User login

Third Universal MI Definition Unveiled

MUNICH – A new universal definition of myocardial infarction has been unveiled, sparked by the development of ever more sensitive cardiac biomarker assays and imaging techniques.

These assays, including the new high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (cTn) assays available throughout Europe and awaiting approval in the United States, have created confusion in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction because they detect small cTn elevations associated with many other clinical conditions such as heart failure, arrhythmias, and pulmonary embolism that are not MIs, but rather myocardial injury with necrosis.

"I think there has been a little bit of a problem in the past where we’ve had too many infarctions [diagnosed] ... where there is some damage or injury to the myocardial cells," said document task force cochair Dr. Kristian Thygeysen, who presented the third universal MI definition at the annual meeting of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).

The expert consensus document, developed by the ESC, American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and World Heart Federation (WHF), maintains the pathological definition of acute MI as myocardial cell death due to prolonged myocardial ischemia, but goes on to refine the definition of MI in five settings, including the controversial area of MIs associated with revascularization procedures.

MI in the PCI Setting

An MI related to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is defined as an elevation of cTn values more than five times the 99th percentile upper reference limit (URL) in the first 48 hours after a procedure in patients with normal baseline troponin values, or a rise of cTn values of more than 20% in patients with elevated baseline levels that are stable or falling.

It also requires one of the following events: symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischemia, new ischemic ECG changes, angiographic findings consistent with a procedural complication, or imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality.

In the previous 2007 document, the troponin threshold had been more than three times the 99th percentile, and was raised based on new prognostic information from long-term follow-up of patients undergoing PCI showing that there is unavoidable injury associated with the procedure, document task force codirector Dr. Joseph Alpert said during the presentation.

CABG-Related MI

Similarly, the 2012 version raises the troponin threshold for MI related to coronary artery bypass graft surgery from five times the 99th percentile URL in the 2007 document to 10 times the 99th percentile in patients with normal cTn baseline values.

It also requires one of the following: new pathological Q waves or new left bundle branch block (LBBB), angiographically documented new graft or new native coronary artery occlusion, or imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality.

Once again, the decision to raise the troponin threshold was made because there is unavoidable injury to the heart during CABG from needle sticks, handling of the heart, and the myocardial preservation procedure, said Dr. Alpert, a professor of medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

Many Sources of Heart Injury

"The problem that every clinician – not just cardiologists, but internists and surgeons – is having with these troponin tests, and particularly with the high-sensitivity test, is that it turns out we’re finding that there are lots and lots of people having heart injuries," he said in an interview. "We’ve known for decades that it’s not uncommon for a very sick patient to have liver injuries, but now we’re saying, ‘My goodness, they’re having heart injuries, and these injuries are not MIs, or at least we have no evidence there is ischemia.’ "

The updated guideline points out that novel procedures such as transcatheter aortic valve implantation or mitral clip may also cause myocardial injury with necrosis, and that "it is likely that, similarly to CABG, the more marked the elevation of the biomarker values, the worse the prognosis – but data on that are not available.&qu

Although high-sensitivity troponin assays are not yet approved in the United States, it is only a matter of time before they are and the financial battle heats up over the distinction between myocardial injury and MI, according to Dr. Alpert. The reason is that there is currently no reimbursement code for patients with myocardial injury, who require substantial time and resources that currently are not being reimbursed.

"We’re pushing to get that code, because when you have an elevated troponin it means something, and it always means something not good," he said in the interview.

Cardiac troponin (I or T) is the preferred biomarker for the definition of acute MI, although less sensitive biomarkers such as the creatine kinase-MB (CKMB) mass can still be used when cardiac troponin is not available, said Dr. Thygesen, with the department of cardiological medicine, Aarhus (Denmark) University.

The criteria for an acute MI include detection of a rise and/or fall of cardiac biomarker values exceeding the 99th percentile URL, plus at least one of the following:

• Symptoms of ischemia.

• New or presumably new significant ST-segment/T wave changes or new LBBB.

• Development of pathological Q waves in the ECG.

• Imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality.

• Identification of an intracoronary thrombus by angiography or autopsy.

The new MI definition is expected to become the gold standard for diagnosis and to be adopted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in clinical trial protocols accepted by the agency. This is significant because it will help standardize the way MI is defined in clinical trials, making comparisons between studies more meaningful, Dr. Thygesen observed.

The expert consensus document, as well as pocket versions, are available on the websites of the ESC, ACC, AHA, and World Heart Federation.

The document is also being copublished in five journals: the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, European Heart Journal, Circulation, Global Heart, and Nature Reviews of Cardiology.

Dr. Thygesen reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Alpert reported consulting for several pharmaceutical firms as well as the North American Center for Continuing Medical Education.

MUNICH – A new universal definition of myocardial infarction has been unveiled, sparked by the development of ever more sensitive cardiac biomarker assays and imaging techniques.

These assays, including the new high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (cTn) assays available throughout Europe and awaiting approval in the United States, have created confusion in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction because they detect small cTn elevations associated with many other clinical conditions such as heart failure, arrhythmias, and pulmonary embolism that are not MIs, but rather myocardial injury with necrosis.

"I think there has been a little bit of a problem in the past where we’ve had too many infarctions [diagnosed] ... where there is some damage or injury to the myocardial cells," said document task force cochair Dr. Kristian Thygeysen, who presented the third universal MI definition at the annual meeting of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).

The expert consensus document, developed by the ESC, American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and World Heart Federation (WHF), maintains the pathological definition of acute MI as myocardial cell death due to prolonged myocardial ischemia, but goes on to refine the definition of MI in five settings, including the controversial area of MIs associated with revascularization procedures.

MI in the PCI Setting

An MI related to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is defined as an elevation of cTn values more than five times the 99th percentile upper reference limit (URL) in the first 48 hours after a procedure in patients with normal baseline troponin values, or a rise of cTn values of more than 20% in patients with elevated baseline levels that are stable or falling.

It also requires one of the following events: symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischemia, new ischemic ECG changes, angiographic findings consistent with a procedural complication, or imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality.

In the previous 2007 document, the troponin threshold had been more than three times the 99th percentile, and was raised based on new prognostic information from long-term follow-up of patients undergoing PCI showing that there is unavoidable injury associated with the procedure, document task force codirector Dr. Joseph Alpert said during the presentation.

CABG-Related MI

Similarly, the 2012 version raises the troponin threshold for MI related to coronary artery bypass graft surgery from five times the 99th percentile URL in the 2007 document to 10 times the 99th percentile in patients with normal cTn baseline values.

It also requires one of the following: new pathological Q waves or new left bundle branch block (LBBB), angiographically documented new graft or new native coronary artery occlusion, or imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality.

Once again, the decision to raise the troponin threshold was made because there is unavoidable injury to the heart during CABG from needle sticks, handling of the heart, and the myocardial preservation procedure, said Dr. Alpert, a professor of medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

Many Sources of Heart Injury

"The problem that every clinician – not just cardiologists, but internists and surgeons – is having with these troponin tests, and particularly with the high-sensitivity test, is that it turns out we’re finding that there are lots and lots of people having heart injuries," he said in an interview. "We’ve known for decades that it’s not uncommon for a very sick patient to have liver injuries, but now we’re saying, ‘My goodness, they’re having heart injuries, and these injuries are not MIs, or at least we have no evidence there is ischemia.’ "

The updated guideline points out that novel procedures such as transcatheter aortic valve implantation or mitral clip may also cause myocardial injury with necrosis, and that "it is likely that, similarly to CABG, the more marked the elevation of the biomarker values, the worse the prognosis – but data on that are not available.&qu

Although high-sensitivity troponin assays are not yet approved in the United States, it is only a matter of time before they are and the financial battle heats up over the distinction between myocardial injury and MI, according to Dr. Alpert. The reason is that there is currently no reimbursement code for patients with myocardial injury, who require substantial time and resources that currently are not being reimbursed.

