User login

Mercury and other risks of cosmetic skin lighteners

Skin hyperpigmentation – whether it is caused by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from acne or trauma to the skin, melasma, autoimmune disorders, or disorders of pigmentation – is a condition where treatment is commonly sought after in dermatology offices. Topical products used to fade hyperpigmented areas of the skin have long been used around the world, and because of safety concerns, regulations aimed at reducing potential harm or adverse effects caused by certain ingredients in these products are increasing in different countries.

For example, while extremely effective at treating most forms of hyperpigmentation, hydroquinone has been definitively linked to ochronosis, kojic acid has been linked to contact dermatitis in humans, and acid peels and retinoids are associated with irritant dermatitis, disruption of the skin barrier, and photosensitivity. In animal studies, licorice root extract has been linked to endocrine and other organ system irregularities.

Kojic acid was banned in Japan in 2003, and subsequently in South Korea and Switzerland because of concerns over animal studies indicating that its fungal metabolite might be carcinogenic (. Hydroquinone is classified as a drug and has been banned for use in cosmetic products in Japan, the European Union, Australia, and several African nations since at least 2006 because of concerns over adrenal gland dysregulation and high levels of mercury in hydroquinone products in those countries. In Africa specifically, South Africa banned all but 2% hydroquinone in 1983, the Ivory Coast banned all skin whitening creams in 2015, and in 2016, Ghana initiated a ban on certain skin products containing hydroquinone.

The United States followed suit in February 2020 with the Food and Drug Administration introducing a ban on all OTC hydroquinone-containing products because of concerns over carcinogenicity in animal studies (which has not been shown in human studies to date). The “Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security” (CARES) Act signed in March 2020 then made the changes effective by halting the sale of OTC hydroquinone products in the United States as of September 2020.

Mercury concerns

Despite these bans, hydroquinone continues to be sold in cosmetics and OTC products around the world and online. And despite being banned or limited in these products, in particular. Mercury has been used in cosmetic products as a skin lightening agent (on its own) and as a preservative.

Mercury has been shown to be carcinogenic, neurotoxic, as well as cytotoxic to the renal and endocrine systems, causes reproductive toxicity, and may be bioaccumulative in wildlife and humans. There is particular concern regarding the risks of exposure in pregnant women and babies because of potential harm to the developing brain and nervous system. Initial signs and symptoms of mercury poisoning include irritability, shyness, tremors, changes in vision or hearing, memory problems, depression, numbness and tingling in the hands, feet, or around the mouth.

Organizations such as the Zero Mercury Working Group (ZMWG) – an international coalition of public interest environmental and health nongovernmental organizations from more than 55 countries, focused on eliminating the use, release, and exposure to mercury – have been working to help ensure safety and mercury levels are below the threshold deemed allowable in hydroquinone-containing products.

On March 10, the ZMWG published the results of a new study demonstrating that skin lighteners containing mercury are still being sold online, despite bans and safety concerns. Ebay, Amazon, Shopee, Jiji, and Flipkart are among the websites still selling high mercury–containing skin lightener products. Some of them were the same offenders selling the banned products in 2019. Of the 271 online products tested from 17 countries, nearly half contained over 1 ppm of mercury, which is the legal limit that has been established by most governments and the Minamata Convention on Mercury. Based on their packaging, the majority of these products were manufactured in Asia, most often in Pakistan (43%), Thailand (8%), China (6%), and Taiwan (4%), according to the report.

In ZMWG’s prior publications, mercury concentrations reported in some of these products ranged from 93 ppm to over 16,000 ppm. Even higher concentrations have been reported by other entities. And according to a World Health Organization November 2019 report, mercury-containing skin lightening products have been manufactured in many countries and areas, including Bangladesh, China, Dominican Republic Hong Kong SAR (China), Jamaica, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, Republic of Korea, Thailand, and the United States. According to the ZMWG, 137 countries have committed to the Minamata Convention to phase out and limit mercury, including in cosmetics.

Despite bans on some of these products, consumers in the United States and other countries with bans and restrictions are still at risk of exposure to mercury-containing skin lighteners because of online sales. Hopefully, the work of the ZMWG and similar entities will continue to help limit potentially harmful exposures to mercury, while maintaining access to safe and effective methods to treat hyperpigmentation.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Lily Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

Skin hyperpigmentation – whether it is caused by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from acne or trauma to the skin, melasma, autoimmune disorders, or disorders of pigmentation – is a condition where treatment is commonly sought after in dermatology offices. Topical products used to fade hyperpigmented areas of the skin have long been used around the world, and because of safety concerns, regulations aimed at reducing potential harm or adverse effects caused by certain ingredients in these products are increasing in different countries.

For example, while extremely effective at treating most forms of hyperpigmentation, hydroquinone has been definitively linked to ochronosis, kojic acid has been linked to contact dermatitis in humans, and acid peels and retinoids are associated with irritant dermatitis, disruption of the skin barrier, and photosensitivity. In animal studies, licorice root extract has been linked to endocrine and other organ system irregularities.

Kojic acid was banned in Japan in 2003, and subsequently in South Korea and Switzerland because of concerns over animal studies indicating that its fungal metabolite might be carcinogenic (. Hydroquinone is classified as a drug and has been banned for use in cosmetic products in Japan, the European Union, Australia, and several African nations since at least 2006 because of concerns over adrenal gland dysregulation and high levels of mercury in hydroquinone products in those countries. In Africa specifically, South Africa banned all but 2% hydroquinone in 1983, the Ivory Coast banned all skin whitening creams in 2015, and in 2016, Ghana initiated a ban on certain skin products containing hydroquinone.

The United States followed suit in February 2020 with the Food and Drug Administration introducing a ban on all OTC hydroquinone-containing products because of concerns over carcinogenicity in animal studies (which has not been shown in human studies to date). The “Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security” (CARES) Act signed in March 2020 then made the changes effective by halting the sale of OTC hydroquinone products in the United States as of September 2020.

Mercury concerns

Despite these bans, hydroquinone continues to be sold in cosmetics and OTC products around the world and online. And despite being banned or limited in these products, in particular. Mercury has been used in cosmetic products as a skin lightening agent (on its own) and as a preservative.

Mercury has been shown to be carcinogenic, neurotoxic, as well as cytotoxic to the renal and endocrine systems, causes reproductive toxicity, and may be bioaccumulative in wildlife and humans. There is particular concern regarding the risks of exposure in pregnant women and babies because of potential harm to the developing brain and nervous system. Initial signs and symptoms of mercury poisoning include irritability, shyness, tremors, changes in vision or hearing, memory problems, depression, numbness and tingling in the hands, feet, or around the mouth.

Organizations such as the Zero Mercury Working Group (ZMWG) – an international coalition of public interest environmental and health nongovernmental organizations from more than 55 countries, focused on eliminating the use, release, and exposure to mercury – have been working to help ensure safety and mercury levels are below the threshold deemed allowable in hydroquinone-containing products.

On March 10, the ZMWG published the results of a new study demonstrating that skin lighteners containing mercury are still being sold online, despite bans and safety concerns. Ebay, Amazon, Shopee, Jiji, and Flipkart are among the websites still selling high mercury–containing skin lightener products. Some of them were the same offenders selling the banned products in 2019. Of the 271 online products tested from 17 countries, nearly half contained over 1 ppm of mercury, which is the legal limit that has been established by most governments and the Minamata Convention on Mercury. Based on their packaging, the majority of these products were manufactured in Asia, most often in Pakistan (43%), Thailand (8%), China (6%), and Taiwan (4%), according to the report.

