User login

Importance of Recognizing Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in the Preoperative Clinic

Importance of Recognizing Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in the Preoperative Clinic

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a relatively common inherited condition characterized by abnormal asymmetric left ventricular (LV) thickening. This can lead to LV outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction, which has important implications for anesthesia management. This article describes a case of previously undiagnosed HCM discovered during a preoperative physical examination prior to a routine surveillance colonoscopy.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 55-year-old Army veteran with a history of a sessile serrated colon adenoma presented to the preadmission testing clinic prior to planned surveillance colonoscopy under monitored anesthesia care. His medical history included untreated severe obstructive sleep apnea (53 apnea-hypopnea index score), diet-controlled hypertension, prediabetes (6.3% hemoglobin A1c), hypogonadism, and obesity (41 body mass index). Medications included semaglutide 1.7 mg injected subcutaneously weekly and testosterone 200 mg injected intramuscularly every 2 weeks, as well as lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide 10 to 12.5 mg daily, which had recently been discontinued because his blood pressure had improved with a low-sodium diet.

A review of systems was unremarkable except for progressive weight gain. The patient had no family history of sudden cardiac death. On physical examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 119/81 mm Hg, pulse was 86 beats/min, and respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min. The patient was clinically euvolemic, with no jugular venous distention or peripheral edema, and his lungs were clear to auscultation. There was, however, a soft, nonradiating grade 2/6 systolic murmur that had not been previously documented. The murmur decreased substantially with the Valsalva maneuver, with no change in hand grip.

Laboratory studies revealed hemoglobin and renal function were within the reference range. A routine 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was unremarkable. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed moderate pulmonary hypertension (59 mm Hg right ventricular systolic pressure), asymmetric LV hypertrophy (2.1 cm septal thickness), and severe LVOT obstruction (131.8 mm Hg gradient). Severe systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve was also present. The LV ejection fraction was 60% to 65%, with normal cavity size and systolic function. These findings were consistent with severe hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). Upon more detailed questioning, the patient reported that over the previous 5 years he had experienced gradually decreasing exercise tolerance and mild dyspnea on exertion, particularly in hot weather, which he attributed to weight gain. He also reported a presyncopal episode the previous month while working in his garage in hot weather for a prolonged period of time.

