User login

Verrucous Plaques on Sun-Exposed Areas

Verrucous Plaques on Sun-Exposed Areas

THE DIAGNOSIS: Hypertrophic Lupus Erythematosus

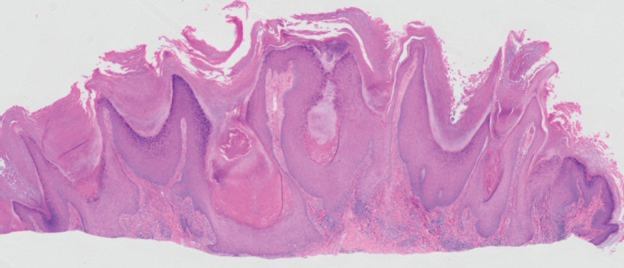

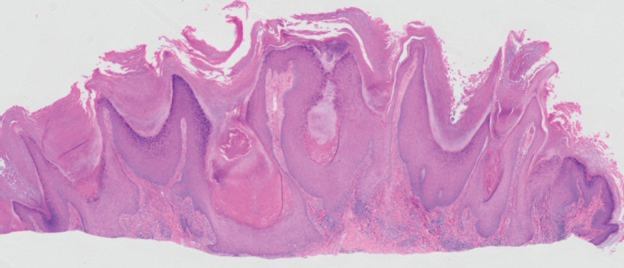

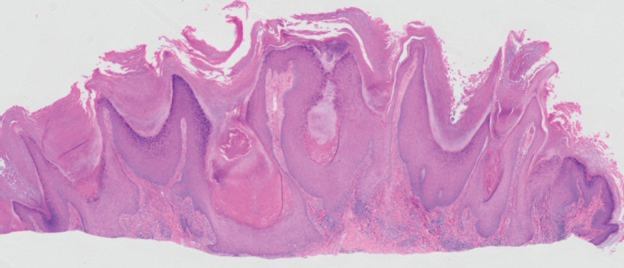

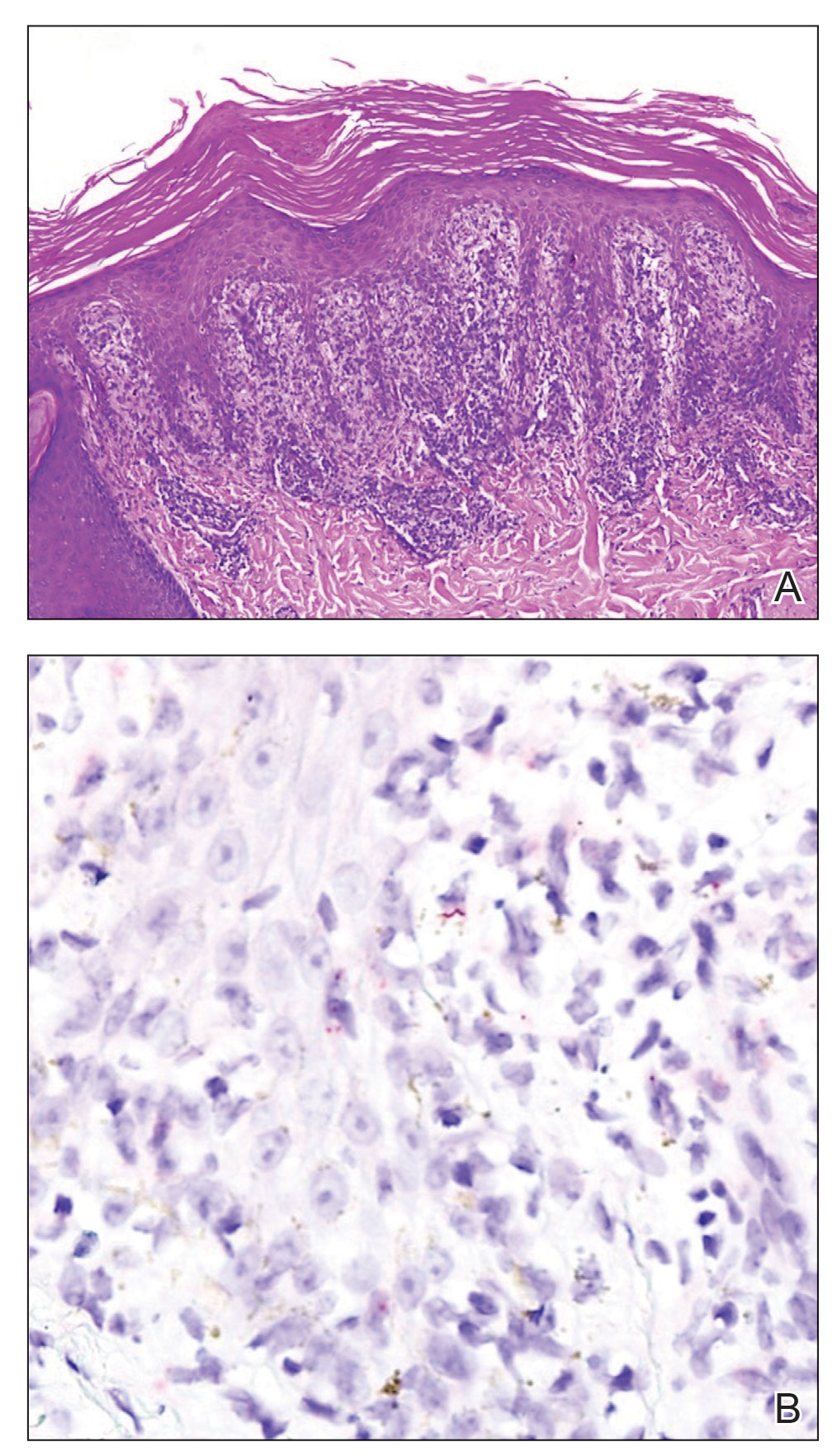

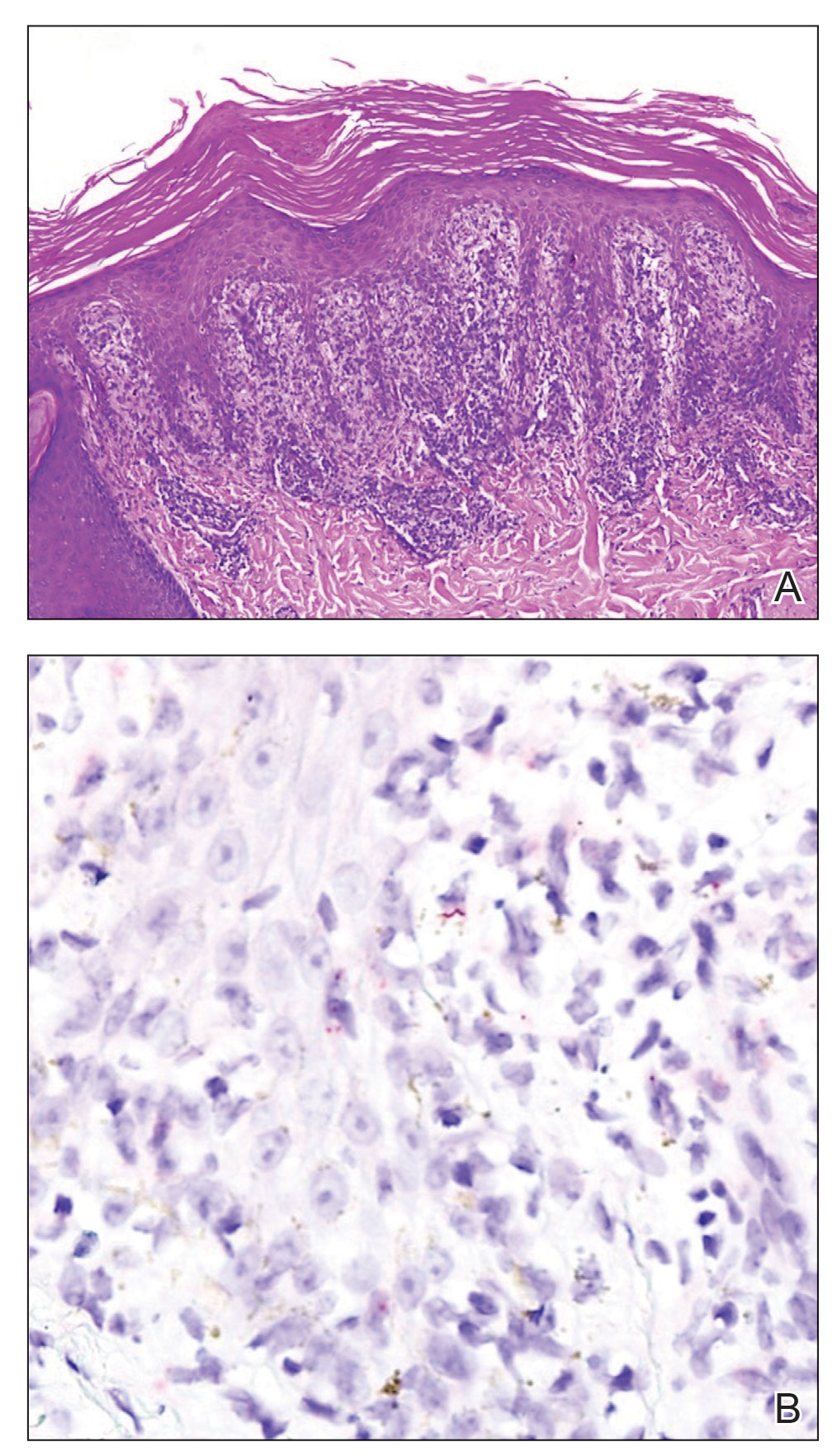

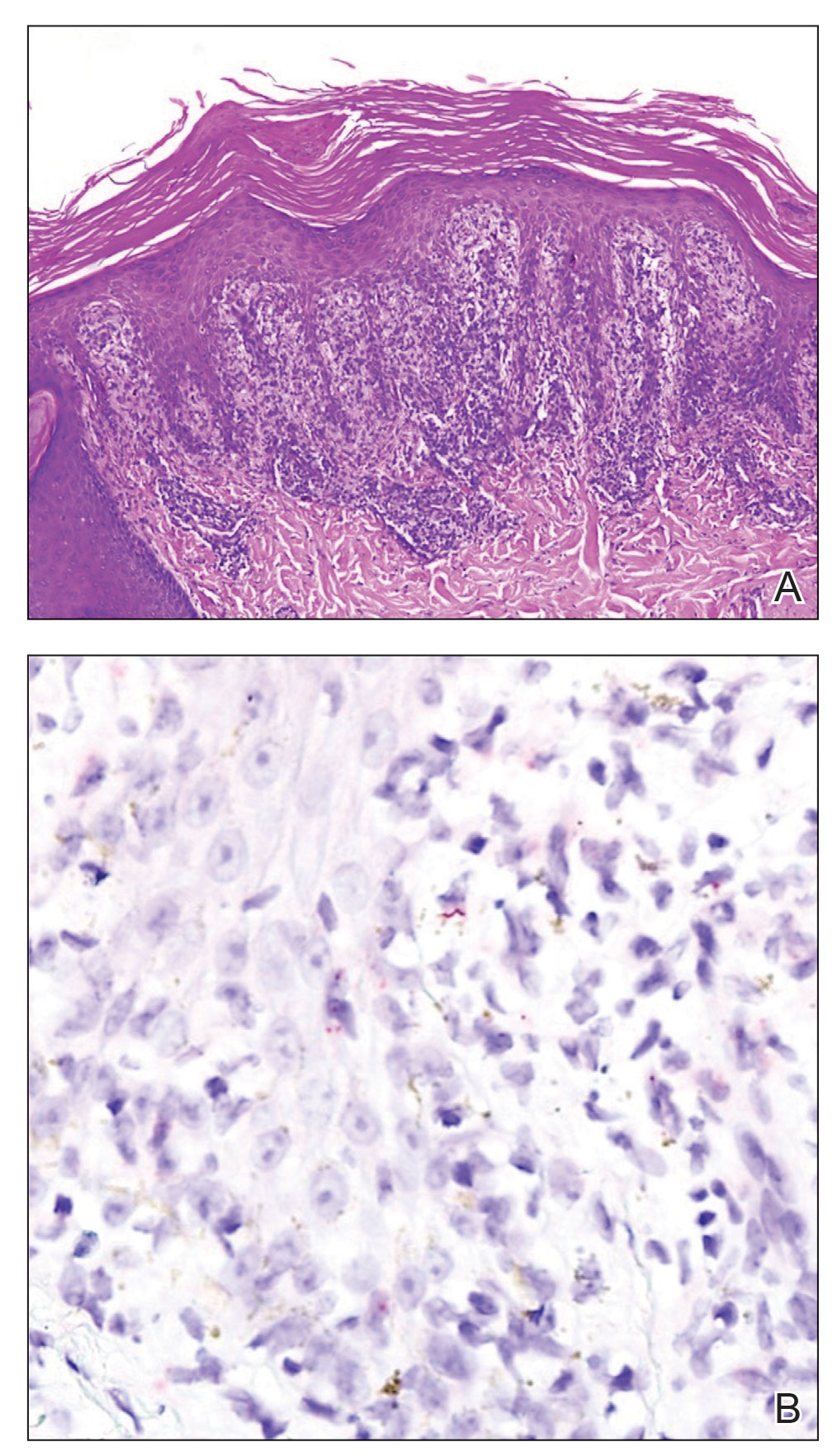

The biopsy of the face collected at the initial appointment revealed interface dermatitis with epidermal hyperplasia with no parakeratosis or eosinophils (Figure 1). Microscopic findings were suggestive of hypertrophic lupus erythematosus (HLE) or hypertrophic lichen planus. The rapid plasma reagin and HIV labs collected at the initial appointment were negative, and a review of systems was negative for systemic symptoms. Considering these results and the clinical distribution of the lesions primarily affecting sun-exposed areas of the upper body, a final diagnosis of HLE was made. The patient was counseled on the importance of photoprotection and was started on hydroxychloroquine.

Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, a rare variant of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), typically manifests as verrucous plaques or nodules commonly found on sun-exposed areas of the body, as was observed in our patient on the face, scalp (Figures 2 and 3), chest, and upper extremities.1 Lesions can have a variable appearance, from hyperkeratotic ulcers to depigmented plaques and keratoacanthomalike lesions.2 On histopathology, HLE falls into the category of lichenoid interface dermatitis and commonly demonstrates hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, follicular plugging, superficial and deep infiltrate, and increased mucin deposition in the dermis.3

Although rare, it is critical to remain vigilant for the development of squamous cell carcinoma in patients with chronic untreated CCLE. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, specifically, is the most likely variant to give rise to invasive squamous cell carcinoma and can be more aggressive as a result of this malignant transformation.3,4 Ruling out squamous cell carcinoma in the setting of HLE can be achieved by staining for CD123, as HLE commonly is associated with many CD123+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells adjacent to the epithelium, unlike squamous cell carcinoma.3 Fortunately no evidence of invasive squamous cell carcinoma, including cellular atypia or increased mitotic figures, was seen on histology in our patient.

A thorough history and physical examination are essential for screening for HLE, as positive antinuclear antibodies are observed only in half of the patients diagnosed with CCLE.5 Furthermore, antinuclear antibodies sometimes can be negative in patients with HLE who have end-stage organ involvement.

Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus can be challenging to treat. First-line therapies include antimalarials, topical steroids, and sun-protective measures. Intralesional triamcinolone injection also can be used as an adjunctive therapy to expedite the treatment response.6 Evidence supports good response following treatment with acitretin or a combination of isotretinoin and hydroxychloroquine.2 Another therapeutic strategy is implementing immunosuppressants such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine for persistent disease. Immunomodulators such as thalidomide historically have been shown to treat severe recalcitrant cases of HLE but typically are reserved for extreme cases due to adverse effects. Biologic agents such as intravenous immunoglobulins and rituximab have been shown to treat CCLE successfully, but routine use is limited due to high cost and lack of strong clinical trials.7