In ZMWG’s prior publications, mercury concentrations reported in some of these products ranged from 93 ppm to over 16,000 ppm. Even higher concentrations have been reported by other entities. And according to a World Health Organization November 2019 report, mercury-containing skin lightening products have been manufactured in many countries and areas, including Bangladesh, China, Dominican Republic Hong Kong SAR (China), Jamaica, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, Republic of Korea, Thailand, and the United States. According to the ZMWG, 137 countries have committed to the Minamata Convention to phase out and limit mercury, including in cosmetics.

Despite bans on some of these products, consumers in the United States and other countries with bans and restrictions are still at risk of exposure to mercury-containing skin lighteners because of online sales. Hopefully, the work of the ZMWG and similar entities will continue to help limit potentially harmful exposures to mercury, while maintaining access to safe and effective methods to treat hyperpigmentation.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Lily Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

Skin hyperpigmentation – whether it is caused by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from acne or trauma to the skin, melasma, autoimmune disorders, or disorders of pigmentation – is a condition where treatment is commonly sought after in dermatology offices. Topical products used to fade hyperpigmented areas of the skin have long been used around the world, and because of safety concerns, regulations aimed at reducing potential harm or adverse effects caused by certain ingredients in these products are increasing in different countries.

For example, while extremely effective at treating most forms of hyperpigmentation, hydroquinone has been definitively linked to ochronosis, kojic acid has been linked to contact dermatitis in humans, and acid peels and retinoids are associated with irritant dermatitis, disruption of the skin barrier, and photosensitivity. In animal studies, licorice root extract has been linked to endocrine and other organ system irregularities.

Kojic acid was banned in Japan in 2003, and subsequently in South Korea and Switzerland because of concerns over animal studies indicating that its fungal metabolite might be carcinogenic (. Hydroquinone is classified as a drug and has been banned for use in cosmetic products in Japan, the European Union, Australia, and several African nations since at least 2006 because of concerns over adrenal gland dysregulation and high levels of mercury in hydroquinone products in those countries. In Africa specifically, South Africa banned all but 2% hydroquinone in 1983, the Ivory Coast banned all skin whitening creams in 2015, and in 2016, Ghana initiated a ban on certain skin products containing hydroquinone.

The United States followed suit in February 2020 with the Food and Drug Administration introducing a ban on all OTC hydroquinone-containing products because of concerns over carcinogenicity in animal studies (which has not been shown in human studies to date). The “Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security” (CARES) Act signed in March 2020 then made the changes effective by halting the sale of OTC hydroquinone products in the United States as of September 2020.

Mercury concerns

Despite these bans, hydroquinone continues to be sold in cosmetics and OTC products around the world and online. And despite being banned or limited in these products, in particular. Mercury has been used in cosmetic products as a skin lightening agent (on its own) and as a preservative.

Mercury has been shown to be carcinogenic, neurotoxic, as well as cytotoxic to the renal and endocrine systems, causes reproductive toxicity, and may be bioaccumulative in wildlife and humans. There is particular concern regarding the risks of exposure in pregnant women and babies because of potential harm to the developing brain and nervous system. Initial signs and symptoms of mercury poisoning include irritability, shyness, tremors, changes in vision or hearing, memory problems, depression, numbness and tingling in the hands, feet, or around the mouth.

Organizations such as the Zero Mercury Working Group (ZMWG) – an international coalition of public interest environmental and health nongovernmental organizations from more than 55 countries, focused on eliminating the use, release, and exposure to mercury – have been working to help ensure safety and mercury levels are below the threshold deemed allowable in hydroquinone-containing products.

On March 10, the ZMWG published the results of a new study demonstrating that skin lighteners containing mercury are still being sold online, despite bans and safety concerns. Ebay, Amazon, Shopee, Jiji, and Flipkart are among the websites still selling high mercury–containing skin lightener products. Some of them were the same offenders selling the banned products in 2019. Of the 271 online products tested from 17 countries, nearly half contained over 1 ppm of mercury, which is the legal limit that has been established by most governments and the Minamata Convention on Mercury. Based on their packaging, the majority of these products were manufactured in Asia, most often in Pakistan (43%), Thailand (8%), China (6%), and Taiwan (4%), according to the report.

In ZMWG’s prior publications, mercury concentrations reported in some of these products ranged from 93 ppm to over 16,000 ppm. Even higher concentrations have been reported by other entities. And according to a World Health Organization November 2019 report, mercury-containing skin lightening products have been manufactured in many countries and areas, including Bangladesh, China, Dominican Republic Hong Kong SAR (China), Jamaica, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Philippines, Republic of Korea, Thailand, and the United States. According to the ZMWG, 137 countries have committed to the Minamata Convention to phase out and limit mercury, including in cosmetics.

Despite bans on some of these products, consumers in the United States and other countries with bans and restrictions are still at risk of exposure to mercury-containing skin lighteners because of online sales. Hopefully, the work of the ZMWG and similar entities will continue to help limit potentially harmful exposures to mercury, while maintaining access to safe and effective methods to treat hyperpigmentation.

Dr. Wesley and Dr. Lily Talakoub are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. This month’s column is by Dr. Wesley. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

The science of clean skin care and the clean beauty movement

. I see numerous social media posts, blogs, and magazine articles about toxic skin care ingredients, while more patients are asking their dermatologists about clean beauty products. So, I decided it was time to dissect the issues and figure out what “clean” really means to me.

The problem is that no one agrees on a clean ingredient standard for beauty products. Many companies, like Target, Walgreens/Boots, Sephora, Neiman Marcus, Whole Foods, and Ulta, have their own varying clean standards. Even Allure magazine has a “Clean Best of Beauty” seal. California has Proposition 65, otherwise known as the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986, which contains a list of banned chemicals “known to the state to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity.” In January 2021, Hawai‘i law prohibited the sale of oxybenzone and octinoxate in sunscreens in response to scientific studies showing that these ingredients “are toxic to corals and other marine life.” The Environmental Working Group (EWG) rates the safety of ingredients based on carcinogenicity, developmental and reproductive toxicity, allergenicity, and immunotoxicity. The Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR), funded by the Personal Care Products Council, consists of a seven-member steering committee that has at least one dermatologist representing the American Academy of Dermatology and a toxicologist representing the Society of Toxicology. The CIR publishes detailed reviews of ingredients that can be easily found on PubMed and Google Scholar and closely reviews animal and human data and reports on safety and contact dermatitis risk.

Which clean beauty standard is best?

I reviewed most of the various standards, clean seals, laws, and safety reports and found significant discrepancies resulting from misunderstandings of the science, lack of depth in the scientific evaluations, lumping of ingredients into a larger category, or lack of data. The most salient cause of misinformation and confusion seems to be hyperbolic claims by the media and clean beauty advocates who do not understand the basic science.

When I conducted a survey of cosmetic chemists on my LinkedIn account, most of the chemists stated that “ ‘Clean Beauty’ is a marketing term, more than a scientific term.” None of the chemists could give an exact definition of clean beauty. However, I thought I needed a good answer for my patients and for doctors who want to use and recommend “clean skin care brands.”

A dermatologist’s approach to develop a clean beauty standard

Many of the standards combine all of the following into the “clean” designation: nontoxic to the environment (both the production process and the resulting ingredient), nontoxic to marine life and coral, cruelty-free (not tested on animals), hypoallergenic, lacking in known health risks (carcinogenicity, reproductive toxicity), vegan, and gluten free. As a dermatologist, I am a splitter more than a lumper, so I prefer that “clean” be split into categories to make it easier to understand. With that in mind, I will focus on clean beauty ingredients only as they pertain to health: carcinogenicity, endocrine effects, nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, etc. This discussion will not consider environmental effects, reproductive toxicity (some ingredients may decrease fertility, which is beyond the scope of this article), ingredient sources, and sustainability, animal testing, or human rights violations during production. Those issues are important, of course, but for clarity and simplicity, we will focus on the health risks of skin care ingredients.