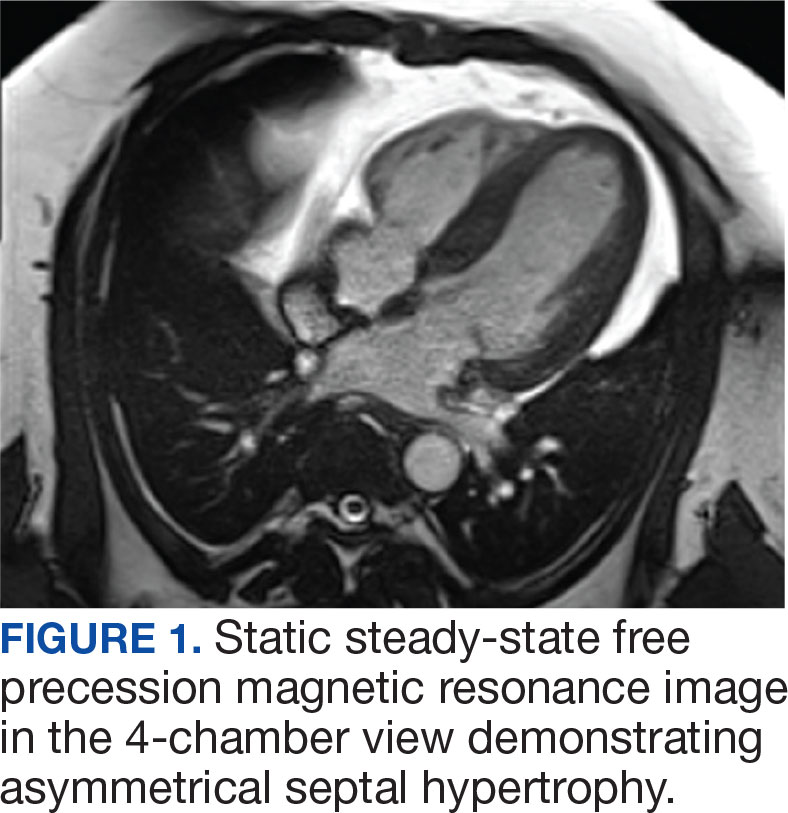

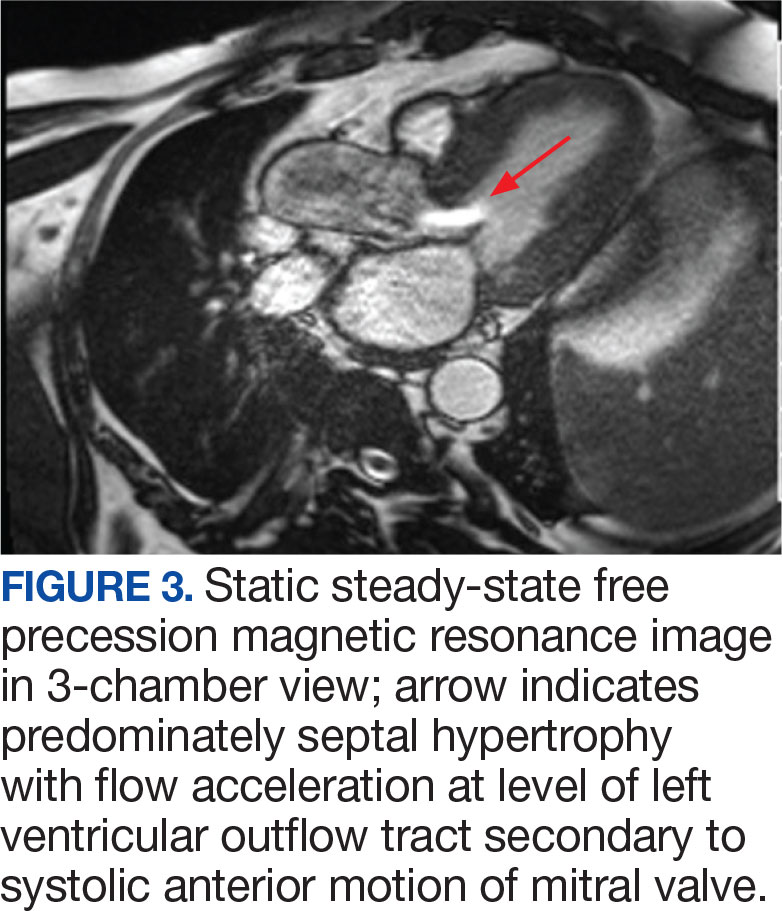

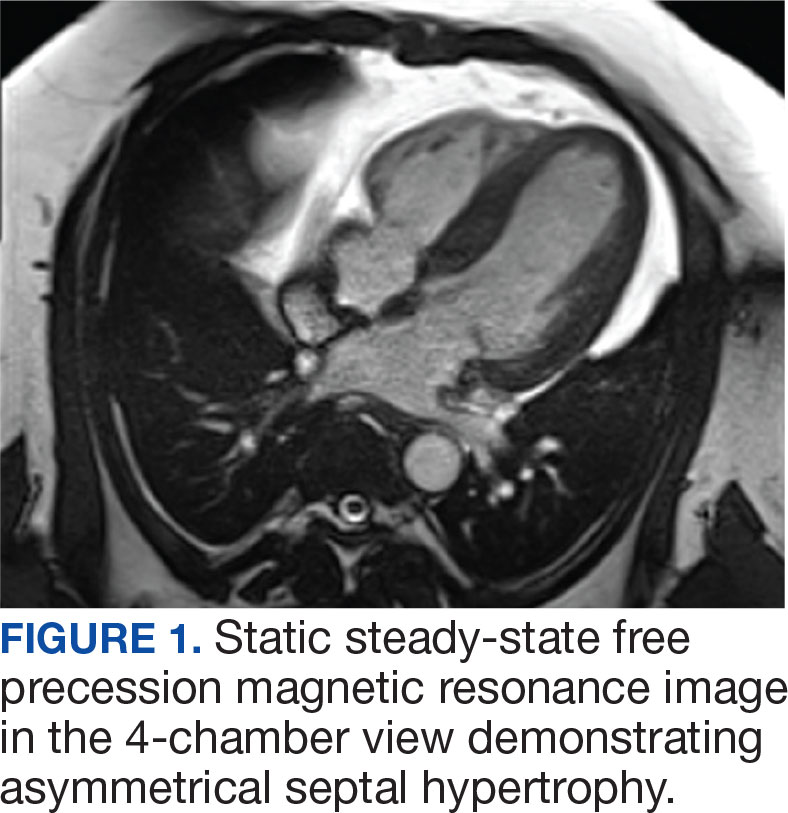

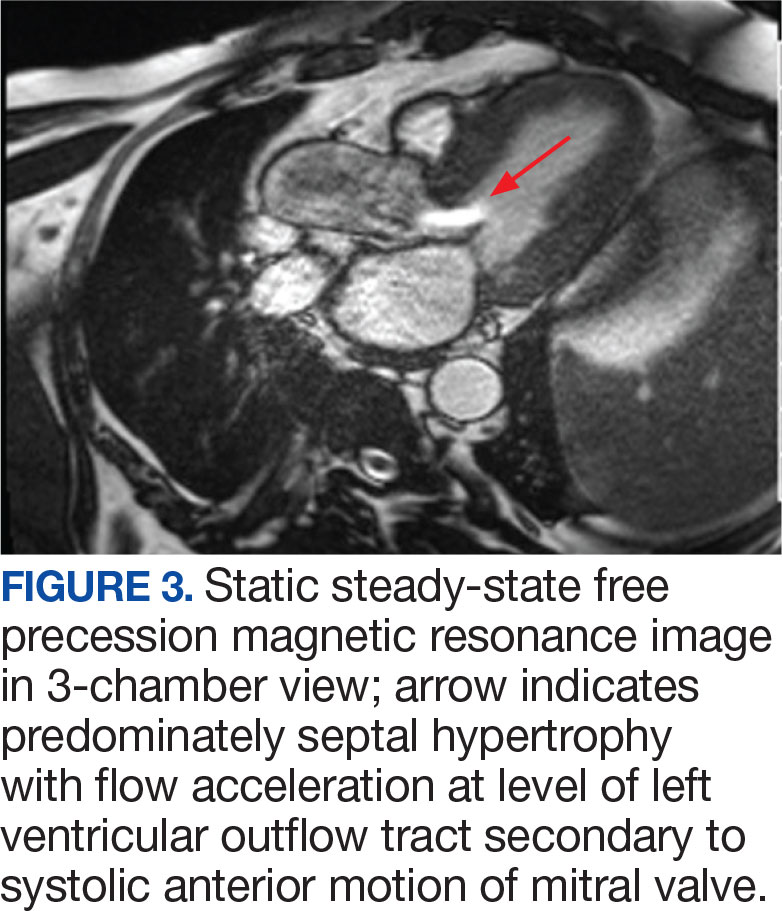

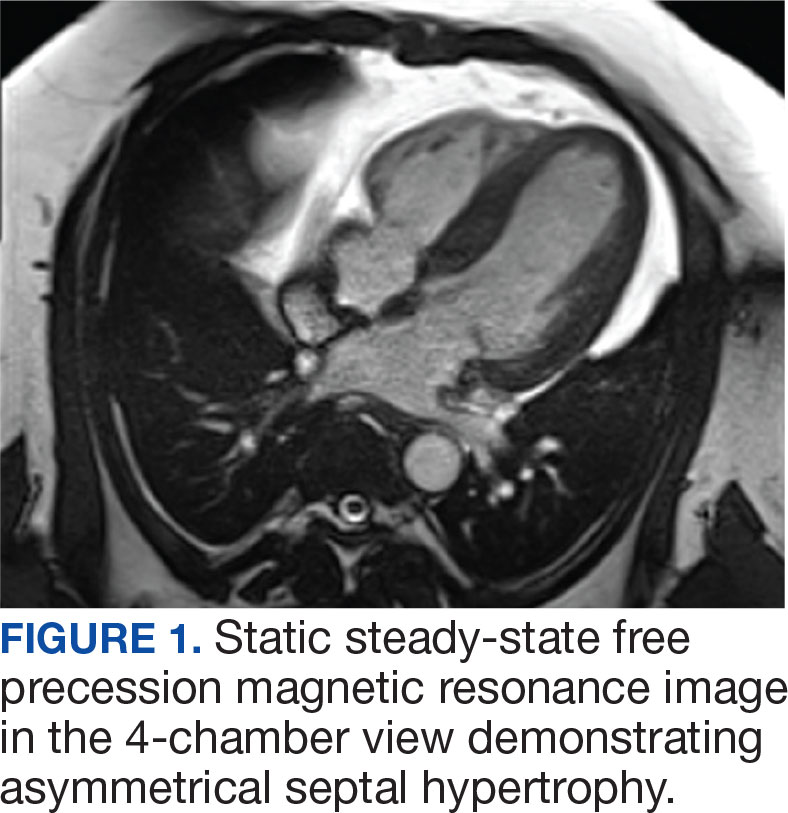

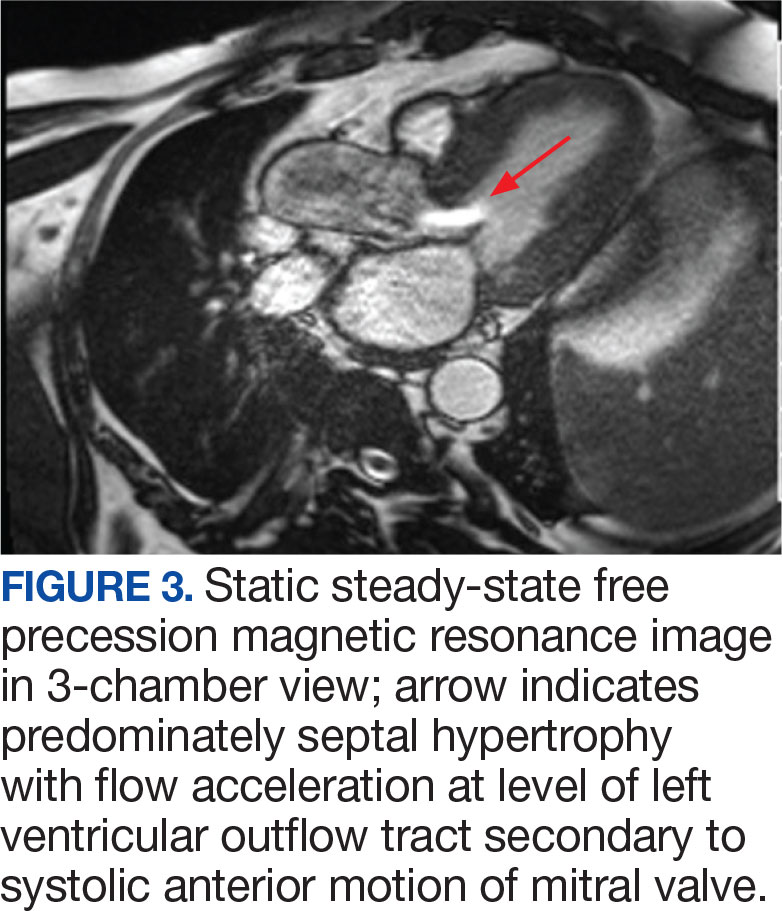

The patient’s elective colonoscopy was canceled, and he was referred to cardiology. While awaiting cardiac consultation, he was instructed to maintain good hydration and avoid any heavy physical activity beyond walking. He was told not to resume his use of lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide. A screening 7-day Holter monitor showed no ventricular or supraventricular ectopy. After cardiology consultation, the patient was referred to a HCM specialty clinic, where a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging confirmed severe asymmetric hypertrophy with resting obstruction (Figures 1-4). Treatment options were discussed with the patient, and he underwent a trial with the Β—blocker metoprolol 50 mg daily, which he could not tolerate. Verapamil extended-release 180 mg orally once daily was then initiated; however, his dyspnea persisted. He was amenable to surgical therapy and underwent septal myectomy, with 12 g of septal myocardium removed. He did well postoperatively, with a follow-up echocardiogram showing normal LV systolic function and no LVOT gradient detectable at rest or with Valsalva maneuver. His fatigue and exertional dyspnea significantly improved. Once the patient underwent septal myectomy and was determined to have no detectable LVOT gradient, he was approved for colonoscopy which has been scheduled but not completed.

DISCUSSION

Once thought rare, HCM is now considered to be a relatively common inherited disorder, occurring in about 1 in 500 persons, with some suggesting that the actual prevalence is closer to 1 in 200 persons.1,2 Most often caused by mutations in ≥ 1 of 11 genes responsible for encoding cardiac sarcomere proteins, HCM is characterized by abnormal LV thickening without chamber enlargement in the absence of any identifiable cause, such as aortic valve stenosis or uncontrolled hypertension. The hypertrophy is often asymmetric, and in cases of asymmetric septal hypertrophy, dynamic LVOT obstruction can occur (known as HOCM). The condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with variable expression and is associated with myocardial fiber disarray, which can occur years before symptom onset.3 This myocardial disarray can lead to remodeling and an increased wall-to-lumen ratio of the coronary arteries, resulting in impaired coronary reserve.

Depending on the degree of LVOT obstruction, patients with HCM may be classified as nonobstructive, labile, or obstructive at rest. Patients without obstruction have an outflow gradient ≤ 30 mm Hg that is not provoked with Valsalva maneuver, administration of amyl nitrite, or exercise treadmill testing.3 Patients classified as labile do not have LVOT obstruction at rest, but obstruction may be induced by provocative measures. Finally, about one-third of patients with HCM will have LVOT gradients of > 30 mm Hg at rest. These patients are at increased risk for progression to symptomatic heart failure and may be candidates for surgical myectomy or catheter-based alcohol septal ablation.4 The patient in this case had a resting LVOT gradient of 131.8 mm Hg on echocardiography. The magnitude of this gradient placed the patient at a significantly higher risk of ventricular dysrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.5

Wall thickness also has prognostic implications. 6 Although any area of the myocardium can be affected, the septum is involved in about 90% cases. In their series of 48 patients followed over 6.5 years, Spirito et al found that the risk of sudden death in patients with HCM increased as wall thickness increased. For patients with a wall thickness of < 15 mm, the risk of death was 0 per 1000 person-years; however, this increased to 18.2 per 1000 person-years for patients with a wall thickness of > 30 mm.7

While many patients with HCM are asymptomatic, others may report dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, presyncope/ syncope, postural lightheadedness, fatigue, or edema. Symptomatology, however, is quite variable and does not necessarily correlate with the degree of outflow obstruction. Surprisingly, some patients with significant LVOT may have minimal symptoms, such as the patient in this case, while others with a lesser degree of LVOT obstruction may be very symptomatic.3,4

Physical examination of a patient with HCM may be normal or may reveal nonspecific findings such as a fourth heart sound or a systolic murmur. In general, physical examination abnormalities are related to LVOT obstruction. Those patients without significant outflow obstruction may have a normal cardiac examination. While patients with HCM may have a variety of systolic murmurs, the 2 most common are those related to outflow tract obstruction and mitral regurgitation caused by systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve.4 The systolic murmur associated with significant LVOT obstruction has been described as a harsh, crescendo-decrescendo type that begins just after S1 and is heard best at the apex and lower left sternal border.4 It may radiate to the axilla and base but not generally into the neck. The murmur usually increases with Valsalva maneuver and decreases with handgrip or going from a standing to a sitting/ squatting position. The initial examination of the patient in this case was not suggestive of HOCM, as confirmed by 2 practitioners (a cardiologist and an internist), each with > 30 years of clinical experience. This may have been related to the patient’s hydration status at the time, with Valsalva maneuver increasing obstruction to the point of reduced flow.