"We’re pushing to get that code, because when you have an elevated troponin it means something, and it always means something not good," he said in the interview.

Cardiac troponin (I or T) is the preferred biomarker for the definition of acute MI, although less sensitive biomarkers such as the creatine kinase-MB (CKMB) mass can still be used when cardiac troponin is not available, said Dr. Thygesen, with the department of cardiological medicine, Aarhus (Denmark) University.

The criteria for an acute MI include detection of a rise and/or fall of cardiac biomarker values exceeding the 99th percentile URL, plus at least one of the following:

• Symptoms of ischemia.

• New or presumably new significant ST-segment/T wave changes or new LBBB.

• Development of pathological Q waves in the ECG.

• Imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality.

• Identification of an intracoronary thrombus by angiography or autopsy.

The new MI definition is expected to become the gold standard for diagnosis and to be adopted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in clinical trial protocols accepted by the agency. This is significant because it will help standardize the way MI is defined in clinical trials, making comparisons between studies more meaningful, Dr. Thygesen observed.

The expert consensus document, as well as pocket versions, are available on the websites of the ESC, ACC, AHA, and World Heart Federation.

The document is also being copublished in five journals: the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, European Heart Journal, Circulation, Global Heart, and Nature Reviews of Cardiology.

Dr. Thygesen reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Alpert reported consulting for several pharmaceutical firms as well as the North American Center for Continuing Medical Education.

MUNICH – A new universal definition of myocardial infarction has been unveiled, sparked by the development of ever more sensitive cardiac biomarker assays and imaging techniques.

These assays, including the new high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (cTn) assays available throughout Europe and awaiting approval in the United States, have created confusion in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction because they detect small cTn elevations associated with many other clinical conditions such as heart failure, arrhythmias, and pulmonary embolism that are not MIs, but rather myocardial injury with necrosis.

"I think there has been a little bit of a problem in the past where we’ve had too many infarctions [diagnosed] ... where there is some damage or injury to the myocardial cells," said document task force cochair Dr. Kristian Thygeysen, who presented the third universal MI definition at the annual meeting of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC).

The expert consensus document, developed by the ESC, American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and World Heart Federation (WHF), maintains the pathological definition of acute MI as myocardial cell death due to prolonged myocardial ischemia, but goes on to refine the definition of MI in five settings, including the controversial area of MIs associated with revascularization procedures.

MI in the PCI Setting

An MI related to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is defined as an elevation of cTn values more than five times the 99th percentile upper reference limit (URL) in the first 48 hours after a procedure in patients with normal baseline troponin values, or a rise of cTn values of more than 20% in patients with elevated baseline levels that are stable or falling.

It also requires one of the following events: symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischemia, new ischemic ECG changes, angiographic findings consistent with a procedural complication, or imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality.

In the previous 2007 document, the troponin threshold had been more than three times the 99th percentile, and was raised based on new prognostic information from long-term follow-up of patients undergoing PCI showing that there is unavoidable injury associated with the procedure, document task force codirector Dr. Joseph Alpert said during the presentation.

CABG-Related MI

Similarly, the 2012 version raises the troponin threshold for MI related to coronary artery bypass graft surgery from five times the 99th percentile URL in the 2007 document to 10 times the 99th percentile in patients with normal cTn baseline values.

It also requires one of the following: new pathological Q waves or new left bundle branch block (LBBB), angiographically documented new graft or new native coronary artery occlusion, or imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality.

Once again, the decision to raise the troponin threshold was made because there is unavoidable injury to the heart during CABG from needle sticks, handling of the heart, and the myocardial preservation procedure, said Dr. Alpert, a professor of medicine at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

Many Sources of Heart Injury

"The problem that every clinician – not just cardiologists, but internists and surgeons – is having with these troponin tests, and particularly with the high-sensitivity test, is that it turns out we’re finding that there are lots and lots of people having heart injuries," he said in an interview. "We’ve known for decades that it’s not uncommon for a very sick patient to have liver injuries, but now we’re saying, ‘My goodness, they’re having heart injuries, and these injuries are not MIs, or at least we have no evidence there is ischemia.’ "

The updated guideline points out that novel procedures such as transcatheter aortic valve implantation or mitral clip may also cause myocardial injury with necrosis, and that "it is likely that, similarly to CABG, the more marked the elevation of the biomarker values, the worse the prognosis – but data on that are not available.&qu

Although high-sensitivity troponin assays are not yet approved in the United States, it is only a matter of time before they are and the financial battle heats up over the distinction between myocardial injury and MI, according to Dr. Alpert. The reason is that there is currently no reimbursement code for patients with myocardial injury, who require substantial time and resources that currently are not being reimbursed.

"We’re pushing to get that code, because when you have an elevated troponin it means something, and it always means something not good," he said in the interview.

Cardiac troponin (I or T) is the preferred biomarker for the definition of acute MI, although less sensitive biomarkers such as the creatine kinase-MB (CKMB) mass can still be used when cardiac troponin is not available, said Dr. Thygesen, with the department of cardiological medicine, Aarhus (Denmark) University.

The criteria for an acute MI include detection of a rise and/or fall of cardiac biomarker values exceeding the 99th percentile URL, plus at least one of the following:

• Symptoms of ischemia.

• New or presumably new significant ST-segment/T wave changes or new LBBB.

• Development of pathological Q waves in the ECG.

• Imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motion abnormality.

• Identification of an intracoronary thrombus by angiography or autopsy.

The new MI definition is expected to become the gold standard for diagnosis and to be adopted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in clinical trial protocols accepted by the agency. This is significant because it will help standardize the way MI is defined in clinical trials, making comparisons between studies more meaningful, Dr. Thygesen observed.

The expert consensus document, as well as pocket versions, are available on the websites of the ESC, ACC, AHA, and World Heart Federation.

The document is also being copublished in five journals: the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, European Heart Journal, Circulation, Global Heart, and Nature Reviews of Cardiology.

Dr. Thygesen reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Alpert reported consulting for several pharmaceutical firms as well as the North American Center for Continuing Medical Education.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF CARDIOLOGY

ESC Guidelines Tackle TAVI

MUNICH – Transcatheter aortic valve implantation should not be performed in patients at intermediate risk for surgery, according to new European guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease.

"We strongly stress that today, TAVI should not be performed in patients at intermediate risk," said task force chair Dr. Alec Vahanian of the department of cardiology at Bichat Hospital, Paris.

This is the first time that TAVI has been addressed in the guidelines, a joint collaboration between the European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery.

The use of TAVI has mushroomed in recent years among high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis and in those who are not candidates for surgery, but also has been performed in patients at lower risk.

The new guidelines update those issued in 2010, and were prompted by new evidence on risk stratification, diagnostic methods, therapeutic options, and the importance of the collaborative approach between cardiologists and cardiac surgeons, Dr. Vahanian said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"The key message – the core of the document – is to stress teamwork," he said.

The guidelines state that TAVI should be undertaken only with a multidisciplinary "heart team" including cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and other specialists, if necessary, and only in hospitals with cardiac surgery on-site.

The indications for TAVI, based on results of the randomized PARTNER trial and large European registries, include patients with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis (AS) who are not suitable for aortic valve replacement (AVR) as assessed by a heart team, and who are likely to gain improvement in their quality of life and are expected to live more than 1 year.

TAVI also should be considered in high-risk patients with severe symptomatic AS who may still be suitable for surgery, but in whom TAVI is favored by a heart team based on the individual risk profile and anatomic suitability, Dr. Vahanian said.