In this month’s column, I will focus on a few ingredients and will continue the discussion in subsequent columns. Please note that commercial standards such as Target standards are based on the product type (e.g., cleansers, sunscreens, or moisturizers). So, when I mention an ingredient not allowed by certain company standards, note that it can vary by product type. My comments pertain mostly to facial moisturizers and facial serums to try and simplify the information. The Good Face Project has a complete list of standards by product type, which I recommend as a resource if you want more detailed information.

Are ethanolamines safe or toxic in cosmetics?

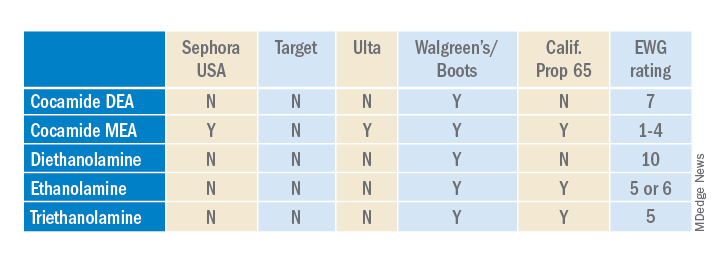

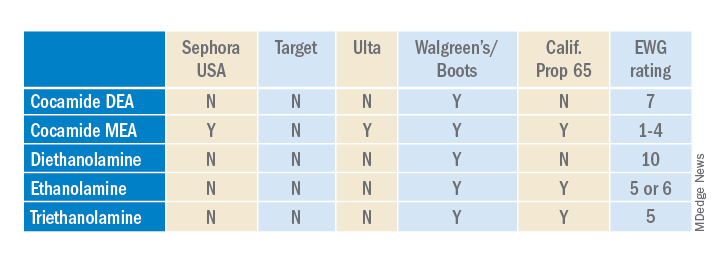

Ethanolamines are common ingredients in surfactants, fragrances, and emulsifying agents and include cocamide diethanolamine (DEA), cocamide monoethanolamine (MEA), and triethanolamine (TEA). Cocamide DEA, lauramide DEA, linoleamide DEA, and oleamide DEA are fatty acid diethanolamides that may contain 4% to 33% diethanolamine.1 A Google search of toxic ingredients in beauty products consistently identifies ethanolamines among such offending product constituents. Table 1 reveals that ethanolamines are excluded from some standards and included in others (N = not allowed or restricted by amount used and Y = allowed with no restrictions). As you can see, the standards don’t correspond to the EWG rating of the ingredients, which ranges from 1 (low hazard) to 10 (high hazard).

Why are ethanolamines sometimes considered safe and sometimes not?

Ethanolamines are reputed to be allergenic, but as we know as dermatologists, that does not mean that everyone will react to them. (In my opinion, allergenicity is a separate issue than the clean issue.) One study showed that TEA in 2.5% petrolatum had a 0.4% positive patch test rate in humans, which was thought to be related more to irritation than allergenicity.2 Cocamide DEA allergy is seen in those with hand dermatitis resulting from hand cleansers but is more commonly seen in metal workers.3 For this reason, these ethanolamines are usually found in rinse-off products to decrease exposure time. But there are many irritating ingredients not banned by Target, Sephora, and Ulta, so why does ethanolamine end up on toxic ingredient lists?

First, there is the issue of oral studies in animals. Oral forms of some ethanolamines have shown mild toxicity in rats, but topical forms have not been demonstrated to cause mutagenicity.1

For this reason, ethanolamines in their native form are considered safe.

The main issue with ethanolamines is that, when they are formulated with ingredients that break down into nitrogen, such as certain preservatives, the combination forms nitrosamines, such as N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA), which are carcinogenic.4 The European Commission prohibits DEA in cosmetics based on concerns about formation of these carcinogenic nitrosamines. Some standards limit ethanolamines to rinse-off products.5 The CIR panel concluded that diethanolamine and its 16 salts are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed and that TEA and TEA-related compounds are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed.6,7 The FDA states that there is no reason for consumers to be alarmed based on the use of DEA in cosmetics.8

The safety issues surrounding the use of ethanolamines in a skin care routine illustrate an important point: Every single product in the skin care routine should be compatible with the other products in the regimen. Using ethanolamines in a rinse-off product is one solution, as is ensuring that no other products in the skin care routine contain N-nitroso compounds that can combine with ethanolamines to form nitrosamines.

Are natural products safer?

Natural products are not necessarily any safer than synthetic products. Considering ethanolamines as the example here, note that cocamide DEA is an ethanolamine derived from coconut. It is often found in “green” or “natural” skin care products.9 It can still combine with N-nitroso compounds to form carcinogenic nitrosamines.

What is the bottom line? Are ethanolamines safe in cosmetics?

For now, if a patient asks if ethanolamine is safe in skin care, my answer would be yes, so long as the following is true:

- It is in a rinse-off product.

- The patient is not allergic to it.

- They do not have hand dermatitis.

- Their skin care routine does not include nitrogen-containing compounds like N-nitrosodiethanolamine (NDELA) or NDEA.

Conclusion

This column uses ethanolamines as an example to show the disparity in clean standards in the cosmetic industry. As you can see, there are multiple factors to consider. I will begin including clean information in my cosmeceutical critique columns to address some of these issues.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Cocamide DE. J Am Coll Toxicol. 1986;5(5).

2. Lessmann H et al. Contact Dermatitis. 2009 May;60(5):243-55.

3. Aalto-Korte K et al. 2014 Mar;70(3):169-74.

4. Kraeling ME et al. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004 Oct;42(10):1553-61.

5. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2015 Sep;34(2 Suppl):84S-98S.

6. Fiume MM.. Int J Toxicol. 2017 Sep/Oct;36(5_suppl2):89S-110S.

7. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2013 May-Jun;32(3 Suppl):59S-83S.

8. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Diethanolamine. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredients/diethanolamine. Accessed Feb. 12, 2022.

9. Aryanti N et al. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2021 Feb 1 (Vol. 1053, No. 1, p. 012066). IOP Publishing.

. I see numerous social media posts, blogs, and magazine articles about toxic skin care ingredients, while more patients are asking their dermatologists about clean beauty products. So, I decided it was time to dissect the issues and figure out what “clean” really means to me.

The problem is that no one agrees on a clean ingredient standard for beauty products. Many companies, like Target, Walgreens/Boots, Sephora, Neiman Marcus, Whole Foods, and Ulta, have their own varying clean standards. Even Allure magazine has a “Clean Best of Beauty” seal. California has Proposition 65, otherwise known as the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986, which contains a list of banned chemicals “known to the state to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity.” In January 2021, Hawai‘i law prohibited the sale of oxybenzone and octinoxate in sunscreens in response to scientific studies showing that these ingredients “are toxic to corals and other marine life.” The Environmental Working Group (EWG) rates the safety of ingredients based on carcinogenicity, developmental and reproductive toxicity, allergenicity, and immunotoxicity. The Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR), funded by the Personal Care Products Council, consists of a seven-member steering committee that has at least one dermatologist representing the American Academy of Dermatology and a toxicologist representing the Society of Toxicology. The CIR publishes detailed reviews of ingredients that can be easily found on PubMed and Google Scholar and closely reviews animal and human data and reports on safety and contact dermatitis risk.

Which clean beauty standard is best?

I reviewed most of the various standards, clean seals, laws, and safety reports and found significant discrepancies resulting from misunderstandings of the science, lack of depth in the scientific evaluations, lumping of ingredients into a larger category, or lack of data. The most salient cause of misinformation and confusion seems to be hyperbolic claims by the media and clean beauty advocates who do not understand the basic science.