About 90% of patients with HCM will have abnormalities on ECG, most commonly LV hypertrophy with a strain pattern. Other ECG findings include: (1) prominent abnormal Q waves, particularly in the inferior (II, III, and aVF) and lateral leads (I, aVL, and V4-V6), reflecting depolarization of a hypertrophied septum; (2) left axis deviation; (3) deeply inverted T waves in leads V2 through V4; and (4) P wave abnormalities indicative of left atrial (LA) or biatrial enlargement. 8 It is notable that the patient in this case had a normal ECG, given that a minority of patients with HCM have been shown to have a normal ECG.9

Echocardiography plays an important role in diagnosing HCM. Diagnostic criteria include the presence of asymmetric hypertrophy (most commonly with anterior septal involvement), systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve, a nondilated LV cavity, septal immobility, and premature closure of the aortic valve. LV thickness is measured at both the septum and free wall; values ≥ 15 mm, with a septal-to-free wall thickness ratio of ≥ 1.3, are suggestive of HCM. Asymmetric LV hypertrophy can also be seen in other segments besides the septum, such as the apex.10

HCM/HOCM is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in young people. The condition also contributes to significant functional morbidity due to heart failure and increases the risk of atrial fibrillation and subsequent stroke. Treatments tend to focus on symptom relief and slowing disease progression and include the use of medications such as Β—blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and the myosin inhibitor mavacamten.11 Select patients, such as those with severe LVOT obstruction and symptoms despite treatment with Β—blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, may be offered septal myectomy or catheter-based alcohol septal ablation, coupled with insertion of an implantable cardiac defibrillator to prevent sudden cardiac death in patients at high arrhythmic risk.1,12

Patients with HCM, particularly those with LVOT obstruction, pose distinct challenges to the anesthesiologist because they are highly sensitive to decreases in preload and afterload. These patients frequently experience adverse perioperative events such as myocardial ischemia, systemic hypotension, and supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmias. Acute congestive heart failure may also occur, presumably due to concomitant diastolic dysfunction. Patients with previously unrecognized HCM are of particular concern, as they may manifest unexpected and sudden hypotension with the induction of anesthesia. There may then be a paradoxical response to vasoactive drugs and anesthetic agents, which accentuate LVOT obstruction. In these circumstances, undiagnosed HCM should be considered, and intraoperative rescue transesophageal echocardiography be performed.13 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, efforts should be made to reduce myocardial contractility and sympathetic discharge (eg, with Β—blockers), increase afterload (eg, with α1 agonists), and improve preload with adequate hydration. Proper resuscitation of hypotensive patients with HCM requires a thorough understanding of disease pathology, as effective interventions may seem to be counterintuitive. Inotropic agents such as epinephrine are contraindicated in HCM because increased inotropy and chronotropy worsen LVOT obstruction. Volume status is often tenuous; while adequate preload is important, overly aggressive fluid resuscitation may promote heart failure. It is important to keep in mind that even patients without resting LVOT obstruction may develop dynamic obstruction with anesthesia induction due to sudden reductions in preload and afterload. It is also important to note that the degree of LV hypertrophy is directly correlated with arrhythmic sudden death. Those patients with LV wall thickness ≥ 30 mm are at increased risk for potentially lethal tachyarrhythmias in the operating room.14

These considerations reinforce the need for proper preoperative identification of patients with HCM. Heightened awareness is key, given the fact that HCM is relatively common and tends to be underdiagnosed in the general population. These patients are generally young, otherwise healthy, and often undergo minor operative procedures in outpatient settings. It is incumbent upon the preoperative evaluator to take a thorough medical history and perform a careful physical examination. Clues to the diagnosis include exertional dyspnea, fatigue, angina, syncope/presyncope, or a family history of sudden cardiac death or HCM. A systolic ejection murmur, particularly one that increases with standing or Valsalva maneuver, and decreases with squatting or handgrip may also raise clinical suspicion. These patients should undergo a full cardiac evaluation, including echocardiography.

CONCLUSIONS

HCM is a common condition that is important to diagnose in the preoperative clinic. Failure to do so can lead to catastrophic complications during induction of anesthesia due to the sudden reduction in preload and afterload, which may cause a significant increase in LVOT obstruction. A high index of suspicion is essential, as clinical diagnosis can be challenging. The physical examination may be deceiving and symptoms are often subtle and nonspecific. It is imperative to alert the anesthesiologist before surgery so the complex hemodynamic management of patients with HOCM can be appropriately managed.

- Cheng Z, Fang T, Huang J, Guo Y, Alam M, Qian H. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: from phenotype and pathogenesis to treatment. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:722340. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.722340

- Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(12):1249-1254. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019

- Hensley N, Dietrich J, Nyhan D, Mitter N, Yee MS, Brady M. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a review. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(3):554-569. doi:10.1213/ ANE.0000000000000538

- Maron BJ, Desai MY, Nishimura RA, et al. Diagnosis and evaluation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(4):372–389. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.002

- Jorda P, Garcia-Alvarez A. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: sudden cardiac death risk stratification in adults. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2018;3(25). doi:10.21542/gcsp.2018.25

- Wigle ED, Sasson Z, Henderson MA, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The importance of the site and the extent of hypertrophy. A review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985;28(1):1-83. doi:10.1016/0033-0620(85)90024-6

- Spirito P, Bellone P, Harris KM, Bernabo P, Bruzzi P, Maron BJ. Magnitude of left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(24):1778–1785. doi:10.1056/ NEJM200006153422403

- Veselka J, Anavekar NS, Charron P. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1253-1267. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31321-6

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Appelbaum E, et al. Significance of false negative electrocardiograms in preparticipation screening of athletes for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(7):1027-1032. doi:10.1016/j. amjcard.2012.05.035

- Losi MA, Nistri S, Galderisi M et al. Echocardiography in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: usefulness of old and new techniques in the diagnosis and pathophysiological assessment. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2010;8(7). doi:10.1186/1476-7120-8-7

- Tian Z, Li L, Li X, et al. Effect of mavacamten on chinese patients with symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the EXPLORER-CN randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;8(10):957-965. doi:10.1001/ jamacardio.2023.3030

- Fang J, Liu Y, Zhu Y, et al. First-in-human transapical beating-heart septal myectomy in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(7):575-586. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.052

- Jain P, Patel PA, Fabbro M 2nd. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction: expecting the unexpected. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32(1):467-477. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2017.04.054

- Poliac LC, Barron ME, Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(1):183-192. doi:10.1097/00000542-200601000-00025

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a relatively common inherited condition characterized by abnormal asymmetric left ventricular (LV) thickening. This can lead to LV outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction, which has important implications for anesthesia management. This article describes a case of previously undiagnosed HCM discovered during a preoperative physical examination prior to a routine surveillance colonoscopy.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 55-year-old Army veteran with a history of a sessile serrated colon adenoma presented to the preadmission testing clinic prior to planned surveillance colonoscopy under monitored anesthesia care. His medical history included untreated severe obstructive sleep apnea (53 apnea-hypopnea index score), diet-controlled hypertension, prediabetes (6.3% hemoglobin A1c), hypogonadism, and obesity (41 body mass index). Medications included semaglutide 1.7 mg injected subcutaneously weekly and testosterone 200 mg injected intramuscularly every 2 weeks, as well as lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide 10 to 12.5 mg daily, which had recently been discontinued because his blood pressure had improved with a low-sodium diet.

A review of systems was unremarkable except for progressive weight gain. The patient had no family history of sudden cardiac death. On physical examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 119/81 mm Hg, pulse was 86 beats/min, and respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min. The patient was clinically euvolemic, with no jugular venous distention or peripheral edema, and his lungs were clear to auscultation. There was, however, a soft, nonradiating grade 2/6 systolic murmur that had not been previously documented. The murmur decreased substantially with the Valsalva maneuver, with no change in hand grip.