He reported a virtual laundry list of absolute and relative contraindications to TAVI, including an inadequate annulus size, defined as less than 10 mm or greater than 29 mm; thrombus in the left ventricle; active endocarditis; plaques with mobile thrombi in the ascending aorta or arch; inadequate vascular access for a transfemoral/subclavian approach; and a very low left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 20%.

Dr. Vahanian said AVR remains suitable for patients with severe symptomatic AS, including those undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery or surgery of the ascending aorta or another valve, as well as those who are suitable for TAVI, but in whom surgery is favored by a heart team. He observed that there was a great deal of debate among the task force members regarding surgery in symptomatic patients with low flow, low- gradient (defined as less than 40 mm Hg) aortic stenosis, and a normal ejection fraction.

"We have to be extremely cautious and treat only the patient while symptomatic and we are absolutely sure, if we can be sure, that the aortic disease is severe," he remarked.

Disclosures were not provided. The Organizing Committee assumed responsibility for ensuring that all potential conflicts of interest relevant to the program are declared to the participants.

MUNICH – Transcatheter aortic valve implantation should not be performed in patients at intermediate risk for surgery, according to new European guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease.

"We strongly stress that today, TAVI should not be performed in patients at intermediate risk," said task force chair Dr. Alec Vahanian of the department of cardiology at Bichat Hospital, Paris.

This is the first time that TAVI has been addressed in the guidelines, a joint collaboration between the European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery.

The use of TAVI has mushroomed in recent years among high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis and in those who are not candidates for surgery, but also has been performed in patients at lower risk.

The new guidelines update those issued in 2010, and were prompted by new evidence on risk stratification, diagnostic methods, therapeutic options, and the importance of the collaborative approach between cardiologists and cardiac surgeons, Dr. Vahanian said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"The key message – the core of the document – is to stress teamwork," he said.

The guidelines state that TAVI should be undertaken only with a multidisciplinary "heart team" including cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and other specialists, if necessary, and only in hospitals with cardiac surgery on-site.

The indications for TAVI, based on results of the randomized PARTNER trial and large European registries, include patients with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis (AS) who are not suitable for aortic valve replacement (AVR) as assessed by a heart team, and who are likely to gain improvement in their quality of life and are expected to live more than 1 year.

TAVI also should be considered in high-risk patients with severe symptomatic AS who may still be suitable for surgery, but in whom TAVI is favored by a heart team based on the individual risk profile and anatomic suitability, Dr. Vahanian said.

He reported a virtual laundry list of absolute and relative contraindications to TAVI, including an inadequate annulus size, defined as less than 10 mm or greater than 29 mm; thrombus in the left ventricle; active endocarditis; plaques with mobile thrombi in the ascending aorta or arch; inadequate vascular access for a transfemoral/subclavian approach; and a very low left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 20%.

Dr. Vahanian said AVR remains suitable for patients with severe symptomatic AS, including those undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery or surgery of the ascending aorta or another valve, as well as those who are suitable for TAVI, but in whom surgery is favored by a heart team. He observed that there was a great deal of debate among the task force members regarding surgery in symptomatic patients with low flow, low- gradient (defined as less than 40 mm Hg) aortic stenosis, and a normal ejection fraction.

"We have to be extremely cautious and treat only the patient while symptomatic and we are absolutely sure, if we can be sure, that the aortic disease is severe," he remarked.

Disclosures were not provided. The Organizing Committee assumed responsibility for ensuring that all potential conflicts of interest relevant to the program are declared to the participants.

MUNICH – Transcatheter aortic valve implantation should not be performed in patients at intermediate risk for surgery, according to new European guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease.

"We strongly stress that today, TAVI should not be performed in patients at intermediate risk," said task force chair Dr. Alec Vahanian of the department of cardiology at Bichat Hospital, Paris.

This is the first time that TAVI has been addressed in the guidelines, a joint collaboration between the European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery.

The use of TAVI has mushroomed in recent years among high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis and in those who are not candidates for surgery, but also has been performed in patients at lower risk.

The new guidelines update those issued in 2010, and were prompted by new evidence on risk stratification, diagnostic methods, therapeutic options, and the importance of the collaborative approach between cardiologists and cardiac surgeons, Dr. Vahanian said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

"The key message – the core of the document – is to stress teamwork," he said.

The guidelines state that TAVI should be undertaken only with a multidisciplinary "heart team" including cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and other specialists, if necessary, and only in hospitals with cardiac surgery on-site.

The indications for TAVI, based on results of the randomized PARTNER trial and large European registries, include patients with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis (AS) who are not suitable for aortic valve replacement (AVR) as assessed by a heart team, and who are likely to gain improvement in their quality of life and are expected to live more than 1 year.

TAVI also should be considered in high-risk patients with severe symptomatic AS who may still be suitable for surgery, but in whom TAVI is favored by a heart team based on the individual risk profile and anatomic suitability, Dr. Vahanian said.

He reported a virtual laundry list of absolute and relative contraindications to TAVI, including an inadequate annulus size, defined as less than 10 mm or greater than 29 mm; thrombus in the left ventricle; active endocarditis; plaques with mobile thrombi in the ascending aorta or arch; inadequate vascular access for a transfemoral/subclavian approach; and a very low left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 20%.

Dr. Vahanian said AVR remains suitable for patients with severe symptomatic AS, including those undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery or surgery of the ascending aorta or another valve, as well as those who are suitable for TAVI, but in whom surgery is favored by a heart team. He observed that there was a great deal of debate among the task force members regarding surgery in symptomatic patients with low flow, low- gradient (defined as less than 40 mm Hg) aortic stenosis, and a normal ejection fraction.

"We have to be extremely cautious and treat only the patient while symptomatic and we are absolutely sure, if we can be sure, that the aortic disease is severe," he remarked.

Disclosures were not provided. The Organizing Committee assumed responsibility for ensuring that all potential conflicts of interest relevant to the program are declared to the participants.

AT THE ANNUAL CONGRESS OF THE EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF CARDIOLOGY

Racemic Epinephrine May Be Better Option for Bronchiolitic Preemies

COVINGTON, KY. – Racemic epinephrine may be more effective in premature than in full-term infants who are hospitalized for bronchiolitis, a chart review suggests.

The positive response rate to inhaled racemic epinephrine was significantly higher at 54.3% among premature infants, compared with 28% among full-term infants (P = .003).

In contrast, there was no significant difference in documented positive response rates to albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin, Volmax, Vospire) among premature and full-term infants (43.4% vs. 38%; P = .18), Dr. Russell J. McCulloh reported in a poster at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

He said that few studies have examined the effectiveness of commonly used bronchiolitis therapies in children with a history of premature birth, even though these children are commonly affected by bronchiolitis and are at higher risk of severe outcomes and prolonged stay.

The chart review included 1,222 infants with and without a history of premature birth who were admitted for bronchiolitis to two academic medical centers. Of these, 229 (19%) were premature.

At baseline, preemies were significantly older than full-term infants (6.6 months vs. 5.4 months) and less likely to have day care exposure (15.3% vs. 24%), but more likely to have a history of wheeze (18% vs. 14%).

Premature patients had a significantly longer mean length of stay of 3.8 days compared with 2.5 days among full-term infants, although this did not differ significantly based on systemic steroid use (31% vs. 27.6%; P = .3), noted Dr. McCulloh of the pediatrics division at Rhode Island Hospital, Providence.

Premature infants were significantly more likely than full-term infants to require an ICU stay (23% vs. 11%), and they trended toward more pneumonia diagnosed (9.3% vs. 6%) and IV hydration (63% vs. 58.4%).

Full-term infants had more fever documented (45% vs. 36%) and urinary tract infections diagnosed (2.4% vs. 0%).

In logistic regression analyses, premature birth was independently associated with improved responsiveness to epinephrine (odds ratio, 1.89), Dr. McCulloh reported at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. McCulloh reported having no conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – Racemic epinephrine may be more effective in premature than in full-term infants who are hospitalized for bronchiolitis, a chart review suggests.