When I conducted a survey of cosmetic chemists on my LinkedIn account, most of the chemists stated that “ ‘Clean Beauty’ is a marketing term, more than a scientific term.” None of the chemists could give an exact definition of clean beauty. However, I thought I needed a good answer for my patients and for doctors who want to use and recommend “clean skin care brands.”

A dermatologist’s approach to develop a clean beauty standard

Many of the standards combine all of the following into the “clean” designation: nontoxic to the environment (both the production process and the resulting ingredient), nontoxic to marine life and coral, cruelty-free (not tested on animals), hypoallergenic, lacking in known health risks (carcinogenicity, reproductive toxicity), vegan, and gluten free. As a dermatologist, I am a splitter more than a lumper, so I prefer that “clean” be split into categories to make it easier to understand. With that in mind, I will focus on clean beauty ingredients only as they pertain to health: carcinogenicity, endocrine effects, nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, etc. This discussion will not consider environmental effects, reproductive toxicity (some ingredients may decrease fertility, which is beyond the scope of this article), ingredient sources, and sustainability, animal testing, or human rights violations during production. Those issues are important, of course, but for clarity and simplicity, we will focus on the health risks of skin care ingredients.

In this month’s column, I will focus on a few ingredients and will continue the discussion in subsequent columns. Please note that commercial standards such as Target standards are based on the product type (e.g., cleansers, sunscreens, or moisturizers). So, when I mention an ingredient not allowed by certain company standards, note that it can vary by product type. My comments pertain mostly to facial moisturizers and facial serums to try and simplify the information. The Good Face Project has a complete list of standards by product type, which I recommend as a resource if you want more detailed information.

Are ethanolamines safe or toxic in cosmetics?

Ethanolamines are common ingredients in surfactants, fragrances, and emulsifying agents and include cocamide diethanolamine (DEA), cocamide monoethanolamine (MEA), and triethanolamine (TEA). Cocamide DEA, lauramide DEA, linoleamide DEA, and oleamide DEA are fatty acid diethanolamides that may contain 4% to 33% diethanolamine.1 A Google search of toxic ingredients in beauty products consistently identifies ethanolamines among such offending product constituents. Table 1 reveals that ethanolamines are excluded from some standards and included in others (N = not allowed or restricted by amount used and Y = allowed with no restrictions). As you can see, the standards don’t correspond to the EWG rating of the ingredients, which ranges from 1 (low hazard) to 10 (high hazard).

Why are ethanolamines sometimes considered safe and sometimes not?

Ethanolamines are reputed to be allergenic, but as we know as dermatologists, that does not mean that everyone will react to them. (In my opinion, allergenicity is a separate issue than the clean issue.) One study showed that TEA in 2.5% petrolatum had a 0.4% positive patch test rate in humans, which was thought to be related more to irritation than allergenicity.2 Cocamide DEA allergy is seen in those with hand dermatitis resulting from hand cleansers but is more commonly seen in metal workers.3 For this reason, these ethanolamines are usually found in rinse-off products to decrease exposure time. But there are many irritating ingredients not banned by Target, Sephora, and Ulta, so why does ethanolamine end up on toxic ingredient lists?

First, there is the issue of oral studies in animals. Oral forms of some ethanolamines have shown mild toxicity in rats, but topical forms have not been demonstrated to cause mutagenicity.1

For this reason, ethanolamines in their native form are considered safe.

The main issue with ethanolamines is that, when they are formulated with ingredients that break down into nitrogen, such as certain preservatives, the combination forms nitrosamines, such as N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA), which are carcinogenic.4 The European Commission prohibits DEA in cosmetics based on concerns about formation of these carcinogenic nitrosamines. Some standards limit ethanolamines to rinse-off products.5 The CIR panel concluded that diethanolamine and its 16 salts are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed and that TEA and TEA-related compounds are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed.6,7 The FDA states that there is no reason for consumers to be alarmed based on the use of DEA in cosmetics.8

The safety issues surrounding the use of ethanolamines in a skin care routine illustrate an important point: Every single product in the skin care routine should be compatible with the other products in the regimen. Using ethanolamines in a rinse-off product is one solution, as is ensuring that no other products in the skin care routine contain N-nitroso compounds that can combine with ethanolamines to form nitrosamines.

Are natural products safer?

Natural products are not necessarily any safer than synthetic products. Considering ethanolamines as the example here, note that cocamide DEA is an ethanolamine derived from coconut. It is often found in “green” or “natural” skin care products.9 It can still combine with N-nitroso compounds to form carcinogenic nitrosamines.

What is the bottom line? Are ethanolamines safe in cosmetics?

For now, if a patient asks if ethanolamine is safe in skin care, my answer would be yes, so long as the following is true:

- It is in a rinse-off product.

- The patient is not allergic to it.

- They do not have hand dermatitis.

- Their skin care routine does not include nitrogen-containing compounds like N-nitrosodiethanolamine (NDELA) or NDEA.

Conclusion

This column uses ethanolamines as an example to show the disparity in clean standards in the cosmetic industry. As you can see, there are multiple factors to consider. I will begin including clean information in my cosmeceutical critique columns to address some of these issues.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Cocamide DE. J Am Coll Toxicol. 1986;5(5).

2. Lessmann H et al. Contact Dermatitis. 2009 May;60(5):243-55.

3. Aalto-Korte K et al. 2014 Mar;70(3):169-74.

4. Kraeling ME et al. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004 Oct;42(10):1553-61.

5. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2015 Sep;34(2 Suppl):84S-98S.

6. Fiume MM.. Int J Toxicol. 2017 Sep/Oct;36(5_suppl2):89S-110S.

7. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2013 May-Jun;32(3 Suppl):59S-83S.

8. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Diethanolamine. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredients/diethanolamine. Accessed Feb. 12, 2022.

9. Aryanti N et al. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2021 Feb 1 (Vol. 1053, No. 1, p. 012066). IOP Publishing.

. I see numerous social media posts, blogs, and magazine articles about toxic skin care ingredients, while more patients are asking their dermatologists about clean beauty products. So, I decided it was time to dissect the issues and figure out what “clean” really means to me.

The problem is that no one agrees on a clean ingredient standard for beauty products. Many companies, like Target, Walgreens/Boots, Sephora, Neiman Marcus, Whole Foods, and Ulta, have their own varying clean standards. Even Allure magazine has a “Clean Best of Beauty” seal. California has Proposition 65, otherwise known as the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986, which contains a list of banned chemicals “known to the state to cause cancer or reproductive toxicity.” In January 2021, Hawai‘i law prohibited the sale of oxybenzone and octinoxate in sunscreens in response to scientific studies showing that these ingredients “are toxic to corals and other marine life.” The Environmental Working Group (EWG) rates the safety of ingredients based on carcinogenicity, developmental and reproductive toxicity, allergenicity, and immunotoxicity. The Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR), funded by the Personal Care Products Council, consists of a seven-member steering committee that has at least one dermatologist representing the American Academy of Dermatology and a toxicologist representing the Society of Toxicology. The CIR publishes detailed reviews of ingredients that can be easily found on PubMed and Google Scholar and closely reviews animal and human data and reports on safety and contact dermatitis risk.

Which clean beauty standard is best?

I reviewed most of the various standards, clean seals, laws, and safety reports and found significant discrepancies resulting from misunderstandings of the science, lack of depth in the scientific evaluations, lumping of ingredients into a larger category, or lack of data. The most salient cause of misinformation and confusion seems to be hyperbolic claims by the media and clean beauty advocates who do not understand the basic science.

When I conducted a survey of cosmetic chemists on my LinkedIn account, most of the chemists stated that “ ‘Clean Beauty’ is a marketing term, more than a scientific term.” None of the chemists could give an exact definition of clean beauty. However, I thought I needed a good answer for my patients and for doctors who want to use and recommend “clean skin care brands.”