Laboratory studies revealed hemoglobin and renal function were within the reference range. A routine 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was unremarkable. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed moderate pulmonary hypertension (59 mm Hg right ventricular systolic pressure), asymmetric LV hypertrophy (2.1 cm septal thickness), and severe LVOT obstruction (131.8 mm Hg gradient). Severe systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve was also present. The LV ejection fraction was 60% to 65%, with normal cavity size and systolic function. These findings were consistent with severe hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). Upon more detailed questioning, the patient reported that over the previous 5 years he had experienced gradually decreasing exercise tolerance and mild dyspnea on exertion, particularly in hot weather, which he attributed to weight gain. He also reported a presyncopal episode the previous month while working in his garage in hot weather for a prolonged period of time.

The patient’s elective colonoscopy was canceled, and he was referred to cardiology. While awaiting cardiac consultation, he was instructed to maintain good hydration and avoid any heavy physical activity beyond walking. He was told not to resume his use of lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide. A screening 7-day Holter monitor showed no ventricular or supraventricular ectopy. After cardiology consultation, the patient was referred to a HCM specialty clinic, where a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging confirmed severe asymmetric hypertrophy with resting obstruction (Figures 1-4). Treatment options were discussed with the patient, and he underwent a trial with the Β—blocker metoprolol 50 mg daily, which he could not tolerate. Verapamil extended-release 180 mg orally once daily was then initiated; however, his dyspnea persisted. He was amenable to surgical therapy and underwent septal myectomy, with 12 g of septal myocardium removed. He did well postoperatively, with a follow-up echocardiogram showing normal LV systolic function and no LVOT gradient detectable at rest or with Valsalva maneuver. His fatigue and exertional dyspnea significantly improved. Once the patient underwent septal myectomy and was determined to have no detectable LVOT gradient, he was approved for colonoscopy which has been scheduled but not completed.

DISCUSSION

Once thought rare, HCM is now considered to be a relatively common inherited disorder, occurring in about 1 in 500 persons, with some suggesting that the actual prevalence is closer to 1 in 200 persons.1,2 Most often caused by mutations in ≥ 1 of 11 genes responsible for encoding cardiac sarcomere proteins, HCM is characterized by abnormal LV thickening without chamber enlargement in the absence of any identifiable cause, such as aortic valve stenosis or uncontrolled hypertension. The hypertrophy is often asymmetric, and in cases of asymmetric septal hypertrophy, dynamic LVOT obstruction can occur (known as HOCM). The condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with variable expression and is associated with myocardial fiber disarray, which can occur years before symptom onset.3 This myocardial disarray can lead to remodeling and an increased wall-to-lumen ratio of the coronary arteries, resulting in impaired coronary reserve.

Depending on the degree of LVOT obstruction, patients with HCM may be classified as nonobstructive, labile, or obstructive at rest. Patients without obstruction have an outflow gradient ≤ 30 mm Hg that is not provoked with Valsalva maneuver, administration of amyl nitrite, or exercise treadmill testing.3 Patients classified as labile do not have LVOT obstruction at rest, but obstruction may be induced by provocative measures. Finally, about one-third of patients with HCM will have LVOT gradients of > 30 mm Hg at rest. These patients are at increased risk for progression to symptomatic heart failure and may be candidates for surgical myectomy or catheter-based alcohol septal ablation.4 The patient in this case had a resting LVOT gradient of 131.8 mm Hg on echocardiography. The magnitude of this gradient placed the patient at a significantly higher risk of ventricular dysrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.5

Wall thickness also has prognostic implications. 6 Although any area of the myocardium can be affected, the septum is involved in about 90% cases. In their series of 48 patients followed over 6.5 years, Spirito et al found that the risk of sudden death in patients with HCM increased as wall thickness increased. For patients with a wall thickness of < 15 mm, the risk of death was 0 per 1000 person-years; however, this increased to 18.2 per 1000 person-years for patients with a wall thickness of > 30 mm.7

While many patients with HCM are asymptomatic, others may report dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, presyncope/ syncope, postural lightheadedness, fatigue, or edema. Symptomatology, however, is quite variable and does not necessarily correlate with the degree of outflow obstruction. Surprisingly, some patients with significant LVOT may have minimal symptoms, such as the patient in this case, while others with a lesser degree of LVOT obstruction may be very symptomatic.3,4

Physical examination of a patient with HCM may be normal or may reveal nonspecific findings such as a fourth heart sound or a systolic murmur. In general, physical examination abnormalities are related to LVOT obstruction. Those patients without significant outflow obstruction may have a normal cardiac examination. While patients with HCM may have a variety of systolic murmurs, the 2 most common are those related to outflow tract obstruction and mitral regurgitation caused by systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve.4 The systolic murmur associated with significant LVOT obstruction has been described as a harsh, crescendo-decrescendo type that begins just after S1 and is heard best at the apex and lower left sternal border.4 It may radiate to the axilla and base but not generally into the neck. The murmur usually increases with Valsalva maneuver and decreases with handgrip or going from a standing to a sitting/ squatting position. The initial examination of the patient in this case was not suggestive of HOCM, as confirmed by 2 practitioners (a cardiologist and an internist), each with > 30 years of clinical experience. This may have been related to the patient’s hydration status at the time, with Valsalva maneuver increasing obstruction to the point of reduced flow.

About 90% of patients with HCM will have abnormalities on ECG, most commonly LV hypertrophy with a strain pattern. Other ECG findings include: (1) prominent abnormal Q waves, particularly in the inferior (II, III, and aVF) and lateral leads (I, aVL, and V4-V6), reflecting depolarization of a hypertrophied septum; (2) left axis deviation; (3) deeply inverted T waves in leads V2 through V4; and (4) P wave abnormalities indicative of left atrial (LA) or biatrial enlargement. 8 It is notable that the patient in this case had a normal ECG, given that a minority of patients with HCM have been shown to have a normal ECG.9

Echocardiography plays an important role in diagnosing HCM. Diagnostic criteria include the presence of asymmetric hypertrophy (most commonly with anterior septal involvement), systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve, a nondilated LV cavity, septal immobility, and premature closure of the aortic valve. LV thickness is measured at both the septum and free wall; values ≥ 15 mm, with a septal-to-free wall thickness ratio of ≥ 1.3, are suggestive of HCM. Asymmetric LV hypertrophy can also be seen in other segments besides the septum, such as the apex.10

HCM/HOCM is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in young people. The condition also contributes to significant functional morbidity due to heart failure and increases the risk of atrial fibrillation and subsequent stroke. Treatments tend to focus on symptom relief and slowing disease progression and include the use of medications such as Β—blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and the myosin inhibitor mavacamten.11 Select patients, such as those with severe LVOT obstruction and symptoms despite treatment with Β—blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, may be offered septal myectomy or catheter-based alcohol septal ablation, coupled with insertion of an implantable cardiac defibrillator to prevent sudden cardiac death in patients at high arrhythmic risk.1,12

Patients with HCM, particularly those with LVOT obstruction, pose distinct challenges to the anesthesiologist because they are highly sensitive to decreases in preload and afterload. These patients frequently experience adverse perioperative events such as myocardial ischemia, systemic hypotension, and supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmias. Acute congestive heart failure may also occur, presumably due to concomitant diastolic dysfunction. Patients with previously unrecognized HCM are of particular concern, as they may manifest unexpected and sudden hypotension with the induction of anesthesia. There may then be a paradoxical response to vasoactive drugs and anesthetic agents, which accentuate LVOT obstruction. In these circumstances, undiagnosed HCM should be considered, and intraoperative rescue transesophageal echocardiography be performed.13 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, efforts should be made to reduce myocardial contractility and sympathetic discharge (eg, with Β—blockers), increase afterload (eg, with α1 agonists), and improve preload with adequate hydration. Proper resuscitation of hypotensive patients with HCM requires a thorough understanding of disease pathology, as effective interventions may seem to be counterintuitive. Inotropic agents such as epinephrine are contraindicated in HCM because increased inotropy and chronotropy worsen LVOT obstruction. Volume status is often tenuous; while adequate preload is important, overly aggressive fluid resuscitation may promote heart failure. It is important to keep in mind that even patients without resting LVOT obstruction may develop dynamic obstruction with anesthesia induction due to sudden reductions in preload and afterload. It is also important to note that the degree of LV hypertrophy is directly correlated with arrhythmic sudden death. Those patients with LV wall thickness ≥ 30 mm are at increased risk for potentially lethal tachyarrhythmias in the operating room.14

These considerations reinforce the need for proper preoperative identification of patients with HCM. Heightened awareness is key, given the fact that HCM is relatively common and tends to be underdiagnosed in the general population. These patients are generally young, otherwise healthy, and often undergo minor operative procedures in outpatient settings. It is incumbent upon the preoperative evaluator to take a thorough medical history and perform a careful physical examination. Clues to the diagnosis include exertional dyspnea, fatigue, angina, syncope/presyncope, or a family history of sudden cardiac death or HCM. A systolic ejection murmur, particularly one that increases with standing or Valsalva maneuver, and decreases with squatting or handgrip may also raise clinical suspicion. These patients should undergo a full cardiac evaluation, including echocardiography.

