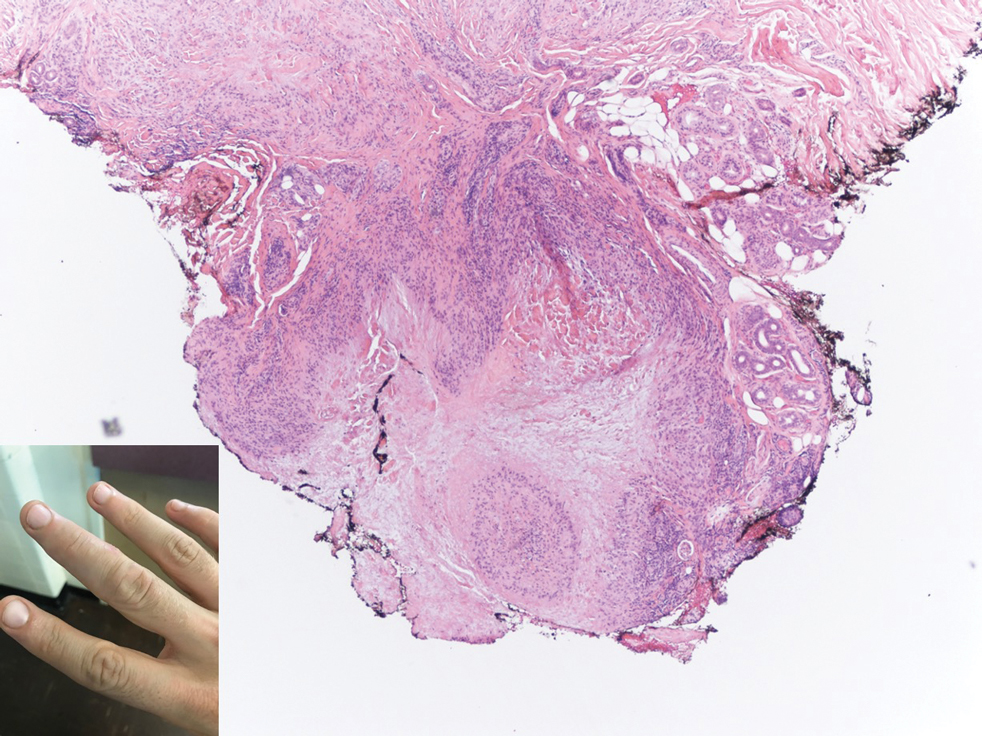

The pathophysiology of Degos disease (malignant atrophic papulosis) is unknown.1 Histopathology demonstrates a wedge-shaped area of dermal necrosis with edema and mucin deposition extending from the papillary dermis to the deep reticular dermis. Occluded vessels, thrombosis, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates also may be seen, particularly at the dermal subcutaneous junction and at the periphery of the wedge-shaped infarction. The vascular damage that occurs may be the result of vasculitis, coagulopathy, or endothelial cell dysfunction.1

Patients typically present with small, round, erythematous papules that eventually develop atrophic porcelain white centers and telangiectatic rims. These lesions most commonly occur on the trunk and arms. In the benign form of atrophic papulosis, only the skin is involved; however, systemic involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system can occur, resulting in bowel perforation and stroke, respectively.1 Although there is no definitive treatment of Degos disease, successful therapy with aspirin or dipyridamole has been reported.1 Eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds C5, and treprostinil, a prostacyclin analog, are emerging treatment options.2,3 The differential diagnosis of Degos disease may include granuloma annulare, guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus, livedoid vasculopathy, and lymphomatoid papulosis.

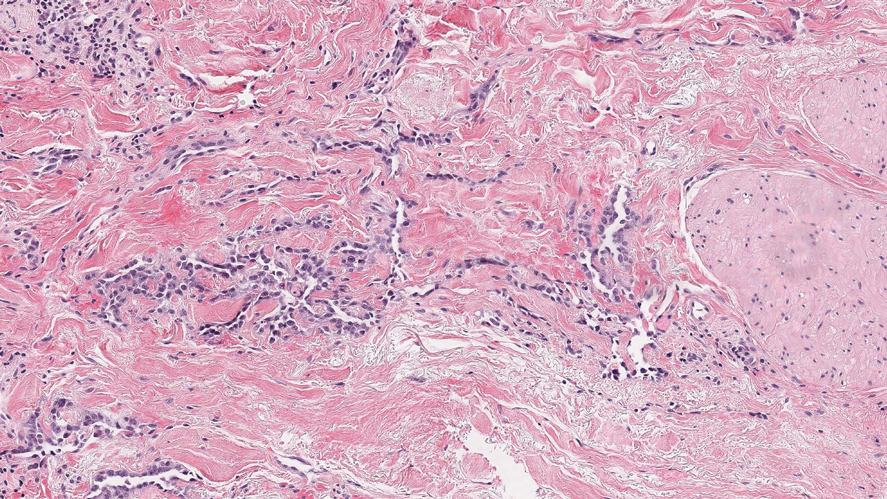

Granuloma annulare may clinically mimic the erythematous papules seen in early Degos disease, and histopathology can be used to distinguish between these two disease processes. Localized granuloma annulare is the most common variant and clinically presents as pink papules and plaques in an annular configuration.4 Histopathology demonstrates an unremarkable epidermis; however, the dermis contains degenerated collagen surrounded by palisading histiocytes as well as lymphocytes. Similar to Degos disease, increased mucin is seen within these areas of degeneration, but occluded vessels and thrombosis typically are not seen (Figure 1).4,5

Guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus initially presents as polygonal, bluish white papules that coalesce into plaques.6 Over time, these lesions become more atrophic and may mimic Degos disease but appear differently on histopathology. Histopathology of lichen sclerosus classically demonstrates atrophy of the epidermis with loss of the rete ridges and vacuolar surface changes. Homogenization of the superficial/papillary dermis with an underlying bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate also is seen (Figure 2).6

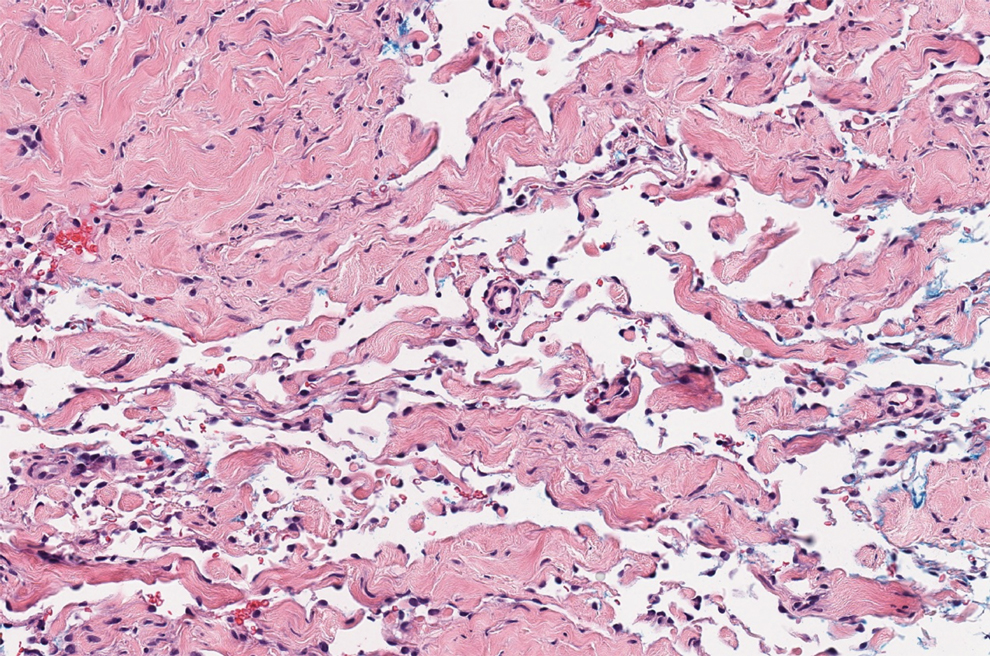

Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by chronic recurrent ulceration of the legs secondary to thrombosis and subsequent ischemia. In the initial phase of this disease, livedo reticularis is seen followed by the development of ulcerations. As these ulcerations heal, they leave behind porcelain white scars referred to as atrophie blanche.7 The areas of scarring in livedoid vasculopathy are broad and angulated, differentiating them from the small, round, porcelain white macules in end-stage Degos disease. Histopathology demonstrates thrombosis and fibrin occlusion of the upper and mid dermal vessels. Very minimal perivascular infiltrate typically is seen, but when it is present, the infiltrate mostly is lymphocytic. Hyalinization of the vessel walls also is seen, particularly in the atrophie blanche stage (Figure 3).7