A dermatologist’s approach to develop a clean beauty standard

Many of the standards combine all of the following into the “clean” designation: nontoxic to the environment (both the production process and the resulting ingredient), nontoxic to marine life and coral, cruelty-free (not tested on animals), hypoallergenic, lacking in known health risks (carcinogenicity, reproductive toxicity), vegan, and gluten free. As a dermatologist, I am a splitter more than a lumper, so I prefer that “clean” be split into categories to make it easier to understand. With that in mind, I will focus on clean beauty ingredients only as they pertain to health: carcinogenicity, endocrine effects, nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, etc. This discussion will not consider environmental effects, reproductive toxicity (some ingredients may decrease fertility, which is beyond the scope of this article), ingredient sources, and sustainability, animal testing, or human rights violations during production. Those issues are important, of course, but for clarity and simplicity, we will focus on the health risks of skin care ingredients.

In this month’s column, I will focus on a few ingredients and will continue the discussion in subsequent columns. Please note that commercial standards such as Target standards are based on the product type (e.g., cleansers, sunscreens, or moisturizers). So, when I mention an ingredient not allowed by certain company standards, note that it can vary by product type. My comments pertain mostly to facial moisturizers and facial serums to try and simplify the information. The Good Face Project has a complete list of standards by product type, which I recommend as a resource if you want more detailed information.

Are ethanolamines safe or toxic in cosmetics?

Ethanolamines are common ingredients in surfactants, fragrances, and emulsifying agents and include cocamide diethanolamine (DEA), cocamide monoethanolamine (MEA), and triethanolamine (TEA). Cocamide DEA, lauramide DEA, linoleamide DEA, and oleamide DEA are fatty acid diethanolamides that may contain 4% to 33% diethanolamine.1 A Google search of toxic ingredients in beauty products consistently identifies ethanolamines among such offending product constituents. Table 1 reveals that ethanolamines are excluded from some standards and included in others (N = not allowed or restricted by amount used and Y = allowed with no restrictions). As you can see, the standards don’t correspond to the EWG rating of the ingredients, which ranges from 1 (low hazard) to 10 (high hazard).

Why are ethanolamines sometimes considered safe and sometimes not?

Ethanolamines are reputed to be allergenic, but as we know as dermatologists, that does not mean that everyone will react to them. (In my opinion, allergenicity is a separate issue than the clean issue.) One study showed that TEA in 2.5% petrolatum had a 0.4% positive patch test rate in humans, which was thought to be related more to irritation than allergenicity.2 Cocamide DEA allergy is seen in those with hand dermatitis resulting from hand cleansers but is more commonly seen in metal workers.3 For this reason, these ethanolamines are usually found in rinse-off products to decrease exposure time. But there are many irritating ingredients not banned by Target, Sephora, and Ulta, so why does ethanolamine end up on toxic ingredient lists?

First, there is the issue of oral studies in animals. Oral forms of some ethanolamines have shown mild toxicity in rats, but topical forms have not been demonstrated to cause mutagenicity.1

For this reason, ethanolamines in their native form are considered safe.

The main issue with ethanolamines is that, when they are formulated with ingredients that break down into nitrogen, such as certain preservatives, the combination forms nitrosamines, such as N-nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA), which are carcinogenic.4 The European Commission prohibits DEA in cosmetics based on concerns about formation of these carcinogenic nitrosamines. Some standards limit ethanolamines to rinse-off products.5 The CIR panel concluded that diethanolamine and its 16 salts are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed and that TEA and TEA-related compounds are safe if they are not used in cosmetic products in which N-nitroso compounds can be formed.6,7 The FDA states that there is no reason for consumers to be alarmed based on the use of DEA in cosmetics.8

The safety issues surrounding the use of ethanolamines in a skin care routine illustrate an important point: Every single product in the skin care routine should be compatible with the other products in the regimen. Using ethanolamines in a rinse-off product is one solution, as is ensuring that no other products in the skin care routine contain N-nitroso compounds that can combine with ethanolamines to form nitrosamines.

Are natural products safer?

Natural products are not necessarily any safer than synthetic products. Considering ethanolamines as the example here, note that cocamide DEA is an ethanolamine derived from coconut. It is often found in “green” or “natural” skin care products.9 It can still combine with N-nitroso compounds to form carcinogenic nitrosamines.

What is the bottom line? Are ethanolamines safe in cosmetics?

For now, if a patient asks if ethanolamine is safe in skin care, my answer would be yes, so long as the following is true:

- It is in a rinse-off product.

- The patient is not allergic to it.

- They do not have hand dermatitis.

- Their skin care routine does not include nitrogen-containing compounds like N-nitrosodiethanolamine (NDELA) or NDEA.

Conclusion

This column uses ethanolamines as an example to show the disparity in clean standards in the cosmetic industry. As you can see, there are multiple factors to consider. I will begin including clean information in my cosmeceutical critique columns to address some of these issues.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann has written two textbooks and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers. Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Galderma, Revance, Evolus, and Burt’s Bees. She is the CEO of Skin Type Solutions Inc., a company that independently tests skin care products and makes recommendations to physicians on which skin care technologies are best. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Cocamide DE. J Am Coll Toxicol. 1986;5(5).

2. Lessmann H et al. Contact Dermatitis. 2009 May;60(5):243-55.

3. Aalto-Korte K et al. 2014 Mar;70(3):169-74.

4. Kraeling ME et al. Food Chem Toxicol. 2004 Oct;42(10):1553-61.

5. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2015 Sep;34(2 Suppl):84S-98S.

6. Fiume MM.. Int J Toxicol. 2017 Sep/Oct;36(5_suppl2):89S-110S.

7. Fiume MM et al. Int J Toxicol. 2013 May-Jun;32(3 Suppl):59S-83S.

8. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Diethanolamine. https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/cosmetic-ingredients/diethanolamine. Accessed Feb. 12, 2022.

9. Aryanti N et al. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2021 Feb 1 (Vol. 1053, No. 1, p. 012066). IOP Publishing.

FDA warns about off-label use of laparoscopic device for aesthetic procedures

The .

The device is cleared by the FDA for “general use of cutting, coagulation, and ablation of soft tissue during open and laparoscopic surgical procedures” but it “has not been determined to be safe or effective for any procedure intended to improve the appearance of the skin,” according to the March 14 statement from the FDA. The statement adds that the agency has received reports describing “serious and potentially life-threatening adverse events with use of this device for certain aesthetic procedures,” including some that have required treatment in an intensive care unit. The statement does not mention whether any cases were fatal.

Adverse events that have been reported include second- and third-degree burns, infections, changes in skin color, scars, nerve damage, “significant bleeding,” and “air or gas accumulation under the skin, in body cavities, and in blood vessels.”

Manufactured by Apyx medical, the device includes a hand piece and generator and uses radiofrequency energy and helium to generate plasma, which is used to “cut, coagulate ... and eliminate soft tissue with heat during surgery,” according to the FDA.

The FDA is advising health care providers not to use the device for dermal resurfacing or skin contraction “alone or in combination with liposuction.”

The statement also advises consumers who are considering an aesthetic skin treatment with this device to consult their health care providers regarding its use – and if they have any problems or are concerned after being treated with this device, to “seek care from a licensed health care provider.”

The FDA is working with Apyx to evaluate information about the use of the device for aesthetic skin procedures and to inform consumers and health care providers about the warning.

Health care providers and consumers should report problems or complications associated with the Renuvion/J-Plasma device to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The .

The device is cleared by the FDA for “general use of cutting, coagulation, and ablation of soft tissue during open and laparoscopic surgical procedures” but it “has not been determined to be safe or effective for any procedure intended to improve the appearance of the skin,” according to the March 14 statement from the FDA. The statement adds that the agency has received reports describing “serious and potentially life-threatening adverse events with use of this device for certain aesthetic procedures,” including some that have required treatment in an intensive care unit. The statement does not mention whether any cases were fatal.

