User login

Safety and Effectiveness of Nonsteroidal Tapinarof Cream 1% Added to Ongoing Biologic Therapy for Treatment of Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis

Safety and Effectiveness of Nonsteroidal Tapinarof Cream 1% Added to Ongoing Biologic Therapy for Treatment of Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis

The estimated prevalence of psoriasis in individuals older than 20 years in the United States has been reported at approximately 3%, or more than 7.5 million people.1 There currently is no cure for psoriasis, and available therapeutics, including phototherapy,2 topical therapies,3 systemic medications,4 and biologic agents,5 are focused only on controlling symptoms. The National Psoriasis Foundation defines an acceptable treatment response for plaque psoriasis as 3% or lower body surface area (BSA) involvement after 3 months of therapy, with a treat-to-target (TTT) goal of 1% or less BSA involvement.6

Cytokines are known to mediate psoriasis pathology, and biologic therapies target the signaling cascade of various cytokines. Biologics approved to treat moderate to severe plaque psoriasis include IgG monoclonal antibodies binding and inhibiting the activity of interleukin (IL)-17 (ixekizumab,7 secukinumab8), IL-23 (guselkumab,9 risankizumab,10 tildrakizumab11), and IL-12/23 (ustekinumab12). Despite targeting these cytokines, biologics may not sufficiently suppress the symptoms of psoriatic disease and their severity in all patients. Adding a topical treatment to biologic therapy can augment clinical response without increasing the incidence of adverse effects13-15 and may reduce the need to switch biologics due to ineffectiveness. Switching biologics likely would increase cost burden to the health care system and/or patient depending on their insurance plan and possibly introduce new safety and/or tolerability issues.16,17

In patients who do not adequately respond to biologics, better responses were reported when topical medications including halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion16 or calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam17,18 were administered. In randomized or open-label, real-world studies, patients with psoriasis responded well when topical medications were added to a biologic, such as tildrakizumab combined with halcinonide ointment 0.1%,19 etanercept combined with topical clobetasol propionate foam,20 or adalimumab combined with calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam.21 No additional safety concerns were observed with the topical add-ons in any of these studies.

Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for topical treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults.22 It is a first-in-class small molecule with a novel mechanism of action that downregulates IL-17A and IL-17F and normalizes the skin barrier through expression of filaggrin, loricrin, and involucrin; it also has antioxidant activity.23 In the phase 3 PSOARING 1 and 2 trials, daily application of tapinarof cream was safe and efficacious in patients with plaque psoriasis,24,25 with a remittive (maintenance) effect of a median of approximately 4 months after discontinuation.25 In these 2 phase 3 studies, tapinarof significantly (P<0.01 at week 12) relieved itch, which was seen rapidly (P<0.05 at week 2),26 improved quality of life,27 and led to high patient satisfaction.27 When tapinarof cream was combined with deucravacitinib in a patient with severe plaque psoriasis, symptoms rapidly cleared, with a 75% decrease in disease severity after 4 weeks.28

The objective of this prospective, open-label, real-world, single-center study was to assess the effectiveness, safety, and remittive (or maintenance) effect of nonsteroidal tapinarof cream 1% added to ongoing biologic therapy in patients with plaque psoriasis who were not adequately responding to a biologic alone.

Methods

Study Design and Participants—This prospective, open-label, real-world, single-center study assessed the safety and effectiveness of

Eligible participants were otherwise healthy males and females aged 18 years and older with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BSA involvement ≥3%) who had been treated with a biologic for 24 weeks or more. Patients were recruited from the Psoriasis Treatment Center of New Jersey (East Windsor, New Jersey). Exclusion criteria were recent use of oral systemic therapies (within 4 weeks of baseline) or topical therapies (within 2 weeks) to treat psoriasis, recent use of UVB (within 2 weeks) or psoralen plus UVA (within 4 weeks) phototherapy, or use of any investigational drug within 4 weeks of baseline (or within 5 pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic half-lives, whichever was longer). Patients who were pregnant or breastfeeding or who had any known hypersensitivity to the excipients of tapinarof cream also were excluded from the study.

Eligible participants received tapinarof cream 1% once daily plus their ongoing biologic for 12 weeks, after which tapinarof was discontinued and the biologic was continued for an additional 4 weeks. A remittive (maintenance) effect was assessed at week 16.

Study Outcomes—Safety and efficacy were evaluated at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. The primary end point was the proportion of patients who reached the TTT goal of 1% or less BSA involvement at week 12. Secondary end points included the proportion of patients with 1% or less BSA involvement at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 16; and PGA scores, composite PGA multiplied by mean percentage of BSA involvement (PGA×BSA), and PASI scores at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. The patient-reported outcomes of Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS) scores also were evaluated at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. In patients who had disease involvement on the scalp or genital region at baseline, Psoriasis Scalp Severity Index (PSSI) and Static Physician’s Global Assessment of Genitalia scores, respectively, were assessed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. Safety was determined by the incidence, severity, and relatedness of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs.

Statistical Analysis—Approximately 30 participants were planned for enrollment and recruited consecutively as they were identified during screening against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Changes from baseline in all outcomes were summarized descriptively. Missing data were not imputed. Given the sample size, no formal statistical analyses were conducted. Safety was summarized by descriptively collating AEs and serious AEs, including their frequency, severity, and treatment relatedness.

Results

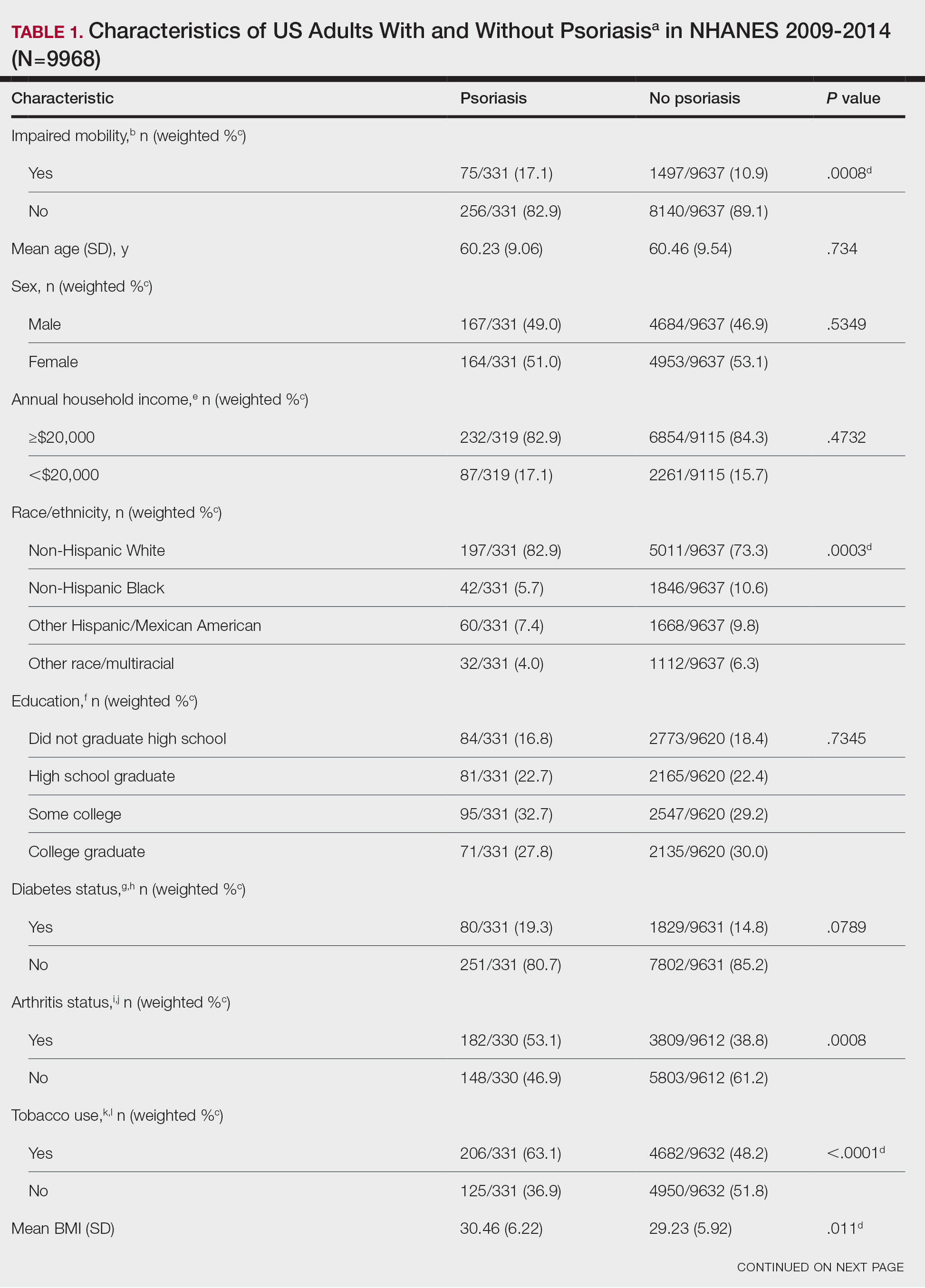

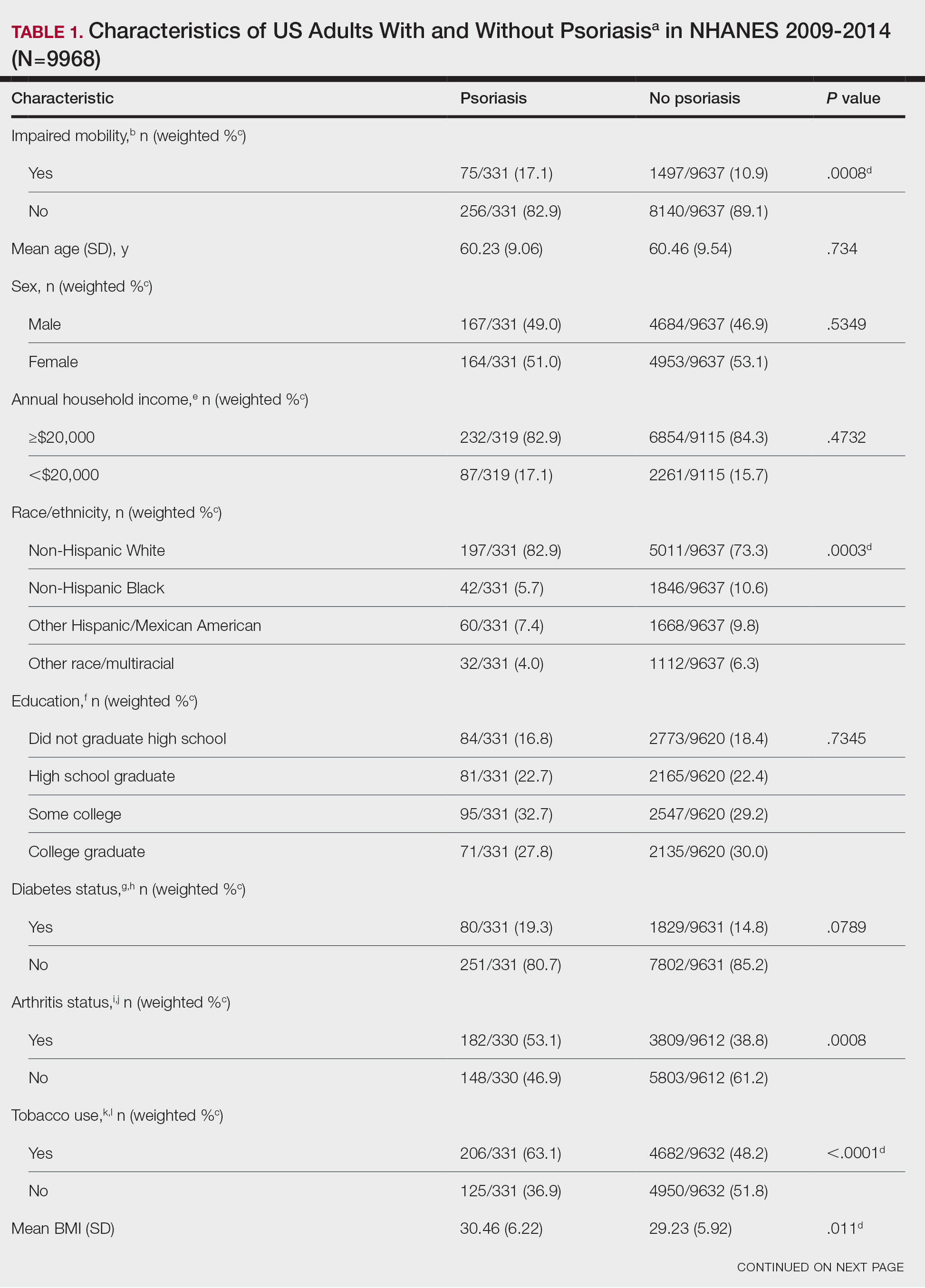

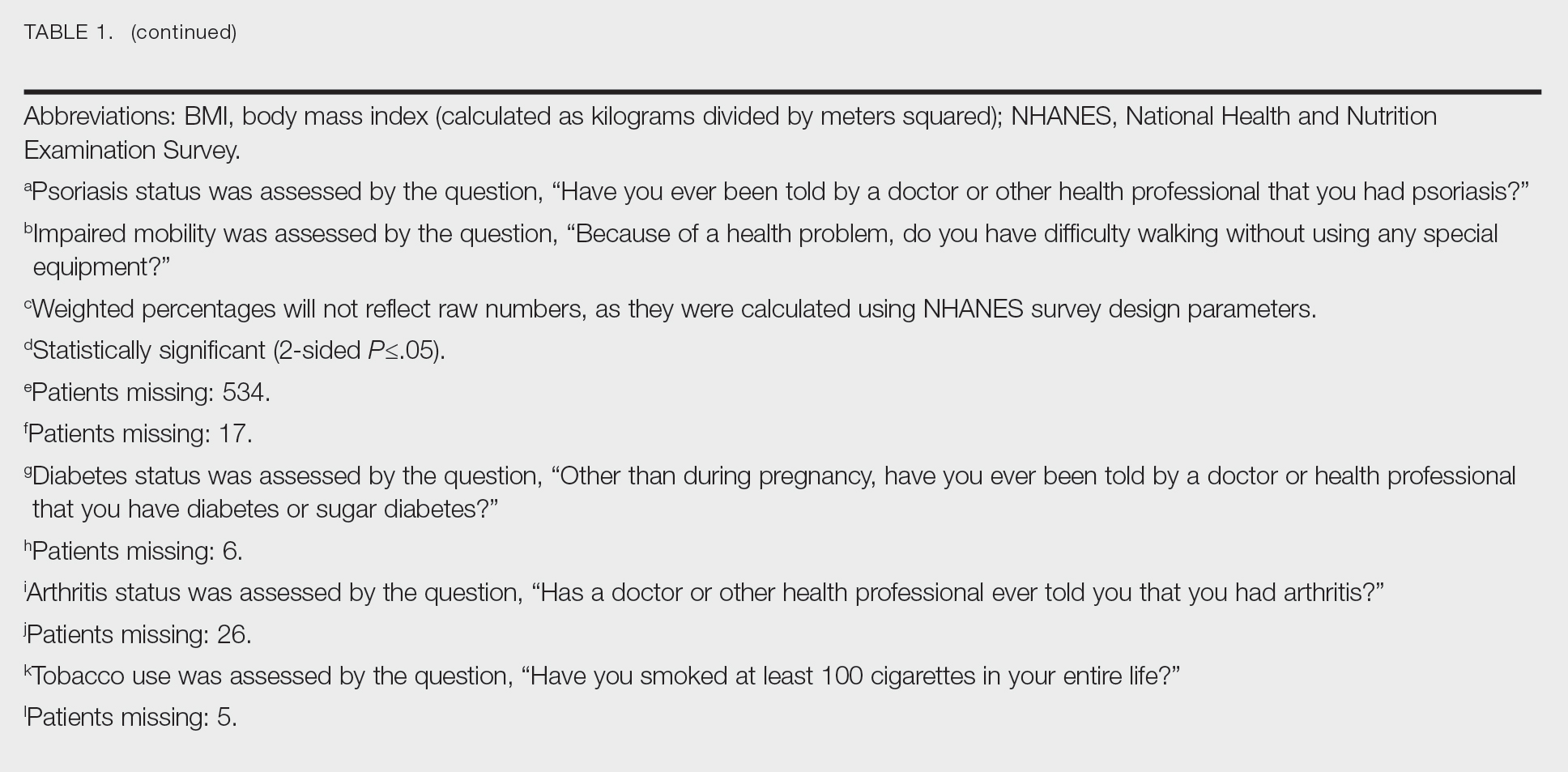

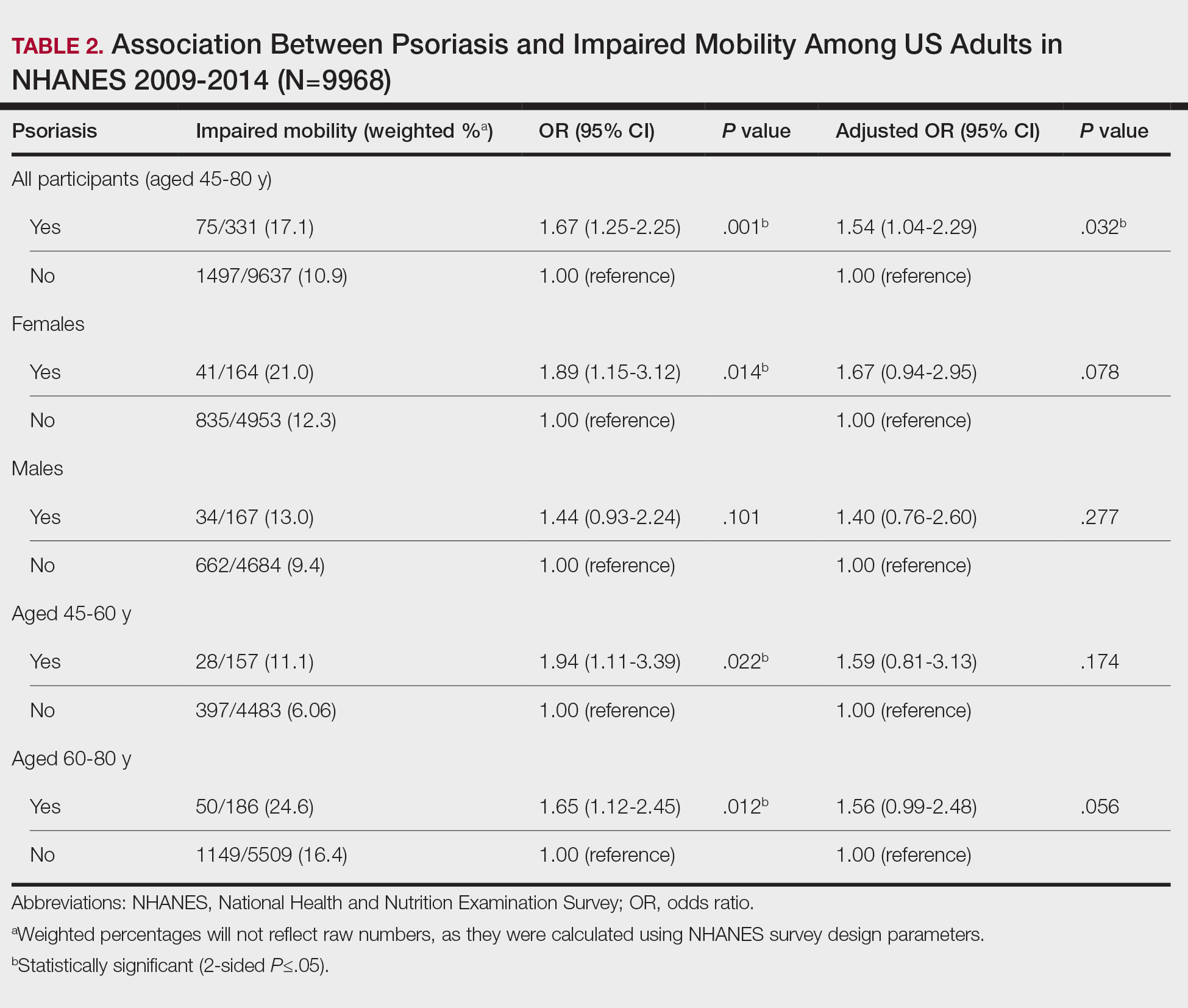

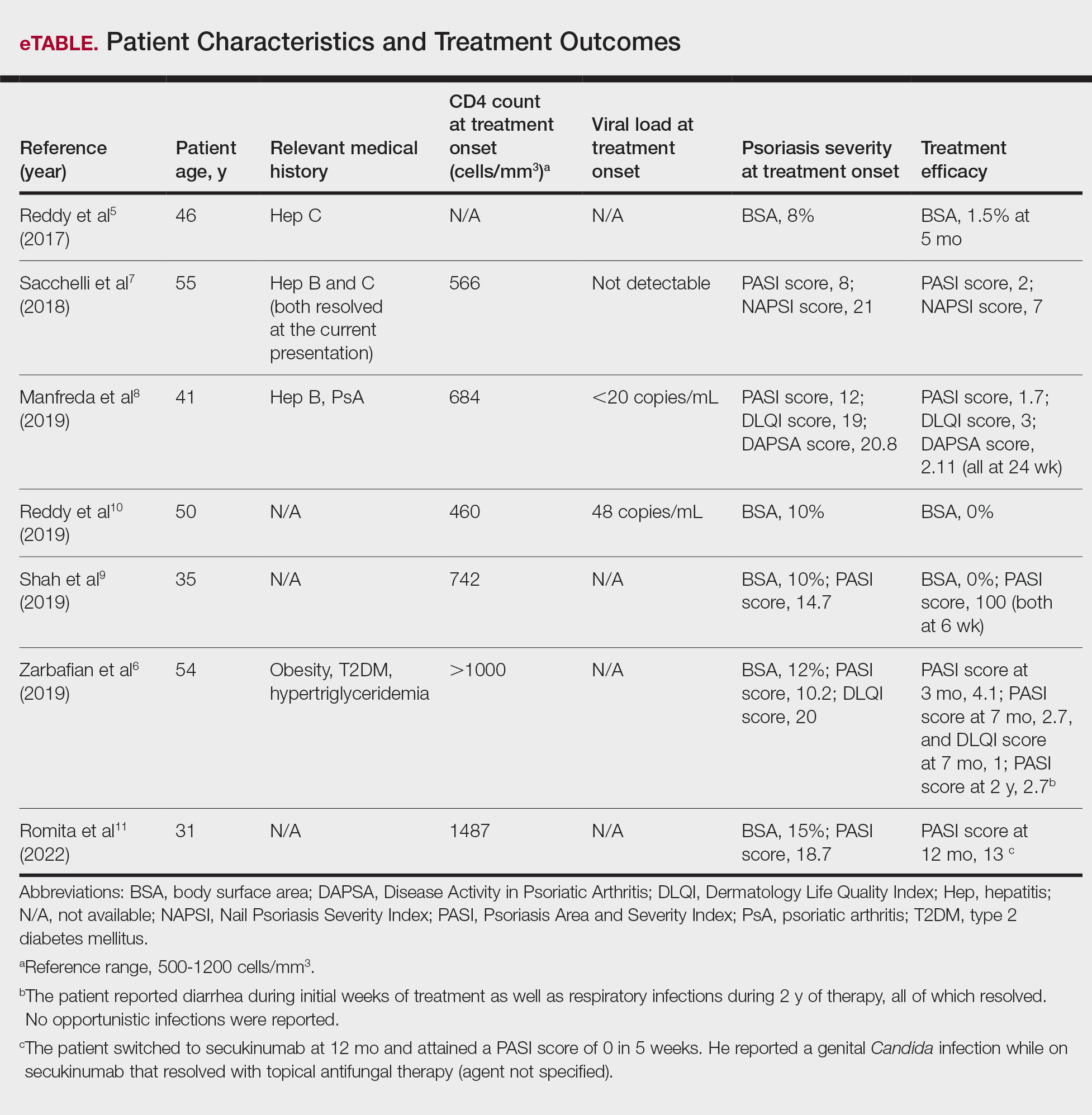

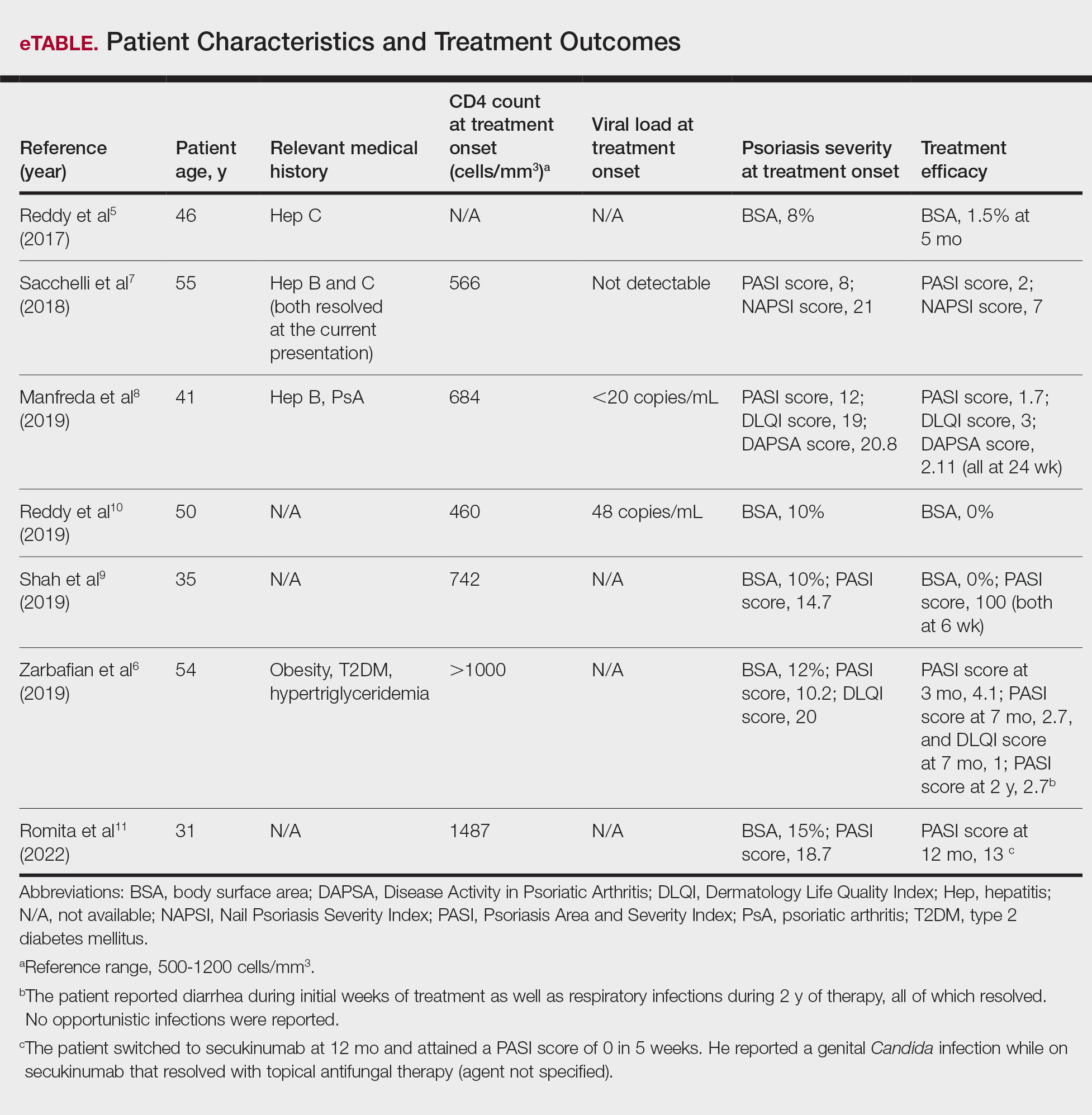

Thirty participants were enrolled in the study, and 20 fully completed the study. Nine discontinued treatment before week 12 (6 were lost to follow-up, 2 were terminated early by the investigators, and 1 voluntarily withdrew); 1 additional participant was lost to follow-up after week 12. Patients were predominantly male (20/30 [66.7%]) and White (21/30 [70.0%]); the mean age of all participants was 55.4 years, and the mean (SD) duration of psoriasis was 21.4 (15.0) years (Table 1). The mean baseline percentage of BSA involvement and mean baseline PGA, PASI, and DLQI scores are shown in Table 1. Most (19/30 [63.3%]) patients received biologics that inhibited IL-23 activity (guselkumab, risankizumab, tildrakizumab), approximately one-third (9/30 [30.0%]) received biologics that inhibited IL-17 activity (ixekizumab, secukinumab), and 2 (6.7%) received biologics that inhibited IL-12/IL-23 activity (ustekinumab)(Table 1).