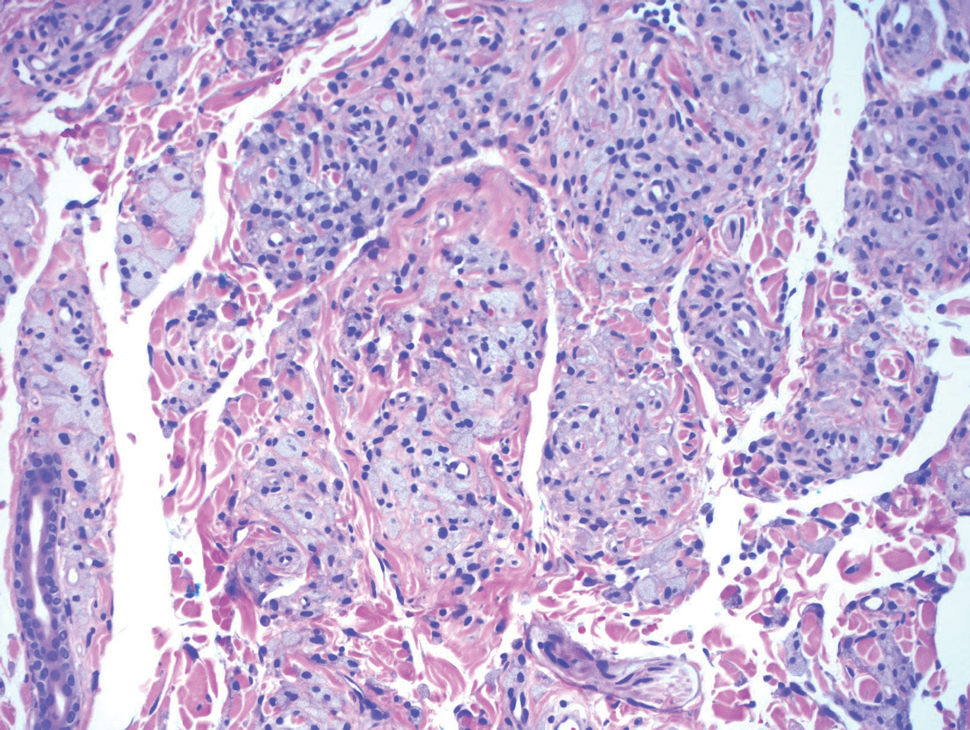

Lymphomatoid papulosis classically presents with pruritic red papules that often spontaneously involute. After resolution of the primary lesions, atrophic varioliform scars may be left behind that can resemble Degos disease.8 Classically, there are 5 histopathologic subtypes: A, B, C, D, and E. Type A is the most common type of lymphomatoid papulosis, and histopathology demonstrates a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate that consists of cells arranged in small clusters. Numerous medium- to large-sized atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm are seen, and mitotic figures are common (Figure 4).8

Our case was particularly interesting because the patient was 2 to 3 weeks pregnant. Degos disease in pregnancy appears to be quite exceptional. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Degos disease and pregnancy revealed only 4 other cases reported in the literature.9-12 With the exception of a single case that was complicated by severe abdominal pain requiring labor induction, the other reported cases resulted in uncomplicated pregnancies.9-12 Conversely, our patient's pregnancy was complicated by gestational hypertension and fetal hydrops requiring a preterm cesarean delivery. Furthermore, the infant had multiple complications, which were attributed to both placental insufficiency and a coagulopathic state.

Our patient also was found to have a heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation on workup. A PubMed search using the terms factor V Leiden mutation and Degos disease revealed 2 other cases of factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos disease.13,14 The importance of factor V Leiden mutations in patients with Degos disease currently is unclear.

- Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)--a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10.

- Oliver B, Boehm M, Rosing DR, et al. Diffuse atrophic papules and plaques, intermittent abdominal pain, paresthesias, and cardiac abnormalities in a 55-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1274-1277.

- Magro CM, Wang X, Garrett-Bakelman F, et al. The effects of eculizumab on the pathology of malignant atrophic papulosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:185.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Tronnier M, Mitteldorf C. Histologic features of granulomatous skin diseases. part 1: non-infectious granulomatous disorders. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:211-216.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Vasudevan B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478‐488.

- Martinez-Cabriales SA, Walsh S, Sade S, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: an update and review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:59-73.

- Moulin G, Barrut D, Franc MP, et al. Familial Degos' atrophic papulosis (mother-daughter). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:149-155.

- Bogenrieder T, Kuske M, Landthaler M, et al. Benign Degos' disease developing during pregnancy and followed for 10 years. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:284-287.

- Sharma S, Brennan B, Naden R, et al. A case of Degos disease in pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2016;9:167-168.

- Zhao Q, Zhang S, Dong A. An unusual case of abdominal pain. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:E1-E2.

- Darwich E, Guilabert A, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Dermoscopic description of a patient with thrombocythemia and factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos' disease. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:604-606.

- Hohwy T, Jensen MG, Tøttrup A, et al. A fatal case of malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos' disease) in a man with factor V Leiden mutation and lupus anticoagulant. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:245-247.

The Diagnosis: Degos Disease

The pathophysiology of Degos disease (malignant atrophic papulosis) is unknown.1 Histopathology demonstrates a wedge-shaped area of dermal necrosis with edema and mucin deposition extending from the papillary dermis to the deep reticular dermis. Occluded vessels, thrombosis, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates also may be seen, particularly at the dermal subcutaneous junction and at the periphery of the wedge-shaped infarction. The vascular damage that occurs may be the result of vasculitis, coagulopathy, or endothelial cell dysfunction.1

Patients typically present with small, round, erythematous papules that eventually develop atrophic porcelain white centers and telangiectatic rims. These lesions most commonly occur on the trunk and arms. In the benign form of atrophic papulosis, only the skin is involved; however, systemic involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system can occur, resulting in bowel perforation and stroke, respectively.1 Although there is no definitive treatment of Degos disease, successful therapy with aspirin or dipyridamole has been reported.1 Eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds C5, and treprostinil, a prostacyclin analog, are emerging treatment options.2,3 The differential diagnosis of Degos disease may include granuloma annulare, guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus, livedoid vasculopathy, and lymphomatoid papulosis.