The positive response rate to inhaled racemic epinephrine was significantly higher at 54.3% among premature infants, compared with 28% among full-term infants (P = .003).

In contrast, there was no significant difference in documented positive response rates to albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin, Volmax, Vospire) among premature and full-term infants (43.4% vs. 38%; P = .18), Dr. Russell J. McCulloh reported in a poster at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

He said that few studies have examined the effectiveness of commonly used bronchiolitis therapies in children with a history of premature birth, even though these children are commonly affected by bronchiolitis and are at higher risk of severe outcomes and prolonged stay.

The chart review included 1,222 infants with and without a history of premature birth who were admitted for bronchiolitis to two academic medical centers. Of these, 229 (19%) were premature.

At baseline, preemies were significantly older than full-term infants (6.6 months vs. 5.4 months) and less likely to have day care exposure (15.3% vs. 24%), but more likely to have a history of wheeze (18% vs. 14%).

Premature patients had a significantly longer mean length of stay of 3.8 days compared with 2.5 days among full-term infants, although this did not differ significantly based on systemic steroid use (31% vs. 27.6%; P = .3), noted Dr. McCulloh of the pediatrics division at Rhode Island Hospital, Providence.

Premature infants were significantly more likely than full-term infants to require an ICU stay (23% vs. 11%), and they trended toward more pneumonia diagnosed (9.3% vs. 6%) and IV hydration (63% vs. 58.4%).

Full-term infants had more fever documented (45% vs. 36%) and urinary tract infections diagnosed (2.4% vs. 0%).

In logistic regression analyses, premature birth was independently associated with improved responsiveness to epinephrine (odds ratio, 1.89), Dr. McCulloh reported at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. McCulloh reported having no conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – Racemic epinephrine may be more effective in premature than in full-term infants who are hospitalized for bronchiolitis, a chart review suggests.

The positive response rate to inhaled racemic epinephrine was significantly higher at 54.3% among premature infants, compared with 28% among full-term infants (P = .003).

In contrast, there was no significant difference in documented positive response rates to albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin, Volmax, Vospire) among premature and full-term infants (43.4% vs. 38%; P = .18), Dr. Russell J. McCulloh reported in a poster at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

He said that few studies have examined the effectiveness of commonly used bronchiolitis therapies in children with a history of premature birth, even though these children are commonly affected by bronchiolitis and are at higher risk of severe outcomes and prolonged stay.

The chart review included 1,222 infants with and without a history of premature birth who were admitted for bronchiolitis to two academic medical centers. Of these, 229 (19%) were premature.

At baseline, preemies were significantly older than full-term infants (6.6 months vs. 5.4 months) and less likely to have day care exposure (15.3% vs. 24%), but more likely to have a history of wheeze (18% vs. 14%).

Premature patients had a significantly longer mean length of stay of 3.8 days compared with 2.5 days among full-term infants, although this did not differ significantly based on systemic steroid use (31% vs. 27.6%; P = .3), noted Dr. McCulloh of the pediatrics division at Rhode Island Hospital, Providence.

Premature infants were significantly more likely than full-term infants to require an ICU stay (23% vs. 11%), and they trended toward more pneumonia diagnosed (9.3% vs. 6%) and IV hydration (63% vs. 58.4%).

Full-term infants had more fever documented (45% vs. 36%) and urinary tract infections diagnosed (2.4% vs. 0%).

In logistic regression analyses, premature birth was independently associated with improved responsiveness to epinephrine (odds ratio, 1.89), Dr. McCulloh reported at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. McCulloh reported having no conflicts of interest.

AT THE PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2012 MEETING

Major Finding: The positive response rate to inhaled racemic epinephrine was 54.3% among premature infants and 28% among full-term infants.

Data Source: The data were from a chart review of 1,222 premature and full-term infants who were admitted with bronchiolitis to two children’s hospitals.

Disclosures: Dr. McCulloh reported having no conflicts of interest.

EEG Monitoring at Core of Status Epilepticus

COVINGTON, KY. – Early electroencephalogram monitoring is playing an increasingly critical role in the recognition and management of status epilepticus, the most common neurologic emergency of childhood.

EEG is important for a definitive diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (SE), particularly in children who have been in a convulsive state and in those with encephalopathy of unknown etiology or a seizure history, Dr. Rajit K. Basu of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center said at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

This view is formed in part by a recent study at his institution, in which video EEG monitoring revealed that more than one-third of children admitted for encephalopathy (35%) were in nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Almost all had convulsive seizures prior to presenting (92%) and more than half were being cared for on the floor (Pediatrics 2012;129:e748-55).

Similarly, an earlier study reported that up to 22% of children who had prolonged EEG monitoring after convulsive SE were found to be in nonconvulsive SE (Neurology 2010;74:636-42).

"These are the kids that I think really fall through the cracks for us – the ones that got a bunch of meds in the ER and are admitted to the floor for observation because they’re ‘sleepy’ or need to ‘wake up,’ " Dr. Basu said. "But you don’t know actually that they’ve recovered, and every minute that you let them go – every minute that you don’t know they’re in nonconvulsive status – is a problem."

He acknowledged that not every institution has the capacity for emergency EEG monitoring but said the idea is for clinicians to think about an EEG at 7 or 8 a.m. rather than 2 p.m.

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defined status epilepticus in 1993 as more than 30 minutes of continuous epileptic activity without complete recovery of consciousness, although more recent definitions have shortened the duration to 20, 15, or even 5 minutes of continuous seizure activity.

Essential to the management of SE is an understanding of the inciting disease and that seizures are neurotoxic, said Dr. Basu, lead for the hospital working group on management of refractory SE.

"Seizures are not a benign thing, even if you stop them," he said. "They’re a pre-status state. Your brain is on fire and that fire needs to be put out."

Multiple diagnostic algorithms for SE exist, including one by the ILAE that is expected to be revised soon, but most are center specific or user specific. The common thread, however, is that time matters, both for treatment response and outcomes.

"If you don’t act quickly, the outcome on the backside is severe," Dr. Basu said. "Even if they don’t die, which some kids unfortunately do, there is an increased incidence of epilepsy syndrome and poor neurologic recovery."

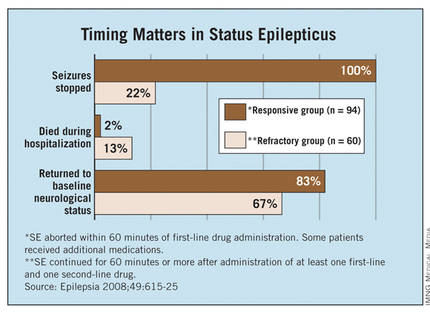

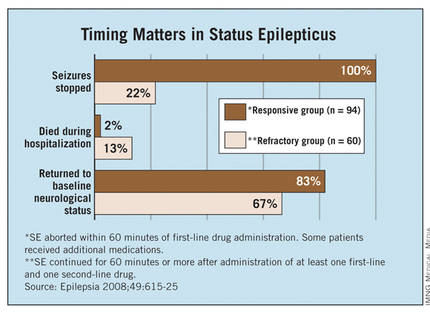

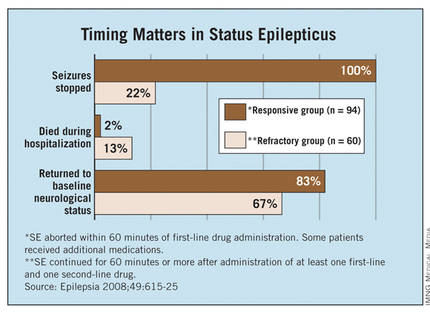

Indeed, the Mayo Clinic reported (Epilepsia 2008;49:615-25) that seizures stopped in 100% of children with SE receiving an additional second-line therapy within less than 60 minutes of the first drug, compared with only 22% of those receiving additional second-line therapy later in the clinical course. (Patients were allowed two second-line therapies before third-line treatment.)