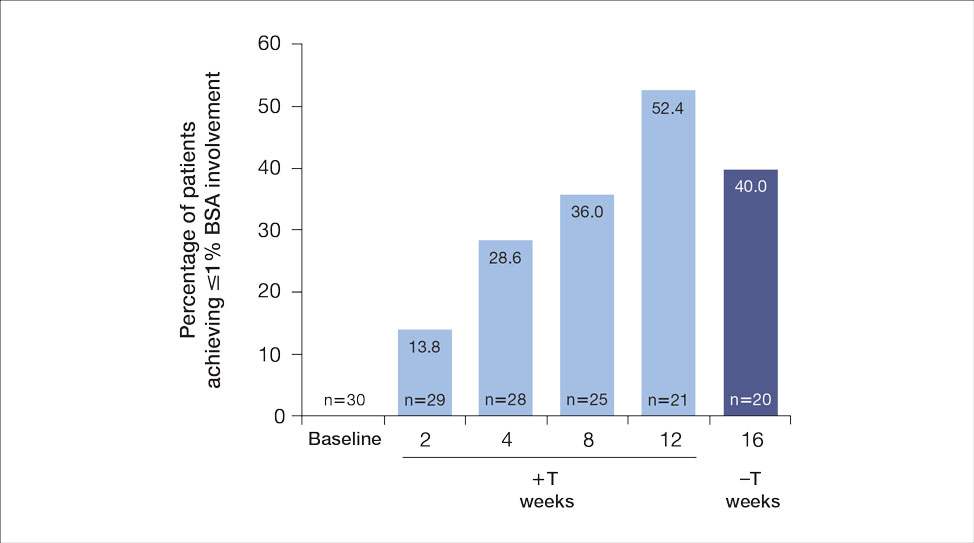

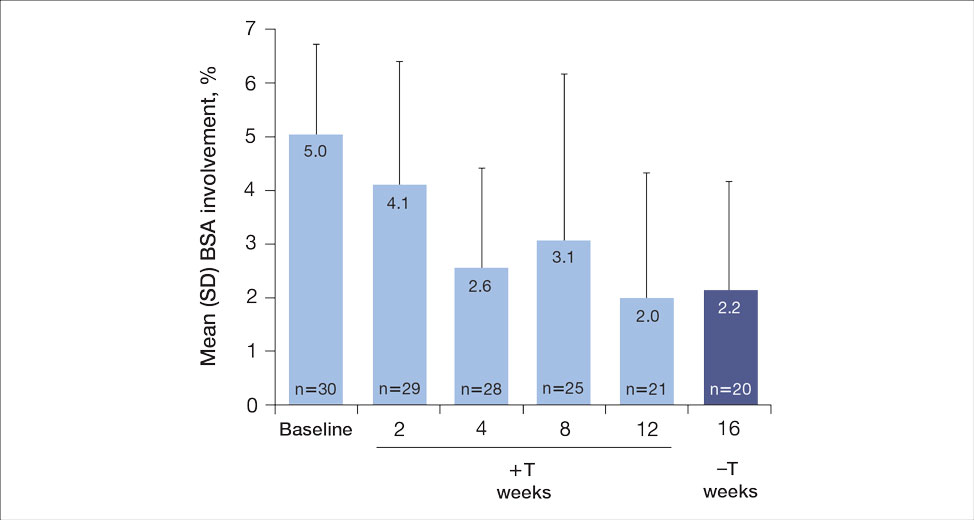

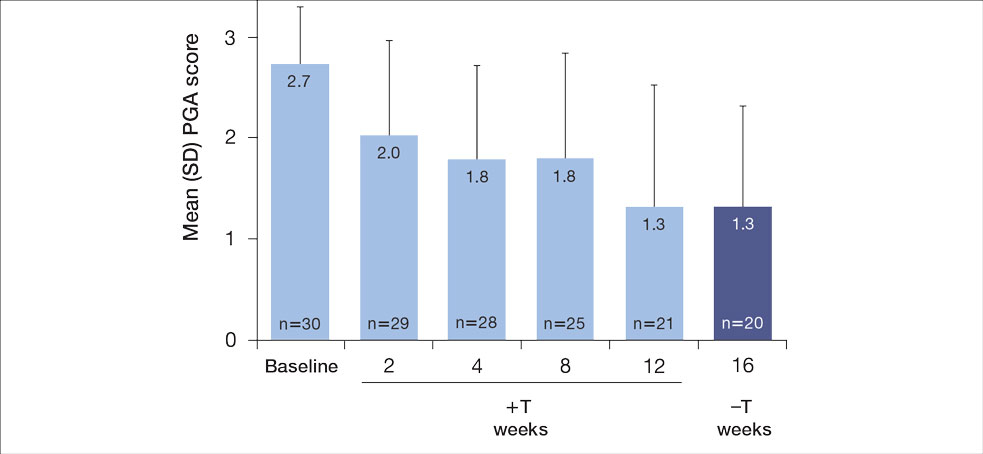

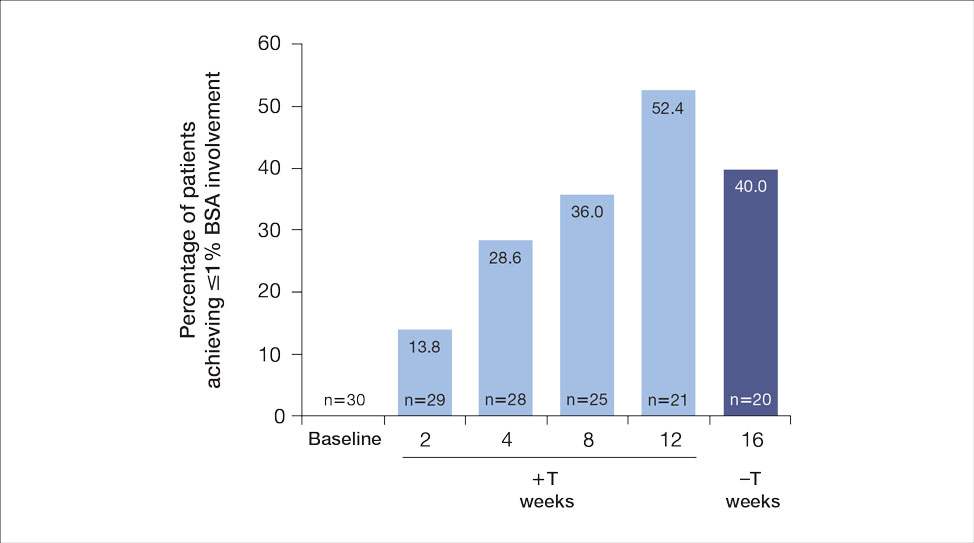

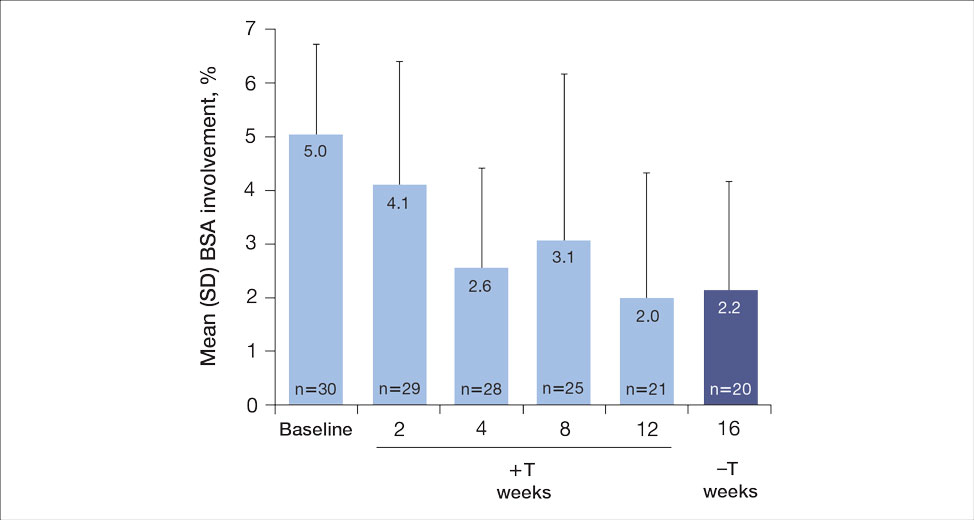

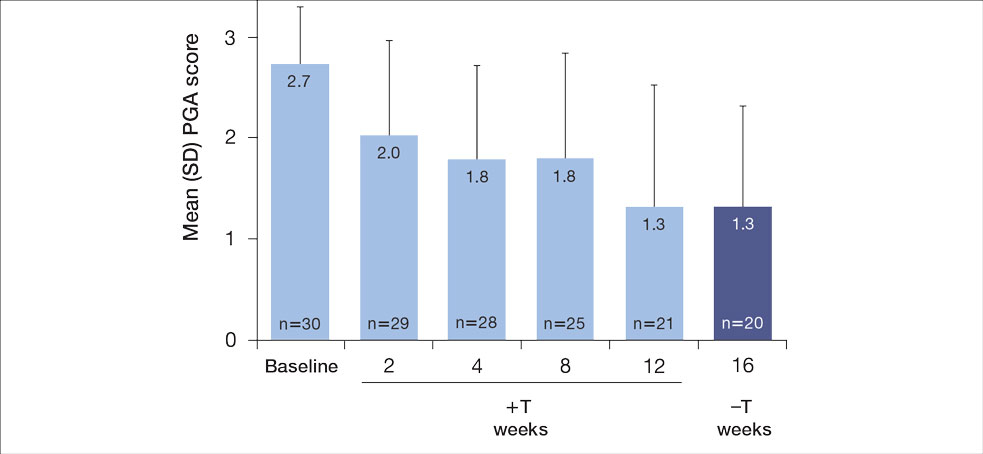

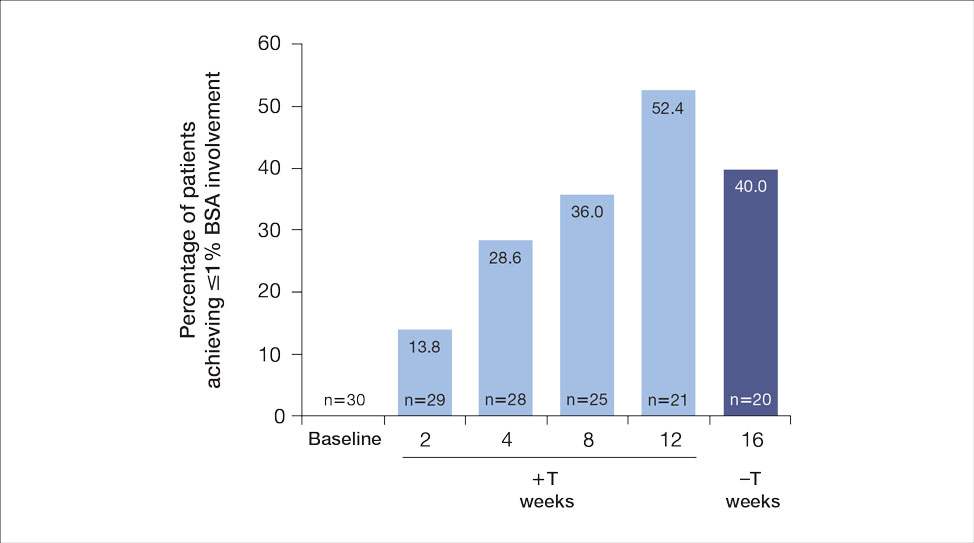

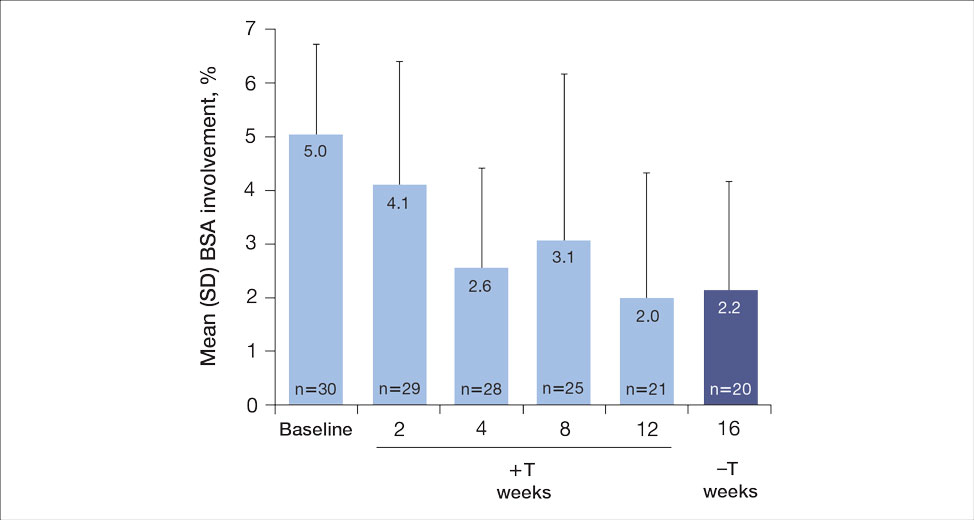

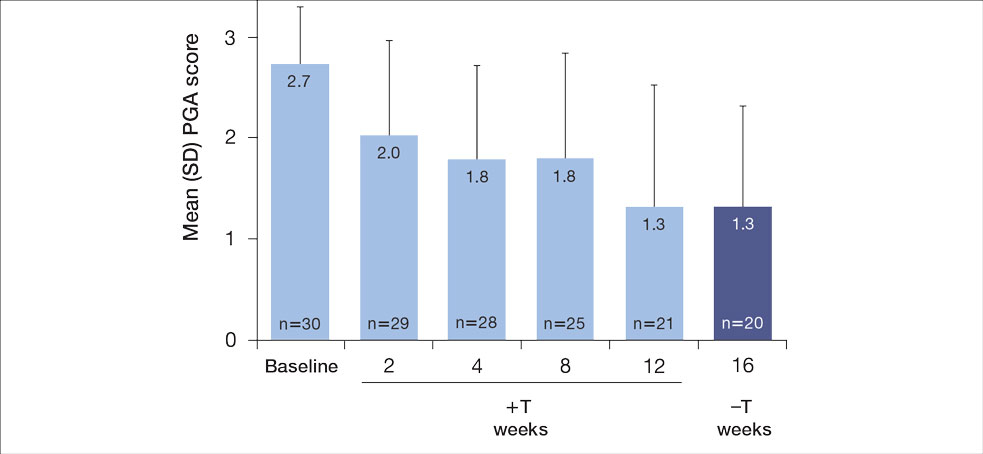

For the primary end point, 52.4% (11/21) of patients reached the TTT goal (BSA involvement ≤1% after 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream added to a prescribed biologic). The proportion of patients reaching the TTT goal increased over time with the combined treatment (eFigure 1). Additionally, the mean percentage of BSA involvement (eFigure 2) as well as the mean values for PGA (eFigure 3) and PGA×BSA decreased over time. The mean percentage of BSA involvement was 5.0% at baseline and dropped to 2.0% by week 12. Similar reductions were observed for PGA and PGA×BSA scores at week 12.

After discontinuing tapinarof cream at week 12 and receiving only the biologic for 4 weeks, the proportion of patients maintaining 1% or less BSA involvement fell to 40.0% (8/20) at week 16, which was closer to that observed at week 8 (36% [9/25]) than at week 12 (52.4% [11/21])(eFigure 1).

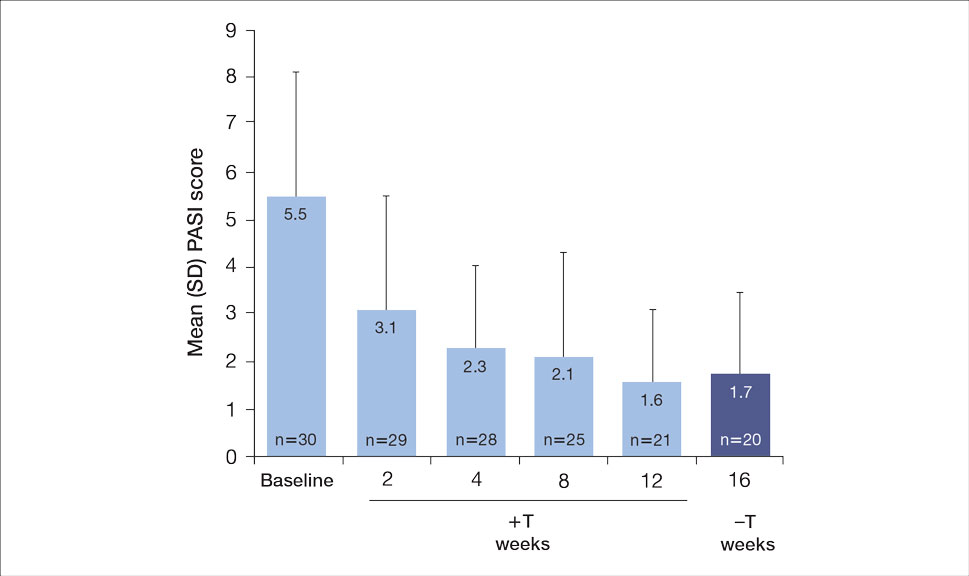

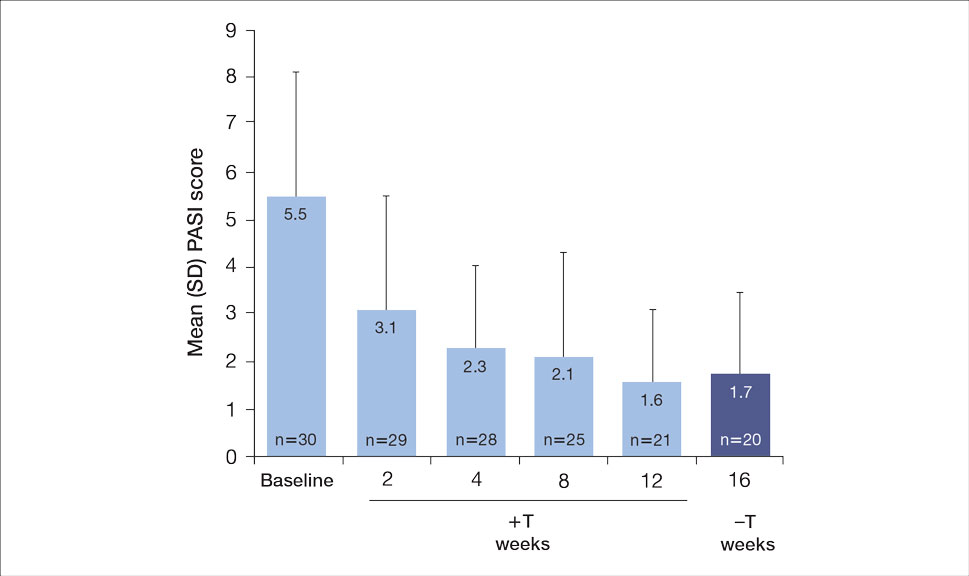

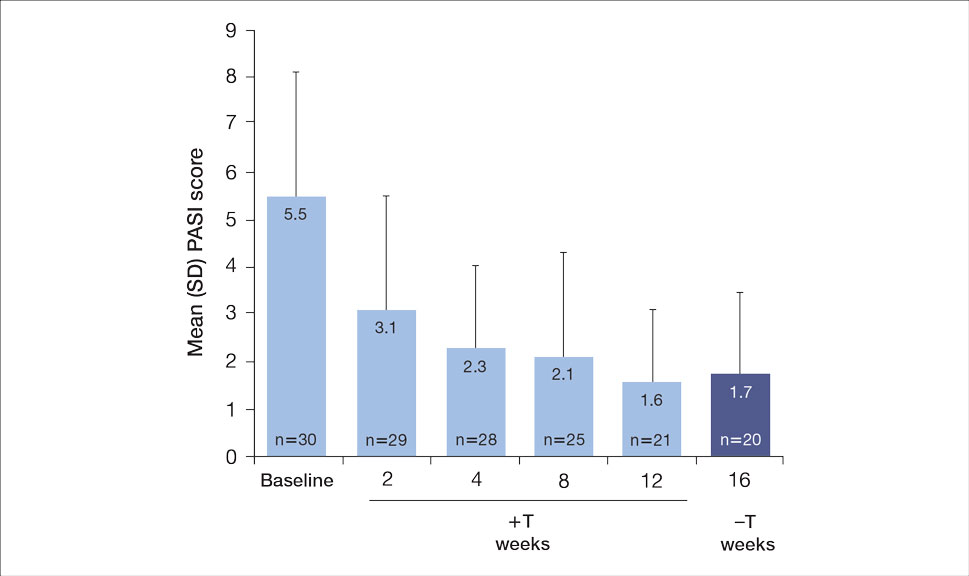

The mean PASI score was 5.5 at baseline, then decreased over time when tapinarof cream was combined with a biologic (eFigure 4), falling to 3.1 by week 2 and 1.6 by week 12; it was maintained at 1.7 at week 16. Nine (30.0%) participants had psoriasis on the scalp at baseline with a mean PSSI score of 2.6, which decreased to 0.83 by week 2. By week 12, the mean PSSI score remained stable at 0.95 in the 2 (9.5%) participants who still had scalp involvement. The mean PSSI score increased slightly to 1.45 after patients received only the biologic for 4 weeks. At baseline, 3 (10.0%) patients had genital involvement (mean Static Physician’s Global Assessment of Genitalia score, 0.27). Symptoms resolved in 2 (66.7%) of these patients at week 2 and stayed consistent until week 16; the third patient withdrew at week 2.

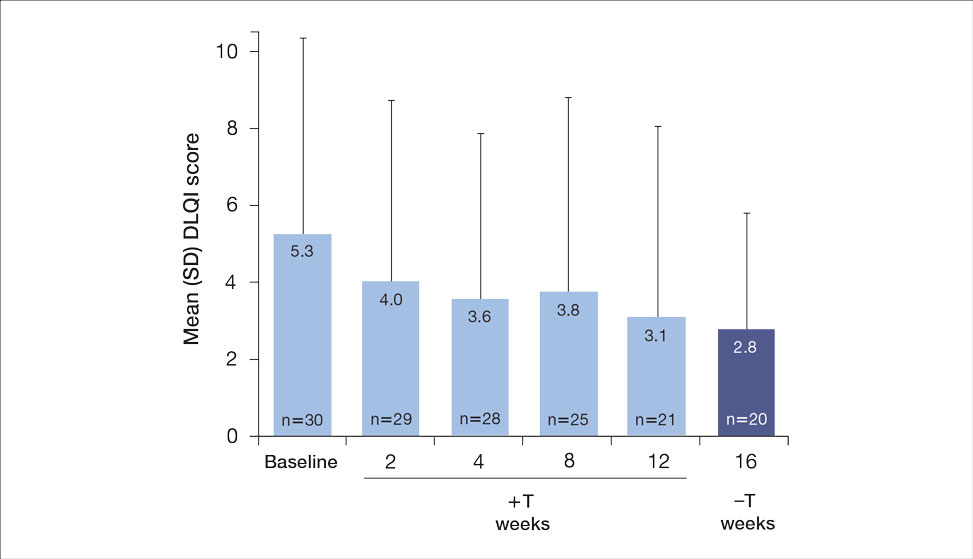

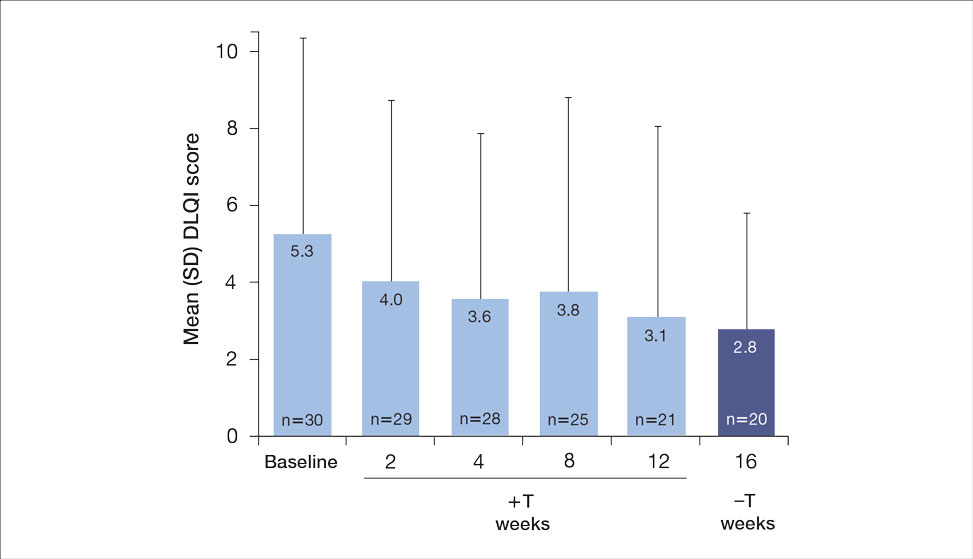

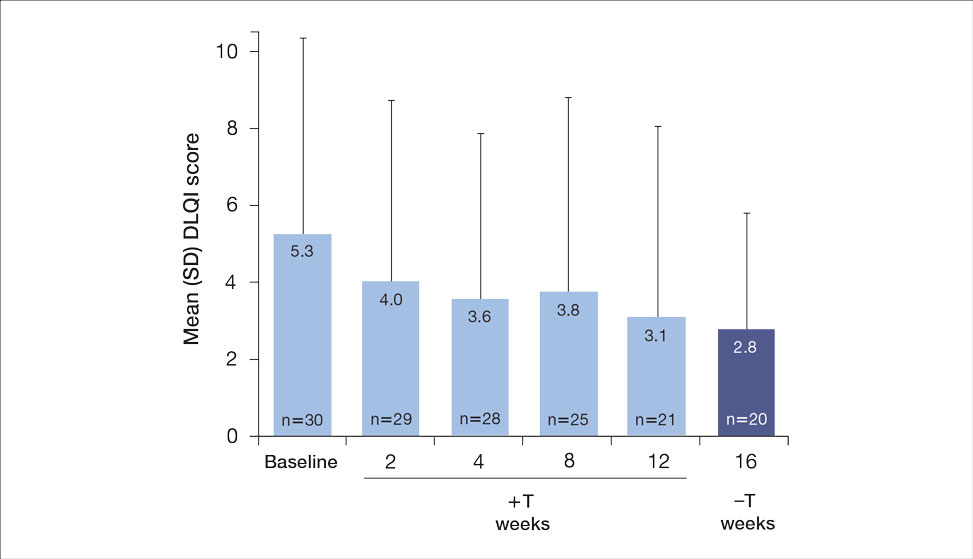

Both DLQI and WI-NRS scores decreased with use of tapinarof cream added to a biologic up to week 12 (eFigures 5 and 6). Mean DLQI scores were 5.3 at baseline and 3.1 at week 12. At week 16, the mean DLQI score remained stable at 2.8. Mean WI-NRS scores decreased from 4.0 at baseline to 2.7 at week 12 with the therapy combination; at week 16, the mean WI-NRS score fell further to 1.8.