Granuloma annulare may clinically mimic the erythematous papules seen in early Degos disease, and histopathology can be used to distinguish between these two disease processes. Localized granuloma annulare is the most common variant and clinically presents as pink papules and plaques in an annular configuration.4 Histopathology demonstrates an unremarkable epidermis; however, the dermis contains degenerated collagen surrounded by palisading histiocytes as well as lymphocytes. Similar to Degos disease, increased mucin is seen within these areas of degeneration, but occluded vessels and thrombosis typically are not seen (Figure 1).4,5

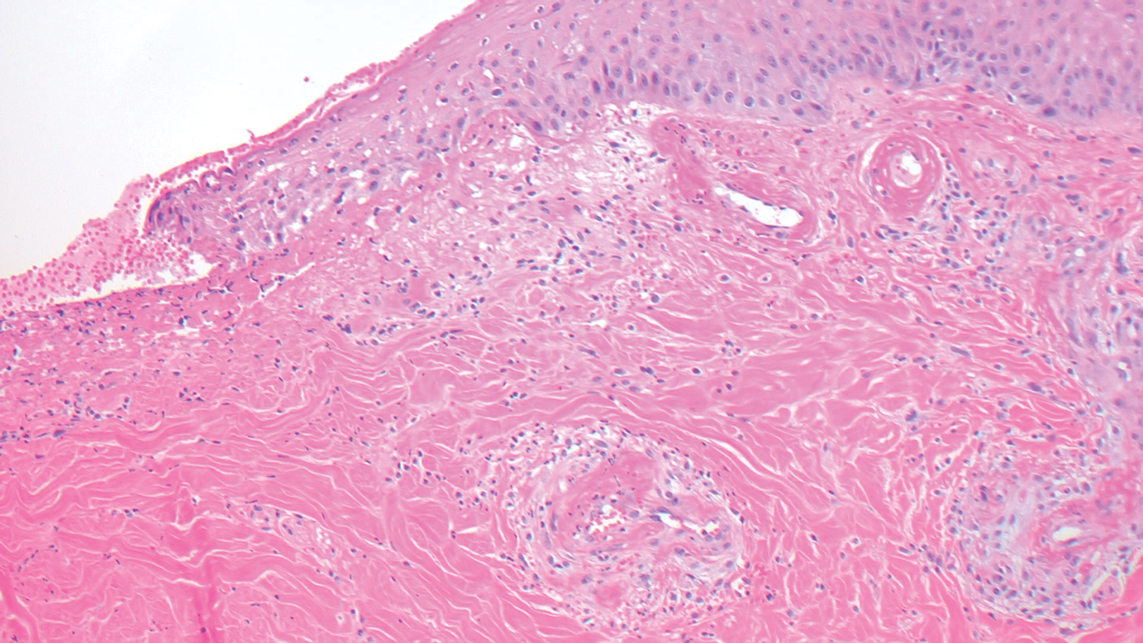

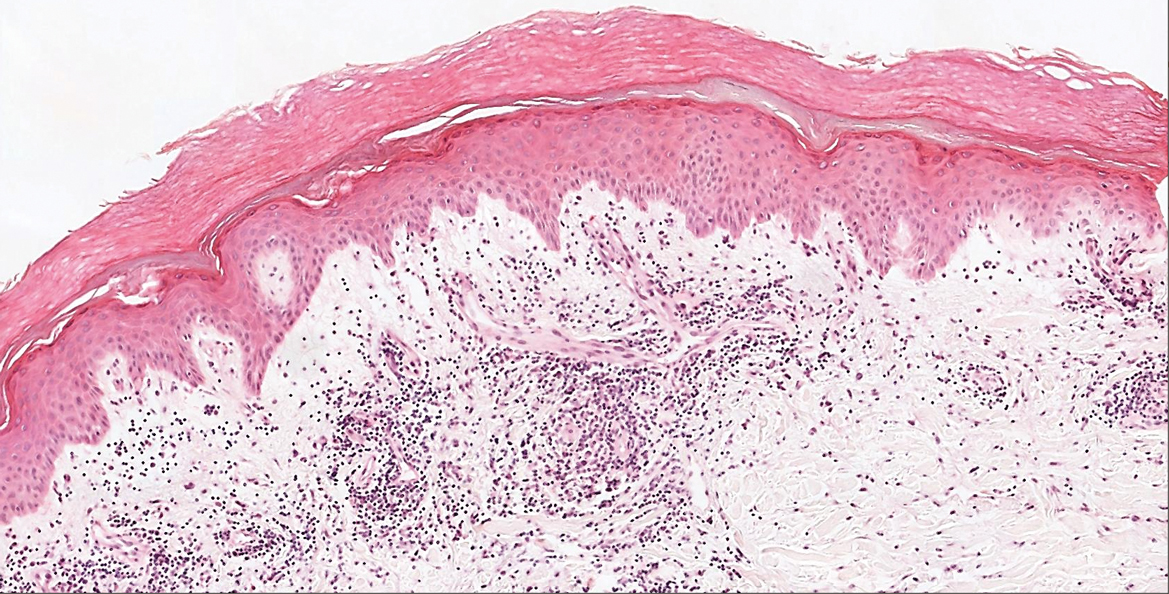

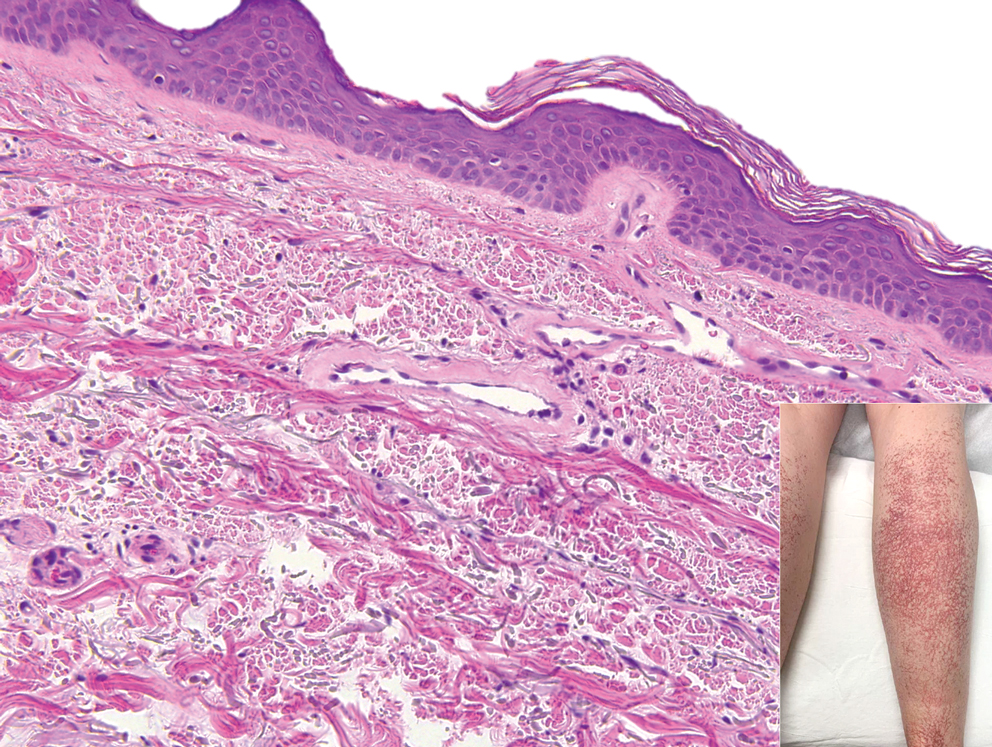

Guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus initially presents as polygonal, bluish white papules that coalesce into plaques.6 Over time, these lesions become more atrophic and may mimic Degos disease but appear differently on histopathology. Histopathology of lichen sclerosus classically demonstrates atrophy of the