There have been reports of experimental therapies such as monoclonal antibodies (eg, anifrolumab and tocilizumab therapy) providing remission for patients with refractory CCLE, but information on their efficacy—specifically in patients with HLE—is lacking.8 Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus and its variants require further investigation regarding which treatment options provide the greatest benefit while minimizing adverse effects.

It is important to distinguish HLE from other potential diagnoses. Features of HLE can mimic hypertrophic lichen planus; however, the latter typically appears on the legs while HLE appears more commonly on the upper extremities and face in a photodistributed pattern.9 Since HLE has a lichenoid appearance histologically, it may appear clinically similar to hypertrophic lichen planus. Although not performed in our patient due to cost, direct immunofluorescence can aid in distinguishing HLE from hypertrophic lichen planus. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus shows a granular pattern of deposition of IgM (primarily), IgG, IgA, and C3. In contrast, hypertrophic lichen planus exhibits cytoid bodies that stain positive for IgM as well as linear deposition of fibrinogen along the basement membrane.3,10

Blastomycosis also can lead to development of verrucous plaques in sun-exposed areas, but the lesions typically originate as pustules that ulcerate over time. Lesions also can manifest with central scarring and a heaped edge.3 Unlike HLE, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with mixed infiltrate and intradermal pustules are seen in blastomycosis.3 Fungal organisms often are seen on pathology and are relatively large and uniform in size and shape, are found within giant cells, and have a thick refractile asymmetrical wall.11 In rupioid psoriasis, skin lesions mostly are widespread and are not limited to sun-exposed areas. Additionally, biopsies from active rupioid lesions typically show psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis with no interface inflammation—a key differentiator.12 In secondary syphilis, chancres often are missed and are not reported by patients. Clinically, secondary syphilis often manifests as scaly patches and plaques with palmar involvement and positive rapid plasma reagin, which was negative in our patient.13 Histologically, secondary syphilis can exhibit a vacuolar or lichenoid interface dermatitis; however, it typically exhibits slender acanthosis with long rete ridges and neutrophils in the stratum corneum.3 Furthermore, plasma cells are present in about two-thirds of cases in the United States, with obliteration of the lumen of small vessels and perivascular histiocytes and lymphocytes with apparent cytoplasm commonly seen on pathology. Silver staining or immunostaining for Treponema pallidum may reveal the spirochetes that cause this condition.3

- Ko CJ, Srivastava B, Braverman I, et al. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus: the diagnostic utility of CD123 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:889-892. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01779.x

- Narang T, Sharma M, Gulati N, et al. Extensive hypertrophic lupus erythematosus: atypical presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:504. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.103085

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Saunders/ Elsevier; 2018.