Adverse events that have been reported include second- and third-degree burns, infections, changes in skin color, scars, nerve damage, “significant bleeding,” and “air or gas accumulation under the skin, in body cavities, and in blood vessels.”

Manufactured by Apyx medical, the device includes a hand piece and generator and uses radiofrequency energy and helium to generate plasma, which is used to “cut, coagulate ... and eliminate soft tissue with heat during surgery,” according to the FDA.

The FDA is advising health care providers not to use the device for dermal resurfacing or skin contraction “alone or in combination with liposuction.”

The statement also advises consumers who are considering an aesthetic skin treatment with this device to consult their health care providers regarding its use – and if they have any problems or are concerned after being treated with this device, to “seek care from a licensed health care provider.”

The FDA is working with Apyx to evaluate information about the use of the device for aesthetic skin procedures and to inform consumers and health care providers about the warning.

Health care providers and consumers should report problems or complications associated with the Renuvion/J-Plasma device to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The .

The device is cleared by the FDA for “general use of cutting, coagulation, and ablation of soft tissue during open and laparoscopic surgical procedures” but it “has not been determined to be safe or effective for any procedure intended to improve the appearance of the skin,” according to the March 14 statement from the FDA. The statement adds that the agency has received reports describing “serious and potentially life-threatening adverse events with use of this device for certain aesthetic procedures,” including some that have required treatment in an intensive care unit. The statement does not mention whether any cases were fatal.

Adverse events that have been reported include second- and third-degree burns, infections, changes in skin color, scars, nerve damage, “significant bleeding,” and “air or gas accumulation under the skin, in body cavities, and in blood vessels.”

Manufactured by Apyx medical, the device includes a hand piece and generator and uses radiofrequency energy and helium to generate plasma, which is used to “cut, coagulate ... and eliminate soft tissue with heat during surgery,” according to the FDA.

The FDA is advising health care providers not to use the device for dermal resurfacing or skin contraction “alone or in combination with liposuction.”

The statement also advises consumers who are considering an aesthetic skin treatment with this device to consult their health care providers regarding its use – and if they have any problems or are concerned after being treated with this device, to “seek care from a licensed health care provider.”

The FDA is working with Apyx to evaluate information about the use of the device for aesthetic skin procedures and to inform consumers and health care providers about the warning.

Health care providers and consumers should report problems or complications associated with the Renuvion/J-Plasma device to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mandelic acid

Acids peels are used to elicit a chemical exfoliation of the skin by hydrolyzing amide bonds between keratinocytes, reducing corneocyte adhesion, as well as inducing an inflammatory reaction stimulating tissue remodeling. Release of cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 by keratinocytes activates fibroblasts to increase the production of matrix metalloproteinases. These are involved in the production of hyaluronic acid and new collagen formation.

Mandelic acid was derived from bitter almonds (mandel is the German word for almond). It is a white powder originally used as an antibiotic for the treatment of urinary tract infections. Its antibacterial properties make it an excellent product for the topical treatment of acne, as well as for use in topical preparations to treat hyperpigmentation and photoaging. In cosmetic use, mandelic acid is a slow acting chemical peel that can be used in all skin types, including sensitive and rosacea-prone skin, as well as skin of color. Its large molecular size allows for the slow penetration of the acid on the skin and thus it can be carefully titrated.

Studies have shown its efficacy in reducing sebum content, acne, acne scarring, and hyperpigmentation. In clinical practice however, the most effective use of this acid is on sensitive skin. It is a great tool for clinicians to use as an effective exfoliant in less acid tolerant skin types. In commercially available concentrations of 5%-45%, mandelic acid can be used alone or in combination with other beta hydroxy peels, depending on the indication.

Most dermatologists and patients prefer in-office peels that induce noticeable peeling and resurfacing of the skin. Mandelic acid is one of the largest alpha hydroxy acids, a lipophilic acid that penetrates the skin slowly and uniformly, making it an ideal peel in sensitive or aging and thin skin types. Although many mandelic acid peels are available, however, there is a paucity of studies comparing their benefits and efficacies.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan O. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Wójcik A et al. Dermatol Alergol. 2013 Jun;30(3):140-5.

2. Soleymani T et al. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(8):21-8.

Acids peels are used to elicit a chemical exfoliation of the skin by hydrolyzing amide bonds between keratinocytes, reducing corneocyte adhesion, as well as inducing an inflammatory reaction stimulating tissue remodeling. Release of cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 by keratinocytes activates fibroblasts to increase the production of matrix metalloproteinases. These are involved in the production of hyaluronic acid and new collagen formation.

Mandelic acid was derived from bitter almonds (mandel is the German word for almond). It is a white powder originally used as an antibiotic for the treatment of urinary tract infections. Its antibacterial properties make it an excellent product for the topical treatment of acne, as well as for use in topical preparations to treat hyperpigmentation and photoaging. In cosmetic use, mandelic acid is a slow acting chemical peel that can be used in all skin types, including sensitive and rosacea-prone skin, as well as skin of color. Its large molecular size allows for the slow penetration of the acid on the skin and thus it can be carefully titrated.

Studies have shown its efficacy in reducing sebum content, acne, acne scarring, and hyperpigmentation. In clinical practice however, the most effective use of this acid is on sensitive skin. It is a great tool for clinicians to use as an effective exfoliant in less acid tolerant skin types. In commercially available concentrations of 5%-45%, mandelic acid can be used alone or in combination with other beta hydroxy peels, depending on the indication.

Most dermatologists and patients prefer in-office peels that induce noticeable peeling and resurfacing of the skin. Mandelic acid is one of the largest alpha hydroxy acids, a lipophilic acid that penetrates the skin slowly and uniformly, making it an ideal peel in sensitive or aging and thin skin types. Although many mandelic acid peels are available, however, there is a paucity of studies comparing their benefits and efficacies.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan O. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Wójcik A et al. Dermatol Alergol. 2013 Jun;30(3):140-5.

2. Soleymani T et al. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(8):21-8.

Acids peels are used to elicit a chemical exfoliation of the skin by hydrolyzing amide bonds between keratinocytes, reducing corneocyte adhesion, as well as inducing an inflammatory reaction stimulating tissue remodeling. Release of cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1 and IL-6 by keratinocytes activates fibroblasts to increase the production of matrix metalloproteinases. These are involved in the production of hyaluronic acid and new collagen formation.

Mandelic acid was derived from bitter almonds (mandel is the German word for almond). It is a white powder originally used as an antibiotic for the treatment of urinary tract infections. Its antibacterial properties make it an excellent product for the topical treatment of acne, as well as for use in topical preparations to treat hyperpigmentation and photoaging. In cosmetic use, mandelic acid is a slow acting chemical peel that can be used in all skin types, including sensitive and rosacea-prone skin, as well as skin of color. Its large molecular size allows for the slow penetration of the acid on the skin and thus it can be carefully titrated.

Studies have shown its efficacy in reducing sebum content, acne, acne scarring, and hyperpigmentation. In clinical practice however, the most effective use of this acid is on sensitive skin. It is a great tool for clinicians to use as an effective exfoliant in less acid tolerant skin types. In commercially available concentrations of 5%-45%, mandelic acid can be used alone or in combination with other beta hydroxy peels, depending on the indication.

Most dermatologists and patients prefer in-office peels that induce noticeable peeling and resurfacing of the skin. Mandelic acid is one of the largest alpha hydroxy acids, a lipophilic acid that penetrates the skin slowly and uniformly, making it an ideal peel in sensitive or aging and thin skin types. Although many mandelic acid peels are available, however, there is a paucity of studies comparing their benefits and efficacies.