epidermis with loss of the rete ridges and vacuolar surface changes. Homogenization of the superficial/papillary dermis with an underlying bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate also is seen (Figure 2).6

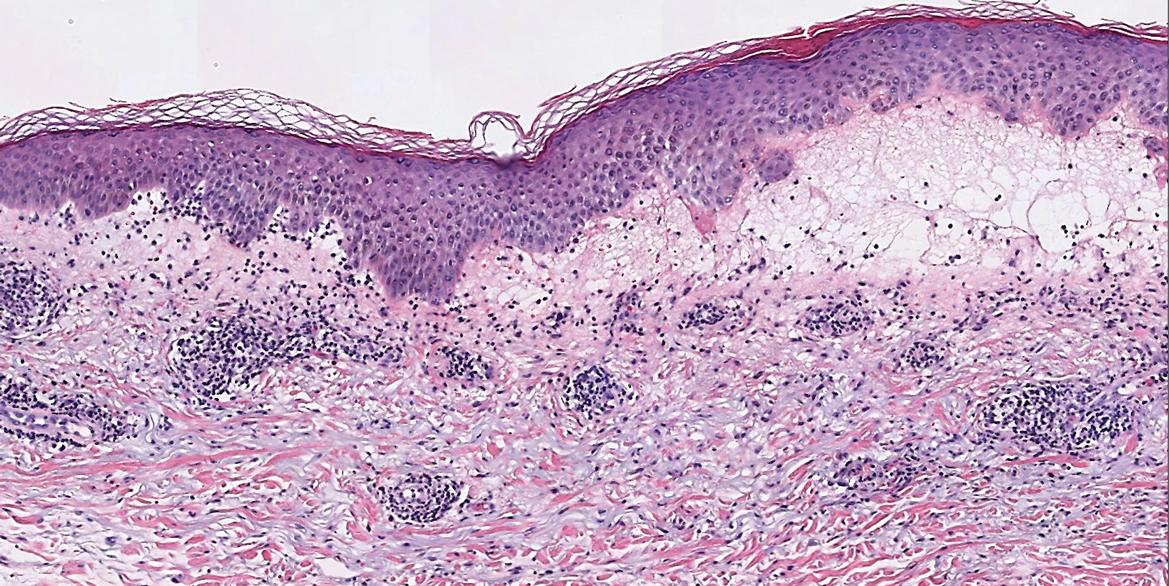

Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by chronic recurrent ulceration of the legs secondary to thrombosis and subsequent ischemia. In the initial phase of this disease, livedo reticularis is seen followed by the development of ulcerations. As these ulcerations heal, they leave behind porcelain white scars referred to as atrophie blanche.7 The areas of scarring in livedoid vasculopathy are broad and angulated, differentiating them from the small, round, porcelain white macules in end-stage Degos disease. Histopathology demonstrates thrombosis and fibrin occlusion of the upper and mid dermal vessels. Very minimal perivascular infiltrate typically is seen, but when it is present, the infiltrate mostly is lymphocytic. Hyalinization of the vessel walls also is seen, particularly in the atrophie blanche stage (Figure 3).7