- Melikoglu MA, Melikoglu M, Demirci E, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus- associated cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eurasian J Med. 2022;54:204-205. doi:10.5152 /eurasianjmed. 2022.21062

- Patsinakidis N, Gambichler T, Lahner N, et al. Cutaneous characteristics and association with antinuclear antibodies in 402 patients with different subtypes of lupus erythematosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:2097-2104. doi:10.1111/jdv.13769

- Kulkarni S, Kar S, Madke B, et al. A rare presentation of verrucous/ hypertrophic lupus erythematosus: a variant of cutaneous LE. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:87. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.126048

- Winkelmann RR, Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: review and assessment of treatment benefits based on Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine criteria. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-38.

- Blum FR, Sampath AJ, Foulke GT. Anifrolumab for treatment of refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:1998- 2001. doi:10.1111/ced.15335

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:E3555. doi:10.7759/cureus.3555

- Demirci GT, Altunay IK, Sarýkaya S, et al. Lupus erythematosus and lichen planus overlap syndrome: a case report with a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. Dermatol Reports. 2011 25;3:E48. doi:10.4081/dr.2011.e48

- Caldito EG, Antia C, Petronic-Rosic V. Cutaneous blastomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1064. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3151

- Ip KHK, Cheng HS, Oliver FG. Rupioid psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:859. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0451

- Trawinski H. Secondary syphilis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118:249. doi:10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0107

THE DIAGNOSIS: Hypertrophic Lupus Erythematosus

The biopsy of the face collected at the initial appointment revealed interface dermatitis with epidermal hyperplasia with no parakeratosis or eosinophils (Figure 1). Microscopic findings were suggestive of hypertrophic lupus erythematosus (HLE) or hypertrophic lichen planus. The rapid plasma reagin and HIV labs collected at the initial appointment were negative, and a review of systems was negative for systemic symptoms. Considering these results and the clinical distribution of the lesions primarily affecting sun-exposed areas of the upper body, a final diagnosis of HLE was made. The patient was counseled on the importance of photoprotection and was started on hydroxychloroquine.

Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, a rare variant of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), typically manifests as verrucous plaques or nodules commonly found on sun-exposed areas of the body, as was observed in our patient on the face, scalp (Figures 2 and 3), chest, and upper extremities.1 Lesions can have a variable appearance, from hyperkeratotic ulcers to depigmented plaques and keratoacanthomalike lesions.2 On histopathology, HLE falls into the category of lichenoid interface dermatitis and commonly demonstrates hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, follicular plugging, superficial and deep infiltrate, and increased mucin deposition in the dermis.3

Although rare, it is critical to remain vigilant for the development of squamous cell carcinoma in patients with chronic untreated CCLE. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, specifically, is the most likely variant to give rise to invasive squamous cell carcinoma and can be more aggressive as a result of this malignant transformation.3,4 Ruling out squamous cell carcinoma in the setting of HLE can be achieved by staining for CD123, as HLE commonly is associated with many CD123+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells adjacent to the epithelium, unlike squamous cell carcinoma.3 Fortunately no evidence of invasive squamous cell carcinoma, including cellular atypia or increased mitotic figures, was seen on histology in our patient.

A thorough history and physical examination are essential for screening for HLE, as positive antinuclear antibodies are observed only in half of the patients diagnosed with CCLE.5 Furthermore, antinuclear antibodies sometimes can be negative in patients with HLE who have end-stage organ involvement.

Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus can be challenging to treat. First-line therapies include antimalarials, topical steroids, and sun-protective measures. Intralesional triamcinolone injection also can be used as an adjunctive therapy to expedite the treatment response.6 Evidence supports good response following treatment with acitretin or a combination of isotretinoin and hydroxychloroquine.2 Another therapeutic strategy is implementing immunosuppressants such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine for persistent disease. Immunomodulators such as thalidomide historically have been shown to treat severe recalcitrant cases of HLE but typically are reserved for extreme cases due to adverse effects. Biologic agents such as intravenous immunoglobulins and rituximab have been shown to treat CCLE successfully, but routine use is limited due to high cost and lack of strong clinical trials.7

There have been reports of experimental therapies such as monoclonal antibodies (eg, anifrolumab and tocilizumab therapy) providing remission for patients with refractory CCLE, but information on their efficacy—specifically in patients with HLE—is lacking.8 Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus and its variants require further investigation regarding which treatment options provide the greatest benefit while minimizing adverse effects.

It is important to distinguish HLE from other potential diagnoses. Features of HLE can mimic hypertrophic lichen planus; however, the latter typically appears on the legs while HLE appears more commonly on the upper extremities and face in a photodistributed pattern.9 Since HLE has a lichenoid appearance histologically, it may appear clinically similar to hypertrophic lichen planus. Although not performed in our patient due to cost, direct immunofluorescence can aid in distinguishing HLE from hypertrophic lichen planus. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus shows a granular pattern of deposition of IgM (primarily), IgG, IgA, and C3. In contrast, hypertrophic lichen planus exhibits cytoid bodies that stain positive for IgM as well as linear deposition of fibrinogen along the basement membrane.3,10

Blastomycosis also can lead to development of verrucous plaques in sun-exposed areas, but the lesions typically originate as pustules that ulcerate over time. Lesions also can manifest with central scarring and a heaped edge.3 Unlike HLE, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with mixed infiltrate and intradermal pustules are seen in blastomycosis.3 Fungal organisms often are seen on pathology and are relatively large and uniform in size and shape, are found within giant cells, and have a thick refractile asymmetrical wall.11 In rupioid psoriasis, skin lesions mostly are widespread and are not limited to sun-exposed areas. Additionally, biopsies from active rupioid lesions typically show psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis with no interface inflammation—a key differentiator.12 In secondary syphilis, chancres often are missed and are not reported by patients. Clinically, secondary syphilis often manifests as scaly patches and plaques with palmar involvement and positive rapid plasma reagin, which was negative in our patient.13 Histologically, secondary syphilis can exhibit a vacuolar or lichenoid interface dermatitis; however, it typically exhibits slender acanthosis with long rete ridges and neutrophils in the stratum corneum.3 Furthermore, plasma cells are present in about two-thirds of cases in the United States, with obliteration of the lumen of small vessels and perivascular histiocytes and lymphocytes with apparent cytoplasm commonly seen on pathology. Silver staining or immunostaining for Treponema pallidum may reveal the spirochetes that cause this condition.3

THE DIAGNOSIS: Hypertrophic Lupus Erythematosus

The biopsy of the face collected at the initial appointment revealed interface dermatitis with epidermal hyperplasia with no parakeratosis or eosinophils (Figure 1). Microscopic findings were suggestive of hypertrophic lupus erythematosus (HLE) or hypertrophic lichen planus. The rapid plasma reagin and HIV labs collected at the initial appointment were negative, and a review of systems was negative for systemic symptoms. Considering these results and the clinical distribution of the lesions primarily affecting sun-exposed areas of the upper body, a final diagnosis of HLE was made. The patient was counseled on the importance of photoprotection and was started on hydroxychloroquine.

Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, a rare variant of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE), typically manifests as verrucous plaques or nodules commonly found on sun-exposed areas of the body, as was observed in our patient on the face, scalp (Figures 2 and 3), chest, and upper extremities.1 Lesions can have a variable appearance, from hyperkeratotic ulcers to depigmented plaques and keratoacanthomalike lesions.2 On histopathology, HLE falls into the category of lichenoid interface dermatitis and commonly demonstrates hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, follicular plugging, superficial and deep infiltrate, and increased mucin deposition in the dermis.3

Although rare, it is critical to remain vigilant for the development of squamous cell carcinoma in patients with chronic untreated CCLE. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus, specifically, is the most likely variant to give rise to invasive squamous cell carcinoma and can be more aggressive as a result of this malignant transformation.3,4 Ruling out squamous cell carcinoma in the setting of HLE can be achieved by staining for CD123, as HLE commonly is associated with many CD123+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells adjacent to the epithelium, unlike squamous cell carcinoma.3 Fortunately no evidence of invasive squamous cell carcinoma, including cellular atypia or increased mitotic figures, was seen on histology in our patient.