CONCLUSIONS

HCM is a common condition that is important to diagnose in the preoperative clinic. Failure to do so can lead to catastrophic complications during induction of anesthesia due to the sudden reduction in preload and afterload, which may cause a significant increase in LVOT obstruction. A high index of suspicion is essential, as clinical diagnosis can be challenging. The physical examination may be deceiving and symptoms are often subtle and nonspecific. It is imperative to alert the anesthesiologist before surgery so the complex hemodynamic management of patients with HOCM can be appropriately managed.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a relatively common inherited condition characterized by abnormal asymmetric left ventricular (LV) thickening. This can lead to LV outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction, which has important implications for anesthesia management. This article describes a case of previously undiagnosed HCM discovered during a preoperative physical examination prior to a routine surveillance colonoscopy.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 55-year-old Army veteran with a history of a sessile serrated colon adenoma presented to the preadmission testing clinic prior to planned surveillance colonoscopy under monitored anesthesia care. His medical history included untreated severe obstructive sleep apnea (53 apnea-hypopnea index score), diet-controlled hypertension, prediabetes (6.3% hemoglobin A1c), hypogonadism, and obesity (41 body mass index). Medications included semaglutide 1.7 mg injected subcutaneously weekly and testosterone 200 mg injected intramuscularly every 2 weeks, as well as lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide 10 to 12.5 mg daily, which had recently been discontinued because his blood pressure had improved with a low-sodium diet.

A review of systems was unremarkable except for progressive weight gain. The patient had no family history of sudden cardiac death. On physical examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 119/81 mm Hg, pulse was 86 beats/min, and respiratory rate was 18 breaths/min. The patient was clinically euvolemic, with no jugular venous distention or peripheral edema, and his lungs were clear to auscultation. There was, however, a soft, nonradiating grade 2/6 systolic murmur that had not been previously documented. The murmur decreased substantially with the Valsalva maneuver, with no change in hand grip.

Laboratory studies revealed hemoglobin and renal function were within the reference range. A routine 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was unremarkable. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed moderate pulmonary hypertension (59 mm Hg right ventricular systolic pressure), asymmetric LV hypertrophy (2.1 cm septal thickness), and severe LVOT obstruction (131.8 mm Hg gradient). Severe systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve was also present. The LV ejection fraction was 60% to 65%, with normal cavity size and systolic function. These findings were consistent with severe hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM). Upon more detailed questioning, the patient reported that over the previous 5 years he had experienced gradually decreasing exercise tolerance and mild dyspnea on exertion, particularly in hot weather, which he attributed to weight gain. He also reported a presyncopal episode the previous month while working in his garage in hot weather for a prolonged period of time.

The patient’s elective colonoscopy was canceled, and he was referred to cardiology. While awaiting cardiac consultation, he was instructed to maintain good hydration and avoid any heavy physical activity beyond walking. He was told not to resume his use of lisinopril-hydrochlorothiazide. A screening 7-day Holter monitor showed no ventricular or supraventricular ectopy. After cardiology consultation, the patient was referred to a HCM specialty clinic, where a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging confirmed severe asymmetric hypertrophy with resting obstruction (Figures 1-4). Treatment options were discussed with the patient, and he underwent a trial with the Β—blocker metoprolol 50 mg daily, which he could not tolerate. Verapamil extended-release 180 mg orally once daily was then initiated; however, his dyspnea persisted. He was amenable to surgical therapy and underwent septal myectomy, with 12 g of septal myocardium removed. He did well postoperatively, with a follow-up echocardiogram showing normal LV systolic function and no LVOT gradient detectable at rest or with Valsalva maneuver. His fatigue and exertional dyspnea significantly improved. Once the patient underwent septal myectomy and was determined to have no detectable LVOT gradient, he was approved for colonoscopy which has been scheduled but not completed.

DISCUSSION

Once thought rare, HCM is now considered to be a relatively common inherited disorder, occurring in about 1 in 500 persons, with some suggesting that the actual prevalence is closer to 1 in 200 persons.1,2 Most often caused by mutations in ≥ 1 of 11 genes responsible for encoding cardiac sarcomere proteins, HCM is characterized by abnormal LV thickening without chamber enlargement in the absence of any identifiable cause, such as aortic valve stenosis or uncontrolled hypertension. The hypertrophy is often asymmetric, and in cases of asymmetric septal hypertrophy, dynamic LVOT obstruction can occur (known as HOCM). The condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with variable expression and is associated with myocardial fiber disarray, which can occur years before symptom onset.3 This myocardial disarray can lead to remodeling and an increased wall-to-lumen ratio of the coronary arteries, resulting in impaired coronary reserve.

Depending on the degree of LVOT obstruction, patients with HCM may be classified as nonobstructive, labile, or obstructive at rest. Patients without obstruction have an outflow gradient ≤ 30 mm Hg that is not provoked with Valsalva maneuver, administration of amyl nitrite, or exercise treadmill testing.3 Patients classified as labile do not have LVOT obstruction at rest, but obstruction may be induced by provocative measures. Finally, about one-third of patients with HCM will have LVOT gradients of > 30 mm Hg at rest. These patients are at increased risk for progression to symptomatic heart failure and may be candidates for surgical myectomy or catheter-based alcohol septal ablation.4 The patient in this case had a resting LVOT gradient of 131.8 mm Hg on echocardiography. The magnitude of this gradient placed the patient at a significantly higher risk of ventricular dysrhythmias and sudden cardiac death.5

Wall thickness also has prognostic implications. 6 Although any area of the myocardium can be affected, the septum is involved in about 90% cases. In their series of 48 patients followed over 6.5 years, Spirito et al found that the risk of sudden death in patients with HCM increased as wall thickness increased. For patients with a wall thickness of < 15 mm, the risk of death was 0 per 1000 person-years; however, this increased to 18.2 per 1000 person-years for patients with a wall thickness of > 30 mm.7

While many patients with HCM are asymptomatic, others may report dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, presyncope/ syncope, postural lightheadedness, fatigue, or edema. Symptomatology, however, is quite variable and does not necessarily correlate with the degree of outflow obstruction. Surprisingly, some patients with significant LVOT may have minimal symptoms, such as the patient in this case, while others with a lesser degree of LVOT obstruction may be very symptomatic.3,4

Physical examination of a patient with HCM may be normal or may reveal nonspecific findings such as a fourth heart sound or a systolic murmur. In general, physical examination abnormalities are related to LVOT obstruction. Those patients without significant outflow obstruction may have a normal cardiac examination. While patients with HCM may have a variety of systolic murmurs, the 2 most common are those related to outflow tract obstruction and mitral regurgitation caused by systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve.4 The systolic murmur associated with significant LVOT obstruction has been described as a harsh, crescendo-decrescendo type that begins just after S1 and is heard best at the apex and lower left sternal border.4 It may radiate to the axilla and base but not generally into the neck. The murmur usually increases with Valsalva maneuver and decreases with handgrip or going from a standing to a sitting/ squatting position. The initial examination of the patient in this case was not suggestive of HOCM, as confirmed by 2 practitioners (a cardiologist and an internist), each with > 30 years of clinical experience. This may have been related to the patient’s hydration status at the time, with Valsalva maneuver increasing obstruction to the point of reduced flow.

About 90% of patients with HCM will have abnormalities on ECG, most commonly LV hypertrophy with a strain pattern. Other ECG findings include: (1) prominent abnormal Q waves, particularly in the inferior (II, III, and aVF) and lateral leads (I, aVL, and V4-V6), reflecting depolarization of a hypertrophied septum; (2) left axis deviation; (3) deeply inverted T waves in leads V2 through V4; and (4) P wave abnormalities indicative of left atrial (LA) or biatrial enlargement. 8 It is notable that the patient in this case had a normal ECG, given that a minority of patients with HCM have been shown to have a normal ECG.9

Echocardiography plays an important role in diagnosing HCM. Diagnostic criteria include the presence of asymmetric hypertrophy (most commonly with anterior septal involvement), systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve, a nondilated LV cavity, septal immobility, and premature closure of the aortic valve. LV thickness is measured at both the septum and free wall; values ≥ 15 mm, with a septal-to-free wall thickness ratio of ≥ 1.3, are suggestive of HCM. Asymmetric LV hypertrophy can also be seen in other segments besides the septum, such as the apex.10

HCM/HOCM is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in young people. The condition also contributes to significant functional morbidity due to heart failure and increases the risk of atrial fibrillation and subsequent stroke. Treatments tend to focus on symptom relief and slowing disease progression and include the use of medications such as Β—blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and the myosin inhibitor mavacamten.11 Select patients, such as those with severe LVOT obstruction and symptoms despite treatment with Β—blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, may be offered septal myectomy or catheter-based alcohol septal ablation, coupled with insertion of an implantable cardiac defibrillator to prevent sudden cardiac death in patients at high arrhythmic risk.1,12

Patients with HCM, particularly those with LVOT obstruction, pose distinct challenges to the anesthesiologist because they are highly sensitive to decreases in preload and afterload. These patients frequently experience adverse perioperative events such as myocardial ischemia, systemic hypotension, and supraventricular or ventricular arrhythmias. Acute congestive heart failure may also occur, presumably due to concomitant diastolic dysfunction. Patients with previously unrecognized HCM are of particular concern, as they may manifest unexpected and sudden hypotension with the induction of anesthesia. There may then be a paradoxical response to vasoactive drugs and anesthetic agents, which accentuate LVOT obstruction. In these circumstances, undiagnosed HCM should be considered, and intraoperative rescue transesophageal echocardiography be performed.13 Once the diagnosis is confirmed, efforts should be made to reduce myocardial contractility and sympathetic discharge (eg, with Β—blockers), increase afterload (eg, with α1 agonists), and improve preload with adequate hydration. Proper resuscitation of hypotensive patients with HCM requires a thorough understanding of disease pathology, as effective interventions may seem to be counterintuitive. Inotropic agents such as epinephrine are contraindicated in HCM because increased inotropy and chronotropy worsen LVOT obstruction. Volume status is often tenuous; while adequate preload is important, overly aggressive fluid resuscitation may promote heart failure. It is important to keep in mind that even patients without resting LVOT obstruction may develop dynamic obstruction with anesthesia induction due to sudden reductions in preload and afterload. It is also important to note that the degree of LV hypertrophy is directly correlated with arrhythmic sudden death. Those patients with LV wall thickness ≥ 30 mm are at increased risk for potentially lethal tachyarrhythmias in the operating room.14

These considerations reinforce the need for proper preoperative identification of patients with HCM. Heightened awareness is key, given the fact that HCM is relatively common and tends to be underdiagnosed in the general population. These patients are generally young, otherwise healthy, and often undergo minor operative procedures in outpatient settings. It is incumbent upon the preoperative evaluator to take a thorough medical history and perform a careful physical examination. Clues to the diagnosis include exertional dyspnea, fatigue, angina, syncope/presyncope, or a family history of sudden cardiac death or HCM. A systolic ejection murmur, particularly one that increases with standing or Valsalva maneuver, and decreases with squatting or handgrip may also raise clinical suspicion. These patients should undergo a full cardiac evaluation, including echocardiography.