Lymphomatoid papulosis classically presents with pruritic red papules that often spontaneously involute. After resolution of the primary lesions, atrophic varioliform scars may be left behind that can resemble Degos disease.8 Classically, there are 5 histopathologic subtypes: A, B, C, D, and E. Type A is the most common type of lymphomatoid papulosis, and histopathology demonstrates a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate that consists of cells arranged in small clusters. Numerous medium- to large-sized atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm are seen, and mitotic figures are common (Figure 4).8

Our case was particularly interesting because the patient was 2 to 3 weeks pregnant. Degos disease in pregnancy appears to be quite exceptional. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Degos disease and pregnancy revealed only 4 other cases reported in the literature.9-12 With the exception of a single case that was complicated by severe abdominal pain requiring labor induction, the other reported cases resulted in uncomplicated pregnancies.9-12 Conversely, our patient's pregnancy was complicated by gestational hypertension and fetal hydrops requiring a preterm cesarean delivery. Furthermore, the infant had multiple complications, which were attributed to both placental insufficiency and a coagulopathic state.

Our patient also was found to have a heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation on workup. A PubMed search using the terms factor V Leiden mutation and Degos disease revealed 2 other cases of factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos disease.13,14 The importance of factor V Leiden mutations in patients with Degos disease currently is unclear.

The Diagnosis: Degos Disease

The pathophysiology of Degos disease (malignant atrophic papulosis) is unknown.1 Histopathology demonstrates a wedge-shaped area of dermal necrosis with edema and mucin deposition extending from the papillary dermis to the deep reticular dermis. Occluded vessels, thrombosis, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates also may be seen, particularly at the dermal subcutaneous junction and at the periphery of the wedge-shaped infarction. The vascular damage that occurs may be the result of vasculitis, coagulopathy, or endothelial cell dysfunction.1

Patients typically present with small, round, erythematous papules that eventually develop atrophic porcelain white centers and telangiectatic rims. These lesions most commonly occur on the trunk and arms. In the benign form of atrophic papulosis, only the skin is involved; however, systemic involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system can occur, resulting in bowel perforation and stroke, respectively.1 Although there is no definitive treatment of Degos disease, successful therapy with aspirin or dipyridamole has been reported.1 Eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds C5, and treprostinil, a prostacyclin analog, are emerging treatment options.2,3 The differential diagnosis of Degos disease may include granuloma annulare, guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus, livedoid vasculopathy, and lymphomatoid papulosis.

Granuloma annulare may clinically mimic the erythematous papules seen in early Degos disease, and histopathology can be used to distinguish between these two disease processes. Localized granuloma annulare is the most common variant and clinically presents as pink papules and plaques in an annular configuration.4 Histopathology demonstrates an unremarkable epidermis; however, the dermis contains degenerated collagen surrounded by palisading histiocytes as well as lymphocytes. Similar to Degos disease, increased mucin is seen within these areas of degeneration, but occluded vessels and thrombosis typically are not seen (Figure 1).4,5

Guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus initially presents as polygonal, bluish white papules that coalesce into plaques.6 Over time, these lesions become more atrophic and may mimic Degos disease but appear differently on histopathology. Histopathology of lichen sclerosus classically demonstrates atrophy of the epidermis with loss of the rete ridges and vacuolar surface changes. Homogenization of the superficial/papillary dermis with an underlying bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate also is seen (Figure 2).6

Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by chronic recurrent ulceration of the legs secondary to thrombosis and subsequent ischemia. In the initial phase of this disease, livedo reticularis is seen followed by the development of ulcerations. As these ulcerations heal, they leave behind porcelain white scars referred to as atrophie blanche.7 The areas of scarring in livedoid vasculopathy are broad and angulated, differentiating them from the small, round, porcelain white macules in end-stage Degos disease. Histopathology demonstrates thrombosis and fibrin occlusion of the upper and mid dermal vessels. Very minimal perivascular infiltrate typically is seen, but when it is present, the infiltrate mostly is lymphocytic. Hyalinization of the vessel walls also is seen, particularly in the atrophie blanche stage (Figure 3).7

Lymphomatoid papulosis classically presents with pruritic red papules that often spontaneously involute. After resolution of the primary lesions, atrophic varioliform scars may be left behind that can resemble Degos disease.8 Classically, there are 5 histopathologic subtypes: A, B, C, D, and E. Type A is the most common type of lymphomatoid papulosis, and histopathology demonstrates a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate that consists of cells arranged in small clusters. Numerous medium- to large-sized atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm are seen, and mitotic figures are common (Figure 4).8