Children in that study’s refractory SE group were significantly less likely than those treated more aggressively to return to baseline neurological status and more likely to die during hospitalization (see graph), and they had a twofold higher risk of developing a new neurological deficit or epilepsy at 4-year follow-up. (Researchers defined the refractory group as "clinical or electrographic seizures lasting longer than 60 minutes despite treatment with at least one first-line AED and one second-line AED.")

"The point is that if you follow some kind of time algorithm and deliver meds early and aggressively, you can get ahead of this and may stop status from developing," Dr. Basu said.

A continuing challenge is predicting which child presenting with SE will progress to refractory SE and likely end up in the ICU on burst suppression. To this end, Cincinnati Children’s recently launched the PARSE (Pediatric Acute Refractory Status Epilepticus) Initiative to derive a predictive model that may actually trigger a change in the "tempo" of SE management, he said.

Until predictive modeling becomes a reality, in-hospital and at-home seizure plans are being created. The London-Innsbruck Colloquium on Acute Seizures and Status Epilepticus has penned several SE protocols, with a recent review (Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011;24:165-70) detailing treatment advances since the first colloquium was held in 2007.

Hospitals are also developing at-home seizure plans that may be tailored to individual at-risk patients, featuring a red, yellow, and green light system similar to that used in at-home asthma action plans. Parents may understand the idea of giving rectal diazepam (Valium, Valrelease) at home, but such remote plans can help address questions such as when a second therapy should be delivered, the correct dosing of benzodiazepines, or when to come to the hospital, Dr. Basu said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. Basu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EEG, nonconvulsive status epilepticus in children, seizures, Dr. Rajit K. Basu, Pediatric Hospital Medicine, convulsive seizures, prolonged EEG monitoring, The International League Against Epilepsy, ILAE,

COVINGTON, KY. – Early electroencephalogram monitoring is playing an increasingly critical role in the recognition and management of status epilepticus, the most common neurologic emergency of childhood.

EEG is important for a definitive diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (SE), particularly in children who have been in a convulsive state and in those with encephalopathy of unknown etiology or a seizure history, Dr. Rajit K. Basu of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center said at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

This view is formed in part by a recent study at his institution, in which video EEG monitoring revealed that more than one-third of children admitted for encephalopathy (35%) were in nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Almost all had convulsive seizures prior to presenting (92%) and more than half were being cared for on the floor (Pediatrics 2012;129:e748-55).

Similarly, an earlier study reported that up to 22% of children who had prolonged EEG monitoring after convulsive SE were found to be in nonconvulsive SE (Neurology 2010;74:636-42).

"These are the kids that I think really fall through the cracks for us – the ones that got a bunch of meds in the ER and are admitted to the floor for observation because they’re ‘sleepy’ or need to ‘wake up,’ " Dr. Basu said. "But you don’t know actually that they’ve recovered, and every minute that you let them go – every minute that you don’t know they’re in nonconvulsive status – is a problem."

He acknowledged that not every institution has the capacity for emergency EEG monitoring but said the idea is for clinicians to think about an EEG at 7 or 8 a.m. rather than 2 p.m.

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defined status epilepticus in 1993 as more than 30 minutes of continuous epileptic activity without complete recovery of consciousness, although more recent definitions have shortened the duration to 20, 15, or even 5 minutes of continuous seizure activity.

Essential to the management of SE is an understanding of the inciting disease and that seizures are neurotoxic, said Dr. Basu, lead for the hospital working group on management of refractory SE.

"Seizures are not a benign thing, even if you stop them," he said. "They’re a pre-status state. Your brain is on fire and that fire needs to be put out."

Multiple diagnostic algorithms for SE exist, including one by the ILAE that is expected to be revised soon, but most are center specific or user specific. The common thread, however, is that time matters, both for treatment response and outcomes.

"If you don’t act quickly, the outcome on the backside is severe," Dr. Basu said. "Even if they don’t die, which some kids unfortunately do, there is an increased incidence of epilepsy syndrome and poor neurologic recovery."

Indeed, the Mayo Clinic reported (Epilepsia 2008;49:615-25) that seizures stopped in 100% of children with SE receiving an additional second-line therapy within less than 60 minutes of the first drug, compared with only 22% of those receiving additional second-line therapy later in the clinical course. (Patients were allowed two second-line therapies before third-line treatment.)

Children in that study’s refractory SE group were significantly less likely than those treated more aggressively to return to baseline neurological status and more likely to die during hospitalization (see graph), and they had a twofold higher risk of developing a new neurological deficit or epilepsy at 4-year follow-up. (Researchers defined the refractory group as "clinical or electrographic seizures lasting longer than 60 minutes despite treatment with at least one first-line AED and one second-line AED.")

"The point is that if you follow some kind of time algorithm and deliver meds early and aggressively, you can get ahead of this and may stop status from developing," Dr. Basu said.

A continuing challenge is predicting which child presenting with SE will progress to refractory SE and likely end up in the ICU on burst suppression. To this end, Cincinnati Children’s recently launched the PARSE (Pediatric Acute Refractory Status Epilepticus) Initiative to derive a predictive model that may actually trigger a change in the "tempo" of SE management, he said.

Until predictive modeling becomes a reality, in-hospital and at-home seizure plans are being created. The London-Innsbruck Colloquium on Acute Seizures and Status Epilepticus has penned several SE protocols, with a recent review (Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011;24:165-70) detailing treatment advances since the first colloquium was held in 2007.

Hospitals are also developing at-home seizure plans that may be tailored to individual at-risk patients, featuring a red, yellow, and green light system similar to that used in at-home asthma action plans. Parents may understand the idea of giving rectal diazepam (Valium, Valrelease) at home, but such remote plans can help address questions such as when a second therapy should be delivered, the correct dosing of benzodiazepines, or when to come to the hospital, Dr. Basu said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. Basu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – Early electroencephalogram monitoring is playing an increasingly critical role in the recognition and management of status epilepticus, the most common neurologic emergency of childhood.

EEG is important for a definitive diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus (SE), particularly in children who have been in a convulsive state and in those with encephalopathy of unknown etiology or a seizure history, Dr. Rajit K. Basu of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center said at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting.

This view is formed in part by a recent study at his institution, in which video EEG monitoring revealed that more than one-third of children admitted for encephalopathy (35%) were in nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Almost all had convulsive seizures prior to presenting (92%) and more than half were being cared for on the floor (Pediatrics 2012;129:e748-55).

Similarly, an earlier study reported that up to 22% of children who had prolonged EEG monitoring after convulsive SE were found to be in nonconvulsive SE (Neurology 2010;74:636-42).

"These are the kids that I think really fall through the cracks for us – the ones that got a bunch of meds in the ER and are admitted to the floor for observation because they’re ‘sleepy’ or need to ‘wake up,’ " Dr. Basu said. "But you don’t know actually that they’ve recovered, and every minute that you let them go – every minute that you don’t know they’re in nonconvulsive status – is a problem."

He acknowledged that not every institution has the capacity for emergency EEG monitoring but said the idea is for clinicians to think about an EEG at 7 or 8 a.m. rather than 2 p.m.

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defined status epilepticus in 1993 as more than 30 minutes of continuous epileptic activity without complete recovery of consciousness, although more recent definitions have shortened the duration to 20, 15, or even 5 minutes of continuous seizure activity.

Essential to the management of SE is an understanding of the inciting disease and that seizures are neurotoxic, said Dr. Basu, lead for the hospital working group on management of refractory SE.

"Seizures are not a benign thing, even if you stop them," he said. "They’re a pre-status state. Your brain is on fire and that fire needs to be put out."