CONCLUSIONS

HCM is a common condition that is important to diagnose in the preoperative clinic. Failure to do so can lead to catastrophic complications during induction of anesthesia due to the sudden reduction in preload and afterload, which may cause a significant increase in LVOT obstruction. A high index of suspicion is essential, as clinical diagnosis can be challenging. The physical examination may be deceiving and symptoms are often subtle and nonspecific. It is imperative to alert the anesthesiologist before surgery so the complex hemodynamic management of patients with HOCM can be appropriately managed.

- Cheng Z, Fang T, Huang J, Guo Y, Alam M, Qian H. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: from phenotype and pathogenesis to treatment. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:722340. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.722340

- Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(12):1249-1254. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019

- Hensley N, Dietrich J, Nyhan D, Mitter N, Yee MS, Brady M. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a review. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(3):554-569. doi:10.1213/ ANE.0000000000000538

- Maron BJ, Desai MY, Nishimura RA, et al. Diagnosis and evaluation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(4):372–389. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.002

- Jorda P, Garcia-Alvarez A. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: sudden cardiac death risk stratification in adults. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2018;3(25). doi:10.21542/gcsp.2018.25

- Wigle ED, Sasson Z, Henderson MA, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The importance of the site and the extent of hypertrophy. A review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985;28(1):1-83. doi:10.1016/0033-0620(85)90024-6

- Spirito P, Bellone P, Harris KM, Bernabo P, Bruzzi P, Maron BJ. Magnitude of left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(24):1778–1785. doi:10.1056/ NEJM200006153422403

- Veselka J, Anavekar NS, Charron P. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1253-1267. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31321-6

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Appelbaum E, et al. Significance of false negative electrocardiograms in preparticipation screening of athletes for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(7):1027-1032. doi:10.1016/j. amjcard.2012.05.035

- Losi MA, Nistri S, Galderisi M et al. Echocardiography in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: usefulness of old and new techniques in the diagnosis and pathophysiological assessment. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2010;8(7). doi:10.1186/1476-7120-8-7

- Tian Z, Li L, Li X, et al. Effect of mavacamten on chinese patients with symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the EXPLORER-CN randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;8(10):957-965. doi:10.1001/ jamacardio.2023.3030

- Fang J, Liu Y, Zhu Y, et al. First-in-human transapical beating-heart septal myectomy in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(7):575-586. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.052

- Jain P, Patel PA, Fabbro M 2nd. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction: expecting the unexpected. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32(1):467-477. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2017.04.054

- Poliac LC, Barron ME, Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(1):183-192. doi:10.1097/00000542-200601000-00025

- Cheng Z, Fang T, Huang J, Guo Y, Alam M, Qian H. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: from phenotype and pathogenesis to treatment. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:722340. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2021.722340

- Semsarian C, Ingles J, Maron MS, Maron BJ. New perspectives on the prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(12):1249-1254. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.019

- Hensley N, Dietrich J, Nyhan D, Mitter N, Yee MS, Brady M. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a review. Anesth Analg. 2015;120(3):554-569. doi:10.1213/ ANE.0000000000000538

- Maron BJ, Desai MY, Nishimura RA, et al. Diagnosis and evaluation of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79(4):372–389. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2021.12.002

- Jorda P, Garcia-Alvarez A. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: sudden cardiac death risk stratification in adults. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2018;3(25). doi:10.21542/gcsp.2018.25

- Wigle ED, Sasson Z, Henderson MA, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. The importance of the site and the extent of hypertrophy. A review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985;28(1):1-83. doi:10.1016/0033-0620(85)90024-6

- Spirito P, Bellone P, Harris KM, Bernabo P, Bruzzi P, Maron BJ. Magnitude of left ventricular hypertrophy and risk of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(24):1778–1785. doi:10.1056/ NEJM200006153422403

- Veselka J, Anavekar NS, Charron P. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1253-1267. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31321-6

- Rowin EJ, Maron BJ, Appelbaum E, et al. Significance of false negative electrocardiograms in preparticipation screening of athletes for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(7):1027-1032. doi:10.1016/j. amjcard.2012.05.035

- Losi MA, Nistri S, Galderisi M et al. Echocardiography in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: usefulness of old and new techniques in the diagnosis and pathophysiological assessment. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2010;8(7). doi:10.1186/1476-7120-8-7

- Tian Z, Li L, Li X, et al. Effect of mavacamten on chinese patients with symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the EXPLORER-CN randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;8(10):957-965. doi:10.1001/ jamacardio.2023.3030

- Fang J, Liu Y, Zhu Y, et al. First-in-human transapical beating-heart septal myectomy in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(7):575-586. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.052

- Jain P, Patel PA, Fabbro M 2nd. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction: expecting the unexpected. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2018;32(1):467-477. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2017.04.054

- Poliac LC, Barron ME, Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(1):183-192. doi:10.1097/00000542-200601000-00025

Importance of Recognizing Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in the Preoperative Clinic

Importance of Recognizing Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in the Preoperative Clinic

A Year 3 Progress Report on Graduate Medical Education Expansion in the Veterans Choice Act

The VHA is the largest healthcare delivery system in the U.S. It includes 146 medical centers (VAMCs), 1,063 community-based outpatient centers (CBOCs) and various other sites of care. General Omar Bradley, the first VA Secretary, established education as one of VA’s 4 statutory missions in Policy Memorandum No.2.1 In addition to training physicians to care for active-duty service members and veterans, 38 USC §7302 directs the VA to assist in providing an adequate supply of health personnel. The 4 statutory missions of the VA are inclusive of not only developing, operating, and maintaining a health care system for veterans, but also including contingency support services as part of emergency preparedness, conducting research, and offering a program of education for health professions.

Background

Today, with few exceptions, the VHA does not act as a graduate medical education (GME) sponsoring institution. Through its Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), the VHA develops partnerships with Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME)/American Osteopathic Association (AOA)-approved medical colleges/universities and with institutions that sponsor Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)/AOA-accredited residency program-sponsoring institutions. These collaborations include 144 out of 149 allopathic medical schools and all 34 osteopathic medical schools. The VHA provided training to 43,565 medical residents and 24,683 medical students through these partnerships in 2017.2 Since funding of the GME positions is not provided through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), program sponsors may use these partnerships to expand GME positions beyond their funding (but not ACGME) cap.

The gap between supply and demand of physicians continues to grow nationally.3,4 This gap is particularly significant in rural and other underserved areas. U.S. Census Bureau data show that about 5 million veterans (24%) live in rural areas.5 Compared with the urban veteran population, the rural veteran experiences higher disease prevalence and lower physical and mental quality-of-life scores.6 Addressing the problem of physician shortages is a mission-critical priority for the VHA.7

With an eye toward enhancing 2 of the 4 statutory missions of the VA and to mitigate the shortage of physicians and improve the access of veterans to VHA medical services, on August 7, 2014, the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (Public Law [PL] 113-146), known as the Choice Act was enacted.8 Title III, §301(b) of the Choice Act requires VHA to increase GME residency positions by:

Establishing new medical residency programs, or ensuring that already established medical residency programs have a sufficient number of residency positions, at any VHA medical facility that is: (a) experiencing a shortage of physicians and (b) located in a community that is designated as a health professional shortage area.

The legislation specifies that priority must be placed on medical occupations that experience the largest staffing shortages throughout the VHA and “programs in primary care, mental health, and any other specialty that the Secretary of the VA determines appropriate.” The Choice Act authorized the VHA to increase the number of GME residency positions by up to 1,500 over a 5-year period. In December 2016, as amended by PL 114–315, Title VI, §617(a), this authorization was extended by another 5 years for a total of 10 years and will run through 2024.9

GME Development/Distribution

To distribute these newly created GME positions as mandated by Congress, the OAA is using a system with 3 types of request for proposal (RFP) applications. These include planning, infrastructure, and position grants. This phased approach was taken with the understanding that the development of new training sites requires a properly staffed education office and dedicated faculty time. Planning and infrastructure grants provide start-up funds for smaller VAMCs, allowing them to keep facility resources focused on their clinical mission.