Our case was particularly interesting because the patient was 2 to 3 weeks pregnant. Degos disease in pregnancy appears to be quite exceptional. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Degos disease and pregnancy revealed only 4 other cases reported in the literature.9-12 With the exception of a single case that was complicated by severe abdominal pain requiring labor induction, the other reported cases resulted in uncomplicated pregnancies.9-12 Conversely, our patient's pregnancy was complicated by gestational hypertension and fetal hydrops requiring a preterm cesarean delivery. Furthermore, the infant had multiple complications, which were attributed to both placental insufficiency and a coagulopathic state.

Our patient also was found to have a heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation on workup. A PubMed search using the terms factor V Leiden mutation and Degos disease revealed 2 other cases of factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos disease.13,14 The importance of factor V Leiden mutations in patients with Degos disease currently is unclear.

- Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)--a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10.

- Oliver B, Boehm M, Rosing DR, et al. Diffuse atrophic papules and plaques, intermittent abdominal pain, paresthesias, and cardiac abnormalities in a 55-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1274-1277.

- Magro CM, Wang X, Garrett-Bakelman F, et al. The effects of eculizumab on the pathology of malignant atrophic papulosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:185.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Tronnier M, Mitteldorf C. Histologic features of granulomatous skin diseases. part 1: non-infectious granulomatous disorders. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:211-216.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Vasudevan B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478‐488.

- Martinez-Cabriales SA, Walsh S, Sade S, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: an update and review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:59-73.

- Moulin G, Barrut D, Franc MP, et al. Familial Degos' atrophic papulosis (mother-daughter). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:149-155.

- Bogenrieder T, Kuske M, Landthaler M, et al. Benign Degos' disease developing during pregnancy and followed for 10 years. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:284-287.

- Sharma S, Brennan B, Naden R, et al. A case of Degos disease in pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2016;9:167-168.

- Zhao Q, Zhang S, Dong A. An unusual case of abdominal pain. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:E1-E2.

- Darwich E, Guilabert A, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Dermoscopic description of a patient with thrombocythemia and factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos' disease. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:604-606.

- Hohwy T, Jensen MG, Tøttrup A, et al. A fatal case of malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos' disease) in a man with factor V Leiden mutation and lupus anticoagulant. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:245-247.

- Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)--a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10.

- Oliver B, Boehm M, Rosing DR, et al. Diffuse atrophic papules and plaques, intermittent abdominal pain, paresthesias, and cardiac abnormalities in a 55-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1274-1277.

- Magro CM, Wang X, Garrett-Bakelman F, et al. The effects of eculizumab on the pathology of malignant atrophic papulosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:185.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Tronnier M, Mitteldorf C. Histologic features of granulomatous skin diseases. part 1: non-infectious granulomatous disorders. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:211-216.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Vasudevan B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478‐488.

- Martinez-Cabriales SA, Walsh S, Sade S, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: an update and review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:59-73.

- Moulin G, Barrut D, Franc MP, et al. Familial Degos' atrophic papulosis (mother-daughter). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:149-155.

- Bogenrieder T, Kuske M, Landthaler M, et al. Benign Degos' disease developing during pregnancy and followed for 10 years. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:284-287.

- Sharma S, Brennan B, Naden R, et al. A case of Degos disease in pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2016;9:167-168.

- Zhao Q, Zhang S, Dong A. An unusual case of abdominal pain. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:E1-E2.

- Darwich E, Guilabert A, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Dermoscopic description of a patient with thrombocythemia and factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos' disease. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:604-606.

- Hohwy T, Jensen MG, Tøttrup A, et al. A fatal case of malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos' disease) in a man with factor V Leiden mutation and lupus anticoagulant. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:245-247.

A 36-year-old pregnant woman presented with painful erythematous papules on the palms and fingers of 2 months’ duration. Similar lesions developed on the thighs and feet several weeks later. Two tender macules with central areas of porcelain white scarring rimmed by telangiectases on the right foot also were present. A punch biopsy of these lesions demonstrated a wedge-shaped area of ischemic necrosis associated with dermal mucin without associated necrobiosis. Fibrin thrombi were seen within several small dermal vessels and were associated with a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Endotheliitis was observed within a deep dermal vessel. Laboratory workup including syphilis IgG, antinuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antigen antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA, antistreptolysin O antibodies, Russell viper venom time, cryoglobulin, hepatitis screening, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), and cytoplasmic ANCA was unremarkable. Hypercoagulable studies including prothrombin gene mutation, factor V Leiden, plasminogen, proteins C and S, antithrombin III, homocysteine, and antiphospholipid IgM and IgG antibodies were notable only for heterozygosity for factor V Leiden.