Dr. Lily Talakoub and Dr. Naissan O. Wesley are cocontributors to this column. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub. Write to them at dermnews@mdedge.com. They had no relevant disclosures.

References

1. Wójcik A et al. Dermatol Alergol. 2013 Jun;30(3):140-5.

2. Soleymani T et al. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11(8):21-8.

The gap in cosmeceuticals education

Starting this month, I will be joining Dr. Leslie S. Baumann as a cocontributor to the Cosmeceutical Critique column, and since this is my first column, I would like to formally introduce myself. I am a cosmetic and general dermatologist in private practice in Miami and a longtime skin care enthusiast. My path toward becoming a dermatologist began when I was working in New York City, my hometown, as a scientific researcher, fulfilling my passion for scientific inquiry. After realizing that I most enjoyed applying discoveries made in the lab directly to patient care, I decided to pursue medical school at New York University before completing a dermatology residency at the University of Miami, serving as Chief Resident during my final year. Although I was born and raised in New York, staying in Miami was an obvious decision for me. In addition to the tropical weather and amazing lifestyle, the medical community in Miami supports adventure, creativity, and innovation, which are key aspects that drew me to the University of Miami and continue to drive my personal evolution in private practice.

I now practice at Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute alongside my mentor, Dr. Baumann. I truly have my dream job – I get to talk skin care and do a wide array of cosmetics procedures, perform skin surgeries, and solve complex medical dermatology cases all in a day’s work. My career sits at the intersection of my passions for science, critical thinking, beauty, aesthetics, and most importantly, engaging with patients.

For my first column, I want to , and I will provide a simple framework to approach the design of skin care regimens and utilization of cosmeceuticals in practice.

The focus of a dermatology residency is on medical and surgical skills. We become experts in diagnosing and treating conditions ranging from life-threatening drug reactions like Stevens-Johnson Syndrome to complex diseases like dermatomyositis, utilizing medications and treatments ranging from cyclosporine and methotrexate to biologics and intravenous immunoglobulin, and performing advanced skin surgeries utilizing flaps and grafts to repair defects.

The discipline of cosmetic dermatology, let alone cosmeceuticals, accounts for a fraction of our didactic and hands-on training. I completed a top dermatology residency program that prepared me to treat any dermatologic condition; however, I honestly felt like I didn’t have a strong understanding of cosmeceuticals and skin care and how to integrate them with prescription therapies when I completed residency, which is a sentiment shared by residents across the country. I remember a study break while preparing for my final board exam when I went into a tailspin for an entire day trying to decode an ingredient list of a new “antiaging serum” and researching its mechanisms of action and the clinical data supporting the active ingredients in the serum, which included bakuchiol and a blend of peptides. As a dermatologist who likes to treat and provide recommendations based on scientific rationale and data to deliver the highest level of care, I admit that I felt insecure not being as knowledgeable about cosmeceuticals as I was about more complex dermatology treatments. As both a cosmetic and general dermatologist, discussing skin care and cosmeceuticals independent of or in conjunction with medical management occurs daily, and I recognized that becoming an expert in this area is essential to becoming a top, well-rounded dermatologist.

A gap in cosmeceutical education in dermatology residency

Multiple studies have established that the field of cosmetic dermatology comprises a fraction of dermatology residency training. In 2013, Kirby et al. published a survey of dermatology instructors and chief residents across the country and found that only 67% of responders reported having received formal lectures on cosmetic dermatology.1 In 2014, Bauer et al. published a survey of dermatology program directors assessing attitudes toward cosmetic dermatology and reported that only 38% of program directors believed that cosmetic dermatology should be a necessary aspect of residency training.2 A survey sent to dermatology residents published in 2012 found that among respondents, more than 58% of residency programs have an “encouraging or somewhat encouraging” attitude toward teaching cosmetic dermatology, yet 22% of programs had a “somewhat discouraging” or “discouraging” attitude.3 While these noted studies have focused on procedural aspects of cosmetic dermatology training, Feetham et al. surveyed dermatology residents and faculty to assess attitudes toward and training on skin care and cosmeceuticals specifically. Among resident respondents, most (74.5%) reported their education on skin care and cosmeceuticals has been “too little or nonexistent” during residency and 76.5% “agree or strongly agree” that it should be part of their education.4 In contrast, 60% of faculty reported resident education on skin care and cosmeceuticals is “just the right amount or too much” (P < .001).

In my personal experience as a resident, discussing skin care was emphasized when treating patients with eczema, contact dermatitis, acne, and hair disorders, but otherwise, the majority of skin care discussions relied on having a stock list of recommended cleansers, moisturizers, and sunscreens. In regards to cosmeceuticals for facial skin specifically, there were only a handful of instances in which alternative ingredients, such as vitamin C for hyperpigmentation, were discussed and specific brands were mentioned. Upon reflection, I wish I had more opportunity to see the clinical benefits of cosmeceuticals first hand, just like when I observe dupilumab clear patients with severe atopic dermatitis, rather than reading about it in textbooks and journals.

While one hypothesis for programs’ limited attention given to cosmetic training may be that it detracts from medical training, the survey by Bauer et al. found that residents did not feel less prepared (94.9%) or less interested (97.4%) in medical dermatology as a result of their cosmetic training.2 In addition, providers in an academic dermatology residency may limit discussions of skin care because of the high patient volume and because extensive skin care discussions will not impact insurance billings. Academic dermatology programs often service patients with more financial constraints, which further limits OTC cosmeceutical discussions. In my residency experience, I had the opportunity to regularly treat more severe and rare dermatologic cases than those I encounter in private practice; therefore, I spent more time focusing on systemic therapies, with fewer opportunities to dedicate time to cosmeceuticals.

Why skin care and cosmeceuticals should be an essential aspect of residency training

Discussing skin care and cosmeceuticals is a valuable aspect of medical and general dermatology, not just aesthetic dermatology. When treating general dermatologic conditions, guidance on proper skin care can improve both adherence and efficacy of medical treatments. For example, an acne study by de Lucas et al. demonstrated that adherence to adjuvant treatment of acne (such as the use of moisturizers) was associated not only with a 2.4-fold increase in the probability of adherence to pharmacological treatment, but also with a significant reduction in acne severity.5 Aside from skin care, cosmeceuticals themselves have efficacy in treating general dermatologic conditions. In the treatment of acne, topical niacinamide, a popular cosmeceutical ingredient, has been shown to have sebosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects, addressing key aspects of acne pathogenesis.6 A double-blind study by Draelos et al. reported topical 2% niacinamide was effective in reducing the rate of sebum excretion in 50 Japanese patients over 4 weeks.6 In several double-blind studies that have compared twice daily application of 4% nicotinamide gel with the same application of 1% clindamycin gel in moderate inflammatory acne over 8 weeks, nicotinamide gel reduced the number of inflammatory papules and acne lesions to a level comparable with clindamycin gel.6 These studies support the use of niacinamide cosmeceutical products as an adjunctive treatment for acne.

With increased clinical data supporting cosmeceuticals, it can be expected that some cosmeceuticals will substitute traditional prescription medications in the dermatologists’ arsenal. For example, hydroquinone – both prescription strength and OTC 2% – is a workhorse in treating melasma; however, there is increasing interest in hydroquinone-free treatments, especially since OTC cosmeceuticals containing 2% hydroquinone were banned in 2020 because of safety concerns. Dermatologists will therefore need to provide guidance about hydroquinone alternatives for skin lightening, including soy, licorice extracts, kojic acid, arbutin, niacinamide, N-acetylglucosamine, and vitamin C, among others.7 Utilizing knowledge of a cosmeceutical’s mechanisms of action and clinical data, the dermatologist is in the best position to guide patients toward optimal ingredients and dispel cosmeceutical myths. Given that cosmeceuticals are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, it is even more important that the dermatologist serves as an authority on cosmeceuticals.