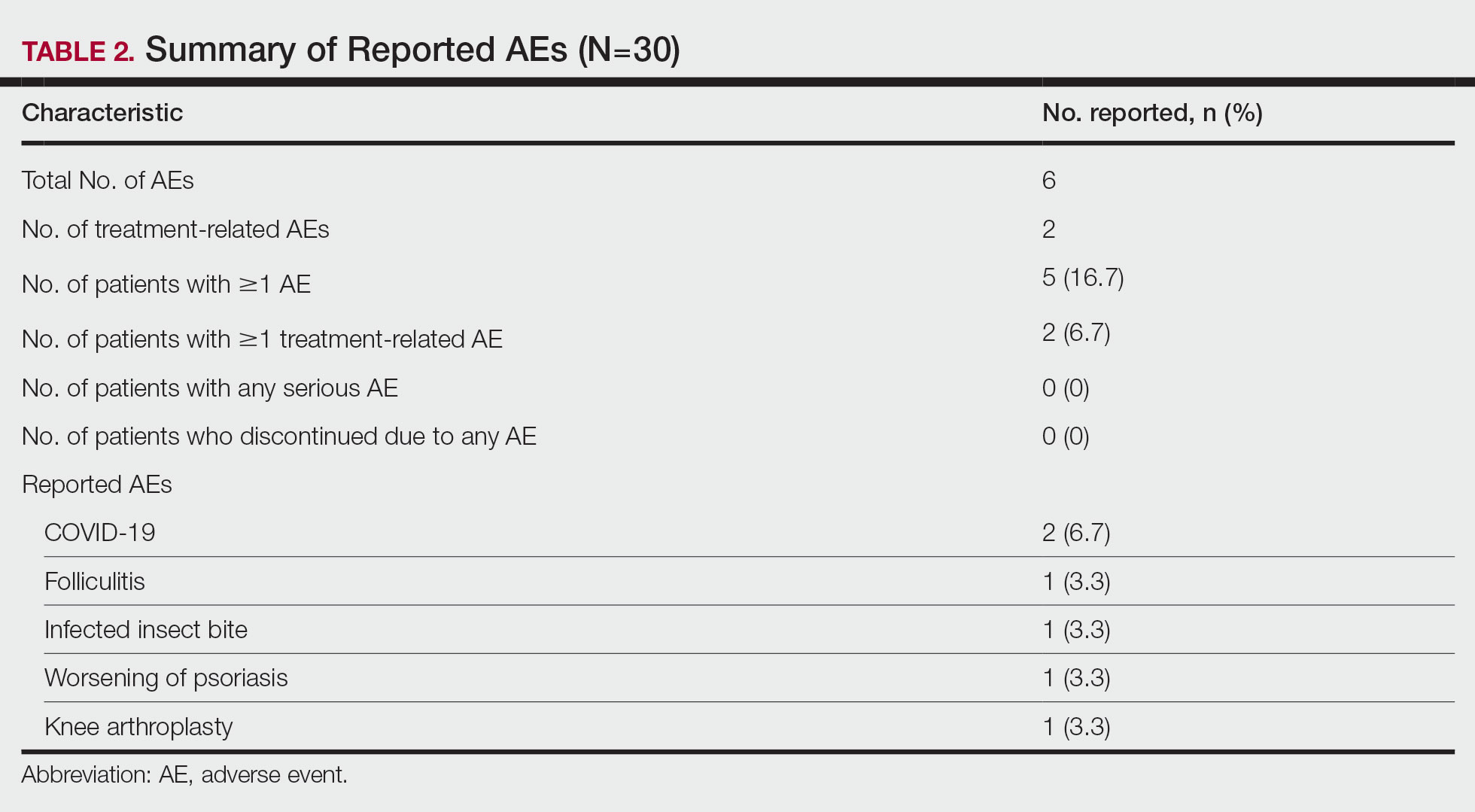

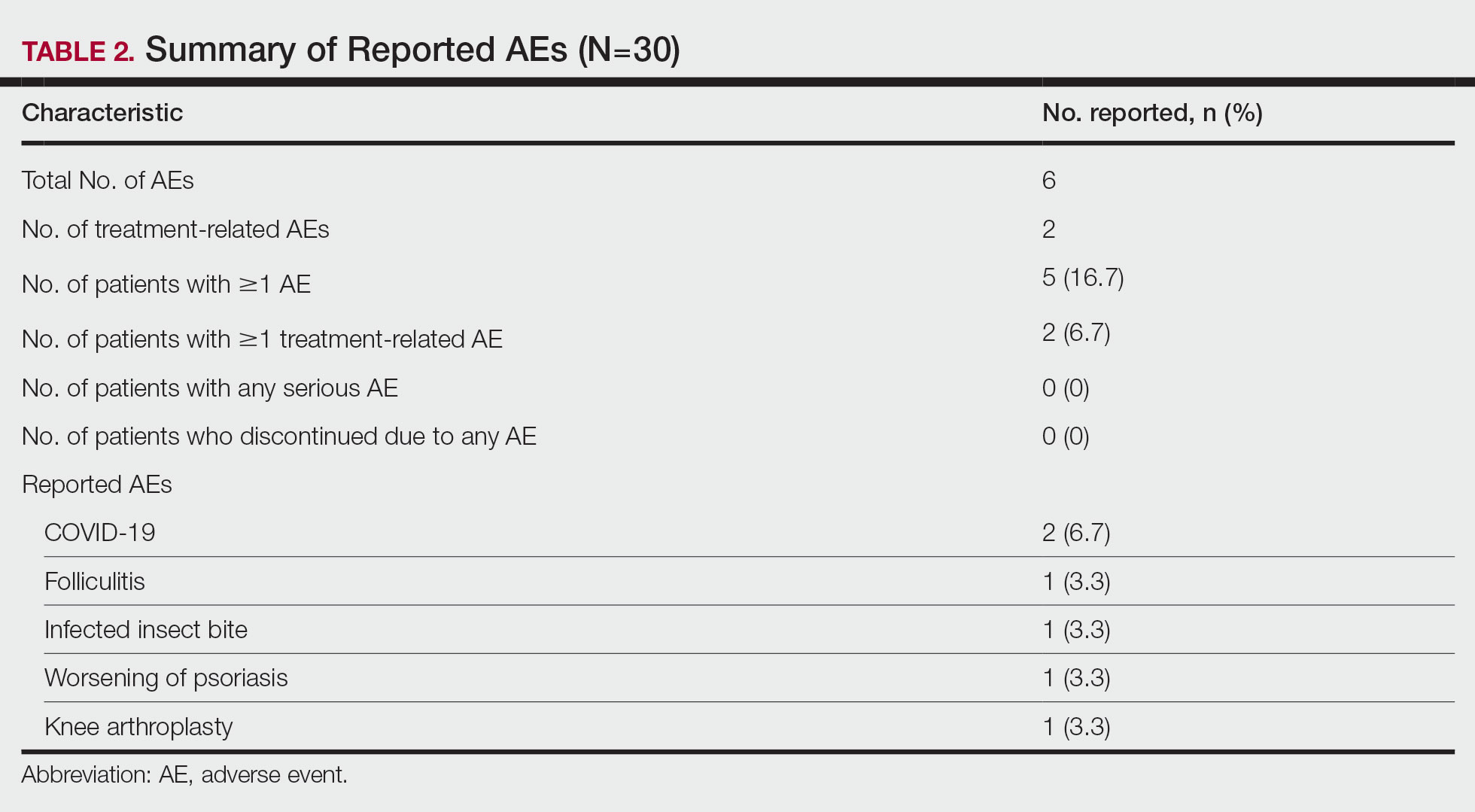

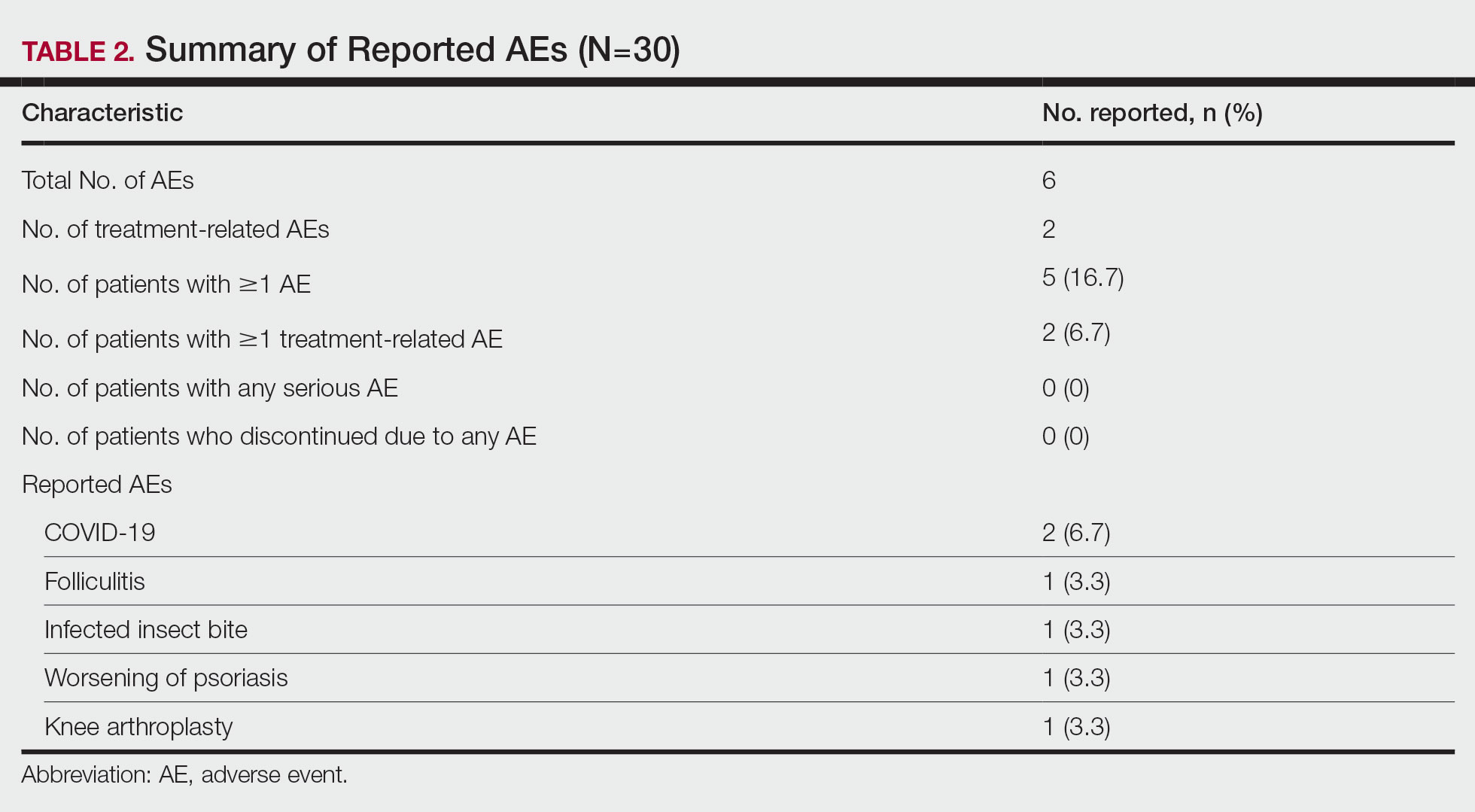

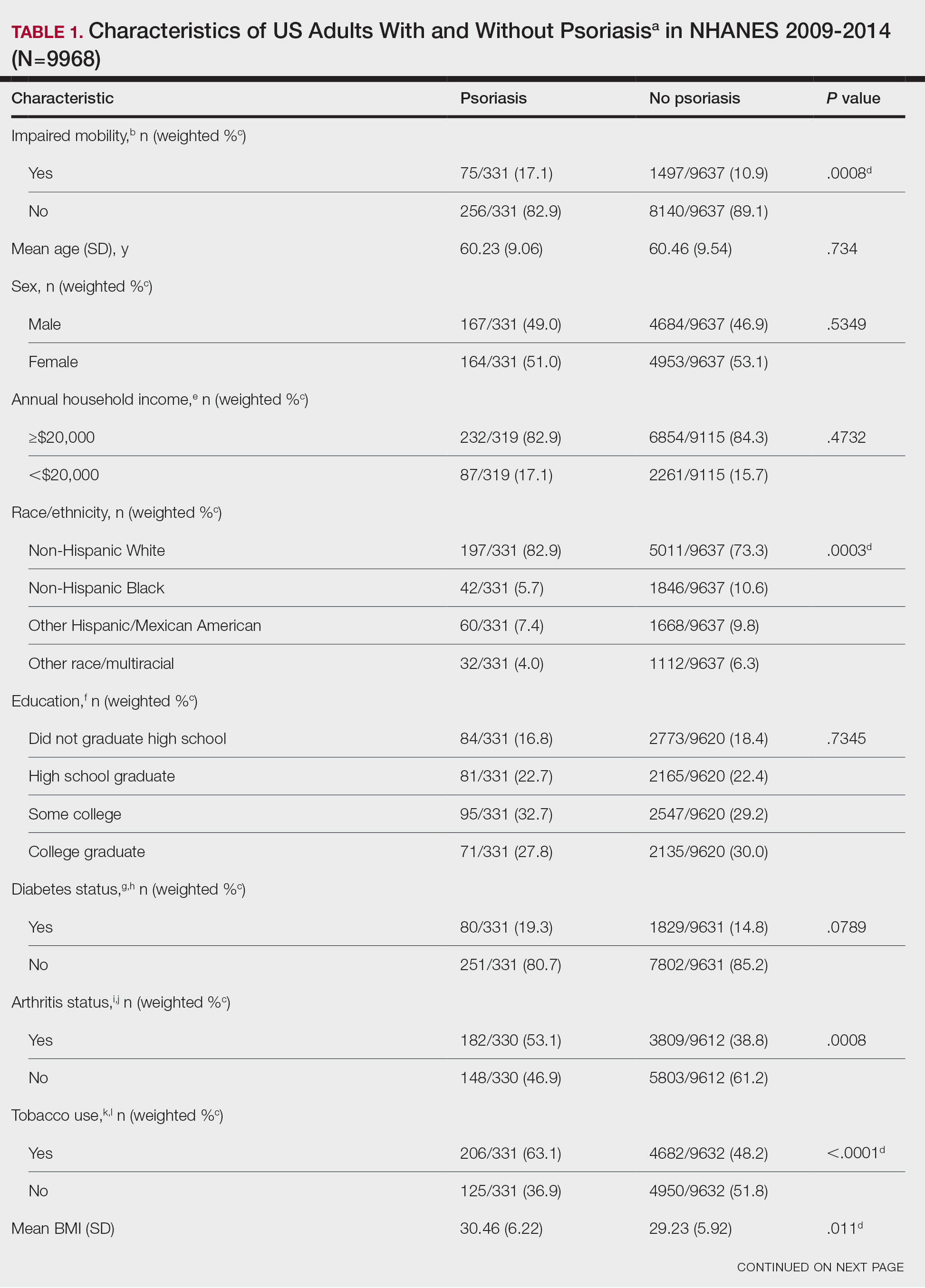

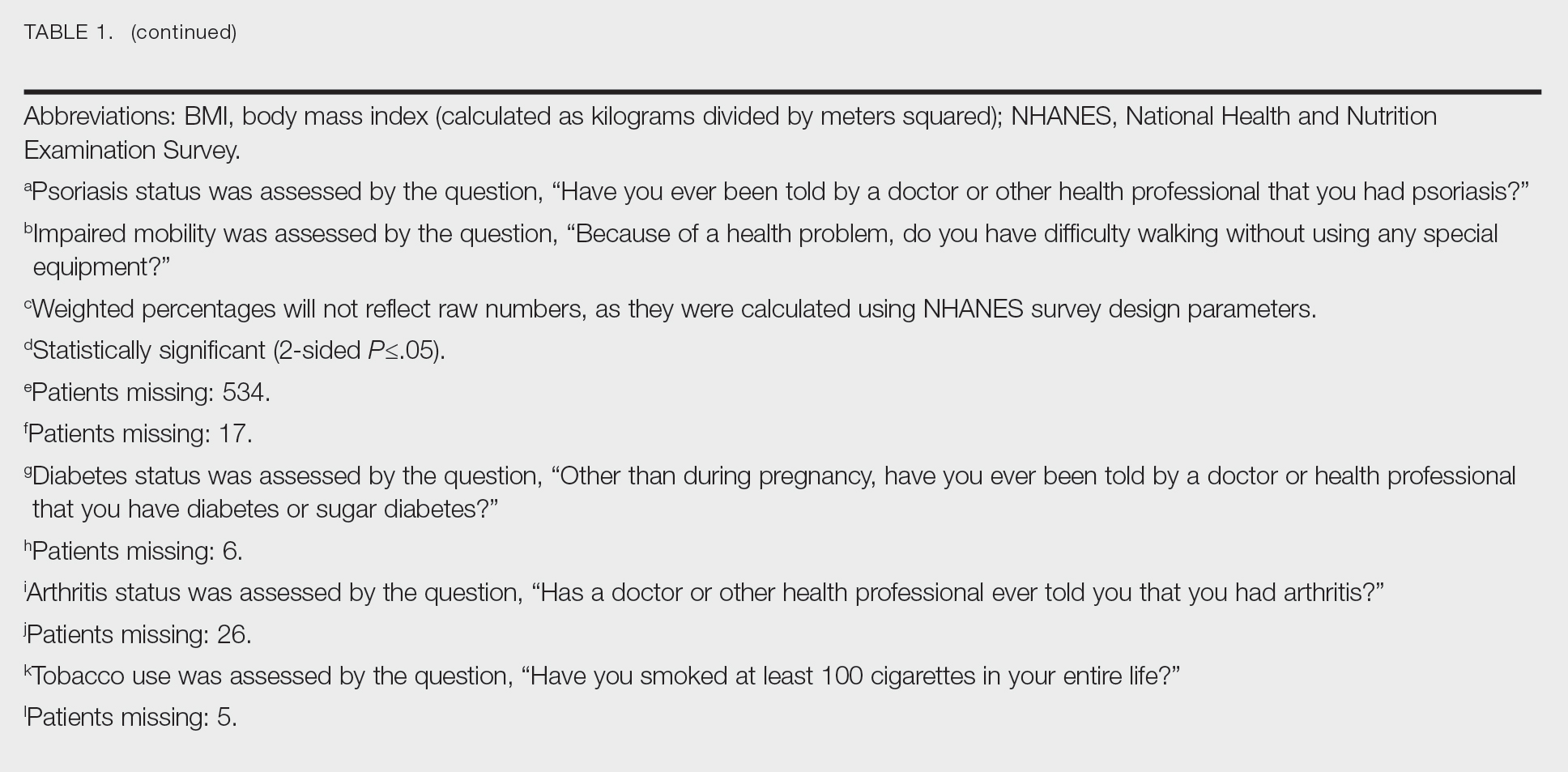

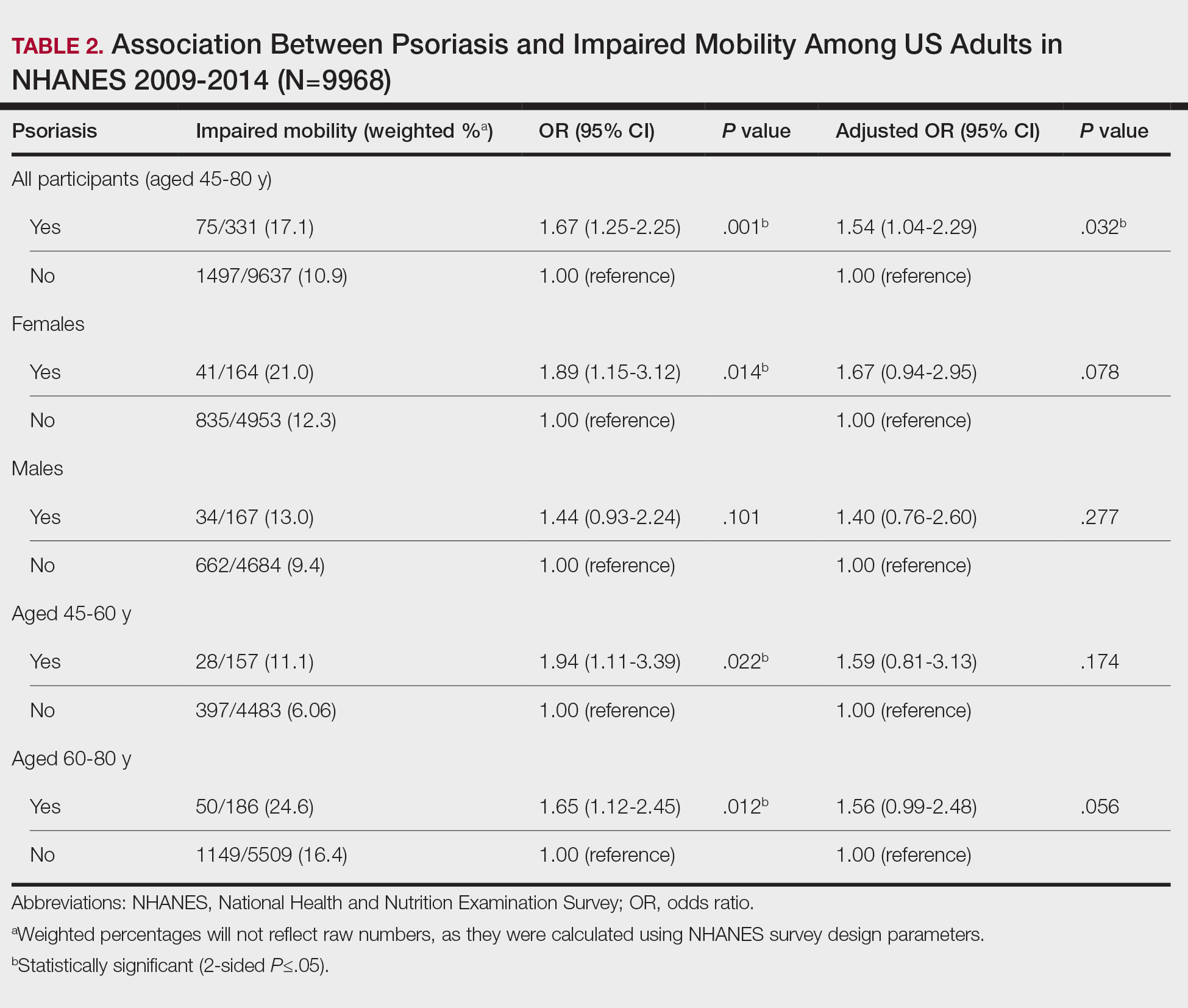

A total of 6 AEs were reported in 5 (16.7%) patients (Table 2). The majority (4/6 [67.0%]) of AEs were considered mild. Two reported cases of COVID-19 were both considered mild and unrelated. Mild folliculitis and moderate worsening of psoriasis in 2 (6.7%) different patients were the only AEs considered related to treatment. No serious AEs were reported, and no patient withdrew from the study due to an AE.

Comment

Disease activity improvements we observed with the nonsteroidal tapinarof cream were consistent with those reported when topical steroidal therapies were given to patients responding poorly to their current biologic. Our primary end point (proportion of patients with BSA involvement ≤1% after 12 weeks) showed that half (52% [11/21]) of patients whose BSA involvement was 3% or greater with a biologic for 24 weeks or more reached the TTT goal after 12 weeks of tapinarof-biologic treatment. Other studies of halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion16 and calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam17,18 added to the current biologic of poor responders found 60% to 68% of patients had reductions in their percentage BSA to 1% or lower at 12 to 16 weeks of treatment. Randomized studies showed etanercept plus topical clobetasol propionate foam20 or adalimumab plus calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam21 similarly enhanced treatment effects vs biologic alone.

A phase 3 PSOARING trial demonstrated benefit from treatment with tapinarof alone, with a remittive effect of approximately 4 months after discontinuation.25 Our data are consistent with these findings, with 40% (8/20) of patients demonstrating a remittive effect 4 weeks after discontinuing tapinarof while receiving a biologic. A similar maintenance effect was reported in another study in 50% (9/18) of patients treated with a biologic plus halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion.16 Additionally, when halcinonide ointment was given to patients receiving tildrakizumab, mean percentage of BSA involvement, PGA scores, PGA×BSA, and DLQI scores improved and were maintained 4 weeks after halcinonide ointment was stopped.19 Thus, topical therapy can augment and extend a biologic’s effect for up to 4 weeks.

In our study, tapinarof cream added to a biologic had a good safety and tolerability profile. Few AEs were recorded, with most being mild in nature, and no serious AEs or discontinuations due to AEs were reported. Only 1 case of mild folliculitis and 1 case of moderate worsening of psoriasis were considered treatment related. Further, no unexpected or new safety signals with the tapinarof-biologic combination were observed compared with tapinarof alone.27Prior studies have found that supplementing a biologic with topical therapy can reduce the probability of patients switching to another biologic.16,19 We previously found that adding halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion16 or calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam17 to a biologic helped reduce the probability of switching biologics from 88% to 90% at baseline to 12% to 24% after 12 weeks of combined therapy. Such combinations also could prevent a less responsive patient from being prescribed a higher biologic dose.19 These are important research findings, as patients—even when not responding well to their current biologic—are more likely to be tolerating that biologic well, and switching to a new biologic may introduce new safety or tolerability concerns. Thus, by enhancing the effect of a biologic with a topical therapy, one can avoid increasing the dose of the current biologic or switching to a new biologic, either of which may increase safety and/or tolerability risks. Switching biologics also has increased cost implications to the health care system and/or the patient. When comparing the cost of adding halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion to a biologic compared with switching to another biologic, the cost was 1.2 to 2.9 times higher to switch, depending on the biologic, compared with a smaller incremental cost increase to add a topical to the current biologic.16 Similar observations were reported with calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam plus a biologic.17 Although we did not evaluate biologic switching here, we anticipate a similar clinical scenario with a tapinarof-biologic combination.

Limitations of our study included the open-label design, lack of a control arm, and the relatively small study population; however, for studies investigating the safety and effectiveness of a treatment in a real-world setting, these limitations are common and are not unexpected. Our results also are consistent with the overall improvement seen in other studies16-21 examining the effects of adding a topical to a biologic. Future research is warranted to investigate a longer remittive effect and potential health care system and patient cost savings without having to switch biologics due to lack of effectiveness.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that adjunctive use of nonsteroidal tapinarof cream 1% may enhance a biologic treatment effect in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, providing an adequate response for many patients who were not responding well to a biologic alone. Clinical outcomes improved with the tapinarof-biologic combination, and a remittive effect was noted 4 weeks after tapinarof discontinuation without any new safety signals. Adding tapinarof cream to a biologic also may prevent the need to switch biologics when patients do not sufficiently respond, preserving the safety and cost associated with a patient’s current biologic.

- Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, et al. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:940-946. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2007

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.042

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.087

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiological therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.044

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:290-298. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.017

- Taltz. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2024.

- Cosentyx. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2023.

- Tremfya. Prescribing information. Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2023.

- Skyrizi. Prescribing information. AbbVie Inc; 2024.

- Ilumya. Prescribing information. Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc; 2020.

- Stelara. Prescribing information. Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2022.

- Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

- Jensen JD, Delcambre MR, Nguyen G, et al. Biologic therapy with or without topical treatment in psoriasis: what does the current evidence say? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:379-385. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0089-1

- Gustafson CJ, Watkins C, Hix E, et al. Combination therapy in psoriasis: an evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:9-25. doi:10.1007/s40257-012-0003-7

- Bagel J, Novak K, Nelson E. Adjunctive use of halobetasol propionate-tazarotene in biologic-experienced patients with psoriasis. Cutis. 2022;109:103-109. doi:10.12788/cutis.0451

- Bagel J, Nelson E, Zapata J, et al. Adjunctive use of calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam in a real-world setting curtails the cost of biologics without reducing efficacy in psoriasis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:1383-1396. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00454-z

- Bagel J, Zapata J, Nelson E. A prospective, open-label study evaluating adjunctive calcipotriene 0.005%/betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% foam in psoriasis patients with inadequate response to biologic therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:611-616.

- Bagel J, Novak K, Nelson E. Tildrakizumab in combination with topical halcinonide 0.1% ointment for treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:766-772. doi:10.36849/jdd.6830

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik L, Callis Duffin K, et al. A randomized study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of adding topical therapy to etanercept in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:385-392. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.03.031

- Thaci D, Ortonne JP, Chimenti S, et al. A phase IIIb, multicentre, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of adalimumab with and without calcipotriol/betamethasone topical treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: the BELIEVE study. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:402-411. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09791.x

- Vtama. Prescribing information. Dermavant Sciences, Inc; 2022.

- Bobonich M, Gorelick J, Aldredge L, et al. Tapinarof, a novel, first-in-class, topical therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist for the management of psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:779-784. doi:10.36849/jdd.7317

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1171

- Kircik L, Zirwas M, Kwatra SG, et al. Rapid improvements in itch with tapinarof cream 1% once daily in two phase 3 trials in adults with mild to severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:201-211. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-01068-x

- Bagel J, Gold LS, Del Rosso J, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:936-944. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.061

- Abdin R, Kircik L, Issa NT. First use of combination oral deucravacitinib with tapinarof cream for treatment of severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2024;23:192-194. doi:10.36849/jdd.8091

The estimated prevalence of psoriasis in individuals older than 20 years in the United States has been reported at approximately 3%, or more than 7.5 million people.1 There currently is no cure for psoriasis, and available therapeutics, including phototherapy,2 topical therapies,3 systemic medications,4 and biologic agents,5 are focused only on controlling symptoms. The National Psoriasis Foundation defines an acceptable treatment response for plaque psoriasis as 3% or lower body surface area (BSA) involvement after 3 months of therapy, with a treat-to-target (TTT) goal of 1% or less BSA involvement.6

Cytokines are known to mediate psoriasis pathology, and biologic therapies target the signaling cascade of various cytokines. Biologics approved to treat moderate to severe plaque psoriasis include IgG monoclonal antibodies binding and inhibiting the activity of interleukin (IL)-17 (ixekizumab,7 secukinumab8), IL-23 (guselkumab,9 risankizumab,10 tildrakizumab11), and IL-12/23 (ustekinumab12). Despite targeting these cytokines, biologics may not sufficiently suppress the symptoms of psoriatic disease and their severity in all patients. Adding a topical treatment to biologic therapy can augment clinical response without increasing the incidence of adverse effects13-15 and may reduce the need to switch biologics due to ineffectiveness. Switching biologics likely would increase cost burden to the health care system and/or patient depending on their insurance plan and possibly introduce new safety and/or tolerability issues.16,17

In patients who do not adequately respond to biologics, better responses were reported when topical medications including halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion16 or calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam17,18 were administered. In randomized or open-label, real-world studies, patients with psoriasis responded well when topical medications were added to a biologic, such as tildrakizumab combined with halcinonide ointment 0.1%,19 etanercept combined with topical clobetasol propionate foam,20 or adalimumab combined with calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam.21 No additional safety concerns were observed with the topical add-ons in any of these studies.

Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for topical treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults.22 It is a first-in-class small molecule with a novel mechanism of action that downregulates IL-17A and IL-17F and normalizes the skin barrier through expression of filaggrin, loricrin, and involucrin; it also has antioxidant activity.23 In the phase 3 PSOARING 1 and 2 trials, daily application of tapinarof cream was safe and efficacious in patients with plaque psoriasis,24,25 with a remittive (maintenance) effect of a median of approximately 4 months after discontinuation.25 In these 2 phase 3 studies, tapinarof significantly (P<0.01 at week 12) relieved itch, which was seen rapidly (P<0.05 at week 2),26 improved quality of life,27 and led to high patient satisfaction.27 When tapinarof cream was combined with deucravacitinib in a patient with severe plaque psoriasis, symptoms rapidly cleared, with a 75% decrease in disease severity after 4 weeks.28

The objective of this prospective, open-label, real-world, single-center study was to assess the effectiveness, safety, and remittive (or maintenance) effect of nonsteroidal tapinarof cream 1% added to ongoing biologic therapy in patients with plaque psoriasis who were not adequately responding to a biologic alone.

Methods

Study Design and Participants—This prospective, open-label, real-world, single-center study assessed the safety and effectiveness of

Eligible participants were otherwise healthy males and females aged 18 years and older with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BSA involvement ≥3%) who had been treated with a biologic for 24 weeks or more. Patients were recruited from the Psoriasis Treatment Center of New Jersey (East Windsor, New Jersey). Exclusion criteria were recent use of oral systemic therapies (within 4 weeks of baseline) or topical therapies (within 2 weeks) to treat psoriasis, recent use of UVB (within 2 weeks) or psoralen plus UVA (within 4 weeks) phototherapy, or use of any investigational drug within 4 weeks of baseline (or within 5 pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic half-lives, whichever was longer). Patients who were pregnant or breastfeeding or who had any known hypersensitivity to the excipients of tapinarof cream also were excluded from the study.

Eligible participants received tapinarof cream 1% once daily plus their ongoing biologic for 12 weeks, after which tapinarof was discontinued and the biologic was continued for an additional 4 weeks. A remittive (maintenance) effect was assessed at week 16.

Study Outcomes—Safety and efficacy were evaluated at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. The primary end point was the proportion of patients who reached the TTT goal of 1% or less BSA involvement at week 12. Secondary end points included the proportion of patients with 1% or less BSA involvement at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 16; and PGA scores, composite PGA multiplied by mean percentage of BSA involvement (PGA×BSA), and PASI scores at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. The patient-reported outcomes of Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS) scores also were evaluated at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. In patients who had disease involvement on the scalp or genital region at baseline, Psoriasis Scalp Severity Index (PSSI) and Static Physician’s Global Assessment of Genitalia scores, respectively, were assessed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. Safety was determined by the incidence, severity, and relatedness of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs.

Statistical Analysis—Approximately 30 participants were planned for enrollment and recruited consecutively as they were identified during screening against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Changes from baseline in all outcomes were summarized descriptively. Missing data were not imputed. Given the sample size, no formal statistical analyses were conducted. Safety was summarized by descriptively collating AEs and serious AEs, including their frequency, severity, and treatment relatedness.

Results

Thirty participants were enrolled in the study, and 20 fully completed the study. Nine discontinued treatment before week 12 (6 were lost to follow-up, 2 were terminated early by the investigators, and 1 voluntarily withdrew); 1 additional participant was lost to follow-up after week 12. Patients were predominantly male (20/30 [66.7%]) and White (21/30 [70.0%]); the mean age of all participants was 55.4 years, and the mean (SD) duration of psoriasis was 21.4 (15.0) years (Table 1). The mean baseline percentage of BSA involvement and mean baseline PGA, PASI, and DLQI scores are shown in Table 1. Most (19/30 [63.3%]) patients received biologics that inhibited IL-23 activity (guselkumab, risankizumab, tildrakizumab), approximately one-third (9/30 [30.0%]) received biologics that inhibited IL-17 activity (ixekizumab, secukinumab), and 2 (6.7%) received biologics that inhibited IL-12/IL-23 activity (ustekinumab)(Table 1).

For the primary end point, 52.4% (11/21) of patients reached the TTT goal (BSA involvement ≤1% after 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream added to a prescribed biologic). The proportion of patients reaching the TTT goal increased over time with the combined treatment (eFigure 1). Additionally, the mean percentage of BSA involvement (eFigure 2) as well as the mean values for PGA (eFigure 3) and PGA×BSA decreased over time. The mean percentage of BSA involvement was 5.0% at baseline and dropped to 2.0% by week 12. Similar reductions were observed for PGA and PGA×BSA scores at week 12.

After discontinuing tapinarof cream at week 12 and receiving only the biologic for 4 weeks, the proportion of patients maintaining 1% or less BSA involvement fell to 40.0% (8/20) at week 16, which was closer to that observed at week 8 (36% [9/25]) than at week 12 (52.4% [11/21])(eFigure 1).

The mean PASI score was 5.5 at baseline, then decreased over time when tapinarof cream was combined with a biologic (eFigure 4), falling to 3.1 by week 2 and 1.6 by week 12; it was maintained at 1.7 at week 16. Nine (30.0%) participants had psoriasis on the scalp at baseline with a mean PSSI score of 2.6, which decreased to 0.83 by week 2. By week 12, the mean PSSI score remained stable at 0.95 in the 2 (9.5%) participants who still had scalp involvement. The mean PSSI score increased slightly to 1.45 after patients received only the biologic for 4 weeks. At baseline, 3 (10.0%) patients had genital involvement (mean Static Physician’s Global Assessment of Genitalia score, 0.27). Symptoms resolved in 2 (66.7%) of these patients at week 2 and stayed consistent until week 16; the third patient withdrew at week 2.

Both DLQI and WI-NRS scores decreased with use of tapinarof cream added to a biologic up to week 12 (eFigures 5 and 6). Mean DLQI scores were 5.3 at baseline and 3.1 at week 12. At week 16, the mean DLQI score remained stable at 2.8. Mean WI-NRS scores decreased from 4.0 at baseline to 2.7 at week 12 with the therapy combination; at week 16, the mean WI-NRS score fell further to 1.8.

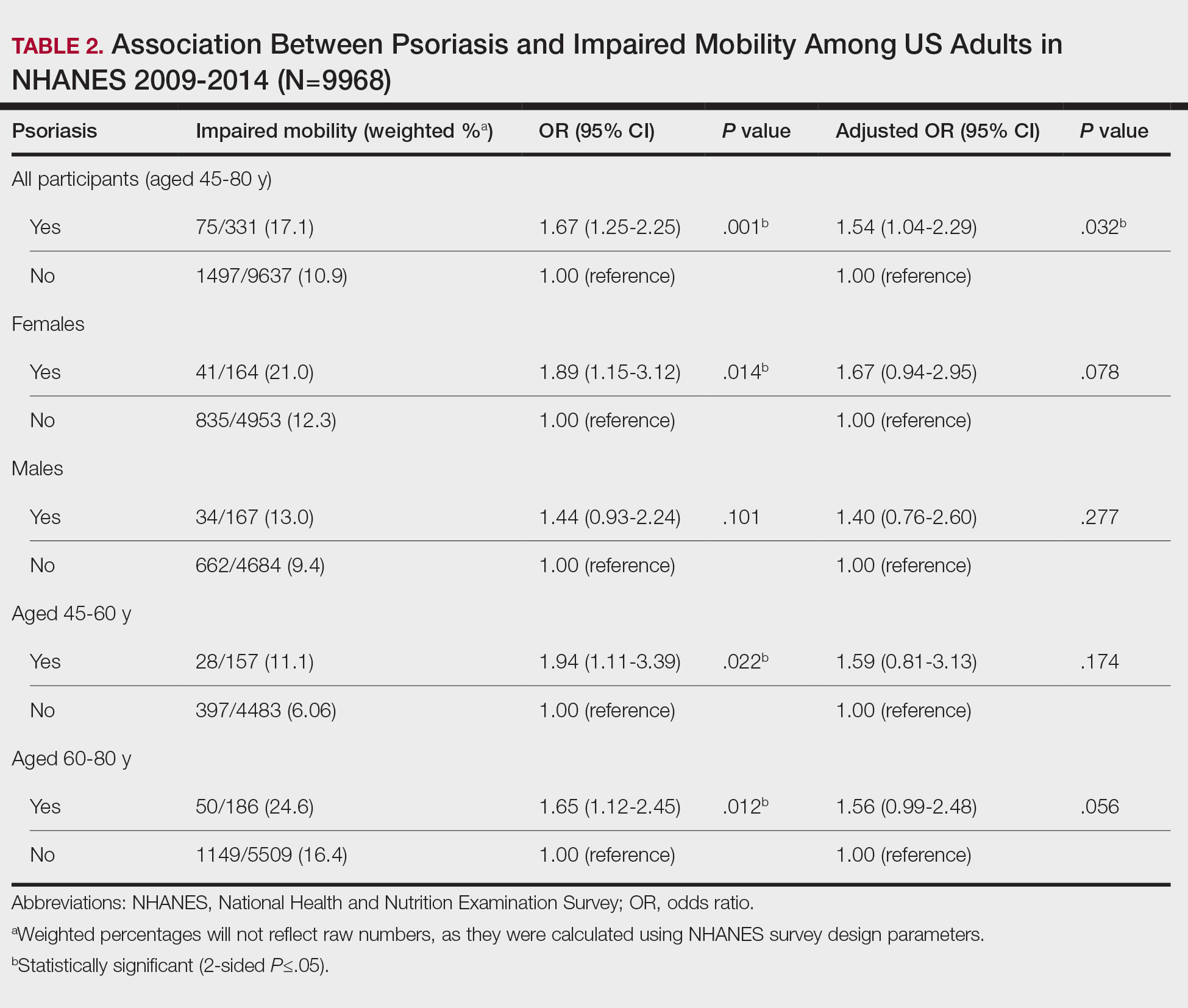

A total of 6 AEs were reported in 5 (16.7%) patients (Table 2). The majority (4/6 [67.0%]) of AEs were considered mild. Two reported cases of COVID-19 were both considered mild and unrelated. Mild folliculitis and moderate worsening of psoriasis in 2 (6.7%) different patients were the only AEs considered related to treatment. No serious AEs were reported, and no patient withdrew from the study due to an AE.

Comment

Disease activity improvements we observed with the nonsteroidal tapinarof cream were consistent with those reported when topical steroidal therapies were given to patients responding poorly to their current biologic. Our primary end point (proportion of patients with BSA involvement ≤1% after 12 weeks) showed that half (52% [11/21]) of patients whose BSA involvement was 3% or greater with a biologic for 24 weeks or more reached the TTT goal after 12 weeks of tapinarof-biologic treatment. Other studies of halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion16 and calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam17,18 added to the current biologic of poor responders found 60% to 68% of patients had reductions in their percentage BSA to 1% or lower at 12 to 16 weeks of treatment. Randomized studies showed etanercept plus topical clobetasol propionate foam20 or adalimumab plus calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam21 similarly enhanced treatment effects vs biologic alone.

A phase 3 PSOARING trial demonstrated benefit from treatment with tapinarof alone, with a remittive effect of approximately 4 months after discontinuation.25 Our data are consistent with these findings, with 40% (8/20) of patients demonstrating a remittive effect 4 weeks after discontinuing tapinarof while receiving a biologic. A similar maintenance effect was reported in another study in 50% (9/18) of patients treated with a biologic plus halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion.16 Additionally, when halcinonide ointment was given to patients receiving tildrakizumab, mean percentage of BSA involvement, PGA scores, PGA×BSA, and DLQI scores improved and were maintained 4 weeks after halcinonide ointment was stopped.19 Thus, topical therapy can augment and extend a biologic’s effect for up to 4 weeks.