A thorough history and physical examination are essential for screening for HLE, as positive antinuclear antibodies are observed only in half of the patients diagnosed with CCLE.5 Furthermore, antinuclear antibodies sometimes can be negative in patients with HLE who have end-stage organ involvement.

Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus can be challenging to treat. First-line therapies include antimalarials, topical steroids, and sun-protective measures. Intralesional triamcinolone injection also can be used as an adjunctive therapy to expedite the treatment response.6 Evidence supports good response following treatment with acitretin or a combination of isotretinoin and hydroxychloroquine.2 Another therapeutic strategy is implementing immunosuppressants such as methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine for persistent disease. Immunomodulators such as thalidomide historically have been shown to treat severe recalcitrant cases of HLE but typically are reserved for extreme cases due to adverse effects. Biologic agents such as intravenous immunoglobulins and rituximab have been shown to treat CCLE successfully, but routine use is limited due to high cost and lack of strong clinical trials.7

There have been reports of experimental therapies such as monoclonal antibodies (eg, anifrolumab and tocilizumab therapy) providing remission for patients with refractory CCLE, but information on their efficacy—specifically in patients with HLE—is lacking.8 Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus and its variants require further investigation regarding which treatment options provide the greatest benefit while minimizing adverse effects.

It is important to distinguish HLE from other potential diagnoses. Features of HLE can mimic hypertrophic lichen planus; however, the latter typically appears on the legs while HLE appears more commonly on the upper extremities and face in a photodistributed pattern.9 Since HLE has a lichenoid appearance histologically, it may appear clinically similar to hypertrophic lichen planus. Although not performed in our patient due to cost, direct immunofluorescence can aid in distinguishing HLE from hypertrophic lichen planus. Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus shows a granular pattern of deposition of IgM (primarily), IgG, IgA, and C3. In contrast, hypertrophic lichen planus exhibits cytoid bodies that stain positive for IgM as well as linear deposition of fibrinogen along the basement membrane.3,10

Blastomycosis also can lead to development of verrucous plaques in sun-exposed areas, but the lesions typically originate as pustules that ulcerate over time. Lesions also can manifest with central scarring and a heaped edge.3 Unlike HLE, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with mixed infiltrate and intradermal pustules are seen in blastomycosis.3 Fungal organisms often are seen on pathology and are relatively large and uniform in size and shape, are found within giant cells, and have a thick refractile asymmetrical wall.11 In rupioid psoriasis, skin lesions mostly are widespread and are not limited to sun-exposed areas. Additionally, biopsies from active rupioid lesions typically show psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia with parakeratosis with no interface inflammation—a key differentiator.12 In secondary syphilis, chancres often are missed and are not reported by patients. Clinically, secondary syphilis often manifests as scaly patches and plaques with palmar involvement and positive rapid plasma reagin, which was negative in our patient.13 Histologically, secondary syphilis can exhibit a vacuolar or lichenoid interface dermatitis; however, it typically exhibits slender acanthosis with long rete ridges and neutrophils in the stratum corneum.3 Furthermore, plasma cells are present in about two-thirds of cases in the United States, with obliteration of the lumen of small vessels and perivascular histiocytes and lymphocytes with apparent cytoplasm commonly seen on pathology. Silver staining or immunostaining for Treponema pallidum may reveal the spirochetes that cause this condition.3

- Ko CJ, Srivastava B, Braverman I, et al. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus: the diagnostic utility of CD123 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:889-892. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01779.x

- Narang T, Sharma M, Gulati N, et al. Extensive hypertrophic lupus erythematosus: atypical presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:504. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.103085

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Saunders/ Elsevier; 2018.

- Melikoglu MA, Melikoglu M, Demirci E, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus- associated cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eurasian J Med. 2022;54:204-205. doi:10.5152 /eurasianjmed. 2022.21062

- Patsinakidis N, Gambichler T, Lahner N, et al. Cutaneous characteristics and association with antinuclear antibodies in 402 patients with different subtypes of lupus erythematosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:2097-2104. doi:10.1111/jdv.13769

- Kulkarni S, Kar S, Madke B, et al. A rare presentation of verrucous/ hypertrophic lupus erythematosus: a variant of cutaneous LE. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:87. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.126048

- Winkelmann RR, Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: review and assessment of treatment benefits based on Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine criteria. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-38.

- Blum FR, Sampath AJ, Foulke GT. Anifrolumab for treatment of refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:1998- 2001. doi:10.1111/ced.15335

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:E3555. doi:10.7759/cureus.3555

- Demirci GT, Altunay IK, Sarýkaya S, et al. Lupus erythematosus and lichen planus overlap syndrome: a case report with a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. Dermatol Reports. 2011 25;3:E48. doi:10.4081/dr.2011.e48

- Caldito EG, Antia C, Petronic-Rosic V. Cutaneous blastomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1064. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3151

- Ip KHK, Cheng HS, Oliver FG. Rupioid psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:859. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0451

- Trawinski H. Secondary syphilis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118:249. doi:10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0107

- Ko CJ, Srivastava B, Braverman I, et al. Hypertrophic lupus erythematosus: the diagnostic utility of CD123 staining. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:889-892. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2011.01779.x

- Narang T, Sharma M, Gulati N, et al. Extensive hypertrophic lupus erythematosus: atypical presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:504. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.103085

- Elston D, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Saunders/ Elsevier; 2018.

- Melikoglu MA, Melikoglu M, Demirci E, et al. Discoid lupus erythematosus- associated cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eurasian J Med. 2022;54:204-205. doi:10.5152 /eurasianjmed. 2022.21062

- Patsinakidis N, Gambichler T, Lahner N, et al. Cutaneous characteristics and association with antinuclear antibodies in 402 patients with different subtypes of lupus erythematosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:2097-2104. doi:10.1111/jdv.13769

- Kulkarni S, Kar S, Madke B, et al. A rare presentation of verrucous/ hypertrophic lupus erythematosus: a variant of cutaneous LE. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:87. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.126048

- Winkelmann RR, Kim GK, Del Rosso JQ. Treatment of cutaneous lupus erythematosus: review and assessment of treatment benefits based on Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine criteria. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-38.

- Blum FR, Sampath AJ, Foulke GT. Anifrolumab for treatment of refractory cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:1998- 2001. doi:10.1111/ced.15335

- Riahi RR, Cohen PR. Hypertrophic lichen planus mimicking verrucous lupus erythematosus. Cureus. 2018;10:E3555. doi:10.7759/cureus.3555

- Demirci GT, Altunay IK, Sarýkaya S, et al. Lupus erythematosus and lichen planus overlap syndrome: a case report with a rapid response to topical corticosteroid therapy. Dermatol Reports. 2011 25;3:E48. doi:10.4081/dr.2011.e48

- Caldito EG, Antia C, Petronic-Rosic V. Cutaneous blastomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1064. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3151

- Ip KHK, Cheng HS, Oliver FG. Rupioid psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:859. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0451

- Trawinski H. Secondary syphilis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021;118:249. doi:10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0107

Verrucous Plaques on Sun-Exposed Areas

Verrucous Plaques on Sun-Exposed Areas

A 54-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to an outpatient dermatology clinic with multiple skin lesions on sun-exposed areas including the face, chest, scalp, and bilateral upper extremities. The patient reported that he had not seen a doctor for 26 years. He noted that the lesions had been present for many years but was unsure of the exact timeframe. Physical examination revealed verrucous plaques with a violaceous rim and central hypopigmentation on the chest, scalp, face, and arms. Scarring alopecia also was noted on the scalp with no associated pain or pruritus. Antinuclear antibody and extractable nuclear antigen tests were negative, and urine analysis was normal. A shave biopsy of the chest was performed for histopathologic evaluation. Rapid plasma reagin tests and HIV antibody tests also were performed.

Cutaneous Collagenous Vasculopathy With Ocular Involvement

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

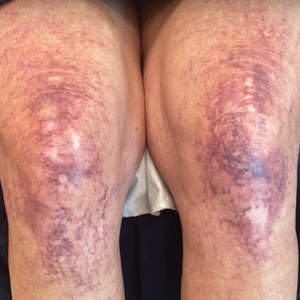

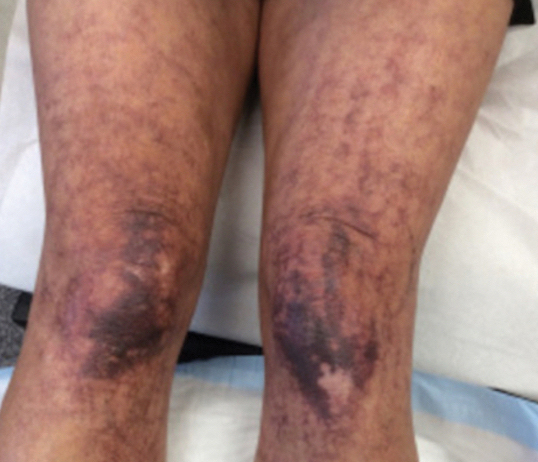

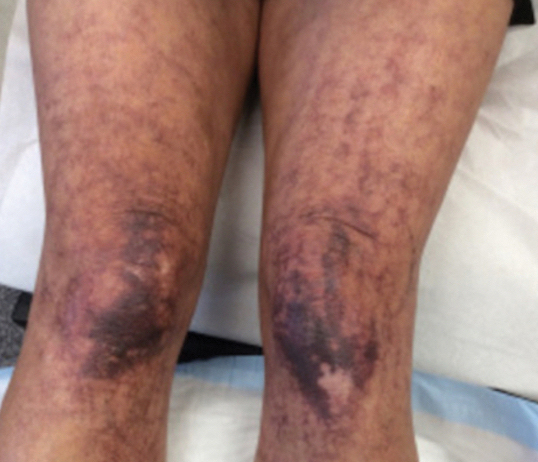

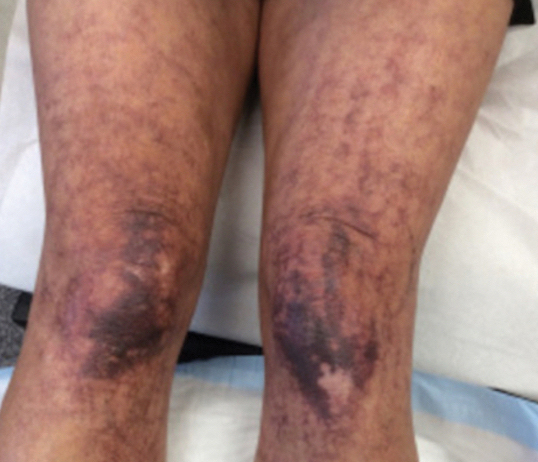

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

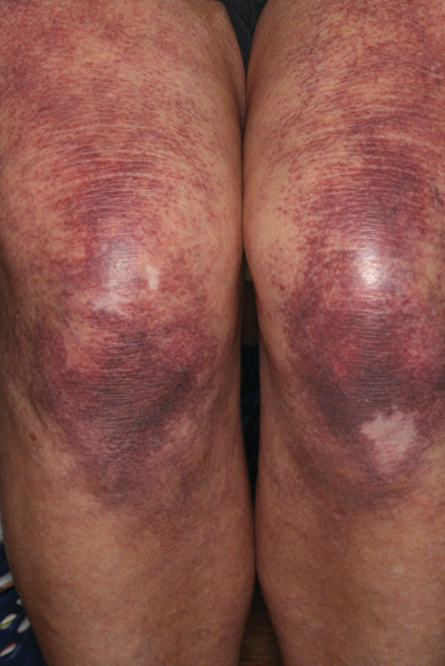

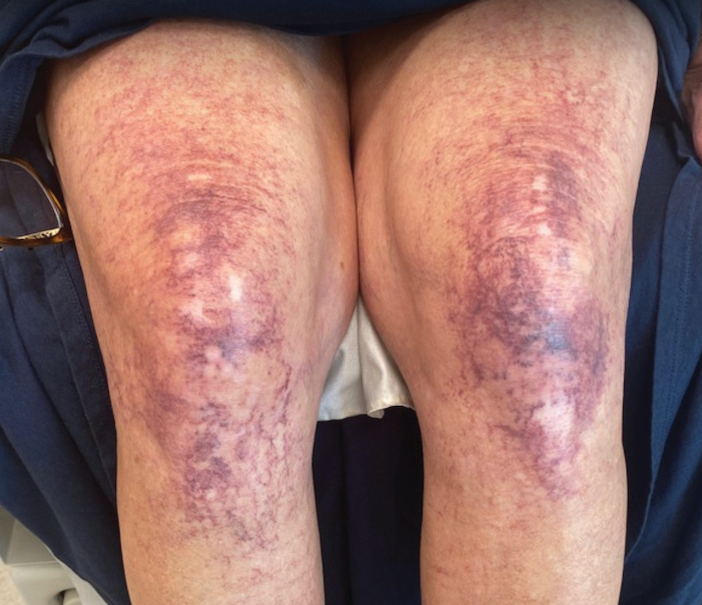

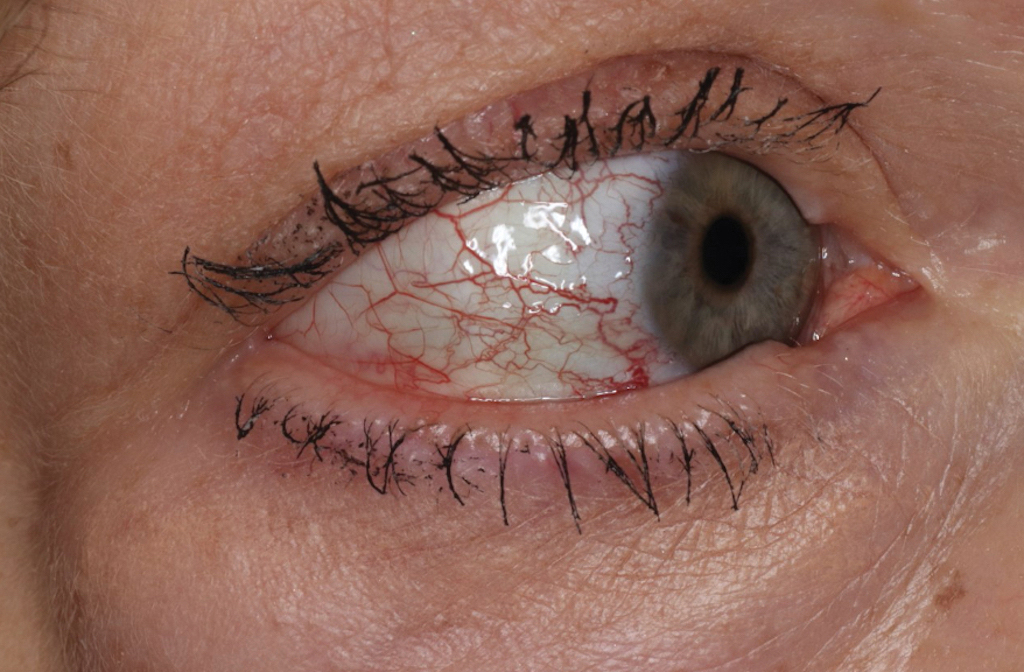

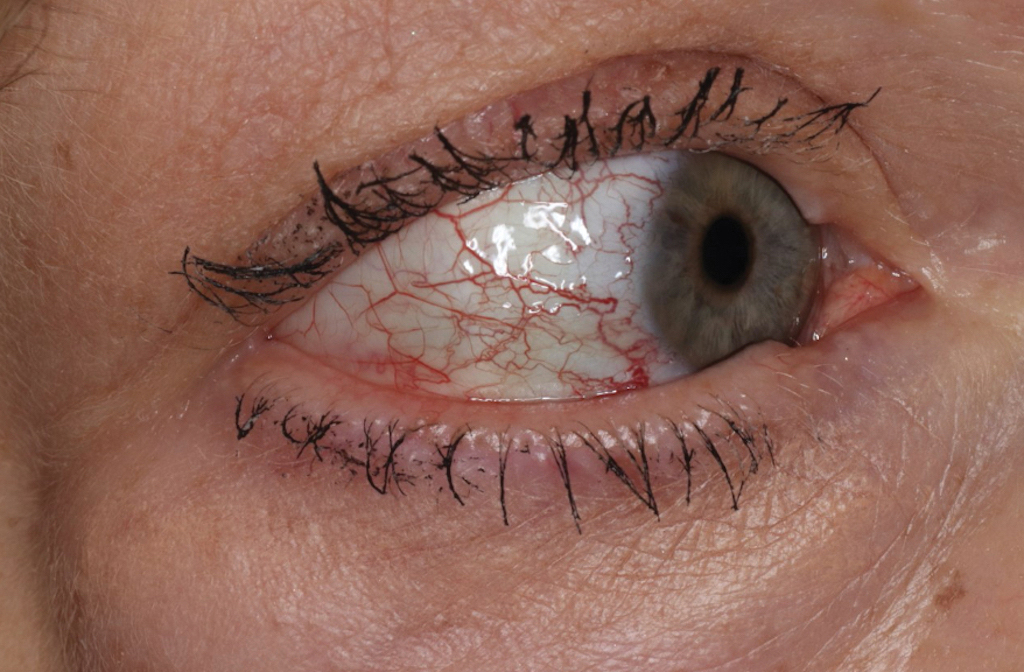

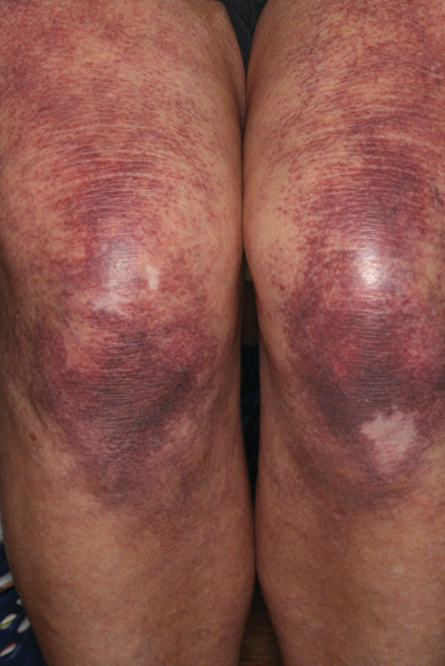

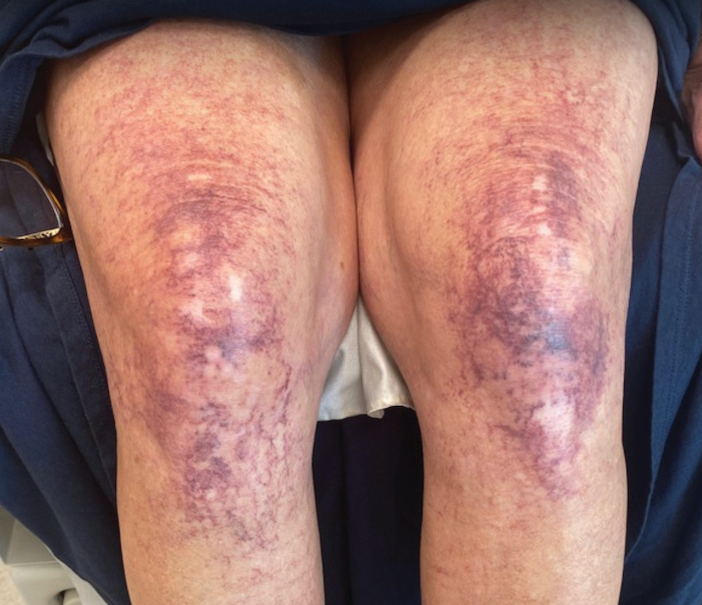

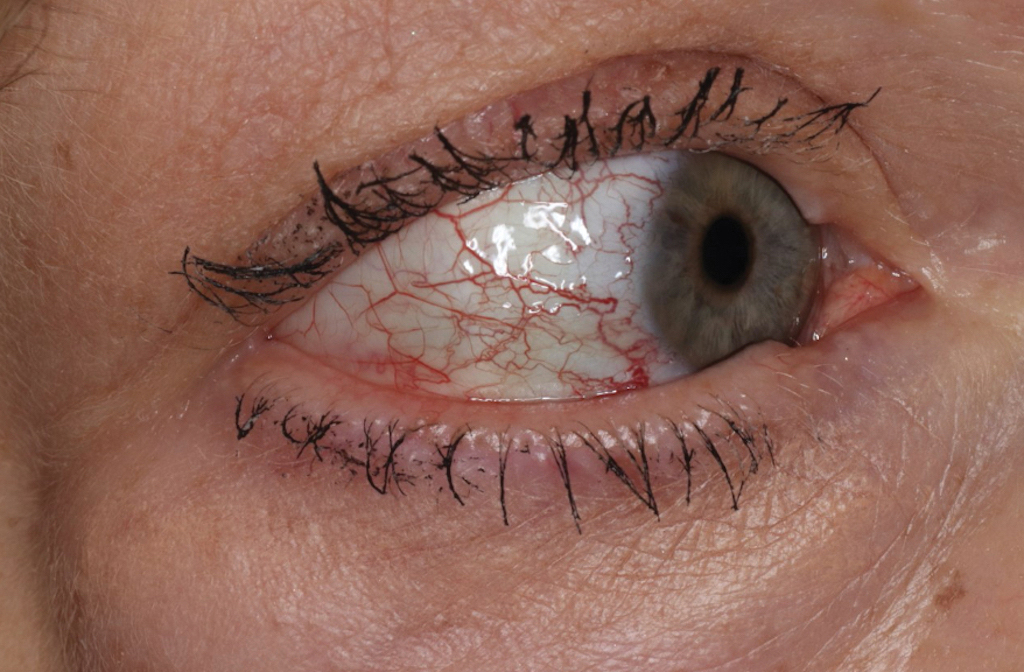

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

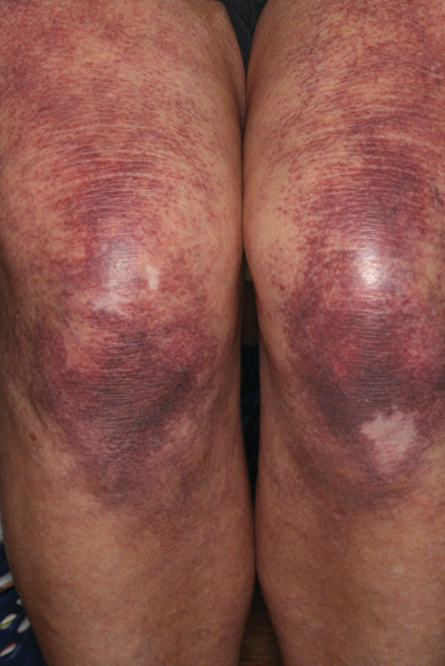

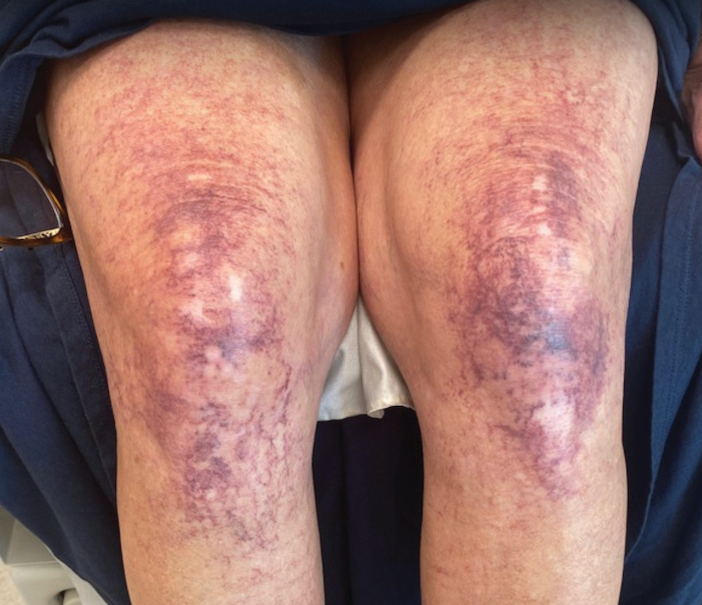

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy (CCV) is an uncommon microangiopathy that presents with progressive telangiectases on the lower extremities that can eventually spread to involve the upper extremities and trunk. Systemic involvement is uncommon. The diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy, which demonstrates dilated capillaries and postcapillary venules with eosinophilic hyalinized walls. Treatment generally has focused on the use of vascular lasers.1 We report a patient with advanced CCV and ocular involvement that responded to a combination of pulsed dye laser (PDL) therapy and sclerotherapy for cutaneous lesions.

A 63-year-old woman presented with partially blanchable, purple-black patches on the lower extremities (Figure 1). The upper extremities had minimal involvement at the time of presentation. A medical history revealed the lesions presented on the legs 10 years prior but were beginning to form on the arms. She had a history of hypertension and bleeding in the retina.

Histopathology revealed prominent dilation of postcapillary venules with eosinophilic collagenous materials in the vessel walls that was positive on periodic acid–Schiff stain, confirming the diagnosis of CCV. The perivascular collagenous material failed to stain with Congo red. Laboratory testing for serum protein electrophoresis, antinuclear antibodies, and baseline hematologic and metabolic panels revealed no abnormalities.

Over 3 years of treatment with PDL, most of the black patches resolved, but prominent telangiectatic vessels remained (Figure 2). Sclerotherapy with polidocanol (10 mg/mL) resulted in clearance of the majority of telangiectatic vessels. After each sclerotherapy treatment, Unna boots were applied for a minimum of 24 hours. The patient had no adverse effects from either PDL or sclerotherapy and was pleased with the results (Figure 3). An ophthalmologist had attributed the retinal bleeding to central serous chorioretinopathy, but tortuosity of superficial scleral and episcleral vessels progressed, suggesting CCV as the more likely cause (Figure 4). Currently, she is being followed for visual changes and further retinal bleeding.

Early CCV typically appears as blanchable pink or red macules, telangiectases, or petechiae on the lower extremities, progressing to involve the trunk and upper extremity.1-3 In rare cases, CCV presents in a papular or annular variant instead of the typical telangiectatic form.4,5 As the lesions progress, they often darken in appearance. Bleeding can occur, and the progressive patches are disfiguring.6,7 Middle-aged to older adults typically present with CCV (range, 16–83 years), with a mean age of 62 years.1,2,6 This disease affects both males and females, predominantly in White individuals.1 Extracutaneous manifestations are rare.1,2,6 One case of mucosal involvement was described in a patient with glossitis and oral erosions.8 We found no prior reports of nail or eye changes.1,2

The etiology of CCV is unknown, but different theories have been proposed. One is that CCV is due to a genetic defect that changes collagen synthesis in the cutaneous microvasculature. Another more widely held belief is that CCV originates from an injury that occurs to the microvasculature endothelial cells. Regardless of the cause of the triggering injury, the result is induced intravascular occlusive microthrombi that cause perivascular fibrosis and endothelial hyperplasia.2,6,7,9

Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy may be influenced by systemic diseases. The most common comorbidities are hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.1,3,6-8 The presentation of CCV with a malignancy is rare; 1 patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma 18 months after CCV, and another patient’s cutaneous presentation led to discovery of pancreatic cancer with metastasis.8,10 In this setting, the increased growth factors or hypercoagulability of malignancy may play a role in endothelial cell damage and hyperplasia. Autoimmune vascular injury also has been suggested to trigger CCV; 1 case involved antiribonucleoprotein antibodies, while another case involved anti–endothelial cell antibody assays.11 In addition, CCV has been reported in hypercoagulable patients, demonstrating another route for endothelial damage, with 1 patient being heterozygous for prothrombin G20210A, a report of CCV in a patient with cryofibrinogenemia, and another patient being found positive for lupus anticoagulant.11,12 Drugs also have been thought to influence CCV, including corticosteroids, lithium, thiothixene, interferon, isotretinoin, calcium channel blockers, antibiotics, hydroxyurea, and antidepressants.7,11

The diagnosis of CCV is confirmed using light microscopy and collagen-specific immunostaining. Examination shows hyaline eosinophilic deposition of type IV collagen around the affected vessels, with the postcapillary venules showing characteristic duplication of the basal lamina.3,9 The material stains positive with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson trichrome.3

Underreporting may contribute to the low incidence of CCV. The clinical presentation of CCV is similar to generalized essential telangiectasia, with biopsy distinguishing the two. Other diagnoses in the differential include hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, which typically would have mucosal involvement; radiating telangiectatic mats and a strong family history; and hereditary benign telangiectasia, which typically presents in younger patients aged 1 year to adolescence.1

Treatment with vascular lasers has been the main focus, using either the 595-nm PDL or the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser.6,13 Pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light devices can improve patient well-being1,2; intense pulsed light allows for a larger spot size and may be preferred in patients with a larger body surface area involved.13 However, a few other treatments have been proposed. One case report noted poor response to sclerotherapy.1 In another case, a patient treated with a chemotherapy agent, bortezomib, for their concurrent multiple myeloma showed notable CCV cutaneous improvement. The proposed mechanism for bortezomib improving CCV is through its antiproliferative effect on endothelial cells of the superficial dermal vessels.8 Our patient did not achieve an adequate response with PDL, but the addition of sclerotherapy with polidocanol induced a successful response.

Patients should be examined for evidence of ocular involvement and referred to an ophthalmologist for appropriate care. Although there is no definite association with systemic illnesses or mediation, recent associations with an autoimmune disorder or underlying malignancy have been noted.8,10,11 Age-appropriate cancer screening and attention to associated signs and symptoms are recommended.

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

- Brady BG, Ortleb M, Boyd AS, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:49-52. https://doi.org/10.1097/dad.0000000000000194

- Castiñeiras-Mato I, Rodríguez-Lojo R, Fernández-Díaz ML, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a case report and review of the literature. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:444-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2015.11.006

- Rambhia KD, Hadawale SD, Khopkar US. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:40-42. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5178.174327

- Conde-Ferreirós A, Roncero-Riesco M, Cañueto J, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: papular form [published online August 15, 2019]. Dermatol Online J. https://doi.org/10.5070/d3258045128

- García-Martínez P, Gomez-Martin I, Lloreta J, et al. Multiple progressive annular telangiectasias: a clinicopathological variant of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy? J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:982-985. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13029

- Sartori DS, de Almeida Jr HL, Dorn TV, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: light and transmission electron microscopy. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:211-213. https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198166

- Basso D, Ribero S, Blazek C, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a rare form of microangiopathy successfully treated with a combination of multiplex laser and optimized pulsed light with a review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232:107-111. https://doi.org/10.1159/000439126

- Dura M, Pock L, Cetkovska P, et al. A case of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with multiple myeloma and with a pathogenic variant of the glucocerebrosidase gene. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:717-721. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14227

- Salama S, Chorneyko K, Belovic B. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy associated with intravascular occlusive fibrin thrombi. J Cutan Pathol. 2014;41:386-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.12285

- Holder E, Schreckenberg C, Lipsker D. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy leading to the diagnosis of an advanced pancreatic cancer. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E699-E701. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.18152

- Grossman ME, Cohen M, Ravits M, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy: a report of three cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:491-495. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.14192

- Eldik H, Leisenring NH, Al-Rohil RN, et al. Cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy in a middle-aged woman with a history of prothrombin G20210A thrombophilia. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:679-682. https://doi.org/10.1111/cup.13895

- Weiss E, Lazzara DR. Commentary on clinical improvement of cutaneous collagenous vasculopathy with intense pulsed light therapy. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1412. https://doi.org/10.1097/DSS.0000000000003209

Practice Points

- Collagenous vasculopathy is an underrecognized entity.

- Although most patients exhibit only cutaneous disease, systemic involvement also should be assessed.

Cutaneous Eruption in an Immunocompromised Patient

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia (Figure 1A). A single spirochete was identified using immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1B). Laboratory workup revealed positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies and reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:2048. A VDRL test performed on a cerebrospinal fluid specimen also was reactive at 1:8. A diagnosis of secondary syphilis with neurologic involvement was made, and the patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G for 14 days. Following treatment, his rapid plasma reagin decreased 4-fold with an improvement in his ocular and cutaneous symptoms.

Mucocutaneus manifestations of secondary syphilis are multitudinous. As in our patient, the classic presentation is a generalized morbilliform and papulosquamous eruption involving the palms (Figure 2) and soles. Split papules at the oral commissures, mucosal patches, and condyloma lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis.1 Patchy nonscarring alopecia is not uncommon and can be the only manifestation of secondary syphilis.2 The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis vary depending on the location and type of the skin eruption. Psoriasiform or lichenoid changes commonly occur in the epidermis and dermoepidermal junction.3 The dermal inflammatory patterns that have been described include granulomatous, nodular, and superficial and deep perivascular inflammation. The infiltrate often is composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes. Reactive endothelial cells and perineural plasma cell infiltrates also are common histologic features.3,4 Spirochetes can be identified in most cases using immunohistochemical staining; however, the absence of spirochetes does not exclude syphilis.3 The sensitivity of immunohistochemical staining in secondary syphilis is reported to be 71% to 100% with a very high specificity.5 The treatment for all stages of syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, and the route of administration and duration of treatment depend on the stage of disease.6

A broad differential diagnosis must be considered when encountering skin eruptions in patients with HIV. Psoriasis usually presents as circumscribed erythematous plaques with dry and silvery scaling and a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the limbs, sacrum, scalp, and nails. Nail manifestations include distal onycholysis, irregular pitting, oil spots, salmon patches, and subungual hyperkeratosis. Alopecia occasionally may be seen within scalp lesions7; however, the constellation of alopecia with a moth-eaten appearance, subungual hyperkeratosis, papulosquamous eruption, and split papules was more suggestive of secondary syphilis in our patient. In immunocompromised patients, crusted scabies can be considered for the diagnosis of papulosquamous eruptions involving the palms and soles. It often presents with symmetric, mildly pruritic, psoriasiform dermatitis that favors acral sites, but widespread involvement can be observed.8 Areas of the scalp and face can be affected in infants, elderly patients, and immunocompromised individuals. Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in scabies.

Sarcoidosis is common in Black individuals, and similar to syphilis, it is considered a great imitator of other dermatologic diseases. Frequently, it presents as redviolaceous papules, nodules, or plaques; however, rare variants including psoriasiform, ichthyosiform, verrucous, and lichenoid skin eruptions can occur. Nail dystrophy, split papules, and alopecia also have been observed.9 Ocular involvement is common and frequently presents as uveitis.10 The pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis is noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, which also may occur in syphilitic lesions9; however, a papulosquamous eruption involving the palms and soles, positive serology, and the finding of interface lichenoid dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia confirmed the diagnosis of secondary syphilis in our patient. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare papulosquamous disorder that can be associated with HIV (type VI/HIVassociated follicular syndrome). It presents with generalized red-orange keratotic papules and often is associated with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen spinulosus.11 Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in pityriasis rubra pilaris.

This case highlights many classical findings of secondary syphilis and demonstrates that, while helpful, routine skin biopsy may not be required. Treatment should be guided by clinical presentation and serologic testing while reserving skin biopsy for equivocal cases.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:595-599.

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention [published online February 8, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

- Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.e1-718.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part II. extracutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:719.e1-730.

- Miralles E, Núñez M, De Las Heras M, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:990-993.

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia (Figure 1A). A single spirochete was identified using immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1B). Laboratory workup revealed positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies and reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:2048. A VDRL test performed on a cerebrospinal fluid specimen also was reactive at 1:8. A diagnosis of secondary syphilis with neurologic involvement was made, and the patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G for 14 days. Following treatment, his rapid plasma reagin decreased 4-fold with an improvement in his ocular and cutaneous symptoms.

Mucocutaneus manifestations of secondary syphilis are multitudinous. As in our patient, the classic presentation is a generalized morbilliform and papulosquamous eruption involving the palms (Figure 2) and soles. Split papules at the oral commissures, mucosal patches, and condyloma lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis.1 Patchy nonscarring alopecia is not uncommon and can be the only manifestation of secondary syphilis.2 The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis vary depending on the location and type of the skin eruption. Psoriasiform or lichenoid changes commonly occur in the epidermis and dermoepidermal junction.3 The dermal inflammatory patterns that have been described include granulomatous, nodular, and superficial and deep perivascular inflammation. The infiltrate often is composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes. Reactive endothelial cells and perineural plasma cell infiltrates also are common histologic features.3,4 Spirochetes can be identified in most cases using immunohistochemical staining; however, the absence of spirochetes does not exclude syphilis.3 The sensitivity of immunohistochemical staining in secondary syphilis is reported to be 71% to 100% with a very high specificity.5 The treatment for all stages of syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, and the route of administration and duration of treatment depend on the stage of disease.6

A broad differential diagnosis must be considered when encountering skin eruptions in patients with HIV. Psoriasis usually presents as circumscribed erythematous plaques with dry and silvery scaling and a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the limbs, sacrum, scalp, and nails. Nail manifestations include distal onycholysis, irregular pitting, oil spots, salmon patches, and subungual hyperkeratosis. Alopecia occasionally may be seen within scalp lesions7; however, the constellation of alopecia with a moth-eaten appearance, subungual hyperkeratosis, papulosquamous eruption, and split papules was more suggestive of secondary syphilis in our patient. In immunocompromised patients, crusted scabies can be considered for the diagnosis of papulosquamous eruptions involving the palms and soles. It often presents with symmetric, mildly pruritic, psoriasiform dermatitis that favors acral sites, but widespread involvement can be observed.8 Areas of the scalp and face can be affected in infants, elderly patients, and immunocompromised individuals. Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in scabies.

Sarcoidosis is common in Black individuals, and similar to syphilis, it is considered a great imitator of other dermatologic diseases. Frequently, it presents as redviolaceous papules, nodules, or plaques; however, rare variants including psoriasiform, ichthyosiform, verrucous, and lichenoid skin eruptions can occur. Nail dystrophy, split papules, and alopecia also have been observed.9 Ocular involvement is common and frequently presents as uveitis.10 The pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis is noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, which also may occur in syphilitic lesions9; however, a papulosquamous eruption involving the palms and soles, positive serology, and the finding of interface lichenoid dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia confirmed the diagnosis of secondary syphilis in our patient. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare papulosquamous disorder that can be associated with HIV (type VI/HIVassociated follicular syndrome). It presents with generalized red-orange keratotic papules and often is associated with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen spinulosus.11 Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in pityriasis rubra pilaris.

This case highlights many classical findings of secondary syphilis and demonstrates that, while helpful, routine skin biopsy may not be required. Treatment should be guided by clinical presentation and serologic testing while reserving skin biopsy for equivocal cases.

The Diagnosis: Secondary Syphilis

Histopathology revealed a lichenoid interface dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia (Figure 1A). A single spirochete was identified using immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1B). Laboratory workup revealed positive IgG and IgM treponemal antibodies and reactive rapid plasma reagin titer of 1:2048. A VDRL test performed on a cerebrospinal fluid specimen also was reactive at 1:8. A diagnosis of secondary syphilis with neurologic involvement was made, and the patient was treated with intravenous penicillin G for 14 days. Following treatment, his rapid plasma reagin decreased 4-fold with an improvement in his ocular and cutaneous symptoms.

Mucocutaneus manifestations of secondary syphilis are multitudinous. As in our patient, the classic presentation is a generalized morbilliform and papulosquamous eruption involving the palms (Figure 2) and soles. Split papules at the oral commissures, mucosal patches, and condyloma lata are the characteristic mucosal lesions of secondary syphilis.1 Patchy nonscarring alopecia is not uncommon and can be the only manifestation of secondary syphilis.2 The histopathologic features of secondary syphilis vary depending on the location and type of the skin eruption. Psoriasiform or lichenoid changes commonly occur in the epidermis and dermoepidermal junction.3 The dermal inflammatory patterns that have been described include granulomatous, nodular, and superficial and deep perivascular inflammation. The infiltrate often is composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histocytes. Reactive endothelial cells and perineural plasma cell infiltrates also are common histologic features.3,4 Spirochetes can be identified in most cases using immunohistochemical staining; however, the absence of spirochetes does not exclude syphilis.3 The sensitivity of immunohistochemical staining in secondary syphilis is reported to be 71% to 100% with a very high specificity.5 The treatment for all stages of syphilis is benzathine penicillin G, and the route of administration and duration of treatment depend on the stage of disease.6

A broad differential diagnosis must be considered when encountering skin eruptions in patients with HIV. Psoriasis usually presents as circumscribed erythematous plaques with dry and silvery scaling and a predilection for the extensor surfaces of the limbs, sacrum, scalp, and nails. Nail manifestations include distal onycholysis, irregular pitting, oil spots, salmon patches, and subungual hyperkeratosis. Alopecia occasionally may be seen within scalp lesions7; however, the constellation of alopecia with a moth-eaten appearance, subungual hyperkeratosis, papulosquamous eruption, and split papules was more suggestive of secondary syphilis in our patient. In immunocompromised patients, crusted scabies can be considered for the diagnosis of papulosquamous eruptions involving the palms and soles. It often presents with symmetric, mildly pruritic, psoriasiform dermatitis that favors acral sites, but widespread involvement can be observed.8 Areas of the scalp and face can be affected in infants, elderly patients, and immunocompromised individuals. Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in scabies.

Sarcoidosis is common in Black individuals, and similar to syphilis, it is considered a great imitator of other dermatologic diseases. Frequently, it presents as redviolaceous papules, nodules, or plaques; however, rare variants including psoriasiform, ichthyosiform, verrucous, and lichenoid skin eruptions can occur. Nail dystrophy, split papules, and alopecia also have been observed.9 Ocular involvement is common and frequently presents as uveitis.10 The pathologic hallmark of sarcoidosis is noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, which also may occur in syphilitic lesions9; however, a papulosquamous eruption involving the palms and soles, positive serology, and the finding of interface lichenoid dermatitis with psoriasiform hyperplasia confirmed the diagnosis of secondary syphilis in our patient. Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a rare papulosquamous disorder that can be associated with HIV (type VI/HIVassociated follicular syndrome). It presents with generalized red-orange keratotic papules and often is associated with acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and lichen spinulosus.11 Unlike in secondary syphilis, patchy alopecia, split papules, and ocular symptoms typically are not observed in pityriasis rubra pilaris.

This case highlights many classical findings of secondary syphilis and demonstrates that, while helpful, routine skin biopsy may not be required. Treatment should be guided by clinical presentation and serologic testing while reserving skin biopsy for equivocal cases.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:595-599.

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention [published online February 8, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

- Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.e1-718.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part II. extracutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:719.e1-730.

- Miralles E, Núñez M, De Las Heras M, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:990-993.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: historical aspects, microbiology, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1-14.

- Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, et al. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:1434-1441.

- Hoang MP, High WA, Molberg KH. Secondary syphilis: a histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation. J Cutan Pathol. 2004; 31:595-599.

- Flamm A, Parikh K, Xie Q, et al. Histologic features of secondary syphilis: a multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:1025-1030.

- Forrestel AK, Kovarik CL, Katz KA. Sexually acquired syphilis: laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention [published online February 8, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983-994.

- Karthikeyan K. Crusted scabies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:340-347.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.e1-718.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part II. extracutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:719.e1-730.

- Miralles E, Núñez M, De Las Heras M, et al. Pityriasis rubra pilaris and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:990-993.

A 29-year-old Black man with long-standing untreated HIV presented with mildly pruritic, scaly plaques on the palms and soles of 2 weeks’ duration. His medical history was notable for primary syphilis treated approximately 1 year prior. A review of symptoms was positive for blurry vision and floaters but negative for constitutional symptoms. Physical examination revealed well-defined scaly plaques over the palms, soles, and elbows with subungual hyperkeratosis. Patches of nonscarring alopecia over the scalp and split papules at the oral commissures also were noted. There were no palpable lymph nodes or genital involvement. Eye examination showed conjunctival injection and 20 cells per field in the vitreous humor. Laboratory evaluation revealed an HIV viral load of 31,623 copies/mL and a CD4 count of 47 cells/μL (reference range, 362–1531 cells/μL). A shave biopsy of the left elbow was performed for histopathologic evaluation.