How to become a master skin care and cosmeceutical prescriber

A common pitfall I have observed among practitioners less experienced with aesthetic-focused skin care and cosmeceuticals is adapting a one-size-fits-all approach. In the one-size-fits-all approach, every patient concerned about aging gets the same vitamin C serum and retinoid, and every patient with hyperpigmentation gets the same hydroquinone prescription, for example. This approach, however, does not take into account unique differences in patients’ skin. Below

is the basic skin care framework that I follow, taught to me by Dr. Baumann. It utilizes an individualized approach based on the patient’s skin qualities to achieve optimal results.

Determine the patient’s skin type (dry vs. oily; sensitive vs. not sensitive; pigmentation issues vs. no hyperpigmentation; wrinkled and mature vs. nonwrinkled) and identify concerns (e.g., dark spots, redness, acne, dehydration).

Separate products into categories of cleansers, eye creams, moisturizers, sun protection, and treatments. Treatments refers to any additional products in a skin care regimen intended to ameliorate a particular condition (e.g., vitamin C for hyperpigmentation, retinoids for fine lines).

Choose products for each category in step 2 (cleansers, eye creams, moisturizers, sun protection, treatments) that are complementary to the patient’s skin type (determined in step 1) and aid the patient in meeting their particular skin goals. For example, a salicylic acid cleanser would be beneficial for a patient with oily skin and acne, but this same cleanser may be too drying and irritating for an acne patient with dry skin.

Ensure that chosen ingredients and products work together harmoniously. For example, while the acne patient may benefit from a salicylic acid cleanser and retinoid cream, using them in succession initially may be overly drying for some patients.

Spend the time to make sure patients understand the appropriate order of application and recognize when efficacy of a product is impacted by another product in the regimen. For example, a low pH cleanser can increase penetration of an ascorbic acid product that follows it in the regimen.

After establishing a basic skin care framework, the next step for beginners is learning about ingredients and their mechanisms of action and familiarizing themselves with scientific and clinical studies. Until cosmeceuticals become an integral part of the training curriculum, dermatologists can gain knowledge independently by reading literature and studies on cosmeceutical active ingredients and experimenting with consumer products. I look forward to regularly contributing to this column to further our awareness and understanding of the mechanisms of and data supporting cosmeceuticals so that we can better guide our patients.

Please feel free to email me at chloe@derm.net or message me on Instagram @DrChloeGoldman with ideas that you would like me to address in this column.

Dr. Goldman is a dermatologist in private practice in Miami, and specializes in cosmetic and general dermatology. She practices at Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute and is also opening a new general dermatology practice. Dr. Goldman receives compensation to create social media content for Replenix, a skin care company. She has no other relevant disclosures.

References

1. Kirby JS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(2):e23-8.

2. Bauer et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(2):125-9.

3. Group A et al. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(12):1975-80.

4. Feetham HJ et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17(2):220-6.

5. de Lucas R et al. BMC Dermatol. 2015;15:17.

6. Araviiskaia E and Dreno BJ. Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30(6):926-35.

7. Leyden JJ et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(10):1140-5.

Starting this month, I will be joining Dr. Leslie S. Baumann as a cocontributor to the Cosmeceutical Critique column, and since this is my first column, I would like to formally introduce myself. I am a cosmetic and general dermatologist in private practice in Miami and a longtime skin care enthusiast. My path toward becoming a dermatologist began when I was working in New York City, my hometown, as a scientific researcher, fulfilling my passion for scientific inquiry. After realizing that I most enjoyed applying discoveries made in the lab directly to patient care, I decided to pursue medical school at New York University before completing a dermatology residency at the University of Miami, serving as Chief Resident during my final year. Although I was born and raised in New York, staying in Miami was an obvious decision for me. In addition to the tropical weather and amazing lifestyle, the medical community in Miami supports adventure, creativity, and innovation, which are key aspects that drew me to the University of Miami and continue to drive my personal evolution in private practice.

I now practice at Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute alongside my mentor, Dr. Baumann. I truly have my dream job – I get to talk skin care and do a wide array of cosmetics procedures, perform skin surgeries, and solve complex medical dermatology cases all in a day’s work. My career sits at the intersection of my passions for science, critical thinking, beauty, aesthetics, and most importantly, engaging with patients.

For my first column, I want to , and I will provide a simple framework to approach the design of skin care regimens and utilization of cosmeceuticals in practice.

The focus of a dermatology residency is on medical and surgical skills. We become experts in diagnosing and treating conditions ranging from life-threatening drug reactions like Stevens-Johnson Syndrome to complex diseases like dermatomyositis, utilizing medications and treatments ranging from cyclosporine and methotrexate to biologics and intravenous immunoglobulin, and performing advanced skin surgeries utilizing flaps and grafts to repair defects.

The discipline of cosmetic dermatology, let alone cosmeceuticals, accounts for a fraction of our didactic and hands-on training. I completed a top dermatology residency program that prepared me to treat any dermatologic condition; however, I honestly felt like I didn’t have a strong understanding of cosmeceuticals and skin care and how to integrate them with prescription therapies when I completed residency, which is a sentiment shared by residents across the country. I remember a study break while preparing for my final board exam when I went into a tailspin for an entire day trying to decode an ingredient list of a new “antiaging serum” and researching its mechanisms of action and the clinical data supporting the active ingredients in the serum, which included bakuchiol and a blend of peptides. As a dermatologist who likes to treat and provide recommendations based on scientific rationale and data to deliver the highest level of care, I admit that I felt insecure not being as knowledgeable about cosmeceuticals as I was about more complex dermatology treatments. As both a cosmetic and general dermatologist, discussing skin care and cosmeceuticals independent of or in conjunction with medical management occurs daily, and I recognized that becoming an expert in this area is essential to becoming a top, well-rounded dermatologist.

A gap in cosmeceutical education in dermatology residency

Multiple studies have established that the field of cosmetic dermatology comprises a fraction of dermatology residency training. In 2013, Kirby et al. published a survey of dermatology instructors and chief residents across the country and found that only 67% of responders reported having received formal lectures on cosmetic dermatology.1 In 2014, Bauer et al. published a survey of dermatology program directors assessing attitudes toward cosmetic dermatology and reported that only 38% of program directors believed that cosmetic dermatology should be a necessary aspect of residency training.2 A survey sent to dermatology residents published in 2012 found that among respondents, more than 58% of residency programs have an “encouraging or somewhat encouraging” attitude toward teaching cosmetic dermatology, yet 22% of programs had a “somewhat discouraging” or “discouraging” attitude.3 While these noted studies have focused on procedural aspects of cosmetic dermatology training, Feetham et al. surveyed dermatology residents and faculty to assess attitudes toward and training on skin care and cosmeceuticals specifically. Among resident respondents, most (74.5%) reported their education on skin care and cosmeceuticals has been “too little or nonexistent” during residency and 76.5% “agree or strongly agree” that it should be part of their education.4 In contrast, 60% of faculty reported resident education on skin care and cosmeceuticals is “just the right amount or too much” (P < .001).

In my personal experience as a resident, discussing skin care was emphasized when treating patients with eczema, contact dermatitis, acne, and hair disorders, but otherwise, the majority of skin care discussions relied on having a stock list of recommended cleansers, moisturizers, and sunscreens. In regards to cosmeceuticals for facial skin specifically, there were only a handful of instances in which alternative ingredients, such as vitamin C for hyperpigmentation, were discussed and specific brands were mentioned. Upon reflection, I wish I had more opportunity to see the clinical benefits of cosmeceuticals first hand, just like when I observe dupilumab clear patients with severe atopic dermatitis, rather than reading about it in textbooks and journals.