In our study, tapinarof cream added to a biologic had a good safety and tolerability profile. Few AEs were recorded, with most being mild in nature, and no serious AEs or discontinuations due to AEs were reported. Only 1 case of mild folliculitis and 1 case of moderate worsening of psoriasis were considered treatment related. Further, no unexpected or new safety signals with the tapinarof-biologic combination were observed compared with tapinarof alone.27Prior studies have found that supplementing a biologic with topical therapy can reduce the probability of patients switching to another biologic.16,19 We previously found that adding halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion16 or calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam17 to a biologic helped reduce the probability of switching biologics from 88% to 90% at baseline to 12% to 24% after 12 weeks of combined therapy. Such combinations also could prevent a less responsive patient from being prescribed a higher biologic dose.19 These are important research findings, as patients—even when not responding well to their current biologic—are more likely to be tolerating that biologic well, and switching to a new biologic may introduce new safety or tolerability concerns. Thus, by enhancing the effect of a biologic with a topical therapy, one can avoid increasing the dose of the current biologic or switching to a new biologic, either of which may increase safety and/or tolerability risks. Switching biologics also has increased cost implications to the health care system and/or the patient. When comparing the cost of adding halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion to a biologic compared with switching to another biologic, the cost was 1.2 to 2.9 times higher to switch, depending on the biologic, compared with a smaller incremental cost increase to add a topical to the current biologic.16 Similar observations were reported with calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam plus a biologic.17 Although we did not evaluate biologic switching here, we anticipate a similar clinical scenario with a tapinarof-biologic combination.

Limitations of our study included the open-label design, lack of a control arm, and the relatively small study population; however, for studies investigating the safety and effectiveness of a treatment in a real-world setting, these limitations are common and are not unexpected. Our results also are consistent with the overall improvement seen in other studies16-21 examining the effects of adding a topical to a biologic. Future research is warranted to investigate a longer remittive effect and potential health care system and patient cost savings without having to switch biologics due to lack of effectiveness.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that adjunctive use of nonsteroidal tapinarof cream 1% may enhance a biologic treatment effect in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, providing an adequate response for many patients who were not responding well to a biologic alone. Clinical outcomes improved with the tapinarof-biologic combination, and a remittive effect was noted 4 weeks after tapinarof discontinuation without any new safety signals. Adding tapinarof cream to a biologic also may prevent the need to switch biologics when patients do not sufficiently respond, preserving the safety and cost associated with a patient’s current biologic.

The estimated prevalence of psoriasis in individuals older than 20 years in the United States has been reported at approximately 3%, or more than 7.5 million people.1 There currently is no cure for psoriasis, and available therapeutics, including phototherapy,2 topical therapies,3 systemic medications,4 and biologic agents,5 are focused only on controlling symptoms. The National Psoriasis Foundation defines an acceptable treatment response for plaque psoriasis as 3% or lower body surface area (BSA) involvement after 3 months of therapy, with a treat-to-target (TTT) goal of 1% or less BSA involvement.6

Cytokines are known to mediate psoriasis pathology, and biologic therapies target the signaling cascade of various cytokines. Biologics approved to treat moderate to severe plaque psoriasis include IgG monoclonal antibodies binding and inhibiting the activity of interleukin (IL)-17 (ixekizumab,7 secukinumab8), IL-23 (guselkumab,9 risankizumab,10 tildrakizumab11), and IL-12/23 (ustekinumab12). Despite targeting these cytokines, biologics may not sufficiently suppress the symptoms of psoriatic disease and their severity in all patients. Adding a topical treatment to biologic therapy can augment clinical response without increasing the incidence of adverse effects13-15 and may reduce the need to switch biologics due to ineffectiveness. Switching biologics likely would increase cost burden to the health care system and/or patient depending on their insurance plan and possibly introduce new safety and/or tolerability issues.16,17

In patients who do not adequately respond to biologics, better responses were reported when topical medications including halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion16 or calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam17,18 were administered. In randomized or open-label, real-world studies, patients with psoriasis responded well when topical medications were added to a biologic, such as tildrakizumab combined with halcinonide ointment 0.1%,19 etanercept combined with topical clobetasol propionate foam,20 or adalimumab combined with calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam.21 No additional safety concerns were observed with the topical add-ons in any of these studies.

Tapinarof is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for topical treatment of plaque psoriasis in adults.22 It is a first-in-class small molecule with a novel mechanism of action that downregulates IL-17A and IL-17F and normalizes the skin barrier through expression of filaggrin, loricrin, and involucrin; it also has antioxidant activity.23 In the phase 3 PSOARING 1 and 2 trials, daily application of tapinarof cream was safe and efficacious in patients with plaque psoriasis,24,25 with a remittive (maintenance) effect of a median of approximately 4 months after discontinuation.25 In these 2 phase 3 studies, tapinarof significantly (P<0.01 at week 12) relieved itch, which was seen rapidly (P<0.05 at week 2),26 improved quality of life,27 and led to high patient satisfaction.27 When tapinarof cream was combined with deucravacitinib in a patient with severe plaque psoriasis, symptoms rapidly cleared, with a 75% decrease in disease severity after 4 weeks.28

The objective of this prospective, open-label, real-world, single-center study was to assess the effectiveness, safety, and remittive (or maintenance) effect of nonsteroidal tapinarof cream 1% added to ongoing biologic therapy in patients with plaque psoriasis who were not adequately responding to a biologic alone.

Methods

Study Design and Participants—This prospective, open-label, real-world, single-center study assessed the safety and effectiveness of

Eligible participants were otherwise healthy males and females aged 18 years and older with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BSA involvement ≥3%) who had been treated with a biologic for 24 weeks or more. Patients were recruited from the Psoriasis Treatment Center of New Jersey (East Windsor, New Jersey). Exclusion criteria were recent use of oral systemic therapies (within 4 weeks of baseline) or topical therapies (within 2 weeks) to treat psoriasis, recent use of UVB (within 2 weeks) or psoralen plus UVA (within 4 weeks) phototherapy, or use of any investigational drug within 4 weeks of baseline (or within 5 pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic half-lives, whichever was longer). Patients who were pregnant or breastfeeding or who had any known hypersensitivity to the excipients of tapinarof cream also were excluded from the study.

Eligible participants received tapinarof cream 1% once daily plus their ongoing biologic for 12 weeks, after which tapinarof was discontinued and the biologic was continued for an additional 4 weeks. A remittive (maintenance) effect was assessed at week 16.

Study Outcomes—Safety and efficacy were evaluated at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. The primary end point was the proportion of patients who reached the TTT goal of 1% or less BSA involvement at week 12. Secondary end points included the proportion of patients with 1% or less BSA involvement at weeks 2, 4, 8, and 16; and PGA scores, composite PGA multiplied by mean percentage of BSA involvement (PGA×BSA), and PASI scores at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. The patient-reported outcomes of Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS) scores also were evaluated at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. In patients who had disease involvement on the scalp or genital region at baseline, Psoriasis Scalp Severity Index (PSSI) and Static Physician’s Global Assessment of Genitalia scores, respectively, were assessed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16. Safety was determined by the incidence, severity, and relatedness of adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs.

Statistical Analysis—Approximately 30 participants were planned for enrollment and recruited consecutively as they were identified during screening against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Changes from baseline in all outcomes were summarized descriptively. Missing data were not imputed. Given the sample size, no formal statistical analyses were conducted. Safety was summarized by descriptively collating AEs and serious AEs, including their frequency, severity, and treatment relatedness.

Results

Thirty participants were enrolled in the study, and 20 fully completed the study. Nine discontinued treatment before week 12 (6 were lost to follow-up, 2 were terminated early by the investigators, and 1 voluntarily withdrew); 1 additional participant was lost to follow-up after week 12. Patients were predominantly male (20/30 [66.7%]) and White (21/30 [70.0%]); the mean age of all participants was 55.4 years, and the mean (SD) duration of psoriasis was 21.4 (15.0) years (Table 1). The mean baseline percentage of BSA involvement and mean baseline PGA, PASI, and DLQI scores are shown in Table 1. Most (19/30 [63.3%]) patients received biologics that inhibited IL-23 activity (guselkumab, risankizumab, tildrakizumab), approximately one-third (9/30 [30.0%]) received biologics that inhibited IL-17 activity (ixekizumab, secukinumab), and 2 (6.7%) received biologics that inhibited IL-12/IL-23 activity (ustekinumab)(Table 1).

For the primary end point, 52.4% (11/21) of patients reached the TTT goal (BSA involvement ≤1% after 12 weeks of treatment with tapinarof cream added to a prescribed biologic). The proportion of patients reaching the TTT goal increased over time with the combined treatment (eFigure 1). Additionally, the mean percentage of BSA involvement (eFigure 2) as well as the mean values for PGA (eFigure 3) and PGA×BSA decreased over time. The mean percentage of BSA involvement was 5.0% at baseline and dropped to 2.0% by week 12. Similar reductions were observed for PGA and PGA×BSA scores at week 12.

After discontinuing tapinarof cream at week 12 and receiving only the biologic for 4 weeks, the proportion of patients maintaining 1% or less BSA involvement fell to 40.0% (8/20) at week 16, which was closer to that observed at week 8 (36% [9/25]) than at week 12 (52.4% [11/21])(eFigure 1).

The mean PASI score was 5.5 at baseline, then decreased over time when tapinarof cream was combined with a biologic (eFigure 4), falling to 3.1 by week 2 and 1.6 by week 12; it was maintained at 1.7 at week 16. Nine (30.0%) participants had psoriasis on the scalp at baseline with a mean PSSI score of 2.6, which decreased to 0.83 by week 2. By week 12, the mean PSSI score remained stable at 0.95 in the 2 (9.5%) participants who still had scalp involvement. The mean PSSI score increased slightly to 1.45 after patients received only the biologic for 4 weeks. At baseline, 3 (10.0%) patients had genital involvement (mean Static Physician’s Global Assessment of Genitalia score, 0.27). Symptoms resolved in 2 (66.7%) of these patients at week 2 and stayed consistent until week 16; the third patient withdrew at week 2.

Both DLQI and WI-NRS scores decreased with use of tapinarof cream added to a biologic up to week 12 (eFigures 5 and 6). Mean DLQI scores were 5.3 at baseline and 3.1 at week 12. At week 16, the mean DLQI score remained stable at 2.8. Mean WI-NRS scores decreased from 4.0 at baseline to 2.7 at week 12 with the therapy combination; at week 16, the mean WI-NRS score fell further to 1.8.

A total of 6 AEs were reported in 5 (16.7%) patients (Table 2). The majority (4/6 [67.0%]) of AEs were considered mild. Two reported cases of COVID-19 were both considered mild and unrelated. Mild folliculitis and moderate worsening of psoriasis in 2 (6.7%) different patients were the only AEs considered related to treatment. No serious AEs were reported, and no patient withdrew from the study due to an AE.

Comment

Disease activity improvements we observed with the nonsteroidal tapinarof cream were consistent with those reported when topical steroidal therapies were given to patients responding poorly to their current biologic. Our primary end point (proportion of patients with BSA involvement ≤1% after 12 weeks) showed that half (52% [11/21]) of patients whose BSA involvement was 3% or greater with a biologic for 24 weeks or more reached the TTT goal after 12 weeks of tapinarof-biologic treatment. Other studies of halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion16 and calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam17,18 added to the current biologic of poor responders found 60% to 68% of patients had reductions in their percentage BSA to 1% or lower at 12 to 16 weeks of treatment. Randomized studies showed etanercept plus topical clobetasol propionate foam20 or adalimumab plus calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam21 similarly enhanced treatment effects vs biologic alone.

A phase 3 PSOARING trial demonstrated benefit from treatment with tapinarof alone, with a remittive effect of approximately 4 months after discontinuation.25 Our data are consistent with these findings, with 40% (8/20) of patients demonstrating a remittive effect 4 weeks after discontinuing tapinarof while receiving a biologic. A similar maintenance effect was reported in another study in 50% (9/18) of patients treated with a biologic plus halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion.16 Additionally, when halcinonide ointment was given to patients receiving tildrakizumab, mean percentage of BSA involvement, PGA scores, PGA×BSA, and DLQI scores improved and were maintained 4 weeks after halcinonide ointment was stopped.19 Thus, topical therapy can augment and extend a biologic’s effect for up to 4 weeks.

In our study, tapinarof cream added to a biologic had a good safety and tolerability profile. Few AEs were recorded, with most being mild in nature, and no serious AEs or discontinuations due to AEs were reported. Only 1 case of mild folliculitis and 1 case of moderate worsening of psoriasis were considered treatment related. Further, no unexpected or new safety signals with the tapinarof-biologic combination were observed compared with tapinarof alone.27Prior studies have found that supplementing a biologic with topical therapy can reduce the probability of patients switching to another biologic.16,19 We previously found that adding halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion16 or calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam17 to a biologic helped reduce the probability of switching biologics from 88% to 90% at baseline to 12% to 24% after 12 weeks of combined therapy. Such combinations also could prevent a less responsive patient from being prescribed a higher biologic dose.19 These are important research findings, as patients—even when not responding well to their current biologic—are more likely to be tolerating that biologic well, and switching to a new biologic may introduce new safety or tolerability concerns. Thus, by enhancing the effect of a biologic with a topical therapy, one can avoid increasing the dose of the current biologic or switching to a new biologic, either of which may increase safety and/or tolerability risks. Switching biologics also has increased cost implications to the health care system and/or the patient. When comparing the cost of adding halobetasol propionate–tazarotene lotion to a biologic compared with switching to another biologic, the cost was 1.2 to 2.9 times higher to switch, depending on the biologic, compared with a smaller incremental cost increase to add a topical to the current biologic.16 Similar observations were reported with calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam plus a biologic.17 Although we did not evaluate biologic switching here, we anticipate a similar clinical scenario with a tapinarof-biologic combination.

Limitations of our study included the open-label design, lack of a control arm, and the relatively small study population; however, for studies investigating the safety and effectiveness of a treatment in a real-world setting, these limitations are common and are not unexpected. Our results also are consistent with the overall improvement seen in other studies16-21 examining the effects of adding a topical to a biologic. Future research is warranted to investigate a longer remittive effect and potential health care system and patient cost savings without having to switch biologics due to lack of effectiveness.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that adjunctive use of nonsteroidal tapinarof cream 1% may enhance a biologic treatment effect in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, providing an adequate response for many patients who were not responding well to a biologic alone. Clinical outcomes improved with the tapinarof-biologic combination, and a remittive effect was noted 4 weeks after tapinarof discontinuation without any new safety signals. Adding tapinarof cream to a biologic also may prevent the need to switch biologics when patients do not sufficiently respond, preserving the safety and cost associated with a patient’s current biologic.

- Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, et al. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:940-946. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2007

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.042

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.087

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiological therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.044

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:290-298. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.017

- Taltz. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2024.

- Cosentyx. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2023.

- Tremfya. Prescribing information. Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2023.

- Skyrizi. Prescribing information. AbbVie Inc; 2024.

- Ilumya. Prescribing information. Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc; 2020.

- Stelara. Prescribing information. Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2022.

- Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

- Jensen JD, Delcambre MR, Nguyen G, et al. Biologic therapy with or without topical treatment in psoriasis: what does the current evidence say? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:379-385. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0089-1

- Gustafson CJ, Watkins C, Hix E, et al. Combination therapy in psoriasis: an evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:9-25. doi:10.1007/s40257-012-0003-7

- Bagel J, Novak K, Nelson E. Adjunctive use of halobetasol propionate-tazarotene in biologic-experienced patients with psoriasis. Cutis. 2022;109:103-109. doi:10.12788/cutis.0451

- Bagel J, Nelson E, Zapata J, et al. Adjunctive use of calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam in a real-world setting curtails the cost of biologics without reducing efficacy in psoriasis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:1383-1396. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00454-z

- Bagel J, Zapata J, Nelson E. A prospective, open-label study evaluating adjunctive calcipotriene 0.005%/betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% foam in psoriasis patients with inadequate response to biologic therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:611-616.

- Bagel J, Novak K, Nelson E. Tildrakizumab in combination with topical halcinonide 0.1% ointment for treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:766-772. doi:10.36849/jdd.6830

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik L, Callis Duffin K, et al. A randomized study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of adding topical therapy to etanercept in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:385-392. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.03.031

- Thaci D, Ortonne JP, Chimenti S, et al. A phase IIIb, multicentre, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of adalimumab with and without calcipotriol/betamethasone topical treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: the BELIEVE study. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:402-411. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09791.x

- Vtama. Prescribing information. Dermavant Sciences, Inc; 2022.

- Bobonich M, Gorelick J, Aldredge L, et al. Tapinarof, a novel, first-in-class, topical therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist for the management of psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:779-784. doi:10.36849/jdd.7317

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1171

- Kircik L, Zirwas M, Kwatra SG, et al. Rapid improvements in itch with tapinarof cream 1% once daily in two phase 3 trials in adults with mild to severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:201-211. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-01068-x

- Bagel J, Gold LS, Del Rosso J, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:936-944. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.061

- Abdin R, Kircik L, Issa NT. First use of combination oral deucravacitinib with tapinarof cream for treatment of severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2024;23:192-194. doi:10.36849/jdd.8091

- Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, et al. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:940-946. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2007

- Elmets CA, Lim HW, Stoff B, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with phototherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:775-804. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.04.042

- Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432-470. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.087

- Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiological therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445-1486. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.044

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029-1072. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057

- Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J, et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:290-298. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.017

- Taltz. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2024.

- Cosentyx. Prescribing information. Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2023.

- Tremfya. Prescribing information. Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2023.

- Skyrizi. Prescribing information. AbbVie Inc; 2024.

- Ilumya. Prescribing information. Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Inc; 2020.

- Stelara. Prescribing information. Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2022.

- Bagel J, Gold LS. Combining topical psoriasis treatment to enhance systemic and phototherapy: a review of the literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:1209-1222.

- Jensen JD, Delcambre MR, Nguyen G, et al. Biologic therapy with or without topical treatment in psoriasis: what does the current evidence say? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:379-385. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0089-1

- Gustafson CJ, Watkins C, Hix E, et al. Combination therapy in psoriasis: an evidence-based review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:9-25. doi:10.1007/s40257-012-0003-7

- Bagel J, Novak K, Nelson E. Adjunctive use of halobetasol propionate-tazarotene in biologic-experienced patients with psoriasis. Cutis. 2022;109:103-109. doi:10.12788/cutis.0451

- Bagel J, Nelson E, Zapata J, et al. Adjunctive use of calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam in a real-world setting curtails the cost of biologics without reducing efficacy in psoriasis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10:1383-1396. doi:10.1007/s13555-020-00454-z

- Bagel J, Zapata J, Nelson E. A prospective, open-label study evaluating adjunctive calcipotriene 0.005%/betamethasone dipropionate 0.064% foam in psoriasis patients with inadequate response to biologic therapy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:611-616.

- Bagel J, Novak K, Nelson E. Tildrakizumab in combination with topical halcinonide 0.1% ointment for treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:766-772. doi:10.36849/jdd.6830

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik L, Callis Duffin K, et al. A randomized study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of adding topical therapy to etanercept in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:385-392. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.03.031

- Thaci D, Ortonne JP, Chimenti S, et al. A phase IIIb, multicentre, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of adalimumab with and without calcipotriol/betamethasone topical treatment in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: the BELIEVE study. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:402-411. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09791.x

- Vtama. Prescribing information. Dermavant Sciences, Inc; 2022.

- Bobonich M, Gorelick J, Aldredge L, et al. Tapinarof, a novel, first-in-class, topical therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist for the management of psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:779-784. doi:10.36849/jdd.7317

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2103629

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.1171

- Kircik L, Zirwas M, Kwatra SG, et al. Rapid improvements in itch with tapinarof cream 1% once daily in two phase 3 trials in adults with mild to severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024;14:201-211. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-01068-x

- Bagel J, Gold LS, Del Rosso J, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: patient-reported outcomes from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:936-944. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.04.061

- Abdin R, Kircik L, Issa NT. First use of combination oral deucravacitinib with tapinarof cream for treatment of severe plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2024;23:192-194. doi:10.36849/jdd.8091

Safety and Effectiveness of Nonsteroidal Tapinarof Cream 1% Added to Ongoing Biologic Therapy for Treatment of Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis

Safety and Effectiveness of Nonsteroidal Tapinarof Cream 1% Added to Ongoing Biologic Therapy for Treatment of Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis

Practice Points

- Patients with moderate to severe psoriasis do not always reach treatment goals with biologic therapy alone.

- Adjunctive use of nonsteroidal tapinarof cream 1% may enhance the effects of ongoing biologic therapy in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, possibly avoiding the need to switch to another biologic.

- Patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are not adequately responding to biologics may benefit from adding tapinarof cream 1% to their current regimen.

Pathogenic Significance of Serum Syndecan-1 and Syndecan-4 in Psoriasis

Pathogenic Significance of Serum Syndecan-1 and Syndecan-4 in Psoriasis

Psoriasis, one of the most researched diseases in dermatology, has a complex pathogenesis that is not yet fully understood. One of the most important stages of psoriasis pathogenesis is the proliferation of T helper (Th) 17 cells by IL-23 released from myeloid dendritic cells. Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α released from Th1 cells and IL-17 and IL-22 released from Th17 cells are known to induce the proliferation of keratinocytes and the release of chemokines responsible for neutrophil chemotaxis.1

Although secondary messengers such as cytokines and chemokines, which provide cell interaction with the extracellular matrix (ECM), have their own specific receptors, it is known that syndecans (SDCs) play a role in ECM and cell interactions and have receptor or coreceptor functions.2 In humans, 4 types of SDCs have been identified (SDC1-SDC4), which are type I transmembrane proteoglycans found in all nucleated cells. Syndecans consist of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan chains that are structurally linked to a core protein sequence. The molecule has cytoplasmic, transmembrane, and extracellular domains.2,3 While SDCs often are described as coreceptors for integrins and growth factor and hormone receptors, they also are capable of acting as signaling receptors by engaging intracellular messengers, including actin-related proteins and protein kinases.4

Prior research has indicated that the release of heparanase from the lysosomes of leukocytes during infection, inflammation, and endothelial damage causes cleavage of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans from the extracellular domains of SDCs. The peptide chains at the SDC core then are separated by matrix metalloproteinases in a process known as shedding. The shed SDCs may have either a stimulating or a suppressive effect on their receptor activity. Several cytokines are known to cause SDC shedding.5,6 Many studies in recent years have reported that SDCs play a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, for which serum levels of soluble SDCs can be biomarkers.7

In this study, we aimed to evaluate and compare serum SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, and IL-17A levels in patients with psoriasis vs healthy controls. Additionally, by reviewing the literature data, we analyzed whether SDCs can be implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and their potential role in this process.

Methods

The study population consisted of 40 patients with psoriasis and 40 healthy controls. Age and sex characteristics were similar between the 2 groups, but weight distribution was not. The psoriasis group included patients older than 18 years who had received a clinical and/or histologic diagnosis, had no systemic disease other than psoriasis in their medical history, and had not used any systemic treatment or phototherapy for the past 3 months. Healthy patients older than 18 years who had no medical history of inflammatory disease were included in the control group. Participants provided signed consent.

Data such as medical history, laboratory findings, and physical specifications were recorded. A Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of 10 or lower was considered mild disease, and a score higher than 10 was considered moderate to severe disease. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to measure SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, and IL-17A levels.

The data were evaluated using the IBM SPSS Statistics V22.0 statistical package program. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. The conformity of the data to a normal distribution was examined using a Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean (SD) and nonnormally distributed variables were expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Data were compared between the 2 study groups using either a student t test (normal distribution) or Mann-Whitney U test (nonnormal distribution). Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Categorical data were compared using a χ2 test. Associations among SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, IL-17A, and other variables were assessed using Spearman rank correlation. A binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine whether serum SDC1 and SDC4 levels were independent risk factors for psoriasis.