Planning grants (of up to $250,000 over 2 years) primarily were designed for VA facilities with no or low numbers of physician residents at the desired teaching location. Priority was given to facilities in rural and/or underserved areas as well as those developing new affiliations. Applications were reviewed by OAA staff along with peer-selected Designated Education Officers (DEOs) from VA facilities across the nation that were not applying for the grants. Awards were based on the priorities mentioned earlier, with additional credit for programs focused on 2 VHA fundamental services areas—primary care and/or mental health training. Facilities receiving planning grants were mentored by an OAA physician staff member, anticipating a 2- to 3-year time line to request positions and begin GME training.

Infrastructure grants (of up to $520,000 used over 2-3 years) were designed as bridge funds after approval of Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act (VACAA) GME positions. Infrastructure grants are appropriate to sustain a local education office, develop VA faculty, purchase equipment, and make minor modifications to the clinical space in the VAMCs or CBOCs to enhance the learning environment during the period before VA supportive funds from the Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) (similar to indirect GME funds from CMS) become available. Applications were managed the same as planning grant submissions.

Position RFPs, unlike planning and infrastructure RFPs, are available to all VAMCs. The primary purpose of the VACAA Position RFP is to fund new positions in primary care and psychiatry. Graduate medical education positions in subspecialty programs also are considered when there is documentation of critical need to improve access to these services. Applications were reviewed by OAA staff along with selected DEOs from VA facilities around the U.S. Award criteria prioritized primary care (family medicine, internal medicine, geriatrics), and mental health (psychiatry and psychiatry subspecialties). Priority also was given to positions in areas with a documented shortage of physicians and areas with high concentrations of veterans.

Current Progress

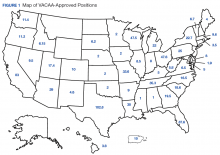

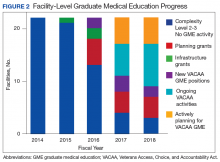

To date the OAA has offered 3 RFP cycles consisting of planning/infrastructure grants, and 4 RFP cycles for salary/benefit support for additional resident full-time equivalent (FTE) positions. Resident positions were defined as residency or fellowship FTEs that were part of an ACGME or AOA-accredited training program. Figure 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of awarded GME positions.

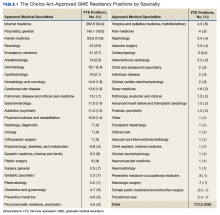

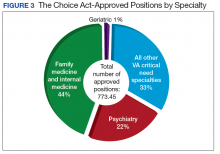

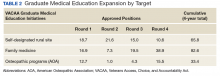

In primary care specialties (family medicine, internal medicine, and geriatrics, a total of 349.4 FTE positions have been approved (Table 1). Due to a low number of applications, only 6.3 of these positions were awarded in geriatrics. In mental health, 167.6 FTE positions have been approved, whereas in critical needs specialties (needed to support rural/underserved healthcare and improve specialty access) 256.5 FTE positions have been added.

Discussion

There are several important desired short-term outcomes from VACAA. The first is improved access to high-quality care for both rural and urban veterans. There is an emphasis on primary care and mental health because shortages in these areas across the U.S. are well established.3,4,10 Likewise, rural areas have been prioritized because often there is a disparity of care.

One area of concern is the small number of applicants in geriatrics. Even with VACAA specifically targeting geriatrics as a primary care specialty, we have only received enough applications to approve 6.3 positions over the first 3 years of the program. As the veteran and overall population in the U.S. ages, it is important to develop a medical workforce that is willing and able to address their needs.

The VACAA statute is not intended to alter medical students’ career choice but rather to provide funded positions for those choosing primary care, geriatrics, psychiatry (including psychiatric subspecialties), and experience in the VA clinical settings. The hope is that this experience will encourage practitioners to competently care for veterans after training in the VA and/or other civilian settings.

By enabling smaller VA facilities to become training sites through planning and infrastructure grants, residents have the opportunity to gain experience in more rural settings. Physicians who choose to train in rural areas are likely to spend time practicing in those areas after they complete training.15 The process of developing facilities with no GME into training sitestakes time and resources. Establishing an education office and choosing site directors and core faculty are all important steps that must be done before resident rotations begin. Resources provided through VACAA have enabled the VHA to reduce the number of VAMCs with no GME activity to just 3.

Another benefit of VACAA GME expansion is the opportunity to engage new LCME/AOA-accredited medical schools and ACGME/AOA-accredited residency-sponsoring institutions.16,17 Representatives of these institutions may have perceived a reluctance of their local VAs to develop GME affiliations in the past. This statute has enabled many VAMCs to use nontraditional training sites and modalities to overcome barriers and create new academic affiliations.

However, VACAA only provides funds for training that occurs in established VA sites of care. This can hinder the development of partnerships where other funding sources are required for non-VA rotations. Another VACAA limitation is that it does not fund undergraduate medical education as does the Armed Forces Health Professional Scholarship Program (HPSP). In addition, the primary financial relationship is between the VA and the sponsoring institution, thus VHA cannot send residents to underserved locations.

Conclusion

The VHA has a rich tradition of educating physician and other health care providers in the U.S. More than 60% of U.S. trained physicians received a portion of their training through VHA.2 Through VACAA GME expansion initiative, the 113th Congress has asked VHA to continue its important training mission “to bind up the Nations wounds” and “to care for him who shall have borne the battle.”18

Acknowledgments

In memoriam – Robert Louis Jesse MD, PhD. Dr. Jesse, the Chief of the Office of Academic Affiliations passed away on September 2, 2017, at age 64. He had an illustrious medical career as a cardiologist and served in many leadership roles including Principal Deputy Under Secretary for Health in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. His expertise, visionary leadership, and friendship will be missed by all involved in the VA’s academic training mission but particularly by those of us who worked for and with him at OAA.

1. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. Policy Memorandum No. 2. Policy in association of veterans’ hospitals with medical schools. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf. Published January 30, 1947. Accessed December 13, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. 2017 statistics: health professions trainees. https://www .va.gov/OAA/docs/OAA_Statistics.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2018.

3. IHS, Inc. The complexities of physician supply and demand 2016 update: projections from 2014 to 2025, final report. https://www.aamc.org/download/458082/data/2016_complexities_of_supply_and_demand_projections.pdf. Published April 5, 2016. Accessed December 13, 2017.

4. Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Tran C, Bazemore AW. Estimating the residency expansion required to avoid projected primary care physician shortages by 2035. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):107-114.

5. Holder KA. Veterans in rural America 2011-2015. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publica tions/2017/acs/acs-36.pdf. Published January 2017. Accessed January 18, 2018.

6. Weeks WB, Wallace AE, Wang S, Lee A, Kazis LE. Rural-urban disparities in health-related quality of life within disease categories of veterans. J Rural Health. 2006;22(3):204-211.

7. U.S. Government Accountability Office. GAO-18-124. VHA Physician Staffing and Recruitment. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687853.pdf. Published October 19, 2017. Accessed January 23, 2018.

8. Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act, section 301 (b): Increase of graduate medical education residency positions, 38 USC § 74 (2014) .

9. Jeff Miller and Richard Blumenthal Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2016, 38 USC §101 (2016).

10. Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Holzer CE, Morrissey JP. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1323-1328.

11. Garibaldi RA, Popkave C, Bylsma W. Career plans for trainees in internal medicine residency programs. Acad Med. 2005;80(5):507-512.

12. West CP, Dupras DM. General medicine vs subspecialty career plans among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2241-2247.

13. Stimmel B, Haddow S, Smith L. The practice of general internal medicine by subspecialists. J Urban Health. 1998;75(1):184-190.

14. Shea JA, Kleetke PR, Wozniak GD, Polsky D, Escarce JJ. Self-reported physician specialties and the primary care content of medical practice: a study of the AMA physician masterfile. American Medical Association. Med Care. 1999;37(4):333-338.

15. Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Paynter NP. Critical factors for designing

16. Accredited MD programs in the United States. http://lcme.org /directory/accredited-u-s-programs/. Updated December 12, 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

17. Osteopathic medical schools. http://www.osteopathic.org/in side-aoa/about/affiliates/Pages/osteopathic-medical-schools.aspx Published 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

18. Lincoln A. Second inaugural address. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/celebrate/vamotto.pdf. Accessed January 8. 2018.

The VHA is the largest healthcare delivery system in the U.S. It includes 146 medical centers (VAMCs), 1,063 community-based outpatient centers (CBOCs) and various other sites of care. General Omar Bradley, the first VA Secretary, established education as one of VA’s 4 statutory missions in Policy Memorandum No.2.1 In addition to training physicians to care for active-duty service members and veterans, 38 USC §7302 directs the VA to assist in providing an adequate supply of health personnel. The 4 statutory missions of the VA are inclusive of not only developing, operating, and maintaining a health care system for veterans, but also including contingency support services as part of emergency preparedness, conducting research, and offering a program of education for health professions.

Background

Today, with few exceptions, the VHA does not act as a graduate medical education (GME) sponsoring institution. Through its Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), the VHA develops partnerships with Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME)/American Osteopathic Association (AOA)-approved medical colleges/universities and with institutions that sponsor Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)/AOA-accredited residency program-sponsoring institutions. These collaborations include 144 out of 149 allopathic medical schools and all 34 osteopathic medical schools. The VHA provided training to 43,565 medical residents and 24,683 medical students through these partnerships in 2017.2 Since funding of the GME positions is not provided through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), program sponsors may use these partnerships to expand GME positions beyond their funding (but not ACGME) cap.