Multiple diagnostic algorithms for SE exist, including one by the ILAE that is expected to be revised soon, but most are center specific or user specific. The common thread, however, is that time matters, both for treatment response and outcomes.

"If you don’t act quickly, the outcome on the backside is severe," Dr. Basu said. "Even if they don’t die, which some kids unfortunately do, there is an increased incidence of epilepsy syndrome and poor neurologic recovery."

Indeed, the Mayo Clinic reported (Epilepsia 2008;49:615-25) that seizures stopped in 100% of children with SE receiving an additional second-line therapy within less than 60 minutes of the first drug, compared with only 22% of those receiving additional second-line therapy later in the clinical course. (Patients were allowed two second-line therapies before third-line treatment.)

Children in that study’s refractory SE group were significantly less likely than those treated more aggressively to return to baseline neurological status and more likely to die during hospitalization (see graph), and they had a twofold higher risk of developing a new neurological deficit or epilepsy at 4-year follow-up. (Researchers defined the refractory group as "clinical or electrographic seizures lasting longer than 60 minutes despite treatment with at least one first-line AED and one second-line AED.")

"The point is that if you follow some kind of time algorithm and deliver meds early and aggressively, you can get ahead of this and may stop status from developing," Dr. Basu said.

A continuing challenge is predicting which child presenting with SE will progress to refractory SE and likely end up in the ICU on burst suppression. To this end, Cincinnati Children’s recently launched the PARSE (Pediatric Acute Refractory Status Epilepticus) Initiative to derive a predictive model that may actually trigger a change in the "tempo" of SE management, he said.

Until predictive modeling becomes a reality, in-hospital and at-home seizure plans are being created. The London-Innsbruck Colloquium on Acute Seizures and Status Epilepticus has penned several SE protocols, with a recent review (Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011;24:165-70) detailing treatment advances since the first colloquium was held in 2007.

Hospitals are also developing at-home seizure plans that may be tailored to individual at-risk patients, featuring a red, yellow, and green light system similar to that used in at-home asthma action plans. Parents may understand the idea of giving rectal diazepam (Valium, Valrelease) at home, but such remote plans can help address questions such as when a second therapy should be delivered, the correct dosing of benzodiazepines, or when to come to the hospital, Dr. Basu said at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Dr. Basu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EEG, nonconvulsive status epilepticus in children, seizures, Dr. Rajit K. Basu, Pediatric Hospital Medicine, convulsive seizures, prolonged EEG monitoring, The International League Against Epilepsy, ILAE,

EEG, nonconvulsive status epilepticus in children, seizures, Dr. Rajit K. Basu, Pediatric Hospital Medicine, convulsive seizures, prolonged EEG monitoring, The International League Against Epilepsy, ILAE,

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2012 MEETING

No Easy Answers as Quality Measures for Pediatric Readmissions Loom

COVINGTON, KY. – A healthy 2-year-old is admitted for incision and drainage of a MRSA thigh abscess and is given intravenous clindamycin during a 1-day hospital stay before being discharged home with a prescription for oral clindamycin.

The child refuses to take the clindamycin at home, and is readmitted 3 days later with a new abscess on her arm that requires a 2-day hospital stay.

Was this readmission preventable?

Some attendees at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting thought it was out of the hospital’s hands, while others suggested the hospital was at fault because clindamycin is such an unpalatable medication that an oral dose should have been given at the hospital, along with instructions for how to make it more palatable at home.

The scenario is part of the ongoing Vanderbilt Readmissions Project, which seeks to identify patient and hospitalization characteristics of 15-day readmissions in children, create a 5-point "preventability scale" for early pediatric readmissions that can be applied by multiple reviewers, and institute measures to decrease potentially preventable readmissions.

What the investigators have found so far is that, even after reviewing the same clinical information for 200 pediatric readmissions, a panel of four knowledgeable pediatricians gave exactly the same ratings in 37.5% of cases, Dr. James C. Gay said. There was 94% agreement on planned readmissions (47/50 cases), but only 19% agreement on unplanned readmissions (28/150).

"Further studies are needed to develop concrete rules for assessing preventability that can be applied reproducibly by multiple reviewers in multiple types of readmissions," he said.

The Vanderbilt findings have financial implications for hospitals, as the federal government has already taken to heart the issue of preventable readmissions following the sentinel article reporting that 19.6% of Medicare beneficiaries were readmitted within 30 days at a cost of $17.4 billion in 2004 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1418-28). Many of these readmissions were thought to be avoidable by improvements in care and the discharge planning processes during the initial hospitalization.

The Affordable Care Act has also taken up the issue, and beginning Oct. 1, 2012, prospective payment system (PPS) hospitals will experience decreased Medicare payments for three index admissions – myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia – with "higher than expected" 30-day readmissions, coauthor Dr. Paul Hain explained at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will calculate hospitals’ actual readmissions, excluding planned readmissions and readmissions unrelated to the index admission, and then compare these to hospitals’ expected readmission rates. Hospitals with "higher than expected" rates will be required to pay back the payments they’ve received for readmissions deemed to be excessive.

Beginning in 2015, the CMS may expand the list of conditions to include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and several cardiac and vascular surgical procedures, he said. Similar penalties are likely to befall children’s hospitals, as rules that start in Medicare trickle down to Medicaid in 3-5 years.

Part of the problem is that researchers have yet to identify what can reliably drive down adult or pediatric readmissions or even determine whether the readmission interval should be 3, 7, 15, 60, 90, 365, or 30 days, as the CMS uses.

"We looked at 30 days, and the noise that comes in is incredible," said Dr. Hain, now with Children’s Medical Center, Dallas. Ultimately, the researchers chose 15 days for their analyses because of the intuitively greater relationship to events in the index hospitalization.

Based on 4-year data from Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tenn., the 15-day readmission rate among non-newborns was 9.6% in 2007, 9.6% in 2008, 8.8% in 2009, and 8.9% in 2010; and among newborns, the rates were 2.5%, 3.2%, 2.5%, and 3.0%, respectively.

The first real global study of pediatric readmissions reported that 16.7% of patients between 2 and 18 years old at 38 U.S. children’s hospitals were readmitted within 365 days, and that readmissions were strongly associated with any complex chronic condition, female gender, older age, black race, public insurance coverage, longer length of stay during the initial admission, and number of previous admissions (Pediatrics 2009;123:286-93).

One year later, the same group reported that the likelihood of readmission among children aged 2-18 years actually increased as a states’ health system performance ranking improved (J. Pediatr. 2010;157:98-102.e1), observed Dr. Gay of the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

Similarly vexing results have been observed among adults. The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., recently reported that general medicine patients with a documented follow-up appointment were slightly more likely to have a hospital readmission, make an emergency department visit, or die within 180 days after discharge than those without an appointment (Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170:955-60).

In the Vanderbilt cohort, the final expert consensus was that 40 early readmissions (20%) were more likely preventable (ratings 4 and 5). Nearly half of these were central venous catheter infections or ventriculo-peritoneal shunt malfunctions in children with serious chronic illnesses.

Extrapolating these results, about 1.7% of all hospital admissions would have a significant degree of preventability, Dr. Gay said. In absolute terms, about 250 admissions per year, or less than one admission per day, would be preventable at the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

"With 80% of readmissions planned or likely not preventable, it seems unreasonable to believe that pediatric readmissions are associated with substandard inpatient care, calling into question the validity of an all-cause readmission rate as a quality measure," he said. "If the responsibility for pediatric readmissions is placed on the hospital, then realistic benchmarks should be established."

Dr. Gay said more data is also needed from across the country, with some of that information trickling in from the recent Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. Various investigators reported that there was no relationship between length of stay and pediatric readmissions; 30-day readmission rates were low at 2%-8% in the top 10 APR-DRG (All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups) hospitals; and significant variability exists in readmission rates across hospitals for 10 of the top 30 APR-DRG index admissions.