Results

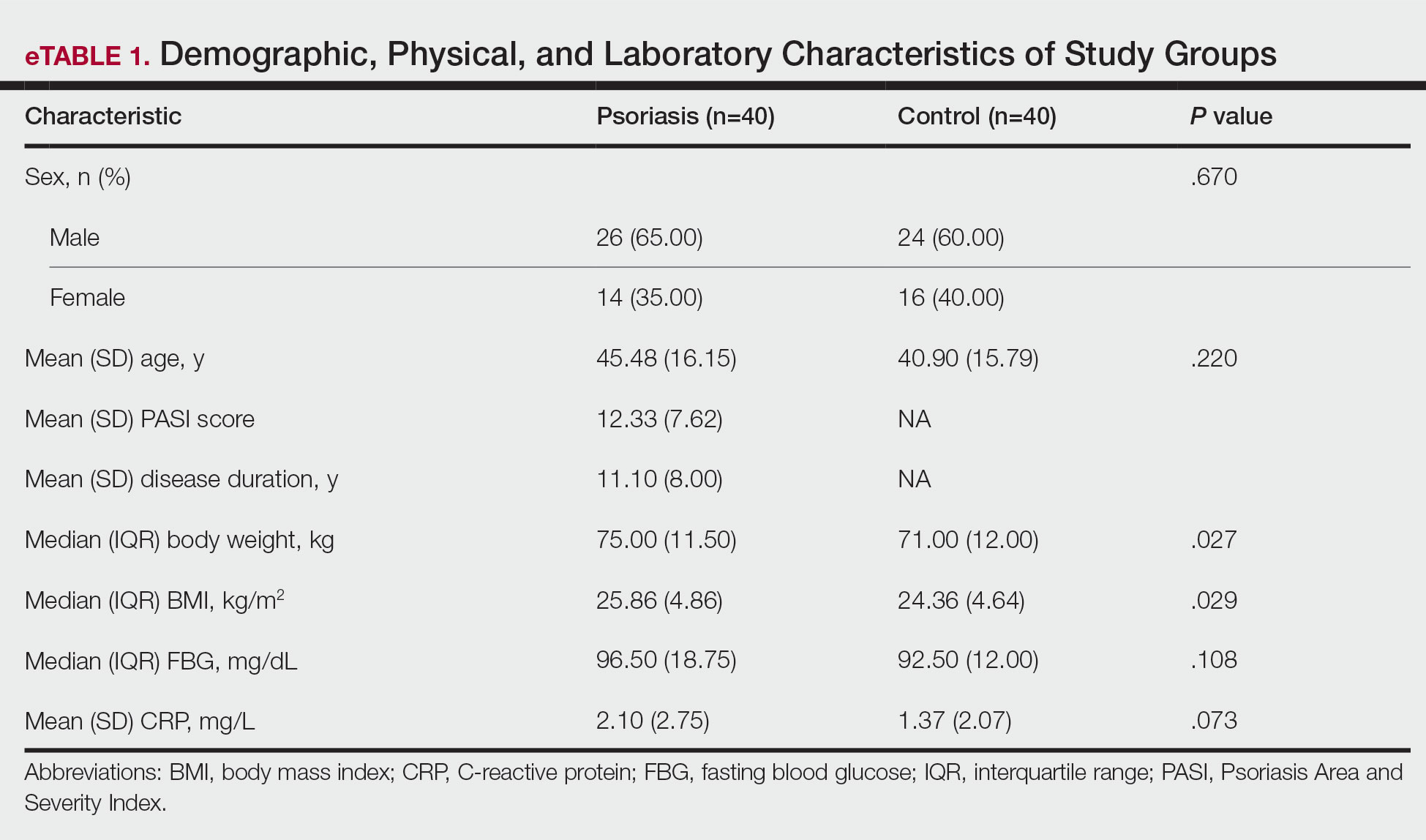

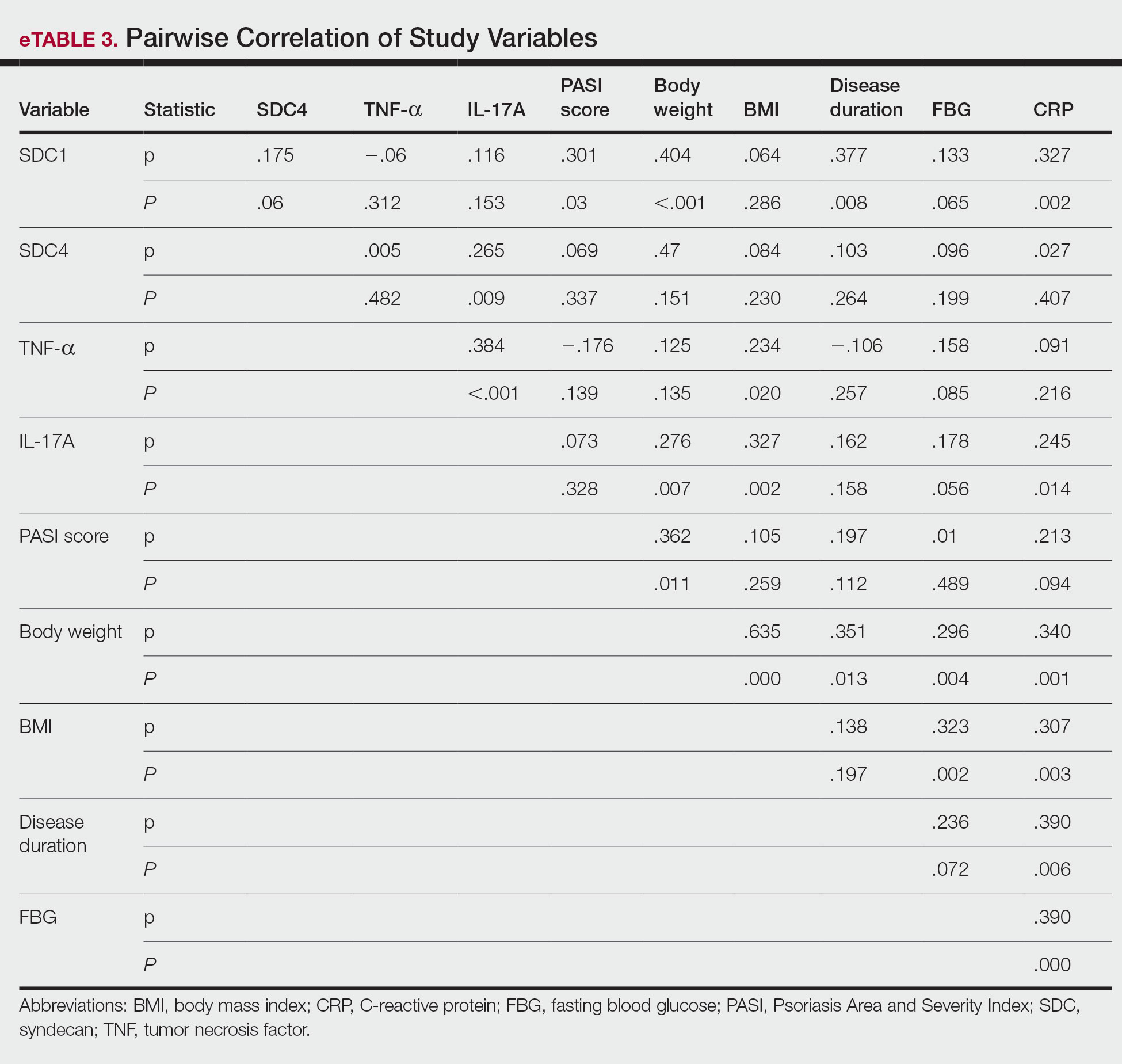

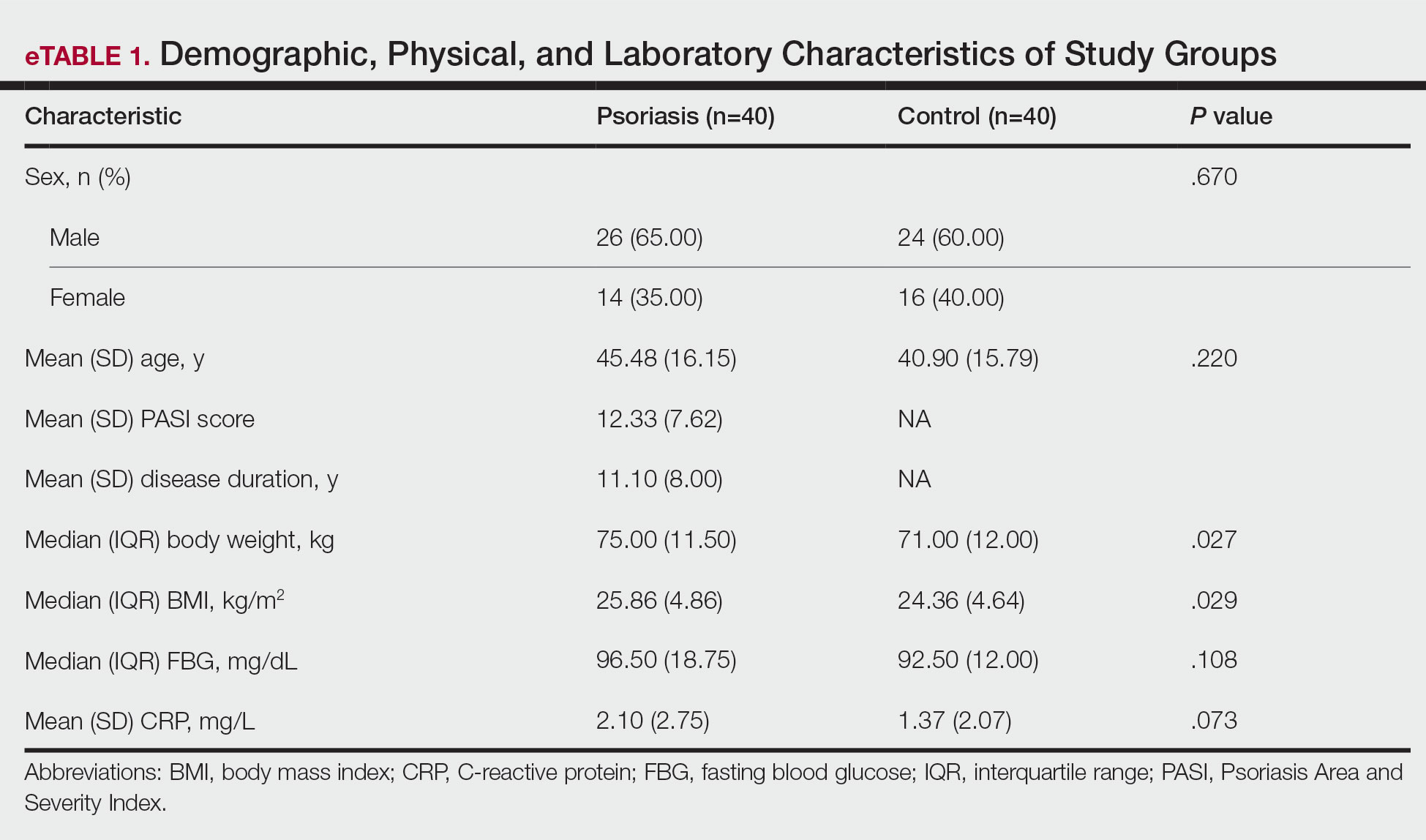

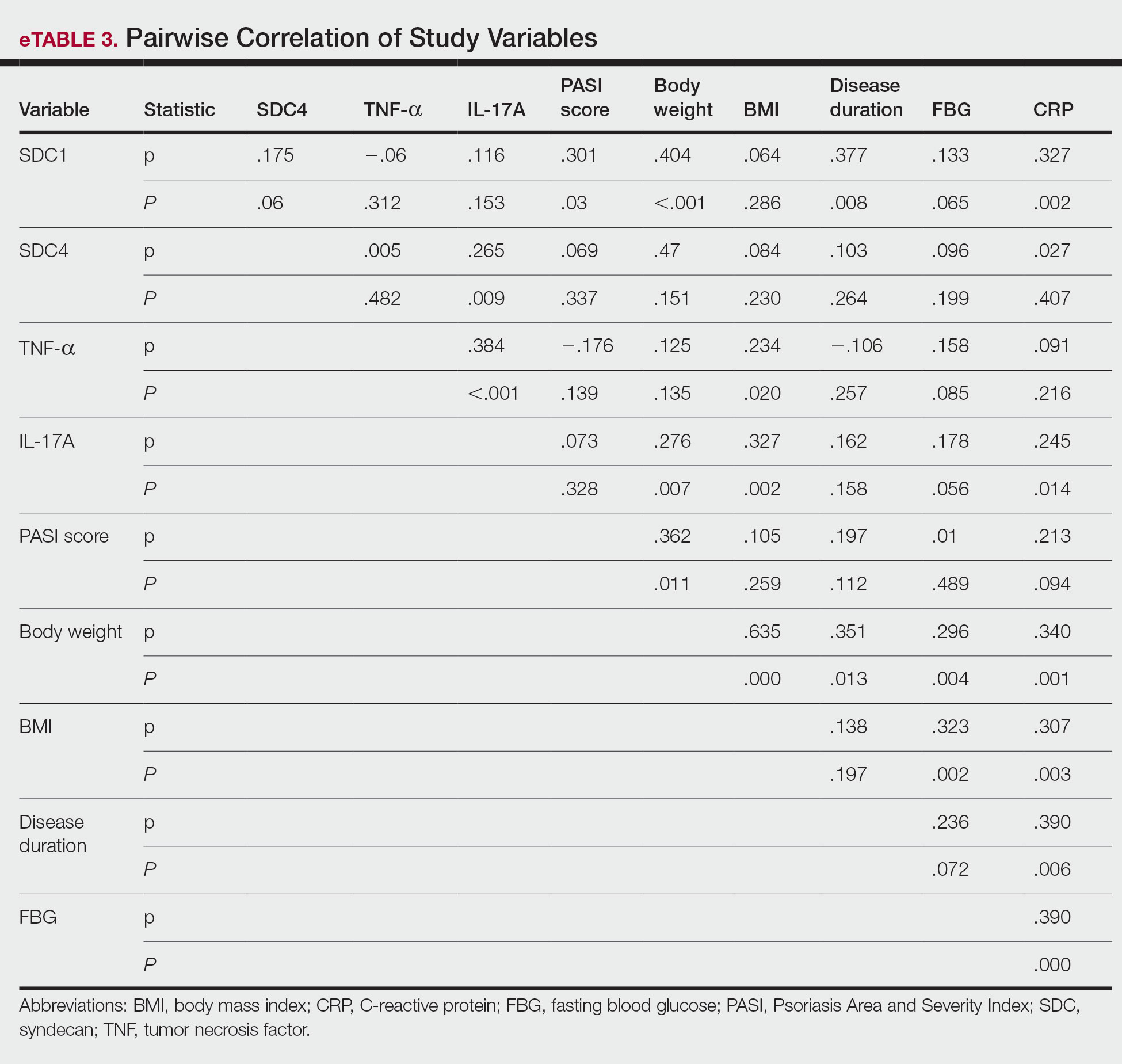

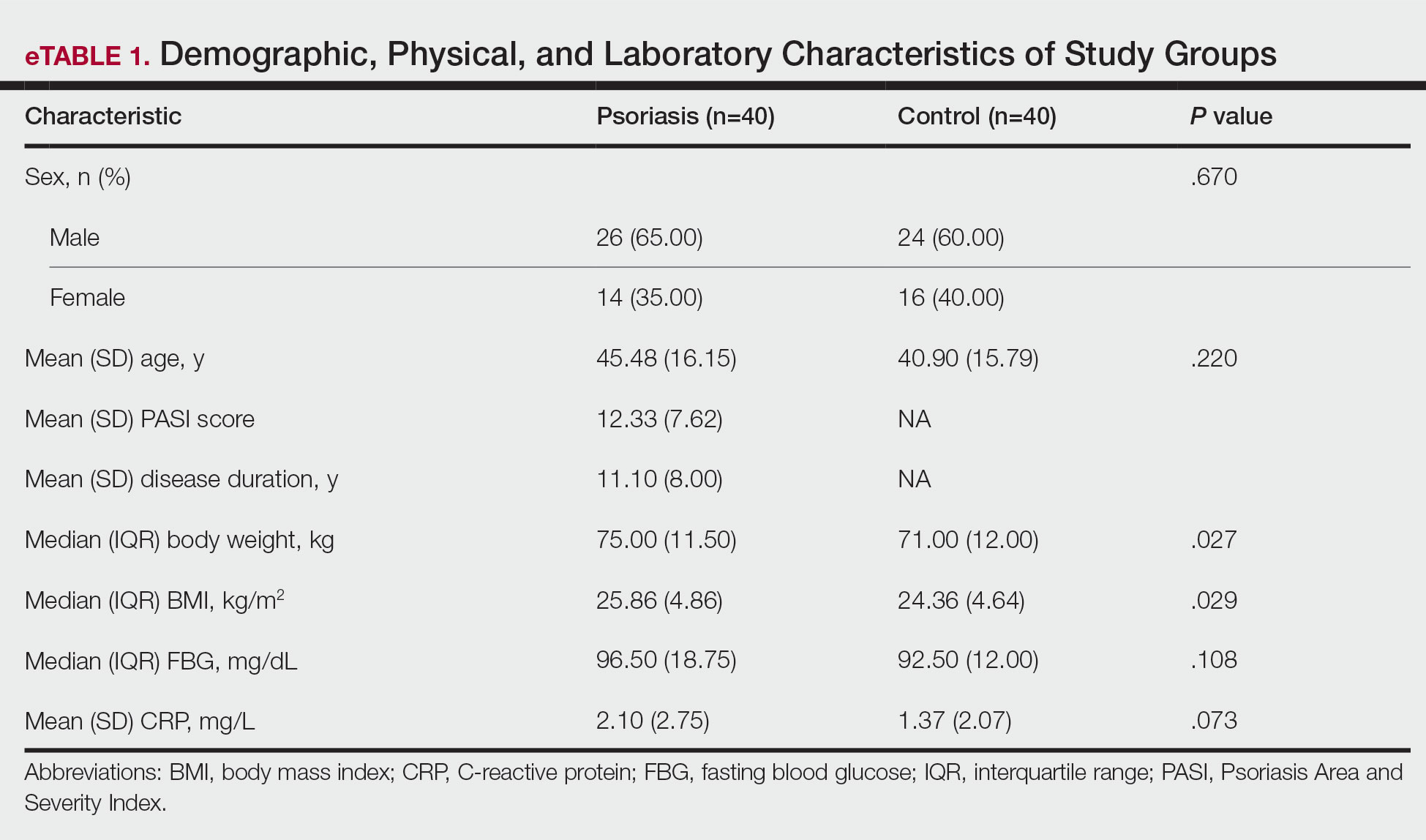

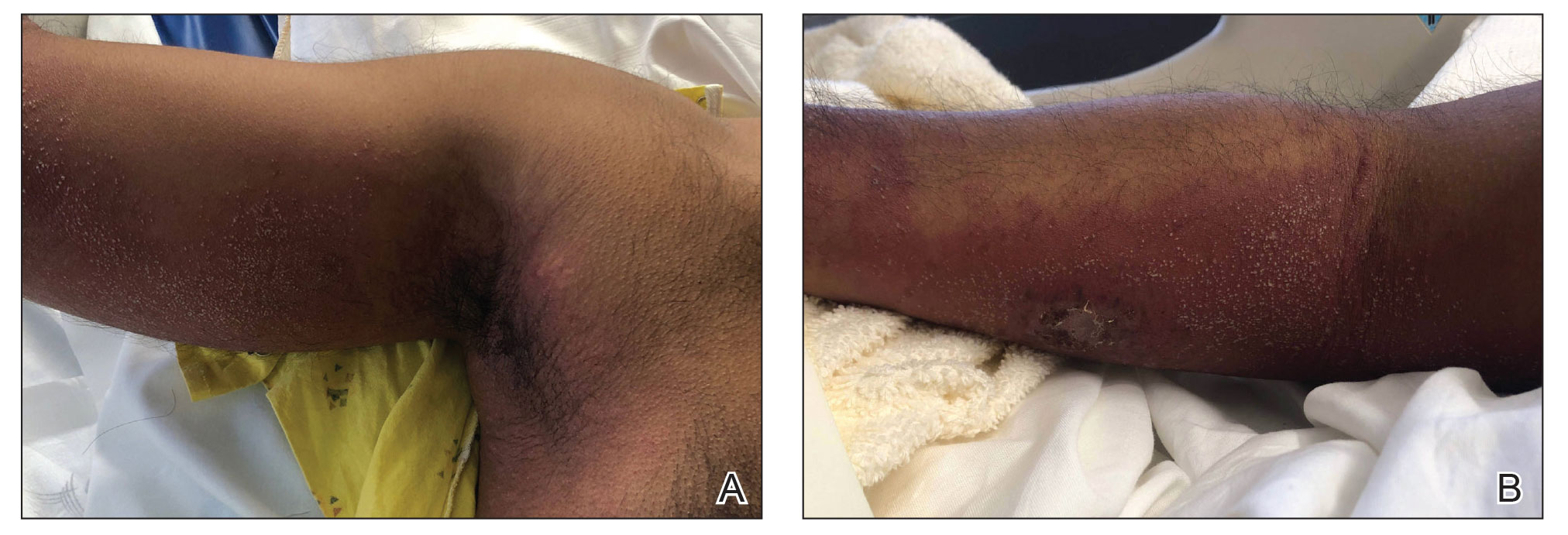

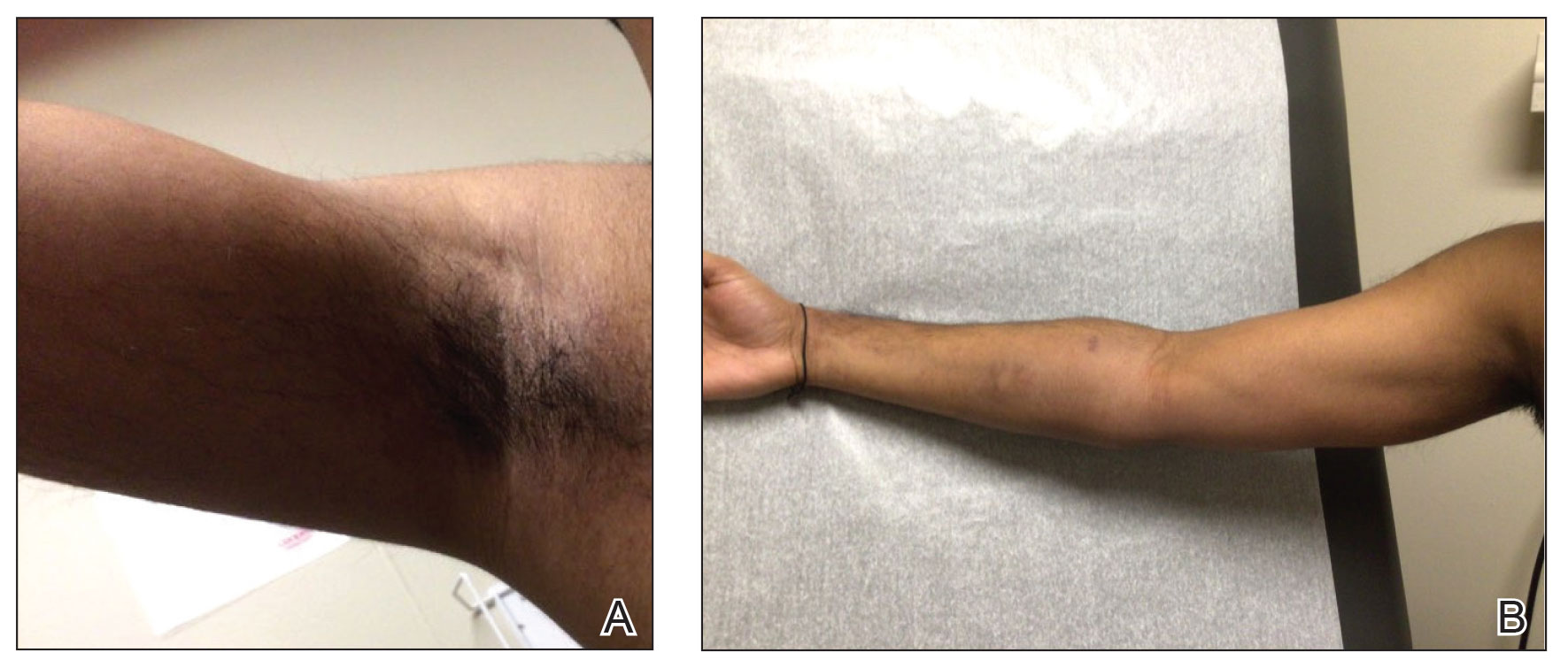

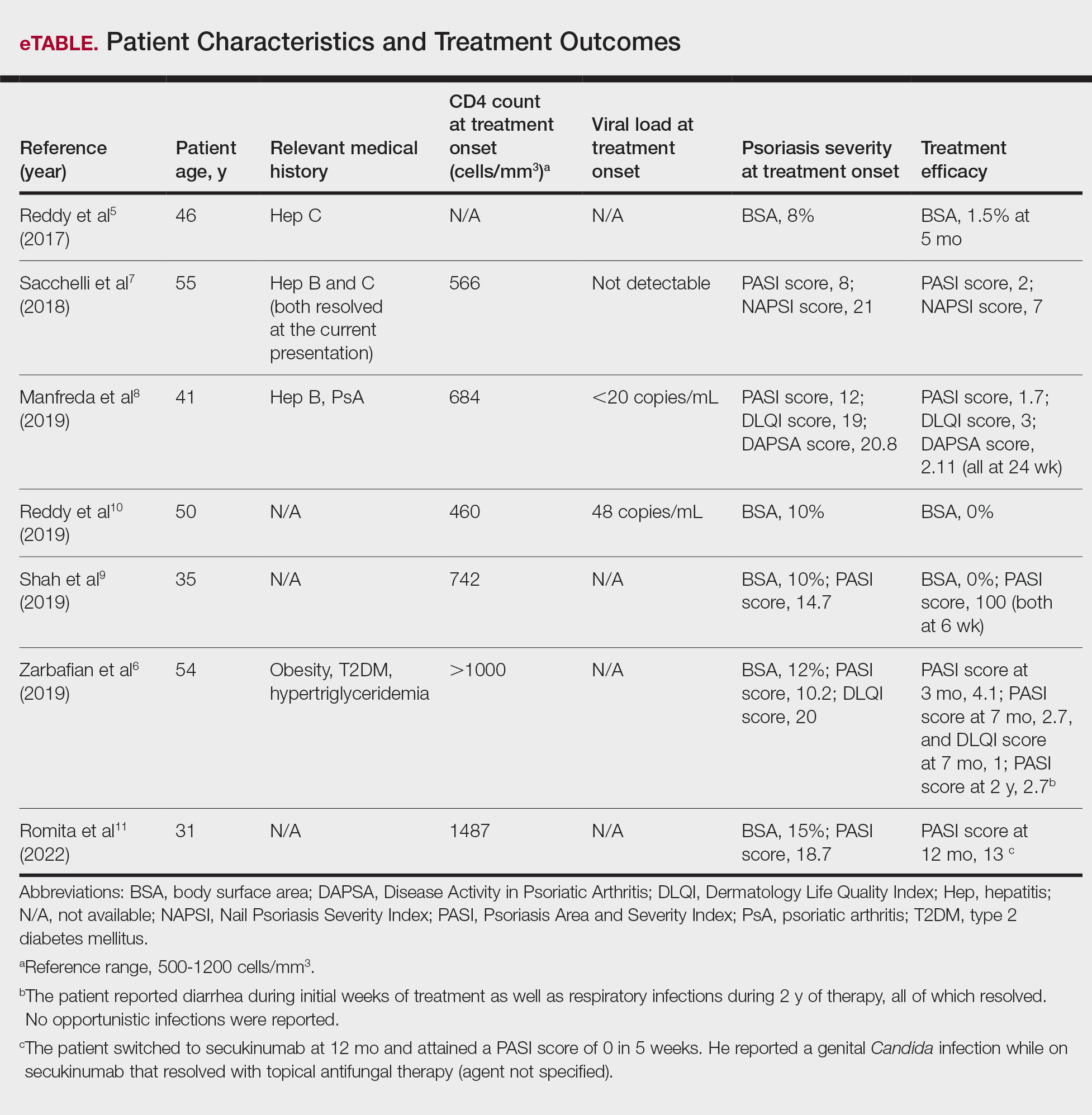

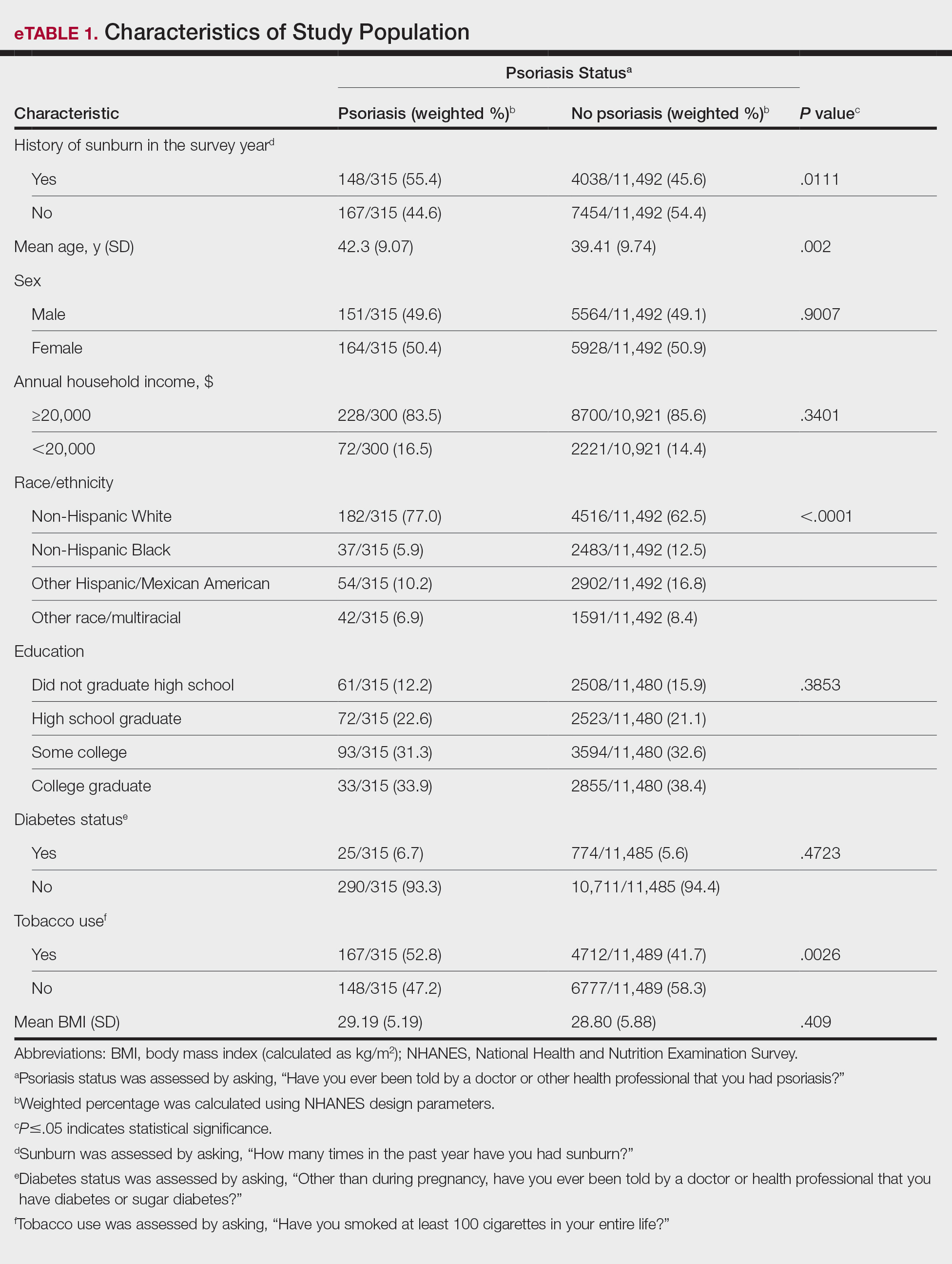

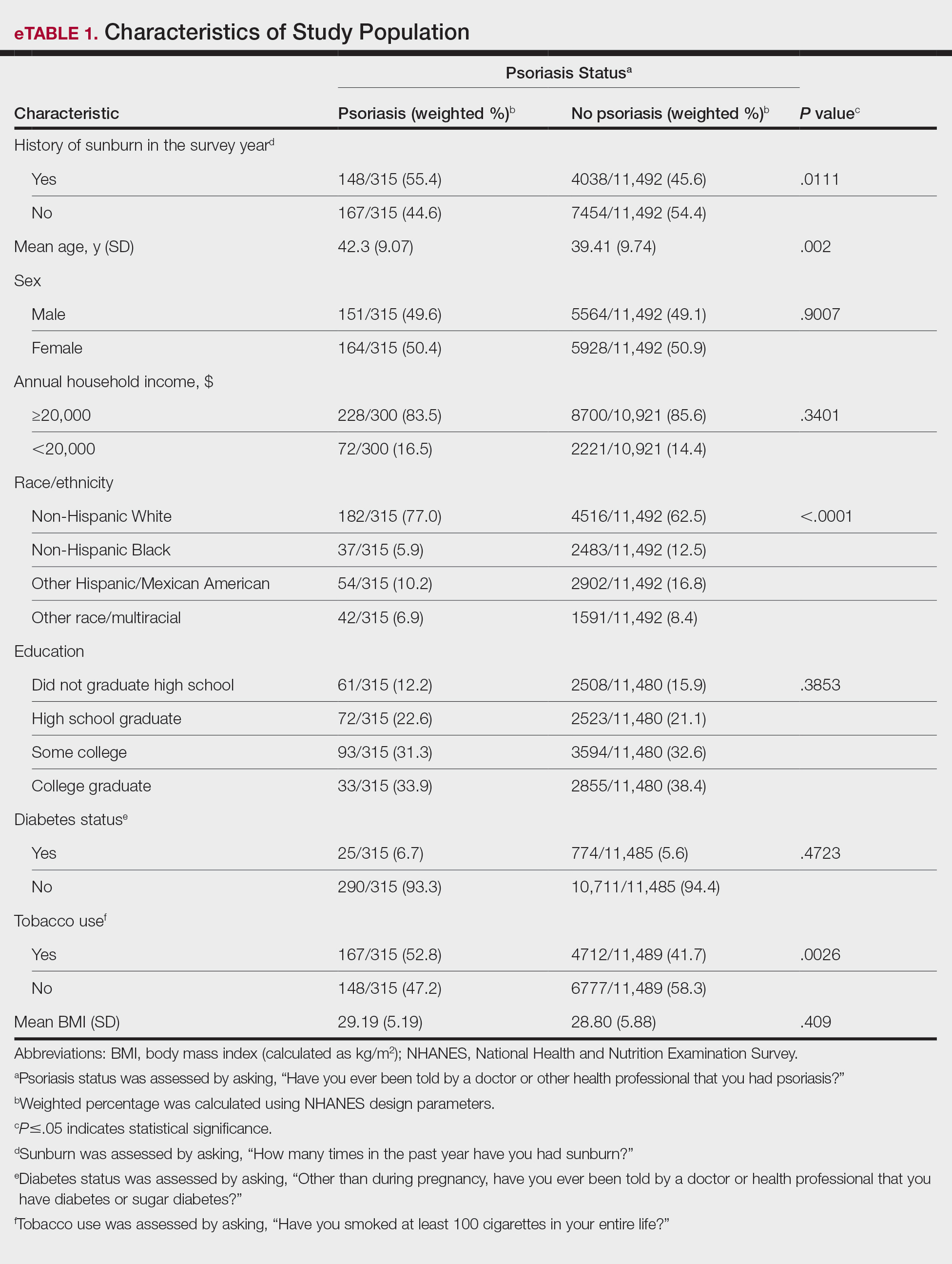

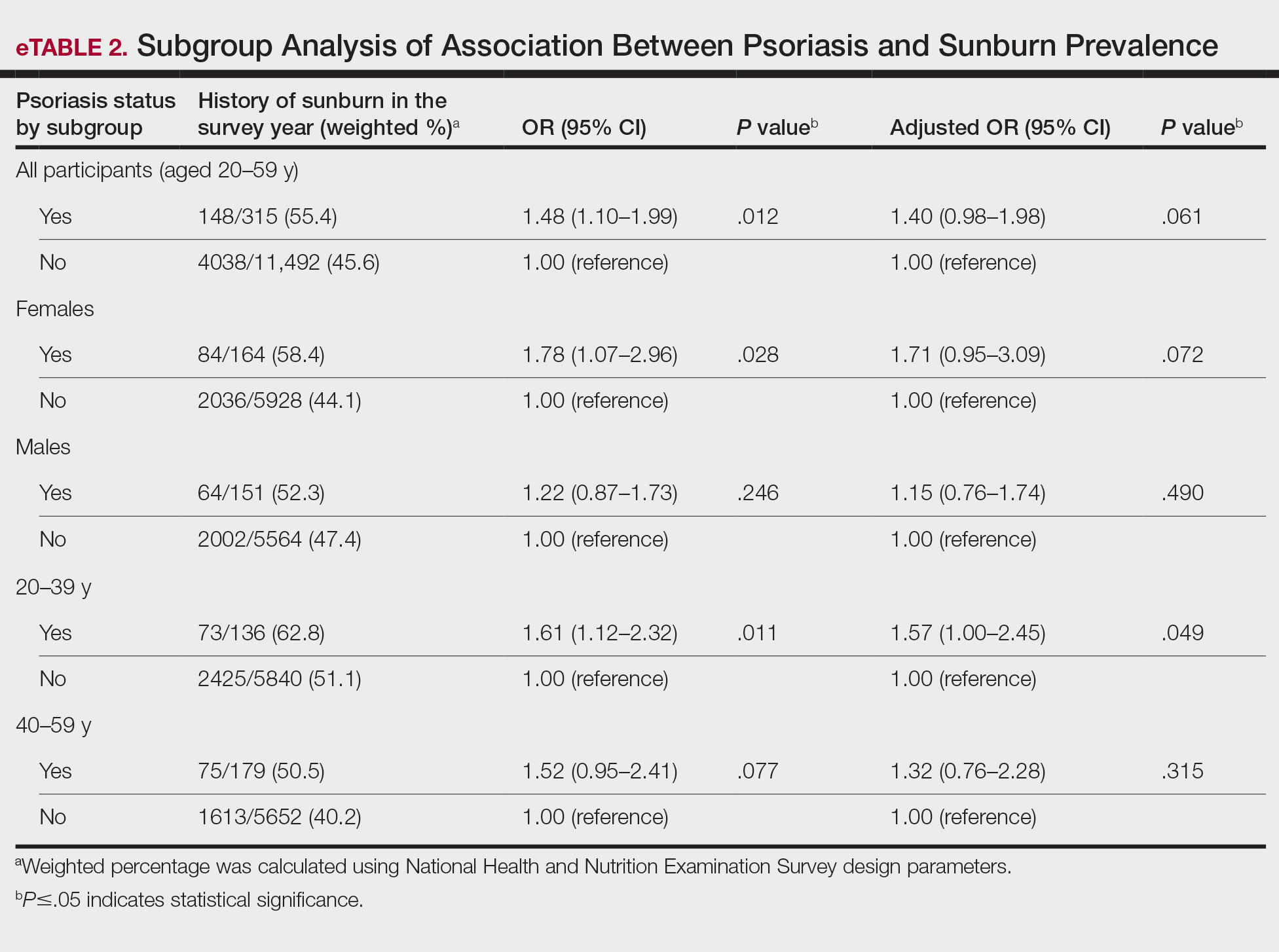

The 2 study groups showed similar demographic characteristics in terms of sex (P=.67) and age (P=.22) distribution. The mean (SD) PASI score in the psoriasis group was 12.33 (7.62); the mean (SD) disease duration was 11.10 (8.00) years. Body weight and BMI were both significantly higher in the psoriasis group (P=.027 and P=.029, respectively) compared with the control group (eTable 1).