The gap between supply and demand of physicians continues to grow nationally.3,4 This gap is particularly significant in rural and other underserved areas. U.S. Census Bureau data show that about 5 million veterans (24%) live in rural areas.5 Compared with the urban veteran population, the rural veteran experiences higher disease prevalence and lower physical and mental quality-of-life scores.6 Addressing the problem of physician shortages is a mission-critical priority for the VHA.7

With an eye toward enhancing 2 of the 4 statutory missions of the VA and to mitigate the shortage of physicians and improve the access of veterans to VHA medical services, on August 7, 2014, the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (Public Law [PL] 113-146), known as the Choice Act was enacted.8 Title III, §301(b) of the Choice Act requires VHA to increase GME residency positions by:

Establishing new medical residency programs, or ensuring that already established medical residency programs have a sufficient number of residency positions, at any VHA medical facility that is: (a) experiencing a shortage of physicians and (b) located in a community that is designated as a health professional shortage area.

The legislation specifies that priority must be placed on medical occupations that experience the largest staffing shortages throughout the VHA and “programs in primary care, mental health, and any other specialty that the Secretary of the VA determines appropriate.” The Choice Act authorized the VHA to increase the number of GME residency positions by up to 1,500 over a 5-year period. In December 2016, as amended by PL 114–315, Title VI, §617(a), this authorization was extended by another 5 years for a total of 10 years and will run through 2024.9

GME Development/Distribution

To distribute these newly created GME positions as mandated by Congress, the OAA is using a system with 3 types of request for proposal (RFP) applications. These include planning, infrastructure, and position grants. This phased approach was taken with the understanding that the development of new training sites requires a properly staffed education office and dedicated faculty time. Planning and infrastructure grants provide start-up funds for smaller VAMCs, allowing them to keep facility resources focused on their clinical mission.

Planning grants (of up to $250,000 over 2 years) primarily were designed for VA facilities with no or low numbers of physician residents at the desired teaching location. Priority was given to facilities in rural and/or underserved areas as well as those developing new affiliations. Applications were reviewed by OAA staff along with peer-selected Designated Education Officers (DEOs) from VA facilities across the nation that were not applying for the grants. Awards were based on the priorities mentioned earlier, with additional credit for programs focused on 2 VHA fundamental services areas—primary care and/or mental health training. Facilities receiving planning grants were mentored by an OAA physician staff member, anticipating a 2- to 3-year time line to request positions and begin GME training.

Infrastructure grants (of up to $520,000 used over 2-3 years) were designed as bridge funds after approval of Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act (VACAA) GME positions. Infrastructure grants are appropriate to sustain a local education office, develop VA faculty, purchase equipment, and make minor modifications to the clinical space in the VAMCs or CBOCs to enhance the learning environment during the period before VA supportive funds from the Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) (similar to indirect GME funds from CMS) become available. Applications were managed the same as planning grant submissions.

Position RFPs, unlike planning and infrastructure RFPs, are available to all VAMCs. The primary purpose of the VACAA Position RFP is to fund new positions in primary care and psychiatry. Graduate medical education positions in subspecialty programs also are considered when there is documentation of critical need to improve access to these services. Applications were reviewed by OAA staff along with selected DEOs from VA facilities around the U.S. Award criteria prioritized primary care (family medicine, internal medicine, geriatrics), and mental health (psychiatry and psychiatry subspecialties). Priority also was given to positions in areas with a documented shortage of physicians and areas with high concentrations of veterans.

Current Progress

To date the OAA has offered 3 RFP cycles consisting of planning/infrastructure grants, and 4 RFP cycles for salary/benefit support for additional resident full-time equivalent (FTE) positions. Resident positions were defined as residency or fellowship FTEs that were part of an ACGME or AOA-accredited training program. Figure 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of awarded GME positions.

In primary care specialties (family medicine, internal medicine, and geriatrics, a total of 349.4 FTE positions have been approved (Table 1). Due to a low number of applications, only 6.3 of these positions were awarded in geriatrics. In mental health, 167.6 FTE positions have been approved, whereas in critical needs specialties (needed to support rural/underserved healthcare and improve specialty access) 256.5 FTE positions have been added.

Discussion

There are several important desired short-term outcomes from VACAA. The first is improved access to high-quality care for both rural and urban veterans. There is an emphasis on primary care and mental health because shortages in these areas across the U.S. are well established.3,4,10 Likewise, rural areas have been prioritized because often there is a disparity of care.

One area of concern is the small number of applicants in geriatrics. Even with VACAA specifically targeting geriatrics as a primary care specialty, we have only received enough applications to approve 6.3 positions over the first 3 years of the program. As the veteran and overall population in the U.S. ages, it is important to develop a medical workforce that is willing and able to address their needs.

The VACAA statute is not intended to alter medical students’ career choice but rather to provide funded positions for those choosing primary care, geriatrics, psychiatry (including psychiatric subspecialties), and experience in the VA clinical settings. The hope is that this experience will encourage practitioners to competently care for veterans after training in the VA and/or other civilian settings.

By enabling smaller VA facilities to become training sites through planning and infrastructure grants, residents have the opportunity to gain experience in more rural settings. Physicians who choose to train in rural areas are likely to spend time practicing in those areas after they complete training.15 The process of developing facilities with no GME into training sitestakes time and resources. Establishing an education office and choosing site directors and core faculty are all important steps that must be done before resident rotations begin. Resources provided through VACAA have enabled the VHA to reduce the number of VAMCs with no GME activity to just 3.

Another benefit of VACAA GME expansion is the opportunity to engage new LCME/AOA-accredited medical schools and ACGME/AOA-accredited residency-sponsoring institutions.16,17 Representatives of these institutions may have perceived a reluctance of their local VAs to develop GME affiliations in the past. This statute has enabled many VAMCs to use nontraditional training sites and modalities to overcome barriers and create new academic affiliations.

However, VACAA only provides funds for training that occurs in established VA sites of care. This can hinder the development of partnerships where other funding sources are required for non-VA rotations. Another VACAA limitation is that it does not fund undergraduate medical education as does the Armed Forces Health Professional Scholarship Program (HPSP). In addition, the primary financial relationship is between the VA and the sponsoring institution, thus VHA cannot send residents to underserved locations.

Conclusion

The VHA has a rich tradition of educating physician and other health care providers in the U.S. More than 60% of U.S. trained physicians received a portion of their training through VHA.2 Through VACAA GME expansion initiative, the 113th Congress has asked VHA to continue its important training mission “to bind up the Nations wounds” and “to care for him who shall have borne the battle.”18

Acknowledgments

In memoriam – Robert Louis Jesse MD, PhD. Dr. Jesse, the Chief of the Office of Academic Affiliations passed away on September 2, 2017, at age 64. He had an illustrious medical career as a cardiologist and served in many leadership roles including Principal Deputy Under Secretary for Health in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. His expertise, visionary leadership, and friendship will be missed by all involved in the VA’s academic training mission but particularly by those of us who worked for and with him at OAA.

The VHA is the largest healthcare delivery system in the U.S. It includes 146 medical centers (VAMCs), 1,063 community-based outpatient centers (CBOCs) and various other sites of care. General Omar Bradley, the first VA Secretary, established education as one of VA’s 4 statutory missions in Policy Memorandum No.2.1 In addition to training physicians to care for active-duty service members and veterans, 38 USC §7302 directs the VA to assist in providing an adequate supply of health personnel. The 4 statutory missions of the VA are inclusive of not only developing, operating, and maintaining a health care system for veterans, but also including contingency support services as part of emergency preparedness, conducting research, and offering a program of education for health professions.

Background

Today, with few exceptions, the VHA does not act as a graduate medical education (GME) sponsoring institution. Through its Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), the VHA develops partnerships with Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME)/American Osteopathic Association (AOA)-approved medical colleges/universities and with institutions that sponsor Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)/AOA-accredited residency program-sponsoring institutions. These collaborations include 144 out of 149 allopathic medical schools and all 34 osteopathic medical schools. The VHA provided training to 43,565 medical residents and 24,683 medical students through these partnerships in 2017.2 Since funding of the GME positions is not provided through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), program sponsors may use these partnerships to expand GME positions beyond their funding (but not ACGME) cap.

The gap between supply and demand of physicians continues to grow nationally.3,4 This gap is particularly significant in rural and other underserved areas. U.S. Census Bureau data show that about 5 million veterans (24%) live in rural areas.5 Compared with the urban veteran population, the rural veteran experiences higher disease prevalence and lower physical and mental quality-of-life scores.6 Addressing the problem of physician shortages is a mission-critical priority for the VHA.7

With an eye toward enhancing 2 of the 4 statutory missions of the VA and to mitigate the shortage of physicians and improve the access of veterans to VHA medical services, on August 7, 2014, the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (Public Law [PL] 113-146), known as the Choice Act was enacted.8 Title III, §301(b) of the Choice Act requires VHA to increase GME residency positions by:

Establishing new medical residency programs, or ensuring that already established medical residency programs have a sufficient number of residency positions, at any VHA medical facility that is: (a) experiencing a shortage of physicians and (b) located in a community that is designated as a health professional shortage area.

The legislation specifies that priority must be placed on medical occupations that experience the largest staffing shortages throughout the VHA and “programs in primary care, mental health, and any other specialty that the Secretary of the VA determines appropriate.” The Choice Act authorized the VHA to increase the number of GME residency positions by up to 1,500 over a 5-year period. In December 2016, as amended by PL 114–315, Title VI, §617(a), this authorization was extended by another 5 years for a total of 10 years and will run through 2024.9

GME Development/Distribution