Subcutaneous, Mucocutaneous, and Mucous Membrane Tumors

The Diagnosis: Granular Cell Tumor

Histopathologic analysis from the axillary excision demonstrated cords and sheets of large polygonal cells in the dermis with uniform, oval, hyperchromatic nuclei and ample pink granular-staining cytoplasm (quiz images). An infiltrative growth pattern was noted; however, there was no evidence of conspicuous mitoses, nuclear pleomorphism, or necrosis. These results in conjunction with the immunohistochemistry findings were consistent with a benign granular cell tumor (GCT), a rare neoplasm considered to have neural/Schwann cell origin.1-3

Our case demonstrates the difficulty in clinically diagnosing cutaneous GCTs. The tumor often presents as a solitary, 0.5- to 3-cm, asymptomatic, firm nodule4,5; however, GCTs also can appear verrucous, eroded, or with other variable morphologies, which can create diagnostic challenges.5,6 Accordingly, a 1980 study of 110 patients with GCTs found that the preoperative clinical diagnosis was incorrect in all but 3 cases,7 emphasizing the need for histologic evaluation. Benign GCTs tend to exhibit sheets of polygonal tumor cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and small central nuclei.3,5 The cytoplasmic granules are periodic acid-Schiff positive and diastase resistant.6 Many cases feature pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, which can misleadingly resemble squamous cell carcinoma.3,5,6 Of note, invasive growth patterns on histology can occur with benign GCTs, as in our patient's case, and do not impact prognosis.3,4 On immunohistochemistry, benign, atypical, and malignant GCTs often stain positive for S-100 protein, vimentin, neuron-specific enolase, SOX10, and CD68.1,3

Although our patient's GCTs were benign, an estimated 1% to 2% are malignant.1,4 In 1998, Fanburg-Smith et al1 defined 6 histologic criteria that characterize malignant GCTs: necrosis, tumor cell spindling, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli, high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, increased mitosis, and pleomorphism. Neoplasms with 3 or more of these features are classified as malignant, those with 1 or 2 are considered atypical, and those with only pleomorphism or no other criteria met are diagnosed as benign.1

Multiple GCTs have been reported in 10% to 25% of cases and, as highlighted in our case, can occur in both a metachronous and synchronous manner.2-4,6 Our patient developed a solitary GCT on the inferior lip 3 years prior to the appearance of 2 additional GCTs within 6 months of each other. The presence of multiple GCTs has been associated with genetic syndromes, such as neurofibromatosis type 1 and Noonan syndrome with multiple lentigines3,8; however, as our case demonstrates, multiple GCTs can occur in nonsyndromic patients as well. When multiple GCTs develop at distant sites, they can resemble metastasis.3 To differentiate these clinical scenarios, Machado et al3 proposed utilizing histology and anatomic location. Multiple tumors with benign characteristics on histology likely represent multiple GCTs, whereas tumors arising at sites common to GCT metastasis, such as lymph node, bone, or viscera, are more concerning for metastatic disease. It has been suggested that patients with multiple GCTs should be monitored with physical examination and repeat magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography every 6 to 12 months.2 Given our patient's presentation with new tumors arising within 6 months of one another, we recommended a 6-month follow-up interval rather than 1 year. Due to the rarity of GCTs, clinical trials to define treatment guidelines and recommendations have not been performed.3 However, the most commonly utilized treatment modality is wide local excision, as performed in our patient.2,4

Melanoma, atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), xanthoma, and leiomyosarcoma may be difficult to distinguish from GCT.1,3,4 Melanoma incidence has increased dramatically over the last several decades, with rates in the United States rising from 6.8 cases per 100,000 individuals in the 1970s to 20.1 in the early 2000s. Risk factors for its development include UV radiation exposure and particularly severe sunburns during childhood, along with a number of host risk factors such as total number of melanocytic nevi, family history, and fair complexion.9 Histologically, it often demonstrates irregularly distributed, poorly defined melanocytes with pagetoid spread and dyscohesive nests (Figure 1).10 Melanoma metastasis occasionally can present as a soft-tissue mass and often stains positive for S-100 and vimentin, thus resembling GCT1,4; however, unlike melanoma, GCTs lack melanosomes and stain negative for more specific melanocyte markers, such as melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART-1).1,3,4

Atypical fibroxanthoma is a cutaneous neoplasm with fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin.11 These tumors typically arise on the head and neck in elderly individuals, particularly men with sun-damaged skin. They often present as superficial, rapidly growing nodules with the potential to ulcerate and bleed.11,12 Histologic features include pleomorphic spindle and epithelioid cells, whose nuclei appear hyperchromatic with atypical mitoses (Figure 2).12 Granular cell changes occur infrequently with AFXs, but in such cases immunohistochemistry can readily distinguish AFX from GCT. Although both tend to stain positive for CD68 and vimentin, AFXs lack S-100 protein and SOX10 expression that frequently is observed in GCTs.3,12

Xanthomas are localized lipid deposits in the connective tissue of the skin that often arise in association with dyslipidemia.13 They typically present as soft to semisolid yellow papules, plaques, or nodules. Their clinical appearance can resemble GCTs; however, histologic analysis enables differentiation with ease, as xanthomas demonstrate characteristic foam cells, consisting of lipid-laden macrophages (Figure 3).13