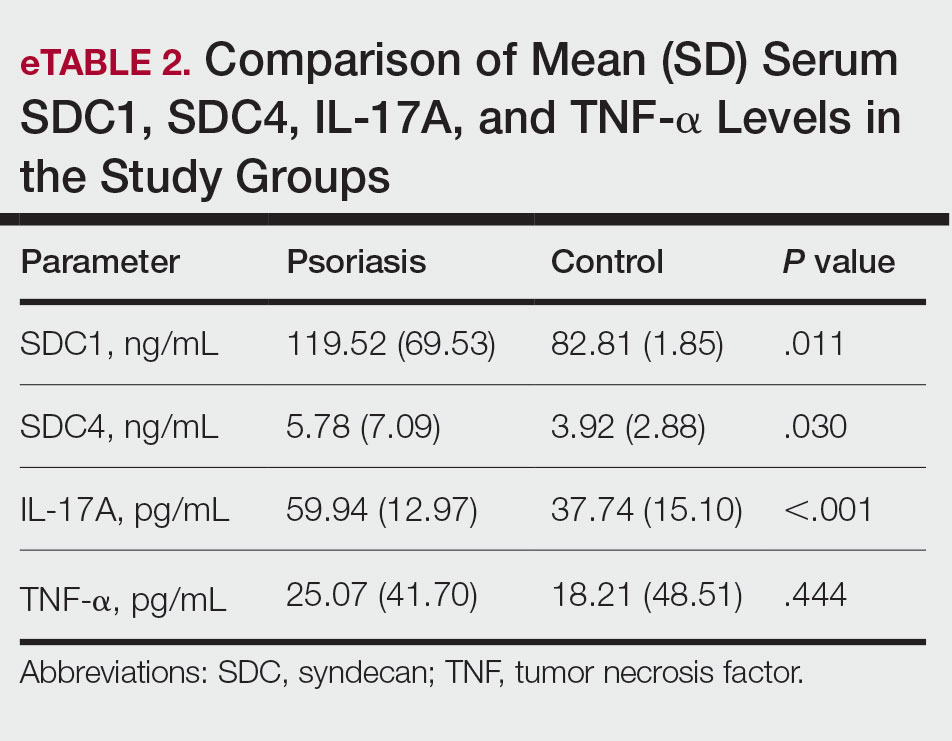

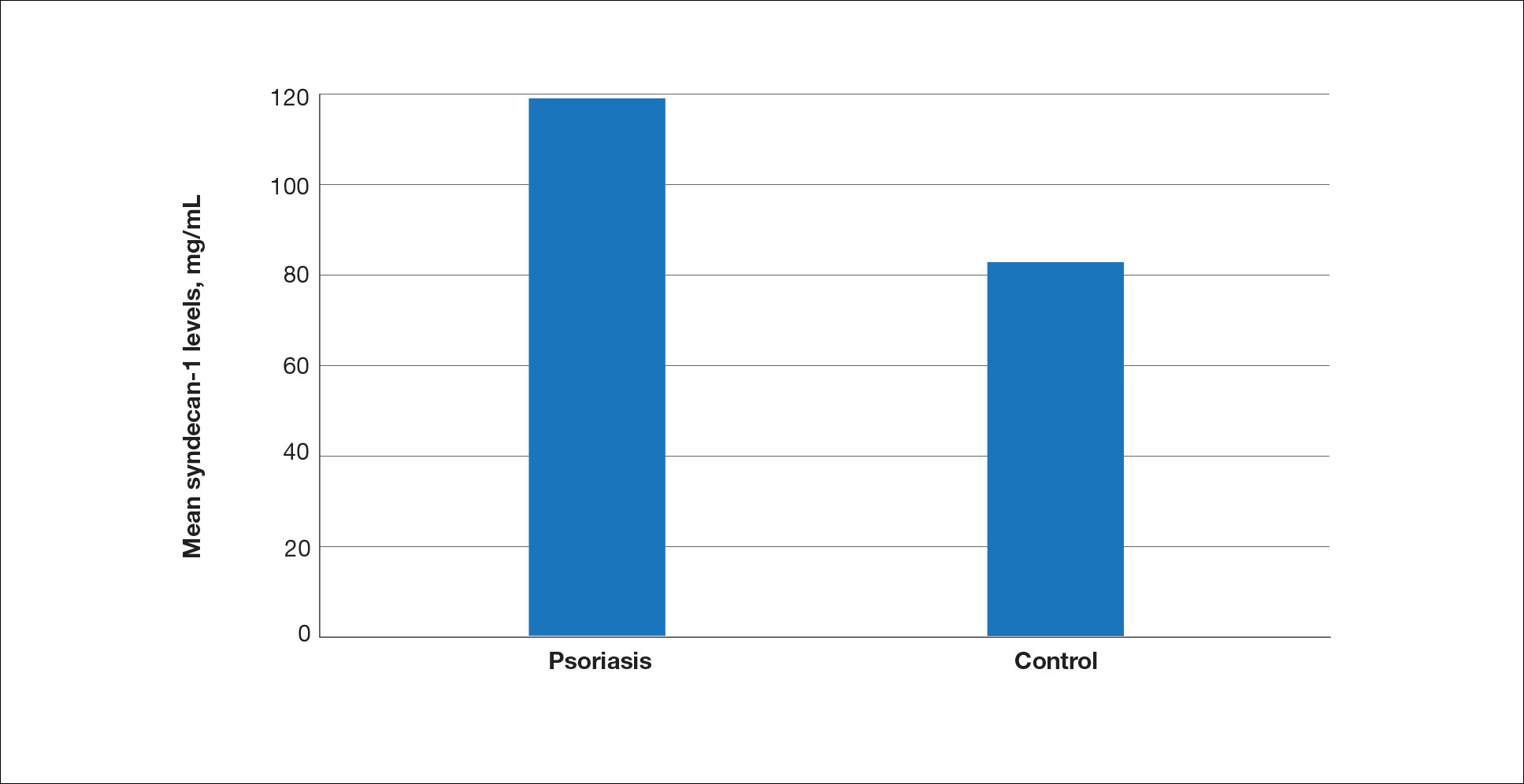

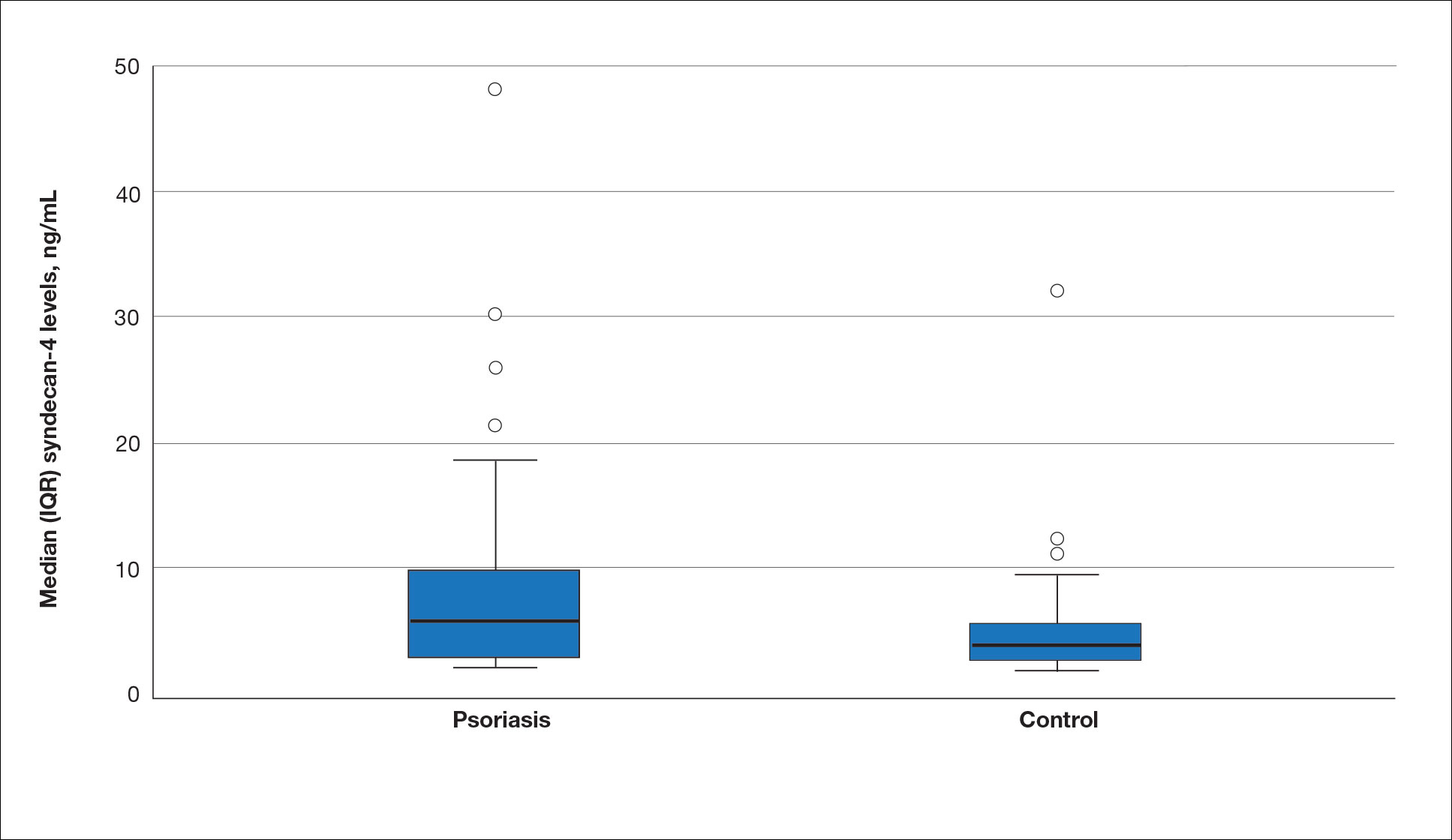

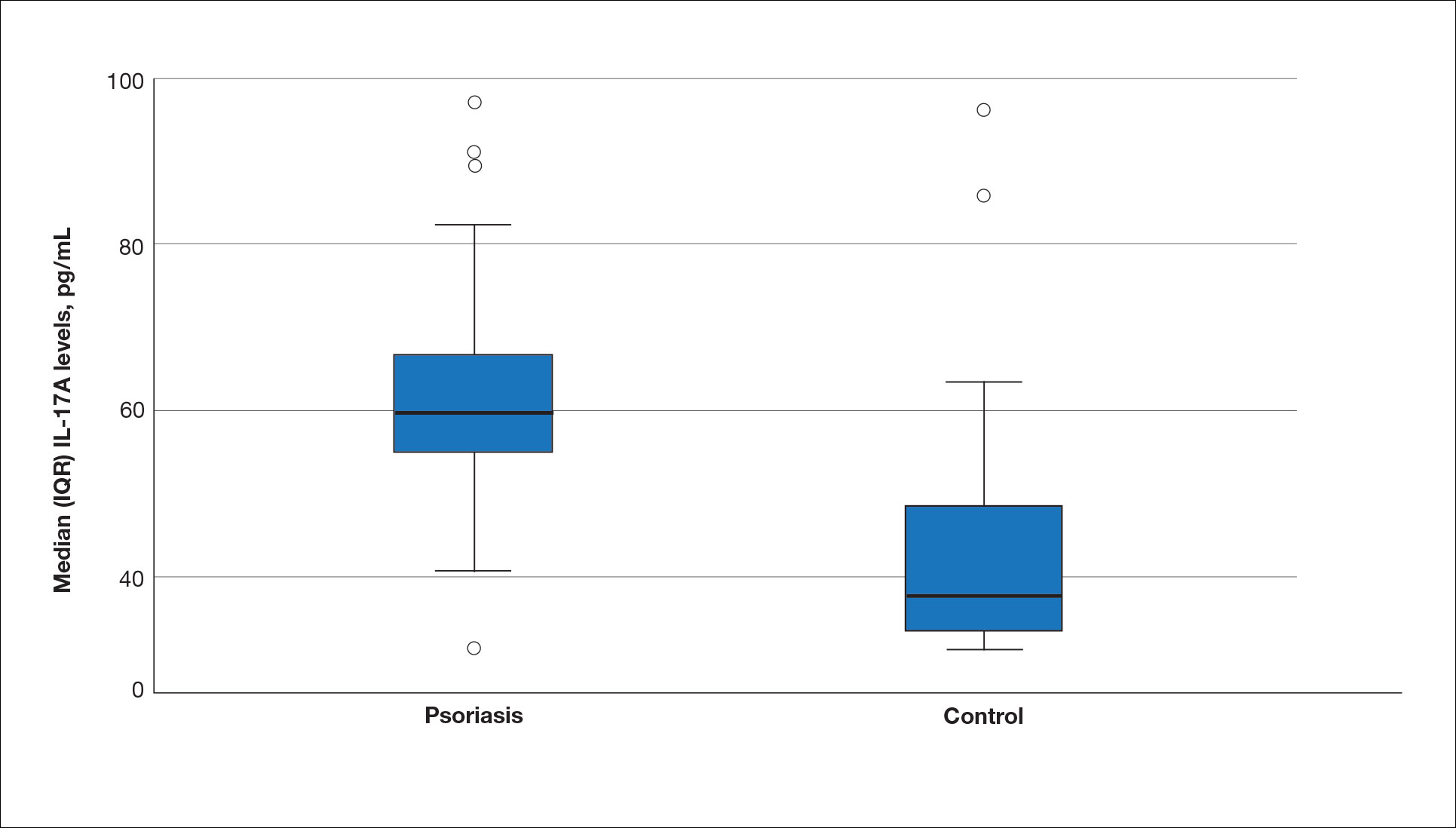

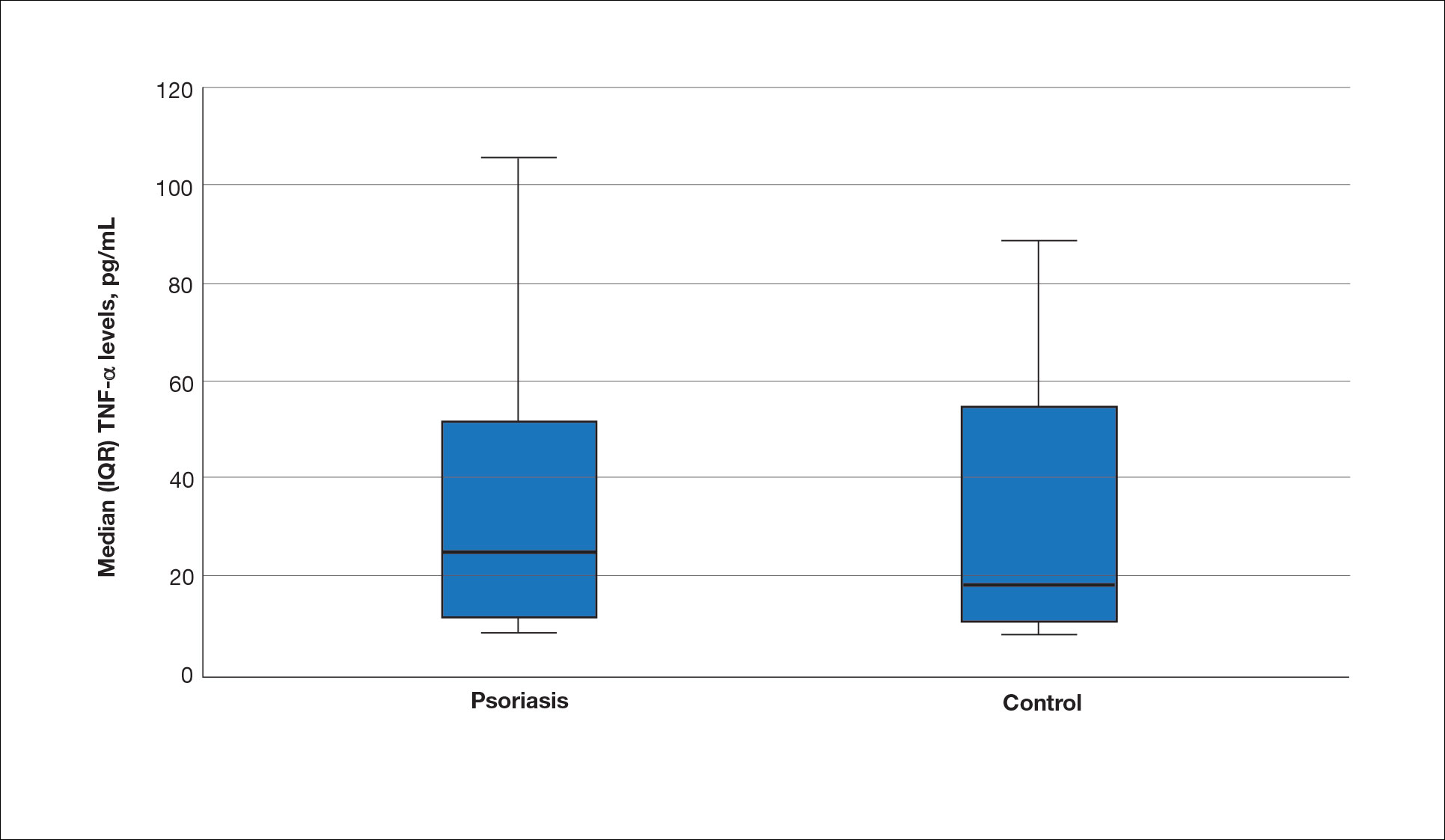

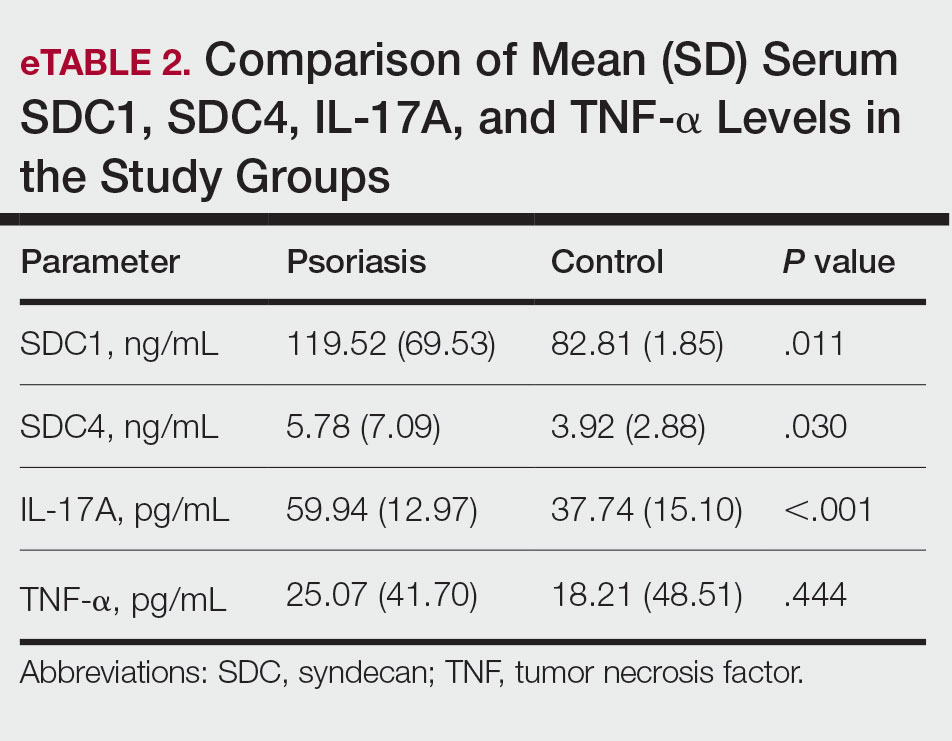

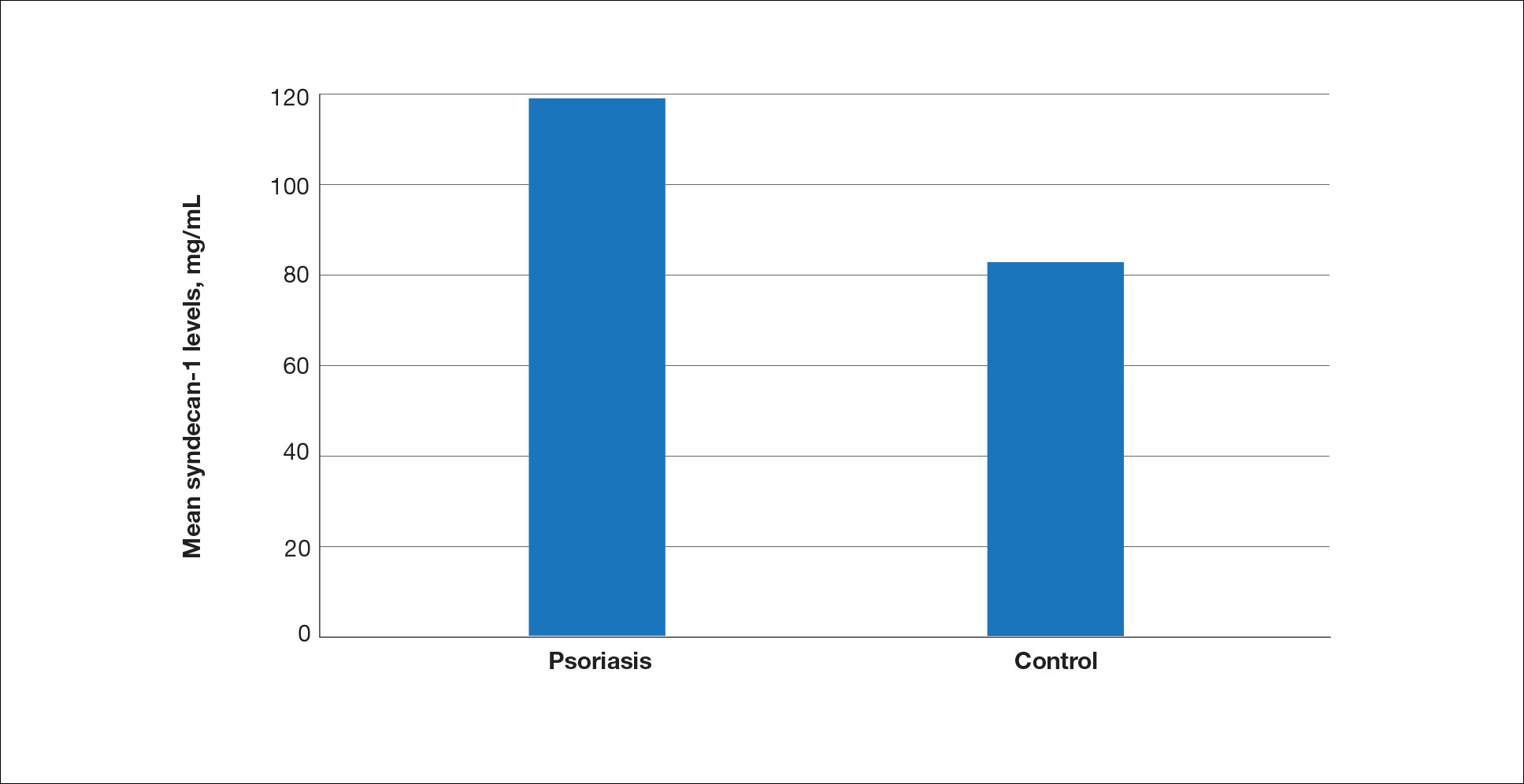

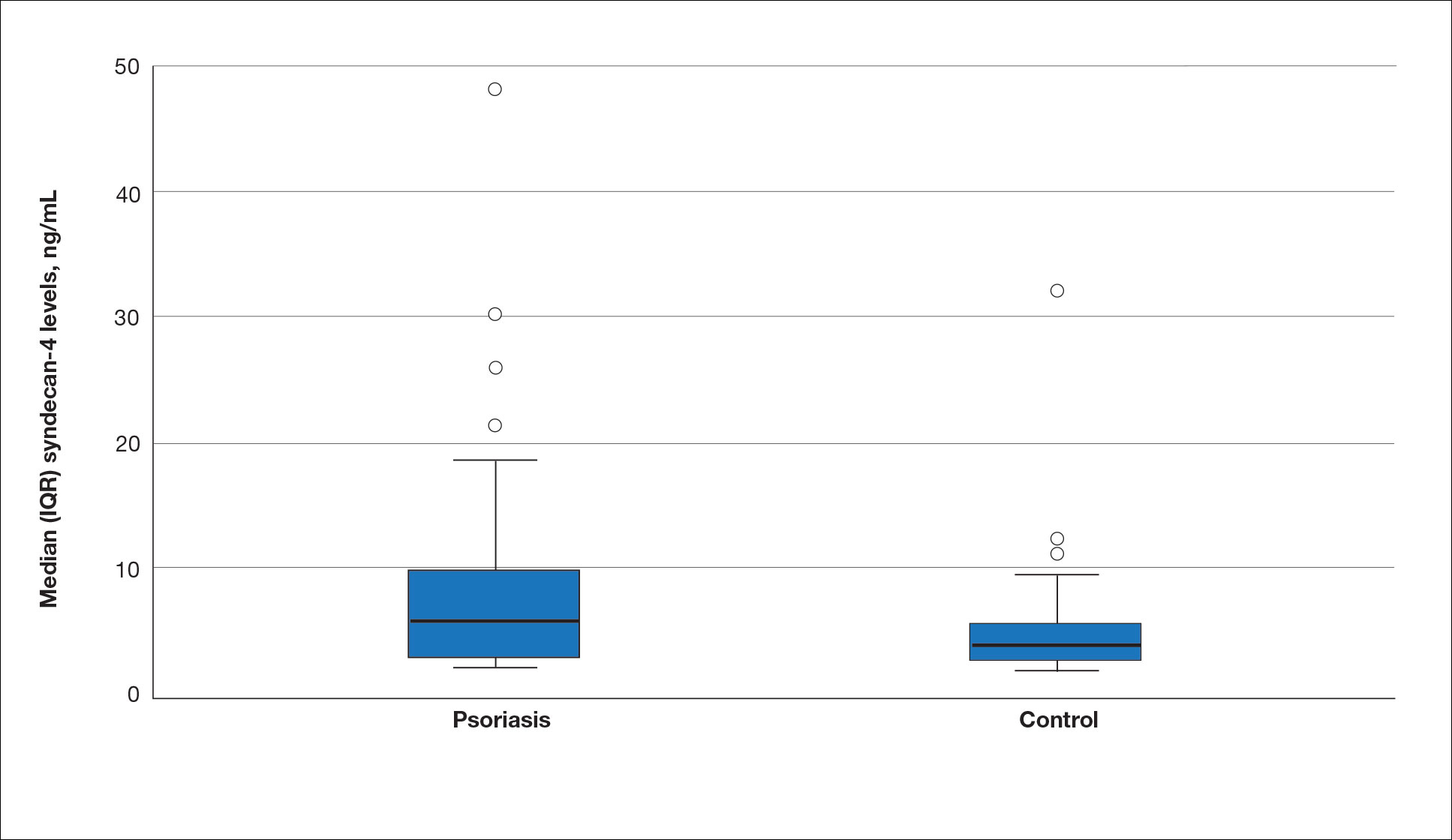

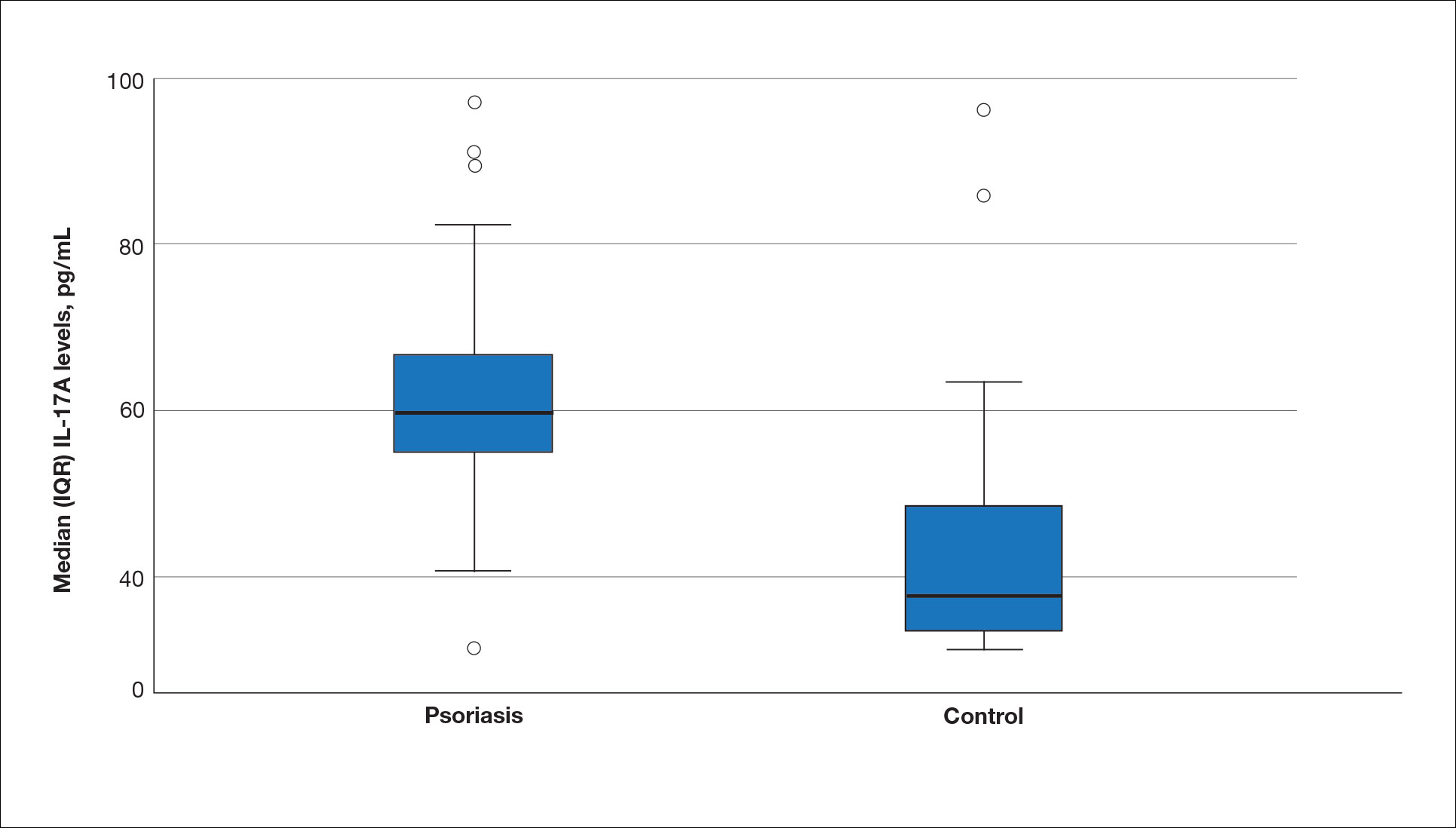

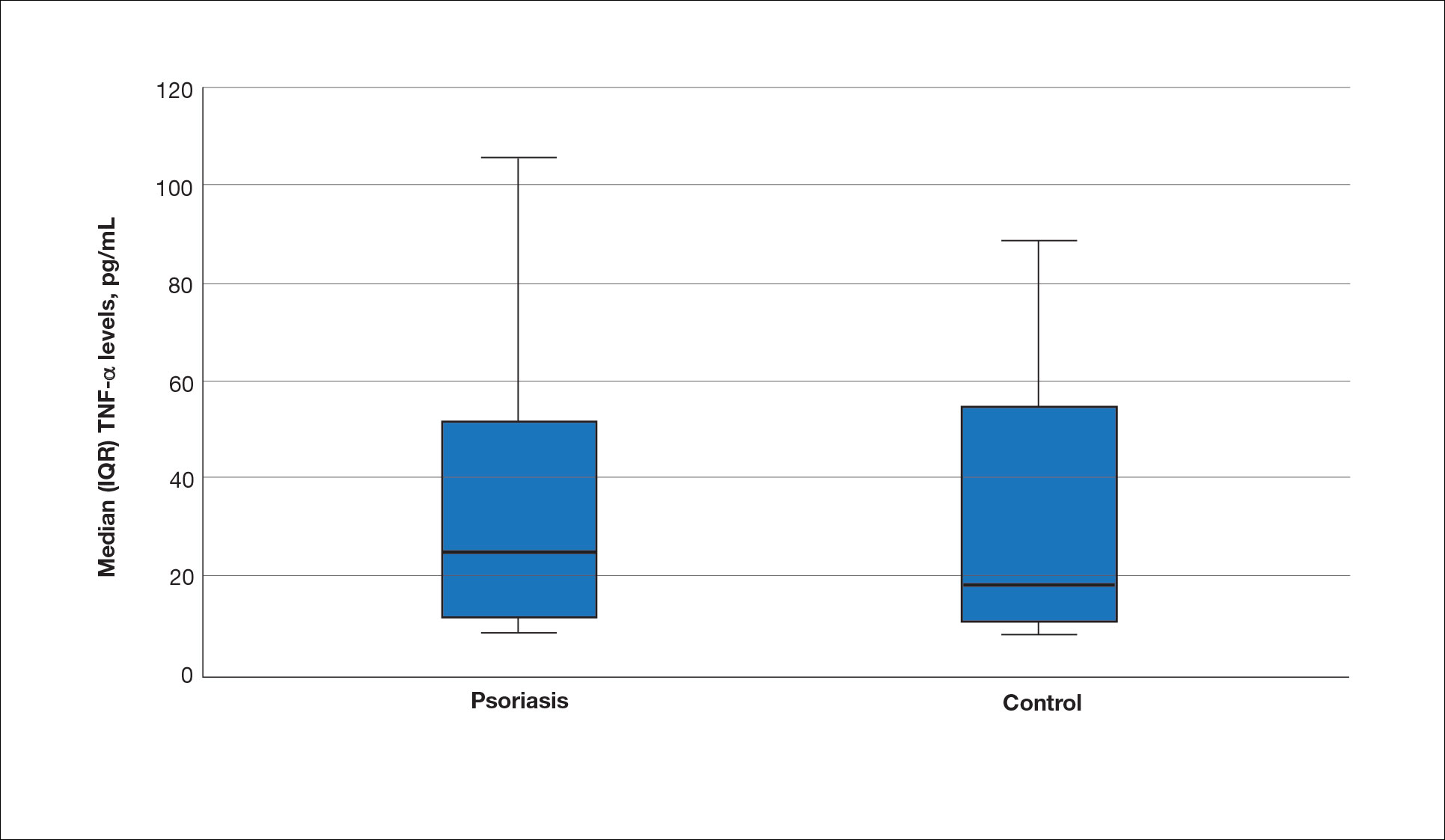

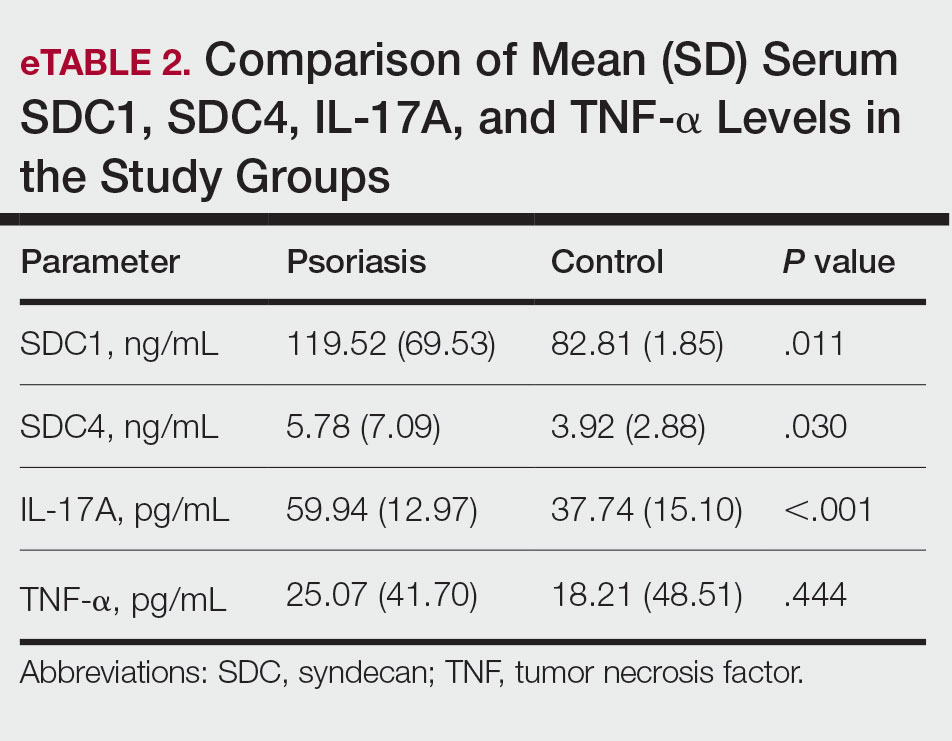

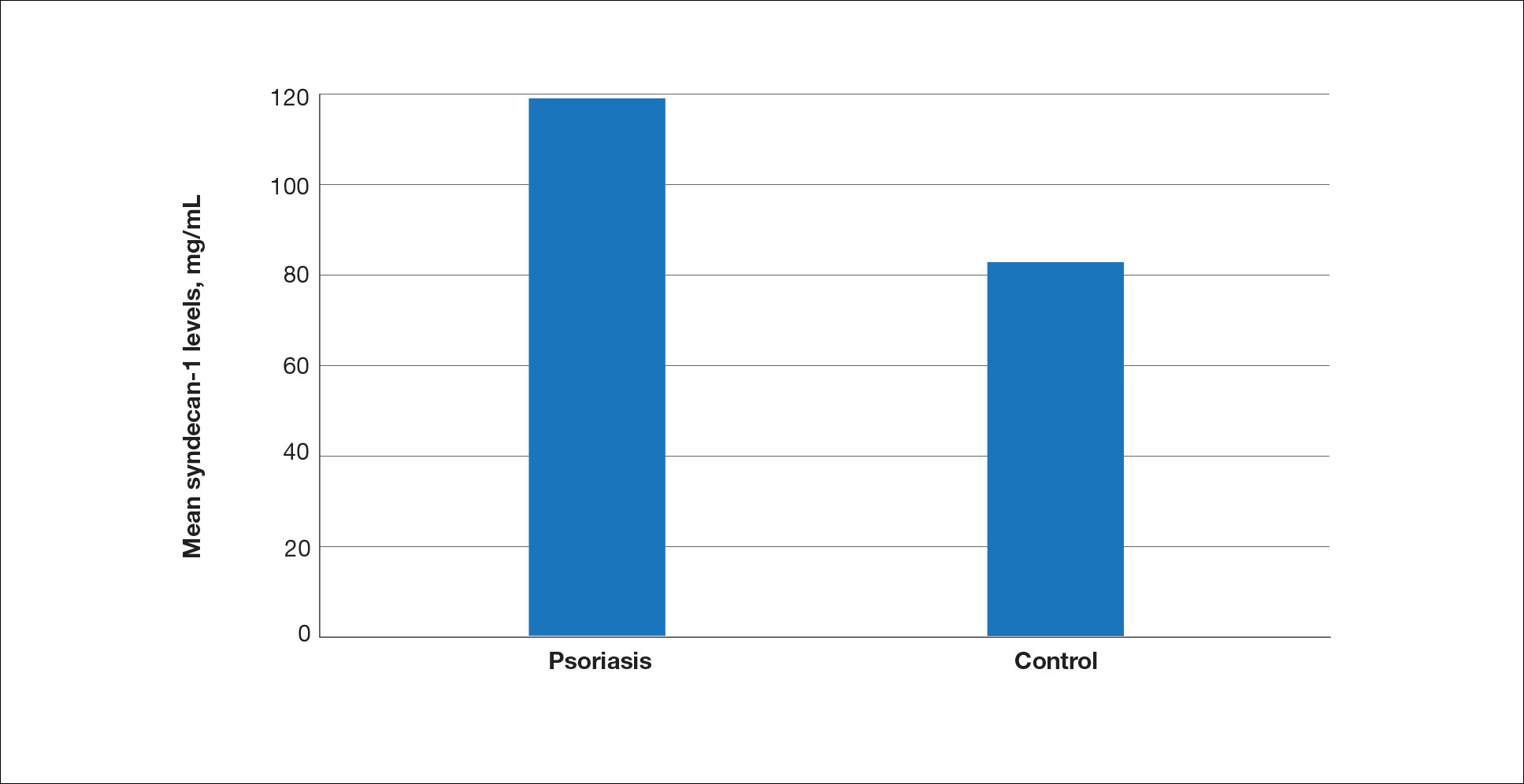

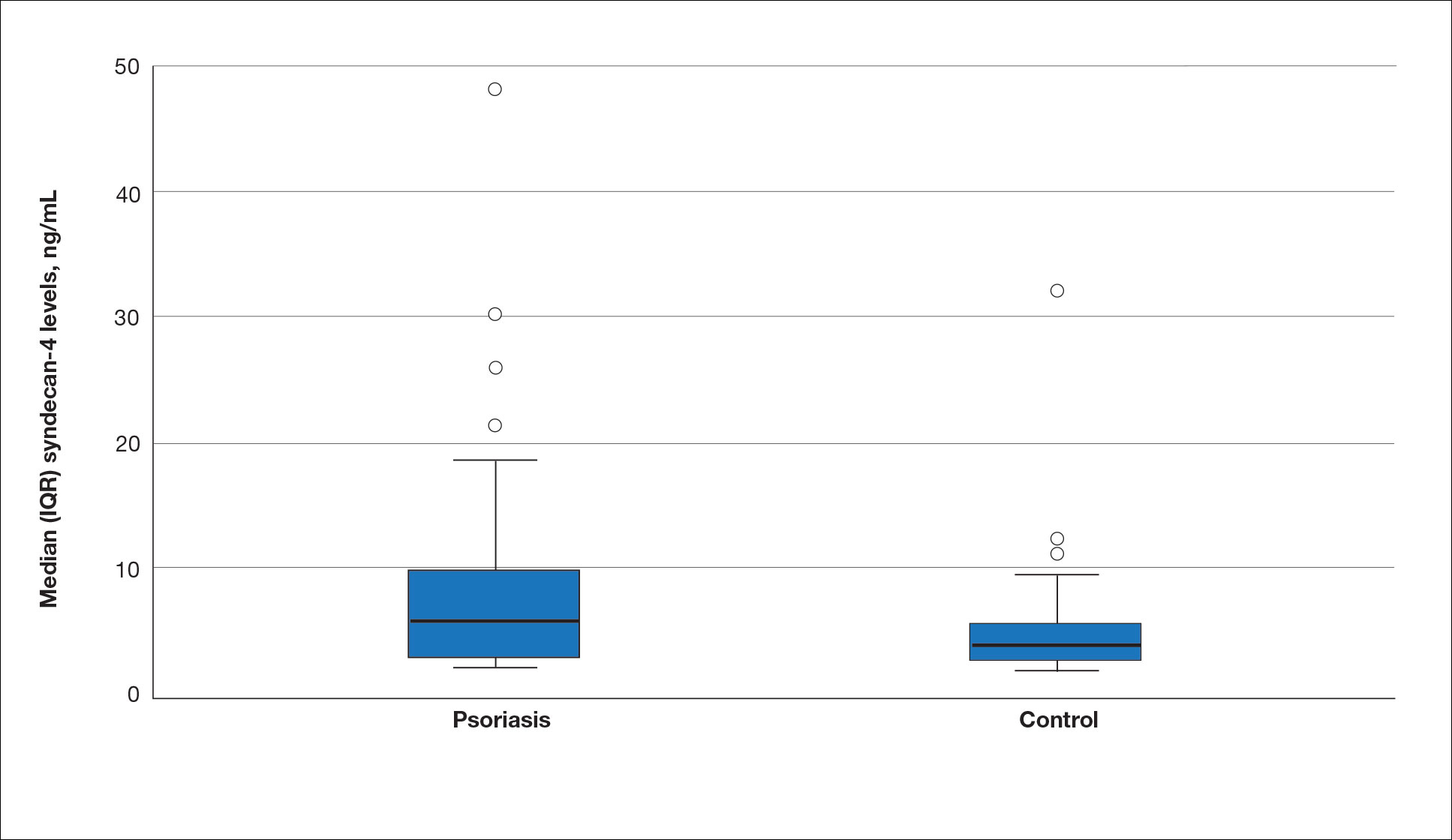

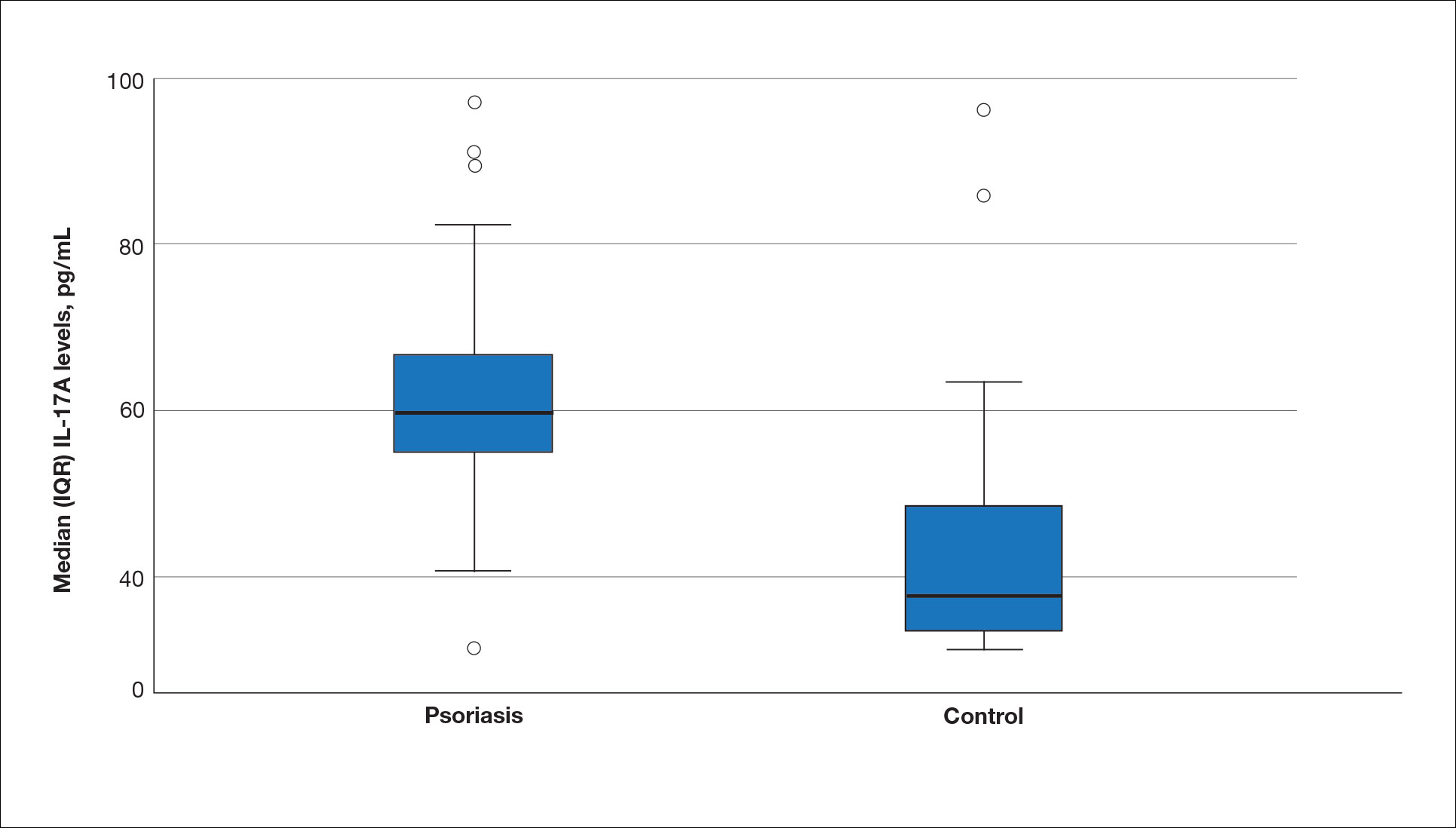

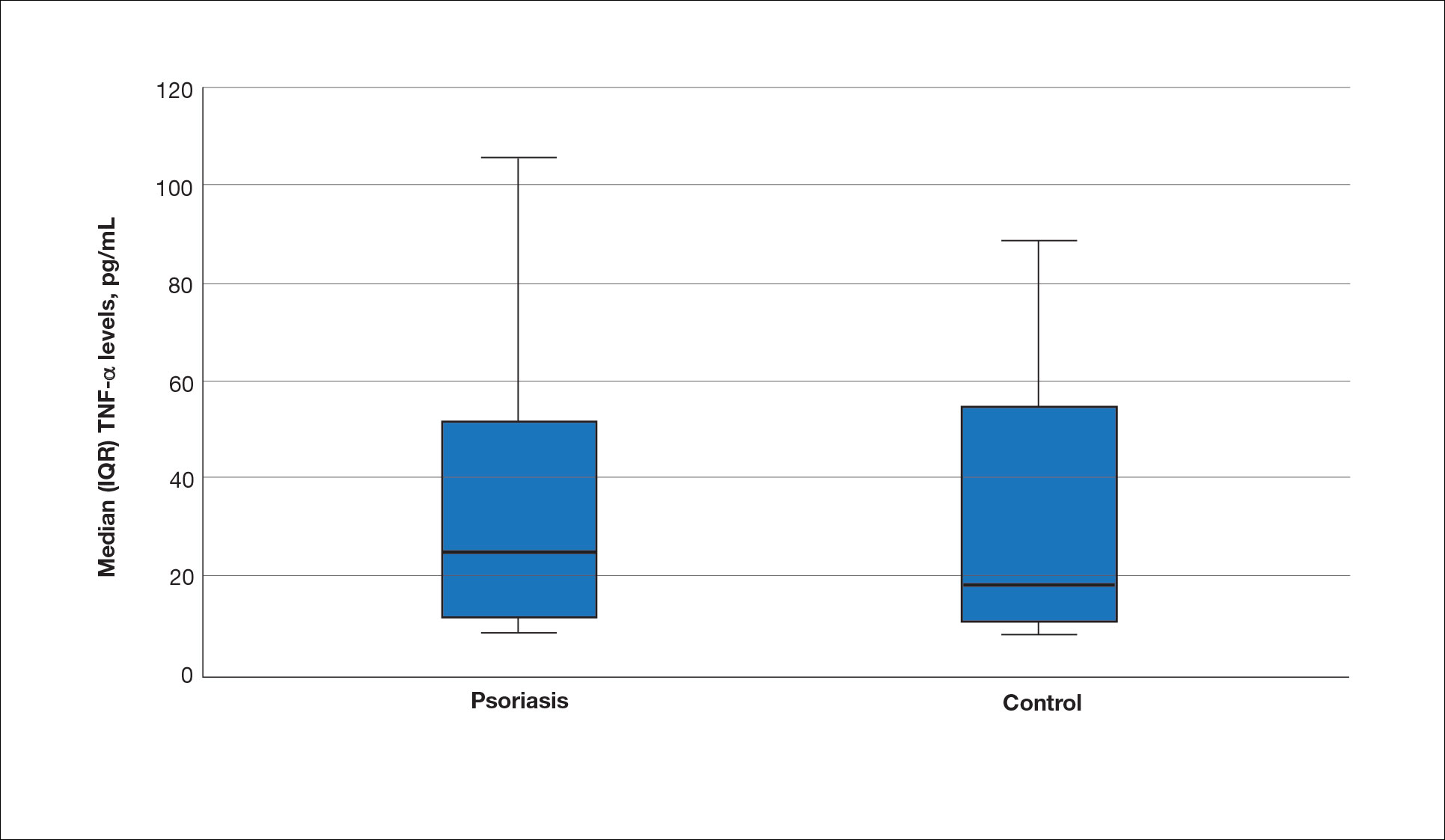

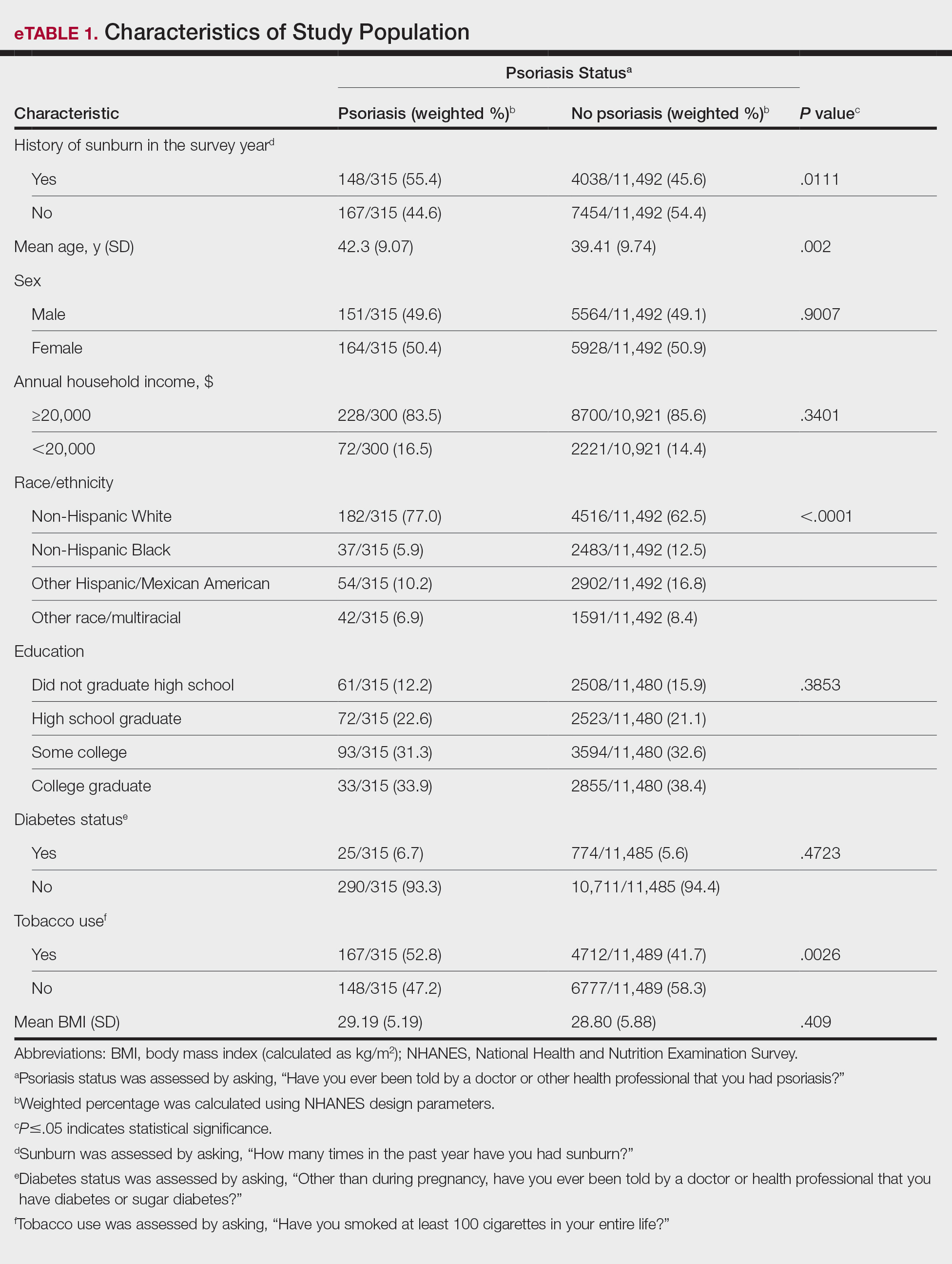

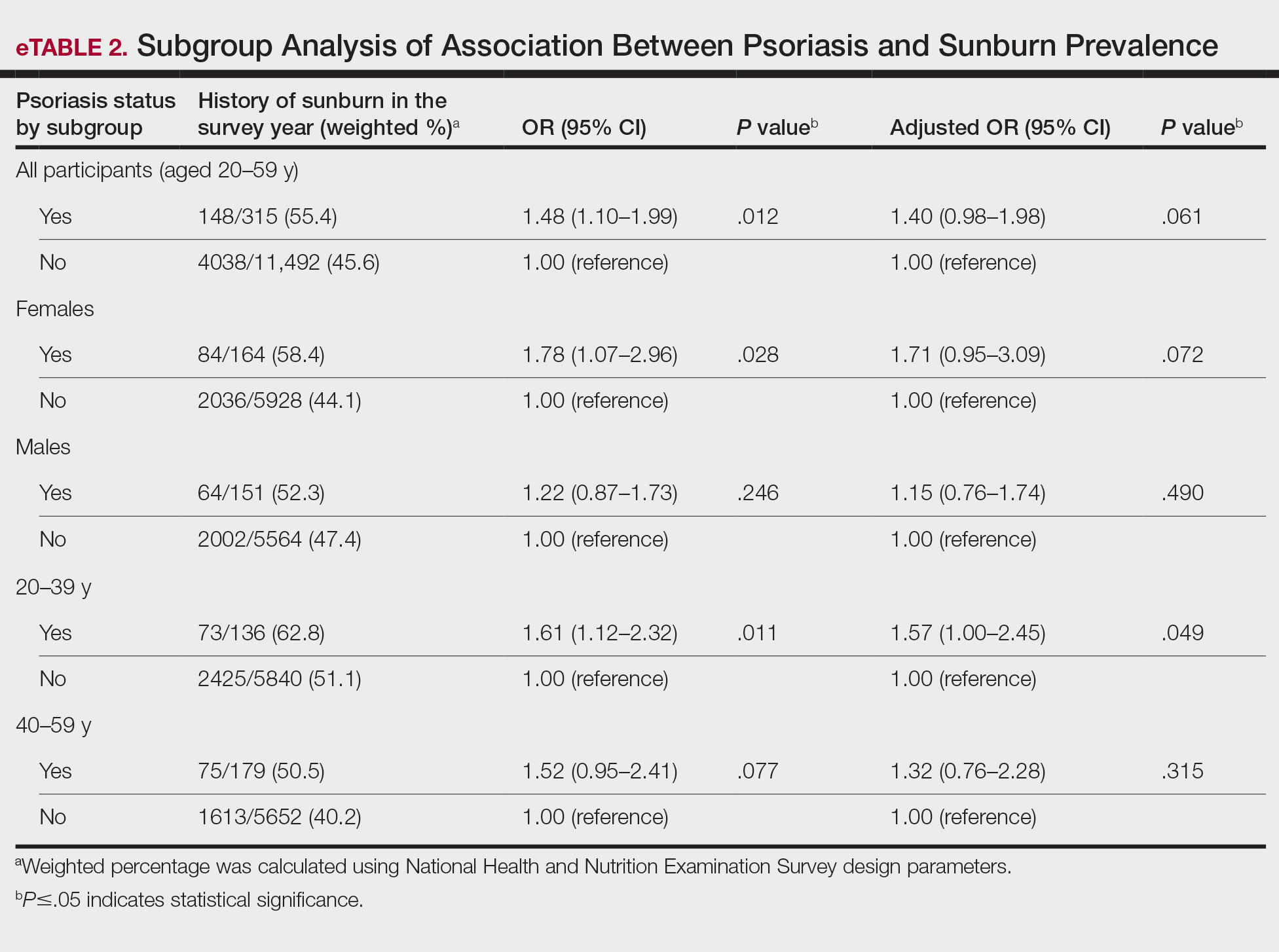

The mean (SD) serum SDC1 level was 119.52 ng/mL (69.53 ng/mL) in the psoriasis group, which was significantly higher than the control group (82.81 ng/mL [51.85 ng/mL])(P=.011)(eTable 2)(eFigure 1). The median (IQR) serum SDC4 level also was significantly higher in the psoriasis group compared with the control group (5.78 ng/mL [7.09 ng/mL] vs 3.92 ng/mL [2.88 ng/mL])(P=.030)(eTable 2)(eFigure 2). The median (IQR) IL-17A value was 59.94 pg/mL (12.97 pg/mL) in the psoriasis group, which was significantly higher than the control group (37.74 pg/mL [15.10 pg/mL])(P<.001)(eTable 2)(eFigure 3). The median (IQR) serum TNF-α level was 25.07 pg/mL (41.70 pg/mL) in the psoriasis group and 18.21 pg/mL (48.51 pg/mL) in the control group; however, the difference was not statistically significance (P=.444)(eTable 2)(eFigure 4).

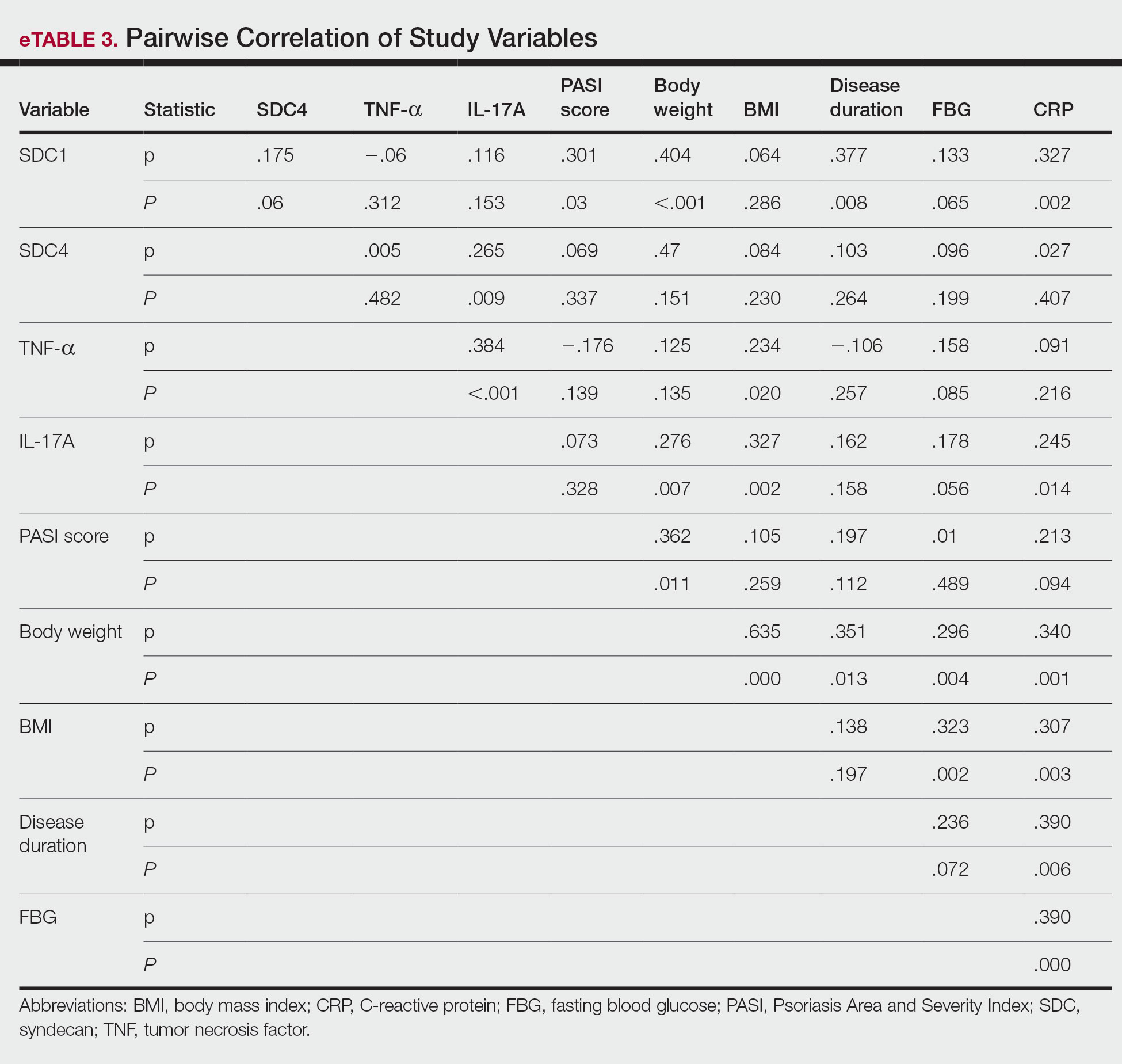

A significant positive correlation was found between serum SDC1 and PASI score (p=0.064; P=.03). Furthermore, significant positive correlations were identified between serum SDC1 and body weight (p=0.404; P<.001), disease duration (p=0.377; P=.008), and C-reactive protein (p=0.327; P=.002). A significant positive correlation also was identified between SDC4 and IL-17A (p=0.265; P=.009). Serum TNF-α was positively correlated with IL-17A (p=0.384; P<.001) and BMI (p=0.234; P=.020)(eTable 3).

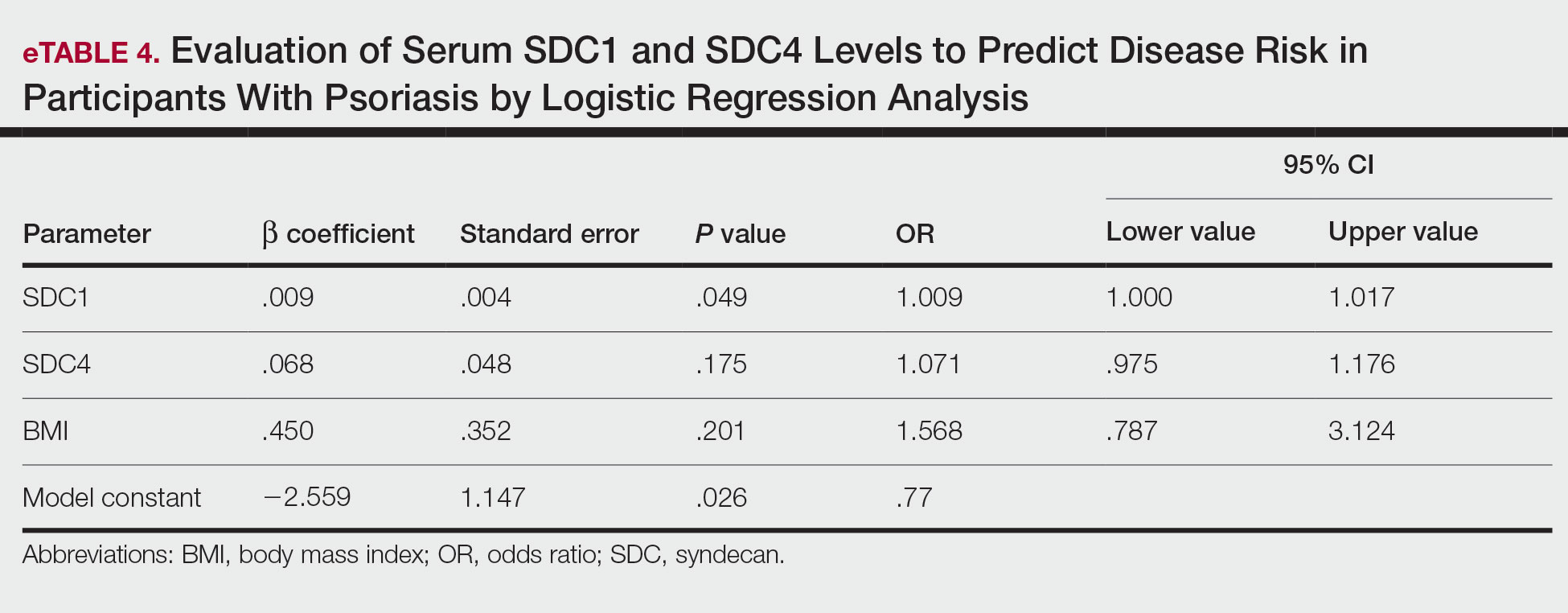

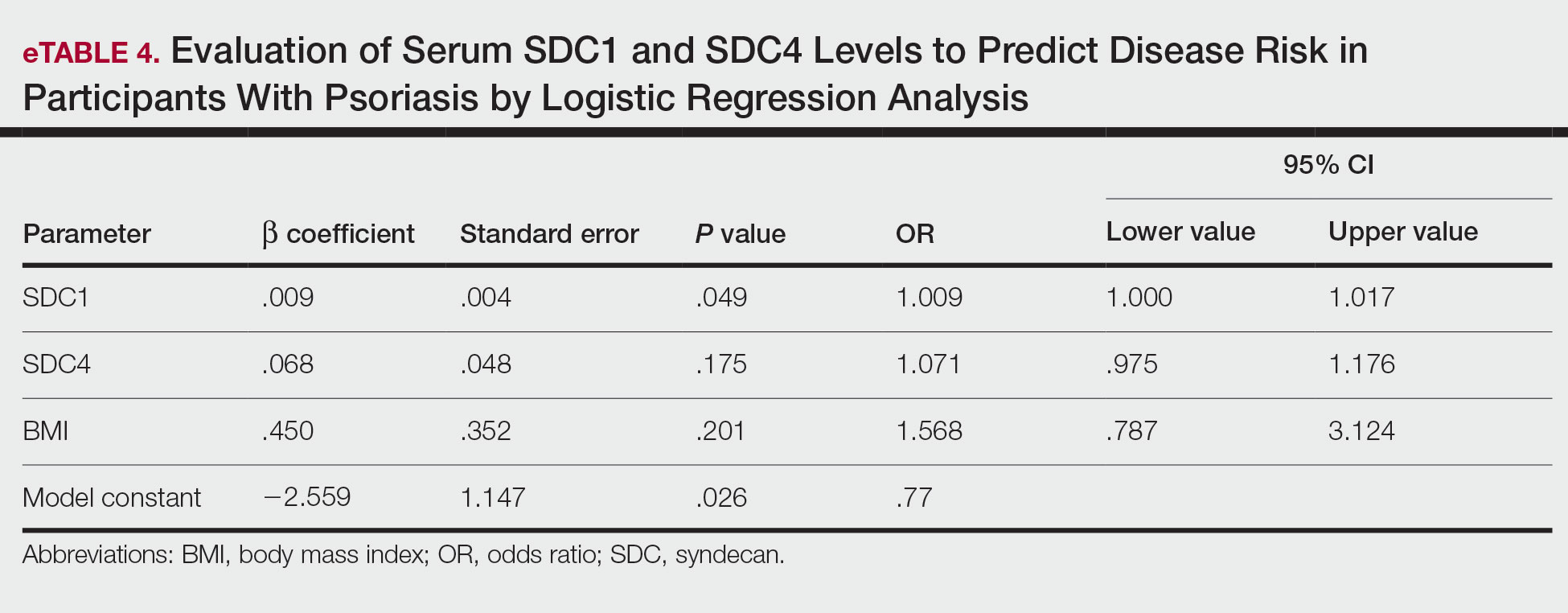

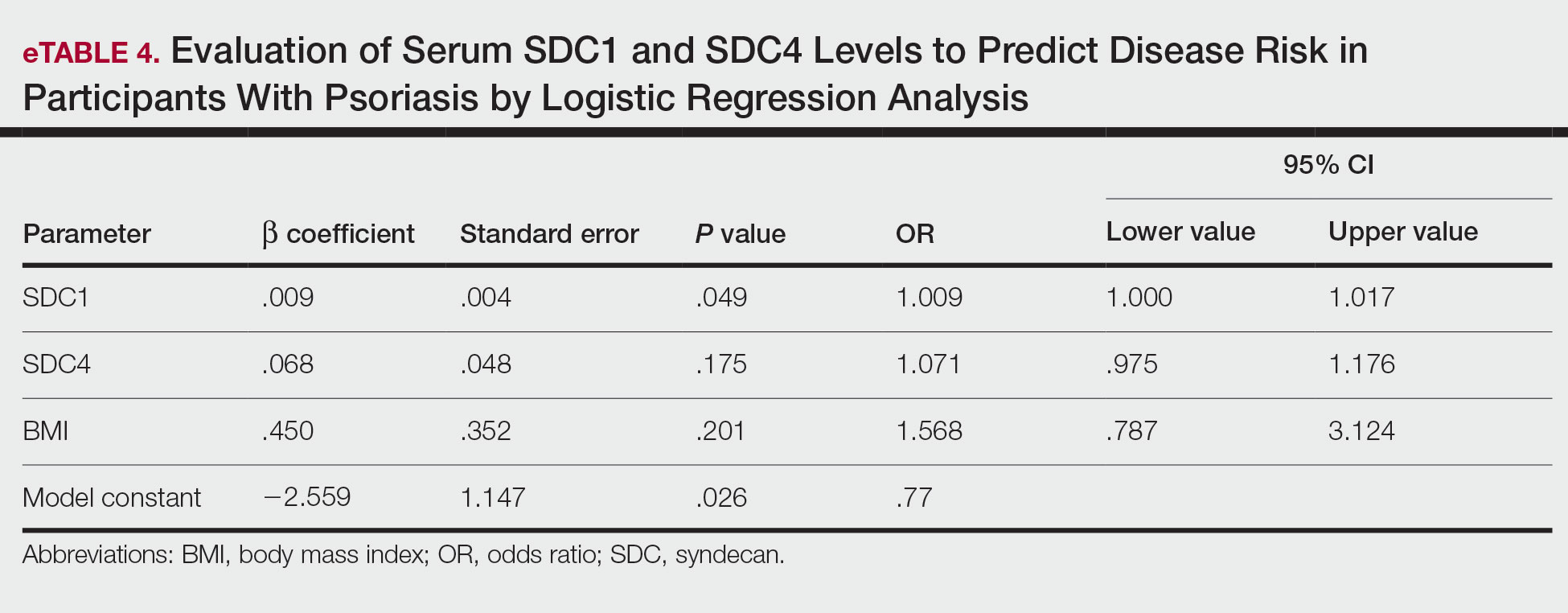

Logistic regression analysis showed that high SDC1 levels were independently associated with the development of psoriasis (odds ratio [OR], 1.009; 95% CI, 1.000-1.017; P=.049)(eTable 4).

Comment

Tumor necrosis factor α and IL-17A are key cytokines whose roles in the pathogenesis of psoriasis are well established. Arican et al,8 Kyriakou et al,9 and Xuan et al10 previously reported a lack of any correlation between TNF-α and IL-17A in the pathogenesis of psoriasis; however, we observed a positive correlation between TNF-α and IL-17A in our study. This finding may be due to the abundant TNF-α production by myeloid dendritic cells involved in the transformation of naive T lymphocytes into IL-17A–secreting Th17 lymphocytes, which can also secrete TNF-α.

After the molecular cloning of SDCs by Saunders et al11 in 1989, SDCs gained attention and have been the focus of many studies for their part in the pathogenesis of conditions such as inflammatory diseases, carcinogenesis, infections, sepsis, and trauma.6,12 Among the inflammatory diseases sharing similar pathogenetic features to psoriasis, serum SDC4 levels are found to be elevated in rheumatoid arthritis and are correlated with disease activity.13 Cekic et al14 reported that serum SDC1 levels were significantly higher in patients with Crohn disease than controls (P=.03). Additionally, serum SDC1 levels were higher in patients with active disease compared with those who were in remission. Correlations between SDC1 and disease severity and C-reactive protein also have been found.14 Serum SDC-1 levels found to be elevated in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus were compared to the controls and were correlated with disease activity.15 Nakao et al16 reported that the serum SDC4 levels were significantly higher in patients with atopic dermatitis compared to controls (P<.01); further, SDC4 levels were correlated with severity of the disease.

Jaiswal et al17 reported that SDC1 is abundant on the surface of IL-17A–secreting γδ T lymphocytes (Tγδ17), whose contribution to psoriasis pathogenesis is known. When subjected to treatment with imiquimod, SDC1-suppressed mice displayed increased psoriasiform dermatitis compared with wild-type counterparts. The authors stated that SDC1 may play a role in controlling homeostasis of Tγδ17

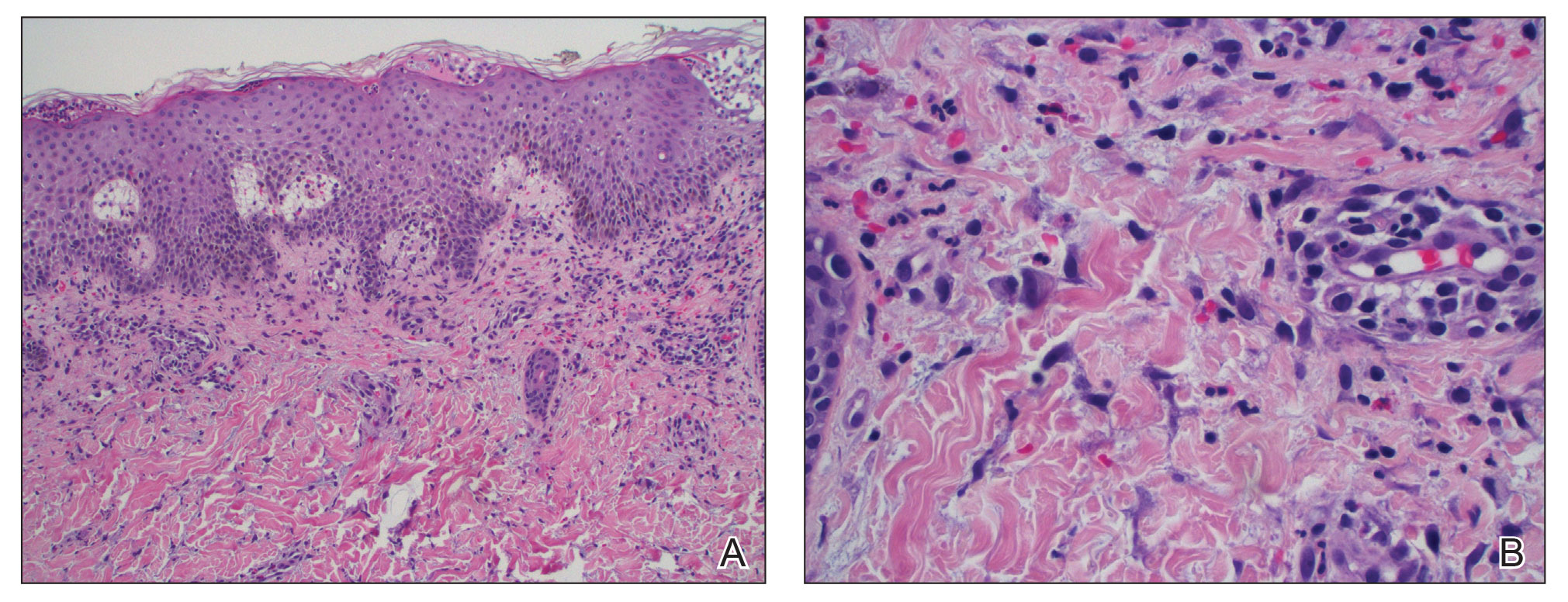

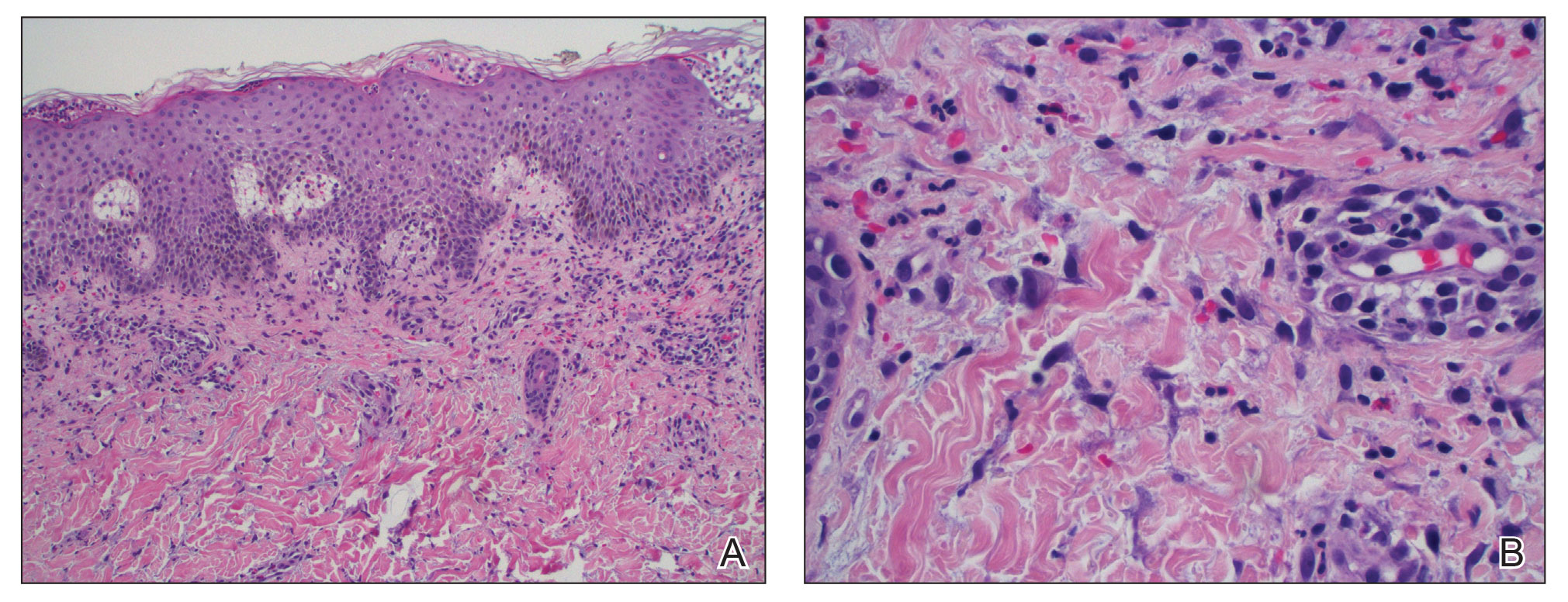

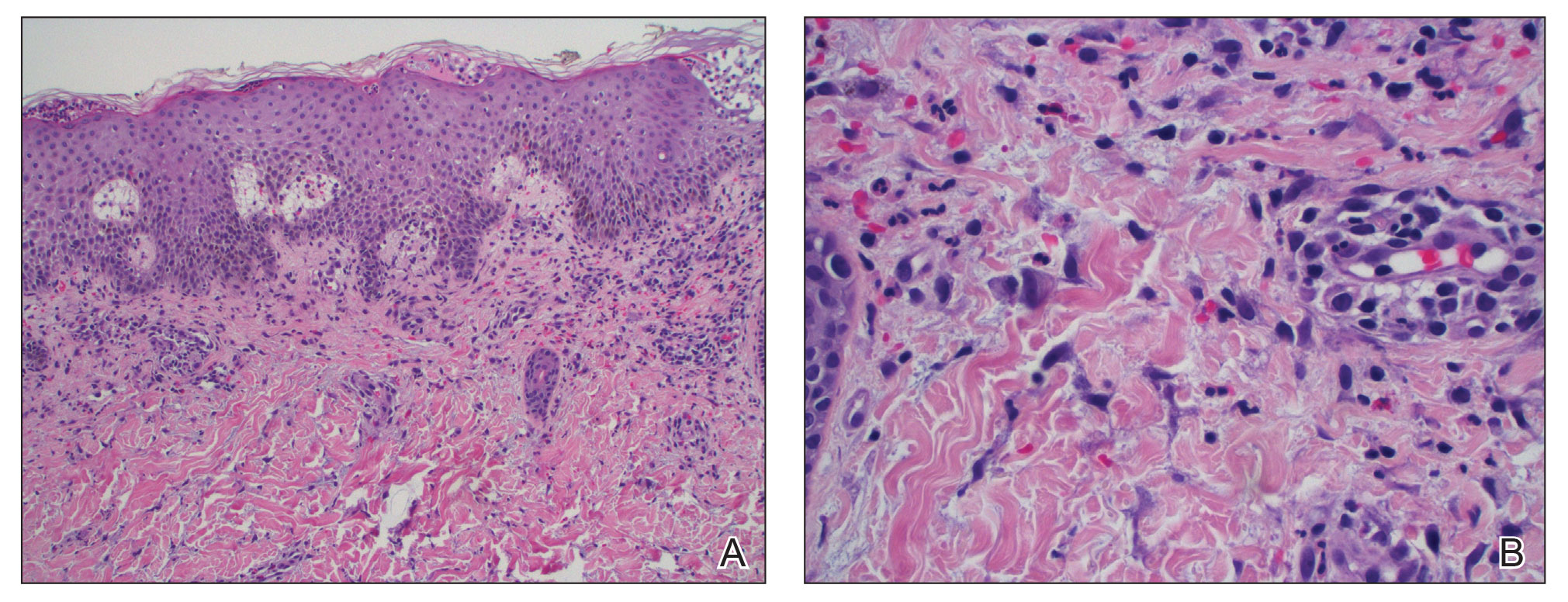

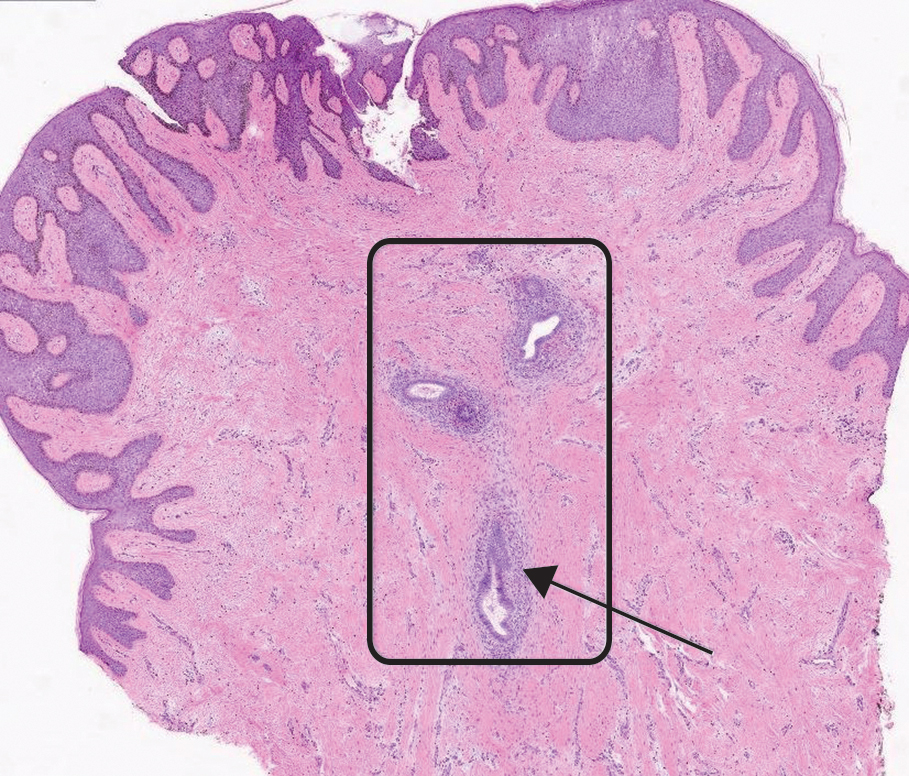

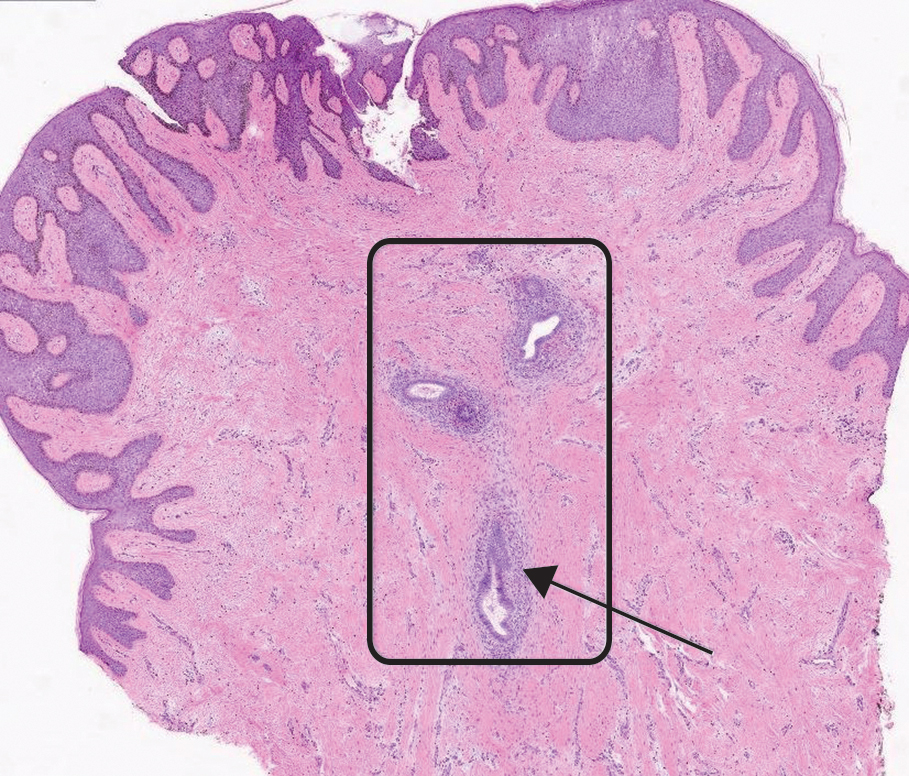

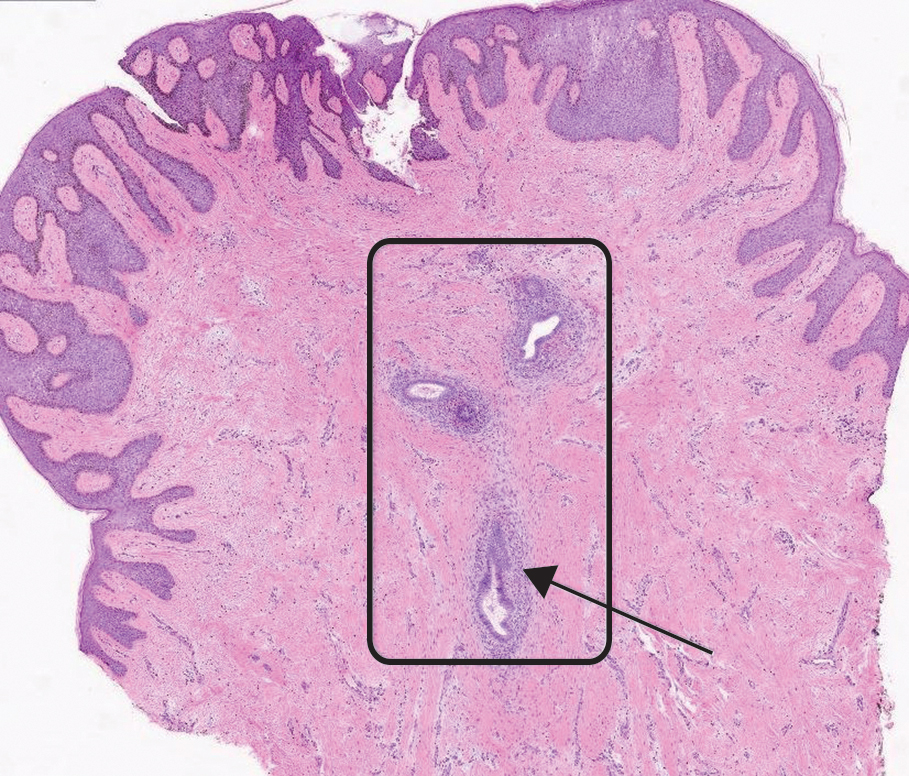

In a study examining changes in the ECM in patients with psoriasis, it was observed that the expression of

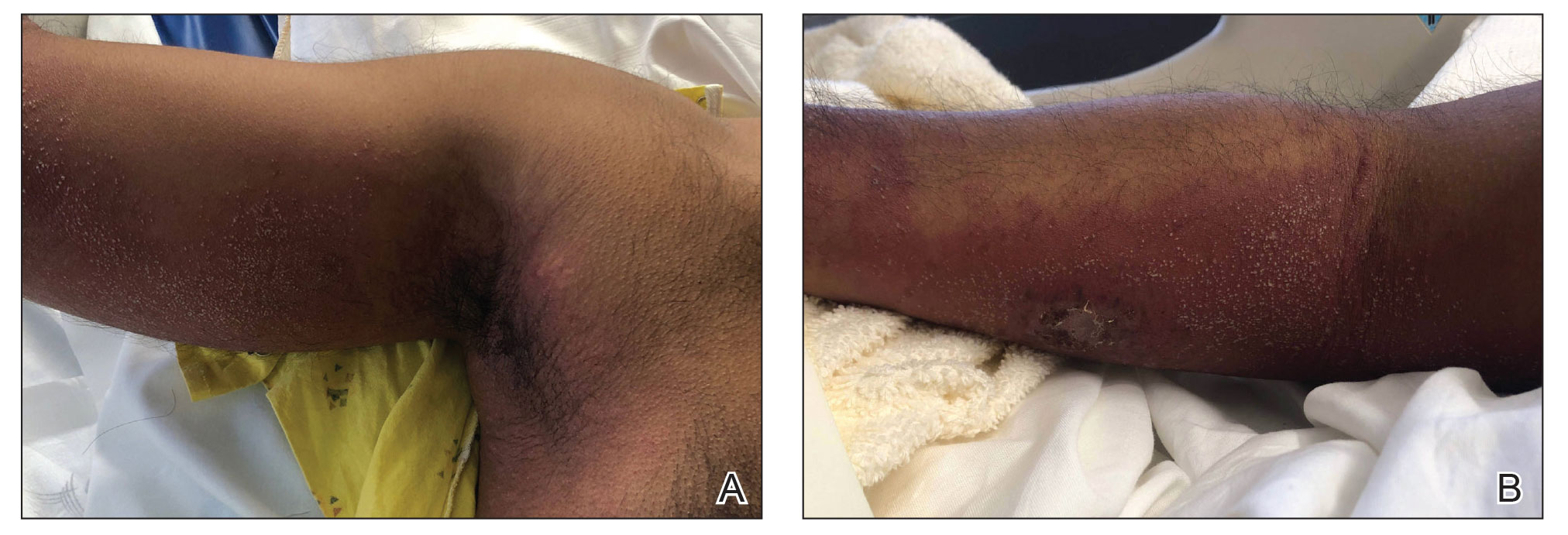

A study conducted by Koliakou et al20 showed that, in healthy skin, SDC1 was expressed in almost the full thickness of the epidermis, but lowest expression was in the basal-layer keratinocytes. In a psoriatic epidermis, unlike the normal epidermis, SDC1 was found to be more intensely expressed in the keratinocytes of the basal layer, where keratinocyte proliferation occurs. In this study, SDC4 was expressed mainly at lower levels in a healthy epidermis, especially in the spinous and the basal layers. In a psoriatic epidermis, SDC4 was absent from all the layers. In the same study, gelatin-based carriers containing anti–TNF-α and anti–IL-17A were applied to a full-thickness epidermis with psoriatic lesions, after which SDC1 expression was observed to decrease almost completely in the psoriatic epidermis; there was no change in SDC4 expression, which also was not seen in the psoriatic epidermis. The authors claimed the application of these gelatin-based carriers could be a possible treatment modality for psoriasis, and the study provides evidence for the involvement of SDC1 and/or SDC4 in the pathogenesis of psoriasis

Limitations of the current study include small sample size, lack of longitudinal data, lack of tissue testing of these molecules, and lack of external validation.

Conclusion

Overall, research has shown that SDCs play important roles in inflammatory processes, and more widespread inflammation has been associated with increased shedding of these molecules into the ECM and higher serum levels. In our study, serum SDC1, SDC4, and IL-17A levels were increased in patients with psoriasis compared to the healthy controls. A logistic regression analysis indicated that high serum SDC1 levels may be an independent risk factor for development of psoriasis. The increase in serum SDC1 and SDC4 levels and the positive correlation between SDC1 levels and disease severity observed in our study strongly implicate SDCs in the inflammatory disease psoriasis. The precise role of SDCs in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and the implications of targeting these molecules are the subject of more in-depth studies in the future.

Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301-1315.

Uings IJ, Farrow SN. Cell receptors and cell signaling. Mol Pathol. 2000;53:295-299.

Kirkpatrick CA, Selleck SB. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans at a glance.J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1829-1832.

Stepp MA, Pal-Ghosh S, Tadvalkar G, et al. Syndecan-1 and its expanding list of contacts. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015;4:235-249.

Rangarajan S, Richter JR, Richter RP, et al. Heparanase-enhanced shedding of syndecan-1 and its role in driving disease pathogenesis and progression. J Histochem Cytochem. 2020;68:823-840.

Gopal S, Arokiasamy S, Pataki C, et al. Syndecan receptors: pericellular regulators in development and inflammatory disease. Open Biol. 2021;11:200377.

Bertrand J, Bollmann M. Soluble syndecans: biomarkers for diseases and therapeutic options. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176:67-81.

Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

Kyriakou A, Patsatsi A, Vyzantiadis TA, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IL12/23 p40, and IL-17 in psoriatic patients with and without nail psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:508178.

Xuan ML, Lu CJ, Han L, et al. Circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines in patients with psoriasis vulgaris of different Chinese medicine syndromes. Chin J Integr Med. 2015;21:108-114.

Saunders S, Jalkanen M, O’Farrell S, et al. Molecular cloning of syndecan, an integral membrane proteoglycan. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1547-1556.

Manon-Jensen T, Itoh Y, Couchman JR. Proteoglycans in health and disease: the multiple roles of syndecan shedding. FEBS J. 2010;277:3876-3889.

Zhao J, Ye X, Zhang Z. Syndecan-4 is correlated with disease activity and serological characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Rheumatol. 2022;62:21.

Cekic C, Kırcı A, Vatansever S, et al. Serum syndecan-1 levels and its relationship to disease activity in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:850351.

Minowa K, Amano H, Nakano S, et al. Elevated serum level of circulating syndecan-1 (CD138) in active systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2011;44:357-362.

Nakao M, Sugaya M, Takahashi N, et al. Increased syndecan-4 expression in sera and skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:655-660.

Jaiswal AK, Sadasivam M, Archer NK, et al. Syndecan-1 regulates psoriasiform dermatitis by controlling homeostasis of IL-17-producing γδ T cells. J Immunol. 2018;201:1651-1661

Wagner MFMG, Theodoro TR, Filho CASM, et al. Extracellular matrix alterations in the skin of patients affected by psoriasis. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:55.

Peters F, Rahn S, Mengel M, et al. Syndecan-1 shedding by meprin β impairs keratinocyte adhesion and differentiation in hyperkeratosis. Matrix Biol. 2021;102:37-69.

Koliakou E, Eleni MM, Koumentakou I, et al. Altered distribution and expression of syndecan-1 and -4 as an additional hallmark in psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:6511.

Doss RW, El-Rifaie AA, Said AN, et al. Cutaneous syndecan-1 expression before and after phototherapy in psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:439-440.

Psoriasis, one of the most researched diseases in dermatology, has a complex pathogenesis that is not yet fully understood. One of the most important stages of psoriasis pathogenesis is the proliferation of T helper (Th) 17 cells by IL-23 released from myeloid dendritic cells. Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α released from Th1 cells and IL-17 and IL-22 released from Th17 cells are known to induce the proliferation of keratinocytes and the release of chemokines responsible for neutrophil chemotaxis.1

Although secondary messengers such as cytokines and chemokines, which provide cell interaction with the extracellular matrix (ECM), have their own specific receptors, it is known that syndecans (SDCs) play a role in ECM and cell interactions and have receptor or coreceptor functions.2 In humans, 4 types of SDCs have been identified (SDC1-SDC4), which are type I transmembrane proteoglycans found in all nucleated cells. Syndecans consist of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan chains that are structurally linked to a core protein sequence. The molecule has cytoplasmic, transmembrane, and extracellular domains.2,3 While SDCs often are described as coreceptors for integrins and growth factor and hormone receptors, they also are capable of acting as signaling receptors by engaging intracellular messengers, including actin-related proteins and protein kinases.4

Prior research has indicated that the release of heparanase from the lysosomes of leukocytes during infection, inflammation, and endothelial damage causes cleavage of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans from the extracellular domains of SDCs. The peptide chains at the SDC core then are separated by matrix metalloproteinases in a process known as shedding. The shed SDCs may have either a stimulating or a suppressive effect on their receptor activity. Several cytokines are known to cause SDC shedding.5,6 Many studies in recent years have reported that SDCs play a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, for which serum levels of soluble SDCs can be biomarkers.7

In this study, we aimed to evaluate and compare serum SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, and IL-17A levels in patients with psoriasis vs healthy controls. Additionally, by reviewing the literature data, we analyzed whether SDCs can be implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and their potential role in this process.

Methods

The study population consisted of 40 patients with psoriasis and 40 healthy controls. Age and sex characteristics were similar between the 2 groups, but weight distribution was not. The psoriasis group included patients older than 18 years who had received a clinical and/or histologic diagnosis, had no systemic disease other than psoriasis in their medical history, and had not used any systemic treatment or phototherapy for the past 3 months. Healthy patients older than 18 years who had no medical history of inflammatory disease were included in the control group. Participants provided signed consent.