"This may be where we need to hone our efforts," Dr. Gay said. "If there’s variability, there may be a reason for that variability that we can have an impact on."

Dr. Gay reported funding support for medical consulting for the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions. Dr. Hain reported no conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – A healthy 2-year-old is admitted for incision and drainage of a MRSA thigh abscess and is given intravenous clindamycin during a 1-day hospital stay before being discharged home with a prescription for oral clindamycin.

The child refuses to take the clindamycin at home, and is readmitted 3 days later with a new abscess on her arm that requires a 2-day hospital stay.

Was this readmission preventable?

Some attendees at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting thought it was out of the hospital’s hands, while others suggested the hospital was at fault because clindamycin is such an unpalatable medication that an oral dose should have been given at the hospital, along with instructions for how to make it more palatable at home.

The scenario is part of the ongoing Vanderbilt Readmissions Project, which seeks to identify patient and hospitalization characteristics of 15-day readmissions in children, create a 5-point "preventability scale" for early pediatric readmissions that can be applied by multiple reviewers, and institute measures to decrease potentially preventable readmissions.

What the investigators have found so far is that, even after reviewing the same clinical information for 200 pediatric readmissions, a panel of four knowledgeable pediatricians gave exactly the same ratings in 37.5% of cases, Dr. James C. Gay said. There was 94% agreement on planned readmissions (47/50 cases), but only 19% agreement on unplanned readmissions (28/150).

"Further studies are needed to develop concrete rules for assessing preventability that can be applied reproducibly by multiple reviewers in multiple types of readmissions," he said.

The Vanderbilt findings have financial implications for hospitals, as the federal government has already taken to heart the issue of preventable readmissions following the sentinel article reporting that 19.6% of Medicare beneficiaries were readmitted within 30 days at a cost of $17.4 billion in 2004 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1418-28). Many of these readmissions were thought to be avoidable by improvements in care and the discharge planning processes during the initial hospitalization.

The Affordable Care Act has also taken up the issue, and beginning Oct. 1, 2012, prospective payment system (PPS) hospitals will experience decreased Medicare payments for three index admissions – myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia – with "higher than expected" 30-day readmissions, coauthor Dr. Paul Hain explained at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will calculate hospitals’ actual readmissions, excluding planned readmissions and readmissions unrelated to the index admission, and then compare these to hospitals’ expected readmission rates. Hospitals with "higher than expected" rates will be required to pay back the payments they’ve received for readmissions deemed to be excessive.

Beginning in 2015, the CMS may expand the list of conditions to include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and several cardiac and vascular surgical procedures, he said. Similar penalties are likely to befall children’s hospitals, as rules that start in Medicare trickle down to Medicaid in 3-5 years.

Part of the problem is that researchers have yet to identify what can reliably drive down adult or pediatric readmissions or even determine whether the readmission interval should be 3, 7, 15, 60, 90, 365, or 30 days, as the CMS uses.

"We looked at 30 days, and the noise that comes in is incredible," said Dr. Hain, now with Children’s Medical Center, Dallas. Ultimately, the researchers chose 15 days for their analyses because of the intuitively greater relationship to events in the index hospitalization.

Based on 4-year data from Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tenn., the 15-day readmission rate among non-newborns was 9.6% in 2007, 9.6% in 2008, 8.8% in 2009, and 8.9% in 2010; and among newborns, the rates were 2.5%, 3.2%, 2.5%, and 3.0%, respectively.

The first real global study of pediatric readmissions reported that 16.7% of patients between 2 and 18 years old at 38 U.S. children’s hospitals were readmitted within 365 days, and that readmissions were strongly associated with any complex chronic condition, female gender, older age, black race, public insurance coverage, longer length of stay during the initial admission, and number of previous admissions (Pediatrics 2009;123:286-93).

One year later, the same group reported that the likelihood of readmission among children aged 2-18 years actually increased as a states’ health system performance ranking improved (J. Pediatr. 2010;157:98-102.e1), observed Dr. Gay of the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

Similarly vexing results have been observed among adults. The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., recently reported that general medicine patients with a documented follow-up appointment were slightly more likely to have a hospital readmission, make an emergency department visit, or die within 180 days after discharge than those without an appointment (Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170:955-60).

In the Vanderbilt cohort, the final expert consensus was that 40 early readmissions (20%) were more likely preventable (ratings 4 and 5). Nearly half of these were central venous catheter infections or ventriculo-peritoneal shunt malfunctions in children with serious chronic illnesses.

Extrapolating these results, about 1.7% of all hospital admissions would have a significant degree of preventability, Dr. Gay said. In absolute terms, about 250 admissions per year, or less than one admission per day, would be preventable at the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

"With 80% of readmissions planned or likely not preventable, it seems unreasonable to believe that pediatric readmissions are associated with substandard inpatient care, calling into question the validity of an all-cause readmission rate as a quality measure," he said. "If the responsibility for pediatric readmissions is placed on the hospital, then realistic benchmarks should be established."

Dr. Gay said more data is also needed from across the country, with some of that information trickling in from the recent Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. Various investigators reported that there was no relationship between length of stay and pediatric readmissions; 30-day readmission rates were low at 2%-8% in the top 10 APR-DRG (All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups) hospitals; and significant variability exists in readmission rates across hospitals for 10 of the top 30 APR-DRG index admissions.

"This may be where we need to hone our efforts," Dr. Gay said. "If there’s variability, there may be a reason for that variability that we can have an impact on."

Dr. Gay reported funding support for medical consulting for the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions. Dr. Hain reported no conflicts of interest.

COVINGTON, KY. – A healthy 2-year-old is admitted for incision and drainage of a MRSA thigh abscess and is given intravenous clindamycin during a 1-day hospital stay before being discharged home with a prescription for oral clindamycin.

The child refuses to take the clindamycin at home, and is readmitted 3 days later with a new abscess on her arm that requires a 2-day hospital stay.

Was this readmission preventable?

Some attendees at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012 meeting thought it was out of the hospital’s hands, while others suggested the hospital was at fault because clindamycin is such an unpalatable medication that an oral dose should have been given at the hospital, along with instructions for how to make it more palatable at home.

The scenario is part of the ongoing Vanderbilt Readmissions Project, which seeks to identify patient and hospitalization characteristics of 15-day readmissions in children, create a 5-point "preventability scale" for early pediatric readmissions that can be applied by multiple reviewers, and institute measures to decrease potentially preventable readmissions.

What the investigators have found so far is that, even after reviewing the same clinical information for 200 pediatric readmissions, a panel of four knowledgeable pediatricians gave exactly the same ratings in 37.5% of cases, Dr. James C. Gay said. There was 94% agreement on planned readmissions (47/50 cases), but only 19% agreement on unplanned readmissions (28/150).

"Further studies are needed to develop concrete rules for assessing preventability that can be applied reproducibly by multiple reviewers in multiple types of readmissions," he said.

The Vanderbilt findings have financial implications for hospitals, as the federal government has already taken to heart the issue of preventable readmissions following the sentinel article reporting that 19.6% of Medicare beneficiaries were readmitted within 30 days at a cost of $17.4 billion in 2004 (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1418-28). Many of these readmissions were thought to be avoidable by improvements in care and the discharge planning processes during the initial hospitalization.

The Affordable Care Act has also taken up the issue, and beginning Oct. 1, 2012, prospective payment system (PPS) hospitals will experience decreased Medicare payments for three index admissions – myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia – with "higher than expected" 30-day readmissions, coauthor Dr. Paul Hain explained at the meeting, which was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will calculate hospitals’ actual readmissions, excluding planned readmissions and readmissions unrelated to the index admission, and then compare these to hospitals’ expected readmission rates. Hospitals with "higher than expected" rates will be required to pay back the payments they’ve received for readmissions deemed to be excessive.

Beginning in 2015, the CMS may expand the list of conditions to include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and several cardiac and vascular surgical procedures, he said. Similar penalties are likely to befall children’s hospitals, as rules that start in Medicare trickle down to Medicaid in 3-5 years.

Part of the problem is that researchers have yet to identify what can reliably drive down adult or pediatric readmissions or even determine whether the readmission interval should be 3, 7, 15, 60, 90, 365, or 30 days, as the CMS uses.

"We looked at 30 days, and the noise that comes in is incredible," said Dr. Hain, now with Children’s Medical Center, Dallas. Ultimately, the researchers chose 15 days for their analyses because of the intuitively greater relationship to events in the index hospitalization.

Based on 4-year data from Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tenn., the 15-day readmission rate among non-newborns was 9.6% in 2007, 9.6% in 2008, 8.8% in 2009, and 8.9% in 2010; and among newborns, the rates were 2.5%, 3.2%, 2.5%, and 3.0%, respectively.

The first real global study of pediatric readmissions reported that 16.7% of patients between 2 and 18 years old at 38 U.S. children’s hospitals were readmitted within 365 days, and that readmissions were strongly associated with any complex chronic condition, female gender, older age, black race, public insurance coverage, longer length of stay during the initial admission, and number of previous admissions (Pediatrics 2009;123:286-93).

One year later, the same group reported that the likelihood of readmission among children aged 2-18 years actually increased as a states’ health system performance ranking improved (J. Pediatr. 2010;157:98-102.e1), observed Dr. Gay of the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

Similarly vexing results have been observed among adults. The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., recently reported that general medicine patients with a documented follow-up appointment were slightly more likely to have a hospital readmission, make an emergency department visit, or die within 180 days after discharge than those without an appointment (Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170:955-60).

In the Vanderbilt cohort, the final expert consensus was that 40 early readmissions (20%) were more likely preventable (ratings 4 and 5). Nearly half of these were central venous catheter infections or ventriculo-peritoneal shunt malfunctions in children with serious chronic illnesses.

Extrapolating these results, about 1.7% of all hospital admissions would have a significant degree of preventability, Dr. Gay said. In absolute terms, about 250 admissions per year, or less than one admission per day, would be preventable at the Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt.

"With 80% of readmissions planned or likely not preventable, it seems unreasonable to believe that pediatric readmissions are associated with substandard inpatient care, calling into question the validity of an all-cause readmission rate as a quality measure," he said. "If the responsibility for pediatric readmissions is placed on the hospital, then realistic benchmarks should be established."

Dr. Gay said more data is also needed from across the country, with some of that information trickling in from the recent Pediatric Academic Societies meeting. Various investigators reported that there was no relationship between length of stay and pediatric readmissions; 30-day readmission rates were low at 2%-8% in the top 10 APR-DRG (All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups) hospitals; and significant variability exists in readmission rates across hospitals for 10 of the top 30 APR-DRG index admissions.

"This may be where we need to hone our efforts," Dr. Gay said. "If there’s variability, there may be a reason for that variability that we can have an impact on."

Dr. Gay reported funding support for medical consulting for the National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions. Dr. Hain reported no conflicts of interest.

AT THE PEDIATRIC HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2012 MEETING

Think Urine When Testing for Concurrent Infection in Pediatric Bronchiolitis

COVINGTON, KY. – Providers continue to rely on blood cultures to detect serious bacterial infections in children with bronchiolitis, even though urinary tract infections are the most common culprit, a chart review shows.

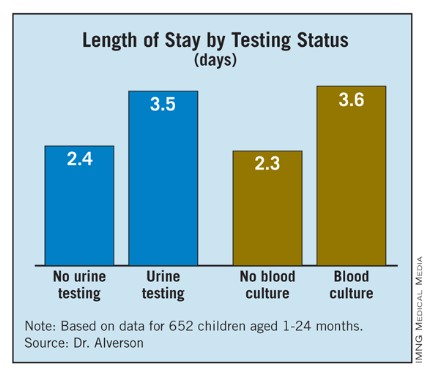

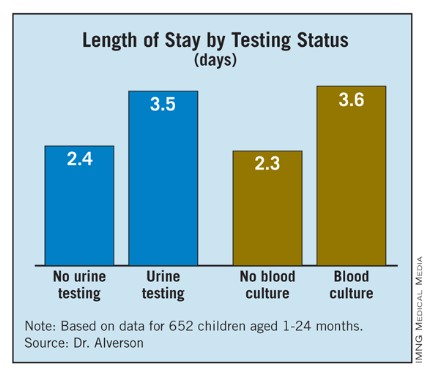

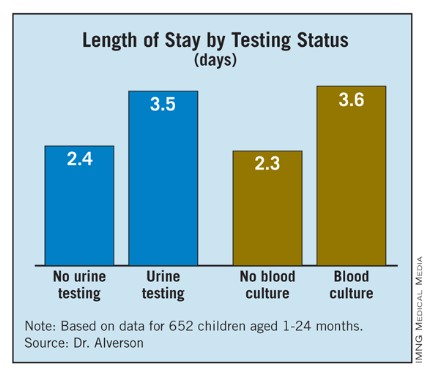

"Even though there is outstanding evidence in the literature that cultures are unnecessary in the vast majority of infants with clinical bronchiolitis, this practice is common, has a cost, and false-positive results can result in prolonged length of stay and exposure to antibiotics that is unnecessary," according to researcher Dr. Brian Alverson.

Dr. Alverson of Hasbro Children’s Hospital in Providence, R.I., said the chart review supports other studies that show that the rate of UTI positivity is approximately the same as reported rates of benign transient bacteriuria in infants. Indeed, the incidence of UTI in the analysis was only 2.9% among patients who underwent urine testing, and the rates of meningitis and bacteremia were zero.

The study comprised 652 children, aged 1-24 months, with a discharge diagnosis of bronchiolitis. Of those, 26% had a blood culture obtained and 18.4% had a urinalysis or urine culture. Of patients undergoing blood cultures, 55% also had a urinalysis or urine culture.

"People who are going to look for infections aren’t looking in the right place," the study’s lead author, Dr. Jamie Librizzi, said at Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2012.

The findings are noteworthy since children in the analysis were discharged during 2007-2008 – after the American Academy of Pediatrics bronchiolitis practice guidelines recommending that clinicians should diagnose bronchiolitis and assess disease severity on the basis of history and physical examination.

The 2006 guidelines (Pediatrics 2006;118:1774-93) state that "the clinical utility of diagnostic testing in infants with suspected bronchiolitis is not well supported by evidence" and that "the occurrence of serious bacterial infections (SBIs) such as urinary tract infections (UTIs), sepsis, and meningitis is very low."

Despite the cohort being drawn from Hasbro Children’s Hospital and University of Missouri Children’s Hospital in Columbia, the misdirected testing could be explained by a knowledge gap and a wide variation in providers including residents, emergency department physicians, and referring community physicians, Dr. Librizzi said.

"Even though we know these guidelines are out there, the practices maybe still haven’t caught up to the evidence," she said. " ... It’s also hard when a kid comes in febrile, not looking great, to sit back and be assured that the numbers are really low for a concurrent infection."

"It’s a good reminder that we still have work to do educating our emergency departments," Dr. Paul Hain, now with Children’s Medical Center, Dallas, commented in a separate interview. "A lot of kids are seen in adult EDs, and folks who are not familiar with children are mostly scared of adult bacteremia and think that blood cultures are what they need, even though bronchiolitis is a special subset."

Children who were evaluated for an SBI received significantly more antibiotics and had significantly longer hospital stays, said Dr. Librizzi, formerly with Hasbro and now a hospitalist fellow at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington.